Anthroposophy, An Introduction

GA 234

1 February 1924, Dornach

4. 'Meditation' and 'Inspiration'

I shall now continue, in a certain direction, the more elementary considerations recently begun. In the first lecture of this series I drew your attention to the heart's real, inner need of finding, or at least seeking, the paths of the soul to the spiritual world. I spoke of this need meeting man from two directions: from the side of Nature, and from the side of inner experience.

Today we will again place these two aspects of human life before us in a quite elementary way. We shall then see that impulses from the subconscious are really active in all man's striving for knowledge in response to the needs of life, in his artistic aims and religious aspirations.

You can quite easily study the opposition, to which I here refer, in yourselves at any moment.

Take one quite simple fact. You are looking, let us say, at some part of your body—your hand, for example. In so far as the act of cognition itself is concerned you look at your hand exactly as at a crystal, or plant, or any other natural object. But when you look at this part of your body and go through life with this perception, you encounter that seriously disturbing fact which intrudes on all human experience and of which I spoke. You find that what you see will one day be a corpse; external Nature, on receiving it, has not the power to do anything else than destroy it. The moment man has become a corpse within the physical world and has been handed over to the elements in any form, there is no longer any possibility that the human form, which has been impressed on all the substances visible in his body, will be able to maintain itself.

All the forces of Nature which you can make the subject of any scientific study are only able to destroy man, never to build him up. Every unprejudiced study that is not guided by theory but controlled by life itself, leads us to say: We look at Nature around us in so far it is intelligible. (We will not speak, for the present, of what external cognition cannot grasp.) As civilised people of today we feel we have advanced very far indeed, for we have discovered so many laws of Nature. This talk of progress is, indeed, perfectly justified. Nevertheless, it is a fact that all these laws of Nature are, by their mode of operation, only able to destroy man, never to build him up. Human insight is unable, at first, to discover anything in the external world except laws of Nature which destroy man.

Let us now look at our inner life. We experience what we call our psychical life, i.e. our thinking, which can confront us fairly clearly, our feeling, which is less clearly experienced, and our willing, which is quite hidden from us. For, with ordinary consciousness, no one can claim insight into the way an intention—to pick up an object, let us say—works down into this very complicated organism of muscle and nerve in order to move, at length, arms and legs. What it is that here works down into the organism, between the formation of the thought and the perception of the lifted object, is hidden in complete darkness. But an indefinite impulse takes place in us, saying: I will this. So we ascribe will to ourselves and, on surveying our inner life, speak of thinking, feeling and willing.

But there is another side, and this introduces us again—in a certain sense—to what is deeply disturbing. We see that all this soul life of man is submerged whenever he sleeps and arises anew when he wakes. If we want to use a comparison we may well say: The soul life is like a flame which I kindle and extinguish again. But we see more. We see this soul life destroyed when certain organs are destroyed. Moreover, it is dependent on bodily development; being dreamlike in a little child and becoming gradually clearer and clearer, more and more awake. This increase in clarity and awareness goes hand in hand with the development of the body; and when we grow old our soul life becomes weaker again. The life of the soul thus keeps step with the growth and decay of the body. We see it light up and die away.

But, however sure we may be that our soul, though dependent in its manifestations on the physical organism, has its own life, its own existence, this is not all we can say about it. It contains an element man must value above all else in life, for his whole manhood—his human dignity—depends on this. I refer to the moral element.

We cannot deduce moral laws from Nature however far we may explore it. They have to be experienced entirely within the soul; there, too, we must be able to obey them. The conflict and settlement must therefore take place entirely within the soul. And we must regard it as a kind of ideal for the moral life to be able, as human beings, to obey moral principles which are not forced upon us. Yet man cannot become an ‘abstract being’ only obeying laws. The moral life does not begin until emotions, impulses, instincts, passions, outbursts of temperament, etc., are subordinated to the settlement, reached entirely within the soul, between moral laws grasped in a purely spiritual way and the soul itself.

The moment we become truly conscious of our human dignity and feel we cannot be like beings driven by necessity, we rise to a world quite different from the world of Nature.

Now the disturbing element that, as long as there has been human evolution at all, has led men to strive beyond the life immediately visible, really springs from these two laws—however many subconscious and unconscious factors may be involved: We see, on the one hand, man's bodily being, but it belongs to Nature that can only destroy it; and, on the other hand, we are inwardly aware of ourselves as soul beings who light up and fade away, yet are bound up with what is most valuable in us—the moral element.

It can only be ascribed to a fundamental insincerity of our civilisation that people deceive themselves so terribly, turning a blind eye to this direct opposition between outer perception and inner experience. If we understand ourselves, if we refuse to be confined and constricted by the shackles which our education, with a definite aim in view, imposes upon us, if we free ourselves a little from these constraints we say at once: Man! you bear within you your soul life—your thinking, feeling and willing. All this is connected with the moral world which you must value above all else—perhaps with the religious source of all existence on which this moral world itself depends. But where is this inner life of moral adjustments when you sleep?

Of course, one can spin philosophic fantasies or fantastic philosophies about these things. One may then say: Man has a secure basis in his ego (i.e. in his ordinary ego-consciousness). The ego begins to think in St. Augustine, continues through Descartes, and attains a somewhat coquettish expression in Bergsonism today. But every sleep refutes this. For, from the moment we fall asleep to the moment of waking, a certain time elapses; and when, in the waking state, we look back on this interval of time, we do not find the ego qua experience. It was extinguished. And yet it is connected with what is most valuable in our lives—the moral element!

Thus we must say: Our body, whose existence we are rudely forced to admit, is certainly not a product of Nature, which has only the power to destroy and disintegrate it. On the other hand, our own soul life eludes us when we sleep, and is dependent on every rising and falling tide of our bodily life. As soon as we free ourselves a little from the constraints imposed on civilised man by his education today, we see at once that every religious or artistic aspiration—in fact, any higher striving—no matter how many subconscious and unconscious elements be involved, depends, throughout all human evolution, on these antitheses.

Of course, millions and millions of people do not realise this clearly. But is it necessary that what becomes a riddle of life for a man be clearly recognised as such? If people had to live by what they are clear about they would soon die. It is really the contributions to the general mood from unclear, subconscious depths that compose the main stream of our life. We should not say that he alone feels the riddles of life who can formulate them in an intellectually clear way and lay them before us: first riddle, second riddle, etc. Indeed, such people are the shallowest.

Someone may come who has this or that to talk over with us. Perhaps it is some quite ordinary matter. He speaks with a definite aim in view, but is not quite happy about it. He wants something, and yet does not want it; he cannot come to a decision. He is not quite happy about his own thoughts. To what is this due? It comes from the feeling of uncertainty, in the subconscious depths of his being, about the real basis of man's true being and worth. He feels life's riddles because of the polar antithesis I have described.

Thus we can find support neither in the corporeal, nor in the spiritual as we experience it. For the spiritual always reveals itself as something that lights up and dies down, and the body is recognised as coming from Nature which can, however, only destroy it.

So man stands between two riddles. He looks outwards and perceives his physical body, but this is a perpetual riddle to him. He is aware of his psycho-spiritual life, but this, too, is a perpetual riddle. But the greatest riddle is this: If I really experience a moral impulse and have to set my legs in motion to do something towards its realisation, it means—of course—I must move my body. Let us say the impulse is one of goodwill. At first this is really experienced entirely within the soul, i.e. purely psychically. How, now, does this impulse of goodwill shoot down into the body? How does a moral impulse come to move bones by muscles? Ordinary consciousness cannot comprehend this. One may regard such a discussion as theoretical, and say: We leave that to philosophers; they will think about it. Our civilisation usually leaves this question to its thinkers, and then despises—or, at least, values but little—what they say. Well; this satisfies the head only, not the heart. The human heart feels a nervous unrest and finds no joy in life, no firm foundation, no security. With the form man's thinking has taken since the first third of the fifteenth century magnificent results in the domain of external science have been achieved, but nothing has or can be contributed towards a solution of these two riddles—that of man's physical body and that of his psychical life. It is just from a clear insight into these things that Anthroposophy comes forward, saying: True; man's thinking, in the form it has so far actually taken, is powerless in the face of Reality. However much we think, we cannot in the very least influence an external process of nature by our thinking.

Moreover, we cannot, by mere thinking, influence our own ‘will-organism’. To feel deeply the powerlessness of this thinking is to receive the impulse to transcend it.

But one cannot transcend it by spinning fantasies. There is no starting point but thought; you cannot begin to think about the world except by thinking. Our thinking, however, is not fitted for this. So we are unavoidably led by life itself to find—from this starting point in thought—a way by which our thinking may penetrate more deeply into existence—into Reality. This way is only to be found in what is described as meditation—for example, in my book: Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment.

Today we will only describe this path in bare outline, for we intend to give the skeleton of a whole anthroposophical structure. We will begin again where we began twenty years ago.

Meditation, we may say, consists in experiencing thinking in another way than usual. Today one allows oneself to be stimulated from without; one surrenders to external reality. And in seeing, hearing, grasping, etc., one notices that the reception of external impressions is continued—to a certain extent—in thoughts. One's attitude is passive—one surrenders to the world and the thoughts come. We never get further in this way. We must begin to experience thinking. One does this by taking a thought that is easily comprehended, letting it stay in one's consciousness, and concentrating one's whole consciousness upon it.

Now it does not matter at all what the thought may signify for the external world. The point is simply that we concentrate our consciousness on this one thought, ignoring every other experience. I say it must be a comprehensible thought—a simple thought, that can be ‘seen’ from all sides [überschaubar]. A very, very learned man once asked me how one meditates. I gave him an exceedingly simple thought. I told him it did not matter whether the thought referred to any external reality. I told him to think: Wisdom is in the light. He was to apply the whole force of his soul again and again to the thought: Wisdom is in the light. Whether this be true or false is not the point. It matters just as little whether an object that I set in motion, again and again, by exerting my arm, be of far-reaching importance or a game; I strengthen the muscles of my arm thereby. So, too, we strengthen our thinking when we exert ourselves, again and again, to per-form the above activity, irrespective of what the thought may signify. If we strenuously endeavour, again and again, to make it present in our consciousness and concentrate our whole soul life upon it, we strengthen our soul life just as we strengthen the muscular force of our arm if we apply it again and again to the same action. But we must choose a thought that is easily surveyed; otherwise we are exposed to all possible tricks of our own organisation. People do not believe how strong is the suggestive power of unconscious echoes of past experiences and the like. The moment we entertain a more complicated thought demonic powers approach from all sides, suggesting this or that to our consciousness. One can only be sure that one is living in one's meditation in the full awareness of normal, conscious life, if one really takes a completely surveyable thought that can contain nothing but what one is actually thinking.

If we contrive to meditate in this way, all manner of people may say we are succumbing to auto-suggestion or the like, but they will be talking nonsense. It all turns on our success in holding a ‘transparent’ thought—not one that works in us through sub-conscious impulses in some way or other. By such concentration one strengthens and intensifies his soul life—in so far as this is a life in thought. Of course, it will depend on a man's capacities, as I have often said; in the case of one man it will take a long time, in the case of another it will happen quickly. But, after a certain time, the result will be that he no longer experiences his thinking as in ordinary consciousness. In ordinary consciousness our thoughts stand there powerless; they are ‘just thoughts’. But through such concentration one really comes to experience thoughts as inner being [Sein], just as one experiences the tension of a muscle—the act of reaching out to grasp an object. Thinking becomes a reality in us; we experience, on developing ourselves further and further, a second man within us of whom we knew nothing before.

The moment now arrives when you say to yourself: True, I am this human being who, to begin with, can look at himself externally as one looks at the things of nature; I feel inwardly, but very dimly, the tensions of my muscles, but I do not really know how my thoughts shoot down into them. But after strengthening your thinking in the way described, you feel your strengthened thinking flowing, streaming, pulsating within you; you feel the second man. This is, to begin with, an abstract characterisation. The main thing is that the moment you feel this second man within you, supra-terrestrial things begin to concern you in the way only terrestrial things did before. In this moment, when you feel your thought take on inner life—when you feel its flow as you feel the flow of your breath when you pay heed to it—you become aware of something new in your whole being. Formerly you felt for example: I am standing on my legs. The ground is below and supports me. If it were not there, if the earth did not offer me this support, I would sink into bottomless space. I am standing on something. After you have intensified your thinking and come to feel the second man within, your earthly environment begins to interest you less than before. This only holds, however, for the moments in which you give special attention to the second man. One does not become a dreamer if one advances to these stages of knowledge in a sincere and fully conscious way. One can quite easily return, with all one's wonted skill, to the world of ordinary life. One does not become a visionary and say: Oh! I have learnt to know the spiritual world; the earthly is unreal and of less value. From now on I shall only concern myself with the spiritual world. On a true, spiritual path one does not become like that, but learns to value external life more than ever when one returns to it. Apart from this, the moments in which one transcends external life in the way described and fixes attention on the second man one has discovered cannot be maintained for long. To fix one's attention in this way and with inner sincerity demands great effort, and this can only be sustained for a certain time which is usually not very long.

Now, in turning our attention to the second man, we find at the same time, that we begin to value the spatial environment of the earth as much as what is on the earth itself. We know that the crust of the earth supports us, and the various kingdoms of Nature provide the substances we must eat if our body is to receive through food the repeated stimulus it needs. We know that we are connected with terrestrial Nature in this way. We must go into the garden to pick cabbages, cook and eat them; and we know that we need what is out there in the garden and that it is connected with our ‘first’ or physical man. In just the same way we learn to know what the rays of the sun, the light of the moon and the twinkling of the stars around the earth are to us. Gradually we attain one possible way of thinking of the spatial environment of the earth in relation to our ‘second man’, as we formerly thought of our first (physical) body in relation to its physical environment.

And now we say to ourselves: What you bear within you as muscles, bones, lung, liver, etc., is connected with the cabbage, the pheasant, etc., out there in the world. But the ‘second man’ of whom you have become conscious through strengthening your thinking, is connected with the sun and the moon and all the twinkling stars—with the spatial environment of the earth. We become more familiar with this environment than we usually are with our terrestrial environment—unless we happen to be food-specialists. We really gain a second world which, to begin with, is spatial.

We learn to esteem ourselves inhabitants of the world of stars as we formerly considered ourselves inhabitants of the earth. Hitherto we did not realise that we dwell in the world of stars; for a science which does not go as far to strengthen man's thinking cannot make him conscious of his connection, through a second man, with the spatial environment of the earth—a connection similar to that between his physical body and the physical earth. Such a science does not know this. It engages in calculations; but even the calculations of Astrophysics, etc., only reveal things which do not really concern man at all, or—at most—only satisfy his curiosity. After all, what does it mean to a man, or his inner life, to know how the spiral nebular in Canes venatici may be thought of as having originated, or as still evolving? Moreover, it is not even true! Such things do not really concern us. Man's attitude towards the world of stars is like that of some disembodied spirit towards the earth—if such a spirit be thought of as coming from some region or other to visit the earth, requiring neither ground to stand on, nor nourishment, etc. But, in actual fact, from a mere citizen of the earth man becomes a citizen of the universe when he strengthens his thinking in the above way.

We now become conscious of something quite definite, which can be described in the following way. We say to ourselves: It is good that there are cabbages, corn, etc., out there; they build up our physical body (if I may use this somewhat incorrect expression in accordance with the general, but very superficial, view). I am able to discover a certain connection between my physical body and what is there outside in the various kingdoms of Nature. But with strengthened thinking I begin to discover a similar connection between the ‘second man’ who lives in me and what surrounds me in supra-terrestrial space. At length one comes to say: If I go out at night and only use my ordinary eyes, I see nothing; by day the sunlight from beyond the earth makes all objects visible. To begin with, I know nothing. If I restrict myself to the earth alone, I know: there is a cabbage, there a quartz crystal. I see both by the light of the sun, but on earth I am only interested in the difference between them.

But now I begin to know that I myself, as the second man, am made of that which makes cabbage and crystal visible. It is a most significant leap in consciousness that one takes here—a complete metamorphosis. From this point one says to oneself: If you stand on the earth you see what is physical and connected with your physical man. If you strengthen your thinking the supra-terrestrial spatial world begins to concern you and the second man you have discovered just as the earthly, physical world concerned you before. And, as you ascribe the origin of your physical body to the physical earth, you now ascribe your ‘second existence’ to the cosmic ether through whose activities earthly things become visible. From your own experience you can now speak of having a physical body and an etheric body. You see, merely to systematise and think of man as composed of various members gives no real knowledge. We only attain real insight into these things by regarding the complete metamorphosis of consciousness that results from really discovering such a second man within.

I stretch out my physical arm and my physical hand takes hold of an object. I feel, in a sense, the flowing force in this action. Through strengthening my thought I come to feel that it is inwardly mobile and now induces a kind of ‘touching’ within me—a touching that also takes place in an organism; this is the etheric organism; that finer, super-sensible organism which exists no less than the physical organism, though it is connected with the supra-terrestrial, not the terrestrial.

The moment now arrives when one is obliged to descend another step, if I may put it so. Through such ‘imaginative’ thinking as I have described we come, at first, to feel this inward touching of the second man within us; we come, too, to see this in connection with the far spaces of the universal ether. By this term you are to understand nothing but what I have just spoken of; do not read into it a meaning from some other quarter. Now, however, we must return again to ordinary consciousness if we are to get further.

You see, if we are thinking of man's physical body in the way described, we readily ask how it is really related to its environment. It is doubtless related to our physical, terrestrial environment; but how?

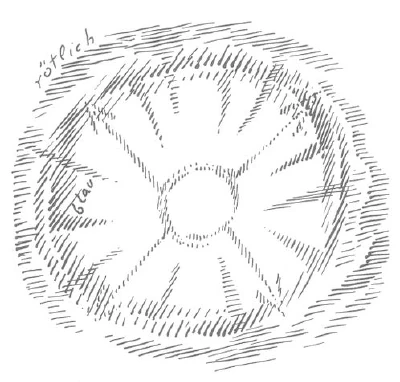

If we take a corpse, which is, indeed, a faithful representation of physical man—even of the living physical man—we see, in sharp contours, liver, spleen, kidney, heart, lung, bones, muscles and nerve strands. These can be drawn; they have sharp contours and resemble in this everything that occurs in solid forms. Yet there is a curious thing about this sharply outlined part of the human organism. Strictly speaking, there is nothing more deceptive than our handbooks of anatomy or physiology, for they lead people to think: there is a liver, there a heart, etc. They see all this in sharp contours and imagine this sharpness to be essential. The human organism is looked upon as a conglomeration of solid things. But it is not so at all. Ten per cent., at most, is solid; the other ninety per cent. is fluid or even gaseous. At least ninety per cent. of man, while he lives, is a column of water.

Thus we can say: In his physical body man belongs, it is true, to the solid earth—to what the ancient thinkers in particular called the ‘earth’. Then we come to what is fluid in man; and even in external science one will never gain a reasonable idea of man until one learns to distinguish the solid man from the fluid man this inner surging and weaving element which really resembles a small ocean.

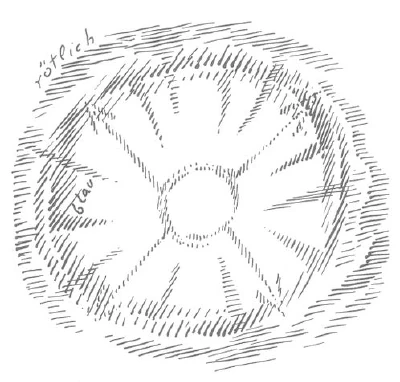

But what is terrestrial can only really affect man through the solid part of him. For even in external Nature you can see, where the fluid element begins, an inner formative force working with very great uniformity. Take the whole fluid element of our earth—its water; it is a great drop. Wherever water is free to take its own form, it takes that of a drop. The fluid element tends everywhere to be drop-like.

What is earthly—or solid, as we say today—occurs in definite, individual forms, which we can recognise. What is fluid, however, tends always to take on spherical form.

Why is this? Well, if you study a drop, be it small or as large as the earth itself, you find it is an image of the whole universe. Of course, this is wrong according to the ordinary conceptions of today; nevertheless it appears so, to begin with, and we shall soon see that this appearance is justified. The universe really appears to us as a hollow sphere into which we look.

Every drop, whether small or large, appears as a reflection of the universe itself. Whether you take a drop of rain, or the waters of the earth as a whole, the surface gives you a picture of the universe. Thus, as soon as you come to what is fluid, you cannot explain it by earthly forces. If you study closely the enormous efforts that have been made to explain the spherical form of the oceans by terrestrial forces, you will realise how vain such efforts are. The spherical form of the oceans cannot be explained by terrestrial gravitational attraction and the like, but by pressure from without. Here, even in external Nature, we find we must look beyond the terrestrial. And, in doing this, we come to grasp how it is with man himself.

As long as you restrict yourself to the solid part of man, you need not look beyond the terrestrial in understanding his form. The moment you come to his fluid part, you require the second man discovered by strengthened thinking. He works in what is fluid.

We are now back again at what is terrestrial. We find in man a solid constituent; this we can explain with our ordinary thoughts. But we cannot understand the form of his fluid components unless we think of the second man as active within him—the second man whom we contact within ourselves in our strengthened thinking as the human etheric body.

Thus we can say: The physical man works in what is solid, the etheric man in what is fluid. Of course, the etheric man still remains an independent entity, but he works through the fluid medium.

We must now proceed further. Imagine we have actually got so far as to experience inwardly this strengthened thinking and, therefore, the etheric—the second—man. This means, that we are developing great inner force. Now, as you know, one can—with a little effort—not only let oneself be stimulated to think, but can even refrain from all thinking. One can stop thinking; and our physical organisation does this for us when we are tired and fall asleep. But it becomes more difficult to extinguish again, of our own accord, the strengthened thinking which results from meditation and which we have acquired by great effort. It is comparatively easy to extinguish an ordinary, powerless thought; to put away—or ‘suggest away’—the strengthened thinking one has developed demands a stronger force, for one cleaves in a more inward way to what one has thus acquired. If we succeed, however, something special occurs.

You see, our ordinary thinking is stimulated by our environment, or memories of our environment. When you follow a train of thought the world is still there; when you fall asleep the world is still there. But it is out of this very world of visible things that you have raised yourself in your strengthened thinking. You have contacted the supra-terrestrial spatial environment, and now study your relationship to the stars as you formerly studied the relation between the natural objects around you. You have now brought yourself into relation with all this, but can suppress it again. In suppressing it, however, the external world, too, is no longer there—for you have just directed all your interest to this strengthened consciousness. The outer world is not there; and you come to what one can call ‘empty consciousness’. Ordinary consciousness only knows emptiness in sleep, and then in the form of unconsciousness.

What one now attains is just this: one remains fully awake, receiving no outer sense impressions, yet not sleeping—merely ‘waking’. Yet one does not remain merely awake. For now, on exposing one's empty consciousness to the indefinite on all sides, the spiritual world proper enters. One says: the spiritual world approaches me. Whereas previously one only looked out into the supra-terrestrial physical environment—which is really an etheric environment—and saw what is spatial, something new, the actual spiritual world, now approaches through this cosmic space from all sides as from indefinite distances. At first the spiritual approaches you from the outermost part of the cosmos when you traverse the path I have described.

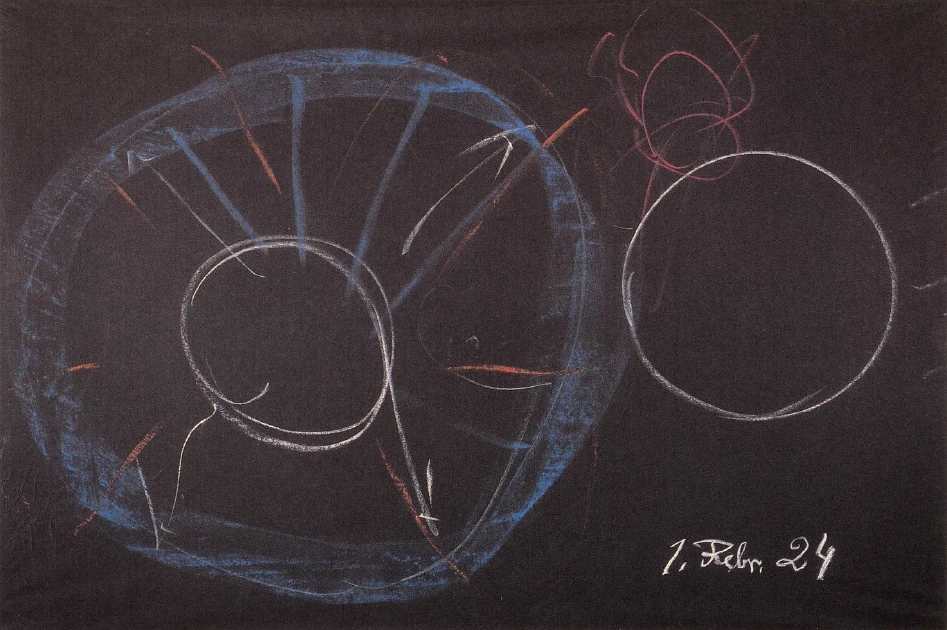

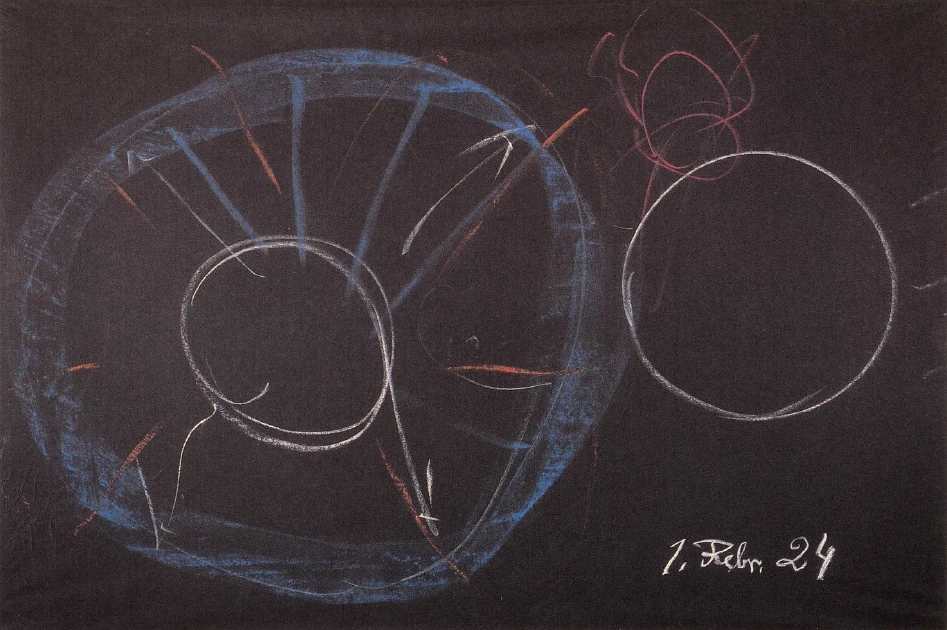

A third thing is now added to the former metamorphosis of consciousness. One now says: I bear with me my physical body (inner circle), my etheric body (blue) which I apprehended in my strengthened thinking, and something more that comes from the undefined—from beyond space. I ask you to notice that I am talking of the world of appearance; we shall see in the course of the next few days how far one is justified in speaking of the etheric as coming from the spatial world, and of what lies beyond us (red) coming from the Undefined. We are no longer conscious of this third component as coming from the spatial world. It streams to us through the cosmic ether and permeates us as a ‘third man’. We have now a right to speak, from our own experience, of a first or physical man, a second or etheric man, and a third or ‘astral man’. (You realise, of course, that you must not be put off by words.) We bear within us an astral or third man, who comes from the spiritual, not merely from the etheric. We can speak of the astral body or astral man.

Now we can go further. I will only indicate this in conclusion so that I can elaborate it tomorrow. We now say to ourselves: I breathe in, use my breath for my inner organisation and breathe out. But is it really true that what people think of as a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen enters and leaves us in breathing?

Well, according to the views of present day civilisation, what enters and leaves is composed of oxygen and nitrogen and some other things. But one who attains ‘empty consciousness’ and then experiences this onrush—as I might call it—of the spiritual through the ether, experiences in the breath he draws something not formed out of the ether alone, but out of the spiritual beyond it. He gradually learns to know the spiritual that plays into man in respiration. He learns to say to himself: You have a physical body; this works into what is solid—that is its medium. You have your etheric body; this works into what is fluid. But, in being a man—not merely a solid man or fluid man, but a man who bears his ‘air man’ within him—your third or astral man can work into what is airy or gaseous. It is through this material substance on the earth that your astral man operates.

Man's fluid organisation with its regular but ever changing life will never be grasped by ordinary thinking. It can only be grasped by strengthened thinking. With ordinary thinking we can only apprehend the definite contours of the physical man. And, since our anatomy and physiology merely take account of the body, they only describe ten per cent of man. But the ‘fluid man’ is in constant movement and never presents a fixed contour. At one moment it is like this, at another, like that—now long, now short. What is in constant movement cannot be grasped with the closed concepts suitable for calculations; you require concepts mobile in themselves—‘pictures’. The etheric man within the fluid man is apprehended in pictures.

The third or astral man who works in the ‘airy’ man, is apprehended not merely in pictures but in yet another way. If you advance further and further in meditation—I am here describing the Western process—you notice, after reaching a certain stage in your exercises, that your breath has become something palpably musical. You experience it as inner music; you feel as if inner music were weaving and surging through you. The third man—who is physically the airy man, spiritually the astral man—is experienced as an inner musical element. In this way you take hold of your breathing.

The oriental meditator did this directly by concentrating on his breathing, making it irregular in order to experience how it lives and weaves in man. He strove to take hold of this third man directly.

Thus we discover the nature of the third man, and are now at the stage when we can say: By deepening and strengthening our insight we learn, at first, to distinguish in man:

the physical body which lives in solid forms on the earth and is also connected with the terrestrial kingdoms,

the fluid man in whom an ever mobile, etheric element lives and which can only be apprehended in images (Bilder)—in moving, plastic images,

the astral man who has his physical copy or image (Abbild) in all that constitutes the stream of inspired air.

This stream enters and takes hold of our inner organisation, expands, works, is transformed and streams out again. That is a wonderful process of becoming. We cannot draw it; we might do so symbolically, at most, but not as it really is. You could no more draw this process than you could draw the tones of a violin. You might do this symbolically; nevertheless you must direct your musical sense to hearing inwardly—i.e. you must attend with your inner, musical ear and not merely listen to the external tones. In this inward way you must hear the weaving of your breath—must hear the human astral body. This is the third man. We apprehend him when we attain to ‘empty consciousness’ and allow this to be filled with ‘inspirations’ from without.

Now language is really cleverer than men, for it comes to us from primeval worlds. There is a deep reason why breathing was once called inspiration. In general, the words of our language say much more than we, in our abstract consciousness, feel them to contain.

These are the considerations that can lead us to the three members of man—the physical, the etheric and the astral bodies—which find expression in the solid, fluid and airy ‘men’ and have their physical counterparts in the forms of the solid man, in the changing shapes of the fluid man and in that which permeates man as an inner music, experienced through feeling. The nervous system is indeed the most beautiful representation of this inner music. It is built from out of the astral body—from out of this inner music; and for this reason it has, at a definite part, the wonderful configuration of the spinal cord with its attached nerve-strands. All this together is a wonderful, musical structure that is continually working upwards into man's head.

A primeval wisdom that was still alive in Ancient Greece, felt the presence of this wonderful instrument in man. For the air assimilated through breathing ascends through the whole spinal cord. The air we breathe in ‘enters’ the cerebro-spinal canal and pulsates upwards towards the brain. This music is actually per-formed, but it remains unconscious; only the upper rebound is in consciousness. This is the lyre of Apollo, the inner musical instrument that the instinctive, primeval wisdom still recognised in man. I have referred to these things before, but it is my present intention to give a resume of what has been developed within our society in the course of twenty-one years.

Tomorrow I shall go further and consider the fourth member of man, the ego organisation proper. I shall then show the connection between these various members of man and his life on earth and beyond it—i.e. his so-called eternal life.

Vierter Vortrag

Ich werde nun in den mehr elementarischen Betrachtungen, die ich in der letzten Zeit begonnen habe, heute nach einer gewissen Richtung hin fortfahren. Ich habe in dem ersten Vortrage dieser Serie darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie von zwei Seiten her dem Menschen das wirklich innerliche Herzensbedürfnis erwächst, die Wege der Seele zur geistigen Welt hin zu finden, oder wenigstens zu suchen. Die eine Seite ist diejenige, die von der Natur her kommt, die andere Seite ist diejenige, die von der inneren Erfahrung, von den inneren Erlebnissen her kommt.

Nun wollen wir uns heute doch noch einmal in ganz elementarer Weise diese beiden Seiten des menschlichen Lebens vor Augen stellen, um dann zu sehen, wie tatsächlich im Unterbewußten Impulse wirken, die von da aus den Menschen in alles hineintreiben, was er an Erkenntnis anstrebt aus den Bedürfnissen seines Lebens heraus, was er an Künstlerischem anstrebt, was er an Religiösem anstrebt und so weiter. Ich möchte sagen, Sie können ganz einfach den Gegensatz, den ich hier meine, an sich selbst in jedem Augenblicke betrachten.

Nehmen Sie eine ganz einfache Tatsache: Sie sehen sich selber in irgendeinem Teil Ihres Körpers einmal an. Sie sehen Ihre Hand an. Sie sehen Ihre Hand genau ebenso an, was zunächst das Anschauen, die Erkenntnis betrifft, wie Sie irgendeinen Kristall, irgendeine Pflanze, irgend etwas in der Natur anschauen.

Indem Sie diesen Teil Ihres physischen Menschen sehen und mit der Anschauung durch das Leben gehen, finden Sie eben jenes, ich möchte sagen, in das ganze menschliche Erleben tragisch Eingreifende, von dem ich gesprochen habe. Sie finden, das, was Sie da sehen, wird einmal Leichnam, wird zu etwas, von dem man sagen muß: Nimmt die äußere Natur es auf, so hat diese äußere Natur eben nicht die Fähigkeit, nicht die Macht, etwas anderes zu tun damit, als es zu zerstören. In dem Augenblicke, wo der Mensch innerhalb der physischen Welt Leichnam geworden ist und in irgendeiner Form dieser Leichnam den Elementen übergeben wird, ist keine Rede mehr davon, daß die menschliche Gestalt in all das Substantielle, das Sie anschauen können an sich selbst, hineingegossen ist, das diese menschliche Gestalt erhalten kann.

Nehmen Sie alle Naturkräfte zusammen, die Sie zum Inhalte irgendwelcher äußeren Wissenschaft machen können, alle diese Naturkräfte sind einzig und allein imstande, den Menschen zu zerstören, aufzubauen niemals. Jede vorurteilsfreie Betrachtung, die nicht aus der Theorie heraus, sondern aus den Erfahrungen des Lebens heraus geholt ist, führt dazu, sich zu sagen: Wir schauen um uns herum die Natur, die wir begreifen — wir wollen jetzt nicht von dem reden, was zunächst durch äußeres Erkennen nicht zu begreifen ist -, wir schauen die Natur, insofern sie zu begreifen ist. Ja, wir sind als Menschheit in der neueren Zeit so stolz darauf geworden, das, was wir durch unsere Einsicht in die Natur erhalten, als die Summe der Naturgesetze anzusehen; wir fühlen uns ungemein vorgeschritten, indem wir so und so viele Naturgesetze kennengelernt haben. Das Reden über den Fortschritt ist sogar durchaus berechtigt. Aber es ist doch einmal so, daß alle diese Naturgesetze in ihrer Wirkungsweise nur die eine Möglichkeit haben, den Menschen zu zerstören, ihn niemals zu bilden. Die menschliche Einsicht gibt ja zunächst keine Möglichkeit, etwas anderes durch das Hinausschauen in die Welt zu erhalten als diese den Menschen zerstörenden Naturgesetze.

Nun blicken wir in unser Inneres. Wir erleben, was wir unser Seelenleben nennen: unser Denken, das ja mit einer ziemlichen Klarheit vor unserer Seele stehen kann; wir erleben unser Fühlen, das schon weniger klar vor unserer Seele steht, und unser Wollen; nun, das steht mit voller Unklarheit vor der Seele. Denn zunächst kann kein Mensch mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein davon sprechen, daß er eine Einsicht darin hat, wie irgendeine Absicht, einen Gegenstand zu ergreifen, hinunterwirkt in diesen ganzen komplizierten Organismus von Muskeln und Nerven, um Arme und Beine zuletzt zu bewegen. Dasjenige, was da hineinarbeitet in unseren Organismus, vom Gedanken ausgehend bis zu dem Augenblick, wo wir wieder den Gegenstand gehoben sehen, ist in völliges Dunkel gehüllt. Aber es wirkt ein unbestimmter Impuls in uns zurück, herauf, der uns sagt: Ich will das. -— Dadurch schreiben wir uns auch das Wollen zu. Und so sagen wir von unserem Seelenleben, wenn wir in uns hineinschauen: Nun Ja, wir tragen in uns ein Denken, ein Fühlen, ein Wollen.

Aber nun kommt die andere Seite, die schon in einer gewissen Beziehung wiederum ins Tragische hineinführt. Wir sehen, daß mit jedem Schlafe dieses ganze Seelenleben des Menschen versinkt und jedesmal beim Aufwachen neu entsteht. So daß, wenn wir einen Vergleich gebrauchen wollen, wir sehr gut sagen können, dieses Seelenleben ist so wie eine Flamme, die ich anzünde und dann wieder auslösche.

Aber wir sehen mehr. Wir sehen, daß mit gewissen Zerstörungen in unserem Organismus dieses Seelenleben mit zerstört wird. Wir sehen außerdem dieses Seelenleben abhängig von der körperlichen Entwickelung dieses Organismus. Im kleinen Kinde ist es traumhaft vorhanden. Es wird allmählich heller und heller. Aber dieses Hellerwerden hängt ja ganz mit der Entwickelung des körperlichen Organismus zusammen. Und wenn man alt wird, wird es wiederum schwächer. Das Seelenleben hängt mit der Entwickelung und mit der Dekadenz des Organismus zusammen. Wir sehen also, wie das aufflammt, abglimmt.

So gewiß wir auch wissen: Das, was wir da als seelisches Leben haben, hat ganz gewiß ein Eigenleben, ein Eigendasein, aber es ist abhängig in seinen Erscheinungen von dem physischen Organismus, so ist das doch nicht alles, was wir über dieses Seelenleben sagen können. Sondern dieses Seelenleben hat einen Einschlag, der vor allen Dingen dem Menschen wertvoll sein muß im Leben, denn von diesem Einschlag hängt eigentlich sein ganzes Menschentum, seine menschliche Würde ab. Das ist der moralische Einschlag.

Wir können noch so weit in der Natur herumgehen, moralische Gesetze können wir aus der Natur nicht gewinnen. Die moralischen Gesetze müssen ganz innerhalb des Seelischen erlebt werden. Aber sie müssen auch innerhalb des Seelischen befolgt werden können. Es muß also eine Auseinandersetzung bloß im Inneren des Seelischen sein. Und wir müssen es ansehen als eine Art Ideal des Moralischen, daß wir als Menschen auch Moralprinzipien folgen können, die uns nicht aufgedrängt sind. Solange wir sagen müssen: Das, was uns unsere Triebe, Instinkte, Leidenschaften, Emotionen und so weiter aufdrängen, ist in uns — gut, es muß der Mensch dies oder jenes verrichten; der Mensch kann nicht ein abstraktes Wesen werden, das bloß moralischen Gesetzen folgt. Aber das Moralische beginnt eben doch erst dann, wenn diese Emotionen, Triebe, Instinkte, Leidenschaften, Temperamentsausbrüche und so weiter unter die Herrschaft dessen gebracht werden, was einer rein seelischen Auseinandersetzung mit den rein geistig erfaßten moralischen Gesetzen entspricht.

In dem Augenblicke, wo wir uns unserer menschlichen Würde recht bewußt werden und fühlen, daß wir nicht sein können wie ein Wesen, das nur von der Notwendigkeit getrieben wird, da erheben wir uns tatsächlich in eine Welt, die eine ganz andere ist als die natürliche Welt.

Und was nun das Beunruhigende ist, was, solange eine menschliche Entwickelung besteht, immer dazu geführt hat, über das unmittelbar sichtbare Leben hinauszustreben, das rührt eigentlich — so sehr dabei unterbewußte und unbewußte Momente mitspielen — von diesen Gesetzen her, daß wir uns auf der einen Seite anschauen als körperliches Wesen, aber dieses körperliche Wesen angehörig sehen einer Natur, die es nur zerstören kann; daß wir auf der anderen Seite uns innerlich erfahren als ein seelisches Wesen; dieses seelische Wesen aber, das glimmt auf, das glimmt ab, und ist doch mit unserem Wertvollsten verbunden, mit dem moralischen Einschlag.

Und es ist nur einer ganz tiefen Unehrlichkeit unserer Zivilisation zuzuschreiben, wenn die Menschen sich in einer furchtbaren Illusion einfach über das hinwegsetzen, was in diesem polarischen Gegensatze zwischen dem Anschauen des Äußeren und dem Erfahren des Inneren besteht. Erfaßt man sich, ohne eingeengt zu sein in jene Fäden, in jene Maschen, in die wir hineingezwängt werden heute durch unsere Erziehung, dadurch, daß diese Erziehung nach einem ganz bestimmten Ziele hin tendiert — hebt man sich ein wenig über dieses Eingezwängtsein hinaus, dann kommt man doch gleich dazu, sich zu sagen: Du, Mensch, du trägst in dir dein Seelenleben, dein Denken, dein Fühlen, dein Wollen. Das hängt zusammen mit der Welt, die dir vor allen Dingen wertvoll sein muß, mit der moralischen Welt, vielleicht mit dem, womit diese moralische Welt wieder zusammenhängt, mit dem religiösen Quell alles Seins. Aber das, was du als Seelenleben, als diese innerliche Auseinandersetzung hast, wo ist es denn, während du schläfst?

Man kann natürlich über diese Dinge philosophisch phantasieren oder phantastisch philosophieren. Dann kann man sagen: Der Mensch hat in seinem Ich, das heißt in dem gewöhnlichen Ich-Bewußtsein, eine sichere Grundlage — das beginnt bei dem heiligen Augustinus so zu denken, das setzt sich fort über Cartesius, das gewinnt einen etwas koketten Ausdruck im Bergsonianismus der Gegenwart -, aber jeder Schlaf widerlegt das. Denn von dem Augenblicke, wo wir einschlafen, bis zu dem Augenblicke, wo wir aufwachen, verfließt eine Zeit für uns. Wenn wir auf sie zurückschauen im wachen Zustande, so ist das Ich eben nicht da als Erlebnis innerhalb dieser Zeit. Es ist ausgelöscht. Und was da ausgelöscht ist, hängt mit dem Wertvollsten, mit dem moralischen Einschlag in unserem Leben zusammen.

So daß wir sagen müssen: Dasjenige, wovon wir in brutaler Weise überzeugt sind, daß es da ist, unser Leib, der ist ganz gewiß aus der Natur heraus entstanden. Aber die Natur hat nur die Macht, ihn zu zerstören, auseinanderzustieben. Dasjenige, was wir auf der anderen Seite erfahren, unser eigenes Seelenleben, das entschlüpft uns in jedem Schlafe; das ist abhängig von jedem Aufstieg oder Abstieg unserer Leiblichkeit. Sobald man sich ein wenig erhebt über die Zwangslage, in die der heutige Zivilisationsmensch durch seine Erziehung versetzt ist, sieht man sofort ein, daß — mögen auch noch so viele unterbewußte, unbewußte Elemente da mitspielen — jedes religiöse, jedes künstlerische, überhaupt jedes höhere Streben der Menschen durch die ganze menschliche Entwickelung hindurch an diesen Gegensätzen hängt.

Gewiß, Millionen und aber Millionen von Menschen machen sich das nicht klar. Aber ist es denn nötig, daß sich der Mensch das, was für ihn zum Lebensrätsel wird, ganz klar macht? Wenn die Menschen von dem, was sie sich klarmachen, leben sollten, so würden sie bald sterben. Der größte Teil des Lebens verfließt eben in dem, was aus unklaren, unterbewußten Tiefen in die allgemeine Lebensstimmung herauffließt. Und wir dürfen nicht sagen, nur derjenige empfinde die Lebensrätsel, der sie in einer intellektuell klaren Weise formulieren kann und einem auf dem Präsentierteller bringt: erstes Lebensrätsel, zweites Lebensrätsel und so weiter. Auf diese Menschen ist sogar das Allerwenigste zu geben. Dasjenige, was da wie tief unten sich bewegt, das sind die Lebensrätsel, die eben erlebt werden. - Da kommt irgendein Mensch. Er hat das oder jenes, vielleicht etwas sehr Alltägliches zu sprechen; aber er spricht so, daß er mit der Aussicht, aus seinem Sprechen etwas zu erreichen für das Leben, durchaus nicht froh wird. Er will etwas, will es wieder nicht. Er kommt nicht zum Entschluß. Er fühlt sich nicht recht wohl bei dem, was er selber denkt. Ja, woher kommt das? Weil er keine Sicherheit hat in den unterbewußten Tiefen seines Wesens über die eigentliche Grundlage des Menschenwesens und der Menschenwürde. Er fühlt die Lebensrätsel. Und das, was er fühlt, kommt eben aus dem polarischen Gegensatz heraus, den ich charakterisiert habe: Daß man sich auf der einen Seite nicht halten kann an die Leiblichkeit, auf der anderen Seite nicht halten kann an die Geistigkeit, wie man sie erlebt; denn die Geistigkeit wird einem fortwährend klar als ein Auf- und Abglimmendes, und die Leiblichkeit wird einem als dasjenige klar, was aus der Natur stammt, was aber von der Natur nur zerstört werden kann.

Und so steht der Mensch da. Auf der einen Seite schaut er nach außen hin seinen physischen Leib an. Sein physischer Leib gibt ihm fortwährend ein Rätsel auf. Auf der anderen Seite schaut er sein Seelisch-Geistiges an, und dieses Seelisch-Geistige gibt ihm fortwährend ein Rätsel auf. Und dabei ist das größte Rätsel dieses: Wenn ich nun wirklich einen moralischen Impuls empfinde und muß meine Beine in Bewegung setzen, um irgend etwas zur Realisierung dieses moralischen Impulses zu tun, so komme ich in die Lage, meinen Körper aus dem moralischen Impuls heraus zu bewegen. Ich habe einen moralischen Impuls, sagen wir den Impuls eines Wohlwollens. Er wird wirklich zunächst rein seelisch erlebt. Wie dieser Impuls des Wohlwollens, der rein seelisch erlebt wird, hinunterschießt in die Körperlichkeit, ist für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein nicht zu durchschauen. Wie kommt ein moralischer Impuls dazu, Knochen in Bewegung zu setzen durch Muskeln? Man kann solch eine Auseinandersetzung als theoretisch empfinden. Man kann sagen, das überlassen wir den Philosophen, die werden darüber schon nachdenken. Gewöhnlich macht es die heutige Zivilisation so, daß sie diese Frage den Denkern überläßt, und dann das, was die Denker sagen, verachtet oder wenigstens gering schätzt. Nun ja, dabei wird nur der menschliche Kopf froh, das menschliche Herz nicht; das menschliche Herz empfindet dabei eine nervöse Unruhe und kommt nicht zu irgendeiner Lebensfreude, Lebenssicherheit, Lebensgrundlage und so fort. Von der Art des Denkens aus, die schon einmal die Menschheit seit dem ersten Drittel des 15. Jahrhunderts angenommen hat, die so großartige Erfolge auf dem Gebiete der äußeren Naturwissenschaft errungen hat, gelangt man eben durchaus nicht dazu, irgend etwas dazu beitragen zu können, diese beiden Dinge, Rätselhaftigkeit des menschlichen physischen Leibes, Rätselhaftigkeit der menschlichen Seelenerfahrungen, irgendwie zu durchdringen. Und gerade aus der klaren Einsicht heraus in dieses kommt Anthroposophie und sagt sich: Gewiß, das Denken, wie es sich nun einmal herausgebildet hat in der Menschheit, ist machtlos gegenüber der Wirklichkeit; wir mögen noch so viel denken, wir können mit unserem Denken nicht im geringsten in ein äußeres Naturgeschehen unmittelbar eingreifen. Aber mit unserem bloßen Denken können wir auch nicht in unseren eigenen Willensorganismus eingreifen. Man muß nur einmal die ganze Machtlosigkeit dieses Denkens gründlich empfinden, dann wird man schon den Impuls erhalten, über dieses gewöhnliche Denken hinauszugehen.

Aber man kann nicht hinausgehen durch Phantasterei, man kann auch nicht von irgendeinem anderen Orte aus anfangen, über die Welt nachzudenken, als vom Denken. Nun ist es aber ungeeignet, dieses Denken. Da handelt es sich darum, daß man eben einfach durch die Lebensnotwendigkeiten dazukommt, von diesem Denken aus einen Weg zu finden, durch den dieses Denken sich tiefer in das Sein, in die Wirklichkeit hineinbohrt. Und dieser Weg bietet sich nur durch dasjenige, was Sie zum Beispiel in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» als die Meditation beschrieben finden.

Wir wollen uns dies heute nur skizzenhaft vor die Seele stellen, denn wir wollen sozusagen die Skizze eines anthroposophischen Gebäudes in ganz elementarer Art liefern. Wir wollen wieder anfangen mit dem, womit wir vor zwanzig Jahren angefangen haben. Wir können sagen: Die Meditation besteht eben darinnen, das Denken in anderer Weise zu erleben, als man es gewöhnlich erlebt. Heute erlebt man das Denken so, daß man sich von außen anregen läßt; man gibt sich hin an die äußere Wirklichkeit. Und indem man sieht und hört und greift und so weiter, merkt man, wie sich gewissermaßen im Erleben das Aufnehmen von äußeren Eindrücken fortsetzt in Gedanken. Man verhält sich passiv in seinen Gedanken. Man gibt sich hin an die Welt, und die Gedanken kommen einem. Auf diese Weise kommt man nie weiter. Es handelt sich darum, daß man beginnt, das Denken zu erleben. Das tut man, indem man einen einfach überschaubaren Gedanken nimmt, diesen leicht überschaubaren Gedanken im Bewußtsein gegenwärtig sein läßt, das ganze Bewußtsein auf diesen überschaubaren Gedanken konzentriert.

Es ist nun ganz gleichgültig, was dieser Gedanke für die äußere Welt bedeutet. Worauf es ankommt, ist lediglich, daß man das Bewußtsein mit Außerachtlassung von allem anderen Erleben auf diesen einen Gedanken konzentriert. Ich sage, es muß ein überschaubarer Gedanke sein. Sehen Sie, ich wurde einmal gefragt von einem sehr gelehrten Manne, wie man meditiert. Ich gab ihm einen furchtbar einfachen Gedanken. Ich sagte ihm, es käme nicht darauf an, ob der Gedanke irgendeine äußere Realität bedeute. Er solle denken: Weisheit ist im Licht. — Er solle immer wieder und wieder seine ganze Seelenkraft dazu verwenden, zu denken: Weisheit ist im Licht. — Ob das nun wahr oder falsch ist, darauf kommt es nicht an. Es kommt ebensowenig darauf an, ob irgend etwas ein weltbewegendes Ding ist oder ein Spiel, wenn wir unseren Arm anstrengen, um es in Bewegung zu setzen und immer wieder in Bewegung zu setzen. Wir verstärken dadurch unsere Armmuskeln. Wir verstärken unser Denken, indem wir uns anstrengen, immer wieder und wiederum diese Tätigkeit auszuüben, gleichgültig was der Gedanke bedeutet. Wenn wir uns immer wieder und wieder seelisch anstrengen, ihn im Bewußtsein gegenwärtig zu machen und das ganze Seelenleben darauf zu konzentrieren, so verstärken wir unser Seelenleben, wie wir die Muskelkraft unseres Armes verstärken, wenn wir sie immer wieder und wieder auf dieselbe Tätigkeit hin konzentrieren. Aber wir müssen einen leicht überschaubaren Gedanken haben. Denn haben wir den nicht, so sind wir allen möglichen Rankünen der eigenen Organisation ausgesetzt. Man glaubt ja gar nicht, wie stark die suggestive Kraft ist, die von Reminiszenzen des Lebens und dergleichen herkommt. In dem Augenblick, wo man nur einen komplizierteren Gedanken faßt, kommen gleich von allen möglichen Seiten dämonische Gewalten, die einem dies oder jenes ins Bewußtsein hineinsuggerieren. Man kann nur sicher sein, daß man mit voller Besonnenheit in der Meditation lebt, mit derselben Besonnenheit, mit der man sonst im Leben steht, wenn man vollbewußter Mensch ist, wenn man tatsächlich einen ganz überschaubaren Gedanken hat, in dem nichts anderes drinnenstecken kann als das, was man gedanklich erlebt.

Wenn man so die Meditation einrichtet, mögen alle möglichen Leute sagen: Du unterliegst einer Autosuggestion oder dergleichen -, das ist natürlich alles unsinniges Zeug. Das hängt lediglich davon ab, ob man es dahin bringt, einen überschaubaren Gedanken zu haben oder ob man einen Gedanken hat, der irgendwie durch unterbewußte Impulse in einem wirkt. Nun hängt es allerdings davon ab - ich habe das oftmals gesagt —, was der Mensch für Fähigkeiten hat; bei dem einen dauert es lang, bei dem anderen kurz. Aber der Mensch kommt durch solche Konzentration dazu, sein Seelenleben, insofern es denkendes Seelenleben ist, zu verstärken, in sich zu erkraften. Und das Ergebnis wird eben dann nach einiger Zeit dieses, daß der Mensch sein Denken nicht so erlebt wie im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein. Im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein erlebt der Mensch so seine Gedanken, daß sie machtlos dastehen. Es sind eben Gedanken. Durch solche Konzentration kommt der Mensch dazu, die Gedanken auch wirklich so zu erleben wie ein innerliches Sein, wie er erlebt die Spannung seines Muskels, wie er erlebt das Ausgreifen, um einen Gegenstand zu erfassen. Das Denken wird in ihm eine Realität. Er erlebt gerade, indem er sich immer mehr und mehr ausbildet, einen zweiten Menschen in sich, von dem er vorher nichts wußte.

Und dann beginnt für den Menschen der Augenblick, wo er sich sagt: Nun ja, ich bin der Mensch, der sich zunächst äußerlich anschauen kann, wie man die Dinge der Natur anschaut. Ich fühle innerlich sehr dunkel meine Muskelspannungen, aber weiß eigentlich nicht, wie meine Gedanken in diese Muskelspannungen hinunterschießen. Aber wenn der Mensch also, wie ich es geschildert habe, sein Denken verstärkt, dann fühlt er gewissermaßen rinnen, strömen, pulsieren das erkraftete Denken in seinem Wesen. Er fühlt einen zweiten Menschen in sich. Aber dies ist ja zunächst eine abstrakte Bestimmung. Die Hauptsache ist, daß in dem Augenblicke, wo man diesen zweiten Menschen in sich fühlt, die außerirdischen Dinge einen so anzugehen beginnen, wie einen vorher nur die irdischen Dinge angegangen haben. Ich meine die räumlich außerirdischen Dinge. In dem Augenblicke, wo Sie fühlen, wie der Gedanke innerliches Leben wird, wo Sie das rinnen fühlen wie die Atemzüge, wenn Sie auf sie aufmerksam sind, in dem Augenblicke fügen Sie zu Ihrer ganzen Menschlichkeit etwas Neues hinzu. Vorher zum Beispiel fühlen Sie: Ich stehe auf meinen Beinen. Da unten ist der Boden. Der Boden trägt mich. Wäre er nicht da und böte mir die Erde nicht einen Boden, ich müßte ins Bodenlose versinken. Ich stehe auf etwas.

Nachher, wenn Sie Ihr Denken in sich erkraftet haben, den zweiten Menschen in sich fühlen, da beginnt für den Augenblick, wo Sie sich besonders für diesen zweiten Menschen interessieren, das was Sie irdisch umgibt, Sie nicht mehr so stark wie vorher zu interessieren. Nicht als ob man ein Träumer, ein Schwärmer werden würde. Man wird es nicht, wenn man in einer innerlich klaren und ehrlichen Weise zu solchen Stufen der Erkenntnis vorrückt. Man kann ganz gut wiederum mit aller Lebenspraxis in die Welt des gewöhnlichen Lebens zurück. Man wird nicht ein Phantast, der sagt: Ach, ich habe die geistige Welt kennengelernt, die irdische ist minderwertig, wesenlos, ich beschäftige mich nur mehr mit der geistigen Welt. Bei einem wirklichen geistigen Weg wird man nicht so, sondern man lernt erst recht das äußere Leben schätzen, wenn man wiederum in dasselbe zurückkehrt. Und die Momente, wo man aus demselben herausgeht in der Art, wie ich es geschildert habe, und wo das Interesse sich heftet an den zweiten Menschen, den man in sich entdeckt hat, können ohnedies nicht lange festgehalten werden; denn werden sie in innerlicher Ehrlichkeit festgehalten, dann gehört eine große Kraft dazu, und diese Kraft kann man nur durch eine gewisse Zeit, die im allgemeinen nicht sehr lange ist, auf einmal aufrechterhalten.

Aber verbunden ist dieses Hinlenken des Interesses auf den zweiten Menschen damit, daß einem die räumliche Umgebung der Erde so wertvoll zu werden beginnt wie sonst dasjenige, was auf der Erde herunten ist. Man weiß, der Erdboden trägt einen. Man weiß, die Erde gibt einem aus ihren verschiedenen Naturreichen die Substanzen, die man essen muß, damit der Leib immer fort und fort durch die Nahrung die Anregung erhält, die er braucht. Man weiß, wie man auf diese Weise mit der irdischen Natur zusammenhängt. Geradeso wie man in den Garten gehen muß, um sich dort ein paar Kohlköpfe zu pflücken, sie dann zu kochen, damit man sie ißt, wie also notwendig ist dasjenige, was da draußen im Garten ist, wie es einen Zusammenhang hat mit dem, was man zunächst als erster, physischer Mensch ist, so lernt man jetzt erkennen, was einem der Sonnenstrahl, was einem das Mondenlicht ist, was einem all dasjenige ist, was Sternengefunkel um die Erde herum ist. Und man erlangt eine Möglichkeit, über dasjenige, was räumlich um die Erde herum ist, nach und nach in bezug auf den zweiten Menschen so zu denken, wie man vorher gedacht hat mit Bezug auf seinen ersten physischen Leib, in bezug auf seine physische Erdenumgebung.

Und man sagt sich: Dasjenige, was du da in dir trägst als Muskeln, als Knochen, als Lunge, Leber und so weiter, das hängt zusammen mit dem Kohlkopf oder dem Fasanen und so weiter, die da draußen in der Welt sind. Dasjenige aber, was du jetzt als zweiten Menschen in dir trägst, was du dir zum Bewußtsein durch die Verstärkung deines Denkens gebracht hast, das hängt zusammen mit Sonne und Mond, mit dem ganzen Sterngefunkel, das hängt zusammen mit der räumlichen Umgebung der Erde. Man wird vertraut, eigentlich vertrauter mit der räumlichen Umgebung der Erde, als man so als gewöhnlicher Mensch, wenn man nicht gerade Nahrungsmittelhygieniker oder so etwas ist, mit der irdischen Umgebung vertraut ist. Man gewinnt wirklich eine zweite, zunächst räumlich zweite Welt.

Man lernt sich als einen Bewohner der Sternenwelt ebenso einschätzen, wie man sich vorher eingeschätzt hat als einen Bewohner der Erde. Vorher hat man sich nämlich nicht als einen Bewohner der Sternenwelt eingeschätzt; denn die Wissenschaft, die nicht bis zum Erkraften des Denkens geht, bringt es nicht dazu, dem Menschen das Bewußtsein beizubringen, daß er für einen zweiten Menschen einen solchen Zusammenhang mit der räumlichen Erdenumgebung hat, wie er als physischer Mensch mit der physischen Erde hat. Das kennt sie nicht. Sie rechnet; aber was da die Rechnung selbst der Astrophysik und so weiter zutage fördert, all das liefert ja nur Dinge, die den Menschen eigentlich nichts angehen, die höchstens seine Wißbegierde befriedigen. Denn schließlich, was hat es denn für eine Bedeutung für den Menschen, für das, was er innerlich erlebt, wenn man weiß, wie man sich nun denken kann - stimmen tut es ja noch außerdem nicht -, daß der Spiralnebel in den «Jagdhunden» entstanden ist oder noch heute in seinen Gestaltungen verläuft. Es geht ja den Menschen nichts an. Der Mensch steht zur Sternenwelt so, wie irgendein leibfreies Wesen, das von irgendwoher käme und auf der Erde sich aufhielte, zu der Erdenwelt stünde, das keine Nahrung und so weiter zu nehmen brauchte, sie nicht zum Stehen brauchte und so weiter. Aber tatsächlich, der Mensch wird aus einem bloßen Erdenbürger ein Weltenbürger, wenn er in dieser Weise sein Denken erkraftet.

Und nun entsteht ein ganz bestimmter Bewußtseinsinhalt. Es entsteht der Bewußtseinsinhalt, der sich in der folgenden Weise charakterisieren läßt. Wir sagen uns: Daß Kohlköpfe sind, Getreide draußen ist, das ist gut für uns, das baut uns den physischen Leib auf, wenn ich diesen Ausdruck, der nicht ganz richtig ist, jetzt gebrauchen darf nach der allgemeinen trivialen Anschauung; es baut uns unseren physischen Leib auf. Und ich konstatiere einen gewissen Zusammenhang zwischen dem, was da draußen in den verschiedenen Reichen der Natur ist, und meinem physischen Leib.

Aber mit dem erkrafteten Denken beginne ich einen ebensolchen Zusammenhang zu konstatieren zwischen meinem zweiten Menschen, der in mir lebt und demjenigen, was im außerirdischen Raum uns umgibt. Man sagt sich zuletzt: Wenn ich in der Nacht hinausgehe und mich nur meiner gewöhnlichen Augen bediene, sehe ich nichts. Wenn ich bei Tag hinausgehe, macht mir das Sonnenlicht, das außerirdische, alle Gegenstände sichtbar. Ich weiß zunächst nichts. Wenn ich mich bloß auf die Erde beschränke, so weiß ich: da ist ein Kohlkopf, dort ist Quarzkristall. Ich sehe beides durch das Sonnenlicht, aber ich interessiere mich auf Erden nur für den Unterschied zwischen dem Kohlkopf und dem Quarzkristall.

Nun beginne ich zu wissen: ich bin selber als zweiter Mensch aus dem gemacht, was mir den Kohlkopf und den Quarzkristall sichtbar macht. Das ist ein ganz bedeutsamer Sprung, den man in seinem Bewußtsein macht. Es ist eine völlige Metamorphose des Bewußtseins. Und von da ab beginnt das, daß man sich sagt: Stehst du auf der Erde, so siehst du das Physische, das mit deinem physischen Menschen zusammenhängt; erkraftest du dein Denken und wird ebenso wie vorher das Physische der Erde für dich eine Welt war, die dich angeht, das außerirdische räumliche Dasein eine Welt, die dich angeht, nämlich dich und den Menschen, den du erst in dir entdeckt hast, dann schreibst du, so wie du der physischen Erde den Ursprung deines physischen Leibes zuschreibst, dem kosmischen Äther, durch dessen Wirkungen die irdischen Dinge erst sichtbar werden, dein zweites Dasein zu. Und du sprichst jetzt aus deiner Erfahrung heraus, so, daß du sagst, du hast deinen physischen Leib und du hast deinen Ätherleib. Es macht natürlich nicht den Inhalt einer Erkenntnis, wenn man bloß systematisiert und den Menschen aus verschiedenen Gliedern bestehend denkt, sondern es macht erst eine wirkliche Einsicht, wenn man die ganze Metamorphose des Bewußtseins ins Auge faßt, die dadurch entsteht, daß man einen solchen zweiten Menschen in sich wirklich entdeckt.

Ich greife mit meinem physischen Arm, und meine physische Hand umfaßt einen Gegenstand. Ich fühle gewissermaßen die Strömung, die da greift. Durch dieses Erkraften des Gedankens fühlt man den Gedanken, wie er in sich beweglich nun auch eine Art Tasten im Menschen bewirkt, eine Art Tasten, das nun auch in einem Organismus lebt, in dem ätherischen Organismus, in dem feineren übersinnlichen Organismus, der ebenso da ist wie der physische Organismus, der nur nicht mit dem Irdischen zusammenhängt, der mit dem Außerirdischen zusammenhängt.

Jetzt kommt der Moment, wo man genötigt ist, ich möchte sagen, wiederum um eine Stufe herunterzusteigen; denn zunächst kommt man schon durch ein solches imaginatives Denken, wie ich es beschrieben habe, dazu, dieses innerliche Ertasten eines zweiten Menschen in sich zu fühlen, kommt auch dazu, das im Zusammenhange zu sehen mit den Weiten des Weltenäthers, wobei Sie sich unter diesen Worten nichts vorstellen sollen als dasjenige, wovon ich eben geredet habe, nicht von irgendwo anders her einen Inhalt dazu nehmend. Aber man ist jetzt genötigt, um weiterzukommen, wiederum zu dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein zurückzukehren,

Nun, sehen Sie, da liegt es uns nahe, wenn wir an den physischen Leib des Menschen denken, in der Art, wie ich es eben jetzt beschrieben habe, uns zu fragen: Wie steht dieser physische Leib des Menschen denn eigentlich zu der Umgebung? Er steht ganz zweifellos zu der physischen Erdenumgebung in einer Beziehung, aber wie?

Wenn wir den Leichnam nehmen - er ist ja ein getreues Abbild des physischen Menschen auch während des Lebens -, ja, dann sehen wir in scharfen Konturen Leber, Milz, Niere, Herz, Lunge, Knochen, Muskeln, Nervenstränge. Das kann man zeichnen, das hat scharfe Konturen. Dadurch ist es ähnlich dem Festen, ähnlich demjenigen, was in festen Formen vorkommt. Aber mit diesem Konturierten im menschlichen Organismus hat es seine eigene Bewandtnis. Es gibt eigentlich nichts Trügerischeres als jene Handbücher, die heute von Anatomie oder Physiologie handeln, denn die Menschen kommen zu der Ansicht: da ist eine Leber, das ist das Herz und so weiter; sie sehen das alles in scharfen Konturen und stellen sich vor, daß die scharfe Konturiertheit wesentlich ist. Man stellt sich schon den menschlichen Organismus so wie ein Konglomerat von festen Dingen vor. Das ist er gar nicht, höchstens zu 10 Prozent, die übrigen 90 Prozent sind nichts Festes im menschlichen Organismus, sind flüssig oder gar luftförmig. Der Mensch ist zu 90 Prozent mindestens eine Wassersäule, wenn er lebt. So daß man sagen kann: Der Mensch gehört allerdings seinem physischen Leibe nach der festen Erde an, dem, was die älteren Denker im besonderen die Erde genannt haben; aber dann beginnt dasjenige, was im Menschen flüssig ist. Man wird nicht eher auch in der äußeren Wissenschaft zu einer vernünftigen Anschauung über den Menschen kommen, ehe man nicht wiederum den festen Menschen für sich unterscheidet und dann den Flüssigkeitsmenschen, dieses innerliche Wogen und Weben, in dem es wirklich ausschaut wie in einem kleinen Meere.

Aber einen eigentlichen Einfluß auf den Menschen hat das Irdische nur in bezug auf das, was in ihm fest ist. Denn auch draußen in der Natur können Sie sehen, wie da, wo das Flüssige beginnt, sofort eine innere Gestaltungskraft auftritt, die mit einer sehr großen Einheitlichkeit wirkt.

Wenn Sie das gesamte Flüssige unserer Erde nehmen, ihr Wasser: es ist ein großer Tropfen. Wenn das Wasser frei sich gestalten kann, wird es tropfenförmig; überall wird das Flüssige tropfenförmig.

Dasjenige, was erdig ist, fest ist, sagen wir heute, das tritt in bestimmten Gestalten auf, die man als besondere Gestalten erkennen kann. Das Flüssige hat immer das Bestreben, tropfig zu werden, die Kugelform anzunehmen.

Und woher kommt denn das? Nun, wenn Sie den Tropfen, ob er nun klein ist oder ob er erdengroß ist, studieren, so finden Sie überall, der Tropfen ist das Abbild des ganzen Weltenalls. Selbstverständlich ist es nach heutigen gewöhnlichen Begriffen falsch, aber es ist so zunächst nach dem Anblick — und wir werden in der nächsten Zeit schon sehen, wie dieser Anblick doch gerechtfertigt ist -, es ist nach dem Anblick richtig: das Weltenall erscheint uns wie eine Hohlkugel, in die wir hineinschauen.

Jeder Tropfen, ob er klein oder groß ist, erscheint uns als eine Spiegelung des Weltenalls selber. Ob Sie den Regentropfen nehmen, oder ob Sie das ganze Erdengewässer nehmen, da sehen Sie an der Oberfläche ein Bild des Weltenalls. Sobald man nämlich ins Flüssige hineinkommt, kann man dieses Flüssige nicht mehr aus den irdischen Kräften erklären. Wenn Sie die unendlichen Bemühungen sehen werden, oder mit Bewußtsein anschauen werden, die Kugelform des Erdengewässers aus den irdischen Kräften selber zu erklären, so werden Sie finden, wie vergeblich diese Bemühungen sind. Aus der irdischen Anziehungskraft und so weiter erklärt sich nicht die Kugelform des Erdengewässers. Die Kugelform des Erdengewässers ist nicht durch Anziehungskraft, sondern durch Druck von außen zu erklären. Da kommen wir sogleich dazu, auch in der äußeren Natur einzusehen, daß wir zur Erklärung des Flüssigen aus dem Irdischen hinausgehen müssen. Und von da aus kommen Sie nun zum Erfassen dessen, wie es beim Menschen ist.

Solange Sie bei dem, was im Menschen fest ist, bleiben, können Sie beim Irdischen bleiben, wenn Sie seine Gestalt verstehen wollen. In dem Augenblicke, wo Sie an sein Flüssiges herankommen, brauchen Sie den in diesem Flüssigen wirkenden zweiten Menschen, zu dem Sie durch das erkraftete Denken kommen.

Jetzt sind wir zum Irdischen wieder zurückgekehrt. Wir finden im Menschen das Feste. Das erklären wir mit unseren gewöhnlichen Gedanken. Was im Menschen flüssig ist, können wir seiner Form nach nicht verstehen, wenn wir nicht in ihm wirksam denken diesen zweiten Menschen, den wir im erkrafteten Denken in uns selber als den Ätherleib des Menschen erfühlen.

Und so können wir sagen: Der physische Mensch wirkt im Festen, der ätherische Mensch wirkt im Flüssigen. Der ätherische Mensch ist damit noch immer etwas Selbständiges natürlich; aber sein Mittel, zu wirken, ist das Flüssige.

Und nun handelt es sich darum, weiterzukommen. Denken Sie, wir haben nun wirklich uns so weit gebracht, dieses erkraftete Denken innerlich zu erleben, also den ätherischen Menschen, diesen zweiten Menschen zu erleben; das setzt voraus, daß wir eine starke innere Impulsivität entfalten.

Nun, Sie wissen ja, wenn man sich ein bißchen anstrengt, so kann man nicht nur sich zum Denken anregen lassen, sondern sich sogar die Gedanken wiederum verbieten. Man kann aufhören zu denken. Das besorgt die physische Organisation. Wenn man müde wird und einschläft, dann hört man auf zu denken. Nun, es wird schwerer, das, was man mit aller Anstrengung in sich hineinversetzt hat, dieses erkraftete Denken, das Ergebnis der Meditation, auch wiederum willkürlich auszulöschen. Ein gewöhnlicher machtloser Gedanke ist verhältnismäßig leicht auszulöschen. Man haftet schon mehr innerlich-seelisch an dem, was man da an erkraftetem Denken in sich entwickelt hat. Man muß dann eine stärkere Kraft gewinnen können, um es sich wieder absuggerieren zu können. Dann aber tritt etwas Besonderes ein.

Wenn Sie das gewöhnliche Denken haben, nun ja, es ist angeregt von der Umgebung oder von den Erinnerungen an die Umgebung. Wenn Sie irgendeinen Gedankenweg machen, dann ist ja noch die Welt da. Sie schlafen ein, dann ist sie auch noch da. Aber Sie haben sich ja gerade aus dieser Welt der Sichtbarkeit hinausgehoben im erkrafteten Denken. Sie haben sich in Zusammenhang gebracht mit der außerirdisch räumlichen Umwelt. Sie betrachten das Verhältnis der Sterne jetzt zu sich, wie Sie früher das Verhältnis der Gegenstände der Reiche der Natur um sich herum betrachtet haben. Sie haben sich mit alledem jetzt in Beziehung gesetzt. Jetzt können Sie das unterdrücken. Aber indem Sie es unterdrücken, ist auch die äußere Welt nicht da, denn Sie haben ja eben Ihr Interesse diesem erkrafteten Bewußtsein zugewendet. Da ist die äußere Welt nicht da. Sie kommen zu dem, was man leeres Bewußtsein nennen kann. Das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein kennt die Leerheit des Bewußtseins nur im Schlafe; dann ist es aber Unbewußtsein.

Aber das ist ja eben, was man jetzt erreicht: voll bewußt zu bleiben, keine äußeren sinnlichen Eindrücke zu haben und dennoch nicht zu schlafen, bloß zu wachen. Aber man bleibt nicht bloß wachend. Jetzt, wenn man das leere Bewußtsein dem Unbestimmten, dem überall Unbestimmten entgegensetzt, jetzt dringt die eigentliche geistige Welt herein. Man sagt: Da kommt sie. Während man früher nur hinausgesehen hat in die außerirdische physische Umgebung, die eigentlich ätherische Umgebung ist, während man das Räumliche gesehen hat, kommt jetzt wie von unbestimmten Fernen durch dieses Kosmische herein von allen Seiten ein Neues, das eigentliche Geistige. Das Geistige kommt von dem Weltenende zuerst herein, wenn man diesen Gang, den ich beschrieben habe, durchmacht.

Und jetzt tritt zu der früheren Metamorphose des Bewußtseins ein Drittes hinzu. Jetzt sagt man sich: Du trägst deinen physischen Leib an dir und deinen Ätherleib, den du im erkrafteten Denken ergriffen hast, und du trägst noch etwas an dir - ich bitte, ich rede von der Welt der Scheinbarkeit, wir werden in den nächsten Tagen sehen, inwiefern es berechtigt ist. Indem da von dem Ätherischen geredet wird (blau): aus dieser Welt des Räumlichen kommt es, aber was da weiter ist außerhalb (rötlich), das kommt herein vom Unbestimmten. Man verliert auch das Bewußtsein, daß es aus dem Räumlichen kommt; das durchsetzt einen wie ein dritter Mensch. Durch den Äther des Kosmos läuft es heran, durchsetzt einen als ein dritter Mensch. Und man beginnt mit Recht durch Erfahrung davon zu reden: man hatte den ersten Menschen, den physischen Menschen; den zweiten Menschen, den ätherischen Menschen; den dritten Menschen, den astralischen Menschen - stoßen Sie sich nicht an Worten, das wissen Sie ja, daß Sie das nicht sollen -, man trägt den astralischen Menschen, den dritten Menschen, an sich. Der kommt aus dem Geistigen, nicht bloß aus dem Ätherischen. Man kann von dem Astralleibe, von dem astralischen Menschen reden.

Und jetzt geht man weiter. Jetzt sagt man sich: Ich atme ein, ich verbrauche meinen Atem zu meiner inneren Organisation, ich atme aus. - Ist es denn wirklich wahr, daß das, was sich die Leute vorstellen als ein Gemisch, ein Gemenge von Sauerstoff und Stickstoff, kommt und fortgeht?

Sehen Sie, was da kommt und fortgeht, das ist nach den Anschauungen der gegenwärtigen Zivilisation aus physikalischem Sauerstoff und Stickstoff und einigem anderen zusammengesetzt. Aber derjenige, der dazukommt, nun aus dem leeren Bewußtsein heraus dieses Heranlaufen möchte ich sagen, des Geistigen durch den Äther zu erleben, der erlebt im Einatmungszug dasjenige, was gestaltet ist nicht aus dem Äther bloß, sondern von etwas außer dem Äther, aus dem Geistigen heraus. Und man erlernt allmählich im Atmungsprozesse einen geistigen Einschlag in den Menschen erkennen. Man lernt erkennend sich zu sagen: Du hast einen physischen Leib. Er greift in das Feste ein; das ist sein Mittel. Du hast deinen ätherischen Leib. Der greift in das Flüssige ein. Indem du ein Mensch bist, der nicht nur fester Mensch, Flüssigkeitsmensch ist, sondern indem du in dir deinen Luftmenschen trägst, dasjenige, was luftförmig ist, gasförmig, kann eingreifen der dritte, der astralische Mensch. Durch dieses Substantielle auf der Erde, durch das Luftförmige, greift der astralische Mensch ein.

Niemals wird das, was im Menschen flüssige Organisation ist, die innerlich ein ebenso regelmäßiges Leben hat, aber ein fortwährend veränderliches, fortwährend wandelndes Leben hat, mit dem gewöhnlichen Denken erfaßt; das, was so Flüssigkeitsmensch ist, das wird nur mit dem erkrafteten Denken erfaßt: Mit dem gewöhnlichen Denken erfassen wir konturiert den physischen Menschen. Und weil unsere Anatomie und Physiologie bloß mit dem gewöhnlichen Menschen rechnen, so zeichnen sie 10 Prozent vom Menschen auf. Aber das, was der Mensch ist als Flüssigkeitsmensch, das ist in einer fortwährenden Bewegung, das zeigt nie eine feste Kontur. Da ist es so, da wieder anders, da lang, da kurz. Was in fortwährender Bewegung ist, das erfassen Sie nicht mit den rechnenden konturierten Begriffen, das erfassen Sie mit den Begriffen, die in sich beweglich sind, die Bilder sind. Den ätherischen Menschen im Flüssigkeitsmenschen erfassen Sie in Bildern.

Und den dritten Menschen, den astralischen Menschen, der im luftförmigen Menschen wirkt, den erfassen Sie nur, wenn $ie ihn nun nicht bloß in Bildern, sondern auf eine noch andere Art ergreifen. Rücken Sie nämlich in Ihrem Meditieren immer weiter und weiter fort - und ich beschreibe damit den abendländischen Meditationsprozeß -, dann merken Sie von einem bestimmten Punkte Ihrer Übungen an, daß der Atem in Ihnen etwas fühlbar Musikalisches wird. Als innere Musik erleben Sie den Atem. Sie erleben sich als von innerer Musik durchwebt und durchwellt. Den dritten Menschen, der physisch der Luftmensch ist, geistig der astralische Mensch ist, den erleben Sie als ein inneres Musikalisches. Sie ergreifen da den Atem.

Der orientalische Meditant hat das direkt gemacht, indem er sich auf das Atmen konzentriert hat, das Atmen unregelmäßig gemacht hat, das Joga-Atmen eingeführt hat, um darauf zu kommen, wie der Atem im Menschen webt und lebt. Er hat dadurch direkt hingearbeitet auf das Ergreifen dieses dritten Menschen.