Man as a Being of Sense and Perception

GA 206

22 July 1921, Dornach

Lecture I

We now have to continue our study of the relationship between man and the world. And to link up what I have to say in the next few days with what I have already said recently, I should like to begin by calling attention to a theme which I treated some time ago—I mean the anthroposophical teaching about the senses.1Die Zwolf Sinne des Menschen in ihrer Beziehung zu Imagination, Inspiration und Intuition, 8th Aug., 1920. (Translation not yet published.)

I said a long time ago, and I am always repeating it, that orthodox science takes into consideration only those senses for which obvious organs exist, such as the organs of sight, of hearing, and so on. This way of looking at the matter is not satisfactory, because the province of sight, for example, is strictly delimited within the total range of our experiences, and so, equally, is, let us say, the perception of the ego of another man, or the perception of the meaning of words. To-day, when everything is in a way turned upside down, it has even become customary to say that when we are face to face with another ego, what we see first is the human form; we know that we ourselves have such a form, that in us this form harbours an ego, and so we conclude that there is also an ego in this other human form which resembles our own. In drawing such a conclusion there is not the slightest real consciousness of what lies behind the wholly direct perception of the other ego. Such an inference is meaningless. For just as we stand before the outer world and take in a certain part of it directly with our sense of sight, so, in exactly the same way, the other ego penetrates directly into the sphere of our experience. We must ascribe to ourselves an ego-sense, just as we do a sense of sight. At the same time we must be quite clear that this ego-sense is something quite other than the development of consciousness of our own ego. Becoming conscious of one's own ego is not actually a perception; it is a completely different process from the process which takes place when we perceive another ego.

In the same way, listening to words and becoming aware of a meaning in them is something quite different from hearing mere tone, mere sound. Although to begin with it is more difficult to point to an organ for the word-sense than it is to relate the ear to the sense of sound, nevertheless anyone who can really analyse the whole field of our experience becomes aware that within this field we have to make a distinction between the sense that has to do with musical and vocal sound and the sense for words.

Further, it is again something quite different to perceive the thought of another within his words, within the structure and relationship of his words; and here again we have to distinguish between the perception of his thought and our own thought. It is only because of the superficial way in which soul-phenomena are studied to-day that no distinction is made between the thought which we unfold as the inner activity of our own soul-life, and the activity which we direct outwards in perceiving another person's thought. Of course, when we have perceived the thought of another, we ourselves must think in order to understand his thought, in order to bring it into connection with other thoughts which we ourselves have fostered. But our own thinking is something quite other than the perception of the thought of another person.

When we analyse the whole range of our experience into provinces which are really quite distinct from one another and yet have a certain relationship, so that we can call them all senses, we get the twelve senses of man which I have often enumerated. The physiological or psychological treatment of the senses is one of the weakest chapters in modern science, for it really only generalises about them.

Within the range of the senses, the sense of hearing, for example, is of course radically different from the sense of sight or the sense of taste. And having come to a clear conception of the sense of hearing or of the sense of sight, we then have to recognise a word-sense, a sense of thought and an ego-sense. Most of the concepts current to-day in scientific treatises on the senses are actually taken from the sense of touch. And our philosophy has for some time been wont to base a whole theory of knowledge on this, a theory which actually consists of nothing but a transference of certain perceptions proper to the sense of touch to the whole sphere of capacity for sense-perception.

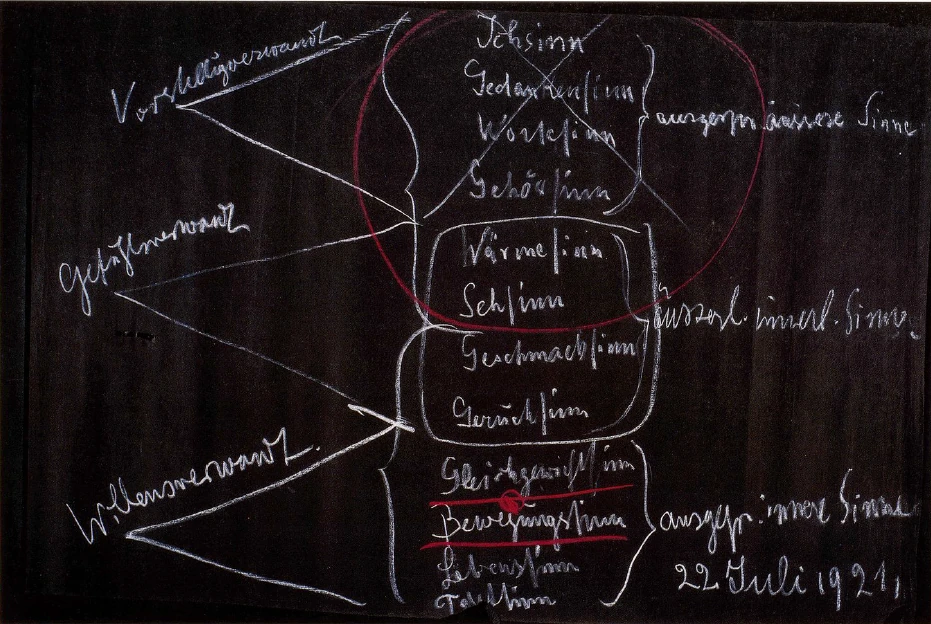

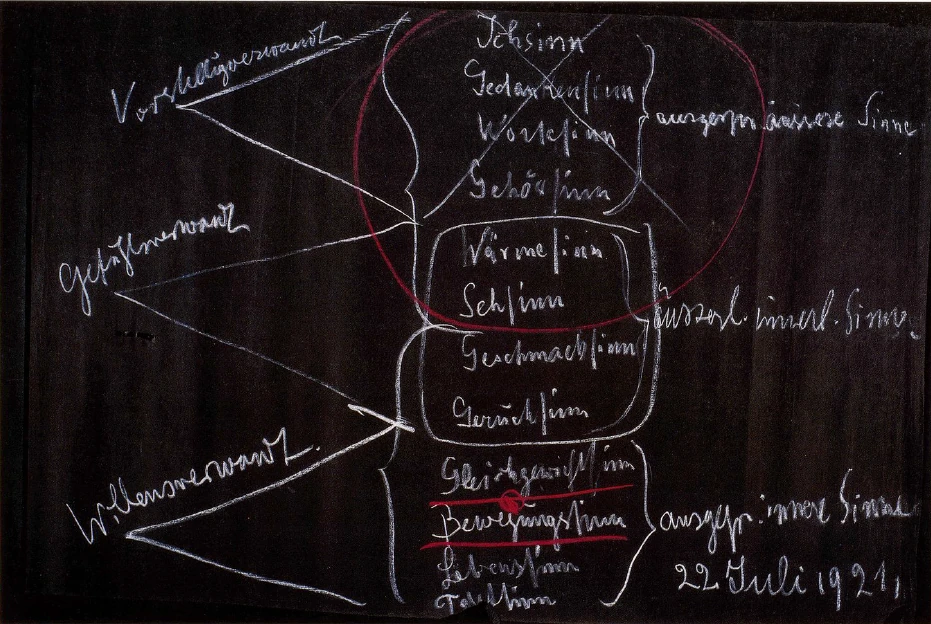

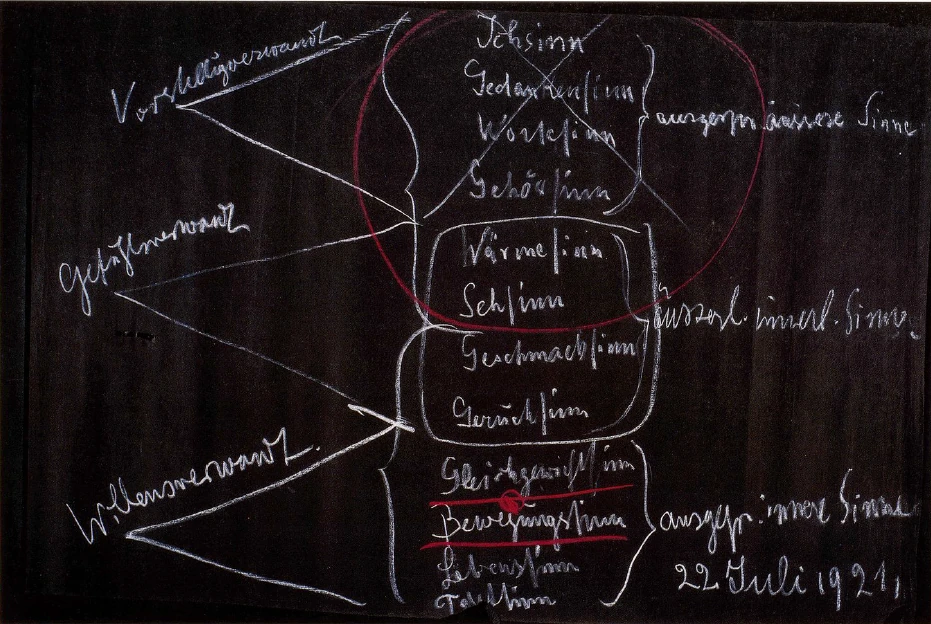

Now when we really analyse the whole range of those external experiences of which we become aware in the same way as we become aware, let us say, of the experiences of sight or touch or warmth, we get twelve senses, clearly distinguishable one from another. On earlier occasions I have enumerated them as follows: First, the ego-sense (see diagram, at end) which, as I have said, is to be distinguished from the consciousness of our own ego. By the ego-sense we mean nothing more than the capacity to perceive the ego of another man. The second sense is the sense of thought, the third the word-sense, the fourth the sense of hearing, the fifth the sense of warmth, the sixth the sense of sight, the seventh the sense of taste, the eighth the sense of smell, the ninth the sense of balance. Anyone who is able to make distinctions in the realm of the senses knows that, just as there is a clearly defined realm of sight, so there is a clearly defined realm from which we receive simply a sensation of standing as man in a certain state of balance. Without a sense to convey this state of standing balanced, or of being poised, or of dancing in balance, we should be entirely unable to develop full consciousness. Next comes the sense of movement. This is the perception of whether we are at rest or in movement. We must experience this within ourselves, just as we experience the sense of sight. The eleventh sense is the sense of life, and the twelfth the sense of touch.

The senses in this group here (see diagram) can be clearly distinguished one from another, and at the same time we can discover what they have in common when we perceive through them. It is our cognitive intercourse with the external world that this group of senses conveys to us in very varying ways. First, we have four senses which unite us with the outer world beyond any doubt. They are the ego-sense, the sense of thought, the word-sense and the sense of hearing. You will unhesitatingly recognise that when we perceive the ego of another person, we are with our entire experience in the outer world, as also when we perceive the thoughts or words of another. As regards the sense of hearing it is not quite so obvious; but that is only because people have taken an abstract view of the matter, and have diffused over the whole of the senses the colouring of a common concept, a concept of what sense-life is supposed to be, and do not consider what is specific in each individual sense. Of course, one cannot apply external experiment to one's ideas upon these matters, but one has to be capable of an inner feeling for these experiences.

Customary thinking overlooks the fact that hearing, since its physical medium is the air in movement, takes us straight into the outer world. And you have only to consider how very external our sense of hearing actually is, compared with the whole of our organic experience, to come to the conclusion that a distinction must be made between the sense of hearing and the sense of sight. In the case of the sense of sight we realise at once, simply by observing its organ, the eye, how what is conveyed by this sense is to a great extent an inner process; it is at least relatively an inner process. When we sleep we close our eyes; we do not shut our ears. Such seemingly simple, trivial facts point to something of deep significance for the whole of human life. And though when we go to sleep we have to shut off our inner senses, because during sleep we must not perceive through sight, yet we are not obliged to close our ears, because the ear lives in the outer world in a totally different way from the eye. The eye is much more a component of our inner life; the sense of sight is directed much more inwards than is the sense of hearing—I am not talking about the apprehension of what is heard; that is something quite different. The apprehension which lies behind the experience of music is something other than the actual process of hearing.

Now these senses, which in essentials form a link between the outer and inner, are specifically outer senses (see diagram). The next four senses, the senses of warmth, sight, taste and smell, are so to say on the border between outer and inner; they are both outer and inner experiences. Just try to think of all the experiences that are conveyed to you by any one of these senses, and you will see how, whilst in them all there is an experience lived in common with the outer world, there is at the same time an experience within yourself. If you drink an acid, and thus call into play your sense of taste, you have undoubtedly an inner experience with the acid, but you have also, on the other hand, an experience that is directed outwards, that can be compared with the experience of another man's ego or of the word. But it would be very bad if in the same way a subjective, inner experience were to be involved in listening to words. Just think, you make a wry face when you drink vinegar; that shows quite clearly that along with the outer experience you have an inner one; the outer and inner experiences merge into one another. If the same thing were to happen in the case of words, if, for example, someone were to make a speech, and you had to experience it inwardly in the way you do when you drink vinegar or wine or something of that sort, then you would certainly never be objectively clear about the man's words, about what he says to you. Just as in drinking vinegar you have an unpleasant experience and in drinking wine a pleasant one, so in the same way you would colour an external experience. You must not colour the external experience when you perceive the words of another. If you see things in the right light, that is just where morality comes in. For there are men—this is especially true as regards the ego-sense, but it also applies to the sense of thought—who are so firmly fixed in their middle senses, in the senses of warmth, sight, taste and smell, that they judge others, or the thoughts of others, in accordance with these senses. Then they do not hear the thoughts of the other men at all, but perceive them in the same way that they perceive wine or vinegar or any other food or drink.

Here we see how something of a moral nature is the outcome of a quite amoral manner of observation. Let us take a man in whom the sense of hearing, and even more the word-sense, the sense of thought and the ego-sense, are poorly developed. Such a man lives as it were without head; he uses his head-senses in the same way as he uses those of a more animal tendency. The animal is unable to perceive objectively in the way that, through the senses of warmth, sight, taste and smell, the man can perceive objective-subjectively. The animal smells; as you may well imagine, it can only in the very slightest degree make objective what it encounters in the sense of smell ... the experience is in a high degree a subjective one. Now all men, of course, have in addition the sense of hearing, the word-sense, the thought-sense and the ego-sense; but those whose whole organisation tends more towards the senses of warmth and sight, still more towards those of taste or even of smell, change everything around them according to their subjective experiences of taste and smell. Such things are to be seen every day. If you want an example, you can see it in the latest pamphlet by X. He is not in the least able to grasp the words or thoughts of another. He seizes hold of everything as if he were drinking wine or vinegar or eating some kind of food. Everything becomes subjective experience. To reduce the higher senses to the character of the lower ones is immoral. It is quite possible to bring the moral into connection with our whole world-conception, whereas at the present time the fact that men do not know how to build a bridge between what they call natural law and what they call morality, acts as a destructive influence undermining our entire civilisation.

When we come to the next four senses, to the sense of balance, the sense of movement, the sense of life and the sense of touch, we come to the specifically inner senses. For, you see, what the sense of balance conveys to us is our own state of balance; what the sense of movement conveys to us is the state of movement in which we ourselves are. Our sense of life is that general perception of how our organs are functioning, of whether they are promoting life or obstructing it. In the case of the sense of touch, it is possible to be deceived; nevertheless, when you touch something, the experience you have is an inner experience. You do not feel this chalk; roughly speaking, what you feel is the impact of the chalk on your skin ... the process can of course be characterised more exactly. In the sense of touch, as in the experience of no other sense in the same way, the experience lies in the reaction of your own inner being to an external process.

But now this last group of senses is modified by something else. You must recall something I said here a few weeks ago.2Lecture V of Irdische und kosmische Gesetzmassigkeiten, 3rd July, 1921. (Translation not yet published.) Let us consider the human being in relation to what he perceives through these last four senses. Although we perceive our own movement, our own balance, in a decidedly subjective manner, this movement and this balance are nevertheless quite objective processes, for physically speaking it is a matter of indifference whether it is a block of wood that is moved, or a man; whether it is a block of wood in balance or a man. In the external physical world a man in movement is exactly the same thing to observe as a block of wood; and similarly with regard to balance. And if you take the sense of life—the same thing applies. Our sense of life conveys to us processes that are quite objective. Imagine a process in a retort: it takes its course according to certain laws; it can be described quite objectively. What the sense of life perceives is such a process, a process which takes place inwardly. If this process is in order, as a purely objective process, this is conveyed to you by the sense of life; if it is not in order, the sense of life conveys this to you also. Even though the process is confined within your skin, the sense of life transmits it to you. To sum up, an objective process is something which has absolutely no specific connection with the content of your soul-life. And the same thing applies to your sense of touch. When we touch something, there is always a change in our whole organic structure. Our reaction is an organic change within us. Thus we have actually something objective in what is brought about through these four senses, something that so places us as human beings in the world that we are like objective beings who can also be seen in the external sense-world.

Thus we may say that these are pronounced inner senses; but what we perceive through them in ourselves is exactly the same as what we perceive in the world outside us. In short, whether we set in motion a log of wood, or whether the human being is in external motion, it makes no difference to the physical course of the process. The sense of movement is only there in order that what is taking place in the outer world may also come to our subjective consciousness.

Thus you see that the truly subjective senses are the senses which are specifically external; it is they which have the task of assimilating into our humanity what is perceived externally through them. The middle group of senses shows an interplay between the outer and the inner world. And through the last group a specific experience of what we are as part of the world-not-ourselves is conveyed to us.

We could carry this study much further; we should then discover many of the distinctive qualities of this sense or that. We only have to become accustomed to the idea that the treatment of the senses must not be limited to describing them according to their more obvious organs, but that we must analyse them according to their field of experience. It is by no means correct, for instance, that no specific organ exists for the word-sense; only its field has not been discovered by the materialistic physiology of to-day. Or take the sense of thought—that too is there, but has not been explored as has, let us say, the sense of sight.

When we consider man in this way, it cannot fail to be borne in upon us that what we usually call soul-life is bound up with what we may call the higher senses. If we want to encompass the content of what we call soul-life, we can scarcely go further than from the ego-sense to the sense of sight. If you think of all that you have through the ego-sense, the sense of thought, the word-sense, the sense of hearing, the sense of warmth and the sense of sight, you have practically the whole range of what we call soul-life. Something of the characteristics of the specifically outer senses still enters a little into the sense of warmth, upon which our soul-life is much more dependent than we usually think. And of course the sense of sight has a very wide significance for our whole soul-life. But with the senses of taste and smell we are already entering into the animal realm, and with the senses of balance, movement and life and so on, we plunge completely into our bodily nature. These senses we perceive altogether inwardly.

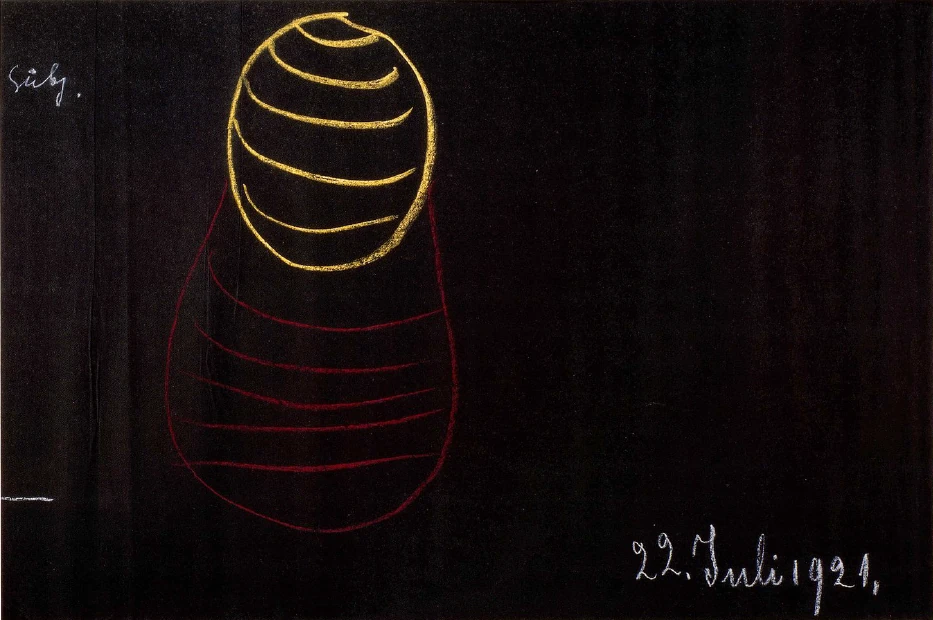

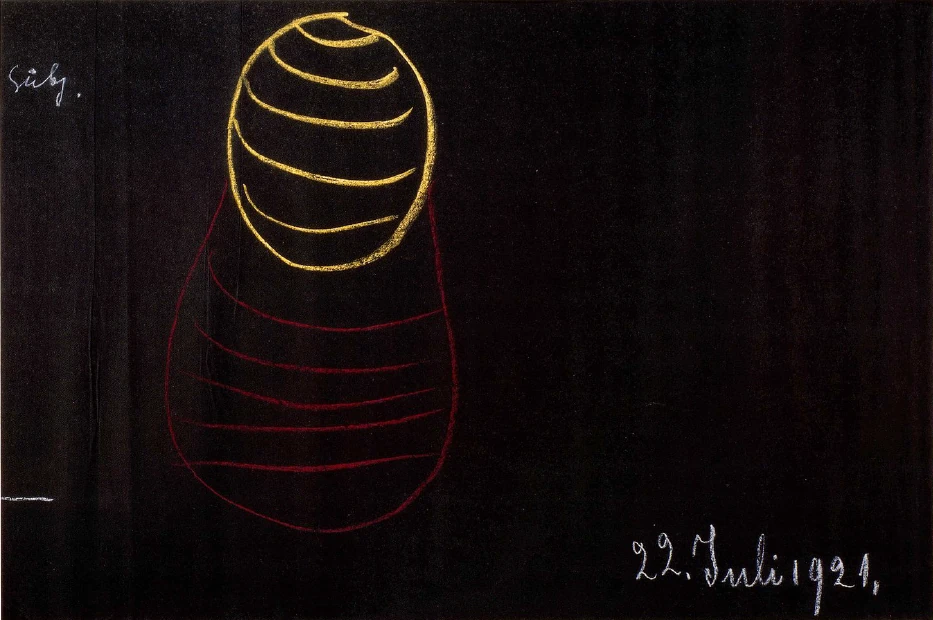

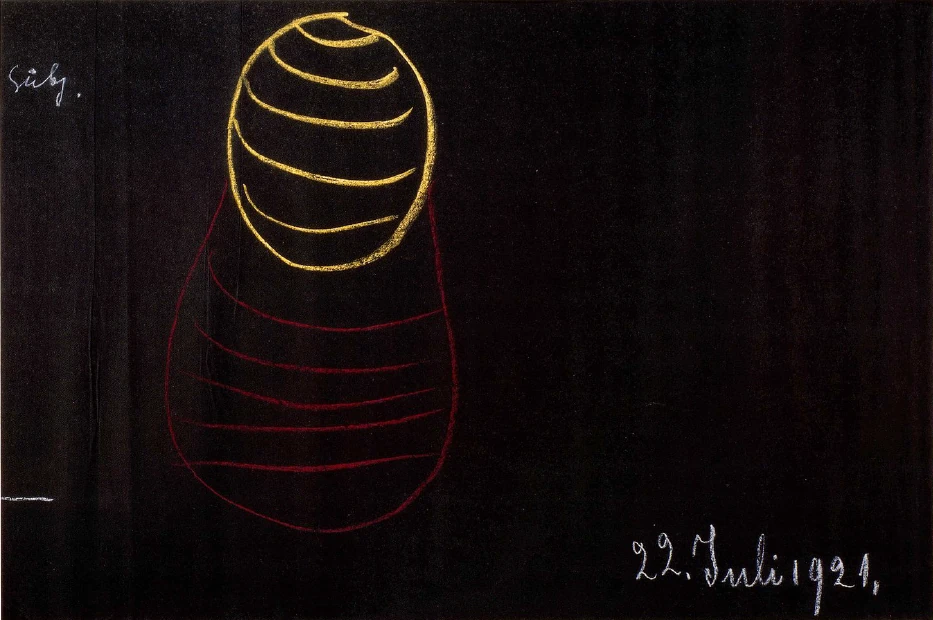

If we want to show this diagrammatically, we should have to show it like this (see diagram). We draw a circle around the upper region; and there in this upper sphere lies our true inner life. Without these external senses, this inner life could not exist. What sort of men should we be if we had no other egos near us, if we were never to perceive words and thoughts? Just imagine! On the other hand, the senses from taste downwards (see diagram B) perceive in an inward direction, transmit primarily inward processes, but processes which become progressively more obscure. Of course, a man must have a clear perception of his own balance otherwise he would become giddy and collapse. To fall into a faint is the same thing for the sense of balance as blindness is for the eyes. But now what these other senses mediate becomes vague and confused. The sense of taste still develops to some extent on the surface. There we do have a clear consciousness of it. But although our whole body tastes (with the exception of the limb-system, but actually even that too), very few men are able to detect the taste of foods in the stomach, because civilisation, or culture, or refinement of taste has not developed so far in that direction. Very few men indeed can still detect the taste of the various foodstuffs in their stomachs. You do still taste them in some of the other organs, but once the foodstuffs are in the stomach, then for most men it is all one what they are—although unconsciously the sense of taste does very clearly continue throughout the whole digestive tract. The entire man tastes what he eats, but the sensation very quickly dies down when what has been eaten has been given over to the body.

The entire man develops throughout his organism the sense of smell, the passive relationship to aromatic bodies. This sense again is only concentrated at the very surface, whereas actually the whole man is taken hold of by the scent of a flower or by any other aromatic substance. When we know that the senses of taste and smell permeate the entire man, we know too what is involved in the experience of tasting or smelling, how the experience is continued further inwards; and when one knows what it is to taste, for instance, one abandons altogether the materialistic conception. And if one is clear that this process of tasting goes through the entire organism, one is no longer inclined to describe the further process of digestion purely from the chemical point of view, as is done by the materialistic science of to-day.

On the other hand, it cannot be gainsaid that there is an immense difference between what I have shown in the diagram as yellow and what I have shown as red (It has not been practicable to produce the diagram in colour.) There is an immense difference between the content of what we have in our soul-life through the ego-sense, word-sense and so on, and the experiences we have through taste, smell, movement, life-sense and so on. And you will understand this difference best if you make clear to yourselves how you receive what you experience in yourselves when you listen, let us say, to the words of another man, or to a musical sound. What you then experience in yourselves is of no significance for the outer process. What difference does it make, to the bell that you are listening to it? The only connection between your inner experience and the process that takes place in the bell is that you are listening to it.

You cannot say the same thing when you consider the objective process in tasting or smelling, or even in touching. There you have to do with a world-process. You cannot separate what goes on in your organism from what takes place in your soul. You cannot say in this case, as in the case of the ringing bell, “What difference does it make to the bell whether I listen to it?” You cannot say, “When I drink vinegar, what has the process which takes place on my tongue to do with what I experience?” That you cannot say. There, an inner connection does obtain; there the objective and the subjective processes are one.

The sins committed by modern physiology in this sphere are well-nigh incredible, when one considers that such a process as tasting is placed in a similar relationship to the soul as that of seeing or hearing. And there are philosophical treatises which speak in a purely general way of sensible qualities and their relation to the soul. Locke, and even Kant, speak generally of a relationship of the outer sense-world to human subjectivity, whereas for all that is shown in our diagram from the sense of sight upwards, we have to do with something quite different from all that the diagram shows from the sense of sight downwards. It is impossible to apply one single doctrine to both these spheres. And it is because men have done so that, from the time of Hume or Locke or even earlier, this great confusion has arisen in the theory of knowledge which has rendered modern conceptions barren right into the sphere of physiology. For one cannot approach the real nature of processes if one thus pursues preconceived ideas without an unprejudiced observation of things.

When we picture the human being in this way, we have to understand that in the one direction we have obviously a life directed inwards, a sphere in which we live for ourselves, related to the outer world merely in perceiving it; in the other direction, of course, we also perceive—but we enter into the world by what we perceive. In short, we may say: What takes place on my tongue when I taste is an entirely objective process in me; when this process goes on in me, it is a world-process that is taking place. But I cannot say that what arises in me as a picture through the sense of sight is a world-process. Were it not to happen, the whole world would remain as it is. The difference between the upper and the lower man must always be borne in mind. Unless we bear this difference in mind we cannot get any further in certain directions.

Now let us consider mathematical truths, the truths of geometry. A superficial observer would say: Oh yes, of course man gets his mathematics out of his head, or from somewhere or other (ideas on the subject are not very precise). But it is not so. Mathematics derives from an altogether different sphere. And if you study the human being, you will get to know the sphere from which mathematics comes. It is from the sense of movement and the sense of balance. It is from such depths that mathematical thought comes, depths to which we no longer penetrate with our ordinary soul-life. What enables us to develop mathematics lives at a deeper level than our ordinary soul-life. And thus we see that mathematics is really rooted in that part of us which is at the same time cosmic. In fact, we are only really subjective in what lies here (see diagram) from the sense of sight upwards. In respect of what lies down there we are like logs, as much so as the rest of the outer world. Hence we can never say that geometry, for instance, has anything of a subjective nature in it, for it originates from that in us wherein we ourselves are objective. It is concerned with the very same space which we measure when we walk, and which our movements communicate to us—the very same space which, when we have elicited it from ourselves in pictorial form, we then proceed to apply to what we see. Nor can there be any question of describing space as in any way subjective, for it does not come from the sphere whence the subjective arises.

Such a way of looking at things as I am now putting before you is poles apart from Kantianism, because Kantianism does not recognise the radical distinction between these two spheres of human life. Followers of Kant do not know that space cannot be subjective, because it arises from that sphere in man which is in itself objective, from that sphere to which we relate ourselves as objects. We are connected with this sphere in a different way from the way in which we are related to the world outside us; but it is nevertheless genuine outer world, especially each night, for while we are asleep we withdraw from it with our subjectivity, our ego and our astral body.

It is essential to understand that to assemble an immense number of external facts for what purports to be science and is intended to promote culture is useless if its thought is full of confused ideas, if this science lacks clear concepts about the most important things. And if the forces of decadence are to be checked and the forces of renewal, of progress, furthered, the essential task which confronts us is to understand the absolute necessity of reaching clear ideas, ideas that are not hazy but clear-cut. We must be absolutely clear that it is useless to proceed from concepts and definitions, but that what is needed is the unprejudiced observation of the field in which the facts lie.

For example, no one is entitled to delimit the sphere of sight as a sense-sphere, if he does not at the same time distinguish the sphere of word-perception as a similar sphere. Only try to organise the sphere of total experience as I have often done, and you will see that it is not permissible to say: We have eyes, therefore we have a sense of sight and we are studying it. But you will have to say: Of course there must be a reason for the fact that sight has a physical-sensible organ of so specific a nature, but this does not justify us in restricting the range of the senses to those which have clearly perceptible physical organs. If we do that it will be a very long time before we shall reach any higher conception; we shall meet only what happens in everyday life. The important thing is really to distinguish between what is subjective in man, what is his inner soul-life, and the sphere wherein he is actually asleep. There, man is a cosmic being in relation to all that is conveyed by his senses. In that sphere he is a cosmic being. In your ordinary soul-life you know nothing of what happens when you move your arm—not at least without a faculty of higher vision. That movement is a will-activity. It is a process which lies as much outside you as any other external process, notwithstanding the fact that it is so intimately connected with you. On the other hand, there can be no idea, no mental image, in which we are not ourselves present with our consciousness. Thus when you distinguish these three spheres, you find something else as well. In all that your ego-sense, your thought-sense, your word-sense, your sense of hearing convey to you, thereby constituting your soul-life, you receive what is predominantly associated with the idea.

In the same way, everything connected with the senses of warmth, sight, taste and smell has to do with feeling. That is not quite obvious with regard to one of these senses, the sense of sight. It is quite obvious with regard to taste, smell and warmth, but if you look into the matter closely you will find that it is also true of sight.

In contrast with this, all that has to do with the senses of balance, movement, life, and even with the sense of touch (although that is not so easy to see, because the sense of touch retires within us) is connected with the will. In human life, everything is connected, and yet everything is metamorphosed. I have tried to-day to summarise for you what I have treated at length on various occasions. And tomorrow and the day after we will carry our study to a conclusion.

Vierzehnter Vortrag

Wir fahren fort in der Betrachtung des Verhältnisses des Menschen zur Welt, und um die Betrachtungen der nächsten Tage an dasjenige anschließen zu können, was ich vorgebracht habe in der letzten Zeit, möchte ich heute zunächst an ein Kapitel unserer anthroposophischen Anschauung anknüpfen, das ich vor längerer Zeit behandelt habe, nämlich an die im anthroposophischen Sinne gehaltene Sinneslehre. Ich sagte vor längerer Zeit und immer wieder, daß ja die äußere Wissenschaft von unseren Sinnen nur diejenigen betrachtet, für die im gröberen Sinne Organe vorhanden sind, wie der Sehsinn, der Gehörsinn und so weiter. Diese Betrachtungsweise kann in einem tieferen Sinne deshalb nicht befriedigen, weil das Gebiet, das zum Beispiel das Sehen von unserer Erfahrung, von unserer Gesamterfahrung umfaßt, ein ebenso abgegrenztes ist innerhalb der Gesamtsumme unserer Erlebnisse, wie, sagen wir die Wahrnehmung des fremden Ich oder die Wahrnehmung der Bedeutung von Worten. Es ist ja heute, wo in einem gewissen Sinne alle Dinge auf den Kopf gestellt werden, durchaus auch üblich geworden, zu sagen: Wenn wir dem fremden Ich gegenüberstehen, dann sehen wir zunächst die menschliche Gestalt. Wir wissen, daß wir diese menschliche Gestalt selber haben, daß bei uns diese menschliche Gestalt ein Ich beherbergt, und so schließen wir, daß auch in der uns ähnlich schauenden fremden menschlichen Gestalt ein Ich enthalten sei. — Es ist nicht das geringste wirkliche Bewußtsein von dem vorhanden, was in der ganzen Unmittelbarkeit der Wahrnehmung des andern Ich liegt, wenn man einen solchen Schluß zugrunde legt. Er ist völlig sinnlos. Denn genau in derselben Weise, wie wir unmittelbar der Außenwelt gegenüberstehen und ein gewisses Gebiet von ihr umfassen durch unseren Sehsinn, ebenso dringt in unser Erlebnisgebiet in unmittelbarer Weise hinein das fremde Ich. Wir müssen, wenn wir uns einen Sehsinn zuschreiben, uns so auch einen Ichsinn zuschreiben.

Es ist dabei vor allen Dingen das festzuhalten, daß dieser Ichsinn durchaus etwas anderes ist als die Entwickelung des Bewußtseins des eigenen Ich. Es ist ein völlig anderer Vorgang, dieses Bewußtwerden des eigenen Ich, was ja eigentlich kein Wahrnehmen ist, und der Vorgang, der sich abspielt, wenn wir ein fremdes Ich als solches wahrnehmen. Ebenso liegt ein ganz anderes zugrunde, wenn wir Worten zuhören und in den Worten eine Bedeutung vernehmen, als dann, wenn wir den bloßen Ton, den bloßen Klang vernehmen. Wenn es auch zunächst schwieriger ist, für den Wortesinn ein menschliches Organ nachzuweisen als für den Tonsinn das Gehörorgan, so muß doch derjenige, der nun wirklich unser gesamtes Erfahrungsfeld analysieren kann, gewahr werden, daß wir innerhalb dieses Erfahrungsfeldes begrenzen müssen auf der einen Seite den Ton- und Lautsinn, den Klangsinn, und auf der andern Seite den Wortesinn. Und wiederum ein anderes ist es, innerhalb der Worte, innerhalb der Wortgestaltungen und innerhalb der Wortzusammenhänge namentlich, den Gedanken des andern wahrzunehmen. Und wiederum müssen wir unterscheiden zwischen dem Wahrnehmen des Gedankens des andern und dem eigentlichen Denken. Nur eben die grobe Art, wie heute Seelenerscheinungen betrachtet werden, die kommt nicht dazu, in dieser feineren Weise zu analysieren zwischen dem Denken, das wir als eine innere Tätigkeit unseres Seelenlebens entfalten, und der nach außen gerichteten Tätigkeit, die im Gedankenwahrnehmen des andern liegt. Gewiß, wir müssen, wenn der Gedanke des andern wahrgenommen wird, um diesen Gedanken zu verstehen, um diesen Gedanken mit andern Gedanken, die wir auch schon gehegt haben, in Beziehung zu bringen, dann denken. Aber dieses Denken ist etwas völlig anderes als das Wahrnehmen des Gedankens des andern.

Dann aber, wenn wir alles das, was nun im Umkreise unserer Gesamterfahrung vorhanden ist, gliedern, analysieren in die Gebiete, die wirklich spezifisch voneinander verschieden sind und die doch wiederum eine gewisse innerliche Verwandtschaft so haben, daß wir sie als Sinne bezeichnen können, dann kommen wir zu den zwölf Sinnen des Menschen, die ich öfter angegeben habe. Heute ist ja eines der schwächsten Kapitel unserer gegenwärtigen Wissenschaft dasjenige, das vom physiologischen oder vom psychologischen Standpunkte die Sinne behandelt, denn im Grunde genommen wird von den Sinnen im Allgemeinen gesprochen.

Nun ist natürlich innerhalb des Sinnesgebietes der Gehörsinn zum Beispiel, sagen wir, radikal verschieden vom Gesichtssinn oder vom Geschmackssinn. Und wiederum, wenn man zu einem deutlichen Begreifen vom Gehörsinn oder vom Gesichtssinn kommt, dann muß man auch einen Wortesinn, einen Gedankensinn und einen Ichsinn unterscheiden. Die meisten Begriffe, die heute gangbar sind, wenn die Wissenschaft von den Sinnen spricht, sind eigentlich von dem Tastsinn genommen. Und unsere Philosophie hat es sich schon einmal angewöhnt, darauf eine ganze Erkenntnistheorie zu gründen, die eigentlich in nichts anderem besteht als in der Übertragung einiger Wahrnehmungen, die auf den Tastsinn bezüglich sind, auf das ganze Gebiet der Wahrnehmungsfähigkeit.

Wenn wir nun in Wirklichkeit analysieren das Gesamtgebiet, den Umkreis unserer äußeren Erlebnisse, die wir in ähnlicher Weise wahrnehmen, sagen wir, wie die Seherlebnisse oder wie die Tasterlebnisse oder wie die Wärmeerlebnisse, dann kommen wir zu zwölf deutlich voneinander unterscheidbaren Sinnen, die ich ja früher öfter in folgender Weise aufgezählt habe: erstens der Ichsinn, der, wie gesagt, zu unterscheiden ist von dem Bewußtsein des eigenen Ich; mit Ichsinn wird nichts anderes bezeichnet als die Fähigkeit, das Ich des andern wahrzunehmen. Das zweite ist der Gedankensinn, das dritte ist der Wortesinn, das vierte ist der Gehörsinn, das fünfte ist der Wärmesinn, das sechste der Sehsinn, das siebente der Geschmackssinn, das achte der Geruchssinn, das neunte der Gleichgewichtssinn. Wer auf diesem Gebiete wirklich analysieren kann, der weiß, daß es ein ganz begrenztes Gebiet des Wahrnehmens gibt, ebenso wie das Gebiet des Sehens, ein begrenztes Gebiet, das uns einfach eine Empfindung davon vermittelt, daß wir als Mensch in einem gewissen Gleichgewichte stehen. Ohne daß ein Sinn uns vermitteln würde dieses Stehen im Gleichgewichte oder dieses Schweben und Tanzen im Gleichgewichte, ohne dies würden wirdurchaus nicht unser Bewußtsein vollständig aufbauen können.

Dann ist der Bewegungssinn das nächste. Der Bewegungssinn ist die Wahrnehmung dessen, ob wir in Ruhe oder in Bewegung sind. Diese Wahrnehmung müssen wir genau ebenso in uns erleben, wie wir erleben unsere Gesichtswahrnehmung. Elftens der Lebenssinn, zwölftens der Tastsinn (siehe Zeichnung Seite 25).

Ichsinn

Gedankensinn

Wortesinn

GehörsinnWärmesinn

Sehsinn

Geschmackssinn

GeruchssinnGleichgewichtssinn

Bewegungssinn

Lebenssinn

Tastsinn

Diese Gebiete, die ich Ihnen hier als Sinnesgebiete aufgeschrieben habe, man kann sie deutlich voneinander unterscheiden, und man kann zugleich in ihnen das Verwandte finden, daß wir uns wahrnehmend durch diese Sinne verhalten. Es ist unser Verkehr mit der Außenwelt, unser erkennender Verkehr mit der Außenwelt, den uns diese Sinne vermitteln; allerdings in einer sehr verschiedenen Weise mit Bezug auf die Außenwelt. Wir haben zunächst vier Sinne, die uns in zweifelloser Weise mit der Außenwelt verbinden, wenn ich das Wort zweifellos in diesem Falle gebrauchen darf; das sind: der Ichsinn, der Gedankensinn, der Wortesinn und der Gehörsinn. Es wird Ihnen ohne weiteres klar sein, daß wir mit unserem ganzen Erleben gewissermaßen in der Außenwelt sind, wenn wir das Ich eines andern wahrnehmen, ebenso wenn wir die Gedanken oder die Worte eines andern wahrnehmen. Nicht so einleuchtend könnte das sein in bezug auf den Gehörsinn; aber das kommt ja nur davon her, weil man in einer Art abstrakter Anschauung über alle Sinne so eine gemeinsame Begriffsnuance ausgegossen hat, die eben ein gemeinsamer Begriff, eine gemeinsame Idee eines Sinneslebens sein soll, und man nicht eigentlich das Spezifische der einzelnen Sinne ins Auge faßt. Natürlich kann man diese Dinge nicht, ich möchte sagen, im äußeren Experimente auf ihre Begriffe bringen, sondern dazu ist schon notwendig, daß man eben die Fähigkeit des Anfühlens der Erlebnisse hat.

Das gewöhnliche Denken befaßt sich ja zum Beispiel gar nicht damit, wie das Hören dadurch, daß der Vermittler des Hörens die bewegte Luft, also ein Physisches ist, im Grunde genommen uns unmittelbar in die Außenwelt hinausbringt. Und wenn Sie einfach ins Auge fassen, wie sehr äußerlich der Gehörsinn eigentlich gegenüber unserem ganzen organischen inneren Erleben ist, so werden Sie bald darauf kommen, daß Sie den Gehörsinn in dieser Weise anders fassen müssen als zum Beispiel den Sehsinn. Beim Sehsinn wird man einfach aus der Betrachtung des Organs, des Auges, bald ersehen können, wie dasjenige, was da vermittelt wird, doch in einem hohen Maße ein innerer Vorgang, wenigstens relativ ein innerer Vorgang ist. Wir schließen das Auge, wenn wir schlafen, wir schließen das Ohr nicht, wenn wir schlafen. In solchen Dingen, die scheinbar triviale, einfache Tatsachen sind, drückt sich aber tief Bedeutsames für das ganze Leben des Menschen aus. Und wenn wir beim Schlafen genötigt sind, unser Inneres abzuschließen, weil wir nicht wahrnehmen sollen durch das Sehen, so sind wir eben nicht genötigt, unser Ohr abzuschließen, weil das in einer ganz andern Weise in der Außenwelt drinnen lebt als das Auge. Das Auge ist viel mehr Bestandteil unseres Inneren. Die Sehwahrnehmung ist viel mehr nach innen gerichtet als die Gehörwahrnehmung. Nicht die Empfindung des Gehörten, das ist ja etwas anderes. Die Empfindung des Gehörten, die dem Musikalischen zugrunde liegt, das ist etwas anderes als der eigentliche Gehörvorgang.

Diese Sinne nun, die im wesentlichen, ich möchte sagen, das Äußere und das Innere vermitteln, das sind ausgesprochen äußere Sinne (siehe Zeichnung Seite 25). Diejenigen Sinne, die sozusagen auf der Kippe stehen zwischen Außerem und Innerem, die ebenso äußeres wie inneres Erleben sind, das sind die vier nächsten Sinne: der Wärmesinn, der Sehsinn, der Geschmackssinn, der Geruchssinn. Versuchen Sie nur einmal die ganze Summe der Erlebnisse, die durch einen dieser Sinne gegeben ist, sich vor Augen zu führen, und Sie werden sehen, wie da auf der einen Seite bei all diesen Sinnen ein Miterleben mit der Außenwelt vorhanden ist, aber zu gleicher Zeit ein Erleben im eigenen Inneren. Wenn Sie Essig trinken, also Ihr Geschmackssinn in Betracht kommt, haben Sie ganz gewiß auf der einen Seite ein inneres Erlebnis mit dem Essig und auf der andern Seite ein Erlebnis, das nach außen gerichtet ist, das man vergleichen kann mit dem Erleben eines äußeren Ich zum Beispiel oder der Worte. Aber es würde sehr schlimm sein, wenn man in demselben Sinne ein subjektives, ein inneres Erlebnis, sagen wir, dem Anhören der Worte beimischen würde. Denken Sie sich einmal, wenn Sie Essig trinken, Sie verziehen das Gesicht; das deutet Ihnen ganz klar an, daß Sie da ein inneres Erlebnis mit dem äußeren Erlebnis haben, daß äußeres Erlebnis und inneres Erlebnis ineinanderschwimmen. Würde dasselbe bei den Worten der Fall sein, wenn Ihnen zum Beispiel einer eine Rede hielte und Sie in derselben Weise innerlich miterleben müßten wie beim Essigtrinken oder beim Moselweintrinken oder dergleichen, dann würden Sie ja niemals in einer objektiven Weise sich über die Worte klar sein, die der andere Ihnen sagt. In demselben Maße, wie Sie beim Essig ein unangenehmes und beim Moselwein ein angenehmes inneres Erlebnis haben, in demselben Maße tingieren Sie ein äußeres Erlebnis. Dieses äußere Erlebnis dürfen Sie nicht tingieren, wenn Sie wahrnehmen, sagen wir, die Worte des andern. Man kann sagen: Hier sieht man das Hereinragen des Moralischen in dem Augenblicke, wo man die Dinge im rechten Lichte sieht. - Denn es gibt allerdings Menschen, die namentlich in bezug auf den Ichsinn, aber auch in bezug auf den Gedankensinn sich so verhalten, daß man sagen kann, die Menschen stecken so stark in ihren mittleren Sinnen, im Wärmesinn, Sehsinn, Geschmackssinn und Geruchssinn drinnen, daß sie auch die andern Menschen oder deren Gedanken so beurteilen. Dann hören sie aber gar nicht die Gedanken oder die Worte des andern, sondern sie nehmen sie so wahr, wie zum Beispiel eben, sagen wir, Moselwein oder Essig oder irgendein anderes Getränk oder eine Speise wahrgenommen wird.

Hier sehen wir, wie etwas Moralisches einfach aus einer sonst ganz amoralischen Betrachtungsweise sich ergibt. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel einen Menschen, bei dem der Gehörsinn, namentlich aber der Wortesinn, der Gedankensinn und der Ichsinn schlecht ausgebildet sind. Ein solcher Mensch lebt gewissermaßen, sagen wir, ohne Kopf, das heißt, er gebraucht seine Kopfsinne auch in einer ähnlichen Weise, wie die mehr schon dem Animalischen zugeneigten Sinne. Das Tier kann nicht in dieser Weise objektiv wahrnehmen, wie es objektiv-subjektiv wahrnehmen kann durch Wärmesinn, Sehsinn, Geschmackssinn, Geruchssinn. Das Tier riecht: Sie können sich vorstellen, daß das Tier in sehr geringem Maße objektiv dasjenige sich vergegenständlichen kann, was ihm entgegentritt, sagen wir zum Beispiel beim Geruchssinn. Es ist in hohem Grade ein subjektives Erlebnis. Nun, natürlich haben ja alle Menschen auch Gehörsinn, Wortesinn, Gedankensinn, Ichsinn; aber diejenigen, die mehr sich hineinlegen mit ihrer ganzen Organisation in den Wärmesinn und Sehsinn, namentlich aber in den Geschmacksoder gar Geruchssinn, die verändern alles nach ihrem subjektiven Geschmack oder nach ihrem subjektiven Riechen der Umgebung. Nicht wahr, solche Dinge kann man ja täglich im Leben wahrnehmen. Wenn Sie ein Beispiel haben wollen, so können Sie ja nur beachten, wie es Menschen gibt, die gar nichts objektiv wahrnehmen können, sondern alles so wahrnehmen, wie man sonst nur durch Geschmacks- und Geruchssinn wahrnimmt. Das können Sie in der neuesten Broschüre des Pfarrers Kully wahrnehmen. Der ist gar nicht imstande, Worte oder Gedanken des andern aufzufassen, er faßt alles so auf, wie man Wein trinkt, oder Essig trinkt, oder irgendeine Speise ißt. Da wird alles subjektives Erlebnis. In demselben Sinne wird es unmoralisch, indem man die höheren Sinne hinunterrückt zum Charakter der niederen Sinne. Es gibt eben durchaus die Möglichkeit, die Moral in Zusammenhang zu bringen mit der ganzen Weltanschauung, während in der Gegenwart das Zerstörerische, das unsere ganze Zivilisation Untergrabende darin liegt, daß man keine Brücke zu schlagen weiß zwischen dem, was man Naturgesetzlichkeit nennt und was man moralisch nennt.

Wenn wir nun zu den nächsten vier Sinnen kommen, zu dem Gleichgewichtssinn, Bewegungssinn, Lebenssinn und Tastsinn, so kommen wir zu ausgesprochen inneren Sinnen. Wir haben es da zunächst mit ausgesprochen inneren Sinnen zu tun. Denn das, was uns der Gleichgewichtssinn übermittelt, ist unser eigenes Gleichgewicht, was uns der Bewegungssinn übermittelt, ist der Zustand der Bewegung, in dem wir sind. Unser Lebenszustand ist dieses allgemeine Wahrnehmen, wie unsere Organe funktionieren, ob sie unserem Leben förderlich sind oder abträglich sind und so weiter. Beim Tastsinn könnte es täuschen; dennoch aber, wenn Sie irgend etwas betasten, so ist das, was Sie da als Erlebnis haben, ein inneres Erlebnis. Sie fühlen gewissermaßen nicht die Kreide, sondern Sie fühlen die zurückgedrängte Haut, wenn ich mich grob ausdrücken darf; der Vorgang ist natürlich viel feiner zu charakterisieren. Es ist die Reaktion Ihres eigenen Inneren auf einen äußeren Vorgang, der da im Erlebnis vorliegt, der in keinem andern Sinneserlebnis in derselben Weise vorliegt wie im Tasterlebnis.

Nun aber wird allerdings diese letztere Gruppe der Sinne durch etwas anderes modifiziert. Da müssen Sie sich erinnern an etwas, das ich vor einigen Wochen hier gesagt habe. Nehmen Sie den Menschen in bezug auf das, was durch diese letzten vier Sinne wahrgenommen wird; es sind, trotzdem wir die Dinge wahrnehmen — unsere eigene Bewegung, unser eigenes Gleichgewicht -, es sind, trotzdem wir das, was wir wahrnehmen, auf entschieden subjektive Weise nach innen hin wahrnehmen, dennoch aber Vorgänge, die ganz objektiv sind. Das ist das Interessante an der Sache. Wir nehmen diese Dinge nach innen hin wahr, aber was wir da wahrnehmen, sind ganz objektive Dinge, denn es ist im Grunde genommen physikalisch gleichgültig, ob, sagen wir, ein Holzklotz sich bewegt oder ein Mensch, ob ein Holzklotz im Gleichgewicht ist oder ein Mensch. Für die äußere physische Welt in ihrer Bewegung ist der sich bewegende Mensch ganz genau ebenso zu betrachten wie ein Holzklotz; ebenso mit Bezug auf das Gleichgewicht. Und wenn Sie den Lebenssinn nehmen, so ist es zunächst allerdings nicht in bezug auf die äußere Welt - scheinbar allerdings nur —, aber es ist so, daß das, was unser Lebenssinn übermittelt, ganz objektive Vorgänge sind. Stellen Sie sich vor einen Vorgang in einer Retorte: er verläuft nach gewissen Gesetzen, kann objektiv beschrieben werden. Das, was der Lebenssinn wahrnimmt, ist ein solcher Vorgang, der nach innen gelegen ist. Ist er in Ordnung, dieser Vorgang, ganz als objektiver Vorgang, so übermittelt Ihnen dieses der Lebenssinn, oder ist er nicht in Ordnung, so überliefert Ihnen der Lebenssinn auch das. Wenn auch der Vorgang in Ihrer Haut eingeschlossen ist, der Lebenssinn übermittelt es. Ein objektiver Vorgang ist schließlich gar nichts, was zunächst mit dem Inhalt Ihres Seelenlebens einen besonderen Zusammenhang hat. Und ebenso beim Tastsinn; es ist immer eine Veränderung in der ganzen organischen Struktur, wenn wir wirklich tasten. Unsere Reaktion ist eine organische Veränderung in unserem Inneren. Wir haben also durchaus in dem, was wir mit diesen vier Sinnen gegeben haben, eigentlich ein Objektives gegeben, ein solches, was uns als Menschen so in die Welt hineinstellt, wie wir im Grunde genommen als objektive Wesen sind, die auch in der Sinneswelt äußerlich gesehen werden können.

So daß wir sagen können, es sind ausgesprochen innere Sinne, aber dasjenige, was wir durch sie wahrnehmen, ist an uns genauso wie das, was wir äußerlich in der Welt wahrnehmen. Ob wir schließlich einen Holzklotz in Bewegung setzen, oder ob der Mensch in äußerer Bewegung ist, darauf kommt es nicht an für den physikalischen Fortgang der Ereignisse. Der Bewegungssinn ist nur da, damit das, was in der Außenwelt geschieht, auch zu unserem subjektiven Bewußtsein kommt, wahrgenommen wird.

Sie sehen also, richtig subjektiv sind gerade die ausgesprochen äußeren Sinne. Die müssen dasjenige, was durch sie wahrgenommen wird, im ausgesprochenen Sinne in unsere Menschlichkeit hereinbefördern. Ich möchte sagen, ein Hin- und Herpendeln zwischen Außen- und Innenwelt stellt die mittlere Gruppe der Sinne dar, und ein ausgesprochenes Miterleben von etwas, was wir sind, indem wir der Welt angehören, nicht uns, ist uns durch die letzte Gruppe der Sinne übermittelt.

Diese Betrachtung könnte man sehr ausdehnen. Man würde vieles finden, was charakteristisch ist für den einen oder für den andern Sinn. Man muß sich eben nur bekanntmachen mit dem Gedanken, daß die Sinneslehre nicht so behandelt werden darf, daß man nur die Sinne beschreibt nach den gröberen Sinnesorganen, sondern nach der Analyse des Erlebnisfeldes. Es ist nämlich gar nicht richtig, daß zum Beispiel für den Wortesinn ein abgetrenntes Organ nicht vorhanden ist; es ist nur von der gewöhnlichen materialistischen Physiologie heute nicht in demselben Sinne in seiner Abgrenzung erforscht wie, sagen wir, das Gehörorgan. Oder der Gedankensinn, er ist auch da, aber er ist nicht in demselben Stil erforscht wie, sagen wir, der Sehsinn oder dergleichen.

Wenn wir so den Menschen übersehen, dann wird es uns stark auffallen müssen, wie eigentlich dasjenige Leben, das wir im gewöhnlichen Wortsinn Seelenleben nennen, gebunden ist an, sagen wir also, die höheren Sinne. Wir können fast nicht weiter gehen, als vom Ichsinn bis zum Sehsinn, wenn wir den Inhalt dessen, was im gewöhnlichen Wortsinn Seelenleben genannt ist, umfassen wollen. Vergegenwärtigen Sie sich alles das, was Sie durch Ichsinn, Gedankensinn, Wortesinn, Lautsinn, Wärmesinn, Sehsinn haben, dann werden Sie ungefähr den Umfang dessen haben, was Sie seelisches Leben nennen. Es ragt eben aus diesen ausgesprochen äußeren Sinnen, von den Eigenschaften dieser ausgesprochen äußeren Sinne noch etwas hinein in den Wärmesinn, von dem wir im Seelenleben viel mehr abhängig sind, als wir gewöhnlich denken. Der Sehsinn hat ja eine ungeheuer weite Bedeutung für das gesamte Seelenleben. Aber wir dringen schon in das Animalische hinunter mit dem Geschmackssinn, mit dem Geruchssinn, und dringen völlig in unsere Körperlichkeit hinunter mit dem Gleichgewichtssinn, Bewegungssinn, Lebenssinn und so weiter. Die nehmen gewissermaßen schon ganz nach innen hin wahr, als dasjenige, was nicht mehr unserem Seelenleben angehört.

Wollten wir schematisch unser menschliches Wesen zeichnen, so müßten wir so zeichnen: Wir müßten sagen, wir umfassen das obere Gebiet, und darinnen, in diesem oberen Gebiete, da ruht unser eigentliches Innenleben (gelb). Dieses Innenleben kann ja gar nicht da sein, wenn wir nicht gerade diese äußeren Sinne haben. Was wären wir als ein Mensch, der keine andern Iche neben sich hätte? Was wären wir als ein Mensch, der niemals Worte, Gedanken und so weiter vernommen hätte? Malen Sie sich das nur aus. Dagegen dasjenige, was dann vom Geschmackssinn nach abwärts liegt, das nimmt nach innen hin wahr, das vermittelt zunächst Vorgänge nach innen (rot). Aber die werden ja immer unklarer und unklarer. Gewiß, der Mensch muß ein ganz deutliches Wahrnehmen haben seines eigenen Gleichgewichtes, sonst würde er ohnmächtig und umfallen. Ohnmächtig umfallen bedeutet für den Gleichgewichtssinn nichts anderes, als blind werden für die Augen. Nun aber, es wird undeutlich, was diese Sinne vermitteln. Der Geschmackssinn, der entwickelt sich, ich möchte sagen, noch gewissermaßen an der Oberfläche, da ist ein deutliches Bewußtsein von diesem Geschmackssinn vorhanden. Aber obwohl unser ganzer Körper, wenigstens mit Ausnahme des Gliedmaßenorganismus - aber auch eigentlich der -, obwohl unser ganzer Körper schmeckt, sind ja die wenigsten Menschen in der Lage, die verschiedenen Speisen noch im Magen zu schmecken, weil nach dieser Richtung heute doch, ja, wie soll ich jetzt sagen, Zivilisation oder Kultur, oder soll ich auch sagen Feinschmeckerei, nicht so weit ausgebildet ist. Die wenigsten Menschen können noch im Magen die verschiedenen Speisen schmecken. Sie schmecken sie gerade noch in den übrigen Organen. Aber wenn sie einmal im Magen sind, dann ist es den meisten Menschen ganz einerlei, wie sie sind, trotzdem unterbewußt der Geschmackssinn sich durch den ganzen Verdauungstrakt in sehr deutlicher Weise fortsetzt. Der ganze Mensch schmeckt im Grunde genommen dasjenige, was er zu sich nimmt, aber es stumpft sehr bald ab, wenn sich das Gegessene dem Körper mitteilt. Der ganze Mensch entwickelt durch seinen Organismus hindurch den Geruchssinn, das passive Verhalten zu den riechenden Körpern. Dieses konzentriert sich wiederum nur, ich möchte sagen, auf das alleroberflächlichste, während eigentlich der ganze Mensch ergriffen wird von einer riechenden Blume oder von irgendeinem andern riechenden Stoff und so weiter. Gerade wenn man dieses weiß, wie der Geschmackssinn und der Geruchssinn den ganzen Menschen durchdringen, dann weiß man auch, was in diesem Erlebnis des Riechens, des Schmeckens enthalten ist, wie sich das fortsetzt nach dem Inneren des Menschen, und man kommt ganz ab von jeder Art materialistischer Auffassung, wenn man weiß, was Schmecken zum Beispiel heißt. Und ist man sich klar darüber, daß dieser Schmeckensvorgang durch den ganzen Organismus geht, dann ist man nicht mehr imstande, so bloß chemiehaft den weiteren Verdauungsvorgang zu schildern, wie er von der heutigen materialistischen Wissenschaft geschildert wird.

Aber auf der andern Seite läßt sich ja nicht leugnen, daß ein gewaltiger Unterschied ist zwischen dem, was ich hier gelb bezeichnet habe, und dem, was ich hier schematisch rot bezeichnet habe: ein gewaltiger Unterschied zwischen dem Inhalt, den wir haben in unserem Seelenleben durch den Ichsinn, Wortesinn und so weiter, und den Erlebnissen, die wir durch Geschmacks-, Geruchs-, Bewegungs-, Lebenssinn und so weiter haben. Es ist ein gewaltiger, ein radikaler Unterschied. Und zwar werden Sie diesen Unterschied am besten einsehen, wenn Sie sich klarmachen, wie Sie aufnehmen, was Sie in sich selbst erleben, wenn Sie, sagen wir, die Worte eines andern Menschen anhören, oder wenn Sie einem Klang zuhören; was Sie da in sich selbst erleben, hat doch zunächst gar keine Bedeutung, also für sich, für den äußeren Vorgang gar keine Bedeutung. Was schert sich die Glocke darum, daß Sie sie hören! Da ist nur eben eine Verbindung zwischen Ihrem inneren Erlebnis und dem Vorgang, der sich in der Glocke abspielt, insofern Sie zuhören.

Dasselbe können Sie nicht sagen, wenn Sie den objektiven Vorgang beim Schmecken ins Auge fassen oder beim Riechen oder gar, sagen wir, beim Tasten. Da liegt durchaus ein Weltenvorgang vor. Was da in Ihrem Organismus vorgeht, das können Sie nicht trennen von demjenigen, was sich in Ihrer Seele abspielt. Sie können nicht sagen in diesem Falle wie bei der Glocke: Was schert sich die Glocke, die da klingt, darum, ob Sie ihr zuhören! - So können Sie nicht sagen: Was schert sich dasjenige, was auf der Zunge vorgeht, wenn Sie Essig trinken, um dasjenige, was Sie erleben! — Das können Sie nicht so sagen, da herrscht ein inniger Zusammenhang. Da ist das, was objektiver Vorgang ist, eins mit dem subjektiven Vorgang.

Die Sünden, die auf diesem Gebiete von der modernen Physiologie gemacht werden, streifen geradezu ans Unerhörte aus dem Grunde, weil man wirklich solch einen Vorgang, wie zum Beispiel das Schmekken, in einer ähnlichen Weise der Seele gegenüberstellt wie, sagen wir, das Sehen oder das Hören. Und es gibt philosophische Abhandlungen, die einfach ganz im allgemeinen von sinnlichen Qualitäten und ihrem Verhältnis zur Seele sprechen. Locke, selbst Kant, sie sprechen im allgemeinen von einem Verhältnis der sinnlichen Außenwelt zu der menschlichen Subjektivität, während etwas ganz anderes vorliegt für alles das, was vom Sehsinn nach aufwärts verzeichnet ist, und in dem, was vom Geschmackssinn nach abwärts verzeichnet ist. Es ist unmöglich, diese beiden Gebiete mit einer einzigen Lehre zu umfassen. Und da man es getan hat, ist diese ungeheure Verwirrung in der Erkenntnistheorie heraufgezogen, die etwa seit Hume oder Locke oder noch früher die modernen Begriffe geradezu verwüstet hat bis herauf in die moderne Physiologie. Denn man kann auf die Natur und das Wesen der Vorgänge nicht kommen, und damit auch nicht auf das Wesen des Menschen, wenn man in dieser Weise nach vorgefaßten Begriffen, ohne eine unbefangene Beobachtung, die Dinge verfolgt.

Wir müssen uns also klar sein, daß, indem wir so den Menschen vor uns hinstellen, wir auf der einen Seite deutlich ein nach innen gerichtetes Leben haben, das der Mensch für sich lebt, indem er einfach wahrnehmend sich zur Außenwelt verhält. Auf der andern Seite nimmt er allerdings auch wahr, aber mit dem, was er wahrnimmt, stellt er sich in die Welt hinein. Es ist, wenn ich mich etwas radikal ausdrücke, zum Schluß wiederum so, daß man sagen muß: Dasjenige, was auf meiner Zunge vorgeht, indem ich schmecke, das ist ganz als objektiver Vorgang in mir; indem er sich in mir abspielt, ist das ein Weltenvorgang. Während ich nicht sagen kann, daß dasjenige, was als Bild in mir ersteht durch das Sehen, zunächst ein Weltenvorgang ist. Es könnte wegbleiben, und die ganze Welt wäre so, wie sie ist. Dieser Unterschied zwischen dem oberen Menschen und dem unteren Menschen, der muß durchaus festgehalten werden. Wenn man ihn nicht festhält, dann wird man auf gewisse Richtungen gar nicht kommen können.

Wir haben mathematische Wahrheiten, geometrische Wahrheiten. Ein oberflächliches Menschenbetrachten denkt: Nun ja, der Mensch nimmt aus seinem Kopfe oder irgendwo heraus — nicht wahr, so bestimmt sind ja die Vorstellungen nicht, die man sich da macht — die Mathematik. — Aber das ist ja nicht so. Diese Mathematik kommt aus ganz andern Gebieten. Und wenn Sie den Menschen betrachten, so haben Sie ja die Gebiete gegeben, aus denen das Mathematische kommt: Es ist der Gleichgewichtssinn, es ist der Bewegungssinn. Aus solchen Tiefen herauf kommt das mathematische Denken, bis zu denen wir nicht mehr hinreichen, hinuntergehen mit unserem gewöhnlichen Seelenleben. Unter unserem gewöhnlichen Seelenleben lebt dasjenige, was uns heraufbefördert, was wir in mathematischen Gebilden entfalten. Und so sehen wir, daß das Mathematische eigentlich wurzelt in dem, was in uns zugleich kosmisch ist. Wir sind ja wirklich subjektiv nur mit dem, was vom Sehsinn hier nach aufwärts liegt; mit dem, was da hinunter liegt, wurzeln wir in der Welt. Wir sind darinnen in der Welt; mit dem, was aber darunter liegt, sind wir wie ein Holzklotz, ebenso wie die ganze übrige Außenwelt. Wir können daher niemals sagen, daß zum Beispiel die Raumlehre irgend etwas Subjektives haben könnte, denn sie entspringt aus dem in uns, worinnen wir selber objektiv sind. Es ist genau derselbe Raum, den wir durchmessen, wenn wir gehen und den uns unsere Bewegungen vermitteln, genau derselbe Raum, den wir dann, wenn wir ihn im Bilde aus uns herausgebracht haben, auf das Angeschaute verwenden. Vom Raume kann auch nicht die Rede sein, daß er irgendwie etwas Subjektives sein könnte, denn er entspringt nicht jenem Gebiete, aus dem das Subjektive entspringt.

Eine solche Betrachtungsweise, wie ich sie jetzt angestellt habe, liegt einfach allem Kantianismus ganz fern, weil der Kantianismus diese radikale Unterscheidung nicht kennt zwischen diesen zwei Gebieten im menschlichen Leben. Er weiß nicht, daß der Raum nichts Subjektives sein kann, weil der Raum aus dem Gebiete im Menschen entspringt, das an sich objektiv ist, demgegenüber wir uns objektiv verhalten. Wir sind nur anders mit ihm verbunden als mit der Außenwelt, aber es ist Außenwelt, richtige Außenwelt, und wird vor allen Dingen jede Nacht Außenwelt, indem wir uns mit unserer Subjektivität, dem Ich und astralischen Leib, schlafend zurückziehen.

Es ist notwendig, daß man einsieht: Es nützt nichts, möglichst viele äußere Tatsachen zusammenzutragen zu einer angeblichen Wissenschaft, die dann die Kultur weiter fördern soll, wenn innerhalb des Vorstellens und des Begreifens der Welt ganz konfuse Begriffe existieren, wenn über die wichtigsten Dinge keine klaren Begriffe existieren. Und das ist dasjenige, was wir als eine unbedingte Aufgabe jetzt vor uns haben, wenn den Niedergangskräften entgegengearbeitet und zu Aufgangskräften hingearbeitet werden soll: daß wir einsehen, wie es vor allen Dingen notwendig ist, zu klaren, nicht verschwommenen, sondern zu klaren Begriffen zu kommen. Man muß schon durchaus einsehen, daß das Ausgehen von Begriffen, das Ausgehen von Definitionen gar nichts bedeutet, sondern das vorurteilsfreie Anschauen der Tatsachengebiete.

Kein Mensch hat das Recht, zum Beispiel das Sehgebiet als etwas zu begrenzen, das er dann als ein Sinnesgebiet charakterisiert, wenn er nicht zugleich, sagen wir, das Gebiet der Wortewahrnehmung als ein ebensolches Gebiet absondert. Versuchen Sie es nur einmal, sich das Gebiet der gesamten Erfahrung so zu gliedern, wie ich das nun schon öfters gemacht habe, und Sie werden sehen, daß Sie sich nicht sagen dürfen: Wir haben Augen, also haben wir einen Sehsinn, und wir betrachten den Sehsinn. - Sondern Sie werden sich sagen müssen: Gewiß, das hängt mit irgend etwas zusammen, daß das Sehen so ausgesprochen physisch-sinnliche Organe hat; aber das berechtigt nicht, das Gebiet der Sinne auf dasjenige zu beschränken, in dem deutlich wahrnehmbare physische Organe vorhanden sind. - Dabei kommen wir noch lange nicht auf irgendeine höhere Anschauung, sondern wir kommen nur auf das, was im gewöhnlichen Menschenleben spielt. Auf das Wichtige kommen wir, daß wir wirklich unterscheiden müssen zwischen dem, was im Menschen subjektiv ist, was im Menschen inneres Seelenleben ist, und worinnen der Mensch eigentlich schläft. Ein kosmisches Wesen ist der Mensch zum Beispiel in bezug auf alles das, was seine Sinne vermitteln; da ist er ein kosmisches Wesen. Sie wissen nichts davon in Ihrem gewöhnlichen Seelenleben, was da vorgeht, wenigstens nicht ohne höhere Anschauung, wenn Sie Ihren Arm bewegen. Das ist Willensentwickelung. Es ist ein Vorgang, der ebenso außer Ihnen liegt wie irgendein anderer äußerer Vorgang. Trotzdem ist er mit Ihnen innig verbunden. Aber er liegt außer Ihrem Seelenleben. Dagegen kann keine Vorstellung da sein, ohne daß wir mit unserem Bewußtsein dabei sind. Sie bekommen daher, wenn Sie diese drei Gebiete gliedern, auch noch ein anderes.

Bei allem, was Ihr Ichsinn, Ihr Gedankensinn, Ihr Wortesinn und Ihr Gehörsinn Ihnen vermitteln, indem diese Vermittelungen zum Seelenleben werden, bekommen Sie ja im eminentesten Sinne alles dasjenige, was vorstellungsverwandt ist. In eben demselben Sinne ist alles, was Wärmesinn, Sehsinn, Geschmacks-, Geruchssinn betrifft, gefühlsverwandt. Bei einigem ist es nicht ganz auffällig, wie beim Sehsinn. Beim Geschmacks-, Geruchs- und Wärmesinn ist es auffällig, aber beim Sehsinn wird derjenige, der genauer darauf eingeht, das auch finden. Dagegen alles das, was mit Gleichgewichtssinn, Bewegungssinn, Lebenssinn zusammenhängt und auch mit dem Tastsinn, obwohl es da schwerer zu bemerken ist, weil der Tastsinn sich ins Innere zurückzieht, alles das ist willensverwandt. Im menschlichen Leben ist eben alles miteinander verwandt und doch alles wiederum metamorphosiert.

So habe ich versucht, Ihnen heute zusammenfassend dasjenige, was ich bei den verschiedensten Gelegenheiten ausgeführt habe, noch einmal zu sagen, damit wir dann die morgige und übermorgige Betrachtung daranschließen können.

Fourteenth Lecture

We continue our consideration of the relationship between human beings and the world, and in order to be able to follow up on what I have said recently, I would like to begin today by returning to a chapter of our anthroposophical view that I dealt with some time ago, namely the anthroposophical understanding of the senses. I said some time ago, and have said repeatedly, that external science considers only those things that are accessible to our senses in the grosser sense, such as the sense of sight, the sense of hearing, and so on. This way of looking at things cannot satisfy us in a deeper sense because the area covered by our experience, by our entire experience, is just as limited within the totality of our experiences as, say, the perception of a foreign ego or the perception of the meaning of words. Today, when everything has been turned upside down in a certain sense, it has become quite common to say: When we encounter a stranger, we first see the human form. We know that we ourselves have this human form, that this human form houses an I within us, and so we conclude that the stranger who looks similar to us also contains an I. — There is not the slightest real awareness of what lies in the whole immediacy of the perception of the other I when one bases one's conclusion on this. It is completely meaningless. For in exactly the same way as we stand directly before the external world and encompass a certain area of it through our sense of sight, so too does the foreign I penetrate directly into our field of experience. If we attribute a sense of sight to ourselves, we must also attribute a sense of self to ourselves.

It is important to note that this sense of self is something entirely different from the development of consciousness of one's own self. This becoming conscious of one's own self, which is not actually perception, is a completely different process from the process that takes place when we perceive a foreign self as such. Similarly, there is something completely different underlying the act of listening to words and perceiving meaning in them than there is in perceiving mere sound, mere noise. Even if it is initially more difficult to identify a human organ for the meaning of words than for the sense of sound, anyone who can truly analyze our entire field of experience must realize that within this field of experience we must distinguish between the sense of sound and the sense of words. And again, it is something else entirely to perceive the thoughts of others within words, within word formations, and within word contexts in particular. And again, we must distinguish between perceiving the thoughts of others and actual thinking. It is precisely the crude way in which soul phenomena are viewed today that fails to analyze in this more subtle way between the thinking that we develop as an inner activity of our soul life and the outward activity that lies in perceiving the thoughts of others. Certainly, when we perceive another person's thoughts, we must think in order to understand them and relate them to other thoughts we have already had. But this thinking is something completely different from perceiving another person's thoughts.

But then, when we structure and analyze everything that is present in the sphere of our total experience into areas that are truly distinct from one another and yet have a certain inner relationship such that we can call them senses, we arrive at the twelve senses of the human being, which I have often mentioned. Today, one of the weakest chapters of our present science is that which deals with the senses from a physiological or psychological point of view, for basically we speak of the senses in general.

Now, within the sensory realm, the sense of hearing, for example, is radically different from the sense of sight or the sense of taste. And again, when we come to a clear understanding of the sense of hearing or the sense of sight, we must also distinguish between a sense of words, a sense of thoughts, and a sense of the self. Most of the terms that are commonly used today when science speaks of the senses are actually taken from the sense of touch. And our philosophy has already taken the habit of basing an entire theory of knowledge on this, which actually consists of nothing more than transferring some perceptions that relate to the sense of touch to the entire realm of perceptibility.

If we now analyze in reality the entire field, the sphere of our external experiences, which we perceive in a similar way, say, like visual experiences or tactile experiences or thermal experiences, then we arrive at twelve clearly distinguishable senses, which I have often listed in the following way: First, the sense of self, which, as I have said, is to be distinguished from the consciousness of one's own self; the sense of self refers to nothing other than the ability to perceive the self of another. The second is the sense of thought, the third is the sense of words, the fourth is the sense of hearing, the fifth is the sense of warmth, the sixth is the sense of sight, the seventh is the sense of taste, the eighth is the sense of smell, and the ninth is the sense of balance. Anyone who can truly analyze this area knows that there is a very limited area of perception, just like the area of sight, a limited area that simply gives us the sensation that we, as human beings, are in a certain state of equilibrium. Without a sense that would convey to us this standing in balance or this floating and dancing in balance, we would not be able to build up our consciousness completely.

Then comes the sense of movement. The sense of movement is the perception of whether we are at rest or in motion. We must experience this perception within ourselves in exactly the same way as we experience our visual perception. Eleventh is the sense of life, twelfth is the sense of touch (see drawing on page 25).

Sense of self

Sense of thought

Sense of words

Sense of hearingSense of warmth

Sense of sight

Sense of taste

Sense of smellSense of balance

Sense of movement

Sense of life

Sense of touch

These areas, which I have listed here as sensory areas, can be clearly distinguished from one another, and at the same time, we can find similarities in them in that we behave perceptively through these senses. It is our interaction with the outside world, our cognitive interaction with the outside world, that these senses convey to us; albeit in very different ways with regard to the outside world. We initially have four senses that connect us unquestionably with the outside world, if I may use the word unquestionably in this case; these are: the sense of self, the sense of thought, the sense of words, and the sense of hearing. It will be immediately clear to you that we are, in a sense, in the external world with our entire experience when we perceive the I of another, just as when we perceive the thoughts or words of another. This may not be so obvious in relation to the sense of hearing, but that is only because, in a kind of abstract view of all the senses, we have poured out a common conceptual nuance that is supposed to be a common concept, a common idea of sensory life, and we do not actually consider the specific nature of the individual senses. Of course, one cannot, I would say, grasp these things in external experiments, but rather it is necessary to have the ability to feel the experiences.

Ordinary thinking does not concern itself, for example, with how hearing, through the fact that the mediator of hearing is moving air, i.e., something physical, basically brings us directly into the external world. And if you simply consider how external the sense of hearing actually is in relation to our entire organic inner experience, you will soon realize that you must understand the sense of hearing in a different way than, for example, the sense of sight. With the sense of sight, you can quickly see from looking at the organ, the eye, how what is being conveyed is, to a large extent, an internal process, at least relatively speaking. We close our eyes when we sleep, but we don't close our ears. In such things, which are seemingly trivial, simple facts, something deeply significant for the whole of human life is expressed. And when we are compelled to shut off our inner life when we sleep, because we are not supposed to perceive through sight, we are not compelled to shut off our ears, because they live in the external world in a completely different way than the eyes. The eye is much more a part of our inner being. Visual perception is much more directed inward than auditory perception. Not the sensation of what is heard, that is something else. The sensation of what is heard, which underlies music, is something different from the actual process of hearing.

These senses, which essentially, I would say, mediate between the external and the internal, are distinctly external senses (see drawing on page 25). Those senses that are, so to speak, on the cusp between the external and the internal, which are both external and internal experiences, are the next four senses: the sense of warmth, the sense of sight, the sense of taste, and the sense of smell. Just try to imagine the sum total of the experiences provided by one of these senses, and you will see how, on the one hand, all these senses involve an experience of the external world, but at the same time an experience within oneself. When you drink vinegar, for example, your sense of taste comes into play, and you certainly have an inner experience of the vinegar on the one hand, and on the other hand an experience that is directed outward, which can be compared to the experience of an external self, for example, or of words. But it would be very bad if you were to add a subjective, inner experience, say, listening to words, in the same sense. Just think, when you drink vinegar, you grimace; this clearly indicates that you have an inner experience with the outer experience, that the outer experience and the inner experience are intertwined. If the same were true of words, if, for example, someone gave a speech and you had to experience it internally in the same way as when drinking vinegar or Moselle wine or the like, then you would never be able to understand the words the other person is saying to you in an objective way. To the same extent that you have an unpleasant inner experience with vinegar and a pleasant inner experience with Moselle wine, to the same extent you color an external experience. You must not color this external experience when you perceive, say, the words of another. One can say: Here one sees the intrusion of morality at the moment when one sees things in their true light. For there are indeed people who behave in such a way, especially with regard to the sense of self, but also with regard to the sense of thought, that one can say that they are so strongly caught up in their middle senses, in the senses of warmth, sight, taste, and smell, that they also judge other people or their thoughts in the same way. Then they do not hear the thoughts or words of others at all, but perceive them as, for example, Moselle wine or vinegar or some other drink or food is perceived.

Here we see how something moral arises simply from an otherwise completely amoral point of view. Take, for example, a person whose sense of hearing, but especially whose sense of words, sense of thoughts, and sense of self, are poorly developed. Such a person lives, so to speak, without a head, that is, he uses his head senses in a similar way to the senses that are more inclined toward the animalistic. Animals cannot perceive objectively in this way, as they can perceive objectively and subjectively through their senses of warmth, sight, taste, and smell. Animals smell: you can imagine that animals are only able to objectively perceive what they encounter to a very limited extent, for example through their sense of smell. It is a highly subjective experience. Now, of course, all humans also have hearing, speech, thought, and ego; but those who are more invested with their entire organization in the senses of warmth and sight, and especially in the senses of taste or even smell, change everything according to their subjective taste or their subjective perception of their surroundings. You can perceive such things every day in life. If you want an example, just consider how there are people who cannot perceive anything objectively, but perceive everything as one would otherwise perceive only through the senses of taste and smell. You can see this in the latest brochure by Pastor Kully. They are completely incapable of understanding the words or thoughts of others; they perceive everything as one perceives wine or vinegar or any other food. Everything becomes a subjective experience. In the same sense, it becomes immoral when the higher senses are reduced to the character of the lower senses. It is entirely possible to relate morality to the entire worldview, whereas in the present day, the destructive force that undermines our entire civilization lies in the fact that we do not know how to build a bridge between what we call natural law and what we call morality.

When we now come to the next four senses, the sense of balance, the sense of movement, the sense of life, and the sense of touch, we come to distinctly inner senses. We are dealing here first with distinctly inner senses. For what the sense of balance conveys to us is our own balance, what the sense of movement conveys to us is the state of movement in which we are. Our state of life is this general perception of how our organs are functioning, whether they are beneficial or detrimental to our life, and so on. The sense of touch can be deceptive; nevertheless, when you touch something, what you experience is an inner experience. In a sense, you do not feel the chalk, but rather, if I may express it crudely, you feel the skin being pushed back; the process is, of course, much more subtle. It is the reaction of your own inner being to an external process that is present in the experience, which is not present in any other sensory experience in the same way as in the tactile experience.