Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

6 September 1919 A.M., Stuttgart

Translated by Katherine E. Creeger

Second Lecture on the Curriculum

Now it’s time to divide up the rest of the subjects and distribute them among the various grades.

It should be very clear that when the children are going on nine—that is, in the third grade—they should begin to study an appropriate selection of animals, which we must always relate to the human being, as in the example I presented to you.1See Practical Advice to Teachers, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1988, lecture 7. This should be continued in the fourth grade, so that during the third and fourth grades we consider the animal kingdom scientifically in its relationship to the human being.

In the fifth grade, we begin to add less familiar animals. We also begin the study of botany as I described it in the theoretical portion of our seminar.2See discussion 9, page 114. In the sixth grade, we continue with botany and begin the study of minerals, which should definitely be done in conjunction with geography.

In the seventh grade we return to the human being and attempt to teach what I pointed to yesterday with regard to what people need to learn about health and nutrition. We also attempt to apply the concepts the children have acquired in the fields of physics and chemistry to developing a comprehensive view of some specific commercial or industrial processes. All this should be developed out of science, in connection with what we are teaching in physics, chemistry, and geography.

In the eighth grade you will have to construct the human being by showing what is built in from the outside—the mechanics of the bones and muscles, the inner structure of the eye, and so on. Once again, you present a comprehensive picture of industrial and commercial relationships as they relate to physics, chemistry, and geography. If you build up your science lessons as we have just described, you will be able to make them incredibly lively and use them to awaken the children’s interest in everything present in the world and in the human being.

Instruction in physics begins in the sixth grade and is linked to what the children have learned in music. We begin the study of physics by allowing acoustics to be born out of music. You should link acoustics to music theory and then go on to discuss the physiology of the human larynx from the viewpoint of physics. You cannot discuss the human eye yet, but you can discuss the larynx. Then, taking up only the most salient aspects, you go on to optics and thermodynamics. You should also introduce the basic concepts of electricity and magnetism now.

The following year, in the seventh grade, you expand on your studies of acoustics, thermodynamics, optics, electricity, and magnetism. Only then do you proceed to cover the most important basic concepts of mechanics—the lever, rollers, wheel and axle, pulleys, block and tackle, the inclined plane, the screw, and so on. After that you start from an everyday process such as combustion and try to make the transition to simple concepts of chemistry.

In the eighth grade you review and expand upon what was done in the seventh and then proceed to the study of hydraulics, of the forces that work through water. You cover everything belonging to hydraulics—water pressure, buoyancy, Archimedes’ principle.

It would be great if we could stay here for three years giving lectures on education and providing examples of all the things you will have to figure out how to do yourselves out of your own inventiveness, but that can’t be. We will have to be content with what has already been presented.

You conclude your study of physics, so to speak, with aerodynamics—that is, the mechanics of gases—discussing everything related to climatology, weather, and barometric pressure. You continue to develop simple concepts of chemistry so that the children also learn to grasp how industrial processes are related to chemical ones. In connection with chemical concepts, you also attempt to develop what needs to be said about the substances that build up organic bodies—starch, sugar, protein, and fat.

We must still apportion everything related to arithmetic, mathematics, and geometry and distribute it among the eight grades.

You know that standard superficial methodology dictates that in the first grade we should deal primarily with numbers up to 100. We can also go along with this, because the range of numbers doesn’t really matter in the first grade, where we stick with simpler numbers. The main issue, regardless of what range of numbers you use, is to teach the arithmetical operations in a way that does justice to what I said before: Develop addition out of the sum, subtraction out of the remainder, multiplication out of the product and division out of the quotient—that is, exactly the opposite of how it’s usually done. Only after you have demonstrated that 5 is 3 plus 2, do you demonstrate the reverse—that adding 2 and 3 yields 5. You must arouse in the children the powerful idea that 5 equals 3 plus 2, but that it also equals 4 plus 1, and so on. Thus, addition is the second step after separating the sum into parts, and subtraction is the second step after asking “What must I take away from a minuend to leave a specific difference?” and so on. As I said before, it goes without saying that you do this with simpler numbers in the first grade, but whether you chose a range of up to 95 or 100 or 105 is basically beside the point.

After that, however, when the second dentition is over, we can immediately begin to teach the children the times tables—even addition, as far as I’m concerned. The point is that children should memorize their times tables and addition facts as soon as possible after you have explained to them in principle what these actually mean—after you have explained this in principle using simple multiplication that you approach in the way we have discussed. That is, as soon as you’ve managed to teach the children the concept of multiplication, you can also expect them to learn the times tables by heart.

Then in the second grade you continue with the arithmetical operations using a greater range of numbers. You try to get the students to solve simple problems orally, in their heads, without any writing. You attempt to introduce unknown numbers by using concrete objects—I told you how you could approach unknown numbers using beans or whatever else is available. However, you should also not lose sight of doing arithmetic with known quantities.

In the third grade everything is continued with more complicated numbers, and the four arithmetical operations practiced during the second grade are applied to certain simple things in everyday life.

In the fourth grade we continue with what was done in the earlier grades, but we must now also make the transition to fractions and especially to decimal fractions.

In the fifth grade, we continue with fractions and decimals and present everything the children need to do independent calculations involving whole numbers, fractions, and decimals.

In the sixth grade we move on to calculating percentages, interest, discounts and the interest on promissory notes, which then forms the basis for algebra, as we have already seen.

I ask you to observe that, until the sixth grade, we have been deriving the geometric shapes—circle, triangle, and so on—from drawing, after having done drawing for the sake of writing in the first few years. Then we gradually made the transition from drawing done for the sake of writing to developing more complicated forms for their own sake—that is, for the sake of drawing, and also to do painting for the sake of painting. We guide instruction in drawing and painting into this area in the fourth grade, and in drawing we teach what a circle is, what an ellipse is, and so on. We develop this out of drawing. We continue this by moving on to three-dimensional forms, using plasticine if it’s available, and whatever else you can get if it isn’t—even if it’s mud from the street, it doesn’t matter! The point is to develop the ability to see and sense forms.

Mathematics instruction, geometry instruction, then picks up on what has been taught in this way in the drawing classes. Only then do we begin to explain in geometrical terms what a triangle, a square, or a circle is, and so on. That is, the children’s spatial grasp of form develops through drawing. We begin to apply geometrical concepts to what they have learned in this way only once they are in the sixth grade. Then we have to make sure that we do something different in drawing.

In the seventh grade, after making the transition to algebra, we teach raising numbers to powers and extracting roots, and also what is known as calculating with positive and negative numbers. Above all, we try to introduce the children to what we might call practical, real-life applications of solving equations.

We continue this in the eighth grade and take the children as far as they can get with it. We also add calculating areas and volumes and the theory of geometrical loci, which we at least touched upon yesterday.

This gives you a picture of what you have to do with the children in mathematics and geometry.

As we have already seen, in the drawing lessons in the first few grades, we first teach the children to have a specific feeling for rounded or angular forms, and so on. From these forms, we develop what we need for teaching writing. In these very elementary stages of teaching drawing, we avoid imitating anything. As much as possible, you should initially avoid allowing the children to copy a chair or a flower or anything else. As much as possible, you should have them produce linear forms—forms that are round, pointed, semicircular, elliptical, straight, and so on. Awaken in the children a feeling for the difference between the curve of a circle and the curve of an ellipse. In short, awaken their feeling for form before their urge to imitate wakes up! Wait until later before allowing them to apply what they have practiced in drawing forms to imitating actual objects. First have them draw angles so that they understand what an angle is through its shape. Then you show them a chair and say, “Look, here’s an angle, and here’s another angle,” and so on. Do not let the children imitate anything until you have cultivated their feeling for independent forms which can be imitated later. Stick to this principle even when you move on to a more independent and creative treatment of drawing and painting.

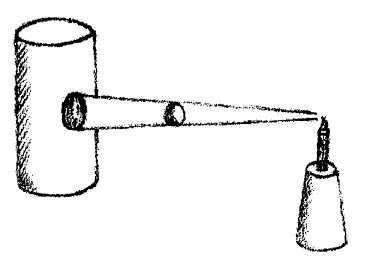

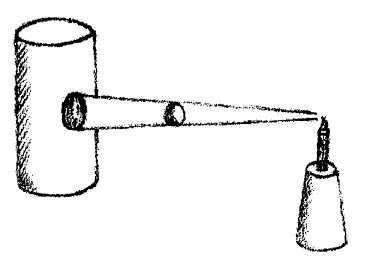

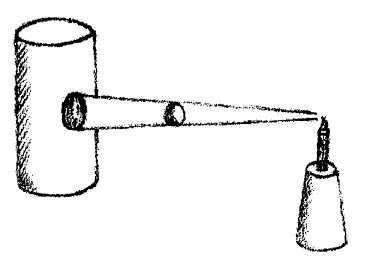

Then in the sixth grade you introduce simple projection exercises and drawing shadows, both freehand and with a ruler and compass and the like. Make sure that the children have a good grasp of the concept and can reproduce in their drawings what the shadow of a sphere looks like on the surface of a cylinder if the cylinder is here and the sphere here and a light is shining on the sphere:

Yes, how shadows are cast! So a simple study of projection and shadows must take place in the sixth grade. The children must get a conception of it and must be able to imitate how more or less regular shapes or physical objects cast their shadows on flat and curved surfaces. In their sixth school year the children must acquire a concept of how the technical aspect unites with the element of beauty, of how a chair can be technically suited for a certain purpose while also having a beautiful form. The children must acquire both a concept and a handson grasp of this union of the technical and the beautiful.

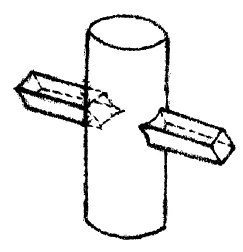

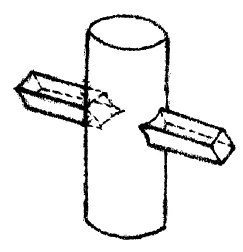

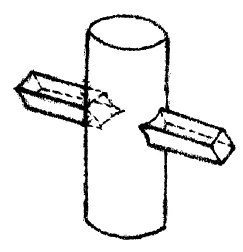

Then, in the seventh grade, everything having to do with one object penetrating another should be covered. As a simple example, you might say, “Here we have a cylinder with a post running through it. The post has to go through the cylinder.” You must demonstrate what kind of a shape the post cuts in the surface of the cylinder when it enters and exits. This is something to learn together with the children. They must learn what happens when objects or surfaces interpenetrate, so that they know that it makes a difference whether a stovepipe goes through the ceiling at a right angle, in which case their intersection is a circle, or at an angle, in which case it is an ellipse. In addition, this is the year when the children must be taught a good conception of perspective. So you do simple perspective drawing with objects foreshortened in the distance and elongated in the foreground, and you draw objects that are partially concealed and so on. Once again, you combine the technical aspect with beauty, so that you awaken in the children an idea of whether or not it is beautiful when some portion of a wall of a house is concealed by a projection, let’s say. Some such projections are beautiful and others are not. These things have a pronounced effect when they are taught to seventh graders in particular—that is, to thirteen- or fourteen-year-olds.

In the eighth grade, all this is raised to an artistic level. All the other subjects must be handled similarly to the ones we have discussed. We will come back to this in the afternoon and still add a few things to complete our curriculum. Above all, we will have to see how music is developed in the first grade out of elements that are as simple and elementary as possible, and how from the third grade on the transition is made to more complicated things. The point is that the children should be able to take in those aspects of playing an instrument—especially of playing an instrument, but also of singing—that have a creative and formative effect on their capabilities.

As special cases among all the other artistic subjects, we will have to emphasize gymnastics and eurythmy, which must both be developed out of the element of music and the other arts.

Weiter Lehrplanvortrag

Wir kommen nun dazu, den weiteren Unterrichtsstoff zu verteilen auf die verschiedenen Schulstufen.

Da seien wir uns nur ja recht klar darüber, daß wir gegen das neunte Jahr zu, also im dritten Schuljahr, damit beginnen, die Tiere in entsprechender Auswahl zu behandeln, und immer so in Beziehung zum Menschen zu bringen, wie ich das probeweise dargestellt habe.

Da setzen wir dann im vierten Schuljahr fort, so daß wir also im dritten und vierten Schuljahr naturwissenschaftlich die Tierwelt in Beziehung zum Menschen der Betrachtung unterwerfen.

Dann gehen wir im fünften Schuljahr dazu über, unbekanntere Tierformen noch hinzuzufügen, beginnen aber auch in diesem fünften Schuljahr mit der Pflanzenlehre und treiben sie dann namentlich so, wie wir das im didaktischen Teil unseres Seminars besprochen haben.

Dann setze man die Pflanzenlehre im sechsten Schuljahr fort und gehe über zur Behandlung der Mineralien. Aber die Behandlung der Mineralien geschehe durchaus im Zusammenhang mit der Geographie.

Im siebenten Schuljahr kehre man wiederum zum Menschen zurück und versuche namentlich das beizubringen, worauf ich gestern hingedeutet habe, was in bezug auf die Ernährungs- und Gesundheitsverhältnisse dem Menschen beigebracht werden sollte. - Und man versuche mit dem, was an physikalischen und chemischen Begriffen gewonnen wird, eine zusammenfassende Anschauung hervorzurufen über Erwerbsverhältnisse, Betriebsverhältnisse — also diesen oder jenen Betrieb - und Verkehrsverhältnisse; das alles im Zusammenhang mit dem physikalischen, chemischen und geographischen Unterricht, aus der Naturgeschichte heraus.

Im achten Schuljahr werden Sie den Menschen so aufzubauen haben, daß Sie dasjenige darstellen, was von außen in ihn hineingebaut ist: die Knochenmechanik, die Muskelmechanik, der innere Bau des Auges und so weiter. - Dann geben Sie jetzt wiederum eine zusammenfassende Darstellung der Betriebsverhältnisse und Verkehrsverhältnisse im Zusammenhang mit Physik, Chemie und Geographie.

Wenn Sie namentlich den naturgeschichtlichen Unterricht so gestalten, wie wir es eben besprochen haben, dann werden Sie ihn ungeheuer lebendig machen können, und Sie werden aus der Naturgeschichte heraus dem Kinde ein Interesse erwecken für alles Weltliche und alles Menschliche.

Mit dem Physikunterricht beginnen wir im sechsten Schuljahr, und zwar so, daß wir ihn durchaus an dasjenige anknüpfen, was die Kinder gewonnen haben durch den Musikunterricht. Wir beginnen den Physikunterricht, indem wir die Akustik herausgebären lassen aus dem Musikalischen. Also Sie knüpfen durchaus die Akustik an die musikalische Tonlehre an und gehen dann über zur Besprechung der physikalisch-physiologischen Beschaffenheit des menschlichen Kehlkopfes. Das menschliche Auge können Sie hier noch nicht besprechen, aber den Kehlkopf können Sie besprechen. Dann gehen Sie über - indem Sie nur die wichtigsten Dinge durchnehmen - zur Optik und zur Wärmelehre. Auch die Grundbegriffe der Elektrizität und des Magnetismus bringen Sie in dieses sechste Schuljahr hinein.

Dann gehen Sie im siebenten Schuljahr über zu der Erweiterung des Akustischen, des Thermischen, also des Wärmelehreunterrichts, des optischen Unterrichts, des Elektrizitäts- und Magnetismusunterrichts. Und erst von da aus gehen Sie über zu den wichtigsten mechanischen Grundbegriffen, also Hebel, Rad an der Welle, Rolle, Flaschenzug, Rollenzug, Schiefe Ebene, Walze, Schraube und so weiter.

Dann gehen Sie aus von einem solchen Vorgang wie von der Verbrennung und suchen von einem solchen alltäglichen Vorgang dann den Übergang zu gewinnen zu einfachen chemischen Vorstellungen.

Im achten Schuljahr erweitern Sie wiederum wiederholentlich dasjenige, was im sechsten gepflogen worden ist, und gehen über zur Hydraulik, also zu der Lehre von der Kraft, die durch das Wasser wirkt. Also alles dasjenige nehmen Sie vor, was zu dem Begriff, wie Seitendruck im Wasser, Auftrieb gehört: alles, was zum Archimedischen Prinzip, was also in die Hydraulik gehört.

Es würde reizvoll gewesen sein, drei Jahre lang über Pädagogik hier Vorträge zu halten, und alles einzelne, was Sie aus eigener Erfindung heraus sich gestalten müssen, auch einmal durch Musterbeispiele zu behandeln. Aber das kann nicht sein. Wir müssen uns eben mit dem begnügen, was wir hier angeführt haben.

Dann schließen Sie gewissermaßen den physikalischen Unterricht ab durch die Aeromechanik, also durch die Mechanik der Luft, wobei alles zur Sprache kommt, was zusammenhängt mit der Klimatologie, Barometer- und Witterungskunde.

Und Sie führen die einfachen chemischen Begriffe weiter, so daß das Kind auch begreifen lernt, wie industrielle Prozesse mit chemischen zusammenhängen. Sie versuchen, im Zusammenhang mit den chemischen Begriffen dasjenige zu entwickeln, was zu sagen ist in bezug auf die Stoffe, die den organischen Körper aufbauen: Stärke, Zucker, Eiweiß, Fett.

Nun wird es uns obliegen, auch alles, was sich auf Rechnen, Mathematik, Geometrie bezieht, zu verteilen auf die acht Schulstufen.

Sie wissen ja, die äußere Methodik schreibt vor, im ersten Schuljahr vorzugsweise die Zahlen im Zahlenraum bis 100 zu behandeln. Man kann sich an das auch halten, denn es ist ziemlich gleichgültig, wenn man bei den einfacheren Zahlen bleibt, wie weit man den Zahlenraum im ersten Schuljahr treibt. Die Hauptsache ist, daß sie, insofern Sie den Zahlenraum gebrauchen, die Rechnungsarten darin so betreiben, daß Sie eben dem Rechnung tragen, was ich gesagt habe: die Addition zuerst aus der Summe heraus, die Subtraktion aus dem Rest heraus, die Multiplikation aus dem Produkt heraus und die Division aus dem Quotienten heraus entwickelt. Also gerade das Umgekehrte von dem, was gewöhnlich gemacht wird. Und erst nachdem man gezeigt hat, 5 ist 3 plus 2, zeigt man das Umgekehrte: durch Addition von 2 und 3 entsteht 5. Denn man muß starke Vorstellungen im Kinde hervorrufen, daß 5 gleich 3 plus 2 ist, daß 5 aber auch 4 plus 1 ist und so weiter. Also die Addition erst als zweites nach der Auseinanderteilung der Summe; und die Subtraktion, nachdem man gefragt hat: Was muß ich von einem Minuenden abziehen, damit ein bestimmter Rest bleibt und so weiter. Wie gesagt, daß man das dann mit den einfacheren Zahlen im ersten Schuljahr macht, ist selbstverständlich. Ob man nun gerade den Zahlenraum bis 100 oder bis 105 oder bis 95 benützt, das ist im Grunde nebensächlich.

Dann aber beginne man, wenn das Kind mit dem Zahnwechsel fertig ist, ja gleich damit, es das Einmaleins lernen zu lassen, und meinetwillen sogar das Einspluseins; wenigstens, sagen wir, bis zur Zahl 6 oder 7. Also das Kind möglichst früh das Einmaleins und Einspluseins einfach gedächtnismäßig lernen zu lassen, nachdem man ihm nur prinzipiell erklärt hat, was das eigentlich ist, es prinzipiell an der einfachen Multiplikation erklärt hat, die man so in Angriff nimmt, wie wir das gesagt haben. Also kaum daß man imstande ist, dem Kinde den Begriff des Multiplizierens beizubringen, übertrage man ihm auch schon die Pflicht, das Einmaleins gedächtnismäßig zu lernen.

Dann führe man im zweiten Schuljahr für einen größeren Zahlenraum die Rechnungsarten weiter. Man versuche, einfache Aufgaben auch ohne Schriftliches, eben im Kopfe, mündlich mit dem Schüler zu erledigen. Man versuche, unbenannte Zahlen womöglich zuerst zu entwickeln an Dingen - ich habe Ihnen ja gesagt, wie Sie an Bohnen oder was auch, die unbenannten Zahlen entwickeln können. Aber man sollte doch auch das Rechnen im Zusammenhang mit benannten Zahlen nicht aus dem Auge verlieren.

Im dritten Schuljahr wird alles für kompliziertere Zahlen fortgesetzt, und es werden schon die vier Rechnungsarten, wie sie im zweiten Schuljahr gepflogen worden sind, in Anwendung gebracht auf gewisse einfache Dinge des praktischen Lebens.

Im vierten Schuljahr wird das fortgesetzt, was in den ersten Schuljahren gepflogen worden ist. Aber jetzt müssen wir übergehen zur Bruchlehre und namentlich zur Dezimalbruchlehre.

Wir wollen dann im fünften Schuljahr mit der Bruchlehre und mit der Dezimalbruchlehre fortsetzen und alles dasjenige an das Kind heranbringen, was ihm die Fähigkeit beibringt, sich innerhalb ganzer, gebrochener, durch Dezimalbrüche ausgedrückter Zahlen frei rechnend zu bewegen.

Dann gehe man im sechsten Schuljahr über zur Zins- und Prozentrechnung, zur Diskontrechnung, zur einfachen Wechselrechnung und begründe damit die Buchstabenrechnung, wie wir es gezeigt haben.

Nun bitte ich zu beachten, daß wir bis zum sechsten Schuljahr die geometrischen Formen: Kreis, Dreieck und so weiter herausgeholt haben aus dem Zeichnen, nachdem wir zuerst in den ersten Jahren das Zeichnen für den Schreibunterricht getrieben haben. Dann sind wir allmählich dazu übergegangen, aus dem Zeichnen, das wir für den Schreibunterricht getrieben haben, beim Kinde kompliziertere Formen zu entwickeln, die um ihrer selbst willen, um des Zeichnens willen betrieben werden; auch Malerisches zu betreiben, das um des Malerischen willen betrieben wird. In diese Sphäre leiten wir den Zeichen- und Malunterricht im vierten Schuljahr, und im Zeichnen lehren wir, was ein Kreis ist, eine Ellipse ist und so weiter. Aus dem Zeichnen heraus lehren wir dieses. Da setzen wir noch fort, durchaus auch immer zu plastischen Formen hinführend, indem wir uns des Plastilins bedienen wenn es zu haben ist; sonst kann man irgend etwas anderes benützen, und wenn es Straßenkot wäre, das macht nichts! -, um auch Formenanschauung, Formenempfindung hervorzuholen.

Von dem, was auf diese Weise im Zeichnen gelehrt worden ist, übernimmt nun der Mathematikunterricht, der geometrische Unterricht das, was die Kinder können. Jetzt geht man erst über dazu, geometriegemäß zu erklären, was ein Dreieck, ein Quadrat, ein Kreis ist und so weiter. Also die raumesmäßige Auffassung dieser Form wird aus dem Zeichnen hervorgeholt. Und was die Kinder aus dem Zeichnen heraus gelernt haben, daran gehe man jetzt im sechsten Schuljahr mit dem geometrischen Begreifen erst heran. Dafür werden wir dann sehen, daß wir in das Zeichnerische etwas anderes aufnehmen.

Im siebenten Schuljahr versuche man, nachdem man zur Buchstabenrechnung übergegangen ist, Potenzieren, Radizieren beizubringen; auch das, was man das Rechnen mit positiven und negativen Zahlen nennt. Und vor allen Dingen versuche man, die Kinder in das hereinzubringen, was im Zusammenhang mit freier Anwendung des praktischen Lebens die Lehre von den Gleichungen genannt werden kann.

Da setze man dann das, was mit der Gleichungslehre zusammenhängt, im achten Schuljahr fort, soweit man die Kinder bringen kann, und füge dazu Figuren- und Flächenberechnungen und die Lehre von den geometrischen Orten, wie wir sie gestern wenigstens gestreift haben.

Das gibt Ihnen ein Bild, wie Sie sich in Mathematik und Geometrie mit den Kindern zu verhalten haben.

Jetzt treiben wir, wie wir gesehen haben, in den ersten Schuljahren den zeichnerischen Unterricht so, daß wir zuerst dem Kinde ein gewisses Empfinden an runden, an eckigen Formen und so weiter beibringen. Aus der Form heraus entwickeln wir das, was wir dann für den Schreibunterricht brauchen. Wir vermeiden es am Beginne dieses elementarischen Zeichenunterrichts ganz, irgend etwas nachzuahmen. Vermeiden Sie es, soviel Sie nur können, das Kind zuerst einen Stuhl oder eine Blume oder irgend etwas nachahmen zu lassen, sondern bringen Sie ihm soviel als möglich Linienformen aus sich selbst hervor: runde, spitzige, halbrunde, elliptische, gerade Formen und so weiter. Rufen Sie im Kinde das Gefühl hervor, was für ein Unterschied ist zwischen Kreisbiegung und Ellipsenbiegung. Kurz, erwecken Sie das Formengefühl, bevor der Nachahmungstrieb erwacht ist! Erst später lassen Sie das, was in den Formen gepflegt worden ist, auf das Nachahmen anwenden. Lassen Sie das Kind erst einen Winkel zeichnen, so daß es in der Form den Winkel begreift. Dann zeigen Sie ihm den Stuhl und sagen ihm: «Siehst du, da ist ein Winkel, und da ist noch einmal ein Winkel» und so weiter. Lassen Sie das Kind nichts nachahmen, bevor Sie nicht in ihm aus innerem Gefühl heraus die Form in ihrer Selbsttätigkeit gepflegt haben, die dann später erst auch nachgeahmt werden kann. Und so halten Sie es auch noch, wenn Sie zur mehr selbständigen Behandlung des Zeichnens und des Malerischen und auch des Bildnerischen übergehen.

Dann lassen Sie im sechsten Schuljahr einfache Projektions- und Schattenlehre auftreten, die Sie sowohl mit freier Hand behandeln wie auch mit dem Lineal und Zirkel und dergleichen. Sehen Sie darauf, daß das Kind einen guten Begriff bekommt und nachzeichnen, nach bilden kann, wie, wenn hier ein Zylinder ist, hier eine Kugel, und die Kugel vom Lichte beschienen wird, wie der Schatten von der Kugel auf dem Zylinder ausschaut. Wie Schatten geworfen werden! Also einfache Projektions- und Schattenlehre muß im sechsten Schuljahr auftreten. Das Kind muß eine Vorstellung bekommen und muß nachahmen können, wie Schatten auf ebenen Flächen, auf gekrümmten Flächen, von anderen mehr oder weniger ebenen oder von körperlichen Dingen geworfen werden. Das Kind muß in diesem sechsten Schuljahr einen Begriff davon bekommen, wie sich Technisches mit Schönem verbindet, wie ein Stuhl zu gleicher Zeit technisch geeignet sein kann für einen Zweck, und wie er nebenbei eine schöne Form haben kann. Und diese Verbindung von Technischem mit Schönem soll dem Kinde in den Begriff, in den Griff hineingehen.

Dann sollte im siebenten Schuljahr alles das gepflegt werden, was sich auf Durchdringungen bezieht. Also als einfaches Beispiel sagen Sie: «Da haben wir einen Zylinder, der wird von einem Pfosten durchdrungen. Der Pfosten muß durchgesteckt werden durch den Zylinder.» Sie müssen zeigen, was da in dem Zylinder für eine Schnittfläche entsteht beim Hiineingehen und beim wieder Herausgehen. Das muß mit

dem Kinde gelernt werden. So etwas muß es lernen, was entsteht, wenn sich Körper oder Flächen gegenseitig durchdringen, so daß es weiß, welcher Unterschied ist, ob eine Ofenröhre oben senkrecht durchs Plafond geht, wobei ein Durchdringen im Kreis erfolgt, oder schief, wobei ein Durchdringen in der Ellipse erfolgt. - Dann muß das Kind in diesem Jahr eine gute Vorstellung beigebracht erhalten vom Perspektivischen. Also einfaches perspektivisches Zeichnen, Verkürzung in der Entfernung, Verlängerung in der Nähe, Überdeckungen und so weiter. Und dann wiederum die Verbindung des Technischen mit dem Schönen, so daß man in dem Kinde eine Vorstellung davon hervorruft, ob es schön oder unschön ist, wenn irgendeine, sagen wir, teilweise Überdeckung einer Wand eines Hauses durch einen Vorsprung hervorgerufen wird. Ein solcher Vorsprung kann schön oder unschön eine solche Wand überdecken. Solche Dinge wirken ungeheuer, wenn sie einem Kinde gerade im siebenten Schuljahre, also wenn es dreizehn, vierzehn Jahre alt ist, beigebracht werden.

Das alles steigert man ins Künstlerische, indem man gegen das achte Schuljahr hingeht.

Und in einer ähnlichen Weise, wie diese Dinge gepflegt worden sind, müssen nun auch die restlichen Dinge gepflegt werden. Wir werden dann heute Nachmittag darauf zurückkommen und einiges noch ergänzend zu unserem Lehrplan hinzuzufügen haben. Da wird vor allen Dingen darauf gesehen werden müssen, wie auch das Musikalische in dem ersten Schuljahr möglichst aus dem Einfachen, Elementarischen hervorgeholt wird, und wie dann in das Kompliziertere übergegangen wird etwa vom dritten Schuljahr an. So daß nach und nach das Kind sowohl am Instrument — und namentlich am Instrument — wie auch im Gesanglichen dasjenige aufnimmt, was gerade bildnerisch, bildend für die Fähigkeiten des Kindes ist.

Herausgeholt werden muß nun aus allem übrigen Künstlerischen das Turnen und die Eurythmie. Aus dem Musikalischen, und auch aus dem sonstigen Künstlerischen, muß das Turnen und die Eurythmie herausgeholt werden.

Further Curriculum Presentation

We now come to the distribution of further teaching material across the various school levels.

Let us be very clear that towards the ninth year, i.e. in the third school year, we begin to deal with a selection of animals, always relating them to humans in the way I have outlined on a trial basis.

We then continue in the fourth school year, so that in the third and fourth school years we examine the animal world in relation to humans from a scientific perspective.

Then, in the fifth school year, we move on to adding lesser-known animal forms, but we also begin botany in this fifth school year and then pursue it in the manner we discussed in the didactic part of our seminar.

Then botany is continued in the sixth school year and we move on to the study of minerals. But the treatment of minerals should be done in connection with geography.

In the seventh school year, we return to the human being and try to teach what I pointed out yesterday, namely what should be taught to human beings in relation to nutrition and health. - And with the knowledge gained in physics and chemistry, an attempt is made to develop a comprehensive view of working conditions, operating conditions — that is, this or that business — and transport conditions; all this in connection with physics, chemistry, and geography lessons, based on natural history.

In the eighth grade, you will have to build up the human being in such a way that you represent what is built into him from the outside: the mechanics of the bones, the mechanics of the muscles, the internal structure of the eye, and so on. - Then give a summary of working conditions and transport conditions in connection with physics, chemistry, and geography.

If you structure natural history lessons in the way we have just discussed, you will be able to make them incredibly lively, and you will awaken in the child an interest in everything worldly and human through natural history.

We begin teaching physics in the sixth grade, linking it closely to what the children have learned in music class. We begin physics lessons by bringing acoustics out of music. So you link acoustics to musical theory and then move on to discussing the physical and physiological nature of the human larynx. You cannot discuss the human eye at this stage, but you can discuss the larynx. Then you move on to optics and thermodynamics, covering only the most important points. You also introduce the basic concepts of electricity and magnetism in this sixth school year.

Then, in the seventh school year, you move on to expanding on acoustics, thermodynamics, i.e., teaching about heat, optics, electricity, and magnetism. And only from there do you move on to the most important basic mechanical concepts, i.e., levers, wheels on shafts, pulleys, block and tackle, inclined planes, rollers, screws, and so on.

Then you start with a process such as combustion and use this everyday process to make the transition to simple chemical mental images.

In the eighth grade, you expand on what was taught in the sixth grade and move on to hydraulics, i.e., the study of the force exerted by water. So you cover everything that belongs to the concept of lateral pressure in water, buoyancy: everything that belongs to Archimedes' principle, i.e., hydraulics.

It would have been appealing to give lectures on pedagogy here for three years and to cover everything you have to develop on your own with examples. But that cannot be. We must be content with what we have presented here.

Then you conclude the physics lessons, so to speak, with aeromechanics, i.e., the mechanics of air, covering everything related to climatology, barometers, and meteorology.

And you continue with simple chemical concepts so that the child also learns to understand how industrial processes are related to chemistry. In connection with the chemical concepts, you try to develop what needs to be said about the substances that make up the organic body: starch, sugar, protein, fat.

Now it will be up to us to distribute everything related to arithmetic, mathematics, and geometry across the eight school grades.

As you know, the external methodology prescribes that in the first school year, numbers up to 100 should preferably be taught. One can adhere to this, because it is fairly irrelevant how far one goes with the numbers in the first school year if one sticks to the simpler numbers. The main thing is that, insofar as you use the number range, you carry out the types of calculation in such a way that you take into account what I have said: addition is developed first from the sum, subtraction from the remainder, multiplication from the product, and division from the quotient. In other words, the opposite of what is usually done. And only after showing that 5 is 3 plus 2 do you show the reverse: adding 2 and 3 makes 5. Because you have to instill in the child a strong mental image that 5 is equal to 3 plus 2, but that 5 is also 4 plus 1, and so on. So addition comes second, after dividing the sum; and subtraction comes after asking: What do I have to subtract from a minuend to get a certain remainder, and so on. As I said, it goes without saying that this is done with simpler numbers in the first year of school. Whether you use the number range up to 100 or up to 105 or up to 95 is basically irrelevant.

But then, once the child has finished teething, start teaching them their times tables right away, and for my sake even one plus one; at least, say, up to the number 6 or 7. So, let the child learn the multiplication tables and one plus one by heart as early as possible, after you have explained to them in principle what this actually is, explained it in principle using simple multiplication, which is tackled as we have said. So as soon as you are able to teach the child the concept of multiplication, you should also give them the task of learning the multiplication tables by heart.

Then, in the second year of school, continue with the types of calculation for a larger number range. Try to do simple tasks with the student orally, without writing, just in your head. Try to develop unnamed numbers first using objects – I have already told you how you can develop unnamed numbers using beans or whatever. But you should not lose sight of arithmetic in connection with named numbers.

In the third school year, everything is continued for more complicated numbers, and the four types of arithmetic, as practiced in the second school year, are already applied to certain simple things in practical life.

In the fourth year of school, what has been practiced in the first years of school is continued. But now we must move on to fractions, and in particular to decimal fractions.

In the fifth year of school, we want to continue with fractions and decimal fractions and teach children everything they need to know to be able to calculate freely with whole numbers, fractions, and decimal fractions.

Then, in the sixth grade, move on to interest and percentage calculations, discount calculations, simple bill of exchange calculations, and use this to establish letter calculations, as we have shown.

Now please note that by the sixth grade, we have brought out the geometric shapes: circle, triangle, and so on, from drawing, after first practicing drawing for writing lessons in the early years. Then we gradually moved on from the drawing we did for writing lessons to developing more complicated shapes with the children, which are done for their own sake, for the sake of drawing; also to doing painting, which is done for the sake of painting. We introduce drawing and painting lessons in the fourth grade, and in drawing we teach what a circle is, what an ellipse is, and so on. We teach this through drawing. We continue to lead them towards plastic forms, using plasticine when it is available; otherwise, anything else can be used, even street dirt, it doesn't matter! – in order to bring out their perception and feeling for form.

Mathematics and geometry lessons now take over what the children have learned in this way through drawing. Now we move on to explaining geometrically what a triangle, a square, a circle, and so on are. In other words, the spatial perception of these shapes is brought out through drawing. And what the children have learned from drawing is now approached in the sixth grade with geometric understanding. To this end, we will then see that we incorporate something else into the drawing.

In the seventh grade, after moving on to letter calculation, we try to teach exponentiation and root extraction, as well as what is called calculating with positive and negative numbers. Above all, we try to introduce the children to what can be called the study of equations in connection with the free application of practical life.

Then, in the eighth grade, continue with what is related to the study of equations, as far as the children can be brought, and add to this the calculation of figures and areas and the study of geometric locations, as we touched on yesterday.

This gives you an idea of how to approach mathematics and geometry with children.

Now, as we have seen, in the first years of school we teach drawing in such a way that we first teach the child a certain feeling for round and angular shapes and so on. From the shape, we develop what we then need for writing lessons. At the beginning of this elementary drawing lesson, we avoid imitating anything at all. As far as possible, avoid letting the child imitate a chair or a flower or anything else at first, but encourage them to produce as many line forms as possible from themselves: round, pointed, semicircular, elliptical, straight forms, and so on. Awaken in the child a sense of the difference between a circular curve and an elliptical curve. In short, awaken their sense of form before their urge to imitate awakens! Only later should you allow them to apply what they have learned about form to imitation. First let the child draw an angle so that they understand the form of the angle. Then show them the chair and say: “You see, there is an angle, and there is another angle,” and so on. Do not let the child imitate anything until you have cultivated the form in its inner feeling through its own activity, which can then be imitated later. And continue in this way when you move on to a more independent approach to drawing, painting, and art.

Then, in the sixth school year, introduce simple projection and shadow theory, which you can teach both freehand and with a ruler, compass, and the like. Make sure that the child gets a good understanding and can trace and draw, for example, if there is a cylinder here and a sphere here, and the sphere is illuminated by light, what the shadow of the sphere looks like on the cylinder. How shadows are cast! So simple projection and shadow theory must be introduced in the sixth grade. The child must get a mental image and be able to imitate how shadows are cast on flat surfaces, on curved surfaces, by other more or less flat or physical objects. In this sixth school year, the child must get an idea of how technology is combined with beauty, how a chair can be technically suitable for a purpose and at the same time have a beautiful form. And this connection between the technical and the beautiful should become part of the child's understanding and grasp.

Then, in the seventh school year, everything related to penetration should be cultivated. So, as a simple example, you say: “Here we have a cylinder that is penetrated by a post. The post must be inserted through the cylinder.” You have to show what kind of intersection surface is created in the cylinder when it goes in and when it comes out again. This must be learned with the child.

It must learn what happens when bodies or surfaces penetrate each other, so that it knows the difference between a stove pipe going vertically through the ceiling, whereby penetration occurs in a circle, and going at an angle, whereby penetration occurs in an ellipse. Then, during this year, the child must be taught a good mental image of perspective. That is, simple perspective drawing, foreshortening in the distance, elongation in the foreground, overlaps, and so on. And then again, the connection between the technical and the beautiful, so that the child develops a mental image of whether it is beautiful or unattractive when, say, part of a wall of a house is partially covered by a projection. Such a projection can cover a wall in a beautiful or unattractive way. Such things have an enormous effect when they are taught to a child in the seventh year of school, that is, when they are thirteen or fourteen years old.All of this is elevated to an artistic level as we approach the eighth grade.

And in a similar way to how these things have been cultivated, the remaining things must now also be cultivated. We will come back to this this afternoon and add a few things to our curriculum. Above all, we will have to see how music can be taught in the first year of school in as simple and elementary a way as possible, and how we can then move on to more complicated things from about the third year onwards. In this way, the child will gradually absorb what is formative and educational for their abilities, both on the instrument — and especially on the instrument — and in singing.

Gymnastics and eurythmy must now be extracted from all other artistic activities. Gymnastics and eurythmy must be extracted from music and other artistic activities.