Art as Seen in the Light of Mystery Wisdom

GA 275

2 January 1915, Dornach

VI. Working with Sculptural Architecture I

It will be relatively easy—I am saying relatively, of course—for a person to take up more or less theoretically what we understand by the spiritual-scientific world outlook, or anthroposophy. But it will not be easy to fill our whole being and life itself with the impulses coming from spiritual science. To absorb anthroposophy theoretically, so that you know that the human being consists of a physical body, an etheric body, an astral body and so on, in the same way as you know that one or another tone has so-and-so many vibrations, or that oxygen combines with hydrogen to make water, is the way we have grown accustomed to learning things through the natural-scientific approach mankind has gradually acquired over the last few centuries.

We are less accustomed, however, to allowing our feelings and attitude of mind to be affected by the kind of knowledge spiritual science has to offer. Yet the kind of approach we must have to spiritual science is fundamentally opposite to the approach we must have to natural science. Emphasis is often laid on the fact that everyone feels that science is dry and stops us having a warm contact with life and its happenings; that dry science has something cold and unfeeling about it and robs things of their dewy freshness. Yet one could say that to a certain extent this has to be so with ordinary science. For there is an enormous difference between the impression made on us by a wonderful cloud formation in the evening or morning sky and the bare reports an astronomer or a meteorologist gives us. There is such abundant richness in the natural world around us that its effect on us is to warm us through and through whereas, in comparison, science, with its concepts and ideas, appears dull and dry, cold, lifeless and loveless. Yet there is every justification to feel this way as far as external, natural-scientific knowledge is concerned.

There are good reasons why external, natural-scientific knowledge has to be like this, but spiritual science is not this kind of knowledge. On the contrary it ought to bring us nearer and nearer to the living abundance and warmth of the outside world and of the world altogether. But this means learning to bring certain impulses to life in us that a person of today hardly possesses at all. A present-day person expects it to be in the nature of what he calls science that it has a cold and sobering effect on him, like the character of Wagner in Goethe's Faust. He expects that if he assimilates science the riddles of nature will be solved, and then he will know how everything is constituted and be perfectly satisfied with what he knows.

Science even makes some people shudder nowadays, for a quite specific reason. They maintain that what made life so rich and fresh in the past, was the fact that man had not solved every riddle and could still wonder about the unsolved ones. And then science comes along, they say, and solves the riddles of nature one after the other. And they imagine how boring life will be in the future when science will have solved all the mysteries and there will be no further possibility of wondering about anything, or having any feelings of an unscientific kind. What terrible desolation would befall mankind; we have every reason to be horrified at the prospect.

But spiritual science can kindle different feelings than these, and although those feelings would be less in keeping with modern times than the solving of riddles, they show how awakening and life-giving spiritual science can be. If we absorb anthroposophy in the right way—not just take notes of what is being said, so that we can make use of them like they do in ordinary science, and perhaps even do a neat diagram, so that we can take it all in at a glance like physics—if we do not do it so much that way, but let what anthroposophy has to say reach our hearts and we unite with it, we shall notice that it comes to life in us and grows, it awakens our independence and initiative and becomes like a new living being within us, that is forever showing new aspects. To approach external nature with our souls thus filled with anthroposophy, is to find more riddles in nature and not less. Everything grows even more puzzling, which broadens instead of impoverishing our life of feeling; you could say that spiritual science makes the world more mysterious.

Of course the world becomes a desolate place when the physicist says to you ‘You see the sunrise . . . .’ and then, showing us a diagram, he tells us which particular refractions are taking place in the rays of light so that the glow of dawn appears. This is certainly horrible, not from the point of view of human reason, but for the human heart and an understanding connected with the heart.

It is quite different when spiritual science tells us, for example, When you see the sunrise or hear one or another piece of music, it must feel to you as though the Elohim were sending their punishing wrath into the world. Then we become aware of the mysterious living weaving of the Elohim behind the glow of dawn. To know the name of the Elohim and to be able to give them a place in the ninefold diagram we have drawn in our notebook, is not knowing anything about the Elohim. But out of the living feeling we can have in looking at the sunrise will come a perception of movement and life in rich abundance, just as we know that when we look at a human being, any amount of conceptual knowledge about him will not tell us the whole of his nature, nor fathom the universal life within him. Likewise, we shall become aware that the dawn is revealing something to us of the unfathomable life of the cosmos.

Spiritual-scientific knowledge makes life more enigmatic and mysterious in a way that kindles richer feelings within us. And it is a fundamental feeling of this kind our souls can acquire, when we bring spiritual science to life within us and when we try to make ourselves at home in the kind of ideas I have just indicated. Then we shall never be tempted to complain that spiritual science only appeals to our heads and does not take hold of our whole being. We just need to be patient until the message of spiritual science becomes a living being within us and forms itself anew, filling us not only with its light but also with its warmth. Then it will take hold of our hearts and our whole being and we shall feel the richer for it, whereas, if we take up spiritual science in the same way as ordinary science, we are bound to feel the poorer.

Yet, on the other hand, it is quite natural that, to begin with, anthroposophy seems to many people to lead to an impoverishment, because they have not yet been able to find the inner life of the message of anthroposophy that can reach their heart, and because anthroposophy does not yet have the same effect on them as, for instance, the warm words of a fellow human being speaking to us. But we have to learn that anthroposophy can become alive that it can give us as much support and encouragement as we can otherwise only receive from another human being.

Our hearts find this so difficult at the present time because we have lost the habit of uniting ourselves with the life of things. It is difficult enough if one tries in small doses to re-introduce this living with things. This was attempted in our four Mystery Plays. You have only to think of the scene in spirit land, in the fifth act of The Soul's Awakening, where Felix Balde is sitting on the left side of the stage—seen from the audience—after he has ascended to Devachan, and a spiritual being on the other side of the stage speaks to him of his experience of weight. Here one should feel the weight that is descending in the distance. When people see something descending, they are accustomed nowadays only to be aware of the descending and only to see the thing higher up to start with, and then coming lower and lower down. They are quite unaccustomed to creeping into things and feeling the experience of weight, feeling the thing pressing down all the time. With an expression like that I am hoping to lift people out of their egoistic bodies right in the middle of the play, and to plunge them into the life of things outside themselves.

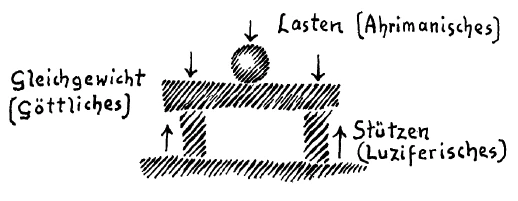

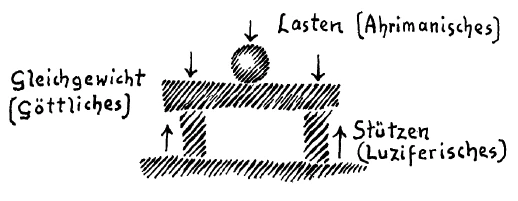

If this cannot happen, then real artistic feeling will not be able to arise again. In order that, for instance, a true feeling for architecture can come again, the concepts we receive from spiritual science must come alive. To begin with it makes very little difference which particular anthroposophical concepts we carry round with us. But if we really do something like this we shall see how much richer our soul life becomes. We shall gain a lot if, for instance, as well as just seeing this diagram we try and submerge ourselves in it and try to feel what is going on: weight pressing down here, and weight being supported there.

We want to go even further and not just look at it, but feel that the beam needs to have a certain strength, otherwise the load will crush it, and the supporting pillars must also have a certain strength, otherwise they too will be crushed. We must feel the way the sphere on top is pressing down, the pillars supporting and the beam keeping the balance. Not until we creep into the elements of weight, support and balance, between the pressing down and the supporting, shall we feel our way into the element of architecture.

But if we follow a structure of this kind not only with our eye but, as it were, crawl into it and experience the weighing down, the supporting and the balance, then we shall feel that our whole organism is becoming involved, and as if we have to call on an invisible brain belonging to our whole being and not just our head. Then we can awaken to the consciousness, ‘Ah! now we are beginning to feel!’ To take our simple example, we shall feel a supporting element, an upward striving, supporting luciferic element; a weighing and pressing down ahrimanic element, and a balance between the luciferic and ahrimanic which is a divine quality. Thus, even lifeless nature becomes filled with Lucifer and Ahriman and their superior ruler, who eternally brings about the balance between them.

If we thus learn to experience the luciferic, ahrimanic and divine elements in architecture, so that architecture affects us inwardly, we shall become conscious of a richer feeling of the world which leads or, one could almost say, pulls the soul into the things of the world; for our soul is now not only within our body's skin but belongs to the cosmos. This is a way of becoming conscious of this. We shall become aware, too, that whereas outside, the architectural element is supporting, weighing down and creating a balance, we ourselves in this encounter with the architectural element, develop a musical mood. Architecture produces a musical mood in our inner being, and we notice that even though the elements of architecture and music appear to be so alien in the outer world, through this musical mood engendered in us, our experience of architecture brings about a reconciliation, a balance between these two elements.

This is where, from our epoch onwards, living progress in the arts will lie, through learning to experience the reconciliation of the arts. This was dimly felt by Wagner, but it can only really come about when the world comes alive with spiritual science.

Reconciling the arts: that is what we attempted to do—for the first time, and in a small, elementary way—in our Goetheanum building. We did not want only to talk in a cold, abstract way about it, but show in the architecture of the building itself an impression, a copy of this reconciling of a musical mood with architectural form. If you study what is presented in our series of pillars and everything connected with them, you will discover that we were making the attempt to bring the elements of support, weighing down and the balance into living movement. Our pillars are not merely supports, and our capitals no longer mere supporting devices, and the architraves that extend above the pillars do not just have the character of rest, serving only to round the pillars off at the top, but they have a character of living growth and movement.

We attempted to bring architectural forms into musical flux, and the feeling one can have from seeing the interplay between the pillars and all that is connected with them, can of itself arouse a musical mood in the soul. It will be possible to feel invisible music as the soul of the columns and the architectural and sculptural forms that belong to them. It is as though a soul element were in them. And the interpenetration of the fine arts and their forms by musical moods has fundamentally to be the ideal of the art of the future. Music of the future will be more sculptural than music of the past. Architecture and sculpture of the future will be more musical than they were in the past. That will be the essential thing. Yet this will not stop music from being an independent art; on the contrary, it will become richer and richer through penetrating the secrets of the tones, as we said yesterday, creating musical forms from out of the spiritual foundations of the cosmos.

However, as everything that is inside must also be outside, in art—all that lives in it must be embodied in a kind of organism—the world of soul within the series of pillars and everything belonging to them must also become embodied. This happens, or at least is about to happen in the painting of the domes. Just as the pillars and everything belonging to them are, as it were, the body of our building, so is all that is going to appear in the domes—when you are inside the building—its soul; and just as the world appears to be filled with spirit, when our organs are directed outwards, our windows executed in the new art of glass shading shall represent the spirit. Body, soul and spirit shall be expressed in our building. Body in the column structure, soul in everything to do with the domes, and spirit in what is in the windows.

Where these things are concerned karma has brought various things about for which we can be grateful, for just in the case of the Goetheanum building, karma has indeed helped us in several matters. The soul of a human being is so constituted that from outside we perceive it in his physiognomy, but we have to have resources like love and friendship to penetrate into a person's soul, if we want to get to know it from inside, as it were.

When I was travelling from Christiania to Bergen on my last lecture tour in Norway, I happened to see a slate quarry which gave me the idea of trying to get slate from there. We were successful, and it really was what one might call a karmic happening, for when we look at the roof of the domes that are now tiled with this slate with its quite unique qualities, we are sure to say that it has something of the quality of the life of the soul, that at one and the same time both discloses and conceals what is within. Now if we really want to feel the domes as soul life we shall have to develop a love for spiritual science. For what is going to be painted inside the domes should really appear to us as a kind of reflected image in colour and form, of what spiritual science can mean to us. To see this we have to go inside. But when the building is really finished, no one will be able to understand what he sees when he goes inside if he has not developed a love for spiritual science; otherwise what he sees there will probably remain something that can cause a bit of a sensation, but will not be anything that particularly appeals to his heart. What he gets from it will easily tempt him to deny that the architecture has anything to offer the feelings.

Just as we have seen in this instance that what comes to life out of anthroposophy can be rediscovered in the world, life can also be fructified through anthroposophy, in realms in which we can more readily see that our heart's understanding needs to be warmed and fructified. For it is not only artistic and scientific areas that are to be fructified by spiritual science, but the whole of life has to be.

Let me take as an example a realm in which we can see particularly well how anthroposophical concepts can come alive in outer life. I will choose the realm of education, any kind of art of education. Let us begin from the fact that children are educated by grown-ups. What does the materialistic age envisage when it speaks of a child being educated by a grown-up? Fundamentally speaking, the materialistic age sees in both of them, both the grown-up and the child, only what you get from a materialistic outlook, namely, a grown-up teaching a child. But it is not like that. Externally the grown-up is only maya, and seen from outside the child is only maya too. There is something in the grown-up not directly contained in maya, namely the invisible man, who passes from one incarnation to another, and there is also an invisible part in the child that goes from incarnation to incarnation.

We shall speak about these things again. But I would like to tell you a few things today from which you will see in the course of time—if you meditate on them—what else there is in spiritual science. I will start with the fact that a person, as he appears in the external world, cannot teach at all, nor can the person who stands before us, externally, as a child, be educated. In reality something invisible in the teacher educates something invisible in the pupil. We shall only understand this properly if we focus our attention on what is gradually unfolding in the growing child, as the outcome of previous incarnations. And when everything coming from previous incarnations has made its appearance, the child withdraws, especially in present times. What we are actually educating is the invisible result of previous incarnations. We cannot educate or have any effect on the visible child. That is how the matter stands with regard to the child.

Now we will look at the teacher. During the first seven years of the child's life he can only educate by means of what the child can imitate; in the second seven years it will be through the influence he has as an authority; and finally in the following seven years it will be through the educational effect of independent judgment. Everything that is active in the teacher all this time is not in his external physical part at all. The part of us which do the educating will not take on physical form until our next incarnation. For all the qualities in us which can be imitated, or the qualities upon which our authority is based, are germinal qualities and will form our next incarnation. When we are teachers our own next incarnation converses with the previous incarnation of the pupil. It is an illusion to think that as present people we speak to the child of the present. We only have the right feeling for this if we say to ourselves, ‘The very best in you which your spirit can think and your soul can feel, and which is preparing itself to make something of you in the next incarnation, can work on the part of the child that is sculpturing its form out of times long past.’ The musical element in us is what enables us to educate. What we should educate in the child is the element of sculpture.

Take as a whole all that I have said in these lectures about the musical element and of how, in its most exalted form, it corresponds to what man meets with in initiation. Music is related to everything that is in a process of development and lies in the future, and the realm of sculpture and architecture is related to what lies in the past. A child is the most wonderful example of sculpture we can see. What we need as teachers is a musical mood, which we can have in the form of a mood pervaded by the future. If you can have this feeling when you are involved in teaching it will add a very special tone to the relationship of the teacher to the child. For it will make the teacher set himself the highest aims, whilst having the greatest measure of understanding for the children's naughtiness. There really is an educational force in this mood.

Once the world comes to see that the right atmosphere for teaching arises when a musical mood in the teacher is combined with seeing the sculptural activity in the pupil; once it is established that this is what is required for a love of teaching, then education will be filled with the right impetus. For then the teacher will speak, think and feel in such a way that in the course of his lessons, what comes from the past will learn to love what reaches out to the future. The result will be a wonderful karmic adjustment between the teacher and his pupils. A wonderful karmic balancing.

If the teacher is egoistic and only tries to make the child an imitation of himself, then the teaching is purely luciferic. Education becomes luciferic when we try as far as possible to turn the pupil into a copy of our own opinions and feelings, and are only happy if we tell the pupil something today and he repeats it word for word tomorrow. That is a purely luciferic education. On the other hand an ahrimanic education comes about if the pupil is as naughty as possible in our lessons and learns from us as little as he possibly can. However, there is a state of balance between these two extremes, just as there is between weighing down and supporting. This is arrived at through the interplay of the musical-sculptural elements I have just been speaking about. We must learn to distinguish between the teacher's intentions and what the child turns out to be. If we have the right mood, then even though we have been trying to teach our pupil something quite specific, we shall be overjoyed to realise that he has not turned out as we intended, but that the child has developed into something quite different from what we intended him to be. This is the remarkable thing, that the teacher can only rid himself of his egoism in teaching, if he overcomes the desire to turn the child into a copy of his own views on what is good and right, and especially of his own favourite thoughts. The best thing we can achieve, as teachers, is to be able to face perfectly calmly the thought of the child becoming as different from us as possible.

But you cannot come along and say, ‘Please give me a recipe for it, write a few rules down for me on how to teach like that.’ That is the remarkable thing about the spiritual world outlook, that you cannot work according to rules, but you really have to absorb spiritual science, so that you are filled with it and your impulses of feeling and will are increased. Then the right thing will happen, whatever particular task you face in life. The essential thing is to tackle it in a living way.

Now you could ask, ‘Which is the right teaching method from the point of view of spiritual science?’ And the correct answer would be, ‘The best spiritual-scientific method of teaching is for as many teachers as possible to engross themselves in spiritual science in a living way, and to acquire the feelings that come from spiritual science’. This is less convenient, of course, than reading a textbook on the art of spiritual-scientific education. Yet spiritual science is forever being asked, ‘What is the spiritual-scientific point of view on this or that?’ Now spiritual science does not have a point of view, or, if you like, it has as many points of view as life itself. But spiritual science itself must become life. Spiritual science must be absorbed and brought to life within us, then it will be able to bear fruit in the various realms of life. People will then get beyond whatever it is that makes life so dry and dead: we could call it the request for uniformity. External science requires uniformity, but spiritual science gives manifoldness and variety, the kind of variety that belongs to life itself. Thus, spiritual science will have to bring transformation into the furthest reaches of life.

Let us look at what some realms of life are like today. Learning takes place up to a particular age; you learn one thing up to one age and something else up to another. Then comes the time when you go out into life, as we say, and do not want to learn any more; even when you go in for a scientific career you do not like having to learn any more. The ones who do go on learning in order to keep up with their science are thought to be the odd ones. In the general run people learn until a certain age and after that they play cards or other useless things in their spare time, or they develop an attitude like this one I came across. I had been invited to give a series of lectures on the history of literature in a circle that included some ladies with a thirst for knowledge. Now it could be said that the softer, or if you prefer it, ‘retarded’ brain that ladies have has retained more the receptivity and flexibility of ancient times, when learning continued throughout life. This is more often found among women than men. But these ladies had the feeling that they ought to bring the gentlemen along too, to the lecture cycle. So the gentlemen were there, and they did not all go to sleep. Some of them really listened. Then there was conversation, tea and cakes, in other words they did what is considered to be essential in some circles, if the lectures are not to be too dry. So there was conversation too. And after I had been lecturing on Goethe's Faust, some of the men summed up their attitude by saying, ‘When you see Faust on the stage it is not really the kind of art you can enjoy, it isn't even recreation, it is science.’ This was their way of saying that when a person has been working in an office all day, or has been serving customers, or standing in a court of law interrogating witnesses and sentencing the accused, by the evening he is in no state to listen to Goethe's Faust any more and needs recreation and not science.

This is an example of a common attitude with which no doubt you are familiar. You only need to mention it, for everyone knows how widespread it is, and that a lot of people would find it strange the way we gather here in such a studious fashion and want to go on learning, despite the fact that several of us are fairly old. They think they know a much better way of spending time. Yet a complete change will have to take place in people's approach to spiritual science, in that they will not just want to let it remain a study, but will want to have a living and permanent relationship with it. This will come. You cannot learn anthroposophy the same way as you learn science, by taking it down in a notebook; anthroposophy must stay alive. It becomes dead if we only learn its content and do not remain connected with it through living activity. It becomes dead and withers away, whereas it should be kept alive. Spiritual science must work in this way to enliven us and keep our hearts receptive for all they can receive from the spiritual worlds, so that we develop further all the time.

There is no doubt that in our epoch humanity shows a quality of old age; on the whole it does not have the kind of youthfulness it had in mythical times. Spiritual science must be people's draught of youth, so that they will feel able to learn from life throughout their lives. Nowadays we can experience odd things in this connection. I know a man with an active mind, a person who has had all kinds of connections with modern intellectual culture all through his life. Now he celebrated his fiftieth birthday recently, and gave a leaflet out on this occasion containing some very peculiar notions. For instance he said—but I want to alter things a little bit, so that you will not guess who it is—he said, ‘I have been offered a post in the realm of art that I had been longing for, for many years. But now that I have reached the age of fifty, old age in fact, I do not really want it any more. For to fill a post of that kind and to inspire the people around you, you need to be young, you need to be full of fantastic illusions. And these illusions have to consist of thinking that what you are doing and the people you have to deal with are the whole world and nothing else matters. What really counts is what is right there. Fifteen years ago I was of an age when I could have done it. Now I am past it. You should not wait until people have grown old before you offer them influential positions, but let them be privy councillors, for instance, when they are between thirty and forty.’ This was the gist of what this ‘old’ man said.

This mood is absolutely in line with the whole quality of our contemporary culture. It is a mood very easily acquired by people who accept what materialistic culture has to say about the human being, for materialism has not the power to penetrate the whole being of man; the content of this materialistic knowledge is not powerful enough to have the kind of influence on his soul life that will last right into old age. Spiritual science proves that even if a person grows old externally he can stay young in soul, and if he has not done anything special by the age of fifty, although he does not need to succumb to the illusion that what he is doing is of prime importance and everything else can fall by the wayside, he can still be young enough to devote all his strength to what he has to do. He can be youthful, in fact childlike enough to concentrate the whole of his forces on what has to be done, just as a child concentrates all his forces in play. Spiritual science must become a magic draught of youth and not just a theory. That is also an impulse of transformation. Tomorrow I will talk about other impulses of transformation.

Sechster Vortrag

Es wird verhältnismäßig dem Menschen heute leicht - ich sage natürlich verhältnismäßig -, dasjenige, was wir unter der geisteswissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung oder Anthroposophie verstehen, mehr oder weniger theoretisch aufzunehmen. Aber schwierig wird es, das ganze Wesen des Menschen, das Leben selber zu durchdringen mit den Impulsen, die aus der Geisteswissenschaft selber kommen. Theoretisch aufnehmen die geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung, so daß man weiß, der Mensch besteht aus dem physischen Leibe, dem ätherischen Leibe, dem astralischen Leibe und so weiter, wie man weiß, der eine oder der andere Ton hat eine so und so hohe Schwingungszahl, oder der Sauerstoff verbindet sich mit dem Wasserstoff zu Wasser, dieses so zu wissen, ist ja der Mensch gewohnt aus der naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung, die sich nach und nach im Laufe der letzten Jahrhunderte in der Menschheit ausgebildet hat.

Aber weniger gewohnt ist der Mensch, auf sein Gefühls- und Gemütsleben Einfluß gewinnen zu lassen das, was aus einer solchen Erkenntnis gewonnen werden kann, wie sie die Geisteswissenschaft darbieten will. Im Grunde genommen ist die Art, wie die Geisteswissenschaft auf den Menschen wirken muß, entgegengesetzt der Art, wie die andere Wissenschaft auf den Menschen wirken muß. Es ist eine ganz allgemeine, oft und oft betonte Empfindung, daß die trockene Wissenschaft den Menschen abbringt von dem warmen Erfühlen des Lebens und seiner Tatsachen, daß die trockene Wissenschaft etwas Kaltes und Nüchternes hat, gleichsam die Frische, das gewisse Taumäßige von den Dingen wegnimmt. Und man kann sagen, daß das bis zu einem gewissen Grade bei der äußeren Wissenschaft der Fall sein muß. Denn welch gewaltiger Unterschied ist doch zwischen dem Eindrucke, den auf uns die wunderbare Wolkenbildung eines Abend- oder Morgenhimmels macht, und den bloßen Mitteilungen, die uns darüber etwa der Astronom oder der Meteorologe machen kann. Wie mit einem Wärmegefühl, ergreifend den ganzen Menschen und ihn durchlebend, erscheint uns die reiche Fülle des natürlichen Daseins um uns herum. Trocken und nüchtern, kalt, leblos und liebeleer erscheint uns die Wissenschaft mit ihren Begriffen und Ideen, die sie uns vermittelt, gegenüber demjenigen, was sonst einen warmen, lebensvollen Eindruck auf uns macht. Und in bezug auf das äußere, naturwissenschaftliche Erkennen ist es ganz gewiß berechtigt, wenn man so empfindet und fühlt.

Daß das äußere, naturwissenschaftliche Erkennen so sein muß, das hat seine guten Gründe, aber ein solches Erkennen soll nicht sein das geisteswissenschaftliche Erkennen. Das soll uns im Gegenteile näher und immer näher bringen der Lebensfülle und Lebenswärme der äußeren Welt und überhaupt der ganzen Welt. Da müssen wir aber allerdings noch lernen, gewisse Impulse in uns zu erregen, die der gegenwärtige Mensch fast gar nicht hat. Der gegenwärtige Mensch erwartet nämlich von dem, was er Wissenschaft nennt, etwas, worin schon liegt, daß uns diese Wissenschaft kalt und nüchtern, in Goethes Sinne gesprochen, Wagner-mäßig berühren muß. Der Mensch erwartet von der Wissenschaft, daß, wenn er diese Wissenschaft in sich aufgenommen hat, ihm die Rätsel der Natur gewissermaßen gelöst seien, daß er jetzt weiß, wie es mit diesen oder jenen Dingen beschaffen ist, und dann ist er zufrieden, wenn er weiß, wie es mit diesen oder jenen Dingen beschaffen ist.

Man kann sogar Menschen in der Gegenwart kennenlernen, denen vor der Wissenschaft aus einem ganz bestimmten Grunde gruselt. Sie sagen nämlich, das volle, frische Leben der Vergangenheit habe geradezu darinnen bestanden, daß der Mensch nicht alle Rätsel gelöst hat, daß er etwas ahnen durfte, was ihm noch nicht gelöst war. Und nun kommt die Wissenschaft, so sagen die Leute, und löst nach und nach die Naturrätsel. Und nun stelle man sich vor, wie langweilig es ist, in der Zukunft auf der Welt zu sein, wenn die Wissenschaft alle Rätsel gelöst haben wird, und man nichts mehr ahnen und außerwissenschaftlich wird empfinden können. Eine furchtbare Öde muß über die Menschheit kommen, und davor kann man ja mit Recht ein Grauen haben.

Aber die Geisteswissenschaft wird andere Empfindungen im Menschen auslösen können, Empfindungen, die allerdings für die Gegenwart weniger bequem sind als das Rätsellösen, die uns aber zugleich darauf hinweisen, wie Leben weckend und Leben schaffend diese Geisteswissenschaft sein kann. Wenn wir nämlich im richtigen Sinne das aufnehmen, was uns die Geisteswissenschaft gibt, wenn wir es nicht so aufnehmen, daß wir nur unser Handbüchlein nehmen und aufschreiben dasjenige, was gerade gesagt wird, um es so zu verwenden wie in der Wissenschaft im äußeren Sinne, und uns vielleicht dann noch ein Schema machen, eine hübsche Einteilung, damit wir die Dinge recht überblicken können wie ein Schema der Physik, wenn wir also weniger dieses machen, sondern in unsere Herzen das einfließen lassen, was die geisteswissenschaftliche Anschauung zu sagen hat, uns richtig durchdringen damit, dann werden wir bemerken, daß es in uns Leben gewinnt, wächst, Selbständigkeit und Selbsttätigkeit in uns entwickelt, daß es wie ein neues lebendiges Wesen in uns wird, das uns immer und immer neue und neue Seiten zeigt. Wenn wir dann mit einer durch die geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung also erfüllten Seele an die äußere Natur herantreten, dann gewahren wir in der Natur nicht weniger Rätsel als früher, sondern mehr Rätsel als früher. Alles wird uns noch rätselvoller, und das Gefühlsleben wird nicht verarmen, sondern es wird bereichert, man könnte sagen, die Welt wird geheimnisvoller durch die geisteswissenschaftliche Erkenntnis.

Allerdings verödet uns die Welt, wenn der Physiker kommt und sagt: Die Morgenröte, du siehst sie —, und er führt uns dann aber zur Wandtafel und zeigt uns, welche besonderen Brechungen die Lichtstrahlen erfahren, damit das Morgenrot erscheint. Gewiß ist das etwas Greuliches, nicht vor dem menschlichen Verstandeserkennen, sondern etwas Greuliches vor dem menschlichen Gemüte.

Anders ist es, wenn die Geisteswissenschaft kommt und uns sagt, um ein Beispiel anzuführen: Wenn du das Morgenrot erblickst, oder diese oder jene Tonmusik hörst, dann muß es dir sein, als ob die Elohim ihren strafenden Zorn durch die Welt senden. Dann gewahren wir hinter der Morgenröte das geheimnisvolle, lebendige Weben der Elohim. Dadurch, daß wir den Namen der Elohim aussprechen und wissen, wohin wir sie zu setzen haben in dem neungliedrigen Schema, das wir uns in unser Notizbuch schrieben, damit haben wir noch nichts erkannt von den Elohim. Aber durch die lebendige Empfindung, die wir haben, indem wir den Blick zur Morgenröte erheben, wird uns eine reiche Fülle lebendigen Webens und Lebens entgegenschauen, wie wir wissen, daß, wenn wir einem Menschen gegenüberstehen, wir sein Wesen nicht ausschöpfen können durch irgendwelche Begriffe, daß wir nicht umfassen können das Universell-Lebendige seines Wesens. So werden wir gewahr, daß in dem, was sich uns als Morgenrot offenbart, nicht umfaßbares Lebendiges des Kosmos uns gegenübersteht.

Rätselvoller und geheimnisvoller und damit reichere Empfindung in uns wirkend wird die Welt durch das geisteswissenschaftliche Erkennen. Das ist solch eine Grundempfindung, die in unsere Seelen einziehen kann, wenn wir die Geisteswissenschaft in uns lebendig machen und wenn wir versuchen, uns heimisch zu machen in solchen Vorstellungen, wie die eben angeregte. Dann werden wir niemals verfallen können in jene Klage gegenüber der Geisteswissenschaft, daß sie nur zu unserem Kopfe spreche, daß sie unseren ganzen Menschen nicht ergreife. Wir müssen nur wirklich Geduld haben, bis das Wort, das die Geisteswissenschaft uns geben will, in uns zum lebendigen Wesen wird, bis es sich selbständig bildet, so daß es uns nicht nur mit seinem Lichte, sondern auch mit seiner Wärme erfüllt. Dann wird es unser Herz, unseren ganzen Menschen ergreifen und wir werden uns reicher fühlen, während wir natürlich, wenn wir die Geisteswissenschaft gerade so aufnehmen wie die andere Wissenschaft, uns verarmt fühlen müssen.

Aber auf der andern Seite ist es wieder ganz naturgemäß, daß die Geisteswissenschaft zunächst auf viele einen verarmenden Eindruck macht, weil sie noch nicht finden können das innerlich Lebendige des Wortes der Geisteswissenschaft, welches das Gemüt ergreifen kann, weil die Geisteswissenschaft auf sie noch nicht so wirkt, wie etwa wirkt das warme Wort eines andern Menschen, der zu uns spricht. Aber wir müssen lernen, daß die Geisteswissenschaft so lebendig wird, daß sie unserer Seele Mut und Vertrauen zusprechen kann wie sonst nur die menschliche Persönlichkeit selber.

Daß dies so schwierig ist für die Herzen der Gegenwart, beruht darauf, daß die Herzen der Gegenwart sich abgewöhnt haben, mit den Dingen selber zu leben, daß das Gefühl des Sich-Einlebens in die Dinge so selten geworden ist. Es wird schon unendlich schwierig, wenn man, ich möchte sagen, in kleinen Dosen versucht, das Mitleben mit den Dingen wiederum lebendig zu machen. Das ist versucht worden in unseren vier Mysterien. Sie müssen nur den Blick auf so etwas lenken wie auf die Szene im Geisterland, im fünften Bild von «Der Seelen Erwachen», wo auf der linken Seite der Bühne — vom Zuschauerraum aus gesehen - der in das Devachan entrückte Felix Balde sitzt, und wie eine geistige Wesenheit auf der andern Seite der Bühne zu diesem spricht von ihrem «Lasten». Da soll man fühlen das Gewicht, das in der Ferne von oben nach unten schwebt. Der Mensch ist heute gewohnt, wenn etwas von oben nach unten schwebt, nur das Schweben zu sehen, nur zu sehen, wie das Ding zuerst einen oberen Ort einnahm, dann einen Ort weiter unten und so weiter. Aber er ist ganz ungewohnt, hineinzukriechen in die Dinge und das Lasten zu empfinden, zu empfinden, daß es an jedem Orte drückt, das Ding. Man möchte mit einem solchen Wort mitten im Drama darinnen die Menschenseele herausholen aus dem egoistischen Leibe und sie hineinversetzen in das Lebendige der Dinge draußen.

Wenn das nicht eintreten kann, so wird ein richtiges künstlerisches Fühlen nicht wieder auferstehen können. Damit zum Beispiel ein Architekturfühlen in richtiger Weise wieder auferstehen kann, muß lebendig werden das, was wir an Begriffen aufnehmen in der Geisteswissenschaft. Zunächst hat es etwas Gleichgültiges an sich, was wir an Begriffen, die wir uns aus der Geisteswissenschaft aneignen, mit der Seele herumtragen in der Welt. Aber wir werden sehen, wenn wir so etwas wirklich tun, wie wir unser ganzes Seelenleben dadurch bereichern. Eine Bereicherung findet zum Beispiel statt, wenn wir versuchen, dieses hier (siehe Zeichnung Seite 118) nicht bloß zu sehen, sondern unterzutauchen in dasselbe und empfinden zu lernen mit dem, was da ist: nämlich hier das Lasten und hier das Stützen.

Wir wollen noch weitergehen und das nicht nur anschauen, sondern fühlen, der Balken muß eine gewisse Stärke haben, sonst wird er von der Last zerdrückt, die Stützen, die Säulen müssen eine gewisse Stärke haben, sonst werden sie zerquetscht. Wir müssen mit der Kugel oben ihr Lasten erleben, mit den Säulen ihr Stützen erleben, mit dem Balken sein Gleichgewicht erleben. Erst dann empfinden wir architektonisch, wenn wir also hineinkriechen in das Lastende, in das Stützende und in das Gleichgewicht zwischen dem Lastenden und dem Stützenden.

Wir werden aber erfühlen, wenn wir nicht bloß mit dem Auge folgen solch einem Gebilde, sondern wenn wir gleichsam hineinkriechen in dasselbe und das Lastende und das Stützende und das Gleichgewicht erfühlen, daß unser ganzer Organismus mit in Anspruch genommen wird, daß wir gleichsam appellieren müssen von unserem Kopfgehirn an ein unsichtbares Gehirn, dem der ganze Mensch angehört. Dann kann in uns lebendig werden das Bewußtsein: Ah, jetzt beginnen wir zu fühlen! - Nehmen wir den geschilderten einfachen Fall: Da fühlen wir ein stützendes, ein hinaufstrebend stützendes Luziferisches; ein lastend hinunterdrückendes Ahrimanisches; ein Gleichgewicht zwischen Luziferischem und Ahrimanischem: ein Göttliches. So belebt sich uns selbst die leblose Natur mit Luzifer und Ahriman und ihrem höheren Herrscher, der das Gleichgewicht ewig bewirkt zwischen Luzifer und Ahriman.

Aber wir werden darauf kommen, wenn wir also erfühlen lernen in dem Architektonischen das Luziferische, Ahrimanische, Göttliche, daß wir innerlich ergriffen werden von dem Architektonischen, daß wir gewahr werden, wie uns ein reicheres Empfinden der Welt die Seele in die Dinge hinaus, man möchte fast sagen, entreißt, in die Welt hinausführt, wie wir allmählich gerade dadurch gewahr werden, daß wir mit unserer Seele nicht nur innerhalb der Haut unseres Leibes sind, sondern dem Kosmos angehören. Das werden wir auf diese Weise gewahr. Damit werden wir aber gewahr, daß, während das Architektonische draußen stützt und lastet und Gleichgewicht schafft, wir selber an dem Architektonischen eine musikalische Stimmung entwickeln. Unser Inneres stimmt sich an dem Architektonischen musikalisch, und wir sehen, während das Architektonische und das Musikalische draußen in der Welt einander scheinbar so fremd gegenüberstehen, daß unser Erleben des Architektonischen, indem uns das Architektonische musikalisch stimmt, die Versöhnung selber, das Gleichgewicht bewirkt.

In diesem aber liegt zugleich die lebendige Fortentwickelung der Kunst von unserer Erdenepoche an: daß man erleben lernt die Versöhnung der Künste. Darinnen liegt, was dunkel geahnt und empfunden worden ist im Wagnertum, was aber wirklich erst erstehen kann, wenn sich die Welt mit der Geisteswissenschaft durchlebt.

Versöhnung der Künste: das haben wir versucht - zum ersten Male, wie in einem kleinen elementaren Anfang - zu geben mit unserem Bau, in dem nicht nur kalt und nüchtern von einer solchen Versöhnung gefabelt werden sollte, sondern wo in der Architektur des Baues selber ein Abdruck, gleichsam eine Siegelprägung vorhanden sein sollte von dieser Versöhnung der musikalischen Stimmung mit der architektonischen Form. Wenn Sie studieren, was sich in unserer Säulenordnung und in dem, was mit ihr zusammenhängt, darstellt, so werden Sie die Entdeckung machen, daß versucht worden ist, das Stützende und Lastende und das Gleichgewichtsmäßige in lebendige Bewegung zu bringen. Unsere Säulen sind nicht bloß Stützen, unsere Kapitäle sind nicht mehr bloß 'Trägervorrichtungen, und dasjenige, was sich über den Säulen als Architrave ausdehnt, trägt nicht mehr den Charakter des bloß auf den Säulen Ruhenden und nach oben Abschließenden, sondern des lebendig Wachsenden, des lebendig Webenden.

In musikalischen Fluß wurde versucht, die architektonischen Formen zu bringen, und die Empfindung, die man haben kann in dem Zusammenwirken unserer Säulen und desjenigen, was mit den Säulen Zusammenhang bringt, kann selber eine musikalische Stimmung in der Seele erregen. Eine unsichtbare Musik kann empfunden werden als die Seele unserer Kolonnen und unserer Architektur- und Skulpturformen, die zu den Kolonnen gehören. Das Seelische ist gewissermaßen darinnen. Und das Durchdringen der bildenden Künste und ihrer Formen mit den musikalischen Stimmungen muß überhaupt das Kunstideal der Zukunft werden. Die Musik der Zukunft wird plastischer sein als die Musik der Vergangenheit. Die Architektur und Skulptur der Zukunft werden musikalischer sein als die Architektur und Skulptur der Vergangenheit. Das wird das Wesentliche sein. Die Musik wird deshalb nicht aufhören, eine selbständige Kunst zu sein, im Gegenteil, sie wird nur reicher und reicher werden dadurch, daß die Musik eindringen wird in das Geheimnis der Töne, wie das gestern angedeutet worden ist, und daß sie dadurch musikalische Formen schaffen wird aus den spirituellen Grundlagen des Kosmos heraus.

Da aber in der Kunst alles, was innen ist, auch außen sein muß, da dasjenige, was da lebt, auch gleichsam in einem Organismus sich verkörpern muß, so muß sich auch die innerhalb der Säulenordnung und innerhalb dem, was dazugehört, schwebende Seelenwelt verkörpern. Das geschieht, soll wenigstens geschehen, in der Ausmalung der Kuppel. So wie gleichsam die Säulen und alles, was dazugehört, der Leib sind unseres Baues, so ist dasjenige, was in den Kuppeln zutage treten wird, wenn man im Bau darinnen ist, das Seelische des Baues, und wie uns der Geist als dasjenige erscheint, was alle Welt erfüllt, wenn die Organe nach außen gerichtet sind, so sollen unsere Fenster mit ihrer neuen Glasradierkunst das Geistige in unserem Bau darstellen. Leib, Seele und Geist sollen ausgedrückt sein in unserem Bau. Der Leib in dem Kolonnenbau, die Seele in alledem, was die Kuppeln betrifft, und der Geist in dem, was in den Fenstern geschaffen wird.

Bei diesen Dingen hat hier das Karma so manches bewirkt, was wir dankbar begrüßen dürfen, denn bei gar manchem hat uns das Karma gerade bei diesem Bau geholfen. Das Seelische eines Menschen ist von außen so, daß wir es in seiner Physiognomie empfinden, daß wir aber durch Mittel, durch die wir in die Seele eines Menschen dringen, durch Liebe und Freundschaft in das Innere dringen müssen, wenn wir die Seele eines Menschen gleichsam von innen kennenlernen wollen.

Als ich bei meinem letzten Vortragszyklus in Norwegen von Kristiania nach Bergen fuhr, konnte ich jene Schieferbrüche sehen, die mir dazumal den Gedanken gaben, zu erstreben, den Schiefer von dorther zu bekommen. Das ist uns gelungen, es ist tatsächlich, man kann sagen, eine karmische Fügung. Aber wenn wir den Blick werfen werden auf das von jenem Schiefer jetzt bedeckte Dach der Kuppeln, mit dem Eigentümlichen, das gerade dieser Schiefer hat, der wie kein anderer Schiefer wirkt, dann müssen wir sagen: das hat etwas von dem Aufschließenden und zugleich Verbergenden des Seelenlebens. Und wir werden, wenn wir die Kuppel wirklich zum Seelenleben machen wollen, Liebe zur Geisteswissenschaft entwickeln müssen. Denn es soll das, was im Inneren der Kuppel gemalt werden wird, uns wirklich entgegentreten wie eine Art Spiegelbild in Farben und Formen, eine Art Spiegelbild dessen, was uns die Geisteswissenschaft sein kann. Dazu müssen wir in das Innere gehen. Aber in das Innere des Baues, wenn er wirklich einmal fertigwerden sollte, wird kein Mensch verständnisvoll gehen können, wenn er nicht die Liebe zur Geisteswissenschaft entwickelt haben wird, sonst wird ihm wahrscheinlich das, was er im Inneren sieht, etwas bleiben, was ein bißchen Sensation hervorrufen kann, aber doch nicht etwas, was zu seinem Herzen ganz besonders spricht. Er wird so etwas haben, dem er leicht geneigt sein wird, als Architektonischem den Gemütsinhalt, den Gemüts- und Empfindungsinhalt abzusprechen.

Haben wir da sehen können, wie wir das, was sich aus der Geisteswissenschaft heraus belebt, in der Welt wiederfinden können, so können wir jetzt sagen: Wir können auch das Leben befruchten von seiten der Geisteswissenschaft aus auf Gebieten, wo wir leichter einsehen, daß wir eine Befruchtung des Gemütes, eine Durchwärmung des Gemütes brauchen. Denn nicht nur diejenigen Dinge, die künstlerisch sind, die wissenschaftlich sind, sollen von der Geisteswissenschaft befruchtet werden, sondern das ganze Leben muß von der Geisteswissenschaft befruchtet werden.

Als Beispiel sei noch ein Gebiet erwähnt, an dem wir ganz besonders sehen können, wie die geisteswissenschaftlichen Begriffe lebendig werden können im äußeren Leben. Ich will als Beispiel das Gebiet der Pädagogik, das Gebiet jeglicher Erziehungskunst wählen. Gehen wir aus von der Erziehung des Kindes durch den erwachsenen Menschen, Was macht sich eigentlich eine materialistische Zeitepoche für eine Vorstellung, wenn sie von der Erziehung des Kindes durch den erwachsenen Menschen spricht? Diese materialistische Zeitepoche sieht im Grunde genommen in beiden, in dem Erwachsenen und in dem Kinde, nur dasjenige, was die materialistische Anschauung gibt: ein Alter erzieht einen Jungen. Aber so ist es ja nicht. Der Alte ist äußerlich nur die Maja und der Junge ist auch äußerlich nur die Maja. In dem Alten haben wir etwas, was nicht in der Maja unmittelbar enthalten ist, den unsichtbaren Menschen, der von Inkarnation zu Inkarnation geht, und im Kinde haben wir auch den unsichtbaren Menschen, der von Inkarnation zu Inkarnation geht.

Wir werden über solche Dinge noch sprechen. Aber ich will heute doch noch einiges anführen, was Ihnen im Verlaufe der Zeit - durch meditative Versenkung — das klarmacht, was es sonst in der Geisteswissenschaft gibt, und will davon ausgehen, daß der Mensch, der uns sonst in der Außenwelt entgegentritt, überhaupt nicht erziehen kann, und daß der Mensch, der uns als Kind in der Außenwelt entgegentritt, überhaupt nicht erzogen werden kann. In der Tat erzieht etwas Unsichtbares in dem Erzieher etwas Unsichtbares in dem zu Erziehenden. Richtig verstehen kann man die Sache nur, wenn man an dem Kinde, das aufwächst und das wir zu erziehen haben, das Augenmerk richtet auf das nach und nach sich entfaltende Ergebnis der vorhergehenden Inkarnationen. Aber wenn alles das, was aus den vorhergehenden Inkarnationen stammt, herausgewachsen ist, da ist es mit der Kindererziehung auch schon aus, da entzieht sich uns das Kind schon, besonders in der Gegenwart. Das, was wir eigentlich erziehen, ist das unsichtbare Ergebnis der früheren Inkarnationen. Das sichtbare Kind können wir nicht erziehen, auf das können wir nicht wirken. Wir wirken in der Tat auf das unsichtbare Ergebnis der früheren Inkarnationen. Das sichtbare Kind können wir nicht erziehen. So ist die Sache, wenn wir den Blick auf das Kind wenden.

Jetzt wenden wir den Blick auf den Erzieher. Der kann während der ersten sieben Jahre nur durch das erziehen, was sich an ihm nachahmen läßt, und durch das, wodurch er als Autorität Einfluß gewinnt während der zweiten sieben Jahre; er kann endlich in den nächsten sieben Jahren einen Einfluß gewinnen durch das, was durch freie Urteilskraft erzieherisch wirkt. Alles was da wirkt in dem Erzieher, ist ganz und gar nicht in dem äußeren physischen Menschen. Was wir da in uns haben als Erzieher, das bekommt seine physische Gestalt erst in unserer nächsten Inkarnation. Denn alles das, was in uns solche Eigenschaften sind, die nachgeahmt werden dürfen, oder was in uns solche Eigenschaften sind, die unsere Autorität begründen, ist keimhaft in uns vorhanden und wird unsere nächste Inkarnation gestalten. Unsere eigene nächste Inkarnation als Erzieher redet mit den früheren Inkarnationen des Zöglings. Das ist Maja, daß wir als jetzige Menschen zum jetzigen Kinde reden. Wir fühlen nur richtig, wenn wir uns sagen: Dein Bestes in dir, was dein Geist denken, deine Seele fühlen kann, was sich vorbereitet in dir, um aus dir etwas zu machen in der nächsten Inkarnation, kann wirken auf das in dem Kinde, was aus uralten Zeiten in dem Kinde sich plastisch bilden will. Musikalisch ist erst in uns das, was erzieherisch wirken kann. Plastisch in dem Kinde sich ausgestaltend ist dasjenige, worauf wir wirken sollen.

Nehmen Sie das zusammen, was ich in diesen Tagen gesagt habe über das Musikalische, wie es entspricht in seiner höchsten Ausgestaltung dem, was in der Initiation an den Menschen herantritt. Das Musikalische bezieht sich auf alles Entwickelungsmäßige, auf das Zukünftige, das Plastisch-Architektonische auf das Vergangene. Das wunderbatste plastische Kunstwerk, das uns entgegentritt, ist das Kind. Das, was wir als Erzieher haben sollen, ist die musikalische Stimmung, die als Zukunftsstimmung in uns sein kann. Das aber zu fühlen, zu fühlen so, wie es jetzt angedeutet worden ist, auf dem pädagogischen Felde, das gibt eine gewisse besondere Nuance dem Sich-Gegenüberstellen als Erzieher dem Kinde, denn das ist geeignet, die höchste Pflichtanforderung an sich selber als Erzieher zu stellen, und das größtmöglichste Maß von Verständnis selbst bei den größten Ungezogenheiten hervorzurufen, die uns von dem Zöglinge entgegengebracht werden können. In dieser Stimmung liegt wirklich eine Kraft der Erziehung.

Wenn die Welt einmal sehen wird, wie dieses musikalische Gestimmtsein des Erziehers, verbunden mit der Anschauung der Plastik des Zöglings, die pädagogische Stimmung zu geben hat, wenn das durchdringen wird, wenn es sein wird das, was man von der erzieherischen Liebe, von der pädagogischen Liebe verlangen wird, dann wird die Pädagogik von der richtigen Luft durchtränkt sein, denn dann werden die Dinge so gesprochen, so gedacht, so gefühlt werden, daß lernen wird das Zukünftige selber das Vergangene lieben im Unterrichte, den der Erzieher erteilt. Dann werden wir finden, daß ein wunderbarer karmischer Ausgleich stattfindet zwischen dem Erzieher und seinem Zöglinge. Ein wunderbarer karmischer Ausgleich.

Wenn der Erzieher egoistisch ist und nur anstrebt, aus dem Zögling dasjenige zu machen, was er selber ist, so ist die Erziehung eine rein luziferische. Luziferisch wird die Erziehung, wenn wir so viel als möglich den Zögling zum Abklatsch unserer eigenen Ansichten und Empfindungen machen wollen, uns nur freuen können, wenn wir heute etwas zum Zögling gesagt haben und er es morgen gleich nachplappert oder nachmacht. Das ist eine rein luziferische Erziehung. Allerdings, eine ahrimanische Erziehung entsteht, wenn der Zögling unter unserer Erziehung so ungezogen als möglich wird und so wenig als möglich von uns annimmt. Aber zwischen diesen zwei Extremen gibt es, ebenso wie zwischen Lasten und Stützen, eine Gleichgewichtslage. Diese wird bewirkt durch das MusikalischPlastische, das ich auseinandergesetzt habe. Da müssen wir unterscheiden lernen die Intentionen des Erziehers von dem, was aus dem Zögling wird. Wenn wir nur richtig gestimmt sind, werden wir die größten Freuden erleben, wenn wir uns bemühen, etwas ganz Bestimmtes an den Zögling heranzubringen, und wir uns sagen können: Nun, das, was du gewollt hast, ist er nicht geworden, aber er ist etwas geworden, zwar nicht das, was wir ihm beigebracht haben, aber er ist etwas geworden. Das ist das Eigentümliche, daß der Erzieher nur dadurch seinen Erzieheregoismus abstreifen kann, wenn er den Wunsch überwindet, daß das, was er als gut und recht ansieht, und namentlich, was er selber gerne denkt, in dem Zögling ein Abklatsch werde. Wenn wir als Erzieher die Gelassenheit erreichen, daß der Zögling uns so unähnlich als möglich werden kann, dann haben wir das Schönste erreicht.

Man kann nun aber nicht sagen: Bitte, gib mir ein Rezept, wie man es macht, schreib mir ein paar Regeln auf, wie man erzieht in solcher Weise. — Das ist eben das Eigentümliche der geistigen Weltanschauung, daß man es nicht so machen kann mit einzelnen Regeln, sondern daß man wirklich auf die Geisteswissenschaft sich einlassen und sie aufnehmen muß, daß man sich durchdringen lassen muß von ihr, daß man die Gefühls- und Willensimpulse in sich bereichern lassen muß. Dann geschieht schon im einzelnen Falle, wo man hingestellt wird zu dieser oder jener Aufgabe im Leben, das Richtige. Die Hauptsache ist, daß wir es lebendig erfassen.

Man könnte nun fragen: Welches ist im Sinne der Geisteswissenschaft die richtige Erziehungsmethode? Die richtige Antwort wäre: Die beste geisteswissenschaftliche Erziehungsmethode bestünde darinnen, daß möglichst viele Erzieher in die Geisteswissenschaft sich lebendig vertiefen und die Gefühle sich aneignen, die aus der Geisteswissenschaft kommen. Das ist allerdings das, was unbequemer ist, als so ein Handbüchlein der geisteswissenschaftlichen Erziehungskunst durchzulesen. Immer und immer wieder wird aber an die Geisteswissenschaft die Frage gestellt: Welches ist, in bezug auf dieses oder jenes, der geisteswissenschaftliche Standpunkt? Ja, die Geisteswissenschaft hat keinen Standpunkt oder, wenn Sie wollen, so viele Standpunkte als das Leben. Aber die Geisteswissenschaft muß selber Leben werden. Die Geisteswissenschaft selber muß man aufnehmen und in sich beleben, dann wird sie auf den verschiedenen Gebieten des Lebens ihre Früchte entfalten können. Dann werden die Menschen hinauskommen über das, was das Leben so austrocknet, was für das Leben so ertötend ist, über das Verlangen nach Einförmigkeit, könnte man sagen. Die äußere Wissenschaft verlangt die Einförmigkeit, die Geisteswissenschaft gibt Mannigfaltigkeit, jene Mannigfaltigkeit, die auch die Mannigfaltigkeit des Lebens selber ist. So wird die Geisteswissenschaft auch in bezug auf das Leben in dessen weitestem Bereich umgestaltend wirken müssen.

Denn nehmen wir einmal das Leben, wie es auf mancherlei Gebieten heute ist. Man lernt bis zu einem gewissen Alter; man lernt bis zu einem gewissen Alter dieses, bis zu einem andern Alter jenes. Dann aber kommt die Zeit, wo man, wie man sagt, ins Leben eintritt und nicht mehr lernen will; selbst wenn man irgendeinen wissenschaftlichen Beruf hat, so will man nicht mehr gern lernen. Diejenigen, die dann noch lernen, mit ihrer Wissenschaft mitgehen, werden in unserer Zeit schon als seltene Tiere angesehen. Aber im ganzen verläuft das Leben doch zumeist so, daß man bis zu einem gewissen Lebensalter lernt und dann seine freie Zeit zubringt mit Kartenspiel oder andern unnützen Dingen, oder daß man solch eine Gesinnung entwickelt, wie sie mir einmal entgegengetreten ist. Ich wurde nämlich einmal aufgefordert von einem Kreise, in dem einige bildungsbedürftige Damen waren, zu einer Serie von literarisch-historischen Vorträgen. Nun kann man sagen, daß das noch weichere, man kann meinetwegen sagen, zurückgebliebenere Gehirn der Damen in unserer Zeit noch etwas mehr behalten hat von jenen alten Zeiten, in denen man bildsam das Gehirn erhalten wollte und das ganze Leben hindurch gelernt hat. In der Frauenwelt findet man das wirklich häufiger als in der Männerwelt. Aber diese Frauen hatten das Gefühl, daß sie zu diesem Vortragszyklus auch die Männer mitbringen müßten. Die Männer waren also dabei. Nicht alle schliefen ein, einzelne hörten wirklich zu. Aber dann wurde gesprochen, Tee getrunken und Kuchen gegessen, also das getan, was in manchen Kreisen als eine ganz notwendige Beigabe angesehen wird, wenn die Vorträge nicht allzu trocken sein sollen. Also es wurde auch gesprochen. Da hörte ich von manchen der Männer, nachdem ich über Goethes «Faust» vorgetragen hatte, das Urteil: Ja, den «Faust» auf der Bühne zu sehen, ist eigentlich kein künstlerischer Genuß, das ist auch kein Vergnügen, das ist eine Wissenschaft. - Und damit wollten sie darauf aufmerksam machen, daß, wenn ein Mensch den ganzen Tag im Büro gearbeitet hat, oder seine Kundschaft bedient hat, oder vor dem Gerichtstische gestanden, Zeugen verhört, Angeklagte verurteilt hat, er dann des Abends nicht mehr Goethes «Faust» anhören kann, sondern etwas braucht, was ein Vergnügen und keine Wissenschaft ist.

Ich will mit diesem nur beispielsweise eine allgemeine Gesinnung in unserer Zeit andeuten, die Ihnen zweifellos bekannt ist. Man braucht sie nur anzuschlagen, so weiß jeder, daß sie sehr, sehr verbreitet ist und daß es viele Menschen gibt, die es ganz gewiß sonderbar finden werden, daß wir uns hier so schulmäßig zusammensetzen und, trotzdem manche von uns schon ein reichliches Alter erreicht haben, immer noch etwas in uns aufnehmen wollen in der Zeit, die man nach ihrer Meinung viel nützlicher verwenden könnte. Aber gerade darinnen wird ein völliger Umschwung sich vollziehen müssen, daß der Mensch nicht bloß den lernmäßigen Zusammenhang mit der Geisteswissenschaft wird haben wollen, sondern den lebendigen, fortdauernden Zusammenhang. Das ist es, was kommen wird. Die Geisteswissenschaft kann man nicht so in sich aufnehmen, wie man kompendienmäßig andere Wissenschaften aufnehmen kann, sondern die Geisteswissenschaft muß lebendig bleiben. Sie wird tot, wenn man ihren Inhalt nur aufgenommen hat und nicht im lebendigen Betriebe vereinigt mit ihr bleibt. Sie wird tot, sie stirbt ab, sie muß aber immer lebendig erhalten bleiben. In diesem Sinne muß die Geisteswissenschaft belebend wirken, sie muß das Menschenherz offen erhalten für alles das, was einfließen kann von der geistigen Welt in das Menschenherz, damit wir einer fortwährenden Evolution unterliegen.

Zweifellos hat unsere Menschheit in unserer Epoche im ganzen etwas, was man nennen kann: sie ist alt geworden, sie hat nicht mehr im ganzen jene Jugendlichkeit, die sie in den mythischen Zeiten hatte. Die Geisteswissenschaft muß wieder ein Verjüngungstrank werden für die Menschen, so daß sie sich fühlen können ihr ganzes Leben hindurch als Schüler des Daseins. Auch da können wir merkwürdige Dinge in der Gegenwart erleben. Ich kenne einen geistig regsamen Mann, einen Mann, der sich sein ganzes Leben lang mit allen möglichen Ingredienzien unserer gegenwärtigen Geisteskultur beschäftigt hat. Er hat vor kurzem seinen fünfzigsten Geburtstag gefeiert. Da hatte er eigentümliche Ansichten in einer Art von Feuilleton geäußert. Er hat zum Beispiel gesagt: Ja, man hat — ich möchte die Sache ein wenig künstlerisch umgestalten, damit man nicht errät, wer es ist - mir angeboten einen künstlerischen Posten, nach dem ich mich viele Jahre gesehnt habe. Aber ich kann ihn jetzt eigentlich nicht mehr so recht wollen, nachdem ich das fünfzigste Jahr, die Greisenjahre, erreicht habe, denn, um einen solchen Posten auszufüllen, um auf die Menschen so zu wirken, die um einen herum sind und die man anregen muß, dazu muß man jung sein, dazu muß man eine phantastische Illusion entwickeln können. Und diese Illusion muß darin: bestehen, daß das, was man da zu tun hat, und daß die Menschen, mit denen man zu tun hat, die ganze Welt sind und daß alles andere wertlos ist. Das eigentlich Wertvolle ist das, was ich da um mich herum habe. Das Alter, in dem ich das hätte machen können, hatte ich vor fünfzehn Jahren. Jetzt ist es vorüber. Man sollte nicht warten, bis die Menschen Greise geworden sind, um sie in einflußreiche Stellungen zu bringen, sondern sie zum Beispiel zu Hofräten machen schon zwischen dem dreißigsten und vierzigsten Jahre. - So ungefähr sagte dieser «alte» Mann.

Es ist eine Stimmung, die durchaus, ich möchte sagen, im Tone oder im Timbre des Tones unserer Zeitkultur liegt. Es ist eine Stimmung, zu der der Mensch sehr leicht kommen kann, wenn er sich auseinandersetzt mit dem, was die materialistische Zeitkultur aus dem Menschen machen kann, denn sie hat nicht die Kraft, den ganzen Menschen zu erfüllen, sie hat nicht die Kraft, den ganzen Menschen durch das, was er an Inhalt aufnimmt, so recht in seinem Gemütsleben zu gestalten, daß das vorhält bis in sein höheres Alter. Die Geisteswissenschaft will aber den Beweis liefern, daß der Mensch, wenn er auch äußerlich alt wird, innerlich seelisch jung bleiben kann, und daß er sehr wohl, wenn er es bis zum fünfzigsten Jahre zu nichts Besonderem gebracht hat, auch noch im fünfzigsten Jahre zwar sich nicht der Illusion hinzugeben vermag, daß das, was er tut, das Wichtigste sei und alles andere dem Weltuntergange verfallen kann. Aber er kann so jung sein, daß er dem, was er zu tun hat, alle seine Kräfte weihen kann. Er kann es so jugendlich, und ich möchte sagen, kindlich erfassen, so daß er alle seine Kräfte konzentriert auf dasjenige, was ihm obliegt, wie das Kind alle seine Kräfte konzentriert auf sein Spiel. Ein verjüngender Zaubertrank, nicht bloß eine Theorie, muß die Geisteswissenschaft werden. Das ist auch ein umgestaltender Impuls. Von andern umgestaltenden Impulsen werde ich morgen sprechen.

Sixth Lecture

It is relatively easy for people today—I say relatively, of course—to accept more or less theoretically what we understand by the spiritual scientific worldview or anthroposophy. But it becomes difficult to permeate the whole being of the human being, life itself, with the impulses that come from spiritual science itself. Theoretically, we accept the spiritual scientific worldview, so that we know that the human being consists of the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body, and so on, just as we know that one tone or another has a certain frequency, or that oxygen combines with hydrogen to form water. Humans are accustomed to knowing this from the scientific worldview that has gradually developed over the last few centuries.

But people are less accustomed to allowing their emotional and mental life to be influenced by what can be gained from such knowledge as spiritual science seeks to offer. Basically, the way spiritual science must affect people is the opposite of the way other sciences must affect them. It is a very general and often emphasized feeling that dry science detracts from people's warm feelings about life and its facts, that dry science has something cold and sober about it, as if it takes away the freshness, the certain dewiness of things. And one can say that this must be the case to a certain extent with external science. For what a tremendous difference there is between the impression made on us by the wonderful cloud formations in the evening or morning sky and the mere information that an astronomer or meteorologist can give us about them. The rich fullness of natural existence around us appears to us as if with a feeling of warmth, gripping the whole person and permeating them. Science, with the concepts and ideas it conveys to us, appears dry and sober, cold, lifeless, and devoid of love in comparison to what otherwise makes a warm, lively impression on us. And with regard to external, scientific knowledge, it is certainly justified to feel and sense this way.

There are good reasons why external, scientific knowledge must be this way, but such knowledge should not be spiritual knowledge. On the contrary, it should bring us closer and closer to the fullness and warmth of life in the external world and in the world as a whole. However, we still have to learn to awaken certain impulses within ourselves that modern humans almost never have. For modern man expects from what he calls science something that is inherently cold and sober, in Goethe's sense of the word, something that must affect us in a Wagnerian way. People expect science to solve the mysteries of nature for them once they have absorbed it, so that they now know how this or that thing works, and then they are satisfied when they know how this or that thing works.One can even meet people today who are horrified by science for a very specific reason. They say that the full, fresh life of the past consisted precisely in the fact that man had not solved all the mysteries, that he was allowed to sense something that was not yet solved for him. And now science comes along, people say, and gradually solves the mysteries of nature. And now imagine how boring it will be to be in the world in the future, when science will have solved all the mysteries and you will no longer be able to sense anything beyond science. A terrible desolation must come over humanity, and one can rightly be horrified by that.

But spiritual science will be able to trigger other feelings in people, feelings that are certainly less comfortable for the present than solving mysteries, but which at the same time show us how life-awakening and life-creating this spiritual science can be. For if we take in what spiritual science gives us in the right sense, if we do not take it in in such a way that we just take our little handbook and write down what is being said in order to use it as in science in the outer sense, and then perhaps make ourselves a diagram, a nice classification, so that we can get a good overview of things, like a diagram of physics, if we do less of this, but instead let what spiritual science has to say flow into our hearts, really let it sink in, then we'll notice that it comes to life within us, grows, develops independence and self-activity in us, that it becomes like a new living being within us, showing us new and new sides over and over again. When we then approach the external world with a soul filled with the spiritual scientific worldview, we perceive no fewer mysteries in nature than before, but more mysteries than before. Everything becomes even more mysterious to us, and our emotional life does not become impoverished, but enriched. One could say that the world becomes more mysterious through spiritual scientific knowledge.

However, the world becomes desolate for us when the physicist comes and says: You see the dawn, but then he leads us to the blackboard and shows us the specific refractions that the rays of light undergo in order for the dawn to appear. Certainly, this is something horrible, not for human intellectual understanding, but something horrible for the human mind.

It is different when spiritual science comes and tells us, to give an example: When you see the dawn, or hear this or that piece of music, it must be as if the Elohim are sending their punishing wrath through the world. Then we perceive behind the dawn the mysterious, living weaving of the Elohim. By pronouncing the name of the Elohim and knowing where to place them in the nine-part scheme we wrote down in our notebook, we have not yet recognized anything of the Elohim. But through the living sensation we have when we raise our gaze to the dawn, a rich abundance of living weaving and life will look back at us, just as we know that when we stand before a human being, we cannot exhaust their essence through any concepts, that we cannot comprehend the universal life of their being. Thus we become aware that in what is revealed to us as the dawn, we are confronted with the incomprehensible living essence of the cosmos.

The world becomes more enigmatic and mysterious, and thus richer in feeling within us, through spiritual scientific knowledge. This is a fundamental feeling that can enter our souls when we bring spiritual science to life within ourselves and when we try to make ourselves at home in ideas such as those just suggested. Then we will never be able to fall into the trap of complaining that spiritual science only speaks to our heads, that it does not grasp our whole being. We just need to be patient until the word that spiritual science wants to give us becomes a living being within us, until it forms independently, so that it fills us not only with its light but also with its warmth. Then it will touch our hearts, our whole being, and we will feel richer, whereas if we take spiritual science in just like other sciences, we will naturally feel impoverished.

But on the other hand, it is quite natural that spiritual science initially makes an impoverishing impression on many people, because they cannot yet find the inner vitality of the word of spiritual science that can capture the mind, because spiritual science does not yet have the same effect on them as, for example, the warm words of another person speaking to us. But we must learn that spiritual science becomes so alive that it can give our soul courage and confidence in a way that only the human personality itself can otherwise do.

The reason this is so difficult for the hearts of the present is that the hearts of the present have lost the habit of living with things themselves, that the feeling of living into things has become so rare. It becomes infinitely difficult when one tries, I would say, in small doses, to revive the experience of living with things. This has been attempted in our four mysteries. You only have to direct your gaze to something like the scene in the spirit world in the fifth picture of “The Awakening of the Soul,” where Felix Balde, transported into Devachan, sits on the left side of the stage—as seen from the auditorium—and a spiritual being on the other side of the stage speaks to him about her “burdens.” There one should feel the weight that floats down from above in the distance. Today, when something floats down from above, people are accustomed to seeing only the floating, to seeing only how the thing first occupied an upper place, then a place further down, and so on. But they are completely unaccustomed to crawling into things and feeling the burden, feeling that the thing presses down in every place. With such a word in the middle of the drama, one would like to take the human soul out of the selfish body and place it in the liveliness of the things outside.

If that cannot happen, then a true artistic feeling will not be able to be resurrected. For example, in order for a feeling for architecture to be resurrected in the right way, what we take in as concepts in spiritual science must come alive. At first, there is something indifferent about the concepts we acquire from spiritual science and carry around with us in the world. But we will see how we enrich our whole soul life when we really do something like this. Enrichment takes place, for example, when we try not just to see this (see drawing on page 118), but to immerse ourselves in it and learn to feel with what is there: namely, the load here and the support here.

Let's go further and not just look at it, but feel it: the beam must have a certain strength, otherwise it will be crushed by the load; the supports, the columns, must have a certain strength, otherwise they will be crushed. We must experience the load with the sphere at the top, experience the support with the columns, experience the balance with the beam. Only then do we perceive architecturally, when we crawl into the load, into the support, and into the balance between the load and the support.

But we will feel, when we do not merely follow such a structure with our eyes, but when we crawl into it, as it were, and feel the weight and the support and the balance, that our whole organism is involved, that we must appeal, as it were, from our head brain to an invisible brain to which the whole human being belongs. Then the awareness can come alive in us: Ah, now we are beginning to feel! Let us take the simple case described: We feel a supporting, upward-striving Luciferic force; a weighing, downward-pressing Ahrimanic force; a balance between the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic: a Divine force. Thus, lifeless nature itself is enlivened for us with Lucifer and Ahriman and their higher ruler, who eternally brings about the balance between Lucifer and Ahriman.

But we will come to this when we learn to feel the Luciferic, Ahrimanic, and Divine in the architectural, when we are inwardly moved by the architectural, when we become aware of how a richer perception of the world carries our soul out into things, one might almost say, snatches our soul out of things and leads it out into the world, how we gradually become aware, precisely through this, that we are not only within the skin of our body with our soul, but that we belong to the cosmos. We become aware of this in this way. But with this we also become aware that, while the architectural supports and weighs down and creates balance outside, we ourselves develop a musical mood in the architectural. Our inner being attunes itself musically to the architectural, and we see that while the architectural and the musical seem so foreign to each other in the outside world, our experience of the architectural, in attuning us musically, brings about reconciliation itself, balance.

But this also contains the living development of art from our earthly epoch onwards: that we learn to experience the reconciliation of the arts. This contains what has been vaguely sensed and felt in Wagnerism, but which can only really come into being when the world is lived through spiritual science.

Reconciliation of the arts: we have attempted to achieve this – for the first time, as a small, elementary beginning – with our building, in which such reconciliation should not only be coldly and soberly fabled, but where the architecture of the building itself should bear an imprint, a seal, as it were, of this reconciliation of musical mood with architectural form. If you study what is represented in our column arrangement and in what is connected with it, you will discover that an attempt has been made to bring the supporting and load-bearing elements and the balance into lively motion. Our columns are not mere supports, our capitals are no longer mere ‘supporting devices’, and that which extends above the columns as an architrave no longer has the character of merely resting on the columns and concluding upwards, but of living growth, of living weaving.

An attempt has been made to bring architectural forms into musical flow, and the sensation one can have in the interaction of our columns and that which connects with the columns can itself evoke a musical mood in the soul. An invisible music can be felt as the soul of our columns and our architectural and sculptural forms that belong to the columns. The spiritual is, in a sense, within it. And the permeation of the visual arts and their forms with musical moods must become the artistic ideal of the future. The music of the future will be more plastic than the music of the past. The architecture and sculpture of the future will be more musical than the architecture and sculpture of the past. That will be the essential thing. Music will therefore not cease to be an independent art; on the contrary, it will only become richer and richer as music penetrates the mystery of sounds, as was indicated yesterday, and thereby creates musical forms from the spiritual foundations of the cosmos.