Imaginative Cognition and Inspired Cognition

GA 209

23 December 1921, Dornach

Translated by Violet E. Watkin

In the course of these lectures I have often explained how a man is not in a sleeping state only during ordinary sleep but that this state also plays into his everyday conscious life. This obliges us indeed to describe the state of complete wakefulness as existing, even in everyday consciousness, for our conceptual life alone. Compared to the conceptual life, what we bear within us as our life of feeling is not so closely connected with our waking state. To the unprejudiced observer our feeling life shows affinity to dream-life; though dream-life runs on in pictures and the life of feeling in the way we all know. Yet we soon realise that, on the one hand, dream-life—which as we know conjures up in pictures, into everyday life, facts unknown to ordinary consciousness—can be judged only by our conceptual faculty of discrimination. It is by means of this same faculty alone that the whole range and significance of our feeling life can be estimated. And what goes on in a will-impulse, in the expression, the working, of the will, is just as hidden from ordinary consciousness as what in dreamless sleep happens to man, as a being of soul and spirit, from the moment of falling asleep to that of waking.

What actually takes place when we perform the simplest act of will, when, let us say, by merely having an impulse to do so we raise an arm or a leg, is in fact just as great a mystery to us as what goes on in sleep. It is only because we can see the result of an act of will that the act itself enters our consciousness.

Having thought of raising our arm—but that is merely a thought—we see when this has taken place how the arm has indeed been raised. It is by means of our conceptual life that we learn the result of an act of will. But the actual carrying out of the deed remains hidden from ordinary consciousness, so that, even during our waking hours, what arises in us as an impulse of will we have to attribute to a sleeping state. And the whole of our life of feeling runs its course just like a dream.

Now what concerns us here is that, when taken as a whole, the facts I have just mentioned can be quite clear to our ordinary consciousness, although perhaps, when given an abstract interpretation certain points may not seem so at once. But by carefully following up the facts in question we shall find what has been said to be correct.

Consciousness when developed is able to follow up these facts. In particular it can observe in detail the conceptual life and the life of the will. We know how through exercises described in several of my works ordinary objective knowledge can be raised to Imaginative knowledge. On being observed this Imaginative knowledge or cognition shows, to begin with, its true relation to the human being as a whole. It will be useful for us, however, to recall certain facts about ordinary consciousness, before going on to what this Imaginative knowledge has chiefly to say about a man's conceptual power and his will.

Let us then look at the actual life of thought—the conceptual life. You will have to admit; If this conceptual life is experienced without prejudice, we shall not feel it to be a reality. Conceptions arise in our life of soul and there is no doubt the inner course of a man's conceptions is something added to the outer course taken by the facts. The outer course of events does not directly demand the accompaniment of an inwardly experienced conception. The fact of which we form an idea could take place without our experiencing it as an idea. Sinking ourselves in these conceptions, however, teaches us too that in them we live in what, compared with the external world, is something unreal. On the other hand, precisely in what concerns the life of will—which seems to ordinary consciousness as if experience in sleep—we become aware of our own reality and of the truth about our relation to the world.

As we form conceptions we find more and more that these conceptions live in us just as the images of objects are there in a mirror. And just as little as, in the case of what is usually called the real world, we feel the mirror-images to be a reality, do we—if our reason is sound—look upon our conceptions as real.

But there is another thing which prevents our ascribing reality to our conceptions, and that is our feeling of freedom. Just imagine that while forming conceptions we lived in them so that they ran on in us in the way nature works. The conceptual life would be like something happening outside in nature, taking place as a necessity. We should be caught up in a chain of necessities from which our thinking would be unable to free itself. We should never have the sense of freedom which, as such, is an actual fact. We experience ourselves as free human beings only when free impulses living in us spring out of pictures having no place in the chain of natural necessities. Only because we live with; our conceptions in pictures outside the necessary natural phenomena are we able, out of such conceptions, to experience free impulses of will.

When observing our conceptual life thus, we perceive it to be entirely unreal; whereas our life of will assures us of our own reality. When the will is in action it brings about changes in world outside—changes we are obliged to regard as real. Through our will we make actual contact with the external world. Therefore, it is only as beings of will that we can perceive ourselves as realities in the external world.

When from these facts—easily substantiated in ordinary consciousness—we go on to those of which Imagination can tell us, we find the following. When we have acquired Imaginative knowledge and, armed with this, try to arrive at a knowledge of man himself, then actually in two respects he appears a quite different being from what he is for ordinary consciousness. To ordinary consciousness our physical body is a self-contained entity at rest. We differentiate between its separate organs and observing an organ in our usual state of consciousness we have the impression of dealing with an independent member of the body which, as something complete in itself, can be drawn in definite outlines.

This ceases the moment we rise to Imaginative knowledge and study from that point of view the life of the body. Then this something at rest shows—if we don't want to be really theoretical, which of course it is always possible to be in a diagram—that it cannot be drawn in definite outline. This cannot be done in the case of lungs, heart, liver and so on, when we rise to Imaginative knowledge. For what this reveals about the body is its never-ending movement. Our body is in a state of continued motion—certainly not something at rest; it is a process, a becoming, a flux, which imaginative cognition brings to our notice. One might say that everything is seething, inwardly on the move, not only in space but, in an intensive way, one thing flows into another. We are no longer confronted by organs at rest and complete; there is active becoming, living, weaving. We cannot speak any more of lungs, heart, liver, but of processes—of the lung-process, heart-process, liver process. And these separate processes together make up the whole process—man. It is characteristic of our study of the human being from the point of view of Imaginative knowledge, that he appears as something moving, something enduring, in a state of perpetual becoming.

Consider what it signifies to have this change in our view of a man; when, that is, we first see the human body with its definitely outlined members, and then direct the gaze of our soul to the inner soul-life, finding there nothing to be drawn thus definitely. In the life of soul, we see what is taking its course in time, something always becoming, never at rest. The soul-life shows itself indeed to be a process perceptible only inwardly, a process of soul and spirit, yet clearly visible. This process in the life of soul, which is there for ordinary consciousness when a man's inner being is viewed without prejudice, this state of becoming in the soul-life, has very little resemblance to the life of the body at rest. It is true that the life of the body also shows movement; breathing is a movement, circulation is a movement. In relation to how a man appears to Imaginative cognition, however, I would describe this as merely a stage on the way to movement. Compared with the delicate, subtle movements of the human physical body revealed to Imaginative cognition, the circulation of the blood, the breathing, and other bodily motions seem relatively static.

In short, the objective knowledge of the human body perceived it ordinary consciousness is very different from what is perceived as the life of soul, that is in a perpetual state of becoming—always setting itself in motion and never resting.

When, however, with Imagination we observe the human body, it becomes inwardly mobile and in appearance more like the soul life. Thus, Imaginative cognition enables us to raise the appearance of the physical body to a level with the soul. Soul and body come nearer to each other. For Imaginative cognition the body in its physical substance appears more like the soul.

But here I have brought two things to your notice which belong to quite different spheres. First, I showed how the physical body appears to Imaginative cognition as something always on the move, always in a state of becoming. Then I pointed out how indeed, for the, inner vision of our usual consciousness, the ordinary life of soul is also ceaselessly becoming, running its course tie—a life, in effect, to which it is impossible to ascribe definite outlines.

When, however, we rise to Imaginative cognition, this life of soul also changes for the inward vision, and changes over in an opposite direction to the life of the body. It is noticeable that when filled with Imaginative knowledge we no longer feel any freedom of movement in our thoughts, in the combining of them with one another. We also feel that by rising to Imaginative cognition our thoughts gain certain mastery over our life of soul. In ordinary consciousness we can add one thought to another, with inner freedom either combine or not combine a subject with a predicate—feel free in our combining of conceptions.

This in not so when we acquire imaginative knowledge. Then in the thought-world we feel as though in something which works through powers of its own. We feel as if caught up in a web of thought, in such a way that the thoughts combine themselves through their own forces, independently of us. We can no longer say I think—but are forced to change it to: It thinks. In fact, we are not free to do otherwise. We begin to perceive thinking as an actual process—feel it to be as real a process in us as in everyday life we experience the gripping of pain and then its passing off, or the coming and going of something pleasant. By arising to Imaginative cognition, we feel the reality of the thought-world—something in the thought-world resembling experience in the physical body.

From his it can be seen how, through Imaginative knowledge, the conceptual life of the soul becomes more like the life of the body, than is the soul-life—as seen through the inner vision of ordinary consciousness. In short, the body grows soul-like. And the soul becomes more like the body, particularly like those bodily processes which to Imaginative consciousness disclose themselves in their becoming.

Thus, for Imaginative cognition the qualities of the soul approach those of the body, and the qualities of the body those of the soul. And we see the soul and spirit interweaving with the bodily-physical the two becoming more alike. It is as though our experience of what is of the soul acquired a materialistic character while our view of the bodily life, physical life generally, were spiritualised

This is an important fact which reveals itself to Imaginative cognition. And when further progress is made to Inspired Cognition, we find another secret about the human being unveiled. Having acquired Inspired knowledge we learn more of the material nature of thinking, of the conceptual faculty; we learn see more deeply into what actually happens when we think.

Now, as I have said, we no longer have freedom in our life of thought. "It thinks,” and we are caught up in the web of this "It thinks.” In certain circumstances the thoughts are the same as those which in ordinary consciousness we combine or separate in freedom, but which in Imaginative experience we perceive to take place as if from inner necessity.

From this we see that it is not in the thought-life, as such, that freedom and necessity are to be found, but in our own attitude, our own relation, to the thought-life of ordinary consciousness. We learn to recognise the actual situation with regard to our experience, in ordinary consciousness, of the unreality of thoughts. We gradually come to understand the reason for this experience, and then the following becomes clear.

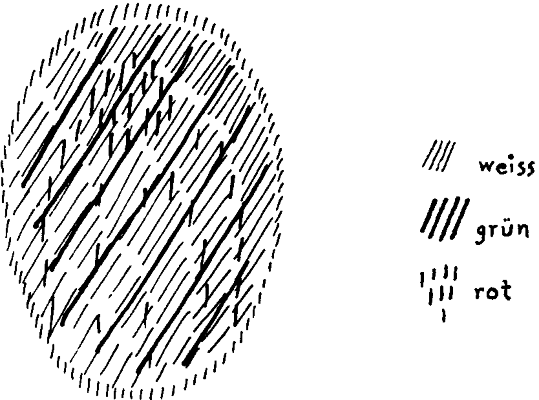

By means of the organic process our organism both takes in and excretes substances. But it is not only a matter of these substances separating themselves from the organic process of the body and being thrown out by the excretory organs—certain of these substances become stored up in us. Having been thrown out of the life-process these remain, to some extent, in the nerve-tract, and in other places in the organism. In our life-process we are continuously engaged in detaching lifeless matter. People able to follow minutely the process of human life can observe this storing up of lifeless matter everywhere in the organism. A great part of this is excreted but there is a general storing up of a certain amount in a more tenuous form. The life of the human organism is such that it is always engaged on the organic process—like this (a drawing was made) But everywhere within the organic process we see inorganic, lifeless matter, not being excreted but stored up (which I indicated here with red chalk): I have drawn these red dots rather heavily because it is chiefly the unexcreted, lifeless matter which withdraws to the organ of the human head, where it remains.

Now the human organism is permeated throughout by the ego (I indicate this with green chalk). Within the organism the ego comes in contact with the lifeless substances which have been separated off and permeates them. So that our organism appears as having, on the one hand, its organic processes permeated by the ego, the process, that is, containing the living substance, and of having also what is lifeless—or shall we say mineralised—in the organism permeated by the ego.

This, then, is what is always going on when we think. Aroused by sense-perceptions outside, or inwardly by memory, the ego gets the upper hand over the lifeless substances, and—in accordance with the stimulation of the senses or of the memories—swings these lifeless substances to and fro in us, we might almost say makes drawings in us with them. For this is no figurative conception; this use of inorganic matter by the ego is absolute reality It might be compared to reducing chalk to a powder and then with a chalky finger drawing all kinds of figures. It is an actual fact that the ego sets this lifeless matter oscillating, masters it, and with it draws figures in us, though the figures are certainly unlike those usually drawn outside. Yet the ego with the help of this lifeless substance does really make drawings and form crystals in us—though not crystals like those found in the mineral kingdom (see red in drawing).

What goes on in this way between the ego and the mineralized substance in us that has detached itself as in a fine but solid state—it is this which provides the material basis of our thinking. In fact, to Inspired cognition the thinking process, the conceptual process, shows itself to be the use them ego makes of the mineralised substance in the human organism.

This, I would point out, gives a more accurate picture of what I have frequently described in the abstract when saying: In that we think we are always dying,—What within us is in a constant state of decay, detaching itself from the living and becoming mineralised, with this the ego makes drawings, actual drawings, of all our thoughts. It is the working and weaving of the ego in mineral kingdom, in that kingdom which alone makes it possible for us to possess the faculty of thinking.

You see it is what I have been describing here which dawned on the materialists of the 19th century, though they misconstrued it. The best advocates of materialism—and one of the best was Czolbe—had a vague notion that while thoughts are flitting through us physical processes are at work. These materialists forget, however,—and this is where error crept in—that it is the purely spiritual ego making drawings in us inwardly with what in mineralized. And on this inward drawing depends what we know of the actual awakening of ordinary consciousness.

Let us now consider the opposite side at the human being, the side of the will-impulses. If you recall what I have been describing, you will perhaps perceive how the ego becomes imprisoned in what has been mineralized within us. But it is able to make use of this mineralised substance to draw with it inwardly. The ego is able to sink right down into what is thus mineralised.

If, on the other hand, we study the life-processes, where the non-mineralised substances are to be found, we come to the material basis of the will. In sleep the ego leaves the physical body, whereas in willing the ego is only driven out of certain parts of the organism. Because of this, at certain moments when this is so, there is nothing mineralised in that region, everything there is full of life. Out of these parts of the organism, where all is alive and from which at that moment nothing mineralised is being detached, the impulses will unfold. But the ego is then driven out; it withdraws into what is mineral. The ego can work on the mineralised substances but not on what is living, from which it is thrust out just us when we are asleep at night our ego is driven out of the whole physical body.

But then the ego is outside the body whereas on mineralisation taking place it is driven inside. It is the life-giving process which thrust the ego out of certain parts of the body; then the ego is as much outside those parts as in sleep it is driven out of the whole body. Hence, we can say that when the will is in action parts of the ego are outside the regions of the physical body to which they are assigned. And those parts of the ego—where are they then? They are outside in the surrounding space and become one with the forces weaving there. By setting our will in action we go outside ourselves with part of our ego, and we take into us forces which have their place in the world outside. When I move an arm, this is not done by anything coming from within the organism but through a force outside, into which the ego enters only by being partly driven out of the arm. In willing go out of my body and move myself by means of outside forces. We do not lift our leg by means of forces within us, but through those actually working from outside. It is the same when an arm is moved. Whereas in thinking, through the relation of the ego to the mineralised part of the organism, we are driven within, in willing just as in sleep we are driven outside. No one understands the will who has not a conception of man as a cosmic being; no one understands the will who is bounded by the human body and does not realise that in willing he takes into him forces lying beyond it.

In willing we sink ourselves into the world, surrender ourselves to it. So that we can say: The material phenomenon that accompanies thinking is a mineral process in us, something drawn by the ego in the mineralised parts of the human organism. The will represents in us a vitalising, a widening of the ego, which then becomes a member of the spiritual world outside, and from there works back upon the body.

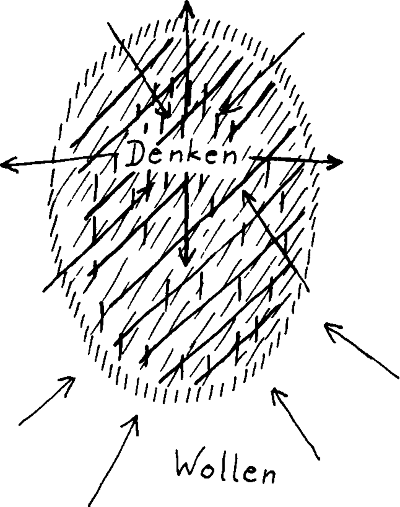

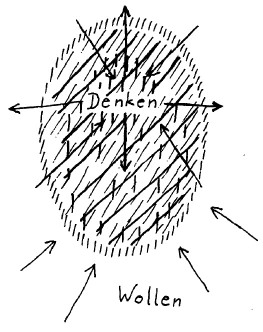

If we want to make a diagram of the relation between think and willing, it must be done in this way (a drawing was made). You see it is quite possible to pass over from an inward view of the soul-life to its physical counterpart, without being tempted to fall one-sidedly into materialism. We learn to recognise what takes place in a material way in thinking and in willing. But once we know how in thinking the ego plays an actual part with the inorganic, and how, on the other hand, through the organic life-giving process in the body it is driven out into the spirit, then we never lose the ego.

In that the ego is driven out of the body it is united with forces of the cosmos; and working in from outside, from the spiritual regions of the cosmos, the ego unfolds the will.

In that the ego is driven out of the body it is united with forces of the cosmos; and working in from outside, from the spiritual regions of the cosmos, the ego unfolds the will.

Materialism is therefore justified on the one hand, whereas on the other it no longer holds good. Simply to attack materialism betrays a superficial attitude. For what in a positive sense the materialist has to say is warranted. He is at fault only when he would approach man's whole wide conception of the world from one side.

In general, when the world and all that happens in it is followed inwardly, spiritually, it is found more and more that the positive standpoints of individual men are warranted, but not those that are negative. And in this connection spiritualism is often just as narrow as materialism. In what he affirms positively the materialist has right on his side, as the spiritualist has on his, when positive. It is only on becoming negative that they stray from the path and fall into error. And it is indeed no trifling error when, in an amateurish fashion, people imagine they have succeeded in their striving for a spiritual world-conception without having any understanding of material processes, and then look down on materialism. The material world is indeed permeated by spirit. But we must not be one-sided; we must learn about its material characteristics as well, recognising that reality has to be approached from various sides if we are to arrive at its full significance.

And that is a lesson best taught by a world-conception such as that offered by Anthroposophy.

Der Mensch Als Erdenwesen Und Himmelswesen III

Des öfteren habe ich im Verlauf dieser Vorträge auseinandergesetzt, wie der Schlafzustand des Menschen nicht nur vorhanden ist für den gewöhnlichen Schlaf, sondern wie er hereinspielt in das bewußte Alltagsleben, und zwar so, daß wir auch innerhalb des bewußten Alltagslebens unterscheiden müssen den vollständigen Wachzustand, der nur vorhanden ist mitBezug auf das Vorstellungsleben, von dem, was wir als Gefühlsleben in uns tragen. Dieses ist nicht in demselben Sinne in unseren Wachzustand eingegliedert wie das Vorstellungsleben, sondern für den unbefangenen Betrachter erweist sich das Gefühlsleben gleich dem Traumleben, nur daß das Traumleben in Bildern verläuft und das Gefühlsleben eben in der Art, wie wir es kennen. Doch wird man sehr leicht gewahr werden, wie man auf der einen Seite das Traumleben, das in der bekannten Weise die Bilder von unbekannten Tatsachen, für dasgewöhnliche Bewußtsein unbekannten Tatsachen, hereinzaubert in das Alltagsleben, nur wird beurteilen können mit unserem vorstellenden Unterscheidungsvermögen. Ebenso können wir, und zwar genau so, die Tragweite, die Bedeutung des Gefühlslebens nur beurteilen durch dieses unterscheidende Vorstellungsleben. Und dasjenige, was verläuft bei einem Willensimpuls, bei dem Ausleben, bei dem Wirken eines Willensimpulses, das ist genauso dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein verborgen wie dasjenige, was mit dem Menschen als einem seelisch-geistigen Wesen geschieht vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen im traumlosen Schlafzustande. Was da eigentlich vorgeht, wenn wir nur die einfachste Willenshandlung vollziehen, sagen wir, wenn wir nur durch einen Willensimpuls unsere Arme oder unsere Beine heben, das bleibt tatsächlich so verborgen wie die Vorgänge des Schlafens. Nur dadurch, daß wir gewissermaßen den Erfolg der Willenshandlung sehen, tritt die Willenshandlung in unser gewöhnliches Bewußtsein herein. Wir sehen, nachdem wir den Gedanken gefaßt haben, den Arm zu heben - das ist aber ein bloßer Gedanke -, und nachdem der Erfolg eingetreten ist, wie der Arm eben sich hebt. Und diesen Erfolg der Willenshandlung lernen wir wiederum durch das Vorstellungsleben kennen. Dasjenige aber, was sich als eigentliche Willenstatsache abspielt, bleibt dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein verborgen, so daß wir alles dasjenige, was Willensimpuls ist, als einen Schlafzustand auch im gewöhnlichen Tagesleben benennen müssen. Und alles dasjenige, was sich als Gefühlsleben abspielt, verläuft gleich dem Traume.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß diese Summe von Tatsachen, die ich eben vorbereitend angeführt habe, ja dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein durchaus einleuchten kann. Wenn man in abstracto dieses andeutet, so wird es vielleicht da oder dort nicht gleich verständlich erscheinen. Aber beim Verfolgen der Bewußtseinstatsachen wird man eben finden, daß das Gesagte durchaus richtig ist. Nun aber kann das entwickelte Bewußtsein diese Tatsachen weiter verfolgen, kann namentlich verfolgen, wie das Vorstellungsleben und das Willensleben für den menschlichen Lebenslauf sich im genaueren gestalten. Wir wissen ja, daß aufgestiegen werden kann durch diejenigen Übungen, die ich geschildert habe in verschiedenen Schriften, von der gewöhnlichen, gegenständlichen Erkenntnis zu der imaginativen Erkenntnis. Diese imaginative Erkenntnis zeigt durch ihre Beobachtung erst, wie es sich eigentlich in Wahrheit mit dem Menschen als einer Totalität verhält. Aber es wird noch nützlich sein, sich an gewisse Tatsachen des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins zu erinnern, bevor ich dasjenige anführe, was die imaginative Erkenntnis zunächst über den Menschen in bezug auf Vorstellen und Wollen zu sagen hat.

Betrachten wir einmal unser eigentliches Denkleben, das Vorstellungsleben. Sie werden sich ohne weiteres sagen müssen: Dieses Vorstellungsieben wird eigentlich nicht bei einem unbefangenen Erleben als Realität empfunden. Die Vorstellungen treten in unserem Seelenleben auf, und es ist ja zweifellos, daß für den äußeren Verlauf einer Tatsache der innere Vorstellungsverlauf des Menschen etwas Hinzugekommenes ist. Der äußere Verlauf der Tatsache verlangt nicht unmittelbar, daß er begleitet werde von dem inneren Erlebnis des Vorstellens. Dieselbe Tatsache, die wir vorstellen, könnte sich auch abspielen, ohne daß wir sie vorstellend erleben. Aber auch das Sich-Versenken in die Vorstellungen lehrt uns, wie wir im Vorstellungsleben in etwas Unrealem zunächst gegenüber der Außenwelt leben. Dagegen gerade mit Bezug auf das Willensleben, das sich für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein wie im Schlafe erlebt ausnimmt, werden wir uns unserer eigenen Realität und der realen Beziehungen von uns zur Welt bewußt. Indem wir bloß vorstellen, müssen wir immer mehr und mehr darauf kommen: Die Vorstellungen leben in uns, wie Bilder von Gegenständen im Spiegel vorhanden sind. Und so wenig wir mit Bezug auf das, was wir gewöhnlich die reale Welt nennen, die Bilder im Spiegel als etwas auch Reales empfinden, ebenso wenig können wir bei gesunder Vernunft die Vorstellungen als solche als etwas Reales empfinden.

Es hindert uns aber noch etwas, die Vorstellungen als etwas Reales aufzufassen. Das ist unser Freiheitsgefühl. Denken Sie sich einmal: Indem wir vorstellen,lebten wir in unseren Vorstellungen so, daß dieseVorstellungen in uns wie Naturwirkungen abliefen. Das Vorstellungsleben wäre so etwas wie ein äußeres Geschehen der Natur, das sich als Notwendiges abspielt. Wir würden da eingesponnen sein in eine Kette von Notwendigkeiten. Wir würden nur dasjenige denken können, was in der Kette der äußeren Naturnotwendigkeiten drinnensteht. Wir würden niemals das Gefühl der Freiheit, das aber als solches eine Tatsache ist, haben können. Als freieMenschen können wir uns nur empfinden, wenn dasjenige, was als freie Impulse in uns lebt, aus Bildern entspringt, die sich heraussetzen aus der gewöhnlichen Kette der notwendigen Naturtatsachen. Nur weil wir in unseren Vorstellungen in Bildern leben, die nicht in die Reihe der notwendigen Naturerscheinungen eingegliedert sind, können wir aus diesen Vorstellungen heraus die freien Willensimpulse erleben.

Wenn wir also das Vorstellungsleben in dieser Art betrachten, empfinden wir es überall als etwas Irreales. Dagegen ist eben das Willensleben dasjenige, was uns unsere Realität versichert. Dasjenige, was als Willenshandlung zutage tritt, bringt Veränderungen in der äußeren Welt hervor, die wir als Realitäten ansehen müssen. Wir greifen durch unseren Willen real in die äußere Welt ein. Deshalb können wir auch nur die Empfindung haben, daß, indem wir Willenswesen sind, wir real in der Außenwelt drinnenstehen. Wenn wir nun von diesen schon durch das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein leicht zu konstatierenden Tatsachen vorschreiten zu dem, was uns die Imagination sagen kann, so gelangen wir zu folgendem: Es ist wirklich so, daß wenn wir die imaginative Erkenntnis uns aneignen und dann von dieser aus versuchen, zu einer Selbsterkenntnis des Menschen zu kommen, dann nimmt sich der Mensch vor dieser imaginativen Erkenntnis zunächst in zweifacher Art als ein ganz anderes Wesen aus, als er es für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein ist. Für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein steht unser physischer Leib so vor uns, daß er gewissermaßen eine in sich abgeschlossene, ruhende Wesenheit ist. Wir unterscheiden am physischen Leibe seine einzelnen Organe, und wir bekommen, indem wir so mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtseinszustand diese einzelnen Organe des physischen Leibes betrachten, den Eindruck, es mit abgeschlossenen Leibesgliedern zu tun zu haben, die wir aufzeichnen können, die also festgeschlossene Konturen haben, die ein in sich Ruhendes sind.

Das hört in dem Augenblicke auf, wo wir zur imaginativen Erkenntnis aufsteigen und dann unser Leibesleben von dem Gesichtspunkte der imaginativen Erkenntnis aus betrachten. Da gibt es also kein Ruhendes, das wir, wenn wir nicht schematisch werden wollen schematisch kann man natürlich alles zeichnen -, als in sich abgeschlossene Figuren zeichnen können. Wir können dasjenige, was uns die imaginative Erkenntnis gibt über Lunge, Herz, Leber und so weiter nicht in abgeschlossenen Konturen aufzeigen, sondern dasjenige, was uns über den physischen Leib die imaginative Erkenntnis gibt, ist ein fortwährendes in sich Bewegliches, ist ein Geschehen, ist kein Ruhendes. Es ist ein Prozeß, ein Werden. Es ist ein Fluß, den wir gewahr werden, wenn wir zur imaginativen Erkenntnis aufsteigen. Alles brodelt, möchte ich sagen, alles bewegt sich innerlich, und zwar nicht nur räumlich, sondern auch in intensivem Sinne; das eine fließt in das andere über. Wir haben nicht mehr ruhende Organe, nicht mehr in sich geschlossene Organe vor uns, wir haben ein lebendiges Werden, ein Leben und Weben vor uns. Wir können nicht mehr sprechen von Lunge, Herz und Leber, sondern wir müssen sprechen von dem Lungenprozeß, von dem Herzensprozeß, von dem Leberprozeß. Und wiederum, diese einzelnen Prozesse setzen sich zusammen zu dem Gesamtprozeß Mensch. Das ist das Eigenrümliche, daß sich der Mensch in dem Augenblicke, wo er vom Gesichtspunkt der imaginativen Erkenntnis aus betrachtet wird, sich ausnimmt als ein in sich Bewegliches, als ein fortdauernd in jedem Augenblicke Werdendes.

Beachten Sie aber, welche Bedeutung dieser veränderte Anblick des Menschen hat. Wenn wir den menschlichen Leib mit seinen festkonturierten Gliedern betrachten und dann den Seelenblick werfen auf unser inneres Seelenleben, dann sehen wir im Seelenleben niemals etwas, was wir mit festen Konturen aufzeichnen könnten. Wir sehen im Seelenleben etwas, was in der Zeit verläuft, was immer wird und niemals ruhend ist. Das Seelenleben stellt sich uns zwar dar als ein nur innerlich geistig-seelisch anschaubarer, aber doch deutlich vorliegender Prozeß. Dieser Prozeß des Seelenlebens, der schon für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein bei einer unbefangenen Innenschau des Menschen da ist, dieses Werden des Seelenlebens ist sehr wenig ähnlich dem in sich ruhenden Leibesleben. Gewiß, das Leibesleben zeigt uns auch Bewegung, die Atmungsbewegung, die Zirkulationsbewegung; allein ich möchte sagen, da haben wir einen Übergang zu dem Beweglichen, als das sich uns der Mensch darstellt vor der imaginativen Erkenntnis. Aber gegenüber den feinen, subtilen Bewegungen, die der imaginativen Erkenntnis sich ergeben von dem menschlichen physischen Leibe, verhält sich dasjenige, was uns als Blutzirkulation, als Atmungsbewegung, als sonstige Bewegung im Leibe auftritt, doch wie ein etwas verhältnismäßig Ruhendes. Kurz, dasjenige, was man mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein in der gegenständlichen Erkenntnis als den menschlichen Leib wahrnimmt, das ist sehr verschieden von dem, was man wahrnimmt als das Seelenleben, das ein immerwährendes Werdendes, ein in sich Bewegliches, ein nie Ruhendes ist. Wenn wir aber imaginativ den menschlichen Leib betrachten, dann wird er innerlich beweglich, das heißt, er wird in seinem Anblicke dem Seelenleben ähnlicher. So liefert uns die imaginative Erkenntnis die Möglichkeit, ich möchte sagen, den Anblick des physischen Leibes in das Seelische heraufzuheben. Seele und Leib nähern sich. Der Leib, der physische Körper wird seelenähnlicher für die imaginative Erkenntnis.

Aber ich habe Ihnen jetzt eigentlich zwei Dinge vorgeführt, welche auf ganz verschiedenen Feldern liegen. Ich habe Ihnen vorgeführt den Anblick, den der physische Leib für die imaginative Erkenntnis bietet, habe Ihnen vorgeführt, daß er da ein in sich Bewegliches, ein fortwährend Werdendes ist, und ich habe Ihnen dann gezeigt, wie schon für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein in der Innenschau das gewöhnliche Seelenleben ein solches Werdendes, ein nie Ruhendes, ein in der Zeit Verlaufendes, ein Leben ist, das wir eben nicht in feste Konturen fassen und etwa in solchen aufzeichnen können.

Wenn wir aber zur imaginativen Erkenntnis aufsteigen, so verändert sich auch für die Innenschau dieses Seelenleben, und es verändert sich in der entgegengesetzten Richtung wie das Leibesleben. Das ist ja das Merkwürdige, daß, indem wir uns mit imaginativen Erkenntnissen durchtränken, wir nicht mehr fühlen diese freie Beweglichkeit in den Gedanken, diese freie Beweglichkeit in der Verbindung des einen Gedankens mit dem andern. Wir fühlen auch, daß, indem wir zur imaginativen Erkenntnis aufsteigen, unsere Gedanken etwas unser Seelenleben Bezwingendes haben. Im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein können wir einen Gedanken zu dem andern hinzufügen. Wir können ganz mit innerlicher Freiheit ein Subjekt mit einem Prädikat verbinden. Wir können es auch unterlassen, und wir fühlen uns frei in dieser Verbindung der einen Vorstellung mit der andern.

Das ist nicht so, wenn wir zur imaginativen Erkenntnis aufsteigen. Da fühlen wir uns in der Gedankenwelt wie in etwas, das sich durch seine eigenen Kräfte abspielt. Da fühlen wir uns wie eingesponnen in das Gedankennetz, so daß sich nicht durch uns, sondern durch die eigenen Kräfte ein Gedanke mit dem andern verbindet. Wir können gar nicht mehr sagen, wenn wir zur imaginativen Erkenntnis aufsteigen: Ich denke. - Wir müssen beginnen dann zu sagen: Es denkt. — Und wir sind in dieses «Es denkt» eingesponnen. Wir fangen an, das Denken als einen realen Prozeß zu empfinden. Wir fühlen es so als einen realen Prozeß in uns, wie wir etwa im gewöhnlichen Alltagsleben fühlen, daß uns dieser Schmerz ergreift und wieder verläßt, diese Lust kommt und wieder geht. Wir fühlen Realität in der Gedankenwelt, indem wir uns zur imaginativen Erkenntnis erheben. Wir fühlen etwas in unserer Gedankenwelt, was ähnlich wird dem Erleben, das wir gegenüber dem physischen Leibe sonst haben. Daraus ersehen Sie, daß durch die imaginative Erkenntnis das vorstellende Seelenleben noch mehr ähnlicher wird dem Leibesleben, als das Seelenleben ähnlich diesem Leibesleben ist, das für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein in Innenschau ergriffen wird. Kurz, für die imaginative Erkenntnis wird der Leib sehr seelenähnlich. Die Seele aber wird leibesähnlich, allerdings ähnlich den Leibesvorgängen, wie sie sich als Werdendes dem imaginativen Bewußtsein enthüllen. So nähert sich das Seelische dem Leiblichen für die imaginative Erkenntnis, und das Leibliche dem Seelischen. Wir sehen gewissermaßen ineinanderdringen, einander ähnlich werden Seelisch-Geistiges und Körperlich-Physisches, indem wir zur imaginativen Erkenntnis aufsteigen. Wir werden gewissermaßen im Erleben des Seelischen von einem Materialismus ergriffen, und unser Anschauen des Leibeslebens, des physischen Lebens überhaupt, wird spiritualisiert. Das ist eine wichtige Tatsache, die sich für die imaginative Erkenntnis ergibt.

Und wenn dann weiter vorgeschritten wird zur inspirierten Erkenntnis, dann enthülltsich uns ein weiteres Geheimnis über die menschliche Wesenheit. Wir lernen nachher durch die inspirierte Erkenntnis das Denken, das Vorstellen nach seinem materiellen Charakter noch mehr kennen. Wir durchschauen, was eigentlich sich abspielt, indem wir denken. Ich sagte: Wir kommen heraus aus der Freiheit des Gedankenlebens. Es denkt, und wir sind in dieses «Es denkt» eingesponnen. Es sind unter Umständen dieselben Gedanken, die wir in freier Weise im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein verbinden und trennen, und die wir im imaginativen Erleben wie in innerer Notwendigkeit sich abspielend verspüren. Daraus ersehen wir, daß nicht im Gedankenleben als solchem Freiheit und Notwendigkeit liegt, sondern in unserem Zustande, in unserem Verhältnisse zu dem Gedankenleben im gewöhnlichen physischen Bewußtsein. Aber wir lernen erkennen, wie es eigentlich steht mit dem im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein vorhandenen Erleben der Irrealität der Gedanken. Wir lernen verstehen, warum wir die Gedanken als irreal erleben. Folgendes nämlich stellt sich heraus: Der organische Prozeß, der in uns vorgeht, verläuft ja so, daß unser Organismus sich Stoffe aneignet und auch Stoffe abscheidet. Aber nicht allein diejenigen Stoffe, welche sich aus dem organischen Prozesse unseres Leibes heraussondern, werden durch die Abscheidungsorgane nach außen gestoßen, sondern es lagern sich fortwährend in uns selber solche Stoffe ab. Die bleiben gewissermaßen längs unserer Nervenbahn und an sonstigen Orten unseres Organismus liegen; die werden ausgestoßen aus dem Lebensprozeß. Wir haben es fortwährend in unserem Lebensprozeß damit zu tun, daß sich Lebloses aussondert. Wer im Genauen verfolgen kann den menschlichen Lebensprozeß, der wird wahrnehmen können, daß sich überall im Organismus unorganische Stoffe ablagern. Die groben Massen werden ausgeschieden; aber in feiner Weise lagern sich überall Stoffe ab. So daß wir sagen können: Der menschliche Organismus lebt so, daß er zunächst den organischen Prozeß in sich trägt, den ich Ihnen hier mit weißer Kreide schematisch darstellen will. Aber innerhalb dieses organischen Prozesses sehen wir überall unorganische, leblose Stoffe, die nicht ausgeschieden werden, sondern sich überall ablagern, die ich hier mit roter Kreide schematisch einzeichnen will. Ich zeichnete oben die roten Punkte besonders dicht, weil hauptsächlich diese sich nicht ausscheidenden leblosen Stoffe in dem Kopforgan des Menschen sich absondern, wo sie liegen bleiben. Nun ist der ganze menschliche Organismus von dem Ich durchdrungen. Ich zeichne mit grüner Kreide dieses Ich in die schematische Zeichnung ein. Es kommt innerhalb unseres Organismus das Ich mit den leblos ausgeschiedenen Stoffen in Berührung. Es durchdtringt sie. Es gibt also in unserem Organismus etwas, das sich so ausnimmt, daß auf der einen Seite das Ich durchdringt den organischen Prozeß, den Prozeß, innerhalb welchem die Stoffe als lebendige Stoffe enthalten sind, daß aber das Ich auch durchdringt dasjenige, was Lebloses, ich möchte sagen, Mineralisiertes in unserem Organismus ist. Wenn wir denken, so geht fortwährend das vor sich, daß, angeregt durch die äußeren Sinneswahrnehmungen oder auch durch die Erinnerungen, das Ich gewissermaßen sich bemächtigt dieser leblosen Stoffe und sie im Sinne der äußeren Sinnesanregungen oder der Anregung durch die Erinnerungen aufpendelt, mit ihnen in uns, ich darf schon sagen, zeichnet. Denn es ist keine bildliche Vorstellung, sondern es entspricht durchaus der Realität, daß dasIch diese unorganischen Stoffe wirklich so verwendet, wie wenn ich etwa jetzt, vergleichsweise gesprochen, mir hier Kreide pulverisieren würde und dann mit dem Finger das Kreidepulver nehmen würde und dann mit diesem bekreideten Finger allerlei Figuren hinzeichnete. Es ist so, daß tatsächlich das Ich diese leblosen Stoffe aufpendelt, sich ihrer bemächtigt und in uns Figuren einzeichnet, die allerdings den Figuren, die wir gewöhnlich äußerlich aufzeichnen, nicht ganz ähnlich sehen. Aber es wird in uns durch das Ich mit Hilfe des leblosen Stoffes tatsächlich gezeichnet, kristallisiert, wenn auch nicht in den Kristallgestalten, die wir im mineralischen Reiche finden (siehe Schema, rot). Dasjenige, was sich so abspielt zwischen dem Ich und dem, was in uns mineralisch geworden ist, und zwar sich als sogar fein-feste, mineralisierte Substanzen absondert, das ist dasjenige, was als Materielles unserem Denken zugrunde liegt. Der inspirierten Erkenntnis ergibt sich also der Denkprozeß, der Vorstellungsprozeß tatsächlich als eine Behandlung des Mineralisierten im menschlichen Organismus durch das Ich. Das ist die genauere Schilderung desjenigen; was ich oftmals abstrakt charakterisiert habe, wenn ich sagte: Indem wir denken, sterben wir fortwährend ab. Das in uns Ersterbende, das sich aus dem Leben Heraushebende, das sich Mineralisierende ist dasjenige, mit dem das Ich in uns zeichnet, und mit dem das Ich tatsächlich die Summe unserer Gedanken zeichnet. Es ist ein Wirken und Weben des Ich im mineralischen Reiche, in jenem mineralischen Reiche, das in uns erst wird, das wir als unser Denken haben.

Sehen Sie, das, was ich Ihnen hier charakterisiere, ist es, was, ich möchte sagen, in einer irrtümlichen Ahnung dem Materialismus des 19. Jahrhunderts aufgegangen ist. Dieser Materialismus kam in seinen besten Vertretern - einer der besten Vertreter dieses Materialismus war ja Czolbe -, zu der Ahnung davon, daß, während in uns Gedanken abfließen, physische Prozesse sich vollziehen; nur vergaß dieser Materialismus, und deshalb war die Ahnung eine irrtümliche, daß es das rein geistige Ich ist, das mit dem Mineralisierten in uns innerlich zeichnet. Gerade das also, was wir als das eigentliche Aufwachen des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins erkennen, das beruht auf diesem innerlichen Zeichnen mit den in uns mineralisierten Stoffen.

Sehen wir jetzt nach der andern Seite des Menschen hin, nach der Seite der Willensimpulse. Wenn Sie auf dasjenige noch einmal zurückblicken, was ich eben charakterisiert habe, so sehen Sie darinnen vielleicht ein Gefangennehmen des Ich durch das Mineralisierte in uns. Unser Ich ist eben in der Lage, mit diesem Mineralisierten zu hantieren, innerlich zu zeichnen. Das Ich kann sich hineinversenken in dasjenige, was in uns mineralisiert wird.

Betrachten wir auf der andern Seite jene Lebensprozesse, in denen eben die nichtmineralisierten, die im lebendigen Prozesse befindlichen Stoffe sind, dann kommen wir, ich möchte sagen, auf das Materielle der Willenswirkungen. Im Schlafe ist ja das Ich aus dem physischen Leibe heraus. Im Wollen ist das Ich aus gewissen Orten unseres Organismus heraus. Das ist dadurch der Fall, daß an diesem Orte sich in gewissen Zeitaugenblicken eben nichts mineralisiert, sondern daß da alles lebt. Aus denjenigen Stellen unseres Organismus, in denen alles lebt, in denen in dem entsprechenden Augenblicke nichts Mineralisiertes sich ablöst, abscheidet, da entfalten sich die Willensimpulse. Da wird aber das Ich ausgestoßen. In das Mineralische wird das Ich hineingezogen. Mit dem Mineralischen kann es hantieren; mit demjenigen, was lebendig ist, kann es nicht hantieren. Aus dem wird es herausgetrieben, wie in der Nacht, wenn wir schlafen, dieses Ich aus dem ganzen physischen Leibe herausgetrieben wird. Nun ist aber dann das Ich außerhalb des Leibes. Durch das Mineralisieren wird das Ich in den Leib hineingetrieben. Durch das Vitalisieren wird das Ich aus Teilen des Leibes herausgetrieben. Es ist dann gerade so außerhalb dieser Teile, wie es im Schlafe ganz außerhalb des physischen Leibes ist. Und wir können daher sagen: bei einer Willensbetätigung sind immer Teile des Ich außerhalb derjenigen Orte des physischen Leibes, denen sie eigentlich zugeteilt sind. Und wo sind dann diese Teile des Ich, die außerhalb der ihnen entsprechenden Teile des physischen Leibes sind? Nun, sie sind eben außerhalb, im übrigen Raume. Sie sind eingegliedert in die Kräfte, welche diesen Raum durchweben. Wir sind, indem wir unseren Willen betätigen, mit einem Teil unseres Ich außerhalb unser. Wir gliedern uns Kräfte ein, die durch die Welt gelegt sind. Wenn ich einen Arm bewege, so bewege ich ihn nicht durch etwas, was im Inneren des Organismus entspringt, sondern durch eine Kraft, die außerhalb meines Armes ist, und in die das Ich hineinkommt dadurch, daß es aus gewissen Orten meines Armes herausgetrieben wird. Im Wollen komme ich außerhalb meines Leibes, und durch Kräfte, die außerhalb meiner liegen, bewege ich mich. Man hebt das Bein nicht durch Kräfte, die im Inneren sind, sondern man hebt das Bein durch Kräfte, die tatsächlich von außerhalb wirken; ebenso den Arm. Während man also im Denken nach innen getrieben wird durch das Verhältnis des Ich. zu dem mineralisierten Teil des menschlichen Organismus, wird man im Wollen geradeso wie im Schlafe. nach außen getrieben. Und niemand versteht das Wollen, der nicht den Menschen als kosmisches Wesen auffaßt, der nicht hinausgeht aus den Grenzen des menschlichen Leibes, der nicht weiß, daß der Mensch im Wollen sich außerhalb seines Leibes liegende Kräfte eingliedert. Wir versenken uns in die Welt, wir geben uns an die Welt hin, indem wir wollen. So daß wir sagen können: Die materielle Begleiterscheinung des Denkens ist ein mineralischer Prozeß in uns, ein Zeichnen des Ich in mineralisierte Teile des menschlichen Organismus. Das Wollen in uns stellt dar ein Vitalisieren, ein Herausbreiten des Ich, ein Eingliedern des Ich in die geistige Außenwelt, und ein Wirken auf den Leib vom Ich aus, aus der geistigen Außenwelt herein.

Wollen wir schematisch das Verhältnis des Denkens zum Wollen zeichnen, so müssen wir das in der folgenden Weise tun. Sie sehen, man kann durchaus den Weg machen von der Innenschau des Seelenlebens zu dem physischen Korrelat dieses Seelenlebens, ohne daß man dadurch versucht wird, in einseitiger Weise in den Materialismus zu verfallen. Man lernt erkennen dasjenige, was sich materiell abspielt im Denken und im Wollen. Aber man verliert niemals das Ich, indem man erkennt, wie das Ich innerlich aktiv wird mit dem Unorganischen im Denken, und auf der andern Seite erkennt, wie das Ich in den Geist hineingetrieben wird durch das organische Vitalisieren im Leib. Indem das Ich aus dem Leibe herausgetrieben wird, wird es mit den Kräften des Kosmos zusammengebracht, und von dem geistigen Teil des Kosmos aus, also von außerhalb herein, entfaltet das Ich das Wollen.

Dadurch ist auf der einen Seite der Materialismus gerechtfertigt, und auf der andern Seite zugleich überwunden. Dilettantisch bleibt es immer, wenn man den Materialismus bloß bekämpft. Denn dasjenige, was er im positiven Sinne zu sagen hat, das ist ein durchaus Berechtigtes. Falsch ist an ihm nur, wenn er einseitig sich zu dem ganzen Um und Auf der Weltanschauung des Menschen machen will. Überhaupt kommt man immer mehr und mehr darauf, wenn man geistig innerlich die Welt und ihr Geschehen verfolgt, daß dasjenige, was die einzelnen menschlichen Standpunkte als Positives zu sagen haben, ein Berechtigtes ist, daß sie unberechtigt erst werden, wenn sie Negatives sagen wollen. Und in dieser Beziehung ist der Spiritualismus oftmals ebenso einseitig wie der Materialismus. In dem, was der Materialismus Positives zu sagen hat, hat er recht; in dem, was der Spiritualismus Positives zu sagen hat, hat er recht. Erst wenn sie beide negativ werden, verfallen sie in das Unrecht und in den Irrtum. Und es ist kein geringer Irrtum, wenn in laienhaft dilettantischer Weise Leute, die sich einbilden, eine spirituelle Weltanschauung sich errungen zu haben, ohne irgend etwas zu verstehen von den materiellen Vorgängen, auf den Materialismus herabsehen. Die materielle Welt ist durchgeistigt; aber man muß sie auch in ihren materiellen Eigentümlichkeiten kennenlernen, nicht einseitig werden, sondern wissen, daß man die Wirklichkeit von den verschiedensten Seiten ansehen muß, um zur vollen Bedeutung dieser Wirklichkeit zu kommen.

Das ist dasjenige, was uns als ein Bestes lehren kann eine Weltanschauung wie diejenige, die als anthroposophische gemeint ist.

Human Beings as Earthly and Heavenly Creatures III

I have often discussed in the course of these lectures how the state of sleep in human beings is not only present during ordinary sleep, but how it also plays a role in conscious everyday life, in such a way that we must also distinguish within conscious everyday life between the complete waking state, which exists only in relation to the life of the imagination, and what we carry within us as the life of feeling. This is not integrated into our waking state in the same sense as the life of imagination, but to the unbiased observer, the life of feeling appears to be the same as the life of dreams, except that the life of dreams proceeds in images and the life of feeling in the way we know it. However, it is very easy to see how, on the one hand, dream life conjures up images of unknown facts, facts unknown to ordinary consciousness, into everyday life in the familiar way, but we can only judge this with our power of imagination. In the same way, we can only judge the scope and meaning of emotional life through this discriminating power of imagination. And what happens during an impulse of the will, during the expression, during the action of an impulse of the will, is just as hidden from ordinary consciousness as what happens to human beings as spiritual beings from the moment they fall asleep until they wake up in a dreamless state of sleep. What actually happens when we perform the simplest act of will, say when we lift our arms or legs through a mere impulse of will, remains as hidden as the processes of sleeping. Only because we see, as it were, the result of the act of will does the act of will enter our ordinary consciousness. After we have formed the thought to lift our arm—which is merely a thought—and after the result has occurred, we see how the arm actually lifts. And we learn about this result of the act of will through our life of imagination. But what actually happens as an act of will remains hidden from ordinary consciousness, so that we must refer to everything that is a volitional impulse as a state of sleep, even in ordinary daily life. And everything that happens as emotional life proceeds like a dream.

Now it is a matter of the fact that this sum of facts, which I have just mentioned in preparation, can indeed be completely understood by ordinary consciousness. If one indicates this in abstracto, it may not appear immediately understandable here and there. But in tracing the facts of consciousness, one will find that what has been said is entirely correct. Now, however, developed consciousness can pursue these facts further, and can pursue in particular how the life of imagination and the life of the will are more precisely structured in the course of human life. We know, of course, that it is possible to ascend from ordinary, objective knowledge to imaginative knowledge through the exercises I have described in various writings. It is only through observation that this imaginative knowledge reveals what is actually true about the human being as a totality. But it will be useful to recall certain facts of ordinary consciousness before I mention what imaginative knowledge has to say about the human being in relation to imagination and will.

Let us consider our actual life of thinking, our life of ideas. You will immediately say to yourselves: this life of ideas is not actually perceived as reality in unbiased experience. Ideas arise in our soul life, and there is no doubt that the inner process of ideas is something added to the external course of a fact. The external course of the fact does not immediately require that it be accompanied by the inner experience of imagining. The same fact that we imagine could also take place without us experiencing it imaginatively. But even immersing ourselves in ideas teaches us how, in our imaginative life, we initially live in something unreal in relation to the external world. In contrast, it is precisely in relation to the life of the will, which for ordinary consciousness seems to take place as if in sleep, that we become aware of our own reality and of our real relationships to the world. By merely imagining, we must increasingly come to realize that ideas live within us like images of objects in a mirror. And just as we do not perceive the images in the mirror as something real in relation to what we usually call the real world, so too, with healthy reason, we cannot perceive ideas as such as something real.But something else prevents us from perceiving ideas as something real. That is our sense of freedom. Just think: by imagining, we would live in our ideas in such a way that these ideas would unfold within us like natural effects. The life of ideas would be something like an external event of nature that unfolds as a necessity. We would be caught up in a chain of necessities. We would only be able to think what is contained in the chain of external natural necessities. We would never be able to experience the feeling of freedom, which is a fact in itself. We can only feel ourselves to be free human beings if what lives in us as free impulses springs from images that stand out from the ordinary chain of necessary natural facts. It is only because we live in our ideas in images that are not integrated into the series of necessary natural phenomena that we can experience the free impulses of the will out of these ideas.

If we consider the life of the imagination in this way, we perceive it everywhere as something unreal. In contrast, the life of the will is what assures us of our reality. What emerges as an act of the will brings about changes in the external world that we must regard as realities. We intervene in the external world through our will. That is why we can only have the feeling that, as beings with a will, we are really present in the external world. If we now proceed from these facts, which are easily ascertainable through ordinary consciousness, to what imagination can tell us, we arrive at the following: It is really the case that when we acquire imaginative knowledge and then try to arrive at a self-knowledge of the human being from this, the human being appears to us, in the light of this imaginative knowledge, in two ways: as a completely different being than he is in ordinary consciousness. To ordinary consciousness, our physical body stands before us as a self-contained, resting entity. We distinguish the individual organs of the physical body, and by looking at these individual organs of the physical body with our ordinary consciousness, we get the impression that we are dealing with separate body parts that we can record, that have fixed contours and are at rest within themselves.

This ceases at the moment when we ascend to imaginative knowledge and then view our bodily life from the standpoint of imaginative knowledge. There is then nothing at rest that we can draw as self-contained figures, unless we want to be schematic (of course, one can draw anything schematically). We cannot show what imaginative knowledge gives us about the lungs, heart, liver, and so on in closed contours, but what imaginative knowledge gives us about the physical body is a continuous movement within itself, an event, not something at rest. It is a process, a becoming. It is a flow that we become aware of when we ascend to imaginative knowledge. Everything is bubbling, I would say, everything is moving inwardly, not only spatially, but also in an intense sense; one thing flows into another. We no longer have organs that are at rest, organs that are closed in on themselves; we have a living becoming, a life and a weaving before us. We can no longer speak of lungs, heart, and liver, but must speak of the lung process, the heart process, the liver process. And again, these individual processes combine to form the overall process of the human being. This is what is unique about the human being: when viewed from the standpoint of imaginative knowledge, he appears as something that is in motion within itself, as something that is constantly becoming at every moment.

But note the significance of this changed view of the human being. When we look at the human body with its firmly contoured limbs and then cast our soul's gaze upon our inner soul life, we never see anything in the soul life that we could record with firm contours. We see in the soul life something that passes in time, that is always becoming and never at rest. The soul life presents itself to us as a process that can only be perceived inwardly, spiritually, and soulfully, but which is nevertheless clearly present. This process of soul life, which is already there for ordinary consciousness in an unbiased introspection of the human being, this becoming of soul life, is very unlike the body life, which is at rest in itself. Certainly, physical life also shows us movement, the movement of breathing, the movement of circulation; but I would say that here we have a transition to the mobile, as the human being presents itself to us before imaginative knowledge. But compared to the fine, subtle movements that reveal themselves to imaginative knowledge from the human physical body, what appears to us as blood circulation, respiratory movement, and other movements in the body is still relatively calm. In short, what we perceive with our ordinary consciousness in objective cognition as the human body is very different from what we perceive as the life of the soul, which is an ever-becoming, self-moving, never resting entity. But when we look at the human body imaginatively, it becomes internally mobile, that is, it becomes more similar to the life of the soul in its appearance. Thus, imaginative knowledge gives us the possibility, I would say, of raising the view of the physical body into the soul. Soul and body come closer together. The body, the physical body, becomes more soul-like for imaginative knowledge.

But I have now actually shown you two things that lie in completely different fields. I have shown you the view that the physical body offers to imaginative knowledge, I have shown you that it is something that is in motion within itself, something that is constantly becoming, and I have then shown you how, even for ordinary consciousness in introspection, the ordinary soul life is such a becoming, a never resting, a passing in time, a life that we cannot grasp in fixed contours and record in such a way.

But when we ascend to imaginative knowledge, this soul life also changes for introspection, and it changes in the opposite direction to physical life. This is indeed remarkable: as we become imbued with imaginative knowledge, we no longer feel this free mobility in our thoughts, this free mobility in the connection between one thought and another. We also feel that as we ascend to imaginative knowledge, our thoughts have something that subjugates our soul life. In ordinary consciousness, we can add one thought to another. We can connect a subject with a predicate with complete inner freedom. We can also refrain from doing so, and we feel free in this connection between one idea and another.

This is not the case when we ascend to imaginative knowledge. There we feel ourselves in the world of thoughts as in something that is unfolding through its own powers. We feel ourselves as if spun into a web of thoughts, so that one thought connects with another not through us but through its own powers. When we ascend to imaginative knowledge, we can no longer say, “I think.” We must begin to say, “It thinks.” And we are caught up in this “it thinks.” We begin to perceive thinking as a real process. We feel it as a real process within us, just as we feel in ordinary everyday life that this pain seizes us and leaves us again, that this pleasure comes and goes again. We feel reality in the world of thoughts when we rise to imaginative knowledge. We feel something in our world of thoughts that becomes similar to the experience we otherwise have with the physical body. From this you can see that through imaginative knowledge, the imaginative life of the soul becomes even more similar to the life of the body than the life of the soul is similar to this life of the body, which is grasped by ordinary consciousness in introspection. In short, for imaginative knowledge, the body becomes very soul-like. The soul, however, becomes body-like, but similar to bodily processes as they reveal themselves to imaginative consciousness as becoming. Thus, for imaginative knowledge, the soul approaches the body, and the body approaches the soul. We see, as it were, the soul-spiritual and the physical interpenetrating each other and becoming similar to each other as we ascend to imaginative knowledge. We are, as it were, seized by a materialism in the experience of the soul, and our view of bodily life, of physical life in general, becomes spiritualized. This is an important fact that emerges for imaginative knowledge.

And when we advance further to inspired knowledge, another secret about the human being is revealed to us. Through inspired knowledge, we subsequently learn even more about thinking and imagining according to their material character. We see through what is actually happening when we think. I said: We emerge from the freedom of thought life. It thinks, and we are entangled in this “it thinks.” Under certain circumstances, these are the same thoughts that we freely connect and separate in ordinary consciousness and that we feel unfolding in imaginative experience as if by inner necessity. From this we see that freedom and necessity do not lie in thought life as such, but in our condition, in our relationship to thought life in ordinary physical consciousness. But we learn to recognize how things actually stand with the experience of the unreality of thoughts that exists in ordinary consciousness. We learn to understand why we experience thoughts as unreal. The following emerges: The organic process that takes place within us proceeds in such a way that our organism appropriates substances and also secretes substances. But it is not only those substances that are secreted from the organic processes of our body that are expelled to the outside by the secretory organs; such substances are also continuously deposited within ourselves. They remain, as it were, along our nerve pathways and in other places in our organism; they are expelled from the life process. We are constantly dealing with the separation of lifeless substances in our life process. Anyone who can follow the human life process closely will be able to perceive that inorganic substances are deposited everywhere in the organism. The coarse masses are excreted, but substances are deposited everywhere in a subtle way. So we can say that the human organism lives in such a way that it first carries within itself the organic process, which I will now sketch schematically with white chalk. But within this organic process we see everywhere inorganic, lifeless substances that are not excreted but are deposited everywhere, which I will now sketch schematically with red chalk. I have drawn the red dots particularly densely at the top because it is mainly these non-excreted lifeless substances that are secreted in the human head, where they remain. Now, the entire human organism is permeated by the I. I draw this I in green chalk in the schematic drawing. Within our organism, the I comes into contact with the lifeless substances that have been excreted. It permeates them. So there is something in our organism that appears to be such that, on the one hand, the ego permeates the organic process, the process within which the substances are contained as living substances, but that the ego also permeates that which is lifeless, I would say mineralized, in our organism. When we think, what happens continuously is that, stimulated by external sensory perceptions or also by memories, the ego, so to speak, takes possession of these lifeless substances and, in accordance with the external sensory stimuli or the stimulation through memories, sets them in motion, draws with them within us, I may even say. For it is not a figurative representation, but corresponds entirely to reality that the I really uses these inorganic substances in the same way as if I were now, comparatively speaking, to powder some chalk here and then take the chalk powder with my finger and draw all kinds of figures with this chalk-covered finger. It is so that the I actually pendulates these lifeless substances, takes possession of them, and draws figures in us, which, however, do not look quite like the figures we usually draw externally. But it is actually drawn and crystallized within us by the I with the help of the lifeless substance, even if not in the crystal forms we find in the mineral kingdom (see diagram, red). What takes place between the I and what has become mineral within us, separating itself as finely solid, mineralized substances, is what underlies our thinking as material. Inspired knowledge thus reveals that the thought process, the process of representation, is actually a treatment of the mineralized in the human organism by the I. This is the more precise description of what I have often characterized abstractly when I said: In thinking, we are constantly dying. That which first dies in us, that which lifts itself out of life, that which mineralizes, is that with which the I draws in us, and with which the I actually draws the sum of our thoughts. It is a working and weaving of the ego in the mineral kingdom, in that mineral kingdom which first becomes within us, which we have as our thinking.

You see, what I am characterizing here is what, I would say, emerged in a mistaken intuition of 19th-century materialism. This materialism, in its best representatives—one of the best representatives of this materialism was Czolbe—came to the intuition that while thoughts flow within us, physical processes take place; but this materialism forgot, and therefore the intuition was mistaken, that it is the purely spiritual ego that draws inwardly with the mineralized in us. Precisely what we recognize as the actual awakening of ordinary consciousness is based on this inward drawing with the mineralized substances in us.

Let us now look at the other side of the human being, the side of the impulses of the will. If you look back at what I have just characterized, you may see in it a capture of the I by the mineralized element within us. Our I is precisely in a position to handle this mineralized element, to draw inwardly. The ego can immerse itself in what is mineralized within us.

If we look at the other side, at those life processes in which the non-mineralized substances are found, those substances that are in the living process, then we come, I would say, to the material aspect of the effects of the will. In sleep, the ego is outside the physical body. In willing, the I is outside certain parts of our organism. This is because at these places, at certain moments in time, nothing mineralizes, but everything is alive. From those parts of our organism where everything is alive, where nothing mineralized detaches or separates at the corresponding moment, the impulses of the will unfold. But there the I is expelled. The ego is drawn into the mineral realm. It can manipulate the mineral realm, but it cannot manipulate that which is alive. It is driven out of the latter, just as during the night, when we sleep, the ego is driven out of the entire physical body. Now, however, the ego is outside the body. Through mineralization, the ego is driven into the body. Through vitalization, the I is driven out of parts of the body. It is then just as outside these parts as it is completely outside the physical body during sleep. And we can therefore say: when the will is active, parts of the I are always outside those places of the physical body to which they are actually assigned. And where then are these parts of the I that are outside the corresponding parts of the physical body? Well, they are outside, in the rest of space. They are integrated into the forces that permeate this space. When we exercise our will, we are outside ourselves with a part of our ego. We integrate forces that are laid through the world. When I move an arm, I do not move it through something that originates inside the organism, but through a force that is outside my arm and into which the I enters by being driven out of certain places in my arm. In willing, I come outside my body, and through forces that lie outside me, I move. You do not lift your leg by means of forces that are inside you, but by means of forces that actually act from outside; the same applies to your arm. So while in thinking you are driven inward by the relationship of the I to the mineralized part of the human organism, in willing you are driven outward, just as in sleep. And no one understands the will who does not conceive of the human being as a cosmic being, who does not go beyond the limits of the human body, who does not know that in the will the human being incorporates forces lying outside his body. We immerse ourselves in the world, we give ourselves to the world by willing. So we can say: The material accompaniment of thinking is a mineral process within us, a drawing of the I into mineralized parts of the human organism. The will within us represents a vitalization, an spreading out of the I, an integration of the I into the spiritual outer world, and an action on the body from the I, from the spiritual outer world.

If we want to schematically draw the relationship between thinking and willing, we must do so in the following way. You see, it is quite possible to make the journey from the introspection of the soul life to the physical correlate of this soul life without being tempted to fall into one-sided materialism. One learns to recognize what happens materially in thinking and willing. But one never loses the I by recognizing how the I becomes active internally with the inorganic in thinking and, on the other hand, by recognizing how the I is driven into the spirit by the organic vitalization in the body. As the ego is driven out of the body, it is brought together with the forces of the cosmos, and from the spiritual part of the cosmos, that is, from outside, the ego unfolds its will.

This justifies materialism on the one hand and overcomes it on the other. It is always amateurish to simply fight against materialism. For what it has to say in a positive sense is entirely justified. It is only wrong when it tries to make itself the whole and only basis of the human worldview. In general, when one follows the world and its events inwardly, one comes to realize more and more that what individual human points of view have to say as positive is justified, and that they become unjustified only when they want to say something negative. And in this respect, spiritualism is often just as one-sided as materialism. Materialism is right in what it has to say that is positive; in what spiritualism has to say that is positive, it is right. Only when both become negative do they fall into error and falsehood. And it is no small error when, in a layman's amateurish way, people who imagine they have attained a spiritual worldview, without understanding anything about material processes, look down on materialism. The material world is permeated by spirit; but one must also get to know it in its material peculiarities, not become one-sided, but know that one must look at reality from the most diverse sides in order to arrive at the full meaning of this reality.

This is what a worldview such as the one referred to as anthroposophical can teach us as the best way forward.