World Economy

GA 340

28 July 1922, Dornach

Lecture V

We are now going to pursue a little further the sequence of events within the economic process which we considered yesterday. The economic process, as we have seen, is set in motion by human Labour working upon Nature, so that from the mere raw Nature-product—which has as yet no value in the economic process—we get the Nature-product transformed by human Labour. At the next stage, Labour is, as it were, caught up by Capital, which divides and organises it, till it eventually disappears in the Capital. For the further advance of the economic process, therefore, Capital itself must labour. But this labour of Capital is not labour in the old sense; rather the Capital is taken up by a purely spiritual activity. The economic process now goes forward by the Spirit “making good” the Capital, giving it additional value, as I described in the last lecture.

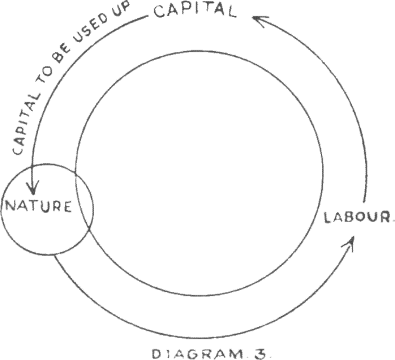

We must try to understand more and more the formula which was indicated yesterday. To this end, let me now describe diagrammatically—symbolically, as it were—what I explained yesterday. We may say: Nature goes under in human Labour (see Diagram 3. We have therefore this stream from Nature into Labour. Nature goes under in Labour. Labour continues to evolve. Then the values evolved stream onward, as it were, till Labour vanishes in Capital. We have traced the process up to this point (see Diagram 3). You can easily continue it for yourselves. The cycle must necessarily be completed in some way. The Capital cannot merely be blocked at this point, for otherwise we should be dealing not with an organic process but with one that would come to an end in Capital. The Capital must disappear once more into Nature. But you must first call to your aid another idea if you wish to understand this rightly.

Consider for a moment the economic process as we have traced it up to the present. First the elaboration of Nature by human Labour, then the organising of Labour by the Spirit and with it the rise of Capital, for Capital is a concomitant of the organising of Labour by the Spirit. Then the existence of Capital as such. Capital passes over from the Spirit which organised the Labour. The Capital becomes independent. The Labour disappears in its turn, and now the Spirit works in the Capital as inventive Spirit in connection with the whole social life. The technical aspect of invention need not concern us here; this will only come into question at a later stage.

If you now review all that I have described to you, you will see that I have presented everything from one side only. This was inevitable; for, apart from a few occasional hints, I have been speaking only of. production. I have indeed included, now and then, ideas that had to do with consumption, especially when we were trying to approach the question of price. But apart from that you will have found practically nothing about consumption in our discussions hitherto. I have been speaking of production. And yet, the economic process does not merely consist of production—it consists also of consumption.

A simple reflection will show you that consumption is exactly the opposite pole to production. We have been endeavouring to find the values that arise in the economic process within the sphere of production. Consumption on the other hand consists in a perpetual elimination of these values. In consumption they are constantly being used up. That is to say, it consists in a constant devaluation of the values. It is this that plays the other important part in the economic process—this constant devaluation of values. Indeed it is just through this that we have a certain right to call the economic an organic process, an organic process in which the Spirit presently intervenes. For it is of the essence of a living organism that something is continually being formed and again unformed. In any organism there must be a continual production and consumption, and this must be so in the economic organism too. There must be a constant producing and a using-up of what is produced.

At this point we begin to see in a different light, and from a different point of view, the value-creating forces which we have been considering. Hitherto we have only shown how values arise as the process of production takes its course. But now, every time a value approaches its moment of devaluation, the whole movement which we have been witnessing hitherto will change. So far, we have been observing a progressive, forward movement. Thus, values arise through the application of Labour to Nature; values arise through the application of the Spirit to Labour; values arise through the application of the Spirit to Capital. All this is a forward movement.

In fact, we have been observing the value-creating movement in the economic process. But as the devaluing factor of consumption enters into the process at every point, there will be something else as well. There will be that development of values which arises as between production and consumption themselves. When a value enters the process of consumption it no longer moves forward. It does not attain a higher degree of value, it no longer moves; for something now stands over against it. This is consumption—the development of a need. Here the value enters into a very' different sphere from that which we have hitherto been studying. We have been considering the value in its progressive, forward movement. (see Diagram 3) Now we must imagine it moving up to a certain point and being there arrested. Every time a value is arrested, there arises, not a further value-creating movement, but a value-creating tension.

This is the second element in the economic process. In the economic process we have not only value-creating movements but value-creating tensions. We can observe such value-creating tensions most conspicuously and simply where a consumer stands face to face with a producer or trader and in the very next moment the creation of value comes to an end, passing over into devaluation. Here there arises a tension—a tension which is maintained in equilibrium by the human need on the other side. Here the value-creating process is arrested. Human need or consumption confronts it and there arises the tension between production and consumption. This tension is also most decidedly a value-creating factor—albeit one that is comparable to a force that is arrested, held in equilibrium, rather than to a force that is working itself out. There is here a true analogy with the contrast in Physics between kinetic and potential energies—between kinetic energies and those energies of position where an equilibrium is brought about. If you do not take into account these energies of tension, these potential energies, in the economic process, you will be driven to the strangest misconceptions. Evolving the ideas as indicated here, we gain an intelligent conception of every economic relationship. Otherwise we are led into the greatest confusion. If, for example, you limit yourself to considering the movements of economic energies, you will never understand why the diamond in the King of England's crown has such an immense value. For here you are at once obliged to have recourse to the idea of economic tension-value. Many economists take into account the rarity of particular products of Nature; but we can never understand rarity as a value-creating factor if we regard the movement in the economic process as the only creator of values. We must also learn to understand how there arises here and there—most of all through consumption, but through other relationships as well—what I would call the creation of value by tensions, situations, equilibria.

Thus you see that devaluation can also take place in the economic process which, as I said, you can therefore regard as an organic process—an organic process in which Spirit constantly intervenes. There must be—or rather, there is constant devaluation. As the values proceed on their way (see Diagram 3) from Nature through Labour to Capital, they will be accompanied by a continual process of devaluation. What would happen if this corresponding devaluation could not take place? You can see this from the diagram.

To make it clear, let us consider the question of credit. To place Capital into the service of the Spirit in the sense which I explained yesterday, the man who produces by means of Spirit becomes a debtor. It is only through his having credit that he becomes or can become a debtor. At this point in our diagram credit steps in—the thing which may be properly called “personal credit.” A man has credit. The credit can be expressed in figures. The Capital which many others advance to him is, so to speak, his personal credit. Now, as you know, this personal credit has a certain consequence, at any rate if we consider it within our present economic conditions. Its economic effect is connected with the rate of interest.

Assume that the rate of interest is low. If as a spiritual creator in the economic process I become a debtor, that is to say, if I demand credit, I shall only have to pay a small sum for it. Having less interest to pay, I can produce my goods more cheaply. Thus I shall have a cheapening effect on the economic process. We may say, therefore: Personal credit cheapens production when the rate of interest falls. So long as the Capital continues to be turned to good account or made valuable by the Spirit in the economic process, it is always so. When the rate of interest goes down, he who requires credit has more freedom of movement. He can play his part far more intensively in the economic process—more intensively, that is to say, for his fellow-men. For if he cheapens his commodities he is playing a fruitful part in the process—at any rate from the point of view of the consumer.

But now let us take the other side. Assume that credit is given on land—“real credit.” When credit is given on land, the situation is essentially different. Assume that the rate of interest is 5%. A person borrowing Capital on the security of land must pay 5%. Capitalising this, you will get the Capital corresponding to the particular piece of land—that is to say, you will get the amount which would have to be paid to buy the piece of land outright. Assume now that the rate of interest falls to 4%. More Capital can then be “credited into” the land—this at any rate is what actually happens. Thus we see everywhere, as a result of a falling rate of interest, land becoming not cheaper but more expensive. When the standard rate of interest goes down, land does not become cheaper but more expensive. “Real credit” makes things more expensive while “personal credit” makes things cheaper. That is to say, real credit makes land more expensive while personal credit makes commodities cheaper. Now this means very much in the economic process. It means that, when Capital returns to Nature and simply unites with Nature in the form of real credit (in other words, when there is a union of Capital with land, that is to say, with Nature), then the economic process will tend more and more in the direction of dearness.

Thus the only sensible thing will be for the Capital at this point (see Diagram 3) not to preserve itself in Nature but rather to vanish into Nature. How then can Capital vanish into Nature? So long as it is at all possible to unite Capital with Nature—that is to say, so long as you can make Nature in its original unelaborated condition more and more expensive through the accumulation of Capital—so long as this is possible, Capital cannot vanish into Nature; on the contrary, it penetrates into Nature and maintains itself there. Thus in all countries where the law of mortgage makes it possible for Capital to unite with Nature, we shall find a congestion of Capital in Nature, i.e., in the land. Instead of the Capital being expended at this point (see Diagram 3)—instead of its disappearing at this point, instead of a value-creating tension arising—there is a further value-creating movement, which is harmful to the economic process. There is only one way of preventing this. In a healthy economic process we must not and cannot give “real credit ”—credit based on the security of land—even to a person working on the land. He too should only receive personal credit—that is to say, credit which will enable him to turn the Capital to good account through the land. If we simply unite the land with the Capital, the Capital will become congested the moment it arrives again at Nature (see the diagram). If on the other hand we unite it with the spiritual capacities of those who have to administer the land and further the economic process by working upon it, then, you see, the Capital vanishes. As it reaches Nature at this point, it will not become congested; it will not be preserved, but will go right on through Nature, back again into Labour, and will begin the cycle once more. It is one of the worst possible congestions in the economic process when Capital is simply united with Nature, that is to say, when (to trace the economic process hypothetically from its initial stages) after Labour and Capital have evolved from the starting-point of Nature, the Capital is enabled to take hold of Nature instead of losing itself in Nature.

At this point you may, of course, make a serious objection. In the course of this movement, you may say, the Capital has come into being. Suppose it now arrives again at Nature and there is too much of it. (It would be different if we were able to lead it over into Labour—if we were able, let us say, to invent new methods so as to further the exploitation of raw products. For in such a case we should be uniting not Nature but Labour with the Capital. If we arrive at this point with our Capital and exploit the raw products in a more economical way, or open out new sources or the like, then we are leading the Capital directly over into Labour). But suppose there is too much Capital. The several owners of Capital will become painfully aware of the fact; they will not be able to start anything with their Capital. This is indeed the case if you look into the matter historically. In actual fact, too much Capital did arise, and the only way out which it could find was to conserve itself in Nature. Thus we witnessed in the economic process the so-called rise in the value of land.

But, ladies and gentlemen, consider the matter in our present, larger context. The Land Reformers always describe these things in an inadequate way, so that the thing cannot be understood. Consider it in a larger context and you will say: If I unite Capital with Nature, the value of Nature will of course be enhanced. The more a thing is mortgaged, the more will eventually have to be paid for it. The value is constantly increased. But is this increase in the value of land a reality? No, it is no reality at all. By nature, land can never receive a greater value. It can at most receive a greater value by being worked upon in a more rational and scientific way, and in that case it is the Labour that increases the value. But to imagine the land itself, the land as such, increased in value is absurd. It is absolute nonsense. If you do improve the quality of the land, you only do so by working upon it. In so far as it is mere Nature, the land can have no value at all. All you can do is to give it a fictitious value by uniting Capital with it. So that we may say: What is called the value of land in the sense of present-day Economics is in real truth none other than the Capital fixed in the land. And the Capital fixed in the land is not a real value but an apparent value—a semblance of a value. That is the point. In the economic process it is high time that we learnt to under-stand the difference between real values and apparent values.

You see, if you have an error in your system of thought you do not observe its full effect to begin with. For however many disturbing processes in the organism are in fact connected with the error in thought, the connection is only recognisable by Spiritual Science. It escapes the crude Natural Science of today. People are unaware, for instance, how digestive and similar troubles in our peripheral organs arise as a result of such errors. But in the economic process it is just the errors and semblances which are obviously effective, which grow real and have real consequences. And, economically speaking, it makes no essential difference whether, for example, I issue money which has no foundation in reality but represents a mere increase in the amount of paper money, or whether I assign capital value to the land. In both cases I am creating fictitious values. By inflating the currency I increase the prices of things numerically, but in the reality of the economic process I effect absolutely nothing except a redistribution which may do immense harm to individuals. In like manner the above-described capitalising of land does harm to those who are involved in the economic process.

It would make a very interesting study to compare, for example, the mortgage laws existing before the War in the Mid-European countries with the English mortgage laws. In the Mid-European countries it was possible to screw the so-called value of land up and up and up without limit. The law itself made this possible. While in England on the other hand it is true to say, in a certain sense, that this is not so. Compare the effect on the economic process in the one case and in the other. The thing would make an interesting subject for a dissertation. It would make a very good subject, to compare statistically the working of the English mortgage laws with those of Germany.

I have thus illustrated the essential point in our present context. At this point (see Diagram 3) Nature simply must not be allowed to tend towards a conservation of Capital. Capital must be allowed to work on, unhindered, into Labour. But what is to happen if it is actually there—more of it than we are able to make use of? The only thing to prevent its being there in excess is to see that it is used up along this path (see diagram), so that in the last resort only so much of it is left at this point as can enter once more into the work to be done upon the land. That is to say only so much of it is left, as is required for this work. The essential and obvious thing is that the Capital should be used up, consumed along this path (see diagram). Indeed—assuming for a moment for the sake of hypothesis that it could be so—it would be a most appalling thing if nothing were consumed along this whole path. We should have to take the products with us. The process only becomes organic through the fact that things are used up. Just as the Nature-products, transformed by human Labour, get used up, just as the Labour which has been organised by Capital gets used up, so in its further path the Capital itself simply must be used up, properly used up. This using up of Capital is a thing which positively must be brought about.

It can only be brought about if the whole economic process from beginning to end—i.e., right up to its return to Nature—is ordered rightly. There must be something there like the “self-regulator” in the human organism. The human organism, at any rate when it is functioning normally, manages to prevent promiscuous deposits of unused foodstuffs. And if unused foodstuffs are deposited here or there, we are ill. Suppose, for instance, that in the process of digestion in the head, substances are deposited, that is to say, an irregular digestive process arises in the head. The substances that are deposited are no longer carried away—that is to say, their consumption is not properly regulated. Then we get migraine conditions. In like manner you will see the same principle at work in all parts of the human organism. The cause of morbid symptoms lies in the inadequate absorption and removal of what has to be digested. It is just the same in the social organism, when that which ought really to be used up at a certain point becomes accumulated. It is a matter of sheer necessity for the Capital to be used up along here, (see Diagram 3) in order that it may not unite with Nature and so become unliving—a petrified deposit, as it were, in the economic process. For capitalised land is in fact an impossible deposit in the economic process.

Let me expressly state that there can be no question here of any sort of political agitation. I simply unfold these matters as they take shape out of the natural process itself. We are only considering the scientific aspect. But a science that deals with human actions cannot possibly be pursued without indicating the kinds of morbid symptoms that can arise; just as we cannot study the human body without indicating the various possible morbid symptoms. There must, therefore, be a proportionate using up, consumption of Capital—certainly not a total consumption, for it is necessary that a certain amount should pass on, so that Nature may be elaborated once more.

This again I can make clear to you by a picture. Consider a farmer in his economic life. He must certainly try to get rid of the yield of his acres; but he must also keep sufficient seed for the next year. Seed must be preserved. This is a very apt comparison, and we may well apply it to the process we are now considering. Capital must be used up, until that alone remains which we may conceive as a kind of seed to kindle the economic process anew—once more from the starting-point of Nature. That alone must remain which may be necessary for a more scientific exploitation of natural resources—of raw products, or for an improvement of the land, let us say, by the creation of better manures and the like. Now in every such case Labour must be applied. Thus it is that amount of Capital, which can work on as Labour, which must be withdrawn from consumption. But before this point in the diagram is reached, the surplus Capital which would otherwise unite with Nature in an inorganic way must be used up.

Here you may say: “Well, tell us how it is to be done? How is it to be brought about that only just enough Capital arrives at this point for use as a seed for the future? Tell us how it is to be done.”

Well, ladies and gentlemen, in the science of Economics we stand on the ground, not of logic, but of reality. We cannot give the kind of answers which are sometimes given, for example, in the theory of ethics. In the theory of ethics we can admonish a criminal very soundly and we shall have done all that is required. But the economic process must go on, and we must speak of realities. When we spoke of Production, showing how it created economic values, we were indeed speaking of realities. And, that Consumption is a reality, everyone is well aware. In Economic Science one must always be speaking of realities. Ideas by' themselves have no effect in the real world. That which will rightly regulate the economic process, at this point in the diagram, finds expression in what I called the “Economic Associations ” in my book The Threefold Commonwealth.

If you make the economic life independent; if you bring together, in Associations suitably composed, the human beings who are actually taking part in the economic life—whether as producers, as traders or as consumers—then, through the economic process itself, these human beings will find it possible to arrest the formation of Capital if it is too intense and to stimulate it if it is too feeble.

This of course implies a right observation of the economic process. For instance, if at any place a certain kind of commodity becomes too cheap or too dear, those concerned must be able truly to observe the fact. The mere fact in itself is not the point. But when, through experiences which can only grow out of the concerted counsels of the Associations, they are able to say, as a result of such experiences: “Five units of money for so and so much salt are too little or too much, the price is too low or too high”—then and then only will they be in a position to take the necessary steps.

If the price of a commodity becomes too cheap, so that those who produce it can no longer receive sufficient remuneration for their excessively cheap services and their excessively cheap products, it will be necessary to assign fewer workers to this particular commodity. Workers will therefore have to be diverted to another piece of work. If, on the other hand, a commodity becomes too dear, workers will have to be led over into this branch of production. Thus the Associations will always be concerned with a proper employment of men in the several branches of the economic life. We must be clear on this. A real rise in the price of a given economic article indicates the necessity for an increase in the number of those who are working on this article, while an undue fall of price calls for measures to divert workers from this field of Labour to another. In reality we can only speak of prices in relation to the distribution of men among the several branches of Labour in a given social organism.

The kind of view that sometimes holds sway today, where people always have the tendency to work with notions rather than realities, is illustrated by some advocates of “free money” [“Freigeldleute”]. To them it appears quite simple. If prices anywhere are too high, so that too much money has to be spent in purchasing a certain article, they say: Let us see to it that the amount of money becomes less; then the commodities will be cheaper, and vice versa. But, if you think it out more deeply, you will find that this signifies nothing else for the economic process in reality, than as if by some mischievous device you were to cause the column of mercury to rise when the thermometer indicates that the room is too cold. You are only trying to cure the symptoms. By giving the money a different value you create nothing real.

You create something real if you regulate the Labour—that is to say, the number of people engaged on a certain kind of work. For the price depends on the number of workers engaged in a given field of work. To try to regulate these things bureaucratically, through the State, would be the worst form of tyranny; but to regulate it by free “Associations,” which arise within the social spheres, where everyone can see what is going on—either as a member, or because his representative sits on the Association, or he is told what is going on, or he sees for himself and realises what is required—that is what we must aim at.

Of course this also involves quite another social need. We must see to it that the worker is not restricted to one solitary manipulation throughout his life, but is able to turn his hand to other things. Moreover, as I beg you to consider, this will be necessary, if only for the reason that otherwise too much Capital would arrive at this point in the diagram. You can use up the surplus Capital, which would be excessive at this point, to instruct and educate the workers in one thing or another, so as to be able to transplant them into other callings. You see, therefore, the moment you think in a rational way, the economic process will correct itself. That is the essential thing. It will never correct itself if you say: “By this or that measure, by inflation or by the issue of such or such official instructions, the thing will be improved.” By such means it will never be improved. It will only be improved by enabling the economic process to be clearly and transparently observed at every place, assuming always that those who make the observations are in a position to follow them out to their logical conclusions.

I wanted to reach this point in our argument today, in order that you might see that there was no question of starting any “agitations” with the “Threefold Commonwealth” as we intended it. We wanted to tell the world what follows from a real and true study of the economic process itself.

Fünfter Vortrag

Wenn wir die Tatsachenfolgen innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses, die wir gestern ins Auge gefaßt haben, uns noch etwas weiter anschauen, so wird sich uns das Folgende ergeben. Wir haben gesehen, wie der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß inGang kommt dadurch, daß zunächst die Natur bearbeitet wird, daß also aus dem bloßen, innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses noch wertlosen, unbearbeiteten Naturprodukte das bearbeitete Naturprodukt entsteht. Dann haben wir gesehen, wie der Prozeß weitergeht dadurch, daß die Arbeit gewissermaßen eingefangen wird von dem Kapital, daß das Kapital die Arbeit gliedert, organisiert, und daß dann die Arbeit in dem Kapital drinnen wiederum verschwindet, so daß für den weiteren Fortschritt des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses das Kapital arbeiten muß. Aber dieses Arbeiten ist nicht mehr in demselben Sinn wie früher ein Arbeiten, sondern es ist ein Aufnehmen des Kapitals von dem bloßen Geistigen. Und indem dann das Geistige, wie ich es gestern beschrieben habe, das Kapital weiter verwertet innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses, geht eben dieser vorwätts.

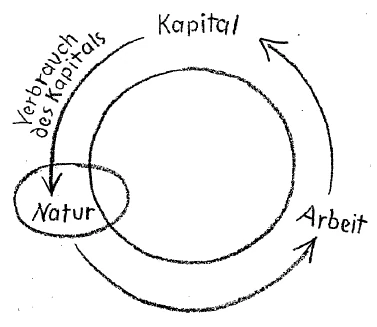

Ich möchte Ihnen das, was ich Ihnen hier auseinandergesetzt habe, damit wir zu einem Begreifen der gestern angedeuteten Formel allmählich aufsteigen können, schematisch, gewissermaßen sinnbildlich darstellen. Wir können sagen: Die Natur geht unter in der Arbeit (siehe Zeichnung 3). So daß wir etwa diese Strömung haben von der Tafel 4a Natur in die Arbeit hinein. Die Natur geht unter in der Arbeit. Die Arbeit entwickelt sich weiter. Die entwickelten Werte strömen gewissermaßen weiter. Die Arbeit verschwindet im Kapital. Und wir haben den Prozeß bis hierher verfolgt (siehe Zeichnung 3). Sie werden ihn sich jetzt leicht fortsetzen können. Es ist notwendig, daß der Kreislauf sich schließt. Das Kapital kann nicht in einfaches Stocken hineinkommen. Sonst hätte man es nicht mit einem organischen Prozeß zu tun, sondern mit einem Prozeß, der im Kapital ersterben würde. Es muß das Kapital wiederum in der Natur verschwinden. Das, daß das Kapital wiederum in der Natur verschwinden muß, das können Sie eigentlich anschaulich verfolgen, aber Sie müssen vorerst noch einen anderen Begriff zu Hilfe nehmen, wenn Sie dieses Verschwinden des Kapitals in der Natur richtig verstehen wollen.

Bedenken Sie doch, was ich eigentlich bis jetzt vor Ihnen hier im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß nur entwickelt habe. Ich habe entwickelt die Bearbeitung der Natur, die Organisierung der Arbeit durch den Geist, und damit die Entstehung des Kapitals, die eine Begleiterscheinung ist der Organisierung der Arbeit durch den Geist. Dann das Vorhandensein des Kapitals, das gewissermaßen die Übernahme des Kapitals aus dem die Arbeit organisierenden Geist ist, diese Verselbständigung des Kapitals, wo die Arbeit verschwindet und wo nun der Geist im Kapital als erfinderischer Geist, aber im sozialen Zusammenhang, arbeitet. Das eigentlich Technische der Erfindungen geht uns hier nichts an, das eigentlich Technische der Erfindungen wird erst in Betracht kommen, wenn wir unsere Auseinandersetzungen weiter verfolgen.

Nun, alles, was ich Ihnen da geschildert habe — überschauen Sie es nur -, das ist von einem einseitigen Standpunkt aus geschildert. Ich mußte es auch von einem einseitigen Standpunkt aus schildern. Denn das ist alles geschildert vom Standpunkt des Produzierens aus. Ich habe im Grunde genommen höchstens andeutungsweise bisher von etwas anderem gesprochen als von der Produktion. Ich habe gewissermaßen nur hereingenommen zuweilen Begriffe, die von der Konsumtion herrühren, wenn es sich darum gehandelt hat, uns der Preisfrage etwas zu nähern; aber von der Konsumtion werden Sie eigentlich noch gar nichts bemerkt haben. Also, ich habe bisher von der Produktion gesprochen. Aber der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß besteht ja nicht bloß in der Produktion, sondern besteht auch außer in der Produktion in der Konsumtion.

Wenn Sie eine einfache Überlegung anstellen, so werden Sie sehen, daß die Konsumtion genau der entgegengesetzte Pol ist von der Produktion. Wir haben uns bemüht, innerhalb der Produktion zu finden Werte, die im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß entstehen; aber die Konsumtion besteht in einem fortwährenden Wegschaffen dieser Werte, in einem fortwährenden Aufbrauchen dieser Werte, also in einer fortwährenden Entwertung dieser Werte. Und das ist in der Tat dasjenige, was im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß die andere Rolle spielt: ein fortwährendes Entwerten der Werte. Dadurch gerade hat man ein gewisses Recht, davon zu sprechen, daß der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß ein organischer ist, ein Prozeß, in den das Geistige dann eingreift; denn ein Organismus besteht eben darinnen, daß er etwas bildet und dann wieder entbildet. Es muß fortwährend im Organismus produziert und verbraucht werden. Das muß auch im volkswirtschaftlichen Organismus da sein. Es muß fortwährend produziert und verbraucht werden.

Damit kommen wir dazu, dasjenige, was eigentlich sich bis jetzt an werterzeugenden Kräften gezeigt hat, noch in einem anderen Licht, von einem anderen Gesichtspunkt aus zu sehen. Bis jetzt haben wir eigentlich nur gezeigt, wie innerhalb oder im Verlauf des Produktionsprozesses Werte entstehen. Nun aber, jedesmal wenn ein Wert vor seiner Entwertung steht, dann verändert sich ja die ganze Bewegung, die wir bisher gesehen haben. Es war eine fortlaufende Bewegung, die wir beobachtet haben: Werte entstehen durch die Anwendung der Arbeit auf die Natur; Werte entstehen durch die Anwendung des Geistes auf die Arbeit; Werte entstehen durch die Anwendung des Geistes auf das Kapital. Und das alles ist eine fortschreitende Bewegung.

Wir können also sagen: Wir haben die wertebildende Bewegung betrachtet innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses. - Es gibt aber dadurch, daß überall in diesen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß nun auch das Entwertende, die Konsumtion eintritt, noch etwas anderes. Es gibt jene Wertentfaltung, welche sich nun ergibt zwischen der Produktion selbst und der Konsumtion. Indem der Wert in die Konsumtion hineingeht, bewegt er sich nicht weiter. Er wird nicht höherwertig. Er bewegt sich nicht weiter. Es steht ihm etwas gegenüber. Es steht ihm eben die Konsumtion mit ihrer Bedürfnisentwickelung gegenüber. Da ist der Wert hineingestellt in etwas ganz anderes, als er bis jetzt in unserer Betrachtung hineingestellt erschien. Bis jetzt haben wir den Wert betrachtet in einer fortlaufenden Bewegung. Nunmehr müssen wir beginnen, den Wert bis zu einem gewissen Punkt zu betrachten, dann aber ihn aufgehalten anzusehen. Jedesmal, wenn der Wert aufgehalten wird, entsteht nicht eine wertbildende Bewegung weiter, sondern eine wertbildende Spannung. Und das ist das zweite Element im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Wir haben im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß nicht nur wertbildende Bewegungen, sondern haben auch wertbildende Spannungen. Und solche wertbildende Spannungen, wir können sie am anschaulichsten eben beobachten, wenn einfach der Konsument dem Produzenten oder Händler gegenübersteht, und wenn im nächsten Augenblick, könnten wir sagen, die Wertbildung aufhört, indem sie in die Entwertung übergeht. Da bildet sich eine Spannung, und diese Spannung, die wird im Gleichgewicht gehalten durch das Bedürfnis von der anderen Seite. Da (siehe Zeichnung) wird der wertbildende Prozeß aufgehalten: das Bedürfnis, der Verbrauch tritt ihm entgegen, und es entsteht die Spannung zwischen Produktion und Konsumtion, die nun durchaus auch ein wertbildender Faktor ist, aber ein solcher wertbildender Faktor, der einem Kraftentwickeln, das aufgehalten wird, das im Gleichgewicht gehalten wird, nicht einem Fortwirken der Kräfte zu vergleichen ist. Sie haben da durchaus ein Analogon zu dem Physikalischen der lebendigen Kräfte und der Spannkräfte, der lebendigen Energien und der Energien der Lage, wo Gleichgewicht erzeugt wird. Wenn man nämlich diese Spannungsenergien im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß nicht ins Auge faßt, so kommt man zu den kuriosesten Anschauungen. Wir werden sehen, wenn man solche Anschauungen entwickelt, wie man da zu Auffassungen eines jeden volkswirtschaftlichen Verhältnisses kommt, wie man aber sonst in die konfusesten Anschauungen hineinkommt. Sie werden, wenn Sie zum Beispiel nur einseitig volkswirtschaftliche Bewegungen der Energien festhalten, nicht begreifen können, warum der Diamant in der Krone von England einen so ungeheuer großen Wert hat; denn da sind Sie zugleich genötigt, zu dem Begriff des volkswirtschaftlichen Spannungswertes Ihre Zuflucht zu nehmen. Ebenso finden Sie heute noch bei vielen Volkswirtschaftern die Seltenheit irgendeines Naturproduktes berücksichtigt. Die Seltenheit wird niemals gefunden werden als wertebildender Faktor, wenn man nur die Bewegung innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses als wertebildend ansieht, wenn man nicht verstehen lernt allmählich, wie eintritt da oder dort, am hervorragendsten durch die Konsumtion, aber auch durch andere Verhältnisse, was die Wertebildung durch Spannungen ist, durch Situationen, durch Gleichgewichtslagen.

Nun sehen Sie also, daß im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, den wir damit durchaus als einen organischen ansehen können, in den fortwährend der Geist eingreift, auch Entwertung eintreten kann. Entwertung muß fortwährend da sein oder ist fortwährend da. So daß wir also sagen werden: Bei diesem Weg, den die Werte durchmachen, von der Natur, der Arbeit zum Kapital, wird eine fortwährende Entwertung gleichzeitig eintreten. Wenn nämlich diese Entwertung nicht in der entsprechenden Weise eintreten könnte, ja, was würde denn dann geschehen? Was dann geschehen würde, kann Ihnen gerade hier an dieser Stelle (siehe Zeichnung 3) anschaulich werden.

Nehmen Sie einmal, um sich das wirklich klarzumachen, die Kreditfrage, das Kreditproblem. Wenn wir in dem Sinne, wie ich das gestern auseinandergesetzt habe, das Kapital in den Dienst des Geistes stellen wollen, so wird ja der geistige Produzent zum Schuldner. Er wird zum Schuldner oder kann zum Schuldner werden nur dadurch, daß er Kredit hat. Hier tritt der Kredit ein (siehe Zeichnung), und zwar dasjenige, was man nennen kann den persönlichen Kredit. Er hat Kredit. Der Kredit ist zahlenmäßig auszudrücken, Was ihm viele andere oder mehrere andere eben an Kapital vorschießen, das ist gewissermaßen sein Personalkredit. Nun, dieser Personalkredit hat ja, wie Sie wissen, eine bestimmte Folge, wenigstens wenn wir ihn innerhalb unserer jetzigen nationalökonomischen Verhältnisse betrachten. Er hat etwas zu tun in seiner volkswirtschaftlichen Wirksamkeit mit dem Zinsfuß.

Nehmen Sie an, der Zinsfuß ist niedrig. Ich habe wenig zu bezahlen an die Menschen, die mir das Kapital vorschießen, wenn ich als geistiger Schöpfer im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß zum Schuldner werde, also zu demjenigen, der Kredit in Anspruch nimmt. Ich kann dadurch, daß ich weniger an Zins zu bezahlen habe, meine Waren billiger herstellen; dadurch werde ich in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß verbilligend einwirken können. Wir können also sagen: der Personalkredit verbilligt die Produktion, wenn der Zinsfuß abnimmt. Wenn wir dieses Verhältnis so lange betrachten, solange das Kapital noch vom Geiste einfach verwertet wird im ökonomischen Prozeß, ist das immer so. Bei sinkendem Zinsfuß kann sich derjenige, der Kredit braucht, leichter rühren, er kann in einer intensiveren Weise eingreifen in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, in intensiverer Weise nämlich für die anderen. Wenn er zunächst Waren verbilligt, so greift er in fruchtbarer Weise zunächst für die Konsumenten ein.

Nun aber stellen wir uns das andere vor. Es wird Kredit gegeben, sogenannter Realkredit, auf Grund und Boden. Wenn Realkredit auf Grund und Boden gegeben wird, so steht die Sache wesentlich anders. Nehmen Sie an, der Zinsfuß ist fünf Prozent. Und derjenige, der Kapital auf den Grund und Boden aufnimmt, muß fünf Prozent bezahlen. Kapitalisieren Sie das, so bekommen Sie das Kapital, das diesem Grund und Boden entspricht, das heißt dasjenige, um das der Grund und Boden gekauft werden muß. Nehmen Sie an jetzt, der Zinsfuß fällt auf vier Prozent, dann kann mehr Kapital in diesen Grund und Boden hineinkreditiert werden, wird wenigstens mehr hineinkreditiert. Und wir sehen überall, daß infolge des sinkenden Zinsfußes Grund und Boden nicht billiger, sondern teurer werden. Grund und Boden werden infolge sinkenden Zinsfußes nicht billiger, sondern teurer. Realkredit verteuert, während Personalkredit verbilligt. Realkredit verteuert den Grund und Boden, während Personalkredit die Waren verbilligt. Das heißt aber eigentlich sehr viel im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß; das heißt, daß, wenn das Kapital nun wiederum zurückkommt zur Natur und sich einfach mit der Natur in Form des Realkredites verbindet, so daß man dann eine Verbindung von Kapital mit Grund und Boden, das heißt mit der Natur hat, man den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß immer mehr und mehr in die Verteuerung hineinführt.

Vernünftig kann es also nur sein innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses, wenn sich das Kapital hier (siehe Zeichnung 3) nicht erhält in der Natur, sondern wenn es in die Natur hinein verschwindet. Auf welche Weise kann es verschwinden in die Natur hinein? Ja, solange Sie überhaupt das Kapital verbinden können mit der Natur, also fortwährend durch die Kapitalbildung die Natur verteuern können in ihrem noch unbearbeiteten Zustande, so lange kann das Kapital in die Natur hinein nicht verschwinden; im Gegenteil, es erhält sich in die Natur hinein. Und in allen Ländern, in denen die Hypothekgesetzgebung dahin geht, daß sich das Kapital mit der Natur verbinden kann, bekommen wir ein Stauen des Kapitals in der Natur im Grund und Boden. Statt daß das Kapital hier (siehe Zeichnung 3) verbraucht werde, das heißt hier verschwinde, statt daß hier eine wertbildende Spannung entsteht, entsteht eine weitere wertbildende Bewegung, die dem volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß schädlich ist. Was davon abhalten kann, ist nur, daß wir demjenigen, der Grund und Boden zu bearbeiten hat, überhaupt nicht einen Realkredit auf den Grund und Boden zusprechen können, wenn der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß gesund ist, sondern auch nur einen Personalkredit, das heißt einen Kredit für die Verwertung des Kapitals durch Grund und Boden. Wenn wir lediglich Grund und Boden verbinden mit dem Kapital, dann staut sich das Kapital, indem es bei der Natur hier ankommt. Wenn es sich aber verbindet mit der geistigen Leistungsfähigkeit desjenigen, der auf Grund und Boden eben die Verwaltung übt, der durch Grund und Boden den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß zu fördern hat, dann verschwindet das Kapital, indem es bei der Natur hier ankommt, dann staut es sich nicht, dann wird es nicht erhalten, sondern dann geht es durch die Natur durch, eben wieder in die Arbeit hinein, und es macht den Kreislauf wiederum. Eine der schlimmsten Stauungen im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß ist diejenige, wo Kapital sich einfach mit der Natur verbindet, wo also, nehmen wir den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß an seinem Anfange - das ist ja nur eine Hypothese -, wo, nachdem sich an die Natur anschließend, Arbeit und Kapital entwickelt haben, dann das Kapital in die Lage kommt, sich der Natur zu bemächtigen, statt sich in die Natur hineinzuverlieren.

Ja, nun werden Sie natürlich einen sehr gewichtigen Einwand haben können, der dahin geht, daß Sie sagen: Ja, nun aber, innerhalb dieser Bewegung ist eben das Kapital entstanden. Wenn es nun da ankommt vor der Natur, und es ist so viel, daß man nicht die Möglichkeit hat, es in die Arbeit zu leiten? Wenn man nicht die Möglichkeit hat, sagen wir, neue Methoden zu finden, um die Rohproduktion zu fördern? Da ist überall nicht die Natur mit dem Kapital verbunden, sondern die Arbeit: wenn wir also hier ankommen mit dem Kapital, und wir machen die Rohproduktion rationeller oder erschließen neue Rohproduktequellen und so weiter, dann können wir hier das Kapital unmittelbar in die Arbeit überleiten. Aber wenn nun zuviel Kapital da ist, empfinden das natürlich die einzelnen Kapitalbesitzer, die nun nichts anfangen können mit ihrem Kapital. Ja, wenn Sie geschichtlich die Sache verfolgen, so ist das auch so, daß in der Tat zuviel Kapital eben entstanden ist, und dadurch das Kapital nur den Ausweg gefunden hat, sich in der Natur zu konservieren. Dadurch haben wir eben gerade den sogenannten Wert, die sogenannte Werterhöhung von Grund und Boden innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses sich herausbilden sehen.

Betrachten Sie aber jetzt in diesem größeren Zusammenhang dasjenige, was durchaus immer ungenügend von den Bodenreformern dargestellt wird, wo die Sache nie verstanden werden kann, so werden Sie sich sagen: Ja, wenn ich das Kapital mit der Natur verbinde, dann wird der Wert der Natur selbstverständlich erhöht. Je mehr Hypotheken auf etwas lasten, desto teurer muß es dann bezahlt werden. Es wird fortwährend erhöht der Wert. Ja, ist denn das aber - die Höherwertung von Grund und Boden -, ist das eine Wirklichkeit? Es ist ja gar keine Wirklichkeit. Naturgemäß kann der Grund und Boden nicht mehr Wert bekommen, er kann mehr Wert höchstens bekommen, wenn eine rationellere Arbeit darauf verwendet wird. Dann ist die Arbeit das Werterhöhende; aber der Grund und Boden als solcher selbst - wenn Sie ihn verbessern, so muß die Arbeit vorangehen -, der Grund und Boden als solcher, werterhöht gedacht, ist ein Unding, ein völliges Unding. Der Grund und Boden, insofern er bloß Natur ist, kann ja noch überhaupt keinen Wert haben. Sie geben ihm ja einen Wert, indem Sie das Kapital mit ihm vereinigen, so daß man sagen kann: Dasjenige, was im heutigen volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhange Wert von Grund und Boden genannt wird, ist in Wahrheit nichts anderes als auf den Grund und Boden fixiertes Kapital; das aber auf dem Grund und Boden fixierte Kapital ist nicht ein wirklicher Wert, sondern ein Scheinwert. Und darauf kommt es an, daß man auch innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses endlich begreifen lernt, was wirkliche Werte sind und was Scheinwerte sind.

Wenn Sie in Ihrem Gedankensystem einen Irrtum haben, dann bemerken Sie ja zunächst nicht die Wirksamkeit dieses Irrtums, weil sich der Zusammenhang zwischen dem Irrtum und allen diesen verschiedenen störenden Prozessen im Organismus, die damit zusammenhängen und die man nur durch Geisteswissenschaft erkennt, weil sich dieser Zusammenhang der heutigen groben Wissenschaft entzieht. Man weiß nicht, wie zum Beispiel in den peripherischen Organen durch Irrtümer Verdauungsstörungen entstehen und so weiter. Aber im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, da wirken eben die Irrtümer, die Scheingebilde, da werden sie real, da haben sie eine Folge. Und es ist eigentlich volkswirtschaftlich kein wesentlicher Unterschied, ob ich, sagen wir, irgendwo Geld ausgebe, das zunächst nicht in irgendeiner Realität begründet ist, sondern das einfach Notenvermehrung ist, oder ob ich dem Grund und Boden Kapitalwert verleihe. Ich schaffe in beiden Fällen Scheinwerte. Durch solche Notenvermehrung erhöhe ich der Zahl nach die Preise, aber in Wirklichkeit tue ich gar nichts im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Ich schichte nur um. Den einzelnen aber kann ich ungeheuer schädigen. So schädigt diejenigen Menschen, die im Zusammenhang im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß drinnenstehen, dieses Kapitalisieren von Grund und Boden.

Sie können ja da ganz interessante Studien anstellen, wenn Sie zum Beispiel vergleichen die Hypothekargesetzgebung, wie sie vor dem Kriege war in mitteleuropäischen Ländern, wo man den Grund und Boden in beliebiger Weise hinaufschrauben konnte, durch die Gesetzgebung selbst bedingt - und wenn Sie in England nehmen die Gesetzgebung, wo der Grund und Boden nicht wesentlich steigen kann in gewisser Weise, wenn Sie sich da die Wirkungen auf den volkswitrtschaftlichen Prozeß anschauen. Doch diese Dinge können ganz interessante Dissertationsthemen abgeben. Einmal die Wirkung der englischen Hypothekargesetzgebung mit der deutschen Hypothekargesetzgebung zahlenmäßig zu vergleichen, würde ein ganz gutes Thema abgeben.

Damit also konnte ich Ihnen anschaulich machen, um was es sich hier eigentlich handelt: daß tatsächlich die Natur hier (siehe Zeichnung 3) nicht zu einer Konservierung des Kapitals führen darf, sondern daß hier das Kapital ungehindert weiterwirken muß wiederum in die Arbeit hinein. Aber wenn es da ist - ich will das noch einmal sagen -, wenn es nicht verwertet werden kann, ja das einzige, wodurch es nicht da ist in einem Maße, in dem es nicht da sein soll, das einzige ist, daß es auf diesem (siehe Zeichnung 3) Wege aufgebraucht wird und daß zuletzt nur so viel da ist, als hier wiederum in die Bearbeitung des Grund und Bodens hineingehen kann, als diese Arbeit braucht. Das Selbstverständlichste ist, daß auf dem Wege hier das Kapital verbraucht wird, daß es konsumiert wird. Es wäre ja auch denken Sie sich das hypothetisch! - etwas Furchtbares, wenn auf dem ganzen Wege hier nichts konsumiert würde. Da würde man die Produkte mitschleppen müssen. Nur dadurch wird die Sache organisch, daß die Dinge aufgebraucht werden. Ebenso aber, wie aufgebraucht wird dasjenige, was erarbeitete Natur ist, wie aufgebraucht wird die durch das Kapital organisierte Arbeit, so muß auf seinem weiteren Wege das Kapital einfach verbraucht werden, richtig verbraucht werden. Ja, dieser Verbrauch des Kapitals, der ist ja etwas, was eben einfach herbeigeführt werden muß.

Das kann nur herbeigeführt werden dadurch, daß der ganze volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß vom Anfang bis zum Ende, das heißt bis zu seiner Rückkehr zur Natur, in richtiger Weise geordnet wird, so daß etwas da ist, wie der Selbstregulator im menschlichen Organismus. Der menschliche Organismus bringt es zustande, daß, wenigstens wenn er normal funktioniert, nicht unverbrauchte Nahrungsstoffe da oder dort abgelagert werden. Und wenn unverbrauchte Nahrungsstoffe da oder dort abgelagert werden, so ist man eben krank, ebenso wie wenn unverbrauchte Teile des Organismus abgelagert werden. Denken Sie sich zum Beispiel, bei der Kopfverdauung werden die Stoffe abgelagert, das heißt es tritt im Kopfe eine unregelmäßige Verdauung ein. Die Sachen werden nicht fortgeschafft, die abgelagert werden. Also der Verbrauch ist nicht ordentlich geregelt. Dann kommen die Migränezustände. So könnten Sie überall sehen im menschlichen Organismus, wie im nicht richtigen Aufnehmen und Wegschaffen des zu Verdauenden, wie da die Ursache von Krankheitserscheinungen liegt. Ebenso ist es im sozialen Organismus in dem Anhäufen von demjenigen, was eigentlich an einer bestimmten Stelle verbraucht werden soll. Es ist einfach notwendig, daß hier (siehe Zeichnung 3) der Verbrauch des Kapitals eintritt, damit mit der Natur nicht das Kapital eben sich zum Unlebendigen verbinden kann, gleichsam zu einem versteinerten Einsatz im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Denn der kapitalisierte Grund und Boden ist eben ein unmöglicher Einsatz im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß.

Ich möchte ausdrücklich bemerken, daß es sich hier nicht handelt um agitatorische Dinge. Ich will die Dinge entwickeln, wie sie sich aus dem natürlichen Prozeß heraus gestalten. Nur das Wissenschaftliche soll hier in Betracht kommen; aber man kann eine Wissenschaft, die mit dem Handeln der Menschen sich beschäftigt, nicht treiben, ohne daß man hinweist darauf, was für Krankheitserscheinungen entstehen können, so wie man auch den menschlichen Organismus nicht betrachten kann, ohne daß man hinweist darauf, was für Krankheitserscheinungen entstehen können. Nun, der entsprechende Verbrauch des Kapitals muß da sein, nur nicht der ganze Verbrauch, sondern was notwendig ist, das ist: daß eben noch etwas übergeht, damit dann die Natur weiter bearbeitet werden kann.

Das aber, was da übergehen muß, das kann ich Ihnen wiederum durch ein Bild klarmachen. Nehmen Sie einen Landmann, der muß volkswirtschaftlich danach trachten, daß er das, was das Erträgnis seiner Äcker ist, daß er das tatsächlich wegschafft und für das nächste Jahr das Saatgut behält. Das Saatgut muß fortbehalten werden, muß konserviert werden. Das ist durchaus ein Bild, das sich anwenden läßt auf diesen Prozeß hier (siehe Zeichnung 3). Das Kapital muß soweit verbraucht werden, daß lediglich noch das bleibt, was als eine Art von Saat für die weitere Anfachung des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses, wiederum von der Natur aus, aufgefaßt werden kann. Also nur das darf bleiben, was etwa rationeller die Förderung von gewissen Rohproduktequellen besorgt, was unter Umständen auch den Boden verbessert, sagen wir, durch Schaffung von besseren Düngesubstanzen. Aber da müssen Sie Arbeit aufwenden. Also es muß das dem Verbrauch entzogen werden, was als Arbeit fortwirken kann; dagegen das muß verbraucht werden vorher, was, wenn es noch hier wäre (siehe Zeichnung 3), sich mit der Natur in unorganischer Weise verbinden würde.

Nun können Sie sagen: Also, sag uns jetzt, wie das geschieht, daß nun gerade richtig hier nur so viel Kapital ankommt, daß dieses Kapital gewissermaßen nur das Saatgut für das folgende ist! Sag uns das!

Nun, wir stehen mit der Volkswirtschaftswissenschaft nicht auf einem logischen Boden, sondern wir stehen mit der Volkswirtschaftswissenschaft auf einem realen Boden. Da kann man nicht Antworten geben, wie man sie unter Umständen, sagen wir, in der bloß theoretischen Ethik bekommt. Nicht wahr, man kann in der theoretischen Ethik einen Verbrecher sehr schön ermahnen und alles Mögliche tun. Da wird man ethisch genug getan haben. Aber das Volkswirtschaftliche, das muß geschehen, das muß sich abspielen. Man muß von Realitäten reden. Wenn man vom Produktionsprozeß redet und zeigt, inwiefern er Werte schafft, redet man von Realitäten. Daß man beim Konsum von Realitäten spricht, weiß ja jeder. Also, man muß in der Volkswirtschaft von lauter Realitäten sprechen. Ideen, die bewirken nichts in der realen Welt. Dasjenige, was den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß in der richtigen Weise regelt, das spricht sich aus in dem, was ich in meinen «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage » die wirklichen Assoziationen genannt habe.

Wenn Sie nämlich das wirtschaftliche Leben auf sich selber stellen und diejenigen Menschen, die am wirtschaftlichen Leben beteiligt sind, sei es als Produzenten, sei es als Händler, sei es als Konsumenten, wenn Sie diese Menschen zusammenfassen entsprechend in Assoziationen, dann werden diese Menschen durch den ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hindurch die Möglichkeit haben, eine zu starke Kapitalbildung aufzuhalten, eine zu schwache Kapitalbildung anzufachen.

Dazu gehört natürlich die richtige Beobachtung des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses. Sie gehört dazu. Wenn also irgendwo eine Warengattung, sagen wir, zu billig wird oder zu teuer wird, so muß man das in der entsprechenden Weise beobachten können, Billiger werden und teurer werden hat ja natürlich noch keine Bedeutung; erst dann, wenn man in der Lage ist, aus den Erfahrungen heraus, die nur im Zusammenberaten der Assoziationen entstehen können, zu sagen: Fünf Geldeinheiten sind für eine Menge Salz zu wenig oder zu viel - erst dann, wenn man wirklich sagen kann, der Preis ist zu hoch oder zu niedrig, dann wird man die nötigen Maßregeln ergreifen können.

Wird der Preis irgendeiner Ware, irgendeines Gutes zu billig, so daß diejenigen Menschen, welche das Gut herstellen, nicht mehr in der entsprechenden Weise für ihre zu billigen Leistungen, für ihre zu billigen Ergebnisse Entlohnung finden können, dann muß man für dieses Gut weniger Arbeiter einstellen, das heißt die Arbeiter nach einer anderen Beschäftigung ableiten. Wird ein Gut zu teuer, dann muß man die Arbeiter herüberleiten. Man hat es zu tun bei den Assoziationen mit einem entsprechenden Beschäftigen von Menschen innerhalb der einzelnen Zweige der Volkswirtschaft. Man muß sich klar darüber sein, daß ein wirkliches Steigen des Preises für einen volkswirtschaftlichen Artikel ein Zunehmen der Menschen, die diesen volkswirtschaftlichen Artikel bearbeiten, bedeuten muß, und daß ein Sinken des Preises, ein zu starkes Sinken des Preises, die Maßregel notwendig macht, die Arbeiter ab- und auf ein anderes Arbeitsfeld herüberzulenken. Wir können von den Preisen nur sprechen im Zusammenhang mit der Verteilung der Menschen innerhalb gewisser Arbeitszweige des betreffenden sozialen Organismus.

Was für Ansichten herrschen zuweilen heute, wo man überall die Tendenz hat, lieber mit Begriffen zu arbeiten als mit Realitäten, das zeigen Ihnen manche Freigeldleute. Die finden es ganz einfach: Wenn Preise, sagen wir, zu hoch sind irgendwo, also man zuviel Geld ausgeben muß für irgendeinen Artikel, so sorge man dafür, daß das Geld geringer wird, dann werden die Waren billiger, und umgekehrt. Wenn Sie aber gründlich nachdenken, so werden Sie finden, daß das ja gar nichts anderes in Wirklichkeit bedeutet für den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, als wenn Sie beim Thermometer so durch eine hinterlistige Vorrichtung, wenn es zu kalt wird, die Thermometersäule zum Steigen bringen. Sie kurieren da nur an den Symptomen herum. Dadurch, daß Sie dem Gelde einen anderen Wert geben, dadurch schaffen Sie nichts Reales.

Reales schaffen Sie aber, wenn Sie die Arbeit, das heißt die Menge der arbeitenden Leute, regulieren; denn es hängt eben der Preis von der Menge der Arbeiter ab, die auf einem bestimmten Felde arbeiten. So etwas durch den Staat ordnen wollen, das würde die schlimmste Tyrannei bedeuten. So etwas durch die freien Assoziationen, die innerhalb der sozialen Gebiete entstehen, zu ordnen, wo jeder den Einblick hat - er sitzt ja in der Assoziation, oder sein Vertreter sitzt darin, oder es wird ihm mitgeteilt, was darin geschieht, oder er sieht es selber ein, was zu geschehen hat -, das ist dasjenige, was zu erstreben ist.

Natürlich ist das andere damit verbunden, daß man nun sorgen muß, daß der Arbeiter nun nicht bloß sein ganzes Leben lang nur irgendeinen Handgriff kann, daß er sich auch anders betätigen kann. Denken Sie, das wird notwendig werden, namentlich notwendig aus dem Grunde, weil sonst zuviel Kapital hier (siehe Zeichnung 3) ankommt. Da können Sie das Kapital, das hier zuviel wäre, dazu verwenden, um den Arbeitern etwas beizubringen, um sie in andere Berufszweige überzuführen. Also, Sie sehen, in dem Augenblick, wo man rationell denkt, da korrigiert sich der nationalökonomische Prozeß — das ist das Wichtige, das Wesentliche -, er korrigiert sich. Aber er wird sich nie korrigieren, wenn man bloß sagen würde, durch das und jenes, durch Inflation oder durch Ausgabe von den oder jenen Verfügungen wird es besser werden. Dadurch wird es nicht besser, sondern lediglich dadurch, daß Sie den Prozeß an jeder Stelle beobachten lassen, und die beobachtenden Leute unmittelbar die Konsequenz ziehen können.

Bis hierher wollte ich heute kommen, damit Sie sehen, daß es sich bei dem, was als Dreigliederung gemeint war, nicht gehandelt hat darum, Agitation zu treiben, sondern der Welt etwas zu sagen, was folgt aus einer realen Betrachtung des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses.

Fifth Lecture

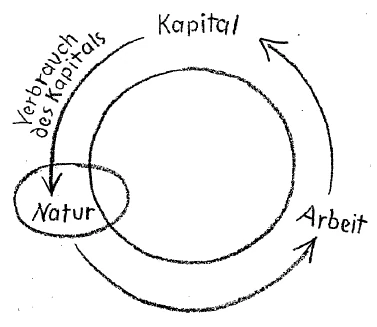

If we take a closer look at the sequence of events within the economic process that we considered yesterday, we will see the following. We have seen how the economic process gets underway by first working with nature, that is, by transforming raw, unprocessed natural products, which are still worthless within the economic process, into processed natural products. Then we saw how the process continues as labor is, in a sense, captured by capital, which structures and organizes labor, and then labor disappears again within capital, so that capital must work for the further progress of the economic process. But this work is no longer work in the same sense as before; rather, it is an absorption of capital from the purely spiritual. And then, as I described yesterday, the spiritual further utilizes capital within the economic process, and this process continues.I would like to present what I have explained here schematically, symbolically, so that we can gradually ascend to an understanding of the formula I indicated yesterday. We can say: Nature perishes in work (see drawing 3). So that we have this flow from Table 4a Nature into work. Nature perishes in labor. Labor continues to develop. The developed values continue to flow, so to speak. Labor disappears into capital. And we have followed the process up to this point (see drawing 3). You will now be able to easily continue it. It is necessary for the cycle to close. Capital cannot simply come to a standstill. Otherwise, we would not be dealing with an organic process, but with a process that would die in capital. Capital must disappear back into nature. You can actually follow this clearly, but you must first use another concept if you want to understand this disappearance of capital into nature correctly.

Consider what I have actually developed before you here in the economic process. I have developed the processing of nature, the organization of work by the mind, and thus the emergence of capital, which is a side effect of the organization of work by the mind. Then the existence of capital, which is, in a sense, the takeover of capital from the mind that organizes labor, this independence of capital, where labor disappears and where the mind now works in capital as an inventive mind, but in a social context. The actual technical aspects of inventions are not our concern here; the actual technical aspects of inventions will only come into consideration when we continue our discussions.

Now, everything I have described to you here—just take a look at it—is described from a one-sided point of view. I also had to describe it from a one-sided point of view. For everything has been described from the standpoint of production. Basically, I have so far only hinted at anything other than production. I have, so to speak, only occasionally included concepts derived from consumption when it came to approaching the question of price; but you will not actually have noticed anything about consumption. So, I have been talking about production so far. But the economic process does not consist solely of production, but also of consumption.

If you think about it, you will see that consumption is the exact opposite of production. We have endeavored to find values within production that arise in the economic process; but consumption consists in the continuous removal of these values, in the continuous use up of these values, that is, in the continuous devaluation of these values. And that is in fact what plays the other role in the economic process: a continuous devaluation of values. This gives us a certain right to say that the economic process is an organic one, a process in which the spiritual intervenes; for an organism consists precisely in forming something and then deforming it again. There must be continuous production and consumption in the organism. This must also be present in the economic organism. There must be continuous production and consumption.

This brings us to seeing what has actually been revealed so far in terms of value-creating forces in a different light, from a different point of view. So far, we have actually only shown how values arise within or in the course of the production process. But now, every time a value is about to be devalued, the whole movement we have seen so far changes. What we have observed is a continuous movement: value is created by applying labor to nature; value is created by applying the mind to labor; value is created by applying the mind to capital. And all of this is a progressive movement.

We can therefore say that we have considered the value-creating movement within the economic process. However, because devaluation, consumption, now also enters into this economic process everywhere, there is something else. There is that unfolding of value which now arises between production itself and consumption. When value enters into consumption, it does not move any further. It does not become more valuable. It does not move any further. It is confronted by something. It is confronted by consumption with its development of needs. Here, value is placed in something completely different from what it appeared to be in our previous consideration. Until now, we have considered value in a continuous movement. Now we must begin to consider value up to a certain point, but then view it as being held back. Every time value is held up, it is not a value-creating movement that continues, but a value-creating tension. And that is the second element in the economic process. In the economic process, we not only have value-creating movements, but also value-creating tensions. And we can observe such value-creating tensions most clearly when the consumer simply faces the producer or dealer, and when, in the next moment, we could say, value creation ceases as it turns into devaluation. This creates a tension, and this tension is kept in balance by the need on the other side. There (see drawing), the value-creating process is halted: the need, consumption, opposes it, and tension arises between production and consumption, which is now also a value-creating factor, but a value-creating factor that cannot be compared to a force that is developed, halted, kept in balance, not a continuing effect of forces. You have here an analogy to the physics of living forces and tensile forces, living energies and the energies of the situation where equilibrium is created. If you do not take these tensile energies into account in the economic process, you arrive at the most curious views. We will see how, when such views are developed, one arrives at conceptions of every economic relationship, but how one otherwise ends up with the most confused views. If, for example, you only consider economic movements of energies from one perspective, you will not be able to understand why the diamond in the crown of England has such enormous value; for then you are forced to resort to the concept of economic tension value. Similarly, many economists today still take into account the rarity of a natural product. Rarity will never be found as a value-creating factor if one only considers movement within the economic process as value-creating, if one does not gradually learn to understand how, here and there, most prominently through consumption, but also through other circumstances, value is created through tensions, through situations, through states of equilibrium.

So you see that in the economic process, which we can certainly regard as organic, in which the mind is constantly intervening, devaluation can also occur. Devaluation must be constantly present or is constantly present. So we will say: on this path that values take, from nature and labor to capital, continuous devaluation will occur at the same time. For if this devaluation could not occur in the appropriate manner, what would happen then? What would happen then can be illustrated to you right here at this point (see drawing 3).

To really understand this, let's take the credit question, the credit problem. If, in the sense I explained yesterday, we want to put capital at the service of the mind, then the intellectual producer becomes a debtor. He becomes a debtor or can become a debtor only because he has credit. This is where credit comes in (see diagram), specifically what can be called personal credit. He has credit. The credit can be expressed in figures. What many others or several others advance to him in capital is, in a sense, his personal credit. Now, as you know, this personal credit has a certain consequence, at least when we consider it within our current national economic conditions. It has something to do with the interest rate in terms of its economic effectiveness.

Suppose the interest rate is low. I have little to pay to the people who advance me the capital when, as an intellectual creator in the economic process, I become a debtor, that is, someone who takes out a loan. Because I have less interest to pay, I can produce my goods more cheaply; this enables me to have a cost-reducing effect on the economic process. We can therefore say that personal credit reduces the cost of production when the interest rate falls. If we consider this relationship as long as capital is still simply exploited by the mind in the economic process, this is always the case. When interest rates fall, those who need credit can move more easily; they can intervene more intensively in the economic process, namely in a more intensive way for others. If they initially reduce the price of goods, they initially intervene in a fruitful way for consumers.

But now let us imagine the opposite. Credit is granted, so-called real credit, on land. When real credit is granted on land, the situation is significantly different. Suppose the interest rate is five percent. And the person who borrows capital on the land has to pay five percent. Capitalize that, and you get the capital that corresponds to this land, that is, the amount for which the land must be purchased. Now suppose the interest rate falls to four percent, then more capital can be credited to this land, or at least more is credited. And we see everywhere that as a result of falling interest rates, land does not become cheaper, but more expensive. Land does not become cheaper as a result of falling interest rates, but more expensive. Real estate loans become more expensive, while personal loans become cheaper. Real estate loans make land more expensive, while personal loans make goods cheaper. But that actually means a great deal in the economic process; it means that when capital returns to nature and simply combines with nature in the form of real credit, so that one then has a connection between capital and land, that is, with nature, one leads the economic process more and more into inflation.

It can therefore only be reasonable within the economic process if capital here (see drawing 3) does not remain in nature, but disappears into nature. How can it disappear into nature? Well, as long as you can connect capital with nature at all, i.e., as long as you can continuously increase the price of nature in its unprocessed state through capital formation, capital cannot disappear into nature; on the contrary, it is preserved in nature. And in all countries where mortgage legislation allows capital to be linked to nature, we see a build-up of capital in nature in the form of land. Instead of capital being consumed here (see Figure 3), i.e., disappearing here, instead of a value-creating tension arising here, a further value-creating movement arises that is detrimental to the economic process. The only thing that can prevent this is that we cannot grant a real estate loan on the land to those who have to work the land at all if the economic process is healthy, but only a personal loan, that is, a loan for the utilization of capital through land. If we merely combine land with capital, then capital accumulates as it arrives here in nature. But if it is linked to the intellectual capacity of those who manage the land, who have to promote the economic process through the land, then the capital disappears when it arrives here in nature, it does not accumulate, it is not preserved, but passes through nature, back into work, and the cycle begins again. One of the worst congestions in the economic process is where capital simply combines with nature, where, let us take the economic process at its beginning – this is only a hypothesis – where, after labor and capital have developed in connection with nature, capital then finds itself in a position to take control of nature instead of losing itself in nature.

Yes, now you may of course have a very weighty objection, which is that you say: Yes, but within this movement, capital has emerged. What if it arrives before nature, and there is so much of it that it is not possible to channel it into labor? What if it is not possible to find, say, new methods to promote raw production? Nature is not connected to capital everywhere, but labor is: so when we arrive here with capital and we make raw material production more efficient or tap into new sources of raw materials and so on, then we can transfer the capital directly into labor here. But if there is too much capital, then of course the individual capital owners, who now have no use for their capital, will feel this. Yes, if you look at the historical development of the matter, it is indeed the case that too much capital has been created, and as a result, capital has found its only way out in conserving itself in nature. As a result, we have seen the emergence of the so-called value, the so-called increase in value of land within the economic process.

But if you now consider this in a broader context, which is always inadequately presented by land reformers, where the matter can never be understood, you will say to yourself: Yes, if I combine capital with nature, then the value of nature is naturally increased. The more mortgages there are on something, the more expensive it has to be paid for. Its value is constantly increasing. Yes, but is that – the increase in the value of land – a reality? It is not a reality at all. Naturally, land cannot increase in value; at most, it can increase in value if more rational work is done on it. Then it is the work that increases the value; but land as such—if you improve it, the work must come first—land as such, thought of as increasing in value, is an absurdity, a complete absurdity. Land, insofar as it is merely nature, cannot have any value at all. You give it value by combining it with capital, so that one can say: What is called the value of land in today's economic context is in truth nothing more than capital fixed to the land; but the capital fixed to the land is not a real value, but an apparent value. And what matters is that, even within the economic process, we finally learn to understand what real values are and what apparent values are.

If you have an error in your system of thought, you do not initially notice the effect of this error, because the connection between the error and all these various disruptive processes in the organism that are related to it can only be recognized through spiritual science, because this connection eludes today's crude science. For example, we do not know how errors cause digestive disorders in the peripheral organs, and so on. But in the economic process, these errors, these illusions, have an effect; they become real and have consequences. And in economic terms, there is actually no significant difference between, say, spending money somewhere that is not initially based on any reality, but is simply an increase in banknotes, and giving capital value to land. In both cases, I create illusory values. By increasing the number of banknotes, I raise prices, but in reality I do nothing in the economic process. I am merely shifting things around. However, I can cause enormous damage to individuals. This capitalization of land damages those people who are involved in the economic process.

You can conduct some very interesting studies here, for example, by comparing mortgage legislation as it was before the war in Central European countries, where land could be inflated in any way, due to the legislation itself , and if you take the legislation in England, where land cannot rise significantly in value in a certain way, and look at the effects on the economic process. But these things can make for very interesting dissertation topics. Comparing the effects of English mortgage legislation with German mortgage legislation in numerical terms would be a very good topic.

So I have been able to illustrate to you what this is actually about: that in fact nature here (see drawing 3) must not lead to the conservation of capital, but that capital must continue to flow unhindered back into labor. But if it is there—I want to say this again—if it cannot be utilized, then the only thing that prevents it from being there to an extent that it should not be there is that it is used up in this way (see drawing 3) and that in the end there is only as much left as can be put back into the cultivation of the land, as this work requires. The most obvious thing is that capital is used up along the way, that it is consumed. It would also be terrible, just imagine it hypothetically, if nothing were consumed along the way. Then one would have to carry the products along. It is only through the consumption of things that the process becomes organic. But just as what has been produced by nature is consumed, just as the labor organized by capital is consumed, so too must capital itself be consumed, properly consumed, as it continues on its way. Yes, this consumption of capital is something that simply has to be brought about.

This can only be brought about by properly organizing the entire economic process from beginning to end, that is, until its return to nature, so that there is something like a self-regulator in the human organism. The human organism ensures that, at least when it is functioning normally, unused nutrients are not deposited here and there. And if unused nutrients are deposited here and there, then one is ill, just as when unused parts of the organism are deposited. Consider, for example, that during head digestion, substances are deposited, which means that irregular digestion occurs in the head. The things that are deposited are not removed. So consumption is not properly regulated. Then migraine conditions occur. You can see everywhere in the human organism how the cause of disease symptoms lies in the incorrect absorption and removal of what is to be digested. The same is true in the social organism in the accumulation of what is actually supposed to be consumed in a certain place. It is simply necessary that here (see drawing 3) the consumption of capital takes place, so that capital cannot combine with nature to form something lifeless, as it were, a fossilized investment in the economic process. For capitalized land is precisely an impossible investment in the economic process.

I would like to expressly note that this is not a matter of agitation. I want to develop things as they arise from the natural process. Only scientific considerations should be taken into account here; but one cannot pursue a science that deals with human actions without pointing out the symptoms of disease that can arise, just as one cannot study the human organism without pointing out the symptoms of disease that can arise. Well, the corresponding consumption of capital must be there, but not the entire consumption, only what is necessary, that is, that something is left over so that nature can continue to be worked on.