World History in the Light of Anthroposophy

and as a Foundation for Knowledge of the Human Spirit

GA 233

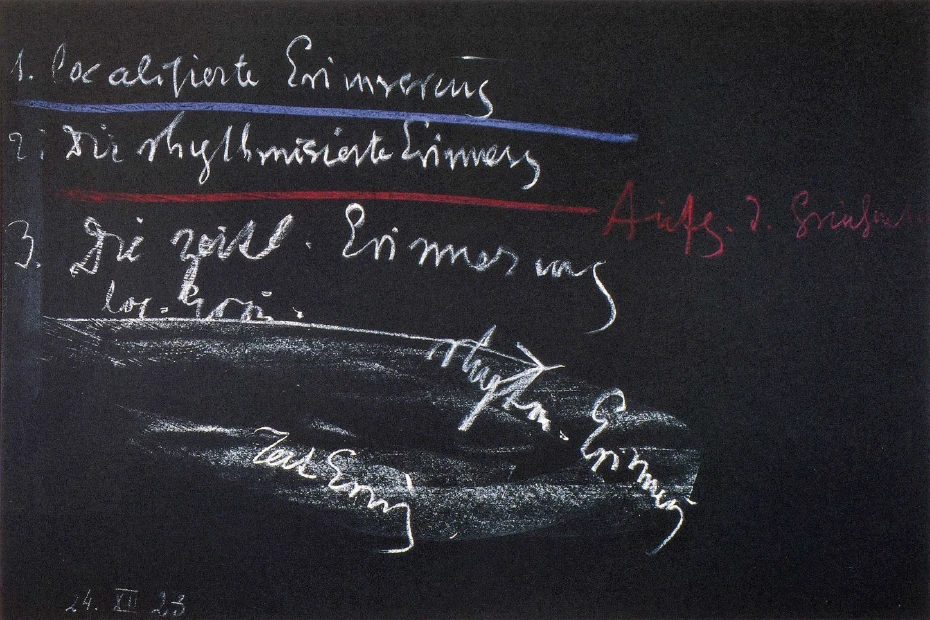

24 December 1923, Dornach

Lecture I

In the evening hours of our Christmas Gathering,1Die Weihnachtstagung zur Begründung der Allgemeinen Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft. Jahresausklang und Jahreswende 1923/24 by Rudolf Steiner, Collected Works, Dornach 1962. I should like to give you a kind of survey of human evolution on the earth, that may help us to become more intimately conscious of the nature and being of present-day man. For at this time in man's history, when we can see already in preparation events of extraordinary importance for the whole civilisation of humanity, every thinking man must be inclined to ask: ‘How has the present configuration, the present make-up of the human soul arisen? How has it come about through the long course of evolution?’ For it cannot be denied that the present only becomes comprehensible as we try to understand its origin in the past.

The present age is however one that is peculiarly prejudiced in its thought about the evolution of man and of mankind. It is commonly believed that, as regards his life of soul and spirit, man has always been essentially the same as he is to-day throughout the whole of the time that we call history. True, in respect of knowledge, it is imagined that in ancient times human beings were childlike, that they believed in all kinds of fancies, and that man has only really become clever in the scientific sense in modern times; but if we look away from the actual sphere of knowledge, it is generally held that the soul-constitution which man has to-day was also possessed by the ancient Greek and by the ancient Oriental. Even though it be admitted that modifications may have occurred in detail, yet on the whole it is supposed that throughout the historical period everything in the life of the soul has been as it is to-day. Then we go on to assume a prehistoric life of man, and say that nothing is really known of this. Going still further back, we picture man in a kind of animal form. Thus, in the first place, as we trace back in historical time, we see a soul-life undergoing comparatively little change. Then the picture disappears in a kind of cloud, and before that again we see man in his animal imperfection as a kind of higher ape-being. Such is approximately the usual conception of to-day.

Now all this rests on an extraordinary prejudice, for in forming such a conception, we do not take the trouble to observe the important differences that exist in the soul-constitution of a man of the present-time, as compared even with that of a relatively not very far distant past,—say, of the 11th, 10th, or 9th century A.D. The difference goes deeper when we compare the constitution of soul in the human being of to-day and in a contemporary of the Mystery of Golgotha, or in a Greek; while if we go over to the ancient Oriental world of which the Greek civilisation was, in a sense, a kind of colony, we find there a disposition of soul utterly different from that of the man of to-day. I should like to show you from real instances how man lived in the East, let us say, ten thousand, or fifteen thousand years ago, and how different he was in nature from the Greek, and how still more different from what we ourselves are.

Let us first call to mind our own soul-life. I will take an example from it. We have a certain experience; and of this experience, in which we take part through our senses, or through our personality in some other way, we form an idea, a concept, and we retain this idea in our thought. After a certain time the idea may arise again out of our thought into our conscious soul-life, as memory. You have perhaps to-day a memory-experience that leads you back to experiences in perception of some ten years ago. Now try and understand exactly what that really means. Ten years ago you experienced something. Ten years ago you may have visited a gathering of men and women. You formed an idea of each one of these persons, of their appearance and so on. You experienced what they said to you, and what you did in common with them. All that, in the form of pictures, may arise before you to-day. It is an inner soul-picture that is present within you, connected with the event which occurred ten years ago. Now not only according to Science, but according to a general feeling,—which is, of course, experienced by man to-day in an extremely weak form, but which nevertheless is experienced,—according to this general feeling man localises such a memory-concept which brings back a past experience, in his head. He says:—‘What lives as the memory of an experience is present in my head.’

Now let us jump a long way back in human evolution, and consider the early population of the Orient, of which the Chinese and Indians as we know them in history were only the late descendants: that is, let us go back really thousands of years. Then, if we contemplate a human being of that ancient epoch, we find that he did not live in such a way as to say: ‘I have in my head the memory of something I have experienced, something I have undergone, in external life.’ He had no such inner feeling or experience; it simply did not exist for him. His head was not filled with thoughts and ideas. The present-day man thinks in his superficial way that as we to-day have ideas, thoughts, and concepts, so human beings always possessed these, as far back as history records; but that is not the case.

If with spiritual insight we go back far enough, we meet with human beings who did not have ideas, concepts, thoughts at all in their head, who did not experience any such abstract content of the head, but, strange as it may seem, experienced the whole head; they perceived and felt their whole head. These men did not give themselves up to abstractions as we do. To experience ideas in the head was something quite foreign to them, but they knew how to experience their own head. And as you, when you have a memory-picture, refer the memory-picture to an experience, as a relationship exists between your memory-picture and the experience, similarly these men related the experience of their head to the Earth, to the whole Earth. They said:—‘There exists in the Cosmos the Earth. And there exists in the Cosmos I myself, and as a part of me, my head; and the head which I carry on my shoulders is the cosmic memory of the Earth. The Earth existed earlier; my head later. That I have a head is due to the memory, the cosmic memory of earthly existence. The earthly existence is always there. But the whole configuration, the whole shape of the human head, is in relation to the whole Earth.’ Thus an ancient Eastern felt in his own head the being of the Earth-planet itself. He said: ‘Out of the whole great cosmic existence the Gods have created, have generated the Earth with its kingdoms of Nature, the Earth with its rivers and mountains. I carry on my shoulders my head; and this head of mine is a true picture of the Earth. This head, with the blood flowing in it, is a true picture of the Earth with the land and water coursing over it. The configuration of mountains on the Earth repeats itself in my head in the configurations of my brain; I carry on my shoulders my own image of the Earth-planet.’ Exactly as our modern man refers his memory-picture to his experience, so did the man of old refer his entire head to the Earth-planet. A considerable difference in inner perception!

Further, when we consider the periphery of the Earth, and fit it, as it were, into our vision of things, we feel this air surrounding the Earth as air permeated by the Sun's warmth and light; and in a certain sense, we can say: ‘The Sun lives in the atmosphere of the Earth.’ The Earth opens herself to the Cosmic universe; the activities that come forth from herself she yields up to the encircling atmosphere, and opens herself to receive the activities of the Sun. Now each human being, in those ancient times, experienced the region of the Earth on which he lived as of peculiar importance. An ancient Eastern would feel some portion of the surface of the Earth as his own; beneath him the earth, and above him the encircling atmosphere turned towards the Sun. The rest of the Earth that lay to left and right, in front and behind—all the rest of the Earth merged into a general whole.

Thus if an ancient Oriental lived, for example, on Indian soil, he experienced the Indian soil as especially important for him; but everything else on the Earth, East, West, South of him, disappeared into the whole. He did not concern himself much with the way in which the Earth in these other parts was bounded by the rest of Cosmic space; while on the other hand not only was the soil on which he lived something important, but the extension of the Earth into Cosmic space in this region became a matter of great moment to him. The way in which he was able to breathe on this particular soil was felt by him as an inner experience of special importance.

To-day we are not in the habit of asking, how does one breathe in this or that place? We are of course still subject to favourable or unfavourable conditions for breathing, but we are no longer so conscious of the fact. For an ancient Oriental this was different. The way in which he was able to breathe was for him a very deep experience, and so were many other things too that depend on the character of the Earth's relation and contact with cosmic space. All that goes to make up the Earth, the whole Earth, was felt by the human being of those early times as that which lived in his head.

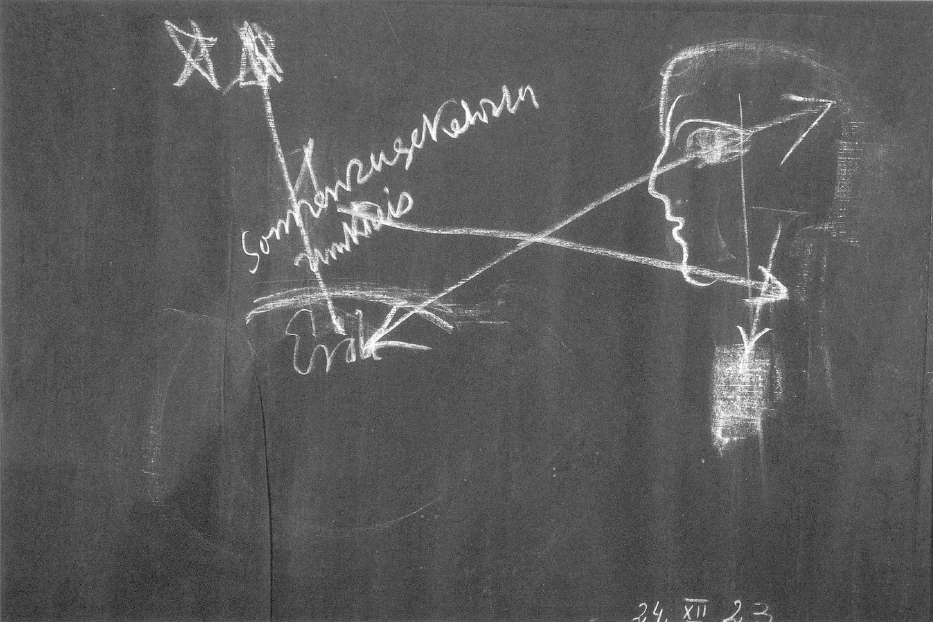

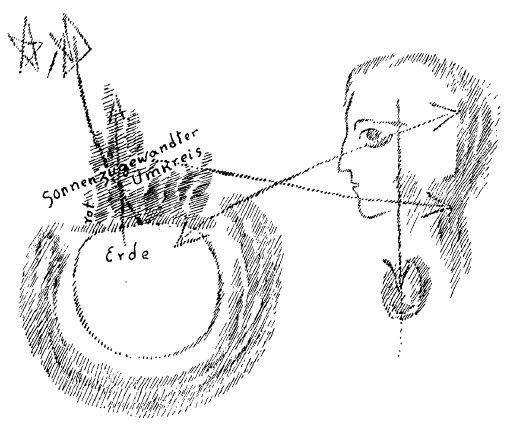

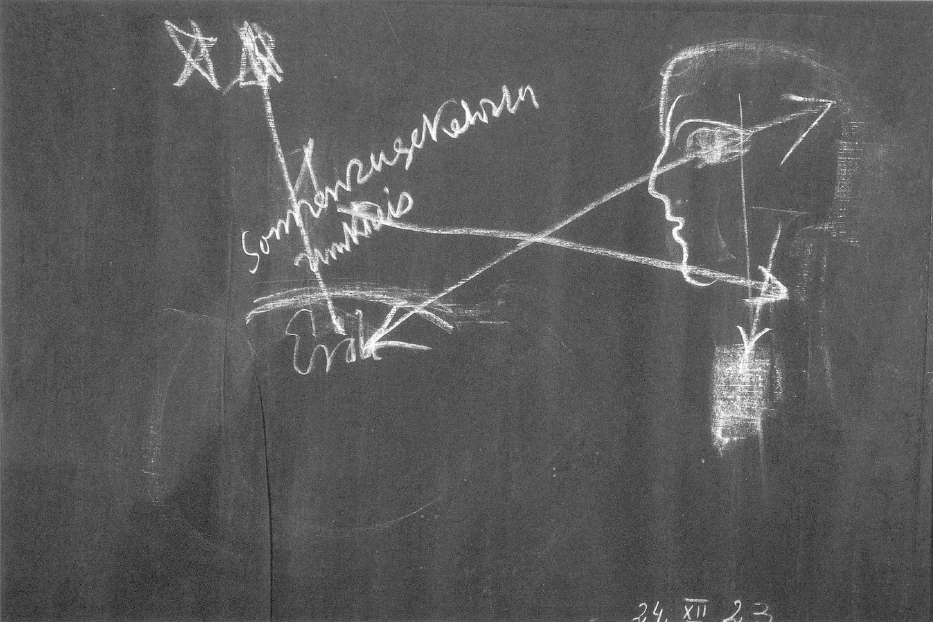

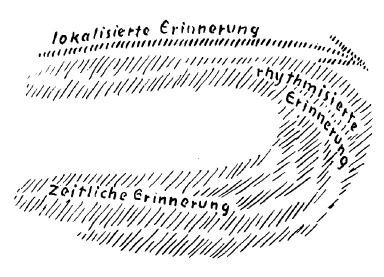

Now the head is enclosed by the hard firm bones of the skull, it is shut in above, on two sides and behind. But it has certain exits; it has a free opening downwards towards the chest. And it was of special importance for the man of olden time to feel how the head opens with relative freedom in the direction of the chest. (See Drawing). And as he had to feel the inner configuration of the head as an image of the Earth, so he had to bring the environment of the Earth, all that is above and around the Earth, into connection with the opening downwards, the turning towards the heart. In this he saw an image of how the Earth opens to the Cosmos. It was a mighty experience for a man of those ancient times when he said: ‘In my head I feel the whole Earth. But this Earth opens to my chest which carries within it my heart. And that which takes place between head, chest and heart is an image of what is borne out from my life into the Cosmos, borne out to the surrounding atmosphere that is open to the Sun.’

A great experience it was for him, and one of deep meaning, when he was able to say: ‘Here in my head lives the Earth. When I go deeper, there the Earth is turning towards the Sun; my heart is the image of the Sun.’ In this way did the man of olden times attain what corresponds to our life of feeling.

We have the abstract life of feeling still. But who of us knows anything directly of his heart? Through anatomy and physiology, we think we know something, but it is about as much as we know of some papier-mâché model of the heart that we may have before us. On the other hand, what we have as a feeling-experience of the world, that the man of olden times did not have. In place of it he had the experience of his heart. Just as we relate our feeling to the world in which we live, just as we feel whether we love a man or meet him with antipathy, whether we like this or that flower, whether we incline towards this or that, just as we relate our feelings to the world—but to a world torn out, as it were, in airy abstraction, from the solid, firm Cosmos—in the same way did the ancient Oriental relate his heart to the Cosmos, that is, to that which goes away from the Earth in the direction of the Sun.

Again, we say to-day: I will walk. We know that our will lives in our limbs. The ancient man of the East had an essentially different experience. What we call ‘will’ was quite unknown to him. We judge quite wrongly when we believe that what we call thinking, feeling and willing were present among the ancient Eastern races. It was not at all the case. They had head experiences, which were Earth experiences. They had chest or heart experiences, which were experiences of the environment of the Earth as far out as the Sun. The Sun corresponds to the heart experience. Then they had a further experience, a feeling of expanding and stretching out into their limbs. They became conscious and aware of their own humanity in the movement of their legs and feet, or of their arms and hands. They themselves were within the movements. And in this expansion of the inner being into the limbs, they felt a direct picture of their connection with the starry worlds. (See Drawing). ‘In my head I have a picture of the Earth. Where my head opens freely downwards into the chest and reaches down to my heart, I have a picture of what lives in the Earth's environment. In what I experience as the forces of my arms and hands, of my feet and legs, I have something which represents the relation the Earth bears to the stars that live far out there in cosmic space.’

When therefore man wanted to express the experience he had as ‘willing’ human being—to use the language of to-day,—he did not say: I walk. We can see that from the very words that he used. Nor did he say: I sit down. If we investigate the ancient languages in respect of their finer content, we find everywhere that for the action which we describe by saying: I walk, the ancient Oriental would have said: Mars impels me, Mars is active in me. Going forward was felt as a Mars impulse in the legs.

Grasping hold of something, feeling and touching with the hands, was expressed by saying: Venus works in me. Pointing out something to another person was expressed by saying: Mercury works in me. Even when a rude person called some one's attention by giving him a push or a kick, the action would be described by saying: Mercury was working in that person. Sitting down was a Jupiter activity, and lying down, whether for rest or from sheer laziness, was expressed by saying: I give myself over to the impulses of Saturn. Thus man felt in his limbs the wide spaces of the Cosmos out beyond. He knew that when he went away from the Earth out into cosmic space, he came into the Earth's environment and then into the starry spheres. If he went downwards from his head, he passed through the very same experience, only this time within his own being. In his head he was in the Earth, in his chest and heart he was in the environment of the Earth, in his limbs he was in the starry Cosmos beyond.

From a certain point of view such an experience is perfectly possible for man. Alas for us, poor men of to-day, who can experience only abstract thoughts! What are these in reality, for the most part? We are very proud of them, but we quite forget what is far beyond the cleverest of them,—our head; our head is much more rich in content than the very cleverest of our abstract thoughts. Anatomy and physiology know little of the marvel and mystery of the convolutions of the brain, but one single convolution of the brain is more majestic and more powerful than the abstract knowledge of the greatest genius. There was once a time on the Earth when man was not merely conscious as we are of thoughts lying around, so to speak, but was conscious of his own head; he felt the head as the image of the Earth, and he felt this or that part of the head—let us say, the optic thalamus or the corpora quadrigemina—as the image of a certain, physical mountainous configuration of the Earth. He did not then merely relate his heart to the Sun in accordance with some abstract theory, he felt: ‘My head stands in the same relation to my chest, to my heart, as the Earth does to the Sun.’ That was the time when man had grown together, in his whole life, with the Cosmic Universe; he had become one with the Cosmos. And this found expression in his whole life.

Through the fact that we to-day put our puny thinking in the place of our head, through this very fact we are able to have a conceptual memory, we are able to remember things in thought. We form pictures in thought of what we have experienced as abstract memories in our head. That could not be done by a man of olden times who did not have thoughts, but still had his head. He could not form memory pictures. And so, in those regions of the Ancient East where people were still conscious of their head, but had as yet no thoughts and hence no memories, we find developed to a remarkable degree something of which people are again beginning to feel the need to-day. For a long time such a thing has not been necessary, and if to-day the need for it is returning it is due to what I can only call slovenliness of soul.

If in that time of which I have spoken one were to enter the region inhabited by people who were still conscious of their head, chest, heart and limbs, one would see on every hand small pegs placed in the earth and marked with some sign. Or here and there a sign made upon a wall. Such memorials were to be found scattered over all inhabited regions. Wherever anything happened, a man would set up some kind of memorial, and when he came back to the place, he lived through the event over again in the memorial he had made. Man had grown together with the earth, he had become one with it with his head. To-day he merely makes a note of some event in his head. As I have pointed out already, we are beginning once more to find it necessary to make notes not only in our head but also in a note-book; this is due as I said, to slovenliness of soul, but we shall nevertheless require to do it more and more. At that time however there was no such thing as making notes even in one's head, because thoughts and ideas were simply nonexistent. Instead, the land was dotted over with signs. And from this habit, so naturally acquired by men in olden times, has arisen the whole custom of making monuments and memorials.

Everything that has happened in the historical evolution of mankind has its origin and cause in the inner being of man. If we were but honest, we should have to admit that we modern men have not the faintest knowledge of the deeper basis of this custom of erecting memorials. We set them up from habit. They are however the relics of the ancient monuments and signs put up by man in a time when he had no memory such as we have to-day but was taught, in any place where he had some experience, there to set up a memorial, so that when he came that way again he might re-experience the event in his head; for the head can call up again everything that has connection with the earth. ‘We give over to the earth what our head has experienced’—was a principle of olden times.

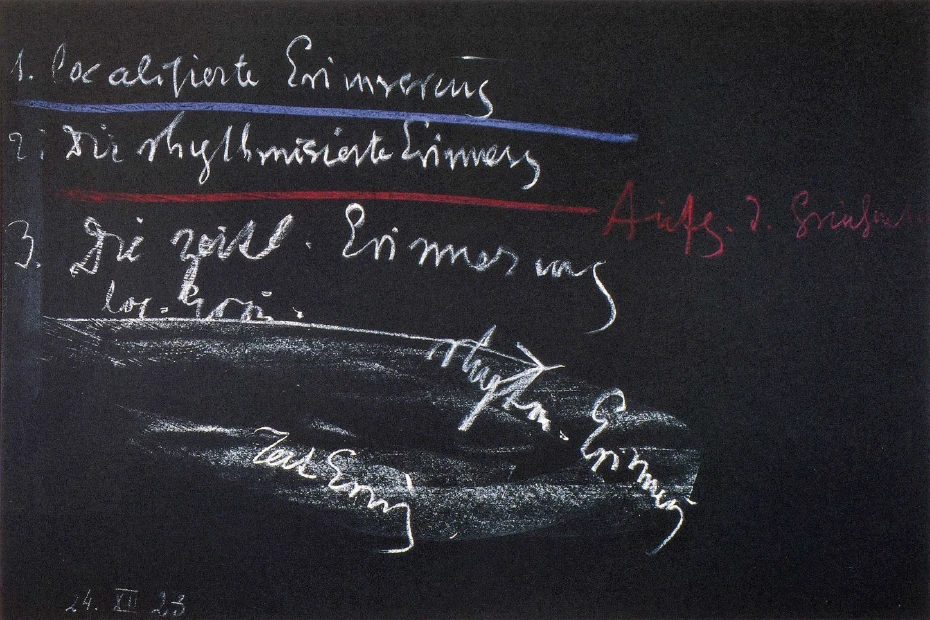

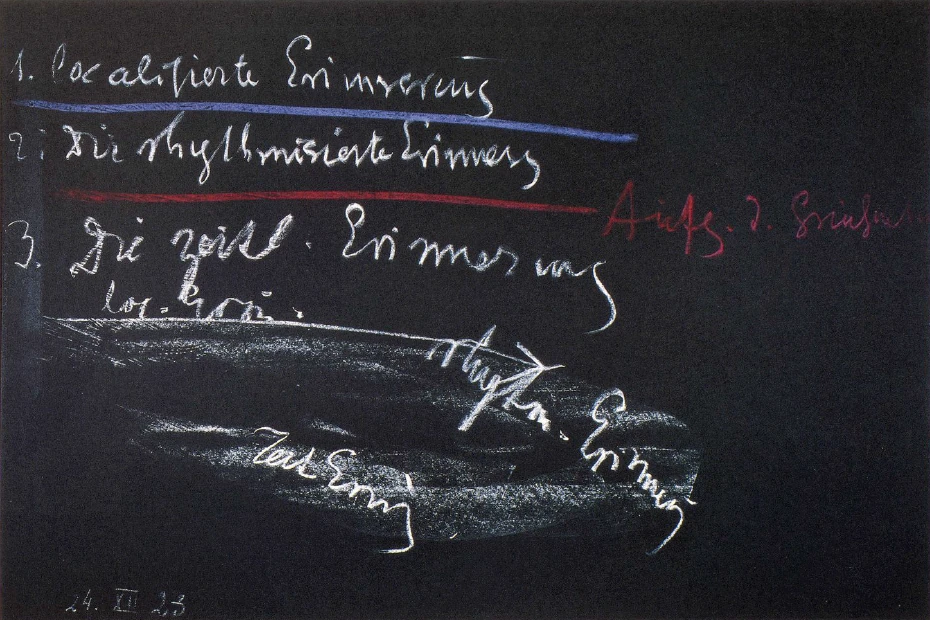

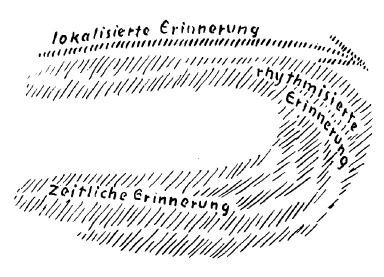

And so we have to point to a very early time in the ancient East, the epoch of localised memory, when everything of the nature of memory was connected with the setting up of signs and memorials on the earth. Memory was not within, but without. Everywhere were memorial tablets and memorial stones. It was localised memory, a remembering connected with place.

Even to-day it is still of no small value for a man's spiritual evolution that he should sometimes make use of his capacity for this kind of memory, for a memory that is not within him but is unfolded in connection with the outer world. It is good sometimes to say: I will not remember this or that, but I will set here or there a sign, or token; or, I will let my soul unfold an experience about certain things, only in connection with signs or tokens. I will, for instance, hang a picture of the Madonna in a corner of my room, and when the picture is before me, I will experience in my soul all that I can experience by turning with my whole soul to the Madonna. For there is a subtle relation to a thing belonging so intimately to the home as does the picture of the Madonna that we meet with in the homes of the people, when we go a little way eastwards in Europe; we have not even to go as far as Russia, we find them everywhere in Central Europe. All experience of this nature is in reality a relic of the epoch of localised memory. The memory is outside, it attaches to the place.

A second stage is reached when man passes from localised to rhythmic memory. Thus we have first, localised memory; and secondly, rhythmic memory.

We have now come to the time when, not from any conscious, subtle finesse, but right out of his own inner being, man had developed the need of living in rhythm. He felt a need so to reproduce, within himself, what he heard that a rhythm was formed. If his experience of a cow, for instance, suggested ‘moo,’ he did not simply call her ‘moo,’ but ‘moo-moo,’—perhaps, in very ancient times, ‘moo-moo-moo.’ That is to say, the perception was as it were piled up in repetition, so as to produce rhythm. You can follow the same process in the formation of many words to-day; and you can observe how little children still feel the need of these repetitions. We have here again a heritage come down from the time when rhythmic memory prevailed, the time when man had no memory at all of what he had merely experienced, but only of what he experienced in rhythmic form,—in repetitions, in rhythmic repetition. There had to be at any rate some similarity between a sequence of words. ‘Might and main,’ ‘stock and stone’—such setting of experience in rhythmic sequence is a last relic of an extreme longing to bring everything into rhythm; for in this second epoch, that followed the epoch of localised memory, what was not set into rhythm was not retained. It is from this rhythmic memory that the whole ancient art of verse developed—indeed all metrical poetry.

Only in the third stage does that develop which we still know to-day,—temporal memory, when we no longer have a point in space to which memory attaches, nor are any longer dependent on rhythm, but when that which is inserted into the course of time can be evoked again later. This quite abstract memory of ours is the third stage in the evolution of memory.

Let us now call to mind the point of time in human evolution when rhythmic memory passes over into temporal memory, when that memory first made its appearance which we with our lamentable abstractness of thought take entirely as a matter of course; the memory whereby we evoke some-thing in picture-form, no longer needing to make use of semi-conscious or unconscious rhythmic repetitions in order to call it up again.

The epoch of the transition from rhythmic memory to temporal memory is the time when the ancient East was sending colonies to Greece,—the beginning of the colonies planted from Asia in Europe. When the Greeks relate stories of the heroes who came over from Asia and Egypt to settle on Grecian soil, they are in reality relating how the great heroes went forth from the land of rhythmic memory to seek a climate where rhythmic memory could pass over into temporal memory, into a remembering in time.

We are thus able to define quite exactly the time in history when this transition took place,—namely, the time of the rise of Greece. For that which may be called the Motherland of Greece was the home of a people with strongly developed rhythmic memory. There rhythm lived. The ancient East is indeed only rightly understood when we see it as the land of rhythm. And if we place Paradise only so far back as the Bible places it, if we lay the scene of Paradise in Asia, then we have to see it as a land where purest rhythms resounded through the Cosmos and awoke again in man as rhythmic memory,—a land where man lived not only as experiencing rhythm in a Cosmos, but as himself a creator of rhythm.

Listen to the Bhagavad-Gita and you will catch the after-echo of that mighty rhythm that once lived in the experience of man. You will hear its echo also in the Vedas, and you will even hear it in the poetry and literature—to use a modern word—of Western Asia. In all these live the echoes of that rhythm which once filled the whole of Asia with majestic content and, bearing within it the mysteries of the environment of the Earth, made these resound again in the human breast, in the beat of the human heart. Then we come to a still more ancient time, when rhythmic memory leads back into localised memory, when man did not even have rhythmic memories but was taught, in the place where he had had an experience, there to erect a memorial. When he was away from the place, he needed no memorial; but when he came thither again he had to recall the experience. Yet it was not he who recalled it to himself; the memorial, the very Earth, recalled it to him. As the head is the image of the Earth, so for the man of localised memory the memorial in the Earth evoked its own image in the head. Man lived completely with the Earth; in his connection with the Earth he had his memory.

The Gospels contain a passage that recalls this kind of memory, where we are told that Christ wrote something in the Earth.

The period we have thus defined as the transition from localised memory to rhythmic memory is the time when ancient Atlantis was declining and the first Post-Atlantean peoples were wandering eastward in the direction of Asia. For we have first the wanderings from ancient Atlantis—the continent that to-day forms the bed of the Atlantic Ocean—right across Europe into Asia, and later the wanderings back again from Asia into Europe. The migration of the Atlantean peoples to Asia marks the transition from localised memory to rhythmic memory, which latter finds its completion in the spiritual life of Asia. The colonisation of Greece marks the transition from rhythmic memory to temporal memory—the memory that we still carry within us to-day.

1. Localised Memory

2. Rhythmic Memory

3. Temporal memory.

And within this evolution of memory lies the whole development of civilisation between the Atlantean catastrophe and the rise of Greece,—all that resounds to us from ancient Asia, coming to us in the form of legend and saga rather than as history. We shall arrive at no understanding of the evolution of humanity on the Earth by looking principally to the external phenomena, by investigating the external documents; rather do we need to fix our attention on the evolution of what is within man; we must consider how such a thing as the faculty of memory has developed, passing in its development from without into the inner being of man.

You know how much the power of memory means for the man of to-day. You will have heard of persons who through some condition of illness suddenly find that a portion of their past life, which they ought to remember quite easily, has been completely wiped out. A terrible experience of this kind befell a friend of mine before his death. One day he left his home, bought a ticket at the railway station for a certain place, alighted there and bought another ticket. He did all this, having lost for the time the memory of his life up to the moment of buying the ticket. He carried everything out quite sensibly. His reason was sound. But his memory was blotted out. And he found himself, when his memory came back, in a Casual Ward in Berlin. It was afterwards proved that in the interval he had wandered over half Europe, without being able to connect the experience with the earlier experiences of his life. Memory did not re-awaken in him till he had found his way—he himself did not know how—into a Casual Ward in Berlin.

This is only one of countless cases which we meet with in life and which show us how the soul-life of the man of to-day is not intact unless the threads of memory are able to reach back unbroken to a certain period after birth.

With the men of olden time who had developed a localised memory, this was not the case. They knew nothing of these threads of memory. They, on the other hand, would have been unhappy in their soul-life, they would have felt as we feel when something robs us of our self, if they had not been surrounded by memorials which recalled to them what they had experienced; and not alone by memorials which they themselves had set up, but memorials too erected by their forefathers, or by their brothers and sisters, similar in configuration to their own and bringing them into contact with their own kinsmen. Whereas we are conscious of something inward as the condition for keeping our Self intact, for these men of bygone times the condition was to be sought outside themselves—in the world without.

We have to let the whole picture of this change in man's soul pass before our eyes in order to realise its significance in the history of man's evolution. It is by observing such things as these that light begins to be thrown upon history. To-day I wanted to show, by a special example, how man's mind and soul have evolved in respect of one faculty—the faculty of memory. We shall go on to see in the course of the succeeding lectures how the events of history begin to reveal themselves in their true shape when we can thus illumine them with light derived from knowledge of the human soul.

Erster Vortrag

In diesen Abendstunden unserer Weihnachtszusammenkunft möchte ich Ihnen einen solchen Überblick der Menschheitsentwickelung auf Erden geben, der dazu führen kann, dasjenige, was der Mensch in der Gegenwatt ist, intimer und intensiver in das Bewußtsein aufzunehmen. Gerade in dieser gegenwärtigen Zeit, in der sich so außerordentlich Bedeutsames, man darf schon sagen, für die ganze Kulturmenschheit vorbereitet, müßte es eigentlich jedem tiefer denkenden Menschen naheliegen, die Frage aufzuwerfen: Wie ist die gegenwärtige Konfiguration, die gegenwärtige Verfassung der menschlichen Seele aus einer Entwickelung langer Zeiten hervorgegangen? - Denn es kann ja nicht geleugnet werden, daß das Gegenwärtige dadurch verständlich wird, daß man es in seinem Hervorgehen aus dem Vergangenen zu begreifen versucht.

Nun ist man aber gerade in der Gegenwart außerordentlich befangen in bezug auf die Entwickelung des Menschen und der Menschheit. Zunächst stellt man sich ja vor, daß der Mensch in bezug auf sein seelisch-geistiges Leben so, wie er jetzt ist, im wesentlichen während der ganzen geschichtlichen Zeit war. Gewiß, mit Bezug auf das eigentlich Wissenschaftliche stellt man sich vor, daß in alten Zeiten die Menschen kindlich waren, an allerlei Phantastereien geglaubt haben und daß die Menschen eigentlich gescheit im wissenschaftlichen Sinne erst in der allerletzten Zeit geworden sind. Aber wenn man davon absieht, was das eigentlich Wissenschaftliche ist, so denkt man sich dann, daß im allgemeinen die Seelenverfassung, die der heutige Mensch hat, auch schon der Grieche, der Orientale, gehabt hat. Wenn man sich auch im Kleinen Modifikationen im Seelenleben denkt, im großen ganzen denkt man sich: während der historischen Zeit ist eben eigentlich alles so gewesen wie heute. Da nimmt man an, daß das geschichtliche Leben ins Vorgeschichtliche verläuft und sagt: Da weiß man nichts Rechtes. - Dann aber geht man weiter zurück: Da war der Mensch noch in seiner tierischen Gestalt. - Geht man also die Geschichte zurück, so stellt man sich das Seelenleben so ziemlich unverändert vor, dann, im Nebel verschwimmend, das Bild und dann der Mensch in tierischer Unvollkommenheit, so ein besseres Affenwesen.

Das ist ja ungefähr die gebräuchliche Vorstellung von heute. Sie beruht eben auf einer außerordentlichen Befangenheit, denn man bemüht sich, indem man eine solche Vorstellung ausbildet, gar nicht zu erkennen, welch tiefgehende Unterschiede schon vorhanden sind in der Seelenverfassung zwischen dem Menschen der Gegenwart und einer verhältnismäßig gar nicht so weit zurückliegenden Zeit, sagen wir, dem 11., 10., 9. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert, oder wie groß der Unterschied in der Seelenverfassung ist zwischen einem heutigen Menschen und einem Zeitgenossen des Mysteriums von Golgatha oder gar einem heutigen Menschen und einem Griechen. Und gehen wir dann in die orientalische Welt zurück, von der gewissermaßen die griechische Zivilisation eine Art Kolonie war, eine Spätkolonie, so kommen wir in Seelenverfassungen des Menschen hinein, die total verschieden sind von der Seelenverfassung des gegenwärtigen Menschen. Und ich möchte gleich an Beispielen, an wirklichen Fällen Ihnen zeigen, wie der Mensch, der vor, sagen wit, zehntausend Jahren etwa oder fünfzehntausend Jahren im Oriente gelebt hat, ganz anders geartet war als wieder der Grieche und als wir selbst etwa.

Stellen wir uns einmal unser Seelenleben vor das Seelenauge hin. Nehmen wir irgend etwas aus unserem eigenen Seelenleben heraus. Wir haben irgendein Erlebnis. Wir bilden uns von diesem Erlebnis, an dem wir durch unsere Sinne oder sonst durch unsere Persönlichkeit beteiligt sind, eine Idee, einen Begriff, eine Vorstellung. Wir behalten diese Vorstellung in unserem Denken, und sie kann wiederum nach einiger Zeit als Erinnerung aus unserem Denken in das bewußte Seelenleben heraufkommen. Sie haben heute, sagen wir, irgendwelches Erinnerungserlebnis, das Sie zurückführt in Ihre wahrgenommenen Erlebnisse vor vielleicht zehn Jahren. Und nun fassen Sie ganz genau, was das eigentlich ist. Etwas haben Sie vor zehn Jahren erlebt. Sagen wir, Sie haben vor zehn Jahren eine Gesellschaft von Menschen besucht, Sie haben die Vorstellung bekommen von jedem einzelnen dieser Menschen, deren Antlitz und so weiter. Sie haben erlebt, was diese Menschen zu Ihnen gesagt haben, was Sie mit ihnen gemeinsam getan haben und so weiter. Das alles kann im Bilde heute vor Ihnen auftauchen. Es ist ein innerliches Seelenbild, das von dem Ereignis von vielleicht vor zehn Jahren in Ihnen vorhanden ist. Und nicht nur nach der Wissenschaft, sondern nach einem allgemeinen Gefühl, das allerdings heute von den Menschen schon außerordentlich schwach erlebt wird, aber das vorhanden ist, lokalisiert man eine solche Erinnerungsvorstellung, die ein Erlebnis wiederum heraufbringt, im menschlichen Haupte. Man sagt sich: Im Kopfe ist dasjenige vorhanden, was als Erinnerung an ein Erlebnis da ist.

Nun, machen wir jetzt einen ziemlich großen Sprung zurück in der Menschheitsentwickelung, und sehen wir uns Bevölkerungen der orientalischen Gegenden einmal an, von denen unsere historisch geschilderten Chinesen, Inder und so weiter eigentlich erst die Nachkommen sind. Also gehen wir wirklich Tausende von Jahren zurück. Wenn wir da einen Menschen dieser alten Zeiten ins Auge fassen, dann lebte der nicht so, daß er sagte: Ich habe in meinem Kopfe die Erinnerung an irgend etwas, was ich im äußeren Leben erfahren habe, durchgemacht habe. - Solch ein inneres Erlebnis hatte er gar nicht, das gab es für ihn nicht. Er hatte nicht Gedanken, Ideen, die seinen Kopf anfüllten. Die Oberflächlichkeit des gegenwärtigen Menschen meint: Heute haben wir Ideen, Begriffe, Vorstellungen; das haben die Menschen in der historischen Zeit immer gehabt. - So ist es aber nicht.

Wenn wir mit geistiger Einsicht weit genug zurückgehen, so treffen wir eben auf Menschen auf, die ganz und gar nicht Ideen, Begriffe, Vorstellungen im Kopfe hatten, die nämlich nicht einen solchen abstrakten Inhalt ihres Kopfes erlebten, sondern, so grotesk es Ihnen erscheinen mag, die den ganzen Kopf erlebten, die ihre Köpfe einfach spürten, einfach empfanden. Mit Abstraktionen in unserem Sinne haben sich diese Menschen nicht abgegeben. Im Kopfe Ideen zu erleben, das kannten sie eben nicht, aber ihren eigenen Kopf erleben, das kannten sie. Und so wie Sie, wenn Sie ein Erinnerungsbild haben an ein Erlebnis, dieses Erinnerungsbild auf das Erlebnis beziehen, wie eine Relation besteht zwischen Ihrem Erinnerungsbild und dem Erlebnis, das da draußen war, so bezogen diese Menschen das Erlebnis ihres Kopfes auf die Erde, auf die ganze Erde. Und sie sagten: Es gibt in der Welt die Erde, es gibt in der Welt mich und an mir meinen Kopf. Und mein Kopf, den ich auf meinen Schultern trage, der ist die kosmische Erinnerung an die Erde. Die Erde ist früher dagewesen, mein Kopf später. Aber daß ich einen Kopf habe, das ist die Erinnerung, die kosmische Erinnerung an das Erdendasein. Das Erdendasein ist noch immer da, aber dasjenige, was die ganze Konfiguration, die ganze Gestaltung des Menschenkopfes ist, das ist in Relation zu der ganzen Erde. - Und so fühlte ein solcher alter Orientale in seinem eigenen Haupte das Wesen des Erdenplaneten selber. Er sagte: Die Götter haben aus dem allgemeinen kosmischen Dasein herauserschaffen, herauserzeugt die Erde mit ihren Reichen der Natur, die Erde mit ihren Flüssen und Bergen. Aber ich selber trage auf meinen Schultern mein Haupt. Dieses Haupt ist ein getreues Abbild der Erde selber. Dieses Haupt mit seinem in ihm fließenden Blute ist ein getreues Abbild der über die Erde fließenden Fluß- und Meeresströmungen. Dasjenige, was auf der Erde an Gebirgskonfiguration ist, wiederholt sich in meinem eigenen Haupte in der Konfiguration meines Gehirnes. Ich trage auf meinen Schultern ein mir zugehöriges Abbild des irdischen Planeten. - Genau so, wie der moderne Mensch sein Erinnerungsbild auf sein Erlebnis bezieht, so bezog dieser Mensch seinen ganzen Kopf auf den Erdenplaneten. Sehen Sie, das war eine beträchtlich andere Innenanschauung des Menschen.

Und weiter. Wenn der Mensch den Umkreis der Erde empfindet und in seine Anschauung faßt, dann wird ihm dieser Umkreis, das Luftige, das die Erde umgibt, erscheinen als von der Sonne und ihrer Wärme und ihrem Lichte durchsetzt, und man kann in gewissem Sinne sagen, daß die Sonne lebt im Luftumkteise der Erde. Die Erde öffnet sich dem Weltenall, indem sie ihre Wirkungen, die sie von sich aussendet, dem Luftkreis übergibt und sich den Sonnenwirkungen erschließt. Und jeder Mensch empfand in diesen alten Zeiten diejenige Gegend der Erde, auf der er gerade lebte, als ganz besonders wichtig, als ganz besonders wesentlich. Und so, sagen wir, empfand ein alter Orientale irgendeinen Teil der Erdoberfläche als seinen Teil, unten die Erde, oben den sonnenzugekehrten Umkreis. Das andere der Erde, links und rechts und vorne und rückwärts, das verschwamm im mehr Allgemeinen (siehe Zeichnung, linker Teil).

Wenn also etwa ein alter Orientale, auf indischem Boden lebend, diesen indischen Boden als für ihn besonders wichtig empfunden hat, dann verschwand ihm dasjenige, was sonst auf der Erde war, ostwärts, südwärts, westwärts, im Allgemeinen. Da kümmerte er sich nicht viel um die Art und Weise, wie die Erde angrenzt an die übrigen kosmischen Räume. Dagegen war ihm der Boden, auf dem er gerade war, besonders wichtig (siehe Zeichnung, links, rot). Das Hinausleben der Erde in den Weltenraum in dieser Gegend wurde ihm besonders wichtig. Wie er atmen durfte auf diesem besonderen Boden, das empfand er als ein für ihn besonders wichtiges Erlebnis. Heute fragen sich die Menschen nicht viel: Wie atmet man auf einem bestimmten Boden? - Sie stehen allerdings unter dem Einfluß günstigerer oder ungünstigerer Atmungsbedingung, aber ins Bewußtsein wird das nicht so aufgenommen. Ein solcher alter Orientale hat eigentlich gerade in der Art und Weise, wie er atmen durfte, ein tiefes Erlebnis gehabt, und so in anderem, was damit zusammenhing, wie die Erde an den Weltenraum hinausgrenzt.

Dasjenige, was die ganze Erde war, das empfand der Mensch als das, was in seinem Haupte lebt. Aber das Haupt, es ist abgeschlossen durch feste Knochenwände nach oben, nach den Seiten, nach hinten. Aber es hat gewisse Ausgänge, ein gewisses freies Öffnen nach unten, nach dem Brustkorb (siehe Zeichnung, rechts). Das war für den alten Menschen von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit, zu fühlen, wie das Haupt mit einer relativen Freiheit sich gegen den Brustkorb hin öffnet. Es empfand dieser Mensch die innere Konfiguration des Hauptes als ein Abbild des Irdischen. Mußte er die Erde in Relation mit seinem Haupte setzen, so mußte er den Umkreis, dasjenige, was über der Erde ist, mit dem, was nun an das Untere in ihm geht, in Relation setzen. Das Sich-Öffnen nach unten, das Zugekehrtsein dem Herzen, das empfand der Mensch als zugeordnet dem Umkreis, als Bild, als Öffnung der Erde in den Kosmos hinaus. Und ein gewaltiges Erlebnis war es für den Menschen, wenn er sagte: In meinem Haupte fühle ich die ganze Erde. Dieses Haupt ist eine kleine Erde. Aber diese ganze Erde öffnet sich in meinen Brustkorb hinein, der mein Herz trägt. Und dasjenige, was da sich abspielt zwischen meinem Haupte und meinem Brustkorb, meinem Herzen, das ist das Abbild dessen, was sich zuträgt von meinem Leben hinaus in den Kosmos, hinaus zu dem sonnenzugekehrten Umkreis. —- Und es war ein wichtiges, gründliches Erlebnis, wenn der alte Mensch sagte: Hier, in meinem Haupte, lebt in mir die Erde. Gehe ich tiefer, so kehrt sich die Erde der Sonne zu (siehe Pfeile), und das Abbild der Sonne ist mein Herz.

Da war der Mensch bei dem angekommen, was in der alten Zeit entspricht unserem Gefühlsleben. Wir haben noch das abstrakte Gefühlsleben, aber wir wissen ja unmittelbar nichts von unserem Herzen. Durch die Anatomie, durch die Physiologie glauben wir etwas davon zu wissen. Aber was da gewußt wird, das ist ja ungefähr ebensoviel wie dasjenige, was wit von einem in Papiermaché nachgebildeten Herzen wissen. Das aber, was wir als Gefühlserlebnis der Welt haben, das hatte der alte Mensch nicht. Er hatte dafür sein Herzerlebnis. Und wie wir unser Gefühl hinausbeziehen auf die Welt, die mit uns lebt, wie wir empfinden, ob wir einen Menschen lieben, ob wir einem Menschen antipathisch begegnen, diese oder jene Blume lieben, dieser oder jener abgeneigt sind, wie wir unser Gefühl auf die Welt beziehen, aber auf eine Welt, die, man möchte sagen, in luftiger Abstraktion herausgerissen ist aus dem soliden festen Kosmos, so bezog der alte Orientale sein Herz auf den Kosmos, das heißt auf dasjenige, was von der Erde in den Umkreis ging, der Sonne zu.

Und wir, wir sagen zum Beispiel heute, wenn wir gehen: Wir wollen gehen. - Wir wissen, unser Wille lebt in unseren Gliedern. Der Mensch des alten Orients, der hatte ein wesentlich anderes Erlebnis. Das, was wir heute Wille nennen, kannte er ja nicht. Es ist ein bloßes Vorurteil, wenn man meint, daß dasjenige, was wir Denken, Fühlen, Wollen nennen, bei den alten orientalischen Völkern vorhanden war. Das war es gar nicht. Sie hatten Kopferlebnisse, die die Erdenerlebnisse waren, Brusterlebnisse oder Herzenserlebnisse, die die Erlebnisse des unmittelbaren Umkreises bis zur Sonne waren. Die Sonne entspricht dem Herzenserlebnis. Aber sie hatten dann das Sich-Dehnen und -Strecken in die Glieder, das Wahrnehmen der eigenen Menschlichkeit im Bewegen der Beine und Füße, im Bewegen der Arme und Hände. Sie waren dadrinnen. Aber in diesem das Innenwesen Hineindehnen in die Glieder empfanden sie doch nicht bloß ein Bild des Umkreises der Erde, sondern sie empfanden direkt ein Bild des Zusammenhanges des Menschen mit den Sternenwelten (siehe Zeichnung Seite 15). In meinem Kopfe habe ich ein Bild der Erde. In dem, was sich im Kopfe frei nach unten dehnt in die Brust hin zum Herzen, habe ich ein Bild dessen, was im Umkreise der Erde ist. In dem, was ich als die Kräfte meiner Arme und Hände, meiner Füße und Beine empfinde, habe ich das, was abbildet das Verhältnis der Erde zu den weit im Weltentaum draußen lebenden Gestirnen.

So daß der Mensch, der in jenen alten Zeiten seine Erlebnisse ausdrückte, die er hatte als, wie wir es heute nennen würden, wollender Mensch, nicht gesagt hat: Ich gehe. - Schon in den Worten lag das nicht. Er hat auch nicht gesagt: Ich setze mich. - Wenn man die alten Sprachen auf diese feinen Inhalte prüfen würde, würde man überall finden, daß für die Tatsache, die wir bezeichnen als: Ich gehe -, das alte Orientalische hatte: Mars impulsiert mich, Mars ist in mir tätig. — Das Vorwärtsgehen, das war das Empfinden der Mars impulse in den Beinen. Das Angreifen von irgend etwas, das Gefühl mit den Händen war so ausgedrückt, daß man sagte: Venus wirkt in mir. — Das Zeigen von etwas, das Weisen, auch wenn ein grober Mensch einem anderen etwas dadurch weisen wollte, daß er ihm einen Tritt gab, alles Weisen wurde so ausgedrückt, daß man sagte, Merkur wirke in dem Menschen. Das Niedersetzen war die Jupitertätigkeit in dem Menschen. Und das Niederlegen, ob es nun im Ausruhen war, ob es aus Faulenzerei war, das war ausgedrückt dadurch, daß man sagte, man gebe sich den Impulsen des Saturn hin. Also man fühlte in seinen Gliedmaßen die Weiten des Kosmos draußen. Der Mensch wußte: wenn er von der Erde aus in die Weltenweiten geht, dann kommt er von der Erde in den Umkreis, in die Gestirnsphäre. Wenn er von seinem Haupte nach abwärts geht, macht er dasselbe in seiner eigenen Wesenheit durch. In seinem Haupte ist er in der Erde, in seinem Brustkorb und Herzen im Umkreise, in seinen Gliedmaßen im Sternenkosmos draußen.

Ich möchte sagen, und von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus kann man das durchaus sagen: Ach, wir armen Menschen der Gegenwart, wir erleben die abstrakten Gedanken. Was sind sie viel? Wir sind ja sehr stolz darauf, aber wir vergessen über den selbst gescheitesten abstrakten Gedanken unseren Kopf. Und unser Kopf ist viel inhaltsreicher als unsere allergescheitesten Gedanken. Eine einzige Gehirnwindung - Anatomie und Physiologie wissen ja nicht viel von dem wunderbaren Geheimnis der Gehirnwindungen - ist etwas Großartigeres, Gewaltigeres als die genialste abstrakte Wissenschaft irgendeines Menschen. - Und es gab eben einmal eine Zeit auf der Erde, wo der Mensch sich bewußt war nicht bloß seiner armseligen Gedanken, sondern seines Kopfes, wo er den Kopf empfand, wo er empfand, meinetwillen sagen wir, den Vierhügelkörper oder die Sehhügel, wo er sie empfand in ihrer Nachbildung einer gewissen physischen Gebirgskonfiguration der Erde; wo der Mensch nicht bloß aus irgendeiner abstrakten Lehre heraus das Herz auf die Sonne bezog, sondern wo er empfand: Wie mein Haupt zu meiner Brust, zu meinem Herzen, so steht die Erde im Verhältnis zur Sonne.

Es war das die Zeit, in welcher der Mensch mit seinem ganzen Leben eben mit dem Weltenall, mit dem Kosmos zusammengewachsen war. Aber dieses Zusammengewachsensein, das drückte sich in seinem ganzen Leben aus. Wir sind ja gerade dadurch, daß wir an die Stelle unseres Kopfes das armselige Denken setzen, allerdings in die Lage versetzt, gedankliche Erinnerungen zu haben. Wir bilden uns Gedankenbilder von dem, was wir durchlebt haben, als abstrakte Erinnerungen unseres Kopfes. Das konnte derjenige, der nicht die Gedanken hatte, sondern noch seinen Kopf empfand, nicht. Der konnte sich nicht Erinnerungen bilden. Kam man daher nach jenen Gegenden des uralten Orients, in denen die Leute sich noch ihrer Köpfe bewußt waren, aber keine Gedanken hatten, also auch keine Erinnerungen hatten, dann findet man in besonderer Ausbildung etwas, was wir wiederum gerade beginnen, nötig zu haben. Eine lange Zeit hatten es die Menschen nicht nötig, und es ist ja eigentlich auch nur eine kleine Schlamperei unseres Seelenlebens, daß wir es wieder nötig haben. Wenn man in jener Zeit, von der ich spreche, in die Gegenden kam, wo die Menschen lebten, die sich ihres Kopfes, ihrer Brust, ihres Herzens, ihrer Gliedmaßen so bewußt waren, wie ich es geschildert habe, dann sah man überall: da ist irgendein kleiner Pflock in die Erde hineingesetzt und irgendein Zeichen daraufgesetzt, da ist an irgendeine Wand irgendein Zeichen gemacht. Alle Lebensgebiete, alle Lebensörtlichkeiten der Menschen waren mit lauter Merkzeichen übersät, denn man hatte noch nicht ein Gedankengedächtnis. Wo irgend etwas geschah, da stellte man gewissermaßen ein kleines Denkmal auf, und wenn man wieder hinkam, dann erlebte man an dem Merkzeichen, das man machte, die Sache wieder. Der Mensch war eben zusammengewachsen in seinem Haupte mit der Erde. Heute macht er bloß eine Notiz in seinem Kopfe - und ich sagte ja schon, wir beginnen schon wiederum damit, Notizen nicht nur im Kopfe zu machen, sondern in unseren Notizbüchern und dergleichen, aber ich sagte auch, das ist ja bloß eine Schlamperei der Seele, aber wir werden es immer mehr und mehr brauchen; aber dazumal gab es das nicht, Notizen im Kopfe zu machen, weil die Gedanken, die Ideen eben nicht vorhanden waren; da wurde alles übersät von Merkzeichen. Und aus dieser naturgemäßen Anlage der Menschen entstand ja das Denkmalwesen.

Alles, was in der Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit aufgetreten ist, ist ja aus dem Inneren der menschlichen Natur heraus bedingt. Man sollte nur ehrlich sein und sich gestehen: Die eigentliche tiefere Grundlage des Denkmalwesens, die kennt ja der gegenwärtige Mensch gar nicht. Er macht aus Gewohnheit Denkmäler. Aber diese Denkmäler sind die Überreste jener alten Merkzeichen, wo der Mensch noch nicht ein solches Gedächtnis hatte wie heute, sondern wo er darauf angewiesen war, an der Stelle, an der er etwas erlebt hatte, ein Merkzeichen anzubringen, und wenn er wieder hinkam, eben das aufleben zu lassen in seinem Kopfe, der alles das aufleben läßt, was irgendwie mit der Erde in Verbindung ist. Der Erde übergeben wir dasjenige, was der Kopf erlebt hat - das war Prinzip in alten Zeiten.

Und ich möchte sagen: Wir haben im alten Oriente eine uralte Zeit zu verzeichnen, die Zeit der lokalisierten Erinnerungen, wo eigentlich alles Erinnerungsmäßige gebunden ist daran, daß man Erinnerungszeichen auf die Erde hinstellte. Die Erinnerung war nicht dadrinnen, die war draußen, überall waren Denkzettel und Denksteine. Man stellte Erinnerungszeichen auf die Erde hin. Das war das lokalisierte Gedächtnis, die lokalisierte Erinnerung.

Für eine spirituelle Entwickelung des Menschen ist es heute noch außerordentlich gut, wenn er etwas anknüpft an dieses nicht im Inneren des Menschen befindliche Erinnerungsvermögen, sondern an jenes Erinnerungsvermögen, das eben eigentlich im Zusammensein des Menschen mit der irdischen Außenwelt sich entfaltet und gestaltet; wenn er sich zum Beispiel sagt: Ich will mich nicht erinnern an dies oder jenes, sondern ich mache mir da oder dort ein Merkzeichen - oder: Ich will überhaupt über gewisse Dinge nur in Gemäßheit von Merkzeichen innere seelische Empfindungen entwickeln. Ich will in meinem Zimmer in einer Ecke ein Madonnenbild aufstellen, und ich will, indem das Madonnenbild vor meine Seele tritt, dasjenige erleben, was ich eben in der Hinlenkung meiner Seele zur Madonna erleben kann. - Denn es ist eine feine Beziehung zu solchen Einrichtungen wie dem Madonnenbilde, das wir in den Wohnungen antreffen, wenn wir nur ein wenig nach dem Osten kommen. Nicht nur in Rußland ist es so, es ist ja überall schon auch im mittleren Osteuropa. Das alles sind im Grunde genommen Überreste aus der Zeit der lokalisierten Erinnerungen. Die Erinnerung haftet außen an dem Orte.

Aber ein zweites Stadium ist das andere, wo der Mensch übergeht von der lokalisierten Erinnerung zu der rhythmisierten Erinnerung. Wir haben also erstens die lokalisierte Erinnerung, zweitens die rhythmisierte Erinnerung. Da hatte der Mensch nun nicht aus irgendeiner schlauen bewußten Finesse heraus, sondern aus seiner inneren Wesenheit heraus das Bedürfnis entwickelt, im Rhythmus zu leben. Er hatte das Bedürfnis entwickelt, wenn er irgend etwas gehört hatte, das so in sich zu reproduzieren, daß ein Rhythmus herauskam. Wenn er die Kuh erlebte - Muh - , dann nannte er sie nicht Muh allein, sondern Muhmuh oder meinetwillen sogar in älteren Zeiten Muhmuhmunh. Das heißt, er türmte das Wahrgenommene so übereinander, daß ein Rhythmus herauskam. In manchen Wortbildungen können Sie das heute noch verfolgen, zum Beispiel der Gaugauch oder Kuckuck. Oder auch dann, wenn die Wortbildungen nicht unmittelbar hintereinander stehen, sehen Sie wenigstens, wie bei Kindern das Bedürfnis noch vorhanden ist, diese Wiederholungen auszubilden. Das ist noch eine Erbschaft aus der Zeit, wo die rhythmisierte Erinnerung Platz gegriffen hat, wo man nichts erinnerte, was man nur einfach erlebte, wo man nur dasjenige erinnerte, was man in Rhythmisierung, also in Wiederholungen, in rhythmischer Wiederholung erlebte. Und so mußte wenigstens zwischen dem, was aufeinanderfolgte, eine Ähnlichkeit sein: Mann und Maus, Stock und Stein. Diese Rhythmisierung des Erlebten, das ist ein letzter Rest einer hochgradigen Sehnsucht, überall zu rhythmisieren, denn was nicht rhythmisiert wurde in dieser zweiten Epoche, nach dem lokalisierten Gedächtnisse, das behielt der Mensch nicht. Und aus diesem rhythmisierten Gedächtnisse hat sich dann eigentlich die gesamte ältere Verskunst herausgebildet, überhaupt die versifizierte Dichtung. Und erst als dritte Stufe hat sich dasjenige gebildet, was wir heute noch kennen: die zeitliche Erinnerung, wo wit nicht mehr räumlich in der Außenwelt den Angriffspunkt der Erinnerung haben, wo wir auch nicht mehr angewiesen sind auf den Rhythmus, sondern wo dasjenige, was sich in die Zeit hineinstellt, später wieder hervorgerufen werden kann. Dieses unser ganz abstraktes Gedächtnis ist erst die dritte Stufe in der Gedächtnisentwickelung.

Und nun fassen Sie den Zeitpunkt genau ins Auge, wo in der Menschheitsentwickelung gerade übergeht die rhythmische Erinnerung in die Zeiterinnerung, wo das zuerst auftritt, was uns in unserer jämmerlichen Abstraktheit des modernen Menschen ganz selbstverständlich ist: das Zeitgedächtnis, wo wir im Bilde das hervorrufen, was wir hervorrufen; wo wir nicht mehr so erleben, daß wir in halb oder ganz unbewußster Tätigkeit etwas in rhythmischer Wiederholung wachgerufen haben müssen, wenn es wieder aufsteigen sollte. Nehmen Sie diesen Zeitpunkt des Überganges der rhythmischen Erinnerung in die zeitliche Erinnerung, dann haben Sie jenen Zeitpunkt, wo der alte Orient eben nach Griechenland herüber kolonisiert, jenen Zeitpunkt, der Ihnen in der Geschichte geschildert wird als die Entstehung der von Asien herüber nach Europa begründeten Kolonien. Was die Griechen erzählen von jenen Heroen, die von Asien oder Ägypten gekommen sind und sich auf griechischem Boden niedergelassen haben, das ist eigentlich die Erzählung, die da heißen müßte: Es zogen aus einmal aus dem Lande, wo da war das rhythmische Gedächtnis, die großen Helden und suchten ein Klima auf, wo das rhythmische Gedächtnis übergehen konnte in das zeitliche Gedächtnis, in die zeitliche Erinnerung.

Damit haben wir den Zeitpunkt des Aufganges des Griechentums streng bezeichnet. Denn was im Oriente als das Mutter- und Stammland des Griechentums dagestanden hat, das ist im Grunde genommen ein Menschengebiet mit ausgebildetem rhythmischem Gedächtnis. Da hat der Rhythmus gelebt. Und eigentlich ist der alte Orient nur dann richtig begriffen von dem Menschen, wenn er ihn vorstellt als das Land des Rhythmus. Und wenn das Paradies nur so weit zurückversetzt wird, als die Bibel es zurückversetzt, dann würden wir, wenn wir das Paradies nach Asien verlegen, es uns vorzustellen haben als das Gebiet, wo die reinsten Rhythmen durch den Kosmos erklangen und im Menschen wiederum anfeuerten das, was sein rhythmisches Gedächtnis war, wo der Mensch als RhythmusErleber in einem Kosmos als Rhythmus-Erzeuger lebte.

Fühlen Sie einmal in der Bhagavad Gita noch etwas nach von dem, was einstmals jenes grandiose Rhythmus-Erleben war, fühlen Sie es nach in der Vedenliteratur, fühlen Sie es selbst in vielem nach, was auch westasiatische Dichtung und westasiatisches Schrifttum ist, wenn wir dieses moderne Wort gebrauchen dürfen: da leben die Nachklänge des einstmals ganz Asien mit majestätischem Inhalt durchgreifenden Rhythmus, der sich widerspiegelte als das Geheimnis des Umkreises der Erde in dem menschlichen Brustkorb, in dem menschlichen Herzen. Und dann kommen wir in noch ältere Zeiten, wo die rhythmische Erinnerung nach rückwärts zurückverläuft in das lokalisierte Gedächtnis, wo die Menschen noch nicht rhythmische Erinnerungen hatten, wo die Menschen darauf angewiesen waren, da, wo sie etwas erlebt hatten, das Merkzeichen hinzustellen. Wenn sie nicht an diesem Orte waren, brauchten sie das nicht; wenn sie an diesen Ort kamen, mußten sie sich erinnern. Aber nicht sie erinnerten sich, das Merkzeichen, die Erde erinnerte sie. Wie die Erde überhaupt dasjenige ist, was den menschlichen Kopf als sein Abbild hat, so hat nun das Merkzeichen in der Erde für diese Menschen der lokalisierten Erinnerungen im Kopfe sein Abbild wiederum hervorgerufen. Der Mensch lebt ganz mit der Erde, der Mensch hat sein Gedächtnis ganz in seiner Verbindung mit der Erde. Das Evangelium erinnert daran nur noch an einer Stelle, wo es mitteilt, daß der Christus etwas in die Erde hineinschreibt.

Und wir haben einen Zeitpunkt festgehalten, wo die lokalisierte Erinnerung übergeht in die rhythmische Erinnerung. Das ist der Zeitpunkt, wo während des Unterganges der alten Atlantis von westwärts nach ostwärts, nach Asien hinüber, die uralten nachatlantischen Völker wandern. Denn wir haben, wenn wir von Europa nach Asien hinübergehen, erst die Wanderung von der alten Atlantis, die ja heute der Boden des Atlantischen Ozeans ist, hinüber nach Asien (siehe Zeichnung), und die Zurückwanderung der Kultur wiederum nach Europa. Beim Herüberwandern der atlantischen Völker nach Asien haben wir den Übergang der lokalisierten Erinnerung in die rhythmisierte Erinnerung, die ihre Vollendung im asiatischen Geistesleben hat. Dann haben wir bei der Kolonisation nach Griechenland herüber den Übergang von der rhythmischen Erinnerung zu der Zeiterinnerung, die wir heute noch in uns tragen.

Und in dieser Ausbildung der Erinnerung liegt die ganze Zivilisation zwischen der atlantischen Katastrophe und der Entstehung der griechischen Zivilisation, liegt alles das, was mehr legendenhaft, mehr sagenhaft als historisch vom alten Asien zu uns herübertönt. Nicht dadurch lernen wit die Entwickelung der Menschen auf der Erde kennen, daß wir das Äußere vor allen Dingen ins Auge fassen, daß wir die äußeren Dokumente prüfen, sondern daß wir die Entwickelung dessen, was im Inneren des Menschen lebt, ins Auge fassen, daß wir ins Auge fassen, wie so etwas wie das Erinnerungsvermögen, die Erinnerungsfähigkeit sich von außen nach dem Inneren entwickelt hat.

Sie wissen ja alle, was diese Erinnerungsfähigkeit für den heutigen Menschen bedeutet. Sie werden schon gehört haben von Menschen, die plötzlich in krankhafter Weise irgendeinen Teil ihres Lebens, an den sie sich erinnern sollten, ausgelöscht haben. Jemand, mit dem ich befreundet war, hat vor seinem Tode ein furchtbares Schicksal dadurch erfahren, daß es ihm passierte, daß er eines Tages sich aus seinem Heim entfernte, sich auf der Bahnstation ein Billett kaufte bis zu einem bestimmten Punkt, dann ausstieg, sich wieder eins kaufte; das alles, indem die Erinnerung an sein Leben bis zum Kaufen dieses Billetts momentan in ihm ausgelöscht war. Er tat alles klug, der Verstand war ganz intakt; das Gedächtnis war ausgelöscht. Und er fand sich dann wiederum, indem das Gedächtnis wieder anknüpfte an früher, in einem Obdachlosenasyl in Berlin, in welchem er sich eingefunden hatte. Man konnte nachher konstatieren, daß er in der Zwischenzeit in halb Europa herumgereist ist, ohne daß er dieses Erlebnis verbinden konnte mit seinen früheren Erlebnissen. Das Gedächtnis dämmerte erst wieder auf, nachdem er auf ihm ganz unbekannte Weise in dieses Berliner Asyl für Obdachlose gekommen ist. Das ist nur ein Beispiel für zahlreiche Fälle, die uns im Leben ja entgegentreten, wo wir sehen, wie das seelische Leben des modernen Menschen eben einfach nicht intakt ist, wenn nicht der Erinnerungsfaden bis zu einem gewissen Zeitpunkt nach unserer Geburt unabgerissen ist.

Das war bei denjenigen Menschen, bei denen die lokalisierte Erinnerung ausgebildet war, nicht der Fall. Die kannten überhaupt diesen Erinnerungsfaden nicht. Aber sie wären unglücklich in ihrem Seelenleben gewesen, sie wären so geworden, wie wir werden, wenn etwas in uns das Selbst auslöscht, wenn sie nicht überall auf ihrem Boden umgeben gewesen wären von Denkzeichen, die sie an das erinnerten, was sie selbst erlebt haben, von Denkzeichen, die sie selber überall errichtet hatten, aber auch von Denkzeichen, die ihre Väter, ihre Schwestern, Brüder und so weiter errichtet hatten, die in ihrer Konfiguration ähnlich schauten ihren eigenen Denkzeichen, und die sie daher zu Verwandtem hinbrachten. Aber dasjenige, was wir innerlich als die Bedingung unseres intakten Selbstes empfinden, das war für diese Menschen ein Äußerliches.

Nur dadurch, daß wir diesen Seelenwandel in der Menschheit vor unserer Seele vorüberziehen lassen, kommen wir auf die ganze Bedeutung dieses Seelenwandels in der historischen Entwickelung der Menschheit. Dadurch, daß man so etwas betrachtet, bekommt die Geschichte erst ihr Licht. Und ich wollte zunächst einmal an einem besonderen Beispiel aufweisen, wie die Seelengeschichte der Menschheit in bezug auf das Erinnerungsvermögen ist. Wir wollen dann in den nächsten Tagen sehen, wie sich die historischen Ereignisse in ihrer wahren Gestalt erst zeigen werden, wenn wir sie beleuchten können mit dem Lichte, das so von der menschlichen Seelenkunde her genommen ist.

First Lecture

During this evening of our Christmas gathering, I would like to give you an overview of the development of humanity on earth that can lead to a more intimate and intense awareness of the human being in the present. Particularly in the present time, when something so extraordinarily significant is in the process of being prepared, one might say for the whole of civilized humanity, it should actually be obvious to every deeper thinking person to raise the question: How has the present configuration, the present state of the human soul, emerged from a development over long periods of time? For it cannot be denied that the present becomes understandable when one tries to grasp it in its emergence from the past.

Now, however, in the present, we are extremely biased with regard to the development of man and humanity. At first, one imagines that man, in terms of his spiritual and intellectual life, has been essentially as he is now throughout all of history. Certainly, with regard to the actual scientific, one imagines that in ancient times people were childlike, believed in all kinds of fantasies, and that people have only become truly intelligent in the scientific sense in the very recent past. But if one disregards what is actually scientific, then one thinks that in general the state of mind that today's man has, the Greek, the Oriental, has also had. Even if you think of minor modifications in the soul life, on the whole you think: during historical time, everything has actually been the same as it is today. You assume that historical life runs into prehistory and say: “We don't really know about that.” But then one goes further back: Man was still in his animal form. So if one goes back in history, one imagines the soul life to be fairly unchanged, then, fading into the mists of time, the image of man in animal imperfection, something like a better ape.

That is roughly the conventional idea of today. It is based on an extraordinary prejudice, because by developing such a notion, one makes no effort to recognize the profound differences that already exist in the state of mind between the human being of the present and a relatively not so distant time, say, the 11th, 10th, 9th century AD, or how great the difference is in the state of mind between a person today and a contemporary of the Mystery of Golgotha, or even between a person today and a Greek. And if we then go back to the oriental world, of which Greek civilization was a kind of colony, a late colony, so to speak, we come upon human mental states that are totally different from the mental state of the present-day person. And I would like to show you, using examples and real cases, how the human being who lived in the Orient ten thousand or fifteen thousand years ago was very different in character from the Greeks and from ourselves.

Let us imagine our soul life in front of the soul eye. Let us take something from our own soul life. We have some kind of experience. We form an idea, a concept, a mental image of this experience, in which we are involved through our senses or otherwise through our personality. We keep this image in our thinking, and after some time it can in turn arise from our thinking into the conscious life of the soul as a memory. Today, let us say, you have some memory experience that takes you back to your perceived experiences perhaps ten years ago. And now you grasp exactly what it is. You experienced something ten years ago. Let us say that ten years ago you visited a group of people, you received an impression of each of these people, their countenance and so on. You experienced what these people said to you, what you did together with them and so on. All of this can arise in the image before you today. It is an inner soul image that is present in you from the event of perhaps ten years ago. And not only according to science, but also according to a general feeling, which is certainly experienced by people today in an extremely weak way, but which is present, one localizes such a memory image, which in turn brings up an experience, in the human head. One says to oneself: what is present in the head is there as a memory of an experience.

Now, let us take a rather large leap back in the development of humanity, and let us look at populations in the oriental regions, of whom our historically described Chinese, Indians and so on are actually only the descendants. So we are really going back thousands of years. If we consider a person from these ancient times, they did not live in such a way that they would say: I have in my head the memory of something that I have experienced in the external world. They did not have such an inner experience; it did not exist for them. They did not have thoughts or ideas filling their heads. The superficiality of the present-day human being means: Today we have ideas, concepts, images; people in historical times have always had that. But it is not like that.

If we go back far enough with spiritual insight, we encounter people who did not have ideas, concepts, or images in their heads at all. They did not experience the abstract content of their heads, but, as grotesque as it may seem to you, they experienced their whole heads, they simply felt their heads. These people did not deal with abstractions in our sense. Experiencing ideas in the head was something they did not know, but they knew what it was like to experience their own head. And just as you, when you have a memory of an experience, relate this memory to the experience, just as there is a relationship between your memory and the experience that was out there, so these people related the experience of their head to the earth, to the whole earth. And they said: There is the earth in the world, there is me in the world and on me my head. And my head, which I carry on my shoulders, that is the cosmic memory of the earth. The earth existed earlier, my head later. But that I have a head, that is the memory, the cosmic memory of the existence on earth. The earthly existence is still there, but that which is the whole configuration, the whole formation of the human head, that is in relation to the whole earth. And so such an ancient Oriental felt in his own head the essence of the earth planet itself. He said: The gods have created and generated out of the general cosmic existence the earth with its realms of nature, the earth with its rivers and mountains. But I myself carry on my shoulders my head. This head is a true reflection of the earth itself. This head, with the blood flowing in it, is a true reflection of the currents of the rivers and seas flowing over the earth. That which is the mountain configuration on the earth is repeated in my own head in the configuration of my brain. I carry on my shoulders my own image of the terrestrial planet. Just as the modern man relates his memory image to his experience, so this man related his whole head to the terrestrial planet. You see, that was a considerably different internal view of man.

And further. When man senses the circumference of the earth and includes it in his view, then this circumference, the airy that surrounds the earth, will appear to him as permeated by the sun and its warmth and light, and one can say in a certain sense that the sun lives in the air surrounding the earth. The earth opens itself to the universe by handing over the effects it sends out from itself to the airy sphere and opening itself to the effects of the sun. And in those ancient times, every person felt that region of the earth on which they happened to live was particularly important, particularly essential. And so, let us say, an ancient Oriental felt that some part of the earth's surface was his, the earth below, the sun-facing perimeter above. The earth's other, left and right and front and back, blurred in the more general (see drawing, left part).

So if, for example, an ancient Oriental living on Indian soil perceived this Indian soil as particularly important to him, then what was otherwise on the earth, east, south, and west of him, disappeared into the general. He did not care much about the way the earth borders on the rest of the cosmic spaces. On the other hand, the soil on which he was standing was particularly important to him (see drawing, left). The way the earth extended into space in this area was particularly important to him. How he was allowed to breathe on this particular soil was an especially important experience for him. Today, people do not ask themselves much: how do you breathe on a particular ground? They are, however, under the influence of more favorable or less favorable breathing conditions, but this is not consciously perceived. Such an ancient Oriental actually had a profound experience precisely in the way he was allowed to breathe, and thus in other things related to it, such as how the earth borders on space.

What the whole earth was, man felt as what lives in his head. But the head is closed off by firm bony walls at the top, on the sides and at the back. It does, however, have certain openings, a certain free opening downwards towards the chest (see diagram, right). It was of very special importance for early man to feel how the head opened with relative freedom towards the chest. This human being felt the inner configuration of the head as an image of the earthly. If he had to relate the earth to his head, he had to relate the circumference, that which is above the earth, to that which now goes to the lower part of him. Man felt this opening downwards, this turning towards the heart, as belonging to the circumference, as an image, as an opening out of the earth into the cosmos. And it was a tremendous experience for man when he said: “In my head I feel the whole earth.” This head is a small earth. But this whole earth opens out into my chest, which carries my heart. And what takes place between my head and my chest, my heart, is the image of what takes place in my life out into the cosmos, out to the sun-facing periphery. —- And it was an important, profound experience when the old man said: Here, in my head, the earth lives in me. If I go deeper, the earth turns to the sun (see arrows), and the image of the sun is my heart.

In this way, the human being had arrived at what, in ancient times, corresponded to our emotional life. We still have an abstract emotional life, but we have no direct knowledge of our hearts. Through anatomy and physiology, we believe we know something about it. But what is known there is about as much as what we know from a heart modeled in papier-mâché. But what we have as an emotional experience of the world, the ancient man did not have. He had his heart experience for that. And just as we extend our feeling to the world that lives with us, just as we feel whether we love a person, whether we encounter a person with antipathy, love this or that flower, dislike this or that, just as we relate our feeling to the world, but to a world that one might say, in airy abstraction, torn out of the solid, firm cosmos, so the ancient Oriental related his heart to the cosmos, that is, to that which went from the earth into the surrounding area, to the sun.

And we, for example, today we say when we leave: We want to leave. - We know our will lives in our limbs. The ancient Oriental, however, had a completely different experience. He did not know what we call will today. It is a mere prejudice to think that what we call thinking, feeling and willing was present in the ancient Oriental peoples. It was not at all. They had head experiences, which were the experiences of the earth, and breast or heart experiences, which were the experiences of the immediate surroundings, including the sun. The sun corresponds to the heart experience. But then they had the stretching and expanding into the limbs, the perception of one's own humanity in the movement of the legs and feet, in the movement of the arms and hands. They were in it. But in this stretching of their inner being into their limbs, they did not just perceive an image of the earth's surroundings, but they directly sensed an image of the connection between the human being and the starry heavens (see drawing on page 15). In my head I have an image of the earth. In that which extends freely downwards from the head into the chest towards the heart, I have an image of what is in the earth's orbit. In that which I feel as the strength of my arms and hands, my feet and legs, I have that which depicts the relationship of the earth to the stars far out in the universe.

So that the person who, in those ancient times, expressed his experiences, which he had as, as we would call it today, a willing human being, did not say: I go. - It was not in the words. He also did not say: I sit down. - If one would check the old languages for these fine contents, one would find everywhere that for the fact that we denote as: I go -, the old Oriental had: Mars impels me, Mars is active in me. - The forward movement, that was the feeling of the Mars impulse in the legs. The feeling of attacking something, the feeling with the hands was expressed in such a way that one said: Venus is working in me. — The action of showing something, of teaching, even if a rough person wanted to teach another person by giving him a kick, all teaching was expressed in such a way that one said that Mercury was working in the person. Sitting down was Jupiter activity in the person. And lying down, whether it was for rest or for idleness, was expressed by saying that one was giving oneself over to the impulses of Saturn. So one felt the vastness of the cosmos outside in one's limbs. Man knew: when he goes out into the world from the earth, then he comes from the earth into the vicinity, into the sphere of the stars. When he goes from his head downwards, he goes through the same in his own being. In his head he is in the earth, in his chest and heart in the surrounding area, in his limbs in the starry cosmos outside.

I would like to say, and from a certain point of view one can say it: Oh, we poor people of the present, we experience abstract thoughts. What are they? We are very proud of them, but we forget our head when we think about even the most ingenious abstract thought. And our head is much richer in content than our most ingenious thoughts. A single convolution of the brain – anatomy and physiology do not know much about the wonderful secret of the brain convolutions – is something more magnificent, more powerful than the most ingenious abstract science of any human being. – And there was once a time on earth when man was aware not only of his poor thoughts, but of his head, when he felt the head, where he felt it in its reproduction of a certain physical mountain configuration of the earth; where man did not just relate the heart to the sun out of some abstract doctrine, but where he felt: as my head is to my chest, to my heart, so is the earth in relation to the sun.

This was the time when man had grown together with the universe, with the cosmos, with his whole life. But this growing together was expressed in his whole life. It is precisely because we have thinking in place of our head that we are able to have mental memories. We form thought images of what we have experienced, as abstract memories of our head. This could not be done by someone who did not have thoughts but still felt his head. He could not form memories. Therefore, when one came to those areas of the ancient Orient where people were still aware of their heads but had no thoughts, and thus had no memories either, then one finds in special training something that we, in turn, are just beginning to need. For a long time, people did not need it, and it is actually only a small sloppiness in our mental life that we need it again. In the times of which I speak, if you came to the regions where people lived who were as aware of their head, their chest, their heart, their limbs as I have described, then you saw everywhere: there is some small peg stuck into the ground and some sign placed on it, there is some sign made on some wall. All areas and places of life were covered with such markers, for people had not yet developed mental memory. Wherever something happened, a small monument was erected, so to speak, and when one came back, one relived the event from the memory mark that one made. Man had simply grown together in his head with the earth. Today he just makes a note in his head - and as I said before, we are already starting to make notes not only in our heads, but in our notebooks and the like, but I also said that this is just a sloppiness of the soul, but we will need it more and more; but in those days it did not exist to make notes in one's head, because the thoughts, the ideas were not there; everything was covered with marks. And from this natural disposition of people, the idea of monuments arose.

Everything that has occurred in the history of the development of mankind is, after all, conditioned by the inner workings of human nature. We should just be honest and admit that the actual deeper basis of the monument-building is something that the modern human being does not even know. He builds monuments out of habit. But these monuments are the remains of those old landmarks where man did not yet have a memory like he has today, but where he had to place a landmark at the place where he had experienced something, and when he came back, to revive it in his mind, which revives everything that is somehow connected to the earth. We hand over to the earth what the head has experienced – that was the principle in ancient times.

And I would like to say: in the old Oriente we have an ancient time, the time of localized memories, when everything that was reminiscent was tied to the fact that memory markers were placed on the earth. The memory was not in it, it was outside, there were memorials and memorials everywhere. One placed memorials on the earth. That was localized memory, localized remembrance.