Social Ideas, Social Reality, Social Practice II

GA 337b

16 August 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

4. The Formation of Social Judgment

Roman Boos: Dear attendees, the question of how judgment is formed in the threefold social organism is to be addressed this evening. Dr. Steiner will give the introductory lecture. I would like to ask you now to take an active part in the discussion, and especially those of you who have something to say about the problems that will be presented today, to speak up then. I now ask Dr. Steiner to begin his lecture.

Rudolf Steiner: Dear attendees! I would like to introduce this evening's discussion with a few remarks about how a social judgment, on which a new social order must be built, can come about. I should say at the outset that it will not be easy to speak about this subject in a popular way. One should actually recognize the impossibility of speaking about this subject in a popular way from the facts that we now live in.

You see, our time is basically in many ways quite opposed to man forming a healthy social judgment. It is true that much is said today about man as a social being, about social conditions and social demands in general. But this talk about social demands is not really based on a deep understanding of what a social being actually is. We need not be surprised at this, because it is only in the present time that we are at the beginning of the time in which humanity is to mature to form a social judgment. In a sense, humanity has not needed to form a social judgment until now. Why? Of course, human beings have always lived in some kind of social circumstances, but basically they have not – not until now – organized these social circumstances out of their social consciousness, out of a real understanding. They have, if I may say so, received them in an ordered way through a kind of instinctive activity. Up to the present form of the state, which, in Europe, is basically no more than three or four hundred years old, people have formed connections more out of their instincts, and it has not actually come to grouping people out of judgment, consideration and understanding. Out of this understanding, out of a truly clear judgment, the threefold social organism wants to tackle the social question. In doing so, it is basically doing something that is still quite unfamiliar to people and that is highly uncomfortable for the vast majority of people today.

What has actually happened? The earlier social associations and the present state association have developed from human instincts, and people today simply accept this association, which is still combined with all sorts of national instincts. They grow into this association. Instinctively, they grow into this association and avoid thinking about it – or at least they avoid thinking about it to a certain extent. At most, one thinks about the extent to which one wants to have a say in the affairs of the state, but the framework of the state is accepted. They accept it, even the most radical wing of the socialists; Lenin and Trotsky also accept the state, the state that is put together out of all sorts of things, but instinctively, the state that was ultimately worked on by the old tsars. They accept it and at most wonder how they should shape what they want within this state. The question of whether the state should be left as it is or whether a different structure should be adopted that is based on understanding is not even raised. But you see, this question – how can the instinctive nature of the old social life be transformed into a social life that is born out of the human soul? – is the main question underlying the impulse for the threefold social organism. This question cannot be resolved in any other way than by the emergence of a more thorough knowledge of the human being, more thorough than the knowledge of the human being that has existed in recent centuries and that exists in the present.

One can say that the impulse for the threefold social order arose directly from the question: How should man come to a judgment about how he should live together with other people? It arose from a correct observation of what man must demand in the present. But most people do not seriously want to respond to the demands of the present. They would prefer to take the existing situation and make more or less radical improvements here and there. For example, it is probably easier to talk to an Englishman about anything but the threefold social order, since he usually takes it for granted that the unified state of England is an ideal that must not be challenged. Wherever you touch on the subject, you notice this prejudice. But this is nothing more than the persistence of the old human instincts in relation to social coexistence, and we must get beyond them. We must come to a conscious coexistence. This is highly inconvenient for people today, because they do not really want to come to a judgment out of an inner activity, out of an inner activity. They would basically like, as I said, to have a say in what is already there, but they do not really want to think thoroughly about how to deal with what is there and how to rectify what has been led into the absurd by the last catastrophes. This absolutely new aspect of threefolding is something that people basically do not want to see. They are not willing to make the effort of forming a social judgment.

You see, the question: how does a social judgment come about? - immediately breaks down into three separate questions when approached in the right spiritual-scientific way. And the sources from which the threefold social organism flows are actually based on this, that the question of how to form a social judgment is immediately divided into three separate questions. It is impossible to arrive at a judgment in the same way in the common spiritual life, in the social spiritual life, as in the legal or state life or in the economic life. Recently an essay appeared in the Berliner Tageblatt entitled 'Political Scholasticism'. In it, a very clever gentleman – journalists are usually clever – makes fun of the fact that in contemporary public life, people strive to separate the political from the economic. He would, of course, also make fun of it and call it a scholastic hair-splitting if one wanted to separate public life into the three parts, the spiritual part, the legal or state part and the economic part, because he has a very special reason, a reason that is so very easy for the man of the present time to understand. He says: Yes, in real life the economic, political and intellectual life is nowhere separated; they flow into each other everywhere, so it is scholastic to separate them. Now, my esteemed audience, I think one could also say that one should not perceive the head and the trunk and the limbs of a person separately, because in real life they belong together. Of course, the three limbs of the social organism also belong together, but one cannot get by if one confuses the one with the other – just as little as nature would get by if it grew a foot or a hand on the shoulders instead of a head, if it were to shape the head into a hand. It is a particular characteristic of these clever people of the present day that they have taken the greatest happiness with the most stupid of our time, because the most stupid today appears to be the most intellectually clever of the great multitude.

What matters is that at the moment when humanity is no longer to enter public life instinctively, but more consciously than before, the whole way in which man stands in the spiritual life of culture, how he stands in the life of law and the state, how he stands in the life of economics, is different. It is just as different as the blood circulation is different in the head, in the feet or in the legs, and different in the heart - and yet the three work together in just the right way when they are organized separately in the right way.

And we too, as human beings, have to form our social judgment in various ways in the field of intellectual life, in the field of legal or state life, and in the field of economic life. But we have to find ways to arrive at a truly sound judgment in the three fields. In general, this path - basically there are three paths - is really quite heavily obstructed by the prejudices of the time. Many obstacles must first be removed from the way.

In order to arrive at a sound social judgment in spiritual life, it must be clear that today's man is utterly incapable of even posing the question: What does social mean in spiritual life? What does human coexistence mean in spiritual terms? We still do not have a knowledge of man that, I would not even say, provides answers to such questions, but I would just say that it encourages such questions. This knowledge of man must first be created by spiritual science and made popular among mankind. One must raise the question properly and reasonably: What difference does it make whether I am facing a human being or whether I, as a lonely observer of nature, have only nature facing me, thus gaining knowledge of this nature by directly facing nature as an observer? I enter into a certain reciprocal relationship with nature; I allow nature to make impressions on me; I process these impressions, form inner images about these impressions by entering into a reciprocal relationship with nature; I take something in from outside, process it inwardly. That is basically the simple fact. It looks the same on the outside when I listen to a person, that is, enter into a spiritual relationship with him, find in his words the meaning that he puts into them. The words of the person make an impression on me; I process them inwardly into ideas. I enter into interaction with other people. One might think that whether I interact with nature or with other people is basically the same. But it is not. Anyone who claims that it is the same has not even looked at the matter in the right way. You have to pay attention to these things.

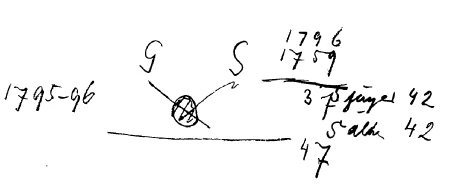

You see, I would now like to give a specific example. There is a fact in German intellectual life without which this German intellectual life is inconceivable. When one describes the intellectual life of a certain area, then one usually describes – depending on what one has reason to do – either the economic conditions of the time when this intellectual life developed, or one describes individual great personalities who, through their ingenious achievements, have fertilized this intellectual life. But now I want to mention a fact of a quite different nature, without which the special character of German intellectual life in the 19th century is inconceivable. I would like to speak of an archetypal phenomenon of social intellectual coexistence: the ten-year intimate relationship between Goethe and Schiller. One cannot say that Goethe gave Schiller something or that Schiller gave Goethe something and that they worked together. That does not capture the fact that I mean, but it is something else. Schiller became something through Goethe that he would never have become alone. Goethe became something through Schiller that he would never have become alone. And if you only have Goethe and only have Schiller and think about their effect on the German people, you do not get what actually happened. Because if you only have Goethe or only have Schiller and consider the effects that emanate from emanating from both, there is not yet what has become, but a third, quite invisible, but of tremendously strong effect, arises from the confluence of the two (It is drawn on the blackboard). You see, that is an archetypal phenomenon of social interaction in the spiritual realm.

What is the actual basis for this? Today's rough science does not study such things, because today's science does not penetrate to the human being at all. Spiritual science will study such things and only through this will it bring light into the social and spiritual life of people. Those of you who have heard something about spiritual science know what I am only briefly hinting at now. Spiritual science shows that the development of the human being is a real, actual fact. It shows that as a person develops, he becomes ever more mature and original, ever bringing forth different and different things from the depths of his being. And if social life suppresses this bringing forth, then that social life is wrong and must be brought into line.

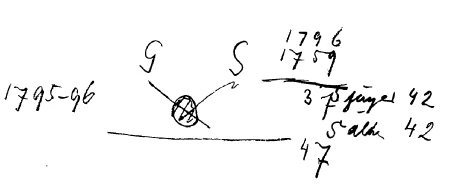

Now, Goethe and Schiller were both individuals and personalities who were socially blessed in the highest sense. When did it happen that one can say that Schiller understood Goethe best, and that Goethe understood Schiller best? They were able to converse with each other best, to exchange their ideas best, and to achieve something together, this invisible something, which in turn had an effect and is one of the most significant facts in German intellectual life. I have tried very hard to determine the year of the most intimate period of their lives together, the time when the ideas of one, I would say, most thoroughly penetrated the ideas of the other. I think it was around 1795 or 1796 (written on the board). 1796, there is really something very special about this collaboration between Goethe and Schiller.

If one now investigates why Schiller of all people understood Goethe best in this year and why Goethe allowed himself to be understood best by Schiller in this year, one comes to this. Schiller was born in 1759; so he was thirty-seven years old in 1796. Goethe was ten years older; so he was forty-seven years old. Now spiritual science shows us that there are various life junctions in human life; they are not usually taken into account today: the change of teeth - the human being becomes something else by surviving the change of teeth, also in the spiritual-soul relationship -, sexual maturity, later transitions - these are less noticeable, but they are still there in the 28th year, again in the 35th and in the 42nd year. If one is really able to observe this inner human life, then one knows that the beginning of the 40s, I would say on average the 42nd year, when the human being develops inwardly, when he undergoes an inner spiritual life, this 42nd year is something very special. Between the 35th year and the 42nd year, what can be called the consciousness soul matures in the human being. And it has become fully mature, this judging consciousness soul, this conscious soul that enters into a relationship with the world entirely from the ego – this consciousness soul becomes mature at that point. Schiller at 37 was five years younger than 42, Goethe at 47 was five years older than 42. Goethe had passed the 42nd year just as much as Schiller was below it.

Schiller was at the same stage in the development of the consciousness soul, Goethe was beyond it; they were at the same distance from it. What does that mean? In relation to the soul, it means a similar contrast. I know that such comparisons are daring, but our language is also coarse, and therefore one can only use daring comparisons when one has important, fundamental facts to cite. For the soul-spiritual, it means a similar contrast as the male and female for the physical-sexual. In relation to physical development, the sexualities are unevenly developed. Out of courtesy to the ladies, and in order not to make the gentlemen arrogant, I will not say which sexuality is a later development and which sexuality is an earlier development, but they are of a different temporal development. It is not the whole human being, the head does not take part in it, so those whose sexuality must be thought of in an earlier stage of development need not feel offended. But it is not so in relation to the soul; there the earlier can come together with the later, then a very special fertilization arises. Then something arises that can only arise through this different kind of combination at different times. This is, of course, a special case; here, in social life, the interplay of soul to soul is formed in a special way. Whenever people influence each other, something arises that can never arise from the mere interaction of human beings and nature. You see, you get a certain idea of what it actually means to let something that comes not from nature but from another human being take effect on you.

This became a very particular problem for me when I immersed myself in Nietzsche, for example. Nietzsche had something that a whole range of people with a similar background to Nietzsche's now also have; it's just that he had it in a particularly radical sense. For example, he looked at philosophers, the ancient Greek philosophers, he looked at Schopenhauer, he looked at Eduard von Hartmann and so on. It can be said that Nietzsche was never really interested in the content of a philosophy. The content of the philosophy, the content of the world view, was actually of no great importance to him; but he was interested in the person. What Thales was thinking as the content of his world view is of no importance to him, but how this person Thales lives his way to his concepts is what interests him. This is what interests him about Heraclitus, not the content of Heraclitus' philosophy. It is precisely that which comes from a human being that has an effect on him, and in this way Nietzsche shows himself to be an especially modern character. But this will become the general constitution of the human soul life. Today people still argue about opinions in many ways. They will have to stop arguing about opinions for the simple reason that everyone must have their own opinion. Just as if you have a tree and photograph it from different sides, it is still the same tree, but the photographs look quite different; so everyone can have their own opinion, depending on - it just depends on the point of view they take. If he is reasonable in today's sense, he no longer argues about opinions, but at most finds some opinions healthy and some unhealthy. He no longer argues about opinions. It would be the same as if someone looked at different photographs and then said: Yes, they are quite different, these are right and those are wrong. At most, one can be interested in how someone arrives at their opinion: whether it is particularly clever or foolish, whether it is low and bears no fruit or whether it is high and beneficial for humanity.

Today it is a matter of really clarifying how people relate to each other in their spiritual and social coexistence, and how one person has something to give to another. This is particularly evident when we see what a growing child must receive from the other person who is his or her teacher. There are quite different forces at work than between Goethe and Schiller, even if they are not placed in such a lofty position, but there are more complicated forces at play. What I am developing here now provides a way to find the path to how one can rise to a truly social judgment in the realm of spiritual life.

You see, I said before that I cannot speak in a particularly popular way today, because if I want to discuss these questions from the point of view of an as yet unknown human science, at least in wider circles, I have to start from that point of view. In my book 'Von Seelenrätseln' (The Riddle of the Soul) I have pointed out how the human being is a threefold being: he is a head human being or nervous-sensory human being, a rhythmic human being, and a metabolic human being. The nerve-sense human being encompasses everything that is the senses and what the organs of the head are. The rhythmic human being, the trunk human being, could also be said to encompass what is rhythmic in the human being, what is the movement of the heart, the movement of the lungs, and so on. The third, the metabolic human being, encompasses everything else.

These three aspects are found in human nature; in a sense they are fundamentally different from each other, but it is difficult to pinpoint their actual differences. In the case of the rhythmic person, the following can be emphasized. You will hear more about the rhythmic in the human being later on this evening when Dr. Boos speaks about the formation of social judgment in legal or state life, which will then make up the second part of the introduction. Dr. Boos will speak about what is particularly close to him, about the formation of social judgment in the second link of the social organism, in legal and state life. But now I would like to emphasize the following: the rhythmic activity in man is particularly evident when we consider how man breathes in the outer air, processes it within himself, how he breathes in oxygen and breathes out carbonic acid. Inhalation – exhalation, inhalation – exhalation: this is one of the rhythms that are active in man. It is a relatively easy process to understand: inhalation – exhalation = rhythmic activity.

The other two activities can perhaps only be understood by starting from this rhythmic activity. In a sense, the whole human being is actually predisposed to rhythmic activity. But with ordinary science, we do not recognize the nervous sensory activity, the actual main activity, at all. It cannot be compared with the activity of the lungs and the heart, with rhythmic activity. I can only mention something that may seem paradoxical to those who are less familiar with spiritual science, with anthroposophy, but which will be confirmed by a real science. In the future, what I am saying now will be known to the world as a completely exact scientific fact when the necessary conditions are understood. During inhalation and exhalation, there is a certain equilibrium. This equilibrium that exists could be depicted as a pendulum that goes back and forth. It goes up just as high on one side as on the other. It swings back and forth. There is also an equilibrium between inhalation and exhalation, inhalation and exhalation and so on.

If a person did not live together with other people in a spiritual and soulful way, if a person were lonely and could only observe nature, that is, could only enter into an interrelationship with nature, look at nature and inwardly process it into images, then something very special would happen to that person. As I said, today this seems highly paradoxical to people, but it is nevertheless the case: his head would become too light. By observing nature, we are, after all, engaged in an activity. We are not doing nothing by observing nature; everything in us is engaged in a certain activity. This activity is, so to speak, a sucking activity at the head of man – not at the whole organism, but at the head of man, a sucking activity. And this sucking activity must be balanced, otherwise our head would become too light; we would become unconscious. It is compensated for by the fact that the head, which has become too light, undergoes a metabolism, blood nourishment, and all that is deposited in the head. And so, by observing nature, we continually have a lightening of the head and a subsequent heaviness due to the digestive activity going up into the head.

This balancing must take place. It is a higher rhythmic activity. But this activity would become extremely one-sided if the human being were only in contact with nature. Man would indeed become too light in his head if he were only in contact with nature outside; he would not send enough balancing metabolic activity up into his head from within. He does this to a sufficient extent when he enters into a relationship with his fellow human beings.

That is why you feel a certain pleasure when you enter into a relationship with your fellow human beings, when you exchange thoughts or ideas with them, when they teach you or the like. It is one thing to walk through nature alone and quite another to stand face to face with a person who expresses his ideas to you. When you are confronted with a person who expresses his ideas to you – you should just consider this carefully in self-observation – then you have a certain feeling of well-being. And he who can analyze this feeling of well-being will find a similarity between it and the feeling he has when he digests. It is a great similarity, only one feeling goes to the stomach, the other goes up to the head. You see, that is precisely the peculiarity of materialism: these subtle material processes in the human body remain closed to materialism. The fact that a hidden digestive activity takes place in the head precisely because one is sitting opposite a person with whom one is talking, with whom one is exchanging ideas, is something that people do not notice through today's crude science. Therefore, they cannot answer social questions, questions about the human context, even if they are quite trivial.

For the spiritual scientist, the anthroposophist, it is quite clear why the coffee sisters are so keen to sit together. They don't just sit together because they like coffee, but because they then digest themselves. The digestion goes to the head, and they feel that as a sense of well-being. And when coffee sister sits next to coffee sister, or even, I can't say coffee brother, but skat brother sits next to skat brother at the twilight drink, and so on, the same thing naturally takes place among men. I don't want to offend anyone, but when people sit together like that, yes, they feel the digestive activity going on behind their heads, and that means a certain sense of well-being. What happens there is really necessary for human life. It is really necessary, but it can be used for higher activity than just for the evening drink and for being a coffee nurse. Just as the blood must not stand still in the human being, so must what happens in the head not stand still. A stunted rhythm would occur in the nervous system if we did not have the right kind of spiritual connection with people outside. Our right humanity, that we become right people, depends on our coming into a reasonable connection with other people.

And so one can only form a social judgment when one realizes what is necessary for the human being – just as necessary as being born. When one realizes that the human being must come into a spiritual and soul connection with other human beings, only then can one form a correct social judgment about the way in which the spiritual element of the social organism must be formed. For then one knows that this social life is based on the fact that man must come into a right individual relationship with man, that no abstract state life must intervene there, that nothing must be organized from above, but that everything depends on the fact that the original original in the human being can approach the original in the other human being, that there is real, genuine freedom, direct freedom from individual to individual, be it in the social coexistence of the teacher with his students, be it in social coexistence in general. People wither away when school regulations or regulations about intellectual social life make it impossible for what is in one person to have a fertilizing effect on what is in another. A truly social judgment in the realm of spiritual life can only develop when that which elevates one person above themselves, when that which is more in one person than in another, can have an effect on the other person and when, in turn, that which is more in the other person than in oneself can have an effect on oneself. One can only understand the necessity of freedom in spiritual life when one realizes that this human coexistence can only develop in a spiritual and psychological way if what comes into existence with us through birth and what develops through our abilities can freely influence other people. Therefore, the spiritual element of the social organism must also be administered only within itself. The person who is active in the spiritual life must at the same time be in charge of the administration of the spiritual life. So: self-administration within this spiritual realm. You see, that is what is very special about this spiritual life, which arises from a true understanding of the human being.

Dr. Boos will then describe the legal life in more detail from the same point of view. The legal life proceeds as follows: when humanity, through the demands of the present, is increasingly moving towards a democratic state, so that the mature human being is confronted by another mature human being, we are not yet dealing with what works across from one person to another in the way I have described for the spiritual life, where the digestive activity shoots up into the head. In the sphere of right living, where one fully developed human being is confronted with another, no such changes take place as in the spiritual life, but only interactions between human being and human being. In the sphere of right living, the effect flows over in such a way that something new arises in the other person. In the sphere of right living, the effect flows over in such a way that something new arises in the other person. In the sphere of right living, the effect flows over in such a way that something new arises in the other person. In the sphere of right living, the effect flows over in such a way that something new arises in the other person. In the sphere of right living, the effect flows over in such a way that something new arises in the other person. In the sphere of right living, the effect flows over in such a way that something new arises in the other person. In the sphere of right living, the effect flows over in such a way that something new arises in the other person. In the sphere of right living, the effect I will now omit this middle aspect and move on to economic life, to the third link in the social organism. This economic life is not really understood today in such a way that a real social judgment can be formed from this understanding. What, in fact, can be called economic life? You see, you can clearly define economic life when you think of it in terms of the social organism. If we take any kind of animal, we cannot say that it lives in a social community in the human sense, because the animal finds what it desires in nature itself. It takes what it needs to live from the external nature; what is initially outside in nature passes into the animal, the animal processes it and releases it again – another kind of interaction. You see: here we have something that, I would say, is organized into nature. Such an animal species, so to speak, only continues the life of nature within itself. Nothing is changed in nature. The animal takes in what is in nature for its nourishment – just as it is in nature. We can find a complete opposite to this, and this contrast is present in zoo animals, which receive everything they eat through human intervention. Here, human reason supplies the animal with nourishment, and the human organization first assesses what the animals then receive. As a result, the animals are actually completely torn out of nature. Domestic animals are also completely torn out of nature; they are, so to speak, so changed that they not only absorb natural food substances into their inner being, but that food prepared by human reason is grafted into them. Domestic animals become a means of expression of that which, so to speak, has been processed spiritually, but they themselves do nothing to it. Animals are either such that they take in what is in nature unchanged in their own activity, or, when humans feed them something, they cannot contribute anything to it; they do not help to prepare what is fed to them.

In the middle, between these two extremes, is human economic activity, insofar as it lives in the social organism, at most not when man is at the lower level of a hunting people, when he still takes what is in nature unchanged, if he enjoys it raw, which he actually no longer does today. But the moment human culture begins in this respect, man takes something that he has already prepared himself, where he changes nature. The animal does not do that, and if it is a domestic animal, something foreign is supplied to it. That is actually economic activity: what man does in communion with nature by supplying himself with changed nature. We can say that all economic activity of man actually lies between these two extremes: between what the animal, which is not yet a social being, takes unchanged from nature, and what the domestic animal takes in, which is now fed entirely in the stable, only with what humans prepare for it. And when man works, he is involved with his economic activity between his inner being and nature. And this economic life that we know in the social organism is actually only a systematic summary of what individuals do in the direction that I have characterized.

Let us compare the economic life in a social context with the spiritual life that we have just characterized. The spiritual life is based on the fact that the individual human being, so to speak, has too much. What people possess spiritually, they usually give away very gladly; they are generous in this way and gladly hand it over to others. In contrast to material possessions, people are not as generous in the same sense; they prefer to keep material possessions for themselves. But what they possess spiritually, they are very happy to give away; they are generous in this way. But this is based on a good universal law. Man can indeed go beyond himself in a spiritual sense; and in the way I have just described it, it is beneficial for the other person when man gives him something, even if he in turn does not accept anything from the other. That is to say, when a person enters social life in a spiritual way, I would say that, in his inner being, he has too much judgment, too many ideas; he is compelled to give, he must communicate with others.

In economic life, it is exactly the opposite. But one can only come to this conclusion if one starts from experience, not from some kind of theoretical science. In economic life, one cannot arrive at a judgment in the same way as in the life of the spirit, that is, from person to person. Rather, in economic life one can only come to a judgment when one stands as an individual human being or as a human being placed in some association in relation to another association. Therefore, the impulse for the threefold social order demands the associative: people must associate according to their occupations or according to producers, consumers and so on. In the economic sphere, the association will be confronted with the association. Let us compare this to the individual human being, who, for my sake, has a lot of spirit in his head; he can share this spirit with many people. One person may absorb it better, another worse, but he can communicate this spirit that he has to many people. So there is the possibility that a person can give what he has of spirit to many people. In economic life, it is exactly the other way around.

At first we have no idea about economic life at all. What I said to some of you yesterday is absolutely true: if you want to judge what is right or wrong, healthy or unhealthy in economic life, and you just want to deduce it from the inner being, then you you are just like that character in a Jean Paul novel who wakes up in the middle of the night in a dark room and thinks about what time it is, who wants to find out what time it is in the dark room where he can't see or hear anything. You can't work out what time it is by thinking about it. You can't come to an economic judgment through thinking or through inner development. You can't even come to an economic judgment when you are negotiating with another person. Goethe and Schiller were good at exchanging spiritual and psychological ideas. Two people together cannot come to an economic judgment. One can only come to an economic judgment when one is faced with a group of people who have had experiences, each in his own field, and when one then takes in as judgment what they, as an association, as a group, have worked out. Just as you have to look at your watch if you want to know what time it is, in order to arrive at an economic judgment, you have to take on board the experiences of an association. And one can hear very beautiful things about the duty of one person towards another, about the rights of one person towards another when they are face to face; but one cannot come to an economic judgment when only one person is confronted with another, but one can only come to an economic judgment if one understands what is laid down in associations, in groups of people, in mutual economic intercourse as economic experience. There, the exact opposite of how one lives together socially, spiritually and soulfully must be present. In the spiritual and soul realm, the individual human being must give to others what he develops within himself. In the economic sphere, the individual must absorb the experiences gained by the association. If I want to form an economic judgment, I can only do so if I have asked associations what experiences they have had with this or that article in production, in mutual dealings, and so on. And this is what it comes down to when forming a social judgment in the economic sphere: that such associations make up the economic body of the threefold social organism and that each individual belongs to such associations. In order to arrive at an economic judgment, from which one can in turn act, the economic experiences of the associations must be available. What we are meant to learn scientifically, cognitively, we must acquire in the free spiritual life through individual experiences. What is to inspire us in our economic will must be experienced by the individual through the experiences handed down to him by associations. Only by uniting with people who are economically active can we ourselves arrive at an economic will.

The formation of judgment in the spiritual-mental and economic spheres is radically different. And an economic life cannot flourish alongside a spiritual life if the two spheres receive orders from one and the same place, but only if the spiritual life is such that the individual can freely hand over to another what he has within it. And economic life can flourish only when the associations are such that the economic branches related to one another by production or consumption are united associatively, and thus the economic judgment, which again underlies the economic will, arises. Otherwise, it becomes a muddle, and we end up with the reactionary, liberal or social ideas of modern times, where we never realize how radically different human activities are in the spiritual, economic and, in the middle, legal or state spheres.

Basically, it is so difficult for people today to arrive at a sound judgment in this area because they have been led astray by the traditional creeds from seeing the real structure of the human being in body, soul and spirit. Man is said to be only a duality, only body and soul. As a result, everything is mixed up. Only when we divide the human being into spirit, soul and body, only when we know how the spirit is that which we bring into existence through birth, how the spirit is that which brings forth the potential for development within us, which we must bring into the social sphere, only then will we get an idea of how this spiritual part of the social organism must have a separate existence. When we know how everything that springs from the soul, which is intimately connected with our rhythmic life, is the product of human beings living together in circles of duty, work and love, then we can see what must be present in the democratic state as the legal organization of the threefold organism. And when we realize that we cannot arrive at an economic judgment and therefore cannot engage in economic activity without being integrated into a fabric of associations in the threefold social organism, then we come to see how only that which is a special kind of judgment in the economic field can lead to help in the future.

It is the task of the present to achieve a true understanding of the human being and, on the basis of this true understanding of the human being, to then arrive at an understanding of what today is striving for a true understanding. Man judges quite differently in the social life in the spiritual realm than in the legal realm, and it is quite different again than in the economic realm. Therefore, if these three very differently structured social contexts are to develop in a healthy way in the future, they must also be administered separately and then work together. Just as in the individual organism it is not possible to form anything other than the shape of a head where the head is to be, nor a hand or foot or heart or liver, so the spiritual organism must not be systematized in the same way as the economic organism or the legal organism. But precisely when they are properly organized in the right place, they work together to form a whole, just as the hand and foot and trunk and head of the human being work together to form a whole. The right unity arises precisely from the fact that each is properly organized in its own way.

As you can see, ladies and gentlemen, the idea presented to humanity in the form of the threefold social organism is truly not a frivolous one, but one that has been extracted from a real science. This science must, of course, first be fought for against all the scientific chaos that prevails today. But it is, I might say, not only a wall, it is a thick barrier of prejudices through which one must first fight, first fight with what must underlie the science of man, and then with what emerges from this true science of man as an impulse for a real social reconstruction. One can say: It makes one's heart bleed when one looks today into this chaos of social misconceptions that reigns everywhere, and at the social drowsiness. And one must say: It is indeed not possible for everyone to make a social new order out of what has been taken up by this European humanity as a prejudice from a mistaken science for three to four centuries. It is a terrible thing when people talk about a social order based on a science that can never justify a social judgment because it does not know man. That science, ladies and gentlemen, does not regard man as man, but only as the highest link in the animal series. It does not ask: What is man? - but: What are the animals? It only says: When the animals develop to the highest level, that is precisely the human being. One does not ask what the human being is, but the animals are there, and in the series of animals, the human being is added as the last one, without saying anything different about the human being than what is said about the animal being. Such a science will never create a social reconstruction.

What is so distressing is not that people today are not radical enough to say to themselves: We must first demand real knowledge, real science – but that they are more faithful today to external scientific authority than Catholics ever were in the past to papal authority. At that time, at least some still rebelled against this papal authority. Today, however, everything is subjugated to scientific authority, even radical socialists like Lunacharsky; when it comes to defending the old science against a renewal of science, he crawls under scientific authority because he cannot imagine that science itself needs to be transformed if we want to make progress. These things must be taken very seriously and they must be said. And no matter how many social clubs, liberal communities, development communities, women's mobs or women's clubs people join, nothing will come of it if the matter is not approached radically, if one does not start from the point where one can arrive at a real social judgment: And this is only a social human knowledge that can give what today's science cannot give. And only a real spiritual science can give a renewal of science.

That is what I wanted to say in introduction to this evening. I now ask Dr. Boos to speak about the second part of the social organism, about the life of rights.

Roman Boos speaks about “The formation of judgment in the legal aspect of the social organism.” After that, a discussion will take place.

Roman Boos: Perhaps someone still has a question to ask, or perhaps someone would like to add something? - That does not seem to be the case. I do not know if Dr. Steiner could be asked for a final word. It is very late and I do not know if there are any other questions that Dr. Steiner would like to address.

Rudolf Steiner: Taking into account the lateness of the hour, I would just like to add a few words, because a closing word is customary at a discussion. This evening's two topics, the demand for a social reorganization on the one hand and on the other hand the necessity to penetrate to the sources of spiritual science, because only there can the forces be found to do justice to the demands of the day, these two things must always be emphasized again in all seriousness from this point of view. This has often been said, but it cannot be said too often.

I began by saying today that people have grown instinctively into the present social orders, and in fact the materialists would also instinctively like to remain in them. They do not want to take into account that today is the time to move on to the activity of judgment, that is, to consciousness, and to create a new social world out of consciousness. But we must penetrate to this consciousness if we do not simply want to continue the disastrous policies of recent years, which have taken hold in such a terrible way and are now being continued within European civilizational life and its appendages. I have already pointed out here how a mind like Oswald Spengler's, which is, after all, ingenious on the one hand but sick on the other, can seriously attempt to prove scientifically that the Occident must have arrived at barbarism, at complete and utter decline, at the beginning of the third millennium. One gets the same pain that I spoke of at the end of my introductory words today when one sees how extraordinarily difficult it is to instill in the minds of the present the sense of the seriousness of the times, and how much more difficult it is to instill the sense of the necessity to carry out a real transformation with the knowledge of the present.

My dear audience, do not say that this knowledge of the present is only found in a few scholars or in some contemporary views of people. No, this knowledge is everywhere, only people do not admit it to themselves. What matters is not whether one holds this or that hypothesis, this or that scientific theory, but whether one's whole life of ideas and feelings is moving in a certain direction, which ultimately amounts to this scientific life of the present, which impoverishes and empties the human being. Of course, some people may not be concerned that it is the consequence of contemporary science that the earth originated from a nebula and will end up in some final state of heat in which all life will be destroyed. Perhaps there are even some who say: That may be, but I don't care. — But, my dear audience, that is not the point. Open any chemistry, any physiology, any zoology or any anthropology today, read five lines in it and take these five lines – it says something along those lines. Regardless of whether you open this or that and take this or that, you are in the direction that leads to these views. Of course, today it is convenient when you want to know something about this or that to resort to the usual things and not to think that even something like this needs a thorough transformation. Today it is convenient if you want to learn something about malachite, to go to the encyclopedia, take out the volume with “M”, open “Malachit” and read what is in there. If you accept it uncritically, regardless of what you otherwise think, and if you are not aware that you are living in a serious time of transformation, then you are asleep, then you are not prepared for what is necessary in today's world. Today it is a matter of not just becoming aware of the seriousness at some times when reflecting on the ultimate problems of world view, but today it is a matter of being aware every minute of the day that it is our duty to work on the transformation, because we live in a thoroughly serious time. And just in these days we are again experiencing the tragedy that the most important problems are unfolding, perhaps even more important than during the external years of war, and that people are trying to sleep as much as possible, not even participating with their consciousness in what is actually taking place.

To accept anthroposophy as a confession does not mean merely to advocate this or that in theory, to speak of etheric body and astral body, of reincarnation and karma. To accept anthroposophy means to be connected in one's feelings, with one's whole being, to that which is now taking place in the day and now in the great epoch as the impulse of a significant transformation. And when you look into the sleeping people today, your heart bleeds. Because today it depends on waking up. And again and again I would like to say, and I would like to conclude every discussion with it: try to get to the sources of spiritual knowledge, because with the water that comes from these sources, you splash yourself from a real source of consciousness. This knowledge touches one's own personality in such a way that one, I would say, takes it up from the deepest depths of one's earthly nature and into one's human inner being: wake up and fulfill your tasks in the face of the great demands of the time.

Roman Boos: It will be announced what will be discussed here a week from today. This concludes today's event.

Die Bildung eines sozialen Urteils

Roman Boos: Sehr verehrte Anwesende, es soll heute Abend behandelt werden die Frage über die Art, wie das Urteil gebildet wird in dem dreigegliederten sozialen Organismus. Herr Dr. Steiner wird den einleitenden Vortrag halten. Ich möchte Sie schon jetzt bitten, dann an der Aussprache rege teilzunehmen, und besonders diejenigen, die zu den Problemen, die heute vorgebracht werden, etwas zu sagen haben, daß die sich dann zu Worte melden. Ich bitte nun Herrn Dr. Steiner, seinen Vortrag zu beginnen.

Rudolf Steiner: Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden! Ich möchte die Diskussion des heutigen Abends einleiten durch einige Bemerkungen über die Art und Weise, wie ein soziales Urteil, auf welches sich eine neue soziale Ordnung doch aufbauen muß, zustandekommen kann. Ich bemerke von vornherein, daß es nicht leicht sein wird, in einer populären Weise gerade über diesen Gegenstand zu sprechen. Man sollte die Unmöglichkeit, über diesen Gegenstand in populärer Weise zu sprechen, aus den Tatsachen, innerhalb welchen wir nun schon einmal leben, eigentlich einsehen.

Sehen Sie, unsere Zeit ist im Grunde genommen in vielem ganz dagegen, daß sich der Mensch ein gesundes soziales Urteil bildet. Es ist ja richtig, daß viel heute gesprochen wird über den Menschen als soziales Wesen, über soziale Verhältnisse und soziale Forderungen überhaupt. Allein, dieses Reden über soziale Forderungen ist nicht gerade von einem tiefen Verständnis dessen getragen, was soziales Wesen eigentlich ist. Man braucht sich deshalb darüber nicht zu wundern, weil eigentlich erst in der Gegenwart der Anfang jener Zeit ist, in der die Menschheit reif werden soll, sich ein soziales Urteil zu bilden. Die Menschheit hat es ja in einem gewissen Sinn nicht nötig gehabt bis jetzt, sich ein soziales Urteil zu bilden. Warum? Der Mensch lebte natürlich immer in irgend welchen sozialen Verhältnissen drinnen, aber er hat im Grunde genommen nicht — bis jetzt nicht - diese sozialen Verhältnisse aus seinem sozialen Bewußtsein heraus, aus einem wirklichen Verständnis heraus geordnet. Er hat sie, wenn ich so sagen darf, geordnet erhalten durch eine Art Instinkttätigkeit. Die Menschen haben bis zu der Form des gegenwärtigen Staates, der ja für Europa im Grunde genommen nicht älter ist als drei bis vier Jahrhunderte, mehr aus ihren Instinkten heraus Zusammenhänge gebildet, und es ist eigentlich nicht dazu gekommen, aus dem Urteil, aus der Überlegung, aus dem Verständnis heraus die Gruppierung der Menschen vorzunehmen. Aus diesem Verständnis heraus, aus einem wirklich klaren Urteil heraus will die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus die soziale Frage in Angriff nehmen. Damit tut sie im Grunde genommen etwas, was dem Menschen bis jetzt ganz ungewohnt ist und was weitaus der größten Anzahl der gegenwärtigen Menschen sogar höchst unbequem ist.

Wozu ist es denn eigentlich bloß gekommen? Aus den Instinkten der Menschen haben sich die früheren sozialen Verbände und der gegenwärtige Staatsverband heraus gebildet, und diesen Verband, der verquickt ist mit allerlei nationalen Instinkten noch, diesen Verband nehmen die Menschen der Gegenwart einfach hin. Sie wachsen in diesen Verband hinein. Instinktiv wachsen sie in diesen Verband hinein und vermeiden es, darüber nachzudenken - oder wenigstens vermeiden sie es bis zu einem gewissen Grad, darüber nachzudenken. Man denkt höchstens darüber nach, wie weit man in den Angelegenheiten des Staates mitreden will, aber den Rahmen des Staates, den nimmt man hin. Man nimmt ihn hin, selbst beim radikalsten Flügel der Sozialisten; auch Lenin und Trotzki nehmen den Staat hin, den Staat, der zusammengebaut ist aus allem möglichen, aber instinktmäßig, an dem zuletzt der alte Zarismus gearbeitet hat. Sie nehmen ihn hin und fragen sich höchstens, wie sie innerhalb dieses Staates dasjenige ausgestalten sollen, was ihnen wünschenswert ist. Zu fragen, ob man diesen Staat so lassen soll oder ob man eine andere Gliederung vornehmen soll, die aus dem Verständnis herausgeholt ist, dazu kommt es nicht. Aber sehen Sie, gerade diese Frage: Wie kann umgewandelt werden das Instinktive des alten sozialen Lebens in ein aus der menschlichen Seele herausgeborenes soziales Leben? -, das ist ja die Hauptfrage, die dem Impuls der Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus zugrundeliegt. Diese Frage, sie kann gar nicht anders gelöst werden, als daß auftaucht eine gründlichere Erkenntnis des Menschen, gründlicher als diejenige Erkenntnis des Menschen, die da war in den letzten Jahrhunderten und die da ist in der Gegenwart.

Man kann sagen, gerade aus der Frage: Wie soll der Mensch zu einem Urteil kommen darüber, wie er mit anderen Menschen zusammenleben soll? —, gerade aus dieser Frage ist der Impuls für die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus entstanden. Er ist entstanden aus einer richtigen Beobachtung desjenigen, was der Mensch in der Gegenwart fordern muß. Aber die meisten Menschen möchten nicht im Ernste irgendwie auf die Forderungen der Gegenwart eingehen. Sie möchten dasjenige, was ist, mitnehmen und nur höchstens da oder dort mehr oder weniger radikale Verbesserungen vornehmen. Ein Beispiel: Man könnte wahrscheinlich, sagen wir, mit einem Engländer über alles mögliche leichter reden als über die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus, wenn er, wie es ja zumeist der Fall ist, es als eine Selbstverständlichkeit betrachtet, daß der Einheitsstaat England ein Ideal ist, an dem als solchem nicht gerüttelt werden darf. Überall, wo man antippt, merkt man gerade dieses Vorurteil. Aber das ist nichts anderes als das Hereinragen der alten Menschheitsinstinkte in bezug auf das soziale Zusammenleben, und über die müssen wir hinauskommen. Zu einem bewußten Zusammenleben müssen wir kommen. Das ist den Menschen der Gegenwart höchst unbequem, denn sie wollen eigentlich nicht aus einer inneren Aktivität heraus, nicht aus einer inneren Betätigung heraus zu einem Urteil kommen. Sie möchten im Grunde genommen, wie ich schon sagte, zwar mitreden bei dem, was schon da ist, aber sie möchten nicht wirklich durchgreifend denken, wie das, was da ist und was ja durch die letzten Katastrophen ins Absurde hineingeführt hat, wie das zurechtzubringen ist. Dieses absolut Neue der Dreigliederung, das will man eigentlich im Grunde genommen nicht ein ne sehen. Man will sich eben eigentlich nicht herbeilassen dazu, ein soziales Urteil zu bilden.

Sehen Sie, die Frage: Wie kommt ein soziales Urteil zustande? -, zerfällt ja sogleich, wenn man ihr in der richtigen Weise geisteswissenschaftlich zu Leibe geht, in drei gesonderte Fragen. Und darauf beruhen eigentlich die Quellen, aus denen die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus fließt, daß diese Frage: Wie bildet man sich ein soziales Urteil? - sogleich in drei gesonderte Fragen sich spaltet. Es ist unmöglich, auf dieselbe Art im gemeinschaftlichen Geistesleben, im sozialen Geistesleben, zu einem Urteil zu kommen wie im Rechts- oder Staatsleben oder im wirtschaftlichen Leben. Es ist neulich im «Berliner Tageblatt» ein Aufsatz erschienen: «Politische Scholastik». Da macht sich ein ganz gescheiter Herr - die Journalisten sind ja gewöhnlich gescheit -, er macht sich darüber lustig, wenn in der Gegenwart im öffentlichen Leben angestrebt wird, das Politische von dem Wirtschaftlichen zu trennen. Er würde sich selbstverständlich auch lustig machen und es eine scholastische Haarspalterei nennen, wenn man das öffentliche Leben in die drei Glieder, das geistige Glied, das Rechts- oder Staatsglied und das wirtschaftliche Glied trennen wollte, denn er hat einen ganz besonderen Grund, einen Grund, der dem Menschen der Gegenwart so unendlich leicht einleuchtet; er sagt: Ja, im wirklichen Leben ist doch das wirtschaftliche vom politischen und vom geistigen Leben nirgends getrennt; die fließen doch überall ineinander, also ist es scholastisch, wenn man sie trennt. Nun, meine verehrten Anwesenden, ich denke, es könnte einer auch sagen, man solle den Kopf und den Rumpf und die Gliedmaßen des Menschen nicht getrennt empfinden, denn sie gehören im wirklichen Leben zusammen. Gewiß, die drei Glieder des sozialen Organismus gehören auch zusammen, aber man kommt nicht zurecht, wenn man das eine mit dem anderen verwechselt — geradesowenig, wie die Natur zurechtkommen würde, wenn sie auf den Schultern [des Menschen] einen Fuß oder eine Hand wachsen lassen würde statt eines Kopfes, wenn sie also den Kopf in Handform gestalten würde. Es ist schon einmal ein besonderes Kennzeichen dieser gescheiten Leute der Gegenwart, daß sie mit dem Allerdümmsten das größte Glück bei unseren Zeitgenommen haben, weil das Allerdümmste heute als das verstandesmäßig Gescheiteste der großen Menge erscheint.

Dasjenige, worauf es ankommt, ist, daß in dem Augenblick, wo die Menschheit nicht mehr instinktiv, sondern bewußter als früher eintreten soll in das öffentliche Leben, die ganze Art, wie der Mensch steht im geistigen Kulturleben drinnen, wie er steht im Rechts- und Staatsleben, wie er steht im Wirtschaftsleben, anders ist. Es ist geradeso anders, wie anders ist die Blutzirkulation im Kopfe, in den Füßen oder in den Beinen und anders ist im Herzen - und dennoch wirken die drei gerade in der richtigen Weise zusammen, wenn sie in der richtigen Weise gesondert organisiert sind.

Und auch wir müssen als Menschen in verschiedener Weise unser soziales Urteil bilden auf dem Gebiete des Geisteslebens, auf dem Gebiete des Rechts- oder Staatslebens und auf dem Gebiete des wirtschaftlichen Lebens. Aber da muß man die Wege finden, wie man zu einem wirklich gesunden Urteil auf den drei Gebieten kommt. Es ist im allgemeinen dieser Weg - im Grunde genommen sind es drei Wege — wirklich recht stark durch die Vorurteile der Zeit verlegt. Da müssen erst viele Hindernisse aus dem Wege geräumt werden.

Um zu einem gesunden sozialen Urteil zu kommen im geistigen Leben, muß man sich klar sein darüber, daß der heutige Mensch ganz und gar ungeeignet ist, sich die Frage auch nur vorzulegen: Was bedeutet denn Soziales im geistigen Leben? Was bedeutet menschliches Zusammenleben in geistiger Beziehung? Wir haben noch keine Menschenkunde, die, ich möchte gar nicht einmal sagen, Antwort gibt auf solche Fragen, sondern ich möchte nur sagen, die anregt zu solchen Fragen. Diese Menschenkunde muß durch die Geisteswissenschaft erst geschaffen werden und in der Menschheit populär gemacht werden. Man muß ordentlich und vernünftig die Frage aufwerfen: Was ist es denn für ein Unterschied, [ob ich einem Menschen gegenüberstehe oder] ob ich als einsamer Naturbetrachter nur die Natur mir gegenüber habe, also mir Erkenntnisse von dieser Natur so verschaffe, indem ich als Mensch direkt mich der Natur als Beobachter gegenüberstelle? Ich trete in ein gewisses Wechselverhältnis zur Natur; ich lasse die Natur Eindrücke auf mich machen; ich verarbeite diese Eindrücke, bilde mir innerlich Vorstellungen über diese Eindrücke, indem ich in ein Wechselverhältnis zur Natur trete; ich nehme etwas auf von außen, verarbeite es innerlich. Das ist im Grunde genommen die einfache Tatsache. Äußerlich angesehen sieht es ebenso aus, wenn ich einem Menschen zuhöre, also zu ihm in eine geistige Beziehung trete, in seinen Worten den Sinn finde, den er in sie hineinlegt. Da machen die Worte des Menschen auf mich einen Eindruck; ich verarbeite sie wieder innerlich zu Vorstellungen. Ich trete in Wechselwirkung zu anderen Menschen. Man könnte glauben: Ob ich nun zur Natur in Wechselwirkung trete oder ob ich zu anderen Menschen in Wechselwirkung trete, das ist im Grunde genommen einerlei. Das ist es eben nicht. Derjenige, der behauptet, das sei einerlei, der hat ja nicht einmal den Blick auf diese Sache in der richtigen Weise gelenkt. Man muß schon auf diese Dinge auch etwas Aufmerksamkeit wenden.

Sehen Sie, ich möchte nun ein konkretes Beispiel anführen. Es gibt im deutschen Geistesleben eine Tatsache, ohne die dieses deutsche Geistesleben gar nicht denkbar ist. Wenn man das Geistesleben eines gewissen Gebietes schildert, dann schildert man gewöhnlich — je nachdem man nun gerade eine Veranlassung hat —, man schildert entweder die wirtschaftlichen Verhältnisse der Zeit, wo sich dieses Geistesleben herausentwickelt hat, oder man schildert einzelne große Persönlichkeiten, die aus ihren genialen Leistungen heraus dieses Geistesleben befruchtet haben. Aber ich meine jetzt eine Tatsache, die ganz anderer Natur ist und ohne die die besondere Art des deutschen Geisteslebens im 19. Jahrhundert gar nicht zu denken ist. Das ist, ich möchte sagen ein Urphänomen sozialen geistigen Zusammenlebens: es ist das zehnjährige, intime Verhältnis von Goethe und Schiller. Man kann nicht sagen, Goethe habe Schiller etwas gegeben oder Schiller habe Goethe etwas gegeben und sie hätten zusammengewirkt. Damit trifft man nicht die Tatsache, die ich meine, sondern es ist etwas anderes. Schiller ist durch Goethe etwas geworden, was er allein niemals geworden wäre. Goethe ist durch Schiller etwas geworden, was er allein niemals geworden wäre. Und hat man bloß den Goethe, und hat man bloß den Schiller und denkt sich ihre Wirkung auf das deutsche Volk es kommt nicht das heraus, was in Wirklichkeit geworden st. Denn hat man bloß Goethe, hat man bloß Schiller, und bedenkt man die Wirkungen, die aus beiden ausströmen, so gibt es noch nicht das, was geworden ist, sondern es entsteht aus dem Zusammenfluß der beiden ein Drittes, ganz Unsichtbares, das aber von ungeheuer starker Wirkung ist (Es wird an die Tafel gezeichnet). Sehen Sie, das ist ein Urphänomen sozialen Zusammenwirkens auf geistigem Gebiete.

Was liegt denn da eigentlich zugrunde? Solche Dinge studiert die heutige, grobe Wissenschaft nicht, weil die heutige Wissenschaft überhaupt nicht bis zum Menschen herandringt. Geisteswissenschaft wird solche Dinge studieren und dadurch erst Licht bringen auch in das soziale geistige Zusammenleben der Menschen. Diejenigen von Ihnen, welche etwas von Geisteswissenschaft gehört haben, wissen dasjenige, was ich jetzt nur kurz andeuten will. Geisteswissenschaft zeigt, daß die Entwicklung des Menschen eine wirkliche, reale Tatsache ist. Sie zeigt, daß ein Mensch, indem er sich entwickelt, immer reifer und rcifer wird, immer anderes und anderes aus den Tiefen seines Wesens hervorbringt. Und wenn das soziale Leben dieses Hervorbringen unterdrückt, so ist dieses soziale Leben eben falsch und muß in andere Bahnen gebracht werden.

Nun, Goethe und Schiller waren beide sozial im höchsten Sinne beglückte Individualitäten, Persönlichkeiten. Wann ist denn dasjenige eingetreten, von dem man sagen kann, Schiller habe Goethe am besten verstanden, Goethe habe Schiller am besten verstanden? Sie haben sich am besten miteinander unterhalten können, am besten miteinander ihre Ideen austauschen können und etwas Gemeinsames, eben dieses Unsichtbare, zustandegebracht, was dann wiederum fortgewirkt hat und was eine der bedeutendsten Tatsachen im deutschen Geistesleben ist. Ich habe mich viel bemüht, das Jahr des intimsten Zusammenlebens der beiden, da, wo die Ideen des einen, ich möchte sagen am gründlichsten in die Ideen des anderen eingedrungen sind, herauszubringen. Ich finde, es ist so um das Jahr 1795 oder 1796 (Es wird an die Tafel geschrieben). 1796, da ist wirklich in diesem Zusammenwirken von Goethe und Schiller etwas ganz Besonderes da.

Wenn man nun nachforscht, warum just Schiller in diesem Jahr Goethe am besten verstanden hat und warum Goethe sich am besten hat verstehen lassen können von Schiller just in diesem Jahre, so kommt man darauf. Nicht wahr, Schiller ist 1759 geboren; er war also im Jahre 1796 siebenunddreißig Jahre alt. Goethe war zehn Jahre älter; er war also siebenundvierzig Jahre alt. Nun zeigt uns die Geisteswissenschaft, daß es verschiedene Lebensknotenpunkte im menschlichen Leben gibt; sie werden heute gewöhnlich nicht berücksichtigt: der Zahnwechsel — der Mensch wird etwas anderes, indem er den Zahnwechsel übersteht, auch in geistigseelischer Beziehung -, die Geschlechtsreife, spätere Übergänge sie sind weniger bemerklich, aber sie sind doch da im 28. Jahre, wiederum im 35. und im 42. Jahr. Wenn man wirklich dieses innere menschliche Leben beobachten kann, so weiß man, daß der Anfang der 40er Jahre, ich möchte sagen im Durchschnitt das 42. Jahr, wenn der Mensch sich innerlich entwickelt, wenn er innerlich ein Geistesleben durchmacht, dieses 42. Jahr etwas ganz Besonderes ist. Zwischen dem 35. Jahr und dem 42. Jahr wird das reif im Menschen, was man die Bewußtseinsseele nennen kann. Und sie ist ganz reif geworden, diese urteilende Bewußtseinsseele, diese bewußte Seele, die ganz aus dem Ich heraus zur Welt in ein Verhältnis tritt — diese Bewußtseinsseele wird da reif. Schiller mit 37 Jahren war fünf Jahre jünger als 42, Goethe mit 47 Jahren war fünf Jahre älter als 42. Goethe hatte das 42. Jahr ebensoweit überschritten wie Schiller darunter war.

Schiller stand in der Entwicklung der Bewußtseinsseele eben darinnen, Goethe war darüber hinaus; sie waren in gleichem Abstand davon. Was bedeutet denn das? Das bedeutet in bezug auf das Seelische wirklich einen ähnlichen Gegensatz - ich weiß, solche Vergleiche sind gewagt, aber unsere Sprache ist ja auch grob, und man kann deshalb nur gewagte Vergleiche gebrauchen, wenn man wichtige, fundamentale Tatsachen anzuführen hat —, das bedeutet für das Seelisch-Geistige einen ähnlichen Gegensatz wie das Männliche und Weibliche für das Physisch-Geschlechtliche. In bezug auf die physische Entwicklung sind eben die Sexualitäten von ungleicher Entwicklung. Ich will jetzt aus Höflichkeit gegen die Damen, und um die Herren nicht hochmütig zu machen, nicht sagen, welche Sexualität eben eine spätere Entwicklung ist, welche Sexualität eine frühere Entwicklung ist, aber sie sind von einer verschiedenen zeitlichen Entwicklung. Es ist ja nicht der ganze Mensch, der Kopf nimmt nicht teil daran, also brauchen sich diejenigen ja nicht gekränkt zu fühlen, deren Sexualität in einer früheren Entwicklungsstufe gedacht werden muß. Aber so ist es nicht in bezug auf das Seelische; da kann das Frühere mit dem Späteren zusammenkommen, dann entsteht eine ganz besondere Befruchtung. Dann entsteht etwas, was eben nur durch diese verschiedene Artung zu verschiedenen Zeiten entstehen kann. Das ist natürlich ein besonderer Fall; da wird im sozialen Zusammenleben das Wechselspiel von Seele zu Seele in einer besonderen Art gebildet. Immer, wenn Menschen aufeinander wirken, entsteht etwas, was niemals durch die bloße Wechselwirkung von Mensch und der betrachteten Natur entstehen kann. Sie sehen, man bekommt einen gewissen Begriff, was das eigentlich heißt, dasjenige auf sich wirken zu lassen, was nicht von der Natur, sondern was von einem anderen Menschen ausgeht.

Mir war das ein ganz besonderes Problem geworden, als ich mich zum Beispiel in Nietzsche vertiefte. Nietzsche hatte etwas, was jetzt schon eine ganze Anzahl von Menschen haben, die eine ähnliche Vorbildung haben, wie Nietzsche sie hatte; er hatte es eben nur in einem ganz besonders radikalen Sinn. Er hat zum Beispiel Philosophen betrachtet, die alten griechischen Philosophen, er hat Schopenhauer betrachtet, er hat Eduard von Hartmann betrachtet und so weiter. Man kann sagen, Nietzsche interessierte eigentlich niemals der Inhalt einer Philosophie. Dieser Inhalt der Philosophie, dieser Inhalt der Weltanschauung, der ist ihm eigentlich höchst gleichgültig; aber ihn interessierte der Mensch. Was der Thales gerade gedacht hat als Inhalt seiner Weltanschauung, das ist ihm gleichgültig, aber wie dieser Mensch Thales zu seinen Begriffen sich heranlebt, das interessiert ihn. Das interessiert ihn bei Heraklit, nicht der Inhalt der Philosophie des Heraklit interessiert ihn. Gerade das, was vom Menschen kommt, das wirkt auf ihn, und dadurch zeigt sich Nietzsche als ein besonders moderner Charakter. Das wird aber allgemeine Konstitution des menschlichen Seelenlebens werden. Heute streiten sich die Menschen noch vielfach über Meinungen. Sie werden einmal aufhören müssen, über Meinungen zu streiten, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil jeder seine eigene Meinung haben muß. Geradeso, wie wenn man einen Baum hat und den von verschiedenen Seiten fotografiert, so ist es immer noch derselbe Baum, aber die Fotografien sehen ganz verschieden aus; so kann jeder seine eigene Meinung haben, je nachdem - es kommt nur auf den Standpunkt an, auf den er sich stellt. Wenn er vernünftig ist im heutigen Sinne, so streitet er sich gar nicht mehr über Meinungen, sondern er findet höchstens manche Meinungen gesund und manche krank. Er streitet nicht mehr über Meinungen. Es wäre ebenso, wie wenn einer verschiedene Fotografien ansieht und dann sagte: Ja, die sind ja ganz verschieden, diese sind richtig, und diese sind falsch. - Es kann einen höchstens interessieren, wie einer zu seiner Meinung kommt: ob das nun besonders geistreich oder töricht ist, ob es niedrig ist und nichts fruchtet oder ob es hoch ist und für die Menschheit förderlich ist — das kann einen interessieren.

Es handelt sich heute darum, wirklich den Blick hell zu machen, wie Mensch zu Mensch steht im geistigen sozialen Zusammenleben, wie der Mensch dem Menschen etwas zu geben hat. Es tritt einem das ja ganz besonders dann entgegen, wenn man sieht, was der Mensch als aufwachsendes Kind empfangen muß von dem anderen Menschen, der seine Lehrerpersönlichkeit ist. Da sind noch ganz andere Kräfte im Spiel als zwischen Goethe und Schiller, wenn sie auch nicht in eine so hohe Lage hinaufversetzt sind, aber es sind kompliziertere Kräfte dabei im Spiel. Das, was ich jetzt hier entwickle, das gibt eine Möglichkeit, den Weg aufzufinden, wie man sich auf dem Gebiete des Geisteslebens zu einem wirklich sozialen Urteil aufschwingen kann.

Sehen Sie, ich sagte schon, ich kann heute, gerade heute, nicht besonders populär sprechen, weil ich ja, wenn ich diese Fragen erörtern will, vom Standpunkte einer heute noch unbekannten Menschenkunde, wenigstens in weiteren Kreisen noch unbekannten Menschenkunde, ausgehen muß. Ich habe in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln» darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie der Mensch ein dreigliedriges Wesen ist: er ist Kopfmensch oder Nervensinnesmensch, rhythmischer Mensch, Stoffwechselmensch. Der Nervensinnesmensch umfaßt alles dasjenige, was die Sinne sind und was die Organe des Hauptes sind. Der rhythmische Mensch, der Rumpfmensch könnte man auch sagen, umfaßt dasjenige, was rhythmisch ist im Menschen, was Herzbewegung, Lungenbewegung ist und so weiter. Der dritte, der Stoffwechselmensch, umfaßt alles übrige.

Diese drei Glieder bestehen in der menschlichen Natur; sie sind in einem gewissen Sinne voneinander grundverschieden, aber man kommt schwer auf ihre eigentlichen Verschiedenheiten. Man kann da beim rhythmischen Menschen das folgende hervorheben. - Von dem Rhythmischen im Menschen werden Sie später noch allerlei hören am heutigen Abend, wenn Dr. Boos sprechen wird über die Bildung des sozialen Urteils im Rechts- oder Staatsleben, was dann den zweiten Teil der Einleitung ausmachen wird. Dr. Boos wird über dasjenige, was ihm besonders naheliegt, über die Bildung des sozialen Urteils im zweiten Gliede des sozialen Organismus, im Rechts- und Staatsleben, sprechen. — Jetzt möchte ich aber das folgende hervorheben: Dasjenige, was rhythmische Tätigkeit im Menschen ist, das tritt uns ja ganz besonders stark entgegen, wenn wir auffassen, wie der Mensch die äußere Luft einatmet, sie in sich verarbeitet, wie er Sauerstoff einatmet und Kohlensäure ausatmet. Einatmung — Ausatmung, Einatmung — Ausatmung: das ist zunächst einer der Rhythmen, die im Menschen tätig sind. Es ist ein verhältnismäßig leicht zu begreiftender Vorgang: Einatmen — Ausatmen = rhythmische Tätigkeit.

Zu den anderen beiden Tätigkeiten kommt man vielleicht nur, wenn man ausgeht von dieser rhythmischen Tätigkeit. In gewissem Sinne ist eigentlich der ganze Mensch zur rhythmischen Tätigkeit veranlagt. Aber man erkennt mit der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft die Nervensinnestätigkeit, die eigentliche Hauptestätigkeit, ja gar nicht. Man kann sie nicht vergleichen mit der Lungen- und Herztätigkeit, mit der rhythmischen Tätigkeit. Ich kann nur etwas anführen, was denjenigen, die mit Geisteswissenschaft, mit Anthroposophie weniger bekannt sind, vielleicht paradox erscheint, was aber von einer wirklichen Wissenschaft erhärtet werden wird. Zukünftig wird das, was ich jetzt sage, als eine ganz exakte wissenschaftliche Tatsache in der Welt dastehen, wenn man die notwendigen Verhältnisse durchschauen wird. Bei Ein- und Ausatmung, da ist ein gewisses Gleichgewicht zunächst vorhanden. Dieses Gleichgewicht, das da vorhanden ist, das könnte man bildhaft darstellen wie ein Pendel, das hin- und hergeht. Es geht auf der einen Seite ebenso hoch hinauf wie auf der anderen Seite. Es schwingt hin und her. So ist auch ein Gleichgewicht vorhanden zwischen Einatmung und Ausatmung, Einatmen und Ausatmen und so weiter.

Wenn nun der Mensch nicht mit anderen Menschen geistigseelisch zusammenleben würde, wenn der Mensch einsam wäre und nur die Natur beobachten könnte, also nur in ein Wechselverhältnis zur Natur treten könnte, die Natur anschauen und sie innerlich zu Vorstellungen verarbeiten könnte, dann würde etwas ganz Besonderes mit dem Menschen geschehen. Wie gesagt, heute erscheint das den Menschen höchst paradox, aber es ist doch so: es würde nämlich sein Kopf zu leicht werden. Indem wir die Natur beobachten, ist ja eine Tätigkeit vorhanden. Wir tun nicht nichts, indem wir die Natur beobachten; da ist alles in uns in einer gewissen Tätigkeit. Diese Tätigkeit, die ist gewissermaßen eine am Menschenhaupte saugende Tätigkeit - nicht am ganzen Organismus, aber am Menschenhaupt saugende Tätigkeit. Und diese saugende Tätigkeit muß ausgeglichen werden, sonst würde unser Kopf zu leicht werden; wir würden ohnmächtig werden. Sie wird dadurch ausgeglichen, daß gewissermaßen der zu leicht gewordene Kopf wiederum einen Stoffwechsel durchmacht, Blut - Ernährung, und das alles schiefßt zum Kopfe hin. Und so haben wir, indem wir die Natur beobachten, fortwährend ein Zuleichtwerden des Kopfes und ein wiederum Schwerwerden dadurch, daß die Verdauungstätigkeit in den Kopf hinautgeht.

Dieser Ausgleich muß stattfinden. Es ist eine höhere rhythmische Tätigkeit. Aber diese Tätigkeit würde höchst einseitig werden, wenn der Mensch nur der Natur gegenüberstünde. Der Mensch würde in der Tat zu leicht werden in seinem Kopfe, wenn er nur außen der Natur gegenüberstünde; er würde nicht von innen genügend ausgleichende Stoffwechseltätigkeit in den Kopf hinaufsenden. Das tut er in ausreichendem Maße, wenn er mit seinen Mitmenschen in ein Verhältnis tritt.

Daher, sehen Sie, kommt es, daß Sie ein gewisses Wohlgefallen fühlen, wenn Sie mit Ihren Mitmenschen in ein Verhältnis treten, in Gedanken- oder Ideenaustausch treten oder wenn sie belehrt werden von ihnen oder dergleichen. Es ist etwas anderes, ob man durch die kalte Natur geht oder ob man einem Menschen gegenübersteht, der einem seine Ideen äußert. Wenn man einem Menschen gegenübersteht, der einem seine Ideen äußert - man soll das nur einmal in sorgfältiger Selbstbeobachtung sich vorlegen -, dann hat man ein gewisses Wohlgefühl. Und der, der dieses Wohlgefühl analysieren kann, der findet eine Ähnlichkeit zwischen diesem Wohlgefühl und dem Gefühl, das er hat, wenn er verdaut. Es ist eine große Ähnlichkeit, nur geht das eine Gefühl nach dem Magen hin, das andere geht nach dem Kopf hinauf. Sehen Sie, das ist gerade das Eigentümliche des Materialismus: Diese feinen materiellen Vorgänge im Menschenleibe bleiben dem Materialismus verschlossen. Daß da eine verborgene Verdauungstätigkeit nach dem Kopfe gerade dadurch stattfindet, daß man einem Menschen gegenübersitzt, mit dem man redet, mit dem man Ideen austauscht, das merken die Menschen durch die heutige grobe Wissenschaft nicht. Daher können sie auch soziale Fragen, Fragen des Menschenzusammenhanges, selbst wenn sie ganz trivial sind, nicht beantworten.

Dem Geisteswissenschaftler, dem Anthroposophen, ist es ganz klar, warum die Kaffeeschwestern so furchtbar gern sich zusammensetzen. Dieses Sich-Zusammensetzen geschieht nicht bloß deshalb, weil ihnen der Kaffee schmeckt, sondern dieses Sich-Zusammensetzen geschieht aus dem Grunde, weil sie dann sich selber verdauen. Es geht die Verdauung nach dem Kopfe, und das fühlen sie als Wohlgefühl. Und indem so Kaffeeschwester neben Kaffeeschwester sitzt oder auch, ich kann nicht sagen Kaffeebruder, aber Skatbruder neben Skatbruder beim Dämmerschoppen und so weiter sitzt, da findet natürlich dasselbe unter Männern statt. Ich will niemanden beleidigen, aber indem die Leute sich so zusammensetzen, Ja, da fühlen sie diese nach dem Haupte gehende Verdauungstätigkeit, und das bedeutet ein gewisses Wohlgefühl. Das, was da geschieht, das ist für das Menschenleben wirklich notwendig. Das ist wirklich notwendig, nur kann man es zu höherer Betätigung verwenden als gerade just zum Dämmerschoppen- und zum Kaffeeschwesterntum. Geradeso, wie das Blut nicht stillstehen darf im Menschen, so darf dasjenige, was da im Haupte sich abspielt, nicht stillstehen. Es würde ein verkümmerter Rhythmus eintreten im Nervensinnessystem, wenn wir nicht in der richtigen Weise mit den Menschen draußen in geistigem Zusammenhange stünden. Unser richtiges Menschentum, daß wir richtig Menschen werden, das hängt davon ab, daß wir mit den anderen Menschen in einen vernünftigen Zusammenhang kommen.