Man as Symphony of the Creative Word

Part Three. The Plant-World and the Elemental Nature-Spirits

GA 230

2 November 1923, Dornach

The World-Word is not some combination of syllables gathered from here or there, but the World-Word is the harmony of what sounds forth from countless beings.

Lecture VII

To the outwardly perceptible, visible world there belongs the invisible world, and these, taken together, form a whole. The marked degree to which this is the case first appears in its full clarity when we turn our attention away from the animals to the plants.

Plant-life, as it sprouts and springs forth from the earth, immediately arouses our delight, but it also provides access to something which we must feel as full of mystery. In the case of the animal, though certainly its will and whole inner activity have something of the mysterious, we nevertheless recognize that this will is actually there, and is the cause of the animal's form and outer characteristics. But in the case of the plants, which appear on the face of the earth in such magnificent variety of form, which develop in such a mysterious way out of the seed with the help of the earth and the encircling air—in the case of the plant we feel that some other factor must be present in order that this plant-world may arise in the form it does.

When spiritual vision is directed to the plant-world, we are immediately led to a whole host of beings, which were known and recognized in the old times of instinctive clairvoyance, but which were afterwards forgotten and today remain only as names used by the poet, names to which modern man ascribes no reality. To the same degree, however, in which we deny reality to the beings which whirl and weave around the plants, to that degree do we lose the understanding of the plant-world. This understanding of the plant-world, which, for instance, would be so necessary for the art of healing, has been entirely lost to present-day humanity.

We have already recognized a very significant connection between the world of the plants and the world of the butterflies; but this too will only come rightly before our souls when we look yet more deeply into the whole weaving and working of plant-life.

Plants send down their roots into the ground. Anyone who can observe what they really send down and can perceive the roots with spiritual vision (for this he must have) sees how the root-nature is everywhere surrounded, woven around, by elemental nature spirits. And these elemental spirits, with an old clairvoyant perception designated as gnomes and which we may call the root-spirits, can actually be studied by an imaginative and inspirational world-conception, just as human life and animal life can be studied in the sphere of the physical. We can look into the soul-nature of these elemental spirits, into this world of the spirits of the roots.

These root-spirits, are, so to say, a quite special earth-folk, invisible at first to outer view, but in their effects so much the more visible; for no root could develop if it were not for what is mediated between the root and the earth-realm by these remarkable root-spirits, which bring the mineral element of the earth into flux in order to conduct it to the roots of the plants. Naturally I refer to the underlying spiritual process.

These root-spirits, which are everywhere present in the earth, get a quite particular sense of well-being from rocks and from ores (which may be more or less transparent). But they enjoy their greatest sense of well-being, because here they are really at home, when they are conveying what is mineral to the roots of the plants. And they are completely enfilled with an inner element of spirituality which we can only compare with the inner element of spirituality in the human eye, in the human ear. For these root-spirits are in their spirit-nature entirely sense. Apart from this they are nothing at all; they consist only of sense. They are entirely sense, and it is a sense which is at the same time understanding, which does not only see and hear, but immediately understands what is seen and heard, which in receiving impressions, receives also ideas.

We can even indicate the way in which these root-spirits receive their ideas. We see a plant sprouting out of the earth. The plant comes, as I shall presently show you, into connection with the extraterrestrial universe; and, particularly at certain seasons of the year, spirit-currents flow from above, from the blossom and the fruit of the plant down into the roots below, streaming into the earth. And just as we turn our eyes towards the light and see, so do the root-spirits turn their faculty of perception towards what seeps downwards from above, through the plant into the earth. What seeps down towards the root-spirits, that is something which the light has sent into the blossoms, which the sun's warmth has sent into the plants, which the air has produced in the leaves, which the distant stars have brought about in the plant's structures. The plant gathers the secrets of the universe, sinks them into the ground, and the gnomes take these secrets into themselves from what seeps down spiritually to them through the plants. And because the gnomes, particularly from autumn on and through the winter, in their wanderings through ore and rock bear with them what has filtered down to them through the plants, they become those beings within the earth which, as they wander, carry the ideas of the whole universe streaming throughout the earth. We look forth into the wide world. The world is built from universal spirit; it is an embodiment of universal ideas, of universal spirit. The gnomes receive through the plants, which to them are the same as rays of light are to us, the ideas of the universe, and within the earth carry them in full consciousness from metal to metal, from rock to rock.

We gaze down into the depths of the earth not to seek there below for abstract ideas about some kind of mechanical laws of nature, but to behold the roving, wandering gnomes, which are the light-filled preservers of world-understanding within the earth.

Because these gnomes have immediate understanding of what they see, their knowledge is actually of a similar nature to that of man. They are the compendium of understanding, they are entirely understanding. Everything about them is understanding, an understanding however, which is universal, and which really looks down upon human understanding as something incomplete. The gnomes laugh us to scorn on account of the groping, struggling understanding with which we manage to grasp one thing or another, whereas they have no need at all to make use of thought. They have direct perception of what is comprehensible in the world; and they are particularly ironical when they notice the efforts people have to make to come to this or that conclusion. Why should they do this? say the gnomes—why ever should people give themselves so much trouble to think things over? We know everything we look at. People are so stupid—say the gnomes—for they must first think things over.

And I must say that the gnomes become ironical to the point of ill manners if one speaks to them of logic. For why ever should people need such a superfluous thing—a training in thinking? The thoughts are already there. The ideas flow through the plants. Why don't people stick their noses as deep into the earth as the plant's roots, and let what the sun says to the plants trickle down into their noses? Then they would know something! But with logic—so say the gnomes—there one can only have odd bits and pieces of knowledge.

Thus the gnomes, inside the earth, are actually the bearers of the ideas of the universe, of the world-all. But for the earth itself they have no liking at all. They bustle about in the earth with ideas of the universe, but they actually hate what is earthly. This is something from which the gnomes would best like to tear themselves free. Nevertheless they remain with the earthly—you will soon see why this is—but they hate it, for the earthly threatens them with a continual danger. The earth continually holds over them the threat of forcing them to take on a particular form, the form of those creatures I described to you in the last lecture, the amphibians, and in particular of the frogs and the toads. The feeling of the gnomes within the earth is really this: If we grow too strongly together with the earth, we shall assume the form of frogs or toads. They are continually on the alert to avoid being caught in a too strong connection with the earth, to avoid taking on earthly form. They are always on the defensive against this earthly form, which threatens them as it does because of the element in which they exist. They have their home in the earthly-moist element; there they live under the constant threat of being forced into amphibian forms. From this they continually tear themselves free, by filling themselves entirely with ideas of the extra-terrestrial universe. The gnomes are really that element within the earth which represents the extra-terrestrial, because they must continually reject a growing together with the earthly; otherwise, as single beings, they would take on the forms of the amphibian world. And it is just from what I may call this feeling of hatred, this feeling of antipathy towards the earthly, that the gnomes gain the power of driving the plants up out of the earth. With the fundamental force of their being they unceasingly thrust away the earthly, and it is this thrusting that determines the upward direction of the plant's growth; they push the plants up with them. It accords with the nature of the gnomes in regard to the earthly to allow the plant to have only its roots in the earth, and then to grow upwards out of the earth-sphere; so that it is actually out of the force of their own original nature that the gnomes push the plants out of the earth and make them grow upwards.

Once the plant has grown upwards, once it has left the domain of the gnomes and has passed out of the sphere of the moist-earthly element into the sphere of the moist-airy, the plant develops what comes to outer physical formation in the leaves. But in all that is now active in the leaves other beings are at work, water-spirits, elemental spirits of the watery element, to which an earlier instinctive clairvoyance gave among others the name of undines. Just as we find the roots busied about, woven-about by the gnome-beings in the vicinity of the ground, and observe with pleasure the upward-striving direction which they give, we now see these water-beings, these elemental beings of the water, these undines in their connection with the leaves.

These undine beings differ in their inner nature from the gnomes. They cannot turn like a spiritual sense-organ outwards towards the universe. They can only yield themselves up to the weaving and working of the whole cosmos in the airy-moist element, and therefore they are not beings of such clarity as the gnomes. They dream incessantly, these undines, but their dream is at the same time their own form. They do not hate the earth as intensely as do the gnomes, but they have a sensitivity to what is earthly. They live in the etheric element of water, swimming and swaying through it, and in a very sensitive way they recoil from everything in the nature of a fish; for the fish-form is a threat to them, even if they do assume it from time to time, though only to forsake it immediately in order to take on another metamorphosis. They dream their own existence. And in dreaming their own existence they bind and release, they bind and disperse the substances of the air, which in a mysterious way they introduce into the leaves, as these are pushed upwards by the gnomes. For at this point the plants would wither if it were not for the undines, who approach from all sides, and show themselves, as they weave around the plants in their dream-like existence, to be what we can only call the world-chemists. The undines dream the uniting and dispersing of substances. And this dream, in which the plant has its existence, into which it grows when, developing upwards, it forsakes the ground, this undine-dream is the world-chemist which brings about in the plant-world the mysterious combining and separation of the substances which emanate from the leaf. We can therefore say that the undines are the chemists of plant-life. They dream of chemistry. They possess an exceptionally delicate spirituality which is really in its element just where water and air come into contact with each other. The undines live entirely in the element of moisture, but they develop their actual inner function when they come to the surface of something watery, be it only to the surface of a water-drop or something else of a watery nature. For their whole endeavour lies in preserving themselves from getting the form of a fish, the permanent form of a fish. They wish to remain in a condition of metamorphosis, in a condition of eternal, endlessly changing transformation. But in this state of transformation in which they dream of the stars and of the sun, of light and of warmth, they become the chemists who now, starting from the leaf, carry the plant further in its formation, after it has been pushed upwards by the power of the gnomes. So the plant develops its leaf-growth, and this mystery is now revealed as the dream of the undines into which the plants grow.

To the same degree, however, in which the plant grows into the dream of the undines, does it now come into another domain, into the domain of those spirits which live in the airy-warmth element, just as the gnomes live in the moist-earthly, and the undines in the moist-airy element. Thus it is in the element which is of the nature of air and warmth that those beings live which an earlier clairvoyant art designated as the sylphs. Because air is everywhere imbued with light, these sylphs, which live in the airy-warmth element, press towards the light, relate themselves to it. They are particularly susceptible to the finer but larger movements within the atmosphere.

When in spring or autumn you see a flock of swallows, which produce as they fly vibrations in a body of air, setting an air-current in motion, then this moving air-current—and this holds good for every bird—is for the sylphs something audible. Cosmic music sounds from it to the sylphs. If, let us say, you are travelling somewhere by ship and the seagulls are flying around it, then in what is set in motion by the seagulls' flight there is a spiritual sounding, a spiritual music which accompanies the ship.

Again it is the sylphs which unfold and develop their being within this sounding music, finding their dwelling-place in the moving current of air. It is in this spiritually sounding, moving element of air that they find themselves at home; and at the same time they absorb what the power of light sends into these vibrations of the air. Because of this the sylphs, which experience their existence more or less in a state of sleep, feel most in their element, most at home, where birds are winging through the air. If a sylph is obliged to move and weave through air devoid of birds, it feels as though it had lost itself. But at the sight of a bird in the air something quite special comes over the sylph. I have often had to describe a certain event in man's life, that event which leads the human soul to address itself as “I”. And I have always drawn attention to a saying of Jean Paul, that, when for the first time a human being arrives at the conception of his “I”, it is as though he looks into the most deeply veiled Holy of Holies of his soul. A sylph does not look into any such veiled Holy of Holies of its own soul, but when it sees a bird an ego-feeling comes over it. It is in what the bird sets in motion as it flies through the air that the sylph feels its ego. And because this is so, because its ego is kindled in it from outside, the sylph becomes the bearer of cosmic love through the atmosphere. It is because the sylph embodies something like a human wish, but does not have its ego within itself but in the bird-kingdom, that it is at the same time the bearer of wishes of love through the universe.

Thus we behold the deepest sympathy between the sylphs and the bird-world. Whereas the gnome hates the amphibian world, whereas the undine is unpleasantly sensitive to fishes, is unwilling to approach them, tries to avoid them, feels a kind of horror for them, the sylph, on the other hand, is attracted towards birds, and has a sense of well-being when it can waft towards their plumage the swaying, love-filled waves of the air. And were you to ask a bird from whom it learns to sing, you would hear that its inspirer is the sylph. Sylphs feel a sense of pleasure in the bird's form. They are, however, prevented by the cosmic ordering from becoming birds, for they have another task. Their task is lovingly to convey light to the plant. And just as the undine is the chemist for the plant, so is the sylph the light-bearer. The sylph imbues the plant with light; it bears light into the plant.

Through the fact that the sylphs bear light into the plant, something quite remarkable is brought about in it. You see, the sylph is continually carrying light into the plant. The light, that is to say the power of the sylphs in the plant, works upon the chemical forces which were induced into the plant by the undines. Here occurs the inter-working of sylph-light and undine-chemistry. This is a remarkable plastic activity. With the help of the upstreaming substances which are worked upon by the undines, the sylphs weave out of the light an ideal plant-form. They actually weave the Archetypal Plant within the plant from light, and from the chemical working of the undines. And when towards autumn the plant withers and everything of physical substance disintegrates, then these plant-forms begin to seep downwards, and now the gnomes perceive them, perceive what the world—the sun through the sylphs, the air through the undines—has brought to pass in the plant. This the gnomes perceive, so that throughout the entire winter they are engaged in perceiving below what has seeped into the ground through the plants. Down there they grasp world-ideas in the plant-forms which have been plastically developed with the help of the sylphs, and which now in their spiritual ideal form enter into the ground.

Naturally those people who regard the plant as something purely material know nothing of this spiritual ideal form. Thus at this point something appears which in the materialistic observation of the plant gives rise to what is nothing other than a colossal error, a terrible error. I will sketch this error for you.

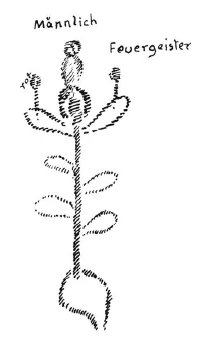

Everywhere you will find that materialistic science describes matters as follows: The plant takes root in the ground, above the ground it develops its leaves, finally unfolding its blossoms, within the blossoms the stamens, then the seed-bud. Now—usually from another plant—the pollen from the anthers, from the pollen vessels, is carried over to the germ which is then fructified, and through this the seed of the new plant is produced. The germ is regarded as the female element and what comes from the stamens as the male—indeed matters cannot be regarded otherwise as long as people remain fixed in materialism, for then this process really does look like a fructification. This, however, it is not. In order to gain insight into the process of fructification, that is to say the process of reproduction, in the plant-world, we must be conscious that in the first place it is from what the great chemists, the undines, bring about in the plants, and from what the sylphs bring about, that the plant-form arises, the ideal plant-form which sinks into the ground and is preserved by the gnomes. It is there below, this plant-form. And there within the earth it is now guarded by the gnomes after they have seen it, after they have looked upon it. The earth becomes the mother-womb for what thus seeps downwards. This is something quite different from what is described by materialistic science.

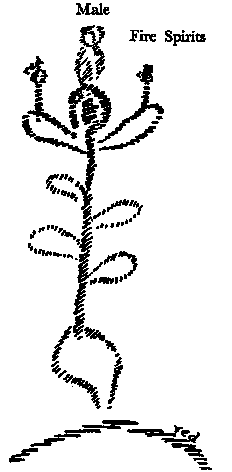

After it has passed through the sphere of the sylphs, the plant comes into the sphere of the elemental fire-spirits. These fire-spirits are the inhabitants of the warmth-light element. When the warmth of the earth is at its height, or is otherwise suitable, they gather the warmth together. Just as the sylphs gather up the light, so do the fire-spirits gather up the warmth and carry it into the blossoms of the plants.

Undines carry the action of the chemical ether into the plants, sylphs the action of the light-ether into the plant's blossoms. And the pollen now provides what may be called little air-ships, to enable the fire-spirits to carry the warmth into the seed. Everywhere warmth is collected with the help of the stamens, and is carried by means of the pollen from the anthers to the seeds and the seed vessels. And what is formed here in the seed-bud is entirely the male element which comes from the cosmos. It is not a case of the seed-vessel being female and the anthers of the stamens being male. In no way does fructification occur in the blossom, but only the pre-forming of the male seed. The fructifying force is what the fire-spirits in the blossom take from the warmth of the world-all as the cosmic male seed, which is united with the female element. This element, drawn from the forming of the plant has, as I told you, already earlier seeped down into the ground as ideal form, and is resting there below. For plants the earth is the mother, the heavens the father. And all that takes place outside the domain of the earth is not the mother-womb for the plant. It is a colossal error to believe that the mother-principle of the plant is in the seed-bud. The fact is that this is the male-principle, which is drawn forth from the universe with the aid of the fire-spirits. The mother comes from the cambium, which spreads from the bark to the wood, and is carried down from above as ideal form. And what now results from the combined working of gnome-activity and fire-spirit activity—this is fructification. The gnomes are, in fact, the spiritual midwives of plant-reproduction. Fructification takes place below in the earth during the winter, when the seed comes into the earth and meets with the forms which the gnomes have received from the activities of the sylphs and undines and now carry to where these forms can meet with the fructifying seeds.

You see, because people do not recognize what is spiritual, do not know how gnomes, undines, sylphs and fire-spirits—which were formerly called salamanders—weave and live together with plant-growth, there is complete lack of clarity about the process of fructification in the plant world. There, outside the earth nothing of fructification takes place, but the earth is the mother of the plant-world, the heavens the father. This is the case in a quite literal sense. Plant-fructification takes place through the fact that the gnomes take from the fire-spirits what the fire-spirits have carried into the seed bud as concentrated cosmic warmth on the little airships of the anther-pollen. Thus the fire-spirits are the bearers of warmth.

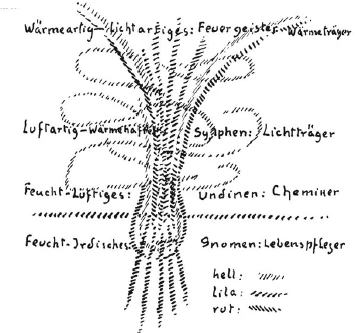

And now you will easily gain insight into the whole process of plant-growth. First, with the help of what comes from the fire-spirits, the gnomes down below instill life into the plant and push it upwards. They are the fosterers of life. They carry the life-ether to the root—the same life-ether in which they themselves live. The undines foster the chemical ether, the sylphs the light-ether, the fire-spirits the warmth ether. And then the fruit of the warmth-ether again unites with what is present below as life. Thus the plants can only be understood when they are considered in connection with all that is circling, weaving and living around them. And one only reaches the right interpretation of the most important process in the plant when one penetrates into these things in a spiritual way.

When once this has been understood, it is interesting to look again at that memorandum of Goethe's where, referring to another botanist, he is so terribly annoyed because people speak of the eternal marriage in the case of the plants above the earth. Goethe is affronted by the idea that marriages should be taking place over every meadow. This seemed to him something unnatural. In this Goethe had an instinctive but very true feeling. He could not as yet know the real facts of the matter, nevertheless he instinctively felt that fructification should not take place above in the blossom. Only he did not as yet know what goes on down below under the ground, he did not know that the earth is the mother-womb of the plants. But, that the process which takes place above in the blossom is not what all botanists hold it to be, this is something which Goethe instinctively felt.

You are now aware of the inner connection between plant and earth. But there is something else which you must take into account.

You see, when up above the fire-spirits are circling around the plant and transmitting the anther-pollen, then they have only one feeling, which they have in an enhanced degree, compared to the feeling of the sylphs. The sylphs experience their self, their ego, when they see the birds flying about. The fire-spirits have this experience, but to an intensified degree, in regard to the butterfly-world, and indeed the insect-world as a whole. And it is these fire-spirits which take the utmost delight in following in the tracks of the insects' flight so that they may bring about the distribution of warmth for the seed buds. In order to carry the concentrated warmth, which must descend into the earth so that it may be united with the ideal form, in order to do this the fire-spirits feel themselves inwardly related to the butterfly-world, and to the insect-creation in general. Everywhere they follow in the tracks of the insects as they buzz from blossom to blossom. And so one really has the feeling, when following the flight of insects, that each of these insects as it buzzes from blossom to blossom, has a quite special aura which cannot be entirely explained from the insect itself. Particularly the luminous, wonderfully radiant, shimmering, aura of bees, as they buzz from blossom to blossom, is unusually difficult to explain. And why? It is because the bee is everywhere accompanied by a fire-spirit which feels so closely related to it that, for spiritual vision, the bee is surrounded by an aura which is actually a fire-spirit. When a bee flies through the air from plant to plant, from tree to tree, it flies with an aura which is actually given to it by a fire-spirit. The fire-spirit does not only gain a feeling of its ego in the presence of the insect, but it wishes to be completely united with the insect.

Through this, however, insects also obtain that power about which I have spoken to you, and which shows itself in a shimmering forth of light into the cosmos. They obtain the power completely to spiritualize the physical matter which unites itself with them, and to allow the spiritualized physical substance to ray out into cosmic space. But just as with a flame it is the warmth in the first place which causes the light to shine, so, above the surface of the earth, when the insects shimmer forth into cosmic space what attracts the human being to descend again into physical incarnation, it is the fire spirits which inspire the insects to this activity, the fire-spirits which are circling and weaving around them. But if the fire-spirits are active in promoting the outstreaming of spiritualized matter into the cosmos, they are no less actively engaged in seeing to it that the concentrated fiery element, the concentrated warmth, goes into the interior of the earth, so that, with the help of the gnomes, the spirit-form, which sylphs and undines cause to seep down into the earth, may be awakened.

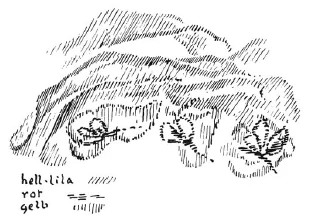

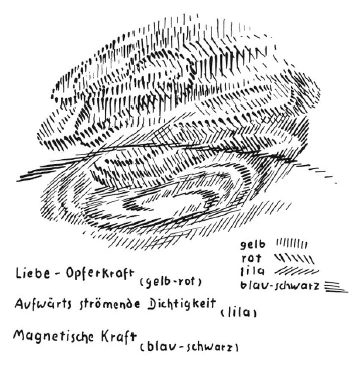

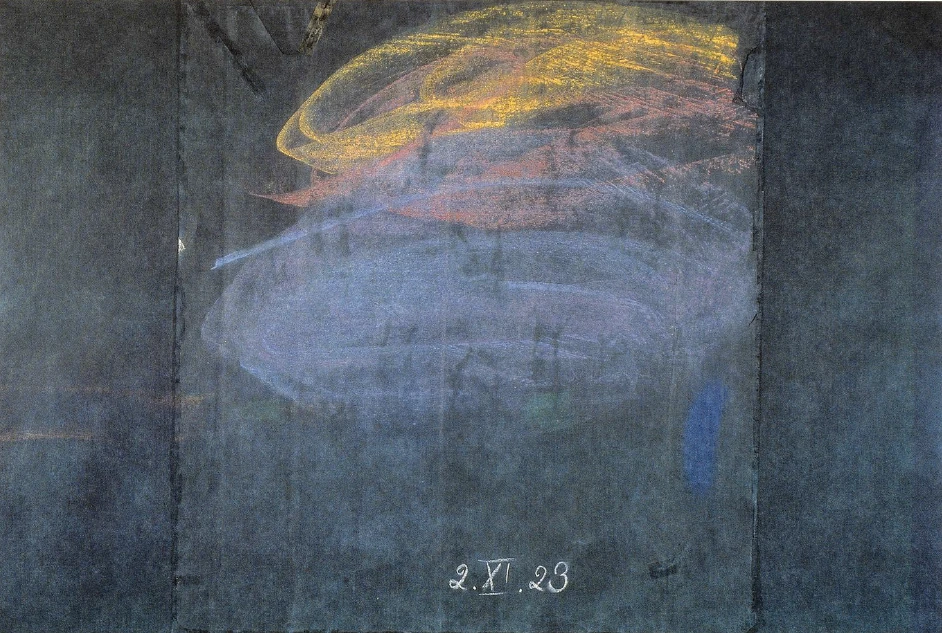

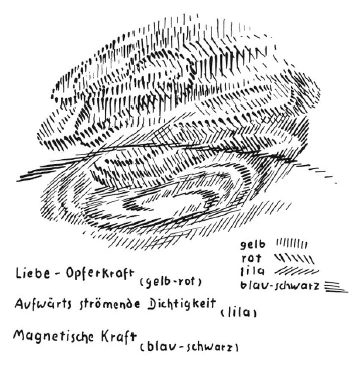

This, you see, is the spiritual process of plant-growth. And it is because the subconscious in man divines something of a special nature in the blossoming, sprouting plant that he experiences the being of the plant as full of mystery. The wonder is not spoiled, the magic is not brushed from the dust on the butterfly's wing. Rather is the instinctive delight in the plant raised to a higher level when not only the physical plant is seen, but also that wonderful working of the gnome-world below, with its immediate understanding and formative intelligence, the gnome-world which first pushes the plant upwards. Thus, just as human understanding is not subjected to gravity, just as the head is carried without our feeling its weight, so the gnomes with their light-imbued intellectuality overcome what is of the earth and push the plant upwards. Down below they prepare the life. But the life would die away were it not formed by chemical activity. This is brought to it by the undines. And this again must be imbued with light. And so we picture, from below upwards, in bluish, blackish shades the force of gravity, to which the impulse upwards is given by the gnomes; and weaving around the plant—indicated by the leaves—the undine-force blending and dispersing substances as the plant grows upwards. From above downwards, from the sylphs, light falls into the plants and shapes an idealized plastic form which descends, and is taken up by the mother-womb of the earth; moreover this form is circled around by the fire-spirits which concentrate the cosmic warmth into the tiny seed-points. This warmth is also sent downwards to the gnomes, so that from out of fire and life, they can cause the plants to arise.

And further we now see that essentially the earth is indebted for its power of resistance and its density to the antipathy of the gnomes and undines towards amphibians and fishes. If the earth is dense, this density is due to the antipathy by means of which the gnomes and undines maintain their form. When light and warmth sink down on to the earth, this is first due to that power of sympathy, that sustaining power of sylph-love, which is carried through the air, and then to the sustaining sacrificial power of the fire-spirits, which causes them to incline downwards to what is below themselves. So we may say that, over the face of the earth, earth-density, earth-magnetism and earth-gravity, in their upward-striving aspect, unite with the downward-striving power of love and sacrifice. And in this inter-working of the downwards streaming force of love and sacrifice and the upwards streaming force of density, gravity and magnetism, in this inter-working, where the two streams meet, plant-life develops over the earth's surface. Plant-life is an outer expression of the inter-working of world-love and world-sacrifice with world-gravity and world-magnetism.

From this you have seen with what we have to do when we direct our gaze to the plant-world, which so enchants, uplifts and inspires us. Here real insight can only be gained when our vision embraces the spiritual, the super-sensible, as well as what is accessible to the physical senses. This enables us to correct the capital error of materialistic botany, that fructification occurs above the earth. What occurs there is not the process of fructification, but the preparation of the male heavenly seed for what is being made ready as the future Plant in the mother-womb of the earth.

Siebenter Vortrag

Zu der äußerlich wahrnehmbaren, sichtbaren Welt gehört die unsichtbare, die mit ihr zusammen ein Ganzes bildet. Zunächst tritt in aller Deutlichkeit hervor, wie sehr das der Fall ist, wenn wir unseren Blick nun von den Tieren abwenden zu den Pflanzen.

Das pflanzliche Dasein, das den Menschen zunächst erfreut, sproßt und sprießt aus der Erde heraus und bildet eigentlich den Anlaß zu etwas, was als geheimnisvoll empfunden werden muß. Beim Tier kann sich der Mensch, wenn ihm auch der Wille des Tieres, die ganze innere Aktivität des Tieres zunächst etwas Geheimnisvolles schon ist, dennoch sagen: Dieser Wille ist eben da, und aus diesem Willen heraus ist dann die Gestalt, sind die Außerungen des Tieres eine Folge. - Aber an der Pflanze, die in einer so mannigfaltigen Gestalt an der Oberfläche der Erde erscheint, die in einer so geheimnisvollen Art aus dem Samen mit Hilfe der Erde und mit Hilfe des Luftkreises zunächst sich entwickelt, muß der Mensch empfinden, wie ein anderes vorhanden sein muß, damit diese Pflanzenwelt ihm eben in der Gestalt entgegentreten kann, in der sie ihm entgegentritt.

Die geistige Anschauung führt uns dann, wenn wir auf die Pflanzenwelt blicken, gleich zu einer Fülle von Wesenheiten, die in den alten Zeiten des instinktiven menschlichen Hellsehertums auch gewußt worden sind, erkannt worden sind, dann aber vergessen worden sind, und heute nur noch Namen darstellen, welche die Dichter verwenden, denen eigentlich eine Realität von der heutigen Menschheit nicht zugeschrieben wird. Aber in demselben Maße, in dem den Wesen, welche die Pflanze umschwirren und umweben, keine Realität zugeschrieben wird, verliert man das Verständnis für die Pflanzenwelt; dieses Verständnis für die Pflanzenwelt, das zum Beispiel so notwendig wäre für die Heilkunst, ist ja eigentlich der heutigen Menschheit ganz verlorengegangen.

Nun haben wir schon einen sehr bedeutsamen Zusammenhang der Pflanzenwelt mit der Schmetterlingswelt erkannt; allein der wird uns auch erst so recht vor die Seele treten, wenn wir noch tiefer hineinschauen in das ganze Weben und Treiben der Pflanzenwelt.

Die Pflanze streckt ihre Wurzel in den Boden. Wer das verfolgen kann, was da eigentlich von der Pflanze in den Boden hineingestreckt wird, der kann mit dem geistigen Blick, und ein solcher muß es ja sein, der die Wurzel richtig durchschaut, zugleich verfolgen, wie überall das Wurzelwesen der Pflanze von Naturelementargeistern umgeben und umwoben wird. Und diese Elementargeister, die eine alte Anschauung als Gnomen bezeichnet hat, die wir Wurzelgeister nennen können, können wir mit einer imaginativen und inspirierten Weltanschauung wirklich so verfolgen, wie wir im Physischen das Menschenleben und das Tierleben verfolgen. Wir können gewissermaßen hineinschauen in das Seelenhafte dieser Elementargeister, dieser Wurzelgeisterwelt.

Diese Wurzelgeister sind ein ganz besonderes Erdenvolk, für den äußeren Anblick zunächst unsichtbar, aber in ihren Wirkungen um so sichtbarer; denn keine Wurzel könnte entstehen, wenn nicht zwischen der Wurzel und dem Erdreich vermittelt würde durch diese merkwürdigen Wurzelgeister, die das Mineralische der Erde in Strömung bringen, um es an die Wurzeln der Pflanze heranzubringen. Natürlich meine ich dabei den geistig zugrundeliegenden Vorgang.

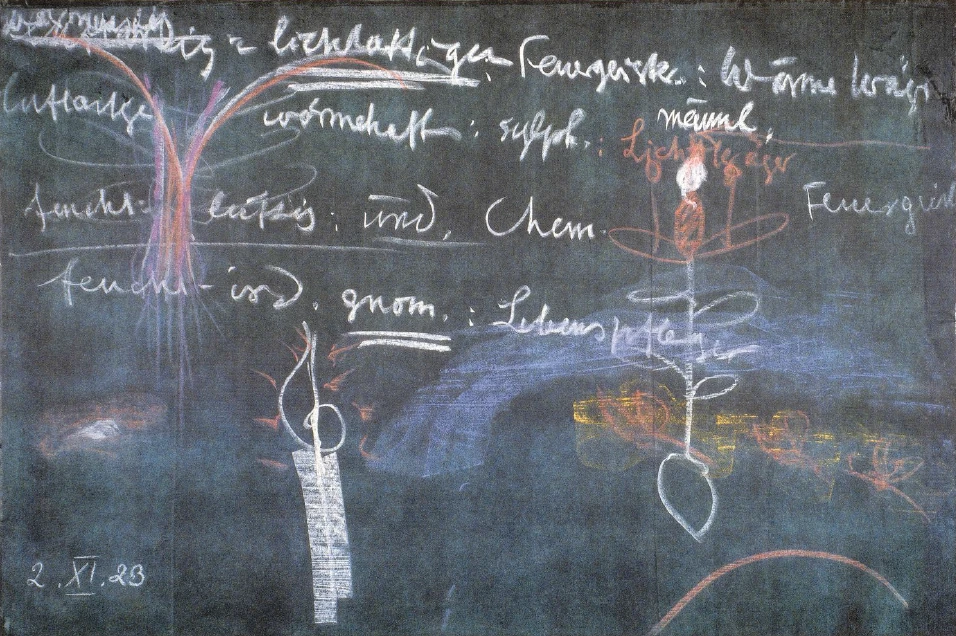

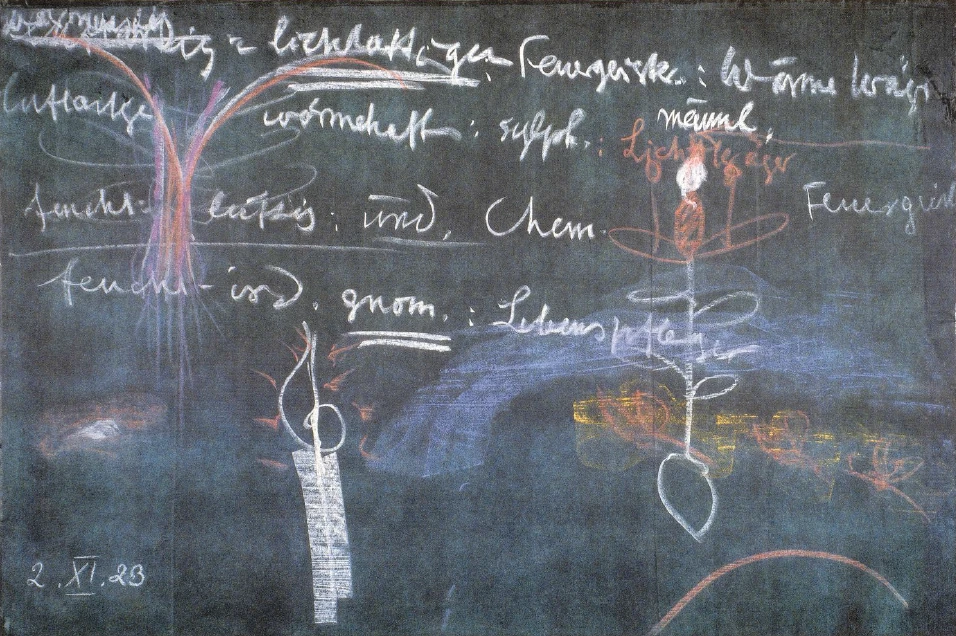

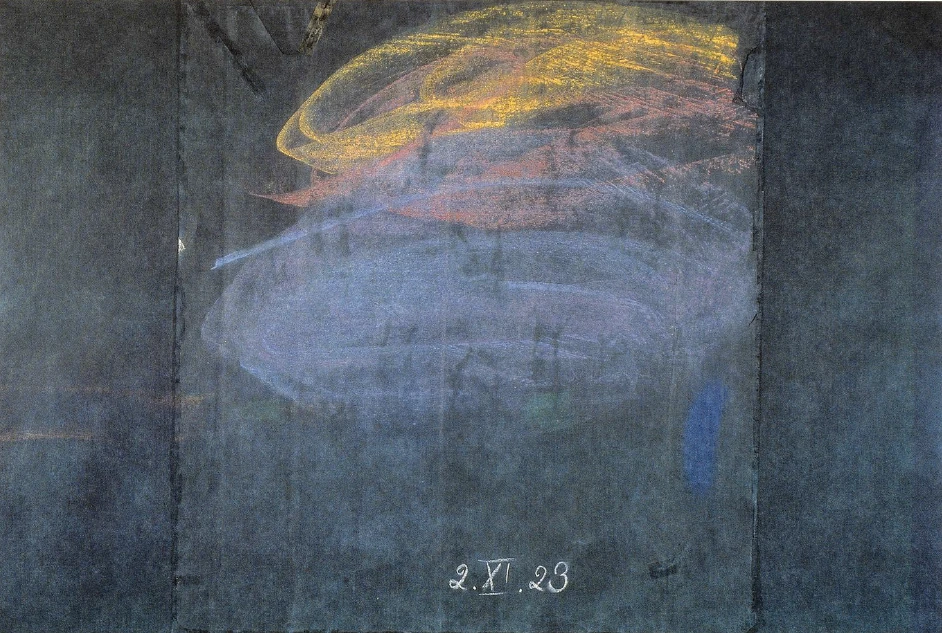

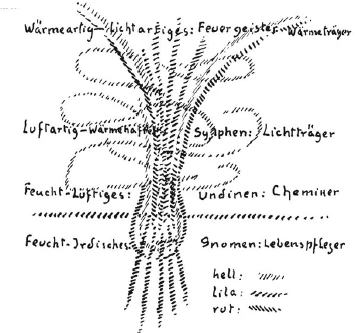

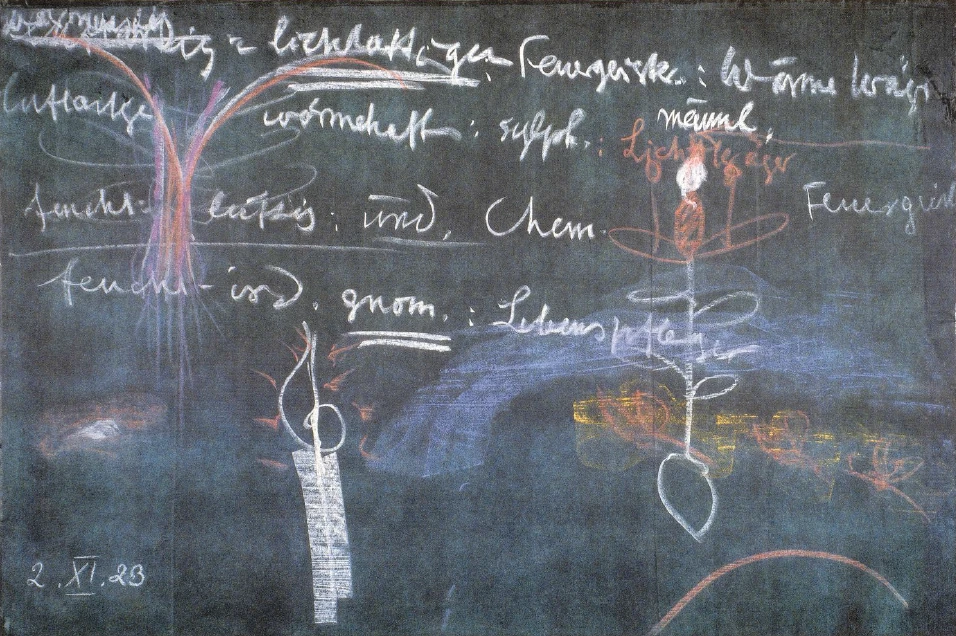

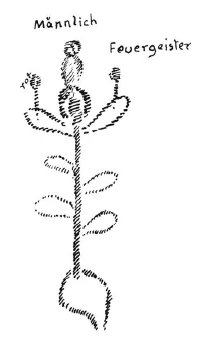

Diese Wurzelgeister, die überall im Erdreich vorhanden sind, die sich ganz besonders wohl fühlen innerhalb der mehr oder weniger durchsichtigen oder auch metallisch durchsetzten Gesteine und Erze, die aber sich am wohlsten fühlen, weil da ihr eigentlicher Platz ist, wenn es sich darum handelt, das Mineralische der Pflanzenwurzel zu vermitteln, diese Wurzelgeister sind ganz erfüllt von einem innerlich Geisthaften, das wir nur vergleichen können mit dem, was wir erfassen können im innerlichen Geisthaften des menschlichen Auges, des menschlichen Ohres. Denn diese Wurzelgeister sind in ihrer Geisthaftigkeit ganz Sinn. Sie sind eigentlich sonst gar nichts, als aus Sinn bestehend, sie sind ganz Sinn, und ein Sinn, der zugleich Verstand ist, der nicht nur sieht und nicht nur hört, der sogleich im Sehen und im Hören das Gesehene und Gehörte versteht, der überall nicht bloß Eindrücke empfängt, sondern überall Ideen empfängt. - Ja, wir können auch hinweisen auf die Art und Weise, wie diese Wurzelgeister ihre Ideen empfangen. Sehen Sie, da sproßt aus der Erde die Pflanze heraus (Tafel 11, links oben / Zeichnung S. 114). Die Pflanze kommt, wie ich gleich nachher zeigen werde, in Verbindung mit dem außerirdischen Weltenall, und zu gewissen Jahreszeiten besonders strömen gewissermaßen Geistströme (lila) von oben, von der Blüte, von der Frucht der Pflanze bis hinunter zur Wurzel, strömen in die Erde hinein. Und wie wir das Auge dem Lichte entgegenstrecken und sehen, so wenden die Wurzelgeister ihre Wahrnehmungsfähigkeit dem entgegen, was durch die Pflanzen von oben herunter in die Erde hineinträufelt. Was ihnen da entgegenträufelt, das ist das, was das Licht in die Blüten hineingeschickt hat, was die Sonnenwärme in die Pflanzen hineingeschickt hat, was die Luft im Blatte angerichtet hat, ja, was ferne Sterne in der Gestaltung der Pflanzen bewirkt haben. Die Pflanze sammelt die Geheimnisse des Weltenalls, senkt sie in den Boden, und die Gnomen nehmen diese Geheimnisse des Weltenalls aus dem, was ihnen durch die Pflanze geistig zuträufelt, in sich auf. Und indem sie, namentlich vom Herbste an durch den Winter hindurch, auf ihren Wanderungen durch Erz und Gestein tragen, was ihnen durch die Pflanzen zugeträufelt ist, werden sie dadurch zu denjenigen Wesen innerhalb der Erde, die die Ideen des ganzen Weltenalls durch die Erde hindurchströmend wandernd tragen. Wir sehen hinaus in die weite Welt. Die Welt ist aus dem Weltengeiste gebaut, eine Verkörperung der Weltenideen, des Weltengeistes. Die Gnomen nehmen durch die Pflanzen, die ihnen dasselbe sind, was uns die Lichtstrahlen sind, die Ideen des Weltenalls auf und tragen sie im Inneren der Erde in voller Bewußtheit von Erz zu Erz, von Stein zu Stein.

Wir schauen in die Tiefen der Erde hinunter, nicht indem wir da unten abstrakte Ideen suchen für irgendwelche bloß mechanisch wirkenden Naturgesetze, sondern wir schauen hinunter in die Tiefen der Erde und sehen die wandernden und wandelnden Gnomen, welche die lichtvollen Bewahrer des Weltenverstandes sind innerhalb der Erde. Weil daher diese Gnomen das, was sie sehen, zugleich wissen, haben sie im Vergleich zu den Menschen ein zwar gleichgeartetes Wissen; sie sind die Verstandeswesen katexochen, sie sind ganz Verstand. Alles ist an ihnen Verstand, aber ein Verstand, der universell ist, der daher auf den menschlichen Verstand eigentlich heruntersieht als auf etwas Unvollkommenes. Die Gnomenwelt lacht uns eigentlich aus mit unserem würgenden, ringenden Verstande, mit dem wir so dies oder jenes manchmal erfassen, während die Gnomen gar nicht nachzudenken brauchen. Sie sehen das, was verständig ist in der Welt, und sie sind insbesondere dann ironisch, wenn sie merken, daß der Mensch sich abmühen muß, um erst auf dieses oder jenes zu kommen. Wie kann man das - sagen die Gnomen -, wie kann man erst sich Mühe geben, nachzudenken? Man weiß ja alles, was man anschaut. Die Menschen sind dumm - so sagen die Gnomen -, denn sie müssen erst nachdenken.

Und ich möchte sagen, bis zur Ungezogenheit ironisch werden die Gnomen, wenn man ihnen von Logik spricht. Denn wozu soll man so ein überflüssiges Ding brauchen, eine Anleitung zum Denken? Die Gedanken sind doch da. Die Ideen strömen durch die Pflanzen. Warum stecken die Menschen nicht ihre Nase so tief in die Erde hinein, wie die Wurzel der Pflanze ist, und lassen sich in die Nase hineinträufeln das, was die Sonne zu den Pflanzen sagt? Dann würden sie etwas wissen! Aber mit Logik — sagen die Gnomen -, da kann man eigentlich immer nur ganz kleine Stücke von Wissen haben.

So sind die Gnomen eigentlich innerhalb der Erde die Träger der Ideen des Universums, des Weltenalls. Aber die Erde selbst haben sie gar nicht gerne. Sie schwirren herum in der Erde mit Ideen vom Weltenall, hassen aber eigentlich das Irdische. Das ist ihnen etwas, dem sie am liebsten entrinnen möchten. Sie bleiben allerdings dennoch bei diesem Irdischen — Sie werden gleich nachher sehen warum -, aber sie hassen es, denn das Irdische bildet für die Gnomen eine fortwährende Gefahr, und zwar deshalb, weil dieses Irdische fortwährend den Gnomen droht, sie sollten eine gewisse Gestalt annehmen: nämlich die Gestaltungen derjenigen Wesen, die ich Ihnen in der letzten Stunde hier beschrieben habe, die Gestaltungen der Amphibien, der Frösche und Kröten namentlich. Und die Empfindung der Gnomen in der Erde ist eigentlich diese: Wenn wir zu stark mit der Erde verwachsen, bekommen wir Frosch- oder Krötengestalt. Und sie sind fortwährend auf dem Sprunge, zu vermeiden, mit der Erde zu stark zu verwachsen, um nicht diese Gestalt zu bekommen; sie wehren sich fortwährend gegen diese Erdengestalt, die ihnen eben in der Weise drohen würde in dem Elemente, in dem sie sind. In dem irdisch-feuchten Elemente halten sie sich auf; da droht ihnen fortwährend die Amphibiengestaltung. Aus der reißen sie sich fortwährend heraus und erfüllen sich ganz mit den Ideen des außerirdischen Universums. Sie sind eigentlich innerhalb der Erde dasjenige, was darstellt das Außerirdische, weil es fortwährend vermeiden muß, mit dem Irdischen zusammenzuwachsen; sonst bekämen die Einzelwesen eben die Gestalt der Amphibienwelt. Und gerade aus diesem, ich möchte sagen Haßgefühl, Antipathiegefühl gegenüber dem Irdischen gewinnen die Gnomen die Kraft, die Pflanzen aus der Erde herauszutreiben. Sie stoßen fortwährend mit ihrer Grundkraft vom Irdischen ab, und mit diesem Abstoßen ist die Richtung des Wachstums der Pflanzen nach oben gegeben; sie reißen die Pflanzen mit. Es ist die Antipathie der Gnomen gegenüber dem Irdischen, was die Pflanzen nur mit ihrer Wurzel im Erdreiche sein läßt, aber dann herauswachsen läßt aus dem Erdreiche, so daß also eigentlich die Gnomen die Pflanzen aus ihrer ureigenen Gestalt der Erde entreißen und nach oben wachsen machen.

Ist dann die Pflanze nach oben gewachsen, hat sie den Bereich der Gnomen verlassen und ist übergetreten aus dem Reiche des Feucht-Irdischen in das Reich des Feucht-Luftigen, dann entwickeln die Pflanzen das, was in den Blättern zur äußeren physischen Gestaltung kommt. Aber in alldem, was nun im Blatte tätig ist, wirken wiederum andere Wesenheiten, Wassergeister, Elementargeister des wäßrigen Elementes, welche eine ältere instinktive Hellseherkunst zum Beispiel Undinen genannt hat. Geradeso wie wir die Wurzel umschwirrt und umwebt von den Gnomenwesen finden, so in der Nähe des Bodens, wohlgefällig das Aufwärtsstreben, das die Gnomen gegeben haben, beobachtend, sehen wir diese Wasserwesen, diese Elementarwesen des Wassers, diese Undinenwesen.

Diese Undinenwesen sind anders ihrer inneren Natur nach als die Gnomen. Sie können sich nicht wie ein Sinnesorgan, wie ein geistiges Sinnesorgan hinauswenden an das Weltenall. Sie können sich eigentlich nur hineinergeben in das Weben und Walten des ganzen Kosmos im luftig-feuchten Elemente, und dadurch sind sie nicht solche helle Geister wie die Gnomen. Sie träumen eigentlich fortwährend, diese Undinen, aber ihr Träumen ist zu gleicher Zeit ihre eigene Gestalt. Sie hassen nicht so stark die Erde wie die Gnomen, aber sie sind sensitiv gegen das Irdische. Sie leben im ätherischen Elemente des Wassers, durchschwimmen und durchschweben es. Und sie sind sehr sensitiv gegen alles, was Fisch ist, denn es droht ihnen die Fischgestalt, die sie auch zuweilen annehmen, aber gleich wieder verlassen, um in eine andere Metamorphose überzugehen. Sie träumen ihr eigenes Dasein. Und im Träumen ihres eigenen Daseins binden sie und lösen sie, binden sie und trennen sie die Stoffe der Luft, die sie auf geheimnisvolle Art in die Blätter hineinbringen und herantragen an dasjenige, was die Gnomen nach aufwärts gestoßen haben. Die Gnomen stoßen das Pflanzenwesen nach aufwärts. (Tafel 11, links oben / Zeichnung S. 114, hell.) Es würde hier verdorren, wenn nicht die Undinenwesen von allen Seiten gewissermaßen herankämen und nun in dieser traumhaften Bewußtheit, in der sie die Pflanzen umschwirren, sich erwiesen, man kann nicht anders sagen, als der Weltenchemiker. Die Undinen träumen das Verbinden und Lösen der Stoffe. Und dieser Traum, in dem die Pflanzen leben, in den die Pflanze hineinwächst, wenn sie nach aufwärts den Boden verläßt, dieser Undinentraum ist der Weltenchemiker, der die geheimnisvolle Verbindung und Lösung der Stoffe, vom Blatte ausgehend, in der Pflanze bewirkt. So daß wir sagen können, die Undinen sind die Chemiker des Pflanzenlebens. Sie träumen von Chemie. Es ist in ihnen eine ungemein zarte Geistigkeit, eine Geistigkeit, die eigentlich ihr Element da hat, wo Wasser und Luft sich berühren. Die Undinen leben ganz im feuchten Elemente; aber ihr eigentliches inneres Wohlgefallen haben sie, wenn sie irgendwo an eine Oberfläche, wenn auch nur an die Oberfläche eines Tropfens oder sonst irgendeines Wäßrigen kommen. Denn ihr ganzes Streben besteht darin, sich davor zu bewahren, ganz die Gestalt, die bleibende Gestalt der Fische zu bekommen. Sie wollen in der Metamorphose bleiben, in der ewigen, der immerwährenden Verwandelbarkeit. Aber in dieser Verwandelbarkeit, in der sie von Sternen und von der Sonne, vom Lichte und von der Wärme träumen, werden sie die Chemiker, die vom Blatte aus nun die Pflanze weiterbringen in ihrer Gestaltung, die Pflanze, die von der Gnomenkraft nach oben geschoben worden ist. Und so entwickelt denn die Pflanze das Blattwachstum (Tafel 11, links oben / Zeichnung S. 114), und das Geheimnisvolle enthüllt sich als Undinentraum, in den die Pflanze hineinwächst.

In demselben Maße aber, in dem die Pflanze in den Undinentraum hineinwächst, gerät sie nach oben nun in ein anderes Bereich, in das Bereich derjenigen Geister, die nun ebenso im luftartig-wärmehaften Elemente leben, wie die Gnomen im feucht-irdischen, die Undinen im feucht-luftigen leben. So im luftartig-wärmehaften Element leben diejenigen Wesenheiten, die eine ältere, instinktive Hellseherkunst als die Sylphen bezeichnet hat. Diese Sylphen, die im luftartig-warmen Elemente leben, dringen aber, weil die Luft überall durchsetzt ist vom Lichte, zum Lichte vor, werden lichtverwandt, und sind namentlich empfänglich für dasjenige, was die feineren, aber größeren Bewegungen innerhalb des Luftkreises sind.

Wenn Sie im Frühling oder Herbst einen Schwalbenschwarm sehen, der in seinem Hinfliegen zugleich den Luftkörper in Schwingungen bringt, einen bewegten Luftstrom hervorruft, so bedeutet dieser bewegte Luftstrom, der aber dann bei jedem Vogel vorhanden ist, für die Sylphen etwas Hörbares. Weltenmusik ertönt daraus den Sylphen. Wenn Sie irgendwo, sagen wir, auf dem Schiffe fahren, und die Möwen heranfliegen, dann ist in dem, was durch den Möwenflug erregt wird, ein geistiges Ertönen, eine geistige Musik, die das Schiff begleitet.

Wiederum sind es die Sylphen, welche in diesem Tönen drinnen sich entfalten und entwickeln und in diesen erregten Luftströmen ihre Heimat finden. Im dem geistig-tönend bewegten Luftelemente finden sie ihre Heimat und nehmen dabei dasjenige auf, was die Kraft des Lichtes in diese Luftschwingungen hineinschickt. Dadurch aber fühlen sich diese Sylphen, welche im Grunde genommen für sich mehr oder weniger schlafende Wesenheiten sind, überall dort am heimischsten, am meisten zuhause, wo der Vogel die Luft durcheilt. Wenn eine Sylphe gezwungen ist, die vogellose Luft zu durchschwirren, dann ist es für sie so, als ob sie sich selbst verloren hätte. Wenn ihr der Anblick des Vogels in der Luft wird, dann kommt etwas ganz Besonderes über die Sylphe. Ich mußte oftmals einen gewissen Vorgang für den Menschen darstellen, jenen Vorgang, der die Menschenseele dazu führt, zu sich «Ich» zu sagen. Ich habe immer aufmerksam gemacht auf den Ausspruch Jean Pauls, daß da der Mensch, wenn er zum ersten Male zu der IchVorstellung kommt, wie in das verhangenste Allerheiligste der Seele hineinsieht. Die Sylphe sieht nicht in ein solches verhangenes Allerheiliges der eigenen Seele hinein, sondern sie sieht den Vogel, und die IchEmpfindung überkommt sie. In dem, was der Vogel, durch die Luft fliegend, in ihr erregt, findet die Sylphe ihr Ich. Und damit, daß das so ist, daß sie am Außeren ihr Ich entzündet, wird die Sylphe die Trägerin der kosmischen Liebe durch den Luftraum. Die Sylphe ist zugleich, indem sie etwa so wie ein menschlicher Wunsch lebt, aber das Ich nicht im Inneren hat, sondern in der Vogelwelt hat, die Trägerin der Liebeswünsche durch das Universum hindurch.

Deshalb ist zu schauen die tiefste Sympathie der Sylphe mit der Vogelwelt. Wie der Gnom die Amphibienwelt haßt, wie die Undine sensitiv ist und sich gewissermaßen nicht nähern mag dem Fische, weg will vom Fisch, ein Grauen in gewissem Sinne empfindet, so will die Sylphe zum Vogel hin, fühlt sich wohl, wenn sie an sein Gefieder herantragen kann die schwebend-tönende Luft. Und wenn Sie den Vogel fragen würden, von wem er singen lerne, dann würden Sie von ihm hören, daß er seinen Inspirator in der Sylphe hat. Die Sylphe hat ein Wohlgefallen an der Vogelgestalt. Aber sie ist abgehalten durch die kosmische Ordnung, Vogel zu werden, denn sie hat eine andere Aufgabe. Sie hat die Aufgabe, in Liebe das Licht an die Pflanzen heranzutragen (Tafel 11, links oben / Zeichnung S. 114, hell und rot). Geradeso wie die Undine der Chemiker ist, ist dadurch die Sylphe für die Pflanze der Lichtträger. Sie durchsetzt die Pflanze mit Licht; sie trägt in die Pflanze das Licht hinein.

Dadurch, daß die Sylphe in die Pflanze das Licht hineinträgt, wird etwas ganz Eigentümliches in der Pflanze geschaffen. Sehen Sie, die Sylphe trägt fortwährend das Licht in die Pflanze hinein. Das Licht, das heißt die Sylphenkraft in der Pflanze, wirkt auf die chemischen Kräfte, welche die Undine in die Pflanze hineinversetzt. Da geschieht das Zusammenwirken von Sylphenlicht und Undinenchemie (Tafel 11, links oben / Zeichnung S. 114, rot). Das ist eine merkwürdige plastische Tätigkeit. Aus dem Lichte heraus weben die Sylphen mit Hilfe der Stoffe, die da hinaufströmen und von den Undinen bearbeitet werden, da drinnen eine ideale Pflanzengestalt. Die Sylphen weben eigentlich die Urpflanze in der Pflanze aus dem Lichte und aus dem chemischen Arbeiten der Undinen. Und wenn die Pflanze gegen den Herbst hin abwelkt und alles, was physische Materie ist, zerstiebt, dann kommen diese Formen der Pflanzen eben zum Herunterträufeln, und die Gnomen nehmen sie jetzt wahr, nehmen wahr, was die Welt, die Sonne durch die Sylphen, die Luft durch die Undinen, an der Pflanze bewirkt hat. Das nehmen die Gnomen wahr. So daß die Gnomen unten den ganzen Winter hindurch beschäftigt sind, wahrzunehmen, was von den Pflanzen hinunterträufelt in den Erdboden. Da fassen sie die Ideen der Welt in den Pflanzenformen, die mit Hilfe der Sylphen plastisch ausgebildet sind, und die in ihrer Geist-Ideengestalt in den Erdboden hineingehen.

Von dieser Geist-Ideengestalt wissen ja diejenigen Menschen natürlich nichts, die die Pflanze nur materiell, als Materielles betrachten. Daher tritt hier an dieser Stelle für die materielle Pflanzenbetrachtung etwas ein, was nichts anderes ist als ein grandioser Irrtum, ein furchtbarer Irrtum. Diesen Irrtum will ich Ihnen skizzieren.

Sie werden von der materialistischen Wissenschaft überall beschrieben finden: da wurzelt die Pflanze im Boden, darüber entfaltet sie ihre Blätter, zuletzt ihre Blüte, in der Blüte die Staubgefäße, dann den Fruchtknoten, und dann wird in der Regel von einer anderen Pflanze der Staub von den Antheren, von den Staubgefäßen, herangetragen, und der Fruchtknoten wird befruchtet, und dadurch entsteht der Same der neuen Pflanze. So wird das überall beschrieben. Es wird gewissermaßen der Fruchtknoten als das Weibliche und das, was von den Staubgefäßen kommt, als das Männliche angesehen, kann auch nicht anders angesehen werden, solange man im Materialistischen steckenbleibt, denn da sieht dieser Prozeß wirklich aus wie eine Befruchtung. Aber so ist es nicht, sondern wir müssen, um überhaupt die Befruchtung, also die Fortpflanzung des Pflanzlichen einzusehen, uns bewußt sein, daß zunächst aus dem, was die großen Chemiker, die Undinen in den Pflanzen bewirken, was die Sylphen bewirken, die Pflanzenform entsteht, die ideale Pflanzenform, welche in den Erdboden sinkt und von den Gnomen bewahrt wird. Da unten ist sie, diese Pflanzenform. Da drinnen ist sie in der Erde gehütet nun von den Gnomen, nachdem sie sie gesehen haben, geschaut haben. Die Erde wird zum Mutterschoß desjenigen, was da hinunterträufelt. Und hier ist etwas ganz anderes, als was die materialistische Wissenschaft beschreibt.

Hier oben (Siehe Zeichnung $. 121) kommt die Pflanze, nachdem sie durch den Sylphenbereich gegangen ist, in die Sphäre der Elementar-Feuergeister. Und die Feuergeister, sie sind die Bewohner des Wärmeartig-Lichtartigen; sie sammeln, wenn dieErdenwärme am höchsten gestiegen oder eben geeignet geworden ist, nun die Wärme auf. Ebenso wie dieSylphen das Licht aufgesammelt haben, so sammeln die Feuergeister die Wärme auf und tragen sie in die Blüten der Pflanzen hinein.

Undinen tragen die Wirkungen des chemischen Äthers in die Pflanzen hinein, Sylphen tragen die Wirkungen des Lichtäthers in die Pflanzen hinein, die Feuergeister tragen die Wirkungen des Wärmeäthers in die Blüten der Pflanzen hinein. Und der Blütenstaub, der ist dasjenige, was nun gewissermaßen das kleine Luftschiffchen abgibt für die Feuergeister, um hineinzutragen die Wärme in den Samen. Die Wärme wird überall gesammelt mit Hilfe der Staubfäden und von den Staubfäden aus übertragen auf den Samen in dem Fruchtknoten. Und dieses, was hier im Fruchtknoten gebildet wird, das ist im Ganzen das Männliche, das aus dem Kosmos kommt. Nicht der Fruchtknoten ist das Weibliche, und die Antheren des Staubfadens wären das Männliche! Da geschieht überhaupt in der Blüte keine Befruchtung, sondern da wird nur der männliche Same vorgebildet. Was als Befruchtung wirkt, das ist nun dasjenige, was von den Feuergeistern in der Blüte als der der Wärme des Weltenalls entnommene weltenmännliche Same ist, der zusammengebracht wird mit dem Weiblichen, das aus der Formung der Pflanze, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe, schon früher als Ideelles hinuntergeträufelt ist in den Erdboden, da drinnen ruht. Für die Pflanzen ist die Erde Mutter, der Himmel Vater. Und alles das, was außerhalb des Irdischen geschieht, ist für die Pflanze nicht Mutterschoß. Es ist ein kolossaler Irrtum, zu glauben, daß das mütterliche Prinzip der Pflanze im Fruchtknoten ist. Da ist gerade das mit Hilfe der Feuergeister aus dem Universum herausgeholte Männliche. Das Mütterliche wird aus dem Kambium der Pflanze, welches sich sowohl gegen die Rinde wie gegen das Holz hin verbreitet, hinuntergetragen als Idealgestalt in der Pflanze. Und dasjenige, was nun entsteht aus dem Zusammenwirken von Gnomenwirkung und Feuergeisterwirkung, das ist Befruchtung. Im Grunde genommen sind die Gnomen die geistigen Hebammen der Pflanzen-Fortpflanzung. Und die Befruchtung findet statt während des Winters drunten in der Erde, wenn der Samen in die Erde hineinkommt und auftrifft auf die Gestalten, die die Gnomen empfangen haben von den Sylphen- und Undinenwirkungen und hintragen, wo diese Gestalten auftreffen können auf den befruchtenden Samen.

Sie sehen: dadurch, daß man das Geistige nicht kennt, daß man nicht weiß, wie mitweben und mitleben mit dem Pflanzenwachstum Gnomen, Undinen, Sylphen und Feuergeister - was früher Salamander genannt worden ist —, dadurch ist man sich sogar ganz unklar über den Vorgang der Befruchtung in der Pflanzenwelt. Also da, außerhalb der Erde geschieht eben gar keine Befruchtung, sondern die Erde ist Mutter der Pflanzenwelt, der Himmel ist Vater der Pflanzenwelt. Das ist in ganz wörtlichem Sinne der Fall. Und die Befruchtung der Pflanzen geschieht dadurch, daß die Gnomen von den Feuergeistern dasjenige nehmen, was die Feuergeister in den Fruchtknoten hineingetragen haben auf den kleinen Luftschiffchen des Antherenstaubes als konzentrierte kosmische Wärme. So sind die Feuergeister Wärmeträger.

Jetzt werden Sie natürlich leicht einsehen, wie eigentlich das ganze Pflanzenwachstum zustande kommt. Erst beleben unten mit Hilfe dessen, was ihnen von den Feuergeistern wird, die Gnomen die Pflanze und stoßen sie nach aufwärts. Sie sind die Lebenspfleger. Sie tragen heran den Lebensäther an die Wurzel; jenen Lebensäther, in dem sie selber leben, den tragen sie an die Wurzel heran. Weiter pflegen in der Pflanze die Undinen den chemischen Äther, die Sylphen den Lichtäther, die Feuergeister den Wärmeäther. Dann verbindet sich wiederum die Frucht des Wärmeäthers mit dem, was unten Leben ist. Und so kann man die Pflanze nur verstehen, wenn man sie im Zusammenhange betrachtet mit alledem, was sie umschwirrt, umwebt und umlebt. Und sogar auf die richtige Interpretation des bei der Pflanze wichtigsten Vorganges kommt man erst dann, wenn man in diese Dinge eindringt, auf geistige Art eindringt.

Es ist interessant, wenn dies einmal erkannt wird, jene Notiz bei Goethe wiederzusehen, wo Goethe in Anknüpfung an einen anderen Botaniker sich so furchtbar ärgert, daß die Leute da reden von den ewigen Hochzeiten da oben auf den Pflanzen. Goethe ärgerte sich, daß über eine Wiese da lauter Hochzeiten ausgebreitet sein sollen. Es erschien ihm das als etwas Unnatürliches. Aber das war ein instinktiv sehr sicheres Gefühl. Goethe konnte nur noch nicht wissen, um was es sich eigentlich handelt, aber es war instinktiv sehr sicher. Er konnte aus seinem Instinkt heraus nicht begreifen, daß da oben in den Blüten die Befruchtung vor sich gehen sollte. Er wußte nur noch nicht, was da unten, unterhalb des Bodens vor sich geht, daß die Erde der Mutterschoß ist für die Pflanzen. Aber daß das, was da oben ist, das nicht ist, wofür es alle Botaniker ansehen, das ist etwas, was Goethe instinktiv gefühlt hat. Nun erkennen Sie auch den innigen Zusammenhang zwischen der Pflanze und der Erde einerseits. Aber noch etwas anderes müssen Sie ins Auge fassen.

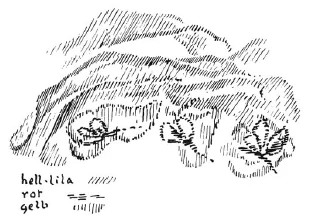

Sehen Sie, wenn nun da oben die Feuergeister herumschwirren, namentlich wenn sie den Antherenstaub vermitteln, dann haben sie nur ein Gefühl. Das ist ein gesteigertes Gefühl gegenüber dem Sylphengefühl. Die Sylphen empfinden ihr Selbst, ihr Ich, indem sie die Vögel schwirren sehen. Die Feuergeister haben dieses noch gesteigert gegenüber der Schmetterlingswelt und überhaupt der ganzen Insektenwelt. Und sie sind es, diese Feuergeister, welche am liebsten der Insektenspur folgen, um eben die Vermittlung der Wärme zu bewirken für den Fruchtknoten. Um das konzentrierte Warme, das hineinkommen muß in die Erde, um sich da zu verbinden mit der ideellen Gestalt, um das hinzutragen, fühlen sich die Feuergeister innig verwandt mit der Schmetterlingswelt und auch überhaupt mit der gesamten Insektenwelt. Sie folgen überall den Spuren der Insekten, die von Blüte zu Blüte schwirren. Und so hat man eigentlich das Gefühl, wenn man diese von Blüte zu Blüte schwirrenden Insekten verfolgt: jedes solche von Blüte zu Blüte schwirrende Insekt hat eigentlich eine ganz besondere Aura, die nicht recht erklärlich ist aus dem bloßen Insekt. Insbesondere die Bienen mit ihrer hellglänzenden, wunderbar leuchtenden, schimmernden, schillernden Aura, die von Pflanze zu Pflanze schwirren, sind außerordentlich schwierig ihrer Aura nach zu erklären. Warum? Weil das Insekt Biene überall begleitet ist von dem Feuergeist, der sich ihm so verwandt fühlt, daß da die Biene ist, und die Biene für das geistige Schauen überall in einer Aura drinnen ist, die eigentlich der Feuergeist ist. Wenn die Biene durch die Luft fliegt von Pflanze zu Pflanze, von Baum zu Baum, so fliegt sie mit einer Aura, die ihr eigentlich von dem Feuergeiste gegeben wird. Der Feuergeist fühlt nicht nur in der Anwesenheit des Insektes sein Ich, sondern er will mit dem Insekt ganz verbunden sein.

Dadurch bekommen aber auch die Insekten jene Kraft, von der ich Ihnen gesprochen habe, die sich selbst im Hinausschimmern in den Kosmos zeigt. Die Insekten bekommen dadurch diese Kraft, die physische Materie, die sich mit ihnen vereinigt, ganz zu durchgeistigen und das durchgeistigte Physische in den Weltenraum hinausstrahlen zu lassen. Aber geradeso wie bei einer Flamme die Wärme es zunächst ist, die das Licht zum Scheinen bringt, so sind es auf der Oberfläche der Erde, wenn die Insekten in den Weltenraum hinausschimmern lassen, was dann den Menschen anzieht, wenn er zur physischen Verkörperung herunterkommen soll: es sind die Insekten (Tafel 11, rechts / Zeichnung, rot und gelb), sind diejenigen Wesenheiten, die entflammt sind zu diesen Taten durch den Kosmos, durch die Feuergeister, die sie umschwirren. Und während die Feuergeister auf der einen Seite tätig sind dafür, daß in den Kosmos die durchfeuerte Materie hinausströmt, sind sie auf der anderen Seite dafür tätig, daß ins Innere der Erde hinein das konzentrierte Feurige, das konzentrierte Warme geht, um aufzuerwecken mit Hilfe der Gnomen die Geistgestalt, die von Sylphen und Undinen hinuntergeträufelt ist in die Erde.

Sehen Sie, das ist der geistige Vorgang des Pflanzenwachstums. Und weil eigentlich das Unterbewußte des Menschen es ahnt, daß mit der blühenden, sprossenden Pflanze es etwas Besonderes ist, erscheint das Pflanzenwesen als ein so Geheimnisvolles. Das Geheimnis wird natürlich nicht zerklüftet, denn den wunderbaren Mysterien wird nicht der Schmetterlingsstaub abgestreift; aber, ich möchte sagen, in einer noch erhöhteren Wunderbarkeit erscheint dasjenige, was sonst in der Pflanze den Menschen entzückt und erhebt, wenn nun eigentlich nicht nur die physische Pflanze da ist, sondern dieses wunderbare Arbeiten da unten der unmittelbar verständigen, ganz Intellekt-bildenden Gnomenwelt, die die Pflanzenkraft zunächst hinaufstoßen. So wie gewissermaßen der menschliche Verstand nicht der Schwerkraft unterworfen ist, wie der Kopf getragen wird, ohne daß wir seine Schwere fühlen, so überwinden die Gnomen mit ihrer Lichtintellektualität das Erdenhafte und stoßen die Pflanze herauf. Sie bereiten unten das Leben. Aber das Leben würde ersterben, wenn es nicht vom Chemismus angefacht würde. Den bringen die Undinen heran. Und das Licht muß das durchströmen.

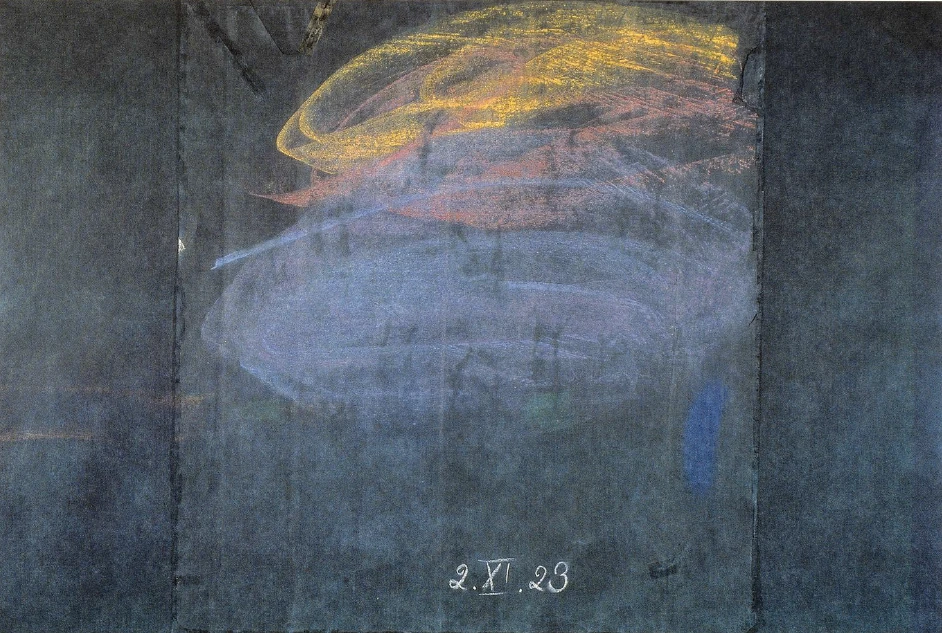

So sehen wir von unten herauf, ich möchte sagen, im BläulichSchwärzlichen die Schwerkraft (Tafel 12 / Zeichnung S. 126), der der Schwung nach oben hin gegeben wird, von den Gnomen ausgehend, und, rings die Pflanze umschwirrend, angedeutet in den Blättern, die Undinenkraft, welche Stoffe mischt und entmischt, indem die Pflanze hinaufwächst. Von oben herunter, von den Sylphengeistern wird hineingeprägt in die Pflanze das Licht, die nun eine plastische Gestalt bilden, die wiederum idealisiert hinuntergeht und vom Mutterschoße der Erde aufgenommen wird. Und dann wiederum wird die Pflanze umschwirrt von den Feuergeistern, die in den kleinen Samenpünktchen konzentrieren die Weltenwärme, die dann mit der Samenkraft den Gnomen hinuntergegeben wird, so daß die Gnomen aus Feuer und Leben da unten die Pflanzen entstehen lassen können.

Wiederum sehen Sie, wie die Erde ihre abstoßende Kraft, ihre Dichtigkeit, im Grunde genommen der Antipathie der Gnomen und Undinen gegen Amphibien und Fische verdankt. Wenn die Erde dicht ist, so ist die Dichtigkeit diese Antipathie, durch welche Gnomen und Undinen ihre Gestalt aufrecht erhalten. Wenn sich Licht und Wärme heruntersenkt auf die Erde, so ist das zu gleicher Zeit der Ausdruck jener Sympathiekraft, der tragenden Sylphen-Liebekraft, die durch den Luftraum getragen wird, und der tragenden Feuergeist-Opferkraft, welche das Sich-Herunterneigende bringt. So daß man sagen kann: Es wächst über der Erde zusammen dasjenige, was Erdendichte, Erdenmagnetismus, Erdenschwere ist, indem es nach aufwärts strebt, zusammen mit der abwärts strebenden Liebe- und Opferkraft. Und in diesem Ineinanderwirken der abwärtsströmenden Liebe-Opferkraft und der aufwärtsströmenden Dichtigkeit, Schwerekraft und magnetischen Kraft, in diesem Zusammenwirken entwickelt sich über dem Erdboden, wo die beiden sich begegnen, das Pflanzenwesen, das ein äußerer Ausdruck des Zusammenwirkens von Weltenliebe, Weltenopfer, Weltenschwere und Weltenmagnetismus ist.

Damit haben Sie gesehen, um was es sich handelt, wenn wir unseren Blick auf die uns so entzückende, erhebende und anmutende Pflanzenwelt richten. Durchschauen können wir sie erst, wenn wir imstande sind, das Geistige, das Übersinnliche zu dem Physischen, zu dem Sinnlichen hinzuzuschauen. Das macht auch zu gleicher Zeit möglich, den Kapitalirrtum der materialistischen Botanik zu korrigieren, als ob da oben die Befruchtung vor sich gehe. Was da vor sich geht, ist nicht die Befruchtung, sondern die Zubereitung des männlichen Himmelssamens der Pflanze für dasjenige, was im Mutterschoße der Erde für die Pflanze vorbereitet wird.

Seventh Lecture

In addition to the externally perceptible, visible world, there is the invisible world, which together with it forms a whole. First of all, it becomes very clear how much this is the case when we turn our gaze from the animals to the plants.

The plant existence that initially delights man sprouts and sprouts out of the earth and actually forms the cause of something that must be perceived as mysterious. In the case of the animal, even if the will of the animal, the whole inner activity of the animal is already something mysterious to him at first, man can still say to himself: This will is just there, and out of this will the form, the manifestations of the animal are a consequence. - But in the plant, which appears in such a manifold form on the surface of the earth, which first develops in such a mysterious way from the seed with the help of the earth and with the help of the air, man must feel how something else must be present so that this plant world can confront him in the form in which it confronts him.

When we look at the plant world, spiritual perception then leads us immediately to a wealth of entities that were also known and recognized in the old times of instinctive human clairvoyance, but were then forgotten and today only represent names used by poets, to which no reality is actually ascribed by mankind today. But to the same extent that no reality is ascribed to the beings that surround and weave around the plant, we lose our understanding of the plant world; this understanding of the plant world, which would be so necessary for the art of healing, for example, has actually been completely lost to mankind today.

Now we have already recognized a very significant connection between the plant world and the butterfly world; but this will only really come to light when we look even deeper into the whole weaving and bustling of the plant world.

The plant stretches its roots into the ground. Whoever can follow what is actually stretched into the soil by the plant, can at the same time follow with the spiritual gaze, and it must be such a gaze that really sees through the root, how everywhere the root being of the plant is surrounded and interwoven by natural elemental spirits. And these elemental spirits, which an old view called gnomes, which we can call root spirits, we can really follow with an imaginative and inspired view of the world in the same way as we follow human life and animal life in the physical. In a way, we can look into the soulfulness of these elemental spirits, this root spirit world.

These root spirits are a very special earth people, at first invisible to the outer sight, but all the more visible in their effects; for no root could come into being if it were not mediated between the root and the earth through these strange root spirits, which bring the mineral substance of the earth into flow in order to bring it to the roots of the plant. Of course, I am referring to the underlying spiritual process.

These root spirits, which are present everywhere in the earth, which feel particularly comfortable within the more or less transparent or also metallically interspersed rocks and ores, but which feel most comfortable because that is their actual place when it is a matter of imparting the mineral substance to the plant root, these root spirits are completely filled with an inner spirituality that we can only compare with what we can grasp in the inner spirituality of the human eye, the human ear. For these root spirits are completely sensual in their spirituality. They are actually nothing else than sense, they are entirely sense, and a sense that is at the same time understanding, that not only sees and not only hears, that immediately understands what it sees and hears, that not only receives impressions everywhere, but receives ideas everywhere. - Yes, we can also point to the way in which these root spirits receive their ideas. You see, the plant sprouts out of the earth (plate 11, top left / drawing p. 114). As I will show later, the plant comes into contact with the extraterrestrial universe, and at certain times of the year in particular, streams of spirits (purple) flow from above, from the blossom, from the fruit of the plant down to the root, flowing into the earth. And just as we stretch our eyes towards the light and see, so the root spirits turn their perceptive faculties towards that which trickles down through the plants from above into the earth. What trickles towards them is what the light has sent into the flowers, what the warmth of the sun has sent into the plants, what the air has done in the leaves, indeed, what distant stars have done in the formation of the plants. The plant collects the secrets of the universe, sinks them into the soil, and the gnomes absorb these secrets of the universe from what is spiritually instilled into them by the plant. And by carrying, especially from autumn through the winter, on their wanderings through ore and rock, what is instilled into them through the plants, they become those beings within the earth who carry the ideas of the whole universe wandering through the earth. We look out into the wide world. The world is built from the world spirit, an embodiment of the world ideas, the world spirit. The gnomes absorb the ideas of the universe through the plants, which are to them what the rays of light are to us, and carry them within the earth in full consciousness from ore to ore, from stone to stone.

We look down into the depths of the earth, not by looking down there for abstract ideas for some merely mechanically working laws of nature, but we look down into the depths of the earth and see the wandering and walking gnomes, who are the light-filled keepers of the world-mind within the earth. Because these gnomes therefore know what they see at the same time, they have knowledge of the same kind as humans; they are the beings of understanding catexochen, they are all understanding. Everything about them is intellect, but an intellect that is universal, which therefore actually looks down on the human intellect as something imperfect. The gnome world actually laughs at us with our choking, struggling intellect, with which we sometimes grasp this or that, while the gnomes do not need to think at all. They see what is intelligible in the world, and they are especially ironic when they realize that man has to struggle to come to this or that. How can one do that - say the gnomes - how can one first make an effort to think? You know everything you look at. People are stupid - say the gnomes - because they have to think first.

And I would say that the gnomes become ironic to the point of naughtiness when you talk to them about logic. Because why would you need such a superfluous thing, a guide to thinking? The thoughts are there. Ideas flow through the plants. Why don't people stick their noses as deep into the earth as the root of the plant is and let what the sun says to the plants drip into their noses? Then they would know something! But with logic - say the gnomes - you can only ever have very small pieces of knowledge.

So the gnomes are actually the bearers of the ideas of the universe, of the universe within the earth. But they don't like the earth itself. They buzz around the earth with ideas of the universe, but actually hate the earthly. It is something they would prefer to escape from. Nevertheless, they remain with this earthly world - you will see why in a moment - but they hate it, for the earthly world is a constant danger to the gnomes, and that is because this earthly world constantly threatens the gnomes, they should take on a certain form: namely the forms of those beings I described to you here in the last hour, the forms of the amphibians, the frogs and toads in particular. And the feeling of the gnomes in the earth is actually this: If we grow too close to the earth, we take on the form of frogs or toads. And they are constantly on the run to avoid growing too strongly into the earth so as not to take on this form; they are constantly defending themselves against this earthly form, which would threaten them in this way in the element in which they are. They dwell in the earthly-humid element; there the amphibian form constantly threatens them. They continually tear themselves out of it and fill themselves completely with the ideas of the extraterrestrial universe. They are actually within the earth that which represents the extraterrestrial, because it must constantly avoid growing together with the earthly; otherwise the individual beings would take on the form of the amphibian world. And it is precisely from this, I would say, feeling of hatred, of antipathy towards the earthly, that the gnomes gain the power to drive the plants out of the earth. They continually repel the earthly with their basic power, and with this repulsion the direction of the plants' growth is given upwards; they pull the plants along with them. It is the antipathy of the gnomes towards the earthly that allows the plants to be only with their root in the earth, but then lets them grow out of the earth, so that the gnomes actually tear the plants from their very own form of the earth and make them grow upwards.

Once the plant has grown upwards, it has left the realm of the gnomes and has passed from the realm of the humid-earthly into the realm of the humid-airy, then the plants develop that which comes to outer physical form in the leaves. But in all that is now active in the leaves, other entities, water spirits, elemental spirits of the watery element, are at work, which an older instinctive clairvoyance called, for example, undines. Just as we find the root surrounded and woven around by the gnome beings, so near the ground, pleasantly observing the upward striving given by the gnomes, we see these water beings, these elemental beings of water, these undine beings.

These undine beings are different in their inner nature from the gnomes. They cannot turn out into the universe like a sensory organ, like a spiritual sensory organ. They can actually only surrender themselves to the weaving and working of the whole cosmos in the airy and humid element, and thus they are not such bright spirits as the gnomes. They are actually constantly dreaming, these undines, but their dreaming is at the same time their own form. They do not hate the earth as much as the gnomes, but they are sensitive to the earthly. They live in the ethereal element of water, swimming and floating through it. And they are very sensitive to everything that is fish, because they are threatened by the fish form, which they sometimes take on, but immediately leave again in order to pass into another metamorphosis. They dream their own existence. And in dreaming their own existence they bind and unbind, bind and separate the substances of the air, which they mysteriously bring into the leaves and carry to that which the gnomes have pushed upwards. The gnomes push the plant being upwards. (Plate 11, top left / drawing p. 114, light.) It would wither here if the undine beings had not approached from all sides, as it were, and now proved themselves in this dreamlike consciousness in which they buzz around the plants, one cannot say otherwise than the world chemist. The undines dream of combining and dissolving substances. And this dream in which the plants live, into which the plant grows when it leaves the ground upwards, this undine dream is the world chemist who brings about the mysterious combination and dissolution of substances in the plant, starting from the leaf. So that we can say that the undines are the chemists of plant life. They dream of chemistry. There is an incredibly delicate spirituality in them, a spirituality that actually has its element where water and air meet. The undines live entirely in the humid element; but their real inner pleasure is when they come to a surface somewhere, even if only to the surface of a drop or some other watery substance. For their whole endeavor consists in preserving themselves from acquiring the form, the permanent form of fish. They want to remain in metamorphosis, in eternal, perpetual transformability. But in this metamorphosis, in which they dream of stars and the sun, of light and warmth, they become the chemists who from the leaf now bring the plant forward in its formation, the plant that has been pushed upwards by the gnome force. And so the plant develops leaf growth (plate 11, top left / drawing p. 114), and the mysterious reveals itself as an undine dream into which the plant grows.

But to the same extent that the plant grows into the undine dream, it now moves upwards into another realm, into the realm of those spirits who now live in the airy-warm element, just as the gnomes live in the humid-earthly, the undines in the humid-airy. Thus in the airy-warm element live those entities which an older, instinctive clairvoyance has called the sylphs. But these sylphs, who live in the airy-warm element, penetrate to the light because the air is permeated everywhere by light, become related to light, and are particularly receptive to that which is the finer but greater movements within the air circle.

When you see a flock of swallows in spring or fall, which at the same time causes the body of air to vibrate as it flies towards you, causing a moving stream of air, then this moving stream of air, which is then present in every bird, means something audible to the sylphs. World music sounds from it to the sylphs. If you are sailing somewhere, say, on a ship, and the seagulls fly in, then there is a spiritual sound, a spiritual music that accompanies the ship in what is aroused by the flight of the seagulls.