Second Scientific Lecture-Course:

Warmth Course

GA 321

10 March 1920, Stuttgart

Lecture X

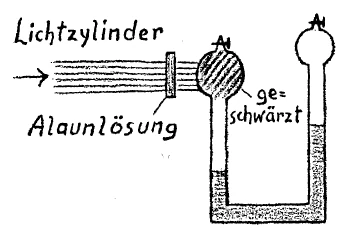

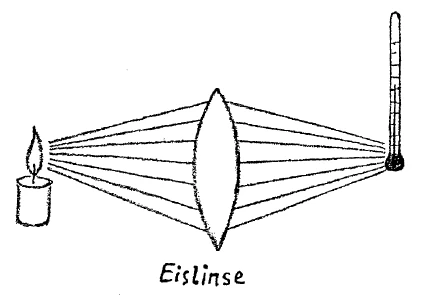

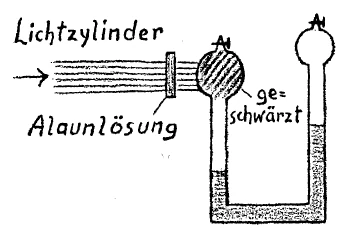

[ 1 ] Before we continue the observations of yesterday which we have nearly brought to a conclusion, let us carry out a few experiments to give support to what we are going to say. First we will make a cylinder of light by allowing a beam to pass through this opening, and into this cylinder we will bring a sphere which is so prepared that the light passes into it, but cannot pass through. What happens we will indicate by this thermometer (see drawing Fig. 1). You will note that this cylinder of energy, let us say, passing into the sphere reveals its effect by causing the mercury column to sink. Thus we are dealing with what we have formerly brought about by expansion. And indeed, in this case we have to assume also that heat passes into the sphere, causes an expansion and this expansion makes itself evident by a depression of the column of mercury. If we placed a prism in the path of the light we would get a spectrum. We do not form a spectrum in this experiment, but we catch the light—gather it up and obtain as a result of this gathering up of what is in the bundle of light, a very market expansion. You can see the definite depression of the mercury. Now we will place in the path of the energy cylinder, an alum solution, and see what happens under the influence of this solution. You will see after a while that the mercury will come to exactly the same level in the right and left hand tubes. This shows that originally heat passed through, but under the influence of the alum solution the heat is shut off, not more goes through. The apparatus then comes only under the influence of the heat generally present in the space around it and the mercury readjusts itself to equilibrium in the two tubes. The heat is stopped as soon as I put the alum solution in the path of the energy cylinder. That is to say, from this cylinder which yields for me both light and heat, I separate out the heat and permit the light to pass through. Let us keep this firmly in mind. Something still rays through. But we see that we can so treat the light-heat mercury that the light passes on and the heat is separated by means of the alum solution.

[ 2 ] This is one thing we must keep in mind simply as a phenomenon. There is another phenomenon to be brought to our attention before we proceed with our considerations. When we study the nature of heat we can do so by warming a body at one particular spot. We then notice that the body gets warm not only at the spot where we are applying the heat, but that one portion shares its heat with the next portion, then this with the next, etc. and that finally the heat is spread over the entire body. And this is not all.

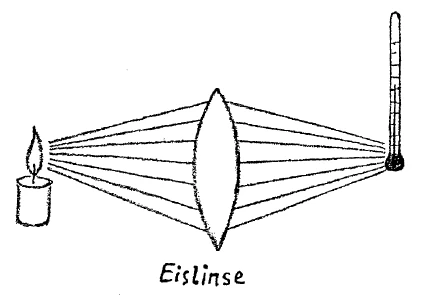

If we simply bring another body in contact with the warm body, the second body will become warmer than it formerly was. In modern physics this is ordinarily stated by saying that heat is spread by conduction. We speak of the conduction of heat. The heat is conducted from one portion of a body to another portion, and it is also conducted from one body to another in contact with the first. A very superficial observation will show you that the conduction of heat varies with different materials. If you grasp a metallic rod in your fingers by one end and hold the other end in a flame, you will soon have to drop it, since the heat travels rapidly from one end of rod to the other. Metals, it is said, are good conductors of heat. On the other hand, if you hold a wooden stick in the flame in the same way, you will not have to drop it quickly on account of the conduction of heat. Wood is a poor conductor of heat. Thus we may speak of good and poor conductors of heat. Now this can be cleared up by another experiment. And this experiment we are unfortunately unable to make today. It has again been impossible to get ice in the form we need it. At a more favorable time the experiment can be made with a lens made of ice as we would make a lens of glass. Then from a source of heat, a flame, this ice lens can be used to concentrate the heat rays just as light rays can be concentrated (to use the ordinary terminology.) A thermometer can then be used to demonstrate the concentration by the ice lens of the heat passing through it. (See above figure ).

[ 3 ] Now you can see from this experiment that it is a question here of something very different from conduction even though there is a transmission of the heat, otherwise the ice lens could not remain an ice lens. What we have to consider is that the heat spreads in two ways. In one form, the bodies through which it spreads are profoundly influenced, and in the other form it is a matter of indifference what stands in the path. In this latter case we are dealing with the propagation of the real being of heat, with the spreading of heat itself. If we wish to speak accurately we must ask what is spreading, then we apply heat and see a body getting warmer gradually piece by piece, we must ask the question: is it not perhaps a very confused statement of the matter when we say that the heat itself spreads from particle to particle through the body, since we are able to determine nothing about the process except the gradual heating of the body?

[ 4 ] You see, I must emphasize to you that we have to make for ourselves very accurate ideas and concepts. Suppose, instead of simply perceiving the heat in the metal rod, you had a large rod, heated it here, and placed on it a row of urchins. As it became warm the urchins would cry out, the first one, then the second, then the third, etc. One after another they would cry out. But it would never occur to you to say that what you heard from the first urchin was conducted to the second, the third, the fourth, etc. When the physicist applies heat at one spot, however, and then perceives it further down the rod, he says: the heat is simply conducted. He is really observing how the body reacts, one part after another, to give him the sensation of warmth, just as the urchins give a yell when they experience the heat. You cannot, however, say that the yells are transmitted.

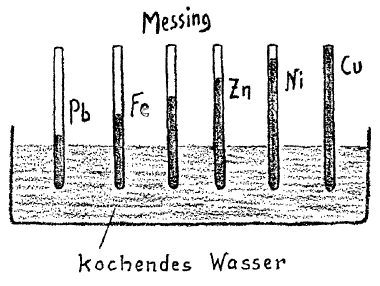

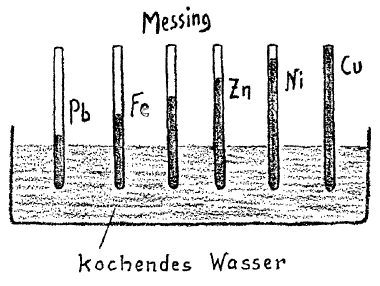

[ 5 ] Now we will perform also an experiment to show how the different metals we have here in the form of rods behave in respect to what we call the conduction, and about which we are striving to get valid ideas. We have hot water in this vessel (Fig. 3). By placing the ends of the rods in the water, they are warmed. Now we will see how this experiment comes out. One rod after another will get warm, and we will have a kind of graduated scale before us. We will be able to see the gradual spreading of the effect of the heat in the different substances. (The rods consisted of copper, nickel, lead, tin, zinc, iron.) The iodide of mercury on the rods (used to indicate rise in temperature) becomes red in the following order: copper, nickel, zinc, tin, iron and lead. The lead is, therefore, among these metals, the poorest conductor of heat, as it is said.

This experiment is shown to you in order to help form the general view of the subject that I have so often spoken to you about. Gradually we will rise to an understanding of what the heat entity is in its reality.

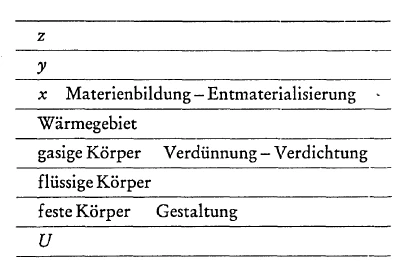

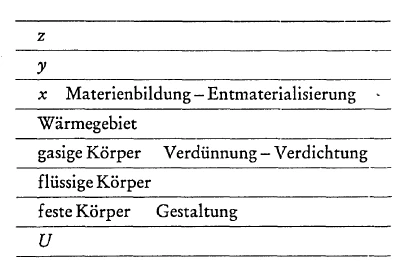

[ 6 ] Now, from our remarks of yesterday we have seen that when we turn our attention to he realm of corporeality, we can in a certain way, set limits to the realm of the solids by following what it is essentially that takes on form. We have the fluids as an intermediate stage and then we go over to the gaseous realm. In the gaseous we have a kind of intermediate state, exactly as we would expect, namely the heat condition. We have seen why we can place it as we do in the series. Then we come, as I have said, into an \(x\) region in which we have to assume materialization and dematerialization, pass then to a \(y\) and a \(z\). This is all similar to the manner in which we find in the light spectrum the transition from green through blue to violet and then apparently on to infinity. Yesterday we convinced ourselves that we have to continue below the solid realm into a \(U\) region. Thus we think of the world of corporeality as arranged in an order analogous to the arrangement in the spectrum. This is exactly what we do when we pursue our thinking in contact with reality.

[ 7 ] Now let us further extend the ideas of yesterday. In the case of the spectrum we conceive of what disappears at the violet end and at the red end in the straight line spectrum as bent into a circle. In exactly the same way we can, in this different realm of states of aggregation, imagine that the two ends of the series do not disappear into infinity. Instead, what apparently goes off into the indefinite on the one side and what goes off into indefiniteness on the other may be considered as bending back (Fig. 1) and then we have before us a circle, or at least a line whose two ends meet.

[ 8 ] The question now arises, what is to be found at the point of juncture? When we observe the usual spectrum, we can in that case find something at this point. In Goethe's sense you know that the spectrum considered as a whole with all its colors included shows as its middle color on one side green, when we make a bright spectrum. On the other side peach blossom which is also a middle color when we make a dark spectrum. Thus we have green, blue, violet extending to peach blossom. By closing the circle we note that at the point where it closes, there is the peach blossom color.

[ 9 ] If we then construct a similar circle in our thinking about the realm states of aggregation, what do we find at the point of juncture? This brings us to an enormously important consideration. What must we place in the spectrum of states of aggregation which will correspond to the peach blossom of the color spectrum? The idea that arises naturally from the facts here may perhaps be easier for you to grasp if I lead you to it as follows: What do we have in reality which disappears as it were in two opposite directions—just as in the color spectrum the tones shade off on the one side into the region beyond the violet and on the other side into the region beyond the red? Ask yourselves what it is. It is nothing more or less than the whole of nature. The whole of nature is included in it. For you cannot in the whole of nature find anything not included in the form categories we have mentioned. Nature disappears from us on the one hand when we go through corporeality into heat and beyond. She disappears from us on the other when we follow form through the solid realm into the sub-solid where we saw the polarization figures as the effect of form on form. The tourmaline crystals show us now a bright field, now a dark one. By the mutual effect of one form on another there appear alternately dark and light fields.

[ 10 ] It is essential for us to determine what we should place here when we follow nature in one direction until we meet what streams from the other side. What stands there? Man as such stands there. The human being is inserted at that point. Man, taking up what comes from both sides is placed at that point. And how does he take up what comes from the two sides? He has form. He is also formed within. When we examine his form among other formed bodies we are obliged to give him this attribute. Thus, the forces that give from elsewhere are within man. And now we must ask ourselves, are these forces to be found in the sphere of consciousness? No, they are not in the human consciousness. Think of the matter a moment. You cannot get a real understanding of the human form from what you can see in either yourselves or other men. You cannot experience it immediately in consciousness. We have a corporeality, but this form is not given in our immediate consciousness. What do we have in our immediate consciousness in the place of form?

Now, my friends, that can be experienced only when one gradually and in an unbiased manner learns to observe the physical development of man. When the human being first enters physical existence, he must be related very plastically to his formative forces. That is, he must do a great deal of body building. The nearer we approach the condition of childhood, the greater the body building, and as we take on years there is a withdrawal of the body building forces. In proportion as the body building forces withdraw, conscious reasoning comes into play. The more the formative forces withdraw the more reasoning advances. We can create ideas in regard to form in proportion as we lose the ability to create form in ourselves. This considered in a matter of fact way, is simply an obvious truth. But now you see, we can say that we experience formative forces—forces that create form outside the body can be experienced. And how do we experience them? In this way, that they become ideas within us. Now we are at the point where we can bring the formative forces to the human being. These forces are not something that can be dreamed about. Answers to the questions that nature puts to us cannot be drawn from speculation or philosophizing, but must be got from reality. And in reality we see that the formative forces show themselves where, as it were, form dissolves into ideas, where it becomes ideas. In our ideas we experience what escapes us as a force while our bodies are building.

[ 11 ] When we place human nature before us in thought, we can state the matter as follows: man experiences as ideas the forces welling up from below. What does he experience coming down from above? What comes into consciousness from the realms of gas and heat? Here again when you look at human nature in an unprejudiced way, you have to ask yourselves: how does the will relate itself to the phenomena of heat?

You need only consider the matter physiologically to see that we go through a certain interaction with the heat being of outer nature in order to function in our will nature. Indeed heat must appear if willing is to become a reality. We have to consider will related to heat. Just as the formative forces of outer objects are related to ideas, so we have to consider what is spread abroad as heat as related to that which we find active in our wills. Heat may be thus looked upon as will, or we may say that we experience the being of heat in our will.

[ 12 ] How can we define form what it approaches us from within-out? We see it, in this form, in any given solid body. We know that if conditions are such that this form can be seized upon by our life processes, ideas will arise. These ideas are not within the outer object. It is somewhat as if I observed the spirit separated from the body in death. When I see form in outer nature, what brings about the form is not there in the object. It is in truth not there. Just as the spirit is not within the corpse but has been in it, so is that which determines form not within the object. If I therefore turn my eyes in an unprejudiced way towards outer nature I have to say: Something works in the process of form building in objects, but in the corpse this something “has been active,” while in the object its activity is becoming. We will see that what is there active lives in our ideas.

If I experience heat in nature, then I experience what works in a certain way as my will. In the thinking and willing man we have what meets us in outer nature as form and heat respectively.

[ 13 ] But now there are all possible intermediate stages between will and thought. A mere intellectual self-examination will soon show you that you never think without exercising the will. Exercise of the will is difficult for modern man especially. The human being is more prone to will unconsciously the course of his thoughts, he does not like to send will impulses into the realm of thought.

Entirely will-free thought content is really never present just as will not oriented by thought is likewise not present. Thus when we speak of thought and will, of ideas and will, we are dealing with extreme conditions, with what from one side builds itself as thought and from the other side builds itself as will. We can therefore say that in experiencing will permeated by thinking and thinking permeated by will, we experience truly and essentially the outer forms of nature and the outer heat being of nature. There is only one possibility for us here and that is to seek in man for essential being of what meets us in outer nature.

[ 14 ] And now pursue these thoughts further. When you follow further the condition of corporeality on the one hand you can say that you proceed along a line into the indeterminate. The opposite must be the case here. And how can we state this? How must it be within man? We must indeed, find again here what goes off into infinity. Instead of it going off into infinity, so that we can no longer follow it, we must picture to ourselves that it moves out of space. What wells up in man from the states of aggregation we must think of as going out of space. That is, the forces that are in heat must so manifest themselves in man that they move out of space. Likewise, the forces that produce form, pass out of space when they enter man.

In other words, in man we have a point where that which appears spatially in the outer world as form and heat, leaves space. Where the impossibility arises, that that which becomes non-spatial can still be held mathematically.

[ 15 ] I think we can see here in a very enlightening way how an observation of nature in accordance with facts obliges us to leave space when we approach man, provided we properly place him in the being of nature. We have to go to infinity above and below (the scale of that states of aggregation.) When we enter the being of man, we leave the realm of space. We cannot find a symbol which expresses spatially how the facts of nature meet us in the being of man. Nature properly conceived, shows us that when we think of her in relation to man, we must leave her. Unless we do, when we consider the content of nature in relation to man, we simply do not come to the human being.

[ 16 ] But what does this mean mathematically? Suppose you set down the lineal series among which you are following states of aggregation to infinity. The words one after another may be considered as positive. Then what works into the nature of man must be set down as negative. If you consider this series as positive, the effects in the human being have to be made negative. What is meant by positive and negative will be cleared up I think by a lecture to be given by one of our members during the next few days. We have to conceive, however, of what comes before our eyes plainly here in this way that the essential nature of heat, insofar as this belongs to the outer world, must be made negative when we follow it into the human being, and likewise the essentiality of form becomes negative when we follow it into man. Actually then, what lives in man as ideas is related to outside form as negative numbers are to positive numbers and vice versa. Let us say, as credits and debits. What are debits on the one hand are credits on the other and vice versa. What is form in the outside world lives in man in a negative sense. If we say “there in the outside world is some sort of a body of a material nature,” we have to add: “if I think about its form the matter must be negative, in a sense, in my thinking.” How is matter characterized by me as a human being? It is characterized by its pressure effects. If I go from the pressure manifestation of matter to my ideas about form, then the negative of pressure, or suction, must come into the picture. That is, we cannot conceive of man's ideas as material in their nature if we consider materiality as symbolized by pressure. We must think of them as the opposite. We must think of something active in man which is related to matter as the negative is to the positive. We must consider this as symbolized by suction if we think of matter as symbolized by pressure. If we go beyond matter we come to nothing, to empty space. But if we go further still, we come to less-than-nothing, to that which sucks up matter. We go from pressure to suction. Then we have that which manifests in us as thinking.

[ 17 ] And when on the other hand you observe the effects of heat, again you go over to the negative when it manifests in us. It moves out of space. It is, if I may extend the picture, sucked up by us. In us it appears as negative. This is how it manifests. Debits remain debits, although they are credits elsewhere. Even though our making external heat negative when it works within us results in reducing it to nothing, that does not alter the matter. Let me ask you again to note: we are obliged by force of the facts to conceive of man not entirely as a material entity, but we must think of something in man which not only is not matter, but is so related to matter as suction is to pressure. Human nature properly conceived must be thought of as containing that which continually sucks up and destroys matter.

[ 18 ] Modern physics, you see, has not developed at all this idea of negative matter, related to external matter as a suction is to a pressure. That is unfortunate for modern physics. What we must learn is that the instant we approach an effect manifest in man himself all our formulae must be given another character. Will phenomena have to be given negative values in contrast to heat phenomena; and thought phenomena have to be given negative values as contrasted to the forces concerned in giving form.

Zehnter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Bevor wir die Betrachtung, die wir gestern fortgesetzt haben, und an deren Ende wir nahezu stehen, weiterführen, wollen wir sie uns noch durch einige Versuche unterstützen. Wir werden zunächst hier einen Lichtzylinder erzeugen, welcher dadurch entsteht, daß wir das Licht hindurchscheinen lassen durch diesen Spalt, und in den Lichtzylinder hineinbringen hier einen Ballon, der angerußt ist, so daß das Licht nicht durchgeht. Wir haben dasjenige, was geschieht, zum Ausdruck gebracht an diesem Thermometer. Sie sehen, unser, sagen wir Energienzylinder bewirkt, indem er uns hier dasjenige durchschickt, was sich durch das Licht äußerlich offenbart, daß hier die Quecksilbersäule sinkt. Wir haben es also zu tun mit dem, was sonst eintritt unter dem Einfluß einer Ausdehnung. Wir müssen also voraussetzen, daß hier Wärme durchgeht und Ausdehnung bewirkt und diese Ausdehnung uns am Sinken der Quecksilbersäule anschaulich wird. So daß wir also sagen können: Es würde ja hier, wenn wir, sagen wir durch ein Prisma, das Lichtbündel auffangen würden, ein Spektrum entstehen. Wir bilden kein Spektrum, sondern wir fangen einfach das Licht auf, sammeln es, und wir bekommen dadurch, daß wir jetzt gesammelt haben, was in diesem Energienzylinder ist, hier eine starke Ausdehnung. Sie sehen, die Quecksilbersäule sinkt sehr stark. Wir stellen jetzt in den Gang des Energienzylinders eine Alaunlösung, und wir wollen sehen, was dadurch eintritt. Wir haben also dasjenige, was da durchgeht, was sich uns auch äußern würde durch seine Lichtseite, dadurch beeinflußt, daß wir ihm entgegengestellt haben eine Alaunlösung, und wir wollen nun sehen, was unter dem Einfluß der Alaunlösung geschieht. Wir können auf diese Weise — Sie werden es zuletzt sehen — den vollkommenen Gleichgewichtszustand der rechten und linken Quecksilbersäule wieder herbeiführen, wodurch Sie sehen werden, daß vorher Wärme durchgegangen ist und jetzt durch die Alaunlösung die Wärme abgehalten wird, also keine mehr durchgeht, sondern nur die im Raum sonst allgemein vorhandene Wärme auch hier zum Ausdruck kommt. Es ist also in dem Augenblick, wo ich in den Energiezylinder hineinstelle die Alaunlösung, die Wärme an ihrem weiteren Fortgehen verhindert. Das heißt, ich sondere aus dem, was sich mir als Licht und Wärme zugleich kundgibt, die Wärme heraus und lasse hier nur das Licht durchstrahlen — zunächst wollen wir nur dieses betrachten, es strahlt auch noch anderes durch. Aber daraus können wir ersehen, daß wir der sich ausbreitenden Licht-Wärme-Energie gegenüber so verfahren können, daß wir das Licht weitergehen lassen und durch die in den Weg gestellte Alaunlösung die Wärme heraussondern können.

[ 2 ] Das ist das eine, was wir zunächst rein als Erscheinung festhalten können. Das andere, was wir, bevor wir in unseren Betrachtungen weitergehen, als Erscheinung uns vor Augen führen wollen, das ist: Wenn wir das Wärmewesen untersuchen wollen, so können wir es in seinem Verhalten zunächst dadurch untersuchen, daß wir irgendeinen Körper an irgendeiner Stelle erwärmen. Wir merken dann, daß der Körper nicht bloß an der einen Stelle, wo wir ihn erwärmen, warm bleibt, sondern daß die Wärme, die ich hinzuführe an einer Stelle, dem nächsten Teil, wiederum dem nächsten Teil und so weiter mitgeteilt wird, so daß zuletzt über den ganzen Körper Wärme ausgebreitet ist. Nicht nur das. Wenn wir nun einen anderen Körper zur Berührung mit dem ersten bringen, wird auch der zweite Körper warm, er wird wärmer werden, als er früher war, und man ist in der gegenwärtigen Physik gewohnt worden, zu sagen: Die Wärme erfährt eine Verbreitung durch Leitung. Man spricht von Wärmeleitung. Die Wärme wird geleitet von einer Stelle eines Körpers zu den anderen, und sie wird auch geleitet von einem Körper zu einem anderen Körper, der mit ihm in Berührung ist. Sie können schon durch ganz oberflächliche Beobachtungen feststellen, daß diese Wärmeleitung eine verschiedene ist bei den verschiedenen Substanzen. Wenn Sie eine Metallstange nehmen, sie in den Fingern halten, mit dem anderen Ende in die Flamme hineingehen, so werden Sie sie wahrscheinlich bald fallen lassen. Die Wärme wird sehr schnell von dem einen Ende zu dem anderen geleitet. Man sagt dann: Ein Metall ist ein guter Wärmeleiter. Wenn Sie dagegen eine Holzstange in die Hand nehmen und in die Flamme halten, werden Sie nicht versucht sein, unter dem Einfluß der Wärmeleitung sie schnell fallen zu lassen. Holz ist ein schlechter Wärmeleiter. Und so kann man von guten und schlechten Wärmeleitern sprechen. Nun aber klärt sich dieses eigentlich erst durch einen anderen Versuch auf. Und diesen anderen Versuch, den können wir nun wiederum heute nicht machen, weil es wieder vergeblich gewesen wäre, wenn wir ein zweites Mal noch versucht hätten, Eis zu besorgen und dann gar das Eis hätten verarbeiten müssen in bestimmter Weise. Das wäre nicht gegangen. In günstigeren Zeiten kann auch ein solcher Versuch einmal gemacht werden: Wenn man unter gewissen Umständen aus Eis eine Linse bereitet, wie man die Glaslinse hat, und dann durch eine Wärmequelle — einfach eine Flamme — Wärme ausstrahlen läßt, so kann man gerade so, wie man nach dem gebräuchlichen Ausdruck sagt, daß sich die Lichtstrahlen sammeln, auch die Wärmestrahlen sammeln und kann durch ein hier hingestelltes Thermometer konstatieren, daß wirklich hier so etwas wie eine Ansammlung von Wärme unter dem Einfluß der Eislinse vorliegt, durch welche die sich ausbreitende Wärme hindurchgegangen ist (siehe Zeichnung).

[ 3 ] Nun können Sie aus diesem Versuch leicht sehen, daß es sich hier nicht um dasselbe handeln kann, wie bei der Wärmeleitung, trotzdem die Wärme sich ausgebreitet hat, denn sonst hätte die Eislinse nicht eine Eislinse bleiben können. Es handelt sich also darum, daß wir zweierlei Arten von Ausbreitung der Wärme haben: eine solche, welche im wesentlichen beeinflußt diejenigen Körper, über die sich die Wärme ausbreitet, und eine solche, bei der dasjenige gleichgültig ist, was der Wärme im Wege steht, wo wir also es zu tun haben müßten mit der Ausbreitung des eigentlichen Wärmewesens, wo wir gewissermaßen die Wärme selber sich ausbreiten sehen. Doch müssen wir, wenn wir genau sprechen, zuerst fragen: Was breitet sich denn eigentlich aus, wenn wir die Wärme einem Körper mitteilen und dann sehen, daß Stück für Stück wärmer wird? Ist es denn nicht vielleicht ein höchst unklarer Ausdruck, wenn wir davon sprechen, daß es die Wärme selbst ist, die sich von einem Stück des Körpers zum anderen ausdehnt, wenn wir nur am Körper selber dieses Wärmerwerden konstatieren?

[ 4 ] Denn sehen Sie, hier muß ich wieder darauf aufmerksam machen, daß es sich darum handelt, wirklich genaue Vorstellungen und Begriffe zu fassen: Nehmen Sie etwa, statt einfach hier (an einer erwärmten Stange) die Wärme zu empfinden, einen ziemlich großen Eisenstab, Metallstab, den Sie an einem Ende erhitzen, aber so, daß es nicht schadet, wenn Sie dann eine Reihe Buben darauf aufstellen. Lassen Sie nun die Buben - es darf aber nicht zu stark sein — schreien, wenn es unten warm wird, so wird wohl zuerst der erste, dann der zweite, dann der dritte schreien und so weiter. Nacheinander schreien die Buben. Aber Sie werden doch nicht versucht sein zu sagen: Das, was ich hier bei dem ersten Buben bemerkt habe, leitet sich fort auf den zweiten, auf den dritten, auf den vierten und so weiter. Aber wenn man hier (an einem Ende) erhitzt und hier (am anderen Ende) dann die Empfindung der Wärme hat, so sagt der heutige Physiker: Die Wärme wird einfach fortgeleitet. Während er doch eigentlich nur dasjenige, was der Körper tut, nämlich ihm die Empfindung der Wärme zu geben, so Stück für Stück beobachtet, wie hier, daß die Buben quieksen, wenn sie die Wärme erfahren. Sie können doch da nicht sagen, daß sich das Schreien fortpflanzt.

[ 5 ] Wir wollen nun auch den Versuch machen, zu zeigen, wie verschiedene Metalle, die hier als Stäbe vorhanden sind, in verschiedener Weise sich verhalten zu dem, was man gewöhnt ist, Wärmeleitung zu nennen, und wir werden nun wirklichkeitsgemäße Begriffe zu bringen ver suchen. Wir geben hier heißes Wasser hinein. Dadurch, daß die Stäbe unten ins Wasser tauchen, werden sie erwärmt. Wir werden nun sehen, welche Wirkung das hier auf unsere Versuchszusammenstellung hat, wie ein Stab nach dem anderen sich erwärmen wird, so daß wir dann tatsächlich eine Art Skala uns vorstellen können. Wir werden die Möglichkeit haben, die Wirkungen der Wärme fortlaufend zu zeigen bei den verschiedenen Substanzen (siehe Zeichnung. Die Stäbe sind angestrichen mit gelbem Quecksilberjodid, das beim Erreichen einer bestimmten Temperatur ins Rötliche umschlägt. Der Farbumschlag steigt an den verschiedenen Stäben verschieden rasch in die Höhe.) Das Blei ist also hier unter diesen Metallen der schlechteste Wärmeleiter, wie man sagt. — Die Versuche werden hier gezeigt aus dem Grunde, damit wir nun.die schon öfter besprochene Überschau uns bilden können über die Erscheinungen inmerhalb des Wärmewesens, um so nach und nach aufzusteigen zur Erkenntnis dessen, was das Wärmewesen in Wirklichkeit ist.

[ 6 ] Nun haben wir schon durch unsere gestern fortgesetzte Betrachtung gesehen, wie wir, wenn wir das Gebiet der Körperlichkeit ins Auge fassen, in einer gewissen Weise unterscheiden können das Gebiet des Festen, in dem wir im wesentlichen verfolgen können dasjenige, was sich gestaltet. Wir haben dann gewissermaßen als eine Zwischenstufe das Flüssige, und gehen dann über zu dem Gasigen. Und wir haben in dem Gasigen Verdichtung und Verdünnung als dasjenige anzusehen, was im Festen der Gestaltung entspricht. Dann haben wir wieder als eine Art Zwischenzustand gerade dasjenige, was wir suchen, die Wärme. Aus welchem Grunde wir sie hierher schreiben dürfen, haben wir gesehen (siehe Schema). Dann kommen wir, wie ich gesagt habe, in eine Art \(x\) hinein, und wir würden, wenn wir den Gedankengang ganz real fortsetzten, zu finden haben Materialisierung und Entmaterialisierung, würden dann aufsteigen müssen zu einem \(y\), zu einem \(z\), wie ich sagte, in ähnlicher Weise, wie wir beim Lichtspektrum den Übergang finden vom Grün durch das Blau zum Violett und dann scheinbar ins Unendliche hinein. Wir haben aber gestern konstatieren müssen, daß wir auch das Gebiet des Festen hier (Schema unten) fortsetzen können in eine Art \(U\) hinein, so daß wir die Gebiete unserer Körperlichkeit durch diese dem Spektrum nachgebildete Anordnung uns vorstellen können; gerade dann uns vorstellen können, wenn wir im Wirklichen verbleiben wollen.

[ 7 ] Nun handelt es sich darum, daß wir den Gedanken weiter verfolgen, den wir schon gestern ausgesprochen haben: Gerade so, wie wir beim Spektrum zusammenfassen können dasjenige, was uns nach dem Violett hin entschwindet und nach dem Rot hin entschwindet, indem wir das nach links und rechts geradlinig sich ausdehnende Spektrum zusammenfassen, kreisförmig, so können wir uns die sich ändernden . Zustandsgebiete der Körperlichkeit nach der einen Seite und nach der anderen Seite so denken, daß sie eigentlich nicht charakterisiert werden durch eine Gerade, die sich nach der einen oder anderen Seite ins Endlose verirrt, sondern daß dasjenige, was hier scheinbar ins Unbestimmte oder Unendliche geht, hier zurückgeht, ebenso dieses, und eigentlich dasjenige, was vorliegt, durch einen Kreis charakterisiert werden kann, durch eine wenigstens in sich selbst zurücklaufende Linie.

[ 8 ] Nun entsteht die Frage: Was können wir da finden, hier? Wenn wir das gewöhnliche Spektrum betrachten, so können wir wenigstens etwas da finden. Im Sinne der Goetheschen Optik betrachtet, wissen Sie, daß wir die Spektralfarben so zusammenstellen können, wenn wir das Spektrum nicht einseitig, sondern mit all seinen möglichen Farben nehmen, daß wir auf der einen Seite haben das Grün, welches gewissermaßen die Mittelfarbe ist, wenn wir ein Helles zum Spektrum machen, auf der anderen Seite die Pfirsichblütenfarbe, welche ebenso Mittelfarbe ist, wenn wir ein Dunkles zum Spektrum machen. Wir haben also Grün, Blau, Violett, verlaufend bis Pfirsichblüte auf der einen Seite und auf der entgegengesetzten Seite Grün, Gelb, Orange, Rot bis Pfirsichblüte. Wir können, indem wir den Kreis schließen, an der Stelle, wo er sich schließt, das Pfirsichblüt bemerken.

[ 9 ] Wenn wir nun hier unseren Zustandskreis für die verschiedenen Zustände der Körperlichkeit schließen, können wir da etwas finden? Jetzt sind wir an einem außerordentlich wichtigen Punkte. Was müssen wir hierher setzen in derselben Art, wie wir hierher beim gewöhnlichen Spektrum, das gewissermaßen uns ein Bild geben soll für das Zustandsspektrum, die Pfirsichblütfarbe setzen? Was müssen wir hierher setzen? Vielleicht wird Ihnen der Gedanke, der hier sich einfach herausspringend aus der Tatsachenwelt ergeben muß, nicht gar so schwer, wenn ich ihn zunächst auf die folgende Weise einzuleiten versuche. Was ist denn dasjenige, was wir da eigentlich vor uns haben, uns gewissermaßen entschwindend nach der einen Seite und nach der anderen Seite, wie uns das Farbenspektrum nach dem Violett auf der einen Seite, nach dem Rot auf der anderen Seite entschwindet? Was ist das, was wir da vor uns haben? Es ist nichts Geringeres im Grunde genommen als die ganze Natur. Sie können in dem, was man als das Reich der Natur bezeichnet, nichts finden, was nicht irgendwo untergebracht werden muß in «Gestaltung», unterhalb von «Gestaltung», in dem, was ich hier noch mit \(x\), \(y\), \(z\) bezeichnet habe und so weiter. (Siehe Schema) Die Natur entschwindet uns auf der einen Seite, wenn wir die körperlichen Zustände durch die Wärme hindurch verfolgen; sie entschwindet uns auf der anderen Seite, wenn wir die Gestaltungen verfolgen, zunächst die Gestaltungen des Reiches des Festen, dann des Unterfesten, die wir in den Polarisationsfiguren sehen, wo Gestalt auf Gestalt wirkt — Sie können sich diese Turmalinzange ansehen, dann sehen Sie ein Helles oder ein Dunkles. Nur durch die Durcheinanderwirkung der Gestalten erscheint das, was einmal dunkel, einmal hell erscheint und so weiter.

[ 10 ] Für uns ist jetzt das Wesentliche, darauf zu kommen, was wir hierher zu setzen haben, wenn wir die Natur verfolgen auf der einen Seite bis dahin, wo sie sich hier begegnet mit dem, was als Strömung charakterisiert werden kann von der anderen Seite her. Was steht da? Da steht nämlich nichts anderes drinnen, als der Mensch als solcher. Da steht der Mensch drinnen. So steht der Mensch drinnen, daß er auffaßt dasjenige, was von der einen Seite kommt und auffaßt dasjenige, was von der anderen Seite kommt. Wie faßt er denn dasjenige auf, was zunächst auf diesem Wege kommt (von unten)? Er ist gestaltet. Wenn wir nach seiner Gestalt fragen unter den Gestalten, die die anderen Körper haben, so müssen wir sagen: Der Mensch hat auch eine ‚Gestalt. Also dasjenige, was als gestaltende Kräfte wirkt, das ist auch in ihm. Nur müssen wir uns fragen: Gehört dasjenige, was als gestaltende Kräfte wirkt, in die Sphäre des Bewußtseins hinein? Bei dem im Menschen entstehenden Bewußtsein nicht. Denn stellen Sie sich einmal vor, Sie würden einen Begriff von der menschlichen Gestalt nicht dadurch bekommen, daß Sie sich selbst annähernd oder daß Sie andere Menschen sehen. Durch inneres Erleben würden Sie einen Begriff von der Gestalt zunächst nicht bekommen können. Wir sind gestaltet, aber in unserem unmittelbaren Bewußtsein haben wir die Gestalt nicht gegeben. Was haben wir statt der Gestalt in unserem unmittelbaren Bewußtsein? Das kann man nur erfahren, wenn man nach und nach vollständig unbefangen, sagen wir, die Entwickelung des Menschen selber im physischen Leben betrachtet. Zunächst, wenn der Mensch in das physische Leben eintritt, da muß er sich sehr plastisch verhalten zu seinen Bildungskräften, das heißt, es muß in ihm viel gestaltet werden. Je mehr wir uns nähern dem vollständigen Kindsein, desto mehr wird in uns gestaltet, und unser Älterwerden ist durchaus begleitet von dem Zurücktreten der Gestaltungskräfte. Und in demselben Maße, als die Gestaltungskräfte zurücktreten, treten unsere bewußstten Vorstellungskräfte auf. Sie kommen aus uns heraus, je mehr die Gestaltungskräfte zurücktreten. Wir können Gestalten um so mehr vorstellen, je mehr wir die Fähigkeit verlieren, uns zu gestalten. Das ist zunächst, wenigstens während der Wachstumsperiode des Menschen, als eine wahrhaftig ebenso deutliche Tatsache zu bemerken, wie andere deutliche Tatsachen zu bemerken sind. Daraus aber ersehen Sie, daß wir sagen können: Die Gestaltungskräfte können wir erleben; dasjenige, was draußen die Körper gestaltet, können wir erleben. Wodurch erleben wir dies? Dadurch, daß es in uns Vorstellung wird. Jetzt sind wir an dem Punkte, wo wir die gestaltende Kraft an den Menschen heranbringen. Die gestaltende Kraft ist nicht das, was man irgendwie erträumen kann. Man muß die Antworten auf die Fragen, vor die uns die Natur stellt, nicht aus dem Spekulieren oder Philosophieren, sondern aus der Wirklichkeit heraus geben. Und in der Wirklichkeit sieht man: Die gestaltende Kraft zeigt sich uns da, wo gewissermaßen die Gestalt selber vor uns sich in unserem Vorstellen auflöst, wo sie zum Vorstellen wird. In der Vorstellung erleben wir das, was sich uns außen entzieht an Kraft, indem sich die Körper gestalten.

[ 11 ] Wenn wir also den Menschen hierher (siehe den Hinweis zu Seite 157) stellen, so können wir sagen: Er erlebt von unten herauf die Gestalten als Vorstellung. Was erlebt er denn von oben herunter, wo zunächst, wenn wir von dem Gasigen ausgehen, das Wärmeartige uns erscheint, was erlebt denn der Mensch da? Nun, hier werden Sie wiederum, wenn Sie unbefangen auf die Erscheinungen am Menschen selber hinschauen, nicht umhin können, sich zu fragen: Wie hängt zusammen der Wille des Menschen zunächst mit den Wärmeerscheinungen? Sie brauchen ja nur, jetzt physiologisch, ins Auge zu fassen, wie wir nötig haben ein gewisses Zusammenarbeiten mit der äußeren Natur, um Wärme zu erzeugen, um zum Wollen zu kommen. Aber indem wir das Wollen zur Wirklichkeit machen, erscheint gerade die Wärme. Die Wärme müssen wir eben dadurch verwandt ansehen mit dem Wollen. Ebenso wie wir die gestaltenden Kräfte außen in den Dingen verwandt ansehen müssen mit dem Vorstellen, müssen wir alles dasjenige, was sich außen als Wärme verbreitet, verwandt ansehen mit demjenigen, was in uns der Wille ist, müssen Wärme also ansehen als Wille, nur daß wir eben in unserem Willen das Wesen der Wärme erleben.

[ 12 ] Wie könnten wir also, wenn uns äußerlich Gestaltung entgegentritt, diese Gestaltung uns definieren? Wir schauen sie an, diese Gestaltung, in irgendeinem festen Körper. Wir wissen: Würde diese Gestaltung unter gewissen Bedingungen durch unseren eigenen Lebensprozeß verwandelt worden sein, so würde die Vorstellung entstanden sein. Diese Vorstellung ist nicht drinnen in der äußeren Gestaltung. Es ist ungefähr so, wie wenn ich das Geistig-Seelische im Tode von einem Leiblichen sich trennen sehe. Wenn ich äußerlich die Gestaltungen in der Natur sehe, so ist dasjenige, was die Gestaltungen bewirkt, nicht da. Es ist in Wahrheit nicht da. Es ist so nicht da, wie das Geistig-Seelische in einem Leichnam nicht da ist, aber drinnen gewesen ist. Wenn ich also mein Auge auf die äußere Natur richte, so muß ich sagen: Da ist irgendwie in der Gestaltung wirksam - ich will jetzt nicht sagen, wirksam gewesen, sondern wirksam werdend, das werden wir noch sehen -, da ist irgendwie wirksam dasselbe, was in mir als Vorstellung lebt. Wenn ich in der Natur Wärme wahrnehme, so ist irgendwie wirksam dasselbe, was in mir als Wille lebt. Im vorstellenden und wollenden Menschen haben wir dasjenige, was draußen in der Natur uns als Gestaltung und als Wärme entgegentritt. |

[ 13 ] Nun aber gibt es ja alle möglichen Zwischenstufen zwischen dem Wollen und Vorstellen. Sie werden bei einem auch nur einigermaßen vernünftigen Selbstbeobachten bald herausfinden, daß Sie eigentlich niemals vorstellen, ohne eine Willensanstrengung zu vollziehen. Eine Willensanstrengung wird allerdings besonders in der Gegenwart bei den meisten Menschen als unbequem empfunden. Man gibt sich mehr dem unbewußten Willen hin, dem Gehen der Gedanken, man liebt es nicht, den Willen hineinzusenden in das Gedankengebiet. Aber ganz willensentblößter Gedankeninhalt ist eigentlich niemals vorhanden, ebensowenig wie ein Wille vorhanden ist, der nicht durch Gedanken orientiert ist. Also, wenn wir von Gedanke und Willen, von Vorstellung und Willen sprechen, so haben wir es eigentlich zu tun nur mit Grenzen, mit dem, was nach einer Seite das Gedankliche, nach der anderen Seite das Willensmäßige ausbildet. Und wir können daher sagen, daß, indem wir den gedankentragenden Willen und den willensträchtigen Gedanken in uns erleben, wir ganz wahrhaftig und wesentlich erleben das äußere Gestalten und das äußere Wärmewesen in der Natur. Es gibt eben keine andere Möglichkeit, als im Menschen aufzusuchen das Wesen desjenigen, was uns äußerlich in seinen Erscheinungen entgegenrritt.

[ 14 ] Und verfolgen Sie diesen Gedanken nun weiter. Wenn Sie den Zuständen der Körperlichkeit nach der einen Seite weiter folgen, so können Sie sagen, Sie müßten linienmäßig den Fortgang ins Unbestimmte verfolgen. Nach der anderen Seite ebenso. Wie muß es aber denn hier im Menschen sein? Gerade das Entgegengesetzte muß hier der Fall sein. Ja, wir müssen dasjenige, was wir hier (siehe Schema Seite 153) ins Unendliche verfolgen, eigentlich zurück verfolgen. Statt daß es ins Unendliche hier so geht, daß wir es eigentlich gar nicht weiter verfolgen können, müssen wir hier (im Menschen) annehmen, daß es aus dem Raum heraus verschwindet; ebenso dasjenige, was von unten nach oben geht, müssen wir so betrachten, daß es aus dem Raum heraus verschwindet. Das heißt: Die Kraft, die in der Wärme liegt, in ihrer Wirkung auf den Menschen muß sie sich so äußern, daß sie in ihm aus dem Raum hinausgeht; ebenso geht die gestaltende Kraft im Menschen aus dem Raum hinaus. Das heißt, wir müssen im Menschen an einen Punkt kommen, wo dasjenige, was sonst räumlich in der Außenwelt erscheint, Gestaltung und Wärmeausbreitung, aus dem Raume hinausgeht, wo die Unmöglichkeit eintritt, das, was wird bei dem Unräumlichwerden, noch mathematisch festhalten zu können.

[ 15 ] Wir sehen hier, wie ich glaube, in einer außerordentlich bedeutungsvollen Weise, wie einfach durch eine sachgemäße Betrachtung der Naturerscheinungen wir gezwungen werden, in dem Augenblick, in welchem wir an den Menschen herantreten und ihn richtig einreihen in das Dasein der Natur, aus dem Raum herauszugehen, genau so, wie wir uns den Raum hier (siehe Schema) unendlich nach oben und unten vorstellen müssen. Indem wir an den Menschen herangehen, müssen wir aus dem Raum heraus. Wir können kein Symbolum finden, welches räumlich ausdrückt, wie sich die Naturerscheinungen im Menschen begegnen. Die Natur richtig vorgestellt, bedeutet, daß wir sie verlassen müssen, wenn wir sie im Verhältnis zum Menschen vorstellen. Wir kommen sonst, indem wir den Inhalt der Natur ins Auge fassen im Verhältnis zum Menschen, gar nicht an den Menschen heran.

[ 16 ] Was heißt nun das aber mathematisch? Nehmen Sie an, Sie bezeichnen jene Linie, durch welche Sie hier verfolgen die Körperzustände ins Unbestimmte, Sie bezeichnen ihre aufeinanderfolgenden Werte als positive. Dann müssen Sie dasjenige, was in den Menschen hineinwirkt, als negativ bezeichnen, und Sie müssen, wenn Sie wiederum diese Linie hier als positiv bezeichnen, dasjenige, was in den Menschen hineinwirkt, als negativ bezeichnen. Was nun auch Positives und Negatives ist- ich glaube, wir werden uns in diesen Tagen, anschließend an einen Vortrag von einem der Herren, über Positives und Negatives zu unterhalten haben —, wie wir es auch aufzufassen haben, was uns hier klar vor Augen tritt, ist, daß wir das Wesenhafte an der Wärme, insofern dieses Wesenhafte der Wärme der Außenwelt angehört, ins Negative überführen müssen, wenn wir es im Menschen verfolgen; wie wir auch das Wesenhafte an der Gestaltung ins Negative überführen müssen, wenn wir es im Menschen verfolgen. So daß sich in der Tat dasjenige, was im Menschen als Vorstellung lebt, zu dem, was in der Welt draußen als Gestaltung lebt, so verhält, wie positive Zahlenreihen zu negativen Zahlenreihen oder umgekehrt, sagen wir: wie Vermögen und Schulden, aber was für den einen Schulden ist, ist für den anderen Vermögen und umgekehrt. Hier kommen wir darauf, daß dasjenige, was draußen in der Welt Gestaltung ist, in dem Menschen als Negatives lebt. Wenn wir also sagen: Draußen in der Welt lebt irgendein Körper, der eine Materie hat, so muß ich sagen: Stelle ich nun seine Gestaltung vor, so muß ich auch die Materie in irgendeiner Weise negativ vorstellen. Wodurch charakterisiert sich denn mir als Mensch zunächst die Materie? Sie charakterisiert sich durch ihre Druckwirkung. Gehe ich von der durch Druckwirkung sich offenbarenden Materie zu meiner Vorstellung der Gestaltung über, so muß das Negative der Druckwirkung da sein: die Saugwirkung. Das heißt, wir können nicht dasjenige, was im Menschen als Vorstellung geschieht, materiell vorstellen, wenn wir das Materielle in Druckwirkung symbolisiert darstellen. Wir müssen das Gegenteil vorstellen. Wir müssen etwas wirksam im Menschen denken, was der Materie so entgegengesetzt ist wie das Negative dem Positiven, Wir müssen uns dasjenige, was wirksam ist — wenn wir die Materie durch Druckwirkung uns symbolisieren -, durch Saugwirkung uns symbolisieren. Indem wir von der Materie weiterschreiten, kommen wir zum Nichts, zum bloßen Raum. Aber indem wir jetzt weiterschreiten, kommen wir zum Weniger-alsNichts, zu dem, was die Materie aufsaugt, wir kommen vom Druck zur Saugwirkung. Da sind wir bei dem, was in uns als Vorstellung sich offenbart.

[ 17 ] Und wenn wir auf der anderen Seite die Wärmewirkungen betrachten, so gehen sie wieder ins Negative über, indem sie in uns übergehen. Sie treten aus dem Raum hinaus. Sie werden, wenn ich das Bild fortführen darf, aufgesogen von uns. Wir haben sie so, daß sie in ihrem Gegenbild sich darstellen. Sie sind nichts anderes - irgendein Vermögen bleibt Vermögen, wenn es auch für den anderen Schulden bedeutet. Dadurch, daß wir genötigt sind, die äußere Wärme, indem sie in uns wirkt, mit negativem Vorzeichen als nichts zu bezeichnen, dadurch wird sie nichts anderes. Sie sehen aber wiederum: Wir sind genötigt durch die Kraft der Tatsachen selber, uns Menschen durchaus nicht materiell vorzustellen, sondern in uns Menschen vorauszusetzen etwas, was nicht nur keine Materie ist, sondern was in all seinen Wirkungen sich zu der Materie so verhält wie die Saugwirkung zur Druckwirkung. Und stellen Sie in Reinheit unser menschliches Wesen vor, so müssen Sie es sich vorstellen als dasjenige, was die Materie fortwährend vernichtet, aufsaugt.

[ 18 ] Daß die moderne Physik diesen Begriff gar nicht entwickelt, diesen Begriff der negativen Materie, die sich zu der äußeren Materie so verhält wie eine Saugwirkung zu einer Druckwirkung, das ist das Unglück dieser modernen Physik. Was wir ausbilden müssen, das ist: In dem Augenblick, wo wir genötigt sind, an irgendwelche Wirkungen heranzutreten, die sich im Menschen selbst offenbaren, all unseren Formeln einen anderen Charakter dadurch zu geben, daß wir für die Willenserscheinungen negative Größen einführen gegenüber den Wärmeerscheinungen; für die Vorstellungserscheinungen negative Größen einführen gegenüber den Gestaltungskräften.

Tenth Lecture

[ 1 ] Before we continue with the discussion we started yesterday, which is now almost complete, let us support it with a few experiments. First, we will create a cylinder of light by shining light through this slit, and then we will place a balloon inside the cylinder of light, which is covered with soot so that the light cannot pass through it. We have expressed what happens on this thermometer. You see, our, let's say, energy cylinder causes the mercury column to sink by sending through what is revealed externally by the light. So we are dealing with what otherwise occurs under the influence of expansion. We must therefore assume that heat passes through here and causes expansion, and this expansion becomes apparent to us in the sinking of the mercury column. So we can say that if we were to catch the beam of light here, say through a prism, a spectrum would be created. We do not form a spectrum, but simply capture the light, collect it, and by collecting what is in this energy cylinder, we obtain a strong expansion here. You can see that the mercury column sinks very strongly. We now place an alum solution in the passage of the energy cylinder and want to see what happens as a result. So we have what passes through, which would also manifest itself to us through its light side, influenced by the fact that we have opposed it with an alum solution, and we now want to see what happens under the influence of the alum solution. In this way, we can—as you will see at the end—restore the perfect state of equilibrium between the right and left mercury columns, whereby you will see that heat passed through before, and now the alum solution is keeping the heat in, so that no more passes through, but only the heat that is generally present in the room is expressed here as well. So, at the moment when I place the alum solution in the energy cylinder, the heat is prevented from continuing to pass through. This means that I separate the heat from what manifests itself to me as both light and heat, and allow only the light to shine through here — for now, let us consider only this, as other things also shine through. But from this we can see that we can deal with the spreading light-heat energy in such a way that we allow the light to continue and separate out the heat by means of the alum solution placed in its path.

[ 2 ] That is one thing we can initially observe purely as a phenomenon. The other thing we want to consider as a phenomenon before we continue with our observations is this: if we want to investigate the nature of heat, we can initially examine its behavior by heating any object at any point. We then notice that the body does not remain warm only at the point where we heat it, but that the heat I apply at one point is communicated to the next part, then to the next part, and so on, so that in the end heat is spread throughout the entire body. Not only that. If we now bring another body into contact with the first, the second body also becomes warm, it becomes warmer than it was before, and in modern physics we are accustomed to saying: Heat is propagated by conduction. We speak of heat conduction. Heat is conducted from one part of a body to another, and it is also conducted from one body to another body that is in contact with it. Even through very superficial observations, you can see that this heat conduction is different for different substances. If you take a metal rod, hold it in your fingers, and put the other end into a flame, you will probably drop it soon. The heat is conducted very quickly from one end to the other. We then say that metal is a good conductor of heat. If, on the other hand, you take a wooden rod in your hand and hold it in the flame, you will not be tempted to drop it quickly under the influence of heat conduction. Wood is a poor conductor of heat. And so we can speak of good and poor conductors of heat. However, this can only really be clarified by another experiment. And we cannot carry out this other experiment today because it would have been futile to try to obtain ice a second time and then have to process the ice in a certain way. That would not have been possible. In more favorable times, such an experiment can be carried out: if, under certain circumstances, you make a lens out of ice, like a glass lens, and then use a heat source—simply a flame — you can, just as the common expression says that light rays are collected, also collect heat rays and, using a thermometer placed here, confirm that there really is something like an accumulation of heat under the influence of the ice lens through which the spreading heat has passed (see drawing).

[ 3 ] Now you can easily see from this experiment that this cannot be the same as heat conduction, even though the heat has spread, because otherwise the ice lens could not have remained an ice lens. So we are dealing with two different types of heat propagation: one that essentially affects the bodies through which the heat spreads, and one in which it does not matter what stands in the way of the heat, where we are dealing with the propagation of the actual heat entity, where we see the heat itself spreading, so to speak. But if we are to be precise, we must first ask: What actually spreads when we transfer heat to a body and then see that it gradually becomes warmer? Isn't it perhaps a highly unclear expression when we say that it is the heat itself that spreads from one part of the body to another, when we only observe this warming on the body itself?

[ 4 ] You see, here I must again draw your attention to the fact that it is a matter of grasping really precise mental images and concepts: instead of simply feeling the heat here (on a heated rod), take a fairly large iron rod, a metal rod, which you heat at one end, but in such a way that it does not cause any harm when you then place a row of boys on it. Now let the boys cry out—but it must not be too strong—when it gets warm at the bottom, so that first the first one will cry out, then the second, then the third, and so on. The boys cry out one after the other. But you will not be tempted to say: What I noticed here with the first boy is carried over to the second, the third, the fourth, and so on. But when you heat it here (at one end) and then feel the warmth here (at the other end), today's physicist says: The heat is simply conducted away. Whereas he is actually only observing what the body does, namely giving it the sensation of heat, piece by piece, as here, where the boys squeal when they experience the heat. You cannot say that the screaming propagates.

[ 5 ] We will now attempt to show how different metals, which are available here in the form of rods, behave in different ways with regard to what we are accustomed to calling heat conduction, and we will try to introduce realistic concepts. We will pour hot water into this. The rods will be heated as they are immersed in the water. We will now see what effect this has on our experiment, how one rod after another will heat up, so that we can actually imagine a kind of scale. We will be able to show the effects of heat continuously on the different substances (see drawing). The rods are coated with yellow mercury iodide, which turns reddish when a certain temperature is reached. The color change rises at different rates on the different rods. Lead is therefore the worst heat conductor among these metals, as they say. — The experiments are shown here so that we can now form the overview we have discussed many times before of the phenomena within the nature of heat, in order to gradually ascend to the knowledge of what the nature of heat really is.

[ 6 ] Now, through our continued observation yesterday, we have already seen how, when we consider the realm of physicality, we can in a certain way distinguish the realm of the solid, in which we can essentially follow that which takes shape. We then have, as it were, the liquid as an intermediate stage, and then move on to the gaseous. And in the gaseous, we have to regard condensation and rarefaction as corresponding to formation in the solid. Then we again have, as a kind of intermediate state, precisely what we are looking for, namely heat. We have seen why we can write it here (see diagram). Then, as I said, we come to a kind of \(x\), and if we were to continue this line of thought in reality, we would find materialization and dematerialization, and would then have to ascend to a \(y\), to a \(z\), as I said, in a similar way to how we find the transition in the light spectrum from green through blue to violet and then seemingly into infinity. However, yesterday we had to conclude that we can also continue the realm of the solid here (diagram below) into a kind of \(U\), so that we can form a mental image of the realms of our physicality through this arrangement modeled on the spectrum; we can form this mental image precisely when we want to remain in reality.

[ 7 ] Now it is a matter of pursuing the thought we already expressed yesterday: just as we can summarize what disappears toward violet and what disappears toward red in the spectrum by summarizing the spectrum extending straight to the left and right, circularly, so we can think of the changing . areas of physicality on one side and on the other in such a way that they are not actually characterized by a straight line that strays endlessly in one direction or the other, but that what here seems to go into the indefinite or infinite goes back here, as does this, and that what is actually present can be characterized by a circle, by a line that at least runs back on itself.

[ 8 ] Now the question arises: What can we find here? If we look at the ordinary spectrum, we can at least find something there. Viewed in terms of Goethe's optics, you know that we can arrange the spectral colors in such a way that, if we take the spectrum not one-sidedly but with all its possible colors, we have green on one side, which is, so to speak, the middle color when we make a light color into a spectrum, and on the other side the color of peach blossoms, which is also a middle color when we make a dark color into a spectrum. So we have green, blue, violet, progressing to peach blossom on one side, and on the opposite side green, yellow, orange, red to peach blossom. By closing the circle, we can see the peach blossom at the point where it closes.

[ 9 ] If we now close our circle of states for the various states of physicality, can we find anything? We are now at an extremely important point. What must we place here in the same way that we place the color of peach blossoms here in the ordinary spectrum, which is supposed to give us a picture of the spectrum of states? What must we put here? Perhaps the idea that must simply spring from the world of facts will not be so difficult for you if I first try to introduce it in the following way. What is it that we actually have before us, disappearing, as it were, on one side and on the other, just as the color spectrum disappears on the one side into violet and on the other into red? What is it that we have before us? It is nothing less than the whole of nature. In what is called the realm of nature, you cannot find anything that does not have to be accommodated somewhere in “form,” below “form,” in what I have here designated with \(x\), \(y\), \(z\), and so on. (See diagram) Nature disappears from us on one side when we follow the physical states through heat; it disappears from us on the other hand when we follow the formations, first the formations of the realm of the solid, then of the sub-solid, which we see in the polarization figures, where form acts on form — you can look at these tourmaline tongs, then you see something light or something dark. Only through the intermingling of the forms does that which appears sometimes dark, sometimes light, and so on, appear.

[ 10 ] For us, the essential thing now is to arrive at what we have to put here when we follow nature on the one hand to the point where it encounters what can be characterized as a current from the other side. What is there? There is nothing else there but the human being as such. Human beings are there. Human beings are there in such a way that they perceive what comes from one side and perceive what comes from the other. How do they perceive what comes first on this path (from below)? They are formed. If we ask about his form among the forms that other bodies have, we must say: Man also has a ‘form’. So that which acts as formative forces is also within him. But we must ask ourselves: Does that which acts as formative forces belong to the sphere of consciousness? Not in the consciousness that arises in humans. For imagine if you did not gain a concept of the human form by approaching yourself or seeing other people. You would not be able to gain a concept of form through inner experience. We are formed, but in our immediate consciousness we do not have form. What do we have in our immediate consciousness instead of form? This can only be experienced if we gradually and completely impartially observe, let us say, the development of the human being itself in physical life. First of all, when a human being enters physical life, they must be very receptive to their formative forces, that is, much must be formed within them. The closer we come to complete childhood, the more is formed within us, and our aging is accompanied by the retreat of the formative forces. And to the same extent that the formative forces recede, our conscious powers of mental image come to the fore. They emerge from within us the more the formative forces recede. The more we lose the ability to form ourselves, the more we can imagine mental images. This is initially, at least during the period of human growth, as clearly observable a fact as other clearly observable facts. But from this you can see that we can say: we can experience the formative forces; we can experience what forms the body outside. How do we experience this? Through it becoming a mental image within us. Now we are at the point where we bring the formative power to human beings. The formative power is not something that can be dreamed up in some way. The answers to the questions that nature poses to us must be given not from speculation or philosophy, but from reality. And in reality we see that the formative power reveals itself to us where, in a sense, the form itself dissolves before us in our mental image, where it becomes a mental image. In our mental image we experience what eludes us externally in terms of power, as the bodies take shape.

[ 11 ] So when we place the human being here (see the note on page 157), we can say: he experiences the forms from below as mental image. What does he experience from above, where, if we start from the gaseous, the warm-like appears to us? What does the human being experience there? Well, here again, if you look impartially at the phenomena in the human being himself, you cannot help but ask yourself: How is the will of the human being initially connected with the phenomena of warmth? You only need to consider, now physiologically, how we need a certain cooperation with external nature in order to generate warmth, in order to arrive at volition. But when we make our will a reality, warmth appears. We must therefore regard warmth as related to the will. Just as we must regard the formative forces outside in things as related to mental image, we must regard everything that spreads outside as warmth as related to what is the will within us, and thus regard warmth as will, except that we experience the essence of warmth in our will.

[ 12 ] So how could we define this form when we encounter it externally? We look at this form in some solid body. We know that if this form had been transformed by our own life process under certain conditions, the mental image would have arisen. This mental image is not contained within the external form. It is roughly the same as when I see the spiritual-soul aspect separating from the physical aspect in death. When I see the external forms in nature, that which causes the forms is not there. It is not really there. It is not there in the same way that the spiritual-soul aspect is not there in a corpse, but has been inside it. So when I turn my gaze to external nature, I must say: somehow the same thing that lives in me as a mental image is at work in the form – I don't want to say has been at work, but is becoming at work, as we shall see – somehow the same thing that lives in me as will is at work. When I perceive warmth in nature, somehow the same thing that lives in me as will is at work. In the imagining and willing human being, we have that which confronts us outside in nature as form and warmth.

[ 13 ] But now there are all kinds of intermediate stages between willing and mental image. If you observe yourself reasonably closely, you will soon discover that you never actually form a mental image without exerting your will. However, most people today find exerting their will uncomfortable. They give themselves over more to the unconscious will, to the flow of thoughts, and do not like to send their will into the realm of thought. But thought content that is completely devoid of will is actually never present, just as there is no will that is not oriented by thought. So when we speak of thought and will, of mental image and will, we are actually dealing only with boundaries, with what forms the intellectual on one side and the volitional on the other. And we can therefore say that by experiencing the thought-bearing will and the will-bearing thought within ourselves, we truly and essentially experience the external forms and the external warmth of nature. There is simply no other possibility than to seek in human beings the essence of that which we encounter externally in its manifestations.

[ 14 ] And now pursue this thought further. If you follow the states of physicality on the one hand, you can say that you must follow the progression into the indefinite in a linear fashion. The same applies on the other hand. But how must it be here in the human being? The exact opposite must be the case here. Yes, we must actually trace back what we are tracing here (see diagram on page 153) into infinity. Instead of it going into infinity here, so that we cannot actually trace it any further, we must assume here (in the human being) that it disappears out of space; likewise, we must regard what goes from below to above as disappearing out of space. This means that the force that lies in warmth, in its effect on human beings, must express itself in such a way that it leaves space within them; likewise, the formative force in human beings leaves space. This means that we must arrive at a point in human beings where that which otherwise appears spatially in the external world, namely formation and the spread of warmth, leaves space, where it becomes impossible to continue to grasp mathematically that which becomes non-spatial.

[ 15 ] Here we see, I believe, in an extraordinarily meaningful way, how simply by observing natural phenomena in an appropriate manner we are compelled, at the moment when we approach human beings and correctly classify them in the existence of nature, to step out of space, just as we must form the mental image of space here (see diagram) as infinitely extending upwards and downwards. When we approach human beings, we must step outside of space. We cannot find a symbol that spatially expresses how natural phenomena encounter each other in human beings. To give a correct mental image of nature means that we must leave it behind when we give it a mental image in relation to human beings. Otherwise, by considering the content of nature in relation to human beings, we cannot approach human beings at all.

[ 16 ] But what does that mean mathematically? Suppose you designate the line through which you trace the states of the body into the indefinite as positive. Then you must designate that which acts upon humans as negative, and if you again designate this line here as positive, you must designate that which acts upon humans as negative. Whatever is positive and negative—I believe we will have to discuss positive and negative in the coming days, following a lecture by one of the gentlemen—however we understand it, what is clear to us here is that we must transform the essential nature of warmth, insofar as this essential nature of warmth belongs to the outside world, into the negative when we follow it in human beings; just as we must transform the essence of form into the negative when we pursue it in human beings. So that in fact what lives in human beings as mental image relates to what lives in the outside world as form in the same way as positive number series relate to negative number series, or vice versa, let us say: like assets and liabilities, but what is a liability for one is an asset for another, and vice versa. Here we come to the conclusion that what is form in the outside world lives as something negative in human beings. So when we say that there is some body in the outside world that has matter, I must say that if I now present its mental image, I must also imagine the matter in some negative way. How does matter first characterize itself to me as a human being? It characterizes itself through its pressure effect. If I move from matter, which reveals itself through its pressure effect, to my mental image of form, then the negative of the pressure effect must be there: the suction effect. This means that we cannot imagine what happens in humans as a mental image in material terms if we symbolize the material in terms of pressure effect. We must imagine the opposite. We must think of something effective in human beings that is as opposed to matter as the negative is to the positive. We must symbolize what is effective — when we symbolize matter through pressure — through suction. As we move on from matter, we come to nothingness, to mere space. But as we continue, we arrive at less than nothing, at that which absorbs matter; we move from pressure to suction. Here we are at what reveals itself to us as a mental image.

[ 17 ] And when we consider the effects of heat on the other side, they again turn into the negative as they pass into us. They step out of space. They are, if I may continue the image, absorbed by us. We have them in such a way that they are represented in their opposite image. They are nothing else—any asset remains an asset, even if it means debt for the other. Because we are compelled to describe the external warmth, as it acts within us, with a negative sign as nothing, it becomes nothing else. But you see again: we are compelled by the force of facts themselves not to form a mental image of human beings as material at all, but to presuppose in us human beings something that is not only not matter, but which in all its effects relates to matter as suction relates to pressure. And if you imagine our human nature in its purity, you must form the mental image of it as that which continually destroys and absorbs matter.

[ 18 ] It is the misfortune of modern physics that it has not developed this concept at all, this concept of negative matter, which relates to external matter as suction relates to pressure. What we must develop is this: at the moment when we are compelled to approach any effects that manifest themselves in human beings, we must give all our formulas a different character by introducing negative quantities for the phenomena of the will as opposed to the phenomena of heat; by introducing negative quantities for the phenomena of imagination as opposed to the forces of formation.