Man as Symphony of the Creative Word

Part One. The Connection between Cosmic Conditions, Earthly Conditions, the Animal World and Man

GA 230

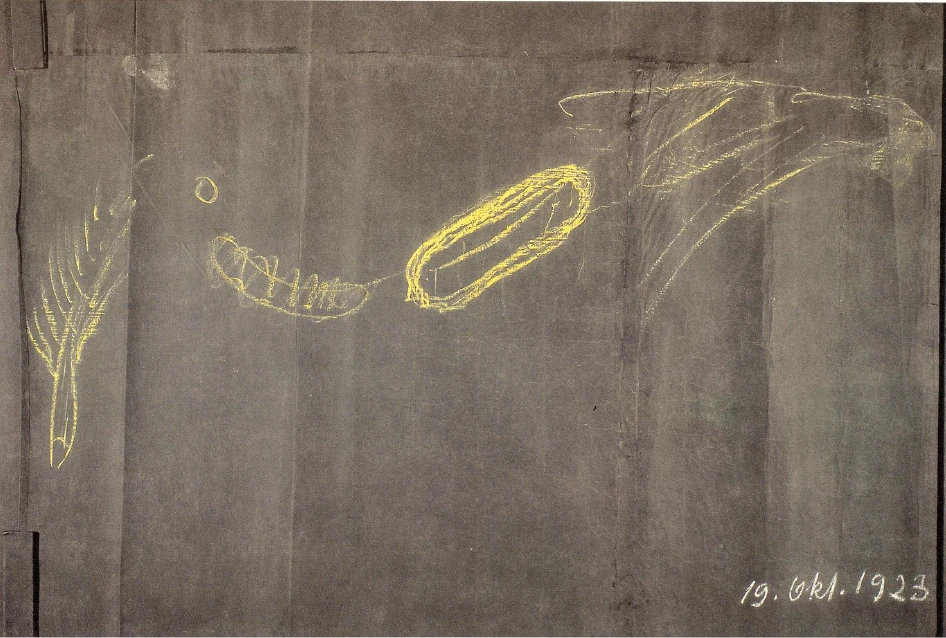

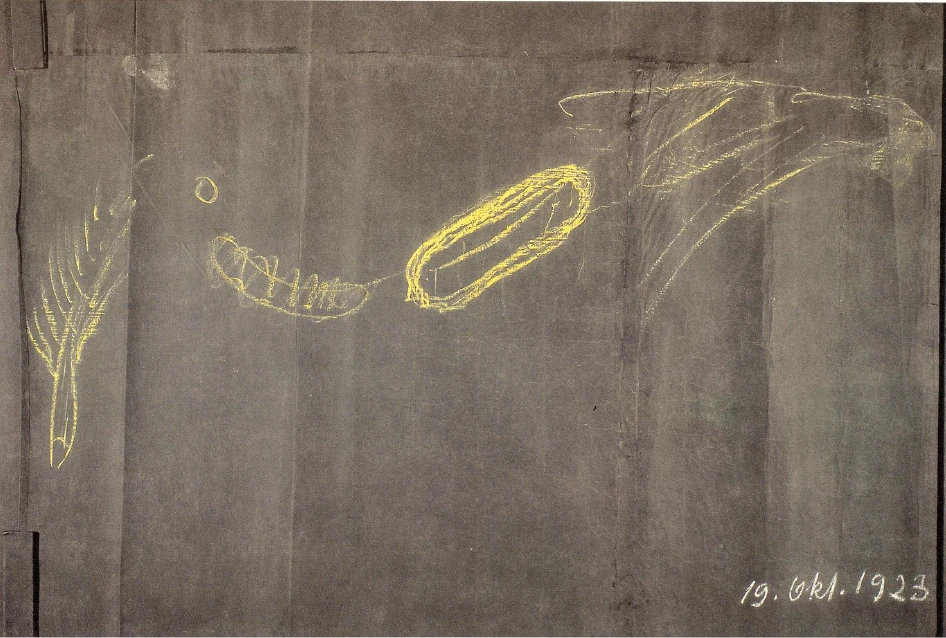

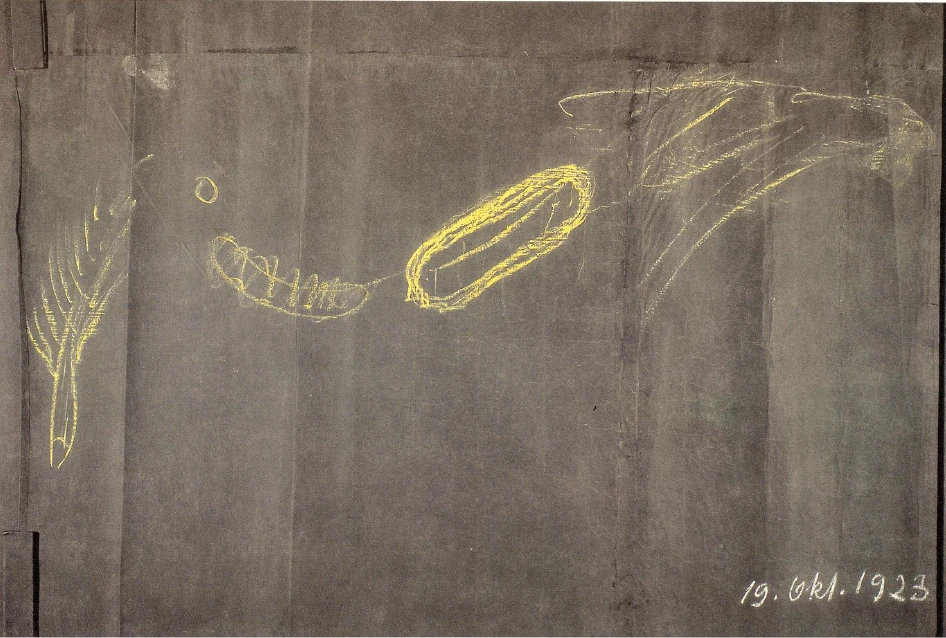

19 October 1923, Dornach

You cannot deal with man through logic alone, but through an understanding that can only be reached when intellect shall see the world as a work of art.

Lecture I

It has often been said in our studies, as was evident in the recent lectures on the cycle of the year and the Michael problem, that man in his whole structure, in the conditions of his life, indeed in all that he is, presents a Little World, a Microcosm over against the Macrocosm: that he actually contains within himself all the laws, all the secrets, of the world. You must not, however, suppose that a full understanding of this quite abstract sentence is a simple matter. You must penetrate into the manifold secrets of the world in order to find these secrets again in man.

Today we will consider this subject along certain lines of approach. We will examine first the world, and then man, in order to find how the human being exists as a Little World within the Great World. Naturally, what can be said about the Great World can never be more than fragmentary. It can never present anything complete in itself; for then our studies would have to traverse the whole world!

Let us first turn our attention to that realm which represents what is immediately above man—the birds, which live essentially in the air.

It certainly cannot escape us that the birds which live in the air, creating the conditions of their existence out of the air, are formed differently from the animals which live either on the actual surface of the earth, or below it. When we consider the kingdom of the birds, we shall naturally find, in accordance with the generally accepted views, that in their case, as with other animals, we must speak of head, limb-system, and so on. But this is a thoroughly inartistic way of looking at things. I have often drawn attention to the fact that, if we are really to understand the world, we cannot remain at the stage of mere intellectual comprehension, but that what is intellectual must gradually change into an artistic conception of the world. Then you will certainly not be able to regard the head of a bird—so dwarfed and stunted in its form when compared to the head in other animals—as a head in the true sense. Certainly from the external, intellectual point of view one can say: The bird has a head, a body, and limbs. But just consider how stunted are the legs of a bird in comparison, let us say, with those of a camel or an elephant, and how dwarfed its head when compared with that of a lion or a dog. There is really hardly anything to speak of in a bird's head; there is hardly more to it than what in a dog or an elephant or a cat, is to be found in the front part of the mouth. I could put it in this way: it is the slightly more complicated front part of a mammal's mouth which corresponds to the head of a bird. And the limb-system in a mammal is completely stunted in the case of a bird. Certainly, an inartistic method of observation does speak about the fore-limbs of a bird as being metamorphosed into wings. But all this is thoroughly inartistic, unimaginative observation. If we would really understand nature, really penetrate into the cosmos, we must consider things in a deeper way—and this most especially in regard to their formative and creative forces. The view that the bird, too, simply has a head, a body and limbs can never lead to a true understanding of a bird's etheric body. For if, through imaginative contemplation, we advance from seeing what is physical in the bird to seeing what is etheric, then in the etheric bird there is only a head. When looking at the etheric bird one immediately comprehends that the bird allows of no comparison with the head, body and limbs of other animals, but must be regarded simply and solely as head, as metamorphosed head. So that the actual bird-head presents only the palate and front parts of the head, in fact the mouth; and what extends backwards, all those parts of the skeleton in the bird which appear similar to ribs and spine, all this is to be looked upon as head—certainly metamorphosed and transformed—but nevertheless as head. The whole bird is really head.

This is due to the fact that, to understand the bird, we must go very, very far back in the planetary evolution of the Earth. The bird has a long planetary history behind it, a much longer planetary history than, for example, the camel. The camel is an animal of much later origin than any bird. Those birds which, like the ostrich, have been forced downwards to the Earth, were the latest to come into existence. Those birds which live freely in the air—eagles, vultures—are very ancient creatures of the Earth. In earlier Earth epochs—Moon-epoch, Sun-epoch—they still possessed within them what later developed from within outwards as far as the skin, and later still formed itself into what you now see in the feathers and the horny beak. What is outer in the bird is of later origin, and came about through the fact that the bird developed its head-nature comparatively early; and in the conditions into which it came in later stages of Earth-evolution, all that it could still add to this head-nature was what lies in its plumage. This plumage was given to the birds by the Moon and the Earth, whereas the rest of its nature comes from much earlier epochs.

But all this has yet a much deeper side. Let us look at the bird in the air—the eagle, let us say, in his majestic flight—upon whom, as though by an outer gift of grace, the rays of the sun and their action bestowed his plumage, bestowed his horny beak—let us look at this eagle as he flies in the air. Certain forces work upon him there. The sun does not only possess the physical forces of light and warmth of which we usually speak. When I described the Druid Mysteries to you, I drew your attention to the fact that spiritual forces too emanate from the sun. It is these forces which give to the different species of birds their variegated colours, the special formation of their plumage. When we penetrate with spiritual perception into the nature of the sun's working, we understand why the eagle has his particular plumage and when we deepen our contemplation of this being of the eagle, when we develop an inner, artistic comprehension of nature which contains the spiritual within it, when we can perceive how formative forces work out of the impulses of the sun—strengthened by other impulses of which I shall speak later—when we see how the sun-impulses stream down over the eagle even before he has emerged from the egg, how they conjure forth the plumage, or, to be more exact, how they conjure it into his fleshy form, then we can ask ourselves: What is the significance of all this for man? The significance of this for man is that it is what makes his brain into the bearer of thoughts. And you have the right insight into the Macrocosm, into Great Nature, when you so regard the eagle that you say: The eagle has his plumage, his bright, many-coloured feathers; in these lives the self-same force which lives in you in that you make your brain into the bearer of thoughts. What makes the convolutions of your brain? What makes your brain capable of taking up that inner salt-force which is the basis of thinking? What really enables your brain to make a thinker of you? It is the same force which gives his feathers to the eagle in the air. Thus we feel ourselves related to the eagle through the fact that we think: we feel the human substitute for the eagle's plumage within us. Our thoughts flow out from the brain in the same way as the feathers stream out from the eagle. [* Homer compares the speed of the Phaeacian ships to a bird's wing or a thought. Odyssey VII. 36.]

When we ascend from the physical level to the astral level, we must make this paradoxical statement: on the physical plane the same forces bring about the formation of plumage as on the astral plane bring about the formation of thoughts. To the eagle they give the formation of feathers; that is the physical aspect of the formation of thoughts. To man they give thoughts; that is the astral aspect of the formation of feathers. Such things are sometimes indicated in a wonderful way in the genius of folk-language. If a feather is cut off at the top and what is inside extracted, country people call this the soul. Certainly many people will see in this name soul only an external description. It is not an external description. For those who have insight a feather contains something tremendous: it contains the secret of the formation of thoughts.

And now let us look away from what lives in the air, and, in order to have a representative example, let us consider a mammal such as the lion. We can really only understand the lion when we develop a feeling for the joy, the inner satisfaction the lion has in living together with his surroundings. There is indeed no animal, unless it be related to the lion, which has such wonderful, such mysterious breathing. In all creatures of the animal world the rhythms of breathing must harmonize with the rhythms of circulation; but whereas the rhythms of blood circulation become heavy through the digestive processes which are dependent on them, the rhythms of breathing become light because they strive to rise up to the lightness of the formation of the brain. In the case of the bird, what lives in its breathing actually lives simultaneously in its head. The bird is all head, and it presents its head outwardly, as it were, towards the world. Its thoughts are the forms of its plumage. For to one who has a feeling for the beauty of nature, there is hardly anything more moving than to feel the inner connection between man's thought—when it is really concrete, inwardly teeming with life—and the plumage of a bird. Anyone who is inwardly practised in such things knows quite exactly when he is thinking like a peacock, when he is thinking like an eagle, or when he is thinking like a sparrow. Apart from the fact that the one is astral and the other physical, these things do actually correspond in a wonderful way. And so it may be said that the bird's life in breathing preponderates to such a degree that the other processes—blood-circulation and so on—are almost negligible. All the heaviness of digestion, yes, even the heaviness of blood-circulation, is done away with in the bird's feeling of itself; it is not there.

In the lion a kind of balance exists between breathing and blood-circulation. Certainly in the case of the lion the blood-circulation is weighed down, but not so much, let us say, as in the case of the camel or the ox. There the digestion burdens the blood-circulation to a remarkable degree. In the lion, whose digestive tract apparatus is comparatively short and is so formed that the digestive process is completed as rapidly as possible, digestion does not burden the circulation to any marked degree. On the other hand, it is also the case that in the lion's head the development of the head-nature is such that breathing is held in balance with the rhythm of circulation. The lion, more than any other animal, possesses an inner rhythm of breathing and rhythm of the heartbeat which are inwardly maintained in balance, which are inwardly harmonized. This is why the lion—when we think of what may be called his subjective life—has that particular way of devouring his food with unbridled voracity, why he literally gulps it down. For he is really only happy when he has swallowed it. He is ravenous for nourishment, because it lies in his nature that hunger causes him much more pain than it causes other animals. He is greedy for nourishment but he is not bent on being a fastidious gourmet! Enjoyment of the taste is not what possesses him, for he is an animal which finds its inner satisfaction in the equilibrium between breathing and blood-circulation. Only when the lion's food has passed over into the blood which regulates the heart-beat, and when the heart-beat has come into reciprocal action with the breathing—for it is a source of enjoyment to the lion when he draws in the breath-stream with deep inner satisfaction—only when he feels in himself the result of his feeding, this inner balance between breathing and blood-circulation, does the lion live in his own element. He lives fully as lion when he experiences the deep inner satisfaction of his blood beating upwards, of his breath pulsing downwards. And it is in this reciprocal crossing of two wave-pulsations that the lion really lives.

Picture the lion, how he runs, how he leaps, how he holds his head, even how he looks around him, and you will see that all this leads back to a continual rhythmic interplay between coming out of balance, and again coming into balance. There is perhaps hardly anything that can touch one in so mysterious a way as the remarkable gaze of the lion, from which so much looks out, something of inner mastery, the mastery of opposing forces. This is what looks out from the lion's gaze: the absolute and complete mastery of the heartbeat through the rhythm of the breath.

And again, let those who have a sense for the artistic understanding of forms look at the form of the lion's mouth, revealing as it does how the heart-beat pulses upwards towards the mouth, but is held back by the breath. If you could really picture this reciprocal contact of heart beat and breathing, you would arrive at the form of the lion's mouth.

The lion is all breast-organ. He is the animal in which the rhythmic system is brought to perfect expression both in outer form and in way of living. The lion is so organized that this inter-action of heart beat and breathing is also brought to expression in the reciprocal relationship of heart and lungs.

So we must say: When we look in the human being for what most closely resembles the bird, though naturally metamorphosed, it is the human head; when we look in the human being for what most closely resembles the lion, it is the region of the human breast, where the rhythms meet each other, the rhythms of circulation and breathing.

And now let us turn our attention away from all that belongs in the upper air to the bird-kingdom; away from all that lives in the circulation of the air immediately adjacent to the Earth, as does the lion; let us consider the ox or cow. In other connections I have often spoken of how enchanting it is to contemplate a herd of cattle, replete and satisfied, lying down in a meadow; to observe this process of digestion which here again is expressed in the position of the body, in the expression of the eyes, in every movement. Take an opportunity of observing a cow lying in the meadow, if from here or there some kind of noise disturbs her. It is really wonderful to see how the cow raises her head, how in this lifting there lies the feeling that it is all heaviness, that it is not easy for the cow to lift the head, as though something very special were within it. When we see a cow in the meadow disturbed in this way, we cannot but say to ourselves: This cow is astonished that she must lift her head for anything but grazing. Why do I lift my head now? I am not grazing, and there is no point in lifting my head unless it is to graze. Only look at the way she does it! All this is to be seen in the way the cow lifts her head. But it is not only in the movement of the lifting of the head. (You cannot imagine the lion lifting his head as the cow does.) It lies also in the form of the head. And if we further observe the animal's whole form, we see it is in fact what I may call an extended digestive system! The weight of the digestion burdens the blood-circulation to such a degree that it overwhelms everything to do with head and breathing. The animal is all digestion. It is infinitely wonderful, when looked at spiritually, to turn one's gaze upwards to the bird, and then to look downwards upon the cow.

Of course, to whatever height one might raise the cow, physically she would never be a bird. But if one could pass over what is physical in the cow—first bringing her into the moisture of the air in the immediate vicinity of the earth, and transforming her etheric form into one corresponding to the moisture; and, next, raising her up higher, bringing her as far as the astral, then up in the heights the cow would be a bird. Astrally she would be a bird.

And you see, it is just here that something wonderful approaches us, if we have insight, compelling us to say, What the bird up in the heights has astrally out of its astral body, what works there, as I have said, upon the formation of its plumage, this the cow has embodied in her flesh, in her muscles, in her bones. What is astral in the bird has become physical in the cow. The appearance is of course different in the astrality, but so it is.

On the other hand, if I reverse the process, and allow what belongs to the astrality of a bird to sink down, thereby bringing about the transformation into the etheric and physical, the eagle would become a cow, because what is astral in the eagle is incorporated into the flesh, into the bodily nature of the cow as she lies on the ground engaged in digestion; for it belongs to this digestive process in the cow to develop a wonderful astrality. The cow becomes beautiful in the process of digestion. Seen astrally, something immensely beautiful lies in this digestion. And when it is said by ordinary philistine concepts, indeed by philistine idealism, that the process of digestion is the most lowly, this must be indicted as untruth, when, from a higher vantage-point, one gazes with spiritual sight at this digestive process in the cow. For this is beautiful, this is grand, this is something of an immense spirituality.

The lion does not attain to this spirituality, much less the bird. In the bird the digestive process is something almost entirely physical. One does of course find the etheric body in the digestive system of the bird, but in its digestive processes one finds very little, indeed almost nothing, of astrality. On the other hand, something is present in the digestive processes of the cow which, seen astrally, is quite stupendous, an entire world.

And now, if we wish to look at what is similar in man, again seeking for the correspondence between what is developed in the cow in a one-sided way, the physical embodiment of a certain astrality, we find this in man—harmoniously adjusted to the other parts of his organism, woven, as it were, into his digestive organs and their continuation—in the limb-system. So in truth what I behold high in the upper air in the eagle; what I behold in the realm where the animal rejoices in the air around him as in the case of the lion; and what I behold when the animal is bound up with the sub-terrestrial earth-forces, which project their working into its digestive organs (as occurs when I look away from the heights into the depths, and bring my understanding to bear on the nature and being of the cow) all these three forms I find united into a harmony in man, into reciprocal balance. I find the metamorphosis of the bird in the human head, the metamorphosis of the lion in the human breast, the metamorphosis of the cow in the digestive system and the system of the limbs—though naturally metamorphosed, tremendously transformed.

When today we contemplate these things and realize that man is actually born out of the whole of nature, that he bears the whole of nature within himself as I have shown, that he bears the bird-kingdom, the lion-kingdom, the essential being of the cow within him, then we get the separate component parts of what is expressed in the abstract sentence: Man is a “Little World”. He is indeed a Little World, and the Great World is within him; and all the creatures which live above in the air, and the animals on the face of the earth whose special element is the air which circulates around them, and the animals which have their special element below the surface of the earth, as it were, in the forces of weight—all these work together in man as a harmonious whole. So that man is in truth the synthesis of eagle, lion, and ox or cow.

When one discovers this again through the investigations of a more modern Spiritual Science, one gains that great respect of which I have often spoken for the old, instinctive, clairvoyant insight into the Cosmos. Then, for instance, one gains a great respect for the mighty imagination that man consists of eagle, lion, and cow or ox, which, harmonized in true proportion, together form the human being in his totality.

But before I pass on—this may be tomorrow—to discuss the separate impulses which lie in the forces weaving around the eagle, around the lion, around the cow, I want to speak of another correspondence between man's inner being and what is outside in the Cosmos.

From what we already know we can now take a further step. The human head seeks for what accords with its nature: it must direct its gaze upwards to the bird-kingdom. If one is to understand the human breast—the heart beat, the breathing—as a secret within the secrets of nature, the gaze must be turned to something of the nature of the lion. And man must try to understand his digestive system from the constitution, from the organization, of the ox or cow. But in his head man has the bearer of his thoughts, in the breast the bearer of his feelings, in his digestive system the bearer of his will. So that in his soul-nature, too, man is an image of the thoughts which weave through the world with the birds and find expression in their plumage, and of the world of feeling encircling the earth, which is to be found in the lion in the balanced life of heart beat and breathing and which, though milder in man, does indeed represent the inner quality of courage—the Greek language made use of the word ![]() 1The quality of the “great soul”, cf. Coeur de Lion. for the qualities of heart and breast, the inner quality of courage in man. And if man wishes to find his will-impulses which, when he gives them external form, are predominantly connected with the metabolism, he must turn his gaze to the bodily form in the cow.

1The quality of the “great soul”, cf. Coeur de Lion. for the qualities of heart and breast, the inner quality of courage in man. And if man wishes to find his will-impulses which, when he gives them external form, are predominantly connected with the metabolism, he must turn his gaze to the bodily form in the cow.

What today sounds grotesque or paradoxical, what may seem almost insane to an age that has retained absolutely no understanding for the relationships of the world, does nevertheless contain a truth which points back to ancient customs. It is a striking phenomenon that Mahatma Gandhi—who has now been presented to the world, more falsely than truly, by Romain Rolland in a rather unpleasant book—that Mahatma Gandhi, who certainly turns his activity in an outward direction, but at the same time stands within the Indian people, somewhat like a rationalist of the eighteenth century over against the ancient Hindu religion—it is striking that in his rationalized Hinduism Gandhi retains the veneration of the cow. This cannot be set aside, says Mahatma Gandhi, who, as you know, was sentenced by the English to six years' imprisonment for his political activity in India. He still retains veneration for the cow.

Things such as these, which have so tenaciously retained their position in spiritual cultures, can only be understood when one is aware of the inner connections, when one really knows what tremendous secrets lie in the ruminating animal, the cow; and how one can venerate in it a lofty astrality, which has, as it were, become earthly, and only thereby more lowly. Such things enable us to understand the religious veneration which is paid to the cow in Hinduism, and which the whole bevy of rationalistic and intellectualistic concepts which have been brought to bear on this subject will never enable us to understand.

And so we see how will, feeling, thought, can be looked for outside in the Cosmos, and correspondingly in the microcosm, man.

There are, however, all kinds of other forces in the human being, and all kinds of other forces outside in nature too. So now I must ask you to consider for the moment the metamorphoses undergone by the creature which later becomes a butterfly.

You know the butterfly lays its egg. Out of the egg comes the caterpillar. The egg contains everything that is the germinal essence of the later butterfly. The caterpillar emerges from the egg into the light-irradiated air. This is the environment into which the caterpillar comes. You must, therefore, envisage how the caterpillar really lives in this sunlit air.

Here you must consider what happens when you are lying in bed at night and have lit the lamp, and a moth flies towards the lamp, and finds its death in the light. This light works upon the moth in such a way that it subjects itself to a search for death. Here we have an example of the action of light upon the living.

Now the caterpillar—I am only indicating these things shortly today; tomorrow and the next day we shall consider them somewhat more exactly—the caterpillar cannot rise up to the source of light, to the Sun, in order to cast itself into it, but it would like to do so. Its desire to do so is just as strong as the moth's, which casts itself into the flame of your bedside lamp, and there meets its death. The moth casts itself into the flame and finds its death in physical fire. The caterpillar seeks the flame just as eagerly, the flame which comes towards it from the Sun. But it cannot throw itself into the Sun; the passing over into warmth, into light, remains for the caterpillar something spiritual. It is as spiritual activity that the whole action of the Sun works upon the caterpillar. It follows each ray of the Sun, this caterpillar; by day it accompanies the rays of the Sun. just as the moth throws itself at once into the flame, giving over its whole moth-substance to the light, so the caterpillar weaves its caterpillar-substance slowly into the light, pauses at night, weaves by day, and spins and weaves around itself the whole cocoon. And we have in the cocoon, in the threads of the cocoon, what the caterpillar weaves out of its own substance as it spins on in the flooding sunlight. And now the caterpillar, which has become a chrysalis, has woven around itself, out of its own substance, the rays of the Sun, which it has incorporated in itself. The moth is consumed quickly in the physical fire. The caterpillar, sacrificing itself, casts itself into the sunlight, and from moment to moment weaves around itself the threads of the Sun's rays which it follows in their course. If you look at the cocoon of the silkworm you are looking at woven sunlight, only the sunlight is embodied through the substance of the silk-spinning caterpillar itself. Now the space it inhabits is inwardly enclosed. The outer sunlight has in a sense been overcome. That part of the sunlight to which I referred when I described the Druidic Mysteries, [* In a lecture to workmen on 11th September, 1923. See also The Evolution of Consciousness, Lectures 8 and 9 (Rudolf Steiner Press).] as entering into the cromlechs, is now inside the cocoon. The Sun, which previously exerted its physical power, causing the caterpillar to spin its own cocoon, now exerts its power upon what is inside, and from out of this it creates the butterfly, which now emerges. Then the whole circle begins anew. Here you have separated out before you in sequence what is, as it were, compressed in the egg of a bird.

Compare this whole process with what happens when a bird lays its eggs. Inside the bird itself, still through a process of metamorphosis, the chalky egg-shell is formed around the egg. The forces of the sunlight make use of the substance of

the chalk to press together the whole sequence of what here in the butterfly is separated off into egg, caterpillar, cocoon. All these processes are compressed at the place where, in the bird's egg, the hard shell forms itself around them. Through this pressing together of processes which otherwise are separated into different stages, the whole embryonic development in the bird is different. All that up to this point of the third stage is completed within the bird, in the butterfly is separated into egg-formation, caterpillar-formation, chrysalis-formation, cocoon-formation. Here all can be seen outwardly, until the butterfly slips out.

And when one now follows the whole process astrally, what is to be seen then? Well, the bird in its whole formation represents the human head, the organ of thought-formation. What does the butterfly represent, the butterfly which in its embryonic formation is so extraordinarily complicated? We find that the butterfly represents a continuation of the function of the head, it represents the forces of the head spread out, as it were, over the whole human body. Here something happens in the whole human being, corresponding to a process in nature but different from the process of the formation of the bird.

When we take into account its etheric and astral nature, we have in the human head something very similar to egg-formation, only metamorphosed. If we had only the function of the head we should form nothing but momentary thoughts. Our thoughts would not sink down more deeply into us, involve the whole human being, and then rise up again as memories. If I look at the momentary thoughts which I form of the outer world, and then look up to the eagle, I say: In the eagle's plumage I see outside myself embodied thoughts; within me these remain as thoughts, but only momentary thoughts. But if I look at what I bear within me as my memories, I find a more complicated process. Deep in the physical body, though certainly in a spiritual way, a kind of egg-formation is taking place. In the etheric this certainly represents something quite different, something which in its external physical aspect resembles the caterpillar-formation. In the astral body, however, in its inner aspect, it is similar to the chrysalis-formation, the cocoon-formation. And when I have a percept which evokes a thought in me, what loosens, ejects, as it were, that thought and presses it downward is like the butterfly laying an egg. The development is then similar to what takes place in the caterpillar; the life in the etheric body offers itself up to the spiritual light, weaves around the thoughts, as it were, an inner astral cocoon-web, from which the memories slip out. If we see the bird's plumage manifested in momentary thoughts, so we must see the butterfly's wings, shimmering with colour, manifested in our memory-thoughts in a spiritual way.

Thus we look around and feel to what an immense degree nature is related to us. We think and see the world of thoughts in the flying birds. We remember, we have memories, and see the world of memory-pictures, living within us, in the fluttering butterflies shimmering in the sunlight. Yes, man is a Microcosm and contains within himself the secrets of the Great World outside. And it is a fact that what we perceive inwardly—our thoughts, our feelings, our will-impulses, our memory-pictures, when regarded from the other side, from without, in a macrocosmic sense, can all be recognized again in the kingdom of nature.

This is to look at reality. Reality of this kind does not allow itself to be grasped by mere thoughts, for to mere thoughts reality is a matter of indifference; they only hold to logic. But this same logic can prove the most contradictory things in the sphere of reality. To make this apparent, let me close with an illustration which will serve to form a bridge to what we shall consider tomorrow.

A certain tribe of African negroes, the Felatas, have a very beautiful fable, from which much can be learned.

Once upon a time a lion, a wolf and a hyena set out upon a journey. They met an antelope. The antelope was torn to pieces by one of the animals. The three travelers were good friends, so now the question arose as to how to divide the dismembered antelope between them. First the lion spoke to the hyena, saying, “You divide it.” The hyena possessed his logic. He is the animal who deals not with the living but with the dead. His logic is naturally determined by the measure of his courage, or rather of his cowardice. According to whether this courage is more or less, he approaches reality in different ways. The hyena said: “We will divide the antelope into three equal parts—one for the lion, one for the wolf, and one for myself.” Whereupon the lion fell upon the hyena and killed him. Now the hyena was out of the way, and again it was a question of sharing out the antelope. So the lion said to the wolf, “See, my dear wolf, now we must share it out differently. You divide it. How would you share it out?” Then the wolf said, “Yes, we must now apportion it differently; it cannot be shared out evenly as before. As you have rid us of the hyena, you as lion must get the first third; the second third would have been yours in any case, as the hyena said, and the remaining third you must get because you are the wisest and bravest of all the animals.” This is how the wolf apportioned it. Then said the lion, “Who taught you to divide in this way?” To which the wolf replied, “The hyena taught me.” So the lion did not devour the wolf, but, according to the wolf's logic, took the three portions for himself.

Yes, the mathematics, the intellectual element, was the same in the hyena and the wolf. They divided the antelope into three parts. But they applied this intellect, this calculation, to reality in a different way. Thereby destiny, too, was essentially altered. The hyena was devoured because his application of the principle of division to reality had different results from that of the wolf who was not devoured. For the wolf related his hyena-logic—he even said himself that the hyena had taught it to him—to quite another reality. He related it to reality in such a way that the lion no longer felt compelled to devour him too.

You see, hyena-logic in the first case, hyena-logic also in the wolf; but in its application to reality the intellectual logical element resulted in something quite different.

It is thus with all abstractions. You can do everything in the world with abstractions just according to whether you relate them to reality in this or that way. We must, therefore, be able to penetrate with insight into a reality such as the correspondence between man, as Microcosm, and the Macrocosm. We must be able to study the human being not with logic only, but in a sense which can never be achieved unless intellectualism is led over into the artistic element of the world. But if you succeed in bringing about the metamorphosis of intellectualism into artistic comprehension, and are able to develop the artistic into the principle of knowledge, then you find what is within man in a human way, not in a natural way, outside in the Macrocosm, in the Great World. Then you find the relationship of the human being to the Great World in a true and real sense.

Erster Vortrag

Es ist in unseren Betrachtungen öfter gesagt worden und spielte auch in den letzten Vorträgen über den Jahreslauf und das Michael-Problem eine gewisse Rolle, daß der Mensch in seinem ganzen Bau, in seinen Lebensverhältnissen, eigentlich in allem, was er ist, eine kleine Welt darstellt, einen Mikrokosmos gegenüber dem Makrokosmos, daß er wirklich in sich enthält alle Gesetzmäßigkeit der Welt, alle Geheimnisse der Welt. Nur müssen Sie sich nicht vorstellen, daß das vollständige Verstehen dieses ja ganz abstrakten Satzes ein einfaches ist. Man muß schon sozusagen in die Mannigfaltigkeit der Weltengeheimnisse eindringen, um dann diese Geheimnisse im Menschen wiederzufinden.

Nun wollen wir heute einmal diese Sache so betrachten, daß wir auf der einen Seite von gewissen Ausgangspunkten aus uns die Welt anschauen und dann den Menschen anschauen, um zu finden, wie der Mensch als eine kleine Welt in der großen Welt darinnen ist. Natürlich ist dasjenige, was man von der großen Welt sagen kann, ja immer ein kleiner Ausschnitt. Es kann nie ein Vollständiges darstellen, sonst müßte man in der Betrachtung wenigstens die ganze Welt durchwandeln. Sehen wir zuerst einmal hin auf dasjenige, was sich uns am allernächsten Oberen, wenn ich so sagen darf, darstellt.

Sehen wir auf diejenige menschliche Umgebung, die in der Tierreihe das Leben sozusagen in den Lüften hat, und zwar diejenige Klasse, welche in der auffallendsten Art das Leben in den Lüften hat: das ist das Vogelgeschlecht.

Es kann einem nicht entgehen, daß der Vogel, der in den Lüften wohnt, der aus den Lüften seine Daseinsbedingungen schöpft, als Tier wesentlich anders gebaut ist als die Tiere, die unmittelbar über dem Erdboden wohnen, oder die etwa gar unter dem Erdboden wohnen. Und wenn wir hinschauen auf das Vogelgeschlecht, so finden wir uns natürlich nach allgemeinen, menschlich üblichen Ansichten genötigt, beim Vogel auch von Kopf und Gliedmaßen und dergleichen zu sprechen. Aber das ist eigentlich im Grunde eine recht unkünstlerische Betrachtungsweise. Und darauf habe ich schon öfter aufmerksam gemacht, daß, wenn man die Welt eigentlich wirklich kennenlernen will, man bei dem intellektualistischen Begreifen nicht stehenbleiben kann, daß das Intellektualistische allmählich hinübergleiten muß in das künstlerische Auffassen der Welt.

Nun, da werden Sie doch nicht den wirklich im Verhältnis zum Haupte, zum Kopfe der anderen Tiere doch außerordentlich verkrüppelten sogenannten Vogelkopf als einen wirklichen Kopf auffassen. Gewiß, äußerlich intellektualistisch betrachtet, kann man sagen: Der Vogel hat einen Kopf, einen Rumpf, der Vogel hat Gliedmaßen. Aber bedenken Sie, wie verkümmert, sagen wir zum Beispiel in bezug auf die Beine eines Kamels oder eines Elefanten die Vogelbeine sind, und wie verkümmert gegenüber meinetwillen dem Haupte eines Löwen, eines Hundes, der Vogelkopf ist. Es ist fast gar nichts Ordentliches darinnen in einem solchen Vogelkopf; es ist eigentlich im Grunde genommen kaum mehr darinnen als das, was beim Hund oder meinetwillen beim Elefanten oder bei der Katze die vordere Maulpartie ist. Ich möchte sagen, ein wenig komplizierter die Mundpartie eines Säugetieres, das ist der Vogelkopf. Und was die Gliedmaßen eines Säugetieres sind, das ist ja vollständig verkümmert beim Vogel. Gewiß, eine unkünstlerische Betrachtungsweise spricht einfach davon, die vorderen Gliedmaßen seien zu Flügeln umgestaltet. Aber das alles ist eben durchaus unkünstlerische Anschauung, unimaginative Anschauung. Will man die Natur wirklich verstehen, will man in den Kosmos wirklich eindringen, so muß man die Dinge schon tiefer, vor allen Dingen in ihren Gestaltungs- und Bildungskräften betrachten.

Die Anschauung, daß einfach der Vogel auch einen Kopf und Rumpf und Gliedmaßen habe, führt niemals dazu, zum Beispiel die Anschauung des Ätherleibes eines Vogels wirklich begreifen zu können. Denn geht man über durch imaginative Anschauung von dem Sehen dessen, was am Vogel physisch ist, zu dem, was am Vogel ätherisch ist, so hat man eben im ätherischen Vogel nur einen Kopf. Vom ätherischen Vogel aus ist der Vogel nur Kopf; vom ätherischen Vogel aus begreift man sogleich, daß der Vogel sich nicht vergleichen läßt mit Kopf, Rumpf und Gliedmaßen anderer Tiere, sondern daß er aufzufassen ist als ein bloßer Kopf, der eben umgestaltet ist, der als Kopf umgestaltet ist. So daß der eigentliche Vogelkopf nur Gaumen und die vorderen Partien, die Mundpartien darstellt, und dasjenige, was weiter nach rückwärts geht, alle die rippenähnlich und rückgratähnlich aussehenden Teile des Skeletts, das ist anzusehen als zwar metamorphosierter, umgestalteter, aber doch als Kopf. Der ganze Vogel ist eigentlich Kopf. Das rührt davon her, daß in der Tat, wenn wir einen Vogel verstehen wollen, wir sehr, sehr weit zurückgehen müssen in der Erden-, in der planetarischen Erdenentwickelung.

Der Vogel hat eine lange planetarische Geschichte hinter sich. Der Vogel hat eine viel längere planetarische Geschichte hinter sich als zum Beispiel, sagen wir das Kamel. Das Kamel ist ein viel später entstandenes Tier als jeglicher Vogel. Diejenigen Vögel, die zur Erde niedergezwungen sind wie der Strauß, das sind die spätest entstandenen Vögel. Diejenigen Vögel, die frei in den Lüften wohnen, Adler, Geier, sind sehr alte Erdentiere. Während sie in früheren Erdperioden, Mondperioden, Sonnenperioden eben durchaus noch alles das an sich hatten, was dann in sie übergegangen ist von innen nach auswärts bis zur Haut, hat sich später im Vogelgeschlecht im wesentlichen das ausgebildet, was Sie heute in den Federn sehen, was Sie im hornigen Schnabel sehen. Das Äußere des Vogels ist späteren Ursprungs, ist dadurch gekommen, daß der Vogel seine Kopfnatur verhältnismäßig früh ausgebildet hat, und unter den Bedingungen, in die er dann in späteren Zeiten der Erdenentwickelung hineingekommen ist, konnte er nur noch außen dasjenige hinzufügen, was in seinem Gefieder liegt. Dieses Gefieder ist dem Vogel zum Beispiel vom Mond und der Erde gegeben worden, während er seine übrige Natur aus viel früheren Zeiten hat.

Aber die Sache hat noch eine viel tiefere Seite. Schauen wir uns einmal den Vogel in den Lüften, sagen wir, den majestätisch dahinfliegenden Adler an, dem gewissermaßen wie ein äußeres Gnadengeschenk die Sonnenstrahlen mit ihrer Wirkung sein Gefieder gegeben haben — ich werde die anderen Wirkungen noch nennen -, seinen hornigen Schnabel gegeben haben; schauen wir uns diesen Adler an, wie er in den Lüften fliegt. Da wirken auf ihn gewisse Kräfte. Die Sonne hat nicht nur jene physischen Licht- und Wärmekräfte, von denen wir gewöhnlich sprechen. Ich habe Sie aufmerksam gemacht damals, als ich über die Druidenmysterien sprach, daß von der Sonne auch geistige Kräfte ausgehen. Auf diese geistigen Kräfte müssen wir hinschauen. Sie sind es, welche den verschiedenen Vogelgeschlechtern ihre Vielfarbigkeit, die besondere Gestaltung ihres Gefieders geben. Wir begreifen, wenn wir dasjenige, was die Sonnenwirkungen sind, geistig durchschauen, warum der Adler gerade sein Gefieder hat.

Dann, wenn wir uns so richtig versenken in diese Adlernatur, wenn wir verstehen, inneres künstlerisches Naturverständnis zu entwickeln, welches das Geistige mitenthält, wenn wir hinschauen können, wie künstlerisch herausgebildet wird aus den Sonnenimpulsen, die verstärkt sind durch andere Impulse, die ich nachher nennen werde, wenn wir das sehen, wie gleichsam diese Sonnenimpulse hinfluten über den Adler, schon bevor er aus dem Ei gekrochen ist, wie sie das Gefieder herauszaubern oder eigentlich, besser gesagt, hineinzaubern in seine Fleischesgestalt, und uns dann fragen: Was bedeutet denn das für den Menschen? - Ja, das bedeutet für den Menschen dasjenige, was sein Gehirn zum Träger der Gedanken macht. Und Sie sehen richtig hin in den Makrokosmos, in die große Natur, wenn Sie den Adler so ansehen, daß Sie sagen: Der Adler hat sein Gefieder, seine vielfarbigen, bunten Federn; in denen lebt dieselbe Kraft, die in dir lebt, indem sie dein Gehirn zum Gedankenträger macht. Dasjenige, was dein Gehirn faltet, was dein Gehirn fähig macht, jene innere Salzkraft aufzunehmen, die die Grundlage des Denkens ist, was dein Gehirn überhaupt dazu macht, dich zu einem Denker zu bilden, das ist dieselbe Kraft, die dem Adler in den Lüften sein Gefieder gibt. - So fühlen wir uns verwandt, indem wir denken, gewissermaßen den menschlichen Ersatz in uns fühlend für das Adlergefieder; unsere Gedanken strömen von dem Gehirn so aus, wie ausfluten von dem Adler die Federn.

Wenn wir von dem physischen Niveau heraufgehen in das astralische Niveau, dann müssen wir den paradoxen Satz aussprechen: Auf dem physischen Plan bewirken dieselben Kräfte die Federnbildung, die auf dem astralischen Plan die Gedankenbildung bewirken. Die Federnbildung geben sie dem Adler; das ist der physische Aspekt der Gedankenbildung. Dem Menschen geben sie die Gedanken; das ist der astralische Aspekt der Federnbildung. Solche Dinge liegen manchmal in einer wunderbaren Weise im Genius der Volkssprache ausgedrückt. Wenn man eine Feder oben abschneidet und herausnimmt das, was da drinnen ist, so nennt das Volk das die Seele. Gewiß werden manche eine äußerliche Bezeichnung in diesem Namen Seele sehen. Es ist keine äußere Bezeichnung, sondern eine Feder enthält für denjenigen, der die Sache durchschaut, etwas Ungeheures: sie enthält das Geheimnis der Gedankenbildung.

Sehen wir jetzt weg von dem Adler, der in den Lüften wohnt, sehen wir, um wieder einen Repräsentanten zu haben, ein solches Säugetier wie den Löwen an. Man kann eigentlich den Löwen nur verstehen, wenn man ein Gefühl dafür entwickelt, welche Freude, welche innere Befriedigung der Löwe hat, mit seiner Umgebung zu leben. Es gibt eigentlich kein Tier, welches nicht löwenverwandt ist, das eine so wundervolle, geheimnisvolle Atmung hat. Es müssen überall beim tierischen Wesen die Atmungsrhythmen zusammenstimmen mit den Zirkulationsrhythmen, nur daß die Zirkulationsrhythmen schwer werden durch den an ihnen hängenden Verdauungsapparat, die Atmungsrhythmen leicht werden dadurch, daß sie anstreben, hinauf in die Leichtigkeit der Gehirnbildungen zu kommen. Es ist beim Vogel so, daß dasjenige, was in seinem Atmen lebt, eigentlich zugleich in seinem Kopfe lebt. Der Vogel ist ganz Kopf, und er trägt sozusagen den Kopf äußerlich für die Welt hin. Seine Gedanken sind die Formen seines Gefieders. Es gibt eigentlich für ein richtiges Naturgefühl, das in Schönheit leben kann, nichts Rührenderes, als die innige Verwandtschaft dessen zu fühlen, was Menschengedanke ist, wenn er so ganz konkret wird, wenn er so ganz innerlich lebendig wird, mit einem Vogelgefieder. Derjenige, der in solchen Dingen eine innere Praxis hat, der weiß ganz genau, wann er pfauenmäßig denkt und wann er adlermäßig denkt und wann er spatzenhaft denkt. Die Dinge sind durchaus so, daß mit Ausnahme davon, daß das eine astralisch, das andere physisch ist, sich die Dinge in einer wunderbaren Art entsprechen. Es ist so. So daß man sagen kann: Der Vogel hat ein so überwiegendes Leben in der Atmung, daß das andere, Blutzirkulation und so weiter, fast verschwindet. Alle Schwere der Verdauung, ja selbst die Schwere der Blutzirkulation ist eigentlich von dem In-sich-Fühlen beim Vogel weggefegt, ist nicht da. Beim Löwen ist das so, daß eine Art von Gleichgewicht besteht zwischen dem Atmen und der Blutzirkulation. Allerdings, die Blutzirkulation wird auch beim Löwen schwer gemacht, aber nicht so schwer wie, sagen wir bei dem Kamel oder bei dem Rind. Da ist die Verdauung etwas, was die Blutzirkulation ungemein belastet.

Beim Löwen, der einen verhältnismäßig sehr kurzen Verdauungsapparat hat und der ganz so gebaut ist, daß die Verdauung auch möglichst schnell sich vollzieht, ist das so, daß die Verdauung keine starke Belastung ist für die Zirkulation. Dagegen ist es wiederum so, daß nach der anderen Seite im Löwenkopf eine solche Entfaltung des Kopfmäßigen ist, daß die Atmung im Gleichgewichte mit dem Zirkulationsrhythmus gehalten ist. Der Löwe ist dasjenige Tier, das am allermeisten einen inneren Rhythmus des Atmens und einen Rhythmus des Herzschlages hat, die sich innerlich die Waage halten, die sich innerlich harmonisieren. Der Löwe hat deshalb auch, wenn wir, ich möchte sagen, auf sein subjektives Leben eingehen, diese eigentümliche Art, mit einer schier unbegrenzten Gier seine Nahrung zu verschlingen, weil er eigentlich froh ist, wenn er sie drunten hat. Er ist gierig auf die Nahrung, weil ihm natürlich der Hunger viel mehr Pein macht als einem anderen Tiere; er ist gierig auf die Nahrung, aber er ist nicht versessen darauf, ein besonderer Gourmand zu sein. Er ist gar nicht darauf versessen, viel zu schmecken, weil er ein Tier ist, das seine innere Befriedigung aus dem Gleichmaß von Atmung und Blutzirkulation hat. Erst wenn der Fraß beim Löwen übergegangen ist in das Blut, das den Herzschlag reguliert, und dieser Herzschlag in ein Wechselverhältnis kommt mit der Atmung, an der der Löwe wieder seine Freude hat, indem er den Atmungsstrom mit einer tiefen inneren Befriedigung in sich hereinnimmt, erst dann, wenn er in sich fühlt die Folge des Fraßes, dieses innere Gleichgewicht zwischen Atmung und Blutzirkulation, dann lebt der Löwe in seinem Elemente. Er lebt eigentlich ganz als Löwe, wenn er die tiefe innere Befriedigung hat, daß ihm sein Blut heraufschlägt, daß ihm seine Atmung hinunterpulsiert. Und in diesem gegenseitigen Berühren zweier Wellenschläge lebt der Löwe.

Sehen Sie sich ihn an, diesen Löwen, wie er läuft, wie er springt, wie er seinen Kopf hält, selbst wie er blickt, so werden Sie sehen, daß das alles zurückführt auf ein fortwährendes rhythmisches Wechselspiel von etwas Aus-dem-Gleichgewicht-Kommen und wieder Ins-Gleichgewicht-Kommen. Es gibt vielleicht kaum etwas, was so geheimnisvoll einen anmuten kann als dieser merkwürdige Löwenblick, der so viel aus sich herausschaut, der herausschaut aus sich etwas von innerlicher Bewältigung, von Bewältigung von entgegengesetzt Wirksamem. Das ist dasjenige, was der Löwenblick nach außen schaut: diese Bewältigung des Herzschlages durch den Atmungsrhythmus in einer schier ganz vollkommenen Weise.

Und wiederum, wer Sinn für künstlerische Auffassung von Gestaltungen hat, der schaue sich das Maul des Löwen an, diesen Bau im Maul des Löwen, der so zeigt: der Herzschlag pulsiert herauf bis zu diesem Maul, aber die Atmung hält ihn zurück. Wenn Sie sich dieses Gegenseitig-sich-Berühren von Herzschlag und Atmung ausmalen, so kommen Sie auf das Löwenmaul.

Der Löwe ist eben ganz Brustorgan. Er ist wirklich das Tier, welches in seiner äußeren Gestalt, in seiner Lebensweise das rhythmische System ganz zum Ausdrucke bringt. Der Löwe ist so organisiert, daß sich dieses Wechselspiel von Herzschlag und Atmen auch in dem gegenseitigen Verhältnis von seinem Herzen und seiner Lunge zum Ausdrucke bringt.

So daß wir wirklich sagen müssen: Wenn wir am Menschen etwas suchen, was dem Vogel am ähnlichsten ist, was nur metamorphosiert ist, so ist es der Menschenkopf; wenn wir am Menschen etwas suchen, was dem Löwen am ähnlichsten ist, so ist es die menschliche Brustgegend, da, wo die Rhythmen sich begegnen, die Rhythmen der Zirkulation und der Atmung.

Und jetzt lenken wir den Blick ab von alledem, was sich uns darbietet oben in den Lüften als das Vogelgeschlecht; was eigentlich, weil es in der Luft, die in der unmittelbaren Umgebung der Erde ist, mit dem Luftkreislauf lebt wie im Löwen; sehen wir uns das Rind an. Ich habe schon öfter in anderen Zusammenhängen darauf hingewiesen, wie reizvoll es ist, eine gesättigte Herde, hingelagert auf der Weide, zu betrachten, dieses Geschäft des Verdauens zu beobachten, das sich in der Lage wiederum, in dem Augenausdruck, in jeder Bewegung ausdrückt. Versuchen Sie es einmal, eine Kuh, die auf der Weide liegt, anzuschauen, wenn meinetwillen etwas da oder dort irgendein Geräusch gab. Es ist ja so wunderbar, zu sehen, wie die Kuh den Kopf hebt, wie in diesem Heben das Gefühl liegt, daß das alles schwer ist, daß man den Kopf nicht leicht heben kann, wie ein ganz Besonderes noch da drinnen liegt. Man kann, wenn man eine Kuh so in einer Störung auf der Weide den Kopf hochheben sieht, auf nichts anderes kommen, als sich sagen: Diese Kuh ist erstaunt darüber, daß sie den Kopf zu etwas anderem als zum Abgrasen heben soll. Warum hebe ich denn jetzt eigentlich den Kopf? Ich grase ja nicht, und es hat keinen Zweck, den Kopf zu heben, wenn ich nicht grase. — Sehen Sie nur, wie das ist! Das ist im Kopfheben des Tieres drinnen. Aber es ist nicht nur im Kopfheben des Tieres drinnen. Sie können sich nicht vorstellen, daß der Löwe den Kopf so hebt, wie die Kuh ihn hebt. Das ist in der Form des Kopfes drinnen. Und geht man weiter, geht man auf die ganze Form des Tieres ein - es ist ja das ganze Tier der, ich möchte sagen ausgewachsene Verdauungsapparat! Die Schwere der Verdauung lastet so auf der Blutzirkulation, daß das alles Kopf und Atmung überwältigt. Es ist ganz Verdauung, das Tier. Es ist wirklich, wenn man das nun geistig anschaut, unendlich wunderbar, wenn man den Blick hinaufwendet zum Vogel, und dann herunterschaut auf die Kuh.

Natürlich, wenn man die Kuh physisch noch so hoch hebt, sie wird kein Vogel. Aber wenn man zu gleicher Zeit das Physische an der Kuh übergehen lassen könnte - zunächst indem man sie in die Lüfte bringt, die der Erde unmittelbar nahe sind, in das Luft-Feuchtige, und wenn man das zugleich überführen könnte in eine Verwandlung ihrer Äthergestalt, die nun angemessen wäre dem Feuchtigen, und sie dann weiterheben würde und würde sie bis zum Astralischen bringen können, dann würde hoch oben die Kuh ein Vogel. Astralisch würde sie ein Vogel.

Sehen Sie, da drängt sich einem eben das Wunderbare auf, daß man sich sagt, wenn man das nun durchschaut: Was der Vogel da oben astralisch hat aus seinem Astralleib, was da arbeitet, wie ich gesagt habe, an der Gestaltung seines Gefieders, das hat die Kuh ins Fleisch, in die Muskeln, in die Knochen hineingebracht. Physisch geworden ist an der Kuh dasjenige, was astralisch ist am Vogel. Es sieht natürlich in der Astralität anders aus, aber es ist so.

Wiederum, wenn ich umgekehrt dasjenige, was der Astralität eines Vogels angehört, herunterfallen ließe, dabei die Umwandelung ins Ätherische und Physische vornehmen würde, dann würde der Adler eine Kuh werden, weil das, was astralisch am Adler ist, verfleischt, verkörperlicht ist in der Kuh, die am Boden liegt, wenn sie verdaut; denn es gehört zu diesem Verdauen bei der Kuh, eine wunderbare Astralität zu entwickeln. Die Kuh wird schön im Verdauen. Es liegt, astralisch angesehen, etwas ungeheuer Schönes darinnen in diesem Verdauen. Und wenn man so aus den gewöhnlichen Philisterbegriffen heraus eben in Philisteridealismus sich sagt: Das Verdauungsgeschäft ist das niedrigste -, dann wird man Lügen gestraft, wenn man von einer höheren Warte aus in geistiger Anschauung dieses Verdauungsgeschäft bei der Kuh anschaut. Das ist schön, das ist großartig, das ist etwas ungeheuer Geistiges.

Zu dieser Geistigkeit bringt es der Löwe nicht; der Vogel erst recht nicht. Beim Vogel ist das Verdauungsgeschäft fast etwas ganz Physisches. Man findet natürlich den Ätherleib im Verdauungsapparat des Vogels, aber man findet sehr wenig, fast gar nichts von Astralität in den Verdauungsvorgängen des Vogels. Dagegen bei der Kuh ist in den Verdauungsvorgängen etwas, was, astralisch angesehen, ganz großartig ist, eine ganze Welt ist. Und da hat man, wenn man jetzt das Ähnliche beim Menschen ansehen will, wiederum diese Korrespondenz zwischen dem, was die Kuh einseitig ausbildet, die physische Verfleischung eines gewissen Astralischen, da hat man das beim Menschen harmonisch zu dem anderen hinzuverwebt in seinen Verdauungsorganen und in ihrer Fortsetzung, in den Gliedmaßen. So daß wirklich das, was ich schaue hoch oben in den Lüften im Adler, was ich schaue da, wo das Tier sich unmittelbar an der Luft erfreut wie beim Löwen, was ich schaue dann, wenn das Tier verbunden ist mit den unterirdischen Erdenkräften, die weiterwirken in seinen Verdauungsorganen, wenn ich also statt in die Höhe, hinunter in die Tiefe schaue und verständnisvoll von da aus das Wesen der Kuh durchdringe, dann habe ich die drei Gestalten, die im Menschen zu einer Harmonie vereinigt sind und sich dadurch ausgleichen: die Metamorphose des Vogels im Menschenhaupt, die Metamorphose des Löwen in der Menschenbrust, die Metamorphose der Kuh in dem Verdauungs- und Gliedmaßenapparat des Menschen, natürlich im Gliedmaßenapparat wieder kolossal metamorphosiert, kolossal umgestaltet.

Wenn man so heute hinschaut auf diese Dinge und wiederum darauf kommt, wie der Mensch eigentlich aus der ganzen Natur heraus geboren ist und in sich die ganze Natur wiederum trägt, so wie ich es dargestellt habe, wie er das Vogelreich, das Löwenreich, das Kuhwesen in sich trägt, dann bekommt man die einzelnen Bestandteile dessen, was der abstrakte Satz sagt: Der Mensch ist eine kleine Welt. - Er ist schon eine kleine Welt, und die große Welt ist in ihm, und all das Getier, welches in den Lüften wohnt, und das Getier, welches um die Erde herum in der kreisenden Luft sein hauptsächlichstes Element hat, und das Getier, welches unter dem Erdboden in den Kräften der Schwere sein hauptsächlichstes Element hat, sie wirken im Menschen zu einer harmonischen Ganzheit zusammen. Und der Mensch ist dann die Zusammenfassung von Adler, Löwe, Stier oder Kuh.

Wenn man das wiederum aus neuerer Geisteswissenschaft heraus erforscht, durchschaut, dann bekommt man diesen großen Respekt, von dem ich öfter gesprochen habe, vor den alten instinktiven hellseherischen Einsichten in den Kosmos; dann bekommt man den großen Respekt zum Beispiel vor so etwas, wie das gewaltige Bild ist von dem Bestehen des Menschen aus Adler, Löwe, Kuh oder Stier, die zusammen, entsprechend sich harmonisierend, den Menschen als eine Ganzheit bilden.

Aber bevor ich übergehe dazu — das kann auch morgen sein -, die einzelnen Impulse zu besprechen, die zum Beispiel in den Kräften, die den Adler umschweben, sind, die in den Kräften sind, die den Löwen umschweben, welche die Kuh umschweben, möchte ich noch eine andere Korrespondenz des Innerlich-Menschlichen mit dem, was draußen im Kosmos ist, besprechen.

Wir bekommen ja jetzt nach dem, was wir schon wissen, die Vorstellung davon. Das menschliche Haupt sucht das seiner Natur Entsprechende: es muß den Blick hinaufrichten zu dem Vogelgeschlecht. Die menschliche Brust, der Herzschlag, die Atmung muß, wenn es sich begreifen will als Geheimnis in den Naturgeheimnissen, hinwenden den Blick zu so etwas, was der Löwe ist. Der Mensch muß seinen Stoffwechselapparat versuchen zu verstehen aus der Konstitution, aus der Organisation des Rindes. Aber der Mensch hat in seinem Haupte die Träger seiner Gedanken, in seiner Brust die Träger seiner Gefühle, in seinem Stoffwechselapparat die Träger seines Willens. So daß also auch seelisch der Mensch ein Abbild ist der mit dem Vogelgeschlecht die Welt durchwebenden Vorstellungen, die sich im Gefieder der Vögel ausdrücken; der die Erde umkreisenden Gefühlswelt, die sich im inneren Ausgleichsleben zwischen Herzschlag und Atmung beim Löwen findet, die gemildert ist beim Menschen, die aber beim Menschen eben das innerliche Mutvolle — die griechische Sprache hatte das Wort mutvoll für die Herzenseigenschaften, für die Brusteigenschaften gebildet darstellt. Und wenn er seine Willensimpulse finden will, die vorzugsweise in seinem Stoffwechsel sitzen, wenn er diese äußerlich gestaltet, schaut er hin auf dasjenige, was fleischlich in der Kuh gestaltet ist.

Das, was heute grotesk, paradox klingt, was vielleicht wahnsinnig erscheint für eine Zeit, die so gar kein Verständnis mehr hat für die geistigen Zusammenhänge der Welt, enthält aber doch eine Wahrheit, auf die alte Gebräuche hindeuten. Sehen Sie, es ist doch eine auffallende Erscheinung, daß jener Mahatma Gandhi, den jetzt mehr schlecht als recht Romain Rolland in einer wenig erfreulichen Schrift der Welt beschrieben hat, daß jener Mahatma Gandhi, der seine Tätigkeit zwar ganz nach außen gewendet hat, aber dabei, innerhalb des indischen Volkes, ich möchte sagen, wie ein nach Indien hinüber versetzter Aufklärer des 18. Jahrhunderts gegenüber der alten Hindureligion dasteht, daß der in seinem aufklärerischen Hinduismus aber eines bewahrt hat: die Verehrung der Kuh. Von der könne man nicht abkommen, sagt der Mahatma Gandhi, der, wie Sie wissen, von den Engländern sechs Jahre schweren Kerkers bekommen hat für seine politische Tätigkeit in Indien. Die Verehrung der Kuh behält er bei.

Solche Dinge, die mit einer Zähigkeit in geistigeren Kulturen sich erhalten haben, begreift man nur, wenn man diese Zusammenhänge kennt, wenn man wirklich weiß, welche ungeheuren Geheimnisse in dem Verdauungstier, der Kuh, leben, und wie man verehren kann, ich möchte sagen, ein irdisch gewordenes und deshalb nur niedrig gewordenes, ein irdisch gewordenes hoch Astralisches in der Kuh. Aus solchen Dingen heraus begreift man auch die religiöse Verehrung, die im Hinduismus der Kuh zukommt, während sie aus all dem rationalistischen und intellektualistischen Begriffsgestrüppe, das man daran hängt, niemals begriffen werden kann.

Und so sehen wir eben, wie Wille, Gefühl, Gedanke gesucht werden können draußen im Kosmos, gesucht werden können im Mikrokosmos in ihrer Korrespondenz.

Aber sehen Sie, wir haben auch noch mancherlei andere Kräfte im Menschen, und wir haben mancherlei anderes in der Natur draußen. Da bitte ich Sie, einmal folgendes zu beachten. Beachten Sie einmal jene Metamorphose, die durchgemacht wird von dem Tiere, das dann ein Schmetterling wird.

Sie wissen, der Schmetterling legt sein Ei. Aus dem Ei kommt die Raupe heraus. Die Raupe also ist aus dem Ei herausgekommen; das Ei enthält ringsum geschlossen alles dasjenige, was Anlage des späteren Tieres ist. Nun kommt die Raupe aus dem Ei. Sie kommt an die lichtdurchflossene Luft. Das ist die Umgebung, in die sie hineinkommt, die Raupe. Da müssen Sie eben ins Auge fassen, wie eigentlich diese Raupe nun in der sonnendurchleuchteten Luft lebt. Das müssen Sie dann studieren, wenn Sie, sagen wir, des Nachts im Bette liegen, die Lampe angezündet haben und eine Motte nach der Lampe fliegt, dem Lichte zufliegt und den Tod findet im Lichte. Dieses Licht wirkt auf die Motte so, daß sie sich unterwirft dem Tod-Suchen. Damit haben wir schon die Wirkung des Lichtes auf das Lebendige.

Nun, die Raupe - ich deute diese Dinge nur aphoristisch an, wir werden sie morgen und übermorgen etwas genauer betrachten - kann nicht zur Lichtquelle hinauf, um sich hineinzustürzen, zur Sonne nämlich, aber sie möchte es; sie möchte es ebenso stark, wie es die Motte will, die sich in die Flamme neben Ihrem Bette wirft und darinnen umkommt. Die Motte wirft sich in die Flamme und findet den Tod im physischen Feuer. Die Raupe sucht ebenso die Flamme, jene Flamme, die ihr entgegenkommt von der Sonne. Aber sie kann sich nicht in die Sonne werfen; der Übergang ins Licht und in die Wärme bleibt bei ihr etwas Geistiges. Die ganze Sonnenwirkung geht auf sie über als eine geistige. Sie verfolgt jeden Sonnenstrahl, diese Raupe, sie geht bei Tag mit dem Sonnenstrahl mit. Geradeso wie sich die Motte einmal ins Licht stürzt und ihre ganze Mottenmaterie hingibt dem Lichte, so webt die Raupe ihre Raupenmaterie langsam in das Licht hinein, setzt bei Nacht ab, webt bei Tag weiter, und spinnt und webt um sich herum den ganzen Kokon. Und im Kokon, in den Kokonfäden haben wir darinnen dasjenige, was aus ihrer eigenen Materie die Raupe, indem sie fortspinnt im strömenden Sonnenlicht, aus sich heraus webt. Jetzt hat die Raupe, die zur Puppe geworden ist, sich die Sonnenstrahlen, die sie nur verkörperlicht hat, aus ihrer eigenen Raupensubstanz um sich herumgewoben. Die Motte verbrennt schnell im physischen Feuer. Die Raupe stürzt sich hinein, sich opfernd, in das Sonnenlicht, und webt um sich in der Richtung des jeweiligen Sonnenlichts, das sie verfolgt, die Fäden des Sonnenlichts. Wenn Sie den Kokon des Seidenspinners nehmen und sehen ihn an: das ist gewobenes Sonnenlicht, nur daß das Sonnenlicht verkörpert ist durch die Substanz der seidenspinnenden Raupe selber. Damit aber ist der Raum innerlich abgeschlossen. Das äußere Sonnenlicht ist überwunden gewissermaßen. Aber dasjenige, was vom Sonnenlichte, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe, in die Kromlechs hineingeht - ich habe es Ihnen bei den Auseinandersetzungen über die Druidenmysterien gesagt -, das ist jetzt da innerlich. Und jetzt hat die Sonne, während sie früher die physische Gewalt ausübte und die Raupe zum Spinnen ihres eigenen Kokons veranlaßte, Gewalt über das Innerliche, schafft aus dem Innerlichen heraus den Schmetterling, der nun auskriecht. Und der Kreislauf beginnt von neuem. Sie haben auseinandergelegt vor sich dasjenige, was im Vogelei zusammengeschoben ist.

Vergleichen Sie mit diesem ganzen Vorgang den Vorgang beim eierlegenden Vogel. Da wird innerhalb des Vogels selber noch durch einen Vorgang, der metamorphosiert ist, die Kalkschale herum gebildet. Da wird die Substanz des Kalkes von den Kräften des Sonnenlichtes verwendet, um eben den ganzen Prozeß desjenigen zusammenzuschieben, was hier auseinandergelegt ist in Ei, Raupe, Kokon. Das alles ist zusammengeschoben da, wo sich, wie zum Beispiel im Vogelei, direkt die harte Schale ringsherum bildet. Da, durch dieses Zusammenschieben eines auseinandergelegten Prozesses, ist der ganze Embryonalvorgang beim Vogel eben ein anderer. Beim Schmetterling haben Sie auseinandergelegt, was beim Vogel sich vollzieht bis hierher, bis zum dritten Stadium; das haben Sie auseinandergelegt beim Schmetterling in die Eibildung, Raupenbildung, Puppenbildung, Kokonbildung. Da können Sie es äußerlich anschauen. Und dann schlüpft der Schmetterling aus.

Wenn man jetzt den ganzen Vorgang astralisch verfolgt, was sieht man dann? Ja, dann stellt der Vogel in seiner ganzen Bildung einen menschlichen Kopf dar. Das Organ der Gedankenbildung stellt er dar. Was stellt der Schmetterling dar, der auch in den Lüften wohnt, aber in seiner Embryonalbildung etwas ungeheuer Komplizierteres ist? Man kommt darauf, daß der Schmetterling dasjenige darstellt, was sozusagen die Kopffunktion in ihrer Fortsetzung zeigt, die Kräfte des Kopfes gewissermaßen ausgedehnt auf den ganzen Menschen. Da geschieht dann etwas im ganzen Menschen, was einem anderen Vorgang in der Natur als der Vogelbildung entspricht.

Im menschlichen Haupte haben wir, wenn wir das Ätherische und Astralische dazunehmen, etwas sehr Ähnliches wie in der Eibildung, nur metamorphosiert. Aber wenn wir bloß die Funktion des Kopfes hätten, würden wir nur augenblickliche Gedanken bilden. Es würden sich nicht die Gedanken mehr in uns hinuntersetzen, den ganzen Menschen in Anspruch nehmen und dann als Erinnerungen wieder auftauchen. Schaue ich meine augenblicklichen Gedanken an, die ich mir an der Außenwelt bilde, und schaue zum Adler auf, dann sage ich: In dem Gefieder des Adlers sehe ich außer mir die verkörperten Gedanken; in mir werden es Gedanken, aber es werden die augenblicklichen Gedanken. Sehe ich auf dasjenige, was ich in mir trage als meine Erinnerungen, so geht ein komplizierterer Prozeß vor sich. Unten im physischen Leib geschieht, auf eine allerdings geistige Art, eine Art Eibildung, die allerdings etwas ganz anderes ist im Ätherischen, etwas, was äußerlich physisch der Raupenbildung ähnlich ist, im astralischen Leib, was innerlich ähnlich ist der Puppenbildung, der Kokonbildung; und dasjenige, was, wenn ich eine Wahrnehmung habe, in mir einen Gedanken auslöst, hinunterschiebt, das ist so, wie wenn der Schmetterling ein Ei legt. Die Umwandlung ist etwas Ähnliches wie das, was mit der Raupe vor sich geht: das Leben im Ätherleib opfert sich hin dem geistigen Lichte, umwebt gewissermaßen den Gedanken mit innerem, astralem Kokongewebe, und da schlüpfen die Erinnerungen aus. Wenn wir das Vogelgefieder sehen in den augenblicklichen Gedanken, so müssen wir den Schmetterlingsflügel, den in Farben schillernden Schmetterlingsflügel, auf geistige Art zustande gekommen sehen in unseren Erinnerungsgedanken.

So blicken wir hinaus und fühlen die Natur ungeheuer verwandt mit uns. So denken wir und sehen die Welt des Gedankens in den fliegenden Vögeln. Und so erinnern wir uns, so haben wir ein Gedächtnis, und sehen die Welt der in uns lebenden Erinnerungsbilder in den im Sonnenlichte schimmernd flatternden Schmetterlingen. Ja, der Mensch ist ein Mikrokosmos und enthält die Geheimnisse der großen Welt draußen. Und es ist so, daß wir gewissermaßen dasjenige, was wir von innen anschauen, unsere Gedanken, unsere Gefühle, unseren Willen, unsere Erinnerungsvorstellungen, daß wir das, wenn wir es von der anderen Seite, von außen, makrokosmisch ansehen, in dem Reiche der Natur wiedererkennen.

Das heißt hinschauen auf die Wirklichkeit. Diese Wirklichkeit läßt sich mit bloßen Gedanken nicht begreifen, denn dem bloßen Gedanken ist die Wirklichkeit gleichgültig; er hält nur auf die Logik. Aber mit derselben Logik kann man das Verschiedenste in der Wirklichkeit belegen. Um das zu veranschaulichen, lassen Sie mich mit einem Bilde schließen, das dann den Übergang zu den morgigen Auseinandersetzungen bilden soll.

Es gibt bei einem afrikanischen Negerstamme, den Fellatas, ein sehr schönes Bild, welches vieles darstellt. Es begaben sich einmal ein Löwe, ein Wolf und eine Hyäne auf die Wanderung. Sie trafen eine Antilope. Die Antilope wurde von einem der Tiere zerrissen. Sie waren gut miteinander befreundet, die drei Tiere, und nun handelte es sich darum, diese zerrissene Antilope zu teilen unter dem Löwen, dem Wolf und der Hyäne. Da sagte der Löwe zunächst zur Hyäne: Teile du. - Die Hyäne hatte ihre Logik. Sie ist dasjenige Tier, welches sich nicht an das Lebende hält, welches sich an das Tote hält. Ihre Logik wird wohl durch diese Art ihres Mutes, eher ihrer Feigheit, bestimmt sein. Je nachdem dieser Mut so oder so ist, geht er so oder so auf das Wirkliche. Die Hyäne sagte: Wir teilen die Antilope in drei gleiche Teile. Einen Teil bekommt der Löwe, einen Teil bekommt der Wolf, einen Teil bekommt die Hyäne, ich selber. - Da zerriß der Löwe die Hyäne, machte sie tot. Jetzt war sie weg. Und nun sollte geteilt werden. Da sagte der Löwe zum Wolf: Sieh einmal, mein lieber Wolf, jetzt müssen wir ja anders teilen. Teile du jetzt. Wie würdest du teilen? - Da sagte der Wolf: Ja, wir müssen jetzt anders teilen, es kann nicht mehr jeder dasselbe bekommen wie früher, und da du uns von der Hyäne befreit hast, mußt du selbstverständlich als Löwe bekommen das erste Drittel. Das zweite Drittel hättest du ja sowieso bekommen, wie die Hyäne sagte, und das dritte Drittel mußt du bekommen, weil du das weiseste und tapferste unter allen Tieren bist. — So teilte der Wolf nun. Da sagte der Löwe: Wer hat dich so teilen gelehrt? - Da sagte der Wolf: die Hyäne hat mich so teilen gelehrt! - Und der Löwe fraß den Wolf nicht auf und nahm die drei Teile nach der Logik des Wolfes.

Ja, die Mathematik, das Intellektualistische war gleich bei der Hyäne und beim Wolf. Sie machten eine Dreiteilung, sie dividierten. Aber sie wendeten diesen Intellekt, die Mathematik, in verschiedener Weise auf die Wirklichkeit an. Dadurch änderte sich auch dasSchicksal wesentlich. Die Hyäne wurde gefressen, weil sie in der Beziehung ihres Teilungsprinzipes zur Wirklichkeit eben etwas anderes gab als der Wolf, der nicht gefressen wurde, weil er in dem Verhältnis seiner Hyänenlogik er sagt ja selbst, die Hyäne habe es ihn gelehrt - diese Logik auf eine ganz andere Wirklichkeit bezog. Er bezog sie eben so auf die Wirklichkeit, daß der Löwe nicht mehr nötig hatte, auch ihn zu fressen.

Sie sehen: Hyänenlogik da, Hyänenlogik auch beim Wolf; aber in der Anwendung auf die Wirklichkeit wird das Intellektualistische, das Logische ein ganz Verschiedenes.

So ist es mit allen Abstraktionen. Sie können mit Abstraktionen alles in der Welt machen, je nachdem Sie sie in dieser oder jener Weise auf die Wirklichkeit anwenden. Daher muß man schon auf so etwas hinschauen können wie die Realität im Entsprechen des Menschen als Mikrokosmos mit dem Makrokosmos. Nicht nur logisch muß man den Menschen betrachten können, sondern in einem Sinne, der niemals ohne das Überführen des Intellektualismus in das Künstlerische der Welt zu erreichen ist. Dann aber, wenn Sie vom Intellektualistischen gewissermaßen die Metamorphose vollziehen können ins künstlerische Erfassen und das Künstlerische als Erkenntnisprinzip ausbilden können, dann finden Sie das, was im Menschen auf eine menschliche Art, nicht auf eine naturhafte Art lebt, im Makrokosmos draußen, in der großen Welt. Dann finden Sie die Verwandtschaft des Menschen mit der großen Welt in einem wahrhaften Sinne.

First Lecture

It has often been said in our reflections and also played a certain role in the last lectures on the course of the year and the Michael problem that man in his whole structure, in his living conditions, in fact in everything that he is, represents a small world, a microcosm in relation to the macrocosm, that he really contains within himself all the laws of the world, all the secrets of the world. But you need not imagine that the complete understanding of this quite abstract proposition is a simple one. You have to penetrate, so to speak, into the multiplicity of the secrets of the world in order to then find these secrets again in man.

Now let us look at this matter today in such a way that, on the one hand, we look at the world from certain starting points and then look at man in order to find how man is a small world within the great world. Of course, what we can say about the great world is always a small section. It can never represent a complete picture, otherwise one would at least have to go through the whole world in the observation. Let us first look at that which is closest to us above all, if I may say so.

Let us look at the human environment, which in the animal kingdom has life in the air, so to speak, and that is the class which has life in the air in the most conspicuous way: that is the bird family.

It cannot escape one's notice that the bird that lives in the air, that draws its conditions of existence from the air, is built essentially differently as an animal than the animals that live directly above the ground, or that even live below the ground. And if we look at the bird species, we naturally find ourselves compelled, according to the general, humanly accepted views, to speak of the head and limbs and the like in birds. But this is actually quite an inartistic way of looking at things. And I have often pointed out that if you really want to get to know the world, you cannot stop at the intellectualistic understanding, that the intellectualistic must gradually slide over into the artistic understanding of the world.

Now, you will not understand the so-called bird's head, which is really extremely crippled in relation to the head, to the head of the other animals, as a real head. Certainly, from an external intellectual point of view, one can say: the bird has a head, a torso, the bird has limbs. But consider how atrophied, let's say, the legs of a camel or an elephant are, and how atrophied the bird's head is compared to the head of a lion or a dog. There is almost nothing orderly in such a bird's head; in fact, there is little more to it than the front part of the mouth of a dog or, for that matter, of an elephant or a cat. I would say that the mouth of a mammal is a little more complicated than the head of a bird. And the limbs of a mammal are completely atrophied in a bird. Certainly, an inartistic way of looking at it simply says that the front limbs are transformed into wings. But all of this is quite simply an inartistic view, an unimaginative view. If you really want to understand nature, if you really want to penetrate the cosmos, you have to look at things more deeply, above all in their formative and formative powers.

The view that a bird simply has a head and a torso and limbs never leads to being able to really grasp the view of a bird's etheric body, for example. For if one goes through imaginative contemplation from seeing what is physical in the bird to what is etheric in the bird, then one has only a head in the etheric bird. From the etheric bird the bird is only a head; from the etheric bird one immediately understands that the bird cannot be compared with the head, torso and limbs of other animals, but that it is to be understood as a mere head that has just been reshaped, that has been reshaped as a head. So that the actual bird's head represents only the palate and the front parts, the mouth parts, and that which goes further back, all the rib-like and spine-like parts of the skeleton, that is to be regarded as metamorphosed, reshaped, but still as a head. The whole bird is actually a head. This stems from the fact that, if we want to understand a bird, we have to go very, very far back in the evolution of the earth, in the planetary evolution of the earth.

The bird has a long planetary history behind it. The bird has a much longer planetary history behind it than, for example, the camel. The camel is a much later evolved animal than any bird. Those birds that are forced down to earth, like the ostrich, are the latest evolved birds. Those birds that live freely in the air, eagles, vultures, are very old earth animals. Whereas in earlier earth periods, moon periods, sun periods, they still had everything about them that then passed over into them from the inside outwards to the skin, later on in the bird's life what you see today in the feathers, what you see in the horny beak, has essentially developed. The exterior of the bird is of later origin, has come from the fact that the bird developed its head nature relatively early, and under the conditions into which it then came in later times of earthly development, it could only add on the outside that which lies in its plumage. This plumage, for example, was given to the bird by the moon and the earth, while the rest of its nature comes from much earlier times.

But there is a much deeper side to the matter. Let us take a look at the bird in the air, let us say, the majestic soaring eagle, to which the sun's rays have given its plumage - I will mention the other effects - and its horned beak as an external gift of grace; let us look at this eagle as it flies in the air. Certain forces act upon it. The sun has not only those physical forces of light and heat of which we usually speak. I drew your attention to the fact, when I spoke about the Druid mysteries, that spiritual forces also emanate from the sun. We must look to these spiritual forces. It is these forces that give the various bird species their multicolored appearance, the special design of their plumage. We understand why the eagle has its plumage when we spiritually see through the effects of the sun.