The Anthroposophic Movement

GA 258

17 June 1923, Dornach

Eighth Lecture

Conclusions: The Anthroposophical Society and Its Future Conduct

To-day we must bring our observations to a sort of conclusion; and the natural and proper conclusion of them will of course be, as I indicated yesterday, to consider the necessary consequence to be drawn for the conduct of the Anthroposophical Society in the future. In order to form a clearer notion of what this conduct should be, let us just look back once more and see how Anthroposophy has grown up out of the whole modern civilization of the day.

You will have seen from the course of our observations during this past week, that in a way the public for Anthroposophy had necessarily to be sought in the first place amongst those circles where a strong impulse had been given towards a deepening of the spiritual life. This impulse came, of course, from many different quarters. But here one needed to look no further for the main impulse for these homeless souls, than to the things which Blavatsky, so to speak, delivered as riddles to this modern age.—Well, we have discussed all that. If, however, we must go back to this in the first place as the impulse for the Anthroposophical Society, on the other hand it must also have been plain, that for Anthroposophy itself such an impulse, or this particular impulse, was not the essential matter; for Anthroposophy itself goes back to other sources. And although—for the very reason that its public happened to come in the way I said—Anthroposophy at first employed outward forms of expression—even for its own wealth of wisdom—that were terms already familiar to these homeless souls, as coming from the quarter connected with Blavatsky,—yet these were just outward forms of expression. If you go back to my own first writings, Christianity as Mystical Fact, Mysticism at the Dawn of the New Age of Thought, you will see, that in reality these writings are in no way traceable to anything whatever coming from Blavatsky, or indeed from that quarter at all, with this one exception of the fact, that the outward forms of expression have been selected incidentally with a view to finding understanding.

One must distinguish, therefore, between what was actual spiritual substance, flowing all through the anthroposophic movement, and what were outward forms of expression, incidentally required by the conditions of the time. That mistakes can arise on this point is simply due to the fact, that people at the present day are so disinclined to go back from the form of outward expression to what is the real heart of the matter.—Anthroposophy can be traced back in a straight line to the note already struck in my Philosophy of Freedom (though then in a philosophic form),—to the note struck in my Goethe writings of the 'eighties.

If you take what is in these writings on Goethe and in the Philosophy of Freedom, the dominant note struck in them is this: That Man, in the innermost part of his being is in connection with a spiritual world; that therefore, if only he looks deep enough back into his own being, he comes to something within himself to which the usual natural science of that day, and also of this, is unable to penetrate, and which can only be contemplated as direct part of a spiritual world-order.

And in face of the terrible, what I might call spiritual chaos of language which this modern civilization has created in all countries, it might really be recognized as inevitable, if one was sometimes obliged to have recourse to what sounded paradoxical terms of expression.

And so I let glimmer faintly, so to speak, through these Goethe writings, that when one rises from contemplation of the world to contemplation of divine spirit, it is necessary to introduce a modification in the idea of Love. Already in these writings on Goethe, I indicated, that the Divinity must be conceived as having shed Itself abroad in infinite love through all existence, and that it has now to be sought in each particular existence;—which leads to something totally different from a confused pantheism.—Only, at that date, there was absolutely no possibility in any way of finding what one might call a philosophic ‘point of connection’. For, easy as it would have been to gain a hearing for a spiritual world-conception such as this, had the age possessed any philosophic ideas on to which to connect, it was equally difficult with the sort of warmed-up Kantianism that at that time existed,—with this sort of philosophy, it was difficult to find any point of connection. And accordingly it was necessary to seek this point of connection in a fuller, more intensive stream of life, in a spiritual life inwardly saturated, so to speak, with spiritual substance.—

And this kind of spiritual life was just what one found manifested in Goethe. And therefore, when I had first had to make public these particular ideas, I could not connect-on with a Theory of Cognition to what was then to be found in the civilization of the day: one had to connect-on to the world-conception of Goethe; and by aid of this Goetheistic world-conception it became possible to take the first step into the spiritual world.

In Goethe, one finds two doors which in a way open into the spiritual world,—which, to a certain degree, give access to it. One finds the first of these doors at the point where one enters upon the study of Goethe's natural-science works. For with the scientific conception of nature which Goethe worked out, he was able, within the bounds of the vegetable-world, to overcome just that disease under which the whole of modern natural science down to this day is suffering. He succeeded in putting living, flexible ideas in place of the dead and dried ones, for the observation of the vegetable-world. And then it was possible to go further, and indicate at any rate ... even though Goethe himself failed with his theory of metamorphosis when he came to the animal king-dom, still it was at any rate possible to indicate a prospect that a similar, only intensified, method of observation, not worked out so far by Goethe, might be applied to the animal kingdom as well. And in my book, Goethe's World-Conception,1 I tried to show how it was possible—only as a sketch to begin with—to push on as far as history, as far as historic life, with the live and live-making ideas from the source.—That was the first door.

Now, in Goethe, one finds no direct line of continuance leading on from this starting-point into the actual spiritual world; from this starting-point one can only work on, as it were, to a certain definite level. And whilst thus working one has the feeling then of grasping the sensible world in a spiritual fashion. When employing Goethe's method, one is moving, rightly speaking, in a spiritual element. And though one is applying this method to the sensible plant-world, or the sensible animal-world, one grasps by this method the spiritual element living and weaving in the plant or in the animal-world.

But Goethe had another door besides in contemplation. And this was most strikingly apparent when one started out from something which Goethe was only able to indicate pictorially,—half symbolically, one might say; when one started out, namely, from his Story of the Green Serpent and the Lovely Lily,2 through which he wished to show how spirit, spiritual agencies, are at work in the evolution of the world, and how the several spheres of the True, the Beautiful, the Good, work together, and that they are actual Spiritual beings one must grasp, not mere abstractions of the mind, if one wants to arrive at a view of the actual life of spirit.

The possibility therefore existed, of connecting-on, to begin with, to this point in Goethe's world conception. Rut then, however, there followed a very particular necessity. For there is one thing above all, you see, which must necessarily present itself to anybody to-day, when it is a question of a world-conception for these homeless souls; and that is the moral and ethical problem, the moral conduct of life.

1 ‘Grundlinien einer Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen Weltanschauung.’

‘Cognitive Theory of Goethe's World-Conception.’

2 See: ‘Goethes Geistesart in ihrer Offenbarung usw.’

In those old times, when men arrived by original clairvoyance at their view of the divine spirit-world, it was, then, a matter-of-course that this divine spiritual world, of which men could rise to a view, was the source of their ethical impulses also. If we look back to very old periods of human evolution, we find a state of things in which, when Man gazed up, say in the good old times, in his first primitive clairvoyance, to the world of Divine Spirit above him, he beheld on the one hand, those living Beings, those Powers, who rule the phenomena of the natural world; and in the phenomena of the natural world, in the workings of wind and weather, in the workings of earth, in mechanic workings, this man of a primal age could see the continuance, the prolongation of what he beheld in the divine spirit-world. But at the same time he could receive from this divine spirit-world the impulses for his own actions.

This is the peculiar thing about the old world-conceptions, which still went along with a primitive clairvoyance, that, if we take, say, the Ancient Egyptian Age, men looked up to the skies in order to learn the workings of the earth, even to learn what they needed to know about the flooding of the Nile; they looked up to the stars; and from the courses of the stars, from the laws of the stars in their courses, they deduced what concerned them for the earth-world,—I mean, for the order of Nature in the earth-world.

And in the same way, too, these people calculated—if I may use the expression—what the impulses should be for ethical life. The impulses of ethical life, too, were drawn from observation of the stars.

And if we then look at things as they are now in recent times, we shall say: Observation of the stars is now carried on in its mathematical aspect only; which amounts to nothing more, than that men carry the mathematics of earth up into the stars of heaven. And they look on earth, and find on the earth what are called ‘laws of nature’.

Well, these ‘laws of nature’, which Goethe found, too, in his time, and which he converted into live ideas,—these ‘laws of nature’ have a certain peculiarity, directly it comes to a view of the world,—to a world-conception. The peculiarity namely is this: that Man,—to go by the laws of nature,—is himself excluded from the World,—that he then, in his own truest, most characteristic being as Man, has no longer any place in the World.

Picture to yourselves the old world-conceptions and how it was there. On the one side we have the world of Divine Spirit. This world of Divine Spirit permeated the phenomena of the natural world. People discovered laws for the natural phenomena; but these laws were recognized as being a kind of reflection from the action of Divine Spirit in the world of Nature. And Man, too, was also there. The same divine spirit-world shed its rays into Man. And so Man had his place within the whole order of the world. He derived, so to speak, the substance of which he was made from the same divine spiritual element of which the substance of the natural world was made.—What happened then?—My dear friends, what then happened, is something that one must regard in all its gravity; for what happened was, that, in a sort of way, a cut was made by natural science across the link that joined the world of Nature to the world of the Divine. The Divine is gone,—gone from the world of Nature. And in the world of Nature the reflections of Divine action are statuated as natural laws, and people speak of ‘laws of Nature’.

To the people of old, these Laws of Nature were the Thoughts of Cod. To the men of to-day they are still of course thoughts, for one has to comprehend them by thoughts; but the explanation lies somehow or other in the phenomena of Nature, which of course are themselves contained under the laws of Nature:—law of gravitation, law of the refraction of light, and all these fine things,—these are what people talk of to-day. But all these things have nothing whatever underneath them, or rather, nothing whatever above them; for there is no sense in talking of all these laws; unless one can talk of them as reflections from the Divine Spirit's action in the natural world.

This is what is felt by minds of greater depth, by homeless souls, in all the talk of the present day about Nature: they feel, with these people who talk about Nature, that one might rightly apply to them the words of Goethe,—or, more correctly, the words of Mephisto: they ‘laugh at themselves, and never know it’.1 People talk of laws of Nature, but these laws of Nature are what has been left behind from the views of the men of old. Only, the views of the men of old had something else beside these laws of Nature, something, namely, that made these laws of Nature possible.

Suppose for a moment that you have a rose-bush. You can always go on having roses from this rose-bush. When the old roses wither, new ones grow again. But if you pick the roses and let the rose-bush die, you cannot still go on having new roses.

But this is just what happened with the science of nature. A rose-bush was once there; it had its roots in God. The laws which men found in the natural world, were the separ-ate roses. These laws, men have picked; they have picked the roses; the rose-bush they have let die. And so we have now in the laws of Nature, something that remains like roses without a rose-bush. And people are blind to it; they have no notion of it in their heads, upon which they set such store in these days. But those people, who are homeless souls, have a very strong notion of it in their hearts: for they can make nothing of these laws of Nature; they feel: These laws of Nature are withered: they shrivel up, when one tries to look at them as a human being.

And so the men of modern times, in so far as they can feel, in so far as they have hearts in their bodies, suffer unconsciously under an impression: ‘They tell us about Nature; but what they tell us withers in our grasp; indeed, it withers us, ourselves, as human beings.’ And mankind is compelled

to accept this as pure truth. Mankind is compelled by fearful force of authority to believe,—whilst in their hearts they feel, that the roses wither, they are compelled to the belief that these roses are the eternal living World-Beings. And people talk about World-Laws! The phenomena pass away, the laws abide for ever!—Natural science, this ‘science of Nature’, ... since what Man is seeking to express as his own consciousness of Human Self is Anthroposophy, then natural Science is,—Anti-Anthroposophy!

But let us look at the other side of it, at the ethical and moral side. The impulses of ethical and moral life came from the same divine source; but just as men had made withered roses of the laws of nature, so they made withered roses of the ethical impulses. The roots were everywhere gone; and so the ethical impulses went fluttering about the civilized world as moral commandments and customs, of which nobody knew the root. How could people possibly help feeling, ‘The moral commandments and customs are there;—but the divine origin is not there.’ And now arose the inevitable question: ‘Yes!—but what is to come of it, if these customs and commandments are not obeyed? It will come to chaos and anarchy in human society! ‘Whilst on the other side, again, there was this question: ‘What is the force of these commandments? What is at the root of them?’—Here, too, people felt this same withering and drying-up.

1 He has the bits then all in his hand:

—One thing, alas! is missing however:

The bond of the spirit to hold them together!

-

Encheiridion, Chemistry calls it;—

Laughs at itself, and never knows it!

(‘Faust’ I.)

That, you see, became the great question. That came to be the question, which arose out of Goetheanism, but to which Goetheanism, in itself, could give no answer.

Goethe gave, so to speak, two starting points, which converged upon one another, but did not meet. What is wanted,—what was wanted,—is the Philosophy of Freedom.

It needed to be shown that Man himself is the seat of the divine impulse, since in Man lies the power to go to the grounds of the spiritual principle both of the natural, as well as the spiritual principle of the moral law.

This led to the intuitionalism of the Philosophy of Freedom; it led to what people termed ethical individualism; ‘ethical individualism’, because in each single human individual was shown to reside the source of the ethical impulses,—in that Divine First Principle to which every man in the innermost part of his being is united.

Now that the age had begun, when the laws of Nature on one hand, and on the other, the moral commandments, had lost all life for men, because the Divine Principle was no longer to be found in the external world—(it could be no otherwise in the age of freedom!)—it was now in Man for we meet with Man in the first place in individual form ... it became now necessary to look in Man for the Divine Principle.

And with this, one has reached a world-conception which,—if you only consider it clearly, you will see,—leads on in straight continuation to what to-day we call Anthroposophy.

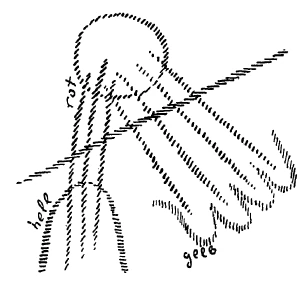

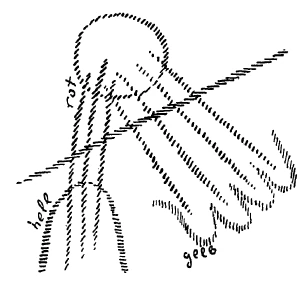

Suppose ... it is rather a primitive sketch, but it will do! ... that these are men. (Sketch in coloured chalks on the blackboard.) These men are connected in the inmost part of their being to a divine spiritual principle. This divine spiritual principle assumes the form of a divine, spiritual order in the world. And by looking at the inside of all men, conjunctively, one penetrates, now, to the divine spiritual principle, as, in old days, one penetrated to the divine spiritual principle when one looked outside one, and by primitive clairvoyance discovered the divine spiritual principle in the outer phenomena.

What had to be done then, was to follow up what was given by Goethe's world-conception on the one hand, and, on the other, by the sheer necessities of human evolution at the end of the nineteenth century; and so push on to the spiritual principle;—not to push on by any external, materialistic means, but by actual direct apprehension of Man's essential being.

Well, with this, the foundations were really laid of Anthroposophy,—if one looks at the matter in life and not in theory. For if anybody were to suggest that the Philosophy of Freedom is very far short of being Anthroposophy, it must seem to one exactly as though somebody said: ‘There was once a Goethe. This Goethe wrote all sorts of works. By “ Goethe ” we understand to-day the creator of Goethe's works.'—And another person were to answer, ‘That's not a logical sequence; for in 1749 there was a baby in Frankfort-on-Main; the baby indeed was quite black at its birth, and they said it couldn't live. If one considers this baby, and all the circumstances connected with it, it is impossible, logically, to deduce the whole of these “Goethe” Works. It is inconsequent:—one must trace Goethe back to his origin. And see whether you can discover Faust in the black-and-blue little boy who was born in 1749 at Frankfort-on-Main!’

You will agree that it is not very sensible to talk like this; but it is just as little sensible to say that Anthroposophy cannot logically follow from the Philosophy of Freedom. The black little baby in Frankfort went on living, and from its life proceeded all that to-day lives in the world's evolution as Goethe. And the Philosophy of Freedom had to go on living; and then, out of it, proceeded Anthroposophy.

Just think what it would be if, instead of actual life, there were to come a professor of philosophic logic, and say that everything which is in East and Wilhelm Meister, etc., must be deduced logically from the blue-and-black little boy of 1749! Do you think he would be able to deduce anything? By no means! He would only demonstrate contradictions—terrible contradictions! ‘I can't make the two things agree! ‘he would say; ‘I find no sequence between this Faust, as written at some time by somebody or other, and the blue-black little boy, as he existed in Frankfort-on-Main.’

And so, too, say the people who deal in fusty book-worm-logic, not in life: ‘From the Philosophy of freedom there is no logical sequence to Anthroposophy.’—Well, my dear friends, if the sequence had been a logical one, then you might have seen how all the schoolmasters would have been busy in 1894, deducing Anthroposophy from the Philosophy of Freedom! They just did nothing of the kind! And afterwards they come, and confess that they cannot deduce it, that they can't bring the two together; and make out a contradiction between what came after and what went before.—The fact is that people in these days have absolutely no capacity,—at a time when so-called logic is cultivated, and philosophy, and such things,—they have absolutely no capacity for entering into real life, for observing what is springing and sprouting up around them, and has more in it than can be seen by the pedantry of logicians.

The first thing to be done, then, in the next place, was to come to relations with all that was pushing its way up, so to speak, out of the present life of the day towards a progressive development of human civilization.

Well, as you know, I tried to do this by picking out two very striking and remarkable instances as subjects for discussion.—The first of these was Nietzsche. Why this particular case should he chosen will be obvious to you from what has gone before. For Nietzsche, namely, presented a personality on the top-surface of the modern stream of civilization, who had grown into the whole evolutionary tendency of world-conception at the present day, and who, in opposition to all the rest, was honest.

What did all the rest say? What did one find to be the general verdict, so to speak, in the 'nineties of the nineteenth century. The general verdict amounted to this:—Natural science must, of course, be right. Natural science, as constituted, is the great authority. We take our stand on the abiding ground of Natural science and peep up at the stars.—Well, of course as a leading instance, even before this, there was the conversation between Napoleon and the famous astronomer Laplace. Napoleon could not understand how, by looking up at the stars with a telescope, one can find God. And the astronomer replied: ‘I do not need the hypothesis’.Of course he didn't need such an hypothesis to see the heavens and their stars with a telescope. But he needed it, the moment he wished to be a man. But the sight of the heavens and the stars with a telescope gave man's own nature nothing, absolutely nothing. The heavens were full of stars; but they were stars of the senses. Otherwise they were empty.

And men looked through the microscope as far as ever one can see, into the tiniest life-germ, into the tiniest part of a life-germ, and ever further. And the microscope was made more perfect, and more perfect still.

But the soul they didn't find. They might look never so long into the microscope; it was empty of any soul. There was nothing there, either of soul or spirit. Neither in the stars was there anything of soul or spirit; nor under the microscope could they find any soul or spirit. And so it went on.

And with this Nietzsche found himself faced.—What did the rest of them say?—They said: ‘Oh, well, one looks through the telescope at the stars, and one sees so many worlds of the senses,—nothing else. But then we have a religious life, a religion, and this tells us that there is a spirit all the same.’ David Friedrich Strauss may talk as much as he pleases and ask at the end: ‘Where, then, is this spirit to be found along any scientific road!’ We stand by the fact, that in the writings handed down to us they talk of the Spirit all the same. We don't find him anywhere, it is true; but nevertheless we believe

1 ‘Ihr Anblick gibt den Engeln Starke.’

‘The sight gives strength unto the Angels,

Though none may sound the depths thereof;’

(‘Faust,’, Prologue in Heaven.)

in him. Science finds him nowhere; and we are bound to believe in Science; which is what it is, because it is bent upon reality;—if it were different, it would have no reality,—and there-fore everything that searches along any other road will come to no reality. We know about reality; and we believe, ... we believe in what is not indeed discovered to be a reality, but what old times tell us about as being a reality.

It was this, you see, that in a soul like Nietzsche's, which was honest, worked downright distraction. There came a day when Nietzsche said: ‘One must cut the account!’—How did he do it? He did it thus: he said: ‘Well then, we have now the reality. The reality is discovered by natural science. All the rest is nothing. Christianity taught that Christ is not to be sought in the reality that one investigates with telescopes and microscopes. But there is no other reality. Therefore, there is no justification for Christianity. Therefore,’ said Nietzsche, ‘I shall write the Anti-Christ.’

When one looks through the microscope and telescope, one discovers no ethical impulses, People accept the old ethical impulses, however, as commandments that flutter around in the air, or are ordered by the official authorities. But they are not to be discovered by scientific research. And so Nietzsche proposed, as the next book to his Anti-Christ, which was the first in his Revaluation, of all Values, to write a second book, in which he showed that all ideals exist, strictly speaking, in Nothing,—for they are not to be found in Reality; and that, therefore, they must be abandoned.

And he proposed then to write a third book: The Moral Principle, certainly, is not derived from the telescope and microscope; therefore, said Nietzsche, I shall argue the case for the Immoral principle.—And accordingly the three first books were to have been called: Revaluation of all Values; first book, The Anti-Christ;—second book, Nihilism, or The Abolition of all Ideals;—third book, Immoralism, or The Abolition of the Universal Moral Order.

It was a dreadful thing, of course. Rut it is the ultimate honest consequence of what are really the other people's premises. One must put things in this way before one's soul in order plainly to perceive the inner nerve of modern civilization.—And this was something that required to be dealt with. One required to show in what a terrible error Nietzsche was involved, and how it must be rectified in each case by assuming Nietzsche's own starting-point, and showing that these starting-points must be taken as leading, in actual fact, not to Nothing, but to a Spiritual Principle.—It was a necessity, therefore, to settle relations with Nietzsche.'

And the same, too, with Haeckel. Here again was a phenomenon with which it was necessary to enter into discussion. Haeckelism had followed up with a certain consequentiality all that natural science can make out of the evolution of sense-organisms. And this was a point to be connected onto in the manner I described to you at the beginning. I did it, as I said, by the aid of Topinard's book, in the very first anthroposophical lectures that I ever gave. One only needed to proceed in this way, and the actual progressive steps led on of themselves into the concrete spiritual world. And the details then came afterwards simply through further investigation, further life with the spiritual world.

I have told you all this for the following reason, namely, to show this:—that in tracing the history of Anthroposophy one must go back to illustrations from the life of our modern civilization.—If one traces back the history of the Anthroposophical Society, one must go back and ask: Where were the people in the first place, who had received a kind of impulse that made them ready to understand spiritual things?

And these were just the people who, from the character of their peculiarly homeless souls, had received such impulses from Blavatsky's quarter.

1 Fr. Nietzsche, ein Kampfer gegen seine Zeit. ( Nietzsche, the Antagonist of his Age.) Phil. Anthr. Verlag.

You see, my dear friends, what at the beginning of the century,—simply from the circumstances of the time,—had gone on side by side: the Theosophical Society and Anthroposophy, was something that now, in this third period (which began, as I told you about 1914), was completely outgrown and done with. There was absolutely nothing left, indeed, to remind one in any way of the old theosophist days. Down to the very forms of expression there was nothing, really, left. As it was, quite at the be-ginning of anthroposophic working, the tendency of the stream itself led the direction of spiritual study on to the Mystery of Golgotha, to the penetration of Christianity; and so, on the other side, the tendency which now set in brought these same spiritual means to bear upon natural science. Only,—I would like to say,—the acquisition of the spiritual means, by which true Christianity could be restored to its place before the eyes of the age,—the acquisition of these means belongs, as a fact, to an earlier time. It begins in the first period already, and is more peculiarly cultivated in the second. What was required for work in the various other directions did not really come out, in the manner I have been describing in these last few days, until the third stage. There then came to be people within the anthroposophic movement itself, who were seeking along the scientific path.

Now for those who are seeking along this scientific path, it is quite necessary, ... I say this in order that fresh misunderstandings may not continually be introduced into the anthroposophic movement ... especially for those who are pursuing this scientific path it is pre-eminently necessary that they should be absolutely filled through and through with what I spoke of yesterday and this morning again, namely, this working from the central source of Anthroposophy. It is here really necessary that people should be quite clear about these things.

My dear friends, it was in the year 1908, I think, that I said once in Nuremberg,—to give a quite definite fact as illustration:—We undoubtedly have a very great evolution in science, owing to the experiments made in recent times. Such investigations made by aid of experiment have brought an enormous amount to light. They turn out well everywhere, for the reason that all through the experimental process a spiritual element is at work, in the form of spiritual beings. For the most part, what happens is,—as I said then,—that the learned scientist goes up to the table of operations, and simply really goes through the manual performances, according as the practice may be, according to the regular methods of the mechanic routine. And then, besides him, there is a whole army at work,—so to speak—of spiritual beings. And it is they, who really do the thing. For, as for the person experimenting at the table, he only provides the opportunities, so that the different things can come out, bit by bit. If this were not the case, the thing wouldn't have gone so particularly well in recent times.

For you see, whenever anybody struck upon something,—like Julius Robert Mayer on his voyage,—he proceeded to clothe it in exceedingly abstract formula. But the other people didn't even understand it. And when, in course of time, Philip Reis was forced upon the telephone: then again the other people didn't understand it. There is really an enormous gulf between what folks understand and what is continually being dug out by experiment. For the spiritual impulses are not the very least under Man's control.

The fact of the matter is this:—Let us go back again to that very distinguished man, Julius Robert Mayer, who to-day, of course, as I said, is a great scientific discoverer, universally acknowledged, but who, so long as he was at school, was always at the bottom of his class. When he was attending the University at Tubingen, they thought of advising him to leave before taking his degree. With pain and grief, however, he succeeded in becoming a doctor, enlisted then as a ship's surgeon, and went on a voyage to India. They met with very rough weather on the voyage, the sailors fell ill, and on arrival he had to bleed a number of them.

Now a doctor, of course, knows that there are two sorts of blood vessels: veins and arteries. Arterial blood spurts out red; veinous blood spurts out bluish. When one lets blood, therefore,—makes an incision in the vein,—the blood. that comes out should be bluish. Julius Robert Mayer had very often to bleed people. Rut with all these sailors, who had made the voyage with him and fallen ill from the exciting times they had gone through at sea, something very curious happened when he made the incision. ‘Good heavens!’ he said to himself, ‘I've gone and struck the wrong place; for it's red blood spurting out of the vein! I must have struck an artery!’ And now the same thing happened again with the next man; and he got quite perplexed and nervous, thinking each time that he must have struck the wrong place; because each time the same thing happened. Finally he came upon the idea that he had made the incisions quite rightly after all; but that the sea, which had made the people ill, must have had some effect upon them, which gradually caused the veinous blood to come out red instead of blue, or at least approximately red, approximately the colour of the arterial blood.

And so, quite unexpectedly, in the process of blood-letting, a modern man, without any sort of spiritual motive leading him to look for any particular mental chain of connections, discovers a stupendous fact. But what does he say to it? As a modern man of science he says: ‘Now I must carefully consider what exactly takes place: Energy is converted into Heat, and Heat into Energy. It will be the same, then, as with the steam-engine. One heats the engine, and the result is Motion, Work; Work produced by Heat; and it will be the same in Man; and because Man is in the tropical zone (the ship had sailed to the tropics), where he is under other conditions of temperature, he therefore does not need to perform the process of con-version into blue blood. According to the law of the transformation of forces in nature, the thing takes place differently. The conditions of temperature in the human organism are different; the blood does not turn so blue in the veins, but remains red.’—The law of the transformation of substances, of forces, which to-day is a recognized law, is deduced from this observation.

Suppose for a moment that something of the kind had happened to a doctor, not in the nineteenth century but, let us say, if we imagine quite different conditions, to one perhaps in the eleventh or twelfth century only. It would never have occurred to this doctor, when he observed such a fact, to deduce from it the ‘mechanical equivalent of heat’. It would never have entered his head to connect anything so abstract with a phenomenon of the kind.

Or even, indeed, if you think of later times:—Paracelsus would certainly never have thought of such a thing,—not even in his sleep; although Paracelsus in his sleep was still a great deal cleverer, of course, than other people when awake,—but such a thing would most certainly not have occurred to him, my dear friends. A doctor such as Paracelsus might have been (and for the nineteenth century, Julius Robert Mayer was much the same as Paracelsus was for his age),—or a hypothetical doctor that lived, let us say if you like, in the tenth, or eleventh, or twelfth century,—what would he have said?

Well, even van Helmont still talks of archeus, that is, of what to-day we should call, conjointly, the etheric and astral bodies; (we have to discover it again by means of Anthroposophy; these terms had been forgotten) ... . A doctor of the twelfth century would have said: ‘In the temperate zone we find in Man a very pronounced inter-action between red blood and blue blood. When we take Man to the torrid zone, the veinous blood and the arterial blood no longer make themselves so vigorously distinct from one another; the blue veinous blood has become redder, and the red arterial blood more blue. There is scarcely any distinction left between them. What can be the origin of this?’—Well, there the doctor of the eleventh or twelfth century would have said (in those days he would have called it archeus, or something of the sort,—what we to-day call the astral body): With Man in the torrid zone,—he would have said,—the archeus sinks less deep into the physical body than it does with Man in the temperate zone. A Man of the temperate zone is more saturated with his astral body, more densely permeated by it; with the Man of the torrid zone, the astral body remains more outside him, even when he is awake. And, as a consequence, this differentiation, which takes place through the action of the astral body upon the blood, takes place more strongly with the Man of the temperate zone, and less strongly with the Man of the torrid zone. The Man of the torrid zone, therefore, has his astral body more free. We have a sign of this in the lesser thickening of the blood. And so he lives instinctively in his astral body, because this astral body is freer. And he becomes, accordingly, not a mechanically-thinking European; he becomes a spiritually-thinking Indian who, at the full flower of his civilization (not now, when it is all in decadence, but at its full flower) naturally has a quite different, a spiritual civilization, a Veda-civilization; whereas the European naturally has a Comtist, or Darwinist, or John Stuart Mill-ist civilization.

Yes, indeed, my dear friends; from this blood-letting a doctor of the eleventh or twelfth century would have arrived at some contemplation, such as this, of the Anthropos. He would still have sailed on into Anthroposophy. He would still have found his way on to the spiritual reality, to the living spirit. Julius Robert Mayer,—the Paracelsus, if you will, of the nineteenth century,—found, in his day, the law: ‘Nothing comes from nothing; therefore, there is a transformation of forces’,—an abstract formula.

The spiritual principle in Man, which can once more be found by means of Anthroposophy, this spiritual principle leads on in turn to Epics. Here we link up with that quest for the moral principles which we started on in the Philosophy of Freedom. Thereby the way is once more opened to Man for a spiritual activity in which he no longer has a gulf between Nature and Spirit, Nature and Ethics, but in which he finds the direct union of both.

One thing, however, will be plain from all I have been showing you, which is this:—The leading lights of modern science arrive at their abstract formulae. And these abstract formula are, of course, buzzing about in the heads of all the people to-day who have received a scientific training. The people who give this scientific training regard this tanglewood of abstract formula as something in which the modern man has to believe. And they look upon it as sheer lunacy for anyone to talk of leading up from the composition of the red and the blue blood to the spiritual principle of Man.

From this, however, you can see all that it means for an actual scientist, if he proposes to come into Anthroposophy. It means something more, besides the mere goodwill. It means, in reality, immense and devoted application to a profundity of study to which people are not accustomed at the present day,—and least of all accustomed, when they have passed through a scientific training.

What is wanted then, here, more especially, is courage, courage, and ever again courage. And with this we touch on the element which we above all things need for our souls, if we are to meet the necessary life-conditions of the Anthroposophical Society. This Society stands, in a way, to-day in diametrical opposition to all that is popular in the world. If it wants to make itself popular, therefore, it can have no possible prospect of succeeding. And therefore what we must not do,—more particularly if we want to spread Anthroposophy through the various branches of actual life; which has been the constant attempt since the year 1919,—we must not take the line of trying to make ourselves popular, but we must go out straight from the centre and essence, and pursue the road marked out by the life of the spirit itself,—as I described to you with reference to the Goetheanum this morning, in this one particular case.—But we must learn to think in this way in all matters; otherwise, we slide off the path; otherwise, we slide off it in such a way that people continually, with more or less justice, confuse us with other movements and judge us from the outside. But if we give ourselves with all energy our own form of structure, then, my dear friends, then we shall be following the road that runs in the direction of the anthroposophic movement and the conditions of its life. But we must teach ourselves the earnestness from which then the needful courage will come.

And we must not forget what is made simply necessary by the fact that we to-day, as Anthroposophists, are only a little handful. It is the hope, truly, of this little handful, that what they are the means of spreading abroad to-day will spread to ever larger and larger numbers of people; and, amongst these people then, there will be a certain direction of mind and knowledge, a certain moral and ethical, a religious direction.

But all these things, which will exist amongst people then through the impulses of Anthroposophy, and will be looked upon as, matters of course,—these things need to exist in a very much higher degree amongst those to-day who are only a little handful; these people must feel the very gravest obligations incumbent upon them towards the spiritual world. And one must understand that, quite instinctively, this will find expression in the verdict of the world around them.

By nothing can the Anthroposophical Society do itself more harm,—intense harm,—than if this Anthroposophical Society fails to give itself, in its members, a general form and style, through which people outside are made aware that, in the very strictest sense of the term, the Anthroposophists will this and that; so that they are able to distinguish them from all other, sectarian or other, movements.

So long as this is not the case, however, the Society cannot fail to call forth the kind of verdict from the outer world, which it does to-day. People don't really quite know what the purpose is of this Anthroposophical Society. They make acquaintance with some of the individual members; and in these there is nothing to be seen of Anthroposophy. Now suppose, let us say, that the Anthroposophists were to proclaim themselves by such a fine and marked sense for truth and circumstantial accuracy, that everybody saw at once: That's an Anthroposophist; one notices that he has such a very delicate sense in all he says, on no account to go further in his statements than strictly accords with the facts;—that, now, would give a certain impression.—However, to-day I don't wish, as I said, to make criticisms, but only to point out the positive things.—Are there signs of this happening? that is the question to be asked.

Or, again, people might say: Yes, those are Anthroposophists! They are very particular in all little matters of good taste. They have a certain artistic sense; the Goetheanum in Dornach must have had some effect after all.—Then again people would know: Anthroposophy certainly gives its members a sort of good taste: one can distinguish them by that from other people.

This is the kind of thing you see,—not so much what can be put into clearly defined propositions, but things of this kind,—that are all part of what the Anthroposophical Society, must study to develop, if it is to fulfil the conditions of its life.

Oh, there has been a great deal of talk about such things. But the question that has again and again to be raised, and one that should occupy a great place in all that is discussed amongst Anthroposophists, is this: How to give the anthroposophic society a quite distinct stamp, so that everyone can tell: Here is something by which this society is so completely distinguished from all the others as to leave no possibility of confusion.

One can only indicate these things as matters more of feeling; for where there is to be life, there can be no fixed programmes. Rut just ask yourselves whether, in the anthroposophic society, we have altogether got beyond the old: ‘One has to do this’, ... ‘One always does that’,... ‘One must be guided by this or the other’, and whether the impulse is always a strong one on every occasion to ask: What does Anthroposophy herself say?—There is no need for it to be set down in a lecture. But the things set down, or spoken, in lectures sink into hearts,—and this gives a certain tendency of direction.

I must say it once more, my dear friends: Until Anthroposophy is taken as a living being, who goes about unseen amongst us, and to whom each feels himself responsible,—not until then will this little band of Anthroposophists go forward as a model band that leads the way. And they should lead the way as a model band,—this little band of Anthroposophists.

When one came into any of the theosophic societies (of which there are many) they had, of course, the three well-known ‘principles’. I have spoken of these yesterday and how we must look upon them. The first principle was the establishment of universal human brotherhood, without distinction of race or nation, etc. I pointed out yesterday that it is a matter for consideration whether in future this should be set up in the form of a dogma. But still, my dear friends, it is significant that people make such a principle at all. Only it must become a reality. It must, little by little, become a reality in actual fact. And this it will do, when Anthroposophy herself is regarded as a living, supersensible, invisible being, going about amongst the Anthroposophists. Then perhaps there may be less talk of brotherhood,—less talk of universal love of mankind, but this love will be more living in men's hearts; and the world will see, from the very tone in which they speak of that which binds them together in Anthroposophy, from the very tone in which one tells the other this or that, it will be evident that it signifies something for the one, that the other too is a person who, like himself, is linked to the Unseen Being, Anthroposophy.—My dear friends, we can choose instead to take another way. We can take the way of simply forming a number of cliques, of going on as the fashion is in the world,—coming together for five-o'clock tea-parties or other social gatherings of the kind, where people drop in just for the purpose of mutual conversation, or at most to sit in company and listen to a lecture. We can do that, too, no doubt, instead. We can form little cliques, of course, instead,—little private circles. Rut an anthroposophic movement, of course, cannot live in a society of this kind. An anthroposophic movement can only live in an Anthroposophical Society which is a reality. But, in such a society, things need to be taken with very serious earnestness; there, one must at every moment of one's life feel that one is an associate of the Unseen Being, Anthroposophy.

If this could become the tone of mind, the tone of actual practice; if,—not in twenty-four hours perhaps, but after a certain length of time,—this could become the tone of mind, then,—let us say in twenty-one years,—there would most certainly arise a certain impulse: The moment people heard anything like what I mentioned yesterday again from the opponents, then the needful impulse would awake in people's hearts;—I am not saying by any means that it need lead at once to any practical action, but the necessary impulse would be there, in people's hearts; and then in good time the actions would come too.

When the actions do not come; when only the opponents act and organize; then it must be that the right impulse is not there; it must be that people still prefer well ... to live on in peace and comfort,—and of course to sit in the audience, when there are lectures on Anthroposophy. But this, at any rate, is not enough if the Anthroposophical Society is to prosper. If the Anthroposophical Society is to prosper, Anthroposophy must really live in it. And if that is the case, then indeed, in the course of twenty-one years, something of importance might come to pass,—or even in a shorter period. When I come to reckon,—why, the society has already existed twenty-one years!

Well, my dear friends, since I do not wish to make criticisms, I would merely ask you yourselves to carry your self-recollection so far as to ask, whether really each single individual at each single post has done that which must be felt to proceed from the very centre of all that is anthroposophic? And if you should happen to find that one or other of you has not as yet felt this, then I would beg you to begin at once, tomorrow, or this very evening; for it would not be a good thing if the Anthroposophical Society were to go to pieces. And it will most certainly go to pieces if (now that in addition to all the other things it already has on hand, it proposes to rebuild the Goetheanum), it will most certainly go to pieces, if that consciousness does not awake, of which I have been speaking in these lectures,—if this self-recollection is not there. And then, my dear friends, if it does fall to pieces, it will fall to pieces very rapidly.—But that is entirely dependent on the will of the people who are in the Anthroposophical Society.

Anthroposophy will quite certainly not be driven out of the world. But it might sink back for tens of years and more, so to speak, into a latent state, and then be taken up again later. An enormous amount would be lost for the evolution of mankind.—This is something to think over, if one intends in earnest to set about that self-recollection which was really my meaning with these lectures. It certainly was not my meaning, however, that there should again be a lot of big talk, and all sorts of programmes set up again, and declarations that ‘should this or that be wanted, we place ourselves entirely at disposal!’ ... those things we always did. What now is needed is that we should look into ourselves and find the inner centre of our own being. And if we pursue this search for the inner centre of our being with aid of the spirit to be found in the anthroposophic wealth of wisdom, we shall then find, too, that anthroposophic impulse, which the Anthroposophical Society needs as a condition of its life.

I particularly wanted in these lectures, my dear friends, not to deal so much in criticism, of which there has been plenty in these last times;—a great deal has been said, scattered about, on one or the other occasion. This time I wanted rather, by a historical review of one or two things,—if I tried to say everything, these lectures would. not be long enough;—but by a historical review of just one or two things, I wanted really through a study of anthroposophical affairs to give just a stimulus towards the actual handling of them in the right way. And these lectures especially, I think, can afford occasion for being thought over, reflected upon, so to speak. That is a thing for which one can always find time; for it can be done between the lines of life,—the lines of a life that brings with it the calls of the outer world.

This, my dear friends, is what I wanted to put before you in these lectures more especially, as a sort of Self-Recollection for the Anthroposophical Society, and to lay it very urgently to your hearts. We have absolute need to-day of this kind of self-recollection. We should not forget that if we go to the sources of anthroposophic life, very much can be done by means of them. If we neglect to do so, we are simply abandoning the paths on which it is possible to do anything.

We are about to enter on tasks of so great a magnitude as the rebuilding of the Goetheanum. Here, truly, our hearts' considerations can go out only from really great impulses; here we can go out from no kind of pettiness. This is what I said this morning to those who were there; and this is what I wished to put before you again to-night from a particular aspect.

Achter Vortrag

Wir werden heute zu einer Art von Abschluß unserer Betrachtungen kommen müssen, und der wird, wie es eigentlich selbstverständlich ist und auch gestern schon erwähnt worden ist, davon handeln müssen, was sich nun als die notwendige Konsequenz ergibt für das Handeln der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft in die Zukunft hinein. Machen wir uns, um dieses Handeln etwas charakterisieren zu können, doch nur einmal klar, wie Anthroposophie herausgewachsen ist aus der ganzen Zivilisation der neueren Zeit.

Sie werden gesehen haben aus den Betrachtungen, die wir acht Tage hindurch gepflogen haben, wie gewissermaßen das Publikum für die Anthroposophie zunächst innerhalb derjenigen Kreise gesucht werden mußte, die einen starken Anstoß bekommen haben nach der Richtung zu einer geistigen Vertiefung hin. Dieser Anstoß kam von den verschiedensten Seiten her. Aber hier war es nötig zunächst nur, den hauptsächlichsten Anstoß für die heimatlosen Seelen zu suchen bei dem, was durch Blavatsky, ich möchte sagen, als Rätsel der neuesten Zeit aufgegeben worden ist.

Nun, das haben wir ja betrachtet. Aber wenn wir so auch für die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft bis zu diesem Anstoß zurückgehen müssen, so muß sich uns auf der anderen Seite auch ergeben haben, wie für die Anthroposophie selbst ein solcher Anstoß oder gerade dieser Anstoß nicht das Wesentliche war. Denn Anthroposophie selbst geht zu anderen Quellen zurück. Wenn auch gerade, weil in der geschilderten Art ihr Publikum sich ergeben hat, selbst in der Ausdrucksform für das anthroposophische Weisheitsgut im Beginne Worte gebraucht worden sind, die diesen heimatlosen Seelen von jener Seite her, die mit Blavatsky zusammenhängt, geläufig waren, so waren das eben doch Ausdrucksformen. Wenn Sie in die ersten Schriften von mir selbst zurückgehen, «Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache», «Die Mystik im Aufgange des neuzeitlichen Geisteslebens», so werden Sie sehen, daß diese Schriften eigentlich in keiner Weise zurückführen zu irgend etwas, was von Blavatskys Seite her oder überhaupt von jener Seite her gekommen ist, mit Ausnahme eben der Tatsache, daß die Ausdrucksform zunächst so gewählt worden ist, daß ein Verständnis erzielt werden konnte.

Also man muß unterscheiden zwischen demjenigen, was als eigentliche Geistessubstanz durch die anthroposophische Bewegung geflossen ist, und demjenigen, was zunächst aus den Zeitverhältnissen heraus die Ausdrucksform sein mußte. Daß auf diesem Gebiete Irrtümer entstehen können, das rührt nur davon her, daß die Menschen in der Gegenwart so wenig geneigt sind, von der äußeren Ausdrucksform aus zurückzugehen zu dem, was eigentlich das Wesen der Sache ist. Anthroposophie führt in gerader Linie zurück zu demjenigen, was, allerdings auf philosophische Art, angeschlagen ist in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit», was angeschlagen ist in meinen Goetheschriften der achtziger Jahre. Wenn Sie das nehmen, was dort in diesen Goetheschriften und in der «Philosophie der Freiheit» als Hauptsächlichstes angeschlagen ist, so ist es dies, daß der Mensch im Innersten seines Wesens in Verbindung ist mit einer geistigen Welt, daß er also dann, wenn er nur tief genug in sein eigenes Wesen zurücksieht, auf etwas kommt in seinem Innern, zu dem die gebräuchliche, die damals und heute noch gebräuchliche Naturwissenschaft nicht vordringen kann, das nur betrachtet werden darf als unmittelbares Glied einer geistigen Weltordnung.

Daß gegenüber der ungeheuren, ich möchte sagen, geistigen Sprachverwirrung, die schon einmal diese neuere Zivilisation für alle Länder hervorgebracht hat, manchmal zu Ausdrücken die Zuflucht genommen werden mußte, die paradox klangen, das sollte man eigentlich als eine Notwendigkeit einsehen. So habe ich durch die Goetheschriften, ich möchte sagen, hindurchschimmern lassen, daß es nötig ist, wenn man von der Betrachtung der Welt zu der Betrachtung des Göttlich-Geistigen aufsteigt, eine Modifikation des Begriffes der Liebe vorzunehmen. Ich habe schon in den Goetheschriften angedeutet, daß die Gottheit so vorzustellen ist, daß sie in unendlicher Liebe in das Dasein ausgeflossen ist und in jedem einzelnen Wesen nun gesucht werden müsse, was etwas ganz anderes gibt als einen verschwommenen Pantheismus. Nun war gar nicht in jener Zeit die Möglichkeit vorhanden, irgendwie, sagen wir, einen philosophischen Anknüpfungspunkt zu gewinnen. Denn so leicht es gewesen wäre, dann mit einer solch spirituellen Weltanschauung durchzudringen, wenn das Zeitalter philosophische Begriffe gehabt hätte, an die hätte angeknüpft werden können, so schwer war es gegenüber dem, was dazumal mehr oder weniger als ein aufgewärmter Kantianismus in der Philosophie da war, irgendeinen Anknüpfungspunkt zu gewinnen. Daher war es notwendig, diesen Anknüpfungspunkt bei einem reicheren, intensiveren Leben zu suchen, bei einem Geistesleben, das eben innerlich, ich möchte sagen, mit spiritueller Substanz durchtränkt ist.

Ein solches Geistesleben war eben dasjenige, was in der Erscheinung Goethes einem entgegentrat. Daher konnte ich, als ich die Ideen, die in Betracht kommen, zuerst zu veröffentlichen hatte, nicht etwa mit einer Erkenntnistheorie an dasjenige anknüpfen, was dazumal in der Zeitzivilisation war, sondern es mußte an die Goethesche Weltanschauung angeknüpft werden, und mit Hilfe der Goetheschen Weltanschauung konnte der erste Schritt hinein in die geistige Welt gemacht werden.

Bei Goethe öffnen sich in einer gewissen Beziehung zwei Tore in die geistige Welt hinein, die, man möchte sagen, bis zu einem gewissen Grade den Zugang ergeben. Das eine Tor wird gefunden da, wo eine Betrachtung von Goethes naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften einsetzt. Denn mit dieser naturwissenschaftlichen Anschauung, die Goethe ausgearbeitet hat, hat er innerhalb der Pflanzenwelt dasjenige überwunden, woran eigentlich die ganze neuere Naturwissenschaft noch immer krankt. Ihm gelang es, bewegliche, lebendige Ideen an die Stelle der toten Ideen für die Betrachtung der Pflanzenwelt zu setzen. Wenn Goethe auch mit seiner Metamorphosenlehre dem Tierreiche gegenüber gescheitert ist, war es doch immerhin noch möglich, darauf hinzuweisen, daß eine ähnliche, nur gesteigerte, von Goethe noch nicht ausgebildete Betrachtungsweise auch für das Tierreich einsetzen könne. Ich habe in meiner «Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen Weltanschauung» versucht zu zeigen, wie man bis zu der Geschichte, bis zum geschichtlichen Leben herauf, zunächst skizzenhaft hat dringen können mit dem, was da an lebendigmachenden Ideen entstanden ist. Das war das eine Tor.

Nun gibt es bei Goethe keine gradlinige Fortsetzung in die wirkliche geistige Welt hinein von diesem Ausgangspunkte aus, sondern man kann von diesem Ausgangspunkte aus gewissermaßen nur bis zu einem bestimmten Niveau hin arbeiten. Dann hat man während dieses Arbeitens das Gefühl: man ergreift die sinnliche Welt auf eine geistige Art. Indem man die Goethesche Methode anwender, bewegt man sich eigentlich in einem geistigen Elemente. Wenn man auch diese Methode auf die sinnliche Pflanzenwelt oder auf die sinnliche Tierwelt anwendet, man ergreift mit dieser Methode dasjenige, was als Geistiges in der Pflanze, in der Tierwelt lebt und webt.

Aber Goethe hat auch noch ein anderes Tor in Aussicht genommen. Das trat am stärksten hervor dann, wenn man einsetzte bei etwas, was Goethe nur in der Lage war, bildhaft, man möchte sagen, halb symbolisch anzudeuten: bei seinem «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie», durch das er darstellen wollte, wie Geistiges, Spirituelles im Werden der Welt tätig ist, wie die einzelnen Sphären des Wahren, des Schönen, des Guten zusammenwirken und wie wirkliche geistige Wesenheiten ergriffen werden müssen, nicht bloße abstrakte Begriffe, wenn man zu einer Betrachtung des wirklichen geistigen Lebens kommen wollte.

Es war also die Möglichkeit vorhanden, zunächst an diesem Punkte der Goetheschen Weltanschauung anzuknüpfen. Aber dann ergab sich erst recht eine gewisse Notwendigkeit. Denn, was ja vor allen Dingen heute dem Menschen vor Augen tritt, wenn es sich um eine Weltanschauung für die heimatlosen Seelen handelt, das ist das Moralisch-Ethische, das sittliche Leben. In jenen alten Zeiten, in denen die Menschen mit einem ursprünglichen Hellsehen zu der Anschauung des Göttlich-Geistigen sich erhoben, war es eine Selbstverständlichkeit, daß von diesem Göttlich-Geistigen, zu dessen Anschauung man sich erheben konnte, auch die sittlichen Impulse herkamen. Wenn wir in sehr alte Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung zurückschauen, dann stellt sich die Sache so dar, daß der Mensch in seinem ursprünglichen primitiven Hellsehen, sagen wir in der guten alten Zeit, bei seinem Aufschauen zu dem GöttlichGeistigen, zu den wesenhaften Kräften emporblickte, welche die Naturerscheinungen regeln. Und in den Naturerscheinungen, in Wind- und Wetterwirkungen, in Erdenwirkungen, in mechanischen Wirkungen konnte dieser Mensch einer ursprünglichen Zeit die Fortsetzung dessen sehen, was er an Göttlich-Geistigem wahrnahm. Aber er konnte zu gleicher Zeit von diesem Göttlich-Geistigen die Impulse für sein Handeln empfangen. Das ist ja das Eigentümliche der alten Weltanschauungen, die noch mit dem primitiven Hellsehen zusammenhingen, daß, sagen wir mit Bezug auf die altägyptische Zeit, die Menschen hinaufgesehen haben zu den Sternen, um die Erdenwirkungen zu erkennen; selbst um für ihr Bedürfnis die Überschwemmungsverhältnisse des Nils zu erkennen. Aus dem Gang der Sterne, aus der Gesetzmäßigkeit der Sterne haben sie dasjenige hergeleitet, was sie für die Erdenwelt in ihrer Naturordnung interessiert hat. Aber in derselben Weise haben diese Menschen dasjenige, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, berechnet, was sittliche Impulse werden sollten. Aus der Sternenbeobachtung wurden auch die sittlichen Impulse geholt.

Sehen wir dann, wie die Lage in der neueren Zeit geworden ist, so müssen wir sagen: Sternenbeobachtung wird nur noch in mathematischer Beziehung gemacht, wobei nichts anderes zustande kommt, als daß man die irdische Mathematik hinaufträgt in den Sternenhimmel. Und auf der Erde werden sogenannte Naturgesetze gesucht und gefunden. Diese Naturgesetze, die auch schon Goethe gefunden hat, die er dann in lebendige Ideen umgestaltet hat, haben, sobald es sich um Weltanschauungen handelt, eine gewisse Eigentümlichkeit, und diese Eigentümlichkeit ist diese, daß der Mensch von der Welt ausgeschaltet wird, wenn er sich an die Naturgesetze halten soll, daß der Mensch mit seinem ureigensten Wesen nicht mehr in der Welt drinnensteht.

Wenn Sie sich das graphisch vorstellen, wie das in den alten Weltanschauungen war, so war auf der einen Seite das GöttlichGeistige (rot). Das Göttlich-Geistige drang in die Naturerscheinungen. Es wurden Gesetze für die Naturerscheinungen gefunden. Die aber erkannte man als etwas, was eine Art Reflex war des göttlich-geistigen Wirkens in der Natur (gelb). Außerdem war der Mensch da (hell). In den Menschen strahlte dasselbe Göttlich-Geistige hinein (rot). Da stand der Mensch innerhalb der Weltenordnung drinnen. Er bekam sozusagen seinen Substanzgehalt von dem Göttlich-Geistigen, von dem die Natur diesen Substanzgehalt bekam. Was trat ein? Man muß das, was eigentlich eingetreten ist, nur in vollem Ernst betrachten. Das trat ein, daß gewissermaßen durch die Naturwissenschaft der Zusammenhang der Natur mit dem Göttlichen gestrichen worden ist. Weg ist das Göttliche von der Natur, und in der Natur selbst werden die Reflexe des Göttlichen als Naturgesetze konstatiert, und man redet von Naturgesetzen.

Den Alten waren diese Naturgesetze Gottesgedanken. Den Neueren sind sie noch immer Gedanken, denn man muß sie ja mit Gedanken fassen. Aber das soll sich in irgendeiner Weise aufklären in den Naturerscheinungen, die in dem darinnen liegen, was die Naturgesetze sind. Von einem Gesetz der Schwere, von Brechungsgesetzen des Lichtes, von allen solchen schönen Dingen redet man nun. Aber das hat gar keinen Boden, beziehungsweise keine Höhe, weil es nur einen Sinn hat, von all diesen Gesetzen zu ‚ reden, wenn man von ihnen reden kann als von Reflexen des göttlich-geistigen Wirkens in der Natur.

Das ist es, was der tiefere Mensch, die heimatlose Seele bei allem heutigen Reden über die Natur fühlt. Sie fühlt, daß diejenigen, die über die Natur reden, mit den Goetheschen Worten belegt werden müssen, oder eigentlich mit den mephistophelischen: spottet ihrer selbst und weiß nicht wie. Man redet von Naturgesetzen, aber diese Naturgesetze sind dasjenige, was von den Anschauungen der Alten übrig geblieben ist. Nur hatten die Anschauungen der Alten noch zu diesen Naturgesetzen dasjenige dazu, was diese Naturgesetze möglich machte.

Denken Sie sich einmal, Sie haben einen Rosenstrauch. Sie können immer wieder Rosen auf dem Rosenstrauch haben. Wenn die alten abdorren, wachsen neue. Wenn Sie aber die Rosen abpflücken und den Rosenstrauch zugrunde gehen lassen, können Sie nicht immer neue Rosen haben. So aber ist es mit der Naturwissenschaft geschehen. Es war ein Rosenstrauch da. Seine Wurzeln waren in der Gottheit. Die Gesetze, die man in der Natur fand, waren die einzelnen Rosen. Diese Gesetze hat man gepflückt. Die Rosen hat man geptlückt. Den Rosenstrauch hat man verdorren lassen. So haben wir jetzt in den Naturgesetzen etwas, was da ist wie die Rosen ohne Rosenstrauch. Davon haben die Menschen nichts. Sie ahnen nichts in dem Kopfe, auf den so viel in der neueren Zeit gegeben wird. Aber die Menschen, die da heimatlose Seelen sind, ahnen davon sehr viel in ihren Herzen, denn sie können mit den Naturgesetzen nichts anfangen. Sie fühlen: Diese Naturgesetze verdorren, wenn man sich als Mensch ihnen gegenüberstellen will.

So steht die moderne Menschheit, insofern sie fühlen kann, insofern sie ein Herz im Leibe hat, unbewußt unter dem Eindrucke: Da wird uns über die Natur etwas gesagt, was uns verdorrt und was uns als Menschen sogar verdorren macht. Die Menschheit wird nun durch furchtbaren Autoritätsglauben gezwungen, dieses als die reine Wahrheit aufzunehmen. Während sie mit dem Herzen fühlt, daß die Rosen verdorren, wird sie gezwungen zu dem Glauben, daß diese Rosen die ewigen Weltwesenheiten sind. Man redet von den ewigen Weltgesetzen. Die Erscheinungen gehen vorüber, die Gesetze aber bleiben immer da. Weil dasjenige, was der Mensch aus sich selber heraus als sein Selbstbewußtsein gestalten will, Anthroposophie ist, so ist die Naturwissenschaft Anti-Anthroposophie.

Sehen wir noch nach der anderen Seite, nach der ethisch-moralischen Seite hin. Aus demselben Quell der Gottheit kamen die sittlich-moralischen Impulse. Aber geradeso, wie man die Naturgesetze zu verdorrenden Rosen macht, so machte man die sittlichen Impulse zu verdorrenden Rosen. Die Wurzel war überall weg, und so schwirrten die sittlichen Impulse als Sittengebote, deren Einwurzelung man nicht kannte, in der Zivilisation umher. Den Menschen war nichts anderes möglich, als zu empfinden: die sittlichen Gebote sind da. Aber der göttliche Ursprung war nicht da, und jetzt entstand die notwendige Frage: Wohin soll es denn kommen, wenn die Sittengebote nicht befolgt werden? Es kommt zum Chaos, zur Anarchie in der menschlichen Sozietät.

Aber auf der anderen Seite steht das: Wie wirken denn diese Gebote? Wo wurzeln sie? Man fühlte auch da das Verdorrende. Das wurde die große Frage, das wurde die Frage, die sich aus dem Goetheanismus ergab, aber innerhalb des Goetheanismus selber nicht beantwortet werden konnte. Goethe setzte, ich möchte sagen, zwei Ausgangspunkte hin, die sich zwar konvergierend gegeneinanderbewegten, aber nicht zusammenkamen. Dasjenige, was notwendig ist, notwendig war, das ist die Philosophie der Freiheit.

Es mußte gezeigt werden, wo im Menschen selber das Göttliche lebt, in dem er sowohl die Geistigkeit der Natur wie namentlich die Geistigkeit der Moralgesetze gründen kann. Das führte zu dem Intuitismus der Philosophie der Freiheit, zu dem, was die Leute ethischen Individualismus nannten. Ethischen Individualismus aus dem Grunde, weil in jedem einzelnen menschlichen Individuum der Quell für die sittlichen Impulse in jenem Göttlichen nachgewiesen werden mußte, womit der Mensch im Innersten seines Wesens zusammenhängt. Nachdem das Zeitalter eingetreten war, wo man auf der einen Seite für die Naturgesetze, auf der anderen Seite für die Moralgebote die Lebendigkeit verloren hatte, weil man im Äußeren das Göttliche nicht mehr fand — im Zeitalter der Freiheit konnte es nicht anders sein —, war es notwendig, im Menschen — denn der Mensch tritt uns zunächst als Individualität entgegen - dieses Göttlich-Geistige zu finden. Damit war aber eine Weltanschauung gewonnen, die Sie sich nur klarmachen wollen, dann werden Sie sehen, daß in ihrer gradlinigen Fortsetzung dasjenige liegt, was wir heute Anthroposophie nennen.

Nehmen Sie an — es ist etwas primitiv gezeichnet, aber es mag doch gelten -—, wir haben hier Menschen. Die Menschen hängen in ihrem innersten Wesen mit einem Göttlich-Geistigen zusammen (rot). Dieses Göttlich-Geistige bildet sich zu einer göttlich-geistigen Weltordnung (gelb). Dadurch, daß das Innere aller Menschen in ihrem Zusammenwirken geschaut wird, dringt man nunmehr in das Göttlich-Geistige ein, wie man in alten Zeiten in das Göttlich-Geistige eingedrungen ist, wenn man nach außen geschaut hat und durch das primitive Hellsehen das Göttlich-Geistige in den äußeren Erscheinungen gefunden hat.

Es handelt sich eben darum, zu dem, was sich auf der einen Seite aus der Goetheschen Weltanschauung ergab und was auf der anderen Seite einfach aus den Notwendigkeiten der menschlichen Entwickelung am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts sich ergab, zur Spiritualität vorzudringen; nicht auf eine äußerlich materialistische Weise, sondern durch eine wirkliche Erfassung des unmittelbaren Menschenwesens.

Nun, damit war aber eigentlich, wenn man die Sache dem Leben nach betrachtet, nicht der Theorie nach, Anthroposophie begründet. Denn wenn man meinen würde, die «Philosophie der Freiheit» sei doch noch keine Anthroposophie, muß es einem geradeso vorkommen, wie wenn jemand sagte: Es gab einen Goethe, dieser Goethe hat alle möglichen Werke geschrieben; wir verstehen heute unter Goethe den Schöpfer seiner Werke. - Nun aber erwidert ein anderer: Ja, das ist eine Inkonsequenz, denn es gab 1749 in Frankfurt am Main ein kleines Kind, das war sogar schwarz geboren, und man sagte, es könne nicht leben. Wenn man alles anschaut, was um dieses Kind war, da kann man davon doch nicht logisch alle Goetheschen Werke ableiten. Das ist eine Inkonsequenz. Man muß doch Goethe bis zu seinem Ursprung zurückverfolgen. Seht an, ob ihr da den Faust findet bei dem blauschwarzen Knaben, der da 1749 in Frankfurt am Main geboren ist!

Nicht wahr, es ist nicht besonders gescheit, wenn man so etwas sagt. Ebensowenig gescheit ist es aber, wenn man sagt, es sei inkonsequent, daß Anthroposophie aus der «Philosophie der Freiheit» hervorgegangen ist. Das schwarze Kind in Frankfurt lebte eben weiter, und aus seinem Leben ging dasjenige hervor, was heute als Goethe in der Weltentwickelung lebt. Die «Philosophie der Freiheit» mußte weiterleben. Dann ging die Anthroposophie aus ihr hervor.

Denken Sie sich einmal, wenn an Stelle des Lebens ein philosophischer Logiker tritt und sagt, es muß auf logische Weise abgeleitet werden aus dem blauschwarzen Knaben von 1749 dasjenige, was in «Faust», in «Wilhelm Meister» und so weiter ist —, glauben Sie, er würde auf logische Weise etwas ableiten? Nein, er würde Widersprüche konstatieren, ungeheure Widersprüche. Er wird sagen: Das bringe ich nicht in Einklang, was da irgendeiner einmal als «Faust» geschrieben hat, mit dem, was da der blauschwarze Knabe in Frankfurt am Main war, das folgt nicht logisch daraus.

So sagen diejenigen, die nicht mit dem Leben zu tun haben, sondern mit Schulstaub-Logik: Aus der «Philosophie der Freiheit» folgt logisch nicht die Anthroposophie.

Wenn es logisch folgen würde, dann hätten Sie nur sehen sollen, wie all die Schulmeister im Jahre 1894 aus der «Philosophie der Freiheit» heraus die Anthroposophie deduziert hätten! Das haben sie hübsch bleiben lassen. Aber hinterher gestehen sie ein, sie können es nicht deduzieren, sie bringen das nicht zusammen, machen das zu einem Widerspruch zwischen dem Späteren und dem Früheren. Man hat eben in der heutigen Zeit gar nicht die Fähigkeit, da, wo man sogenannte Logik, Philosophie und so weiter entwickelt, auf das Leben einzugehen, auf dasjenige, was sprießt und sproßt, was mehr ist, als logischer Pedantismus in ihm sehen kann.

Nun handelte es sich darum, des weiteren zunächst sich auseinanderzusetzen mit demjenigen, was aus dem unmittelbaren Leben der Gegenwart heraus gewissermaßen nach einer Fortentwickelung der menschlichen Zivilisation aufstrebte.

Sie wissen, ich habe versucht, zwei bedeutende Erscheinungen herauszuheben, um mich mit denen auseinanderzusetzen. Die erste war Nietzsche. Warum das der Fall sein mußte, das werden Sie aus den bisherigen Betrachtungen gesehen haben, denn in Nietzsche trat eine Persönlichkeit an die Oberfläche der neueren Zivilisationsentwickelung, die hineinwuchs in die Weltanschauungsentwickelung der Gegenwart und die im Gegensatz zu den anderen ehrlich war.

Was sagten die anderen? Was fand man als allgemeines Urteil, möchte man sagen, in den neunziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts? Im allgemeinen Urteil fand man dieses: Die Naturwissenschaft hat selbstverständlich recht. Die Naturwissenschaft, wie sie besteht, ist die große Autorität. Wir stellen uns auf den Boden der Naturwissenschaft, gucken in die Sterne hinauf. Nun, da war ja schon vorliegend das Gespräch zwischen Napoleon und dem großen Astronomen Laplace. Napoleon konnte nicht begreifen, wie man, wenn man mit Teleskopen nach den Sternen sieht, Gott finden könne. Der Astronom sagte ihm: Ich brauche diese Hypothese nicht. Er brauchte die Hypothese natürlich nicht zum Anblicke des Sternenhimmels mit dem Teleskop. Aber er brauchte sie in demselben Momente, wo er Mensch sein wollte. Aber der Anblick des Sternenhimmels mit dem Teleskop gab eben dem Menschtum nichts, nichts gab er ihm. Der Himmel war voller Sterne, aber voller Sinnensterne, und im übrigen leer.

Man sah durch die Mikroskope, so weit als man nur sehen kann, bis in die kleinsten Lebewesen, bis in die kleinsten Teile eines Lebewesens und so weiter hinein. Man machte die Mikroskope immer vollkommener und vollkommener. Aber die Seele fand man nicht. Man konnte noch so lange hineingucken ins Mikroskop, von Seele war es leer. Nichts war da von Seele oder Geist. Nicht in den Sternen war etwas da von Seele oder Geist, nicht unter dem Mikroskop war Seele oder Geist zu finden. Und so ging es weiter. Dem sah sich Nietzsche gegenüber. Die anderen, was sagten sie? Man blickt durch das Teleskop in die Sterne, man erblickt dann Sinneswelten, sonst nichts. Aber wir haben ein religiöses Leben, eine Religion, die sagt uns, daß es doch einen Geist gibt. David Friedrich Strauß hat lang gut reden, wenn er die Konsequenz zieht: Wo ist jetzt dieser Geist auf wissenschaftlichem Wege zu finden? Wir bleiben dabei stehen, daß uns in den Schriften, die uns überliefert sind, doch vom Geist gesprochen wird. Wir finden ihn zwar nirgends, aber wir bekennen uns zu ihm, Nirgends findet diesen Geist die Wissenschaft, an die wir verpflichtet sind zu glauben, die deshalb so ist, wie sie ist, weil sie Realität haben will. Wäre sie anders, so hätte sie keine Realität. Also alles, was anders forscht, findet keine Realität! Also wissen wir von der Realität und glauben an dasjenige, was zwar nicht als Realität gefunden wird, wovon uns aber die alten Zeiten erzählen, daß es Realität sein soll.

Das war es, was eine solche Seele wie die Nietzschesche, die doch ehrlich war, geradezu auseinandertrieb. Nietzsche sagte eines Tages: Da muß ein Strich gemacht werden. Wie machte er das? Er machte das so, daß er sagte: Also nun haben wir die Realität. Die Realität wird erforscht von der Naturwissenschaft. Das andere ist nichts. Das Christentum hat gelehrt, daß der Christus nicht gesucht werden muß in der Realität, die man aufsucht mit Teleskop, Mikroskop. Aber eine andere Realität gibt es nicht. Also gibt es auch keine Berechtigung für das Christentum. Also, sagte Nietzsche, schreibe ich den « Antichrist».

Wenn man durch Mikroskop und Teleskop schaut, findet man keine sittlichen Impulse. Die Leute nehmen aber die alten sittlichen Impulse als Gebote an, die herumschwirren oder die von den Behörden befohlen werden. Sie sind aber nicht zu finden, wenn man wissenschaftlich forscht. Also wollte Nietzsche sein zweites Buch, nach dem «Antichrist», der das erste Buch sein sollte, in seiner «Umwertung aller Werte» schreiben: als zweites Buch, wo er zeigte, daß alle Ideale eigentlich im Nichts sind, denn in der Realität werden sie nicht gefunden, und daß man sie fahren lassen müsse.

Und er wollte sein drittes Buch schreiben. Der Moralismus schöpft gewiß nicht aus dem Teleskop und Mikroskop: also begründe ich, sagte Nietzsche, den Immoralismus. Daher hätten die drei ersten Bücher heißen sollen: Umwertung aller Werte, der Antichrist, erstes Buch; der Nihilismus oder die Aufhebung aller Ideale, zweites Buch; der Immoralismus oder Aufhebung der gesamten sittlichen Weltordnung, drittes Buch.

Das war selbstverständlich etwas Furchtbares, aber es war die letzte ehrliche Konsequenz dessen, was die anderen eigentlich begründet haben. Man muß die Dinge so vor die Seele hinstellen, damit man die inneren Nerven der modernen Zivilisation durchschaut. Damit mußte man sich auseinandersetzen. Es mußte gezeigt werden, in welch ungeheurem Irrtum Nietzsche befangen ist und wie er richtiggestellt werden muß, so daß man überall seinen Ausgangspunkt aufnimmt und zeigt, wie diese Ausgangspunkte in der Tat so gefaßt werden müssen, daß sie nicht ins Nichts, sondern in die Spiritualität hineinführen. Es war also eine notwendige Auseinandersetzung mit Nietzsche da.