Soul Economy

Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education

GA 303

26 December 1921, Stuttgart

IV. Education Based on Knowledge of the Human Being III

When trying to understand the world through a natural scientific interpretation of its phenomena, whether through cognition or through everyday life, people tend to consider conditions only as they meet them in the moment. Such a statement might seem incorrect to those who merely look at the surface of things, but as we proceed, it will become evident that this is indeed true. We have grown accustomed to investigate the human physical organism with the accepted methods of biology, physics, and anatomy, but (though this may appear wrong at first) in the results we find only what the present moment reveals to us.

For example, we might observe the lungs of a child, of an adult, and of an older person, in their stages from the beginning to the end of life, and we reach certain conclusions. But we do not really penetrate the element of time at all in this way, because we limit ourselves to spatial observations, which we then invest with qualities of time. We are doing the same thing, to use a simile, when we read the time by looking at a clock. We note the position of the hands in the morning, for example, and positions in space indicate the time for us. We may look at the clock again at noon and deduce the passage of time from the spatial changes of its hands. We take our bearing in the course of time from the movements of the clock’s hands from point to point in space. This has become our way of judging time in everyday life. But through this method we cannot experience the true nature of time. Yet only by penetrating time with the same awareness we use to experience space can we correctly assess human life between birth and death. I would like to illustrate these theoretical remarks with examples to show the importance of living into the dimension of time, especially if you want to practice the art of education.

Let us take as our example a child who is full of reverence toward adults. Anyone with a healthy instinct would consider such an attitude in a child as something wholesome, especially if such reverence is justified, as indeed it should be on the part of the adult. However, people usually think no further, but merely attribute a feeling of reverence toward adults to certain aspects of childhood and leave it at that. But we cannot recognize the importance of such reverence unless we include the entire course of a human life in our considerations.

As we grows older, we may have the opportunity to observe old people. We may discover that some of them have the gift of bringing soul comfort to those who need it. Often it is not what they have to say that acts as balm on a suffering soul, but just the tone of voice or the way they speak. If now you follow this old person’s life back to childhood, you find that, as a child, that individual was full of reverence and respect for adults. Naturally, this attitude of reverence will disappear in later life, but only on the surface. Deep down, it will gradually transform, only to reemerge later as the gift of bringing solace and elevation to suffering and troubled minds.

One could also say it this way: If a young child has learned to pray and has learned to develop an inner mood of prayer, this mood will enter the subconscious and transform into the capacity of blessing in the ripeness of old age. When we meet old people whose mere presence radiates blessing upon those around them, you find that in their childhood they experienced and developed this inner mood of prayer. Such a transformation can be discovered only if one has learned to experience time as concretely as we generally experience space. We must learn to recognize the time element with the same awareness with which we experience space. Time must not be experienced only in spatial terms, as when we look at a clock. What I have been trying to illustrate regarding the moral aspects of life needs to become very much a part of our concept of the human being—certainly if we are going to develop a true art of education. I would like to elaborate this in greater detail.

If we compare human beings with the animals, we find that from the moment of birth, animals (especially the higher species) are equipped with all the faculties needed for living. A chick leaving its shell does not need to learn to walk and is immediately adapted to its surroundings. Each animal’s organs are firmly adapted to the specific needs of its species. This is not at all true, however, of human beings, who come into this world completely helpless. Only gradually do we develop the capacities and skills needed for life. This is because the most important period in our earthly life is between the end of childhood and the beginning of old age. This central period of maturity is the most important feature of human life on earth. During that time, we adapt our organism to external life by gaining aptitudes and skills. We develop a reciprocal relationship to the outer world, based on our range of experience. This central period, when human organs maintain the ability to evolve and adapt, is completely missing in the life of animals. The animal is born in a state that is fundamentally comparable to an old person, whose organic forms have become rigid. If you want to understand the nature of an animal’s relationship to its surroundings, look at it in terms of our human time of old age.

Now we can ask whether an animal shows the characteristics of old age in its soul qualities. This is not the case, because in an animal there is also the opposite pole, which counteracts this falling into old age, and this is the animal’s capacity of reproduction. The ability to reproduce, whether in the human or animal kingdom, always engenders forces of rejuvenation. While animal fall prey to the influences of aging too quickly on the one hand, on the other they are saved from premature aging because of the influx of reproductive forces until maturity.

If you can observe an animal or an animal species without preconceived ideas, you will conclude that, when the animal is capable of reproduction, it has reached a stage equivalent to that of old age in a human being. The typical difference in the human being is the fact that both old age and childhood (when the child’s reproductive system is slowly maturing) are placed on either end of the human central period, and during this period the human organism remains flexible, enabling human beings to relate and adapt individually to the environment. Through this arrangement, a human being will be a child at the right time, then leave childhood at the right time to enter maturity. And a person leaves maturity when it is time to enter old age.

If you look at human life from this aspect of time, you also understand certain abnormalities. You may encounter people who (if I may put it this way) slip prematurely into old age. I am not thinking so much of the obvious features typically associated with old age, such as grey hair or baldness; even a bald-headed person may still be childish. I am thinking of the more subtle indications, detectable only by more intimate observations. One could call such features the signs of a senile soul life, manifesting in people who should still be in the central period of flexibility and adaptability. But the opposite may also happen; a person may be unable to leave the stage of childhood at the right time and carry infantile features into the central stage of life. In this case, strange things may happen in the life of that person—the symptoms of which we can only touch on today. When we include the time element in our picture of the human being, we can diagnose aberrations in human behavior.

We know that, as we approach old age, we lose flexibility especially in the head. Consequently, all the capacities that we have acquired during life attain more of a soul and spiritual quality. But this is possible only at the expense of the head as a whole assuming certain animal-like qualities. From a physical point of view, an old person goes through conditions similar to those of a newborn animal. To a certain extent one becomes “animalized.” Thus old people gain something that they may preserve for the rest of their lives, provided their education was right. Their spiritual, soul experiences of the outer world no longer enter fully into the human organization. The cranium becomes ossified and fixed. Old people thus depend more on soul and spiritual links with the surrounding world. They are no longer able to transform outer events into inward qualities as well as they once did. Thus, a kind of animalization of the upper regions takes place.

It is possible for this animalization of the head structure to occur prematurely—during the middle period of life—but because we remain human despite such a tendency, we do not encounter external symptoms. Rather, we must look for certain changes in the soul realm. If the characteristic relationship of the older person to the outer world manifests prematurely—and this can happen even during childhood—a person’s experiences is drawn too much into the physical system, since the general flexibility of the rest of the human organization, typical of the younger age, naturally retains the upper hand. In this case, a person will experience inwardly, and too early, a relationship to the outer world typical of old age. Interaction between inner and outer world would thus be linked too much to the physical organization, bringing about soul properties more like that in the animal world than in normal human beings.

One can say (if you want to express it in this way) that animals have the advantage of a certain instinct over human beings, an instinct that links them more directly and intimately to the environment than is true of the normal human being. It is not simply a myth, but completely reflects the peculiarities of animal life, that certain animals will leave a place that is in danger of a natural catastrophe. Animals are gifted with certain prophetic instincts of self-preservation. It is also true that animals experience far more intensely the changing seasons than do human beings. They can sense the approaching time for migration, because they have an intimate and instinctive relationship with the environment. If we could look into an animal’s soul, we would find—although entirely unconsciously—an instinctive wisdom of life that manifests as the animal’s ability to live entirely within the manifold processes and forces of nature.

Now, if a person falls victim to encroaching age too early, this animal-like instinctive experience of the surroundings begins to develop, though in a sublimated form because it is lifted into the human sphere. Lower forms of clairvoyance, such as telepathy, telekinesis and so on—described correctly or wrongly—occur abnormally in human life and are simply the result of this premature aging in the central period of life. When this process of aging occurs at the proper time, people experience it in a healthy way, whereas if it appears in the twenties, a person gains clairvoyance of a low order. The symptoms of premature aging represent an abnormality in life that does not manifest outwardly but in a more hidden way. If these forms of lower clairvoyance were studied from the aspect of premature aging, a people would gain far deeper insight into these phenomena. This is possible, however, only when people observe life in a more realistic way. It is not good enough to investigate what we see with our eyes at the present moment. People must learn to recognize indications in these symptoms of a time shift from later to earlier stages of life.

We will see in the next few days how healing processes can occur through exact insight into human nature. It is possible that a kind of animalization could manifest not as an outwardly visible aging process but as a close, instinctive relationship to the environment encroaching on the lower regions of the human being and otherwise characteristic of an animal. The resulting phenomena of telepathy, telekinesis, and so on do not become less interesting because they are recognized for what they really are—the intrusion of a later stage of life upon an earlier, not manifestations of the spirit world. By developing time consciousness, we can fathom the very depths of human nature. To live in the dimension of time is to survey the course of time until we can see into both the past and future from the present moment.

You can get a sense of how present-day observation (though externally it may appear otherwise) is very remote from this more inward means of observation, which is more concurrent with time and its flow. Inadequate interpretation of what we encounter in life is the result of modern methods of observation. Contemporary scientific explanations and their effects on life are full of anemic interpretations.

Looking at the course of human life, we discover that the opposite of what we just described can also happen when childishness is carried into maturity. It is characteristic of children that they not only experience the external world less consciously than adults, but their experiences are also much more intimately connected with metabolic changes. When children see colors, their impressions strongly affect the metabolic processes; a child takes in outer sensory impressions all the way into the metabolism. It is not a mere metaphor to say that children digest their sensory impressions, because their digestion responds to all of their outer experiences. An old person develops certain animal characteristics within the physical, but a child’s entire life is filled with a sensitivity toward the vegetative organic processes that also affect the child’s soul life. Unless we are aware of this, we cannot understand a child’s nature.

In later years, human beings leave the digestive and metabolic processes more or less on their own; experiences of the external world are more independent of those processes. They do not allow their soul and spiritual reactions toward the outer world to affect the metabolism to the extent that a child does. The response of adults to their surroundings is not accompanied by the same liveliness of glandular secretion as in children.

Children take in outer impressions as if they were edible substances, but adults leave their digestion to itself, and this alone makes them adults under normal circumstances. But there are cases where certain vegetative and organic forces, which are properly at work during childhood, continue to work in an adult, affecting the psyche as well. In this case, other abnormal symptoms are also liable to occur. An example will make this clear. Imagine, for example, a girl who comes to love a dog that has made a deep impression on her nature. If she has carried childishness into later life, this tenderness will work right into the metabolism. Organic processes that correspond to her feelings of affection will be established. In this situation, digestive processes occur not only after eating or as the result of normal physical activities, but certain areas within the digestive system will develop a habit of secreting and regenerating substances in response to the strong emotions evoked by the love for the animal. The dog will become indispensable to the well-being of her vegetative system. And what happens if the dog dies? The connection in outer life is broken; the organic processes continue by force of inertia, but they are no longer satisfied. Her feelings miss something they had gotten used to, and inner troubles and strange disturbances may follow. A friend may suggest getting a new dog to restore the previous state of health, since the inner organic processes would again find satisfaction through external experiences. We will see later, however, that there are better ways to cure such an abnormality, but anyone may reasonably try to solve the problem this way.

There are of course many other examples, less drastic than a deep affection for a dog. If an adult has not outgrown certain childhood forces that absorb external impressions into the digestive system, and if that adult can no longer satisfy this abnormal habit, certain cravings within the vegetative organism will result. But there are other things that may have been loved and lost that cannot be replaced; then a person remains dissatisfied, morose, and psychosomatic. One must try to find the true causes of the seemingly inexplicable symptoms that arise from the depths of the unconscious. There are people who can sense what needs to be done to alleviate suffering caused by unsatisfied emotions that affect inner organic processes. They manage to coax and to bring to consciousness what the patient wants to recall, and in this way they can help a great deal.

Because of the present condition of our civilization, there are many who have not progressed from childhood to adulthood in the normal way, and the ensuing symptoms, both light and serious, have been widely noted. Whereas this led naturally to conversations in ordinary life among helpful, interested people, the situation has stimulated—in many respects rightly so—psychological research, and a new scientific terminology has sprung up. The patient’s psyche is examined through investigation of dreams or by freely or involuntarily giving oneself away. In this way, unfulfilled urges arise from the subconscious into consciousness. This new branch of science is called psychology or psychoanalysis, the science of probing the hidden regions of the soul. However, we are not dealing with “hidden regions of the soul,” but with the remains of vegetative organic processes left behind and craving satisfaction. When thwarted desires have been diagnosed, one can help patients readapt, and here lies the value of psychoanalysis.

When judging these things, anthroposophy, or spiritual science, finds itself in a difficult position. It has no quarrel with the findings of natural science; on the contrary, spiritual science is quite prepared to recognize and accept whatever remains properly within its realm. Similarly, spiritual science accepts psychoanalysis within its proper limits. But spiritual science tries to see all problems and questions within the widest context, encompassing the entire universe and the whole human being. It feels it is necessary to broaden the arbitrary restrictions laid down by natural science, which even today often investigates in an unprofessional and superficial way. Anthroposophy has no wish and no intention to quarrel and only puts what is stated in a lopsided way into a wider perspective. Yet this approach is distasteful and unacceptable to those who prefer to wear blinders, and, consequently, furious attacks are made against anthroposophy. Spiritual science must defend itself against an imbalanced attitude, but it will never be aggressive. This has to be said regarding the present currents of thought, as we find in psychoanalysis.

A person may draw the last period of life too much into middle age and, with it, experience abnormal relationships with the external world, manifesting as lower forms of clairvoyance, such as telepathy. In this case, one’s horizon extends beyond the normal human scope in an animal-like fashion. It is important to distinguish the two opposing situations, since a person may also move in the other direction by pushing what properly belongs to childhood into later periods of life. As a result, one becomes enmeshed too strongly with the physical organism, with the result that organic surges swamp the psyche, causing disturbances and inner abnormalities. Such a person suffers from a relationship that is too close to one’s own organic system. This relationship has been diagnosed by psychoanalysis, which should nevertheless direct its attention toward the human organs to understand the roots of this problem.

If we desire a comprehensive knowledge of the human being, it is absolutely necessary to include the entire human life between birth and death in our considerations. It is essential to focus on the effects of passing time and to inwardly live with and experience those effects. Spiritual science pursues knowledge of the whole human being by penetrating the suprasensory, using its own specific methods and fully considering the time element, which is generally ignored completely in our present stage of civilization. Imagination, inspiration and intuition, which are the specific methods of spiritual scientific work, must be built on an experience of time.

Imagination, inspiration and intuition, the ways leading to suprasensory cognition, should not be seen as faculties beyond ordinary human life but as a continuation, or extension, of ordinary human capacities. Spiritual science dismisses the bias that maintains we can attain this sort of cognition only through some special grace; spiritual science holds that we can become conscious of certain faculties lying deep within us and that we have the power to train them. The usual kind of knowledge gotten through modern scientific training and in ordinary practical life must certainly be transcended.

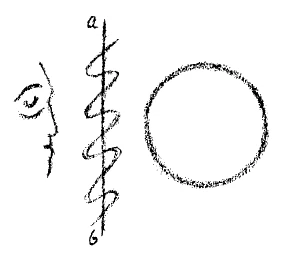

What happens when we try to comprehend the world around us—not as scientifically trained specialists but as ordinary people? We are surrounded by colors, sounds, varying degrees of warmth, and so on, all of which I would like to call the tapestry of the sensory world. We surrender to these sensory impressions and weave them without thoughts. If you think about the nature of memories rising in your soul, you will find that they are the result of sensory impressions woven into our thoughts. Our whole life depends on imparting this texture of sensory impressions and thoughts to our soul life. But what really happens? Look at the diagram. Let the line a to b represent the tapestry of the sensory world around us, consisting of colors, sounds, smells, and so on. We give ourselves up to our observation, this tapestry of the senses, and weave its impressions with our thinking (indicated here by the wavy line).

When living in our senses, we unite all our experiences with our thoughts. We interpret the sensory stimuli through thinking. But when we project our thoughts into our surroundings, this tapestry becomes a barrier for us, a metaphorical canvas upon which we draw and paint all our thoughts, but which we cannot penetrate. We cannot break through this incorporeal wall with ordinary consciousness. As the thoughts are stopped by this canvas, they are inscribed upon it.

The only possibility of penetrating this wall is gained by raising one’s consciousness to the state of imagination through systematic and regular meditation exercises. It is equally possible to undergo an inner training in meditation as a method of research in an outwardly directed study of chemistry or astronomy. If you read my book How to Know Higher Worlds and the second part of An Outline of Esoteric Science, you can convince yourselves that, if you want to reach the final goal, the methods for such meditative exercises are certainly not simple and less time-consuming than those needed to study astronomy or chemistry. On the other hand, it is relatively easy to read books giving information about such exercises and, using one’s common sense, examine the truths of spiritual scientific research. You do not have to take these on authority. Even if you cannot investigate the spiritual world yourself, it is possible to test given results by studying the specific methods employed.

Meditative practice is based on freeing ourselves from outer sensory impressions. In meditation, we do not surrender to sensory impressions, but to the life of thinking. However, by dwelling again and again in meditation on a given thought or mental image—one that is easily and fully comprehensible—we gradually bring our life of thought to such a strength and inner substance that we learn to move in it with the same certainty we have in our sensory impressions. You have all experienced the difference between the striking effects of outer sensory impressions and the rather limp and pale world of our thoughts during ordinary consciousness. Sensory impressions are intense and alive. We give ourselves up to them. Thoughts, on the other hand, turn pale and become abstract and cold. But the very core of meditating is learning, through regular practice, to imbue thoughts with the same intensity and life that normally fills our sensory experiences. If we succeed in grasping a meditation with the same inner intensity that we experience through the stimulus of a color, for example, then we have enlivened, in the right way, the underlying thoughts of a meditation. But all this must happen with the same inner freedom employed in the normal weaving of thoughts or ordinary sense perceptions. Just as we do not allow ourselves to be taken over by nebulous moods or mystical dreaming, or become fatuous visionaries when observing the external world, we must not lose our firm ground when meditating in the right way. The same sane mood with which we perceive the world around us must also take hold when we meditate.

This attitude of taking outer sensory perceptions as an example for one’s conduct when meditating is characteristic of the anthroposophic method. There are plenty of vague mystics who disparage sensory perceptions as inferior and advise leaving them behind. They claim that, when you meditate, you should reach a state of mystic dreaming. The result, of course, is a condition of half sleep, certainly not meditation. Spiritual science pursues the opposite goal, considering the quality, intensity, and liveliness of sensory perception as an example to be followed until the meditator moves inwardly with the same freedom with which one encounters sensory perceptions. We need not fear we will become dried up bores. The meditative content (which we experience objectively in meditative practice) saves us from that. Because of the inner content that we experience while freeing ourselves from ordinary life, there is no need to enter a vague, trance-like state while meditating.

Correct meditation allows us to gain the ability to move freely in our life of thinking. This in turn redeems the thoughts from their previous abstract nature; they become image-like. This happens in full consciousness, just as all healthy thinking takes place. It is essential that we do not lose full consciousness, and this distinguishes meditation from a hallucinatory state. Those who give themselves up to hallucinations, becoming futile enthusiasts or visionaries, relinquish common sense; on the other hand, those who wish to follow the methods advocated here must make sure common sense accompanies all their weaving thought imagery. And what does this lead to? Though fully awake, we experience the pictorial quality of the dream world. The significant difference between imagination and dream images is that we are completely passive when experiencing the imagery of dreams. If they arise from the subconscious and enter our waking state, we can observe them only after they have occurred. When practicing imagination, on the other hand, we initiate them ourselves; we create images that are not mere fantasy, but differ in intensity and strength from the fantasy as do dream images. The main point is that we initiate the images ourselves, and this frees us from the illusion that they are a manifestation of the external world. Those given up to hallucinations, however, always believe that what comes to them represents reality, because they know that they did not create what they see. This is the cause of the deception. Those who practice imagination through meditation cannot possibly believe that the images they create represent external reality. The first step toward suprasensory cognition depends on freeing ourselves from the illusion that the images we have created—having the same intensity as those of the dream world—are real. This, however, is obvious, because the meditator remains fully aware of having initiated them in complete freedom. Only the insane would mistake them for outer reality.

Now, in the next step in meditation we acquire the ability to allow these images to vanish without a trace. This is not as easy as one might expect, because, unless the one meditating has created them in full freedom, the images become quite fascinating and fix themselves on the mind like parasites. One has to become strong enough to let such pictures disappear at will. This second step is equally important as the first. In ordinary life, we need the ability to forget; otherwise we would have to go through life with the total of all our memories. Similarly, the complete extinction of meditative images is as important as their initial creation.

When we have thoroughly practiced these exercises, we have done something to our soul life that might be compared to the strengthening of muscles through repeated bending and stretching. By learning to weave and form images and then to obliterate them—and all this is done in complete freedom of the will—we have performed an important training of the soul. We will have developed the faculty of consciously forming images that, under normal circumstances, appear only in dreams, during a state that escapes ordinary consciousness and is confined to the time between falling asleep and awaking. Now, however, this condition has been induced in full consciousness and freedom. Training in imagination means training the will to consciously create images and to consciously remove them from the mind. And through this, we acquire yet another faculty.

Everyone has this faculty automatically—not during sleep, but at the moments of awaking and falling asleep. It is possible that what was experienced between these two points in time comes to us as remnants of dreams, often experienced as though they come from the beyond. Naturally, it is equally possible that what we encounter on awaking surprises us so much that all memories of dreams sink below the threshold of consciousness. In general, we can say that, because dream imaginations are experienced involuntarily, something chaotic and erratic that normally lies beyond consciousness finds its way to us. If, while fully awake, we develop the ability of creating and of obliterating imaginations, we may reach a condition of emptied consciousness. This is like a new awakening, then, from beyond the tapestry of the sensory world; spiritual entities pass through the tapestry to reach us on paths smoothed by the meditation content (see the circle in the diagram). While thus persevering in emptied consciousness, we push through the barrier of the senses, and images come to us from beyond the sensory world, carried by inspiration. We enter the world beyond the sensory world. Through imagination, we prepare for inspiration, which involves the ability to experience consciously something that happens unconsciously at the moment of awaking. Right at the moment of awaking, something from beyond our waking soul life enters consciousness, so that something beyond the conscious sensory world enters us if, through imagination, we have trained our soul as described.

In this way, we experience the spiritual world beyond the world of the senses. The faculties of suprasensory cognition are extensions of those naturally given to us in ordinary life. It is one of the main tasks of spiritual science to train and foster the development of these higher faculties. And grasping the time element in human life is fundamental to such development.

If you look at the preparatory exercises for imagination, inspiration, and intuition as given in How to Know Higher Worlds or An Outline of Esoteric Science, you find that everything said there aims at one thing: learning to experience the flow of time. The human being goes through the various stages of experience in the world, first as a child, then as a mature person, and finally as an old person; otherwise, one may suffer from an abnormal overlap of one stage into the other. It is not imagination itself, but the meditative preparation, that should give the possibility of developing the full potential and of learning how to give ourselves to the world out of the fullness of life. To this end harmony must be brought about between the specific contributions to the world of childhood, middle age, and old age. These must flow together harmoniously into a worldview capable of reaching the spiritual world. Human beings in their wholeness, which includes the domain of time, must be actively engaged in work in the world. To achieve a worldview that reaches beyond the barriers of the sensory world, human beings must preserve the freshness of experience proper to youth; the clarity of thought and the freedom of judgment proper to the central period of life; and the power of loving devotion toward life that can reach perfection in old age. All these qualities are a necessary preparation for the proper development of imagination, inspiration, and intuition.

Vierter Vortrag

Bei allen gegenwärtigen Betrachtungen, die ja dann ihren Ausdruck auf dem Erkenntnisgebiete und auch in der Lebenspraxis durch die intellektualistisch-naturalistische Welterklärung finden, legt man eigentlich eine Beobachtung desjenigen zugrunde, was dem Menschen im gegenwärtigen Augenblicke vorliegt. Aus Äußerlichkeiten könnte das anders erscheinen. Allein im weiteren Verlaufe dieser Darstellungen wird schon ersichtlich sein, daß es sich da eben doch um Äufßerlichkeiten handelt. Wir untersuchen den Menschen seiner Organisation nach durch die gewöhnliche Methode der Biologie, der Physiologie, der Anatomie, und wir machen uns da eigentlich immer mit demjenigen zu tun, was uns der gegenwärtige Augenblick bedeutet. Allerdings, es sieht zunächst anders aus. Wir untersuchen zum Beispiel die Lunge eines Kindes, die Lunge eines reifen Menschen, die Lunge eines Greises und stellen den augenblicklichen Befund fest. Dann ziehen wir unsere Schlußfolgerungen für den menschlichen Lebenslauf. Aus den Veränderungen der Lunge von der Kindheit bis zur Greisenhaftigkeit schließen wir etwas über die menschliche Entwickelung. Aber dasjenige, was wir da für den eigentlichen Verlauf tun, ist nicht ein Hineinleben in den zeitlichen Verlauf, sondern es ist doch ein Stehenbleiben bei dem Räumlichen, und den zeitlichen Verlauf schließen wir nur aus den räumlichen Veränderungen. Wir machen es ja so, wie wir es etwa bei unserer Beobachtung der Uhr machen. Wir beobachten die Uhr, sagen wir am Morgen, in ihrer Zeigerstellung und orientieren uns aus einem Räumlichen über die Zeit. Wir beobachten die Uhr dann am Mittag, orientieren uns wiederum aus einem Räumlichen über die Zeit. Wir schließen vom Räumlichen auf die Zeit. Diese Art, sich ins Leben hineinzustellen, ist überhaupt unsere gewöhnliche geworden. Wir beobachten den Augenblick, den wir erleben. Wir erleben ihn an dem Räumlichen. Aber nicht in der gleichen Weise erleben wir das innere Werden der Zeit. Nur dadurch kann man das Wesen des menschlichen Lebenslaufes zwischen Geburt und Tod richtig beurteilen, daß man sich ebenso lebendig in die Zeit versetzen kann, wie wir es gewohnt worden sind, uns in den Raum zu versetzen. Ich will das durch einige Beispiele erläutern, gerade mit Bezug auf das Menschenleben, was ich soeben theoretisch ausgesprochen habe. Denn gerade für denjenigen, der Erziehungs- und Unterrichtskunst üben will, ist dieses Sich-Einleben in den zeitlichen Verlauf von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit. Das sieht man aus solchen Beispielen.

Man nehme an, ein Kind entwickle eine ganz besondere Ehrfurcht für Erwachsene. Ein gesundes Empfinden wird gerade das beim Kind als etwas Gesundes ansehen, was eben das Kind zu einer solchen selbstverständlichen Ehrfurcht vor dem Erwachsenen führt, wenn diese Ehrfurcht durch die Eigenschaft des Erwachsenen berechtigt ist, und das soll ja so sein. Wir werden davon in den weiteren Vorträgen gerade im Sinne einer Erziehungs- und Unterrichtskunst zu sprechen haben. Jetzt will ich das nur als Beispiel anführen.

Nun beschränkt man sich gewöhnlich darauf, daß man sagt: Es gibt Kinder, die entwickeln eine solche Ehrfurcht. - Man schreibt das gewissen Eigentümlichkeiten gewisser kindlicher Wesen zu, und man begnügt sich mit dem Augenblick. Man gelangt niemals zu einer Erkenntnis der ganzen Bedeutung dieser Ehrfurcht, wenn man nicht das ganze menschliche Leben betrachtet. Man wird dann allmählich in die Lage kommen, den oder jenen Menschen in einem späten, vielleicht sehr späten Lebensalter zu beobachten, und man wird finden, daß es Menschen gibt, welche die Eigentümlichkeit haben, in selbstverständlicher Art andere, die einen Trost brauchen, zu trösten, anderen, die eine Erbauung brauchen aus der Not des Lebens heraus, eine solche Erbauung zu geben. Oftmals ist es wahrhaftig nicht einmal der Inhalt desjenigen, was solche tröstenden, erhebenden Menschen sagen; es liegt im Timbre, im Klang der Stimme; es ist die Art und Weise, wie sie sprechen. Geht man dann im Lebenslaufe solcher Menschen auf das Kindesalter zurück, dann findet man: das sind Menschen, die in ihrem Kindesalter ganz besonders der Ehrfurcht beflissen waren, der Hochachtung vor dem Erwachsenen. Dieses ehrfürchtige Sich-Verhalten zu den Erwachsenen, das verschwindet dann im Laufe der Zeit, lebt in den Untergründen des Lebenslaufes und tritt im reifen Alter in der Gabe, Erbauung, Erhebung zu bieten, wiederum auf.

Man kann das in einer gewissen Weise Geschilderte auch in der folgenden Art aussprechen. Man kann sagen: Wenn ein Kind so richtig aus dem Inneren heraus hat beten lernen, die Betstimmung hat entwickeln lernen, so geht diese Bestimmung in der angedeuteten Weise während des mittleren Stadiums des Lebens in die Untergründe des Lebens hinein und kommt in sehr späten Lebensaltern wieder heraus und äußert sich dann als eine gewisse Gabe des Segnens, die von anderen Menschen empfunden wird. Aber gerade bei solchen Menschen, deren Dasein im späteren Alter segnend wirkt für den Mitmenschen, wird man wiederum finden: sie haben die betende Stimmung in ihrer Kindheit zu eigen gehabt. — Solche Dinge findet man nur, wenn man ebenso mit der Zeit leben lernt, wie wir das mit dem Raume gewohnt geworden sind. Und es muß schon ein Wissen geben, das in der Zeit ebenso lebt wie im Raume, nämlich unmittelbar, nicht durch Schlußfolgerungen aus dem Räumlichen, wie wir es mit der Uhr machen.

Das, was ich Ihnen da, ich möchte sagen, für das moralisch-innerliche Leben durch ein paar Beispiele veranschaulicht habe, das muß aber, wenn es zu einer wirklichen Erziehungs- und Unterrichtskunst kommen soll, schon in den Anfängen der allgemeinen Menschenbetrachtung durchaus auch angewender werden. Und das kann in der folgenden Weise geschehen.

Wenn wir den Menschen, wie er uns als Ganzes im Leben entgegentritt, mit dem Tiere vergleichen, dann finden wir, daß das Tier, insbesondere das höhere Tier, gleich so geboren wird, daß es die ihm im Leben notwendigen Geschicklichkeiten besitzt. Das auskriechende Hühnchen ist schon ganz seiner Umgebung angepaßt, braucht nicht mehr zu lernen; seine Organe besitzen eine so feststehende Plastizität, wie das betreffende 'Tier nach seiner besonderen Art sie eben nötig hat. Das ist beim Menschen ja nicht der Fall. Der Mensch wird hilflos geboren, er muß erst durch die Außenwelt seine besondere Geschicklichkeit auf gewissen Gebieten erwerben. Das verdankt der Mensch dem Umstande, daß das Wichtigste in seinem irdischen Lebenslaufe eine mittlere Etappe ist zwischen der Kindheit und dem Greisenalter im weiteren Sinne. Diese mittlere Etappe, diese Zeit der Reife ist für das Leben des Menschen auf der Erde hier das Allerwichtigste. Da paßt er seine Organisation durch Erwerbung der Geschicklichkeit dem äußeren Leben an. Da tritt er mit der äußeren Welt in erfahrungsgemäße Beziehung. Diese mittlere Etappe, in der die Organe noch ihre labile Plastizität haben, fehlt eigentlich dem Tier vollständig. Das Tier wird schon so in das Leben hineingeboren, wie wir Menschen im Grunde erst als Greise werden, wo unsere Formen fest werden, wo unseren Formen eine feststehende Plastizität eigen ist. Will man die Animalität verstehen in ihrer Beziehung zur Welt, so versteht man sie eigentlich nur richtig, wenn man sie mit der menschlichen Greisenhaftigkeit vergleicht.

Es kann aber dann die Frage auftauchen: Äußert sich nicht das Tier auch in seinen seelischen Eigenschaften sogleich in Greisenhaftigkeit? — Das ist nicht der Fall, weil ein anderer Pol noch da ist im Tiere, der diesem Greisigen entgegenwirkt, und das ist die Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit. Die Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit ist zugleich für den Menschen, der sie trägt oder für das Wesen, das sie trägt, ein Verjüngendes. Und indem das Tier auf der einen Seite die Greisenhaftigkeit entwickelt, auf der anderen Seite aber in diese Greisenhaftigkeit die Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit hineinfließt, bleibt es in einer gewissen Weise doch bewahrt vor dem zu frühen Ergreisen, bis es fortpflanzungsfähig wird.

Können Sie aber ein Tier oder eine Tierart unbefangen betrachten, dann werden Sie sich sagen: in dem Momente, wo das Tier bei der Fähigkeit anlangt, Nachkommenschaft zu erzeugen, ist es eigentlich schon in die Greisenhaftigkeit hineingekommen. Das ist gerade das Eigentümliche beim Menschen, daß sowohl Greisenhaftigkeit wie Kindhaftigkeit - denn während der Kindhaftigkeit entwickelt sich langsam die Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit-an die Enden des Lebens gestellt sind, und in der Mitte die organisch-plastische Etappe drinnen liegt, die sich durch die Beziehung mit der Außenwelt an diese Außenwelt anpassen kann. Und man kann es in einem gewissen Sinne das Normale des Menschenlebens nennen, daß diese mittlere Etappe in der richtigen Weise bei dem Menschen vorhanden ist. Dann werden gewissermaßen in der richtigen Zeit die Menschen Kinder sein, aufhören in der richtigen Zeit, Kinder zu sein, ins Reifealter eintreten, und sie werden auch in der richtigen Zeit aus dem Reifealter in das Greisenalter eintreten.

Wenn man diesen ganzen Lebensweg des Menschen mit einem SichHineinversetzen in das Zeitliche betrachtet, dann kommt man gerade von da aus auch zu der Betrachtung der Abnormitäten. Man kann nämlich bei gewissen menschlichen Individuen sehen, wie sie es, wenn ich so sagen darf, nicht verstehen, die Greisenhaftigkeit lange genug zurückzuhalten. Ich denke jetzt gar nicht an diejenige Greisenhaftigkeit, die gleich graue Haare oder frühzeitig kahlen Schädel bekommt, diese Greisenhaftigkeit meine ich nicht, denn man kann lange, wenn man einen kahlen Schädel bekommen hat, noch ein Kindskopf geblieben sein, aber ich meine diejenige Greisenhaftigkeit, die sich mehr innerlich, organisch äußert, und die auch nur einer inneren Lebensbeobachtung, einer intimen Lebensbeobachtung gegenüber sichtbar wird: die seelische, wenn wir sie so nennen dürfen, Greisenhaftigkeit, die dann in das Leben hereinspielt, wenn dieses Leben äußerlich durchaus in der plastischen Etappe ist.

Es kann aber auch das Umgekehrte eintreten: der Mensch kann in seinem Lebenslauf nicht in der rechten Zeit die Kindhaftigkeit verlassen. Dann spielt die Kindhaftigkeit in das mittlere Lebensalter hinein; dann trägt er dasjenige, was er eigentlich nur innerlich-seelisch als Kind haben sollte, in das mittlere Alter hinein. Und durch dieses entsteht im menschlichen Lebenslaufe ganz besonders Eigentümliches, das wir heute skizzenhaft zu betrachten haben werden.

Betrachtet man das menschliche Leben von diesem Gesichtspunkre aus in seinem zeitlichen Verlaufe, so kann man von dem sogenannten normalen Menschenleben zu den verschiedenen Abnormitäten dieses Menschenlebens kommen. Indem wir als Mensch der Greisenhaftigkeit entgegengehen, verliert ja insbesondere unsere Kopf-, unsere Hauptesorganisation die innere Beweglichkeit, die bewegliche Plastik. Wir werden steifer, unplastischer in bezug auf die Hauptesorganisation, wenn es gegen das Lebensende zugeht. Und alle diejenigen Fähigkeiten, die wir uns im Leben erworben haben, werden im Greisenalter seelischer, geistiger. Aber das geschieht auf Kosten einer Animalisierung unserer Hauptesorganisation. Wir werden physisch so, wie das Tier vom Anfange an ist. Wir werden gewissermaßen animalisiert. Dadurch erkaufen wir uns dasjenige, was wir, wenn die Erziehung richtig ist, vielleicht für das ganze Leben noch haben können an geistig-seelischem Zusammenhang mit dem Leben, wir erkaufen uns das dadurch, daß in diesem späteren Lebensalter gewissermaßen das, was wir geistig-seelisch mit der Welt erleben, nicht mehr so recht in unsere Organisation hineingeht. Der Schädel ist zu steif, plastisch zu fest geworden. Wir hantieren in dem Greisenalter daher mehr mit dem, was uns seelisch-geistig mit der Außenwelt verbindet. Wir nehmen nicht mehr in gleich starkem Maße wie früher dasjenige, was wir an der Außenwelt erfahren, in unsere Innerlichkeit hinein. Eine Animalisierung unserer oberen Organisation tritt ein.

Diese Animalisierung unserer oberen Organisation, die kann nun tatsächlich deplaciert schon in dem frühen Reifealter eintreten, in der innerlichen Weise, wie ich das auseinandergesetzt habe. Weil aber der Mensch selbstverständlich noch immer Mensch bleibt, also auch, wenn er gewissermaßen seiner Kopforganisation nach animalisiert ist, doch Mensch ist, so tritt uns das, was hier in Betracht kommt, nicht in äußerlichen Merkmalen entgegen, sondern eben in innerlich-seelischen Eigentümlichkeiten. Das geschieht so: Wenn diese besondere Art, mit der Außenwelt in Verbindung zu kommen, die der Greis oder die Greisin hat, zu früh eintritt, sie kann sogar schon im Kindesalter eintreten, so tritt diese -- weil ja dann doch natürlich die Plastizität im übrigen Menschen noch überwiegt — zurück in die physische Organisation und man erlebt dasjenige, was man in einem gesunden Verhältnis zur Außenwelt erlebt, wenn man verstanden hat, in der richtigen Zeit Greis zu werden, auf innerliche Art früher. Man verbindet es mit seinem Physischen. Man nimmt es auf in seine physische Organisation, und es kommen dadurch Eigenschaften zustande, die dem Animalischen, dem Tierhaften ähnlicher werden, als sie sonst bei normalen Menschen sind.

Das Tier hat, man kann sagen, wenn man will, vor dem Menschen einen gewissen Instinkt voraus, der es mit seiner Umgebung in einem höheren Maße verbindet, als der Mensch im normalen Zustande mit seiner Umgebung verbunden ist. Es ist keineswegs eine Legende, sondern entspricht durchaus den Eigentümlichkeiten des tierischen Lebens, daß gewisse Tiere, wenn Naturereignisse herannahen, die ihrem Leben gefährlich werden, von diesen Orten, wo die Gefahr eintreten könnte, wegziehen. Tiere haben eine gewisse instinktive, prophetische Gabe, wenn es sich um die Bewahrung ihres Lebens handelt. Es ist auch durchaus richtig geschildert, wenn man sagt, das Tier empfinde in einem viel höheren Maße als der Mensch den Lauf der Jahreszeiten mit. Das Tier empfindet das Herannahen jener Zeit, in der es fortfliegen muß, wenn es ein Wandertier ist, um andere Orte aufzusuchen. Das Tier hat also eine intime instinktive Beziehung zur Umgebung. Und könnte man in das hineinschauen, was da im tierischen Seelenleben vor sich geht, so würde man, zwar ganz eingekleidet in das Unbewußte, aber doch sehen, wie das Tier eine instinktive Lebensweisheit hat, die sich als ein Zusammenleben mit dem ganzen Naturverlaufe äußert.

Wenn der Mensch in der angedeuteten Weise frühzeitig die Greisenhaftigkeit in sein Leben hereinbekommt, dann tritt, nun allerdings nicht gleich wie beim Tier, weil beim Menschen alles in das Menschliche heraufgehoben wird, aber es tritt doch dieses instinktive Erleben der Umwelt auf. Und dasjenige, was man heute kennt, vielfach richtig, vielfach auch falsch beschreibt als niederes Hellsehen, als Telepathie, als Teleplastie, als Telekinesie, Dinge also, die abnorm im Menschenleben auftreten, das ist nichts anderes als ein Hereinspielen der Greisenhaftigkeit in das frühere Erleben des Menschen. Man kann die Greisenhaftigkeit eben zur richtigen Zeit erleben, dann erlebt man sie als gesunder Mensch. Wenn man die Greisenhaftigkeit schon mit zwanzig Jahren erlebt, wird man im niederen Sinne ein Hellseher. Es äußern sich eben die Dinge, die als Offenbarung der frühzeitigen Greisenhaftigkeit auftreten und Abnormitäten des Lebens darstellen, nicht so sehr in den äußeren als in den inneren Merkmalen. Man würde in das, was als niederes Hellsehen, als Telepathie, Telekinesie, Teleplastie vorhanden ist, was ja bis zu gewissen Graden schon sehr gut erforscht ist, viel tiefere Blicke hinein tun, wenn man den Gesichtspunkt in der richtigen Weise würdigen könnte, daß man es da mit einem frühzeitigen innerlichen Vergreisen zu tun hat.

Aber man muß dann zu einer wirklichen Lebensbetrachtung vorschreiten. Man muß im gegenwärtigen Augenblicke nicht nur dasjenige sehen, was räumlich vor einem steht, sondern man muß ihn so interpretieren können, daß man weiß: wenn man den Menschen im gegenwärtigen Augenblicke betrachtet und er diese und jene Eigentümlichkeiten zeigt, so rührt das davon her, daß dasjenige, was eigentlich später sein soll, in ein Früheres hereinspielt.

Wir werden in den nächsten Tagen sehen, wie gerade Heilprozesse durch ein solches Hineinschauen in die menschliche Natur in einer exakten Weise zustande kommen können. Es ist durchaus also eine Art Animalisierung des Menschen möglich, die sich dann aber nicht in einem äußerlichen Greisenhaftwerden äußert, sondern dadurch, daß die sonst im tierischen Instinkt auf tierhafte Art auftretenden Beziehungen zur Umwelt ins Menschliche, aber ins Niedrig-Menschliche herauf übersetzt werden.

Für die unbefangene Weltbetrachtung verlieren ja natürlich die Eigentümlichkeiten der Telepathie, Telekinesie, Teleplastie nicht. das Bedeutungsvolle, wenn man sie in dieser Weise nicht als eine Äußerung eines Übersinnlichen betrachtet, sondern als dasjenige, was sich ergibt durch das Hereinspielen eines Späteren in das frühere menschliche Leben. Man lernt dadurch gerade auch die menschliche Wesenheit in ihrem Grundcharakter erkennen, daß man sie so zeitlich betrachtet; denn zeitlich betrachten heißt eben: nicht aus den verschiedenen Augenblicken des Lebens Schlüsse ziehen über Lebensverläufe, sondern innerlich mitleben mit der Zeit und auch sehen können, wie das Spätere, statt später zum Vorschein zu kommen, sich früher auslebt. Zeitlich anschauen, heißt: die Zeit überblicken in der Anschauung, und im gegenwärtigen Augenblicke Vergangenheit und Zukunft sehen können.

Sie werden selber fühlen, wie eigentlich unserer gegenwärtigen Betrachtung, wenn das auch äußerlich anders aussieht, diese innerliche, der Zeit und ihrem Verlauf gemäße Anschauungsweise durchaus fernliegt. Daher kommen dann die ungenügenden Interpretationen desjenigen, was im Leben auftritt. Und von diesen ungenügenden Interpretationen ist ja heute das sogenannte wissenschaftliche Erkennen und die Wirkung des wissenschaftlichen Erkennens auf das Leben voll.

Aber auch der umgekehrte Fall kann eintreten: es kann das Kindhafte in das spätere, reife Leben des Menschen hineinspielen. Das Kindhafte besteht darinnen, daß nicht nur in instinktiver Weise durch die Kopforganisation die Verhältnisse der Umwelt erlebt werden, sondern die Kopforganisation lebt im Stoffwechsel intensiv dasjenige mit, was sein Verhältnis zur Außenwelt ist. Wenn das Kind Farben sieht, so geschehen in ihm lebhafte Stoffwechselvorgänge. Das Kind konsumiert gewissermaßen die äußeren Eindrücke auch bis in seinen Stoffwechsel hinein. Man kann durchaus sagen, ohne bildlich, sondern ganz real zu sprechen: die Magenfunktion des Kindes richtet sich nicht nur nach den Speisen wegen des Geschmackes und ihrer Verdaulichkeit, sondern auch nach den Farbeneindrücken der Umgebung. Sie richtet sich nach dem, was das Kind aus der Umgebung herein erlebt. So daß man sagen kann: Bei dem Greise haben wir eine Animalisierung des Lebens in physischer Beziehung; bei dem Kinde haben wir das ganze Leben erfüllt von einer Sensitivität des vegetativ-organischen Prozesses.

Der vegetativ-organische Prozeß, nicht der animalisch-organische, sondern der vegetativ-organische Prozeß erlebt bei dem Kinde mit alles, was es in der Außenwelt erfährt. Das geht eben durchaus bis in die seelischen Eigenschaften hinein. So daß wir bei dem Kinde niemals zu einer vollständigen Erkenntnis kommen, wenn wir uns nicht auch fragen: Wie konsumiert das Kind bis in seinen Stoffwechsel hinein seine Eindrücke? — Darin besteht ja das sogenannte normale Menschenleben, daß der Mensch dann im späteren, reifen Alter seinen Stoffwechsel mehr sich selbst überläßt, daß er das Leben mit der Außenwelt wiederum in einer selbständigeren Weise erlebt, daß der Mensch dasjenige, was er seelisch-geistig mit der Außenwelt erlebt, nicht so wie das Kind hinunterläßt in den Stoffwechsel, daß nicht immer von einer so lebendigen, innerlichen Drüsenabsonderung, wie es beim Kinde der Fall ist, alle äußeren Beziehungen zur Außenwelt begleitet werden.

Das Kind konsumiert dasjenige, was es in der Außenwelt erlebt, ich möchte sagen, wie eine Nahrung. Und der spätere, reife Mensch überläßt seinen Stoffwechsel sich selber. Er ist nur dadurch eben ein reifer Mensch im normalen Leben, daß die Dinge nicht so tief in seine vegetativ-organischen Prozesse hineingehen. Aber es kann das bei gewissen Individuen bleiben. Gewisse Individuen können die Kindhaftigkeit in das spätere Leben hineintragen. Dann behalten sie eben diese Eigenschaft, daß sie das äußere Erleben mit ihren organischen Prozessen verbinden, daß sie auch Seelisches noch mit ihren organisch-vegetativen Prozessen verbinden.

Nehmen wir ein Beispiel: Jemand, der schon ein gewisses Reifealter erlangt hat, entfaltet eine besondere Liebe, nun, sagen wir, zu einem Hund. Solche intensive Hundelieben gibt es ja. Und gerade solche Lieben sind oftmals mit einer starken Intensität des Erlebens verbunden. Wenn dann bei einem solchen Menschen das vorliegt, daß er etwas von der Kindhaftigkeit in das spätere reife Alter hineingetragen hat, oder auch, daß er in der Kindheit die Kindhaftigkeit in einem gesteigerten Maße erlebt, dann bleibt es bei dieser Liebe nicht allein bei dem seelischen Bezug zur Außenwelt, sondern diese Liebe ruft organische, vegetative Prozesse hervor. Der Organismus erlebt diese Liebe mit. Es geschieht immer etwas, wenn diese Liebe lebhaft empfunden wird, auch in den Stoffwechselvorgängen. Die Stoffwechselvorgänge gewöhnen sich dann, nicht nur dem normalen Verdauen, dem normalen Herumgehen in der Welt, dem sonstigen normalen Leben zu dienen, sondern ein gewisses Gebiet, eine gewisse Provinz des Stoffwechsels gewöhnt sich auch daran, solche Absonderungen und wiederum Regenerationen zu haben, wie es diesem besonderen Falle der lebhaften Empfindung dieser Hundeliebe entspricht. Eine gewisse Provinz der Organisation bedarf dieser besonderen Veränderung, die da innerlich rein organisch-vegetativ eintritt im Gefolge der Hundeliebe.

Und nun nehmen Sie an, der Hund stirbt. Die äußere Lebensbeziehung kann sich nicht mehr entwickeln, sie ist nicht mehr da. Der Hund ist gestorben; aber eine innere Provinz des Vegetativ-Organischen hat sich gewöhnt, solche Prozesse zu entwickeln. Es kommt beim Menschen dazu, daß dieser Organprozeß, der jetzt nicht mehr seine Befriedigung hat, dem die äußere Anschauung fehlt, weiter funktioniert, aber eben nicht mehr befriedigt wird, weil sein äußeres Korrelat nicht mehr da ist. Solche organische Prozesse haben ihre innere Trägheit; sie setzen sich fort. Das rumort im Inneren des Menschen. Und es können die sonderbarsten Störungen zurückbleiben, wenn zum Beispiel eine Hundeliebe so in die Organ-Vegetativprozesse aufgenommen ist und der Hund dann stirbt.

Ist ein vernünftiger Mensch da, der auch einige Lebenspraxis hat, was wird dieser Mensch tun? Nun, er wird sich wahrscheinlich darum bemühen, daß ein anderer Hund gekauft wird und dann Sorge dafür tragen, daß der betreffende frühere Hundebesitzer diesen neuen Hund ebenso liebgewinnen kann. Wenn er das erreicht hat, dann hat er eigentlich eine heilsame Handlung vollzogen; denn jetzt kann sich der innere organische Prozeß wiederum an dem äußeren Erleben befriedigen. Wir werden allerdings im Laufe dieser Vorträge sehen, daß es auch noch gescheitere Behandlungsmethoden gibt, aber ich meine, ein mittelvernünftiger Mensch wird so ungefähr handeln.

Nun gibt es ja aber allerdings solche Erlebnisse der Außenwelt, die nicht so drastisch sind wie gerade eine Hundeliebe. Unzähliges können wir an der Außenwelt erleben. Und wenn dann das erlebende Individuum die Kindhaftigkeit, das heißt, dieses Konsumieren der Außenwelt in sich lebendig erhalten hat, dann wird bei einem solchen Individuum etwas vom Rumoren im vegetativen Organismus zurückbleiben, wenn ihm das Erleben entzogen wird, wenn es also das, woran sich innere Prozesse entwickelt haben, nicht mehr äußerlich erleben kann. Diese Dinge gibt es im menschlichen Leben, wo man aufsuchen muß, woher ein solcher innerer Zustand kommt, der unerklärlich aus den menschlichen Tiefen aufsteigt. Der Mensch wird dadurch unbefriedigt, moros, hypochondrisch, bekommt alle möglichen Folgezustände. Geht man dem nach, so findet man, daß ihm irgend etwas durch das Leben oder durch Sonstiges entzogen ist, was eigentlich schon in den vegetativ-organischen Prozessen sein Korrelat gefunden hat. Wenn ein solcher Mensch mit seinem Bewußtsein auf die Außenwelt hinschaut, kann er sich nicht mehr die Befriedigung verschaffen für das, was in seinem Organismus drinnen rumort. Es geht etwas in seinem Organismus vor, was eigentlich außen angeschaut oder wenigstens gedacht sein will, und was er nicht denken kann, weil die Veranlassung dazu nicht da ist.

Wiederum finden wir lebenspraktische Leute, die haben die Eigentümlichkeit, daß sie instinktiv solche Dinge aus dem Menschen herauswittern, wenn er sie hat, und dann finden sie die Möglichkeit, allerlei zu ihm zu sprechen, was diese Dinge aus den unbestimmten Tiefen des Vegetativ-Organischen heraufbringt und sie ins Gedankenleben, ins Vorstellungsleben erhebt, so daß der Mensch das denken kann, vorstellen kann, was er eigentlich zu denken, vorzustellen begehrt. Wer das Leben beobachten kann, wird unzählige solche Zusprüche im Leben finden, wo einfach ein vegetativ-organischer Inhalt, der aus früherer Enttäuschung, aus einem früheren Entziehen eines Lebensinhaltes herrührt, dadurch geheilt, abgeleitet wird, daß man wenigstens in dem Eindringlichen der menschlichen Zusprache an den Menschen herantritt und auch in sein Bewußtseinsleben einführt, was er braucht.

Da es in der Gegenwart durch die besondere Artung unserer Zivilisation wirklich recht viele Individuen gibt, welche ihr Kindhaftes in ihr Reifealter hereinspielen haben, so hat man das, was ich jetzt anführte, in leichten und schweren Fällen viel bemerkt. Während man im gewöhnlichen Leben nicht viel Aufsehens damit macht, von Zuspruch spricht, der in liebevoller Hingabe der einen Person an die andere manches Heilsame bewirken kann, hat man das auch einfließen lassen, in vieler Beziehung mit Recht einfließen lassen in die wissenschaftlich-psychologische Betrachtungsweise. Man hat solche Menschen vor sich, die ein solches innerliches Rumoren haben. Wir wissen jetzt, es rührt dieses innerliche Rumoren von zurückgebliebenen, aus Lebensenttäuschungen und dergleichen zurückgebliebenen vegetativ-organischen Prozessen her. Man hat solche Menschen vor sich. Man muß sich dann, wenn man die Sache ins wissenschaftliche Gebiet überführt, natürlich auch wissenschaftlich ausdrücken. Man untersucht dann den betreffenden Menschen. Und aus seinem bisherigen Lebenslauf, den man durch Beichten oder durch die Träume, die er hat, oder durch sonst etwas auskundschaftet, findet man, was nötig ist, um dem Menschen dasjenige ins Bewußtsein überzuführen, was eben vom unterbewußten Vegetativ-Organischen begehrt wird. Man nennt das dann analytische Psychologie oder Psychoanalyse. Man spricht dann, selbstverständlich wissenschaftlich sich ausdrückend, von «verborgenen Seelenprovinzen». Es sind nicht «verborgene Seelenprovinzen», sondern es sind vegetativ-organische Prozesse, die in der geschilderten Weise zurückbleiben, die nach Erfüllung von außen begehren. Und man sucht nach dem, was man dem Menschen als eine solche Erfüllung bieten kann. Man sagt: Man sorgt für die Abreagierung solcher verhaltener Prozesse. — Sehen Sie, in dem, was ich eben angedeutet habe, liegt das Berechtigte der sogenannten analytischen Psychologie oder der Psychoanalyse.

Anthroposophie ist immer solchen Dingen gegenüber, die ja auf ihrem Gebiete durchaus als berechtigt auftreten, in einer besonderen Lage. Anthroposophie ist eigentlich gar nicht von sich aus streitsüchtig. Sie anerkennt gern all das, was innerhalb desjenigen Horizontes auftritt, in dem es berechtigt ist. So wird sie innerhalb des Horizontes, in dem sie berechtigt ist, selbstverständlich auch die Psychoanalyse anerkennen. Aber Anthroposophie muß die Dinge aus der menschlichen Vollnatur und aus einer totalen Welterklärung heraus suchen, muß also gewissermaßen die kleinen Kreise, die in etwas dilettantenhafter, laienhafter Art auch heute von Wissenschaftern getrieben werden, in gröBere Kreise einbeziehen. Sie hat deshalb keine Veranlassung zu streiten. Sie schließt nur das, was einseitig erklärt wird, in den großen Kreis ein. Sie fängt daher in der Regel von sich aus nicht zu streiten an. Aber die anderen streiten, denn die wollen bei ihrem kleinen Kreise bleiben. Die sehen in ihrer Art nur das, was in diesem kleinen Kreise ist. Und weil sie dasjenige, was von einem größeren Horizont ist und sie eigentlich im Grunde genommen fördert, gar nicht besonders verlockt, weisen sie es wütend ab. So daß in der Regel Anthroposophie nur genötigt ist, sich gegen die Einseitigkeiten zu wehren, die sie attackieren. Das ist etwas, was besonders gegenüber solchen Zeitströmungen, wie der psychoanalytischen, gesagt werden muß.

Das besonders Eigentümliche ist ja dieses, daß wir also sehen: wenn der Mensch dazu kommt, sein Lebensende zu stark in die mittlere Lebensetappe hereinzuziehen, dann entstehen die abnormen Beziehungen zu der Außenwelt, Telepathie, Hellsehen im niederen Sinne. Der Mensch erweitert in instinktiver Weise seinen Horizont über seine Lebenskreise hinaus. Wenn der Mensch nach der umgekehrten Richtung geht, wenn er das, was an seinen Lebensanfang in die Kindhaftigkeit hineingehört, in die späteren Lebensepochen hineinschiebt, dann dringt er mit seinem Wesen zu tief in sein Organisches hinein, dann wirft das Organische Wogen herauf, dann entstehen Abnormitäten nach dem Inneren; er tritt gewissermaßen mit seinem eigenen organischen Inneren in eine zu nahe Beziehung. Und diese Beziehungen stellen sich eben dann so heraus, wie sie von der analytischen Psychologie beschrieben werden, die aber eigentlich hinuntergehen müßte in die Organologie, damit sie wirklich erfaßt werden.

Zu einer vollständigen Menschenerkenntnis ist eben durchaus das Hereinziehen des zeitlichen Lebensverlaufes zwischen Geburt und Tod notwendig. Und eine solche vollständige Menschenerkenntnis ist daher darauf angewiesen, gerade alles Augenmerk auf den zeitlichen Verlauf des Lebens hinzulenken, den zeitlichen Verlauf des Lebens mitzuerleben. Gerade deshalb muß Anthroposophie, indem sie durch ihre besondere Methode ins Übersinnliche und dadurch in eine vollständige Menschenerkenntnis eindringen will, sie muß sich an das Einleben im Zeitlichen halten können. Der Mensch beachtet eben im Sinne der heutigen Zivilisation dieses Zeitliche nicht. Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition, welches die besonderen Erkenntnismethoden der Anthroposophie sind, müssen durchaus auf einem zeitlichen Erleben des Daseins aufgebaut sein.

Imagination, Inspiration und Intuition soll nun nicht etwas sein, was sich als ein ganz Fremdes ins Menschenleben hineinstellt und als Fremdes zur übersinnlichen Erkenntnis führen soll, sondern etwas, was durchaus in der Fortsetzung der gewöhnlichen menschlichen Fähigkeiten liegt. Es wird also von Anthroposophie nicht behauptet, daß irgendwelche besondere Begnadigungen vorliegen müßten, um zu Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition zu kornmen, sondern daß der Mensch sich gewisser tiefer in ihm liegenden Fähigkeiten bewußt werden könne, die er ganz sachgemäß entwickeln kann. Aufgestiegen werden muß durchaus von jener Art von Erkenntnis, die wir uns im gewöhnlichen Leben im heutigen wissenschaftlichen Erkennen und in der heutigen Lebenspraxis aneignen.

Wie verfahren wir denn da eigentlich, indem wir erkennende Menschen werden? Ich meine jetzt erkennende Menschen eben nicht nur als wissenschaftlich erkennende Menschen, sondern erkennende Menschen durchaus nur in dem Sinne, wie wir es sein müssen, um unser Leben in praktischer Weise durchzuführen. Wir haben dasjenige um uns herum, was wir nennen möchten den Sinnesteppich: die Farbenwelt, die Tonwelt, die Welt der Wärmeverhältnisse und so weiter, alles dasjenige, was auf unsere Sinnesorgane Eindruck macht. Wir geben uns diesem Sinneseindrucke hin und verweben diese Sinneseindrücke mit demjenigen, was wir denken, mit den Gedanken. Wenn Sie sich überlegen, was, wenn Sie sich Ihrem eigenen inneren Leben etwas erinnernd hingeben, was da den Inhalt dieses Seelenlebens ausmacht: es sind Sinneseindrücke, die in die Gedanken hineingewoben sind. Wir leben ganz und gar dadurch, daß wir in unser Seelisches ein solches Gewebe von Sinneseindrücken und Gedanken hereinnehmen.

Was geht da eigentlich vor? Nun, betrachten Sie in dieser schematischen Zeichnung diese Linie a bis b als den Sinnesteppich, als die sich um uns herum ausbreitenden Farben, Töne, Gerüche und so weiter. Der Mensch gibt sich seiner Beobachtung, diesem Sinnesteppich hin, und er verwebt die Eindrücke durch seine Gedanken, die ich hier als die rote Schlangenlinie zeichne. Der Mensch verbindet, indem er sich dem Sinnesleben hingibt, gedanklich alles, was er in dieser Sinneswelt erlebt. Er interpretiert die Sinneswelt durch seine Gedanken. Dadurch, daß er gewissermaßen alles, was er an Gedanken entwickelt, in diese Sinneswelt hineinlegt, bildet diese Sinneswelt für ihn eine Grenze, eine Wand, durch die er nicht durchkommen kann. Er zeichnet gewissermaßen alle seine Gedanken auf dieser Wand auf, aber er durchstößt die Wand nicht im heutigen normalen Bewußtsein. Die Gedanken machen halt an dieser Wand und zeichnen auf dieser Wand.

Hinaus kommt man über dieses Haltmachen an der Wand dadurch, daß man zunächst die imaginative Erkenntnis ausbildet durch das, was man Meditation in systematisch-regelmäßiger Weise nennen kann. Diese Meditation kann als eine innerliche Forschungsmethode ebenso ausgebildet werden, wie die äußerliche chemische oder astronomische Versuchsmethode ausgebildet werden kann. Sie können sich aus meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» und aus dem zweiten Teil meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» sogar überzeugen, daß die Methoden, sich in dieser Meditation zu bewegen, keineswegs einfach und weniger langwierig sind, als die Methoden, die man sich aneignen muß, um ein Astronom oder ein Chemiker zu werden, wenn man bis zu den letzten Konsequenzen eben kommen will. Es ist allerdings ein verhältnismäßig leichtes, die Lektüre solcher Werke zu pflegen, welche Anleitungen zu den entsprechenden Übungen geben, und dann so weit zu kommen, daß man mit Zuhilfenahme des gesunden Menschenverstandes auch wirklich sich innerlich von der Wahrheit dessen überzeugen kann, was von anthroposophischen Forschungen gesagt wird. Man braucht es nicht auf Autorität hinzunehmen. Auch wenn man es nicht selber erforschen kann, so kann man es prüfen, wenn man nur auf die Eigentümlichkeit der Forschungsmethode eingeht.

Nun, dieses ganze Üben beruht ja darauf, daß man von einem Eingehen auf die Sinneseindrücke absieht. Den Sinneseindrücken: gibt man sich nicht hin im Meditieren, man gibt sich allein dem Gedankenleben hin. Dieses Gedankenleben aber muß, durch ein festes Ruhen auf gewissen leicht überschaubaren Gedanken, zu einer solchen Lebendigkeit, zu einer solchen Intensität gebracht werden, wie es sonst nur das äußere Sinnesleben hat. Sie wissen ja, es ist etwas ganz anderes, wenn wir den äußeren Sinneseindrücken hingegeben sind, als wenn wir mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nur unserer blassen, unlebendigen Gedankenwelt hingegeben sind. Die Sinneseindrücke wirken lebendig, intensiv auf uns. Wir sind an sie hingegeben. Die Gedanken verblassen, sie werden abstrakt, sie werden kalt. Aber darin besteht gerade das Wesen des Meditierens, daß wir es durch Übung dahin bringen, in dem bloßen Gedankenweben mit einer solchen Intensität und Lebhaftigkeit darinnen zu leben wie sonst im äußeren Sinnesleben. Wenn man einen Meditationsgedanken in einer solchen inneren Lebendigkeit erfassen kann, wie sie sonst vorhanden ist, wenn man sich einer Farbe hingibt, dann hat man den Meditationsgedanken in der richtigen Weise ins Leben hereingestellt. Alles das aber muß mit einer solchen inneren Freiheit geschehen, wie eben das normale Gedankenweben und das sinnliche Wahrnehmen geschieht. Wie wir uns da nicht nebulosen Stimmungen, mystischen Verträumtheiten hingeben, wenn wir die äußere Welt beobachten, wie wir da nicht zum Schwärmer werden, so dürfen wir es auch nicht, wenn wir in dieser Weise richtig meditieren. Genau dieselbe Stimmung muß in diesem Meditieren enthalten sein, wie sonst im äußerlichen, sinnlichen Wahrnehmen.

Das ist das Eigentümliche der anthroposophischen Methode, daß sie die Sinneswahrnehmung geradezu zum Muster nimmt. Sonstige nebulose Mystiker findet man ja, die sagen: Sinneswahrnehmungen - etwas sehr Minderwertiges! Die muß man verlassen. Man muß ins Traumhafte, ins Mystische, ins Sinnesabgewandte sich versetzen! - Dadurch kommt natürlich nur ein halber Schlaf zustande, nicht ein wirkliches Meditieren. Die Anthroposophie verfolgt den entgegengesetzten Weg: Sie nimmt sich das Sinneswahrnehmen geradezu zum Muster in bezug auf seine Qualität, Intensität, in bezug auf seine Lebhaftigkeit. So daß sich der Mensch in diesem Meditieren so frei bewegt, wie er sich in der Sinneswahrnehmung sonst bewegt. Er fürchtet sich dabei gar nicht, daß er zum trockenen Nüchterling wird. Die Dinge, die er auf diese Weise in aller Objektivität erlebt, die halten ihn schon von der trockenen Philistrosität ab und er hat nicht nötig, wegen der Objekte, die er erlebt, um der Überwindung der Alltäglichkeit willen sich in traumhafte Nebulositäten zu erheben.

Indem der Mensch also richtig meditiert, gelangt er dazu, sich in Gedanken frei zu bewegen. Dadurch aber werden die Gedanken selber befreit von ihrem vorherigen abstrakten Charakter, sie werden bildhaft. Und das tritt jetzt beim vollen Wachbewußtsein ein, mitten unter dem anderen gesunden Denken. Das darf man nämlich nicht verlieren. Der Halluzinant, der Schwärmer, der ist in dem Momente, wo er halluziniert, schwärmt, ganz Halluzinant, ganz Schwärmer, da setzt er den gesunden Menschenverstand ganz weg; das darf derjenige, der die hier beschriebenen Methoden befolgt, nicht. Der hat immer den gesunden Menschenverstand neben sich. Den nimmt er durch all dasjenige mit, was er da im bildhaften Gedankenleben erlebt. Und was tritt dadurch ein? Ja, sehen Sie: bei vollem Wachzustande tritt dasjenige ein, was sonst nur das unbewußte Leben formt an der Bildhaftigkeit des Traumes. Aber das ist gerade der Unterschied der Imagination gegenüber dem Traume: beim Traume wird alles in uns gemacht; dann dringt es aus unerkannten Tiefen herein in das Wachleben, und wir können es nur hinterher beobachten. Bei der Imagination, bei der Vorbereitung zur Imagination, beim meditativen Inhalt machen wir das selbst, was sonst in uns gemacht wird. Wir werfen uns auf zu Schöpfern von Bildern, die nicht bloße Phantasiebilder sind, sondern an Intensität, an Lebendigkeit sich von den Phantasiebildern ebenso unterscheiden wie die Traumbilder von den bloßen Phantasiebildern. Aber wir machen das alles selbst, und darauf kommt es an. Und indem wir es selbst machen, sind wir auch von einer gründlichen Illusion befreit, die nämlich darinnen besteht, daß man dasjenige, was man so selber macht, als eine Kundgebung aus der objektiven Außenwelt ansehen könnte. Das wird man nie, denn man ist sich bewußt, daß man dieses ganze Bildgewebe selber macht. Der Halluzinant, der hält seine Halluzinationen für Wirklichkeit. Er hält Bilder für Wirklichkeit, weil er sie ja nicht selber macht, weil er weiß, daß sie gemacht werden. Dadurch entsteht für ihn die Täuschung, daß sie Wirklichkeit seien. Derjenige, der sich durch Meditation für die Imagination vorbereitet, kann gar nicht in den Fall kommen, das, was er da selber ausbildet, für wirkliche Bilder zu halten. Eine erste Stufe zur übersinnlichen Erkenntnis wird gerade darinnen bestehen, daß man illusionsfrei wird dadurch, daß man das ganze Gewebe, das man jetzt als die innere Fähigkeit, Bilder von solcher Lebendigkeit, wie sonst die Traumbilder sind, hervorzurufen, daß man das in völlig freier Willkür gestaltet. Und man müßte selbstverständlich ja jetzt verrückt sein, wenn man das für Wirklichkeit hielte!

Nun, die nächste Etappe in diesem Meditieren besteht darinnen, daß man sich wiederum die Fähigkeit erwirbt, diese Bilder, die etwas Faszinierendes haben, und die, wenn der Mensch sie nicht in vollständiger Freiheit wie beim Meditieren entwickelt, tatsächlich sich wie die Parasiten festsetzen, daß man diese Bilder aus dem Bewußtsein wiederum ganz verschwinden lassen kann, daß man auch die innere Willkür erhält, diese Bilder, wenn man will, wiederum völlig verschwinden zu lassen. Diese zweite Etappe ist so notwendig wie die erste. So wie im Leben gegenüber dem Erinnern das Vergessen notwendig ist — sonst würden wir immer mit der ganzen Summe unserer Erinnerungen herumgehen -, so ist auf dieser ersten Stufe des Erkennens das Abwerfen der imaginativen Bilder so notwendig als das Weben, das Gestalten dieser imaginativen Bilder.

Aber, indem man das alles durchgemacht hat, durchgeübt hat, hat man etwas mit dem Seelischen vollzogen, was man vergleichen könnte damit, wenn man einen Muskel immerfort gebraucht, wenn man ihn immerfort übt, so wird er stark. Man hat jetzt eine Übung in der Seele dadurch vollzogen, daß man Bilder weben, Bilder gestalten lernt, und sie wiederum unterdrückt, und daß das alles vollständig in dem Bereich unseres freien Willens steht. Sehen Sie, man ist dadurch, daß man die Imagination ausgebildet hat, zu der bewußten Fähigkeit gekommen, Bilder zu gestalten, wie sie sonst das unbewußte Leben des Traums gestaltet, da drüben in der Welt, die man sonst mit seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nicht überblickt, die in die Zustände zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen hineinverlegt sind. Jetzt entfaltet man diese selbe Tätigkeit bewußt herüber. Man entfaltet also in jener Meditation, die abzielt auf das imaginative Erkennen, den Willen, die Fähigkeit zu erringen, bewußt Bilder zu schaffen, und wiederum die Fähigkeit, bewußt Bilder aus dem Bewußtsein wegzuschaffen. Dadurch kommt eine andere Fähigkeit.

Diese Fähigkeit ist eine solche, die sonst unwillkürlich vorhanden ist nicht während des Schlafens, sondern im Momente des Aufwachens und Einschlafens. Der Moment des Aufwachens und Einschlafens kann sich so gestalten, daß man das, was man vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen erlebt hat, in den Traumresten herübernimmt, dann von dorther dasjenige, was drüben ist, beurteilt. Es kann uns aber auch dasjenige, dem wir uns öffnen beim Aufwachen, gleich so überraschen, daß alle Erinnerung an den Traum hinuntersinkt. Im allgemeinen kann man sagen: In den Träumen ragt etwas Chaotisches, etwas wie erratische Gebilde von einem außer dem gewöhnlichen Wachleben Liegenden in das Wachleben herein. Es ragt dadurch herein, daß der Mensch während des Schlafens die bildhafte, die Imaginationen schaffende Tätigkeit entwickelt. Entwickelt er im Wachleben die Imaginationen schaffende Tätigkeit und die Imaginationen wegschaffende Tätigkeit, kann er also aus seiner Vorbereitung zur Imagination zu einem bewußtseinsleeren Zustand kommen: dann ist es so wie ein Aufwachen, und dann dringen von jenseits des Sinnesteppichs — was ich jetzt hier in der Zeichnung mit einem roten Kreis bezeichnet habe -, da dringen dann auf den durch die Meditation entwickelten Gedankenbahnen diejenigen Wesenhaftigkeiten durch den Sinnesteppich durch in uns ein, die jenseits dieses Sinnesteppichs sind. Wir durchstoßen den Sinnesteppich, wenn wir nach den gemachten Bildern mit leerem Bewußtsein verharren; dann kommen die Bilder herein durch Inspiration aus dem Jenseits der Sinneswelt. Wir treten in diejenige Welt ein, die jenseits der Sinneswelt liegt. Wir bereiten uns durch das imaginative Leben zur Inspiration vor. Und die Inspiration besteht darinnen, daß wir bewußt so etwas erleben können wie sonst unbewußt den Moment des Aufwachens. Wie im Moment des Aufwachens in unser waches Seelenleben etwas von jenseits des wachen Seelenlebens hereinkommt, so kommt dann, wenn wir durch die Imagination unser Seelenleben so ausgebildet haben, wie ich es geschildert habe, etwas von jenseits des Bewußtseins des Sinnesteppichs herein.

Wir erleben auf diese Weise die geistige Welt, die hinter der Sinneswelt ist. Es ist durchaus das, was als solche Fähigkeiten zur übersinnlichen Erkenntnis angeeignet wird, eine Fortsetzung desjenigen, was der Mensch schon im gewöhnlichen Leben als Fähigkeit hat. Und darauf beruht Anthroposophie, daß solche Fähigkeiten weiter ausgebildet werden. Sie muß sich aber dabei ganz und gar auf dasjenige stützen, was sich der Mensch durch ein zeitliches Erfassen der Lebens- und Daseinsläufe aneignet.