The Human Soul in Relation to World Evolution

GA 212

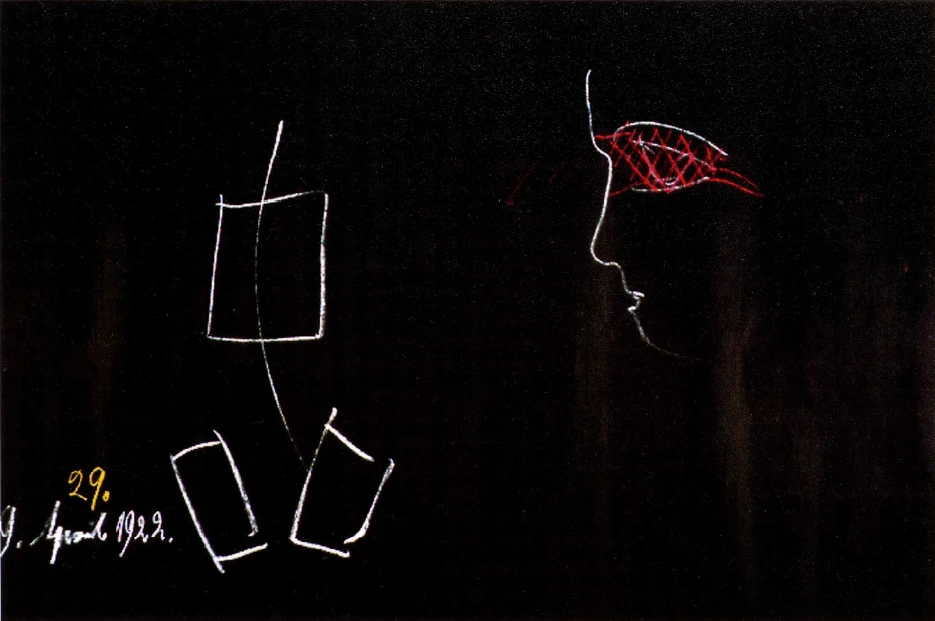

29 April 1922, Dornach

Translated by Rita Stebbing

1. The Human Soul in Relation to World Evolution

[ 1 ] The Human Soul in Relation to World Evolution is the title given to this course of lectures. However, man's experience of his inner life does not at first induce him to ask about its connection with general world evolution—at least not consciously. Yet unconsciously he does continuously ask: How do I as man belong within the evolution of the universe as a whole? It is true to say that, particularly, man's religious life has always arisen as a direct result of this unconscious questioning in the depth of the human soul. The way man through religion feels himself more or less clearly related to something eternal prompts this questioning.

[ 2 ] Man feels self-contained within his soul; he feels himself within his experiences of the external world; i.e., in what remains within him as memory from his impressions. This calls up in him thoughts and feelings concerning the world and its further destiny and so on. When he looks at his life of will and actions he has to admit that from the deepest regions of his inner being, regions of which he has at first no conscious knowledge, there well up impulses of thinking, feeling and willing.

[ 3 ] Man's experience when he begins to observe his inner life, when he engages in what is usually termed introspection, is of his concepts derived from sense perception, of will impulses that come to expression in external action and of memories of past events. He experiences this as something isolated within himself. However, a more penetrating insight into his own being will soon make it clear that this kind of self-observation does not satisfy the deeper needs of man's soul. In the depths of his innermost being he is obliged to ask: What is that in me which belongs to something causative, perhaps to something eternal, and which lies at the heart of all the passing phenomena before me in Nature and in human life?

[ 4 ] There is a tendency in man to seek, at first, the deeper reality of his being in feeling and sensation. This leads him to questions which arise out of his religious or scientific knowledge such as: Where are the roots of my innermost being? Do they stem from an objective reality, a cosmic reality? Is perhaps their origin something which though external is yet akin to my innermost self? Is their nature such that they will satisfy the deepest needs of my soul to have originated from them? A person's inner mood and attitude to life will depend upon whether he is able to find answers of one kind or another to these questions which are fraught with significance for his inner life.

[ 5 ] These introductory remarks are meant to draw attention to the fact that man's soul life harbors a contradiction. This comes to expression, on the one hand, in his feeling of isolation within his thinking, feeling and willing, and, on the other, in that he feels dissatisfied with this situation. The feeling of dissatisfaction is enhanced through the fact that the body is seen to partake of the same destiny as other objects of nature in that it comes into being and again passes away. Furthermore, since to external observation the life of soul appears to dissolve when the life of the body is extinguished, it is not possible to ascertain to what extent, if at all, the soul partakes of something eternal.

[ 6 ] The kind of self-observation possible in ordinary life is not, to begin with, in accord with the soul's deepest needs. When eventually this contradiction, connected as it is with man's whole destiny and with the experiences of his humanity, is felt deeply enough he discovers that the surging, weaving life of soul flows towards two poles. In one direction lies the conceptual life, in the other that of the will impulses. Between thinking and will lies the sphere of feeling. He becomes aware that concepts and ideas formed, let us say, in response to external perception, are accompanied by feelings which bestow on them warmth of soul. In the other direction he becomes aware that his impulses of will are also accompanied by feelings. We determine an action in response to certain feelings. And we accompany the result with feelings of either satisfaction or dissatisfaction. We see, as it were, at one pole the life of ideas, of concepts and mental pictures, at the other the life of will impulses and in between, linking itself to either, the life of feeling.

[ 7 ] When we observe our mental life we have to admit, if we are honest, that in ordinary life it comes about simply in response to our experiences of the external world, that is to say, in answer to the totality of our sense impressions. Indeed in a certain sense we continue our sense experiences in our inner life; we give them a certain coloring so to speak. In fact, we often reproduce them in memory with a quite different coloring from what was originally experienced in direct perception. Nevertheless, provided we do not indulge in dreams but confront our fantasies without illusion, we shall always find our conceptual life prompted by external sense perception. When we withdraw to some extent from external perception and, without falling asleep or arousing will impulses, live in our conceptual life, then all kinds of memories of external observations—often altered perceptions—arise in consciousness. But when we close, so to speak, all our senses and live in concepts only, we are quite aware of the picture character of what we experience. We feel we are dealing with images of whatever the concepts convey. We experience their fleeting nature; they enter our consciousness and again vanish. We cannot directly ascertain if they contain any reality or if they are indeed pictures only. We may assume that they are based on reality, but a reality we cannot take hold of because concepts are experienced as pictures.

[ 8 ] Our experience of will is radically different. Ordinary consciousness cannot penetrate the will. Our consciousness can take hold of a thought or an indefinite instinctive impulse to do something, say raise our arm. The arm movement follows immediately and we see it. Two mental pictures are involved in this process, first the picture of deciding to raise the arm, then the picture of the arm raised. Of that which takes place in the will between the two concepts we have at first no consciousness at all. We are as unconscious of what takes place in our will as we are of everything in the state of sleep. As regards the will we are asleep even when awake. Our will as such escapes our consciousness when we carry out an action, whereas in regard to our concepts, while we do not know how they are related to reality, we do grasp them in lucid clarity in our ordinary consciousness.

[ 9 ] However, we do know something about the will. When will is real and not mere wish it becomes action. It expresses itself emphatically as reality. We have a concept—i.e., a picture: I will raise my arm. Ordinary consciousness knows nothing of what happens next, but the arm is raised. A concrete process is taking place in the external world. What lives in the will becomes external reality just as processes of nature are external reality.

[ 10 ] Concepts and ideas have a picture quality. To begin with we do not know what the relationship is between the reality and that which mental pictures express. As regards will we know quite concretely that it is connected with reality. But unlike mental pictures we cannot survey it clearly.

[ 11 ] In between the two, lie sensation and feeling which color the mental pictures, and color also the will impulses. Our feelings partake of the lucid clarity of mental pictures on the one hand and on the other of the darkness and unconsciousness of will impulses. We see, let us say, a rose; we form a mental picture of it and turn our gaze away. We retain the rose as a memory picture. Since we, as human beings, are not quite indifferent to things we feel delight in the rose; it gives us pleasure. We feel an inner satisfaction in the existence of the rose. However, to begin with we cannot say how these feelings of pleasure and satisfaction arise within us. Exactly how they come about remains obscure to ordinary consciousness. But that they are connected with the mental picture is completely clear. The feeling tinges, colors, as it were, the mental picture. When we have a clear mental picture of the rose we also have a clear mental picture of what pleases us. The clarity of our mental pictures communicates itself to our feeling.

[ 12 ] By contrast, an impulse of will to some action wells up from the depth of our inner being. That this is so needs only to be tested. We often find ourselves impelled by instinct to an action. Our mental picture of a deed may tell us that it ought not to be done at all. We are dissatisfied with what we are doing. Yet when we look back at our inner life we find that a definite feeling was the cause of action, a feeling of which we may disapprove, but whose origin remains in the dark unconscious depth of our inner life. Thus, our feelings participate very differently in the bright clarity of our mental life from the way they participate in the dark dullness of the life of will.

[ 13 ] Therefore, our soul life appears threefold: as thinking—i.e., forming concepts and mental pictures—as feeling and as will. The two opposite poles, thinking and will, are completely different in character.

[ 14 ] Our mental life refers us in the first instance to the sense world. However, we take in not merely simple perceptions such as, let us say, red, blue, C sharp, G major, warmth, cold, pleasant or unpleasant smells, sweet, sour and so on. These can be directly ascribed to the sense world and so can a continuous stream of such sensations. But we also take in more complex external events. Let us say we have before us a human being; countless sense impressions stream towards us—the expression on his face, his walk, his gestures and many others. We could name a host of individual sensations. However, they all combine to form a unity which we experience as the person we see. It can be said that through our sense perceptions we experience the world.

[ 15 ] In the narrower sense it is only the actual sense perceptions themselves that are directly connected with us. Our soul life is in touch most of all with single perceptions like red, blue, C sharp, G major, warmth, cold, etc. Yet even our more complex experiences are in the last resort arrived at through sense perception. We mentioned the example of meeting another human being; we could also think of an occurrence, in which we are not directly involved, meeting us as an external objective event. In the case of the red of the rose we know we are directly involved since we expose our eye to it. We could take a more complex example. Let us say we saw a mother giving her little son a rose. Here the event takes place apart from us, we are not so closely connected with it. We are even less in direct contact when we remember some complex event, where perhaps sense perception had no direct contact with the external object. We remember perhaps what we know about the Rose of Schiras,1Shiraz: Town in southern Iran known for its roses. which we have not seen but learned about some other way. We may have read about it, in which case our sense perceptions were those of printers' ink in the form of letters on paper; or someone told us about it. All such sense impressions point to something completely separate from us. In this way we can discover the difference between sense perceptions that are more closely connected with our soul life and those we know of only indirectly.

[ 16 ] Something similar applies to the pole of will. It is an expression of will when I move an arm. What takes place is connected solely with my organism. I am in close touch with what results from my will impulse. I am as closely connected with it as I am with direct sense perception. But now consider a situation where my will impulse results not only in a movement of an arm but in my chopping wood; then what happens through my will separates itself from me. It becomes an external event which is just as much a result of my will impulse as are the arm movements, but it detaches itself from me and becomes something objective in the external world. And just think of all the complicated events that can come about through will impulses! When you now examine the matter more closely you will be able to compare what on the one hand enters into us when direct sense perceptions lead us to external events existing apart from us, and what goes out from us in that the will impulses separate themselves from the results they produce solely out of our organism. These then become external processes separated from us. Thus, are we placed within the world through the two poles of our being.

[ 17 ] Contemplation along these lines makes us realize that we are related to the world in two different ways. We have one kind of relationship to objects and processes which enter our consciousness through our senses. They are there apart from us and we become aware of them through sense perception. We are related differently to what comes about through our will impulses. Yet that, too, is something that then exists in the world. They are both external realities. If I imagine myself out of the picture and only look at what is there apart from me, then what is left in the case of sense perceptions is the external reality. In the case of will impulses, if I think myself away and look only at what came into existence through me, then again what is left is an external reality. In both cases I am related to something that exists outside and apart from me. In the outer world, the two merge with one another.

[ 18 ] Let us say I chop wood. First, I see the block of wood before me. Perhaps I see not merely the wood but a complex external occurrence. I see someone bring the wood and place it before me to chop. I make ready to do so. All the time I am guided by sense perceptions. First, I have a piece of wood of a certain size. I then chop it and now it is different. The change has come about through me (see diagram). Sense perceptions merge into one another, so that what occurs through me and what occurs apart from me form a continuous stream of events.

[ 19 ] One must be able to feel how the very riddle of the soul is contained in the simple fact that, on the one hand, we see around us objects and events that are given, complete in themselves, and, on the other, things whose existence is due solely to us. One can say that this simple fact characterizes our soul's relation to its surroundings. Nothing very special has been said by this characterization, but at least a certain aspect of the riddle has been presented.

[ 20 ] Let us now consider the problem from another aspect. We are beings who possess sense organs, through which we gain a certain insight into our surroundings. We also possess limbs that enable us to move about. Basically, all that we accomplish in the world through our will comes about by means of our limbs. Thus, we have on the one hand the senses and on the other our limbs. On the basis of all the facts presented so far, we can say that the nature of our limbs and the nature of our sense organs are also polar opposites. In the case of our sense organs the external world approaches and stops at this boundary, so to speak. The external world as such does not actually enter into us, whereas an external world has its beginning through our limbs as it detaches itself from us and continues its existence apart from us. This suggests that there must be a connection between senses and limbs. The essential nature of man's senses can perhaps best be recognized if we consider the eye. The eye is a comparatively independent organ, set into its bone cavity. Only at the back of the eye do blood veins and nerves continue into the rest of the organism. Apart from this connection the eye is relatively independent.

[ 21 ] A whole series of physical processes take place in the eye, at least processes that can be interpreted as being physical. Speaking symbolically, we could say that light approaches and penetrates the eye and becomes modified to some extent. At present I shall not describe the physical and chemical processes as I wish to speak about soul life, not about physiology. But I want to draw your attention to the fact that the eye has a sort of independent life.

[ 22 ] This independent life can even be compared with what takes place in a purely physical instrument, in a kind of camera obscura, which is a copy of the eye and into which light falls in a similar way. Certain processes occur which are like those in the eye, though admittedly they are not living processes like those in the eye; they do not become sensation or perception. But we can reproduce certain processes which take place in the eye and bring them to manifestation in a physical instrument. So, we see that something akin to a physical process is unconsciously taking place in a comparatively independent organ. What does enter consciousness is the external illumined object, whereas what resembles a physical process takes its course unconsciously in man, independently of him. This is due to the relative independence of man's organ of sight from the rest of his organism. Something similar could be said about the other sense organs, though it is less obvious with them. The eye was chosen because it is the most characteristic.

[ 23 ] Thus, we see that sense perception is a relatively independent process. And when we consider the processes taking place in the eye itself (see diagram) we can actually say that even what is transmitted by nerves and blood is like a continuation of processes taking place in the external world. So much are they alike that we can reproduce them physically as I have indicated. It is as if the external world made inroads into the inner being of man. What takes place outside continues, so to speak, into our physical body; this is one aspect of sense perception. How we unite what thus pours in like a stream from outside with our inner life, we shall speak about in the course of these lectures.

[ 24 ] There is, however, another side to sense perception. Let us continue with the example of the eye. I do not want now to speak about the blind, but to consider lack of sight from a general human viewpoint. We shall later consider all these things more especially from an anthroposophical, spiritual- scientific viewpoint. Let us imagine being robbed of the sense of sight. It is easy to recognize that there would then be a deficiency in our inner life. We should lack all that otherwise flows in through the sense of sight. Imagine what it must be like within the soul when it is so dark because light is unable to enter. Even in ordinary life we know that to be in darkness can cause fear, especially in persons of a certain temperament. People who become blind or are born blind are not really, at least not consciously, in this position, though they do experience something similar to someone who is temporarily in darkness. The fact that vague feelings of fear are connected with the experience of darkness shows that there is a relationship between our state of soul and what streams into us through our eyes. And it is easy to see that the state of soul would in turn affect the bodily constitution.

[ 25 ] Someone who is condemned to a certain melancholy by having to live in darkness through being deprived of light, will transfer the effect of his melancholy to certain finer structures of the eye. We must realize that man would be different if he did not receive into his organism what he does receive through his soul's experience of light. This soul experience of brightness is diffused over our whole inner being. Light permeates us to such a degree that it affects certain vascular reactions and glandular secretions. These would function differently without the refreshing, quickening effect of light weaving through the organism. Darkness, too, affects secretion and circulation but in a different way. In short, we must realize that while we are indebted to the eye for being able to form mental pictures of a certain aspect of the objects and processes in our surrounding, we are also indebted to it for a certain inner condition even of the physical body. In a sense, we are what light makes of us.

[ 26 ] We have seen that the eye is not only a sense organ through which we receive pictures of the external world; we also experience brightness or darkness through it. This causes all kinds of instinctive processes to refresh or oppress our soul life and even our body. How we are depends upon what we experience through the sense of sight.

[ 27 ] Let us now leave the eye and turn our attention to the lungs. The lungs, too, are in connection with the external world. They take oxygen from the external air and modify it. Our life is maintained by the breathing of the lungs. Unless we are an Indian yogi, we do not in normal life notice the function of our lungs. But it affects us differently if the lung has a healthy perception of the air or whether through illness it does not perceive the air in the right way. How we are depends upon how we breathe through our lungs. In ordinary consciousness we are not aware that we perceive through the lungs. But organically we are the way we are through the way our lungs function.

[ 28 ] While the function of the eye—and this can be said about each of the external senses—is perception, it also has another more subtle function. This other function must be brought to consciousness before we can know that through the experience of brightness or darkness something takes place in us which is not so obvious, or radical and pronounced, as the lungs' intake of oxygen. Man is aware of what he owes to the lungs' intake of oxygen because it is a robust and strongly vitalizing process, whereas what he receives through the eye, in addition to actual sight, is a more intimate, more subtle vitalizing process. So we can say: What is strongly pronounced in an organ like the lung is only indicated in a subtle way in the case of a sense organ like the eye.

[ 29 ] In my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment and the second part of Occult Science—An Outline you will find descriptions of exercises that will develop faculties of knowledge which otherwise lie fallow. Such exercises completely transform man's inner being. In the case of the lung the result of this transformation is that it attains a function which is similar to that of the eye, with the result that to higher vision the lung's vitalizing function retreats. Higher insight is less concerned with the effect of the breath on our organism. The lung becomes transformed into an organ of perception, not the physical lung but a finer part, the etheric part of the lung. Through the exercises we transform the finer structure of the lung into something akin to what the eye is without our doing. Nature made our eye into an organ of sight as well as an organ that sustains us. To ordinary consciousness the lung is primarily an organ that sustains. When we attain knowledge of higher worlds we transform the lung into an organ of perception. Its finer, etheric part becomes a higher sense organ.

[ 30 ] When we experience the lung's etheric nature we must describe it as a higher sense organ, for its etheric body perceives; however, inasmuch as it contains the physical lung it is also an organ that sustains and vitalizes. So you see, when we attain knowledge of higher worlds the lung, from being an ordinary non-perceiving bodily organ dedicated to growth and life processes, becomes an organ of perception in a higher sense.

[ 31 ] The same applies to the heart and other organs, the kidneys, the stomach and so on. All man's organs can, through higher development, become organs of perception. This means that they become sense organs in their higher, etheric nature or even in their more spiritual astral nature.

[ 32 ] When we consider our environment in relation to our sense organs we have to say: On the one hand our senses mediate perceptions, on the other they mediate vitality. When we consider our inner organs: lung, heart and so on, we find that these organs primarily sustain and vitalize us. We can, however, develop them through methods described in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment', then they become sense organs. Just as we see through the eyes a certain aspect of the external physical world, its light and color, so do we become aware of certain aspects of the external spiritual world through the etheric organ of the lungs, and another aspect through the etheric organ of the heart. We can transform our whole organism into a sense organism.

[ 33 ] To ordinary consciousness the external world presses in on man only as far as the surface of his senses, where it becomes image. To higher consciousness it presses deeper, only what presses deeper is an external spiritual world. As he attains knowledge of higher worlds, and transforms his inner organs into sense organs, man gradually becomes inwardly as transparent as the eye. The external world permeates him.

[ 34 ] It must be realized that as long as we remain in ordinary consciousness we can only know our senses from their external aspect. But ask yourself if it is possible to acquire insight into the ethnology of all the races on earth if one knows or has heard of only three? It is not possible, for one must be able to compare. Imagine the opportunity we shall have for making comparison—also in regard to the external senses—when we are in a position to examine the nature of the inner organs as sense organs.

[ 35 ] This leads to a quite special kind of knowledge of man. We learn of the possibilities that lie within us, of what we are destined to become. It also poses significant questions: If our lungs can become a sense organ when we take our higher development in hand, then what is the situation, for example, in regard to the eye or some other sense organ? We saw the lung develop from being a vital organ to become a sense organ. Was the eye, perhaps in an earlier evolution of the world, not yet sense organ but only vital organ? Did it at that time sustain the organism in a way similar to that of the lung today? Has the eye in the course of evolution become an organ of perception through a different process from our conscious cultivation of higher cognition?

[ 36 ] We have seen that the possibility to become higher senses lies in our vital organs. We have seen how a sense organ comes into being. We must at least ask the question, if, during evolution, the opening of our present senses came about in a similar way. Should we perhaps trace mankind's evolution back to a time when man had not as yet turned his present senses outwards, to a time when perhaps these senses were inner vital organs and man, as regards his present senses, was blind and deaf? Man's eyes and also his ears must of course have been quite different in form and served different purposes.

[ 37 ] We see how knowledge of man, possible through external means, is supplemented when knowledge of higher worlds is attained.

[ 38 ] Most of you will have heard me describe man's being from many different points of view. Today, by way of introduction, I have indicated certain things from yet another aspect. You will be able to see from this how spiritual science may start investigation from the most varied viewpoints and, by combining the results, arrive at a comprehensive understanding of the being of man.

[ 39 ] It is often imagined that anthroposophical research is a straight continuation of one or two definitions of higher worlds to be found in non-anthroposophical writings. This is not the case; what is gained from one aspect can be illumined and enlarged from other aspects. These will fit together into the totality of a spiritual-scientific truth that carries within it its own proof. This approach is often severely censured because people believe that reality can be investigated from one standpoint only.

[ 40 ] In our materialistic age someone who is accustomed to physical proof may say that Anthroposophy is not built on a firm foundation, whereas science is based on direct observation. That assertion is the equivalent to someone saying that the earth cannot possibly float freely in space—all bodies must rest on something if they are not to fall. Therefore the earth must rest on a mighty cosmic block if it is not to fall down. But the proposition that everything must be supported by the ground holds good only for objects on earth. It no longer holds good for cosmic bodies. It is folly to transfer laws that apply on earth to cosmic bodies and their interrelationships. They mutually support each other and so do anthroposophical truths. They lead us out of our habitual world into other worlds where truths mutually support each other. And, more to the point, truth supports itself.

[ 41 ] This is what I wished to say today as introduction to these lectures. I wanted to show that it is possible, in speaking of the soul, for a spiritual-scientific method of research to take as its starting point considerations that are open to sensible interpretation by ordinary consciousness.

[ 42 ] I could only make a beginning today in describing how higher consciousness sees the lung, for example, on the way to becoming a sense organ. However, we shall continue this line of investigation so that in the coming days we may learn more about the nature of man's life of soul and its relation to world evolution.