Man and the World of Stars

GA 219

22 December 1922, Dornach

VII. Inner Processes in the Human Organism. Sense-Perception, Breathing, Sleeping, Waking, Memory

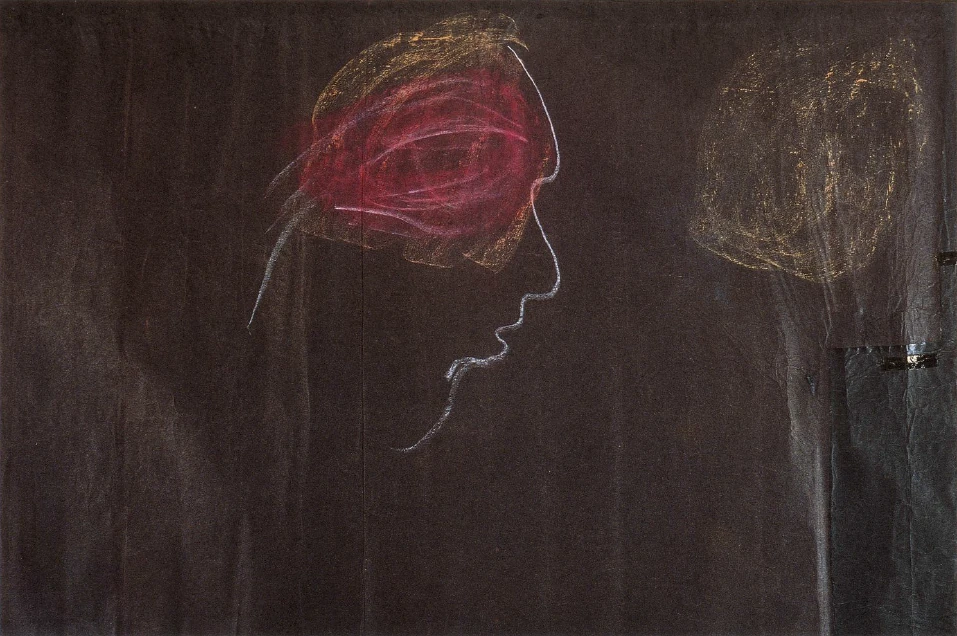

Man perceives the things of the world through his senses but with his ordinary consciousness he does not perceive what takes place within the senses themselves. Were he to do this in everyday life he would not be able to perceive the outer world. The senses must, as it were, renounce themselves if they are to bring to man's cognizance what lies outside the senses in the world immediately surrounding him on Earth. If our ear could speak or our eye could speak, if we could by this means become aware of the processes taking place in those organs, we should not be able to hear what is outwardly audible nor see what is outwardly visible. But it is precisely this that enables man to know the world round about him, in so far as he is an Earth-being; he does not, however, thereby learn to know himself. This presupposes that during the process of acquiring self-knowledge one is able to suspend all cognition of the outer world, so that for a time nothing at all is experienced from the external world.

In Spiritual Science it has always been the endeavor to discover methods through which man may acquire true self-knowledge, and you are aware from the many different lectures I have given, that by this self-knowledge I do not mean the ordinary kind of brooding contemplation of the everyday self; for all that a man experiences thereby is simply a reflex picture of the external world. He learns nothing that is new; he merely gets to know, as it were in a mirror, what he has experienced in the outer physical world. True self-knowledge must, as you know, proceed through methods which silence not only the earthly outer world, but also the everyday soul-content which, as it exists in actual consciousness, is simply a mirror-picture of the outer world. And through the methods described in the book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment, you know that spiritual research advances first to what is called Imaginative Cognition. Whoever advances to this Imaginative Cognition has before him, to begin with, everything from the supersensible world that can clothe itself in the images and pictures of this form of higher knowledge. And when he has acquired the inner faculty of Imaginative vision of the world, he is in a position to follow what takes place in the human sense-organs.

It would not be possible to follow what takes place in the sense-organs if something were to go on there only while the outer world were being perceived through them. When I am seeing an object of the outer world, my eye is still. When I am hearing some sound of the outer world my ear is still. This means that what the ear becomes aware of is not what goes on within the ear itself but what is continuing from the external world into the ear. But if, for example, the ear were only to be active in connection with the external world as long as outer perception were taking place, we should never be able to observe the process that goes on in the ear itself, independently of the outer world. But you all know that a sense-impression has an after-effect in the senses, apart from the fact that the senses always take part even when we are merely thinking actively in our ordinary consciousness.

It is possible to withdraw entirely from the external world in so far as it is a world of color, of sound, of smell, and so forth, and give attention only to what goes on within, or by means of, our sense-organs themselves. When we reach this point we have taken the first step towards acquiring true knowledge of man. To take the simplest example, let us say we want to understand how an impression made upon the eye from outside dies away. A person who has acquired the faculty of Imaginative Cognition is able, because he is perceiving nothing in the external world, to follow this dying away of the sense-impression. That is to say, he is following a process in which the sense-organ as such is involved, although at this moment it is actually not in connection with the external world. Or, let us say, someone can picture vividly to himself something he has seen, realizing how the organ of sight participated in the living thought of the colors, and so on. The same can be done in the case of all the senses. Then such a person actually becomes aware that what takes place within the senses themselves can only be perceived by Imaginative Cognition. A world of Imaginations appears before our soul as if by magic when we live, not in the external world, but in the senses themselves. And then we realize that our senses actually belong to a world other than the one we perceive through them in our Earth-existence. Nobody who is truly in a position, through the acquisition of Imaginative Knowledge, to observe the activity of his own senses, can ever doubt that man, as a being of sense, belongs to the supersensible world.

In the book Occult Science, I have called the world that man learns to know by thus withdrawing his attention from the outer world and living within his own senses, the world of the Angeloi, the Beings who stand one stage higher than man. What is it that actually happens in our senses? We can fathom it if we are able to observe the inner activity of the senses while we are not actually perceiving with them. Just as we can remember an experience that took place years before, although it is no longer present, so, if we are able to observe the senses while they are not engaged in any act of perception, we can acquire knowledge of what happens there. It cannot be called remembrance, for that would convey a fallacious idea; nevertheless, in what we perceive we can at the same time perceive the processes that are engendered in the senses by the outer world through color, sound, smell, taste, touch, and so forth.

In this way we can penetrate into something of which man is otherwise unconscious, namely, the activity of his own senses while the outer world is transmitting its impressions to him. And here we become aware that the breathing process—the inbreathing of the air, the distribution of the air in the human organism, the outbreathing—works in a remarkable way through the whole organism. When we breathe in, the inhaled air passes into the very finest ramifications of the senses, and here the rhythmical breathing comes into contact with what is called in Spiritual Science, the astral body of man. What goes on in the senses depends upon the astral body coming into contact with the rhythmical breathing process. Thus when you hear a tone, it is because in your organ of hearing the astral body can come into contact with the vibrating air. It cannot do this in any other part of the human organism, but only in the senses. The senses are present in man in order that the astral body can contact what arises in the human body through the breath. And this happens not only in the organ of hearing but in every sense-organ; even in the sense of touch or feeling that extends over the whole organism the astral body actually comes in contact with the rhythmical breathing, that is to say, with the action of the air in our organism.

It is precisely when studying these things that we realize how necessary it is to keep in mind that man is not merely a solid structure, but almost 90% a column of water; as the air circulates all the time in the inner processes of his body, he is also an air-organism. And the air-organism, with its weaving life, comes into contact, in the sense-organs, with man's astral body. This takes place in very manifold ways in the sense-organs, but speaking generally it may be said that this meeting is the essential factor in all sensory processes.

To observe how an astral body comes into contact with the air is not possible unless we enter the Imaginative world. With Imaginative Cognition other conditions are perceived in the environment of the Earth where the astral forces come into contact with the air. But within us as human beings, what is of essential importance is that the astral body comes into contact with the breathing process and with what is actually sent by the breathing process through the bodily organism.

Thus we learn to know the weaving activity of the Beings belonging to the hierarchy of the Angeloi. The only true picture we can have of it is that in the unconscious process which takes its course in sense-perception, this world of supersensible Beings is working and weaving, passing in and out, as it were, through the doors of our senses. When we hear and when we see, this is a process that does not take place only through our arbitrary will, but belongs also to the objective world, operating in a sphere where we men are not even present, yet through which we are truly men, men endowed with senses.

You see, when our astral body between waking and falling asleep enters into relation in the sphere of our senses with the air that has now become rhythmical breathing and has therefore changed in character, we learn, so to say, to know the outermost periphery of man. But we learn to know still more of man if we can reach the higher stage of supersensible cognition called Inspiration in the books already mentioned.

At this point we must think of how man is subject to the alternating states of waking and sleeping life. Sense-perception too is subject to alternation. Perceptions would not have the right effect upon our consciousness if we were not able continually to interrupt the process involved. You know from purely external experiences that prolonged surrender to a sense-perception impairs consciousness of it. We must again and again withdraw from a given sense-impression, that is to say, we must alternate between the impression and a condition when we have no impression. For our consciousness to be normal as regards sense-impressions depends upon our being able also to withdraw the senses from the impression that is being made upon them; sense-perception must always be subject to these brief alternating conditions. These alternations also occur in longer periods of our life, for we alternate once in every twenty-four hours between waking and sleeping.

You are aware that when we pass over into the condition of sleep, our astral body and ego leave our physical and etheric bodies. Consequently between going to sleep and waking the astral body enters into relation with the outer world, whereas between waking and going to sleep it is related only to what goes on within the human body. Picture to yourselves these two states, or these two processes: the astral body between waking and going to sleep in connection with what occurs within the human physical and etheric bodies, and the astral body between going to sleep and waking in connection with the outer world, no longer with the physical and etheric bodies of man himself.

The spheres of the senses in us are already almost an outer world—if I may use an expression which, though paradoxical, you will understand. Think, for example, of the human eye. It is like an independent being—naturally I mean this only analogously—but it is truly like an independent being placed there in a cavity in the skull, then continuing further towards the interior with comparative independence. The eye itself, although permeated with life, is remarkably like a physical apparatus. The processes in the eye and the processes in a physical apparatus can be characterized in a remarkably similar way. The soul, it is true, comprises the processes arising in the eye, but, as I have often said, the sense-organs or the spheres of the senses are like gulfs which the outer world extends into us, as it were, and in the spheres of the senses we participate far more in the outer world than we do in the other domains of our organism.

When we turn our attention to some inner organ such as the kidneys, for example, we cannot say that there we share in something external by virtue of experiencing the processes of the organ itself. But in experiencing what goes on in the senses, we experience the outer world at the same time. I beg you to disregard entirely things that may be known to you from treatises on the physiology of the senses and so forth. I am not now referring to any of these things but to the fact that is perfectly accessible to ordinary human understanding, namely, that the process which takes place in the senses can more readily be grasped as something that extends into us from without and in which we participate, than as something we bring about inwardly through our organism. Hence it is also a fact that in the senses our astral body is practically in the outer world. Especially when we have deliberately surrendered ourselves to sense-perceptions of the outer world, our astral body is actually almost entirely submerged in the outer world, though not to the same extent in the case of all the senses. It is completely submerged in the outer world while we sleep. So that from this point of view sleep is a kind of enhancement of surrender of the senses to the outer world. When your eyes are closed, your astral body also withdraws more into the interior of the head; it belongs more to you yourself. When you look out in the normal way, then the astral body draws into the eye and participates in the outer world. If it passes entirely out of your organism, then you go to sleep. Surrender of the senses to the outer world is, in fact, not what is ordinarily supposed, but as regards consciousness is really a stage on the way to going to sleep.

Thus in acts of sense-perception man participates to some extent in the outer world; in sleep he participates in it fully. With Inspiration (knowledge through Inspiration) he can become aware of what is going on in the world in which he is with his astral body between sleeping and waking.

With Inspired Cognition, however, man can become aware of something else, namely the moment of waking. The moment of waking is as it were something that is more intense, more vivid, but may nevertheless be compared with closing the eyes.

When I am standing in front of a color, I surrender my astral body to that in the eye which, as I said, is nearly outside, namely, the process occasioned by a color from the external world making an impression upon my eye. When I close my eyes I draw my astral body back into myself; when I wake, I draw my astral body back from the outer world, from the Cosmos. Often, infinitely often during the waking life of day, in connection with the eyes or the ears, for example, I do the same with my astral body as I do on waking, only then my whole organism is involved as a totality. On waking I draw back my whole astral body. Naturally, this process of drawing back the astral body on waking remains unconscious in the ordinary way, just as the sense-process itself remains unconscious. But if this moment of waking becomes a conscious experience for one who has reached the stage of Inspiration, it is at once evident that this entrance of the astral body takes place in a quite different world from that in which we otherwise live; above all it is very often obvious how difficult it is for the astral body to come back again into the physical and etheric bodies. Hindrances are there.

It can truly be said that one who begins to be aware of this process of the return of the astral body into the physical and etheric bodies experiences spiritual storms and percussions. These spiritual storms show that the astral body is diving down into the physical and etheric bodies but these bodies are not like the descriptions given by anatomists and physiologists, for they too belong to a spiritual world. Both the so-called physical body and the somewhat nebulous etheric body are rooted in a spiritual world. In its real nature the physical body reveals itself as something quite different from the material image presented to the eye or to ordinary science.

This descent of the astral body into the physical and etheric bodies can appear in imagery of infinite variety. Let us say a burning piece of wood drops spluttering into water—that is the simplest, the most abstract analogy for the experience that may arise in one who is just beginning to have knowledge of this process. But then it becomes inwardly real in manifold ways, and is afterwards completely spiritualized inasmuch as what at first can only be compared in its appearance to a raging storm becomes permeated subsequently with harmonious movements, giving the impression that something is speaking, is saying or announcing something.

What is thus announced clothes itself to begin with in pictures of reminiscences from ordinary life; but this changes in course of time and we gradually come to experience a world that is also around us but in which our experiences cannot be called reminiscences of ordinary perceptions, because they are of an entirely different character and because they show us in themselves that this is a different world. It can be perceived that man with his astral body passes out of his environment into the physical and etheric bodies by way of the whole breathing process. The astral body that is active in the senses contacts the delicate ramifications of the breathing process and penetrates into the subtle rhythms in which the breathing process reaches into the sphere of the senses. At the moment of waking the astral body leaves the outer world, enters into the physical and etheric bodies and seizes hold of the breathing process which has been left to itself during the period of sleep. Along the paths of the breathing processes, of the moving breath, the astral body enters into the physical and etheric bodies and spreads out as does the breath itself.

At the moment of waking, ordinary consciousness swiftly obtrudes itself into the perception of the outer world, and quickly unites experience of the breathing process with experience of the organism as a whole. Consciousness at the stage of Inspiration can separate this flow of the astral body along the paths of the breathing rhythm and become aware of the rest of the organic process—although naturally the latter does not take its course on its own. Not only at this moment of waking, but at every moment the movement of the breath in the human organism is of course connected inwardly with the other processes in the organism. But in the higher consciousness of Inspiration the two can be separated. We follow how the astral body, moving along the paths of the rhythmical breathing, enters into the physical body, and then we learn to know something that otherwise remains completely unconscious.

After having experienced all the states of consciousness which accompany this entrance of the astral body and are objective—not subjective—states of feeling, the knowledge comes to us that man, inasmuch as he is not merely a being of sense but also a being of breath, has his roots in the world I have called in Occult Science the world of the Archangeloi. Just as the Beings of the supersensible world standing one stage above man are active in his sense-processes, so are the Beings of the spiritual world standing two stages above him active in his breathing process. They pass in and out, as it were, as he goes to sleep and wakes.

Something of great significance for human life presents itself to us when we observe these processes. If our waking life was not interrupted by sleep, although impressions of the outer world would come to us, these impressions would last only for a short time. We could not develop a lasting power of memory. You know how fleetingly the pictures work in the senses as after-images. Processes activated more deeply in the organism continue to work for a longer time; but the after-effects would not continue for more than a few days if we did not sleep.

What is it that actually goes on in sleep? Here I must remind you of something I said here very recently, describing how during sleep, with his astral body and his ego, man always lives through in backward order what he has experienced in the physical world in the preceding waking period. Let us take a regular waking period and a regular sleeping period—it is however just the same for irregular periods. A man wakes up on a certain morning, busies himself during the day, goes to rest in the evening and sleeps through the night for about a third of the time he has been awake. Between waking and going to sleep he has a series of experiences, daytime experiences. During sleep he actually lives through in backward order what had been experienced during the day. The life of sleep goes backward with greater rapidity, so that only a third of the time is needed.

What has actually happened? If we were to sleep according to the laws of the physical world—I do not now mean the body, for the body sleeps according to those laws as a matter of course—but if in the conditions of existence outside the physical and etheric bodies, in our ego and our astral body, our sleep were governed by the same laws which govern our waking life by day, this movement backwards would not be possible, for we should simply have to go forward with the flow of time. We are subject to altogether different laws when in our astral body and ego we are outside the physical and etheric bodies.

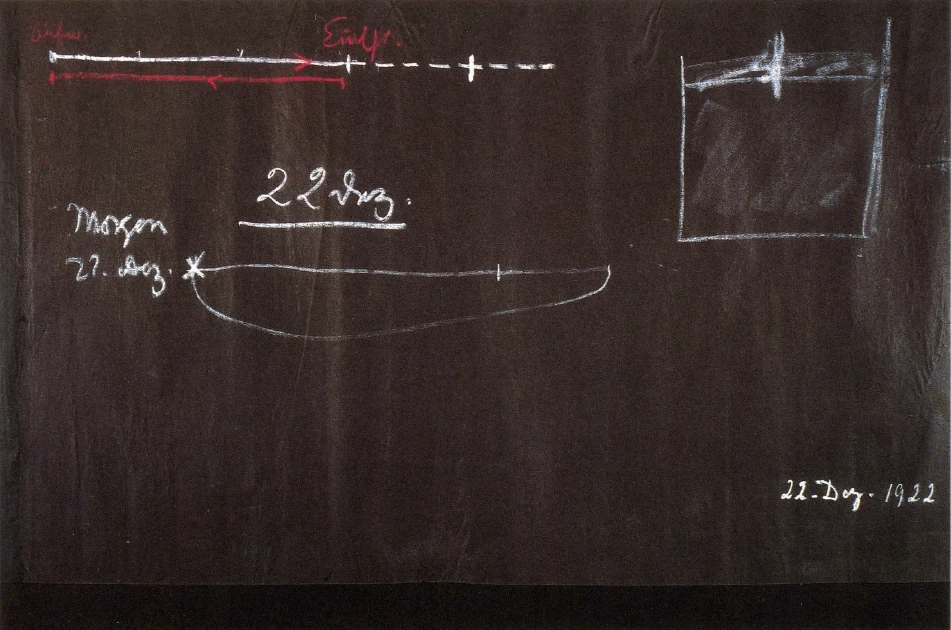

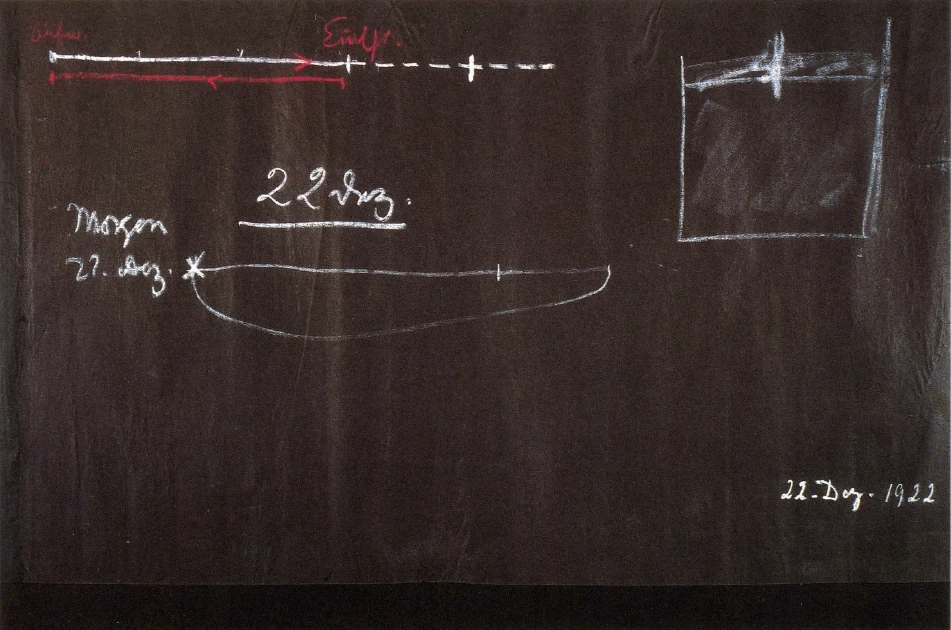

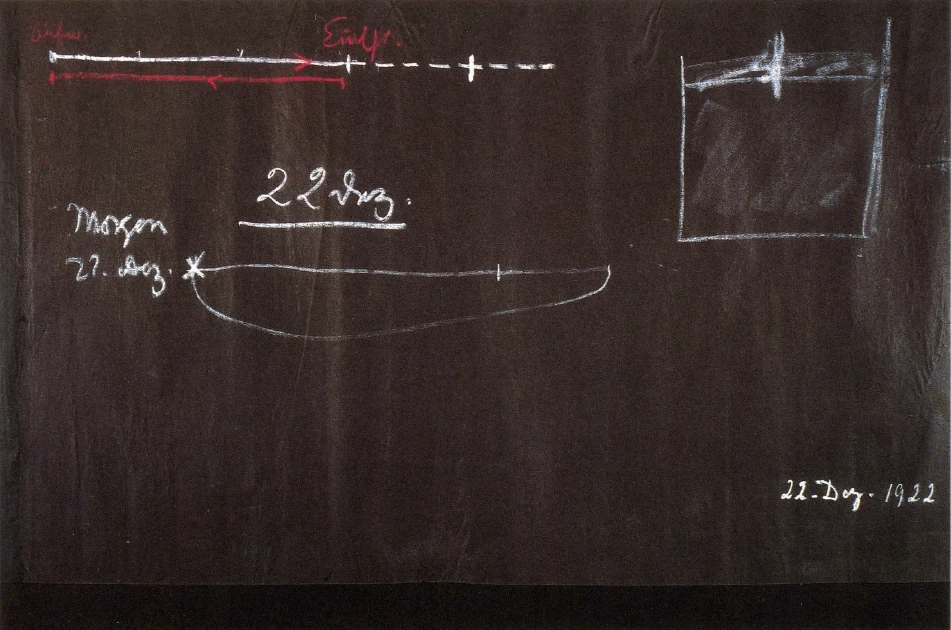

Now think of the following. Today is the 22nd December; this morning was for you, when you woke from sleep, the morning of the 22nd December. Presently you will go to sleep and by the time you wake tomorrow, your experiences in their backward order, will have brought you again to the morning of today, the 22nd December. So you have gone through an inner process in which you have turned back. When you wake tomorrow, the morning of 23rd December, the process will have carried you back to the morning of the 22nd December. You wake up; at the same moment—because now your astral body, contrary to the laws it has been obeying during your sleep, makes the jerk through your body into the ordinary physical world—at the same moment you are compelled in your inmost soul-life to go forward quickly with your ego and astral body to the morning of the 23rd December. You actually pass through this process inwardly.

I want you to grasp in its full significance what I am now going to say. If you have some kind of gas in a closed vessel, you can compress this gas so that it becomes denser. That is a process in Space. But it can be compared—naturally only compared—with what I have just been describing to you. You go back in your astral body and your ego to the morning of December 22nd, and then, when you next wake, you jerk quickly forward to the morning of December 23rd. You impel your soul forward in Time. And through this process your soul-being, your astral body, becomes so condensed within Time, that it carries the impressions of the outer world not only for a short period, but as enduring memory. Just as any gas that is condensed exercises a stronger pressure, has more inner power, so does your astral body acquire the strong power of remembrance, of memory, through this inner condensation in Time.

This gives us an idea of something that otherwise always escapes our consciousness. We are apt to conceive that Time flows on evenly, and that everything taking place in Time also flows on evenly with it. As regards Space we know that whatever is extended in Space can be condensed; its inner power of expansion increases. But what lives in Time, the element of soul, can be condensed too—I am speaking figuratively, of course—and then its inner power increases. And for man, one of these powers is the power of memory.

We actually owe this power of remembrance, of memory, to what happens during our sleep. From the time of going to sleep until waking we are in the world of the Archangeloi, and together with the Beings of that hierarchy we cultivate this power of memory. Just as we cultivate the power of sense-perception and the combining of sense-perceptions together with the Beings of the hierarchy of the Angeloi, so do we cultivate this power of memory, which is a more in ward power, more connected with the centre of our being, in communion with the world of the Archangeloi.

True knowledge of man does not exist in a nebulous, mystic form of brooding introspection; true knowledge of man, with every further step that is taken into the inner life, leads at the same time into higher worlds. We have spoken today of two such steps. If we contemplate the sphere of the senses we are in the sphere of the Angeloi; if we contemplate the sphere of memory, we are in the sphere of the Archangloi. Self-knowledge is at the same time knowledge of the Gods, knowledge of Spirit, because every step that leads into man's inner being leads ipso facto into the spiritual world. And the deeper the penetration within, the higher—to use a paradox—is the ascent into the world of spiritual Beings. Self-knowledge, if it is earnest, is true World-knowledge, namely, knowledge of the spiritual content of the World.

From what has been said you can understand why in ancient times, when certain oriental peoples were striving to acquire an instinctive kind of spiritual vision, the aim was to make the breathing process into a conscious process by means of special breathing exercises. In point of fact, as soon as the breathing process becomes a conscious process, we enter into a spiritual world.

I need not say again today that those ancient practices should not be repeated by modern man with his different constitution, but should be replaced by others which are set forth in the books mentioned. It can however be said with truth in the case of both kinds of knowledge, the knowledge based upon the old, mystical clairvoyance and the knowledge yielded by the exact clairvoyance proper to the modern age, that genuine observation of the processes which take place inwardly in man leads at the same time into the spiritual world.

There are people who say: All this is unspiritual, for the aim is to investigate the senses, the breathing. They call it materialistic self-knowledge in comparison with nebulous mystical experience. But let them try to practice it for once! They will soon discover that genuine knowledge of the sense-process reveals it to be a spiritual process and that to regard it as a material process is sheer illusion. And the same applies to the breathing process. The breathing process is a material process only when seen externally. Seen from within, it is through and through a spiritual process, actually taking its course in a world far higher than the world we perceive through our senses.

Siebenter Vortrag

Der Mensch nimmt durch seine Sinne die Dinge der Welt wahr, aber er nimmt nicht mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein wahr, was sich innerhalb seiner Sinne selber abspielt. Würde er das im gewöhnlichen Leben tun, so würde er nicht die äußere Welt wahrnehmen können. Die Sinne müssen sozusagen sich selbst verleugnen, wenn sie zur Kenntnis des Menschen bringen wollen, was außerhalb der Sinne in der uns zunächst auf der Erde umgebenden Welt liegt. Redeten gewissermaßen unsere Ohren, redeten unsere Augen, würden wir also die Vorgänge, die sich in unseren Ohren, in unseren Augen abspielen, wahrnehmen, dann würden wir nicht hören können, was äußerlich hörbar ist, wir würden nicht sehen können, was äußerlich sichtbar ist. Aber gerade dadurch lernt der Mensch die Welt um sich her kennen, insofern er zunächst ein Erdenwesen ist, er lernt aber nicht sich selbst kennen. Sich selbst kennenlernen setzt voraus, daß man während dieses Vorganges der Selbsterkenntnis die Erkenntnis der Außenwelt zum Stillstand bringen kann, daß man also von der Außenwelt nichts erfährt.

Es war von jeher das Bestreben innerhalb der geisteswissenschaftlichen Forschung, solche Methoden ausfindig zu machen, durch die der Mensch sich wirklich selbst erkennen kann, und Sie wissen aus den verschiedensten Vorträgen, die ich gehalten habe, daß ich mit dieser Selbsterkenntnis nicht jenes allgemeine Hineinbrüten in das alltägliche Selbst meine, denn dadurch erfährt man doch von nichts anderem als von einer Art Reflexbild der äußeren Welt. Man lernt gewissermaßen nichts Neues kennen. Man lernt nur wie im Spiegel kennen, was man mit der sinnlichen Außenwelt erlebt hat. Wirkliche Selbsterkenntnis muß, wie Sie wissen, nach Methoden sinnen, welche nicht nur die gewöhnliche irdische Außenwelt zum Schweigen bringen, sondern welche auch das gewöhnliche alltägliche seelische Innere — das auch nichts anderes ist, insofern es im wirklichen Bewußtsein vorhanden ist, als ein Spiegelbild der Außenwelt -— zum Schweigen bringen. Und durch diejenigen Methoden, die Sie geschildert finden in meiner Schrift «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», wissen Sie, daß die Geistesforschung zunächst zur sogenannten imaginativen Erkenntnis vorschreitet. Wer zu solcher imaginativen Erkenntnis vorschreitet, hat allerdings zunächst alles das aus der übersinnlichen Welt vor sich, was sich in die Bilder der imaginativen Erkenntnis kleiden kann. Aber wenn er sich die seelische Praxis erworben hat, um überhaupt imaginativ die Welt anschauen zu können, dann ist er in der Lage, gerade dasjenige zu verfolgen, was in den menschlichen Sinnesorganen sich abspielt. Man würde das, was sich in den Sinnesorganen abspielt, nicht verfolgen können, wenn überhaupt nur dann etwas in den Sinnesorganen vorginge, wenn man durch sie die Außenwelt wahrnimmt.

Sehe ich einen Gegenstand der Außenwelt, so schweigt mein Auge. Höre ich irgendeinen Tonzusammenhang der Außenwelt, so schweigt mein Ohr; das heißt, es wird durch das Ohr nicht der Vorgang im Innern des Ohres wahrgenommen, sondern es wird das wahrgenommen, was von der Außenwelt sich in das Ohr hinein fortsetzt. Aber wenn zum Beispiel das Ohr nur eine Tätigkeit mit Bezug auf die Außenwelt ausführen würde, solange diese äußere Wahrnelimung da ist, so würden wir niemals dazu kommen, den Vorgang, der sich unabhängig von der Außenwelt im Ohr selbst abspielt, beobachten zu können. Sie alle wissen aber, daß ein Sinneseindruck in den Sinnen nachwirkt, abgesehen davon, daß die Sinne auch immer mittun, wenn wir auch nur mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein lebhaft denken.

Es kann schon so sein, daß wir gewissermaßen von der ganzen äußeren Welt abstrahieren, insofern sie eine Farbenwelt, eine Tonwelt, eine Geruchswelt und so weiter ist, und dennoch demjenigen uns hingeben, was in unseren Sinnesorganen selbst, beziehungsweise durch sie vorgeht. Wenn wir dazu kommen, dann kommen wir zu wirklicher Menschenerkenntnis, und zwar zu der ersten Stufe der Menschenerkenntnis. Sagen wir zum Beispiel nur — wir wollen das Einfachste ins Auge fassen -, wir wollen uns klar darüber werden, wie im Auge ein Eindruck, den die Außenwelt auf es ausübt, abklingt. Wer nun die Gabe der imaginativen Erkenntnis sich erworben hat, verfolgt dann, indem er nichts außen sieht, dieses Abklingen des Sinneseindruckes, das heißt ein Geschehen, einen Vorgang, der das Sinnesorgan als solches in Anspruch nimmt, ohne daß das Sinnesorgan in diesem Augenblicke mit der Außenwelt in Korrespondenz ist. Oder es verfolgt jemand, der, in lebendiger Art denkend, sich das Gesehene vergegenwärtigen kann, das Mitspielen des Sehorganes bei solchem lebhaften Denken an Farben und dergleichen. So kann man das für alle Sinne machen. Dann wird man in der Tat gewahr, daß dasjenige, was in den Sinnen der Menschen selber vorgeht, nur Gegenstand einer imaginativen Erkenntnis sein kann.

Sogleich gewissermaßen zaubert sich vor unsere Seele hin eine Welt von Imaginationen, wenn wir nicht in der Außenwelt, wenn wir in den Sinnen leben. Und da merken wir, wie in der Tat unsere Sinne selber einer andern Welt angehören als der, welche wir durch sie innerhalb unseres Erdendaseins wahrnehmen. Niemand, der wirklich durch imaginative Erkenntnis in der Lage ist, seine eigene Sinnestätigkeit zu beobachten, kann jemals einen Zweifel darüber fassen, daß der Mensch schon als ein Sinneswesen der übersinnlichen Welt angehört. Die Welt, die man da kennenlernt, indem man in dieser Weise sozusagen sich zurückzieht von der äußeren Welt und in seinen eigenen Sinnen lebt, ist jene, die ich auch in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» als die Welt der Angeloi beschrieben habe, die Welt derjenigen Wesen, die eine Stufe über dem Menschen stehen.

Was geschieht denn eigentlich in unseren Sinnen? Wir können es durchschauen, wenn wir in dieser Weise das Innere der Sinne beobachten, während wir nicht wahrnehmen. Geradeso wie wir eine Erinnerung haben können von dem, was wir vor Jahren erlebt haben, trotzdem es jetzt gegenwärtig nicht da ist, können wir, wenn wir die Sinne beobachten können, ohne daß sie wahrnehmen, auch in dem, was wir da beobachten, eine Erkenntnis gewinnen. Es ist nicht Erinnerung zu nennen, weil das einen sehr ungenauen Begriff gäbe, aber wir können dennoch in dem, was wir da wahrnehmen, auch das mitwahrnehmen, was wir durch die Außenwelt in den Sinnen als Vorgänge haben, wenn wir der ganzen farbigen und tönenden und riechenden und schmeckenden, tastbaren Welt und so weiter gegenüberstehen.

Wir können auf diese Weise in etwas eindringen, was sonst dem Menschen immer unbewußt bleibt: die Tätigkeit seiner eigenen Sinne, während seine Tätigkeit ihm die Außenwelt vermittelt. Und da werden wir gewahr, daß der Atmungsprozeß, das Einatmen der Luft, das Verteilen der Luft im menschlichen Organismus, das Wiederausatmen, in einer außerordentlichen Art durch den ganzen Organismus wirkt. Wenn wir einatmen, geht zum Beispiel die eingeatmete Luft bis in die feinsten Verzweigungen der Sinne. Und in diesen feinsten Verzweigungen der Sinne begegnet sich der Atmungsrhythmus mit dem, was wir in der Geisteswissenschaft den astralischen Leib des Menschen nennen. Das, was in den Sinnen vorgeht, beruht darauf, daß der astralische Leib des Menschen den Atmungsrhythmus spürt. Hören Sie also einen Ton, so geschieht das, weil in Ihrem Gehörorgan der astralische Leib mit der schwingenden Luft in eine Berührung kommen kann. Das kann er nicht zum Beispiel in irgendeinem andern Organ des menschlichen Organismus, das kann er nur in den Sinnen. Die Sinne sind überhaupt im Menschen da, damit sich der astralische Leib mit demjenigen begegnen kann, was durch den Atmungsrhythmus in dem menschlichen Leibe entsteht. Und das geschieht nicht etwa nur im Gehörorgan, das geschieht in jedem Sinnesorgan. In jedem, auch in dem über den ganzen Organismus ausgebreiteten Tast- oder Gefühlssinn ist es so, daß sich der astralische Leib mit dem Atmungsrhythmus begegnet, also mit den Taten der Luft in unserem Organismus.

Gerade wenn man so etwas betrachtet, merkt man ganz besonders, wie sehr man nötig hat, zur Betrachtung des ganzen Menschen ins Auge zu fassen, daß der Mensch nicht nur ein Gebilde im festen Aggregatzustande ist, er ist zu fast neunzig Prozent eine Wassersäule, und er hat fortwährend den Wechsel der Luft in seinen inneren Vorgängen, er ist also auch ein Luftorganismus. Und dieser Luftorganismus, der ein Webend-Lebendes darstellt, begegnet sich in dem Sinnesorgan mit dem astralischen Leib des Menschen. Das geschieht allerdings in den Sinnesorganen in der mannigfaltigsten Weise, aber im allgemeinen kann man sagen, daß diese Begegnung das Wesentliche des Sinnesvorganges ist. Das kann man äußerlich nicht betrachten, wie sich ein Astralisches mit der Luft begegnet, ohne daß man in die imaginative Welt eintritt. Allerdings, wenn man zur imaginativen Erkenntnis kommt, sieht man auch anderes in der irdischen Umgebung, das sich so abspielt, daß ein Astralisches nur mit der Luft in Begegnung kommt. Aber in uns als Menschen ist das ein Wesentliches, daß das Astralische sich mit den Atmungsvorgängen begegnet, und zwar substantiell mit dem, was durch den Atmungsvorgang durch den menschlichen Organismus geschickt wird.

Da lernen wir also das Weben und Wesen derjenigen Wesenheiten kennen, welche der Hierarchie der Angeloi angehören, so daß wir als Menschen es uns nur so vorstellen dürfen, daß in dem unbewußten Vorgang, der sich im sinnlichen Wahrnehmen abspielt, diese Welt übersinnlicher Wesen webt und lebt, gewissermaßen durch die Tore unserer Sinne aus- und eingeht. Hören wir, oder sehen wir, so ist das ein Prozeß, der sich nicht nur durch unsere Willkür abspielt, sondern der auch der objektiven Welt angehört, der vorgeht in einer Welt, in der wir zunächst als Menschen nicht einmal darinnen sind, durch die wir aber eigentlich Menschen, und zwar schon sinnenbegabte Menschen sind.

Wenn unser astralischer Leib zwischen dem Aufwachen und Einschlafen innerhalb der Gebiete unserer Sinne mit der zum Atmungsrhythmus gewordenen und natürlich veränderten Luft in Beziehung tritt, so lernen wir, ich möchte sagen, die äußerste Peripherie des Menschen kennen. Aber wir können zu noch weiterem aufsteigen. Wir können noch mehr vom Menschen kennenlernen. Das geschieht auf folgende Weise. Es ergibt sich das jener Stufe der übersinnlichen Erkenntnis, die ich in den angedeuteten Schriften als die inspirierte Erkenntnis bezeichnet habe.

Da muß man ins Auge fassen, wie der Mensch dem Wechselzustande unterliegt zwischen Wachen und Schlafen. Dieser Zustand als solcher ist gar nicht so ferne der sinnlichen Wahrnehmung. Auch unsere sinnliche Wahrnehmung unterliegt einem Wechsel. Wir würden zwar Wahrnehmungen haben, allein die hätten für unser Bewußtsein nicht-die richtige Bedeutung, wenn wir nicht fortwährend das Wahrnehmen unterbrechen könnten. Sie wissen auch aus reinen Äußerlichkeiten, daß das lange Sich-Hingeben an einen Sinneseindruck das Bewußtsein von diesem Sinneseindruck beeinträchtigt. Wir müssen gewissermaßen von einem einzelnen Sinneseindruck den Sinn immer wieder abheben, müssen also zwischen dem Eindruck und einem Zustand wechseln, wo wir den Eindruck nicht haben. Und daß unser Bewußtsein in Ordnung ist in bezug auf die Sinneseindrücke, beruht darauf, daß wir immer diese Sinne auch zurückziehen können von ihren Eindrücken, daß wir eigentlich fortwährend in kurzen Wechselzuständen das sinnliche Wahrnehmen ausüben. Das üben wir für längere Strecken unseres Erlebens aus, indem wir im Verlauf von vierundzwanzig Stunden immer wechseln zwischen Wachen und Schlafen.

Sie wissen, indem wir in den Schlafzustand übergehen, tritt unser astralischer Leib mit unserem Ich aus unserem physischen Leib und Ätherleib heraus. Und dieser astralische Leib also tritt zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen zu der äußeren Welt in Beziehung, während er zwischen dem Aufwachen und Einschlafen nur mit dem in Beziehung war, was innerhalb des menschlichen Leibes vor sich geht. Fassen Sie diese zwei Zustände oder diese zwei Geschehnisse einmal ins Auge: der astralische Leib zwischen dem Aufwachen und Einschlafen in Beziehung zu dem, was innerhalb des menschlichen physischen und ätherischen Leibes vor sich geht, und der astralische Leib zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen in Beziehung zu dem, was die äußere Welt ist, nicht mehr in Beziehung zu dem, was physischer und ätherischer Leib des Menschen selbst ist.

Die Sinnesgebiete in uns — ich möchte mich des paradoxen Ausdruckes bedienen, Sie werden schon verstehen, was ich meine - sind schon fast eine Außenwelt. Betrachten Sie einmal das menschliche Auge zum Beispiel: es ist wie eine unabhängige Wesenheit — das ist alles nur vergleichsweise, selbstverständlich -, aber es ist wirklich wie eine unabhängige Wesenheit da hineingelegt in eine Höhle des Schädels, setzt sich dann weiter nach innen mit verhältnismäßiger Selbständigkeit fort. Aber wenn Sie das Auge selbst betrachten: es ist zwar durchlebt, aber es ist merkwürdig ähnlich einem physikalischen Apparat. Wir können so merkwürdig ähnlich im Auge die Vorgänge charakterisieren, wie wir sie auch in einem physikalischen Apparat charakterisieren. Die Seele umfaßt gewiß die Vorgänge, die auf diese Weise entstehen, aber man kann schon sagen, daß die Sinnesorgane das sind, was ich öfter als Bezeichnung dafür gewählt habe: daß die Sinnesorgane oder die Sinnesgebiete wie Golfe sind, welche die Außenwelt in unser eigenes menschliches Innere hineinsendet. Es setzt sich gewissermaßen die Außenwelt in uns hinein fort in den Sinnen, und wir Menschen nehmen in unserem Sinnesgebiete an der Außenwelt viel mehr teil als in den andern Gebieten unseres Organismus.

Wenn man irgendein Organ, sagen wir die Niere oder ein anderes inneres Organ des menschlichen Organismus, ins Auge faßt, kann man nicht sagen, daß man da an irgend etwas Äußerem teilnimmt, indem man die Vorgänge des Organs in sich erlebt. Aber indem wir dasjenige erleben, was sich in den Sinnen abspielt, erleben wir die Außenwelt mit. Ich bitte, da ganz abzusehen von Ihnen etwa bekannten Dingen aus der Sinnesphysiologie und so weiter. Die meine ich jetzt gar nicht, sondern ich meine den durchaus dem gewöhnlichen Menschenverstand zugänglichen Tatbestand, daß wirklich der Vorgang, der sich im Sinnesgebiet abspielt, eher aufgefaßt werden kann wie etwas, das sich von außen in uns hineinerstreckt und was wir mitmachen, als etwas, das wir innerlich durch unsere Organisation be_ wirken.

Deshalb ist es auch, daß in den Sinnen unser astralischer Leib nahezu in der Außenwelt ist. Insbesondere, wenn wir vollwillentlich an die Außenwelt sinnlich wahrnehmend hingegeben sind, ist unser astralischer Leib tatsächlich fast in die Außenwelt eingesenkt, nicht für alle Sinne gleich, aber er ist fast in die Außenwelt eingesenkt. Ganz eingesenkt ist er, wenn wir schlafen, so daß der Schlaf gewissermaßen von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus eine Art Steigerung ist des sinnlichen Hingegebenseins an die Außenwelt. Wenn Sie Ihre Augen zuhaben, dann zieht sich auch Ihr astralischer Leib mehr in das Innere des Kopfes zurück, er gehört mehr Ihnen selbst an. Wenn Sie ordentlich nach außen gucken, dann zieht sich der astralische Leib in das Auge hinein und nimmt an der Außenwelt teil. Geht er ganz heraus aus Ihrem Organismus, so schlafen Sie. Sinnliches Hingegebensein an die Außenwelt ist nämlich nicht das, was man gewöhnlich meint, sondern es ist eigentlich eine Etappe auf dem Wege zum Einschlafen in bezug auf die Charakteristik des Bewußtseins.

So nimmt man als Mensch beim sinnlichen Wahrnehmen fast an der Außenwelt teil, beim Schlafen nimmt man ganz an der Außenwelt teil. Dann kann man dasjenige, was da vorgeht in der Welt, in der man nun drinnen ist mit seinem astralischen Leibe zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen, mit inspirierter Erkenntnis wahrnehmen. Aber man kann mit dieser inspirierten Erkenntnis dann auch noch etwas anderes wahrnehmen, nämlich den Moment des Aufwachens, das Wiederum-Zurückgehen. Es wird gewissermaßen der Moment des Aufwachens etwas, das nur intensiver, stärker ist, aber sich doch mit dem Augenschließen vergleichen läßt.

Wenn ich einer Farbe gegenüberstehe, gebe ich meinen astralischen Leib an dasjenige im Auge hin, was nahezu, sagte ich, außen ist, nämlich an den Prozeß, der dadurch hervorgerufen wird, daß eine Farbe von der Außenwelt aus auf mein Auge einen Eindruck macht. Schließe ich das Auge, so ziehe ich meinen astralischen Leib in mich selber zurück. Wache ich auf, so ziehe ich meinen astralischen Leib aus der Außenwelt, aus dem ganzen Kosmos zurück. Ich mache nämlich oftmals, unendlich oft während des Tagwachens, zum Beispiel in bezug auf die Augen, in bezug auf die Ohren, dasselbe mit meinem astralischen Leib, was ich — nur in Totalität, in bezug auf den ganzen Organismus — beim Aufwachen mache. Ich nehme meinen ganzen astralischen Leib zurück beim Aufwachen. Dieses Zurücknehmen des astralischen Leibes beim Aufwachen bleibt natürlich auch für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein unbewußt, so wie der sinnliche Vorgang selber unbewußt bleibt. Aber wenn für denjenigen, der mit inspirierter Erkenntnis begabt ist, dieser Moment des Aufwachens bewußt wird, dann zeigt es sich schon, daß dieses Hereinkommen des astralischen Leibes einer ganz andern Welt angehört als der, in der wir sonst sind, und vor allen Dingen ist es sehr häufig stark wahrzunehmen, wie schwer es der astralische Leib hat, wiederum in den physischen und Ätherleib zurückzukommen. Da sind Hemmnisse vorhanden.

Man kann sagen, daß derjenige, der beginnt, diesen Vorgang des Zurückkehrens des astralischen Leibes in den physischen Leib und in den Ätherleib wahrzunehmen, geistige Gewitter erlebt mit allerlei Gegenschlägen, geistige Gewitter mit solchen Gegenschlägen, die zeigen, daß der astralische Leib untertaucht in den physischen und in den Ätherleib, daß aber jetzt der physische und der Ätherleib bei diesem Untertauchen nicht so ausschauen, wie der Anatom und der Physiologe sie beschreiben, sondern daß sie etwas sind, was auch einer geistigen Welt angehört. Was sonst der unschuldige physische Leib ist, oder was vermutet wird als der etwas nebulose unschuldige Ätherleib, das stellt sich dar als in einer geistigen Welt wurzelnd. In seiner Wahrheit stellt sich der physische Leib als etwas ganz anderes dar, als was er äußerlich in einem sinnlichen Abbilde für das Auge oder für die gewöhnliche Wissenschaft erscheint.

In tausendfachen Mannigfaltigkeiten kann dieses Untertauchen des astralischen Leibes in den physischen und in den Ätherleib erscheinen, wie etwa, wenn ein brennendes Holzstück untertaucht mit Gebrause in Wässeriges. Das ist noch die einfachste, die abstrakteste Art, die demjenigen, der eben anfängt, so etwas zu erkennen, zunächst erscheinen kann. Dann aber konkretisiert sich der Vorgang innerlich sehr mannigfaltig, durchgeistigt sich aber nachher damit, daß dasjenige, was vorerst nur, ich möchte sagen, sich in seiner Erscheinung mit brausendem Gewitter, mit aufsteigenden Stürmen vergleichen läßt, daß das sich mit harmonischen Bewegungsvorgängen durchdringt, die aber in allen ihren Teilen zu gleicher Zeit etwas sind, von dem man sagen muß: Es spricht, es sagt etwas, es kündet etwas an.

Zunächst allerdings kleidet sich das, was sich da ankündigt, in Reminiszenzen aus dem gewöhnlichen Leben. Aber das formt sich im Laufe der Zeit um, und man erfährt nach und nach eben vieles von einer Welt, die auch um uns ist, und in der man Dinge erlebt, von denen man nicht sagen kann, daß sie Reminiszenzen sind aus dem gewöhnlichen Wahrnehmen, weil sie ganz und gar anderer Natur sind, weil man wirklich bei diesem Erleben weiß, daß man es mit einer andern Welt zu tun hat. Da merkt man, daß der Mensch, indem er mit seinem astralischen Leib aus seiner Umgebung in seinen physischen und Ätherleib hereinkommt, das jetzt auf dem Wege des Vollatimungsprozesses tut. Der astralische Leib, der in den Sinnen tätig ist, berührt die feinen Verzweigungen des Atmungsvorganges, greift gewissermaßen in die feinen Rhythmen ein, in denen sich der Atmungsvorgang in die Sinnesgebiete fortsetzt. Der beim Aufwachen aus der Außenwelt in den physischen und Ätherleib hereinziehende Astralleib ergreift den ganzen Atmungsprozeß, der sich zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen selbst überlassen ist. Auf den Bahnen der Atmungsprozesse, der Atmungsbewegungen, kommt der astralische Leib hinein in den physischen und Ätherleib, breitet sich aus, wie sich der Atem selber ausbreitet.

Das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein stößt, möchte ich sagen, rasch beim Aufwachen hinein in die Wahrnehmung der äußeren Welt, verbindet schnell das Erleben des Atmungsprozesses mit dem gesamtorganischen Erleben. Das inspirierte Bewußtsein kann dieses Fortlaufen des astralischen Leibes auf den Bahnen des Atmungsrhythmus trennen und den übrigen organischen Prozeß gesondert wahrnehmen. Er verläuft natürlich nicht gesondert. Nicht nur in diesem Augenblicke, sondern in jedem Augenblicke steht natürlich im menschlichen Organismus die Atmungsbewegung in innigem Zusammenhang mit den übrigen Vorgängen im Organismus. Aber in der Erkenntnis, in der inspirierten Erkenntnis kann das abgetrennt werden. Man verfolgt, wie der astralische Leib auf den Wegen des Atmungsrhythmus in den physischen Leib hereinkommt, und lernt da etwas kennen, was sonst völlig unbewußt bleibt. Nachdem man alle die Zustände durchgemacht hat, welche objektive — nicht subjektive — Gefühlszustände sind, die dieses Hereinkommen begleiten, weiß man, daß, indem der Mensch nun nicht bloß ein Sinnenwesen, sondern ein Atmungswesen ist, er in derjenigen Welt wurzelt, welche ich in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft» die Welt der Archangeloi genannt habe. Geradeso wie die eine Stufe über den Menschen stehenden Wesenheiten der übersinnlichen Welt in seinem Sinnesprozeß tätig sind, sind tätig in seinem Atmungsprozesse die zwei Stufen über den Menschen stehenden geistigen Wesenheiten. Sie gehen gewissermaßen ein und aus mit unserem Einschlafen und Aufwachen.

Nun stellt sich uns, wenn wir diese Vorgänge betrachten, etwas sehr Bedeutsames für das menschliche Leben vor unsere Seele. Wenn wir ein Leben hätten, das nicht vom Schlafe unterbrochen wäre, so würden wir Eindrücke der Außenwelt empfangen, aber diese Eindrücke würden nur kurz vorhalten. Ein bleibendes Erinnerungsvermögen könnten wir nicht entwickeln. Sie wissen, wie flüchtig die Bilder in den Sinnen als Nachbilder wirken. Allerdings, was tiefer im Organismus angeregt wird, wirkt länger. Aber es wirkte doch nicht länger als einige Tage nach, wenn wir nicht schlafen würden.

Was geht denn eigentlich im Schlafe vor? Da muß ich Sie erinnern an eine Auseinandersetzung, die ich vor kurzem hier gegeben habe, und in der ich Ihnen geschildert habe, wie der Mensch tatsächlich zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen mit seinem astralischen Leibe und seinem Ich eigentlich immer rückwärts durchlebt, was er in der vorhergehenden Wachperiode in der physischen Welt erlebt hat. Nehmen wir ein regelmäßiges Wachen und regelmäßiges Schlafen an — es ist allerdings auch für das unregelmäßige ganz ähnlich -, nehmen wir also an, wir wachen an einem Morgen auf, beschäftigen uns während des Tages, gehen abends zur Ruhe und schlafen die Nacht hindurch ungefähr ein Drittel der Zeit, die wir wachen. Ein solcher Mensch erlebt also zwischen dem Aufwachen und Einschlafen eine Reihe von Erlebnissen, eben seine Tageserlebnisse. Er erlebt während des Schlafzustandes wirklich in rückwärtiger Bewegung dasjenige, was während des Tages erlebt worden ist. Und zwar geht das Schlafleben mit einer größeren Schnelligkeit zurück, so daß Sie nur ein Drittel der Zeit dazu brauchen.

Nun aber, was ist denn da eigentlich geschehen? Wenn die Sache so wäre, daß Sie nach den Gesetzen der physischen Welt schliefen ich meine jetzt nicht, daß der Körper nach den Gesetzen der äußeren physischen Welt schläft, das tut er selbstverständlich, aber wenn Sie in den Zuständen außerhalb des physischen und des Ätherleibes, wenn Sie also in Ihrem Ich und in Ihrem astralischen Leib nach denselben Gesetzen schlafen würden, nach denen Sie bei Tag wachen -, dann würden Sie diese Bewegung nicht ausführen können, denn Sie müßten einfach mit der Zeit weitergehen. Es sind durchaus andere Gesetze, denen wir da unterliegen, wenn wir in unserem astralischen Leib und in unserem Ich außerhalb des physischen und des Ätherleibes sind. Und äußerlich angesehen, wie ist denn da die Sache eigentlich? Nun, bedenken Sie, heute ist also der 22.Dezember, heute morgen beim Aufwachen waren Sie am Morgen des 22. Dezember. Nun gehen Sie nachher schlafen, dann werden Sie, wenn Sie morgen aufwachen, mit Ihrem Rückwärtserleben bei heute morgen dem 22.Dezember sein. Sie haben also innerlich einen Prozeß durchgemacht, dutch den Sie sich zurückgedreht haben. Indem Sie am Morgen des 23. Dezember aufwachen, sind Sie mit diesem Prozeß am Morgen des 22. Dezember angekommen. Sie wachen auf. In demselben Momente sind Sie genötigt, indem Ihr astralischer Leib jetzt, entgegen den Gesetzen, die er zwischen Ihrem Einschlafen und Aufwachen eingehalten hat, den Ruck durch Ihren Leib in die gewöhnliche physische Welt macht, in Ihrem innersten Seelenwesen mit Ihrem Ich und mit Ihrem astralischen Leibe rasch zu dem Morgen des 23. Dezember vorzurücken. Diesen Prozeß machen Sie tatsächlich im Innern durch.

Ich bitte Sie nun, das, was ich hier sage, in seinem vollen Ernste, das heißt in seiner vollen Bedeutung aufzufassen. Wenn Sie, sagen wir in einem Gefäß, das durch irgendeine Vorrichtung geschlossen ist, einen gasförmigen Körper haben, so können Sie diesen gasförmigen Körper zusammendrücken: er wird immer dichter und dichter. Das ist ein räumlicher Vorgang. Aber er ist zu vergleichen — natürlich nur zu vergleichen - mit dem, was ich Ihnen eben beschrieben habe. Sie gehen zurück in Ihrem astralischen Leib und in Ihrem Ich bis zum Morgen des 22.Dezember und rücken rasch vor beim Aufwachen zum Morgen des 23. Dezember. Sie schieben innerhalb der Zeit Ihr Seelenwesen vorwärts. Das ist eine Verdichtung der Zeit, oder eigentlich genauer gesagt desjenigen, was in der Zeit lebt. Und durch diesen Vorgang wird unser Seelisches, unser astralischer Leib innerhalb der Zeit so verdichtet, daß er die Eindrücke der Außenwelt nicht nur kurz, sondern als bleibendes Gedächtnis trägt. So wie irgendein Gas, das Sie verdichten, einen stärkeren Druck ausübt, also innerlich mehr Kraft hat, so bekommt Ihr astralischer Leib die starke Kraft der Erinnerung, die starke Kraft des Gedächtnisses durch dieses innerliche Zusammenschieben in der Zeit.

Man bekommt auf diese Weise eine Vorstellung von etwas, das einem eigentlich sonst immer entgeht. Man stellt sich die Zeit als etwas vor, das gleichmäßig fortläuft, und alles, was in der Zeit sich abspielt, läuft auch gleichmäßig mit der Zeit fort. Beim Raum weiß man: was im Raume ausgedehnt ist, kann verdichtet werden, es wächst seine innere Expansionskraft. Aber auch was in der Zeit lebt, das Seelische, kann - es ist allerdings vergleichsweise gesprochen — verdichtet werden, dann wächst seine innere Kraft. Und für den Menschen ist eine dieser Kräfte die Erinnerungskraft.

Diese Erinnerungskraft verdanken wir in der Tat dem Vorgange während unseres Schlafes. Vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen sind wir in der Welt der Archangeloi, und mit den Wesen der Hierarchie der Archangeloi zusammen bilden wir diese Kraft unseres Gedächtnisses aus. So wie wir die Kraft des sinnlichen Wahrnehmens und des Kombinierens der sinnlichen Wahrnehmungen mit den Wesenheiten der Hierarchie der Angeloi ausbilden, so bilden wir diese mehr verinnerlichte, mehr mit dem Zentrum zusammenhängende Kraft des Erinnerns in der Welt der Archangeloi aus.

Wahre Menschenerkenntnis gibt es nicht im nebulos-mystischen Sinne, wo man hineinbrütet in sich, wahre Menschenerkenntnis führt bei jedem Schritt, den man ins Innere macht, sogleich in höhere Welten hinauf. Wir haben heute von zwei solchen Schritten gesprochen. Schaut man das Gebiet der Sinne an — man ist in dem Gebiete der Angeloi; schaut man das Gebiet der Erinnerung an man ist in dem Gebiete der Archangeloi. Selbsterkenntnis heißt zugleich Götter-Erkenntnis, Geist-Erkenntnis, weil jeder Schritt, der in das menschliche Innere führt, zugleich in die geistige Welt hineinführt. Und je tiefer man in das Innere dringt, desto höher — möchte ich sagen, um dieses Paradoxon zu gebrauchen - steigt man in die Welt der geistigen Wesenheiten hinauf. Selbsterkenntnis ist wirkliche Welterkenntnis, nämlich Erkenntnis des geistigen Inhaltes der Welt, wenn diese Selbsterkenntnis eine ernste ist.

Auch wiederum aus dieser Auseinandersetzung können Sie sehen, warum in älteren Zeiten, wo unter den orientalischen Völkern eine instinktive Art des geistigen Anschauens erstrebt worden ist, der Atmungsprozeß durch besondere Atmungsübungen zu einem bewußten Vorgang gemacht werden sollte. Man tritt, sobald der Atmungsprozeß bewußt wird, in eine geistige Welt ein. Ich brauche heute nicht wieder zu sagen, daß jene älteren Übungen von dem heutigen Menschen mit seiner veränderten Konstitution nicht wiederholt werden sollen, sondern durch andere zu ersetzen sind, die Sie in den genannten Büchern beschrieben finden. Aber für beide Arten von Erkenntnissen - für die Erkenntnis der älteren mystischen Clairvoyance, für die Erkenntnis der neueren exakten Clairvoyance — gilt das: daß man durch wirkliche Beobachtung derjenigen Vorgänge, die sich im Menschen innerlich abspielen, zugleich in die geistige Welt hineinkommt.

Es gibt Menschen, die sagen: Ja, aber auf diese Weise gerät man ins Ungeistige hinein. Man will die Sinnesvorgänge untersuchen, Atmungsvorgänge untersuchen. — Manche Menschen nennen das gegenüber einer nebulosen Mystik dann sogar materialistische Selbsterkenntnis. Man soll es nur einmal versuchen! Man wird sehen, daß der Sinnesprozeß sogleich ein geistiger wird, wenn man ihn wirklich kennenlernt, und daß es nur eine Illusion ist, wenn man ihn für einen materiellen Prozeß hält. Ebenso der Atmungsprozeß. Der Atmungsprozeß ist nur nach außen angesehen ein materieller Prozeß. Nach innen angesehen ist er durch und durch ein geistiger Prozeß, sogar ein solcher, der sich in einer weit höheren Welt abspielt als derjenigen, die wir durch unsere Sinne wahrnehmen.

Morgen wird mein Vortrag sein, der sich an den heutigen anschließen soll, vielleicht aber mehr hinüberleiten wird in eine Art von Weihnachtsbetrachtung.

Seventh Lecture

Man perceives the things of the world through his senses, but he does not perceive with ordinary consciousness what takes place within his senses themselves. If he did so in ordinary life, he would not be able to perceive the outer world. The senses must, so to speak, deny themselves if they are to bring to man's knowledge what lies outside the senses in the world that initially surrounds us on earth. If our ears were to speak, if our eyes were to speak, if we were to perceive the processes that take place in our ears and in our eyes, then we would not be able to hear what is outwardly audible, we would not be able to see what is outwardly visible. But it is precisely through this that man gets to know the world around him, insofar as he is initially an earthly being, but he does not get to know himself. Getting to know oneself presupposes that during this process of self-knowledge one can bring the knowledge of the outside world to a standstill, i.e. that one learns nothing of the outside world.

It has always been the endeavor within spiritual scientific research to find such methods by which man can really recognize himself, and you know from the various lectures I have given that by this self-knowledge I do not mean that general brooding into the everyday self, for in this way one learns of nothing other than a kind of reflex image of the outer world. In a sense, you don't get to know anything new. One only gets to know, as in a mirror, what one has experienced with the sensual outer world. Real self-knowledge, as you know, must seek methods which not only silence the ordinary earthly outer world, but which also silence the ordinary everyday inner soul - which is also nothing other than a reflection of the outer world, insofar as it is present in real consciousness. And through those methods which you will find described in my writing “How does one attain knowledge of the higher worlds?”, you know that spiritual research first proceeds to so-called imaginative knowledge. Whoever advances to such imaginative cognition, however, first has before him everything from the supersensible world that can be clothed in the images of imaginative cognition. But when he has acquired the spiritual practice to be able to look at the world imaginatively at all, then he is in a position to follow precisely that which takes place in the human sense organs. One would not be able to follow what takes place in the sense organs if there were only something going on in the sense organs when one perceives the outside world through them.

If I see an object in the outside world, my eye is silent. If I hear some sound context of the outside world, my ear is silent; that is, the ear does not perceive the process inside the ear, but perceives what continues from the outside world into the ear. But if, for example, the ear were only to carry out an activity with reference to the external world as long as this external perception is there, we would never be able to observe the process that takes place in the ear itself, independently of the external world. But you all know that a sensory impression continues to have an effect on the senses, apart from the fact that the senses are always involved when we think vividly even with ordinary consciousness.

It can be the case that we abstract, so to speak, from the whole external world, insofar as it is a world of color, a world of sound, a world of smell and so on, and yet devote ourselves to what happens in our sense organs themselves, or through them. When we come to this, then we come to real knowledge of man, namely to the first stage of knowledge of man. Let us just say, for example - let us consider the simplest thing - that we want to become aware of how an impression made on the eye by the outside world is reflected in it. He who has now acquired the gift of imaginative cognition then, seeing nothing outside, follows this fading away of the sense impression, that is, an event, a process, which makes use of the sense organ as such, without the sense organ being in correspondence with the outer world at that moment. Or someone who, thinking in a lively way, is able to visualize what he sees, follows the interplay of the visual organ in such lively thinking of colors and the like. This can be done for all the senses. Then you will indeed realize that what happens in the senses of people themselves can only be the object of imaginative cognition.

A world of imaginations immediately conjures up before our soul, so to speak, when we are not living in the external world, when we are living in the senses. And then we realize how, in fact, our senses themselves belong to a different world than the one we perceive through them within our earthly existence. No one who is really able to observe his own sensory activity through imaginative cognition can ever doubt that man already belongs to the supersensible world as a sensory being. The world that one gets to know by withdrawing in this way, so to speak, from the outer world and living in one's own senses, is the world that I have also described in my “Secret Science in Outline” as the world of the Angeloi, the world of those beings who are one step above man.

>What actually happens in our senses?What actually happens in our senses? We can see through it if we observe the interior of the senses in this way, while we do not perceive. Just as we can have a memory of what we experienced years ago, even though it is not there now, if we can observe the senses without them perceiving, we can also gain an insight into what we are observing. It is not to be called memory, because that would give a very imprecise concept, but we can nevertheless also perceive in what we perceive there what we have through the outside world in the senses as processes when we are confronted with the whole colorful and sounding and smelling and tasting, tactile world and so on.

In this way we can penetrate into something that otherwise always remains unconscious to man: the activity of his own senses, while his activity conveys the outer world to him. And then we become aware that the breathing process, the inhalation of air, the distribution of air in the human organism, the exhalation of air, works in an extraordinary way through the whole organism. When we inhale, for example, the inhaled air reaches the finest branches of the senses. And it is in these finest ramifications of the senses that the breathing rhythm meets with what we in spiritual science call the astral body of the human being. What happens in the senses is based on the fact that the human astral body senses the rhythm of breathing. So if you hear a sound, this happens because the astral body can come into contact with the vibrating air in your organ of hearing. It cannot do this, for example, in any other organ of the human organism, it can only do so in the senses. The senses are there in the human being so that the astral body can come into contact with that which arises in the human body through the respiratory rhythm. And this does not only happen in the organ of hearing, it happens in every sense organ. In every sense, including the sense of touch or feeling spread over the whole organism, the astral body meets with the respiratory rhythm, that is, with the acts of the air in our organism.

It is precisely when you look at something like this that you realize how necessary it is to consider the whole human being, that the human being is not only a structure in a solid aggregate state, he is almost ninety percent a water column, and he constantly has the change of air in his inner processes, he is therefore also an air organism. And this air organism, which represents a weaving living being, meets the astral body of the human being in the sense organ. This happens in the sense organs in the most varied ways, but in general one can say that this encounter is the essence of the sensory process. It is not possible to observe externally how an astral being meets the air without entering the imaginative world. However, when one comes to imaginative cognition, one also sees other things in the earthly environment that take place in such a way that an astral being only comes into contact with the air. But in us as human beings it is essential that the astral meets with the respiratory processes, and indeed substantially with that which is sent through the human organism by the respiratory process.

Thus we get to know the weaving and being of those entities that belong to the hierarchy of the Angeloi, so that we as humans can only imagine it in such a way that in the unconscious process that takes place in sensory perception, this world of supersensible beings weaves and lives, so to speak, goes out and in through the gates of our senses. When we hear or see, it is a process that not only takes place through our will, but which also belongs to the objective world, which takes place in a world in which we are not even in it as human beings at first, but through which we are actually human beings, and indeed already sensually gifted human beings.

When our astral body, between waking and falling asleep, enters into a relationship within the realms of our senses with the air, which has become a breathing rhythm and is naturally altered, we get to know, I would say, the outermost periphery of the human being. But we can go even further. We can get to know even more of the human being. This happens in the following way. This results in that level of supersensible knowledge which I have called inspired knowledge in the writings alluded to above.

There one must consider how man is subject to the alternating state between waking and sleeping. This state as such is not so far removed from sensory perception. Our sensory perception is also subject to alternation. We would indeed have perceptions, but they would not have the right meaning for our consciousness if we could not continually interrupt perception. You also know from pure outward appearances that the prolonged devotion to a sensory impression impairs the consciousness of this sensory impression. To a certain extent, we have to repeatedly withdraw the sense from a single sensory impression, i.e. we have to switch between the impression and a state in which we do not have the impression. And the fact that our consciousness is in order with regard to sensory impressions is based on the fact that we can always withdraw these senses from their impressions, that we are actually constantly practicing sensory perception in short alternating states. We practise this for longer stretches of our experience by constantly alternating between waking and sleeping over the course of twenty-four hours.

You know that when we enter the state of sleep, our astral body with our ego emerges from our physical body and etheric body. And so this astral body enters into a relationship with the outer world between falling asleep and waking up, whereas between waking up and falling asleep it was only in relationship with what goes on within the human body. Consider these two states or these two events: the astral body between waking and falling asleep in relation to what is going on within the human physical and etheric body, and the astral body between falling asleep and waking up in relation to what is the outer world, no longer in relation to what is the physical and etheric body of man himself.

The sensory areas within us - I would like to use the paradoxical expression, you will understand what I mean - are almost an external world. Look at the human eye, for example: it is like an independent entity - this is all only comparative, of course - but it really is like an independent entity placed in a cave in the skull, and then continues inwards with relative independence. But if you look at the eye itself: it is indeed lived through, but it is strangely similar to a physical apparatus. We can characterize the processes in the eye as strangely similar to the way we characterize them in a physical apparatus. The soul certainly comprises the processes that arise in this way, but one can already say that the sense organs are what I have often chosen to call them: that the sense organs or the sense areas are like gulfs that the outside world sends into our own human interior. In a sense, the outside world continues into us in the senses, and we humans participate in the outside world much more in our sensory area than in the other areas of our organism.

If you look at any organ, let us say the kidney or another internal organ of the human organism, you cannot say that you participate in anything external by experiencing the processes of the organ within you. But by experiencing that which takes place in the senses, we also experience the external world. I would ask you to refrain from talking about things you are familiar with from sensory physiology and so on. I am not referring to these at all, but to the fact, which is quite accessible to common sense, that the process that takes place in the sensory field can really be understood as something that extends into us from the outside and which we participate in, rather than something that we influence internally through our organization.

This is also why our astral body is almost in the outside world in the senses. In particular, when we are fully conscious of the external world through our senses, our astral body is actually almost submerged in the external world, not for all senses equally, but it is almost submerged in the external world. It is completely immersed when we sleep, so that from this point of view sleep is, so to speak, a kind of intensification of sensual surrender to the outside world. When you have your eyes closed, then your astral body also withdraws more into the interior of your head, it belongs more to yourself. If you look properly outwards, then the astral body withdraws into the eye and participates in the outside world. If it leaves your organism completely, you are asleep. Sensual surrender to the outside world is not what is usually meant, but it is actually a stage on the way to falling asleep with regard to the characteristics of consciousness.

So, as a human being, one almost participates in the outside world during sensory perception, and during sleep one participates completely in the outside world. Then one can perceive with inspired cognition what is going on in the world in which one is now inside with one's astral body between falling asleep and waking up. But you can also perceive something else with this inspired cognition, namely the moment of waking up, of going back again. In a way, the moment of waking up becomes something that is only more intense, stronger, but can still be compared to closing your eyes.

When I face a color, I surrender my astral body to that in the eye which is almost, I said, outside, namely to the process which is caused by the fact that a color from the outside world makes an impression on my eye. When I close my eye, I withdraw my astral body into myself. When I wake up, I withdraw my astral body from the outside world, from the whole cosmos. For I often, infinitely often, do the same with my astral body during daytime waking, for example in relation to the eyes, in relation to the ears, as I do - only in totality, in relation to the whole organism - when I wake up. I take back my whole astral body when I wake up. This withdrawal of the astral body on waking naturally remains unconscious to the ordinary consciousness, just as the sensory process itself remains unconscious. But when this moment of awakening becomes conscious for the one who is gifted with inspired knowledge, then it is already apparent that this coming in of the astral body belongs to a completely different world than the one in which we are otherwise, and above all it is very often strongly perceptible how difficult it is for the astral body to come back into the physical and etheric body. There are obstacles there.

One can say that he who begins to perceive this process of the return of the astral body into the physical body and into the etheric body experiences spiritual thunderstorms with all kinds of counterblows, spiritual thunderstorms with such counterblows that show that the astral body is submerged into the physical and etheric bodies, but that now the physical and etheric bodies do not look as the anatomist and physiologist describe them during this submersion, but that they are something that also belongs to a spiritual world. What is otherwise the innocent physical body, or what is assumed to be the somewhat nebulous innocent etheric body, presents itself as rooted in a spiritual world. In its truth, the physical body presents itself as something quite different from what it appears externally in a sensory image to the eye or to ordinary science.

This submersion of the astral body into the physical and etheric body can appear in a thousand different ways, such as when a burning piece of wood is submerged in water with a roar. This is still the simplest, the most abstract way that can initially appear to someone who is just beginning to recognize something like this. Then, however, the process concretizes itself inwardly in a very manifold way, but later spiritualizes itself in such a way that that which at first can only, I would like to say, be compared in its appearance to a roaring thunderstorm, to rising storms, that it permeates itself with harmonious processes of movement, which, however, in all their parts at the same time are something of which one must say: It speaks, it says something, it announces something.

At first, however, what announces itself is clothed in reminiscences from ordinary life. But in the course of time this is transformed, and little by little we experience much of a world that is also around us, and in which we experience things that cannot be said to be reminiscences of ordinary perception, because they are of a completely different nature, because in this experience we really know that we are dealing with another world. There one realizes that the human being, by entering with his astral body from his surroundings into his physical and etheric body, is now doing so by way of the full breathing process. The astral body, which is active in the senses, touches the fine ramifications of the breathing process, intervenes, so to speak, in the fine rhythms in which the breathing process continues into the sensory areas. The astral body, which moves from the outer world into the physical and etheric body on waking, takes hold of the whole breathing process, which is left to itself between falling asleep and waking up. Along the paths of the respiratory processes, the respiratory movements, the astral body enters the physical and etheric body, spreads out as the breath itself spreads out.

The ordinary consciousness, I would like to say, quickly enters into the perception of the outer world upon waking, quickly connects the experience of the breathing process with the overall organic experience. The inspired consciousness can separate this continuation of the astral body on the paths of the respiratory rhythm and perceive the remaining organic process separately. Of course it does not proceed separately. Not only at this moment, but at every moment in the human organism, the respiratory movement is of course intimately connected with the other processes in the organism. But in cognition, in inspired cognition, this can be separated. One follows how the astral body enters the physical body via the respiratory rhythm and learns something that otherwise remains completely unconscious. After one has gone through all the states which are objective - not subjective - states of feeling that accompany this coming in, one knows that, since man is now not merely a sense being but a breathing being, he is rooted in that world which I have called in my “Secret Science” the world of the Archangeloi. Just as the beings of the supersensible world who are one level above man are active in his sensory process, so the spiritual beings who are two levels above man are active in his breathing process. They go in and out, so to speak, with our falling asleep and waking up.

Now, when we look at these processes, something very significant for human life presents itself to our souls. If we had a life that was not interrupted by sleep, we would receive impressions from the outside world, but these impressions would only last for a short time. We would not be able to develop a lasting memory. You know how fleeting the images in the senses are as afterimages. However, what is stimulated deeper in the organism has a longer effect. But it wouldn't last longer than a few days if we didn't sleep.

What actually happens during sleep? I must remind you of a discussion I recently gave here, in which I described how, between falling asleep and waking up, the human being actually always relives backwards with his astral body and his ego what he experienced in the previous waking period in the physical world. If we assume regular waking and regular sleeping - although it is quite similar for the irregular - let us assume that we wake up in the morning, occupy ourselves during the day, go to rest in the evening and sleep through the night for about a third of the time that we are awake. Between waking up and going to sleep, such a person experiences a series of experiences, his daytime experiences. During the sleep state he really experiences in a backward movement that which has been experienced during the day. And the sleep life goes back with greater speed, so that you only need a third of the time for this.