Agriculture

GA 327

12 June, 1924 Koberwitz

Lecture IV

My dear friends,

You have now seen what is essential in the discovery of spiritual-scientific methods for Agriculture, as it is for other spheres of life. Nature and the working of the Spirit throughout Nature must be recognised on a large scale, in an all-embracing sphere. Materialistic science has tended more and more to the investigation of minute, restricted spheres. True, this is not quite so bad in Agriculture; here they do not always go on at once to the very minute—the microscopically small, with which they are wont to deal in other sciences. Nevertheless, here too they deal with narrow spheres of activity, or rather, with conclusions which they feel able to draw from the investigation of narrow and restricted spheres. But the world in which man and the other earthly creatures live cannot possibly be judged from such restricted aspects.

To deal with the realities of Agriculture as the customary science of to-day would do, is as though one would try to recognise the full being of man, starting from the little finger or from the lobe of the ear and trying to construct from thence the total human being. Here again we must first establish a genuine science—a science that looks to the great cosmic relationships. This is most necessary nowadays. Think how the customary science of to-day, or yesterday, has to correct itself. You need only remember the absurdities that prevailed not long ago in the science of human nutrition, for example. The Statements were “absolutely scientific”—“scientifically proven”—and indeed, if one concentrated on the limited aspects which were brought forward, one could not make objection to the proofs. It was scientifically proven that a human being of average weight (eleven to twelve stone) requires about four-and-one-quarter of protein a day for adequate nourishment. It was, so to speak, an established fact of science. And yet, to-day no man of science believes in this proposition. Science has corrected itself in the meantime. To-day as everybody knows, four-and-one-quarter oz. of albuminous food are not only unnecessary but positively harmful, and a man will remain most healthy if he only eats one-and-three-quarter oz. a day.

In this instance, science has corrected itself, and it is well-known that if superfluous protein is consumed, it will create by-products in the intestines—by-products which have a toxic effect. Examine not only the period of life in which the protein is taken, but the whole life of the human being, and you recognise that the arterial sclerosis of old age is largely due to the toxic effect of superfluous protein. In this way scientific investigation are often erroneous—in relation to man, for instance—inasmuch as they only deal with the given moment. A normal human life lasts longer than ten years, and the harmful effects of the seemingly good causes which they mistakenly strive to produce, often do not emerge for a long time. Spiritual Science will not fall so easily into such errors.

I do not wish to join in the facile criticisms which are so frequently made against orthodox science because it has to correct itself as in this instance. One can understand that it cannot be otherwise. No less facile, on the other hand, are the attacks that are made on Spiritual Science when it begins to enter into practical life, recognising as it does the wider connections. For in these larger relationships of life, Spiritual Science is impressed by those substances and forces which go out eventually into the spiritual realm. It does not merely recognise the coarse material forces and substantialities.

This applies also to Agriculture, and notably when we come to the question of manuring. The very way the words are often put by scientists when they come to the manuring question, shows how little idea they really have of what manuring signifies in the economy of Nature. How often do we hear the phrase: “Manure contains the necessary foodstuffs for the plants.” I spoke these introductory sentences just now—referring to the nourishment of man—not without reason. I wanted to show you how science has had to correct itself in this instance, notably in the most recent period. Why has it to correct itself? Because it takes its start from an altogether false idea of nutrition—whether of man or of any other living creature.

Do not be angry with me for saying these things so openly and clearly. The idea used to be that the essential thing in human nutrition is what a man daily consumes. Undoubtedly, our daily food is important. But the greater part of what we daily eat is not there to be received as substance into the body—to be deposited in the body substantially. By far the greater part is there to give the body the forces which it contains, and so to call forth in the body inner mobility, activity. The greater part of what man thus receives into himself is cast out again.

Therefore the important question in the metabolic process is not the proportion of weights, but it is this: Are the foodstuffs providing us with the proper living quality of forces? We need these living forces, for example, when we walk or when we work—nay, when we only move our arms about. What the body needs, on the other hand, so as to deposit substances in itself—to provide itself with substances (which are expelled again every seven or eight years as the substance of the body is renewed)—this, for the most part, is received through the sense-organs, the skin and the breathing. Whatever the body has to receive and deposit in itself as actual substance—this it is constantly receiving in exceedingly minute doses, in a highly diluted state. It is only in the body that it becomes condensed. The body receives it from the air and thereupon hardens and condenses it, till in the nails and pair for instance it has to be cut off.

It is completely wrong to set up the formula: “Food received—Passage through the body—Wearing-away of nails and skin, and the like.” The true formula is thus: “Breathing, or reception of substances in an even finer state through the sense-organs (even the eyes)—Passage through the organism—Excretion in the widest sense.” On the other hand, what we receive through our stomach is important by virtue of its inherent life and mobility—as of a fuel. It is important inasmuch as it introduces the necessary forces for the will which is at work in the body. This is the truth—the simple result of spiritual research.

Over against this truth, it is heart-rending to see the ideas of modern science proclaiming the exact opposite. I say heart-rending, because we must admit, it is very difficult to come to terms at all with this science of to-day, even in the most essential questions. Yet somehow we must come to terms with it. For in practical life, the science of to-day would very soon lead into an absolute blind alley. While it pursues its present path it is simply incapable of understanding certain matters even when they force themselves on its attention.

I am not speaking of the experiments. What science says of the experiments is generally true. The experiments are very useful. It is the theorising about them which is so bad. Unfortunately, the practical instructions which science claims to give for various branches of life generally come from the theorising. You see how difficult it is to come to any understanding with this science, and yet—sooner or later we must do so. This understanding must be found, precisely for the most practical domains of life—and notably for Agriculture.

For all the different spheres of farming life we must gain insight into the working of the substances and forces, and of the Spiritual too. Such insight is necessary, so as to treat things in the right way. After all, a baby—so long as it does not know what a comb is for will merely bite into it, treating it in an impossible and style-less fashion. We too shall treat things in an impossible and style-less fashion, so long as we do not know what their true essence is ...

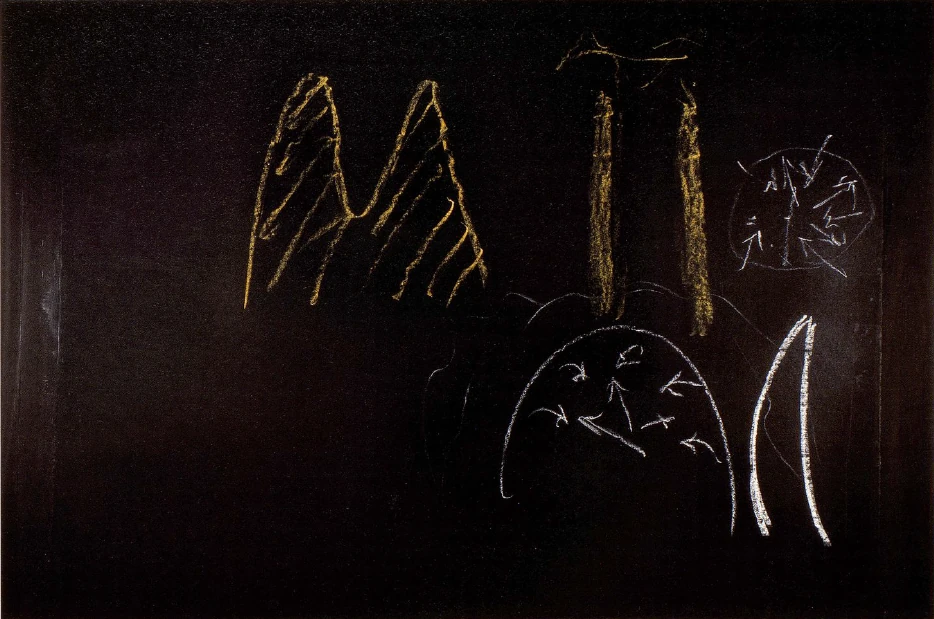

Consider a tree for example. A tree is different from an ordinary annual, which remains at the merely herbaccous stage. A tree surrounds itself with rind and bark, etc. What is the essence of the tree, by contrast to the annual? Let us compare such a tree with a little mound of earth which has been cast up, and which—we will assume—is very rich in humus, containing an unusual amount of vegetable matter more or less in process of decomposition, and perhaps of animal decomposition-products too.(Diagram 7).

Let us assume: this is the hillock of earth, rich in humus. And I will now make a hollow in it, like a crater. And let this (in the second drawing) be the tree: outside, the more or less solid parts, while inside is growing what leads eventually to the formation of the tree as a whole. It may seem strange to you that I put these two things side by side. But they are more nearly related than you would think.

In effect, earthly matter—permeated, as I have now described it, by humus-substances in process of decomposition—such earthly matter contains etherically living substance. Now this is the important point: Earthly matter, which by its special constitution reveals the presence in it of etherically living substance, is always on the way to become plant-integument. It only does not go far enough in the process to become such plant-integument as is drawn up, for instance, into the rind or bark of a tree.

You may conceive it thus (although in Nature it does not go so far): Imagine this hillock of earth being formed, with a hollow in the middle—a mound of earth, with humus entering into it, working in the earthly soil with the characteristic properties which proceed from the ethereal and living element. It does not happen so in Nature, but instead of it, the “mound of earth”—transmuted into a higher form of evolution—is gathered up around the plant so as to enclose it.

In effect, whenever in any given locality you have a general level or niveau, separating what is above the earth from the interior, all that is raised above this normal level of the district will show a special tendency to life—a tendency to permeate itself with ethereal vitality. Hence you will find it easier to permeate ordinary inorganic mineral earth with fruitful humus-substance, or with any waste product in process of decomposition—you will find it easier to do this efficiently if you erect mounds of earth, and permeate these with the said substance. For then the earthly material itself will tend to become inwardly alive—akin to the plant-nature. Now the same process takes place in the forming of the tree. The earth itself is “hollowed upward” to surround the plant with its ethereal and living properties. Why so?

I am telling you all this to awaken in you an idea of the really intimate kinship between that which is contained within the contours of the plant and that which constitutes the soil around it. It is simply untrue that the life ceases with the contours—with the outer periphery of the plant. The actual life is continued, especially from the roots of the plant, into the surrounding soil. For many plants there is absolutely no hard and fast line between the life within the plant and the life of the surrounding soil in which it is living.

We must be thoroughly permeated with this idea, above all if we would understand the nature of manured earth, or of earth treated in some similar way. To manure the earth is to make it alive, so that the plant may not be brought into a dead earth and find it difficult, out of its own vitality, to achieve all that is necessary up to the fruiting process. The plant will more easily achieve what is necessary for the fruiting process, if it is immersed from the outset in an element of life. Fundamentally, all plant-growth has this slightly parasitic quality. It grows like a parasite out of the living earth. And it must be so.

In many districts, we cannot reckon upon Nature herself letting fall into the earth enough organic residues, and decomposing them sufficiently, to permeate the earth with the requisite degree of life. We must come to the assistance of plant-growth by manuring the earth. We need to do so least of all in those districts where “black earth,” as it is called, prevails. For in “black earth”—at any rate in certain districts—Nature herself sees to it that the soil is sufficiently alive.

Thus we need to understand what is the essential point. But we must understand something else as well. We must know how to gain a kind of personal relationship to all things that concern our farming work, and above all—though it may be a hard saying—a personal relationship to the manure, especially to the task of working with the manure. It may seem an unpleasant task, but without this personal relation it is impossible. Why so? You will see it at once if you can go into the question: What is the essence of any living thing? A living thing always has an outer and an inner side. The “inner” is inside some kind of skin, the “outer” is outside the skin.

Consider now the inner side. It not only has streams of forces going outward in the direction of these arrows (Diagram 8); the inner life of an organic entity also includes currents of forces going inward from the skin—currents of forces that are pressed back. Moreover, outside it the organic entity is surrounded by manifold streams of forces.

Now there is something that expresses quite exactly—yet in a kind of personal way—how the organic entity establishes the right relationship between its inner and its outer side. All that goes on by way of forces and activities within it, stimulating and maintaining life within the organism—all that is inside the contours of the skin—all this (I beg you once more to forgive the hard saying) must smell inwardly, nay we might even say it must inwardly stink.

Life itself essentially consists in this, that what would otherwise scatter its scent abroad is held together, so that the aromatic elements do not ray outward too strongly, but are retained within. Towards the outer world, the organism must live in this way: through the contours of its skin it must let out as little as possible of that which engenders the scent-kindling life within it. So we might say: an organic body is the healthier, the more it smells inwardly and the less outwardly. Towards the outer world, the organism—notably the plant-organism—is predestined not to give off smell, but on the contrary to absorb it.

Perceive the helpful effect of a fragrant aromatic meadow, full of plants with aromatic scent! Then you become aware of the marvelous mutual aid prevailing in all life. The aromatic property which here expands and which is different from the mere aroma of life—it spreads its scent abroad for reasons which we may yet be able to describe, and it is this which works from without upon the plants.

These things we must have in a living and personal relationship; only then are we really in the life of Nature. The point is now to recognise the following. Manuring and everything of the kind consists essentially in this, that a certain degree of livingness must be communicated to the soil, and yet not only livingness. For the possibility must also be given to bring about in the soil what I indicated yesterday, namely to enable the nitrogen to spread out in the soil in such a way that with its help the life is carried along certain fines of forces, as I showed you. That is to say: in manuring we must bring to the earth-kingdom enough nitrogen to carry the living property to those structures in the earth-kingdom to which it must be carried—under the plant, where the plant-soil has to be. This is our task, and we must fulfil it in a scientific way.

There is one fact which can already give you a strong indication of what is needed. If you use mineral, purely mineral substances as manure, you will never get at the real earthy element; you will penetrate at most to the watery element of the earth. With mineral manures you can influence the watery content of the earth, but you do not penetrate sufficiently to bring to life the earth-element itself. Plants, therefore, which stand under the influence of mineral manures will have a kind of growth which betrays the fact that it is supported only by a quickened watery substance, not by a quickened earthy substance.

We can best approach these matters by turning, to begin with, to the most unassuming kind of manure. I mean the compost, which is sometimes even despised. In compost we have a means of kindling the life within the earth itself. We include in compost any kind of refuse to which little value is attached; refuse of farm and garden, from grass that we have let decay, to that which comes from fallen leaves or the like, nay, even from dead animals ... These things should not by any means be despised, for they preserve something not only of the ethereal but even of the astral. And that is most important. From all that has been added to it, the compost heap really contains ethereal and living elements and also astral. Living ethereal and astral elements are contained in it—though not so intensely as in manure or in liquid manure, yet in a more stable form. The ethereal and astral settle down more firmly in the compost; especially the astral.

The point is how to make use of this property in the right way. The influence of the astral on the nitrogen is marred in the presence of an all-too thriving ethereal element. Hypertrophy of the ethereal in the heap of compost does not give the astral a chance, so to speak. Now there is something in Nature, the excellence of which for Nature herself I have already described to you from several standpoints, and that is the chalky or limestone element. Bring some of this perhaps in the form of quicklime—into the heap of compost, and you will get this result: Without inducing the evaporation of the astral over-strongly, the ethereal is absorbed by the quicklime, and therewith oxygen too is drawn in, and the astral is made splendidly effective.

You thereby obtain quite a definite result. When you manure the soil with this compost, you communicate to it something which tends very strongly to permeate the earthy element with the astral, without going by the roundabout way of the ethereal. Think, therefore: the astral, without first passing via the ethereal, penetrates strongly into the earthy element. Thereby the earthy element is strongly astralised, if I may put it so, and through this astralising process is permeated by the nitrogen-content, in such a way that something arises very similar to a certain process in the human organism.

The process in the human organism to which I now refer is plant-like; plant-like, however, in the sense that it does not care to go on as far as the fruiting process, but is content to stop, as it were, at the stage of leaf- and stalk-formation. The process we here communicate to the Earth—we need it within us in order especially to bring into the foodstuffs that inner quickness and a mobility which, as I told you, is so necessary. And we shall kindle in the soil itself the same inner quickness and mobility if we treat it as I have now described. We then prepare the soil so that it brings forth something especially good for animals to consume; for in its further course it works in such a way that they develop inner mobility; their body becomes inwardly quick and alive.

In other words, we shall do well to manure our meadows and pastures with such compost. And if we do this properly—especially if we observe the other procedures which are necessary—we shall get very good pasture-food, good even as hay when it has been mown down. However, in order to proceed rightly in such matters we must always be able to see the whole. Our detailed measures must still depend on our inner feeling, to a Large extent. This inner feeling will develop rightly, once we perceive the whole nature of the process.

For instance, if we just leave the pile of compost as I described it hitherto, it may easily come about that it will scatter its astral content on all sides. The point will be for us to develop the necessary personal relationship to these things. We must try to bring the compost-heap into such a condition that it smells as little as possible. This we can easily attain, to begin with, by piling it up in thin layers, covering it layer by layer with something else, for instance granulated peat, and then another layer and so on. That which would otherwise evaporate and scatter its scent abroad, is thereby held together. The nitrogen, in fast, is that which strongly tends to seek the wide expanse—in manifold forms and compounds. Now it is held together.

What I chiefly wish to indicate is that we must treat the whole agricultural life with the conviction that we need to pour vitality, nay even astrality, in all directions, so as to make it work as a totality.

Taking our start from this, another thing will result. Have you ever thought why cows have horns, or why certain animals have antlers? It is a most important question, and what ordinary science tells us of it, is as a rule one-sided and superficial. Let us then try to answer the question, why do cows have horns? I said just now that an organic or living entity need not only have streams of forces pouring outward: it can also have streams of forces pouring inward. Now imagine such an organic entity—of a lumpy and massive shape. It would have streams of forces going outward and streams of forces going inward. It would be very irregular; a lumpy organism—an ungainly creature. We should have strange-looking cows if this were all. They would be lumpy, with tiny appendages for feet, as indeed they are in the early embryonic stages. They would remain so; they would look quite grotesque.

But the cow is not like that. The cow has proper horns and hoofs. What happens at the places where the horns grow and the hoofs? A locality is formed which sends the currents inward with more than usual intensity. In this locality the outer is strongly shut off; there is no communication through a permeable skin or hair. The openings which otherwise allow the currents to pass outward are completely closed. For this reason the horn-formation is connected with the entire shaping of the animal. The forming of horns and hoofs is connected with the whole shape and form of the creature.

With the forming of antlers it is altogether different. Here the point is, not that the streams are carried back into the organism, but on the contrary, that certain streams are carried a certain way outward. There are valves, so to speak, whereby certain streams and currents are discharged outwardly. Such streams need not always be liquid or aeriform; they may also be currents of forces, localised in the antlers. The stag is beautiful because it has an intense communication with the surrounding world, inasmuch as it sends certain of its currents outward, and lives with its environment, thereby receiving all that works organically in the nerves and senses. So it becomes a quick and nervous animal. In a certain respect, all animals possessing antlers are filled with a gentle nervousness and quickness. We see it in their eyes.

The cow has horns in order to send into itself the astral-ethereal formative powers, which, pressing inward, are meant to penetrate right into the digestive organism. Precisely through the radiation that proceeds from horns and hoofs, much work arises in the digestive organism itself. Anyone who wishes to understand foot-and-mouth disease—that is, the reaction of the periphery on the digestive tract—must clearly perceive this relationship. Our remedy for foot-and-mouth disease is founded on this perception.

Thus in the horn you have something well adapted by its inherent nature, to ray back the living and astral properties into the inner life. In the horn you have something radiating life—nay, even radiating astrality. It is so indeed: if you could crawl about inside the living body of a cow—if you were there inside the belly of the cow you—would smell how the astral life and the living vitality pours inward from the horns. And so it is also with the hoofs.

This is an indication, pointing to such measures as we on our part may recommend for the purpose of still further enhancing the effectiveness of what is used as ordinary farm-yard-manure. What is farm-yard-manure? It is what entered as outer food into the animal, and was received and assimilated by the organism up to a certain point. It gave occasion for the development of dynamic forces and influences in the organism, but it was not primarily used to enrich the organism with material substance. On the contrary, it was excreted. Nevertheless, it has been inside the organism and has thus been permeated with an astral and ethereal content. In the astral it has been permeated with the nitrogen-carrying forces, and in the ethereal with oxygen-carrying forces. The mass that emerges as dung is permeated with all this.

Imagine now: we take this mass and give it over to the earth, in one form or another (we shall go into the details presently). What we are actually doing is to give the earth something ethereal and astral which has its existence by rights, inside the belly of the animal and there engenders forces of a plant-like nature. For the forces we engender in our digestive tract are of a plant-like nature. We ought to be very thankful that the dung remains over at all; for it carries astral and ethereal contents from the interior of the organs, out into the open. The astral and ethereal adheres to it. We only have to preserve it and use it in the proper way.

In the dung, therefore, we have before us something ethereal and astral. For this reason it has a life-giving and also astralising influence upon the soil, and, what is more, in the earth-element itself; not only in the watery; but notably in the earthy element. It has the force to overcome what is inorganic in the earthy element.

What we thus give over to the earth must of course have lost its original form, i.e., the form it had before it was consumed as food. For it has passed through an organic process in the animal's digestive, metabolic system. In some sense it will be in process of dissolution and disintegration. But it is best of all if it is just at the point of dissolution by virtue of its own inherent ethereal and astral forces. Then come the little parasites—the minutest of living creatures—and find in it a good nutritive soil. These parasitic creatures are therefore generally supposed to have something to do with the goodness of the manure. In reality they are only indicators of the fact that the manure itself is in such and such a condition. As indicators of this they may well be of great importance; but we are under an illusion if we suppose that the manure can be fundamentally improved by inoculation with bacteria or the like. It may be so to outer appearance, but it is not so in reality. (I shall go into the matter at a later stage. Meanwhile, let us proceed).

We take manure, such as we have available. We stuff it into the horn of a cow, and bury the horn a certain depth into the earth—say about 18 in. to 2 ft. 6 in., provided the soil below is not too clayey or too sandy. (We can choose a good soil for the purpose. It should not be too sandy). You see, by burying the horn with its filling of manure, we preserve in the horn the forces it was accustomed to exert within the cow itself, namely the property of raying back whatever is life-giving and astral. Through the fact that it is outwardly surrounded by the earth, all the radiations that tend to etherealise and astralise are poured into the inner hollow of the horn. And the manure inside the horn is inwardly quickened with these forces, which thus gather up and attract from the surrounding earth all that is ethereal and life-giving.

And so, throughout the winter—in the season when the Earth is most alive—the entire content of the horn becomes inwardly alive. For the Earth is most inwardly alive in winter-time. All that is living is stored up in this manure. Thus in the content of the horn we get a highly concentrated, life-giving manuring force. Thereafter we can dig out the horn. We take out the manure it contains.

During our recent tests (in Dornach), as our friends discovered for themselves, when we took out the manure it no longer smelt at all. This was a very striking fast. It had no longer any smell, though naturally it began to smell a little when treated once more with water. This shows that all the odoriferous principles are concentrated and assimilated in it. Indeed it contains an immense ethereal and astral force; and of this you can now make use. When it has spent the winter in the earth, you take the stuff out of the horn and dilute it with ordinary water—only the water should perhaps be slightly warmed.

To give an impression of the quantitative aspect: I always found, having first looked at the area to be manured, that a surface, say, about as big as the patch from the third window here to the first foot-path, about 1,200 square metres (between a quarter- and third-acre) is adequately provided for if we use one hornful of this manure, diluted with about half a pailful of water. You must, however, thoroughly combine the entire content of the horn with the water. That is to say, you must set to work and stir. Stir quickly, at the very edge of the pail, so that a crater is formed reaching very nearly to the bottom of the pail, and the entire contents are rapidly rotating. Then quickly reverse the direction, so that it now seethes round in the opposite direction.

Do this for an hour and you will get a thorough penetration. Think, how little work it involves. The burden of work will really not be very great. Moreover, I can well image that—at any rate in the early stages—the otherwise idle members of a farming household will take pleasure in stirring the manure in this way. Get the sons and daughters of the house to do it and it will no doubt be wonderfully done.

It is a very pleasant feeling to discover how there arises after all, from what was altogether scentless to begin with, a rather delicately sustained aroma. This personal relationship to the matter (and you can well develop it) is extraordinarily beneficial—at any rate for one who likes to see Nature as a whole and not only as in the Baedeker guide-books.

Our next task will be to spray it over the tilled land so as to unite it with the earthly realm. For small surfaces you can do it with an ordinary syringe; it goes without saying, for larger surfaces you will have to devise special machines. But if you once resolve to combine your ordinary manuring with this kind of “spiritual manure,” if I may call it so, you will soon see how great a fertility can result from such measures. Above all, you will see how well they lend themselves to further development. For the method I have just described can be followed up at once by another, namely the following.

Once more you take the horns of cows. This time, however, you fill them not with manure but with quartz or silica or even orthorclase or feldspar, ground to a fine mealy powder, of which you make a mush, say of the consistency of a very thin dough. With this you fill the horn. And now, instead of letting it “hibernate,” you let the horn spend the summer in the earth and in the late autumn dig it out and keep its contents till the following spring.

So you dig out what has been exposed to the summery life within the earth, and now you treat it in a similar way. Only in this case you need far smaller quantities. You can take a fragment the size of a pea, or maybe only the size of a pin's head, and distribute it by stirring it up well in a bucket of water. Here again, you will have to stir it for an hour, and you can now use it to sprinkle the plants externally. It will prove most beneficial with vegetables and the like.

I do not mean that you should water them with it in a crude way; you spray the plants with it, and you will presently see how well this supplements the influence which is coming from the other side, out of the earth itself, by virtue of the cow-horn manure. And now, suppose you extend this treatment to the fields on a large scale. After all, there is no great difficulty in doing so. Why should it not be possible to make machines, able to extend over whole fields the slight sprinkling that is required? If you do this, you will soon see how the dung from the cow-horn drives from below upward, while the other draws from above—neither too feebly, nor too intensely. It will have a wonderful effect, notably in the case of cereals.

These things are derived from a larger sphere—not from what you do just at the moment with the single Thing in hand, as though you would build up the entire human being theoretically from a single finger. No doubt, by such methods too, something is attained, which I by no means wish to under-estimate. Yet with all their investigations nowadays, people are trying to discover, as they put it, what is likely to be most productive for the farmer, and in the last resort it only amounts to this: they try to find how the production may be made financially most profitable. It really amounts to little more than that. The farmer may not always think of it; but unconsciously this is the underlying thought. He is astonished when by some measure he gets great results for the moment—say he gets big potatoes; or anything else that swells and has a comely size. But he does not pursue the investigation far enough beyond this point.

In effect, this is not at all the most important point. The important thing is, when these products get to man, that they should be beneficial for his life. You may cultivate some fruit of field or orchard in its appearance absolutely splendid, and yet, when it comes to man it may only fill his stomach without organically furthering his inner life. But the science of to-day is incapable of following the matter up to the point of finding how man shall get the best kind of nourishment for his own organism. It simply does not find the way to this.

How different it is in all that is here said out of Spiritual Science Underlying it, as you have seen, is the entire household of Nature. It is always conceived out of the whole. Therefore each individual measure is truly applicable to the whole, and so it should be. If you pursue agriculture in this way, the result can be no other than to provide the very best for man and beast. Nay more, as everywhere in Spiritual Science, here too we take our start above all from man himself. Man is the foundation of all these researches, and the practical hints we give will all result from this. The end in view is the best possible sustenance of human nature. This form of study and research is very different from what is customary nowadays.1The two Preparations mentioned in this lecture are now known as Preparations 500 and 501. The Preparations described in Lecture 5 are referred to in current literature as Preparations 502-507. During the past thirty-four years, the methods of making and applying the Preparations have been worked out, but quite intentionally, precise details have not been added to the present text because the Course of Lectures was intended to give principles, not technicalities, of their application. Further details of the method can be obtained by writing to the Bio-Dynamic Agricultural Association, Rudolf Steiner House, 35 Park Road, London, N.W.1.

Discussion

Question: Should the dilution be continued arithmetically?

Answer: In this respect, no doubt, certain things will yet have to he discussed. Probably, with an increasing area you will need more water and proportionately fewer cow-horns. You will be able to manure large areas with comparatively few cow-horns. In Dornach we had twenty-five cow-horns; to begin with we had a fairly Large garden to treat. First we took one horn to half a bucketful. Then we began again, taking a whole bucketful and two cow-horns. Afterwards we had to manure a relatively larger area. We took seven cow-horns and seven bucketfuls.

Question: Could one use a mechanical stirrer to stir up the manure for larger areas, or would this not be permissible?

Answer: This is a thing you can either take quite strictly, or else you can make up your mind to slide into substitute methods. There can be no doubt, stirring by hand has quite another significance than mechanical stirring. A mechanist, of course, will not admit it. But you should consider well what a great difference it makes, whether you really stir with your hand or in a mere mechanical fashion. When you stir manually, all the delicate movements of your hand will come into the stirring. Even the feelings you have may then come into it.

Of course the people of to-day will not believe that it makes any difference; but you can tell the difference even in medical mattes. Believe me, it is not a matter of indifference whether a medicament is prepared more manually or mechanically. When a man works at a thing himself, he gives something to it which it retains. To mention one example, this is notably the case with the Ritter remedies, with which some of you are no doubt familiar. You must not smile at such things. I have often been asked what I think of the Ritter remedies. You are perhaps aware that there are some who sing hymns of praise on their behalf, while others spread the tale that they have no particular effect.

Undoubtedly they have an effect. But I am firmly convinced that if these remedies were brought on to the market in the usual way they would very largely lose their influence. With these remedies especially, it makes a great difference if the doctor himself possesses the remedy and gives it to his patient directly. When the doctor gives such a thing to his patient, when it is all taking place in a comparatively small circle, he brings a certain enthusiasm with him. You may say the enthusiasm as such weighs nothing; you cannot weigh it. Nevertheless it enters into the vibrations if the doctors are enthusiastic. Light has a strong effect on the remedies; why not enthusiasm? Enthusiasm mediates; it can have a great effect. Enthusiastic doctors of to-day can achieve great results. Precisely in this way, the Ritter remedies can have a far-reaching influence.

With enthusiasm, great effects can be called forth. But if you begin to do it in an indifferent and mechanical fashion, the effects will soon evaporate. It makes a difference whether you do the thing with all that proceeds from the human hand—believe me, very much can issue from the hand—or whether you do it with a machine. By and by, however, it might prove to be great fun—this stirring; and you would no longer dream of a mechanical stirrer even when many cow-horns were needed. Eventually, I can imagine, you will do it on Sundays as an after-dinner entertainment. Simply by having many guests invited and doing it on Sundays, you will get the best results without machines!

Question: No doubt there will be a little technical difficulty in distributing half a bucketful of water over one-fifth of an acre. But when you increase the number of cow-horns the difficulty will rapidly increase—quite out of proportion to the number. Can the given quantity of water be diluted still more, or is it essential to preserve the proportion of half a bucketful? Must you take about half a bucketful to one-fifth of an acre?

Answer: No doubt it will be possible as you suggest. But I think the method of stirring would then have to be changed. You might do it in this way. Stir up a cow-hornful completely in half a bucket of water, and then dilute it to a bucketful; but you will then have to stir it again.

On the whole, I think it would be best to stir only half a bucketful at a time. Reckon up, in the given instance, how much less of the stuff you need, even if it should be less than the contents of a cowhorn. It all depends on your bringing about a thoroughly intimate permeation. You are far from achieving a true permeation when you merely tip the stuff into water and stir it up a little. You must bring about a very intimate permeation. If you merely shake in the more or less condensed substance, or if you fall to stir it vigorously, you will not have a thorough mixture. Therefore I think it will be easier to stir several half-bucketfuls with small amounts of substance than to dilute the water again and stir it up a second time.

Question: Some solid matter will remain over, no doubt, even then. May the liquid afterwards be strained so that it can be distributed with a mechanical spray?

Answer: I do not think it will be necessary. For if you stir it quickly, you will obtain a fairly cloudy liquid, and you need not trouble whether any foreign bodies are left in it. You will not find it difficult to distribute the manure; pure cow-manure is best for the purpose, but even if there are foreign bodies in it, I do not think you need go to the trouble of cleansing it. If there are foreign bodies, they might even have a beneficial effect and do no harm. As a result of the concentration and subsequent dilution, it is only the radiant effect that works; it is no longer the substances as such, but the dynamic radiant activity. Thus there would be no danger, for example, of your getting potato plants with long shoots und nothing else upon them at the place where your foreign bodies happened to fall. I do not think there would be any such danger.

Question: I only had in mind the mechanical spray.

Answer: Certainly you can strain the liquid; it will do it no harm. It might be simplest to have your mechanical spray fitted with a sieve from the outset.

Question: You did not say whether the stuff from the horn should be weighed out, so as to get a definite proportion. Speaking of half a bucketful, did you refer to a Swiss bucket, or a precise measure of litres?

Answer: I took a Swiss bucket, the ordinary bucket they use for milking in Switzerland. The whole thing was tested practically, in the direct perception of it. You should now reduce it to the proper weights and measures.

Question: Can the cow-horns be used repeatedly, or must they always be taken from freshly slaughtered beasts?

Answer: We have not tested it, but from my general knowledge I think you should be able to use the cow-horns three or four times running. After that they will no longer work so well. There might even be this possibility: Use the cow-horns for three or four years in succession; then keep them in the cow-stable for a time, and use them again another year. This too might be possible. But I have no idea how many cow-horns an agricultural area can normally have at its disposal; whether or not it is necessary to be very economical in this respect. That is a question I cannot decide at the moment.

Question: Where can you get the cow-horns? Must they be taken from Eastern-European or Mid-European districts?

Answer: It makes no difference where you get them from—only not from the refuse yard. They must be as fresh as possible. However, strange as it may sound, it is a fact that Western life—life in the Western hemisphere—is quite a different thing from life in the Eastern hemisphere. Life in Africa, Asia or Europe has quite another significance than life in America Possibly, therefore, horns from American cattle would have to be more effective in a rather different way. Thus it might prove necessary to tighten the manure rather more in these horns—to make it denser, hammer it more tightly.

It is best to take horns from your own district. There is an exceedingly strong kinship between the forces in the cow-horns of a certain district and the forces generally prevailing in that district. The forces of horns from abroad might come into conflict with what is there in the earth of your own country. You must also remember, it will frequently happen that the cows from which you get the horns in your own district are not really native to the district. But you can get over this difficulty. When the cows have been living and feeding on a particular soil for three or four years, they belong to the soil (unless they happen to be Western cattle).

Question: How old may the horns be? Should they be taken from an old or a young cow?

Answer: All these things must be tested. From the essence of the matter, I should imagine that cattle of medium age would be best.

Question: How big should they be?

Answer: Dr. Steiner draws on the board the actual size of the horn—about 12 to 16 inches long (Diagram 9), i.e. the normal size of horn of “Allgäu” cattle, for example.

Question: Is it not also essential whether the horn is taken from a castrated ox, or from a male or female animal?

Answer: In all probability the horn of the ox would be quite ineffective, and the horn of the bull comparatively weak. Therefore I speak of cow-horns; cows as a rule are female. I mean the female animal.

Question: What is the best time to plant cereals?

Answer: The exact answer will be given when I come to sowing in the main lectures. It is very important, needless to say, and it makes a great difference whether you do it more or less near to the winter months. If near to the winter months, you will bring about a strong reproductive power in your cereals; if farther from the winter months, a strong nutritive power.

Question: Could the cow-horn manure also be distributed with sand? Is rain of any importance in this connection?

Answer: As to the sand you may do so; we have not tested it, but there is nothing to be said against it. The effect of rain would also have to be tested. Presumably it would bring about no change; it might even tend to establish the thing more firmly. On the other hand, we are dealing with a very high concentration of forces, and possibly the minute impact of the falling raindrops might scatter the effect too much. It is a very delicate process; everything must be taken into account. There is nothing to be said against spreading sand with the cow-manure.

Question: In storing the cow-horns and their contents, how should one prevent any harmful influences from gaining access?

Answer: In these matters it is generally true to say that you do more harm by removing the harmful influences, so-called, than by leaving them alone. Nowadays, as you know, people are always wanting to “disinfect” things. Undoubtedly they go too far in this. With our medicaments, for example, we found that if we wished absolutely to prevent the possibility of mould, we had to use methods which interfere with the real virtue of the medicament.

I for my part have no great respect for these “harmful influences.” They do not do nearly so much harm. The best thing is, not to go out of our way in devising methods of purification, but to let well alone.

(We only put pig's bladder over the top to prevent the soil from falling in.)

To try to clean the horns by any special methods is not at all to be recommended. We must familiarise ourselves with the fact that “dirt” is not always dirt. If, for example, you cover your face with a thin layer of gold, it is “dirt” and yet, gold is not dirt. Dirt is not always dirt. Sometimes it is the very thing that acts as a preservative.

Question: Should the extreme “chaoticizing” of the seed, of which you spoke, be supported or enhanced by any special methods?

Answer: You could do so, but it would be superfluous. If the seed-forming process occurs at all, the maximum of chaos will come of its own accord. There is no need to support it. It is in manuring that the support is needed. In the seed-forming process, I do not think it will be necessary to enhance the chaos any more. If there is fertilising seed at all, the chaos is complete. You could do it, of course, by making the soil more silicious. It is through silica that the essential cosmic forces work.

Whatever cosmic forces are caught up by the earth, work through the silica. You could do it in this way, but I do not believe it is necessary.

Question: How Large should the experimental plots be? Will it not also be necessary to do something for the cosmic forces that should be preserved until the new plant is formed?

Answer: You might experiment as follows. It is comparatively easy to give general guiding lines; but the most suitable scale on which to work is a thing you must test for yourselves. It will not, however, be difficult to make experiments on this question. Set out your plants in two separate beds, side by side—a bed of wheat, say, and a bed of sainfoin. Then you will find this possibility. In the one plant—wheat—which of its own accord tends easily to lasting seed-formation, you will retard the seed-forming process by the use of silica. Meanwhile, with the sainfoin, you will find the seed-forming process quite suppressed or very much retarded.

To investigate these things, you can always take this as a basis of comparison: Study the properties of cereals—wheat, for example—and then compare them with the analogous properties of sainfoin, or leguminosae generally. You will thus have the most interesting experiments on seed-formation.

Question: Does it matter when the diluted stuff is brought on to the fields?

Answer: Undoubtedly it does. You can generally leave the cow-horns in the earth until you need them. They will not deteriorate, even if after hibernating they are left for a while during the summer. If, however, you do need to keep them elsewhere, having taken them out of the earth, you should make a box, upholster it well with a cushion of peat-moss on all sides, and put the cow-horns inside. Then the strong inner concentration will be preserved. In any case. it is inadvisable to keep the watery fluid after dilution. You must do the stirring not too long before you use the liquid.

Question: If we want to treat the winter corn, must we use the cow-horns a whole quarter after taking them out of the earth?

Answer: It does not matter essentially, but it will always be better to leave them in the earth until you need them. If you are going to use them in the early autumn, leave them in the earth until you need them. It will in no way harm the manure.

Question: With the fine spraying of the liquid due to the spraying machine, will not the etheric and astral forces be wasted?

Answer: Certainly not; they are intensely bound. Altogether, when you are dealing with spiritual things—unless you drive them away yourself from the outset—you need not fear that they will run away from you nearly as much as with material things.

Question: How should one treat the cow-horns with mineral content, after they have spent the summer in the earth?

Answer: It will not hurt to take them out and keep them anywhere you like; you can throw them in a heap anywhere. It will not hurt the stuff, when it has once spent the summer in the earth. Let the sun shine on them; it will not hurt, it will even do them good.

Question: Must the horns be buried at the same place—on the same field which you will afterwards be wanting to manure, or can they he buried all together at any place you choose?

Answer: It makes so little difference that you need not worry about it. In practice, it will he best to look for a place where the soil is comparatively good. I mean, where the earth is not too highly mineral, but contains plenty of humus. Then you can bury all the cow-horns you need in one place.

Question: What about using machines on the farm? Is it not said that machines should not be used at all?

Answer: That cannot really be answered purely as a farming question. Within the social life of to-day, it is hardly a practical, hardly a topical question to ask whether machines are allowable. You can hardly be a farmer nowadays without using machines. Needless to say, not all operations are so nearly akin to the most intimate processes of Nature as the stirring of which we were speaking just now. Just as we did not want to mix up such an intimate process of Nature with purely mechanical elements, so it is with regard to the other things of which you are thinking. Nature herself, in any case, sees to it that where machines are out of place you can do very little with them. A machine will not help in the seed-forming process, for example; Nature does it for herself.

Really I think the question is not very practical. How can you do without machines nowadays? On the other hand, I may remark that as a farmer you need not just be crazy on machines. If one has a particular craze for machines, he will undoubtedly do worse as a farmer, even if his new machine is an improvement, than if he goes an using his old machine until it is worn out. However, in the strict sense of the word these are no longer purely farming questions.

Question: Could the given quantity of cow-horn manure, diluted with water, be used on half the area you indicated?

Answer: Then you would get rampant growths; you would get the result I hinted at just now in another connection. If, for example, you did this in potato-growing or the like, you would get rampant plants with highly ramified stems; what you are really wanting would not develop properly. Apply the stuff in excess and you will get what are generally known as rank patches.

Question; What about a fodder plant, which you want to grow rampant—spinach for instance?

Answer: There, too, I think we shall only use the half-bucketful with the one cow-horn. That is what we did in Dornach with a patch that was mainly vegetable garden. For plants that are grown over larger areas, you will need far less in proportion. It is already the optimum amount.

Question: Does it matter what kind of manure you use—cow- or horse- or sheep-manure?

Answer: Undoubtedly cow-manure is best for this procedure. Still, it might also be well to investigate whether or no horse-manure could be used. lf you want to treat horse-manure in this way, you will probably find that you need to wrap the horn up to some extent in horse-hair taken from the horse's mane. You will thus make effective the forces which in the horse—as it has no horns—are situated in the mane.

Question: Should it be done before or after sowing the seed?

Answer: The proper thing is to do it before. We shall see how it works; this year we began rather late, and some things will be done after sowing. We shall see whether it makes any difference. However, as a normal matter of course, you should do it before sowing, so as to influence the soil itself beforehand.

Question: Can the same cow-horns that have been used for manure be used for the mineral substance too?

Answer: Yes, but here too you cannot use them more than three or four times. After that they lose their forces.

Question: Does it matter who does the work? Can anyone you choose do the work, or should it be an anthroposophist?

Answer: That is the question. If you raise such a question at all nowadays, you will be laughed at, no doubt, by many people. Yet I need only remind you that there are people whose flowers, grown in the window-box, thrive wonderfully, while with others they do not thrive at all but fade and wither. These are simple facts.

These things that take place through human influence, though they cannot be outwardly explained, are inwardly quite clear and transparent. Moreover, such things will come about simply as a result of the human being practising meditation; preparing himself by meditative life, as I described it in yesterday's lecture. For when you meditate you live quite differently with the nitrogen which contains the Imaginations. You thereby put yourself in a position which will enable all these things to be effective; you put yourself in this position over against the whole world of plant-growth.

However, these things are no longer as clear to-day as they used to be in olden times, when they were universally accepted. For there were times when people knew that by certain definite practices they could make themselves fitted to tend the growth of plants. Nowadays, when such things are not observed, the presence of other people disturbs them. These delicate and subtle influences are lost when you are constantly living and moving among men and women who take no notice of such things. Hence, if you try to apply them, it is very easy to prove them fallacious. And I am loth to speak openly as yet about these things in a large company of people. The conditions of life nowadays are such that it is only too easy to refute them.

A very ticklish question was raised, for example, by our friend Stegemann in the discussion in the Hall the other day, namely, whether parasites could be combated by such means—by means of concentration or the like. There can be no question about it that you can, provided you did it in the right way. Notably you would want to choose the proper season—from the middle of January to the middle of February—when the earth unfolds the greatest forces, the forces that are most concentrated in the earth itself. Establish a kind of festival time, and practise certain concentrations during the season, and the effects might well be evident.

As I said, it is a ticklish question, but it can be answered positively along these lines. The only condition is that it must be done in harmony with Nature as a whole. You should be well aware that it makes all the difference whether you do an exercise of concentration in the winter-time or at midsummer. How much is contained in many of the old folk-proverbs! Even the people of to-day might still derive many a valuable hint from these.

I could have mentioned it in yesterday's lecture: Among the many things I should have done in this present incarnation, but did not find it possible to do, was this. When I was a young man I had the idea to write a kind of “peasant's philosophy,” setting down the conceptual life of the peasants in all the things that touch their lives. It might have been very beautiful. The statement of the Count, that peasants are stupid, would have been refuted. A subtle wisdom would have emerged—a philosophy dilating upon the intimacies of Nature's life—a philosophy contained in the very formation of the words. One marvels to see how much the peasant knows of what is going on in Nature.

To-day, however, it would no longer be possible to write a peasant's philosophy. These things have been almost entirely lost. It is no longer as it was fifty or forty years ago. Yet it was wonderfully significant; you could learn far more from the peasants than in the University. That was an altogether different time. You lived with the peasants in the country, and when those people came along with their broad-brimmed hats, introducing the Socialist Movement of to-day, they were only the eccentricities of life. To-day the whole world is changed. The younger ladies and gentlemen here present have no idea how the world has changed in the last thirty or forty years. How much has been lost of the true peasants' philosophy, of the real beauty of the folk-dialects! It was a kind of cultural philosophy.

Even the peasants' calendars contained what they no longer contain to-day. Moreover, they looked quite different—there was something homely about them. I, in my time, knew peasants' calendars printed on very poor paper, it is true; inside, however, the planetary signs were painted in colours, while on the cover, as the first thing to meet the eye, there was a tiny sweet which you might tick whenever you use the book. In this way too it was made tasty; and of course the people used it one after another.

Question: When larger areas are to be manured, must the number of cow-horns be determined purely by feeling?

Answer: No, I should not advise it. In such a case, I think, we really must be sensible. This, therefore, is my advice. Begin by testing it thoroughly according to your feeling. When you have done all you can to get the most favourable results in this way, then set to work and translate your results into figures for the sake of the world as it is to-day. So you will get the proper tables which others can use after you.

If anyone is inclined to do it out of pure feeling, by all means let him do so. But in his attitude to others he should not behave as though he did not value the tables. The whole thing should be translated into calculable figures and amounts for the sake of others; it is necessary nowadays. You need cows' horns to do it with, but you do not exactly need to grow bulls' horns in representing it! These are the things that lead so easily to opposition. I should advise you as far as possible to compromise in this respect, and bear in mind the judgments of the world at large.

Question: Is the quick-lime treatment of the compost-heap, in the percentages as given nowadays, to be recommended?

Answer: The old method will undoubtedly prove beneficial, only you must treat it specifically, according to the nature of your soil—whether it be more sandy or marshy. For a sandy soil you will need rather less quicklime. A marshy ground will need rather more quicklime on account of the formation of oxygen.

Question: How about digging up and turning over the compost heap?

Answer: That is not bad for it. When you have dug it up and turned it, you should, however, provide for its proper protection by putting a layer of earth all around it. Cover it over with earth; peat-earth or granulated peat is very good for the purpose.

Question: What kind of potash did you mean, when you said it might be used if necessary in the transition stage?

Answer: Kali magnesia.

Question: What is the best way of using the rest of the manure after the cow-horns have been filled? Should it be brought on to the fields in autumn, so as to undergo the winter experience? or should it be set aside until the spring?

Answer You must remember that the cow-horn manuring is not intended as a complete Substitute for ordinary manuring. You should go on manuring as before. The new method should be regarded as a kind of extra, largely enhancing the effect of the manuring hitherto applied. The latter should continue as before.

Vierter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

[ 1 ] Sie haben ja gesehen, es handelt sich bei der Auffindung von geisteswissenschaftlichen Methoden auch für die Landwirtschaft darum, gewissermaßen die Natur und die Wirkung des Geistes in der Natur im Großen anzuschauen, in seinem umfassenden Kreise, während die materialistisch gefärbte Wissenschaft immer mehr und mehr dazu gekommen ist, in die kleinen Kreise, in das Kleine, hineinzugehen. Wenn man es auch bei so etwas wie der Landwirtschaft nicht immer gleich mit dem Allerkleinsten, dem mikroskopisch Kleinen, zu tun hat, womit man es in den anderen Naturwissenschaften so oft zu tun hat, so hat man es doch zu tun mit demjenigen, was in kleinen Kreisen wirkt und aus der Wirkung der kleinen Kreise erschlossen werden kann. Aber die Welt, in der der Mensch und andere Erdenwesen leben, sie ist ja durchaus nicht etwas, was man nur von kleinen Kreisen aus beurteilen kann. So zu verfahren gegenüber dem, was eigentlich in Betracht kommt gerade zum Beispiel bei der Landwirtschaft, wie heute die landläufige Wissenschaft verfährt, würde ebenso sein, wie wenn man die ganze Wesenheit des Menschen erkennen wollte, sagen wir, aus seinem kleinen Finger und aus dem Ohrzipfel, und von da aus sich aufbauen wollte dasjenige, was im Großen und Ganzen in Betracht kommt. Demgegenüber müssen wir stellen wiederum -und das ist heute so notwendig wie nur irgend möglich - eine wirkliche Wissenschaft, die auf die großen Weltzusammenhänge geht.

[ 2 ] Wie sehr stark Wissenschaft im heutigen landläufigen Sinne oder in dem landläufigen Sinn von vor einigen Jahren sich selber korrigieren muss, das geht hervor aus den wissenschaftlichen Torheiten, die vor gar nicht langer Zeit zum Beispiel in Bezug auf die Ernährung des Menschen geherrscht hatten. Die Dinge waren alle ganz wissenschaftlich, sie waren auch wissenschaftlich bewiesen, und man konnte gegen den Beweis, wenn man sich nur darauf verlegte, was da eben in Betracht gezogen wurde, auch gar nichts einwenden. Es war als wissenschaftlich bewiesen, dass ein Mensch, der da ein mittleres Körpergewicht von siebzig bis fünfundsiebzig Kilogramm hat, dass ein solcher Mensch etwa hundertzwanzig Gramm Eiweiß als Nahrung braucht. Nun, wie gesagt, das war sozusagen wissenschaftlich bewiesen. Heute glaubt kein Mensch, der wissenschaftliche Ansichten hat, mehr an diesen Satz. Denn die Wissenschaft hat sich selber korrigiert. Heute weiß jeder Mensch, dass hundertzwanzig Gramm Eiweißnahrung nicht nur nicht notwendig, sondern direkt schädlich sind, und dass der Mensch eigentlich am gesündesten bleibt, wenn er nur fünfzig Gramm täglich in sich aufnimmt. Da hat sich die Wissenschaft selber korrigiert. Heute weiß man, dass es wirklich so ist, dass, wenn überflüssiges Eiweiß aufgenommen wird, das Eiweiß im Darm Zwischenprodukte erzeugt, die Giftwirkungen haben. Und wenn man nicht nur die unmittelbaren Lebensepochen des Menschen, worin man ihm das Eiweiß verabreicht, bloß untersucht, sondern das ganze Leben des Menschen, so erkennt man, dass von diesen Giftwirkungen des überflüssigen Eiweißes hauptsächlich die Arterienverkalkung im Alter herrührt. So sind die wissenschaftlichen Untersuchungen zum Beispiel in Bezug auf den Menschen oftmals dadurch irrig, dass sie nur auf den Augenblick sehen. Aber ein Menschenleben dauert doch eben, wenn es normal ist, länger als zehn Jahre, und die schädlichen Wirkungen von den so herbeigesehnten scheinbar günstigen Ursachen, die stellen sich oftmals sehr spät ein.

[ 3 ] Geisteswissenschaft kann in einen solchen Fehler eben weniger verfallen. Gewiss, ich will gar nicht einstimmen in die billige Kritik, die ja sehr häufig geübt wird aus dem Grunde, weil die landläufige Wissenschaft sich in solcher Art korrigieren muss, wie ich es eben ausgesprochen habe. Man kann gut einsehen, dass das nicht anders sein kann und dass es notwendig ist. Aber auf der anderen Seite ist es ebenso billig, über Geisteswissenschaft herzufallen, wenn sie ins praktische Leben eingreifen will, weil sie nun eben einmal genötigt ist, auf die größeren Zusammenhänge des Lebens zu sehen, und weil ihr da in die Augen fallen diejenigen Kräfte und Substanzen, die dann in das Geistige hereingehen, nicht bloß die grobmateriellen Kräfte und Substanzialitäten. Das gilt durchaus auch für die Landwirtschaft, und es gilt insbesondere dann, wenn in der Landwirtschaft infrage kommt die Düngungsfrage.

[ 4 ] Schon wie so häufig, ich möchte sagen, die Worte gesetzt werden heute gerade von den Wissenschaftern, wenn die Düngungsfrage in Betracht kommt, schon das zeigt, dass man eigentlich wenig wirkliche Anschauung davon hat, was das Düngen im Haushalt der Natur eigentlich wirklich bedeutet. Man hört heute sehr oft die Phrase: Der Dünger enthalte die Futterstoffe für die Pflanzen. Nun ja, ich habe die paar Sätze, die ich vorausgeschickt habe, aus dem Grunde gesagt, um Ihnen zu zeigen, wie in Bezug auf das Futter beim Menschen gerade in der neuesten Zeit, in der unmittelbaren Gegenwart, die Wissenschaft sich korrigieren musste. Da musste sie sich korrigieren, weil sie eben von einer ganz falschen Anschauung ausgeht in Bezug auf die Ernährung irgendeines Wesens.

[ 5 ] Sehen Sie, man glaubte nämlich, das Allerwichtigste in der Ernährung - nehmen Sie nicht übel, dass ich die Dinge so unbefangen sage - sei dasjenige, was man täglich isst. Nun, das ist schon wichtig, was man täglich isst. Aber der meiste Teil dessen, was man täglich isst, ist gar nicht dazu da, um als Substanz in den Körper aufgenommen zu werden und im Körper abgelagert zu werden. Sondern der meiste Teil ist da, damit er die Kräfte, die er in sich enthält, an den Körper abgibt, den Körper in Regsamkeit bringt. Und der meiste Teil desjenigen, was man auf diese Weise in sich aufnimmt, wird eigentlich wieder ausgeschieden, sodass man sagen muss, nicht um eine gewichtsmäßige Anordnung im Stoffwechsel handelt es sich hauptsächlich, sondern darum handelt es sich, ob wir mit den Nahrungsmitteln die Lebendigkeit der Kräfte in der richtigen Weise in uns aufnehmen können. Denn diese Lebendigkeit brauchen wir zum Beispiel, wenn wir gehen oder wenn wir arbeiten, überhaupt, wenn wir die Arme bewegen.

[ 6 ] Dagegen dasjenige, was der Körper in der Weise braucht, um die Substanzen in sich abzulagern, um sich sozusagen zu bereichern mit Substanzen - jenen Substanzen, die man dann wiederum abstößt, wenn man alle sieben bis acht Jahre seine Körpersubstanz erneuert -, das wird zum allergrößten Teile aufgenommen durch die Sinnesorgane, durch die Haut, durch die Atmung. Sodass dasjenige, was der Körper eigentlich substanziell in sich aufnehmen, was er ablagern muss, das nimmt er in äußerst feiner Dosierung auf, fortwährend, und verdichtet es erst im Organismus. Er nimmt es aus der Luft auf, verhärtet und verdichtet dann das so weit, dass man es dann in Nägeln, Haaren und so weiter abschneiden muss. Es ist ganz falsch, die Formel aufzustellen: Aufgenommene Nahrung, Durchgang durch den Körper, Nägel- und Hautabschuppung und dergleichen, sondern man muss formulieren: Atmung, feinste Aufnahme durch die Sinnesorgane, sogar durch die Augen, Durchgang durch den Organismus, Ausstoßen. Während in der Tat dasjenige, was wir durch den Magen aufnehmen, wichtig ist dadurch, dass es innere Regsamkeit hat wie ein Heizmaterial, die Kräfte zum Willen, der im Körper wirkt, in den Körper einführt.

[ 7 ] Nun sehen Sie: Man wird ja ganz verzweifelt, wenn man an dieses, was die Wahrheit ist, was sich einfach ergibt aus geistiger Forschung, herankommen sieht die Ansichten der heutigen Wissenschaft, die genau das Umgekehrte davon verficht. Man wird deshalb verzweifelt, weil man sich sagt, dass es so schwierig ist, mit dieser heutigen Wissenschaft in den wichtigsten Fragen sich überhaupt zu verständigen. Und ein solches Verständnis muss kommen; denn die heutige Wissenschaft würde absolut in eine Sackgasse führen gerade gegenüber dem praktischen Leben. Und sie kann auf ihren Wegen einfach gewisse Dinge, auf die sie fast mit der Nase gestoßen wird, nicht verstehen. Ich rede gar nicht von den Experimenten. Das ist in der Regel wahr, was die Wissenschaft sagt darüber. Die Experimente kann man ganz gut brauchen; was dann theoretisiert wird, ist schlimm. Aus dem gehen die praktischen Winke für die verschiedenen Gebiete des Lebens leider hervor. Wenn man auf das alles sieht, sieht man die Schwierigkeit der Verständigung. Aber auf der anderen Seite muss diese Verständigung kommen auf den allerpraktischsten Gebieten des Lebens, zu denen die Landwirtschaft gehört.

[ 8 ] Sehen Sie, man muss schon Einsichten haben auf den verschiedensten Gebieten des landwirtschaftlichen Lebens über die Wirkungsweise des Stofflichen, der Kräfte und auch über die Wirkungsweise des Geistigen, wenn man die Dinge in der richtigen Weise behandeln will. Das Kind, solange es nicht weiß, wozu ein Kamm ist, beißt hinein, verwendet ihn ganz im stillosen, unmöglichen Sinne. Und so wird man auch die Dinge im stillosen, unmöglichen Sinne verwenden, wenn man nicht weiß, was ihr Wesen ist, wie sich eigentlich die Sache bei denen verhält, auf die es ankommt.

[ 9 ] Betrachten wir da einmal, um zu einer Vorstellung zu kommen, einen Baum. Sehen Sie, ein Baum unterscheidet sich von einer ganz gewöhnlichen jahresmäßigen Pflanze, die bloß Kraut bleibt. Er umgibt sich mit der Rinde, mit der Borke und so weiter. Was ist nun eigentlich das Wesen dieses Baumes im Gegensatz zur einjährigen Pflanze? Vergleichen wir einmal einen solchen Baum mit einem Erdhügel, der aufgeworfen ist und der außerordentlich humusreich ist, der außerordentlich viel, mehr oder weniger in Zersetzung begriffene Pflanzenstoffe in sich hält, vielleicht auch tierische Zersetzungsstoffe in sich enthält.

[ 10 ] Nehmen wir an, das wäre der Erdhügel, in den ich eine kraterförmige Vertiefung hineinmachen will, humusreicher Erdhügel, und das wäre der Baum. Außen das mehr oder weniger Feste, und innerlich wächst das, was dann zur Ausgestaltung des Baumes führt. Es wird Ihnen sonderbar erscheinen, dass ich diese zwei Dinge nebeneinanderstelle. Aber sie haben mehr Verwandtschaft miteinander, als Sie meinen. Denn Erdiges, das in dieser Weise, wie ich es beschrieben habe, von humusartigen Substanzen durchzogen ist, die in Zersetzung begriffen sind, solches Erdiges hat Ätherisch-Lebendiges in sich. Und darauf kommt es an. Wenn wir ein solches Erdiges haben, das in seiner besonderen Beschaffenheit uns zeigt, dass es Ätherisch-Lebendiges in sich hat, so ist es eigentlich auf dem Wege, die Pflanzenumhüllung zu werden. Es bleibt nur nicht. Es kommt nicht dazu, die Pflanzenumhüllung zu werden, die sich hineinzieht in die Rinde, in die Borke des Baumes. Und Sie können sich vorstellen, es kommt in der Natur nicht dazu. Es ist so, dass einfach, statt dass ein solcher Erdhügel gebildet wird und da Humusartiges hineinkommt, das durch die besonderen charakteristischen Eigentümlichkeiten wirkt im Erdboden, die vom Ätherisch-Lebendigen ausgehen, sich einfach der Hügel in einer höheren Entwicklungsform um die Pflanze herumschließt.

[ 11 ] Wenn nämlich für irgendeinen Ort der Erde ein Niveau, das Obere der Erde, vom Inneren der Erde sich abgrenzt, so wird alles dasjenige, was sich über diesem normalen Niveau einer bestimmten Gegend erhebt, eine besondere Neigung zeigen zum Lebendigen, eine besondere Neigung zeigen, sich mit Ätherisch-Lebendigem zu durchdringen. Sie werden es daher leichter haben, gewöhnliche Erde, unorganische, mineralische Erde, fruchtbar zu durchdringen mit humusartiger Substanz oder überhaupt mit einer in Zersetzung begriffenen Abfallsubstanz, wenn Sie Erdhügel aufrichten und diese damit durchdringen. Dann wird das Erdige selber die Tendenz bekommen, innerlich lebendig, pflanzenverwandt zu werden. Derselbe Prozess geht vor bei der Baumbildung. Die Erde stülpt sich auf, umgibt die Pflanze, gibt ihr Ätherisch-Lebendiges um den Baum herum. Warum?

[ 12 ] Sehen Sie, ich sage das alles aus dem Grunde, um Ihnen eine Vorstellung davon zu erwecken, dass eine innige Verwandtschaft besteht zwischen demjenigen, was in die Konturen dieser Pflanze einbeschlossen ist, und demjenigen, was der Boden um die Pflanze herum ist. Es ist gar nicht wahr, dass das Leben mit der Kontur, mit dem Umkreis der Pflanze aufhört. Das Leben als solches setzt sich fort namentlich von den Wurzeln der Pflanze aus in den Erdboden hinein, und es ist für viele Pflanzen gar keine scharfe Grenze zwischen dem Leben innerhalb der Pflanze und dem Leben im Umkreise, in dem die Pflanze lebt. Vor allen Dingen muss man von diesem durchdrungen sein, muss dieses gründlich verstehen, um das Wesen einer gedüngten Erde oder einer sonstwie ähnlich bearbeiteten Erde wirklich verstehen zu können.

[ 13 ] Man muss wissen, dass das Düngen in einer Verlebendigung der Erde bestehen muss, damit die Pflanze nicht in die tote Erde kommt und es schwer hat, aus ihrer Lebendigkeit heraus das zu vollbringen, was bis zur Fruchtbildung notwendig ist. Sie vollbringt leichter das, was zur Fruchtbildung notwendig ist, wenn sie schon ins Leben hineingesenkt wird. Im Grunde genommen hat alles Pflanzenwachstum dieses leise Parasitäre, dass es sich eigentlich auf der lebendigen Erde wie ein Parasit entwickelt. Und das muss sein. Wir müssen, da wir in vielen Gegenden der Erde nicht darauf rechnen können, dass die Natur selber genügend organische Abfälle in die Erde hineinversenkt, die sie dann so weit zersetzt, dass wirklich die Erde genügend durchlebt wird, wir müssen dem Pflanzenwachstum mit der Düngung zu Hilfe kommen in gewissen Gegenden der Erde. Am wenigsten in den Gegenden, wo sogenannte Schwarzerde ist. Denn diese ist eigentlich so, dass die Natur selber das besorgt, dass die Erde genügend lebendig ist, wenigstens in gewissen Gegenden.

[ 14 ] Sie sehen, dass man also wirklich verstehen muss, um was es sich da handelt. Nun muss man aber noch etwas anderes verstehen, man muss verstehen - es ist ein hartes Wort -, eine Art persönliches Verhältnis zu all dem zu gewinnen, was in der Landwirtschaft in Betracht kommt, vor allen Dingen ein persönliches Verhältnis zum Dünger und namentlich zu dem Arbeiten mit dem Dünger. Das erscheint als eine unangenehme Aufgabe; aber ohne dieses persönliche Verhältnis geht es nicht. Warum? Sehen Sie, es wird Ihnen das sogleich ersichtlich sein, wenn Sie auf das Wesen irgendeines Lebendigen überhaupt eingehen können. Wenn Sie auf das Wesen eingehen, so hat das Lebendige immer eine Außenseite und eine Innenseite. Die Innenseite liegt innerhalb irgendeiner Haut, die Außenseite liegt außerhalb der Haut. Jetzt fassen Sie einmal die Innenseite ins Auge.

[ 15 ] Die Innenseite hat nicht nur Kraftströme, die nach außen gehen, in der Richtung dieser Pfeile, sondern das innere Leben eines Organischen hat auch Kraftströme, die von der Haut nach innen gehen, die zurückgedrängt werden. Nun ist das Organische umgeben außen von allen möglichen Kraftstrrömungen. Nun gibt es etwas, was in ganz exakter Weise, aber in einer Art persönlicher Weise zum Ausdruck bringt, wie sich das Organische das Verhältnis seines Inneren und Äußeren gestalten muss. Alles dasjenige, was da an Kraftwirkungen im Innern des Organischen vor sich geht und eigentlich im Innern des Organismus, also innerhalb seiner Hautkonturen, das Leben anregt und erhält, alles das muss - verzeihen Sie wieder den harten Ausdruck - in sich riechen, man könnte auch sagen stinken. Und darin besteht im Wesentlichen das Leben, dass dieses, was sonst, wenn es verduftet, den Geruch verbreitet, stattdessen zusammengehalten wird, dass die Dinge nicht nach außen zu stark ausstrahlen, die duften, sondern dass die Dinge im Innern zurückgehalten werden, die da duften. Nach außen hin muss der Organismus in der Weise leben, dass er möglichst wenig von dem, was dufterregendes Leben in ihm erzeugt, durch seine begrenzende Haut nach außen lässt, sodass man sagen könnte, ein Organisches ist umso gesünder, je mehr es im Innern und je weniger es nach außen riecht.

[ 16 ] Denn nach außen hin ist der Organismus, namentlich der Pflanzenorganismus, dazu prädestiniert, Geruch nicht abzugeben, sondern aufzunehmen. Und wenn man durchschaut das Fördernde einer aromatisch riechenden Wiese, die von aromatisch riechenden Pflanzen durchsetzt ist, so wird man aufmerksam auf das gegenseitig im Leben sich Unterstützende. Dieses Duftende, das sich da ausbreitet und das anders ist als der bloße Lebensduft, duftet aus Gründen, die wir wohl noch werden beibringen können, und ist das, was von außen jetzt auf die Pflanze wirkt. Alle diese Dinge muss man lebendig im persönlichen Verhältnis eigentlich haben, dann steckt man drinnen in der wirklichen Natur.