Fall and Redemption

GA 220

21 January 1923, Dornach

Translator Unknown

You have seen from these lectures that I feel duty bound to speak at this time about a consciousness that must be attained if we are to accomplish one of the tasks of the Anthroposophical Society. And to begin with today, let me point to the fact that this consciousness can only be acquired if the whole task of culture and civilization is really understood today from the spiritual-scientific point of view. I have taken the most varied opportunities to try, from this point of view, to characterize what is meant by the fall of man, to which all religions refer. The religions speak of this fall of man as lying at the starting point of the historical development of mankind; and in various ways through the years we have seen how this fall of man—which I do not need to characterize in more detail today—is an expression of something that once occurred in the course of human evolution: man's becoming independent of the divine spiritual powers that guided him.

We know in fact that the consciousness of this independence first arose as the consciousness soul appeared in human evolution in the first half of the fifteenth century. We have spoken again and again in recent lectures about this point in time. But basically the whole human evolution depicted in myths and history is a kind of preparation for this significant moment of growing awareness of our freedom and independence.

This moment is a preparation for the fact that earthly humanity is meant to acquire a decision-making ability that is independent of the divine spiritual powers. And so the religions point to a cosmic-earthly event that replaces the soul-spiritual instincts—which alone were determinative in what humanity did in very early times—with just this kind of human decision making. As I said, we do not want to speak in more detail about this now, but the religions did see the matter in this way: With respect to his moral impulses the human being has placed himself in a certain opposition to his guiding spiritual powers, to the Yahweh or Jehovah powers, let us say, speaking in Old Testament terms. If we look at this interpretation, therefore, we can present the matter as though, from a definite point in his evolution, man no longer felt that divine spiritual powers were active in him and that now he himself was active.

Consequently, with respect to his overall moral view of himself, man felt that he was sinful and that he would have been incapable of falling into sin if he had remained in his old state, in a state of instinctive guidance by divine spiritual powers. Whereas he would then have remained sinless, incapable of sinning, like a mere creature of nature, he now became capable of sinning through this independence from the divine spiritual powers. And then there arose in humanity this consciousness of sin: As a human being I am sinless only when I find my way back again to the divine spiritual powers. What I myself decide for myself is sinful per se, and I can attain a sinless state only by finding my way back again: to the divine spiritual powers.

This consciousness of sin then arose most strongly in the Middle Ages. And then human intellectuality, which previously had not yet been a separate faculty, began to develop. And so, in a certain way, what man developed as his intellect, as an intellectual content, also became infected—in a certain sense rightly—with this consciousness of sin. It is only that one did not say to oneself that the intellect, arising in human evolution since the third or fourth century A.D., was also now infected by the consciousness of sin. In the Scholastic wisdom of the Middle Ages, there evolved, to begin with, an ‘unobserved’ consciousness of sin in the intellect.

This Scholastic wisdom of the Middle Ages said to itself: No matter how effectively one may develop the intellect as a human being, one can still only grasp outer physical nature with it. Through mere intellect one can at best prove that divine spiritual powers exist; but one can know nothing of these divine spiritual powers; one can only have faith in these divine spiritual powers. One can have faith in what they themselves have revealed either through the Old or the New Testament.

So the human being, who earlier had felt himself to be sinful in his moral life—‘sinful’ meaning separated from the divine spiritual powers—this human being, who had always felt morally sinful, now in his Scholastic wisdom felt himself to be intellectually sinful, as it were. He attributed to himself an intellectual ability that was effective only in the physical, sense-perceptible world. He said to himself: As a human being I am too base to be able to ascent through my own power into those regions of knowledge where I can also grasp the spirit.

We do not notice how connected this intellectual fall of man is to his general moral fall. But what plays into our view of human intellectuality is the direct continuation of his moral fall.

When the Scholastic wisdom passes over then into the modern scientific view of the world, the connection with the old moral fall of man is completely forgotten. And, as I have often emphasized, the strong connection actually present between modern natural-scientific concepts and the old Scholasticism is in fact denied altogether. In modern natural science one states that man has limits to his knowledge, that he must be content to extend his view of things only out upon the sense-perceptible physical world. A Dubois-Reymond, for example, and others state that the human being has limits to what he can investigate, has limits to his whole thinking, in fact.

But that is a direct continuation of Scholasticism. The only difference is that Scholasticism believed that because the human intellect is limited, one must raise oneself to something different from the intellect—to revelation, in fact—when one wants to know something about the spiritual world.

The modern natural-scientific view takes half, not the whole; it lets revelation stay where it is, but then places itself completely upon a standpoint that is possible only if one presupposes revelation. This standpoint is that the human ability to know is too base to ascend into the divine spiritual worlds.

But at the time of Scholasticism, especially at the high point of Scholasticism in the middle of the Middle Ages, the same attitude of soul was not present as that of today. One assumed then that when the human being used his intellect he could gain knowledge of the sense-perceptible world; and he sensed that he still experienced something of a flowing together of himself with the sense-perceptible world when he employed his intellect. And one believed then that if one wanted to know something about the spiritual one must ascend to revelation, which in fact could no longer be understood, i.e., could no longer be grasped intellectually. But the fact remained unnoticed—and this is where we must direct our attention!—that spirituality flowed into the concepts that the Schoolmen, set up about the sense world. The concepts of the Schoolmen were not as unspiritual as ours are today. The Schoolmen still approached the human being with the concepts that they formed for themselves about nature, so that the human being was not yet completely excluded from knowledge. For, at least in the Realist stream, the Schoolmen totally believed that thoughts are given us from outside, that they are not fabricated from within. Today we believe that thoughts are not given from outside but are fabricated from within. Through this fact we have gradually arrived at a point in our evolution where we have dropped everything that does not relate to the outer sense world.

And, you see, the Darwinian theory of evolution is the final consequence of this dropping of everything unrelated to the outer sense world. Goethe made a beginning for a real evolutionary teaching that extended as far as man. When you take up his writing in this direction, you will see that he only stumbled when he tried to take up the human being. He wrote excellent botanical studies. He wrote many correct things about animals. But something always went wrong when he tried to take up the human being. The intellect that is trained only upon the sense world is not adequate to the study of man. Precisely Goethe shows this to a high degree. Even Goethe can say nothing about the human being. His teaching on metamorphosis does not extend as far as the human being. You know how, within the anthroposophical world view, we have had to broaden this teaching on metamorphosis, entirely in a Goethean sense, but going much further.

What has modern intellectualism actually achieved in natural science? It has only come as far as grasping the evolution of animals up to the apes, and then added on the human being without being able inwardly to encompass him. The closer people came to the higher animals, so to speak, the less able their concepts became to grasp anything. And it is absolutely untrue to say, for example, that they even understand the higher animals. They only believe that they understand them.

And so our understanding of the human being gradually dropped completely out of our understanding of the world, because understanding dropped out of our concepts. Our concepts became less and less spiritual, and the unspiritual concepts that regard the human being as the mere endpoint of the animal kingdom represent the content of all our thinking today. These concepts are already instilled into our children in the early grades, and our inability to look at the essential being of man thus becomes part of the general culture.

Now you know that I once attempted to grasp the whole matter of knowledge at another point. This was when I wrote The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity and its prelude Truth and Science although the first references are present already in my The Science of Knowing: Outline of an Epistemology Implicit in the Goethean World View written in the 1880's. I tried to turn the matter in a completely different direction. I tried to show what the modern person can raise himself to, when—not in a traditional sense, but out of free inner activity—he attains pure thinking, when he, attains this pure, willed thinking which is something positive and real, when this thinking works in him. And in The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity I sought, in fact, to find our moral impulses in this purified thinking.

So that our evolution proceeded formerly in such a way that we more and more viewed man as being too base to act morally, and we extended this baseness also into our intellectuality.

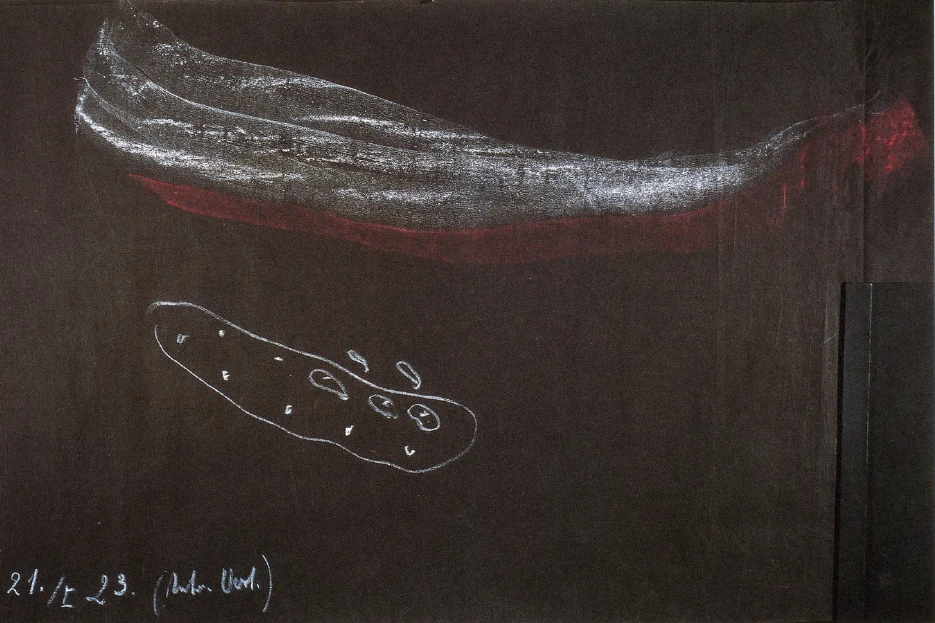

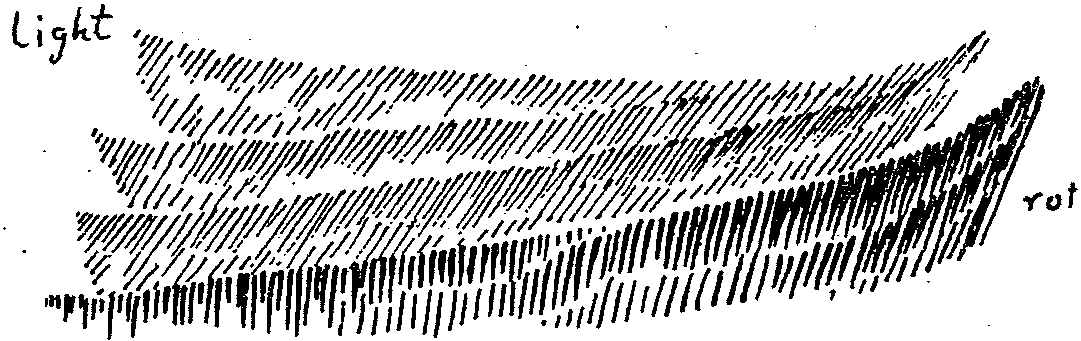

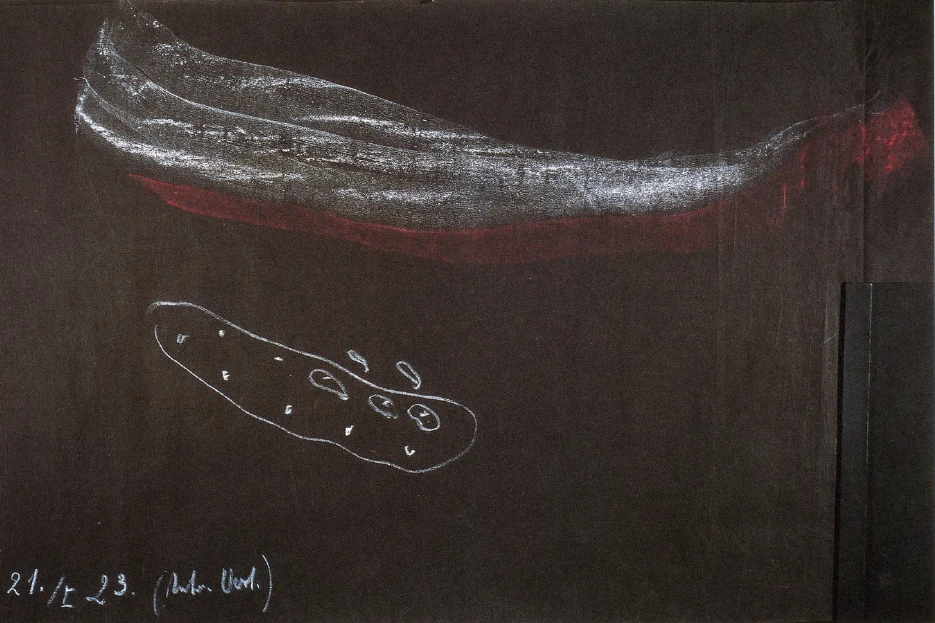

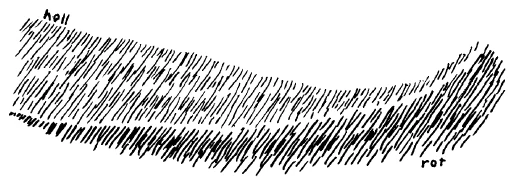

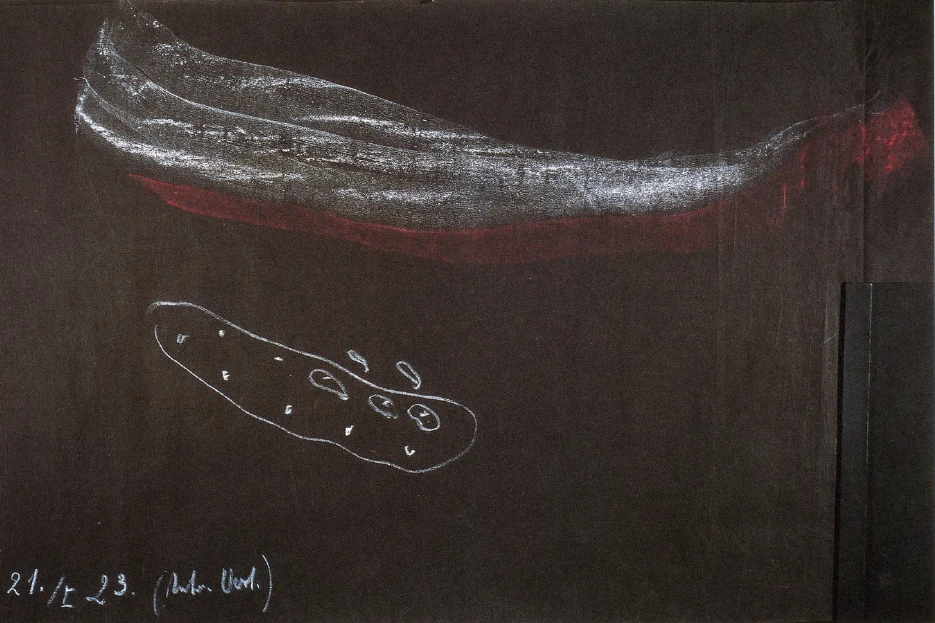

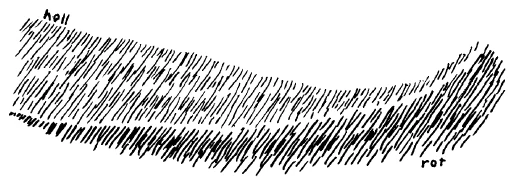

Expressing this graphically, one could say: The human being developed in such a way that what he knew about himself became less and less substantial. It grew thinner and thinner (light color). But below the surface, something continued to develop (red) that lives, not in abstract thinking, but in real thinking.

Now, at the end of the 19th century, we had arrived at the point of no longer noticing at all what I have drawn here in red; and through what I have drawn here in a light color, we no longer believed ourselves connected with anything of a divine spiritual nature. Man's consciousness of sin had torn him out of the divine spiritual element; the historical forces that were emerging could not take him back. But with The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity I wanted to say: Just look for once into the depths of the human soul and you will find that something has remained with us: pure thinking, namely, the real, energetic thinking that originates from man himself, that is no longer mere thinking, that is filled with experience, filled with feeling, and that ultimately expresses itself in the will. I wanted to say that this thinking can become the impulse for moral action. And for this reason I spoke of the moral intuition which is the ultimate outcome of what otherwise is only moral imagination. But what is actually intended by The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity can become really alive only if we can reverse the path that we took as we split ourselves off more and more from the divine spiritual content of the world, split ourselves off all the way down to intellectuality. When we again find the spirituality in nature, then we will also find the human being again.

I therefore once expressed in a lecture that I held many years ago in Mannheim that mankind, in fact, in its present development, is on the point of reversing the fall of man. What I said was hardly noticed, but consisted in the following: The fall of man was understood to be a moral fall, which ultimately influenced the intellect also. The intellect felt itself to be at the limits of its knowledge. And it is basically one and the same thing—only in a somewhat different form—if the old theology speaks of sin or if Dubois-Reymond speaks of the limits of our ability to know nature. I indicated how one must grasp the spiritual—which, to be sure, has been filtered down into pure thinking—and how, from there, one can reverse the fall of man. I showed how, through spiritualizing the intellect, one can work one's way back up to the divine spiritual.

Whereas in earlier ages one pointed to the moral fall of man and thought about the development of mankind in terms of this moral fall of man, we today must think about an ideal of mankind: about the rectifying of the fall of man along a path of the spiritualization of our knowing activity, along a path of knowing the spiritual content of the world again. Through the moral fall of man, the human being distanced himself from the gods. Through the path of knowledge he must find again the pathway of the gods. Man must turn his descent into an ascent. Out of the purely grasped spirit of his own being, man must understand, with inner energy and power, the goal, the ideal, of again taking the fall of man seriously. For, the fall of man should be taken seriously. It extends right into what natural science says today. We must find the courage to add to the fall of man, through the power of our knowing activity, a raising of man out of sin. We must find the courage to work out a way to raise ourselves out of sin, using what can come to us through a real and genuine spiritual-scientific knowledge of modern times.

One could say, therefore: If we look back into the development of mankind, we see that human consciousness posits a fall of man at the beginning of the historical development of mankind on earth. But the fall must be made right again at some point: It must be opposed by a raising of man. And this raising of man can only go forth out of the age of the consciousness soul. In our day, therefore, the historic moment has arrived when the highest ideal of mankind must be the spiritual raising of ourselves out of sin. Without this, the development of mankind can proceed no further.

That is what I once discussed in that lecture in Mannheim. I said that, in modern times, especially in natural-scientific views, an intellectual fall of man has occurred, in addition to the moral fall of man. And this intellectual fall is the great historical sign that a spiritual raising of man must begin.

But what does this spiritual raising of man mean? It means nothing other, in fact, than really understanding Christ. Those who still understood something about him, who had not—like modern theology—lost Christ completely, said of Christ that he came to earth, that he incarnated into an earthly body as a being of a higher kind. They took up what was proclaimed about Christ in written traditions. They spoke, in fact, about the mystery of Golgotha.

Today the time has come when Christ must be understood. But we resist this understanding of Christ, and the form this resistance takes is extraordinarily characteristic. You see, if even a spark of what Christ really is still lived in those who say that they understand Christ, what would happen? They would have to be clear about the fact that Christ, as a heavenly being, descended to earth; he therefore did not speak to man in an earthly language, but in a heavenly one. We must therefore make an effort to understand him. We must make an effort to speak a cosmic, extraterrestrial language. That means that we must not limit our knowledge merely to the earth, for, the earth was in fact a new land for Christ. We must extend our knowledge out into the cosmos. We must learn to understand the elements. We must learn to understand the movements of the planets. We must learn to understand the star constellations, and their influence on what happens on earth. Then we draw near to the language that Christ spoke.

That is something, however, that coincides with our spiritual raising of man. For why was man reduced to understanding only what lives on earth? Because he was conscious of sin, in fact, because he considered himself too base to be able to grasp the world in its extraterrestrial spirituality. And that is actually why people speak as though man can know nothing except the earthly. I characterized this yesterday by saying: We understand a fish only in a bowl, and a bird only in a cage. Certainly there is no consciousness present in our civilized natural science that the human being can raise himself above this purely earthly knowledge; for, this science mocks any effort to go beyond the earthly. If one even begins to speak about the stars, the terrible mockery sets in right away, as a matter of course, from the natural-scientific side.

If we want to hear correct statements about the relation of man to the animals, we must already turn our eye to the extraterrestrial world, for only the plants are still explainable in earthly terms; the animals are not. Therefore I had to say earlier that we do not even understand the apes correctly, that we can no longer explain the animals. If one wants to understand the animals, one must take recourse to the extraterrestrial, for the animals are ruled by forces that are extraterrestrial. I showed you this yesterday with respect to the fish. I told you how moon and sun forces work into the water and shape him out of the water, if I may put it so. And in the same way, the bird out of the air. As soon as one turns to the elements, one also meets the extraterrestrial. The whole animal world is explainable in terms of the extraterrestrial. And even more so the human being. But when one begins to speak of the extraterrestrial, then the mockery sets in at once.

The courage to speak again about the extraterrestrial must grow within a truly spiritual-scientific view; for, to be a spiritual scientist today is actually more a matter of courage than of intellectuality. Basically it is a moral issue, because what must be opposed is something moral: the moral fall of man, in fact.

And so we must say that we must in fact first learn the language of Christ, the language ton ouranon, the language of the heavens, in Greek terms. We must relearn this language in order to make sense out of what Christ wanted to do on earth.

Whereas up till now one has spoken about Christianity and described the history of Christianity, the point now is to understand Christ, to understand him as an extraterrestrial being. And that is identical with what we can call the ideal of raising ourselves from sin.

Now, to be sure, there is something very problematical about formulating this ideal, for you know in fact that the consciousness of sin once made people humble. But in modern times they are hardly ever humble. Often those who think themselves the most humble are the most proud of all. The greatest pride today is evident in those who strive for a so-called ‘simplicity’ in life. They set themselves above everything that is sought by the humble soul that lifts itself inwardly to real, spiritual truths, and they say: Everything must be sought in utter simplicity. Such naive natures—and they also regard themselves as naive natures—are often the most proud of all today. But nevertheless, during the time of real consciousness of sin there once were humble people; humility was still regarded as something that mattered in human affairs. And so, without justification, pride has arisen. Why? Yes, I can answer that in the same words I used here recently. Why has pride arisen? It has arisen because one has not heard the words “Huckle, get up!” [From the Oberufer Christmas plays.] One simply fell asleep. Whereas earlier one felt oneself, with full intensity and wakefulness, to be a sinner, one now fell into a gentle sleep and only dreamed still of a consciousness of sin. Formerly one was awake in one's consciousness of sin; one said to oneself: Man is sinful if he does not undertake actions that will again bring him onto the path to the divine spiritual powers. One was awake then. One may have different views about this today, but the fact is that one was awake in one's acknowledgment of sinfulness. But then one dozed off, and the dreams arrived, and the dreams murmured: Causality rules in the world; one event always causes the following one. And so finally we pursue what we see in the starry heavens as attraction and repulsion of the heavenly bodies; we take this all the way down into the molecule; and then we imagine a kind of little cosmos of molecules and atoms.

And the dreaming went further. And then the dream concluded by saying: We can know nothing except what outer sense experience gives us. And it was labeled ‘supernaturalism’ if anyone went beyond sense experiences. But where supernaturalism begins, science ends.

And then, at gatherings of natural scientists, these dreams were delivered in croaking tirades like Dubois-Reymond's Limits of Knowledge. And then, when the dream's last notes were sounded—a dream does not always resound so agreeably; sometimes it is a real nightmare—when the dream concluded with “Where supernaturalism begins, science ends,” then not only the speaker but the whole natural-scientific public sank down from the dream into blessed sleep. One no longer needed any inner impulse for active inner knowledge. One could console oneself by accepting that there are limits, in fact, to what we can know about nature, and that we cannot transcend these limits. The time had arrived when one could now say: “Huckle, get up! The sky is cracking!” But our modern civilization replies: “Let it crack! It's old enough to have cracked before!” Yes, this is how things really are. We have arrived at a total sleepiness, in our knowing activity.

But into this sleepiness there must sound what is now being declared by spiritual-scientific anthroposophical knowledge. To begin with, there must arise in knowledge the realization that man is in a position to set up the ideal within himself that we can raise ourselves from sin. And that in turn is connected with the fact that along with a possible waking up, pride—which up till now has only been present, to be sure, in a dreamlike way—will grow more than ever. And (I say this of course without making any insinuations) it has sometimes been the case that in anthroposophical circles the raising of man has not yet come to full fruition. Sometimes, in fact, this pride has reached—I will not say a respectable—a quite unrespectable size. For, it simply lies in human nature for pride to flourish rather than the positive side.

And so, along with the recognition that the raising of man is a necessity, we must also see that we now need to take up into ourselves in full consciousness the training in humility which we once exercised. And we can do that. For, when pride arises out of knowledge, that is always a sign that something in one's knowledge is indeed terribly wrong. For when knowledge is truly present, it makes one humble in a completely natural way. It is out of pride that one sets up a program of reform today, when in some social movement, let's say, or in the woman's movement one knows ahead of time what is possible, right, necessary, and best, and then sets up a program, point by point. One knows everything about the matter. One does not think of oneself at all as proud when each person declares himself to know it all. But in true knowledge, one remains pretty humble, for one knows that true knowledge is acquired only in the course of time, to use a trivial expression.

If one lives in knowledge, one knows, with what difficulty—sometimes over decades—one has attained the simplest truths. There, quite inwardly through the matter itself, one does not become proud. But nevertheless, because a full consciousness is being demanded precisely of the Anthroposophical Society for humanity's great ideal today of raising ourselves from sin, watchfulness—not Hucklism, but watchfulness—must also be awakened against any pride that might arise.

We need today a strong inclination to truly grasp the essential being of knowledge so that, by virtue of a few anthroposophical catchwords like ‘physical body,’ ‘etheric body,’ ‘reincarnation,’ et cetera, we do not immediately become paragons of pride. This watchfulness with respect to ordinary pride must really be cultivated as a new moral content. This must be taken up into our meditation. For if the raising of man is actually to occur, then the experiences we have with the physical world must lead us over into the spiritual world. For, these experiences must lead us to offer ourselves devotedly, with the innermost powers of our soul. They must not lead us, however, to dictate program truths. Above all, they must penetrate into a feeling of responsibility for every single word that one utters about the spiritual world. Then the striving must reign to truly carry up into the realm of spiritual knowledge the truthfulness that, to begin with, one acquired for oneself in dealing with external, sense-perceptible facts. Whoever has not accustomed himself to remaining with the facts in the physical sense world and to basing himself upon them also does not accustom himself to truthfulness when speaking about the spirit. For in the spiritual world, one can no longer accustom oneself to truthfulness; one must bring it with one.

But you see, on the one hand today, due to the state of consciousness in our civilization, facts are hardly taken into account, and, on the other hand, science simply suppresses those facts that lead onto the right path. Let us take just one out of many such facts: There are insects that are themselves vegetarian when fully grown. They eat no meat, not even other insects. When the mother insect is ready to lay her fertilized eggs, she lays them into the body of another insect, that is then filled with the eggs that the insect mother has inserted into it. The eggs are now in a separate insect. Now the eggs do not hatch out into mature adults, but as little worms. But at first they are in the other insect. These little worms, that will only later metamorphose into adult insects, are not vegetarian. They could not be vegetarian. They must devour the flesh of the other insect. Only when they emerge and transform themselves are they able to do without the flesh of other insects. Picture that: the insect mother is herself a vegetarian. She knows nothing in her consciousness about eating meat, but she lays her eggs for the next generation into another insect. And furthermore; if these insects were now, for example, to eat away the stomach of the host insect, they would soon have nothing more to eat, because the host insect would die. If they ate away any vital organ, the insect could not live. So what do these insects do when they hatch out? They avoid all the vital organs and eat only what the host insect can do without and still live. Then, when these little insects mature, they crawl out, become vegetarian, and proceed to do what their mother did.

Yes, one must acknowledge that intelligence holds sway in nature. And if you really study nature, you can find this intelligence holding sway everywhere. And you will then think more humbly about your own intelligence, for first of all, it is not as great as the intelligence ruling in nature, and secondly, it is only like a little bit of water that one has drawn from a lake and put into a water jug. The human being, in fact, is just such a water jug, that has drawn intelligence from nature. Intelligence is everywhere in nature; everything, everywhere is wisdom. A person who ascribes intelligence exclusively to himself is about as clever as someone who declares: You're saying that there is water out there in the lake or in the brook? Nonsense! There is no water in them. Only in my jug is there any water. The jug created the water.

So, the human being thinks that he creates intelligence, whereas he only draws intelligence from the universal sea of intelligence.

It is necessary, therefore, to truly keep our eye on the facts of nature. But facts are left out when the Darwinian theory is promoted, when today's materialistic views are being formulated; for, the facts contradict the modern materialistic view at every point. Therefore one suppresses these facts. One recounts them, to be sure, but actually aside from science, anecdotally. Therefore they do not gain the validity in our general education that they must have. And so one not only does not truly present the facts that one has, but adds a further dishonesty by leaving out the decisive facts, i.e., by suppressing them.

But if the raising of man is to be accomplished, then we must educate ourselves in truthfulness in the sense world first of all and then carry this education, this habitude, with us into the spiritual world. Then we will also be able to be truthful in the spiritual world. Otherwise we will tell people the most unbelievable stories about the spiritual world. If we are accustomed in the physical world to being imprecise, untrue, and inexact, then we will recount nothing but untruths about the spiritual world.

. You see, if one grasps in this way the ideal whose reality can become conscious to the Anthroposophical Society, and if what arises from this consciousness becomes a force in our Society, then, even in people who wish us the worst, the opinion that the Anthroposophical Society could be a sect will disappear. Now of course our opponents will say all kinds of things that are untrue. But as long as we are giving cause for what they say, it cannot be a matter of indifference to us whether their statements are true or not.

Now, through its very nature, the Anthroposophical Society has thoroughly worked its way out of the sectarianism in which it certainly was caught up at first, especially while it was still connected to the Theosophical Society. It is only that many members to this day have not noticed this fact and love sectarianism. And so it has come about that even older anthroposophical members who were beside themselves when the Anthroposophical Society was transformed from a sectarian one into one that was conscious of its world task, even those who were beside themselves have quite recently gone aside again. The Movement for Religious Renewal, when it follows its essential nature, may be ever so far removed from sectarianism. But this Movement for Religious Renewal has given even a number of older anthroposophists cause to say to themselves: Yes, the sectarian element is being eradicated more and more from the Anthroposophical Society. But we can cultivate it again here! And so precisely through anthroposophists, the Movement for Religious Renewal is being turned into the crassest sectarianism, which truly does not need to be the case.

One can see how, therefore, if the Anthroposophical Society wants to become a reality, we must positively develop the courage to raise ourselves again into the spiritual world. Then art and religion will flourish in the Anthroposophical Society. Although for now even our artistic forms have been taken from us [through the burning of the Goetheanum building on the night of December 31, 1922], these forms live on, in fact, in the being of the anthroposophical movement itself and must continually be found again, and ever again.

In the same way, a true religious deepening lives in those who find their way back into the spiritual world, who take seriously the raising of man. But what we must eradicate in ourselves is the inclination to sectarianism, for this inclination is always egotistical. It always wants to avoid the trouble of penetrating into the reality of the spirit and wants to settle for a mystical reveling that basically is an egotistical voluptuousness. And all the talk about the Anthroposophical Society becoming much too intellectual is actually based on the fact that those who say this want, indeed, to avoid the thoroughgoing experience of a spiritual content, and would much rather enjoy the egotistical voluptuousness of soulful reveling in a mystical, nebulous indefiniteness. Selflessness is necessary for true anthroposophy. It is mere egotism of soul when this true anthroposophy is opposed by anthroposophical members themselves who then all the more drive anthroposophy into something sectarian that is only meant, in fact, to satisfy a voluptuousness of soul that is egotistical through and through.

You see those are the things, with respect to our tasks, to which we should turn our attention. By doing so, we lose nothing of the warmth, the artistic sense, or the religious inwardness of our anthroposophical striving. But that will be avoided which must be avoided: the inclination to sectarianism. And this inclination to sectarianism, even though it often arrived in a roundabout way through pure cliquishness, has brought so much into the Society that splits it apart. But cliquishness also arose in the anthroposophical movement only because of its kinship—a distant one to be sure—with the sectarian inclination. We must return to the cultivation of a certain world consciousness so that only our opponents, who mean to tell untruths, can still call the Anthroposophical Society a sect. We must arrive at the point of being able to strictly banish the sectarian character trait from the anthroposophical movement. But we should banish it in such a way that when something arises like the Movement for Religious Renewal, which is not meant to be sectarian, it is not gripped right away by sectarianism just because one can more easily give it a sectarian direction than one can the Anthroposophical Society itself.

Those are the things that we must think about keenly today. From the innermost being of anthroposophy, we must understand the extent to which anthroposophy can give us, not a sectarian consciousness, but rather a world consciousness. Therefore I had to speak these days precisely about the more intimate tasks of the Anthroposophical Society.

Neunter Vortrag

Sie haben aus den vorherigen Andeutungen gesehen, daß es mir obliegt, in dieser Zeit über das Bewußtsein zu sprechen, das als eine von den Aufgaben der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft erobert werden muß. Und ich möchte heute zunächst darauf hindeuten, wie dieses Bewußtsein nur dadurch errungen werden kann, daß die ganze Kultur- und Zivilisationsaufgabe in der Gegenwart wirklich erfaßt wird vom geisteswissenschaftlichen Standpunkt aus. Bei den verschiedensten Gelegenheiten habe ich versucht, von diesem Standpunkt aus zu charakterisieren, was mit dem in allen Religionsbekenntnissen erwähnten Sündenfall der Menschheit gemeint ist. Die Religionsbekenntnisse sprechen von diesem Sündenfall, der im Ausgangspunkt der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit liegt, und wir haben durch die verschiedenen Auseinandersetzungen in den verflossenen Jahren gesehen, wie dieser Sündenfall, den ich ja heute nicht genauer zu charakterisieren brauche, ein Ausdruck ist für das, was einmal im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung eingetreten ist: das Selbständigwerden des Menschen gegenüber den ihn führenden göttlich-geistigen Mächten.

Wir wissen ja, daß das Bewußtsein von dieser Selbständigkeit erst eingetreten ist, als die Bewußtseinsseele in der Menschheitsentwikkelung sich zeigte, also mit der ersten Hälfte des 15. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts. Von diesem Zeitpunkt haben wir immer wieder und wiederum in den letzten Betrachtungen gesprochen. Aber im Grunde genommen ist die ganze, durch die Geschichte und durch die Mythen charakterisierte Menschheitsentwickelung eine Art von Vorbereitung für diesen wichtigen Moment des Bewußtwerdens des Menschen seiner Freiheit, seiner Selbständigkeit, eine Vorbereitung für die Tatsache, daß die Menschheit auf Erden dazu kommen soll, gegenüber den göttlich-geistigen Mächten eine selbständige Entschlußfähigkeit zu erringen. Und so weisen die Religionsbekenntnisse hin auf ein kosmisch-irdisches Ereignis, durch das die geistig-seelischen Instinkte, die in ganz alten Zeiten für das, was die Menschheit tat, allein maßgebend waren, abgelöst wurden eben durch diese freie Entschlußfassung des Menschen. Wie gesagt, wir wollen jetzt nicht davon sprechen, wie das im Genaueren aufzufassen ist — aber die Sache wird ja von den Religionsbekenntnissen so aufgefaßt, daß in bezug auf die moralische Impulsivität des Menschen dieser Mensch sich in einer gewissen Weise in Gegensatz gestellt hat gegenüber den führenden geistigen, sagen wir also, wenn wir mit dem Alten Testamente sprechen, gegenüber den Jahve- oder Jehova-Mächten. Es ist also zunächst die Sache so darzustellen, wenn wir auf diese Interpretation hinschauen, als ob der Mensch von einem bestimmten Zeitpunkt seiner Entwickelung an nicht mehr gefühlt hätte, daß in ihm die göttlich-geistigen Mächte tätig waren und daß er nun selber tätig war.

Damit ist dann eingetreten, mit Bezug auf die moralische Gesamtauffassung- des Menschen, daß er sich als sündig fühlte, während er unfähig gewesen wäre, in die Sünde zu verfallen, wenn er im alten Stande geblieben wäre, in dem Stande des instinktiven Geführtwerdens durch göttlich-geistige Mächte. Während er da unfähig zu sündigen, also sündlos geblieben wäre wie ein bloßes Naturgeschöpf, ist er fähig geworden zu sündigen durch dieses Selbständigwerden gegenüber den göttlich-geistigen Mächten. Und es trat dann in der Menschheit dieses Sündenbewußtsein auf: Ich als Mensch bin nur dann nicht sündig, wenn ich meinen Weg wiederum zurückfinde zu den göttlich-geistigen Mächten. Was ich durch mich selber beschließe, das ist als solches sündhaft, und ich kann nur die Sündlosigkeit erringen dadurch, daß ich den Weg zu den göttlich-geistigen Mächten wiederum zurückfinde.

Am stärksten ist dieses Sündenbewußtsein dann aufgetreten im Mittelalter. Und da begann auch die Intellektualität der Menschen, die eigentlich vorher noch nicht eine abgesonderte Fähigkeit war, sich zu entwickeln. So wurde gewissermaßen das, was der Mensch als Intellekt, als seinen intellektuellen Inhalt entwickelte, auch und zwar mit einem gewissen Recht - angesteckt von diesem Sündenbewußtsein. Nur sagte man es sich nicht, daß der Intellekt, der in der Entwickelung seit dem 3., 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert heraufkam, nun auch angesteckt ist von dem Sündenbewußtsein. Es entwickelte sich zunächst das unbemerkte Sündenbewußtsein des Intellektes in der scholastischen Weisheit des Mittelalters.

Diese scholastische Weisheit des Mittelalters sagte sich: Wenn man den Intellekt in noch so scharfsinniger Weise als Mensch entwickelt, so kann man durch ihn doch nur die äußere physische Natur auffassen. Man kann durch den bloßen Intellekt höchstens beweisen, daß es ein Dasein göttlich-geistiger Kräfte gibt; aber man kann nichts erkennen von diesen göttlich-geistigen Kräften, man kann nur an die göttlich-geistigen Kräfte glauben. Man kann an das glauben, was sie selbst, sei es durch das Alte oder das Neue Testament, geoffenbart haben.

Also der Mensch, der sich in früheren Zeiten sündhaft in bezug auf seine Moralität gefühlt hat - sündhaft aber heißt: abgesondert von den göttlich-geistigen Mächten -, dieser Mensch, der sich die Zeit über moralisch sündhaft gefühlt hat, fühlte sich gewissermaßen in der scholastischen Weisheit intellektuell sündhaft. Er schrieb sich nur die Fähigkeit zu, einen Intellekt zu haben für die physisch-sinnliche Welt. Er sagte sich: Ich bin als Mensch zu schlecht, um durch eigene Kraft hinaufzukommen in diejenige Region des Erkennens, wo ich auch den Geist erfassen kann. -— Man bemerkt nicht, wie abhängig dieser intellektuelle Sündenfall von dem allgemein moralischen Sündenfall ist. Es ist die direkte Fortsetzung des moralischen Sündenfalles, was da in die Auffassung der menschlichen Intellektualität hineinspielt.

Wenn dann die scholastische Weisheit übergeht in die moderne naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung, dann wird völlig vergessen der Zusammenhang mit dem alten moralischen Sündenfall, und es wird sogar geleugnet, wie ich oft betont habe, der intensiv vorhandene Zusammenhang der modernen naturwissenschaftlichen Begriffe mit der alten Scholastik. Und man redet in der neueren Naturwissenschaft davon, daß der Mensch Grenzen der Erkenntnis habe, daß er sich begnügen müsse, seine Anschauung nur über die sinnlich-physische Welt auszudehnen. Es redet ein Du Bois-Reymond davon, es reden andere davon, daß der Mensch Grenzen seiner Forschung, überhaupt seines ganzen Denkens habe.

Das ist aber eine direkte Fortsetzung der Scholastik. Der Unterschied ist nur der, daß die Scholastik angenommen hat: Wenn also der menschliche Intellekt begrenzt ist, so muß man sich zu etwas anderen erheben, als der Intellekt ist, nämlich zur Offenbarung, wenn man über die geistige Welt etwas wissen will. Die moderne naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung nimmt die Hälfte statt des Ganzen, läßt die Offenbarung bleiben wo sie ist, stellt sich aber dann ganz auf den Standpunkt, der nur, wenn man die Offenbarung voraussetzt, eine Möglichkeit hat - sie stellt sich auf den Standpunkt: Die menschliche Erkenntnisfähigkeit ist zu schlecht, um hinaufzukommen in die göttlich-geistigen Welten.

Nun war aber zur Zeit der Scholastik, namentlich zur Zeit der Hochblüte der Scholastik in der Mitte des Mittelalters, nicht solche Seelenverfassung vorhanden wie heute. Dazumal nahm man an: wenn der Mensch seinen Intellekt anwendet, dann kann er dadurch sich Erkenntnisse von der sinnlichen Welt verschaffen, und man verspürte, man erlebte noch etwas von dem Zusammenfließen des Menschen mit der sinnlichen Welt, wenn man den Intellekt anwendete. Und man war dann der Meinung, daß man aufsteigen müsse zur Offenbarung, die eben nicht mehr begriffen, also nicht mehr intellektuell erfaßt werden kann, wenn man über das Geistige etwas wissen will. Aber es war noch unvermerkt — und auf das muß man hinschauen! - in die Begriffe, welche die Scholastiker über die Sinnenwelt aufstellten, Geistigkeit hineingeflossen. Die Begriffe der Scholastiker waren nicht so geistlos, wie es die heutigen sind. Die ‚Scholastiker kamen noch mit ihren Begriffen, die sie sich über die Natur bildeten, an den Menschen heran, so daß der Mensch von der Erkenntnis noch nicht ganz ausgeschlossen war. Denn die Scholastiker waren, wenigstens in ihrer realistischen Strömung, durchaus der Meinung, daß die Gedanken den Menschen von außen gegeben werden, nicht von innen fabriziert werden. Heute ist man der Meinung, daß die Gedanken nicht von außen gegeben werden, sondern von innen fabriziert werden. Dadurch ist der Mensch dazu gekommen, nach und nach in seiner Entwickelung alles fallenzulassen, was sich nicht auf die äußere Sinneswelt bezieht.

Und, sehen Sie, der letzte Ausfluß davon, daß man alles hat fallenlassen, was sich nicht auf die äußere Sinneswelt bezieht, das ist die moderne, im darwinistischen Sinne gehaltene Entwickelungslehre. Goethe hat den Ansatz gemacht zu einer wirklichen Entwickelungslehre, die bis zum Menschen heraufgeht. Wenn Sie seine Schriften nach dieser Richtung durchnehmen, so werden Sie sehen, daß er immer nur gestrauchelt hat, wenn er zum Menschen kommen wollte. Er hat noch eine ausgezeichnete Pflanzenlehre geschrieben, er hat über das Tier manches Zutreffende geschrieben, allein es hapert immer, wenn er zum Menschen kommen will. Der Intellekt, der bloß auf die Sinneswelt angewendet wird, reicht nicht aus, um zum Menschen heranzukommen. Das zeigt sich gerade bei Goethe in so hohem Maße: auch Goethe kann über den Menschen nichts sagen. Seine Metamorphosenlehre erstreckt sich nicht bis zum Menschen herauf. Sie wissen, wie wir diese Metamorphosenlehre, ganz im Goetheschen Sinne, aber weit über ihn hinausgehend, haben erweitern müssen innerhalb der anthroposophischen Weltanschauung.

Wozu ist denn der moderne Intellektualismus in der Naturwissenschaft eigentlich gekommen? Er ist nur dazu gekommen, die Entwickelung der Tiere bis herauf zum Affen zu begreifen, und er hat dann den Menschen angeschlossen, ohne innerlich zum Menschen vorrücken zu können. Ich möchte sagen, die Begriffe wurden, je mehr der Mensch an die höheren Tiere herankam, immer unfähiger, noch etwas zu begreifen. Und es ist gar nicht wahr, daß der Mensch zum Beispiel die höheren Tiere noch begreift. Er glaubt nur, daß er sie begreife.

Und so fiel allmählich die Auffassung des Menschen ganz aus der Weltauffassung heraus, weil aus den Begriffen die Auffassung herausfiel. Die Begriffe wurden immer geistloser und geistloser, und die geistlosen Begriffe, die den Menschen nur als den Schlußpunkt der Tierreihe ansehen, die bilden heute den Inhalt alles Denkens; die werden schon den Kindern in den ersten Schuljahren eingeflößt, und es wird dadurch zur allgemeinen Bildung, nicht mehr auf das Wesen des Menschen hinschauen zu können.

Nun wissen Sie ja, daß ich versuchte, die ganze Erkenntnis einmal an einem anderen Ende anzufassen. Das war, als ich meine «Philosophie der Freiheit» und deren Vorspiel «Wahrheit und Wissenschaft» verfaßte, obwohl die Anklänge schon in meiner «Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen Weltanschauung» in den achtziger Jahren stehen. Ich habe versucht, nach einer ganz anderen Ecke hin die Sache zu wenden. Ich habe versucht, dasjenige zu zeigen, zu dem sich der moderne Mensch aufschwingen kann, wenn er nun nicht im traditionellen Sinne, sondern aus freier innerer Gestaltung heraus zum reinen Denken kommt, zu diesem willensmäßigen reinen Denken, das etwas Positives, Reales ist, wenn es in ihm wirkt. Und ich habe in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» die moralischen Impulse aus diesem gereinigten Denken gesucht.

So daß also die Entwickelung vorher so gegangen ist, daß man immer mehr und mehr dahin kam, den Menschen als zu schlecht aufzufassen zum moralischen Handeln, und man hineintrug dieses Zuschlechtsein des Menschen auch in seine Intellektualität. Wenn ich mich graphisch ausdrücken soll, so möchte ich sagen: Es entwikkelte sich der Mensch so, daß immer dünner wurde dasjenige, was er als Mensch von sich wußte. Immer dünner wurde das (hell). Aber unter der Oberfläche entwickelte sich doch immerfort das (rot), was im wirklichen, nicht im abstrakten Denken lebt.

Nun war am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts der Zeitpunkt gekommen, wo man dieses, was ich rot charakterisiert habe, eben gar nicht mehr bemerkt hat, und durch das, was ich hell charakterisiert habe, glaubte man sich nicht mehr in Verbindung mit irgend etwas Göttlich-Geistigem. Das Sündenbewußtsein hat den Menschen aus dem Göttlich-Geistigen herausgerissen; die historischen Kräfte, die heraufkamen, konnten ihn nicht hineinziehen.

Aber ich wollte mit meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» sagen: Seht nur einmal in die Tiefe der Seele hinein, da werdet Ihr finden, daß dem Menschen etwas geblieben ist, nämlich das wirkliche, energische von ihm selbst kommende Denken, das reine Denken, das nicht mehr bloßes Denken ist, das voller Empfindung, voller Gefühl ist, und das zuletzt im Willen sich auslebt, und daß dieses der Impuls werden kann für moralisches Handeln. — Und ich sprach aus diesem Grunde von moralischer Intuition, in die zuletzt einlauft das, was sonst nur moralische Phantasie ist. Aber so richtig lebendig werden kann das, was eigentlich gemeint ist mit der «Philosophie der Freiheit», nur, wenn man den Weg, den man gegangen ist — nämlich sich immer mehr und mehr abzuspalten, bis zur Intellektualität hin sich abzuspalten von dem göttlich-geistigen Inhalt der Welt -, wenn man diesen Weg wieder zurückmacht. Wenn man wieder findet die Geistigkeit in der Natur, dann wird man auch wieder den Menschen finden. Und deshalb habe ich einmal in einem Vortrag, den ich vor vielen Jahren in Mannheim gehalten habe, ausgeführt — was sehr wenig bemerkt worden ist —, daß tatsächlich die Menschheit in ihrer heutigen Entwickelung an dem Punkt steht, den Sündenfall zurückzumachen. Nämlich: der Sündenfall wurde aufgefaßt als ein moralischer Sündenfall, er hat zuletzt auch den Intellekt beeinflußt; der Intellekt fühlte sich an den Grenzen der Erkenntnis. Und ob der alte Theologe von der Sünde oder Du Bois-Reymond von den Grenzen des Naturerkennens spricht, ist im Grunde genommen ein und dasselbe, nur in einer etwas andern Form. Ich machte darauf aufmerksam, wie man nun erfassen muß das allerdings bis zum reinen Denken filtrierte Geistige, und wie man von da den Sündenfall rückgängig machen kann, wie man sich durch die Spiritualisierung des Intellektes wiederum zum Göttlich-Geistigen hinaufarbeiten kann.

Wenn also in alten Zeiten hingewiesen worden ist auf den moralischen Sündenfall und die Entwickelung der Menschheit gedacht worden ist im Sinne dieses moralischen Sündenfalles, so hat man heute an ein Ideal der Menschheit zu denken, an die Ausbesserung dieses Sündenfalles auf dem Wege der Spiritualisierung des Erkennens, auf dem Wege der Wiedererkennung des geistigen Inhaltes der Welt. Der Mensch hat sich durch den moralischen Sündenfall von den Göttern..entfernt. Er muß durch den Erkenntnisweg die Bahn der Götter wieder finden. Der Mensch muß seinen Abstieg in einen Aufstieg verwandeln. Der Mensch muß aus dem rein erfaßten Geiste seines eigenen Wesens durch innere Energie und Kraft das Ziel, das Ideal fassen, den Sündenfall wiederum ernst zu nehmen. Denn ernst zu nehmen ist er. Er erstreckt sich bis zu den Reden der Naturerkenntnis in unsere Gegenwart herein. Der Mensch muß den Mut fassen, zum Sündenfall nach und nach durch die Kraft seines Erkennens ein Aus-der-Sünde-sich-Erheben hinzuzufügen, eine Sündenerhebung herauszuarbeiten aus dem, was ihm werden kann durch eine wirkliche, echte geisteswissenschaftliche Erkenntnis der neueren Zeit.

So könnte man sagen: Blicken wir zurück in die Entwickelung der Menschheit, so setzt das Menschenbewußtsein an den Anfang der historischen Entwickelung der Menschheit auf Erden den Sündenfall. Aber der Sündenfall muß einmal wiederum ausgeglichen werden: es muß ihm entgegengesetzt werden eine Sündenerhebung. Und diese Sündenerhebung kann nur aus dem Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele hervorgehen. Also es ist in unserer Zeit der historische Moment gekommen, wo das höchste Ideal der Menschheit sein muß die spirituelle Sündenerhebung. Ohne diese kann die Entwikkelung der Menschheit nicht weitergehen.

Das ist es, was ich in jenem Mannheimer Vortrage einmal auseinandersetzte. Ich sagte, es ist zu dem moralischen Sündenfall in der neueren Zeit, namentlich in den naturwissenschaftlichen Anschauungen, auch noch der intellektualistische Sündenfall gekommen, und der ist das große historische Zeichen dafür, daß die spirituelle Sündenerhebung beginnen müsse.

Was heißt denn aber diese spirituelle Sündenerhebung? Die heißt ja nichts anderes, als den Christus wirklich verstehen. Diejenigen, die noch etwas davon verstanden haben, die nicht mit der neueren Theologie den Christus vollständig verloren haben, die haben so von dem Christus gesprochen, daß er auf die Erde gekommen ist, daß er als ein Wesen höherer Art sich in einem irdischen Leibe verkörpert hat. Sie haben angeknüpft in den Schriftentraditionen an dasjenige, was über den Christus verkündigt ist. Man hat eben über das Mysterium von Golgatha gesprochen.

Heute aber ist die Zeit gekommen, wo der Christus verstanden werden muß. Man wehrt sich gegen dieses Verstehen des Christus, und die Art, wie man sich wehrt, ist außerordentlich charakteristisch. Sehen Sie, wenn nur noch ein Fünkchen von dem, was der Christus wirklich ist, in denen lebte, die da sagen, daß sie den Christus verstehen, was müßte denn dann eintreten? Dann müßten sie sich doch klar sein: Der Christus ist als ein himmlisches Wesen auf die Erde herabgestiegen; er hat also zu den Menschen nicht eine irdische, sondern eine himmlische Sprache gesprochen. Also müssen wir uns bemühen, ihn zu verstehen, müssen wir uns bemühen, eine kosmische, eine außerirdische Sprache zu sprechen. Das heißt, wir müssen unsere Wissenschaft nicht bloß auf die Erde beschränken, denn die war ja neues Land für den Christus, wir müssen unsere Wissenschaft ausdehnen in das Kosmische. Wir müssen verstehen lernen die Elemente, wir müssen verstehen lernen die Planetenbewegungen, wir müssen verstehen lernen die Sternkonstellationen und ihren Einfluß auf das, was auf Erden geschieht. Dann nähern wir uns der Sprache, die der Christus gesprochen hat.

Das aber ist etwas, was zusammenfällt mit der spirituellen Sündenerhebung. Denn warum wurde der Mensch herabgedrückt, nur das zu verstehen, was auf Erden lebt? Weil er eben das Sündenbewußtsein hatte, weil er sich für zu schlecht hielt, um die Welt in ihrer Geistigkeit im Außerirdischen zu begreifen. Und deshalb ist es, daß eigentlich so geredet wird, als ob der Mensch außer dem Irdischen nichts erkennen könne. Ich habe es gestern damit charakterisiert, daß ich sagte: Der Mensch versteht den Fisch nur auf dem Tisch, und den Vogel auch nur auf dem Tisch, in dem Käfig. - Ein Bewußtsein davon, daß der Mensch sich erheben kann über diese rein irdische Erkenntnis, ein solches Bewußtsein ist ganz gewiß in unserer zivilisierten Naturwissenschaft nicht vorhanden, denn sie spottet über alles Hinausgehen über das Irdische. Wenn man nur anfängt, von den Sternen zu reden, so ist natürlich gleich der furchtbare Spott der naturwissenschaftlichen Richtung da.

Wenn wir noch zutreffende Worte hören wollen über den Zusammenhang des Menschen und der Tierheit, müssen wir den Blick auf das Außerirdische richten, denn aus dem Irdischen sind nur noch die Pflanzen erklärlich, nicht mehr die Tiere. Deshalb mußte ich vorhin sagen: Der Mensch versteht ja den Affen auch nicht recht, es sind die Tiere nicht mehr erklärlich. Wenn man die Tiere verstehen will, muß man schon seine Zuflucht nehmen zum Aufßerirdischen, denn sie sind von Kräften beherrscht, die außerirdisch sind. Ich habe es Ihnen gestern am Fisch gezeigt. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, wie Sonnen- und Mondenkräfte ins Wasser wirken beim Fisch und ihn, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, herausgestalten aus dem Wasser; ebenso den Vogel aus der Luft. Sobald man übergeht zu den Elementen, kommt man auch zum Außerirdischen. Die ganze Tierwelt ist erklärlich aus dem Außerirdischen, und der Mensch erst recht. Aber wenn man anfängt, von dem Aufßerirdischen zu sprechen, dann kommt eben gleich der Spott. Der Mut, von dem Außerirdischen wieder zu sprechen, er muß erwachsen innerhalb einer wirklichen geisteswissenschaftlichen Anschauung. Denn Geisteswissenschafter zu sein ist heute eigentlich mehr eine Sache des Mutes als der Intellektualität. Es ist im Grunde genommen etwas Moralisches, weil es auch einem Moralischen, nämlich dem moralischen Sündenfall entgegengesetzt werden muß.

Und so müssen wir sagen: Wir müssen ja erst die Sprache des Christus lernen, nämlich die Sprache τῶν οὐρανῶν — ton uranón —, die Sprache der Himmel im griechischen Sinne. Diese Sprache müssen wir wieder lernen, um einen Sinn zu verbinden mit dem, was der Christus auf Erden wollte. Also während man bisher von dem Christentum gesprochen hat, die Geschichte des Christentums beschrieben hat, handelt es sich heute darum, den Christus zu verstehen, ihn als ein außerirdisches Wesen zu verstehen. Und das ist identisch mit dem, was man das Ideal der Sündenerhebung nennen kann.

Nun ist allerdings mit der Prägung dieses Ideales ein sehr Schwieriges verbunden, denn Sie wissen ja, das Sündenbewußtsein hat die Menschen demütig gemacht. Sie sind in der neueren Zeit allerdings nur sehr selten noch demütig. Oftmals sind diejenigen, die sich am demütigsten wähnen, die Allerhochmütigsten. Den größten Hochmut findet man heute bei denen, die nach der sogenannten Einfachheit des Lebens streben. Die setzen sich über alles das hinweg, was von der demütigen Seele in innerer Erhebung an wirklichen geistigen Wahrheiten gesucht wird, und sagen: Das muß alles in purer Einfachheit gesucht werden. Solche naive Naturen - sie sehen sich nämlich selber als naive Naturen an -, die sind heute oftmals die allerhochmütigsten. Aber immerhin, es gab während der Zeit des realen Sündenbewußtseins demütige Menschen; die Demut wurde noch als etwas angesehen, was im Menschheitsweben gilt. Und es ist nach und nach ohne Berechtigung heraufgekommen der Hochmut. Warum? Ja, das kann ich wiederum mit ähnlichen Worten sagen, mit denen ich in dieser Zeit hier zu Ihnen gesprochen habe. Warum ist denn der Hochmut heraufgekommen? Er ist heraufgekommen, weil man nicht gehört hat das «Stichl, steh auf!». Man schlief nämlich ein. Während man früher in aller Intensität wachend sich als Sünder gefühlt hat, schlief man nun sanft ein und träumte nur noch vom Sündenbewußtsein. Vorher wachte man im Sündenbewußtsein, da sagte man: Der Mensch ist sündhaft, wenn er nicht Handlungen unternimmt, die ihn wieder auf die Bahn nach den göttlich-geistigen Mächten bringen. -— Da wachte man. Man mag heute das anschauen wie man will, aber man wachte im Bekenntnis der Sündhaftigkeit. Nun aber duselte man ein — und da kamen die Traume, und die Träume raunten: Es herrscht in der Weit eine Kausalordnung in dem Sinne, daß das Vorhergehende immer das Nachfolgende bewirkt. Und so kommen wir dazu, das, was wir im Sternenhimmel sehen, als Anziehung und Abstoßung der Himmelskörper bis an die Moleküle hin zu verfolgen, eine Art kleinen Weltensystems zwischen Molekülen und Atomen anzunehmen.

Und es ging das Träumen weiter. Und dann endigte der Traum damit, daß man sagte: Wir können nichts erkennen als das, was die äußere sinnliche Erfahrung gibt. Und man nannte es Supernaturalismus, wenn man über die sinnlichen Erfahrungen hinausgeht. Aber wo Supernaturalismus beginnt, da hört die Wissenschaft auf. Und nun wurden in krächzenden Tiraden diese Träume, wie zum Beispiel in Du Bois-Reymonds «Über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens», in Naturforscherversammlungen vorgetragen. Und wenn dann der Traum ausklang — manchmal klingt er ja nicht so wohllautend aus, wenn er ein wirklicher Nachtalp ist -, wenn aber dieser Traum ausklang: Wo Supernaturalismus beginnt, da hört die Wissenschaft auf —, da schlief nicht nur der Redner, sondern da schlief das ganze naturforschende Publikum nun vom Traum in einen seligen Schlaf hinüber. Man brauchte nicht mehr irgendwie einen inneren Impuls zur Aktivität der inneren Erkenntnis; man konnte sich trösten, daß eben der Mensch Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis hat, “und daß er nicht hinauskommen kann über diese Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis. Die Zeit war herangekommen, wo man schon sagen konnte: Stichl, steh auf, der Himmel kracht scho - aber die Zivilisation der Neuzeit erwiderte: Laß’n nur krachen, er is scho alt genua dazua! — Ja, die Dinge sind tatsächlich so. Und damit sind wir in eine vollständige Schläfrigkeit des Erkennens hineingekommen.

Aber es muß in diese Schläfrigkeit hineintönen dasjenige, was durch geisteswissenschaftliche, anthroposophische Erkenntnis geltend gemacht wird. Daß der Mensch in der Lage ist, das Ideal von der Sündenerhebung in sich aufzustellen, das muß zunächst aus der Erkenntnis herauskommen. Und das ist nun wiederum damit verknüpft, daß mit einem eventuellen Wachwerden auch der bisher allerdings nur traumhaft vorhandene Hochmut erst recht wachsen kann. Und es hat sich ja manchmal - das ist selbstverständlich ganz ohne Anspielung gesagt -, es hat sich ja manchmal herausgestellt, daß in anthroposophischen Kreisen noch nicht die Sündenerhebung völlig gereift ist, aber daß manchmal schon dieser Hochmut eine ganz, ich will nicht sagen anständige, sondern eine ganz unanständige Größe erreicht hat. Denn es ist schon einmal in der Natur des Menschen gelegen, daß der Hochmut eher gedeiht als das, was die Lichtseite der Sache ist. Und so muß eben mit der Notwendigkeit der Sündenerhebung zugleich eingesehen werden, daß der Mensch die Erziehung in Demut, die er durchgemacht hat, nun mit vollem Bewußtsein auch in sich aufnehmen muß. Und er kann das ja. Denn wenn aus der Erkenntnis Hochmut kommt, dann ist das immer ein Zeichen davon, daß es eigentlich mit der Erkenntnis gewaltig hapert. Denn wenn die Erkenntnis wirklich da ist, dann macht sie auf ganz naturgemäße Weise demütig. Hochmütig wird man, wenn man heute ein Programm aufstellt, ein Reformprogramm, wenn man innerhalb, sagen wir, der sozialen Bewegung oder der Frauenbewegung von vornherein weiß, was das Mögliche, das Richtige, das Notwendige, das Beste ist, und nun Programmpunkte erstens, zweitens, drittens und so weiter aufstellt. Da weiß man alles, um was es sich handelt, da denkt man gar nicht daran, hochmütig zu sein, indem man sich zugleich, jeder einzelne, für allwissend erklärt. Aber bei einer wirklichen Erkenntnis bleibt man hübsch demütig, denn man weiß, daß eine wirkliche Erkenntnis nur erlangt wird - ich will mich trivial ausdrücken — im Laufe der Zeit.

Lebt man in der Erkenntnis, so weiß man, wie schwer man sich die einfachsten Wahrheiten manchmal Jahrzehnte hindurch errungen hat. Da wird man schon innerlich durch die Sache selber nicht hochmütig. Es muß aber doch die Aufmerksamkeit darauf gelenkt werden, daß, indem gerade von der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft verlangt werden muß ein volles Bewußtsein des heutigen großen Menschheitsideales der Sündenerhebung, zu gleicher Zeit auch die Wachsamkeit — nicht die Stichlhaftigkeit, sondern die Wachsamkeit — für den etwa heraufkommenden Hochmut geweckt werden muß.

Der Mensch bedarf heute eines starken Hinneigens dazu, das Wesen der Erkenntnis wirklich zu erfassen, damit er nicht mit ein paar anthroposophischen Formeln über physischen Leib und Ätherleib und Reinkarnation und so weiter sogleich ein Ausbund von Hochmütigkeit wird. Diese Wachsamkeit gegenüber dem gewöhnlichen Hochmut muß als ein neuer moralischer Inhalt wirklich gepflegt werden. Das muß in die Meditation aufgenommen werden. Denn soll die Sündenerhebung wirklich zustande kommen, dann müssen die Erfahrungen, die wir mit der physischen Welt machen, uns selber hinüberleiten in die geistige Welt. Dann müssen sie uns zur opferwilligen Hingabe mit den innersten Kräften der Seele führen, nicht aber zum Diktieren von Programmwahrheiten. Dann müssen sie vor allen Dingen eindringen in das Verantwortlichkeitsgefühl gegenüber jedem einzelnen Worte, das man über die geistige Welt ausspricht. Dann muß das Bestreben herrschen, die Wahrhaftigkeit, die man sich zuerst angeeignet hat an den äußeren sinnlichen Tatsachen, wirklich hinaufzutragen in das Gebiet des geistigen. Erkennens. Wer sich nicht angewöhnt hat, in der physischen Sinnenwelt bei den Tatsachen zu bleiben und auf Tatsachen sich zu stützen, der gewöhnt sich auch, wenn er vom Geiste spricht, nicht Wahrhaftigkeit an. Denn in der geistigen Welt kann man sich nicht mehr die Wahrhaftigkeit angewöhnen, die muß man mitbringen.

Aber sehen Sie, auf der einen Seite wird heute aus dem Zivilisationsbewußtsein heraus den Tatsachen wenig Rechnung getragen, auf der andern Seite werden aber von der Wissenschaft einfach diejenigen Tatsachen ausgemerzt, welche auf richtige Pfade führen. Ich will aus der Reihe vieler Tatsachen nur eine einzige herausheben. Es gibt Insekten, die sind selber Vegetarier, wenn sie erwachsen sind. Sie fressen nichts Fleischliches, nicht einmal andere Insekten. Wenn nun die Insektenmutter zum Legen der Eier kommt, die befruchtet sind, so legt sie diese Eier in ein anderes Insekt hinein, so daß solch ein Insekt mit lauter solchen Eiern angefüllt ist durch den Legestachel der Insektenmutter. Da sind die Eier nun in einem fremden Insekt drinnen. Nun kriechen ja nicht die vollendeten Insekten aus, sondern kleine Maden. Diese sind aber zuerst in dem fremden Insekt drinnen. Diese kleinen Maden, die sich erst später metamorphosieren zu den vollendeten Insekten, sind nun keine Vegetarier. Sie könnten nicht Vegetarier sein, sie müssen das Fleisch von dem andern Insekt verzehren. Erst wenn sie herauskommen und sich umwandeln, können sie das Fleisch anderer Insekten entbehren. Denken Sie, die Insektenmutter ist selber Vegetarierin, sie weiß in ihrem Bewußtsein nichts von Fleischesserei, aber sie legt ihre Eier für die künftige Generation in ein anderes Insekt hinein.

Und weiter: wenn diese Insekten nun zum Beispiel den Magen anfressen würden bei ihrem Insekt, in welchem sie drinnenstecken, dann würden sie ja bald nichts mehr zu fressen haben, denn das Insekt könnte dann nicht leben; wenn sie irgendein lebenswichtiges Organ anfressen würden, könnte das Insekt nicht leben. Was tun diese Insekten, die eben ausgekrochen sind? Sie vermeiden jedes lebenswichtige Organ und fressen nur dasjenige auf, was das Insekt nicht zum Leben braucht, was es entbehren kann, so daß es weiterleben kann. Dann, wenn diese kleinen Insekten reif sind, kriechen sie aus und werden Vegetarier und setzen das wiederum fort, was ihre Insektenmutter getan hat.

Ja, da müssen Sie doch sagen: In der Natur waltet Verstand. Und Sie können, wenn Sie die Natur wirklich studieren, überall diesen waltenden Verstand finden. Und über Ihren eigenen Verstand werden Sie dann bescheidener denken, denn der ist erstens nicht so groß wie der Verstand, der da in der Natur waltet, zweitens aber ist er nur so etwas wie ein bißchen Wasser, das man aus einem See geschöpft und in eine Kanne getan hat. Der Mensch ist nämlich in Wirklichkeit eine solche Kanne, die den Verstand der Natur auffaßt. In der Natur ist überall Verstand, alles ist überall Weisheit. Derjenige, der nur dem Menschen für sich selbst Verstand zuschreibt, ist ungefähr so gescheit wie einer, der da sagt: In dem See draußen oder in dem Bach soll Wasser sein? Das ist Unsinn, da ist kein Wasser drinnen. In meiner Kanne allein ist Wasser, die Kanne hat das Wasser hervorgebracht. — So denkt der Mensch, er bringe den Verstand hervor, während er ihn nur aus dem allgemeinen Meere des Verstandes schöpft. |

Es ist also notwendig, daß man die Tatsachen der Natur wirklich ins Auge faßt. Aber die werden ja gerade ausgelassen, wenn darwinistische Theorie getrieben wird, wenn die heutigen materialistischen Anschauungen geprägt werden, denn sie widersprechen an allen Ecken und Enden dem modernen materialistischen Anschauen. Also man unterschlägt diese Tatsachen. Gewiß, man erzählt sie, aber eigentlich neben der Wissenschaft, anekdotenhaft. Daher bekommen sie auch nicht die Geltung in der allgemeinen Volkspädagogik, die sie haben müssen. Und so stellt man nicht nur die Tatsachen, die man hat, nicht in Wahrhaftigkeit dar, sondern man hat noch die Unwahrhaftigkeit, die schlagenden Tatsachen auszulassen, das heißt zu unterschlagen.

Aber wenn es zur Sündenerhebung kommen soll, dann muß der Mensch sich zuerst an der Sinnenwelt zur Wahrhaftigkeit erziehen und diese Erziehung, diese Angewöhnung dann in die geistige Welt hineintragen. Dann wird er auch in der geistigen Welt wahrhaftig sein können. Sonst erzählt er den Leuten die unglaublichsten Geschichten von der geistigen Welt. Hat er sich für die physische Welt Ungenauigkeit, Unwahrhaftigkeit, Unexaktheit angewöhnt, dann erzählt er lauter Unwahrheiten über die geistige Welt.

Wenn man so das Ideal faßt, dessen sich die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft als eine Realität bewußt werden kann, und wenn geltend gemacht wird, was aus einem solchen Bewußtsein kommt, dann muß selbst bei dem Übelwollendsten der Glaube verschwinden, daß die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft eine Sekte sein kann. Nun, selbstverständlich werden die Gegner alles mögliche sagen, was nicht wahr ist. Aber es kann uns nicht gleichgültig sein, ob das wahr oder unwahr ist, was die Gegner sagen, solange wir Veranlassung dazu geben.

Nun hat sich durch das Wesen der Sache die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft aus der Sektiererei, in der sie ja gewiß anfangs befangen war, insbesondere solange sie mit der Theosophischen Gesellschaft verbunden war, gründlich herausgearbeitet. Nur haben viele Mitglieder das heute noch nicht bemerkt und lieben die Sektiererei. Und so ist es zustande gekommen, daß selbst ältere anthroposophische Mitglieder, die fast zerspringen wollten unter der Umwandlung der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft aus einer sektiererischen in etwas, was sich seiner Weltaufgabe bewußt ist, sie, die fast zerspringen wollten, in der allerneuesten Zeit einen Sprung machten. Ebenso fern aller Sektiererei, wenn sie ihrem Wesen folgt, kann die Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung sein. Aber diese Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung hat zunächst einer Anzahl selbst älterer Anthroposophen die Veranlassung gegeben, sich zu sagen: Ja, in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft, da wird das sektiererische Wesen immer mehr und mehr ausgemerzt — hier können wir es wiederum pflegen! — Und so wird gerade durch Anthroposophen vielfach die religiöse Erneuerungsbewegung zu der wüstesten Sektiererei gemacht, was sie wahrlich gar nicht zu sein brauchte.

Man sieht also, wie — wenn die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft eine Realität werden will — der Mut, sich in die geistige Welt wiederum zu erheben, positiv gepflegt werden muß. Dann wird schon Kunst und Religion sprießen in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft. Wenn uns zunächst auch unsere künstlerischen Formen genommen sind, sie leben eben im Wesen der anthroposophischen Bewegung selber und müssen immer wieder und wiederum gefunden werden.

Ebenso lebt die wahre religiöse Vertiefung in denen, welche den Weg in die geistige Welt zurückfinden, welche die Sündenerhebung ernsthaft nehmen. Aber was wir in uns selber ausmerzen müssen, das ist der Hang zur Sektiererei, denn er ist immer egoistisch. Er will immer die Umständlichkeit vermeiden, in die Realität des Geistes hineinzudringen, um sich zu begnügen mit einem mystischen Schwelgen, das im Grunde genommen eine egoistische Wollust ist. Und alles Reden davon, daß die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft

viel zu intellektualistisch geworden ist, beruht eigentlich darauf, daß diejenigen, die so reden, eben das konsequente Erleben eines geistigen Inhaltes vermeiden wollen und viel mehr die egoistische Wollust des seelischen Schwelgens in einer mystischen, nebulosen Unbestimmtheit wollen. Selbstlosigkeit ist notwendig zur wirklichen Anthroposophie. Ein bloßer Seelenegoismus ist es, wenn dieser wirklichen Anthroposophie von den anthroposophischen Mitgliedern selber widerstrebt wird und sie nun erst recht hineintreiben in ein sektiererisches Wesen, das eben nur die seelische Wollust befriedigen soll, die durch und durch etwas Egoistisches ist.

Das sind die Dinge, die wir uns vor Augen führen müssen hinsichtlich unserer Aufgabe. Dadurch wird nichts verlorengehen von der Wärme, von dem künstlerischen Sinn und der religiösen Innigkeit des anthroposophischen Strebens. Aber es wird vermieden werden, was vermieden werden muß: der sektiererische Hang. Und dieser sektiererische Hang, er hat so manches die Gesellschaft Auflösende gebracht, wenn er auch oft auf dem Umwege des reinen Cliquenwesens gekommen ist. Aber Cliquenwesen entstand innerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung auch nur wegen seiner Verwandtschaft — es ist allerdings eine weite, eine entfernte Verwandtschaft - mit dem sektiererischen Hang. Wir müssen zurückkommen zu der Pflege eines gewissen Weltbewußtseins, so daß nur noch Gegner, welche absichtlich die Unwahrheit sagen wollen, die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft eine Sekte nennen können. Wir müssen dazu kommen, streng abweisen zu können den sektiererischen Charakterzug der anthroposophischen Bewegung. So sollen wir ihn aber abweisen, daß, wenn etwas auftaucht, was selber nicht sektiererisch gedacht ist, wie die religiöse Erneuerungsbewegung, es nicht sogleich ergriffen wird, weil man es leichter im sektiererischen Sinne gestalten kann als die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft selber.

Das sind die Dinge, die wir heute scharf bedenken müssen. Wir müssen heute aus dem innersten Wesen der Anthroposophie heraus verstehen, inwiefern die Anthroposophie dem Menschen ein Weltbewußtsein geben kann, nicht ein sektiererisches Bewußtsein. Deshalb mußte ich in diesen Tagen gerade von diesen engeren Aufgaben der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft sprechen.

Ninth Lecture

You have seen from the previous allusions that it is incumbent upon me at this time to speak about the consciousness that must be conquered as one of the tasks of the Anthroposophical Society. And I would like to begin today by pointing out how this consciousness can only be conquered by truly grasping the whole task of culture and civilization in the present from the standpoint of spiritual science. On various occasions I have tried to characterize from this point of view what is meant by the fall of mankind mentioned in all religious creeds. The religious creeds speak of this fall from grace, which lies at the starting point of the historical development of mankind, and we have seen through the various debates over the past years how this fall from grace, which I do not need to characterize more precisely today, is an expression of what once occurred in the course of mankind's development: the independence of man from the divine-spiritual powers guiding him.

We know that the awareness of this independence only occurred when the consciousness soul appeared in the development of mankind, that is, in the first half of the 15th century AD. We have spoken of this point in time again and again in the last observations. But basically the whole development of mankind, characterized by history and myths, is a kind of preparation for this important moment of man's becoming aware of his freedom, his independence, a preparation for the fact that mankind on earth is to come to the point of gaining an independent ability to make decisions vis-à-vis the divine-spiritual powers. And so the religious creeds point to a cosmic-earthly event through which the spiritual-soul instincts, which in very ancient times were the sole determining factor for what mankind did, were replaced by precisely this free decision-making of man. As I said, we do not want to speak now of how this is to be understood in more detail - but the matter is understood by the religious creeds in such a way that with regard to the moral impulsiveness of man, this man has placed himself in a certain way in opposition to the leading spiritual, let us say, if we speak with the Old Testament, to the Yahweh or Jehovah powers. Thus, if we look at this interpretation, the matter must first be presented as if man, from a certain point in his development, no longer felt that the divine-spiritual powers were active in him and that he was now active himself.

With regard to the overall moral conception of man it then occurred that he felt himself to be sinful, while he would have been incapable of falling into sin if he had remained in the old state, in the state of being instinctively led by divine-spiritual powers. While there he would have remained incapable of sinning, i.e. sinless like a mere natural creature, he became capable of sinning through this independence from the divine-spiritual powers. And this awareness of sin then arose in humanity: I as a human being am only then not sinful if I find my way back to the divine-spiritual powers. What I decide through myself is sinful as such, and I can only attain sinlessness by finding my way back to the divine-spiritual powers.

This awareness of sin emerged most strongly in the Middle Ages. And it was then that people's intellectuality, which had not really been a separate faculty before, began to develop. Thus, to a certain extent, what man developed as intellect, as his intellectual content, was also - and with a certain right - infected by this consciousness of sin. Only it was not said that the intellect, which came up in the development since the 3rd, 4th century AD, is now also infected by the consciousness of sin. The unnoticed sin-consciousness of the intellect first developed in the scholastic wisdom of the Middle Ages.

This scholastic wisdom of the Middle Ages said to itself: If one develops the intellect as a human being, no matter how astutely, one can still only grasp the external physical nature through it. The most one can prove by the mere intellect is that there is an existence of divine-spiritual forces; but one can recognize nothing of these divine-spiritual forces, one can only believe in the divine-spiritual forces. One can believe in what they themselves have revealed, be it through the Old or the New Testament.

So the man who in earlier times felt sinful with regard to his morality - but sinful means: separated from the divine-spiritual powers - this man, who felt morally sinful throughout time, felt intellectually sinful, so to speak, in scholastic wisdom. He only ascribed to himself the ability to have an intellect for the physical-sensual world. He said to himself: "I am too bad as a human being to be able to ascend by my own power to that region of knowledge where I can also grasp the spirit. -- One does not realize how dependent this intellectual fall from grace is on the general moral fall from grace. It is the direct continuation of the moral fall that plays into the conception of human intellectuality.

When scholastic wisdom then passes over into the modern scientific view, then the connection with the old moral fall is completely forgotten, and it is even denied, as I have often emphasized, the intensely existing connection of the modern scientific concepts with the old scholasticism. And in the newer natural science it is said that man has limits of knowledge, that he must be content to extend his perception only beyond the sensory-physical world. A Du Bois-Reymond speaks of this, others speak of the fact that man has limits to his research, to his entire thinking in general.

But this is a direct continuation of scholasticism. The only difference is that scholasticism assumed this: If the human intellect is limited, then one must rise to something other than the intellect, namely to revelation, if one wants to know something about the spiritual world. The modern scientific view takes the half instead of the whole, leaves revelation where it is, but then takes the standpoint that only has a possibility if one presupposes revelation - it takes the standpoint that human cognitive ability is too poor to ascend to the divine-spiritual worlds.