Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

9 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture IX

We have now reached a point in our studies from which we must proceed with extreme caution, in order to see where there is a danger of allowing our thought to depart from reality and to see also when we are avoiding this danger, by keeping within the bounds of what is real.

Last time, we suggested the comparison of two facts: The appearance within the planetary system of the cometary phenomena, and, alas within the planetary system, though perhaps not bearing quite the same relationship to it, all that we observe in the phenomena of fertilization. In order, however, to come to ideas about this which are at all justified, we must first see whether it is indeed possible to find connections between two so widely separated things, with which we are confronted in the external world of facts. In scientific method, we shall not make real progress, unless we can refer from one realm of facts to another, manifesting something of a similar nature and thus leading us on.

We have seen how on the one hand we have to use the element of figure and form, the mathematical, and then how we are again and again impelled to come to terms in one way or another with the qualitative aspect, in some way to find a qualitative approach. And so today we will bring in something which arises in regard to man if one really studies this man, who is, after all, in some way an image of the heavenly phenomena,—as the many statements in these lectures may enable us to deduce. Yet we still have to establish in what way he is this image. If this is what he is, we must first of all gain a clear understanding of man himself. We must understand the picture from which we intend to take our start,—understand its inner perspective. Just as in looking at a painting one must know what a foreshortening means, and so on, in order to pass from the picture to the real spatial relationships and to relate the picture to what it represents in reality, so, if we would approach reality in the universe, interpreting it through man, we must first be clear about man. Now it is, extraordinarily difficult, as a human being, to come near to the human being with palpable ideas. Therefore, I should like today to bring before your souls what I might call “palpably impalpable” thought-pictures arising from quite simple foundations, ideas with which most of you are probably already well acquainted, but which we must nevertheless bring before our minds in a certain connection. These ideas, which seem in part to be quite easy to grasp and yet again, beyond certain limits, to elude our comprehension, will afford us a means of orientation in the striving to take hold of the outer world through ideas.

It may appear somewhat forced to keep emphasizing the necessity of referring back to man's life of pictorial imagination in order to understand the phenomena of the heavens. But after all it is obvious that however carefully we may describe the heavenly phenomena, we have, to begin with, nothing more than a form of optical picture, permeated with mathematical thoughts. What Astronomy gives us has fundamentally the character of a picture. To be on the right path, we must therefore concern ourselves with the arising of the picture in man, otherwise we shall gain no true relationship to what Astronomy can say to us. And so I should like today to proceed from some quite simple mathematics and to show you how, in a different domain from that to which we were led through the ratios of the periods of revolution of the planets, there appears within Mathematics itself this element of the incomprehensible, the impalpable. We meet with it when in a certain connection we study quite familiar curves. (As I said, many of you already know what I am about to describe, I only want to elucidate the subject today from a particular aspect.)

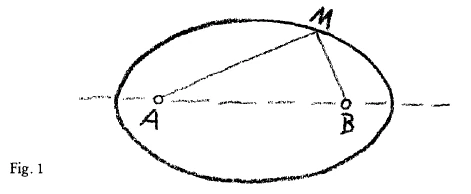

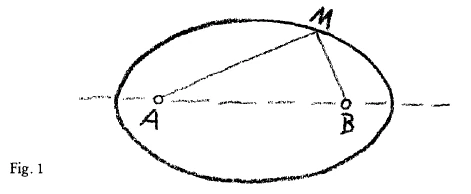

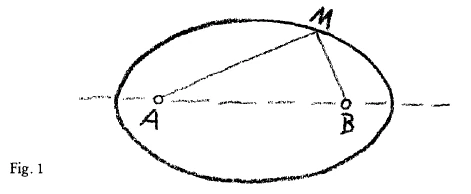

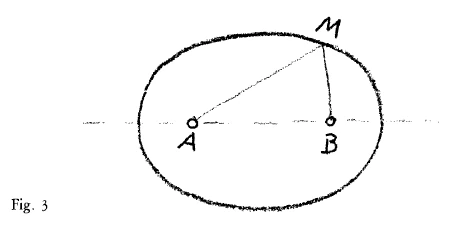

Consider the Ellipse, with its two foci \(A\) and \(B\), and you know that it is a definition of the ellipse that for any point \(M\) of the curve, the sum of its distances \((a + b)\) from the two foci remains constant. It is characteristic of the ellipse, that the sum of the distances of any one of its points from two fixed points, the two foci, remains constant (Fig. 1).

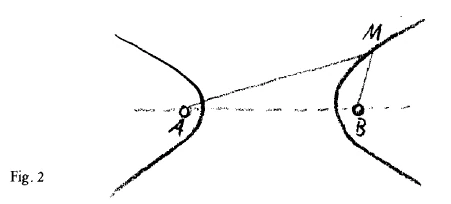

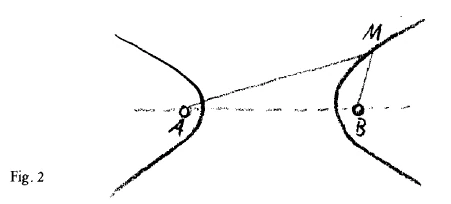

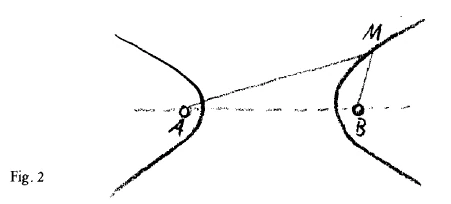

Then we have a second curve, the Hyperbola (Fig. 2). You know that it has two branches. It is defined in that the difference of the distances of any point of the curve from the two foci, \((b - a)\) is a constant magnitude. In the ellipse, then, we have the curve of the constant sum, in the hyperbola, the curve of constant difference, and we must now ask: What is the curve of constant product?

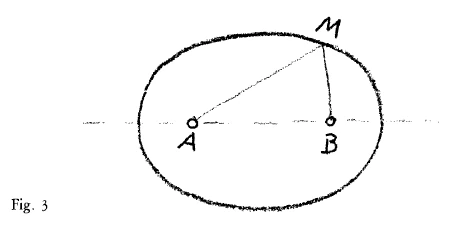

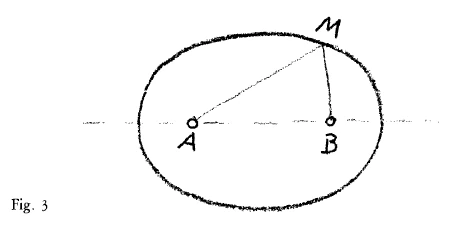

I have often drawn attention to this: The curve of constant product is the so-called Curve of Cassini (Fig. 3). We find it when, having two points, \(A\) and \(B\), we consider a point M in regard to its distances from \(A\) and \(B\), and establish the condition that the two distances \(AM\) and \(BM\) multiplied together should equal a constant magnitude. For the sake of simplicity in the calculation, I will call the constant magnitude \(b^2\) and the distance \(AB\), \(2a\). If we take the mid-point between \(a\) and \(b\) as the center of the axes of a co-ordinate system and calculate the ordinates for each point that fulfills these conditions,—take \(C\) as the center of the co-ordinate system and let the point whose ordinate we will call y move round so that for each point of the curve \(AM \cdot BM = b^2\), we get the following equation. (I will only give you the result, for the simply reason that everyone can easily work out the calculation for himself; it is to be found in any mathematical text-book relating to the subject.) We find for \(y\) the value:

$$y=±\sqrt{-(a^2+x^2)±\sqrt{b^4+4a^2x^2}}$$

Taking here into account that we cannot use the negative sign because we should then have an imaginary y, and considering therefore taking only the positive sign, we have:

$$y=±\sqrt{-(a^2+x^2)+\sqrt{b^4+4a^2x^2}}$$

If we then draw the corresponding curve, we have a curve, rather like but not identical with an ellipse, called the curve of Cassini (Fig. 4). It is symmetrical to the left and right of the ordinate axis and about and below the abscissa axis.

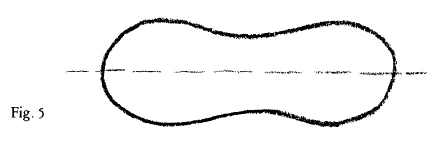

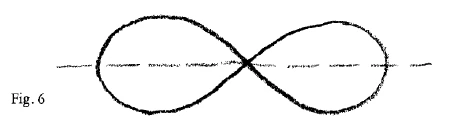

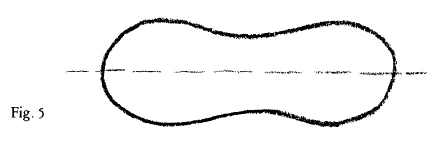

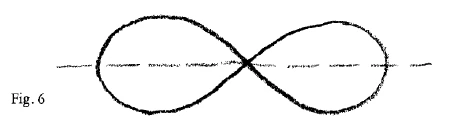

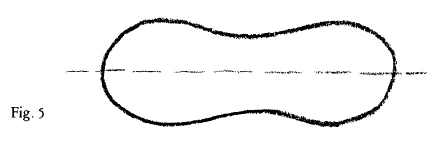

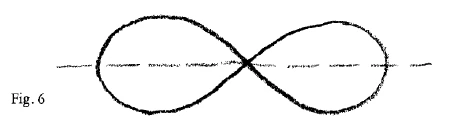

But now, this curve has various forms, and for us at any rate this is the important thing about it. The curve has different forms, according to whether b, as I have taken it here, is greater than \(a\), equal to \(a\), or less than \(a\). The curve I have just drawn arises when \(b ˃ a\), and furthermore when another condition is fulfilled, namely, that \(b\) is also greater than or equal to \(a\sqrt{2}\). Moreover, when \(b \gt a\sqrt{2}\), there is a distinct curvature above and below, If \(b =a\sqrt{2}\), then at this point above and below, the line of the curve becomes straightened, m it flattens so much that it almost becomes a straight line (Fig. 4). If, however, \(b \lt a\sqrt{2}\), then the whole course of the curve is changed and it takes on this form (Fig. 5). And if \(b = a\), the curve passes over into a quite special form, it changes into this form (Fig. 6). It runs back into itself, cuts through itself and comes out on the other side, and we obtain the special form of the Lemniscate. The lemniscate, then, is a special form of Curve of Cassini—these curves are so named after their discoverer. The particular form assumed by the curve is determined by the ratio between the constant magnitudes which appear in the equation characterizing the curve. In the equation, we have only these two constant magnitudes, b and a, and the form of the curve depends on the ratio between them.

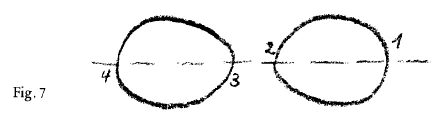

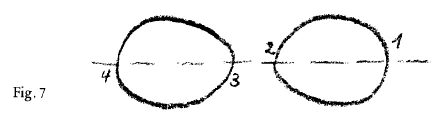

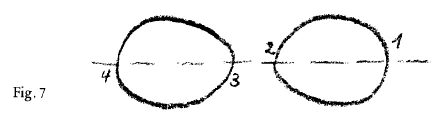

Then the third case is possible, that \(b \lt a\). If \(b \lt a\), we can still find values for the curve. We can always solve the equation and obtain values for the curve, ordinates and abscissae, even when b is smaller than a, only the curve then undergoes yet another metamorphosis. For when \(b \lt a\), we find two branches of the curve, which look something like this (Fig. 7). We have a discontinuous curve. And here we come to the point where the mathematics itself confronts us with what I called the “palpably impalpable”, something that is difficult to grasp in space. For in the sense of the mathematical equation, this is not two curves, but one; it is a single curve in exactly the same way as all these are single curves (Figs. 3 through 5). In this one (the lemniscate) there is already a transition. The point which describes the curve takes this path, goes round underneath, cuts its previous path here and continues on here (Fig. 7). Here, we must picture the following: If we let the point M move along this line, it does not simply cross over from one side to the other,—it does not do this. It runs along the path just as in the other curves, describes a curve here, but then manages to turn up again here (Fig. 7) You see, that which carries the point along the line disappears here in the middle. If you want to understand the curve you can only imagine that it disappears in the middle. If you try to form a continuous mental picture of this curve, what must you do?

It is quite easy, is it not, to imagine curves such as thes. (I only say this in parenthesis for the ordinary philistine!) You can go on imagining points along the curve and you do not find that the picture breaks off. Here (in the lemniscate) admittedly, you have to modify the comfortable way of simply going round and round, but still it goes on continuously. You can keep hold of the mental picture. But now, when you come to this curve (Fig. 7), which is not so commonplace, and you want to image it, then, in order to keep the continuity of the idea you will have to say: Space no longer gives me a point of support. In crossing over to the other branch in my imagination, unless I break the continuity and regard the one branch as independent of the other, I must go out of space; I cannot remain in space. So you see, Mathematics itself provides us with facts which oblige us to go out of space, if we would preserve the continuity of the idea. The reality itself demands of us that in our ideas we go out of space. Even in Mathematics therefore we are confronted with something which shows us that in some way we must leave space behind, if the pure idea is to follow its right path. Having ourselves and going the idea is beginning to think the process through, we must go on thinking in such a way that space is no longer of any help to us. If this were not so, we should not be able to calculate all possibilities in the equation.

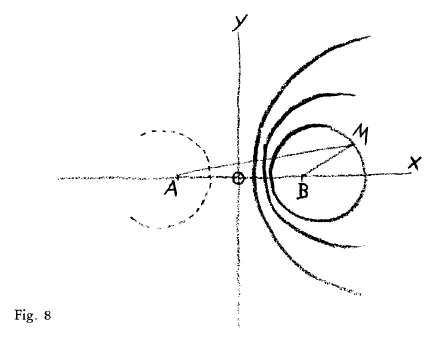

In pursuing similar line of thought, we meet with other instances of this kind. I will only draw your attention to the next step, which ensures if one things as follows. The ellipse is the locus of the constant sum,—it is defined by the fact that is is the curve of constant sum. The hyperbola is the curve of constant difference. The curve of Cassini in its various forms is the curve of constant product. There must then be a curve of constant quotient also, if we have here A, here B, here a point M, and then a constant quotient to be formed through the division of BM by AM. We must be able to find different points, \(M_1\), \(M_2\), etc., for which

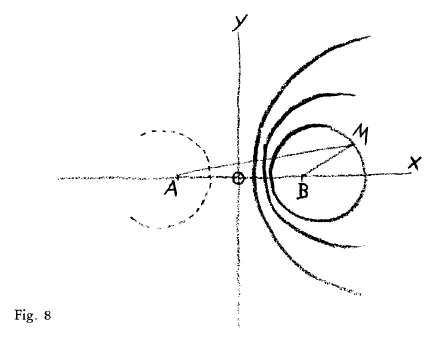

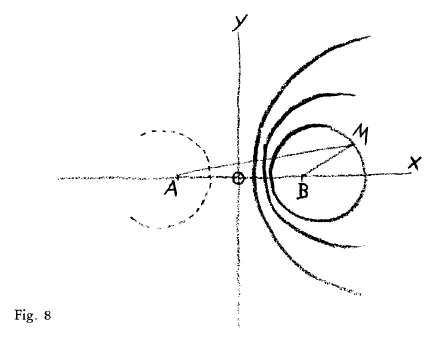

$$\frac{BM_1}{AM_1}=\frac{BM_2}{AM_2}$$etc. are equal to one another and always equal to a constant number. This curve is, in fact, the Circle. If we look for the points \(M_1\), \(M_2\) etc. we find a circle which has this particular relationship to thee points \(A\) and \(B\) (Fig. 8). So that we can say: Besides the usual, simple definition of a circle—namely, that it is the locus of a point whose distance from a fixed point remains constant—there is another definition. The circle is that curve, very point of which fulfills the condition that its distances from two fixed points maintain a constant quotient.

Now, in considering the circle in this way there is something else to be observed. For you see, if we express this

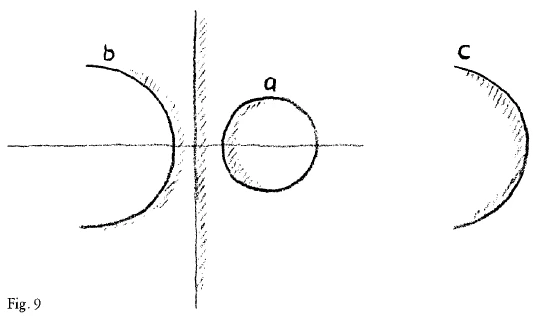

$$\frac{BM}{AM}=\frac{m}{n}$$(it could of course be expressed in some other way), we always obtain corresponding values in the equation, and we can find the circle. In doing this we find different forms of the circle (that is, different proportions between the radius of the circle and the length of the straight line \(AB\)), according to the proportion of m to n. These different forms of the circle behave in such a way that their curvature becomes less and less. When \(n\) is much greater than m, we find a circle with a very strong curvature; when n is not so much greater, the curvature is less. The circle becomes larger and larger the smaller the difference between \(n\) and \(m\). And if we follow this proportion of m to n still further, the circle gradually passes over into a straight line. You can follow this in the equation. It passes over into the ordinate axis itself. The circle becomes the ordinate axis when \(m=n\), that is, when the quotient \(m:n = 1\). In this way the circle gradually changes into the ordinate axis, into a straight line.

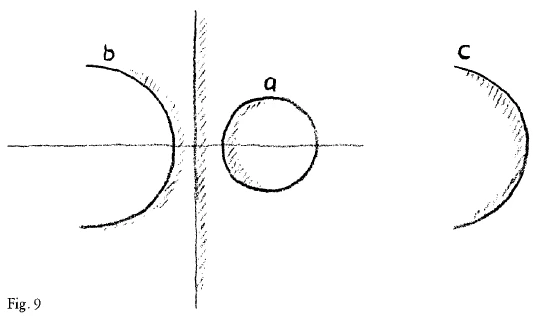

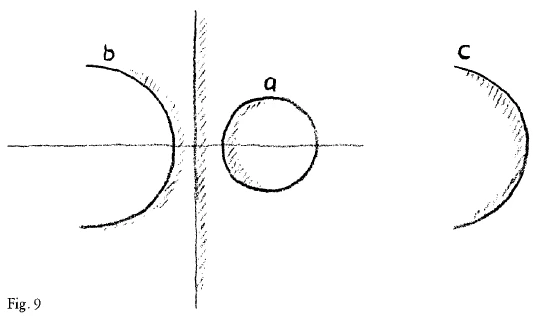

You need not be particularly astonished at this. It is quite possible to imagine. But something very different happens it we wish to follow the process still further. The circle has flattened more and more, and through becoming flatter from within, as it were, it changes into a straight line. It does this because the constant ratio in the equation undergoes a change. Through this the circle becomes a straight line. But this constant ratio can of course grow beyond \(1\), so that the arcs of the circles appear here (on the left of the \(y\)-axis). What must we do, however, if we try to follow it in our imagination? We have to do something quite peculiar. We have, in fact, to think of a circle which is not curved towards the inside, but is curved towards the outside. Of course, I cannot draw this circle, but it is possible to think of a circle which is curved towards the outside.1If it were drawn it would look like an ordinary circle, only one would have to bear in mind that “outside” and “inside” had changed places. (Editor's note.) In an ordinary circle the curvature is towards the inside, it is not? If we follow the line round it returns into itself. But defining the circle in this other way, if we use the necessary constant, we obtain a straight line. The curvature is still on this side (right of the \(y\)-axis). But it now makes things not nearly so comfortable for us as before! Previously, the curvature always turned towards the center of the circle, while now (in the case of the straight line), we are shown that the center is somewhere in the infinite distance, as one says. Following on from this, there arises for us the idea of a circle which is curved towards the outside. Its curvature is then no longer as it is here (Fig. 9a)—that would be the ordinary, commonplace, philistine circle,—but its curvature is here (Fig. 9b). Therefore, the inside of this circle is not here; this is the outside; the inside of this circle (Fig. 9c) is to the right.

Now compare what I have just put before you. I have described the curve of Cassini, with its various forms, the lemniscate and the form in which there are two branches. And now we have pictured the circle in such a way that at one time it is curved in the familiar way, with the inside here and the outside here; while in a second form of circle (in drawing it we are only indicating what is meant) we find that the curvature is this way round, with an inside here and an outside here. Comparing it with the Cassini curve, the first form of the circle would correspond to the closed forms, as far as the lemniscate. After this we have another kind of circle, which must be thought of in the other direction, being curved this way, with the inside here and the outside here. You see, when we are concerned with the constant product we find forms of the curve of Cassini where, it is true, we are thrown out of space, yet we can still draw the other branch on the other side. The other branch is once more in space, although in order to pass from the one to the other we are thrown out of space. Here, in the case of the circle, however, the matter becomes still more difficult. In the transition from circle to straight line we are, indeed, thrown out of space, and moreover, we can no longer draw a self-contained form at all. This we are unable to do. In passing over from the curve of constant product to the curve of constant quotient, we are only just able to indicate the thought spatially.

It is extraordinarily important that we concern ourselves with the creating of ideas which, as it were, will still slip into such curve-forms. I am convinced that most people who concern themselves with mathematics take note of such discontinuities, but then make the thought more comfortable by simply holding to the formula and not passing on to what should accompany the mathematical formula in true continuity of thought. I have also never seen that in the treatment of Mathematics as subject matter for education any great value is laid upon the forming of such thoughts in imagination.—I do not know,—I ask the mathematicians present, Herr Blümel, Herr Baravalle, if this is so; whether in modern University education any importance is attached to this? (Dr. Unger here mentioned the use of the cinema.) Yes, but that is a pretense. It is only possible to represent such things within empirical space by means of the cinema or in similar ways, it some sort of deception is introduced. It cannot be pictured fully in real space without the effect being achieved through some form of deception. The point is, whether there is anywhere in the sphere of reality something which obliges us to think realistically in terms of such curves. This is the question I am now asking. Before passing on, however, to describe what might perhaps correspond to these things in the realm of reality, I should like to add something which may perhaps make it easier for you to pass transition from these abstract ideas to the reality. It is the following.

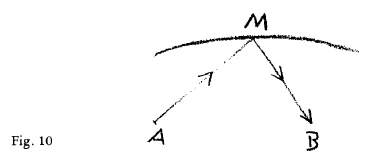

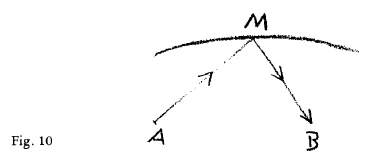

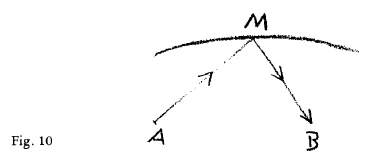

You can set another problem in the sphere of theoretical Astronomy, theoretical Physics. You can say: Let us suppose that here as \(A\), is a source of light, and this source of light in a illumines a point \(M\) (Fig. 10). The strength of the light shining from \(M\) is observed from \(B\). That is, with the necessary optical instruments, observation is made from \(B\) of the strength of the light shining from the point \(M\), which is illumined from \(A\). And of course, the strength of the light would vary, according to the distance between \(B\) and \(M\). But there is a path which could be described by the point \(M\), such that, being illumined from A, it always shines back to \(B\) with the same intensity. There is such a path; and we can therefore ask: What must be the locus of a point, illumined from a fixed point \(A\), such that, seen from another fixed point \(B\), its light is always of the same intensity? This curve—the curve in which such a point would have to move—is the curve of Cassini! From this you see that something which takes on a qualitative nature is set into spatial connection, fitting into a complicated curve. The quality that we must see in the beam of light—for the intensity of light is a quality—depends in this case on the element of form in the spatial relationships.

I only wished to bring this forward for you to see that there is at least some way of leading over from what can be grasped in geometrical form to what is qualitative. This way is a long one, and what we will now discuss is something to which I want to draw your attention, although it would take months to present in all detail. You must be fully aware that I only intend to give you guiding lines; it is left to you to develop them further and to go into all the details which would testify to the truth of what is said. For you see, the connection which must be formed between spiritual science and empirical sciences of today demands very far-reaching and extensive work. But when lines of direction are once given, this work can to some extent be undertaken and carried forward. It is at all events possible. One must only be able in a quite definite way to penetrate into the empirical phenomena.

If we now tackle the problem from quite another angle,—we have sought to some degree to understand it from the mathematical aspect, then, to anyone who is studying the human organism, there is something which cannot escape unnoticed, something which has often been brought forward in our circle, especially in the talks which accompanied the course of lectures on Medicine in Dornach in the spring of 1920. It is not to be overlooked that certain relationships exist between the organisation of the head and the rest of the human organisation, for example the metabolism. There is indeed a connection, indefinable to begin with, between what takes place in the third system of the human being—in all the organs of metabolism—and what takes place in the head. The relationship is there, but it is hard to formulate. Clearly as it emerges in various phenomena,—for example, it is obvious that certain illnesses are connected with skull or head deformities and the like, and these things can easily be traced by one who tries to follow them with biological reasoning,—it nevertheless difficult to grasp this relationship in imagination. People do not usually get beyond the point of saying that there must be some sort of connection between what takes place in the head, for instance, and in the rest of the human organism. It is a picture which is difficult to form, just because it is so very hard for people to make the transition from the quantitative aspect to the qualitative. If we are not educated through spiritual-scientific methods to find this transition, quite independently of what outer experience offers,—to extend to what is qualitative the kind of thought we use for what is quantitative, if we do not methodically train ourselves to do this, then, my dear friends, there will always be an apparent limit to our understanding of the external phenomena.

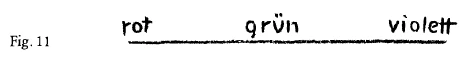

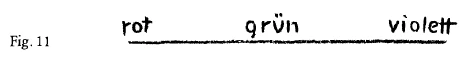

Let me indicate but one way in which you can train yourselves methodologically to think the qualitative in a similar way as you think the quantitative. You are all acquainted with the phenomenon of the solar spectrum, the usual continuous spectrum. You know that we have there the transition of colour from red to violet. You know, too, that Goethe wrestled with the problem of how this spectrum is in a sense the reverse of what must arise if darkness be allowed to pass through the prism in the same way as is usually done with light. The result is a kind of inverted spectrum, and as you know Goethe arranged this experiment also. In the ordinary spectrum, the green passes over on the one side towards the violet and on the other towards the red; whereas in the spectrum obtained by Goethe in applying a strip of darkness to the prism there is peach-blossom in the middle and then again red on the one side and violet on the other (Fig. 11). The two colour bands are obtained, the centres of which are opposite to one another, qualitatively opposite, and both bands seem to stretch away as it were into infinity. But now, one can imagine that this axis, the longitudinal axis of the ordinary spectrum, is not simply a straight line, but a circle, as indeed every straight line is a circle. If this straight line is a circle, it returns into itself, and we can consider the point where the peach-blossom appears to be the same point as the one in which the violet, stretching to the right, meets the red, which stretches to the left. They meet in the infinite distance to the right and left. If we were to succeed—maybe you know that one of the first experiments to be made in our newly established physical laboratory is to be in this direction—if we were to succeed in bending the spectrum in a certain way into itself, then even those who are not willing to grasp the matter to begin with in pure thought will be able to see that we are here concerned with something real and of a qualitative nature.

We come to certain limiting ideas in Mathematics, where—as in Synthetic Geometry—we are obliged to regard the straight line as a circle in a quite real though inner sense; where we are obliged to admit of the infinitely distant point of a straight line as being only one point; or to understand as bounding a plane, not some line above and then again below, but a single straight line; or to think of the boundary of infinite space, not in the nature of something spherical, but as a plane. Such ideas, however, also become, in a way, limiting ideas for sense-perceptible empirical reality, and we are made to realise it if we insist on restricting ourselves to sense-perceptible reality.

This brings us to something which would otherwise always remain perpetually in the dark. I have already mentioned it. It invites us really to think-through the thought-pictures to which we come when we allow the lemniscate-form of the Cassini curve to pass over into the double-branched form,—the form with the two branches for which we must go out of space,—and them compare this with what confronts us in the empirical reality.

You are indeed already doing this, my dear friends, when you apply Mathematics in one way or another to the empirical reality. You call a triangle a triangle, because you have first constructed it mathematically. You apply to the outer form what has been evolved in an inner constructive way within you. The process I have just described is only more complicated, but it is the same process when you think of the two branches of that particular form of the Cassini curve as one. Apply this thought to the correspondence between the human head and the rest of the human organism and you will have to realise that in the head there is a connection with the remaining organism of precisely such a character as is expressed by the equation which requires, not a continuous curve, but a discontinuous one. This cannot be followed anatomically; you must go out beyond what the body comprises physically, if you would find the connection of what comes to expression in the head with what comes to expression in the metabolic system. It is essential to approach the human organism with thoughts which are quite unattainable if for every element of the thought you insist on an entire correspondence within the sense-perceptible empirical realm. We must reach out to something else, beyond the sense-perceptible empirical realm, if we are to find what this relationship really is within the human being.

Such a study, if one really gives oneself up to it and carried it out methodically, is extraordinarily rich in its results. The human organisation is of such a nature that it cannot be embraced by the anatomical approach alone. Just as we are driven out of space in the Cassini curve, so in the study of man we are driven out of the body, by the method of study itself. You see, it is quite possible to understand in the first place in thought, that in a study of the whole man we are driven out of the realm of what can be grasped in a physical-empirical sense. To put forward such things is no offence against scientific principles. Such ideas are far removed from the purely hypothetical fantasies which are often entertained in connection with natural phenomena, for they refer to the whole way in which man is membered into the universe. You are not looking for something which is otherwise non-existent, but rather for something which is exactly the same as what is expressed in the relationship between a man thinking mathematically and the empirical reality.

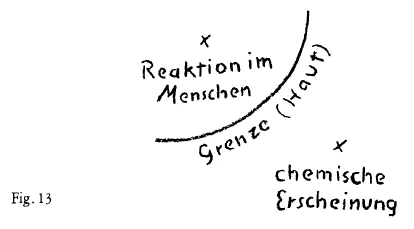

It is not a question of looking for hypotheses which in the end are unjustifiable; it is a question, since the reality is obviously complicated, of looking for other cognitive relations to the inner reality, in addition to the simple relation of mathematical man to empirical reality. When once you have accepted such thoughts, you will also be led to ask whether what takes place outside the human being in other domains besides the astronomical,—for example, in those phenomena which we call the chemical and physical,—whether those same phenomena, which we regard as chemical phenomena outside of man, take the same course within man, when he is alive, as they do outside him, or whether here, too, a transition is necessary which leads in some way out of space.

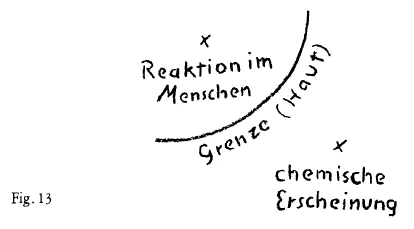

Now consider the important question arising out of this. Suppose we have here some kind of chemical phenomena and here the boundary leading over to the inside of the human being (Fig. 13). Supposing that this chemical phenomenon were able to call forth another, so that the human being reacted here (inside); then, if we remain in the field of the empirical, space would of course be the mediator. If, however, the continuance of this phenomenon within the human being comes about by virtue of the fact, say, that the human being is nourished by food, and the processes already taking place outside him continue inside him, then the question arises: Does the force which is at work in the chemical process remain in the same space when it taking place within man as when it is taking its course outside him? Or must we perhaps go out of space?

And there you have what is analogous to the circle which changes over into a straight line. If you look for its other form, where what is usually turned outward is now turned inward, you are entirely outside of space.

The question is, whether we do not need such ideas as these, thought-pictures which, while remaining continuous, go right out of space,—when we follow the course of what happens outwardly, outside of man, into the interior of the human being. The only thing to be said against such things, my dear friends, is that they certainly impose greater demands on the human capacity of understanding than the ideas with which he phenomena are approached today. They might therefore be rather awkward in University education. They are, no doubt, thoroughly awkward, for they imply that before approaching the phenomena we must awaken in ourselves what will enable us to understand them. Nothing like this exists in our educational system today; but it must come, it must certainly come, otherwise simply in speaking of a phenomenon we get into the greatest disparities, without in any way seeing the reality. Just think what happens when someone observes the circle as it curves to this side (Fig. 9a), and then sees how it curves to this side (Fig. 9b), but then remains a philistine and simple does not conceive that the circle now curves towards the other side. He says: This is impossible, the circle cannot curve this way; I must put the curvature this way round, I must simply place myself on the other side. What he is speaking about seems to be one and the same thing; but he has changed his point of view.

In this way today we make matters simple, in describing what is within the human being in comparison with what takes place in Nature outside him. We say: What is within man does not exist at all; I must simply place myself within man and say that the curvature is facing this way (Fig. 9c). I will then consider what is inside, without taking into account that I have reversed the curvature. I will make the interior of the human being into an outer Nature. I simply imagine outer Nature to continue through the skin into the interior. I turn myself round, because I am not willing to admit the other form of curvature, and then I theorise. That is the trick which is performed today, only in order to adhere to more comfortable motions. There is no desire to accent what is real; in order not to have to do so, we simply turn ourselves round, and—this is now a comparison—instead of looking at the human from in front, we look at Nature from behind and thus arrive in this way at all the various theories concerning man.

We will continue, then, tomorrow.

Neunter Vortrag

Wir sind jetzt an einem Punkt unserer Betrachtungen angekommen, von dem aus wir gewissermaßen außerordentlich vorsichtig weiterschreiten müssen, damit wir klar sehen, inwieweit die Gefahr besteht, aus der Realität hinauszukommen mit den Vorstellungen, oder ob wir eben innerhalb realer Vorstellungen bleiben, das heißt der Gefahr entgehen.

Nun handelt es sich ja darum, daß wir das letzte Mal hingestellt haben gewissermaßen als ein Postulat, einfach die beiden Tatsachen zu vergleichen: Innerhalb des Planetensystems das Auftreten der kometarischen Erscheinungen und - schließlich ja auch innerhalb des Planetensystems, wenn es auch vielleicht nicht in demselben Zusammenhang damit steht - dasjenige, was wir beobachten in den Erscheinungen der Befruchtung. Um aber hier überhaupt zu Vorstellungen zu kommen, die in irgendeiner Weise berechtigt sind, muß man einmal sehen, ob es denn möglich ist, zwischen zwei Dingen, die uns so entfernt in der äußeren Tatsachenwelt entgegentreten, Beziehungen aufzusuchen. Und wir werden methodologisch zu keinem Ziel kommen, wenn wir nicht auf irgend etwas hinweisen können, wo etwas Ähnliches vorliegt, das uns dann in der Betrachtungsweise weiterleiten könnte.

Wir haben ja gesehen, wie wit auf der einen Seite das Figurale, das Formhafte, das Mathematische anwenden müssen, wie wir aber immer wiederum dazu gedrängt werden, das Qualitative in irgendeiner Weise zu fassen, dem Qualitativen irgendwie näherzukommen. Wir wollen deshalb heute etwas einfügen, was sich mit Bezug auf den Menschen ergibt, wenn man diesen Menschen betrachtet, der ja schließlich doch ein Abbild ist, wie wir aus allen einzelnen Dingen dieser Vorträge entnehmen können, ein Abbild der Himmelserscheinungen in irgendeiner Weise, die wir noch festzustellen haben. Da der Mensch das ist, so müssen wir irgendwie über den Menschen selbst erst uns Klarheit verschaffen. Wir müssen gewissermaßen das Bild verstehen, von dem wir ausgehen wollen, wir müssen die innere Perspektive verstehen. Wie man bei einem gemalten Bilde auch zunächst sich klar sein muß, was irgendeine Verkürzung oder so etwas bedeutet, um von dem Bilde auf die Raumverhältnisse überzugehen, um also das Bild auf seine Wirklichkeit zu beziehen, so müssen wir, wenn wir auf die Realität im Weltenall interpretierend vom Menschen aus eingehen wollen, zuerst über den Menschen uns klar sein. Nun ist es aber außerordentlich schwierig, dem Menschen, der man ja selber ist, mit irgendwelchen faßbaren Vorstellungen beizukommen. Daher möchte ich heute Ihnen aus sehr einfachen Verhältnissen, ich möchte sagen, faßbar-unfaßbare Vorstellungen vor die Seele führen, Vorstellungen, die wahrscheinlich die meisten von Ihnen längst gut kennen, aber die wir doch in einem gewissen Zusammenhang uns vor die Seele führen müssen, damit wir an diesen Vorstellungen, die zum Teil scheinbar recht gut zu fassen sind, zum Teil aber durchaus wiederum unfaßbar erscheinen in gewissen Grenzen, uns orientieren in bezug auf das Ergreifen überhaupt der Außenwelt durch die Vorstellungen.

Es könnte erzwungen erscheinen, daß hier immer wiederum betont wird, daß man, um die Himmelserscheinungen zu begreifen, auf das Vorstellungsleben des Menschen zurückgehen muß. Aber es ist doch klar, daß wir, wenn wir auch noch so vorsichtig Beschreibungen der Himmelserscheinungen geben, darin ja doch zunächst nichts anderes haben als eine Art optischer Bilder, durchtränkt von allerlei mathematischen Vorstellungen. Dasjenige gerade, was uns die Astronomie gibt, hat den Grundcharakter, ein bloßes Bild zu sein. Wir müssen daher eingehen auf die Entstehung des Bildes im Menschen, wenn wir zurechtkommen wollen, sonst werden wir gar keine richtige Stellung gewinnen können zu dem, was uns die Astronomie sagen kann. Und da möchte ich heute von etwas ganz einfachem Mathematischen ausgehen, um Ihnen zu zeigen, wie auf einem anderen Gebiet als dem, auf das wir geführt worden sind durch die Verhältniszahlen der Umlaufzeiten der Planeten, innerhalb der Mathematik selbst eine Art Unfaßbares auftritt. Das tritt uns entgegen, wenn wir gebräuchliche Kurven in einem gewissen Zusammenhang betrachten. Viele von Ihnen kennen die Sache schon, ich möchte nur von einem besonderen Gesichtspunkte aus sie heute beleuchten.

Wenn wir dasjenige betrachten, was Sie als Ellipse kennen mit ihren zwei Brennpunkten \(A\) und \(B\), so wissen Sie ja, daß die Ellipse dadurch charakterisiert ist, daß irgendein Punkt \(M\) der Ellipse so sich verhält, daß die Summe seiner Abstände \(a + b\) von den zwei Brennpunkten stets konstant bleibt. Das ist die Charakteristik der Ellipse, daß die Summe der Abstände irgendeines ihrer Punkte von zwei fixen Punkten, den zwei Brennpunkten, konstant bleibt (Fig. 1).

Dann haben wir eine zweite Kurve, die Hyperbel (Fig. 2). Sie wissen ja, sie hat zwei Äste. Sie ist dadurch charakterisiert, daß die Differenz \(a-b\) der Abstände irgendeines Punktes von den zwei Brennpunkten eine konstante Größe ist. Nun hätten wir also in der Ellipse die Kurve der konstanten Summe, in der Hyperbel die Kurve der konstanten Differenz, und wir werden uns nun fragen müssen: Welches ist die Kurve des konstanten Produktes?

Ich habe ja schon öfter darauf aufmerksam gemacht, diese Kurve des konstanten Produktes ist die sogenannte Cassinische Kurve (Fig. 3). Betrachten wir die Sache in der folgenden Weise: Wir haben hier zwei Punkte \(A\) und \(B\), und wir betrachten einen Punkt \(M\) in bezug auf seine Abstände von \(A\) und \(B\). Wir haben also den einen Abstand AM, den anderen Abstand \(BM\), und wir stellen die Forderung, daß diese beiden Abstände, miteinander multipliziert, gleich seien einer konstanten Größe. Ich will diese konstante Größe, weil das die Rechnung vereinfacht, \(b^2\) nennen, und den Abstand \(AB\) will ich \(2a\) nennen. Wenn wir die Mitte zwischen \(A\) und \(B\) als den Mittelpunkt eines Koordinatenachsen-Systems annehmen \(O\) und für jeden Punkt, der diese Bedingung erfüllt, die Ordinate berechnen - wenn wir also hier herumlaufen lassen den Punkt, so daß immer bei jedem Punkt dieser Kurve \(AM \cdot BM = b^2\) bleibt -, so bekommen wir für die Ordinate irgendeines Punktes, die wir y nennen, die folgende Gleichung - ich werde Ihnen nur die Resultate mitteilen, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil ja die Ausrechnung jeder auf einfache Weise sich verschaffen kann. Sie ist in jedem mathematischen Lehrbuch, das diese Dinge enthält, zu finden. Wir bekommen für \(y\) den Wert:

$$ y = \pm \sqrt{- (a^2 + x^2) \pm \sqrt{b^4 + 4a^2x^2}} $$

Wenn man hier (vor der inneren Wurzel) berücksichtigt, daß wir ja das negative Vorzeichen nicht brauchen können zunächst, weil wir dadurch imaginäre y bekommen würden, also nur das positive Vorzeichen berücksichtigen, so bekommen wit:

$$ y = \pm \sqrt{- (a^2 + x^2) + \sqrt{b^4 + 4a^2x^2}} $$

Wenn wir dann die entsprechende Kurve ziehen, bekommen wir eine ellipsenähnliche, aber durchaus nicht mit der Ellipse zusammenfallende Linie, welche die Cassinische Kurve nach ihrem Entdecker genannt wird. Sie ist nach links und rechts symmetrisch zur Ordinatenachse, nach oben und unten symmetrisch zur Abszissenachse. Das ist, was festgehalten werden muß.

Nun aber hat diese Kurve verschiedene Formen, und das ist das Wichtige an ihr, für uns wenigstens. Diese Kurve hat verschiedene Formen, je nachdem \(b\), wie ich es hier angenommen habe, größer ist als \(a\), oder \(b\) gleich ist \(a\), oder \(b\) kleiner ist als \(a\). Die Kurve, die ich eben aufgezeichnet habe, entsteht dann, wenn \(b > a \) und außerdem noch eine gewisse Bedingung erfüllt wird, nämlich diejenige, daß \(b\) auch größer oder gleich ist \(a\sqrt{2}\). Und zwar, wenn \( b \gt a\sqrt{2}\), so haben wir hier oben und unten eine deutliche Krümmung. Wenn \( b = a\sqrt{2}\), so geht an diesem Punkte oben und unten die Kurve in die Gerade über, es flacht sich die Kurve so ab, daß sie oben und unten fast eine Gerade ist (Fig. 4). Kommen wir aber dazu, daß \( b \lt a\sqrt{2}\), dann ändert sich der ganze Verlauf der Kurve. Sie bekommt diese Form (Fig. 5). Und ist nun \(b = a\), dann geht die Kurve in eine ganz spezielle Form über, in diese Form (Fig. 6). Sie läuft gewissermaßen in sich zurück, durchschneidet sich selber und findet sich wiederum, und wir bekommen die spezielle Form der Lemniskate, so daß also die Lemniskate eine besondere Form der Cassinischen Kurve ist. Die besondere Form wird hervorgerufen durch das Verhältnis der in der Gleichung der Kurve, der Charakteristik der Kurve vorkommenden konstanten Größen. Wir haben in der Gleichung nur diese zwei konstanten Größen \(b\) und \(a\), und von dem Verhältnis dieser zwei konstanten Größen hängt die Form der Kurve \(ab\).

Nun ist aber noch der dritte Fall möglich, daß \(b \lt a\). Wenn \(b \lt a\), so bekommt man auch Werte für die Kurve. Man kann immer die Gleichung auflösen und bekommt Werte für die Kurve, Ordinaten und Abszissen, auch wenn man \(b\) kleiner hat als \(a\), nut setzt gewissermaßen die Kurve ihr eigentümliches Verhalten fort. Denn dann, wenn \(b \lt a\), bekommen wir zwei Äste der Kurve, die ungefähr so aussehen (Fig. 7). Wir bekommen eine diskontinuierliche Kurve. Hier stehen wir eben an dem Punkte, wo gewissermaßen in der Mathematik uns entgegenspringt das Faßbar-Unfaßbare, das heißt, das im Raum schwer zu Fassende. Denn das sind im Sinne ihrer mathematischen Gleichung nicht zwei Kurven, das ist eine Kurve, genau ebenso eine Kurve, wie diese oder diese oder diese (Fig. 3-5). Bei dieser da (Lemniskate) liegt die Sache schon im Übergang. Da macht der Punkt, den die Kurve beschreibt, diesen Weg, geht hier herunter, durchschneidet hier seinen früheren Weg und findet sich wiederum. Hier (Fig. 7) müssen wir uns vorstellen: Wenn wir den Punkt \(M\) bewegen lassen in dieser Linie - er durchläuft nicht etwa die Bahn einfach hier herüber, das tut er nicht, sondern er durchläuft geradeso wie hier (Lemniskate) den Weg, beschreibt hier eine Kurve und kommt dann wiederum dazu, sich hier zu finden.

Also Sie sehen: Dasjenige, was den Punkt durch die Linien trägt, das verschwindet hier in der Mitte. Sie können sich nur vorstellen, daß das in der Mitte verschwindet, wenn Sie die Kurve verstehen wollen. Wenn Sie hier versuchen, eine Vorstellung sich zu bilden, die im Vorstellen rein kontinuierlich bleibt, was müssen Sie denn da tun? Nicht wahr, wenn Sie sich eine solche Kurve (die ersten drei Formen) vorstellen — das sage ich nur in Parenthese für gewöhnliche Philister -, dann ist das leicht. Sie können immerfort einen Punkt vorstellen und Sie kommen nicht dazu, daß Ihre Vorstellung abreißt. Hier (bei der Lemniskate) müssen Sie ja allerdings schon die bequeme Art, einfach herumzugehen, modifizieren. Da geht es aber noch immer. Sie können das Vorstellen festhalten. Aber jetzt weiter, wenn Sie bei dieser Kurve (Form mit zwei Ästen), die eben nicht eine Philisterkurve ist, ankommen, wenn Sie die votstellen wollen, dann müssen Sie, um im kontinuierlichen Vorstellen zu bleiben, sich sagen: Der Raum gibt mir dazu keinen Anhaltspunkt mehr. Ich muß, indem ich hier (von 1 nach 2) vorschreite mit meinem Vorstellen, wenn ich nicht das Vorstellen abreißen und den anderen Ast isoliert für sich betrachten will, ich muß mit meinem Vorstellen aus dem Raum heraus (nach 3 bis 4), ich kann nicht drinnen bleiben im Raum. Also Sie sehen, die Mathematik selber liefert uns Tatsachen, die es für uns notwendig machen, aus dem Raum herauszugehen, wenn wir im kontinuierlichen Vorstellen bleiben wollen. Die Wirklichkeit, sie ist so, daß sie an uns den Anspruch stellt, aus dem Raum herauszugehen mit unserem Vorstellen. Da also tritt uns etwas innerhalb der Mathematik selber auf, wo gewissermaßen sich zeigt, daß wir den Raum verlassen müssen, wenn wir einfach mit dem Vorstellen zurechtkommen wollen. In dem, was wir selber mit dem Vorstellen angerichtet haben, indem wir angefangen haben zu denken, müssen wir in einer solchen Weise weiter denken, daß uns der Raum nichts mehr hilft. Sonst würde nicht allen Möglichkeiten in der Gleichung Rechnung getragen werden.

Nun, solche Dinge treffen wir, wenn wir ein ähnliches Vorstellen durchmachen, mehrere. Ich will nur noch auf das Allernächstliegende aufmerksam machen, das dann für Ste sich realisiert, wenn Sie nun die Frage aufwerfen: Also, die Ellipse ist der geometrische Ort der konstanten Summe, sie ist dadurch charakterisiert, daß sie die Linie der konstanten Summe ist. Die Hyperbel ist die Kurve der konstanten Differenz. Die Cassinische Kurve mit ihren verschiedenen Formen ist die Linie des konstanten Produkts. Es muß also auch irgendwie, wenn wir hier \(A\), hier \(B\) haben, hier einen Punkt \(M\) und nun \(BM\) durch \(AM\) als Quotienten bilden, es muß auch eine solche Linie der konstanten Quotienten sich finden. Wir müssen also verschiedene Punkte finden, \(M_1\), \(M_2\) usw., für die immer

$$\frac{BM_1}{AM_1} = \frac{BM_2}{AM_2}$$

usw. einander gleich sind und immer einer bestimmten konstanten Zahl gleich sind. Diese Kurve ist ja der Kreis. Wir bekommen dann, wenn wir die Punkte \(M_1\), \(M_2\) suchen, einen Kreis, der etwa in diesem Verhältnis zu den Punkten \(A\) und \(B\) liegt (Fig. 8). So daß wir sagen können: Es gibt neben der Definition des Kreises, die die triviale Definition ist - daß nämlich der Kreis der geometrische Ort aller Punkte ist, die von einem festen Punkt gleich weit abstehen -, eine andere Definition des Kreises: Der Kreis ist diejenige Linie, bei der jeder Punkt die Bedingung erfüllt, daß seine Abstände von zwei konstanten Punkten, zwei fixen Punkten, in ihren Quotienten gleich sind.

Nun, hier beim Kreis haben wir die Möglichkeit, noch auf etwas anderes hinzuschauen. Denn sehen Sie, wenn wir \(BM:AM\) ausdrücken dutch \(m:n\), also

$$\frac{BM}{AM} = \frac{m}{n}$$

so bekommen wir immer entsprechende Werte in der Gleichung. Wir können den Kreis irgendwo finden. Und wenn man das tut, so bekommt man verschiedene Formen des Kreises, je nachdem das Verhältnis von \(m\) zu \(n\) ist: Wenn \(n\) stark größer ist als \(m\), bekommen wir einen stark gebogenen Kreis; wenn \(n\) kleiner wird, bekommen wir einen geringer gebogenen Kreis (Fig. 8, rechts), und so wird der Kreis immer größer, je weniger sich \(m\) von \(n\) unterscheidet. Und der Kreis geht dann, wenn man dieses Verhältnis \(m:n\) weiter verfolgt, allmählich über in eine Gerade. Sie können das in der Gleichung verfolgen. Er geht über in die Ordinatenachse selber. Der Kreis wird die Ordinatenachse, wenn \(m = m\), wenn also der Quotient \(m:n\) gleich \(1\) wird. Auf diese Weise geht also der Kreis allmählich über in die Ordinatenachse, in eine Gerade.

Es braucht Ihnen nicht besonders verwunderlich zu erscheinen, daß dies geschieht. Das ist ja etwas, was man sich vorstellen kann. Nun aber liegt die Sache dann anders, wenn man hier weitergehen will, wenn man sich sagt, der Kreis flacht sich immer mehr und mehr ab und wird gewissermaßen durch Abflachen von innen eine Gerade. Er wird es dadurch, daß einfach das konstante Verhältnis in dieser Gleichung eine Änderung erfährt. Es kann natürlich dieses konstante Verhältnis auch noch über 1 hinauswachsen, so daß die Kreisbögen hier erscheinen (links von der \(y\)-Achse), aber was hat man dann nötig mit seiner Vorstellung zu tun? Man hat etwas ganz Besonderes nötig. Man hat sich dann nämlich einen Kreis zu denken, der nicht nach innen gekrümmt ist, sondern der nach außen gekrümmt ist. Ich kann Ihnen natürlich diesen Kreis nicht aufzeichnen, aber es ist ein Kreis denkbar, der nach außen gekrümmt ist.

Nicht wahr, beim gewöhnlichen Kreis haben wir die Krümmung nach innen (Kreis a der Fig. 9, schraffierte Seite). Wenn wir seinen Weg verfolgen, so schließt er sich. Wenn wir die Konstante, die wir in der Gleichung haben, in entsprechender Weise nehmen, so bekommen wir eine Gerade. Die hat ihre Krümmung hier wiederum (rechts der Geraden, schraffierte Seite). Aber diese Krümmung, die macht es uns nicht so bequem, wie es uns die andere Krümmung machte. Die andere Krümmung tendiert überall nach dem Mittelpunkt des Kreises. Diese Krümmung (bei der Geraden) verweist uns darauf, daß der Mittelpunkt irgendwo in unendlicher Entfernung liegt, wie man sagt. Aber nun entsteht uns hier (links der Geraden) der Gedanke eines Kreises, der nach außen gekrümmt ist. Seine Krümmung ist dann nicht da (Kreis b, nicht schraffierte Seite), das wäre ja der Philisterkreis, sondern seine Krümmung ist da (Kreis b, schraffierte Seite). Und eben deshalb ist nicht dieses hier (nicht schraffiert) die Innenseite des Kreises, sondern das Außen des Kreises, und das da (schraffiert) ist das Innen des Kreises.

Und nun bitte ich Sie, vergleichen Sie damit dasjenige, was ich Ihnen hier dargestellt habe: die Cassinische Kurve mit ihren Unterarten, mit der Lemniskate und der Form, wo sie die zwei Äste hat. Und jetzt haben wir den Kreis dargestellt so, daß er einmal eine solche (gewöhnliche) Krümmung hat, daß dieses hier sein Innen, das sein Außen ist. Wir haben eine zweite Form des Kreises (\(b\)) - man kann jetzt nur den Kreis andeuten -, wo die Krümmung hier ist (außen) und hier ein Innen (schraffiert) und hier ein Außen (nicht schraffiert). Die erste Form des Kreises würde etwa entsprechen, wenn wir sie vergleichen mit der Cassinischen Kurve, den geschlossenen Formen derselben bis zur Lemniskate. Und wir haben jetzt einen zweiten Kreis (\(b\)), der nach dieser Richtung gedacht werden muß (nach außen), der seine Krümmung hier hat, sein Innen hier, sein Außen hier. Sie sehen, die Realität ist hier so, daß, wenn wir es mit dem Produkt zu tun haben, wir Formen der Cassinischen Kurve bekommen, wo wir, wenn wir aus dem Raum herausgeworfen werden, wiederum auf der anderen Seite den anderen Ast zeichnen können. Der liegt dann im Raume wieder drinnen. Aber wir werden, um von einem zum anderen zu kommen, aus dem Raume eben herausgeworfen. Hier, beim Kreis, wird die Sache schon schwieriger. Hier werden wir ja ganz gewiß auch beim Übergang vom Kreis in die Gerade aus dem Raum herausgeworfen, aber wir können dann überhaupt nicht mehr irgend etwas Geschlossenes zeichnen. Wir kommen nicht dazu. Wir können den Gedanken gerade noch räumlich andeuten, wenn wir übergehen von der Kurve des konstanten Produktes zur Kurve des konstanten Quotienten.

Es ist außerordentlich bedeutsam, daß man sich abgibt mit dem Erzeugen von Vorstellungen, die, möchte ich sagen, in solche Kurvenformen noch hineinschlüpfen. Ich bin überzeugt davon, daß die meisten derjenigen Menschen, die sich mit Mathematik abgeben, zwar zu solchen Diskontinuitäten übergehen, aber dann sich das Vorstellen doch eigentlich etwas bequem machen, indem sie sich bloß an dasjenige halten, was eben die Formeln sind und nicht übergehen zu irgend etwas, was nun die Formeln begleiten soll als eine wirklich kontinuierliche Vorstellung. Ich habe auch noch niemals gesehen, daß in der Behandlung des mathematischen Lehrstoffes ein großer Wert darauf gelegt wird, solche Vorstellungen auszubilden. Nun weiß ich nicht, ich frage die anwesenden Mathematiker, Herrn Blümel, Herrn Baravalle, ob das nicht so ist, ob also irgendwie heute im Hochschulunterricht ein großer Wert darauf gelegt wird? (Herr Dr.Carl Unger macht aufmerksam auf kinematographische Darstellungen.) Ja, das ist ein Pseudoverlauf, wenn man es irgendwie innerhalb des empirischen Raumes machen will, also durch solchen Kinematographen oder dergleichen. Dann muß man hier einen Schwindel einfügen. Es ist nicht möglich, es im empirischen Raum adäquat darzustellen, man muß einen Schwindel einfügen.

Es handelt sich nun darum, ob es irgendwo in der Realität etwas gibt, was uns nötigt, in solchen Kurven real zu denken. Das ist dasjenige, was ich als Frage aufwerfen möchte. Dazu aber möchte ich, noch bevor ich übergehe zur Charakteristik dessen, was etwa in der Wirklichkeit dem entsprechen könnte, etwas einfügen, was Ihnen vielleicht den Übergang zu der Wirklichkeit von diesen abstrakten Vorstellungen erleichtern kann. Das ist das Folgende. Sie können auch noch ein anderes Problem in der theoretischen Astronomie, in der theoretischen Physik stellen. Sie können nämlich das Problem stellen: Nehmen wir an, hier wäre eine Lichtquelle in \(A\) und diese Lichtquelle in \(A\) beleuchte einen Punkt \(M\) (Fig. 10). Dieser Punkt \(M\) würde mit Bezug auf die Stärke seines Leuchtglanzes in \(B\) beobachtet. Also, man beobachtet von \(B\) aus irgendwie mit den entsprechenden optischen Instrumenten den Leuchtglanz des Punktes \(M\), der von \(A\) beleuchtet ist. Wir würden ja selbstverständlich die Stärke dieses Leuchtglanzes verschieden sehen, je nachdem \(B\) von \(M\) entfernt ist. Aber es gibt eine Bahn, die dieser Punkt \(M\) beschreiben kann, die so verläuft, daß, wenn er von \(A\) beleuchtet ist, er in \(B\) immer mit derselben Glanzstärke strahlt. Es gibt eine solche Bahn.

Wir können also fragen: Welches muß die Bahn eines Punktes sein, der von einem fixen Punkte \(A\) beleuchtet wird, damit er in einem anderen fixen Punkte \(B\) im Glanz immer dieselbe Stärke hat? Und diese Kurve, in der ein solcher Punkt sich bewegt, das ist die Cassinische Kurve! Sie sehen daraus, daß hier sich hineinstellt in ein Raumverhältnis, in eine komplizierte Kurve dasjenige, was nun schon in das Qualitative hinüberfällt. Die Qualität, die wir ja schon im Leuchtglanz sehen, in der Stärke des Glanzes sehen müssen, diese Qualität wird hier abhängig von dem Figuralen in den Raumverhältnissen.

Nun, ich wollte dieses nur anführen, damit Sie sehen, daß allerdings eine Art Weg hinüberführt aus dem figural-geometrisch zu Erfassenden in das Qualitative. Aber dieser Weg ist in einer gewissen Beziehung doch wiederum weit. Und wir wollen jetzt auf etwas übergehen, was allerdings, um es in allen Einzelheiten darzustellen, Monate fordern würde, auf das ich Sie aber hinweisen will. Und Sie müssen dabei durchaus berücksichtigen, daß ich ja nur Richtlinien angeben will, deren weitere Ausführung, namentlich deren Ausführung in bezug auf die Einzelheiten, wo Sie sie immer verifiziert finden werden, eigentlich Ihnen überlassen bleibt. Denn sehen Sie, das, was als eine Beziehung zwischen Geisteswissenschaft und den heutigen empirischen Wissenschaften eintreten muß, das ist eine sehr breite Arbeit, eine ungeheuer breite Arbeit. Aber wenn Richtlinien einmal gegeben sind, so kann diese Arbeit in einer gewissen Weise ausgeführt werden. Sie ist möglich. Man muß sich nur hineinfinden in die empirischen Erscheinungen in einer ganz bestimmten Weise.

Wenn wir nun das Problem von einem ganz anderen Orte aus ergreifen — wir haben es jetzt gewissermaßen von der mathematischen Seite her zu ergreifen versucht -, so kann demjenigen, der sich mit der menschlichen Organisation befaßt, etwas doch nicht entgehen, was innerhalb unseres Kreises ja schon öfter hervorgehoben worden ist, insbesondere auch in vieler Beziehung betont worden ist bei den Besprechungen, die sich an den Dornacher Ärztekurs im Frühling 1920 angeschlossen haben. Es kann ihm nicht entgehen, daß gewisse Verhältnisse bestehen zwischen der Organisation des Hauptes und der übrigen Organisation des Menschen, zum Beispiel der Organisation des Stoffwechsels. Es ist ein zunächst undefinierbarer Zusammenhang zwischen dem, was sich in dem dritten menschlichen System, im Stoffwechselsystem mit seinen Organen abspielt, und dem, was sich im Haupte abspielt. Dieses Verhältnis, das da vorhanden ist, das ist aber schwer zu fassen. So klar es in der Erscheinung auftritt, so klar man zum Beispiel sieht, daß mit gewissen Erkrankungen Schädel-, Kopfdeformationen zusammenhängen und ähnliche Dinge, so klar solche Dinge verfolgbar sind für den, der sie vernünftig biologisch verfolgt, so schwer sind sie vorstellungsgemäß zu fassen. Gewöhnlich bleiben dann die Leute stehen dabei, daß sie sagen: Es muß irgendeinen Zusammenhang geben zwischen dem, was sich im Haupt abspielt, und demjenigen, was sich in der übrigen Organisation des Menschen abspielt. - Es ist das deshalb eine schwer vollziehbare Vorstellung, weil es dem Menschen so schwer wird, eben gerade aus dem Quantitativen ins Qualitative überzugehen. Wenn man nicht erzogen wird durch eine geisteswissenschaftliche Methodologie, diesen Übergang doch zu finden und ganz unabhängig von dem, was einem die äußere Erfahrung bietet, doch gewissermaßen dieselbe Art des Vorstellens, die man im Quantitativen anwendet, auch auf das Qualitative auszudehnen, wenn man sich nicht methodologisch dazu erzieht, dann wird sich immer für unser Begreifen eine scheinbare Grenze der äußeren Erscheinungen aufrichten.

Ich möchte nur auf eines hinweisen, wie Sie sich erziehen können methodologisch, das Qualitative in einer ähnlichen Weise zu denken wie das Quantitative. Es ist Ihnen allen bekannt die gewöhnliche Erscheinung des Sonnenspektrums, des gewöhnlichen kontinuierlichen Spektrums. Sie wissen, da gehen wir von der Farbe des Rot zu der Farbe des Violett. Nun wissen Sie ja alle, daß Goethe mit dem Problem gerungen hat, wie dieses Spektrum in gewissem Sinne das umgekehrte Spektrum ist von dem, was enstehen muß, wenn man gewissermaßen die Dunkelheit geradeso behandelt durch das Prisma, wie man gewöhnlich die Helligkeit behandelt. Man bekommt dann eine Art umgekehrten Spektrums, das Goethe ja auch

angeordnet hat. Nicht wahr, beim gewöhnlichen Spektrum haben wir das Grün, hier nach dem Violetten gehend, auf der andern Seite nach dem Rot gehend (Fig. 11), und bei dem Spektrum, das Goethe bekommt, wenn er ein schwarzes Band auflegt, hat er hier das Pfirsichblüt und wiederum auf der einen Seite das Rot, auf der andern Seite das Violett (Fig. 12). Man bekommt gewissermaßen zwei Farbbänder, die in der Mitte einander entgegengesetzt sind, qualitativ entgegengesetzt sind, und die beide zunächst für uns, man möchte sagen, nach der Unendlichkeit verlaufen. Aber man kann sich zunächst einfach denken, daß diese Achse, die Längsachse des gewöhnlichen Spektrums, nicht eine einfache Gerade ist, sondern ein Kreis ist, wie ja jede Gerade ein Kreis ist. Wenn diese Gerade ein Kreis ist, dann kehrt sie in sich selbst zurück und dann können wir einfach diesen Punkt hier, in dem das Pfirsichblüt erscheint, als den anderen Punkt betrachten, in dem sich trifft das Violett, das nach rechts geht, und das Rot, das nach links geht. Es trifft sich ja links und rechts in unendlicher Entfernung. Aber wenn es uns gelingen würde - ich weiß nicht, ob Sie wissen, daß gerade nach dieser Richtung eine der ersten Versuchsanordnungen in unserem physikalisch-wissenschaftlichen Institut gemacht werden soll -, das Spektrum in gewisser Weise in sich zu biegen, dann würden auch diejenigen, die zunächst aus den Gedanken heraus die Sache nicht begreifen wollen, sehen, wie man es tatsächlich hier auch mit Qualitativem zu tun hat. Solche Vorstellungen sind Endvorstellungen des Mathematischen, wo wir genötigt sind, wie auch in der synthetischen Geometrie, die Gerade auch innerlich sachlich durchaus als einen Kreis anzusehen, wo wir genötigt sind, als unendlich fernen Punkt einer Geraden nur einen anzunehmen; wo wit genötigt sind, als eine Grenze der Ebene nicht oben und unten irgendeine Linie anzunehmen, sondern eine einzige Gerade als Grenze der Ebene anzunehmen; wo wir genötigt sind, die Grenzen des unendlichen Raumes nicht zu denken etwa sphärisch oder so etwas, sondern als eine Ebene. Aber solche Vorstellungen werden, wenn wit nur die sinnliche empirische Wirklichkeit betrachten wollen, auch in einer gewissen Weise Endvorstellungen der sinnlich-empirischen Wirklichkeit.

Nun, das leitet uns auf etwas, was sonst immer dunkel bleiben wird. Ich habe es eben erwähnt. Es leitet uns darauf, jene Vorstellungen, die wir gewinnen können, wenn wir die Lemniskatenform der Cassinischen Kurve übergehen lassen in die Zwei-Ast-Form, diese Zwei-Ast-Form, wo wit aus dem Raum heraus müssen, einmal ordentlich zu denken und dann das zu vergleichen mit demjenigen, was sich uns in der empirischen Wirklichkeit darbietet. Sie tun ja auch nichts anderes, wenn Sie die Mathematik sonst auf die empirische Wirklichkeit anwenden. Dasjenige, was Sie gegeben haben in dem Dreieck, das nennen Sie ein Dreieck, weil Sie sich das Dreieck zuerst mathematisch konstruiert haben. Sie wenden das, was innerlich konstruktiv in Ihnen ausgebildet ist, auf die äußere Form an. Es ist nur der Vorgang komplizierter, den ich jetzt angebe, aber es ist derselbe Vorgang, wenn Sie als eins denken die zwei Äste der zwei-ästigen Cassinischen Kurve. Wenden Sie diese Vorstellung an auf dasjenige, was im Haupte des Menschen den Dingen im übrigen Organismus entspricht, dann müssen Sie so denken, daß da im Haupte eine Abhängigkeit ist von dem übrigen Organismus, ausdrückbar durch einen ebensolchen Zusammenhang, durch die Gleichung, die aber eine diskontinuierliche Kurve verlangt. Sie können dies nicht verfolgen durch die anatomisierende Methode. Sie müssen aus dem, was den Körper physisch umfaßt, heraus, wenn Sie das, was im Haupte sich ausdrückt, in seinem Zuammenhang mit dem, was sich im Stoffwechsel-Organismus ausdrückt, verfolgen wollen. Sie müssen also durchaus mit Vorstellungen den menschlichen Organismus verfolgen, die nicht zu bekommen sind, wenn man für jedes einzelne Glied dieser Vorstellung eine adäquate sinnlich-empirische haben will. Man muß aus dem Sinnlich-Empirischen heraus zu etwas anderem, wenn man finden will, welches dieser Zusammenhang im Menschen ist.

Das ist, wenn man es weiter nun methodologisch verfolgt, wenn man sich wirklich einläßt auf eine solche Betrachtung, etwas, was außerordentlich aufschlußreich ist. Denn es gliedert in der Tat die menschliche Organisation in etwas ein, was nicht umfaßt werden kann, wenn man nur anatomisiert. Man wird, geradeso wie man durch die Cassinische Kurve herausgetrieben wird aus dem Raum, bei der Betrachtung des Menschen herausgetrieben aus dem Körper durch die Betrachtungsweise selbst. Es ist zunächst vorstellungsgemäß zu fassen, daß man, um den ganzen Menschen zu betrachten, herausgetrieben wird aus dem, was physisch-empirisch am Menschen zu fassen ist. Es ist durchaus nicht irgendeine Versündigung gegen die Wissenschaftlichkeit, wenn man solche Dinge anführt. Sie sind weit entfernt von dem, was öfter als reine Phantasien hypothetisch über die Naturerscheinungen gegeben wird. Denn diese Dinge gehen wirklich zurück auf die ganze Art, wie der Mensch in der Welt drinnensteht. Und Sie suchen nicht nach irgend etwas, was sonst nicht vorhanden ist, sondern Sie suchen nach etwas, was ganz dasselbe ist wie dasjenige, was sich im Verhältnis des mathematisierenden Menschen zur empirischen Wirklichkeit ausdrückt.

Es ist gar nicht die Frage, irgendwelche unberechtigte Hypothetisiererei zu suchen, sondern es ist nur die Frage, da die Wirklichkeit offenbar eine komplizierte ist, auch noch andere Erkenntnisverhältnisse zur inneren Wirklichkeit zu suchen, als es das einfache ist des mathematisierenden Menschen zu der physisch-empirischen Wirklichkeit. Und wenn Sie einmal auf solche Dinge hingesehen haben, dann werden Sie auch hingeleitet zu suchen, wie dasjenige, was außerhalb des Menschen geschieht auf anderen Gebieten als auf dem astronomischen, was geschieht außerhalb des Menschen zum Beispiel innerhalb derjenigen Erscheinungen, die wir die chemischen, die physikalischen nennen, dann werden Sie hingeleitet zu suchen, ob denn dieselben Erscheinungen, die wir außen als die chemischen betrachten, im Menschen, wenn er lebt, auch so verlaufen wie außerhalb des Menschen, oder ob sie da auch einen Übergang brauchen, der gewissermaßen aus dem Raum hinausführt.

Nun bedenken Sie die wichtige Frage, die daraus entsteht. Wir würden hier irgendeine chemische Erscheinung haben, hier die Grenze gegen das Innere des Menschen (Fig. 13). Würde diese chemische Erscheinung eine andere so hervorrufen können, daß der Mensch da (drinnen) reagiert, so würde selbstverständlich der Raum der Vermittler sein, wenn wir im empirischen Felde bleiben. Wenn aber diese Erscheinung sich fortsetzt im Menschen dadurch etwa, daß sich der Mensch durch die Nahrung ernährt und die Prozesse sich im Innern fortsetzen, dann ist die Frage: Bleibt das, was da an Kraft wirkt in der chemischen Tatsache, in demselben Raum dtinnen, in dem es sich abspielte draußen, wenn es sich im Menschen fortsetzt? Oder müssen wir vielleicht aus dem Raum heraus? Und da haben Sie das Analogon mit dem Kreis, der in eine gerade Linie übergeht. Und wenn Sie seine andere Form suchen, wo dasjenige, was sonst nach außen gewendet ist, nach innen gewendet ist, so sind Sie ganz aus dem Raume heraus.

Es ist die Frage, ob wir nicht solche Vorstellungen brauchen, die ganz aus dem Raume herausgehen, wenn sie kontinuierlich bleiben sollen, wenn wir das, was außen geschieht außerhalb des Menschen, weiter verfolgen in seinem Verlauf, wenn es sich nach dem Innern des Menschen hin fortsetzt. Das einzige, was zu sagen ist gegen solche Dinge, das ist, daß sie allerdings größere Anforderungen an die menschliche Kapazität stellen als diejenigen, mit denen man heute an die Erscheinungen herantritt, und daß sie deshalb auch im Hochschulunterricht unangenehm sind. Sie sind recht unangenehm, denn man müßte da eigentlich verlangen, daß der Mensch erst, bevor er herantritt an die Erscheinungen, etwas aufnehmen würde, was ihn befähigt, diese Erscheinungen zu erfassen. Es ist heute gar nichts Ähnliches überhaupt im Verlauf unseres Unterrichtes vorhanden, aber das muß hinein, das muß unbedingt hinein, sonst geraten wir einfach, von einer Erscheinung redend, durchaus ins Disparateste hinein, ohne daß wir irgendwie auf die Realität hinsehen. Denn bedenken Sie einmal: Was würde geschehen, wenn jemand den Kreis beobachtet, wie er sich nach dieser Seite krümmt (Fig.9, \(a\)), und er würde das hier betrachten, das sich nach dieser Seite krümmt (\(b\)), aber er bleibt der Philister, er geht absolut nicht ein darauf, daß sich jetzt der Kreis nach dieser Seite hin krümmt. Er sagt: Das gibt es ja gar nicht, daß sich der Kreis so krümmt, ich muß die Krümmung hierhetsetzen (Kreis \(c\) statt \(b\)), ich muß mich einfach auf die andere Seite stellen. Er spricht in diesem Falle scheinbar über dasselbe, nur verändert er seinen Standpunkt.

So macht man es nämlich heute einfach, indem man den Menschen innerlich schildert im Verhältnis zu dem, wie man die äußere Natur schildert. Man sagt: Dasjenige, was im Menschen drinnen ist, das gibt es ja gar nicht, sondern ich stelle mich in den Menschen hinein und sage: Dahin (c) ist die Krümmung gerichtet. Ich betrachte also das Innere ohne Rücksicht darauf, daß sich mir die Krümmung umdtreht. Ich mache das, was im Innern des Menschen ist, zu einer äußeren Natur. Ich setze mir einfach durch die Haut hindurch die äußere Natur fort. Ich drehe mich um, weil ich nicht mitgehen will mit der andersgearteten Krümmung, und dann theoretisiere ich, — Das ist das Kunststück, das heute eigentlich ausgeführt wird und das nur ausgeführt wird zur Festhaltung bequemer Vorstellungen. Man will nicht mit der Wirklichkeit gehen, und damit man das nicht zu tun braucht, kehrt man sich einfach um, und statt daß man den Menschen - das ist jetzt ein Vergleich - von der Vorderseite betrachtet, betrachtet man die Natur von der Hinterseite und gelangt dadurch zu den verschiedenen Theorien über den Menschen.

Hier wollen wir dann morgen weiter fortfahren.

Ninth Lecture

We have now reached a point in our considerations from which we must proceed with extreme caution, so to speak, in order to see clearly to what extent there is a danger of straying from reality with our mental images, or whether we remain within the realm of realistic mental images, that is, avoid the danger.

Now, the point is that last time we put forward, as it were, a postulate, simply to compare the two facts: within the planetary system, the occurrence of cometary phenomena and — ultimately, also within the planetary system, even if it may not be related to it in the same context — what we observe in the phenomena of fertilization. But in order to arrive at mental images that are in any way justified, we must first see whether it is possible to find connections between two things that appear so distant from each other in the external world of facts. And we will not achieve anything methodologically if we cannot point to something similar that could then guide us further in our consideration.

We have seen how, on the one hand, we must apply the figurative, the formal, the mathematical, but how we are always pressed to grasp the qualitative in some way, to somehow get closer to the qualitative. So today we want to add something that arises in relation to the human being when we look at this human being, who is, after all, an image, as we can gather from all the individual points in these lectures, an image of the phenomena of the heavens in some way, which we still have to determine. Since the human being is this, we must first somehow gain clarity about the human being itself. We must, so to speak, understand the image from which we want to proceed; we must understand the inner perspective. Just as with a painted picture, we must first be clear about what any foreshortening or something similar means in order to move from the picture to the spatial relationships, in order to relate the picture to its reality. so if we want to interpret reality in the universe from the perspective of human beings, we must first be clear about human beings. Now, however, it is extremely difficult to come to terms with human beings, who are ourselves, with any kind of tangible mental images. Therefore, today I would like to present to you, from very simple circumstances, I would say, tangibleintangible mental images, mental images that most of you are probably already familiar with, but which we must nevertheless bring to mind in a certain context so that we can orient ourselves in relation to grasping the outside world through mental images, which in some cases seem quite tangible, but in others appear completely intangible within certain limits.

It may seem forced to emphasize again and again that in order to understand celestial phenomena, we must return to the mental images of human beings. But it is clear that no matter how carefully we describe celestial phenomena, we still have nothing more than a kind of optical image, saturated with all kinds of mathematical ideas. What astronomy gives us has the fundamental character of being a mere image. We must therefore go into the origin of the image in human beings if we want to get along, otherwise we will not be able to gain a correct position on what astronomy can tell us. And today I would like to start with something very simple in mathematics to show you how, in a field other than the one we have been led to by the ratios of the orbital periods of the planets, something incomprehensible arises within mathematics itself. We encounter this when we consider common curves in a certain context. Many of you are already familiar with this, but I would like to shed light on it today from a special point of view.

If we consider what you know as an ellipse with its two foci \(A\) and \(B\), you know that the ellipse is characterized by the fact that any point \(M\) on the ellipse behaves in such a way that the sum of its distances \(a + b\) from the two foci always remains constant. This is the characteristic of the ellipse, that the sum of the distances of any of its points from two fixed points, the two foci, remains constant (Fig. 1).

Then we have a second curve, the hyperbola (Fig. 2). As you know, it has two branches. It is characterized by the fact that the difference \(a-b\) between the distances of any point from the two foci is a constant quantity. So now we have the curve of constant sum in the ellipse and the curve of constant difference in the hyperbola, and we must ask ourselves: Which is the curve of constant product?

I have already pointed out several times that this curve of constant product is the so-called Cassini curve (Fig. 3). Let us consider the matter in the following way: We have two points \(A\) and \(B\), and we consider a point \(M\) in relation to its distances from \(A\) and \(B\). So we have one distance AM and another distance \(BM\), and we require that these two distances, when multiplied together, be equal to a constant quantity. To simplify the calculation, I will call this constant quantity \(b^2\), and I will call the distance \(AB\) \(2a\). If we take the midpoint between \(A\) and \(B\) as the center point of a coordinate axis system \(O\) and calculate the ordinate for each point that satisfies this condition calculate the ordinate—if we let the point run around here so that \(AM \cdot BM = b^2\) remains true for every point on this curve—then we obtain the following equation for the ordinate of any point, which we call y. I will only give you the results, for the simple reason that anyone can easily work out the calculation themselves. It can be found in any mathematics textbook that covers these topics. We obtain the following value for \(y\):

$$ y = \pm \sqrt{- (a^2 + x^2) \pm \sqrt{b^4 + 4a^2x^2}} $$

If we take into account here (before the inner root) that we cannot use the negative sign at first, because this would give us an imaginary y, and therefore only consider the positive sign, we get:

$$ y = \pm \sqrt{- (a^2 + x^2) + \sqrt{b^4 + 4a^2x^2}} $$

If we then draw the corresponding curve, we get a line that resembles an ellipse but does not coincide with it, which is called the Cassini curve after its discoverer. It is symmetrical to the ordinate axis to the left and right, and symmetrical to the abscissa axis to the top and bottom. This is what must be noted.

However, this curve has different shapes, and that is what is important about it, at least for us. This curve has different shapes depending on whether \(b\), as I have assumed here, is greater than \(a\), or \(b\) is equal to \(a\), or \(b\) is less than \(a\). The curve I have just drawn is created when \(b > a \) and a certain condition is also satisfied, namely that \(b\) is also greater than or equal to \(a\sqrt{2}\). Specifically, if \( b \gt a\sqrt{2}\), we have a distinct curvature at the top and bottom. If \( b = a\sqrt{2}\), then at this point the curve transitions into a straight line at the top and bottom, flattening out so that it is almost a straight line at the top and bottom (Fig. 4). However, if \( b \lt a\sqrt{2}\), then the entire course of the curve changes. It takes on this shape (Fig. 5). And if \(b = a\), then the curve transitions into a very special shape, this shape (Fig. 6). It runs back into itself, so to speak, intersects itself and finds itself again, and we get the special shape of the lemniscate, so that the lemniscate is a special form of the Cassini curve. The special shape is caused by the ratio of the constant quantities occurring in the equation of the curve, the characteristic of the curve. We only have these two constant quantities \(b\) and \(a\) in the equation, and the shape of the curve depends on the ratio of these two constant quantities.

However, there is a third possible case, namely that \(b \lt a\). If \(b \lt a\), we also obtain values for the curve. You can always solve the equation and obtain values for the curve, ordinates, and abscissas, even if \(b\) is smaller than \(a\), but the curve continues its peculiar behavior, so to speak. Because then, when \(b \lt a\), we get two branches of the curve that look something like this (Fig. 7). We get a discontinuous curve. Here we are at the point where, in mathematics, we encounter the tangible-intangible, that is, that which is difficult to grasp in space. For in the sense of their mathematical equation, these are not two curves, but one curve, just as much a curve as this one or this one or this one (Fig. 3-5). In this case (lemniscate), the matter is already in transition. The point described by the curve follows this path, goes down here, intersects its previous path here, and finds itself again. Here (Fig. 7), we must mentally image that if we move the point \(M) move along this line, it does not simply travel across here, it does not do that, but rather, just like here (lemniscate), it travels along the path, describes a curve here, and then finds itself here again.

So you see: that which carries the point through the lines disappears here in the middle. You can only form a mental image of it disappearing in the middle if you want to understand the curve. If you try to form a mental image here that remains purely continuous in your mental image, what do you have to do? Isn't it true that if you imagine such a curve (the first three shapes) — I'm just saying this in parentheses for ordinary philistines — then it's easy. You can always imagine a point and you don't get to the point where your mental image breaks off. Here (with the lemniscate), however, you already have to modify the comfortable way of simply walking around. But it still works. You can hold on to the mental image. But now, when you arrive at this curve (shape with two branches), which is not a philistine curve, if you want to imagine it, then, in order to remain in continuous mental image, you must say to yourself: Space no longer gives me any reference point for this. As I proceed here (from 1 to 2) with my mental image, if I do not want to break off my mental image and consider the other branch in isolation, I must take my mental image out of space (to 3 to 4), I cannot remain inside the space. So you see, mathematics itself provides us with facts that make it necessary for us to leave the space if we want to remain in continuous mental image. Reality is such that it demands that we leave the space with our mental image. So something occurs to us within mathematics itself, where it becomes apparent, as it were, that we must leave the space if we simply want to cope with our mental image. In what we ourselves have done with our mental image by starting to think, we must continue to think in such a way that space no longer helps us. Otherwise, not all possibilities would be taken into account in the equation.

Well, we encounter several such things when we go through a similar mental image process. I just want to draw your attention to the most obvious one, which then becomes real for Ste when you raise the question: So, the ellipse is the geometric locus of the constant sum; it is characterized by being the line of the constant sum. The hyperbola is the curve of constant difference. The Cassini curve, with its various forms, is the line of constant product. So somehow, if we have \(A\) here, \(B\) here, a point \(M\) here, and now form \(BM\) by \(AM\) as quotients, there must also be such a line of constant quotients. So we must find different points, \(M_1\), \(M_2\), etc., for which always

$$\frac{BM_1}{AM_1} = \frac{BM_2}{AM_2}$$