The Origins of Natural Science

GA 326

25 December 1922, Dornach

Lecture II

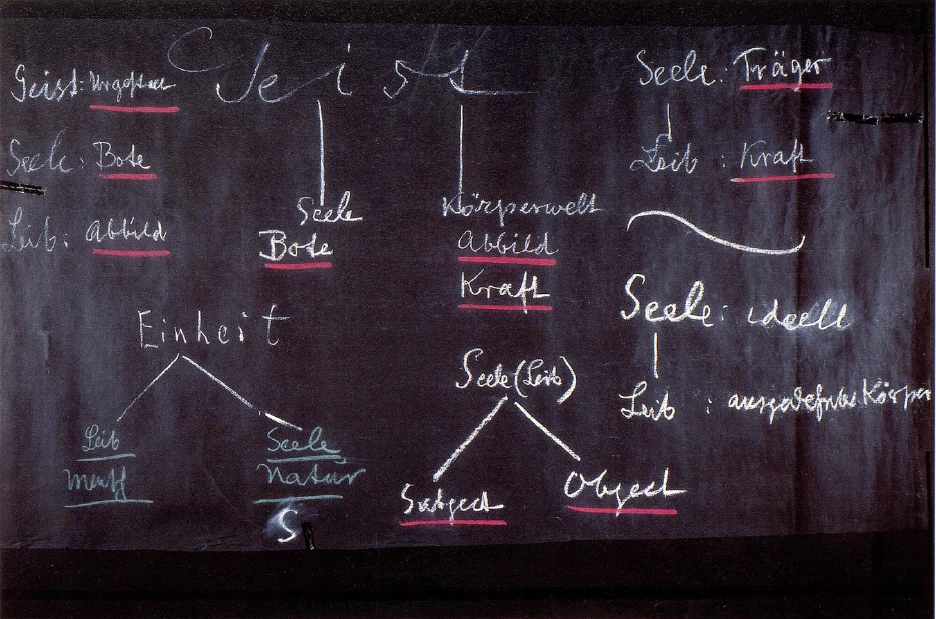

The view of history forming the basis of these lectures may be called symptomatological What takes place in the depths of human evolution sends out waves, and these waves are the symptoms that we will try to describe and interpret. In any serious study of history, this must be the case. The processes and events occurring at any given time in the depths of evolution are so manifold and so significant that we can never do more than hint at what is going on the depths. This we do by describing the waves that are flung up. They are symptoms of what is actually taking place.

I mention this because, in order to characterize the birth of the scientific form of thinking and research I described two men, Meister Eckhart and Nicholas Cusanus, in my last lecture. What can be historically observed in the soul and appearance of such men I consider to be symptoms of what goes on in the depths of general human development; this is why I give such descriptions. There are in any given case only a couple of images cast up to the surface that we can intercept by looking into one or another soul. Yet, by doing this, we can describe the basic nature of successive time periods.

When I described Cusanus yesterday, my intention was to suggest how all that happened in the early fifteenth century in mankind's spiritual development, which was pressing forward to the scientific method of perception, is symptomatically revealed in his soul. Neither the knowledge that the mind can gather through the study of theology nor the precise perceptions of mathematics can lead any longer to a grasp of the spiritual world. The wealth of human knowledge, its concepts and ideas, come to a halt before that realm. The fact that one can do no more than write a “docta ignorantia” in the face of the spiritual world comes to expression in Cusanus in a remarkable way. He could go no further with the form of knowledge that, up to his time, was prevalent in human development.

As I pointed out, this soul mood was already present in Meister Eckhart. He was well versed in medieval theological knowledge. With it, he attempted to look into this own soul and to find therein the way to the divine spiritual foundations. Meister Eckhart arrived at a soul mood that I illustrated with one his sentences. He said—and he made many similar statements—“I sink myself into the naught of the divine, and out of nothing become an I in eternity.” He felt himself arriving at nothingness with traditional knowledge. Out of this nothingness, after the ancient wisdom's loss of all persuasive power he had to produce out of his own soul the assurance of his own I, and he did it by this statement.

Looking into this matter more closely, we see how a man like Meister Eckhart points to an older knowledge that has come down to him through the course of evolution. It is knowledge that still gave man something of which he could say: This lives in me, it is something divine in me, it is something. But now, in Meister Eckhart's own time, the most profound thinkers had been reduced to the admission: When I seek this something here or there, all knowledge of this something does not suffice to bring me certainty of my own being. I must proceed from the Something to the Nothing and then, in an act of creation, kindle to life the consciousness of self out of naught.

Now, I want to place another man over against these two. This other man lived 2,000 years earlier and for his time he was as characteristic as Cusanus (who followed in Meister Eckhart's footsteps) was for the fifteenth century. This backward glance into ancient times is necessary so that we can better understand the quest for knowledge that surfaced in the Fifteenth Century from the depths of the human soul. The man whom I want to speak about today is not mentioned in any history book or historical document, for these do not go back as far as the Eighth Century B.C. Yet, we can only gain information concerning the origin of science if, through spiritual science, through purely spiritual observation, we go farther back than external historical documents can take us. The man I have in mind lived about 2,000 years prior to the present period (the starting point of which I have assigned to the first half of the fifteenth century.) This man of pre-Christian times was accepted into a so-called mystery school of Southeastern Europe. There he heard everything that the teachers of the mysteries could communicate to their pupils concerning spiritual wisdom, truths concerning the spiritual beings that lived and still live in the cosmos. But the wisdom that this man received from his teachers was already more or less traditional. It was a recollection of far older visions, a recapitulation of what wise men of a much more ancient age had beheld when they directed their clairvoyant sight into the cosmic spaces whence the motions and constellations of the stars had spoken to them. To the sages of old, the universe was not the machine, the mechanical contraption that it is for men of today when they look out into space to the wise men of ancient times. The cosmic spaces were like living beings, permeating everything with spirit and speaking to them in cosmic language. They experienced themselves within the spirit of world being. They felt how this, in which they lived and moved, spoke to them, how they could direct their questions concerning the riddles of the universe to the universe itself and how, out of the widths of space, the cosmic phenomena replied to them. This is how they experienced what we, in a weak and abstract way, call “spirit” in our language. Spirit was experienced as the element that is everywhere and can be perceived from anywhere. Men perceived things that even the Greeks no longer beheld with the eye of the soul, things that had faded into a nothingness for the Greeks.

This nothingness of the Greeks, which had been filled with living content for the earliest wise men of the Post-Atlantean age,19Post-Atlantean Age: cf. Rudolf Steiner, An Outline Of Occult Science (Spring Valley, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1984). was named by means of words customary for that time. Translated into our language, though weakened and abstract, those words would signify “spirit.” What later became the unknown, the hidden god, was called spirit in those ages when he was known. This is the first thing to know about those ancient times.

The second thing to know is that when a man looked with his soul and spirit vision into himself, he beheld his soul. He experienced it as originating from the spirit that later on became the unknown god. The experience of the ancient sage was such that he designated the human soul with a term that would translate in our language into “spirit messenger” or simply “messenger.”

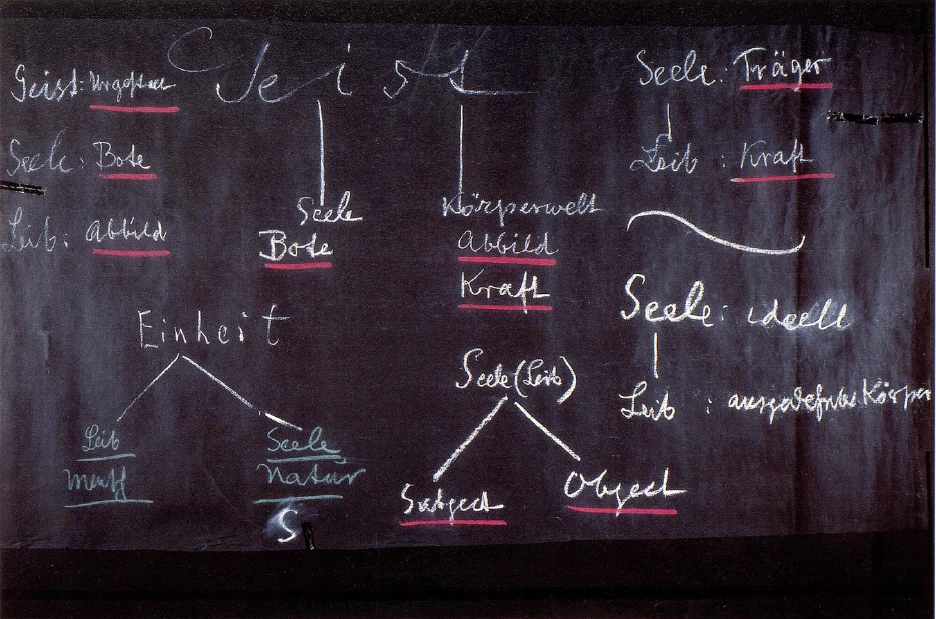

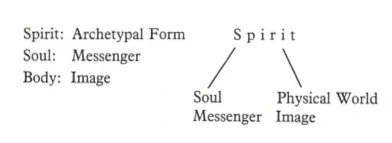

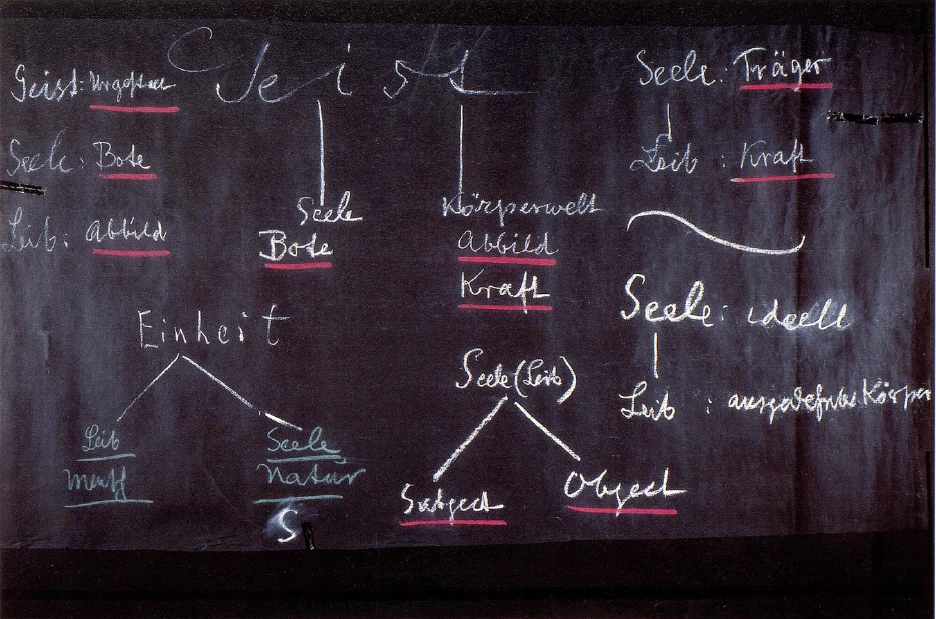

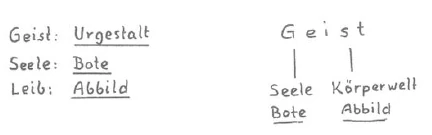

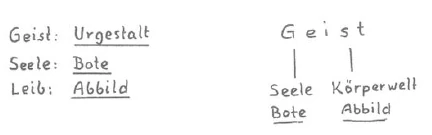

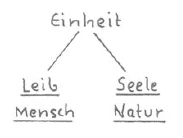

If we put into a diagram what was actually seen in those earliest times, we can say: The spirit was considered the world-embracing element, apart from which there was nothing and by which everything was permeated. This spirit, which was directly perceptible in its archetypal form, was sought and found in the human soul, inasmuch as the latter recognized itself as the messenger of this spirit. Thus the soul was referred to as the “messenger.”

If we put into a diagram what was actually seen in those earliest times, we can say: The spirit was considered the world-embracing element, apart from which there was nothing and by which everything was permeated. This spirit, which was directly perceptible in its archetypal form, was sought and found in the human soul, inasmuch as the latter recognized itself as the messenger of this spirit. Thus the soul was referred to as the “messenger.”

A third aspect was external nature with all that today is called the world of physical matter, of bodies. I said above that apart from spirit there was nothing, because spirit was perceived by direct vision everywhere in its archetypal form. It was seen in the soul, which realized the spirit's message in its own life. But the spirit was likewise recognized in what we call nature today, the world of corporeal things. Even his bodily world was looked upon as an image of the spirit.

In those ancient times, people did not have the conceptions that we have today of the physical world. Wherever they looked, at whatever thing or form of nature, they beheld an image of the spirit, because they were still capable of seeing the spirit, a fragment of nature. Inasmuch as all other phenomena of nature were images of the spirit, the body of man too was an image of the spirit. So when this ancient man looked at himself, he recognized himself as a threefold being. In the first place, the spirit lived in him as in one of its many mansions. Man knew himself as spirit. Secondly, man experienced himself within the world as a messenger of this spirit, hence as a soul being. Thirdly, man experienced his corporeality; and by means of this body he felt himself to be an image of the spirit.20A literal translation of the transcript would read: “As body; and as body, as an image of the spirit.” Hence, when man looked upon his own being, he perceived himself as a threefold entity of spirit, soul, and body: as spirit in his archetypal form; as soul, the messenger of god; as body, the image of the spirit.

This ancient wisdom contained no contradiction between body and soul or between nature and spirit; because one knew: Spirit is in man in its archetypal form; the soul is none other than the message transmitted by spirit; the body is the image of spirit. Likewise, no contract was felt between man and surrounding nature because one bore an image of spirit in one's own body, and the same was true of every body in external nature. Hence, an inner kinship was experienced between one's own body and those in outer nature, and nature was not felt to be different from oneself. Man felt himself at one with the whole world. He could feel this because he could behold the archetype of spirit and because the cosmic expanses spoke to him. In consequence of the universe speaking to man, science simply could not exist. Just as we today cannot build a science of external nature out of what lives in our memory, ancient man could not develop one because, whether he looked into himself or outward at nature, he beheld the same image of spirit. No contrast existed between man himself and nature, and there was none between soul and body. The correspondence of soul and body was such that, in a manner of speaking, the body was only the vessel, the artistic reproduction, of the spiritual archetype, while the soul was the mediating messenger between the two. Everything as in a state of intimate union. There could be no question of comprehending anything. We grasp and comprehend what is outside our own life. Anything that we carry within ourselves is directly experienced and need not be first comprehended.

Prior to Roman and Greek times, this wisdom born of direct perception still lived in the mysteries. The man I referred to above heard about his wisdom, but he realized that the teachers in his mystery school were speaking to him only out of a tradition preserved from earlier ages. He no longer heard anything original, anything gained by listening to the secrets of the cosmos. This man undertook long journeys and visited other mystery centers, but it was the same wherever he went. Already in the Eight Century B.C., only traditions of the ancient wisdom were preserved everywhere. The pupils learned them from the teachers, but the teachers could no longer see them, at least not in the vividness of ancient times.

But this man whom I have in mind had an unappeasable urge for certainty and knowledge. From the communications passed on to him, he gathered that once upon a time men had indeed been able to hear the harmony of the spheres from which resounded the Logos that was identical with the spiritual archetype of all things. Now, however, it was all tradition. Just as 2,000 years later Meister Eckhart, working out the traditions of his age, withdrew into his quiet monastic cell in search of the inner power source of soul and self, and at length came to say, “I sink myself into the nothingness of God, and experience in eternity, in naught, the ‘I’,”—just so, the lonely disciple of the late mysteries said to himself: “I listen to the silent universe and fetch21I listen to the silent universe: cf. Rudolf Steiner, Truth-Wrought Words. (Spring Valley, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1979). the Logos-bearing soul out of the silence. I love the Logos because the Logos brings tidings of an unknown god.”

This was an ancient parallel to the admission of Meister Eckhart. Just as the latter immersed himself into the naught of the divine that Medieval theology had proclaimed to him and, out of this void, brought out the “I,” so that ancient sage listened to a dumb and silent world; for he could no longer hear what traditional wisdom taught him. The spirit-saturated soul had one drawn the ancient wisdom from the universe. This had not turned silent, but still he had a Logos-bearing soul. And he loved the Logos even though it was no longer the godhead of former ages, but only an image of the divine. In other words, already then, the spirit had vanished from the soul's sight. Just as Meister Eckhart later had to seek the “I” in nothingness, so at that time the soul had to be sought in the dispirited world.

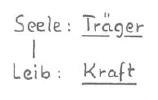

Indeed, in former times the souls had the inner firmness needed to say to themselves: In the inward perception of the spirit indwelling me, I myself am something divine. But now, for direct perception, the spirit no longer inhabited the soul. No longer did the soul experience itself as the spirit's messenger, for one must know something in order to be its messenger. Now, the soul only felt itself as the bearer of the Logos, the spirit image; though this spirit image was vivid in the soul. It expressed itself in the love for this god who thus still lived in his image in the soul. But the soul no longer felt like the messenger, only the carrier, of an image of the divine spirit. One can say that a different form of knowledge arose when man looked into his inner being. The soul declined from messenger to bearer.

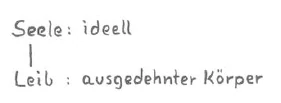

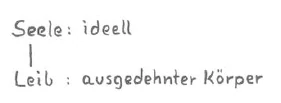

Soul: Bearer

Body: Force

Since the living spirit had been lost to human perception, the body no longer appeared as the image of spirit. To recognize it as such an image, one would have had to perceive the archetype. Therefore, for this later age, the body changed into something that I would like to call “force.” The concept of force emerged. The body was pictured as a complex of forces, no longer as a reproduction, an image, that bore within itself the essence of what it reproduced. The human body became a force which no longer bore the substance of the source from which it originated.

Not only the human body, but in all of nature, too, forces had to be pictured everywhere. Whereas formerly, nature in all its aspects had been an image of spirit, now it had become forces flowing out of the spirit. This, however, implied that nature began to be something more or less foreign to man. One could say that the soul had lost something since it no longer contained direct spirit awareness. Speaking crudely, I would have to say that the soul had inwardly become more tenuous, while the body, the external corporeal world, had gained in robustness. Earlier, as an image, it still possessed some resemblance to the spirit. Now it became permeated by the element of force. The complex of forces is more robust than the image in which the spiritual element is still recognizable. Hence, again speaking crudely, the corporeal world became denser while the soul became more tenuous. This is what arose in the consciousness of the men among whom lived the ancient wise man mentioned above, who listened to the silent universe and from its silence, derived the awareness that at least his soul was a Logos-bearer.

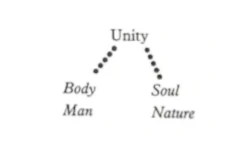

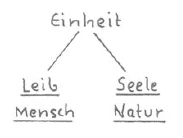

Now, a contrast that had not existed before arose between the soul, grown more tenuous, and the increased density of the corporeal world. Earlier, the unity of spirit had been perceived in all things. Now, there arose the contrast between body and soul, man and nature. Now appeared a chasm between body and soul that had not been present at all prior to the time of this old sage. Man now felt himself divided as well from nature, something that also had not been the case in the ancient times. This contrast is the central trait of all thinking in the span of time between the old sage I have mentioned and Nicholas Cusanus.

Men now struggle to comprehend the connection between, on one hand, the soul, that lacks spirit reality, and on the other hand, the body that has become dense, has turned into force, into a complex of forces.

And men struggle to feel and experience the relationship between man and nature. But everywhere, nature is force. In that time, no conception at all existed as yet of what we call today “the laws of nature.” People did not think in terms of natural laws; everywhere and in everything they felt the forces of nature. When a man looked into his own being, he did not experience a soul that—as was the case later one—bore within itself a dim will, an almost equally dim feeling, and an abstract thinking. Instead, he experienced the soul as the bearer of the living Logos, something that was not abstract and dead, but a divine living image of God.

We must be able to picture this contrast, which remained acute until the eleventh or Twelfth century. It was quite different from the contrasts that we feel today. If we cannot vividly grasp this contrast, which was experienced by everyone in that earlier epoch, we make the same mistake as all those historians of philosophy who regard the old Greek thinker Democritus22Democritus: c. 460–360 B.C. From his numerous writings about philosophy, mathematics, physics, medicine, psychology, and technology, only some fragments and an index remain. The remark mentioned is a report from Aristotle, Metaphysics 1:4: “That is why they (Leucippus and Democritus) say that the non-existent exists just as much as the existent, just as emptiness is just as good as fullness, and they posit these as material causes.” of the fifth century B.C. as an atomist in the modern sense, because he spoke of “atoms.” The words suggest a resemblance, but no real resemblance exists. There is great difference between modern-day atomists and Democritus. His utterances were based on the awareness of the contrast described above between man and nature, soul and body. His atoms were complexes of force and as such were contrasted with space, something a modern atomist cannot do in that manner. How could the modern atomist say what Democritus said: “Existence is not more than nothingness, fullness is not more than emptiness?” It implies that Democritus assumed empty space to possess an affinity with atom-filled space. This has meaning only within a consciousness that as yet has no idea of the modern concept of body. Therefore, it cannot speak of the atoms of a body, but only of centers of force, which, in that case, have an inner relationship to what surrounds man externally. Today's atomist cannot equate emptiness with fullness. If Democritus had viewed emptiness the way we do today, he could not have equated it with the state of being. He could do so because in this emptiness he sought the soul that was the bearer of the Logos. And though he conceived his Logos in a form of necessity, it was the Greek form of necessity, not our modern physical necessity. If we are to comprehend what goes on today, we must be able to look in the right way into the nuances of ideas and feelings of former times.

There came the time, described in the last lecture, of Meister Eckhart and Nicholas Cusanus, when even awareness of the Logos indwelling the soul was lost. The ancient sage, in listening to the universe, only had to mourn the silence, but Meister Eckhart and Cusanus found the naught and had to seek the I out of nothingness. Only now, at this point, does the modern era of thinking begin. The soul now no longer contains the living Logos. Instead, when it looks into itself, it finds ideas and concepts, which finally lead to abstractions. The soul has become even more tenuous. A third phase begins. Once upon a time, in the first phase, the soul experienced the spirit's archetype within itself. It saw itself as the messenger of spirit. In the second phase, the soul inwardly experienced the living image of God in the Logos, it became the bearer of the Logos.

Now, in the third phase, the soul becomes, as it were, a vessel for ideas and concepts. These may have the certainty of mathematics, but they are only ideas and concepts. The soul experiences itself at its most tenuous, if I may put it so. Again the corporeal world increases in robustness. This is the third way in which man experiences himself. He cannot as yet give up his soul element completely, but he experiences it as the vessel for the realm of ideas. He experiences his body, on the other hand, not only as a force but as a spatial body.

Soul: Realm of Ideas

Body: Spatial Corporeality

The body has become still more robust. Man now denies the spirit altogether. Here we come to the “body” that Hobbes, Bacon,23Francis Bacon: (also Francis Bacon of Verulam), London 1561–1626 Highgate. Lawyer, doctor, politician, diplomat, essayist, philosopher and humanist. The leading English government liberal, successful during 1603–1621. In these years his main work was developed. The philosophy of his age he found stuck in hopeless experiments to solve insolvable problems with Aristotelian logic. The only source of sure knowledge and abilities for him was natural science. He saw a renewal of the spiritual and economic life in this science. Principal works: Novum Organum (an inductive logic contradicting that of Aristotle (the old Organum); De Dignitate et Augmentis Scientiarum; a Critical Encyclopedia of all Science; Sylva Sylvarum: Preliminary Announcement of Procedure and Method (this remained in preparation). His literary success was astonishing, and it greatly furthered the materialistic world view. cf. Riddles of Philosophy. and Locke spoke of. Here, we meet “body” at its densest. The soul no longer feels a kinship to it, only an abstract connection that gets worse in the course of time.

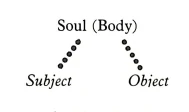

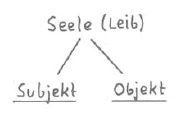

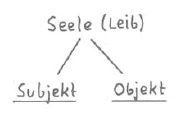

In place of the earlier concrete contrast of soul and body, man and nature, another contrast arises that leads further and further into abstraction. The soul that formerly appeared to itself as something concrete—because it experienced in itself the Logos-image of the divine—gradually transforms itself to a mere vessel of ideas. Whereas before, in the ancient spiritual age, it had felt akin to everything, it now sees itself as subject and regards everything else as object, feeling no further kinship with anything.

The earlier contrast of soul and body, man and nature, increasingly became the merely theoretical epistemological contrast between the subject that is within a person and the object without. Nature changed into the object of knowledge. It is not surprising that out of its own needs knowledge henceforth strove for the “purely objective.”

But what is this purely objective? It is no longer what nature was to the Greeks. The objective is external corporeality in which no spirit is any longer perceived. It is nature devoid of spirit, to be comprehended from without by the subject.

Precisely because man had lost the connection with nature, he now sought a science of nature from outside. Here, we have once again reached the point where I concluded yesterday. Cusanus looked upon what should have been the divine world to him and declared that man with his knowledge must stop short before it and, if he must write about the divine world, he must write a docta ignorantia. And only faintly, in symbols taken from mathematics, did Cusanus want to retain something of what appeared thus to him as the spiritual realms.

About a hundred years after the Docta Ignorantia appeared in 1440, the De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium appeared in 1543. one century later, Copernicus, with his mathematical mind, took hold of the other side, the external side of what Cusanus could not fully grasp, not even symbolically, with mathematics. Today, we see how in fact the application of this mathematical mind to nature becomes possible the moment that nature vanishes from man's immediate experience. This can be traced even in the history of language since “Nature” refers to something that is related to “being born,” whereas what we consider as nature today is only the corporeal world in which everything is dead. I mean that it is dead for us since, of course, nature contains life and spirit. But it has become lifeless for us and the most certain of conceptual systems, namely, the mathematical, is regarded as the best way to grasp it.

Thus we have before us a development that proceeds with inward regularity. In the first epoch, man beheld god and world, but god in the world and the world in god: the one-ness, unity. In the second epoch, man in fact beheld soul and body, man and nature; the soul as bearer of the living Logos, the bearer of what is not born and does not die; nature as what is born and dies. In the third phase man has ascended to the abstract contrast of subject (himself) and object ( the external world.) The object is something so robust that man no longer even attempts to throw light on it with concepts. It is experienced as something alien to man, something that is examined from outside with mathematics although mathematics cannot penetrate into the inner essence. For this reason, Cusanus applied mathematics only symbolically, and timidly at that.

The striving to develop science must therefore be pictured as emerging from earlier faculties of mankind. A time had to come when this science would appear. It had to develop the way it did. We can follow this if we focus clearly on the three phases of development that I have just described.

We see how the first phase extends to the Eighth Century B.C. to the ancient sage of Southern Europe whom I have described today. The second extends from him to Nicholas Cusanus. We find ourselves in the third phase now. The first is pneumatological, directed to the spirit in its primeval form. The second is mystical, taking the world in the broadest sense possible. The third is mathematical. Considering the significant characteristics, therefore, we trace the first phase—ancient pneumatology—as far as the ancient Southern wise man. Magical mysticism extends from there to Meister Eckhart and Nicholas Cusanus. The age of mathematizing natural science proceeds from Cusanus into our own time and continues further. More on this tomorrow.

Zweiter Vortrag

Die Geschichtsbetrachtung, welche diesen Vorträgen zugrunde liegt, ist eine symptomatologische, wie ich sie nennen möchte, das heißt, es soll versucht werden, durch eine solche Geschichtsbetrachtung dasjenige, was in den Tiefen der Menschheitsentwickelung vor sich geht, gewissermaßen durch die aus diesem Strome der Menschheitsentwickelung aufgeworfenen Wellen, welche die Symptome sind, zu charakterisieren. Das muß eigentlich bei jeder wahren Geschichtsbetrachtung aus dem Grunde geschehen, weil das Geschehen, die Summe der Vorgänge, die eigentlich in jedem Zeitpunkte in den Tiefen der Menschheitsentwickelung liegen, so mannigfaltig, so intensiv bedeutsam sind, daß man immer nur eben hindeuten kann auf dasjenige, was in den Tiefen liegt, durch die Schilderung der aufgeworfenen Wellen, welche eben symptomatisch andeuten dasjenige, was wirklich vorgeht.

Ich erwähne dies aus dem Grunde heute, weil ich gestern zur Charakterisierung der Geburt naturwissenschaftlicher Denk- und Forschungsweisen geschildert habe die beiden Persönlichkeiten, den Meister Eckhart und namentlich Nikolaus den Kusaner. Wenn solche Persönlichkeiten hier geschildert werden, so geschieht es aus dem Grunde, weil dasjenige, was in der Seele und im ganzen Auftreten solcher Persönlichkeiten geschichtlich zu beobachten ist, eben auch von mir als Symptome angesehen wird für dasjenige, was in den Tiefen des allgemeinen Menschheitswerdens vorgeht. Es sind ja immer nur, ich möchte sagen, ein paar an die Oberfläche getriebene Bilder, die man dadurch auffangen kann, daß man in die eine oder in die andere Menschenseele hineinblickt. Dann schildert man aber dadurch das Grundwesen der einzelnen Zeitabläufe. So war es gemeint, wenn ich gestern Nikolaus den Kusaner schilderte, um anzudeuten, wie in seiner Seele sich symptomatisch offenbart alles dasjenige, was eigentlich in der geistigen Menschheitsentwickelung, zur naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtungsweise hindrängend, im Beginne des 15. Jahrhunderts sich abspielt. Daß weder alles dasjenige Wissen, das man gewissermaßen in der Seele ansammeln kann dadurch, daß man auf der einen Seite sich hingibt dem, was die Erkenntnis auf dem theologischen Boden bis dahin hervorgebracht hat, noch auch die sichere mathematische Anschauungsweise hinführen können bis zum Ergreifen der geistigen Welt, so daß man haltmachen muß mit der ganzen menschlichen Begriffs- und Ideenerkenntnis vor dieser geistigen Welt und gegenüber dieser geistigen Welt nur eine «Docta ignorantia» schreiben könne, das ist dasjenige, was in Nikolaus dem Kusaner auf eine so großartige Weise zum Ausdrucke kommt. Damit aber hat er gewissermaßen abgeschlossen mit der Art von Welterkenntnis, wie sie bis zu ihm in der Menschheitsentwickelung heraufgekommen ist. Und ich konnte hinweisen darauf, wie jene Seelenstimmung schon vorhanden ist bei dem Meister Eckhart, der gründlich bewandert ist in der theologisierenden Erkenntnis des Mittelalters, und der mit dieser theologisierenden Erkenntnis hineinblicken will in die eigene Menschenseele, um in dieser Menschenseele den Weg zu finden zu den göttlich-geistigen Weltengründen. Und er, dieser Meister Eckhart, kommt zu einer Seelenstimmung, die ich gestern mit einem seiner Sätze Ihnen andeutete. Er sagte — und er sagte Ähnliches wiederholt -: Ich versenke mich in das Nichts der Gottheit und werde aus dem Nicht in Ewigkeit ein Ich. - Er fühlt sich angekommen bei dem Nicht mit der alten Erkenntnis und muß aus diesem Nicht, das heißt aus dem Versiegen aller überzeugenden Kräfte des alten Wissens, durch einen, ich möchte sagen, Urspruch aus der Seele herausholen die Gewißheit des eigenen Ich.

Wenn man näher auf eine solche Sache hinschaut, dann kommt man darauf, wie so jemand wie damals der Meister Eckhart hindeutet auf eine ältere Seelenerkenntnis, die bis zu ihm herauf in der Menschheitsentwickelung gekommen ist, die noch den Menschen etwas gegeben hat, von dem er sagen konnte: Das lebt in mir; das ist ein Göttliches in mir, das ist etwas. — Jetzt aber waren die tiefsten Geister des Zeitalters bei dem Bekenntnis angekommen: Wenn ich das Etwas da, wenn ich das Etwas dort aufsuche, dann reicht alle Erkenntnis dieses Etwas nicht aus, um eine Gewißheit zu finden über das eigene Sein. Und ich muß von dem Etwas zu dem Nichts gehen, um eben mit einem Urspruch gewissermaßen in mir aufleben zu lassen aus dem Nichts heraus das Bewußtsein vom Ich.

Und nun möchte ich gegenüberstellen diesen beiden Persönlichkeiten eine andere, welche etwa zweitausend Jahre vorher gelebt hat, eine Persönlichkeit, die ebenso charakteristisch ist für ihr Zeitalter, wie charakteristisch ist etwa der Kusaner, fußend auf dem Meister Eckhart, für den Beginn des 15. Jahrhunderts. Wir werden dieses Zurückgehen in ältere Zeiten brauchen, um besser verstehen zu können dasjenige, was dann aus den Untergründen des menschlichen Seelenlebens an Erkenntnisstreben im 15. Jahrhundert aufgetaucht ist. Die Persönlichkeit, von der ich Ihnen da heute reden will, von der meldet allerdings kein Geschichtsbuch, kein historisches Dokument, denn die gehen in solchen Sachen nicht zurück bis etwa ins 8. vorchristliche Jahrhundert. Dennoch können wir uns nur Kunde über dasjenige, was den eigentlichen Ursprung der Naturwissenschaft charakterisiert, holen, wenn wir durch Geisteswissenschaft, durch die rein geistige Beobachtung weiter zurückgehen, als äußere historische Dokumente uns verkünden. Eine Persönlichkeit, die, wie gesagt, ja nur durch Geistesschau gefunden werden kann, über zweitausend Jahre vor diesem Zeitalter, dessen Anfangspunkt ich gestern als in der ersten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts liegend bezeichnet habe. Das ist eine Persönlichkeit des vorchristlichen Lebens, welche aufgenommen wurde in eine der südeuropäischen sogenannten Mysterienschulen, da gehört hatte alles dasjenige, was diese Mysterienlehrer ihren Schülern zu sagen hatten, diese geistig-kosmischen Weistümer, geistig-kosmischen Wahrheiten, Wahrheiten über die geistigen Wesenheiten, welche im Kosmos lebten und leben. Aber diese Persönlichkeit, die ich meine, die hörte von den Mysterienlehrern schon dazumal eine Weisheit, die mehr oder weniger nur noch traditionell war, die die Wiedergabe war von viel, viel älteren Schauungen der Menschheit, die Wiedergabe war desjenigen, was viel ältere erkennende Weise geschaut haben, wenn sie den damals hellseherischen Blick hinausrichteten immer wieder und wiederum in die Weltenweiten, und wenn aus diesen Weltenweiten, wie es ja war, zu ihnen gesprochen haben die Bewegungen der Sterne, die Konstellationen der Sterne, auch gesprochen haben manche anderen Vorgänge in den Weltenweiten. Diesen alten Weisen war das Weltenall nicht jene Maschine oder jenes maschinenähnliche Gebilde, das es den heutigen Menschen ist, wenn sie hinausblicken in den Weltenraum, sondern es waren ihnen die Weltenweiten etwas, in dem sich diese Weisen vorkamen wie in einem allebendigen, alldurchwebenden, alldurchgeistigten Wesen, das zu ihnen eine kosmische Sprache redete. Sie fühlten sich in dem Weltenwesen des Geistes selber darinnen, und sie fühlten, wie dasjenige, in dem sie lebten und webten, zu ihnen sprach, wie sie gewissermaßen an die Welt selber die Fragen stellen konnten, welche die Rätsel der Welt bedeuten, und wie ihnen die Erscheinungen aus den Weiten antworteten. Das wurde als dasjenige empfunden, was wir etwa ganz abgeschwächt und abstrakt in unserer Sprache den Geist nennen. Und der Geist wurde eigentlich als dasjenige empfunden, was überall ist, was aber auch von überallher wahrgenommen werden kann. Man blickte in Welteninhalte, von denen schon die Griechen nichts mehr mit dem Seelenblicke sahen, die schon für die Griechen ein Nichts geworden waren. Und man nannte dieses Nichts der Griechen, das aber noch ein vollinhaltliches Etwas für die ältesten Weisen der nachatlantischen Zeit war, man nannte das eben mit jenen Worten, die damals üblich waren, und die eben in unserer Sprache abgeschwächt und abstrakt «Geist» heißen würden. Also das später Unbekannte, den später verborgenen Gott, nannte man, als er noch bekannt war, Geist. Das war das erste für jene älteren Zeiten.

Das zweite war, daß der Mensch, wenn er in sich selber hineinsah, seine Seele sah mit dem Seelenblicke, mit dem nach inwärts gerichteten Geistesblicke. Und diese Seele empfand er als dasjenige, was herkam von dem Geiste, der später der unbekannte Gott geworden ist, und er empfand seine eigene Seele so, dieser älteste Weise, und mit ihm die Menschheit, die sich zu diesem ältesten Weisen bekannte, daß man die Bezeichnung, die damals aus diesen Anschauungen heraus dem menschlichen Seelenwesen hat gegeben werden können, umgewandelt in unsere Sprache, Geistbote oder schlechthin Bote nennen könnte, So daß man also sagen kann, wenn man schematisch darstellen will, was für diese ältesten Zeiten als Anschauung galt: Als Weltumfassendes, außer dem nichts anderes ist, und das in jedem Etwas zu finden ist, galt damals der Geist. Und der Geist, der in seiner Urgestalt unmittelbar wahrnehmbar war, wurde wieder gesucht in der menschlichen Seele, und er wurde gefunden, indem diese menschliche Seele sich selber als den Boten dieses Geistes erkannte. So daß man sagen kann: Die Seele wurde angesehen als Bote.

Und als drittes hatte man um sich herum die äußere Natur mit demjenigen, was wir heute das Wesen, das Körperwesen nennen. Ich sagte, außer dem Geiste gab es kein Etwas, denn der Geist ward überall geschaut, er ward erkannt in seiner Urgestalt durch unmittelbares Schauen. Er ward erkannt in der menschlichen Seele, die die Botschaft von ihm in ihrem eigenen Leben verwirklichte. Er ward aber auch erkannt in demjenigen, was wir heute die Natur nennen, die Körperwelt. Und diese Körperwelt, sie wurde angesehen als Abbild des Geistes.

So hatte man in jenen alten Zeiten nicht diejenigen Vorstellungen von der Körperwelt, die man heute hat. Wo immer man hinschaute auf irgendein Naturgebilde, schaute man, weil man eben den Geist überall schauen konnte, in jedem Naturgebilde ein Abbild des Geistes. Dasjenige Abbild des Geistes, das einem am nächsten stand, das war der Menschenleib, der Körper des Menschen, dieses Stück Natur. Aber indem alle anderen Naturgebilde Abbilder des Geistes waren, war auch dieser Menschenleib Abbild des Geistes. Schaute daher dieser ältere Mensch auf sich selbst zurück, so erkannte er sich als ein dreifaches Wesen. Erstens wohnte in ihm der Geist in seiner Urgestalt, wie in einem seiner Häuser. Der Mensch erkannte sich als Geist. Zweitens fühlte sich innerhalb der Welt der Mensch als Bote dieses Geistes, und insofern als Seelenwesen. Drittens fühlte sich der Mensch als Leib, und durch den Leib als Abbild des Geistes. So daß wir sagen können: Wenn der Mensch auf sich selbst zurückblickte, so erkannte er sich in der Dreiheit seines Wesens nach Geist, Seele, Leib; nach Geist als in seiner Urgestalt, nach der Seele als dem Gottesboten, nach dem Leibe als dem Abbild des Geistes.

In dieser älteren Weisheit der Menschen gab es keinen Widerspruch zwischen Leib und Seele, keinen Widerspruch zwischen Natur und Geist, denn man wußte: Geist ist in seiner Urgestalt im Menschen; dasjenige, was die Seele ist, ist nichts anderes als der weitergetragene, der als Botschaft weitergetragene Geist; der Leib ist das Abbild des Geistes. Aber man fühlte auch keinen Gegensatz zwischen dem Menschen und der umliegenden Natur, denn man trug in dem eigenen Leib das Abbild des Geistes in sich, und man sah in jedem Körper draußen ein Abbild des Geistes. So wurde der eigene Leib in Verwandtschaft empfunden mit allen Naturkörpern. Man erkannte ein innerlich Verwandtes, wenn man hinausschaute in die Körperwelt und wenn man hinschaute auf den Menschenleib. Man fühlte die Natur nicht als etwas anderes. Als eine Einheit, ein Monon fühlte sich der Mensch mit der ganzen übrigen Welt. Das fühlte er dadurch, daß er eben die Urgestalt des Geistes wahrnehmen konnte, daß die Weltenweiten zu ihm sprachen. Und die Folge dieses Sprechens der Weltenweiten zu dem Menschen war, daß es eigentlich keine Naturwissenschaft geben konnte. Geradeso wie wir keine Wissenschaft der äußeren Natur begründen können von demjenigen, was in unserer Erinnerung lebt, so konnte dieser ältere Angehörige der Menschheit keine äußere Naturwissenschaft begründen, denn er sah das Bild des Geistes, wenn er in sich selber hineinschaute, und er erkannte wiederum dieses Bild des Geistes, wenn er in die äußere Natur hinausschaute. Ein Gegensatz zwischen sich selber als Mensch und Natur war nicht da, ebensowenig ein Gegensatz zwischen Seele und Leib, denn Seele und Leib entsprachen einander so, daß der Leib, ich möchte sagen, nur die Schale, das Abbild, das künstlerische Abbild der geistigen Urgestalt war und die Seele der vermittelnde Bote zwischen den beiden. Alles war in inniger Einheit. Von einem Begreifen konnte gar nicht die Rede sein, denn man begreift dasjenige, was außerhalb des eigenen Lebens liegt, während man dasjenige, was man in sich selbst trägt, unmittelbar erlebt, nicht erst begreift.

Solche Weisheit in unmittelbarer Anschauung lebte in den ältesten Mysterien der Menschheit noch vor der Griechen- und Römerzeit. Von solcher Weisheit hörte jene Persönlichkeit, die ich heute meine. Von solcher Weisheit hörte sie, und sie sah, daß die Lehrer ihres Mysteriums eigentlich im Grunde genommen nur noch als Überlieferung aus älteren Zeiten das hatten, was sie zu ihm sprechen konnten. Sie hörte nicht mehr Ursprüngliches, aus dem Hinhorchen auf die Geheimnisse des Kosmos Erkanntes. Und diese Persönlichkeit machte sich auf weite Reisen, besuchte andere Mysterien, und im Grunde genommen erfuhr sie überall in diesem 8. Jahrhunderte der vorchristlichen Zeit schon ein Ähnliches. Überall waren nur noch die Überlieferungen alter Weisheit vorhanden. Die Schüler lernten sie von den Lehrern, die selber nicht mehr schauen konnten, wenigstens nicht in der Lebhaftigkeit der alten Zeiten.

Aber die Persönlichkeit, die ich meine, hatte aus den Tiefen der Menschennatur heraus den ungeheuren Drang nach Gewißheit, nach Wissen. Sie hörte aus den Mitteilungen, daß man einmal eine Sphärenharmonie wirklich hören konnte, daß aus dieser Sphärenharmonie der Logos heräustönte, der Logos, der identisch war mit der geistigen Urgestalt aller Dinge. Aber eben nur Überlieferungen hörte sie. Und ebenso, wie sich später, zweitausend Jahre später aus den Überlieferungen seines Zeitalters heraus etwa der Meister Eckhart in sein stilles Kämmerchen gesetzt hat auf der Suche nach der inneren Kraft der Seele und des Ich und zu dem Ausspruche gekommen ist: Ich versenke mich in das Nichts der Gottheit und erlebe in Ewigkeit im Nicht das Ich -, so sagte sich jener alte, einsame Schüler der Spätmysterien: Ich horche hin auf das stumme Weltenall und aus der Stummheit hole ich mir die logostragende Seele. Ich liebe den Logos, denn der Logos kündet von einem unbekannten Gotte.

Das war das ältere Parallelbekenntnis zu demjenigen des Meisters Eckhart. Wie der Meister Eckhart sich mit den Kräften seiner Seele hineinversenkt hat in das Nicht der Gottheit, von dem ihm die Theologie des Mittelalters sprach, wie er aus diesem Nicht heraus das Ich geholt hat, so horchte hin jener alte Weise auf eine stumme Welt, denn dasjenige, wovon ihm die überlieferte Weisheit sprach, das hörte er nicht mehr. Er konnte nur hinhorchen in ein stummes Weltenall. Und er holte sich, wie früher die geistdurchtränkte Seele sich die alte Weisheit geholt hat, er holte sich aus dem stummen Weltenall die logostragende Seele. Und er liebte den Logos, der nicht mehr die Gottheit selber der alten Zeit war, sondern nur noch ein Bild der Gottheit der alten Zeiten. Mit anderen Worten: Der Geist war bereits in jenen Zeiten der Seele entschwunden, und so wie später der Meister Eckhart in der ernichteten Welt das Ich suchen mußte, so mußte in der entgeisteten Welt die Seele gesucht werden.

Oh, in früheren Zeiten hatten die Seelen gewissermaßen die innere Festigkeit, die sie brauchten, um sich sagen zu können: Ich bin selbst ein Göttliches in dem inneren Wahrnehmen des Geistes, der in mir west. Jetzt aber wohnte der Geist für die unmittelbare Anschauung nicht mehr in ihr, jetzt fühlte sich die Seele nicht mehr als den Boten des Geistes. Denn um Bote von etwas zu sein, muß man es kennen. Jetzt fühlte sich die Seele als Logosträger, als Träger des Geistesbildes, wenn auch dieses Geistesbild ganz lebendig war in ihr, wenn auch dieses Geistesbild sich ausdrückte in der Liebe zu dem Gotte, der sich so noch in seinem Bilde in der Seele auslebte. Aber die Seele empfand sich nicht mehr als Bote, die Seele empfand sich als Träger, Träger des Bildes des göttlichen Geistes. Und so kann man sagen, wenn man wieder schematisch darstellen will: Jetzt entstand eine andere Menschenkenntnis, wenn der Mensch in sein Inu. res blickte: Seele — Träger. Die Seele ward vom Boten zum Träger:

Dadurch aber, daß man gewissermaßen aus der Anschauung den einstmals lebendigen Geist verloren hatte, dadurch war auch der Leib nicht mehr Abbild dieses Geistes. Um ihn als Abbild zu erkennen, hätte man die Urgestalt erkennen müssen. Der Leib wurde für diese spätere Anschauung etwas anderes. Er wurde dasjenige, was ich nennen möchte: die Kraft. Der Kraftbegriff trat jetzt ein. Er wurde als Kraftzusammenhang vorgestellt, nicht mehr ein Bild, das das Wesen des Abgebildeten in sich trägt, nicht mehr ein Abbild - eine Kraft, die nicht das Wesen desjenigen, aus dem sie entspringt, in sich trägt, das wurde der Menschenleib. Und vom Menschenleib aus mußte man auch in der Natur überall Kräfte vorstellen. War die Natur früher überall Abbild des Geistes, war sie jetzt zu den aus dem Geiste fließenden Kräften geworden. Damit aber fing die Natur an, dem Menschen mehr oder weniger ein Fremdes zu sein. Man möchte sagen: Die Seele hat etwas verloren, denn sie hat das unmittelbare Geistbewußtsein nicht mehr in sich. — Wenn ich mich grob ausdrücken sollte, müßte ich sagen: Die Seele ist in sich dünner geworden; der Körper, die äußere Körperwelt hat an Robustheit gewonnen. Sie hatte früher das noch Geistähnliche des Abbildes. Jetzt wurde sie durchsetzt von dem Kraftmäßigen. Der Kraftzusammenhang ist robuster als das Bild, dem der geistige Inhalt noch anzusehen ist. Soll ich mich wieder grob ausdrücken, müßte ich sagen: Die Körperwelt ist dichter geworden, während die Seele dünner geworden ist. Das war dasjenige, was in das Bewußtsein derjenigen Menschen überging, zu deren ersten jener alte Weise gehörte, der hinhorchte auf das stumme Weltenall, und aus der Stummheit des Weltenalls sich das Bewußtsein herausholte, daß seine Seele wenigstens Logosträger ist.

Und jetzt entstand zwischen der dünner gewordenen Seele und dem dichter Gewordenen der Körperwelt der Gegensatz, der früher nicht da war. Früher hat man die Einheit des Geistes in allem gesehen. Jetzt entstand der Gegensatz zwischen Leib und Seele, Mensch und Natur, so daß jetzt auftrat der Abgrund zwischen Leib und Seele, der früher gar nicht vorhanden war, bevor jener alte Weise, von dem ich Ihnen heute erzählt habe, gesprochen hat, daß aber der Mensch sich auch fühlte abgegrenzt von der Natur, was ebenfalls in der alten Zeit nicht gefühlt wurde. Und dieser Gegensatz, er bildet im Grunde genommen den Kerninhalt alles Denkens in der Zeit zwischen jenem alten Weisen, von dem ich Ihnen heute erzählt habe, und Nikolaus Cusanus.

Da ringt die Menschheit, zu begreifen den Zusammenhang auf der einen Seite zwischen Seele und Leib, der Seele, welcher Geistwirklichkeit fehlt, dem Leib, der dicht geworden ist, zur Kraft, zum Kraftzusammenhang geworden ist. Und es ringt die Menschheit nach einem Empfinden des Verhältnisses zwischen Mensch und Natur. Aber die Natur ist überall Kraft. Eine Vorstellung von dem, was wir heute Naturgesetze nennen, ist eigentlich in diesem Zeitalter, da wo seine besonders charakteristischen Epochen liegen, gar nicht vorhanden. Man redete nicht in Gedanken von Naturgesetzen, man fühlte überall Naturkräfte. Aus allem heraus erlebte man Naturkräfte. Und wenn man in sich hineinschaute, so fühlte man nicht eine Seele, die wie später ein dumpfes Wollen, ein fast ebenso dumpfes Fühlen und ein abstraktes Denken in sich trägt, sondern man fühlte eine Seele, welche Träger des lebendigen Logos ist, von dem man zwar weiß, er ist nicht tot, er ist ein göttliches, lebendiges Abbild des Gottes.

Man muß sich hineinversetzen können in diesen Gegensatz, der bis ins 11., 12. Jahrhundert vorhanden war in aller Schärfe, und der ein ganz anderer ist als diejenigen Gegensätze, die heute von der Menschheit gefühlt werden. Wenn man sich nicht mit lebendigem Bewußtsein in diesen ganz andersartigen Gegensatz einer älteren Menschheitsepoche hineinversetzen kann, dann passiert einem das, was allen Geschichtsschreibern der Philosophie passiert, daß sie den alten griechischen Demokritus aus dem 5. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert so beschreiben, als ob er im modernen Sinne ein Atomist gewesen wäre, weil er Atome angenommen hat. Wenn Worte einen kleinen Schein von Ähnlichkeit andeuten, dann ist die Ähnlichkeit noch nicht vorhanden. Zwischen dem modernen Atomisten und dem Demokritus ist ein gewaltiger Unterschied, weil Demokritus überhaupt aus jenem Gegensatze, den ich eben charakterisiert habe, von Mensch und Natur, Seele und Leib heraus redet, so daß seine Atome durchaus noch Kraftzusammenhänge sind, und als solche Kraftzusammenhänge von ihm entgegengestellt werden in einer Weise dem Raume, wie der moderne Atomist seine Atome nicht dem Raum gegenüberstellen kann. Wie sollte der moderne Atomist sagen, was Demokritus gesagt hat: Das Sein ist nicht mehr als das Nichts, das Volle ist nicht mehr als das Leere. Das heißt, Demokritus nimmt an, daß der leere Raum eine Verwandtschaft hat mit dem im Atom erfüllten Raum. Das hat nur einen Sinn innerhalb eines Bewußtseins, das überhaupt den modernen Körperbegriff noch gar nicht kennt, also auch nicht von Atomen eines Körpers sprechen kann, sondern selbstverständlich nur von Kraftpunkten spricht, die eine innerliche Verwandtschaft dann haben mit demjenigen, was außer dem Menschen ist. Der heutige Atomist kann das Leere nicht dem Vollen gleichsetzen. Denn wenn Demokritus das Leere so vorgestellt hätte, wie wir heute vom Leeren sprechen, so hätte er es nicht dem Sein gleichsetzen können. Er kann es gleichsetzen, weil er in diesem Leeren drinnen sucht dasjenige, was Seelenträger ist, Seele, welche Träger des Logos ist. Wenn er diesen Logos auch mit einer Art von Notwendigkeit vorstellt, so ist es die griechische Notwendigkeit, nicht unsere heutige Naturnotwendigkeit. Darauf kommt es an, wenn man verstehen will, was heute ist, daß man in der richtigen Weise in die Vorstellungs- und Empfindungsnuance der älteren Zeiten hineinschauen kann.

Und nun kam die Zeit, die ich eben gestern charakterisiert habe, die Zeit des Meisters Eckhart, die Zeit des Nikolaus Cusanus, in der auch das Bewußtsein von dem in der Seele lebenden Logos verloren ward. Der Meister Eckhart und der Kusaner fanden da, wo der alte Meister beim Hinhorchen in das Weltenall nur über die Stummheit zu klagen hatte, da fanden sie das Nichts, und mußten aus dem Nicht das Ich suchen. Damit aber beginnt überhaupt erst die neuere Zeit des menschlichen Denkens. Jetzt hat die Seele nicht mehr den lebendigen Logos in sich, jetzt hat sie die Ideen und Begriffe in sich, wenn sie in sich hineinschaut, die Vorstellungen, dasjenige, was zuletzt zu den Abstraktionen führt. Jetzt ist sie noch dünner geworden. Die dritte Phase der menschlichen Anschauung beginnt. Einstmals in der ersten Phase hat die Seele in sich des Geistes Urgestalt erlebt. Sie war sich Geistesbote. Die zweite Phase: Die Seele erlebt in sich das lebendige Gottesbild im Logos, sie wird sich Logosträger.

Jetzt, in der dritten Phase, wird sie gewissermaßen Behältnis von Ideen und Begriffen, die in der Sicherheit der Mathematik zwar zum Vorschein kommen, die aber eben Begriffe und Ideen sind. Sie fühlt sich innerlich am verdünntesten, möchte man sagen. Und wiederum wächst der Körperwelt Robustheit zu. Es entsteht die dritte Art, wie sich der Mensch fühlt. Er kann sein Seelisches noch nicht ganz aufgeben, aber er fühlt dieses Seelische als den Behälter des Ideellen und er fühlt den Leib nun nicht mehr bloß als Kraft, sondern als ausgedehnten Körper.

Der Körper ist noch robuster geworden. Er ist in der Anschauung zu dem geworden, was den Geist nunmehr völlig verleugnet. Hier begegnet uns erst der Körper, von dem dann Hobbes, Bacon sprachen, Locke sprach, hier begegnet uns der Körper, der am dichtesten geworden ist, und zu dem das Innere des Menschen keine Verwandtschaft mehr fühlen kann, sondern nur noch eine abstrakte Beziehung, die sich immer mehr und mehr herausbildet in der Entwickelung des menschlichen Anschauens.

An die Stelle des früher konkreten Gegensatzes Seele und Leib, Mensch und Natur, tritt jetzt ein anderer Gegensatz, der immer mehr und mehr in die Abstraktion hineinkommt. Dasjenige, das sich früher noch, weil es in sich das Logosbild der Gottheit fühlte, in sich konkret vorkam, das verwandelte sich allmählich bloß zum Gefäß des Ideellen, es wurde sich Subjekt, und stellte sich das, mit dem es gar keine Verwandtschaft mehr fühlte - während es alle Verwandtschaft in der alten Geistzeit gefühlt hat -, als Objekt gegenüber.

Der frühere menschliche Gegensatz von Seele und Leib, von Mensch und Natur, wurde der immer mehr und mehr bloß erkenntnistheoretische Gegensatz zwischen dem Subjekt, das in einem ist, und dem Objekt, das draußen ist. Die Natur verwandelte sich in das Objekt des Erkennens. Kein Wunder, daß die Erkenntnis aus dem eigenen Bedürfnisse heraus nach dem objektiven schlechthin strebte.

Was aber ist dieses Objektive? Dieses Objektive ist nicht mehr dasjenige, was dem Griechen die Natur war, dieses Objektive ist von äußerer Körperlichkeit, in der kein Geistiges mehr geschaut wird. Es ist die Natur, die geistlos geworden ist, die von außen, vom Subjekt aus begriffen werden soll. Weil der Mensch erst aus seinem Wesen herausverloren hat den Zusammenhang mit der Natur, suchte er eine Naturwissenschaft von außen. Da sind wir wiederum auf dem Punkte, mit dem ich gestern den Schluß machen konnte, indem ich sagte, der Kusaner sah auf das, was ihm die göttliche Welt sein sollte, und er sagte: Man muß vorher haltmachen mit der Erkenntnis, man muß schreiben, wenn man von der göttlichen Welt schreibt, von einer docta ignorantia. — Und leise nur wollte er in den Symbolen, die aus der Mathematik genommen sind, etwas festhalten von dem, was so als das Geistige ihm erschien. Aber er war sich bewußt, das kann man nicht, das Geistige in mathematischen Symbolen festhalten.

Und ich sagte, etwa hundert Jahre darnach — 1440 ist die «Docta ignorantia» erschienen, 1543 «De revolutionibus orbium coelestium» -, also etwa ein Jahrhundert später bemächtigt sich mit mathematischem Geiste Kopernikus gewissermaßen der anderen, der äußeren Seite desjenigen, was der Kusaner nicht mit der Mathematik, nicht einmal symbolisch voll erfassen konnte. Und wir sehen heute, wie tatsächlich die Anwendung dieses mathematischen Geistes auf die Natur in dem Momente möglich wird, wo dem Menschen aus dem unmittelbaren Erleben die Natur entfällt. Das kann man bis in die Sprachgeschichte hinein nachweisen, denn «Natur» deutet noch hin auf etwas, was mit dem Geborenwerden verwandt ist, während dasjenige, was heute als die Natur angesehen wird, bloß die Körperwelt ist, die aber in sich nur das Tote enthält - ich meine für das menschliche Anschauen natürlich, denn die Natur enthält heute noch immer selbstverständlich das Leben und den Geist, aber für das menschliche Anschauen ist sie ein Totes geworden, zu dessen Erfassung vor allen Dingen zunächst das sicherste Begriffswissen gelten soll, das mathematische.

So sehen wir eine mit innerer Gesetzmäßigkeit ablaufende Entwickelung der Menschheit vor uns: Die erste Epoche, wo der Mensch Gott und Welt gesehen hat, aber Gott in der Welt, die Welt in Gott, das Monon, die Einheit; die zweite Epoche, wo der Mensch gesehen hat in der Tat Seele und Leib, Mensch und Natur, die Seele als Träger des lebendigen Logos, als Träger dessen, was nicht entsteht und nicht vergeht, die Natur als dasjenige, was entsteht und stirbt; die dritte Phase, wo der Mensch aufgestiegen ist zu dem abstrakten Gegensatz: Subjekt, das er selber ist, Objekt, das die Außenwelt ist. Das Objekt ist das Robusteste, in das mit den Begriffen hineinzuleuchten gar nicht mehr versucht wird, das empfunden wird als das dem Menschen Fremde, das von außen untersucht wird mit der Mathematik, welche kein Talent dazu hat, in das Innere als solches zu dringen, daher sie auch der Kusaner nur symbolisch auf das Innere, und das schüchtern, anwandte.

So muß man sich aus älteren Anlagen der Menschheit das Bestreben hervorgegangen denken, Naturwissenschaft zu entwickeln. Es mußte die Epoche einmal herankommen an die Menschen, wo diese Naturwissenschaft entstehen mußte. Sie mußte auch so werden, wie sie ist. Das sehen wir gerade, wenn wir scharf die Phasen ins Auge fassen, die ich charakterisiert habe in der geistigen Menschheitsentwickelung, wenn wir ins Auge fassen, wie die erste Phase hingeht bis zu jenem alten südlichen Weisen des 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhunderts, den ich Ihnen heute charakterisiert habe, die zweite von ihm bis zu Nikolaus Cusanus. Die dritte Phase, in der stehen wir drinnen. Die erste ist pneumatologisch, nach dem Geist in seiner Urgestalt gerichtet; die zweite ist mystisch, wenn man das Wort mystisch im weitesten Sinne nimmt; die dritte ist mathematisch. So — wenn wir die eigentlichen charakteristischen Merkmale nehmen - zählen wir die erste Phase bis zu dem alten südlichen Weisen, den ich Ihnen heute geschildert habe; bis zu ihm zählen wir die alte Pneumatologie. Von ihm bis zu dem Meister Eckhart und dem Nikolaus Cusanus zählen wir die magische Mystik. Von dem Kardinal Nikolaus Cusanus bis in unsere Zeit und weiter zählen wir die Zeit der mathematisierenden Naturwissenschaft.

Darauf wollen wir dann morgen weiter bauen.

Second lecture

The view of history underlying these lectures is what I would call symptomatic, that is, it attempts to characterize what is happening in the depths of human development through the waves thrown up by this stream of human development, which are the symptoms. This must actually be done in every true view of history, because the events, the sum of the processes that actually lie in the depths of human development at every moment, are so manifold and intensely significant that one can only ever point to what lies in the depths by describing the waves that are thrown up, which symptomatically indicate what is really going on.I mention this today because yesterday, in characterizing the birth of scientific thinking and research methods, I described two personalities, Meister Eckhart and, in particular, Nicholas of Cusa. When such personalities are described here, it is because what can be observed historically in the soul and in the entire appearance of such personalities is also regarded by me as symptoms of what is going on in the depths of the general development of humanity. I would say that these are always just a few images that have been brought to the surface, which can be captured by looking into one human soul or another. But in doing so, one describes the fundamental nature of the individual stages of time. This is what I meant yesterday when I described Nicholas of Cusa, to indicate how everything that was actually happening in the spiritual development of humanity at the beginning of the 15th century, pushing toward a scientific way of looking at things, was symptomatically revealed in his soul. That neither all the knowledge that one can accumulate in the soul, so to speak, by devoting oneself on the one hand to what theological knowledge has produced up to that point, nor the secure mathematical way of looking at things can lead to a grasp of the spiritual world, so that one must stop with all human conceptual and ideological knowledge before this spiritual world and can only write a “Docta ignorantia” in relation to this spiritual world, is what comes to expression in such a magnificent way in Nicholas of Cusa. With this, however, he has, in a sense, broken with the kind of world knowledge that had arisen in human development up to his time. And I was able to point out how this mood of the soul is already present in Meister Eckhart, who is thoroughly versed in the theological knowledge of the Middle Ages and who wants to use this theological knowledge to look into his own human soul in order to find the way to the divine-spiritual foundations of the world in this human soul. And he, this Meister Eckhart, arrives at a mood of the soul which I indicated to you yesterday with one of his sentences. He said — and he said something similar repeatedly —: I immerse myself in the nothingness of the Godhead and out of this nothingness I become an I in eternity. He feels he has arrived at nothingness with his old knowledge and must, out of this nothingness, that is, out of the drying up of all the convincing powers of his old knowledge, draw from his soul, I would say, a primal utterance, the certainty of his own I.

If one looks more closely at such a thing, one comes to realize how someone like Meister Eckhart at that time was pointing to an older knowledge of the soul that had come up to him in the development of humanity, which still gave people something of which they could say: That lives in me; that is something divine in me, that is something. But now the deepest spirits of the age had arrived at the confession: If I seek that something there, if I seek that something there, then all knowledge of that something is not enough to find certainty about one's own being. And I must go from that something to nothingness in order to bring to life within myself, as it were, with a primal utterance, the consciousness of the I out of nothingness.

And now I would like to contrast these two personalities with another who lived about two thousand years earlier, a personality who is just as characteristic of his age as, for example, the Kusaner, based on Meister Eckhart, is characteristic of the beginning of the 15th century. We will need to go back to earlier times in order to better understand what emerged from the depths of the human soul in the 15th century in the form of a quest for knowledge. The personality I want to talk to you about today is not mentioned in any history book or historical document, because they do not go back that far, to around the 8th century BC. Nevertheless, we can only gain knowledge about what characterizes the actual origin of natural science if we go back further than external historical documents tell us, through spiritual science, through purely spiritual observation. This is a personality who, as I said, can only be found through spiritual insight, more than two thousand years before the age whose starting point I described yesterday as lying in the first half of the 15th century. This is a personality from pre-Christian life who was accepted into one of the so-called mystery schools of southern Europe, where everything that these mystery teachers had to say to their disciples was heard, these spiritual-cosmic teachings, spiritual-cosmic truths, truths about the spiritual beings that lived and live in the cosmos. But this personality I am referring to heard from the mystery teachers even back then a wisdom that was more or less only traditional, that was the reproduction of much much older visions of humanity, the reproduction of what much older wise men had seen when they repeatedly directed their clairvoyant gaze out into the world wide, and when, as was indeed the case, the movements of the stars, the constellations of the stars, and many other processes in the world wide spoke to them. To these ancient sages, the universe was not the machine or machine-like structure that it is to people today when they look out into space, but rather the vastness of the worlds was something in which these sages felt themselves to be in an all-living, all-pervading, all-spiritual being that spoke to them in a cosmic language. They felt themselves to be within the world-being of the spirit, and they felt how that in which they lived and wove spoke to them, how they could, as it were, ask the world itself the questions that the riddles of the world meant, and how the phenomena from the vastness answered them. This was perceived as what we call, in a very weakened and abstract form, the spirit in our language. And the spirit was actually perceived as that which is everywhere, but which can also be perceived from everywhere. People looked into the contents of worlds which even the Greeks could no longer see with their soul's eye, which had already become nothing for the Greeks. And this nothingness of the Greeks, which was still a something full of content for the oldest sages of the post-Atlantean era, was called by the words that were common at that time, and which in our language would be called, in a weakened and abstract form, “spirit.” So what later became unknown, the God who later became hidden, was called spirit when it was still known. That was the first thing in those ancient times.

The second thing was that when man looked within himself, he saw his soul with the soul's gaze, with the inward-directed gaze of the spirit. And he perceived this soul as that which came from the spirit that later became the unknown God, and he perceived his own soul in this way, this oldest sage, and with it humanity, which professed this oldest way, that the designation which could then be given to the human soul being out of these views, converted into our language, could be called spirit messenger or simply messenger. So that one can say, if one wants to represent schematically what was considered a view in those oldest times: At that time, the spirit was regarded as the all-encompassing world, outside of which nothing else existed, and which could be found in everything. And the spirit, which was directly perceptible in its original form, was sought again in the human soul, and it was found when this human soul recognized itself as the messenger of this spirit. So that one can say: The soul was regarded as a messenger.

And thirdly, people had around them the external nature with what we today call the essence, the physical being. I said that apart from the spirit there was nothing, for the spirit was seen everywhere, it was recognized in its original form through direct perception. It was recognized in the human soul, which realized its message in its own life. But it was also recognized in what we today call nature, the physical world. And this physical world was regarded as the image of the spirit.

In those ancient times, people did not have the same mental images of the physical world that we have today. Wherever one looked at any natural formation, one saw an image of the spirit, because one could see the spirit everywhere. The image of the spirit that was closest to us was the human body, this piece of nature. But since all other natural formations were images of the spirit, the human body was also an image of the spirit. Therefore, when these older people looked back on themselves, they recognized themselves as threefold beings. First, the spirit dwelt in them in its original form, as in one of its houses. Man recognized himself as spirit. Secondly, within the world, man felt himself to be the messenger of this spirit, and in this respect as a soul being. Thirdly, man felt himself to be a body, and through the body, an image of the spirit. So we can say that when man looked back on himself, he recognized himself in the trinity of his being: spirit, soul, and body; spirit in its original form, soul as the messenger of God, and body as the image of the spirit.

In this older wisdom of human beings, there was no contradiction between body and soul, no contradiction between nature and spirit, for it was known that spirit is in its original form in human beings; that which is the soul is nothing other than the spirit carried on, carried on as a message; the body is the image of the spirit. But they also felt no opposition between themselves and the surrounding nature, because they carried the image of the spirit within their own bodies, and they saw in every body outside themselves an image of the spirit. Thus, they felt their own bodies to be related to all natural bodies. They recognized an inner kinship when they looked out into the physical world and when they looked at the human body. Nature was not felt as something different. Man felt himself to be one with the whole rest of the world, as a unity, a monon. He felt this because he was able to perceive the archetypal form of the spirit, because the worlds spoke to him. And the consequence of this speaking of the worlds to man was that there could be no natural science. Just as we cannot establish a science of external nature from what lives in our memory, so these older members of humanity could not establish an external natural science, for they saw the image of the spirit when they looked within themselves, and they recognized this image of the spirit again when they looked out into external nature. There was no opposition between themselves as human beings and nature, nor was there any opposition between soul and body, for soul and body corresponded to each other in such a way that the body was, I might say, only the shell, the image, the artistic image of the spiritual archetype, and the soul was the mediating messenger between the two. Everything was in intimate unity. There could be no question of understanding, for one understands that which lies outside one's own life, while that which one carries within oneself is experienced directly, not first understood.

Such wisdom in direct perception lived in the oldest mysteries of humanity even before the Greek and Roman times. The personality I am referring to today heard of such wisdom. She heard of such wisdom, and she saw that the teachers of her mystery really had nothing more than traditions from earlier times to pass on to her. She no longer heard anything original, anything gained from listening to the secrets of the cosmos. And this person set out on long journeys, visited other mysteries, and basically experienced the same thing everywhere in this 8th century BC. Everywhere there were only the traditions of ancient wisdom. The students learned them from teachers who themselves could no longer see, at least not in the vividness of ancient times.

But the personality I am referring to had, from the depths of human nature, an immense urge for certainty, for knowledge. They heard from the messages that once upon a time it was possible to hear the harmony of the spheres, that from this harmony of the spheres the Logos resounded, the Logos that was identical with the spiritual archetype of all things. But she heard only traditions. And just as later, two thousand years later, out of the traditions of his age, Meister Eckhart sat down in his quiet little room in search of the inner power of the soul and the ego and came to the conclusion: I immerse myself in the nothingness of the Godhead and experience the I in eternity in nothingness—so said that old, lonely disciple of the late mysteries: I listen to the silent universe and from the silence I draw the Logos-bearing soul. I love the Logos, for the Logos proclaims an unknown God.

This was the older parallel confession to that of Meister Eckhart. Just as Meister Eckhart immersed himself with the powers of his soul into the nothingness of the Godhead, of which medieval theology spoke to him, just as he drew the I out of this nothingness, so that old sage listened to a silent world, for he no longer heard what the wisdom handed down to him spoke of. He could only listen to a silent universe. And he drew from the silent universe the soul that carried the logos, just as the spirit-filled soul of old had drawn the ancient wisdom. And he loved the Logos, which was no longer the divinity of old, but only an image of the divinity of old. In other words, the spirit had already disappeared from the soul in those times, and just as Meister Eckhart later had to search for the self in the destroyed world, so the soul had to be sought in the spiritless world.

Oh, in earlier times, souls had, as it were, the inner strength they needed to be able to say: I am myself a divine being in the inner perception of the spirit that dwells within me. But now the spirit no longer dwelt within them for immediate perception; now the soul no longer felt itself to be the messenger of the spirit. For in order to be the messenger of something, one must know it. Now the soul felt itself to be the bearer of the Logos, the bearer of the image of the spirit, even though this image of the spirit was very much alive within it, even though this image of the spirit expressed itself in love for the God who was still living out his image in the soul. But the soul no longer felt itself to be a messenger; the soul felt itself to be a bearer, a bearer of the image of the divine spirit. And so, if we want to represent this schematically again, we can say that a different understanding of human nature arose when people looked into their inner being: soul — carrier. The soul was transformed from a messenger into a carrier.

But because one had, in a sense, lost sight of the once living spirit, the body was no longer an image of that spirit. In order to recognize it as an image, one would have had to recognize the original form. The body became something else for this later perception. It became what I would like to call: the force. The concept of force now entered. It was imagined as a connection of forces, no longer an image that carries the essence of the depicted within itself, no longer an image—a force that does not carry within itself the essence of that from which it springs, that became the human body. And from the human body, one had to imagine forces everywhere in nature. Whereas nature had previously been everywhere an image of the spirit, it had now become the forces flowing from the spirit. With this, however, nature began to be more or less foreign to human beings. One might say that the soul has lost something, because it no longer has immediate spiritual consciousness within itself. If I were to express myself crudely, I would have to say: the soul has become thinner within itself; the body, the outer physical world, has gained in robustness. It used to have the spirit-like quality of an image. Now it has been permeated by force. The connection between forces is more robust than the image in which the spiritual content can still be seen. To express myself crudely again, I would have to say: the physical world has become denser, while the soul has become thinner. This was what passed into the consciousness of those people to whom that old sage belonged, who listened to the silent universe and drew from the silence of the universe the consciousness that his soul is at least the bearer of the Logos.

And now, between the soul, which had become thinner, and the physical world, which had become denser, there arose a contrast that had not existed before. In the past, people saw the unity of the spirit in everything. Now the contrast between body and soul, human being and nature arose, so that now there appeared the abyss between body and soul that had not existed before that ancient sage, of whom I have told you today, spoke, but that human beings also felt themselves separated from nature, which was likewise not felt in ancient times. And this contrast basically forms the core content of all thinking in the period between that old sage I told you about today and Nicholas of Cusa.

Humanity is struggling to understand the connection between the soul, which lacks spiritual reality, and the body, which has become dense, a force, a connection of forces. And humanity is struggling to find a sense of the relationship between man and nature. But nature is power everywhere. A mental image of what we today call the laws of nature did not actually exist in this age, in which its most characteristic epochs lie. People did not think in terms of the laws of nature; they felt the forces of nature everywhere. They experienced the forces of nature in everything. And when one looked within oneself, one did not feel a soul that, as later, carries within itself a dull will, an almost equally dull feeling, and abstract thinking, but one felt a soul that is the bearer of the living Logos, which one knows is not dead, but is a divine, living image of God.

One must be able to put oneself into this contrast, which existed in all its sharpness until the 11th and 12th centuries, and which is quite different from the contrasts felt by humanity today. If one cannot put oneself into this completely different contrast of an older epoch of humanity with living consciousness, then one does what all historians of philosophy do, namely describe the ancient Greek Democritus from the 5th century BC as if he were an atomist in the modern sense because he assumed atoms. If words suggest a slight resemblance, then the resemblance does not yet exist. There is a huge difference between the modern atomist and Democritus, because Democritus completely disregards the opposition I have just characterized between man and nature, soul and body, so that his atoms are still entirely force relationships, and as such are opposed by him to space in a way that the modern atomist cannot oppose his atoms to space. How could the modern atomist say what Democritus said: Being is no more than nothingness, the full is no more than the empty. That is to say, Democritus assumes that empty space has a relationship with the space filled with atoms. This only makes sense within a consciousness that does not yet know the modern concept of the body at all, and therefore cannot speak of atoms of a body, but only of points of force, which then have an inner relationship with that which is outside of man. Today's atomist cannot equate emptiness with fullness. For if Democritus had imagined emptiness as we speak of it today, he could not have equated it with being. He can equate it because he seeks within this emptiness that which is the bearer of the soul, the soul which is the bearer of the Logos. If he also imagines this Logos with a kind of necessity, it is the Greek necessity, not our present-day natural necessity. If one wants to understand what is happening today, it is important to be able to look correctly into the nuances of the mental images and feelings of earlier times.

And now came the time I characterized yesterday, the time of Meister Eckhart, the time of Nicholas of Cusa, when the consciousness of the Logos living in the soul was also lost. Master Eckhart and Cusanus found that where the old master, listening to the universe, could only complain of silence, they found nothingness, and had to seek the I out of nothingness. But this is where the newer era of human thinking really begins. Now the soul no longer has the living Logos within itself; now, when it looks within itself, it has ideas and concepts, mental images, that which ultimately leads to abstractions. Now it has become even thinner. The third phase of human perception begins. Once, in the first phase, the soul experienced the archetype of the spirit within itself. It was a messenger of the spirit. The second phase: the soul experiences within itself the living image of God in the Logos; it becomes a bearer of the Logos.

Now, in the third phase, it becomes, as it were, a repository of ideas and concepts which, although they emerge in the certainty of mathematics, are nevertheless concepts and ideas. One might say that it feels most diluted inwardly. And once again, the physical world grows in robustness. The third way in which humans feel emerges. They cannot yet completely abandon their soul, but they feel this soul as the container of the ideal, and they no longer feel the body merely as a force, but as an extended physical entity.