Spiritual Science and Medicine

GA 312

23 March 1920, Dornach

Lecture III

I propose to incorporate all the inquiries and requests I have received in the course of these lectures. Of course they contain repetitions, so I shall group the answers together, as far as possible. For it makes a difference whether we discuss what has been asked or suggested, before or after a certain basis has been laid down. Therefore, I shall try, in today's address, to establish such a basis for every future consideration, taking into account what I have had from you in the way of requests and suggestions.

You will remember that we first considered the form and inner forces of the osseous and muscular systems, that yesterday we reviewed illustrative examples of the process of disease, and the requisites of curative treatment; and that we took as our starting point on that occasion, the circulation in the cardiac system.

Today I shall describe the introductory principles of a conception that may be derived from a deeper study of human nature regarding the possibility and the essentials of healing in general. Special points will be dealt with in subsequent comments, but it is my intention to begin with these basic principles.

If we examine the medical curriculum of today we shall find, roughly speaking, that therapeutics are dealt with concurrently with pathology, although there is no clear and evident connection between the two. And in therapeutics at the present time, purely empirical methods generally prevail. It is hardly possible to discover a rational cure, combining practice with sound principles, in the domain of therapeutics. We are also aware that in the course of the nineteenth century, these deficiencies in the medical conception led to what was termed the Nihilist School. This Nihilism laid all stress on diagnosis, was content to recognise disease, and on the whole, was sceptical as regards any rationale of healing.

But in a purely rational approach to medicine, we might surely expect something suggesting lines of treatment to be given together with diagnosis? The connection between therapeutics and pathology must not be external only. The nature of disease must be recognised to such a degree that some idea can be formed from it as to the appropriate methods of the curative process.

And thus the question arises: How far does the whole intricate web of natural processes admit of curative Media and curative processes? An interesting axiom of Paracelsus has often been quoted, to this effect: the medical man must pass Nature's examination. But it cannot be maintained that the more recent literature dealing with Paracelsus has made much use of this axiom; for, if it had, there would be definite attempts made to unravel the curative processes from Nature herself. Of course, there are such attempts, in those processes of disease in which Nature herself gives counsel. But these examples are more or less exceptions, for there have already been injuries of one kind or another; whereas a genuine study of Nature would be a study of normal processes.

This leads to a further inquiry. Is there really any possibility of observing normal processes—in the current sense of the term—in Nature, in order to gather from them some conception of the healing method? You will immediately perceive the serious difficulty in this connection. We can of course, only observe curative processes in Nature in a normal way, if diseased processes are normally present in Nature. So we are confronted with this: Are there processes of disease in Nature itself, so that we can pass Nature's examination and thus learn how to heal them?

We shall try today to advance somewhat nearer to the answering of this question, which will be fully dealt with in the course of these lectures. But one can say at once in this connection that the path here indicated has been made impassable by the natural scientific basis of medicine as practised today. This means very “heavy going,” in the face of prevailing assumptions, for curiously enough, the materialistic tendency of the nineteenth century has led to a complete misconception of the functions of that system of the human organism with which we must now deal in sequence to the osseous, muscular and cardiac systems, viz. the nervous system.

It has gradually become the fashion to burden the nervous system with all the soul functions and to resolve all that man accomplishes of a soul and spirt nature into parallel processes which are then supposed to be found in the nervous system. As you are aware, I have felt bound to protest against this kind of nature study in my book Concerning the Problems of the Soul.

In this work, I first of all tried (and many empirical data confirm this truth, as we shall see) to prove, that only the processes proper to the formation of images are connected with the nervous system, whilst all the processes of feeling are linked—not indirectly but directly—with the rhythmic processes of the organism. The Natural Scientist of today assumes—as a rule—that the feeling processes are not directly connected with the rhythmic system, but that these bodily rhythms are transmitted to the nervous system, and thus indirectly, the feeling life is expressed through the nerve system.

Further I have tried to show that the whole life of our will depends directly on the metabolic system and not through the intermediary of the nerves. Thus the nervous system does nothing more than perceive will processes. The nervous system does not put into action the “will” but that which takes place through will within us, is perceived.

All the views maintained in that book can be thoroughly corroborated by biological facts, whereas the contrary assumption of the exclusive relation of the nerve system to the soul, cannot be proved at all. I should like to put this question to healthy unbiased reason: how can the fact that a so-called motor nerve and a sensory nerve can be cut, and subsequently grown together, so that they form one nerve, be harmonised with the assumption that there are two kinds of nerves: motor and sensory? There are not two kinds of nerves. What are termed “motor” nerves are those sensory nerves that perceive the movements of our limbs, that is, the process of metabolism in our limbs when we will. Thus in the motor nerves we have sensory nerves that merely perceive processes in ourselves, while the sensory nerves proper perceive the external world.

There is much here of enormous significance to medicine, but it can only be appreciated if the true facts are faced. For it is particularly difficult to preserve the distinction between motor and sensory nerves, in respect of the symptoms enumerated yesterday, as appertaining to tuberculosis. Therefore reasonable scientists have for some time assumed that every nerve has in itself a double conduction, one from the centre to the periphery, and also one from the periphery to the centre. Thus each motor nerve would have a complete double “circuit,” and if the explanation of any condition—such as hysteria—is to be based on the nervous system, one has to assume the existence of two nerve currents running in opposite directions. You see: as soon as one gets down to the facts, one must postulate qualities of the nervous system directly contrary to the accepted theories. Inasmuch as these conceptions about the nervous system have arisen, access has actually been barred to all knowledge of what goes on in the organism below the nervous system as in hysteria for example. In the preceding lecture, we defined this as caused by metabolic changes; and these are only perceived and registered by the nerves. All this should have received attention. But instead of such attentive study, there has been a wholesale attribution of symptoms and conditions to “nerves” alone, and hysteria was diagnosed as a kind of vulnerability and disequilibrium of the nervous system. This has led further. It is undeniable that among the more remote causes of hysteria are some that originate in the soul: grief, disappointment, disillusion, or deep-seated desires which cannot be fulfilled and may lead to hysterical manifestations. But those who have, so to speak, detached all the rest of the human organism from the life of the soul, and only admit a genuine direct connection between that life and the nervous system, have been compelled to attribute everything to “nerves.” Thus there has arisen a view which does not correspond in the least with the facts, and furthermore offers no available link between the soul and the human organism. The soul-forces are only admitted to contact with the nervous system, and are excluded from the human organism as a whole. Or, alternatively, motor nerves are invented, and expected to exercise an influence on the circulation, etc., an influence which is entirely hypothetical.

These errors helped to mislead the best brains, when hypnotism and “suggestion” came into the field of scientific discussion. Extraordinary cases have been experienced and recorded, though certainly some time ago. Thus, ladies afflicted with hysteria completely mystified and misled the most capable physicians, who swallowed wholesale all that these patients told them, instead of inquiring into the causes within the organism. In this connection, it is perhaps of interest to remind you of the mistake made by Schleich, in the case of a male hysteric. Schleich was fated to fall into this error, although he was quite well accustomed to think over matters thoroughly. A man who had pricked his finger with an inky pen, came to him and said that the accident would certainly prove fatal that same night, for blood poisoning would develop, unless the arm was amputated. Schleich, not being a surgeon, could not amputate. He could only seek to calm the man's fears, and carry out the customary precautions, suction of the wound, etc., but not remove an arm on the mere assertion of the patient himself. The patient then went to a specialist, who also declined to amputate. But Schleich felt uncomfortable about the case, and inquired early the next morning, and found that the patient had died in the night. And Schleich's verdict was: Death through Suggestion. And that is an obvious—terribly obvious explanation. But an insight into the nature of man forbids us to suppose that this death was due to suggestion in the manner assumed. If death through suggestion is the diagnosis, there had been a thorough confusion of cause and effect. For there was no blood poisoning—the autopsy proved this; but the man died, to all appearance, from a cause which was not understood by the physicians, but which must obviously have been deep-seated and organic. And this deep-seated organic cause had already—on the previous day—made the man somewhat awkward and clumsy, so that he stuck an inky pen into his finger, which is an action most people avoid. This was a result of his awkwardness. But this external and physical clumsiness was concurrent with an increased inner power of vision, and under the influence of disease, he foresaw that his death would occur that night. His death had not the least connection with the fact that he hurt his finger with an ink-stained pen, although this was the cause of his sensations, owing to the cause of death which he carried within him. Thus the whole course of events is merely externally linked with the internal processes which caused the death. There is no question of “death through suggestion” here. He foresaw his own death, however, and interpreted everything that happened, so as to fit into this sentiment This one example will show you how extremely cautious we must be, if we are to reach an objective judgment of the complicated processes of nature. In these matters one cannot take the simplest facts as a starting point.

Now we must pose this question: Does sensory perception, and all that resembles such perception, offer us any basis on which to estimate the somewhat dissimilar influences which are expected to affect the human constitution, through materia medica?

We have three kinds of influence upon the human organism in its normal state: the influences through sense perception, which then extend to the nervous system; the influences working through the rhythmic system, breathing and blood circulation; and those working through metabolism. These three normal relationships must have some sort of analogies in the abnormal relationships which we establish between the curative media—which we must after all take in some way from the external world of nature—and the human organism. Undoubtedly the most evident and definite results of this interaction between the external world and the human organism, are those affecting the nervous system. So we must ask ourselves this question: How can we rationally conceive a connection between man himself and that which is external nature; a connection of which we wish to avail ourselves, whether through processes, or substances with medicinal properties for human healing? We must form a view of the exact nature of this interaction between man and the external world, from which we take our means of healing. For even if we apply cold water treatment, we apply something external. All that we apply is applied from outside to the processes peculiar to man, and we must therefore form a rational concept of the nature of this connection between man and the external process.

Here we come to a chapter where again there is in the orthodox study of medicine a sheer aggregate instead of an organic connection. Granted that the medical student hears preliminary lectures on natural science; and that on this preparatory natural science, general and special pathology, general therapeutics and so forth, are then built up, but once lectures on medicine proper have begun, not much more is heard of the relationship between the processes discussed in these lectures, and the activities of external nature, especially in connection with healing methods. I believe that medical men who have passed through the professional curriculum of today, will not only find this a defect on the theoretical and intellectual side, but will even have a strong feeling of uncertainty when they come to the practical aspect, as to whether this or that remedy should be applied to influence the diseased process. A real knowledge of the relationship between the remedy indicated and what happens in the human body is actually extremely rare. So the very nature of the subject makes a major reform of the medical curriculum imperative.

I shall now try to illustrate the extent of the difference between certain external processes and human processes, by means of examples drawn from the former category. I propose to begin with what we can observe in plants and lower forms of animals, passing on from these to processes that can be activated through agencies derived from the vegetable, animal and especially the mineral kingdoms.

But we can only approach a characterisation of pure mineral substances, if we start from the most elementary conceptions of natural science, and then go on to the results, let us say, of the introduction of arsenic or tin into the human organism. But, first and foremost, we must emphasise the complete difference between the metamorphoses of growth in the human organism, and in external objects.

We shall not be able to escape forming some notion of the actual principle of growth, of the vital growth of and in mankind, and conceiving the same principle in external entities as well. But the difference is of fundamental significance. For instance, I would ask you to observe a very common natural object: the so-called locust tree, Robina pseudacacia. If the leaves of this plant are cut off where they join the petioles, there occurs an interesting metamorphosis; the truncated leaf stalk becomes blunt and knobby, and takes over the functions of the leaves. Here we find a high degree of activity on the part of something inherent in the whole plant; something that we will provisionally and by hypothesis term a “force,” which manifests itself if we prevent the plant from using its normally developed organ.

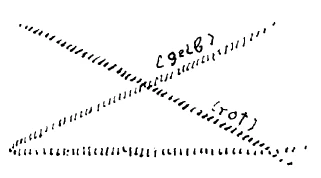

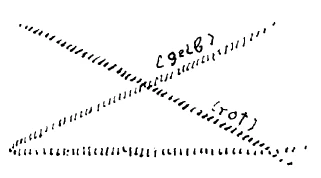

Now, observe, further, there is still a trace in mankind of what is so conspicuously present in the simple growing plant. For instance, if a man is prevented for one reason or another, from using one of his arms or hands for any purpose, the other arm or hand grows more powerful, stronger, and also physically larger. We must bring together facts like these. This is the path that leads to the cognition of remedial possibilities. In external nature these trends develop to extremes. For instance, this has been observed: A plant has grown on the slope of a mountain; certain of its stems develop in such a way that the leaves remain undeveloped; on the other hand the stem curves round and becomes an organ of support. The leaves are dwarfed; the stem twists round, becomes a supporting organ, and finds its base. These are plants with transformed stems, whose leaves have atrophied. (See Diagram 6).

Such facts point to inherent formative forces in the plant itself enabling it to adapt itself, within wide limits, to its environment. The same forces, active and constructive from within, are also revealed among lower organisms in an interesting way.

Take, for example, any embryo which has reached the gastrula stage of development. You can cut up this gastrula, dividing it through the middle, and each half rounds out and evolves the potentiality within itself of growing its own three portions of the intestine—the fore, middle and hind portion, independently. This means that if the gastrula is cut in two, we find that each half behaves just as the whole gastrula would have behaved. You know that this experiment can even be applied to forms of animal life as high in the scale as earthworms; that when portions are removed from these creatures, they are restored, the animal drawing on its internal formative forces to rebuild out of its own body the portion of which it has been deprived. We must point to these formative forces objectively; not as hypotheses, assuming the existence of some sort of vital force, but as matters of fact. For if we observe exactly what occurs here, and follow its various stages, we have this result. For instance, take a frog, and remove a portion in a very early stage of development, the bulk of the mutilated organism replaces the amputated portion by growing it again. A critic of a materialistic turn of mind, will say; Oh yes, the wound is the seat of tonic forces, and through these the new growth is added. But this cannot be assumed.

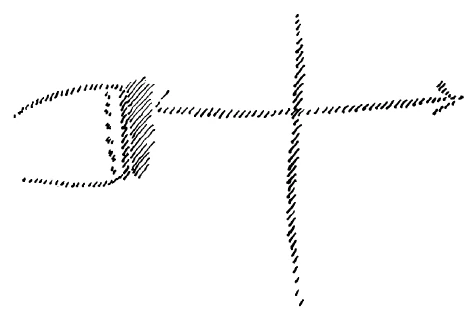

Suppose that it were the case, and I were to remove a part of an organism, and a new part grows on the site of the injury (b) (See Diagram 7) through the tonic force (c) located here; then the new growth should strictly speaking be the immediately adjacent part, its neighbour in the intact and perfect organism. Actually, however, this does not happen; if portions of the larval frog are amputated, what grows from the site of the injury are extremities, tails or even heads; and in other creatures antennae. Not, that is to say, the strictly adjacent parts, but those of most use to the organism. Therefore, it is quite impossible that the normally adjacent structure develops at the point of amputation through the specially localised tonic forces; instead, we are obliged to assume that, in these re-growths or repairs, the whole organism takes part in some way.

And so it is really possible to trace what happens in lower organisms. As I have indicated the path to follow you can extend its application to all the cases recorded, and see in all of them, that one can only achieve a conception of the matter along this line of thought.

And in man, you will have to conclude, however, that things do not happen in this way. It would be extremely pleasant and convenient to be able to cut off a finger or an arm, in the certainty that it would be grown again! But this simply does not happen. And the question is: what becomes of those forces, growth forces, which show themselves unmistakably in the case of animals, when it comes to the human organism? Are they lost in it? or are they non-existent?

Anyone who can observe Nature objectively knows that only by this line of inquiry can we arrive at a sound conception of the link between physical and spiritual in man. For the forces we learnt to know as plastic formative forces, which mould forms straight from the living substance, are simply lifted out of the organs, and exist entirely in the soul and spiritual functions.

Because they have been so lifted, and are no longer within the organs as formative forces, man has them as separate forces, in the functions of soul and spirit. If I think or feel, I think and feel by virtue of the same forces that work plastically in the lower animals or the vegetable world. Indeed I could not think if I did not perform my thinking, feeling and willing with these same forces, which I have drawn out of matter. So, when I contemplate the lower organisms, I must say to myself; the power inherent in them, which manifests as a formative force, is the same as I carry within me; but I have drawn it out from my organs and hold it apart. I think and feel and will with the same powers that are formative and active plastically, in the lower organisms.

Anyone wishing to be a sound psychologist, whose statements have substance, and not mere words, as is usual today, would have so to follow up the processes of thinking, feeling and willing, as to show that the very same activities in the regions of soul and spirit manifest themselves on the lower level as plastic formative forces.

Observe for yourselves how we can achieve within the soul things we can no longer achieve within our organism. We can complete trains of thought that have escaped us by producing them out of others. Our activity here is quite similar to organic production; what appears first is not the immediately neighboring, but one lying far removed. There is a complete parallelism between what we experience inwardly through the soul, and the external formative forces and principles of Nature. There is a perfect correspondence between them. We must emphasise this correspondence, and show that man faces the same formative principles in the external world, as he has drawn from his own organism for the life of his soul and spirit, and which therefore in his own organism no longer underlie the substance.

Moreover, we have not drawn these elements in equal proportions from all parts. We can only approach the human organism properly, if we have first armed ourselves with the preliminary knowledge outlined here. For if you observe all the components of our nervous system, you will find the following peculiarity: what we are accustomed to term nerve-cells (neurons) and the nerve tissue, and so forth, develop comparatively slowly in the early stages of growth; they are not very advanced cellular formations. So that we might reasonably expect these so-called nerve-cells to display the characteristics of earlier primitive cellular structures yet, they do not do so at all. For instance, they are not capable of reproducing themselves; nerve-cells, like the cells of the blood, are indivisible. Thus we find that in a relatively early stage of evolution, they have been deprived of a capacity that belongs to cells external to man. They remain at an earlier stage of evolution; they are, so to speak, paralysed at this stage. What has been paralysed in them, separates off and becomes the soul and spirit element. So that, in fact, with our soul and spiritual processes we return to what was once formative in organic substance. And we are only able to attain to this because we bear in us the nervous substances which we destroy or at least cripple in a relatively early stage of growth.

In this way we can approach the inherent nature of the nerve substance. The result explains why this substance has the peculiarity both of resembling primitive forms, even in its later developments; and yet of serving what is usually termed the highest faculty of mankind, the activity of the spirit.

I will interpolate here a suggestion rather outside the subject we are at present considering. In my opinion, even a superficial observation of the human head with its various enclosed nerve centres, reminds one rather of lower forms than highly developed species of animal life, in that the nerve centres are enclosed in a firm armour of bone. The human head actually reminds us of prehistoric animals. It is only somewhat transformed. And if we describe the lower animal forms, we generally do so by referring to their external skeleton, whereas the higher animals and man have their bony structure inside. Nevertheless our head, our most highly evolved and specialised part, has an external skeleton. This resemblance is at least a sort of leit-motif for our preceding considerations.

Now let us suppose that we have occasion, because of some condition that we term disease, (I shall deal with this in more detail later) to bring back into our organism what has thus been removed. If we replace or restore these formative forces of external nature—of which we have deprived our organism because we use them for the soul and spirit—by means of a plant product or some other substance used as a remedy—we thereby reunite with the organism something that was lacking. We help the organism by adding and returning what we first took away in order to become human. Here you see the dawn of what can be termed the process of healing: the employment of those external forces of nature, not normally present in man, to strengthen some faculty or function. Take as an example—purely by way of illustration—a lung. Here too we shall find that we have drawn away formative principles to augment our soul and spiritual powers. If we discover among the products of the vegetable kingdom, the exact forces thus drawn from the lung and re-introduce them in a case of disturbance of the lung system, we help to restore that organ's activity. So the question arises; which forces of external nature are similar to the forces that underlie the human organs and have been extracted in the service of soul and spirit? Here you will find the path, leading from the method of trial and error in therapy, to a sort of “rationale” of therapy.

In addition to the errors fostered in respect of the nervous system—which refers to the inner human being—there is another very considerable error, regarding extra-human nature. This I will just touch on today and explain more fully later.

During the age of materialism, people accustomed themselves to think of a sort of evolution of natural objects, from the so-called simplest to the most complex. The lower organisms were first studied in their structural evolution, then the more complex; and then attention was directed to structures outside the organic realm, that is in the mineral kingdom. The mineral kingdom was envisaged merely as being simpler than the vegetable. This has led to all those strange questions and speculations, concerning the origin of life from the mineral kingdom, a changing over of substance occurring at some unknown point in time, from a merely inorganic to an organic activity. This was the Generation Aequivoca or spontaneous generation, which provoked so many controversies.

However an unbiased examination certainly does not confirm this view. On the contrary, we must put the following proposition to ourselves. In a way, just as we can conceive of a sort of evolution from plant life on through animal life to man, so it is not possible to conceive of another evolution, from organisms, in this case, plants, to the minerals, inasmuch as the latter are deprived of life. As I have said, this is only a hint which will be made clearer in later lectures. But we shall only avoid going astray here, if we do not think of evolution as ascending from the mineral through the vegetable and animal forms to mankind, but if we postulate a starting point in the center, as it were, with our evolutionary sequence ascending from plant through animal life to man, and another, descending to the mineral kingdom.

Thus the central point of departure would lie not in the mineral kingdom, but somewhere in the middle kingdoms of nature. There would be two trends of evolution, an upward and a downward. In this way we should come to perceive, in passing downwards from plant to mineral, and especially—as we shall see—to that particularly important mineral group, the metals, that in this descending evolutionary sequence, forces are manifest which have peculiar relationships to their opposites in the ascending trend of evolution. In short: what are those special forces inherent in mineral substances, which we can only study if we consider here the formative forces which we have studied in lower organic forms, and apply the same methods?

In mineral substances such formative forces manifest themselves in crystallisation. Crystallisation reveals quite definitely a factor in operation on the descending line of evolution that is in some manner interrelated—but not identical—with that which manifests as formative forces on the ascending line. Then if we bring to the living organism that force which inheres in mineral substances, a new question arises. We have already been able to answer a previous and similar inquiry: if we restore the formative forces that we have absorbed from our organism by our soul and spiritual activities by means of vegetable and animal substances, we help the organism thus treated. But what would be the effect of applying these other, different, forces coming from the descending evolutionary line, that is from the mineral world, to the human organism? This is the question which I will put to you today, and which will be answered in detail, in the course of our considerations.

But with all this, we have not yet been able to contribute anything of real help to the question at the forefront of our programme for today, viz: Can we gather by careful listening a healing process straight from nature itself?

Here it depends on whether we approach nature with real insight—and we have attempted to get at least an outline of such understanding—whether certain processes will reveal their inherent secret. There are two processes in the human organism—as also among animals, which are of less interest to us at the moment—which appear in a certain sense directly contrary to one another, when looked at in the light of the concepts with which we are now equipped. Moreover these two processes are to a great extent polar to one another; but not wholly so, and I lay special stress on this not wholly, so please bear it in mind to avoid misconstruction of my present line of argument. They are the formation of blood, and the formation of milk, as they take place in the human body.

Even externally and superficially these processes differ greatly. The formation of blood, is, so to speak, very deep seated and hidden in the recesses of the human organism. The formation of milk finally tends towards the surface. But the most fundamental difference is that the formation of blood is a process bearing very strong potentialities of itself, producing formative forces. The blood has the formative power in the whole domestic economy of the human organism, to use a commonplace expression. It has retained in some measure the formative forces we have observed in lower organisms. And modern science could base itself on something of immense significance, in the observation and study of the blood; but it has not yet done so in a rational manner. Modern science could base itself on the fact that the main constituents of blood are the red corpuscles, and that these again are not capable of reproducing themselves. They share this limitation of potentiality with the nerve-cells. But, in emphasising this attribute held in common, all depends on the cause; is the cause the same in both cases? It is not, for we have not extracted the formative forces from our blood to anything like the same extent as from our nerve substance. Our nerve substance is the basis of our mental life, and is greatly lacking in internal formative force. During the whole span of life from birth, the nerve substance of man is worked upon by or is dependent on external impressions. The internal formative force is superseded by the faculty of simple adaptation to external influences. Conditions are different in the blood, which has kept to a great extent its internal formative force. This internal formative force, as the facts show, is also present in a certain sense in milk; for if this were not so, we could not give milk to young babies, as the most wholesome form of nourishment. It contains a similar formative potentiality as the blood; in this respect both vital fluids have something in common.

But there is also a considerable difference. Milk has formative potentiality; but lacks a constituent that is most essential to blood, or has it only in the smallest quantity. This is iron, fundamentally the only metal in the human organism that forms such compounds within the organism as display the true phenomenon of crystallisation.

Thus, even if milk also contains other metals in minute amounts, there is this difference: that blood essentially requires iron, which is a typical metal. Milk, although also potentially formative, does not require iron as a constituent. Why does the blood need iron?

This is one of the crucial questions of the whole science of medicine. The blood actually needs iron (we shall sift and collect the material evidence for the facts I have sketched today). Blood is that substance of the human organism, which is diseased through its own nature, and must be continuously healed by iron. This is not the case with milk. Were it so, milk could not be a formative medium for mankind, as it actually is; a formative medium administered from outside.

When we study the human blood, we study something that is constantly sick, from the very nature of our constitution and organism. Blood by its very nature is sick and needs to be continuously cured by the addition of iron. This means that a continuous healing process is carried on within us, in the essential process of our blood. If the medical man is “a candidate for Nature's examination,” he must study first of all, not an abnormal but a normal process of nature. And the process essential to the blood is certainly “normal,” and at the same time a process in which nature itself must continually heal, and must heal by means of the administration of the requisite mineral, iron. To depict what happens to our blood by means of a graph, we must show the inherent constitution of blood itself, without any admixture of iron, as a curve or line sloping downwards, and finally arriving at the point of complete dissolution of the blood. (See Diagram 8, red). whereas the effect of iron in the blood is to raise the line continuously upwards as it heals. (yellow line).

There indeed we have a process which is both normal and a standard pattern to be followed if we want to think of the processes of healing. Here we can really pass Nature's examination, for we see how nature works, bringing the metal and its forces which are external to mankind, into the human frame. And at the same time, we learn how the blood, which needs must remain inside the human organism, must be healed and how what flows out of the human organism, namely milk does not need to be healed, but which if it has formative forces, can wholesomely transmit them to another organism. Here we have a certain polarity—and mark well, a certain, not a complete polarity—between blood and milk, which must have attention and observation, for we can learn very much from it.

Dritter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich werde alle die Wünsche, die mir vorgelegt worden sind, im Laufe der Vorträge selbst verarbeiten. Es ist dazu natürlich, da einiges in Wiederholung auftritt, notwendig, daß wenigstens bis zu einem gewissen Teile die Wünsche alle beisammen sind, und dann ist es auch nicht einerlei, ob man die Dinge, die hier gefragt oder angedeutet sind, bespricht, bevor man eine gewisse Grundlage geschaffen hat, oder nachher. Daher werde ich möglichst heute schon mit Berücksichtigung dessen, was ich in Ihren Wünschen bemerkt habe, noch versuchen, für alle folgenden Betrachtungen eine Grundlage zu schaffen.

[ 2 ] Sie haben gesehen, daß von mir versucht worden ist, für die erste Betrachtung von der Formung und inneren Wirksamkeit des Knochen- und Muskelsystems auszugehen, und daß wir gestern schon vorgedrungen sind wenigstens zunächst zur exempelartigen Betrachtung des Krankheitsprozesses und den Notwendigkeiten des Heilverfahrens und daß wir, um an einem Exempel die entsprechende Betrachtung anknüpfen zu können, von der Zirkulation in dem Herzsystem ausgehen mußten.

[ 3 ] Nun möchte ich heute einiges auch noch prinzipiell Einleitendes ausführen über eine Anschauung, die man gewinnen kann aus einer tieferen Menschheitsbetrachtung über die Möglichkeit und das Wesen des Heilens überhaupt. Auf Spezielles soll dann in den folgenden Betrachtungen eingegangen werden, aber ich möchte diese prinzipiellen Auseinandersetzungen vorausschicken.

[ 4 ] Wenn man sich vorstellt, wie eigentlich das heutige medizinische Studium geartet ist, so wird man doch wenigstens in der Hauptsache finden, daß die Therapie neben der Pathologie einhergeht, ohne daß ein klar durchschaubarer Zusammenhang zwischen den beiden besteht. Insbesondere in der Therapie ist ja die bloße empirische Methode vielfach heute das Alleinherrschende. Etwas Rationelles, etwas, worauf man im Praktischen nun wirklich mit Prinzipien aufbauen könnte, ist insbesondere in der Therapie kaum zu finden. Wir wissen, daß diese Mängel der medizinischen Denkweise im Laufe des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts sogar zu der Schule des medizinischen Nihilismus geführt haben, der alles auf die Diagnose legte und eigentlich damit zufrieden war, wenn Krankheiten erkannt wurden, und sich im allgemeinen recht skeptisch gegenüber irgendeiner Ratio in der Heilung verhalten hat. Nun müßte man, wenn man rein, ich möchte sagen, vernunftgemäß Forderungen an das medizinische Wesen stellt, doch eigentlich sagen, es muß mit der Diagnose zusammen schon etwas gegeben sein, was auf die Heilung hinweist. Es darf nicht bloß ein äußerer Zusammenhang zwischen Therapie und Pathologie herrschen. Man muß gewissermaßen das Wesen der Krankheit doch schon so erkennen können, daß man aus dem Wesen der Krankheit heraus sich eine Anschauung über den Heilungsprozeß bilden kann.

[ 5 ] Das hängt natürlich zusammen mit der Frage: Inwiefern kann es überhaupt im ganzen Zusammenhang der Naturprozesse Heilmittel und Heilprozesse geben? Es wird ja sehr häufig ein ganz interessanter Spruch von Paracelsus zitiert: Der Arzt müsse durch der Natur Examen gehen. Aber man kann nicht sagen, daß die neuere Paracelsus-Literatur gerade mit einem solchen Ausspruch viel anzufangen weiß, denn sie müßte doch sonst darauf aus sein, der Natur selbst Heilungsprozesse abzulauschen. Nun gewiß, es wird das versucht, wenn Krankheitsprozesse vorliegen, gegen die sich die Natur selbst einen Rat schafft. Aber es geht doch wiederum darauf hinaus, die Natur in bezug auf ihre Heilverfahren auch nur gewissermaßen in Ausnahmefällen, wenn schon Schädigungen da sind und die Natur sich hilft, zu beobachten, während eine wirkliche Naturbeobachtung doch diejenige ist, daß man normale Prozesse beobachtet. Und die Frage müßte entstehen: Gibt es denn eine Möglichkeit, normale Prozesse in der Natur zu beobachten, gewissermaßen das, was man normale Prozesse nennt, um an ihnen irgend etwas von einer Anschauung über das Heilverfahren zu gewinnen? — Sie werden ja sogleich bemerken, daß das mit einer etwas bedenklichen Frage zusammenhängt. Man kann natürlich in der Natur nur Heilungsprozesse beobachten in normaler Weise, wenn Krankheitsprozesse in der Natur normal vorhanden sind. Und die Frage tritt vor uns auf: Sind denn in der Natur als solcher schon Krankheitsprozesse vorhanden, so daß man durch der Natur Examen gehen kann und durch sie heilen lernen kann? — Der Beantwortung dieser Frage, die sich natürlich erst im Laufe der Vorträge vollständig geben lassen wird, werden wir uns aber heute wenigstens um ein Stück zu nähern versuchen. Aber man kann dabei gleich sagen, daß eigentlich durch die naturwissenschaftliche Grundlegung der Medizin, wie sie heute üblich ist, der Weg, der hier vorgezeichnet wird, überschüttet wird. Er läßt sich bei den gegenwärtigen Voraussetzungen außerordentlich schwer gehen, denn es ist sehr merkwürdig, daß gerade die materialistische Tendenz im neunzehnten Jahrhundert dazu geführt hat, nun das nächste System, das ich hier dem Knochen-, Muskel- und Herzsystem anfügen muß, eigentlich in seinen Funktionen vollständig zu verkennen, nämlich das Nervensystem.

[ 6 ] Es ist nach und nach üblich geworden, dem Nervensystem sozusagen alles Seelische aufzuhalsen und alles Seelisch-Geistige, das sich im Menschen vollzieht, in Parallelvorgänge aufzulösen, die dann im Nervensystem zu finden sein sollen. Nun wissen Sie, daß ich Einspruch erheben mußte gegen diese Art von Naturbetrachtung in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln», in dem ich zunächst zu zeigen versuchte — und vieles, was beizubringen ist aus der Erfahrung zur Erhärtung dieser Wahrheiten, wird sich uns gerade bei diesen Betrachtungen ergeben —, daß nur die eigentlichen Vorstellungsprozesse mit dem Nervensystem zusammenhängen, während nicht in indirekter, sondern in direkter Weise alle Gefühlsprozesse zusammenhängen mit den rhythmischen Vorgängen im Organismus. Der heutige Naturwissenschafter denkt eigentlich normalerweise so, daß Gefühlsprozesse unmittelbar nichts mit dem rhythmischen System zu tun haben, sondern nur dadurch, daß sich diese rhythmischen Prozesse auf das Nervensystem übertragen, denkt er, daß sich das Gefühlsleben auch durch das Nervensystem auslebe. Und ebenso versuchte ich zu zeigen, daß das gesamte Willensleben direkt, nicht indirekt durch das Nervensystem, zusammenhängt mit dem Stoffwechselsystem. So daß für das Nervensystem auch in bezug auf die Willensprozesse nichts übrigbleibt als die Wahrnehmung dieser Willensprozesse. Durch das Nervensystem wird nicht irgendein Wille in Szene gesetzt, sondern dasjenige, was durch den Willen geschieht in uns, wird wahrgenommen. Alles dasjenige, was da von mir geltend gemacht worden ist, kann durchaus belegt werden mit den entsprechenden Tatsachen der Biologie, währenddem die entgegengesetzte Anschauung von der alleinigen Zuordnung des Nervensystems zum Seelenleben eben gar nicht belegt werden kann. Ich möchte nur einmal sehen, wie bei völlig gesunder Vernunft die Tatsache, daß man einen sogenannten motorischen Nerv durchschneidet, einen sensitiven Nerv durchschneidet, sie dann zusammenwachsen lassen kann und daß dann daraus wiederum ein einheitlicher Nerv entsteht, in Zusammenhang gebracht werden sollte mit der anderen Annahme, daß es sensitive und motorische Nerven gebe. Die gibt es eben nicht, sondern dasjenige, was man motorische Nerven nennt, sind nichts anderes als sensitive Nerven, die die Bewegungen unserer Glieder wahrnehmen, also dasjenige, was im Stoffwechsel unserer Glieder vor sich geht, wenn wir wollen. Wir haben also auch in den motorischen Nerven in Wahrheit sensitive Nerven, die nur in uns selber wahrnehmen, während die eigentlich sensitiv genannten Nerven die Außenwelt wahrnehmen.

[ 7 ] In dieser Richtung liegt etwas, was für die Medizin von ungeheurer Bedeutung ist, was aber erst gewürdigt werden kann, wenn man den Tatbestand selbst ordentlich ins Auge fassen wird. Denn gerade den Krankheitserscheinungen gegenüber, von denen ich gestern zur Gewinnung des Beispiels der Tuberkulose ausgegangen bin, ist es ja schwer, mit der Teilung in sensitive und motorische Nerven auszukommen. Vernünftige Naturforscher haben daher schon angenommen, daß jeder Nerv eine Leitung habe nicht nur von der Peripherie nach innen oder umgekehrt, sondern immer auch eine Leitung von der Peripherie nach dem Zentrum, beziehungsweise von dem Zentrum nach der Peripherie. Ebenso würde dann jeder motorische Nerv zwei Leitungen haben, das heißt: wenn man vom Nervensystem aus irgend etwas erklären will, wie zum Beispiel die Hysterie, so hat man schon nötig, zwei Leitungen, die zueinander im entgegengesetzten Sinne laufen, anzunehmen. Also man hat, sobald man auf Tatsachen eingeht, durchaus schon nötig, solche Eigenschaften der Nerven anzunehmen, die eigentlich den Hypothesen über das Nervensystem vollständig widersprechen. Dadurch, daß man so über das Nervensystem denken lernte, hat man eigentlich alles das zugeschüttet, was man wissen sollte über dasjenige, was im Organismus sonst unter dem Nervensystem liegt, was zum Beispiel bei der Hysterie vorgeht. Wir haben es gestern charakterisiert durch Vorgänge im Stoffwechsel, was zum Beispiel bei der Hysterie vorgeht und was durch die Nerven bloß wahrgenommen wird. Man hätte auf das sehen müssen. Statt dessen hat man die Hysterie nur gesucht in einer Art Erschütterbarkeit und Erschütterung des Nervensystems allein und hat alles in das Nervensystem verlegt.

[ 8 ] Dadurch ist noch etwas anderes gekommen. Man kann ja nicht leugnen, daß unter den etwas ferneren Ursachen der Hysterie auch seelische Ursachen liegen, Kummer, auch erlittene Enttäuschungen, irgendwelche erfüllbaren oder unerfüllbaren inneren Erregungen, die dann auslaufen in hysterische Erscheinungen. Damit, daß man gewissermaßen den ganzen übrigen Organismus vom Seelenleben abgetrennt hat und nur das Nervensystem mit dem Seelenleben in einen eigentlichen direkten Zusammenhang bringt, ist man genötigt, alles auf das Nervensystem abzuladen. Dadurch kam eine Anschauung heraus, die sich erstens dann nicht im allergeringsten eigentlich mehr mit den Tatsachen deckt und die zweitens gar keine Handhabe bietet, das Seelische noch heranzubringen an den menschlichen Organismus. Man bringt es eigentlich nur heran an das Nervensystem. Man bringt es nicht heran an den ganzen menschlichen Organismus. Höchstens dadurch, daß man eben motorische Nerven erfindet, die es gar nicht gibt, und daß man von den Funktionen der motorischen Nerven dann eine Beeinflussung der Zirkulation und so weiter erwartet, die nun immer im äußersten Maße zum Hypothetischen gehört.

[ 9 ] Was ich da auseinandergesetzt habe, hat namentlich auch dahin geführt, die gescheitesten Leute auf Irrpfade zu leiten, als so etwas auftauchte wie die Suggestion und die Hypnose. Da hat man es erleben können — es liegt jetzt schon wiederum etwas zurück —, daß hysterische Damen die allergescheitesten Ärzte irregeführt haben, an der Nase herumgeführt haben, weil man einfach hereingefallen ist auf alles mögliche, was solche Leute den Ärzten vorgemacht haben, und nicht hat eingehen können auf dasjenige, was eigentlich im Organismus vorliegt. Es ist doch vielleicht nicht uninteressant, in diesem Zusammenhange darauf hinzuweisen — obwohl es sich dabei nicht um eine hysterische Dame, sondern um einen hysterischen Mann handelt -, in welchen Irrtum Schleich verfallen ist, verfallen mußte, der über solche Dinge ja eigentlich ganz gut nachzudenken gewöhnt war, als zu ihm als Arzt ein Mann kam, der sich mit der tintigen Feder in den Finger gestochen hatte und sagte, das werde ganz gewiß in der nächsten Nacht zum Tode führen, eine Blutvergiftung werde eintreten und der Arm müsse amputiert werden. Es ist selbstverständlich, daß Schleich als Chirurg die Amputation nicht vornehmen konnte. Er konnte den Mann nur beruhigen und die nötigen Dinge machen, die da gemacht werden: Aussaugung der Wunde und so weiter, aber er konnte selbstverständlich ihm den Arm nicht abschneiden auf dessen bloße Aussage hin, daß er in der nächsten Nacht eine Blutvergiftung haben werde. Der betreffende Patient ging dann noch zu einer Autorität, die ihm selbstverständlich den Arm auch nicht abschnitt. Aber Schleich wurde die Sache etwas unheimlich. Gleich am Morgen erkundigte er sich — der Patient war in der Nacht wirklich gestorben. Und Schleich konstatierte: Tod durch Suggestion.

[ 10 ] Es liegt so nahe, es liegt so furchtbar nahe, zu konstatieren: Tod durch Suggestion. Aber bei einer Einsicht in die menschliche Wesenheit geht es einfach nicht, diesen Tod durch Suggestion in dieser Weise zu denken, sondern es handelt sich darum, daß hier, wenn man Tod durch Suggestion diagnostiziert, sofort eine gründliche Verwechslung von Ursache und Wirkung eintritt. Es trat auch keine Blutvergiftung ein — das hat die Sektion ergeben —, sondern der Betreffende starb, wie es schien, an einer Ursache, die den Ärzten nicht bekanntgeworden ist, aber für jemanden, der die Sache durchschauen kann, ganz unbedingt an einer Ursache, die tief im Organismus begründet war. Und diese Ursache, die tief im Organismus begründet war, hat diesen Menschen schon am vorhergehenden Tag etwas tapperig und unsicher gemacht, so daß er sich, was man sonst nicht tut, mit der tintigen Feder in den Finger stach. Das war schon eine Folge seiner Tapperigkeit. Aber während er äußerlich-physisch tapperig wurde, wurde sein inneres Schauvermögen etwas erhöht, und unter dem Einflusse der Krankheit hatte er eine prophetische Voraussicht seines in der Nacht eintretenden Todes. Dieser Tod hing nicht im geringsten zusammen mit dem, daß er sich mit der tintigen Feder in den Finger stach, sondern der Tod war die Ursache dessen, was er fühlte dadurch, daß er die Todesursache in sich trug, und alles, was vor sich gegangen ist, ist eben nichts anderes als etwas, was ganz äußerlich zusammenhängt mit den eigentlichen inneren Prozessen, die den Tod herbeigeführt haben. Es ist gar keine Rede davon, daß hier «Tod durch Suggestion» eingetreten ist. Denn auch der Glaube und alles das, was der Mann hatte, hatte nichts zu tun mit der Herbeiführung seines Todes, sondern hatte tiefere Ursachen. Aber er sah den Tod voraus und interpretierte alles dasjenige, was geschah, in diese Voraussicht des Todes hinein. Sie sehen an diesem Beispiel zugleich, wie ungemein vorsichtig man sein muß, wenn man über die komplizierten Vorgänge in der Natur ein sachgemäßes Urteil gewinnen will. Man kann da nicht ausgehen von dem Allereinfachsten.

[ 11 ] Nun wird man aber die Frage aufwerfen müssen: Gibt uns die Sinneswahrnehmung und alles, was der Sinneswahrnehmung ähnlich ist, einen Anhaltspunkt für, ich möchte sagen, die etwas anders gearteten Einflüsse, die von Heilmitteln auf den menschlichen Organismus ausgehen sollen?

[ 12 ] Nicht wahr, wir haben dreierlei Einflüsse auf den menschlichen Organismus im Normalzustande: Erstens denjenigen durch die Sinneswahrnehmungen, der sich dann im Nervensystem fortsetzt. Zweitens denjenigen durch das rhythmische System, das Atmen und die Zirkulation, und drittens denjenigen durch den Stoffwechsel. Diese drei normalen Beziehungen, die müssen irgendwelche Analoga haben in den abnormen Beziehungen, die wir herstellen zwischen den Heilmitteln, die wir ja auch in irgendeiner Weise aus der äußeren Natur nehmen müssen, und dem menschlichen Organismus. Am deutlichsten tritt allerdings dasjenige, was zwischen der Außenwelt und dem menschlichen Organismus geschieht, in dem Einfluß auf das Nervensystem auf. Wir müssen uns daher fragen: Wie können wir uns rationell einen Zusammenhang denken zwischen dem Menschen selbst und dem, was außermenschliche Natur ist und was wir verwenden wollen, sei es als Vorgänge, sei es substantiell als Heilmittel, zur menschlichen Heilung? Wir müssen eine Ansicht darüber gewinnen, wie das Wechselverhältnis des Menschen zur außermenschlichen Natur ist, aus der wir unsere Heilmittel nehmen. Denn selbst wenn wir Kaltwasserkuren anwenden, so wenden wir etwas Außermenschliches an. Alles, was angewendet wird, ist angewendet vom Außermenschlichen auf die menschlichen Prozesse, und wir müssen uns eine rationelle Ansicht darüber verschaffen, wie der Zusammenhang zwischen dem Menschen und den außermenschlichen Prozessen ist.

[ 13 ] Da kommt man allerdings auf ein Kapitel, wo wiederum statt eines organischen Zusammenhanges in unserem gebräuchlichen medizinischen Studium das reine Aggregat herrscht. Der Mediziner hört zwar vorbereitende Naturwissenschaft vortragen, dann wird aber auf diese vorbereitende Naturwissenschaft das allgemeine und spezielle Pathologische, das allgemeine Therapeutische aufgebaut und so weiter, und es ist nicht mehr viel zu vernehmen, wenn die eigentlichen medizinischen Vorträge anfangen, von dem, wie sich diese Prozesse, die in den eigentlich medizinischen Vorträgen besprochen werden, und namentlich wie sich die Heilmaßnahmen verhalten zu den Vorgängen in der äußeren Natur. Ich glaube, die durch die heutige medizinische Schulung gegangenen Ärzte werden dies nicht nur äußerlich verstandesmäßig als einen Mangel empfinden, sondern sie werden es gar stark in der Empfindung, die sich ihnen dann aufdrängt, wenn sie praktisch eingreifen sollen in die Krankheitsprozesse, als ein Gefühl in sich tragen, als ein gewisses Gefühl der Unsicherheit, wenn das oder jenes verwendet werden soll. Es ist doch sehr selten eine wirkliche Erkenntnis der Beziehung des zu verwendenden Heilmittels zu dem, was im Menschen vorgeht, in Wirklichkeit vorhanden. Hier handelt es sich darum, daß geradezu durch die Natur der Sache selbst auf eine ganz notwendige Reform des medizinischen Studiums hingewiesen wird.

[ 14 ] Nun möchte ich heute zunächst davon ausgehen, an gewissen Prozessen der außermenschlichen Natur anschaulich zu machen, wie verschieden in vieler Beziehung diese Prozesse von den Prozessen der menschlichen Natur sind. Ich möchte ausgehen von den Prozessen, die wir zunächst an niederen Tieren und Pflanzen beobachten können, um von da aus dann den Weg zu jenen Prozessen zu finden, die hervorgerufen werden können durch das Außermenschliche überhaupt, das wir dem Pflanzenreich oder dem Tierreich und namentlich dem Mineralreich entnehmen. Aber wir werden uns dieser Charakteristik der reinen mineralischen Substanzen erst nähern können, wenn wir eben von ganz elementaren naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen ausgehen, dann zu dem aufsteigen, was zum Beispiel geschieht, wenn wir, sagen wir, Arsen oder Zinn oder irgend etwas anderes als Heilmittel in den menschlichen Organismus einführen. Da muß zunächst darauf hingewiesen werden, daß ganz anders, als das bei der menschlichen Natur selbst der Fall ist, die Wachstumsmetamorphosen bei außermenschlichen Wesen liegen.

[ 15 ] Wir werden nicht umhin können, das eigentliche Prinzip des Wachsens, des lebendigen Wachsens im Menschen irgendwie zu denken und es auch zu denken bei den außermenschlichen Wesenheiten. Aber die Differenz, die da auftritt, ist von einer grundlegenden Bedeutung. Betrachten Sie, zum Beispiel etwas sehr Naheliegendes, die gewöhnliche sogenannte falsche Akazie, die Robinia pseudacacia. Wenn Sie dieser die Blätter an den Blattstielen abschneiden, so entsteht das Interessante, daß die Blattstiele durch eine Metamorphose etwas umgewandelt werden und daß dann diese umgewandelten knolligen Blattstiele die Funktion der Blätter übernehmen. Da ist in einem hohen Maße etwas tätig, was wir zunächst hypothetisch eine Kraft nennen wollen, die in der ganzen Pflanze steckt und die sich dann äußert, wenn wir die Pflanze verhindern, ihr normal ausgebildetes Organ für bestimmte Funktionen zu verwenden. Daß, ich möchte sagen, noch ein Rest von dem vorhanden ist, was da in ganz ausgesprochenem Maße bei der einfacher wachsenden Pflanze der Fall ist, das zeigt sich daran, daß, sagen wir, bei einem Menschen, der durch irgend etwas verhindert ist, den einen Arm oder die eine Hand zu irgendwelchen Funktionen zu gebrauchen, die andere kräftiger sich ausbildet, stärker sich ausbildet und auch physisch größer wird und so weiter. Wir müssen schon solche Dinge miteinander verbinden, denn das ist der Weg, der zur Erkenntnis der Möglichkeit einer Heilweise führt.

[ 16 ] Nun, bei der außermenschlichen Natur geht die Sache sehr weit. Man kann zum Beispiel folgendes beobachten: Nehmen wir an, es wachse eine Pflanze auf einem Bergabhange, so geschieht es, daß solche Pflanzen gewisse Blattstiele so entwickeln, daß sie die Blätter unausgebildet lassen; die bleiben weg. Dagegen biegt sich der Blattstiel um und wird zum Stützorgan. Die Blätter verkümmern (siehe Zeichnung Seite 63), der Blattstiel biegt sich um, wird zum Stützorgan, stützt sich auf: Pflanzen mit umgebildeten Blattstielen, bei denen die Blätter verkümmern. Das weist auf innere Bildungskräfte der Pflanze hin, die bewirken, daß die Pflanze in einer weitgehenden Weise sich an die durch ihre Umgebung bedingte Lebensweise anpassen kann. Nun, die Kräfte, die dadrinnen wirksam sind, treten uns aber namentlich bei niederen Organismen in einer ganz interessanten Art entgegen.

[ 17 ] Wenn Sie zum Beispiel irgendeinen Embryo nehmen, der bis zum Gastrulastadium vorgerückt ist, so können Sie die Gastrula zerschneiden, in der Mitte auseinanderschneiden, und jedes Stück ründet sich wiederum und bildet in sich die Möglichkeit aus, die drei Stücke von Vorder-, Mittel- und Enddarm für sich auszubilden. Wir schneiden also die Gastrula auseinander und finden, daß sich jedes Stück so verhält, wie sich das unzerschnittene Ganze verhalten haben würde. Sie wissen, daß man diesen Versuch ausdehnen kann bis zu niederen Tieren, sogar Regenwürmern, und daß, wenn man gewissen niederen Tieren Stücke abschneidet, sich das wiederum ergänzt, so daß es aus seinen inneren Bildungskräften heraus wiederum dasjenige bekommt, was wir ihm abgeschnitten haben. Auf diese Bildungskräfte muß sachlich hingewiesen werden, nicht hypothetisch, indem man irgendeine Lebenskraft annimmt, sondern es muß sachlich auf diese Bildungskräfte hingewiesen werden. Denn, wenn man genauer zusieht, wenn man wirklich verfolgt, was da eigentlich vorliegt, so sieht man zum Beispiel folgendes: Man sieht, daß, wenn man, sagen wir, einem Froschorganismus in einem sehr frühen Stadium etwas abschneidet, sich der übrige Organismus, der abgeschnittene Organismus wieder ansetzt. Wer etwas materialistisch in seiner Denkweise geartet ist, der wird sagen: Nun ja, in der Wunde, da liegen Spannkräfte, und durch diese Spannkräfte in der Wunde setzt sich dasjenige, was da neuerdings wächst, an. — Aber das kann nicht so der Fall sein. Denn wäre das der Fall, daß wenn ich einen Organismus hier abschneide (siehe Zeichnung Seite 65) und sich hier an der Wunde Neues ansetzt durch die Spannkraft, die ja hier liegt — dann müßte sich doch hier das ansetzen, was das nächste Stück wäre, also dasjenige, was unmittelbar benachbart ist im vollkommenen Organismus. Das ist ja aber nicht der Fall in Wirklichkeit, sondern in der Wirklichkeit erscheinen, wenn man etwas abschneidet bei Froschlarven, Endorgane, der Schwanz oder Kopf sogar, bei anderen Tieren Fühlfäden, also diejenigen, die gar nicht hier angrenzen, sondern diejenigen, die der Organismus zunächst braucht, wachsen da heraus. Es ist also ganz unmöglich, daß durch die unmittelbar hier innewohnenden Spannkräfte sich dasjenige hier ansetzt, was sich hier ausbiidet, sondern es ist notwendig, anzunehmen, daß bei diesen Ansätzen der ganze Organismus in irgendeiner Weise beteiligt ist.

[ 18 ] So kann man wirklich dasjenige verfolgen, was in niederen Organismen vor sich geht. Sie können nun, da ich Ihnen den Weg angegeben habe, wie man so etwas verfolgt, wenn Sie das ausdehnen über all die Erfahrungen, die bis heute in der Literatur verzeichnet sind, überall sehen, wie man nur auf diesem Wege überhaupt zu einer Anschauung über diese Sache kommt. Sie werden kaum einen anderen Gedanken hegen können als den: Beim Menschen ist das nun eben nicht so. — Es wäre ja sehr niedlich, wenn man ihm einen Finger oder Arm abschneiden könnte und er den Finger oder Arm wieder ersetzen würde. Er tut es eben nicht. Es ist die Frage: Ja, wie ist es denn mit den Kräften, die nun ein Tafel 5 mal Wachstumsbildungskräfte sind und die sich hier ganz deutlich zeigen, wie ist es denn mit diesen Kräften im menschlichen Organismus? Sind sie da verlorengegangen, sind sie da gar nicht vorhanden?

[ 19 ] Wer sachgemäß die Natur zu beobachten versteht, der weiß, daß man nur auf diesem Wege überhaupt zu einer naturgemäßen Anschauung über den Zusammenhang des Geistigen und Physischen beim Menschen kommen kann. Beim Menschen sind nämlich diese Kräfte, die wir hier, ich möchte sagen, als plastische kennenlernen, die hier unmittelbar Formen aus der Substanz heraus ausbilden, einfach herausgehoben aus den Organen und sind nur in dem, was bei ihm seelisch-geistig ist, vorhanden. Da sind sie nämlich vorhanden. Dadurch, daß sie aus den Organen herausgehoben sind, daß sie nicht Bildungskräfte der Organe geblieben sind, hat sie der Mensch extra. Er hat sie in seinen geistig-seelischen Funktionen. Wenn ich denke oder fühle, so denke ich und fühle ich mit denselben Kräften, die da in dem niederen Tier oder in der Pflanzenwelt plastisch tätig sind. Ich könnte eben nicht denken, wenn ich nicht mit denselben Kräften, die ich aus der Materie herausgezogen habe, das Denken und das Fühlen und das Wollen vollziehen würde. Schaue ich also auf die niederen Organismen hinaus, so muß ich mir sagen: Das, was da drinnen steckt, was die plastischen Kräfte sind, das ist dasselbe, was ich auch in mir trage. Aber ich habe es aus meinen Organen herausgenommen, habe es für sich und denke und fühle und will mit denselben Kräften, die da draußen in der niederen Organismenwelt plastisch tätig sind.

[ 20 ] Wer nun ein Psychologe werden will mit Substanz in seinen psychologischen Aufstellungen, nicht mit bloßen Worten, wie man heute Psychologie konstruiert, der müßte eigentlich die Denk- und Fühl- und Willensprozesse so verfolgen, daß er in ihnen aufzeigt, nur eben geistig-seelisch verlaufend, dieselben Vorgänge, die da unten in den plastischen Gestaltungen erscheinen. Sehen Sie nur einmal nach, wie wir innerlich in unserem seelischen Prozeß tatsächlich das ausführen können, was wir im Organismus nicht mehr ausführen können: Gedankenreihen, die uns verlorengegangen sind, aus anderen heraus zu ergänzen, und wie wir da so ähnlich verfahren, wie ich das hier gesagt habe, daß nicht das unmittelbar Angrenzende, sondern das weit davon Abliegende erscheint.

[ 21 ] Es besteht ein vollständiger Parallelismus zwischen dem, was wir innerlich-seelisch erleben, und dem, was in der äußeren Welt gestaltende Naturkräfte, gestaltende Naturprinzipien sind. Ein vollständiger Parallelismus besteht da. Auf diesen Parallelismus muß man hinweisen und zeigen, daß der Mensch in der Außenwelt im Grunde genommen als Gestaltungsprinzipien das hat, was er innerlich als sein seelisch-geistiges Leben aus seinem eigenen Organismus herausgenommen hat, was daher bei seinem eigenen Organismus nicht mehr der Materie, der Substanz zugrunde liegt. Aber nun, wir haben es nicht aus allen Teilen des Organismus gleich stark herausgenommen, wir haben es in verschiedener Weise herausgenommen. Und erst, wenn man gewissermaßen ausgerüstet ist mit solch einer Vorkenntnis, wie wir sie jetzt entwickelt haben, kann man an den menschlichen Organismus in entsprechender Weise herantreten. Denn betrachten Sie all dasjenige, was unser Nervensystem zusammensetzt, Sie werden das Eigentümliche finden: gerade was man gewöhnlich als Nervenzellen und dasjenige, was man als Nervengewebe und so weiter bezeichnet, das sind eigentlich Gebilde, verhältnismäßig auf frühen Entwickelungsstadien zurückgeblieben, nicht sehr vorgeschrittene Zellgebilde sind das, so daß man sagen könnte: man müßte eigentlich erwarten, daß gerade diese sogenannten Nervenzellen den Charakter früherer primitiver Zellbildungen zeigen. Das tun sie in anderer Beziehung wiederum ganz und gar nicht, denn sie sind zum Beispiel nicht fortpflanzungsfähig. Nervenzellen, ebenso wie Blutzellen, sind unteilbar, wenn sie ausgebildet sind, sie sind nicht fortpflanzungsfähig. Es ist ihnen also in einem verhältnismäßig frühen Stadium eine Fähigkeit, die den außermenschlichen Zellen zukommt, entzogen; die ist ihnen entzogen. Sie bleiben auf einer frühen Entwickelungsstufe stehen, werden gewissermaßen auf dieser Entwikkelungsstufe abgelähmt. Das, was in ihnen abgelähmt wird, das sondert sich ab als Seelisch-Geistiges. So daß wir in der Tat mit unserem seelisch-geistigen Prozesse zurückkehren zu dem, was einmal in der organischen Substanz sich gebildet hat, das wir aber nur dadurch erreichen, daß wir in uns die Nervensubstanz tragen, die wir in einem verhältnismäßig frühen Stadium abtöten, ablähmen wenigstens.

[ 22 ] Auf diese Weise kann man sich dem eigentlichen Wesen der Nervensubstanz nähern. Man bekommt dann heraus, warum diese Nervensubstanz diese Eigentümlichkeit an sich trägt, daß sie auf der einen Seite eigentlich ziemlich den primitiven Bildungen ähnlich sieht, sogar in dem, was sie weiter ausbildet, den primitiven Bildungen ähnlich sieht, und doch dem dient, was man gewöhnlich beim Menschen das Höchste nennt, der geistigen Tätigkeit.

[ 23 ] Ich glaube — das ist nur ein Einschiebsel, das soll nicht zur eigentlichen Betrachtung gehören —, daß schon die oberflächliche Betrachtung des menschlichen Hauptes, in dem der Mensch seine verschiedenen Nervenzellen umschließt, in diesem Umschlossensein von Zellen durch einen festen Panzer, eher erinnert an niedere Tiere als an hochentwickelte Tiere. Gerade unser Kopf erinnert eigentlich, ich möchte sogar sagen, an vorweltliche Tiere. Er erscheint nur umgebildet. Und wenn wir von niederen Tieren sprechen, so sagen wir gewöhnlich: Die haben ein Außenskelett, während die höheren Tiere und der Mensch ein Innenskelett haben; aber nur unser Kopf, da, wo wir am höchsten entwickelt sind, hat ein Außenskelett. Das ist immerhin etwas, was wenigstens eine Art Leitmotiv sein könnte für das, was eben angeführt worden ist.

[ 24 ] Nun denken Sie sich nur, wenn wir dasjenige, was wir so unserem Organismus entzogen haben, durch irgend etwas, das wir eine Krankheit nennen — ich werde noch genauer darauf zu sprechen kommen — veranlaßt, ihm zuführen — also denken Sie, diese Bildungskräfte, die in der außermenschlichen Natur vorhanden sind, die wir unserem Organismus entzogen haben, weil wir sie für das Geistig-Seelische verwenden, wenn wir diese dadurch, daß wir eine Pflanze oder so etwas verwenden, als Heilmittel dem Organismus wieder zuführen, so verbinden wir den Organismus mit dem, was ihm zunächst fehl. Wir kommen ihm zu Hilfe, indem wir ihm das zusetzen, was wir ihm erst dadurch, daß wir Mensch geworden sind, genommen haben.

[ 25 ] Sie sehen hier schon zunächst etwas aufdämmern, was man als Heilprozeß bezeichnen kann: das Zuhilfenehmen derjenigen Kräfte in der Natur draußen, die wir als normaler Mensch nicht haben, wenn wir sie gebrauchen, damit irgend etwas in uns stärker wird, als es beim normalen Menschen ist. Nehmen wir also, um einmal konkret zu sprechen, aber nur beispielsweise, irgendeines unserer Organe, sagen wir meinetwillen unsere Lunge oder so etwas; es würde sich auch bei solchen Organen herausstellen, daß wir ihnen Bildungsprinzipien entnommen haben, um sie für das GeistigSeelische zu haben. Kommen wir nun gerade im Pflanzenteich auf diejenigen Kräfte, die wir da aus der Lunge herausgenommen haben, und führen sie bei irgendeiner Störung des Lungensystems dem Menschen zu, so kommen wir seiner Lungentätigkeit zu Hilfe. Sie sehen, es würde die Frage entstehen: Welche Kräfte in der außermenschlichen Natur sind den Kräften ähnlich, die den menschlichen Organen zugrunde liegen, die aber zur geistig-seelischen Tätigkeit herausgezogen sind? — Sie sehen hier einen Weg, von der bloßen Probiermethode der Therapie zu einer Art Ratio in der Therapie zu kommen.

[ 26 ] Nun liegt aber neben den Irrtümern, denen man sich hingegeben hat in bezug auf das Nervensystem, die Irrtümer in bezug auf das Innermenschliche sind, ein sehr beträchtlicher Irrtum vor in bezug auf die außermenschliche Natur, den ich heute nur andeuten, später aber noch näher ausführen will. Man ist allmählich dazu gekommen im materialistischen Zeitalter, eine Art Evolution der äußeren Wesen zu denken von dem sogenannten Einfachsten bis zu dem Kompliziertesten hin. Man hat dann, nachdem man zuerst seine Betrachtung ausgedehnt hat über die niederen Organismen, die Umwandelung der Formen studiert bis zu den kompliziertesten Organismen, dann auch ins Auge gefaßt das, was nicht Organismen sind, zum Beispiel das mineralische Reich. Das mineralische Reich hat man so ins Auge gefaßt, daß man sich gesagt hat: Das mineralische Reich ist eben einfacher als das Pflanzenreich. — Das hat schließlich dazu geführt, all die sonderbaren Fragen aufkommen zu lassen über die Entstehung des Lebens aus dem mineralischen Reich, über irgendein einmal vorhandenes Bedingtsein des Zusammenkommens der Substanzen aus ihrem bloßen unorganischen Agieren zu einem organischen Agieren. Die Generatio aequivoca ist dasjenige, was viele Diskussionen hervorgerufen hat.

[ 27 ] Nun, einer unbefangenen Betrachtungsweise ergibt sich aber durchaus nicht das Richtige dieser Anschauung, sondern man muß sich sagen: In einer gewissen Weise läßt sich überhaupt ebenso, wie sich eine Art Evolution denken läßt von den Pflanzen hin durch die Tiere zum Menschen, wiederum eine Art Evolution denken von den Organismen, also von den Pflanzen hin zu den Mineralien, indem ihnen das Leben genommen wird. — Wie gesagt, ich will das heute nur andeuten, es wird in den folgenden Betrachtungen deutlicher herauskommen. Man kommt nur zurecht, wenn man die Evolution gar nicht so denkt, daß man vom Mineral heraufgeht über das Pflanzliche durch das Tierische zum Menschen, sondern wenn man den Ausgangspunkt in der Mitte nimmt und irgendwo eine Evolution denkt, die vom Pflanzlichen heraufgeht durch das Tierische zum Menschen, und eine andere Evolution, die hinuntergeht zum Mineralischen, wenn man also den Anfang nicht im Mineral setzt, sondern wenn man ihn mitten in die Natur hineinsetzt, so daß das eine entsteht durch eine aufsteigende, das andere durch eine niedersteigende Evolution. Dadurch aber wird man dazu kommen, einzusehen, daß, indem man von der Pflanze zum Mineral hinuntergeht und namentlich, wie wir sehen werden, zu dem ganz besonders bedeutsamen Mineral, dem Metall, daß da in der niedergehenden Evolution Kräfte auftreten können, die nun in einem ganz besonderen Verhältnisse zu dem Spiegelbild, der aufgehenden Evolution, stehen.

[ 28 ] Kurz, die Frage stellt sich uns vor die Seele: Was sind in den Mineralien für ganz besondere Kräfte vorhanden, die wir nur studieren können, wenn wir hier diese Bildungskräfte, die wir an den niederen Organismen studiert haben, studieren? — Bei den Mineralien sehen wir sie auftreten in der Kristallisation. Die Kristallisation zeigt uns ganz entschieden etwas, was auftritt, wenn wir die niedergehende Evolution betrachten, was irgendwie nur im Zusammenhang stehen kann, aber nicht das gleiche ist, mit dem, was auftritt an Gestaltungskräften, wenn wir die aufsteigende Evolution betrachten. Führen wir daher dem Organismus dasjenige zu, was als Kräfte in den Mineralien ist, so entsteht eine neue Frage. Wir haben antworten können auf eine ähnliche Frage: Wenn wir die bildenden Kräfte, die wir durch das Geistig-Seelische unserer Organisation weggenommen haben, dem menschlichen Organismus aus dem pflanzlichen, tierischen Reiche zuführen, so helfen wir dem Organismus. Was aber tritt ein, wenn wir die andersartigen Kräfte, die in der absteigenden Evolution, also im Mineralreich liegen, nun dem menschlichen Organismus zuführen würden? Das ist die Frage, die ich heute hinstellen will und die sich uns im Laufe der Betrachtungen eingehend beantworten soll.

[ 29 ] Nun aber, bei alledem sind wir ja noch nicht dahin gekommen, irgend etwas beitragen zu können im rechten Sinne zu der Frage, die wir heute an die Spitze der Betrachtung gestellt haben: ob wir der Natur nun selber einen Heilungsprozeß ablauschen können. Bei einer solchen Frage handelt es sich immer darum, daß man mit den richtigen Einsichten — und wir haben ja versucht, solche Einsichten wenigstens skizzenhaft uns zu verschaffen über solche Dinge — an die Natur herangeht, daß sich dann gewisse Vorgänge in ihrer Wesenheit erst enthüllen. Darauf kommt es an.

[ 30 ] Nun, sehen Sie, gibt es im menschlichen Organismus zwei Prozesse — es gibt sie auch im Tierischen, aber das kann uns jetzt weniger interessieren —, die sich in gewissem Sinne, wenn wir sie ausgerüstet mit den Ideen, die wir jetzt gewonnen haben, betrachten, als entgegengesetzte Prozesse darstellen. Diese beiden entgegengesetzten Prozesse sind nicht ganz — ich betone das ausdrücklich und bitte das zu beachten, damit dies, was ich jetzt ausführe, nicht mißverstanden werden könne -—, aber bis zu einem hohen Grade polarische Prozesse. Und diese Prozesse sind: die Blurbildung und die Milchbildung, wie sie im menschlichen Organismus auftreten. Blutbildung und Milchbildung — schon äußerlich unterscheiden sich die Blut- und Milchbildung in ganz wesentlicher Weise. Die Blurbildung ist, ich möchte sagen, sehr stark in die verborgene Seite des menschlichen Organismus zurückverlegt. Die Milchbildung ist etwas, was zuletzt mehr nach der Oberfläche tendiert. Aber der wesentlichste Unterschied zwischen der Blutbildung und der Milchbildung ist doch der, daß die Blutbildung sehr stark die Fähigkeit in sich trägt, selbst Bildungskräfte zu bilden, wenn wir den Menschen selbst betrachten. Das Blut ist ja dasjenige, dem wir bildende Kräfte zuschreiben müssen im ganzen Haushalt des menschlichen Organismus, wenn wir den philiströsen Ausdruck gebrauchen dürfen. Das Blut hat also in einer gewissen Beziehung noch die Bildungskräfte, die wir hier in dem niederen Organismus wahrnehmen; die hat das Blut in sich. Aber gerade die neuere Wissenschaft könnte sich hier auf etwas sehr Wichtiges stützen, wenn sie das Blut betrachtet, tut es aber bis heute nicht eigentlich in einem wirklich vernünftigen Sinn. Sie könnte sich darauf stützen, daß der Hauptbestandteil des Blutes die roten Blutkörperchen sind, die wiederum nicht vermehrungsfähig sind, die wiederum die Eigentümlichkeit haben, daß sie nicht vermehrungsfähig sind. Das haben sie mit den Nervenzellen gemeinschaftlich. Aber wenn man eine solche gemeinsame Eigenschaft hervorhebt, so kommt es immer darauf an, ob der Grund, warum das ist, in beiden Fällen derselbe ist. Der Grund kann nicht derselbe sein, denn aus dem Blute haben wir nicht in demselben Maße herausgenommen die Bildefähigkeit, wie wir sie aus der Nervensubstanz herausgenommen haben. Die Nervensubstanz, die ja gerade dem Vorstellungsleben zugrunde liegt, entbehrt in einem hohen Grade die innere Bildungsfähigkeit. Die Nervensubstanz wird beim Menschen noch während seines Lebens nach der Geburt weit hinaus von den äußeren Eindrücken abhängig nachgebildet. Also die innere Bildungsfähigkeit weicht da zurück gegenüber der Fähigkeit, sich den äußeren Einflüssen einfach anzupassen. Beim Blute ist das anders. Das Blut hat sich in hohem Grade die innere Bildungsfähigkeit bewahrt. Diese innere Bildungsfähigkeit, sie ist ja, wie Sie aus den Tatsachen des Lebens wissen, auch in einem gewissen Sinne bei der Milch vorhanden. Denn wäre sie bei der Milch nicht vorhanden, so würden wir nicht die Milch gerade als gesundes Nahrungsmittel den Säuglingen geben können. Dasjenige, was die Säuglinge brauchen, ist die Milch. Es ist in ihr eine ähnliche Bildefähigkeit wie im Blute. So daß also mit Bezug auf die Bildefähigkeit eine gewisse Ähnlichkeit besteht zwischen dem Blute und der Milch.

[ 31 ] Nun ist aber ein sehr beträchtlicher Unterschied. Die Milch, sie hat diese Bildefähigkeit. Sie hat aber etwas nicht, was das Blut zu seinem Bestande im höchsten Maße braucht, wenigstens hat sie das nur in sehr geringem Maße, in verschwindend geringem Maße: Eisen, das einzige Metall im Grunde genommen im menschlichen Organismus, das in seinen Verbindungen im Menschen, im menschlichen Organismus selbst ordentliche Kristallisationsfähigkeit zeigt. Also wenn die Milch auch andere Metalle in geringen Mengen hat, so ist der Unterschied jedenfalls da, daß das Blut zu seinem Bestande das Eisen braucht, ein ausgesprochenes Metall. Die Milch, die die Bildungsfähigkeit auch hat, braucht dieses Eisen nicht. Nun entsteht die Frage: Warum braucht das Blut das Eisen?

[ 32 ] Das ist eigentlich eine Kardinalfrage der ganzen medizinischen Wissenschaft. Das Blut braucht das Eisen nämlich. Wir werden die Materialien schon herbeitragen zu diesen Tatsachen, die ich heute hingeworfen habe; ich will zunächst erhärten, wie das Blut diejenige Substanz im menschlichen Organismus ist, die einfach durch ihre eigene Wesenheit krank ist und fortwährend durch das Eisen geheilt werden muß. Das ist bei der Milch nicht der Fall. Wäre die Milch in demselben Sinne krank wie das Blut, so würde die Milch in solcher Art, wie es geschieht, nicht ein Bildemittel sein können für den Menschen selber, ein äußerlich ihm zugefügtes Bildemittel sein können.

[ 33 ] Betrachtet man das Blut, so betrachtet man dasjenige, welches im Menschen einfach um der menschlichen Konstitution willen, um der Organisation willen fortwährend etwas Krankes ist. Das Blut ist einfach durch seine eigene Wesenheit krank und muß fortwährend kuriert werden durch den Eisenzusatz. Das heißt, wir haben in dem Prozesse, der in unserem Blute sich vollzieht, einen fortwährenden Heilungsprozeß in uns. Will der Arzt durch der Natur Examen gehen, so muß er vor allen Dingen nicht einen schon abnormen Prozeß der Natur betrachten, sondern einen normalen Prozeß. Und der Blutprozeß ist sicher ein normaler, aber er ist zu gleicher Zeit ein solcher, wo fortwährend die Natur selbst heilen muß, wo fortwährend die Natur durch das zugesetzte Mineral, durch das Eisen heilen muß. So daß wir, wenn wir uns dasjenige graphisch darstellen wollten, was mit dem Blute geschieht, sagen müssen: Dasjenige, was das Blut durch seine eigene Konstitution ohne das Eisen hat, ist eine Kurve oder eine Linie, die abwärts führt und die ankommen würde zuletzt bei der vollständigen Auflösung des Blutes (siehe Zeichnung Seite 74, rot), während dasjenige, was das Eisen im Blute bewirkt, es fortwährend aufwärts führt, es fortwährend heilt (gelbe Linie).

[ 34 ] Wir haben in der Tat da einen Prozeß, der ein normaler ist und der zu gleicher Zeit ein solcher ist, der nachgebildet werden muß, wenn wir überhaupt an Heilungsprozesse denken wollen. Da können wir wirklich durch der Natur Examen gehen, denn da sehen wir, wie die Natur Prozesse vollführt, indem sie dasjenige, was außermenschlich ist, das Metall mit seinen Kräften, dem Menschlichen zuführt. Und wir sehen zu gleicher Zeit, wie dasjenige, was im Organismus unbedingt bleiben will, wie das Blut, geheilt werden muß, und wie das, was aus dem Organismus herausstrebt, wie die Milch, nicht geheilt zu werden braucht, wie sie, wenn sie Bildekräfte enthält, in gesunder Weise Bildekräfte in den anderen Organismus überführen kann. Das ist eine gewisse Polarität, und ich sage: eine gewisse, nicht eine ganze Polarität zwischen dem Blute und der Milch, die aber ins Auge gefaßt werden muß, denn man kann daran eben sehr viel studieren. Da wollen wir dann morgen fortsetzen.