Man and the World of Stars

GA 219

The Spiritual Communion of Mankind

29 December 1922, Dornach

III. From Man's Living Together with the Course of Cosmic Existence Arises the Cosmic Cult

The object of the lectures I gave here immediately before Christmas was to indicate man's connection with the whole Cosmos and especially with the forces of spirit-and-soul pervading the Cosmos. Today I shall again be dealing with the subject-matter of those lectures but in a way that will constitute an entirely independent study.

The life of man, as far as it consists of experiences of outer Nature as well as of the inner life of soul and spirit, lies between two poles; and many of the thoughts which necessarily come to man about his connection with the world are influenced by the realization that these two polar opposites exist.

On the one side, man's life of thinking and feeling is confronted by what is called ‘natural necessity.’ He feels himself dependent upon adamantine laws which he finds everywhere in the world outside him and which also penetrate through him, inasmuch as his physical and also his etheric organisms are part and parcel of this outer world. On the other hand, he is deeply sensible—it is a feeling that is bound to arise in every healthy-minded person—that his dignity as man would not be fully attained if freedom were not an integral element in his life between birth and death. Necessity and freedom are the polar opposites in his life.

You are aware that in the age of natural science—the subject with which I am dealing in another course of lectures1The Birth of Natural Science in World-History and Its Subsequent Development. Course of 9 lectures given at Dornach from 24th December, 1922 to 6th January, 1923. here there is a strong tendency to extend the sway of necessity that is everywhere in evidence in external Nature, to whatever originates in the human being himself, and many representative scientists have come to regard freedom as an impossibility, an illusion that exists only in the human soul, because when a man is faced with having to make a decision, reasons for and reasons against it work upon him. These reasons themselves are, however, under the sway of necessity; hence—so say these scientists—it is really not the man who makes the decision but whatever reasons are the more numerous and the weightier. They triumph over the other less numerous and less weighty reasons, which also affect him. Man is therefore carried along helplessly by the victors in the struggle between impulses that work upon him of necessity. Many representatives of this way of thinking have said that a man believes himself to be free only because the polarically opposite reasons for and against any decision he may be called upon to make, present such complications in their totality that he does not notice how he is being tossed hither and thither; one category of reasons finally triumphs; one scale in a delicately poised balance is weighed down and he is carried along in accordance with it.

Against this argument there is not only the ethical consideration that the dignity of man would not be maintained in a world where he was merely a plaything of conflicting yes-and-no impulses, but there is also this fact, that the feeling of freedom in the human will is so strong that an unbiased person has no sort of doubt that if he can be misled as to its existence, he can equally well be misled by the most elementary sense-perceptions. If the elementary experience of freedom in the sphere of feeling could prove to be deceptive, so too could the experience of red, for instance, or of C or C sharp and so on. Many representatives of modern natural scientific thought place such a high value upon theory that they allow the theory of a natural necessity which is absolute, has no exceptions and embraces human actions and human will, to tempt them into disregarding altogether an experience such as the sense of freedom!

But this problem of necessity and freedom, with all the phenomena associated with it in the life of soul—and these phenomena are very varied and numerous—is a problem linked with much more profound aspects of universal existence than are accessible to natural science or to the everyday experience of the human soul. For at a time when man's outlook was quite different from what it is today, this disquieting, perplexing problem was already a concern of his soul.

You will have gathered from the other course of lectures now being given here that the natural scientific thinking of the modern age is by no means so very old. When we go back to earlier times we find views of the world that were as one-sidedly spiritual as they have become one-sidedly naturalistic today. The farther back we go, the less of what is called ‘necessity’ do we find in man's thinking. Even in early Greek thought there was nothing of what we today call necessity, for the Greek idea of necessity had an essentially different meaning. But if we go still farther back we find, instead of necessity, the working of forces, and these, in their whole compass, were ascribed to a divine-spiritual Providence. Expressing myself rather colloquially, I would say that to a modern scientific thinker, the Nature-forces do everything; whereas the thinker of olden times conceived of everything being done by spiritual forces working with purposes and aims as man himself does, only with purposes far more comprehensive than those of man could ever be. Yet even with this view of the world, entirely spiritual as it was, man turned his attention to the way in which his will was subject to divine-spiritual forces; and just as today, when his thinking is in line with natural science he feels himself subject to the forces and laws of Nature, so in those ancient times he felt himself subject to divine-spiritual forces and laws. And for many who in those days were determinists in this sense, human freedom, although it is a direct experience of the soul, was no more valid than it is for our modern naturalists. These modern naturalists believe that necessity works through the actions of men; the men of olden times thought that divine-spiritual forces, in accordance with their purposes, work through human actions.

It is only necessary to recognize that the problem of freedom and necessity exists in these two completely opposite worlds of thought to realize that quite certainly no examination of the surface-aspect of conditions and happenings can lead to any solution of this problem which penetrates so deeply into all life and into all evolution.

We must look more deeply into the process of world-evolution—world-evolution as the course of Nature on the one side and as the unfolding of spirit on the other—before it is possible to grasp the whole meaning and implications of a problem as vital as this; insight can indeed only come from anthroposophical thinking.

The course of Nature is usually studied in an extremely restricted way. Isolated happenings and processes of a highly specialized kind are studied in the laboratories, brought within the range of telescopes or subjected to experiment. This means that observation of the course of Nature and of world-evolution is confined within very narrow limits. And those who study the domain of soul and spirit imitate the scientists and naturalists. They fight shy of taking into account the whole man when they are considering his life of soul. Instead of this they specialize in order to accentuate some particular thought or sentient experience with important bearings, and hope in this way eventually to build up a psychology, just as efforts are made to build up a body of knowledge of the physical world out of single observations and experiments conducted in chemical and physical laboratories, in clinics and so forth.

Yet in reality these studies never lead to any comprehensive understanding either of the physical world or of the world of soul-and-spirit. As little as it is the intention here to disparage the justification of these specialized investigations—for they are justified from points of view often referred to in my lectures—as strongly it must be emphasized that unless the world itself, unless Nature herself reveals to man somewhere or other what results from the interworking of the details, he will never be able to build up from his single observations and experiments a picture of the structure of the world that is confirmed by the actual happenings. Liver cells and minute activities of the liver, brain-cells and minute cerebral processes can be investigated and greater and greater specialization may take place in these domains; but these investigations, because they lead to particularization and not to the whole, will give no help towards forming a view of the human organism in its totality, unless from the very beginning a man has a comprehensive, intuitive idea of this totality to help him in forming the separate investigations into a unified whole. In like manner, as long as chemistry, astro-chemistry, physics, astro-physics, biology, restrict themselves to the investigation of isolated details, they will never be able to give a picture of how the different forces and laws in our world-environment work together to form a whole, unless man develops the faculty of perceiving in Nature outside something similar to what can be seen as the totality of the human organism, in which all the separate processes of liver, kidneys, hearts, brain, and so forth, are included. In other words, we must be able to point to something in the universe in which all the forces we behold in our environment work together to form a self-contained whole.

Now it may be that certain processes in the human liver and human brain will not for a long time to come be detected with enough accuracy to be accepted by biology. But at all events, as long as men have been able to look at other men, they have always said: The processes of liver, stomach, heart, etc. work together within the boundary of the skin to form a whole. Without being obliged to look at each and all of the separate details, we have before us the sum-total of the chemical, physical and biological processes belonging to man's nature.

Is it possible also to have before us as a complete whole the sum-total of the forces and laws of Nature that are at work around us? In a certain way it is possible. But in order not to be misunderstood I must emphasize the fact that such totalities are always relative. For instance, we can group together the processes of the outer ear and then have a relative whole. But we can also group together the processes in that part of the organ of hearing which continues on to the brain and then we have another relative whole; taking the two groups together, we have another, greater whole, which in turn belongs to the head, and this again to the whole organism. And it will be just the same when we try to comprehend in one complete picture the laws and forces that come primarily into consideration for man.

A first complete whole of this kind is the cycle of day and night. Paradoxical as this seems at first hearing, in this cycle of day and night a number of natural laws around us are gathered together into one whole. During the course of a day and night, processes are going on in our environment and penetrating through us which, if separated out, prove to be physical and chemical processes of every possible different kind. We can say: The cycle of the day is a time-organism, a time-organism embracing a number of natural processes which can be studied individually.

A greater ‘totality’ is the course of the year. If we review all the changes which affect the earth and mankind during the course of the year in the sphere surrounding us—in the atmosphere, for example—we shall find that all the processes taking place in the plants and also in the minerals from one Spring to the next, form in their time-sequence an organic whole, although otherwise they reveal themselves to us and also to different scientific investigations as separate phenomena. They form a whole, just as the processes taking place in the liver, kidneys, spleen and so forth form a whole in the human organism. The course of the year is actually an organic whole—the expression is not quite exact but words of some kind have to be used—the year is an organic sum-total of occurrences and facts which it is customary in natural science to investigate singly.

Speaking in what sounds a rather trivial way, but you will realize that the meaning is very profound, we might say: if man is to avoid having to surrounding Nature the very abstract relationship he adopts to descriptions of chemical and physical experiments, or to what is often taught today in botany and zoology, the time-organisms of the course of the day and the course of the year must become realities for him—realities of cosmic existence. He will then find in them a certain kinship with his own constitution.

Let us begin by thinking of the cycle of the year. Reviewing it as we did in the lecture before Christmas, we find a whole series of processes in the sprouting, growing plants which first produce leaves and, later on, blossoms. An incalculable number of natural processes reveal themselves from the life in the root, on into the life in the green leaves and in the colored petals. And we have an altogether different kind of process before us when we see, in Autumn, the fading, withering and dying of outer Nature.

The cosmic happenings around us form an organic unity. In Summer we see how the Earth opens out all her organs to the Cosmos and how her life and activities rise towards the cosmic expanse. This applies not only to the plant world but to the animal world too in a certain sense—especially to the lower animals. Think of all the activity in the insect world during the Summer, how this activity seems to rise up from the Earth and is given over to the Cosmos, especially to the forces coming from the Sun. During Autumn and Winter we see how everything that from the time of Spring onwards reached out towards the cosmic expanse, falls back again into the earthly realm, how the Earth as it were gradually increases her hold upon all growing life, brings it to the stage of apparent death, or at least to a state of sleep—how the Earth closes all her organs against the influences of the Cosmos. Here we have two contrasting processes in the course of the year, embracing countless details but nevertheless representing a complete whole.

If with the eyes of the soul we contemplate this yearly cycle, which can be regarded as a complete whole because from a certain point it simply repeats itself, recurring in approximately the same way, we find in it nothing else than Nature-necessity. And in our own earthly lives we human beings follow this Nature-necessity. If our lives followed it entirely we should be completely under its domination. Now it is certainly true that those forces of Nature which come especially into consideration for us as Earth-dwellers are present in the course of the year; for the Earth does not change so quickly that the minute changes taking place from year to year make themselves noticeable during a man's life, however old he may live to be.—So by living each year through Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter, we partake with our own bodies in Nature-necessity.

It is important to think in this way, for it is only actual experience that gives knowledge; no theory ever does so. Every theory starts from some special domain and then proceeds to generalize. True knowledge can only be acquired when we start from life and from experience. We must not therefore consider the laws of gravity by themselves, or the laws of plant life, or the laws of animal instinct, or the laws of mental coercion, because if we do, we think only of their details, generalize them, and then arrive at entirely false conclusions. We must have in mind where the Nature-forces are revealed in their cooperation and mutual interaction—and that is in the cyclic course of the year.

Now even supervisial study shows that man is relatively free in his relation to the course of the year, but Anthroposophy shows this even more clearly. In Anthroposophy we turn our attention to the two alternating conditions in which every human being lives during the 24 hours of the day, namely, the sleeping state and the waking state. We know that during the waking state the physical, etheric and astral bodies and the Ego-organism form a relative unity in the human being. In the sleeping state the physical and etheric bodies remain behind in the bed, closely interwoven, and the Ego and the astral body are outside the physical and etheric bodies.

If with the means provided by anthroposophical research—of which you will have read in our literature—we study the physical and etheric bodies of man during sleep and during waking life, the following comes to light. When the Ego and the astral body are outside the physical and etheric organism during sleep, a kind of life begins in the latter which is to be found in external Nature in the mineral and plant kingdoms only. And the reason why the physical and etheric organisms of man do not gradually pass over into a sum-total of plant or mineral processes is simply due to the fact that the Ego and astral body are within them for certain periods. If the return of the Ego and astral body were too long delayed, the physical and etheric bodies would pass over into a mineral and vegetative form of life. As it is, a tendency to become vegetative and mineralized commences in man after he falls asleep, and this tendency has the upper hand during sleeping life.

If with the insight afforded by anthroposophical research, we contemplate the human being while he is asleep, we see in him—of course with the inevitable variations—a faithful copy of what the Earth is throughout Spring and Summer. Mineral and vegetative life begins to bud in him, although naturally in quite a different way from what happens in the green plants which grow out of the Earth. Nevertheless, with one variation, what goes on during sleep in the physical and etheric organism of man is a faithful image of the period of Spring and Summer on the Earth. In this respect, the organism of man of the present epoch is in tune with external Nature. His physical eyes can survey it. He beholds its sprouting, budding life. As soon as he attains to Inspiration and Imagination, a picture of Summer is revealed to him when physical man is asleep. In sleep, Spring and Summer are there for the physical and etheric bodies of man. A budding, sprouting life begins. And when we wake, when the Ego and astral body returns, all this budding life in the physical and etheric bodies withdraws and for the eye of seership, life in the physical and etheric organism begins to be very similar to the life of the Earth during Autumn and Winter. When we follow the human being through one complete period of sleeping and waking life, we have before us in miniature an actual microcosmic reflection of Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. If we follow man's physical and etheric organism through a period of 24 hours, contemplating it in the light of Spiritual Science, we pass, in the microcosmic sense, through the course of a year. Accordingly, if we consider only that part of man which remains behind in the bed when he is asleep or moves around when he is awake during the day, we can say that the course of the year is completed microcosmically in him.

But now let us consider the other part of man's being which releases itself in sleep—the Ego and astral body. If again we use the kinds of knowledge available in spiritual investigation, namely Inspiration and Intuition, we shall find that the Ego and astral body are given over while man is asleep to spiritual Powers within which they will not, in the normal condition, be able to live consciously until a later epoch of the Earth's existence. From the time of going to sleep until the time of waking, the Ego and astral body are withdrawn from the world just as the Earth is withdrawn from the Cosmos during Winter. During sleep, Ego and astral body are actually in their Winter period. So that in the being of man during sleep there is an intermingling of conditions which are only present at one and the same time on opposite hemispheres of the Earth's surface; for during sleep man's physical and etheric bodies have their Summer and his Ego and astral body their Winter.

During waking life, conditions are reversed. The physical and etheric organism is then in its Winter period. The Ego and astral body are given over to what can stream from the Cosmos to man in his waking state. So when the Ego and astral body come down into the physical and etheric organism, they (i.e. Ego and astral body) have their Summer period. Once more we have the two seasons side by side, but now Winter in the physical and etheric organism, Summer in the Ego and astral body.

On the Earth, Summer and Winter cannot be intermingled. But in man, the microcosm, Summer and Winter intermingle all the time. When man is asleep his physical Summer mingles with spiritual Winter; when he is awake his physical Winter mingles with spiritual Summer. In external Nature, Summer and Winter are separated in the course of the year. In man, Summer and Winter mingle all the time from two different directions. In external Nature on Earth, Winter and Summer follow one another in time. In the human being, Winter and Summer are simultaneous, only they interchange, so that at one time there is Spirit-Summer together with Body-Winter (waking life), and at another, Spirit-Winter together with Body-Summer (sleeping life).

Thus the laws and forces in external Nature around us cannot neutralize each other in any one region of the Earth, because they work in sequence, the one after the other in time; but in man they do neutralize each other. The course of Nature is such that just as through two opposing forces a state of rest can be brought about, so can an untold number of natural laws neutralize and cancel out each other. This happens in the human being with respect to all laws of external Nature, inasmuch as he sleeps and wakes in the regular way. The two conditions which appear as Nature-necessity only when they succeed each other in time, are coincident and consequently neutralized in man—and it is this that makes him a free being.

Freedom can never be understood until it is realized how the Summer and Winter forces of man's spiritual life can neutralize the Summer and Winter forces of his outer physical and etheric nature.

External Nature presents to us pictures which we must not see in ourselves, either in the waking or in the sleeping state. On no account must this happen. On the contrary, we must say that these pictures of the course and order of Nature lose their validity within the constitution of man, and we must turn our gaze elsewhere. For when the course of Nature within the human being no longer disturbs us, it becomes possible for the first time to gaze at man's spiritual, moral and psychic make-up. And then we begin to have an ethical and moral relationship to him, just as we have a corresponding relationship to Nature.

When we contemplate our own being with the aid of knowledge acquired in this way, we find, telescoped into one another, conditions which in the external world are spread across the stream of time. And there are many other things of which the same could be said. If we contemplate our inner being and understand it rightly in the sense I have indicated today, we bring it into a relationship with the course of time different from the one to which we are accustomed today.

The purely external mode of scientific observation does not reach the stage where the investigator can say: In the being of man you must hear sounding together what can only be heard as separate tones in the flow of Time.—But if you develop spiritual hearing, the tones of Summer and Winter can be heard ringing simultaneously in man, and they are the same tones that we hear in the outer world when we enter into the flow of Time itself. Time becomes Space. The whole surrounding universe also resounds to us in Time: expanded widely in Space, there ring forth what resounds from our own being as from a centre, gathered as it were, in a single point.

This is the moment, my dear friends, when scientific study and contemplation becomes artistic study and contemplation: when art and science no longer stand in stark contrast as they do in our naturalistic age, but when they are interrelated in the way sensed by Goethe when he said that art reveal; those secrets of Nature without which we can never fully understand her. From a certain point onwards it is imperative that we should understand the form and structure of the world as artistic creation. And once we have taken the path from the purely scientific conception of the world to artistic understanding, we shall also be ready to take the third step, which leads to a deepening of religious experience.

When we have found the physical forces and the forces of soul-and-spirit working together in the inner centre of our being, we can also behold them in the Cosmos. Human willing rises to the level of artistic creative power and finally achieves a relationship to the world that is not merely passive knowledge but positive, active surrender. Man no longer looks at the world abstractly, with the forces of his head, but his vision becomes more and more an activity of his whole being. Living together with the course of cosmic existence becomes a happening different in character from his connection with the facts and events of everyday life. It becomes a ritual, a cult, and the cosmic ritual comes into being in which man can have his place at every moment of his life. Every earthly cult and ritual is a symbolic image of this cosmic cult and ritual—which is higher and more sublime than all earthly cults.

If what has been said today has been thoroughly grasped, it will be possible to study the relationship of the anthroposophical outlook to any particular religious cult. And this will be done during the next few days, when we shall consider the relationship between Anthroposophy and different forms of cult.

Zehnter Vortrag

In den Vorträgen, die ich unmittelbar vor Weihnachten hier gehalten habe, war es gegeben, auf den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem ganzen Kosmos hinzuweisen, insbesondere auch auf das, was den Kosmos als geistig-seelische Mächte durchwebt und durchlebt. Ich möchte in einer gewissen Art wiederum heute an das Damalige anknüpfen in einer allerdings davon unabhängigen, selbständigen Betrachtung.

Das menschliche Leben, so wie es durchgemacht wird als Miterleben der Natur und als inneres Leben der menschlichen Seele und des menschlichen Geistes, steht zwischen zwei Polen, und eine große Anzahl von Gedanken, die sich die Menschen über ihren Zusammenhang mit der Welt machen müssen, wird von dem Ausblick auf diese zwei polarischen Gegensätze beeinflußt.

Auf der einen Seite steht vor dem menschlichen Denken und Empfinden die sogenannte Naturnotwendigkeit. Der Mensch fühlt sich abhängig und muß sich abhängig fühlen von den notwendig, man möchte sagen ehern wirkenden Gesetzen, die er überall draußen in der Welt findet, und die dadurch, daß sein physischer und auch sein ätherischer Organismus in diese Außenwelt eingeschaltet sind, auch durch ihn hindurchgehen.

Auf der andern Seite lebt dann in demMenschen dieEmpfindung -und in jeder gesunden Menschennatur muß sich diese Empfindung einstellen -, daß des Menschen Würde nicht voll erfüllt wäre, wenn ihm nicht in seinem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod die Freiheit zukäme. Das sind die beiden polarischen Gegensätze: Notwendigkeit und Freiheit.

Sie wissen, wie sehr das naturwissenschaftliche Zeitalter, das ich in der andern Klasse von Vorträgen bespreche, die ich jetzt zu geben habe, wie sehr dieses naturwissenschaftliche Zeitalter die Notwendigkeit des Geschehens, die man draußen überall in der Natur findet, auch auf alles dasjenige ausdehnt, was vom Menschen selbst ausgeht, und wie es in vielen seiner Vertreter nach und nach dazu gekommen ist, Freiheit als etwas Unmögliches zu betrachten, als eine Illusion, die nur dadurch in der Menschenseele lebt, daß der Mensch, wenn er mit seinem Willen vor eine Entscheidung hingestellt wird, auf der einen Seite die Gründe für, auf der andern Seite die Gründe dagegen hat, die mit Notwendigkeit von beiden Seiten aus auf ihn wirken. Und eigentlich ist es nicht er nach dieser Anschauung, der die Entscheidung trifft, sondern zuletzt sind es doch diejenigen Gründe, welche die stärkste Kraft und die stärkste Summe repräsentieren. Sie siegen über die andern Gründe, die auch mit einer gewissen Notwendigkeit auf den Menschen wirken, die aber geringere Kraft und eine geringere Summe haben. Und der Mensch wird einfach mitgerissen, möchte man sagen, von der Resultierenden der mit Notwendigkeit auf ihn wirkenden Impulse. Daß er sich für frei hält - so sagen viele Vertreter dieser Anschauung -, rührt nur davon her, daß die einander entgegengesetzten polarischen Ja- und Nein-Gründe in ihrer Gesamtheit etwas so Kompliziertes darstellen, daß der Mensch nicht merkt, wie er hin- und hergerissen wird, und wie zuletzt sozusagen in feinem Waagebalkenausschlag die eine Kategorie der Gründe siegt und er eben von dieser mitgerissen wird.

Demgegenüber steht aber nicht nur die ethische Erwägung, daß des Menschen Würde in der Welt nicht erfüllt wäre, wenn er also ein Spielball der Ja- und Nein-Impulse wäre, sondern es steht dem gegenüber, daß im menschlichen Wollen das Freiheitsgefühl lebt, daß für den Unbefangenen es eigentlich ganz zweifellos ist, daß, wenn er durch irgendeine Theorie an diesem Freiheitsgefühl irre werden muß, er eigentlich ebensogut an den einfachen elementaren Sinnesempfindungen irre werden müßte. Wenn das ganz elementare in der menschlichen Gefühlssphäre vorhandene Freiheitserlebnis trügen könnte, so könnte auch trügen das Rot-Erlebnis, das Cis- oder C-Erlebnis und so weiter. Und es ist immerhin charakteristisch, daß die neuere naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung in vielen ihrer Vertreter das Theoretische so hochschätzt, daß sie sich durch das Theoretische von der absoluten, ausnahmslosen Naturnotwendigkeit, die auch die menschlichen Handlungen, den menschlichen Willen umfassen soll, dazu versuchen läßt, einfach über eine Erfahrung, wie sie das Freiheitserlebnis darstellt, hinwegzugehen.

Aber diese Frage, Notwendigkeit und Freiheit, mit allen ihren Begleiterscheinungen im seelischen Leben — und die sind außerordentlich reichlich -, ist eine solche, die mit viel Tieferem im Weltenlaufe zusammenhängt als mit dem, was naturwissenschaftlich oder auch in der unmittelbaren alltäglichen menschlichen Seelenerfahrung zu finden ist. Denn als die menschliche Anschauung noch ganz anders war, war schon diese bange Zweifelsfrage vor die menschliche Seele getreten.

Sie haben gesehen aus der andern Klasse von Vorträgen, die ich hier zu halten habe, daß das eigentliche Naturdenken, das naturwissenschaftliche Denken der neueren Zeit, gar nicht so alt ist. Wenn wir in ältere Zeiten zurückgehen, so finden wir ein menschliches Denken, menschliche Anschauungen, die ebensosehr einseitig spirituell sind, wie die heutigen Anschauungen einseitig naturalistisch geworden sind. Wir finden, je mehr wir in ältere Epochen zurückgehen, wie immer weniger im menschlichen Anschauen gerade das vorhanden ist, was wir heute Naturnotwendigkeit nennen. Auch im älteren griechischen Anschauen war nichts von dem vorhanden, was wir heute Naturnotwendigkeit nennen, denn die griechische Notwendigkeit war in ihrem eigentlichen Gedankentimbre doch etwas ganz anderes.

Aber wenn wir noch weiter zurückgehen, so finden wit, daß an der Stelle der Naturnotwendigkeit ganz und gar Kräftewirkungen stehen, Wirkungen, die dem ganzen Umfange nach einer göttlich-geistigen Vorsehung zugeschrieben werden. Heute, wenn ich mich trivial ausdrücken darf, machen für den eigentlich naturwissenschaftlich Denkenden alles die Naturkräfte, einstmals machten für den Denker der alten Zeiten alles geistig gedachte Kräfte, die mit Absichten wirkten, wie der Mensch selber mit Absichten wirkt, nur daß deren Absichten weit umfassender waren, als es die menschlichen Absichten sein können. Aber auch innerhalb dieser Weltanschauung, die ganz spirituell war, wendete der Mensch seinen Blick hin auf die Bestimmung seines Willens durch göttlich-geistige Mächte, und wie er sich heute durch Naturkräfte und Naturgesetze determiniert fühlt, wenn er im naturwissenschaftlichen Sinne denkt, so fand er sich dereinst durch göttlich-geistige Kräfte oder göttlich-geistige Gesetze determiniert. Und für viele, die in diesem älteren spiritualistischen Sinne deterministisch gesinnt waren, galt die Freiheit des Menschen, trotzdem sie ein unmittelbares Erlebnis ist, ebensowenig wie für die heutigen Naturalisten. Heute denken die Naturalisten: durch das menschliche Handeln hindurch wirkt die Naturnotwendigkeit. Dazumal dachten die Spiritualisten: durch das menschliche Handeln hindurch wirken die göttlich-geistigen Kräfte nach ihren Absichten.

Man braucht sich einfach nur vorzuhalten, wie auf diesen völlig entgegengesetzten Anschauungswelten die Frage nach Freiheit und Notwendigkeit daliegt, und man wird sich sagen: An der Oberfläche der Dinge und der Geschehnisse kann ganz gewiß nichts ausgemacht werden über diese tief in alles Leben und allen Weltenlauf hineindringende Frage. - Man muß schon in dasjenige, was Weltenlauf ist Weltenlauf auf der einen Seite als Naturlauf, Weltenlauf auf der andern Seite als Geistesentfaltung -, tiefer hineinblicken, wie es nur mit anthroposophischer Anschauungsweise möglich ist, um überhaupt auf den ganzen Sinn dieser den Menschen aufrüttelnden Frage zu kommen.

Nun betrachtet man gewöhnlich den Naturlauf in einer außerordentlich eingeschränkten Weise. Heute wird der Naturlauf so betrachtet, daß man versucht, herausgerissene Geschehnisse, herausgerissene Vorgänge speziellster Art in das Beobachtungszimmer, ja wohl gar in das Blickfeld des Teleskops zu bringen oder dem Experimente zu unterwerfen, und man steht damit innerhalb eines ganz engen Gebietes, auf das man die Beobachtung des Naturlaufes, des Weltenlaufes überhaupt beschränkt. Man möchte sagen, diejenigen, die das Geistige und Seelische betrachten, machen es den Naturbeobachtern nach. Man scheut sich davor, die Totalität des Menschen in bezug auf sein seelisches Leben ins Auge zu fassen. Man «spezialisiert» sich, um irgendeinen einzelnen Gedanken oder Gefühlsfetzen mit kleinen Beziehungen herzustellen, und man hofft, daß man aus solchen kleinen Beziehungen ebenso einmal eine Psychologie zusammenstellen werde, wie man versucht, eine Art Weltanschauung des Physischen aus den Einzelbeobachtungen und Einzelexperimenten zu gewinnen, die man im physikalisch-chemischen Kabinett, in der Klinik und dergleichen vollführt.

Aber alle diese Betrachtungen führen eigentlich in Wirklichkeit niemals zu einer Gesamtauffassung, weder auf physischem noch auf geistig-seelischem Gebiet. Und so wenig als hier gegen die Berechtigung dieser Spezialuntersuchungen irgend etwas gesagt werden soll sie sind von den Gesichtspunkten aus berechtigt, die ich in meinen Vorträgen oftmals angeführt habe -, so stark muß aber doch betont werden: wenn die Natur, wenn die Welt nicht selbst irgendwo dem Menschen vorführt, was aus dem Zusammenwirken der Einzelheiten hervorgeht, dann wird der Mensch niemals sich ein vom Weltengeschehen durchleuchtetes Weltengebäude aus seinen Einzelbeobachtungen und Einzelexperimenten zusammenstellen können.

Geradeso wie man Leberzellen und kleine Lebervorgänge, wie man Gehirnzellen und kleine Gehirnvorgänge untersuchen kann, wie man sich nach diesen Richtungen immer mehr spezialisieren kann, und wie man aus diesen Untersuchungen, weil sie geradezu in die Vereinzelung und nicht in das Ganze hineinführen, niemals eine Anschauung über die Gesamtheit des menschlichen Organismus gewinnen kann, wenn man nicht von vornherein in einer geistig umfassenden, empfindenden Idee diese Gesamtheit, diese Totalität des menschlichen Organismus vor sich hat, um dann mit ihrer Hilfe eben wiederum die einzelnen Untersuchungen zu einem Ganzen zu machen, ebensowenig werden jemals Chemie oder Astrochemie, Physik oder Astrophysik oder Biologie, insofern sie sich auf Einzeluntersuchungen beschränken, ein Bild davon geben können, wie die verschiedenen, in unserer Weltenumgebung lebenden Naturkräfte und Naturgesetze zu einem Ganzen zusammenwirken, wenn nicht die Fähigkeit in dem Menschen entsteht, etwas Ähnliches draußen in der Natur zu schauen, wie man es gegenüber den Einzelheiten, den Lebervorgängen, den Nierenvorgängen, den Herzvorgängen, den Gehirnvorgängen, in der Totalität des menschlichen Organismus schauen kann. Es hängt einfach davon ab, daß man irgendwo im Weltenwesen etwas aufzeigen kann, wo alle die Kräfte, die uns in unserer Umgebung erscheinen, zu einer geschlossenen Totalität zusammenwirken.

Nicht wahr, wir können sagen: Vielleicht werden gewisse Vorgänge in der menschlichen Leber, im menschlichen Gehirn erst in sehr später Zeit so entdeckt werden, daß man daran eine biologische Befriedigung hat. - Aber jedenfalls kann man und konnte man immer, solange Menschen Menschen angeschaut haben, sagen: Dasjenige, was in der Leber, was im Magen, was im Herzen in gegenseitiger Wechselwirkung steht, wirkt innerhalb der menschlichen Hautgrenze zu dem menschlichen Ganzen zusammen. Man hat einmal, ohne daß man nötig hat, auf die Einzelheiten hinzuschauen, in reiner Totalität das Zusammenwirken alles desjenigen vor sich, was für die menschliche Natur in Betracht kommt an chemischen, an physischen, an biologischen Wirkungen, man hat das in einem geschlossenen Ganzen vor sich.

Kann man so auch in einem geschlossenen Ganzen die Summe der Naturkräfte und Naturgesetze vor sich haben, die um den Menschen herum wirken? Man kann es in einer gewissen Weise. Ich betone ausdrücklich noch, damit ich nicht mißverstanden werde, daß natürlich solche Totalitäten immer relativ sind, daß wir auch, sagen wir, im Menschen die Vorgänge unseres äußeren Ohres zusammenfassen können und dann ein relatives Ganzes haben. Wir können aber auch die Vorgänge der Fortsetzung des Gehörorgans nach dem Gehirn hin zusammenfassen und haben da auch ein relatives Ganzes. Fassen wir beide zusammen, so haben wir ein größeres relatives Ganzes, das wiederum dem Kopf und dieser wiederum dem ganzen Organismus angehört. So wird es auch sein, wenn wir versuchen, die Gesamtheit im Menschlichen, als für den Menschen zunächst in Betracht kommende Kräfte und Gesetze, in einer Totalanschauung zu umfassen.

Nun, ich möchte sagen, eine solche erste Totalanschauung ist der Tageslauf. So paradox das für das erste Hören klingt: es ist der Tageslauf in einer gewissen Beziehung eine Zusammenfassung einer gewissen Summe von Naturgesetzen um uns herum in diesem Ganzen. Während des Tageslaufes gehen einfach in unserer Umgebung und durch uns hindurch Prozesse vor sich, welche, wenn man sie auseinanderlegt, in die verschiedensten physikalischen und chemischen Prozesse und so weiter zerfallen. Man kann sagen, eine Art Zeitorganismus ist der Tageslauf, ein Zeitorganismus, der in sich eine Summe von Naturprozessen faßt, die wir sonst im einzelnen studieren können.

Und eine größere Totalität ist der Jahreslauf. Wenn Sie nämlich zum Jahreslauf übergehen und alles ins Auge fassen, was während des Jahreslaufes mit der Erde und der Menschheit zusammenhängend im äußeren Sphärenbereich an Veränderungen geschieht - nehmen wir nur an im Luftkreise -, wenn Sie alles das zusammenfassen, was vom Frühling bis wieder zum Frühling an Vorgängen in den Pflanzen und auch in den Mineralien geschieht, dann haben Sie eine zeitlich organische Zusammenfassung von dem, was Ihnen sonst zerstreut bei den verschiedenen Naturuntersuchungen erscheint, so wie wir im menschlichen Organismus eine Zusammenfassung haben der Leber-, Nieren-, Milzvorgänge und so weiter. Es ist in der Tat der Jahreslauf eine organische Summierung — es ist nicht genau gesprochen, aber man muß eben Worte gebrauchen - von dem, was wir sonst im einzelnen naturwissenschaftlich untersuchen.

Man möchte sagen, etwas leichthin, aber es ist etwas sehr Tiefes damit gemeint, wie Sie fühlen werden: Damit der Mensch nicht jenes abstrakte Verhältnis zur Naturumgebung hat, das er zu den Beschreibungen der physikalischen und chemischen Experimente hat, oder zu dem, was ihm heute vielfach in der Pflanzenlehre oder Tierlehre gesagt wird, müssen ihm im Kosmos der Tageslauforganismus, der Jahreslauforganismus vorgestellt werden. Da findet er gewissermaßen seinesgleichen. - Und daß er seinesgleichen findet, das wollen wir ein wenig betrachten.

Gehen wit zunächst auf den Jahreslauf ein. Wir haben, wenn wir ihn in einer ähnlichen Weise überblicken, wie das schon das letzte Mal vor Weihnachten geschehen ist, eine Summe von Prozessen in den sprießenden, sprossenden Pflanzen, die zu den grünen Laubblättern, später zu den Blüten hineilen. Wir haben eine unermeßliche Summe von Naturprozessen, die sich vom Leben in der Wurzel zum Leben in den grünen Laubblättern abspielen, zum Leben in den farbigen Blumenblättern. Und wir haben wiederum eine ganz andere Art von Prozessen, wenn wir im Herbste das Welken, das Abdorren und Hinsterben der äußeren Natur sehen. Wir haben wirklich zusammengefaßt in eine organische Einheit das um uns herumliegende Weltengeschehen. Wir sehen, wenn wir den Sommer durchmachen, was auf der Erde herauswächst, einschließlich der tierischen Welt, insbesondere der niederen Tierwelt. Betrachten Sie das Wirken und Wimmeln der Insektenwelt, wie das gewissermaßen sich von der Erde abhebt, wie es hingegeben ist dem Kosmos, namentlich alldem, was in der Sonnenwirkung aus dem Kosmos sich zusammensetzt. Wir sehen da, wie die Erde gewissermaßen alle ihre Organe den Weltenweiten öffnet und wie dadurch auch die aufsteigenden Prozesse aus der Erde hervorkommen und nach den Weltenweiten hin tendieren. Wir sehen, wie vom Herbste an und durch den Winter hindurch dasjenige, was vom Frühling an aufsprießt und nach den Weltenweiten strebt, wiederum ins Irdische zurückfällt, wie die Erde, ich möchte sagen, immer mehr Gewalt bekommt über alles, was sprießendes, sprossendes Leben ist, wie sie dieses sprießende, sprossende Leben gewissermaßen in eine Art Scheintod bringt, wenigstens in einen Schlaf hüllt, wie also die Erde all ihre Organe schließt gegenüber den Einflüssen der kosmischen Weiten. Wir sehen hier zwei Gegensätze im Jahreslauf, die unermeßlich viele Einzelheiten in sich haben, die aber in sich ein geschlossenes Ganzes darstellen.

Und wenn wir den seelischen Blick über einen solchen Jahreslauf hinschweifen lassen, der schon dadurch ein geschlossenes Ganzes darstellt, daß er einfach von einem bestimmten Punkte an sich wiederholt, wiederum in einer annähernd gleichen Weise abläuft, dann finden wir, daß in ihm nichts anderes ist als Naturnotwendigkeit. Und wir Menschen machen im Erdenlauf diese Naturnotwendigkeit mit. Machten wir sie ganz mit, dann wären wir dieser Naturnotwendigkeit auch unbedingt unterworfen. Nun sind gewiß in dem Jahreslauf zunächst diejenigen Naturkräfte und Naturmächte vorhanden, die für uns Menschen als Erdenbürger in Betracht kommen, denn die Erde ändert sich nicht so schnell. Wir werden auch zu andern Kreisläufen in den nächsten Tagen noch kommen, aber die Erde ändert sich nicht so schnell, daß sich etwa während eines Menschenlebens, wenn der Mensch auch noch so alt wird, die kleinen Veränderungen, die von Jahr zu Jahr auftreten, bemerkbar machen. Wir machen also jedes Jahr, indem wir im Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter drinnenstehen, mit unserem eigenen Leibe die Naturnotwendigkeit mit.

So muß man betrachten, denn nur die wirkliche Erfahrung gibt Erkenntnis. Keine Theorie gibt Erkenntnis. Jede Theorie geht von irgendeinem speziellen Gebiete aus und verallgemeinert dieses Gebiet. Wirkliche Erkenntnisse bekommt man nur, wenn man vom Leben und von Erfahrungen ausgeht. Man muß daher nicht vereinzelt die Gesetze der Gravitation, die Gesetze des vegetabilischen Lebens, die Gesetze der tierischen Instinkte, die Gesetze des menschlichen Gedankenzwanges ins Auge fassen, denn die faßt man dann immer in ihren Einzelheiten ins Auge, verallgemeinert sie und kommt dann zu ganz falschen Verallgemeinerungen. Man muß das ins Auge fassen, wo sich die Naturkräfte in ihrem wechselweisen Zusammenwirken zeigen. Das ist der Jahreslauf.

Nun zeigt schon eine oberflächliche Betrachtungsweise, daß der Mensch eine relative Freiheit gegenüber dem Jahreslauf hat. Aber eine anthroposophische Betrachtungsweise zeigt das noch stärker. Bei dieser anthroposophischen Betrachtungsweise wenden wir den Blick hin auf die zwei Wechselzustände, in denen jeder Mensch innerhalb vierundzwanzig Stunden lebt: auf den Schlafzustand und auf den Wachzustand. Und wir wissen: während des Wachzustandes sind physischer Leib, ätherischer Leib, astralischer Leib und Ich-Organismus eine relative Einheit im Menschen. Im Schlafzustand bleiben im Bette zurück physischer Leib und ätherischer Leib im innigen Durcheinanderweben, und außerhalb des physischen und ätherischen Leibes sind das Ich und der astralische Leib. Wenn wir nun mit all den Mitteln, die uns anthroposophische Forschung gibt und die Sie aus unserer Literatur kennen, darauf hinschauen, was dieser physische Leib und der ätherische Organismus des Menschen im Schlafe und was sie im Wachen sind, dann ergibt sich das Folgende.

Wenn das Ich und der astralische Leib außer dem physischen und ätherischen Organismus sind, dann beginnt im physischen und ätherischen Organismus ein Leben, das wir äußerlich mit der Natur nur im mineralischen und im pflanzlichen Gebiete verwirklicht sehen. Mineralisches und pflanzliches Leben für sich beginnt da. Daß der physische Organismus und der ätherische Organismus des Menschen nicht allmählich überhaupt nur in eine Summe von Prozessen übergehen, die mineralisch und pflanzlich sind, rührt nur davon her, daß sie so organisiert sind, wie das dem zeitweilig in ihm befindlichen astralischen Leib mit dem Ich entspricht. Sie würden in das mineralische und pflanzliche Leben übergehen, wenn der Mensch mit seinem Ich und seinem astralischen Leib zu spät in den physischen und Ätherleib zurückkäme. Es beginnt aber sogleich, nachdem der Mensch eingeschlafen ist, die Tendenz in ihm, mineralisch-vegetabilisch zu werden. Diese Tendenz bekommt die Oberhand während des Schlaflebens.

Wenn man mit den Mitteln der anthroposophischen Forschung hinschaut auf den schlafenden physischen Menschen, dann sieht man in diesem schlafenden Menschen - selbstverständlich mit der nötigen Variante - ein getreuliches Abbild desjenigen, was die Erde von der Frühlings- durch die Sommerszeit hindurch ist. Es sprießt und sproßt das Mineralisch-Pflanzliche heraus, allerdings in anderer Form, als das bei den grünen Pflanzen der Fall ist, die aus der Erde wachsen. Aber mit einer Variante, sage ich, ist dasjenige, was während des Schlafes im menschlichen physischen und ätherischen Organismus vor sich geht, ein getreuliches Abbild der Frühlings- und Sommerszeit der Erde. Für diese äußere Natur ist der Mensch der gegenwärtigen Weltenepoche organisiert. Er kann seinen physischen Blick über diese äußere Natur hinschweifen lassen. Er schaut das sprießende, sprossende Leben. In dem Augenblicke, wo sich der Mensch Inspiration und Imagination erwirbt, wird ihm einfach durch die Schlafenszeit des physischen Menschen der Anblick einer Sommerszeit enthüllt. Schlafen heißt: der Frühling und Sommer stellen sich ein für den physischen und Ätherleib. Sprießendes und sprossendes Leben beginnt.

Und wenn wir aufwachen, wenn das Ich und der astralische Leib wiederum zurückkehren, dann tritt all das sprießende und sprossende Leben des physischen und ätherischen Leibes zurück. Es beginnt für den geistsehenden Blick das Leben im physischen und ätherischen Organismus des Menschen dem Herbst- und Winterleben der Erde sehr ähnlich zu werden. Und man hat tatsächlich, wenn man den Menschen in einer Wachens- und Schlafensperiode hintereinander verfolgt, in kurzem ein mikrokosmisches Abbild von Herbst, Winter, Frühling, Sommer. Sie brauchen nur einen Menschen geisteswissenschaftlich vierundzwanzig Stunden hindurch als physischen und ätherischen Organismus zu verfolgen, und Sie machen einen Jahreslauf im Mikrokosmischen durch. So daß man sagen kann, wenn man bloß auf dasjenige vom Menschen schaut, was im Bette liegen bleibt oder bei Tag herumläuft: der Jahreslauf vollzieht sich mikrokosmisch.

Aber betrachten wir jetzt auf der andern Seite dasjenige, was sich im Schlafe trennt: das Ich und den astralischen Leib des Menschen. Da werden wir finden, wenn wir wiederum mit geisteswissenschaftlichen Forschungsmitteln, mit der Inspiration und Intuition vorgehen, daß, während der Mensch schläft, das Ich und der astralische Leib an geistige Mächte hingegeben sind, innerhalb welcher sie bewußt erst in einer späteren Erdenepoche im normalen Zustande werden leben können. Und wir werden sagen müssen: Während des Schlafens, vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen, sind das Ich und der astralische Leib der Welt so entzogen, wie die Erde während der Winterszeit den kosmischen Weiten entzogen ist. — Ich und astralischer Leib sind wirklich während des Schlafes in ihrer Winterszeit. So daß der Mensch während des Schlafes ineinandergemischt hat, was die Erde zunächst nur für ihre entgegengesetzten Kugeloberflächen hat: daß er nämlich in der Tat während des Schlafes in bezug auf sein physisches und ätherisches Wesen Sommerszeit und für sein Ich und astralisches Wesen Winterszeit hat.

Und umgekehrt ist es während des Wachens. Da haben der physische und ätherische Organismus Winterszeit. Das Ich und der astralische Organismus sind hingegeben demjenigen, was ihnen zunächst aus den kosmischen Weiten im wachen menschlichen Zustande entgegentreten kann. Tauchen also Ich und astralischer Leib in den physischen und ätherischen Leib unter, dann sind das Ich und der astralische Leib in der Sommerszeit. Wiederum sind nebeneinander Winterszeit im physisch-ätherischen Organismus, Sommerszeit im Ich und astralischen Organismus.

Wenn Sie die Erde nehmen: sie muß auch auf ihren verschiedenen Gebieten Sommer und Winter zugleich haben, die können Sie aber nicht ineinanderschieben. Im Menschen schieben sich fortwährend mikrokosmisch Sommer und Winter ineinander. Schläft der Mensch, so ist sein physischer Sommer mit dem geistigen Winter vermischt; wacht der Mensch, so ist sein physischer Winter mit dem geistigen Sommer vermischt. Der Mensch hat in der äußeren Natur im Jahreslauf getrennt Winter und Sommer; in sich vermischt er von zwei verschiedenen Seiten her fortwährend Winter und Sommer.

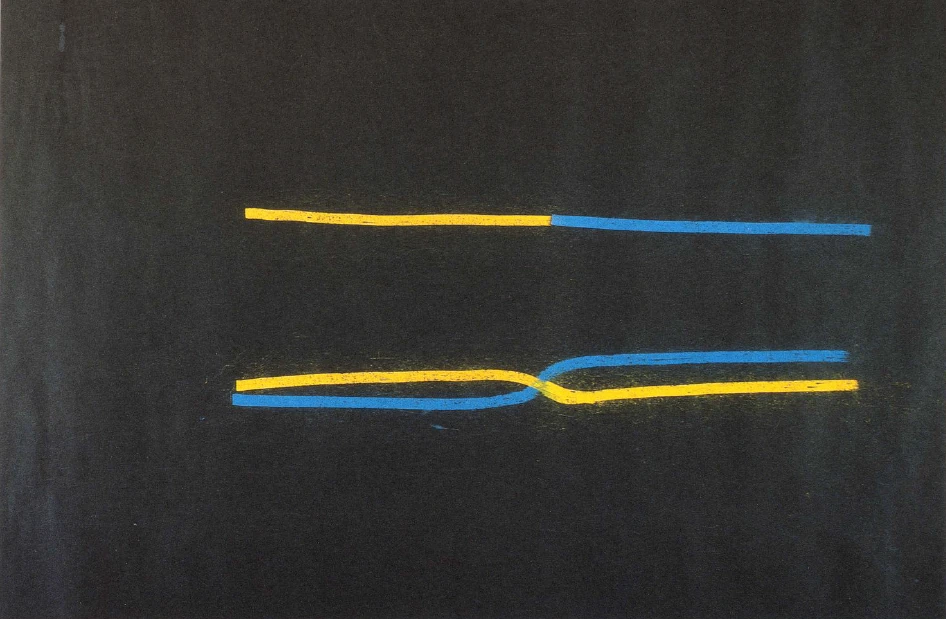

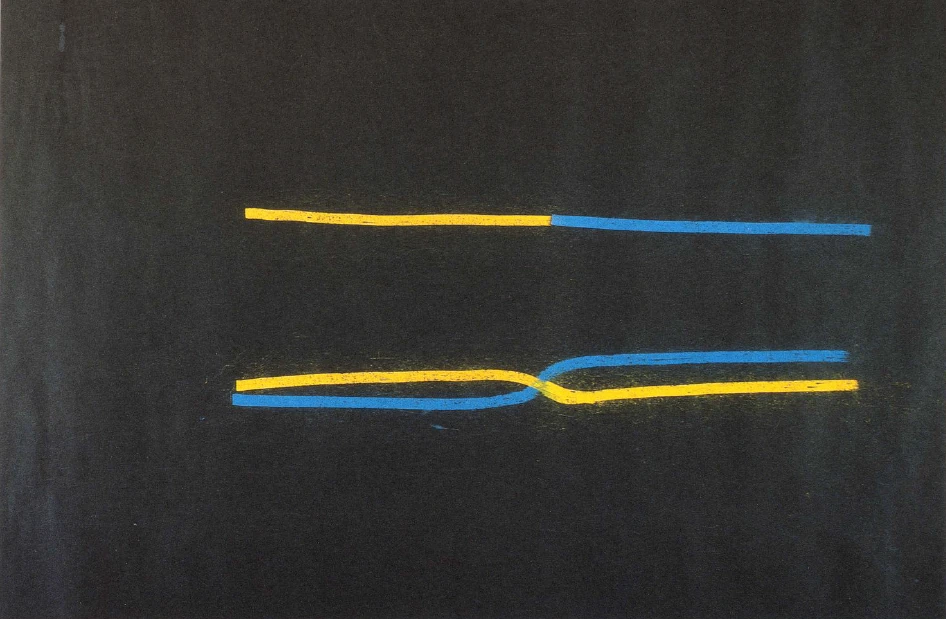

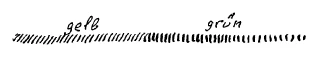

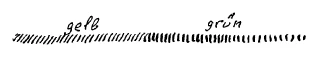

Ist es also im äußeren Naturlaufe so, daß, wenn ich schematisch zeichnen soll, Winterszeit und Sommerszeit nacheinander gezeichnet werden müssen für ein Erdgebiet, also zeitlich sich folgend, so muß ich für das menschliche Wesen diese beiden Strömungen nebeneinander zeichnen, allerdings in einer eigentümlichen Weise, ich muß sie so nebeneinander zeichnen:

Also beim menschlichen Wesen ist immer zugleich im Innern Winter und Sommer. Nur wechselt das eine Mal Geist-Sommer mit Körper-Winter, das andere Mal Geist-Winter mit Körper-Sommer.

Was wit also im äußeren Naturlaufe, diesem Kompendium der Naturkräfte und Naturgesetze, in unserer Umgebung so haben, daß es sich für ein Erdgebiet nicht neutralisieren kann, weil es nacheinander wirkt, das neutralisiert sich im menschlichen Wesen, hebt sich da auf. Der Naturlauf ist ein solcher, daß geradeso, wie durch zwei entgegengesetzte Kräfte eine Ruhelage hervorgebracht werden kann, sich auch Unsummen von Naturgesetzmäßigkeiten neutralisieren, aufheben können. Das geschieht im Menschen mit Bezug auf alle äußeren Naturgesetze dadurch, daß er in der gesetzmäßigen Weise schläft und wacht, wie er es eben tut.

Weil sich im Menschen also dasjenige, was nur als Naturnotwendigkeit erscheint, wenn es in der Zeit auseinandergelegt wird, ineinanderschiebt, neutralisiert, macht ihn das zum freien Wesen. Daher gibt es kein Verständnis der Freiheit, wenn der Mensch nicht versteht, wie zu seiner physisch-ätherischen Außennatur, in der Sommer und Winter sein kann, jeweilig die entgegengesetzten Winter und Sommer seines geistigen Lebens neutralisierend hinzukommen.

Sie sehen also, wenn wir in die äußere Natur schauen, bekommen wir Bilder, die wir gar nicht in uns hineinschauen dürfen, weder in den Wach- noch in den Schlafzustand. Wir dürfen sie gar nicht in uns hineinschauen, sondern wir müssen uns sagen: Innerhalb der Menschennatur verlieren diese Bilder des Naturlaufes ihre Gültigkeit, und wir müssen auf etwas anderes hinschauen. -— Und wenn uns der Naturlauf innerhalb der Menschennatur nicht mehr stört, bekommen wir die Möglichkeit, auf des Menschen geistig-moralisch-seelische Wesenheit erst recht hinzuschauen. Wir bekommen auf dieselbe Weise ein ethisches, ein moralisches Verhältnis zum Menschen, wie wir zu der Natur ein natürliches Verhältnis bekommen.

Wenn wir mit so gewonnenen Erkenntnissen uns selbst anschauen — es gibt noch vieles andere, das in einer ähnlichen Weise charakterisiert werden kann -, dann bekommen wir ineinandergeschoben, was in dem Zeitenlauf ausgebreitet ist. Schauen wir hinein in unser Inneres, verstehen wir dieses Innere richtig in dem heute dargestellten Sinne, so bringen wir es anders in das Verhältnis zum Zeitenlaufe, als man das heute gewohnt ist.

Die bloß äußerlich-wissenschaftliche Betrachtungsweise schwingt sich nicht dazu auf, sich zu sagen: Wenn du in den Menschen hineinschaust, mußt du zusammenklingend empfinden dasjenige, was im Zeitenlauf nur als einzelne Töne empfunden werden kann. Entwickelst du das geistige Ohr, so klingen im Menschen zusammen in einem Augenblicke die Sommer- und Wintertöne, die man draußen in der Welt hört, wenn man in den Zeitenlauf selber eintritt. - Die Zeit wird wirklich zum Raume. Der Weltenumkreis, auch der Zeit nach, tönt uns entgegen, auseinandergezogen in die Weiten dasjenige, was aus uns selber herausklingt wie aus einem Zentrum, wie in einem Punkte gesammelt.

Da tritt in der Tat der Moment ein, wo wissenschaftliche Betrachtung in künstlerische Betrachtung einmündet, wo Kunst und Wissenschaft einander nicht mehr gegenüberstehen so, wie das im naturalistischen Zeitalter der Fall ist, sondern wo sie sich so gegenüberstehen, wie es zum Beispiel auch, wenn auch in einer nicht sehr starken Nuance, Goethe empfunden hat, indem er sagte: Die Kunst eröffnet eine Art Naturgeheimnisse, ohne die man die Natur niemals vollständig versteht. - Man muß die künstlerische Weltengestaltung verstehen von einem gewissen Punkte an. Und hat man einmal diesen Weg gemacht aus der bloßen begriffswissenschaftlichen Gestaltung zum Kunsterkennen hin, dann macht man auch den dritten Schritt, den zur religiösen Vertiefung.

Hat man in sich im Zentrum die physischen und seelischen und geistigen Weltenkräfte zusammenwirkend gefunden, schaut man sie draußen in den Weltenweiten. Das menschliche Wollen erhebt sich zum künstlerischen Schaffen und zuletzt zu einem solchen Verhältnisse zur Welt, das nicht bloß ein passives Erkennen ist, sondern das eine positive Hingabe ist, die ich so charakterisieren möchte, daß ich sage: Der Mensch sieht nicht mehr in abstrakter Weise mit den Kräften seines Kopfes in die Welt hinein, sondern er beginnt mehr und mehr mit seiner ganzen Wesenheit hineinzuschauen. Und das Zusammenleben mit dem Weltenlaufe wird ihm ein Geschehen von anderer Art als das Zusammenleben mit den Alltagstatsachen. Das Zusammenleben mit dem Weltenlauf wird ihm zum Kultus, und es entsteht der kosmische Kultus, in dem der Mensch in jedem Augenblicke seines Lebens darinnenstehen kann.

Von diesem kosmischen Kultus ist jeder Erdenkultus ein symbolisches Abbild. Dieser kosmische Kultus ist das Höhere gegenüber jedem Erdenkultus. Und wenn wir uns richtig durchdringen mit dem, was heute gesagt worden ist, haben wir die Möglichkeit gewonnen, das Verhältnis anthroposophischen Weltenausblickes zu irgendeinem religiösen Kultus zu betrachten. Und das werden wir in den nächsten Tagen tun: die Beziehungen der Anthroposophie zu den verschiedenen Kultusformen ein wenig ins Auge fassen.

Tenth Lecture

In the lectures that I gave here immediately before Christmas, it was given to point out the connection of the human being with the whole cosmos, in particular also to that which weaves through and lives through the cosmos as spiritual-soul powers. In a certain way, I would like to pick up on what I said back then, albeit in an independent, autonomous way.

Human life, as it is lived through as a co-experience of nature and as the inner life of the human soul and the human spirit, stands between two poles, and a large number of thoughts that people must have about their connection with the world are influenced by the view of these two polar opposites.

On the one hand, the so-called necessity of nature stands before human thought and feeling. Man feels himself dependent and must feel himself dependent on the necessary, one might say eternal, laws which he finds everywhere outside in the world and which, because his physical and also his etheric organism are involved in this outside world, also pass through him.

On the other hand, there lives in man the feeling - and in every healthy human nature this feeling must arise - that man's dignity would not be fully fulfilled if he were not granted freedom in his life between birth and death. These are the two polar opposites: Necessity and freedom.

You know how much the scientific age, which I am discussing in the other class of lectures I have to give now, how much this scientific age extends the necessity of events, which one finds everywhere in nature outside, to everything that emanates from man himself, and how, in many of its representatives, it has gradually come to regard freedom as something impossible, as an illusion that lives in the human soul only through the fact that man, when he is confronted with a decision with his will, has on the one side the reasons for, on the other side the reasons against, which act on him with necessity from both sides. And actually, according to this view, it is not he who makes the decision, but ultimately it is those reasons which represent the strongest force and the strongest sum. They triumph over the other reasons, which also act on the human being with a certain necessity, but which have less power and a smaller sum. And man is simply carried away, one would like to say, by the resultant of the impulses that act upon him with necessity. The fact that he believes himself to be free - so say many proponents of this view - only stems from the fact that the opposing polar yes and no reasons in their totality represent something so complicated that man does not realize how he is being torn back and forth, and how in the end one category of reasons wins out in a fine balance, so to speak, and he is swept along by it.

On the other hand, however, there is not only the ethical consideration that man's dignity in the world would not be fulfilled if he were a plaything of yes and no impulses, but there is also the fact that the feeling of freedom lives in the human will, that for the unbiased it is actually quite clear that if he must be misled by some theory about this feeling of freedom, he would actually just as well be misled by the simple elementary sensations. If the very elementary experience of freedom existing in the human emotional sphere could be deceptive, then the red experience, the C sharp or C experience and so on could also be deceptive. And it is, after all, characteristic that the newer scientific world view in many of its representatives values the theoretical so highly that it allows itself to be tempted by the theoretical of the absolute, unexceptional necessity of nature, which is also supposed to encompass human actions, the human will, to simply pass over an experience such as the experience of freedom.

But this question, necessity and freedom, with all their accompanying phenomena in the life of the soul - and these are extraordinarily abundant - is one that is connected with much deeper things in the course of the world than with what can be found in the natural sciences or in the immediate everyday experience of the human soul. For when the human view was still quite different, this anxious question of doubt had already come before the human soul.

You have seen from the other class of lectures I have to give here that the actual thinking about nature, the scientific thinking of more recent times, is not so old. If we go back to older times, we find human thinking, human views that are just as one-sidedly spiritual as today's views have become one-sidedly naturalistic. The more we go back to older epochs, the less and less we find in human thinking precisely what we today call the necessity of nature. Even in the older Greek view there was nothing of what we today call natural necessity, because Greek necessity was something quite different in its actual thought-timbre.

But if we go even further back, we find that in the place of natural necessity there are entirely force effects, effects that are attributed in their entirety to a divine-spiritual providence. Today, if I may express myself trivially, for those who actually think in terms of natural science, everything is done by the forces of nature; once, for the thinkers of old, everything was done by spiritually conceived forces that worked with intentions, just as man himself works with intentions, only that their intentions were far more comprehensive than human intentions can be. But even within this world view, which was entirely spiritual, man turned his gaze to the determination of his will by divine-spiritual powers, and just as today he feels himself determined by natural forces and natural laws when he thinks in the scientific sense, so once he found himself determined by divine-spiritual forces or divine-spiritual laws. And for many who were deterministic in this older spiritualistic sense, the freedom of man, although it is an immediate experience, was no more valid than for today's naturalists. Today the naturalists think that the necessity of nature works through human action. Back then, the spiritualists thought that the divine-spiritual forces work through human action according to their intentions.

You only need to consider how the question of freedom and necessity lies on the surface of these completely opposing worlds of perception, and you will say to yourself: on the surface of things and events, nothing can certainly be made out about this question that penetrates deep into all life and all the course of the world. - One must look more deeply into that which is the course of the world - the course of the world on the one hand as the course of nature, the course of the world on the other hand as the unfolding of the spirit - as is only possible with an anthroposophical way of looking at things, in order to arrive at the whole meaning of this question which stirs man.

Now the course of nature is usually viewed in an extraordinarily limited way. Today, the course of nature is viewed in such a way that one attempts to bring events that have been torn out, processes of the most special kind into the observation room, indeed even into the field of vision of the telescope, or to subject them to experimentation, and one thus stands within a very narrow area to which one restricts the observation of the course of nature, of the course of the world in general. One might say that those who observe the spiritual and mental are imitating the observers of nature. They shy away from considering the totality of man in relation to his spiritual life. One “specializes” in order to produce some individual thought or fragment of feeling with small relationships, and one hopes that one will one day compile a psychology from such small relationships, just as one tries to gain a kind of world view of the physical from the individual observations and individual experiments carried out in the physico-chemical cabinet, in the clinic and the like.

But all these observations never actually lead to an overall view, neither in the physical nor in the spiritual-emotional field. And as little as anything is to be said here against the justification of these special investigations - they are justified from the points of view that I have often cited in my lectures - it must nevertheless be strongly emphasized: if nature, if the world itself does not show man somewhere what emerges from the interaction of the details, then man will never be able to put together a world structure illuminated by world events from his individual observations and individual experiments.

Just as one can study liver cells and small liver processes, just as one can study brain cells and small brain processes, just as one can specialize more and more in these directions, and just as one can never gain an insight into the whole from these investigations, because they lead to isolation and not to the whole, can never gain an insight into the totality of the human organism if one does not have this totality, this totality of the human organism before one in a spiritually comprehensive, sentient idea from the outset, in order to then, with its help, make the individual investigations into a whole, nor will chemistry or astrochemistry, physics or astrophysics or biology, insofar as they are limited to individual investigations, ever be able to give a picture of how the various natural forces and laws of nature living in our world environment work together to form a whole, unless the ability arises in man to see something similar outside in nature, as one can see it in relation to the details, the liver processes, the kidney processes, the heart processes, the brain processes, in the totality of the human organism. It simply depends on the fact that somewhere in the world being something can be shown where all the forces that appear to us in our environment work together to form a closed totality.

Not true, we can say: perhaps certain processes in the human liver, in the human brain, will only be discovered at a very late stage in such a way that we can derive biological satisfaction from them. - But in any case, one can and has always been able to say, as long as people have looked at people, that what interacts in the liver, what interacts in the stomach, what interacts in the heart, interacts within the human skin boundary to form the human whole. For once, without having to look at the details, we have before us in pure totality the interaction of everything that comes into consideration for human nature in terms of chemical, physical and biological effects; we have this before us in a closed whole.

Can one also have the sum of the forces and laws of nature that work around the human being in a closed whole? It is possible in a certain way. I emphasize explicitly, so that I am not misunderstood, that of course such totalities are always relative, that we can also, let us say, summarize in man the processes of our outer ear and then have a relative whole. But we can also summarize the processes of the continuation of the auditory organ towards the brain and there we also have a relative whole. If we combine both, we have a larger relative whole, which in turn belongs to the head and this in turn belongs to the whole organism. It will also be the same if we try to encompass the totality of the human being, as the forces and laws that initially come into consideration for the human being, in a total view.

Now, I would like to say that such a first total view is the course of the day. As paradoxical as this may sound at first hearing, the course of the day is in a certain respect a summary of a certain sum of natural laws around us in this whole. During the course of the day, processes simply take place in our environment and through us, which, if you break them down, break down into the most diverse physical and chemical processes and so on. One can say that the course of the day is a kind of temporal organism, a temporal organism that contains within itself a sum of natural processes that we can otherwise study in detail.

And a greater totality is the course of the year. For if you turn to the course of the year and consider all the changes that take place in the outer spheres in connection with the earth and humanity during the course of the year - let us assume only in the air - if you summarize all the processes that take place in the plants and also in the minerals from spring until spring again, then you have a temporally organic summary of what otherwise appears to you scattered in the various studies of nature, just as in the human organism we have a summary of the processes of the liver, kidneys, spleen and so on. In fact, the course of the year is an organic summation - it is not exactly said, but one must use words - of what we otherwise examine in detail in the natural sciences.

One would like to say, somewhat lightly, but something very profound is meant by it, as you will feel: So that man does not have the abstract relationship to the natural environment that he has to the descriptions of physical and chemical experiments, or to what he is often told today in plant science or animal science, he must be introduced to the daily cycle organism, the annual cycle organism in the cosmos. There he finds his equal, so to speak. - And the fact that it finds its equal is something we want to look at a little.

First let us look at the course of the year. If we look at it in a similar way as we did last time before Christmas, we have a sum of processes in the sprouting, budding plants, which rush towards the green leaves and later towards the blossoms. We have an immeasurable sum of natural processes that take place from life in the roots to life in the green leaves, to life in the colorful petals. And again we have a quite different kind of process when we see the withering, withering and dying of outer nature in autumn. We have really summarized into an organic unity the world events around us. When we go through the summer, we see what grows out of the earth, including the animal world, especially the lower animal world. Look at the activity and teeming of the insect world, how it stands out, as it were, from the earth, how it is devoted to the cosmos, namely to everything that is composed of the cosmos in the effect of the sun. We see how the earth opens all its organs, so to speak, to the realms of the world and how, as a result, the ascending processes emerge from the earth and tend towards the realms of the world. We see how, from autumn onwards and through the winter, that which sprouts up from spring and strives towards the cosmic expanses falls back again into the earthly, how the earth, I would like to say, gains more and more power over everything that is sprouting, sprouting life, how it brings this sprouting, sprouting life into a kind of suspended animation, at least into a sleep, how the earth thus closes all its organs to the influences of the cosmic expanses. We see here two opposites in the course of the year, which have immeasurably many details in them, but which in themselves represent a unified whole.

And if we let the soul's gaze wander over such a course of the year, which already represents a closed whole by the fact that it simply repeats itself from a certain point onwards, again in approximately the same way, then we find that there is nothing else in it but natural necessity. And we humans participate in this natural necessity in the course of the earth. If we took part in it completely, then we would also be absolutely subject to this natural necessity. Now, in the course of the year, those forces and powers of nature are certainly present which are relevant to us humans as earthlings, for the earth does not change so quickly. We will also come to other cycles in the coming days, but the earth does not change so quickly that the small changes that occur from year to year become noticeable during a human life, no matter how old a person becomes. So every year, as we stand inside in spring, summer, fall and winter, we participate in the necessities of nature with our own bodies.

This is the way to look at it, because only real experience gives knowledge. No theory gives knowledge. Every theory starts from some special field and generalizes this field. Real knowledge can only be gained by starting from life and experience. It is therefore not necessary to consider the laws of gravitation, the laws of vegetable life, the laws of animal instincts, the laws of human mental compulsion in isolation, for one then always considers them in their details, generalizes them and then arrives at quite false generalizations. We must look at where the forces of nature show themselves in their alternating interaction. That is the course of the year.

Now even a superficial view shows that man has a relative freedom in relation to the course of the year. But an anthroposophical approach shows this even more strongly. In this anthroposophical approach we look at the two alternating states in which every human being lives within twenty-four hours: the sleeping state and the waking state. And we know that during the waking state the physical body, etheric body, astral body and ego-organism are a relative unity in the human being. In the sleeping state, the physical body and the etheric body remain in bed, intimately interwoven, and outside the physical and etheric bodies are the ego and the astral body. If we now look at what this physical body and the etheric organism of the human being are in sleep and what they are in waking, using all the means that anthroposophical research gives us and which you know from our literature, then the following results.

If the ego and the astral body are outside the physical and etheric organism, then a life begins in the physical and etheric organism that we see realized externally with nature only in the mineral and vegetable realms. Mineral and vegetable life begins there. The fact that the physical organism and the etheric organism of the human being do not gradually merge into a sum of mineral and vegetable processes is only due to the fact that they are organized in a way that corresponds to the astral body with the ego that is temporarily within it. They would pass over into mineral and vegetable life if the human being with his ego and his astral body were to return too late to the physical and etheric body. Immediately after the human being falls asleep, however, the tendency to become mineral-vegetable begins in him. This tendency gains the upper hand during sleep life.

If one looks at the sleeping physical human being with the means of anthroposophical research, then one sees in this sleeping human being - of course with the necessary variation - a faithful image of what the earth is from the spring through the summer time. The mineral-vegetable sprouts and shoots forth, albeit in a different form than is the case with the green plants that grow out of the earth. But with one variation, I say, that which takes place during sleep in the human physical and etheric organism is a faithful reflection of the spring and summer time of the earth. The human being of the present world epoch is organized for this outer nature. He can let his physical gaze wander over this outer nature. He sees the sprouting, sprouting life. At the moment when man acquires inspiration and imagination, the sight of a summer time is revealed to him simply through the sleeping time of the physical man. Sleeping means that spring and summer come to the physical and etheric body. Sprouting and budding life begins.

And when we wake up, when the ego and the astral body return, then all the sprouting and budding life of the physical and etheric body recedes. For the spirit-seeing eye, life in the physical and etheric organism of the human being begins to resemble the autumn and winter life of the earth. And if you follow the human being in a waking and sleeping period one after the other, you actually have a microcosmic image of fall, winter, spring and summer in a short time. You need only follow a human being spiritually and scientifically for twenty-four hours as a physical and etheric organism, and you will experience the course of a year in the microcosm. So that one can say, if one only looks at what remains of the human being lying in bed or walking around during the day: the course of the year takes place microcosmically.

But let us now look on the other side at that which separates itself in sleep: the ego and the astral body of man. There we will find, if we again proceed with spiritual-scientific means of research, with inspiration and intuition, that while the human being is asleep, the ego and the astral body are surrendered to spiritual powers within which they will only be able to live consciously in a normal state in a later earthly epoch. And we will have to say: During sleep, from falling asleep to waking up, the ego and the astral body are as withdrawn from the world as the earth is withdrawn from the cosmic expanses during wintertime. - The ego and the astral body are really in their winter time during sleep. So that man during sleep has mixed into one another what the earth initially has only for its opposite spherical surfaces: that he indeed has summertime during sleep in relation to his physical and etheric being and wintertime for his ego and astral being.

And the reverse is true during waking. There the physical and etheric organism have winter time. The ego and the astral organism are devoted to that which can initially confront them from the cosmic expanses in the waking human state. When the ego and the astral body submerge into the physical and etheric body, then the ego and the astral body are in summertime. Again, winter time is in the physical-etheric organism, summer time in the ego and astral organism.

If you take the earth: it must also have summer and winter at the same time in its different areas, but you cannot push them into one another. In the human being, summer and winter are constantly pushed into each other microcosmically. When man is asleep, his physical summer is mixed with the spiritual winter; when man is awake, his physical winter is mixed with the spiritual summer. In outer nature, man has separate winter and summer in the course of the year; within himself he continually mixes winter and summer from two different sides.

If it is therefore so in the outer course of nature that, if I am to draw schematically, winter time and summer time must be drawn one after the other for an earth area, therefore following each other in time, then I must draw these two currents next to each other for the human being, however in a peculiar way, I must draw them next to each other like this: