Karmic Relationships Volume III

GA 237

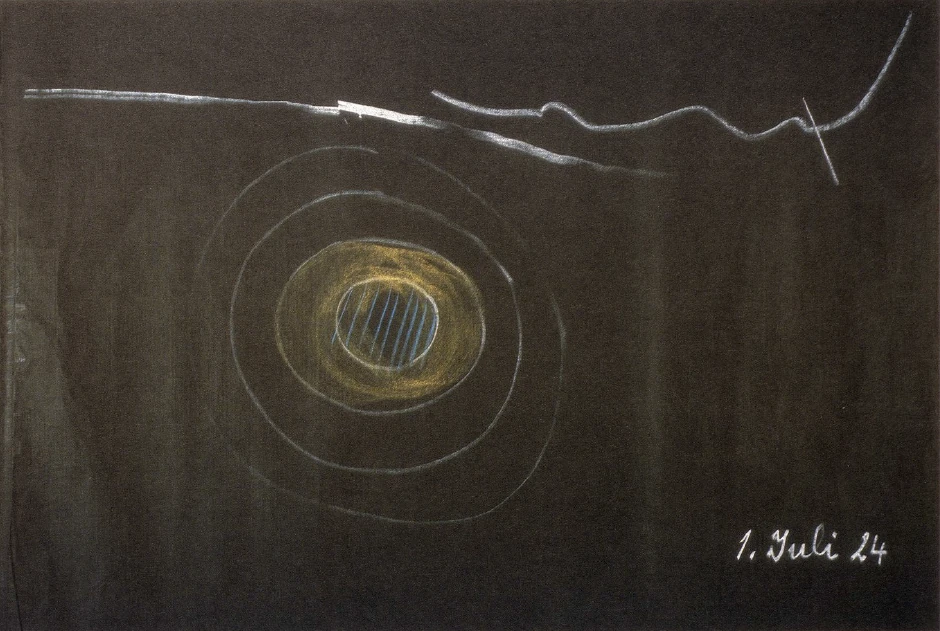

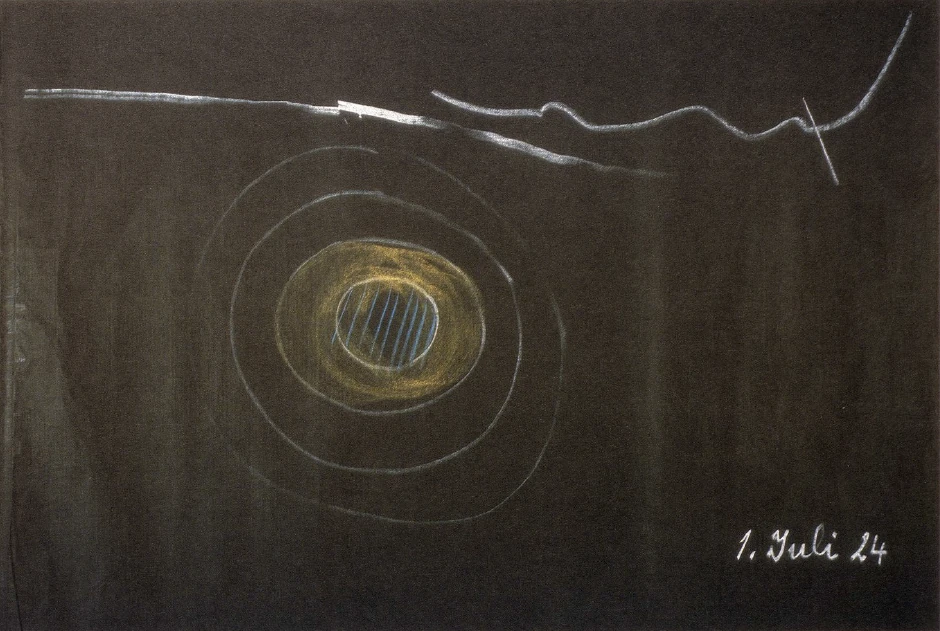

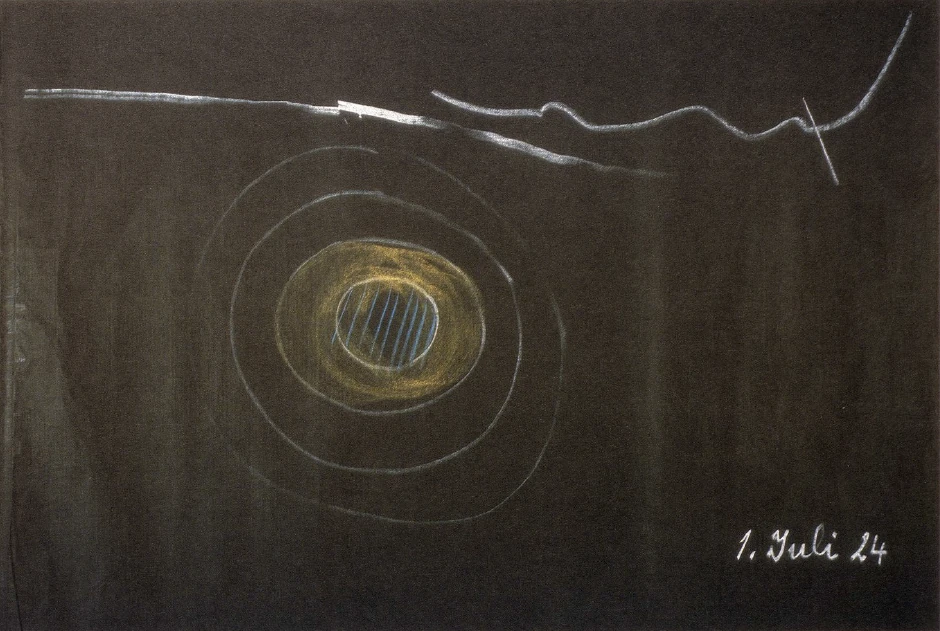

1 July 1924, Dornach

Translated by Frank Thomas Smith

Lecture I

For those of you who are able to be here today I wish to give a kind of interlude in the studies we have been pursuing for some time. What I shall say today will serve to illustrate and explain many questions that may emerge out of the subjects we have treated until now. At the same time it will help to throw light on the mood of soul of the civilisation of the present time.

For years past, we have had to draw attention to a certain point of time in that evolution of civilisation which is concentrated mainly in Europe. The time I mean lies in the 14th or 15th century or around the middle of the Middle Ages. It is the moment in the evolution of humanity when intellectualism began—when people began mainly to pay attention to the intellect, the life of thought, making the intellect the judge of what shall be thought and done among them.

Since the age of the intellect is with us today, we can certainly gain a good idea of what intellectualism is. We need but experience the present time to gain a notion of what came to the surface of civilisation in the 14th and 15th centuries. But as to the mood of soul which preceded this, we are no longer able to feel it in a living way. People who study history nowadays generally project what they are accustomed to see in the present time back into the historic past, and they have little idea how altogether different people were in mind and spirit before the present epoch. Even when they let the old documents speak for themselves, they largely read into them the way of thought and outlook of the present.

To spiritual-scientific study many things will appear differently. Let us turn our gaze for example to those historic personalities who were influenced on the one hand by Arabism, the civilisation of Asia—influenced by what lived and found expression in the Mohammedan religion, while on the other hand they were influenced by Aristotelianism. Let us consider these personalities, who found their way in the course of time through Africa to Spain, and deeply influenced the thinkers of Europe down to Spinoza and even beyond him. We gain no real conception of them if we imagine their mood of soul as though they had been like people of the present time with the only difference that they were ignorant of so and so many things subsequently discovered. (Roughly speaking, this is how they are generally thought of today). The whole way of thought and outlook, even of the people who lived in the above described stream of civilisation as late as the 12th century A.D., was altogether different from that of today.

Today, when man reflects upon himself, he feels himself as the possessor of thoughts, feelings, and impulses of will which lead to action. Above all, man ascribes to himself the ‘I think,’ the ‘I feel’ and the ‘I will.’

But in the personalities of whom I am now speaking, the ‘I think’ was by no means yet accompanied by the same feeling with which we today would say ‘I think.’ This could only be said of the ‘I feel’ and the ‘I will.’ In effect, those human beings ascribed to their own person only their feeling and their willing. Out of an ancient background of culture they rather lived in the sensation ‘It thinks in me’ than that they thought ‘I think.’ Doubtless they thought ‘I feel,’ ‘I will,’ but they did not think ‘I think’ in the same measure. On the other hand they said to themselves—and what I shall now describe was an absolutely real conception to them: The thoughts live in the Sublunary Sphere. The thoughts are everywhere within this sphere, which is determined when we imagine the earth at a certain point, and the moon at another, followed by Mercury, Venus, etc. They not only conceived the Earth as a dense and rigid cosmic mass, but as a second thing belonging to it they conceived the Lunar Sphere, reaching up to the moon. And as we say, ‘In the air in which we breathe is oxygen,’ so did these people say (it is only forgotten now that it ever was so):—‘In the ether which reaches up to the Moon, there are the thoughts.’ And as we say ‘We breathe in the oxygen of the air,’ so did these people say—not ‘We breathe in the thoughts’—but ‘We perceive the thoughts, receive them into ourselves.’ They were conscious of the fact that they received the thoughts.

Today, no doubt, a person can also familiarise himself with such an idea as a theoretical concept. He may even understand it with the help of Anthroposophy, but as soon as it becomes a question of practical life he forgets it. For then at once he has the rather strange idea that the thoughts spring forth within himself—which is just as though he were to think that the oxygen he receives in breathing were not received by him but sprang forth from within him.

For the personalities of whom I am now speaking, it was a profound feeling and an immediate experience: ‘I have not my own thoughts as my own possession. I cannot really say, I think. Thoughts exist, and I receive them unto myself.’

We know that the oxygen of the air circulates through our organism in a comparatively short time. We count these cycles by the pulse-beat. This happens quickly. The people of whom I am now speaking did indeed imagine the receiving of thoughts as a kind of breathing, but it was a very slow breathing. It consisted in this: At the beginning of his earthly life, man becomes capable of receiving the thoughts. As we hold the breath within us for a certain time—between our in-breathing and out-breathing—so did those people conceive a certain fact, as follows: They imagined that they held the thoughts within them, yet only in the sense in which we hold the oxygen which belongs to the outer air. They imagined that they held the thoughts during the time of their earthly life, and breathed them out again—out into the cosmic spaces—when they passed through the gate of death.

Thus it was a question of in-breathing—the beginning of life; holding the breath—the duration of earthly life; out-breathing—the sending forth of the thoughts into the universe.

People who had this kind of inner experience felt themselves in a common atmosphere of thought with all others who had the same experience. It was a common atmosphere of thought reaching beyond the earth, not only a few miles, but as I said, up to the orbit of the moon.

This idea was wrestling for the civilisation of Europe at that time. It was trying to spread itself ever more and more, impelled especially by those Aristotelians who came from Asia into Europe along the path I have just indicated. Let us suppose for a moment that it had really succeeded. What would then have come about?

In that case, my dear friends, that which was destined after all to find expression in the course of earthly evolution could never have come to expression in the fullest sense: I mean the Consciousness Soul. The human beings of whom I am now speaking stood in the last stage of evolution of the Intellectual or Mind-Soul. In the 14th and 15th century, the Consciousness Soul was to arise, which, if it found extreme expression, would lead all civilisation into intellectualism.

The population of Europe in its totality, in the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries, was by no means in a position merely to submit to the outpouring of a conception such as was held by the people whom I have now described. For if they had done so, the evolution of the Consciousness Soul would not have come about. Though it was determined in the councils of the Gods that the Consciousness Soul should evolve, nevertheless it could not evolve out of the mere independent activity of all European humanity. A special impulse had to be given towards the development of the Consciousness Soul itself.

And so, beginning in the time which I have now described, we witness the rise of two spiritual streams. One was represented by the quasi-Arabian philosophers who, working from Western Europe, influenced European civilisation very strongly—far more so than is commonly supposed. The other was the stream which fought against the former one with the utmost intensity and severity, representing it to Europe as the most heretical of all.

For a long time after, this conflict was felt with great intensity. You may still feel this if you consider the pictures in which Dominican Monks, or St. Thomas Aquinas alone, are represented in triumph—that is to say, in the triumph of an altogether different conception which emphasised above all things the individual and personal being of man, and worked to the end that man might acquire his thoughts as his own property. In these pictures we see the Dominicans portrayed, treading the representatives of Arabism under foot. The Arabians are there under their feet—they are being trodden underfoot.

The two streams were felt in this keen contrast for a long time after. An energy of feeling such as is contained in these pictures no longer exists in the humanity of today, which is rather apathetic. We need such energy of feeling very badly, not only for the things for which they battled, but for other things as well.

Let us consider for a moment what they imagined. The in-breathing of thoughts as the cosmic ether from the Sublunary Sphere—that is the beginning of life. The holding of the breath—that is the earthly life itself. The out-breathing—that is the going forth of the thoughts once more, but with an individually human colouring, into the cosmic ether, into the impulses of the sphere beneath the Moon, of the Sublunary Sphere.

What then is this out-breathing? It is the very same, my dear friends, of which we speak when we say: In the three days after death the etheric body of man expands. Man looks back upon his etheric body slowly increasing in magnitude. He sees how his thoughts spread out into the cosmos. It is the very same, only it was then conceived, if I may say so, from a more subjective standpoint. It was indeed quite true, how these people felt and experienced it. They felt the cycle of life more deeply than it is felt today.

Nevertheless, if their idea had become dominant in Europe, only a feeble feeling of the I would have evolved in the people of European civilisation. The Consciousness Soul would not have been able to emerge; the I would not have grasped itself in the ‘I think.’ The idea of immortality would have become vaguer and vaguer. People would increasingly have fixed their attention on that which lives and weaves in the far reaches of the Sublunary Sphere as a remnant of the human being who has lived here on this earth.

They would have felt the spirituality of the earth as its extended atmosphere. They would have felt themselves belonging to the earth, but not as individuals distinct from the earth. Through their feeling of “It thinks in me,” the people whom I described above felt themselves intimately connected with the earth. They did not feel themselves as individualities in the same degree as the people of the rest of Europe were beginning to feel themselves, however indistinctly.

We must, however, also bear in mind the following. Only the spiritual stream of which I have just spoken was aware of the fact that when a person dies the thoughts he received during his earthly life are living and weaving in the cosmic ether that surrounds the earth. This idea was violently attacked by those other personalities who arose chiefly within the Dominican Order. They declared that man is an individuality, and that we must concentrate above all on his individuality which passes through the gate of death, not on what is dissolved in the universal cosmic ether. This was emphasised, albeit not exclusively,—emphasised representatively, I would say,—by the Dominicans. They stood up vigorously for the idea of the individuality of man, as against the other stream which I characterised before. But precisely as a result of this a certain condition came about. For let us now consider these representatives of individualism.

After all, it was the individually coloured thoughts which passed into the universal ether. And those who fought against the former stream—just because they were still vividly aware that this was being said, that this idea existed,—were troubled and disquieted by what was really there.

This anxiety, notably among the greatest thinkers,—this anxiety as a result of the forces expanding and dissolving and passing on the human thoughts to the cosmic ether,—did not really come to an end until the 16th or 17th century.

We must somehow be able to transplant ourselves into the inner life of soul of these people, especially those who belonged to the Dominican Order. Only then do we gain an idea of how much they were disquieted by what was really left as an heritage from the dead,—which they, with their conception, no longer could nor dared believe in.

We must transplant ourselves into the hearts and minds of these people. No great man of the 13th or 14th century could have thought so dryly, so abstractly or in such cold and icy concepts as the people of today. When the people of today are defending ideas or theories, it seems as though it were a recognised condition for so doing that one's heart should first be torn out of one's body. At that time it was not so. At that time there was deep feeling, there was heart in all that men upheld as their ideas. But in a case such as I am now citing, this heart also involved an intense inner conflict.

That philosophy, which proceeded from the Dominican Order, evolved under the most appalling inner conflicts. I mean that philosophy which afterwards had such a strong influence on life—for life at that time was still far more dependent on the authority of individual men. There was no such popular education at that time. All culture and education—all that the people knew—eventually merged into the possession of a few. And as a consequence, these few reached up far more to a real philosophic life and striving. And in all that then flowed out into civilisation, these inner conflicts which they lived through were contained.

Today one reads the works of the Scholastics and is conscious only of the driest thoughts. But it is the readers of today who are dry. Those who wrote these works were by no means dry in heart or mind. They were filled with inner fire in relation to their thoughts. Moreover, this inner fire was due to the striving to hold at bay the objective influence of thoughts.

When a person of today thinks on philosophic questions or questions of worldview, nothing is there, so to speak, to worry him. A man of today can think the greatest nonsense—he thinks it in perfect calm and peace of mind. Humanity has already evolved for so long within the Consciousness Soul that no such disquieting occurs, as would occur, for instance, if individuals among us felt how the thoughts of men appear when they flow out after death into the ethereal environment of the earth. Today such things as could still be experienced in the 13th or 14th century are quite unknown. Then it would happen that a younger priest would come to an older priest, telling of the inner tortures which he was undergoing in remaining true to his religious faith, and expressing it in this wise: ‘I am pursued by the ghosts of the dead.’

Speaking of the ghosts of the dead, they meant precisely what I have just described. That was a time when people could still grow deeply into what they learned. In such a community—a Dominican community for instance,—they learned that man is individual and has his own individual immortality. They learned that it is a false and heretical idea to conceive, with respect to thought, a kind of universal soul comprising all the earth. They learned to attack this heresy with all their might. And yet, in certain moments when they took deep counsel with themselves, they would feel the objective and influential presence of the thoughts which were left behind as relics by the dead. Then they would say to themselves, ‘Is it quite right for me to be doing what I am doing? Here is something intangible working into my soul. I cannot rise against it—I am held fast by it.’

The intellects of that time, many of them at any rate, were still so constituted that they were generally aware of the speaking of the dead, at least for some days after death. And when one had ceased to speak another would begin. With respect to such things too, they felt themselves immersed in the all-pervading spiritual—or at the very least, ethereal—essence of the universe.

Coming into our own time, this living feeling with the Universal All has ceased. In return for it we have achieved conscious life in the Consciousness Soul, while all the spiritual reality that surrounds us (surrounds us as a reality, no less so than tables or chairs, trees or rivers) works only upon the depths of our subconscious. The inwardness of life, the spiritual inwardness, has passed away. It must first be acquired again by spiritual-scientific knowledge livingly received.

We must think livingly upon the knowledge of spiritual science, and we shall do so if we dwell upon such facts of life as lie by no means very far behind us. Imagine a Scholastic thinker or writer of the 13th century. He writes down his thoughts. Nowadays it is easy work to think, for people have grown accustomed to think intellectually. At that time it was only at the beginning, and was still difficult. Man was still conscious of a tremendous inner effort. He was conscious of fatigue in thinking even as in hewing wood, if I may use the trivial comparison. Today the thinking of many people has become quite automatic. Today we are scarcely overcome by the longing to follow up every one of our thoughts with our own human personality! We hear a person of today letting one thought arise out of another like an automaton. We cannot follow, we do not know why, for there is no inner necessity in it. And yet so long as a man is living in the body he should follow up his thoughts with his own personality. Afterwards they will soon take a different course; they will spread out and expand when he is dead.

So a person could be sitting there at that time, defending with every weapon of sharp incisive thought the doctrine of individual man in order to save the doctrine of individual immortality. He could be arguing with polemics against Averroes, or others of that stream of thought which I described at the beginning of this lecture. But there was another possibility. For especially in the case of an outstanding person like Averroes, that which proceeded from him, dissolving after his death like a kind of ghost in the Sublunary Sphere, might well be gathered up again by the Moon itself at the end of that Sphere, and remain behind. Having enlarged and expanded, it might even be reduced again, shape and form be given to it, till it was consolidated once again into an essence built, if I may say so, in the ether. That could well happen. Then the man would be sitting there, trying to lay the foundations of individualism, carrying on his polemic against Averroes; and Averroes would appear before him as a threatening figure, disturbing his mind.

The most important of the Scholastic writings which arose in the 13th century were directed against Averroes, who was long dead. They made polemics against the man long dead, against the doctrine which he had left behind. Then he arose to prove to them that his thoughts had become condensed, consolidated once again and thus were living on.

There were indeed these inner conflicts before the beginning of the new age of consciousness. And they were such that we today should see once more their full intensity and depth and inwardness. Words after all are words. The people of later times can but receive what lies behind the words with such ideas as they possess. But within the words there were often rich contents of inner life. They pointed to a life of soul such as I have now described.

These, then, are the two streams, and they have remained active, basically speaking, to this day. The one—albeit now only working from the spiritual world, yet all the stronger there,—would like to convince man that a universal life of thoughts surrounds the earth, and that in thoughts man breathes in soul and spirit. The other stream desires above all to point out that man should make himself independent of such universality. The former stream is more like a vague intangible presence in the spiritual environment of the earth, perceptible today to many people (for there are still such people) when in certain nights they lie on their beds and listen to the void, and out of the void all manner of doubts are born in them as to what they are asserting today so definitely and so surely in their own individuality.

Meanwhile in others, who always sleep soundly because they are so well satisfied with themselves, we have the unswerving emphasis on the individual principle.

This battle is smouldering still at the very foundations of European culture. It is here to this day; and in the things that are taking place outwardly on the surface of our life, we have scarcely anything other than the beating of the surface-waves from what is still present in the depths of souls—a relic of the deeper and intenser inner life of earlier times.

Many souls of that time are here again in present earthly life. In a certain way they have conquered what then disquieted them so much in their surface consciousness—disquieted them at least in certain moments of their surface consciousness.

But in the depths it smoulders all the more in many minds and hearts today. Spiritual science, once again, is here to draw attention also to such historic facts as these.

But we must not forget the following. In the same measure in which people become unconscious during earthly life of what is there none the less, namely the thoughts in the ether in the immediate environment of the earth—in the same measure, therefore, in which they acquire the ‘I think’ as their own possession—their human soul is narrowed down. Man passes through the gate of death with a contracted soul.

The narrowed soul has carried untrue, imperfect, inconsistent earthly thoughts into the cosmic ether, and these work back again upon the minds of men. Thence there arise such social movements as we see today. We must understand these too as to their inner origin. Then we shall recognise that there is no other cure, no other healing for these social ideas, destructive as they often are, than the spreading of the truth about the spiritual life and being.

Call to mind the lectures we have given here, especially the historic ones taking into account the concept of reincarnation and leading to so many definite examples. These lectures will have shown you how things work beneath the surface of external history. You will have seen how what lived in one historic age is carried over into a later one by people returning into earthly life. But everything spiritual plays its part between death and a new birth in moulding what is carried by man from one earth-life into another.

Today it would be good if many souls would attain for themselves that objectivity to which we can address ourselves, awakening an inner understanding, when we describe the people who lived in the twilight of the Intellectual or Mind-Soul age.

Some of the people who lived at that time are here again today. Deep in their souls they underwent the evening twilight of an age, and through the constant attacks they suffered from the ghosts of which I have now spoken, they have absorbed deep doubts about the validity of intellectualism.

This doubt can well be understood. For around the 13th century there were many people—men of knowledge who stood in the midst of learning, almost entirely theological as it then was—people for whom it was a deep question of conscience: What will happen now ?

Such souls had often carried with them into that time mighty contents from their former incarnations. They gave it an intellectual colouring; but they felt this all as a declining stream. While at the rising stream—pressing forward as it was to individuality—they felt the pangs of conscience. Until at length those philosophers arose who stood under an influence which has really killed all meaning. To speak radically: those who stood under the influence of Descartes! For many, even among those who had their place in the Scholasticism of an earlier time, had already fallen into the Cartesian way of thought. I do not say that they became philosophers. These things underwent many changes. When people begin to think along these lines the strangest nonsense becomes self-evident. To Descartes, as you know, is due the saying ‘I think, therefore I am.’

Countless clever thinkers have accepted this as true: ‘I think, therefore I am.’ Yet the result is this: From morning until evening I think, therefore I am. Then I fall asleep. I do not think, therefore I am not. I wake up again, I think, therefore I am. I fall asleep, and as I now do not think, I am not. This then is the consequence: A person not only falls asleep, but ceases to be when he falls asleep. There is no less fitting proof of the existence of the spirit of man than the theorem: ‘I think.’ Yet this began to be the most widely accepted statement in the age of evolution of consciousness (the age of the Consciousness Soul). When we point to such things today it is like a sacrilege, but we cannot help ourselves!

But over against all this I will now tell you of a kind of conversation. Though it is not historically recorded, by spiritual research it can be discovered among the real things that happened. It was a conversation that took place between an older and a younger Dominican, somewhat as follows:

The younger man said, ‘Thinking takes hold of men. Thought, the shadow of reality, takes hold of them. In ancient times thought was always the last revelation of the living Spirit from above. But now thought is the very thing that has forgotten that living Spirit. Now it is experienced as a mere shadow. Verily, when a man sees a shadow, he knows the shadow points to some reality. The realities are there indeed. Thinking itself is not to be attacked, but only the fact that we have lost the living Spirit from our thinking.’

The older man replied, ‘In thinking, through the very fact that man is turning his attention with loving interest to outer Nature, (while he accepts Revelation as Revelation and does not seek to approach it with his thinking),—in thinking, to compensate for the former heavenly reality, an earthly reality must be found once more.’

‘What will happen?’ said the younger man. ‘Will European humanity be strong enough to find this earthly reality of thought, or will it only be weak enough to lose the heavenly reality?’

This dialogue truly contains all that still holds good with regard to European civilisation. For after the intermediate time, with the darkening of the living quality of thought, humanity must now attain to living thinking once more. Otherwise humanity will remain weak and the reality of thought will lose its own reality. Therefore it is most necessary, since the our Christmas Conference impulse, that we in the Anthroposophical Movement speak without reserve in forms of living thought. For otherwise it will come about more and more that even the things we know from this source or from that—for instance that man has a physical body, an etheric body and an astral body—will only be grasped with the forms of dead thinking.

These things must not be grasped with the forms of dead thinking. For then they become distorted, misrepresented truth, and not the truth itself.

That is what I wanted to say today. We must attain a living, sympathetic interest, a longing to go beyond ordinary history and to attain that history which must and can be read in the living Spirit, the history which shall more and more be cultivated in the Anthroposophical Movement. Today, my dear friends, I wished to place before your souls the concrete outline of our programme in this direction.

Much has been said today in aphorism. The inner connection will dawn upon you if you attempt not so much to follow up with the intellect, but to feel with your whole being what has been said today. You must attempt to feel it knowingly, to know it feelingly, in order that not only what is said but what is heard within our circles may be sustained more and more by real spirituality.

We need education to spiritual hearing, spiritual listening. Only then shall we develop true spirituality among us. I wanted to awaken this feeling in you today; not so much to give a systematic lecture, but to speak to your hearts, albeit calling to witness, as I did, many a concrete spiritual fact.

Erster Vortrag

Ich möchte heute für diejenigen, die eben da sein können, einiges ausführen, was eine Art Episode sein kann innerhalb der Betrachtungen, die wir hier nun schon seit einiger Zeit pflegen. Es soll, was ich sage, zur Illustration und Erklärung von manchem dienen, was aus dem bisher Behandelten wie eine Frage auftauchen kann, und es soll zu gleicher Zeit dadurch einiges Licht auf die Seelenverfassung der gegenwärtigen Zivilisation fallen.

Wir haben ja durch Jahre hindurch schon immer auf einen ganz bestimmten Zeitpunkt der im wesentlichen europäischen Zivilisationsentwickelung aufmerksam machen müssen, der da liegt in der Mitte des Mittelalters, um das 14., 15. Jahrhundert. Wir weisen damit auf denjenigen Punkt in der Menschheitsentwickelung hin, wo der Intellektualismus beginnt, wo die Menschen damit beginnen, vorzugsweise auf das Denken, auf den Intellekt aufzupassen und ihn zum Richter zu machen über dasjenige, was unter Menschen gedacht und getan werden soll.

Nun kann man sich ja, weil das Zeitalter des Intellektes heute da ist, durch das Miterleben der Gegenwart allenfalls eine rechte Vorstellung machen von dem, was Intellektualismus ist, was eben im 14. und 15. Jahrhundert an die Oberfläche der Zivilisation gekommen ist. Aber die Seelenverfassung, die vorangegangen ist, die fühlt man heute eigentlich nicht mehr in lebendiger Art. Wenn man Geschichte betrachtet, so projiziert man eigentlich dasjenige, was man in der Gegenwart zu sehen gewöhnt ist, auch weiter nach rückwärts im geschichtlichen Ablauf, und man bekommt nicht viel Vorstellung davon, wie ganz andersartig die Geister vor diesem Zeitraum waren. Und wenn man Urkunden sprechen läßt, so liest man eben in die Urkunden zum großen Teil schon dasjenige hinein, was heutige Denkungs- und Anschauungsart ist.

Der geisteswissenschaftlichen Betrachtung stellt sich eben manches ganz und gar anders dar. Und wenn man zum Beispiel den Blick auf jene Persönlichkeiten hinwendet, die aus dem Arabismus, aus der Kultur Asiens heraus auf der einen Seite beeinflußt waren von dem, was im Mohammedanismus als Religion sich ausgelebt hat, auf der anderen Seite aber auch beeinflußt waren von dem Aristotelismus, wenn man auf diese Persönlichkeiten schaut, die dann den Weg herüber über Afrika nach Spanien gefunden haben, die dann tief beeinflußt haben die Geister Europas, bis zu Spinoza und über Spinoza hinaus wiederum weiter die Geister Europas beeinflußt haben, dann gewinnt man über sie keine Anschauung, wenn man sich ihre Seelenverfassung so vorstellt, wie wenn sie einfach Menschen der Gegenwart gewesen wären, nur daß sie so und so viele Dinge noch nicht gewußt haben, die später gefunden worden sind. Denn so ungefähr stellt man sie sich ja vor. Aber die Denk- und Anschauungsweise auch noch derjenigen Persönlichkeiten aus der angedeuteten Zivilisationsrichtung, die etwa im 12. Jahrhundert lebten, war ganz anders als die heutige.

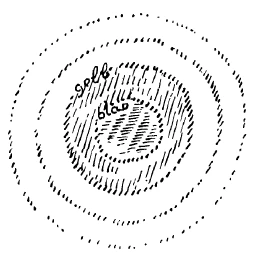

Heute fühlt sich der Mensch, wenn er so auf sich selbst zurückblickt, als der Besitzer von Gedanken, Gefühlen, Willensimpulsen, die dann zur Tat werden. Vor allen Dingen schreibt sich der Mensch eben zu das «ich denke», das «ich fühle», das «ich will». Bei diesen Geistern, bei diesen Persönlichkeiten, von denen ich jetzt rede, war das «ich denke» noch gar nicht von solcher Empfindung begleitet, mit der wir heute sagen: Ich denke -, sondern nur das «ich fühle» und «ich will». Diese Menschen haben ihrer eigenen Persönlichkeit nur ihr Fühlen und ihr Wollen zugeschrieben. Aus altzivilisatorischen Untergründen heraus lebten sie viel mehr in der Empfindung «es denkt in mir», als daß sie gedacht hätten «ich denke». Sie dachten wohl: «ich fühle, ich will», aber sie dachten durchaus nicht in demselben Maße: «ich denke», sondern sie sagten sich — und das ist eine ganz reale Anschauung gewesen, die ich Ihnen jetzt mitteilen will —: Gedanken sind in der sublunarischen Sphäre, da leben die Gedanken. — Überall sind diese Gedanken in derjenigen Sphäre, die gegeben ist dadurch, daß wir uns die Erde (siehe Zeichnung, blau) vorstellen an einem gewissen Punkt, den Mond hier an einem anderen, dann Merkur, Venus und so weiter. Sie dachten sich die Erde als dichte, feste Weltenmasse, aber sie dachten sich als zweites, was dazu gehört, die lunarische Sphäre bis zum Monde hinauf (gelb).

Und so wie wir sagen, in der Luft, in der wir atmen, ist Sauerstoff, so sagten diese Leute - es ist eben ganz vergessen worden, daß das so war -: In dem Äther, der bis zum Mond hinaufreicht, sind Gedanken. — Und wie wir sagen, wir atmen den Sauerstoff der Luft ein, so sagten diese Menschen allerdings nicht: wir atmen die Gedanken ein, aber: wir perzipieren die Gedanken, wir nehmen die Gedanken auf. Und sie waren sich dessen bewußt, daß sie sie aufnehmen.

Sehen Sie, heute kann ein Mensch sich so etwas meinetwillen auch als Begriff zu eigen machen. Er kann vielleicht sogar aus der Anthroposophie heraus so etwas einsehen. Aber er vergißt es ja gleich wieder, wenn es aufs praktische Leben ankommt. Wenn es aufs praktische Leben ankommt, dann macht er sich gleich eine ganz merkwürdige Vorstellung, er macht sich die Vorstellung, daß die Gedanken in ihm entspringen, was ganz gleich wäre, wie wenn er meinte, daß der Sauerstoff, den er aufnimmt, nicht von außen aufgenommen würde, sondern aus ihm heraus entspränge. Für die Persönlichkeiten, von denen ich spreche, war eben ein tiefes Gefühl, ein unmittelbares Erlebnis: Ich habe nicht meine Gedanken als meinen Besitz, ich darf eigentlich nicht sagen, «ich» denke, sondern «Gedanken sind», und ich nehme sie auf, diese Gedanken.

Nun, vom Sauerstoff der Luft wissen wir, daß er in verhältnismäßig kurzer Zeit den Kreislauf durch unseren Organismus durchmacht. Wir zählen solche Kreisläufe nach den Pulsschlägen. Das geschieht schnell. Die Persönlichkeiten, von denen ich spreche, stellten sich schon das Aufnehmen der Gedanken wie eine Art von Atmen vor, aber ein sehr langsames Atmen, ein Atmen, das darin besteht, daß im Beginne des Erdenlebens der Mensch fähig wird, die Gedanken aufzunehmen. So wie wir den Atem eine gewisse Zeit zwischen der Einatmung und der Ausatmung in uns halten, so stellten sich diese Menschen auch einen Tatbestand vor, dahingehend, daß sie nun die Gedanken halten, aber eben nur so, wie wir den Sauerstoff, der der äußeren Luft angehört, halten. So stellten sie sich es vor: sie halten die Gedanken, und zwar während der Zeit ihres Erdenlebens, und sie atmen sie wieder aus, hinaus in die Weltenweiten, wenn sie durch die Pforte des Todes gehen. So daß man es also zu tun hatte mit einem Einatmen: Lebensbeginn; Atemhalten: Dauer des Erdenlebens; Ausatmen: Hinaussenden der Gedanken in die Welt. Menschen, die so innerlich erlebten, fühlten sich mit allen anderen, die gleich erlebten, in einer gemeinschaftlichen Gedankenatmosphäre, die nicht bloß einige Meilen über die Erde hinaufging, sondern die eben bis zum Mondenumkreis ging.

Man kann sich nun vorstellen, daß diese Anschauung, die damals um die europäische Zivilisation gekämpft hat, sich immer weiter und weiter ausbreiten wollte, namentlich von jenen Aristotelikern aus, die von Asien herüber nach Europa auf dem Wege gekommen sind, den ich angedeutet habe. Man könnte sich nun vorstellen, daß diese Anschauung sich wirklich ausgebreitet hätte. Was wäre geworden?

Ja, es wäre dann nicht dazu gekommen, daß im vollsten Sinne des Wortes sich das hätte ausleben können, was sich doch im Laufe der Erdenentwickelung hat ausleben müssen: nämlich die Bewußtseinsseele. Diejenigen Menschen, von denen ich da spreche, standen sozusagen im letzten Stadium der Entwickelung der Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele. Heraufkommen sollte im 14. und 15. Jahrhundert die Bewußtseinsseele, die eben alles in der Zivilisation in Intellektualismus überführte, wenn sie im Extrem sich auslebte.

Die europäische Bevölkerung war in ihrer Totalität im 10., 11., 12. Jahrhundert keineswegs durchaus befähigt, eine solche Anschauung, wie die der Persönlichkeiten, die ich charakterisiert habe, einfach über sich ergehen zu lassen, denn die Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele wäre dann ausgeblieben. Wenn es auch sozusagen im Ratschluß der Götter bestimmt war, daß die Bewußtseinsseele sich entwickele, so war es doch so, daß diese Bewußtseinsseele sich nicht aus der Eigentätigkeit der europäischen Menschheit in ihrer Totalität heraus hat entwickeln können, sondern es mußte gewissermaßen ein Impuls kommen, der dahin ging, die Bewußtseinsseele besonders zu entwickeln.

So daß wir heraufkommen sehen von dem Zeitalter an, das ich jetzt charakterisiert habe, zwei Geistesströmungen. Die eine Geistesströmung war sozusagen bei den arabisierenden Philosophen vertreten, die vom Westen Europas herein die europäische Zivilisation stark beeinflußten, viel stärker, als man heute glaubt. Die andere Strömung war diejenige, welche in schärfster Weise diese Strömung, die ich charakterisierte, bekämpfte, welche in schärfster Strenge diese Anschauung als die ketzerischste für Europa hinstellte. Wie stark das noch lange gefühlt wurde, das, meine lieben Freunde, empfinden Sie, wenn Sie Bilder anschauen, wo etwa Dominikanermönche oder Thomas von Aquino selber im Triumphe dargestellt werden, im Triumphe einer ganz anderen Anschauung, einer Anschauung, die vor allen Dingen die Individualität, das Persönliche des Menschen betont, die dahin arbeitet, daß der Mensch sich seine Gedanken als sein Eigentum aneignet, und wo diese Dominikaner dargestellt werden, wie sie die Vertreter des Arabismus mit Füßen treten. Die sind unter ihren Füßen, die werden getreten. In solchem Gegensatz hat man eben die beiden Strömungen lange empfunden. Eine Gefühlsenergie, wie sie in einem solchen Bilde liegt, ist eigentlich in der heutigen, etwas apathischen Menschheit nicht mehr vorhanden. Wir brauchen sie allerdings nicht für jene Dinge, für die damals gekämpft worden ist, aber wir brauchen sie für andere Dinge wiederum gar sehr!

Bedenken wir einmal, was da vorgestellt wurde: Einatmung der Gedanken aus dem Weltenäther, aus der sublunarischen Sphäre: Lebensanfang; Atemhalten: Erdenleben; Ausatmung: wiederum Hinaustreten der Gedanken, aber mit der individuell menschlichen Färbung, in den Weltenäther, in die Impulse der Sphäre unter dem Monde, in die Impulse der sublunarischen Sphäre.

Was ist denn dieses Ausatmen? Ganz genau dasselbe, meine lieben Freunde, wie das, von dem wir sagen: in den drei Tagen nach dem Tode vergrößert sich der Ätherleib des Menschen. Der Mensch sieht zurück auf den sich langsam vergrößernden Ätherleib, er sieht, wie sich seine Gedanken hinaus ausbreiten in den Kosmos. Es ist ja ganz dasselbe, was nur, ich möchte sagen, von einem subjektiveren Standpunkte aus dazumal dargestellt worden ist. Also es ist ja immer wiederum wahr, wie diese Leute dazumal empfanden und erlebten. Sie empfanden den Kreislauf des Lebens tiefer, als er heute empfunden werden kann.

Aber dennoch: wären ihre Anschauungen herrschend geworden in Europa in der Form, in der sie damals da waren, dann wäre nur ein schwaches Ich-Gefühl bei den Menschen der europäischen Zivilisation zur Entwickelung gekommen. Die Bewußtseinsseele hätte nicht heraustreten können, das Ich hätte sich in dem «ich denke» nicht erfaßt, der Unsterblichkeitsgedanke wäre immer verschwommener und verschwommener geworden. Die Menschen hätten immer mehr und mehr auf dasjenige hingeblickt, was so im allgemeinen in der sublunarischen Sphäre herumwellt und -webt, wenn es übriggeblieben ist von dem Menschen, der hier auf dieser Erde gelebt hat. Man hätte die Geistigkeit der Erde als ihre erweiterte Atmosphäre gefühlt, man hätte sich mit der Erde gefühlt, aber nicht als individueller Mensch, abgesondert von der Erde; denn die Menschen, die ich charakterisierte, die fühlten sich eigentlich durch dieses «es denkt in mir» mit der Erde innig zusammenhängend. Sie fühlten sich nicht in demselben Grade als Individualitäten, wie dies die Menschen im übrigen Europa anfingen zu fühlen, wenn auch in unklarer Weise.

Dann aber müssen wir doch auch das Folgende berücksichtigen: Nur diese geistige Strömung, von der ich sprach, wußte davon, daß, wenn der Mensch stirbt, die von ihm während des Erdenlebens aufgenommenen Gedanken im Weltenäther, der die Erde umgibt, wellen und weben. Und diese Anschauung wurde also von denjenigen Persönlichkeiten, die ja namentlich aus dem Dominikanerorden hervorgingen, scharf bekämpft, und scharf wurde geltend gemacht: Der Mensch ist eine Individualität, man hat vor allen Dingen auf dasjenige zu sehen, was vom Menschen als Individualität durch die Pforte des Todes geht, nicht auf das, was sich auflöst im allgemeinen Weltenäther. Das wurde eben vorzugsweise, obwohl nicht allein von den Dominikanern, aber ich möchte sagen, repräsentativ von den Dominikanern betont. Diese Anschauung von der Individualität des Menschen wurde scharf und energisch vertreten gegenüber der ersten Richtung, die ich charakterisiert habe. Aber gerade dies bewirkte einen ganz bestimmten Zustand.

Denn sehen wir einmal hin auf die Vertreter, sagen wir also jetzt, des Individualismus. Es waren ja da diese individuell gefärbten Gedanken, die in den allgemeinen Weltenäther übergingen. Und diejenigen, die gegen diese Strömung kämpften, die wurden gerade dadurch, daß sie noch wußten, noch lebendig wußten: da wird das behauptet, diese Anschauung ist da — beunruhigt gerade von dem, was wirklich da war. Diese Beunruhigung durch die sich vergrößernden und auflösenden und die menschlichen Gedanken an den Weltenäther abgebenden Kräfte, diese Beunruhigung gerade der hervorragendsten Denker, die hörte ja erst im 16., 17. Jahrhundert auf.

Man muß sich schon in die Seelenverfassung namentlich solcher Leute, die dem Dominikanerorden angehört haben, hineinversetzen können, um zu ermessen, wie gerade diese Leute beunruhigt wurden durch dasjenige, was vorhanden ist als Hinterlassenschaft von den verstorbenen Menschen, und an das sie nicht mehr mit ihrer Anschauung sozusagen glauben dürfen, glauben können. Man muß sich hineinversetzen in die Gemüter dieser Menschen. So trocken, so abstrakt, so eisig begrifflich, wie die Menschen heute denken, konnte ja ein hervorragender Geist im 13., 14. Jahrhundert nicht denken. Heute kommen einem ja die Menschen vor, wenn sie irgendwelche Anschauungen vertreten, als wenn es als eine Bedingung gälte für das Vertreten von Anschauungen, daß einem erst das Herz aus dem Leibe gerissen wird. Dazumal war es nicht so. Dazumal war Innigkeit, ich möchte sagen Herzlichkeit in all dem, was man als Ideen vertrat. Dadurch aber, daß diese Herzlichkeit vorhanden war, war auch in einem solchen Falle wie dem, den ich hier anführe, ein starker innerer Kampf vorhanden.

Und unter den furchtbarsten inneren Kämpfen hat sich dasjenige ausgebildet, was zum Beispiel vom Dominikanerorden als eine gewisse Philosophie ausgegangen ist, die dann später das Leben, weil das ja noch viel mehr auf Autorität einzelner Menschen gebaut war, stark beeinflußte. Solch eine allgemeine Bildung gab es ja damals noch nicht; es strömte in alles, was Bildung war, was überhaupt die Leute wußten, dasjenige hinein, was wenige besaßen, die daher auch mehr hinaufragten zu dem, was philosophisches Leben und Streben war. In all dem, was da in die Zivilisation einfloß, war enthalten, was in solchen inneren Kämpfen durchlebt wurde. Heute liest man die Schriften der Scholastiker und empfindet nur trockene Gedanken. Aber trocken sind ja eigentlich bloß die Leser heute. Diejenigen Menschen, die sie geschrieben haben, waren schon nicht trocken in ihrem Gemüte. Die waren voll inneren Feuers gegenüber ihren Gedanken. Und dieses innere Feuer kam eben von dem Bestreben, abzuweisen den objektiven Gedankeneinfluß.

Wenn heute einer denkt über Weltanschauungsfragen, so beirrt ihn ja eigentlich nichts. Man kann heute den größten Unsinn denken, und man denkt ihn ganz ruhig, weil für die Menschheit, die schon so lange innerhalb der Bewußtseinsseele sich entwickelt hat, keine Beunruhigung von der Art eintritt, daß die einzelnen empfinden würden, wie nun die Gedanken der Menschen sich ausnehmen, wenn sie nach dem Tode hinausfließen in die Ätherumgebung der Erde. Heute sind ja ganz unbekannt solche Dinge, wie sie noch im 13., 14. Jahrhundert erlebt werden konnten, wo jüngere Priester zu älteren Priestern kamen und noch die inneren Qualen, die sie durchmachten im Beständigbleiben in ihrem Religionsbekenntnisse, dadurch ausdrückten, daß sie sagten: Mich quälen die Gespenster der Toten.

Denn mit den Gespenstern der Toten war das eben gemeint, was ich jetzt charakterisiert habe. Da konnten die Menschen noch hineinwachsen in dasjenige, was sie eben lernten. Man lernte innerhalb einer gewissen Gemeinschaft, sagen wir einer Dominikanergemeinschaft, daß der Mensch individuell ist, auch seine individuelle Unsterblichkeit hat. Man lernte, daß es eine falsche, ketzerische Anschauung ist, wenn in bezug auf das Denken eine All-Erdenseele angeschaut wird, man lernte das scharf bekämpfen. Aber man empfand in gewissen Augenblicken, in denen man so recht mit sich selber zu Rate ging, das objektive Wirken der Gedanken von den Überresten der verstorbenen Menschen und sagte sich dann: Ist es denn ganz richtig, daß ich das tue, was ich tue? Da ist etwas Unbestimmtes, das in meine Seele hineinwirkt. Ich komme nicht auf dagegen. Ich werde festgehalten. Ja, die Intellekte der Menschen, oder wenigstens vieler Menschen, waren eben zu jener Zeit noch so geordnet, daß für sie die Toten wenigstens noch tagelang nach dem Tode recht allgemein sprachen. Und hatte der eine aufgehört zu sprechen, so fing ein anderer an. Man fühlte sich auch in bezug auf solche Dinge dann ganz darinnen im allgemeinen Geistigen des Weltenalls, wenigstens noch im Ätherischen.

Dieses Miterleben mit dem Weltenall, das hat in unsere Zeiten herein eben ganz aufgehört. Und dafür haben wir das Leben in der Bewußtseinsseele errungen. Und all das, was uns als eine Realität ebenso umgibt wie Tische und Stühle, wie Bäume und Flüsse, was uns als eine geistige Realität umgibt, das wirkt nur noch auf die Tiefen des Unterbewußtseins der Menschen. Die Innerlichkeit des Lebens, die geistige Innerlichkeit des Lebens, die hat eben aufgehört. Die wird erst wiederum errungen in einer lebendig aufgenommenen geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkenntnis.

Und so lebendig müssen wir über eine geisteswissenschaftliche Erkenntnis denken, wie es sich uns ergibt, wenn wir solche Erscheinungen, die noch gar nicht so lange hinter uns liegen, anschauen. Man denke sich den scholastischen Denker oder Schriftsteller des 13. Jahrhunderts. Er schreibt seine Gedanken hin. Heute ist denken leicht, denn die Menschen haben sich schon gewöhnt, intellektualistisch zu denken. Dazumal fing es eben an, da war es noch schwer. Da war man sich noch bewußt einer ungeheuren inneren Anstrengung, da war man sich bewußt einer Ermüdung durch das Denken wie durch das Holzhacken, wenn ich mich trivial ausdrücken darf. Heute ist ja das Denken vieler Menschen schon ganz automatisch geworden. Und ist man denn heute etwa von der Sehnsucht befallen, jeden seiner Gedanken mit seiner menschlichen Persönlichkeit zu verfolgen? Man hört zu, wie die Menschen heute wie ein Automat einen Gedanken aus dem anderen hervorgehen lassen können, so daß man gar nicht nachkommt, daß man auch gar nicht weiß, warum; denn da ist nichts von einer Notwendigkeit vorhanden. Aber solange der Mensch im Leibe lebt, soll er mit seiner Persönlichkeit seine Gedanken verfolgen. Dann nehmen sie schon einen anderen Gang: sie breiten sich aus, wenn er gestorben ist.

Ja, so konnte man sitzen in der damaligen Zeit und die Lehre von dem individuellen Menschen zur Rettung der Lehre von der individuellen Unsterblichkeit mit allen scharf einschneidenden Gedanken verteidigen, polemisch werden gegen Averroes oder sonstige Leute von jener ersten Richtung, die ich heute charakterisiert habe. Dann war aber eine Möglichkeit vorhanden: es war die Möglichkeit vorhanden, daß dasjenige, was gerade von einer solchen hervorragenden Persönlichkeit wie Averroes nach dem Tode wie eine Art Gespenst in der sublunarischen Sphäre sich aufgelöst hat, wiederum am Ende der subJunarischen Sphäre — eben durch den Mond selber — gerade stark gesammelt worden und geblieben ist, nach der Vergrößerung sogar wieder verkleinert worden ist und ihm Gestalt gegeben worden ist, so daß es wiederum zu einem, ich möchte sagen, im Äther aufgebauten Wesen konsolidiert worden ist. Das konnte geschehen. Dann saß man und versuchte, den Individualismus zu begründen: Man polemisierte gegen Averroes - und Averroes erschien, erschien drohend und beirrte das Gemüt. Gegen den längst verstorbenen Averroes standen im 13. Jahrhundert die wichtigsten scholastischen Schriftsteller auf. Gegen den längst Gestorbenen polemisierte man, gegen dasjenige, was als Lehre geblieben ist: er bewies einem, daß seine Gedanken wiederum verdichtet, konsolidiert worden sind und weiterleben!

Diese inneren Kämpfe, die dem Anfang des Bewußtseinszeitalters vorangegangen sind, sind schon so, daß man heute auf ihre ganze Intensität, auf ihre Innigkeit hinschauen sollte. Worte sind schließlich Worte, und die späteren Menschen nehmen eben das, was hinter den Worten ist, mit denjenigen Begriffen, die sie haben. Aber solche Worte schlossen manchmal reiches Seelenleben ein, deuteten hin auf Seelenleben, wie ich sie eben jetzt charakterisiert habe.

Und so haben wir zwei Strömungen, die im Grunde genommen bis zum heutigen Tage wirksam geblieben sind. Wir haben die eine Strömung, die gern — jetzt nur noch von der geistigen Welt, aber da um so stärker - dem Menschen klarmachen möchte, daß ein allgemeines Gedankenleben die Erde umgibt, daß man in Gedanken drinnen seelisch-geistig atmet, und die andere Strömung, die vor allem den Menschen hinweisen will darauf, daß er sich unabhängig machen sollte von solcher Allgemeinheit, daß er sich in seiner Individualität erleben sollte. Die eine Strömung, die erste, mehr wie ein unbestimmtes Raunen in der geistigen Erdenumgebung, ist heute für viele Menschen, die schon auch vorhanden sind, nur noch wahrnehmbar, wenn in besonders gestalteten Nächten die Leute auf ihrem Lager liegen und dem Unbestimmten zuhören, und wo aus diesem Unbestimmten heraus alle möglichen Zweifel geboren werden an dem, was die Leute heute aus ihrer Individualität heraus mit solcher Bestimmtheit behaupten. Wir haben bei anderen Leuten, die immer gut schlafen, weil sie mit sich selbst zufrieden sind, dann das strenge Betonen des individuellen Prinzips.

Und dieser Kampf lodert eigentlich auf dem Grunde der europäischen Zivilisation. Er lodert bis zum heutigen Tage. Und in den Dingen, die sich äußerlich an der Oberfläche unseres Lebens abspielen, haben wir im Grunde genommen kaum etwas anderes als eben oberflächliche Wellenschläge dessen, was in der Tiefe der Seelen schon einmal vorhanden ist als Überrest jenes tieferen, jenes intensiveren Seelenlebens der damaligen Zeit.

Nun sind ja so manche Seelen aus der damaligen Zeit wiederum im gegenwärtigen Erdenleben da. Sie haben in einer gewissen Weise besiegt, was sie dazumal in starkem Maße für das Oberbewußtsein beunruhigt hat, wenigstens für gewisse Augenblicke im Oberbewußtsein beunruhigt hat. Aber in der Tiefe lodert das in zahlreichen Gemütern heute um so mehr. Geisteswissenschaft ist eben wiederum dazu da, um auch auf solche historische Erscheinungen hinzuweisen.

Nun aber dürfen wir das Folgende nicht vergessen. In demselben Maße, in dem die Menschen im Erdenleben unbewußt werden für dasjenige, was doch da ist: die Äthergedanken der nächsten Erdenumgebung, in demselben Maße, in dem sich daher die Menschen ihren Eigenbesitz, das «ich denke» aneignen, in demselben Maße engt sich die menschliche Seele ein, und der Mensch geht mit einer eingeengten Seele durch die Pforte des Todes. Diese eingeengte Seele hat dann unwahre, unvollständige, sich widersprechende irdische Gedanken in den Weltenäther hineingetragen. Die wirken nun auch wieder zurück auf die Gemüter der Menschen. Und daraus entstehen soziale Bewegungen, wie wir sie eben heute entstehen sehen. Die muß man ihrer inneren Entstehungsweise nach begreifen, dann wird man auch einsehen, daß es kein Heilmittel gibt gegen diese oftmals so zerstörerischen sozialen Anschauungen als die Verbreitung der Wahrheit über das geistige Leben und Wesen.

Sie haben ja schon aus den Vorträgen gesehen, die hier gerade als historische Vorträge mit Berücksichtigung des Reinkarnationsgedankens gehalten worden sind und die zu ganz konkreten Beispielen geführt haben, wie unter der Oberfläche der äußeren Geschichte die Dinge wirken, wie dasjenige, was in einem Zeitalter lebt, in ein späteres Zeitalter durch die ins Leben wiederkommenden Menschen ins Leben hinübergetragen wird. Aber es wirkt ja alles, was an Geistigem vorhanden ist zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, mit an der Gestaltung dessen, was von einem Erdenleben ins andere durch Menschen getragen wird. Heute wäre es etwas Gutes, würden zahlreiche Seelen sich jene Objektivität erwerben, zu der man Verständnis erweckend sprechen kann, wenn man gerade diejenigen Menschen charakterisiert, die in der Abendröte des Verstandes- oder Gemütszeitalters gelebt haben.

Diese Menschen, die damals gelebt haben, zum Teil jetzt wieder da sind, die haben gerade diese Abendröte eines Zeitalters tief in ihrer Seele miterlebt: Sie haben durch ihre fortwährenden Anfechtungen von jenen Gespenstern, von denen ich gesprochen habe, im Grunde doch einen tiefen Zweifel aufgenommen an der einzigartigen Gültigkeit des Intellektualistischen. Dieser Zweifel ist zu begreifen. Denn so im 13. Jahrhundert hat es viele Menschen gegeben, die erkennende Menschen waren, die dazumal im ja fast durchaus theologisierenden Wissenschaftsbetrieb darinnen waren und die es als eine tiefe Gewissensfrage behandelten: Was wird denn nun eigentlich?

Solche Seelen haben oftmals für die damalige Zeit Großes, Gewaltiges aus ihren früheren Inkarnationen in diese Zeit hineingetragen. Sie haben es schon in intellektualistische Färbung gebracht, aber sie empfanden das Ganze als eine Niedergangsströmung, und sie empfanden Gewissensbisse bei der aufgehenden Strömung, die nach Individualität hindrängte — bis dann diejenigen Philosophen kamen, die unter einem bestimmten Einfluß standen, der eigentlich allen Sinn totgeschlagen hat. Wenn man radikal spricht, kann man auch sagen: bis die kamen, die unter dem Einfluß von Descartes, von Cartesius standen; denn auch sehr viele von denen, die in der früheren Scholastik drinnengestanden hatten, waren ja der Denkweise des Cartesius sozusagen zum Opfer gefallen. Ich sage nicht, daß sie Philosophen geworden sind. — Diese Dinge verwandelten sich ja, und wenn die Menschen anfangen, in diesen Richtungen zu denken, dann werden Dinge zu Selbstverständlichkeiten, die merkwürdiger Unsinn sind; denn von Descartes kommt ja her der Satz: Cogito ergo sum — Ich denke, also bin ich.

Meine lieben Freunde, das galt unzähligen scharfsinnigen Denkern als eine Wahrheit: Ich denke, also bin ich. Die Folge davon ist, vom Morgen bis zum Abend: ich denke, also bin ich. Ich schlafe ein: ich denke nicht, also bin ich nicht. Ich wache wieder auf: ich denke, also bin ich. Ich schlafe ein, also, da ich nicht denke, bin ich nicht. — Und die notwendige Konsequenz ist: man schläft nicht nur ein, man hört auf zu sein, wenn man einschläft! Es gibt keinen weniger geeigneten Beweis für das Dasein des Geistes des Menschen als den Satz: Ich denke, also bin ich. Dennoch fing dieser Satz an, im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsentwickelung als der maßgebende Satz zu gelten.

Man ist heute genötigt, wenn man auf solche Dinge aufmerksam macht, den Anschein eines Sakrilegs auf sich zu nehmen. Aber gegenüber dem allem möchte ich hinweisen auf eine Art Gespräch, das nicht historisch verzeichnet ist, das aber durch geistige Forschung heraus gefunden werden kann unter den Tatsachen, die geschehen sind, ein Gespräch, das stattgefunden hat zwischen einem älteren und einem jüngeren Dominikaner, und das etwa so gelautet hat.

Der Jüngere sagt: Denken ergreift die Menschen. Denken — der Schatten der Wirklichkeit — ergreift die Menschen. Denken war ja immer in alten Zeiten die letzte Offenbarung des lebendigen Geistes von oben. Jetzt ist es dasjenige, das vergessen hat diesen lebendigen Geist von oben, jetzt wird es als bloßer Schatten erlebt. Wahrlich sagte dieser Jüngere -, wenn man einen Schatten sieht, dann deutet dieser Schatten auf Realitäten hin: die Realitäten sind schon da! Also nicht das Denken als solches ist damit angefochten, aber daß man aus dem Denken den lebendigen Geist verloren hat.

Der Ältere sagte: Es muß eben in dem Denken — dadurch, daß der Mensch seine Blicke liebevoll hinwendet auf die äußere Natur und Offenbarung als Offenbarung hinnimmt, nicht mit dem Denken an die Offenbarung herangeht -, es muß eben in dem Denken für die frühere himmlische Realität wiederum eine irdische Realität gefunden werden.

Was wird eintreten? — sagte der Jüngere. Wird die europäische Menschheit so stark sein, um diese irdische Realität des Denkens zu finden, oder wird sie nur so schwach sein, um die himmlische Realität des Denkens zu verlieren?

Darinnen, in diesem Zwiegespräch, liegt eigentlich alles, was in bezug auf die europäische Zivilisation heute noch gelten kann. Denn nach jener Zwischenzeit mit der Verdunkelung der Lebendigkeit im Denken, die nun da war, muß eben wiederum das Erringen des lebendigen Denkens eintreten, sonst wird die Menschheit schwach bleiben und die eigene Realität über der Realität des Denkens verlieren. Daher ist es schon notwendig, daß seit dem Eintreten unseres Weihnachtsimpulses in der anthroposophischen Bewegung rückhaltlos gesprochen werde in Form des lebendigen Denkens. Sonst kommen wir immer mehr und mehr dazu, daß auch dasjenige, was da oder dorther gewußt wird daß der Mensch physischen Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib hat -, nur mit den Formen des toten Denkens erfaßt wird. Aber das darf nicht mit den Formen des toten Denkens erfaßt werden, denn dann ist es eigentlich eine entstellte Wahrheit, nicht die Wahrheit selber.

Das ist, was ich heute charakterisieren wollte. Wir müssen dazu kommen, mit innerem Anteil über die gewöhnliche Geschichte hinaus Sehnsucht nach derjenigen Geschichte zu haben, die im Geiste gelesen werden muß und gelesen werden kann. Diese Geschichte, sie soll immer mehr und mehr in der anthroposophischen Bewegung gepflegt werden. Heute wollte ich, ich möchte sagen, mehr das Konkret-Programmatische nach dieser Richtung hin vor Ihre Seele stellen, meine lieben Freunde. Manches ist aphoristisch gesagt worden, aber der Zusammenhang in diesen Aphorismen, die ich heute gesprochen habe, wird Ihnen aufgehen, wenn Sie versuchen, das, was ausgesprochen werden wollte, weniger intellektualistisch zu verfolgen, als vielmehr es mit dem ganzen Menschen zu erfühlen - erkennend es erfühlen, fühlend es erkennen —, damit immer mehr und mehr wirklich von Spiritualität getragen werde nicht nur, was innerhalb unserer Kreise gesagt wird, sondern auch das, was innerhalb unserer Kreise gehört wird.

Erziehung brauchen wir zum spirituellen Anhören, dann werden wir unter uns die Spiritualität entwickeln. Diese Empfindung wollte ich heute anregen, nicht einen systematischen Vortrag halten, sondern mehr oder weniger - allerdings mit Berufung auf allerlei geistige Tatsachen — zu Ihren Herzen sprechen.

First Lecture

Today I would like to explain a few things for those who can be present, which may be a kind of episode within the considerations we have been cultivating here for some time now. What I say will serve to illustrate and explain some of the questions that may arise from what we have discussed so far, and at the same time it will shed some light on the state of mind of contemporary civilization.

Over the years, we have always had to draw attention to a very specific point in the development of essentially European civilization, which lies in the middle of the Middle Ages, around the 14th and 15th centuries. We are thus pointing to that point in the development of mankind where intellectualism begins, where people begin to pay attention to thinking, to the intellect, and to make it the judge of what is to be thought and done among people.

Now, because the age of the intellect is here today, one can at best form a proper idea of what intellectualism is by experiencing the present, which came to the surface of civilization in the 14th and 15th centuries. But the state of mind that preceded it can no longer be felt in a vivid way today. When you look at history, you actually project what you are used to seeing in the present further backwards in the course of history, and you don't get much idea of how completely different the spirits were before this period. And if you allow documents to speak, you read into them to a large extent what is today's way of thinking and seeing things.

From the point of view of the humanities, many things are quite different. And if you look, for example, at those personalities who, on the one hand, were influenced by Arabism, by the culture of Asia, by what was lived out as religion in Mohammedanism, but on the other hand were also influenced by Aristotelianism, if you look at these personalities who then found their way across Africa to Spain, who then deeply influenced the spirits of Europe, up to Spinoza and beyond Spinoza in turn further influenced the spirits of Europe, then one does not gain a view of them if one imagines their state of mind as if they had simply been people of the present, only that they did not yet know so and so many things that were later found. For that is roughly how one imagines them. But the way of thinking and viewing even those personalities from the indicated civilization who lived around the 12th century was quite different from that of today.

Today, when we look back on ourselves in this way, we feel that we are the owners of thoughts, feelings and impulses of will that then become action. Above all, man ascribes to himself the “I think”, the “I feel”, the “I want”. With these spirits, with these personalities of whom I am now speaking, the “I think” was not yet accompanied by the kind of feeling with which we say today: I think - but only the “I feel” and “I want”. These people attributed only their feelings and their will to their own personality. From ancient civilizational backgrounds they lived much more in the feeling “it thinks in me” than that they thought “I think”. They certainly thought: “I feel, I will”, but they did not think to the same extent: “I think”, but they said to themselves - and this was a quite real view, which I now want to share with you -: Thoughts are in the sublunary sphere, that is where thoughts live. - Everywhere these thoughts are in that sphere which is given by the fact that we imagine the earth (see drawing, blue) at a certain point, the moon here at another, then Mercury, Venus and so on. They thought of the earth as a dense, solid world mass, but they thought of the lunar sphere up to the moon (yellow) as the second thing that belongs to it.

And just as we say that there is oxygen in the air in which we breathe, so these people said - it has just been completely forgotten that this was so -: There are thoughts in the ether that reaches up to the moon. - And just as we say that we breathe in the oxygen of the air, so these people did not say: we breathe in thoughts, but: we perceive thoughts, we take in thoughts. And they were aware that they were absorbing them.

You see, today a person can also adopt something like this as a concept for my sake. He may even be able to understand something like this from anthroposophy. But he immediately forgets it again when it comes to practical life. When it comes to practical life, he immediately forms a very strange idea, he forms the idea that the thoughts arise within him, which would be quite the same as if he thought that the oxygen he absorbs is not absorbed from outside, but arises from within him. For the personalities of whom I speak, it was a deep feeling, an immediate experience: I do not have my thoughts as my possession, I may not actually say “I” think, but “thoughts are”, and I take them in, these thoughts.

Now, we know that the oxygen in the air passes through our organism in a relatively short time. We count such cycles according to pulse beats. This happens quickly. The personalities of whom I speak already imagined the taking in of thoughts as a kind of breathing, but a very slow breathing, a breathing which consists in the fact that at the beginning of life on earth man becomes capable of taking in thoughts. Just as we hold our breath for a certain time between inhalation and exhalation, so these people also imagined a state of affairs in which they now hold thoughts, but only in the same way that we hold the oxygen that belongs to the outer air. This is how they imagined it: they hold the thoughts during the time of their life on earth, and they breathe them out again into the world when they pass through the gate of death. So that one had to do with an inhalation: beginning of life; holding the breath: duration of life on earth; breathing out: sending thoughts out into the world. People who experienced inwardly in this way felt that they were part of a common atmosphere of thought with all others who experienced in the same way, an atmosphere which did not merely extend a few miles above the earth, but which went as far as the orbit of the moon.

You can now imagine that this view, which at that time fought for European civilization, wanted to spread further and further, especially from those Aristotelians who came over to Europe from Asia along the path I have indicated. One could now imagine that this view had really spread. What would have happened?

Yes, it would then not have been possible for that which has had to live itself out in the fullest sense of the word in the course of earthly development, namely the consciousness soul. The people I am talking about were, so to speak, in the last stage of the development of the intellectual or emotional soul. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the consciousness soul was to emerge, which transformed everything in civilization into intellectualism when it lived itself out in the extreme.

The European population in its totality in the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries was by no means capable of simply accepting such a view as that of the personalities I have characterized, because the development of the consciousness soul would then have failed to occur. Even if it was, so to speak, determined in the counsel of the gods that the consciousness soul should develop, it was nevertheless the case that this consciousness soul could not have developed out of the independent activity of European humanity in its totality, but an impulse had to come, so to speak, that went towards developing the consciousness soul in particular.

So that we see two spiritual currents coming up from the age that I have now characterized. One current of thought was represented, so to speak, by the Arabizing philosophers, who strongly influenced European civilization from the west of Europe, much more strongly than is believed today. The other current was the one that fiercely fought against this current, which I have characterized, and which in the strongest terms presented this view as the most heretical for Europe. How strongly this was felt for a long time, my dear friends, you will feel when you look at pictures where, for example, Dominican monks or Thomas Aquino himself are depicted in triumph, in the triumph of a completely different view, a view that above all emphasizes the individuality, the personal nature of man, that works towards man appropriating his thoughts as his own, and where these Dominicans are depicted trampling the representatives of Arabism underfoot. They are under their feet, they are being trampled on. The two currents have long been perceived in such opposition. The kind of emotional energy contained in such an image is actually no longer present in today's somewhat apathetic humanity. However, we do not need it for the things that were fought for back then, but we need it very much for other things!

Let us consider what was presented there: Inhalation of thoughts from the world ether, from the sublunar sphere: beginning of life; holding breath: Earth life; exhalation: thoughts again emerge, but with the individual human coloring, into the world ether, into the impulses of the sphere under the moon, into the impulses of the sublunar sphere.

What then is this exhalation? Exactly the same, my dear friends, as that of which we say: in the three days after death the etheric body of man enlarges. Man looks back at the slowly enlarging etheric body, he sees how his thoughts spread out into the cosmos. It is quite the same thing that has been described, I would say, from a more subjective point of view. So it is always true again how these people felt and experienced back then. They felt the cycle of life more deeply than it can be felt today.

But nevertheless, if their views had become dominant in Europe in the form in which they were then, then only a weak sense of self would have developed in the people of European civilization. The soul of consciousness would not have been able to emerge, the ego would not have grasped itself in the “I think”, the idea of immortality would have become more and more blurred. People would have looked more and more to that which generally waves and weaves around in the sublunar sphere, if it remained of the human being who had lived here on this earth. One would have felt the spirituality of the earth as its extended atmosphere, one would have felt oneself with the earth, but not as an individual human being, separated from the earth; for the human beings whom I characterized actually felt themselves intimately connected with the earth through this “it thinks in me”. They did not feel themselves as individualities to the same degree as people in the rest of Europe began to feel, albeit in an unclear way.

But then we must also consider the following: Only this spiritual current, of which I spoke, knew that when man dies, the thoughts absorbed by him during his life on earth undulate and weave in the world ether that surrounds the earth. And this view was therefore fiercely opposed by those personalities who emerged from the Dominican Order in particular, and it was sharply asserted that man is an individuality, that one must above all look at that which passes from man as an individuality through the gate of death, not at that which dissolves in the general world ether. This was emphasized preferably, although not only by the Dominicans, but I would like to say representatively by the Dominicans. This view of the individuality of man was sharply and energetically advocated in opposition to the first direction I have characterized. But it was precisely this that brought about a very specific state of affairs.

For let's take a look at the representatives of, let's say, individualism. There were these individually colored thoughts that merged into the general world ether. And those who fought against this current were disturbed precisely by the fact that they still knew, still vividly knew: this is what is claimed, this view is there - disturbed precisely by what was really there. This disquiet caused by the enlarging and dissolving forces and by the human thoughts being released into the ether of the world, this disquiet of the most outstanding thinkers, only ceased in the 16th and 17th centuries.

You have to be able to put yourself in the shoes of people who belonged to the Dominican Order in order to appreciate how these very people were troubled by the legacy of the deceased, in which they could no longer believe, so to speak, with their own views. You have to put yourself in the shoes of these people. An outstanding mind in the 13th and 14th centuries could not think in such a dry, abstract, icy, conceptual way as people do today. Today, when people hold views of any kind, it seems as if it were a condition for holding views that one's heart must first be torn out of one's body. It wasn't like that in those days. At that time there was intimacy, I would like to say cordiality, in all that one represented as ideas. But because this cordiality was present, there was also a strong inner struggle in a case like the one I am citing here.

And among the most terrible inner struggles, that which emerged from the Dominican Order, for example, as a certain philosophy, which later strongly influenced life, because it was built much more on the authority of individual people. Such a general education did not yet exist at that time; everything that was educational, everything that people knew, was influenced by what a few possessed, who therefore also had more of an interest in philosophical life and striving. Everything that flowed into civilization contained what was lived through in such inner struggles. Today one reads the writings of the scholastics and feels only dry thoughts. But only the readers today are actually dry. The people who wrote them were not dry in their minds. They were full of inner fire towards their thoughts. And this inner fire came from the desire to reject the objective influence of thought.

When someone thinks about worldview issues today, nothing really moves them. One can think the greatest nonsense today, and one thinks it quite calmly, because for humanity, which has already developed for so long within the consciousness soul, there is no disquiet of the kind that would cause individuals to feel how people's thoughts will turn out when they flow out into the etheric environment of the earth after death. Today such things are quite unknown, as they could still be experienced in the 13th, 14th century, where younger priests came to older priests and still expressed the inner torments they went through in remaining constant in their religious creed by saying: I am tormented by the ghosts of the dead.

For by the ghosts of the dead was meant what I have now characterized. People were still able to grow into what they had just learned. Within a certain community, let's say a Dominican community, they learned that man is an individual, that he also has his own individual immortality. They learned that it is a false, heretical view when an all-earth soul is considered in relation to thinking, and they learned to fight it fiercely. But at certain moments, when one really came to terms with oneself, one felt the objective working of the thoughts of the remains of deceased people and then said to oneself: Is it quite right that I should do what I am doing? There is something indeterminate working in my soul. I can't get up against it. I am held fast. Yes, people's intellects, or at least the intellects of many people, were still so organized at that time that for them the dead continued to speak quite generally at least for days after death. And when one had stopped speaking, another began. With regard to such things, one felt oneself to be completely within the general spirituality of the universe, at least still in the etheric.

This co-experience with the universe has completely ceased in our times. And instead we have attained life in the consciousness soul. And everything that surrounds us as a reality, like tables and chairs, like trees and rivers, that surrounds us as a spiritual reality, now only affects the depths of people's subconscious. The inwardness of life, the spiritual inwardness of life, has just ceased. It is only attained again in a vividly received spiritual-scientific knowledge.

And we must think as vividly about a spiritual-scientific knowledge as we do when we look at such phenomena that lie not so long behind us. Think of the scholastic thinker or writer of the 13th century. He writes down his thoughts. Today it is easy to think, because people have already become accustomed to thinking intellectually. Back then, it was still difficult. Back then, people were aware of the tremendous inner effort, they were aware of the fatigue caused by thinking, like chopping wood, if I may put it trivially. Today, many people's thinking has become completely automatic. And are people today afflicted by the longing to pursue their every thought with their human personality? One listens to how people today can let one thought emerge from another like an automaton, so that one cannot keep up, that one does not even know why; for there is nothing of necessity there. But as long as man lives in the body, he should pursue his thoughts with his personality. Then they already take a different course: they spread out when he has died.

Yes, in those days one could sit and defend the doctrine of the individual man in order to save the doctrine of individual immortality with all sharply incisive thoughts, becoming polemical against Averroes or other people of that first direction which I have characterized today. But then there was a possibility: there was the possibility that that which had been dissolved after death like a kind of ghost in the sublunar sphere by such an outstanding personality as Averroes, could have been and remained strongly collected again at the end of the sublunar sphere - precisely by the moon itself - and after enlargement could even have been reduced again and given form, so that it could have been consolidated again into a being, I would like to say, built up in the ether. That could happen. Then one sat and tried to justify individualism: One polemicized against Averroes - and Averroes appeared, appeared threateningly and troubled the mind. In the 13th century, the most important scholastic writers stood up against the long-dead Averroes. They polemicized against the long-dead man, against what remained as doctrine: he proved that his thoughts had been condensed, consolidated and lived on!

These inner struggles that preceded the beginning of the age of consciousness are already such that today we should look at their full intensity, their intimacy. After all, words are words, and later people take what is behind the words with the concepts they have. But such words sometimes included rich soul life, indicated soul life, as I have just characterized it.