The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

24 March 1919, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

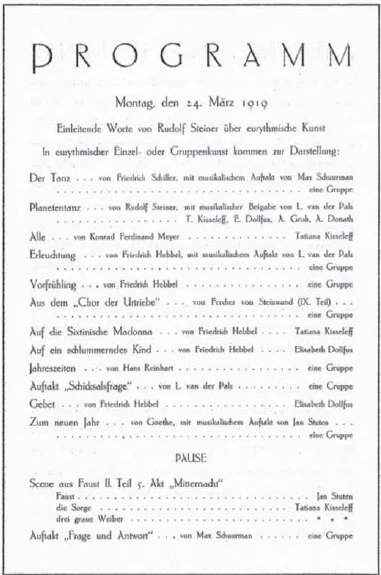

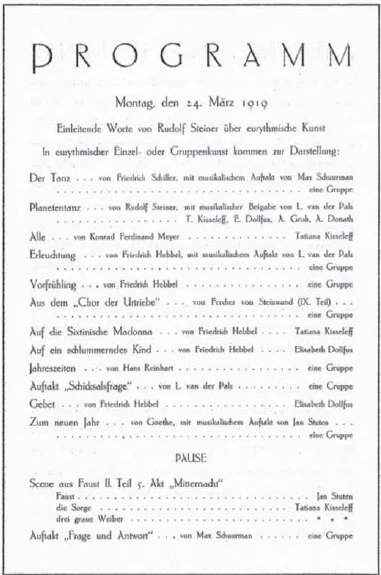

9. Eurythmy Performance

Dear attendees!

Please allow me to say a few words by way of introduction to our eurythmy performance. This will seem all the more justified given that what is presented will not be something that is complete in itself, but rather an attempt, or perhaps I could say the mere intention of an attempt. For it is obvious that this particular form of movement art, which is to be presented in eurythmy, is confused with all kinds of neighboring arts, dance-like and similar arts. These neighboring arts have, as we well know, achieved great perfection in the present day. And if there were any belief that we wanted to compete with these neighboring arts, then this would be a false belief. It is not about something that is to compete in this way, but about a special form of movement art that is based on its own laws and that is intended to be a beginning, initially just a beginning of something that can perhaps be achieved in its direction.

It is based, like everything that is to be presented here at the Goetheanum, on the foundations of Goethe's world view. However, it is not the case that we only want to reproduce what is in the finished form of Goethe's world view, but rather that we want to keep alive, almost a century after Goethe's death, that has been given to the world through Goethe's world and art view, that we would like to develop that which has been initiated through Goethe for the development of humanity, in the sense of modern human conceptions.

Goethe's unique quality is that everything that has been incorporated into his art, his conception of art, is based on his comprehensive world view, which had nothing merely soberly theoretical about it – and therefore does not have the same sobering effect on artistic creation and perception as dry, sober rationalistic world views. It is from Goethe's great and powerful view of nature that his whole conception of art emerged. And you will allow me to try to hint at something that is particularly important to us in the development of the eurythmic arts, starting with a single detail.

I must refer to what is known as Goethe's theory of metamorphosis. This is a magnificent conception of the nature of all living things. More than one might think lies in Goethe's view that the colored petal of a flower is only a transformation of the green leaf of the plant, that even the stamens, the pistil of the plant, which are not at all similar in appearance to the leaves, are transformed petals. For Goethe, everything about a plant is a leaf, a transformed leaf.

And so, in turn, the whole plant is only a correspondingly differentiated, developed leaf for him. And each individual leaf is a whole plant for him, only more simply formed. This is Goethe's basic view of all living things. Every single part of a living being is, in a sense, a repetition of the whole living thing. And in turn, the whole living thing is only a more complicatedly developed organism of precisely that which is present in the individual main parts. And this is especially the case with humans. That which a person is as a whole is present in his individual, essential parts.

What Goethe had incorporated into his way of thinking for the design of living beings up to and including humans can now be applied not only to the design of the individual parts of a living being and of the whole living being, but also to activity. For example, it can be said that the activity performed by the human larynx and its neighboring organs is a microcosmic repetition of the potential movements that are inherent in the human being as a whole. In turn, everything that can be brought out of the whole human being in the way of movement and creative possibilities can be a reflection of what is revealed in the larynx when speaking or singing in the sequence of sounds, the sequence of tones, in the lawful connection of the tones and so on. We turn, by listening to singing, to speaking, to artfully shaped speech, our attention first to the sound and the sequence of sounds; but the intuitive recognition, that which looks at what is merely is predisposed to as possibilities of movement in the larynx, or that intuitive imagination can gain an insight into what passes over into the air vibrations, into the air rhythm, when a person sings or speaks artfully, can be expressed by the whole human being.

This is the basis of our art of movement, our eurythmy. To a certain extent, one can say that in eurythmy, as we understand it, the whole human being should act as a visible larynx, as if one were suddenly able to see what the air accomplishes in terms of inner mobility and movement when we hear a sound or a sequence of sounds.

In expressing his view of art with the beautiful words: “He to whom nature reveals her manifest secret feels the longing for her best interpreter, art,” Goethe pointed to a secret of artistic feeling in general. And with regard to the human being itself, our eurythmy seeks to transform what is naturally present in the human being into art. I am only describing the elementary foundations of our eurythmy to you, dear audience. What is brought out of the natural essence of man is not transformed into artistic creation according to abstract knowledge, but according to artistic feelings. It must, however, be judged directly in contemplation. All artistic feeling is based on this alone, that something deeper in the essence of things is taken in by the human being in direct contemplation and is pleasing. Recognizing this, Goethe once said, “Style, artistic style, is based on the foundations of knowledge, on the essence of things, insofar as it is allowed to us to present it in visible and tangible forms.

The style of our eurythmy is based on the essence of the human being, insofar as it is permitted to depict this essence in movement as visibly as the sounds audibly represent what lives in the human soul.

This is how our art of movement came about. However, since not only that which is inherent in the movements of the larynx lives in the sound, but since the sound and the sequence of sounds in singing and artistic speech is illuminated by soul feelings, warmed through by soul moods , and in the artistic shaping of speech in rhythms, rhymes, alliterations, assonance and so on, then this must also be expressed when creating a kind of visible speech. In this sense, the individual person who performs eurythmy presents, in front of the larynx as such, what the neighboring organs of the larynx are; what pervades the spoken or sung word in the soul will be presented through groups and group movements, the mutual relationship of the persons in groups, and so on.

The essential thing here is that everything that is expressed through eurythmy never expresses — as is the case with neighboring arts — a mere momentary alignment of the gesture, of the facial expression, with that which lives in the soul. Rather, our eurythmy is an inwardly lawful art, like the musical art itself, which lives in melody and harmony. Nothing in any gesture is arbitrary. Much more important than the individual gesture is the succession of gestures. It is truly a musical art that is visibly expressed in our eurythmy.

And one can also say: when two eurythmists present one and the same thing, it is to be presented in the same way. Subjective differences can only arise because the perceptions are so different, as, for example, two pianists present a Beethoven sonata differently according to their different perceptions. But the subjective differences and arbitrariness in the field of eurythmy cannot be greater than in this field.

Anything that is merely pantomime or mimic is strictly excluded, and if you see any of this in our performance, it is because we have not yet achieved the perfection we are striving for. But such perfection must unfold over time from this eurythmic art.

What I have just presented to you has been done by me in order to show how this eurythmic art has been derived from the nature of the human being itself, how the human being, in accordance with the potentialities of movement that are present in him, becomes a work of art in eurythmy. This, too, is in the spirit of Goethe, as he so beautifully expresses it in his book on Winckelmann: “Man, placed at the summit of nature, beholds nature as a whole and brings forth a summit, taking order, harmony and measure together, in order to finally rise to the production of the work of art.

In this way, we try on the one hand to bring the artistic aspect of language to the ear through the musically designed, and at the same time, to a certain extent, to allow the whole person as a larynx to express what can be revealed in the sound and the sequence of sounds, in the tone and the sequence of tones.

In this sense, I ask you to take our still weak attempt. We are not at all presumptuous to think that what we can offer is more than a beginning in the indicated direction. But we are also convinced that it is a beginning of a truly new art form, which, however, may only be able to be developed over a long period of time. We believe that it will be possible – either through ourselves or, if we are unable to do so, through others – to develop this art form into something that can stand alongside the other arts that humankind has produced. With this in mind, I ask you once again to take note of our modest attempt.

9. Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Sehr verehrte Anwesende!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich unserer eurythmischen Aufführung einige Worte zur Einleitung voranschicke. Es wird dies umso gerechtfertigter erscheinen, als es sich bei dem Dargestellten durchaus nicht handeln wird um irgendetwas in sich schon Vollkommenes, sondern um einen Versuch, vielleicht könnte ich sagen, um die bloße Absicht eines Versuches. Denn cs liegt ja nahe, dass diese besondere Form von Bewegungskunst, die in der Eurythmie dargeboten werden soll, verwechselt wird mit allerlei Nachbarkünsten, tanzartigen und dergleichen Künsten. Diese Nachbarkünste haben in der Gegenwart ja — das wissen wir wohl - eine große Vollkommenheit erreicht. Und wenn der Glaube entstünde, dass wir mit diesen Nachbarkünsten konkurrieren wollten, dann wäre dieses ein falscher Glaube. Nicht um irgendetwas, was so konkurrieren soll, handelt es sich hier, sondern um eine besondere Form von Bewegungskunst, die auf ihren eigenen Gesetzen beruht und die sein soll ein Anfang, zunächst bloß ein Anfang zu etwas, was in ihrer Richtung erreicht werden kann vielleicht einmal.

Es ruht, wie alles dasjenige, was hier in diesem Goetheanum einmal vorgeführt werden soll, auf den Grundlagen der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung. Allerdings nicht so, dass wir gewissermaßen nur das wiedergeben wollten, was in dem Fertigen der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung liegt, sondern es handelt sich darum, dass wir bald ein Jahrhundert nach Goethes Tode lebendig erhalten möchten dasjenige, was an Welt- und Kunstanschauung durch Goethe der Welt gegeben worden ist, dass wir ausbilden möchten dasjenige, was durch Goethe für die Menschheitsentwicklung eingeleitet worden ist, im Sinne der modernen Menschheitsvorstellungen.

Bei Goethe liegt ja das Eigentümliche vor, dass alles dasjenige, was in seine Kunst, seine Kunstauffassung, eingeflossen ist, ruht auf seiner umfassenden Weltanschauung überhaupt, die nichts bloß nüchtern Theoretisches hatte - und daher nicht in derselben Weise wie sonst trockene, nüchterne rationalistische Weltanschauungen ernüchternd auf das Kunstschaffen und Kunstempfinden wirken [muss]. Goethes große, gewaltige Naturanschauung, sie ist es, aus der auch sein ganzes Kunst-Auffassen hervorgegangen ist. Und Sie werden mir gestatten, dass ich von einer Einzelheit her versuche, zunächst dasjenige etwas anzudeuten, auf das es uns bei [der] Ausbildung der eurythmischen Kunst besonders ankommt.

Ich muss da hindeuten auf dasjenige, was ja bekannt ist unter dem Namen der Goethe’schen Metamorphosenlehre. Das ist eine großartige Auffassung von der Natur alles Lebendigen. Mehr als man meint, liegt in der Goethe’schen Anschauung, dass das gefärbte Blumenblatt nur ist eine Umwandlung des grünen Laubblattes der Pflanze, dass selbst die äußerlich gar nicht den Laubblättern ähnlich gestalteten Staubgefäße, der Stempel der Pflanze, umgewandelte Blumenblätter sind. Alles an der Pflanze ist für Goethe Blatt, verwandeltes Blatt.

Und so ist ihm aber auch wiederum die ganze Pflanze nur ein entsprechend differenziertes, ausgestaltetes Blatt. Und jedes einzelne Blatt ist ihm eine ganze Pflanze, nur einfacher gestaltet. Das ist Goethes Grundauffassung aber von allem Lebendigen. Jedes einzelne Glied eines Lebendigen ist gewissermaßen eine Wiederholung des ganzen Lebewesens. Und wiederum das ganze Lebewesen ist nur ein komplizierter ausgestalteter Organismus eben desjenigen, was in den einzelnen Hauptgliedern vorhanden ist. Und so ist es insbesondere beim Menschen. Dasjenige, was der Mensch im Ganzen ist, ist veranlagt in seinen einzelnen, wesentlichen Gliedern.

Was Goethe so für die Gestaltung der Lebewesen bis herauf zum Menschen in seine Vorstellungsart aufgenommen hatte, das kann man nun auch anwenden nicht nur auf die Gestaltung der einzelnen Glieder eines Lebewesens und des ganzen Lebewesens, sondern man kann es anwenden auch auf die Tätigkeit. Man kann zum Beispiel sagen, dass dasjenige, was als Tätigkeit ausführt der menschliche Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane, im Kleinen eine Wiederholung ist desjenigen, was als Bewegungsmöglichkeiten im ganzen Menschen veranlagt ist, dass hinwiederum alles dasjenige, was aus dem ganzen Menschen an Bewegungs-, an Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten herausgeholt werden kann, ein Abbild sein kann desjenigen, was im Kehlkopf beim Sprechen, beim Singen in der Lautfolge, der Tonfolge, in dem gesetzmäßigen Zusammenhang der Töne und so weiter sich offenbart. Wir wenden, indem wir dem Singen, dem Sprechen, dem kunstvoll gestalteten Sprechen zuhören, unsere Aufmerksamkeit zunächst auf den Ton und die Tonfolge; aber das intuitive Erkennen, dasjenige, was hinschaut auf dasjenige, was im Kehlkopf bloß an Bewegungsmöglichkeiten veranlagt ist, oder das cine intuitive Vorstellung sich verschaffen kann von demjenigen, was übergeht in die Luftschwingungen, in den Luftrhythmus, wenn der Mensch singt oder kunstvoll spricht, das kann durch den ganzen Menschen zum Ausdruck kommen.

Das liegt unserer Bewegungskunst, unserer Eurythmie, zugrunde. Gewissermaßen kann man sagen, dass in der eurythmischen Darstellung, wie wir sie meinen, der ganze Mensch wie ein sichtbarer Kehlkopf wirken soll, so wirken soll, wie wenn man plötzlich sehend würde über dasjenige, was die Luft an innerer Beweglichkeit und Bewegsamkeit vollbringt, wenn wir den Laut und die Lautfolge hören.

Indem Goethe seine Kunstanschauung mit den schönen Worten ausgesprochen hat: Wem die Natur ihr offenbares Geheimnis offenbart, der fühlt die Sehnsucht nach ihrer besten Auslegerin, der Kunst, hat er auf ein Geheimnis des künstlerischen Empfindens überhaupt hingedeutet. Und mit Bezug auf den Menschen selbst wird gesucht in unserer Eurythmie dasjenige, was natürlich im Menschen veranlagt ist, in Kunst umzusetzen. Ich schildere Ihnen damit ja allerdings nur, sehr verehrte Anwesende, die gewissermaßen elementarischen Grundlagen unserer Eurythmie. Indem das, was so herausgeholt ist aus der natürlichen Wesenheit des Menschen, nicht nach einer abstrakten Erkenntnis, sondern nach künstlerischen Empfindungen umgesetzt wird in künstlerisches Gestalten, muss es allerdings unmittelbar im Anschauen beurteilt werden. Allein darauf beruht ja alles künstlerische Empfinden, dass ein tiefer im Wesen der Dinge Liegendes in unmittelbarer Anschauung wohlgefällig vom Menschen aufgenommen wird. Dies erkennend, sagte Goethe schön einmal: Der Stil, der künstlerische Stil, beruht auf den Grundfesten der Erkenntnis, auf dem Wesen der Dinge, insofern es uns erlaubt ist, es in sichtbaren und gf[reif]lichen Gestalten darzustellen.

Der Stil unserer Eurythmie beruht auf dem Wesen des Menschen, insoferne es erlaubt ist, dieses Wesen so sichtbarlich in der Bewegung darzustellen, wie durch den Laut hörbar dargestellt wird dasjenige, was in der menschlichen Seele lebt.

So ist unsere Bewegungskunst entstanden. Da aber im Laut nicht bloß nur dasjenige lebt, was in den Bewegungen des Kehlkopfes veranlagt ist, sondern da der Laut und die Lautfolge im Singen und künstlerischen Sprechen durchleuchtet wird von Seelenempfindungen, durchwärmt wird von Seelenstimmungen, beim künstlerischen Gestalten des Gesprochenen in Rhythmen, in Reimen, in Alliterationen, in Assonanz und so weiter übergeht, so muss, wenn man gewissermaßen ein sichtbarliches Sprechen schafft, auch dieses, das Sprechen Durchziehende zum Ausdrucke kommen. In diesem Sinne stellt der einzelne Mensch, der Eurythmie darstellt bei uns, vor den Kehlkopf als solchen dasjenige, was Nachbarorgane des Kehlkopfes sind; dasjenige, was seelisch das Gesprochene, das Gesungene durchtönt, durchwellt, das wird durch Gruppen und die Gruppenbewegungen, gegenseitigem Verhältnis der Personen in Gruppen und so weiter zur Darstellung kommen.

Das Wesentliche ist dabei, dass alles das, was durch die Eurythmie zum Ausdrucke kommt, niemals ausdrückt — wie es bei den Nachbarkünsten der Fall ist - ein bloß augenblickliches Zusammenstimmen der Geste, des Mimischen mit demjenigen, was in der Seele lebt, sondern unsere Eurythmie ist eine innerlich gesetzmäßige Kunst wie die musikalische Kunst selbst, die in Melodie und Harmonie lebt. Nichts Willkürliches ist in irgendeiner Geste enthalten. Viel wichtiger als die einzelne Geste ist die Aufeinanderfolge der Geste. Es ist tatsächlich eine sichtbarlich zum Ausdrucke kommende musikalische Kunst, die in unserer Eurythmie vorliegt.

Und man kann auch sagen: Wenn zwei Eurythmisten ein und dieselbe Sache darstellen, so ist sie auf dieselbe Art darzustellen. Subjektive Verschiedenheiten können nur eintreten dadurch, dass die Auffassungen so verschieden sind, wie etwa zwei Klavierspieler eine Beethovensonate nach ihren verschiedenen Auffassungen verschieden darstellen. Aber größer als die subjektive Verschiedenheit auf diesem Gebiet ist auch die subjektive Verschiedenheit und Willkür auf eurythmischem Gebiete nicht.

Alles bloß Pantomimische, alles bloß Mimische ist strengstens ausgeschlossen, und wenn Sie noch etwas davon in unserer Darstellung sehen werden, so rührt das eben davon her, dass wir noch nicht jene Vollkommenheit erreicht haben, die wir anstreben. Allein eine solche Vollkommenheit muss im Laufe der Zeit aus dieser eurythmischen Kunst sich eben gerade entfalten.

Das, was ich Ihnen nun dargestellt habe, ist deshalb von mir ausgeführt worden, um anzuzeigen, wie diese eurythmische Kunst herausgeholt ist aus dem Wesen des Menschen selbst, wie der Mensch selbst nach dem, was in ihm an Bewegungsmöglichkeiten veranlagt ist, in der Eurythmie zum Kunstwerk wird. Auch das ist im Sinne Goethes, nach dem, was er so schön in seinem Buche über Winckelmann sagt: Indem der Mensch auf den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist, sieht er sich wieder als eine ganze Natur an und bringt in dieser wiederum einen Gipfel hervor, nimmt Ordnung, Harmonie und Maß zusammen, um sich endlich zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes zu erheben.

So versuchen wir auf der einen Seite, das Künstlerische der Sprache durch das musikalisch Gestaltete zum Gehör zu bringen, und parallel damit gewissermaßen den ganzen Menschen als Kehlkopf ebenfalls ausdrücken zu lassen dasjenige, was im Ton und der Tonfolge zur Offenbarung kommen kann, im Laut und in der Lautfolge zur Offenbarung kommen kann.

In diesem Sinne bitte ich Sie, unseren zunächst noch schwachen Versuch aufzunehmen. Wir sind durchaus nicht so unbescheiden, dasjenige, was wir bieten können, für mehr zu halten als einen Anfang in der angedeuteten Richtung. Aber wir sind auch überzeugt davon, dass es ein Anfang zu einer wirklich neuen Kunstform ist, die allerdings vielleicht im Laufe einer langen Zeit erst wird ausgebildet werden können. Wir glauben eben, dass es möglich sein wird - entweder noch durch uns selbst, oder, wenn wir das nicht können, durch andere -, diese Kunstform zu etwas zu bringen, das sich neben die anderen Künste, die die Menschheit hervorgebracht hat, wird würdig hinstellen können. - In diesem Sinne bitte ich Sie nochmals, unsern schwachen Versuch aufzunehmen.