Man as a Being of Sense and Perception

GA 206

24 July 1921, Dornach

Lecture III

This cleft in human nature of which I have been speaking also finds expression in everyday communal life. You find it in the relationship of two human capacities which even the most casual examination shows as belonging by their very nature to the life of both soul and body. You have on the one hand the faculty of memory, an important factor in soul-life, but bound up with the bodily life; and on the other hand a capacity less noticeable, because men give themselves to it more or less naively and uncritically—I mean the capacity for love. Let me say from the outset that, whether we are speaking about the being of man himself or of his relationship to the world, we must start from the reality and not from any preconceived idea. I have often made use of a somewhat trite illustration of what it means to proceed from ideas instead of from reality. Someone sees a razor and says, “That is a knife, a knife is used for cutting up food!” So he takes the razor for cutting up food, because it is a knife. Scientific conceptions about birth and death as they relate to man and animal are somewhat like this, though people are not generally aware of it, believing the subject to be a very learned one. Sometimes these ideas are even made to cover the plants. The scientists form an idea of what birth is, or what death is, just as one forms an idea of what a knife is, and then go on from that idea, which of course expresses a certain series of facts, to examine human death, animal death and even plant death, all in the same way, without taking into account that what is usually comprised in the idea of death might be something quite different in man from what it is in animals. We must take our start from the reality of the animal and the reality of man, not from some idea we have formed of the phenomenon of death.

We form our ideas about memory in somewhat the same way. It is particularly so when the concept of memory is applied indifferently to both man and animal, with the object of finding similarities between them. Our attention has been drawn, for example, to something that happened in the case of the famous Professor Otto Liebmann. An elephant, on his way to the pond to drink, is in some way offended by a passer-by, who does something to him. The elephant passes on; but when he comes back again, and finds the man still there, he spouts water over him from his trunk—because, so says the theoriser, he has obviously remarked, has stored up in his memory, the injury received.

The outer appearance of the thing is of course, seen from such a theoretical standpoint, very misleading, but not more so than the attempt to cut one's meat at table with a razor. The point is that one must always start from reality and not from ideas acquired from one series of phenomena and then transferred arbitrarily to another series. Usually people completely fail to see how widespread to-day is the error in scientific method I have just described.

The human faculty of memory must be understood entirely out of human nature itself. To do this one needs an opportunity of watching how the memory develops in the course of the development of the individual. Anyone who can make such a study will be able to note that memory expresses itself quite differently in the very little child from the way it expresses itself from the ages of six, seven or eight onwards. In later years memory assumes much more of a soul-character, whereas in the earliest years of a child's life one can clearly see to what a large extent it is bound up with organic conditions, and how it then extricates itself from those conditions. And if you look at the connection between the child's memories and his formation of concepts you will see that his formation of concepts is very dependent upon what he experiences in his environment through sense-perception, through all the twelve varieties of sense-perception that I have distinguished.

It is most fascinating, and at the same time extraordinarily important, to see how the concepts that the child forms depend entirely upon the experiences he undergoes; above all upon the behaviour of those around him. For in the years with which we are here concerned the child is an imitator, an imitator even as regards the concepts he forms. On the other hand, it will easily be seen that the faculty of memory arises more out of the child's inward development, more out of his whole bodily constitution—very little indeed out of the constitution of the senses and therefore of the human head. One can detect an inner connection with the way the child is constituted, whether the formation of his blood, the nourishment of his blood, is more or less normal, or whether it is abnormal. It will be readily remarked that children with a tendency to anæmia have difficulties in remembering; while on the other hand such children form concepts and ideas more easily.

I can only hint at these things, for in the last resort everyone, if he has been given the right lines to go upon, must seek his own confirmation of them in life itself. He will then find that it is from the head-organisation—that is, from the nerve-senses organisation—and thus from experiences arising out of perception, that the child forms concepts; but that the faculty of memory, interwoven as it were with the formation of concepts, develops out of the rest of the organism. And if one pursues this study further, particularly if one tries to discover what lies behind the very individual manner of memory-formation, how it differs in children who tend to a short, squat figure and in those who tend to shoot up, one will find a connection clearly indicated between the phenomena of growth as a whole and formation of the power of memory.

Now I have said on earlier occasions that the formation of the head represents a metamorphosis of the human being's organic structure, apart from the head organisation, in an earlier earth-life. Thus what we carry about in a particular earth-life as our head is the transformed body (apart from the head) of the previous earth-life, but especially the transformed metabolic-limb system; or what to-day is metabolic-limb man is transformed during the life between death and rebirth into the head-formation of the next earthly life. One must of course not think of it in a materialistic way; it has nothing to do with the matter that fills out the body, but with the relationships of forms and forces.

Thus, when we see that the child's faculty of forming concepts, his faculty of thought, depends upon his head-formation, we can also say that his capacity for thought is connected with his earlier life on earth.

On the other hand, what develops in us as the faculty of memory depends primarily on how we are able to maintain in a well-organised condition the metabolic-limb system of this present earth-life. The two things go together: one of them a man brings with him from his previous earth-life, and the other, the faculty of memory, he acquires through organising and maintaining a new organism.

From this you will understand that ordinary memory, which we have primarily for use between birth and death and which we cultivate in connection with this earth-life, does not suffice to enable us to look back into the life before birth, to look back into our pre-natal life. Hence it is necessary—this is something I constantly emphasise when I am expounding the methodology of the subject—for us to acquire the ability to go behind this memory, to learn to understand clearly that it is something that is of service to us between birth and death, but that we have to develop a higher faculty which traces in a backward direction, entirely in the manner of memory, what has taken shape in us as the power of thought. Anyone who constructs an abstract theory of knowledge substitutes a word for a deed. For example, he says, “Mathematical concepts are a priori,” because they do not have to be acquired through experience, because their certainty does not have to be confirmed by experience; they lie behind experience, a priori. That is a phrase. And to-day this phrase is to be heard over and over again in the mouths of Kantians. This a priori really means that we have experienced these ideas in our previous earth-life; but they are none the less experiences acquired by humanity in the course of its evolution. The simple fact is that humanity is in such a stage of its evolution that most men, civilised men at any rate, bring mathematical concepts with them, and these have only to be awakened.

There is of course an important pedagogic difference between the process of awakening mathematical concepts and that of imparting such thoughts and ideas as have to be acquired through external experience, and in which the faculty of memory plays an essential role. One can also, especially if one has acquired a certain power of insight into the peculiarities of human evolution, distinguish clearly between two types of growing children—those who bring much from their previous earth lives and to whom it is therefore easy to communicate ideas, and others who have less facility in the formation of ideas but are good at noticing the qualities of external things, and therefore easily absorb what they can take in through their own observation. But in this the faculty of memory is at work, for one cannot easily learn about external things in the way in which things have to be taught in school. Of course a child can form a concept, but he cannot learn in such a way as to reproduce what he has learnt unless a clear faculty of memory is there. Here, in short, one can perceive quite exactly the flowing together of two streams in human evolution.

Now what is it exactly that lies behind this! Just think—on the one hand you have the human being shaping his concept-forming faculty through his head-organisation. Why does he do that? You have only to look at the human head-organisation with understanding to say why.

You see, the head-organisation makes its appearance comparatively early in embryonal life, before the essentials of the rest of the organisation are added. Embryology furnishes definite proof of what Anthroposophy has to say about human evolution. But you need not go so far, you need only look at the adult man. Look at his head-organisation. To begin with, it is so fashioned as to be the most perfect part of the human organisation taken as a whole. Well, perhaps this idea is open to dispute; but there is another idea that cannot be gainsaid, if only one looks at it in the right way; that is the idea that we are related to our head in experience quite differently from the way we are related to the rest of our organism. We are aware of the rest of our organism in quite a different way from the way we are aware of our head. The truth is that our head effaces itself in our own soul-life. We have far more organic consciousness of the whole of the rest of our organism than we have of our head. Our head is really the part of us that is obliterated within our organisation.

Moreover this head stands apart from the relationships of the rest of our organism with the world, first of all through the way the brain is organised. I have often called attention to the fact that the brain is so heavy that it would crush everything that lay beneath it were it not swimming in the cerebral fluid, thereby losing the whole of the weight that a body would have that was made of brain fluid and was the same size as the brain; thus the brain loses weight in the ratio of from 1,300 or 1,400 grammes to 20 grammes. But this means that while the human being, in so far as he stands on the earth, has his natural weight, the brain is lifted out of this relationship with gravity in which the human being is involved. But even if you do not stress this inward phenomenon, but confine yourself to what is external, you might well say that in the whole way in which you bear your head, in the way you carry it through the world, it is like a lord or lady sitting in a carriage. The carriage has to move on, but when it does so, the lord or lady sitting in it is carried along without having to make any exertion. Our head is related to the rest of our organism somewhat in this way. Many other things help to bring this about. Our head is, so to speak, lifted out of all our other connections with the world. That is precisely because in our head we have in physical transformation what our soul, together with the rest of our organism, experienced in an earlier earth-life.

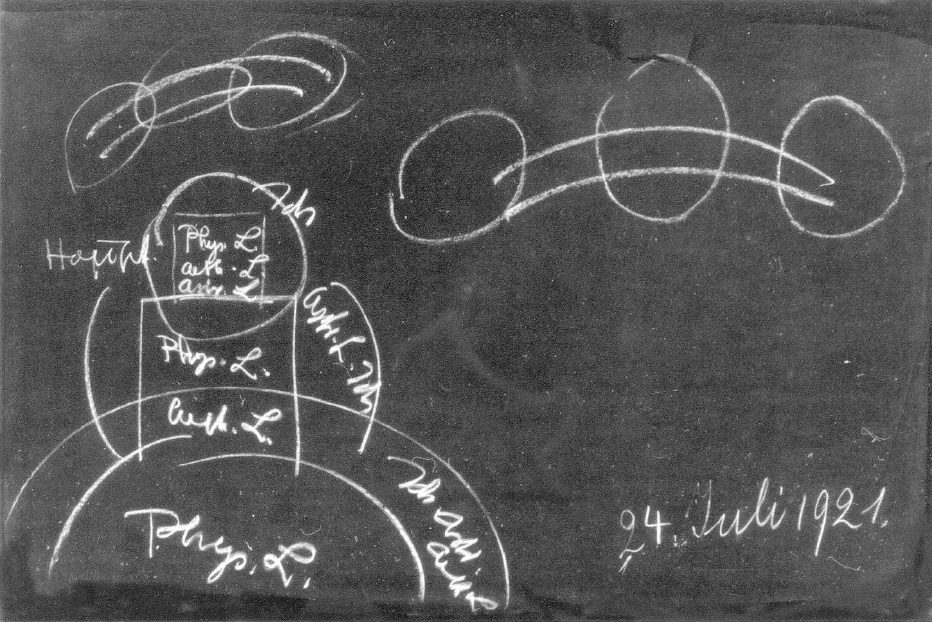

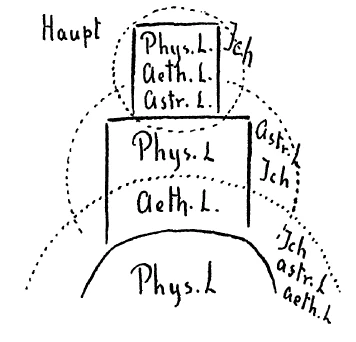

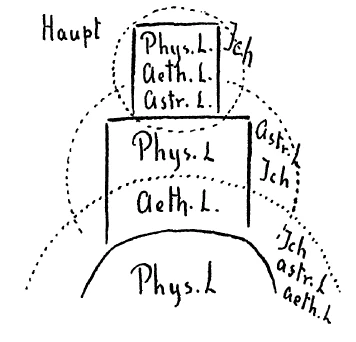

If you study the four principal members of the human organisation in the head—physical body, ether body, astral body and ego—it is really only the ego that has a certain independence. The other three members have created images of themselves in the physical formation of the head. Of this, too, I once gave a convincing proof: On this occasion I should like to lead up to it by telling a story, rather than in a theoretical way.

I once told you that many years ago, when circumstances had brought about the foundation of the Giordano Bruno Society, I was present at a lecture on the brain given by a thoroughgoing materialist. As a materialist, of course, he made a sketch of the structure of the brain, and proved that fundamentally this structure was the expression of the life of the soul. One can quite well do that.

Now the president of the society was the headmaster of a grammar-school, not a materialist, but a hide-bound Herbartian. For him there was nothing but the philosophy of Herbart. He said that, as a Herbartian, he could be quite satisfied with the presentation; only he did not take what the lecturer had drawn, from his standpoint of strict materialism, to be the matter of the brain. Thus when the other man had sketched the parts of the brain, the connecting tissues and so on, the Herbartian was quite willing to accept the sketch; it was quite acceptable to the Herbartian, who was no materialist, for, said he, where the other man had written parts of the brain, he needed only to write idea-complexes, and instead of brain fibres he only had to write association fibres. Then he was describing something of a soul-nature—idea-complexes—where the other was describing parts of the brain. And where the other drew brain-fibres, he put association-fibres, those formations that John Stuart Mill had so fantastically imagined as going from idea to idea, entirely without will, automatically, all kinds of formations woven by the soul between the idea-complexes! One can find good examples of that in Herbart also.

Thus both men could find a point of contact in the sketch. Why? Simply because the human brain really is in this respect an extraordinarily good imprint of the soul-spiritual. The soul-spiritual makes a very good imprint of itself on the brain. It certainly has had time during the period between death and new birth to call into existence this configuration, which then so wonderfully expresses its soul-life in the observable plastic formations of the brain.

Let us now pass on to the psychological exposition given by Theodore Ziehen. We find that he also describes the parts of the brain and so on in a materialistic way, and it all seems very plausible. It is also extremely conscientious. One can in fact do that; if one looks at man's intellectual life, the life of ideas, one can find a very exact reproduction of it in the brain. But—with such a psychology one does not get as far as feeling, still less as far as will. If you look at such a psychology as Ziehen's, you will find that feeling is nothing more than a feeling-stress of the idea, and that will is entirely lacking. The fact is that feeling and will are not related in the same way to what has already been formed, already been given shape. Feeling is connected with the human rhythmic system; it is still in full movement, it has its configuration in movement. And will, which is connected above all with the plastic coming-into-existence and fading-away which take place in metabolism, cannot portray itself in reflected images, as is possible with ideas. In short, in the life of ideas, in the faculty of ideation, we have something of soul-life that can express itself plastically, pictorially, in the head. But there we are in the realm of the astral body; for when we form ideas, the entire activity of ideation belongs to the astral body. Thus the astral body creates its image in the human head. It is only the ego that still remains somewhat mobile. The etheric body has its exact imprint in the head, and the physical body most definitely so of all. On the other hand, in the rhythmic system there is no imprint of the astral body as such, but only of the etheric and physical bodies. And in the metabolic system only the physical body has its mirror-image.

To summarise, you can think of the matter in this way. In the head you have physical body, etheric body and astral body, in such a way that they are portrayed in the physical; that in fact their impression can be detected in the physical forms. It is not possible to understand the human head in any other way than by seeing it in these three forms. The ego is still free in relation to the head.

If we pass on to the rest of the human organisation, to the breathing-system, for instance, we find the physical and etheric bodies have their imprints within it; but the astral body and the ego have no such imprints; they are to a certain extent free. And in the metabolic-limb system we have the physical body as such, and the ego, astral body and etheric body are free. We have not only to recognise the presence of one of these members, but to distinguish whether it is in the free or the bound condition. Of course it is not that an astral body and an etheric body have no basis in the head; they permeate the head too. But they are not free within it, they are imprinted in the head-organisation. On the other hand, the astral body, for example, is quite free throughout the rhythmic system, particularly in the breathing. It acts freely. It does not merely permeate the system, but it is actively present within it.

Now let us put two things together. The one is that we can affirm a connection between the faculty of memory and the organisation outside the head; the other is that we have to look outside the head also for the feeling and willing organisations. You see we are now coupling together the feeling world of the soul and the world of memory. And if you take note of your own experience in relation to these two things, you will discover that there is a very close connection between them.

The way in which we can remember depends essentially on the way we can participate in things, on how far we can enter into them with that part of our organisation which lies outside the head. If we are very much head-men, we shall understand a great deal, but remember little in such a way that we grow together with it. There is a significant connection between the capacity for feeling and the faculty of memory. But at the same time we see that the human organisation apart from the head, in the early stages of its development, becomes more like the head. If you take the embryonal life, then, to begin with, the human being is practically all head; the rest is added. When the child is born—just think how imperfect is the rest of the organisation in comparison with the head! But it is attached to the head. Between birth and death the rest of the organisation becomes more and more like the head-organisation, and shows this notably in the emergence of the second teeth. The first teeth, the so-called milk teeth, are derived more from the head-organisation. It will be easy to demonstrate this anatomically and physiologically when suitable methods are applied. To spiritual scientific investigation it is unquestionable. In the second teeth the entire man plays his part. The teeth which are derived more from the head-organisation are cast out. The rest of the man assists in the formation of the second teeth.

In fact, in the first and second teeth we have a kind of image translated into the physical—an image of the formation of concepts and memory respectively. The milk teeth are formed out of the human organism rather in the way concepts are formed, except that concepts of course are translated into the sphere of the mental life, whereas the second teeth are derived out of the human organism more in the way the faculty of memory is derived. One only has to be capable of recognising these very subtle differences in human nature.

When you grasp such a thing as this, then you will of course see that one can really understand the structure of matter—particularly when it comes to organic life—only if one understands it in its spiritual formation. The thorough-going materialist looks at the material man, studies the material man. And anyone who starts from the reality and not from his materialistic prejudices, will at once see in the child that this human head is formed out of the super-sensible, through a metamorphosis of his previous earthly life, and then he sees that the rest is added out of the world into which the child is now transplanted; the rest is added, but that too is formed out of the spiritual, out of the super-sensible of this world.

It is important to pay attention to such a view. For the point is that we should not speak abstractly of the material world and of the spiritual world, but we should acquire an insight into the way the material world originates in the spiritual world; an insight, so to speak, into the way the spiritual world is imaged in the material world. Only we must not thereby remain in the abstract, but must enter into the concrete. We must be able to acquire an insight into the difference between the head and the rest of the organism. Then in the very forms of the head we shall see a somewhat different derivation from the spiritual world, compared with what we see in the rest of the organism. For the rest of the organism is added to us entirely in the present earth-life, whilst the head organisation, down to its very shape, we bring with us out of our previous earth-life. Whoever reflects upon this will see the folly of such an objection to Anthroposophy as has again recently been made, in a debate which took place in Munich, by Eucken—so highly respected by many people despite his journalistic philistinism. By putting forward the foolish idea that what one can perceive is material, Eucken raised the objection that Anthroposophy is materialistic. Naturally, if one invents such a definition, one can prove what one will; but anyone who does so is certainly ill-acquainted with the accepted method of proof. It is a question of grasping how the material, in its emergence from the spiritual, can be regarded as bearing witness to the spiritual world.

Again—and to-day I can only go as far as this—if you grasp the connection between the birth of memory and the forces of growth, you will thereby recognise an interplay between what we call material and what in later life, from seven to eight years of age onwards, develops as the soul-spiritual life. It really is a fact that what shows itself later in more abstract intellectual form as the faculty of memory is active, to begin with, in growth. It is really the same force. The same method of observation must be applied to this as is applied, let us say, when we speak of latent heat and free heat. Heat which is free, which is released from its latent condition, behaves externally in the physical world like the force which, after having been the source of the phenomena of growth in the earliest years of childhood, then manifests itself in the inner life as the force of memory. What lies behind the phenomena of growth in earliest childhood is the same thing as what later makes its appearance in its own proper form as the faculty of memory.

I developed this more fully in the course of lectures given here in the Goetheanum last autumn.1Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis, 27th Sept. to 2nd Oct., 1920 (Translated as "The Boudaries of Natural Science.) You will see how one can discover along these lines an intimate connection between the soul-spiritual and the bodily-physical, and how therefore we have in the faculty of memory something which on the one hand appears to us as of a soul-spiritual nature, and on the other hand, when it appears in other cosmic connections, manifests as the force of growth.

We find just the opposite when we consider the human capacity for love, which shows itself on the one hand to be entirely bound up with the bodily nature, and which on the other hand we can grasp, exactly like the faculty of memory, as the most soul-like function. So that in fact—this I will explain more fully in later lectures—in memory and love you have capacities in which you can experience the interplay between the spiritual and the bodily, and which you can also associate with the whole relationship between man and the world.

In the case of memory we have already done this, for we have related ideation with previous earth-lives, and the faculty of memory with the present earth-life. In later lectures we shall see that we can experience the same thing as regards the capacity for love. One can show how it is developed in the present earth-life, but passes over through the life between death and rebirth into the next earthly life.

Why are we making a point of this? Because to-day man needs to be able to make the transition from the soul-spiritual to the bodily-physical. In the soul-spiritual we experience morality; within the physical-bodily we experience natural necessity. As things are seen to-day, if one is honest in each sphere one has to admit that there is no bridge between them. And I said yesterday that because there is no such bridge, people make a distinction between what they call real knowledge, based upon natural causality, and the content of pure faith, which is said to be concerned with the world of morality—because natural causality on the one hand, and the life of the soul-spirit on the other, exist side by side without any connection. But the whole point is that in order to recover a fully human consciousness, we need to build a bridge between these two.

Above all we must remember that the moral world cannot exist without postulating freedom; the natural world cannot exist without necessity. Indeed, there could be no science if there were not this necessity. If one phenomenon were not of necessity caused by another in natural continuity, everything would be arbitrary, and there could be no science. An effect could arise from a cause that one could not predict! We get science when we try to see how one thing proceeds from another, that one thing proceeds from another. But if this natural causality is universal, then moral freedom is impossible; there can be no such thing. Nevertheless the consciousness of this moral freedom within the realm of soul and spirit, as a fact of direct experience, is present in every man.

The contradiction between what the human being experiences in the moral constitution of his soul and the causality of nature is not a logical one, but a contradiction in life. This contradiction is always with us as we go through the world; it is part of our life. The fact is that, if we honestly admit what we are faced with, we shall have to say that there must be natural causality, there must be natural necessity, and we as men are ourselves in the midst of it. But our inner soul-spiritual life contradicts it. We are conscious that we can make resolutions, that we can pursue moral ideals which are not given to us by natural necessity. This is a contradiction which is a contradiction of life, and anyone who cannot admit that there are such contradictions simply fails to grasp life in its universality. But in saying this we are saying something very abstract. It is really only our way of expressing what we encounter in life. We go through life feeling ourselves all the time actually at variance with external nature. It seems as if we are powerless, as if we must feel ourselves at variance with ourselves. To-day we can feel the presence of these contradictions in many men in a truly tragic way.

For example, I knew a man who was quite full of the fact that there is necessity in the world in which man himself is involved. Theoretically, of course, one can admit such a necessity and at the same time not trouble much about it with one's entire manhood. Then one goes through the world as a superficial person and one will not be inwardly filled with tragedy. Be that as it may, I knew a man who said, “Everywhere there is necessity and we men are placed within it. There is no doubt about it, science forces us to a recognition of this necessity. But at the same time necessity allows bubbles to arise in us which delude us with hopes of a free soul-life. We have to see through that delusion, we have to look upon it as hot air. This too is a necessity.”

That is man's frightful illusion. That is the foundation of pessimism in human nature. The man who has little idea of how deeply such a thing can work into the human soul will not be able to enter into the feeling that this contradiction in life, which is absolutely real, can undermine the whole soul, and can lead to the view that life in its inmost nature is a misfortune. Confronted by the conflict between scientific certainty and the certitude of faith, it is only thoughtlessness and lack of sensitivity that prevent men from coming to such inner tragedy in their lives. For this tragic attitude towards life is really the one that goes with the plight of soul to which mankind can come to-day.

But whence comes the impotence which results in such a tragic attitude to life! It comes from the fact that civilised humanity has for centuries allowed itself to become entangled in certain abstractions, in intellectualism. The most this intellectualism can say is that natural necessity deludes us by strange methods with a feeling of freedom, but that there is no freedom. It exists only in our ideas. We are powerless in the face of necessity.

Then comes the important question—is that truest? And now you see that the lectures I have been giving for weeks actually all lead up to the question: “Are we really powerless? Are we really so impotent in the face of this contradiction?” Remember how I said that we have in our lives not only an ascending development, but a declining one; that our intellectual life is not bound up with the forces of growth, but with the forces of death, the forces of decay; that in order to develop intelligence we need to die. You will remember how I showed here several weeks ago the significance of the fact that certain elements with specific affinities and valencies—carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur—combine to form protein. They do so not by ordinary chemical combination, but on the, contrary by becoming utterly chaotic. You will then see that all these studies are leading up to this—to make it clear to you that what I have told you is not just a theoretical contradiction, but an actual process in human nature. We are not here merely in order, through living, to sense this contradiction, but our inner life is a continual process of destruction of what develops as causality in outer nature. We men really dissolve natural causality within ourselves. What outside is physical process, chemical process, is developed within us in a reverse direction, towards the other side. Of course we shall see this clearly only if we take into consideration the upper and the lower man, if we grasp by means of the upper man what emerges from metabolism by way of contra-mechanisation, contra-physicalisation, contra-chemicalisation. If we try to grasp the contra-materialisation in the human being, then we do not have merely a logical, theoretical contradiction in ourselves, but we have the real process—we have the process of human development, of human becoming, as the thing in us that itself counteracts natural causality, and human life as consisting in a battle against it. And the expression of this struggle, which goes on all the while to dissolve the physical synthesis, the chemical synthesis, to analyse it again—the expression of this analytic life in us is summed up in the awareness: “I am free.” What I have just put before you in a few words—the study of the human process of becoming as a process of combat against natural causality, as a reversal of natural causality—we shall make the subject of forthcoming lectures.

Sechzehnter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Jenen Schnitt durch das Wesen des Menschen, von dem ich gesprochen habe, Sie finden ihn auch im alltäglichen menschlichen Gesamtleben zum Ausdruck kommend. Sie finden ihn vor allen Dingen, wenn Sie sachgemäß das Verhältnis zweier menschlicher Fähigkeiten untersuchen, die durch ihre eigene Beschaffenheit auch bei oberflächlicher Betrachtung sich als sowohl dem seelischen Leben wie auch dem körperlich-leiblichen Leben angehörig erweisen. Sie finden auf der einen Seite als eine wichtige, sagen wir, Tatsache des Seelenlebens im menschlichen Leben eben mit dem körperlichen Leben verbunden die Fähigkeit des Gedächtnisses, der Erinnerung, und Sie finden auf der andern Seite, sagen wir, eine Kraft im menschlichen Leben, deren Wesenheit weniger ins Auge gefaßt wird, weil sie mehr eine Fähigkeit ist, der man sich naiv hingibt, ohne sie näher zu prüfen oder gar zu analysieren: das ist die Kraft der menschlichen Liebe. Es muß von vornherein gesagt werden, daß, wenn man über solche Dinge erstens mit Bezug auf die Wesenheit des Menschen, dann aber auch mit Bezug auf das Verhältnis des Menschen zur Welt spricht, man sich darüber klar sein muß, daß man von der Wirklichkeit, nicht von irgendeiner Vorstellung auszugehen hat. Ich habe öfter den zwar banalen Vergleich für das Ausgehen von Vorstellungen-statt von der Wirklichkeit gebraucht: Jemand sieht ein Rasiermesser, und er sagt, das sei ein Messer, ein Messer gehöre zum Schneiden der Speisen; also nimmt er das Rasiermesser zum Schneiden der Speisen, weil es ein Messer ist.

[ 2 ] So ungefähr, obwohl man es gewöhnlich nicht glaubt, weil man die Sache für sehr gelehrt hält, sind die Auffassungen, die, sagen wir, zum Beispiel wissenschaftlich denkende Menschen über den Tod oder über die Geburt haben mit Bezug auf Menschen und Tiere. Manchmal dehnt man sogar dann solche Vorstellungen auch auf Pflanzen aus. Man macht sich eine Vorstellung darüber, wie man sich eine Vorstellung darüber macht, was ein Messer ist, und geht dann von dieser Vorstellung, die natürlich der Repräsentant einer gewissen Tatsachenreihe ist, aus und untersucht in gleicher Weise, sagen wir, den Tod beim Menschen, bei Tieren und eventuell sogar bei den Pflanzen, ohne zu berücksichtigen, daß vielleicht dasjenige, was man im allgemeinen in der Vorstellung des Todes zusammenfaßt, etwas ganz anderes sein könnte bei den Menschen und bei den Tieren. Man hat von der Wirklichkeit des Tieres und von der Wirklichkeit des Menschen auszugehen, nicht von der Erscheinung des Todes, die man repräsentiert sein läßt durch irgendeine Vorstellung.

[ 3 ] In einer ähnlichen Weise sind dann die Vorstellungen geschmiedet, die man zum Beispiel mit Bezug auf das Gedächtnis hat. Mit Bezug auf das Gedächtnis zeigt sich das ganz besonders dort, wo in der Absicht, ein Gleiches bei Menschen und bei Tieren zu finden, der Gedächtnisbegriff in einer undifferenzierten Weise auf beide angewendet wird. Man macht darauf aufmerksam - es ist das sogar sehr berühmten Professoren passiert wie Otto Liebmann -, daß zum Beispiel ein Elefant, der auf seinem Wege zur Schwemme ist, wo er Wasser zu trinken hat, irgend etwas von einem Insult durch einen vorübergehenden Menschen bekommt; der tut ihm etwas. Der Elefant geht vorüber. Aber als er wieder zurückgeht und der Mensch dann wieder dasteht, da spritzt ihn der Elefant aus seinem Rüssel mit Wasser an. Weil der Elefant - so sagt der Erkenntnistheoretiker — sich selbstverständlich gemerkt hat, in seinem Gedächtnis aufbewahrt hat dasjenige, was ihm der Mensch getan hat.

[ 4 ] Das äußere Aussehen der Sache ist natürlich durchaus für eine solche erkenntnistheoretische Betrachtung, man möchte sagen, sehr verführerisch, aber eben nicht verführerischer als das Unterfangen, mit einem Rasiermesser das Fleisch bei Tisch zu zerschneiden. Es handelt sich eben durchaus darum, daß man überall von der Wirklichkeit ausgeht und nicht von Vorstellungen, die man an irgendeiner Erscheinungsreihe gewonnen hat und die man dann in beliebiger Weise wesenhaft auf eine andere Erscheinungsreihe überträgt. Man macht sich gewöhnlich gar nicht klar, wie weitverbreitet der eben angeführte methodologische Fehler in unseren heutigen wissenschaftlichen Untersuchungen eigentlich ist.

[ 5 ] Dasjenige, was als Gedächtnis, als Erinnerungsvermögen beim Menschen vorliegt, muß durchaus aus der menschlichen Natur heraus selbst begriffen werden. Und da handelt es sich darum, daß man sich zunächst eine Möglichkeit schafft, zu beobachten, wie das Gedächtnis im Verlauf der menschlichen Entwickelung selber wird. Derjenige, der so etwas beobachten kann, der wird bemerken können, daß sich das Gedächtnis bei dem Kinde noch in einer ganz andern Weise äußert als beim Menschen etwa vom sechsten, siebenten, achten Jahre an. Das Gedächtnis bekommt in den letztangeführten Jahren vielmehr einen seelischen Charakter, während man deutlich merken kann, wie sehr in den ersten Kinderjahren dieses Gedächtnis gebunden ist an die organischen Zustände, wie es sich herauswindet aus diesen organischen Zuständen. Und derjenige, der das Verhältnis der Erinnerungen zu der kindlichen Begriffsbildung ins Auge faßt, der wird merken, wie sich die Begriffsbildung in der Tat stark anlehnt an dasjenige, was das Kind aus seiner Umgebung durch seine Sinneswahrnehmung, durch alle die zwölf angeführten Sinneswahrnehmungen erlebt. Es ist außerordentlich reizvoll, aber auch außerordentlich bedeutsam, zu sehen, wie die Begriffe, die sich das Kind bildet, ganz und gar abhängen von der Erfahrung, der das Kind unterworfen wird, namentlich von dem Verhalten der Umgebung. Das Kind ist ja in den Jahren, die hier in Betracht kommen, ein Nachahmer, und auch in bezug auf seine Begriffsbildung ein Nachahmer. Dagegen wird man leicht bemerken können, wie die Fähigkeit der Erinnerung mehr aus dem Inneren der kindlichen Entwickelung aufsteigt, wie sie mehr zusammenhängt mit der ganzen körperlichen Konstitution, sogar sehr wenig mit der Konstitution der Sinne und dadurch der Konstitution des menschlichen Hauptes. Dagegen wird man einen innigen Zusammenhang verspüren können zwischen der Art, wie das Kind mehr oder weniger, wenn man so sagen könnte, normal oder unnormal zum Beispiel in bezug auf seine Blutbildung, in bezug auf seine Bluternährung beschaffen ist. Man wird leicht bemerken, daß bei Kindern, die nach dem Anämischen hinneigen, die Gedächtnisbildung Schwierigkeiten hat. Dagegen wird man bemerken, daß in einem solchen Falle die Begriffsbildung, die Vorstellungsbildung weniger Schwierigkeiten hat.

[ 6 ] Ich kann auf diese Dinge nur hindeuten, denn im Grunde genommen muß jeder, wenn er die Richtlinien zu einer solchen Beobachtung empfangen hat, aus dem Leben heraus sich die Daten suchen, und er wird sie finden. Er wird dann finden, daß in der Tat beim Kinde von der Hauptesorganisation, das heißt von der Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, also von den Erlebnissen, von der Wahrnehmung aus die Begriffsbildung erfolgt; daß aber dasjenige, was, ich möchte sagen, die Begriffsbildung durchwebt als Erinnerungsvermögen, sich herausentwickelt aus dem übrigen Organismus außer dem Hauptesorganismus. Und setzt man diese Beobachtung fort, versucht man, namentlich dahinterzukommen, wie eigentümlich sich verhält die Art, namentlich der Gedächtnisbildung bei Kindern, welche etwa neigen zu einer kurzen, kleinen, gedrungenen Gestalt und bei Kindern, die dazu neigen, hoch aufzuschießen, so wird man finden, daß da tatsächlich sich deutlich ausspricht ein Zusammenhang zwischen den Wachstumserscheinungen im ganzen und zwischen dem, was als Gedächtniskraft sich im Menschen ausbildet.

[ 7 ] Nun habe ich bei früheren Gelegenheiten gesagt: Die menschliche Hauptesbildung als solche stellt sich ja dar als eine Metamorphose der organischen Bildung des Menschen des früheren Erdenlebens, aber abgesehen von der Hauptesbildung. Also was wir in einem gewissen Erdenleben als unser Haupt an uns tragen, das ist der umgestaltete Körper außer dem Haupte, namentlich aber der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselmensch des früheren Erdenlebens. Man darf sich das natürlich nicht materialistisch vorstellen. Mit der materiellen Ausfüllung hat das nichts zu tun, sondern mit der Form und mit dem Kräftezusammenhang. Dasjenige, was heute der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus ist bei einem Menschen, das ist im nächsten Erdenleben, metamorphosisch umgewandelt durch das Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, die Hauptesbildung.

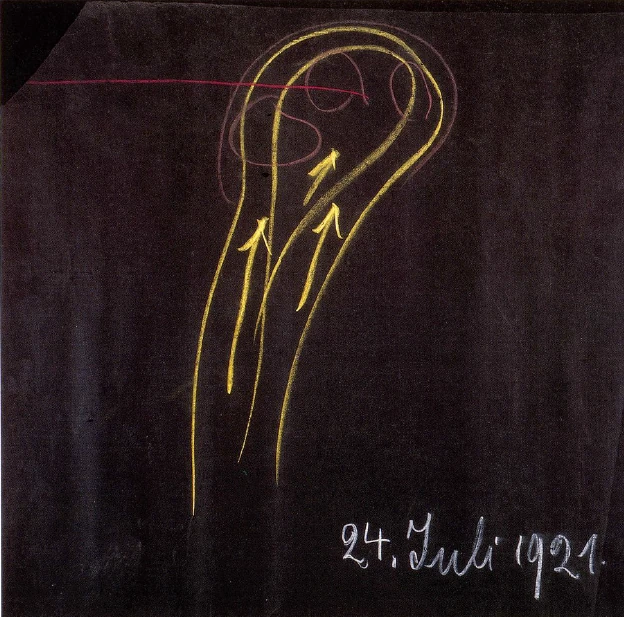

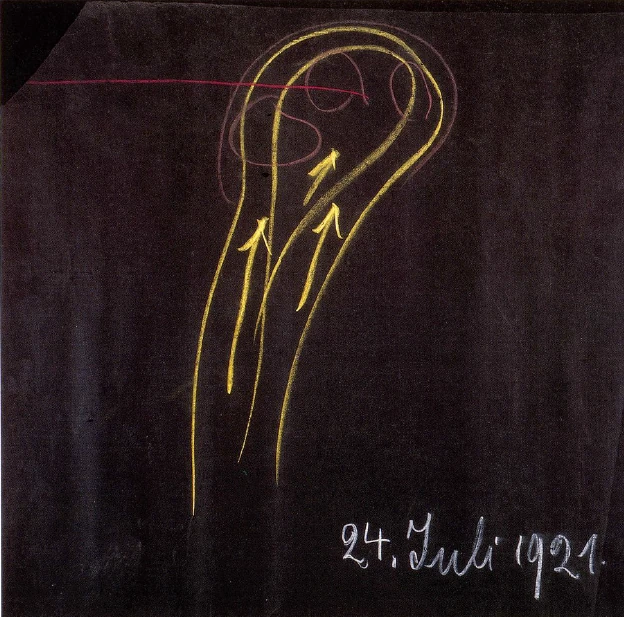

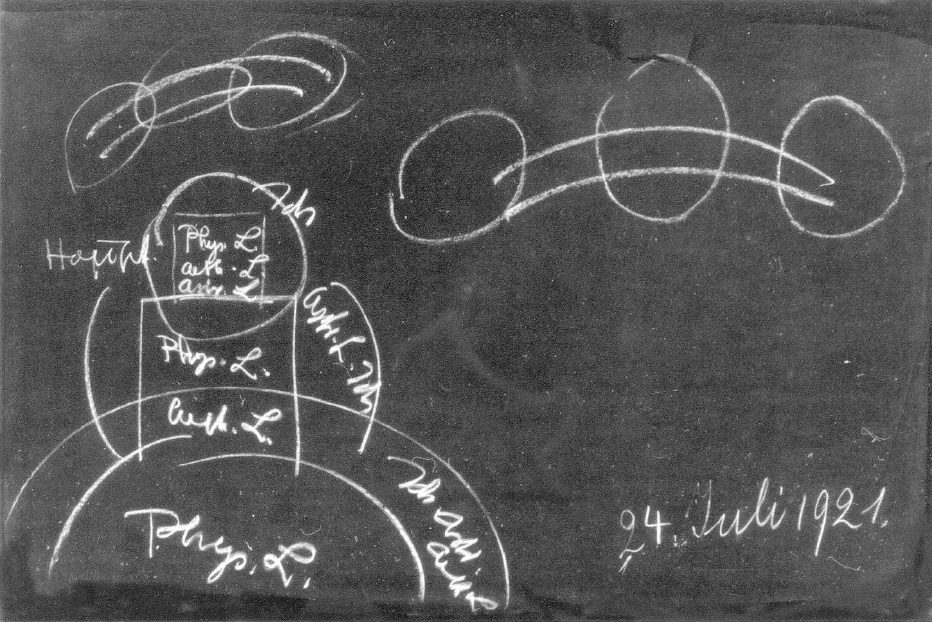

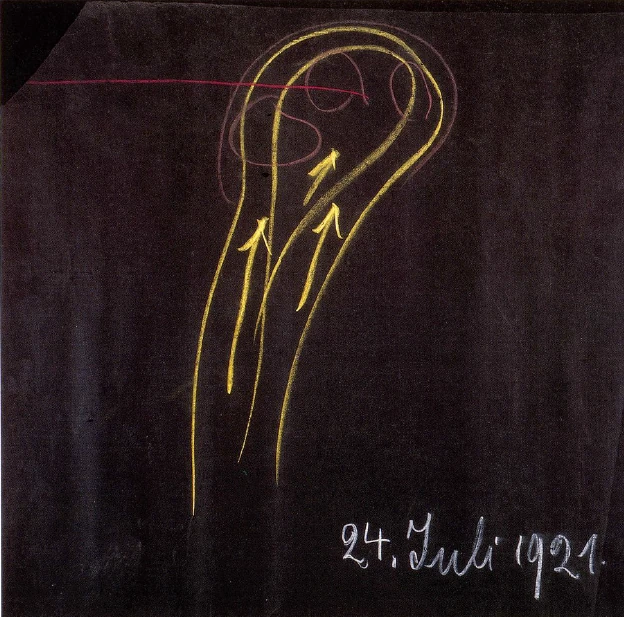

[ 8 ] So können wir uns ja auch sagen, wenn wir sehen, wie beim Kinde abhängt sein Begriffsvermögen, sein Vorstellungsvermögen von dieser Hauptesbildung, daß gewissermaßen die Vorstellungsfähigkeit zusammenhängt mit dem früheren Erdenleben (siehe Zeichnung, rot). Dagegen das, was sich uns als Erinnerungsvermögen eingliedert, steigt auf aus demjenigen, was wir zunächst in diesem Erdenleben als unseren Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenmenschen eben anorganisiert erhalten (blau). Es schließen sich da zwei Dinge zusammen: das eine, was der Mensch sich mitbringt aus früheren Erdenleben, und das andere, die Erinnerungsfähigkeit, was er sich dadurch erwirbt, daß er einen neuen Organismus angegliedert erhält.

[ 9 ] Sie werden daher begreifen, daß dasjenige Gedächtnis, das man zunächst für den Gebrauch zwischen Geburt und Tod hat und das man ja angegliedert erhält in diesem Erdenleben, zunächst nicht ausreicht, um zurückzuschauen in das vorgeburtliche Leben, in das präexistente Leben. Da ist notwendig, was ich immer betone, wenn ich das Methodologische der Sache auseinandersetze, daß man hinter dieses Gedächtnis mit seinen Fähigkeiten kommt und daß man deutlich einsehen lernt, daß das Gedächtnis etwas ist, was uns dient zwischen Geburt und Tod, daß man aber eine höhere Fähigkeit entwickeln muß, die ganz nach Gedächtnisweise zurückverfolgt das, was sich in uns als Begriffsvermögen ausgestaltet. Der abstrakte Erkenntnistheoretiker, der setzt an die Stelle einer Tatsache ein Wort. Er sagt zum Beispiel: Mathematische Begriffe, weil sie nicht durch Erfahrung erworben zu werden brauchen, beziehungsweise weil ihre Gewißheit nicht aus der Erfahrung belegt zu werden braucht, seien a priori. — Das ist ein Wort: sie sind vor der Erfahrung gelegen, a priori. Und man kann ja dieses Wort bei Kantianern heute immer wieder und wiederum hören. Aber dieses a priori bedeutet eben nichts anderes, als daß wir diese Begriffe in den früheren Erdenleben erfahren haben; aber sie sind nicht minder eben Erfahrungen, von der Menschheit angeeignet im Laufe ihrer Entwickelung. Nur ist die Menschheit gegenwärtig in einem Stadium ihrer Entwickelung, wo sich eben die meisten Menschen, wenigstens die zivilisierten Menschen, diese mathematischen Begriffe schon mitbringen und man sie nur aufzuwecken braucht.

[ 10 ] Es ist natürlich ein bedeutsamer pädagogisch-didaktischer Unterschied im Aufwecken der mathematischen Begriffe und im Beibringen von solchen Vorstellungen und Begriffen, die aus der äußeren Erfahrung gewonnen werden müssen und bei denen das Erinnerungsvermögen eine wesentliche Rolle spielt. Man kann auch, namentlich wenn man sich ein gewisses Anschauungsvermögen aneignet für die menschliche Entwickelung in ihren Besonderheiten, deutlich zwei Typen von aufwachsenden Kindern unterscheiden: solche, die sich viel mitbringen aus früheren Erdenleben und denen daher leicht Begriffe beizubringen sind; dagegen kann man andere finden, die weniger sicher sind in ihren Begriffsbildungen, die sich aber leicht die Eigenschaften äußerer Dinge merken und daher leicht dasjenige aufnehmen, was sie durch eigene Beobachtung aufnehmen können. Da hinein spielt aber das Erinnerungsvermögen, denn man kann äußere Dinge nicht leicht in der Weise lernen, wie es dann schulmäßig gelehrt werden muß. Man kann dann natürlich einen Begriff bilden, aber man kann sie nicht so lernen, daß man an ihnen das Gelernte wiederzugeben vermag, wenn nicht ein deutliches Erinnerungsvermögen vorliegt. Kurz, man kann da das Zusammenfließen zweier Strömungen in der menschlichen Entwickelung sehr genau wahrnehmen.

[ 11 ] Nun, was liegt denn da eigentlich zugrunde? Bedenken Sie, auf der einen Seite ist der Mensch aus seiner Hauptesorganisation heraus das Begriffsbildungsvermögen gestaltend. Warum tut er das? Sie brauchen nur mit Verständnis die menschliche Hauptesorganisation zu betrachten, so werden Sie sich sagen können, warum. Diese menschliche Hauptesorganisation, sie tritt schon im embryonalen Leben verhältnismäßig früh auf, bevor die andere Organisation, gerade ihrem Wesentlichen nach, angegliedert ist. Die Embryologie ist ja durchaus ein Beleg für das, was Anthroposophie in bezug auf die Menschheitsentwickelung zu sagen hat. Aber Sie brauchen nicht so weit zu gehen, Sie brauchen bloß gewissermaßen den ausgewachsenen Menschen ins Auge zu fassen. Sehen Sie sich diese Hauptesorganisation an. Sie ist erstens darauf angelegt, daß man’ im Haupte relativ das Vollkommenste der ganzen menschlichen Organisation hat. Nun, diese Vorstellung könnte man anfechten. Dagegen eine andere ist nicht anzufechten, wenn sie nur in der richtigen Weise angeschaut wird. Das ist diese, daß wir in unserem Erleben uns ja ganz anders zu unserem Haupte stellen als zu unserem übrigen Organismus. Unseren übrigen Organismus verspüren wir in einer ganz andern Weise als unser Haupt. Unser Haupt löscht sich ja in unserem eigenen Seelenleben im Grunde genommen aus. Wir haben viel mehr organisches Bewußtsein von unserem gesamten übrigen Organismus als von unserem Haupte. Unser Haupt ist eigentlich dasjenige, was sich innerhalb unserer Organisation auslöscht.

[ 12 ] Dieses Haupt hebt sich auch heraus aus unserem übrigen Zusammenhange mit der Welt, erstens innerlich schon durch unsere Gehirnorganisation. Ich habe die Tatsache oftmals hervorgehoben: das Gehirn hat eine so große Schwere, daß es alles, was darunterliegt, zerdrücken würde, wenn es nicht im Gehirnwasser schwimmen würde und dadurch das ganze Gewicht verliert, das ein Körper haben würde, der aus Gehirnwasser besteht und ebenso groß wäre wie das Gehirn; so daß das Gehirn, sagen wir etwa in dem Verhältnis von eintausenddreihundert bis eintausendvierhundert Gramm zu zwanzig Gramm an Gewicht verliert. Das heißt aber, da der Mensch, insofern er auf der Erde steht, durchaus sein natürliches Gewicht hat, ist das Gehirn herausgehoben aus diesen Schwereverhältnissen, in denen es im Menschen natürlich sitzt, nicht in seiner Absolutheit, aber indem es im Menschen sitzt. Aber selbst wenn Sie nicht auf dieses Innerliche gehen, wenn Sie auf das Außerliche gehen, man möchte sagen, die ganze Art, wie Sie Ihre Köpfe tragen, ist ja eigentlich so, daß dieser Kopf, indem man ihn durch die Welt trägt, sich verhält wie ein Herr oder eine Dame, die in einer Droschke sitzen. Die Droschke, die muß sich weiterbewegen, aber indem sich die Droschke weiterbewegt, strengt sich der Herr oder die Dame in der Droschke gar nicht an, um weiterzukommen. Ungefähr in demselben Verhältnis ist auch unser Haupt zu unserem Organismus. Dazu ließen sich viele Dinge noch anführen. Auch unser Haupt ist in einem gewissen Sinne herausgehoben aus unserem übrigen Verhältnis zur Welt. Das ist eben aus dem Grunde, weil wir in unserem Haupte gewissermaßen in physischer Umgestaltung dasjenige haben, was unsere Seele zusammen mit unserem übrigen Organismus erlebte in einem früheren Erdenleben.

[ 13 ] Wenn Sie beim Haupte die vier Hauptglieder der menschlichen Organisation betrachten, physischen Leib, Atherleib, astralischen Leib und Ich, so ist für das Haupt eigentlich nur das Ich dasjenige, was eine gewisse Selbständigkeit hat. Die andern Glieder haben sich eigentlich ihr Abbild geschaffen in diesem menschlichen Haupte, in der physischen Gestaltung des menschlichen Hauptes. Ich habe auch dafür einmal einen ganz schlagenden Beleg angeführt, ich will ihn hier anführen mehr durch das Wiedergeben einer Geschichte als rein theoretisch. Aber ich habe schon einmal die Sache angeführt.

[ 14 ] Ich sagte Ihnen: Ich nahm einmal teil — viele Jahre sind es jetzt her -, als man aus gewissen Voraussetzungen heraus die Giordano Bruno-Gesellschaft gegründet hatte, an einem Vortrage, den ein richtiger, waschechter Materialist gehalten hat über das menschliche Gehirn. Er hat als waschechter Materialist selbstverständlich die Struktur des Gehirnes gezeichnet und nachgewiesen, wie diese Struktur des Gehirnes im Grunde genommen das Seelenleben ausdrückt. Man kann das auch sehr gut.

[ 15 ] Vorsitzender jenes Vereines war nun ein Gymnasialdirektor, der nicht Materialist war, aber dafür ein waschechter philosophischer Herbartianer. Für den gab es nur Herbartsche Philosophie. Der sagte: Eigentlich könne er als Herbartianer ganz zufrieden sein mit den Darstellungen; nur sagte er, dasjenige, was der andere aufgezeichnet hat aus seinem waschechten Materialismus heraus, nehme er nicht als die Materie des Gehirnes. Wenn der also, nicht wahr, aufgezeichnet hat Gehirnpartien, Verbindungsfasern und so weiter, so nahm der Herbartianer die Zeichnung ganz willig hin. Die Zeichnung, die gefiel ihm ganz gut, dem Herbartianer, der kein Materialist war, denn er sagte, er brauche ja nur dafür, wofür der andere Gehirnpartien hinzeichnete, Vorstellungskomplexe hinzuzeichnen, und statt der Gehirnfasern zeichne er Assoziationsfasern; dann zeichne er etwas Seelisches, Vorstellungskomplexe, wo der andere Gehirnpartien zeichne. Und wo der andere Gehirnfasern gezeichnet hat, da zeichne er Assoziationsfasern; zum Beispiel diejenigen Gebilde, die John Stuart Mill so wunderbar herausphantasiert hat, die von Vorstellung zu Vorstellung gehen. Nicht wahr, ganz willenlos, automatisch spinnt da die Seele allerlei Dinge zwischen den Vorstellungskomplexen. Man findet das ja auch bei Herbart ganz schön.

[ 16 ] Aber in der Zeichnung konnten beide ganz gut zusammentreffen. Warum? Aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil in der Tat in bezug darauf das menschliche Gehirn ein außerordentlich guter Abdruck ist des Seelisch-Geistigen. Das Seelisch-Geistige drückt sich einfach im Gehirn sehr gut ab. Es hat ja auch Zeit gehabt, dieses Seelisch-Geistige, durch die ganze Zeit zwischen dem Tod und der neuen Geburt diese Konfiguration hervorzurufen, die dann in der äußeren Plastik des Gehirnes das Seelenleben wunderbar ausdrückt.

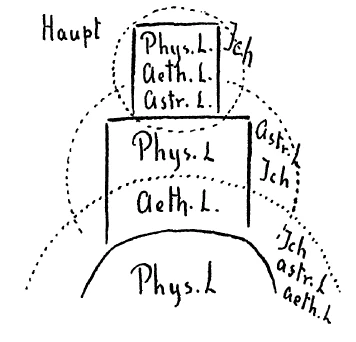

[ 17 ] Gehen wir von dieser Geschichte nun etwa zu der Darstellung der Psychologie, wie sie Theodor Ziehen gibt, da finden wir, daß Theodor Ziehen auch so materialistisch die Gehirnpartien und so weiter beschreibt, und das Ganze macht einen außerordentlich glaubwürdigen Eindruck. Es ist auch außerordentlich gewissenhaft. Man kann in der Tat das tun. Man kann, wenn man das menschliche intellektualistische Leben, das Vorstellungsleben ins Auge faßt, einen sehr genauen Abdruck im Gehirn finden. Aber man kommt mit einer solchen Psychologie nur nicht bis zum Fühlen, und am wenigsten bis zum Wollen. Schauen Sie sich an solch eine Psychologie, wie die von Ziehen ist, so werden Sie finden: das Fühlen ist für ihn überhaupt nichts als eine Gefühlsbetonung der Vorstellung, und das eigentliche Wollen fällt ganz heraus aus der psychologischen Betrachtungsweise. Das ist gar nicht drinnen, weil in der Tat das Fühlen und das Wollen nicht in derselben Weise zusammenhängen mit demjenigen, was schon gestaltet ist. Das Fühlen hängt zusammen mit dem rhythmischen System des Menschen; das ist noch in voller Bewegung. Das hat seine Bildlichkeit in Bewegungen. Und das Wollen, das überhaupt mit plastisch Entstehendem und Vergehendem im Stoffwechsel zusammenhängt, das kann nicht eine solche Abbildlichkeit aufweisen, wie das für das Vorstellen möglich ist. Kurz, wir haben im Vorstellungsleben beziehungsweise in der Vorstellungsfähigkeit etwas in bezug auf Seelisches, was sich plastisch-bildhaft im Haupte ausdrückt: da stehen wir aber innerhalb des menschlichen astralischen Leibes. Denn indem wir vorstellen, gehört diese ganze Tätigkeit des Vorstellens dem menschlichen astralischen Leibe an. So daß also schon der menschliche astralische Leib sein Abbild sich schafft im menschlichen Haupte. Nur das Ich, das bleibt noch etwas Bewegliches. Der ätherische Leib hat nun sein ganz genaues Abbild im menschlichen Haupte, und der physische Leib erst recht. Dagegen ist in dem übrigen Organismus, zum Beispiel im rhythmischen Organismus, der astralische Leib als solcher durchaus nicht abgebildet, sondern nur der ätherische Leib und der physische Leib. Und im Stoffwechselorganismus ist gar nur der physische Leib abgebilder.

[ 18 ] Zusammengefaßt können Sie sich die Sache so vorstellen: Wenn Sie das Haupt haben, so haben Sie im Haupte physischen Leib, ätherischen Leib, astralischen Leib, so daß diese im Physischen ihre Abbildung haben, daß Sie tatsächlich in den physischen Formen die Abbildungen nachweisen können. Sie verstehen das menschliche Haupt gar nicht anders, als daß Sie tatsächlich diese drei Formen in dem menschlichen Haupte sehen. Noch in einem freien Verhältnis ist dasjenige, was das Ich ist (siehe Zeichnung).

[ 19 ] Gehen wir über zu der übrigen Organisation des Menschen, also zu der Atmungsorganisation zum Beispiel, dann haben wir den physischen Leib und den ätherischen Leib, die ihre Abbilder darinnen haben. Aber der astralische Leib und das Ich haben nicht ihre Abbilder, die sind gewissermaßen frei. Und im menschlichen Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenmenschen haben wir den physischen Leib als solchen, und frei haben wir Ich, astralischen Leib und ätherischen Leib. Sie müssen unterscheiden zwischen dem Vorhandensein und dem Frei- oder Gebundensein. Natürlich ist es nicht so, als ob dem menschlichen Haupte nicht auch ein astralischer Leib und ein Ätherleib zugrunde läge. Die durchsetzen natürlich auch das menschliche Haupt; aber sie sind nicht frei dadrinnen, sondern sie haben in der Organisation ihr Abbild. Dagegen ist der astralische Leib zum Beispiel in der ganzen rhythmischen, namentlich in der Atmungsorganisation frei. Er betätigt sich als solcher. Er füllt das nicht bloß aus, sondern er ist gegenwärtig drinnen tätig.

[ 20 ] Nun, nehmen wir zwei Dinge zusammen. Das eine ist dieses, daß wir konstatieren können eine Beziehung des menschlichen Erinnerungsvermögens zu der Organisation außerhalb des Hauptes, und daß wir die menschliche Gefühls- und Willensorganisation auch außerhalb des Hauptes suchen müssen. Sie sehen, jetzt gliedern sich zusammen die Gefühlswelt der Seele und die Gedächtniswelt. Und wenn Sie nun empirisch, wirklich erfahrungsgemäß den Zusammenhang zwischen Gefühlsleben und Erinnerungsvermögen ins Auge fassen, so werden Sie diesen Zusammenhang als einen sehr engen konstatieren können.

[ 21 ] Die Art und Weise, wie wir uns erinnern können, hängt im wesentlichen davon ab, wie wir vermöge unserer außerhauptlichen Organisation teilnehmen können an den Dingen, wie weit wir drinnenstehen können in den Dingen. Wenn wir starke Kopfmenschen sind, werden wir vieles begreifen, aber an weniges uns so erinnern, daß wir mit ihm zusammengewachsen sind. Es gibt, ich möchte sagen, einen bedeutsamen Bezug zwischen dem Gefühlsvermögen und dem Erinnerungsvermögen. Aber zugleich sehen wir, daß die menschliche außerhauptliche Organisation sich ja im Beginne der Entwickelung der hauptlichen nähert. Wenn Sie das Embryonalleben nehmen, so ist der Mensch ganz im Anfange fast nur Haupt. Das andere sind Ansätze. Wenn das Kind geboren ist: denken Sie nur, wie unvollkommen im Verhältnis zum Haupte eigentlich die übrige Organisation ist! Aber sie gliedert sich ihm an. Die übrige Organisation, sie wird schon im Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod der Hauptesorganisation immer ähnlicher, und namentlich prägt sich dieses Ähnlichwerden aus in dem Hervorschießen der zweiten Zähne. Dasjenige, was der Mensch als erste Zahnung hat, die sogenannten Milchzähne - und das wird, wenn nur die entsprechenden Methoden angewendet werden, sich leicht auch anatomischphysiologisch nachweisen lassen, geisteswissenschaftlich ist es ohne Frage -, die ersten Zähne, die Milchzähne sind in der Tat mehr aus der Hauptesorganisation heraus. An der andern Zahnung beteiligt sich der volle Mensch. Diejenigen Zähne, die mehr aus der Hauptesorganisation heraus sind, werden ausgestoßen. Der übrige Mensch betätigt sich an der zweiten Zahnung.

[ 22 ] Man hat in der Tat mit Bezug auf das Physische eine Art Abbild in den ersten Zähnen und in den zweiten Zähnen mit Bezug auf Begriffsbildung und Gedächtnis. Man möchte sagen, die Milchzähne werden mehr aus der Hauptesorganisation heraus gebildet, so wie die Begriffe, bloß daß die Begriffe natürlich ins Intellektualistisch-Geistige heraufgesetzt sind; und die zweiten Zähne, die sind mehr so aus der ganzen menschlichen Organisation herausgeholt wie das Erinnerungsvermögen. Man muß nur auf solche feinen Unterschiede in der menschlichen Organisation eingehen können.

[ 23 ] Wenn Sie solch eine Sache ins Auge fassen, dann werden Sie ja einsehen, wie man eigentlich das Materielle in seiner Formung, in seiner Gestaltung — namentlich, wenn man ins Organische heraufkommt — nur erfassen kann, wenn man es erfaßt aus der geistigen Gestaltung heraus. Nicht wahr, der waschechte Materialist sieht sich den materiellen Menschen an, studiert den materiellen Menschen. Und derjenige, der auf die Wirklichkeit geht, nicht auf seine materialistischen Vorurteile, der sieht zunächst einmal dieses menschliche Haupt beim Kinde aus dem Übersinnlichen herausgestaltet, allerdings durch Metamorphose des früheren Erdenlebens herausgestaltet, und er sieht dann angegliedert aus der Welt, in die dieses Kind jetzt in diesem Erdenleben versetzt ist, das andere, aber auch aus dem Geistigen, aus dem Übersinnlichen dieser Welt herausgestaltet.

[ 24 ] Es ist wichtig, gerade auf solch eine Anschauung seine Aufmerksamkeit zu wenden; denn darauf kommt es an, daß jemand nicht in einer abstrakten Weise spricht von materieller Welt und von geistiger Welt, sondern daß er eine Anschauung gewinnt von dem Hervorgehen der materiellen Welt aus der geistigen Welt, gewissermaßen von der Abbildlichkeit der geistigen Welt in der materiellen Welt. Nur darf man dabei nicht im Abstrakten stehenbleiben, sondern muß in das Konkrete gehen. Man muß eine Anschauung sich verschaffen können von dem Unterschiede des menschlichen Hauptes vom übrigen Organismus. Dann sieht man in den Formen des menschlichen Hauptes eben etwas anderes, auch in seinem Hervorgehen aus der geistigen Welt, als man im übrigen Organismus sieht. Denn der übrige Organismus ist eben durchaus uns angegliedert in einem entsprechenden Erdenleben, während wir die Hauptesbildung bis in seine Formung hinein als Ergebnis früherer Erdenleben mitnehmen. Wer das bedenkt, wird sehen, wie töricht zum Beispiel solch ein Einwand gegen Anthroposophie ist, wie er neulich wiederum - Sie können das in einem Bericht der gegenwärtigen Nummer der Dreigliederungszeitung nachlesen - in einer Münchner Diskussion, die hervorgerufen worden ist über Anthroposophie von dem, von so vielen Leuten trotz seiner feuilletonistischen Philisterei hochgeehrten Eucken, gemacht worden ist. Eucken erhob den Einwand gegen Anthroposophie, daß sie materialistisch sei, indem er hinpfahlte den törichten Begriff: Dasjenige, was man wahrnehmen kann, das ist materiell. — Selbstverständlich, wenn man solch eine Definition macht, dann kann man beweisen, was man mag; nur ist man eben schlecht bekannt mit der Methode des Beweisens überhaupt. Es handelt sich durchaus darum, das zu fassen, wie das Materielle in seinem Hervorgehen aus dem Geistigen gerade als ein Zeuge für die geistige Welt angeschaut werden kann. Wenn Sie aber wiederum - und nur bis zu diesem Punkte möchte ich zunächst heute gehen — ins Auge fassen, wie man dieses Werden des Gedächtnisses erschauen kann in seiner Verwandtschaft mit den übrigen Wachstumskräften des Menschen, so werden Sie ein Ineinanderspielen bemerken desjenigen, was man sonst materiell nennt und desjenigen, was da namentlich im späteren Leben, vom siebenten, achten Jahre an, sich als geistig-seelisches Leben entwickelt.

[ 25 ] Es ist wirklich so, daß dasjenige, was später mehr in der abstrakt-intellektualistischen Form in der Erinnerungskraft zutage tritt, zuerst sich mitbeteiligt an dem Wachstum. Es ist wirklich dieselbe Kraft. Es muß da dieselbe Betrachtungsweise angewendet werden, die angewendet wird, sagen wir, wenn von gebundener und freier Wärme gesprochen wird. Wärme, die frei wird, die aus ihrem latenten Zustand in Freiheit übergeht, verhält sich äußerlich in der physischen Welt wie jene Kraft, die dann anschaulich für das innere Leben als Erinnerungskraft zutage tritt und in den ersten Kindheitsjahren den Wachstumserscheinungen zugrunde liegt. Es ist dasselbe, was den Wachstumserscheinungen zugrunde liegt in den ersten Kindheitsjahren und was dann als die Kraft der Erinnerungsfähigkeit mehr in seiner ureigenen Gestalt erscheint.

[ 26 ] Ich habe das im Herbstkurse hier im Goetheanum noch des genaueren entwickelt. Aber Sie sehen daraus, wie man gerade auf diesem Wege einen intimen Bezug zwischen dem Seelisch-Geistigen und Leiblich-Physischen finden kann, wie wir also in der Gedächtniskraft etwas haben, was auf der einen Seite uns seelisch-geistig erscheint, auf der andern Seite uns erscheint, indem es in anderem Weltenzusammenhange auftritt, als Wachstumskraft.

[ 27 ] Genau den entgegengesetzten Fall haben Sie, wenn Sie die Liebefähigkeit des Menschen ins Auge fassen. Die Liebefähigkeit, die auf der einen Seite durchaus sich erweist als an die Körperlichkeit gebunden, die können Sie wiederum als die seelischeste Funktion ins Auge fassen, genauso wie die Gedächtniskraft. So daß Sie in der Tat — das letztere werde ich in späteren Vorträgen noch genauer ausführen - in Gedächtnis und Liebe etwas haben, wo Sie, ich möchte sagen, das Zusammenspiel des Geistigen und des Leiblichen ganz erfahrungsgemäß sehen können und es auch beziehen können auf das ganze Verhältnis des Menschen zur Welt.

[ 28 ] Beim Gedächtnis haben wir das schon getan, indem wir zurückbezogen haben das Vorstellungsbild auf frühere Erdenleben, die Kraft des Gedächtnisses aber auf das gegenwärtige Erdenleben. Wir werden sehen in späteren Vorträgen, daß man mit der Liebekraft ebenso verfahren kann. Man kann zeigen, wie sie sich entwickelt in dem gegenwärtigen Erdenleben, aber durchgeht durch das Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt in das nächste Erdenleben hinüber, wie sie es gerade ist, die an der Metamorphosierung des übrigen außerhauptlichen menschlichen Organismus in das nächste Erdenleben hinüberarbeitet.

[ 29 ] Warum stellen wir diese ganze Betrachtung an? Wir stellen sie an, weil man heute eine Möglichkeit braucht, von dem Geistig-Seelischen hinüberzukommen zu dem Leiblich-Physischen. Innerhalb des GeistigSeelischen erleben wir das Moralische, innerhalb des Physisch-Leiblichen erleben wir die Naturnotwendigkeit. Zwischen beiden besteht für die heutige Anschauung, wenn man ehrlich auf beiden Gebieten ist, eben keine Brücke. Und ich habe gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß, weil eine solche Brücke nicht besteht, die Leute ja sogar unterscheiden zwischen dem sogenannten echten Wissen, das sich auf die Naturkausalität bezieht, und dem bloßen Glaubensinhalt, der sich auf die moralische Welt beziehen soll, weil unzusammenhängend nebeneinanderstehen auf der einen Seite die Naturkausalität, auf der andern Seite das seelisch-geistige Leben. Aber es handelt sich durchaus darum, daß wir, um zu einem vollen Menschenbewußtsein wiederum zu kommen, dieses Brückenschlagen zwischen dem einen und dem andern brauchen.

[ 30 ] Da ist vor allen Dingen notwendig zu berücksichtigen, daß die moralische Welt ohne die Statuierung der Freiheit nicht bestehen kann, die natürliche Welt nicht bestehen kann ohne die Notwendigkeit, nach welcher das eine aus dem andern hervorgeht. Es könnte im Grunde gar keine Wissenschaft geben, wenn es diese Notwendigkeit nicht geben würde. Würde nicht notwendig eine Erscheinung aus der andern hervorgehen im Naturzusammenhang, würde da alles willkürlich sein, so könnte es ja keine Wissenschaft geben. Es könnte nun ja alles dasjenige, was man eben nicht wissen kann, aus dem andern hervorgehen, nicht wahr! Also es ist klar: Wissenschaft ist zunächst da, wenn man in ihr nur sehen will, wie eines aus dem andern hervorgeht, daß eines aus dem andern hervorgeht. Aber wenn diese Naturkausalität ganz allgemein ist, dann ist eine moralische Freiheit unmöglich, dann kann sie nicht da sein. Aber das Bewußtsein dieser moralischen Freiheit innerhalb des Seelisch-Geistigen, das ist als eine unmittelbar erfahrbare Tatsache in jedem Menschen vorhanden.

[ 31 ] Der Widerspruch zwischen dem, was der Mensch erlebt in seiner moralischen Seelenkonstitution und in der Naturkausalität, ist nicht ein logischer, sondern ein Lebenswiderspruch. Wir gehen fortwährend mit diesem Widerspruch durch die Welt. Er gehört zum Leben. Es ist in der Tat so, daß, wenn wir uns ehrlich gestehen, was da vorliegt, wir uns sagen müssen: Naturkausalität, Notwendigkeit, sie muß es geben, und wir gehen selber als Menschen durch diese Notwendigkeit. Aber unser inneres, seelisch-geistiges Leben widerspricht dem. Wir sind uns bewußt: Wir können Entschlüsse fassen, wir können moralischen Idealen folgen, die uns nicht innerhalb der Naturkausalität gegeben sind. Es ist dieses ein Widerspruch, der ein Lebenswiderspruch ist. Und derjenige, der nicht zugeben kann, daß solche Widersprüche im Leben drinnenstehen, der faßt einfach das Leben nicht in seiner Allseitigkeit. Aber wenn wir das so ausdrücken, ist es recht abstrakt. Es ist eigentlich im Grunde genommen stets nur eine Art von Auffassung, die wir dem Leben entgegenbringen. Wir gehen durch das Leben und fühlen uns eigentlich fortwährend mit der äußeren Natur im Widerspruch. Es scheint, als ob wir machtlos wären, als ob wir uns eben im Widerspruch fühlen müßten.

[ 32 ] Man kann diese Widersprüche zum Beispiel heute bei manchen Menschen gerade in einer recht tragischen Weise erleben. Ich habe zum Beispiel einen Menschen gekannt, der tatsächlich ganz erfüllt war davon, daß es eine Notwendigkeit in der Welt gibt, der auch der Mensch eingegliedert ist. Man kann natürlich theoretisch eine solche Notwendigkeit zugeben und sich mit seinem ganzen Menschen nicht viel darum kümmern; dann geht man eben als Trivialling durch die Welt und wird nicht von einer inneren Tragik erfüllt. Aber wie gesagt, ich kannte immerhin einen Menschen, der sagte: Es ist ja überall Notwendigkeit, und wir Menschen sind hineingestellt in diese Notwendigkeit. Es ist nicht anders, denn die Wissenschaft zwingt uns zur Anerkennung dieser Notwendigkeit. Aber diese Notwendigkeit läßt zu gleicher Zeit Blasen in uns aufsteigen, Blasen, die Schaum sind und die uns vorgaukeln ein freies Seelenleben. Das müssen wir durchschauen, als Blasen ansehen. Das ist auch eine Notwendigkeit.

[ 33 ] Das ist die furchtbare Illusion des Menschen. Das ist dieBegründung des Pessimismus in der menschlichen Natur. Wer wenig Idee davon hat, wie tief so etwas in der Seele eines Menschen wirken kann, der wird nicht nachfühlen können, wie hier der durchaus reale Lebenswiderspruch die ganze menschliche Seele durchwühlen kann und selbst zu der Anschauung führen kann, daß zu leben durch seine eigene Wesenheit ein Unglück ist. Es ist nur die Gedankenlosigkeit und die Empfindungslosigkeit gegenüber demjenigen, was uns heute auf der einen Seite wissenschaftliche Gewißheit und auf der andern Seite Glaubensgewißheit geben wollen, die die Menschen nicht kommen lassen zu solcher inneren Lebenstragik. Denn eigentlich wäre gegenüber der heutigen möglichen Seelenverfassung der Menschheit diese Lebenstragik die gegebene Seelenverfassung.

[ 34 ] Aber woher rührt denn das Unvermögen, das zu solcher Lebenstragik führt? Es rührt daher, daß wir uns seit Jahrhunderten eben eingesponnen haben als zivilisierte Menschheit in gewisse Abstraktionen, in einen Intellektualismus. Dieser Intellektualismus kann sich höchstens sagen: Es gaukelt uns die Naturnotwendigkeit durch merkwürdige Richtungen ein Freiheitsgefühl vor. Das ist aber nicht vorhanden. Es ist nur in unseren Ideen vorhanden. Wir sind ohnmächtig gegenüber der Naturnotwendigkeit.

[ 35 ] Die große Frage entsteht: Sind wir das nun wirklich? - Und nun merken Sie, wie die Vorträge, die ich nun seit Wochen hier gehalten habe, eigentlich alle auf die Frage hintendieren: Sind wir es in Wirklichkeit? Sind wir in Wirklichkeit so ohnmächtig mit diesem Widerspruch? - Erinnern Sie sich, wie ich gesagt habe, daß wir im menschlichen Leben nicht nur eine aufsteigende, sondern auch eine absteigende Entwickelung haben, daß unser intellektuelles Leben nicht gebunden ist an die Wachstums-, sondern an die Absterbekräfte, an die absterbende Entwickelung, daß wir das Sterben brauchen, gerade um die Intelligenz zu entwickeln. Erinnern Sie sich daran, wie ich vor einigen Wochen hier gezeigt habe, was es für eine Bedeutung hat, daß mit bestimmten Affinitäten und Wertigkeitskräften in der Welt bestehende Elemente, meinetwillen Kohlenstoff, Sauerstoff, Wasserstoff, Stickstoff, Schwefel sich verbinden zu dem Eiweißstoff; wie ich Ihnen gezeigt habe, worauf dieses Verbinden beruht, wie es gerade nicht auf dem Chemisieren, sondern auf dem Chaotischwerden beruht, und Sie werden sehen, alle diese Betrachtungen tendieren dahin, das, was ich angedeutet habe, nicht nur als einen theoretischen Widerspruch aufzudecken, sondern als einen Prozeß in der menschlichen Natur. Wir sind nicht nur, indem wir als Menschen leben, dazu da, einen solchen Widerspruch zu empfinden, sondern unser inneres Leben ist ein fortwährender Zerstörungsprozeß desjenigen, was außen in der Natur als Naturkausalität sich entwickelt. Wir lösen in uns Menschen die Naturkausalität in Wirklichkeit auf. Dasjenige, was außen die physikalischen Vorgänge, die chemischen Vorgänge vorstellen, in uns wird es rückgängig entwickelt, wird es nach der andern Seite entwickelt. Natürlich wird uns das nur dann klar, wenn wir den unteren und den oberen Menschen ins Auge fassen, wenn wir dasjenige, was im unteren Menschen vom Stoffwechsel heraufkommt, in seiner Entmechanisierung, Entphysizierung, Entchemisierung durch den oberen Menschen ins Auge fassen. Wenn wir die Entstofflichung im Menschen ins Auge zu fassen suchen, dann haben wir nicht nur einen logischen, theoretischen Widerspruch in uns, sondern wir haben den realen Prozeß: wir haben den Menschenwerde- und Menschenentwickelungsprozeß als denjenigen in uns, der selber kämpft gegen die Naturkausalität, und das Menschenleben als ein solches, welches darinnen besteht, daß es ein Kampf ist gegen die Naturkausalität. Und der Ausdruck dieses Kampfes, der Ausdruck desjenigen, was in uns fortwährend die physische Synthese, die chemische Synthese löst, wiederum analysiert, der Ausdruck des analytischen Lebens in uns faßt sich zusammen in der Empfindung: Ich bin frei.

[ 36 ] Dasjenige, was ich Ihnen jetzt in ein paar Worten hingestellt habe, also die Betrachtung des Menschen in seinem Werdeprozesse als einem Kampfprozesse gegen die Naturkausalität, als eine umgekehrte Naturkausalität, das wollen wir in den nächsten Vorträgen nun hier betrachten.

Sixteenth Lecture

[ 1 ] The division of human nature that I have spoken of can also be found expressed in everyday human life as a whole. You find it above all when you properly examine the relationship between two human faculties which, even on superficial observation, prove by their very nature to belong both to the soul life and to the physical life. On the one hand, you find the ability to remember, which is an important fact of the soul life in human life, connected with physical life. On the other hand, you find a force in human life whose essence is less obvious because it is more of an ability that we naively surrender to without examining it more closely or even analyzing it: the power of human love. It must be said from the outset that when one speaks of such things, first in relation to the essence of the human being, but then also in relation to the relationship of the human being to the world, one must be clear that one must start from reality, not from some idea. I have often used the banal comparison of starting from ideas rather than reality: someone sees a razor and says that it is a knife, that a knife is for cutting food; so he takes the razor to cut food because it is a knife.

[ 2 ] This is roughly how, although one does not usually believe it because one considers the matter to be very scholarly, the views that, say, scientifically minded people have about death or birth in relation to humans and animals are formed. Sometimes such ideas are even extended to plants. One forms an idea about how one forms an idea of what a knife is, and then, starting from this idea, which is of course representative of a certain series of facts, one investigates in the same way, say, death in humans, in animals, and possibly even in plants, without taking into account that what one generally summarizes in the idea of death could be something completely different in humans and animals. One must start from the reality of the animal and the reality of the human being, not from the phenomenon of death, which one allows to be represented by some idea.

[ 3 ] In a similar way, ideas are formed, for example, with regard to memory. With regard to memory, this is particularly evident where, in an attempt to find similarities between humans and animals, the concept of memory is applied to both in an undifferentiated manner. It has been pointed out—even by very famous professors such as Otto Liebmann—that, for example, an elephant on its way to a watering hole where it can drink water is insulted by a passerby who does something to it. The elephant walks on. But when it returns and the person is still standing there, the elephant sprays water at him from its trunk. Because the elephant, according to the epistemologist, has naturally remembered and stored in its memory what the person did to it.

[ 4 ] The external appearance of the matter is, of course, very tempting for such an epistemological consideration, but no more tempting than the undertaking of cutting meat at the table with a razor. It is essential to proceed from reality everywhere, and not from ideas that have been gained from some series of appearances and then arbitrarily transferred to another series of appearances as if they were essential. People usually do not realize how widespread the methodological error just mentioned actually is in our scientific investigations today.

[ 5 ] What exists in humans as memory, as the faculty of recollection, must be understood entirely from human nature itself. And here it is important to first create a possibility for observing how memory itself develops in the course of human evolution. Anyone who can observe this will notice that memory manifests itself in children in a completely different way than in people from about the age of six, seven, or eight. In the latter years, memory takes on a more spiritual character, while it is clear how much memory is bound to organic conditions in the early years of childhood, how it emerges from these organic conditions. And anyone who considers the relationship between memories and the formation of concepts in children will notice how the formation of concepts is in fact strongly based on what the child experiences from its environment through its sensory perception, through all twelve of the sensory perceptions mentioned above. It is extremely fascinating, but also extremely significant, to see how the concepts that children form depend entirely on the experiences to which they are subjected, namely on the behavior of their environment. During the years under consideration here, children are imitators, and they are also imitators in their concept formation. In contrast, it is easy to see how the ability to remember arises more from within the child's development, how it is more closely related to the entire physical constitution, and even very little to the constitution of the senses and thus to the constitution of the human head. On the other hand, one can sense an intimate connection between the way in which the child is more or less, if one may say so, normal or abnormal, for example in relation to its blood formation or its blood nutrition. It is easy to notice that children who tend toward anemia have difficulties with memory formation. On the other hand, one will notice that in such cases, the formation of concepts and ideas is less difficult.

[ 6 ] I can only point to these things, because basically everyone who has received the guidelines for such an observation must seek the data from life itself, and they will find it. They will then find that in children, concept formation does indeed take place in the head, that is, in the nervous-sensory organization, and thus from experience and perception; but that what I would call the memory, which permeates concept formation, develops from the rest of the organism outside the head. And if one continues this observation, if one tries to find out how peculiar the nature of memory formation is in children who tend to be short, small, and stocky, and in children who tend to shoot up tall, one will find that there is indeed a clear connection between the growth phenomena as a whole and between what what develops in humans as memory.

[ 7 ] Now, I have said on previous occasions that the formation of the human head as such represents a metamorphosis of the organic formation of the human being in its earlier earthly life, but apart from the formation of the head. So what we carry as our head in a certain earthly life is the transformed body apart from the head, namely the limb-metabolic human being of the earlier earthly life. Of course, this should not be imagined in a materialistic way. It has nothing to do with material substance, but with form and the interrelationship of forces. What is today the limb-metabolism organism in a human being is, in the next earthly life, metamorphically transformed through the life between death and new birth, the formation of the head.

[ 8 ] We can also say this when we see how a child's ability to understand and imagine depends on this head formation, that the ability to imagine is connected, in a sense, with the previous earthly life (see drawing, red). In contrast, what we incorporate as memory rises from what we initially receive in this earthly life as our metabolic-limb human being, which is inorganic (blue). Two things come together here: one is what the human being brings with them from previous earthly lives, and the other is the ability to remember, which they acquire by being incorporated into a new organism.