The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

16 August 1919, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

19. Eurythmy Performance

Dear attendees!

The eurythmic art that we are presenting to you today is an art form that strives to make use of new means of expression, means of expression that are inherent in the human limbs themselves. The development of this eurythmic art is based entirely on the Goethean world view, on which, after all, everything that you see realized here in this building is based. And in fact, an attempt has been made to artistically shape in a particular, limited area that which, in Goethe's great world view, has still not been fully appreciated today, and is still awaiting its full appreciation. I do not want to precede the eurythmic presentation with long-winded theoretical discussions, but what Goethe gave as the results of his observations in his world view is never one-sidedly scientific. It is always imbued with artistic spirit. And it is this Goethean artistic spirit that we would like to see permeate this art of spatial movement that we call eurythmy.

In his understanding of the living world, Goethe goes far beyond what science already recognizes today. And it is to be hoped that precisely that which Goethe himself describes as his metamorphic view will acquire great significance for the future of humanity.

If I am to present the simplest of Goethe's worldviews to you, it is that for Goethe, every single plant leaf is a whole plant – only in terms of its structure – and the whole plant is in turn a complex leaf. All the individual organs of the plant are only transformed leaves, and are therefore basically one and the same. The outer form repeats the essential in the most diverse ways. What Goethe wrote down in his magnificent essay on plants in 1790 can be applied to understanding all living things in nature. It can be applied in particular to understanding the human being.

But we can go further. We can also look at the human being in terms of Goethe's world view by interpreting the expression of a single organ as the movement of the whole person, or vice versa. The movements that the whole person can carry out, can make, appear as the repetition, the more complicated repetition, of that which an organ of the human body carries out.

For us, my dear audience, what comes into consideration here is what the human larynx and its neighboring organs carry out when a person speaks. In ordinary life and in that revelation of human nature that is expressed in poetry or the art of recitation, people's attention is drawn to what can be heard through the activity of the larynx and its neighboring organs. But if we have the opportunity to see with supersensible vision what is at work in the human larynx and its neighboring organs, if we have the opportunity to see through the tendencies and impulses of movement that are active while we speak, then we can, so to speak, form a visible language out of it, which the whole human being performs.

You need only imagine, my dear audience, that as we speak, the air is continually moving in waves through the larynx and its neighboring organs. And the manifestation of these undulating movements is, after all, the heard word. These undulations, when seen in their essence, can be transferred to the whole human being. And so, when you watch the characters on the stage, you will, in a sense, see the whole human being as a large larynx, which, in its individual parts, performs that which is performed invisibly when you listen to the speech.

These are the new means of expression for this eurythmic art of movement. According to Goethe's artistic philosophy, all art is based on a mysterious revelation of nature, on the revelation of natural laws that would never be recognized without art. For Goethe, that which can be artistically shaped moves into the sphere of knowledge. He says: Art is based on a mysterious recognition, insofar as it allows us to penetrate the essence of things visibly and tangibly.

And it is particularly interesting to penetrate that which is present in the whole human being as a possibility of movement. So you will see a visible language in eurythmy. And that which is otherwise expressed in our language, namely that which is expressed in artistically and poetically shaped language, can also be expressed through our eurythmic art.

When you see an individual in a standing position, the movements they perform are a transformed, enlarged larynx. But when the individual human being or groups of people carry out their movements in space here on the stage, these movements reveal everything that warms our language from the soul, everything that can penetrate our language as enthusiasm, everything that can also penetrate our language as pain and suffering. All these nuances of the soul that pass through language can be expressed through this spatial-movement art.

Nothing in this art is arbitrary. Just as music itself is based on — and is very similar to — the eurythmic art, or rather the eurythmic art is similar to music. Just as the musical art regularly and lawfully follows its tones in the melodious element, and how it combines tones in the harmonic element, so too is everything in the eurythmic art inwardly lawful. You must not think that it is a mere art of gesturing, a mere mimic art. It is not a peculiar attunement of what lives in the human being with the outer movement that is striven for here, but the connection between what wants to express itself in the soul and the movement that is made is a very inner, lawful one. And the sequence of movements is as internally lawful as in music.

Therefore, the art of eurythmy can be accompanied by music. On the one hand, it parallels the musical arts. On the other hand, it parallels the art of recitation. So you will hear one and the same motif of the human soul musically, see it presented in eurythmy and hear it in recitation.

One cannot recite to the eurythmic art as one likes to recite today. The eurythmic art in particular forces one to lead the art of recitation back to its actual artistic element. Today one actually recites prosaically. The highest value is placed on expressing the content of the poetry in the recitation. But for the truly artistically perceptive person, this is not the main thing. The rhythmic element, which is also expressed here in the movements of the people and groups of people in space, the rhythmic element, the whole inner shaping of the supporting element, is what is most important to the poet.

I need only remind you that a poet like Schiller never first had the content, or at least often did not first have the content of a poem in his soul; but before he knew what he was writing about, what the content of the poem should be, an indeterminate melodious tone formation went through his soul and he formed the poem according to this tone formation. Therefore, the art of recitation that must accompany our eurythmy today will still be misunderstood in many ways, because we have to go back to older forms of recitation.

I would also like to remind you that in his time, Goethe still wanted to express the formative, actually artistic aspect of the language form. When he rehearsed his “Iphigenia”, he had a baton in his hand so that the language would not be spoken prosaically, but so that the iambs, the rhythm of the language, would really be expressed. which today would be perceived as unnatural, because in our materialistic time the actual artistic feeling has declined and one also wants to emphasize the special content in recitation, in the art of lecturing.

If you do notice elements of pantomime in our eurythmic performances, I would ask you to bear in mind that we are still at the very beginning of our artistic development. This is why there are still some imperfections. But all pantomime and random gestures are actually still imperfections. If two performers, two completely different performers, were to perform the same thing eurythmically at different times and in different places, they would do so in the same way because eurythmy has an inner lawfulness, so that the individual differences would only be as great as when two pianists play one and the same Beethoven sonata according to their individual peculiarities. So this inner lawfulness is, of course, what we strive for. Everything that is striven for with the means you have just characterized for the art of eurythmy must flow into the spatial movement in such a way that the immediate view has an aesthetic, artistic effect.

But this is also the basis of Goethe's philosophy: in all art, we perceive the inner laws and harmony of nature directly, by excluding the intellect. Goethe once expressed this very beautifully when he said: “Man, placed at the summit of nature, beholds himself in turn as a whole of nature, taking in order, measure, meaning, and harmony, in order to finally rise to the production of a work of art.”

It is particularly appealing to elevate that which is inherent in man himself to a work of art. This inward disposition of the human being, conceived as a work of art, conceived as a work of art in accordance with the nature of the moving human being: that is eurythmy, the same eurythmy that vibrates invisibly in our sequence of sounds when we speak, when we name, when we repeat poetic and artistic utterances. Nevertheless, I would ask you to be lenient in your judgment of what we will present to you today. We ourselves are the harshest critics of what we are already able to do with this eurythmic art. We know that everything is still in the process of becoming, that everything is still imperfect. But we hope that we ourselves, or if not ourselves, then others, will bring it to perfection. And when what is only intended today is fully expressed as the eurythmic art, then this eurythmic art will be able to stand alongside other arts as a fully significant art. However, we do not want to compete with neighboring arts, such as the now so popular dance arts. Eurythmy should be something completely different. It should express what the human being has within himself as a movement disposition: soulful movement.

And so we also believe that eurythmy will one day play a major role in teaching and education, in that mere physical movement in gymnastics will then be imbued with soul, in that eurythmy will take the place of mere physical gymnastics. This will probably enable eurythmy to be integrated into the overall culture of the human spirit, on the one hand as an art form and on the other as something that plays a major role in the overall education of the human being.

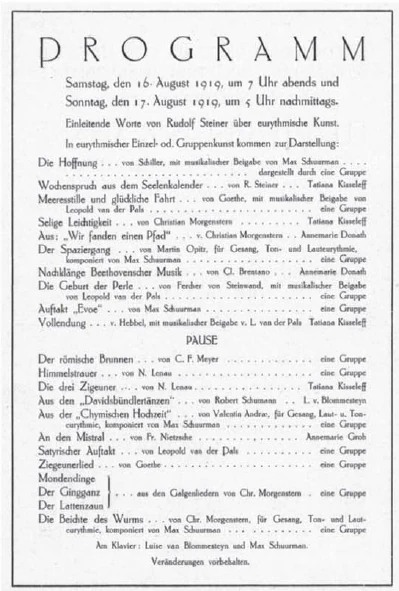

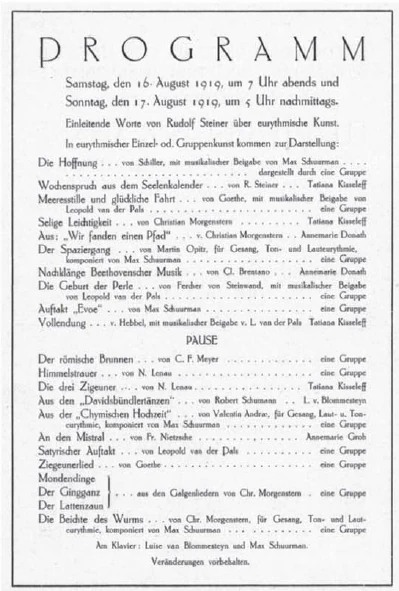

We do indeed know that all of this is still in its infancy today, and so I ask you to bear with us as we perform. Regarding the program before the intermission, I would like to add that the Nietzsche poem 'My Happiness' will be inserted after 'Stroll'. So the program before the intermission has been extended by two numbers.

19. Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Die eurythmische Kunst, von der wir Ihnen heute eine Probe vorführen dürfen, ist eine Kunstform, welche sich neuer Ausdrucksmittel zu bedienen strebt, der Ausdrucksmittel, welche veranlagt sind in den menschlichen Leibesgliedern selbst. Die Ausbildung dieser eurythmischen Kunst ruht ganz auf der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung, auf der ja im Grunde alles dasjenige ruht, was Sie hier in diesem Bau verwirklicht sehen. Und zwar ist der Versuch gemacht, dasjenige, was in Goethes großer Weltanschauung heute noch immer nicht voll gewürdigt ist, was noch auf seine volle Würdigung wartet, das auf einem bestimmten begrenzten Gebiete künstlerisch auszugestalten. Ich möchte nicht gerade theoretische Auseinandersetzungen weitläufiger Art der eurythmischen Darstellung voranschicken - allein: Bei Goethe ist dasjenige, was er als Beobachtungsergebnisse seiner Weltauffassung gegeben hat, immer nicht einseitig wissenschaftlich. Es ist immer durchtränkt von künstlerischer Gesinnung. Und diese Goethe’sche künstlerische Gesinnung, von ihr möchten wir, dass sie auch durchdringe diese Raumbewegungskunst, die wir als Eurythmie bezeichnen.

Goethe geht in der Auffassung der lebendigen Welt weit über dasjenige hinaus, was heute schon die Wissenschaft anerkennt. Und es steht zu hoffen, dass gerade dasjenige, was Goethe selber als seine Metamorphosen-Anschauung bezeichnet, für die Zukunft der Menschheit eine große Bedeutung gewinnen wird.

Wenn ich das Einfachste dieser Goethe’schen Weltanschauung Ihnen vorführen soll, so ist es das, dass für Goethe jedes einzelne Pflanzenblatt eine ganze Pflanze ist - nur eben der Anlage nach - und die ganze Pflanze ist wiederum ein kompliziertes Blatt. Alle einzelnen Organe der Pflanze sind nur umgestaltete Blätter, sind also im Grunde genommen ein und dasselbe. Die äußere Form wiederholt das Wesentliche in mannigfaltigster Art. Dasjenige, was Goethe in seiner großartigen Abhandlung über die Pflanze 1790 niedergeschrieben hat, das lässt sich anwenden auf das Begreifen alles Lebendigen in der Natur. Es lässt sich insbesondere anwenden in Bezug auf das Begreifen des Menschen.

Man kann aber weitergehen. Man kann auch den Menschen so im Sinne dieser Goethe’schen Weltanschauung betrachten, dass man die Äußerung eines einzelnen Organes wiederum so auffasst, wie die Bewegung des ganzen Menschen beziehungsweise umgekehrt. Dasjenige, was der ganze Mensch an Bewegungen ausführen kann, an Bewegungen machen kann, es erscheint als die Wiederholung, als die kompliziertere Wiederholung desjenigen, das ein Organ des menschlichen Leibes ausführt.

Für uns kommt, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, hier in Betracht dasjenige, was, wenn der Mensch spricht, sein Kehlkopf und dessen Nachbarorgane ausführen. Im gewöhnlichen Leben und in derjenigen Offenbarung der Menschennatur, die als dichterische oder als rezitatorische Kunst zum Ausdrucke kommt, da ist die Aufmerksamkeit der Menschen auf dasjenige gelenkt, was hörbar wird durch die Tätigkeit des Kehlkopfes und seiner Nachbarorgane. Hat man aber die Möglichkeit, dasjenige, was im menschlichen Kehlkopf und seinen Nachbarorganen wirkt, übersinnlich zu schauen, hat man die Möglichkeit, die Bewegungstendenzen und Bewegungsantriebe, die tätig sind, während wir sprechen, zu durchschauen, dann kann man daraus gewissermaßen eine sichtbare Sprache formen, die der ganze Mensch ausführt.

Sie brauchen sich ja nur vorzustellen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass, während wir sprechen, durch den Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane fortwährend die Luft in wellige Bewegungen kommt. Und die Offenbarung dieser welligen Bewegungen ist ja das gehörte Wort. Diese welligen Bewegungen in ihrem Wesen geschaut, lassen sich übertragen auf den ganzen Menschen. Und so werden Sie gewissermaßen in den Darstellungen der Personen auf der Bühne sehen den ganzen Menschen als einen großen Kehlkopf, der in seinen einzelnen Gliedern dasjenige ausführt, sichtbarlich, was unsichtbar ausgeführt wird, wenn Sie dem Sprechen zuhören.

Das sind die neuen Ausdrucksmittel für diese eurythmische Bewegungskunst. Es beruht ja nach Goethes künstlerischer Gesinnung alle Kunst auf einer geheimnisvollen Offenbarung der Natur, auf der Offenbarung von Naturgesetzen, die man ohne die Kunst gar niemals erkennen würde. Für Goethe rückt dasjenige, was man künstlerisch gestalten kann, in die Sphäre der Erkenntnis. Er sagt: Die Kunst beruht auf einem geheimnisvollen Erkennen, insoferne es uns gestattet ist, das Wesen der Dinge als sichtbarlich und greiflich zu durchdringen.

Und insbesondere ist es interessant zu durchdringen dasjenige, was im ganzen Menschen als Bewegungsmöglichkeit vorhanden ist. So werden Sie in der Eurythmie eine sichtbare Sprache sehen. Und dasjenige, was sonst in unserer Sprache zum Ausdruck kommt, namentlich dasjenige, was in der künstlerisch-dichterisch gestalteten Sprache zum Ausdrucke kommt, auch das lässt sich ausdrücken durch unsere eurythmische Kunst.

Der einzelne Mensch, wenn Sie ihn im Stehen sehen, was er da an Bewegungen ausführen kann, das ist ein umgestalteter großer Kehlkopf. Wenn aber der einzelne Mensch oder Menschengruppen im Raume hier auf der Bühne ihre Bewegungen ausführen, so offenbaren diese Bewegungen alles dasjenige, was unsere Sprache durchwärmt vom seelischen Gemüte aus, was als Enthusiasmus durch unsere Sprache dringen kann, was auch als Schmerz und Leid durch unsere Sprache dringen kann. Alle diese Nuancen des Seelischen, die durch die Sprache gehen, man kann sie durch diese Raumbewegungskunst zum Ausdrucke bringen.

Dabei ist in dieser Kunst nichts willkürlich. So wie die Musik selber beruht — die durchaus ähnlich ist der eurythmischen Kunst beziehungsweise die eurythmische Kunst ist ähnlich der Musik -, so wie die musikalische Kunst regelmäßig, gesetzmäßig ihre Töne folgen lässt im melodiösen Elemente, wie sie die Töne zusammenstellt im harmonischen Elemente, so ist auch alles innerlich gesetzmäßig in der eurythmischen Kunst. Sie dürfen nicht denken, dass das eine bloße Gebärdenkunst ist, eine bloß mimische Kunst ist. Nicht ein eigentümliches Zusammenstimmen desjenigen, was im Menschen lebt, mit der äußeren Bewegung wird hier angestrebt, sondern der Zusammenhang zwischen dem, was in der Seele sich aussprechen will, und der Bewegung, die gemacht wird, ist ein ganz innerlich gesetzmäßiger. Und die Aufeinanderfolge der Bewegungen ist so innerlich gesetzmäßig wie in der Musik.

Daher kann eurythmische Kunst begleitet werden vom Musikalischen. Die musikalische Kunst geht ihr auf der einen Seite parallel. Auf der anderen Seite geht ihr die Rezitationskunst parallel. So werden Sie ein und dasselbe Motiv der menschlichen Seele musikalisch hören, eurythmisch dargestellt sehen und in Rezitation hören.

Man kann nicht so rezitieren zur eurythmischen Kunst, wie man heute liebt zu rezitieren. Gerade die eurythmische Kunst zwingt, auch die Rezitationskunst wiederum zurückzuführen zu ihrem eigentlichen künstlerischen Elemente. Heute rezitiert man eigentlich prosaisch. Man legt den höchsten Wert darauf, den Inhalt der Dichtung in der Rezitation zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Aber das ist dem wirklich künstlerisch erfassenden Menschen nicht die Hauptsache. Das Rhythmische, das ebenfalls hier in den Bewegungen der Menschen und Menschengruppen im Raume zum Ausdrucke kommt, das Rhythmische, die ganze innere Gestaltung des tragenden Elementes, das ist dasjenige, was dem Dichter die Hauptsache ist.

Ich brauche nur daran zu erinnern, dass solch ein Dichter wie Schiller niemals zuerst den Inhalt, oder wenigstens oftmals nicht zuerst den Inhalt eines Gedichtes in der Seele hatte; sondern bevor er wusste, über was er dichtete, was der Inhalt des Gedichtes werden sollte, ging eine unbestimmte melodiöse Tongestaltung durch seine Seele und nach dieser Tongestaltung formte er das Gedicht. Daher wird dasjenige, was als rezitatorische Kunst heute unsere Eurythmie begleiten muss, noch vielfach missverstanden werden, weil wir zurückgehen müssen auf ältere Formen des Rezitierens.

Auch daran möchte ich noch erinnern, dass Goethe zu seiner Zeit noch durchaus dieses gestaltende, eigentlich Künstlerische der Sprachform zum Ausdruck bringen wollte. Wenn er seine «Iphigenie» einstudierte, hatte er den Taktstock in der Hand, damit nicht prosaisch gesprochen wurde, sondern damit die Jamben, damit der Rhythmus der Sprache wirklich zum Ausdrucke kam - etwas, was man heute als unnatürlich empfinden würde, weil in unserer materialistischen Zeit das eigentlich künstlerische Empfinden zurückgegangen ist und man auch in der Rezitation, in der Vortragskunst das Besondere des Inhalts in den Vordergrund stellen will.

Wenn Sie in unseren eurythmischen Darstellungen doch noch Pantomimisches bemerken werden, so bitte ich Sie, das zu betrachten so, dass wir mit unserer Kunst eben durchaus im Anfange erst stehen. Daher hat sie noch manches Unvollkommene. Aber alles Pantomimische, alle Zufallsgesten sind eigentlich noch Unvollkommenheiten. Wenn zwei Darstellende, zwei ganz verschiedene Darsteller zu verschiedenen Zeiten und an verschiedenen Orten dasselbe eurythmisch darstellen würden, so würden sie es, weil die Eurythmie eine innerliche Gesetzmäßigkeit hat, in gleicher Art so darstellen, dass die individuellen Verschiedenheiten nur so große sind, wie wenn zwei Klavierspieler nach ihren individuellen Eigentümlichkeiten ein und dieselbe Beethoven-Sonate spielen. - Also diese innere Gesetzmäßigkeit, die ist dasjenige, was angestrebt wird selbstverständlich. Alles dasjenige, was mit den eben Ihnen charakterisierten Mitteln für die eurythmische Kunst angestrebt wird, es muss so ausfließen in die Raumbewegung, dass der unmittelbare Anblick ästhetisch, künstlerisch wirkt.

Aber darauf beruht ja auch Goethes Gesinnung: In aller Kunst lassen wir mit Ausschaltung des Verstandes unmittelbar die innere Gesetzmäßigkeit und Harmonie der Natur wahrnehmen. Goethe drückt das einmal sehr schön aus, indem er sagt: Indem der Mensch auf den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist, sieht er sich wiederum als eine ganze Natur an, nimmt Ordnung, Maß, Bedeutung, Harmonie zusammen, um sich endlich zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes zu erheben.

Besonders reizvoll ist cs, dasjenige, was im Menschen selbst veranlagt ist, zum Kunstwerke zu erheben. Diese innerliche Veranlagung des Menschen, als Kunstwerk gedacht, den sich bewegenden Menschen naturgemäß, gesetzmäßig als Kunstwerk gedacht: Das ist Eurythmie, dieselbe Eurythmie, welche durchvibriert unsichtbar in unserer Lautfolge, indem wir sprechen, namentlich, indem wir Dichterisch-Künstlerisches nachsprechen. Dennoch darf ich Sie bitten, dasjenige, was wir Ihnen heute vorführen werden, mit Nachsicht zu beurteilen. Wir sind selbst die strengsten Kritiker desjenigen, was wir jetzt schon mit dieser eurythmischen Kunst können. Denn wir wissen, dass noch alles im Werden, alles noch unvollkommen ist. Aber dasjenige, was in unserer Absicht liegt, wir hoffen, dass wir es noch selber, oder wenn wir nicht selber, so andere es zur Vollendung bringen werden. Und dass dann, wenn dasjenige, was heute nur beabsichtigt ist, in voller Weise als eurythmische Kunst zum Ausdrucke kommt - dann wird sich diese eurythmische Kunst neben anderen, neben die anderen Künste als vollbedeutende Kunst hinstellen können. Nicht konkurrieren aber möchten wir mit nachbarlichen Künsten wie zum Beispiel den heute so beliebten Tanzkünsten. Eurythmie soll etwas ganz anderes sein. Sie soll dasjenige zum Ausdruck bringen, was der Mensch in sich selber als Bewegungsanlage hat: Beseelte Bewegung.

Und so glauben wir auch, dass die Eurythmie einmal im Unterricht, in der Erziehung eine große Rolle spielen wird, indem das bloß körperliche Bewegen im Turnen dann durchseelt werden wird, indem an die Stelle der bloß körperlichen Turnkunst die durchseelte Eurythmie tritt. Das wird die Eurythmie wahrscheinlich einmal hineinstellen können in die menschliche Gesamtgeisteskultur auf der einen Seite als Künstlerisches, auf der anderen Seite als dasjenige, was als die Gesamtpädagogik des Menschen eine große Rolle spielt.

Wir wissen in der Tat, dass das alles heute noch ein Anfang ist, und deshalb bitte ich Sie, mit Nachsicht unsere Aufführung zu betrachten. Für das Programm vor der Pause habe ich noch anzugeben, dass nach dem «Spaziergang» eingefügt werden wird das NietzscheGedicht «Mein Glück». Sodass also das Programm vor der Pause um zwei Nummern vergrößert ist.