Education

GA 307

14 August 1923, Ilkley

IX. Arithmetic, Geometry, History

Arithmetic and geometry, indeed all mathematics, occupy a unique position in education. Education can only be filled with the necessary vitality and give rise to a real interplay between the soul of the teacher and the soul of the child, if the teacher fully realizes the consequences of his actions and methods. He must know exactly what effect is made on the child by the treatment he receives in school, or anywhere else.

Man is a being of body, soul and spirit; his bodily nature is formed and moulded by the spirit. The teacher, then, must always be aware of what is taking place in the soul and spirit when any change occurs in the body, and again, what effect is produced in the body when influences are brought to bear on the life of spirit or soul.

Anything that works upon the child's conceptual and imaginative faculties, anything that is to say of the nature of painting or drawing which is then led over into writing, or again, botany taught in the way indicated yesterday, all this has a definite effect. And here, above all, we must consider a higher member of man's being, a member to which I have already referred as the etheric body, or body of formative forces. The human being has, in the first place, his physical body. It is revealed to ordinary physical sense-perception. Besides this physical body, however, he has an inner organization, perceptible only to Imaginative Cognition, a super-sensible, etheric body. Again he has an organization perceptible only to Inspiration, the next stage of super-sensible knowledge. (These expressions need not confuse us; they are merely terms.) Inspiration gives insight into the so-called astral body and into the real Ego, the Self of the human being.

From birth till death, this etheric body, this body of formative forces which is the first super-sensible member of man's being never separates from the physical body. Only at death does this occur. During sleep, the etheric organization remains with the physical body lying there in bed. When man sleeps, the astral body and Ego-organization leave the physical and etheric bodies and enter them again at the moment of waking.

Now it is the physical and etheric bodies which are affected when the child is taught arithmetic or geometry, or when we lead him on to writing from the basis of drawing and painting. All this remains in the etheric body and its vibrations persist during sleep. On the other hand, history and such a study of the animal kingdom as I spoke of in yesterday's lecture work only upon the astral body and Ego-organization. What results from these studies passes out of the physical and etheric bodies into the spiritual world during sleep.

If, therefore, we are teaching the child plant-lore or writing, the effects are preserved by the physical and etheric bodies during sleep, whereas the results of history lessons or lessons on the nature of man are different, for they are carried out into the spiritual world by the Ego and astral body. This points to an essential difference between the effects produced by the different lessons.

We must realize that all impressions of an imaginative or pictorial nature made on the child have the tendency to become more and more perfect during sleep. On the other hand, everything we tell the child on the subject of history or the being of man works on his organization of soul and spirit and tends to be forgotten, to fade away and grow dim during sleep. In teaching therefore, we have necessarily to consider whether the subject-matter works upon the etheric and physical bodies or upon the astral body and Ego-organization.

Thus on the one hand, the study of the plant kingdom, the rudiments of writing and reading of which I spoke yesterday affect the physical and etheric bodies. (I shall speak about the teaching of history later on.) On the other hand, all that is learnt of man's relation to the animal kingdom affects the astral body and Ego-organization, those higher members which pass out of the physical and etheric bodies during sleep. But the remarkable thing is that arithmetic and geometry work upon both the physical-etheric and the astral and Ego. As regards their role in education arithmetic and geometry are really like a chameleon; by their very nature they are allied to every part of man's being. Whereas lessons on the plant and animal kingdoms should be given at a definite age, arithmetic and geometry must be taught throughout the whole period of childhood, though naturally in a form suited to the changing characteristics of the different life-periods.

It is all-important to remember that the body of formative forces, the etheric body, begins to function independently when it is abandoned by the Ego and astral body. By virtue of its own inherent forces, it has ever the tendency to bring to perfection and develop what has been brought to it. So far as our astral body and Ego are concerned, we are—stupid, shall I say? For instead of perfecting what has been conveyed to these members of our being, we make it less perfect. During sleep, however, our body of formative forces continues to calculate, continues all that it has received as arithmetic and the like. We ourselves are then no longer within the physical and etheric bodies; but supersensibly, they continue to calculate or to draw geometrical figures and perfect them. If we are aware of this fact and plan our teaching accordingly, great vitality can be generated in the being of the child. We must, however, make it possible for the body of formative forces to perfect and develop what it has previously received.

In geometry, therefore, we must not take as our starting point the abstractions and intellectual formulae that are usually considered the right groundwork. We must begin with inner, not outer perception, by stimulating in the child a strong sense of symmetry for instance.

Even in the case of the very youngest children we can begin to do this. For example: we draw some figure on the blackboard and indicate the beginning of the symmetrical line. Then we try to make the child realize that the figure is not complete; he himself must find out how to complete it. In this way we awaken an inner, active urge in the child to complete something as yet unfinished. This helps him to express an absolutely right conception of something that is a reality. The teacher, of course, must have inventive talent but that is always a very good thing. Above all else the teacher must have mobile, inventive thought.

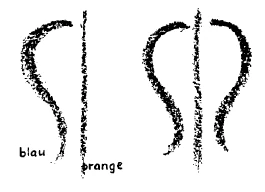

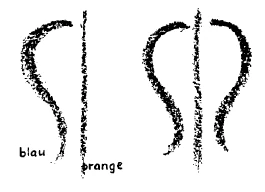

When he has given these exercises for a certain time, he will proceed to others. For instance, he may draw some such figure as this (left) on the blackboard, and then he tries to awaken in the child an inner conception of its spatial proportions. The outer line is then varied and the child gradually learns to draw an inner form corresponding to the outer (right). In the one the curves are absolutely straightforward and simple. In the other, the lines curve outwards at various points. Then we should explain to the child that for the sake of inner symmetry

he must make in the inner figure an inward curve at the place where the lines curve outwards in the outer figure. In the first diagram a simple line corresponds to another simple line, whereas in the second, an inward curve corresponds to an outward curve.

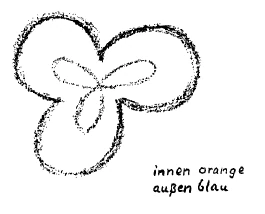

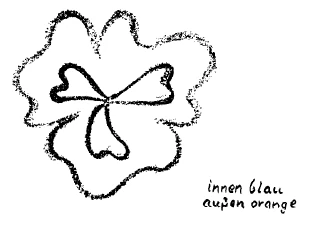

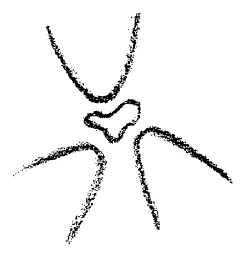

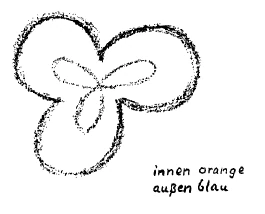

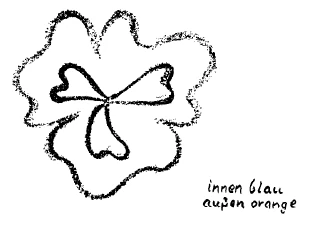

Or again we draw something of this kind, where the figures together form a harmonious whole. We vary this by leaving the forms incomplete, so that the lines flow away from each other to infinity. It is as if the lines were running away and one would like to go with them. This leads to the idea that they should be bent inwards to regulate and complete the figure, and so on. I can only indicate the principle of the thing. Briefly, by working in this way, we give the child an idea of “a-symmetrical symmetries” and so prepare the body of formative forces in his waking life that during sleep it elaborates and perfects what has been absorbed during the day. Then the child will wake in an etheric body, and a physical body also, inwardly and organically vibrant. He will be full of life and vitality. This can, of course, only be achieved when the teacher has some knowledge of the working of the etheric body; if there is no such knowledge, all efforts in this direction will be mechanical and superficial.

A true teacher is not only concerned with the waking life but also with what takes place during sleep. In this connection it is important to understand certain things that happen to us all now and again. For instance, we may have pondered over some problem in the evening without finding a solution. In the morning we have solved the problem. Why? Because the etheric body, the body of formative forces, has continued its independent activity during the night.

In many respects waking life is not a perfecting but a disturbing process. It is necessary for us to leave our physical and etheric bodies to themselves for a time and not limit them by the activity of the astral body and Ego. This is proved by many things in life; for instance by the example already given of someone who is puzzling over a problem in the evening. When he wakes up in the morning he may feel slightly restless but suddenly finds that the solution has come to him unconsciously during the night. These things are not fables; they actually happen and have been proved as conclusively as many another experiment. What has happened in this particular case? The work of the etheric body has continued through the night and the human being has been asleep the whole time. You will say: “Yes, but that is not a normal occurrence, one cannot work on such a principle.” Be that as it may, it is possible to assist the continued activity of the etheric body during sleep, if, instead of beginning geometry with triangles and the like, where the intellectual element is already in evidence, we begin by conveying a concrete conception of space. In arithmetic, too, we must proceed in the same way. I will speak of this next.

A pamphlet on physics and mathematics written by Dr. von Baravalle (a teacher at the Waldorf School) will give you an excellent idea of how to bring concreteness into arithmetic and geometry. This whole mode of thought is extended in the pamphlet to the realm of physics as well, though it deals chiefly with higher mathematics. If we penetrate to its underlying essence, it is a splendid guide for teaching mathematics in a way that corresponds to the organic needs of the child's being. A starting-point has indeed been found for a reform in the method of teaching mathematics and physics from earliest childhood up to the highest stages of instruction. And we can apply to the domain of arithmetic what is said in this pamphlet about concrete conceptions of space.

Now the point is that everything conveyed in an external way to the child by arithmetic or even by counting deadens something in the human organism. To start from the single thing and add to it piece by piece is simply to deaden the organism of man. But if we first awaken a conception of the whole, starting from the whole and then proceeding to its parts, the organism is vitalised. This must be borne in mind even when the child is learning to count. As a rule we learn to count by being made to observe purely external things—things of material, physical life.

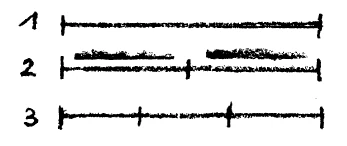

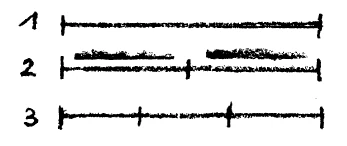

First we have the 1—we call this Unity. Then 2, 3, 4, and so forth, are added, unit by unit, and we have no idea whatever why the one follows the other, nor of what happens in the end. We are taught to count by being shown an arbitrary juxtaposition of units. I am well aware that there are many different methods of teaching children to count, but very little attention is paid nowadays to the principle of starting from the whole and then proceeding to the parts. Unity it is which first of all must be grasped as the whole and by the child as well. Anything whatever can be this Unity. Here we are obliged to illustrate it in a drawing. We must therefore draw a line; but we could use an apple just as well to show what I shall now show with a line.

This then is 1. And now we go on from the whole to the parts, or members. Here then we have made of the 1 a 2, but the 1 still remains. The unit has been divided into two. Thus we arrive at the 2. And now we go on. By a further partition the 3 comes into being, but the unit always remains as the all-embracing whole. Then we go on through the 4, 5, and so on. Moreover, at the same time and by other means we can give an idea of the extent to which it is possible to hold together in the mind the things that relate to number and we shall discover how really limited man is in his power of mental presentation where number is concerned.

In certain nations to-day the concept of number that is clearly held in the mind's eye only goes up to 10. Here in this country money is reckoned up to 12. But that really represents the maximum of what is mentally visualised for in reality we then begin over again and in fact count what has been counted. We first count up to 10, then we begin counting the tens, 2 times 10=20, 3 times 10=30. Here we are no longer considering the things themselves. We begin to calculate by using number itself, whereas the more elementary concept requires the things themselves to be clearly present in the mind.

We are very proud of the fact that we are far advanced in our methods of counting compared with primitive peoples who depend on their ten fingers. But there is little foundation for this pride. We count up to 10 because we sense our hands as members. We feel our two hands symmetrically with their 10 fingers. This feeling also arises and is inwardly experienced by the child, and we must call forth the sense of number by a transition from the whole to the parts. Then we shall easily find the other transition which leads us to the counting in which one is added to another. Eventually, of course, we can pass on to the ordinary 1, 2, 3, etc. But this mere adding of one or more units must only be introduced as a second stage, for it has significance only here in physical space, whereas to divide a unity into its members has an inner significance such that it can continue to vibrate in the etheric body even though quite beneath our consciousness. It is important to know these things.

Having taught the child to count in this way, the following will also be important. We must not pass on to addition in a lifeless, mechanical way merely adding one item to another in series. Life comes into the thing when we take our start not from the parts of the addition sum but from the sum total itself. We take a number of objects; for example, a number of little balls. We have now got far enough in counting to be able to say: Here are 14 balls. Now we divide them, extending this concept of a part still further. Here we have 5, here 4, here 5 again. Thus we have separated the sum into 5 and 4 and 5. That is, we go from the sum to the items composing it, from the whole to the parts. The method we should use with the child is first to set down the sum before him and then let the child himself perceive how the given sum can be divided into several items.

This is exceedingly important. Just as to drive a horse we do not harness him tail foremost, so in the teaching of arithmetic we must have the right direction. We must start from a whole which is always actually present, from a reality, from what is present as a whole and then pass on to the separate parts; later, we find our way to the ordinary addition sum.

Continuing thus, from the living whole to the separate parts, one touches the reality underlying all arithmetical calculations: i.e., the setting in vibration of the body of formative forces. This body needs a living stimulus for its formative activity and once energised it will continually perfect the vibrations without the need of drawing upon the astral body and Ego-organization with their disturbing elements.

Your teaching work will also be essentially enhanced and vivified if you similarly reverse the other simple forms of calculation. To-day, one might say, they are standing on their heads and must be reversed. Try, for instance, to bring the child to say: “If I have 7, how much must I take away to get 3,” instead of “What remains over if I take 4 from 7?” That we have 7 is the real thing and that 3 remains is also real; how much must we take away from 7 to get 3? Beginning with this form of thought we stand in the midst of life, whereas with the opposite form we are dealing with abstractions. Proceeding in this way, we can easily find our way further. Thus, once more, in multiplication and division we should not ask what will result when we divide 10 into two parts, but how must we divide 10 to get the number 5. The real aspect is given; moreover in life we want eventually to get at something which has real significance. Here are two children, 10 apples are to be divided among them. Each of them is to get 5. These are the realities. What we have to deal with is the abstract part that comes in the middle. Done in this way, things are always immediately adapted to life and should we succeed in this, the result will be that what is the usual, purely external way of adding, by counting up one thing after another with a deadening effect upon the arithmetic lessons, will become a vivifying force, of especial importance in this branch of our educational work. And it is evident that precisely by this method we take into account the sub-conscious in man, that is, the part which works on during sleep and which also works subconsciously during the waking hours. For one is aware of a small part only of the soul's experience; nevertheless the rest is continually active. Let us make it possible for the physical and etheric bodies of the child to work in a healthy way, realizing that we can only do so if we bring an intense life, an awakened interest and attention, especially into our teaching of arithmetic and geometry.

The question has arisen during this Conference as to whether it is really a good thing to continue the different lessons for certain periods of time as we do in the Waldorf School. Now a right division of the lessons into periods is fruitful in the very highest degree. “Period” teaching means that one lesson shall not perpetually encroach upon another. Instead of having timetables setting forth definite hours:—8 – 9, arithmetic, 9 – 10, history, religion, or whatever it may be, we give one main lesson on the same subject for two hours every morning for a period of three, four, or five weeks. Then for perhaps five or six weeks we pass on to another subject, but one which in my view should develop out of the other, and which is always the same during the two hours. The child thus concentrates upon a definite subject for some weeks.

The question was asked whether too much would not be forgotten, whether in this way the children would not lose what they had been taught. If the lessons have been rightly given, however, the previous subject will go on working in the subconscious regions while another is being taken. In “period” lessons we must always reckon with the subconscious processes in the child. There is nothing more fruitful than to allow the results of the teaching given during a period of three or four weeks to rest within the soul and so work on in the human being without interference.

It will soon be apparent that when a subject has been rightly taught and the time comes round for taking it up again for a further period it emerges in a different form from what it does when it has not been well taught. To make the objection that because the subjects will be forgotten it cannot be right to teach in this way, is to ignore the factors that are at work. We must naturally reckon on being able to forget, for just think of all we should have to carry about in our heads if we could not forget and then remember again! The part played by the fact of forgetting therefore as well as the actual instruction must be reckoned with in true education.

This does not mean that it should be a matter for rejoicing whenever children forget. That may safely be left to them! Everything depends on what has so passed down into the subconscious regions, that it can be duly recalled. The unconscious belongs to the being of man as well as the conscious. In regard to all these matters we must realize that it is the task of education to appeal not only to the whole human being, but also to his different parts and members. Here again it is essential to start from the whole; there must first be comprehension of the whole and then of the parts. But to this end it is also necessary to take one's start from the whole. First we must grasp the whole and then the parts. If in counting we simply place one thing beside another, and add, and add, and add, we are leaving out the human being as a whole. But we do appeal to the whole human being when we lay hold of Unity and go from that to Numbers, when we lay hold of the sum, the minuend, the product and thence pass on to the parts.

The teaching of history is very open to the danger of our losing sight of the human being. We have seen that in really fruitful education everything must be given its right place. The plants must be studied in their connection with the earth and the different animal species in their connection with man. Whatever the subject-matter, the concrete human element must be retained; everything must be related in some way to man.

But when we begin to teach the child history, we must understand that at the age when it is quite possible for him to realize the connection of plant-life with the earth and the earth itself as an organism, when he can see in the human being a living synthesis of the whole animal kingdom, he is still unable to form any idea of so-called causal connections in history. We may teach history very skilfully in the ordinary sense, describing one epoch after another and showing how the first is the cause of the second; we may describe how in the history of art, Michelangelo followed Leonardo da Vinci, for instance, in a natural sequence of cause and effect. But before the age of twelve, the child has no understanding for the working of cause and effect, a principle which has become conventional in more advanced studies. To deduce the later from the earlier seems to him like so much unmusical strumming on a piano, and it is only by dint of coercion that he will take it in at all. It has the same effect on his soul as a piece of stone that is swallowed and passes into the stomach. Just as we would never dream of giving the stomach a stone instead of bread, so we must make sure that we nourish the soul not with stones but with food that it can assimilate. And so history too, must be brought into connection with Man and to that end our first care must be to awaken a conception of the historical sequence of time in connection with the human being.

Let us take three history books, the first dealing with antiquity, the second with the Middle Ages, and the third with our modern age. As a rule, little attention is paid to the conception of time in itself. But suppose I begin by saying to the child: “You are now ten years old, so you were alive in the year 1913. Your father is much older than you and he was alive in the year 1890; his father, again, was alive in 1850. Now imagine that you are standing here and stretching your arm back to someone who represents your father; he stretches his arm back to his father (your grandfather), now you have reached the year 1850.” The child then begins to realize that approximately one century is represented by three or four generations. The line of generations running backwards from the twentieth century brings him finally to his very early ancestors. Thus the sixtieth generation back leads into the epoch of the birth of Christ. In a large room it will be possible to arrange some sixty children standing in a line, stretching an arm backwards to each other. Space is, as it were, changed into time.

If the teacher has a fertile, inventive mind, he can find other ways and means of expressing the same thing—I am merely indicating a principle. In this way the child begins to realize that he himself is part of history; figures like Alfred the Great, Cromwell and others are made to appear as if they themselves were ancestors. The whole of history thus becomes an actual part of life at school when it is presented to the child in the form of a living conception of time.

History must never be separated from the human being. The child must not think of it as so much book-lore. Many people seem to think that history is something contained in books, although of course it is not always quite as bad as that. At all events, we must try by every possible means to awaken a realization that history is a living process and that man himself stands within its stream.

When a true conception of time has been awakened, we can begin to imbue history with inner life and soul, just as we did in the case of arithmetic and geometry, by unfolding not a dead but a living perception. There is a great deal of quibbling to-day about the nature of perception, but the whole point is that we must unfold living and not dead perception. In the symmetry-exercises of which I spoke, the soul actually lives in the act of perception. That is living perception. Just as our aim is to awaken a living perception of space, so must all healthy teaching of history given to a child between the ages of nine and twelve be filled with an element proceeding in this case not from the qualities of space, but from the qualities of heart and soul.

The history lessons must be permeated through and through with a quality proceeding from the heart. And so we must present it as far as possible in the form of pictures. Figures, real forms must stand there and they must never be described in a cold, prosaic way. Without falling into the error of using them as examples for moral or religious admonition, our descriptions must nevertheless be coloured with both morality and religion. History must above all lay hold of the child's life of feeling and will. He must be able to enter into a personal relationship with historic figures and with the modes of life prevailing in the various historical epochs. Nor need we confine ourselves merely to descriptions of human beings. We may, for instance, describe the life of some town in the twelfth century, but everything we say must enter the domains of feeling and will in the child. He must himself be able to live in the events, to form his own sympathies and antipathies. His life of feeling and will must be stimulated.

This will show you that the element of art must everywhere enter into the teaching of history. The element of art comes into play when, as I often describe it, a true economy is exercised in teaching. This economy can be exercised if the teacher has thoroughly mastered his subject-matter before he goes into the classroom; if it is no longer necessary for him to ponder over anything because if rightly prepared it is there plastically before his soul. He must be so well prepared that the only thing still to be done is the artistic moulding of his lesson. The problem of teaching is thus not merely a question of the pupil's interest and diligence, but first and foremost of the teacher's interest, diligence and sincerity.

No lesson should be given that has not previously been a matter of deep experience on the part of the teacher. Obviously, therefore, the organization of the body of teachers must be such that every teacher is given ample time to make himself completely master of the lessons he has to give.

It is a dreadful thing to see a teacher walking round the desks with a book in his hands, still wrestling with the subject-matter. Those who do not realize how contrary such a thing is to all true principles of education do not know what is going on unconsciously in the souls of the children, nor do they realize the terrible effect of this unconscious experience. If we give history lessons in school from note-books, the child comes to a certain definite conclusion, not consciously, but unconsciously. It is an unconscious, intellectual conclusion, but it is deeply rooted in his organism: “Why should I learn all these things? The teacher himself doesn't know them, for he has to read from notes. I can do that too, later on, so there is no need for me to learn them first.” The child does not of course come to this conclusion consciously, but as a matter of fact when judgments are rooted in the unconscious life of heart and mind, they have all the greater force. The lessons must pulsate with inner vitality and freshness proceeding from the teacher's own being. When he is describing historical figures for instance the teacher should not first of all have to verify dates. I have already spoken of the way in which we should convey a conception of time by a picture of successive generations. Another element too must pervade the teaching of history. It must flow forth from the teacher himself. Nothing must be abstract; the teacher himself as a human being must be the vital factor.

It has been said many times that education should work upon the being of man as a whole and not merely on one part of his nature. Important as it is to consider what the child ought to learn and whether we are primarily concerned with his intellect or his will, the question of the teacher's influence is equally important. Since it is a matter of educating the whole nature and being of man, the teacher must himself be “man” in the full sense of the word, that is to say, not one who teaches and works on the basis of mechanical memory or mechanical knowledge, but who teaches out of his own being, his full manhood. That is the essential thing.

Zehnter Vortrag

Eine Ausnahmestellung nimmt in Unterricht und Erziehung Rechnen, Arithmetik und Geometrie, also das Mathematische, ein. Man sollte eigentlich als Lehrer immer ganz genau wissen, was man in der Schule oder überhaupt dem Kinde gegenüber tut, was durch irgendeine Handhabung an dem Kinde geschieht. Nur wenn diese Voraussetzung erfüllt ist, wenn der Lehrer weiß, welche Konsequenz für das Kind das eine oder das andere hat, das er tut, dann kann eigentlich der Unterricht die entsprechende Lebendigkeit haben und auch eine wirkliche Kommunikation zwischen der Seele des Lehrers und des Kindes hervorrufen.

Nun ist der Mensch einmal ein Wesen, das aus Körper, Seele und Geist gegliedert ist und bei dem das Körperliche vom Geistigen gestaltet, geformt wird; so daß der Lehrer immer auch wissen muß, was bei einer körperlichen Gestaltung in der Seele, im Geiste eigentlich vorgeht, und wiederum, welche Folge für den Körper etwas hat, wenn auf den Geist oder auf die Seele gewirkt wird.

Wenn wir dem Kinde etwas beibringen, was auf sein bildhaftes Vorstellen wirkt, also fast alles dasjenige, was wir gestern anführen konnten als Malerisches, Zeichnerisches, das dann zum Schreiben führt, wenn wir dem Kinde etwas wie die Pflanzenkunde in dem Sinne beibringen, wie wir das gestern ausgeführt haben, dann wirkt dies auf das Kind so, daß dabei vorzugsweise dasjenige berücksichtigt wird, was ich auch schon in diesen Vorträgen als ein höheres Glied in der menschlichen Wesenheit, als den Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib charakterisiert habe.

Der Mensch hat ja zunächst seinen physischen Leib. Man nimmt ihn durch gewöhnliche physische Sinneswahrnehmungen eben wahr. Der Mensch hat aber außer diesem physischen Leib eine innere Organisation, die nur wahrgenommen werden kann durch Imagination, durch die imaginative Erkenntnis: einen übersinnlichen Leib, Ätherleib, Bildekräfteleib. Und dann hat der Mensch in sich eine Organisation, welche nur wahrgenommen werden kann durch Inspiration. Man braucht sich dabei, ich sagte es schon einmal, nicht an den Ausdrücken zu stoßen; sie sind eine Terminologie, die man eben brauchen muß. Durch Inspiration bekommt man eine Einsicht in den sogenannten astralischen Leib und in das eigentliche Ich des Menschen, in das eigentliche Selbst des Menschen.

Nun ist die Sache so, daß von der Geburt bis zum Tode der Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib, diese erste übersinnliche Organisation, sich niemals vom physischen Leib trennt. Erst mit dem Tode geschieht das. Im Schlafzustande läßt der Mensch seinen Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib bei dem physischen Leibe zurück. Physischer Körper und Ätherkörper bleiben im Bette liegen, wenn der Mensch schläft; der astralische Leib und die Ich-Organisation gehen beim Einschlafen aus dem physischen Leib und dem Ätherleib heraus und gehen beim Aufwachen wieder in diese hinein.

Wenn wir nun dem Kinde zum Beispiel etwas beibringen aus Rechnen oder Geometrie oder aus denjenigen Gebieten, die ich gestern angeführt habe als zeichnendes Malen, malendes Zeichnen, als Übergang zum Schreiben, so wird durch diesen Unterricht der physische Leib und der Ätherleib beeinflußt. Und wenn wir dem Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib das beibringen, was ich gestern hier skizziert habe, wenn wir ihm etwas beibringen von Rechnen oder Geometrie, so behält er das auch während des Schlafes, so schwingt er auch während des Schlafes fort.

Wenn wir dem Kinde dagegen etwas beibringen von Geschichte oder von jener Tierkunde, von der ich gestern gesprochen habe, so wirkt das nur auf den astralischen Leib und die Ich-Organisation. Das nimmt der Mensch beim Einschlafen aus seinem physischen und Ätherleib heraus mit in die geistige Welt.

Das ist also ein großer Unterschied, ob ich Schreiben oder Pflanzenkunde lehre, das behält die körperliche und die ätherische Organisation im Bette zurück, das schwingt weiter, oder ob ich Geschichte oder Menschenkunde lehre, die nimmt das Ich und der astralische Leib jedesmal beim Schlaf in die geistige Welt mit hinaus. Das bedeutet einen gewaltigen Unterschied in der Wirkung auf den Menschen.

Sie müssen sich klar darüber sein, daß all die bildhaften, imaginativen Eindrücke, die ich auf das Kind mache, sogar während des Schlafes die Tendenz haben, sich zu vervollkommnen, vollkommener zu werden. Dagegen muß dasjenige, was wir zum Beispiel aus Geschichte oder Menschenkunde dem Kinde beibringen, auf die eigentlich seelisch-geistige Organisation wirken, und das hat die Tendenz, während des Schlafens vergessen zu werden, unvollkommener zu werden, blaß zu werden. Es ist daher notwendig, daß wir beim Unterricht darauf Rücksicht nehmen, ob wir einen Stoff haben, der zum Ätherleib und zum physischen Leibe spricht, oder ob wir einen Stoff haben, der zur Ich-Organisation und zur astralischen Organisation spricht.

Diejenigen Dinge nun, die ich gestern angeführt habe als Pflanzenkunde, als dasjenige, was zum Schreiben und Lesen führt, das spricht alles zum physischen Leib und zum Ätherleib. Wir werden noch über den geschichtlichen Unterricht uns zu verständigen haben. Wir haben schon über den tierkundlichen und menschenkundlichen Unterricht Richtlinien gegeben; der spricht zu dem, was aus physischem Leib und Ätherleib herausgeht während des Schlafes. Rechnen, Geometrie spricht zu beiden; das ist das Merkwürdige. Und daher ist wirklich in bezug auf den Unterricht und die Erziehung Rechnen sowohl wie Geometrie, man möchte sagen, wie ein Chamäleon; sie passen sich durch ihre eigene Wesenheit dem Gesamtmenschen an. Und während man bei Pflanzenkunde, Tierkunde, Rücksicht darauf nehmen muß, daß sie in einer gewissen Ausgestaltung, so wie ich das gestern charakterisiert habe, in ein ganz bestimmtes Lebensalter hineinfallen, hat man bei Rechnen und Geometrie darauf zu sehen, daß sie durch das ganze kindliche Lebensalter hindurch getrieben werden, aber entsprechend geändert werden, je nachdem das Lebensalter seine charakteristischen Eigenschaften verändert.

Insbesondere aber hat man darauf zu sehen, daß - ja, es muß das schon gesagt werden — der Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib etwas ist, was mit sich auch fertig wird, auch auskommt, wenn es allein gelassen wird von unserem Ich und unserem astralischen Leib. Der Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib hat durch seine eigene innere Schwingungskraft immer die Tendenz, das was wir ihm beibringen, von selbst zu vervollkommnen, weiterzubilden. In bezug auf astralischen Leib und Ich sind wir dumm. Wir machen dasjenige, was wir in dieser Beziehung als Mensch beigebracht bekommen, unvollkommner. Und so ist es tatsächlich wahr, daß übersinnlich unser Bildekräfteleib vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen dasjenige, was wir ihm als Rechnen beigebracht haben, fortrechnet. Wir sind gar nicht in unserem physischen und Ätherleib drinnen, wenn wir schlafen; aber die rechnen fort, die zeichnen übersinnlich ihre Geometriefiguren fort, vervollkommnen sie. Und wenn wir das wissen und den ganzen Unterricht daraufhin anlegen, so bekommen wir durch einen richtig gearteten Unterricht eine ungeheure Lebendigkeit im ganzen Weben und Wesen des Menschen zustande. Wir müssen nur in entsprechender Weise diesem Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib Gelegenheit geben, die Dinge, die wir ihm beibringen, weiter zu vervollkommnen.

Dazu ist es nötig, daß wir zum Beispiel in der Geometrie nicht mit jenen Abstraktionen, mit jenen intellektualistischen Gestaltungen beginnen, mit denen man gewöhnlich sich denkt, daß die Geometrie anfangen müsse; sondern es ist nötig, daß man mit einer nicht äußerlich gearteten, sondern innerlich gearteten Anschauung beginne, daß man in dem Kinde zum Beispiel einen starken Sinn für Symmetrie erwecke,

Man kann mit den kleinsten Kindern schon in dieser Beziehung anfangen. Zum Beispiel:man zeichne auf die Tafel irgendeine Figur (blau), mache dem Kinde dann dazu einen solchen Strich (orange) und zeichne ihm dann ein Stückchen des Symmetrischen, und versuche das Kind dazu zu bringen, dies als etwas nicht Vollendetes zu betrachten, als etwas, das erst fertig vorgestellt werden muß. Man versuche mit allen möglichen Mitteln das Kind dazu zu bringen, daß es von sich aus nun die Ergänzung bildet. Auf diese Weise bringt man in das Kind hinein diesen inneren aktiven Drang, unvollendete Dinge fertigzumachen, dadurch überhaupt in sich eine richtige Wirklichkeitsvorstellung auszubilden. Der Lehrer muß dazu Erfindungsgabe haben, aber es ist ja überhaupt gut, wenn der Lehrer die hat: bewegliches, erfindungsreiches Denken, das ist das, was der Lehrer braucht. - Hat der Lehrer durch ein erfindungsreiches, bewegliches Denken eine Zeitlang solche Übungen gemacht, so gehe er zu anderen über. Er zeichne zum Beispiel dem Kinde solch eine Figur auf und versuche, in dem Kinde ein innerliches, raumhaftes Vorstellen von dieser Figur hervorzurufen.

Und dann versuche er den Übergang zu finden, indem er die Figur (orange) so zeichnet, daß das Kind, wenn man das Äußere variiert, darauf kommt, die innere Figur nun auch entsprechend der äußeren Figur zu machen. Hier (bei dem ersten Schema) ist die Linie einfach gewunden; hier bekam sie eine Ausbuchtung. Nun versuche man dem Kinde klarzumachen: wenn es jetzt die innere Figur macht, muß es, damit die innere Symmetrie herauskomme, an die Stelle, wo außen eine Ausbuchtung ist, innen eine Einbuchtung setzen, so daß, wie hier (beim ersten Schema) die einfache Linie der einfachen Linie entspricht, hier der Ausbuchtung eine Einbuchtung entspricht. - Oder man versuche folgendes:

Man versuche dem Kinde diese Figur vorzuzeichnen (die innere) und dann die entsprechende äußere Linie dazu, so daß das eine Figurenharmonie ergibt. Und jetzt versuche man von dieser Figur den Übergang dazu zu finden, diese äußeren Figuren nun hier nicht zusammenlaufen, sondern auseinanderlaufen zu lassen, so daß sie fortlaufen ins Unbestimmte. Nun bekommt das Kind die Vorstellung, daß einem dieser Punkt davonlaufen will und man mit den Linien nachlaufen muß, daß man gar nicht nachkommen kann, daß dieser Punkt fortgeflogen ist; und es bekommt dann die Vorstellung, daß es die entsprechende Figur auch in entsprechender Weise anordnen muß, daß es, weil dies fortlief, nun dieses besonders einwärts formen muß und dergleichen. Ich kann nur das Prinzipielle hier erklären. Kurz, man bekommt auf diese Weise die Möglichkeit, daß das Kind auch asymmetrische Symmetrien zur Anschauung sich bringt. Und dadurch bereitet man während des Wachens den Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib dazu vor, während des Schlafens fortwährend weiterzuschwingen, aber in diesen Schwingungen das beim Wachen Durchgemachte zu vervollkommnen. Dann wacht der Mensch, das Kind, am Morgen auf in einem innerlich bewegten und organisch bewegten Bildekräfteleib, und damit auch physischen Leib. Das bringt eine ungeheure Lebendigkeit in den Menschen hinein.

Man kann das natürlich nur dadurch erreichen, daß man etwas weiß, wie der Bildekräfteleib wirkt, sonst wird man immer äußerlich mechanisch an dem Kinde herumhantieren.

Derjenige, der ein wirklicher Lehrer ist, nimmt eben nicht bloß das zu Hilfe, was während des Wachens vorgeht für das menschliche Leben, sondern auch dasjenige, was während des Schlafes vorgeht. Man muß sich der Bedeutung entsprechender Tatsachen durchaus klar sein, muß sich erinnern können, wie man zuweilen am Abend schon als Erwachsener nachgedacht hat über irgendein Problem: man konnte es nicht lösen —- am Morgen fällt es einem zu. Warum? Weil der Ätheroder Bildekräfteleib die Nacht hindurch für sich gearbeitet hat.

Für manche Dinge ist das Wachleben nicht eine Vervollkommnung, sondern eine Störung. Wir müssen unseren physischen und Ätherleib eine Weile für sich lassen und ihn nicht dumm machen durch unser Ich und durch unseren astralischen Leib. Die Fälle zeigen das, die nun wirklich im Leben vorkommen können, vielfach vorgekommen sind, wo jemand am Abend studiert und studiert und nicht darauf kommt, wie er ein Problem lösen soll. Er wacht am Morgen auf; er ist zwar etwas unruhig, aber er geht an seinen Schreibtisch und siehe, er hat in der Nacht, ohne daß er zum Bewußtsein gekommen ist, das Problem gelöst!

Das sind nicht Fabeln, diese Dinge kommen vor, sind ebenso wie . andere Experimente gut ausprobiert. Was ist da geschehen? Da hat der Ätherleib in der Nacht fortgearbeitet; der Mensch ist gar nicht einmal aufgewacht. Nun, das ist abnorm, das ist nicht anzustreben.

Aber das unbewußte Fortschwingen des Äther- oder Bildekräfteleibes, es ist dadurch anzustreben, daß man nicht die Geometrie anfängt mit Dreiecken und so weiter, wo immer schon das Intellektualistische hineinspielt, sondern mit dem anschaulichen Raumvorstellen. In einer ähnlichen Weise muß dann mit dem Rechnen vorgegangen werden.

Sie bekommen eine ausgezeichnete Vorstellung, wie Sie sich in dieser Weise das anschauliche Mathematische zurechtlegen können, so wie es in Arithmetik, Geometrie waltet, wenn Sie die Broschüre studieren, die Dr. von Baravalle zur Pädagogik der Physik und Mathematik geschrieben hat.

Sie sehen dort zu gleicher Zeit eine Ausdehnung dieser ganzen Denkweise auf das Physikalische. Und trotzdem es sich zumeist auf höhere Partien des Mathematischen bezieht, wird es, wenn man in seinen Geist eindringt, ein ausgezeichneter Leitfaden sein, um den Unterricht auf diesem Gebiete in einer der menschlichen Organisation entsprechenden Richtung pflegen zu können. Mit diesem Büchelchen ist wohl geradezu eine Art von Ausgangspunkt geschaffen für eine Reform des mathematisch-physikalischen Unterrichts von dem ersten kindlichen Lebensalter bis hinauf zu den höchsten Stufen des Unterrichtes. Man muß dasjenige, was hier in bezug auf das Anschaulich-Räumliche gesagt worden ist, nun auch ausdehnen können auf das Rechnerische. Da handelt es sich namentlich darum, daß alles dasjenige, was in äußerlicher Weise das Rechnen und schon das Zählen an das Kind heranbringt, eigentlich die menschliche Organisation ertötet. Alles dasjenige, was vom Einzelnen ausgeht, Stück an Stück reiht, das ertötet die menschliche Organisation. Dasjenige, was vom Ganzen ausgeht zu den Gliedern, zuerst die Vorstellung des Ganzen hervorruft, dann die der Teile, das belebt die menschliche Organisation. Das ist etwas, was schon beim Zählenlernen in Betracht kommt. Wir lernen die Zahlen in der Regel dadurch, daß wir uns an das ganz Äußerliche, im physisch-sinnlichen Leben Vorsichgehende halten.

Wir lernen zählen, indem wir eins haben; das nennen wir die Einheit. Dann fügen wir dazu zwei, drei, vier, und so geht es fort, wir legen Erbse zu Erbse, und es ist gar keine Vorstellung, keine Idee da, warum das eine zum anderen gelegt wird, was daraus eigentlich wird. Man lernt zählen, indem an die Willkür des Nebeneinanderlegens appelliert wird. Ich weiß wohl, daß in vielfacher Weise diese Willkür variiert wird, allein dasjenige, um was es sich handelt, wird heute noch im allergeringsten Maße irgendwo berücksichtigt: daß von einem Ganzen ausgegangen wird und zu den Teilen, Gliedern, fortgeschritten werde. Die Einheit ist dasjenige, was zunächst vorgestellt werden soll auch vom Kinde als ein Ganzes. Irgend etwas, was es auch ist, ist eine Einheit. Nun, wenn man genötigt ist, die Sache durch Zeichnen zu vergegenwärtigen, muß man eine Linie hinzeichnen; man kann auch einen Apfel benützen, um dasselbe zu machen, was ich jetzt mit der Linie machen werde. Da ist eins, und nun geht man von dem Ganzen zu den Teilen, zu den Gliedern, und jetzt hat man aus eins eine Zwei gemacht.

Die Einheit ist geblieben. Die Einheit ist in zwei geteilt worden. Man hat die Einheit «entzwei» geteilt, dadurch ist die Zwei entstanden. Nun geht man weiter, es entsteht durch weitere Gliederung die Drei. Die Einheit bleibt immer als das Umfassende bestehen; und so schreitet man weiter durch die Vier, Fünf, und man kann zugleich durch andere Mittel eine Vorstellung hervorrufen, wie weit man die Dinge zusammenhalten kann, die auf die Zahlen sich beziehen. Man wird dabei die Entdeckung machen, daß eigentlich der Mensch in bezug auf das Anschauliche der Zahl beschränkt ist.

Bei gewissen Völkern der modernen Zivilisation umfaßt man eigentlich nur den überschaulichen Zahlbegriff bis zehn; hier in England, kann man im Geld bis zwölf rechnen. Das ist aber auch etwas, was schon das höchste in dem Überschaulichen darstellt. Dann fängt man ja eigentlich wieder an, dann zählt man eigentlich die Zahlen; man zählt zuerst die Dinge bis zehn, aber dann fängt man an, die Zehn zu zählen: zweimal zehn = zwanzig, dreimal zehn = dreißig. Man bezieht sich da schon gar nicht mehr auf die Dinge, sondern man geht dazu über, die Zahl selbst auf das Rechnen anzuwenden, weil durch den Elementarbegriff schon die Dinge selbst als ein Anschauliches verlangt werden. Und wenn gar das moderne Anschauen so stolz darauf ist, daß wir es in bezug auf das Zählen so weit gebracht haben, während die wilden Völker auf ihre zehn Finger angewiesen sind, so ist es mit dem Stolz gar nicht so weit her, sondern wir zählen bis zehn, weil wir die Glieder spüren, die Gliederung der Hände die darinnen liegt, daß wir symmetrisch die Hände empfinden, die zehn Finger. Dieses Empfinden ist demgemäß auch herausgeholt, ist erlebt, und man muß in dem Kinde den Übergang hervorrufen von dem Ganzen, der Einheit in die Teile als Zahl. Dann wird man leicht jenen anderen Übergang zum Zählen finden können, indem man eines an das andere legt. Man kann ja dann übergehen zu eins, zwei, drei und so weiter. Also das rein additive Zählen, das ist dasjenige, was erst in zweiter Linie kommen darf; denn das ist eine Tätigkeit, die lediglich hier im physischen Raume eine Bedeutung hat, während das Gliedern der Einheit eine solche innere Bedeutung hat, daß es wiederum fortschwingt im ätherischen Leib, auch wenn der Mensch nicht dabei ist. Darauf kommt es an, daß man diese Dinge weiß.

Ebenso handelt es sich darum, daß, wenn wir das Zählen auf diese Weise überwunden haben, wir nun nicht leblos mechanisch zum Addieren übergehen, wo wir dann Addend zu Addend reihen. Das Lebendige kommt in die Sache hinein, wenn wir nicht von den Teilen der Addition ausgehen, sondern von der Summe; wenn wir also eine Anzahl von Dingen, sagen wir, eine Anzahl von Kugeln hinwerfen nun, im Zählen sind wir so weit, daß wir sagen können, das sind vier zehn Kugeln. Jetzt gliedere ich dieses, indem ich den Begriff des Teiles fortsetze. Ich habe hier fünf, hier vier, hier wiederum fünf; so daß ich die Summe auseinandergeworfen habe in fünf, vier, fünf. Ich gehe also über von der Summe zu den Addenden, von dem Ganzen zu den Teilen, und versuche beim Kinde so vorzugehen, daß ich immer die Summe gewissermaßen hinstelle und das Kind darauf kommen lasse, wie sich die Summe gliedern kann in die einzelnen Addenden.

Also ist es außerordentlich wichtig, daß man, wie man beim Fahren die Pferde nicht beim Schwanze aufzäumt, sondern beim Kopfe, ebenso seelisch mit dem Rechnen vorgehe; daß man tatsächlich von der Summe, die eigentlich in allem immer gegeben ist, von dem Ganzen ausgeht: das ist das Reale. Vierzehn Apfel, die sind das Reale — nicht die Addenden sind das Reale; die verteilen sich nach den Lebensverhältnissen in der verschiedensten Weise. So daß man also ausgeht von dem, was immer das Ganze ist, und übergeht zu den Teilen. Dann wird man den Weg wiederum zurückfinden zu dem gewöhnlichen Addieren.

Aber man hat eben, wenn man so vorgeht, wenn man vom ganz Lebendigen übergeht zum Teilen, erreicht, daß dasjenige, was zugrunde liegt dem Rechnen, der Bildekräfteleib, der eben lebendige Anregung haben will zum Bilden, in Schwingungen versetzt wird, die er dann vervollkommnend fortsetzt, ohne daß wir dann mit unserem störenden astralischen Leib und der Ich-Organisation dabei zu sein brauchen.

Ebenso wird der Unterricht in einer ganz besonderen Weise belebt, wenn man die anderen Rechnungsarten vom Kopf, wo sie heute vielfach stehen, wiederum auf die Beine stellt; wenn man zum Beispiel darauf hinarbeitet, das Kind dazu zu bringen, daß es sagt: Wenn man sieben hat, wieviel muß man wegnehmen, damit man drei bekommt? nicht: Was bekommt man, wenn man von sieben vier wegnimmt? -, sondern umgekehrt: Wenn man sieben hat — das ist das Reale — und was man bekommen will, ist wiederum das Reale. Wieviel muß man von sieben wegnehmen, damit man drei bekommt? — Mit dieser Form des Denkens steht man im Leben zunächst drinnen, während man mit der anderen Form in der Abstraktion drinnen steht. So daß man, wenn man in dieser Art verfährt, dann sehr leicht zu dem anderen zurückkehren kann.

In derselben Weise soll man beim Multiplizieren, beim Dividieren vorgehen, nicht fragen: Was entsteht, wenn man zehn in zwei teilt? —, sondern: Wie muß man zehn teilen, damit man fünf bekommt? - Man hat ja das Reale als Gegebenes, und im Leben soll dasjenige herauskommen, was dann eine Bedeutung hat. Zwei Kinder sind da, unter denen sollen zehn Äpfel geteilt werden, jedes soll fünf bekommen: das sind die Realitäten. Was man dazu tun muß, das ist das Abstrakte, das in die Mitte hineinkommt. So sind die Dinge immer unmittelbar dem Leben angepaßt. Gelingt einem dieses, dann ergibt sich, daß wir dasjenige, was wir heute in additiver Weise, in rein äußerlich nebeneinanderfügender Weise vielfach vornehmen und wodurch wir ertötend wirken, gerade im rechnenden Unterricht als Belebendes haben. Und darauf ist zu sehen gerade bei diesem Unterricht, daß wir wirklich auch das Unterbewußte des Menschen, das heißt dasjenige berücksichtigen, was in den Schlaf hineinwirkt und was auch sonst unterbewußt wirkt, wenn der Mensch wach ist. Denn der Mensch denkt ja nicht immer an alles, sondern er denkt an einen kleinen Teil desjenigen, was er seelisch erlebt hat; das andere arbeitet aber immer fort. Gönnen wir es dem Kinde, daß in gesunder Weise sein physischer und sein Ätherleib fortarbeiten. Das können wir aber nur, wenn wir wirklich Spannung, Interesse, Leben hineinbringen gerade in den Rechnungs- und Geometrieunterricht.

Es ist in diesen Tagen einmal gefragt worden, ob es denn gut sei, den Unterricht epochenweise zu erteilen, so wie er in der Waldorfschule erteilt wird. Wenn er richtig erteilt wird, dann ist gerade das epochenweise Erteilen dasjenige, was am allerfruchtbarsten sich erweist. Epochenartiger Unterricht heißt: ich nehme nicht so, daß fortwährend eines das andere beeinträchtigt, etwa von acht bis neun Uhr Rechnen, von neun bis zehn Uhr Geschichte oder Religion oder irgend etwas, was gerade paßt, oder je nachdem der Lehrer in den Stundenplan hineinkommt; sondern ich setze mir drei, vier, fünf Wochen vor, in denen morgens durch zwei Stunden der Hauptunterricht in einem Fach erteilt wird. Es wird immer dasselbe getrieben. Dann wiederum durch fünf bis sechs Wochen im Hauptunterricht irgend etwas, das sich meinetwillen aus dem anderen entwickelt, aber wiederum in diesen zwei Stunden das gleiche. So daß durch Wochen hindurch das Kind auf etwas Bestimmtes konzentriert ist.

Nun entstand die Frage, ob denn dadurch nicht zu viel vergessen werde, ob dadurch nicht die Kinder wiederum das alles aus der Seele herausbekommen, was man in sie hineingebracht hat? Wird aber der Unterricht in der richtigen Weise getrieben, dann arbeitet ja während der Zeit, in welcher ein anderer Gegenstand gegeben wird, der frühere Gegenstand in den unterbewußten Regionen fort. Man muß in einem solchen Epochenunterricht gerade mit dem rechnen, was unbewußt arbeitet; und es gibt nichts Fruchtbareres, als wenn man einen Unterricht, den man durch drei, vier Wochen erteilt hat, in seinen Konsequenzen ruhen läßt, damit er nun ohne Zutun des Menschen weiter im Menschen arbeitet. Dann wird man schon sehen: hat man richtig unterrichtet, und frischt gedächtnismäßig die Sache wieder auf, dann kommt es bei der nächsten Epoche, wo dasselbe Fach getrieben wird, in ganz anderer Weise wieder herauf, als wenn man es eben nicht richtig getrieben hat. Aber mit solchen Dingen rechnet man gar nicht, wenn man den Einwand macht: ob auch die Dinge so richtig getrieben werden, da die Dinge vergessen werden könnten! Der Mensch muß ja so viel mit dem Vergessen rechnen. Denken Sie nur, was wir nicht alles im Kopfe haben müßten, wenn wir nicht richtig vergessen könnten und das Vergessene wiederum heraufbringen könnten! Deshalb muß ein richtiger Unterricht nicht nur mit dem Unterricht, sondern auch mit dem Vergessen richtig rechnen.

Das bedeutet nicht, daß man entzückt darüber zu sein braucht, daß die Kinder vergessen, das besorgen sie schon von selbst; sondern darauf kommt es an, was in die unterbewußten Regionen so hinuntergegangen ist, daß es dann in entsprechender Weise wieder heraufgeholt werden kann. Zu dem ganzen Menschen gehört eben nicht bloß das Bewußte, sondern auch das jeweilig Unbewußte. Und in bezug auf alle diese Dinge muß eben gesagt werden: Der Unterricht und die Erziehung haben nicht nur an den ganzen Menschen zu appellieren, sondern auch an die Teile, an die Glieder des Menschen. — Aber dann ist es auch notwendig, vom Ganzen auszugehen, das Ganze zunächst zu ergreifen und dann die Teile, während man sich sonst um den ganzen Menschen gar nicht kümmert, wenn man im Zählen eins zum anderen legt, wenn man im Zählen Addend zu Addend gibt. An den ganzen Menschen richtet man sich, wenn man die Einheit ins Auge faßt und von da zu den Zahlen übergeht, wenn man die Summe, den Minuenden ins Auge faßt, den Quotienten, das Produkt, und von da zu den Gliedern übergeht.

Insbesondere ist der geschichtliche Unterricht sehr leicht der Gefahr ausgesetzt, daß er zu stark vom Menschen losgelöst werde. Wir haben gesehen, wie es zu einem fruchtbaren Unterricht nötig ist, ein jegliches Ding an seinen richtigen Platz zu stellen. Wir haben gesehen, wie es für die Pflanzenkunde nötig ist, die Pflanze im Zusammenhang mit der Erde zu betrachten, und wie es für die Tierkunde nötig ist, die fächerartig ausgebreiteten Tierarten im Zusammenhange mit dem Menschen zu betrachten. So aber muß auch der Geschichtsunterricht durchaus, ich möchte sagen, menschlich anschaulich bleiben und die Dinge an den Menschen noch heranbringen.

Wenn wir das Kind oder den Schüler und die Schülerin in die Geschichte einführen, handelt es sich darum, daß wir verstehen lernen, daß in der Zeit, in der das Kind sehr wohl ganz lebendig dazu veranlagt ist, die Pflanze im Zusammenhang mit der Erde und die Erde selber als einen Organismus zu betrachten, in der Zeit, in der es noch ganz gut das gesamte Tierreich im Menschen lebendig zusammengefaßt schauen kann, es gerade sogenannte Kausalzusammenhänge in der Geschichte absolut nicht zu fassen in der Lage ist. Wir können noch so schön, wie wir es ja heute besonders gewöhnt sind, die gebräuchlichen Geschichtsbetrachtungen durchnehmen, eine Epoche nach der anderen schildern und immer darstellen, wie das eine aus dem anderen, wie die Wirkung aus der Ursache hervorgeht. Wir können schön schildern in der Kunstgeschichte zum Beispiel den Leonardo, und dann den Michelangelo als Wirkung und so weiter. Von alledem, was heute, ich möchte sagen, unter den Erwachsenen konventionell geworden ist, kausal leitende Motive in der Geschichte zu suchen, von alldem kann der Mensch vor dem zwölften Jahr überhaupt nichts verstehen. Wie eine Art ganz willkürlichen Trommelns oder unmusikalischen Klavierklimperns am Ohre vorbeigeht, so geht eine Geschichtsbetrachtung, welche, wie man sagen kann, kausal das Spätere aus dem Vorigen herleitet, an dem Kinde vorüber. Und es kann das Kind nur durch Zwang dazu veranlaßt werden, eine solche Geschichtsbetrachtung irgendwie in die Seele aufzunehmen. Dann aber wird sie aufgenommen von der Seele, wie vom Magen aufgenommen werden eine Portion Steine, die verschluckt werden müssen. Wir müssen ja durchaus darauf sehen, daß wir seelisch ebensowenig Steine verabreichen statt eines Genießbaren, wie wir dem Magen Steine statt Brot verabreichen dürfen. Darum handelt es sich: tatsächlich lebendig die Geschichte, das geschichtliche Leben an den Menschen heranzubringen. Dazu haben wir vorerst nötig, einen mit dem Menschen verbundenen geschichtlichen Zeitbegriff zu erwecken.

Wenn wir da ein Buch haben über das Altertum, das zweite Buch über das Mittelalter, das dritte über die Neuzeit, wie wenig wird eigentlich darauf gesehen, daß geschichtlicher Zeitbegriff drinnen waltet! Wenn ich aber davon ausgehe, daß ich dem Kinde sage: Du bist jetzt zehn Jahre alt, du hast also schon im Jahre 1913 gelebt. Dein Vater, der ist viel älter als du, der hat schon im Jahre 1890 gelebt, und dessen Vater hat wiederum schon im Jahre 1850 gelebt. Stelle dir also vor, sage ich zu dem Kinde, da stehst du, du gibst deinen Arm nach rückwärts, fassest deinen Vater an den Seiten an, der gibt wiederum seine Arme nach rückwärts und faßt seinen Vater an, deinen Großvater und so weiter, da kommst du bis zum Jahre 1850 zurück. Und dann denkst du dir immer, jeder faßt seinen Vater an! Ungefähr um ein Jahrhundert kommt man immer zurück, wenn man in die dritte, vierte folgende Generation geht, wenn Angehörige von drei oder vier folgenden Generationen ihren Vater oder ihre Mutter anfassen. Wir leben jetzt im 20. Jahrhundert. Wenn wir so die Reihe aufstellen und immer einer den anderen nach rückwärts anfaßt, so kommt man zu den Vorvätern oder Vormüttern zurück. Und kommt man zu dem sechzigsten Vorvater oder zu der sechzigsten Vormutter zurück, stehen also sechzig hintereinander, die gedacht werden nach rückwärts verlaufend in der Zeit - man kann sich in einem großen Saal fast dies vorstellen, wie da sechzig hintereinander stehen -, der Raum verwandelt sich in die Zeit: da hat man in diesem Sechzigsten denjenigen Vorfahren erreicht, der zur Zeit von Christi Geburt gelebt hat.

Man hat auf diese Weise an den Menschen herangebracht — man kann ja, wenn man erfinderisch ist, auch noch andere Mittel finden, aber ich will nur das Prinzip andeuten, daß er nun selber in der Geschichte drinnen steht, und daß diejenigen Menschen, die als Alfred der Große, als Cromwell und so weiter bekannt sind, dann immer so bestimmt werden können, als wenn sie ein Vorfahre wären. Man kann auf diese Weise die ganze Geschichte unmittelbar in das Schulehalten hineinstellen. Es wird an das Kind die Geschichte in einem lebendigen geschichtlichen Zeitbegriffe herangebracht.

Das ist notwendig, daß man auch da die Sache nicht absondert vom Menschen, daß der Mensch nicht glaubt, es stehe die Geschichte in einem Buch oder dergleichen. Es braucht ja nicht gleich so arg zu sein, aber manche haben schon die Vorstellung, die Geschichte stehe eigentlich in einem Buche. Aber es müssen alle Mittel angewendet werden, um die Vorstellung hervorzurufen, daß die Geschichte etwas Lebendiges sei, und daß man selbst drinnen steht in diesem Lebendigen.

Dann handelt es sich darum, daß, wenn man eine Zeitvorstellung in lebendiger Art hervorgerufen hat, man dazu vorschreiten kann, innerlich das Geschichtliche zu beleben, wie man das Rechnerische, das Geometrische dadurch belebt, daß man nicht eine tote Anschauung entwickelt. Es phantasieren alle Leute heute so viel von Anschauung, aber es handelt sich darum, daß man eine lebendige Anschauung entwickeln muß, nicht eine Anschauung erreicht, die auch tot sein kann. Wenn man jene Symmetrie-Übungen macht, dann lebt in der Anschauung drinnen die Seele: das ist lebendige Anschauung. Wie man da die lebendige Anschauung im Raume und so weiter versuchen muß, so muß man versuchen, für einen gesunden geschichtlichen Unterricht des Kindes zwischen dem neunten und zwölften Lebensjahre dasjenige hineinzubringen, was eben von innen nun beleben kann, nicht vom Räumlichen, sondern von der Seele her, vom Herzen her beleben kann.

Der Geschichtsunterricht muß ganz besonders vom Herzen aus belebt werden. Man stelle daher die Geschichte möglichst ideal in Bildern hin. Figuren, Gestalten sollen dastehen; aber diese Gestalten sollen nicht kalt geschildert werden, sondern immer soll, ohne daß man mit den geschichtlichen Figuren den Unfug treibt, moralische oder religiöse Ermahnungen damit zu geben, dennoch gerade das religiöse Element, das moralische Element, in die lebendige Schilderung der geschichtlichen Gestalten, der geschichtlichen Figuren die Farbe hineinbringen. Das Kind muß vorzugsweise durch die Geschichte in Gefühl und Wille ergriffen werden, das heißt, es muß ein persönliches Verhältnis gewinnen können zu den geschichtlichen Gestalten, auch zu der Schilderung der Lebensweise in einzelnen Epochen der Weltgeschichte.

Man braucht bei der Gestaltung nicht bloß an den Menschen zu denken. Man kann zum Beispiel schildern, wie es, sagen wir, in einer Stadt im 12. Jahrhundert vor sich gegangen ist. Aber dasjenige, was man da schildert, das muß in Gefühl und Wille des Kindes hineingehen. Das Kind muß sich selber drinnen formen in dem, wie es sich drinnen bewegt, wie ihm die Dinge sympathisch und antipathisch werden. Gefühl und Wille müssen erregt werden.

Sie sehen aber, wie gerade in den geschichtlichen Unterricht auf diese Art das künstlerische Element hineinkommen muß. Dieses künstlerische Element kommt in die Dinge dann hinein, wenn der Unterricht, so wie ich es oftmals nenne, ökonomisch erteilt wird.

Ökonomisch wird der Unterricht erteilt, wenn der Lehrer eigentlich die Hauptsache für sich ganz erledigt hat, bis zur Überreife erledigt hat, sobald er das Schulzimmer betritt, wenn er da nicht mehr nötig hat, über irgend etwas nachzudenken, wenn ihm die Lehrstunden durch seine eigene Vorbereitung in plastischer Weise vor der Seele stehen. Ökonomisch erteilt man einen Unterricht, wenn man so vorbereitet ist, daß für den Unterricht selbst nur noch die künstlerische Gestaltung übrigbleibt. Daher ist jede Unterrichtsfrage nicht bloß eine Frage des Interesses, des Fleißes, der Hingebung der Schüler, sondern in erster Linie eine Frage des Interesses, des Fleißes, der Hingebung der Lehrer.

Keine Unterrichtsstunde sollte erteilt werden, die nicht vorher vom Lehrer im Geiste voll erlebt worden ist. Daher muß selbstverständlich das Lehrerkollegium so gestaltet sein, daß für den Lehrer absolut die Zeit vorhanden ist, alles auch für sich voll und intensiv zu erleben, was er dann in die Schule hineinzutragen hat.

Etwas Schreckliches ist es, Lehrer, die noch zu kämpfen haben mit dem Lehrstoff, mit einem Buche vor den Bänken der Schüler herumgehen zu sehen! Wer das furchtbar Unpädagogische dieser Sache nicht empfindet, der weiß eben nicht, was alles unbewußt in den Kinderseelen vor sich geht, und wie dieses Unbewußte eine ungeheure Rolle spielt. Geschichte mit einem Notizbuch in der Schule vorzubringen, das ruft, nicht im Oberbewußtsein, aber im Unterbewußtsein, bei den Kindern ein ganz bestimmtes Urteil hervor. Das ist ein intellektualistisches Urteil, ein Urteil, das auch nicht bewußt wird, aber das in dem Organismus des Menschen tief drinnen sitzt: Warum sollte denn ich das alles wissen? Der weiß es doch auch nicht, oder die weiß es doch auch nicht, die muß es erst ablesen; das kann ich ja später einmal auch tun, ich brauche es nicht erst zu lernen. - Das ist nicht ein in der Form dem Kinde zum Bewußtsein kommendes Urteil, aber die anderen Urteile sind viel wichtiger, die unbewußt im Gemüt und Gefühl drunten sitzen.

Daher handelt es sich darum, daß mit innerer Lebendigkeit und Frische aus dem Menschen selbst heraus der Unterricht gegeben wird, ohne daß der Kampf besteht, wenn man zum Beispiel die geschichtlichen Gestalten hinmalen soll, sich selber erst die Daten zu vergegenwärtigen. Gerade beim geschichtlichen Unterricht ist es notwendig, daß er nicht nur so zum Menschen spricht, wie ich es in bezug auf den historischen Zeitbegriff mit den hintereinandergestellten Generationen gezeigt habe, sondern daß er auch aus dem Menschen unmittelbar elementar hervorquillt, daß nichts Abstraktes wirkt, sondern der Lehrer als Mensch wirke, namentlich im geschichtlichen Unterricht. Und wenn so oft gesagt worden ist, man habe, wenn man unterrichtet, zum ganzen Menschen hin zu wirken, nicht zu einem Teil des Menschen, so handelt es sich darum, daß man vor allen Dingen auch folgendes zu betonen hat: ebenso wichtig, wie immer davon zu sprechen, was das Kind lernen muß, ob das Kind intellektualistisch oder dem Willen nach erzogen werden soll, ebenso notwendig für die Pädagogik ist es, die Frage zu entscheiden: Wie hat der Lehrer zu wirken? Soll der ganze Mensch erzogen werden, so muß der Erzieher ein ganzer Mensch sein, das heißt, nicht ein Mensch, der aus dem mechanischen Gedächtnis heraus schafft und erzieht, oder aus einer mechanistischen Wissenschaft, sondern der aus dem Menschen heraus, aus dem ganzen, vollen Menschen heraus erzieht und unterrichtet. Darauf kommt es an!

Tenth Lecture

Arithmetic, geometry, and mathematics in general occupy a special position in teaching and education. As a teacher, one should always know exactly what one is doing in school or with children in general, what happens to the child as a result of any particular action. Only when this prerequisite is fulfilled, when the teacher knows what consequences his or her actions will have for the child, can the lesson really come alive and bring about genuine communication between the soul of the teacher and the soul of the child.

Now, human beings are creatures composed of body, soul, and spirit, in which the physical is shaped and formed by the spiritual; so the teacher must always know what is actually going on in the soul and spirit when the body is being shaped, and, conversely, what effect something has on the body when it affects the spirit or soul.

When we teach a child something that affects their visual imagination, i.e., almost everything we mentioned yesterday as pictorial, drawing, which then leads to writing, when we teach the child something like botany in the sense we explained yesterday, then this has an effect on the child in such a way that preference is given to what I have already characterized in these lectures as a higher member of the human being, as the etheric or image-forming body.

Human beings first have their physical body. We perceive it through ordinary physical sensory perceptions. But in addition to this physical body, human beings have an inner organization that can only be perceived through imagination, through imaginative knowledge: a supersensible body, an etheric body, a formative body. And then human beings have an organization within themselves that can only be perceived through inspiration. As I have said before, one should not be put off by the terms used; they are simply terminology that must be used. Through inspiration, one gains insight into the so-called astral body and into the actual I of the human being, into the actual self of the human being.

Now, the fact is that from birth to death, the etheric or formative body, this first supersensible organization, never separates from the physical body. This only happens at death. In the state of sleep, the human being leaves his etheric or formative body with the physical body. The physical body and etheric body remain in bed when the human being sleeps; the astral body and the ego organization leave the physical body and etheric body when the human being falls asleep and return to them when he wakes up.

If we now teach a child something from arithmetic or geometry, for example, or from the areas I mentioned yesterday as drawing, painting, and transitioning to writing, this teaching influences the physical body and the etheric body. And when we teach the etheric or image-forming body what I outlined here yesterday, when we teach it something about arithmetic or geometry, it retains this during sleep, it continues to vibrate during sleep.

If, on the other hand, we teach the child something about history or the zoology I spoke about yesterday, this only affects the astral body and the ego organization. When the human being falls asleep, they take this with them from their physical and etheric bodies into the spiritual world.

So there is a big difference between teaching writing or botany, which remains in the physical and etheric organization in bed and continues to vibrate, and teaching history or anthropology, which the ego and astral body take with them into the spiritual world every time they sleep. This makes a huge difference in the effect on the human being.

You must be aware that all the pictorial, imaginative impressions I make on the child tend to perfect themselves, to become more complete, even during sleep. On the other hand, what we teach the child from history or anthropology, for example, must have an effect on the actual soul-spiritual organization, and this tends to be forgotten during sleep, to become imperfect, to fade. It is therefore necessary that we take into account in our teaching whether we have material that speaks to the etheric body and the physical body, or whether we have material that speaks to the ego organization and the astral organization.

The things I mentioned yesterday as botany, as that which leads to writing and reading, all speak to the physical body and the etheric body. We will still have to agree on history lessons. We have already given guidelines for zoology and anthropology lessons; these speak to what emanates from the physical body and etheric body during sleep. Arithmetic and geometry speak to both; that is the remarkable thing. And therefore, in relation to teaching and education, arithmetic and geometry are, one might say, like chameleons; they adapt themselves to the whole human being through their own essence. And while in botany and zoology one must take into account that they fall into a very specific age group in a certain form, as I characterized yesterday, in arithmetic and geometry one must ensure that they are taught throughout the entire childhood, but are modified accordingly as the age group changes its characteristic properties.

In particular, however, we must bear in mind that — yes, it must be said — the etheric or formative body is something that can cope and manage on its own, even when left alone by our ego and our astral body. Through its own inner vibrational power, the etheric or formative body always has the tendency to perfect and further develop what we teach it. In relation to the astral body and the ego, we are stupid. We make what we are taught in this regard as human beings more imperfect. And so it is indeed true that, supersensibly, our formative body continues to calculate what we have taught it as arithmetic from the moment we fall asleep until we wake up. We are not at all inside our physical and etheric bodies when we sleep; but they continue to calculate, they continue to draw their geometric figures supersensibly, perfecting them. And when we know this and base all our teaching on it, we achieve, through properly designed teaching, an enormous vitality in the whole weaving and being of the human being. We only have to give this etheric or formative body the opportunity, in the appropriate way, to further perfect the things we teach it.

To do this, it is necessary that we do not begin geometry, for example, with those abstractions, those intellectualistic constructions with which one usually thinks geometry must begin; Instead, it is necessary to begin with an inner rather than an outer perception, for example, by awakening in the child a strong sense of symmetry.

One can begin with the youngest children in this regard. For example: draw any figure (blue) on the blackboard, then make a line (orange) for the child and draw a piece of the symmetrical figure, and try to get the child to see this as something unfinished, something that first has to be imagined as complete. Try by all possible means to get the child to complete the picture on its own. In this way, you instill in the child this inner active urge to finish unfinished things, thereby developing a correct perception of reality within itself. The teacher must have inventiveness for this, but it is good if the teacher has this anyway: flexible, inventive thinking is what the teacher needs. Once the teacher has done such exercises for a while with inventive, flexible thinking, they should move on to others. For example, they should draw such a figure for the child and try to evoke an inner, spatial image of this figure in the child.

And then he should try to find the transition by drawing the figure (orange) in such a way that when the exterior is varied, the child comes to the conclusion that the inner figure should now also be made to correspond to the outer figure. Here (in the first diagram) the line is simply curved; here it has been given a bulge. Now try to explain to the child: when they make the inner figure, in order for the inner symmetry to emerge, they must place an indentation on the inside where there is a bulge on the outside, so that, as here (in the first diagram) the simple line corresponds to the simple line, here the bulge corresponds to an indentation. - Or try the following:

Try sketching this figure (the inner one) for the child and then the corresponding outer line, so that the two figures are in harmony. Now try to find the transition from this figure to the other, so that the outer figures do not converge here, but diverge, running off into the indefinite. Now the child gets the idea that one of these points wants to run away and you have to run after it with the lines, that you can't keep up, that this point has flown away; and then it gets the idea that it must arrange the corresponding figure in a corresponding way, that because this ran away, it must now shape it particularly inwardly, and so on. I can only explain the principle here. In short, in this way, the child is given the opportunity to visualize asymmetrical symmetries. And in this way, during waking hours, the etheric or formative body is prepared to continue vibrating during sleep, but to perfect in these vibrations what has been experienced during waking hours. Then the human being, the child, wakes up in the morning with an internally and organically moved formative body, and thus also a physical body. This brings tremendous vitality into the human being.

Of course, this can only be achieved by knowing how the image-forming body works, otherwise one will always be fiddling around with the child in an outwardly mechanical way.

A true teacher does not only make use of what happens during waking life, but also of what happens during sleep. One must be absolutely clear about the significance of corresponding facts, must be able to remember how, as an adult, one has sometimes thought about a problem in the evening: one could not solve it — but in the morning it occurs to one. Why? Because the etheric or formative body has worked for itself throughout the night.

For some things, waking life is not a perfection, but a disturbance. We must leave our physical and etheric bodies alone for a while and not make them stupid through our ego and our astral body. This is demonstrated by cases that can actually occur in life, and have occurred many times, where someone studies and studies in the evening and cannot figure out how to solve a problem. He wakes up in the morning; he is a little restless, but he goes to his desk and lo and behold, during the night, without him being aware of it, he has solved the problem!

These are not fables; these things happen and have been well tested, just like other experiments. What happened there? The etheric body continued to work during the night; the person did not even wake up. Now, that is abnormal; it is not something to strive for.

But the unconscious oscillation of the etheric or formative body should be strived for by not beginning geometry with triangles and so on, where intellectualism always comes into play, but with vivid spatial imagination. A similar approach must then be taken to arithmetic.

You will get an excellent idea of how you can arrange the visual mathematics in this way, as it prevails in arithmetic and geometry, if you study the brochure written by Dr. von Baravalle on the pedagogy of physics and mathematics.

There you will also see an extension of this whole way of thinking to physics. And although it mostly refers to higher areas of mathematics, if you delve into its spirit, it will be an excellent guide for teaching in this field in a way that is appropriate to human organization. This little book provides a starting point for reforming the teaching of mathematics and physics from early childhood up to the highest levels of education. What has been said here with regard to visual and spatial concepts must now be extended to arithmetic. The point here is that everything that introduces children to arithmetic and even counting in an external way actually kills the human organism. Everything that starts from the individual and strings things together piece by piece kills the human organism. That which proceeds from the whole to the parts, first evoking the idea of the whole, then that of the parts, enlivens the human organism. This is something that already comes into play when learning to count. We usually learn numbers by sticking to the very external, to what is happening in physical, sensory life.