Architecture, Sculpture and Painting of the First Goetheanum

GA 288

12 June 19020, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

V. The Goetheanum in Dornach

A public lecture at the Stuttgart Art Building

When the spiritual science, the aims and nature of which I have been honored to present in lectures in Stuttgart every year for almost two decades, gained greater currency, namely when artistic work was created from this spiritual science, the intention arose to create a central building for this spiritual science that would be particularly appropriate for it, somewhere where it would be fitting. This idea has become a reality in that we performed the Mystery Dramas in an ordinary theater in Munich from 1909 to 1913. These plays were intended to be born out of the spirit of this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science in their entire structure and attitude.

What the supporters of this spiritual science had in mind, on the one hand, as the actual meaning of their world view, and, on the other hand, as the artistic expression of this world view, was initially brought about by the intention, just mentioned, to stage their own play, which was to be the representative, the outward representative of this spiritual science. In Munich, this did not succeed due to the lack of cooperation on the part of the relevant artists. Since I have set myself a different task today, I do not want to talk about everything that led to the construction of this building on a hill in a remote location in northwestern Switzerland, in the canton of Solothurn, where, at the time we began building, there were no restrictive building laws and one could build as one wished. As I said, all this has led to the fact that I do not want to go into it today. But I would like to talk about the sense in which the intention should be understood, especially for the spiritual science meant here.

When one speaks of world views, world view directions or world view currents, then one usually has in mind a sum of ideas that often have a more or less theoretical or popular character, but which mostly exhaust themselves in the fact that they simply want to express themselves through communication, through the mere word, and then at most expect from the world that the word, which is formulated in a certain way programmatically, is actually carried out in reality. From the outset, what is meant here as anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is not predisposed in the same way as other world views. It is, if I may express it this way, imbued from beginning to end with a sense of reality. That is why it had to lead, even in difficult times in this present age, to direct penetration into what the attempt at a social reconstruction of modern civilization is. If a world view that is more in the realm of ideas needs a structure of its own for its cultivation, then, depending on one's means, one usually contacts someone whom one assumes to be professionally capable of constructing a structure from the relevant styles. One contacts such a personality or a series of such personalities in order to then create, as it were, a house, a framework for the cultivation of such a worldview. However, this could not have corresponded to the whole structure of our anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, for the simple reason that this spiritual science is not something that expresses itself only in ideas, but because it wants to express itself in all forms of life.

Now I would like to use a simple comparison to suggest how this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science had to express itself in its own framework, both in terms of trees and in artistic terms. Take any fruit, let us say a nut. Inside the nut is the fruit, and around it is the shell. Let us first look at the hard shell inside the green shell. If you study the whole configuration, the shape of the nut shell, you will say to yourself: it could not be any different than it is, because the nut is as it is. You cannot help but think to yourself: the nut creates its shell, and everything about it that is visible through the shell must be an expression of what the nut itself is. Thus, a frame is quite appropriate in nature, in all creation, for what it frames.

If you do not think abstractly, if you do not think theoretically, if you do not think from a world view that moves only in ideas, but that wants to be in all reality and in all life, then you feel compelled to do everything you do in a certain way, as the creative forces in the universe do. And so, if we had built with some alien architectural style, with something that had grown out of those building methods that are common today, a framework for an anthroposophically oriented worldview and its cultivation, there would have been two things: on the one hand, a building that expresses itself entirely from within, that says something for itself, that stands in its own artistic formal language. And then one would have entered and represented something inside, cultivated something that could only relate to the building in a very superficial way. One would hear words spoken in such a building, one would see plays performed on the stage (since these are intended) and other artistic performances; one would have heard and seen and beheld something that wants to present itself as something new in modern civilization. One would have turned one's eye away from what one might have seen on the stage; one would have turned one's ear away from what one might have heard, and one would have looked at the building forms — these would have become two essentially different things. The spiritual science meant here could not aspire to this. It had to strive in harmony with all world-building. It had to trust itself to express itself in artistic forms as well as in building forms. It had to claim that what forms itself into words, what forms itself into drama or into another form of artistic expression, is also capable of directly shaping itself into all the details of what is now the shell. Just as the nut fruit creates its shell out of its own essence, so too did a spiritual science such as this, whose essence is not understood in the broadest circles today because it breathes precisely this spirit of reality, had to create its own framework. Everything that the eye sees in this framework must be a direct expression of what is present as living life in this world view, as must the formed word.

And there were some pitfalls to avoid. For those who have a certain inclination to make a building appropriate to a worldview are often, let us say, somewhat mystical or otherwise inclined, and they then have the urge to express what is expressed in the worldview in external symbols, in some mystical formations. But this merely leads to such a framing becoming something in the most eminent sense inartistic. And if one had performed a building bearing symbols, one would have wanted to express in allegorical or symbolic form what underlies anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, so nothing would have emerged but something in the most eminent sense inartistic.

Indeed, I must even admit that some people who have come to what is referred to here as anthroposophically oriented spiritual science with their views and currents of life, as contributors or advisors, in the early days of our work in Dornach, were quite inclined to express everything that spiritual science contains in old symbolic or similar forms. I might also mention that those people, who are so numerous, who either out of a certain lack of understanding or out of malicious intent talk about the Dornach building, keep coming to the world with the idea that one can find symbols for this or that, allegorical expressions for this or that.

Now, ladies and gentlemen, it must be admitted that even in what I have to show you this evening, anyone who does not look closely and with a lively sense of perception can find something to use as an expression: There are many allegorical or symbolic elements. In reality, there is not a single symbol or allegory in the Dornach building, but everything that is there is there entirely so that the inner experience of the spirit, which on the one hand is to be grasped in ideas that are expressed in lectures or the like, is experience is to be completely dissolved into artistic forms, that nothing else is asked for in artistic creation in Dornach than: what the line is like, what the form is like, what that is which can be shaped as an artistic form of expression in sculpture, in architecture, in painting, and so on. And many a person who comes to Dornach and asks what this or that means is always given the same answer by me: I ask them to look at the things; basically, they all mean nothing other than what flows into the eye. People often say that this or that means this or that. But then I am obliged to talk to them about the distribution of colors and the like.

I have now tried to show how the building, as a shell, very much in the spirit of nature's own creation, forms the framework for anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. But for that very reason the whole idea of the building had to strive for something new. Now, in all that I am going to say today, I ask you to bear in mind that, of course, much criticism can be made of the Dornach building, that many objections can be raised. And I give you the assurance: the person who perhaps objects most of all is myself. For I am fully aware that the Dornach building is a beginning; that the Dornach building stands as a first attempt to create a certain stylistic form that cannot even be characterized in words today, because its details are not formed from abstract thoughts, but from what is experienced in a living way in that beholding of the spirit that is meant by our spiritual science.

I may mention just one difference at the outset: if we compare the various architectural styles, which, in a certain development of form, still find expression today wherever buildings are constructed, it is apparent everywhere that, basically, the mathematical, the geometrical, the symmetrical, that which perhaps follows in the rhythm of the line, the mechanical, the dynamic, etc., all flow into architecture. From the basic feeling – I am not saying from the basic idea, I am saying from the basic feeling – of our spiritual science, the daring attempt was once made, I know it, to create an organic building idea, not a mechanical-dynamic, but to create an organic building idea, and this under the influence of that which Goethe incorporated into his great, powerful view of nature under the influence of the idea of metamorphosis. The Dornach building, as far as this can be realized in architecture, should not merely represent the symmetrical, the dynamic, the mechanical, the geometrical; it should represent something that can be looked at, I do not say grasped, but looked at as a building organism, as the form for something living.

In this case, however, it is a matter of every detail in an organism being exactly as it should be in its place. You cannot imagine the ear lobe in a human organism being formed any differently than it is. So we tried to make our building in Dornach a completely organic, internally organic unit by placing each individual part in the whole in such a way that it appears as a necessary structure in its place; that every detail is an expression of the whole, just as a fingertip or an earlobe is an expression of the whole human organism.

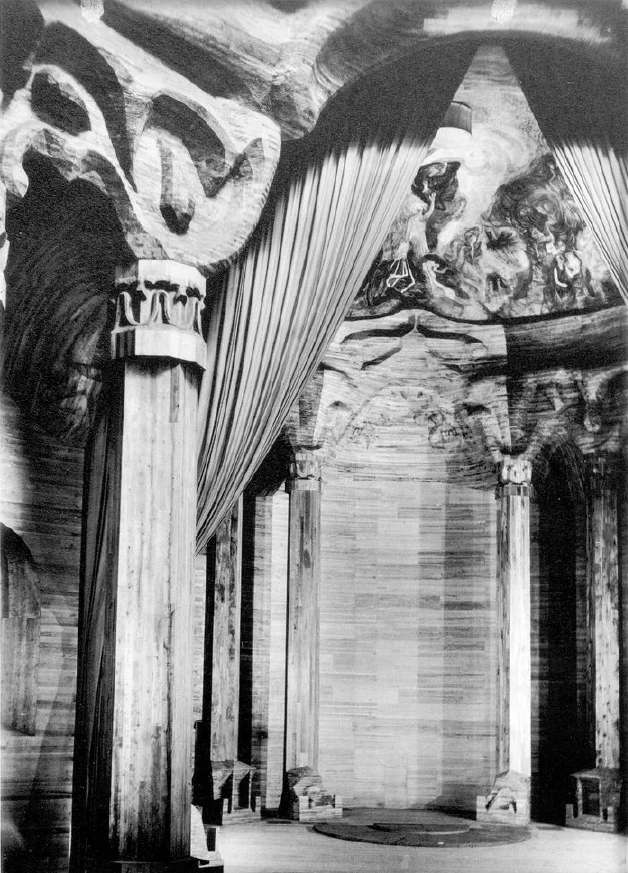

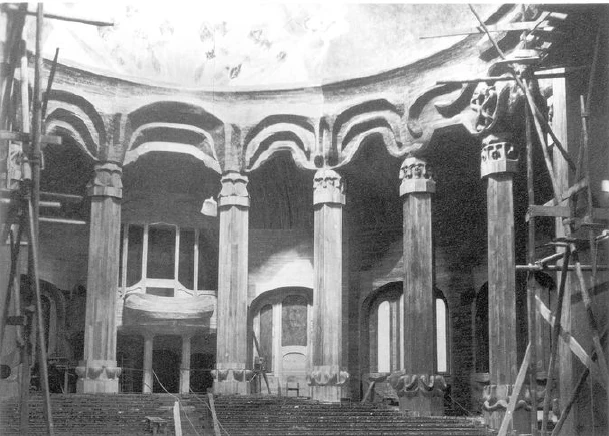

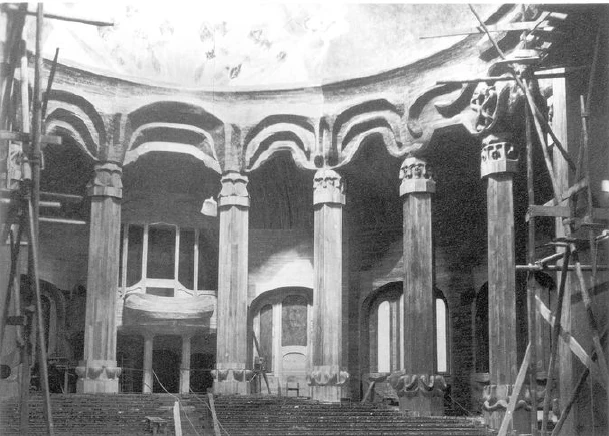

That is one thing that has been attempted. As I said, it is a beginning, an attempt, and I know how many imperfections it has and how much can be objected to from the point of view of architecture and sculpture and so on. The other thing is what I would like to say in advance, namely that our world view itself demands that the whole idea of building be formulated differently from the way in which the idea of building is usually formulated. If we consider ordinary buildings – I will mention just one – we find that they are closed off from the outside by walls to a certain degree. Even the Greek buildings were closed off to a certain degree. What is required by the Dornach building is that the wall itself be treated in a completely different way than it is usually treated. The person who enters the Dornach building should not have the feeling that, having a wall around him, he is closed off in an inner space. Rather, everything should be artistically designed so that, to a certain extent, the wall itself is suspended; that the wall itself - please do not misunderstand me - the wall itself becomes artistically transparent, so that one gets the feeling - transparent is of course only spoken in comparison - you are not closed off, but everything that is wall, everything that is dome, opens up a feeling that it is broken through, that it cancels itself out, that you are in a feeling connection with the whole great universe. Far out into infinity, the soul is meant to feel connected to this through what the forms evoke; the forms of the columns, the walls, the forms of the dome paintings, etc.

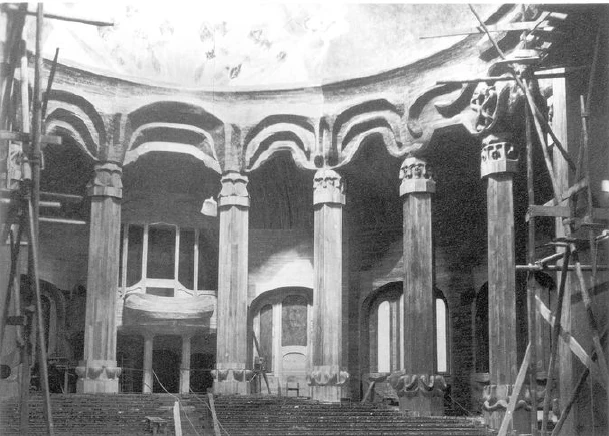

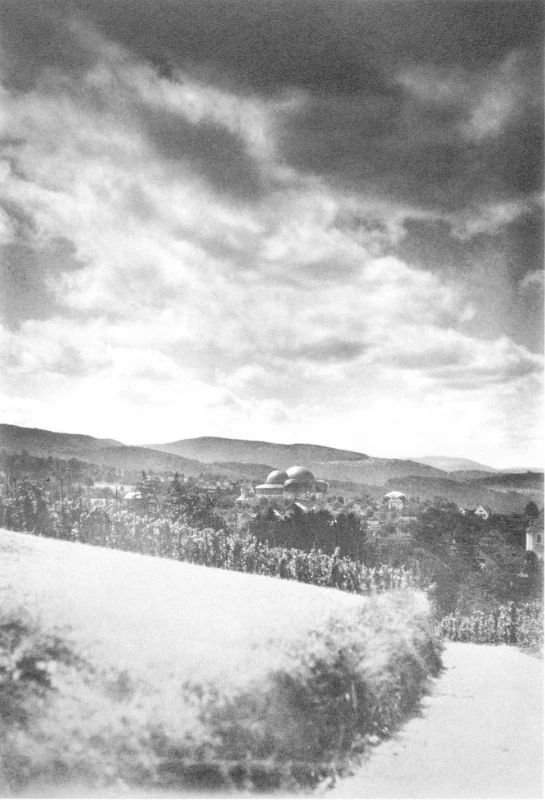

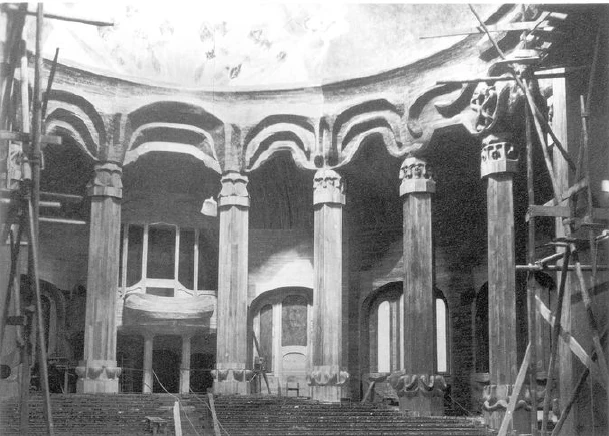

The building in Dornach is a double-domed structure, consisting of a small and a large domed space that do not stand side by side but interlock. The small domed room, that is, the circular room covered by a smaller dome, will be used for presenting mystery dramas, for dramatic performances in general, for other artistic performances, such as eurythmy. But there are also other things planned. Then there is the large domed room, which is connected to the smaller one in the segment of the dome. It is intended as an auditorium; so that those who approach this building must immediately be imbued with a certain feeling by this outer form.

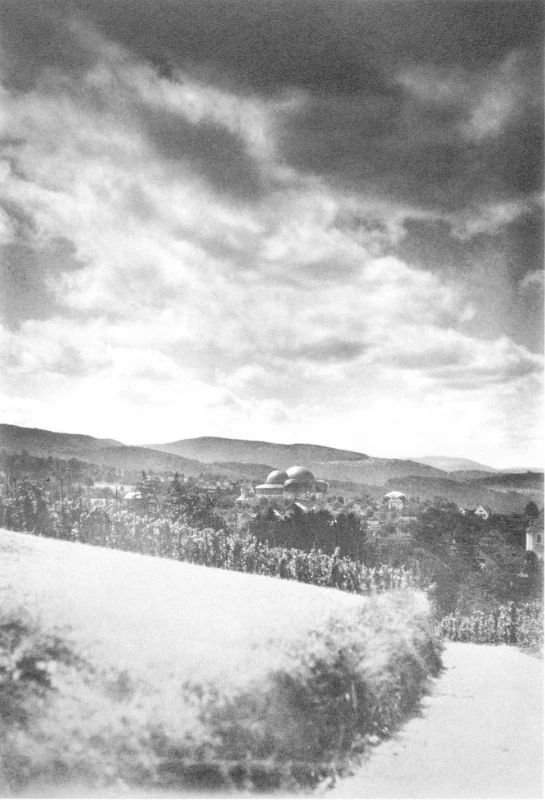

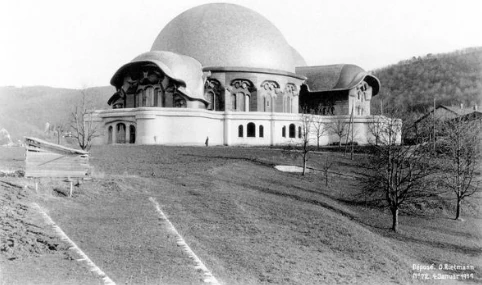

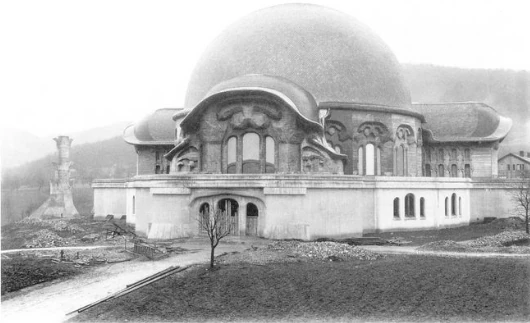

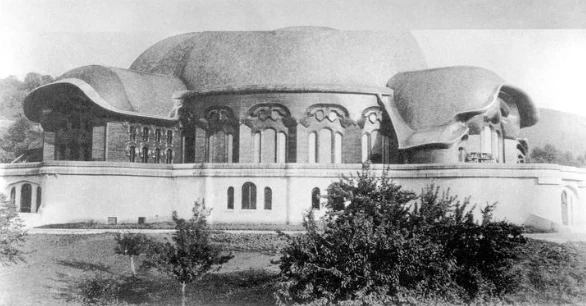

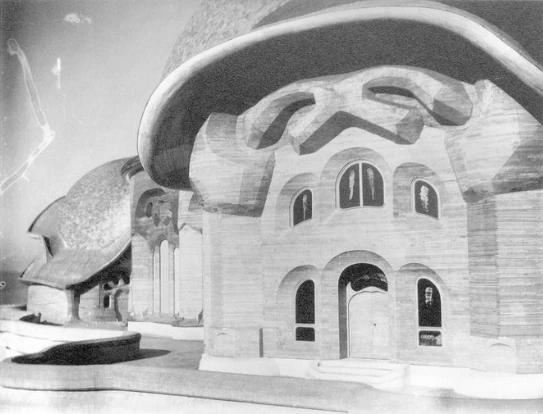

We will begin by looking at our building as it presents itself to someone approaching it from the northeast.

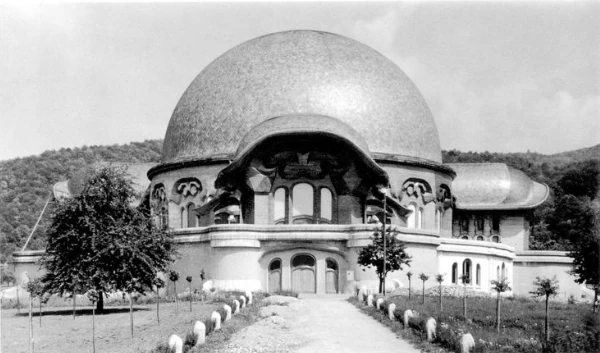

So, as you can see, we have a double-domed structure. This is the auditorium, and here is the stage. The two domes are inserted into each other by, if I may say so, a special technical feat, because this insertion was difficult. The person who approaches this building – which, I believe, is particularly appropriate in its artistic expression of the special mountain formation of the Jura region in which it is built – should have the feeling that something is present that reveals itself in a duality. The person who enters the building finds themselves in the large domed room. Inside, he may have the feeling: here something is seen, something heard. And this something, which is experienced in a sense in the heights of spiritual life, which is to reveal itself to an inclined audience, should already express itself as a feeling to those who approach the building.

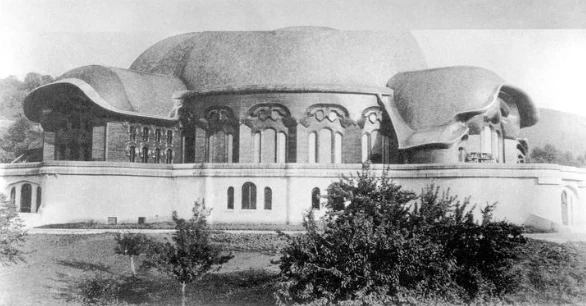

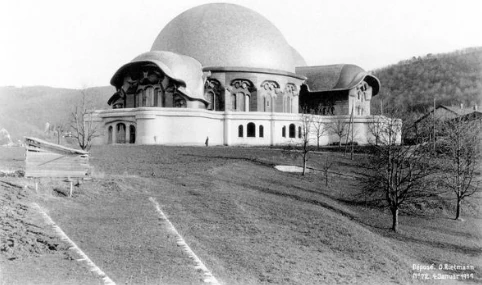

But initially, every single detail of the outer forms is attuned in such a way that one has an impression from the outside, so to speak – I could not express it in terms of ideas or thoughts – but through the forms, through the artistic language forms, one has an impression from the outside of what is actually being proclaimed inside as spiritual science. I would now like to show you another approach to the building, which presents itself when approaching it from the north:

Here is the building, here the main entrance, here a nearby building that has experienced very special challenges. I would just like to mention in this picture: the lower part of the building is a concrete structure. It has a walkway here. The entire building stands on the concrete rotunda. The entire double-domed structure is a wooden construction.

I note that the task was not only to create a shell for spiritual science in this building, but also to find a style for this very special institution that could be derived from concrete. That, ladies and gentlemen, is what is not really understood today, that we have to create out of the material everywhere. Today we see how sculptors create things that they shape, I would say, by having some kind of novelistic idea or a novelistic harmony of ideas, which are then shaped in any material, in bronze or the like. But we have to come back to having such an intense feeling for the material that we ourselves, even with this brittle, I mean artistically brittle, this abstract concrete material, gain the ability to create forms of design out of the material.

It is certainly the case that today people will not understand you if you say to them: I am going to paint a picture; in the middle I have this or that figure, on the sides this or that figure, I now want to do that, can you do something like that? And one answers: Yes, you can do anything, but it is a matter of what becomes of the colors. You cannot talk about a picture differently than from within the colors. Even in many artistic circles today, there is little understanding when one tries to think that which lives artistically as something quite separate from everything that is not direct contemplation, direct experience of feeling.

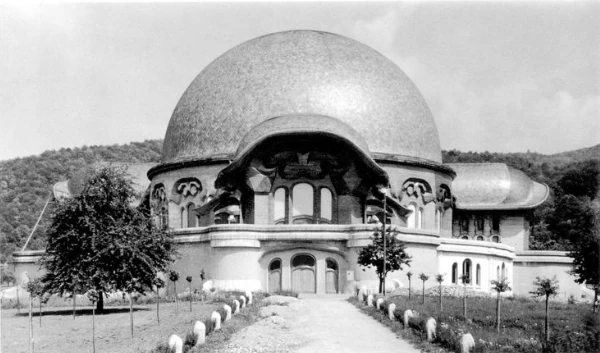

As the third picture, I would like to show you another aspect of the building. You can see the small dome, the large dome. Here, seen from the outside, the auditorium. The whole thing sits on the concrete substructure here. Here are the side wings, which fit into the building at the point where the two domes merge.

This is a slightly closer view of the structure. You will be entering from down here. The cloakrooms are located in the concrete substructure. There is a stairwell at the front of the interior. You can come up to this level through the wooden structure, but you can also come up here, where there is a walkway. You can walk around a large part of the structure here during the intervals between performances.

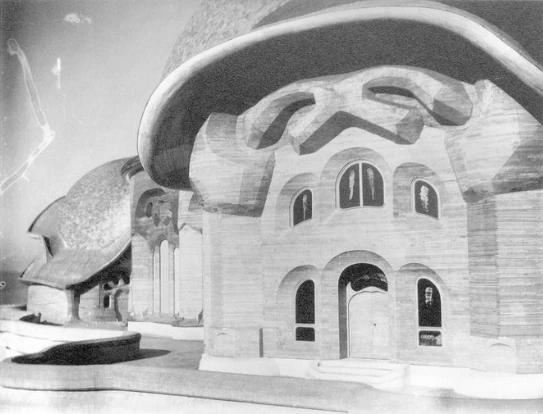

This is the main entrance from the terrace. You can already see that all the forms from the dynamic geometry have been transposed into the organic, into the living. There is nothing in this building that has not been created in the spirit in which I meant the design of the earlobe on the human body earlier. So everything, every detail and the whole, is designed in such a way that not geometric forms, but organic forms are present; but not, I would like to point out, organic forms that are modeled on this or that organic limb. That was not the intention at all. When I had first designed this structure in the wax model, from which the building then emerged, it was not a matter of reproducing anything naturalistically in organic forms, but rather of immersing myself in the creative essence of nature itself, of making what Goethe calls the truth, so to speak, of how nature lives in its creation.

Now, of course, nature does not create such structures. Therefore, one does not find those organic forms in nature that can occur in such a structure, but by having the whole structure like an organic being in its intuition, in its imagination, the inner creation is formed in such detail that detail that, without imitating anything in nature, one is compelled to shape a structure like the one above the main entrance in the same way that a plant leaf is shaped out of the essence of the plant organism. So without imitating anything naturalistically, natural creation should reveal itself everywhere without symbolism and allegory, purely by proceeding in the design of the building forms as one can imagine that nature itself lives in its creation.

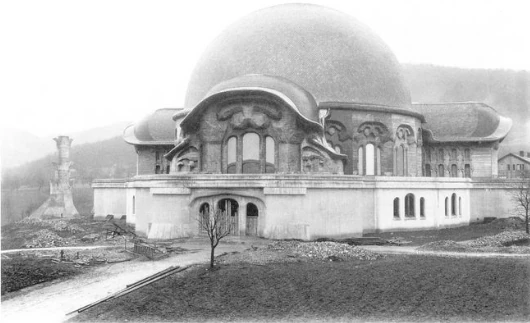

Once again, closer to the building. We are in front of the main entrance. This is where people will enter first. These are the cloakrooms. Then you come up through the stairwell and enter a vestibule, which I will also show later. This is the north side. Behind here are the storage rooms, the rooms for the equipment and the cloakrooms for the stage plays.

Another view of the main entrance. Here, the smaller dome is completely covered by the large dome. The two side wings were intended as dressing rooms for the performers.

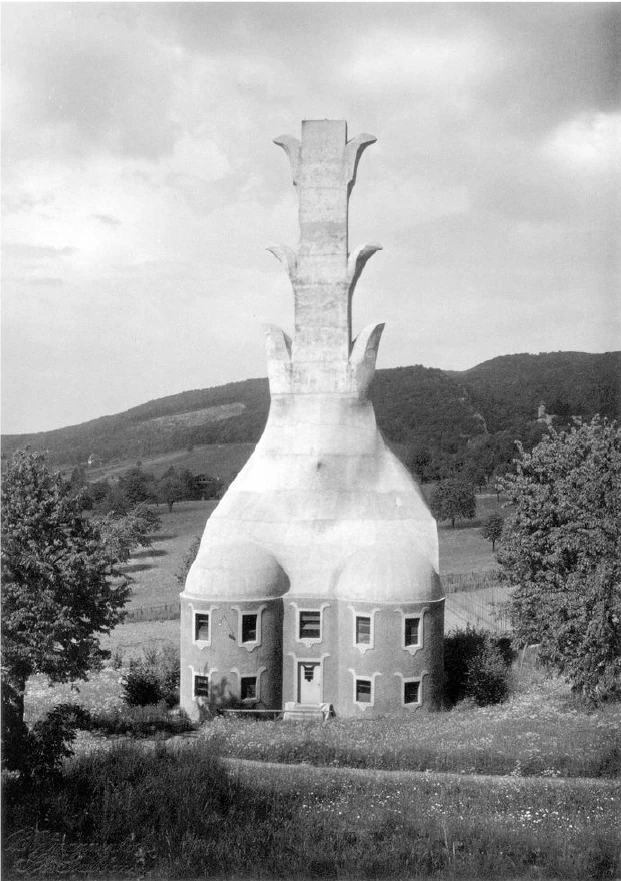

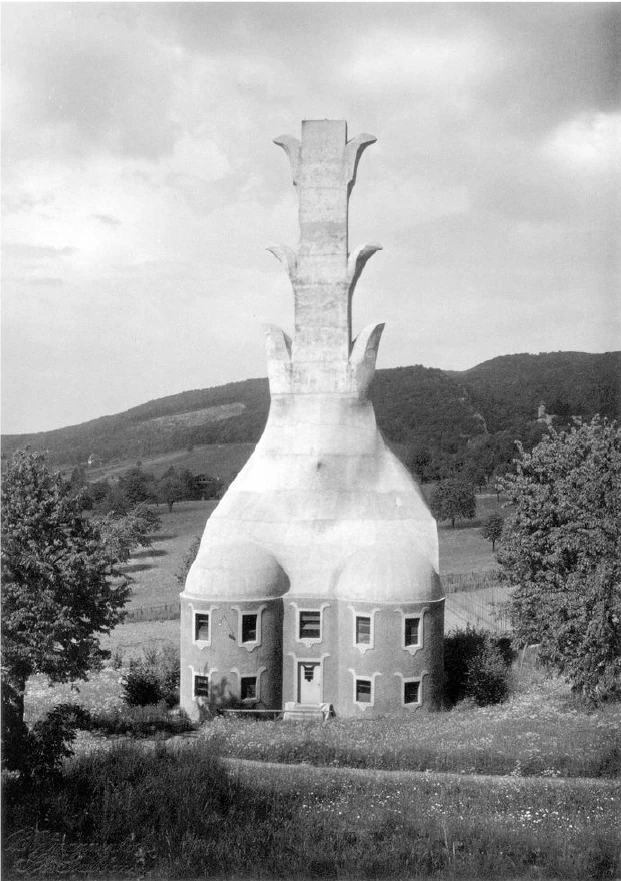

This is a piece of the side wall. Next to it is the house that the man who was able to give us the land for this building had built. This house was built for him in a style that is certainly, since it is all a beginning, completely thought out in all its individual forms using the concrete material. That is what I would like to say about this house.

Here you can see one of the side wings, which, as I said, are intended to provide dressing rooms for those performing in the stage festival. If you walk around here, you will come to the main entrance. Here is a piece of the facade of such a side wing. It has been attempted to follow Goethe's idea of metamorphosis – not in a pedantic way, but in the spirit of transforming the ever-identical, of transforming the ever-uniform, to form everything as an organic unity, so that the motif above the main entrance is repeated here, but in a different form. As you will see in Dornach in general, what Goethe calls changeability in organic structures has been tried to be expressed in the building idea everywhere.

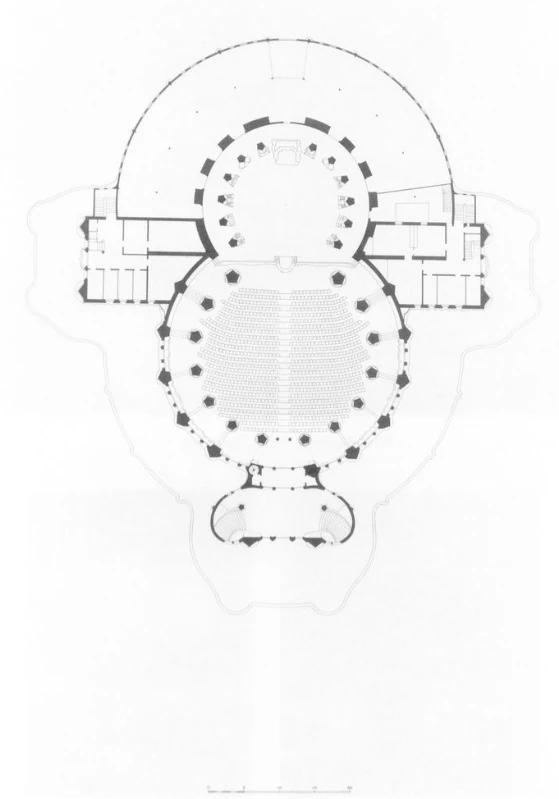

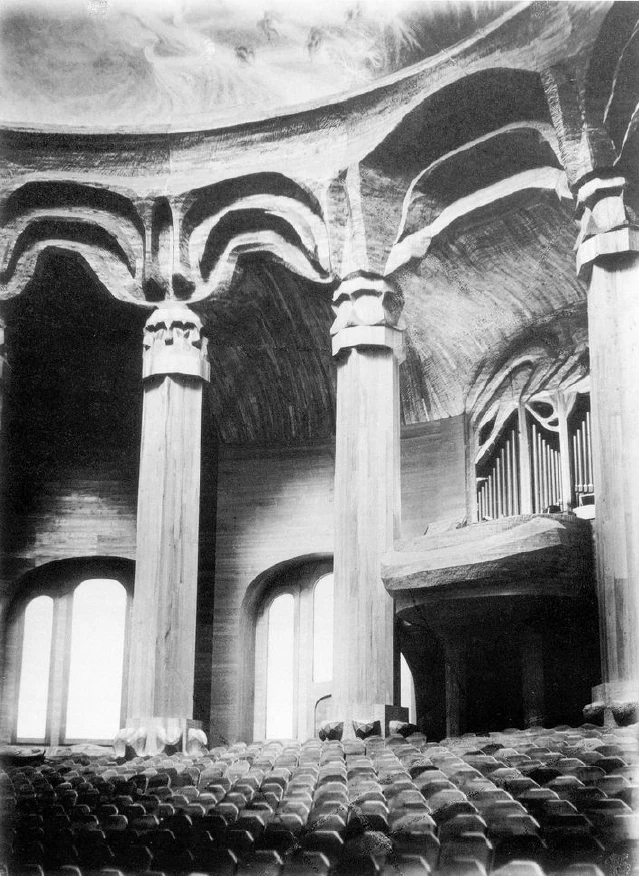

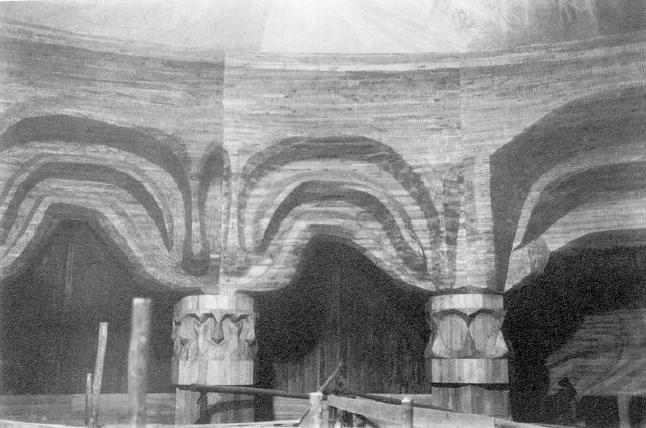

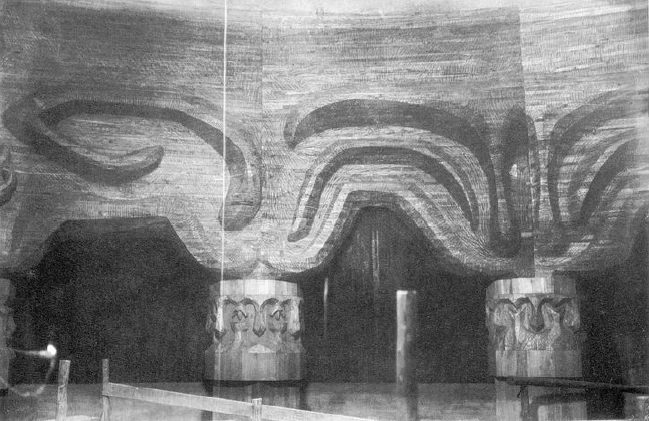

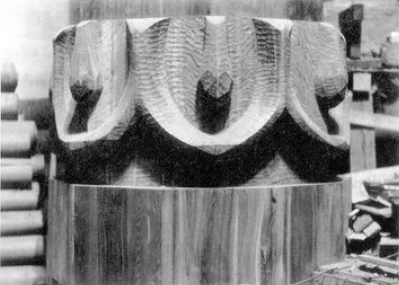

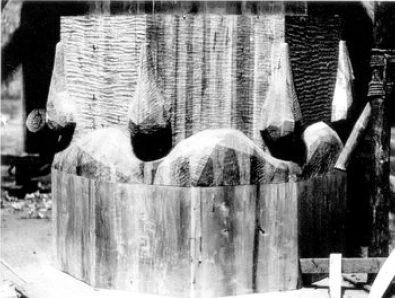

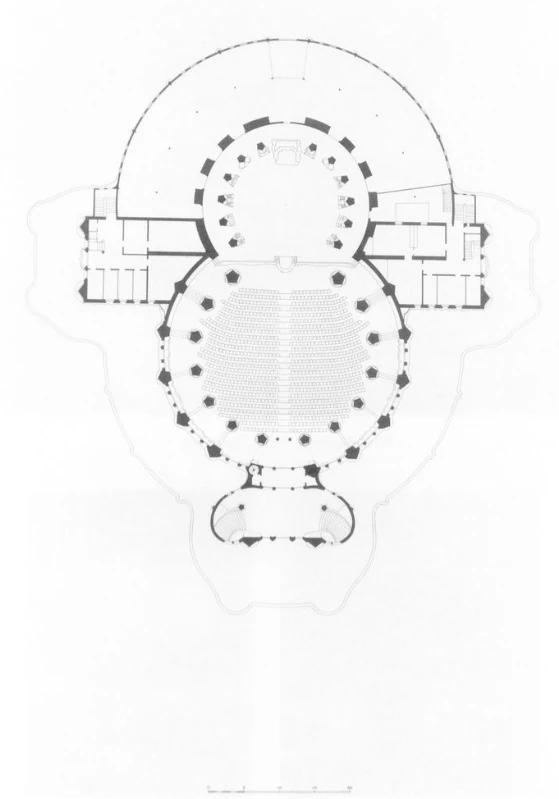

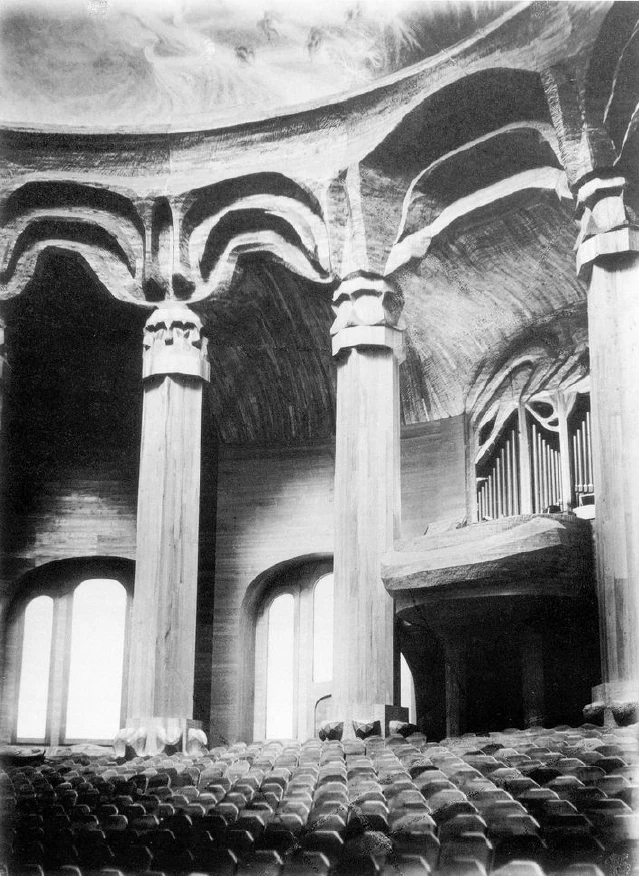

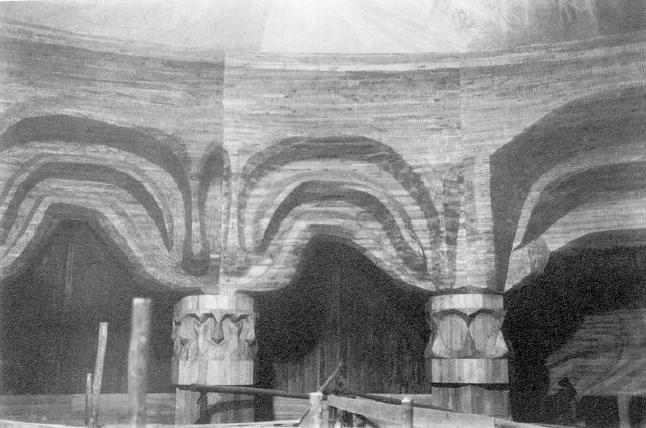

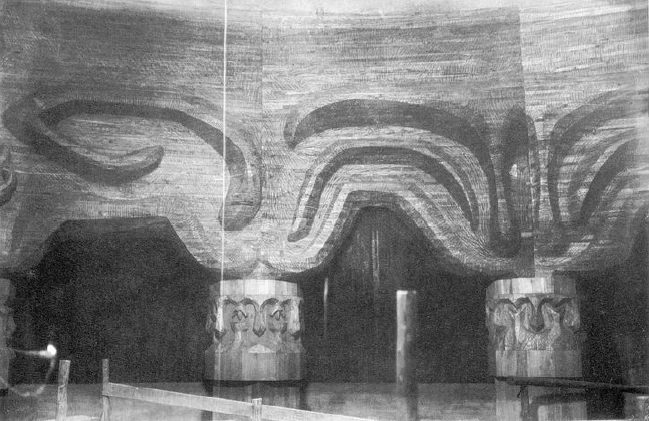

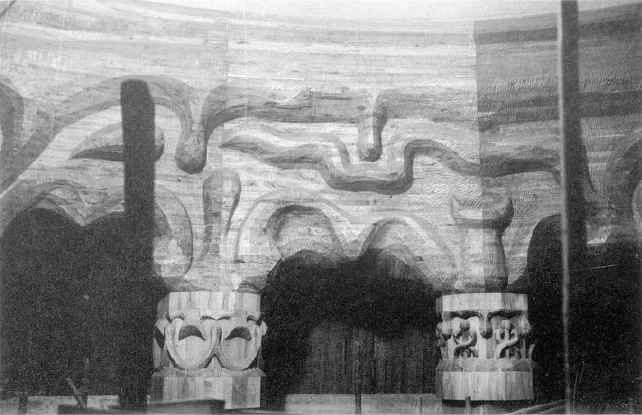

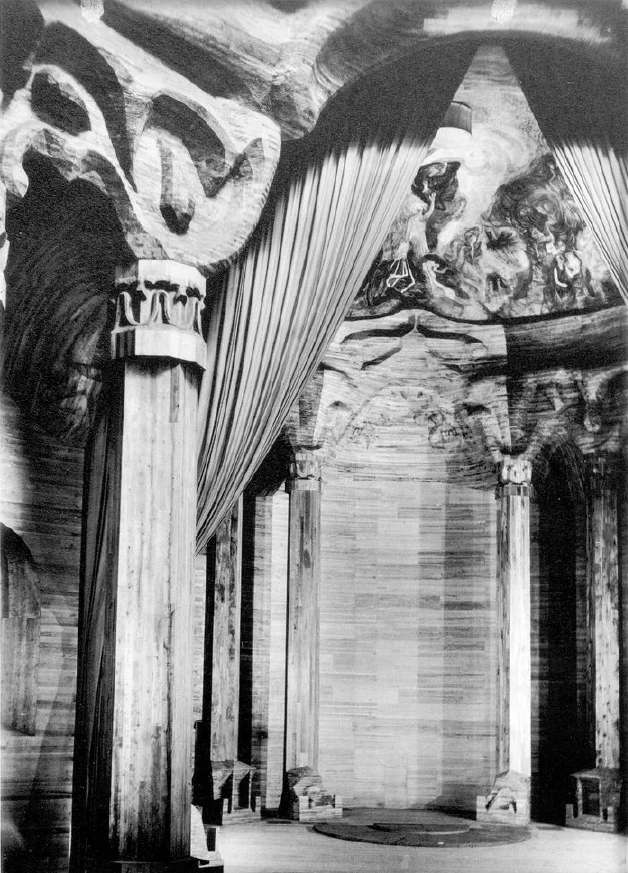

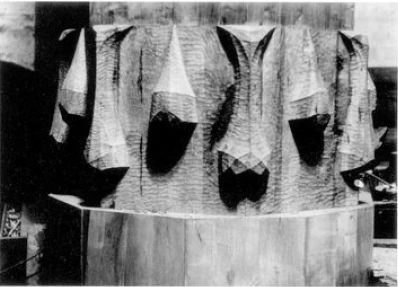

Here is the floor plan, here is the entrance, and there is the auditorium, which will hold about nine hundred to a thousand people. When you come out of the main entrance here, you walk through the space that is vaulted by the organ room above. You then come in here. The line that goes in this direction is the only symmetrical one in this building. Nothing else is oriented in a symmetrical way except for what lies to the left and right of this axis of symmetry. Therefore, as you enter the room, you see a row of columns. These columns are formed in such a way that only the symmetrical pairs always have the same pedestals, the same capitals and the same decoration in general. The formation of the capital progresses as one moves from the entrance towards the stage, so that each successive capital is formed in such a way from the previous one that the space of the architrave above a column is formed from the spatial design of the architrave above the previous column, so that the metamorphosis view is expressed in the right sense.

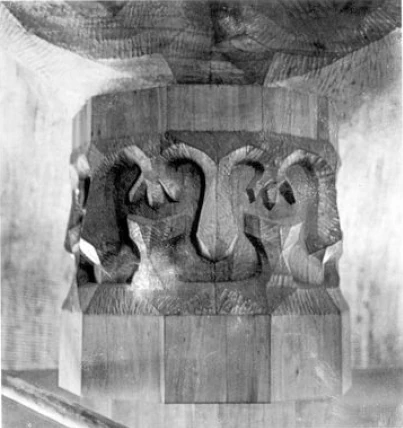

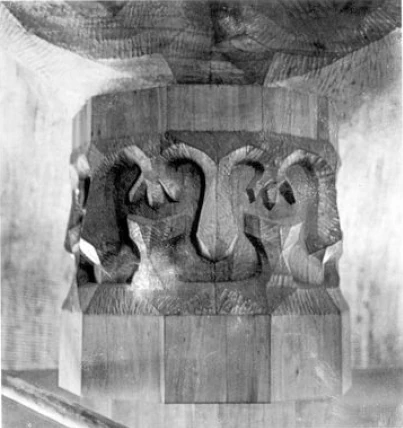

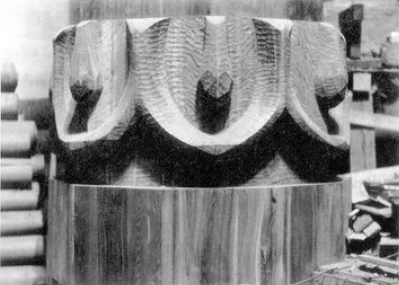

It is, I dare say, a great thing to attempt such a thing: here you have a first capital with very definite forms that arise inwardly for you as you shape them. And as you say to yourself, now it is so that it must remain in the place where it is, then the feeling comes: That is also to be transformed, just as in a plant growing out of the ground, a subsequent leaf is something metamorphosed in relation to the preceding leaf. There you shape the next form out of the previous one. There the next form presents itself as something absolutely necessary. People often come to Dornach and ask: What does this or that chapter mean? My task is simply to say: look! It is not a matter of someone finding an abstract, complicated meaning, but of sensing how the following chapter always grows out of the previous one in organic necessity.

The smaller dome, framed by twelve columns, and the fourteen columns here, will provide space for the presentation of stage plays. Often, people also count when they come: one, two, three, four, five, six, seven. Seven columns! Then they say: They are mystics, they bring in the superstitious number seven. I can only say: Then nature is also superstitious. The rainbow has seven color shades, we have seven tones in music, the octave is the repetition of the prime. What is so self-evidently expressed in nature is repeated in the direct experience of creating something metamorphic. And I may well say: it was far from my mind to pursue some mystical number seven, but it was obvious to me to think of one capital out of the other. And then a wonderful thing happened – if I may call it a miracle – that just as there are seven colors in the rainbow, without any mysticism, simply by shaping the form, when you are finished with the seventh form, you can't think of anything more. That's how you get the seven forms. With the seventh, you can't think of a single small artistic idea, so you just know you've finished.

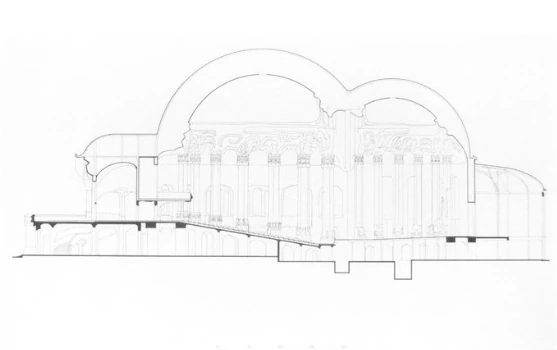

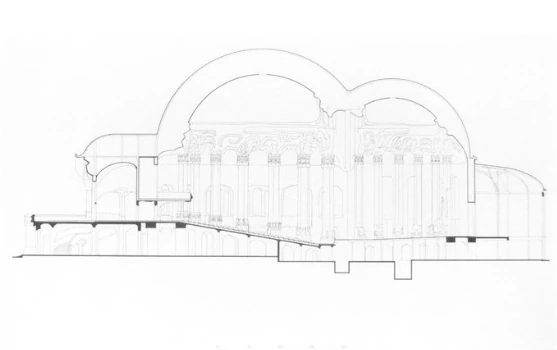

This is a section through the original model. It is cut through the axis of symmetry, so that you can see the formation of the columns in progress, the architraves on top, the bases. So this is the model on which the construction was based.

Another section, a kind of drawing section through the building. Here is the concrete substructure. Here we have to show how the two domes are joined together. But here too, two domes are joined together, leaving the space between them free.

I originally had a specific idea in mind when arranging the double dome. When building such a thing, the most important thing is the acoustics, and I had the idea that if you connect two such domes with a connection that is as light as possible, a kind of soundboard must be created.

Furthermore, not for mystical reasons but for very real ones, I had the seven columns made out of different types of wood. All of this, of course, yields a great deal when one tries to think and feel it all together. But many people know how difficult it is to get the acoustics right in a hall. Basically, everything was thought out, down to the choice of materials – as I said, the columns are made of different types of wood – and into this soundboard, so that both the sound that develops in the musical sense and the sound of the spoken word are accentuated in a beautiful acoustic way throughout the entire room.

Just as the whole thing is an experiment, and one could not think that the most perfect thing could be created in the very first attempt, so I could not indulge in the illusion that the perfect acoustics had been created. But we were able to experience how the intuitions revealed something in the very last few days. The organ was installed as the first musical instrument. It was completed, and it became apparent to us that the entire structure, in terms of music, reveals itself acoustically in a very unique way. And I dare to hope – things are not yet ready, that can prove this – but when everything is there, including the curtain, that then the acoustics, including those for the spoken word, will also reveal themselves. But in any case, the one rehearsal for the intuitive design of a space with regard to the acoustics, the one rehearsal in terms of the music, seems to me – and as it seems to everyone who has heard the organ there in the last few days – to have actually been successful.

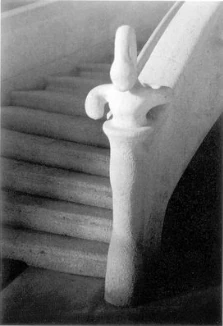

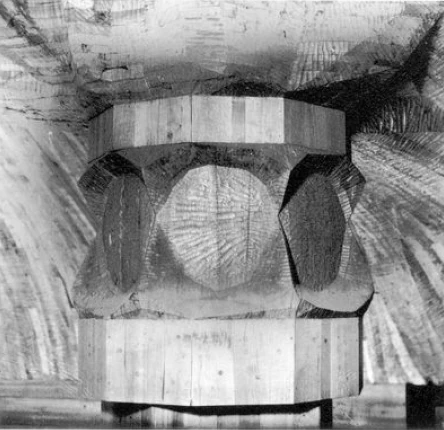

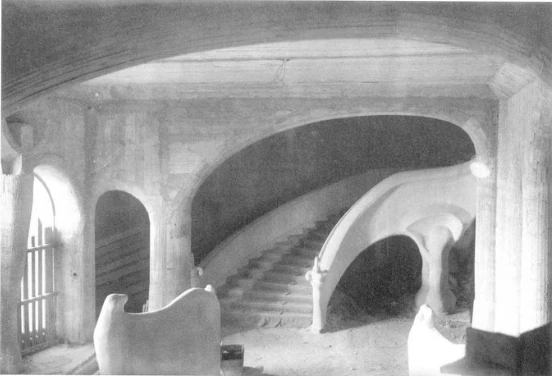

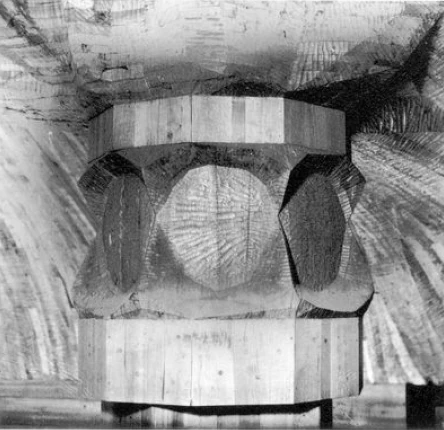

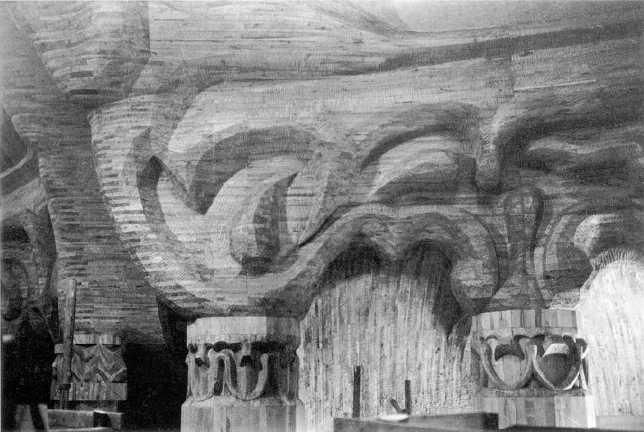

A little way into that staircase, which you enter when you come through the main entrance into the interior. You see here a capital above a column. You see this capital formed in a very special way. Every single form, every single surface, every single curve is conceived with the space in which it is located in mind. The line and surface run this way because this is where you come out, because there is little to bear. Here the column braces itself against the building. Here the individual forms must be shaped differently. Just as nature creates differently when it creates a muscle, depending on what it has to bear, so we must experience how the forms must be when each individual link in its place is to be thought of as it can only be in this place through the nature and essence of the whole.

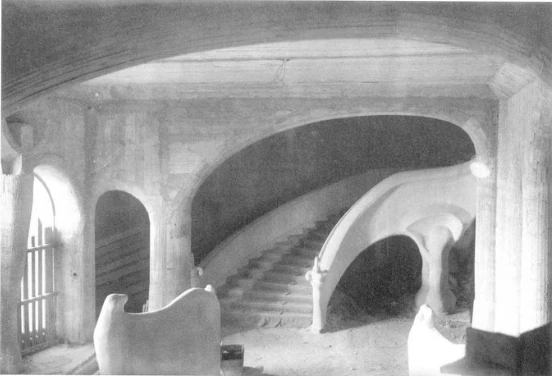

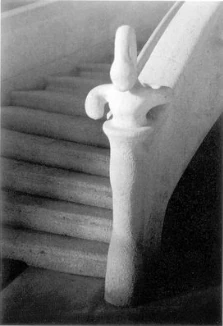

This is the staircase itself. The staircase goes up here. What I showed before is the vestibule above the concrete room. This is where I am standing, and this is where you would stand when you enter the building. Here is the banister for the staircase that leads up from the lower concrete substructure to the building, which is then made of wood, to the actual auditorium. I have tried here to transform a support from the merely geometrically mechanical to the organic.

Let me reiterate: I am, of course, aware of all the objections from the point of view of conventional architecture, but it has at least been attempted, and I have the feeling, however imperfect everything is, however many objections there may be, that a start has been made that paves the way for a new architectural style that will be further developed. Perhaps it will lead to something quite different from what has been built in Dornach, but if you don't even start with something, nothing new will come of it. Therefore, even if it goes completely wrong, something new should be attempted here: the development of the mechanical-dynamic form into organic forms. The concrete is worked in such a way that the beam expresses in its own form what it bears; on the other hand, it is shown here how it only forms outwards, bearing nothing.

Here you can see a radiator screen. The individual radiators are covered at the bottom with concrete screens and at the top with wooden screens. These screens are designed in such a way that their plastic forms reflect something that, in its formation, is, so to speak, in between animal and plant forms. It comes from the earth, as if organically grown, but not symbolically, but artistically designed. In creating this, one has the feeling of something coming into being if the earth itself allowed something like this to grow out of its principle of growth. If you take this staircase, you will come to the room that was shown before, and through that you then enter the actual auditorium.

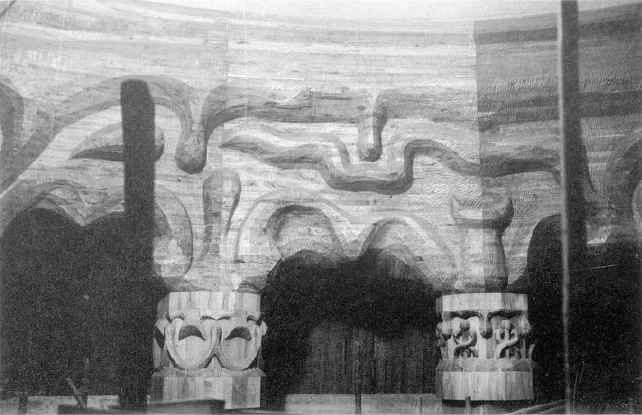

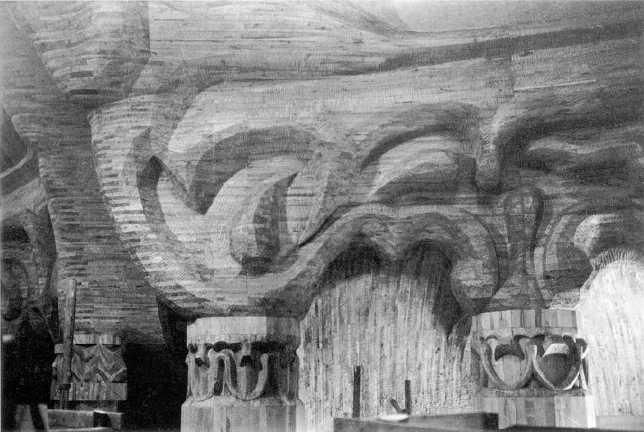

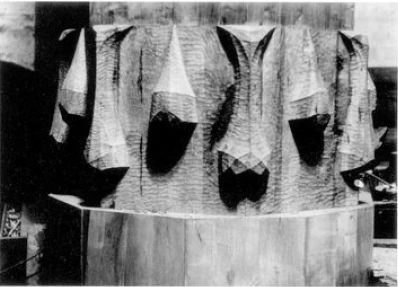

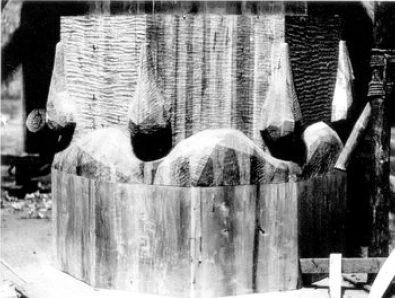

So this is where you come in, enter the auditorium. Here on the left and right are the first two columns. You can see how the simplest capital structure, the simplest architrave structure, is used here. And now you will see how each subsequent capital structure attempts to create something that necessarily grows out of what has gone before, just as a subsequent plant leaf, which is more complicated and more dissipated in form, always grows out of the one that went before.

Here is the first column individually. It is always important to me that one sees that the essential is not: what does the individual column mean? Some people have done a terrible disservice by always talking about the meanings of the Dornach columns; it is important to me that the artistic form must be questioned. Therefore, I will always show the one column and the next one, so that it becomes clear how simply, artistically, the next form was attempted to be derived from the preceding one.

So here, continuing from the simple column – that is the left aspect – we have the second column. It is designed in such a way that what goes down here goes up there. Just as a plant leaf develops from another, this capital form is derived from the preceding one through artistic experience, and this architrave form from the preceding one.

The second column by itself. Now the following two columns, always to illustrate how the next column is to be artistically designed from the previous one. There now follow several column pictures, initially single ones, then in twos.

Everything that one experiences artistically is actually formed in one's imagination as a matter of course. One cannot help it, it just happens. One can hardly say anything else about it either. But the strange thing is: when one simply transfers one's own experience into the forms, then one gradually feels how one creates in harmony with nature's own creative process. One feels the life that lies in the shaping of one metamorphosis out of another, in intimate harmony with natural creation. And so I believe that those who experience – not intellectually, but with lively feeling – what develops there as one capital out of the other actually get a more vivid sense of development than can be given by anything in modern science. For when we speak of development, we usually mean that each successive structure is more complicated than the one that precedes it. This is not true. When one inwardly experiences a development such as this evolution of columns and architraves, then at first the simple develops into the complicated. But then one reaches a height, and then the structures become simpler again. You are amazed when you see the results of artistic necessity, how you create in harmony with nature. Because that is how it is in nature too. An example: the most perfect eye is the human eye, but it is not the most complicated eye. The animal eye is much more complicated than the human eye; in certain animals there are fans and xiphoid processes; in humans this has been absorbed again. The shape is simplified. You don't follow that when you create something like this from abstract ideas, but it presents itself to you as something self-evident in the form.

The next two columns. Here we come to something that the abstract mystic or mystical abstractor might say: “He formed the caduceus here.” I did not form the caduceus, I let the preceding forms grow. It formed by itself. It emerges organically, by itself, from the preceding form. I had to say to myself: “If the preceding column grows just like that, it will come out like that, one from the other.”

Two consecutive columns showing how the forms become simpler as development progresses.

Here we are already approaching the gap where the auditorium borders on the stage.

Here the first column of the stage area; here the last of the auditorium, here the gap for the curtain.

Here you can see into the small domed room. If you stand in the auditorium and look that way, you get a view similar to this. The top of the dome, initially carved and then painted. We won't look at the painting here, we'll come to that later.

Here I would like to show the order of the individual columns, so that one can get an overview of how the matter progresses from the simplest. All the individual columns are formed individually for each column, and symmetry is only found in relation to the main axis of symmetry of the building.

Here are the figures on the pedestals. I also tried to give the pedestals a metamorphic appearance.

I would like to ask you to take a look at something that is not quite finished yet: the room in which the organ is built. The idea was to avoid making the organ look as if it had simply been placed in the room, and instead to make the whole structure appear to grow out of the room. That is why the architecture around the organ is designed to match the way the organ pipes have to be constructed. It is not finished, as I said. There are still things to be added here.

This is what you see when you enter the small domed room from the auditorium. The end of the small domed room. A number of forms have been carved out of the wood. All of them have been carved out of the rounded surface of the wood, a number of forms that are a summary of the forms found on the capitals and architraves. So that, standing in the auditorium, one has the forms of capitals and architraves, and when one looks up into the small domed space, as a conclusion to all this on a spherical surface, which is like the formal synthesis, the formal synthesis of what can be seen on the individual forms of the architraves and capitals. And now I have to move on to something about which I will have to say a few words.

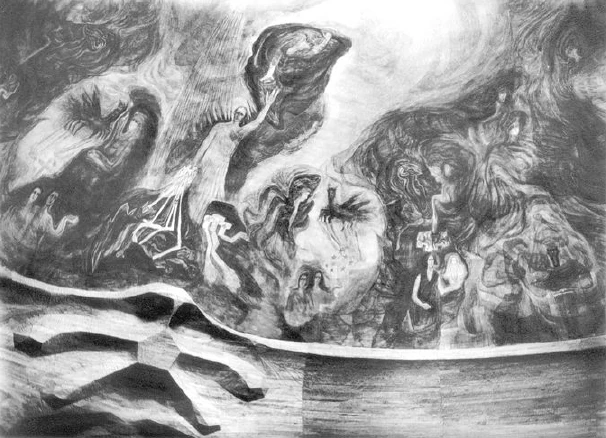

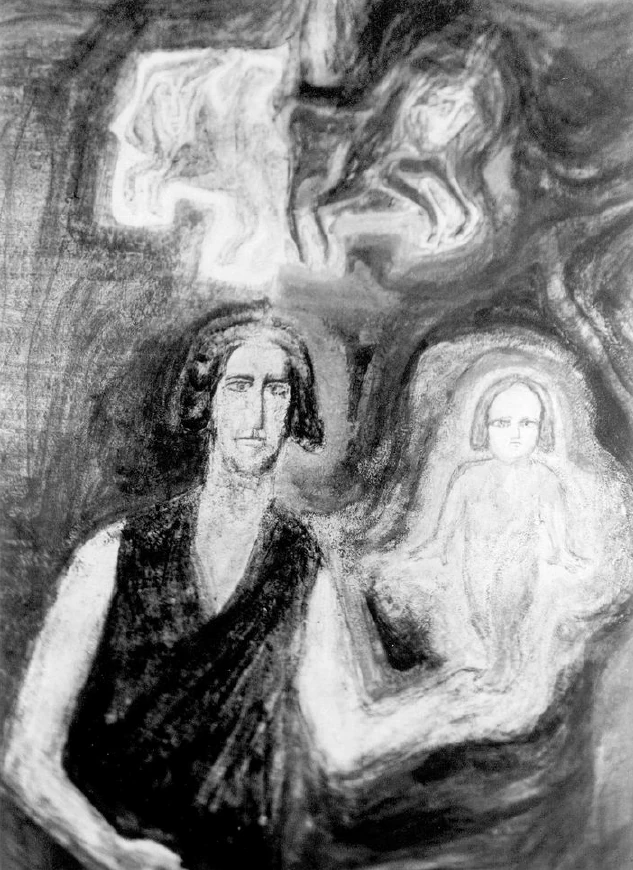

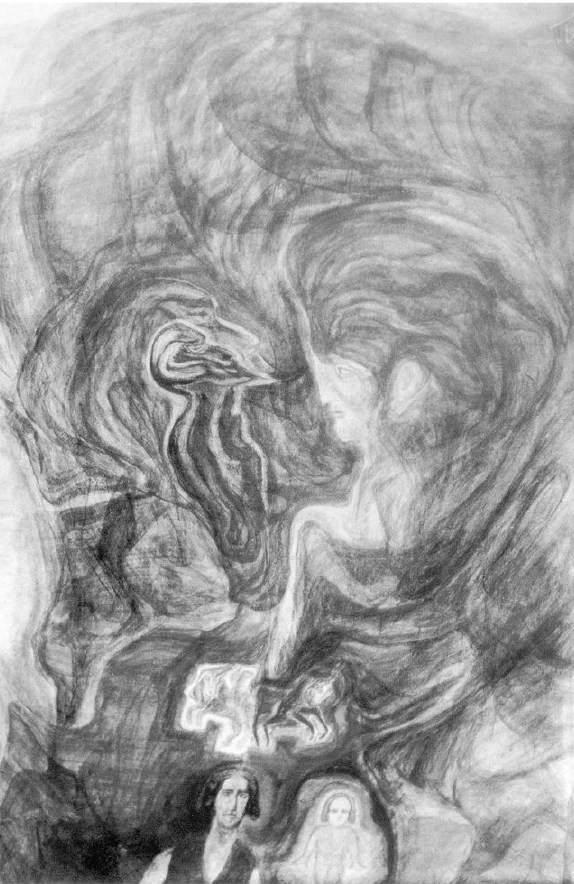

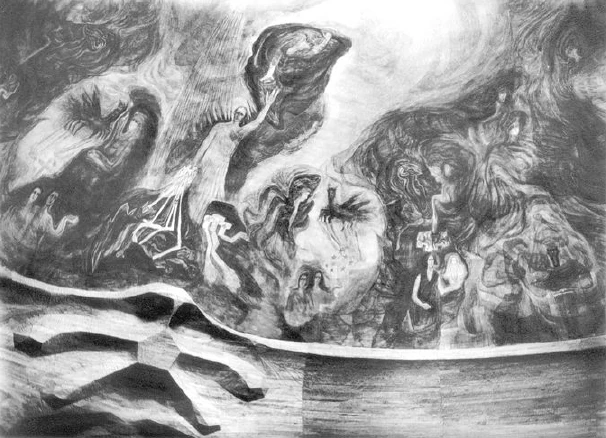

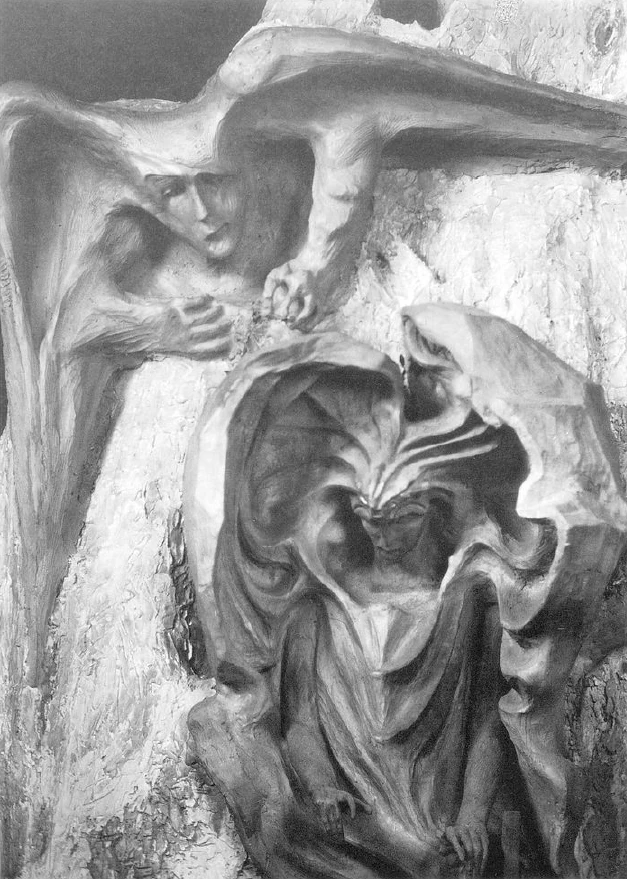

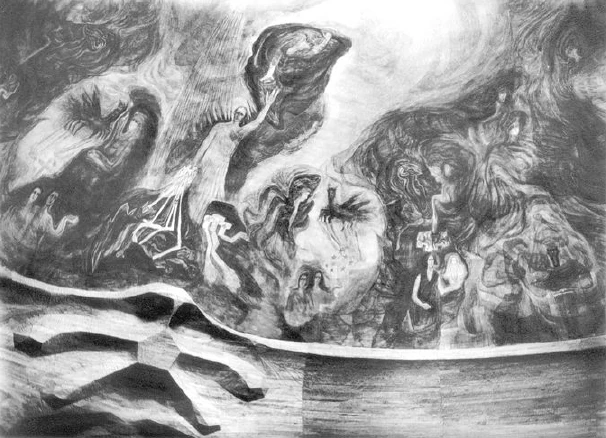

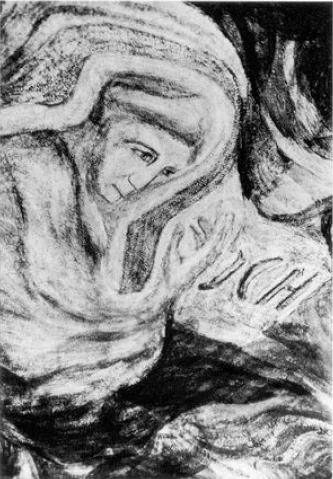

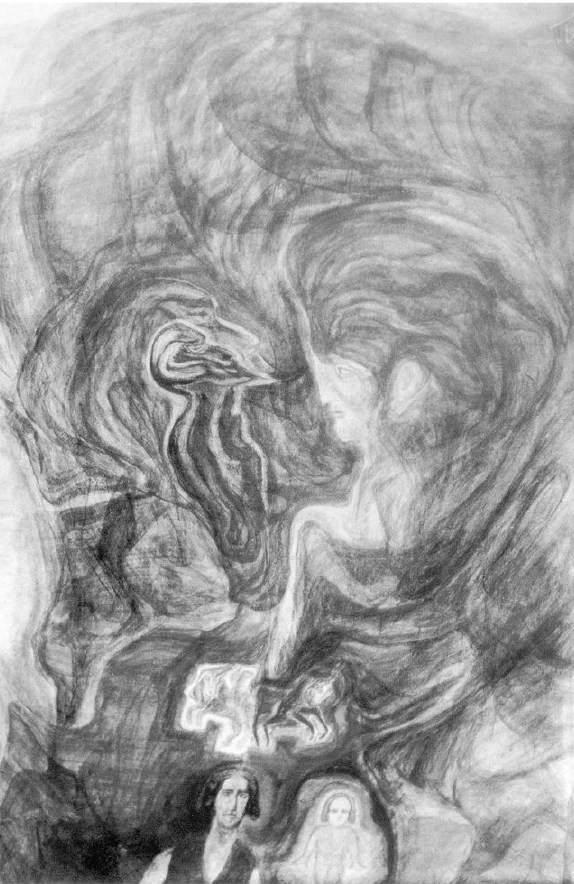

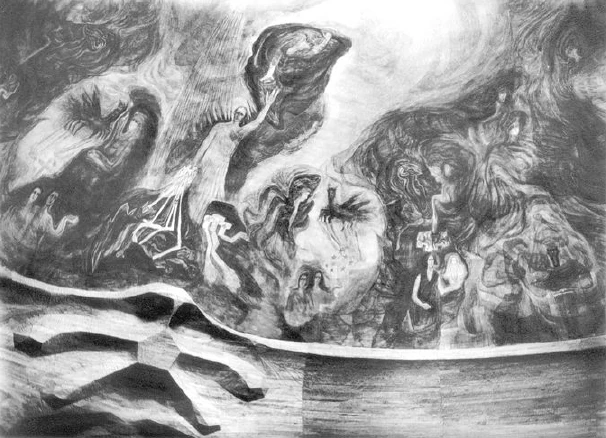

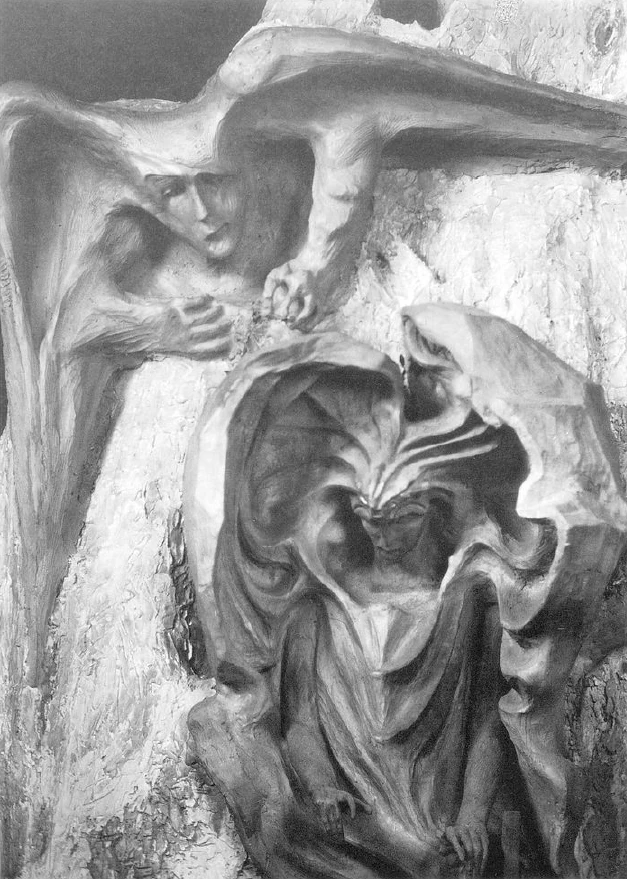

This is what the small domed room looks like when it is painted. Both domed rooms are painted with motifs that actually only arise when you live very inwardly with what we call anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. When you live very inwardly with this, then, I would like to say again, picturesqueness also emerges all by itself. Just as the word is formed by wanting to express the inner spiritual experience through the word, so this inner spiritual experience, which is truly not so poor that it could only express itself in abstract thoughts and ideas, but can express itself in everything that is a form of life and the purpose of life, is transformed. And motifs that are just as much alive in the one who lives in the inner contemplation of the spiritual world, as it is conveyed through spiritual science, are also painted in the large and small dome in such a way that one does not have the feeling of being closed off by the dome, but rather that one has the feeling, through what is painted on the wall, that the domes form themselves far out into infinity. I want to discuss, because I can't explain everything, only what is painted here in the small domed room, so that you can see it immediately when you look from the auditorium into the small domed room.

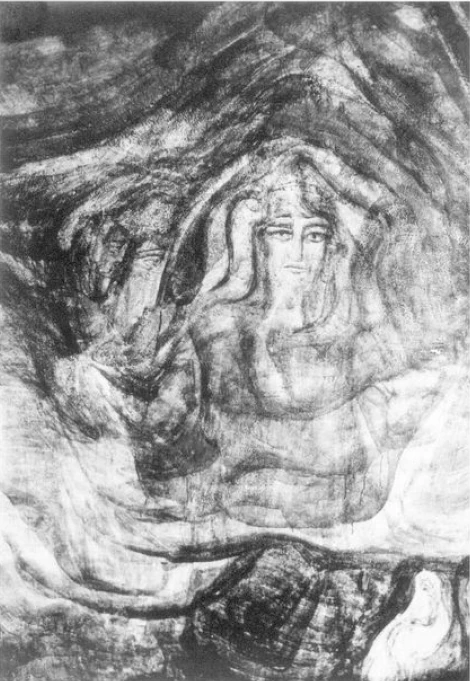

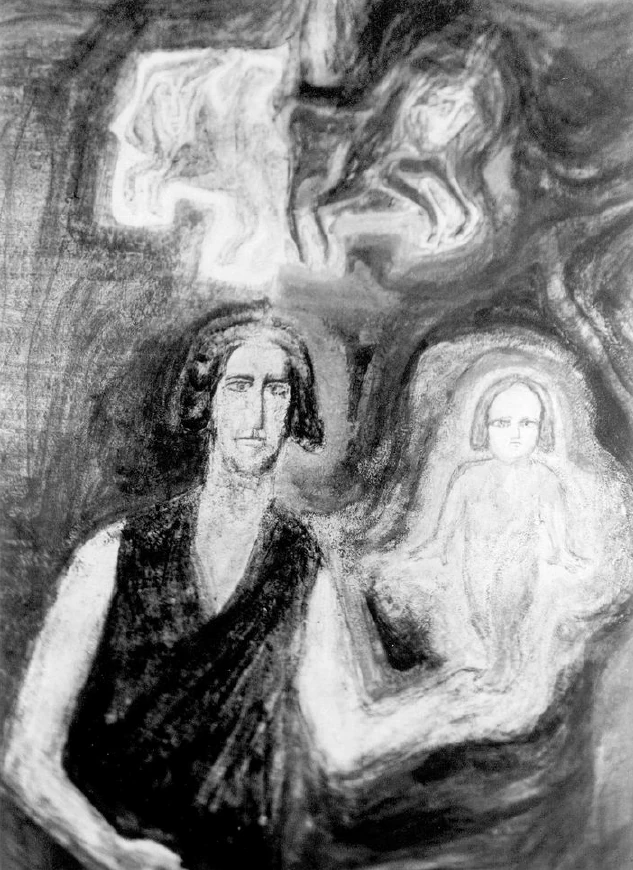

There is a central figure. It represents to me, as it were, the representative of humanity as such. At the same time, it is the artistic expression of that which lives in the human form. So that even in its natural human form, the human being must constantly seek balance between two extremes. What the human being actually is is something that should be expressed by the content of all anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. This cannot truly be said in one or even many lectures, but comes to expression in the fullness of all spiritual science. But one can say the following, which is still somewhat abstract but already points to what is experienced as human essence in the human being. One can express it in soul terms as follows:

In fact, human beings are always engaged in an inner battle between something that works in him in such a way that he wants to rise above his station. All that is fanciful, enthusiastic, mystical, theosophical, that seeks to lift man in the wrong way above himself, so that he no longer remains on the firm ground of reality, all that is one extreme. This is what some people tend towards, what every human nature secretly tends towards, and what every human nature must overcome through its health. Enthusiasm, fantasy, one-sided mysticism, one-sided theosophy, in short: everything that makes man want to rise above himself, is one thing in the soul. The other thing that is in the human soul and must be overcome through inner struggle is what constantly pulls him down to earth; expressed in spiritual terms: the philistine, the bourgeois, the materialist, the merely intellectual, the abstract, the calculating. And that is the essence of man, that he seeks to find harmony between the two opposite poles.

In physiological terms: the same thing that appears physically when a person wants to go beyond themselves is also expressed physiologically in the fact that a person can become feverish, develop pleurisy, that human nature is led into dissolution. The other extreme, that which develops in the soul as mere intellect, as narrow-mindedness, as philistinism and materialism, is what causes the ossification of human nature and leads to one-sided calcification, to ossification. Between these two physiological extremes, human nature fluctuates and seeks balance.

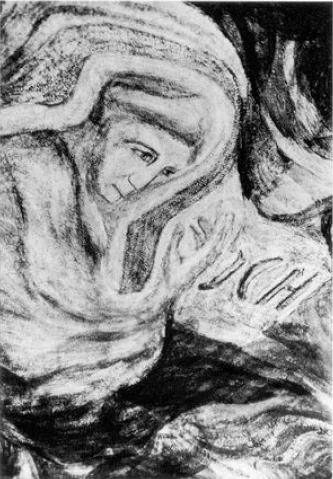

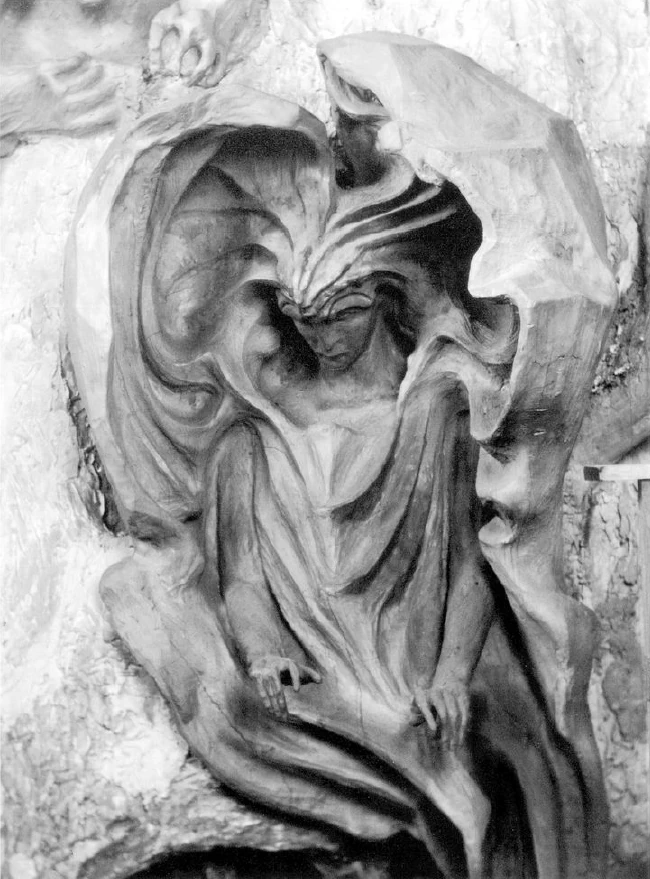

The intention is not to present an idea, but rather – both pictorially up there and sculpturally in the group of figures down here – to show how the representative of humanity lives in the middle between the two extremes that I have depicted. And so, above the central figure, which expresses the representative of humanity, there appears, at the top, a luciferic figure that expresses everything that is enthusiastic, fanciful, feverish, and pleurisy-ridden, etc., that wants to lead people beyond their heads. And at the bottom, protruding out of the cave, is the representative of everything ossified, everything philistine, everything that leads to sclerosis in its one-sidedness.

This central figure is designed in such a way that there is nothing aggressive about it. The left arm points upwards, the right downwards. Every effort has been made to represent love embodied in this representative of humanity, right down to the fingertips. And just as I am convinced that the trivial figure of Christ, as we usually see it, bearded, only came into being in the fifth or sixth century, so I am convinced, from spiritual scientific sources, which I can't talk about, but only because of lack of time, I am convinced that the figure that is depicted here is a real image of the one who walked in Palestine at the beginning of our era as the Christ-Jesus figure. And there should be nothing aggressive about it, even if the figure of Lucifer is painted, poetically shaped, falling and even breaking into pieces, not through an attack on the part of Christ Jesus, but because in his Luciferic nature he cannot bear the proximity of embodied love.

And if Ahriman, down there, the representative of the ossifying principle, the being that carries within itself everything that seeks to bind human beings to the earth, everything that does not want to let them go, suffers torment, ground. This is not because the figure of Christ hurls lightning bolts, but because this ahrimanic entity, through its own soul condition, so to speak, out of embodied love, casts lightning bolts for its own torment.

Here I really tried to depict love both plastically and pictorially in this central figure. And in a similar way, the inner experiences of spiritual science are given in the pictures on either side of this central group. But I can only show you the content of what is painted here. But that is not the main thing. In the first of my Mystery Dramas it is stated that in truth only that corresponds to modern ideas about painting in which the form of the color is the work. And here in this small dome an attempt was once made to create everything that was to be created out of color. If someone asks about the meanings, they are at most what one has tried to attach to the color scheme. I have to keep saying: one sees the color spot there or there, and what is in its vicinity as color spots, that is more important to me than what is meant there in a novelistic way.

An attempt has been made to realize this – I know all the counter-arguments – but it has been made, to realize what appears to me to be the case: I actually perceive every line in nature, when it is reproduced by drawing or painting, as a lie. The truth in nature is color. One is not concerned with the horizon line, but above with the blue firmament, below with the green sea, and where the two colors meet, the line and the form arise by themselves. This is how I have tried to paint here: everything from the color. The line should be the creature of the color.

Here you can see a section of the painting more clearly.

Here is a kind of rule of thumb. Here is the only word written out with letters that can be seen as a word in the whole structure. Nowhere is there anything symbolic that could be expressed in words; only here at this point, where an attempt has been made to convey the sensation as an experience through color, which occurred around the 16th century, when humanity developed more and more towards an individualistic soul life; there, knowledge took on very special forms. Those who speak of knowledge in such abstract terms, as many epistemologists do, really know nothing of the inner experience of knowledge. Today, knowledge is only known by those who can see before their soul how, in the process of limiting human life, childhood emerges from the spiritual world.

Here the child and on the other side, death. In the middle, the realization, the realization that brings it to the individualism of the ego-grasping. That which humanity has felt as actual cultural thoughts, for example in the 16th century, is attempted here to be expressed through color. I can only show you the content, which is not the main thing. But I think that precisely because this content is imperfectly depicted here, it evokes the feeling that something is still missing here, without which this thing cannot truly be what it should be. Anyone who sees this should feel that there should be color: here the child in its particularity, here the self, there a kind of fist-like figure, and below that death.

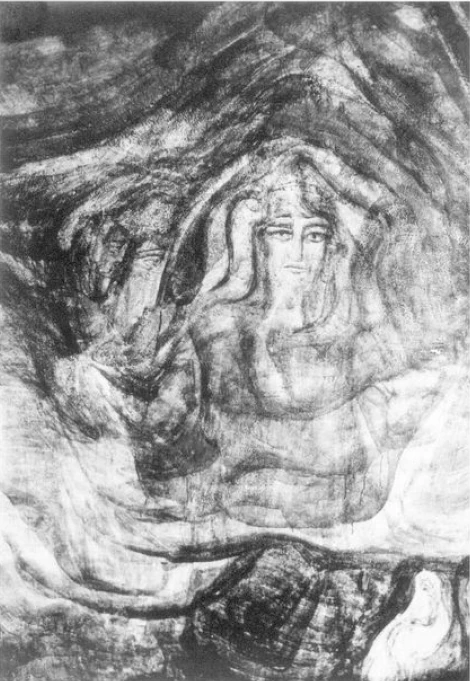

Here a little further. With the first figure we were still touching the auditorium. Here we come to the middle of the small domed room. There we have a figure that is supposed to represent how the spiritual was experienced by a cognizant human being in ancient Greece. The sensations, as they pass through human spiritual culture, should be seen in colors on the wall.

Here is the figure, which is, as it were, the inspiring figure above the Faust figure. You always see the inspired below, with a kind of genius above. Here is the genius of Faust, who appears as a kind of inspirer of Faust.

Here is the figure that can be seen above the Greek figure as an inspiring figure. It was a natural development that the genius of the sentient and cognizant entity was depicted as Apollo with the lyre. This is a higher inspiring entity that is always above the one who is down below, who is sitting down below, as it were, on the column. The inspiring figures are painted in the dome space.

Here below is an Egyptian figure, leading the Egyptian soul-life. The two figures shown before (Fig. 75) stand above her and represent the inspirers; the entities that are meant to pour the soul-life into them. Fig. 44 (Fig. 77):

Here I have tried to show how the civilization that I would describe as that of the Persian Zarathustra culture, which dates back to primeval times and has a view of the world as dual, ambivalent, as a world in which light and darkness cast their effects, how this view of the world has spread from Asia through Central Europe, and how it is still expressed in Goetheanism, where man experiences it. That is the essence of our Germanic-German culture: we always experience this contrast between light and darkness, which is already expressed in the old Zarathustra culture, this contrast that cuts so deeply into our souls when, on the one hand, we feel something that wants to grow beyond us like light; on the other hand, something that, like heaviness, wants to pull us into the earth. This is how the dualism that is felt should be expressed.

Above them you can see two figures. Sometimes you get fed up when you have been working on something like this for months. I got fed up while forming these two figures, in these figures, in which the inadequate and the ugly come to life, to recreate something like Mr. and Mrs. Wilson. That was something like a bugbear. But the other thing is that, basically, something lives in the Germanic-German soul when it experiences the thought of realization, which can only be endured if one recognizes full life in harmony with where life innocently enters physical existence from spiritual worlds.

Here you have, so to speak, an inspiring summary of everything that appears as duality: the being of light, the Luciferic, that which tempts people to fall into raptures; the other is the pedantic, the philistine, the Ahrimanic, which would like to drag people down. No civilization experiences this dualism as deeply and dramatically as the one within which there is a transitional context for contexts that go back to ancient times to the Zarathustra culture and find their expression in all that has become Goetheanism, which we still feel by spiritual science itself compels us to present the representative of humanity as he must seek the balance between the Luciferic, the mystical, the enthusiastic, the theosophical, and the Ahrimanic, the pedantic, ossified, philistine, sclerotic, and so on.

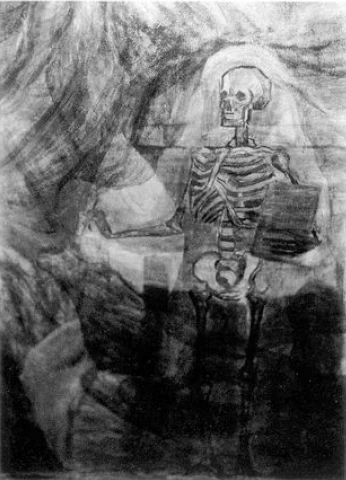

Here is the one figure, the ahrimanic, philistine, pedantic one, with the forehead set far back; the whole built as man would become if he were pure intellect. Only by the heart working its way up into the head do we avoid one extreme, how we would become if we only developed the things that form the skull, but which cannot form themselves according to their own inner forces because this is counteracted by the heart and the whole of the rest of the human being.

Here the other aspect, counteracting the Ahrimanic aspect. Between these two aspects, man must always seek his equilibrium. Christ is the great Master who leads us on the path to find this balance.

Here we come up against the central group. This is what will arise when dualism has developed to the point where the human being feels himself to be twofold, as a higher and a lower human being; that he has his shadow within himself, but as a shadow that he digests spiritually and mentally.

As a kindly genius that is above him.

Here a centaur, inspiring him what needs to be overcome in us as animality. Up here the centaur form, inspiring a future culture, next to the genius, the angelic, what approaches man on the other side.

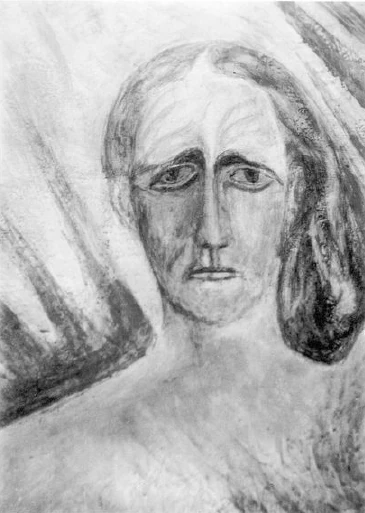

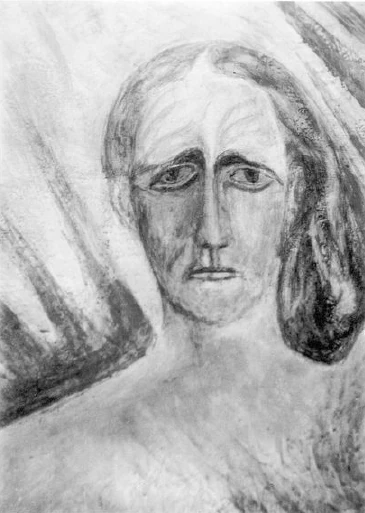

Here is the central figure, Christ, not by attaching a vignette to him, but by placing him as the central figure. One should feel artistically: this is the figure in which the divine has appeared on earth. One should feel it from the form, from the line, from the surfaces and here from the color.

Figure 53 (illustration unclear): Here, at this point, it has, so to speak, been completely successful, even if it is only an attempt, to create everything out of color, without line.

Here is the head of the Representative of Man. Above it, Luciferic; below, Ahrimanic. This is the head that appears to me, from the spiritual vision – as far as one can form it – as the true form of the one who lived in Palestine at the starting point of Christianity as the Christ.

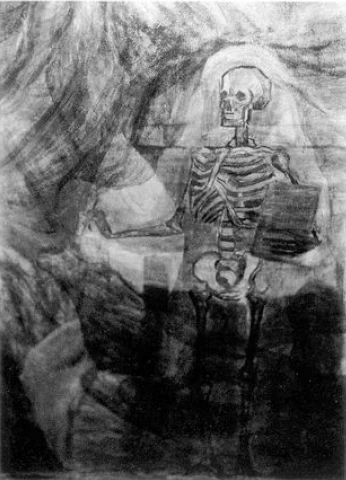

Here is the figure of Lucifer, collapsing into himself. It is painted in red and worked out of red. Picture 56 (Fig. 86): Below, the figure of Ahriman.

Here is the head, as the human head would be if it were not softened by the rest of the human being.

Here is the lightning bolt that must be drawn from the Christ principle.

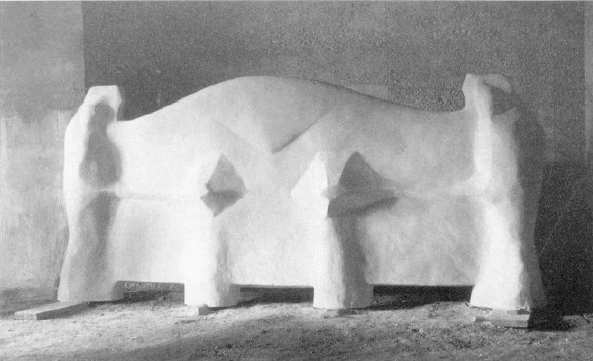

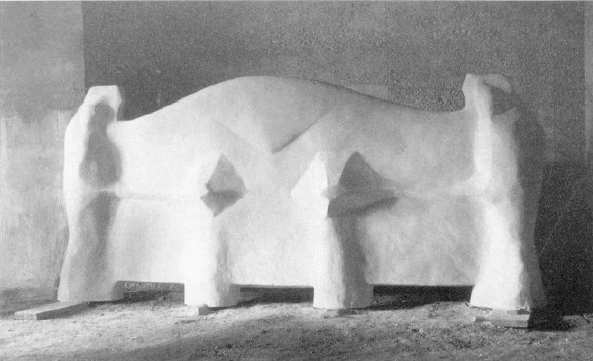

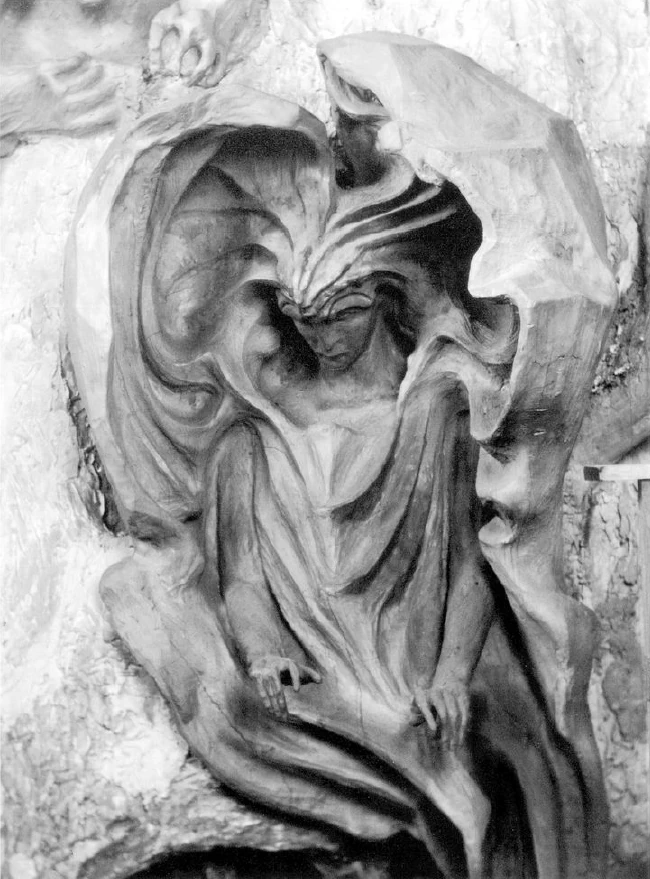

Here I then move on to showing an illustration of a group of people. This group of people now also represents the representative of humanity. Above them are two figures, one again representing the rapturous, the mystical and so on. And as paradoxical as it may sound, this is designed in its forms as it presents itself in an inner spiritual vision if one wants to represent what man would be like if he formed himself according to the feverish, the pleuritic, the enthusiastic-fantastic.

Here the head, here the arm, and the peculiar thing that arises: that the larynx, ear and chest come together and merge into the wing. You feel what becomes an expressionist work of art. This is something that the non-understanding person might call symbolic. It is not symbolic, it is observed as only an organic-physical form can be observed.

Here again this figure, and here the figure at the very top on one side of the group of wood. It turned out that we needed something purely to balance the gravity conditions so that the whole group would support itself. It became so that I had to dare to create something quite asymmetrical, a kind of elemental spirit, growing out of the rock form, but here made of wood. If you abandon yourself to the rock formations, look at them and let your imagination create, saying to yourself: nature has decided on their formation, but if they were to continue, what would arise? You end up with something that approaches the higher form but is not it. I tried to create that in this figure. Above are two luciferic figures, below two ahrimanic figures, and up there this entity, which was dared to be formed completely asymmetrical, because it occurs in a place where the symmetrical would be in contradiction to the whole, and which looks somewhat mischievously humorously at what is forming there as the human struggle. I say “mischievously humorous” because there are indeed entities in the spiritual world that look with a certain humor at the inner tragedy of the human soul struggle. Picture 62 (Fig. 94):

Here you see a photograph of my original wax model of the Ahriman figure, the Ahriman head, the original pedant, the original philistine, the head that would have formed if the other human-forming forces had not counteracted the head-forming forces. Once you have created something like this, you know that you have nothing more to add to it. If you then want to create the head for Ahriman, who lives down in the rocky cave and is in conflict with Lucifer, this head also undergoes a metamorphosis, and the place where it needs to be in the body goes through a corresponding metamorphosis.

Here, seen from the side, is the head of the central figure, of whom I have just shown the painted form; that figure, carved out of wood, is, in my opinion, supposed to represent Christ Jesus walking in Palestine.

It is remarkable; while I was creating this, it became clear to me once again that one should actually create all Christian motifs in wood. The warmth of the wood – this statue is made of elm wood – is necessary for Christian motifs. An Apollo, an Athena is better in marble; Christian motifs are better in wood. It was always a real pain for me to see Michelangelo's Pieta in Rome, the mother with the body of Christ on her lap. I would have liked to see this Pieta - which I nevertheless greatly admire, of course - in wood instead of marble. I don't yet know the reasons myself. Such things cannot be easily explained. But I think the Aperçu is correct that everything Christian must be represented in wood.

Now, regarding the group that I just showed, which forms the center of the building, there is one more thing. If we follow the development of architecture, and consider only two or three stages, we must say: let us look at a Greek temple. It is not quite complete if it does not have its god inside. You cannot think of a Greek temple in general, but only of a temple of Apollo, a temple of Athena. It is the god's dwelling.

Let us move from Greek architecture to Gothic. The Gothic cathedral is not complete unless the community is within it.

We live in an age in which the community is becoming individualized. Therefore, the social question is the most important question of our time, because people live according to their individuality. Grasping the deepest nerve of our contemporary culture, we must look at what a building that belongs to a community must be a framework for today: for the people themselves. Therefore, the representative of human self-knowledge, the trinity between man, as he struggles in his soul between the enthusiastic-mystical and the pedantic-philistine, materialistic, this trinity should be placed at the center of the building, just as the god stands in the Greek temple, as the community praises in the Gothic cathedral. In this way, the spectator area should be pervaded by the pictorial and plastic sound of the “know thyself,” not in abstract forms, but artistically embodied in the Trinity of which I have so often spoken and which, in my opinion, is the Trinity of the culture of the future of humanity. Therefore, this wooden figure did not have to be erected at the center of the building, but as the central figure of the building.

Here an adjoining building, a neighboring building. Again a metamorphosis of the two domes. Here the architectural idea has been developed into a different form. The main building has windows for which a special type of glasswork has been invented. What I said earlier – that those inside this building feel at one with the whole universe, not closed off – should be expressed through the windows. That is why all the windows are large panes of glass in a single color. These panes – red, green, blue – are engraved, etched out of the glass, which then gives the glass its visual effect. This visual effect is there when the sun shines through the windows. This glass etching was tried for the first time in this building. And here, with the glass window in front of you without sunlight, you can physically feel a kind of score; together with the sun, it becomes a work of art. And you feel in the building: when the sunlight floods in through red, green, and blue panes, what the sun paints with its light lives in these windows, so that it is a representation of human death, sleep, waking, and so on; but nowhere is it symbolic, rather these states of consciousness are experienced vividly within.

These glass windows were to be made in this smaller building. And because the first person to work there was called Taddäus Rychter, this house was called “the Richter house”. So it does not have this name because we want to implement the threefold social order, as some people have said, and so we would have built a legal building in which we would have had our own jurisdiction. That is not the case. This should be noted by those who have done something wrong; they will be convicted according to Swiss law.

This is the entrance gate. Everything about it, down to the locks and door handles, is designed in line with the organic architectural concept, so that everything has to be the way it is in its place. Hence the need for a separate lock for these structures.

Here you can see the one that has experienced the most challenges. One day I said to myself: there must be a heating house, a firing plant, near the building. One could have done something that would not have been in the spirit of the overall architectural concept of the Goetheanum; a red chimney would have stood there. But I tried to create a utilitarian building out of concrete. I tried, in turn, to form a shell around the heating elements and the firing machines that are inside, just as the nut fruit forms a shell around itself. Also around what comes out as smoke. The whole is only complete when smoke comes out. So there, too, an attempt is made to carry out a building idea in such a way that, despite the utilitarian idea being carried out, what is created out of the utilitarian form is that which, in utilitarian building, the artistic form-giver currently strives for.

The same building from the side.

By now, enough time has passed and I have kept you waiting for a long time with a large number of pictures that were intended to show you something that is being built in Dornach as the Goetheanum, as a free university for spiritual science. What I have shown you in a series of pictures is intended to provide an initial framework for the work that has arisen from the spirit of spiritual science, which I have now been able to present in Stuttgart for almost two decades. A building was to be erected in Dornach that would not only have an external connection to this spiritual science, in that it serves the cultivation of spiritual science, but that would also be an expression in every detail of life in this spiritual science, just as the word that is formed and through which this spiritual science is proclaimed is intended to be a direct expression of the ideal that can be experienced in this spiritual science.

This spiritual science should not be abstract, theoretical, unworldly or unreal. This spiritual science should be able to intervene in reality everywhere. Therefore, it had to create a building style, a framework that emerged from itself just as a nutshell emerges from a nut. Of course, one will rightly be able to object to some things that are also before my mind's eye. But there was always a certain sense of encouragement while I was working on this building idea and all its details, what went through my mind when I was a very young man in the 1880s and heard the Viennese architect von Ferstel, who built the Viennese Votivkirche, give his inaugural address on the development of architectural styles. With a certain emphasis, Ferstel, the great architect, exclaimed: “Architectural styles are not invented, architectural styles arise.

I always said to myself: But then we live today in a time in which everything spiritual must change in the human soul in such a way that a new architectural style must necessarily arise from this change of the spiritual. And that something like this must be possible was always before me. I believed that it must be possible, and therefore I did not shrink from seeking such an architectural style, even if it was initially in a very imperfect design, from anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. A second time, if I were ever to supervise such a building again, it would be quite different. But one only learns by approaching reality, when one wants to deal not with abstract ideas, with something symbolic and allegorical, but with something vividly artistic and real in life. Spiritual science needs at least the beginning of a new architectural style, a new artistic formal language. No matter how imperfect it may be, present-day human civilization demands it! And those who have stood by me in such great numbers have seen it with me and have submitted to the first attempt at realizing this aspiration. And even if many still look with a sneer at what rises up as the Goetheanum, as a free college on the Jura hill in northwestern Switzerland — which is now difficult to reach from here, but otherwise easy to reach because it is only half an hour across the border — what stands there is already visited by thousands and thousands from all countries, especially from Switzerland itself. The eurythmy performances are also well attended, every Saturday and Sunday, and the lectures that I already give for the public in this school enjoy a certain interest even in circles that do not belong to the Anthroposophical Society. Dornach is beginning to open up to the world. It will still cost great sacrifices. We will still need many resources to really develop what is intended. But from what is there today, what is still unfinished, it can be seen that there can be a world view that not only thinks but also builds. On the other hand, we would like to show the world through the Federation for Threefolding that this world view can also have a socially constructive effect on the immediate life of the individual and of humanity. However great the faults of this structure, which is the external representative of our world view, our spiritual-scientific world view, and however much it is still rightly subject to criticism today, it had to be ventured. It had to be placed in our present civilization. And in the face of all contradictions - or rather in the face of all approval of the present - I would like to say, in harmony with all the friends who have helped me in such great numbers in erecting this building, in the face of what is intended here, the modest, summarizing word:

What has been willed must first become the right thing in later times, but a start had to be made. And speaking on behalf of all those who have been active in Dornach, I can summarize the attitude out of which flowed what I have tried to show you today: we dared to do it despite the difficulties, and we will continue to dare to do it!

Das Goetheanum in Dornach

Öffentlicher Vortrag im Stuttgarter Kunstgebäude

Als die Geisteswissenschaft, über deren Ziele und Wesen ich ja nun auch schon seit fast zwei Jahrzehnten jedes Jahr in Stuttgart Vorträge halten durfte, eine größere Ausbreitung gewann, namentlich als aus dieser Geisteswissenschaft heraus künstlerisches Schaffen sich gestaltete, da entstand die Absicht, irgendwo, wo es angemessen sein sollte, für diese Geisteswissenschaft einen ihr besonders entsprechenden Zentralbau zu schaffen. Die Idee hat sich insbesondere dadurch zu einer gewissen Realität verdichtet, dass wir in den Jahren 1909 bis 1913 in München in einem gewöhnlichen Theater aufzuführen hatten Mysteriendramen, welche in ihrem ganzen Aufbau, in ihrer ganzen Haltung herausgeboren sein sollten aus dem Geiste dieser anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft.

Dasjenige, was den Trägern dieser Geisteswissenschaft vorschwebte auf der einen Seite als der eigentliche Sinn ihrer Weltanschauung, was ihnen vorschwebte andererseits als künstlerische Ausgestaltung dieser Weltanschauung, das brachte zunächst die eben angedeutete Absicht, einen eigenen Bau aufzuführen, der der Repräsentant sein sollte, der äußerliche Repräsentant für diese Geisteswissenschaft. In München ist es wegen des geringen Entgegenkommens der maßgebenden Künstlerschaft nicht gelungen. Da ich mir heute eine andere Aufgabe gestellt habe, so möchte ich nicht sprechen über alles das, was dann dazu geführt hat, auf einem in freier Lage stehenden Hügel im Nordwesten der Schweiz im Kanton Solothurn diesen Bau aufzuführen, wo es damals, als wir zu bauen begannen, noch keine beengenden Baugesetze gab, sondern wo man bauen konnte, wie man wollte. Was alles, wie gesagt, dazu geführt hat, das will ich heute nicht erst auseinandersetzen. Doch möchte ich aber davon sprechen, in welchem Sinne die Absicht aufgefasst werden müsste, gerade für die hier gemeinte Geisteswissenschaft einen Bau zu gestalten.

Wenn man sonst von Weltanschauungen, von Weltanschauungsrichtungen oder Weltanschauungsströmungen spricht, dann hat man gewöhnlich im Auge eine Summe von Ideen, die oftmals einen mehr oder weniger theoretischen oder populären Charakter tragen, die aber doch zumeist sich darin erschöpfen, dass sie sich eben ideenhaft durch Mitteilung, durch das bloße Wort aussprechen wollen, und dann höchstens von der Welt erwarten, dass das Wort, das in einer gewissen Weise programmmäßig gestaltet wird, in Wirklichkeit übergeführt werde. Dasjenige, was hier gemeint ist als anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft, ist von vornherein nicht so veranlagt wie andere Weltanschauungen. Es ist, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, vom Anfang bis zum Ende durchdrungen von Wirklichkeitssinn. Deshalb musste es ja auch in schwerer Zeit in dieser Gegenwart dazu führen, unmittelbar einzudringen in dasjenige, was der Versuch eines sozialen Neuaufbaues der modernen Zivilisation ist. Wenn nun eine Weltanschauung, die sich mehr im Ideenhaften hält, einen eigenen Bau zu ihrer Pflege braucht, dann setzt man sich in der Regel in Verbindung, je nachdem man viele oder wenig Mittel hat, mit irgendjemandem, von dem man voraussetzt, dass er fachgemäß aus den maßgebenden Stilrichtungen heraus in der Lage ist, einen Bau aufzuführen. Man setzt sich mit einer solchen Personlichkeit oder mit einer Reihe von solchen Persönlichkeiten in Verbindung, um dann gewissermaßen ein Haus, eine Umrahmung für die Pflege einer solchen Weltanschauung zu schaffen. Der ganzen Anlage unserer anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft hätte das aber nicht entsprechen können, aus dem einfachen Grunde nicht, weil eben diese Geisteswissenschaft nicht etwas ist, was sich nur in Ideen ausdrückt, sondern weil sie sich ausdrücken will in allen Lebensformen.

Nun möchte ich einen einfachen Vergleich gebrauchen, um anzudeuten, wie gerade baumäßig und künstlerisch sich ausdrücken musste in ihrer eigenen Umrahmung diese anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft. Nehmen Sie irgendeine Frucht, sagen wir die Nuss. Die Nuss ist innen Frucht, rundherum hat sie eine Schale. Ich will zunächst die harte Schale innerhalb der grünen Schale betrachten. Wenn Sie die ganze Konfiguration, die Gestaltung der Nussschale studieren, so werden Sie sich sagen: Die könnte nicht anders sein, als sie ist, da die Nuss so ist, wie sie ist. Man kann nicht anders als sich denken: Die Nuss schafft sich ihre Schale, und alles, was an geringsten Kleinigkeiten von der Schale sichtbarlich ist, das muss ein Ausdruck sein desjenigen, was die Nussfrucht selber ist. So ist eine Umrahmung ganz angemessen in der Natur, in allem Geschöpflichen dem, wofür sie Umrahmung ist.

Denkt man nun nicht abstrakt, denkt man nicht theoretisch, denkt man nicht aus einer Weltanschauung, die sich bloß in Ideen bewegt, sondern die in aller Wirklichkeit und in allem Leben drinnen stehen will, dann fühlt man sich gezwungen, alles, was sie tut, in einer gewissen Beziehung auch so zu tun, wie es die schöpferischen Kräfte im Weltenall tun. Und so wäre denn, wenn man mit irgendeinem fremdartigen Baustil, mit irgendetwas, was herausgewachsen wäre aus jenen Bauweisen, die heute einmal üblich sind, gebaut hätte eine Umrahmung für anthroposophisch-orientierte Weltanschauung und ihre Pflege, es wäre dagewesen zweierlei: auf der einen Seite ein Bau, der sich ganz aus sich heraus ausspricht, der für sich etwas sagt, der in seiner eigenen künstlerischen Formensprache dasteht. Und dann wäre man hineingegangen und hätte drinnen etwas vertreten, etwas gepflegt, was eigentlich nur in einer ganz äußerlichen Weise selbstverständlich zu diesem Bau stehen könnte. Man würde Worte hören in einem solchen Bau, man würde Bühnenspiele betrachten (da diese ja beabsichtigt sind) und anderes Künstlerische aufgeführt sehen; man würde - ich habe ja darüber öfter gesprochen, und auch während dieses meines Stuttgarter Aufenthaltes spreche ich in drei Vorträgen über das Wesen dieser Geisteswissenschaft - man würde etwas gehört, etwas gesehen und erschaut haben, was als ein Neues sich hereinstellen will in die moderne Zivilisation. Man hätte dann das Auge hinweggewendet von dem, was man vielleicht auf der Bühne gesehen hätte; man hätte das Ohr abgewendet von dem, was man gehört hätte, und man hätte die Bauformen ins Auge gefasst - das wären zwei voneinander wesensverschiedene Dinge geworden. So konnte die hier gemeinte Geisteswissenschaft gar nicht streben. Sie musste streben im Einklang mit allem Weltenschaffen. Sie musste sich zugetrauen, ebenso wie sie sich ausspricht in Ideen, sich auszusprechen in künstlerischen, auch in Bauformen. Sie musste Anspruch darauf machen, dass dasjenige, was zum Worte sich bildet, was zum Drama oder zu einer anderen künstlerischen Ausdrucksart sich bildet, auch fähig ist, sich unmittelbar hineinzugestalten in alle Einzelheiten desjenigen, was nun die Schale ist. So wie die Nussfrucht sich ihre Schale schafft aus ihrer eigenen Wesenheit heraus, so musste eine solche Geisteswissenschaft, deren Wesen ja heute in weitesten Kreisen, weil sie eben gerade diesen Wirklichkeitsgeist atmet, nicht begriffen wird, so musste gerade eine solche Weltanschauungsrichtung sich ihre eigene Umrahmung schaffen. Alles das, was das Auge da sieht in dieser Umrahmung, musste ebenso ein unmittelbarer Ausdruck desjenigen sein, was als lebendiges Leben vorhanden ist in dieser Weltanschauung, wie das gebildete Wort.

Und es waren manche Klippen dabei zu umgehen. Denn diejenigen, die eine gewisse Neigung haben, einen Bau angemessen zu machen einer Weltanschauung, die sind oftmals, nun sagen wir einmal, etwas mystischer oder sonst wie veranlagter Natur, und sie haben dann den Drang, das, was sich in der Weltanschauung ausdrückt, in äußeren Symbolen, in irgendwelchen mystischen Gestaltungen zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Das führt aber lediglich dazu, eine solche Umrahmung zu etwas im eminentesten Sinne Unkünstlerischem zu machen. Und hätte man einen Symbole tragenden Bau aufgeführt, hätte man dasjenige ausdrücken wollen in allegorischer oder symbolischer Form, was der anthroposophisch-orientierten Geisteswissenschaft zugrunde liegt, so wäre nichts anderes entstanden als etwas im eminentesten Sinne Unkünstlerisches.

Ja, ich muss sogar gestehen, dass gar manche, die mit ihren Anschauungen, mit ihren Lebensströmungen eingelaufen sind in dasjenige, was hier anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft genannt wird, als Mitwirkende auch oder Mitratende, im Beginne unseres Bauens in Dornach durchaus die Neigung hatten, zum Ausdruck zu bringen alles dasjenige, was Geisteswissenschaft enthält in alten symbolischen oder dergleichen Formen. Ich darf vielleicht auch erwähnen, dass diejenigen Menschen, die ja so zahlreich sind, die entweder aus einem gewissen Unverstand oder auch aus böswilliger Absicht heraus über den Dornacher Bau reden, immer wieder der Welt kommen damit, da finde man für das oder jenes Symbole, da finde man allegorische Ausdrücke für das oder jenes.

Nun, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, es wird zugegeben werden müssen, dass auch in dem, was ich Ihnen heute Abend vorzuführen habe, derjenige, der nicht genau und nicht mit lebendiger Empfindung zuschaut, etwas finden kann, wovon er den Ausdruck gebrauchen kann: Da ist manches allegorisch oder symbolisch gemeint. In Wirklichkeit ist im Dornacher Bau kein einziges Symbol, keine einzige Allegorie, sondern alles das, was da vorhanden ist, das ist durchaus so, dass das innerliche Erleben des Geistes, wie er auf der einen Seite gefasst werden soll in Ideen, die in Vorträgen oder dergleichen zum Ausdruck kommen, dass dieses innerliche Erleben ganz in künstlerische Formen aufgelöst sein soll, dass nichts anderes gefragt wird beim künstlerischen Schaffen in Dornach als: wie die Linie ist, wie die Form ist, wie dasjenige ist, was sich als künstlerische Ausdrucksform eben in der Plastik, in der Architektur, in der Malerei usw. gestalten lässt. Und gar mancher, der da kommt in Dornach und fragt, was bedeutet das oder jenes, der bekommt von mir immer wieder und wiederum die Auskunft: Ich bitte, die Sachen anzuschauen; es bedeutet alles nichts anderes im Grunde als dasjenige, was in das Auge einfließt. Es handelt sich oftmals darum, dass die Leute sagen: Das bedeutet dieses oder jenes. Ich aber bin dann genötigt, ihnen von der Farbenverteilung und dergleichen zu sprechen.

Nun habe ich versucht darzustellen, wie gewissermaßen als eine Schale, ganz im Sinne des Naturschaffens selber, der Bau die Umrahmung für anthroposophisch orientierte Geistes wissenschaft bildet. Gerade deshalb aber musste im Grunde genommen der ganze Baugedanke auch nach etwas Neuem streben. Nun bitte ich, bei alledem, was ich heute sagen werde, zu berücksichtigen, dass ja selbstverständlich viel Kritik geübt werden kann an dem Dornacher Bau, dass vieles eingewendet werden kann. Und ich gebe Ihnen die Versicherung: Derjenige, der vielleicht am allermeisten einwendet, der bin ich selber. Denn ich bin mir vollkommen bewusst, dass der Dornacher Bau ein Anfang ist; dass der Dornacher Bau als ein erster Versuch dasteht, eine gewisse Stilform zu schaffen, die heute noch gar nicht einmal in Worten irgendwie charakterisiert werden kann, weil ihre Einzelheiten nicht aus abstrakten Gedanken heraus gebildet sind, sondern aus dem, was lebendig erlebt wird in jenem Schauen des Geistes, das mit unserer Geisteswissenschaft gemeint ist.

Nur einen gewissen Unterschied darf ich von vorneherein angeben: Wenn wir die verschiedenen Baustile überschen, welche in einer gewissen Formentwicklung auch heute da, wo man baut, eben ihren Ausdruck finden, dann zeigt sich allüberall, dass im Grunde genommen in die Architektur einfließt das Mathematische, das Geometrische, das Symmetrische, dasjenige, was vielleicht im Rhythmus der Linie nach verläuft, das Mechanische, das Dynamische usw. Aus dem Grundempfinden - ich sage nicht aus dem Grundgedanken, ich sage aus dem Grundempfinden - unserer Geisteswissenschaft heraus wurde einmal der, ich weiß es, gewagte Versuch gemacht, einen organischen Baugedanken zu gestalten, nicht einen mechanisch-dynamischen, sondern einen organischen Baugedanken zu gestalten, und zwar unter dem Einfluss desjenigen, was Goethe seiner großen, gewaltigen Naturanschauung einverleibt hat unter dem Einfluss des Metamorphosengedankens. Dasjenige, was der Dornacher Bau ist, soll, soweit es in der Architektur sich verwirklichen lässt, nicht bloß Symmetrisches, Dynamisches, Mechanisches, Geometrisches darstellen, es soll darstellen etwas, was angeschaut werden kann, ich sage nicht aufgefasst, sondern angeschaut werden kann als ein Bauorganismus, als die Form für etwas Lebendiges.

Da handelt es sich dann allerdings darum, dass in einem Organismus jede Einzelheit so ist, wie sie an ihrem Orte gerade sein muss. Sie können sich an einem menschlichen Organismus das Ohrläppchen nicht anders gestaltet denken, als es ist. So wurde versucht, dass unser Dornacher Bau eine vollständig organische, innerlich organische Einheit ist, indem wir jeden einzelnen Teil in das Ganze so hineinstellten, dass er an seinem Ort als ein notwendiges Gebilde erscheint; dass jede Einzelheit so ein Ausdruck ist des Ganzen wie eine Fingerspitze ‚oder ein Ohrläppchen ein Ausdruck ist für den ganzen menschlichen Organismus.

Das ist das eine, was versucht wurde. Wie gesagt, es ist ein Anfang, ein Versuch, und ich weiß, wie viele Unvollkommenheiten er hat, und wie viel einzuwenden ist vom Standpunkt der architektonischen und Bildhauerkunst und so weiter. Das andere ist, was ich vorausschicken möchte, dass verlangt wurde von unserer Weltanschauung selbst, den ganzen Baugedanken anders zu gestalten, als der Baugedanke gewöhnlich gestaltet ist. Wenn wir nämlich die gewöhnlichen Bauwerke ins Auge fassen - ich will nur das eine erwähnen -, so finden wir sie auch nach außen von Wänden abgeschlossen, bis zu einem gewissen Grade. Sogar die griechischen Bauten waren abgeschlossen bis zu einem gewissen Grade. Dasjenige nun, was der Dornacher Bau ist, das erfordert, dass schon die Wand in einer ganz anderen Weise behandelt werde, als sie sonst behandelt wird. Derjenige, der den Dornacher Bau betritt, soll, indem er eine Wandung um sich hat, nicht das Gefühl haben, er sei da abgeschlossen in einen inneren Raum. Sondern alles soll künstlerisch so gestaltet sein, dass gewissermaßen die Wand sich selbst aufhebt; dass die Wand selber - ich bitte mich nicht misszuverstehen - die Wand selber künstlerisch durchsichtig werde, sodass man das Gefühl bekommt - durchsichtig ist natürlich nur im Vergleich gesprochen -, man sei nicht abgeschlossen, sondern alles dasjenige, was Wand ist, was Kuppel ist, eröffne einem die Empfindung, dass es durchbrochen ist, dass es sich selber aufhebt, dass man mit dem ganzen großen Weltenall in einer empfindungsgemäßen Verbindung stehe. Weit hinaus in die Unendlichkeiten soll die Seele sich diesem verbunden fühlen durch dasjenige, was die Formen hervorrufen; die Formen der Säulen, der Wandung, die Formen der Kuppelmalerei usw.

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, der Dornacher Bau ist ein Doppelkuppelbau, sodass er besteht aus einem kleinen und einem großen Kuppelraum, die nicht nebeneinander stehen, sondern ineinandergreifen. Der kleine Kuppelraum, also jener Raum, der kreisförmig ist und von einer kleineren Kuppel überdeckt wird, der wird dienen zur Darstellung von Mysteriendramen, von Dramatischem überhaupt, von anderen künstlerischen, z.B. von eurythmischen Darstellungen. Aber auch durchaus andere Dinge sind da noch geplant. Dann der große Kuppelraum, der sich im Kreissegment der Kuppel anschließt an den kleineren. Er ist als ein Zuschauerraum gedacht; sodass denjenigen, der sich nähert diesem Bau, sogleich durch diese äußere Form eine gewisse Empfindung beschleichen muss.

Wir werden beginnen damit, dass wir ins Auge fassen unseren Bau, wie er sich etwa demjenigen darbietet, der sich ihm von Nordost her nähert.

Es handelt sich also darum, dass wir einen Doppelkuppelbau haben. Dieses ist der Zuschauerraum, hier der Bühnenraum. Hier sind die zwei Kuppeln ineinandergefügt durch, wie ich sagen darf, ein besonderes technisches Kunststück; denn diese Ineinanderfügung war schwierig. Es soll demjenigen, der sich diesem Bau nähert — der, wie ich glaube, auch ganz besonders angemessen ist in seiner künstlerischen Ausdrucksform der besonderen Gebirgsformation jenes Jura-Gebietes, in dem er errichtet ist —, es soll den, der sich diesem Bau nähert, die Empfindung beschleichen: Da ist etwas vorhanden, was sich in einer Zweiheit offenbart. Derjenige, der den Bau betritt, befindet sich im großen Kuppelraum. Darinnen kann er das Gefühl haben: Hier wird etwas geschaut, etwas gehört. Und dieses Etwas, was gewissermaßen in den Höhen des geistigen Lebens erfahren wird, das sich offenbaren soll einer geneigten Zuschauermenge, das soll sich schon als Empfindung demjenigen ausdrücken, der sich dem Bau nähert,