The Kingdom of Childhood

GA 311

20 August 1924, Torquay

Lecture VIII

The first question is as follows:

What is the real difference between multiplication and division in this method of teaching? Or should there be no difference at all in the first school year

The question probably arises from my statement that in multiplication the so-called multiplicand (one factor) and the product are given, and the other factor has to be found. Of course this really gives what is usually regarded as division. If we do not keep too strictly to words, then on the same basis we can consider division, as follows:

We can say: if a whole is divided in a certain way, what is the amount of the part? And you have only another conception of the same thing as in the question: By what must a number be multiplied in order to get a certain other number?

Thus, if our question refers to dividing into parts, we have to do with a division: but if we regard it from the standpoint of “how many times ...” then we are dealing with a multiplication. And it is precisely the inner relationship in thought which exists between multiplication and division which here appears most clearly.

But quite early on it should be pointed out to the child that it is possible to think of division in two ways. One is that which I have just indicated; here we examine how large each part is if we separate a whole into a definite number of parts. Here I proceed from the whole to find the part: that is one kind of division. In the other kind of division I start from the part, and find out how often the part is contained in the whole: then the division is not a separation into parts, but a measurement. The child should be taught this difference between separation into parts and measurement as soon as possible, but without using pedantic terminology. Then division and multiplication will soon cease to be something in the nature of merely formal calculation, as it very often is, and will become connected with life.

So in the first school years it is really only in the method of expression that you can make a difference between multiplication and division; but you must be sure to point out that this difference is fundamentally much smaller than the difference between subtraction and addition. It is very important that the child should learn such things.

Thus we cannot say that no difference at all should be made between multiplication and division in the first school years, but it should be done in the way I have just indicated.

At what age and in what manner should we make the transition from the concrete to the abstract in Arithmetic?

At first one should endeavour to keep entirely to the concrete in Arithmetic, and above all avoid abstractions before the child comes to the turning point of the ninth and tenth years. Up to this time keep to the concrete as far as ever possible, by connecting everything directly with life.

When we have done that for two or two-and-a-half years and have really seen to it that calculations are not made with abstract numbers, but with concrete facts presented in the form of sums, then we shall see that the transition from the concrete to the abstract in Arithmetic is extraordinarily easy. For in this method of dealing with numbers they become so alive in the child that one can easily pass on to the abstract treatment of addition, subtraction, and so on.

It will be a question, then, of postponing the transition from the concrete to the abstract, as far as possible, until the time between the ninth and tenth years of which I have spoken.

One thing that can help you in this transition from the abstract to the concrete is just that kind of Arithmetic which one uses most in real life, namely the spending of money; and here you are more favourably placed than we are on the Continent, for there we have the decimal system for everything. Here, with your money, you still have a more pleasing system than this. I hope you find it so, because then you have a right and healthy feeling for it. The soundest, most healthy basis for a money system is that it should be as concrete as possible. Here you still count according to the twelve and twenty system which we have already “outgrown,” as they say, on the Continent. I expect you already have the decimal system for measurements? (The answer was given that we do not use it for everyday purposes, but only in science.) Well, here too, you have the pleasanter system of measures! These are things which really keep everything to the concrete. Only in notation do you have the decimal system.

What is the basis of this decimal system? It is based on the fact that originally we really had a natural measurement. I have told you that number is not formed by the head, but by the whole body. The head only reflects number, and it is natural that we should actually have ten, or twenty at the highest, as numbers. Now we have the number ten in particular, because we have ten fingers. The only numbers we write are from one to ten: after that we begin once more to treat the numbers themselves as concrete things.

Let us just write, for example: 2 donkeys. Here the donkey is the concrete thing, and 2 is the number. I might just as well say: 2 dogs. But if you write 20, that is nothing more than 2 times 10. Here the 10 is treated as a concrete thing. And so our system of numeration rests upon the fact that when the thing becomes too involved, and we no longer see it clearly, then we begin to treat the number itself as something concrete, and then make it abstract again. We should make no progress in calculation unless we treated the number I itself, no matter what it is, as a concrete thing, and afterwards made it abstract. 100 is really only 10 times 10. Now, whether I have 10 times 10, and treat it as 100, or whether I have 10 times 10 dogs, it is really the same. In the one case the dogs, and in the other the 10 is the concrete thing. The real secret of calculation is that the number itself is treated as something concrete. And if you think this out you will find that a transition also takes place in life itself. We speak of 2 twelves—2 dozen—in exactly the same way as we speak of 2 tens, only we have no alternative like “dozen” for the ten because the decimal system has been conceived under the influence of abstraction. All other systems still have much more concrete conceptions of a quantity: a dozen: a shilling. How much is a shilling? Here, in England, a shilling is 12 pennies. But in my childhood we had a “shilling” which was divided into 30 units, but not monetary units. In the village in I which I lived for a long time, there were houses along the village street on both sides of the way. There were walnut trees everywhere in front of the houses, and in the autumn the boys knocked down the nuts and stored them for the winter. And when they came to school they would boast about it. One would say: “I've got five shillings already,” and another: “I have ten shillings of nuts.” They were speaking of concrete things. A shilling always meant 30 nuts. The farmers' only concern was to gather the nuts early, before all the trees were already stripped! “A nut-shilling” we used to say: that was a unit. To sell these nuts was a right: it was done quite openly.

And so, by using these numbers with concrete things—one dozen, two dozen, one pair, two pair, etc., the transition from the concrete to the abstract can be made. We do not say: “four gloves,” but: “Two pairs of gloves;” not: “Four shoes,” but “two pairs of shoes.” Using this method we can make the transition from concrete to abstract as a gradual preparation for the time between the ninth and tenth years when abstract number as such can be presented.1It should be noted that before this transition from the concrete to the abstract dealt with above, a rhythmic approach is used in the teaching of the rudiments of number, e.g. the tables, in the lower classes.

When and how should drawing be taught?

With regard to the teaching of drawing, it is really a question of viewing the matter artistically. You must remember that drawing is a sort of untruth. What does drawing mean? It means representing something by lines, but in the real world there is no such thing as a line. In the real world there is, for example, the sea. It is represented by colour (green); above it is the sky, also represented by colour (blue). If these colours are brought together you have the sea below and

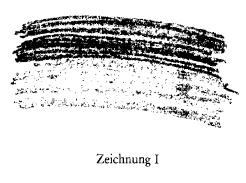

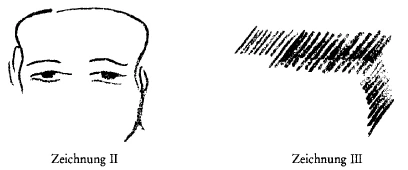

the sky above (see sketch). The line forms itself at the boundary between the two colours. To say that here (horizontal line) the sky is bounded by the sea, is really a very abstract statement. So from the artistic point of view one feels that the reality should be represented in colour, or else, if you like, in light and shade. What is actually there when I draw a face? Does such a thing as this really exist? (The outline of a face

is drawn.) Is there anything of that sort? Nothing of the kind exists at all. What does exist is this: (see shaded drawing). There are certain surfaces in light and shade, and out of these a face appears. To bring lines into it, and form a face from them, is really an untruth: there is no such thing as this.

An artistic feeling will prompt you to work out what is really there out of black and white or colour. Lines will then appear of themselves. Only when one traces the boundaries which arise in the light and shade or in the colour do the “drawing lines” appear.

Therefore instruction in drawing must, in any case, not start from drawing itself but from painting, working in colour or in light and shade. And the teaching of drawing, as such, is only of real value when it is carried out in full awareness that it gives us nothing real. A terrible amount of mischief has been wrought in our whole method of thinking by the importance attached to drawing. From this has arisen all that we find in optics, for example, where people are eternally drawing lines which are supposed to be rays of light. Where can we really find these rays of light? They are nowhere to be found. What you have in reality is pictures. You make a hole in a wall; the sun shines through it and on a screen an image is formed. The rays can perhaps be seen, if at all, in the particles of dust in the room—and the dustier the room, the more you can see of them. But what is usually drawn as lines in this connection is only imagined. Everything, really, that is drawn, has been thought out. And it is only when you begin to teach the child something like perspective, in which you already have to do with the abstract method of explanation that you can begin to represent aligning and sighting by lines.

But the worst thing you can do is to teach the child to draw a horse or a dog with lines. He should take a paint brush and make a painting of the dog, but never a drawing. The outline of the dog does not exist at all: where is it? It is, of course, produced of itself if we put on paper what is really there.

We are now finding that there are not only children but also teachers who would like to join our school. There may well be many teachers in the outer world who would be glad to teach in the Waldorf School, because they would like it better there. I have had really quite a number of people coming to me recently and describing the manner in which they have been prepared for the teaching profession in the training colleges. One gets a slight shock in the case of the teachers of History, Languages, etc., but worst of all are the Drawing teachers, for they are carrying on a craft which has no connection whatever with artistic feeling: such feeling simply does not exist.

And the result is (I am mentioning no names, so I can speak freely) that one can scarcely converse with the Drawing teachers: they are such dried-up, such terribly “un-human” people. They have no idea at all of reality. By taking up drawing as a profession they have lost touch with all reality. It is terrible to try to talk to them, quite apart from the fact that they want to teach drawing in the Waldorf School, where we have not introduced drawing at all. But the mentality of these people who carry on the unreal craft of drawing is also quite remarkable. And they have no moisture on the tongue—their tongues are quite dry. It is tragic to see what these drawing teachers gradually turn into, simply because of having to do something which is completely unreal.

I will therefore answer this question by saying that where-ever possible you should start from painting and not from drawing. That is the important thing.

I will explain this matter more clearly, so that there shall be no misunderstanding. You might otherwise think I had something personal against drawing teachers. I would like to put it thus: here is a group of children. I show them that the sun is shining in from this side. The sun falls upon something and makes all kinds of light, (see sketch). Light is shed upon everything. I can see bright patches. It is because the sun is shining in that I can see the bright patches everywhere. But above them I see no bright patches, only darkness (blue). But I also see darkness here, below the bright patches: there will perhaps be just a little light here. Then I look at something which, when the light falls on it in this way, looks greenish in colour. Here, where the light falls, it is whitish, but then, before the really black shadow occurs, I see a greenish colour; and here, under the black shadow, it is also greenish, and there are other curious things to be seen in between the two. Here the light does not go right in.

You see, I have spoken of light and shadow, and of how there is something here on which the light does not impinge: and lo, I have made a tree! I have only spoken about light and colour, and I have made a tree. We cannot really paint the tree: we can only bring in light and shade, and green, or,

a little yellow, if you like, if the fruit happens to be lovely apples. But we must speak of colour and light and shade; and so indeed we shall be speaking only of what is really there—colour, light and shade. Drawing should only be done in Geometry and all that is connected with that. There we have to do with lines, something which is worked out in thought. But realities, concrete realities must not be drawn with a pen; a tree, for example, must be evolved out of light and shade and out of the colours, for this is the reality of life itself.2The sketch was made on the blackboard with coloured chalks but it has only been possible to reproduce it in black and white.

It would be barbarous if an orthodox drawing teacher came and had this tree, which we have drawn here in shaded colours, copied in lines. In reality there are just light patches and dark patches. Nature does that. If lines were drawn here, it would be an untruth.

Should the direct method, without translation, be used, even for Latin and Greek?

In this respect a special exception must be made with regard to Latin and Greek. It is not necessary to connect these directly with practical life, for they are no longer alive, and we have them with us only as dead languages. Now Greek and Latin (for Greek should actually precede Latin in teaching) can only be taught when the children are somewhat older, and therefore the translation method for these languages is, in a certain way, fully justified.

There is no question of our having to converse in Latin and Greek, but our aim is to understand the ancient authors. We use these languages first and foremost for the purposes of translation. And thus it is that we do not use the same methods for the teaching of Latin and Greek as those which we employ with all living languages.

Now once more comes the question that is put to me whenever I am anywhere in England where education is being discussed:

How should instruction in Gymnastics be carried out, and should Sports be taught in an English school, hockey and cricket, for example, and if so in what way?

It is emphatically not the aim of the Waldorf School Method to suppress these things. They have their place simply because they play a great part in English life, and the child should grow up into life. Only please do not fall a prey to the illusion that there is any other meaning in it than this, namely, that we ought not to make the child a stranger to his world. To believe that sport is of tremendous value in development is an error. It is not of great value in development. Its only value is that it is a fashion dear to the English people, and we must not make the child a stranger to the world by excluding him from all popular usages. You like sport in England, so the child should be introduced to sport. One should not meet with philistine opposition what may possibly be philistine itself.

With regard to “how it should really be taught,” there is very little indeed to be said. For in these things it is really more or less so that someone does them first, and then the child imitates him. And to devise special artificial methods here would be something scarcely appropriate to the subject.

In Drill or Gymnastics one simply learns from anatomy and physiology in what position any limb of the organism must be placed in order that it may serve the agility of the body. It is a question of really having a sense for what renders the organism skilled, light and supple; and when one has this sense, one has then simply to demonstrate. Suppose you have a horizontal bar: it is customary to perform all kinds of exercises on the bar except the most valuable one of all, which consists in hanging on to the bar, hooked on, like this ... then swinging sideways, and then grasping the bar further up, then swinging back, then grasping the bar again. There is no jumping but you hang from the bar, fly through the air, make the various movements, grasp the bar thus, and thus, and so an alternation in the shape and position of the muscles of the arms is produced which actually has a healthy effect upon the whole body.

You must study which inner movements of the muscles have a healthy effect on the organism, so that you will know what movements to teach. Then you have only to do the exercises in front of the children, for the method consists simply in this preliminary demonstration.3A method of Gymnastic teaching on the lines indicated above was subsequently worked out by Fritz Graf Bothmer, teacher of Gymnastic s at the Waldorf School, Stuttgart.

How should religious instruction be given at the different ages?

As I always speak from the standpoint of practical life, I have to say that the Waldorf School Method is a method of education and is not meant to bring into the school a philosophy of life or anything sectarian. Therefore I can only speak of what lives within the Waldorf School principle itself.

It was comparatively easy for us in Württemberg, where the laws of education were still quite liberal: when the Waldorf School was established we were really shown great consideration by the authorities. It was even possible for me to insist that I myself should appoint the teachers without regard to their having passed any State examination or not. I do not mean that everyone who has passed a State examination is unsuitable as a teacher! I would not say that. But still, I could see nothing in a State examination that would necessarily qualify a person to become a teacher in the Waldorf School.

And in this respect things have really always gone quite well. But one thing was necessary when we were establishing the school, and that was for us definitely to take this standpoint: We have a “Method-School”; we do not interfere with social life as it is at present, but through Anthroposophy we find the best method of teaching, and the School is purely a “Method-School.”

Therefore I arranged, from the outset, that religious instruction should not be included in our school syllabus, but that Catholic religious teaching should be delegated to the Catholic priest, and the Protestant teaching to the pastor and so on.

In the first few years most of our scholars came from a factory (the Waldorf-Astoria Cigarette Factory), and amongst them we had many “dissenting” children, children whose parents were of no religion. But our educational conscience of course demanded that a certain kind of religious instruction should be given them also. We therefore arranged a “free religious teaching” for these children, and for this we have a special method.

In these “free Religion lessons” we first of all teach gratitude in the contemplation of everything in Nature. Whereas in the telling of legends and myths we simply relate what things do—stones, plants and so on—here in the Religion lessons we lead the child to perceive the Divine in all things. So we begin with a kind of “religious naturalism,” shall I say, in a form suited to the children.

Again, the child cannot be brought to anunderstanding of the Gospels before the time between the ninth and tenth years of which I have spoken. Only then can we proceed to a consideration of the Gospels in the Religion lessons, going on later to the Old Testament. Up to this time we can only introduce to the children a kind of Nature-religion in its general aspect, and for this we have our own method. Then we should go on to the Gospels but not before the ninth or tenth year, and only much later, between the twelfth and thirteenth years, we should proceed to the Old Testament.4This paragraph can easily be misunderstood unless two other aspects of the education are borne in mind. Firstly: Here Dr. Steiner is only speaking of the content of the actual Religion lessons. In the class teaching all children are introduced to the stories of the Old Testament. Secondly, quite apart from the Religion lessons the Festivals of the year are celebrated with all children in a Rudolf Steiner School, in forms adapted to their ages. Christmas takes a very special place, and is prepared for all through Advent by carol singing, the daily opening of a star-window in the “Advent Calendar,” and the lighting of candles on the Advent wreath hung in the classroom. At the end of the Christmas term the teachers perform traditional Nativity Plays as their gift to the children. All this is in the nature of an experience for the children, inspired by feeling and the Christmas mood. Later, in the Religion lessons, on the basis of this experience, they can be brought to a more conscious knowledge and understanding of the Gospels.

This then is how you should think of the free Religion lessons. We are not concerned with the Catholic and Protestant instruction: we must leave that to the Catholic and Protestant pastors. Also every Sunday we have a special form of service for those who attend the free Religion lessons. A service is performed and forms of worship are provided for children of different ages. What is done at these services has shown its results in practical life during the course of the years; it contributes in a very special way to the deepening of religious feeling, and awakens a mood of great devotion in the hearts of the children.

We allow the parents to attend these services, and it has become evident that this free religious teaching truly brings new life to Christianity And there is real Christianity in the Waldorf School, because through this naturalistic religion during the early years the children are gradually led to an understanding of the Christ Mystery, when they reach the higher classes.

Our free Religion classes have, indeed, gradually become full to overflowing. We have all kinds of children coming into them from the Protestant pastor or the Catholic priest, but we make no propaganda for it. It is difficult enough for us to find sufficient Religion teachers, and therefore we are not particularly pleased when too many children come; neither do we wish the school to acquire the reputation of being an Anthroposophical School of a sectarian kind. We do not want that at all. Only our educational conscience has constrained us to introduce this free Religion teaching. But children turn away from the Catholic and Protestant teaching and more and more come over to us and want to have the free Religion teaching: they like it better. It is not our fault that they run away from their other teachers: but as I have said, the principle of the whole thing was that religious instruction should be given, to begin with, by the various pastors. When you ask, then, what kind of religious teaching we have, I can only speak of what our own free Religion teaching is, as I have just described it.

Should French and German be taught from the beginning, in an English School? If the children come to a Kindergarten Class at five or six years old, ought they, too, to have language lessons?

As to whether French and German should be taught from the beginning in an English School, I should first like to say that I think this must be settled entirely on grounds of expediency. If you simply find that life is making it necessary to teach these languages, you must teach them. We have introduced French and English into the Waldorf School, because with French there is much to be learnt from the inner quality of the language, not found elsewhere, namely, a certain feeling for rhetoric which it is very good to acquire: and English is taught because it is a universal world language, and will become so more and more.

Now, I should not wish to decide categorically whether French and German should be taught in an English School, but you must be guided by the circumstances of life. It is not at all so important which language is chosen as that foreign languages are actually taught in the school.

And if children of four or five years do already come to school (which should not really be the case) it would then be good to do languages with them also. It would be right for this age. Some kind of language teaching can be given even before the age of the change of teeth, but it should only be taught as a proper lesson after this change. If you have a Kindergarten Class for the little children, it would be quite right to include the teaching of languages but all other school subjects should as far as possible be postponed until after the change of teeth.

I should like to express, in conclusion, what you will readily appreciate, namely, that I am deeply gratified that you are taking such an active interest in making the Waldorf School Method fruitful here in England, and that you are working with such energy for the establishment of a school here, on our Anthroposophical lines. And I should like to express the hope that you may succeed in making use of what you were able to learn from our Training Courses in Stuttgart, from what you have heard at various other Courses which have been held in England, and, finally, from what I have been able to give you here in a more aphoristic way, in order to establish a really good school here on Anthroposophical lines. You must remember how much depends upon the success of the very first attempt. If it does not succeed, very much is lost, for all else will be judged by the first attempt. And indeed, very much depends on how your first project is launched: from it the world must take notice that the matter is neither something which is steeped in abstract, dilettante plans of school reform, nor anything amateur but something which arises out of a conception of the real being of man, and which is now to be brought to bear on the art of education. And it is indeed the very civilisation of today, which is now moving through such critical times, that calls us to undertake this task, along with many other things.

In conclusion I should like to give you my right good thoughts on your path—the path which is to lead to the founding of a school here on Anthroposophical lines.

Fragenbeantwortung

Die erste Frage, die gestellt ist, lautet:

Was ist in dieser Unterrichtsmethode eigentlich der Unterschied zwischen Multiplizieren und Dividieren? Oder soll es in den ersten Schuljahren überhaupt keinen solchen Unterschied geben?

Die Frage geht ja wahrscheinlich daraus hervor, daß ich sagte, man solle das Multiplizieren so treiben, daß zum Vorschein kommt der sogenannte Multiplikand, ein Faktor, nicht das Produkt, und daß der andere Faktor gesucht werde. Das gibt natürlich eigentlich im gewöhnlichen Sinne des Wortes eine Division. Das sieht man gewöhnlich als Division an. Man kann, wenn man sich nicht zu stark an Worte hält, dann dem ganz entsprechend das Dividieren in der folgenden Weise auffassen.

Man kann sagen: Wenn man ein Ganzes in einer gewissen Weise teilt, wieviel beträgt dann der Teil? Und man hat nur in anderer Auffassung dasselbe wie bei der Frage: Mit was muß man eine Zahl vervielfältigen, multiplizieren, damit man eine gewisse Zahl bekommt?

Wenn man also die Frage hinorientiert auf das Teilen, hat man es mit einer Division zu tun. Wenn man die Frage hinorientiert auf das Vervielfältigen, hat man es mit einer Multiplikation zu tun. Und gerade die innige Verwandtschaft im Denken, die zwischen der Multiplikation und der Division besteht, die kommt dabei durchaus zum Vorschein.

Nun aber sollte das Kind frühzeitig darauf hingewiesen werden, daß es eigentlich eine zweifache Möglichkeit gibt, die Division aufzufassen. Die eine Möglichkeit ist die, die ich jetzt angedeutet habe. Da untersucht man, wie groß der Teil ist, wenn ich ein Ganzes in eine bestimmte Anzahl von Teilen gliedere. Da gehe ich von dem Ganzen aus und suche den Teil. Das ist eine Art der Division.

Die andre Art ist diese, wenn ich von dem Teil ausgehe und suche, wie oft der Teil in dem Ganzen drinnen steckt. Dann ist die Division nicht ein Teilen, sondern ein Messen. Und dieser Unterschied zwischen Teilen und Messen sollte womöglich bald, ohne daß man eine pedantische Terminologie braucht, dem Kinde auch beigebracht werden. Dann hört das Dividieren und das Multiplizieren bald auf, etwas bloß formal Rechnerisches zu sein, wie es sehr häufig ist, und wird angelehnt an das Leben.

So werden Sie eigentlich mehr nur an der Ausdrucksweise für die ersten Schuljahre schon einen Unterschied zwischen Multiplizieren und Dividieren haben können; aber man sollte eben auch durchaus bemerklich machen, daß dieser Unterschied im Grunde genommen ein viel kleinerer ist als der zwischen Subtrahieren und Addieren. Und gerade darauf kommt es sehr stark an, daß solche Dinge dem Kinde eingehen.

Man kann also nicht sagen, daß in den ersten Schuljahren überhaupt kein Unterschied gemacht werden soll; aber er soll eben so gemacht werden, wie ich ihn eben jetzt angedeutet habe.

In welchem Alter und wie soll man in der Rechnung vom Konkreten zum Abstrakten übergehen?

Über diese Frage ist so zu denken: Man soll zunächst versuchen, alles im Rechnen im Konkreten zu halten, und vor allen Dingen ganz absehen von aller Abstraktion bis zu dem Lebenspunkt zwischen dem 9. und 10. Jahre. Bis dahin soll man womöglich versuchen, so weit im Konkreten zu bleiben, als es nur irgendwie möglich ist, also alles an das Leben unmittelbar anzuknüpfen.

Dann, wenn man das durch 2 bis 2 1/2 Jahre getan hat und wirklich darauf gesehen hat, nicht mit abstrakten Zahlen zu rechnen, sondern mit konkreten Tatsachen, die in Rechenform gebracht werden, dann wird man sehen, daß gerade beim Rechnen der Übergang ins Abstrakte außerordentlich leicht ist. Er ist leicht aus dem Grunde, weil man in dem Kinde durch eine solche Behandlungsweise der Zahl solches Leben in den Zahlen hervorgebracht hat, daß man dann leicht zu der abstrakten Behandlung von Addition, Subtraktion und so weiter übergehen kann.

Es wird sich also darum handeln, daß man den Übergang vom Konkreten zum Abstrakten möglichst verschiebt bis zu dem Lebenspunkt, den ich da zwischen dem 9. und 10. Lebensjahre angegeben habe.

Eine große Hilfe für den Übergang vom Konkreten ins Abstrakte beim Rechnen ist das Rechnen da, wo man es ja am meisten im Leben braucht, beim Zahlen, beim Geldausgeben; und da sind Sie hier in einer günstigeren Lage als wir drüben auf dem Kontinent, denn wir drüben auf dem Kontinent haben in bezug auf alles das Dezimalsystem. Sie haben hier mit Ihrem Gelde noch ein sympathischeres System als das Dezimalsystem. Ich weiß nicht, ob Sie es als sympathischer empfinden; aber wenn Sie es nicht als sympathischer empfänden als das Dezimalsystem, so wäre das krankhaft. Gesund ist lediglich dies, ein möglichst konkretes Zahlensystem im Gelde zu haben. Sie zählen hier noch nach dem 12er- und 20er-System, was wir, wie man sagt, schon überwunden haben auf dem Kontinent. Das Dezimalsystem werden Sie ja wohl beim Messen auch schon haben?

Ein Teilnehmer sagt, daß man es im allgemeinen Leben nicht habe, nur im Wissenschaftlichen.

Also auch da haben Sie noch das sympathischere Meßsystem! Das sind Dinge, die alles eigentlich im Konkreteren erhalten. Nur im Zahlenschreiben haben Sie auch das Dezimalsystem.

Worauf beruht dieses Dezimalsystem? Es beruht darauf, daß man es ursprünglich eigentlich naturgemäß hat. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, nicht der Kopf bildet die Zahl, sondern der ganze Körper bildet die Zahl. Der Kopf spiegelt nur die Zahl ab, und es ist natürlich, daß man 10 oder höchstens 20 als Zahl wirklich hat. Nun hat man zunächst die Zahl 10, weil man 10 Finger hat. Wir schreiben ja überhaupt nur von 1 bis 10, dann beginnen wir wieder die Zahlen wie ein konkretes Ding zu behandeln.

Schreiben wir zum Beispiel einmal: 2 Esel. Da ist der Esel ein konkretes Ding und 2 ist die Zahl. Ich könnte ebensogut 2 Hunde sagen. Aber wenn Sie 20 schreiben, so ist das auch nichts anderes als 2 mal 10. Da ist 10 behandelt wie ein konkretes Ding. Und so beruht unser Zahlensystem darauf, daß wir von da an, wo uns die Geschichte schwummelig wird, wo wir die Sache nicht mehr überschauen, anfangen, die Zahl selber als etwas Konkretes zu behandeln, und sie dann wieder abstrahieren. Wir würden gar nicht vorwärtskommen im Rechnen, wenn wir nicht die Zahl selber, gleichgültig, was sie ist, als ein konkretes Ding behandeln würden und wieder abstrahieren würden. 100 ist ja nur 10mal 10. Ob ich nun 10mal 10 habe und als 100 behandle oder ob ich 10mal 10 Hunde habe, es ist eigentlich dasselbe, einmal die Hunde, das andre Mal die 100 als konkretes Ding. So ist gerade das Geheimnis des Rechnens, daß man die Zahl selber wiederum als etwas Konkretes behandelt. Und wenn Sie dies bedenken, so werden Sie finden, daß da ja auch im Leben ein Übergang stattfindet. Man spricht von 2 Zwölfen, 2 Dutzend, gerade so wie man von 2 Zehnern spricht. Nur hat man für die Zehn nicht eine solche Benennung, weil das Dezimalsystem schon unter den Auspizien der Abstraktheit gefaßt worden ist. Alle anderen Systeme, die fassen noch in viel konkreterer Weise eine Quantität auf, ein Dutzend, einen Schilling. Wieviel ist ein Schilling? Ein Schilling ist 12 Pence hier.

Ein Schilling ist aber unter Umständen eine Quantität von 30 Stück und das faßt man als eine Einheit auf. Sehen Sie, in dem Dorf, wo ich lange Zeit gelebt habe, da war es so, daß längs der Dorfstraße auf beiden Seiten Häuser waren. Überall waren Nußbäume davor. Und wenn der Herbst gekommen ist, haben die Buben die Nüsse herabgeworfen und sie für den Winter aufbewahrt. Und wenn sie dann in die Schule kamen, dann renommierten sie. Der eine sagte: «Ich habe schon 5 Schilling», der andere sagte: «Ich habe schon 10 Schilling Nüsse.» Sie betrachteten die konkreten Dinge. Ein Schilling, das waren immer 30 Stück. Die Bauern, die mußten nur sehen, daf3 sie noch ihre Nüsse einernteten, bevor die gesamten Bäume von Nüssen befreit waren. Ein Nuß-Schilling, so sagte man auch, also eine Einheit. Diese sich zu erkaufen, war ein Recht, es geschah unter aller Augen.

Und so kann man gerade, indem man dieses Zählen benützt mit Konkretem, 1 Dutzend, 2 Dutzend, 1 Paar, 2 Paar und so weiter, den Übergang vom Konkreten ins Abstrakte finden. Man sagt ja auch nicht 4 Handschuhe, sondern 2 Paar Handschuhe, nicht 4 Schuhe, sondern 2 Paar Schuhe. Indem man das benützt, kann man den Übergang vom Konkreten ins Abstrakte machen und auf diese Weise alles langsam vorbereiten. Und man geht dann eigentlich erst zu der abstrakten Zahl über zwischen dem 9. und 10. Lebensjahre.

Wann und wie sollte man Zeichenunterricht erteilen?

Beim Zeichenunterricht handelt es sich wirklich darum, daß man die Frage ein wenig ins künstlerische Licht rückt. Sie müssen bedenken, daß Zeichnen eigentlich zunächst eine Art von Verlogenheit ist. Was bedeutet denn Zeichnen? Zeichnen bedeutet etwas darsiellen durch Striche.

Nun, in Wirklichkeit gibt es eigentlich gar keine Striche. Es gibt in Wirklichkeit das zum Beispiel: Hier ist das Meer (siehe Zeichnung ]). Es stellt sich als Farbe dar (grün); darüber ist der Himmel. Er stellt sich wiederum dar als Farbe (blau). Bringt man die beiden Farben hin, dann hat man unten das Meer, oben den Himmel (siehe Zeichnung I). Der Strich macht sich selber da, wo die Farben aneinandergrenzen. Zu sagen, hier (siehe Zeichnung, Horizontlinie) grenzt Himmel an Meer, ist eigentlich schon eine sehr bedeutsame Abstraktion. Daher wird man künstlerisch zunächst das Gefühl haben, man sollte die Wirklichkeit so darstellen, daß man sie in Farben oder meinetwillen auch in Hell-Dunkel erfaßt.

Was ist denn vorhanden, wenn ich ein Gesicht darstelle? Ist denn jemals das vorhanden? (Die Umrisse eines Gesichtes werden gezeichnet. Zeichnung IL.) Gibt es denn so etwas? So etwas gibt es ja gar nicht. Dasjenige, was es gibt, ist dieses (es wird schraffiert, Zeichnung III). Nun, und so weiter, es gibt gewisse Flächen in HellDunkel, und daraus wird dann ein Gesicht. Linien hinzumachen und daraus ein Gesicht zu bilden, ist ja eine Verlogenheit. Das gibt es ja gar nicht.

Wenn man künstlerisch empfindet, wird man überall das Gefühl bekommen, aus dem Schwarz-Weiß oder aus der Farbe herauszuarbeiten, was da ist. Die Linien kommen dann von selber. Erst wenn einer hergeht und demjenigen, was sich ihm im Hell-Dunkel oder in den Farben zeigt - Grenzen der Farben, die sich von selbst ergeben -, wenn er diesem nachfährt, dann entstehen die zeichnerischen Linien.

Daher darf jedenfalls der Zeichenunterricht nicht ausgehen von dem Zeichnen, sondern er muß ausgehen von dem Malen, von dem Farbegeben, vom Hell-Dunkel.

Und der Zeichenunterricht als solcher hat einen realen Wert eigentlich nur dann, wenn er mit dem Bewußtsein entwickelt wird, daß er nichts Reales gibt. Es hat ja ungeheuren Unfug bewirkt in unserer ganzen Denkweise, daß die Menschen so viel aufs Zeichnen gegeben haben. Dadurch ist all das entstanden, was man, sagen wir, in der Optik hat, wo man ewig Linien aufzeichnet, die Lichtstrahlen sein sollen. Ja, wo gibt es denn solche Lichtstrahlen in Wirklichkeit? Nirgends nämlich. Was man hat in der Wirklichkeit, sind Bilder. Man macht irgendwo ein Loch in der Wand; die Sonne scheint herein, auf einem Schirm bildet sich ein Bild. Man kann höchstens im Staub im Zimmer die Bilder sehen - und je schmutziger das Zimmer ist, desto mehr kann man nach der Richtung sehen -, wiederum die Bilder sehen, die das Licht hervorruft aus den Staubkörnchen. Aber was man da gewöhnlich als Linien, als sogenannte Lichtstrahlen, zeichnet, das ist ja nur hinzugedacht. Alles, was eigentlich gezeichnet wird, ist gedacht. Und erst wenn man beginnt, so etwas wie Perspektive dem Kinde beizubringen, wobei man direkt ja schon in der Art und Weise des Erklärens die Abstraktheit hat, kann man anfangen, das Visieren, das Sehen in Linien darzustellen.

Aber ja nicht das Kind lehren, durch Striche ein Pferd zu zeichnen oder einen Hund, sondern das Kind soll den Pinsel nehmen und soll den Hund malen, hinmalen. Also jedenfalls nicht zeichnen. Diese Grenze vom Hund ist ja gar nicht vorhanden. Wo ist sie? Sie ergibt sich ja von selber, wenn man das zu Papier bringt, was da ist. Unsere Waldorfschule wird jetzt nicht nur von den Kindern gesucht, sondern sogar von den Lehrern. Es möchten sehr viele Menschen, die in der Welt draußen Lehrer sind, auch in der Waldorfschule angestellt werden, weil es ihnen da besser gefällt. Nun, da kamen in der letzten Zeit wirklich recht viele Leute an mich heran und produzierten sich in der Art, wie sie durch die Seminare eben vorbereitet sind, um nun Lehrer zu sein. Man bekommt ja schon einen geringen Schreck auch vor den Geschichtslehrern und den Sprachlehrern und so weiter, aber das Schrecklichste sind die Zeichenlehrer, denn die betreiben ein Handwerk, das es überhaupt nicht gibt für ein künstlerisches Empfinden; das gibt es gar nicht.

Und die Folge davon ist - ich nenne ja keine Namen, deshalb kann ich auch unbefangen sprechen -, daß man mit den Zeichenlehrern kaum reden kann, denn das sind so vertrocknete Menschen, so schrecklich unmenschliche Menschen. Sie haben gar keine Idee von einer Wirklichkeit. Dadurch, daß sie das Zeichnen als Beruf haben, sind sie herausgekommen aus jeder Wirklichkeit. Es ist schrecklich, mit ihnen zu reden, ganz abgesehen davon, daß sie Zeichnen lehren wollen in der Schule, das wir in der Waldorfschule gar nicht eingeführt haben. Aber auch die Seelenkonfiguration dieser Menschen, die diese unwirkliche Kunst des Zeichnens treiben, ist eben eine ganz merkwürdige. Die Leute haben nie Flüssigkeit auf der Zunge, immer eine ganz trockene Zunge. Schrecklich ist es, wie die Zeichenlehrer allmählich werden, bloß weil sie etwas ganz Unwirkliches treiben. Die gestellte Frage möchte ich schon dadurch beantworten, daß gesagt werde: Es soll womöglich überall vom Malen und nicht vom Zeichnen ausgegangen werden. Das ist das Wesentliche.

Ich will die Frage noch etwas deutlicher erläutern, damit Sie die Sache nicht mißverstehen. Sie könnten sonst glauben, daß ich etwas persönlich gegen Zeichenlehrer hätte. Ich möchte einmal folgendes sagen: Da sitzt irgendeine Kinderschar. Da scheint von dieser Seite, so sage ich zu dieser Kinderschar, die Sonne herein. Diese Sonne, die fällt da auf etwas auf, macht allerlei Lichter, überall Lichter (es wird gezeichnet, siehe Zeichnung Seite 137). Ich sehe lichte Flecken. Das Sonnenlicht fällt da überall auf, überall. Werl die Sonne so herscheint, sehe ich da überall lichte Flecken (in der Zeichnung weiß). Da drüben, da sehe ich keine lichten Flecken, da sehe ich Dunkles (blau). Das Dunkle sehe ich aber auch da unter den lichten Flecken, nur so, ganz wenig. Dann sehe ich auf etwas, was, wenn das Licht so drauffällt, sich darstellt im Grünlichen. Grünlich stellt es sich dar. Da fällt das Licht darauf, das wird weißlich. Aber dann, bevor der richtige schwarze Schatten kommt, da sehe ich es grünlich, und hier unter dem schwarzen Schatten ist auch Grünliches, und dann sind solche merkwürdige Dinge dazwischen. Da will das Licht nicht recht hinein.

Sehen Sie, jetzt habe ich von Licht und Schatten gesprochen, und daß da etwas ist, wo das Licht nicht angreift, und ich habe einen Baum gemacht. Ich habe nur vom Licht gesprochen, von Farbe gesprochen, und ich habe einen Baum gemacht. Man kann doch den Baum nicht malen; man kann nur Licht und Schatten und Grün, und höchstens noch, wenn die Früchte schöne Äpfelchen sind, Gelbes da hineinsetzen meinetwillen. Aber man soll von Farbe und Licht und Schatten sprechen. Und so soll man tatsächlich von dem sprechen, was wirklich da ist, nur von Farbe und Licht und Schatten. Zeichnen soll man nur in der Geometrie und in dem, was mit der Geometrie zusammenhängt. Da hat man es mit Linien zu tun. Das ist aber auch Gedachtes. Währenddem man Realitäten, konkrete Realitäten, nicht mit der Feder zeichnen soll, sondern einen Baum zum Beispiel entstehen lassen soll aus Hell-Dunkel und aus den Farben. Das ist dasjenige, was wirklich im Leben darinnensteht.

Es wäre zum Beispiel eine Barbarei, wenn nun ein richtiger Zerchenlehrer käme und den gemalten Baum hier mit den Linien nachmachen ließe. In Wirklichkeit sind da helle Flecken und dunkle Flekken. Das macht die Natur. Würde einer da Linien zeichnen, so wäre das eine Verlogenheit.

Soll man die direkte Methode ohne Übersetzen auch für Latein und Griechisch anwenden?

Mit Latein und Griechisch ist allerdings in dieser Beziehung eben eine Ausnahme zu machen. Lateinisch und Griechisch brauchen doch nicht unmittelbar an das Leben angepaßt zu werden, denn diese Sprachen leben ja nicht mehr, und wir haben sie ja eigentlich nur als tote Sprachen unter uns vorhanden. So daß beim Unterricht im Lateinischen und Griechischen - eigentlich sollte man ja mit dem Griechischen beginnen und ins Lateinische hinein fortsetzen -, so daß bei diesem Unterricht, der übrigens nicht gleich beim Kinde eintreten kann, sondern erst im späteren Lebensalter, die Übersetzungsmethode durchaus in einer gewissen Weise berechtigt sein kann.

Wir haben es ja nicht damit zu tun, daß wir uns im Lateinischen und Griechischen unterhalten, sondern um die alten Autoren zu verstehen. Wir wenden diese Sprachen an im eminentesten Sinne, um gerade das Übersetzen zu betreiben. Wann gebraucht man Latein? Als Arzt braucht man Latein. Und warum heute noch? Das ist ja hervorgegangen aus dem Fortsetzen eines alten Gebrauches. Alte Gebräuche erben sich fort, ohne daß man weiß, was für einen Sinn sie haben.

So ist es mit vielen Dingen, zum Beispiel mit Orden und Ehrenzeichen. Sie hatten seinerzeit eine große Bedeutung, waren auch tief symbolische Zeichen. Aber heute kann man das nicht mehr sagen. Sie haben sich fortgeschleppt als Gewohnheiten. Und so ist es auch damit, daß zum Beispiel der Arzt immerhin ein Interesse daran hat, daß er sich am Krankenbett mit einem anderen unterhalten kann und die Dinge benennen kann, ohne daß er den Kranken beunruhigt, also eine Sprache gebraucht, die der andere nicht verstehen kann. Da denkt man ja nur daran, das ins Lateinische umzusetzen, was man denkt. Und so ist es auch, daß wir diese selbe Methode im Griechischen und Latein nicht gebrauchen, die wir aber bei allen lebenden Sprachen anwenden.

Nun kommt wieder die Frage, die ja jedesmal bei meiner Anwesenheit in England, wenn irgendwie von Pädagogik die Rede ist, gestellt wird.

Wie soll man Turnunterricht treiben, und soll man in einer englischen Schule Sport treiben, zum Beispiel Hockey, Cricket und so weiter, und wie?

Es ist durchaus nicht die Absicht der Waldorfschul-Methode, diese Dinge zu unterdrücken. Sie können schon betrieben werden, einfach weil sie im englischen Leben eine große Rolle spielen und das Kind ins Leben hineinwachsen soll. Nur soll man sich nicht der Illusion hingeben, daß das eine andre Bedeutung hat als eben diese, daß man das Kind nicht weltfremd machen soll. Zu glauben, daß Sport für die Entwickelung einen furchtbar großen Wert hat, das ist ein Irrtum. Er hat nicht den großen Wert für die Entwickelung; er hat nur einen Wert, weil er eben eine beliebte Mode ist, und man soll durchaus das Kind nicht zum Weltfremdling machen und es von allen Moden ausschließen. Man liebt Sport in England, also soll man das Kind auch in den Sport einführen. Man soll nicht irgendwie sich philiströs gegen dasjenige stemmen, nun ja, was vielleicht philiströs ist.

Und in bezug auf das Eigentliche «wie das gelehrt werden soll», da wird ja außerordentlich wenig zu sagen sein, denn das ergibt sich bei diesen Dingen wirklich mehr oder weniger dadurch, daß man es vormacht und das Kind nachmachen läßt. Da auch noch besondere künstliche Methoden auszusinnen, das wäre doch etwas, was zu wenig sachgemäß wäre.

Im Turnen, - also Gymnastikunterricht - da handelt es sich darum, daß man tatsächlich aus der Anatomie und der Physiologie erfährt, in welche Lage irgendein Glied des Organismus gebracht werden soll, damit es der Leichtigkeit des Organismus dient. Da handelt es sich darum, daß wirklich auch gefühlt werde, was den Organismus geschickt, leicht, beweglich macht. Und dann, wenn man das fühlt, dann handelt es sich auch nur ums Vormachen. Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben ein Reck. Gewöhnlich werden alle möglichen Übungen daran gemacht. Die fruchtbarste Übung am Reck wird gewöhnlich nicht gemacht. Sie besteht darinnen, daß man am Reck hängt, so eingehäkelt, und dann schwingt, und nun das Reck so erfaßt, wiederum zurück, wiederum erfaßt. Man springt ja nicht, sondern man hängt am Reck, fliegt durch die Luft, macht die verschiedenen Bewegungen, faßt das Reck so und so, und dadurch kommt eine Abwechslung in der Konfiguration der Armmuskeln zustande, die tatsächlich auf den ganzen Organismus in gesundender Weise einwirkt.

Man muß studieren, welche Bewegungen, welche inneren Bewegungen der Muskeln auf den Organismus gesund wirken, und dann bekommt man heraus, welche Bewegungen man lehren soll. Und dann braucht man sie einfach vorzumachen; denn die Methode besteht da eben im Vormachen.

Wie soll der Religionsunterricht in den verschiedenen Lebensaltern erteilt werden?

Da ich immer nur vom Praktischen aus spreche, so muß ich sagen, die Waldorfschul-Methode ist eine Erziehungsmethode, nicht irgend etwas, was eine Weltanschauung oder etwas Sektiererisches in die Schule hineintragen soll. So kann ich auch da nur von dem Leben in dem Waldorfschul-Prinzip selber sprechen.

Wir haben es verhältnismäßig leicht gehabt in Württemberg, wo noch ein ganz liberales Schulgesetz war, als die Waldorfschule eingerichtet worden ist. In Württemberg hat man uns wirklich großes Entgegenkommen gezeigt von seiten der Behörden. Es war sogar möglich, daß ich darauf bestehen konnte, die Lehrer selber anzustellen, ohne Rücksicht darauf, ob sie irgendein staatliches Examen gemacht hatten oder nicht. Ich will ja nicht sagen, daß jeder ungeeignet wird zum Lehrer, der ein staatliches Examen macht! Ich will das nicht sagen. Aber immerhin, ich sah in einem staatlichen Examen keine Bedingung, daß man in der Waldorfschule Lehrer werden konnte.

Und so ist es immer in dieser Beziehung eigentlich recht gut gegangen. Aber eines war doch notwendig, schon bei der Einrichtung, daß wir ganz entschieden uns auf den Standpunkt stellten: Wir haben eine Methodenschule. Wir mischen uns nicht hinein in das, wie das soziale Leben gegenwärtig nun einmal ist. Sondern wir finden durch Anthroposophie die beste Methode zu lehren, haben also eine reine Methodenschule.

Daher habe ich die Sache so eingerichtet, daß der Religionsunterricht von vornherein nicht in unseren Schullehrplan einbezogen worden ist, sondern daß der katholische Religionsunterricht dem katholischen Priester, der evangelische Unterricht dem evangelischen Pfarrer und so weiter übergeben wurde.

In den ersten Jahren kamen die meisten Schüler aus einer Fabrik, aus der Moltschen Fabrik zunächst; da kamen viele Dissidentenkinder, Kinder von religionslosen Eltern. Da verlangte aber natürlich unsere pädagogische Gewissenhaftigkeit, ihnen auch einen gewissen Religionsunterricht zu geben. Für diese Kinder haben wir einen freien Religionsunterricht eingerichtet. So daß wir eine Methode zunächst haben für diesen freien Religionsunterricht.

Für diesen freien Religionsunterricht lehren wir zunächst Dankbarkeit beim Betrachten aller Dinge der Natur. Während man sonst in Legenden, Mythen, einfach erzählt, was die Dinge treiben, Steine, Pflanzen und so weiter, handelt es sich da darum, überall den kindlichen Blick auf das Empfinden des Göttlichen in allen Dingen hinzulenken. Also wir beginnen in einer gewissen Weise mit einer Art, ich möchte sagen, religiösem Naturalismus in kindlicher Form.

Das Kind versteht von den Evangelien wiederum nichts vor dem Zeitpunkte zwischen dem 9. und 10. Jahre, den ich angegeben habe. Erst da kann man dann auf die Evangelien übergehen, später auf das Alte Testament. Also es kann sich nur darum handeln, den Kindern zunächst im allgemeinen eine Art Naturreligion beizubringen. Für die haben wir dann unsere Methode. Eine vorgeschriebene Religion würde natürlich auch in ähnlicher Weise vorgehen müssen. Sie würde das benützen müssen, was diese vorgeschriebene Religion positiv hat, um es in einer allgemeineren Weise, noch ohne Anlehnung an die biblische Geschichte, dem Kinde zunächst beizubringen.

Dann, zwischen dem 9. und 10. Jahre erst, sollte man auf die Evangelien, und gar erst viel später auf das Alte Testament übergehen, erst vom 12., 13. Jahre an.

So würde man sich etwa den freien Religionsunterricht zu denken haben. Um den katholischen und evangelischen Unterricht kümmern wir uns nicht. Den lassen wir halt den katholischen und evangelischen Pfarrer erteilen. Für den freien Religionsunterricht haben wir auch an jedem Sonntag eine Art Kultus. Ein besonderer Kultus ist vorhanden für alle, ein besonderer Kultus ist für diejenigen vorhanden, die dann die Schule mit dem 14. Jahr verlassen. Dasjenige, was da an Kultus gemacht wird, hat sich wirklich praktisch ergeben im Laufe der Jahre; er dient außerordentlich gut zur Vertiefung des religiösen Gefühls, wird von den Kindern außerordentlich weihevoll empfunden.

Wir lassen bei diesem Kultus auch die Eltern beiwohnen, und es hat sich herausgestellt, daß das in einer außerordentlich günstigen Weise zur Wiederbelebung des Christentums dient, dieser freiwillige Religionsunterricht. Und es ist gutes Christentum in der Waldorfschule, weil durch diese naturalistische Religion in den ersten Jahren das Kind allmählich hinaufgehoben wird zum Begreifen des Christus-Geheimnisses in den höheren Klassen.

Es ist unser freier Religionsunterricht allmählich wirklich überlaufen von Teilnehmern. Es kommen alle möglichen Kinder auch herüber von dem evangelischen Pfarrer und dem katholischen Priester. Aber wir treiben keine Agitation. Wir können ohnehin schwer gerade Religionslehrer finden, und deshalb sehen wir es nicht einmal besonders gern, wenn zu viele Kinder herüberkommen, auch schon deshalb nicht, damit die Schule nicht in den Geruch kommt, eine anthroposophische Konfessionsschule zu sein. Das wollen wir durchaus nicht. Nur unser pädagogisches Gewissen hat uns gedrängt, diesen freien Religionsunterricht einzuführen. Aber die Kinder laufen davon im katholischen und evangelischen Religionsunterricht, kommen immer mehr herüber und wollen den freien Religionsunterricht haben. Er gefällt ihnen besser. Das ist nicht unsere Schuld, daß sie dort davonlaufen. Ich weiß nicht, ob es unsere Schuld ist, daß sie zu uns kommen. Aber wie gesagt, prinzipiell war die Einrichtung so: Der Religionsunterricht wurde von den betreffenden Pfarrern zunächst gegeben. Wenn Sie also fragen, was wir für einen Religionsunterricht haben, so kann ja nur dasjenige von mir vertreten werden, was als freier Religionsunterricht bei uns ist und was ich eben geschildert habe.

Sollen die Gegenstände des Epochenunterrichts in einer bestimmten Reihenfolge genommen werden?

Das ist natürlich etwas, worüber viel diskutiert werden könnte, aber einen großen praktischen Wert würde das nicht haben. Es wird sich in den ersten Klassen ja um nicht viel anderes handeln, als daß man Epochen abwechseln läßt mehr für den Unterricht, der im Schreiben, dann beim allmählichen Übergang in das Lesen erteilt wird, dann Rechnen und weniges andere. Man wird finden, ob man die Dinge in der einen oder in der anderen Reihenfolge nimmt, daß es keine übergroße Bedeutung hat. So daß wir bisher wenigstens in unseren Erfahrungen nicht irgendwie Veranlassung genommen haben, auf eine solche Reihenfolge besonders Rücksicht zu nehmen.

Soll man in einer englischen Schule Französisch und Deutsch vom Anfang an unterrichten? Wenn die Kinder mit 5 oder 6 Jahren in die Schule kommen, in eine Art Kindergartenklasse, soll man diesen auch Sprachunterricht erteilen?

Da möchte ich zunächst bemerken, ob man in einer englischen Schule Französisch und Deutsch von Anfang an unterrichten soll, das ist, glaube ich, nur aus reinen Opportunitätsgründen zu entscheiden. Wenn man eben findet, daß das Leben es notwendig macht, gerade diese Sprache zu betreiben, so soll man es tun. Wir haben in der Waldorfschule Französisch und Englisch eingeführt aus dem Grunde, weil am Französischen noch viel innerlich gelernt werden kann, was an einer anderen Sprache nicht gelernt werden kann, ein gewisses rhetorisches Gefühl, was ganz gut ist, wenn es da ist. Und Englisch aus dem Grunde, weil es eben Weltsprache ist und immer mehr und mehr Weltsprache werden wird.

Nun, ich möchte das nicht unbedingt entscheiden, ob in englischen Schulen Französisch und Deutsch gelehrt werden soll, sondern man soll sich eben danach richten, wie es die Lebensverhältnisse notwendig machen. Es wird gar nicht so wichtig sein, welche anderen Sprachen man wählt, sondern daß überhaupt andere Sprachen getrieben werden.

Ebenso wird es gut sein, wenn man die Kinder im 5. und 6. Jahre schon in die Schule bringt - was man eigentlich nicht tun sollte -, wenn man mit ihnen dann schon Sprachen treibt. Das gehört in dieses Lebensalter. Sprachen kann man auch vor dem Zahnwechselzeitalter etwas betreiben. Schulmäßig es betreiben sollte man aber erst nach dem Zahnwechsel. Wenn schon die Kinder in eine Art Kindergartenklasse gebracht werden, sollte man dies dazu benützen, um ihnen gerade Sprachunterricht beizubringen, und womöglich den anderen Unterricht hinausschieben, bis der Zahnwechsel eintritt.

Ich möchte, was Ihnen selbstverständlich klingen wird, zum Schluß noch aussprechen, daß es mich tief befriedigt hat, daß Sie ein so tätiges Interesse daran haben, die Waldorfschul-Methode hier in England fruchtbar werden zu lassen, daß Sie mit solcher Energie daran arbeiten, hier eine Schule nach unserer anthroposophischen Methode einzurichten. Und ich möchte die Hoffnung aussprechen, daß es Ihnen gelingen möchte, dasjenige, was Sie lernen konnten aus unseren Seminarkursen in Stuttgart, was Sie gehört haben in den verschiedenen anderen Kursen, die auch hier in England gehalten worden sind und was ich zuletzt hier an einzelnen aphoristischen Bemerkungen geben konnte - daß Sie all das benützen können, um eine recht gute Schule nach anthroposophischer Methode hier in England zu begründen.

Sie müssen nur bedenken, wieviel davon abhängt, daß wirklich der erste Versuch, der gemacht wird, gelingt. Gelingt er nicht, dann ist ja viel verloren, denn dann wird nach dem ersten Versuch alles übrige beurteilt. Und es hängt sehr viel davon ab, daß Sie den ersten Ansatz in einer Weise machen, daß die Welt merkt: Es ist etwas, was weder in abstrakten, dilettantischen Schulreformplänen schwelgt, noch irgend etwas, was sonst Laienhaftes ist, es ist etwas, was wirklich aus dem Erfassen der Menschenwesenheit hervorgeht, was dann übergehen soll in die pädagogische Kunst und was tatsächlich neben vielem anderen von unserer in so schwieriger Lage befindlichen Zivilisation gefordert wird.

Damit möchte ich Ihnen recht gute Gedanken mitgeben auf den Weg zur Begründung der hiesigen Schule nach anthroposophischer Methode.

Questions and Answers

The first question asked is:

What is the difference between multiplication and division in this teaching method? Or should there be no such difference at all in the early years of school?

The question probably arises from my statement that multiplication should be done in such a way that the so-called multiplicand, a factor, is revealed, not the product, and that the other factor is sought. Of course, in the usual sense of the word, this actually results in division. It is usually regarded as division. If one does not adhere too strictly to words, one can then understand division in the following way.

One can say: if one divides a whole in a certain way, how much is the part? And one has only a different interpretation of the same question: by what must one multiply a number in order to obtain a certain number?

So if you focus the question on division, you are dealing with division. If you focus the question on multiplication, you are dealing with multiplication. And it is precisely the intimate relationship in thinking that exists between multiplication and division that comes to the fore here.

However, children should be made aware at an early stage that there are actually two ways of understanding division. One way is the one I have just described. Here, you examine how big the part is when you divide a whole into a certain number of parts. You start with the whole and look for the part. This is one type of division.

The other type is when I start with the part and look for how many times the part is contained in the whole. Then division is not a matter of dividing, but of measuring. And this difference between dividing and measuring should be taught to the child as soon as possible, without the need for pedantic terminology. Then division and multiplication will soon cease to be merely formal calculations, as is very often the case, and will be based on real life.

Thus, you will actually only be able to differentiate between multiplication and division in terms of expression during the first years of school; but it should also be made clear that this difference is basically much smaller than that between subtraction and addition. And it is very important that such things are understood by the child.

So it cannot be said that no distinction should be made at all in the first years of school, but it should be made in the way I have just indicated.

At what age and how should one move from the concrete to the abstract in arithmetic?

This question should be considered as follows: one should first try to keep everything concrete in arithmetic and, above all, refrain from any abstraction until the age of 9 or 10. Until then, one should try to remain as concrete as possible, i.e., relate everything directly to life.

Then, once you have done this for two to two and a half years and have really made sure not to calculate with abstract numbers, but with concrete facts that have been converted into mathematical form, you will see that the transition to the abstract is extremely easy, especially in arithmetic. It is easy because, through this approach to numbers, you have brought such life into the numbers in the child that you can then easily move on to the abstract treatment of addition, subtraction, and so on.

It will therefore be a matter of postponing the transition from the concrete to the abstract as long as possible until the point in life that I have indicated between the ages of 9 and 10.

A great help for the transition from the concrete to the abstract in arithmetic is arithmetic where it is most needed in life, in counting, in spending money; and here you are in a more favorable position than we are over on the continent, because over on the continent we have the decimal system for everything. Here, you have an even more appealing system than the decimal system for your money. I don't know if you find it more appealing, but if you didn't find it more appealing than the decimal system, that would be pathological. The only healthy thing is to have a number system that is as concrete as possible in money. Here you still count according to the 12 and 20 systems, which we, as they say, have already overcome on the continent. You probably already have the decimal system for measuring, too?

One participant says that it is not used in everyday life, only in science.

So even there you still have the more appealing measurement system! These are things that actually keep everything more concrete. Only in writing numbers do you also have the decimal system.

What is this decimal system based on? It is based on the fact that we originally have it naturally. I have told you that it is not the head that forms the number, but the whole body. The head only reflects the number, and it is natural that we really have 10 or at most 20 as a number. Now we first have the number 10 because we have 10 fingers. We only write from 1 to 10, then we start treating numbers as concrete things again.

Let's write, for example: 2 donkeys. Here, the donkey is a concrete thing and 2 is the number. I could just as well say 2 dogs. But when you write 20, it is nothing more than 2 times 10. Here, 10 is treated as a concrete thing. And so our number system is based on the fact that, from the point where history becomes vague, where we can no longer grasp the whole picture, we begin to treat the number itself as something concrete, and then abstract it again. We would not be able to make any progress in arithmetic if we did not treat the number itself, regardless of what it is, as a concrete thing and then abstract it again. 100 is just 10 times 10. Whether I have 10 times 10 and treat it as 100, or whether I have 10 times 10 dogs, it is actually the same thing, once the dogs, the other time the 100 as a concrete thing. So the secret of arithmetic is precisely that one treats the number itself as something concrete. And if you consider this, you will find that there is also a transition in life. We speak of 2 twelves, 2 dozen, just as we speak of 2 tens. Only, there is no such designation for ten, because the decimal system has already been conceived under the auspices of abstraction. All other systems conceive of quantity in a much more concrete way, a dozen, a shilling. How much is a shilling? A shilling is 12 pence here.

But a shilling can also be a quantity of 30 pieces, and that is understood as a unit. You see, in the village where I lived for a long time, there were houses on both sides of the village street. There were walnut trees in front of them everywhere. And when autumn came, the boys threw the nuts down and stored them for the winter. And when they came to school, they boasted. One said, “I already have 5 shillings,” and another said, “I already have 10 shillings worth of nuts.” They looked at concrete things. A shilling was always 30 pieces. The farmers just had to make sure they harvested their nuts before the trees were completely stripped of them. A nut shilling, as it was also called, was a unit of currency. Buying it was a right, and it happened in full view of everyone.

And so, by using this counting with concrete things, 1 dozen, 2 dozen, 1 pair, 2 pairs, and so on, one can find the transition from the concrete to the abstract. One does not say 4 gloves, but 2 pairs of gloves, not 4 shoes, but 2 pairs of shoes. By using this, one can make the transition from the concrete to the abstract and in this way slowly prepare everything. And then one actually only moves on to abstract numbers between the ages of 9 and 10.

When and how should drawing lessons be taught?

Drawing lessons are really about putting the question in an artistic light. You have to remember that drawing is actually a kind of deception at first. What does drawing mean? Drawing means representing something through lines.

Well, in reality, there are no lines at all. In reality, there is, for example: here is the sea (see drawing ]). It is represented as a color (green); above it is the sky. It is also represented as a color (blue). If you bring the two colors together, you have the sea below and the sky above (see drawing I). The line creates itself where the colors meet. To say that here (see drawing, horizon line) the sky meets the sea is actually a very significant abstraction. Therefore, artistically, one will initially feel that reality should be depicted in such a way that it is captured in colors or, for that matter, in light and dark.

What is there when I depict a face? Is it ever there? (The outlines of a face are drawn. Drawing IL.) Is there such a thing? There is no such thing. What there is is this (it is hatched, drawing III). Well, and so on, there are certain areas in light and dark, and from these a face is formed. Adding lines to form a face is a deception. That does not exist at all.

If you have an artistic sensibility, you will feel compelled to work out what is there from the black and white or from the color. The lines then come by themselves. Only when someone approaches and follows what is revealed to them in the light and dark or in the colors—the boundaries of the colors that arise by themselves—only then do the lines of the drawing emerge.

Therefore, drawing lessons must not start with drawing, but with painting, with the application of color, with light and dark.

And drawing lessons as such only have real value if they are developed with the awareness that there is nothing real. It has caused tremendous mischief in our whole way of thinking that people have placed so much importance on drawing. This has given rise to everything that we have, say, in optics, where lines are constantly being drawn that are supposed to be rays of light. Yes, where are such rays of light to be found in reality? Nowhere, in fact. What we have in reality are images. You make a hole in the wall somewhere; the sun shines in, and an image forms on a screen. At most, you can see the images in the dust in the room – and the dirtier the room is, the more you can see in that direction – again, the images that the light creates from the dust particles. But what we usually draw as lines, as so-called rays of light, is only added by our imagination. Everything that is actually drawn is imagined. And only when you begin to teach a child something like perspective, whereby you already have abstraction in the way you explain it, can you begin to represent aiming, seeing in lines.

But don't teach the child to draw a horse or a dog with lines; instead, the child should take the brush and paint the dog, paint it. In any case, don't draw it. The boundary of the dog doesn't exist at all. Where is it? It emerges by itself when you put what is there on paper. Our Waldorf school is now sought after not only by children, but also by teachers. Many people who are teachers in the outside world would also like to be employed at the Waldorf school because they like it better there. Well, quite a few people have approached me recently and presented themselves in the way they have been prepared to be teachers through the seminars. You do get a slight shock from the history teachers and the language teachers and so on, but the most terrible are the art teachers, because they practice a craft that does not exist at all for artistic sensibility; it doesn't exist at all.

And the result of this is – I'm not naming any names, so I can speak impartially – that it's almost impossible to talk to art teachers, because they are such dried-up people, such terribly inhuman people. They have no idea of reality. Because they have drawing as their profession, they have removed themselves from all reality. It's awful to talk to them, quite apart from the fact that they want to teach drawing in school, which we haven't introduced at all in Waldorf schools. But the soul configuration of these people who practice this unreal art of drawing is also very strange. These people never have any moisture on their tongues, always a very dry tongue. It is terrible how drawing teachers gradually become like this, simply because they pursue something completely unreal. I would like to answer the question posed by saying that, wherever possible, painting should be the starting point, not drawing. That is the essential point.

I would like to explain the question a little more clearly so that you do not misunderstand. Otherwise, you might think that I have something personal against drawing teachers. Let me say the following: There is a group of children sitting there. The sun is shining in from this side, I say to this group of children. This sun, which is shining on something there, creates all kinds of lights, lights everywhere (it is being drawn, see drawing on page 137). I see light spots. The sunlight falls everywhere, everywhere. Where the sun shines like this, I see light spots everywhere (white in the drawing). Over there, I don't see any light spots, I see darkness (blue). But I also see the darkness under the light spots, just a little bit. Then I see something that, when the light falls on it, appears greenish. It appears greenish. When the light falls on it, it becomes whitish. But then, before the real black shadow comes, I see it greenish, and here under the black shadow there is also something greenish, and then there are such strange things in between. The light doesn't really want to go in there.

You see, now I've talked about light and shadow, and that there is something where the light doesn't reach, and I've made a tree. I've only talked about light, talked about color, and I've made a tree. You can't paint the tree; you can only paint light and shadow and green, and at most, if the fruits are beautiful little apples, you can add yellow for my sake. But one should talk about color and light and shadow. And so one should actually talk about what is really there, only about color and light and shadow. One should only draw in geometry and in what is related to geometry. There one is dealing with lines. But that is also something imagined. Whereas realities, concrete realities, should not be drawn with a pen, but a tree, for example, should be created from light and dark and from colors. That is what really exists in life.

It would be barbaric, for example, if a proper art teacher came along and had the painted tree copied here with lines. In reality, there are light spots and dark spots. That is what nature does. If someone were to draw lines there, it would be dishonest.

Should the direct method without translation also be used for Latin and Greek?

However, an exception must be made in this regard for Latin and Greek. Latin and Greek do not need to be directly adapted to life, because these languages are no longer alive, and we actually only have them among us as dead languages. So that when teaching Latin and Greek – one should actually start with Greek and continue with Latin – so that in this teaching, which, incidentally, cannot begin with children, but only at a later age, the translation method can certainly be justified in a certain way.

We are not concerned with conversing in Latin and Greek, but with understanding the ancient authors. We use these languages in the most eminent sense, precisely for the purpose of translation. When is Latin needed? Doctors need Latin. And why is it still needed today? It has emerged from the continuation of an ancient custom. Old customs are passed on without anyone knowing what purpose they serve.

This is the case with many things, for example, medals and decorations. They used to be very important and were also deeply symbolic. But today, this is no longer the case. They have been carried on as customs. And so it is also the case that, for example, the doctor has an interest in being able to talk to someone else at the patient's bedside and name things without disturbing the patient, i.e., using a language that the other person cannot understand. One thinks only of translating one's thoughts into Latin. And so it is that we do not use this same method in Greek and Latin, but we do use it in all living languages.

Now comes the question that is asked every time I am in England, whenever the subject of education comes up.

How should physical education be taught, and should sports such as hockey, cricket, and so on be played in English schools, and how?

It is by no means the intention of the Waldorf school method to suppress these things. They can be practiced, simply because they play a major role in English life and the child should grow into life. However, one should not succumb to the illusion that this has any other meaning than precisely this, that the child should not be made unworldly. To believe that sport is of tremendous value for development is a mistake. It is not of great value for development; it is only of value because it is a popular fashion, and one should certainly not make the child unworldly and exclude them from all fashions. People love sports in England, so children should also be introduced to sports. One should not somehow take a philistine stance against what may be philistine.

And with regard to the actual “how it should be taught,” there is very little to say, because with these things it really comes down more or less to showing the child how to do it and letting them imitate you. To devise special artificial methods would be something that would be too inappropriate.

In gymnastics, i.e., physical education, the aim is to learn from anatomy and physiology what position any limb of the organism should be placed in so that it serves the ease of the organism. The aim is to really feel what makes the organism agile, light, and mobile. And then, once you feel that, it's just a matter of demonstrating it. Suppose you have a horizontal bar. Usually, all kinds of exercises are done on it. The most fruitful exercise on the horizontal bar is usually not done. It consists of hanging on the bar, hooked in, and then swinging, and now grasping the bar, swinging back, grasping it again. You don't jump, but hang on the bar, fly through the air, do the various movements, grasp the bar in this way and that, and this brings about a change in the configuration of the arm muscles, which actually has a healing effect on the whole organism.

One must study which movements, which internal movements of the muscles, have a healthy effect on the organism, and then one can figure out which movements to teach. And then one simply needs to demonstrate them, because the method consists precisely in demonstrating them.

How should religious education be taught at different ages?

Since I always speak from a practical point of view, I must say that the Waldorf school method is a method of education, not something that is intended to bring a worldview or something sectarian into the school. So I can only speak about life in the Waldorf school principle itself.

We had it relatively easy in Württemberg, where there was still a very liberal school law when the Waldorf school was established. In Württemberg, the authorities showed us great goodwill. It was even possible for me to insist on hiring the teachers myself, regardless of whether they had passed any state exams or not. I don't want to say that everyone who passes a state exam is unsuitable to be a teacher! I don't want to say that. But at any rate, I did not see a state exam as a prerequisite for becoming a teacher at a Waldorf school.

And so things have always gone quite well in this regard. But one thing was necessary, right from the start, that we took a very firm stand: we have a school of methodology. We do not interfere in the way social life is at present. Instead, we find the best method of teaching through anthroposophy, so we have a pure school of methodology.

That is why I arranged things so that religious instruction was not included in our school curriculum from the outset, but that Catholic religious instruction was handed over to the Catholic priest, Protestant instruction to the Protestant pastor, and so on.