Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner

GA 300b

5 December 1921, Stuttgart

Forty-First Meeting

Dr. Steiner: I would like to hear everything about the class schedule.

The new class schedule is described. All of the foreign language classes are in the morning. There were no changes in personnel. Once, a language class had to be moved from 12:00 until 1:00. An attempt was made to group the students. A few times Latin and Greek had to be put after eurythmy, but otherwise the language class immediately followed main lesson.

Dr. Steiner: You will have to do it that way if nothing else is possible.

A teacher: I would prefer having the 4a language class in the afternoon instead of from 12:00 until 1:00.

Dr. Steiner: Then we will do it in the afternoon.

A teacher: Is that true otherwise?

Dr. Steiner: When the respective teachers demand it. It is important that the teachers agree.

The religious instruction is described. Voice instruction is always in the morning. Eurythmy, mostly. All the handwork and shop classes are in the afternoon as well as gymnastics, but Wednesday afternoon had to be used also. If Wednesday afternoons are to be held free, then gymnastics and some of the shop classes would have to be in the morning.

Dr. Steiner: There is nothing to say against having some things at the end of the morning under certain circumstances. It is, of course, not good when the children move from the practical into the completely theoretical. We should try to keep a Wednesday free. Gymnastics should also not be done before the theoretical periods. It was badly scheduled on Wednesday only because the gymnastics teacher was excluded from the meeting.

A teacher: The parents have arranged a number of things under the assumption that Wednesday is free.

Dr. Steiner: Surely we can get the parents to choose another day. The teachers need to be able to come to the faculty meetings. That is important. The teachers could meet on Saturday. There is too much to do. Let us try to keep Wednesday afternoon. I think it is best if we do gymnastics in the afternoon.

A teacher: We carried out the division between the humanistic and business courses of study.

Dr. Steiner: Then this class schedule is possible, and we will see if it is satisfactory.

A teacher: I would like to teach foreign languages in my first-grade class.

Dr. Steiner: Of course, that is possible. That is how it should have been from the beginning.

The fourth-grade teacher would like a fourth period of foreign language.

Dr. Steiner: We carefully considered the number of hours, but we should allow you to decide. It needs to be something that is not required.

I think, if everyone is satisfied with it, we could actually begin with the class schedule. It would be nice if you could start on Thursday, December 7. Then, on Saturday, when I can look at things again, everything will be under way.

They present the individual class schedules.

Dr. Steiner: The first grade only has class once in the afternoon. 2a and 2b, as well. 3a is only on Monday afternoon. 3b, only Tuesday afternoon. The same is true of the 4a and 4b classes. 5a has class on three afternoons, two of which are the Catholic religion class. 5b also has handwork and eurythmy on two afternoons. 6a, three afternoon classes. That is not too much. For the time being, only the teachers are carrying too much.

Dr. Steiner goes through the list with the teachers, determines how many hours each teaches, and how many hours beyond a reasonable limit each is teaching. He assumes that each teacher should teach sixteen to seventeen hours per week. Thus, for example, N., who teaches twenty hours, is teaching three to four hours too many.

Dr. Steiner: Now we have determined that. In normal life, the teachers would demand extra pay for these hours. However, I think we should try to get an additional language teacher. I would also like an additional gymnastics teacher.

A teacher asks whether the provisional plan for decreasing the teaching load should be tried.

Dr. Steiner: Y. already has too many hours. We could do that only if we could find some trade. If, for example, you, Miss Z., would take over one of the religion classes, then Y. could trade. Make the change with whoever appears most burdened. Mrs. W. has the greatest tendency to give up time. We will wait until Tittmann comes to answer the question of V.

V. defends himself.

Dr. Steiner: There are also inner reasons. You should be happy we expect more of you. You are more robust. I think you are quite strong. You certainly must admit that you are more robust than Mrs. W. We will see that we get Tittmann here as soon as possible.

A teacher: The class teachers have asked if they could teach gymnastics to their own classes.

Dr. Steiner: There is nothing to say against that if it does not become a burden. I certainly see no reason why two classes cannot have gymnastics with their teachers in the same room. That would, in fact, be quite good, if it is possible, because we would then achieve a pedagogical goal. We need to remove nervousness from our teaching. If we cannot do that, it would be a sign of nervousness. Actually, we should see it as an ideal that we could teach mathematics in one corner, French in another, astronomy and eurythmy in the others, so that the children have to pay more attention to their own work.

A teacher: That is also relevant for eurythmy?

Dr. Steiner: I would be happy if you could do it, because it is pedagogically valuable. teachers would, of course, need to be able to get along with each other.

A teacher: The religion teachers would like to keep the room they have had for the Sunday services. It should be used only for that.

Dr. Steiner: I agree. What is important in these Sunday services is the attitude among those present. We can best achieve that by maintaining that arrangement.

A teacher: Should Miss R. and Mr. W. hold the services?

Dr. Steiner: They should both celebrate the sacraments. That is an obvious condition for the independent religious instruction. I would like to say something more. Experience has shown that the Independent Religious Instruction consists not only in what we teach during religion class, not only what we teach through feeling, but that a certain relationship needs to develop between the religion teacher and the student. You can develop that through the celebration of a sacrament. If someone else does the service, then, for the student who receives the sacrament from someone else, a large part of the intangibles necessary for teaching religion are missing between the students and the religion teacher. The reverse is also true. If someone gives the sacrament without teaching religion, that person falls into a difficult position that can hardly be justified. It is easier to justify teaching religion without leading a service than it is to justify leading a service without teaching religion. Through the service, we bring religious instruction out of empty theory. It is based upon a relationship between the religion teacher and the students. As I have said in connection with the sacrament, you should decide.

A teacher: I did not understand that.

Dr. Steiner: Now that we have completed things, in selecting a teacher for religion my first question is if he or she can lead the Sunday service. You might have the wrong impression. If the question is which one of you here do I think is appropriate, then I could reply, “Only those who I think are appropriate to give the service.” Many people could teach religion, but the giving of the sacraments can hardly be done by anyone other than the two whom I mentioned. You should not be angry that I am speaking quite straightforwardly in this connection, but each of you should know what I think of your capabilities, at least for now. That may change, though.

The children need to become mature enough. This nonsense with a special confirmation class needs to stop. They should attend the Youth Service when they have reached a certain level of maturity, but that maturity cannot be taught. They will simply reach it, and for that reason, we should not have any special confirmation class. Only the person giving religious instruction should hold the Youth Service.

A teacher asks about the decorations in the service room.

Dr. Steiner: I would like to think about that. I think it would be nice to have a harmonium. We want to be careful about how we develop the service. There is not much to say about the text except that the Gospels are still missing. There is still much we can do in connection with music and also paintings. In contrast, though, there is something else we need to consider, namely, the participation of the faculty.

There are two sides to the question. There is the very real question of whether things are moving too rapidly here. The services permeated by a religious renewal have the possibility of becoming something quite great. On the other hand, I hear in town among those who are working on this religious renewal that a religious community of a hundred members consists only of anthroposophists who are forming a sect. You see, there is a danger connected with all this. It is already present. I also hear that, “Those members who have not yet joined are being pressured.” The religious renewal was intended for those outside the Society. You need to be clear that such things have two sides, and that the primary thing is that our anthroposophical friends, both inside the school and outside, need to see that their mission is to straighten out people who are falling into an erroneous path. Those things connected with the most noble intent also have the greatest dangers. This is something that must be taken seriously. Before this religious renewal has withstood the test whether it is true and proper, we can certainly not say that we should respect someone who does not attend less than someone who does.

It would be best if we create a service for the children that has a great deal of warmth and heart, if we did everything possible to create an attitude that is serious without being oppressive, but on the other hand, to keep it as simple as possible.

A teacher: We have thought about some questions we would like to ask you. The question arose in connection with teaching foreign language about the musical/language and the sculptural/ painting streams. They were often mentioned in the course.

Dr. Steiner: There are also a number of references to that in that short cycle of four lectures on pedagogy that I gave in September of 1920.

You will forgive me if I mention that, but I believe it contains everything you need to come to more concrete actions.

Concerning teaching modern languages—if you use the same methods, the effects upon the child will compensate each other, since the child’s head dies through French to the same extent as the child’s metabolism is enlivened through English. The difficulty arises, and this is something that just occurred to me, when you remove English for some of the children. Socially, that is unnatural. It should not happen, but there is nothing more we can do. We cannot have both English and the ancient languages. But, particularly during the present stages of their development, these two languages compensate one another unbelievably well. Take, for example, Mr. B’s French class today. He developed something extremely important for the more quiet listeners. The French language is in a process of eliminating all the “S’s”. It would not be proper to say Aisne (An). You can hear the “s”. But, during the Battle of the Marne, it was referred to only as “An”. In English, many suffixes are moving toward removing an “s.” When you use the same methods, these are completely compensating, particularly during the ages of nine and ten. Otherwise, it is best to do as little French grammar as possible. In contrast, it is good you emphasize the grammatical aspect of English around the age of eleven or twelve. I will discuss that in more detail later, but for now I wanted only to make a preliminary mention of it in order to hear from you how things are going.

A question is asked about the stages of language teaching.

Dr. Steiner: There are stages. It would be interesting to look at this question in connection with other things. I intend to write an essay about Deinhardt’s book about the basic elements of aesthetic principles in instruction. Of course, these things are overemphasized by Deinhardt as well as Schiller, but it is easy to discuss them. It would be good to mention the publisher at the same time. Perhaps one of the faculty members could write a critique of the book in relation to Schiller. You are not familiar with the book? It is difficult to read. Steffen was asked to write an introduction to this book, but he found it terribly boring. That is only because of his long sentences. An Austrian can understand having such long sentences in a book. Sometimes you have to stand on your head in order to understand such sentences, but Steffen does not like that.

A teacher: We assumed such things would result in a textbook.

Dr. Steiner: That would be a good idea.

A teacher asks about how to ask questions using the Socratic method.

Dr. Steiner: There is something about that in my lecture cycles.

A teacher asks about having English as an elective in the upper grades.

Dr. Steiner: That would be possible.

A teacher asks a question about mathematics.

Dr. Steiner: I would be happy to explain that if you would try to use such things in a non-pedantic way. You should remember that such rules are always flexible, so they must never become pedantic. Particularly concerning spatial questions, it is always bad when things become too rigid.

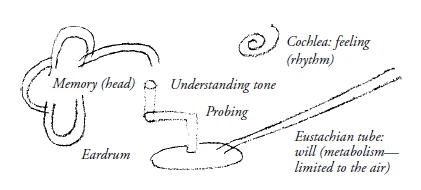

Dr. Steiner: You need to understand the small bones within the ear, the hammer, stirrup, the oval window, the anvil, as small limbs, as arms or legs that touch the eardrum. A sense of touch enters the understanding of tone. The spiral, which is filled with liquid, is a metamorphosed intestine of the ear. A feeling for tone lives in it. What you carry within you as an understanding of language is active within the eustachian tubes that support the will to understand. Tone is primarily held in the three semicircular canals. They act as a memory for tone. Each sense is actually an entire human being.

I often say such things as a paradigm in order to animate people like Baumann and Schwebsch to get to work and write a book about all their experiences. They said such things this morning. You only need to be more specific and things will seem plausible to them. Dr. Steiner is asked to open the new school building after Christmas.

Dr. Steiner: That is difficult, since not all the classes will be moving in. Quite a number will remain in the temporary buildings, so if we make this a particular celebration, those children staying in the temporary buildings will feel they are not as good as those moving into the new building. We need to consider the effects of a special ceremony upon those children remaining in the temporary buildings. It would be a different question if we were to open a new hall, such as a gymnasium. However, if we were to do this, it would fill the whole building with an inner disturbance.

I want to characterize Leisegang as a philosopher, a caricature of a philosopher. He is just a windbag. What he is as a philosopher is complete nonsense. You can do this in a pedantic way: What are the characteristics of a philosopher? A philosopher needs a firm foundation under his feet, but all his assumptions are incorrect. You could actually prove that he, in fact, has no real foundation.

If you proceed that way in philosophy, that is what happens. I do not know of any profession where such a person would belong. He certainly could not make jokes in the newspaper because he doesn’t have enough of a sense of humor.

Einundvierzigste Konferenz

Am 4. Dezember reiste Rudolf Steiner von Dornach an, hielt abends einen Mitgliedervortrag, am nächsten Tag war eine Konferenz mit den Lehrern, und noch in derselben Nacht reiste er weiter nach Berlin. Dort fanden eine Eurythmieaufführung und ein Mitgliedervortrag statt, und in der Nacht vorn B. auf den 9. I)c•r.ember reiste er zurück nach Stuttgart. Am Mittag war Konferenz, am Abend Mitgliedervortrag, am nächsten Tag die Fahrt nach Dornach.

Themen [41. und 42. Konferenz]: Erfahrungen mit dem neuen Stundenplan. Kritik von Eltern und Schülern. Lehrerbelastung. Religionsunterricht und Religionslehrer. Die Christengemeinschaft. Über das Ohr. Jeder Sinn ist ein kleiner Mensch. Stenografieunterricht. Die Vorbereitung des Besuches der Engländer. Zum Parzival — als Thema für den Religions- und als Thema für den historischen Unterricht.

Bemerkungen: Da Steiner immer noch die nötige Frische, den richtigen Wurf und Schneid im Schulehalten vermisste, ging er penibel bei allen Kollegen deren Stundenbelastung durch. Die Religionslehrer sollten in der Lage sein, auch die Sonntagshandlungen zu halten. Die ersten Gemeinden der im Entstehen begriffenen Bewegung zur religiösen Erneuerung bestanden fast nur aus Anthroposophen, die Bewegung war aber nicht dafür gedacht. Steiner bat uni diesbezügliche Wachheit.

Die beiden Konferenzen atmeten eine gewisse Entspannung nach den Turbulenzen der vergangenen Monate. Die Vorbesprechung zum Besuch der Engländer war ein mildes, humorvolles und selbstkritisches Kapitel der Völkerpsychologie. Wenn sie im Januar kämen, versprach er, vorbeizukommen.

Die Konferenz schloss mit einem bedeutenden Kapitel zum historisch-literarischen Parzival-Unterricht. Steiner war das Wissenschaftlich-Etymologische gleich wichtig wie das Moralisch-Ethische.

RUDOLF STEINER: Alles, was zum Stundenplan gehört, bitte ich zu sagen.

EUGEN KOLIAWO referiert über den neuen Stundenplan: Aller Sprachunterricht vormittags. Keine Personaländerungen. Einmal musste eine Sprachstunde von zwölf bis eins liegen. Es ist Gruppenbildung versucht worden. Einige Male hat man Lateinisch und Griechisch nach Eurythmie legen müssen, sonst immer Sprachunterricht nach Hauptunterricht.

RUDOLF STVANER: Man wird es so machen müssen, wenn es nicht anders geht.

ERICH SCHWEBCH: Ich würde lieber eine Sprachstunde in der 4a auf den Nachmittag legen statt von zwölf bis eins.

RUDOLF STEINER: Dann machen wir es an einem Nachmittag.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Soll das auch sonst gelten?

RUDOLF STEINER: Wenn es verlangt wird von den betreffenden Lehrern. Es wird sich darum handeln, dass die betreffenden Lehrer damit einverstanden sind. Dann lassen wir Dr. Treichler am Vormittag und das andere am Nachmittag.

EUGEN KOLISKO referiert über den Religionsunterrieht. Gesang ist überall vormittags.

RUDOLF STEINER: Da sind die Gesangslehrer einverstanden.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Es ist mit zwei Gesangssälen gerechnet. Bis der zweite fertig ist, müssen einige Stunden am Nachmittag gegeben werden, [vor Weihnachten].

RUDOLF STEINER: Dann muss es gemacht werden.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Eurythmie ist meist vormittags. Handwerk und Handarbeit alles nachmittags, Turnen auch, man hat dazu auch einen Mittwochnachmittag benutzen müssen. Wenn Mittwochnachmittag frei sein soll, müsste man auch Turnen und zum Teil auch Handwerk auf einen Vormittag legen,

RUDOLF STEINER: Es ist nichts dagegen einzuwenden, dass unter Umständen die Sache in die letzten Vormittagsstunden gesetzt würde. Es ist natürlich nicht gut, wenn die Kinder vorn Praktischen ganz ins Theoretische kommen. Wenn wir einen Mittwoch freikriegen können, so sollten wir es doch anstreben. [Turnen sollte auch nicht vor theoretischen Stunden liegen. Es] ist nur deshalb am Mittwochnachmittag schlecht platziert, weil der Turnlehrer ausgeschlossen wäre von den Konferenzen.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Die Eltern haben sich in vielen Dingen darauf eingerichtet, dass der Mittwoch frei ist.

RUDOLF STEINER: Man müsste doch die Eltern veranlassen können, dass sie einen anderen Tag wählen. Die Lehrer sollten möglichst Gelegenheit haben, sich zu finden in den Konferenzen. Das ist etwas Wichtiges. Es könnte ja Sonnabend dieses Sich-Finden der Lehrer stattfinden. Es wird sonst zu viel aufgebuckelt. Wollen wir es [doch] versuchen mit dem Mittwochnachmittag. Ich glaube, es ist das Beste, wenn Turnen auf Nachmittag verlegt ist.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Die Spaltung zwischen Humanistischem und Realistischem ist durchgeführt.

RUDOLF STEINER: Dann wäre der Stundenplan ein möglicher, und ob er zufriedenstellend ist, 'werden wir sehen].

BETTINA MELLINGER möchte die Sprachen in ihrer 1. Klasse selbst übernehmen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Natürlich kann es sein. Es hätte von Anfang sein sollen. Eigentlich ist im Wesentlichen [Lücke in der Mitschrift].

ANNA FRIEDA NAEGELIN möchte die Hohlstunden forthaben. JOHANNES GEYER möchte in der 4. Klasse eine vierte Sprachstunde haben.

RUDOLF STEINER: Die Stundenzahl ist sorgfältig erwogen. Mindestens müsste man es freistellen. Es müsste etwas sein, was nicht ganz verpflichtet.

Ich denke, wir können den Stundenplan, wenn er wirklich allseitig befriedigt, zunächst einführen. [...] [Zwischenfrage zum Gesangsunterricht.]

Dann wäre es schön, wenn Sie es durchführen könnten, sodass man ihn am Donnerstag, [den 7. Dezember], einführt. Dann ist am Samstag, wie ich durchschauen kann, das im vollen Betrieb.

ERICH SCHWEBCH legt die Klassenstundenpläne vor fSteiners Wunsch vorn 24. November. die Stundenpläne pro Klasse verfügbar zu haben, wird hiermit entsprochen].

RUDOLF STEINER liest vor: Die 1. Klasse hat nur einmal Nachmittagsunterricht. 2a und b auch nur einmal. 3a bloß Montagnachmittag. 3b bloß Dienstagnachmittag. 4a bloß Montagnachmittag. 4b bloß Dienstagnachmittag. 5a drei Nachmittage, davon zwei katholischen Unterricht. 5b auch Handarbeit und Eurythmie an zwei Nachmittagen, 6a drei Nachmittage. Es ist nicht überlastend. Überlastet sind vorläufig die Lehrer.

Es wird gefragt wegen Konfirmandenunterricht.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Für die evangelischen Schüler, darauf müssen wir Rücksicht nehmen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das geht ja.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Einige Lehrer sind sehr belastet. Bernhardi 20 Stunden, Melliger 22, Plincke 23, Treichler 25 Stunden. Es wäre wünschenswert, wenn von diesen Lehrern zusammen zehn Stunden abgegeben werden könnten. Einige Lehrer haben angeboten, Stunden zu übernehmen, aber es reicht nicht.

RUDOLF STEINER geht die Liste der Lehrer durch, stellt bei jedem fest, wie viel Stunden er gibt, und um wie viel Stunden er zu viel hat. Dabei geht er von 16 bis 17 Wochenstunden als der erstrebenswerten Zahl aus; zum Beispiel einer hat 20 Stunden, also drei bis vier Stunden zu viel.

RUDOLF STEINER: Nun, wenn man dem Tittmann noch schreiben würde. Jedenfalls können Sie ihm schreiben, ob er sich augenblicklich gleich freimachen könnte.

Baravalle, Baumann, Graf Bothmer hat den Vormittag zu seiner Eigenkultur. Friedenreich ist reichlich besetzt. Da wird man später abhelfen können. Röschl, wie viel haben Sie Stunden? 14 Stunden. Man müsste das theoretisch klar haben. Kolisko 15, Frau Kolisko 2, Lämmert 21, Leinhas 9, Mellinger hat zu viel um 5 bis 6 Stunden. Frau Molt, Naegelin das ist gerade gut. Plincke hat zu viel um 6 bis 7 Stunden. Röhrle, Rutz zu viel um 2. [Ruhtenberg zu viel um 2.] Stein 15. Frau Stein, Stockmeyer, Strakosch. Schwebsch hat zu viel uni 8 bis 9 Stunden. Schubert 5 bis 6. Treichler zu viel 8 bis 9 Stunden. Uhland auch zu viel 4 bis 5 Stunden. Wolffhügel geht, Baravalle geht, Baumann geht. Bernhardi zu viel uni 4 Stunden. Bothmer geht. Boy zu viel 2 bis 3 Stunden. Doflein 2. Friedenreich, das ist natürlich zu viel, Gesang 4, dann kommen Violinstunden. Zu viel 3 bis 4. Geyer geht. Hahn hat zu viel um 4 bis 5. Handarbeit geht. Killian hat zu viel uni 3.

Nur dass das einmal festgestellt ist. Im profanen Leben würden für diese Stunden die Lehrer Tantiemen fordern. Aber ich denke, wir wollen es mit der Vermehrung [um den einen neuen Sprachlehrer] Tittmann probieren. Dann würde ich gerne [noch] einen Turnlehrer haben.

EUGEN KOLISKO fragt, ob man den provisorischen Entlastungsvorschlag durchführen soll.

RUDOLF STEINER: Hahn hat schon zu viel Stunden. Das würde nur gehen, wenn ein Tausch stattfinden könnte. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel eine Religionsklasse übernehmen können, Fräulein Dr. Röschl, dann kann Hahn tauschen. Wechsel mit dem, dem es zunächst am meisten über zu sein scheint. [Frau] Plincke ist am meisten abgeberisch gesinnt. Frau Plincke und Mellinger. Bei Treichler warten wir, bis der Tittmann kommt.

RUDOLF TRFICHLER wehrt sich.

RUDOLP ST EINER: Es gibt auch innere Gründe. Seien Sie froh, wenn man Ihnen mehr zutraut. Sie sind robuster. Ich finde Sie sehr robust. Sie müssen zugeben, dass Sie robuster sind als Frau Plincke. Bei Fräulein Mellinger ist das, dass sie trotzdem noch so viel hat. — Wir werden so schnell wie möglich sorgen, dass wir Tittmann kriegen.

Wenn Herr Rutz einverstanden ist, dann könnte [ihm] auch Frau Plincke die Klasse [4h] übergeben. Es wäre wünschenswert, dass die Änderungen, die jetzt vollzogen werden, dass die bleiben, dass die nicht wieder umgeändert werden.

HERBERT HAHN: Welche Gruppe soll ich an Fräulein Dr. Röschl abgeben?

RUDOLF STEINER: 10. und 11. Nun möchte ich hören, was die Schüler für Gesichter machen werden, wenn sie statt eines Lehrers eine Lehrerin haben werden. Ich würde es bedauern, wenn Sie die 4. und 7. abgeben würden. Ich würde für richtiger enden, wenn Fräulein Röschl die 10. und 11. übernimmt.

Wir haben Herrn Arenson im Unterricht gehabt. Es ist merkwürdig, dieses Disziplinarische, das ist jetzt so, dass es in gewissen Klassen kaum Schwierigkeiten macht. in den Klassen, wo ich heute war, sind sie musterhaft brav gewesen. Bei Boy waren sie ausgezeichnet aufmerksam. Bei Treichler waren sie [es] auch. Wenn man den Kindern erzählt, ist es immer etwas besser. Heute war die Disziplin eine außerordentlich gute. Ich glaube nicht, dass sie braver gewesen sind als sonst.

Fräulein Röschl möchte den Unterricht nach Weihnachten übernehmen.

Ich möchte den Tausch so machen, dass die Änderungen nicht so geschehen, dass neue Überlastungen geschehen. Würden wir jetzt sehen den Unterricht von Fräulein Mellinger geben, Fräulein Bernhardi kann erst Französisch loswerden, bis Hahn den Unterricht loswird. Hospitieren Sie am Freitag, und dann wollen wir sehen. Dann müssen wir warten, bis Tittmann da ist. Fräulein Bernhardi würde ich bitten, es so lange zu behalten, bis Tittmann kommt, damit Sie hospitieren können.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Die Klassenlehrer haben gefragt, ob sie [die] Turnstunden in ihren Klassen übernehmen können.

RUDOLF STEINER: Dagegen ist nichts einzuwenden, wenn [eine] Entlastung dabei ist, Pastor Geyer könnte es machen. Ich halte es nicht für ausgeschlossen, dass zwei Klassen bei zwei Lehrern in demselben Saal Turnen haben. Das wäre eine außerordentlich gute Sache, wenn es sich durchführen lässt, weil man dadurch einen pädagogischen Zweck erreicht. Wir müssen den Unterricht ganz vorn Nervösen herausbringen. Dass es nicht der Fall sein kann, das ist ein Zeichen von Nervosität. Eigentlich müsste man als Ideal in einer Ecke Mathematik, [in den anderen] Französisch, Astronomie und Eurythmie unterrichten können, sodass die Kinder ihre Aufmerksamkeit auf ihre eigene Tätigkeit richten müssen.

ELISABETH BAUMANN: Könnten wir das auch auf die Eurythmie beziehen?

RUDOLF STEiNER: Ich wäre froh, wenn Sie es könnten, weil es pädagogisch wertvoll wäre. Die Lehrer müssten sich immer wieder gut vertragen.

EUGEN KOLISKO über einen Tausch von Killian und Boy.

RUDOLF STEiNFR: Da bekommt aber Boy dadurch 21 Stunden und Killian 17 Stunden.

Ich würde doch meinen, dass wir die weiteren Verschiebungen lassen, bis Herr Tittmann da ist.

ERNST UEHLE: Die Religionslehrer möchten den [bisherigen] Raum für die Sonntagshandlungen behalten; er sollte ausschließlich dafür da sein.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ich bin damit einverstanden. Bei dieser Sonntagshandlung kommt es darauf an, dass die Stimmung für diejenigen vorhanden ist, [für] die diese Sonntagshandlung zu vollziehen ist. Es würde am besten dadurch erreicht werden, dass dieses Arrangement getroffen wird.

HERBERT HAHN: Sollen auch Fräulein Dr. Röschl und Herr Wolffhügel die Handlung machen?

RUDOLF STEINER: Beide müssen die Handlungen zelebrieren.

MAX WOLFFHÜGEL: Daran habe ich nicht gedacht.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das ist eine selbstverständliche Bedingung {für den Freien Religionsunterricht]. Ich will das Folgende dazu sagen. Nicht wahr, die Erfahrung, das Erlebnis, hat gezeigt, dass wir den Freien Religionsunterricht nicht bloß darin bestehen haben, dass wir etwas lehren in einer Religionsstunde, auch nicht bloß gemütvoll lehren, sondern dass jenes bestimmte Verhältnis außerdem sich noch herstellt zwischen Religionslehrer und Schüler, das hergestellt wird durch eine Kultushandlung. Und wenn die Kultushandlung jemand anderer verrichtet, so verliert der Religionslehrer für die Schüler, die die Kultushandlung von jemand anderem bekommen, einen guten Teil der Imponderabilien für den Religionsunterricht. Und umgekehrt, der einen Kultus verrichtet, ohne Religionsunterricht [zu geben], der kommt in eine schiefe Stellung hinein, die kaum zu recht-fertigen ist. Es ist noch eher zu rechtfertigen, Religionsunterricht zu erteilen ohne Kultus als Kultus ohne Religionsunterricht. Es ist der Religionsunterricht dadurch herausgehoben von der leeren Theorie. Er ist gegründet auf ein Verhältnis des Religionslehrers zu den Schülern. Als ich gesagt habe, Sie sollten sich entschließen, so habe ich es mit Bezug auf den Kultus gesagt.

MAX WOLFFHÜGEL: Das habe ich noch nicht aufgefasst.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ich würde bei einem Religionslehrer jetzt, nachdem wir die Sache vollständig eingerichtet haben, mich in erster Linie fragen: Kann er den Kultus ausführen? Sie würden auch ein falsches Urteil gewinnen. Wenn es sich darum handeln sollte, wen ich [für] geeignet halte von den hier befindlichen Freunden, so würde man sagen können, [nur] die, welche ich zum Kultus geeignet finde; aber Religionslehrer könnte noch so mancher sein, Die Kultushandlungen könnten kaum von jemand anderem ausgeführt werden als von beiden, die jetzt noch genannt sind, Und Baumann würde ich in Betracht ziehen können. Sie müssen nicht böse sein, dass man in dieser Beziehung aufrichtig sprechen muss, dass jeder wissen muss, wofür er geeignet gehalten wird. Zunächst! Das kann sich ändern.

Zur Jugendfeier müssen die Menschen [von selbst] reif werden. [Der Unfug eines separaten Konfirmandenunterrichts muss aufhören. Die Jugendfeier muss eintreten, wenn eine gewisse Reife vorhanden ist. Aber diese Reife kann man nicht lehren.] [Also] nicht erst unterrichten, [sondern] es ist ein Konstatieren. Daher darf kein besonderer Religionsunterricht als Konfirmandenunterricht eintreten. [Es soll auch nur der die Jugendfeier halten, der den Religionsunterricht erteilt.]

Ein Lehrer fragt nach der künstlerischen Ausgestaltung des Handlungsraumes.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ich will mir das durch die Seele ziehen lassen. Ich würde meinen, wenn Sie ein Harmonium kriegen könnten, wäre es gut. Das wollen wir sorgfältig feststellen, wie wir das ausbauen. Über die sprachliche Form ist nichts zu sagen, als dass die Evangelientexte noch fehlen. Musikalisch und in Bezug auf das Bildnerische lässt es sich mehr ausbauen. Dagegen wäre natürlich eine andere Sache zu erwägen, die aber vielleicht schon geleistet ist. Das ist, wie es steht mit der Teilnahme der gesamten Lehrerschaft?

Die Sache hat zwei Seiten. Es ist stark die Frage, ob in dieser Beziehung etwas übereilt werden darf. Die mit Kultus durchsetzte religiöse Erneuerung hätte hier den Keim in sich, etwas [sehr] Großes zu werden. Dagegen höre ich aus einer Stadt, in der auch schon diese religiöse Erneuerung arbeitet, folgendes Urteil über [deren] Arbeit. «Heute steht die Angelegenheit so, dass eine religiöse Gemeinde von hundert Mitgliedern aus nur Anthroposophen vorhanden ist, von denen sektiererische Tendenzen vertreten werden.» Sie sehen, es sind Gefahren verbunden. Sie sind vorhanden. «Diejenigen Mitglieder, welche sich noch nicht angeschlossen haben, werden gepresst.» Die religiöse Erneuerung war für Außenstehende bestimmt. Sie müssen sich klar sein, dass diese Dinge zwei Seiten haben, und dass vor allen Dingen auch diejenigen, die jetzt unsere anthroposophischen Freunde sind, innerhalb dieser Schule und außerhalb dieser Schule ihre Mission darin sehen müssen, ein wenig denen die Köpfe zurechtzurichten, die also da auf eine abschüssige Bahn kommen könnten. Die Dinge, die mit dem Edelsten zusammenhängen, schließen auch die größten Gefahren in sich. Das darf nicht mit Unernst genommen werden. Bevor nicht diese religiöse Erneuerung die absolute Probe abgelegt hat, dass sie wahr und richtig ist, darf durchaus nicht so etwas geltend gemacht werden, als ob man weniger respektiert würde.

Es ist schon besser, wenn wir zunächst den Kultus für die Kinder mit einer großen Innigkeit und Herzlichkeit einrichten, wenn wir alles tun, wodurch die Stimmung entsteht, dass er etwas Ernstes ist, ohne schwül zu sein, aber wenn wir auf der anderen Seite ihn so schlicht haken, als es möglich ist.

HERBERT HAHN: Wir haben uns einige Fragen überlegt, die wir Herrn Doktor gerne vorlegen möchten. Über den Sprachunterricht, ob es möglich ist, den musikalisch-sprachlichen Strom im werdenden Menschen in Form einer einzelnen Betrachtung zu verfolgen.

ERICH SCHWEBSCH: ln den Kursen ist oft die Rede von dem plastisch-malerischen Strom.

RUDOLF STEINER: Mehr noch ist angedeutet in diesem kleinen Zyklus, den ich als kleinen [pädagogischen] Zyklus von vier Vorträgen gehalten habe, 1920 [im September].

Wenn Sie nur so gut wären, ich erwähne ihn nur deshalb, weil ich schon glaube, dass er alles enthält, [und] dass Sie das konkretisieren [können].

Zum neusprachlichen Unterricht: Wenn man die Methode gleichmacht, so kompensieren sich die Dinge [in ihren Wirkungen für das Kind], weil es durch das Französische in seinem Kopf [ebenso stark] erstirbt, wie es durch das Englische im Stoffwechsel angeregt wird. Die Schwierigkeit tritt ja — und das ist mir jetzt durch die Seele gezogen — [dann] ein, wenn man das Englische für gewisse Schüler herausnimmt. Das ist eine sozial unnatürlich Sache; es sollte nicht der Fall sein, aber wir können uns nicht anders helfen. Wir können nicht Englisch und die antiken Sprachen haben. Aber gerade im jetzigen Stadium ihrer Entwicklung sind diese beiden [Sprachen] so unglaublich einander kompensierend. So zum Beispiel, wenn Sie heute die französische Stunde von Herrn Boy nehmen, der hat für stille Zuhörer etwas außerordentlich Wichtiges entwickelt. Die französische Sprache ist daran, alle die s (verstummen zu lassen]. Es ist gar keine Rede davon, dass man Aisne (= Än) gesagt hat, sondern man hat [das] s gehört. [Bei] der Schlacht an der Marne hat es nur [noch] Aisne (= Än) geheißen. Im Englischen sind viele Nachsilben auf dem Wege, so ein verschämtes s herauszukriegen. Die vollständige Kompensierung ist [besonders] vorhanden zwischen dem neunten und zehnten Lebensjahr, wenn man die gleichen Methoden anwendet, Vorher ist es gut, wenn man das Französische möglichst wenig [und spät] grammatisch behandelt. In Ihrer Klasse hat es mich nicht gestört. Dagegen ist es beim Englischen gut, wenn man im elften und zwölften Jahr doch immer wiederum bei der Sprache auf etwas Theoretisches aufmerksam macht, auf das Grammatisch-Syntaktische. So werden wir das ausbauen. Ich wollte dies zunächst präliminarisch anführen, um zu hören, ob es geht. Die zweite Seite geht eben dahin, das gehört zu den Sachen, die ich anstrebe zu halten.

ERIcH SCHWEBSCH fragt nach den Stufen des Sprachunterrichts.

RUDOLF STEINER: Es sind Stufen da.

ERICH SCHWEBSCH [vermutlich]: Würden Sie, Herr Doktor, angeben diese Stufen? Bisher sind die Sachen so entstanden, dass ich etwas vorgeschlagen habe und dann zu Herrn Doktor gegangen bin und gefragt habe.

RUDOLF STEINER: Es wäre interessant, diese Dinge im Zusammenhang mit den anderen zu behandeln. Ich habe vor, einen Aufsatz zu schreiben über das Buch von Deinhardt, über die ersten Elemente des ästhetischen Prinzips für den Unterricht. Es wird natürlich sowohl von Schiller und von Deinhardt selbst überspannt. Aber man kann das sehr leicht auseinandersetzen.

Nun wäre es gut, wenn man es zu gleicher Zeit benützen würde, um dem Verlag gegenüber das Buch zu erwähnen. Es könnte jemand aus dem Lehrerkreis über das Buch eine produktive Kritik schreiben, in Anlehnung an Schiller. Sie kennen das Buch noch nicht? Das Buch ist schwierig zu lesen. Der Steffen wurde zuerst aufgefordert, zu diesem Buch eine Vorrede zu schreiben, aber er hat es gräulich langweilig gefunden. Das ist aber lediglich durch die Bandwurmsätze. Dass solche Bandwurmsätze darin sind, das begreift der Österreicher. Bei manchen Sätzen muss man schon Purzelbäume schlagen. Steffen kann es nicht ausstehen.

ERICH SCHWEBSCH: Wir sind davon ausgegangen, dass aus solchen Dingen ein Lehrbuch entstünde.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das wäre sehr gut.

HERBERT HAHN fragt nach der Methode der Fragestellung.

RUDOLF STEINER: Da ist etwas darin in den Zyklen.

MARIA RÖSCHL fragt nach wahlfreiem englischen Unterricht in den Oberklassen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Den wahlfreien englischen Unterricht können die Kinder haben.

HERMANN VON BARAVALLE stellt eine mathematische Frage.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ich bin gern bereit, einzugehen, wenn Sie versuchen werden, diese Dinge nicht pedantisch anzuwenden. Wenn Sie bedenken, dass die Gesetze fortwährend biegsam sein können, sodass das die Dinge sind, die nie pedantisiert werden dürfen. Sobald da Philistrosität beginnt, dann ist es schlimm, wo überhaupt räumliche Fragen sind.

ERICH SCHWERSCH fragt nach dem menschlichen Ohr.

RUDOLF STEINER: [Die Gehörknöchelchen, Hammer, Amboss, Steigbügel und ovales Fenster, sind als Glied aufzufassen, als Arm oder Bein, das das Trommelfell abtastet. Ein Abtastesinn zum Verstehen des Tones.

Die Schnecke, die mit Flüssigkeit gefüllt ist, ist ein höheres, metamorphosiertes Gedärm des Ohres; in ihr lebt das Gefühl des Tones. Die eustachische Trompete, darin wirkt das, was man selber im Sprachverständnis in sich trägt, was als Wille dem Verstehen entgegenkommt. In den drei Bogen, den drei halbzirkelförmigen Kanälen, wird der Ton im Wesentlichen behalten; das ist das Gedächtnis für den Ton. Jeder Sinn ist eigentlich ein ganzer Mensch.]

Diese Dinge sind, manchmal einfach paradigmatisch gesagt, dazu da, um solche Leute wie Baumann und Schwebsch aufzuregen, damit sie losgehen und alle ihre Erlebnisse da heraufholen, [als] ein Buch über solche Bemerkungen. Sie haben heute Morgen solche Sachen gesagt. Man muss das alles spezifizieren. Es wird ihnen plausibel erscheinen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Zwei Liederhefte erscheinen jetzt von Baumann.

PAUL BAUMANN: Zwei Lieder [zu Texten] von Ihnen sind darinnen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ich freue mich sehr. Legen Sie mir die Fragen vor, ich komme am Samstag noch einmal durch.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Fräulein Hofmann aus Heidelberg hat Herrn Uehli gesprochen.

RUDOLF STE1NER: Fräulein Hofmann würde in Betracht kommen als Lehrerin im Allgemeinen. Ich habe Fräulein Hofmann auf die Zukunft verwiesen. Sie kommt als Lehrerin im Allgemeinen in Betracht. Es muss nach und nach sorgfältig die Auswahl gemacht werden. Was ich so gerne hätte, die Gräfin Hamilton als Lehrerin. Sie kann noch nicht genügend Deutsch.

KARL STOCKMEYE.R bittet darum, Herr Doktor möge nach Weihnachten den Neubau eröffnen.

RUDOLF STEENER: Es ist schwierig, das zu machen. Es ziehen nicht alle Klassen hinein. Es bleiben in der Baracke eine ganze Anzahl von Klassen zurück, und wenn man dies zu einer besonders feierlichen [Sache] macht, so entstehen Gefühle in den Kindern, die zurückbleiben, die wirklich, auf die andere Waagschale geworfen, [gegen]über dem, was man durch die Feier macht, schwer wiegen. Wir müssen das schon psychologisch ins Auge fassen; wenn man eine Feier veranstaltet für etwas, was man eröffnet hat, und dann lässt man eine Anzahl von Kindern in der Baracke zurück. Es würde gehen, einen Saal einzuweihen. Das ganze Haus ruft aber, wenn es eingeweiht wird, innere Rankünen hervor. Die Turnhalle kann man eröffnen.

Ich will Leisegang als Philosophen charakterisieren. Man muss ihn als Karikatur von einem Philosophen charakterisieren. Er ist ein Windbeutel. Es ist doch ein Unsinn, rein von dem Standpunkt aus beurteilt, was er für ein Philosoph ist. Sie können es philiströs-pedantisch machen: Was muss ein Philosoph haben? Er muss fußen können auf den tatsächlichen Unterlagen. Alle die tatsächlichen Unterlagen sind falsch. Sie können ihm nachweisen, dass er keine tatsächlichen Grundlagen hat. Er ist ein Philosoph, der sich die Dinge [Lücke in der Mitschrift].

Wenn man so in der Philosophie verfährt, dann ist es eben so. Ich weiß überhaupt nicht einen Beruf, wo ein solcher Mensch hingehört. Witze machen in einer Zeitung, dazu wird er zu wenig Witz haben.

Forty-first Conference

On December 4, Rudolf Steiner traveled from Dornach, gave a lecture to members in the evening, held a conference with the teachers the next day, and traveled on to Berlin that same night. There he attended a eurythmy performance and gave a lecture to members, and on the night before December 9, he traveled back to Stuttgart. There was a conference at noon, a lecture for members in the evening, and the next day the trip to Dornach.

Topics [41st and 42nd conferences]: Experiences with the new timetable. Criticism from parents and students. Teacher workload. Religious education and religious education teachers. The Christian Community. About the ear. Every sense is a little person. Shorthand lessons. Preparing for the visit of the English. Parzival — as a topic for religious education and as a topic for history lessons.

Comments: Since Steiner still felt that the school lacked the necessary freshness, drive, and vigor, he meticulously reviewed the workload of all his colleagues. Religious education teachers should also be able to conduct Sunday services. The first communities of the emerging movement for religious renewal consisted almost exclusively of anthroposophists, but the movement was not intended to be so. Steiner asked for vigilance in this regard.

The two conferences exuded a certain relaxation after the turbulence of the past months. The preliminary discussion of the English visit was a mild, humorous, and self-critical chapter in the psychology of nations. If they came in January, he promised to drop by.

The conference concluded with an important chapter on the historical-literary teaching of Parsifal. For Steiner, the scientific-etymological was just as important as the moral-ethical.

RUDOLF STEINER: Please tell me everything that is part of the timetable.

EUGEN KOLIAWO reports on the new timetable: All language lessons in the morning. No personnel changes. Once, a language lesson had to be scheduled from twelve to one. An attempt was made to form groups. A few times, Latin and Greek had to be scheduled after eurythmy, otherwise language lessons always followed the main lesson.

RUDOLF STVANER: We will have to do it this way if there is no other option.

ERICH SCHWEBCH: I would prefer to schedule a language lesson in 4a in the afternoon instead of from twelve to one.

RUDOLF STEINER: Then we will do it one afternoon.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Should this also apply in other cases?

RUDOLF STEINER: If the teachers concerned request it. It will be a matter of the teachers concerned agreeing to it. Then we will leave Dr. Treichler in the morning and the other in the afternoon.

EUGEN KOLISKO talks about religious education. Singing is everywhere in the morning.

RUDOLF STEINER: The singing teachers agree.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Two singing rooms are planned. Until the second one is ready, some lessons will have to be given in the afternoon [before Christmas].

RUDOLF STEINER: Then it must be done.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Eurythmy is mostly in the morning. Handicrafts and needlework are all in the afternoon, as is gymnastics, so we also had to use one Wednesday afternoon for this. If Wednesday afternoon is to be free, gymnastics and some of the crafts would also have to be moved to the morning.

RUDOLF STEINER: There is no objection to the matter being moved to the last hours of the morning under certain circumstances. Of course, it is not good if the children move from practical to theoretical subjects. If we can get Wednesday free, we should strive to do so. [Gymnastics should also not take place before theoretical lessons. It] is only poorly placed on Wednesday afternoons because the gymnastics teacher would be excluded from the conferences.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Parents have adjusted to many things, including having Wednesdays off.

RUDOLF STEINER: It should be possible to persuade parents to choose another day. Teachers should have as many opportunities as possible to meet in conferences. This is important. These teacher meetings could take place on Saturdays. Otherwise, there will be too much pressure. Let's try Wednesday afternoon. I think it would be best to move gym class to the afternoon.

EUGEN KOLISKO: The division between humanities and sciences has been implemented.

RUDOLF STEINER: Then the timetable would be possible, and whether it is satisfactory, we will see].

BETTINA MELLINGER would like to take over the languages in her 1st grade herself.

RUDOLF STEINER: Of course, that is possible. It should have been that way from the beginning. Actually, it is essentially [gap in the transcript].

ANNA FRIEDA NAEGELIN would like to have the free periods. JOHANNES GEYER would like to have a fourth language lesson in the 4th grade.

RUDOLF STEINER: The number of lessons has been carefully considered. At the very least, it should be optional. It should be something that is not entirely compulsory.

I think we can introduce the timetable for now, if it really satisfies everyone. [...] [Interjection about singing lessons.]

Then it would be nice if you could implement it so that it can be introduced on Thursday [December 7]. Then, as I understand it, it will be in full operation on Saturday.

ERICH SCHWEBCH presents the class timetables in accordance with Steiner's request of November 24. The request to have the timetables available for each class is hereby fulfilled].

RUDOLF STEINER reads aloud: The 1st grade has only one afternoon class. 2a and b also only one. 3a only on Monday afternoons. 3b only on Tuesday afternoons. 4a only on Monday afternoons. 4b only on Tuesday afternoons. 5a three afternoons, two of which are Catholic lessons. 5b also handicrafts and eurythmy on two afternoons, 6a three afternoons. It is not overloading. For the time being, the teachers are overloaded.

There is a question about confirmation classes.

KARL STOCKMEYER: We have to take this into consideration for the Protestant students.

RUDOLF STEINER: That's fine.

EUGEN KOLISKO: Some teachers are very overworked. Bernhardi has 20 hours, Melliger 22, Plincke 23, Treichler 25 hours. It would be desirable if these teachers could give up a total of ten hours. Some teachers have offered to take on extra hours, but it is not enough.

RUDOLF STEINER goes through the list of teachers, noting how many hours each one teaches and how many hours they have too many. He assumes that 16 to 17 hours per week is the desirable number; for example, one teacher has 20 hours, which is three to four hours too many.

RUDOLF STEINER: Well, if you could write to Tittmann. In any case, you can write to him and ask if he could take time off right away.

Baravalle, Baumann, Count Bothmer has the morning for his own culture. Friedenreich is quite busy. We'll be able to remedy that later. Röschl, how many hours do you have? 14 hours. We need to be clear about that in theory. Kolisko 15, Mrs. Kolisko 2, Lämmert 21, Leinhas 9, Mellinger has too many, 5 to 6 hours. Mrs. Molt, Naegelin, that's just right. Plincke has too many, 6 to 7 hours. Röhrle, Rutz too much by 2. [Ruhtenberg too much by 2.] Stein 15. Mrs. Stein, Stockmeyer, Strakosch. Schwebsch has too much uni 8 to 9 hours. Schubert 5 to 6. Treichler too much 8 to 9 hours. Uhland also too much 4 to 5 hours. Wolffhügel goes, Baravalle goes, Baumann goes. Bernhardi too much uni 4 hours. Bothmer leaves. Boy too much 2 to 3 hours. Doflein 2. Friedenreich, that's too much, of course, singing 4, then violin lessons. Too much 3 to 4. Geyer leaves. Hahn has too much by 4 to 5. Handicrafts leaves. Killian has too much uni 3.

Just so that's clear. In everyday life, teachers would demand royalties for these hours. But I think we want to try adding [the one new language teacher] Tittmann. Then I would like to have [another] gym teacher.

EUGEN KOLISKO asks whether the provisional relief proposal should be implemented.

RUDOLF STEINER: Hahn already has too many hours. That would only work if an exchange could take place. If, for example, you can take over a religion class, Dr. Röschl, then Hahn can swap. Swap with the one who seems to have the most to spare at first. [Mrs.] Plincke is the most willing to give up. Mrs. Plincke and Mellinger. With Treichler, we'll wait until Tittmann comes.

RUDOLF TRFICHLER objects.

RUDOLP ST EINER: There are also internal reasons. Be glad that people have more confidence in you. You are more robust. I find you very robust. You have to admit that you are more robust than Ms. Plincke. With Ms. Mellinger, it's that she still has so much. — We will make sure we get Tittmann as soon as possible.

If Mr. Rutz agrees, then Mrs. Plincke could also hand over class [4h] to him. It would be desirable for the changes that are now being made to remain in place and not be changed again.

HERBERT HAHN: Which group should I hand over to Miss Dr. Röschl?

RUDOLF STEINER: 10th and 11th. Now I would like to hear what faces the students will make when they have a female teacher instead of a male teacher. I would regret it if you were to hand over the 4th and 7th grades. I would find it more appropriate if Miss Röschl took over the 10th and 11th grades.

We had Mr. Arenson in class. It's strange, this disciplinary issue, which is now such that it hardly causes any difficulties in certain classes. In the classes I was in today, they were exemplary. They were extremely attentive with Boy. They were also attentive with Treichler. When you tell the children, it's always a little better. Today, the discipline was exceptionally good. I don't think they were better behaved than usual.

Miss Röschl would like to take over the lessons after Christmas.

I would like to make the change in such a way that it does not result in new workloads. If we were to see Miss Mellinger's lessons now, Miss Bernhardi can only get rid of French until Hahn gets rid of his lessons. Observe on Friday, and then we'll see. Then we'll have to wait until Tittmann is here. I would ask Miss Bernhardi to keep it until Tittmann arrives so that you can observe.

EUGEN KOLISKO: The class teachers have asked if they can take over the physical education lessons in their classes.

RUDOLF STEINER: There is no objection to this if [a] relief is provided, Pastor Geyer could do it. I don't think it's out of the question for two classes to have gym with two teachers in the same hall. That would be an extremely good thing, if it can be done, because it would serve an educational purpose. We have to bring the lessons right to the forefront of nervousness. The fact that this cannot be the case is a sign of nervousness. Ideally, mathematics should be taught in one corner, French, astronomy, and eurythmy in the other, so that the children have to focus their attention on their own activities.

ELISABETH BAUMANN: Could we also apply this to eurythmy?

RUDOLF STEINER: I would be happy if you could, because it would be pedagogically valuable. The teachers would have to get along well with each other.

EUGEN KOLISKO on swapping Killian and Boy.

RUDOLF STEINER: But that would give Boy 21 hours and Killian 17 hours.

I would suggest that we leave the further changes until Mr. Tittmann is here.

ERNST UEHLE: The religion teachers would like to keep the [previous] room for Sunday services; it should be used exclusively for that purpose.

RUDOLF STEINER: I agree. For this Sunday service, it is important that the atmosphere is right for those for whom this Sunday service is to be performed. This would best be achieved by making this arrangement.

HERBERT HAHN: Should Dr. Röschl and Mr. Wolffhügel also perform the service?

RUDOLF STEINER: Both must celebrate the ceremonies.

MAX WOLFFHÜGEL: I hadn't thought of that.

RUDOLF STEINER: That is a self-evident condition [for free religious education]. I would like to say the following about this. Isn't it true that experience has shown that free religious education does not consist merely of teaching something in a religion class, nor even of teaching in a pleasant manner, but that a certain relationship is also established between the religion teacher and the student, which is created through a ritual act? And if the ritual is performed by someone else, the religion teacher loses a good part of the imponderables for religious education for the students who receive the ritual from someone else. Conversely, those who perform a ritual without [giving] religious education find themselves in a precarious position that is difficult to justify. It is more justifiable to teach religious education without ritual than to perform ritual without religious education. This distinguishes religious education from empty theory. It is based on the relationship between the religious education teacher and the students. When I said that you should make up your mind, I was referring to the ritual.

MAX WOLFFHÜGEL: I haven't understood that yet.

RUDOLF STEINER: Now that we have everything completely set up, the first thing I would ask myself about a religious education teacher is: Can he perform the cult? You would also come to the wrong conclusion. If it were a question of who I consider suitable among the friends here, one could say [only] those whom I find suitable for the cult; but there could still be many who could be religion teachers. The cult acts could hardly be performed by anyone other than the two who have now been named, and I could consider Baumann. You must not be angry that one must speak sincerely in this regard, that everyone must know what they are considered suitable for. For now! That may change.

People must mature [on their own] for the youth celebration. [The nonsense of separate confirmation classes must stop. The youth celebration must take place when a certain maturity is present. But this maturity cannot be taught.] [So] it is not a matter of teaching, [but] of observation. Therefore, no special religious instruction should take the place of confirmation classes. [Only those who teach religious education should hold the youth celebration.]

A teacher asks about the artistic design of the activity room.

RUDOLF STEINER: I want to let that sink into my soul. I would think that if you could get a harmonium, that would be good. We want to carefully determine how we will develop this. There is nothing to say about the linguistic form, except that the Gospel texts are still missing. Musically and in terms of the visual arts, there is room for further development. On the other hand, there is another matter to consider, which may already have been dealt with. That is, what is the situation regarding the participation of the entire teaching staff?

There are two sides to this issue. It is very much a question of whether anything should be rushed in this regard. The religious renewal, imbued with culture, has the potential to become something [very] great. On the other hand, I hear the following assessment of [their] work. “Today, the situation is such that there is a religious community of one hundred members consisting solely of anthroposophists, who represent sectarian tendencies.” You see, there are dangers involved. They are real. “Those members who have not yet joined are being pressured.” The religious renewal was intended for outsiders. You must be aware that there are two sides to these things and that, above all, those who are now our anthroposophical friends, both within and outside this school, must see it as their mission to set straight the minds of those who could be heading down a slippery slope. The things that are connected with the noblest also involve the greatest dangers. This must not be taken lightly. Until this religious renewal has passed the absolute test of being true and right, it must not be claimed that one is less respected.

It is better if we first establish the cult for the children with great sincerity and warmth, if we do everything we can to create an atmosphere that shows it is something serious without being stuffy, but if, on the other hand, we keep it as simple as possible.

HERBERT HAHN: We have considered a few questions that we would like to put to the doctor. Regarding language teaching, whether it is possible to follow the musical-linguistic stream in the developing human being in the form of a single observation.

ERICH SCHWEBSCH: In the courses, there is often talk of the plastic-pictorial stream.

RUDOLF STEINER: Even more is hinted at in this little cycle, which I gave as a small [educational] cycle of four lectures in 1920 [in September].

If only you were so good, I mention it only because I already believe that it contains everything, [and] that you can concretize it.

On modern language teaching: If you equalize the method, things compensate each other [in their effects on the child], because French deadens the mind [just as strongly] as English stimulates the metabolism. The difficulty arises—and this has now crossed my mind—when English is removed for certain students. This is socially unnatural; it should not be the case, but we cannot help ourselves. We cannot have English and the ancient languages. But at this stage of their development, these two [languages] complement each other so incredibly well. For example, if you take Mr. Boy's French lesson today, he has developed something extremely important for silent listeners. The French language is in the process of silencing all the s's. There is no question of saying Aisne (= Än), but rather [the] s is heard. [During] the Battle of the Marne, it was [still] called Aisne (= Än). In English, many suffixes are on their way to getting rid of that shy s. Complete compensation is [particularly] evident between the ages of nine and ten, when the same methods are used. Before that, it is good to deal with French grammar as little [and as late] as possible. It didn't bother me in your class. In contrast, in English it is good to draw attention to something theoretical, to grammar and syntax, in the eleventh and twelfth years. So we will expand on that. I wanted to mention this preliminarily to see if it works. The second page is just that, it's one of the things I'm striving to maintain.

ERIcH SCHWEBSCH asks about the stages of language teaching.

RUDOLF STEINER: There are stages.

ERICH SCHWEBSCH [presumably]: Would you, Doctor, specify these stages? So far, things have developed in such a way that I have made a suggestion and then gone to the Doctor and asked him.

RUDOLF STEINER: It would be interesting to deal with these things in connection with the others. I intend to write an essay on Deinhardt's book, on the first elements of the aesthetic principle for teaching. Of course, it is exaggerated by both Schiller and Deinhardt himself. But one can very easily disentangle that.

Now it would be good to use this opportunity to mention the book to the publisher. Someone from the teaching circle could write a productive critique of the book, based on Schiller. You don't know the book yet? The book is difficult to read. Steffen was first asked to write a preface to this book, but he found it terribly boring. But that's only because of the long-winded sentences. The Austrian understands that there are such long-winded sentences in it. Some sentences make you want to do somersaults. Steffen can't stand it.

ERICH SCHWEBSCH: We assumed that such things would result in a textbook.

RUDOLF STEINER: That would be very good.

HERBERT HAHN asks about the method of questioning.

RUDOLF STEINER: There is something about that in the cycles.

MARIA RÖSCHL asks about optional English lessons in the upper grades.

RUDOLF STEINER: The children can have optional English lessons.

HERMANN VON BARAVALLE asks a mathematical question.

RUDOLF STEINER: I am happy to agree, if you try not to apply these things pedantically. If you bear in mind that the laws can be flexible, so that these are things that must never be treated pedantically. As soon as philistinism sets in, it is bad wherever there are spatial questions.

ERICH SCHWERSCH asks about the human ear.

RUDOLF STEINER: [The ossicles, hammer, anvil, stirrup, and oval window, are to be understood as limbs, like arms or legs, that probe the eardrum. A sense of probing to understand sound.

The cochlea, which is filled with fluid, is a higher, metamorphosed intestine of the ear; the feeling of sound lives in it. The Eustachian tube is where what one carries within oneself in terms of language comprehension, what comes to understanding as will, is at work. In the three arches, the three semicircular canals, the sound is essentially retained; this is the memory for sound. Every sense is actually a whole human being.]

These things are, sometimes simply put paradigmatically, there to excite people like Baumann and Schwebsch, so that they go and bring up all their experiences, [as] a book about such remarks. They said such things this morning. You have to specify all of that. It will seem plausible to them.

RUDOLF STEINER: Two songbooks by Baumann are now being published.

PAUL BAUMANN: Two songs [to texts] by you are in them.

RUDOLF STEINER: I am very pleased. Present the questions to me, I will come back on Saturday.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Miss Hofmann from Heidelberg spoke to Mr. Uehli.

RUDOLF STEINER: Miss Hofmann would be considered as a teacher in general. I have referred Miss Hofmann to the future. She is generally suitable as a teacher. The selection must be made carefully, step by step. What I would really like is Countess Hamilton as a teacher. She does not yet know enough German.

KARL STOCKMEYER asks the Doctor to open the new building after Christmas.

RUDOLF STEENER: It is difficult to do that. Not all classes are moving in. A number of classes will remain in the barracks, and if you make this a particularly festive occasion, it will create feelings in the children who are left behind that, when weighed against what you are doing with the celebration, will really carry a lot of weight. We have to consider this from a psychological point of view; when you organize a celebration for something you have opened, and then leave a number of children behind in the barracks. It would be possible to inaugurate a hall. But the whole house evokes inner resentment when it is inaugurated. The gymnasium can be opened.

I want to characterize Leisegang as a philosopher. He must be characterized as a caricature of a philosopher. He is a windbag. It is nonsense, judged purely from the point of view of what kind of philosopher he is. You can make it philistine and pedantic: what must a philosopher have? He must be able to base himself on actual documents. All the actual documents are false. You can prove to him that he has no actual basis. He is a philosopher who [gap in the transcript].

If you proceed in this way in philosophy, then that's just the way it is. I don't know of any profession where such a person belongs. He wouldn't be funny enough to write jokes in a newspaper.