Therapeutic Insights: Earthly and Cosmic Laws

GA 205

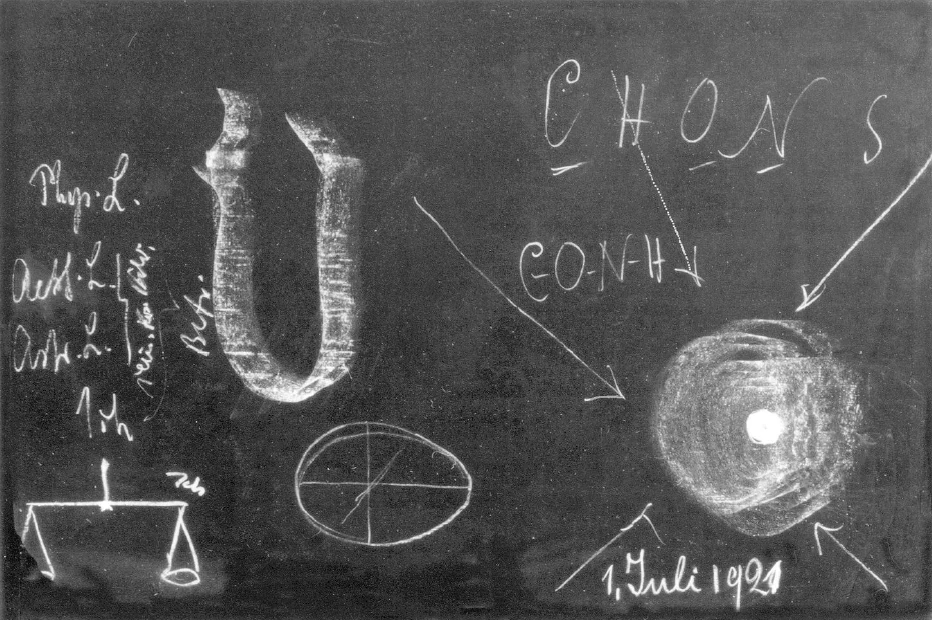

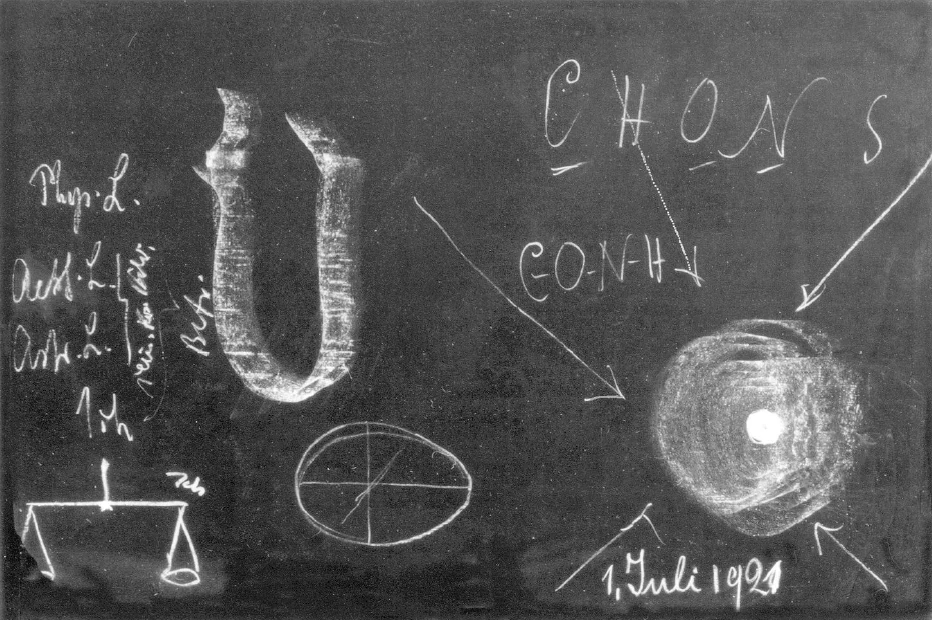

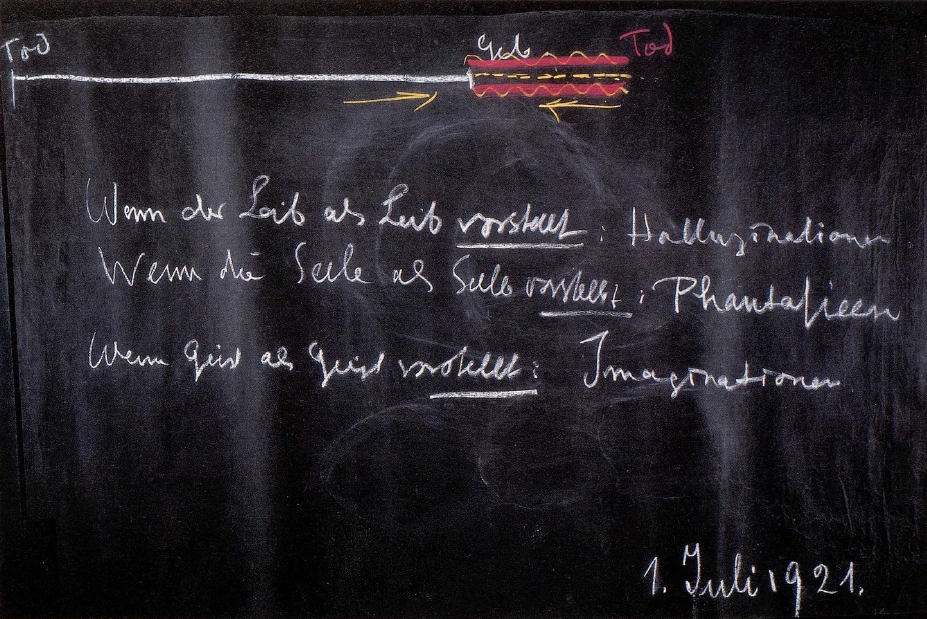

1 July 1921, Dornach

Lecture III

I would like today to consider briefly something in connection with the subject dealt with last week and also earlier, something that can lead on to the further development of our studies. In experiencing the world around us, we see, in the world and also in ourselves, many things as being abnormal, perhaps even diseased, and indeed, this is quite justified from one point of view; but when we perceive something as abnormal or diseased in an absolute sense, we have not yet understood the world. Indeed, we often block the path to an understanding of the world if we simply remain with such evaluations of existence as healthy and ill, right and wrong, true and false, good and evil, etc. For what appears as diseased or abnormal from one point of view is from another point of view fully justified within the whole of world relationships. I will give you a concrete case, so that you may see what I mean.

The appearance of so-called hallucinations, or visions, is looked upon quite rightly as something diseased. Hallucinations, pictures that appear before human consciousness and that do not reveal a corresponding reality upon closer, critical examination—such hallucinations, such visions, are something diseased if we consider them from the standpoint of human life as it unfolds between birth, or conception, and death. When we describe hallucinations as something abnormal, however, as something that certainly does not belong to the normal course of life between birth and death, we have in no way grasped the inherent nature of hallucination.

Let us now set aside all such judgments regarding hallucination. Let us consider how it appears when we observe someone during a hallucination. The hallucination appears as a picture that is bound up with the whole subjective life, with the inner life, in a more intensive way than the usual outer perception, which is transmitted through the senses. Hallucination is experienced inwardly far more intensely than sense perception. Sense perception can be penetrated at the same time by sharp, critical thoughts, but one who is under the influence of hallucinations does not permeate them with sharp, critical thoughts. He lives in a hovering, weaving picture element.

What is this element in which man lives when he is suffering from hallucinations? You see, we cannot understand this if we know only what enters ordinary human consciousness between birth and death. In this consciousness the content of hallucination enters as something that is unjustified under all circumstances. Hallucination must be seen from an entirely different point of view; then we can approach its essence. This point of view is found when in the course of development leading to a higher vision man learns to know the living and weaving that are active between death and a new birth, particularly the living and weaving of his own being, when this life is but a few decades from his approaching birth, or conception. If, therefore, we attain the capacity enabling us to live into what is experienced quite normally when a human being is nearing birth or conception, we live into the true form of what appears in life between birth and death in an abnormal way as hallucination.

Just as here in the life between birth and death we are surrounded by the world of colors, by the world that we feel with every breath of air, etc.—in short, by the world we picture to be the one we experience between birth and death—so our own soul-spiritual being lives, between death and a new birth, in an element that is altogether identical with what can appear in us as hallucination. We are born, as it were, out of the element of hallucination, particularly in our bodily nature. What appears as hallucination hovers and breathes through the world that lies at the foundation of our present one; in being born, we rise out of this element, which can then appear abnormally to the soul in the world of hallucinations. What are hallucinations, then, within everyday consciousness?

When the human being has passed through the experiences of the life between death and a new birth and has entered into physical, sensory existence through conception and birth, certain spiritual beings of the higher hierarchies, with whom we are already acquainted, have had an intuition, and the result of this intuition is the physical body. We may say, therefore, that certain beings have intuitions; the result of these intuitions is the human physical body, which can only come into existence by being permeated by the soul, rising out of the element of hallucination. What takes place, however, when hallucinations appear in a diseased way within ordinary consciousness? I can only make this clear in a pictorial way, but this is natural enough since hallucinations are themselves pictures. It is self-evident that in this case we can reach no result by using abstract concepts—we must explain it in a pictorial way.

Think of the following: as I have recently explained to you, the human physical body actually consists of solid substance only to the slightest extent necessary to preserve the solid contours. The largest proportion is watery; it also consists of the element of air, and so forth. This human physical body has a certain consistency, it has a certain natural density. If, now, this natural density is changed into an unnatural one, if it is interfered with—picture, symbolically, that the elasticity of this physical body were to be decreased—then the original hallucinatory element out of which it is born would be pressed out, just as water is pressed out of a sponge. The appearance of this hallucinatory nature is due only to the fact that the original element out of which the body arises, out of which it is formed, is pressed out of the physical body. The illness that expresses itself in a hallucinatory life of consciousness always points to something unhealthy in the physical body, which presses its own substance spiritually, as it were, out of itself.

This leads us to the fact that, in a certain sense, our thinking is indeed what materialists state it to be. Our physical body is, in reality, an image of what “pre-existed” before birth, or conception, in the spiritual worlds. It is an image. And thinking that arises in ordinary consciousness—that thinking which is the pride of modern man—is not unjustly described by materialists as something entirely bound up with the physical body. It is simply the case that this thinking, which has served modern man particularly since the birth of the modern scientific way of thinking, since the fifteenth century—this thinking perishes as such with the physical body, it ceases when the physical body ceases to exist. What you often find in the Roman Catholic philosophy of today—the philosophy current today, not the one of the earlier centuries—according to which the abstract, intellectual activity of the soul survives death, this is incorrect, it is not true. This thinking, which is characteristic of the soul life of the present, is thoroughly bound up with the physical body. The part that survives the physical body can only be perceived when we reach the next higher stage of cognition, in Imaginative cognition, in pictorial mental images, and so forth.

You might argue that in this case a person who has no capacity for forming pictorial mental images would not have immortality. The question cannot be posed in this way, however, for it means nothing at all to say that a person does not have pictorial mental images. You can say that in your everyday consciousness you do not have pictorial mental images, that you do not bring them into your everyday consciousness, but pictorial mental images, imaginations, are constantly forming themselves within us; it is just that they are used in the organic processes of life. They become the forces out of which man continuously builds up his organism anew. Our materialistic philosophy and our materialistic natural science believe that during sleep man rebuilds his worn-out organs out of something unspecified—out of what does not seem to concern modern science very much. This is not what takes place, however; rather, it is precisely during our waking life—even when we do not go beyond the everyday intellectual consciousness—that we are constantly forming imaginations; we digest these imaginations, as it were, by means of the soul element and build up the body out of them. These imaginations are not perceived as separate entities by our ordinary consciousness, because they are building up the body. The evolution to a higher vision is based upon the fact that we partially withdraw, as far as the outer world is concerned, this work from the physical body, and that we bring to consciousness what otherwise boils and seethes in the depths of this physical body. For this reason spiritual science should accompany this higher vision; otherwise such a vision could not continue for very long, since it would undermine the health of the organism. The imaginative activity is thus very present in the ordinary life of the soul, but between birth and death it is digested and absorbed by the body. We thus may say that here, too, an unconscious activity takes place during ordinary life, but that if it is brought to consciousness it reveals itself as hallucination. Hallucination consists entirely of something that is an ordered, elementary activity in existence. It must not, however, appear in our consciousness at the wrong time. Hallucination in its ordinary manifestation must remain, as it were, more in the unconscious realms of our existence.

When the-body presses out, as it were, its primal substance, it comes to the point of incorporating this pressed-out primal substance into ordinary consciousness, and then hallucinations appear. Hallucinating means nothing other than that the body sends up into consciousness what should really be used within the body for digestion, growth, etc.

This is also connected with what I have so often explained in relation to the illusions that people have in connection with certain mystics. They fear that we will strip the mystic of his holiness if we point out his foundation. Take, for instance, hallucinations that have a beautiful and poetic character such as those described by Mechtild of Magdeburg or St. Theresa. They are indeed beautiful, but what are they, in reality?

If we can see beyond the surface of such things, we shall find that they are hallucinations that have been pressed out of the organs of the body; they are its primal substance. If we wish to describe what is truly there when these most beautiful, mystical poems well up into consciousness, we must sometimes describe, in the case of Mechtild of Magdeburg or St. Theresa, processes very much akin to those of digestion.

We should not say that this takes away the aroma from some of the historical manifestations of mysticism. The great sensual delight that many people feel when they think of mysticism, or when they wish to experience mysticism themselves, can be guided back onto the right path, as it were. Many mystical experiences, however, are nothing but an inner sensual delight, which can indeed rise into consciousness as something poetic and beautiful. What is destroyed by knowledge, however, is only a prejudice, an illusion. He who is really willing to penetrate into the innermost recesses of the human being must participate in the experience that shows him, rather than the beautiful descriptions of the mystic, the conformations of his organs—liver, lungs, etc.—as they are formed out of the cosmos, out of the hallucination of the cosmos. Fundamentally, mysticism does not thereby lose its aroma, but rather a higher knowledge reveals itself if we can describe how the liver forms itself out of the hallucinating cosmos, how, in a certain sense, it is formed out of what appears condensed within itself as metamorphosed spirit, as metamorphosed hallucination. In this way, we look into the bodily nature and see the connection of this bodily nature with the whole cosmos.

Now, however, the very clever people will come—we must always consider these clever people when we present the truth, for they raise their objections whenever we try to do so—these very clever people will say: what is this you are telling us, that the human body is formed out of the universe! Why, we know very well that the human being is born out of the mother's body. We know what it looks like as an embryo, and so on! A thoroughly false conception lies at the basis of such objections, but we will bring them to mind once more, although similar things have already been contemplated on other occasions.

If we regard the various forms of outer nature—let us remain at first in the mineral world—we find the most manifold forms. We speak of them as crystal forms. We also find other forms in nature, however, and we find that a certain configuration, an inner configuration, arises when, let us say, carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur are combined. We know that when carbon and oxygen combine and form carbon dioxide, a gas of a certain density arises. When carbon combines with nitrogen, cyanuric acid arises, and so on. Substances are formed that a chemist can always trace; they do not always appear in an outer crystallization, but they have an inner configuration. In modern times—this inner configuration has even been designated by means of the well-known structural formulae in chemistry.

Something has always been taken for granted in this, namely that the molecules, as they are called, become more and more complicated the more we ascend from mineral, inorganic substance to organic substance. We say that the organic molecule, the cellular molecule, consists of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, and sulfur. It is said that they are connected in some way but in a very complicated way. One of the ideals of natural science is to discover how these individual atoms in the complicated organic molecules are connected. Nevertheless, science admits that it will still be some time before we shall discover how one atom is connected with another within organic substance, within the living molecule. The mystery here, however, is this, that the more organic a substance is, the less one atom will be chemically connected with another, for the substances are whirled about chaotically, and even ordinary protein molecules, for instance in the nerve substance or blood substance, are in reality inwardly amorphous forms; they are not complicated molecules but inorganic matter inwardly torn asunder, inorganic matter that has rid itself of the crystallization forces, the forces that hold molecules together and connect the atoms with one another. This is already the case in the ordinary molecules of the organs, and it is most of all the case in the embryonic molecules, in the protein of the germ.

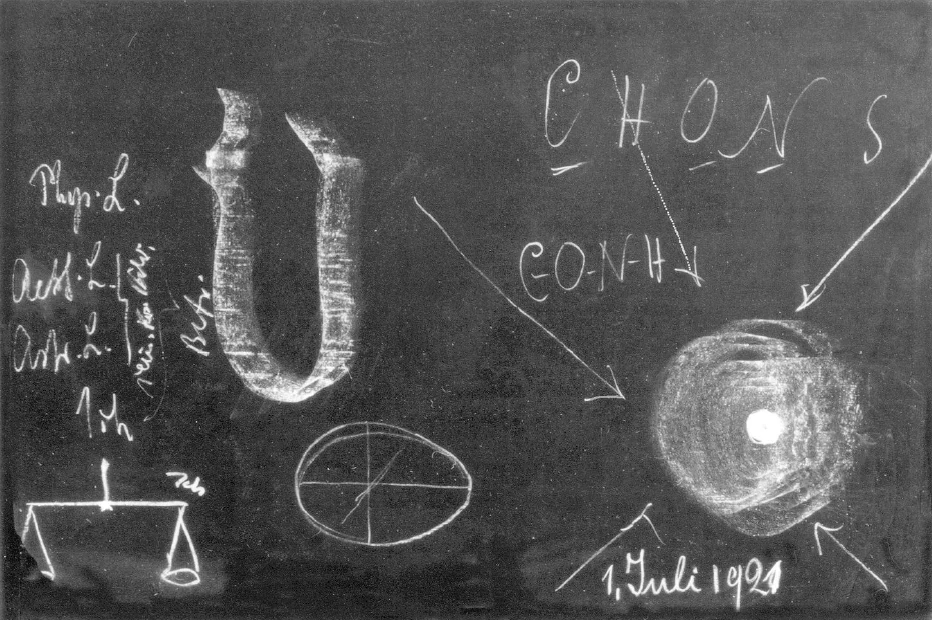

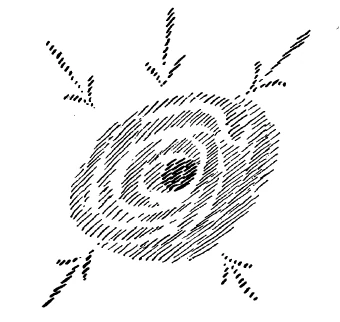

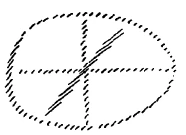

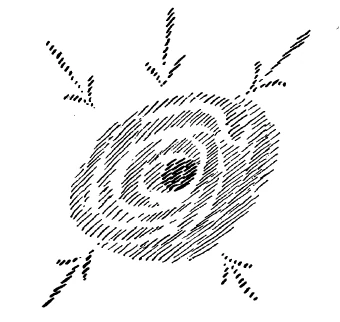

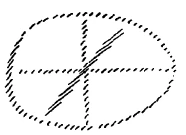

If I draw the organism here (see drawing), and here the germ—and therefore the beginning of the embryo—the germ is the most chaotic of all as far as the conglomeration of material substance is concerned. This germ is something that has emancipated itself from all forces of crystallization, from all chemical forces of the mineral kingdom, and so on. Absolute chaos has arisen in this one spot, which is held together only by the rest of the organism. Because of the fact that here this chaotic protein has appeared, there is the possibility for the forces of the entire universe to act upon this protein, so that this protein is in fact a copy of the forces of the entire universe. Precisely those forces that then become formative forces for the etheric body and for the astral body are present in the female egg cell, without fertilization yet having taken place. Through fertilization, this formation also acquires the physical body and the I, the sheath of the I, and therefore that which constitutes the formation of the I. This arises through fertilization, and this here (see drawing) is a pure cosmic picture, is a picture from the cosmos, because the protein emancipates itself from all earthly forces and thus can be determined by what is extraterrestrial. In the female egg cell, earthly substance is in fact subject to cosmic forces. The cosmic forces create their own image in the female egg cell. This is even true to the extent that in certain formations of the egg, in the case of certain classes of animals—birds, for instance—something very important can be seen in the form of the egg itself. This cannot be perceived, of course, in the higher animals or in the human being, but in the formation of the hen's egg, you can find this image of the cosmos. The egg is nothing other than a true image of the cosmos. The cosmic forces work on this protein, which has emancipated itself from the earthly. The egg is absolutely a copy of the cosmos, and philosophers should not speculate on the three dimensions of space, for if we only rightly knew where and how to look, we could find presented everywhere clarification of the riddles of the world. The hen's egg is a simple, visible proof of the fact that one axis of the world is longer than the other two. The borders of the hen's egg, the eggshell, are a true picture of our space. It will indeed be necessary—this is a digression for mathematicians—for our mathematicians to study the relationships between Lubatscheffski's geometry, for instance, or Riemann's definition of space, and the hen's egg, the formation of the hen's egg. A great deal can be learned through this. Problems must really be tackled concretely.

You see, by placing before our souls this determinable protein, we discover the influence of the cosmos upon it, and we can also describe in detail how the cosmos acts upon it. Indeed, it is true that we cannot as yet go very far in this direction, for if human beings were able to see how such things can be extended, such a science would be misused in the most terrible way, particularly in the present time, when the moral level of the civilized population of the earth is extraordinarily low.

We have observed to some extent how our body comes to form mental images: it presses out of itself the hallucinatory world out of which it originated. We carry about with us not only the body but also the soul element. We will be able to observe this better if we leave out of consideration for the moment the soul element and look instead at the spiritual element. You see, my dear friends, just as here between birth and death we look at ourselves from outside and say that we carry a body, so we have a spiritual existence between death and a new birth. This corresponds to an inner perception, but between death and a new birth we speak—if I may express myself in this way—of our spiritual element in just the same way as we speak here in our physical life of our body. Here we are accustomed to speak of the spiritual as being the actual primal foundation of everything, but this is actually an illusory way of expressing it. We should speak of the spiritual as that which belongs to us between death and a new birth. Just as between birth and death we possess a body, just as here we are embodied, so between death and a new birth we are “enspirited.” This spiritual, however, does not cease when we take up the body that is formed out of the hallucination of the world; it continues to be active.

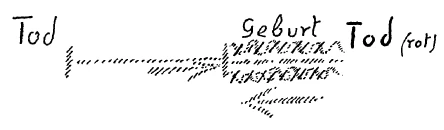

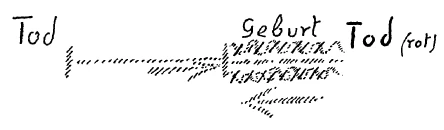

Imagine the moment of conception—or any other moment between conception and birth. The precise moment does not matter so much; imagine any moment in which the human being is descending from the spiritual into physical existence. You will have to say that from this moment onward, physical existence incorporates itself into the soul-spiritual element of the human being. The soul-spiritual undergoes, as it were, a metamorphosis toward the physical. The force, however, that was ours between death and a new birth does not cease at the moment when we enter physical, sensory existence; it continues to be active, but in quite a peculiar way. I would like to illustrate this schematically (see drawing).

Consider the force that has been active within you in the spiritual world since your last death and that works until what I shall call birth, your present birth. The forces of the physical and etheric bodies and so on continue to be active, followed by a new death. This force that we possess until birth persists, however—and yet we might say that it does not persist, for its actual essence has been poured into the bodily nature, spiritualizing it. What persists of this force continues at the same time in the same direction, only as pictures; it has merely a picture-existence, so that between birth and death we carry livingly in us the picture of what we possessed between death and a new birth. This picture is the force of our intellect. Between birth and death, our intellect is not a reality at all but is the picture of our existence between death and a new birth.

This knowledge not only solves the riddles of cognition but also the riddles of civilization. The entire configuration of our modern civilization, which is based upon the intellect, becomes evident if we know that it is a civilization of pictures, a civilization that has not been created by any form of reality but by a picture—although created by a picture of the spiritual reality. We have an abstract spiritual civilization. Materialism is an abstract spiritual civilization. One thinks the most finely spun thoughts if one denies the thoughts and becomes a materialist. Materialistic thoughts are really quite perspicacious, but of course they come into error, for the picture of a world, not a world itself, produces our civilization.

You see, my dear friends, this is a difficult conception, but let us make an effort to understand it. You find it easy to conceive pictures in space. If you stand before a mirror, you ascribe no reality to your reflection in the mirror; you ascribe reality to your own self, not to the picture. What thus occurs here in space also actually takes place in time. What you experience as your intellect is a reflected image, with its mirroring surface turned back to your former existence. In yourselves, in your bodily nature, you have a mirroring surface, but this mirror is active in time, and it reflects the picture of life before birth. The perceptions of existence are continually cast into this intellectual image: the sense perceptions. It mingles therein with sense perceptions, and for this reason we do not perceive that this is actually a reflection. We live in the present. If by means of the exercises I have described in my book, How to Attain Knowledge of the Higher Worlds, we succeed in throwing out sense perceptions and living into this picture existence, then we really come to our life before birth, pre-existent life. Pre-existence then is a fact. The picture of pre-existence is indeed within us; we must only penetrate to it. Then we will succeed in perceiving this pre-existence.

Basically every human being is able, if he does not succumb to other phenomena, to fall into a healthy sleep when he shuts out sense perceptions. This is the case with most human beings. They shut out sense perceptions, but then thinking is also no longer there. If sense perceptions can really be shut out, however, while at the same time thinking remains alive, then we no longer look into the world of space but back into the time through which we lived between our last death and this birth. This is seen at first very unclearly, but one knows that the world into which one then looks is the world between death and this most recent birth. In order to reach the truth, a true insight, we must not fall asleep when sense perceptions are suppressed. Our thinking must remain just as alive as is the case with the help of the sense perceptions or when permeated by sense perceptions.

If we look through our own being toward pre-existent life, however, and then naturally continue our training, the concrete configurations also appear in the spiritual world. Then a spiritual environment rises up around us, and the very opposite takes place of what takes place in the physical world: we do not press out of our body its hallucinations; instead we pull ourselves out of our body and place ourselves into our pre-existent life, our life before birth, where we are filled with spiritual reality. We dive into the world in which hallucinations surge. And in perceiving its realities, we do not perceive hallucinations but imaginations. Thus we perceive imaginations when we rise to spiritual vision.

It is of course absurd, and even indecent, I might say, when someone who wishes to be a scientist today continually comes forward with the following objection to anthroposophy: anthroposophy probably offers merely hallucinations; it cannot be distinguished from hallucinations. Yet if these people were only to study more closely the entire method of investigation applied in spiritual science, they would find that exactly here a very sharp and precise boundary is made between hallucination and Imagination.

What lies between the two? I have already drawn your attention to the fact that between birth and death we assume a bodily garment, and between death and a new birth a spiritual garment. The soul element is the mediator between the two. The spiritual is brought into physical existence through the life of the soul. What we experience in physical life is, in its turn, brought into the spiritual through the soul element when we die. The soul element is the mediator between body and spirit.

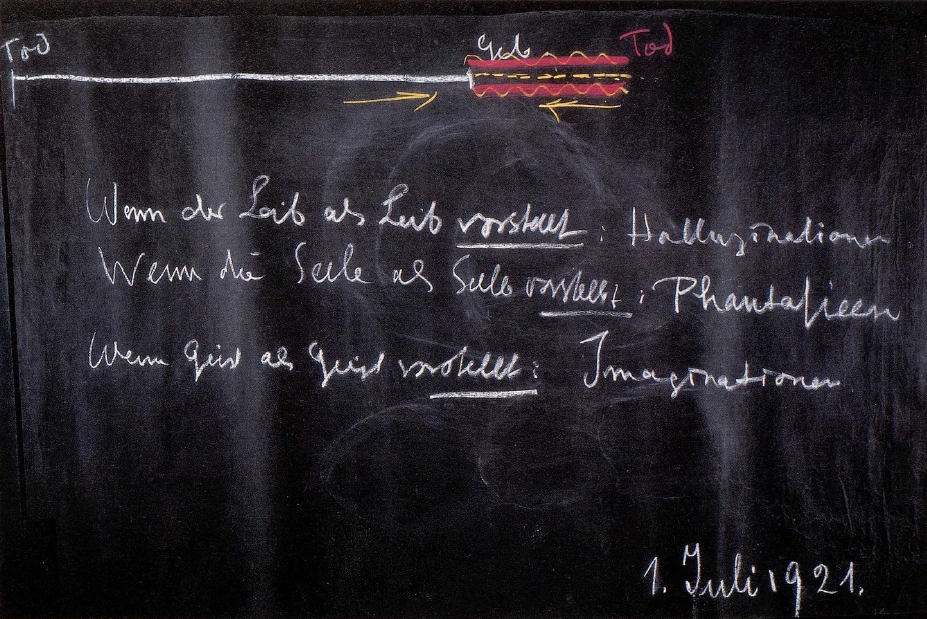

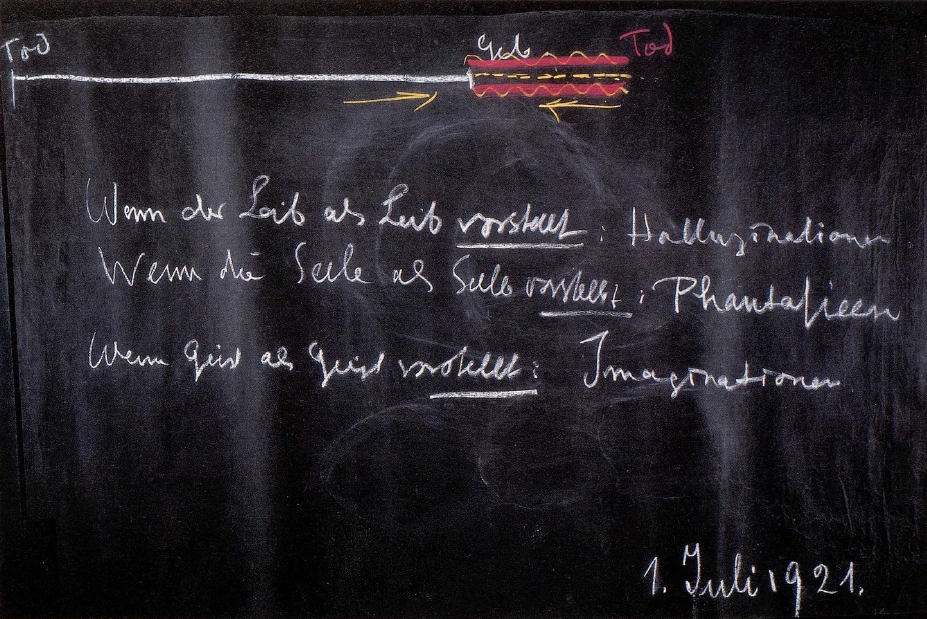

If the body conceptualizes as body, it conceives hallucinations; that is, it brings hallucinations into consciousness. If the spirit conceptualizes as spirit, then it has imaginations; if the soul, which is the mediator between the two, begins to conceptualize, that is, if the soul conceptualizes as soul, then neither will the unjustified hallucinations pressed out of the body arise, nor will the soul penetrate to spiritual realities. Instead it will reach an undefined intermediary stage; these are fantasies. Picture the body; between birth and death it is not an instrument for conceptualizing. If between birth and death it conceptualizes nevertheless, it does so in an unjustified and abnormal way, and hallucinations thus arise. If the spirit conceptualizes in really rising out of the body to realities, then it has imaginations. The soul forms the mediator between hallucinations and imaginations in faintly outlined fantasies.

If the body conceptualizes as body, hallucinations arise.

If the soul conceptualizes as soul, fantasies arise.

If the spirit conceptualizes as spirit, imaginations arise.

In describing these processes, we are describing real processes. In intellectual thinking we have only the pictures of the soul's pre-existent life—the pictures, therefore, of a life that is permeated through and through with imaginations, a life that arises out of the hallucinatory element. Our intellectual life is not real, however. We ourselves are not real in our thinking, but we develop ourselves to a picture in that we think. Otherwise we could not be free. Man's freedom is based on the fact that our thinking is not real if it does not become pure thinking. A mirror image cannot be a causa. If you have before you a mirror image—something that is merely an image, and if you act in accordance with this image, this is not the determining element. If your thinking is a reality, then there is no freedom. If your thinking is a picture, then your life between birth and death is a schooling in freedom, because no causes reside in thinking. A life that is a life in freedom must be one devoid of causes.

The life in fantasies is not entirely free, but it is real, real as a life of conceptions (Vorstellungsleben). The free life that is in us is not a real life as far as thinking is concerned, but when we have pure thinking and out of this pure thinking develop the will toward free deeds, we grasp reality by a corner. Where we ourselves endow the picture with reality out of our own substance, free action is possible.

This is what I wished to present, in a purely philosophical way, in 1893 in my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, in order to have a foundation for further studies.

Fünfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich möchte heute im Zusammenhange mit den Ausführungen, die ich vor acht Tagen und früher gemacht habe, einiges wie eine Episode ausführen, das uns dann zur Fortsetzung unserer Betrachtungen hinüberleiten kann. Wir sehen, indem wir die Welt erleben, an der Welt und an uns manches als abnorm, vielleicht auch als krankhaft an, und das gewiß von einem Gesichtspunkte aus mit Recht; aber damit, daß wir im absoluten Sinne irgend etwas als abnorm oder als krankhaft ansehen, haben wir die Welt noch nicht verstanden. Ja, wir versperren uns oftmals den Weg zum Verständnis der Welt, wenn wir bei solchen Abschätzungen des Daseins, wie gesund und krank, richtig, unrichtig, wahr, falsch, gut, böse und so weiter einfach stehenbleiben. Denn was von einem Gesichtspunkte aus sich als krankhaft, als abnorm ausnimmt, hat von einem andern Gesichtspunkte aus im Ganzen des Weltzusammenhanges seine volle Berechtigung. Ich will gleich einen konkreten Fall anführen und Sie werden sehen, was gemeint ist.

[ 2 ] Mit Recht sieht man das Auftreten sogenannter Halluzinationen oder auch Visionen als etwas Krankhaftes an. Halluzinationen, Gebilde, die vor dem menschlichen Bewußtsein auftreten und für die bei einer genaueren kritischen Prüfung der Mensch nicht die entsprechende Realität finden kann, solche Halluzinationen, solche Visionen sind etwas Krankhaftes, wenn wir sie betrachten von dem Gesichtspunkte des menschlichen Lebens, so wie es sich uns darstellt zwischen der Geburt oder der Empfängnis und dem Tode. Aber damit, daß wir die Halluzinationen als etwas Abnormes bezeichnen, als etwas, was ja ganz gewiß nicht hereingehört in den normalen Ablauf des Lebens zwischen Geburt und Tod, haben wir das Wesen der Halluzinationen eben durchaus nicht begriffen.

[ 3 ] Sehen wir jetzt einmal ab von einer jeglichen solchen Beurteilung der Halluzinationen. Nehmen wir sie so, wie sie bei dem Halluzinierenden auftritt. Sie tritt auf als ein Bild, das in einer intensiveren Weise mit der ganzen Subjektivität, mit dem Eigenleben verbunden ist als die gewöhnliche äußere Wahrnehmung, die durch die Sinne vermittelt wird. Die Halluzination wird intensiver innerlich erlebt als die Sinneswahrnehmung. Die Sinneswahrnehmung verträgt es außerdem, durchsetzt zu werden mit scharfen kritischen Gedanken; der Halluzination gegenüber vermeidet es der Halluzinierende, sie mit scharfen kritischen Gedanken zu durchsetzen. Er lebt in der schwebenden, webenden Bildlichkeit.

[ 4 ] Was ist denn das, in dem der Mensch da lebt? Ja, man kann das nicht kennenlernen, wenn man nur dasjenige kennt, was in das gewöhnliche menschliche Bewußtsein zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode eintritt. Denn in dieses Bewußtsein tritt unter allen Umständen der Inhalt der Halluzination als etwas Unberechtigtes hinein. Es muß die Halluzination von einem ganz andern Gesichtspunkte gesehen werden; dann kann man ihrem Wesen nahekommen. Und dieser Gesichtspunkt ergibt sich, wenn im Verlaufe der Entwickelung zu höherem Schauen der Mensch dazu kommt, sein eigenes Leben und Weben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt kennenzulernen, namentlich das Leben und Weben der eigenen Wesenheit, wenn dieses Leben der Geburt, der Konzeption zu, schon um Jahrzehnte nahe kommt. Wenn man also die Fähigkeit erlangt, sich in dasjenige einzuleben, in dem ja auf ganz normale Weise der Mensch lebt, wenn er sich der Geburt oder der Konzeption nähert, dann lebt man sich in die wahre Gestalt dessen ein, was unnormal, als Halluzination im Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod auftritt.

[ 5 ] Wie wir hier im Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod umgeben sind von der Welt der Farben, von der Welt, die wir in jedem Lufthauch und so weiter fühlen, kurz, von der Welt, die wir uns eben vorstellen als von uns erlebt zwischen Geburt und Tod, so lebt unser eigenes seelisch-geistiges Wesen zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt in einem Elemente, das durchaus identisch ist mit dem, was in uns auftritt in der Halluzination. Wir werden gewissermaßen, und zwar gerade unserer Leiblichkeit nach, aus dem Elemente der Halluzination heraus geboren. Was in der Halluzination auftritt, das, ich möchte sagen, durchschwebt und durchweht die Welt, die der unsrigen zugrunde liegt, und wir tauchen auf, indem wir geboren werden, aus diesem Elemente, das uns abnorm in der halluzinatorischen Welt vor die Seele treten kann.

[ 6 ] Was ist denn dann die Halluzination im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein? Nun, wenn der Mensch das Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt durchlebt hat, sich durch Konzeption und Geburt in das physisch-sinnliche Dasein hereinbegeben hat, dann haben gewisse geistige Wesenheiten jener höheren Hierarchien, die wir kennengelernt haben, eine Intuition gehabt, und das Ergebnis dieser Intuition, das ist der physische Leib. So daß wir sagen können: Gewisse Wesenheiten haben Intuitionen; das Ergebnis dieser Intuitionen ist der menschliche physische Leib, der nur dadurch entstehen kann, daß ihn die Seele durchdringt, indem sie auftaucht aus dem Elemente der Halluzinationen. Was geschieht, wenn nun in krankhafter Weise Halluzinationen vor dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein auftreten? Ich kann Ihnen das eigentlich nur bildlich veranschaulichen, aber es ist natürlich, daß ich es Ihnen nur bildlich veranschaulichen kann, denn Halluzinationen sind ja Bilder; also ist es selbstverständlich, daß man da mit abstrakten Begriffen nicht viel ausmachen kann, daß man da bildlich veranschaulichen muß.

[ 7 ] Nun denken Sie sich das Folgende: Dieser menschliche physische Leib ist ja, wie ich Ihnen neulich ausgeführt habe, nur zum geringsten Teile eigentlich so, daß man ihn in festen Konturen hat; er ist zum größten Teile wässerig, er ist auch luftförmig und so weiter. Dieser menschliche physische Leib hat eine gewisse Konsistenz, er hat eine gewisse natürliche Dichte. Wenn nun diese natürliche Dichte zu einer unnatürlichen gemacht wird, wenn sie unterbrochen wird - stellen Sie sich vor symbolisch, dieser physische Leib würde etwas zusammengezogen in seiner Elastizität -, dann wird das ursprüngliche halluzinatorische Element, aus dem heraus er geboren ist, herausgepreßt, so wie das Wasser aus einem Schwamm herausgepreßt wird. Nichts anderes ist das Entstehen des halluzinatorischen Wesens, als daß aus dem physischen Leib das eigene Element, aus dem heraus er entsteht, aus dem heraus er geformt wird, aus ihm ausgepreßt wird. Und das Krankwerden, das sich äußert im halluzinatorischen Bewußtseinsleben, das weist immer auf eine Ungesundheit des physischen Leibes hin, der sich geistig gewissermaßen aus sich herauspreßt.

[ 8 ] Wir werden ja durch diese Tatsache darauf hingewiesen, daß unser Denken in einem gewissen Sinne durchaus das ist, wovon der Materialismus redet. Unser physischer Leib ist wirklich in gewissem Sinne ein Abbild von dem, was präexistent, vor der Geburt oder vor der Konzeption, in geistigen Welten vorhanden ist. Er ist ein Abbild. Und das Denken, das im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein auftritt, dasjenige Denken, auf das die Gegenwart am meisten stolz ist, das erklären die Materialisten nicht mit Unrecht als etwas, was ganz und gar an den physischen Leib gebunden ist. Es ist einfach so: Dieses Denken, dessen sich der heutige Mensch, namentlich seit der Geburt der neueren naturwissenschaftlichen Denkweise, seit dem 15. Jahrhundert, bedient, dieses Denken geht als solches mit dem physischen Leib zugrunde, hört auf mit dem physischen Leibe. Das, was Sie oftmals in der heute gebräuchlichen, aber erst in der heute, nicht in früheren Jahrhunderten gebräuchlichen katholischen Philosophie finden, als ob das abstrakte, intellektuelle Getriebe der Seele den Tod überdauerte, das ist falsch, das ist nicht richtig. Denn dieses Denken, das gerade das charakteristische Seelenleben der Gegenwart darstellt, das ist durchaus gebunden an den physischen Leib. Was den physischen Leib überdauert, das tritt erst in der nächsthöheren Stufe der Erkenntnis auf, in dem Imaginieren, in dem bildlichen Vorstellen und so weiter.

[ 9 ] Sie werden sagen: Ja, dann hat derjenige, der keine bildlichen Vorstellungen hat, überhaupt keine Unsterblichkeit! - Die Frage kann man so gar nicht stellen: Man habe keine bildlichen Vorstellungen - denn das heißt gar nichts. Sie können sagen: Ich habe keine bildlichen Vorstellungen in meinem Alltagsbewußtsein, ich bringe sie nicht in mein Alltagsbewußtsein herein. - Aber bildhafte Vorstellungen, Imaginationen bilden sich fortwährend in einem aus, nur werden sie verwendet im organischen Prozeß des Lebens; sie werden die Kräfte, aus denen der Mensch fortwährend seinen Organismus neu aufbaut. Unsere materialistische Philosophie und unsere materialistische Naturwissenschaft meint, daß, wenn der Mensch schläft, er aus irgend etwas die verbrauchten Organe wiederum aufbaut; aus was, darüber macht sich die Naturwissenschaft dann nicht viel Kopfzerbrechen. So ist es aber nicht, sondern gerade in unserem Wachleben bilden wir fortwährend, auch wenn wir nur das alltägliche intellektualistische Bewußtsein entwickeln, Imaginationen, und diese Imaginationen, die verdauen wir gewissermaßen seelisch, und davon bauen wir unseren Leib auf. Weil diese Imaginationen den Leib aufbauen, deshalb werden sie für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein nicht abgesondert wahrgenommen. Die Entwickelung zum höheren Schauen beruht darauf, daß wir uns partiell, für außen, diesem Arbeiten am physischen Leibe entziehen, und daß wir dasjenige, was sonst im physischen Leibe unten kocht und brodelt, heraufbringen in das Bewußtsein. Daher gehört zum höheren Schauen Geisteswissenschaft, weil das ja nicht lange anhalten kann, denn sonst würde der Organismus in seiner Gesundheit untergraben. Also ist auch das Imaginieren durchaus beim gewöhnlichen Seelenleben vorhanden, nur wird es in den Leib hinein verdaut zwischen Geburt und Tod. So daß wir sagen können: Auch da geschieht während des gewöhnlichen Lebens eine unterbewußte Tätigkeit, die auch nichts anderes ist als etwas, das, wenn es zum Bewußtsein kommt, ein Halluzinieren ist. — Das Halluzinieren ist durchaus etwas, was eine geregelte elementarische Tätigkeit im Dasein ist. Es darf eben nur nicht zur Unzeit in unserem Bewußtsein auftreten. Es muß das Halluzinieren, so wie es gewöhnlich auftritt, gewissermaßen mehr das Unterbewußte unseres Daseins sein. Und wenn der Leib auspreßt, ich möchte sagen, seine Ursubstanz, dann kommt er eben dazu, dieses Ausgepreßte seiner Ursubstanz dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein einzuverleiben, und dann treten Halluzinationen auf. Halluzinieren heißt nichts anderes als, der Leib schickt ins Bewußtsein dasjenige herauf, was er eigentlich verwenden sollte zum Verdauen, zum Wachsen oder zu sonst etwas in sich.

[ 10 ] Das hängt wiederum mit dem zusammen, was ich oftmals auseinandergesetzt habe mit Bezug auf die Illusionen, die sich die Menschen gegenüber gewissen Mystikern machen. Es ist so, wie wenn man, ich möchte sagen, das Heilige wegwischen würde von den Mystikern, wenn man auf das zugrunde Liegende aufmerksam macht. Ich sagte: Nehmen Sie solche Halluzinationen, die einen wunderschönen poetischen Charakter haben, wie diejenigen, die solche Persönlichkeiten, wie Mechthild von Magdeburg oder auch die Heilige Therese beschreiben. Ja, schön sind die Dinge, aber was sind sie in Wirklichkeit? — Wer diese Dinge durchschaut, der findet: Sie sind aus den Organen des Organismus herausgepreßtes Halluzinieren. Sie sind die Ursubstanz. Und wer die Wahrheit beschreiben will, muß schon manchmal Vorgänge, die dem Verdauen sehr verwandt sind, bei der Mechthild von Magdeburg oder der Heiligen Therese beschreiben, wenn dann die schönsten mystischen Poesien dem Bewußtsein entquellen.

[ 11 ] Man sollte eigentlich nicht sagen, daß dadurch das Aroma hinweggenommen wird von manchen Erscheinungen der geschichtlichen Mystik. Die Wollust, die manche Menschen empfinden, wenn sie an Mystik denken, oder wenn sie selber Mystik erleben wollen, diese Wollust wird allerdings damit etwas auf das Richtige zurückgeführt. Und vieles mystische Erleben ist eben nichts anderes als innere Wollust, die durchaus poetisch schön für das Bewußtsein zum Vorschein kommen kann. Aber das, was da zerstört wird, ist ja nur ein zerstörtes Vorurteil, eine zerstörte Illusion. Derjenige, der wirklich in dieses menschliche Innere vordringen will, der muß schon einmal das mitmachen, daß er nun nicht die wunderschönen Beschreibungen solcher Mystiker findet, sondern die Herausgestaltungen seiner Organe, Leber, Lunge und so weiter, aus dem Kosmos, aus dem Halluzinieren des Kosmos. Und im Grunde genommen ist nicht das Aroma von der Mystik weggenommen, sondern eine höhere Erkenntnis eröffnet, wenn wir sagen können, wie die Leber sich herausbildet aus dem halluzinierenden Kosmos, wie sie gewissermaßen sich zusammensetzt aus dem, was in sich verdichtet, als umgewandelter Geist, als umgewandelte Halluzination erscheint. Auf diese Weise sieht man in das Leibliche hinein, und man sieht den Zusammenhang dieses Leiblichen mit dem ganzen Kosmos.

[ 12 ] Ja, nun wird aber natürlich der ganz gescheite Mensch kommen und man hat ja immer, wenn man die Wahrheit auseinandersetzen will, etwas Rücksicht zu nehmen auf die ganz gescheiten Menschen, die dann ihre Einwendungen machen, wenn man versucht, die Wahrheit auseinanderzusetzen -, und dieser ganz gescheite Mensch wird sagen: Was erzählst du uns da, daß sich die menschliche Gestalt aus dem Kosmos herausbildet! Wir wissen doch, daß der Mensch aus dem Mutterleibe herausgeboren wird. Wir wissen doch, wie er als Embryo aussieht und so weiter! — Ja, da liegt eben eine durch und durch falsche Vorstellung zugrunde, die wir, obwohl wir Ähnliches schon vor unsere Seele haben treten lassen, nochmals ins Auge fassen wollen.

[ 13 ] Wenn wir die Gestalten der äußeren Natur überschauen — bleiben wir zunächst einmal bei der mineralischen Welt stehen -, so finden wir da die mannigfaltigsten Gestalten. Wir sprechen sie als Kristallgestalten an. Aber wir finden auch andere Gestalten in der Natur, und wir finden, daß eine gewisse Konfiguration, innerliche Konfiguration herauskommt, wenn sich, sagen wir, Kohlenstoff, Wasserstoff, Sauerstoff, Stickstoff, Schwefel miteinander verbinden. Wir wissen: Wenn sich Kohlenstoff und Sauerstoff zu Kohlensäure verbinden, entsteht ein Gas von einer gewissen Schwere; wenn sich Kohlenstoff mit Stickstoff verbindet, entsteht das Zyangas und so weiter. Aber da bilden sich immer Stoffe, denen der Chemiker nachgehen kann, die gewissermaßen nun nicht immer eine äußerliche Kristallisation haben, aber eine innerliche Konfiguration. Man hat sogar in der neueren Zeit diese innere Konfiguration angedeutet durch die bekannten Strukturformeln der Chemie.

[ 14 ] Nun hat man immer eine gewisse Voraussetzung gemacht. Das ist diese. Man hat die Voraussetzung gemacht: Die Moleküle, wie man sagt, werden immer komplizierter und komplizierter, je mehr man aus dem mineralischen Unorganischen zum Organischen heraufkommt. Und man sagt: Das organische Molekül, das Zellenmolekül besteht aus Kohlenstoff, Sauerstoff, Stickstoff, Wasserstoff und Schwefel. Die sind in irgendeiner Weise verbunden. Aber sehr kompliziert sind sie verbunden -, sagt man. Und man betrachtet es als ein Ideal der Naturwissenschaft, darauf zu kommen, wie nun diese einzelnen Atome in den komplizierten organischen Molekülen verbunden sein können. Man sagt sich zwar: Das wird noch lange dauern, bis man finden wird, wie Atom an Atom lagert in dem Organischen, in dem lebendigen Molekül. - Aber das Geheimnis besteht darin: Je organischer ein Stoffzusammenhang wird, desto weniger bindet sich chemisch das eine an das andere, desto chaotischer werden die Stoffe durcheinandergewirbelt; und schon die gewöhnlichen Eiweißmoleküle, meinetwegen in der Nervensubstanz, in der Blutsubstanz, sind eigentlich im Grunde genommen innerlich amorphe Gestalten, sind nicht komplizierte Moleküle, sondern sind innerlich zerrissene anorganische Materie, anorganische Materie, die sich entledigt hat der Kristallisationskräfte, der Kräfte überhaupt, die die Moleküle zusammenhalten, die die Atome aneinandergliedern. Das ist schon in den gewöhnlichen Organmolekülen der Fall, und am meisten ist es der Fall in den Embryomolekülen, in dem Eiweiß des Keimes.

[ 15 ] Wenn ich hier schematisch den Organismus und hier den Keim, also den Beginn des Embryos zeichne, so ist der Keim das allerchaotischste an Zusammenwürfelung des Stofflichen. Dieser Keim ist etwas, was sich emanzipiert hat von allen Kristallisationskräften, von allen chemischen Kräften des Mineralreiches und so weiter. Es ist absolut an einem Orte das Chaos aufgetreten, das nur durch den andern Organismus zusammengehalten wird. Und wir haben dadurch, daß hier dieses chaotische Eiweiß auftritt, die Möglichkeit gegeben, daß die Kräfte des ganzen Universums auf dieses Eiweiß wirken, daß dieses Eiweiß in der Tat ein Abdruck von Kräften des ganzen Universums wird. Und zwar sind zunächst diejenigen Kräfte, die dann formbildend sind für den ätherischen Leib und für den astralischen Leib, in der weiblichen Eizelle vorhanden, ohne daß noch die Befruchtung eingetreten ist. Durch die Befruchtung wird dieser Gestaltung auch noch dasjenige einverleibt, was physischer Leib und was Ich ist, was Ich-Hülle, also Gestaltung des Ich ist. Das also hier ist vor der Befruchtung und dieses hier ist rein kosmisches Bild, ist Bild aus dem Kosmos heraus, weil sich das Eiweiß eben emanzipiert von allen irdischen Kräften und dadurch determinierbar ist durch das, was außerirdisch ist. In der weiblichen Eizelle ist in der Tat irdische Substanz den kosmischen Kräften hingegeben. Die kosmischen Kräfte schaffen sich ihr Abbild in der weiblichen Eizelle. Das geht so weit, daß bei gewissen Gestaltungen des Eies, zum Beispiel in gewissen Tierklassen, Vögeln, selbst in der Gestaltung des Eies etwas sehr Wichtiges gesehen werden kann. Das kann natürlich nicht bei höheren Tieren und nicht beim Menschen wahrgenommen werden, aber in der Gestaltung des Eies bei Hühnern können Sie das Abbild des Kosmos finden. Denn das Ei ist nichts anderes als das wirkliche Abbild des Kosmos. Die kosmischen Kräfte wirken hinein auf das determinierte Eiweiß, das sich emanzipiert hat vom Irdischen. Das ende Ei ist durchaus ein Abdruck des Kosmos, und die Philosophen sollten nicht spekulieren, wie die drei Dimensionen des Raumes sind, denn wenn man nur richtig weiß, wo man hinzuschauen hat, so kann man überall die Weltenrätsel anschaulich dargestellt finden. Daß die eine Weltenachse länger ist als die beiden andern, dafür ist ein Beweis, ein anschaulicher Beweis einfach das Hühnerei, und die Grenzen des Hühnereies, die Eierschalen, sind ein wirkliches Bild unseres Raumes. Es wird schon notwendig sein — das ist eine Zwischenbemerkung für Mathematiker -, daß unsere Mathematiker sich damit befassen, welches die Beziehungen sind zwischen der Lobatschewskijschen Geometrie zum Beispiel oder der Riemannschen Raumdefinition, und dem Hühnerei, der Gestaltung des Hühnereies. Daran ist außerordentlich viel zu lernen. Die Probleme müssen eigentlich im Konkreten angefaßt werden.

[ 16 ] Sie sehen, wir finden da, indem wir uns das determinierbare Eiweiß vor die Seele rücken, das Hereinwirken des Kosmos, und wir können im einzelnen aussprechen, wie der Kosmos hereinwirkt. Es ist ja allerdings wahr: Man kann an dieser Stelle heute noch nicht sehr weit gehen, denn würden die Menschen durchschauen, wie sich diese Betrachtungen nun weiter fortsetzen ließen, so würde heute noch der fürchterlichste Unfug mit einem solchen Wissen getrieben werden, insbesondere in der Gegenwart eines außerordentlichen moralischen Tiefstandes der zivilisierten Erdenbevölkerung.

[ 17 ] Nun haben wir gewissermaßen betrachtet, wie unser Leib zu Vorstellungen kommt: er preßt aus sich heraus die halluzinatorische Welt, aus der er entstanden ist. Außer dem Leibe tragen wir mit unserem Wesen herum unser Seelisches. Wir werden es besser betrachten, wenn wir zunächst das Seelische einmal auslassen und nach dem andern, nach dem Geistigen hinschauen. Geradeso wie wir zwischen Geburt und Tod hier herumgehen, uns von außen beschauen und sagen: Wir tragen unseren Leib an uns -, so haben wir zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt ein geistiges Dasein. Das entspricht ja einem innerlichen Beschauen, aber wir reden, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt von unserem Geistigen auch nicht anders, als wir hier im physischen Leben von unserem Leibe reden. Man gewöhnt sich hier, von dem Geistigen als dem eigentlichen Urgrund von allem zu reden. Aber das ist eigentlich eine illusorische Ausdrucksweise. Man sollte von dem Geistigen als dem reden, was einem eigen ist zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt. So wie einem der Leib hier zwischen Geburt und Tod eigen ist, so wie man hier verleiblicht ist, ist man zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt vergeistigt. Und dieses Geistige, das hört nicht etwa auf, wenn wir den Leib annehmen, der sich aus der Welthalluzination herausbildet, sondern es wirkt nach.

[ 18 ] Stellen Sie sich den Moment der Konzeption beziehungsweise einen Moment zwischen der Konzeption und der Geburt vor. Es kommt nicht darauf an, daß wir gerade diesen Zeitpunkt genau ins Auge fassen, aber stellen Sie sich irgendeinen Zeitpunkt vor, den der Mensch durchschreitet, indem er aus dem Geistigen ins physische Dasein heruntersteigt, so werden Sie sich sagen: Von diesem Zeitpunkte an gliedert sich physisches Dasein in das Geistig-Seelische des Menschen hinein. Das Geistig-Seelische macht gewissermaßen die Metamorphose durch nach dem Physischen hin. Nun hört aber die Kraft, die uns eigen war zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, nicht etwa auf mit diesem Moment, wo wir ins physisch-sinnliche Dasein hereintreten, sondern sie wirkt fort, aber sie wirkt in einer ganz eigentümlichen Weise fort. — Ich möchte das schematisch so darstellen.

[ 19 ] Nehmen Sie also die Kraft von dem letzten Tod, die da in der geistigen Welt in Ihnen wirkt, bis - ich will es Geburt nennen - in die gegenwärtige Geburt herein. Da wirken dann weiter die Kräfte des physischen Leibes, Ätherleibes und so weiter. Da wäre ein neuer Tod (rot, dunkel schraffiert). Aber diese Kraft, die uns da eigen war bis zu der Geburt, die dauert fort, und doch wieder nicht fort, möchte man sagen; denn ihre eigentliche Wesenheit hat sie ergossen in das Leibliche, das sie durchgeistigt. Was hier fortdauert von dieser Kraft, was gleichsam in derselben Richtung läuft, das sind nur Bilder, das ist nur ein Bilddasein. So daß wir zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode in uns lebendig das Bild dessen haben, was wir zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt hatten. Und dieses Bild ist die Kraft unseres Intellektes. Unser Intellekt ist nämlich gar nicht eine Realität zwischen Geburt und Tod, sondern er ist das Bild unseres Seins zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt.

[ 20 ] Diese Erkenntnis löst nicht nur Erkenntnisrätsel, sondern zugleich Kulturrätsel. Die ganze Konfiguration unserer neuzeitlichen Kultur, die ja vom Intellekt abhängt, die wird einem anschaulich, wenn man weiß, das ist eine Bildkultur, das ist eine Kultur, die von gar keiner Realität geschaffen ist, die von dem Bild, allerdings jetzt sogar von einem Bild der spirituellen Realität, geschaffen ist. Wir haben eine abstrakte geistige Kultur. Der Materialismus ist ja eine abstrakte geistige Kultur; man denkt in den feinsten Gedanken, wenn man die Gedanken verleugnet und Materialist wird. Die materialistischen Gedanken waren im Grunde genommen recht scharfsinnig, aber sie gingen natürlich in den Irrtum hinein. Es ist durchaus das Bild einer Welt, das da kulturwirkend ist, nicht eine Welt selbst.

[ 21 ] Diese Vorstellung ist schwierig; aber bemühen Sie sich, sie zu haben. Sie finden es nur leicht, im Raume Bilder vorzustellen. Wenn Sie vor einem Spiegel stehen, so schreiben Sie dem Bilde, das Ihnen erscheint, keine Realität zu, sondern sich selbst schreiben Sie die Realität zu, nicht dem Bilde. Was hier räumlich sich abspielt, das spielt sich hier wirklich zeitlich ab. Sie haben in dem, was Sie als Intellekt erleben, das Spiegelbild, das eigentlich zurück sich spiegelt, das nach Ihrem früheren Dasein zurück sich spiegelt. In Ihnen, in Ihrer Leiblichkeit haben Sie eine spiegelnde Platte, nur daß sie in der Zeit wirkt, und die wirft zurück das Bild von dem vorgeburtlichen Leben. Nur werden fortwährend in dieses intellektualistische Bild die Seinswahrnehmungen hineingeworfen, die Sinneswahrnehmungen. Es vermischen sich die Sinneswahrnehmungen darinnen. Deshalb nimmt man nicht wahr, daß es eigentlich zurückgeworfen wird. Man lebt in der Gegenwart. Kommt man durch solche Übungen, wie ich sie beschrieben habe in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» dazu, die Sinneswahrnehmungen wirklich herauszuwerfen und lebendig in diesem Bildsein zu leben, dann gelangt man dadurch tatsächlich in das vorgeburtliche, in das präexistente Leben hinein. Es ist dann die Präexistenz eine Tatsache. DasBild des Präexistenten istja in uns, wir müssen es nur durchschauen; dann gelangen wir dazu, hineinzuschauen in dieses Präexistente.

[ 22 ] Im Grunde genommen hat jeder Mensch diese Möglichkeit, wenn er nur eben nicht in das andere Phänomen verfällt, daß er, wenn er die Sinneswahrnehmungen ausschaltet, in einen gesunden Schlaf versinkt. Das ist ja bei den meisten Menschen der Fall. Sie schalten die Sinneswahrnehmungen aus, dann ist aber auch das Denken nicht mehr da. Aber wenn man die Sinneswahrnehmungen wirklich ausschalten kann und das Denken noch lebhaft bleibt, dann sieht man nicht hinein in die Raumeswelt, sondern zurück in die Zeit, die man zuletzt verlebt hat zwischen dem letzten Tod und dieser Geburt. Man sieht sie zunächst sehr undeutlich, aber man weiß: die Welt, in die man hineinschaut, das ist die Welt zwischen dem Tod und dieser letzten Geburt. Die Wahrheit, eine wahre Überschau von dem zu bekommen, das hängt nur davon ab, daß man nicht einschläft, wenn man die Sinneswahrnehmungen unterdrückt, daß das Denken so lebhaft bleibt, wie es mit Hilfe der Sinneswahrnehmungen oder im Besitze der Sinneswahrnehmungen ist.

[ 23 ] Wenn man aber in dieser Weise also durch sich hindurchsieht nach seinem präexistenten Leben und dann natürlich weiter sich schult, dann treten die konkreten Konfigurationen auch in dieser geistigen Welt auf, dann ersteht vor uns eine geistige Umwelt. Dann tritt das Entgegengesetzte ein. Wir leben hier innerhalb der physischen Welt. Wir pressen nicht aus unserem Leibe seine Halluzinationen heraus, aber wir holen uns aus unserem Leibe heraus und versetzen uns in unser präexistentes Leben, füllen uns dort mit geistiger Wirklichkeit an. In die Welt, die in Halluzinationen flutet, in die tauchen wir unter, und indem wir ihre Realitäten wahrnehmen, nehmen wir nun nicht Halluzinationen wahr, sondern Imaginationen. Indem wir uns also zum geistigen Anschauen erheben, nehmen wir Imaginationen wahr.

[ 24 ] Es ist natürlich tölpelhaft, es ist nicht einmal anständig, möchte ich sagen, wenn jemand heute Wissenschafter sein will und immer wieder und wiederum mit dem Einwande gegen Anthroposophie kommt: Nun ja, was da in Anthroposophie geboten wird, das könnte ja auch bloß halluzinatorisch sein; man kann das nicht von Halluzination unterscheiden. - Es sollten nur jene Leute sich wirklich befassen mit der ganzen Methode des Forschens in der Geisteswissenschaft, dann würden sie finden, daß gerade da ganz scharf und präzise die Grenze gezogen wird zwischen Halluzinationen und der Imagination.

[ 25 ] Und was liegt zwischen beiden? Nun, ich habe Sie jetzt aufmerksam gemacht auf der einen Seite auf das leibliche Umkleidetsein zwischen Geburt und Tod, auf der andern Seite auf das geistige Umkleidetsein zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Das Seelische ist die Vermittelung zwischen beiden. Das Geistige wird hereingetragen in das physische Dasein durch das seelische Leben; das, was im Physischen erlebt wird, wird wiederum durch das Seelische hinausgetragen durch den Tod ins Geistige. Das Seelische ist der Vermittler zwischen Leib und Geist.

[ 26 ] Wenn der Leib als Leib vorstellt, stellt er Halluzinationen vor, beziehungsweise er bringt Halluzinationen in das Bewußtsein herein. Wenn der Geist als Geist vorstellt, hat er Imaginationen. Wenn nun die Seele, die die Vermittlerin ist zwischen beiden, ihrerseits ins Vorstellen kommt, wenn also die Seele als Seele vorstellt, dann entstehen weder die unberechtigten, dem Leibe abgepreßten Halluzinationen, noch dringt sie vor zu den geistigen Realitäten, aber sie hat das unkonturierte Zwischenfeld: das sind die Phantasien. So daß Sie sagen können: Stellt der Leib vor - er ist nicht im Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod zum Vorstellen da, aber stellt er dennoch vor, stellt er also unberechtigt, anormal vor, so entstehen Halluzinationen. Stellt der Geist vor, indem er sich wirklich heraushebt aus dem Leibe und zu Realitäten kommt, so hat er Imaginationen. Die Seele bildet die Vermittlerin zwischen den Halluzinationen und den Imaginationen in den nicht scharf konturierten Phantasien.

Wenn der Leib als Leib vorstellt: Halluzinationen

Wenn die Seele als Seele vorstellt: Phantasien

Wenn der Geist als Geist vorstellt: Imaginationen

[ 27 ] Und indem wir diese Vorgänge hier schildern, schildern wir reale Vorgänge. Im intellektualistischen Denken haben wir ja nur das Bild des präexistenten Seelenlebens, das Bild also eines durch und durch imaginierten Lebens, das auftaucht aus dem Halluzinatorischen. Aber real ist unser intellektuelles Leben nicht. Wir selbst sind nicht real, indem wir denken, sondern wir entwickeln uns zum Bilde, indem wir denken. Sonst könnten wir auch nicht frei sein. Die Freiheit des Menschen beruht darauf, daß unser Denken nicht real ist, wenn es reines Denken wird. Ein Spiegelbild kann nicht eine Causa sein. Wenn Sie irgendein Spiegelbild vor sich haben, etwas was bloß Bild ist und Sie richten sich darnach, dann determiniert es nicht. Wenn Ihr Denken eine Realität ist, gibt es keine Freiheit. Wenn Ihr Denken Bild ist, dann ist Ihr Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod die Schule der Freiheit, weil keine Causa im Denken liegt. Und Causa-los muß das Leben sein, das ein Leben in Freiheit ist.

[ 28 ] Das Leben in Phantasie dagegen ist nicht völlig frei; dafür ist es real, als Vorstellungsleben real. Das freie Leben, das in uns ist, ist dem Denken nach kein reales Leben, sondern indem wir das reine Denken haben und aus dem reinen Denken heraus den Willen zur freien Tat entwickeln, erfassen wir im reinen Denken dieRealität an einem Zipfel. Aber da, wo wir selbst aus unserer Substanz dem Bilde Realität verleihen, da ist die freie Handlung möglich. Das wollte ich schon in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» 1893 darstellen auf rein philosophische Weise, um eben einen Unterbau zu haben für ein Späteres. Darauf wollen wir dann morgen weitere Betrachtungen gründen.

Fifth Lecture

[ 1 ] Today, in connection with the remarks I made eight days ago and earlier, I would like to relate something like an episode that may lead us to continue our reflections. As we experience the world, we see many things in the world and in ourselves as abnormal, perhaps even pathological, and from one point of view this is certainly justified; but by considering something abnormal or pathological in an absolute sense, we have not yet understood the world. Indeed, we often block our path to understanding the world when we simply stop at such assessments of existence as healthy and sick, right and wrong, true and false, good and evil, and so on. For what appears from one point of view to be pathological or abnormal has, from another point of view, its full justification in the totality of the world context. I will give you a concrete example and you will see what I mean.

[ 2 ] It is right to regard the occurrence of so-called hallucinations or visions as something pathological. Hallucinations, images that appear before the human consciousness and for which, upon closer critical examination, the human being cannot find any corresponding reality, such hallucinations, such visions, are something pathological when we consider them from the point of view of human life as it presents itself to us between birth or conception and death. But by describing hallucinations as something abnormal, as something that certainly does not belong in the normal course of life between birth and death, we have failed to understand the nature of hallucinations at all.

[ 3 ] Let us now disregard any such assessment of hallucinations. Let us take them as they appear to the hallucinator. They appear as images that are more intensely connected with the whole subjectivity, with the inner life, than ordinary external perceptions conveyed by the senses. Hallucinations are experienced more intensely internally than sensory perceptions. Sensory perceptions can also be interspersed with sharp critical thoughts; the hallucinator avoids interspersing hallucinations with sharp critical thoughts. He lives in a floating, weaving imagery.

[ 4 ] What is it in which human beings live? Yes, one cannot know this if one knows only what enters into ordinary human consciousness between birth and death. For in this consciousness, the content of hallucinations enters under all circumstances as something unjustified. Hallucinations must be viewed from a completely different perspective; only then can one come close to their essence. And this perspective arises when, in the course of development toward higher vision, human beings come to know their own life and weaving between death and a new birth, namely the life and weaving of their own being, when this life approaches birth, conception, already decades earlier. So when one acquires the ability to live in that state in which human beings live in a completely normal way as they approach birth or conception, then one lives in the true form of what appears as abnormal, as a hallucination, in the life between birth and death.

[ 5 ] Just as we are surrounded here in life between birth and death by the world of colors, by the world we feel in every breath of air and so on, in short, by the world we imagine ourselves to experience between birth and death, so our own spiritual being lives between death and a new birth in an element that is entirely identical to what occurs within us in hallucinations. We are, in a sense, born out of the element of hallucination, precisely because of our physicality. What occurs in hallucinations, I would say, floats and blows through the world that underlies ours, and we emerge, when we are born, from this element, which can appear abnormally to our soul in the hallucinatory world.

[ 6 ] What, then, is hallucination in ordinary consciousness? Well, when a human being has lived through the life between death and a new birth, has entered into physical-sensory existence through conception and birth, then certain spiritual beings of those higher hierarchies that we have come to know have had an intuition, and the result of this intuition is the physical body. So we can say: certain beings have intuitions; the result of these intuitions is the human physical body, which can only come into being when the soul permeates it, emerging from the element of hallucinations. What happens when hallucinations appear in a pathological way before ordinary consciousness? I can only illustrate this figuratively, but it is natural that I can only illustrate it figuratively, because hallucinations are images; so it is obvious that one cannot do much with abstract concepts, that one must illustrate figuratively.

[ 7 ] Now think about the following: As I explained to you recently, this human physical body is, in reality, only to a very small extent made up of solid contours; for the most part, it is watery, it is also airy, and so on. This human physical body has a certain consistency, it has a certain natural density. Now, when this natural density is transformed into an unnatural one, when it is interrupted—imagine symbolically that this physical body is somehow contracted in its elasticity—then the original hallucinatory element from which it was born is squeezed out, just as water is squeezed out of a sponge. The emergence of the hallucinatory being is nothing other than the squeezing out of the physical body of its own element, from which it arises, from which it is formed. And the illness that manifests itself in the hallucinatory life of consciousness always points to an unhealthy physical body, which is, in a sense, squeezing itself out spiritually.

[ 8 ] This fact points out to us that our thinking is, in a certain sense, exactly what materialism speaks of. Our physical body is really, in a certain sense, an image of what is pre-existent, before birth or before conception, in spiritual worlds. It is an image. And the thinking that occurs in ordinary consciousness, the thinking of which the present is most proud, is not wrongly explained by materialists as something that is completely bound to the physical body. It is simply this: this thinking, which modern man has been using since the birth of the modern scientific way of thinking, since the 15th century, this thinking as such perishes with the physical body, ceases with the physical body. What you often find in Catholic philosophy today, but which was not common in earlier centuries, as if the abstract, intellectual workings of the soul survive death, is wrong, it is not correct. For this thinking, which is precisely the characteristic soul life of the present, is entirely bound to the physical body. What survives the physical body only appears in the next higher stage of knowledge, in imagination, in pictorial representation, and so on.

[ 9 ] You will say: Yes, then those who have no pictorial ideas have no immortality at all! - The question cannot be put that way: to have no pictorial ideas - that means nothing. You can say: I have no pictorial ideas in my everyday consciousness, I do not bring them into my everyday consciousness. But pictorial ideas, imaginations, are constantly forming within us; they are only used in the organic process of life; they become the forces from which man constantly rebuilds his organism. Our materialistic philosophy and our materialistic natural science believe that when a person sleeps, they rebuild their exhausted organs from something; natural science does not bother much about what that something is. But this is not the case. Rather, it is precisely in our waking life that we are constantly forming imaginations, even when we are only developing our everyday intellectual consciousness, and we digest these imaginations, so to speak, spiritually, and build our body from them. Because these imaginations build the body, they are not perceived separately by ordinary consciousness. The development toward higher vision is based on our partially withdrawing ourselves, outwardly, from this work on the physical body and bringing up into consciousness that which otherwise boils and bubbles below in the physical body. Spiritual science therefore belongs to higher vision, because it cannot last long, otherwise the organism would be undermined in its health. Imagination is therefore also present in ordinary soul life, but it is digested into the body between birth and death. So we can say that during ordinary life there is also a subconscious activity which is nothing other than something that, when it comes to consciousness, is hallucination. Hallucination is definitely something that is a regular elementary activity in existence. It just must not appear in our consciousness at the wrong time. Hallucination, as it usually occurs, must be, in a sense, more the subconscious of our existence. And when the body expels, I would say, its primordial substance, it then incorporates this expelled primordial substance into ordinary consciousness, and hallucinations occur. Hallucinating means nothing other than the body sending up to consciousness what it should actually be using for digestion, growth, or something else within itself.

[ 10 ] This is again connected with what I have often discussed in relation to the illusions that people have about certain mystics. It is as if one were to wipe away the sacred from the mystics when one draws attention to what lies beneath. I said: Take hallucinations that have a beautiful poetic character, such as those described by personalities such as Mechthild of Magdeburg or Saint Therese. Yes, these things are beautiful, but what are they in reality? — Anyone who sees through these things will find that they are hallucinations squeezed out of the organs of the organism. They are the primordial substance. And anyone who wants to describe the truth must sometimes describe processes that are very similar to digestion in Mechthild of Magdeburg or Saint Teresa, when the most beautiful mystical poetry springs from consciousness.

[ 11 ] One should not actually say that this takes away the aroma of some phenomena of historical mysticism. The lust that some people feel when they think of mysticism, or when they want to experience mysticism themselves, is indeed brought back to its proper place. And much mystical experience is nothing more than inner sensual pleasure, which can certainly emerge in a poetically beautiful way for consciousness. But what is destroyed is only a destroyed prejudice, a destroyed illusion. Anyone who really wants to penetrate this human interior must first go through the experience of not finding the beautiful descriptions of such mystics, but rather the elaborations of their organs, liver, lungs, and so on, from the cosmos, from the hallucinations of the cosmos. And basically, it is not the aroma that is taken away from mysticism, but a higher knowledge is opened up when we can say how the liver emerges from the hallucinatory cosmos, how it is, in a sense, composed of what condenses within itself and appears as transformed spirit, as transformed hallucination. In this way, one sees into the physical body and one sees the connection of this physical body with the entire cosmos.

[ 12 ] Yes, but now, of course, the very clever person will come along, and when one wants to discuss the truth, one always has to take into consideration the very clever people who will raise their objections when one tries to discuss the truth—and this very clever person will say: What are you telling us, that the human form develops out of the cosmos! We know that human beings are born out of the womb. We know what they look like as embryos and so on! — Yes, there is a thoroughly false idea underlying this, which we want to take another look at, even though we have already allowed something similar to enter our minds.

[ 13 ] When we survey the forms of external nature — let us remain with the mineral world for the moment — we find the most varied forms. We refer to them as crystal forms. But we also find other forms in nature, and we find that a certain configuration, an inner configuration, emerges when, say, carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur combine with each other. We know that when carbon and oxygen combine to form carbon dioxide, a gas of a certain weight is produced; when carbon combines with nitrogen, hydrogen cyanide is produced, and so on. But substances are always formed that chemists can investigate, which do not always have an external crystallization, but an internal configuration. In recent times, this internal configuration has even been indicated by the well-known structural formulas of chemistry.

[ 14 ] Now, a certain assumption has always been made. This is what it is. The assumption has been made that molecules, as they say, become more and more complicated the further one moves from the mineral inorganic to the organic. And one says: The organic molecule, the cell molecule, consists of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, and sulfur. These are connected in some way. But they are connected in a very complicated way, it is said. And it is considered an ideal of natural science to discover how these individual atoms can be connected in the complicated organic molecules. It is said that it will take a long time to find out how atoms are arranged in organic matter, in living molecules. But the secret is this: the more organic a substance becomes, the less chemically bound the individual components are to each other, the more chaotic the substances become; and even ordinary protein molecules, for example in nerve tissue or blood, are basically amorphous structures, not complex molecules, but are internally torn inorganic matter, inorganic matter that has rid itself of the crystallizing forces, of the forces that hold the molecules together, that link the atoms together. This is already the case in ordinary organic molecules, and it is most evident in the embryo molecules, in the protein of the germ.

[ 15 ] If I draw here schematically the organism and here the germ, that is, the beginning of the embryo, then the germ is the most chaotic jumble of matter. This germ is something that has emancipated itself from all crystallizing forces, from all chemical forces of the mineral kingdom, and so on. Chaos has arisen in one place, held together only by the other organism. And through the appearance of this chaotic protein, we have been given the opportunity for the forces of the entire universe to act upon this protein, so that this protein actually becomes an imprint of the forces of the entire universe. Initially, the forces that are formative for the etheric body and the astral body are present in the female egg cell without fertilization having yet taken place. Through fertilization, this form is also incorporated into what is the physical body and what is the I, what is the I-shell, that is, the formation of the I. So this here is before fertilization, and this here is a purely cosmic image, an image from the cosmos, because the protein emancipates itself from all earthly forces and is therefore determinable by what is extraterrestrial. In the female egg cell, earthly substance is indeed surrendered to cosmic forces. The cosmic forces create their image in the female egg cell. This goes so far that in certain formations of the egg, for example in certain classes of animals, birds, even in the formation of the egg itself, something very important can be seen. Of course, this cannot be perceived in higher animals or in humans, but you can find the image of the cosmos in the structure of the egg in chickens. For the egg is nothing other than the real image of the cosmos. The cosmic forces work into the determined egg white, which has emancipated itself from the earthly. The finished egg is definitely an imprint of the cosmos, and philosophers should not speculate about the three dimensions of space, because if you know exactly where to look, you can find the mysteries of the world clearly represented everywhere. The fact that one axis of the world is longer than the other two is proven by a vivid example: the chicken egg. The boundaries of the chicken egg, the eggshell, are a real image of our space. It will be necessary—this is an aside for mathematicians—for our mathematicians to examine the relationships between Lobachevsky's geometry, for example, or Riemann's definition of space, and the chicken egg, the shape of the chicken egg. There is an extraordinary amount to learn from this. The problems must actually be tackled in concrete terms.

[ 16 ] You see, by focusing our minds on the determinable protein, we find the influence of the cosmos, and we can describe in detail how the cosmos influences it. It is true, however, that we cannot go very far at this point, because if people were to see how these considerations could be taken further, the most terrible nonsense would be perpetrated with such knowledge, especially in the present state of extraordinary moral decline of the civilized population of the earth.

[ 17 ] Now we have considered, in a sense, how our body arrives at ideas: it presses out of itself the hallucinatory world from which it arose. In addition to the body, we carry our soul around with us. We will examine this better if we first leave the soul aside and look at the spiritual. Just as we walk around here between birth and death, looking at ourselves from the outside and saying, “We carry our body with us,” so we have a spiritual existence between death and a new birth. This corresponds to an inner contemplation, but between death and rebirth, if I may express it this way, we speak of our spirit no differently than we speak of our body here in physical life. Here, we are accustomed to speaking of the spirit as the actual source of everything. But this is actually an illusory way of expressing it. One should speak of the spiritual as that which is proper to us between death and new birth. Just as the body is proper to us here between birth and death, just as we are embodied here, so between death and new birth we are spiritualized. And this spiritual does not cease when we take on the body that emerges from the world hallucination, but continues to have an effect.

[ 18 ] Imagine the moment of conception, or a moment between conception and birth. It does not matter whether we focus precisely on this moment, but imagine any moment that a human being passes through as they descend from the spiritual into physical existence, and you will say to yourself: from this moment on, physical existence is integrated into the spiritual-soul life of the human being. The spiritual-soul element undergoes a kind of metamorphosis toward the physical. However, the force that was ours between death and a new birth does not cease at the moment we enter physical-sensory existence, but continues to work in a very peculiar way. — I would like to illustrate this schematically.

[ 19 ] So take the power from the last death, which is working in you in the spiritual world, until — I will call it birth — it enters into the present birth. Then the forces of the physical body, the etheric body, and so on continue to work. There would be a new death (red, darkly hatched). But this force that was ours until birth continues, and yet it does not continue, one might say; for its actual essence has poured itself into the physical body, which it spiritualizes. What continues here from this force, what runs in the same direction, so to speak, are only images, a pictorial existence. So that between birth and death we have alive within us the image of what we had between death and a new birth. And this image is the power of our intellect. For our intellect is not at all a reality between birth and death, but is the image of our being between death and a new birth.