Education as a Social Problem

GA 296

11 August 1919, Dornach

III. Commodity, Labor, and Capital

What I have to say today will be a kind of interlude. I should like to speak briefly about three concepts which, if they are fully understood, can bring about an understanding of outer social life. I say expressly outer social life because these three concepts originate from people's cooperation in outer affairs. I refer to the concepts commodity, labor, capital. I have already told you that modern political economy in all its shadings endeavors in vain to arrive at complete clarity about these concepts. That was not possible after men began to think consciously in a political-economic fashion. Prior to the middle of the fifteenth century there can be no question of people consciously comprehending their mutual social relationships. Life took its course more or less unconsciously, instinctively, in regard to the social forces playing between man and man. Since then, however, in the age when the consciousness-soul is being developed, people have had to think more and more consciously about social relationships. And so, every kind of idea and direction in the life of human society has arisen. This begins with the school of the Mercantilists, then the school of the Physiocrats, Adam Smith, the various Utopian streams, Proudhon, Fourrier, and so on, right up to modern social-democracy on one side and modern academic political economy on the other.

It is interesting to compare the modern social-democratic theory based on Marx and Engels, with modern academic political economy, which is completely unproductive. It produces no concepts capable of permeating the social will. Nothing results from the confused, chaotic concepts of modern academic political economy if we pose the question of what is to happen in social life, because this academic economy is infected by the concepts of modern science. You know that in spite of the great and admirable progress of natural science, which is not denied by spiritual science, this modern science in the schools and universities completely rejects all that springs from the spirit. As a result, political economy wants only to observe what happens in economic life. But this has become almost impossible in recent times because the more people have evolved in the modern age the less have they had thoughts that could cope with economic facts. Economic facts took their own course mechanically, as if by themselves; they were not accompanied by human thinking. Therefore, observing these thought-bereft facts of the world market cannot lead to laws, and has not done so, because our political economy is practice without theory, without ideas, and our social-democratic endeavors are theory without practice. The socialistic theory can never be put into practice, for it is a theory without insight into practical life. We suffer in modern times from the fact that we have an economic life that is practice without ideas, and with it the mere theory of the social democrats without the possibility of introducing this theory into economic life. Thus, we have reached a turning point in the historical evolution of mankind.

Since social life has to be founded upon the relation of man to man it will be easy for you to realize that a certain attitude has to underlie all human endeavor to found a socially just life. That is what is so important in the threefold membering of the social organism, namely, that this certain attitude, this feeling, be generated in the interrelated spheres of social action. Without this mood of soul among men social life cannot flourish. This soul quality will definitely be taken into account by the threefold social organism. I should therefore like to point today to certain aspects of this matter.

If you think of social life as an organism you will have to imagine that something of a soul-spiritual nature streams through it. Just as in the human and animal organism the blood is the bearer of the air that is inhaled and exhaled, so something must breathe through, must circulate through the entire social organism.

Here we come to a chapter that is hard for modern man to comprehend because he is so little prepared for it; but it must be comprehended if there is to be any question at all of a social reformation. The fact that in the social life of the future the content of human conversation will be of special significance, is something that must be understood. Results will depend upon what people take seriously when they exchange their ideas, their sensations, their feelings. The views that hold sway among men are not insignificant if they wish to become social beings. It is necessary for the future that general education be governed not merely by concepts derived from science or industry, but by concepts that can be the basis for imaginations. Improbable as it may seem to modern man, nevertheless it will not be possible to develop a social life if people are not given imaginative concepts; that is to say, concepts which shape the human mind quite differently from the merely abstract concepts of cause and effect, energy and matter, and so forth, that are derived from natural science. These concepts derived from science which govern everything today, even art, will be of no avail in the social life of the future. For that we must make it possible again to comprehend the world in pictures.

What is meant by that I have repeatedly indicated, also in regard to the question of education. I have said: If we intimately occupy ourselves with children it is easy to impart to them, let us say, the idea of immortality by showing them the chrysalis of a butterfly, how it opens and the butterfly emerges and flies away. We then can make clear to the child, “Your body is like the chrysalis, and in it there lives something like the butterfly, but it is invisible. When you come to die, with you too the butterfly emerges and flies into the spiritual world.” Through such comparisons we bring about an imaginative effect. But we must not merely think out such a comparison; this would only be acting in the manner of the scientific view. What is the attitude of people with present-day education as they hear such a comparison? Modern men, even when they are barely grown up, are very clever, exceedingly clever. They do not consider at all that one might be clever differently from the way they, in their abstract concepts, deem themselves clever. Men are very peculiar in regard to their modern cleverness!

A few weeks ago, I gave a lecture in a certain city. It was followed by a meeting of a political science association in which a university professor—a clever man of our time, of course—spoke about my lecture and what was connected with it. He was of the opinion that not only the views I had advanced but also those to be found in my books, are infantile. Well, I understand such a judgment. I understand it especially well when the man is a university professor. I understand it for the reason that science, which he represents, has quite lost all imaginative life and considers infantile what it does not comprehend. It is characteristic of modern men in their cleverness that they say: If we are to employ such an image, which compares the immortal soul with the butterfly emerging from the chrysalis, we, the clever ones, know that it is an image we have made; we have passed beyond the content of such an image. But the child is childlike, so we compare what we know in our concepts with this image, yet we ourselves do not believe in it. The secret of the matter is, however, that in that case the child does not believe in it either. The child is only taken hold of by the picture if we ourselves believe in it. The genuine spiritual-scientific attitude is to restore in us the faculty of seeing in nature not the ghost-like things of which science speaks, but the pictorial, the imaginative. What emerges from the chrysalis and is present in the butterfly is really an image for the immortality of the soul placed into the order of nature by the divine world order. If there were no immortal soul there would be no butterfly emerging from the chrysalis. There can be no real image if truth is not the basis for it. So it is with all of nature. What natural science offers is a ghost. We can comprehend nature only if we know that it is an image for something else.

Likewise, people must accustom themselves to considering the human head as an image of a heavenly body. The human head is not round in order to resemble a head of cabbage, but rather to resemble the form of a celestial body. The whole of nature is pictorial and we must find our way into this imagery. Then there will radiate into the hearts, the souls and minds, even into the heads—and this is most difficult—what can permeate man if he takes in pictures. In the social organism we will have to speak with each other about things that are expressed in pictures. And people will have to believe in these pictures. Then there will come from scientific circles persons able to speak about the real place of commodities in life, because the commodity produced corresponds to a human need. No abstract concepts can grasp this human need in its social value. Only that person can know something about it whose soul has been permeated by the discernment that springs from imaginative thinking. Otherwise there will be no socialization. You may employ in the social organism those who rightly ascertain what is needed, but if at the same time imaginative thinking is not incorporated in the social organism through education it is impossible to arrive at an organic social structure. That means, we must speak in images. However strange it may sound to the socialistic thinker of today, it is necessary that in order to arrive at a true socializing we must speak from man to man in pictures, which induce imaginations. This indeed is how it must happen. What is a commodity will be feelingly understood by a science that gains understanding through pictures, and by no other science.

In the society of the future a proper understanding of labor will have to be a dominating element. What men say today about labor is sheer nonsense, for human labor is not primarily concerned with the production of goods. Karl Marx calls commodities crystallized labor power. This is nonsense, nothing else; because what takes place when a man works is that he uses himself up in a certain sense. You can bring about this self-consumption in one way or another. If you happen to have enough money in the bank or in your purse you can exert yourself in sports and use your working power in this way. You also might chop wood or do some other chore. The work may be the same whether you chop wood or engage in a sport. The important thing is not how much work-power you exert, but for what purpose you use it in social life. Labor as such has nothing to do with social life insofar as this social life is to produce goods or commodities. In the threefold social organism, therefore, an incitement to labor will be needed which is completely different from the one that produces goods. Goods will be produced by labor because labor has to be used for something. But that which must be the basis for a man's work is the joy and love for work itself. We shall only achieve a social structure for society if we find the methods for inducing men to want to work, so that it becomes natural for them, a matter of course, that they work.

This can only happen in a society in which one speaks of inspired concepts. In future, men will never be warmed through by joy and love for work—as was the case in the past when things were instinctive and atavistic—if society is not permeated by such ideas and feelings as enter the world through the inspiration of initiates. These ideas must carry people along in such a way that they know: We have the social organism before us and we must devote ourselves to it. That is to say, work itself takes hold of their souls because they have an understanding for the social organism. Only those people will have such understanding who have heard and taken in those inspired concepts; that is to say, those imparted by spiritual science. In order that a love for work be re-born throughout mankind we cannot use those hollow concepts proclaimed today. We need spiritualized sciences which can permeate hearts and souls; permeate them in such a way that men will have joy and love for work. Labor will be placed alongside commodities in a society that not only hears about pictures through the educators of society, but also hears of inspirations and such concepts as are necessary to provide the means of production in our complicated society, and the necessary foundation upon which men can exist.

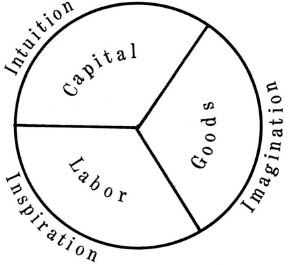

For this we further need to circulate intuitive concepts in society. The concepts about capital that you find in my book, The Threefold Social Order, will only flourish in a society which is receptive to intuitive concepts. That means: Capital will find its rightful place when men will acknowledge that intuition must live in them; commodity will find its rightful place when the necessity for imagination is acknowledged; and labor will find its rightful place when the necessity of inspiration is acknowledged.

If you take the above diagram and do not write the three concepts one below the other but in the way I have done here, then you can learn a lot from it if you permeate it with all the concepts to be found in my book about the threefold membering of the social organism. There are connections, back and forth, between labor and commodities; between commodities and capital, inasmuch as capital buys commodities; connections between labor and capital, and so on. Only, these three concepts must be arranged as shown.

Above everything, we must understand it is correct to say that in future the social order must become humanized. But it is necessary also to understand that the social order must be brought into being by men themselves; that they be willing to make up their minds to listen to the science of the initiates about imaginations, inspirations, and intuitions. This is a serious matter, for I am herewith stating nothing less than the fact that without the science of the spirit there will not take place in future any social transformation. That is the truth. It will never be possible to arouse in men the understanding necessary for matters like intuition, inspiration, imagination, if you abandon the schools to the State. For what does the State make out of schools?

Just think of something which has eminently to do with both the school and the State. I must confess I think it is something terrible, but people do not notice it. Think of civil rights, for example.1Translators' note: It must be emphasized that in Rudolf Steiner's social thinking these rights are only those which apply to everyone equally. It rules out the special connotations the expression has acquired in recent years, particularly in the United States of America. These rights are supposed to arise in the sense of those practices people today consider the proper thing. Parliaments decide about civil rights (I am speaking of democracy, not at all of monarchy). Civil rights are established through the representatives of everyone who has come of age. They are then incorporated in the body of law. Then the professor comes along and studies the law. Then he lectures on what he finds there as the declared civil rights. That is to say, the State at this point takes science in tow in the most decided way. The professor of civil rights may not lecture on anything but what is declared as rights in the State. Actually, the professor is not even needed, because one could record the State's laws for a phonograph and place this on the speaker's desk and let it run. This then is science.

I am citing an extreme case. You will scarcely assert that the majority decisions of parliaments today are inspired. The situation will have to be reversed. In spiritual life, in the universities, civil rights must come into existence as a science purely out of man's spiritual comprehension. The State can only attain its proper function if this is given to it by people. Some believe that the threefold membering of the social organism wants to turn the world upside down. Oh, no! The world is already upside down; the threefold order wishes to put it right-side up. This is what is important.

We have to find our way into such concepts or we move toward mechanizing the spirit, falling asleep and vegetizing the soul, and animalizing the body.

It is very important that we permeate ourselves with the conviction that we have to think thus radically if there is to be hope for the future. Above everything it is necessary for people to realize that they will have to build the social organism upon its three healthy members. They will only learn the significance of imagination in connection with commodities if economic life is developed in its pure form, and men are dependent upon conducting it out of brotherliness. The significance of inspiration for labor, producing joy and love for work, will only be realized if one person joins another as equals in parliaments, if real equality governs; that is, if every individual be permitted to contribute whatever of value lives in him. This will be different with each person. Then the life of rights will be governed by equality and will have to be inspired, not decided upon by the narrow-minded philistines as has been more and more the trend in ordinary democracy.

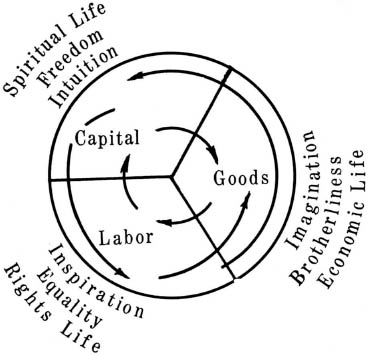

Capital can only be properly employed in the social organism if intuition will rise to freedom, and freedom will blossom from out the independently developing life of the spirit. Then there will stream out of spiritual life into labor what has to stream into it. I shall indicate the streams by arrows (Figure 2). When so organized these three spheres will permeate one another in the right way.

One of the first objections I met with in Germany was that people said: “Now he even wants to `three-member' the social organism! But the social organism must be a unity!” Men are simply hypnotized by this idea of unity, because they have always considered the State as something uniform. They are accustomed to this concept. A man who speaks of this unity appears to me like a man who says, “Now he even wants to have a horse that stands on four legs; a horse must be a unity, it cannot be membered into four legs.” Nobody will demand such a thing, of course, nor do I wish to put the “horse” State, the social organism, on one leg but upon its healthy three legs. Just as the horse-unit does not lose its unity by standing on four legs, likewise the social organism does not lose its unity by placing it upon its healthy three members. On the contrary, it acquires its unity just by placing it upon its healthy three members. Men today are entirely unable to free themselves from their accustomed concepts. But it is most important that we do not merely believe that single external establishments have to be transformed, but that it is our ideas, our concepts, our feelings that have to be transformed. Indeed, we may say that we need different heads on our shoulders if we wish to approach the future in a beneficial way. This is what is necessary and what is so hard for men to get accustomed to, because our old heads are so dear to us, these old heads that are only accustomed to thinking what they have thought for ages. Today we have consciously to transform what lives in our souls.

Now do not think this is an easy task. Many people believe today that they have already transformed their thoughts; they do not notice that they have remained the same old ones, especially in the field of education. Here you can have strange experiences. We tell people of the concepts spiritual science produces in the field of education. You may talk today to very advanced teachers, directors, and superintendents of schools; they listen to you and say, “Well, I thought that a long time ago; indeed, I am of exactly the same opinion.” In reality, however, they hold the very opposite opinion to what you tell them. They express the opposite opinion with the same words. In this way people pass each other by today. Words have lost connection with spirituality. It has to be found again or we cannot progress.

Social tasks, therefore, lie much more in the sphere of the soul than we ordinarily realize.

Dritter Vortrag

Was ich heute werde zu sagen haben, wird eine Art Episode sein. Ich möchte, wie ich Ihnen schon mitgeteilt habe, über drei Begriffe kurz sprechen. Über drei Begriffe, welche, vollständig verstanden, zugleich bewirken das Verständnis des äußeren sozialen Lebens. Ich sage ausdrücklich: des äußeren sozialen Lebens, denn die drei Begriffe sind durchaus dem äußerlichen Zusammenwirken und Zusammenarbeiten der Menschen entnommen. Es sind die drei Begriffe Ware, Arbeit, Kapital. Nun habe ich Ihnen bereits gesagt, daß sich die neuere Nationalökonomie aller Schattierungen vergeblich bemüht, über diese Begriffe in vollständige Klarheit zu kommen. Das war nicht möglich, seit die Menschen begonnen haben, bewußt volkswirtschaftlich zu denken. Vor dem Beginn des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes, also vor dem Zeitpunkt, der da fällt in die Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts, kann überhaupt nicht die Rede davon sein, daß die Menschen ihre gegenseitigen sozialen Beziehungen in bewußter Weise aufgefaßt haben. Das Leben verlief mehr oder weniger unbewußt, instinktiv mit Bezug auf dasjenige, was sozial von Mensch zu Mensch spielte. Seit dieser Zeit aber mußten die Menschen, weil ja die Bewußtseinsseele in diesem Zeitalter sich ausbildet, immer mehr und mehr bewußt nachdenken über die sozialen Beziehungen. Und so haben sich denn alle möglichen Richtungen und Anschauungen herausgebildet über das soziale menschliche Zusammenleben. Es beginnt das mit der Schule der Merkantilisten, dann mit der Schule der Physiokraten, mit Adam Smith, mit den verschiedenen utopistischen Strömungen, Prondhon, Fourier und so weiter, bis zu der neueren Sozialdemokratie auf der einen Seite, und zu der neueren Schulnationalökonomie auf der anderen Seite. Es ist interessant, die neuere sozialdemokratische Theorie, welche fußt auf Marx, Engels und anderen, zu vergleichen mit der neueren Schulnationalökonomie. Die neuere Schulnationalökonomie ist ganz unproduktiv. Sie bringt überhaupt nichts hervor von Begriffen, die in das soziale Wollen einfließen können. Man hat nichts aus den wirren chaotischen Begriffen der modernen Schulnationalökonomie, wenn man in dieser Richtung die Frage aufwirft: Was soll in sozialer Beziehung geschehen? Denn diese Schulnationalökonomie ist ganz angefressen von Anschauungen, die überhaupt in der neueren Wissenschaft herrschen. Und Sie wissen ja, daß trotz des großen, bewundernswerten Fortschrittes der Naturwissenschaften, der durchaus eben von der Geisteswissenschaft nicht geleugnet werden soll, die moderne Schulwissenschaft eigentlich sich bekennt zu der Ablehnung eines jeglichen, das aus dem Geiste hervorquillt. Und so will die Nationalökonomie nur beobachten dasjenige, was im ökonomischen Leben geschieht. Aber das Beobachten desjenigen, was im ökonomischen Leben geschieht, das ist etwas fast Unmögliches in der neueren Zeit, aus dem Grunde, weil die Menschen, je mehr sie herauf sich entwickelt haben in diese neuere Zeit, überhaupt nicht mehr Gedanken gehabt haben, welche die ökonomischen Tatsachen getragen hätten. Die ökonomischen Tatsachen liefen mechanisch von selbst dahin; die Menschen folgten ihnen nicht mit den Gedanken nach. Daher kann die Beobachtung dieser gedankenlosen Tatsachen des Weltmarktes nicht zu Gesetzen führen und hat auch nicht zu Gesetzen geführt, denn unsere Volkswirtschaft ist eine Praxis ohne Theorie, ohne Anschauung, ohne Begriffe, ohne Idee, Und unsere sozialdemokratische Bestrebung, die ist eine Theorie ohne Praxis. So genommen, wie sie ist, diese sozialistische Theorie, kann sie niemals in die Praxis umgesetzt werden; sie ist eine T'heorie ohne Einsicht in die Praxis. Wir leiden gerade in der modernen Zeit darunter, daß wir auf der einen Seite haben das wirtschaftliche Leben, eine Praxis ohne Ideen, und auf der anderen Seite die bloße Theorie der Sozialdemokraten ohne die Möglichkeit, diese T’heorie in das wirkliche Wirtschaftsleben einzuführen. Wir sind in dieser Beziehung wirklich an einem Wendepunkt der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit angekommen. Und Sie werden es eigentlich leicht begreifen, weil ja soziales Leben begründet sein muß auf der Beziehung von Mensch zu Mensch, daß zugrunde liegen muß dem, was die Menschen anstreben, wenn sie soziales gerechtes Leben begründen wollen, eine gewisse Stimmung. Und sehen Sie, darum handelt es sich bei der Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus, daß eine gewisse Stimmung hervorgerufen werde, eine Stimmung in zusammengehörigen sozialen Gebieten. Ohne diese Stimmung zwischen den Menschen kann das soziale Leben nicht wirklich erblühen. Und dieser Stimmung soll gerade Rechnung getragen werden durch die soziale Dreigliederung. Heute möchte ich, wie gesagt, episodisch nur auf einiges nach dieser Richtung hinweisen.

Wenn Sie sich das soziale Leben als einen Organismus denken, so müssen Sie sich ja vorstellen, daß, allerdings ins Geistig-Seelische herauf umgesetzt, diesen Organismus etwas durchströmt. Wie zum Beispiel den menschlichen und den tierischen Organismus das Blut als Träger der eingeatmeten und umgewandelten Luft, so muß den ganzen sozialen Organismus etwas tragen, etwas durchwehen, etwas durchzirkulieren.

Hier kommen wir auf dasjenige Kapitel, welches dem gegenwärtigen Menschen so schwer verständlich ist, weil er in seinem Gemüte sehr wenig darauf vorbereitet ist, aber welches auch verstanden werden muß, wenn überhaupt von einer sozialen Neugestaltung, von einem sozialen Aufbau im Ernste die Rede sein soll. Verstanden wird werden müssen, daß im sozialen Leben der Zukunft etwas davon abhängt, wovon sich die Menschen gegenseitig unterhalten, was die Menschen ernst nehmen, indem sie gegenseitig ihre Ideen, ihre Empfindungen, ihre Gefühle austauschen. Es ist nicht gleichgültig, was unter denMenschen an Anschauungen lebt, wenn sie soziale Wesen werden wollen. Und notwendig ist es für die Zukunft, daß nicht bloß Begriffe in der allgemeinen Bildung herrschen, welche aus der Naturwissenschaft oder aus der Industrie entnommen sind, sondern daß Begriffe herrschen, welche Grundlagen sein können für etwas Imaginatives, So unwahrscheinlich das dem heutigen Menschen ist, sozialisieren wird man nicht, wenn man nicht zu gleicher Zeit den Menschen beibringt imaginative Begriffe, das heißt Begriffe, welche das Gemüt des Menschen ganz anders gestalten, als die bloßen abstrakten Begriffe von Ursache und Wirkung, Kraft und Stoff und Materie und so weiter, die aus dem naturwissenschaftlichen Leben herkommen. Mit diesen Begriffen, die aus dem naturwissenschaftlichen Leben herkommen und von denen heute alles beherrscht ist, sogar die Kunst, mit diesen Begriffen läßt sich im sozialen Leben der Zukunft nichts anfangen. Wir müssen in die Lage kommen, im sozialen Leben der Zukunft die Welt wiederum in Bildern zu verstehen.

Was damit gemeint ist, habe ich ja schon zu wiederholten Malen angedeutet, auch wiederum mit Bezug auf die Erziehungsfrage. Ich habe mit Bezug auf die Erziehungsfrage folgendes gesagt. Ich habe gesagt, man kann den Kindern, wenn man sich intim mit ihnen beschäftigt, gut beibringen, sagen wir die Idee der Unsterblichkeit der Seele, indem man einfach dem Kinde zeigt eine Schmetterlingspuppe und ihm zeigt, wie die Puppe sich aufbricht und der Schmetterling aus der Puppe ausfliegt; dann macht man dem Kinde klar: Sieh einmal, so wie die Puppe ist, so ist dein Leib, und da drinnen lebt etwas wie ein Schmetterling, nur ist das unsichtbar. Wenn du in den Tod kommst, so fliegt auch bei dir der Schmetterling heraus in die geistige Welt. — Durch solche Vergleiche wirkt man bildlich. Aber es ist nicht bloß notwendig, daß man einen solchen Vergleich ausdenkt; da würde man eben im Sinne der naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung handeln, wenn man ihn ausdenkt. Denn was bringen denn die Menschen aus der heutigen Zeitbildung gewöhnlich, wenn sie einen solchen Vergleich je einmal machen, ihm für eine Stimmung entgegen? Die Menschen der heutigen Zeit, wenn sie kaum erwachsen sind, sind sehr gescheit, außerordentlich gescheit. Sie bedenken gar nicht, daß man auf eine andere Weise vielleicht gescheit sein kann, als sie selbst in ihren abstrakten Begriffen sich vorstellen, daß sie gescheit sind. Es ist nämlich ganz merkwürdig, wie die Menschen mit Bezug auf diese ihre heutige Gescheitheit sind!

An einen Vortrag, den ich vor Wochen einmal gehalten habe, hat sich dann angeschlossen in einem staatswissenschaftlichen Verein der betreffenden Stadt eine Versammlung, und da hat über den Vortrag und das, was damit zusammenhing, gesprochen ein Universitätsprofessor, also selbstverständlich ein gescheiter Mann der Gegenwart, nicht wahr. Der hat gefunden, daß die Anschauungen, die ich nicht nur in jenem Vortrage vorgebracht habe, sondern die in allen meinen Büchern stehen, infantil sind, das heißt, auf der Kindheitsstufe der Menschheit stehen. Sehen Sie, ich begreife ganz gut solch ein Urteil von einem gescheiten Menschen der Gegenwart; besonders begreife ich es sehr gut, wenn er gerade Universitätsprofessor ist. Ich begreife es aus dem Grunde, weil ja aus der Wissenschaft, die da gemeint ist, alles wirklich bildhafte Leben heraußen ist und daher alles, was verstanden oder besser gesagt nicht verstanden wird — kindlich gefunden wird. Ja, sehen Sie, das ist eben gerade dieses eigentümliche, daß die Menschen in der heutigen Gescheitheit kommen und sagen: Wenn wir einmal ein solches Bild anwenden wollen, wie: die unsterbliche Seele läßt sich vergleichen mit dem Schmetterling, der aus der Puppe herausfliegt, dann sind wir die Gescheiten, wir wissen selbstverständlich, daß das ein Bild ist, das wir gemacht haben; wir sind hinaus über dasjenige, was ein solches Bild enthält, Aber das Kind ist kindlich, für das vergleicht man, was man in Begriffen weiß, mit diesem Bilde; aber wir selber glauben nicht daran. - Das Geheimnis besteht nur darinnen, daß dann das Kind auch nicht daran glaubt. Das Geheimnis liegt darinnen, daß das Kind nur wirklich ergriffen wird von dem Bilde, wenn man selber daran glaubt. Und dazu soll uns eben wirkliche geisteswissenschaftliche Stimmung wiederum zurückbringen, daß wir in der Natur nicht sehen jene gespenstischen Dinge, von denen uns die Naturwissenschaft spricht, sondern wiederum sehen das Bildliche, das Imaginative. Dasjenige, was aus der Puppe auskriecht und in dem Schmetterling vorliegt, ist wirklich ein von der göttlichen Weltordnung in die Naturordnung hineingestelltes Bild für die Unsterblichkeit der Seele. Und es gäbe den Schmetterling nicht, der aus der Puppe auskriecht, wenn es nicht eine unsterbliche Seele gäbe. Denn es kann nicht ein Bild geben — und das ist ein Bild -, wenn nicht die Wahrheit zugrunde liegt dem Bilde. Und so ist es mit der ganzen Natur. Dasjenige, was die Naturwissenschaft gibt, ist Gespenst. Der Natur selber kommt man nur bei, wenn man weiß, sie ist Bild von etwas anderem.

Und so werden sich die Menschen auch bequemen müssen, zum Beispiel das menschliche Haupt als ein Bild eines Himmelskörpers anzusehen. Das menschliche Haupt ist nicht bloß rund, so wie es ist, damit es etwa einem Kohlkopf ähnlich sehen soll, sondern das menschliche Haupt ist so, wie es ausgestaltet ist, eine Nachbildung eines Himmelskörpers. Bildhaft ist die ganze Natur, und hineinfinden muß man sich in diese Bildhaftigkeit, dann wird ausstrahlen in die Herzen, in die Seelen, in die Gemüter, in die Köpfe sogar, obwohl das am schwersten ist, dasjenige, was durchströmen kann den Menschen, wenn er Bilder auffaßt. Wir werden miteinander reden müssen in dem sozialen Organismus von Dingen, die in Bildern gesprochen sind. Und diese Bilder wird man uns glauben müssen. Dann werden aus der Wissenschaft hervorgehen diejenigen Menschen, die da sprechen können erst über das wirkliche Hineinstellen der Ware in den sozialen Organismus; denn die Ware, die erzeugt wird, entspricht dem menschlichen Bedürfnis. Keine abstrakten Begriffe können dieses menschliche Bedürfnis in seiner sozialen Wertung erfassen, sondern nur dasjenige menschliche Gemüt kann etwas darüber wissen, das durchtränkt worden ist von derjenigen Stimmung, die aus dem imaginativen Vorstellen kommt. Anders wird es keine Sozialisierung geben. Sie können im sozialen Organismus die richtigen Leute anstellen, welche die Bedürfnisse feststellen: wenn Sie nicht zu gleicher Zeit eine imaginative Vorstellung hineinerziehen in den sozialen Organismus, so ist es unmöglich, eine soziale Gestaltung des sozialen Organismus herauszubekommen; das heißt, es muß von Bildern geredet werden. So sonderbar es dem heute sozialistisch Denkenden klingt, es sei zum Sozialisieren notwendig, daß im sozialen Organismus die Menschen zu den Menschen in Bildern reden, welche Imaginationen anregen, so muß es doch geschehen.

Das ist es, worauf es ankommt. Und dasjenige, was Ware ist, man wird es fühlend verstehen in einer Wissenschaft, in der für Bilder Verständnis ist — in keiner anderen.

In der Gesellschaft, welche die Gesellschaft der Zukunft sein soll, da wird außerdem in einer richtigen Weise herrschen müssen die Arbeit. Wie heute unter den Menschen von der Arbeit geredet wird, das ist geradezu eine Torheit, denn die Arbeit als solche hat im Grunde genommen gar nichts zu tun mit der Erzeugung der Güter. Karl Marx nennt die Ware kristallisierte Arbeitskraft. Das ist bloßer Unsinn, nichts weiter. Denn dasjenige, um was es sich handelt, wenn der Mensch arbeitet, das ist, daß er in einer gewissen Weise sich selbst verbraucht. Nun können Sie dieses Selbstverbrauchen bewirken entweder auf die eine oder auf die andere Weise. Sie können, wenn Sie gerade genügend auf einer Bank oder in Ihrem Portemonnaie haben, Sport treiben und sich bei diesem anstrengen und Ihre Arbeitskraft auf diesen Sport verwenden. Sie können aber auch Holz hacken oder irgend etwas anderes tun. Die Arbeit kann ganz die gleiche sein, wenn Sie Holz hacken oder wenn Sie Sport treiben. Nicht davon hängt es ab, wieviel Arbeitskraft Sie anwenden, sondern wozu diese Arbeitskraft angewendet wird im sozialen Leben. Arbeitskraft an sich hat mit dem sozialen Leben nichts zu tun, insofern dieses soziale Leben Güter oder Waren erzeugen soll. Daher wird es nötig sein im dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus, daß ein ganz anderer Antrieb zur Arbeit da sein muß als derjenige, Güter zu erzeugen. Die Güter müssen gewissermaßen durch die Arbeit erzeugt werden, weil die Arbeit eben auf etwas verwendet wird. Aber dasjenige, was zugrunde liegen muß, damit der Mensch arbeitet, das muß die Lust und Liebe zur Arbeit sein. Und wir kommen nicht früher zu einer sozialen Gestaltung des sozialen Organismus, als wenn wir die Methoden finden, daß der Mensch arbeiten will, daß es ihm eine Selbstverständlichkeit ist, daß er arbeitet.

Das kann in keiner anderen Gesellschaft geschehen, als in einer solchen Gesellschaft, in der Sie von inspirierten Begriffen reden. Niemals wird in der Zukunft so wie in der Vergangenheit, wo die Dinge instinktiv und atavistisch waren, Lust und Liebe zur Arbeit die Menschen durchglühen, wenn Sie die Gesellschaft nicht durchdringen mit solchen Ideen, mit solchen Empfindungen, die durch Inspiration der Eingeweihten in die Welt kommen. Diese Begriffe müssen die Menschen so tragen, daß die Menschen wissen: Wir haben den sozialen Organismus vor uns und wir müssen uns ihm widmen; das heißt, daß die Arbeit selber in ihre Seele fährt, weil sie Verständnis haben für den sozialen Organismus. Solches Verständnis werden keine anderen Menschen haben, als diejenigen, zu welchen von inspirierten Begriffen, das heißt von Geisteswissenschaft geredet wird. Das heißt, wir brauchen, damit die Arbeit wiederum erstehe unter den Menschen, nicht jene hohlen Begriffe, von denen heute deklamiert wird, sondern wir brauchen geistige Wissenschaften, mit denen wir die Herzen, die Seelen durchdringen. Dann wird diese geistige Wissenschaft die Herzen, die Seelen so durchdringen, daß die Menschen Lust und Liebe zur Arbeit haben werden, und es wird sich die Arbeit hinstellen neben die Ware in einer Gesellschaft, die nicht nur von Bildern hört, durch jene, welche die Pädagogen der Gesellschaft sind, sondern die auch hört von Inspirationen und solchen Begriffen, die notwendig sind, damit in unserer komplizierten Gesellschaft die Produktionsmittel da sind und damit der Boden in entsprechender Weise unter den Menschen wirke,

Dazu ist notwendig, daß intuitive Begriffe in dieser Gesellschaft verbreitet werden. Diese Begriffe, die Sie finden in meinem Buch «Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage» über das Kapital, die werden nur in einer Gesellschaft erblühen, die empfänglich ist für intuitive Begriffe. Das heißt: Es wird sich hineinstellen das Kapital in den sozialen Organismus, wenn man wiederum zugeben wird, daß in den Menschen Intuition sein soll. Die Ware wird sich in der richtigen Weise hineinstellen, wenn man zugeben wird, daß Imagination sein soll; und die Arbeit wird sich in der richtigen Weise hineinstellen, wenn man zugeben wird, daß Inspiration sein soll.

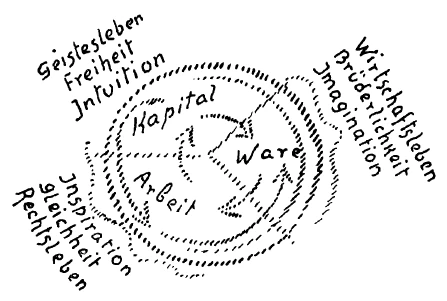

Wenn Sie dieses Schema nehmen, wenn Sie nicht die drei Begriffe untereinander schreiben, sondern wenn Sie sie so schreiben, wie ich sie in dieses Schema hineingestellt habe, dann können Sie von diesem Schema, wenn Sie es mit all den Begriffen durchdringen, die in meinem Buche stehen über die Dreigliederung, sehr viel lernen. Denn es bestehen Beziehungen hin und her von Arbeit zu Ware, von Ware zu Kapital, indem das Kapital die Ware kauft; es bestehen Beziehungen zwischen Arbeit und Kapital und so weiter, nur müssen Sie sie in dieser Weise anordnen, die drei Begriffe. (Siehe Schema.)

Das ist es, was wir vor allen Dingen verstehen müssen, daß es schon recht ist, wenn man davon redet, in der Zukunft müsse die Menschheit durchdringen die soziale Ordnung; daß aber es notwendig ist, daß diese soziale Ordnung von den Menschen selber verwirklicht wird, indem die Menschen sich bequemen, der Wissenschaft der Eingeweihten zuzuhören von den Imaginationen, Inspirationen und Intuitionen. Es ist eine ernste Sache, denn ich sage Ihnen ja nichts Geringeres damit, als daß es ohne Geisteswissenschaft keine soziale Umgestaltung für die Zukunft gibt; aber das ist wahr. Sie werden niemals die Möglichkeit bekommen, die Menschen zum Verständnis zu bringen in einer solchen Weise, wie es notwendig ist in bezug auf diese Dinge wie Intuition, Imagination, Inspiration, wenn Sie zum Beispiel die Schule dem Staate überlassen. Denn was machen die Staaten aus den Schulen?

Nicht wahr, betrachten Sie etwas, was ganz eminent schulmäßig auf der einen Seite und staatsmäßig auf der andern Seite ist. Ja, ich muß Ihnen gestehen, ich finde, es ist etwas Furchtbares! Aber dieses Furchtbare bemerken die Menschen der Gegenwart nicht; dies, was es mit dem Staatsrecht zum Beispiel ist. Das Staatsrecht, es soll ja entstehen im Sinne derjenigen Lebensgewohnheiten, welche die Menschen heute noch als das Richtige in ihre Seele aufnehmen, dadurch, daß meinetwillen Parlamente — ich will auf den Demokratismus schauen, will gar nicht einmal auf das Monarchische, sondern meinetwillen auf den Demokratismus schauen -, also dadurch, daß Parlamente da sind, werden die staatsrechtlichen Dinge beschlossen: da macht man das Staatsrecht, da macht es jeder mündig gewordene Mensch durch seinen Vertreter, das Staatsrecht. Da werden die Dinge beschlossen, dann stehen sie in den Gesetzessammlungen. Dann kommt der Professor, der studiert die Gesetzessammlungen, und dann unterrichtet er dasjenige, was in den Geserzessammlungen steht, selbstverständlich als Staatsrecht, denn das trägt er als Staatsrecht vor. Das heißt, der Staat nimmt ins Schlepptau die Wissenschaft gerade in diesem Punkt im eminentesten Sinn. Der Staatsrechtslehrer darf nichts anderes vortragen als dasjenige, was im Staate als Recht da ist. Man brauchte gar nicht einmal im Grunde genommen den Professor, wenn man in der Lage wäre, die staatsrechtlichen Gesetze auf Rollen zu schreiben, in irgendeinen Phonographen hineinzutun: dann könnte man auch den Phonographen aufs Katheder stellen, der brauchte ja nur das abzurasseln, was die Parlamente beschlossen haben. Das ist dann die Wissenschaft.

Das ist nur auf einem extremen Gebiete. Sehen Sie, das ist nichts Inspiriertes, denn Sie werden kaum in der Lage sein zu behaupten, daß das, was in den Parlamenten als Majoritätsbeschlüsse heute zustandekommt, so recht inspirierte Tatsachen sind. Aber umgekehrt muß die Sache werden. Im Geistesleben drinnen, an den Universitäten muß das Staatsrecht entstehen als Wissenschaft zunächst, rein aus der menschlichen geistigen Auffassung heraus. Nur dann kann der Staat die richtige Konfiguration bekommen, wenn die Menschen sie ihm geben. Manche Menschen glauben, die Dreigliederung will die Welt auf den Kopf stellen. O nein, die Welt steht auf dem Kopf, die Dreigliederung will sie nur auf die Beine stellen. Das ist dasjenige, worauf es ankommt.

Sehen Sie, es handelt sich vor allen Dingen heute, in solche Begriffe sich hineinzufinden, sonst gehen wir entgegen der Mechanisierung des Geistes, der Einschläferung, das heißt Vegerarisierung der Seele und der Animalisierung, das heißt der instinktiven Gestaltung der Leiber.

Es ist sehr wichtig, sich zu durchdringen mit der Überzeugung, daß in so radikaler Weise gedacht werden muß, wenn der Zukunft irgendein Heil erblühen soll. Es ist also vor allen Dingen notwendig, daß die Menschen einsehen, daß sie den sozialen Organismus auf seine drei gesunden Glieder werden stellen müssen. Was Imagination in bezug auf Ware bedeutet, man wird es nur lernen, wenn das Wirtschaftsleben rein herausgestaltet ist und die Menschen darauf angewiesen sind, das Wirtschaftsleben in Brüderlichkeit zu verwalten. Was Inspiration für die Arbeit bedeutet — daß sie Lust und Liebe zur Arbeit hervorbringt -, das wird nur dann in der Welt sein, wenn in der Tat von den Leuten, die inspiriert sind, durchdrungen wird wenigstens dasjenige, was dann im Parlament als Gleicher zum Gleichen sich gesellt, wenn wirkliche Gleichheit herrscht, das heißt, wenn jeder geltend machen kann das, was in ihm ist, Aber das wird sehr verschieden sein bei dem einen und bei dem andern. Dann wird herrschen können diese Gleichheit im Rechtsleben, und das Rechtsleben wird inspiriert werden müssen — nicht aus dem Banausentum heraus beschlossen, worauf die gewöhnliche Demokratie immer mehr und mehr hingearbeitet hat.

Und das Kapital wird nur richtig verwertet werden können im sozialen Organismus, wenn die Intuition sich erheben wird zu der Freiheit und die Freiheit erblühen wird aus dem selbst sich entwickelnden Geistesleben. Dann wird herüberströmen aus dem Geistesleben in die Arbeit dasjenige, was herüberzuströmen hat. Es werden solche Ströme sein (siehe die Pfeile). Und diese drei Gebiete werden gerade, wenn sie so gegliedert werden, sich in der richtigen Weise durchdringen.

Einer der ersten Vorwürfe, der mir in Deutschland gemacht worden ist, das war der, daß man gesagt hat: Nun will er gar noch das soziale Leben dreigliedern! Das soziale Leben muß eine Einheit sein! — Aber die Menschen sind nur hypnotisiert von dieser Einheit, weil sie immer den Staat eben als etwas Einheitliches angesehen haben. Sie sind eingewöhnt in diese Begriffe vom einheitlichen Staat. Und derjenige, der von dieser Einheit spricht, der kommt mir vor wie einer, der sagt: Jetzt will der gar einen Gaul haben, der auf vier Füßen steht, der Gaul muß doch eine Einheit sein, der kann doch nicht in vier Beine gegliedert sein. -— Das wird natürlich keiner verlangen. Aber ich will auch nicht den Gaul-«Staat» oder den sozialen Organismus auf ein Bein stellen, sondern auf seine gesunden drei Beine. Und wie die Gauleinheit nicht dadurch seine Einheit verliert, daß er auf vier Beinen steht, so auch der soziale Organismus dadurch nicht, daß man ihn auf seine gesunden drei Glieder stellt. Er kriegt sie gerade dadurch, seine Einheit, daß man ihn auf seine gesunden drei Glieder stellt. Die Menschen können eben heute durchaus nicht von ihren gewohnten Begriffen loskommen. Aber das ist heute das Wichtigste, daß wir nicht bloß glauben, daß einzelne äußerliche Einrichtungen umgewandelt werden sollen, sondern daß wir unsere Ideen, unsere Begriffe, unsere Empfindungen umgestalten müssen. Wir können schon sagen: Wir brauchen andere Köpfe auf unseren Schultern, wenn wir der Zukunft der Menschheit in heilsamer Weise entgegengehen wollen. Das ist notwendig, daß wir andere Köpfe auf unsere Schultern bekommen. Dahinein können sich die Menschen so schwer gewöhnen, weil ihnen die alten Köpfe so lieb sind, diese alten Köpfe, die gewohnt sind, nur dasjenige zu denken, was seit langer Zeit zu denken sich die Menschen gewöhnt haben. Heute müssen wir in bewußter Weise umgestalten das, was in unseren Seelen lebt. Und halten Sie das nicht für eine leichte Aufgabe: Gar mancher glaubt heute, daß er seine Begriffe ja schon umgewandelt hat, er merkt gar nicht, wie sie die alten geblieben sind, besonders auf dem Gebiete des Erziehungswesens. Da macht man kuriose Erfahrungen. Man redet den Leuten von dem, was die Geisteswissenschaft als Begriffe auf dem Gebiete der Pädagogik erzeugt. Sie können heute mit sehr, sehr fortgeschrittenen Lehrern, Schulinspektoren, -direktoren und so weiter reden, die hören Ihnen zu und sagen: Ja, das habe ich schon lange gedacht, ja, das ist ganz meine Meinung. — Aber er hat in Wirklichkeit die entgegengesetzte Meinung von der, die man ihm sagt. Er hat in Wirklichkeit die entgegengesetzte Meinung wie ich, aber er sagt die entgegengesetzte Meinung mit denselben Worten. Er sagt dieselben Worte - und hat die entgegengesetzte Meinung! Und so gehen die Menschen heute aneinander vorbei. Die Worte haben längst den Zusammenhang mit der Geistigkeit verloren, und dieser Zusammenhang muß unbedingt wieder gefunden werden, sonst kommen wir nicht vorwärts.

Also soziale Aufgaben liegen viel mehr im Seelischen, als wir gewöhnlich meinen.

Third Lecture

What I have to say today will be a kind of episode. As I have already told you, I would like to talk briefly about three concepts. Three concepts which, when fully understood, also lead to an understanding of external social life. I say explicitly: external social life, because the three concepts are taken entirely from the external interaction and cooperation of human beings. The three concepts are goods, labor, and capital. Now, I have already told you that modern economics of all shades has tried in vain to achieve complete clarity on these concepts. This has not been possible since people began to think consciously in terms of economics. Before the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, that is, before the middle of the 15th century, there can be no question of people having consciously understood their mutual social relationships. Life proceeded more or less unconsciously, instinctively, with regard to what was socially at stake between people. Since that time, however, because the conscious soul is developing in this age, people have had to think more and more consciously about social relationships. And so all kinds of directions and views have emerged about social human coexistence. It began with the school of the mercantilists, then with the school of the physiocrats, with Adam Smith, with the various utopian currents, Proudhon, Fourier, and so on, up to the newer social democracy on the one hand, and the newer school of political economy on the other. It is interesting to compare the newer social democratic theory, which is based on Marx, Engels, and others, with the newer school of national economics. The newer school of national economics is completely unproductive. It produces nothing at all in the way of concepts that can flow into social will. The confused and chaotic concepts of modern classical economics are of no use when one asks the question: What should happen in social relations? For classical economics is completely infected by the views that prevail in modern science. And you know that despite the great, admirable progress of the natural sciences, which should certainly not be denied by the humanities, modern academic science actually professes to reject anything that springs from the spirit. And so economics only wants to observe what happens in economic life. But observing what happens in economic life is almost impossible in modern times, because the more people have developed in these modern times, the less they have thought about the economic facts. Economic facts have run their course mechanically; people have not followed them with their thoughts. Therefore, the observation of these thoughtless facts of the world market cannot lead to laws and has not led to laws, because our national economy is a practice without theory, without insight, without concepts, without ideas. And our social democratic endeavour is a theory without practice. Taken as it stands, this socialist theory can never be put into practice; it is a theory without insight into practice. In modern times, we suffer from the fact that, on the one hand, we have economic life, a practice without ideas, and, on the other hand, the mere theory of the Social Democrats without the possibility of introducing this theory into real economic life. In this respect, we have truly arrived at a turning point in the historical development of humanity. And you will easily understand this, because social life must be based on the relationship between people, and what people strive for when they want to establish a socially just life must be based on a certain mood. And you see, that is what the threefold social organism is all about, that a certain mood is created, a mood in related social areas. Without this mood between people, social life cannot really flourish. And it is precisely this mood that is to be taken into account by the threefold social organism. Today, as I said, I would like to point out just a few things in this direction.

If you think of social life as an organism, you must form in your mind the mental image that something flows through this organism, albeit translated into the spiritual-soul realm. Just as blood carries the inhaled and transformed air through the human and animal organisms, so something must carry, blow through, and circulate through the entire social organism.

Here we come to the chapter that is so difficult for people today to understand, because they are very little prepared for it in their minds, but which must also be understood if there is to be any serious talk of social reorganization, of social reconstruction. It must be understood that in the social life of the future, something depends on what people talk about with each other, what people take seriously when they exchange their ideas, their impressions, their feelings. It is not irrelevant what views people hold if they want to become social beings. And it is necessary for the future that general education should not be dominated solely by concepts taken from science or industry, but that it should be dominated by concepts that can form the basis for something imaginative. As unlikely as it may seem to people today, you cannot socialize people unless you teach them imaginative concepts at the same time, that is, concepts that shape the human mind in a completely different way than the mere abstract concepts of cause and effect, force and substance and matter and so on, which come from the life of natural science. These concepts, which come from the natural sciences and dominate everything today, even art, will be of no use in the social life of the future. We must enable ourselves to understand the world in images again in the social life of the future.

I have already indicated what this means on several occasions, also with reference to the question of education. I have said the following with regard to the question of education. I have said that if you engage intimately with children, you can easily teach them, say, the idea of the immortality of the soul, simply by showing the child a butterfly chrysalis and showing them how the chrysalis breaks open and the butterfly flies out of it; then you make it clear to the child: Look, your body is like the chrysalis, and something like a butterfly lives inside it, only it is invisible. When you die, the butterfly will also fly out into the spiritual world. Such comparisons have a vivid effect. But it is not merely necessary to think up such a comparison; in doing so, one would be acting in accordance with the scientific worldview. For what is the usual reaction of people of today's education when they ever make such a comparison? People today, when they are barely adults, are very clever, extraordinarily clever. They do not consider at all that one can perhaps be clever in a different way than they themselves form a mental image of in their abstract concepts of cleverness. It is quite remarkable how people are with regard to their present-day cleverness!

A lecture I gave a few weeks ago was followed by a meeting at a political science association in the city in question, where a university professor, and therefore naturally a clever man of the present day, spoke about the lecture and related topics. He found that the views I expressed not only in that lecture but also in all my books are infantile, that is, at the childhood stage of humanity. You see, I understand such a judgment from an intelligent person of the present day very well; I understand it particularly well when he is a university professor. I understand it because, in the science that is meant here, all truly pictorial life is excluded and therefore everything that is understood, or rather not understood, is considered childish. Yes, you see, that is precisely what is peculiar about people today's intelligence, when they say: If we want to use an image such as: the immortal soul can be compared to a butterfly flying out of its chrysalis, then we are the intelligent ones, we know of course that this is an image we have created; we are beyond what such an image contains. But the child is childlike, comparing what it knows in concepts with this image; but we ourselves do not believe in it. The mystery lies only in the fact that the child does not believe in it either. The mystery lies in the fact that the child is only really moved by the image if one believes in it oneself. And this is precisely what a true spiritual scientific attitude should bring us back to, so that we do not see in nature those ghostly things that natural science tells us about, but rather see the pictorial, the imaginative. What emerges from the chrysalis and is present in the butterfly is truly an image placed in the natural order by the divine world order to represent the immortality of the soul. And the butterfly that emerges from the chrysalis would not exist if there were no immortal soul. For there can be no image — and this is an image — unless the image is based on truth. And so it is with the whole of nature. What natural science provides is a ghost. One can only approach nature itself if one knows that it is an image of something else.

And so people will also have to resign themselves to viewing the human head, for example, as an image of a celestial body. The human head is not merely round, as it is, so that it should resemble a cabbage, but the human head, as it is shaped, is a replica of a celestial body. All of nature is pictorial, and one must find one's way into this pictoriality, then what can flow through human beings when they perceive images will radiate into their hearts, souls, minds, and even their heads, although that is the most difficult thing. We will have to talk to each other in the social organism of things that are spoken in images. And people will have to believe us about these images. Then science will produce those people who can speak about the real insertion of goods into the social organism, for the goods that are produced correspond to human needs. No abstract concepts can grasp this human need in its social evaluation, but only the human mind that has been imbued with the mood that comes from an imaginative mental image can know anything about it. Otherwise, there will be no socialization. You can employ the right people in the social organism to determine needs, but if you do not at the same time instill an imaginative mental image into the social organism, it will be impossible to achieve a social structure of the social organism; that is, it is necessary to speak in images. As strange as it may sound to socialist thinkers today, it is necessary for socialization that people in the social organism speak to each other in images that stimulate the imagination; this must be done.

That is what matters. And what is a commodity will be understood intuitively in a science that understands images — in no other.

In the society that is to be the society of the future, work will also have to prevail in the right way. The way people talk about work today is downright foolish, because work as such has basically nothing to do with the production of goods. Karl Marx calls commodities crystallized labor power. That is mere nonsense, nothing more. For what is at stake when a person works is that he consumes himself in a certain way. Now, you can bring about this self-consumption in one way or another. If you have enough money in the bank or in your wallet, you can do sports and exert yourself in this way, using your labor power for this sport. But you can also chop wood or do something else. The work can be exactly the same when you chop wood or when you do sports. It does not depend on how much energy you expend, but on what this energy is used for in social life. Energy in itself has nothing to do with social life, insofar as this social life is supposed to produce goods or commodities. Therefore, in the threefold social organism, it will be necessary to have a completely different motivation for work than that of producing goods. Goods must, in a sense, be produced through work, because work is used for something. But what must underlie human work is the desire and love of work. And we will not achieve a social structure of the social organism until we find methods that make people want to work, that make it a matter of course for them to work.

This cannot happen in any other society than one in which you speak of inspired concepts. Never in the future, as in the past, when things were instinctive and atavistic, will the desire and love of work inflame people if you do not permeate society with such ideas, with such feelings, which come into the world through the inspiration of the initiated. These concepts must carry people in such a way that they know: we have the social organism before us and we must devote ourselves to it; that is, work itself enters their souls because they have an understanding of the social organism. No other people will have such an understanding except those to whom inspired concepts, that is, spiritual science, are spoken. This means that in order for work to arise again among people, we do not need the hollow concepts that are declaimed today, but rather we need spiritual sciences with which we can penetrate hearts and souls. Then this spiritual science will penetrate hearts and souls in such a way that people will have a desire and love for work, and work will stand alongside goods in a society that not only hears about images from those who are the educators of society, but also hears about inspirations and such concepts that are necessary so that the means of production are available in our complicated society and so that the ground works in the appropriate way among people.

For this to happen, it is necessary that intuitive concepts be disseminated in this society. These concepts, which you will find in my book “The Key Points of the Social Question” about capital, will only flourish in a society that is receptive to intuitive concepts. This means that capital will find its place in the social organism if we admit that humans should have intuition. Commodities will find their rightful place when it is acknowledged that imagination should exist; and labor will find its rightful place when it is acknowledged that inspiration should exist.

If you take this diagram, if you do not write the three terms one below the other, but write them as I have placed them in this diagram, then you can learn a great deal from this diagram if you permeate it with all the terms that are in my book on the threefold structure. For there are relationships back and forth between labor and goods, between goods and capital, in that capital buys goods; there are relationships between labor and capital, and so on, but you have to arrange the three terms in this way. (See diagram.)

This is what we must understand above all else: that it is right to say that in the future humanity must penetrate the social order; but that it is necessary for this social order to be realized by human beings themselves, by human beings being willing to listen to the science of the initiates, to the imaginations, inspirations, and intuitions. This is a serious matter, for I am telling you nothing less than that without spiritual science there can be no social transformation for the future; but that is true. You will never have the opportunity to bring people to understand in the way that is necessary with regard to such things as intuition, imagination, and inspiration if, for example, you leave the schools to the state. For what do states do with schools?

Isn't that so? Consider something that is eminently school-like on the one hand and state-like on the other. Yes, I must confess to you, I find it terrible! But the people of the present do not notice this terrible thing; this, for example, is what constitutional law is. Constitutional law is supposed to arise in accordance with the habits of life that people today still accept as right in their hearts, in that, for my part, parliaments—I want to look at democracy, not even at monarchy, but for my part at democracy—in that, because parliaments exist, matters of constitutional law are decided: that is where constitutional law is made, that is where every person who has come of age makes constitutional law through their representative. That is where things are decided, then they are recorded in the collections of laws. Then comes the professor, who studies the collections of laws, and then he teaches what is in the collections of laws, of course as constitutional law, because that is what he presents as constitutional law. This means that the state takes science in tow in the most eminent sense in this particular point. The teacher of constitutional law may not teach anything other than what is law in the state. In fact, there would be no need for a professor if one were able to write the constitutional laws on rolls and put them into a phonograph: then one could also put the phonograph on the lectern, which would only need to reel off what the parliaments had decided. That would then be science.

That is only in an extreme area. You see, it is not inspired, because you will hardly be able to claim that what is decided by majority vote in parliaments today are truly inspired facts. But the opposite must be the case. In intellectual life, in the universities, constitutional law must first arise as a science, purely out of human intellectual understanding. Only then can the state acquire the right configuration, when people give it to it. Some people believe that the threefold social order wants to turn the world upside down. Oh no, the world is upside down; the threefold social order only wants to put it back on its feet. That is what matters.

You see, today it is above all a matter of familiarizing ourselves with such concepts, otherwise we are heading towards the mechanization of the spirit, the numbing, that is, the vegetative state of the soul and the animalization, that is, the instinctive shaping of the body.

It is very important to be thoroughly convinced that we must think in such a radical way if any salvation is to blossom in the future. It is therefore necessary above all that people realize that they must base the social organism on its three healthy limbs. What imagination means in relation to goods can only be learned when economic life is purely structured and people are dependent on managing economic life in brotherhood. What inspiration means for work — that it produces pleasure and love for work — will only be present in the world when those who are inspired are imbued with at least that which then joins equal to equal in parliament when true equality reigns, that is, when everyone can assert what is within them. But this will be very different for each individual. Then this equality can prevail in legal life, and legal life will have to be inspired — not decided out of philistinism, which ordinary democracy has increasingly worked towards.

And capital will only be properly utilized in the social organism when intuition rises to freedom and freedom blossoms from the self-developing spiritual life. Then what has to flow over will flow over from the spiritual life into work. These will be such streams (see the arrows). And these three areas, precisely when they are structured in this way, will interpenetrate in the right way.

One of the first criticisms leveled at me in Germany was that I wanted to divide social life into three parts. Social life must be a unity! But people are only hypnotized by this unity because they have always viewed the state as something unified. They are accustomed to these concepts of a unified state. And anyone who talks about this unity seems to me like someone who says: Now he wants to have a horse that stands on four feet; a horse must be a unity, it cannot be divided into four legs. Of course, no one would demand that. But I don't want to put the horse “state” or the social organism on one leg, but on its healthy three legs. And just as the horse does not lose its unity by standing on four legs, neither does the social organism by being placed on its healthy three limbs. It gains its unity precisely by being placed on its three healthy limbs. People today are simply unable to break away from their familiar concepts. But the most important thing today is that we do not merely believe that individual external institutions should be transformed, but that we must transform our ideas, our concepts, our feelings. We can already say: we need different heads on our shoulders if we want to approach the future of humanity in a healthy way. It is necessary that we get different heads on our shoulders. People find it so difficult to get used to this because they are so fond of their old heads, these old heads that are accustomed to thinking only what people have been accustomed to thinking for a long time. Today we must consciously transform what lives in our souls. And don't think this is an easy task: many people today believe that they have already transformed their concepts, but they don't realize how old they have remained, especially in the field of education. This leads to curious experiences. You talk to people about the concepts that spiritual science has developed in the field of education. Today you can talk to very, very advanced teachers, school inspectors, principals, and so on, who listen to you and say: Yes, I have thought that for a long time, yes, that is exactly my opinion. — But in reality, he has the opposite opinion to the one he tells you. In reality, he has the opposite opinion to mine, but he expresses the opposite opinion with the same words. He says the same words — and has the opposite opinion! And so people today pass each other by. Words have long since lost their connection with spirituality, and this connection must be rediscovered, otherwise we will not move forward.

One of the first criticisms leveled at me in Germany was that I wanted to divide social life into three parts. Social life must be a unity! But people are only hypnotized by this unity because they have always viewed the state as something unified. They are accustomed to these concepts of a unified state. And anyone who talks about this unity seems to me like someone who says: Now he wants to have a horse that stands on four feet; a horse must be a unity, it cannot be divided into four legs. Of course, no one would demand that. But I don't want to put the horse “state” or the social organism on one leg, but on its healthy three legs. And just as the horse does not lose its unity by standing on four legs, neither does the social organism by being placed on its healthy three limbs. It gains its unity precisely by being placed on its three healthy limbs. People today are simply unable to break away from their familiar concepts. But the most important thing today is that we do not merely believe that individual external institutions should be transformed, but that we must transform our ideas, our concepts, our feelings. We can already say: we need different heads on our shoulders if we want to approach the future of humanity in a healthy way. It is necessary that we get different heads on our shoulders. People find it so difficult to get used to this because they are so fond of their old heads, these old heads that are accustomed to thinking only what people have been accustomed to thinking for a long time. Today we must consciously transform what lives in our souls. And don't think this is an easy task: many people today believe that they have already transformed their concepts, but they don't realize how old they have remained, especially in the field of education. This leads to curious experiences. You talk to people about the concepts that spiritual science has developed in the field of education. Today you can talk to very, very advanced teachers, school inspectors, principals, and so on, who listen to you and say: Yes, I have thought that for a long time, yes, that is exactly my opinion. — But in reality, he has the opposite opinion to the one he tells you. In reality, he has the opposite opinion to mine, but he expresses the opposite opinion with the same words. He says the same words — and has the opposite opinion! And so people today pass each other by. Words have long since lost their connection with spirituality, and this connection must be rediscovered, otherwise we will not move forward.

So social tasks lie much more in the soul than we usually think.