Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

25 August 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Four

RUDOLF STEINER: We will now continue the work we have set out to do, and we will pass on to what will be said about how to deal with arithmetic from the perspective of the temperaments. We must primarily consider what procedure we should follow in teaching arithmetic.

Someone showed how to explain a fraction by breaking a piece of chalk.

RUDOLF STEINER: First, I have just one thing to say: I would not use chalk, because it is a great pity to break chalk. I would choose something less valuable. A bit of wood or something like that would do, wouldn’t it? It is not good to accustom young children to destroy useful things.

Question: Does a child who slouches and lacks a proper vertical position find it more difficult to understand spatial and geometrical forms because of such a problem?

RUDOLF STEINER: Not to any perceptible degree. Things of this kind depend more on the tendencies found in the construction of the human organism rather than on the build of an individual. This was once brought very forcibly to my attention after a lecture in Munich. I had explained in the lecture that it has a certain significance for the whole structure of the human being that the backbone is in line with the diameter of the Earth, while the line of the animal’s back is at a right angle to it. Afterward a learned doctor from Karlsruhe came and asserted that when a person is asleep the spine is in a horizontal position! I replied, “It’s not a question of whether a person can move the backbone into various positions, but that the whole human structure is arranged architecturally so that the backbone is ordinarily vertical, although it can be placed at a slant or any other position.”

If you did not consider this you could never understand how certain potentials found in the intellect appear, even when the senses themselves are not active—for example, in someone born blind. The human being is constructed so that the intellect has certain tendencies in the direction of the eyes, and thus, even in the case of those born blind, it is still possible to evoke mental images that are connected with the eyes, such as in the case of someone like the blind Helen Keller. What is important is the tendency, the general dispositions of the human organism, rather than what may be the result of a chance situation here or there. I would now like to add the following to what was said. It is not so much a question of criticizing these things, because that can always be done. What matters is that things of this kind are brought up and that we try to understand them.

Let’s start with addition, and first see what our view of addition should be. Let’s suppose I have some beans or a heap of elderberries. For our present task I will assume that the children can count, which indeed they must learn to do first. A child counts them and finds there are 27. “Yes,” I say. “27—that is the sum.” We proceed from the sum, not from the addenda. You can follow the psychological significance of this in my theory of knowledge.1See Rudolf Steiner, Goethe’s World View, and The Science of Knowing: Outline of an Epistemology Implicit in the Goethean World View, both Mercury Press, Spring Valley, NY, 1992 and 1988. We must now divide the whole into the addenda, into parts or into little heaps. We will have one heap of, let’s say, 12 elderberries, another heap of 7, still another of say 3, and one more, let’s say 5; this will represent the whole number of our elderberries: \(27 = 12 + 7 + 3 + 5\).

We work out our arithmetical process from the sum total 27. I would allow this process to be done by several children with a pronounced phlegmatic temperament. You will gradually come to realize that this kind of addition is particularly suited to the phlegmatics. Then, since the process can be reversed, I would call on some choleric children, and gather the elderberries together again, this time arranging them so that \(5 + 3 + 7 + 12 = 27\). In this way the choleric children do the reverse process. But addition in itself is the arithmetical rule particularly suited to phlegmatic children.

Now I choose one of the melancholic children and say, “Here is a little pile of elderberries. Count them for me.” The child discovers that there are, let’s say, 8. Now, I say, “I don’t want 8, I only want 3. How many elderberries must you take away to leave me only 3?” The child will discover that 5 must be removed. Subtraction in this form is the one of the four rules especially suited to melancholic children.

Then I call on a sanguine child to do the reverse process. I ask what has been taken away, and I have this child tell me that if I take 5 from 8, I’ll have 3 left. Thus, the sanguine child does the reverse arithmetical process. I would only like to add that the melancholic children generally have a special connection with subtraction when done as I have described.

Now I take a child from the sanguine group. Again I put down a pile of elderberries, but I must be sure the numbers fit. I must arrange it beforehand, otherwise we find ourselves involved in fractions. I have the child count out 56 elderberries. “Now look; here I have 8 elderberries, so now tell me how many times you find 8 elderberries contained in 56.” So you see that multiplication leads to a dividing up. The child finds that the answer is 7. Now I let the sum be done in reverse by a melancholic child and say, “This time I do not want to know how often 8 is contained in 56, but what number is contained 7 times in 56." I always allow the reverse process to be done by the opposite temperament.

Next I introduce the choleric to division, from the smaller number to the greater, by saying, “Look, here you have a little pile of 8; I want you to tell me what number contains 8 seven times.” Now the child must find the answer: 56, in a pile of 56. Then I have the phlegmatic children work out the opposite process: ordinary division. The former is the way I use division for the choleric child, because the rule of arithmetic for the choleric children is mainly in this form division.

By continuing in this way I find it possible to use the four rules of arithmetic to arouse interest among the four temperaments. Adding is related to the phlegmatic temperament, subtracting to the melancholic, multiplying to the sanguine, and dividing—working back to the dividend—to the choleric. I ask you to consider this, following what N. has been telling us.

It is very important not to continue working in a singular way, doing nothing but addition for six months, then subtraction, and so on; but whenever possible, take all four arithmetical rules fairly quickly, one after another, and then practice them all—but at first only up to around the number 40. So we shall not teach arithmetic as it is done in an ordinary curriculum. By practicing these four rules, however, they can be assimilated almost simultaneously. You will find that this saves a great deal of time, and in this way the children can work one rule in with another. Division is connected with subtraction, and multiplication is really only a repetition of addition, so you can even change things around and give subtraction, for example, to the choleric child.

It was suggested that one begin with solid geometry.

RUDOLF STEINER: With adults it is possible to begin with solids, but why should you want to go from solids to plane surfaces with a child? You see, three-dimensional space is never easy to picture, least of all for a child. You cannot impart anything to a child but a vague idea of space. Indeed, the child’s imagination will suffer if expected to imagine solid bodies.

You are assuming that the solid is the actual thing and the line abstract; but this is not so. A triangle is in itself something very concrete; it exists in space. Children see things mainly in surfaces. It is an act of violence to force a child into the third dimension, the idea of depth. If children are to apply their imagination to a solid, then they must first have the necessary elements within to build up this imaginative picture. For example, children must really have a clear picture of a line and a triangle before a tetrahedron can be understood. It is better for them to first have a real mental picture of a triangle; the triangle is an actuality, not merely an abstraction taken from the solid.

I would recommend that you teach geometry, not as solid geometry first, but as plane geometry, giving figures with plane surfaces between them; this is preferable, because children like to use their powers of understanding for such things; beginning with plane geometry will support them. You can add further to the effect by connecting it with drawing lessons. Children can draw a triangle relatively early, and you should not wait too long before having them copy what they see.

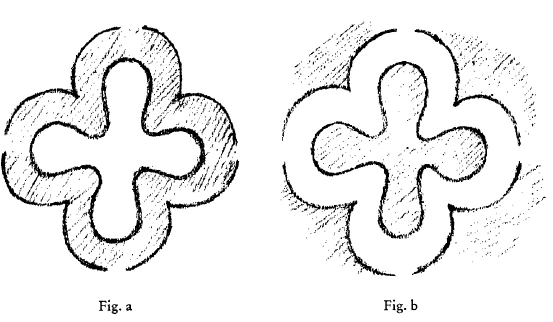

The figure shown yesterday was repeated, this time for a choleric child and for a phlegmatic child.

RUDOLF STEINER: That is a very good design for the choleric child. For the phlegmatic child I would prefer to make it speckled, I would rather have it checkered. It would be possible to use your design, but it would not arouse the phlegmatic child’s attention enough.

The drawings for the melancholic and the sanguine child were presented.

RUDOLF STEINER: In using this method you will find that the needs of the sanguine and melancholic child can be met in the following ways. For the sanguine you should constantly make use of varied repetition. You might have the child draw a design like this:

And then three more like it:

and then one more, so that the emphasis is on repetition:

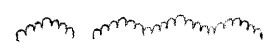

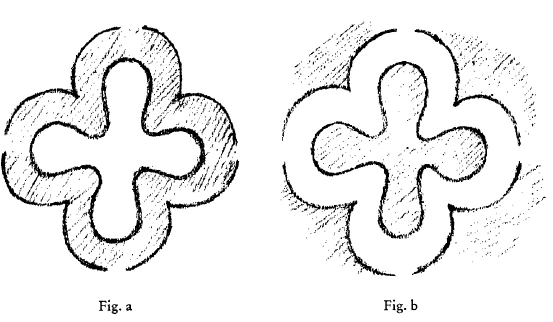

For the melancholic child it would be good to give a design in which careful thought plays some part.

Suppose you have a melancholic child first draw a form like this (figure a), and then the counter-form (figure b), so that they complement one another. This will arouse the child’s imagination. I will shade the original form like this (a) and the opposite form like this (b) and you will see that what is shaded in one form would be left blank in the other. If you think of the blank part as filled in, you would get the first form again. In this way the outer forms in the second drawing are the opposite of the inner, and this design is the opposite of those based on repetition. Choose something requiring thought and connected with observation for the melancholic children, and something in which repetition plays a part (creepers, tendrils, and so on) for the sanguine children.

The story of “Mary’s Child” was told in the style for phlegmatic children.

RUDOLF STEINER: It is important to cultivate well-articulated speech and then help the children to get out of their dialect.2This does not imply that Rudolf Steiner was unaware of the importance of dialect in its right place. Frau Dr. Steiner will demonstrate.

Someone told the story of “The Long-Tailed Monkey” for phlegmatic children.

RUDOLF STEINER: For a story of this kind there are certain aids to storytelling that I would suggest you use. Just for the phlegmatics it would be good to pause occasionally mid-sentence, look at the children, and use the pause to let the imagination work. You can arouse their curiosity at critical points so that they can think on in advance a little and complete the picture for themselves. “The king’s daughter ... was ... very beautiful ... but ... she was not equally ... good.” This use of pauses in narration works strongest with phlegmatic children.

A fairy story was told for phlegmatic children.

RUDOLF STEINER: You must make use of a moment of surprise and curiosity.

Someone told an animal story for sanguine children about a horse, a donkey, and a camel. “Which do you like best, the horse or the donkey?”

RUDOLF STEINER: Some melancholics will prefer the donkey. With these descriptions of animals I would ask you to remember that, as far as possible, they should lead the child to observe animals, for descriptions of this kind can contain true natural history.

Someone else told the story of a monkey who escaped into the rafters—first for sanguines and then for melancholics.

RUDOLF STEINER: Yes, in certain cases that would make a very good impression on the melancholic children, but here also it is my opinion that you could develop it a little further in order to encourage animal observation as such.

I would like to remind you that consideration of the child’s temperament should not be neglected, but you can safely use the first three to five weeks to observe the temperaments of your pupils and then divide them into groups as spoken of here.

It would also be good to consider the extremes of the various temperaments. Goethe’s world view led him to express the beautiful idea that one can understand the normal by studying the abnormal. Goethe views an abnormal plant—a misshapen plant—and from the nature of the malformation he learns to understand the normal plant. In the same way you can find the connections between the absolutely normal and the malformations of the body-soul nature, and you yourselves can find the way from the temperaments to what is abnormal in the soul life.

If the melancholic temperament becomes abnormal and does not remain within the boundaries of the soul, but rather encroaches on the body, then insanity arises. Insanity is the abnormal development of a predominantly melancholic temperament. The abnormal development of the phlegmatic temperament is mental deficiency. The abnormal development of the sanguine is foolishness, or stupidity. The abnormal development of the choleric is rage. When a person is in an emotional state you will sometimes see these attacks of insanity, mental deficiency, foolishness, or rage arising from otherwise normal soul conditions. It is indeed necessary that you focus your attention and observation on the entire soul life.

Now we will move on to the solution of our other problem. I said: Suppose that you, my friends, had children of eight or nine years old in your class. What would you do if, three or four weeks after the beginning of term, you noticed that a phlegmatic, a choleric, and a melancholic child were, to some extent, becoming the three “Cinderellas” of the class, so that all the others pushed them around and no one wanted to play with them and so on? If this had happened, what would you as teachers do about it?

Various teachers expressed opinions.

RUDOLF STEINER: You should never allow the children to inform against each other; you must find other ways of discovering what has caused them to be “Cinderellas.” As teachers, you see, you will often find that you have to help raise the children. If they get into all sorts of naughty ways, their fathers and mothers will come and say, for example, “My child tells lies.” You would seldom go wrong to give this advice: say to the parents, “Imagine a case, a story, in which an untruthful child is placed in a ridiculous position—where the child, because of lying, is led into a situation that appears absurd even to the child. If you tell the child a story of this kind, and then another, and still another like it, you will as a rule cure your child of the tendency to lie.”

Similarly, you will find it helpful to insert into a story everything that has been said about the three “Cinderellas,” everything you can hear and discover about these children, and then you can tell this story to the whole class. The effect of this will be that the three “Cinderellas” will be somewhat comforted and the others somewhat ashamed. If you do this you will certainly find that, even at the first attempt, and even more after the second, you will succeed in restoring a friendly, social atmosphere, a mutual sympathy among the children. You should continue with a similar story throughout the term.

Tomorrow we will take another case that also happens sometimes, which certainly cannot be treated by telling a story that comforts some of the children and shames the others. Suppose you had children of eight or nine years old in your class, and one of these small fries had discovered a particularly mischievous trick. These things do happen. It had been learned outside the school and succeeded in infecting all the others so that the whole class was at it during recess.

An ordinary schoolmaster would go to the extreme of punishing the whole class, but I hope that by tomorrow you will think of a more rational—that is a more effective—method, because this old way of punishing places the teacher in the wrong relationship with the children, and this will not fail to have an effect. The aftereffect is not good.

I have a special case in mind that really happened, where a certain teacher did not act very wisely. One little rascal had conceived the idea of spitting on the ceiling and had actually succeeded. It was a long time before the teacher discovered the culprit. He could not pick out any one child, because they had all done it; the whole classroom was damaged.

Please think over this case of moral delinquency by tomorrow. All you really know is that the whole class had been infected. You cannot begin with the assumption that you know who the ringleader was. You will have to consider whether it wouldn’t be better to give up all thought of discovering the culprit by getting the children to tell on each other. How would you act in this case?

Vierte Seminarbesprechung

Rudolf Steiner: Wir werden nun fortfahren in der Aufgabe, die wir uns gestellt haben, und werden übergehen zu dem, was Herr N. uns zu sagen hat über die Behandlung des Rechnens unter dem Gesichtspunkt der Temperamente der Kinder. Es wird sich mehr handeln um die Art des Verhaltens beim Rechnenlehren.

N. entwickelt das Klarmachen eines Bruches, indem er ein Stück Kreide zerbrechen läßt.

Rudolf Steiner: Ich hätte nur zunächst das eine zu bemerken, daß ich zum Beispiel nicht Kreide verwenden würde, weil es zu schade ist, die Kreide zu zerbrechen. Ich würde einen wertloseren Gegenstand aussuchen. Es würde genügen ein Stück Holz oder so etwas, nicht wahr? Es ist nicht gut, die Kinder frühzeitig daran zu gewöhnen, nützliche Gegenstände zu zerbrechen,

N. fragt, wenn das Kind keine ganz vertikale Richtung hält, sich nicht gerade hält, ob dann dadurch die Erfassung räumlicher und geometrischer Formen erschwert wäre?

Rudolf Steiner: In einem bemerkbaren Maße ist das nicht vorhanden. Es kommt bei solchen Dingen viel mehr auf die Tendenzen an, nach denen der menschliche Organismus aufgebaut ist, als auf den Bau der einzelnen menschlichen Persönlichkeiten. Es hat sich das mir einmal besonders stark entgegengestellt nach einem Vortrag in München, wo ich ausführte, daß es eine gewisse Bedeutung hat für den Bau des Menschen, daß sein Rückgrat in der Linie eines Erddurchmessers liegt, während das Tier seine Rückenlinie waagerecht darauf hat. Nachher kam ein gelehrter Arzt aus Karlsruhe und machte geltend, daß der Mensch, wenn er schläft, sein Rückgrat ja in horizontaler Linie habe! — Da sagte ich: Nicht darauf kommt es an, ob der Mensch sein Rückgrat in verschiedene Stellungen bringen kann, sondern darauf, daß der ganze menschliche Bau architektonisch so angeordnet ist, daß sein Rückgrat in der Normalhaltung vertikal ist, wenn er es auch in schiefe oder andere Lagen bringen kann. — Sie würden, wenn Sie das nicht in Betracht zögen, niemals verstehen können, wie gewisse Hinordnungen für die menschlichen Sinne, die sich noch im Intellekt finden, doch auftreten zum Beispiel bei Blindgeborenen. Der Mensch ist als Wesen so aufgebaut, daß sein Intellekt auf sein Auge hin tendiert, so daß man selbst bei Blindgeborenen noch Vorstellungen hervorrufen kann, die auf das Auge hin gerichtet sind, wenn ein Mensch so geartet ist, wie zum Beispiel die blinde Helen Keller. Es kommt an auf die Tendenz, auf die Anlagen im allgemeinen des menschlichen Organismus, nicht auf das, was zufällige Lagen hervorbringen können.

Dann möchte ich das Folgende an Herrn Ns. Ausführungen anschließen. Es kommt weniger darauf an, daß wir diese Dinge kritisieren, denn das kann man immer. Es kommt darauf an, daß solche Dinge vorgebracht werden, und daß wir versuchen, uns in solche Dinge hineinzufinden.

Gehen wir einmal von der Addition aus, und zwar so, wie wir die Addition auffassen. Nehmen wir an, ich habe Bohnen oder ein Häufchen Holunderkügelchen. Nun will ich für den heutigen Fall annehmen, daß die Kinder schon zählen können, was sie ja auch erst lernen müssen. Das Kind zählt, es hat 27. — «27», sage ich, «das ist die Summe.» Wir gehen aus von der Summe, nicht von den Addenden! Die psychologische Bedeutung davon können Sie in meiner Erkenntnistheorie verfolgen. Diese Summe teilen wir jetzt ab in Addenden, in Teile oder in Häufchen. Ein Häufchen Holunderkügelchen, sagen wir 12; weiter ein Häufchen, sagen wir 7; weiter eines, sagen wir 3; weiter eines, sagen wir 5. Dann werden wir die Holunderkügelchen erschöpft haben: \(27 = 12 + 7 + 3 + 5\). Wir machen ja den Rechnungsvorgang von der Summe 27. Solch einen Vorgang lasse ich nun eine Anzahl von Kindern machen, welche ausgesprochen phlegmatisches Temperament haben. Man wird sich allmählich bewußt werden, daß diese Art des Addierens besonders geeignet ist für Phlegmatiker. - Dann werde ich mir, weil ja der Vorgang zurückverfolgt werden kann, cholerische Kinder aufrufen und werde die Holunderkügelchen wieder zusammenwerfen lassen, aber so, daß es geordnet ist gleich 5 und 3 und 7 und 12 sind 27. Also das cholerische Kind macht den umgekehrten Vorgang. Das Addieren ist ganz besonders die Rechnungsart der phlegmatischen Kinder.

Nun nehme ich jemand heraus aus den melancholischen Kindern. Ich sage: «Hier ist ein Häufchen Holunderbeerchen; zähle sie mal ab!» Es kriegt heraus, sagen wir einmal 8. «Siehst du, ich will nicht haben 8, ich will nur haben 3. Wieviel muß weggelegt werden von den Holunderkügelchen, damit ich nur 3 bekomme?» Dann wird es darauf ankommen, daß 5 weggenommen werden müssen. Das Subtrahieren in dieser Form ist vor allem die Rechnungsart der melancholischen Kinder. — Nun rufe ich ein sanguinisches Kind auf und lasse die Rechnung zurück machen. Nun sage ich: «Was ist weggenommen worden?» Und ich lasse mir sagen: Wenn ich 5 von 8 wegnehme, so bleiben mir 3 übrig. — Das sanguinische Kind lasse ich wieder die umgekehrte Rechnungsart ausführen. Ich will nur sagen, daß «vorzugsweise» die Subtraktion — aber so ausgeführt, wie wir es tun — für die melancholischen Kinder ist.

Nun nehme ich mir ein Kind vor aus der Gruppe der Sanguiniker. Ich werfe wieder eine Anzahl Holunderkügelchen hin, ich sorge aber dafür, daß es in irgendeiner Weise paßt. Nicht wahr, ich muß das ja schon anordnen, sonst würde die Sache zu rasch ins Bruchrechnen hineinführen. Also, nun lasse ich zählen: 56 Holunderkügelchen. — «Nun sieh einmal an, da habe ich 8 Holunderkügelchen. Nun mußt du mir sagen, wie oft die 8 Holunderkügelchen in den 56 drinnen sind.» Sie sehen, die Multiplikation führt zu einer Division. Es bekommt heraus 7. Nun lasse ich die Rechnung zurückmachen von dem melancholischen Kinde und sage: «Nun will ich aber nicht untersuchen, wie oft die 8 enthalten sind in den 56, sondern wie oft ist die 7 enthalten in 56? Wie oft kommt die 7 heraus?» Ich lasse die umgekehrte Rechnung immer von dem entgegengesetzten Temperament ausführen.

Dem Choleriker lege ich vor zunächst die Division, vom Kleinen zum Größten, indem ich sage: «Siehe, da hast du das Häufchen von 8. Ich will von dir nun wissen, in welcher Zahl die 8 siebenmal drinnensteckt.» Und er muß herauskriegen: in 56; in einem Häufchen von 56. Dann lasse ich das Umgekehrte, die gewöhnliche Division, von dem phlegmatischen Kinde machen. Für das cholerische Kind wende ich in dieser Form die Division an. Denn in dieser Form ist sie insbesondere die Rechnungsart der cholerischen Kinder.

Auf diese Weise, indem ich es fortwährend so durchführe, bekomme ich gerade für die vier Rechnungsarten die Möglichkeit, sie zu gebrauchen für die Heranziehung der vier Temperamente: das Additive ist verwandt dem Phlegmatischen, das Subtrahieren dem Melancholischen, das Multiplizieren dem Sanguinischen, das Dividieren, mit dem Zurückgehen zu dem Dividenden, dem Cholerischen. — Das ist es, was ich Sie bitte, im Anschluß zu dem von Herrn N. Gesagten zu beachten.

Es ist von besonderer Wichtigkeit, daß man nicht langweilig fortarbeitet: ein halbes Jahr bloß addiert, dann subtrahiert und so weiter, sondern wir werden diese vier Rechnungsarten womöglich nicht allzu langsam nacheinander durchnehmen, und dann alle vier üben! Zuerst nur bis 40 etwa. So werden wir Rechnen lehren nicht nach dem gewöhnlichen Stundenplan, sondern so, daß durch das Üben diese vier Arten fast gleichzeitig angeeignet werden. Sie werden finden, daß es auf diese Weise sehr ökonomisch geht, und daß man die Kinder die Dinge ineinanderarbeiten lassen kann. — Es ist ja die Division verwandt mit der Subtraktion, und die Multiplikation ist eigentlich nur eine wiederholte Addition. So daß man also auch umwechseln und zum Beispiel das cholerische Kind an die Subtraktion heranbringen kann.

K. macht den Vorschlag, mit dem Stereometrischen zu beginnen.

Rudolf Steiner: Für Erwachsene kann man von Körpern ausgehen, aber warum haben Sie die Sehnsucht, bei dem Kinde vom Körper auszugehen und von da zur Fläche zu gehen? Sehen Sie, es ist das Räumliche im allgemeinen unübersichtlich, sehr unübersichtlich vor allem für das Kind. Man wird nicht leicht dem Kinde eine andere als eine sehr verschwommene Vorstellung vom Raume beibringen können. Es leidet sogar die Phantasie darunter, wenn man dem Kinde zumutet, daß es gleich Körper vorstellen soll.

Sie gehen davon aus, daß der Körper das Konkrete ist, die Linie das Abstrakte; das ist nicht der Fall. Ein Dreieck ist als solches schon ganz konkret, ist für sich etwas im Raum. Das Kind sieht stark flächenhaft. Es ist vergewaltigt, wenn es in die dritte Dimension, in die Tiefendimension gehen soll. Wenn das Kind seine Phantasie anwenden soll, um sich den Körper vorzustellen, dann muß es die Elemente zu diesem Phantasievorstellen vorher schon haben. Es muß sich eigentlich schon die Linie und das Dreieck vorstellen können, ehe es sich zum Beispiel den Tetraeder vorstellen kann. Es ist besser, wenn das Kind vorher schon eine wirkliche Vorstellung vom Dreieck hat. Das Dreieck ist eine Sache für sich, es ist nicht bloß eine Abstraktion vom Körper. Ich würde glauben, daß man Geometrie nicht zuerst als Stereometrie, sondern als Planimetrie lehren soll, als Lehre von Figuren und dazwischenliegenden Flächen, was sehr wünschenswert ist, weil das dem, worauf das Kind sein Auffassungsvermögen gern richten will, Unterstützung bringen kann, auch durch Verbindung der Geometrie mit dem Zeichenunterricht. Ein Dreieck wird ein Kind verhältnismäßig bald zeichnen, und man sollte nicht zu lange warten mit dem Nachzeichnen dessen, was das Kind geometrisch anschaut.

E. gibt das gestrige Zeichenmotiv heute für ein cholerisches Kind (Farbtafel, Figur 3) und für ein phlegmatisches Kind.

Rudolf Steiner: Für das cholerische Kind ist das ein sehr gutes Motiv. Für das phlegmatische Kind würde ich die Sache vorziehen, gesprenkelt zu machen, das heißt also, so kariert würde ich es für das phlegmatische Kind vorziehen (Farbtafel, Figur 4). Ihres hier ist eine Möglichkeit, aber es wird das phlegmatische Kind doch zu wenig aufmerksam gemacht.

Dann gibt T. Zeichnungen für das melancholische und für das sanguinische Kind.

Rudolf Steiner: Bei dieser Methode wird in Betracht kommen, daß man dem sanguinischen und melancholischen Kinde sicher dadurch entgegenkommen könnte, daß man beim sanguinischen Kinde sehr viel auf die Wiederholung hält, auf variierte Wiederholung. Man lasse vielleicht das sanguinische Kind ein Motiv so zeichnen:

Dann noch einmal drei solche Dinger:

Dann noch einmal:

so daß viel auf die Wiederholung hinauskommt.

Beim melancholischen Kinde würde es gut sein, dasjenige zu beachten, wohinein doch etwas das Nachdenken spielt. Nehmen wir an, das melancholische Kind sollte zunächst eine solche Form (Zeichnung a) ausbilden und dann die Gegenform (Zeichnung b), so daß es sich ergänzt.

Dadurch kommt die Phantasie in Regsamkeit. Ich will dasjenige schraffieren, was die ursprüngliche Form (a) ist, und die Gegenform (b) so. Dasjenige, was hier (a) schraffiert ist, würde hier (b) leer sein. Wenn Sie sich das Leere ausgefüllt denken, würden Sie diese Form (a) wieder herausbekommen. Dadurch sind die äußeren (b) entgegengesetzte Formen von den inneren (a). — Sie haben also hier das Entgegengesetzte von solchen Zeichnungen, wo Wiederholung auftritt. Hier etwas, was gedanklich ist, mit der Anschauung vereinigt für das melancholische Kind. Und wo Wiederholung auftritt, Ranken und so weiter, das ist für das sanguinische Kind.

A. erzählt das Märchen vom «Marienkind» in der Fassung für phlegmatische Kinder.

Rudolf Steiner: Es wäre wichtig, sich an eine gut artikulierte Sprache zu gewöhnen und so die Kinder aus der Mundart herauszuführen. Frau Dr. Steiner wird vorsprechen.

D. erzählt das Märchen vom «Meerkätzchen» in der Fassung für phlegmatische Kinder.

Rudolf Steiner: Ich würde nur raten, versuchen Sie in einem solchen Falle auch Nebenhilfen des Erzählens zu benützen. Ich würde gerade dem phlegmatischen Kinde gegenüber öfter mal mit dem Satze einhalten, dann die Kinder angucken, dann das ausnützen, daß die Phantasie weiterarbeitet. Diese Neugierde an wichtigen Stellen erregen, damit sie ein wenig schon weiterdenken und selber sich ausmalen: «Die Königstochter, — die war — sehr schön, — aber — weniger - gut!» Dieses Ausnützen ist gerade für phlegmatische Kinder am wirksamsten.

R. erzählt das «Sesammärchen» für Phlegmatiker.

Rudolf Steiner: Das Überraschungsmoment benützen, das Neugiermoment.

L. erzählt für sanguinische Kinder eine Tiergeschichte von Pferd, Esel, Kamel. Welches ist euch lieber, das Pferd oder der Esel?

Rudolf Steiner: Einige Melancholiker werden den Esel lieber haben. - Ja, was ich bei diesen Tierbeschreibungen bitten würde, das wäre nur, möglichst darauf Rücksicht zu nehmen, daß das Kind angeleitet wird zur Beobachtung der Tiere, daß in solchen Beschreibungen wirkliche Naturgeschichte liegen könnte.

M. gibt für Sanguiniker und Melancholiker die Schilderung eines Affen, der in das Dachgebälk floh.

Rudolf Steiner: Ja, das würde auf den Melancholiker unter Umständen einen ganz guten Eindruck machen, aber auch da meine ich, daß es noch etwas auszubilden wäre dahin, daß die Tierbeobachtung als solche gefördert würde.

Ich möchte nur bemerken, daß die Berücksichtigung des 'Temperamentes des Kindes nicht außer acht gelassen werden sollte, daß man aber ruhig die ersten drei bis fünf Wochen dazu verwenden sollte, die Temperamente der Schüler zu beobachten und sie dann so in Gruppen zu teilen, wie wir es hier besprochen haben.

Sie werden gut tun, wenn Sie auch die Extreme der Temperamente ins Auge fassen würden. Goethe hat ja aus seiner Weltanschauung heraus den schönen Gedanken geprägt, daß am Abnormen studiert werden könne das Normale. Goethe sieht eine abnorme Pflanze an,

eine mißbildete Pflanze, und an der Art der Mißbildung lernt er das Normale kennen. So kann man auch Verbindungslinien ziehen von dem durchaus Normalen zu den Mißbildungen des leiblich-seelischen Wesens, und Sie werden selbst die Linie finden von den Temperamenten zu dem abnormen Seelenwesen.

Wenn das melancholische Temperament abnorm ausartet und nicht innerhalb der seelischen Grenzen bleibt, sondern ins Körperliche übergreift, so entsteht der Wahnsinn. Der Wahnsinn ist die Ausartung des im wesentlichen melancholischen Temperamentes. Die Ausartung des phlegmatischen Temperamentes ist der Schwachsinn oder Blödsinn. Die Ausartung des Sanguinischen ist die Narrheit. Die Ausartung des Cholerischen ist die Tobsucht. Sie werden aus ganz normalen Seelenzuständen manchmal, wenn der Mensch im Affekt ist, solche Anwandlungen aufsteigen sehen von Wahnsinn, von Schwachsinn, von Narrheit, von Tobsucht. Es ist schon notwendig, daß man sich einstellt auf die Beobachtung des ganzen Seelenlebens.

Jetzt wollen wir an die Erledigung der anderen Aufgabe gehen. Ich sagte, was würden sich unsere Freunde zur Aufgabe stellen, wenn sie bei acht- bis neunjährigen Kindern, die sie vor sich haben, die Erfahrung machen, daß drei bis vier Wochen nachdem die Schule begonnen hat, ein phlegmatisches Kind, ein cholerisches und ein melancholisches Kind gewissermaßen die drei Aschenbrödel der Klasse werden, daß sie von allen gepufft werden, daß niemand mit ihnen umgeht und so weiter. Also, wenn das passiert wäre, wie würden sich die Lehrenden und Unterrichtenden hierzu verhalten?

Verschiedene Teilnehmer äußern sich darüber.

Rudolf Steiner: Nie die Kinder sich gegenseitig denunzieren lassen, sondern man sollte auf andere Weise herausbekommen, was die Ursache ihres Aschenbrödeltums ist. Die Kinder brauchen nicht selber Schuld zu sein.

Sehen Sie, man kommt oftmals in den Fall, helfen zu sollen bei der Kindererziehung. Wenn die Kinder in allerlei Unarten hineinkommen, so kommen Mütter und Väter, die sagen zum Beispiel: Mein Kind lügt. - Nun würde man wohl kaum fehlgehen, folgenden Rat zu geben. Man sagt: Denken Sie sich einen Fall aus, eine Erzählung, in der ein lügenhaftes Kind ad absurdum geführt wird, indem das Kind durch seine Lüge selber in eine Situation geführt wird, die es als unvernünftig ansehen muß. Wenn man dem Kinde eine solche Erzählung erzählt, dann noch eine, dann noch eine in der Art, dann heilt man das Kind gewöhnlich von seinem Lügenhang.

In ähnlicher Art würde ich eine Abhilfe darin finden, wenn Sie die verschiedenen Dinge, die heute über die drei Aschenbrödel gesagt wurden, und alles, was Sie über diese Kinder herausbekommen und erfahren können, in eine Erzählung bringen, die Sie dann vor der ganzen Klasse vorbringen, wodurch Sie bewirken, daß die drei Aschenbrödel sich etwas trösten, die anderen sich etwas schämen. Wenn Sie das bewirken, werden Sie wohl schon auf den ersten Anhub, und wenn Sie es zum zweitenmal wiederholen, werden Sie sicher wieder soziale Zustände, ein gegenseitiges Sich-in-Sympathie-Begegnen bei den Kindern erzielen. Eine solche Erzählung ist sehr schwierig. Aber eine Skizze sollte gemacht werden bis zum Ende des Seminars.

Für morgen einen anderen Fall, der auch vorkommt, und der ganz sicher nicht durch eine Erzählung wird zu behandeln sein, indem Sie die einen Kinder trösten, die anderen beschämen.

Denken Sie, Sie hätten wiederum verhältnismäßig junge, acht- bis neunjährige Kinder in Ihrer Klasse, und einer dieser Knirpse wäre hinter eine besondere Ungezogenheit gekommen. So etwas kommt vor. Er hat sie draußen kennengelernt, und es ist ihm gelungen, die ganze Klasse damit anzustecken, so daß die ganze Klasse während der Pause die Ungezogenheit ausübt.

Ein schematischer Schullehrer wird dahin kommen, die ganze Klasse zu bestrafen. Aber ich hoffe, Sie werden bis morgen eine etwas rationellere, das heißt wirksamere Methode herausbringen. Denn diese alte Art zu strafen, führt dazu, daß der Lehrer in eine schiefe Stellung kommt. Bei Schlagen und Nachsitzen bleibt immer etwas zurück. Es ist nicht gut, wenn etwas zurückbleibt.

Ich habe einen besonderen Fall im Auge, der wirklich vorgekommen ist, und wo sich der betreffende Lehrer nicht sehr günstig verhalten hat: Da war nun der Knirps dazu gekommen - und es ist ihm gelungen — auf den Plafond, auf die Decke des Zimmers zu spucken. Der Lehrer ist sehr lange nicht daraufgekommen. Man konnte keinen herauskriegen, denn alle hatten es nachgemacht, und das ganze Klassenzimmer war verschandelt.

Diesen moralischen Fall bitte ich bis morgen auszudenken. Sie wissen im allgemeinen nur, daß die ganze Klasse angesteckt worden ist. Sie werden nicht von der Voraussetzung ausgehen dürfen, daß Sie von vornherein wissen, wer der Anstifter ist. Sie werden zu bedenken haben, ob es nicht besser ist, auf das Herausbringen durch Denunziation zu verzichten.

Wie würden Sie sich dazu verhalten?

Fourth Seminar Discussion

Rudolf Steiner: We will now continue with the task we have set ourselves and move on to what Mr. N. has to say about teaching arithmetic from the perspective of children's temperaments. It will be more about the type of behavior involved in teaching arithmetic.

N. demonstrates how to explain a fraction by breaking a piece of chalk.

Rudolf Steiner: I would just like to point out that I would not use chalk, for example, because it is a shame to break the chalk. I would choose a less valuable object. A piece of wood or something like that would suffice, wouldn't it? It is not good to accustom children at an early age to breaking useful objects.

N. asks whether it would be more difficult for the child to grasp spatial and geometric forms if they do not hold themselves completely upright, if they do not stand straight.

Rudolf Steiner: To a noticeable degree, this is not the case. In such matters, the tendencies according to which the human organism is structured are much more important than the structure of individual human personalities. This was particularly strongly opposed to me once after a lecture in Munich, where I explained that it is of some significance for the structure of the human being that his spine lies in line with the diameter of the earth, while the animal has its spine horizontal to it. Afterwards, a learned doctor from Karlsruhe came up and pointed out that when a human being sleeps, his spine is horizontal! I replied: It is not important whether humans can place their spine in different positions, but rather that the entire human structure is architecturally arranged in such a way that the spine is vertical in the normal posture, even if it can be placed in slanted or other positions. "If you did not take this into account, you would never be able to understand how certain orientations for the human senses, which are still found in the intellect, nevertheless occur, for example, in people who were born blind. Human beings are constructed in such a way that their intellect tends toward their eyes, so that even in people born blind, it is still possible to evoke mental images that are directed toward the eyes, if a person is of a certain nature, such as the blind Helen Keller. What matters is the tendency, the general predisposition of the human organism, not what accidental situations may produce.

I would like to add the following to Mr. N's remarks. It is less important that we criticize these things, because that can always be done. What is important is that such things are brought up and that we try to understand them.

Let's start with addition, as we understand it. Let's assume I have beans or a pile of elderberries. Now, for today's case, let's assume that the children already know how to count, which they first have to learn. The child counts and has 27. “27,” I say, “that's the sum.” We start from the sum, not from the addends! You can follow the psychological significance of this in my theory of knowledge. We now divide this sum into addends, into parts or into piles. A pile of elderberries, let's say 12; then another pile, let's say 7; then another, let's say 3; then another, let's say 5. Then we will have used up all the elderberries: \(27 = 12 + 7 + 3 + 5\). We are doing the calculation based on the sum of 27. I now have a number of children who have a distinctly phlegmatic temperament do this calculation. It will gradually become apparent that this type of addition is particularly suitable for phlegmatic children. Then, because the process can be traced back, I will call on choleric children and have them throw the elderberries together again, but in such a way that it is orderly: 5 and 3 and 7 and 12 are 27. So the choleric child does the reverse process. Addition is particularly the type of calculation that phlegmatic children are good at.

Now I pick someone out from among the melancholic children. I say: “Here is a pile of elderberries; count them!” They come up with, let's say, 8. “You see, I don't want 8, I only want 3. How many elderberries do I have to take away so that I only get 3?” Then it will be necessary to take away 5. Subtraction in this form is primarily the method of calculation used by melancholic children. — Now I call on a sanguine child and have them do the calculation backwards. Now I say, “What has been taken away?” And I let them tell me: if I take 5 away from 8, I have 3 left. — I let the sanguine child perform the reverse calculation again. I just want to say that subtraction — but performed as we do it — is “preferably” for melancholic children.

Now I take a child from the group of sanguine children. I throw down a number of elderberries again, but I make sure that it fits in some way. Right, I have to arrange it that way, otherwise the task would lead too quickly to fraction calculations. So, now I let them count: 56 elderberries. — "Now look, I have 8 elderberries. Now you have to tell me how many times the 8 elderberries are contained in the 56.“ You see, multiplication leads to division. The answer is 7. Now I have the melancholic child do the calculation and say: ”Now I don't want to examine how many times the 8 is contained in the 56, but how many times is the 7 contained in 56? How many times does 7 come out?“ I always have the opposite temperament do the reverse calculation.

I first present the choleric child with the division, from the smallest to the largest, by saying: ”Look, here you have a pile of 8. I now want you to tell me in which number 8 is contained seven times." And they have to figure out: in 56; in a pile of 56. Then I let the phlegmatic child do the reverse, the usual division. I use this form of division for the choleric child. Because in this form, it is particularly the type of calculation used by choleric children.

In this way, by continuously carrying it out in this manner, I gain the opportunity to use the four types of calculation for the four temperaments: addition is related to the phlegmatic, subtraction to the melancholic, multiplication to the sanguine, and division, with its return to the dividend, to the choleric. — This is what I ask you to bear in mind in connection with what Mr. N. said.

It is particularly important not to work in a boring way: spending half a year just adding, then subtracting, and so on. Instead, we will go through these four types of arithmetic one after the other, as quickly as possible, and then practice all four! At first, only up to about 40. So we will teach arithmetic not according to the usual timetable, but in such a way that through practice these four types are learned almost simultaneously. You will find that this is very economical and that the children can be allowed to work things out for themselves. Division is related to subtraction, and multiplication is actually just repeated addition. So you can also switch things around and, for example, introduce the choleric child to subtraction.

K. suggests starting with stereometry.

Rudolf Steiner: For adults, you can start with solids, but why do you feel the need to start with solids with children and then move on to surfaces? You see, space in general is confusing, very confusing, especially for children. It is not easy to teach children anything other than a very vague mental image of space. Even their imagination suffers when you expect children to imagine solids right away.

You assume that the body is concrete and the line is abstract; that is not the case. A triangle is already quite concrete as such; it is something in space in its own right. Children see things very much in terms of surfaces. It is a violation to expect them to enter the third dimension, the dimension of depth. If the child is to use its imagination to picture the body, it must already have the elements for this mental image. It must actually be able to picture the line and the triangle before it can picture the tetrahedron, for example. It is better if the child already has a real idea of the triangle. The triangle is a thing in itself; it is not merely an abstraction from the body. I would believe that geometry should not be taught first as stereometry, but as planimetry, as the study of figures and the surfaces between them, which is very desirable because it can support what the child wants to focus its comprehension on, also by connecting geometry with drawing lessons. A child will be able to draw a triangle relatively quickly, and one should not wait too long to trace what the child sees geometrically.

E. gives yesterday's drawing motif today for a choleric child (color plate, figure 3) and for a phlegmatic child.

Rudolf Steiner: This is a very good motif for the choleric child. For the phlegmatic child, I would prefer to make it speckled, that is, I would prefer it to be checkered for the phlegmatic child (color chart, figure 4). Yours here is one possibility, but it does not attract the phlegmatic child's attention enough.

Then T. gives drawings for the melancholic and sanguine child.

Rudolf Steiner: With this method, it is worth considering that the sanguine and melancholic child could certainly be accommodated by placing a great deal of emphasis on repetition, on varied repetition, with the sanguine child. Perhaps the sanguine child could be asked to draw a motif like this:

Then three more of these:

Then once more:

so that much comes down to repetition.

With melancholic children, it would be good to pay attention to what they are thinking about. Let's assume that the melancholic child should first form one shape (drawing a) and then the opposite shape (drawing b), so that they complement each other.

This stimulates the imagination. I want to shade what is the original form (a) and the counterform (b) like this. What is hatched here (a) would be empty here (b). If you imagine the empty space filled in, you would get this shape (a) again. Thus, the outer (b) shapes are opposite to the inner (a) shapes. — So here you have the opposite of those drawings where repetition occurs. Here is something that is conceptual, combined with visual imagery for the melancholic child. And where repetition occurs, vines and so on, that is for the sanguine child.

A. tells the fairy tale of “Marienkind” in the version for phlegmatic children.

Rudolf Steiner: It would be important to get used to well-articulated language and thus lead the children out of the dialect. Dr. Steiner will speak.

D. tells the fairy tale of the “Sea Kitten” in the version for phlegmatic children.

Rudolf Steiner: I would only advise you to try to use additional aids to storytelling in such cases. Especially with phlegmatic children, I would pause frequently, then look at the children, and then take advantage of the fact that their imagination continues to work. Arouse their curiosity at important points so that they think a little further and imagine for themselves: “The king's daughter — she was — very beautiful — but — not so good!” This technique is most effective for phlegmatic children.

R. tells the “Sesame Fairy Tale” for phlegmatic children.

Rudolf Steiner: Use the element of surprise, the element of curiosity.

L. tells a story about a horse, a donkey, and a camel for sanguine children. Which do you prefer, the horse or the donkey?

Rudolf Steiner: Some melancholic children will prefer the donkey. Yes, what I would ask with these animal descriptions is simply to take care, as far as possible, that the child is guided to observe the animals, that such descriptions could contain real natural history.

M. gives a description of a monkey that fled into the roof beams for sanguine and melancholic children.

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, that might make a very good impression on melancholic children, but even there I think that something still needs to be developed in order to encourage animal observation as such.

I would just like to note that the temperament of the child should not be ignored, but that the first three to five weeks should be used to observe the temperaments of the students and then divide them into groups as we have discussed here.

You would do well to consider the extremes of temperament as well. Goethe, based on his worldview, coined the beautiful idea that the abnormal can be used to study the normal. Goethe looks at an abnormal plant,

a malformed plant, and from the nature of the malformation he learns about the normal. In this way, one can also draw lines connecting the thoroughly normal to the deformities of the physical and spiritual being, and you will find the line yourself from the temperaments to the abnormal soul being.

When the melancholic temperament degenerates abnormally and does not remain within the limits of the soul, but spills over into the physical, madness arises. Madness is the degeneration of the essentially melancholic temperament. The degeneration of the phlegmatic temperament is imbecility or idiocy. The degeneration of the sanguine temperament is folly. The degeneration of the choleric temperament is rage. You will sometimes see such impulses of madness, imbecility, folly, and rage arise from completely normal states of mind when a person is in the throes of emotion. It is necessary to prepare oneself for the observation of the entire emotional life.

Now let us move on to the other task. I said, what would our friends set themselves as a task if they experienced with eight- to nine-year-old children in front of them that three to four weeks after school had started, a phlegmatic child, a choleric child, and a melancholic child became, in a sense, the three Cinderellas of the class, that they were pushed around by everyone, that no one associated with them, and so on. So, if that had happened, how would the teachers and educators have responded?

Various participants comment on this.

Rudolf Steiner: Never let the children denounce each other, but find out in other ways what is the cause of their Cinderella status. The children themselves are not necessarily to blame.

You see, one often finds oneself in the position of having to help with the upbringing of children. When children develop all kinds of bad habits, mothers and fathers come and say, for example, “My child lies.” Now, one would hardly be wrong in giving the following advice. You say: Think of a story in which a lying child is led to absurdity by his own lie, which puts him in a situation that he must consider unreasonable. If you tell the child such a story, then another, then another of the same kind, you will usually cure the child of his tendency to lie.

In a similar vein, I would find a remedy if you were to put the various things that were said today about the three Cinderellas, and everything you can find out and learn about these children, into a story that you then present to the whole class, thereby causing the three Cinderellas to feel some comfort and the others to feel some shame. If you achieve this, you will probably succeed at the first attempt, and if you repeat it a second time, you will certainly achieve social harmony and mutual sympathy among the children. Such a story is very difficult to write. But a draft should be made by the end of the seminar.

For tomorrow, another case that also occurs and that will certainly not be dealt with by telling a story in which you comfort some children and shame others.

Imagine that you have relatively young children, aged eight to nine, in your class, and one of these little ones has gotten up to some particularly naughty behavior. This kind of thing happens. He learned it outside school and managed to infect the whole class with it, so that the whole class engages in this misbehavior during recess.

A schematic schoolteacher will end up punishing the whole class. But I hope that by tomorrow you will come up with a somewhat more rational, i.e., more effective method. Because this old way of punishing puts the teacher in an awkward position. When you hit and give detention, something always remains. It's not good when something remains.

I have a particular case in mind that really happened, and where the teacher in question did not behave very favorably: The little boy had managed to spit on the ceiling of the room. The teacher didn't notice for a long time. It was impossible to find out who had done it, because everyone had copied him and the whole classroom was ruined.

Please think about this moral case by tomorrow. You only know that the whole class has been infected. You cannot assume that you know who the instigator is from the outset. You will have to consider whether it is not better to refrain from exposing them by denouncing them.

How would you respond to this?