Spiritual Ground of Education

GA 305

23 August 1922, Oxford

VII. The Organisation of the Waldorf School

When we speak of organisation to-day we commonly imply that something is to be organised, to be arranged. But in speaking of the organisation of the Waldorf School I do not and cannot mean it in this sense, for really one can only organise something which has a mechanical nature. One can organise the arrangements in a factory where the parts are bound into a whole by the ideas which one has put into it. The whole exists and one must accept it as an organism. It must be studied. One must learn to know its arrangements as an organism, as an organisation.

A school such as the Waldorf School is an organism in this sense, as a matter of course,—but it cannot be organised, as I said before in the sense of making a program laying down in paragraphs how the school shall be run: Sections: 1, 2, 3, etc. As I said, I am fully convinced—and I speak without irony—that in these days if five or twelve people sit down together they can work out an ideal school plan, not to be improved upon, people are so intelligent and clever nowadays: Paragraphs 1, 2, etc., up to 12 and so on; the only question which arises is: can it be carried out in practice? And it would very soon be apparent that one can make charming programs, but actually when one founds a school one has to deal with a finished organism.

This school, then, comprises a staff of teachers; and they are not moulded out of wax. Your section 1 or section 5 would perhaps lay down: the teacher shall be such and such. But the staff is not composed of something to be moulded like wax, one has to seek out each single teacher and take him with the faculties which he has. Above all it is necessary to understand what these faculties are. One must know to start with, whether he is a good elementary teacher or a good teacher for higher classes. It is as necessary to under-stand the individual teacher as it is, in the human organism, to understand the nose or the ear if one is to accomplish something. It is not a question of having theoretical principles and rules, but of meeting reality as it comes. If teachers could be kneaded out of wax then one could make programs. But this cannot be done. Thus the first reality to reckon with is the college of teachers. And this one must know intimately. Thus it is the fundamental principle of the organisation of the Waldorf School that, since I am the director and spiritual adviser to the Waldorf School, I must know the college of teachers intimately, in all its single members, I must know each single individuality.

The second thing is the children, and here at the start we were faced with certain practical difficulties in the Waldorf School. For the Waldorf School was founded in Stuttgart by Emil Molt from the midst of the emotions and impulses of the years 1918 and 1919, after the end of the war. It was founded, in the first place as a social act. One saw that there was not much to be done with adults as far as social life was concerned; they came to an understanding for a few weeks in middle Europe after the end of the war. After that, they fell back on the views of their respective classes. So the idea arose of doing something for the next generation. And since it happened that Emil Molt was an industrialist in Stuttgart, we had no need to go from house to house canvassing for children, we received the children of the workers in his factory. Thus, at the beginning, the children we received from Molt's factory, about 150 of them, were essentially proletarian children. These 150 children were supplemented by almost all the anthroposophical children in Stuttgart and the neighbourhood; so that we had something like 200 children to work with at the beginning.

This situation brought it about that the school was practically speaking a school for all classes (Einheitschule). For we had a foundation of proletarian children, and the anthroposophical children were mostly not proletarian, but of every status from the lowest to the highest. Thus any distinctions of class or status were ruled out in the Waldorf School by its very social composition. And the aim through-out has been, and will continue to be, solely to take account of what is universally human. In, the Waldorf School what is considered is the educational principles and no difference is made in their application between a child of the proletariat and a child of the ex-Kaiser—supposing it to have sought entry into the school. Only pedagogic and didactic principles count, and will continue to count. Thus from the very first, the Waldorf School was conceived as a general school.

But this naturally involved certain difficulties, for the proletarian child brings different habits with him into the school from those of children of other status. And these contrasts actually turned—out to be exceedingly beneficial, apart from a few small matters which could be got over with a little trouble. What these things were you can easily imagine; they are mostly concerned with habits of life, and often it is not easy to rid the children of all they bring with them into the school. Although even this can be achieved if one sets about it with good will. Nevertheless, many children of the so-called upper classes, unaccustomed to having this or that upon them, would sometimes carry home the unpleasant thing, whereupon unpleasant comments would be made by their parents.

Well, as I said, here on the other hand were the children. These were what I might call the tiny difficulties. A greater difficulty arose from the fact that the ideal of the Waldorf School was to educate purely in accordance with knowledge of man, to give the child week by week, what the child's own nature demanded.

In the first instance we arranged the Waldorf School as an elementary school of 8 classes, so that we had in it children from 6 or 7 to 14 or 15 years old. Now these children came to us at the beginning from all kinds of different schools. They came with previous attainments of the most varied kinds; certainly not always such as we should have considered suitable for a child of 8 or 11 years old. So that during the first year we could not count on being able to carry out our ideal of education; nor could we proceed according to plan: 1, 2, etc., but we had to proceed in accordance with the individualities of the children we had in each particular class. Nevertheless this would only have been a minor difficulty. The greater difficulty is this, that no method of education however ideal it is must tear a man out of his connections in life. The human being is not an abstract thing to be put through an education and finished with, a human being is the child of particular parents. He has grown up as the product of the social order. And after his education he must enter this social order again. You see, if you wanted to educate a child strictly in accordance with an idea, when he was 14 or 15 he would no doubt be very ideal, but he would not find his place in modern life, he would be quite at sea. Thus it was not merely a question of carrying out an ideal, nor is it so now in the Waldorf School. The point is so to educate the child that he remains in touch with present-day life, with the social order of to-day. And here there is no sense in saying: the present social order is bad. Whether it be good or bad, we simply have to live in it. And this is the point, we have to live in it and hence we must not simply withdraw the children from it. Thus I was faced with the exceedingly difficult task of carrying out an educational idea on the one hand while on the other hand keeping fully in touch with present-day life.

Naturally the education officers regarded what was done in other schools as a kind of ideal. It is true they always said: one cannot attain the ideal, one can only do one's best under the circumstances. Life demands this or that of us. But one finds in actual practice when one has dealings with them that they regard all existing arrangements set up either by state authorities or other authorities as exceptionally good, and look upon an institution such as the Waldorf School as a kind of crank hobby, a vagary, something made by a person a little touched in the head.

Well you know, one can often let a crank school like this carry on and just see what comes of it. And in any case it has to be reckoned with. So I endeavoured to come to terms with them through the following compromise. In a memorandum, I asked to he allowed three years grace to try out my ‘vagary,’ the children at the end of that time, to be sufficiently advanced to be able to enter ordinary schools. Thus I worked out a memorandum showing how the children when they had been taken to the end of the third elementary class, namely in their 9th year, should have accomplished a certain stage, and should be capable of entering the 4th class in another school. But during the intermediate time, I said, I wanted absolute freedom to give the children week by week, what was requisite according to a knowledge of man. And then I requested to have freedom once more from the 9th to the 12th year. At the end of the 12th year the children should have again reached a stage such as would enable them to enter an ordinary school; and the same thing once again on their leaving school. Similarly with regard to the children,—I mean, of course, the young ladies and gentlemen—who would be leaving school to enter college, a university or any other school for higher education: from the time of puberty to the time for entering college there should be complete freedom: but by that time they should be far enough advanced to be able to pass into any college or university—for naturally it will be a long time before the Free High School at Dornach will be recognised as giving a qualification for passing out into life.

This arrangement to run parallel with the organisation of ordinary schools was an endeavour to accord our own intentions and convictions with things as they are, to make a certain harmony. For there is nothing unpractical about the Waldorf School, on the contrary, on every point this ‘vagary’ aims at realising things which have a practical application to life.

Hence also, there is no question of constructing the school on the lines of some bad invention—then indeed it would be a construction, not an organisation,—but it is truly a case of studying week by week the organism that is there. Then an observer of human nature—and this includes child nature—will actually light upon the most concrete educational measures from month to month. As a doctor does not say at the very first examination everything that must be done for his patient, but needs to keep him under observation because the human being is an organism, so much the more in such an organism as a school must one make a continuous study. For it can very well happen that owing to the nature of the staff and children in 1920—say—one will proceed in a manner quite different from one's procedure with the staff and children one has in 1924. For it may be that the staff has increased and so quite changed, and the children will certainly be quite different. In face of this situation the neatest possible sections 1 to 12 would be of no use. Experience gained day by day in the classroom is the only thing that counts.

Thus the heart of the Waldorf School, if I speak of its organisation, is the teachers' staff meeting. These staff meetings are held periodically, and when I can be in Stuttgart they are held under my guidance, but in other circumstances they are held at frequent intervals. Here, before the assembled staff, every teacher throughout the school will discuss the experiences he has in his class in all detail. Thus these constant staff meetings tend to make the school into an organism in the same way as the human body is an organism by virtue of its heart. Now what matters in these staff meetings is not so much the principles but the readiness of all teachers to live together in goodwill, and the abstention from any form of rivalry. And it matters supremely that a suggestion made to another teacher only proves helpful when one has the right love for every single child. And by this I do not mean the kind of love which is often spoken about, but the love which belongs to an artistic teacher.

Now this love has a different nuance from ordinary love. Neither is it the same as the sympathy one can feel for a sick man, as a man, though this is a love of humanity. But in order to treat a sick man one must also be able—and here please do not misunderstand me—one must also be able to love the illness. One must be able to speak of a beautiful illness. Naturally for the patient it is very bad, but for him who has to treat it it is a beautiful illness. It can even in certain circumstances be a magnificent illness. It may be very bad indeed for the patient but for the man whose task it is to enter into it and to treat it lovingly it can be a magnificent illness. Similarly, a boy who is a thorough ne'er-do-well (a ‘Strick’ as we say in German) by his very roguery, his way of being bad, of being a ne'er-do-well can be sometimes so extraordinarily interesting, that one can love him extraordinarily. For instance, we have in the Waldorf School a very interesting case, a very abnormal boy. He has been at the Waldorf School from the beginning, he came straight into the erst class. His characteristic was that he would run at a teacher as soon as he had turned his back, and give him a bang. The teacher treated this rascal with extraordinary love and extraordinary interest. He fondled him, led him back to his place, gave no sign of having noticed that he had been banged from behind. One can only treat this child by taking into consideration his whole heredity and environment. One has to know the parental milieu in which he has grown up, and one must know his pathology. Then, in spite of his rascality one can effect something with him, especially if one can love this form of rascality. There is something lovable about a person who is quite exceptionally rascally.

A teacher has to look upon these things in a different way from the average person. Thus it is very important for him to develop this special love I have spoken of. Then in the staff meeting one can say something to the point. For nothing helps one so much in dealing with normal children as to have observed abnormal children.

You see healthy children are comparatively hard to study for in them every characteristic is toned down. One does not so easily see how it stands with a certain characteristic and what relation it has to others. In an abnormal child, where one character complex predominates one very soon finds the, way to treat this particular character complex, even if it involves a pathological treatment. And this experience can be applied to normal children.

Such then, is the organisation; and such as it is it has brought credit to the Waldorf School in so far as the number of children has rapidly increased; whereas we began the school with about 200 children we now have nearly 700. And these children are of all classes, so that the Waldorf School is now organised as a general school [‘Einbeitschule.’] in the best sense of the word. For most of the classes, particularly in the lower classes, we have had to arrange parallel classes because we received too many children for a single class; thus we have a first class A, and a first class B and so on. This has made, naturally, increasingly great demands on the Waldorf School. For where the whole organisation is to be conceived from out of what life presents, every new child modifies its nature; and the organism with this new member requires a fresh handling and a further study of man.

The arrangement in the Waldorf School is that the main lesson shall take place in the morning. The main lesson begins in winter at 8 or 8:15, in summer a little earlier. The special characteristic of this main lesson is that it does away with the ordinary kind of time table. We have no time table in the ordinary sense of the word, but one subject is taken throughout this erst two hour period in the morning—with a break in it for younger children,—and this subject is carried on for a space of four or six weeks and brought to a certain stage. After that, another subject is taken. For children of higher classes, children of 11, 12, or 13 years old what it comes to is that instead of having: 8 – 9 Religion, 9 – 10 Natural History, from 10 – 11 Arithmetic,—that is, instead of being thrown from one thing to another,—they have for example, in October four weeks of Arithmetic, then three weeks of Natural History, etc.

It might be objected that the children may forget what they learn because a comprehensive subject taken in this way is hard to memorise. This objection must be met by economy in instruction and by the excellence of the teachers. The subjects are recapitulated only in the last weeks of the school year so as to gather up, as it were, all the year's work. In this manner, the child grows right into a subject.

The language lesson, which, with us, is a conversation lesson, forms an exception to this arrangement. For we begin the teaching of languages, as far as we can,—that is English and French—in the youngest classes of the school; and a child learns to speak in the languages concerned from the very beginning. As far as possible, also, the child learns the language without the meaning being translated into his own language. (Translator's Note: i.e. direct method). Thus the word in the foreign language is attached to the object, not to the word in the German language. So that the child learns to know the table anew in some foreign language,—he does not learn the foreign word as a translation of the German word Tisch. Thus he learns to enter right into a language other than his mother tongue; and this becomes especially evident with the younger children. It is our practice moreover to avoid giving the younger children any abstract, theoretical grammar. Not until a child is between 9 and 10 years old can he understand grammar—namely, when he reaches an important turning point of which I shall be speaking when. I deal with the boys and girls of the Waldorf School.

This language teaching mostly takes place between 10 and 12 in the morning. This is the time in which we teach what lies outside the main lesson—which is always held in the first part of the morning. (The Waldorf School began at 8 a.m.) Thus any form of religion teaching is taken at this time. And I shall be speaking further of this teaching of religion, as well as about moral teaching and discipline, when I deal with the theme ‘the boys and girls of the Waldorf School.’ But I want for the moment to emphasise the fact that the afternoon periods are all used for singing, music and eurhythmy lessons. This is so that the child may as far as possible participate with his whole being in all the education and instruction he receives.

The instruction and education can appeal the better to the child's whole nature because it is conceived as a whole in the heart of the teachers' meetings, as I have described. This is particularly noticeable when the education passes over from the more psychic domain into that of physical and practical life. And particular attention is paid in the Waldorf School to this transition into physical and practical life.

Thus we endeavour that the children shall learn to use their hands more and more. Taking as a start, the handling little children do in their toys and games, we develop this into more artistic crafts but still such as come naturally from a child.

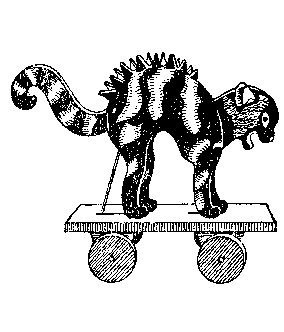

This is the sort of thing we produce (Tr. Note: showing toys etc.) this is about the standard reached by the 6th school year. Many of these things belong properly to junior classes, but as I said, we have to make compromises and shall only be able to reach our ideal later on—and then what a child of 11 or 12 now does, a child of 9 will be able to do. The characteristic of this practical work is that it is both spontaneous and artistic. The child works with a will on something of his own choosing, not at a set task. This leads on to handwork or woodwork classes in which the child has to carve and make all kinds of objects of his own planning. And one discovers how much children can bring forth where their education is founded in real life. I will give an example. We get the children to carve things which shall be artistic as well as useful. In this for instance: (Tr. Note: holding up a carved wooden bowl) one can put things. We get the children to carve forms like this so that they may acquire feeling for form and shape sprung from themselves; so that the children shall make something which derives its form from their own will and pleasure. And this brings out a very remarkable thing.

Suppose we have taken human anatomy at some period with this class, a thing which is particularly important for this class in the school (VI). We have explained the forms of the bones, of the skeletal system, to the children, also the external form of the body and the functions of the human organism. And since the teaching has been given in an artistic form, in the manner I have described, the children have been alive to it and have really taken it in. It has reached as far as their will, not merely to the thoughts in their heads. And then, when they come to do things like this (Carved bowl) one sees that it lives on in their hands. The forms will be very different according to what we may have been teaching. It comes out in these forms. From the children's plastic work one can tell what was done in the morning hours from 8 – 10, because the instruction given permeates the whole being.

This is achieved only when one really takes notice of the way things go on in nature. May I say a very heretical thing: people are very fond of giving children dolls, especially a ‘lovely’ doll. They do not see that children really don't want it. They wave it away, but it is pressed upon them. Lovely dolls, all painted! It is much better to give children a handkerchief, or, if that can't be spared, some piece of stuff; tie it together, make the head here, paint in the nose, two eyes etc.—healthy children far prefer to play with these than with ‘lovely’ dolls, because here is something left over for their fantasy; whereas the most magnificent doll, with red cheeks etc., leaves nothing over for the fantasy to do. The fine doll brings inner desolation to the child. (Tr. Dr. Steiner demonstrated what he was saying with his own pocket handkerchief.)

Now, in what way can we draw out of a child the things he makes? Well, when children of our VIth class in the school come to produce things from their own feeling for form, they look like this,—as you can see from this small specimen we have brought with us. (Wooden doll.) The things are just as they grow from the individual fantasy of any child.

It is very necessary, however, to get the children to see as soon as possible that they want to think of life as innately mobile not innately rigid. Hence, when one is getting the child to create toys,—which for him are serious things, to be taken in earnest,—one must see to it that the things have mobility. You see a thing like this—to my mind a most remarkable fellow—(carved bear)—children do entirely themselves, they also put these strings on it without any outside suggestion,—so that this chap can wag his tongue when pulled: so (bear with attached strings). Or children bring their own fantasy into play: they make a cat, not just a nice cat, but as it strikes them: humped, without more ado and very well carried out.

I hold it to be particularly valuable for children to have to do, even in their toys, with things that move,—not merely with what is at rest, but with things which involve manipulation. Hence children make things which give them enormous joy in the making. They do not only make realistic things, but invent little fellows like these gnomes and suchlike things (Showing toys).

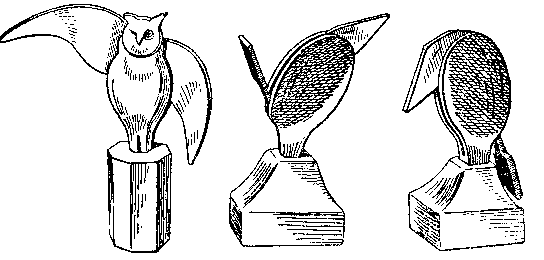

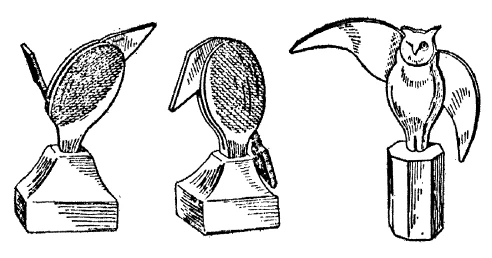

They also discover how to make more complicated things like this; they are not told that this is a thing that can be made, only the child is led on until he comes to make a lively fellow like this of his own accord. (Movable raven. ‘Temperaments Vogel’)—now you can see he looks very depressed and sad.

(The head and tail of the temperament bird can be moved up or down. Dr. Steiner had them both up at first, and then turned them both down.)

And when a child achieves a thing like this (a yellow owl with movable wings) he has wonderful satisfaction. These things are done by children of 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 years old. So far only these older ones have done it, but we intend to introduce it gradually into the younger classes, where of course the forms will be simpler.

Now we have further handwork lessons in addition to this handicraft teaching. And here it should be borne in mind that throughout the Waldorf School boys and girls are taught together in all subjects. Right up to the highest class boys and girls are together for all lessons. (durcheinandersitzen: i.e.=sit side by side, or beside each other.) So that actually, with slight variations of course (and as we build up the higher classes there will naturally have to be differentiation)—but on the whole the boys actually learn to do the same things as the girls. And it is remarkable how gladly little boys will knit and crochet and girls do work that is usually only given to boys. This has a social result also: Mutual understanding between the sexes, a thing of the very first importance to-day. For we are still very unsocial and full of prejudice in this matter. So that it is very good when one has results such as I will now proceed to show.

In Dornach we had a small school of this kind. Now in the name of Swiss freedom it has been forbidden, and the best we can do is to undertake the instruction of more advanced young ladies and gentlemen; for Swiss freedom lays it down that no free schools shall exist in competition with state schools.—Well, of course, such a thing is not a purely pedagogical question.—But in Dornach we tried for a time to run a small school of this nature, and in it boys and girls did their work together. This is a boy's work; it was done in Dornach by a little American boy of about nine years old. (Tea cosy; Kaffee Warmer.) This is the work of a boy not a girl. And in the Waldorf School, as I have said, boys and girls work side by side in the handwork lessons. All kinds of things are made in handwork. And the boys and girls work together quite peaceably. In these two pieces of work, for instance, you will not be able to decide without looking to the detail what difference is to be seen between boys' and girls' work. (Two little cloths).

Now in the top classes which, at the present stage of our growth, contain boys and girls of 16 and 17, we pass on to the teaching of spinning and weaving as an introduction to practical life for the children, so that they may make a con-tact with real life; and here in this one sphere we find a striking difference: the boys do not want to spin like the girls, they want to assist the girls. The girls spin and the boys want to fetch and carry, like attendant knights. This is the only difference we have found so far, that in the spinning lesson the boys want to serve the girls. But apart from this we have found that the boys do every kind of handwork.

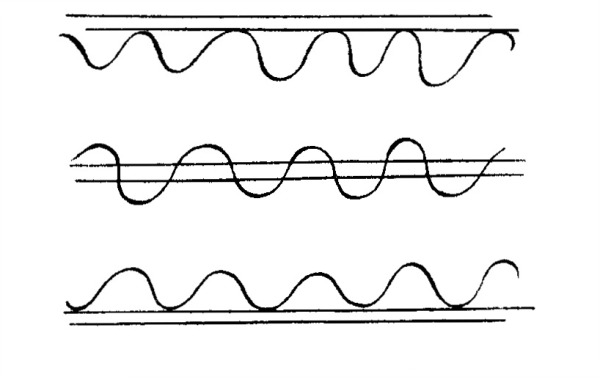

You will observe that the aim is to build up the hand-work and needlework lesson in connection with what is learned in the painting lesson. And in the painting lesson the children are not taught to draw (with a brush) or make patterns (‘Sticken’). But they learn to deal freely and spontaneously with the element of colour itself. Thus it is immensely important that children should come to a right experience of colour. If you use the little blocks of colour of the ordinary paint box and let the child dip his brush in them and on the palette and so paint, he will learn nothing. It is necessary that children should learn to live with colour, they must not paint from a palette or block, but from a jar or mug with liquid colour in it, colour dissolved in water. Then a child will come to feel how one colour goes with another, he will feel the inner harmony of colours, he will experience them inwardly. And even if this is difficult and inconvenient—sometimes after the painting lesson the class-room does not look its best, some children are clumsy, others not amenable in the matter of tidiness—even if this, way does give more trouble, yet enormous progress can be made when children get a direct relation to colour in this way, and learn to paint from the living nature of colour itself, not by trying to copy something in a naturalistic way. Then colour mass and colour form come seemingly of their own accord upon the paper. Thus to begin with, both at the Waldorf School and at Dornach, what the children paint is their experience of colour. It is a matter of putting one colour beside another colour, or of enclosing one colour within other colours. In this way the child enters right into colour, and little by little, of his own accord he comes to produce form from out of colour. As you see here, the form arises without any drawing intervening, from out of the colour. (showing paintings by Dornach children). This is done by the some-what more advanced children in Dornach, but the little children are taught on the same principle in the Waldorf School Here, for instance, we have paintings representative of the painting teaching in the Waldorf School which shows the attempt to express colour experience. Here, what is attempted, is not to paint some thing, but to paint experience of colour. The painting of something can come much later on. If the painting of something is begun too soon a sense for living reality is lost and gives place to a sense for what is dead.

If you proceed in this way, when you come to the treatment of any particular object in the world it will be far livelier than it would be without such a foundation. You see children who have previously learned to live in the element of colour, can make the island of Sicily, for instance, look like this, (coloured map) and we get a map. In this way, artistic work is related to the geography teaching.

When the children have acquired a feeling for colour harmony in this way they come on to making useful objects of different kinds. This is not first drawn, but the child has acquired a feeling for colour, and so later he can paint or shape such a thing as this book cover, or folio. The important thing is to arouse in the child a real feeling for life. And colour and form have the power to lead right into life.

Now sometimes you find a terrible thing done: the teacher will let a child make a neckband, and a waist band and a dress hem, and all three will have on them the very same pattern. You see this sometimes. Naturally it is the most horrible thing in the world to an artistic instinct. The child must be taught very early that a band designed for the neck has a tendency to open downwards, it has a downward direction; that a girdle or waistband tends in both directions, (i.e. both upwards and downwards); and that the hem of the dress at the bottom must show an upward tendency away from the bottom. Hence one must not perpetrate the atrocity of teaching the child simply to make an artistic pattern of one kind on a band, but the child must learn how the band should look according to whether it is in one position or another on a person.

In the same way, one should know when making a book cover, that when one looks at a book, and opens it so, there is a difference between the top and the bottom. It is necessary that the child should grow into this feeling for space, this feeling for form. This penetrates right into his limbs. This is a teaching that works far more strongly into the physical organism, than any work in the abstract. Thus the treatment of colour gives rise to the making of all kinds of useful objects; and in the making of these the child really comes to feel colour against colour and form next to form, and that the whole has a certain purpose and therefore I make it like this.

These things in all detail are essential to the vitality of the work. The lesson must be a preparation for life. Now among these exhibits you will find all sorts of interesting things. Here, for instance, is something done by a very little girl, comparatively speaking.

I cannot show you everything in the course of this lecture, but I would like to draw your attention to the many charming objects we have brought with us from the Waldorf School. You will find here two song books composed by Herr Baumann which will show you the kind of songs and music we use in the Waldorf School. Here are various things produced by one of the girls—since owing to the customs we could not bring a great deal with us—in addition to our natural selves. But all these things are carried out plasticly, are modelled, as is shown here. You see the children have charming ideas: (apes); they capture the life in things; these are all carved in wood. (Showing illustrations of wood-carving by children of the Waldorf School reproduced by one of the girls.)

You see here (maps) how fully children enter into life when the principle from which they start is full of life. You can see this very well in the case of these maps: first they have an experience of colour and this is an experience of the soul. A colour experience gives them a soul experience. Here you see Greece experienced in soul. When the child is at home in the element of colour, he grows to feel in geography: I must paint the island of Crete, the island of Candia in a particular colour, and I must paint the coast of Asia Minor so, and the Peleponesus so. The child learns to speak through colour, and thus a map can actually be a production from the innermost depths of the soul.

Think what an experience of the earth the child will have when this is how he has seen it inwardly, when this is how he has painted Candia or Crete or the Peleponesus or Northern Greece; when he has had the feelings which go with such colours as these; then Greece itself can come alive in his soul the child can awaken Greece anew from his own soul. In this way the living reality of the world becomes part of a man's being. And when you later confront the children with the dry reality of everyday life they will meet it in quite a different way, because they have had an artistic, living experience of the elements of colour in their simple paintings, and have learned to use its language.

Die Waldorfschule als Organismus

Wenn von Organisation gesprochen wird, so meint man heute gewöhnlich, daß man irgend etwas organisieren soll, irgend etwas einrichten soll. Wenn ich heute sprechen möchte von der Organisation der Waldorfschule, so ist es und kann es nicht in diesem Sinne gemeint sein, denn organisieren kann man eigentlich nur dasjenige, was in einem gewissen Sinne mechanisch ist. Man kann die Einrichtung einer Fabrik, irgendeine andere Institution organisieren, wo die Teile zu einem Ganzen durch den Gedanken, den man hineinprägt, zusammengehalten werden sollen. Aber denken Sie sich nur, wie absurd es sein würde, wenn man verlangen würde, man solle den menschlichen Organismus organisieren. Er ist organisiert, er ist da, und man muß ihn als einen Organismus hinnehmen. Man muß ihn studieren. Man muß seine Einrichtungen als die eines Organismus, als einer Organisation kennenlernen.

In diesem Sinne ist eine Schule, wie sie die Waldorfschule ist, von vornherein ein Organismus und kann nicht dadurch organisiert werden, daß man - ich habe das schon angedeutet — ein Programm entwirft, wie nun die Schule eingerichtet sein soll: Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2 und so weiter. Ich habe schon gesagt, ich bin von vornherein völlig überzeugt, ohne Ironie, daß, wenn sich heute 5 oder 12 Menschen zusammensetzen — und heute sind ja die Menschen alle sehr klug, sehr gescheit —, sie werden ein ideales Schulprogramm ausarbeiten können, worinnen gar nichts zu verbessern ist: Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2 und so weiter. Paragraph 12 und so weiter; und die Frage entsteht dann bloß: Kann man das in der Praxis durchführen? — Und da wird sich sehr bald herausstellen, daß sehr schöne Programme gemacht werden können, aber in der Praxis hat man einen vollendeten Organismus vor sich, wenn man eine Schule einrichtet.

Diese Schule besteht dann aus einer Lehrerschaft, die man ja nicht aus Wachs knetet. Paragraph 1 oder Paragraph 5 würde vielleicht heißen: der Lehrer soll so oder so sein. Die Lehrerschaft besteht ja nicht aus etwas, was man aus Wachs knetet, sondern man muß den einzelnen Lehrer suchen; man muß ihn hinnehmen mit den Fähigkeiten, die er hat. Man muß vor allen Dingen verstehen, welche Fähigkeiten er hat. Man muß verstehen, ob er zunächst ein guter Elementarlehrer ist, oder ob er ein guter Lehrer für die höheren Klassen ist. Es handelt sich also darum, geradeso wie man beim menschlichen Organismus, um ihn zu verstehen, die Nase oder das Ohr verstehen muß, so muß man den einzelnen Lehrer verstehen, wenn man überhaupt etwas machen will. Auf abstrakte Programmgrundsätze kommt es nicht an, sondern auf die Realitäten, die man vor sich hat. Könnte man die Lehrer aus Wachs kneten, so könnte man Programme machen. Aber das kann man nicht. So hat man zunächst als die eine Realität das Lehrerkollegium vor sich. Das muß man genau kennen. Das ist vor allen Dingen der erste Grundsatz in der Organisation der Waldorfschule, daß das Lehrerkollegium mir selbst, da ich die Waldorfschule geistig zu leiten habe, in allen seinen einzelnen Individualitäten genau bekannt ist.

Das zweite sind die Kinder, und in dieser Richtung war es mit einigen praktischen Schwierigkeiten verknüpft, aus der Waldorfschule etwas zu machen. Denn diese Waldorfschule wurde zunächst aus all den Emotionen heraus, die im Jahre 1918, 1919 da waren, nachdem der Krieg beendet war, von Emil Molt in Stuttgart begründet. Sie wurde begründet, weil man glaubte, damit zunächst eine soziale Tat zu tun. Man sah, mit den Erwachsenen ist in sozialer Beziehung nicht außerordentlich viel anzufangen; die verstanden sich ein paar Wochen lang in Mitteleuropa nach der Beendigung des Krieges. Nachher verfielen sie sogleich wiederum in diejenigen Urteile, die aus den verschiedenen Klassen sich herausgebildet haben. Daher kam man auf den Gedanken, zunächst für die nächste Generation zu sorgen. Und man brauchte, weil gerade eben Emil Molt, ein Industrieller in Stuttgart, die Schule begründete, zunächst nicht hausieren zu gehen, um Kinder zu bekommen, sondern man bekam die Kinder seiner Fabrik. Es waren also im wesentlichen zunächst Proletarierkinder, etwa 150 Kinder aus der Moltschen Fabrik, die wir bekamen. Diese etwa 150 Kinder wurden dann ergänzt durch weitaus die meisten Kinder aus der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft in Stuttgart und Umgebung; so daß wir also etwa mit gegen 200 Kindern im Beginne zu arbeiten hatten.

Nun war damit aber zugleich ein Moment gegeben, das die Schule im idealen Sinne zu einer Einheitsschule machte. Denn wir hatten einen Grundstock von Proletarierkindern, und die Anthroposophenkinder waren zunächst nicht Proletarierkinder, sondern aus allen möglichen Ständen, von den untersten bis zu den obersten. Es war also von vornherein alles Standesmäßige, Klassenmäßige ausgeschaltet auch durch die soziale Grundlage in der Waldorfschule. Und das wurde ja auch durchaus angestrebt und wird weiter angestrebt, daß in Betracht kommt allein, ganz allein das allgemein Menschliche. Nur pädagogischdidaktische Grundsätze gibt es für die Waldorfschule, gar keine Rücksicht darauf, ob ein Kind ein Proletarierkind ist, oder ob es selbst das Kind des ehemaligen Kaisers gewesen wäre, wenn es die Aufnahme in die Waldorfschule gesucht hätte. Bloß pädagogisch-didaktische Grundsätze galten und werden gelten. So war die Waldorfschule von Anfang an als eine Einheitsschule gedacht.

Aber damit waren natürlich auch Schwierigkeiten gegeben, denn das Proletarierkind bekommt man mit anderen Lebensgewohnheiten im 6., 7. Jahre in die Schule herein als das Kind aus anderen Ständen. Aber in dieser Beziehung zeigten sich sehr bald die Gegensätze als sogar außerordentlich wohltuend, wenn auch von Kleinigkeiten natürlich dabei abgesehen werden muß, die mit einer gewissen Mühe dann zu überbrücken sind. Diese Kleinigkeiten können Sie sich ja auch leicht denken; sie beziehen sich zumeist auf äußere Lebensgewohnheiten, und es ist manchmal nicht leicht, alles dasjenige aus den Kindern herauszubringen, was sie in die Schule mit hereinbringen. Aber auch das ist mit einigem gutem Willen durchaus ja zu erreichen, obwohl manche Kinder aus sogenannten höheren Ständen, die nicht gewöhnt sind, das eine oder das andere an sich zu tragen, dann das Unangenehme nach Hause bringen und das von den Eltern in unangenehmer Weise zu Hause bemerkt wird.

Nun, so hatte man also die Kinderschaft auf der anderen Seite. Das waren zunächst, ich möchte sagen, die kleineren Schwierigkeiten. Die größere Schwierigkeit entstand daraus, daß für die Waldorfschule das Ideal vorlag, rein im Sinne der Menschenerkenntnis zu erziehen, jede Woche das an das Kind heranzubringen, was das Kind selber forderte.

Nun richteten wir aber die Waldorfschule sogleich ein als eine achtklassige Elementarschule, so daß wir Kinder drinnen hatten vom 6. oder 7. bis zum 14., 15. Jahre. Diese Kinder bekamen wir zunächst aus den verschiedensten Schulen heraus. Sie hatten die allerverschiedensten Vorbildungen, durchaus nicht diejenige immer, die wir etwa für ein acht- oder elfjähriges Kind für die richtige ansehen mußten. So daß wir also in dem ersten Jahre durchaus nicht mit dem völlig rechnen konnten, was wir als das Ideal der Erziehung ansehen. Da konnte wiederum nicht nach Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2 gegangen werden, sondern da mußte nach den Individualitäten der Kinder, die man in jede einzelne Klasse hereinbekam, vorgegangen werden. Und trotzdem, dieses wäre noch die geringere Schwierigkeit gewesen.

Die größere Schwierigkeit ist diese, daß keine noch so ideale Erziehungsmethode den Menschen herausreißen darf aus dem Leben. Der Mensch ist ja nicht irgend etwas Abstraktes, was man durch die Erziehung hinstellen kann und dann ist es fertig, sondern der Mensch ist das Kind gewisser Eltern. Er ist herausgewachsen aus der sozialen Ordnung. Er muß, nachdem er erzogen worden ist, wieder hinein in diese soziale Ordnung. Sehen Sie, wenn Sie ein Kind so erziehen wollten, wie es absolut der Idee entspricht, so werden Sie es mit 14, 15 Jahren so haben, daß das allerdings sehr ideal sein kann, aber das Kind findet sich nicht zurecht im heutigen Leben, es weiß nichts anzufangen. So daß also nicht bloß ein Ideal zu verwirklichen war und auch jetzt noch nicht ist in der Waldorfschule, sondern es handelt sich darum, das Kind so zu erziehen, daß es immer den Anschluß findet an das heutige Leben, an die heutige soziale Ordnung. Da nützt es nichts, zu sagen, diese soziale Ordnung ist schlecht. Wir müssen doch, ob sie nun gut oder schlecht ist, darinnen einfach leben. Und darum handelt es sich, daß wir darinnen leben müssen, daß wir also die Kinder nicht einfach aus ihr herausziehen dürfen. So hatte ich also die außerordentlich schwere Aufgabe vor mir, auf der einen Seite eine Idee der Erziehung zu erfüllen, auf der anderen Seite mit dem vollen Leben der Gegenwart zu rechnen.

Selbstverständlich mußten die Schulbehörden dasjenige, was in den anderen Schulen geleistet wird, als eine Art Ideal ansehen. Sie sagen zwar immer: das Ideal kann man nicht erreichen, man kann nur das Möglichste tun, die Lebenspraxis fordert das oder jenes. Aber gerade in der Praxis, wenn man mit ihnen zu tun hat, dann sehen sie doch alles dasjenige, was schon eingerichtet ist von seiten der Staatsbehörden oder der entsprechenden Behörden, als etwas außerordentlich Gutes an, und dasjenige, was so eingerichtet wird wie die Waldorfschule, für eine Art Schrulle, für etwas, was man macht, wenn man nicht ganz besonnen ist unter dem Hute!

Nun, nicht wahr, man läßt manchmal solch eine Schrulle gewähren, weil man sich sagt: Na, das wird sich schon zeigen, was es ist. -— Aber immerhin, man muß auch damit rechnen, und so versuchte ich durch folgenden Kompromiß zurechtzukommen. Ich schlug vor in einem Memorandum, mir für dasjenige, was meine Schrulle ist, jeweilig drei Jahre Zeit zu lassen, um dann die Kinder so weit zu haben, daß sie den Anschluß an die gewöhnlichen Schulen finden können. So also arbeitete ich ein Memorandum aus dahingehend, daß die Kinder, wenn sie aufgenommen werden, bis zur Vollendung der 3. Elementarklasse, also dem 9. Jahre, das Ziel erreicht haben, daß sie in einer anderen Schule in die 4. Klasse eintreten können. Nur für die Zwischenzeit, sagte ich, wolle ich absolute Freiheit haben, jede Woche dasjenige den Kindern geben zu können, was aus Menschenerkenntnis folgt. Dann wiederum verlangte ich Freiheit vom 9. bis zum 12. Jahre. Nach der Vollendung des 12. Jahres sollten die Kinder wiederum ein solches Ziel erreicht haben, daß sie in die gewöhnliche äußere Schule eintreten können, und wiederum, wenn sie die Schule verlassen haben. Ebenso wird es sein, wenn nun die Kinder, ja, wie gesagt, die jungen Damen und die jungen Herren die Schule verlassen, um an die Universität oder eine andere Hochschule zu kommen, für die Zeit der Geschlechtsreife bis zum Beginn der Hochschulzeit soll völlige Freiheit sein; dann aber sollen sie so weit sein, daß sie in eine beliebige Hochschule, Universität, übertreten können, denn die Dornacher Freie Hochschule wird noch lange nicht als etwas anerkannt sein, in das übergetreten werden kann, wenn die Leute ins Leben hinaus wollen, selbstverständlich.

So also wurde schon mit diesem Parallelismus mit dem gewöhnlichen Schulwesen versucht, dasjenige, was eigentlich gewollt werden muß, mit demjenigen, was eben da ist, in Einklang zu bringen, in eine gewisse Harmonie zu bringen. Denn in keinem Punkte wird in der Waldorfschule irgend etwas angestrebt, was unpraktisch ist, sondern überall in jedem Punkte wird durch diese Schrulle zu verwirklichen versucht dasjenige, was wirklich lebenspraktisch ist.

Daher kann es sich auch nicht darum handeln, aus irgendeinem gescheiten Einfall im Kopfe die Schule nun zu konstruieren — denn eine Konstruktion, nicht eine Organisation würde entstehen -, sondern es kann sich nur darum handeln, dasjenige, was man schon als einen Organismus hat, wirklich von Woche zu Woche zu studieren. Und da ergeben sich in der Tat für denjenigen, der nun Menschenbeobachtung, das heißt auch Kinderbeobachtung hat, die konkretesten Erziehungsmaßregeln von Monat zu Monat. So wie schließlich auch der Arzt, wenn er einen Menschen vor sich hat, nicht bei der ersten Untersuchung gleich sagen kann, was alles geschehen soll, sondern erst nach und nach den Menschen studieren muß, weil der Mensch ein Organismus ist, so handelt es sich also auch darum, daß man einen solchen Organismus, wie es die Schule ist, aber noch mehr fortwährend studiert. Denn es kann zum Beispiel sein, daß man durch die besondere Art von Lehrerschaft und Kinderschaft, die man, sagen wir, im Jahre 1920 vor sich hat, ganz anders vorgehen muß als bei der Lehrerschaft und Schülerschaft, die man im Jahre 1924 vor sich hat, weil unter Umständen die Lehrerschaft eine andere sein kann durch Zuwachs, und die Kinderschaft wird schon ganz gewiß eine andere sein. Demgegenüber könnten Paragraph 1 bis Paragraph 12 so schön wie möglich sein, aber sie taugten nichts; es taugt nur das, was man wirklich durch die Beobachtung eines jeden Tages aus der Klasse herausträgt.

Und deshalb ist das Herz der Waldorfschule, wenn ich von ihrer Organisation spreche, die Lehrerkonferenz, es sind die Lehrerkonferenzen, die von Zeit zu Zeit immer abgehalten werden. Wenn ich selbst in Stuttgart sein kann, geschieht sie unter meiner Leitung, sonst aber finden diese Lehrerkonferenzen auch in verhältnismäßig sehr kurzen Zwischenräumen statt. Da wird wirklich bis ins Einzelnste hinein alles vor der gesamten Lehrerschaft verhandelt über die gesamte Schule, was der einzelne Lehrer in seiner Klasse an Erfahrungen machen kann. So daß fortwährend diese Lehrerkonferenzen die Tendenz haben, die Schule so als einen ganzen Organismus zu gestalten, wie der menschliche Leib ein Organismus ist dadurch, daß er ein Herz hat. Da handelt essich allerdings bei diesen Lehrerkonferenzen viel weniger umabstrakte Grundsätze, sondern überall bei den Lehrern um den guten Willen zum Zusammenleben, um das Hintanhalten jeder Art von Rivalität. Und vor allen Dingen handelt es sich darum, daß man etwas, was dem anderen nützt, nur vorbringen kann, wenn man die entsprechende Liebe zu jedem einzelnen Kinde hat. Aber ich meine dabei nicht jene Liebe, von der man oft spricht, sondern jene Liebe, die man gerade als artistischer Lehrer hat.

Diese Liebe, die hat noch eine andere Nuance als die gewöhnliche Liebe. Es ist ja wiederum eine andere Nuance, aber dennoch, wer mit kranken Menschen als Menschen innig Mitleid haben kann, hat zunächst die allgemeine Menschenliebe. Aber um einen Kranken zu behandeln, muß man auch - bitte, mißverstehen Sie das nicht, aber es ist so die Liebe zur Krankheit haben können. Man muß auch sprechen können von einer schönen Krankheit. Die ist natürlich sehr schlimm für den Patienten, aber sie ist für denjenigen, der sie behandeln muß, eine schöne Krankheit. Eine prachtvolle Krankheit kann sie unter Umständen sein. Sie mag sehr schlimm sein für den Patienten, sie ist aber für den, der sich hineinversetzen muß, der sie mit Liebe behandeln können muß, eine prachtvolle Krankheit. Und so ist auch ein völlig nichtsnutziger Knabe, ein Strick, wie man im Deutschen sagt, der ist unter Umständen durch die Art, wie er sein Stricktum auslebt, wie er schlimm ist, wie er nichtsnutzig ist, zuweilen so außerordentlich interessant, daß man ihn außerordentlich lieben kann. Zum Beispiel, wir haben einen sehr interessanten Fall in der Waldorfschule, einen Jungen, der sehr abnorm ist. Er saß von Anfang an in der Waldorfschule, er kam gleich in die erste Klasse. Er hatte die Eigentümlichkeit, daß, wenn sich der Lehrer umdrehte, so lief er auf den Lehrer zu und gab ihm einen Schlag. Der Lehrer behandelte mit einer außerordentlichen Liebe und mit einem außerordentlichen Interesse diesen Nichtsnutz. Er streichelte ihn, führte ihn an seinen Platz zurück, tat gar nicht, als ob er es bemerkt hätte, daß der ihm hinten einen Schlag gegeben hatte. Dieser Knabe kann nur dadurch behandelt werden, daß man seine ganze Genesis ins Auge faßt. Man muß kennen, aus welchem elterlichen Milieu er herausgewachsen ist und muß seine Pathologie kennen. Aber dann kommt man auch mit ihm trotz seiner Nichtsnutzigkeit vorwärts, wenn man gerade diese Art von Nichtsnutzigkeit lieben kann. Es hat etwas Liebenswürdiges, wenn jemand ganz besonders stark niichtsnutzig ist.

Das ist also für den Erzieher ganz anders, als es ist für denjenigen, der mehr von außen die Dinge betrachtet. Und so handelt es sich wirklich darum, daß man diese besondere Liebe entwickle, von der ich jetzt gesprochen habe. Dann weiß man auch in der Lehrerkonferenz etwas Entsprechendes zu sagen. Denn nichts ist nützlicher für die Maßnahmen, die man bei gesunden Kindern zu ergreifen hat, als dasjenige, was man bei abnormen Kindern beobachten kann.

Sehen Sie, gesunde Kinder sind verhältnismäßig schwer zu studieren, weil bei ihnen alle Eigenschaften verwaschen sind. Man kommt nicht so leicht darauf, wie die einzelne Eigenschaft da drinnen sitzt, und wie sie sich mit der anderen zusammenschließt. Bei einem kranken Kinde, wo ein Eigenschaftskomplex vorliegt, da kommt man sehr bald darauf, den besonderen Eigenschaftskomplex auch pathologisch zu behandeln. Das kann man dann anwenden bei gesunden Kindern.

Durch solch eine Organisation haben wir es immerhin dazu gebracht, daß die besondere Art der Waldorfschule in kurzer Zeit gewürdigt worden ist dadurch, daß die Zahl der Kinder, die wir im Beginne hatten — gegen 200 sagte ich —, rasch wuchs, und nun haben wir bereits die Zahl von gegen 700 Kindern erreicht, die nun aber aus allen Klassen sind (bis zur 12.), so daß die Waldorfschule jetzt wirklich im besten Sinne des Wortes als eine Einheitsschule organisiert dasteht. Wir mußten für die meisten Klassen, namentlich für die unteren, Parallelklassen errichten, so daß wir eine 1. Klasse A, eine 1. Klasse B und so weiter haben, weil wir eben nach und nach zuviel Kinder für die eine Klasse bekommen haben. Dadurch werden ja natürlich immer größere Aufgaben an die Waldorfschule gestellt. Denn wenn man versucht, die ganze Organisation aus dem Leben heraus zu denken, so gibt jedes Kind, das man bekommt, eine neue Lektion und eine neue Art, in welche man sich hineinfinden muß, um wiederum mit dem Organismus, der ein neues Glied bekommen hat, durch das entsprechende Menschenstudium zurechtzukommen.

Wir haben die Waldorfschule so eingerichtet, daß zunächst der Hauptunterricht am Morgen erteilt wird. Im Sommer etwas früher, im Winter etwa um 8 oder 81/& Uhr beginnt der Hauptunterricht. Dieser Hauptunterricht hat die Eigentümlichkeit, daß für ihn das, was man gewöhnlich den Stundenplan nennt, abgeschafft ist. Stundenplan im gewöhnlichen Sinne haben wir nicht, sondern es wird eine Materie zunächst für diesen zweistündigen Vormittagsunterricht, der für die kleineren Kinder noch einmal durch eine Pause unterbrochen wird, es wird eine Materie für diesen zweistündigen Vormittagsunterricht genommen, und die wird in vier oder sechs Wochen vollendet. Dann wird eine andere Materie vorgenommen. Das stellt sich dann so heraus, daß die Kinder nicht haben von 8 bis 9 Religion, von 9 bis 10 Naturgeschichte, von 10 bis 11 Rechnen - also immer in etwas anderes hineingeworfen werden, sondern sie haben zum Beispiel im Oktober vier Wochen Rechnen, dann drei Wochen Naturgeschichte und so weiter.

Dasjenige, was da etwa getadelt werden könnte, weil die Kinder vielleicht etwas vergessen würden, weil das aus dem Gedächtnis wiederum entschwindet, was als eine zusammenhängende Materie durchgenommen worden ist, das muß ersetzt werden durch die Ökonomie des Unterrichts und die Tüchtigkeit der Lehrerschaft. Nur in den letzten Wochen eines Schuljahres werden die Materien wiederholt, so daß eine Art Zusammenfassung für das Schuljahr da ist. Dadurch wächst das Kind ganz mit irgendeiner Materie zusammen.

Eine Ausnahme damit muß gemacht werden für den Fremdsprachenunterricht, der eigentlich bei uns ein Sprechunterricht ist. Denn in der Waldorfschule wird es so gemacht, daß schon mit dem Kinde, wenn es die Elementarschule betritt, der Unterricht in den fremden Sprachen, soweit wir es jetzt können, Englisch und Französisch, begonnen wird, und das Kind lernt gleich vom Anfange an sprechen in der betreffenden Sprache. Das Kind lernt möglichst mit Umgehung auch nur des Gedankenübersetzens die Sprache. Es wird also das Wort in der fremden Sprache angeknüpft an den Gegenstand, nicht an das Wort in der deutschen Sprache. So daß das Kind den Tisch neu kennenlernt in irgendeiner fremden Sprache, nicht an dem deutschen Worte «Tisch» lernt es übersetzungsweise das Fremdwort. Es lernt also tatsächlich, und das zeigt sich insbesondere bei jüngeren Kindern, sich auch hineinleben in eine Sprache, die nicht seine Muttersprache ist. Dabei befolgen wir, daß abstrakt Grammatisches, intellektuell Grammatisches an die ganz jungen Kinder überhaupt nicht herangetragen wird. Das Grammatische kann erst von den Kindern verstanden werden zwischen dem 9. und 10. Jahre, an jenem wichtigen Punkt, von dem ich schon gesprochen habe.

Dieser Sprachunterricht wird im wesentlichen erteilt zwischen 10 und 12 Uhr vormittags. Diese Zeit ist also diejenige, wo wir, wenn ich so sagen darf, dasjenige unterrichten, was außer den Hauptunterricht, der immer in den ersten Morgenstunden erteilt wird, fällt, In diese Zeit hinein fällt dann auch alles dasjenige, was etwa Religionsunterricht ist. Über diesen Religionsunterricht, auch über den Moralunterricht und die Disziplin, werde ich noch später sprechen. Aber jetzt möchte ich vor allen Dingen betonen, daß für die Nachmittagsstunden alles Gesangliche, Musikalische und das Eurythmische gesetzt wird. Da soll das Kind womöglich dasjenige, was in Unterricht und Erziehung ist, mit seinem ganzen Menschen durchmachen.

Und darauf, daß alles, was erzogen und unterrichtet wird, an den ganzen Menschen herankommt, kann nun insbesondere Rücksicht genommen werden, wenn der Unterricht in der Art, wie ich es geschildert habe, aus dem Herzen der Lehrerkonferenzen heraus ein Ganzes ist. Das merkt man insbesondere dann, wenn man den Unterricht aus dem mehr Seelischen herüberlaufen läßt in das mehr völlig PhysischPraktische des Lebens. Und auf dieses Hinüberlaufen in das PhysischPraktische des Lebens, darauf ist der Waldorfschul-Unterricht in erster Linie angelegt.

Und so wird hingearbeitet, daß immer mehr und mehr die Kinder ihre Hände gebrauchen lernen, wobei herausgearbeitet werden muß aus dem, was Händegebrauch im Spiel erst war bei dem ganz kleinen Kinde durch ein gewisses artistisch, künstlerisches Element hindurch, das aber aus dem Kinde selbst hervorgeholt werden soll.

Das erreichen wir dadurch, daß wir die Kinder allerlei praktische Arbeiten machen lassen. Wir sind es jetzt nur in der Lage vom 6. Schuljahr ab; manche von diesen Dingen gehören in ein früheres Alter, aber — ich habe es schon erwähnt — wir mußten eben Kompromisse schließen, das Ideal wird man erst später erreichen können, dann wird das, was jetzt ein elf- oder zwölfjähriges Kind macht, auch ein neunjähriges Kind machen können auch in bezug auf praktische Arbeiten. Aber diese praktischen Arbeiten tragen den Charakter des freien Arbeitens und des Hineintragens ins Künstlerische. Das Kind soll aus dem Willen heraus arbeiten, nicht aus irgend etwas, was ihm vorgeschrieben ist.

So führen wir in einer Art von Handfertigkeitsunterricht das Kind hinein, allerlei Gegenstände zu schnitzen, allerlei Gegenstände zu verfertigen, die es aus seiner Idee heraus verarbeitet. Man macht die Erfahrung, wie in einem auf das Lebendige gebauten Unterricht tatsächlich die Kinder die Dinge aus sich herausholen. Ich will ein Beispiel sagen. Wir lassen die Kinder Dinge schnitzen, die halb künstlerisch, halb nützlich sind. Man kann zum Beispiel in diese Schale irgend etwas hineintun. Wir lassen die Kinder das schnitzen in den Formen, so daß die Kinder ein Form-, ein Gestaltungsgefühl aus sich heraus bekommen, so daß die Kinder etwas schaffen, was aus ihrem Willen heraus und aus ihrem Wohlgefallen heraus die Form bekommt. Aber dabei stellt sich etwas sehr Merkwürdiges heraus.

Nehmen Sie einmal an, wir haben zu irgendeiner Zeit menschliche Anatomie in der Klasse getrieben so, wie es für diese Klasse in der Schule ganz besonders notwendig ist. Wir haben den Kindern erklärt die Form des Knochensystems, wir haben den Kindern erklärt auch die Form des äußeren Körpers, die Lebensweise des menschlichen Organismus. Die Kinder haben das, indem der Unterricht so artistisch gestaltet wird, wie ich es dargestellt habe in den letzten Tagen, lebendig aufgenommen. Es ist bis in ihren Willen gegangen, nicht bloß in ihre Gedanken, in ihre Köpfe. Und dann sieht man, wenn sie nun darangehen, so etwas zu machen, daß das in ihren Händen weiterlebt. Die Formen werden andere, je nach dem wir im Unterricht das eine oder das andere treiben. Es lebt sich in den Formen aus. Man sieht es dem, was die Kinder plastisch schaffen, an, was in den Stunden morgens von 8 bis 10 Uhr getrieben wird, weil das, was als Unterricht erteilt werden soll, eben in den ganzen Menschen hineingeht.

Das erreicht man nur, wenn man eben Rücksicht darauf nimmt, wie in der Natur gearbeitet wird. Gestatten Sie mir, etwas recht Ketzerisches zu sagen: man liebt es ja, den Kindern Puppen in die Hand zu geben, ganz besonders «schöne» Puppen. Man merkt nicht, daß die Kinder das eigentlich nicht wollen. Sie weisen es zurück, aber man drängt es ihnen auf. Schöne Puppen, schön angestrichene! Viel besser ist es, den Kindern ein Taschentuch zu geben, oder wenn ein Taschentuch zu schade ist, irgend etwas anderes; man macht die Sache zusammen, macht hier einen Kopf, malt eine Nase, zwei Augen und so weiter und damit spielen gesunde Kinder viel lieber als mit «schönen» Puppen, weil da für ihre Phantasie noch etwas übrig bleibt; währenddem, wenn die Puppe möglichst schön gestaltet ist, mit roten Wangen sogar, für die Phantasie nichts übrig bleibt. Das Kind verödet innerlich neben der schönen Puppe.

Das weist aber hin auf die Art und Weise, wie man aus dem Kinde hervorholen soll dasjenige, was es nun selber gestaltet. Und da, sehen Sie, wenn unsere Kinder im 6. Schuljahr herankommen in der Schule, die Dinge nun selber aus ihrem Formgefühl heraus zu entwickeln, dann zeigen sie sich so, wie es in diesen kleinen Musterbeispielen der Fall ist, die wir mitgebracht haben (Holzpuppen). Die Dinge sind so, wie sie ganz aus der Individualität irgendeines Kindes herauswachsen.

Es handelt sich aber insbesondere darum, daß man Kinder früh darauf aufmerksam macht, wie sie aus der inneren Beweglichkeit heraus, nicht aus innerer Starrheit heraus eigentlich sich das Leben denken wollen. Daher, wenn man die Kinder allmählich aus dem Spielwesen heraus dasjenige, was ja für sie seriös ist, seinen Ernst hat, gestalten läßt, so muß man versuchen, Beweglichkeit iin dieSache hineinzubringen. Sehen Sie, solche Sachen, was, wie ich glaube, ein ganz außerordentlicher Kerl ist (geschnitzter Bär), machen die Kinder ganz von der Picke auf, und sie machen auch diese Zugdinge selber daran, ohne daß man sie dazu anleitet, so daß sich dann bei einem solchen Kerl auch die Zunge bewegt, wenn er so getrieben wird. Oder die Kinder tragen ihre Phantasie hinein in die Sache; sie machen eine Katze nicht so, daß sie artig ist, sondern machen das, was sie bemerken, ohne daß sie die tieferen Zusammenhänge kennen, den Katzenbuckel, ganz ordentlich hinein.

Besonderen Wert lege ich immer darauf, daß Kinder auch bei Spielzeugen sich schon hineinfinden in das, was sich bewegt, was also nicht bloß ruht, sondern bei dem man handeln lernt. So fabrizieren dann die Kinder Dinge, die ihnen außerordentlich Freude gewähren, wenn sie sie nach und nach fertigbringen. Sie machen nicht bloß realistische Dinge, sondern ganz aus ihrer eigenen Idee heraus machen sie solche Gnomengeschichten und dergleichen.

Sie finden durchaus auch die Möglichkeit, in komplizierterer Weise solche Dinge zusammenzusetzen; es wird ihnen nicht gesagt, daß man das machen kann, sondern das Kind wird nur darauf geführt, so daß es von selbst solch einen lustigen Kerl (beweglicher Rabe) machen kann, und dann wiederum sieht er griesgrämig aus, traurig.

Und wenn das Kind dann so etwas fertigbringt (Eule mit beweglichen Flügeln), dann ist es ganz besonders befriedigt! Das machen also die Kinder zwischen dem 11. bis 15. Jahre, jetzt noch die älteren, aber wir werden es dann allmählich zurückzuführen haben in noch frühere Klassen, wo die Formen dann einfacher werden.

Nun, außer diesem Handfertigkeitsunterricht haben wir einen eigentlichen Handarbeitsunterricht. Und da ist das zu bemerken, daß in der Waldorfschule immer für alles Knaben und Mädchen durcheinandersitzen. Wir haben durchaus bis in die höchste Klasse hinauf Knaben und Mädchen durcheinandersitzen. So daß in der Tat, mit geringen Varianten natürlich, und je weiter wir hinaufkommen werden in die höheren Klassen, so muß natürlich differenziert werden, aber es ist so, daß im ganzen tatsächlich der Knabe dieselben Arbeiten lernt, die das Mädchen lernt, und es stellt sich heraus in einer merkwürdigen Weise, wie gern die kleinen Knaben stricken oder häkeln, und wie die Mädchen auch Arbeiten machen, die man sonst nur die Knaben machen läßt. Dadurch wird auch sozial etwas erreicht: das gegenseitige Verständnis der Geschlechter, was ja in erster Linie heute angestrebt werden muß, wo wir in dieser Beziehung sozial noch gar nicht vorgeschritten sind, wo wir unter den größten Vorurteilen leben. Und es ist ja tatsächlich so, daß es eine Wohltat ist, wenn so etwas erreicht wird wie das, was ich Ihnen zum Beispiel durch das Folgende zeigen will.

Wir haben auch eine solche kleine Schule in Dornach gehabt. Sie ist uns jetzt wegen der schweizerischen Freiheit ja verboten worden, und wir können da nur anfangen, für vorgeschrittene junge Damen und Herren Unterricht zu erteilen, weil die Freiheit es notwendig macht, daß freie Schulen neben den Staatsschulen eben nicht errichtet werden. Nun, nicht wahr, das ist etwas, was ja nicht mit der eigentlichen Pädagogik zusammenhängt. Aber wir haben eine Zeitlang versuchen können, auch in Dornach in einer kleinen Schule zu arbeiten. Es wird ja in der nächsten Zeit wahrscheinlich möglich sein, dennoch eine solche freie Schule in Basel zu bekommen. — Aber in der Waldorfschule, wie gesagt, arbeiten im Handarbeitsunterricht Knaben und Mädchen durcheinander. Da wird alles mögliche dann im Handarbeitsunterricht zustande gebracht. Knaben und Mädchen arbeiten da ganz friedlich zusammen. Sie werden zum Beispiel hier bei diesen beiden Arbeiten nicht leicht unterscheiden können sogar, wenn Sie nicht auf Feinheiten eingehen, worinnen die Unterschiede der Knaben- und Mädchenarbeit liegen (zwei Deckchen).

Das einzige, was sich in merkwürdiger Art herausgestellt hat, das ist — wir gehen dann in der höchsten Klasse, die wir bis jetzt gebildet hatten, in der die sechzehn-, siebzehnjährigen Knaben und Mädchen durcheinander sind, über auch zu Spinnen und Weben, so daß tatsächlich die Menschen ins praktische Leben eingeführt werden, das Leben auch kennenlernen -, nun ist das Merkwürdige: spinnen wollen die Knaben nicht, dabei wollen sie nämlich den Mädchen helfen. Die Mädchen sollen spinnen, und die Knaben wollen dann Zuträger sein, sie wollen da eine Art Ritterschaft ausüben. Das ist das einzige, was sich bis jetzt herausgestellt hat, daß beim Spinnen die Knaben die Mädchen bedienen wollen. Aber im übrigen haben wir gesehen, daß die Knaben alle möglichen Handarbeiten machen.

Es wird nun auch versucht, aus demjenigen, was als Malunterricht angestrebt wird, den Handarbeitsunterricht zu gestalten. Nicht etwa, daß man etwa aufzeichnen und dann sticken läßt, sondern tatsächlich, daß man die Kinder zuerst ganz aus ihrem Menschenwesen heraus die Farbe behandeln läßt. Da ist es natürlich ungeheuer wichtig, daß man zunächst das richtige Erleben des Farbigen im Kinde erzeugt. Wenn Sie die kleinen Farben nehmen, die man gewöhnlich bekommt in den Handlungen, und die Kinder mit dem Pinsel von den kleinen Farben von der Palette herab malen lassen, lernen sie gar nichts. Das ist notwendig, daß man mit der Farbe leben lernt, nicht von der Palette herab malen läßt, sondern aus dem Tiegel im Wasser aufgelöste Farben nimmt. Da bekommt das Kind das Gefühl, wie Farbe neben Farbe leben kann, das Gefühl für innere Harmonik und für inneres Farbenerleben. Und wenn das auch manchmal Schwierigkeiten bietet - die Klasse sieht manchmal nicht gut aus, nachdem Malunterricht erteilt worden ist, weil nicht alle sehr geschickt sind, manchmal nicht sehr gelehrig sind in dieser Beziehung -, wenn das auch Schwierigkeiten macht, es gibt doch ungeheure Fortschritte, wenn man so die Kinder zunächst ins Farbenelement einführt, so daß sie aus dem Farbenerleben heraus, ohne daß sie naturalistisch etwas nachahmen wollen, zunächst malen lernen. Dann gibt sich schon selbst, ich möchte sagen, die Farbenfläche und Farbenform über die Papierfläche drüber. Und so wird so gemalt in der Waldorfschule, und auch in Dornach wird so gemalt, daß die Kinder zunächst das Farbenerleben malen. Es kommt überall auf die Nebeneinanderstellung, Übereinanderstellung der Farben an. So lebt sich das Kind in die Farbe ein, und dann kommt es schon nach und nach von selbst dazu, aus der Farbe die Form zu holen. Sie sehen, wie hier — bei allerdings vorgeschrittenen Kindern — schon, ohne daß man auf das Zeichnen ausgeht, hervorgeholt ist aus der Farbe ein Geformtes, ein Gestaltetes. Aber nach demselben Prinzip wird auch bei den kleinen Kindern unterrichtet. Wir haben hier zum Beispiel solche Blätter, welche das Farberleben anstreben. Da wird nicht etwas gemalt, sondern da wird aus der Farbe heraus gelebt. Das Etwas-Malen kann erst viel später kommen. Wenn man zu früh anfängt, etwas zu malen, dann verliert sich der Sinn für das Lebendige, dann kommt der Sinn für das Tote herauf.

Wenn man dann in dieser Weise vorgeht, so ist der Übergang zu irgend etwas Gegenständlichem in der Welt ein viel lebendigerer, als wenn man nicht diese Grundlage schafft. Sehen Sie, Kinder, die erst aus der Farbe heraus haben leben lernen, die malen dann die Insel Sizilien im Zusammenhang mit dem Geographieunterricht zum Beispiel, und es kommt dann eine Landkarte zustande. Und so gliedert sich zusammen künstlerisches Arbeiten und sogar geographischer Unterricht.

Wenn man auf diese Weise ein Gefühl für Farbenharmonik hervorruft, dann bringt man es zustande, daß die Kinder Gegenstände, die irgendwie dem Leben dienen, dann machen. Dieser Einband ist nicht zuerst aufgezeichnet, sondern das Kind lernt in Farbe zu erleben, und nachher so etwas, was etwa ein Bucheinband ist, zu gestalten. Dabei handelt es sich darum, das wirkliche Lebensgefühl bei dem Kinde zu erwecken. Es gibt die Möglichkeit, gerade durch Form und Farbe stark hineinzuführen in das Leben.

Man kann zuweilen finden, daß das Schreckliche geschieht, daß irgend jemand an ein Kleid ein Halsband machen läßt, dann einen Gürtel, unten einen Kleidersaum, und daran hat er dasselbe Muster. Man kann das zuweilen sehen. Es ist natürlich das Schrecklichste, was im Leben passieren kann, aus künstlerischen Instinkten heraus. Das Kind muß frühzeitig lernen, daß ein Band, das für den Hals angebracht ist, die Tendenz hat, nach unten sich irgendwie zu öffnen, nach unten zu wirken; daß der Gürtel beiderseitig wirken muß, und daß der Saum des Kleides unten, daß der nach oben irgendwie streben muß und unten aufstehen muß; daß also nicht das Schreckliche geschieht, daß ein Kind lernt, einfach ein Band künstlerisch ausbilden, sondern es muß wissen, wie das Band aussehen muß, je nachdem es an diesem oder jenem Teil des Menschen sitzt. So zum Beispiel muß man wissen, wenn ein Bucheinband gemacht wird, daß wenn man das Buch anschaut, man es so aufmacht. Es muß zwischen oben und unten ein Unterschied sein. Dieses Raumgefühl, dieses Formgefühl, in das muß das Kind notwendigerweise hineinwachsen. Das geht dann bis in die Glieder. Das ist ein Unterricht, der zuweilen viel stärker in das Physische hineinwirkt als ein abstraktes Turnen. Und so sehen Sie, wächst aus der Farbenbehandlung eben dasjenige heraus, was dann allerlei nützliche Gegenstände werden, die dann behandelt werden in der Weise, daß wirklich das Kind empfindet Farbe neben Farbe und Form auf Form, und das Ganze gehört zu etwas, und daher mache ich es so.

Das ist dasjenige, das in jede Einzelheit hineingehört, in das Lebendige des Arbeitens. Der Unterricht soll eben eine Vorschule für das Leben sein. Sie werden da unter den Arbeiten allerlei interessante Dinge finden, sogar hier etwas, was ein verhältnismäßig sehr kleines Mädchen gemacht hat (Eierwärmer).

Ich kann Ihnen im Vortrag nicht alles zeigen, ich möchte nur noch darauf aufmerksam machen, daß wir hier allerlei Schönheiten aus der Waldorfschule mitgebracht haben. Hier finden Sie auch zwei Liederbücher von Herrn Baumann, dem Leiter des Musikalischen in der Waldorfschule, aus denen Sie entnehmen werden, welche Art von Liedern und Musikstoffen wir überhaupt in der Waldorfschule behandeln. Dann haben wir von einem der Mädchen — weil wir natürlich wegen der Grenzschwierigkeiten nicht viele Dinge mitbringen konnten - noch allerlei Dinge, die Sie hier vervielfältigt sehen. Das ist aber alles plastisch in der Art ausgeführt, wie es hier ist. Sie sehen, die Kinder haben ganz nette Einfälle; sie fassen doch eben das Leben auf; die Sachen sind aus Holz geschnitzt.

Sie können hieran (Landkarte) noch sehen, wie in das volle Leben dann hineingeführt werden kann, wenn man gerade schon lebensvoll von dem ersten Prinzip ausgeht. Das können Sie hier an dieser Landkarte sehen: man hat zuerst das Farbenerleben, und dann erlebt man ganz seelisch, indem man zuerst das Farbenerleben hat, erlebt man seelisch, Sie sehen hier Griechenland, seelisch erlebt. Es wächst das Kind, indem es zuerst in die Farbenerlebnisse hinein sich findet für dasjenige, was es aus dem Geographieunterricht bekommt, wächst es hinein, sich zu sagen: die Insel Kreta, die muß ich in einer bestimmten Farbe malen, und die kleinasiatische Küste so, den Peloponnes so. Das Kind lernt durch die Farbe künstlerisch sprechen, und es wird eine Landkarte tatsächlich dadurch ein innerliches seelisches Produkt.

Denken Sie nur, wie die Kinder nacherleben die Erde, wenn sie so aus dem Inneren heraus, nachdem sie zunächst so, wie der hier Kreta angestrichen hat oder den Peloponnes oder das nördliche Griechenland, wenn sie bei jeder solchen Farbe die entsprechende Empfindung haben, dann wird ja in ihrer Seele auch lebendig dasjenige, was Griechenland ist, und es schafft das Kind gewissermaßen Griechenland aufs neue gewissermaßen aus sich selbst heraus. Der Mensch nimmt auf diese Weise die Welt wirklich lebendig in sich auf. Und ganz anders leben die Dinge in den Kindern, wenn man sie auf diese Weise die Realität, die ganz gewöhnliche trockene Realität des Tages nacherleben läßt, nachdem sie zuerst die Elemente, durch die sie sich aussprechen, ich möchte sagen, die Farbensilben und Worte, künstlerisch erleben lernen an den einfachen Malereien.

The Waldorf School as an Organism

When we talk about organization today, we usually mean that something needs to be organized or set up. When I talk about the organization of the Waldorf School today, I do not mean it in this sense, because organization is really only possible for things that are mechanical in a certain sense. One can organize the establishment of a factory or any other institution where the parts are to be held together as a whole by the idea that is imprinted on them. But just imagine how absurd it would be to demand that the human organism be organized. It is organized, it is there, and one must accept it as an organism. One must study it. One must get to know its institutions as those of an organism, as those of an organization.

In this sense, a school such as the Waldorf School is an organism from the outset and cannot be organized by designing a program, as I have already indicated, for how the school should be set up: Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2, and so on. I have already said that I am completely convinced, without irony, that if five or twelve people get together today — and today people are all very clever, very intelligent — they will be able to work out an ideal school program in which there is nothing to improve: Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2, and so on. Paragraph 12 and so on; and then the only question that arises is: Can this be implemented in practice? — And it will very soon become apparent that very nice programs can be made, but in practice, when you set up a school, you are faced with a complete organism.

This school then consists of a teaching staff that cannot be molded out of wax. Paragraph 1 or Paragraph 5 might say: the teacher should be this way or that way. The teaching staff is not something that can be molded from wax, but one must seek out individual teachers; one must accept them with the abilities they have. Above all, one must understand what abilities they have. One must understand whether they are first and foremost a good elementary school teacher or whether they are a good teacher for the higher grades. So, just as one must understand the nose or the ear in order to understand the human organism, one must understand the individual teacher if one wants to achieve anything at all. It is not abstract program principles that matter, but the realities that one has before one. If one could mold teachers out of wax, one could make programs. But that is not possible. So, first of all, one has the teaching staff as a reality. One must know them well. Above all, the first principle in the organization of the Waldorf school is that I, as the spiritual leader of the Waldorf school, must know the teaching staff well in all their individualities.

The second factor is the children, and in this respect there were some practical difficulties involved in making something of the Waldorf school. For this Waldorf school was initially founded by Emil Molt in Stuttgart out of all the emotions that existed in 1918 and 1919 after the war had ended. It was founded because people believed that it was initially a social act. It was recognized that not much could be done with adults in social terms; they got along for a few weeks in Central Europe after the end of the war. After that, they immediately fell back into the prejudices that had developed among the different classes. That is why the idea arose to first take care of the next generation. And because Emil Molt, an industrialist in Stuttgart, had just founded the school, there was no need to go door to door to recruit children; instead, the children from his factory were enrolled. So, initially, we mainly had proletarian children, about 150 children from Molt's factory. These 150 children were then supplemented by the vast majority of children from the Anthroposophical Society in Stuttgart and the surrounding area, so that we had around 200 children to work with at the beginning.

At the same time, however, this created a situation that made the school a unified school in the ideal sense. For we had a foundation of proletarian children, and the anthroposophical children were not proletarian children at first, but came from all walks of life, from the lowest to the highest. So from the outset, all class distinctions were eliminated, also through the social foundation of the Waldorf school. And that was definitely the aim, and continues to be the aim, that only the generally human aspect is taken into consideration. The Waldorf school is based solely on pedagogical and didactic principles, with no consideration given to whether a child is a proletarian child or whether it would have been the child of the former emperor if it had sought admission to the Waldorf school. Only pedagogical and didactic principles applied and will continue to apply. Thus, from the very beginning, the Waldorf school was conceived as a unified school.