The Remedy for Our Diseased Civilisation

GA 206

6 August 1921, Dornach

Translator Unknown

[ 1 ] Yesterday I have tried to explain to you that, from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, the sensualistic or materialistic world-conception was gradually approaching a certain culminating point, and that this culminating point had been reached towards the end of the nineteenth century. Let us observe how the external facts of human evolution present themselves under the influence of the materialistic world-conception. This materialistic world-conception cannot be considered as if it had merely been the outcome of the arbitrary action of a certain number of leading personalities. Although many sides deny this, the materialistic conception is nevertheless based upon something through which the scientific convictions and scientific results of investigation of the nineteenth and early twentieth century have become great. It was necessary that humanity should attain these scientific results. They were prepared in the fifteenth century and they reached a certain culminating point, in the nineteenth century, at least in so far as they were able to educate mankind. And again, upon the foundation of this attitude towards science, nothing else could develop, except a certain materialistic world-conception.

[ 2 ] Yesterday I did not go beyond the point of saying: The chief thing to be borne in mind has become evident in a positively radical manner, at least in the external symptoms, in what may be designated as Haeckel's attitude towards those, for instance, who opposed him in the last decade of the nineteenth century and in the early twentieth century. What occurred there, and what had such an extraordinarily deep influence upon the general culture of humanity, may be considered without taking into consideration the special definition which Haeckel gave to his world-conception, and even without considering the special definition which his opponents gave to their so-called refutations. Let us simply observe the fact that, on the one hand, we have before us what people thought to win through a careful study of material processes, rising as far as the human being. To begin with, this was to be the only contents of a world-conception; people believed that only this enabled them to stand upon a firm ground. It was something completely new in comparison with what was contained, for instance, in the medieval world-conception.

[ 3 ] During the past three, four, five centuries, something entirely new had been gained in regard to a knowledge of Nature, and nothing had been gained in regard to the spiritual world. In regard to the spiritual world, a philosophy had finally been reached, which saw its chief task, as I have expressed myself yesterday, in justifying its existence, at least to a certain extent. Theories of knowledge were written, with the aim of stating that it was still possible to make philosophical statements, at least in regard to some distant point, and that perhaps it could be stated that a super-sensible world existed, but that it could not be recognised; the existence of a super-sensible world could, at the most, be assumed.

The sensualists, whose cleverest representative, as explained to you yesterday, was Czolbe, the sensualists therefore spoke of something positive, which could be indicated as something tangible. Thus the philosophers and those who had become their pupils in popularizing things, spoke of something which vanished the moment one wished to grasp it.

[ 4 ] A peculiar phenomenon then appeared in the history of civilisation; namely, the fact that Haeckel came to the fore, with his conception of a purely naturalistic structure of the world, and the fact that the philosophical world had to define its attitude towards, let us call it, Haeckelism. The whole problem may be considered, as it were, from an aesthetic standpoint. We can bear in mind the monumental aspect—it is indifferent whether this is right or wrong—of Haeckel's teachings, consisting in a collection of facts which conveyed, in this comprehensive form, a picture of the world. You see, the way in which Haeckel stood within his epoch, was characterised, for instance, by the celebration of Haeckel's sixtieth birthday at Jena, in the nineties of the last century. I happened to be present. At that time, it was not necessary to expect anything new from Haeckel. Essentially, he had already declared what he could state from his particular standpoint and, in reality, he was repeating himself.

[ 5 ] At this Haeckel-celebration, a physiologist of the medical faculty addressed the assembly. It was very interesting to listen to this man and to consider him a little from a spiritual standpoint. Many people were present, who thought that Haeckel was a significant personality, a conspicuous man. That physiologist, however, was a thoroughly capable university professor, a type of whom we may say: If another man of the same type would stand there, he would be exactly the same. It would be difficult to distinguish Mr. A from Mr. B or Mr. C. Haeckel could be clearly distinguished from the others, but the university professor could not be distinguished from the others. This is what I wish you to grasp, as a characteristic pertaining more to the epoch, than to the single case.

[ 6 ] The person who stood there as Mr. A, who might just as well have been Mr. B or Mr. C, had to speak during this Haeckel celebration. I might say that every single word revealed how matters stood. Whereas a few younger men (nearly all of them were unsalaried lecturers, but in Jena they nevertheless held the rank of professors; they received no salary, but they had the right to call themselves professors) spoke with a certain emphasis, realising that Haeckel was a great personality, the physiologist in question could not see this. If this had been the case, it would not be possible to speak of A, B and C in the same way in which I have now spoken of them. And so he praised the “colleague” Haeckel, and particularly emphasized this. In every third sentence he spoke of the “colleague” Haeckel, and meant by this that he was celebrating the sixtieth birthday of one of his many colleagues, a birthday like that of so many others. But he also said something else. You see, he belonged to those who do nothing but collect scientific facts, facts out of which Haeckel had formed a world-conception; he was one of those who content themselves with collecting facts, because they do not wish to know anything about the possibility of forming a conception of the world. Consequently, this colleague did not speak of Haeckel's world-conception.

[ 7 ] But, from his standpoint, he praised Haeckel, he praised him exceedingly, by indicating that, apart from Haeckel's statements concerning the world and life, one could contemplate what the “colleague” Haeckel had investigated in his special sphere: Haeckel had prepared so and so many thousands of microscopic slides, so and so many thousands of microscopic slides were available in this or in that sphere ... and so on, and so on ... and if one summed up the various empirical facts which Haeckel had collected, if these were put together and elaborated, one could indeed say that they constituted a whole academy.

This colleague, therefore, had implicitly within him quite a number of similar “colleagues” for whom he stood up. He was, as it were, a colleague of the medical faculty.

[ 8 ] During the banquet, Eucken, the philosopher, held a speech. He revealed (one might also say, he hid) what he had to say, or what he did not wish to say, by speaking of Haeckel's neck-ties and the complaints of Haeckel's relatives when they spoke more intimately of “papa”, or the man, Haeckel. The philosopher spoke of Haeckel's untidy neck-ties for quite a long time, and not at all stupidly ... and this was what philosophy could bring forward at that time! This was most characteristic ... for even otherwise, philosophy could not say much more; it was just an abstract and thorny bramble of thoughts. By this, I do not in any way pass judgment or appraise, for we may allow the whole thing to work upon us in an aesthetic way ... and from what comes to the fore symptomatically, we may gather that materialism gradually came to the surface in more recent times, and that it was able to give something. Philosophy really had nothing more to say: this was merely the result of what had arisen in the course of time. We should not think that philosophy has anything to say in regard to spiritual science.

[ 9 ] Let us now consider the positive fact which is contained in all that I have explained to you; let us consider it from the standpoint of the history of civilisation.

On the one hand, and this is evident from our considerations of yesterday, we have within the human being, as an inner development, intellectualism, a technique of thinking which Scholasticism had unfolded in its most perfect form before the natural-scientific epoch. Then we have intellectualism applied to an external knowledge of Nature. Something has thus arisen, which acquires a great historical significance in the nineteenth century, particularly towards its end. Intellectualism and materialism belong together.

[ 10 ] If we bear in mind this phenomenon and its connection with the human being, we must say: Such a world-conception grasps above all the head, the nerve-sensory part of what exists in the human being, in the threefold human being, namely the nerve-sensory part, with the life of thoughts, the rhythmical part, with the life of feeling, and the metabolic part, with the life of the will. Hence, this nerve-sensory part of the human being above all has developed during the nineteenth century. Recently, I have described to you from another standpoint, how certain people, who felt that the head of man, the nerve-sensory part of man had been developed in a particular way through the spiritual culture of the nineteenth century, began to fear and tremble for the future of humanity. I have described this to you in connection with a conversation which I had several decades ago with the Austrian poet, Hermann Rollet. Hermann Rollet was thoroughly materialistic in his world-conception, because those who take science as their foundation and those in whom the old traditional thoughts have paled, cannot be anything else. But at the same time he felt—for he had a poetical nature, an artistic nature and had published the beautiful book, “Portraits of Goethe”—at the same time he felt that the human being can only grow in regard to his nerve-sensory organisation, in regard to his life of thoughts. He wished to set this forth objectively. So he said: In reality, it will gradually come about that the arms, feet and legs of the human being shall grow smaller and smaller, and the head shall grow larger and larger (he tried to picture the approaching danger spatially), and then ... when the earth shall have continued for a while in this development, the human being (he described this concretely) shall be nothing but a ball, a round head rolling along over the surface of the earth.

We may feel the anxiety for the future of human civilisation which lies concealed in this picture. Those who do not approach these things with spiritual-scientific methods of investigation, merely see the outer aspect. If we wish to penetrate through the chaos of conceptions which now lead us to such an evil, we should also contemplate things from the other aspect. Someone might say: What has come to the fore as a materialistic world-conception can only be grasped by a small minority; the great majority lives in traditional beliefs in regard to the feelings connected with a world-conception.—But this is not the case on the surface, I might say, in regard to all the thought-forms connected with what the human beings thinks within his innermost depths in regard to his environment and the world. In our modern civilisation we find that what is contained in Haeckel's “Riddles of the World”, does not merely live in those who have found a direct pleasure in Haeckel's “Riddles of the World”, perhaps least of all in these men. Haeckel's “Riddles of the World” are, fundamentally speaking, merely a symptom of what constitutes to-day the decisive impulses of feeling throughout the civilised international world.

We might say: These impulses of feeling appear in the most characteristic way in the outwardly pious Christians, particularly in the outwardly pious Roman Catholics. Of course, on Sundays they adhere to what has been handed down dogmatically; but the manner in which they conceive the rest of life, the remaining days of the week, has merely found a comprehensive expression within the materialistic world-conception of the nineteenth century. This is altogether the popular world-conception even in the most distant country villages. For this reason, we cannot say that it can only be found among a dwindling minority. Indeed, formulated concepts may be found there, but these are only the symptoms. The essential point, the reality, is undoubtedly the characteristic of the modern epoch. We may study these things through the symptoms, but we should realise: When we speak of Kant, from the second half of the eighteenth century onwards, we merely speak of a symptom which pertained to that whole period; and in the same way we merely speak of a symptom, when we mention the things to which I have alluded yesterday and which I am considering to-day. For this reason, the things which I am about to say should be borne in mind very clearly.

You see, the human being can only be active intellectually and he can only surrender himself to the material things and phenomena (within, they are undoubtedly the counter-part of intellectualism) during the daytime, while he is awake, from the moment of waking up to the moment of falling asleep. Even then, he cannot do it completely, for we know that the human being does not only possess a life of thoughts, the human being also possesses a life of feeling. The life of feeling is inwardly equivalent to the life of dreams; the life of dreams takes its course in pictures; the life of feelings, in feelings. But the inner substantial side is that part in man which experiences the dream-pictures; it is that part which experiences feelings within the human life of feeling. Thus we may say: During his waking life, from the moment of waking up to the moment of falling asleep, the human being dreams awake within his feelings. What we experience in the form of feelings, is permeated by exactly the same degree of consciousness as the dream-representations, and what we experience within our will, is fast asleep; it sleeps even when we are otherwise awake. In reality, we are only awake in our life of thoughts. You fall asleep at night, and you awake in the morning. If a certain spiritual-scientific knowledge does not throw light upon that which takes place from the moment of falling asleep to the moment of waking up, it escapes your consciousness, you do not know anything about it within your consciousness... At the most, dream-pictures may push through. But you will just as little recognise their significance for a world-conception, as you recognise the importance of feelings for a world-conception. Human life is constantly interrupted, as it were, by the life of sleep. [ 11 ] In the same way in which the life of sleep inserts itself, from the standpoint of time, within man's entire soul-life, so the world of feelings, and particularly the world of the impulses of the will, inserts itself into human life. We dream through the fact that we feel; we sleep through the fact that we will. Just as little as you know what occurs to you during sleep, just as little do you know what takes place with you when you lift your arm through your will. The real inner forces which there hold sway, are just as much hidden in the darkness of consciousness, as the condition of sleep is hidden in the darkness of consciousness.

[ 12 ] We may therefore say: The modern civilisation, which began in the fifteenth century and reached its climax in the nineteenth century, merely lays claim on one third of the threefold human being: the thinking part of man, the head of man. And we must ask: What occurs within the dreaming, feeling part of the human being, within the sleeping, willing part of the human being, and what occurs from the time of falling asleep to the time of waking up?

[ 13 ] Indeed, as human beings, we may be soundly materialistic within our life of thoughts. This is possible, for the nineteenth century has proved it. The nineteenth century has also proved the justification of materialism; for it has led to a positive knowledge of the material world, which is an image of the spiritual world. We may be materialists with our head ... but in that case we do not control our dreaming life of feeling, nor our sleeping life of the will. These become spiritually inclined, particularly the life of the will.

[ 14 ] It is interesting to observe, from a spiritual-scientific standpoint, what takes place in that case. Imagine a Moleshott, or a Czolbe, who only acknowledge sensualism, or materialism with their heads; but below, they have their will, the volitive part of man, with its entirely spiritual inclinations (but the head does not know this); it reckons with the spiritual and with spiritual worlds. They also have within them the feeling part of man; it reckons with ghostly apparitions. If we observe things carefully, we have before us the following spectacle: There sits a materialistic writer, who inveighs terribly against everything of a spiritual nature existing within his sentient and volitive parts; he grows furious, because there is also a part within him, which is spiritualistic and altogether his opponent.

[ 15 ] This is how things take their course. Idealism and spiritualism exist ... particularly in the subconsciousness of man's will, and the materialists, the sensualists, are the strongest spiritualists.

[ 16 ] What lives in a corporeal form within the sentient part of man? Rhythm: the circulation of the blood, the breathing rhythm, and so forth. What lives within the volitive part of man? The metabolic processes. Let us study, to begin with, these metabolic processes. While the head is skillfully engaged in elaborating material things and material phenomena into a materialistic science, the metabolic part of man, which takes hold of the complete human structure, works out the very opposite world-picture; it elaborates a thoroughly spiritualistic world-picture, which the materialists, in particular, bear within them unconsciously. But within the metabolic part of man, this influences the instincts and the passions. There it produces the very opposite of what it would produce if it were to claim the whole human being. When it permeates the instincts, ahrimanic powers get hold of it, and then it is not active in a divine-spiritual sense, but it is active in an ahrimanic-spiritual sense. It then leads the instincts to the highest degree of egoism. It develops the instincts in such a way that the human being then merely makes claims and demands; he is not led to social instincts, to social feelings, and so forth. Particularly the individual side becomes an egoistic element of the instincts. This has been formed, if I may use this expression, below the surface of the materialistic civilisation; this has appeared in the world-historical events, and this is now evident. What has developed below the surface, as a germ, what has arisen in the depths of man's volitive part, where spirituality has seized the instincts, this now appears in the world-historical events. If the development were to continue in this consistent way, we would reach, at the end of the twentieth century, the war of all against all; particularly in that sphere of the evolution of the earth in which the so-called civilisation has unfolded. We may already see what has thus developed, we may see it raying out from the East and asserting itself over a great part of the earth. This is an inner connection. We should be able to see it. In an outward symptomatic form, it reflects itself in what I have already explained, in what others have also remarked. I have said that philosophical systems, such as those of Avenarius or Mach, are certainly rooted, in so far as the conceptions permeate the head, in the best and most liberal bourgeois conceptions of the nineteenth century... They are sound, clean people, whom we cannot in any way reproach, if we bear in mind the moral conceptions of the nineteenth century; nevertheless, in the books of Russian writers, who knew how to describe their epoch, you may read that the philosophy of Avenarius and of Mach has become the philosophy of the Bolshevik government. This is not only because conspicuous Bolshevik agitators have, for instance, heard Avenarius at Zurich, or Mach's pupil, Adler, but impulses of an entirely inner character are at work there. What Avenarius once brought forward, and the things which he said can, of course appear to the head as altogether clean, bourgeois views, as a praiseworthy, bourgeois mentality, but in reality it has formed the foundation of what has kindled instincts in a spiritual manner within the depths of humanity and has then brought forth the corresponding fruits; for it has really produced these fruits. You see, I must continually call attention to the difference between real logic, a logic of reality, and the merely abstract logic of the intellect. [ 17 ] Not even with the best will, or rather, with the worst will, can anyone extract out of the philosophy of Avenarius or of Mach the ethics of the Bolsheviks, if we may call them ethics; this cannot be deduced through logic, for it follows an entirely different direction. But a living logic is something quite different from an abstract logic. What may be deduced logically, need not really take place; the very opposite can take place. For this reason, there is such a great difference between the things to which we gradually learn to swear in the materialistic epoch, between the abstract thinking logic, which merely takes hold of the head, and the sense of reality, which is alone able at the present time to lead us to welfare and security.

[ 18 ] At the present time, people are satisfied if an un-contradicted logic can be adduced for a world-conception. But, in reality, this is of no importance whatever. It is not only essential to bear in mind whether or not a conception may be logically proved, for, in reality, both a radical materialism and a radical spiritualism, with everything which lies in between, may be proved through logic. The essential point to-day is to realise that something need not be merely logical, but that it must correspond with the reality, as well as being logical. It must correspond with reality. And this corresponding with reality can only be reached by living together with reality. This life in common with reality can be reached through spiritual science.

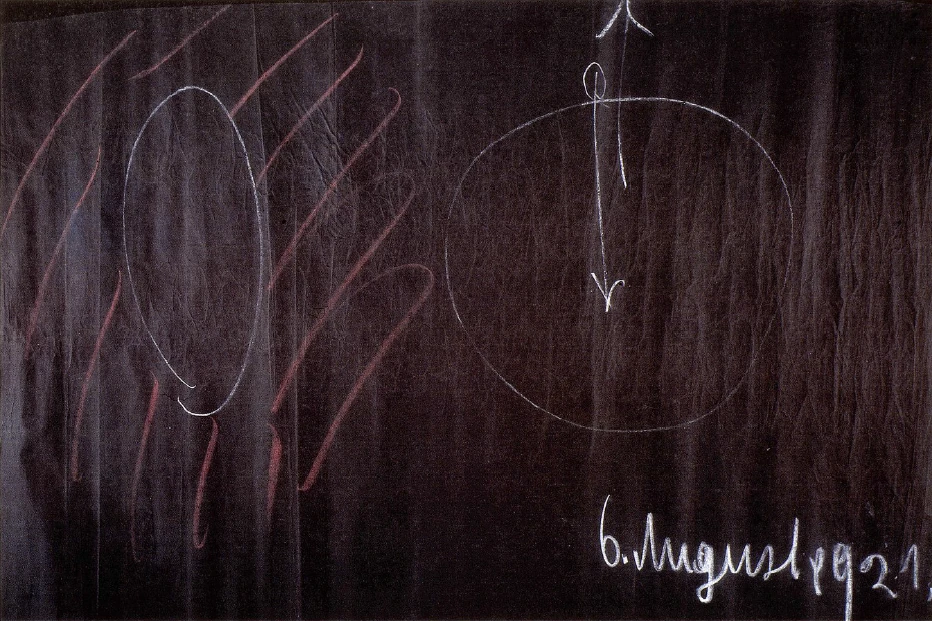

[ 19 ] What is the essential point in regard to the things which I have explained to you to-day? Many things are connected with spiritual science, but in regard to what I have said to-day it is essential to bear in mind that knowledge should once more be raised from depths which do not merely come from the head, but from the whole human being. We might say: If a human being, who in the more recent course of time has undergone a training in knowledge, if such a human being observes the world, he will do it in such a way that he remains inside his own skin and observes what is round about him outside his skin. I would like to draw this as follows:—Here is the human being. Outside, is everything which forms the object of man's thoughts. (A drawing is made.) Now the human being endeavours to gain within him a knowledge of the things which are outside; he reckons, as it were, with a reciprocal relation between his own being and the things which are outside his skin. Characteristic of this way of reckoning with such a reciprocal relationship are, for instance, the logical investigations of John Stuart Mill, or philosophical structures resembling those of Herbert Spencer, and so forth.

[ 20 ] If we rise to a higher knowledge, the chief thing to be borne in mind is no longer the human being who lives inside his own skin ... for everything which lives inside his skin is reflected in the head, it is merely a “head”-knowledge ... but the chief thing to be borne in mind is the human being as a whole. The whole human being is, however, connected with the whole earth. What we generally call super-sensible knowledge is, fundamentally speaking, not a relation between that which lies enclosed within the skin of man and that which lies outside the human skin, but it is a relation between that which lies within the earth and that which is outside the earth. The human being identifies himself with the earth. For this reason, he strips off everything which is connected with one particular place of the earth: nationality, and so forth. The human being adopts the standpoint of the earth-being, and he speaks of the universe from the standpoint of the earth-being. Try to feel how this standpoint is, for instance, contained in the series of lectures which I have delivered at the Hague, [“What is the Significance of an Occult Development of Man for His Involucres and for His Own Self?”] where I have spoken of the connection between the single members of man's being and his environment, but where I really intended to speak of man's coalescence with his environment—where the human being is not only considered from the standpoint of a certain moment, for instance, on the 13th of May, but where he is considered from the standpoint of the whole year in which he lives, and of its seasons, from the standpoint of the various localities in which he dwells, and so forth. This enables man to become a being of the earth; this enables him to acquire certain cognitions which represent his efforts to grasp what is above the earth and under the earth, for this alone can throw light upon the conditions of the earth.

[ 21 ] Spiritual science, therefore, does not rise out of the narrow-minded people who have founded the intellectual and materialistic science of the nineteenth century, with the particular form of materialism which has unchained unsocial instincts; but spiritual science rises out of the whole human being, and it even brings to the fore things in which the human being takes a secondary interest. Although even spiritual science apparently develops intellectual concepts, it is nevertheless able to convey real things which contain a social element in the place of the anti-social element.

[ 22 ] You see, in many ways we should consider the world from a different standpoint than the ordinary one of the nineteenth century and of the early twentieth century. At that time it was considered as praiseworthy that social requirements and social problems were so amply discussed. But those who have an insight into the world, merely see in this a symptom showing the presence of a great amount of unsocial feelings in the human beings. Just as those who speak a great deal of love, are generally unloving, whereas those who have a great amount of love do not speak much of love, so the people who continually speak of social problems, as was the case in the last third of the nineteenth century, are, in reality, completely undermined by unsocial instincts and passions.

[ 23 ] The social system which came to the fore in Eastern Europe is nothing but the proof of every form of unsocial and anti-social life. Perhaps I may insert the remark that anthroposophical spiritual science is always being reproved that it speaks so little of God. Particularly those who always speak of God reprove the anthroposophical spiritual science for speaking so little of God. But I have often said: It seems to me that those who are always speaking of God do not consider that one of the ten commandments says: Thou shalt not take the name of God in vain ... and that the observance of this commandment is, in a Christian meaning, far more important than continually speaking of God. Perhaps, at first, it may not be possible to see what is really contained in the things which are given in the form of spiritual-scientific ideas, from out a spiritual observation. One might say: Well, spiritual science is also a science which merely speaks of other worlds, instead of the materialistic worlds. But this is not so. What is taken up through spiritual science, even if we ourselves are not endowed with spiritual vision, is something which educates the human being. Above all, it does not educate the head of man, but it educates the whole of man, it has a real influence upon the whole of man. It corrects particularly the harm done by the spiritual opponent who lives within the sensualists and materialists, the opponent who has always lived within them.

[ 24 ] You see, these are the occult connections in life. Those who see, with a bleeding heart, the opponent who lived within the materialists of the nineteenth-century, that is to say, within the great majority of men, are aware of the necessity that the spiritualist within the human being should now rise out of subconsciousness into consciousness. He will then not stir up the instincts in his ahrimanic shape, but he will really be able to found upon the earth a human structure which may be accepted from a social standpoint.

In other words: If we allow things to take their course, in the manner in which they have taken their course under the influence of the world-conception which has arisen in the nineteenth century and in the form in which we can understand it, if we allow things to take this course, we shall face the war of all against all, at the end of the twentieth century. No matter what beautiful speeches may be held, no matter how much science may progress, we would inevitably have to face this war of all against all. We would see the gradual development of a type of humanity devoid of every kind of social instinct, but which would talk all the more of social questions.

[ 25 ] The evolution of humanity needs a conscious spiritual impulse in order to live. For we should always make a distinction between the value which a particular wisdom, or anything else in life, may possess in itself, and its value for the evolution of humanity. The intellectualism which forms part of materialism has furthered human development in such a way that the life of thoughts has reached its highest point. To begin with, we have the technique of thinking contained in Scholasticism, which constituted the first freeing deed; and then, in more recent times, we have the second freeing deed in natural science. But what was meanwhile raging in the subconsciousness, was the element which made the human being the slave of his instincts. He must again be set free. He can only be freed through a science, a knowledge, a spiritual world-conception, which becomes just as widely popular as the materialistic science: he can only be set at liberty through a spiritual world-conception, which constitutes the opposite pole of what has developed under the influence of a science dependent solely upon the head. This is the standpoint from which the whole matter should be considered again and again; for, as already stated, no matter how much people may talk of the fact that a new age must arise out of an ethical element, out of a vivification of religiousness, and so forth, nothing can, in reality, be attained through this, for in so doing we merely serve the hypocritical demands of the epoch. We should indeed realise that something must penetrate into the human souls, something which spiritualises the human being, even as far as his moral impulses, his religious impulses are concerned, which spiritualises him in spite of the fact that, apparently, it speaks in a theoretical manner of how the Earth has developed out of the Moon, the Sun and Saturn. Just as in the external world it is impossible to build up anything merely through wishes, no matter how excellent these wishes may be, so it is also impossible to build up anything in the social world merely through pious sermons, merely by admonishing people to be good, or merely by explaining to them what they should be like. Even what exists to-day as a world-destructive element, has not arisen through man's arbitrary will, but it has arisen as a result of the world-conception which has gradually developed since the beginning of the fifteenth century. What constitutes the opposite pole, what is able to heal the wounds which have been inflicted, must again be a world-conception. We should not shrink in a cowardly way from representing a world-conception which has the power of permeating the moral and religious life. For this alone is able to heal.

[ 26 ] Those who have an insight into the whole connection of things, begin to feel something which has really always existed where people have known something concerning real wisdom. I have already spoken to you of the ancient Mystery-sites. You may find these things described from the aspect of spiritual science in the anthroposophical literature. There, you will find that an ancient instinctive wisdom had once been developed, and that afterwards it transformed itself into the intellectualistic, materialistic knowledge of modern times. Even if, with the aid of the more exoteric branches of knowledge of ancient times, we go back, for instance, into medicine, as far as Hippocrates, leaving aside the more ancient, Egyptian conceptions of medicine, we shall find that the doctor was always, at the same time, a philosopher. It is almost impossible to think that a doctor should not have been a philosopher as well, and a philosopher a doctor, or that a priest should not have been all three things in one. It was impossible to conceive that it could be otherwise. Why? Let us bear in mind a truth which I have often explained to you:

[ 27 ] The human being knows that there is the moment of death, this one moment when he lays aside the physical body, when his spiritual part is connected with the spiritual world in a particularly strong way. Nevertheless this is but a moment. I might say: an infinite number of differences is integrated in the moment of death, and throughout our life this moment is contained within us in the form of differentials. For, in reality, we die continually! Already when we are born, we begin to die; there is a minute process of death in us at every moment. We would be unable to think, we would be unable to think out a great part of our soul-life and, above all, of our spiritual life, if we did not continually have death within us. We have death within us continually, and when we are no longer able to withstand, we die in one moment. But otherwise, we die continually during the whole time between birth and death.

[ 28 ] You see, an older and more instinctive form of wisdom could feel that human life is, after all, a process of death. Heraclitus, a straggler along the path of ancient wisdom, has declared that human life is a process of death, that human feeling is an incessant process of illness. We have a disposition to death and illness. What is the purpose of the things which we learn? They should be a kind of medicine; learning should be a healing process. To have a world-conception should constitute a healing process.

[ 29 ] This was undoubtedly the feeling of the doctors of ancient times, since they healed upon a materialistic basis only when this was absolutely necessary, when the illness was acute; they looked upon human life itself as a chronic illness. One who was both a philosopher and a doctor, also felt that as a healer he was connected with all that constitutes humanity upon the earth; he felt that he was also the healer of what is generally considered as normal, although this, too, is ill and contains a disposition to death.

You see, we should again acquire such feelings for a conception of the world; a world-conception should not only be a formal filling of the head and of the mind with knowledge, but it should constitute a real process within life: the purpose of a world-conception should be that of healing mankind.

[ 30 ] In regard to the historical development of our civilisation, we are not only living within a slow process of illness, but at the present time we are living within an acute illness of our civilisation. What arises in the form of a world-conception should be a true remedy; it should be a truly medical science, a cure. We should be permeated by the conviction that such a world-conception should be really significant for what rises out of our modern civilisation and culture; we should be filled with the conviction that this world-conception really has a true meaning, that it is not merely something formal, something through which we gain knowledge, through which we acquire the concepts of the things which exist outside, or through which we learn to know the laws of Nature and to apply them technically. No, in every true world-conception there should be this inner character intimately connected with man's being, namely, that out of this true world-conception we may obtain the remedies against illness, even against the process of death; the remedies which should always be there. So long as we do not speak in this manner and so long as this is not grasped, we shall only speak in a superficial way of the evils of our time, and we shall not speak of what is really needed.

[ 1 ] Gestern versuchte ich darzulegen, wie von der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts ab ein gewisser Höhepunkt in der sensualistischen oder materialistischen Weltanschauung sich allmählich heranbildete und wie gegen das Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts, wenigstens von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus, dieser Höhepunkt erreicht war. Sehen wir uns zunächst einmal an, wie die äußeren Tatsachen der Menschheitsentwickelung sich dargestellt haben unter dem Einflusse der materialistischen Weltanschauung. Diese materialistische Weltanschauung kann ja nicht etwa so angesprochen werden, als ob sie bloß hervorgegangen sei aus der Willkür einer Anzahl von führenden Persönlichkeiten. Denn, auch wenn man das auf verschiedenen Seiten ableugnet, diese materialistische Anschauung fußt gerade auf demjenigen, wodurch die wissenschaftlichen Überzeugungen und wissenschaftlichen Forschungsergebnisse des 19. und des beginnenden 20. Jahrhunderts groß geworden sind. Die Menschheit hat zu diesen wissenschaftlichen Ergebnissen kommen müssen. Sie haben sich vorbereitet im 15. Jahrhundert und haben einen gewissen Höhepunkt, wenigstens insofern sie menschheitserziehend sind, eben im 19. Jahrhundert erreicht. Wiederum konnte sich auf Grundlage dieser Wissenschaftsgesinnung nichts anderes ausbilden als eine gewisse materialistische Weltanschauung.

[ 2 ] Ich bin gestern dabei stehengeblieben, zu sagen: Geradezu radikal hervorgetreten ist das, um was es sich da eigentlich handelte — wenigstens in den Symptomen nach außen hin -, in dem, was man charakterisieren kann als die Stellung Haeckels etwa zu denjenigen, die dann im letzten Jahrzehnt des 19. Jahrhunderts und im Beginne des 20. Jahrhunderts gegen ihn aufgetreten sind. Man kann das, was sich da abgespielt hat und was doch außerordentlich tief eingegriffen hat in die allgemeine Bildung der Menschheit, gewissermaßen betrachten, ganz ohne Rücksicht zu nehmen auf die besondere Formulierung, die Haeckel seiner Weltanschauung gegeben hat und auch schließlich auf die besondere Formulierung, welche die Gegner ihren sogenannten Widerlegungen gegeben haben. Man kann einfach darauf sehen, daß auf der einen Seite dasjenige stand, was man glaubte, aus einer sorgfältigen Betrachtung des materiellen Geschehens bis herauf zum Menschen heraus gewinnen zu können. Nur das sollte zunächst in einer Weltanschauung sein, nur da glaubte man, auf sicherem Boden zu stehen. Es war das durchaus etwas Neues gegenüber dem, was etwa mittelalterlicher Inhalt der Weltanschauung war.

[ 3 ] In bezug auf das Naturwissen hatte man seit drei, vier, fünf Jahrhunderten etwas entschieden Neues gewonnen, in bezug auf die geistige Welt nichts. In bezug auf die geistige Welt war man endlich zu einer Philosophie gekommen, welche sozusagen ihre Hauptaufgabe, wie ich es gestern ausgedrückt habe, darin gesehen hat, wenigstens noch ihr Dasein in einer gewissen Weise zu rechtfertigen. Erkenntnistheorien wurden geschrieben in der Absicht, zu sagen, daß man doch noch in bezug auf einen abgelegenen Punkt irgend etwas philosophisch zu sagen habe; daß man vielleicht sich getrauen dürfe zu sagen, daß es eine übersinnliche Welt gibt, aber man könne sie nicht erkennen, man könne höchstens eben die Annahme einer übersinnlichen Welt machen. So sprachen die Sensualisten, als deren geistreichen Vertreter ich Ihnen gestern Czolbe angeführt habe, von etwas, was positiv war, worauf man als auf etwas Greifbares hinweisen konnte. Und so sprachen die Philosophen und diejenigen, die ihre Schüler in der Popularisierung geworden waren, von etwas, das eigentlich sofort zerflatterte, wenn man es irgendwie anfassen wollte.

[ 4 ] Nun stellte sich das eigentümliche kulturhistorische Phänomen ein, daß Haeckel auftrat mit einer Zusammenstellung der rein naturalistischen Konstruktion der Welt, und daß nun Stellung genommen werden sollte von seiten der philosophischen Welt gegen diesen, sagen wir, Haeckelismus. Man könnte ja das ganze Problem, ich möchte sagen, einmal ästhetisch betrachten. Man könnte hinschauen auf das Monumentale, das - ob es nun wahr oder falsch ist - in Haeckel hervorgetreten ist in der Zusammenfassung von Tatsachen, die eben in ihrer Zusammenfassung durchaus schon ein Weltbild gaben. Mir erschien recht charakteristisch für die Art und Weise, wie Haeckel in seinem Zeitalter drinnenstand, alles das, was sich abspielte bei der Feier etwa des sechzigsten Geburtstages Haeckels in den neunziger Jahren in Jena, wo ich dabei war. Von Haeckel selbst brauchte man dazumal ja nichts Neues mehr zu erwarten. Er hatte im wesentlichen ausgesprochen, was er von seinem Gesichtspunkte aussprechen konnte und wiederholte sich eigentlich.

[ 5 ] Da sprach dann bei dieser Haeckel-Feier ein Physiologe von der medizinischen Fakultät. Es war außerordentlich interessant, dem Mann zuzuhören und ihn ein wenig vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus zu betrachten. Es waren bei dieser Haeckel-Feier eine ganze Anzahl von Menschen da, die in Haeckel eine bedeutende Persönlichkeit sahen, sozusagen einen überragenden Menschen. Aber jener Physiologe war ein durchaus tüchtiger Universitätsprofessor, von jener Sorte unter den Tüchtigen, von denen man sagen konnte: Nun, hätte man einen andern von der Sorte hingestellt, so wäre es dasselbe gewesen; man könnte nicht gut den A vom B oder vom C unterscheiden. Haeckel konnte man von allen andern unterscheiden, aber ihn, den Universitätsprofessor, konnte man nicht unterscheiden von den andern. Das ist etwas, was ich bitte, mehr als eine Charakteristik des Zeitalters aufzufassen als gerade dieser einzelnen Angelegenheit.

[ 6 ] Nun handelte es sich darum, daß ja derjenige, der nun so dastand als der A — der ebensogut der B oder C hätte sein können -, sprechen sollte bei einer Haeckel-Feier. Ich möchte sagen, in jedem einzelnen Worte sah man, was da eigentlich vorlag! Während einige jüngere Leute mit einer gewissen Emphase sprachen, mit dem Bewußtsein, daß in Haeckel eine Persönlichkeit da wäre — sie waren höchstens Privatdozenten, die dann aber in Jena immer schon außerordentliche Professoren waren, denn diese waren unhonoriert und man gab ihnen nur den Titel; es waren aber eigentlich Privatdozenten —, gab es so etwas für den betreffenden Physiologen nicht; denn gäbe es das, so könnte man ja nicht von A und B und C in derjenigen Weise reden, wie ich jetzt geredet habe; daher feierte er, wie er ausdrücklich betonte, den «Kollegen» Haeckel. Nach jedem dritten Satze sprach er von dem Kollegen Haeckel, damit andeutend, daß es eben der sechzigste Geburtstag irgendeines Kollegen ist, wie jedes andern auch. Nun handelte es sich aber darum, auch etwas zu sagen. Ja, nicht wahr, er gehörte als solcher Repräsentant in die Reihe derjenigen, die überhaupt eben nur wissenschaftliche Daten sammeln — jene Daten, aus denen Haeckel eine Weltanschauung gemacht hatte —, aber die sich mit diesem Datensammeln begnügten, weil sie eben überhaupt von der Möglichkeit einer Weltanschauung gar nichts wissen wollten. Also über die Weltanschauung Haeckels sprach dieser Kollege nicht.

[ 7 ] Nun rühmte er aber eigentlich Haeckel gerade von seinem Standpunkte aus in einer außerordentlichen Weise, indem er andeutete: Man könne, ganz abgesehen davon, was Haeckel über Welt und Leben behauptet hat, durchaus hinsehen auf dasjenige, was der Kollege Haeckel auf dem Gebiete dieses Spezialgebietes erforscht hat. Es liegen im Kabinett so und so viele Tausend mikroskopische Präparate von Haeckel, es liegen auf diesem und jenem Gebiete so und so viele Tausende Präparate vor und so weiter, und man könnte schon sagen, wenn man nun zusammenrechnete, was alles dieser Haeckel an einzelnen, rein empirischen Dingen gesammelt, zusammengestellt, verarbeitet hatte, es sei schon eine ganze Akademie. - Also dieser Kollege hatte schon implizite eine ganze Anzahl solcher «Kollegen» im Leibe drinnen, für die er seinen Mann gestanden hatte. Nun, das war gewissermaßen ein Kollege von der medizinischen Fakultät.

[ 8 ] Dann sprach beim eigentlichen Festmahl Eucken, also der Philosoph. Nun, der hatte das, was er zu sagen hatte, oder was er nicht zu sagen hatte, dadurch geoffenbart - man könnte auch sagen kaschiert -, daß er von den Schlipsen, von den unordentlich gebundenen Schlipsen sprach und von den Klagen, welche namentlich die Familie Haeckels vorzubringen hatte, wenn sie im intimen Kreise über Papa oder über den Mann sich unterhielten. Über die unsorgfältig gebundenen Schlipse hat der Philosoph ziemlich lange gesprochen, gar nicht ungeistreich, aber wie gesagt, es war dasjenige, was dazumal die Philosophie zu sagen hatte. Es war schon recht charakteristisch, denn viel mehr hatte die Philosophie auch sonst nicht zu sagen. Es war alles abstraktes Gestrüppe, was vorgebracht wurde. Damit ist gar nichts über Wertungen und dergleichen gesagt; man kann ja die ganze Sache auch ästhetisch auf sich wirken lassen und aus dem, was sich symptomatisch darlebt, ersehen, wie heraufgestrebt hat in der neueren Zeit der Materialismus, der etwas gab. Die Philosophie hatte wirklich nichts mehr zu sagen, da sie eben eine Dependence war desjenigen, was sich im Laufe der Zeit heraufgebildet hatte. Man darf ja auch nicht glauben, daß die Philosophie zur Geisteswissenschaft etwas zu sagen hat. Das hat ja neulich Eucken wohl bewiesen in jener Diskussion, die in einer sehr anregenden Weise in der letzten oder vorletzten Nummer der Dreigliederungszeitung erzählt ist, wo sich die ganze Euckensche Rederei in ihrer absoluten Inhaltslosigkeit enthüllte.

[ 9 ] Nehmen wir aber nun die Tatsache, welche die positive Tatsache ist in alldem, was ich gesagt habe, und nehmen wir sie einmal eben kulturgeschichtlich. Wir haben auf der einen Seite — das geht ja wohl aus den gestrigen Darlegungen hervor - innerlich im Menschen entwickelt den Intellektualismus, wie ihn vor dem naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter als Gedankentechnik die Scholastik bis zur höchsten Blüte gebracht hat. Wir haben dann angewendet den Intellektualismus auf das äußere Naturwissen. Wir haben dadurch dasjenige zustande gebracht, was im 19. Jahrhundert, namentlich gegen das Ende hin, mit einer großen historischen Bedeutung dasteht: Intellektualismus und Materialismus gehören zusammen.

[ 10 ] Wenn man diese Erscheinung in ihrer Beziehung zum Menschen selbst ins Auge faßt, so muß man sagen: Von demjenigen, was am Menschen ist, von dem dreigliedrigen Menschen, der da der Nerven-Sinnesmensch mit dem Vorstellungsleben ist, der rhythmische Mensch mit dem Gefühlsleben, der Stoffwechselmensch mit dem Willensleben, von diesem dreigliedrigen Menschen wird ja durch eine solche Weltanschauung vor allen Dingen erfaßt der Kopfmensch, der Nerven-Sinnesmensch. Dieser Nerven-Sinnesmensch ist daher auch am stärksten ausgebildet worden im 19. Jahrhundert. Ich habe es Ihnen ja neulich von einem gewissen andern Gesichtspunkte geschildert, wie es Leuten, die so etwas gefühlt haben, daß dieser Kopfmensch, dieser Nerven-Sinnesmensch eigentlich durch die Geisteskultur des 19. Jahrhunderts besonders ausgebildet wird, angst und bange für die Zukunft der Menschheit geworden ist. Ich habe es Ihnen geschildert an einem Gespräch, das ich einmal vor Jahrzehnten mit dem österreichischen Dichter Hermann Rollett hatte. Hermann Rollett war eigentlich, seiner Weltanschauung nach — weil ja derjenige, der auf Wissenschaft fußt und bei dem die alten traditionellen Vorstellungen verblaßt waren, im Grunde gar nicht anders konnte —, durch und durch materialistisch gesinnt. Aber er fühlte zu gleicher Zeit - denn er war eine Dichternatur, eine Künstlernatur, er hat ja das schöne Werk «Goethe-Bildnisse» herausgegeben -, wie ja der Mensch nur wächst in bezug auf seine Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, mit Bezug auf sein Vorstellungsleben. Er wollte das anschaulich darstellen. Daher sagte er: Eigentlich wird es nach und nach so werden, daß Arme und Füße und Beine vom Menschen immer kleiner und kleiner werden und der Kopf immer größer. - Er wollte sich räumlich dasjenige vorstellen, was da eigentlich im Anzuge war. Dann wird, wenn die Erde noch eine Weile in dieser Entwickelung so fortgeht, der Mensch - er stellte das anschaulich dar — nur noch eine Kopfkugel sein, die sich so fortkugelt, die so fortrollt über die Erdoberfläche hin. Man kann fühlen, welche Kulturbangigkeit sich in einem solchen Dinge verbirgt. Nun aber sieht derjenige, der nicht mit geisteswissenschaftlichen Forschungsmethoden an diese Dinge herangeht, nur die Außenseite der Sache. Man muß, wenn man das Chaos der Anschauungen, das in der Gegenwart zu solchem Unheil führt, durchdringen will, eben die Sache auch von der andern Seite ansehen. Denn es könnte einem ja einfallen zu sagen: Dasjenige, was da als materialistische Weltanschauung aufgetreten ist, das umfaßt doch nur eine kleine Minorität; die große Majorität lebt noch in bezug auf Weltanschauungsempfinden in den traditionellen Bekenntnissen. — Ja, mit Bezug auf eine, ich möchte sagen, gewisse Oberfläche, ja. Aber mit Bezug auf alle Gedankenformen, mit Bezug auf das, was der Mensch in seinem Innersten über seine Umgebung und über die Welt denkt, ist das doch nicht der Fall. Unsere Gegenwartskultur ist so, daß dasjenige, was in Haeckels «Welträtsel» lebt, durchaus nicht etwa bloß bei denen lebt - vielleicht bei denen am wenigsten -, die direkt einen Gefallen gefunden haben an Haeckels «Welträtsel». Haeckels «Welträtsel» sind ja nur ein Symptom für das, was im Grunde genommen durch die ganze zivilisierte Welt international heute die maßgebenden Empfindungsimpulse darstellt. Man möchte sagen, am charakteristischesten sind diese Empfindungsimpulse bei den äußerlich frommen Christen, besonders bei den äußerlich frommen Katholiken. Gewiß, die bekennen sich am Sonntag zu dem, was die Dogmatik überliefert hat; aber die Art und Weise, wie sie das nächste Leben, die übrigen Wochentage auffassen, das hat ja eine Art zusammenfassenden Ausdrucks gefunden in der materialistischen Weltanschauung des 19. Jahrhunderts. Bis in die entferntesten Dörfer auf dem Lande draußen ist ja das durchaus die populäre Weltanschauung. Daher darf man nicht sagen, es sei nur bei einer verschwindend geringen Minorität vorhanden. Gewiß, formulierte Begriffe sind bei ihr so vorhanden, aber das sind ja nur die Symptome. Dasjenige, worauf es ankommt, die Realität, die ist durchaus das Charakteristikon des gegenwärtigen Zeitalters. An den Symptomen kann man die Dinge studieren, aber man muß sich bewußt sein, daß, geradeso wie wenn man von der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts von Kant spricht, man nur von einem Symptom spricht für etwas, was in der ganzen Zeit enthalten war, man auch nur von einem Symptom spricht, wenn man von diesen Dingen spricht, die ich gestern angeschlagen habe und heute in diesen Betrachtungen fortführe. Daher kommt das schon sehr stark in Betracht, was ich jetzt sagen will. Sehen Sie, der Mensch kann ja intellektualistisch tätig sein und hingegeben sein den materiellen Dingen und Erscheinungen, die durchaus im Inneren das Gegenstück sind zum Intellektualismus, nur während des Tagwachens, vom’ Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen, und da nicht einmal ganz. Wir wissen ja, der Mensch hat nicht nur ein Vorstellungsleben, der Mensch hat ein Gefühlsleben. Das Gefühlsleben ist innerlich gleichwertig mit dem Traumleben. Das Traumesleben läuft in Bildern ab, das Gefühlsleben läuft in Gefühlen ab. Aber die innere substantielle Seite ist dasjenige, was im Menschen die Traumbilder erlebt, ist dasjenige, was im menschlichen Gefühlsleben die Gefühle durchmacht. So daß wir sagen können, während des Wachens, vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen träumt der Mensch wachend in seinem Gefühl. Was wir an Gefühlen erleben, das ist ganz genau von demselben Bewußtseinsgrad durchzogen wie die Traumvorstellungen, und was wir in unseren Willensimpulsen erleben, das schläft, das schläft, auch wenn wir sonst wach sind. Wir sind in Wahrheit nur wach in unserem Vorstellungsleben. Sie schlafen des Abends ein, Sie wachen des Morgens auf. Wenn Ihnen dasjenige, was vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen vorgeht, nicht erhellt wird durch eine gewisse geisteswissenschaftliche Erkenntnis, so entzieht es sich Ihrem Bewußtsein, so wissen Sie in Ihrem Bewußtsein nichts davon. Traumbilder drängen sich höchstens hinein. Die werden Sie aber ebensowenig anerkennen als bedeutsam für eine Weltanschauung, wie Sie anerkennen die Gefühle als bedeutsam für eine Weltanschauung. Gewissermaßen wird immer das menschliche Leben durchbrochen durch das Schlafesleben.

[ 11 ] Aber geradeso, wie sich der Zeit nach dieses Schlafesleben hineinstellt in das volle menschliche Seelenleben, so stellt sich die Welt der Gefühle, und namentlich die Welt der Willensimpulse in dieses Menschenleben hinein. Wir träumen, indem wir fühlen; wir schlafen, indem wir wollen. Sowenig wie Sie wissen, was mit Ihnen vorgeht während des Schlafes, so wenig wissen Sie, was da vorgeht, wenn Sie durch Ihren Willen den Arm erheben. Die eigentlichen inneren Kräfte, die da walten, die sind genau ebenso im Dunkel des Bewußtseins, wie der Schlafeszustand im Dunkel des Bewußtseins ist.

[ 12 ] So daß wir sagen können: Von diesem dreigliedrigen Menschen wurde durch die neuere Kultur, die eingeleitet wird im 15. Jahrhundert und ihren Höhepunkt erlangt im 19. Jahrhundert, nur ein Drittel in Anspruch genommen, der Vorstellungsmensch, der Kopfmensch. Und man muß fragen: Was ging denn nun vor in dem träumenden, fühlenden Menschen, in dem schlafenden, wollenden Menschen, und was ging vor zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen?

[ 13 ] Ja, wir können als Menschen gut materialistisch sein in unserem Vorstellungsleben. Das können wir schon, das 19. Jahrhundert hat es gezeigt. Das 19. Jahrhundert hat auch gezeigt die Berechtigung dieses Materialismus; er hat ja zu positiven Erkenntnissen der materiellen Welt, die ein Abbild ist der geistigen Welt, geführt. Wir können Materialisten sein mit dem Kopfe, aber wir haben dann nicht in unserer Gewalt unser träumendes Gefühlsleben, nicht in unserer Gewalt unser schlafendes Willensleben. Die werden nun, insbesondere das Willensleben, in derselben Zeit spiritualistisch gesinnt.

[ 14 ] Es ist interessant, vom geisteswissenschaftlichen Gesichtspunkte aus zu betrachten, was da eigentlich vorgeht. Stellen Sie sich einen Moleschott, einen Czolbe vor, die mit ihrem Kopfe einzig und allein den Sensualismus, den Materialismus anerkennen: da unten haben sie ihren Willensmenschen, der ist ganz spiritualistisch gesinnt — nur weiß der Kopf nichts davon -, der rechnet mit Geistigem und Geisteswelten. Sie haben ihren Gefühlsmenschen: der rechnet mit Gespenstererscheinungen. Und wir haben, wenn wir richtig beobachten, das Schauspiel, daß der materialistische Schriftsteller sitzt und furchtbar auf alles dasjenige schimpft, was da als spirituelle Natur in seinem Gefühlsmenschen und Willensmenschen steckt; der nun wütend wird, weil er auch Spiritualist ist, der in ihm rumort, der ein völliger Gegner ist.

[ 15 ] So ist es gewesen. Der Idealismus, der Spiritualismus war da. Er war im Willensunterbewußtsein der Menschen namentlich da, und die stärksten Spiritualisten waren die Materialisten, waren die Sensualisten!

[ 16 ] Aber was lebt denn in dem Gefühlsmenschen leiblich? Es lebt der Rhythmus, die Blutzirkulation, der Atmungsrhythmus und so weiter. Was lebt in dem Willensmenschen? Der Stoffwechsel. Betrachten wir zunächst diesen Stoffwechsel. Während der Kopf sich beschäftigt mit geistvoller Verarbeitung materieller Dinge und materieller Erscheinungen zu einer materialistischen Wissenschaft, arbeitet der Stoffwechselmensch, der nun auch durchaus die volle menschliche Struktur hat, das entgegengesetzte Weltbild aus. Der arbeitet ein durch und durch spiritualistisches Weltbild aus, das nun gerade die Materialisten unbewußt in sich tragen. Aber das wirkt im Stoffwechselmenschen auf die Instinkte, auf die Triebe: da wirkt es das Gegenteil von dem, was es bringen würde, wenn es den ganzen Menschen in Anspruch nehmen würde. Da durchsetzt es die Instinkte, da wird es erfaßt von ahrimanischen Gewalten, da wirkt es nun nicht im göttlich-geistigen Sinne, sondern da wirkt es im ahrimanisch-geistigen Sinne. Da bringt es die Instinkte zum höchsten Grade des Egoismus. Da bringt es die Instinkte so zur Entwickelung, daß der Mensch nur zu Forderungen des Lebens kommt, nicht gewiesen wird auf soziale Triebe, auf soziales Mitgefühl und dergleichen. Da wird namentlich das Individuelle herausgestaltet bis zum Egoistischen der Instinkte. Und das bildete sich, wenn ich so sagen darf, unter der Oberfläche dieser materialistischen Zivilisation heraus, und das erschien in den welthistorischen Ereignissen, das erscheint jetzt. Dasjenige, was sich unter der Oberfläche, in den Tiefen der Willensmenschen, wo sich die Spiritualität der Instinkte bemächtigt hat, dazumal im Keime ausbildete, das erscheint jetzt in den welthistorischen Ereignissen. Und würde die Entwickelung nur fortfahren, diese Konsequenzen auszubilden, wir würden am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts angekommen sein in dem Kriege aller gegen alle, gerade in demjenigen Gebiete der Erdenentwickelung, in dem sich die sogenannte neuere Zivilisation entwickelt hat. Und wir sehen dasjenige, was da sich ausgebildet hat, schon von Osten ausstrahlend über einen großen Teil der Erde sich geltend machen. Da ist ein innerer Zusammenhang. Man muß ihn aber nur sehen.

[ 17 ] Außerlich symptomatisch spiegelt er sich in dem, was ich auch schon betont habe, was ja auch von andern bemerkt worden ist. Ich sagte, solche Philosophen, wie Avenarius, wie Mach, sie sind gewiß mit ihren Anschauungen, insofern die Anschauungen den Kopf durchsetzen, wurzelnd in den liberalistischen besten bürgerlichen Anschauungen des 19. Jahrhunderts, saubere Leute, denen man nichts vorwerfen kann, wenn man die Moralanschauungen des 19. Jahrhunderts ins Auge faßt und dennoch, Sie können es bei russischen Schriftstellern, die verstanden haben, ihre Zeit zu schildern, nachlesen, wie Avenariussche, wie Machsche Philosophie die bolschewistische Staatsphilosophie geworden ist. Das ist nicht bloß aus dem Grunde, weil hervorragende bolschewistische Agitatoren eben Avenarius zum Beispiel in Zürich gehört haben, oder den Mach-Schüler Adler gehört haben, sondern da wirken durchaus innere Impulse. Dasjenige, was Avenarius einmal vorgetragen hat, es konnte natürlich dem Kopf nach durchaus saubere bürgerliche Gesinnung, lobenswerte bürgerliche Gesinnung sein; real war es die Grundlage für dasjenige, was in den Untergründen der Menschheit die Instinkte spirituell entflammte, und was dann praktisch die entsprechenden Früchte trug, weil es diese Früchte durchaus zeitigt. Sie sehen hier - ich muß immer wieder darauf aufmerksam machen - den Unterschied zwischen realer Logik, Wirklichkeitslogik und der bloß abstrakten Verstandeslogik. Niemand wird aus Avenariusscher oder Machscher Philosophie herausschälen können, mit dem besten oder, ich könnte auch sagen, mit dem allerschlechtesten Willen nicht herausschälen können die Ethik der Bolschewisten, wenn man das Ethik nennen kann. Das folgt nicht abstrakt logisch. Da folgt etwas ganz anderes. Aber die lebendige Logik ist eine ganz andere als die abstrakte Logik. Dasjenige, was man aus irgend etwas logisch ableiten kann, das muß sich in Wirklichkeit nicht ergeben, es kann sich das Gegenteil davon ergeben. Deshalb ist ein so großer Unterschied zwischen dem, auf das man immer mehr und mehr im materialistischen Zeitalter schwören lernte, der abstrakten Gedankenlogik, die nur den Kopf ergreift, und dem Wirklichkeitssinn, der allein in unserer Zeit zum Heile führen kann.

[ 18 ] In unserer Zeit ist man zufrieden, wenn für eine Weltanschauung die widerspruchslose Logik aufgewiesen werden kann. Daran liegt aber nämlich in Wirklichkeit gar nichts. Es kommt gar nicht allein darauf an, ob eine Anschauung logisch festgelegt werden kann, denn im Grunde genommen ist ebensogut der radikale Materialismus logisch festzulegen, wie der radikale Spiritualismus logisch festzulegen ist, und alles, was dazwischen ist. Es kommt heute darauf an, daß man einsehe, daß etwas nicht bloß logisch zu sein habe, sondern wirklichkeitsgemäß neben logisch sein müsse, wirklichkeitsgemäß sein müsse. Und die Wirklichkeitsgemäßheit wird eben nur erreicht durch ein Zusammenleben mit der Wirklichkeit. Dieses Zusammenleben mit der Wirklichkeit wird durch Geisteswissenschaft heranerzogen.

[ 19 ] Um was handelt es sich in bezug auf das, was ich heute gesagt habe? Es handelt sich ja bei Geisteswissenschaft um sehr vieles, aber mit Bezug auf dasjenige, was ich heute gesagt habe, um was handelt es sich da? Ja, da handelt es sich darum, daß wirklich nun ein Wissen hervorgeholt wird aus denjenigen Untergründen, die nicht bloß aus dem Kopfe kommen, die aus dem ganzen Menschen kommen. Man könnte sagen: Wenn derjenige Mensch, der sich selbst einmal im Laufe der neueren Zeit erkennend heranerzogen hat, die Welt betrachtet, dann betrachtet er sie so, daß er innerhalb seiner Haut lebt und dasjenige um sich herum betrachtet, was außerhalb seiner Haut ist. Schematisch möchte ich das so zeichnen: Da ist der Mensch. Außer dem Menschen ist alles dasjenige, worüber der Mensch sinnt (siehe Zeichnung, rot). Und nun erstrebt er, über dasjenige etwas zu wissen, in sich etwas zu wissen, was da außerhalb seiner ist. Er rechnet gewissermaßen mit dem Wechselverhältnis zwischen dem, was außerhalb seiner Haut ist. Und ganz charakteristisch für das Rechnen mit einem solchen Wechselverhältnis sind die logischen Untersuchungen wie die von John Stuart Mill; charakteristisch sind philosophische Gedankengebäude wie das von Herbert Spencer und so weiter.

[ 20 ] Steigt man auf zur höheren Erkenntnis, dann ist es nicht mehr der Mensch, der innerhalb seiner Haut lebt — denn alles dasjenige, was innerhalb seiner Haut lebt, wird im Kopfe gespiegelt, es ist doch nur Kopfwissen -, sondern da ist es der ganze Mensch. Aber der ganze Mensch ist verbunden mit der ganzen Erde. Im Grunde genommen ist die Erkenntnis, die man übersinnliche Erkenntnis nennt, nicht eine Auseinandersetzung zwischen dem, was innerhalb der menschlichen Haut liegt, mit dem, was außerhalb der menschlichen Haut liegt, sondern sie ist eine Auseinandersetzung zwischen dem, was innerhalb der Erde ist, mit demjenigen, was außerhalb der Erde ist. Der Mensch identifiziert sich mit der Erde. Daher streift er auch alles dasjenige ab, was gebunden ist an einen Fleck der Erde, Nationalität und so weiter. Der Mensch nimmt den Standpunkt des Erdenwesens ein und redet vom Standpunkte des Erdenwesens über das Weltenall. Versuchen Sie es zu fühlen, wie von diesem Standpunkte aus gesprochen wird, sagen wir in einer solchen Vortragsreihe, wie ich sie gehalten habe im Haag, wo gesprochen wird über den Zusammenhang der einzelnen Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit mit der Umgebung, wo aber eigentlich gemeint war dieses Zusammengewachsensein des Menschen mit seiner Umgebung, wo der Mensch betrachtet wurde, nicht bloß wie er, sagen wir, am 13. Mai ist in dem einen Augenblicke, sondern wie er das ganze Jahr hindurch in den Jahreszeiten lebt, mit den einzelnen Lokalitäten lebt und so weiter. Dadurch aber gerade wird der Mensch Erdenwesen; dadurch gewinnt er dann auch gewisse Kenntnisse, die eine Auseinandersetzung des Menschen sind mit dem, was über dem Irdischen ist, mit dem, was unter dem Irdischen ist, wodurch die Erdenverhältnisse erst klar werden.

[ 21 ] Geisteswissenschaft geht also nicht hervor aus diesem engbegrenzten Menschen, aus dem die intellektualistische, materialistische Wissenschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts hervorgeht mit ihrer Form der Entfesselung der unsozialen Instinkte, sondern Geisteswissenschaft geht aus dem ganzen Menschen hervor, bringt dasjenige, was den einzelnen Menschen in zweiter Linie erst berührt, in den Vordergrund. Dadurch ist es ihr gegeben, indem sie scheinbar auch nur intellektualistische Begriffe entwickelt, in diesen Begriffen zugleich reale Dinge zu geben, die aber an der Stelle des Antisozialen das Soziale geben.

[ 22 ] Man muß die Welt vielfach von einem andern Gesichtspunkte betrachten, als man es gewöhnlich im 19. Jahrhundert und im Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts getan hat. Man hat es ja lobenswert gefunden, daß man so viel von sozialen Forderungen, von sozialem Wesen gesprochen hat. Für den, der die Welt durchschaut, ist das ja nur ein Zeichen, daß man so viel Unsoziales in sich hat. Geradeso wie derjenige, der sehr viel von Liebe redet, in der Regel ein liebeloses Wesen ist, und derjenige, der viel von Liebe in sich hat, wenig von Liebe redet, so ist derjenige in der Regel eigentlich ganz durchwühlt von unsozialen Trieben und Instinkten, der immerzu von sozialen Dingen redet, so wie man das gerade im letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts gewohnt worden ist.

[ 23 ] Das soziale System, das im Osten Europas sich geltend macht, ist ja nichts anderes als die Probe aufs Exempel alles un- und widersozialen Lebens. Ich darf hier vielleicht einflechten, daß immer wieder und wiederum an anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft herangetragen wird der Vorwurf - ich habe ihn auch neulich erst wieder gehört -, sie spreche so wenig von Gott. Insbesondere diejenigen, die fortwährend von Gott sprechen, machen es der anthroposophischen Geisteswissenschaft zum Vorwurf, daß sie so wenig von Gott spreche. Ich habe ja oftmals gesagt, mir kommt vor, daß diejenigen, die immer von Gott sprechen, nicht berücksichtigen, daß es ja eines der Zehn Gebote gibt, das heißt: Du sollst den Namen des Gottes nicht eitel aussprechen — und daß die Bewahrung dieses Gebotes viel wichtiger ist im christlichen Sinne, als fortwährend von Gott zu sprechen. Man kann vielleicht demjenigen, was als geisteswissenschaftliche Ideen gegeben wird aus geistiger Beobachtung heraus, zunächst gar nicht anmerken, was es in Wirklichkeit ist. Man kann sagen: Nun ja, auch eben eine Wissenschaft, die nur von andern Welten spricht, als die materialistischen Welten sind. — Aber so ist es nicht. Dasjenige, was da aufgenommen wird mit diesem Begriff, ganz ohne daß man selber okkulte Schauungen hat, das erzieht ja den Menschen. Vor allen Dingen erzieht es nicht den Kopfmenschen, sondern es erzieht den ganzen Menschen und es wirkt nun im regelrechten Sinne auf diesen ganzen Menschen. Es korrigiert gerade dasjenige, was angerichtet worden ist durch den spirituellen Gegner des Sensualisten und Materialisten, der ja immer in denen war.

[ 24 ] So sind die geheimen Zusammenhänge im Leben. Wer mit blutendem Herzen sieht, wie in den Materialisten des 19. Jahrhunderts, das heißt in der großen Mehrzahl der Menschen, der Gegner gesteckt hat, der weiß auch, wie sehr die Notwendigkeit besteht, daß jetzt aus dem Unterbewußten ins Bewußtsein heraufziehe dieser Spiritualist. Dann wird er nicht in seiner ahrimanischen Gestalt die Instinkte aufrütteln, dann wird er tatsächlich eine sozial mögliche Struktur der Menschen auf der Erde begründen können. In andern Worten: Wenn man die Dinge so laufen läßt, wie ich sie unter dem Einflusse der in begreiflicher Weise heraufgekommenen Weltanschauung im 19. Jahrhundert für das 20. Jahrhundert entwickelt habe, so werden wir am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts stehen vor dem Kriege aller gegen alle! Da mögen die Menschen noch so schöne Reden halten, noch so viele wissenschaftliche Fortschritte gemacht werden, wir würden stehen vor diesem Krieg aller gegen alle. Wir würden eine Menschheit heranzüchten sehen, welche keine sozialen Instinkte mehr hat, um so mehr aber reden würde von sozialen Dingen.

[ 25 ] Es braucht die Menschheitsentwickelung den spirituellen, den bewußt spirituellen Impuls zum Leben. Denn man muß immer unterscheiden zwischen der Wertschätzung, die irgendeine Weisheit oder sonst etwas im Leben an sich hat, und dem, was es hat für die Entwickelung der Menschheit. Der Intellektualismus, der mit dem Materialismus zusammengehört, er hat die Menschheit so entwickelt, daß er das Vorstellungsleben zu der höchsten Höhe gebracht hat: zunächst in der Scholastik, im Scholastizismus die Denktechnik, die die erste Befreiungstat war, dann in dem Naturwissen in der neueren Zeit, der zweiten Befreiungstat. Aber dasjenige, was im Unterbewußten mittlerweile wütete, war das, was den Menschen in seinen Instinkten versklavt hat. Diese müssen wiederum befreit werden. Die können nur befreit werden, wenn wir eine Wissenschaft, eine Erkenntnis, wenn wir eine bis ebenso weithin popularisierte spirituelle Weltanschauung haben, wie wir die materialistische popularisiert haben; wenn wir eine spirituelle Weltanschauung haben, die nun den Gegenpol bildet für dasjenige, was sich unter der reinen Kopfwissenschaft herausgebildet hat. Von diesem Gesichtspunkte muß man die Sache immer wieder und wieder betrachten; denn, wie gesagt, die Menschen mögen noch so viel davon reden, daß von der Ethik, von der Belebung der Religiosität und so weiter ein neues Zeitalter heraufkommen müsse - damit kann man ja nichts in Wirklichkeit erreichen; damit frönt man ja selber nur den Lügenanforderungen des Zeitalters. Man muß tatsächlich sich klar sein, daß so etwas, wie es in die menschliche Seele einziehen muß trotzdem es scheinbar so theoretisch davon spricht, wie die Erde aus Mond, Sonne und Saturn heraus sich entwickelt hat -, wenn es richtig aufgefaßt wird, bis in die moralischen Impulse, in die religiösen Impulse herein den Menschen spiritualisiert. Geradesowenig wie man irgend etwas in der äußeren Welt mit den bloßen Wünschen aufbauen kann, wenn diese Wünsche auch noch so gut sind, ebensowenig kann man in der sozialen Welt etwas aufbauen mit den bloßen frommen Predigten, mit den bloßen Ermahnungen der Menschen zum Gutsein, mit dem bloßen Sprechen davon, man soll so oder so sein. Dasjenige, was heute weltzerstörerisch da ist, ist auch nicht entstanden durch den Willkürwillen der Menschen, sondern es ist entstanden als eine Folge dessen, was als Weltanschauung seit dem Beginne des 15. Jahrhunderts heraufgekommen ist. Dasjenige, was den Gegenpol darstellen wird, das, was heilen wird die Wunden, die geschlagen sind, das wird wiederum und muß wiederum eine Weltanschauung sein. Und man sollte nicht feig zurückschrecken vor dem Vertreten einer Weltanschauung mit ihrer das Moralische, das Religiöse durchsetzenden Kraft, denn dies allein kann heilen.

[ 26 ] Derjenige, der diesen ganzen Zusammenhang durchschaut, der bekommt wiederum eine Empfindung von dem, was man im Grunde genommen immer gehabt hat da, wo man von wirklicher Weisheit etwas wußte. Ich habe ja auch schon gesprochen von den alten Mysterienstätten. Sie finden es auch im Sinne der Geisteswissenschaft dargestellt in der anthroposophischen Literatur. Da kann man ersehen, wie sich eine ältere instinktive Weisheit entwickelt, wie sie sich dann umwandelt in das Intellektualistische, Materialistische der neueren Zeit. Aber selbst wenn man zurückgeht zu den mehr exoterischen Wissenschaften der älteren Zeiten, sagen wir, wenn man zurückgeht im Medizinischen bis zu Hippokrates, gar nicht zu sprechen von älterer ägyptischer medizinischer Anschauung, so ist überall der Arzt zu gleicher Zeit der Philosoph. Man kann sich eigentlich gar nicht denken, wie der Arzt nicht zu gleicher Zeit der Philosoph und der Philosoph nicht zu gleicher Zeit der Arzt sein sollte, und der Priester nicht beides und alle drei sein sollte. Man konnte sich das nicht denken. Warum nicht? Nehmen Sie eine Wahrheit, die ich öfters ausgesprochen habe.

[ 27 ] Der Mensch kennt ja eigentlich, nicht wahr, den Moment des Todes, diesen einen Moment, wo man nun wirklich den physischen Leib ablegt und wo das Geistige mit der geistigen Welt zusammenhängt, besonders stark zusammenhängt. Aber das ist ja nur in einem Moment. Ich möchte sagen, es sind unendlich viele Differentiale integriert da, wo der Moment des Todes eintritt, die als Differentiale immer in uns enthalten sind während unseres ganzen Lebens. Wir sterben ja fortwährend. Wenn wir geboren werden, fangen wir schon an zu sterben, und in jedem Moment ist ein minutiöses Sterben in uns. Und wir könnten nicht denken, wir könnten einen großen Teil unseres seelischen Lebens, vor allem aber das geistige Leben gar nicht ausdenken, wenn wir nicht fortwährend den Tod in uns hätten. Wir haben ja fortwährend den Tod in uns, und wenn wir nicht mehr können, sterben wir in einem Augenblick. So sterben wir aber kontinuierlich zwischen Geburt und Tod.

[ 28 ] Eine ältere, instinktive Weisheit hat nun gefühlt: Das menschliche Leben ist eigentlich ein Sterben. Heraklit, als ein Nachzügler uralter Weisheit, hat es ja auch ausgesprochen: Das menschliche Leben ist ein Sterben. Das menschliche Fühlen ist ein fortwährendes Kranksein. Man hat die Neigung zum Sterben und zum Kranksein. Und was man lernt, wozu muß es denn da sein? Es muß sein wie eine Arzenei. Es muß das Lernen ein Heilungsprozeß sein. Eine Weltanschauung haben, muß ein Heilprozeß sein.

[ 29 ] Dieses Gefühl hatten durchaus die Ärzte, da sie nur da, wo es notwendig war, auf materiellem Gebiete heilten, wenn die Krankheit akut war. Aber das menschliche Leben sahen sie nur an wie eine chronische Krankheit. Und derjenige, der ein Philosoph oder Arzt war, fühlte sich mit dem, was Erdenmenschheit war, auch als der Heiler, er fühlte sich nur als der Heiler für das, was man gewöhnlich für das Normale ansieht, was aber auch eigentlich krank ist, die Anlage zum Sterben ist. Diese Gefühle müssen wir für die Weltanschauung wieder bekommen, daß sie nicht nur ein formales Anfüllen ist des Kopfes, des Geistes, ein Anfüllen mit Erkenntnissen, sondern ein realer Prozeß im Leben; daß die Weltanschauung dazu dient, die Menschheit zu heilen.

[ 30 ] Nun leben wir tatsächlich in bezug auf unsere kulturhistorische Entwickelung nicht bloß in einer langsamen Krankheit, sondern wir leben gegenwärtig in einer akuten Kulturkrankheit. Dasjenige, was als Weltanschauung auftritt, muß eine wirkliche Arzenei sein, muß eine wirkliche medizinische Wissenschaft sein, eine Kur. Von der realen Bedeutung einer solchen Weltanschauung, wie sie hier gemeint ist, für das gegenwärtige Zivilisations- und Kulturergebnis muß man durchdrungen werden. Durchdrungen sein davon, daß tatsächlich mit Weltanschauung etwas Reales gemeint ist, nicht bloß dieses Formale: Man will etwas wissen, man will gewissermaßen die Begriffe für dasjenige, was draußen als Sache ist, in sich haben, man will Naturgesetze kennenlernen und sie technisch anwenden. — Nein, dieses Innerliche, dieses mit dem Menschen Verknüpfte muß da sein, wo eine wahre Weltanschauung ist, auf daß gewonnen werden können aus dieser wahren Weltanschauung die für Krankheiten, ja für einen Sterbeprozeß wirksamen Heilmittel, die fortwährend da sein müssen. Solange man nicht so redet und solange man nicht solches versteht, wird man immer nur obenhin reden über die Übel unserer Zeit und nicht reden über dasjenige, was notwendig ist.

Von diesen Dingen wollen wir dann morgen weiter sprechen.

[ 1 ] Yesterday I tried to show how, from the mid-19th century onwards, a certain climax in the sensualist or materialist world view gradually emerged and how, towards the end of the 19th century, at least from a certain point of view, this climax had been reached. Let us first look at how the external facts of human development have presented themselves under the influence of the materialistic world view. This materialistic world view cannot be said to have emerged merely from the arbitrariness of a number of leading personalities. For, even if this is denied on various sides, this materialistic view is based precisely on the scientific convictions and scientific research results of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Humanity had to arrive at these scientific results. They were prepared in the 15th century and reached a certain climax, at least insofar as they educate humanity, in the 19th century. Again, on the basis of this scientific attitude, nothing else could develop than a certain materialistic world view.

[ 2 ] Yesterday I stopped at saying: What it was actually about emerged quite radically – at least in terms of the outward symptoms outwardly, - in what can be characterized as Haeckel's position in relation to those who then, in the last decade of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, opposed him. One can, as it were, observe what took place there and what had an extraordinarily profound effect on the general education of humanity, without taking into account the specific formulation that Haeckel gave to his world view and also, ultimately, the specific formulation that his opponents gave to their so-called refutations. We can simply see that on the one hand there was what one believed one could gain from a careful observation of material events up to the level of man. Only that should be in a worldview, only there did one believe that one was on safe ground. It was something completely new compared to the medieval content of the worldview.