The Anthroposophic Movement

GA 258

14 June 1923, Dornach

Fifth Lecture

Anti-Christianity

It is not without significance to observe in the anthroposophic movement itself, particularly amongst those first people who began, as one might say, by being just an ordinary audience, how the ground had, so to speak, to be conquered for Christianity. For the theosophic movement, in its association with Blavatsky's special personality, started out in every way from an anti-christian orientation.

This anti-christian orientation, which I mentioned in connection with the same phenomenon in a very different person, Friedrich Nietzsche, is one which I should like to examine a little in a clearer light before going further.

We must be quite clear ... it follows, indeed, from all the various studies which, in our circles more especially, have been directed to the Mystery of Golgotha ... we must be quite clear that the Mystery of Golgotha intervened as a fact in the evolution of mankind on earth. It must be taken, in the first place, as a fact. And if you go back to my book, Christianity as Mystical Fact, and the treatment of the subject there, you will find already the attempt made there to examine the whole Mystery-life of ancient times with a view to the various impulses entering into it; and then to show how the different forces at work in the different, individual mysteries all came together in one, met in a harmony, and thereby made it possible for that which first, in the Mysteries, came before men so to speak in veiled form, to be then displayed openly before all men as an historic fact. So that in the Mystery of Golgotha we have the culmination in an external fact of the total essence of the ancient Mysteries. And then, that the whole stream of mankind's evolution became necessarily changed through the influences that came into it from the Mystery of Golgotha.—This is what I tried to show in this particular book.

Now, as I have often pointed out, at the time when the Mystery of Golgotha was enacted as a fact, there were still in existence remnants of the ancient Mystery-Wisdom. And by aid of these remnants of ancient Mystery-Wisdom, which passed on into the Gospels, as I described in the book,—it was possible for men to approach this Unique Event, which first really gives the Earth's evolution its meaning. The methods of knowledge which they needed to understand the Mystery of Golgotha could be taken from the ancient Mysteries. Rut it must be noted at the same time, that the whole life of the Mysteries is disappearing,—disappearing in the sense in which in old times it had existed and found its crown and culmination in the Mystery of Golgotha. And I pointed out too, that really, in the fourth century after Christ, all those impulses vanish, which mankind could still receive direct from the ancient way of knowledge, and that of this ancient way of knowledge there only remains more or less a tradition; so that here or there it is possible—for particular persons, for peculiar individuals, to bring these traditions again to life; but a continuous stream of evolution, such as the Mysteries presented in the old days, has ceased. And so all means, really, of under-standing the Mystery of Golgotha is lost.

The tradition continued to maintain itself. There were the Gospels,—at first kept secret by the ecclesiastical community, and then made public to the people in the various countries. There were the ritual observances. It was possible, during the further course of human history in the West, to keep the Mystery of Golgotha alive, so to speak, in remembrance. But the possibility of thus keeping it alive ceased with the moment when, in the fifth post-atlantean century, intellectualism came on the scene, with all that I spoke of yesterday as modern education. At this time there entered into mankind a science of natural objects,—a science which, were it only to evolve further the same methods as it has done hitherto, could never possibly lead to a comprehension of the spiritual world. To do so, these scientific methods require to be further extended: they require the extension they receive through anthroposophy. Rut if one stopped short at these natural science methods in their mere beginnings, as introduced by Copernicus, Galileo and the rest, then, in the picture of the natural world, as so seen, there was no place for the Mystery of Golgotha.

Now only just consider what this means. In none of the ancient religions was there any cleft between the Knowledge of the World and what we may call the Knowledge of God. Worldly learning, profane learning, flowed over quite in course of nature into theology. In all the heathen religions there is this unity between the way in which they explain the natural world, and in which they then mount up in their explanation of the natural world, to a comprehension of the divine one, of the manifold. divinity that works through the medium of the natural world, ‘Forces of nature,’ forces of the abstract kind, such as we have to-day, such as are generally accepted on the compulsion of scientific authority,—such ‘forces of nature’ were not what people had in those days. They had live beings, beings of the natural world, who guided, who directed, the various phenomenon of nature; beings to whom one could build a bridge across from that which is in the human soul itself. So that in the old religions, there was nowhere that split, which exists between what is the modern science of the natural world, and what is supposed to be a comprehension of the spiritual and divine one.

Now Anthroposophy will never make any pretension that it is going, itself, to establish the grounds of religion. But although religion must be always something that rests upon itself and forms in itself an independent stream in the spiritual life of mankind; yet, on the other hand, man's nature simply demands that there should be an accordance between what is knowledge and what is religion. The human mind must be able to pass over from knowledge to religion without having to jump a gulf; and it must again be able to pass over from religion to knowledge, without having to jump a gulf. But the whole form and character assumed by modern knowledge renders this impossible. And this modern knowledge has become very thoroughly popularized, and dominates the mass of mankind with tremendous authority. In this way no bridge is possible between knowledge of this kind and the life of religion;—above all, it is not possible to proceed from scientific knowledge to the nature of the Christ. Ever more and more, as modern science attempted to approach the nature of the Christ, it has scattered it to dust, dispelled and lost it.

Well, if you consider all this, you will then be able to understand what I am going to say, not now about Blavatsky, but about that very different person, Nietzsche.—In Nietzsche we have a person who has grown up out of a Protestant parsonage in Central Europe,—not only the son of religious-minded people in the usual sense, but the son of a parochial clergyman. He goes through all the modern schooling; first, as a boy at a classical school. But since he was not what Schiller calls a ‘bread-and-butter scholar,’ but a ‘lover of learning’, ... you know the sharp distinction made by Schiller in his inaugural address between the bread-and-butter scholar and the lover of learning ... so Nietzsche's interest widens out over everything that is knowable by the methods of the present age. And so he arrives consciently and in a very uncompromising way at that split-in-two, to which all modernly educated minds really come, but come unconsciently, because they delude themselves, because they spread a haze over it. He arrives at a tone of mind which I might describe somewhat as follows:—

He says:—Here we have a modern education. This modern education nowhere works on in a straight line to any clear account of the Christ-Jesus, without jumping a gap on the road. And now, stuck into the midst of this modern education which has grown up, we have something which has remained left over as Christianity, and which talks in words that no longer bear any relation whatever to the various forms of statement, the terms of description, derived from modern scientific knowledge. And he starts by saying to himself very definitely: If one in any way proposes to come to a real relation with modern scientific knowledge, and still at the same time to preserve inwardly any sort of lingering feeling for what is traditionally told about the Christ,—then one will need to be a liar. He puts this to himself; and then he makes his decision. He decides for modern education; and thereby arrives at a complete and uncompromising denunciation of all that he knows of Christianity.

More scathing words were never uttered about Christianity than those uttered by Nietzsche, the clergyman's son. And he feels it, with really, I might say, his whole man. One need only take such an expression of his as this,—I am simply quoting; I am, of course, not advocating what Nietzsche says; I am quoting it only—but one need only take such an expression as this, where he says: Whatever a modern theologian holds to be true is certainly false. One might indeed make this a direct criterion of truth.—One may know what is false—according to Nietzsche's view,—from what a modern theologian calls true. That is pretty much his definition, one of Nietzsche's definitions, as regards Truth. He decides, moreover, that the whole of modern philosophy has too much theological blood in its veins. And then he formulates his tremendous denunciation of Christianity, which is of course, a blasphemy, but at any rate an honest blasphemy, and therefore more deserving of consideration than the dishonesties so common in this field to-day. And this is the point which one must keep in sight: that a person like Nietzsche, who for once was in earnest in the attempt to comprehend the Mystery of Golgotha, was not able to do so with the means that exist,—not even by means of the Gospels as they exist.

We have now in our Anthroposophy interpretations of all the four Gospels. And what emerges from the Gospels as the result of such interpretation is emphatically rejected the theologians of all the churches. But Nietzsche in that day did not possess it. It is the most difficult thing in the world, my dear friends, for a scientific mind (and almost all people at the present day may be said in this sense to have, however primitively, scientific minds), to attain possession of the Mystery of Golgotha. What is needed in order to do so?

To attain to this Mystery of Golgotha, what is needed, is not a renewal of the ancient form of Mysteries, but the discovery of a quite new form of Mystery. The rediscovery of the spiritual world in a completely new form,—this is what is necessary. For, through the old Mysteries, not excepting the Gnosis, the Mystery of Golgotha could only be uttered haltingly and brokenly. Men's minds grasped it haltingly and brokenly. And this halting, broken utterance must to-day be raised to speech.

It was this urgent need to raise the old halting utterance to speech which was at work in the many homeless souls of whom I am speaking in these lectures. With Nietzsche it went so far as a definite and drastic—not denial only—but appalling denunciation of Christianity.

Blavatsky, too, drew her impulse mainly from the life of the old Mysteries. And, truly speaking, if one takes the whole of Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine, one cannot but see in it a sort of resurrection of the old Mysteries,—in the main nothing new. The most important part of what one finds revealed in the works of Blavatsky is simply a resurrection of the old Mysteries, a resurrection of the know-ledge through which in the old Mysteries men had become acquainted with the divine spirit-world.

But all of these Mysteries are only able to comprehend what is a preparation for the Christ. The people, who, at the time when Christianity began, were still in a way con-versant with the old Mysteries and their impulses,—these persons had a positive ground still, from which to approach the Unique Event of Golgotha. So that down, in fact, to the fourth century, there were people who still could approach the Event of Golgotha on positive ground. They were still able in a real sense to comprehend the Greek Fathers of the Church, in whom there are everywhere connections with the old Mysteries, and who—rightly understood—speak in quite a different key from the later Fathers of the Latin Church.

Within what dawned upon Blavatsky's vision there lay the ancient wisdom, which sees the natural world and spirit-world in one. And much as a soul, one might say, before the Mystery of Golgotha, beheld the world of Nature and Spirit, so Blavatsky beheld it now again. That way,—she said to herself—lies the Divine and Spiritual; that way a vista opens up for men into the region of divine spirit. And from this aspect she then turned her eyes upon what modern tradition and the modern creeds say about Christ-Jesus.

The Gospels, of course, she had no means of understanding as they are understood in Anthroposophy: and the understanding that is brought to them from elsewhere was not of a kind that could approach what Blavatsky had to offer in the way of spiritual knowledge. Hence her contempt for all that was said about the Mystery of Golgotha in the outside world. She said to herself, as it were: ‘What all these people say about the Mystery of Golgotha is on a far lower level than the sublime wisdom transmitted by the ancient Mysteries. And so the Christian God too must be on a lower level than what they had in the ancient Mysteries.’

The fault lay not with the Christian God; the fault lay with the ways in which the Christian God was interpreted. Blavatsky simply did not know the Mystery of Golgotha in its essential being; she could only judge of it from what people were able to say about it. Such things must be regarded with perfect objectivity. For as a fact, from the time of the fourth century after Christ, when with the last remnants of Greek civilization the sun of the old Mysteries had set, Christianity was taken over and adopted by Romanism. Romanism had no power, from its external civilization, to open up any real road on into the spirit. And so Romanism simply yoked Christianity to an external impulse. And this Romanized Christianity was, in the main, the only one known to Nietzsche and Blavatsky.

One can understand then that the souls I described as homeless souls, who had gleams from their former earth-lives, and were principally concerned to find a way back into the spiritual world, took the first thing that presented itself. They wanted only to get into the spiritual world, even at the risk of doing without Christianity. Some link between their souls and the spiritual worlds,—that was what these people wanted.

And so one met with the people who at that time were groping their way towards the Anthroposophical Society.

Let us be quite clear, then, as to the position which Anthroposophy held towards these people, when it now came upon the scene,—towards these people who were homeless souls. They were, as we saw, questing souls, questioning souls; and the first thing necessary was to recognize: What are these souls asking? What are the questions stirring in their inmost depths?—And if now from the anthroposophic side a voice began to speak to these souls, it was because these souls were asking questions about things, to which Anthroposophy believed that it could give the answers. The other people of the present day have no questions; in them the questions are not there.

Anthroposophy, therefore, had no sort of call to go to the theosophists in search of knowledge. For Anthroposophy, Blavatsky's phenomenal appearance, and what had come into the world with it, was so far a fact of great importance. But what Anthroposophy had to consider, was not the knowledge that came from this quarter, but principally the need for learning to know the questions, the problems that were perplexing a number of souls.

One might have said, had. there been any possibility at that time of putting it plainly into words: As to what the leaders of the Theosophical Society have given the people, one doesn't need to concern oneself at all; one's concern is with what the people's souls are asking, what their souls want to know. And therefore these people were, after all, the right people in the first instance for Anthroposophy.

And in what form did the answers require to be worded?—Well, let us take the matter as positively, as matter-of-factly, as possible. Here were these questioning souls: one could plainly read their questions. They had the belief that they could arrive at an answer to their questions through the kind of thing which is found in Mrs. Besant's Ancient Wisdom: Now you can easily tell yourselves that it would have been obviously very foolish to say to these people that there are a number of things in this book, Ancient Wisdom, which are no longer appropriate to the modern age; for then one would have offered these souls nothing; one would only have taken something away from them. There could only be one course, and that was, really to answer their questions; whereas from the other side they got no proper answer. And the practical introduction to really answering was that, whilst Ancient Wisdom ranked at that time as a sort of canonical work amongst these people, I did not much trouble about this Ancient Wisdom, but wrote my book, Theosophy, and so gave an answer to the questions which I knew to be really asked. That was the positive answer; and beyond this there was no need to go. One had now to leave the people their perfect liberty of choice: Will you go on taking up Ancient Wisdom? or will you take up Theosophy?

In epochs of momentous decision, when world-history is being made, things do not lie so rationalistically, along straight lines of reasoning, as people are apt to conceive.

And so I could very well understand, when theosophists attended that other set of lectures on ‘Anthroposophy’, which I gave in those days, at the founding of the German Section, that these theosophists said the same thing as I have been pointing out to you here: ‘But that doesn't in the very least agree with what Mrs. Besant says!’ Of course it didn't agree, and couldn't agree! For the answer had to be one which proceeded from all that the mind of this age can give out of its deeper consciousness. And so it came about,—just to give for the moment the broader lines only,—that, as a fact, to begin with—down to about 1907—every step on behalf of Anthroposophy had to be conquered in opposition to the traditions of the Theosophical Society. The only people, to begin with, whom one could reach with these things, were the members of the Theosophical Society. Every step had to be conquered. And controversy at that time would have had no sense whatever; the only thing was to hope and build upon the alternative selection.

Matters went on by no means without internal obstacles. Everything—in my opinion at least—had its proper place, in which it must be done properly. In my Theosophy I went, I think, no single step beyond what it was possible at that period to give out for a number of people publicly. The wide circulation which the hook has found since then of itself shows that the supposition was a right one: Thus far one could go.

With the people who were more intently seeking, and had, accordingly, come into the stream set going by Blavatsky, with these people it was possible to go further. And with these one now had to make a beginning towards going further. I could give you any number of instances; but I will pick out just one, to show how, step by step, the attempt was made to get away from an old, bad tradition, and come to what was right for the present day, to the results of direct present-day research.

For instance, there was the description usually given in the Theosophical Society of the way Man travels through so-called kamaloca, after death. The description of this, as given by the leading people in the Theosophical Society could only be obviated in my Theosophy by my leaving the Time notion so far out of account in this book. In the circles inside the society, however, I tried to work with the right notions of time.

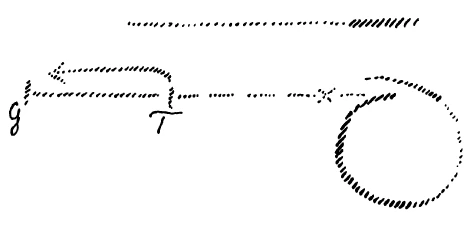

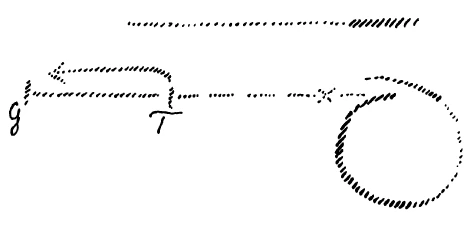

So it came about that I delivered lectures in various towns, amongst what was then the Dutch Section of the Theosophical Society, on the Life between Death and New Birth, and there for the first time, quite at the beginning of my activities, pointed out that it is really nonsense to conceive of it simply so, that if this, B D, is the life on earth from birth to death, that then the passage through kama-loca were simply a piece joined on, as it were, in one's consciousness. I showed, that time, here, must be conceived backwards; and I depicted the life of kama-loca as a living backwards, stage by stage, only three times as quick as the ordinary earth-life, or the life that was spent on earth: B ---------- D.

In outer life, of course, nobody to-day has any conception of this going on backwards as a reality, a reality in the spiritual field; for Time is simply conceived as a straight line from beginning to end; and a going on backwards is something of which people to-day form no notion whatever.

Now the theory was, amongst the leaders of the Theosophical Society, that they were renewing the teachings of the old wisdom. They took Blavatsky's book as a basis; and all sorts of writings came out, linked onto Blavatsky's book. But in these writings everything was presented to the mind in just the same way as things are conceived under the materialist world-conception of modern-times. And why?—Because they would have needed to become again knowing, not merely to renew the old knowledge, if they had wanted to find the truth of the matter.

The old things were for ever being quoted. Amongst other things always being quoted from Buddha and the old Oriental wisdom, was the Wheel of Births. Rut that a wheel is not of such a nature that one can draw a wheel as a straight line—, this the people did not reflect; and that one can only draw a wheel as running back into itself.

—There was no vitality in this revival of ancient wisdom, for the simple reason that there was no direct knowledge.

What was needed, in short, was: that something should be brought into the world by direct, living knowledge; and then this might also throw light upon the old, primeval wisdom.

And so one conclusion, from these first seven years especially of anthroposophic labour, amounted to this: that there were people who were ... well ... just as well pleased that there should not be any renovations, or,—as they called it,—‘innovations’ in the theosophic field; and who said: Oh, all that he says is just the same thing as the other! There's no difference! The differences are quite inessential! And so they were argued away. But this awful thing that I had, so to speak, ‘gone and done’ at the very beginning of my work in the Dutch Section of the Theosophical Society, when I lectured ‘from the life’ instead of simply rehearsing the doctrines contained in the canonical books of the Theosophical Society as the others did,—that was never forgotten! It never was forgotten. And those of you, who may perhaps go back in memory to those days in the growth of our movement, need only recall in the year 1907, when the Congress was held in Munich, at a time when we were still within the fold of the Theosophical Society, how the Dutch Theosophists turned up all primed and loaded, and were quite furious at this intrusion of a foreign body, as they felt it to be. They had no sense, that here a thing of the living present was matched against something merely of tradition,—they simply felt it to be a foreign body.

But something else could not fail to occur even then. And at that time the conversation took place in Munich between Mrs. Besant and myself, in which it was definitely settled that what I have to stand for, the Anthroposophy which I have to represent, would carry on its work in perfect independence, without any regard to anything else whatever that might play a part in the Theosophical Society. This was definitely settled, as a modus vivendi, so to speak, under which life could go on.

Even in those days, however, in the Theosophical Society, there were already dawning signs on the horizon of those absurdities by which it afterwards did for itself. For as a vehicle for a spiritual movement, the society to-day—despite the number of members still on its lists—may truly be said to have done for itself. Things, you know, may live on a long while as dead bodies, even after they are done for. But what was the Theosophical Society is to-day no longer living.

One thing, however, must be clearly understood: At the time when Anthroposophy first began its work, the Theosophical Society was full of a spiritual life, which, though traditional, nevertheless rested on sound bases, and was rich in material. What had come into the world through Blavatsky was there; and the people really lived in the things that had come into the world through Blavatsky.

Blavatsky had now, however, been dead for ten years past as regards earthly life. And one can but say of the tone in the Theosophical Society, that what lived on in it as a sequel of Blavatsky's influence and work was some-thing quite sound as a piece of historical culture, and could undoubtedly give the people something. Still, there were even then unmistakable germs of decay already present. The only question was, whether these germs of decay might not possibly be overcome; or whether they must inevitably lead to some kind of total discord between Anthroposophy and the old Theosophical Society.

Now one must say that amongst the tendencies that existed in the theosophic movement, even from the days of Blavatsky, there was one tendency in particular that was a terribly strong disintegrating element.

One must make a distinction, when considering the subject in the way I am doing now. One must make a clear distinction, between what was flung as spiritual information into the midst of modern life through the instrumentality of Blavatsky, and what was a result of the particular way in which Blavatsky was prompted to give out this information, out of her own person, in the manner I described. For in Blavatsky there was, to begin with, this particular kind of personality,—such as I described to you recently,—one who simply, having once been given, so to speak, an instigation from some quarter—through a betrayal, if you like,—then, out of her own person, as though in recollection of a previous life of incarnation on earth, and though only as a reawakening of an old wisdom, yet did bring wisdom into the world, and transmitted it in book-form to mankind.—This second fact one must keep quite distinct from the first. For this second fact, that Blavatsky was instigated in a particular way to what she did, introduced elements into the theosophic movement which were different from what they should have been if the theosophic movement was to be one of a purely spiritual character.

That it was not. For the fact of the matter was, that Blavatsky in the first instance received an instigation from a quarter of which I will say no more, and put forth, out of herself, what is in her Isis Unveiled; and that then, through all sorts of machinations, it came about that Blavatsky, the second time, was subjected to the influence of esoteric teachers from the Orient; and behind these there was a certain tendency of a political-cultural kind and egoistic in character. From the very first, there lay an orientalist policy of a one-sided character in what it was now hoped to obtain in a roundabout way by means of Blavatsky. Within it all lay the tendency to show the materialistic West, how far superior the spiritual knowledge of the East is to the materialism of the West. Within it was concealed the tendency to achieve, in the first place, a spiritual, but, more generally, any kind of dominion, an ‘empire’ of some kind, of the Orient over the Occident: And this was to be done, in the first place, by indoctrinating the spirituality or unspirituality of the West with the traditions of Eastern wisdom.—Hence came what I might call that shifting of the axis which took place, from the altogether-European of Isis Unveiled, to the altogether-Oriental of Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine.

There was every variety of factor here at work; but one of the factors was this one, that wanted, namely, to join India on to Asia and so create an Indo-Asiatic Empire with the assistance of Russia. And so this ‘Doctrine’ of Blavatsky's was inoculated with the Indian vein, in order, in this way, to conquer the West spiritually.

Now this, you see, is a one-sided vein, egoistic,—nationally egoistic. And this one-sided vein was there from the very beginning. It met one directly with symptomatic significance. The first lecture I ever heard from Mrs. Besant was on ‘Theosophy and Imperialism’. And when one inwardly tried to answer the question: Does really the main impulse of this lecture lie in the continuation-line of the strictly spiritual element in Blavatsky? or does the main impulse of this lecture lie in the continuation-line of what went along with it;—then one could only say: the latter.

With Mrs. Annie Besant it was often the case, that she said things of which she by no means knew the ultimate grounds. She took up the cudgels for something or other of which the ultimate grounds were unknown to her; she was ignorant of the connections that lay at their root. But if you read this lecture, ‘Theosophy and Imperialism’ (which is printed), and read it understandingly, with all that lies underneath it, you will then see for yourselves, that, supposing there were somebody who wanted to split India off from England,—to split it off in a certain sense spiritually after a spiritual fashion,—a good way of taking the first unobtrusive step, would be with a tendency such as there was in this lecture.

This was always the beginning of the end with all such spiritual streams and spiritual societies, that they began to mix up one-sided political interests with their own sphere. Whereas a spiritual movement—above all to-day—can only possibly pursue its course through the world, and it is indeed, to-day, one of the most vital life conditions for a spiritual movement that would lead to real, actual spirituality, that it should be universally human, wholly and undividedly human. And everything else, which is not wholly and universally human, which sets out in any way to split the body of mankind, is from the first an element of destruction in any spiritual movement that would lead to the real spirit-world.

Just consider how deep one strikes with all such things into the sub-conscious regions of man's being. And hence it is one of the life-conditions of any such spiritual movement,—for instance, such as the anthroposophical movement, too, would be,—that there should be at least an earnest, honest endeavour to get beyond all partial, sectional interests in mankind, and really to rise to the universal interests of all mankind. And therein lay the ruin of the theosophic movement, that from the beginning it had an element of that kind in it. On occasion, as we know, this kind of element is quite capable of reversing steam: later, during the Great War, this opposite tendency turned very anglo-chauvinist. Rut this very circumstance should make it perfectly clear, that it is quite impossible successfully to cultivate a real spiritual movement, so long as there is some kind of sectionalism which one is not pre-pared to leave behind one.

Amongst the external dangers, therefore, which beset the anthroposophic movement to-day, there is this especially: That people in the present age, which is wandering astray in nationalisms on all sides, have yet so little courage to get beyond these nationalisms.

What then lies at the root of a one-sidedness like that of which we were speaking?—At its root lies the desire to acquire power as a society through something else than simply the revelations of the spiritual source itself. And one can but say that whereas, at the turn of the century, there was still a fairly healthy sense in the Theosophical Society as regards conscious aspirations after power, this was by 1906 all gone, and there existed a strong ambition for power.

It is necessary, do you see, that one should clearly recognize this growth of the anthroposophical life out of universal human interests, common to the whole of mankind; and that one should clearly see, that it was only because the questioners were there, in the Theosophical Society, and because of this only, that Anthroposophy was obliged to take growth in the Theosophical Society, to take up its lodging there, one might say, for a while; since otherwise it had nowhere to lodge.

The first period—so to speak—was scarcely over, when, as you know, the whole impossibility of the theosophical movement for Western life demonstrated itself quite peculiarly in the question of the Christ. For what with Blavatsky was in the main a theory,—although a theory that rested on emotions,—namely, the depreciation of Christianity, was afterwards carried in the theosophic movement to such a very practical depreciation of Christianity, as the education of a boy in whom they said they were going to train-up the soul of the re-arisen Christ.

One could hardly conceive anything more nonsensical. And yet an Order was founded amongst the Theosophical Society for the promotion of this Christ-Birth in a boy, who really, as one might say, was already there.

And now it very soon came to the perfection of nonsense.—With all such things, of course, there very soon come muddles which border terribly close on falsehoods. In 1911, then, there was to be a Congress of the Theosophical Society in Genoa. The things leading to this nonsense were already in full bloom, and it was necessary for me to announce as my lecture for this Genoa Congress From Buddha to Christ. It must then necessarily have come to a clear and pregnant settlement of relations; for the things, that were everywhere going about, would then necessarily have come to a head. But, lo and behold! the Genoa Congress was cancelled.—Of course excuses can be found for all such things. The reasons that were alleged all looked really uncommonly like excuses.

And so the anthroposophic movement may be said to have entered on its second period, pursuing its own straight course; which originally began, as I said, with my delivering a lecture, quite at the beginning, to a non-theosophical public, of whom only one single person remains, (who is still there!) and no more, although a number of persons attended the lecture at the time. Anyhow, the first lecture I delivered (it was a cycle of lectures, in fact) bore the title From Buddha to Christ. And in 1911 I proposed again to deliver the cycle From Buddha to Christ. That was the straight line. But the theosophical movement had got into a horrible zigzag.

Unless one takes the history of the anthroposophic movement seriously, and is not afraid to call these things by their right name, one will not be able to give the proper reply to the assertions continually being made about the relation of Anthroposophy to Theosophy by those surface triflers, who will not take the trouble to learn the real facts, and refuse to see, that Anthroposophy was from the very first a totally separate and distinct thing, but that the answers, which Anthroposophy has the power to give, were naturally given to those people who happened to be asking the questions.

One may say, then, that down to the year 1914 was the second period of the anthroposophic movement. It really did nothing very particular—at least, so far as I was concerned—towards regulating relations with the theosophic movement. The Theosophical Society regulated relations by excluding the Anthroposophical one. But one was not affected by it. Seeing that from the first one had not been very greatly affected by being included, neither was one now very greatly affected by being excluded. One went on doing exactly the same as before. Being excluded made not the slightest change in what had gone on before, when one was included.

Look for yourselves at the way things went, and you will see that, except for the settlement of a few formalities, nothing whatever happened inside the anthroposophic movement itself down to the year 1914, but that everything that happened, happened on the side of the Theosophical Society.

I was invited in the first place to give lectures there. I did so; I gave anthroposophic lectures. And I went on doing so. The lectures for which I was originally invited are the same newly reprinted in my book, Mysticism at the Dawn of the New Age of Thought. And I then carried on further what is written in this Mysticism at the Dawn of the New Age of Thought, and developed it in a variety of directions.

By this same society, with the same views, I was then excluded, and of course, my followers, too. For one and the same thing I was first included, and afterwards excluded. Yes ... that is the fact of the matter. And no one can rightly understand the history of the anthroposophic movement, unless they keep plainly in sight as a fundamental fact, that as regards the relation to the theosophic movement, it made no difference whether one were in- or excluded.

This is something for you to reflect upon very thoroughly in self-recollection. I beg you to do so. And then, on the grounds of this, I should like tomorrow to give a sketch of the latest and most difficult phase, from 1914 until now, and then to go into various details again later, in the subsequent lectures.

Fünfter Vortrag

Es ist schon von Bedeutung, darauf hinzusehen, wie gewissermaßen innerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung gerade bei denjenigen, die zuerst gewöhnliche Zuhörer, könnte man sagen, waren, das Christentum erobert werden mußte. Denn die theosophische Bewegung ist in Anlehnung an die Persönlichkeit der H. P. Blavatsky durchaus ausgegangen von einer antichristlichen Orientierung. Und diese antichristliche Orientierung, die ich auch in Zusammenhang gebracht habe mit derselben Orientierung bei einer anderen Persönlichkeit, bei Friedrich Nietzsche, diese antichristliche Orientierung möchte ich zunächst noch ein wenig beleuchten.

Man muß sich darüber klar sein, und das geht ja aus den verschiedensten Betrachtungen hervor, die gerade innerhalb unserer Kreise angestellt worden sind über das Mysterium von Golgatha, daß das Mysterium von Golgatha zunächst als eine Tatsache in die Entwickelung der Menschheit auf Erden sich hineingestellt hat. Als Tatsache ist es zunächst zu nehmen. Wenn Sie zurückgehen auf die Darstellung in meinem Buche «Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache», dann werden Sie finden, daß dort der Versuch gemacht ist, das gesamte Mysterienwesen der alten Zeiten nach seinen Impulsen zu erkennen und dann zu zeigen, wie die verschiedenen Kräfte, die in den einzelnen Mysterien gespielt haben, sich vereinigt, harmonisiert und dadurch möglich gemacht haben, daß dasjenige, was zunächst in den Mysterien, man möchte sagen, auf eine verborgene Weise den Menschen entgegengetreten ist, in offener Weise als eine historische Tatsache vor die Menschen hingestellt worden ist. So daß in dem Mysterium von Golgatha in einer äußeren Tatsache die Krönung des gesamten alten Mysterienwesens vorliegt. Wie dann die ganze Entwickelung der Menschheit eine andere werden mußte unter den Einflüssen des Mysteriums von Golgatha, das habe ich gerade in jenem Buche ja zu zeigen versucht.

Nun waren, wie ich auch schon öfter betont habe, zur Zeit, als das Mysterium von Golgatha sich als eine Tatsache abspielte, Reste der alten Mysterienweisheit vorhanden. Man konnte mit Hilfe dieser Reste der alten Mysterienweisheit, die so in die Evangelien übergegangen sind, wie ich es in jenem Buche dargestellt habe, an dieses Ereignis, das eigentlich der Erdenentwickelung erst ihren Sinn gibt, herantreten. Die Erkenntnismittel zum Verstehen des Mysteriums von Golgatha konnte man aus den alten Mysterien nehmen. Aber zu gleicher Zeit muß ja verzeichnet werden, daß das Mysterienwesen in jenem Sinne, in dem es in alten Zeiten da war, verschwindet und in dem Mysterium von Golgatha seine Krönung gefunden hat.

Auch das habe ich ja erwähnt, wie im 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert eigentlich die unmittelbar noch vom Menschen ergriffenen Impulse der alten Erkenntnis schwinden, und von dieser alten Erkenntnis nur mehr oder weniger Traditionelles vorhanden bleibt, so daß da oder dort möglich ist, daß durch besondere Menschen, durch besondere Persönlichkeiten diese Traditionen wiederum belebt werden. Aber eine so fortlaufende Mysterienentwickelung, wie sie im Altertum vorhanden war, findet nicht mehr statt. So ist eigentlich verlorengegangen das Mittel, um das Mysterium von Golgatha zu verstehen.

Die Tradition hat sich forterhalten. Die Evangelien waren da, zunächst geheimgehalten von der kirchlichen Gemeinschaft, dann für die einzelnen Völker veröffentlicht. Die Kulte waren da. Es war möglich, in der fortlaufenden Geschichte der abendländischen Menschheit das Mysterium von Golgatha gewissermaßen wie in der Erinnerung lebendig zu erhalten. Aber die Möglichkeit dieser Lebendighaltung hörte auf in dem Momente, als im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum der Intellektualismus mit dem, was ich gestern moderne Bildung genannt habe, auftrat. Da trat in die Menschheit herein eine Wissenschaft über die natürlichen Dinge, eine Wissenschaft, aus der nimmermehr, wenn sie ihre Methoden nur in der Weise entwickelt, wie sie es bisher getan hat, ein Begreifen der geistigen Welt hervorgehen konnte. Da mußten diese Methoden eben in der Weise erweitert werden, wie es durch die Anthroposophie geschieht. Aber wenn man bei den von Kopernikus, Galilei und so weiter nur eingeleiteten naturwissenschaftlichen Methoden stehenblieb, dann hatte innerhalb einer solchen Naturbetrachtung das Mysterium von Golgatha keinen Platz.

Nun bedenken Sie doch nur folgendes: In allen alten Religionen gab es keinen Zwiespalt zwischen der Welterkenntnis und, sagen wir, der Gotteserkenntnis. In einer ganz naturgemäßen Weise mündete die weltliche, die profane Wissenschaft in die Theologie hinein. Alle heidnischen Religionen haben das, daß eine Einheit bei ihnen bildet die Art, wie sie die Natur erklären, und wie sie dann in ihrer Naturerklärung aufsteigen zu einem Begreifen des Göttlichen, des mannigfaltigen Göttlichen, das eben durch die Natur wirkt.

Solche Naturkräfte abstrakter Art, wie wir sie heute haben, wie sie unter zwingender Autorität anerkannt werden, hatte man nicht. Man hatte Naturwesen, welche die Natur in ihren verschiedenen Erscheinungen lenkten, leiteten, zu denen man eine Brücke hinüberbauen konnte von dem aus, was in der Menschenseele selber ist. So daß nirgends jener Riß war in den alten Religionen, der da besteht zwischen dem, was neuere Naturwissenschaft ist und demjenigen, was Erfassen des Göttlich-Geistigen sein soll.

Nun wird Anthroposophie niemals behaupten, daß sie irgendwie selbst Religion-begründend auftreten will. Aber auf der anderen Seite ist es einfach eine menschliche Forderung, daß, wenn auch Religion immer etwas Selbständiges, eine selbständige geistige Strömung in der Menschheit sein muß, doch ein Einklang bestehen muß zwischen dem, was Erkenntnis ist, und dem, was Religion ist. Man muß, ohne über einen Abgrund zu springen, hinüberkommen können in das Religiöse vom Erkennen aus, und man muß wieder vom Religiösen in das Erkennen herüberkommen können, ohne über einen Abgrund springen zu müssen. Das ist bei der ganzen Konstitution, die die neuere Erkenntnis angenommen hat, nicht möglich. Und diese Erkenntnis ist durchaus populär geworden und bezwingt die Menschen mit einer ungeheuren Autorität. In dieser Art ist eine Brücke zwischen dieser Erkenntnis und dem religiösen Leben nicht möglich, vor allen Dingen ist es nicht möglich, vom Wissenschaftlichen aus das Wesen des Christus zu finden. Indem immer mehr und mehr die neuere Wissenschaft an das Wesen des Christus herangetreten ist, hat sie es zerstäubt, hat sie es verloren.

Wenn Sie dies bedenken, dann werden Sie das folgende begreifen können. Ich will zunächst von dem der Blavatsky fernstehenden Nietzsche sprechen. Da ist in Nietzsche ein Mensch, der herausgewachsen ist aus einem mitteleuropäischen protestantischen Pfarrhause, der Sohn nicht nur frommer Leute in dem modernen Sinn, sondern der Sohn eines praktizierenden Pastors. Er macht die moderne Bildung durch, macht sie zunächst als Gymnasiast durch. Da er aber nicht dasjenige ist, was Schiller den Brotgelehrten nennt, sondern ein philosophischer Kopf — Sie wissen ja, Schiller hat in seiner Antrittsrede scharf den Unterschied hervorgehoben zwischen dem Philosophenkopf und dem Brotgelehrten -, so verbreitert sich sein Interesse über alles dasjenige, was aus den Methoden der Gegenwart heraus Erkenntnis werden kann. Nun kommt er - aber auf eine radikale Weise — bewußt in jenen Zwiespalt hinein, in den eigentlich alle modernen gebildeten Gemüter hineinkommen, aber unbewußt, weil sie sich Illusionen darüber machen, weil sie einen Nebel darüber breiten. Er kommt zu einer Stimmung, die ich etwa im folgenden charakterisieren möchte.

Er sagt: Da haben wir nun eine moderne Bildung. Diese moderne Bildung arbeitet nirgends in gerader Linie, ohne einen Abgrund zu überspringen, zu einer Charakteristik des Christus Jesus hinüber. Nun stellt sich hinein in das, was die moderne Bildung geworden ist, das, was als Christentum geblieben ist, das in Worten spricht, die gar kein Verhältnis mehr haben zu den verschiedenen Formulierungen, Charakterisierungen, welche von der modernen Wissenschaft herkommen. Fr sagt sich zunächst scharf: Soll man irgendwie ein Verhältnis gewinnen zur modernen Wissenschaft und dann noch in irgendeiner Weise innerlich nachfühlen dasjenige, was traditionell über den Christus gesagt wird, dann muß man lügen. So sagt er sich. Und nun entscheidet er sich. Er entscheidet sich für die moderne Bildung und kommt dadurch zu einer ganz radikalen Anklage dessen, was er nun vom Christentum kennt.

Schärfere Worte sind ja niemals über das Christentum gesprochen worden, als sie Nietzsche gesprochen hat, der Pastorssohn. Und er empfindet das, ich möchte sagen, wirklich mit seinem ganzen Menschen. Man braucht nur ein solches Wort von ihm zu nehmen - ich zitiere nur, ich vertrete selbstverständlich nicht dasjenige, was Nietzsche gesagt hat, sondern ich zitiere es —, wo er sagt: Dasjenige, was ein moderner Theologe für wahr hält, ist sicher falsch. Ja, man kann geradezu ein Kriterrum der Wahrheit daraus machen: Man erkennt, im Sinne von Nietzsche, was falsch ist, wenn ein moderner Theologe das wahr nennt. Das ist ungefähr seine Definition, eine seiner Definitionen über Wahrheit. Und er findet, daß die ganze moderne Philosophie zu viel Theologenblut im Leibe hat. Er formuliert dann diese ungeheure Anklage gegen das Christentum, die natürlich eine Blasphemie ist, aber die eben eine ehrliche Blasphemie ist, und die deshalb immerhin berücksichtigenswerter ist als die Verlogenheiten, die auf diesem Gebiete heute so vielfach getrieben werden. Das muß man nur festhalten, daß es sich darum handelt, daß eine solche Persönlichkeit wie Nietzsche, die einmal mit dem Begreifenwollen des Mysteriums von Golgatha Ernst machte, das eben mit den Mitteln, die vorhanden sind, auch mit den Evangelien, so wie sie da sind, nicht konnte.

Wir haben innerhalb unserer Anthroposophie nun über alle vier Evangelien Interpretationen. Was durch diese Interpretationen die Evangelien werden, das lehnen die Theologen aller Bekenntnisse ganz entschieden ab. Das hatte aber Nietzsche nocht nicht. Es ist das Allerschwierigste für einen wissenschaftlichen Geist — und fast sind alle Menschen heute schon, wenn auch in primitiver Weise, in diesem Sinne wissenschaftliche Geister —-, das Mysterium von Golgatha zu erobern. Denn was ist dazu notwendig? Gerade um das Mysterium von Golgatha zu erobern, ist notwendig nicht eine Erneuerung des alten Mysterienwesens, sondern das Auffinden eines ganz neuen Mysterienwesens. Das Auffinden der geistigen Welt in völlig neuer Form, das ist nötig. Denn mit den alten Mysterien, einschließlich der Gnosis, konnte man eben über das Mysterium von Golgatha nur noch stammeln. Man begriff es stammelnd. Und man muß dieses Stammeln heute zum Sprechen bringen.

Diesen Drang, das alte Stammeln zum Sprechen zu bringen, das hatten eben die vielen heimatlosen Seelen, von denen ich in diesen Betrachtungen spreche. Nietzsche brachte es eben zu einer radikal formulierten, nicht nur Absage, sondern furchtbaren Anklage des Christentums. Blavatsky bekam ja ihre Anregung im Grunde genommen auch von dem alten Mysterienwesen. Wenn man die ganze «Geheimlehre» der Blavatsky nimmt, muß man darinnen eigentlich etwas wie eine Auferstehung der alten Mysterien sehen, im Grunde nichts Neues. Das Wichtigste, was bei Blavatsky in ihren Werken zutage tritt, ist eben Auferstehung der alten Mysterien, Auferstehung jener Erkenntnisse, durch die in den alten Mysterien das Göttlich-Geistige erkannt worden ist.

Aber alle diese Mysterien können nur das begreifen, was Vorbereitung für den Christus ist. Diejenigen, die noch zur Zeit der Entstehung des Christentums in einer gewissen Weise mit den Impulsen der alten Mysterien vertraut waren, konnten sich positiv dem Ereignis von Golgatha gegenüberstellen. So daß bis ins 4. Jahrhundert eben Leute sich noch positiv dem Ereignis von Golgatha gegenüberstellen konnten. Man begriff im wirklichen Sinne die griechischen Kirchenväter noch, wie sie überall Zusammenhänge haben mit den alten Mysterien, wie sie, richtig verstanden, aus einem ganz anderen Ton heraus reden als die späteren lateinischen Kirchenväter.

Innerhalb desjenigen, was der Blavatsky aufging, war eben jene alte Weisheit enthalten, die Natur und Geist in einem schaute. Und so wie, ich möchte sagen, eine Seele vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha Natur und Geist geschaut hat, so schaute auch wiederum Blavatsky. Da, sagte sie sich, kommt man zum Göttlich-Geistigen, da eröffnet sich dem Menschen der Ausblick in das Göttlich-Geistige. Von da aus wendete sie dann den Blick auf dasjenige, was die moderne Tradition und die modernen Bekenntnisse von dem Christus Jesus sagen. Natürlich, die Evangelien, die konnte sie nicht so verstehen, wie sie in der Anthroposophie verstanden werden, und dasjenige Verständnis, das von woanders herkam, war nicht geeignet, heranzureichen an das, was Blavatsky an Geist-Erkenntnis bringen konnte. Daher ihre Verachtung für dasjenige, was in der Welt draußen über das Mysterium von Golgatha gesagt wurde. Sie sagte sich etwa: Was die Leute alle über das Mysterium von Golgatha sagen, das steht auf einem viel niedrigeren Niveau als all die majestätische Weisheit, welche die alten Mysterien gebracht haben. Also der Christengott steht auf einem niedrigeren Niveau als dasjenige, was alte Mysterien gehabt haben.

Es war nicht die Schuld des Christengottes, es war aber die Schuld der Interpretierungen des Christengottes. Blavatsky kannte eben das Wesen des Mysteriums von Golgatha nicht, sondern konnte es auch nur beurteilen nach dem, was man darüber sagen konnte. Auf diese Dinge muß man durchaus mit aller Objektivität hinschauen. Denn est ist ja, nachdem im 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert eigentlich das alte Mysterienwesen mit den letzten Resten des Griechentums seiner Abendröte zuneigte, das Christentum von dem Römertum aufgenommen worden. Das Römertum war außerstande, aus seiner äußerlichen Bildung heraus einen wirklichen Weg zum Geiste zu eröffnen. Das Römertum zwang dem Christentum eben ein äußerliches Moment auf. Und das romanisierte Christentum, das ist dasjenige, das im Grunde genommen Nietzsche und Blavatsky allein kannten.

So muß man verstehen, daß, weil es den Seelen, die ich als heimatlose Seelen bezeichnete, in denen frühere Erdenleben aufleuchten, vorzugsweise darum zu tun war, einen Weg in die geistige Welt hinein wiederzufinden, sie zunächst dasjenige nahmen, was sich ihnen gab. Sie wollten nur in die geistige Welt hinein, selbst auf die Gefahr hin, daß ihnen damit kein Christentum gegeben war. Einen Zusammenhang der Seele mit dem Geiste wollten die Menschen. So traf man diejenigen Menschen, die zunächst ihren Weg in die Theosophische Gesellschaft suchten.

Nun muß man sich nur klar darüber sein, welche Stellung die auftretende Anthroposophie diesen Menschen, diesen heimatlosen Seelen gegenüber hatte. Nicht wahr, das waren suchende Seelen, das waren fragende Seelen. Und zunächst handelte es sich darum, zu erkennen: Was fragen diese Seelen, welche Fragen leben ihnen in ihrem tiefsten Inneren? — Und wenn nun von anthroposophischer Seite aus zu diesen Seelen gesprochen worden ist, so war es deshalb, weil diese Seelen Fragen hatten über die Dinge, auf welche Anthroposophie glaubte antworten zu können. Die anderen Menschen der Gegenwart haben ja keine Fragen, ihnen fehlen die Fragen.

Anthroposophie hatte also gar nicht die Aufgabe, unter den Theosophen Erkenntnis zu suchen. Für sie war es zunächst eine " wichtige Tatsache, was mit der Erscheinung der Blavatsky in die Welt getreten ist. Aber dasjenige, was sie zu beobachten hatte, war nicht die Erkenntnis, die von jener Seite kam, sondern es war im wesentlichen die Notwendigkeit, die Fragen, die Rätselfragen kennenzulernen, die in einer Anzahl von Seelen waren.

Man hätte, wenn man dazumal überhaupt die Möglichkeit gehabt hätte, die Sache klar auszudrücken, sagen können: Um dasjenige, was von den Führern der Theosophischen Gesellschaft den Menschen gegeben worden ist, braucht man sich gar nicht zu kümmern, aber um das muß man sich kümmern, was die Seelen fragen, was sie wissen wollen. Deshalb waren dennoch diese Menschen eben zunächst die richtigen Menschen für die Anthroposophie.

In welcher Formulierung mußten die Antworten erfließen? Nun, nehmen Sie die Sache so positiv, so tatsächlich als möglich. Da waren diese fragenden Seelen. Ihre Fragen konnte man erkennen. Sie hatten den Glauben, daß sie durch so etwas Antwort bekommen auf ihre Fragen, wie es zum Beispiel Annie Besants Buch «Uralte Weisheit» enthält. Nun werden Sie sich sehr leicht sagen können: Es wäre selbstverständlich töricht gewesen, den Leuten zu sagen, das oder jenes ist in dem Buch «Uralte Weisheit» für die neuere Zeit nicht mehr geeignet, denn da hätte man ja diesen Seelen nichts geboten, sondern ihnen nur etwas weggenommen. Es konnte sich nur darum handeln, ihre Fragen wirklich zu beantworten, während sie von der anderen Seite keine reinliche Antwort bekamen. Die wirkliche Beantwortung wurde nun so eingeleitet, daß, während zunächst die «Uralte Weisheit» sozusagen ein dogmatisches Buch unter diesen Menschen war, ich mich wenig um die «Uralte Weisheit» kümmerte, sondern mein Buch «Theosophie» schrieb und Antwort auf die Fragen gab, von denen ich wußte, daß sie gestellt werden. Das war die positive Antwort. Und weiter brauchte man nicht zu gehen. Man mußte den Leuten nun völlig die Freiheit lassen: Wollt ihr weiter die «Uralte Weisheit» in die Hand nehmen, oder wollt ihr die «Theosophie» in die Hand nehmen.

In weltgeschichtlichen Zeitaltern, in denen sich Wichtiges entscheiden muß, können die Dinge nicht so rationalistisch geradlinig liegen, wie man sich gewöhnlich vorstellt. So fand ich es denn durchaus begreiflich, daß, als Theosophen bei meinem damaligen Vortragszyklus über Anthroposophie bei der Begründung der deutschen Sektion erschienen waren, diese Theosophen gesagt haben, worauf ich Sie ja in diesen Betrachtungen schon aufmerksam gemacht habe: Ja, aber das stimmt ganz und gar nicht überein mit dem, was Mrs. Besant sagt.

Selbstverständlich stimmte es nicht, konnte auch nicht stimmen, denn es sollte aus dem, was aus dem Bewußtsein, aus dem vertieften Bewußtsein der Gegenwart heraus gegeben werden kann, die Antwort sich finden. Und so ist es schon geworden, wenn ich zunächst, ich möchte sagen, mehr die großen Fäden charakterisieren will, daß zunächst etwa bis zum Jahre 1907 jeder Schritt für die Anthroposophie erobert werden mußte gegen die Tradition der Theosophischen Gesellschaft. Man konnte zunächst nur an die Mitglieder der Theosophischen Gesellschaft die Dinge heranbringen. Jeder Schritt mußte erobert werden. Polemisches hätte dazumal gar keinen Sinn gehabt, sondern einzig und allein das Hoffen, das Bauen auf die Selektion.

Die Dinge trugen sich durchaus nicht ohne innere Hemmungen zu. Jedes mußte an seiner richtigen Stelle, wenigstens nach meiner Meinung, richtig getan werden. Ich habe, wie ich glaube, in meiner «Theosophie» keinen Schritt über dasjenige hinaus getan, was dazumal für eine Anzahl von Menschen zu veröffentlichen möglich war. Die Verbreitung, die mittlerweile das Buch gefunden hat, zeigt ja, daß das eine richtige Voraussetzung war. So weit konnte man gehen.

Unter denen, die intensiver suchten, die also in die Strömung, die durch Blavatsky angeregt worden war, hineingekommen waren, konnte man weiter gehen. Da mußte man den Anfang damit machen, nun weiter zu gehen. Da könnte ich Ihnen die einzelnen Beispiele alle charakterisieren. Ich will aber nur eines herausgreifen, wie der Versuch gemacht worden ist, Schritt für Schritt aus dem schlecht Traditionellen in das richtig Gegenwärtige, in das unmittelbar gegenwärtig Erforschte hineinzukommen.

Da war die Schilderung in der Theosophischen Gesellschaft üblich, wie der Mensch das, was man Kamaloka nannte, nach dem Tode durchmacht. Diese Schilderung, wie sie bei den führenden Persönlichkeiten der Theosophischen Gesellschaft gegeben worden ist, konnte in meinem Buche «Theosophie» nur dadurch umgangen werden, daß ich zunächst mit dem Zeitbegriff dort nicht gerechnet habe. Aber innerhalb der Kreise der Gesellschaft wollte ich mit dem richtigen Zeitbegriff rechnen.

So kam es, daß ich innerhalb der damaligen holländischen Sektion der Theosophischen Gesellschaft in verschiedenen Städten Vorträge hielt über das Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, und da zum ersten Mal, ganz im Anfange meines Wirkens, aufmerksam darauf gemacht habe, daß es ja ein Unsinn ist, so ohne weiteres vorzustellen, daß, wenn dies das Erdenleben von der Geburt bis zum Tode ist, dann Kamaloka so durchgemacht wird, als ob im Bewußtsein sich einfach ein Stück anstückelte (siehe Zeichnung, oben).

Ich habe gezeigt, daß da die Zeit rückwärts vorgestellt werden muß, und ich schilderte, wie das Kamaloka-Leben ein Rückwärtsleben ist, Etappe für Etappe, nur dreimal so schnell als das gewöhnliche Erdenleben oder als das auf der Erde zugebrachte Leben.

Im äußeren Leben hat ja heute natürlich kein Mensch eine Vorstellung davon, daß dieses Rückwärtsverlaufen eine Realität ist, eine Realität im geistigen Gebiete, denn die Zeit wird einfach als eine gerade Linie vom Anfang zum Ende vorgestellt, und von einem Rückwärtsverlaufen haben die Leute heute gar keinen Begriff.

Nun gab man unter den Führern der Theosophischen Gesellschaft vor, die alte Weisheitslehre zu erneuern. Man knüpfte an Blavatskys Buch an. Es erschienen in Anknüpfung an Blavatskys Buch allerlei Schriften. Aber da wurde alles so vorgestellt, wie die Dinge ganz im Sinne der materialistischen Weltanschauung der neueren Zeit vorgestellt werden. Warum? Weil man wieder hätte erkennen müssen, nicht bloß alte Erkenntnis wieder erneuern müssen, wenn man auf das Richtige hätte kommen wollen. Es wurden immer die alten Sachen zitiert. Auch das Rad der Geburten von Buddha und von der alten orientalischen Weisheit wurde immer zitiert. Aber daß ein Rad nicht so ist, daß man eine gerade Linie als Rad zeichnen kann, das berücksichtigen die Leute nicht, und daß man ein Rad nur zeichnen kann, wenn es zurück in sich selber verläuft (siehe Zeichnung). Es war kein Leben in dieser Wiederbelebung der alten Weisheit, weil eben nicht eine unmittelbare Erkenntnis da war. Kurz, es war nötig, daß durch unmittelbare Erkenntnis etwas geschaffen würde, was dann auch die uralte Weisheit beleuchten könnte.

So ergab sich gerade in den ersten sieben Jahren des anthroposophischen Wirkens eigentlich dies, daß da auch Leute waren — nun ja, denen es ganz recht war, daß, wie sie es nannten, nicht eine Erneuerung auf theosophischem Feld da war. Sie sagten: Das, was da . gesagt wird, unterscheidet sich nicht von dem anderen; die Unterschiede sind unwesentlich. Da wurden sie wegdisputiert. Aber was dazumal gleich im Beginne des Wirkens innerhalb der holländischen Sektion der Theosophischen Gesellschaft von mir sozusagen dadurch angerichtet worden ist, daß ich nun aus dem Lebendigen heraus diese Vorträge gehalten habe, nicht einfach dogmatisch nachgesprochen habe, wie es die übrigen taten, das, was in den Dogmenbüchern der Theosophischen Gesellschaft stand, das wurde niemals vergessen. Niemals wurde es vergessen. Es müssen diejenigen, die vielleicht sich an jene Zeiten unserer Entwickelung erinnern, nur zurückdenken, wie da im Jahre 1907, als in München der Kongreß stattfand, wo wir ja noch innerhalb des Schoßes der Theosophischen Gesellschaft waren, die holländischen Theosophen ganz geladen gekommen sind und furchtbar wild darüber waren, daß sich ein Fremdkörper, wie sie es empfanden, hineinschob. Sie spürten nicht, daß ein lebendiges Gegenwärtiges sich gegen ein bloß Traditionelles stellte, sondern sie empfanden das eben als einen Fremdkörper.

Aber etwas anderes mußte damals schon eintreten. Damals fand schon jenes Gespräch zwischen Frau Besant und mir in München statt, worinnen festgestellt worden ist, daß dasjenige, was ich zu vertreten habe, als Anthroposophie zu vertreten habe, völlig selbständig wirken wird, ohne Rücksicht auf irgend etwas, was innerhalb der Theosophischen Gesellschaft sonst sich geltend macht. Das wurde dazumal, ich möchte sagen, als ein Modus, unter dem man leben konnte, festgestellt.

Allerdings, schon dazumal dämmerten auf dem Horizont der Theosophischen Gesellschaft jene Absurditäten herauf, durch die sie sich dann zugrunde gerichtet hat. Denn heute kann man sagen, daß, wenn sie auch noch viele eingeschriebene Mitglieder hat, sie sich als eine geistige Bewegung tragende Gesellschaft zugrunde gerichtet hat. Nicht wahr, die Dinge leben als Leichnam noch lange fort, nachdem sie sich zugrunde gerichtet haben. Aber dasjenige, was Theosophische Gesellschaft war, lebt heute eben nicht mehr.

Man muß sich nur darüber ganz klar sein: In der Zeit, in der Anthroposophie zu wirken begann, war die Theosophische Gesellschaft voll von einer, wenn auch traditionellen, so doch begründeten und inhaltreichen Geistigkeit. Dasjenige, was durch Blavatsky in die Welt gekommen ist, war eben da, und man lebte eigentlich in dem, was durch Blavatsky in die Welt gekommen ist.

Nun war aber Blavatsky bereits ein Jahrzehnt tot für das irdische Leben. Man kann nur sagen: Die Stimmung innerhalb der Theosophischen Gesellschaft, dasjenige, was als Fortsetzung des Blavatskyschen Wirkens da war, war etwas kulturgeschichtlich durchaus Festes, etwas, was den Leuten durchaus etwas geben konnte. Aber es ‘waren eben doch schon dazumal gewisse Keime des Verfalls da. Nur war die Frage, ob nicht etwa diese Keime des Verfalls überwunden werden konnten, oder ob sie zu einer Art von völliger Disharmonie zwischen der Anthroposophie und der alten 'Theosophischen Gesellschaft führen mußten.

Nun muß man sagen, daß eine von den Strömungen, die da innerhalb der theosophischen Bewegung schon seit Blavatskys Zeiten her waren, eigentlich ein furchtbar stark zersetzendes Element war. Man muß einfach trennen, wenn man die Sache so betrachten will, wie ich es jetzt tue, dasjenige, was durch die Blavatsky als geistiger Inhalt in das moderne Leben hineingeworfen worden ist, von dem, was bewirkt worden ist durch die Art, wie Blavatsky angeregt wurde, aus sich heraus in der charakterisierten Weise dann diesen Inhalt zu geben. Denn zunächst lag in Blavatsky eine Persönlichkeit vor, die eben so war, wie ich sie Ihnen in den letzten Tagen beschrieben habe; die einfach, wenn sie sozusagen einen Einschlag bekam von irgendeiner Seite her, meinetwillen durch Verrat, in der Weise, wie ich es gesagt habe, dann doch aus sich selbst heraus — wie in der Erinnerung an eine frühere Lebensverkörperung auf Erden, und wenn auch nur als Wiedererweckung des Alten — geschaffen, und der Menschheit Weisheit in Buchform überliefert hat. Diese zweite Tatsache muß man voll trennen von der ersten, denn durch diese zweite Tatsache, daß Blavatsky auf eine besondere Art angeregt worden ist zu dem, was sie getan hat, kamen Elemente in diese theosophische Bewegung hinein, die nun nicht mehr so waren, wie sie hätten sein müssen, wenn die theosophische Bewegung eine rein geistige Bewegung hätte werden sollen.

Das war sie nämlich nicht. Denn die Sache war doch so, daß Blavatsky zunächst von einer Seite her, über die ich nicht weiter sprechen will, eine Anregung bekommen hat, und dann dasjenige aus sich herausgesetzt hat, was in der «Entschleierten Isis» steht. Dann ist durch allerlei Machinationen das zustande gekommen, daß Blavatsky von orientalischen Geheimlehrern eine zweite Beeinflussung erlitten hat, und hinter denen steckte eine kulturpolitische Tendenz egoistischer Art. Es steckte von allem Anfang an eine Ostpolitik einseitiger Art in dem, was man nun auf dem Umwege durch Blavatsky erreichen wollte. Da steckte darinnen die Tendenz, dem materialistischen Abendlande zu zeigen, wie viel mehr wert die geistige Erkenntnis des Morgenlandes ist als der Materialismus des Abendlandes. Es steckte darinnen die Tendenz, eine Art zunächst geistigen, aber dann im weiteren Sinne überhaupt eine Art Imperium des Orients über das Abendland zu gewinnen, indem man zunächst der Geistigkeit des Abendlandes, oder meinetwillen der Ungeistigkeit des Abendlandes, morgenländische Weisheit überlieferte. Daher wurde, ich möchte sagen, jene Drehung vollzogen vom ganz Europäischen in der «Entschleierten Isis» zu dem ganz Orientalischen in der Blavatskyschen «Geheimlehre».

Es wirkten da die verschiedensten Faktoren mit. Aber einer dieser Faktoren war eben der, welcher Indien an Asien anschließen wollte, um ein asiatisch-indisches Imperium mit Hilfe des russischen Reiches zu schaffen. Und so bekam diese Lehre den indischen Einschlag, um auf diese Weise geistig das Abendland zu besiegen. Sehen Sie, das ist ein einseitig egoistischer, national-egoistischer Einschlag. Der lag von allem Anfange an darinnen, trat einem symptomatisch bedeutsam entgegen. Der erste Vortrag, den ich von Annie Besant gehört habe, handelte über Theosophie und Imperialismus. Und wenn man sich die Frage beantworten wollte: Liegt der eigentliche Grundimpuls dieses Vortrages in der Fortsetzung des eigentlich Geistigen bei der Blavatsky, oder liegt der Grundimpuls dieses Vortrages in der Fortsetzung desjenigen, was da nebenher gegangen war? — so mußte man das Letztere sagen.

Annie Besant war oftmals so, daß sie Dinge sagte, von denen sie durchaus nicht die letzten Gründe kannte. Sie ging für irgend etwas ins Zeug, wovon sie nicht die letzten Gründe kannte. Die letzten Zusammenhänge waren ihr unbekannt. Aber wenn Sie ganz verständig den Vortrag «Theosophie und Imperialismus» lesen, der gedruckt ist, mit allen Untergründen lesen, dann werden Sie eben einsehen: Wenn irgend jemand Indien von England losreißen wollte, in einem gewissen Sinne auf eine geistige Weise losreißen wollte, so kann man den ersten unvermerkten Schritt mit einer solchen Tendenz, wie sie in jenem Vortrage war, unternehmen.

Das war immer der Anfang vom Ende von solchen geistigen Strömungen und geistigen Gesellschaften, daß sie angefangen haben, einseitig Politisches in ihre Sphäre zu mischen, während eine geistige Bewegung gerade heute nur dann in der Welt ihren Fortgang nehmen kann, wenn sie allmenschlich ist, ja es heute eine der wesentlichsten Lebensbedingungen einer geistigen Bewegung ist, die in die wirkliche reale Geistigkeit hineinführen soll, ganz allmenschlich zu sein. Und alles dasjenige, was nicht ganz allmenschlich ist, was in irgendeiner Weise auf Spaltung der Menschheit hinausgeht, das ist von vorneherein ein zerstörendes Element für eine geistige Bewegung, die in die wirkliche, reale Geisteswelt hineinführen soll.

Aber bedenken Sie doch nur einmal, wie stark man mit solchen Dingen in die unterbewußten Regionen des Menschen hineingreift. Da gehört es eben zu den Lebensbedingungen einer solchen geistigen Bewegung, wie sie zum Beispiel auch die anthroposophische sein will, daß man wenigstens das ehrliche, ernste Bestreben hat, herauszukommen aus allen Partialinteressen der Menschheit und sich wirklich aufzuschwingen zu den allgemeinen Interessen der Menschheit. Und das war das Verderbliche der theosophischen Bewegung, daß sie vom Anfange an ein solches Element in sich hatte. Gelegentlich kann ein solches Element auch einmal den Dampf drehen: während des Weltkrieges ist dann diese andere Tendenz sehr englisch-chauvinistisch geworden. Aber gerade bei dieser Gelegenheit muß man sich eben völlig klar werden, daß es ganz unmöglich ist, eine reale geistige Bewegung zum Gedeihen zu bringen, wenn irgendein Partikularismus so vorliegt, daß man aus ihm nicht heraus will.

Daher ist unter den äußeren Gefahren, die heute gegen die anthroposophische Bewegung da sind, vor allen Dingen die, daß die Menschen in diesem Zeitalter, das überall abirrt in Nationalismen, so wenig tapfer sind, sich herauszuarbeiten aus den Nationalismen.

Aber worinnen wurzelt denn wieder so etwas, wie diese Einseitigkeit war? Sie wurzelt in dem, daß man als Gesellschaft Macht gewinnen will durch etwas anderes als durch die Offenbarung des Geistigen selber. Das kann man schon sagen: Während noch viel Gesundes in bezug auf Machtbewußtseins-Entfaltung um die Wende des 19. Jahrhunderts in der Theosophischen Gesellschaft war, war das 1906 schon fast ganz verschwunden, und es war ein starkes Machtstreben da.

Es ist notwendig, daß man dieses Herauswachsen des Anthroposophischen aus allgemeinen Menschheitsinteressen wirklich einsieht und sich klar darüber ist, daß nur deshalb, weil dort in der Theosophischen Gesellschaft die Fragesteller waren, das Anthroposophische in die Theosophische Gesellschaft hineinwachsen mußte, ich möchte sagen, eine Zeitlang «Logis» nehmen mußte, denn sonst bekam es kein «Logis».

Nicht wahr, bald nachdem sozusagen die erste Periode vorüber war, zeigte sich insbesondere an der Christus-Frage die ganze Unmöglichkeit der theosophischen Bewegung für das abendländische Leben. Denn was bei Blavatsky im Grunde genommen eine Theorie, wenn auch eine von Emotionen getragene Theorie war, die Geringschätzung des Christentums, das wurde nachher in der theosophischen Bewegung zu einer so praktischen Geringschätzung des Christentums, daß ein Bube erzogen wurde, von dem man sagte: In dem wird man die Seele des wiedererstandenen Christus heranziehen. Man konnte sich ja kaum etwas Absurderes denken. Aber aus der Theosophischen Gesellschaft heraus wurde ein Orden begründet, um nun diese Christus-Geburt in einem Knaben, der eigentlich schon da war, zu bewerkstelligen.

Nun ging es sehr bald dem vollständig Absurden zu. Es kommen bei solchen Dingen sehr bald natürlich Unklarheiten dazu, die furchtbar nahe an Unwahrheit grenzen. 1911 sollte in Genua ein Kongreß der Theosophischen Gesellschaft sein. Die Dinge waren schon im Flor, die zu solchen Absurditäten führten, und es war nötig, daß ich für diesen Genueser Kongreß meinen Vortrag ansagte: «Von Buddha zu Christus». Da hätte es zu einer prägnanten, klaren Auseinandersetzung kommen müssen, denn es hätte dazumal dasjenige sich ausleben müssen, was überall da war. Doch siehe, der Genueser Kongreß wurde abgesagt. Natürlich finden sich für solche Dinge Ausreden. Alle die Dinge, die vorgebracht worden sind, sahen eben Ausreden wirklich außerordentlich ähnlich.

So kann man sagen, daß die anthroposophische Bewegung in ihre zweite Periode trat, indem sie ihren geraden Weg ging, der eingeleitet war eben dadurch, daß ich ganz im Anfang einen Vortrag hielt vor einem nicht-theosophischen Publikum, von dem nur eine einzige Persönlichkeit — nicht mehr! — geblieben ist, die jetzt noch da ist, trotzdem dazumal zahlreiche Persönlichkeiten den Vortrag angehört hatten. Der erste Vortrag aber, den ich gehalten habe, ein Vortragszyklus war es sogar, hatte den Titel: «Von Buddha zu Christus». 1911 wollte ich wieder den Zyklus halten: «Von Buddha zu Christus». Das war die gerade Linie! Aber die theosophische Bewegung war in eine greuliche Zickzacklinie hineingekommen.

Wenn man die Geschichte der anthroposophischen Bewegung nicht ernst nimmt und diese Dinge nicht beim rechten Namen nennen will, so wird man auch nicht in der richtigen Weise auf dasjenige entgegnen können, was immer wiederum jene Oberflächlinge über die Beziehungen von Anthroposophie und Theosophie vorbringen, indem man sich absolut nicht davon unterrichten will, wie Anthroposophie vom Anfange an eben etwas ganz Selbständiges war, aber wie es natürlich war, zu antworten mit den Antworten, die sie den Menschen geben kann, die eben als Fragende da waren.

So möchte man sagen: Bis zum Jahre 1914 ging die zweite Periode der anthroposophischen Bewegung. Sie hat eigentlich, wenigstens was mich anbetrifft, gar nichts Besonderes getan, um das Verhältnis zur theosophischen Bewegung zu regeln. Die Theosophische Gesellschaft hat das Verhältnis geregelt, indem sie die Anthroposophen ausgeschlossen hat. Aber es interessierte einen nicht, Weil es einen von Anfang an nicht sehr stark interessiert hat, daf man eingeschlossen war, hat es einen jetzt auch nicht sehr stark interessiert, daß man ausgeschlossen war. Man tat ganz genau in derselben Weise fort wie früher. Das Ausgeschlossensein änderte gar nichts an dem, was früher geschehen war, während man eingeschlossen war.

Sehen Sie sich nur an, wie die Dinge gegangen sind, so werden Sie sehen, daß eben mit Ausnahme der Abwickelung einiger Formalitäten innerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung überhaupt nichts geschehen ist bis zum Jahre 1914, sondern daß alles, was geschehen ist, von seiten der Theosophischen Gesellschaft geschehen ist. Ich bin eingeladen worden zunächst, dort Vorträge zu halten. Das habe ich getan. Ich habe anthroposophische Vorträge gehalten. Das habe ich auch ferner getan. Auf die Vorträge hin, die wieder abgedruckt sind in meinem Buche: «Die Mystik im Aufgange des neuzeitlichen Geisteslebens», bin ich eingeladen worden. Dann habe ich das, was in der «Mystik im Aufgange des neuzeitlichen Geisteslebens» geschrieben ist, nach den verschiedensten Seiten weiter ausgeführt.

Von dieser selben Gesellschaftsanschauung bin dann ich und selbstverständlich meine Anhänger ausgeschlossen worden. Ich bin ganz wegen derselben Sache zuerst eingeschlossen und nachher ausgeschlossen worden. Ja, so liegt schon die Sache. Man wird eben die Geschichte der anthroposophischen Bewegung nicht verstehen, wenn man nicht das als eine fundamentale Sache wirklich richtig ins Auge fassen kann, daß kein Unterschied war gegenüber der theosophischen Bewegung, ob man ein- oder ausgeschlossen war.

Das ist etwas, was Sie so recht in Selbstbesinnung bedenken mögen; das bitte ich Sie. Dann möchte ich auf Grund dessen morgen die letzte Phase, die schwierigste, die von 1914 bis jetzt, skizzieren, um auf Einzelheiten später noch in den folgenden Vorträgen einzugehen.

Fifth Lecture

It is important to note how, within the anthroposophical movement, Christianity had to be conquered, especially among those who were initially ordinary listeners, so to speak. For the theosophical movement, based on the personality of H. P. Blavatsky, definitely started from an anti-Christian orientation. And this anti-Christian orientation, which I have also linked to the same orientation in another personality, Friedrich Nietzsche, is something I would like to shed a little light on first.

It must be clear, and this is evident from the various considerations that have been made within our circles about the mystery of Golgotha, that the mystery of Golgotha first entered into the development of humanity on earth as a fact. It must first be taken as a fact. If you go back to the description in my book Christianity as a Mystical Fact, you will find that an attempt is made there to recognize the entire mystery system of ancient times according to its impulses and then to show how the various forces that played a part in the individual mysteries united, harmonized, and thereby made it possible for what initially, in the mysteries, one might say, in a hidden way, was presented to people in an open way as a historical fact. So that in the mystery of Golgotha, the crowning glory of the entire ancient mystery system is present in an external fact. How the entire development of humanity had to change under the influence of the Mystery of Golgotha is what I have attempted to show in that book.

Now, as I have often emphasized, at the time when the Mystery of Golgotha was taking place as a fact, remnants of the ancient mystery wisdom were still present. With the help of these remnants of ancient mystery wisdom, which have been passed down in the Gospels, as I have described in that book, it was possible to approach this event, which actually gives meaning to the development of the earth. The means of knowledge for understanding the Mystery of Golgotha could be taken from the ancient mysteries. But at the same time, it must be noted that the mystery system in the sense in which it existed in ancient times is disappearing and has found its culmination in the Mystery of Golgotha.

I have also mentioned how, in the 4th century AD, the impulses of ancient knowledge that were still directly accessible to human beings began to fade, and only more or less traditional elements of this ancient knowledge remained, so that here and there it was possible for special individuals, special personalities, to revive these traditions. But a continuous development of mysteries, as existed in ancient times, no longer takes place. Thus, the means of understanding the mystery of Golgotha has actually been lost.