Agriculture

GA 327

7 June 1924, Koberwitz

Lecture I

My dear friends,

With profound thanks I look back on the words which Count Keyserlingk has just spoken. For the feeling of thanks is not only justified on the part of those who are able to receive from Anthroposophical Science. One can also feel deeply what I may call the thanks of Anthroposophia itself—thanks which in these hard times are due to all who share in anthrosposophical interests.

Out of the spirit of Anthroposophia, therefore, I would thank you most heartily for the words you have just spoken. Indeed, it is deeply gratifying that we are able to hold this Agriculture Course here in the house of Count and Countess Keyserlingk. I know from my former visits what a beautiful atmosphere there is in Koberwitz—I mean also the spiritual atmosphere. I know that the atmosphere of soul and spirit which is living here is the best possible premiss for what must be said during this Course.

Count Keyserlingk has told us that there may be some discomforts for one or another among us. He was speaking especially of the eurhythmists; though it may be the “discomforts” are shared by some of our other visitors from a distance. Yet on the other hand, considering the purpose of our present gathering, it seems to me we could scarcely be accommodated better for this Lecture Course than here, in a farm so excellent and so exemplary.

Whatever comes to light in the realms of Anthroposophia, we also need to live in it with our feelings—in the necessary atmosphere. And for our Course on Farming this condition will most certainly be fulfilled at Koberwitz. All this impels me to express our deeply felt thanks to Count Keyserlingk and to his house. In this I am sure Frau Doctor Steiner will join me. We are thankful that we may spend these festive days—I trust they will also be days of real good work—here in this house.

I cannot but believe: inasmuch as we are gathered here in Koberwitz, there will prevail throughout these days an agricultural spirit which is already deeply united with the Anthroposophical Movement. Was it not Count Keyserlingk who helped us from the very outset with his advice and his devoted work, in the farming activities we undertook at Stuttgart under the Kommende Tag Company? His spirit, trained by his deep and intimate Union with Agriculture, was prevalent in all that we were able to do in this direction. And I would say, forces were there prevailing which came from the innermost heart of our Movement and which drew us hither, quite as a matter of course, the moment the Count desired us to come to Koberwitz.

Hence I can well believe that every single one of us has come here gladly for this Agriculture Course. We who have come here can express our thanks just as deeply and sincerely, that your House has been ready to receive us with our intentions for these days. For my part, these thanks are felt most deeply, and I beg Count Keyserlingk and his whole house to receive them especially from me. I know what it means to give hospitality to so many visitors and for so many days, in the way in which I feel it will be done here. Therefore I think I can also give the right colouring to these words of thanks, and I beg you to receive them, understanding that I am well aware of the many difficulties which such a gathering may involve in a house remote from the City. Whatever may be the inconveniences of which the Count has spoken—representing, needless to say, not the “Home Office” but the “Foreign Office”—whatever they may be, I am quite sure that every single one of us will go away fully satisfied with your kind hospitality.

Whether you will go away equally satisfied with the Lecture-Course itself, is doubtless a more open question, though we will do our utmost, in the discussions during the succeeding days, to come to a right understanding on all that is here said. You must not forget: though the desire for it has been cherished in many quarters for a long time past, this is the first time I have been able to undertake such a Course out of the heart of our anthroposophical striving. It pre-supposes many things.

The Course itself will show us how intimately the interests of Agriculture are bound up, in all directions, with the widest spheres of life. Indeed there is scarcely a realm of human life which lies outside our subject. From one aspect or another, all interests of human life belong to Agriculture. Here, needless to say, we can only touch upon the central domain of Agriculture itself, albeit this of its own accord will lead us along many different side tracks—necessarily so, for the very reason that what is here said will grow out of the soil of Anthroposophia itself.

In particular, you must forgive me if my introductory words to-day appear—inevitably—a little far remote. Not everyone, perhaps, will see at once what the connection is between this introduction and our special subject. Nevertheless, we shall have to build upon what is said to-day, however remote it may seem at first sight. For Agriculture especially is sadly hit by the whole trend of modern spiritual life. You see, this modern spiritual life has taken on a very destructive form especially as regards the economic realm, though its destructiveness is scarcely yet divined by many.

Our real underlying intentions, in the economic undertakings which grew out of the Anthroposophical Movement, were meant to counteract these things. These undertakings were created by industrialists, business men, but they were unable to realise in all directions what lay in their original intentions, if only for the reason that the opposing forces in our time are all too numerous, preventing one from calling forth a proper understanding for such efforts. Over against the “powers that be,” the individual is often powerless. Hitherto, not even the most original and fundamental aspects of these industrial and economic efforts, which grew out of the heart of the Anthroposophical Movement, have been realised. Nay, they have not even reached the plane of discussion. What was the real, practical point? I will explain it in the case of Agriculture, so that we may not be speaking in vague and general, but in concrete terms.

We have all manner of books and lecture courses on Economics, containing, among other things, chapters on the economic aspects of Agriculture. Economists consider, how Agriculture should be carried on in the light of social-economic principles. There are many books and pamphlets on this subject: how Agriculture should be shaped, in the light of social and economic ideas. Yet the whole of this—the giving of economic lectures an the subject and the writing of such books—is manifest nonsense. Palpable nonsense, I say, albeit that is practised nowadays in the widest circles. For it should go without saying, and every man should recognise the fact: One cannot speak of Agriculture, not even of the social forms it should assume, unless one first possesses as a foundation a practical acquaintance with the farming job itself. That is to say, unless one really knows what it means to grow mangolds, potatoes and corn! Without this foundation one cannot even speak of the general economic principles which are involved. Such things must be determined out of the thing itself, not by all manner of theoretic considerations.

Nowadays, such a statement seems absurd to those who have heard University lectures on the economics of Agriculture. The whole thing seems to them so well established. But it is not so. No one can judge of Agriculture who does not derive his judgment from field and forest and the breeding of cattle. All talk of Economics which is not derived from the job itself should really cease. So long as people do not recognise that all talk of Economics—hovering airily over the realities—is mere empty talk, we shall not reach a hopeful prospect, neither in Agriculture nor in any other sphere.

Why is it that people think they can talk of a thing from theoretic points of view, when they do not understand it? The reason is, that even within their several domains they are no longer able to go back to the real foundations. They look at a beetroot as a beetroot. No doubt it has this or that appearance; it can be cut more or less easily, it has such and such a colour, such and such constituents. All these things can no doubt be said. Yet therewithal you are still far from understanding the beetroot. Above all, you do not yet understand the living-together of the beetroot with the soil, with the field, the season of the year in which it ripens, and so forth.

You must be clear as to the following (I have often used this comparison for other spheres of life): You see a magnetic needle. You discern that it always points with one end approximately to the North, and with the other to the South. You think, why is it so? You look for the cause, not in the magnetic needle, but in the whole Earth, inasmuch as you assign to the one end of the Earth the magnetic North Pole, and to the other the magnetic South.

Anyone who looked in the magnet-needle itself for the cause of the peculiar position it takes up, would be talking nonsense. You can only understand the direction of the magnet-needle if you know how it is related to the whole Earth. Yet the same nonsense (as applied to the magnetic needle) is considered good sense by the men of to-day when applied to other things.

There, for example, is the beetroot growing in the earth. To take it just for what it is within its narrow limits, is nonsense if in reality its growth depends on countless conditions, not even only of the Earth as a whole, but of the cosmic environment. The men of to-day say and do many things in life and practice as though they were dealing only with narrow, limited objects, not with effects and influences from the whole Universe. The several spheres of modern life have suffered terribly from this, and the effects would be even more evident were it not for the fact that in spite of all the modern science a certain instinct still remains over from the times when men were used to work by instinct and not by scientific theory.

To take another sphere of life: I am always glad to think that those whose doctors have prescribed how many ounces of meat they are to eat, and how much cabbage (some of them even have a balance beside them at the table and carefully weigh out everything that comes on to their plate)—it is all very nice; needless to say, one ought to know such things—but I am always glad to think how good it is that the poor fellow still feels hungry, if, after all, he has not had enough to eat! At least there is still this instinct to tell him so.

Such instincts really underlay all that men had to do before a “science” of these things existed. And the instincts frequently worked with great certainty. Even to-day one is astonished again and again to read the rules in the old “Peasants' Calendars.” How infinitely wise and intelligent is that which they express! Moreover, the man of pure instincts is well able to avoid superstition in these matters: and in these Calendars, beside the proverbs full of deep meaning for the sowing and the reaping, we find all manner of quips, intended to set aside nonsensical pretentions. This for example:—If the cock crows on the dunghill, It'll rain—or it'll stay still.” So the needful dose of humour is mingled with the instinctive wisdom in order to ward off mere superstition.

We, however, speaking from the point of view of Anthroposophical Science, do not desire to return to the old instincts. We want to find, out of a deeper spiritual insight, what the old instincts—as they are growing insecure—are less and less able to provide. To this end we must include a far wider horizon in our studies of the life of plant and animal, and of the Earth itself. We must extend our view to the whole Cosmos.

From one aspect, no doubt, it is quite right that we should not superficially connect the rain with the phases of the Moon. Yet on the other hand there is a true foundation to the story I have often told in other circles. In Leipzig there were two professors. One of them, Gustav Theodor Fechner, often evinced a keen and sure insight into spiritual matters. Not altogether superstitiously, from pure external observations he could see that certain periods of rain or of no rain were connected, after all, with the Moon and with its coursing round the earth.

He drew this as a necessary conclusion from the statistical results. That however was a time when orthodox science already wanted to overlook such matters, and his colleague, the famous Professor Schleiden, poured scorn on the idea “for scientific reasons.” Now these two professors of the University of Leipzig also had wives. Gustav Theodor Fechner, who was a man not without humour, said: “Well, let our wives decide.”

In Leipzig at that time the water they needed for washing clothes was not easy to obtain, and a certain custom still prevailed. You had to fetch your water from a long distance. Hence they were wont to put out pails and barrels to catch the rain water.

This was Frau Prof. Schleiden's custom as well as Frau Prof. Fechner's. But they had not room enough to put out their barrels in the yard at the same time. So Prof. Fechner said: “If my honoured colleague is right, if it makes no difference, then let Frau Prof. Schleiden put out her barrel when by my indications, according to the phases of the Moon, there will be less rain. If it is all nonsense, Frau Prof. Schleiden will surely be glad to do so.”

But, lo and behold, Frau Prof. Schleiden rebelled. She preferred the indications of Prof. Fechner to those of her own husband. And so indeed it is. Science may be perfectly correct. Real life, however, often cannot afford to take its cue from the “correctness” of science!

But we do not wish to speak only in this way. We are in real earnest about it. I only wanted to point out the need to look a little farther afield than is customary nowadays. We must do so in studying that which alone makes possible the physical life of man on Earth—and that, after all, is Agriculture. I do not know whether the things which can be said at this stage out of Anthroposophical Science will satisfy you in all directions, but I will do my best to explain what Anthroposophical Science can give for Agriculture.

To-day, by way of introduction, I will indicate what is most important for Agriculture in the life of the Earth. Nowadays we are wont to attach the greatest importance to the physical and chemical constituents. To-day, however, we will not take our Start from these; we will take our start from something which lies behind the physical and chemical constituents and is nevertheless of great importance for the life of plant and animal.

Studying the life of man (and to a certain extent it applies to animal life also), we observe a high degree of emancipation of human and animal life from the outer Universe. The nearer we come to man, the greater this emancipation grows. In human and animal life we find phenomena appearing—to begin with—quite independent not only of the influences from beyond the Earth, but also of the atmospheric and other influences of the Earth's immediate environment. Moreover, this not only appears so; it is to a high degree correct for many things in human life.

True, it is well-known that the pains of certain illnesses are intensified by atmospheric influences. There is, however, another fact of which the people of to-day are not so well aware. Certain illnesses and other phenomena of human life take their course in such a way that in their time-relationships they copy the external processes of Nature. Yet in their beginning and end they do not coincide with these Nature-processes. We need only call to mind one of the most important phenomena of all, that of female menstruation. The periods, in their temporal course, imitate the course of the lunar phases, but they do not coincide with the latter in their beginning and ending. And there are many other, less evident phenomena, both in the male and in the female organism, representing imitations of rhythms in outer Nature.

If these things were studied more intimately, we should for example have a better understanding of many things that happen in the social life by observing the periodicity of the Sun-spots. People only fail to observe these things because that in human life which corresponds to the periodicity of the Sun-spots does not begin when they begin, nor does it cease when they cease. It has emancipated itself. It shows the same periodicity, the identical rhythm, but its phases do not coincide in time. While inwardly maintaining the rhythm and periodicity, it makes them independent—it emancipates itself.

Anyone, of course, to whom we say that human life is a microcosm and imitates the macrocosm, is at liberty to reply. That is all nonsense! If we declare that certain illnesses show a seven day's fever period, one may object: Why then, when certain outer phenomena appear, does not the fever too make its appearance and run parallel, and cease with the external phenomena? It is true that the fever does not; but, though its temporal beginning and ending do not coincide with the outer phenomena, it still maintains their inner rhythm. This emancipation in the Cosmos is almost complete for human life; for animal life it is less so; plant life, an the other hand, is still to a high degree immersed in the general life of Nature, including the outer earthly world.

Hence we shall never understand plant life unless we bear in mind that everything which happens on the Earth is but a reflection of what is taking place in the Cosmos. For man this fact is only masked because he has emancipated himself; he only bears the inner rhythms in himself. To the plant world, however, it applies in the highest degree. That is what I should like to point out in this introductory lecture.

The Earth is surrounded in the heavenly spaces, first by the Moon and then by the other planets of our planetary system. In an old instinctive science wherein the Sun was reckoned among the planets, they had this sequence: Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn. Without astronomical explanations I will now speak of this planetary life, and of that in the planetary life which is connected with the earthly world.

Turning our attention to the earthly life on a large scale, the first fact for us to take into account is this. The greatest imaginable part is played in this earthly life (considered once more on a Large scale, and as a whole) by all that which we may call the life of the silicious substance in the world. You will find silicious substance for example, in the beautiful mineral quartz, enclosed in the form of a prism and pyramid; you will find the silicious substance, combined with oxygen, in the crystals of quartz.

Imagine the oxygen removed (which in the quartz is combined with silicious substance) and you have so-called silicon. This substance is included by modern chemistry among the “elements,” oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, sulphur, etc. Silicon therefore, which is here combined with oxygen, is a “chemical element.”

Now we must not forget that the silicon which lives thus in the mineral quartz is spread over the Earth so as to constitute 27-28% of our Earth's crust. All other substances are present in lesser quantities, save oxygen, which constitutes 47-48%. Thus an enormous quantity of silicon is present. Now, it is true this silicon, occurring as it does in rocks like quartz, appears in such a form that it does not seem very important when we are considering the outer, material aspect of the Earth with its plant-growth. (The plant-growth is frequently forgotten).

Quartz is insoluble in water—the water trickles through it. It therefore seems—at first sight—to have very little to do with the ordinary, obvious conditions of life. But once again, you need only remember the horse-tail—equisetum—which contains 90% of silica—the same substance that is in quartz—very finely distributed.

From all this you can see what an immense significance silicon must have. Well-nigh half of what we meet on the Earth consists of silica. But the peculiar thing is how very little notice is taken of it. It is practically excluded to-day even from those domains of life where it could work most beneficially.

In the Medicine that proceeds from Anthroposophical Science, silicious substances are an essential constituent of numerous medicaments. A large class of illnesses are treated with silicic acid taken internally, or outwardly as baths. In effect, practically everything that shows itself in abnormal conditions of the senses is influenced in a peculiar way by silicon. (I do not say what lies in the senses themselves, but that which shows itself in the senses, including the inner senses—calling forth pains here or there in the organs of the body).

Not only so; throughout the “household of Nature,” as we have grown accustomed to call it, silicon plays the greatest imaginable part, for it not only exists where we discover it in quartz or other rocks, but in an extremely fine state of distribution it is present in the atmosphere. Indeed, it is everywhere. Half of the Earth that is at our disposal is of silica.

Now what does this silicon do? In a hypothetical form, let us ask ourselves this question. Let us assume that we only had half as much silicon in our earthly environment. In that case our plants would all have more or less pyramidal forms. The flowers would all be stunted. Practically all plants would have the form of the cactus, which strikes us as abnormal. The cereals would look very queer indeed. Their stems would grow thick, even fleshy, as you went downward; the ears would be quite stunted—they would have no full ears at all.

That on the one hand. On the other hand we find another kind of substance, which must occur everywhere throughout the Earth, albeit it is not so widespread as the silicious element. I mean the chalk or limestone substances and all that is akin to these—limestone, potash, sodium substances. Once more, if these were present to a less extent, we should have plants with very thin stems—plants, to a large extent, with twining stems; they would all become like creepers. The flowers would expand, it is true, but they would be useless: they would provide practically no nourishment. Plant-life in the form in which we see it to-day can only thrive in the equilibrium and co-operation of the two forces—or, to choose two typical substances, in the co-operation of the limestone and silicious substances respectively.

Now we can go still farther. Everything that lives in the silicious nature contains forces which comes not from the Earth but from the so-called distant planets, the planets beyond the Sun—Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. That which proceeds from these distant planets influences the life of plants via the silicious and kindred substances into the plant and also into the animal life of the Earth. On the other hand, from all that is represented by the planets near the Earth—Moon, Mercury and Venus—forces work via the limestone and kindred substances. Thus we may say, for every tilled field: Therein are working the silicious and the limestone natures; in the former, Saturn, Jupiter and Mars; and in the latter, Moon, Venus and Mercury.

In this connection let us now look at the plants themselves. Two things we must observe in the plant life. The first thing is that the entire plant-world, and every single species, is able to maintain itself—that is to say, it evolves the power of reproduction. The plant is able to bring forth its kind, and so on. That is the one thing. The other is, that as a creature of a comparatively lower kingdom of Nature, the plant can serve as nourishment for those of the higher kingdoms.

At first sight, these two currents in the life and evolution of the plant have little to do with one another. For the process of development from the mother plant to the daughter plant, the granddaughter plant and so on, it may well seem a matter of complete indifference to the formative forces of Nature, whether or no we eat the plant and nourish ourselves thereby. Two very different sets of interests are manifested here. Yet in the whole nexus of Nature's forces, it works in this way:—

Everything connected with the inner force of reproduction and growth—everything that contributes to the sequence of generation after generation in the plants—works through those forces which come down from the Cosmos to the Earth: from Moon, Venus and Mercury, via the limestone nature. Suppose we were merely considering what emerges in plants such as we do not eat—plants that simply renew themselves again and again. We look at them as though the cosmic influences from the forces of Venus, Mercury and Moon did not interest us. For these are the forces involved in all that reproduces itself in the plant-nature of the Earth.

On the other hand, when plants become foodstuffs to a large extent—when they evolve in such a way that the substances in them become foodstuffs for animal and man, then Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, working via the silicious nature, are concerned in the process. The silicious nature opens the plant-being to the wide spaces of the Universe and awakens the senses of the plant-being in such a way as to receive from all quarters of the Universe the forces which are moulded by these distant planets. Whenever this occurs, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn are playing their part. From the sphere of the Moon, Venus and Mercury, on the other hand, is received all that which makes the plant capable of reproduction.

To begin with, no doubt this appears as a simple piece of information. But truths like this, derived from a somewhat wider horizon, lead of their own accord from knowledge into practice. For we must ask ourselves: If forces come into the Earth from Moon, Venus and Mercury and become effective in the life of plants, by what means can the process be more or lese quickened or restrained? By what means can the influences of Moon or Saturn on the life of plants be hindered, and by what means assisted?

Observe the course of the year. It takes its course in such a way that there are days of rain and days without rain. As to the rain, the modern physicist investigates practically no more than the mere fact that when it rains, more water falls upon the Earth than when it does not rain. For him, the water is an abstract substance composed of hydrogen and oxygen. True, if you decompose water by electrolysis, it will fall into two substances, of which the one behaves in such and such a way, and the other in another way. But that does not yet tell us anything complete about water itself. Water contains far, far more than what emerges from it chemically, in this process, as oxygen and hydrogen.

Water, in effect, is eminently suited to prepare the ways within the earthly domain for those forces which come, for instance, from the Moon. Water brings about the distribution of the lunar forces in the earthly realm. There is a definite connection between the Moon and the water in the Earth. Let us therefore assume that there have just been rainy days and that these are followed by a full Moon. In deed and in truth, with the forces that come from the Moon on days of the full Moon, something colossal is taking place on Earth. These forces spring up and shoot into all the growth of plants, but they are unable to do so unless rainy days have gone before.

We shall therefore have to consider the question: Is it not of some significance, whether we sow the seed in a certain relation to the rainfall and the subsequent light of the full Moon, or whether we sow it thoughtlessly at any time? Something, no doubt, will come of it even then. Nevertheless, we have to raise this question: How should we best consider the rainfall and the full Moon in choosing the time to sow the seed? For in certain plants, what the full Moon has to do will thrive intensely after rainy days and will take place but feebly and sparingly after days of sunshine. Such things lay hidden in the old farmers' rules; they quoted a certain verse or proverb and knew what they must do. The proverbs to-day are outworn superstitions, and a science of these things does not yet exist; people are not yet willing enough to set to work and find it.

Furthermore, around our Earth is the atmosphere. Now the atmosphere above all—beside the obvious fact that it is airy—has the peculiarity that it is sometimes warmer, sometimes cooler. At certain times it shows a considerable accumulation of warmth, which, when the tension grows too strong, may even find relief in thunderstorms. How is it then with the warmth? Spiritual observation shows that whereas the water has no relation to silica, this warmth has an exceedingly strong relation to it.

The warmth brings out and makes effective precisely those forces which can work through the silicious nature, namely, the forces that proceed from Saturn, Jupiter and Mars. These forces must be regarded in quite a different way than the forces from the Moon. For we must not forget that Saturn takes thirty years to revolve round the Sun, whereas the Moon with its phases takes only thirty or twenty-eight days. Saturn is only visible for fifteen years. It must therefore be connected with the growth of plants in quite a different way, albeit, I need hardly say, it is not only working when it shines down upon the Earth; it is also effective when its rays have to pass upward through the Earth.

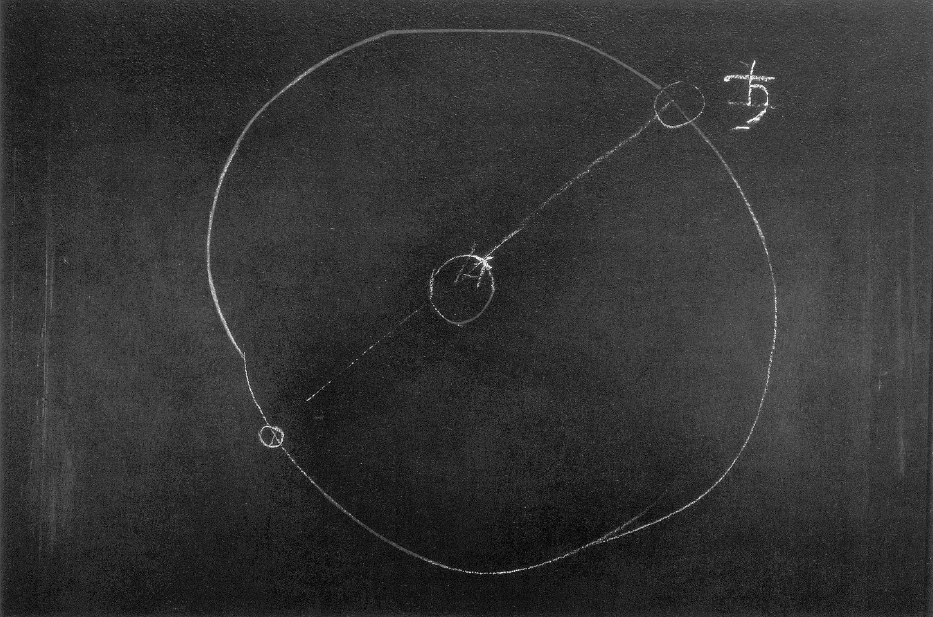

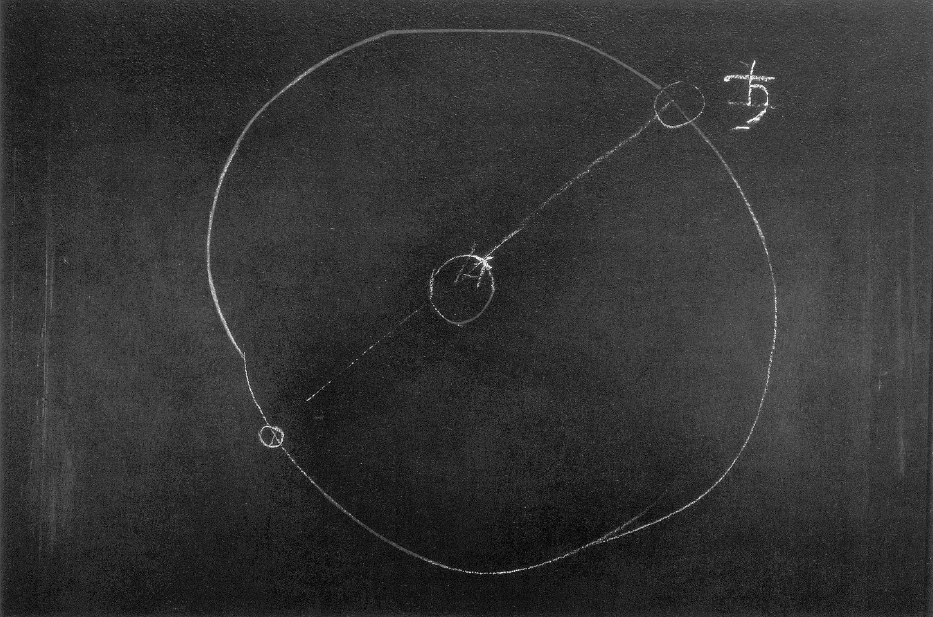

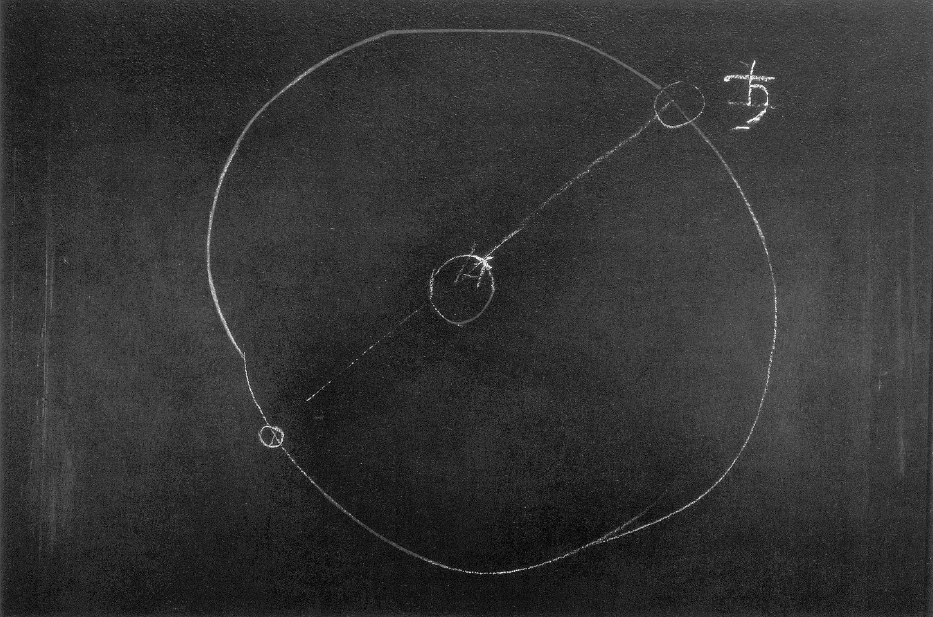

Saturn goes slowly round, in thirty years. Let us draw it thus (Diagram 1): here is the course of Saturn. Sometimes it shines directly on to a given spot of the Earth. But it can also work through the Earth upon this portion of the Earth's surface. In either case the intensity with which the Saturn-forces are able to approach the plant life of the Earth is dependent on the warmth-conditions of the air. When the air is cold, they cannot approach; when the air is warm, they can.

And where do we see the working of these forces in the plant's life? We see it, not so much where annual plants arise, coming and going in a season and only leaving seeds behind. We see what Saturn does with the help of the warmth-forces of our Earth, whenever the perennial plants arise. The effects of these forces, which pass into the plant-nature via the warmth, are visible to us in the rind and bark of trees, and in all that makes the plants, perennial. This is due to the simple fact that the annual life of the plant—its limitation to a short length of life—is connected with those planets whose period of revolution is short. That, on the other hand, which frees itself from the transitory nature—that which surrounds the trees with bark and rind, and makes them permanent—is connected with the planetary forces which work via the forces of warmth and cold and have a long period of revolution, as in the case of Saturn: thirty years; or Jupiter: twelve years.

If someone wishes to plant an oak, it is of no little importance whether or no he has a good knowledge of the periods of Mars; for an oak, rightly planted in the proper Mars-period, will thrive differently from one that is planted in the Earth thoughtlessly, just when it happens to suit.

Or, if you wish to plant coniferous forests, where the Saturn-forces play so great a part, the result will be different if you plant the forest in a so-called ascending period of Saturn, or in some other Saturn period. One who understands can tell precisely, from the things that will grow or will not grow, whether or no they have been planted with an understanding of the connections of these forces. That which does not appear obvious to the external eye, appears very clearly, none the less, in the more intimate relationships of life.

Assume for instance that we take, as firewood, wood that is derived from trees which were planted in the Earth without understanding of the cosmic rhythms. It will not provide the same health-giving warmth as firewood from trees that were planted intelligently. These things enter especially into the more intimate relationships of daily life, and here they show their great significance. Alas! the life of people has become almost entirely thoughtless nowadays. They are only too glad if they do not need to think of such things. They think it must all go on just like any machine. You have all the necessary contrivances; turn on the switch, and it goes. So do they conceive, materialistically, the working of all Nature.

Along these lines we are eventually led to the most alarming results in practical life. Then the great riddles arise. Why, for example, is it impossible to-day to eat such potatoes as I ate in my youth? It is so; I have tried it everywhere. Not even in the country districts where I ate them then, can one now eat such potatoes. Many things have declined in their inherent food-values, notably during the last decades.

The more intimate influences which are at work in the whole Universe are no longer understood. These must be looked for again along such lines as I have hinted at to-day. I have only introduced the subject; I have only tried to show where the questions arise—questions which go far beyond the customary points of view. We shall continue and go deeper in this way, and then apply, what we have found, in practice.

Erster Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

[ 1 ] Mit tiefem Danke sehe ich auf die Worte zurück, die eben der Herr Graf Keyserlingk gesprochen hat. Denn es ist ja durchaus nicht bloß die Empfindung des Dankes derjenigen, die aus der Anthroposophie etwas entgegennehmen können, berechtigt, sondern es ist sozusagen auch wirklich der Dank der anthroposophischen Sache, der in unserer heutigen schwierigen Zeit allen Teilnehmern an anthroposophischen Interessen gezollt werden muss, ein solcher, den man tief empfinden kann. Und so möchte ich gerade aus dem Geiste anthroposophischer Gesinnung heraus in allerherzlichster Weise danken für die eben ausgesprochenen Worte.

[ 2 ] Es ist ja eine tiefbefriedigende Tatsache, dass es möglich ist, diesen landwirtschaftlichen Kursus gerade hier im Hause des Grafen und der Gräfin Keyserlingk abhalten zu können. Aus meinen früheren Besuchen weiß ich, welch wunderschön wirkende Atmosphäre, ich meine vor allem auch die geistig-seelische Atmosphäre, es hier in Koberwitz gibt, und wie gerade dasjenige, was hier an geistig-seelischer Atmosphäre lebt, ja die schönste Vorbedingung ist für dasjenige, was innerhalb dieses Kurses gesprochen werden soll.

[ 3 ] Wenn der Graf darauf aufmerksam gemacht hat, dass es für den einen oder den anderen - in diesem Falle waren es die Eurythmiedamen, es können ja auch andere Besucher von auswärts davon betroffen sein — vielleicht manches Unannehmliche geben kann, so muss auf der anderen Seite in Bezug auf das, was uns eigentlich zusammengebracht hat, doch gesagt werden: Ich glaube, wir könnten für diesen landwirtschaftlichen Kursus kaum irgendwo besser untergebracht sein als gerade inmitten einer so ausgezeichneten und so musterhaft betriebenen Landwirtschaft. Zu allem, was auf anthroposophischem Felde zutage tritt, gehört ja das, dass man auch sozusagen in der nötigen Empfindungsumgebung drinnen stecken kann. Und das wird für die Landwirtschaft ganz sicher hier der Fall sein können.

[ 4 ] Nun, das alles veranlasst mich, dem Hause des Grafen Keyserlingk den allertiefgefühltesten Dank auszusprechen, dem ja gewiss auch Frau Doktor Steiner beistimmen wird dafür, dass wir diese Festes-, ich denke, es werden auch Arbeitstage sein, gerade hier werden verleben können. Ich muss ja dabei bedenken, dass, ich möchte sagen, gerade dadurch, dass wir hier in Koberwitz sind, ein schon mit der anthroposophischen Bewegung verbundener landwirtschaftlicher Geist in diesen Festestagen walten wird. War es doch der Graf Keyserlingk, der von Anfang den Bestrebungen, die wir, ausgehend vom «Kommenden Tag», für die Landwirtschaft in Stuttgart entwickelten, mit Rat und Tat und aufopferungsvoller Arbeit zur Seite stand, der ja seinen aus einem so gründlichen Zusammengewachsensein mit der Landwirtschaft herangezogenen Geist in dem walten ließ, was wir in Bezug auf die Landwirtschaft tun konnten. Es war schon, ich möchte sagen, aus dem Innersten unserer Bewegung dadurch etwas an Kräften waltend, die wie mit einer gewissen Selbstverständlichkeit uns hierher zogen nach Koberwitz in dem Augenblicke, wo uns der Graf hier haben wollte. Deshalb kann ich auch versichern, dass ich glauben kann, dass jeder eigentlich gerne hier nach Koberwitz für die Abhaltung dieses Kursus gegangen ist. Das begründet, dass wir, die wir gekommen sind, ebenso tief unseren Dank dafür auszusprechen haben, ihn sehr gerne aussprechen dafür, dass das Haus Keyserlingk sich bereit erklärt hat, uns mit diesen Bestrebungen in diesen Tagen aufzunehmen.

[ 5 ] Was mich betrifft, so ist dieser Dank allerherzlichst gefühlt, und ich bitte das Haus Keyserlingk, ihn von mir ganz besonders entgegenzunehmen. Ich weiß, was es heißt, durch längere Tage hindurch in einer solchen Weise, wie ich es fühle, dass es geschehen wird, so viele Besucher aufzunehmen, und kann, glaube ich, daher auch in diesen Dank die nötige Nuance legen, und bitte auch, diese durchaus so aufzunehmen, dass ich auch die Schwierigkeiten durchaus bedenken kann, die der Abhaltung einer solchen Veranstaltung in einem Hause, das weit abliegt von der Stadt, entgegenstehen. Ich bin überzeugt davon, dass — wie auch jene Unannehmlichkeiten, von denen Graf Keyserlingk als in diesem Fall Vertreter selbstverständlich nicht der inneren, sondern der auswärtigen Politik der hiesigen Vortragsveranstaltungen gesprochen hat, sich ausnehmen werden - unter allen Umständen jeder von uns befriedigt hinweggehen wird, was anbetrifft die Bewirtung und die Aufnahme hier.

[ 6 ] Nun, ob Sie ebenso befriedigt hinweggehen können von dem Kursus selber, das ist natürlich durchaus die Frage, die wahrscheinlich immer diskutabler werden wird, trotzdem wir ja alles tun wollen, um uns auch in den späteren Tagen in allerlei Diskussionen über das Gesagte zu verständigen. Denn Sie müssen bedenken, es ist ja, obzwar von vielen Seiten ein lang gehegter Wunsch nach einem solchen Kursus bestand, zum ersten Mal, dass ich aus dem Schoß des anthroposophischen Strebens heraus einen solchen Kursus übernehme. Ein solcher Kursus erfordert gar mancherlei, denn er wird uns selber zeigen, wie die Interessen der Landwirtschaft nach allen Seiten hin mit dem größten Umkreise des menschlichen Lebens verwachsen sind und wie eigentlich es kaum ein Gebiet des Lebens gibt, das nicht zu der Landwirtschaft gehört. Von irgendeiner Seite, aus irgendeiner Ecke gehören alle Interessen des menschlichen Lebens in die Landwirtschaft hinein. Wir können selbstverständlich hier nur das zentrale Gebiet des Landwirtschaftlichen berühren. Allein, das wird uns wie von selbst führen zu manchem Seitenwege, der vielleicht gerade deshalb - weil das, was hier gesagt ist, durchaus auf anthroposophischem Boden gesagt werden soll, sich gerade dadurch als notwendig ergibt. Insbesondere werden Sie mir verzeihen müssen, wenn die heutige Einleitung zunächst so weit hergeholt werden muss, dass vielleicht nicht jeder gleich sieht, welche Verbindung zwischen der Einleitung bestehen wird und dem, was wir speziell landwirtschaftlich zu verhandeln haben. Trotzdem wird aber dasjenige, was da aufgebaut werden soll, auf diesem heute zu Sagenden, scheinbar etwas ferner Liegenden, fußen müssen.

[ 7 ] Gerade die Landwirtschaft ist ja auch in einer gewissen Weise betroffen, in ernstlicher Weise betroffen worden durch das ganze neuzeitliche Geistesleben. Sehen Sie, dieses ganze neuzeitliche Geistesleben hat ja insbesondere in Bezug auf [den] wirtschaftlichen Charakter zerstörerische Formen angenommen, deren zerstörerische Bedeutung von vielen Leuten heute noch kaum geahnt wird. Und solchen Dingen hat entgegenarbeiten wollen dasjenige, was in den Absichten lag der wirtschaftlichen Unternehmungen aus unserer anthroposophischen Bewegung heraus. Diese wirtschaftlichen Unternehmungen sind von Wirtschaftern und Kommerziellen geschaffen worden, allein sie haben es nicht vermocht, dasjenige, was eigentlich ursprüngliche Intentionen waren, nach allen Seiten hin zu verwirklichen, einfach auch schon aus dem Grunde nicht, weil in unserer Gegenwart allzu viele widerstrebende Kräfte da sind, um das rechte Verständnis für eine solche Sache hervorzurufen. Der einzelne Mensch ist vielfach den wirksamen Mächten gegenüber machtlos, und dadurch ist eigentlich nicht einmal bis jetzt das Allerursprünglichste in diesen wirtschaftlichen Bestrebungen, die aus dem Schoße der anthroposophischen Bewegung hervorgegangen sind, es ist das Allerwesentlichste nicht einmal zur Diskussion gekommen. Denn um was hat es sich praktisch gehandelt?

[ 8 ] Ich will es an dem Beispiel der Landwirtschaft einmal erörtern, damit wir nicht im Allgemeinen, sondern im Konkreten sprechen. Es gibt heute zum Beispiel allerlei sogenannte nationalökonomische Bücher und Vorträge, die haben auch Kapitel über die Landwirtschaft vom sozialökonomischen Standpunkt aus. Man denkt nach, wie man die Landwirtschaft gestalten soll aus sozialökonomischen Prinzipien heraus. Es gibt Schriften heute, die handeln von den sozialökonomischen Ideen, wie man die Landwirtschaft gestalten soll. Das Ganze, sowohl das Abhalten von nationalökonomischen Vorträgen wie das Schreiben von solchen Büchern, ist ein offenbarer Unsinn. Aber offenbarer Unsinn wird heute in weitesten Kreisen geübt. Denn selbstverständlich sollte jeder erkennen, dass man über die Landwirtschaft nur sprechen kann, auch in ihrer sozialen Gestaltung, wenn man die Sache der Landwirtschaft zuerst als Unterlage hat, wenn man wirklich weiß, was Rübenbau, Kartoffelbau, Getreidebau bedeuten. Ohne das kann man auch nicht über die nationalökonomischen Prinzipien sprechen. Diese Dinge müssen aus der Sache heraus, nicht aus irgendwelchen theoretischen Erwägungen festgestellt werden. Wenn man so etwas spricht heute vor denjenigen Menschen, die an der Universität eine Anzahl von Kollegs gehört haben über Nationalökonomie in Bezug auf die Landwirtschaft, dann kommt ihnen das ganz absurd vor, weil ihnen die Sache so festzustehen scheint. Das ist aber nicht der Fall; über die Landwirtschaft kann nur derjenige urteilen, der sein Urteil vom Feld, vom Wald, von der Tierzucht hernimmt. Es sollte einfach alles Gerede aufhören über Nationalökonomie, das nicht aus der Sache selber herausgenommen ist. Solange man das nicht einsehen wird, dass es ein bloßes Gerede ist, was über den Dingen schwebend in nationalökonomischer Beziehung gesagt wird, solange wird es zu nichts Aussichtsvollem kommen, nicht auf diesem landwirtschaftlichen, nicht auf anderem Gebiete.

[ 9 ] Dass es so ist, dass man glaubt, aus den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten her über die Dinge reden zu können, [...] das kommt nur davon her, dass man wiederum innerhalb der einzelnen Lebensgebiete selber nicht auf die Grundlagen zurückgehen kann. Dass man eine Rübe ja als eine Rübe ansieht - gewiss, sie schaut so und so aus, lässt sich leichter oder schwerer schneiden, hat diese Farbe und diese oder jene Bestandteile in sich -, das alles kann man sagen. Aber damit ist die Rübe noch lange nicht verstanden und vor allen Dingen nicht das Zusammenleben der Rübe mit dem Acker, mit der Jahreszeit, in der sie reift und so weiter, sondern man muss sich über Folgendes klar sein:

[ 10 ] Ich habe öfters einen Vergleich gebraucht, um auf anderen Lebensgebieten das klarzumachen. Ich sagte: Man sieht eine Magnetnadel, man entdeckt, dass diese Nadel immer mit dem einen Ende nahezu nach Norden, mit dem anderen nach Süden zeigt. Man denkt nach, warum das ist, man sucht die Ursache dazu nicht in der Magnetnadel, sondern in der ganzen Erde, indem man ihrer einen Seite den magnetischen Nordpol, ihrer anderen den magnetischen Südpol gibt. Würde jemand in der Magnetnadel selber die Ursache suchen, dass sie sich in einer so [eigensinnigen] Weise hinstellt, so würde er einen Unsinn reden. Denn in ihrer Lage kann man die Magnetnadel nur verstehen, wenn man weiß, in welcher Beziehung sie zur ganzen Erde steht.

[ 11 ] Alles das, was für die Magnetnadel als ein Unsinn erscheint, das gilt für viele andere Dinge den Menschen als Sinn. Wenn Sie die Rübe in der Erde wachsen haben: Sie so zu nehmen, wie sie ist, in ihren engen Grenzen, ist in dem Augenblick ein Unding, wenn die Rübe in ihrem Wachstum vielleicht abhängig ist von unzähligen Umständen, die gar nicht auf der Erde, sondern in der kosmischen Umgebung der Erde vorhanden sind. Und so erklärt man heute vieles, so richtet man vieles im praktischen Leben ein, als ob man es nur zu tun hätte mit den eng umgrenzten Dingen und nicht mit den Wirkungen, die aus der ganzen Welt kommen. Die einzelnen Lebensgebiete haben furchtbar darunter gelitten und würden diese Leiden viel mehr zeigen, wenn nicht, ich möchte sagen, trotz aller Wissenschaft der neueren Zeit, noch ein gewisser Instinkt vorhanden wäre aus derjenigen Zeit, wo man mit dem Instinkt und nicht mit der Wissenschaft gearbeitet hat. Wenn diejenigen Menschen, die von ihren Ärzten verschrieben haben, wie viel Gramm Fleisch sie essen sollen, wie viel Kohl, damit das zur richtigen menschlichen Physiologie stimmt - es haben manche Leute neben sich eine Waage und wiegen sich alles das zu, was da auf den Teller kommt -, das ist ja schön, selbstverständlich, man soll so etwas wissen, aber ich muss immer wieder denken: Es ist doch gut, dass der Betreffende auch den Hunger spürt, wenn er mit dem Zugewogenen noch nicht genug hat, dass noch dieser Instinkt vorhanden ist.

[ 12 ] So war der Instinkt eigentlich allem zugrunde liegend, was Menschen tun mussten, bevor eine Wissenschaft auf diesem Gebiete da war. Und diese Instinkte haben manchmal ganz sicher gewaltet, und man kann heute noch immer außerordentlich überrascht sein, wenn man in solchen alten Bauernkalendern die Bauernregeln liest, wie ungeheuer weise und verständlich das ist, was sie ausdrücken. Denn, um in solchen Dingen nicht abergläubisch zu sein, dazu hat doch auch der instinkthaft sichere Mensch die Möglichkeit. Ebenso wie man für die Sache außerordentlich tiefsinnige Aussprüche hat, die für die Aussaat und Ernte gelten, findet man [...] Firlefanzereien, solche Aussprüche wie: «Kräht der Hahn auf dem Mist, so regnet es, oder es bleibt, wie es ist.» Der nötige Humor ist auch in diesem Instinkthaften überall darinnen, um Abergläubische abzuweisen.

[ 13 ] Es handelt sich, wenn hier vom anthroposophischen Gesichtspunkte aus gesprochen wird, wirklich darum, nicht zurückzugehen zu den alten Instinkten, sondern aus einer tieferen geistigen Einsicht heraus das zu finden, was die unsicher gewordenen Instinkte immer weniger geben können. Dazu ist notwendig, dass wir uns einlassen auf eine starke Erweiterung der Betrachtung des Lebens der Pflanzen, der Tiere, aber auch des Lebens der Erde selbst, auf eine starke Erweiterung nach der kosmischen Seite hin.

[ 14 ] Es ist ja doch so, dass gewiss von einer Seite her es ganz richtig ist, Regenwitterung in trivialer Weise nicht mit den Mondphasen in Beziehung zu bringen, aber auf der anderen Seite besteht auch wiederum das, was sich einmal zugetragen hat. Ich habe es schon öfter in anderen Kreisen erzählt, dass in Leipzig zwei Professoren tätig waren, wovon der eine, Gustav Theodor Fechner, ein in geistigen Dingen mit so manchen sicheren Einblicken behafteter Mann, aus äußeren Beobachtungen heraus nicht so ganz nur mit Aberglauben hinblicken konnte darauf, dass gewisse Epochen des Regnens und Nichtregnens doch wiederum mit dem Monde und seinem Gange um die Erde zusammenhängen. Es hat sich das für ihn als eine Notwendigkeit aus statistischen Untersuchungen ergeben. Aber sein Kollege, der berühmte Professor Schleiden, der stellte in einer Zeit, in der man über solche Dinge hinwegsah, aus wissenschaftlichen Vernunftgründen alles das in Abrede. Nun hatten die beiden Professoren an der Leipziger Universität auch Frauen. Und Gustav Theodor Fechner, der ein etwas humorvoll angelegter Mensch war, sagte: Es sollen mal unsere Frauen entscheiden. Nun war damals in Leipzig noch eine gewisse Sitte. Es war das Wasser, das man zum Waschen der Wäsche brauchte, nicht so leicht zu erhalten. Man musste es weit herholen. Man stellte also die Krüge und Bottiche auf und fing das Regenwasser auf. Das tat sowohl die Frau Professor Schleiden wie die Frau Professor Fechner. Aber sie hatten nicht genügend Platz, um gleichzeitig die Bottiche aufzustellen. Da sagte der Professor Fechner: Wenn das ganz gleichgültig ist, wenn mein verehrter Kollege recht hat, dann soll einmal die Frau Professor Schleiden ihre Bottiche in der Zeit aufstellen, in der nach meinen Angaben nach der Mondphase weniger Regen kommt, und meine Frau wird den Bottich aufstellen in der Zeit, in der nach meiner Berechnung mehr Regenwasser kommt. Wenn das alles Unsinn ist, wird die Frau Professor Schleiden das ja gerne tun. - Und siehe da, die Frau Professor Schleiden ließ sich das nicht gefallen, sondern sie richtete sich lieber nach den Angaben von Professor Fechner als nach ihrem eigenen Gatten.

[ 15 ] So ist es schon einmal. Die Wissenschaft kann ja richtig sein, aber die Praxis kann sich auf dieses Richtige der Wissenschaft nicht einlassen. Wir wollen nicht in dieser Weise sprechen, wir wollen ja ernsthaft sprechen. Es sollte das nur gesagt sein, um uns darauf hinzuweisen, dass man etwas weitersehen muss, als man heute gewohnt ist zu schen, wenn man nach dem hinschaut, das dem Menschen das physische Leben auf der Erde allein möglich macht, und das ist doch die Landwirtschaft.

[ 16 ] Ich kann nicht wissen, ob dasjenige, was heute schon aus Anthroposophie heraus gesagt werden kann, uns wird nach allen Seiten befriedigen können. Aber es soll versucht werden, das zu sagen, was aus Anthroposophie heraus für die Landwirtschaft gegeben werden kann.

[ 17 ] Damit möchte ich einleitungsweise beginnen, hinzuweisen auf Wichtigstes in unserem irdischen Dasein für die Landwirtschaft. Wir haben ja heute so die Gewohnheit, wenn wir von etwas reden, den hauptsächlichsten Wert zu legen auf die chemisch-physikalischen Bestandteile. Nun wollen wir einmal nicht ausgehen von den chemisch-physikalischen Bestandteilen, sondern wollen einmal ausgehen von etwas, was hinter den chemisch-physikalischen Bestandteilen steht und doch von einer ganz besonderen Wichtigkeit ist für das Leben der Pflanze auf der einen Seite, des Tieres auf der anderen Seite. Sehen Sie, wenn wir das Leben des Menschen betrachten und in einem gewissen Grade auch das Leben des Tieres betrachten, so haben wir eine starke Emanzipation des menschlichen und tierischen Lebens von der äußeren Welt zu verzeichnen. Je mehr wir zum Menschen heraufkommen, eine umso stärkere Emanzipation haben wir zu verzeichnen. Wir finden Erscheinungen im menschlichen und tierischen Leben, die uns zunächst heute ganz unabhängig erscheinen von der außerirdischen oder auch den unmittelbar die Erde umgebenden atmosphärischen und dergleichen Einflüssen. Das scheint nicht nur so, sondern ist sogar in Bezug auf vieles im menschlichen Leben außerordentlich richtig. Gewiss, wir wissen, dass durch gewisse atmosphärische Einflüsse die Schmerzen gewisser Krankheiten stärker werden. Wir wissen schon weniger, dass gewisse Krankheiten im Menschen so ablaufen, oder auch sonstige Lebenserscheinungen so ablaufen, dass sie in ihren Zeitverhältnissen nachbilden äußere Naturvorgänge. Aber sie stimmen in Anfang und Ende nicht mit diesen Naturvorgängen überein. Wir brauchen uns ja nur daran zu erinnern, dass eine der allerwichtigsten Erscheinungen, die weiblichen Menses, in ihrem Verlaufe zeitlich Nachbildungen sind des Verlaufes der Mondphasen, allein in Anfang und Ende stimmen sie nicht damit überein. Es gibt zahlreiche andere feinere Erscheinungen, sowohl im männlichen wie im weiblichen Organismus, welche Nachbildungen sind von natürlichen Rhythmen.

[ 18 ] Wenn man viel intimer auf die Dinge eingehen würde, würde man zum Beispiel vieles, was sich im sozialen Leben abspielt, besser verstehen, wenn man die Periodizität der Sonnenflecken richtig verstehen würde. Man sieht aber auf solche Dinge nicht hin, weil das, was im menschlichen sozialen Leben der Periodizität der Sonnenflecken entsprechen kann, nicht dann anfängt, wenn die Sonnenflecken anfangen, und dann aufhört, wenn die Sonnenflecken aufhören, sondern weil es sich davon emanzipiert hat. Es zeigt dieselbe Periodizität, es zeigt denselben Rhythmus, aber nicht das zeitliche Zusammenfallen. Es hält innerlich fest die Periodizität und den Rhythmus, aber macht diese Periodizität und diesen Rhythmus selbstständig, emanzipiert sich davon. Es kann nun jeder kommen, dem man sagt: Das menschliche Leben ist ein Mikrokosmos, es ahmt nach den Makrokosmos, und kann sagen: Das ist ja ein Unsinn. Wenn man nun behauptet, es gibt für gewisse Krankheiten eine siebentägige Fieberperiode, so könnte er einwenden: Dann müsste ja, wenn irgendwelche äußeren Erscheinungen eintreten, auch das Fieber erscheinen und den äußeren Erscheinungen parallel laufen und dann aufhören, wenn die äußeren Erscheinungen aufhören. - Das tut das Fieber zwar nicht, aber es hält den inneren Rhythmus fest, wenn auch nicht der zeitliche Anfang und das zeitliche Ende mit den äußeren Erscheinungen zusammenfallen.

[ 19 ] Diese Emanzipation ist für das menschliche Leben fast vollständig im Kosmos durchgeführt. Für das Tierische schon etwas weniger, aber das Pflanzliche ist zu einem hohen Grade noch durchaus drinnenstehend im allgemeinen Naturleben auch [des Außerirdischen]. Und daher wird es ein Verständnis des Pflanzenlebens gar nicht geben können, ohne dass bei diesem Verständnis berücksichtigt wird, wie alles das, was auf der Erde ist, eigentlich nur ein Abglanz dessen ist, was im Kosmos vor sich geht. Beim Menschen kaschiert sich das nur, weil er sich emanzipiert hat. Er trägt nur den inneren Rhythmus in sich. Beim Pflanzlichen ist es noch im eminentesten Sinne der Fall. Und darauf möchte ich in diesen Einleitungsworten heute hinweisen.

[ 20 ] Sehen Sie, die Erde ist zunächst umgeben im Himmelsraum von dem Mond und dann den anderen Planeten unseres Planetensystems. Man hat in einer alten instinktiven Wissenschaft, in der man die Sonne zu den Planeten gerechnet hat, diese Reihenfolge gehabt: Mond, Merkur, Venus, Sonne, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn. Nun möchte ich ohne alle astronomischen Auseinandersetzungen auf das planetarische Leben hinweisen, auf das, was zusammenhängt in diesem planetarischen Leben mit dem Irdischen. Da haben wir zunächst, wenn wir hinschauen auf das irdische Leben im Großen, die Tatsache zu berücksichtigen, wie in diesem irdischen Leben im Großen wiederum eine denkbar größte Rolle spielt alles das, was ich nennen möchte das Leben der Kieselsubstanz in der Welt. Kieselsubstanz finden Sie ja zum Beispiel in unserem schönen Quarz in die Gestalt des Prismas und der Pyramide eingeschlossen. Sie finden diese Kieselsubstanz, verbunden mit Sauerstoff, in unseren Quarzkristallen; wenn man sich den Sauerstoff wegdenkt, der im Quarz mit dem Kiesel verbunden ist, das sogenannte Silicium. So haben wir diese Substanz, die die Chemie heute zu den Elementen - Sauerstoff, Stickstoff, Wasserstoff, Schwefel und so weiter - zählt, dieses Silicium, das sich mit dem Sauerstoff verbindet, so haben wir den Kiesel als ein chemisches Element. Aber wir dürfen nicht vergessen, dass das, was da im Quarz als Silicium lebt, zu siebenundzwanzig bis achtundzwanzig Prozent auf unserer Erdoberfläche verbreitet ist. Alle anderen Substanzen sind in weniger Prozent vorhanden, nur der Sauerstoff in siebenundvierzig bis achtundvierzig Prozent. Es ist ungeheuer viel Silicium vorhanden. Nun gewiss, dieses Silicium, wenn es sich findet in solchen Gesteinen wie dem Quarz, so tritt es in einer solchen Form auf, die, wenn man das äußere Materielle, den Erdboden betrachtet mit seinem Pflanzenwachstum — den vergisst man eben -, keine große Bedeutung zeigt. Denn es ist nicht löslich im Wasser. Es ist wasserundurchgängig. Also mit den allgemeinen banalen, trivialen Lebensbedingungen scheint es zunächst nicht viel zu tun zu haben. Wenn Sie aber wiederum nehmen den Ackerschachtelhalm, das Equisetum, so haben Sie in ihm zu neunzig Prozent Kieselsäure drin, dasselbe, was im Quarz ist, in sehr feiner Verteilung. Aus alledem können Sie ersehen, welch ungeheure Bedeutung der Kiesel, das Silicium, haben muss. Es ist ja fast die Hälfte dessen, dem wir auf der Erde begegnen, aus Kiesel bestehend.

[ 21 ] Nun liegt das Merkwürdige vor, dass dieser Kiesel so wenig bemerkt wird, dass er sogar von den Dingen, in denen er außerordentlich wohltätig wirken kann, heute noch so ziemlich ausgeschlossen ist. In der aus der Anthroposophie hervorgehenden Medizin bildet die Kieselsubstanz einen wesentlichen Bestandteil sehr vieler Heilmittel. Ein ganzer Trakt von Krankheiten wird durch inneres Eingeben oder Baden mit Kieselsäure behandelt, weil fast alles das, was sich in Krankheitsfällen in abnormen Zuständen der Sinne zeigt, was nicht in den Sinnen selber liegt, sondern in den Sinnen zeigt, auch in den inneren Sinnen, was da oder dort in den Organen Schmerzen hervorruft, weil alles das in merkwürdiger Weise beeinflusst wird gerade von Silicium. Silicium spielt aber auch überhaupt in dem, was man — man hat ja dieses althergebrachte Wort — den Haushalt der Natur nennt, die denkbar größte Rolle. Denn das Silicium ist nicht nur da vorhanden, wo wir es finden, im Quarz oder in anderem Gestein, das Silicium ist in außerordentlich feiner Verteilung auch in der Atmosphäre, es ist überall eigentlich vorhanden. Die Hälfte der uns zur Verfügung stehenden Erde ist ja eigentlich Kiesel, denn achtundvierzig Prozent sind es. Sehen Sie: Was tut denn dieser Kiesel? Ja, das müssen wir uns fragen in einer hypothetischen Form.

[ 22 ] Nehmen wir einmal an, wir hätten nur die Hälfte von Kiesel in unserer Erdenumgebung, da würden wir Pflanzen haben, die alle mehr oder weniger pyramidale Formen hätten. Die Blüten würden alle verkümmert sein, und wir würden etwa die für uns so abnorm erscheinenden Kakteenformen fast in allen Pflanzen haben. Die Getreideformen würden ganz komisch ausschauen: Die Halme würden nach unten dick, sogar fleischig werden, die Ähren verkümmern, wir würden keine vollen Ähren haben.

[ 23 ] Nun sehen Sie, das ist auf der einen Seite. Wir finden auf der anderen Seite, dass, wenn auch nicht so ausgebreitet wie die Kieselsubstanz, Kalksubstanz und Verwandtes wiederum überall in der Erde sich finden muss, Kalk, Kali, Natriumsubstanz sich finden muss. Wären diese wiederum weniger vorhanden, als sie sind, dann würden wir bekommen Pflanzen mit ausschließlich dünnem Stängel, Pflanzen, die etwa zum großen Teil gewundene Stängel hätten, wir würden lauter Schlingpflanzen bekommen. Die Blüten würden zwar auseinandergehen, aber sie würden taub sein; sie würden auch keine besonderen Nährstoffe liefern. Nur in dem Equilibrium, in dem Zusammenwirken dieser beiden Kräfte - wenn ich zwei Substanzen herausgreife -, in dem Zusammenwirken von kalkähnlichen und kieselähnlichen Substanzen gedeiht das Pflanzenleben in der Form, wie wir es heute sehen.

[ 24 ] Nun aber wiederum weiter. Sehen Sie, das alles, was im Kieseligen lebt, hat Kräfte, die nicht von der Erde stammen, sondern von den sogenannten sonnenfernen Planeten: Mars, Jupiter, Saturn. Dasjenige, was ausgeht von diesen Planeten, wirkt auf dem Umwege durch das Kieselige und Verwandtes auf das Pflanzenleben. Aber von all demjenigen, was erdennahe Planeten sind: Mond, Merkur, Venus, wirken die Kräfte auf dem Umwege des Kalkigen auf das Pflanzliche, auch auf das tierische Leben der Erde herein. So können wir sprechen jedem Acker gegenüber, der bebaut ist: Da drinnen wirkt Kieseliges und wirkt Kalkiges. Im Kieseligen wirken Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, im Kalkigen Mond, Venus, Merkur.

[ 25 ] Nun schauen wir uns demgegenüber die Pflanzen selber an. Zweierlei müssen wir am Pflanzenleben beobachten. Das Erste ist dasjenige, dass das ganze Pflanzenwesen und auch die einzelne pflanzliche Art in sich selber sich erhält, die Reproduktionskraft, die Fortpflanzungskraft entwickelt, dass also die Pflanze ihresgleichen hervorbringen kann und so weiter. Das ist das eine. Das andere ist, dass die Pflanze als ein Wesen eines verhältnismäßig niederen Naturreiches den Wesen der höheren Naturreiche zur Nahrung dient. D zwei Strömungen im Werden der Pflanze haben zunächst wenig miteinander zu tun. Denn in Bezug auf den Vorgang der Entwicklung von der Pflanzenmutter zur Pflanzentochter, Enkel und so weiter kann es den Bildekräften der Natur ganz gleichgültig sein, ob wir die Pflanze essen und uns dadurch ernähren oder nicht. Es sind zwei ganz verschiedene Interessen, die sich da drinnen äußern, und [zwar] wirken in dem Kräftezusammenhange des Natürlichen die Dinge so, dass alles dasjenige, was mit der inneren Reproduktionskraft, mit dem Wachstum zusammenhängt, was dazu beiträgt, dass Pflanzengeneration auf Pflanzengeneration folgt, in dem wirkt, was von Mond, Venus, Merkur auf dem Umwege des Kalkigen vom Kosmos auf die Erde hereinwirkt. Schauen wir einfach das an, was bei solchen Pflanzen zutage tritt, die wir nicht essen, die sich einfach immer erneuern, so sehen wir so hin, als ob uns nur interessieren würde das kosmische Hereinwirken durch die Kräfte von Venus, Merkur, Mond; die sind beteiligt an dem, was auf der Erde im Pflanzenwesen sich reproduziert.

[ 26 ] Aber wenn Pflanzen im eminentesten Sinne Nahrungsmittel werden, wenn sie sich so entwickeln, dass sich in ihnen die Substanzen zum Nahrungsmittel ausgestalten für Tier und Mensch, dann sind daran beteiligt Mars, Jupiter, Saturn auf dem Umwege des Kieseligen. Das Kieselige schließt auf das Pflanzenwesen in die Weltenweiten hinaus und erweckt die Sinne des Pflanzenwesens so, dass aufgenommen wird aus allem Umkreise des Weltenalls dasjenige, was diese erdenfernen Planeten ausgestalten; daran sind beteiligt Mars, Jupiter, Saturn. Aus dem Umkreise von Mond, Venus, Merkur hingegen wird dasjenige aufgenommen, was die Pflanze zur Fortpflanzung fähig macht. Nun, das erscheint zunächst nur wie ein Gegenstand des Wissens. Aber solche Dinge, die von einem etwas weiteren Horizont hergenommen sind, führen ganz von selbst vom Erkennen auch zum Praktischen hin.

[ 27 ] Sehen Sie, wir müssen uns nun fragen, da von Mond, Venus, Merkur Kräfte auf die Erde hereingehen und diese Kräfte zur Wirksamkeit kommen im Pflanzenleben: Wodurch wird das befördert oder mehr oder weniger gehemmt? Wodurch wird befördert, dass der Mond oder der Saturn auf das Pflanzenleben wirkt, und wodurch wird es gehemmt?

[ 28 ] Wenn man beobachtet den Lauf des Jahres, so verläuft dieses ja so, dass es Regentage und Nichtregentage gibt. Der Physiker von heute untersucht ja eigentlich am Regen nur dasjenige, dass eben beim Regen mehr Wasser auf die Erde fällt als beim Nichtregnen. Und das Wasser ist ihm ein abstrakter Stoff, bestehend aus Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff, und er kennt das Wasser nur als dasjenige, was aus Wasser- und Sauerstoff besteht. Wenn man das Wasser durch die Elektrolyse zerlegt, zerfällt es in zwei Stoffe, von denen sich der eine so, der andere so betätigt. Aber damit hat man noch nichts Umfassendes über das Wasser gesagt. Das Wasser birgt vieles andere noch als bloß dasjenige, was dann chemisch als Sauerstoff und Wasserstoff erscheint. Wasser ist im eminentesten Sinne dazu geeignet, denjenigen Kräften, die zum Beispiel vom Monde kommen, die Wege zu weisen im Erdenbereiche, sodass das Wasser die Verteilung der Mondenkräfte im Erdenbereiche bewirkt. Zwischen Mond und Wasser auf der Erde besteht eine gewisse Art von Zusammenhang. Nehmen wir also an, es sind eben Regentage vergangen, auf diese Regentage folgt Vollmond. Ja, mit den Kräften, die vom Monde kommen in Vollmondtagen, geht ja auf der Erde etwas Kolossales vor. Die schießen herein in das ganze Pflanzenwachstum. Sie können nicht hereinschießen, wenn die Regentage nicht vorangegangen sind. Wir werden also zu sprechen haben davon, ob es eine Bedeutung hat, wenn wir Samen aussäen, nachdem in einer gewissen Beziehung Regen gefallen ist und darauf Vollmondschein kommt, oder ob man gedankenlos zu einer jeden Zeit aussäen darf. Gewiss, herauskommen wird auch dann etwas, aber die Frage ist aufgeworfen: «Ist es gut, sich zu richten mit der Aussaat nach Regen und Vollmondschein?» - weil eben dasjenige, was der Vollmond tun soll, bei gewissen Pflanzen wuchtig und stark nach Regentagen, schwach und spärlich nach Sonnenscheintagen vor sich geht. Solche Dinge lagen in den alten Bauernregeln. Da sagte man einen Spruch und wusste, was zu tun ist. Sprüche sind heute alter Aberglaube, und eine Wissenschaft über diese Dinge gibt es noch nicht, zu der will man sich nicht bequemen.

[ 29 ] Weiter: Wir finden um unsere Erde herum die Atmosphäre. Ja, die Atmosphäre hat vor allen Dingen außer demjenigen, dass sie luftartig ist, die Eigentümlichkeit, manchmal wärmer, manchmal kälter zu sein. Zu gewissen Zeiten zeigt sie eine beträchtliche Wärmeanhäufung, die sich dann sogar, wenn die Spannung zu stark ist, in Gewittern entlädt. Nun, wie ist es denn mit der Wärme? Da zeigt die geistige Beobachtung, dass, während das Wasser keinen Bezug zum Kiesel hat, diese Wärme dennoch einen ungeheuer starken Bezug zum Kiesel hat, geradezu diejenigen Kräfte, die durch das Kieselige wirken können, zu besonderer Wirksamkeit bringt, und das sind die Kräfte, die von Saturn, Jupiter, Mars ausgehen. Diese Kräfte, die von Saturn, Jupiter, Mars ausgehen, müssen in einem ganz anderen Stile betrachtet werden als die Kräfte des Mondes. Denn wir müssen bedenken: Der Saturn braucht dreißig Jahre in seiner Umdrehung um die Sonne, der Mond nur dreißig oder achtundzwanzig Tage zu seinen Phasen. Saturn ist also nur fünfzehn Jahre sichtbar. Er muss in ganz anderer Weise zusammenhängen mit dem Pflanzenwachstum. Nun allerdings, er ist nicht bloß wirkend, wenn er auf die Erde herunterscheint, er ist auch wirksam, wenn seine Strahlen durch die Erde durchgehen müssen.

[ 30 ] Wenn er in dreißig Jahren so langsam herumgeht, so werden wir, wenn wir die Sache zeichnen, da den Saturn[um]gang haben und finden, dass er zuweilen direkt auf einen Fleck Erde scheint; aber dann auch durch die Erde hindurch diesen Fleck bearbeiten kann. Da ist es immer abhängig von dem Wärmezustand in der Luft, wie stark die Saturnkräfte an das Pflanzenleben der Erde herankönnen. Bei kalter Luft können sie nicht heran, bei warmer Luft können sie heran. Und dasjenige, was sie tun, worin sehen wir das im Pflanzenleben? Das sehen wir, wenn nun nicht einjährige Pflanzen entstehen, die im Jahreslaufe entstehen und wiederum vergehen, nur Samen hinterlassen, sondern was der Saturn tut mit Hilfe der Wärmekräfte unserer Erde, das sehen wir, wenn Dauerpflanzen entstehen. Denn diese Kräfte, die auf dem Umwege durch die Wärme ins Pflanzliche gehen, deren Wirkungen sehen wir in der Rinde und der Borke der Bäume, in alledem, was die Pflanze zu einer Dauerpflanze macht.

[ 31 ] Das rührt davon her, weil eben zusammenhängt das einjährige Leben der Pflanze und das Beschränktsein der Pflanze auf kurze Lebensfrist mit den Planeten, die kurze Umlaufzeiten haben. Dagegen dasjenige, was sich herausreißt aus diesem Vorübergehenden, was die Bäume mit Borke, mit Rinde umgibt, was sie dauernd macht, das hängt zusammen mit den Planetenkräften, die auf dem Umwege mit den Kräften von Wärme und Kälte wirken und die eine lange Umlaufzeit haben, wie der Saturn dreißig, der Jupiter zwölf Jahre. Es ist daher schon von Bedeutung, wenn einer einen Eichbaum pflanzen will und er sich gut versteht auf Marsperioden. Denn ein Eichbaum, richtig angepflanzt in der entsprechenden Marsperiode, wird ja anders gedeihen, als wenn man ihn gedankenlos, einfach wenn es einem passt, in die Erde hineinversetzt. Oder haben Sie Anlagen von Nadelholzwäldern, wo die Saturnkräfte eine so große Rolle spielen, [dann] wird [dort] ganz anderes entstehen, wenn man in einer sogenannten Aufgangsperiode des Saturn oder in einer anderen Periode den Nadelwald anpflanzt. Und derjenige, der solche Dinge durchschaut, der kann ganz genau sagen, in den Dingen, die wachsen wollen oder nicht wachsen wollen, ob man das mit dem Verständnis des Kräftezusammenhanges gemacht hat oder nicht. Denn dasjenige, was nicht so offen fürs Auge zutage tritt, das tritt in den intimeren Verhältnissen des Lebens doch recht zutage.

[ 32 ] Nehmen wir zum Beispiel an, wir verwenden Holz von Bäumen, die unverständig in Bezug auf die Weltperioden auf die Erde gepflanzt sind, zum Brennen, so gibt uns das keine so gesunde Wärme, als wenn wir Hölzer verwenden, die mit Verständnis gepflanzt sind. Gerade in den intimeren Verhältnissen des täglichen Lebens, in das diese Dinge so hineinspielen, gerade da zeigt sich die ungeheuer groRe Bedeutung einer solchen Sache, aber das Leben ist heute für die Leute schon fast ganz gedankenlos geworden. Man ist froh, wenn man an solche Dinge nicht zu denken braucht. Man denkt sich, die ganze Sache muss so vor sich gehen wie eine Maschine; da hat man die entsprechenden Vorrichtungen, zieht man die Maschine auf, so geht sie. So stellt man sich vor - nach materialistischer Art -, dass es in der ganzen Natur auch geht. Aber dadurch kommt man schon zu solchen Dingen, die sich dann im praktischen Leben ungeheuerlich ausmachen. Da kommen dann die großen Rätsel.

[ 33 ] Warum ist es heute unmöglich, solche Kartoffeln zu essen, wie ich sie noch in meiner Jugend gegessen habe? Es ist so, ich habe dies überall probiert. Man kann nicht mehr solche Kartoffeln essen, auch da nicht, wo ich sie damals gegessen habe. Es ist im Laufe der Zeit manches durchaus zurückgegangen in seiner inneren Nährkraft. Die letzten Jahrzehnte zeigen das im eminentesten Sinne. Weil man gar nicht mehr versteht die intimeren Wirkungen, die im Weltenall wirkend sind und die doch wiederum gesucht werden müssen auf einem solchen Wege, wie ich ihn heute einleitend nur angedeutet habe. Ich wollte nur hinweisen, wo Fragen sind, die weit über heutige Gesichtskreise hinausgehen. Wir werden das nicht nur fortsetzen, sondern auch vertieft auf die Praxis anwenden.

First Lecture

My dear friends!

[ 1 ] It is with deep gratitude that I look back on the words just spoken by Count Keyserlingk. For it is not only those who can benefit from anthroposophy who are entitled to feel gratitude; it is also, so to speak, the anthroposophical cause itself that deserves our gratitude in these difficult times, a gratitude that can be felt deeply by all those who are interested in anthroposophy. And so, in the spirit of anthroposophy, I would like to express my heartfelt thanks for the words that have just been spoken.

[ 2 ] It is indeed a deeply satisfying fact that it is possible to hold this agricultural course here in the home of Count and Countess Keyserlingk. From my previous visits, I know what a wonderful atmosphere there is here in Koberwitz, especially the spiritual atmosphere, and how this spiritual atmosphere is the most beautiful prerequisite for what is to be discussed in this course.

[ 3 ] If the Count has pointed out that there may be some inconveniences for one or the other—in this case it was the eurythmy ladies, but other visitors from outside may also be affected—then on the other hand, with regard to what actually brought us together, it must be said: I believe that we could hardly be better accommodated for this agricultural course than here, in the midst of such excellent and exemplary farming. Everything that comes to light in the anthroposophical field requires that one be immersed, so to speak, in the necessary environment of feeling. And that will certainly be the case here for agriculture.

[ 4 ] Well, all this prompts me to express my deepest gratitude to Count Keyserlingk, and I am sure Dr. Steiner will agree, for allowing us to spend these festive days, which I think will also be days of work, here. I must remember that it is precisely because we are here in Koberwitz that an agricultural spirit already associated with the anthroposophical movement will prevail during these festive days. It was Count Keyserlingk who, from the very beginning, supported the efforts we developed for agriculture in Stuttgart, based on the “Coming Day,” with advice, practical help, and self-sacrificing work, who let his spirit, which had grown out of such a thorough familiarity with agriculture, prevail in what we were able to do in relation to agriculture. I would say that it was something from the very heart of our movement that drew us here to Koberwitz with a certain naturalness at the moment when the Count wanted us here. That is why I can assure you that I believe everyone was actually happy to come here to Koberwitz for this course. This is why we who have come here are equally grateful and very happy to express our thanks to the Keyserlingk family for agreeing to welcome us here during these days of endeavour.

[ 5 ] As for me, this gratitude is felt most sincerely, and I ask the Keyserlingk family to accept it from me in particular. I know what it means to welcome so many visitors over several days in the way that I feel it will happen, and I believe that I can therefore express this gratitude with the necessary nuance. I also ask that you accept it in such a way that you can fully appreciate the difficulties involved in holding such an event in a house that is so far from the city. I am convinced that—just as the inconveniences mentioned by Count Keyserlingk, who in this case was of course speaking not as a representative of domestic policy but of foreign policy with regard to the local lecture events, will be overlooked—each and every one of us will leave satisfied with the hospitality and reception here.

[ 6 ] Now, whether you will be equally satisfied with the course itself is, of course, a question that will probably become increasingly debatable, even though we want to do everything we can to reach an understanding in the coming days in all kinds of discussions about what has been said. For you must bear in mind that, although there has been a long-standing desire for such a course from many quarters, this is the first time that I have taken on such a course from within the bosom of the anthroposophical movement. Such a course requires many things, for it will show us how the interests of agriculture are intertwined in every way with the widest circles of human life and how there is hardly any area of life that does not belong to agriculture. From every side, from every corner, all the interests of human life belong to agriculture. Of course, we can only touch on the central area of agriculture here. However, this will naturally lead us to many side paths, which may be necessary precisely because what is said here is to be said on anthroposophical ground. In particular, you will have to forgive me if today's introduction has to be so far-fetched that perhaps not everyone will immediately see the connection between the introduction and what we have to discuss specifically in relation to agriculture. Nevertheless, what is to be built up here will have to be based on what is to be said today, which may seem somewhat remote.

[ 7 ] Agriculture in particular has been affected in a certain way, seriously affected by the whole of modern intellectual life. You see, this entire modern intellectual life has taken on destructive forms, particularly in relation to the economic character, the destructive significance of which is still hardly appreciated by many people today. And it was precisely these things that the economic enterprises arising from our anthroposophical movement sought to counteract. These economic enterprises were created by economists and businesspeople, but they were unable to realize what were actually the original intentions in all respects, simply because there are too many opposing forces in our present time to bring about the right understanding for such a thing. The individual human being is often powerless in the face of effective forces, and as a result, even the most fundamental aspects of these economic endeavors that have emerged from the bosom of the anthroposophical movement have not even been discussed. For what has been at stake in practical terms?

[ 8 ] I would like to discuss this using the example of agriculture, so that we are not speaking in general terms but in concrete terms. Today, for example, there are all kinds of so-called national economic books and lectures that also have chapters on agriculture from a socio-economic point of view. People think about how agriculture should be organized on the basis of socio-economic principles. There are writings today that deal with socio-economic ideas on how agriculture should be organized. The whole thing, both the giving of lectures on national economics and the writing of such books, is obvious nonsense. But obvious nonsense is practiced today in the widest circles. For it should be self-evident that one can only talk about agriculture, including its social organization, if one first has a basic understanding of agriculture, if one really knows what beet cultivation, potato cultivation, and grain cultivation mean. Without this, one cannot talk about national economic principles. These things must be determined from the facts themselves, not from some theoretical considerations. When you say something like this today to people who have attended a number of lectures at university on national economics in relation to agriculture, it seems completely absurd to them because the matter seems so clear-cut to them. But that is not the case; only those who base their judgment on the field, the forest, and animal husbandry can judge agriculture. All talk about economics that is not based on the facts themselves should simply stop. As long as people fail to realize that what is said about things in terms of economics is mere talk, floating above reality, nothing promising will come of it, neither in agriculture nor in any other field.

[ 9 ] The fact that people believe they can talk about things from a wide variety of perspectives [...] stems solely from the fact that they are unable to go back to the fundamentals within the individual areas of life themselves. That one sees a turnip as a turnip—certainly, it looks this way or that way, is easier or harder to cut, has this color and these or those components—all that can be said. But that does not mean that you understand the turnip, and above all, it does not mean that you understand how the turnip coexists with the field, with the season in which it ripens, and so on. Instead, you have to be clear about the following: