Colour

Part II

GA 202

5 December 1920, Dornach

1. Thought and Will as Light and Darkness

It is a one-sided view of the world to consider it, like Hegel, as permeated by what one might call cosmic thought. It is equally one-sided to consider, like Schopenhauer, that Nature has a basis of free-will. These two particular tendencies apply to western human nature, which leans more towards the side of thought. Hegel's philosophy has another form in the eastern view of the universe. In Schopenhauer's there is a tendency which really suits the oriental, and is shown by the fact that Schopenhauer has a particular preference for Buddhism, and the oriental view in general.

But really every such method of observation can be judged only if surveyed from the point of view which is given by Spiritual Science. From this point of view such a grouping together of the world under the heading either of thought of will appears to be something abstract, and, as we have often said, the more modern development of man still leans towards such abstractions. Spiritual Science must bring man back again to a concrete view of the world, in agreement with reality. And it is precisely to such a view that the inner reasons for the presence of these one-sided philosophies will appear. What such men as Hegel and Schopenhauer, who are after all great and important intelligences, see, is of course visible in the world; but it must be seen in the right way.

Now let us today, to begin with, understand clearly that we, as human beings, experience thought in ourselves. When a man speaks of his thought-experiences, it means that he has this thought-experience direct. He could naturally not have it unless the world were filled with thought. For how should a man, who perceives the world by his senses, be able to think, as a result of this sensory perception, unless the thought were already in the world?

But as we know from other studies, the organization of the human head is constructed in such a way as to be specially capable of taking in thought from the world. It is formed indeed from thought. It points at the same time to our previous existence on earth. We know that the head is really the result, the metamorphosed result of the previous life, while the organization of the human limbs points to a future life on earth. Roughly speaking, we have our head because our limbs have been metamorphosed from the previous life into the head. The limbs we now have, with everything belonging to them, will be metamorphosed into the head we shall carry in our next earth-life. At present, in our life between birth and death, thoughts function in our head. These thoughts, as we have also seen, are the reshaping of what functioned as will in our limbs in our previous existence. And again, what functions as will in our present limbs will be reshaped and changed into thoughts in our next life on earth.

The will thus appears as the seed, as it were, of thought. What is at first will becomes thought later on. If we look at ourselves as human beings with heads, we must look back to our past, for in this past we had the character of will. If we look into the future, we must take into account the character of will in our present limbs and must say: This is what in future will become our head: thinking man. But we continually carry both these in us. We are created out of the universe because thought from a previous age is organized in us in conjunction with will, which leads over into the future.

Now that which thus arranges the composition of man in this way becomes particularly observable if considered from the point of view of spiritual-scientific research.

The man who can develop himself so far as to have knowledge of Imagination, of Inspiration and of Intuition sees not merely the head of a human being, but he sees objectively the thinking man which his head makes him. He looks, as it were, in the direction of the thoughts. So that we may say with those abilities which man normally requires between birth and death, the head appears in the shape and form in which we see it. Through developed knowledge of Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition the strength of thought, which is after all the basis of the head's organization, that which comes down from earlier incarnations, becomes visible—if we use the term metaphorically. How does it become visible? In such a way, dear friends, that we can only use the expression: it becomes as if it gave forth light.

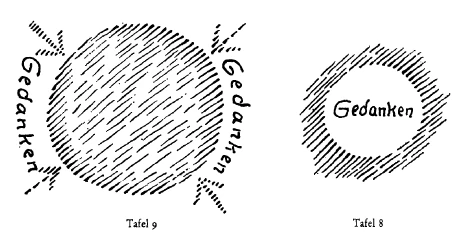

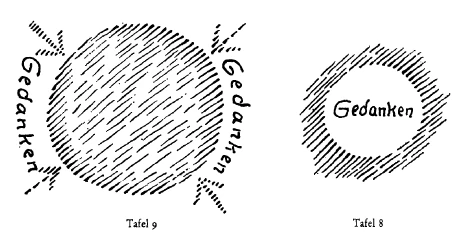

Certainly, when people, who want to keep to the materialistic point of view, criticize these things, one sees at once how little the present generation is capable of understanding at all what they mean. I have in my Theosophy and in other writings, points out sufficiently clearly that it is not a question of thinking in terms of a new physical world, a new edition of it, as it were, if we contemplate thinking man in Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition; on the contrary, this experience is exactly the same as one has in regard to light in the physical external world. Put accurately it is like this: Man has a certain experience in connection with external light. He has the same experience, in imagination, in connection with the thought-element of the head. Thus the thought-element (See Diagram 1) viewed objectively, is seen as light, or better, experienced as light. Being thinking men, we live in light. We see the external light with physical senses; the light which becomes thought we do not see, because we live in it, because as thinking men, it is ourselves. You cannot see that which you yourselves are. If you emerge from this thought and enter upon Imagination and Inspiration, you put yourself opposite to it and can see the thought-element as light. So that in speaking of the whole world, we may say: We have the light in us; only it does not appear to us as light because we live within it, and because while we use the light, while we have it, it becomes thought within us. You control the light, as it were, you take up the light in yourself which otherwise appears outside you. You differentiate it in yourself. You work in it. This is precisely your thinking, it is a working in light. You are a light-being. You do not know it, because you live within the light. But your thinking which you unfold, is living in the light. And I you look at thought from the outside, you see, altogether, light.

Think now of the Universe (Circle.) You see it radiated with light—by day of course; but in reality you are looking at this Universe from the outside ... we now do the opposite. First we had the human head (Thought in the diagram), which contains thought in its development. Seen from outside, it has light. In the Universe we have light which is seen by the senses. If we come out of the Universe, and regard it from outside, what does it look like then? Like a web of thoughts. The Universe from within—light; from outside—thought. The head from within—thought, from outside—light.

This is a way of viewing the cosmos which can be extremely useful and suggestive to you, if you wish to make use of it, if you really penetrate into such things. Your thought and whole soul-life will become much more active than it otherwise is, if you learn to put this thought before you: if I were to come out of myself—as indeed a person who goes to sleep I continually do, and look back at my head, at myself therefore as a thinking man, I should see myself radiating forth light. If I were to leave the light-flooded world, and look at it from outside, I should see it as a picture of thought, as a thought-being. You observe, light and thought go together; they are identical, but seen from different sides.

Now the thought that is in us is really a survival from earlier times, the most mature thing in us, the result of former lives on earth; what formerly was will has become thought, and thought appears as light. As a consequence you will find: where light is, there is thought—but how? In thought or put differently, in light, a previous world continually dies.

That is one of the world-secrets. We look out into the Universe. It is full of light, in which thought lives. But in this thought-filled light there is a dying world. The world is continually dying in light.

When someone like Hegel regards the world, he really looks at the perpetually dying part of it. Those who have this particular tendency, become, for the most part, men of thought. And in dying the world becomes beautiful. The Greeks, who were really people of innate human nature, had their external pleasure when beauty shone in the dying world. For the world's beauty shines in the light in which it dies. The world does not become beautiful if it cannot die, for in dying the world becomes luminous. So that it is really beauty which is created from the radiance of the continuously dying world. Thus we regard the world quantitatively. The modern world began with Galileo and others to consider the world quantitatively, and our Scientists today are particularly proud when they can put natural phenomena into terms of lifeless mathematics. It is true Hegel used more pregnant concepts than the mathematical ones to understand the world; but what attracted him most was maturity and decay. Hegel's attitude to the world was like that of a man in front of a tree laden with blossom. At the moment when the fruit is about to develop, but is not yet there, when the blossom is at its fullest, there works in the tree that power of light, which is light-borne thought. That was Hegel's position. He looked at the blossom at its maximum, at that which becomes most completely concrete.

Schopenhauer was different. In order to test his influence, we must look at the other side of human things, at the beginnings. It is the will-element which we carry in our bodies. And we experience this—I have often pointed out—just as we experience the world in sleep. It is unconscious in us. Can we look at this will-element from outside, as we look at thought? Let us take the will developing in some human limb or other, and let us ask ourselves: if we were to look at this will from the other side, from the standpoint of Imagination, of Inspiration, and of Intuition, what then happens? What is the parallel here to seeing thought as light? What do we regard the will if we look at it with the trained power of sight, with clairvoyance? Yes: if we do this, we also get something which we can see from outside. If we look at thought with the power of clairvoyance, we perceive light. If we look at will with the power of clairvoyance, it becomes always thicker and thicker till it becomes matter. You have no other option, if you agree with Schoenhauer, but to believe that man is really a being of will. Had Schopenhauer been clairvoyant, this being of will would have confronted him as a matter-machine, for matter is the outer side of will. Within, matter is will, as light is thought. From outside, will is matter, as thought is outwardly light. For this reason I pointed out tin former addresses: If man dives down mystically into his will-nature, then those who only toy with Mysticism and really only strive after a sensuous experience of their Ego and of the worst egoism, believe they will find the spirit. But if they went far enough with this introspection, they would discover the true material nature of man's interior. For it is nothing less than a diving down into matter. If you dive down into the will-nature, you will find the true nature of matter. The scientific philosophers of today are only telling fairy-stories when they talk about matter consisting of molecules and atoms. You find the true nature of matter by diving down mystically into yourself. There you find the other side of will, and that is matter. And in this matter, that is in Will, is revealed finally the continually beginning, continually germinating world.

You look out onto the world. You are surrounded with light, and the light is the death-bed of a previous world. You tread on hard matter, the strength of the world bears you up. In light shines beauty in the form of thought, and in the gleam of beauty the previous world dies. The world discloses itself in it strength and might and power, but also in its darkness. The world of the future discloses itself in darkness, in the elements of material will.

If physicists were for once to talk sense, they would not produce speculations about atoms and molecules, but they would say: The visible world consists of the past, and carries in it not molecules and atoms, but the future. And you would be right in saying of the world that the past appears to us in the present, and the past wraps up everywhere the future, for the present is only the total effect of past and future. The future is what lies in the strength of matter. The past is what shines in the beauty of light, which includes, of course, sound and warmth.

And thus man can understand himself only if he takes himself as a seed of futurity, enclosed in the past, in the light-aura of thought. We might say that looked at spiritually man is the past in so far as he shines in his beauty-aura, but in this past-aura is incorporated a darkness mingling with the light, which rays forth out of the past, a darkness which carries over into the future. Light shines out of the past; darkness leads into the future. Light is nature in terms of thought, darkness is nature in terms of will. Hegel leaned toward the light that develops in the processes of growth and in the ripest blooms. Schopenhauer, as philosopher, is like a man standing in front of a tree, who has really no joy in the magnificence of its flower, but has an inner urge to wait till the seeds of the fruit bursts forth. That pleases him, that the power of growth is there, it stimulates him and makes his mouth water to think peaches are going to grow out of the peach-blossom. He turns from light-nature to light. What stirs him, viz., what develops from the light-nature of the bloom as the stuff that he can roll round with his tongue, or the future fruit, is as a matter of act the double nature of the world. To see the world properly you must see it in its double nature, for only then do you realize the concreteness of the world, whereas otherwise you see only its abstractness. When you go out and look at the trees in blossom, you are really living on the past. You look at nature in spring and you can say: What the gods have done to the world in past ages is revealed in the beauty of spring blossom. You look at the fruitful autumn world and say: There begins a new act of the gods, there falls something which however has the power of further development, of development into the future.

Thus it is a question not merely of making for oneself a picture of the world through speculation, but of taking in the world with the whole man. One can in actual fact comprehend the past in plum blossom, and eel the future in the plum. The taste of it on the tongue is closely connected with that out of which one rises again, like the Phoenix from his ashes—into the future. There you comprehend the world in feeling, and it was in this way that Goethe really pondered on everything he wanted to see and feel in the world. For instance he considered the green plant-world. He had not, of course, the advantages of modern Spiritual Science, but in considering the greenness of the plant-world, which had not quite reached the stage of bloom, he had after all the element that has come down from the past into the present; for in the plant the past appears already in the bloom; but what is not quite so much of the past is the leaf's greenness.

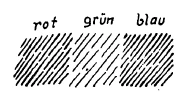

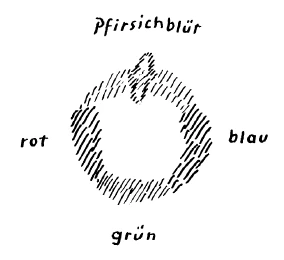

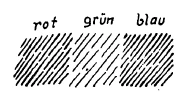

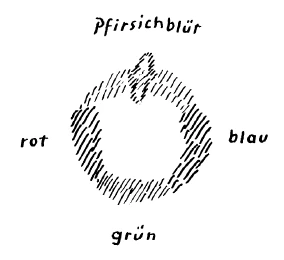

The greenness of Nature is that which, as it were, has not yet decayed, which is not so much in the grip of the past. It is this which unfolds itself as green. (See Diagram 2) But that which points to the future is what emerges from the darkness. There where the green is graded off to the bluish tone, there is that which proves itself to be of the future (blue.) On the other hand, there where we are directed to the past, where the ripening force is, which brings things to flower, there is warmth (red,) where light not only shines forth, but inwardly fills itself with force, where it becomes warmth. Now one ought really to draw the whole thing so that one says: You have the green, the plant-world (thus would Goethe feel, even if he has not transformed it into Spiritual or Occult Science;) bordering on it you have the darkness, where the green is darkened into blue. The part that increases its light and becomes filled with warmth, would close again towards the top. But you yourself—as man—are there, there you have within you what you have externally in the green plant-world; there you are, as human etheric body, and I have often said, peach-coloured. And that is the colour which appears here when the blue crosses over to the red. That is our own colour. So that, looking out on the coloured world, one can say: There one is oneself in the peach-colour, and has the green opposite; one has on the one hand the bluish, the dark, on the other side the light colour, the reddish-yellow. But because one is inside the peach-colour, because one lives in it, one can in ordinary life perceive it as little as one perceives thought as light. One does not perceive or observe one's own experience, and therefore one overlooks the peach-colour and sees only the red which one enlarges on the one side, and the blue which one enlarges towards the other side; and thus we see such a rainbow-spectrum. But this is only a deception. You would get the real spectrum if you bent this colour-strip into a circle. In actual fact one does bend it just because as human being one stands within the peach-colour, and so sees the coloured world only from blue to red and from red to blue through green. Were you to have this aspect, precisely then every rainbow would appear as a self-contained circle, as a circular section of a cylinder.

I mention this last only to call your attention to the fact that a philosophy of Nature such as Goethe's is at the same time a spiritual philosophy. In approaching Goethe, the researcher of Nature, we may say that he has as yet no Spiritual Science, but his view of Natural Science was such that it was quite on the lines of Spiritual Science. The essential thing for us today is that the world, including man, is an inter-penetration of thought-light, light-thought with will-matter, matter-will; and the concrete element in it is built up in the most various ways, or permeated with the content of thought-light, light-thought, matter-will and will-matter.

You must look at the Cosmos qualitatively in this way, not merely quantitatively, to get the truth of it. Then also there creeps into this Cosmos a continuous dying away, a dying of the past in light, and a opening up of the future in the darkness. The old Persians, when they felt the past decaying in light, with their instinctive clairvoyance, they called it Ahura Mazdao, and when they felt the future in the darkening will, they called it Ahriman.

And now you have these two world-entities, light and darkness—the living thought, the decaying past, in light, and the growing will, the coming future, in darkness. If we get so far that we regard thought no longer merely in its abstractness, but as light, that we regard the will no longer merely in its abstractness, but as darkness, in its material nature; if we get so far as to be able to regard the warmth-content, for example, of the light-spectrum, as being connected with the past, and the material side, the chemical side of the spectrum as being connected with the future, we pass over from the purely abstract to the concrete. We are no longer such dried-up, pedantic thinkers, merely working with the head; we know that what does work in our heads is really the light that surrounds us. And we are no longer such prejudiced people as to have only pleasure in light: we know also that in the light is death, a dying world. We can sense the world-tragedy in the light. We can also get from the abstract thought to the rhythm of the world. And in darkness we see the seeds of the future. We find indeed therein the impetus for such passionate natures as Schopenhauer. In short, we penetrate from the abstract into the concrete. World-pictures rise before us instead of mere thoughts or abstract will-impulses.

In the next lecture we shall seek—in what has developed concretely for us so remarkably,—thought into light and will into darkness—we shall seek the origin of good and evil. We shall penetrate from the world within into the Cosmos and there seek not only in an abstract or religious-abstract world the causes of good and evil, but we shall see how we break through to a knowledge of good and evil, after having made a beginning by realizing thought in its light, and having felt will in it darkness.

Licht und Finsternis als Zwei Welt-Entitaäten

Aus den gestrigen Darlegungen wird Ihnen hervorgegangen sein, daß man die Welt einseitig betrachtet, wenn man sie so betrachtet, wie das in besonders hervorragender Weise bei Hegel zum Vorschein kommt, wenn man sie so betrachtet, als ob sie durchzogen wäre von dem, was man den kosmischen Gedanken nennen kann. Ebenso einseitig betrachtet man die Welt, wenn man das Grundgefüge willensartiger Natur denkt. Es ist das die Idee Schopenhauers, die Welt willensartiger Natur zu denken. Wir haben gesehen, daß auch diese besondere Neigung, möchte ich sagen, die Welt anzusehen, sie als Gedankenwirkung anzusehen, hinweist auf die westliche Menschennatur, die mehr nach der Gedankenseite hin tendiert. Wir haben ja nachweisen können, wie Hegels Gedankenphilosophie eine andere Gestalt in den westlichen Weltanschauungen hat, und wie in Schopenhauers Empfindungen die Neigung lebt, die eigentlich den Menschen des Orients eigen ist, was sich ja darin zeigt, daß Schopenhauer die besondere Vorliebe für den Buddhismus, überhaupt für orientalische Weltanschauung hat.

Nun ist im Grunde genommen jede solche Betrachtungsweise nur zu beurteilen, wenn man sie von jenem Gesichtspunkte aus überschauen kann, den die Geisteswissenschaft gibt. Von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus erscheint allerdings eine solche Zusammenfassung der Welt unter dem Gesichtspunkte des Gedankens oder unter dem Gesichtspunkte des Willens als etwas Abstraktes, und es ist ja insbesondere die neuere Zeit der Menschheitsentwickelung, die, wie wir öfter betont haben, noch zu solchen Abstraktionen neigt. Geisteswissenschaft muß die Menschheit wiederum zurückbringen zu einem konkreten Auffassen, zu einem wirklichkeitsgemäßen Auffassen der Welt. Aber gerade einem solchen wirklichkeitsgemäßen Auffassen der Welt werden die inneren Gründe erscheinen können, warum solche Einseitigkeiten Platz greifen. Das, was solche Menschen sehen, wie Hegel, Schopenhauer, die ja immerhin große, bedeutende, geniale Geister sind, das ist natürlich durchaus in der Welt vorhanden; es muß nur in der richtigen Weise angeschaut werden.

Wir wollen uns heute zunächst einmal klar werden darüber, daß wir in uns als Menschen den Gedanken erleben. Wenn also der Mensch von seinem Gedankenerlebnis spricht, so hat er dieses Gedankenerlebnis unmittelbar. Er könnte dieses Gedankenerlebnis natürlich nicht haben, wenn nicht die Welt von Gedanken durchsetzt wäre. Denn wie sollte der Mensch, indem er die Welt sinnlich wahrnimmt, aus seinem sinnlichen Wahrnehmen heraus den Gedanken gewinnen, wenn der Gedanke nicht in der Welt als solcher vorhanden wäre.

Nun ist aber, wie wir ja aus anderen Betrachtungen wissen, die menschliche Hauptesorganisation so gebaut, daß sie eben besonders fähig ist, den Gedanken hereinzunehmen aus der Welt. Sie ist aus den Gedanken heraus geformt, aus den Gedanken heraus gebildet. Die menschliche Hauptesorganisation aber weist uns ja zu gleicher Zeit nach dem vorigen Erdenleben hin. Wir wissen, daß das menschliche Haupt eigentlich das metamorphosische Ergebnis der vorigen Erdenleben ist, während die menschliche Gliedmaßenorganisation auf die künftigen Erdenleben hinweist. Grob gesprochen: Unseren Kopf haben wir dadurch, daß unsere Gliedmaßen aus dem vorhergehenden Erdenleben sich zum Kopf metamorphosiert haben. Unsere Gliedmaßen, wie wir sie jetzt an uns tragen, mit alledem, was zu ihnen gehört, werden sich metamorphosieren zu dem Haupte, das wir in dem nächsten Erdenleben an uns tragen werden. In unserem Haupte arbeiten ja gegenwärtig, vorzugsweise in dem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, die Gedanken. Diese Gedanken sind, wie wir auch gesehen haben, zugleich die Umgestaltung, die Metamorphose desjenigen, was in unseren Gliedmaßen in dem vorigen Erdenleben als Wille wirkte. Und dasjenige wiederum, was als Wille wirkt in unseren gegenwärtigen Gliedmaßen, das wird zum Gedanken umgebildet sein in dem nächsten Erdenleben.

Wenn Sie das überschauen, können Sie sich sagen: Der Gedanke, er erscheint eigentlich als dasjenige, was in der Menschheitsevolution fortdauernd als Metamorphose aus dem Willen hervorgeht. Der Wille erscheint eigentlich als dasjenige, was gewissermaßen der Keim des Gedankens ist. - So daß wir sagen können: Es entwickelt sich der Wille allmählich in den Gedanken hinein. Was zuerst Wille ist, wird später Gedanke. Wenn wir Menschen uns betrachten, so müssen wir, wenn wir uns als Hauptesmenschen ansehen, zurückblicken auf unsere Vorzeit, indem wir in dieser Vorzeit den Willenscharakter hatten. Wenn wir nach der Zukunft schauen, müssen wir uns gegenwärtig den Willenscharakter in unseren Gliedmaßen zuschreiben und müssen sagen: Das wird in der Zukunft dasjenige, was in unserem Haupte ausgebildet wird, der Gedankenmensch. Aber wir tragen fortwährend diese beiden in uns. Wir sind gewissermaßen bewirkt aus dem Weltenall dadurch, daß sich in uns der Gedanke aus der Vorzeit mit dem Willen, der in die Zukunft hinein will, zusammenorganisiert.

Nun wird das, was so den Menschen gewissermaßen aus dem Zusammenfluß von Gedanke und Wille organisiert, deren Ausdruck dann die äußere Organisation ist, das, was den Menschen gewissermaßen so durchorganisiert, besonders anschaulich, wenn man es vom Standpunkte geisteswissenschaftlicher Forschung betrachtet.

Derjenige, der sich hinaufentwickeln kann zu den Erkenntnissen der Imagination, der Inspiration, der Intuition, der sieht ja am Menschen nicht bloß den äußerlich sichtbaren Kopf, sondern er sieht objektiv dasjenige, was durch das Haupt Gedankenmensch ist. Er sieht gewissermaßen auf die Gedanken hin. So daß wir sagen können: Mit denjenigen Fähigkeiten, die dem Menschen als die zunächst normalen zukommen zwischen Geburt und Tod, zeigt sich das Haupt in der Konfiguration, in der es eben einmal da ist. Durch die entwickelte Erkenntnis in Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition wird auch das Gedanklich-Kraftliche, was ja der Hauptesorganisation zugrunde liegt, was von den früheren Inkarnationen herüberkommt, sichtbar, wenn wir uns dieses Ausdruckes in übertragenem Sinne bedienen. Wie wird es sichtbar? So, daß wir für dieses Sichtbarwerden, für dieses selbstverständlich geistig-seelische Sichtbarwerden nur den Ausdruck brauchen können: es wird wie leuchtend.

Gewiß, wenn die Menschen, die durchaus auf dem Gesichtspunkte des Materialismus stehenbleiben wollen, solche Sachen kritisieren, dann sieht man sogleich, wie stark der gegenwärtigen Menschheit die Empfindungsfähigkeit fehlt, um aufzufassen, was mit solchen Dingen eigentlich gemeint ist. Ich habe deutlich genug in meiner «Theosophie» und in anderen Schriften darauf hingewiesen, daß es sich darum handelt, daß natürlich nicht eine neue physische Welt, gewissermaßen eine neue Auflage der physischen Welt erscheint, wenn in Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition hingeschaut wird auf das, was der Gedankenmensch ist. Aber dieses Erlebnis ist eben durchaus dasselbe, was man der physischen Außenwelt gegenüber am Lichte hat. Genau gesprochen müßte man sagen: Der Mensch hat am äußeren Lichte ein gewisses Erlebnis. Dasselbe Erlebnis, das der Mensch durch die sinnliche Anschauung des Lichtes in der äußeren Welt hat, hat er gegenüber dem Gedankenelemente des Hauptes für die Imagination. So daß man sagen kann: Das Gedankenelement, objektiv geschaut, wird als Licht geschaut, besser gesagt, als Licht erlebt. - Wir leben, indem wir denkende Menschen sind, im Lichte. Das äußere Licht sieht man mit physischen Sinnen; das Licht, das zum Gedanken wird, sieht man nicht, weil man darinnen lebt, weil man es selber ist als Gedankenmensch. Man kann dasjenige nicht sehen, was man zunächst selber ist. Wenn man heraustritt aus diesen Gedanken, wenn man in die Imagination, Inspiration eintritt, dann stellt man sich ihm gegenüber, und dann sieht man das Gedankenelement als Licht. So daß wir, wenn wir von der vollständigen Welt reden, sagen können: Wir haben das Licht in uns; nur erscheint es uns da nicht als Licht, weil wir darinnen leben, und weil, indem wir uns des Lichtes bedienen, indem wir das Licht haben, es in uns zum Gedanken wird. - Sie bemächtigen sich gewissermaßen des Lichtes; das Licht, das Ihnen sonst draußen erscheint, das nehmen Sie in sich auf. Sie differenzieren es in sich. Sie arbeiten in ihm. Das ist eben Ihr Denken, das ist ein Handeln im Lichte. Sie sind ein Lichtwesen. Sie wissen nicht, daß Sie ein Lichtwesen sind, weil Sie im Lichte drinnen leben. Aber Ihr Denken, das Sie entfalten, das ist das Leben im Lichte. Und wenn Sie das Denken von außen anschauen, dann sehen Sie durchaus Licht.

Denken Sie sich nun das Weltenall [siehe Zeichnung]. Sie sehen es — bei Tag natürlich — vom Lichte durchströmt, aber stellen Sie sich vor, Sie sähen dieses Weltenall von außen an. Und jetzt machen wir das Umgekehrte. Wir haben soeben das Menschenhaupt gehabt, das im Innern den Gedanken in seiner Entwickelung hat, und äußerlich Licht schaut. Im Weltenall haben wir Licht, das sinnlich angeschaut wird. Kommen wir aus dem Weltenall heraus, betrachten wir das Weltenall von außen [Pfeile], als was erscheint es da? Als ein Gefüge von Gedanken! Das Weltenall - innerlich Licht, von außen angesehen Gedanken. Das Menschenhaupt - innerlich Gedanke, von außen gesehen Licht.

Das ist eine Art der Anschauung des Kosmos, die Ihnen ungemein nützlich und aufschlußreich sein kann, wenn Sie sie verwerten wollen, wenn Sie wirklich auf solche Dinge eingehen. Es wird Ihr Denken, Ihr ganzes Seelenleben viel beweglicher werden, als es sonst ist, wenn Sie lernen, sich vorzustellen: Würde ich aus mir herauskommen, wie es ja fortwährend der Fall ist, wenn ich einschlafe, und zurückschauen auf mein Haupt, also auf mich als Gedankenmenschen, so sähe ich mich leuchtend. Würde ich aus der Welt, aus der durchleuchteten Welt herauskommen, die Welt von außen sehen, so würde ich sie als ein Gedankengebilde sehen. Ich würde die Welt als Gedankenwesenheit wahrnehmen. - Sie sehen, Licht und Gedanke gehören zusammen, Licht und Gedanke sind dasselbe, nur von verschiedenen Seiten gesehen.

Nun ist aber der Gedanke, der in uns lebt, eigentlich dasjenige, was aus der Vorzeit herüberkommt, was das Reifste in uns ist, das Ergebnis früherer Erdenleben. Was früher Wille war, ist Gedanke geworden, und es erscheint der Gedanke als Licht. Daraus werden Sie empfinden können: Wo Licht ist, ist Gedanke, aber wie? Gedanke, in dem eine Welt fortwährend erstirbt. Eine Vorwelt, eine vorzeitige Welt erstirbt im Gedanken, oder anders ausgesprochen, im Lichte. Das ist eines der Weltengeheimnisse. Wir schauen hinaus in das Weltenall. Es ist durchströmt vom Lichte. Im Lichte lebt der Gedanke. Aber in diesem gedankendurchdrungenen Lichte lebt eine ersterbende Welt. Im Lichte erstirbt fortwährend die Welt.

Indem so ein Mensch wie Hegel die Welt betrachtet, betrachtet er eigentlich das fortwährende Ersterben der Welt. Diejenigen Menschen werden ganz besonders Gedankenmenschen, welche zum Sinkenden, Ersterbenden, Sich-Ablähmenden der Welt eine besondere Neigung haben. Und im Ersterben wird die Welt schön. Die Griechen, die innerlich eigentlich durch und durch von lebendiger Menschenwesenheit waren, nach außen hatten sie ihre Freude, wenn in dem Ersterben der Welt die Schönheit erglänzte. Denn in dem Lichte, in dem die Welt erstirbt, erglänzt die Schönheit der Welt. Die Welt wird nicht schön, wenn sie nicht sterben kann, und indem sie stirbt, leuchtet sie, die Welt. So daß es eigentlich die Schönheit ist, welche aus dem Lichtesglanze der fortwährend ersterbenden Welt erscheint. So betrachtet man das Weltenall qualitativ. Mit Galilei hat die neuere Zeit begonnen, die Welt quantitativ zu betrachten, und man ist heute besonders stolz darauf, wenn man, wie es überall in unseren Wissenschaften geschieht, wo man es nur tun kann, die Naturerscheinungen durch die Mathematik, also durch das Tote begreifen kann. Hegel hat allerdings inhaltsvollere Begriffe verwendet zum Begreifen der Welt, als die mathematischen es sind; aber für ihn war besonders anziehend das Reifgewordene, das Ersterbende. Man möchte sagen: Hegel stand der Welt so gegenüber wie ein Mensch, der einem Baum gegenübersteht, der gerade strotzend von Blütenentfaltung ist. Im Momente, wo die Früchte sich entfalten wollen, aber noch nicht da sind, wo die Blüten zum äußersten gekommen sind, da wirkt in dem Baum die Lichtesgewalt, da wirkt in dem Baum dasjenige, was lichtgetragener Gedanke ist. So stand Hegel vor allen Erscheinungen der Welt. Er betrachtete die äußerste Blüte, dasjenige, was sich ganz und gar ins Konkreteste entfaltet.

Schopenhauer stand anders vor der Welt. Wenn wir den Schopenhauerschen Impetus prüfen wollen, dann müssen wir auf das andere im Menschen schauen, auf dasjenige, was beginnt. Es ist das Willenselement, das wir in unseren Gliedmaßen tragen. Ja, das erleben wir eigentlich so — ich habe öfter darauf hingewiesen -, wie wir die Welt erleben im Schlafe. Wir erleben es unbewußt, das Willenselement. Können wir denn auch dieses Willenselement irgendwie so von außen anschauen, wie wir den Gedanken von außen anschauen? Nehmen wir den Willen, irgendwie in einem menschlichen Gliede sich entfaltend, und fragen wir uns, wenn wir den Willen nun von der anderen Seite anschauen würden, wenn wir also vom Standpunkte der Imagination, der Inspiration, der Intuition den Willen betrachten: Was ist denn das Parallele im Anschauen gegenüber dem, daß wir den Gedanken als Licht schauen? Wie schauen wir den Willen, wenn wir ihn mit der entwickelten Kraft des Anschauens, der Hellsichtigkeit betrachten? Wenn wir den Willen mit der entwickelten Kraft des Anschauens, der Hellsichtigkeit betrachten, dann wird auch etwas erlebt, was wir äußerlich sehen. Wenn wir den Gedanken mit der Kraft des Hellsehens betrachten, wird Licht erlebt, Leuchtendes erlebt. Wenn wir den Willen mit der Kraft des Hellsehens betrachten, so wird er immer dicker und dicker, dieser Wille, und er wird Stoff. Wäre Schopenhauer hellsichtig gewesen, so würde dieses Willenswesen als ein Stoffautomat vor ihm gestanden haben, denn das ist die Außenseite des Willens, der Stoff. Innerlich ist der Stoff Wille, wie das Licht innerlich Gedanke ist. Und äußerlich ist der Wille Stoff, wie der Gedanke äußerlich Licht ist. Deshalb konnte ich auch bei früheren Betrachtungen darauf hinweisen: Wenn der Mensch in seine Willensnatur mystisch hinuntertaucht, so glauben diejenigen, die eigentlich mit der Mystik nur Faxen treiben, in Wirklichkeit aber nach dem Wohlbefinden, nach dem Erleben des ärgsten Egoismus streben, dann glauben solche In-sich-Hineinschauer, sie würden den Geist finden. Aber wenn sie weit genug kämen mit diesem In-sichHineinschauen, würden sie die wahre stoffliche Natur des Menscheninneren entdecken. Denn es ist nichts anderes als ein Untertauchen in den Stoff. Wenn man in die Willensnatur untertaucht, da enthüllt sich einem die wahre Natur des Stoffes. Die Naturphilosophen in der Gegenwart phantasieren ja nur, wenn sie sagen, daß der Stoff aus Molekülen und Atomen bestehe. Die wahre Natur des Stoffes findet man, wenn man mystisch in sich untertaucht. Da findet man die andere Seite des Willens, und die ist Stoff. Und in diesem Stoff, also in dem Willen enthüllt sich im Grunde genommen dasjenige, was fortwährend beginnende, keimende Welt ist.

Sie schauen hinaus in die Welt: Sie sind vom Licht umflossen. In dem Lichte erstirbt eine vorzeitige Welt. Sie treten auf den harten Stoff auf — die Stärke der Welt trägt Sie. In dem Lichte erstrahlt gedanklich die Schönheit. In dem Erglänzen der Schönheit erstirbt die vorzeitige Welt. Die Welt geht auf in ihrer Stärke, in ihrer Kraft, in ihrer Gewalt, aber auch in ihrer Finsternis. In Finsternis geht sie auf, die zukünftige Welt, im stofflich-willensartigen Elemente.

Wenn die Physiker einmal ernsthaft reden werden, dann werden sie sich nicht jenen Spekulationen hingeben, in denen heute von den Atomen und Molekülen gefaselt wird, sondern sie werden sagen: Die äußere Welt besteht aus Vergangenheit, und im Inneren trägt sie nicht Moleküle und Atome, sondern Zukunft. Und wenn man einmal sagen wird: Uns erscheint strahlend die Vergangenheit in der Gegenwart, und die Vergangenheit hüllt die Zukunft überall ein -, dann wird man von der Welt richtig reden, denn die Gegenwart ist überall nur dasjenige, was Vergangenheit und Zukunft zusammen wirken. Die Zukunft ist dasjenige, was eigentlich in der Stärke des Stoffes liegt. Die Vergangenheit ist dasjenige, was in der Schönheit des Lichtes erglänzt, wobei Licht für alles Sich-Offenbarende gesetzt ist, denn natürlich, auch was im Tone erscheint, was in der Wärme erscheint, ist hier ünter dem Lichte gemeint.

Und so kann sich der Mensch nur selber verstehen, wenn er sich auffaßt als Zukunftskern, der umhüllt ist von dem, was ihm von der Vergangenheit herrührt, von der Lichtaura des Gedankens. Man kann sagen: Geistig gesehen ist der Mensch Vergangenheit, wo er in seiner Schönheitsaura erstrahlt, aber eingegliedert ist dieser Vergangenheitsaura, was als Finsternis sich beimischt dem Lichte, das aus der Vergangenheit herüberstrahlt, und was in die Zukunft hinüberträgt. Das Licht ist dasjenige, was aus der Vergangenheit herüberstrahlt, die Finsternis, was in die Zukunft hinüberweist. Das Licht ist gedanklicher Natur, die Finsternis ist willensartiger Natur. Hegel war dem Lichte zugeneigt, das sich entfaltet in dem Wachstumsprozesse, in den reifsten Blüten. Schopenhauer ist als Weltenbetrachter wie ein Mensch, der vor einem Baume steht und eigentlich keine Freude hat an der Blütenpracht, sondern der eine innerliche Anstachelung hat, nur zu warten, bis da aus den Blüten überall die Keime für die Früchte hervorsprießen. Das freut ihn, daß da drinnen Wachstumskraft ist, das stachelt ihn an, es wässert sich ihm der Mund, wenn er daran denken kann, daß da aus der Pfirsichblüte die Pfirsiche werden. Er wendet sich von der Lichtnatur dem zu, was ihn von innen ergreift, was sich aus der Lichtnatur der Blüte entfaltet als dasjenige, was stofflich auf seiner Zunge zerfließen kann, was sich als Früchte in die Zukunft hinüberentwickelt. Es ist tatsächlich die Zwienatur der Welt, und man betrachtet die Welt nur richtig, wenn man sie in ihrer Zwienatur betrachtet, denn dann kommt man darauf, wie diese Welt konkret ist, während man sie sonst nur in ihrer Abstraktheit betrachtet. Wenn Sie hinausgehen und sehen sich an die Bäume in ihrer Blüte, dann leben Sie eigentlich von der Vergangenheit. Also Sie betrachten die Frühlingsnatur der Welt und Sie können sich sagen: Was Götter in vergangenen Zeiten hineingewirkt haben in diese Welt, das offenbart sich in der Blütenpracht des Frühlings. Sie betrachten die fruchtende Welt des Herbstes, und Sie können sagen: Da beginnt eine neue Göttertat, da fällt ab, was aber weiterer Entwickelung fähig ist, was in die Zukunft sich hineinentwickelt.,

So handelt es sich darum, daß man nicht bloß durch Spekulation ein Bild der Welt sich erwirbt, sondern daß man innerlich mit dem ganzen Menschen die Welt ergreift. Man kann tatsächlich in der Pflaumenblüte, ich möchte sagen, die Vergangenheit ergreifen, in der Pflaume die Zukunft erfühlen. Was einem in die Augen hereinscheint, das hängt innig zusammen mit dem, aus dem man geworden ist aus der Vergangenheit heraus. Was einem auf der Zunge im Geschmack zerschmilzt, das hängt innig zusammen mit demjenigen, aus dem man wiederersteht, wie der Phönix aus seiner Asche, in die Zukunft hinein. Da ergreift man die Welt in Empfindung. Und nach solchem «in Empfindung die Welt ergreifen» hat eigentlich Goethe getrachtet bei allem, was er in der Welt erschauen, empfinden wollte. Er hat zum Beispiel hingeschaut nach der grünen Pflanzenwelt. Er hatte ja nicht, was man heute als Geisteswissenschaft haben kann, aber indem er die Grünheit der Pflanzenwelt anschaute, hatte er doch in der Grünheit der Pflanze, die noch nicht ganz bis zum Blütenhaften sich entfaltet hatte, dasjenige, was in die Gegenwart hereinragt von dem eigentlich Vergangenen des Pflanzenhaften; denn in der Pflanze erscheint schon die Vergangenheit in der Blüte; aber, was noch nicht ganz so vergangen ist, das ist die Grünheit des Blattes.

Sieht man die Grünheit der Natur, so ist das gewissermaßen etwas, was noch nicht so weit erstorben ist, was noch nicht so von der Vergangenheit ergriffen ist [siehe Zeichnung grün]. Das aber, was nach der Zukunft hinweist, ist dasjenige, was aus dem Finstern, aus dem Dunkeln herauskommt. Da, wo das Grün zum Bläulichen abgestuft ist, da ist das, was sich in der Natur als das Zukünftige erweist [blau].

Dagegen da, wo wir gewiesen werden in die Vergangenheit, wo dasjenige liegt, was reift, was die Dinge zum Blühen bringt, da ist die Wärme [rot], wo das Licht sich nicht nur aufhellt, sondern wo es sich innerlich durchdringt mit Kraft, wo es in die Wärme übergeht. Nun müßte man das Ganze eigentlich so zeichnen, daß man sagt: Man hat das Grüne, die Pflanzenwelt - so würde Goethe empfinden, wenn er es auch noch nicht in Geisteswissenschaft oder Geheimwissenschaft umgesetzt hat -, daranknüpfend die Finsternis, wo sich das Grüne bläulich abstuft. Das sich Aufhellende, von Wärme Erfüllende aber, das würde sich wiederum anschließen nach der oberen Seite hin. Da steht man aber selbst als Mensch, da hat man als Mensch innerlich das, was man in der grünen Pflanzenwelt äußerlich hat, da ist man innerlich als menschlicher Ätherleib, wie ich oftmals gesagt habe, pfirsichblütfarbig. Das ist auch die Farbe, die hier erscheint, wenn das Blau in das Rote übergreift. Das ist man aber selber. So daß man eigentlich, wenn man in die farbige Welt hinaussieht, sagen kann: Man steht selber in dem Pfirsichblütigen drinnen, hat gegenüber das Grün. Das bietet sich einem dann objektiv in der Pflanzenwelt dar. Man hat auf der einen Seite das Bläuliche, Finstere, auf der anderen Seite das Helle, Rötlich-Gelbliche. Aber weil man in dem Pfirsichblütigen drinnen ist, weil man da drinnen lebt, kann man das zunächst im gewöhnlichen Leben ebensowenig wahrnehmen, wie man den Gedanken als Licht wahrnimmt. Was man erlebt, das nimmt man nicht wahr, deshalb läßt man da das Pfirsichblüt aus und sieht nur auf das Rot hin, das man auf der einen Seite erweitert, und nach dem Blau hin, das man nach der anderen Seite erweitert; und so erscheint einem solch ein Regenbogenspektrum. Das ist aber nur eine Täuschung. Das wirkliche Spektrum würde man bekommen, wenn man dieses Farbenband kreisförmig biegen würde. Man biegt es in der Tat gerade, weil man als Mensch in dem Pfirsichblütigen drinnensteht, und so übersieht man nur von Blau bis zu Rot und von Rot bis zu Blau durch das Grün die farbige Welt. In dem Augenblicke, wo man diesen Aspekt haben würde, würde jeder Regenbogen als Kreis erscheinen, als in sich gebogener Kreis, als Rolle mit Kreisdurchschnitt.

Das letzte habe ich nur erwähnt, um Sie darauf aufmerksam zu machen, daß so etwas wie die Goethesche Naturanschauung durchaus zu gleicher Zeit eine Geistanschauung ist, daß sie dem geistigen Anschauen voll entspricht. Wenn man an Goethe, den Naturforscher, herantritt, so kann man sagen: Er hat eigentlich noch keine Geisteswissenschaft, aber er hat die Naturwissenschaft so betrachtet, daß es ganz im Sinne der Geisteswissenschaft ist. Was uns aber heute ganz wesentlich sein muß, das ist dieses, daß die Welt einschließlich des Menschen ein Durchorganisieren von Gedankenlicht, Lichtgedanken mit Willensstoff, Stoffwille ist, und daß dasjenige, was uns konkret entgegentritt, in der verschiedensten Weise aufgebaut oder mit Inhalt durchzogen ist aus Gedankenlicht, Lichtgedanken, Stoffwille, Willensstoft.

So muß man qualitativ den Kosmos betrachten, nicht bloß quantitativ, dann kommt man mit diesem Kosmos zurecht. Dann gliedert sich aber auch hinein in diesen Kosmos ein fortwährendes Ersterben, ein Ersterben der Vorzeit im Lichte, ein Aufgehen der Zukunft in der Finsternis. Die alten Perser nannten aus ihrem instinktiven Hellsehen heraus, das, was sie als die ersterbende Vorzeit im Lichte fühlten, Ahura Mazdao, was sie als die Zukunft im finsteren Willen fühlten, Ahriman.

Und nun haben Sie diese zwei Welt-Entitäten, das Licht und die Finsternis: im Lichte den lebenden Gedanken, die ersterbende Vorzeit; in der Finsternis den entstehenden Willen, die kommende Zukunft. Indem wir so weit kommen, daß wir den Gedanken nicht mehr in seiner Abstraktheit bloß betrachten, sondern als Licht, den Willen nicht mehr in seiner Abstraktheit betrachten, sondern als Dunkelheit, ja in seiner materiellen Natur betrachten, indem wir dazu kommen, die Wärmeinhalte zum Beispiel des Lichtspektrums als mit der Vergangenheit, die Stoffseite, die chemische Seite des Spektrums mit der Zukunft zusammenfallend betrachten zu können, gehen wir aus dem bloßen Abstrakten ins Konkrete heraus. Wir sind nicht mehr solche ausgedörrte, pedantische, bloß mit dem Kopfe arbeitende Denker, wir wissen, das, was da in unserem Kopfe drinnnen denkt, ist eigentlich dasselbe, was uns als Licht umflutet. Und wir sind nicht mehr solche vorurteilsvolle Menschen, daß wir an dem Lichte bloß Freude haben, sondern wir wissen: In dem Lichte ist der Tod, eine ersterbende Welt. Wir können an dem Lichte auch die Weltentragik empfinden. Wir kommen also aus dem Abstrakten, aus dem Gedanklichen in das Flutende der Welt hinein. Und wir sehen in dem, was Finsternis ist, den aufgehenden Teil der Zukunft. Wir finden sogar das darinnen, was solche leidenschaftliche Naturen wie Schopenhauer aufstachelt. Kurz, wir dringen aus dem Abstrakten ins Konkrete hinein. Weltengebilde entstehen vor uns, statt bloßer Gedanken oder abstrakter Willensimpulse.

Das haben wir heute gesucht. Das nächste Mal werden wir in dem, was sich uns heute merkwürdig konkretisiert hat — der Gedanke zum Licht, der Wille zur Finsternis —, suchen den Ursprung von Gut und von Böse, Wir dringen also von der Innenwelt in den Kosmos hinein und suchen im Kosmos wiederum nicht bloß in einer abstrakten oder . religiös-abstrakten Welt die Gründe für Gut und Böse, sondern wir wollen sehen, wie wir durchbrechen zu einer Erkenntnis von Gut und Böse, nachdem wir den Anfang damit gemacht haben, daß wir den Gedanken in seinem Lichte ergriffen, den Willen in seinem Finsterwerden erfühlt haben. Davon dann das nächste Mal weiter.

Light and Darkness as Two World Entities

From yesterday's explanations, you will have gathered that one views the world one-sidedly if one views it in the way that is particularly evident in Hegel, if one views it as if it were permeated by what can be called the cosmic idea. One views the world just as one-sidedly when one thinks of the basic structure of volitional nature. It is Schopenhauer's idea to think of the world as volitional nature. We have seen that this particular tendency, I might say, to view the world as the effect of thought, points to Western human nature, which tends more toward the intellectual side. We have been able to demonstrate how Hegel's philosophy of thought takes on a different form in Western worldviews, and how Schopenhauer's sensibilities reflect a tendency that is actually characteristic of Oriental people, as evidenced by Schopenhauer's particular fondness for Buddhism and Oriental worldviews in general.

Now, basically, any such view can only be judged if it can be viewed from the perspective provided by spiritual science. From this point of view, however, such a summary of the world from the perspective of thought or will appears as something abstract, and it is especially the more recent period of human development that, as we have often emphasized, still tends toward such abstractions. Spiritual science must bring humanity back to a concrete understanding, to a realistic understanding of the world. But it is precisely in such a realistic understanding of the world that the inner reasons why such one-sidedness takes hold will become apparent. What such people as Hegel and Schopenhauer, who are after all great, significant, and brilliant minds, see is of course entirely present in the world; it just needs to be viewed in the right way.

Today, we want to start by clarifying that we experience thoughts within ourselves as human beings. So when a person speaks of their experience of thought, they have this experience of thought directly. Of course, they could not have this experience of thought if the world were not permeated by thoughts. For how could human beings, perceiving the world through their senses, gain thoughts from their sensory perception if thoughts did not exist in the world as such?

Now, as we know from other considerations, the human head is structured in such a way that it is particularly capable of taking in thoughts from the world. It is formed out of thoughts, shaped out of thoughts. At the same time, however, the human head organization points us to our previous earthly life. We know that the human head is actually the metamorphic result of previous earthly lives, while the human limb organization points to future earthly lives. Roughly speaking, we have our head because our limbs from our previous earthly life have metamorphosed into the head. Our limbs, as we now carry them, with all that belongs to them, will metamorphose into the head that we will carry in our next earthly life. Thoughts are currently at work in our head, especially in the life between birth and death. As we have also seen, these thoughts are at the same time the transformation, the metamorphosis of what worked as will in our limbs in the previous earthly life. And what works as will in our present limbs will in turn be transformed into thought in the next earthly life.

When you understand this, you can say to yourself: Thought actually appears as that which continually emerges from the will as a metamorphosis in human evolution. The will actually appears as that which is, in a sense, the seed of thought. So we can say: The will gradually develops into thought. What is first will later becomes thought. When we look at ourselves as human beings, if we see ourselves as head-people, we must look back on our past, in which we had the character of will. When we look to the future, we must currently attribute the character of will to our limbs and say: in the future, this will become what is formed in our heads, the thinking human being. But we constantly carry both of these within us. We are, in a sense, brought about by the universe through the fact that the thought from the past is organized within us together with the will that wants to move into the future.

Now, what is organized in human beings, as it were, from the confluence of thought and will, the expression of which is then the outer organization, becomes particularly clear when viewed from the standpoint of spiritual scientific research.

Those who can develop themselves to the insights of imagination, inspiration, and intuition see in human beings not only the externally visible head, but also objectively see what is thought-human through the head. They see, as it were, the thoughts. So we can say that with the abilities that come naturally to human beings between birth and death, the head shows itself in the configuration in which it happens to be. Through the developed knowledge of imagination, inspiration, and intuition, the mental-emotional forces that underlie the organization of the head, which come over from previous incarnations, also become visible, if we use this expression in a figurative sense. How does it become visible? In such a way that we can only use the expression “it becomes luminous” for this becoming visible, for this self-evident spiritual-soul becoming visible.

Certainly, when people who want to remain firmly rooted in materialism criticize such things, one immediately sees how much the present-day human race lacks the sensitivity to understand what is actually meant by such things. I have pointed out clearly enough in my “Theosophy” and in other writings that it is not, of course, a new physical world, a new edition of the physical world, that appears when we look with imagination, inspiration, and intuition at what the thinking human being is. But this experience is exactly the same as what one has in relation to the physical outer world in the light. To be precise, one would have to say: Man has a certain experience in relation to the outer light. The same experience that human beings have through the sensory perception of light in the external world, they have in relation to the thought element of the head for the imagination. So that one can say: the thought element, viewed objectively, is seen as light, or rather, experienced as light. As thinking human beings, we live in the light. We see external light with our physical senses; we do not see the light that becomes thought, because we live within it, because we ourselves are it as thinking human beings. We cannot see that which we ourselves are. When we step out of these thoughts, when we enter into imagination and inspiration, we stand opposite it, and then we see the element of thought as light. So that when we speak of the complete world, we can say: We have the light within us; only it does not appear to us as light because we live within it, and because, as we make use of the light, as we have the light, it becomes thought within us. You take possession of the light, so to speak; you take in the light that otherwise appears to you outside. You differentiate it within yourself. You work in it. That is your thinking, that is acting in the light. You are a being of light. You do not know that you are a being of light because you live inside the light. But your thinking, which you unfold, is life in the light. And when you look at thinking from the outside, you see light.

Now think of the universe [see drawing]. You see it — during the day, of course — flooded with light, but imagine you were looking at this universe from the outside. And now let's do the opposite. We have just had the human head, which has the thought in its development on the inside and sees light on the outside. In the universe, we have light that is perceived by the senses. If we come out of the universe and look at it from the outside [arrows], what does it appear to be? A structure of thoughts! The universe — light on the inside, thoughts when viewed from the outside. The human head — thoughts on the inside, light when viewed from the outside.

This is a way of looking at the cosmos that can be extremely useful and insightful if you want to make use of it, if you really engage with such things. Your thinking, your entire soul life, will become much more flexible than it otherwise is if you learn to imagine: If I were to step outside of myself, as is constantly the case when I fall asleep, and look back at my head, that is, at myself as a thinking human being, I would see myself glowing. If I were to step out of the world, out of the illuminated world, and see the world from the outside, I would see it as a thought construct. I would perceive the world as a thought entity. You see, light and thought belong together; light and thought are the same, only seen from different sides.

But now the thought that lives in us is actually that which comes over from prehistoric times, that which is most mature in us, the result of earlier earthly lives. What was once will has become thought, and thought appears as light. From this you will be able to sense: where there is light, there is thought, but how? Thought in which a world continually dies away. A pre-world, a pre-time world dies in thought, or in other words, in light. That is one of the secrets of the world. We look out into the universe. It is permeated by light. Thought lives in light. But in this light permeated by thought, a dying world lives. In light, the world continually dies.

When a person like Hegel looks at the world, he is actually looking at the world's constant dying. Those people who have a special affinity for the sinking, dying, withering away of the world become particularly thoughtful people. And in dying, the world becomes beautiful. The Greeks, who were actually thoroughly imbued with living humanity, outwardly rejoiced when beauty shone forth in the dying of the world. For in the light in which the world dies, the beauty of the world shines forth. The world does not become beautiful if it cannot die, and as it dies, the world shines. So it is actually beauty that emerges from the light of the ever-dying world. This is how one views the universe qualitatively. With Galileo, the modern era began to view the world quantitatively, and today we are particularly proud when, as happens everywhere in our sciences wherever it is possible, we can understand natural phenomena through mathematics, that is, through the dead. Hegel certainly used more meaningful concepts to understand the world than mathematical ones, but he was particularly attracted to what had ripened, what was dying. One might say that Hegel viewed the world like a person standing in front of a tree bursting with blossoms. At the moment when the fruits are about to unfold but are not yet there, when the blossoms have reached their peak, the power of light is at work in the tree, that which is light-bearing thought is at work in the tree. This is how Hegel stood before all the phenomena of the world. He looked at the utmost blossom, that which unfolds itself completely into the most concrete.

Schopenhauer viewed the world differently. If we want to examine Schopenhauer's impetus, we must look at the other aspect of human beings, at that which is beginning. It is the element of will that we carry in our limbs. Yes, we actually experience this — as I have often pointed out — in the same way that we experience the world in sleep. We experience it unconsciously, the element of will. Can we also view this element of will from the outside, just as we view thoughts from the outside? Let us take the will, unfolding somehow in a human limb, and ask ourselves, if we were to view the will from the other side, if we were to view the will from the standpoint of imagination, inspiration, intuition: What is the parallel in viewing this to seeing thoughts as light? How do we see the will when we view it with the developed power of observation, of clairvoyance? When we view the will with the developed power of observation, of clairvoyance, then we also experience something that we see externally. When we contemplate thought with the power of clairvoyance, we experience light, we experience something luminous. When we contemplate the will with the power of clairvoyance, this will becomes thicker and thicker, and it becomes matter. If Schopenhauer had been clairvoyant, this being of will would have stood before him as a material automaton, for that is the outer aspect of the will, the material. Internally, matter is will, just as light is internally thought. And externally, will is matter, just as thought is externally light. That is why I was able to point out in earlier reflections: When human beings mystically delve into their will nature, those who are actually only fooling around with mysticism, but in reality are striving for well-being, for the experience of the worst egoism, then such introspectives believe they will find the spirit. But if they went far enough with this looking within themselves, they would discover the true material nature of the human inner being. For it is nothing other than a descent into matter. When one descends into the nature of the will, the true nature of matter is revealed. Contemporary natural philosophers are only fantasizing when they say that matter consists of molecules and atoms. The true nature of matter is found when one mystically submerges oneself. There one finds the other side of the will, and that is matter. And in this matter, that is, in the will, what is essentially revealed is the world that is constantly beginning, germinating.

You look out into the world: you are surrounded by light. In the light, a premature world dies. You step onto the hard matter — the strength of the world carries you. In the light, beauty shines in your mind. In the radiance of beauty, the premature world dies. The world dawns in its strength, in its power, in its might, but also in its darkness. In darkness it dawns, the future world, in the material-volitional element.

When physicists finally speak seriously, they will not indulge in the speculations that today ramble on about atoms and molecules, but will say: The outer world consists of the past, and inside it carries not molecules and atoms, but the future. And once it is said: The past appears radiant to us in the present, and the past envelops the future everywhere — then we will speak correctly about the world, for the present is everywhere only that which the past and future work together to create. The future is what actually lies in the strength of matter. The past is what shines in the beauty of light, whereby light is set for everything that reveals itself, for of course, what appears in sound, what appears in warmth, is also meant here under light.

And so human beings can only understand themselves if they conceive of themselves as a core of the future, enveloped by what comes to them from the past, from the light aura of thought. One can say: spiritually speaking, human beings are the past, where they shine in their aura of beauty, but integrated into this aura of the past is what mingles with the light that shines from the past as darkness and carries over into the future. Light is what shines from the past, darkness what points to the future. Light is of a mental nature, darkness is of a volitional nature. Hegel was inclined toward the light that unfolds in the process of growth, in the ripest blossoms. As an observer of the world, Schopenhauer is like a person standing in front of a tree who does not really enjoy the splendor of the blossoms, but who has an inner urge to wait until the buds for the fruits sprout from the blossoms everywhere. He is pleased that there is growth power inside, it spurs him on, his mouth waters when he thinks about the peach blossoms turning into peaches. He turns away from the light nature to what moves him from within, what unfolds from the light nature of the blossom as that which can melt on his tongue, which develops into fruit in the future. It is indeed the dual nature of the world, and one can only view the world correctly when one views it in its dual nature, for then one realizes how concrete this world is, whereas otherwise one views it only in its abstractness. When you go outside and look at the trees in bloom, you are actually living from the past. So you look at the spring nature of the world and you can say to yourself: what the gods have wrought in this world in times past is revealed in the splendor of spring blossoms. You look at the fruitful world of autumn and you can say: a new divine deed is beginning, that which is capable of further development is falling away, that which will develop into the future.

So it is a matter of not merely acquiring a picture of the world through speculation, but of grasping the world inwardly with your whole being. You can actually grasp the past in the plum blossom, I would say, and feel the future in the plum. What shines into one's eyes is intimately connected with what one has become out of the past. What melts on one's tongue in taste is intimately connected with what one is reborn from, like the phoenix from its ashes, into the future. That is how one grasps the world in feeling. And Goethe actually sought to “grasp the world through feeling” in everything he wanted to see and feel in the world. For example, he looked at the green plant world. He did not have what we today call spiritual science, but by looking at the greenness of the plant world, he saw in the greenness of the plant, which had not yet fully blossomed, that which protrudes into the present from the actual past of the plant; for in the plant, the past already appears in the blossom; but what is not yet completely past is the greenness of the leaf.

When we see the greenness of nature, it is, in a sense, something that has not yet died, that has not yet been seized by the past [see drawing green]. But what points to the future is that which emerges from the darkness, from the gloom. Where the green gradates into blue, there is that which proves to be the future in nature [blue].

On the other hand, where we are led into the past, where that which ripens, that which brings things to bloom, is located, there is warmth [red], where the light not only brightens, but where it is imbued with inner strength, where it transitions into warmth. Now one would actually have to draw the whole thing in such a way that one says: one has the green, the plant world – this is how Goethe would feel, even if he had not yet translated it into spiritual science or secret science – followed by the darkness, where the green gradates into blue. But the brightening, the filling with warmth, would in turn follow on the upper side. But there you stand as a human being, and as a human being you have within you what you have outside in the green plant world; inwardly, as I have often said, you are peach blossom-colored as a human etheric body. That is also the color that appears here when the blue merges into the red. But that is what you yourself are. So that when you look out into the world of colors, you can actually say: you yourself are standing inside the peach blossom, with the green opposite you. That is what presents itself objectively in the plant world. On one side you have the bluish, dark colors, on the other side the light, reddish-yellow colors. But because you are inside the peach blossom, because you live there, you cannot perceive this in ordinary life, just as you cannot perceive thoughts as light. You don't perceive what you experience, so you leave out the peach blossom and only see the red, which you extend on one side, and the blue, which you extend on the other side; and so you see a rainbow spectrum. But that is only an illusion. You would get the real spectrum if you bent this band of colors into a circle. In fact, you bend it straight because, as a human being, you are standing inside the peach blossom, and so you only see the colored world from blue to red and from red to blue through the green. The moment you had this perspective, every rainbow would appear as a circle, as a circle bent in on itself, as a roll with a circular cross-section.

I only mentioned the latter to draw your attention to the fact that something like Goethe's view of nature is at the same time a view of the spirit, that it fully corresponds to spiritual contemplation. When approaching Goethe, the natural scientist, one can say: He does not actually have a spiritual science yet, but he viewed natural science in such a way that it is entirely in line with spiritual science. But what must be essential for us today is this: that the world, including human beings, is a thoroughgoing organization of thought-light, light-thoughts with will-substance, substance-will, and that what we encounter in concrete form is structured in the most diverse ways or permeated with content from thought-light, light-thoughts, substance-will, will-substance.

We must therefore view the cosmos qualitatively, not merely quantitatively, and then we will be able to cope with this cosmos. But then a continuous dying away is also integrated into this cosmos, a dying away of the past in the light, a rising of the future in the darkness. The ancient Persians, out of their instinctive clairvoyance, called what they felt as the dying past in the light Ahura Mazdao, and what they felt as the future in the dark will Ahriman.

And now you have these two world entities, light and darkness: in the light, the living thoughts, the dying past; in the darkness, the emerging will, the coming future. By reaching the point where we no longer view thoughts in their abstractness, but as light, and no longer view the will in its abstractness, but as darkness, yes, in its material nature, by coming to be able to regard the heat contents, for example, of the light spectrum as coinciding with the past, and the material side, the chemical side of the spectrum, as coinciding with the future, we move from the merely abstract to the concrete. We are no longer such dry, pedantic thinkers who work only with our heads; we know that what thinks in our heads is actually the same thing that surrounds us as light. And we are no longer such prejudiced people that we merely enjoy the light, but we know: in the light is death, a dying world. We can also feel the tragedy of the world in the light. So we come out of the abstract, out of the intellectual, into the flood of the world. And we see in what is darkness the dawning part of the future. We even find in it what excites such passionate natures as Schopenhauer. In short, we penetrate from the abstract into the concrete. World structures arise before us, instead of mere thoughts or abstract impulses of will.

That is what we have been looking for today. Next time, we will search for the origin of good and evil in what has become strangely concrete for us today — the thought of light, the will to darkness. So we penetrate from the inner world into the cosmos, and in the cosmos we seek not merely in an abstract or religiously abstract world the reasons for good and evil, but we want to see how we can break through to an understanding of good and evil, having begun by grasping the thought in its light and feeling the will in its darkening. More on this next time.