The Ear

GA 218

9 December 1922, Stuttgart

Translated by George and Mary Adams

Once before I spoke to you of certain spiritual facts concerning the relation of man to the super-sensible worlds—or, as I might equally well express it, the relation of man's earthly life to his life between death and a new birth. For seen from a human point of view man's life between birth and death—interwoven as it is with the physical world of sense—may be held in the main to represent this physical world itself. While the life of man between death and a new birth, when he is altogether interwoven within the super-sensible or spiritual world, represents—seen from a human standpoint once more—the super-sensible world as such.

Today we will continue this line of thought for certain other facts and conclusions of great importance to human life.

Through anthroposophical Spiritual Science we become aware, above all, that man as he stands before himself in the physical world represents—within this physical world—a true image of the Supersensible. Consider on the other hand a mineral object. We cannot say that, such as it is, it is an immediate image of the Supersensible. As to what the mineral nature is, you may read of this in my Theosophy. Of man, however, we must say that in many respects he cannot be understood at all on the basis of what we see around us in the world of the physical senses. On this basis we can understand why, for example, salt assumes a cubical form. True, these things are not yet entirely clear to science today, but from what is already clear it can be said that a crystal of common salt is intelligible on the foundation of what can be ascertained directly in the realm of the sense-perceptible. A human eye or ear on the other hand are not intelligible on the basis of what the physical senses can perceive. Nor can they arise within this domain. The form of the eye or of the ear—both the inward form and the outer configuration—this is a thing that man brings with him as a plan or tendency through birth. Nor does he even receive it through the forces that work, say, in the process of fertilisation or in the body of the mother.

True, it is customary to force all these things which are not understood under the general title of heredity; but in so doing we do but give ourselves up to an illusion. For the truth is that the inner form of the eye or of the ear is already planned and laid out as it were in advance. It is built up in the Spirit, in the pre-earthly life of man, in communion with higher spiritual Beings, with the sublime Beings of the Hierarchies. To a very large extent, man between death and a new birth builds up his own physical body in a spirit-form—as it were a spiritual seed or germ. This Spirit seed, having contracted it sufficiently (if we may use this image), he then sends down into the line of physical inheritance. The Spiritual is thus filled with physical, sense-perceptible material, and so becomes the physical seed, perceptible within the world of sense. But the whole form—the inner form for instance of an eye, or of an ear—is formed and moulded by the work man does between death and a new birth in co-operation with super-sensible, spiritual Beings. Therefore, we may say: Observe a human eye! We cannot assert that it is intelligible like the salt crystal, on the basis of what we see around us with our senses; nor can we say this of the human ear. Rather must we say: To understand a human eye or human ear we must have recourse to those Mysteries which are only to be discovered in the super-sensible world. We must realise that a human ear, for example, is formed and created out of the super-sensible world; and only after it has thus been formed can it undertake its task as a sense-organ—the task of physically hearing the sounds and notes within the atmosphere, within the sphere of Earth. In these respects, we may truly say, man is an image of processes and realities of Being in the spiritual worlds.

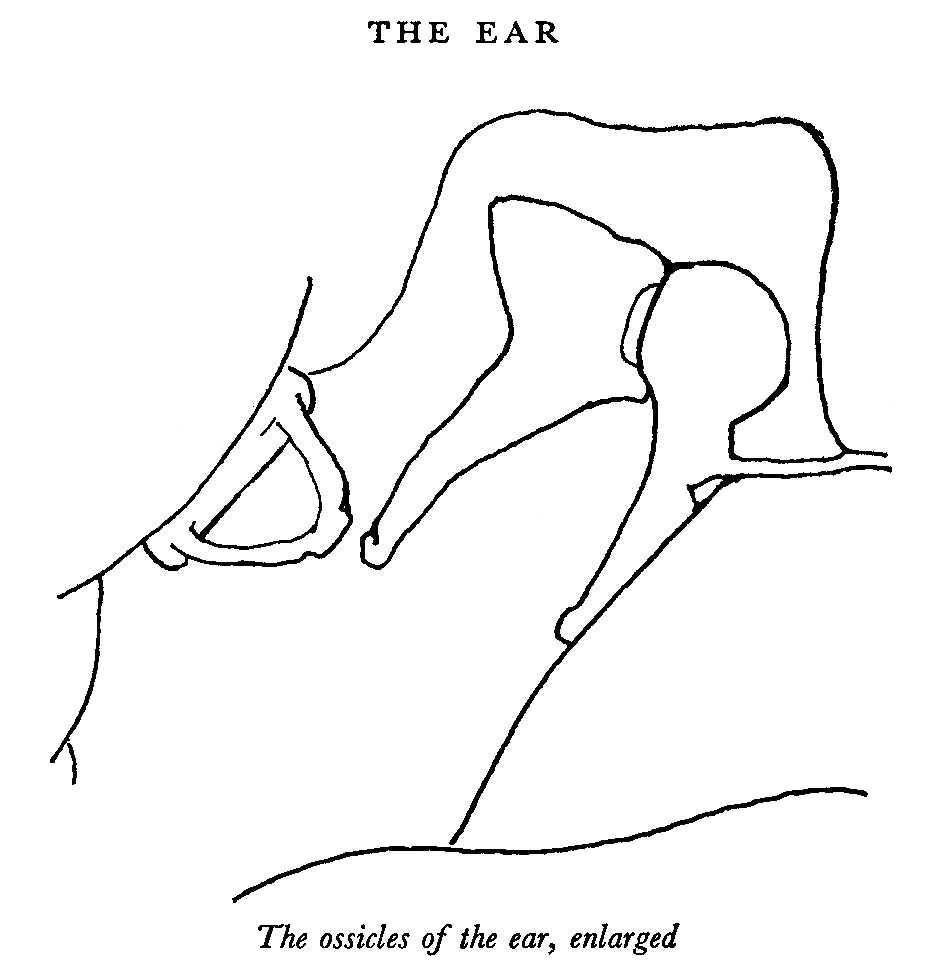

Let us consider such a thing in detail. Observe the inner formation of the human ear. Passing inward through the auditory canal you come to the so-called tympanum or drum. Behind this you find a number of minute bones, or ossicles. External science calls them ‘hammer’, ‘anvil’ and ‘stirrup’ (malleus, incus, stapes). Behind these again, you come to the inner ear, of the configuration of which I shall not speak in detail.

The names of these minute ossicles immediately behind the drum—the names, that is to say, which external science gives them—already show that this science is quite unaware of what they really are. For this is how it appears when illuminated with anthroposophical spiritual science. Passing now from within outward, that which adjoins the inward portion of the inner ear, and which science calls the stapes or stirrup, appears in the light of spiritual science as a metamorphosis of a human thigh-bone with its attachment to the hip. And the little bone which science calls the incus or anvil, appears as a transformed knee-cap. Finally, that which passes from the incus to the tympanum or drum appears as a metamorphosis of the lower part of the leg including the foot. But the ‘foot’ in this case rests not on the earthly ground but on the drum of the ear. Within your ear you actually have a human member—a transformed metamorphosed limb. You might also describe it thus: First, the upper arm (only that in the arm the ‘knee-cap’ is undeveloped, that is to say there is no anvil), and then the lower arm—the other ossicle which rests upon the drum. Just as you touch and feel the ground with your feet, so do you touch and feel the drum of the ear with the foot of this little ossicle. Only the foot with which you walk about is coarsely formed. Coarsely you feel the ground with the sole of your foot, while with this hand or foot which is there within your ear you constantly touch and feel the delicate vibration of the drum.

Let us now go farther back, within the ear. We come to the so-called cochlea or ‘snail-shell’. It is filled with a watery fluid, which is necessary for the act of hearing. What the ‘foot’ touches and feels upon the drum has to be transmitted back to this spiral cochlea, situated within the cavity of the ear. And now once more: Above the thigh we have the inner organs, the abdominal organs. The cochlea within the ear is none other than a beautiful, elaborate metamorphosis of these inner organs. And so you can imagine, there inside the ear there lies a human being, whose head is immersed in your own brain. Indeed, we bear within us a whole number of ‘human beings’, more or less metamorphosed or transformed, and this is one of them.

What does all this signify? If you study the origin and growth of man not only with the crude science of the senses; if you are aware that this human embryo as it develops in the mother's womb is the image of what went before it in the pre-earthly life; then you will also realise the following. In the first stages of development in embryonic life, it is above all the head that is planned and formed. The other organs are comparatively small appendages. Now—if it only depended on the inner potentialities inherent in the germ, within the mother's womb—these appendages, these little stumps which afterwards become the legs and feet, could equally become a kind of ear. They actually have the inner tendency, the potentiality to become an ear. That is to say, man might grow in such a way as to have an ear not only here, and here, but an ear downward too. I admit, this is a strange saying. Nevertheless, it is the truth. Man might become an ear downward too. Why does he not? Because at a certain stage of embryonic development he already comes into the domain of the earthly force of gravity. Gravity which causes the stone to fall to Earth—gravity, implying weight—weighs upon that which tends to become the ear, transforms it and re-shapes it. And so it becomes the lower man in his entirety. Under the influence of earthly gravity, the ‘ear’ which tends to grow downward is changed into the lower man. Why then does not the ear itself change in this way? Why do not its ossicles change into fine small legs right and left? For the simple reason that through the whole position of the human embryo in the mother body, the ear is protected from entering into the domain of gravity, as happens with the little embryonic stumps that afterwards become the legs. The embryonic ear does not enter the domain of gravity. Hence it preserves the plan and tendency which it received in the spiritual world in the pre-earthly life. It is in fact a pure image of the spiritual worlds. Now what is there in the spiritual worlds? I have often spoken of it. The music of the spheres is a reality. As soon as we come into the spiritual world which lies beyond the soul-world, we are in a world which lives altogether in sound and song, in melody and harmony, and harmonies of spoken sound. Out of these inner relationships of sound the human ear is formed. Hence we may say that in our ear we have an actual recollection of our spiritual and pre-earthly existence. In our lower human organisation we have forgotten the pre-earthly life; we have adapted our organism to the earthly force of gravity and to all that comes from the principle of weight. Thus if we rightly understand how the form of man comes into being, we can always tell, of any system of organs, how its configuration reveals either its adaptation to the Earth or its continued adaptation to the pre-earthly life.

And now remember: even after we are born, we still continue what was planned and begun in the embryonic life. To walk upright, to enter fully into the forces of gravity, is a thing we only learn to do after our birth. Only then do we learn to orientate ourselves into the three dimensions of space. But the ear tears itself free from the three dimensions of space and preserves its membership of the spiritual world. We human beings are altogether formed in this way. Partly we are a living monument to what we did in unison with higher Beings between death and a new birth; while on the other hand we also bear witness to the fact that we have incorporated ourselves into this Earth existence, wherein the forces of gravity and weight hold sway.

These transformations, however, not only take their course in the direction I have described, but in the opposite direction too. With your legs you walk about on Earth. And—if you will forgive my saying so—you either walk to good deeds or to bad; to better or to worse. Now as to the movements of your legs, on Earth, to begin with, it is no doubt a matter of indifference whether you walk to good deeds or to bad. But true as it is that the lower man is metamorphosed from the plan of an ear into that form wherewith he stands upon the Earth, it is also true that the moral effects which are brought about by your walking—whether you go out to do good deeds or bad—are all transformed after you pass through the gate of Death—not immediately but after a certain time—transformed into the sounds as of a heavenly speech and music.

Assume for instance that a man went out to do an evil deed. On Earth we can at most describe and register precisely how his legs were moving. But the evil deed clings to the movements of the legs when he passes through the gate of Death. Then, when he has laid aside his physical body and his etheric body, all that lay inherent in these movements of the legs is transformed into a harsh discord in the spiritual world. And the whole of the lower man is now transformed again into a head-organisation. The way you move here upon Earth—taking always the moral colouring, the moral quality of it—this is transformed into a head-system after your death. And with these ears you hear how you behaved morally down in this earthly world. Your morality becomes a beautiful, your immorality an ugly music. And the harmonious and dissonant sounds become the Words, uttered as it were by the Hierarchies, the judges of your deeds, whose Words you hear.

Thus you can see in the form of man himself, how the transformation from the Spiritual world into the world of sense, and from this world back again into the Spiritual, takes place by metamorphosis and metamorphoses again. Your head-system is exhausted in the present earthly incarnation. Here the head-system lives and thrives, in order to perceive the Spiritual within the realms of sense. But after death the head falls away. And the rest of the human being, with the exception of the head, is transformed again after death into a head-organisation in the Spirit, to become an actual head once more in the next earthly life. Thus the fact of repeated earthly lives is expressed in the very form and figure of man. No-one understands the human head, who does not regard it as the transformation of a human body—the body of the last earthly life. No-one understands the present body who does not see in it the germ of a head, for the next earthly life. To understand man fully, all that we perceive about him with our senses needs to be penetrated with ideas about the Supersensible.

We may adduce many another concrete fact in this direction. Last time I spoke to you here, I told you how man between death and a new birth experiences a condition wherein he becomes altogether one in his inner being with the Beings of the Hierarchies. He actually forgets himself, he is the Hierarchies himself. Nor would he ever become aware of himself unless he were able, in turn, to extinguish this feeling of the Hierarchies within him. Then, as it were, he goes out of himself, but it is just in so doing that he finds himself. Here upon Earth we find ourselves by looking away from the outer world and concentrating upon our inner being. Between death and a new birth we find ourselves by looking away from what is within us—that is to say, from the Hierarchies within us. In this way we become aware of ourselves.

Now the forces which remain to us from this ‘becoming aware of ourselves’ are none other than the forces of Memory, while the forces which remain to us from our union with the other Beings—the Beings of the Hierarchies—are the moral forces of Love whereby we on Earth expand our being in love to other beings. Thus in the faculty of Love here upon Earth we have an echo of the living in unison with the Hierarchies. While in Memory we have an echo of that other condition which was ours between death and a new birth, wherein we freed ourselves from the Hierarchies and found ourselves. As I said last time, this is not unlike the breathing process. We have to breathe in to fill ourselves with life. Then in a manner of speaking we breathe out the air of death. For life is impossible in the air which we breathe out. Likewise we breathe, as it were, in the Spirit, in the world between death and a new birth. We unite ourselves with the Beings of the Hierarchies and go out of them again. Here on this Earth we have a kind of echo of that heavenly breathing. In that we can walk here upon Earth, we adapt ourselves to earthly gravity. It is the principle of weight. I spoke in this connection of a transformed, metamorphosed ear. In like manner—if only we are able to look at it in the right way—we can still feel that we possess in our apparatus of speech and song a metamorphosis of what was planned in the spiritual World through which we passed in the pre-earthly life. It is only here on Earth that we adapt our organs of speech to human speech. In plan and tendency, between death and a new birth we receive unto ourselves the Logos—the Cosmic Word—the Cosmic speech. Out of this Cosmic speech our whole organ of speech and song is formed and created to begin with. Just as we transform this ‘ear’ that reaches downward, into the apparatus of walking and orientation in space, so do we transform the organ of speech and song. But in this case the metamorphosis is not so far-reaching. In the former case there remains behind, in the ear itself, a faithful image of what was formed in the pre-earthly life in spiritual worlds. With the organ of speech there is an intermediate position.

Not until we are here on Earth do we learn to speak. Yet this, in a deeper sense, is an illusion. In truth it is the Cosmic speech which forms our larynx and all our organs of speech and song. We only forget the Cosmic Logos, when we turn toward the Earth and pass through embryonic life. And we refresh once more what was impressed in our unconscious being, when in our early childhood we acquire human speech.

Nevertheless, in this human speech the earthly element is clearly perceptible, side by side with that which is formed out of the Spiritual. We could pronounce no consonants if we could not adapt ourselves to the things of the outer world. In the consonants we always have after-formations, imitations of what the outer world presents to us. Anyone who has a feeling for it will feel the one consonant reminiscent of something hard and angular, the other reminiscent of the quality of velvet. In the consonant we adapt ourselves to the forms and shapes of the outer world. In the vowels we give out our own inner being. He who says Ah, knows that in the Ah he expresses something that lives in his inner soul as a feeling of wonder or astonishment. Likewise in the O there is an inner quality. Every vowel expresses some element of the inner life.

In time to come there will be an interesting branch of knowledge, permeated with spiritual science. It will be found that in languages in which the consonants predominate, human beings can far less be called to account morally, because they are much less responsible for their deeds, than in those languages where vowels predominate. For the vowels are an echo of our living together with the spiritual Hierarchies. This is a thing that we bring with us, we carry it down on to the Earth and it remains with us; it is our own revelation. While in the consonants we adapt ourselves to the outer world. The world of consonants is earthly; and if we could imagine a language containing only consonants, an initiate would say of such a language: ‘It is for the earthly realm; and if you would possess the Heavenly, you must add the vowels to it. But have a care! for you will then become responsible to the Divine. You may not treat it so profanely then, as you can treat the consonants.’

The old Hebrews took this into account. Only the consonants are written out fully, the vowels only indicated. In our language in effect the Heavenly and Earthly sound together. Here once again we see how we have in the middle man something that is ordered as it were in two directions, towards the Heavenly and towards the Earthly. The head is altogether related to the heavenly. The other pole of man is related to the earthly, but strives towards the Heavenly—strives in such a way that it becomes the Heavenly, when man has passed through the gate of death. The middle man, to whom the breathing belongs—and with the breathing the activity of speech and song—brings the Heavenly and the Earthly together. Hence the middle man contains above all the artistic faculty of man, the artistic tendency, which is always to unite the Heavenly with the Earthly.

And so we may say: Regard the growing human being. He is born without orientation in the outer world. He cannot yet walk or stand. True, he has already the potentiality to enter into the ordering of earthly gravity. For he received this tendency already in the embryonic life before his birth, when—apart from the head—gravity took hold of him. An organ like the human eye or ear has in fact been wrested away from the incursions of gravity. The act of orientation in space now finds expression in the little child's learning to walk and to stand upright. We only finish learning this after our birth. For we are born not yet orientated for walking. If we retained the orientation we then have, we should at most perhaps be able to sleep on Earth. For in effect, the little bone in the ear, which represents the foot, is horizontally directed. We might at most be able to sleep, but we could not walk. Similar things would need to be said about the human eye.

This, then, is one thing that we finish learning here on Earth. We adapt to the earthly forces of gravity what we acquired in the pre-earthly life. And when we learn to speak and sing, it is a second act of adaptation: we adapt ourselves to our environment in the surrounding sphere, in the horizon of the Earth. Lastly we learn to think. For we are born in truth unorientated for walking and standing, and we are born speechless, and even thoughtless. It cannot be said that the little baby is already able to think. These three things, we finish learning on the Earth. Nevertheless they are metamorphoses of other faculties which we possessed in the pre-earthly life. For each one of the three is a living monument of what was planned in us in a spiritual form in our pre-earthly life.

Our Memory here on the Earth is the echo of our being-within-ourselves in the Spiritual World. And Love, in all its forms, is the echo of our being-poured-out into the world of the Hierarchies. We have, as we have seen, our bodily faculties: Walking, Speaking, Singing and Thinking (for it is only prejudice to imagine that thought on the earth is a spiritual faculty; our earthly thinking is essentially bound to the physical body, just as our walking is)—these outstanding faculties of the body are transformations, metamorphoses, of the spiritual. Then, in the soul, we have the outstanding faculties of soul: Memory and Love, once more as transformations out of the spiritual. And what have we spiritually on the Earth? It is our faculty of sense-perception. Our seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and so forth: all this is sense-perception; and the organs for this sense-perception, situated as they are at the outer periphery of our organism, are formed and built out of the highest Spiritual regions. Out of the harmony of the Spheres the ear is formed, so much so that it remains protected from the force of gravity. The whole way the ear is placed into this fluid, has the purpose of protecting it from the force of gravity. The ear is situated in the fluid in such a way that gravity cannot come near it. Truly the ear is no earthly citizen; in all its organisation it is a citizen of the Spiritual world. Likewise the eye, and the other sense-organs too. Observe then the body in its Walking, Speaking, Singing, Thinking: we have the transformations of the spiritual from the pre-earthly life. Lastly the senses: they are the transformation of the highest Spiritual from the pre-earthly life.

Here it is that we with our anthroposophical spiritual science take our start on the one hand from Goetheanism, from what was already known to Goethe. We, of course, have to go farther, in a way entirely consistent with Goethe. I have often quoted Goethe's saying that ‘the eye is formed in the Light and for the Light’. Yes, my dear friends, but not in the light or for the light that we see. Consider a human being, a human countenance: the high forehead, the prominent nose, the eyes, the physiognomy. We add to it the living gesture. If we merely registered the spatial forms by some kind of apparatus, we should still have the forms. But when we see a human being, we are not content merely to photograph the spatial forms as with an outward apparatus. We look through the spatial movement of the gestures to the soul that lies behind. Likewise the sunlight: it penetrates towards us. There is the outer sun, the sunlight comes to us. That is only the ‘front’ of it; behind it is the ‘other side’ of the sunlight—the soul, the Spirit of the sunlight, and in this soul and Spirit we ourselves indwell between death and a new birth. There the Light is something altogether different. When you speak of the ‘look’ of a man, you mean the life of soul that comes out to meet you through his eyes; you really mean what lies behind the eye, within the soul. And if I now speak of the Spiritual in the light, I too mean what lies ‘behind’, within the sun. That is the Spirit, the soul of the light. The finished eye sees the ‘front’ of the light, the physical aspect; but the eye itself was formed by the soul and Spirit of the light, by that which lies ‘behind’. Thus having understood Goethe's saying, we should put it thus: ‘The eye which sees the light is formed by the soul and Spirit of the light, ere ever it assumes physical existence here on Earth.’

In the whole human being we see transformed spiritual being, which is to be transformed back again. At death you give your physical sense-organs to the Earth, but that which is living in the physical sense-organs lights up between death and a new birth, and becomes your inner being-together, your communion with the spiritual Being of the Hierarchies. Now we understand how the earthly world of sound is the physical reflection of the heavenly harmony of the Spheres, and how man is a product not of these earthly forces but of heavenly forces, who places himself into the midst of the earthly. Moreover, we see how he places himself into the midst of the earthly. He would become an ear downward; and if he remained in this state he certainly would not walk, but would assume another kind of movement; for he would have to move on the waves of cosmic Harmonies, even as the tiny image, the little bone in the ear, moves on the waves of the drum. With the ear we learn to hear; with the larynx and other organs that lie towards and within the mouth itself, we learn to speak and sing. You hear some word, for instance Baum or Tree. You yourself can speak the word Tree. In your ear, in organs formed and modelled after heavenly activities, as I described just now, there lives what you express in the simple word Tree. Again, you yourself can say the word. What does it signify that you can say the word Tree? By the larynx, by the organs of the mouth, etc., the earthly air is brought into such formations that the word Tree is expressed. There in reality you have a second ear, over against your hearing. And there is yet a third, which is only insufficiently perceived. When you hear the word Tree, you yourself with your etheric body—not with your physical but with your etheric body—speak the word Tree very quietly to yourself; and through the so-called Eustachian tube, which passes from the mouth into the ear, the word Tree sounds forth ethereally, going out to meet the word that comes to you from without; and the two meet, and thus you understand the word. Otherwise you would only hear it and it would be nothing in particular. You understand it by saying back through the Eustachian tube what comes towards you from outside. In that the vibrations from outside meet the vibrations from within, and interpenetrate, the inner man understands what comes to him from without.

You see how wonderfully all things work and weave into one another in the human organism. But that is not all; another thing too is connected with it. Suppose it is your intention to learn about the human being, the organisation of his ear, his eye, his nose and so forth. Good and well! You say to yourself: science has made magnificent advances, and these advances of science—though they are a little expensive nowadays1Through the inflation of the mark.—still, you can buy them if you can obtain the necessary number of marks. You buy a text-book of anatomy or physiology according as you want to learn about the forms or the functions. You go to a University and listen to what is said there about the eye or ear; or you read it for yourself. But I think your heart will still be left cold. Let outer physical science describe the ear to you; your heart is left cold, it is not really interested. The thing is objective enough in that sense! But if I describe it to you as I have done just now, if I show how your understanding of the word Tree comes about; and how the ear is an after-image of Heavenly activities: I should like to know the soul whose life of feeling would not be stirred by this, who would not feel the wonder of it, who would not really feel with such a description. True, the description has been given imperfectly today; it could be given more perfectly. Then it would appear still more strongly. But in very truth, one would have to be inwardly dried up if at such a description one did not feel wonder and reverence for the Universe and for the way in which Man himself is placed out of the spiritual world into the physical. Such is the quality of anthroposophical Spiritual Science. It describes things no less objectively than ordinary science; for nothing at all subjective is mingled with it, when I describe how the ear is formed and shaped out of the Heavenly spheres. And yet the heart, the life of feeling is immediately called into play. The second member of the human life of soul, intimately connected as it is with the wholeness of our humanity, is called into play. Whatever the head acquires through such a science, the heart is immediately taken hold of by it. Thus, anthroposophical science goes to the heart of man. It is not a science of the head, it is a science that goes straight to the heart. It fills not only the head, it fills and fulfils the human being of the blood, the circulation, the heart.

Or again, take in real earnest what I said just now. When we move our legs ... well, you can study the mechanism of the movements in the ordinary way. Take one of these textbooks of Physiology; let the mechanism of the movements of the legs be explained to you. One thing will certainly not be kindled in you—the feeling of responsibility. But when you discover that the good or evil purpose to which your legs are moving rings out towards you after death from the Divine Worlds as harmony or dissonance; that the Divine Words of Judgment on all your actions sound towards you; the moment you discover this, your science is accompanied by a feeling of responsibility, and this will then accompany also the actions of your Will. Not only our life of Feeling but our life of Will is called into play by what we learn—to begin with, for our heads—just as objectively as in outer science. Yet it strikes down into the man of Feeling and into the man of Will. Anthroposophical science speaks to the whole man. Increasingly in modern time we have come to regard that alone as science which speaks only to the head; but speaking only to the head, it leaves the Feeling cold and does not in any way call forth the Will. This is the critical point at which we stand. It follows that the knowledge of super-sensible worlds must be attained by the whole man. Already when we arise to Imaginative cognition we must come to it by inner activity. Ordinary learning is acquired in certain circles (which are indeed well suited to this purpose)—it is acquired by ‘swotting’. Acquired thus, it is incorporated in the memory. But let us suppose that by such exercises as are described in ‘Knowledge of Higher Worlds and its Attainment,’ you reach Imaginative cognition. Or suppose you are so constituted that the world of spiritual concepts is already given to you as a native talent and predisposition of your life, as I described it in my book on ‘Goethe's World-conception.’ (For already then you are in the process of etheric cognition which is at the same time living inner experience.) Then you cannot give yourself thus passively to the world. Spiritual science cannot be ‘swotted’. That, maybe, is a bad joke, but after all, it is they who are only used to ‘swotting’ who chiefly look down on spiritual science. Spiritual science, as you are well aware, must be acquired with inner activity. We ourselves in our inner life must do something for it, we must be inwardly alert and quick. Even then, it will always happen that what we attain at first in spiritual Imagination is quickly lost. It is fleeting, it disappears quickly. It is not easily incorporated in our memory. After three days all that we have attained in this region—that is to say, only by the ordinary effort to bring it to Imagination—is certain to have disappeared. It is for the same reason that the memory in the etheric body after death disappears after three days. For it is the same activity after death, when we remember through the etheric body for about three days. The period varies; you can read about this in my ‘Occult Science,’ but we remember for approximately three days—that is to say, so long as we possess the etheric body. In the same manner he who has reached some discovery by etheric cognition knows that it will have flown away after three days, if he does not make every effort to bring it down into the ordinary concepts.

Formerly I always had recourse to the method of putting down at once, in writing or in little drawings, all that I attained in this way. For the head is called into play. It is not a question of mediumistic writing, nor does one write it down in order afterwards to read it. Indeed in my present way of life that would be immensely difficult. Recently when I was in Berlin I saw again what quantities of notebooks have accumulated there. If I wanted to read anything of it, I should not have it handy when I was in Stuttgart or in Dornach. No, it is not a question of reading it afterwards; the point is only to be engaged in this activity, which is an activity of the head. For then we unite the Imaginative thinking with the ordinary thinking. Then we can remember it, give lectures on it. If we did not make such efforts we could at most talk about it on the very next day. Afterwards it would have disappeared, just as the panorama of our life disappears three days after our death.

You see, therefore, that Imaginative thinking is already related to the whole human being. The whole human being must be living in Imaginative Knowledge. With the higher forms of Knowledge it is still more so. Therefore you need not wonder if the appeal of such knowledge is to the whole man. Then too we feel there is infinitely more in the world than is perceptible to the outer senses. And above all, we feel how it is possible to live in a world in which Space no longer has any meaning. Musical experience is already a foretaste, if I may so describe it, of the Non-spatial. For the spatial is outside of us; it is outwardly existent. But in the inner experience which is realised through music, the spatial element scarcely plays a part. There is at most an echo of it. And in Imaginative cognition, gradually, the spatial ceases altogether. All things become temporal. The temporal signifies the same for the Imaginative realm as the spatial element for the physical. Moreover, this will lead us to yet another thing, namely, that the element of time is really permanent; it is a thing that remains. He who arises to Imaginative knowledge gradually learns to perceive at every point of his past Earth-existence (and this is only the beginning). He may be quite an old man; he now becomes eighteen years old again. He perceives his youth as vividly as he perceived it when he was eighteen years old. Suppose for instance that when you were eighteen years old you lost someone who was very dear to you. Think how vivid the experience was at that time. Think how faint it is in your memory after thirty years. There need not even be a lapse of thirty years; it very soon grows faint, even with those who are most rich in feeling; and in outer earthly life it must be so. But though in the subsequent ‘present’ it fades away, it nevertheless remains, as an essential part of the human being; and we can actually transplant ourselves into it again. Indeed, after our death we are thus transplanted. Then we experience the same thing again with the same intensity. Whatever a man has gone through belongs to him. It remains; it is only for his perception, for his vision, that it is past. Hence, too, it has its real significance.

If you were born at the age of seven—if you lived till your seventh year in some other state of existence, say as an embryo—if you were only born at the age of seven, yet so as to receive your second teeth at once, having had the first already in the former state; then you could never become a religious man or woman. For the predisposition to a religious nature could not work on into an earthly life which had begun in that way. All the religious tendency which you possess—you bear it within you because the first seven years of your life are present in you. You do not perceive them as a living present; nevertheless they are there in you as such. In the first seven years of life we are absolutely devoted to the outer world; truly that is a religious feeling. Only we afterwards transfer it to another realm. In our first seven years we have an impulse of imitation for all things that surround us. Afterwards we have the same sense of devotion to the things of soul and spirit.

And if we were born in the fourteenth year of our life—born in the state of puberty—we should never become moral men and women. For the moral qualities must be acquired by the inner development of the rhythmic life between the seventh and the fourteenth year. Hence we can have so great an influence on the moral education of man, in the first or elementary period of school life.

All this we afterwards bear within us. Indeed we constantly bear everything within us. If you cut your toe, it is far removed from your head, but you still experience through the head the pain you feel there. If today you feel religious, there is active within you what you experienced in soul—only then it was in respect to the outer world—until your seventh year, until the change of teeth. Just as you experience the pain in the toe through the activity of your head, so what you experienced before your seventh year is still active in your fortieth year; it is still there.

There is an important consequence of this. Many people say, Anthroposophical spiritual science is all very well; it teaches us about the spiritual worlds. But why need we know all these things about the experiences between death and a new birth? When we die we shall go into those worlds in any case, we shall discover it all in good time. Why need we make an effort between birth and death? We shall go there, presumably, whatever happens.

It is not really so. For the life of time is a reality. As the spatial is a reality here in the physical, so is the temporal—indeed, even the super-temporal—a reality in the spiritual world. Here on Earth the child-like man is still within you in your later life. When you pass through the gate of death the whole of time is within you in a single moment. It belongs to you, it is part and parcel of you. As a man of the world of space you might say: What need have I of an eye? The light is there around me in any case. The eye is only there to see the light, and I have the light around me anyhow. It would be the same, in another realm, to say ‘Why do we need a Spiritual Science here on Earth? When we enter the realm of Spirits the spiritual light will be around us anyhow.’ It is no wiser than to say, ‘The light is there in any case. Why should I need an eye?’ For what a man learns through Anthroposophical spiritual science is not lost to him in the spiritual world after death. It is the eye through which he then perceives the spiritual light. And if on Earth—this applies to the present stage of human evolution—he evolves no spiritual science, he has no eye through which he can see the spiritual world, and he is as if he were dazzled by what he experiences.

In ancient times people still had an instinctive clairvoyance as a late flower of their pre-earthly life. But this is past, it has died away. The old instinctive clairvoyance is no longer there. In the intervening stage of human evolution men have had to acquire the feeling of inner freedom. They have now entered once more upon the stage where they need an eye for the spiritual world into which they will enter after death. This eye they will not have if they do not acquire it here on Earth. As the physical eye must be acquired in the pre-earthly life, so must the eye, for the perception of the spiritual world, be acquired here on earth through spiritual science, active spiritual knowledge. I do not mean through clairvoyance—that is an individual affair—but through the understanding, with healthy intelligence, of what is discovered by clairvoyant research. It is simply untrue to say that one must see into the spiritual world oneself in order to believe what the clairvoyants see. It is not so. Use your healthy human understanding, and you will see that the ear is in truth an organ of Heaven. Such a fact can only be found by clairvoyant research. Once found it can be seen and recognised. We need only be prepared to think the thing out, and feel it through and through. It is this recognition by healthy human understanding, of what is given out of the spiritual world—it is not the clairvoyance, but the activity of knowledge—which provides us with spiritual eyes after death. The clairvoyant has to acquire this spiritual eye just the same as other men. For what we gain by Imaginative Cognition, what we perceive in seership, falls away and vanishes after a few days. It only does not do so if we bring it down to the standpoint of ordinary understanding, and in that case we are obliged to understand it in the very same way in which it is understood by those to whom we communicate it. In effect, clairvoyance as such is not the essential task of man on earth. Clairvoyance must only be there in order that the super-sensible truths may be found. But the task of man on earth is to understand the super-sensible truths with ordinary, healthy human understanding.

This is exceedingly important. Yet this is the very thing which many people—including some of the finer spirits—at the present day will not admit. A little while ago, in Berlin, I had been explaining this point in a public lecture. Someone then described it as a special sin to say that the truth of Spiritual Science was to be seen with healthy human understanding. For he declared, quite dogmatically, that the intellect if healthy sees nothing spiritual; and, conversely, an intellect that sees spiritual things cannot be said to be healthy. This objection was actually made. Such a thing is characteristic, for what it amounts to in the long run is that these people are saying to themselves, ‘Anyone who asserts anything spiritual has a diseased mind.’ No further wisdom beyond this is required! But such wisdom, unhappily, is widespread nowadays. You see from this how true it is—what I have always said—that the time has come again when mankind absolutely needs to receive the spiritual, to incarnate the spiritual, and live with it. Hence, my dear friends, we should not only acquire anthroposophical spiritual science theoretically. In all of us who acquire spiritual science, the consciousness should live, that we are the kernel of a humanity which will grow and grow, until it comes about once more that only he who is conscious of his connection with the spiritual is seen as having found his full humanity. Then there will come over mankind a powerful feeling, a feeling that it is above all important to put into effect in education, in teaching. Ordinary head-knowledge is morally neutral. But we find the spiritual sphere, as soon as we reach up to it, permeated everywhere by morality. You need only remember what I said: It is in being together with the higher Hierarchies that we develop Love. Morality on Earth is only an image of the experience in heavenly spheres. And how do we experience that which we call the Good? We experience it thus: Man is in truth not only a physical but a spiritual being. And if he truly lives his way into the spiritual world, he learns to receive—with the Spirit—the Good into himself.

That, too, is the essential thought of the Philosophy of Freedom,—of Spiritual Activity. Man learns to receive, with the Spirit, what is Good. And if he does not receive the Good into himself, he is not a full human being, but stunted and crippled. It is as though both his arms had been shot away. If his arms are taken from him he is physically crippled; if the Good is lacking to him he is crippled in soul and spirit. Transform this thought, with all its influence on will and feeling, into a method of education. Educate in such a way that when the age of puberty arrives—for it must be developed by that time—man has the living feeling: ‘If I am not good, I am not a whole man—I have not the right to call myself a man.’ Then you will have good moral instruction, true moral teaching of mankind, as against which all emphasis on moral preaching and the like is worth nothing.

Educate the human being so that he feels the moral element within him as an essential part of his own human individuality, and feels himself crippled when he lacks it—feels that he is not a full human being when he does not possess it. Then, in time, he will discover the moral life entirely within himself. Well may it be that all your philosophic pedants will call this a dreadful principle—un-German, or what you will. In truth it is the purest product of the German spirit.2To find within oneself the source of moral impulses is of course, as Rudolf Steiner indicated from his Philosophy of Freedom onwards, a general human task. But to those who attacked his ‘ethical individualism’ as un-German, Rudolf Steiner could show that such thoughts had deep roots in German spiritual life—in Schiller, Goethe and Fichte, for example. (Tr.) It is the principle that brings the Spirit as near as possible to Man himself—and not alone to Man in general, but to the single human individual directly, for this is necessary in our time. During the present epoch only the single human being—the individual himself—reaches his full responsibility.

Der Mensch Und Die Übersinnlichen Welten Hören, Sprechen, Singen, Gehen, Denken

Das letzte Mal durfte ich Ihnen sprechen von gewissen spirituellen Tatsachen, die sich auf die Beziehung des Menschen zu übersinnlichen Welten erstreckten. Ich könnte auch ebensogut sagen, auf die Beziehung des menschlichen Erdendaseins zu dem Dasein zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Denn vom menschlichen Gesichtspunkte aus gesehen ist es ja so, daß des Menschen Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod durch sein Verwobensein mit der physisch-sinnlichen Welt, auch im wesentlichen diese physisch-sinnliche Welt darstellt, daß aber das Leben des Menschen zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, weil der Mensch da ganz hineinverwoben ist in die geistige, übersinnliche Welt, vom menschlichen Standpunkte aus gesehen eben die übersinnliche Welt als solche darstellt.

Ich möchte heute für einige andere Tatsachen und für einige wichtige menschliche Folgerungen diese Betrachtung vor Ihnen fortsetzen. Vor allen Dingen kann man sich durch die anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft so recht bewußt werden, wie der Mensch, der vor sich selber in der physischen Welt steht, in dieser physischen Welt ein wirkliches Abbild ist des Übersinnlichen. Wenn wir ein Mineralisches betrachten, so können wir nicht sagen, daß das so, wie es ist, unmittelbar ein Abbild ist des Übersinnlichen. Was es ist, das können Sie ja aus meinem Buche «Theosophie» entnehmen. Beim Menschen aber können wir sagen, daß er in vieler Beziehung gar nicht verstanden werden kann aus demjenigen, was wir in der physisch-sinnlichen Welt um uns herum sehen. Aus demjenigen, was wir in der physisch-sinnlichen Welt sehen, können wir verstehen, warum die Salzgestalt würfelförmig wird. Gewiß, solche Dinge sind heute der Wissenschaft noch nicht ganz durchsichtig, aber aus dem, was schon der Wissenschaft durchsichtig ist, kann man sagen, ein Salzkristall ist zu begreifen aus demjenigen, was unmittelbar im Bereiche des Sinnlich-Wahrnehmbaren erkundet werden kann. Ein menschliches Auge oder ein menschliches Ohr ist nicht zu begreifen aus demjenigen, was in der physisch-sinnlichen Welt mit physischen Sinnen wahrnehmbar ist. Es kann nicht daraus entstehen. Die Form, sowohl die innere Form wie auch die äußere Konfiguration eines Auges oder eines Ohres, sie bringt sich in der Anlage der Mensch durch die Geburt mit, und er erlangt sie auch nicht durch die Kräfte, die, sagen wir, durch die Befruchtung oder im Leibe der Mutter wirken. Man preßt allerdings alles dasjenige, was man in dieser Beziehung nicht versteht, in das Wort «Vererbung» hinein. Aber damit gibt man sich nur einer Illusion hin. Denn die Wahrheit ist doch diese, daß man in der inneren Formung eines Auges oder eines Ohres etwas hat, was veranlagt wird, gewissermaßen voraus im Geiste aufgebaut wird in dem vorirdischen menschlichen Dasein, und zwar in Gemeinschaft mit höheren geistigen Wesenheiten, mit den Wesenheiten der höheren Hierarchien. Der Mensch baut sich eben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt in vieler Beziehung seinen physischen Leib in einer Geistform, in einem Geistkeime auf, und versenkt dann diesen Geistkeim, nachdem er ihn gewissermaßen verkleinert hat, soweit es nötig ist, in die physische Vererbungslinie. Und dadurch füllt sich das Geistige mit physisch-sinnlicher Substanz aus und wird zum sinnlich-physischen Keim. Aber die ganze Form, die innere Form eines Auges, die innere Form eines Ohres, sie sind herausgestaltet aus der Arbeit, die der Mensch vollbringt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt mit übersinnlichen geistigen Wesen zusammen. Und deshalb können wir sagen: Wenn wir ein menschliches Auge betrachten, so dürfen wir nicht behaupten, dieses menschliche Auge sei wie ein Salzkristall begreifbar aus dem, was sinnlich um uns herum wahrgenommen werden kann, oder das Ohr sei begreifbar aus dem, was um uns herum wahrgenommen werden kann -, sondern wir müssen sagen: Wollen wir ein menschliches Auge begreifen, wollen wir ein menschliches Ohr begreifen, dann müssen wir unsere Zuflucht nehmen zu denjenigen Geheimnissen, die wir erkunden können in der übersinnlichen Welt, müssen uns klar sein darüber, daß so ein menschliches Ohr zum Beispiele — bleiben wir bei diesem stehen — aus der übersinnlichen Welt heraus gebildet wird und dann erst, nachdem es gebildet worden ist, seine sinnliche Aufgabe antritt innerhalb der Luftsphäre, überhaupt innerhalb der Erdensphäre, auf physische Weise Töne oder Laute zu hören. Wir können also sagen: in solcher Beziehung ist der Mensch Abbild von Vorgängen und von Wesenhaftem in der übersinnlichen Welt.

Betrachten wir eine solche Sache einmal in ihren Einzelheiten. Wenn Sie das menschliche Ohr in seiner innerlichen Formung ins Auge fassen, so treffen Sie zuerst, wenn Sie durch den äußeren Gehörgang durchsehen, auf das sogenannte Trommelfell. Hinter diesem Trommelfell sitzen kleine, winzig kleine Knöchelchen; die äußere Wissenschaft spricht von Hammer, Amboß, Steigbügel. Man kommt dann weiter hinter diesen Knöchelchen in das innere Ohr hinein. Ich will nicht ausführlich über diese Konfiguration des inneren Ohres sprechen. Aber schon die Bezeichnungen, die diese winzigen Knöchelchen haben, die man gleich hinter dem 'Trommelfell trifft, die Bezeichnungen, die diesen Knöchelchen die äußere Wissenschaft gibt, zeigen, daß eben diese äußere Wissenschaft gar keine Ahnung von dem hat, was da eigentlich vorliegt. Wenn man mit anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft diese Sache zu durchleuchten versteht, dann nimmt sich - ich will jetzt in der Betrachtung von innen nach außen gehen — dasjenige, was zuerst mehr auf dem inneren Teil des inneren Ohres aufsitzt, und was die Wissenschaft Steigbügel nennt, das nimmt sich aus wie ein umgewandelter, metamorphosierter menschlicher Oberschenkel mit seinem Ansatz an der Hüfte. Und dasjenige, was die Wissenschaft Amboß nennt, dieses kleine Knöchelchen, das nimmt sich aus wie eine umgewandelte Kniescheibe, und dasjenige, was von diesem Amboß dann zum 'Trommelfell hingeht, das nimmt sich aus wie ein umgewandelter Unterschenkel mit dem Fuß daran. Und der Fuß stützt sich in diesem Falle beim Ohr eben nicht auf den Erdboden, sondern auf das Trommelfell. Sie haben tatsächlich ein menschliches Glied im Inneren des Ohres, das umgewandelte Gliedmaße ist. Sie können auch sagen: Oberarm -, nur ist beim Arme die Kniescheibe nicht ausgebildet, es fehlt der Amboß; Sie können sagen: Unterarm - anderes kleines Gehörknöchelchen, das dann auf dem Trommelfell aufsitzt. Und ebenso wie Sie mit Ihren beiden Beinen den Erdboden befühlen, so befühlen Sie mit dem Fuß des kleinen Gehörknöchelchens das Trommelfell. Nur ist Ihr Erdenfuß, mit dem Sie herumgehen, grob gebildet. Da fühlen Sie grob den Fußboden mit der Fußsohle, während Sie das feine Erzittern des Trommelfells fortwährend abtasten mit dieser Hand oder mit diesem Fuße, den Sie da drinnen im Ohre haben. Wenn Sie weiter nach hinten gehen, so finden Sie darinnen die sogenannte Ohrschnecke. Diese Ohrschnecke, die ist mit einer Flüssigkeit gefüllt. Das alles ist zum Hören notwendig. Es muß sich das, was der Fuß abtastet am 'Trommelfell, fortsetzen nach dieser im Inneren der Ohrhöhlung liegenden Schnecke. Oberhalb unserer Oberschenkel liegt das Eingeweide. Diese Schnecke im Ohr ist nämlich ein sehr schön ausgebildetes Eingeweide, ein umgewandeltes Eingeweide, so daß Sie eigentlich sich vorstellen können, da drinnen im Ohre liegt in Wirklichkeit ein Mensch. Der Kopf ist in das eigene Gehirn hineingesenkt. Wir tragen überhaupt in uns eine ganze Anzahl von mehr oder weniger metamorphosierten Menschen. Das ist einer, der da drinnen sitzt.

Ja, was liegt denn da eigentlich vor? Sehen Sie, derjenige, der nun nicht mit der bloßen groben sinnlichen Wissenschaft das Werden des Menschen studiert, sondern der weiß, daß dieser Menschenkeim, der sich im Leibe der Mutter ausbildet, eben das Abbild ist desjenigen, was im vorirdischen Leben vorangegangen ist, der weiß auch, daß in den ersten Stadien der Kindeskeimesentwickelung eigentlich im wesentlichen der Kopf veranlagt ist. Das andere sind kleine Ansatzorgane. Die Ansatzorgane, die als Stümpelchen da sind und die dann die menschlichen Beine und Füße werden, die könnten nämlich, wenn es nur auf die inneren Möglichkeiten ankäme, aus dem Keim heraus, der im Mutterleibe ist, ebensogut eine Art Ohr werden. Die haben durchaus die Anlage, ein Ohr zu werden. Das heißt, der Mensch könnte auch so wachsen, daß er nicht ein Ohr nur hier hätte und hier, sondern daß er ein Ohr nach unten hätte. Das ist zwar paradox gesprochen, aber diese Paradoxie ist völlige Wahrheit. Der Mensch könnte auch nach unten ein Ohr werden. Warum wird er denn kein Ohr nach unten? Er wird aus dem Grunde kein Ohr, weil er in einem gewissen Stadium schon seiner Keimesentwickelung in den Bereich der irdischen Schwerkraft kommt. Die Schwerkraft, die einen Stein zur Erde fallen läßt, die das Gewicht bedeutet, diese Schwerkraft lastet an dem, was ein Ohr werden will, gestaltet es um, und es wird der ganze untere Mensch überhaupt daraus. Unter der Wirkung der irdischen Schwerkraft wird das Ohr, das nach unten wachsen will, der untere Mensch. Warum wird denn das Ohr nicht auch so, daß es seine Gehörknöchelchen so zu hübschen Beinchen links und rechts macht? Einfach aus dem Grund, weil durch die ganze Lage des menschlichen Keimes im Mutterleib das Ohr davor geschützt ist, in den Bereich der Schwerkraft so zu kommen, wie die Beinstummeln; es kommt nicht in den Bereich der Schwerkraft. Daher bewahrt das Ohr noch dasjenige weiter fort, was es als Anlage im vorirdischen Dasein in der geistigen Welt erhalten hat; es ist ein reines Abbild dieser geistigen Welten. Was ist denn aber in diesen geistigen Welten? Nun, davon habe ich oftmals gesprochen, die Sphärenmusik ist eine Realität, und sobald wir in die geistige Welt kommen, die hinter der Seelenwelt liegt, sind wir in einer Welt, die überhaupt in Laut und Ton, in Melodie und Harmonie und Lautzusammenklängen lebt. Und aus diesen Laut- und Tonzusammenhängen formt sich das menschliche Ohr heraus. Daher können wir sagen, in unserem Ohre haben wir eine Erinnerung an unser geistiges, vorirdisches Dasein; in unserer unteren menschlichen Organisation haben wir vergessen das vorirdische Dasein und den Organismus angepaßt an die Erdenschwerkraft, an alles dasjenige, was vom Gewicht kommt. So daß, wenn man richtig versteht die Formung des Menschen, die Gestaltung des Menschen, man immer sagen kann, irgendein Organsystem zeigt, daß es angepaßt ist an die Erde, aber ein anderes Organsystem zeigt, daß es noch angepaßt bleibt an das vorirdische Dasein. Denken Sie doch, daß wir ja eigentlich, auch wenn wir schon geboren sind, noch fortsetzen dasjenige, was schon im Keimeszustand veranlagt wird. Aufrecht gehen, uns vollständig einfügen in die Schwerkraft, uns orientieren in den drei Dimensionen des Raumes, das lernen wir erst, wenn wir schon geboren sind. Aber das Ohr reißt sich heraus aus diesen drei Dimensionen des Raumes und behält die Eingliederung, die Anpassung in und an die geistige Welt. Wir sind als Menschen immer so gebildet, daß wir zum Teile eben ein lebendiges Denkmal sind für dasjenige, was wir im Verein mit höheren Wesen zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt gemacht haben, und auf der anderen Seite ein Zeugnis dafür, daß wir uns eingliedern in das Erdendasein, das von der Schwerkraft, von dem Gewichte beherrscht wird.

Aber solche Umgestaltungen, sie sind nicht bloß in der Richtung verlaufend, wie ich eben gesagt habe, sondern auch in umgekehrter Richtung. Mit Ihren Beinen gehen Sie auf der Erde herum. Und Sie gehen — verzeihen Sie — zu guten, besseren und zu schlechteren Taten. Aber schließlich, für die Beinbewegungen bleibt es zunächst auf der Erde neutral, ob man zu guten oder zu bösen Taten geht. Aber ebenso wahr als es ist, daß sich der untere Mensch aus einer Ohranlage umwandelt zu demjenigen, als was er auf der Erde steht mit seinen Beinen, ebenso wahr ist es, daß alles Moralische, was durch das Gehen bewirkt worden ist, ob Sie zu guten oder zu schlechten Taten gegangen sind, sich umwandelt, nachdem der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist — nicht gleich, aber nach einiger Zeit - in Töne und Laute.

Wir nehmen also an, der Mensch sei zu einer schlechten Tat gegangen. Hier ist es höchstens so, daß wir nur verzeichnen können, wie sich die Beine bewegen. Aber den Beinbewegungen haftet die schlechte Tat an, wenn Sie durch die Pforte des Todes schreiten. Da verwandelt sich, nachdem der Mensch den physischen Leib abgelegt hat und nachdem er auch seinen Ätherleib abgelegt hat, alles, was in den Bewegungen der Beine lag, es verwandelt sich in einen Mißton, in eine Dissonanz in der geistigen Welt. Und der ganze untere Mensch verwandelt sich zurück in eine Kopforganisation. Die Art, wie Sie sich hier auf der Erde bewegen, wird, indem wir die moralische Nuancierung nehmen, zur Kopforganisation nach Ihrem Tode. Und Sie hören mit diesen Ohren, wie Sie sich moralisch benommen haben hier in der Erdenwelt. Ihre Moralität wird schöne, Ihre Unmoralität wird häßliche Musik. Und aus den konsonierenden oder dissonierenden Tönen heraus werden die Worte, wie von den höheren Hierarchien als Richtern gesprochen über Ihre Taten, von Ihnen gehört werden.

So können Sie an dem Menschen selber sehen, wie durch Wandlung und Umwandlung der Übergang von der geistigen Welt in die sinnliche und von der sinnlichen wiederum in die geistige Welt stattfindet. Ihre Hauptesorganisation ist erschöpft in der gegenwärtigen Erdeninkarnation. Da ist die Hauptesorganisation dazu gediehen, innerhalb des Sinnlichen das Geistige wahrzunehmen. Aber das Haupt verfällt nach dem Tode. Der andere Mensch außer dem Haupte wandelt sich nach dem Tode wiederum zurück geistig in ein Haupt, in eine Hauptesorganisation, und dieser andere Mensch wird im nächsten Erdenleben wiederum ein Haupt. So drückt sich schon in der menschlichen Gestalt die Tatsache der wiederholten Erdenleben aus. Niemand versteht das Haupt des Menschen, den Kopf, wenn er ihn nicht ansieht als eine Umwandlung eines Leibes aus dem vorhergehenden Erdenleben. Niemand versteht den jetzigen Leib, wenn er in ihm nicht sieht den Keim eines Kopfes im nächsten Erdenleben. Und zum vollständigen Verständnis des Menschen gehört eben die Durchdringung dessen, was wir sinnlich wahrnehmen mit den Anschauungen über das Übersinnliche.

Wir können nach dieser Richtung noch manches andere Konkrete anführen. Ich habe Ihnen das letzte Mal gesagt, als ich hier zu Ihnen sprechen durfte, der Mensch erlebt in der Zeit zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt den Zustand, daß er ganz eins wird in seinem Inneren mit den Wesen der höheren Hierarchien. Da vergißt er sich eigentlich. Er ist die höheren Hierarchien selber. Er würde niemals zu sich kommen, wenn er nicht wiederum auslöschen könnte dieses Fühlen der höheren Hierarchien in sich. Dann geht er gewissermaßen aus sich heraus; aber er kommt gerade dadurch zu sich selber. Hier auf Erden kommen wir zu uns selber, wenn wir von der Außenwelt absehen und uns in unser Inneres konzentrieren. Zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt kommen wir zu uns selber, wenn wir von dem absehen, was in uns ist — nämlich die höheren Hierarchien —, dann kommen wir zu uns selber. Und die Kräfte, die uns bleiben von diesem Zu-uns-selber-Kommen, das sind die Kräfte der Erinnerung, des Gedächtnisses. Die Kräfte, die uns bleiben von dem Verbundensein mit den anderen Wesen der höheren Hierarchien, das sind die moralischen Kräfte, die Kräfte der Liebe, wodurch wir unser eigenes Wesen auf Erden liebend über die anderen Wesen ausdehnen. So daß wir in dem Liebenkönnen hier auf dieser Erde einen Nachklang haben zu dem Leben in Einheit mit den höheren Hierarchien, und in dem Erinnern, in dem Gedächtnisse haben wir einen Nachklang zu dem anderen Zustand, in dem wir auch sind zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, zu dem Uns-Befreien von den höheren Hierarchien und Zu-uns-selber-Kommen.

Nun sehen Sie, ich habe schon letzthin darauf hingedeutet, das ist etwas, was dem Atmungsprozeß ähnlich ist. Wir müssen einatmen, uns beleben; wir atmen sozusagen die Todesluft aus, denn in dem, was ausgeatmet wird, kann ja nicht gelebt werden. So atmen wir gewissermaßen geistig in der Welt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Wir vereinigen uns mit den Wesen der höheren Hierarchien, gehen wieder aus ihnen heraus. Hier auf dieser Erde haben wir einen Nachklang, ich möchte sagen, dieser Himmelsatmung. In dem, daß wir hier auf dieser Erde gehen können, passen wir uns der Schwerkraft der Erde an. Es ist das Gewicht. Umgewandeltes Ohr, habe ich gesagt. In einer ähnlichen Weise verspüren wir auch noch, wenn wir die Sache richtig betrachten können, wie wir in unserem Sprach-, in unserem Gesangsapparat eine Umwandlung desjenigen haben, was veranlagt ist in der geistigen Welt, die wir im vorirdischen Dasein durchmachen. Wir passen hier auf dieser Erde erst unsere Sprachorgane der Menschensprache an. In der Anlage zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt nehmen wir den Logos, das Weltenwort, die Weltensprache in uns auf, und aus dieser Weltensprache ist zunächst auch unser ganzes Sprach- und Gesangsorgan herausgebildet. So wie wir dieses nach unten sich streckende Ohr umwandeln in die Orientierungs- und Gehapparate, aber nicht so stark, wandeln wir auch das Sprach- und Gesangsorgan um. Beim Ohr, da bleibt nur ein treues Abbild, möchte ich sagen, desjenigen, was sich in der geistigen Welt im vorirdischen Dasein gebildet hat, beim Sprachorgan liegt die Sache mitten drinnen. Wir lernen ja erst Pech hier auf der Erde. Aber das ist eigentlich nur eine Illusion. In Wahrheit bildet uns die Weltensprache unseren Kehlkopf und unsere ganzen Sprach- und Gesangsorgane. Nur vergessen wir den Weltenlogos, indem wir uns zur Erde neigen und durch das Keimesleben durchgehen. Und das, was sich ins Unbewußte hineingedrängt hat, das frischen wir hier auf, indem wir uns die Menschensprache aneignen.

Aber in dieser Menschensprache, da ist in Wahrheit im Grunde genommen sowohl das Irdische deutlich wahrnehmbar, wie auch dasjenige, was vom Geistigen gebildet ist. Wir könnten keine Konsonanten sprechen, wenn wir nicht uns anpassen könnten an die Dinge der Außenwelt. In den Konsonanten haben wir immer Nachbildungen desjenigen, was die Außenwelt uns darbietet. Derjenige, der dafür ein Gefühl hat, der wird schon fühlen, wie ein Konsonant an etwas Eckiges, der andere an etwas Samtartiges ihn erinnert. Im Konsonanten haben wir etwas, worin wir uns anpassen an die Formen, an die Gestaltungen der Außenwelt. In den Vokalen geben wir unser eigenes Inneres. Wer A sagt, weiß, daß er etwas, was in seiner Seelenverfassung wie Verwunderung, wie Staunen lebt, im A zum Ausdrucke bringt. Im O ist ebenfalls ein Inneres, und jeder Vokal drückt ein Inneres aus.

Sehen Sie, es wird einmal eine von Geisteswissenschaft durchdrungene interessante Wissenschaft geben, die konstatieren wird, daß in Sprachen, in denen die Konsonanten vorwiegen, viel weniger die Menschen moralisch angeklagt werden können, weil sie viel weniger verantwortlich sind für ihre Taten als in solchen Sprachen, wo die Vokale vorwiegen. Denn die Vokale sind der Nachklang an unser Zusammenleben mit den geistigen Hierarchien. Das bringen wir mit, das tragen wir hier auf die Erde herein. Und es bleibt in uns. Es ist unsere eigene Offenbarung. In den Konsonanten passen wir uns an die äußere Welt an. Die ist irdisch, die Konsonantenwelt. Und würden wir uns eine Sprache denken können, die nur Konsonanten hat, so würde diese Sprache eine solche sein, von der etwa ein Eingeweihter sagen würde: Sie ist für das Irdische; willst du das Himmlische haben, dann mußt du die Vokale dazunehmen. Aber da gib acht, denn da wirst du dem Göttlichen gegenüber verantwortlich, das darfst du nicht so profan behandeln wie die Konsonanten.

Das haben ja die alten Hebräer getan. Da haben Sie ja die Vokale nur angedeutet, die Konsonanten bloß geschrieben. Kurz, in unserer Sprache klingt zusammen das Himmlische und das Irdische, Und wiederum sehen wir, wie wir etwas, das dem mittleren Menschen angehört, haben, was gleichsam nach zwei Seiten hingeordnet ist: nach dem Himmlischen und nach dem Irdischen. Der Kopf ist ganz nach dem Himmlischen hingeordnet, der andere Mensch nach dem Irdischen, strebt aber nach dem Himmlischen hin, strebt dahin so, daß er es wird, wenn er durch die Pforte des Todes getreten ist. Der mittlere Mensch, dem die Atmung angehört, und der Atmung eingegliedert Gesang und Sprache, verbindet das Himmlische mit dem Irdischen. Daher ist dieser mittlere Mensch in jeder Beziehung vorzugsweise die künstlerische Veranlagung des Menschen, die immer das Himmlische mit dem Irdischen verbindet. So können wir auch sagen: Nun ja, wenn wir den werdenden Menschen betrachten, er wird geboren ohne Orientierung in der Welt, er kann noch nicht gehen, nicht stehen. Er hat zwar schon die Anlage, sich der Schwerkraft einzuordnen; das hat er schon vor der Geburt bekommen, indem die Schwerkraft sich seiner bemächtigt hat außerhalb des Kopfes. So etwas wie das Ohr und das Auge sind der Schwerkraft entrungen gewesen. Wir haben die Orientierung im Raume sich ausdrückend in dem Lernen des aufrechten Gehens und Stehens. Wir lernen das erst fertig, wenn wir schon geboren sind. Aus der geistigen Welt werden wir noch nicht so gestaltet, daß wir die Orientierung im Raume vollständig haben. Wenn wir so orientiert wären, könnten wir auf der Erde vielleicht schlafen, denn schließlich das Gehörknöchelchen, das den Fuß darstellt, das ist horizontal gerichtet. Wir könnten allenfalls schlafen, aber wir könnten nicht gehen. Ähnliches müssen wir vom Auge sagen. Also das eine, was wir fertiglernen hier auf der Erde, das ist die Anpassung unseres vorirdisch Erworbenen an die Schwerkraft der Erde. Das zweite, indem wir die Sprache und den Gesang lernen, ist die Anpassung an die Umgebung im Umkreis der Erde. Und dann lernen wir noch denken. Denn wir werden tatsächlich unorientiert zum Gehen und Stehen, sprachlos und nun schließlich auch gedankenlos geboren. Denn man kann nicht sagen, die kleinen Kinder können schon denken. Diese drei Dinge lernen wir fertig auf Erden. Aber diese Dinge sind alle drei metamorphosierte andere Fähigkeiten, die wir haben im vorirdischen Dasein. Sie zeigen alle drei, wie sie lebendige Denkmäler sind dessen, was im vorirdischen Dasein veranlagt war auf geistige Weise.

Nun aber, das letzte Mal habe ich Ihnen gezeigt: die Erinnerung ist hier auf der Erde der Nachklang unseres Bei-sich-Seins in der geistigen Welt. Die Liebe in allen Formen ist der Nachklang unseres Ausgegossenseins in die Welt der höheren Hierarchien. Und jetzt haben wir eigentlich schon unsere körperlichen Fähigkeiten, Gehen, Sprechen, Singen und Denken — das ist nur ein Vorurteil, wenn man glaubt, daß das Denken auf der Erde eine geistige Fähigkeit ist, das Erdendenken ist durchaus an den physischen Leib gebunden, ebenso wie das Gehen -, so daß wir die körperlich hervorragendsten Eigenschaften als Umwandlung, als Metamorphose vom Geistigen haben. Seelisch die hervorragendsten seelischen Fähigkeiten, Erinnerung, Liebe, Umwandlung aus dem Geistigen. Und was wir auf der Erde Geistiges haben, was ist denn das? Das ist gerade die sinnliche Wahrnehmung. Daß wir sehen, daß wir hören, daß wir riechen, schmecken und so weiter, das ist gerade die sinnliche Wahrnehmung, und die Organe dieser sinnlichen Wahrnehmung, die auf der äußeren Peripherie unseres Organismus liegen, die werden gerade aus den höchsten geistigen Regionen heraus gebildet. Aus der Sphärenharmonie das Ohr. So stark wird das Ohr aus der Sphärenharmonie heraus gebildet, daß es geschützt bleibt vor der Schwerkraft. Und die ganze Einlagerung des Ohres in dieser Flüssigkeit bezweckt, daß das Ohr geschützt ist gegen die Schwerkraft. Das Ohr ist auch in die Flüssigkeit so hineingelagert, daß die Schwerkraft nicht heran kann; dieses Ohr ist wirklich nicht ein Erdenbürger, dieses Ohr in seiner ganzen Organisation ist ein Bürger der höchsten geistigen Welt. Ebenso das Auge, und ebenso die anderen Sinnesorgane. Sehen wir auf den Körper im Gehen, Sprechen, Singen, Denken, so haben wir da die Umwandlung von Geistigem im vorirdischen Dasein. Sehen wir das Seelische, Erinnerung und Liebe: Umwandlung von Geistigem im vorirdischen Dasein. Sehen wir auf die Sinne: sie sind gerade Umwandlung des höchsten Geistigen im vorirdischen Dasein.

Hier ist es, wo wir mit anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft auf der einen Seite anknüpfen an den Goetheanismus, an dasjenige, was Goethe schon wußte, wo wir aber, ganz im Goetheschen Stile natürlich, weitergehen. Ich habe oftmals den Satz zitiert aus Goethe: Das Auge wird «am Lichte fürs Licht» gebildet. — Ja, aber nicht an dem Licht und für das Licht, das wir sehen. Das Licht, das wir sehen, von dem könnte nie ein Auge gebildet werden in seinen inneren Formkräften. Aber nehmen Sie einen Menschen, ein menschliches Antlitz. Nehmen Sie dieses menschliche Antlitz, die erhabene Stirn, die vorspringende Nase, die Augen, die Physiognomie. Wir fügen die Geste hinzu. Würden wir das bloß durch einen Registrierapparat räumlich aufnehmen, bekämen wir allerdings die Formen. Aber wenn wir einen Menschen anschauen, sind wir nicht damit zufrieden, daß wir räumlich die Formen mit einem Registrierapparat aufnehmen könnten, sondern wir schauen durch die räumlichen Bewegungen der Gesten auf das Seelische, das dahinter liegt. Sonnenlicht dringt zu uns. Draußen ist die Sonne, Sonnenlicht kommt zu uns. Das ist die vordere Seite. Die hintere Seite des Sonnenlichtes, der Geist des Sonnenlichtes ist dahinter. Und in dieser Seele und in diesem Geiste sind wir drinnen zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Da ist das Licht etwas anderes. Wenn Sie vom Blick sprechen und Sie meinen das Seelische, das uns durch das Auge entgegenkommt, so meinen Sie eigentlich das, was hinter dem Auge liegt im Seelischen. Wenn ich jetzt von dem Geistigen im Lichte spreche, meine ich auch dasjenige, was in der Sonne dahinter liegt. Das ist der Geist des Lichtes, das ist die Seele des Lichtes. Das Auge, das schon fertig ist, sieht die Vorderseite des Lichtes, das Physische. Aber das Auge wird von dem Geistigen, von dem Seelischen des Lichtes, von dem, was dahinter liegt, gebildet. So müßte man sagen, wenn man den Goetheschen Satz verstanden hat: Das Auge sieht das Licht, wird aber gebildet durch die Seele, durch den Geist des Lichtes, bevor es hier auf dieser Erde physische Wesenheit annimmt.

Im ganzen Menschen sehen wir umgestaltete geistige Wesenheit, die wiederum zurückgestaltet wird. Sie übergeben mit dem Tode der Erde Ihre physischen Sinnesorgane. Aber dasjenige, was in den physischen Sinnesorganen lebt, das leuchtet auf zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt und wird gerade Ihr inneres Zusammensein mit den geistigen Wesenheiten der höheren Hierarchien. Und jetzt begreifen Sie, inwiefern die irdische tönende Welt der physische Abglanz der Himmelssphärenharmonien ist und wie der Mensch nicht ein Ergebnis dieser Erdenkräfte ist, sondern ein Ergebnis der Himmelskräfte und sich in diese Erdenkräfte hineinstellt. Und wir sehen, wie er sich hineinstellt. Er würde Ohr nach unten, und müßte, wenn er in dieser Situation bliebe, jedenfalls nicht gehen, sondern er müßte eine andere Art der Bewegung bekommen, er müßte sich auf den Wellen der Weltenharmonien bewegen, so wie sich im kleinen Nachbilde das Ohrknöchelchen auf den Wellen des Trommelfelles bewegt. Mit dem Ohre lernen wir hören, mit dem Kehlkopf und den Organen, die gegen den Mund zu liegen bis zum Munde hin, lernen wir sprechen und singen.

Sie hören, sagen wir, irgendein Wort: «Baum.» Sie können selbst das Wort «Baum» sprechen, verbinden damit einen Sinn. Was heißt das: Sie hören das Wort «Baum»? Das heißt, es lebt in Ihrem Ohre auf die Art, wie ich es jetzt geschildert habe, in Organen, die himmlischen Tätigkeiten nachgebildet sind, dasjenige, was Sie in dem einfachen Wort «Baum» aussprechen. Sie können das Wort «Baum» sagen. Was bedeutet das, Sie können das Wort «Baum» sagen? Das bedeutet, die irdische Luft wird durch den Kehlkopf und die Werkzeuge Ihres Mundes und so weiter in eine solche Formation gebracht, daß das Wort «Baum» zur Offenbarung kommt. Aber das ist das zweite Ohr gegenüber dem Hören. Das dritte ist aber etwas anderes, das nur nicht genügend wahrgenommen wird. Wenn Sie das Wort «Baum» hören, dann sprechen Sie mit Ihrem ätherischen Leibe leise — nicht mit ihrem physischen Leibe, aber mit ihrem ätherischen Leibe -, leise auch «Baum». Und durch die sogenannte eustachische Trompete, die vom Munde in das Ohr geht, tönt ätherisch das Wort «Baum» dem von außen kommenden Wort «Baum» entgegen. Die zwei begegnen sich und dadurch verstehen Sie das Wort «Baum». Sonst würden Sie das hören, und es wäre irgend etwas. Verstehen tun Ste es dadurch, daß Sie dasjenige, was von außen kommt, durch die eustachische Trompete zurücksagen. Und indem so die Schwingungen von außen sich begegnen mit den Schwingungen von innen und sich ineinanderlegen, versteht der innere Mensch dasjenige, was von außen kommt.

Sie sehen, wie wunderbar die Dinge im menschlichen Organismus ineinandergreifen. Damit ist aber etwas anderes verbunden, und das ist das Folgende. Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie haben die Absicht, den Menschen kennenzulernen in bezug auf seine Ohrenorganisation, Augenorganisation und Nasenorganisation und so weiter. Gut. Sie sagen sich, die Wissenschaft ist großartig vorgeschritten, und diese Fortschritte der Wissenschaft sind ja heute zwar etwas teuer zu erhalten, aber man kann sie immerhin doch erhalten, wenn man sich die nötigen Mark verschafft; man kauft sich eine Physiologie oder Anatomie, je nachdem man eben die Gestalt oder die Funktionen kennenlernen will, oder man läßt sich einschreiben an einer Universität und hört sich an, was da gesagt wird über das Auge, das Ohr, oder man liest es. Sie können ja dabei sehr vieles lernen, aber ich glaube, in einem gewissen Sinne bleibt Ihr Gemüt dabei doch kalt. Es ist schon so, es bleibt das Gemüt kalt. Lassen Sie sich ein Ohr beschreiben von der äußeren Physiologie: Ihr Gemüt bleibt kalt, wird gar nicht engagiert. Die Sache ist in diesem Sinne recht objektiv. Wenn ich Ihnen aber die Sache so beschreibe, wie ich Ihnen jetzt beschrieben habe, wie das Verstehen des Wortes «Baum» zustande kommt, wie das Ohr ein Nachbild ist von himmlischer Tätigkeit, ich möchte einmal diejenige Seele kennenlernen, die dabei nicht in ein Gefühlsleben kommt, die nicht das Wunderbare der Sache empfindet, die nicht auch etwas fühlt bei einer solchen Darstellung. Man müßte ja wirklich innerlich vertrocknet sein, wenn man nicht von einer solchen Darstellung — gewiß, sie ist heute unvollkommen gegeben worden, sie könnte noch vollkommener gegeben werden, da würde das noch stärker hervortreten — zur Bewunderung der Welt und zur Bewunderung des Hereingestelltseins des Menschen aus der geistigen Welt in die physische käme.

Das ist das, was anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft hat. Sie stellt ebenso objektiv dar wie die andere Wissenschaft. Denn da ist gar nichts Subjektives hineingemischt, wenn ich beschreibe, daß das Ohr aus den Himmelssphären heraus gestaltet ist. Aber sogleich wird das Gefühl, das Gemüt engagiert. Das zweite Glied des menschlichen Seelenlebens, das innig zusammenhängt mit dem, wie wir sind als ganze Menschen, wird dabei engagiert. Mit anderen Worten: das, was der Kopf erwirbt durch solche Wissenschaft, davon wird zugleich das Herz engagiert. Dadurch geht anthroposophische Wissenschaft auf das Herz des Menschen, sie ist nicht Kopfwissenschaft, ist Wissenschaft, die zugleich auf das Herz geht; füllt nicht nur den Kopf, sondern füllt den Menschen an, der Blutkreislauf zugleich hat, der Herz hat. Und wiederum, wenn Sie das ernst nehmen, was ich gesagt habe, wenn wir unsere Beine bewegen, nun ja, man kann den Mechanismus der Beinbewegung heute studieren. Aber nehmen Sie sich so ein Physiologiebuch, lassen Sie sich den Mechanismus der Beinbewegung auseinandersetzen, eines wird ganz gewiß bei Ihnen nicht angeregt: das Verantwortlichkeitsgefühl. In dem Augenblick, wo Sie erfahren, daß dasjenige, wozu, zu etwas Gutem oder etwas Schlechtem, die Beine sich bewegen, Ihnen nach dem Tode von Götterwelten entgegenklingt als Konsonanz oder Dissonanz, und die richtenden Worte über Ihre Handlungen Ihnen entgegenklingen, in demselben Augenblicke wird das Wissen von dem Menschen begleitet von dem Verantwortlichkeitsgefühl, das die Willenshandlungen dann begleitet. Und nicht nur unser Gefühlsleben, sondern auch unser Willensleben wird in Anspruch genommen von demjenigen, was wir ebenso objektiv lernen zunächst für den Kopf wie die äußere Wissenschaft. Aber es stößt in den Gefühlsmenschen und in den Willensmenschen hinein. Daher spricht anthroposophische Wissenschaft zu dem ganzen Menschen, während wir immer mehr und mehr dazu gekommen sind, nur dasjenige als Wissen zu betrachten, was nur zum Kopfe spricht. Aber was nur zum Kopfe spricht, läßt das Gemüt kalt und den Willen nimmt es gar nicht in Anspruch.