Karmic Relationships II

GA 236

6 April 1924, Dornach

Lecture I

We will now continue our study of karma. I have pointed out to you how the impulses in the souls of human beings work on and are transplanted, as it were, from one earthly life into another, so that the fruits of an earlier epoch are carried over to a later one by men themselves.

An idea such as this must not be received merely as a theory; it should take hold of our very hearts and souls. We should feel that we who are now here have been many times in earthly existence, and that in every life we assimilated the culture and civilisation then around us; we took it into our souls and carried it over into the next incarnation, after working upon it spiritually between death and a new birth. Only when we look back in this way do we really feel ourselves standing within the community of mankind.

In order to be able to feel this, in order that in the coming lectures we may pass on to questions which concern us more intimately and will bring home to us the actual effects of karmic connections, I have found it necessary to give concrete examples. And I have tried to show you by these examples how the effects of what a man experienced and achieved in olden times, remain, and continue to work into the present, inasmuch as his achievements and experiences form part of his karma.

I spoke, for example, of Haroun al Raschid, that illustrious follower of Mohammed in the 8th and 9th centuries, who was the figure-head of a wonderful life of culture far surpassing anything to be found in Europe in those days.1See Volume 1, lecture X; also Cosmic Christianity lecture II (given by Rudolf Steiner in Torquay, 14th August, 1924). Such culture as existed in Europe at that time—it was during the reign of Charlemagne—was extremely primitive; whereas over in the East at the Court of Haroun al Raschid there came together everything that an Asiatic civilisation fructified from Europe could produce—the fruits of Greek culture and of ancient Oriental culture in practically every domain of life and knowledge. Architecture, astronomy (in the form in which it was pursued in those days), philosophy, mysticism, the arts, geography, poetry—all these branches of culture flourished at the Court of Haroun al Raschid.

Haroun al Raschid gathered around him the best of those who were of real account in Asia at that time. For the most part they were men who had been trained and educated in the Initiate Schools. Let me tell you of one of these personalities at the Court of Haroun al Raschid. The East, too, had reached its own Middle Ages, and this personality had been able to assimilate, in a rather more intellectual way, wonderful treasures of the spirit that had been carried over from long past ages into those later times. In a much earlier period he had himself been an Initiate.

Now as I have told you, it may easily happen that a personality who was an Initiate in a former age does not appear as one when he reincarnates, because he is obliged to adapt himself to the body at his disposal and to the educational facilities available at the time. Nevertheless he bears within him all that he acquired and experienced during his life as an Initiate.

In the case of Garibaldi, we have seen how in that he became a kind of seer in his life of will, giving himself up to the circumstances of the immediate present, he lived out all that he had been as an Irish Initiate.2See Vol. I, lectures XI and XII. We can see that while participating in the events of the day he bears within him impulses of quite a different character from those which an ordinary man could have gained from his education and environment. The impulse of Garibaldi's Irish initiation was still active; it was merely under the surface. And when some special experience or stroke of destiny befell Garibaldi there may very probably have welled up in him in the form of Imaginations, all that he bore within him from his life as an Irish Initiate.

So it has always been; and so it is to this day. A man may have been an Initiate in a certain epoch, and because in a later epoch he must make use of a body unable to contain all the impulses that are alive in his soul, he does not appear as an Initiate; nevertheless the impulse of initiation is at work in his deeds or relationships in life. So it was in the case of the personality who lived at the Court of Haroun al Raschid. He had once been an Initiate of a very high degree. He was not able to carry over in outwardly perceptible form the whole content of his earlier initiation, but nevertheless he was a shining light in the Oriental culture of the 8th and 9th centuries. For he was, so to speak, the organiser of all the sciences and arts studied and practised at the Court of Haroun al Raschid.

We have already spoken of the path taken by the individuality of Haroun al Raschid in later times. When he passed through the gate of death there remained with him the urge to carry further into the West the Arabism that was already spreading in that direction. And, as you know, Haroun al Raschid, whose field of vision embraced all the several arts and sciences, reincarnated as Lord Bacon of Verulam, the famous reformer of modern philosophy and science. All that had been within Haroun al Raschid's field of vision came forth again, in a Western guise, in Bacon.

The spiritual path taken by Bacon led from Bagdad, his home in Asia, to England. And from England, Bacon's work for the sciences spread over Europe more widely and with greater force than is generally realised.

After they had passed through the gate of death, these two personalities, Haroun al Raschid and his great counsellor—the outstanding personality who had been a high Initiate in earlier times—separated, in order to carry out a common work. As I have told you, Haroun al Raschid himself, who had occupied a position of great power and splendour, chose the path which led to England, where, as Lord Bacon of Verulam, he accomplished what he did for science, for the sphere of knowledge in general. The other soul, the soul of the man who had been his counsellor chose the path leading to Middle Europe, in order to meet there what was coming over from Bacon. The dates do not, it is true, absolutely coincide; but that is not important in a matter where actual time means little. Impulses separated by hundreds of years may often work simultaneously in a later civilisation.

The counsellor of Haroun al Raschid chose the path through Eastern to Middle Europe—chose it during his life between death and a new birth. And he was born again in Middle Europe; he was born into the spiritual life of Middle Europe as Amos Comenius.

These are remarkable events, of profound significance in history. Haroun al Raschid goes through his later evolution in such a way as to lead over from West to East a stream of culture that is abstract and bound up with the outer senses; whereas Amos Comenius unfolds his activity from the East, from Siebenbürgen in what is now Czechoslovakia, coming to Germany and afterwards undergoing exile in Holland, bringing with him his profoundly significant impulses for the development of thought and knowledge. If you follow his life you will see how he comes forward as the champion of the new pedagogy and as the author and originator of the so-called Pansophia. What he had formerly brought from his initiation in very ancient times and developed at the Court of Haroun al Raschid—all this he now brought to the movements of the day. It was the time when the Order of the Moravian Brothers had been founded, when Rosicrucianism had already been at work for several centuries; it was the time, too, when the Chymical Wedding had appeared, and also the Reformation of Science, by Valentin Andreae. And into the midst of all these movements which sprang from the selfsame source, came Comenius, that significant figure of the l7th century, with his message and his impulse.

You have there three successive earthly lives of importance, and it is by studying the more significant incarnations that one can learn how to study those of less importance and finally begin to understand one's own karma.—Three significant earthly lives follow one another. First we see, far away in Asia, the very same individuality who afterwards appears in Amos Comenius; we see him receiving in the places of the ancient Mysteries all the wisdom possessed by Asia in far distant ages; we see him carrying this over into his next incarnation, living at the Court of Haroun al Raschid, becoming there the great organiser and administrator of all that flourished under the aegis and protection of Haroun al Raschid. And then he appears again, this time going forth as it were to meet Bacon, who is the reincarnated Haroun al Raschid; he meets him in European civilisation where the impulses which both of them had caused to flow into this European civilisation are at work.

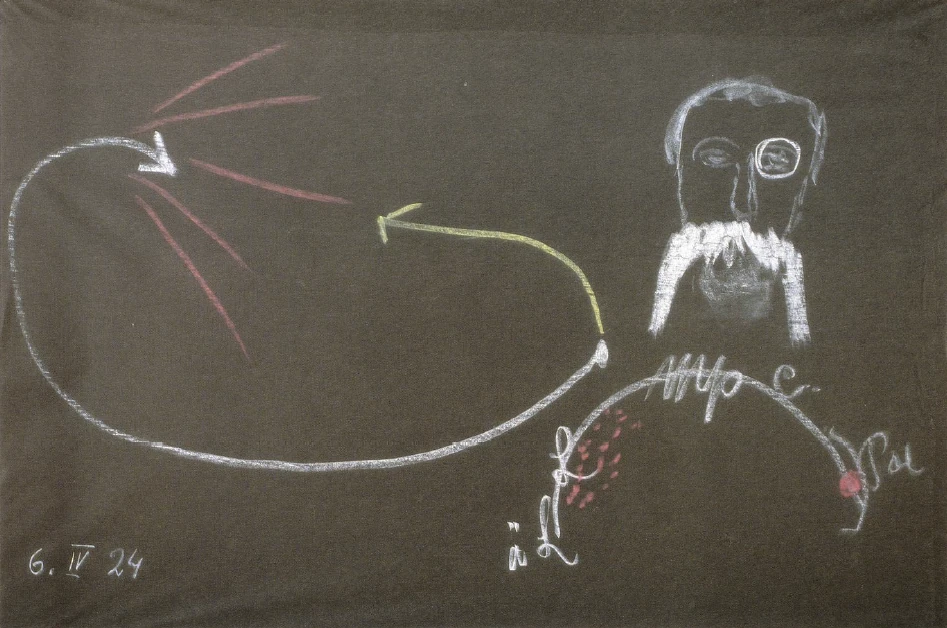

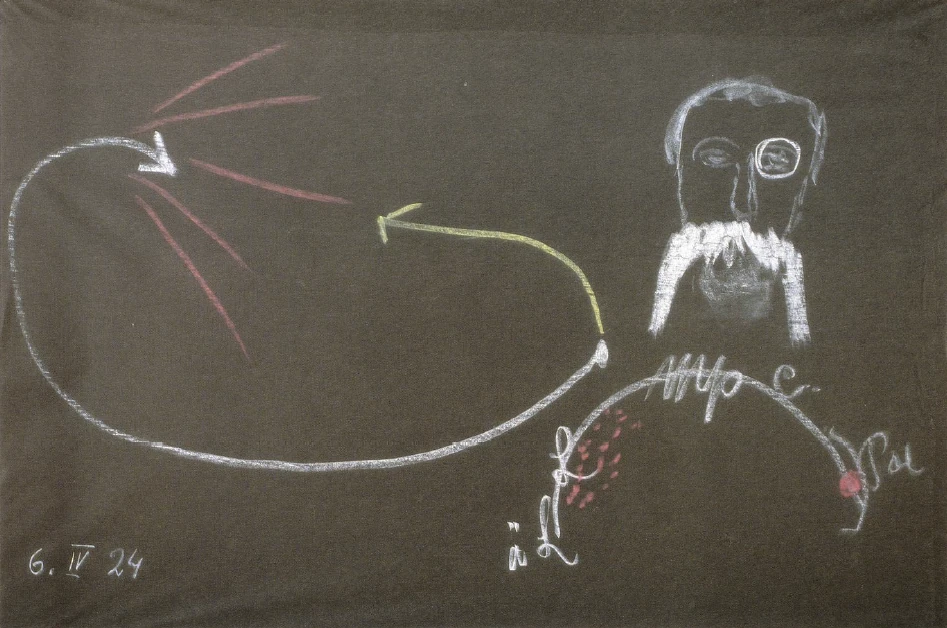

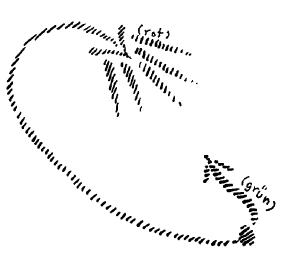

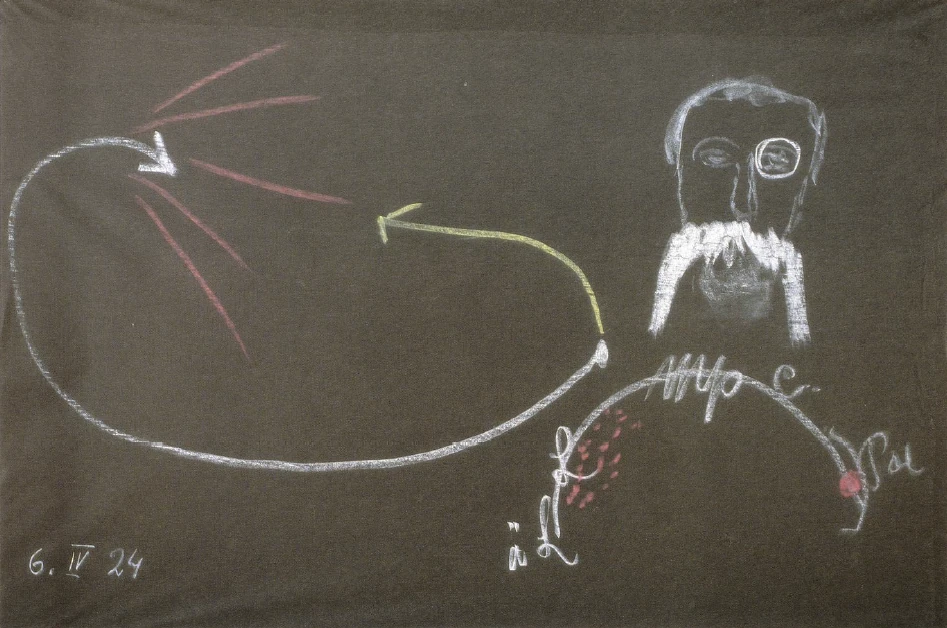

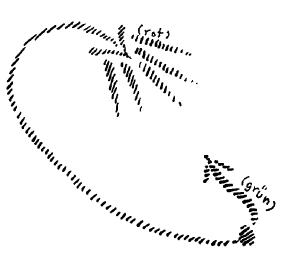

What I am now saying, my dear friends, has really great point and meaning. For if you will study the letters that were written and that build, as it were, a road from Bacon to Comenius—naturally they do so in a roundabout way, as is also the case with letters to-day!—if you will study the letters that were exchanged between Baconians, or between people in very close connection with the Baconian culture and the followers of the Comenius school, of the Comenius wisdom, you will be able to discern in the writing and answering of these letters the very same event that I have sketched diagrammatically on the blackboard.

The letters that were written from West to East and from East to West represent the living confluence of the two souls who meet one another in this way, having themselves laid the foundation for this meeting when they worked together over in the East during the 8th and 9th centuries. Now they unite again, to work once more in co-operation; this time they work from opposite directions, yet no less harmoniously.

This is the way in which history should be studied in order to gain insight into the working of human forces and the part they play in history.

Again, let us take another case.—It happened that peculiar circumstances drew my attention to certain events that occurred in the region we should now call the north-east of France. These events also took place in the 8th–9th century—a little later, however, than the time of which we were just now speaking. It was before the formation of large States, in the days when events took place more within smaller circles of people.

In the region, then, which to-day we should call the north-east of France, lived a personality who was full of ambitions. He had a large estate and he governed it remarkably well, quite unusually systematically for the time in which he lived. He knew what he wanted; there was a strange mixture of adventurousness and conscious purpose in him. And he made expeditions, some of which were more and some less successful; he would gather soldiers and make predatory expeditions, minor campaigns carried out with a small troop of men with the object of plunder.

With such a band of men he once set out from north-east France. Now it happened that during his absence another personality, somewhat less of an adventurer than himself, but full of energy, took possession of all his land and property.—It sounds fictitious to-day, but such things actually happened in those days.—And when the owner returned home—he was all alone—he found another man in possession of his estate. In the situation that developed he was no match for the man who had seized his property. The new possessor was more powerful; he had more men, more soldiers. The rightful owner was no match for him.

In those times it did not happen that if anyone were unable to go on living in his own home and estate he immediately went away into some foreign country. The rightful owner was an adventurer, certainly, but emigration was not such an easy matter then; he had neither the wherewithal nor the facilities. And so he became a kind of serf, he with his followers—a kind of serf attached to his own estate. His own property had been wrested from him and he, together with a number of those who once used to accompany him on adventures were forced to work as serfs.

In all these people who were now serfs where formerly they had been masters, a certain attitude of mind began to assert itself, an attitude of mind most derogatory to the principle of overlordship. On many a night in those well wooded parts, fires were burning, and round the fires these men came together and hatched all manner of plots against those who had taken possession of their property.

In point of fact, the dispossessed owner, who from being the master of a large estate had become a serf, more or less a slave, filled all the rest of his life—as much of it as he was not compelled to give to his work—with making plans for regaining his property. He hated the man who had seized it from him.

And then, when these two personalities passed through the gate of death, they experienced in the spiritual world between death and rebirth, all that souls have been able to experience since that time, shared in it all, and came again to earth in the 19th century. The man who had lost home and property and had become a kind of slave, appeared as Karl Marx, the founder of modern socialism. And the man who had seized his estate appeared as his friend Engels. The actions which had brought them into conflict were metamorphosed in the course of the long journey between death and a new birth into an impulse and urge to balance out and set right what they had done to one another.

Read what went on between Marx and Engels, observe the peculiar configuration of Marx's mind, and remember at the same time what I have told you of the relationship between these two individuals in the 8th–9th century, and you will find a new light falling upon every sentence written by Marx and Engels. You will not be in danger of saying, in abstract fashion: This thing in history is due to this cause, and the other to the other cause. Rather will you see the human beings who carry over the past into another age, in such a way that although admittedly it appears in a somewhat different form, there is nevertheless a certain similarity.

And what else could be expected? In the 8th–9th century, when men sat together at night around a fire in the forest, they spoke in quite a different style from that customary in the 19th century, when Hegel had lived, when things were settled by dialectic. Try all the same to picture to yourselves the forest in north-eastern France in the 9th century. There sit the conspirators, cursing, railing in the language of the period. Translate it into the mathematical-dialectical mode of speech of the 19th century, and you have what comes to expression in Marx and Engels.

Such things lead us away from sensationalism—which creeps all too easily into ideas relating to the concrete facts of reincarnation—towards a true understanding of history. And the best way to steer clear of sensationalism is, instead of giving way to a feverish desire to know the details of reincarnation, instead of that, to try to understand in the light of the repeated earthly lives of individual human beings, those things in history that bring weal or woe, happiness or grief to mankind.

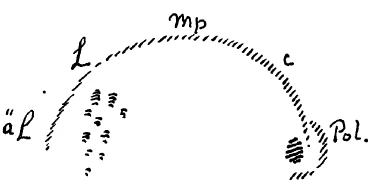

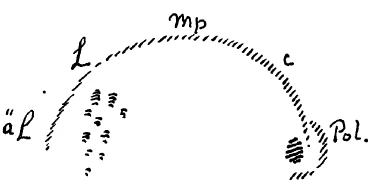

It was this point of view that while I was still living in Austria—although in Austria one is really within the German world—I was particularly interested in a certain personality who was a Polish member of the Reichstag. Those of you who have been attending lectures for a long time will remember that I have often spoken of Otto Hausner, the Austrian-Polish member of the Reichstag who was so active in the seventies of last century. Truth to tell, ever since I heard and saw Otto Hausner in the Austrian Reichstag about the end of the seventies and beginning of the eighties, the picture of this remarkable man has been before my mind's eye. He wore a monocle; he looked at you sharply with the other eye, but all the time the eye behind the monocle was watching for the weak points in his opponent. And while he spoke, he was looking to see whether the dart had struck home.

Now Hausner had a remarkable moustache—in my autobiography I did not want to go into all these details—and he used to accompany what he said with his moustache, so that the moustache made a kind of Eurythmy of the speech he poured out against his opponents!

It is interesting when you picture it all.—Extreme Left, Left, Middle Party, Czech Club (as it was called) and then Extreme Right, Polish Club. Here stood Hausner, and over on the extreme Left were his opponents. That was where all of them were.

The curious thing was that when, over the question of the occupation of Bosnia, Hausner was on the side of Austria, he received tumultuous applause from these people on the Left. When, later, he spoke about the building of the Arlberg railway, the most vehement opposition came from the same people on the extreme Left. And the situation remained so, in regard to everything he said after that.

Very many warnings and prophetic utterances made by Otto Hausner in the seventies and eighties have, however, since proved true. One often has occasion nowadays to look back in thought to what Otto Hausner used to say.

Now there was one feature that appeared in almost every speech Otto Hausner made, and this, among other less significant details in his life, gave me the impulse to investigate the course of his karma. Otto Hausner could hardly make a speech without uttering a kind of panegyric, as it were in parenthesis, on Switzerland. He was forever holding up Switzerland to Austria as a pattern. Because in Switzerland three nationalities get on well together, are indeed quite exemplary in this respect, he wanted the thirteen nationalities of Austria to take example from Switzerland and live together in the same federal unity as do the three nationalities of Switzerland. Again and again he would come back to this theme. It was quite remarkable.

In Hausner's speeches there was irony, there was humour, there was logic—not always, but very often—and there was the panegyric on Switzerland. It was perfectly clear that this panegyric arose out of a pure feeling of sympathy; this feeling gripped hold of him; he wanted to say these things. And moreover he knew how to shape his speech so that no one, except a group of German-Liberals on the Left, was seriously provoked or offended by it.

It was most interesting to see how, when some Left Liberal member had spoken, Otto Hausner would get up to oppose him, and with his monocled eye never turn his gaze aside for a moment but pour upon the Left Wing a perfectly incredible torrent of abuse and scorn. There were men of importance and standing among them, but he spared none. And there was always breadth of view in what he said; he was one of the most cultured members of the Austrian Reichstag.

The karma of such a man may readily arouse interest. I took my start from this passion of his for returning again and again to praise of Switzerland, and further, from the fact that once in a speech subsequently published as a brochure, German Culture and the German Empire, he collected together in a spirit of impishness and yet at the same time with nothing short of genius, all there was to be said for German culture and the German people and against the German Empire. There was really something grandly prophetic about this speech that was made in the early eighties, scuttling the German Empire as it were, saying all manner of harsh things about it, calling it the wrecker and destroyer of the true being and nature of the Germans. That was the second thing—this singular ‘loving hatred’, if I may put it so, and ‘hating love’ for all that is truly German, and for the German Empire.

And the third thing was the extraordinary interest which made itself manifest when Hausner spoke of the Arlberg Tunnel, of the plan to build the Arlberg railway from Austria to Switzerland and thus unite Middle Europe with the West. Needless to say, here too he introduced his song of praise for Switzerland, for the railway was to run into Switzerland. But when he spoke of this railway—and his speech was well-seasoned, though delivered with perfect delicacy—one really had the feeling: the man is basing it all on tendencies and proclivities he must have acquired in some remarkable way in a former earthly life.

Everyone was talking in those days of the enormous advantages that would accrue to European civilisation from the alliance of Germany with Austria. At that very time Hausner was developing in the Austrian Parliament his idea of the Arlberg railway; he was saying, and naturally all the others were going for him hammer and tongs about it, that the Arlberg railway must be built, because a State as he pictured Austria, uniting thirteen nations after the pattern of Switzerland, must have a choice of allies; when it suits her, Austria has Germany, and when it suits her she must also have a strategic route from Middle Europe to the West, so that she may be able to have France for an ally when she wishes. Naturally, when such an opinion was expressed in the Austria of those times, it received short answer! It was reported that Hausner was ironed out flat! In truth, however, it was a marvellous speech, highly spiced and full of poignancy. And this speech, I would have you note, pointed in the direction of the West.

Holding these three things together in mind, I discovered that the individuality of Otto Hausner had wandered across Europe from West to East at the time when Gallus and Columbanus [Not St. Columba, but a slightly younger Irish monk—St. Columbanus (sometimes called Columba the Younger).] were journeying in the same direction. He set out with men who had been inspired by the Irish initiation, for the purpose of bringing Christianity to those regions. In company with them, his aim was to carry Christianity to the East. On the way, somewhere in the neighbourhood of the Alsace of to-day, he found himself extraordinarily attracted by the relics of ancient Germanic paganism, by the old memories of the gods, the old forms of worship, the figures and statues of the gods that he found in Alsace, and also in Germany and Switzerland. He received all this into his heart and mind in a deeply significant way.

Afterwards there developed in him, on the one hand, a liking for the Germanic nature and, on the other hand a counterforce which came from the feeling that he had gone too far in that past life. He underwent a drastic inner change, an inner metamorphosis, and this showed itself in the wide and comprehensive outlook he possessed in this later incarnation. He could speak of the German people and culture and of the German Empire like one who has once had close and intimate contact with these things, and yet who feels all the time that he ought not to have been influenced by them. He should have been spreading Christianity. He had come into these parts while his duty lay elsewhere.—One could hear it in the very tone of his speeches.—And he wanted to go back and make good again! Hence his passion for Switzerland; hence his passion for the building of the Arlberg railway. Even in outward appearance, he did not really look Polish. Hausner himself used often and often to say that he was not a Pole at all by physical descent but only by civilisation and education, and that ‘Raetian-German’ blood flowed in his veins. He had brought over from an earlier incarnation the tendency to look towards the region where once he had been, whither he had accompanied St. Columbanus and St. Gallus with the resolve to spread Christianity, but where, instead, the old Germanic religion and culture had captured him and held him fast. And so it came about that he did his best, as it were, to be born again in a family as little Polish as possible, far away from the land in which he had lived in his earlier life, far removed from it and yet so that he could look longingly towards it.

These are examples which I wanted to unfold before you to-day in order to show you how strange and remarkable is the path of karmic evolution.—In the next lecture we shall consider the question of how good and evil develop through successive incarnations of human beings, and through the course of history. By studying in this way the more important and significant examples that meet us in history, we shall be able to throw light on relationships belonging more to everyday life.

Erster Vortrag

Lassen Sie mich jetzt an dasjenige anknüpfen, was ich über das Karma in der letzten Zeit hier vorgetragen habe. Ich habe Ihnen gezeigt, wie durch die Geschichte hindurch die seelischen Impulse der Menschen von einem Erdenleben zu dem anderen sich hinüber fortpflanzen, so daß immer von einer früheren Epoche in die spätere Epoche dasjenige geleitet wird, was die Menschen selber hinübertragen.

Ein solcher Gedanke soll nicht nur theoretisch an uns herantreten, ein solcher Gedanke soll unser Empfindungsleben, soll unsere ganze Seele, soll unser Herz ergreifen. Wir sollen fühlen, wie wir, die ja im Grunde genommen so, wie wir hier sind, viele Male innerhalb des Erdendaseins vorhanden waren, jedesmal, wenn wir da vorhanden waren, in unsere Seele aufgenommen haben, was im Umkreise der Zivilisation war. Wir haben das mit unserer Seele verbunden. Wir haben es immer herübergetragen in die nächste Inkarnation, nachdem wir es vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus durchgearbeitet hatten zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, so daß, wenn wir so zurückblicken, wir eigentlich uns erst recht drinnenstehend fühlen in der Gesamtheit der Menschheit. Und damit wir dieses fühlen können, damit wir gewissermaßen mehr übergehen können in den nächsten Vorträgen zu dem, was, ich möchte sagen, uns ganz intim selber angeht und das Hineinstellen in den karmischen Zusammenhang uns nahebringt, damit das geschehen könne, sollten ja konkrete Beispiele vorgeführt werden. Und ich suchte an solchen konkreten Beispielen zu zeigen, wie das, was irgendeine Persönlichkeit in alten Zeiten erlebt, ausgearbeitet hat, bis in die Gegenwart herein wirksam geblieben ist, weil es eben innerhalb des Karmas stand.

Ich habe zum Beispiel hingewiesen auf Harun al Raschid, habe hingewiesen darauf, wie Harun al Raschid, dieser merkwürdige Nachfolger Mohammeds im 8. und im 9. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert, im Mittelpunkte stand eines wunderbaren Kulturlebens, eines Kulturlebens, welches weit alles überflügelte, was gleichzeitig in Europa war. Denn das, was gleichzeitig in Europa war, war eigentlich eine primitive Kultur. Während der Zeit, als in Europa Karl der Große herrschte, floß dort am Hofe Harun al Raschids, im Orient drüben, alles das zusammen, was an asiatischem, von Europa befruchtetem Zivilisationsleben nur zusammenfließen konnte: die Blüte dessen, was die griechische Kultur, was die altorientalischen Kulturen auf allen Gebieten des Lebens hervorgebracht hatten. Architektur, Astronomie, wie sie damals getrieben wurde, Philosophie, Mystik, Künste, Geographie, Dichtung, sie blühten am Hofe Harun al Raschids.

Und Harun al Raschid versammelte um sich eigentlich die besten derjenigen, die in Asien dazumal irgend etwas bedeuteten. Das waren ja zum großen Teile solche, die noch innerhalb der Eingeweihtenschulen, innerhalb der Initiationsschulen ihre Bildung fanden. Und Harun al Raschid hatte in seiner Umgebung eine Persönlichkeit — ich möchte nur diese eine Persönlichkeit erwähnen -, die in jener Zeit — wir stehen ja damit schon im Mittelalter auch für den Orient — zunächst in einer mehr intellektuellen Art aufnehmen konnte, was an wunderbarem Geistesgut von alten Zeiten her in die damals neueren überbracht wurde. Eine Persönlichkeit lebte da am Hofe Harun al Raschids, die in viel älteren Zeiten selbst durch die Initiation durchgegangen war.

Sie haben ja gehört von mir, wie es sehr wohl sein kann, daß wenn irgendeine Persönlichkeit, die für ein Zeitalter als ein Initiierter dasteht, wiederkommt — weil sie den Leib benutzen muß, der ihr eben zur Verfügung stehen kann, benutzen muß die Erziehungsverhältnisse, die ihr dann zur Verfügung stehen -, daß eine solche Eingeweihten-Persönlichkeit dann nicht als ein Eingeweihter erscheint, trotzdem sie alle diejenigen Dinge in ihrer Seele trägt, die sie geschaut hat während ihres Initiationslebens.

So haben wir ja bei Garibaldi kennengelernt, wie er das, was er als einstmaliger irischer Initiierter war, ausgelebt hat als ein Visionär des Willens, hingegeben an die Verhältnisse seiner unmittelbaren Gegenwart. Aber erkennbar ist an ihm, wie er, indem er sich hineinstellt in diese Verhältnisse seiner Umgebung, dennoch in sich andere Impulse trägt, als diejenigen sind, die ein gewöhnlicher Mensch hätte aufnehmen können aus der Erziehung, der Umgebung. Es wirkte eben in Garibaldi der Impuls, der ihm kam von der irischen Einweihung her. Sie war nur verdeckt, und wahrscheinlich, wenn Garibaldi irgendeinen besonderen Schicksalsschlag oder sonst etwas erlebt hätte, das herausgefallen wäre aus dem, was in der damaligen Zeit erlebt werden konnte, dann wäre plötzlich aus seinem Inneren all das in Form von Imaginationen hervorgequollen, was er aus seiner irischen Einweihungszeit in sich trug.

Und so ist es immer gewesen bis heute. Es kann einer ein Eingeweihter sein in einer bestimmten Epoche, und weil er eben in einer späteren Epoche einen Leib benützen muß, der nicht aufnimmt, was die Seele in sich schließt, erscheint der Betreffende in diesem Zeitalter nicht als ein Eingeweihter, sondern es lebt der Einweihungsimpuls in seinen Taten oder in irgendwelchen anderen Verhältnissen. Und so war es auch, daß eine Persönlichkeit, die einmal ein höherer Eingeweihter war, am Hofe Harun al Raschids lebte. Diese Persönlichkeit, trotzdem sie nicht in einer äußerlich offenbaren Weise den Einweihungs-, den Initiationsinhalt in die spätere Zeit, in die Zeit Harun al Raschids hinübertragen konnte, war aber doch eine der glänzendsten Persönlichkeiten innerhalb der orientalischen Kultur im 8., 9. Jahrhundert. Sie war sozusagen der Organisator all desjenigen, was an Wissenschaften und Künsten am Hofe des Harun al Raschid vorhanden war.

Nun haben wir ja schon besprochen, welchen Weg die Individualität des Harun al Raschid durch die Zeiten hindurch genommen hart. Als er durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen war, blieb in ihm der Drang, mehr nach dem Westen zu kommen, dasjenige, was sich an Arabismus nach dem Westen hin ausbreitete, mit eigener Seele nach dem Westen zu tragen. Dann hat ja Harun al Raschid, der hinüberblickte über die Gesamtheit der einzelnen orientalischen Wissens- und Kunstzweige, seine Wiederverkörperung gefunden als der berühmte Baco von Verulam, der Organisator und Reformator des neueren philosophischen und wissenschaftlichen Geisteslebens. Wir sehen das, was Harun al Raschid gewissermaßen um sich herum gesehen hat, aber übersetzt ins Abendländische, in Bacon wiederum auftreten.

Und nun nehmen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, diesen Weg, den von Bagdad aus, von der asiatischen Heimat, Harun al Raschid genommen hat nach England. Von England aus breitete sich ja dann in einer stärkeren, intensiveren Weise, als man gewöhnlich denkt, das, was Bacon gedacht hat in bezug auf die Organisierung der Wissenschaften, über Europa aus (siehe Zeichnung, rot).

Nun kann man etwa sagen: diese beiden Persönlichkeiten, Harun al Raschid und sein großer Ratgeber, die überragende Persönlichkeit, die in früheren Zeiten ein tiefer Eingeweihter war, sie trennten sich; aber sie trennten sich im Grunde genommen zu gemeinsamem Wirken, nachdem sie durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen waren. Harun al Raschid selber, der in glanzvollem Fürstentum gelebt hatte, erwählte den Weg, den ich Ihnen gezeigt habe, bis nach England herein, um als Baco von Verulam in bezug auf die Wissenschaft zu wirken. Die andere Seele, die Seele seines Ratgebers, sie wählte den Weg herüber (grüner Pfeil), um sich innerhalb Mitteleuropas zu begegnen mit dem, was von Bacon ausging. Wenn auch die Zeitalter nicht ganz stimmen, so hat das nichts weiter zu sagen, denn das hat für dasjenige, für das die Zeit selber nicht die tiefe Bedeutung hat, auch nicht solch große Bedeutung; denn manches, was oftmals Jahrhunderte auseinanderliegt, das wirkt zusammen in der späteren Zivilisation.

Der Ratgeber Harun al Raschids, er wählte den Weg durch den Osten Europas hindurch nach Mitteleuropa hinein während seines Lebens zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Und er wurde wiedergeboren in Mitteleuropa, in mitteleuropäisches Geistesleben hinein, als Amos Comenius.

Und so haben wir dieses merkwürdige, große, bedeutsame Schauspiel in dem geschichtlichen Werden, daß sich Harun al Raschid entwickelt, um vom Westen nach Osten eine Kulturströmung einzuleiten, die abstrakt, äußerlich-sinnlich ist; und von Osten herüber hat ja Amos Comenius in Siebenbürgen, in der heutigen Tschechoslowakei, bis nach Deutschland herein seine Tätigkeit entwickelt und ist dann in holländischer Verbannung gewesen. Amos Comenius hat — wer sein Leben verfolgt, wie er es darlebt als der Reformator der neueren Pädagogik für die damalige Zeit und als der Verfasser der sogenannten «Pansophia», kann es sehen -, er hat herübergetragen dasjenige, war er am Hofe Harun al Raschids aus älterer Einweihung heraus entwickelt hat. In der Zeit, als der Bund der «Mährischen Brüder» gegründet wurde, in der Zeit auch, als das Rosenkreuzertum schon einige Jahrhunderte hindurch gewirkt hatte, als die «Chymische Hochzeit» erschien, die «Reformation der ganzen Welt» von Valentin Andreae, da hat Amos Comenius, dieser große, bedeutende Geist des 17. Jahrhunderts, in all das, was da kam angeregt aus derselben Quelle heraus, seine bedeutsamen Anregungen hineingebracht.

Und so sehen Sie drei hintereinander liegende bedeutsame Erdenleben - und an bedeutsamen Erdenleben kann man eben die weniger bedeutenden dann studieren und sich selber hinaufranken zum Begreifen des eigenen Karma -, so sehen Sie diese drei bedeutsamen Inkarnationen hintereinander liegen: Zunächst tief drinnen in Asien dieselbe Individualität, die dann später erscheint als Amos Comenius, in alter Mysterienstätte aufnehmend alle Weisheit einer uralten Zeit Asiens. Sie trägt diese Weisheit hinüber bis zur nächsten Inkarnation, in der sie am Hofe Harun al Raschids lebt, hier sich entwickelnd zum großartigen Organisator dessen, was unter der Obhut und unter dem Fürsorgesinn des Harun al Raschid blüht und gedeiht. Dann erscheint sie wieder, um gewissermaßen dem Baco von Verulam, der der wiederverkörperte Harun al Raschid ist, entgegenzukommen und sich mit ihm im Hinblick auf dasjenige, was beide auszuströmen haben in die europäische Zivilisation, innerhalb dieser europäischen Zivilisation von neuem zu begegnen.

Was ich hier sage, das ist schon von einer großen Bedeutung. Denn verfolgen Sie nur die Briefe, die geschrieben wurden und die den Weg machten - natürlich auf ein kompliziertere Art, als das bei Briefen der Fall ist, die heute geschrieben werden — von Baconianern oder Leuten, die in irgendeiner Weise der Bacon-Kultur nahestanden, zu den Anhängern der Comenius-Schule, der Comenius-Weisheit. Da können Sie in Schreiben und Antwortschreiben verfolgen, was ich Ihnen hier mit ein paar Strichen (siehe Zeichnung) an die Tafel gezeichnet habe.

Dasjenige, was an Briefen von Westen nach Osten und von Osten nach Westen geschrieben wurde, das war das lebendige Zusammenströmen zweier Seelen, die auf diese Art sich begegneten, nachdem sie die Grundlage zu dieser Begegnung gelegt hatten, als sie gemeinsam im Orient drüben im 8. und 9. Jahrhundert wirkten und dann sich zu entgegengesetztem und doch harmonisch zusammenwirkendem Tun wiederum vereinten.

Sehen Sie, so kann Geschichte studiert werden, so sehen wir die lebendigen Menschenkräfte in die Geschichte hineinwirken!

Oder nehmen wir einen anderen Fall. Es ergab sich mir aus ganz besonderen Verhältnissen heraus, daß sozusagen der Blick auf gewisse Ereignisse hingelenkt wurde, die, wir würden heute sagen, im Nordosten Frankreichs sich abspielten, aber sich abspielten auch im 8., 9. Jahrhundert, etwas später als die Zeit ist, von der ich jetzt gesprochen habe. Es spielten sich da besondere Ereignisse ab. Es war ja eine Zeit, in der noch nicht die großen Staatenbildungen da waren, in der deshalb dasjenige, was geschah, mehr innerhalb kleinerer Kreise der Menschheit geschah.

Da hatte denn eine Persönlichkeit von energischem Charakter einen gewissen großen Besitz eben in dem Gebiet, das wir heute den Nordosten Frankreichs nennen würden. Dieser Mann verwaltete den Besitz in einer außerordentlich geordneten Weise, in einer für die damalige Zeit außerordentlich systematischen Weise, möchte ich sagen. Er wußte, was er wollte, und war eine merkwürdige Mischung von einem zielbewußten Menschen und einer Abenteurernatur, so daß er mit mehr oder weniger Erfolg kleine Kriegszüge machte von seinem Eigentum aus, mit Leuten, die sich, wie das ja dazumal üblich war, als Krieger angezogen hatten. Es waren das kleine Heerhaufen, mit denen zog man aus und suchte das oder jenes zu erbeuten.

Mit einer Schar solcher Krieger zog der Betreffende von dem Nordosten Frankreichs aus. Und die Sache machte sich so, daß eine andere Persönlichkeit, etwas weniger Abenteuer als er selber, aber energisch, während der Abwesenheit des Eigentümers des Landgutes — heute erscheint das paradox, dazumal konnte eben so etwas geschehen - sich des Landgutes und des ganzen Besitztums bemächtigte. Als der Betreffende nach Hause kam - er war alleinstehend -, fand er, daß ein anderer Besitzer sich seines Landgutes bemächtigt hatte. Und die Verhältnisse entwickelten sich so, daß in der Tat der Betreffende nicht aufkam gegen den jetzigen Besitzer. Der war der Mächtigere, hatte mehr Mannen, hatte mehr Krieger um sich. Er kam gegen ihn nicht auf.

Nun waren die Dinge damals nicht so, daß man etwa, wenn man in seiner Heimat nicht fortkam, gleich in fremde Gegenden zog. Gewiß, diese Persönlichkeit war ja ein Abenteurer; aber das ergab sich doch nicht wiederum so rasch, er hatte nicht die Möglichkeit dazu, so daß der Betreffende mit einer Schar von Anhängern sogar eine Art Leibeigener wurde an seinem eigenen früheren Besitzerhof. Er mußte nun wie ein Leibeigener arbeiten mit einer Schar von denen, die mit ihm auf Abenteuer ausgezogen waren, während ihm sein Eigentum entrissen worden war.

Da geschah es, daß bei all den Leuten, die da Leibeigene geworden waren, während sie früher die Herren waren, eine ganz besonders, ich möchte sagen, dem Herrschaftsprinzip abträgliche Gesinnung entstand. Und es brannten in diesen Gegenden, die bewaldet waren, in mancher Nacht die Feuer da, wo man zusammenkam und wo man allerlei Verschwörungen besprach gegen diejenigen, welche sich des Eigentums bemächtigt hatten.

Es war einfach so, daß der Betreffende, der vom großen Besitzer mehr oder weniger zum Leibeigenen, zum Sklaven geworden war, sein übriges Leben nunmehr damit ausfüllte, abgesehen von dem, was er arbeiten mußte, Pläne zu schmieden, wie man etwa wiederum zu Besitz und Eigentum kommen könne. Man haßte denjenigen, der sich des Eigentums bemächtigt hatte.

Nun, sehen Sie, diese beiden Persönlichkeiten von damals gingen in ihren Individualitäten durch die Pforte des Todes, machten in der geistigen Welt zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt alles das mit, was seit jener Zeit eben mitgemacht werden konnte, und erschienen im 19. Jahrhundert wiederum. Derjenige, der Haus und Hof verloren hatte und zu einer Art von leibeigenem Sklaven geworden war, erschien als Karl Marx, der Begründer des neueren Sozialismus. Und der andere, der ihm dazumal seinen Gutshof abgenommen hatte, erschien als sein Freund Engels. Was sie dazumal miteinander auszumachen hatten, das prägte sich um während des langen Weges zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt in den Drang, das, was sie einander zugefügt hatten, auszugleichen.

Und lesen Sie, was sich zwischen Marx und Engels abgespielt hat, lesen Sie all das, was die besondere Geisteskonfiguration des Karl Marx ist, und halten Sie das damit zusammen, daß im 8., 9. Jahrhundert dieselben Individualitäten ja vorhanden waren, so wie ich es Ihnen erzählt habe. Dann wird Ihnen, ich möchte sagen, auf jeden Satz bei Marx und Engels ein neues Licht fallen, und Sie werden nicht in die Gefahr kommen, in abstrakter Art zu sagen, das eine ist durch dieses in der Geschichte verursacht, das andere ist durch jenes verursacht, sondern Sie sehen die Menschen, die etwas herübertragen in eine andere Zeit, das allerdings ganz anders erscheint, aber doch wiederum eine gewisse Ähnlichkeit mit dem früheren hat.

Was glauben Sie: im 8., 9. Jahrhundert, da hat man sich an Waldfeuern zusammengesetzt, da hat man in anderer Weise gesprochen, als man im 19. Jahrhundert zu sprechen Veranlassung hatte, wo Hegel gewirkt hatte, wo alles mit Dialektik abgemacht wurde. Aber versuchen Sie einmal sich vorzustellen den Wald im Nordosten Frankreichs im 9. Jahrhundert: da sitzen die Verschwörer, die Flucher, die Schimpfer in ihrer damaligen Sprache. Und übersetzen Sie sich das ins Mathematisch-Dialektische des 19. Jahrhunderts, dann haben Sie dasjenige, was bei Marx und Engels steht.

Das sind die Dinge, die von dem bloß Sensationellen, das man leicht verbinden kann mit Ideen über konkrete Reinkarnationsverhältnisse, herausführen und in das Verständnis des geschichtlichen Lebens hineinführen. Und man bewahrt sich am besten vor Irrtümern, wenn man nicht auf das Sensationelle ausgeht, wenn man nicht nur wissen will: Wie ist es mit der Wiederverkörperung? — sondern wenn man alles das, was im geschichtlichen Werden mit Wohl und Wehe, mit Leid und Freude der Menschheit zusammenhängt, aus den wiederkehrenden Erdenleben der einzelnen Menschen zu begreifen versucht.

So war mir immer in der Zeit, als ich noch in Österreich lebte, trotzdem ich in Österreich innerhalb des Deutschtums stand, eine Persönlichkeit besonders interessant, die ein polnischer Reichsratabgeordneter war. Ich glaube, viele von Ihnen werden sich erinnern, daß ich des öfteren von dem österreichisch-polnischen Reichsratsabgeordneten Otto Hausner, der in den siebziger Jahren ganz besonders wirkte, gesprochen habe. Diejenigen, die länger schon hier sind, werden sich erinnern. Und mir steht wirklich, seitdem ich im österreichischen Reichsrat Ende der siebziger Jahre, Anfang der achtziger Jahre immer wieder und wiederum Otto Hausner gehört und gesehen habe, mir steht dieser merkwürdige Mann immer vor Augen: Er hat in dem einen Auge ein Monokel; mit dem anderen Auge blickte er grundgescheit, aber so, daß er die Schwächen der Gegner mit dem anderen Auge, das durchs Monokel guckte, erlauerte. Während er redete, prüfte er dann, ob der Pfeil gesessen hat.

Dabei konnte er, der einen ganz merkwürdigen Schnurrbart hatte ich habe das in meiner Lebensbeschreibung nicht bis in diese Einzelheiten ausführen wollen —, mit diesem Schnurrbart in merkwürdiger Art das, was er sagte, begleiten, so daß dieser Schnurrbart eine ganz merkwürdig bewegliche Eurythmie dessen war, was er dem gegnerischen Abgeordneten auf die beschriebene Weise ins Gesicht schleuderte.

Es war nun ein interessantes Bild. Stellen Sie sich vor: äußerste Linke, Linke, Mittelpartei, Tschechischer Klub, dann äußerste Rechte, Polenklub; hier stand Hausner, und hier waren alle seine Gegner auf der äußersten Linken. Da waren sie alle; und das Kurioseste war, daß, als Hausner gelegentlich der Frage der bosnischen Okkupation für Österreich war, er einen stürmischen Beifall von diesen Leuten da auf der Linken hatte. Als er später über den Bau der Arlbergbahn sprach, da hatte er einen absoluten Widerspruch bei denselben Leuten auf der äußersten Linken. Und dieser Widerspruch blieb dann bei alldem, was er später zum Ausdruck brachte.

Aber gar manches von dem, was gerade Otto Hausner in den siebziger und achtziger Jahren als Warner, als Prophet gesagt hat, das hat sich bis in unsere Tage herein wörtlich erfüllt. Gerade heute hat man Veranlassung, oftmals zurückzudenken an das, was Otto Hausner damals geredet hat.

Nun, eines trat bei Otto Hausner fast bei jeder Rede hervor, und das wurde für mich, neben einigen anderen, wiederum nicht sehr bedeutenden Dingen des Hausner-Lebens, der Impuls, den karmischen Gang bei dieser Persönlichkeit zu verfolgen.

Otto Hausner konnte kaum eine Rede halten, ohne daß er so in Parenthesen eine Art Panegyrikus auf die Schweiz hielt. Immer stellte er die Schweiz Österreich als Muster hin. Weil in der Schweiz drei Nationalitäten sich gut vertragen, in Beziehung auf das Vertragen mustergültig sind, wollte er auch, daß sich die dreizehn österreichischen Nationalitäten die Schweiz zum Muster nehmen und diese dreizehn sich in ähnlicher Weise, föderalistischer Weise vertragen würden wie diese drei Nationalitäten in der Schweiz. Er kam immer wieder darauf zurück, es war merkwürdig. Die Hausnerschen Reden hatten Ironie, hatten Humor, auch innere Logik; nicht immer, aber oftmals wieder kam der Panegyrikus auf die Schweiz. Da konnte man immer sehen: das Entwickeln einer reinen Sympathie; es sticht ihn, er will das sagen. Dann wußte er seine Reden so auszurichten, daß eigentlich weiter niemand außer einer Gruppe von links, von liberalen Abgeordneten - aber diese schrecklich! - sich ärgerte. Es war sehr interessant zu sehen, wenn so irgendein linksliberaler Abgeordneter geredet hatte, wie dann Otto Hausner sich zur Gegenrede erhob und mit seinem bemonokelten Auge keinen Blick von ihm abwandte, aber die unglaublichsten Schnödigkeiten hinüberrollen ließ nach der Linken. Es waren bedeutende Männer da, aber vor keinem machte er halt. Und seine Gesichtspunkte waren im Grunde genommen immer große; er war einer der gebildesten Männer des österreichischen Reichsrats.

Das Karma eines solchen Menschen kann einen schon interessieren. Ich ging nun davon aus, daß er so diese Nebenleidenschaft hatte, immer wiederum auf eine Lobrede auf die Schweiz zurückzukommen, und dann, daß er einmal in einer Rede über «Deutschtum und Deutsches Reich», die auch als Broschüre erschienen ist, mit einer großen Nichtsnutzigkeit, aber mit Genialität alles zusammengestellt hatte, was sich für das Deutschtum und gegen das Deutsche Reich von dazumal sagen ließ. Es ist wirklich auch da etwas grandios Prophetisches darinnen in dieser Rede, die im Beginn der achtziger Jahre gehalten worden ist, in der sozusagen das Deutsche Reich in den Grund gebohrt wird, ihm alles Schlechte nachgesagt wird, in der es der Ruinierer des deutschen Wesens genannt wird, Und bewiesen wurden diese Sätze. Das war das zweite, sein eigentümlicher, ich möchte sagen, liebender Haß und seine hassende Liebe für Deutschtum und Deutsches Reich.

Und das dritte war, wie Otto Hausner wirklich mit einer ungeheuren Lebendigkeit damals sprach, als der Arlbergtunnel, die Arlbergbahn gebaut werden sollte, die Bahn, die von Österreich herüber nach der Schweiz geht und die also Mitteleuropa mit dem Westen verbinden sollte. Natürlich brachte er auch damals sein Loblied auf die Schweiz, denn die Bahn sollte ja in die Schweiz hineinführen. Aber man hatte, als er diese Rede hielt, die ja gesalzen und gepfeffert war, aber in einer wirklich delikaten Weise, man hatte da wirklich das Gefühl: der Mann, der weiß von Dingen auszugehen, die auf eine merkwürdige Weise in einem früheren Erdenleben in ihm veranlagt sein müssen.

Es war ja dazumal gerade überall die Rede von dem grandiosen Vorteil, den die europäische Zivilisation von dem deutsch-österreichischen Bündnis haben werde. Otto Hausner entwickelte damals im österreichischen Parlamente - worüber natürlich die anderen alle ihn furchtbar niederschmetterten — die Idee, die Arlbergbahn müsse gebaut werden, weil ein Staat, wie er sich Österreich vorstellte, nach dem Muster der Schweiz, dreizehn Nationen vereinigend, die Wahl haben müsse, sich seine Bundesgenossen zu suchen; und wenn es ihm paßt, hat er Deutschland zum Bundesgenossen, und wenn es ihm paßt, muß er einen strategischen Weg von Mitteleuropa nach dem Westen haben, um Frankreich zum Bundesgenossen haben zu können. Natürlich, als in dem damaligen Österreich das ausgesprochen wurde, da wurde er, wie man in Österreich sagte, schön niedergebügelt. Aber es war wirklich eine in herrlichster Weise mit allen Gewürzen durchsetzte Rede. Diese Rede, die gab die Direktion nach dem Westen hinüber.

Und indem ich diese Dinge zusammenhielt, fand ich dann, wie herüberwanderte von Westen nach Osten durch die Nordschweiz, in der Zeit, als Gallus, Columban auch herübergezogen sind, die Individualität des Otto Hausner. Das Christentum sollte er bringen. Er zog mit denjenigen Menschen, die von irischen Einweihungen angeregt worden waren, herüber. Er sollte mit ihnen das Christentum herüberverpflanzen. Auf dem Wege, ungefähr in der Gegend des heutigen Elsaß, wurde er ungeheuer angezogen von den Altertümern des germanischen Heidenwesens, angezogen von alledem, was im Elsaß, was in alemannischen Gegenden, was in der Schweiz hier an alten Göttererinnerungen, Götterverehrungen, Götterbildnissen, Götterstatuen vorhanden war. Das nahm er in tiefbedeutsamer Weise auf.

Und da entwickelte sich in ihm etwas, was man auf der einen Seite Hinneigung zum germanischen Wesen nennen kann, auf der anderen Seite aber wiederum entwickelte sich die Gegenkraft dazu: die Empfindung, daß er damals zu weit gegangen wäre. Und das, was er in einer gewaltigen inneren Umwandlung, in einer gewaltigen inneren Metamorphose erlebt hat, das erschien dann in diesen umfassenden Gesichtspunkten. Er konnte über Deutschtum und Deutsches Reich reden wie einer, der einmal bei all diesen Dingen intim dabeigewesen ist, der aber doch sie eigentlich aufgenommen hat, ohne daß er es sollte. Er hätte ja das Christentum verbreiten sollen. Er war sozusagen, ohne daß er es sollte, hineingekommen in die Gegenden — das hörte man selbst seinen Redewendungen an -, und er wollte wieder zurück, um diese Dinge gutzumachen. Daher seine Leidenschaft für die Schweiz, daher seine Leidenschaft für den Bau der Arlbergbahn. Man kann schon sagen, selbst in der äußeren Gestalt, wenn Sie sich dieses anschauen, drückte sich das aus - er sah eigentlich nicht polnisch aus. Und Hausner sagte auch bei jeder Gelegenheit, daß er ja nicht einmal der physischen Abstammung nach ein Pole sei, sondern nur der Zivilisation und Erziehung nach, daß «rätisch-alemannische» Blutkügelchen, wie er sich ausdrückte, in seinen Adern rollten. Er hatte aber aus einer früheren Inkarnation sich das hinübergenommen, daß er immer nach der Gegend schaute, wo er einmal gewesen war, in die er mit dem Columban und dem heiligen Gallus gezogen war, wo er das Christentum verbreiten wollte, aber eigentlich vom Germanentum festgehalten worden war. So machte er sozusagen den Versuch, in einer möglichst wenig polnischen Familie wiederum geboren zu werden, und fernzustehen, aber doch zu gleicher Zeit mit Sehnsucht gegenüberzustehen demjenigen, in dem er früher ganz drinnengestanden hatte.

Sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, das sind Beispiele, die ich Ihnen zunächst einmal heute entwickeln wollte, um Sie darauf aufmerksam zu machen, wie merkwürdig der Gang der karmischen Entwickelung ist. Wir werden nun das nächste Mal mehr eingehen auf die Art und Weise, wie das Gute und das Böse sich entwickelt durch die Inkarnationen der Menschen hindurch und durch das geschichtliche Leben. Wir werden auf diese Weise aber in der Lage sein, gerade von den bedeutenderen Beispielen, die in der Geschichte uns entgegentreten, ein Licht verbreiten zu können über mehr alltägliche Verhältnisse.

First Lecture

Let me now follow on from what I presented here last time about karma. I have shown you how, throughout history, the spiritual impulses of human beings propagate themselves from one life on earth to another, so that what human beings themselves carry over from an earlier epoch to a later epoch is always passed on.

Such a thought should not only approach us theoretically, such a thought should seize our emotional life, our whole soul, our heart. We should feel how we, who have basically been here many times in our earthly existence, have absorbed into our souls what was around civilization each time we were there. We have connected this with our soul. We have always carried it over into the next incarnation, after we had worked through it from the spiritual point of view between death and a new birth, so that when we look back in this way, we actually feel that we are really standing within the totality of humanity. And so that we can feel this, so that in the next lectures we can, so to speak, move on to what, I would like to say, concerns us intimately and brings us closer to the karmic context, so that this can happen, concrete examples should be presented. And I tried to use such concrete examples to show how what some personality experienced and worked out in ancient times has remained effective right up to the present day because it was within karma.

For example, I have referred to Harun al Rashid, I have pointed out how Harun al Rashid, this strange successor of Mohammed in the 8th and 9th centuries after Christ, stood at the center of a wonderful cultural life, a cultural life that far surpassed everything that was going on in Europe at the same time. For what was in Europe at the same time was actually a primitive culture. During the time when Charlemagne reigned in Europe, at the court of Harun al Rashid, in the Orient over there, everything that could only flow together in the life of Asian civilization that had been fertilized by Europe flowed together: the flowering of what Greek culture and the ancient Oriental cultures had produced in all areas of life. Architecture, astronomy as it was practiced at the time, philosophy, mysticism, the arts, geography and poetry all flourished at the court of Harun al Rashid.

And Harun al Rashid actually gathered around him the best of those who were of any significance in Asia at the time. For the most part, they were those who had been educated in the schools of initiation. And Harun al Rashid had a personality in his entourage - I would like to mention just this one personality - who at that time - we are already in the Middle Ages for the Orient - was initially able to absorb in a more intellectual way the wonderful spiritual knowledge that was brought from ancient times to the then newer ones. A personality lived at the court of Harun al Rashid who had gone through initiation himself in much older times.

You have heard from me how it may very well be that when some personality who stands there as an initiate for an age returns - because he must use the body that is available to him, must use the educational conditions that are then available to him - that such an initiate-personality then does not appear as an initiate, even though he carries in his soul all those things that he has seen during his initiatory life.

So we have seen in Garibaldi how he lived out what he was as a former Irish initiate as a visionary of the will, devoted to the circumstances of his immediate presence. But what is recognizable about him is how, by placing himself in these conditions of his surroundings, he nevertheless carries within himself impulses other than those that an ordinary person could have absorbed from his upbringing and environment. The impulse that came to him from the Irish initiation was at work in Garibaldi. It was only concealed, and it is likely that if Garibaldi had experienced some particular stroke of fate or something else that stood out from what could be experienced at that time, then suddenly everything that he carried within him from his Irish initiation would have burst forth from within him in the form of imaginations.

And so it has always been until today. One can be an initiate in a certain epoch, and because in a later epoch he has to use a body that does not absorb what the soul has enclosed within itself, the person concerned does not appear as an initiate in this age, but the initiatory impulse lives in his deeds or in some other circumstances. And so it was that a personality who was once a higher initiate lived at the court of Harun al Rashid. This personality, although he could not carry over the content of initiation into the later period, into the time of Harun al Rashid, in an outwardly obvious way, was nevertheless one of the most brilliant personalities within oriental culture in the 8th and 9th centuries. She was, so to speak, the organizer of all the sciences and arts at the court of Harun al Rashid.

Now we have already discussed the hard path that the individuality of Harun al Rashid took through the ages. When he had passed through the gate of death, the urge remained in him to come more to the West, to carry the Arabism that was spreading to the West to the West with his own soul. Then Harun al Rashid, who looked over the entirety of the individual oriental branches of knowledge and art, found his reincarnation as the famous Baco of Verulam, the organizer and reformer of the newer philosophical and scientific intellectual life. We see what Harun al Rashid saw around him, so to speak, but translated into the Western world, appearing again in Bacon.

And now, my dear friends, take the path that Harun al Rashid took from Baghdad, from his Asian homeland, to England. It was from England that what Bacon had in mind with regard to the organization of the sciences spread across Europe in a stronger, more intensive way than is usually thought (see drawing, red).

Now one can say roughly: these two personalities, Harun al Raschid and his great advisor, the outstanding personality who was a deep initiate in earlier times, they separated; but they basically separated to work together after they had passed through the gate of death. Harun al Rashid himself, who had lived in splendorous princedom, chose the path I have shown you, all the way into England, to act as Baco of Verulam in relation to science. The other soul, the soul of his advisor, chose the path across (green arrow) to meet within Central Europe with that which emanated from Bacon. Even if the ages are not quite right, this has nothing more to say, because it does not have such great significance for that for which time itself does not have such deep meaning; for many things that are often centuries apart work together in later civilization.

The advisor of Harun al Rashid, he chose the path through Eastern Europe to Central Europe during his life between death and a new birth. And he was reborn in Central Europe, into Central European intellectual life, as Amos Comenius.

And so we have this strange, great, significant spectacle in the historical development that Harun al Raschid developed in order to initiate a cultural current from the West to the East, which is abstract, external-sensual; and from the East Amos Comenius developed his activity in Transylvania, in today's Czechoslovakia, as far as Germany and was then in Dutch exile. Amos Comenius - whoever follows his life as he lived it as the reformer of the newer pedagogy for the time and as the author of the so-called “Pansophia” can see it - carried over what he had developed at the court of Harun al Raschid from older initiations. At the time when the League of Moravian Brethren was founded, at the time when Rosicrucianism had already been at work for several centuries, when the “Chymical Wedding” appeared, the “Reformation of the Whole World” by Valentin Andreae, Amos Comenius, this great, important spirit of the 17th century, brought his significant impulses into all that came from the same source.

And so you see three significant earth lives lying one behind the other - and in significant earth lives you can then study the less significant ones and work your way up to understanding your own karma - so you see these three significant incarnations lying one behind the other: First, deep within Asia, the same individuality that later appears as Amos Comenius, absorbing all the wisdom of an ancient time in Asia in an ancient place of mystery. It carries this wisdom over to the next incarnation, in which it lives at the court of Harun al Rashid, where it develops into the great organizer of all that flourishes and thrives under the care and benevolence of Harun al Rashid. Then she reappears to meet Baco of Verulam, who is the re-embodied Harun al Raschid, and to meet him anew within this European civilization with regard to what both have to emanate into European civilization.

What I am saying here is already of great significance. For just follow the letters that were written and that made their way - naturally in a more complicated way than is the case with letters that are written today - from Baconians or people who were in some way close to the Baconian culture to the followers of the Comenius school, the Comenius wisdom. You can follow in letters and replies what I have drawn here on the board with a few strokes (see drawing).

The letters that were written from West to East and from East to West were the living confluence of two souls who met in this way after they had laid the foundation for this encounter when they worked together in the Orient over there in the 8th and 9th centuries and then reunited in opposing and yet harmoniously interacting activities.

You see, this is how history can be studied, this is how we see the living forces of man working into history!

Or let's take another case. It came to me from very special circumstances that my attention was drawn, so to speak, to certain events that took place, we would say today, in the north-east of France, but which also took place in the 8th, 9th century, somewhat later than the time I have now spoken of. Special events took place there. It was a time when the great states had not yet been formed, so what was happening was taking place more within smaller circles of humanity.

Then a person of energetic character had a certain large estate in what we would today call the north-east of France. This man managed the property in an extraordinarily orderly way, in an extraordinarily systematic way for the time, I would say. He knew what he wanted and was a strange mixture of a purposeful man and an adventurous nature, so that he made small military campaigns from his property with more or less success, with people who, as was customary in those days, had dressed themselves as warriors. They were small bands of soldiers, with whom they went out and sought to capture this or that.

With a band of such warriors, the man in question set out from the north-east of France. And it so happened that another personage, somewhat less adventurous than himself, but energetic, seized the estate and the whole property during the absence of the owner of the estate - today this seems paradoxical, but in those days such a thing could happen. When the person concerned came home - he was single - he found that another owner had seized his estate. And the circumstances developed in such a way that the person in question could not stand up to the current owner. He was the more powerful, had more men, had more warriors around him. He could not stand up to him.

Now things weren't like that in those days, when you couldn't get on in your homeland, you immediately moved to foreign lands. Certainly, this personage was an adventurer; but that did not come about so quickly, he did not have the opportunity, so that the person concerned, with a band of followers, even became a kind of serf in his own former owner's court. He now had to work like a serf with a band of those who had gone out with him on adventures while his property had been snatched from him.

Then it happened that among all the people who had become serfs, whereas they had previously been lords, a particularly, I might say, inimical attitude arose. And in these wooded areas, fires burned many a night where people gathered and discussed all kinds of conspiracies against those who had seized their property.

It was simply that the person concerned, who had more or less become a serf, a slave, from the great owner, now filled the rest of his life, apart from the work he had to do, with making plans as to how to regain possession and ownership. They hated the one who had seized their property.

Now, you see, these two personalities of that time went through the gate of death in their individualities, went through everything in the spiritual world between death and a new birth that could be experienced since that time, and reappeared in the 19th century. The one who had lost house and home and had become a kind of serf slave appeared as Karl Marx, the founder of modern socialism. And the other, who had taken his estate from him, appeared as his friend Engels. What they had to make up with each other at the time was transformed during the long journey between death and a new birth into the urge to make up for what they had inflicted on each other.

And read what took place between Marx and Engels, read all that is the particular mental configuration of Karl Marx, and keep it together with the fact that the same individualities were present in the 8th, 9th century, just as I have told you. Then, I would say, a new light will fall on every sentence in Marx and Engels, and you will not run the risk of saying in an abstract way that one is caused by this in history, the other is caused by that, but you will see people who carry something over into another time, which admittedly appears quite different, but again has a certain similarity with the earlier one.

What do you think: in the 8th, 9th century, people sat together around forest fires, people spoke in a different way than they had reason to speak in the 19th century, when Hegel was at work, when everything was settled with dialectics. But try to imagine the forest in north-eastern France in the 9th century: there sit the conspirators, the cursers, the scolds in their language of the time. And translate that into the mathematical-dialectical language of the 19th century and you have what Marx and Engels wrote.

These are the things that lead away from the merely sensational, which can easily be combined with ideas about concrete reincarnation relationships, and into the understanding of historical life. And the best way to protect oneself from error is not to focus on the sensational, not just to ask: What about reincarnation? - but if you try to understand everything that is connected with the weal and woe, suffering and joy of humanity in historical development from the recurring earthly lives of individual people.

So, when I was still living in Austria, even though I was part of the German community in Austria, I was always particularly interested in a personality who was a Polish member of the Imperial Council. I think many of you will remember that I have often spoken of the Austrian-Polish member of the Reichsrat, Otto Hausner, who was particularly active in the 1970s. Those of you who have been here longer will remember. And ever since I heard and saw Otto Hausner again and again in the Austrian Reichsrat in the late seventies and early eighties, this strange man has always stood before my eyes: he had a monocle in one eye; with the other eye, he looked with a clear head, but in such a way that he could see the weaknesses of his opponents with the other eye, which looked through the monocle. While he talked, he then checked whether the arrow had hit the mark.

At the same time, he, who had a very strange moustache - I didn't want to go into these details in my biography - was able to accompany what he said with this moustache in a strange way, so that this moustache was a very strangely moving eurythmy of what he hurled into the opposing deputy's face in the manner described.

It was an interesting picture. Imagine: far left, left, center party, Czech Club, then far right, Polish Club; here was Hausner, and here were all his opponents on the far left. They were all there; and the most curious thing was that when Hausner was in favor of Austria on the question of the Bosnian occupation, he had a stormy applause from these people on the left. Later, when he spoke about the construction of the Arlberg railroad, he met with absolute opposition from the same people on the far left. And this contradiction remained with everything he later expressed.

But quite a lot of what Otto Hausner said in the seventies and eighties as a warner, as a prophet, has been literally fulfilled to this day. Today in particular, we often have cause to think back to what Otto Hausner said back then.

Well, one thing stood out in almost every speech by Otto Hausner, and that became for me, in addition to a few other, again not very significant things in Hausner's life, the impulse to follow the karmic course of this personality.

Otto Hausner could hardly give a speech without delivering a kind of panegyric on Switzerland in parentheses. He always presented Switzerland as a model for Austria. Because in Switzerland three nationalities get along well, are exemplary in terms of getting along, he also wanted the thirteen Austrian nationalities to take Switzerland as a model and for these thirteen to get along in a similar, federalist way as these three nationalities in Switzerland. He kept coming back to this, it was strange. Hausner's speeches had irony, had humor, also inner logic; not always, but often the panegyric came back to Switzerland. You could always see the development of pure sympathy; it stung him, he wanted to say that. Then he knew how to direct his speeches in such a way that no one except a group on the left, of liberal deputies - but these terrible ones! - were annoyed. It was very interesting to see how Otto Hausner, when some left-wing liberal member of parliament had spoken, would rise to speak against him, not taking his monocled eyes off him, but letting the most incredible snottiness roll over to the left. There were important men there, but he stopped at none of them. And his points of view were basically always great; he was one of the most educated men in the Austrian Imperial Council.

The karma of such a person can be interesting. I now assumed that he had this side passion of always coming back to a speech in praise of Switzerland, and then that he had once, in a speech on “Germanness and the German Reich”, which was also published as a brochure, compiled with great uselessness, but with genius, everything that could be said for Germanness and against the German Reich of that time. There really is something grandly prophetic in this speech, which was given at the beginning of the 1980s, in which the German Reich is, so to speak, drilled to the ground, accused of everything bad, in which it is called the ruiner of the German essence, and these sentences were proven. That was the second, his peculiar, I would say, loving hatred and his hating love for Germanness and the German Reich.

And the third was how Otto Hausner really spoke with tremendous vivacity at the time when the Arlberg Tunnel, the Arlberg Railway, was to be built, the railroad that would run from Austria to Switzerland and connect Central Europe with the West. Of course, he also sang Switzerland's praises at the time, as the railroad was to run into Switzerland. But when he gave this speech, which was salty and peppery, but in a really delicate way, you really had the feeling that this man knew how to start from things that must have been strangely predisposed in him in a previous life on earth.

At that time, there was talk everywhere of the great advantage that European civilization would gain from the German-Austrian alliance. At that time Otto Hausner developed the idea in the Austrian parliament - about which, of course, the others all shattered him terribly - that the Arlberg Railway must be built because a state, as he imagined Austria to be, uniting thirteen nations on the model of Switzerland, must have the choice of choosing its allies; and if it suits it, it has Germany as an ally, and if it suits it, it must have a strategic route from Central Europe to the West in order to be able to have France as an ally. Of course, when this was said in Austria at the time, he was, as they said in Austria, nicely beaten down. But it really was a speech that was wonderfully spiced up with all the spices. The management passed this speech on to the West.

And by keeping these things together, I then found the individuality of Otto Hausner, as he migrated from west to east through northern Switzerland, at the time when Gallus and Columban also migrated here. He was to bring Christianity. He came over with those people who had been inspired by Irish initiations. He was to transplant Christianity with them. On the way, approximately in the area of today's Alsace, he was enormously attracted by the antiquities of Germanic paganism, attracted by everything that existed here in Alsace, in Alemannic regions, in Switzerland, in the form of old memories of the gods, worship of the gods, images of the gods, statues of the gods. He absorbed this in a deeply meaningful way.

And something developed in him that on the one hand could be called an inclination towards the Germanic essence, but on the other hand a counterforce developed: the feeling that he had gone too far back then. And what he experienced in a tremendous inner transformation, in a tremendous inner metamorphosis, then appeared in these comprehensive points of view. He could talk about Germanness and the German Reich like someone who had once been intimately involved in all these things, but who had actually absorbed them without being supposed to. He should have spread Christianity. He had, so to speak, entered these regions without being supposed to - you could hear that even in his phrases - and he wanted to go back to make up for it. Hence his passion for Switzerland, hence his passion for the construction of the Arlberg Railway. You could say that even his outward appearance, if you look at it, expressed this - he didn't actually look Polish. And Hausner also said at every opportunity that he was not even a Pole by physical descent, but only by civilization and upbringing, that “Rhaetian-Alemannic” blood globules, as he put it, rolled through his veins. However, he had carried over from an earlier incarnation that he always looked to the region where he had once been, where he had moved with Columban and St. Gallus, where he had wanted to spread Christianity but had actually been held down by Germanism. So he attempted, so to speak, to be born again into a family that was as little Polish as possible, and to stand far away, but at the same time to stand with longing towards the one in which he had once stood completely inside.

You see, my dear friends, these are examples that I wanted to develop for you today in order to draw your attention to how strange the course of karmic development is. Next time we will go into more detail about the way in which good and evil develop through the incarnations of human beings and through historical life. In this way, however, we will be able to shed light on more everyday circumstances, especially from the more significant examples that confront us in history.