Karmic Relationships I

GA 235

24 February 1924, Dornach

Lecture IV

Today I wish to bring before you certain broader aspects concerning the development of karma, for we shall presently enter more and more into those matters which can only be illustrated—shall we say—by particular assumptions.

To gain a true insight into the progress of karma we must be able to imagine how man gathers his whole organisation together when he descends out of the spiritual world into the physical. You will understand that in the language of today there are no suitable forms of expression for these events which are practically unknown to our present civilisation. Therefore the terms we employ cannot but be inexact. When we descend out of the spiritual into the physical world, for a new life on earth, we have our physical body prepared for us, to begin with, by the stream of inheritance. This physical body is none the less connected in a certain sense, as we shall see, with the experiences we undergo between death and a new birth. Today, however, it will suffice us to bear in mind that the physical body is given to us from the earthly side, whereas those members which we may describe as the higher members of the human being—the ether-body, astral body and Ego—come down out of the spiritual world.

Take first the ether-body. Man draws it together from the whole universal ether, before he unites himself with the physical body which is given to him by heredity. The union of the soul-spiritual man as Ego, astral body, and ether-body, with the physical human embryo, can only take place inasmuch as the ether-body of the mother-organism gradually withdraws itself from the physical embryo.

Man therefore unites himself with the physical germ after having drawn together his ether-body from the universal ether. The more precise description of these events will occupy us at a later stage. For the moment we are mainly interested in the general question, whence come the several members which the human being has in earthly life between birth and death? The physical organism comes, as we have seen, from the stream of inheritance, and the ether-organism from the universal ether from which it is first drawn together. As to the astral organism, we may truly say that the human being remains in all respects unconscious of it, or only subconsciously aware of it, during his earthly life. This astral body contains all the results of his life between death and a new birth. For between death and a new birth—according to what he has become through his preceding lives on earth, man enters into manifold relations with other human souls who are in the life between death and a new birth, and also with the spiritual Beings of a higher cosmic order who do not descend to earth in a human body, but have their being in the spiritual world.

All that a man brings over from his former lives on earth—precisely according to how he was and what he did—meets with the sympathy or antipathy of the beings whom he learns to know during his passage through the world between death and a new birth.

Not only is it of great significance for karma, what sympathies and antipathies he meets among the higher Beings according to the things he did in his preceding earthly life. Not only so; it is also of deep significance that he now comes into relation to those human souls to whom he was related on the earth, and there takes place a wonderful “reflection” as between his being and the being of the souls to whom on earth he was related. Let us assume he had a good relation to a soul whom he now meets again between death and a new birth. All that the good relationship implies, was living in him during his former life, or lives on earth; and this good relationship will now be mirrored in the other soul when he encounters him between death and a new birth.

Yes, it is really so. As he goes through the life between death and a new birth, man sees himself reflected everywhere in the souls with whom he is now living, because in effect he was living with them on the earth. If he did good to another human being, something is mirrored to him from the other's soul. If he did evil, something is mirrored likewise ... And he now has the feeling—if I may use the word “feeling” with the reservations I made at the beginning—he has the feeling: “This human soul, you helped. All you experienced in helping him, all that you felt for this soul, the feelings that led you on to act thus helpfully towards him, your own inner experiences during the deed that helped him, are coming back to you now from his soul.” Yes, they are actually mirrored to you from the other's soul.

Or again, you did harm to a human soul. That which was living in you while you did him harm, is mirrored back. And so you have your former earthly lives (and notably your last life) before you as though in a far and wide-spread reflector, mirrored by the souls with whom you were together.

Especially with respect to your life of action, you have the impression that it is receding from you. Between death and a new birth you lose the Ego-feeling—the sense of “I” which was yours when in the body on earth. Indeed, you have lost it long ago. But you now get the feeling of “I” from this far-spread reflection. You come to life in the mirroring of your deeds, in the souls with whom you were during your earthly life.

On earth, your “I,” your Ego, was in the body—as it were, a point. Between death and a new birth, it is mirrored to you from the surrounding circumference. This life is an intimate being-together with the other human souls—according to the relations you have entered into with them.

And this is a reality in the spiritual world. When we go through a room hung with many mirrors, we see ourselves reflected in each one. But—in ordinary human parlance—we know that the reflections are “not there.” They do not remain when we go away; we are reflected no longer. But that which is reflected here in human souls remains; stays in existence. And there comes a time in the last third of the life between death and a new birth when we form our astral body out of these mirrored pictures. We draw all this into our astral body. In deed and truth, when we descend from the spiritual world into the physical, we carry in our astral body what we have re-absorbed into ourselves, according to the way our actions of the former life on earth were mirrored in other souls between death and a new birth. This gives us the impulses which impel us towards or away from the human souls with whom we are born again in the physical body.

In this way the impulse to karma in a new earthly life is formed between death and a new birth—though I shall have to describe it more in detail in the near future; for we must take the Ego also into account.

Now we can trace how an impulse from one life works on into other lives. Take, for example, the impulse of love. We can do our deeds, in relation to other men, out of the impulse which we call love. It makes a great difference whether we do them out of a mere sense of duty, convention, respectability and so on, or whether we do them out of a greater or lesser degree of love.

Assume that in one earthly life a man is able to perform actions sustained by love, warmed through and through by love. It remains as a real force in his soul. What he takes with him as an outcome of his deeds, what is now mirrored in the other souls, comes back to him as a reflected image. And as he forms from this his astral body, with which he descends on to the earth, the love of the former earthly life, the love which he poured out and which was now returned to him from other souls, is changed to joy and gladness.

Such is the metamorphosis—if so we may describe it. A man does something for his fellow-men, something sustained by love. Love pouring out from him accompanies the actions which help his fellow-men. In the passage through life between death and a new birth, this outpouring love of the one life on earth is transmuted, metamorphosed, into joy that streams in towards him.

If you experience joy through a human being in one earthly life, you may be sure it is the outcome of the love you unfolded towards him in a former life. This joy flows back again into your soul during your life on earth. You know the inner warmth which comes with joy, you know what joy can mean to one in life—especially that joy which comes from other human beings. It warms life and sustains it—as it were, gives it wings. It is the karmic result of love that has been expended.

But in our joy we again experience a relation to the human being who gives us joy. Thus, in our former life on earth, we had something within us that made the love flow out from us. In our succeeding life, already we have the outcome of it, the warmth of joy, which we experience inwardly once more. And this again flows out from us. A man who can experience joy in life, is again something for his fellow-men—something that warms them. He who has cause to go through life without joy is different to his fellow-men from one to whom it is granted to go through life with joyfulness.

Then, in the life between death and a new birth once more, what we thus experienced in joy between birth and death is reflected again in the many souls with whom we were on earth and with whom we are again in yonder life. And the manifold reflected image which thus comes back to us from the souls of those we knew on earth, works back again once more. We carry it into our astral body when we come down again into the next life on earth—that is the third in succession. Once more it is instilled, imprinted into our astral body. What is it in its outcome now? Now it becomes the underlying basis, the impulse for a quick and ready understanding of man and the world. It becomes the basis for that attunement of the soul which bears us along inasmuch as we have understanding of the world. If we find interest and take delight in the conduct of other men, if we understand their conduct and find it interesting in a given earthly life, it is a sure indication of the joy in our last incarnation and of the love in our incarnation before that. Men who go through the world with a free mind and an open sense, letting the world flow into them, so that they understand it well—they have attained through love and joy this relation to the world.

What we do in our deeds out of love is altogether different from what we do out of a dry and rigid sense of duty. You will remember that I have always emphasised in my books: it is the deeds that spring from love which we must recognise as truly ethical; they are the truly moral deeds. How often have I indicated the great contrast in this regard, as between Kant and Schiller. Kant, both in life and in knowledge, “kantified” everything (“Kante,” in German, means a hard edge or angle.—Note by translator.) In science, through Kant, all became hard and angular; and so it is in human action. “Duty, thou great and sublime name, thou who containest nothing of comfort or ease ... ”—this passage I quoted in my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity to the pretended anger (not the sincere, but the pretended, hypocritical anger) of many opponents, while over against it I set what I must establish as my view: “Love, thou who speakest with warmth to the soul ...”

Over against the dry and rigid Kantian concept of duty Schiller himself found the words: “Gern dien' ich dem Freunde, doch tue ich es leider mit Neigung, drum wurmt es mich oft, dass ich nicht tugenhaft bin.” (Gladly I serve my friends, yet alas, I do it with pleasure, wherefore it oftentimes gnaws me, I am not virtuous.) For in the Kantian ethic, that is not virtuous which we do out of real inclination, but only that which we do out of the rigid concept of duty.

Well, there are human beings who, to begin with, do not attain to love. Because they cannot tell their fellow-man the truth out of love (for if you love a man, you will tell him the truth, and not lies), because they cannot love, they tell the truth out of a sense of duty. Because they cannot love, out of a sense of duty they refrain from thrashing their fellow-man or from boxing his ears or otherwise offending him, the moment he does a thing they do not like. There is indeed a difference between acting out of a rigid sense of duty—necessary as it is in social life, necessary for many things—there is all the difference between this and the deeds of love.

Now the deeds that are done out of a rigid concept of duty, or by convention or propriety, do not call forth joy in the next life on earth. They too undergo that mirroring in other souls of which I spoke before; and, having done so, in the next life on earth they call forth what we may thus describe: “You feel that people are more or less indifferent to you.” How many a person carries this through life. He is a matter of indifference to others, and he suffers from it. Rightly he suffers from it, for men are there for one another; man is dependent on not being a matter of indifference to his fellows. What he thus suffers is simply the outcome of a lack of love in a former life on earth, when he behaved as a decent man because of rigid duty hanging over him like a sword of Damocles. I will not say a sword of steel; that would be disquieting, no doubt, for most dutiful people; so let us say, a wooden sword of Damocles.

Now then, we are in the second earthly life.

That which proceeds as joy from love, in the third life becomes as we have seen, a free and open heart, bringing the world near to us, giving us open-minded insight into all things beautiful and good and true. While as to that which comes to us as the indifference of other men—what we experience in this way in one earthly life, will make us in the next life (that is, in the third) a person who does not know what to do with himself. Such a person, already in school, has no particular use for the things the teachers are doing with him. Then, when he grows a little older, he does not know what to become—mechanic or Privy Councilor, or whatever it may be. He does not know what to do with his life; he drifts through life without direction. In observation of the outer world, he is not exactly dull. Music, for instance—he understands it well enough, but it gives him no pleasure. After all, it is a matter of indifference whether the music is more or less good, or bad. He feels the beauty of a painting or other work of art; but there is always something in his soul that vexes: “What is the good of it anyhow? What's it all for?” Such are the things that emerge in the third earthly life in karmic sequence.

Now let us assume, on the other hand, that a man does positive harm to another, out of hatred or antipathy. We can imagine every conceivable degree. A man may harm his fellows out of a positively criminal sense of hatred. Or—to omit the intermediate stages—he may merely be a critic. To be a critic, you must always hate a little—unless you are one who praises; and such critics are few nowadays. It is uninteresting to show recognition of other people's work; it only becomes interesting when you can be witty at their expense.

Now there are all manner of intermediate stages. But it is a matter here of all those human deeds which proceed from a cold antipathy—antipathy of which people are often not at all clearly aware—or, at the other extreme, from positive hatred. All that is thus brought about by men against their fellows, or against sub-human creatures—all this finds vent in conditions of soul which in their turn are mirrored in the life between death and a new birth. Then, in the next earthly life, out of the hatred is born what comes to us from the outer world as pain, distress, unhappiness caused from outside—in a word, the opposite of joy.

You will reply: we experience so much of suffering and pain; is it all really due to hatred—greater or lesser hatred—in our preceding life? “I cannot possibly imagine,” man will be prone to say, “that I was such a bad lot, that I must experience so much sorrow because I hated so much.” Well, if you want to think open-mindedly of these things, you must be aware how great is the illusion which lulls you to sleep (and to which you therefore readily give yourself up) at this point. You suggest-away from your conscious mind the antipathies you are feeling against others. People go through the world with far more hatred than they think—far more antipathy, at least. It is a fact of life: hatred gives satisfaction to the soul, and for this reason, as a rule, it is not at first experienced in consciousness. It is eclipsed by the satisfaction it gives. But when it returns as pain and suffering that comes to us from outside, it is no longer so; we notice the suffering quickly enough.

Well, my dear friends, to picture, if I may, in homely and familiar fashion, the possibilities there are in this respect, think of an afternoon-tea, a real, genuine, gossiping party where half-a-dozen (half-a-dozen is quite enough) aunts or uncles—yes, uncles, too—are sitting together expatiating on their fellows. Think of it. How many antipathies are given vent to, what volumes of antipathy are poured out over other men and women, say in the course of an hour and a half—sometimes it lasts longer. In pouring out the antipathy they do not notice it; but when it comes back in the next earthly life, they notice it soon enough. And it does come back, inexorably.

Thus, in effect, a portion (not all, for we shall still learn to know other karmic connections) of what we experience as suffering that comes to us from outside in one earthly life, may very well be due to our own feelings of antipathy in former lives on earth.

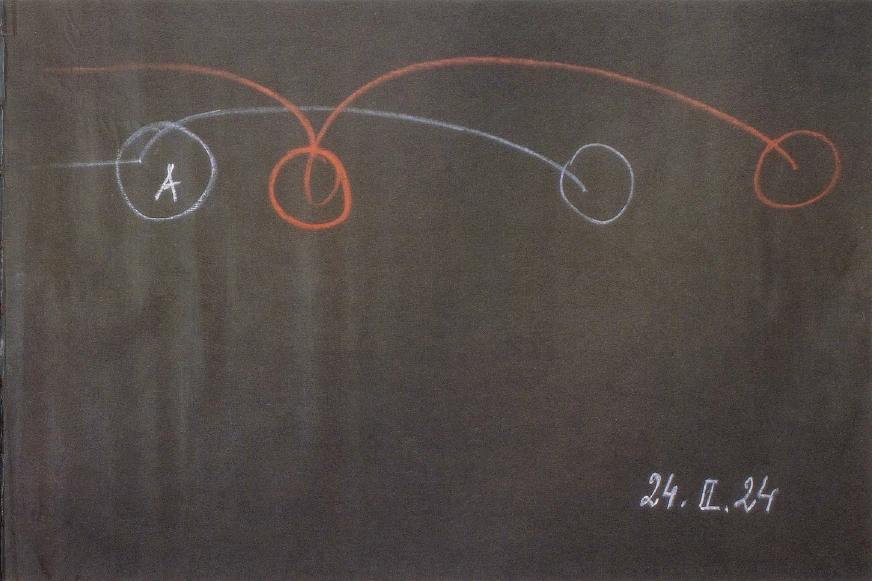

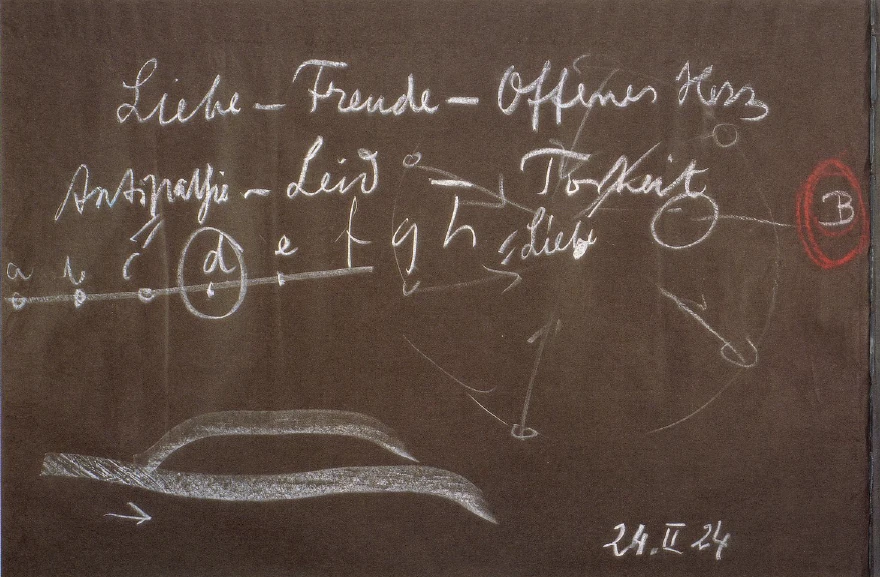

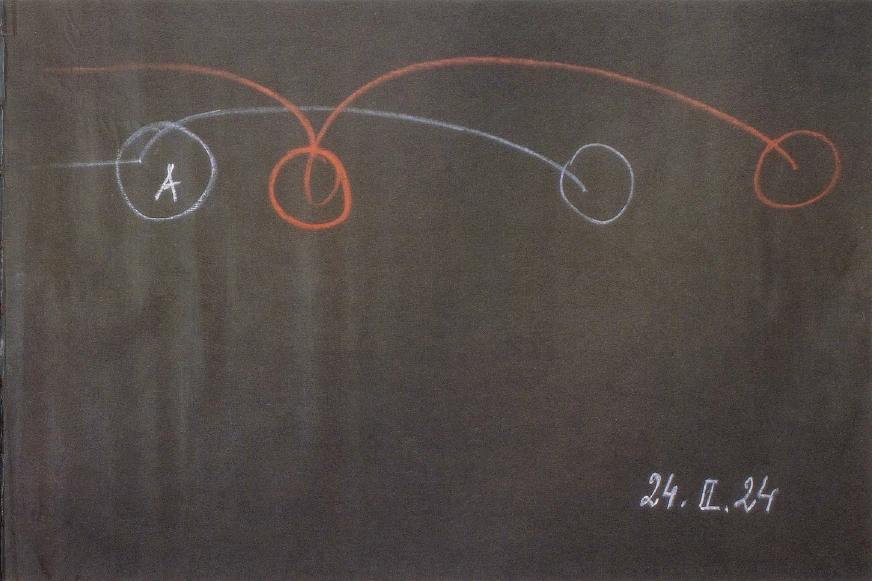

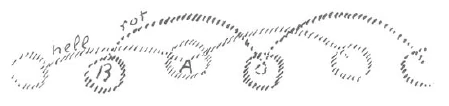

But with all this, we must never forget that karma—whatsoever karmic stream it may be—must always begin somewhere. If these are a succession of earthly lives:

a b c (d) e f g h

and this one, (d), is the present life, it does not follow that all pain which comes to us from without, is due to our former life on earth. It may also be an original sorrow, the karma of which will work itself out only in the next life on earth. Therefore I say, a part—even a considerable part—of the suffering that comes to us from outside is a result of the hatred we conceived in former lives.

And now, as we go on again into the third life, the outcome of the suffering which came to us (though only of that suffering which came, as it were, out of our own stored-up hatred), the outcome of the pain which was thus spent in our soul is a kind of mental dullness—dullness as compared with quick, open-minded insight into the world.

There may be a man who meets the world with a phlegmatic indifference. He does not confront the things of the world, or other men with an open heart. The fact is, very often, that he acquired this obtuseness of spirit by his sufferings in a former life on earth, the cause of which lay in his own karma. For the suffering which subsequently finds expression in this way, in dullness of soul, is sure to have been the result of feelings of hatred, at least in the last earthly life but one. You can be absolutely sure of it: stupidity in any one life is always the outcome of hatred in this or that preceding life. Yet, my dear friends, the true concept of karma must not only be based on this; it is not only to enable us to understand life. No, we must also conceive it as an impulse in life. We must be conscious that there is not only an a b c d, but an e f g h. That is to say, there are the coming earthly lives and what we develop as the content of our soul in this life will have its outcome and effect in the next life. If anyone wants to be extra stupid in his next earthly life but one, he need only hate very much in this life. But the converse is also true: if he wants to have free and open insight in the next earthly life but one, he need only love extra much in this life.

The insight into and knowledge of karma only gains real value when it flows into our will for the future, plays its part in our will for the future. And the moment has now come in human evolution when the unconscious cannot go on working as it did when our souls were passing through their former lives on earth. Men are becoming increasingly free and conscious. Since the first third of the 15th century we are in the age when men are becoming ever more free and conscious. And so for those men who are men of the present time, a next earthly life will already contain a dim feeling of preceding lives on earth. A man of today, if it occurs to him that he is not very bright, does not ascribe it to himself, but to his native limitations; following the current theories of materialism, he will generally ascribe it to his physical nature. Not so the men who return as the reincarnation of those of today. They will already possess at least a dim, disquieting feeling: if they are not very bright, somewhere or other there must have been something connected with feelings of antipathy or hatred.

And, if we now speak of a Waldorf School educational method, naturally for the present we must take account of the prevailing earthly civilisation. We cannot yet educate frankly towards a consciousness of life in terms of reincarnation, so to speak. For the people of today have not yet a feeling—not even a dim feeling—of their repeated earthly lives. Nevertheless, the beginnings that have been made with the Waldorf School method will go on developing, if they are truly received. They will develop in the coming centuries, in this direction. This principle will be consciously applied in moral education. If a child has little talent, if a child is dull, It is somehow due to former lives in which he developed much hatred. With the help of spiritual science, you will try to find against whom the hatred may have been directed. For the men and women who were hated then, against whom the deeds inspired by hatred were done, must be there again somewhere or other in the child's environment. Education in coming centuries will have to be placed far more definitely into life. When you see what is coming to expression in such a child, in the metamorphosis of unintelligence in this life, you will then have to recognise from what quarters it is mirrored or rather was mirrored in the life between death and new birth. Then you will do something as educator so that this child will develop an especial love towards those for whom he felt specific hatred in former lives on earth. You will soon see the beneficial result of a love thus specifically roused and directed. The child's intelligence, nay, the whole life of his soul, will brighten.

It is not the general theories about karma which will help us in education, but this concrete way of looking into life, to see where the karmic connections lie. You will soon notice it; after all, the fact that destiny has brought these children together in one class is not a mere matter of indifference. People will get beyond the hideous carelessness that prevails in these things nowadays, when the “human material”—for so they often call it—which is thrown together in a class, is actually conceived as though it were bundled together by mere chance; not as though destiny had brought these human beings together. People will get beyond this appalling indifference. Then they will gain a new outlook as educators; they will be able to perceive the wonderful karmic threads that are woven between the one child and the other, as a result of their former lives.

Then they will bring consciously into the children's development that which can create a balance. For karma is, in a certain sense, inexorable. Out of an iron necessity we may write down the unquestioned sequence:

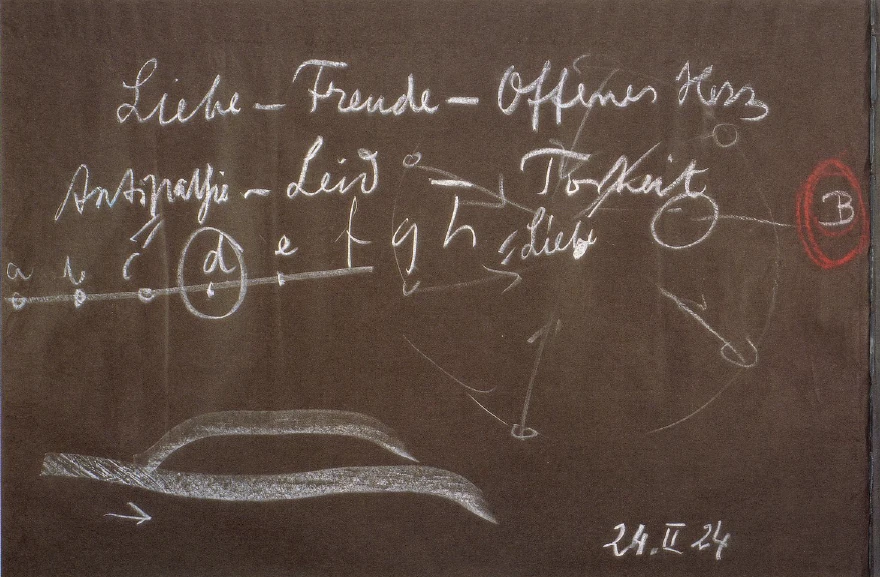

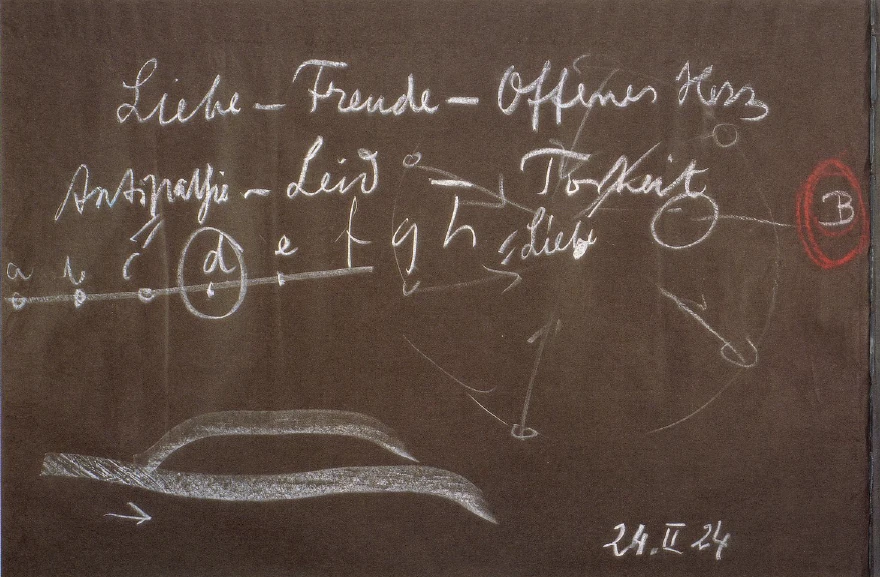

Love—Joy—an open heart.

Antipathy or Hatred—Suffering—Stupidity.

These are necessary connections. Nevertheless, we also stand face to face with a necessity when we see a river run its course; yet rivers have been regulated, their, course has been known to be altered.

So likewise it is possible, as it were, to regulate the karmic stream, to work into it, to affect its course. Yes, it is possible.

If therefore in childhood you notice there is a tendency to dullness and stupidity and you perceive the connections, if now you guide the child to develop love in its heart, if you discover (which would be possible already today for people with a delicate observation of life), if you discover which are the other children to whom the child is karmically related, and you now bring the child to love them especially, to do deeds of love towards these other children—then you will give, to the antipathy that was, a counter-weight in the love: and in a next earthly life the dullness will have been improved.

There are educators, trained, as it were, by their own instinct who often do these things instinctively. Instinctively they will bring dull-witted children to the point where they develop love, thus educating them by degrees into more intelligent and perceptive beings.

It is only when we come to these things that our insight into the karmic connections becomes of real service to life.

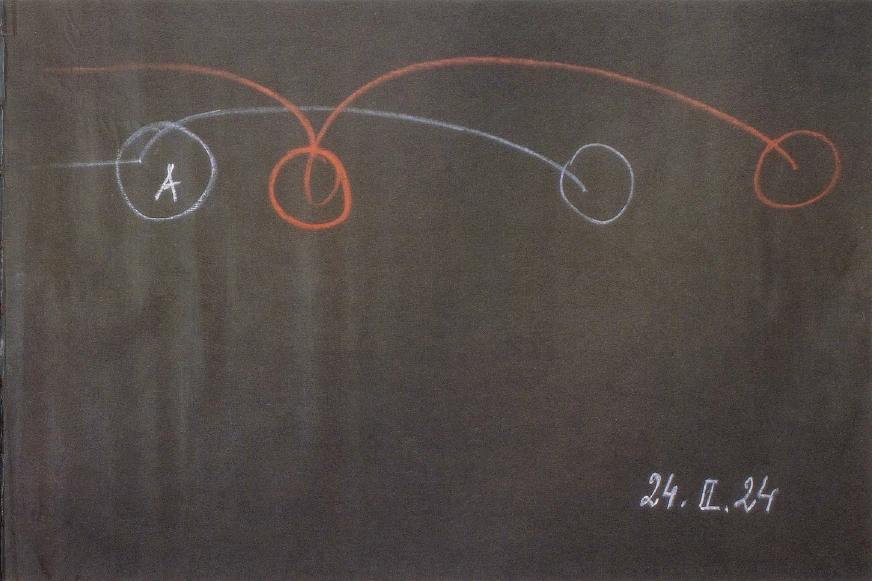

Before we go on to pursue the detailed questions of karma, one other general question will naturally come before our souls. What sort of person is it—generally speaking—whom you may confront so as to know that you are karmically related to one another? I must reply with a word which is sometimes used in a rather off-hand way nowadays: such a person is a “contemporary”; he is with us simultaneously on the earth.

Bearing this in mind, you will say to yourself: If you are with certain human beings in a life on earth, then you were with them in a former life (generally speaking, at least; there may of course, be displacements). And you were with them again in a life before it.

Now what of those who live fifty years later than you? They again were with other human beings in their former lives on earth. As a general rule, according to this line of thought, the human beings of the B series—shall I call it—will not come together with human beings of the A series.

It is an oppressive thought, but it is true. I shall afterwards speak of other doubts and questions, such as arise, for instance, when people say—as they so often do—“Humanity goes on increasing and increasing on the earth,” and other things of that kind. Today, however, I want to put this thought before you; perhaps it is an oppressive thought, but it is none the less true. It is a fact that the continued life of mankind on earth takes place in rhythms. One shift of human beings—if I may put it so—goes on, as a general rule, from one life to the next; so does another shift, and they are in a certain sense separated from one another. They do not find their way together in the earthly life, but only in the long intervening life between death and a new birth. There, indeed, they find their way together, but not in the earthly life. We come down again and again with a limited circle of people. Precisely from the point of view of reincarnation, to be contemporaries is a thing of inner importance, inner significance.

Why is it so? I can assure you, on the basis of spiritual science, this question, which may well occupy one intellectually to begin with, has caused me the greatest imaginable pain. For it is necessary to bring out the truth, the inner nature of the fact. Thus you may ask: Why was I not a contemporary of Goethe's? Not having been a contemporary of Goethe's in this life, generally speaking—according to these truths—you can more or less conclude that you have never lived with him on earth. Goethe belongs to another shift.

What lies behind this? You must reverse the question; but to do so, you must have a real feeling, a perception of what the life of men together really is. You must be able to ask yourself a question on which I shall have very much to say in the near future: What is it really to be another man's contemporary? What is it, on the other hand, only to be able to know of him from history, as far as earthly life is concerned? What is it like?

We must indeed have a free mind, a sensitive heart, to answer these intimate questions: What is it like—with all the accompanying inner experiences of the soul—when a contemporary man is speaking to you, or doing any actions that come near you? What is it like? And having gained the necessary perception of this, you must then be able to compare it with what it would be like if you encountered a person who is not your contemporary, and probably has never been so in any life on earth, whom you may none the less revere—more, perhaps, than any of your contemporaries. What would it be like if you met him as a contemporary? In a word—forgive the personal note—what would it be like if I were a contemporary of Goethe? If you are not an insensitive, indifferent kind of person ... Needless to say, if you are insensitive and have no feeling for what a contemporary can be, you are scarcely in a position to answer such a question. What would it be like if I, walking down the Schillergasse, let us say, towards the Frauenplan in Weimar, had suddenly encountered “the fat Privy Councilor,” say in the year 1826 or 1827? One knows quite well, one could not have borne it. You can stand your contemporary; you cannot bear a man who, in the nature of the case, cannot be your contemporary. In a sense, he acts like a poison on your inner life. You can only bear him inasmuch as he is not your contemporary, but your predecessor or successor.

Of course, if you have no feeling for such things, they remain in the unconscious; but you can well imagine a man who has an intimate feeling for spiritual things ... if he knew that as he went down the Schillergasse towards the Frauenplan in Weimar, he would encounter the “fat Privy Councilor”—Goethe, with the double chin—he would feel himself inwardly impossible. A man who has no feeling for such things—he no doubt would just have taken off his hat!

These things are not to be explained out of the earthly life. The reasons why we cannot be contemporary with a man are in fact, not contained within the earthly life. To see them, we must penetrate into the spiritual facts. Therefore, for earthly life, such things appear paradoxical. Nevertheless, they are as I have said.

I can assure you, with genuine love I wrote the introduction to Jean Paul's works, published in the Cotta'sche Bibliothek der Weltliteratur. Yet, if I had ever had to sit side by side with Jean Paul at Bayreuth, it would have given me a stomach-ache, without doubt! That does not hinder one's having the highest reverence. And it is so for every human being—only with most people it remains in the sub-conscious, in the astral or in the ether-body; it does not affect the physical. The experience of the soul which affects the physical body must also become conscious.

You must be well aware of this, my dear friends. If you want to gain knowledge of the spiritual world, you cannot escape hearing of things which will seem grotesque and paradoxical. The spiritual world is different from the physical. Of course, it is easy enough for anyone to turn to ridicule the statement that if I had been a contemporary of Jean Paul's, it would have given me a stomach-ache to have to sit beside him. That is quite true—it goes without saying for the everyday, banal, Philistine world of earthly life. But the laws of the banal and Philistine world do not determine the spiritual facts. You must accustom yourselves to think in other forms of thought, if you wish to understand the spiritual world; you must be prepared to experience many surprising things. When the everyday consciousness reads about Goethe, it may naturally feel impelled to say: “How I should like to have known him personally, to have shaken him by the hand!” and so on. It is a piece of thoughtlessness; for there are laws according to which we are predestined for a given epoch of the earth. In this epoch we can live. It is just as in our physical body we are predestined for a certain pressure of air; we cannot rise above the earth to a height where the pressure no longer suits us. Nor can a man who is destined for the 20th century live in the time of Goethe.

These were the things I wanted to bring forward about karma, to begin with.

Vierter Vortrag

Heute möchte ich zunächst einige umfassendere Gesichtspunkte in bezug auf die Entwickelung des Karmas bringen, um dann allmählich immer mehr und mehr auf diejenigen Dinge eingehen zu können, die eigentlich nur durch die, wenn ich so sagen soll, speziellen Ausführungen wenigstens veranschaulicht werden können, Wir müssen uns, wenn wir in den Gang des Karmas Einsicht gewinnen wollen, vorstellen können, wie eigentlich der Mensch beim Heruntersteigen aus der geistigen Welt in die physische Welt seine ganze Organisation zusammensetzt.

Sie werden ja begreifen, daß es in der gegenwärtigen Sprache nicht eigentlich geeignete Ausdrücke gibt für Vorgänge, die in der gegenwärtigen Zivilisation ziemlich unbekannt sind, und daß daher die Ausdrücke für das, was da geschieht, eigentlich nur ungenau sein können. Wir haben, wenn wir aus der geistigen in die physische Welt heruntersteigen zu einem Erdenleben, zunächst unseren physischen Leib durch die Vererbungsströmung vorbereitet. Dieser physische Leib, wir werden sehen, wie er dennoch in einer gewissen Beziehung mit dem zusammenhängt, was der Mensch zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt erlebt. Für heute kann es uns genügen, wenn wir uns eben darüber klar sind, daß dieser physische Leib uns eigentlich von der Erde aus gegeben wird. Diejenigen Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit dagegen, welche als höhere Glieder angesprochen werden können, ätherischer Leib, astralischer Leib und Ich, die kommen ja herunter aus der geistigen Welt.

Den ätherischen Leib zieht der Mensch gewissermaßen aus dem ganzen Weltenäther heran, bevor er sich mit dem physischen Leib, der ihm durch die Abstammung gegeben wird, vereinigt. Es kann eine Vereinigung des seelisch-geistigen Menschen nach Ich, astralischem Leib und ätherischem Leib mit dem physischen Menschenembryo nur dadurch erfolgen, daß sich der ätherische Leib des mütterlichen Organismus allmählich von dem physischen Menschenkeim zurückzieht.

Der Mensch also vereinigt sich mit dem physischen Menschenkeim, nachdem er seinen ätherischen Leib aus dem allgemeinen Weltenäther herangezogen hat. Die genaueren Beschreibungen dieser Vorgänge sollen uns später beschäftigen. Jetzt soll uns vorzugsweise interessieren, woher die einzelnen Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit kommen, die der Mensch während seines Erdenlebens zwischen Geburt und Tod hat.

Der physische Organismus also kommt aus der Abstammungsströmung, der ätherische Organismus aus dem Weltenäther, aus dem er herangezogen wird. Der astralische Organismus — er bleibt ja, man möchte sagen, in jeder Beziehung während des Erdenlebens dem Menschen unbewußt oder unterbewußt -, er enthält alles dasjenige, was Ergebnisse des Lebens zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt sind.

Und zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt ist es ja so, daß der Mensch nach Maßgabe dessen, was er geworden ist durch die vorigen Erdenleben, in der mannigfaltigsten Weise zu anderen Menschenseelen in Beziehung kommt, die sich auch zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt befinden, oder zu anderen geistigen Wesenheiten höherer Weltenordnung, die nicht in einem Menschenleibe zur Erde herabsteigen, sondern in der geistigen Welt ihr Dasein haben.

Alles das, was der Mensch herüberbringt aus früheren Erdenleben, nach dem, wie er war, nach dem, was er getan hat, das findet die Sympathie oder Antipathie der Wesenheiten, die er kennenlernt, indem er durchgeht durch die Welt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Da ist für das Karma nicht nur von einer großen Bedeutung, welche Sympathien und Antipathien bei höheren Wesenheiten der Mensch findet durch das, was er getan hat im vorigen Erdenleben, sondern da ist vor allen Dingen von einer großen Bedeutung, daß der Mensch in Beziehung kommt zu denjenigen Menschenseelen, mit denen er auf Erden in Beziehung war, und daß eine eigentümliche Spiegelung stattfindet zwischen seinem Wesen und dem Wesen derjenigen Seelen, mit denen er auf Erden in Beziehung war. Nehmen wir an, irgend jemand hat zu einer Seele, die er nun wieder trifft zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, eine gute Beziehung gehabt. In ihm hat gelebt während früherer Erdenleben alles das, was eine gute Beziehung begleitet. Dann spiegelt sich diese gute Beziehung in der Seele, wenn diese Seele zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt getroffen wird. Und es ist wirklich so, daß der Mensch bei diesem Durchgange durch das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt in den Seelen, mit denen er nun zusammenlebt, weil er mit ihnen auf Erden zusammengelebt hat, überall sich selbst gespiegelt sieht. Hat man einem Menschen etwas Gutes zugefügt, es spiegelt sich etwas von der Seele herüber; hat man ihm etwas Böses zugefügt, es spiegelt sich etwas von der Seele herüber. Und man hat das Gefühl — wenn ich mich da des Ausdruckes «Gefühl» mit der Einschränkung, die ich im Beginne meiner Auseinandersetzungen gemacht habe, bedienen darf -: du hast diese Menschenseele gefördert. Was du da erlebt hast durch die Förderung, was du da empfunden hast für diese Menschenseele, was aus Empfindungen heraus zu deinem Verhalten geführt hat, deine eigenen inneren Erlebnisse während der Tat dieser Förderung, sie kommen zurück von dieser Seele. Sie spiegeln sich von dieser Seele aus. Eine andere Seele - man hat sie geschädigt; dasjenige, was in einem gelebt hat während dieser Schädigung, es spiegelt sich.

Und man hat eigentlich wie in einem mächtigen, ausgebreiteten Spiegelungsapparat seine vorigen Erdenleben, namentlich das letzte, aus den Seelen, mit denen man zusammen war, gespiegelt vor sich. Und man bekommt gerade bezüglich seines Tatenlebens den Eindruck: das alles geht von einem fort. Man verliert, oder hat eigentlich längst verloren, zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, das Ich-Gefühl, das man auf Erden im Leibe gehabt hat; man bekommt aber das IchGefühl von dieser ganzen Spiegelung. Man lebt in all den Seelen mit den Spiegelungen seiner Taten auf, mit denen man im Erdenleben zusammen war.

Auf Erden war das Ich als ein Punkt gewissermaßen. Hier zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt spiegelt es sich überall aus dem Umkreise. Es ist ein inniges Zusammensein mit den anderen Seelen, aber ein Zusammensein nach Maßgabe der Beziehungen, die man mit ihnen angeknüpft hat.

Und das ist alles in der geistigen Welt eine Realität. Wenn wir durch irgendeinen Raum gehen, der viele Spiegel hat, sehen wir uns in jedem Spiegel gespiegelt. Aber wir wissen auch: das ist — der gewöhnlichen Menschensprache nach -— nicht da; wenn wir weggehen, bleibt es nicht, spiegeln wir uns nicht mehr. Aber das, was sich da in den Menschenseelen spiegelt, das bleibt, das bleibt vorhanden. Und es kommt eine Zeit im letzten Drittel zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, da bilden wir uns aus diesen Spiegelbildern unseren astralischen Leib. Da ziehen wir das zusammen zu unserem astralischen Leib, so daß wir durchaus in unserem astralischen Leib, wenn wir von der geistigen Welt in die physische heruntersteigen, dasjenige tragen, was wir in uns wieder aufgenommen haben nach der Spiegelung, die unsere Taten im vorigen Erdenleben in anderen Seelen gefunden haben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt.

Das aber gibt uns die Impulse, die uns drängen zu den Menschenseelen, oder abdrängen von den Menschenseelen, mit denen wir dann im physischen Leib zugleich wiederum geboren werden. "

Und auf diese Art - ich werde demnächst noch ausführlicher den Vorgang zu beschreiben haben, indem ich später auch auf das Ich Rücksicht zu nehmen haben werde -, aber auf diese Art bildet sich zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt der Impuls zum Karma im neuen Erdenleben aus.

Und da läßt sich verfolgen, wie ein Impuls des einen Lebens in die anderen Leben hinüberwirkt. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel den Impuls der Liebe. Wir können unsere Taten den anderen Menschen gegenüber aus dem heraus verrichten, was wir Liebe nennen. Es ist ein Unterschied, ob wir unsere Taten aus bloßem Pflichtgefühl heraus verrichten, aus Konvention, aus Anstand und so weiter, oder ob wir sie aus einer größeren oder geringeren Liebe heraus verrichten.

Nehmen wir an, ein Mensch bringt es dazu, Handlungen zu verrichten in einem Erdenleben, die von der Liebe getragen sind, die durchwärmt sind von der Liebe. Ja, das bleibt als Kraft in seiner Seele vorhanden. Und was er nun mitnimmt als Ergebnis seiner Taten, und was sich da spiegelt in den Seelen, das kommt auf ihn zurück eben als Spiegelbild. Und indem der Mensch sich seinen astralischen Leib daraus bildet, mit dem er herunterkommt zur Erde, wandelt sich die Liebe des vorigen Erdenlebens, die von dem Menschen ausgeströmt ist, rückkommend von anderen Menschen, in Freude. So daß also, indem der Mensch seinen Mitmenschen gegenüber in einem Erdenleben irgend etwas tut, was von Liebe getragen ist, wobei also die Liebe von ihm ausströmt, mit den Taten mitgeht, die den anderen Menschen fördern, dann die Metamorphose beim Durchgang durch das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt so ist, daß sich, was ausströmende Liebe in einem Erdenleben ist, im nächsten Erdenleben metamorphosiert, verwandelt in an den Menschen heranströmende Freude.

Erleben Sie durch einen Menschen Freude, meine lieben Freunde, in einem Erdenleben, so können Sie sicher sein, daß diese Freude das Ergebnis der Liebe ist, die Sie ihm gegenüber in einem vorigen Erdenleben entfaltet haben. Diese Freude strömt nun wiederum in Ihre Seele zurück während des Erdenlebens. Sie kennen jenes innerlich Erwärmende der Freude. Sie wissen, was Freude im Leben für eine Bedeutung hat, Freude insbesondere, die von Menschen kommt. Sie wärmt das Leben, sie trägt das Leben, sie gibt dem Leben, können wir sagen, Schwingen. Sie ist karmisch das Ergebnis aufgewendeter Liebe.

Aber wir erleben ja wiederum an der Freude eine Beziehung zu dem anderen Menschen, der uns Freude macht. So daß wir in den früheren Erdenleben innerlich etwas gehabt haben, was ausströmen machte die Liebe; in den folgenden Erdenleben haben wir schon als Ergebnis innerlich erlebend die Wärme der Freude. Das ist wiederum etwas, was von uns ausströmt. Ein Mensch, der im Leben Freude erleben darf, ist auch wiederum etwas für die anderen Menschen, was erwärmende Bedeutung hat. Ein Mensch, der Gründe dafür hat, freudelos durchs Leben zu gehen, ist anders zu den anderen Menschen als ein Mensch, der in Freuden darf durch das Leben gehen.

Das aber, was da erlebt wird in der Freude zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, das wiederum spiegelt sich in den verschiedensten Seelen, mit denen man auf Erden zusammen war, und die jetzt auch in dem Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt sind. Und dieses Spiegelbild, das in vielfacher Weise dann von den Seelen der uns bekannten Menschen kommt, das wirkt wiederum zurück. Wir tragen es wiederum in unserem astralischen Leib, wenn wir zum nächsten — also jetzt sind wir beim dritten Erdenleben -, zum nächsten Erdenleben heruntersteigen. Und wiederum ist es eingeschaltet, eingeprägt unserem astralischen Leibe. Und jetzt wird es in seinem Ergebnis zur Grundlage, zum Impuls des leichten Verstehens von Menschen und Welt. Es wird zur Grundlage derjenigen Seelenverfassung, die uns trägt dadurch, daß wir die Welt verstehen. Wenn wir Freude haben können an dem interessanten Verhalten der Menschen, verstehen das interessante Verhalten der Menschen in einer Erdeninkarnation, so weist uns das zurück auf die Freude der vorhergehenden, auf die Liebe der weiter vorangehenden Erdeninkarnation. Menschen, die mit freiem, offenem Sinn so durch die Welt gehen können, daß der freie, offene Sinn die Welt in sie hereinströmen läßt, so daß sie für die Welt Verständnis haben, das sind Menschen, die diese Stellung zur Welt sich durch Liebe und Freude errungen haben.

Das ist etwas ganz anderes, was wir in den Taten aus der Liebe heraus tun, als dasjenige, was wir aus starrem, trockenem Pflichtgefühl heraus tun. Sie wissen ja, wie ich in meinen Schriften immer darauf gesehen habe, die Taten, die aus der Liebe kommen, als die eigentlich ethischen, als die eigentlich moralischen aufzufassen.

Ich habe oftmals auf den großen Gegensatz hinweisen müssen, der in dieser Beziehung zwischen Kant und Schiller besteht. Kant hat ja eigentlich im Leben und in der Erkenntnis alles verkantet. Es ist alles eckig und kantig in der Erkenntnis durch Kant geworden, und so auch das menschliche Handeln: «Pflicht, du erhabener, großer Name, der du nichts Beliebtes, was Einschmeichelung bei sich führt, in dir fassest...» und so weiter. Ich habe die Stelle in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» zum geheuchelten Ärger vieler Gegner — nicht zum wirklichen, zum geheuchelten Ärger vieler Gegner - zitiert und habe dasjenige dagegengestellt, was ich selber als meine Anschauung anerkennen muß: Liebe, du warm zur Seele sprechender Impuls — und so weiter.

Schiller, gegenüber dem starren, trockenen Pflichtbegriffe Kants, hat ja die Worte geprägt: «Gerne dien’ ich den Freunden, doch tu’ ich es leider mit Neigung, und so wurmt es mich oft, daß ich nicht tugendhaft bin.» Denn nach Kantscher Ethik ist dasjenige, was man aus Neigung tut, nicht tugendhaft, sondern dasjenige, was man aus dem starren Pflichtbegriff heraus tut.

Nun, es gibt eben Menschen — die kommen nicht zum Lieben zunächst. Aber weil sie dem anderen Menschen nicht aus Liebe die Wahrheit sagen können — man sagt zu dem anderen Menschen, wenn man Liebe für ihn hat, die Wahrheit und nicht die Lüge -, aber weil sie nicht lieben können, sagen sie die Wahrheit aus Pflichtgefühl; weil sie nicht lieben können, vermeiden sie es aus Pflichtgefühl, den anderen gleich zu prügeln oder ihn mit Ohrfeigen zu traktieren, anzustoßen und dergleichen, wenn er irgend etwas tut, was ihnen nicht gefällt. Es ist eben ein Unterschied zwischen dem Handeln aus starrem Pflichtbegriff, das aber durchaus im sozialen Leben notwendig ist, für viele Dinge notwendig ist, und zwischen den Taten der Liebe.

Nun, die Taten, die in starrem Pflichtbegriff oder in Konvention, «weil sich’s so schickt», getan werden, die rufen im nächsten Erdenleben nicht Freude hervor, sondern, indem sie eben so wie ich es geschildert habe, durch jene Spiegelung durch die Seelen gehen, rufen sie im nächsten Erdenleben etwas hervor, was man nennen könnte: Man spürt, man ist den Menschen mehr oder weniger gleichgültig. Und das, was mancher durchs Leben trägt, daß er den Menschen gleichgültig ist und daran leidet — man leidet mit Recht daran, wenn man den anderen Menschen gleichgültig ist, denn die Menschen sind füreinander da, und der Mensch ist darauf angewiesen, daß er den anderen Menschen nicht gleichgültig ist —, das, was man da erleidet, das ist eben das Ergebnis des Mangels an Liebe in einem vorigen Erdenleben, wo man sich als anständiger Mensch deshalb betragen hat, weil die starre Pflicht über einem hing wie ein Damoklesschwert, ich will nicht sagen wie ein stählernes, denn das würde beunruhigend sein für die meisten Pflichtmenschen, sondern eben wie ein hölzernes.

Nun aber sind wir beim zweiten Erdenleben. Was als Freude von der Liebe kommt, das wird im dritten Erdenleben, wie wir gesehen haben, ein offenes, freies Herz, das uns die Welt nahebringt, das uns für alles Schöne, Wahre, Gute den freien, einsichtsvollen Sinn gibt. Das, was als Gleichgültigkeit von seiten anderer Menschen zu uns strömt, und was wir dadurch erleben in einem Erdenleben, das macht uns für das dritte, also für das nächste Erdenleben, zu einem Menschen, der nichts Rechtes mit sich anzufangen weiß. Wenn er in die Schule kommt, weiß er nicht, was er mit dem anfangen soll, was die Lehrer mit ihm tun. Wenn er etwas älter wird, weiß er nicht, ob er Schlosser oder Hofrat werden soll. Er weiß nichts mit sich im Leben zu machen. Er geht eigentlich ohne Richtung, direktionslos im Leben dahin. In bezug auf die Anschauung der äußeren Welt ist er nicht gerade stumpf. Er kann zum Beispiel Musik schon verstehen, aber er hat keine Freude dran. Es ist ihm schließlich gleichgültig, ob es mehr oder weniger gute oder mehr oder weniger schlechte Musik ist. Er empfindet schon die Schönheit irgendeines malerischen oder sonstigen Werkes, aber immer kratzt es ihn in der Seele: Wozu eigentlich das alles? und so weiter. Das sind Dinge, die wiederum im dritten Erdenleben im karmischen Zusammenhange sich einstellen.

Nehmen wir aber an, der Mensch begeht gewisse Schädigungen seiner Mitmenschen aus dem Haß oder aus einer Neigung zur Antipathie heraus. Man kann da an alle Stufen denken, welche dabei vorkommen können. Es kann einer, sagen wir, mit verbrecherischem Haßgefühl seine Mitmenschen schädigen. Er kann aber auch, ich lasse die Zwischenstufen aus, er kann aber auch ein Kritiker sein. Man muß, um Kritiker zu sein, immer ein bißchen hassen, wenn man nicht ein lobender Kritiker ist, und die sind ja heute selten, denn das ist nicht interessant, die Dinge anzuerkennen. Interessant wird es ja nur, wenn man Witze macht über die Dinge. Nun gibt es ja alle möglichen Zwischenstufen. Aber es handelt sich hier um dasjenige an Menschentaten, das aus kalter Antipathie, aus einer gewissen Antipathie, über die man sich oftmals gar nicht klar wird, bis zum Haß hin hervorgeht. Alles das, was in dieser Weise von Menschen bewirkt wird gegenüber anderen Menschen oder selbst gegenüber untermenschlichen Wesenheiten, all das lädt sich wiederum in Seelenzuständen ab, die sich nun auch spiegeln in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Und da kommt dann im nächsten Erdenleben aus dem Haß dasjenige heraus, was uns zuströmt von der Welt als leidvolles Wesen, als Unlust, die von außen verursacht wird, als das Gegenteil der Freude.

Sie werden sagen: Ja, wir erleben doch so viel Leid, soll das wirklich alles von größerem oder geringerem Haß im vorigen Erdenleben herrühren? Ich kann doch von mir unmöglich denken, daß ich ein so schlechter Kerl gewesen bin — so wird der Mensch leicht sagen -, daß ich so viel Unlust erleben kann, weil ich so viel gehaßt habe! Ja, wenn man auf diesem Gebiete vorurteilslos denken will, dann muß man sich schon klarmachen, wie groß die Illusion ist, die einem wohltut und der man daher sehr leicht sich hingibt, wenn es sich darum handelt, irgendwelche Antipathiegefühle gegen andere Menschen sich abzusuggerieren. Die Menschen gehen mit viel mehr Haß, als sie denken, eigentlich durch die Welt, wenigstens mit viel mehr Antipathie. Und es ist nun schon einmal so: Haß, er wird zunächst, weil er der Seele ja Befriedigung gibt, gewöhnlich gar nicht erlebt. Er wird zugedeckt durch die Befriedigung. Wenn er zurückkommit als Leid, das uns von außen zuströmt, dann wird eben das Leid bemerkt.

Aber denken Sie nur einmal daran, meine lieben Freunde, um, ich möchte sagen, in einer ganz trivialen Art sich vorzustellen, was da als Möglichkeit vorliegt, denken Sie nur einmal an einen Kaffeeklatsch, an einen so richtigen Kaffeeklatsch, wo ein Halbdutzend — es genügt schon! - irgendwelcher Tanten oder Onkels — es können auch Onkels sein — beisammensitzen und über ihre Mitmenschen sich ergehen! Denken Sie, wieviel da an Antipathien in anderthalb Stunden - manchmal dauert es länger — abgeladen wird auf die Menschen! Indem das ausströmt, bemerken es die Leute nicht; aber wenn es im nächsten Erdenleben zurückkommt, da wird es sehr wohl bemerkt. Und es kommt unweigerlich zurück.

So daß tatsächlich ein Teil — nicht alles, wir werden noch andere karmische Zusammenhänge kennenlernen -, so daß ein Teil dessen, was wir in einem Erdenleben an von außen zugefügtem Leid empfinden, tatsächlich von Antipathiegefühlen in früheren Erdenleben herrühren kann.

Bei alledem muß man sich natürlich stets klar sein, daß ja das Karma, daß irgendeine karmische Strömung irgendwo einmal anfangen muß. So daß, wenn Sie zum Beispiel hier hintereinanderliegende Erdenleben haben

a b c (d) e f g h

und dieses d das gegenwärtige Erdenleben ist, so muß natürlich nicht aller Schmerz, der uns von außen zukommt, im früheren Erdenleben begründet sein. Es kann auch ein ursprünglicher Schmerz sein, der dann im nächsten Erdenleben sich erst karmisch auslebt. Aber deshalb sage ich: Ein großer Teil jenes Leides, das uns von außen zuströmt, ist die Folge von Haß, der in früheren Erdenleben aufgebracht worden ist.

Wenn wir nun zum dritten Erdenleben wieder übergehen, dann ist das Ergebnis dessen, was da als Leid uns zuströmt — aber nur das Ergebnis desjenigen Leides, das uns aus sozusagen aufgespeichertem Haß zukommt -, dann ist das Ergebnis dieses Leides, das sich dann in der Seele ablädt, zunächst eine Art Stumpfheit des Geistes, eine Art Stumpfheit der Einsicht gegenüber der Welt. Und wer gleichgültig und phlegmatisch der Welt gegenübersteht, nicht mit offenem Herzen den Dingen oder den Menschen gegenübersteht, bei dem liegt oftmals eben das vor, daß er sich diese Stumpfheit erworben hat durch das in seinem eigenen Karma verursachte Leid eines vorigen Erdenlebens, das aber zurückgehen muß, wenn es in dieser Weise in einer stumpfen Seelenverfassung sich ausdrückt, auf Haßgefühle mindestens im drittletzten Erdenleben. Man kann nämlich immer sicher sein: Töricht in irgendeinem Erdenleben zu sein, ist immer die Folge von Haß in einem bestimmten früheren Erdenleben.

Aber sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, das Verständnis für das Karma soll nicht nur darauf beruhen, daß wir das Karma zum Begreifen des Lebens auffassen, sondern daß wir es auch als Impuls des Lebens auffassen können, daß wir uns eben bewußt sind, daß es mit dem Leben nicht bloß ein «a, b, c, d» gibt (siehe Schema), sondern auch ein «e, f, g, h», daß auch kommende Erdenleben da sind, und daß dasjenige, was wir in einem gegenwärtigen Erdenleben an Inhalt in unserer Seele entwickeln, Wirkungen, Ergebnisse im nächsten Erdenleben haben wird. Wenn einer in dem drittnächsten Erdenleben besonders töricht sein will, braucht er im gegenwärtigen Erdenleben ja nur sehr viel zu hassen. Wenn einer aber im drittnächsten Erdenleben einen freien, offenen Sinn haben will, braucht er ja nur in diesem Erdenleben besonders viel zu lieben. Und erst dadurch gewinnt die Einsicht, die Erkenntnis des Karmas ihren Wert, daß sie in unseren Willen für die Zukunft einströmt, in diesem Willen für die Zukunft eine Rolle spielt. Es ist durchaus so, daß gegenwärtig derjenige Zeitpunkt für die Menschheitsentwickelung vorhanden ist, wo nicht mehr in derselben Art, wie das früher der Fall war, während unsere Seelen durch frühere Erdenleben gegangen sind, das Unbewußte weiterwirken kann, sondern die Menschen werden immer freier und bewußter. Seit dem ersten Drittel des 15. Jahrhunderts haben wir das Zeitalter, in dem die Menschen immer freier und bewußter werden. Und so wird für diejenigen Menschen, welche Menschen der Gegenwart sind, ein nächstes Erdenleben schon ein dunkles Gefühl der vorigen Erdenleben haben. Und so wie der heutige Mensch, wenn er an sich bemerkt, daß er nicht besonders klug ist, das nicht sich selber, sondern eben seiner Anlage zuschreibt, gewöhnlich es in seiner physischen Natur sucht nach der Ansicht des heutigen Materialismus, so werden die Menschen, die diejenigen sein werden, welche wiederkommen aus den Gegenwartsmenschen, wenigstens schon ein dunkles Gefühl haben, das sie beunruhigen wird: Wenn sie nicht besonders klug sind, so muß da irgend etwas gewesen sein, das mit Haß- und Antipathiegefühlen zusammenhing.

Und wenn wir heute reden von einer Waldorfschul-Pädagogik, so müssen wir natürlich der gegenwärtigen Erdenzivilisation Rechnung tragen. Da können wir noch nicht mit voller Offenheit so erziehen, daß wir sozusagen für das Bewußtsein in wiederholten Erdenleben erziehen, denn die Menschen haben heute auch noch nicht einmal ein dunkles Gefühl für die wiederholten Erdenleben. Aber die Ansätze, die gerade in der Waldorfschul-Pädagogik gemacht werden, sie werden sich, wenn sie aufgenommen werden, in den nächsten Jahrhunderten dahin weiter entwickeln, daß man in die ethische, in die moralische Erziehung das hineinbeziehen wird: Ein wenig begabtes Kind geht zurück auf frühere Erdenleben, in denen es viel gehaßt hat, und man wird dann an der Hand der Geisteswissenschaft aufsuchen, wen es gehaßt haben könnte. Denn die müssen sich in irgendwelcher Umgebung wiederfinden, die Menschen, die gehaßt worden sind und denen gegenüber Taten begangen worden sind aus dem Haß. Und man wird die Erziehung nach und nach in den kommenden Jahrhunderten viel mehr ins Menschenleben hineinstellen müssen. Man wird bei einem Kinde sehen müssen, woher sich spiegelt oder spiegelte in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt dasjenige, was da in einer Metamorphose des Unverstandes sich auslebt im Erdenleben. Und dann wird man etwas tun können, damit im kindlichen Alter zu denjenigen Menschen besondere Liebe entwickelt wird, zu denen in früheren Erdenleben ein besonderer Haß vorhanden war. Und man wird sehen, daß durch eine solche konkret aufgewendete Liebe der Verstand, überhaupt die ganze Seelenverfassung sich aufhellen wird. Nicht in allgemeinen Theorien über das Karma wird dasjenige liegen, was der Erziehung helfen kann, sondern in dem konkreten Hineinschauen in das Leben, um zu bemerken, wie die karmischen Zusammenhänge sind. Man wird schon bemerken: daß schließlich Kinder in einer Klasse zusammengetragen werden vom Schicksal, das ist doch nicht ganz gleichgültig. Und wenn man hinauskommen wird über jene scheußliche Sorglosigkeit, die in bezug auf solche Dinge heute herrscht, wo man ja das, was an «Menschenmaterial» — man nennt es ja oftmals so — zusammengewürfelt ist in einer Klasse, wirklich so auffaßt, als ob es zusammengewürfelt wäre vom Zufall, nicht zusammengetragen wäre vom Schicksal, wenn man hinauskommen wird über diese scheußliche Sorglosigkeit, dann wird man gerade als Erzieher in Aussicht nehmen können, was da für merkwürdige karmische Fäden von dem einen zu dem anderen gesponnen sind durch frühere Leben. Und dann wird man in die Entwickelung der Kinder dasjenige hineinnehmen, was da ausgleichend wirken kann. Denn Karma ist in einer gewissen Beziehung etwas, was einer ehernen Notwendigkeit unterliegt. Wir können aus einer ehernen Notwendigkeit heraus unbedingt aufstellen die Reihe:

Liebe - Freude - offenes Herz.

Antipathie oder Haß — Leid - Torheit.

Das sind unbedingte Zusammenhänge. Aber es ist auch so, daß geradeso wie man einer unbedingten Notwendigkeit gegenübersteht, wenn ein Fluß läuft und dennoch man schon Flüsse reguliert hat, ihnen einen anderen Lauf gegeben hat, es auch möglich ist, die karmische Strömung, ich möchte sagen, zu regulieren, in sie hineinzuwirken. Das ist möglich.

Wenn Sie also bemerken, im kindlichen Alter ist Anlage zur Torheit, und Sie kommen darauf, das Kind anzuleiten, besonders in seinem Herzen Liebe zu entwickeln, und wenn Sie - und das würde für Menschen, die eine feine Lebensbeobachtung haben, schon heute möglich sein —, wenn Sie entdecken, mit welchen anderen Kindern das Kind karmisch verwandt ist, und das Kind dazu bringen, gerade diese Kinder zu lieben, ihnen gegenüber Taten der Liebe zu tun, dann werden Sie sehen, daß Sie der Antipathie ein Gegengewicht in der Liebe geben können, und in einer nächsten Inkarnation, in einem nächsten Erdenleben damit die Torheit verbessern können.

Es gibt ja wirklich, ich möchte sagen, instinktgeschulte Erzieher, die oftmals so etwas aus ihrem Instinkte heraus tun, die schlecht veranlagte Kinder dazu bringen, lieben zu können, und sie dadurch zu auffassungsfähigeren Menschenwesen allmählich heranerziehen. Diese Dinge, sie machen eigentlich erst die Einsicht in die karmischen Zusammenhänge zu einem Lebensdienlichen.

Nun, bevor wir weitergehen in der Betrachtung von Einzelheiten des Karmas, muß sich ja noch eine Frage vor unsere Seele stellen. Fragen wir uns: Was ist denn der Mensch, demgegenüber man sich, im allgemeinen wenigstens, in einem karmischen Zusammenhange wissen kann? Ich muß einen Ausdruck gebrauchen, der heute oftmals in einem etwas spöttischen Sinne gebraucht wird: Ein solcher Mensch ist ein Zeitgenosse. Er ist eben zu gleicher Zeit mit uns auf der Erde. Und wenn Sie dies bedenken, so werden Sie sich sagen: Wenn Sie in einem Erdenleben mit gewissen Menschen zusammen sind, so waren Sie auch in einem früheren Erdenleben — wenigstens im allgemeinen, die Dinge können sich auch etwas verschieben — mit den Menschen zusammen, und ebenso wiederum in einem früheren Erdenleben.

Ja, aber nun diejenigen, die fünfzig Jahre später leben als Sie, die waren im früheren Erdenleben wiederum zusammen mit Menschen! Im allgemeinen werden die Menschen, ich will sagen der B-Reihe, mit den Menschen der A-Reihe, nach diesem Gedanken, den wir hier entwickelt haben, nicht zusammenkommen. Das ist ein bedrückender Gedanke, aber ein wahrer Gedanke.

Über andere Zweifelsfragen, die sich ergeben dadurch, daß die Menschen oftmals sagen: die Menschheit vermehrt sich auf der Erde und so weiter, werde ich ja später sprechen. Aber ich möchte Ihnen jetzt diesen Gedanken nahelegen; er ist ein vielleicht bedrückender Gedanke, aber er ist ein wahrer Gedanke: Es ist tatsächlich so, daß das fortlaufende Leben der Menschen auf der Erde in Rhythmen sich vollzieht. Ich möchte sagen, ein Menschenschub geht im allgemeinen fort von einem Erdenleben zum anderen, ein anderer Menschenschub geht fort von einem Erdenleben zum anderen, und die sind in einer gewissen Weise voneinander getrennt, finden sich nicht im Erdenleben zusammen. In dem langen Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, da findet man sich schon zusammen; aber im Erdenleben ist es in der Tat so, daß man immer wiederum mit einem beschränkten Kreis von Leuten auf die Erde herunterkommt. Gerade für die wiederholten Erdenleben hat die Zeitgenossenschaft eine innere Bedeutung, eine innere Wichtigkeit.

Und warum das? Ich kann Ihnen sagen, diese Frage, die einen zunächst verstandesmäßig beschäftigen kann, diese Frage hat mir wirklich auf geisteswissenschaftlichem Boden die denkbar größten Schmerzen gemacht, weil es ja nötig ist, über diese Frage die Wahrheit herauszubringen, den inneren Sachverhalt herauszubringen. Und da kann man sich fragen — verzeihen Sie, daß ich ein Beispiel gebrauche, das wirklich, ich möchte sagen, eine Rolle für mich spielt, nur in bezug auf die Untersuchung -: Warum warst du nicht ein Zeitgenosse von Goethe? Dadurch, daß du nicht ein Zeitgenosse von Goethe bist, kannst du ungefähr schließen im allgemeinen nach dieser Wahrheit, daß du niemals mit Goethe zusammen auf der Erde gelebt hast. Er gehört zu einem anderen Schub von Menschen.

Was liegt da eigentlich dahinter? Da muß man die Frage umkehren. Aber um eine solche Frage umzukehren, muß man einen offenen, freien Sinn haben für menschliches Zusammenleben. Man muß sich fragen können, und über diese Frage werde ich nun in der nächsten Zeit sehr viel zu reden haben hier: Wie ist es denn eigentlich, Zeitgenosse eines Menschen zu sein, und wie ist es, von einem Menschen nur aus der Geschichte wissen zu können für das Erdenleben? Wie ist denn das?

Nun, sehen Sie, da muß man eben einen freien, offenen Sinn haben für die Beantwortung der intimen Frage: Wie ist es mit allen inneren Begleiterscheinungen der Seele, wenn ein Zeitgenosse mit dir spricht, Handlungen verrichtet, die an dich herankommen -, wie ist das? Und man muß das dann vergleichen können, nachdem man sich die nötige Erkenntnis erworben hat, wie das wäre, wenn man mit einer Persönlichkeit zusammenkäme, die nicht ein Zeitgenosse ist, vielleicht in gar keinem Erdenleben ein Zeitgenosse war — die man deshalb doch aufs höchste verehren kann, viel mehr als alle Zeitgenossen —, wie es wäre, wenn man mit ihr als Zeitgenosse zusammenträfe? Also, wie wäre es, wenn — verzeihen Sie das Persönliche - ich ein Zeitgenosse von Goethe gewesen wäre? Ja, wenn man kein gleichgültiger Mensch ist — selbstverständlich, wenn man ein gleichgültiger Mensch ist und eben nicht Verständnis hat für dasjenige, was ein Zeitgenosse sein kann, dann kann man sich auch nicht gut die Antwort darauf geben -, dann kann man fragen: Wie wäre es, wenn ich nun in der Schillergasse von Weimar hinuntergegangen wäre gegen den Frauenplan und mir «der dicke Geheimrat» entgegengekommen wäre, meinetwillen im Jahre 1826, 1827? - Nun, man weiß ganz gut, das hätte man nicht vertragen! Den «Zeitgenossen» verträgt man. Denjenigen, mit dem man nicht Zeitgenosse sein kann, verträgt man nicht; er würde in einer gewissen Weise wie vergiftend auf das Seelenleben wirken. Man verträgt ihn, weil man nicht Zeitgenosse ist, sondern Nachfolger oder Vorgänger. Gewiß, wenn man für diese Dinge kein Empfinden hat, so bleiben sie im Unterbewußten. Man kann sich vorstellen, daß einer eine feine Empfindung für Geistiges hat und weiß: Wenn er die Schillerstraße in Weimar hinunterginge gegen den Frauenplan und würde als Zeitgenosse dem dicken Geheimrat Goethe mit dem Doppelkinn etwa begegnet sein, er würde sich wie innerlich unmöglich gefühlt haben. Derjenige aber, der keine Empfindung dafür hat, nun, er hätte vielleicht gegrüßt.

Ja, sehen Sie, diese Dinge sind eben nicht aus dem Erdenleben, weil die Gründe, warum wir nicht Zeitgenossen irgendeines Menschen sein können, eben nicht innerhalb des Erdenlebens sind, weil man da schon hineinschauen muß in geistige Zusammenhänge; deshalb nehmen sie sich für das Erdenleben zuweilen paradox aus. Aber es ist so, es ist durchaus so.

Ich kann Ihnen die Versicherung geben, ich habe in wahrer Liebe eine Einleitung zu Jean Paul geschrieben, die in der Cottaschen «Bibliothek der Weltliteratur» erschienen ist. Hätte ich jemals in Bayreuth mit Jean Paul selber zusammensitzen müssen — Magenkrämpfe hätte ich ganz bestimmt bekommen. Das hindert nicht, daß man die höchste Verehrung hat. Aber das ist für jeden Menschen der Fall, nur bleibt es eben bei den meisten Menschen im Unterbewußten, bleibt im astralischen oder im ätherischen Leib, greift auch nicht den physischen Leib an. Denn das seelische Erlebnis, das den physischen Leib angreifen muß, muß eben zum Bewußtsein kommen. Aber Sie müssen auch darüber sich klar sein, meine lieben Freunde: Ohne das geht es nicht ab, wenn man Erkenntnisse über die geistige Welt gewinnen will, daß man Dinge zu hören bekommt, die einem grotesk, paradox erscheinen, eben weil die geistige Welt anders ist als die physische Welt.

Natürlich kann jemand leicht spotten, wenn irgendwie behauptet wird: Wäre ich Zeitgenosse von Jean Paul gewesen, dann würde ich Magenkrämpfe bekommen haben, wenn ich mit ihm zusammengesessen hätte. — Das ist natürlich für die gewöhnliche, banale, philiströse Welt des irdischen Lebens, ganz selbstverständlich, durchaus wahr; aber die Gesetze der banal-philiströsen Welt gelten nicht für die geistigen Zusammenhänge. Man muß sich daran gewöhnen, in anderen Denkformen denken zu können, wenn man die geistige Welt verstehen will. Man muß sich daran gewöhnen, schon durchaus das Überraschende zu erleben. Wenn das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein über Goethe liest, so kann es sich natürlich gedrängt fühlen, zu sagen: Den hätte ich gern auch persönlich gekannt, ihm die Hand gedrückt und dergleichen. Das ist eine Gedankenlosigkeit, denn es gibt Gesetze, nach denen wir eben für ein bestimmtes Erdenzeitalter vorbestimmt sind und in diesem Zeitalter leben können. Geradeso wie wir für einen bestimmten Luftdruck für unseren physischen Leib vorbestimmt sind, und uns nicht erheben können über die Erde bis zu einem Luftdruck, der uns nicht genehm ist, ebensowenig kann ein Mensch, der für das 20. Jahrhundert bestimmt ist, im Zeitalter Goethes leben.

Das ist dasjenige, was ich zunächst über das Karma habe vorbringen wollen.

Fourth Lecture

Today I would first like to bring some more comprehensive points of view with regard to the development of karma, in order to then gradually be able to go more and more into those things that can actually only be at least illustrated by the, if I may say so, special explanations, We must, if we want to gain insight into the course of karma, be able to imagine how man actually puts together his whole organization when he descends from the spiritual world into the physical world.

You will understand that in the present language there are not really suitable expressions for processes that are quite unknown in the present civilization, and that therefore the expressions for what happens there can only be imprecise. When we descend from the spiritual into the physical world for an earthly life, we have first prepared our physical body through the hereditary current. We will see how this physical body is nevertheless connected in a certain way with what the human being experiences between death and a new birth. For today it may suffice for us to realize that this physical body is actually given to us from the earth. Those members of the human being, however, which can be addressed as higher members, etheric body, astral body and ego, come down from the spiritual world.

The human being draws the etheric body, so to speak, from the whole world ether before it unites with the physical body, which is given to him through descent. A union of the soul-spiritual human being according to ego, astral body and etheric body with the physical human embryo can only take place through the gradual withdrawal of the etheric body of the maternal organism from the physical human germ.

The human being thus unites with the physical human germ after it has drawn its etheric body from the general world ether. The more detailed descriptions of these processes will occupy us later. For now, we are primarily interested in where the individual limbs of the human being come from, which the human being has during his life on earth between birth and death.

The physical organism thus comes from the stream of descent, the etheric organism from the world ether from which it is drawn. The astral organism - one might say it remains unconscious or subconscious to the human being in every respect during life on earth - contains everything that is the result of life between death and a new birth.

And between death and a new birth it is so that man, according to what he has become through the previous earth lives, comes into relationship in the most manifold way with other human souls, which are also between death and a new birth, or with other spiritual beings of a higher world order, which do not descend to earth in a human body but have their existence in the spiritual world.

All that which man brings over from earlier earth lives, according to how he was, according to what he has done, that finds the sympathy or antipathy of the beings which he gets to know by passing through the world between death and a new birth. It is not only of great importance for karma what sympathies and antipathies the human being finds with higher beings through what he has done in the previous life on earth, but it is above all of great importance that the human being comes into relationship with those human souls with whom he was in relationship on earth, and that a peculiar reflection takes place between his nature and the nature of those souls with whom he was in relationship on earth. Let us assume that someone has had a good relationship with a soul that he now meets again between death and a new birth. Everything that accompanies a good relationship has lived in him during previous lives on earth. Then this good relationship is reflected in the soul when this soul is met between death and a new birth. And it is really the case that during this passage through life between death and a new birth, the human being sees himself reflected everywhere in the souls with whom he now lives together, because he has lived together with them on earth. If you have done something good to a person, something is reflected in the soul; if you have done something bad to him, something is reflected in the soul. And one has the feeling - if I may use the term “feeling” with the restriction I made at the beginning of my arguments - that you have fostered this human soul. What you experienced there through the nurturing, what you felt for this human soul, what led to your behavior out of feelings, your own inner experiences during the act of this nurturing, they come back from this soul. They are reflected from this soul. Another soul - you have harmed it; that which lived in you during this harm is reflected.

And you actually have your previous lives on earth, especially the last one, reflected before you from the souls you were with, as if in a powerful, extended mirroring apparatus. And one gets the impression, especially with regard to one's life of deeds, that all this is passing away. Between death and a new birth one loses, or has actually long since lost, the sense of self that one had in the body on earth; but one gets the sense of self from this whole reflection. One lives in all the souls with the reflections of one's deeds with which one was together in earthly life.

On earth, the ego was a point, so to speak. Here, between death and a new birth, it is reflected everywhere from the surrounding world. It is an intimate togetherness with the other souls, but a togetherness according to the relationships one has established with them.

And this is all a reality in the spiritual world. When we walk through any room that has many mirrors, we see ourselves reflected in every mirror. But we also know that - according to ordinary human language - it is not there; when we leave, it does not remain, we are no longer reflected. But that which is reflected in human souls remains, remains there. And there comes a time in the last third between death and a new birth when we form our astral body from these mirror images. Then we draw it together into our astral body, so that when we descend from the spiritual world into the physical world, we carry in our astral body that which we have taken up again after the reflection that our deeds in the previous earthly life have found in other souls between death and a new birth.

But this gives us the impulses that push us towards the human souls, or push us away from the human souls, with whom we are then born again in the physical body at the same time.

And in this way - I will soon have to describe the process in more detail, as I will also have to take the ego into consideration later - but in this way, between death and a new birth, the impulse to karma is formed in the new life on earth.

And there we can follow how an impulse of one life works over into the other lives. Take, for example, the impulse of love. We can carry out our deeds towards other people out of what we call love. It makes a difference whether we do our deeds out of a mere sense of duty, out of convention, out of decency and so on, or whether we do them out of a greater or lesser love.

Let us assume that a person manages to perform actions in an earthly life that are borne by love, that are warmed by love. Yes, that remains as a force in his soul. And what he now takes with him as a result of his deeds, and what is reflected in the souls, comes back to him as a mirror image. And by forming his astral body out of it, with which he comes down to earth, the love of the previous life on earth, which flowed out from man, coming back from other men, changes into joy. So that when a person does something towards his fellow human beings in an earthly life that is borne by love, whereby love emanates from him, goes along with the deeds that promote the other person, then the metamorphosis in the passage through life between death and a new birth is such that what is emanating love in one earthly life metamorphoses in the next earthly life, transforms into joy flowing towards the person.

If you experience joy through a person, my dear friends, in an earthly life, then you can be sure that this joy is the result of the love that you unfolded towards him in a previous earthly life. This joy now flows back into your soul during your life on earth. You know the inner warming effect of joy. You know what joy means in life, especially joy that comes from people. It warms life, it sustains life, it gives life, we could say, vibrations. It is karmically the result of love expended.

But we in turn experience joy as a relationship with the other person who gives us joy. So that in the earlier earth lives we had something inwardly that made love flow out; in the following earth lives we already experience the warmth of joy inwardly as a result. This, in turn, is something that emanates from us. A person who is allowed to experience joy in life is also something that has a warming effect on other people. A person who has reasons to go through life without joy is different to other people than a person who is allowed to go through life with joy.

But that which is experienced in the joy between birth and death is in turn reflected in the most diverse souls with whom one was together on earth and who are now also in the life between death and a new birth. And this reflection, which then comes in many ways from the souls of the people we know, has an effect in turn. We carry it again in our astral body when we descend to the next - that is, now we are in the third earth life - to the next earth life. And again it is switched on, imprinted in our astral body. And now, as a result, it becomes the basis, the impulse for an easy understanding of people and the world. It becomes the basis of that state of soul which sustains us through our understanding of the world. If we can take pleasure in the interesting behavior of people, understand the interesting behavior of people in an earth incarnation, then this points us back to the joy of the previous earth incarnation, to the love of the further preceding earth incarnation. People who can walk through the world with a free, open mind in such a way that the free, open mind allows the world to flow into them, so that they have understanding for the world, are people who have acquired this position towards the world through love and joy.

What we do out of love is quite different from what we do out of a rigid, dry sense of duty. You know how I have always made sure in my writings that the deeds that come from love are understood to be the truly ethical, the truly moral deeds.

I have often had to point out the great contrast that exists between Kant and Schiller in this respect. Kant actually canted everything in life and in knowledge. Everything has become angular and angular in knowledge through Kant, and so has human action: “Duty, you sublime, great name, who do not grasp in yourself anything popular that leads to ingratiation...” and so on. I have quoted the passage in my “Philosophy of Freedom” to the feigned annoyance of many opponents - not to the real, feigned annoyance of many opponents - and have set against it that which I myself must recognize as my view: Love, you impulse that speaks warmly to the soul - and so on.