World Economy

GA 340

2 August 1922, Dornach

Lecture X

We must now consider something which I indicated yesterday when speaking to a few among you. I mean the relation between Labour and that which happens when Nature is transformed and elaborated into an object of economic value. In the further course, as we saw, organised Labour—divided Labour—is caught up, in a certain sense, by Capital; and Capital eventually emancipates itself and passes over completely into free spiritual activity, if we may so describe it. From all this you will observe that while there is no such thing as a direct economic value in Labour (this has already been explained), nevertheless, it is Labour which sets economic value in motion. The Nature-product, as such, comes into economic circulation by being worked upon; and the elaboration which gives it its value is the real reason why the object of economic value begins to move. It is so at least within a certain sphere. Subsequently it is the human Spirit working in Capital which keeps the movement going. To begin with, therefore, we have to do with movement. For as soon as we enter the sphere of Capital, we have to reckon with the movement that takes place through Trade Capital, Loaned Capital and eventually through Production Capital proper—Industrial Capital.

Speaking of this movement, we must be aware of one thing above all, namely this: There must be something to bring the values into economic circulation. To get the right idea in this respect, we must today concern ourselves with a somewhat ticklish question of Economics. This question cannot be seen clearly unless we try again and again to discover from direct economic experience what can be said about it and in a certain way to verify things.

I refer in the first place to that which we may call economic profit. The question of profit is extremely difficult. Let us imagine, for instance, that a purchase is taking place: A buys from B. In ordinary lay thinking, we generally apply the concept of profit to the seller only. The man who sells is supposed to make a profit. It is, of course, really an exchange between what the buyer gives and what the seller gives; but if you think the matter through exactly, you can by no means admit that the seller alone makes a profit in the case of purchase and also of barter. For if the seller alone were to profit, then in the total economic life the buyer would always be placed at a disadvantage, whenever a simple exchange takes place. The buyer would always be at a disadvantage; and you will readily admit that this cannot be so; otherwise every transaction of purchase would be an exploitation of the buyer and that is obviously not the case. We are well aware that the man who buys wants to buy advantageously, not at a disadvantage; there can be no doubt about that. Thus, the buyer too can buy in such a way as to make a profit. We have therefore this peculiar phenomenon: Two people make an exchange, and—at any rate in the normal process of purchase and sale—each one of them must make a profit. For practical Economics it is far more important to consider this than is generally realised.

Let us therefore suppose that I sell something and receive money for it. I must gain by giving my commodity away and getting money for it. I must desire the money more than I do the commodity. The buyer on the other hand must desire the commodity more than he desires the money. This, then, is what takes place in the reciprocity of exchange. Both objects passing in exchange—the one in one direction and the other in the other—increase in value. By the bare process of exchange, the things exchanged on both sides become of greater value. How can this be?

Only in this way: When I sell something and receive money for it, I am enabled to do more with the money than he who gives it can do. Conversely, the other man, who receives the commodity, must be able to do more with it than I can. This therefore is the position: The two of us, the buyer and the seller, must stand in different economic situations. The increase of value can only come about through that which lies behind the actual process of purchase and sale. Thus, when I sell something, I must be so placed, economically speaking, that the money has a greater value in my hands than it has in his; while in his case, by virtue of his particular connection with the economic system as a whole, the commodity has a greater value in his hands than it has in mine.

In Economics, you will perceive, we cannot merely consider the actual fact of buying or selling in the abstract. The essential question is: What are the respective economic relationships in which the buyer and the seller stand? If we look at things precisely, we are led, as so often, from what takes place immediately before our eyes at any given place to the whole interconnected economic system. This can also be seen by taking another illustration.

We can observe the real facts if we take our start from barter. Fundamentally speaking, the line of thought I have just opened out can tell you, what is quite true, that barter is not entirely transcended even by the introduction of money into an economic community. In effect, we still barter commodities for money. Precisely inasmuch as both parties make a profit in the transaction, we shall see that the important point is not the mere fact that the one possesses a commodity while the other possesses money. The real point is this: What can each party make of that which he receives? What can he do with it by virtue of his particular economic situation?

To understand it more exactly, let us turn back to the most primitive form of barter. That will throw light on what obtains in circumstances economically more complicated. Suppose that I buy peas. I can do many different things with these peas. I can eat them. And so, assuming that barter is the order of the day and that I have exchanged some other thing which I have manufactured—that is, some commodity—for peas, I get the peas by means of barter and I can, if I like, eat them. But suppose I have acquired a very, very large number of peas, so many that I cannot eat them all—not even if I have a large family—then I shall find someone who may be needing peas, and I shall exchange them with him for something which I in my turn require. I give him peas in return for something which I for my part can use. Substantially, the peas have remained the same; but economically they have not remained the same at all. Economically they have changed, through the very fact that I, instead of consuming them myself, have passed them into circulation, myself merely effecting a transfer of them in the economic process. Economically speaking, what have the peas become by this process? Given the necessary conditions including a statute enacting that everything shall be exchangeable for peas (a sufficient number of peas would have to be produced and it would have to be the law that everything can be exchanged for peas)—and then the peas would be money. In such a case, peas would have become money in the economic process. I mean it literally, in the true sense of the word “money.” A thing does not become money by being essentially different from other things existing in the economic process. It becomes money by undergoing—at a particular point of this process—a transformation from commodity to money. This has been the case with all money: all money has at one time or another been turned from a commodity into money.

Hence you will see once more that with the economic process we always come to the human being: we can do no other than place the living human being into the process. The human being is there in the economic process in any case as a consumer. As a consumer, he stands within it from the very outset. But if he plays an active part in some respect which does not lie within the sphere of consumption, he enters into quite another relationship with the economic life than that which he has as a pure consumer. Such things must be taken into account if we would work towards the formation of true economic judgments, the kind of judgments, in fact, which must above all be formed in what I have called the “Associations.” Within the Associations there must be people who by their practical experience can form their judgments on the basis of such points of view.

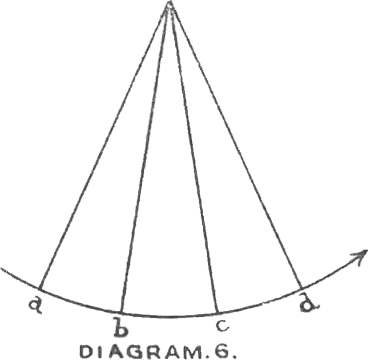

Now the point is: If we have any kind of elaborated Nature or divided Labour in the economic process, we must investigate what it is that brings these economic elements into movement, into circulation. Yesterday, in another circle, I said that we ought to bring into our economic thinking the work or Labour which is active in the economic process, in precisely the same way that the physicist, for example, brings the concept of “work” into his thinking about Physics. The physicist does this by developing a formula, wherein Mass and Velocity occur. Mass is a thing which we determine by the balance. It is with the help of the balance that we are enabled to determine it. Apart from such quantitatively determinable mass, there would be nothing to move forward in the process of “work” in the sense of Physics. The question arises: Is there anything similar in the economic process, so that here, too, Labour or work gives value to the objects, and then at a later stage the active entry of the Spirit gives them value? Is there anything in the economic process comparable, as it were, to the weight of an object in the process of “work” in the sense of Physics? If I describe diagrammatically the progression of the several economic processes, I

see at once that something must be there to bring the whole thing into movement—to push or press the economic element, so to speak, from here to here (see Diagram 6). Moreover, the thing would be still more pronounced if there were not only a pressure working from here to here, but in addition a suction from the other side, so that the whole thing were driven forward by a real force present in the economic process. The economic process would, in fact, have to contain something that drives it forward.

What is it then that drives it forward? I showed you a little while ago how certain forces constantly arise, in the case of both the buyer and the seller. With everyone who has something to do with any other human being in the economic process—not at all in the moral but in the purely economic sense—advantage or profit arises. There is no place within the economic process where we cannot speak of advantage or profit. Nor is this profit anything merely abstract; the immediate economic desire of the man attaches to it, and it must needs be so. Whether he is a buyer or a seller, his economic craving attaches to the profit, to the advantage of the transaction. It is really this attachment to profit which generates the economic process and is the force in it. It is the thing that corresponds to Mass in the process of “work” in the sense of Physics.

You will observe that we have thus revealed something very weighty in the economic process—literally weighty, I would say. Weight, you will admit, is a most prominent thing in purely material products—those products for which the stomach craves. It is the stomach which tells the purchaser that the fruit is more advantageous than the money, in the moment at which he makes the exchange. Here, then, we have in the human being himself the driving motor. And in other cases too—not only in the case of material goods—there must be such a driving force. You need but consider that the mood or feeling of making an advantageous deal is also present in me when I sell a thing and receive money for it. I know that I by my faculties or opportunities shall be able to do more with the money than with the commodities which I possess. At this point, I am already taking a hand in the process with my spiritual faculties.

Transfer this idea to the sum-total of Loaned Capital in any economic organism, and you will soon see: Those who desire to undertake or to do anything, and who need Loaned Capital for the purpose, have precisely the same motive force in their need for Capital as is inherent in the striving for profit. Only, the Loaned Capital works as a kind of suction. If we regard advantage or profit as an impelling, pushing force, the effect of Loaned Capital is one of suction. Moreover, it sucks in the same direction in which advantage or profit pushes. Thus, in profit and in Loaned Capital respectively, we have the forces of pressure and of suction in the economic process.

We thus gain a clear picture of the fact: Inasmuch as the economic process consists in movement and everything must be brought about in it by movement, we must place the human being in it everywhere. For an objective science of Economics this may be uncomfortable; man is a kind of incommensurable magnitude, he is changeable, we have to reckon with him in so many different ways. But there is no getting away from it, this is the fact; and we must reckon with the human being in many different ways.

Now we have seen that, in the process of lending, a kind of suction takes place in the economic process. You know there were times when it was considered immoral to take an interest on loans; it was only considered moral to lend free of interest. Under these conditions there would be no profit in lending. This is indeed the fact. Originally, lending did not arise from the profit one derives from it, that is to say, from the interest; but it arose from the following presumption. If I lend someone something, he can do something with it which I cannot do. Take the simplest instance: Suppose that someone is in dire need and that he can alleviate his need if I am in the position to lend him something. Under conditions more primitive than those of to-day, he would not pay me interest, but the presumption would be that if I, too, am ever in need, he in his turn will help me out. Wherever you trace the matter back in history, you will see that this is the pre-supposition of lending: The other man will lend to me in turn when need arises. It even applies to more complicated social conditions, for the same thing happens when someone borrows money from a money-lending firm and requires guarantors. It has always been the experience of money-lenders that mutual aid plays a great part even in this service. A comes to a money-lender and brings B and C with him to stand sureties; they enter their names as guarantors. In such a case, money-lending firms always reckon on the probability that if B ever comes to borrow money, he will bring with him A and C; or again, B having paid his debt, C will arrive one day and will bring with him A and B as guarantors. In certain circles this is taken as a matter of course. Economists declare that such a law can be assessed just as well as any that can be clothed in mathematical formula. Of course these things are to be taken with the well-known grain of salt which we must always take into account. Our power to do so is part of the mobility of the economic process.

To sum up, therefore, we must say: Originally, there is no return for the service of lending, save the presumption that the borrower will lend to us again; or if not that, that at least he will help us in borrowing, as we helped him. Notably where it is a question of lending and borrowing, human mutuality or “give and take” enters the economic process in a striking way.

If this be so, what is interest? Interest—as has already been remarked by some economists—interest is what I receive if I renounce this “mutuality,” that is to say, if I lend someone something and we agree that he shall be under no obligation to lend to me. If I renounce this mutual right, he pays me interest for it. Interest therefore resolves something which takes place between two human beings; it is a compensation for the human mutuality which plays in the economic process.

This is, however, something which we must set in its right place in the whole economic process. In doing so we must of course remember that there is no sense nowadays in studying economic processes other than those which stand entirely under the sign of the division of Labour; for it is these with which we are in fact concerned. When Labour is divided and distributed, human beings grow dependent on the principle of mutuality to a far greater extent than is the case when every man not only grows his own cabbages but also makes his own hats and boots. It is with the division of Labour that the dependence on mutuality comes. In the division of Labour we have a process working in such a way that the several currents diverge. Yet in the economic process as a whole we see it come about that all these different streams tend to unite again, only in a different way, through the exchange which, in the case of a more complicated economic process, takes place with the help of money. Thus at a certain stage the division of Labour makes mutuality a necessity. In other words, it involves the same element in human intercourse which we find in the case of lending and borrowing. Where much is lent, this principle of mutuality is inherently involved, but in this case it can be redeemed by interest. For interest is mutuality realised. It has been transformed into the abstract form of money. The forces of mutuality are the interest; only they have undergone a metamorphosis. And what we see quite plainly here in the payment of interest takes place throughout the economic process.

This is the great difficulty which besets the formation of economic ideas. You cannot form them in any other way than by conceiving things pictorially. No abstract concept can enable you to grasp the economic process; you must grasp it in pictures. Whereas it is just this which makes the learned world so uneasy today—this demand, no matter in what sphere of thought, that we should pass from the mere abstract concepts to ideation of an imaginative kind. Yet we can never found a real science of Economics without developing pictorial ideas; we must be able to conceive all details of our Economic Science in imaginative pictures. And these pictures must contain a dynamic quality; we must become aware how such a process works under each new form that it assumes.

You will understand me rightly if you will acknowledge to yourselves that there are actually human beings in the economic process—no doubt at its more primitive stages—who are quite unable to think in the way you have learned—or are supposed to have learned—to think in the course of your studies. Nevertheless, they are often excellent husbandmen, excellent economists. They feel precisely whether a given object can be bought or not be bought at such and such a price—whether or no it will be advantageous to buy it. Sometimes a peasant, for example, has not the remotest notion of economic concepts; yet, having attained a certain age, having simply observed the conditions of the market here or there in his district, he knows with precision—without relying on any theoretical concepts—what the picture signifies, when he gives a certain sum of money for a horse or plough. Of course he may make a mistake, but you may do that even if you have studied the logic of Economics!—but the mistakes will not be the most important thing. The picture that is composed before his mind—the picture of a certain sum of money and a plough—calls forth in him the immediate feeling that he can still afford to give so and so much more money, or else that he cannot. He has it directly out of his feeling-experience. Now even in the most complicated economic process, this feeling-experience is not to be eliminated. That is thinking in pictures.

To form abstract ideas would only be fruitful if we could say definitely: One thing is a commodity and another thing is money and we are trading the commodity for money, the money for the commodity. If that were all, it would be simple; but as I showed you just now, even peas may become money. It is simply not true that we in the economic process can grasp anything of it by working abstract concepts into it; it is only by working imaginative perceptions into it that we can grasp anything of it. For instance, we may have the imaginative perception of peas on their way from the market-stall to the mouths of the people only. That is one definite picture. Or we may have the imaginative perception of peas being used as money. That is another picture. Even in Economic Science we must work towards such pictures, pictures taken from what is immediate perception. This means, in other words, that to act rightly in the economic sense, we must make up our minds to enter into the events of production, trade and consumption, with a picture-thinking. We must be ready to enter into the real process; then we shall get approximate conceptions—only approximate ones, it is true—but conceptions which will be of real use to us when we wish to take an actual part in the economic life. Above all, such conceptions will be of use to us when what we do not know by our own sensibility (supposing we ourselves have not arrived through sensibility at the corresponding pictures) is supplemented or corrected by others who are associated with us. There is no other possibility. Economic judgments cannot be built on theory; they must be built on living association, where the sensitive judgments of people are real and effective; for it will then be possible to determine out of the association—out of the immediate experiences of those concerned—what the value of any given thing can be.

Strange as it may sound, it is not possible to determine theoretically wherein the value of a product may consist. We can only say; A product enters into the economic life as a whole through the several parts of the economic process; and its value at a given place must be judged and estimated by association.

How can it be done? How is it that such judgments can be formed—judgments which if they arise in the true way in the economic process do actually arrive at the truth? You can understand it best by analogy with any human or animal organism. The human or animal organism assimilates the foodstuffs that come into it. If I may draw your attention to the scientific facts in this sphere, I may say for example: The human being absorbs the food, permeates it with ptyalin and pepsin, passes it through the stomach, through the intestines. No matter whether the food is flesh or vegetable, the first thing necessary is for the food that is thus passed through the organism to be killed; its life must be quelled. All life must be eliminated from what we have in our intestines. Thereupon, that which we have in our intestinal organs is sucked up by the lymphatic glands and called to life again within ourselves. That which passes from the lymphatic glands through the lymphatic vessels into the blood consists of nature-products (plant or animal) which have died and have been called to life again. Now if you wanted to determine theoretically how much a certain lymphatic gland should receive and call to life again, you simply could not do so: for in one man a lymphatic gland must absorb more, and in another less. Not only so; in one and the same man a lymphatic gland at one place must absorb more and a lymphatic gland at another place must absorb less. Digestion is a most complicated process; no human science could keep pace with this wisdom of the lymphatic glands, with all their beautiful division of labour.

In such a case we are not dealing with judgments propounded, but judgments working in reality. In deed and truth, between our intestinal organs and our arteries, such a sum total of Intelligence is working that nothing comparable to it is to be found in all our human science.

So it is with the economic process. The economic process can only be sound when such a wise self-active Intelligence is working within it. And this can only happen if human beings are united together—human beings who have the economic process within them as pictures, piece by piece; and, being united in the Associations, they complement and correct one another, so that the right circulation can take place in the whole economic process.

Of course, the right mentality is needed for such a thing as this, but the mentality alone is not enough. You may even found Associations, Associations whose members have a great deal of economic insight; yet if something else is not contained within the Associations, all their insight will be of little avail. Something else must be contained in the Associations, and will be contained in them once the necessity of such Associations is recognised. There must be in them the community-spirit—the sense of community, the sense for the economic process as a whole. The individual who immediately uses what he buys can do no other than satisfy his own egoistic sense. Indeed he would come off very badly if he did not satisfy his own egoistic sense. As a single man in the economic life, he cannot say, if someone offers him a coat for 40 francs: “Oh, no, that price does not suit me; I will give you 60 francs for it!” That will not do; at this point the individual within the economic process can do absolutely nothing. But the moment the life of Associations enters the economic process, it is no longer a question of immediate personal interest. The wide outlook over the economic process will be active; the interest of the other fellow will be actually there in the economic judgment that is formed. In no other way can a true economic judgment come about. Thus we are impelled to rise from the economic processes to the mutuality, the give and take between man and man, and furthermore to that which will arise from this, namely the objective community-spirit working in the Associations. This will be a community-spirit, not proceeding from any “moralic acid” but from a realisation of the necessities inherent in the economic process itself.

I should like this to be observed in relation to all the discussions that are opened up, for instance, by my book The Threefold Commonwealth. There is no lack of people nowadays who say: “Our economic life will be good—ever so good—if once you human beings are good; you must become good.” Think of the people like Professor Förster and his kind, who go about preaching: “If men will only become selfless, if they will only fulfil the categorical imperative of selflessness, the economic life will become good.” Such judgments are really of no more worth than this one: If my mother-in-law had four wheels and a handle in front, she would be a bus! Truly the premiss and the conclusion stand in no better connection than this, except that I have expressed it rather more radically.

What underlies The Threefold Commonwealth is none of this moralic acid, which can, no doubt, play a great role in another field. Rather the purpose is to show, simply out of the economic facts, how selflessness cannot help being inherent in the very circulation of the elements of economic life. This is the case, even in the detailed instances. Take, for example, the case where someone is in a position to receive Loaned Capital on credit and is thus enabled to establish an undertaking or an institution and to produce by means of it. He goes on producing so long as his own personal faculties are united with the institution. Afterwards, the thing he has worked up will be handed on in the most intelligent way to some other individual who has the necessary faculties. It will be transferred by a gift—a gift, not from one man to another, but one that takes place through the whole course of economic life. We need only consider how such gifts will be able to be made in an intelligent way by the threefold social organism. Here the domain of economics borders on the social element in man, in the most comprehensive meaning of the term. It touches on that which needs to be conceived for the social organism as a whole.

And you can see it also from the other side. I pointed out how in the simple case of exchange, where money becomes more and more important, or indeed where exchange is recognised at all, the economic life enters directly into the region of law and rights. Moreover the moment Intelligence is to enter the economic life, we must allow to flow into the economic domain that which prevails in the free life of the Spirit. The three members of the social organism must stand in the right relation to one another, so that they may work on one another in the right way.

This was the real meaning of The Threefold Commonwealth—not the splitting into parts of the three members; the splitting apart is always there. The point is rather to find how the three members can be brought together, so that they may really work in the social organism with inherent intelligence, just as the nerves-and-senses system, the heart-and-lungs system, and the metabolic system, for example, work together in the natural organism of man. That is the point, and of this we shall have more to say in the near future.

Zehnter Vortrag

Nun, es ist nötig, daß heute etwas hier besprochen wird, was gestern schon einigen angedeutet worden ist. Das ist das Verhältnis zwischen der volkswirtschaftlichen Arbeit und demjenigen, was zugrunde liegt, wenn Natur durch Bearbeitung umgewandelt wird in ein volkswirtschaftliches Wertobjekt. Dann geschieht ja im weiteren Verlauf dieses, daß die organisierte oder gegliederte Arbeit aufgefangen wird in gewissem Sinn von dem Kapital, das sich dann emanzipiert und vollständig in die, man möchte sagen, freie Geistigkeit übergeht. So daß Sie daraus entnehmen können, daß man in der Arbeit nicht etwas von einem unmittelbaren volkswirtschaftlichen Wert hat - das haben wir ja schon auseinandergesetzt -, wohl aber, daß man in der Arbeit dasjenige hat, was den volkswirtschaftlichen Wert bewegt. Das Naturprodukt als solches kommt in die volkswirtschaftliche Zirkulation dadurch hinein, daß es bearbeitet wird. Und die Bearbeitung, die ihm den Wert gibt, die ist eigentlich die Ursache, warum sich zunächst wenigstens innerhalb eines gewissen Gebietes das volkswirtschaftliche Wertobjekt bewegt. Später ist es dann der in dem Kapital wirkende Menschengeist, der die Bewegung fortsetzt. Zunächst haben wir es zu tun mit dem Bewegen; denn sobald wir in die Kapitalsphäre hineinkommen, haben wir es zu tun mit der Bewegung durch das Handelskapital, dann durch das Leihkapital und dann durch das eigentliche Produktionskapital: durch das Industriekapital.

Wenn wir nun von dieser Bewegung sprechen, so müssen wir uns vor allen Dingen darüber klar sein, daß etwas da sein muß, das die Werte in die volkswirtschaftliche Zirkulation hineinbringt. Und um da zurechtzukommen, müssen wir uns heute schon einmal beschäftigen mit einer, ich möchte sagen, etwas kniffligen volkswirtschaftlichen Frage, die nicht ohne weiteres einzusehen ist, wenn man nicht versucht, das, was darüber gesagt werden kann, in der volkswirtschaftlichen Erfahrung immer weiter aufzusuchen und gewissermaßen die Dinge zu verifizieren.

Es kommt zunächst das in Betracht, was man nennen kann den volkswirtschaftlichen Gewinn. Die Gewinnfrage aber, sie ist eine außerordentlich schwierige Frage. Denn, nehmen wir an, daß sich abspielt ein Kauf. Der A kauft beim B. Nun, man wendet gewöhnlich im laienhaften Denken den Begriff des Gewinnes auf den Verkäufer allein an. Der Verkäufer soll gewinnen. Dann haben wir ja eigentlich nur den Austausch zwischen dem, was der Käufer gibt, und dem, was der Verkäufer gibt. Nun werden Sie aber keineswegs, wenn Sie die Sache genau durchdenken, zugeben können, daß bei einem Kauf oder auch bei einem Tausch lediglich der Verkäufer gewinnt; denn wenn lediglich der Verkäufer gewinnen würde im volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang, so würde ja der Käufer immer der Benachteiligte sein müssen, wenn ohne weiteres ein Austausch stattfinden würde. Der Käufer müßte immer der Benachteiligte sein. Das werden Sie aber von vornherein zugeben, daß das nicht sein kann. Sonst würden wir es bei jedem Kauf zu tun haben mit einer Übervorteilung des Käufers; das ist aber doch ganz offenbar nicht der Fall. Denn wir wissen ja, daß derjenige, der kauft, durchaus vorteilhaft kaufen will, nicht unvorteilhaft. Unbedingt. Also auch der Käufer kann so kaufen, daß auch er einen Gewinn hat. Wir haben also die merkwürdige Erscheinung, daß zwei austauschen und jeder muß — wenigstens im normalen Kaufen und Verkaufen - eigentlich gewinnen. Das ist viel wichtiger zu beachten in der praktischen Volkswirtschaft, als man gewöhnlich denkt.

Nehmen wir also an, ich verkaufe irgend etwas, bekomme dafür Geld; so muß ich dadurch gewinnen, daß ich meine Ware weggebe und Geld dafür bekomme. Ich muß das Geld mehr begehren als die Ware. Der Käufer, der muß die Ware mehr begehren als das Geld. So daß beim gegenseitigen Austausch das stattfindet, daß das Ausgetauschte, sowohl das, was hinübergeht, wie das, was zurückgeht, mehr wert wird. Also durch den bloßen Austausch wird dasjenige, was ausgetauscht wird, mehr wert, sowohl auf der einen wie auf der anderen Seite. Nun, wie kann das eigentlich sein?

Das kann ja nur dadurch sein, daß, wenn ich etwas verkaufe und Geld dafür bekomme, das Geld mir die Möglichkeit bietet, mehr damit zu erreichen als derjenige, der mir das Geld gibt; und der andere, der die Ware bekommt, muß mit der Ware mehr erreichen, als ich mit der Ware erreichen kann. Es liegt also das vor, daß wir - jeder, der Käufer und der Verkäufer - in einem anderen volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang drinnenstehen müssen. Diese Höherbewertung kann erst durch das zustande kommen, was hinter dem Verkauf und Kauf liegt. Also ich muß, wenn ich verkaufe, in einem solchen volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang drinnenstehen, daß durch diesen volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang bei mir das Geld einen größeren Wert hat als bei dem anderen, und bei ihm die Ware einen größeren Wert hat als bei mir durch den volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang.

Daraus wird Ihnen aber schon hervorgehen, daß es in der Volkswirtschaft nicht allein darauf ankommen kann, ob man überhaupt kauft oder verkauft, sondern es kommt darauf an, in welchem volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang Käufer und Verkäufer stehen. Wir werden also geführt, wenn wir genau uns die Sachen anschauen, von demjenigen, was sich unmittelbar an einem Orte abspielt, wiederum, wie wir schon öfter geführt worden sind, zum ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang. Dieser volkswirtschaftliche Zusammenhang enthüllt sich uns aber noch bei einer anderen Gelegenheit.

Das kann man bemerken, wenn man ausgeht zunächst von dem Tauschhandel. Im Grunde genommen gerade eine solche Betrachtung, wie ich sie jetzt angestellt habe, kann Ihnen ja sagen: Eigentlich ist auch dadurch, daß Geld eingeführt wird in irgendeine Volkswirtschaft, der Tauschhandel nicht vollständig überwunden; denn man tauscht halt einfach Waren gegen Geld. Und gerade dadurch, daß jeder gewinnt, werden wir schen, daß etwas ganz anderes das Wichtige ist, als daß der eine die Ware, der andere das Geld hat. Dasjenige ist das ‘ Wichtigste, was jeder mit dem machen kann, was er bekommt, durch seinen volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang.

Aber wenden wir uns, um diese Sache genauer zu verstehen, zurück zum primitivsten Tauschhandel. Er wird uns dann zunächst beleuchten, was in einem komplizierteren volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang ist. Nehmen Sie an, ich kaufe Erbsen. Nun, wenn ich Erbsen kaufe, dann kann ich mit diesen Erbsen das Verschiedenste anfangen. Ich kann sie essen. Nehmen wir also an, wenn ich Tauschhandel pflege, ich tausche mir Erbsen ein für irgend etwas anderes, das ich fabriziert habe, was also Ware ist. Also ich tausche Erbsen ein. Ich kann sie essen; aber ich kann auch recht viele Erbsen eintauschen, recht, recht viele Erbsen eintauschen, und so viele, daß ich sie dann nicht aufessen kann, selbst mit einer großen Familie nicht aufessen kann. Nun wende ich mich an jemanden, der diese Erbsen brauchen kann und tausche mir bei dem etwas ein, was ich jetzt wiederum brauchen kann. Ich gebe ihm Erbsen für das, was ich nun wiederum brauchen kann. Die Erbsen sind substantiell dasselbe geblieben; volkswirtschaftlich sind sie durchaus nicht dasselbe geblieben. Volkswirtschaftlich haben sie sich dadurch geändert, daß ich diese Erbsen nicht selber konsumiert habe, sondern sie weiter in die Zirkulation gebracht habe und bei mir nur den Übergang im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß geschaffen habe. Was sind denn diese Erbsen volkswirtschaftlich jetzt bei mir geworden durch einen solchen Vorgang? Sehen Sie, es brauchte nur, sagen wir, gewisser Voraussetzungen und außerdem noch der gesetzmäßigen Festsetzung, daß man alles für Erbsen eintauschen soll - es müßten genügend Erbsen dann hervorgebracht werden und die gesetzliche Bestimmung müßte da sein, daß man alles für Erbsen eintauschen kann, dann wären die Erbsen das Geld. Es sind also im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß die Erbsen Geld geworden, ganz richtig im wahren Sinn des Wortes sind die Erbsen Geld geworden. Also, etwas wird nicht dadurch Geld, daß es, sagen wir, etwas anderes ist, als was sonst im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß da ist, sondern dadurch, daß es an einer bestimmten Stelle im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß eben eine Umwandlung von Ware in Geld durchmacht. Und das hat alles Geld durchgemacht. Alles Geld hat sich einmal aus Ware in Geld verwandelt.

Auch daraus können wir wiederum sehen, daß wir mit dem volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß an den Menschen herankommen, daß wir also gar nicht anders können, als den Menschen hineinstellen in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Nun wird ja ohnedies schon der Mensch in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hineingestellt als Konsument. Dadurch steht er ja schon von vornherein drinnen. Und gerade, wenn er volkswirtschaftlich in etwas tätig ist, was nicht innerhalb des Gebietes des Konsumierens liegt, dann stellt er sich in ein ganz anderes Verhältnis durch seinen volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang, als er sich hineinstellt als ein bloßer Konsument. Diese Dinge müssen alle berücksichtigt werden, wenn man darauf hinarbeiten will, ein volkswirtschaftliches Urteil zu bilden. Und volkswirtschaftliche Urteile müssen ja in demjenigen gebildet werden, was ich die Assoziationen nenne, Es müssen also in den Assoziationen durchaus Leute sein, die aus der Praxis heraus ihr Urteil nach solchen Gesichtspunkten bilden.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß wir, wenn wir irgend bearbeitete Natur oder gegliederte Arbeit im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß drinnen haben, daß wir dann untersuchen müssen, was gewissermaßen diese volkswirtschaftlichen Elemente in Bewegung, in Zirkulation bringt. Es ist gestern an einer andern Stelle darauf aufmerksam gemacht worden, daß man ja in das volkswirtschaftliche Denken hineinbringen sollte die Arbeit, die im Wirtschaftsprozeß tätig ist, ebenso wie zum Beispiel der Physiker die Arbeit in sein physikalisches Denken hineinbringt. Da muß dann gesagt werden: Ja, der Physiker bringt in sein physikalisches Denken die Arbeit dadurch hinein, daß er eine Formel sich ausbildet, in der Masse und Geschwindigkeit ist. — Nicht wahr, Masse aber ist etwas, was wir durch die Waage bestimmen. Wir haben also eine Möglichkeit, die Masse durch die Waage zu bestimmen. Ohne daß wir die Masse durch die Waage bestimmen könnten, hätten wir nichts, was da fortschreitet im physikalischen Arbeitsprozeß. Die Frage muß für uns entstehen: Ist nun etwas Ähnliches auch vorhanden im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, so daß die Arbeit den Dingen Wert erteilt und auch später das geistige Eingreifen wieder den Dingen Wert erteilt? Ist im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß etwas drinnen, das sich vergleichen läßt gewissermaßen mit dem Gewichte, das irgendein Gegenstand hat, wenn man bei ihm reden will von physikalischer Arbeit? Nun, wenn ich einfach schematisch aufzeichne den Fortgang der volkswirtschaftlichen Einzelprozesse, so zeigt mir das, daß etwas da sein muß, das die ganze Sache in Bewegung bringt, das gewissermaßen die volkswirtschaftlichen Elemente von hier (siehe Zeichnung 6) nach hier drückt. Und die Sache würde noch bestimmter sein, wenn nicht nur von hier nach hier gedrückt würde, sondern wenn auch extra von der anderen Seite eine Saugwirkung stattfinden würde, wenn also das Ganze durch eine im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß befindliche Kraft weitergetrieben würde. Dann müßte in diesem volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß etwas da sein, was weitertreibt.

Nun, was ist das, was da weitertreibt? Ich habe es Ihnen gerade vorhin gezeigt, daß fortwährend gewisse Kräfte entstehen, sowohl beim Käufer wie beim Verkäufer; bei jedem, der mit dem anderen etwas zu tun hat im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, gar nicht im moralischen Sinn, sondern im rein volkswirtschaftlichen Sinn, entsteht Vorteil und Gewinn. So daß es keine Stelle im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß gibt, wo nicht von Vorteil und Gewinn gesprochen werden muß. Und dieser Gewinn, der ist nicht etwas bloß Abstraktes; dieser Gewinn, an dem hängt das unmittelbare wirtschaftliche Begehren des Menschen und muß daran hängen. Ob der Betreffende Käufer oder Verkäufer ist, es hängt sein wirtschaftliches Begehren an diesem Gewinn, an diesem Vorteil. Und dieses Hängen an diesem Vorteil ist dasjenige, was eigentlich den ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hervorbringt, was die Kraft in ihm ist. Es ist dasjenige, was beim physikalischen Arbeitsprozeß die Masse darstellt.

Bedenken Sie, daß man damit eigentlich etwas außerordentlich Gewichtiges im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß aufgezeigt hat, man möchte sagen, etwas wirklich Gewichtiges. Nicht wahr, das Gewicht tritt ja am meisten hervor bei den rein materiellen Erzeugnissen, bei den Erzeugnissen, die der Magen begehrt. Daher erklärt der Magen, daß allerdings für den Käufer, sagen wir, das Obst vorteilhafter ist als das Geld in dem Moment, wo er den Tausch besorgt. Da haben wir also durchaus in dem Menschen selber diesen Motor, der da treibt. Aber auch bei anderem als bei dem, das nur materielle Güter darstellt, haben wir diesen treibenden Motor. Bedenken Sie nur einmal, daß ja diese Stimmung, in Vorteil, in Gewinn sich hineinzuleben, auch vorhanden ist, wenn ich verkaufe, Geld bekomme: ich weiß, daß ich nun durch meine Fähigkeiten mit diesem Gelde mehr machen kann als mit den Waren, die ich habe. Da schon greife ich mit meinen geistigen Fähigkeiten ein.

Und übertragen Sie sich das jetzt einmal auf die gesamte Summe des Leihkapitals in einem volkswirtschaftlichen Körper, da werden Sie sehr bald sehen können, daß diejenigen, die irgend etwas unternehmen oder ausführen wollen und dazu Leihkapital brauchen, eben in dem Bedürfnis nach Leihkapital ganz genau denselben Motor haben, welcher liegt im Gewinnstreben. Nur wirkt das Leihkapital eigentlich, wenn ich den Gewinn als ein Schieben betrachte, wie aufsaugend; es wirkt saugend, aber nach derselben Richtung hin, wohin auch die Gewinne drücken. So daß wir in den Gewinnen und im Leihkapital durchaus dasjenige haben, was im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß drückt und saugt.

Wir bekommen dadurch eine deutliche Anschauung davon, daß, insofern der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß eigentlich nur in der Bewegung besteht und durch die Bewegung im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß alles eigentlich bewirkt werden soll, was durch ihn bewirkt werden kann, daß wir überall in diesen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß den Menschen einfügen müssen, den Menschen hineinstellen müssen. Das kann ja für die objektive Volkswirtschaft etwas unbequem sein, weil der Mensch eine Art von inkommensurabler Größe ist, weil er wandelbar ist, weil man in verschiedener Weise auf ihn rechnen muß; aber das ist nun einmal da und es muß mit ihm in verschiedener Weise gerechnet werden.

Nun sehen wir aber schon, daß beim Leihen eine Art von Saugwirkung stattfindet innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses. Sie wissen ja, daß es Zeiten gegeben hat, in denen das Zinsnehmen für Geliehenes als unmoralisch galt. Und es galt nur als moralisch, zinslos zu leihen. Da wäre kein Vorteil gewesen bei dem Leihen. In der Tat: das Leihen ging eigentlich ursprünglich nicht aus von dem Vorteil, den man durch das Leihen hat, von dem Zins; sondern das Leihen ging unter primitiveren Verhältnissen, als die heutigen sind, aus von der Voraussetzung, daß, wenn ich jemand etwas leihe und der kann etwas damit machen, was ich nicht machen kann - sagen wir nur: er ist in Not und er kann seiner Not abhelfen, wenn ich ihm etwas zu leihen imstande bin -, daß er mir jetzt nicht hohen Zins bezahlt, sondern daß, wenn ich wiederum etwas brauche, er mir auch wiederum aushilft. Überall in der Geschichte, wo Sie zurückgehen, werden Sie sehen, daß die Voraussetzung des Leihens die ist, daß der andere wiederum zurückleiht, wenn es nötig ist.

Das wird sogar auf die komplizierteren sozialen Verhältnisse übertragen. Sie haben das zum Beispiel, wenn, sagen wir, jemand bei einer Leihanstalt etwas ausleiht, und er braucht dazu zwei Gutsteher, die da kommen und für ihn gutstehen müssen, daß die Leihanstalten dann immer die eigentümliche Erfahrung gemacht haben, daß selbst für diesen Dienst die Gegenseitigkeit eine außerordentlich große Rolle spielt. Denn, wenn der \(A\) kommt zu einer Leihanstalt und bringt den \(B\) und \(C\) mit, die Gutsteher sind, die also ihre Namen eintragen als Gutstehende, so rechnen die Leihanstalten immer darauf, daß dann der \(B\) kommt und bringt den \(A\) und \(C\) mit, und wenn der B die Sache bezahlt hat, dann kommt der \(C\) und bringt den \(A\) und \(B\) mit als Gutsteher. Und es gilt das unter gewissen Menschen als etwas ganz Selbstverständliches. So daß Volkswirtschafter behaupten, eine solche Gesetzmäßigkeit sei mit demselben Rechte zu behaupten, wie irgend etwas, was durch mathematische Formeln festgesetzt ist. Nun sind natürlich diese Dinge mit dem bekannten Gran Salz zu verstehen; man muß da immer mit der nötigen Zutat rechnen. Aber das gehört eigentlich auch in die Beweglichkeit des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses hinein, daß man damit rechnen kann.

So daß man sagen kann: Ursprünglich ist das Entgelt des Leihens bloß die Voraussetzung, daß einem der Beliehene wieder leiht, beziehungsweise wenn er einem nicht wieder leiht, wenigstens beim eigenen Leihen hilft, wenn man ihm beim Leihen geholfen hat. Es kommt gerade, wenn es sich um das Leihen handelt, die menschliche Gegenseitigkeit in einer ganz eklatanten Weise in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hinein.

Was ist denn dann, wenn die Dinge so sind, der Zins? Der Zins das ist übrigens schon von einzelnen Volkswirtschaftern bemerkt worden -, der Zins ist dasjenige, das ich bekomme, wenn ich auf die Gegenseitigkeit verzichte, wenn ich also jemand etwas leihe und ausmache mit ihm, daß er mir niemals etwas zu leihen braucht; dann, wenn ich also auf diese Gegenseitigkeit verzichte, dann bezahlt er mir dafür den Zins. Der Zins ist die Ablösung geradezu für etwas, was zwischen Mensch und Mensch spielt, ist die Vergeltung für dasjenige, was im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß als menschliche Gegenseitigkeit spielt.

Nun sehen wir da etwas auftreten, was wir nur in der richtigen Weise hineinstellen müssen in den ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Wir müssen dabei natürlich immer ins Auge fassen, daß es ja heute nur einen Sinn hat, solche volkswirtschaftliche Prozesse zu betrachten, die ganz im Zeichen der Arbeitsteilung stehen; denn mit solchen haben wir es ja im wesentlichen zu tun. Wenn die Arbeit auseinandergeteilt wird, dann geschieht das, daß die Menschen in einem viel höheren Grade auf die Gegenseitigkeit angewiesen sind, als wenn jeder sich nicht nur seinen eigenen Kohl baut, sondern auch seine eigenen Stiefel und Hüte fabriziert. Mit der Arbeitsteilung kommt das Angewiesenwerden auf die Gegenseitigkeit. Und so sehen wir in der Arbeitsteilung einen Prozeß, der eigentlich so verläuft, daß die einzelnen Strömungen auseinandergehen.

Aber wir sehen im ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß wiederum das auftreten, daß alle diese Strömungen sich vereinigen wollen, nur in einer anderen Weise, durch den x entsprechenden Austausch, der sich also im komplizierten volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß mit Hilfe des Geldes vollzieht. Die Arbeitsteilung macht also notwendig auf einer gewissen Stufe die Gegenseitigkeit, das heißt dasselbe im menschlichen Verkehr, was wir finden zum Beispiel beim Beleihen. Wo viel geliehen wird, da haben wir drinnen dieses Prinzip der Gegenseitigkeit, das aber nun abgelöst werden kann durch den Zins. Dann haben wir im Zins die realisierte Gegenseitigkeit. Wir haben sie nur in die abstrakte Form des Geldes verwandelt. Aber die Kräfte der Gegenseitigkeit sind eben einfach der Zins, sind metamorphosiert, sind etwas anderes geworden. Was wir da ganz deutlich sehen beim Zinszahlen, das findet aber überall im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß statt.

Darauf beruht die große Schwierigkeit, die besteht beim Bilden von volkswirtschaftlichen Vorstellungen; denn Sie können gar nicht anders volkswirtschaftliche Vorstellungen bilden, als lediglich indem Sie etwas bildhaft auffassen. Begriffe gestatten Ihnen gar nicht, den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß zu erfassen, Sie müssen ihn in Bildern erfassen. Das ist dasjenige, was heute nun von aller Gelehrtheit außerordentlich unbequem empfunden wird, wenn irgendwo gefordert wird, daß etwas übergehen soll aus der bloßen Abstraktheit der Begriffe in die Bildhaftigkeit. Wir werden aber niemals eine wirkliche Volkswirtschaftswissenschaft begründen können, ohne daß wir zu bildhaften Vorstellungen übergehen, ohne daß wir also in die Lage kommen, uns die einzelnen volkswirtschaftlichen Detailprozesse bildhaft vorzustellen und sie so vorzustellen, daß wir im Bilde selber etwas Dynamisches drinnen haben und wissen, wie solch ein volkswirtschaftlicher Detailprozeß wirkt, wenn er so oder so gestaltet ist.

Was da eigentlich in Betracht kommt, das werden Sie dann richtig verstehen, wenn Sie sich sagen, daß ja schließlich auch im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, wenn auch auf primitiveren Stufen, Menschen drinnen stehen, die eigentlich in dem Sinn, wie Sie es im Verlaufe Ihrer Studien gelernt haben oder wenigstens hätten lernen sollen, die in dem Sinn nicht denken können. Diese Leute können manchmal ganz ausgezeichnete Wirtschafter sein, können manchmal ganz ausgezeichnet empfinden, ob irgend etwas gerade noch gekauft werden kann oder nicht gekauft werden kann, ob es Vorteil gibt oder nicht Vorteil gibt, wenn ich irgend etwas kaufe. So wird unter Umständen ein Bauer, der von volkswirtschaftlichen Begriffen keinen blauen Dunst hat, noch viel weniger als das hat, und der, wenn er ein gewisses Alter erreicht hat, sich eben nur angeschaut hat da oder dort in seiner Nähe die Marktverhältnisse, ganz richtig wissen - er kann sich natürlich irren, aber das kann man ja auch, wenn man volkswirtschaftliche Logik getrieben hat, es handelt sich ja nur darum, daß die Irrtümer nicht überwiegen -, der wird durchaus wissen, ohne auf Begriffen zu fußen, was das Bild bedeutet, wenn er eine gewisse Summe Geldes für ein Pferd gibt oder für einen Pflug gibt. Dieses Bild, das sich ihm zusammenstellt — eine gewisse Summe Geldes und ein Pflug -, das ruft in ihm unmittelbar die Empfindung hervor: er kann noch so viel Geld geben oder er kann es nicht mehr geben. Er hat es unmittelbar aus der empfundenen Erfahrung. Nun, auch im allerkompliziertesten volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß ist diese empfundene Erfahrung nicht auszuschalten. Das ist aber bildhaftes Vorstellen.

Abstraktes Vorstellen würde fruchtbar sein, wenn wir sagen könnten: Etwas ist Ware, etwas ist Geld, und wir handeln Ware für Geld und Geld für Ware. - Wenn wir das sagen könnten, da wäre die Sache einfach; aber ich habe Ihnen ja doch gerade vorhin gezeigt: selbst Erbsen könnten Geld werden. Es ist gar nicht wahr, daß wir im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß etwas davon haben, wenn wir Begriffe in ihn hineinarbeiten. Wir haben erst etwas, wenn wir Anschauungen in ihn hineinarbeiten. Wenn wir also die Anschauung haben: da wandern die Erbsen von dem Markttisch nur in die Münder der Leute, dann haben wir ein bestimmtes Bild. Wenn wir die andere Anschauung haben: da werden die Erbsen als Geld verwendet, dann haben wir ein anderes Bild.

Und auf solche Bilder - Bilder aus dem unmittelbar Anschaulichen muß hingearbeitet werden, auch in der Volkswirtschaft. Das heißt aber mit anderen Worten: Wenn wir Volkswirtschaft richtig treiben wollen, müssen wir uns bequemen, in bildhafter Weise uns einzulassen auf Produktions-, Handels- und Konsumtionsereignisse. Wir müssen uns auf den realen Prozeß durchaus einlassen, dann bekommen wir annähernde Vorstellungen —- auch nur annähernde Vorstellungen, aber doch solche annähernde Vorstellungen, daß uns diese etwas nutzen, wenn wir im Wirtschaftsleben selbst drinnen handeln sollen, und daß sie uns vor allen Dingen etwas nutzen, wenn das, was wir nicht selber empfindend wissen, woraus wir nicht selber uns empfindend Bilder gemacht haben, wenn das uns korrigiert wird durch die anderen, die mit uns in Assoziationen verbunden sind. Es gibt keine andere Möglichkeit, als das wirtschaftliche Urteil nicht zu bauen auf Theorie, sondern es zu bauen auf die lebendige Assoziation, wo die empfindenden Urteile der Menschen nun real wirksam sind, wo aus der Assoziation heraus fixiert werden kann aus den unmittelbaren Erfahrungen, wie der Wert von irgend etwas sein kann.

So sonderbar das klingt, man sage nicht: Man kann theoretisch bestimmen, worinnen der Wert eines Produktes bestehen kann - sondern man sage: Ein Produkt kommt durch die volkswirtschaftlichen Vorgänge in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hinein und was es wert ist an einer bestimmten Stelle, das hat zu beurteilen die Assoziation.

Worauf beruht es denn, daß sich solche Urteile bilden können, die nun wirklich, wenn sie in der richtigen Weise entstehen im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, auch das Richtige treffen, worauf beruht denn das? Worauf das beruht, das können Sie am besten einsehen durch Analogie mit irgendeinem menschlichen oder tierischen Organismus. Dieser menschliche oder tierische Organismus, der verarbeitet die Nahrungsmittel, die in ihn hineinkommen. Wenn ich Sie zum Beispiel dabei aufmerksam machen soll auf etwas, was auf diesem Gebiete wissenschaftlich ist, so möchte ich sagen: Der Mensch nimmt die Nahrung auf, durchsetzt sie mit Ptyalin, Pepsin, treibt sie durch seinen Magen, treibt sie durch seine Gedärme. Dasjenige, was da notwendig ist, gleichgültig, ob Fleisch oder Pflanzen die Nahrung sind, was da hineingetrieben wird, muß zunächst abgetötet, abgelähmt werden. Das Leben muß heraus sein aus dem, was wir in den Gedärmen haben. Da wird dasjenige, was wir in den Gedärmen haben, aufgesogen durch die Lymphdrüsen und in uns selber wieder neu belebt, so daß also dasjenige, was dann von den Lymphdrüsen aus durch die Lymphgefäße geht in das Blut hinein, daß das wiederbelebte abgestorbene Naturprodukte sind, tierischer oder pflanzlicher Art. Wenn Sie nur bestimmen wollten theoretisch, wieviel da eine Lymphdrüse aufnehmen soll zur Wiederbelebung, dann würden Sie das nicht können; denn bei dem einen Menschen muß eine Lymphdrüse mehr, beim andern muß eine Lymphdrüse weniger aufnehmen. Aber nicht nur das, sondern beim selben Menschen muß eine an einem Orte gelegene Lymphdrüse mehr, eine am andern Orte gelegene Lymphdrüse weniger aufnehmen. Das ist ein außerordentlich komplizierter Prozeß, das Verdauen. Keine menschliche Wissenschaft könnte nachkommen dieser Weisheit der Lymphdrüsen, die sich alle so hübsch in die Arbeit teilen. Wir haben es da eben nicht zu tun mit den gefällten Urteilen, sondern mit real wirkenden Urteilen. Tatsächlich, zwischen unseren Gedärmen und unseren Blutadern spielt sich eine solche Summe von Vernunft ab, daß Sie in menschlicher Wissenschaft noch lange nicht irgend etwas finden, was sich mit dem vergleichen läßt.

So nur auch ist es möglich, wenn in dieser Weise selbsttätige Vernunft sich geltend macht im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesse, daß dieser in gesunder Konstitution ist. Das kann aber nicht auf andere Weise sein, als daß die Menschen vereinigt sind, die nun wirklich in Bildern den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß Stück für Stück innehaben und dadurch, daß sie vereinigt sind in den Assoziationen, eben sich gegen- ° seitig ergänzen, gegenseitig korrigieren, so daß die richtige Zirkulation im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß vor sich gehen kann.

Nun handelt es sich natürlich darum, daß man zu einer solchen Sache Gesinnung braucht, aber daß die Gesinnung allein nicht ausreicht. Sie können meinetwillen Assoziationen begründen, die starke wirtschaftliche Einsichten haben; wenn in diesen Assoziationen etwas nicht drinnen ist, so werden auch die Einsichten nicht viel helfen. Darinnen sein muß in solchen Assoziationen dasjenige, was man eben darinnen haben wird, wenn solche Assoziationen überhaupt nur als notwendig anerkannt werden; darinnen wird in diesen Assoziationen Gemeinsinn sein müssen, wirklicher Sinn für den ganzen Verlauf des ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses. Denn der einzelne, der unmittelbar verbraucht, was er einkauft, der kann nur seinen egoistischen Sinn befriedigen. Er würde eigentlich auch sehr schlecht laufen, wenn er seinen egoistischen Sinn nicht befriedigen würde. Er kann ja unmöglich, wenn er als einzelner Mensch in der Volkswirtschaft drinnensteht, sagen, wenn ihm einer einen Rock anbietet, sagen wir, für vierzig Franken: Es paßt mir nicht, ich gebe dir sechzig Franken. — Das geht nicht. Es ist etwas, wobei der einzelne im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß gar nichts machen kann. Dagegen in dem Augenblick, wo sich in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß das assoziative Wesen hineinstellt, in diesem Augenblick wird ja das unmittelbar persönliche Interesse nicht da sein, sondern die Überschau wird tätig sein über den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß; es wird das Interesse des anderen mit in dem volkswirtschaftlichen Urteil darinnen sein. Und ohne das kann nämlich ein volkswirtschaftliches Urteil nicht zustande kommen, so daß wir heraufgetrieben werden aus den volkswirtschaftlichen Vorgängen in die Gegenseitigkeit von Mensch zu Mensch und in das hinein, was sich dann aus der Gegenseitigkeit von Mensch zu Mensch des weiteren entwickelt: das ist in Assoziationen wirkender objektiver Gemeinsinn - Gemeinsinn, der nicht hervorgeht aus irgendwelcher Moralinsäure, sondern aus der Erkenntnis der Notwendigkeiten des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses.

Das ist dasjenige, was ich möchte, daß es bemerkt würde bei solchen Auseinandersetzungen, wie sie zum Beispiel in den «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» angeschlagen sind. Es fehlt heute nicht an Menschen, die herumgehen und sagen: Unsere Volkswirtschaft wird gut, furchtbar gut, wenn ihr Menschen gut werdet. Ihr Menschen müßt gut werden! - Stellen Sie sich einmal vor solche Foersters und dergleichen, die überall herumgehen und predigen, wenn die Menschen nur selbstlos werden, wenn sie den kategorischen Imperativ der Selbstlosigkeit erfüllen, dann wird schon die Wirtschaft gut werden! Aber solche Urteile sind eigentlich nicht viel mehr wert als auch das: Wenn meine Schwiegermutter vier Räder hätte und vorne eine Deichsel, wäre sie ein Omnibus, — denn es steht tatsächlich die Voraussetzung mit der Konsequenz in keinem besseren Zusammenhang als da, nur etwas radikaler ausgedrückt.

Dasjenige, was den «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» zugrunde liegt, ist nicht diese Moralinsäure, was auf anderem Felde schon seine große Rolle spielen kann; sondern es ist das, daß aus der volkswirtschaftlichen Sache selbst heraus gezeigt werden soll, wie die Selbstlosigkeit rein in der Zirkulation der volkswirtschaftlichen Elemente drinnenstecken muß. Das ist sogar bei den Beispielen der Fall. Wenn also einer in der Lage ist, Leihkapital auf Kredit zu bekommen, dadurch eine Unternehmung herstellen kann, eine Institution herstellen kann, mit dieser Institution produzieren kann, so produziert er so lange, als seine eigenen Fähigkeiten mit dieser betreffenden Institution verbunden sind. Nachher geht durch eine nicht von Mensch zu Mensch bewirkte, sondern durch eine im volkswirtschaftlichen Gang sich vollziehende Schenkung in der vernünftigsten Weise das, was da gewirkt hat, auf den über, der die nötigen Fähigkeiten dazu hat. Und es ist nur nachzudenken, wie durch eine Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus eben Vernunft in diese Schenkung hineinkommen kann. Da grenzt das Volkswirtschaftliche an das, was nun im umfassendsten Sinn überhaupt das Soziale im Menschen ist, was zu denken ist für den gesamten sozialen Organismus.

Und das können Sie sich ja auch von der anderen Seite vorhalten. Ich habe Ihnen gezeigt, wie beim einfachen Tausch, indem es sich immer mehr und mehr um Geld handelt, oder indem der Tausch überhaupt anerkannt wird, daß da die Volkswirtschaft unmittelbar hineinkommt in das Gebiet des Rechtswesens. In dem Augenblick, wo Vernunft in die Volkswirtschaft hineinkommen soll, handelt es sich ja darum, daß man wiederum dasjenige, was im freien Geistesleben figuriert, in die Volkswirtschaft hineinströmen lassen kann. Dazu müssen eben die drei Glieder des sozialen Organismus in dem richtigen Verhältnis stehen, daß sie in der richtigen Weise aufeinander wirken. Das meinte eigentlich die Dreigliederung; nicht die Auseinanderspaltung in die drei Glieder! Die Auseinanderspaltung ist eigentlich immer da; es handelt sich nur darum, daß man findet, wie die drei Glieder zusammengebracht werden können, so daß sie nun tatsächlich im sozialen Organismus mit einer solchen inneren Vernunft wirken, wie, sagen wir, das Nerven-Sinnessystem, das Herz-Lungensystem und das Stoflwechselsystem im menschlichen natürlichen Organismus wirken. Darum handelt es sich. Davon wollen wir dann morgen weiter reden.

Tenth Lecture

Now, it is necessary to discuss something here today that was already hinted at yesterday. That is the relationship between economic work and what underlies the transformation of nature into an object of economic value through cultivation. Then, in the further course of this, organized or structured labor is absorbed, in a certain sense, by capital, which then emancipates itself and completely transitions into, one might say, free spirituality. So you can conclude from this that work does not have any immediate economic value – we have already discussed this – but that work does have what drives economic value. The natural product as such enters into economic circulation through being processed. And the processing that gives it value is actually the reason why the economic object of value moves, at least within a certain area at first. Later, it is the human spirit acting in capital that continues the movement. First of all, we are dealing with movement; for as soon as we enter the sphere of capital, we are dealing with movement through commercial capital, then through loan capital, and then through actual production capital: through industrial capital.

When we talk about this movement, we must first and foremost be clear that there must be something that brings values into economic circulation. And in order to get to grips with this, we must first deal with what I would call a somewhat tricky economic question, which is not easy to understand unless one tries to seek out what can be said about it in economic experience and, in a sense, to verify things.

First of all, there is what can be called economic profit. But the question of profit is an extremely difficult one. Let's assume that a purchase is taking place. A buys from B. Now, in layman's terms, the concept of profit is usually applied to the seller alone. The seller is supposed to profit. Then we actually only have the exchange between what the buyer gives and what the seller gives. However, if you think about it carefully, you will not be able to admit that in a purchase or even in an exchange, only the seller gains; because if only the seller were to gain in an economic context, the buyer would always have to be at a disadvantage if an exchange took place without further ado. The buyer would always have to be at a disadvantage. But you will admit from the outset that this cannot be the case. Otherwise, every purchase would involve the buyer being taken advantage of, but this is clearly not the case. For we know that the person who buys wants to buy advantageously, not disadvantageously. Absolutely. So the buyer can also buy in such a way that he too makes a profit. We therefore have the strange phenomenon that two people exchange goods and everyone must – at least in normal buying and selling – actually gain. This is much more important to note in practical economics than is usually thought.

So let's assume that I sell something and receive money in return; I must gain from giving away my goods and receiving money for them. I must desire the money more than the goods. The buyer must desire the goods more than the money. So that in a mutual exchange, what is exchanged, both what goes out and what comes back, becomes more valuable. Thus, through the mere exchange, what is exchanged becomes more valuable on both sides. Now, how can that actually be?

This can only be because when I sell something and receive money for it, the money offers me the opportunity to achieve more with it than the person who gives me the money; and the other person, who receives the goods, must achieve more with the goods than I can achieve with them. So what we have here is that we – both the buyer and the seller – must be part of a different economic context. This higher valuation can only come about through what lies behind the sale and purchase. So when I sell, I must be in such an economic context that, through this economic context, the money has a greater value for me than for the other person, and the goods have a greater value for him than for me through the economic context.

From this, however, it will already be clear to you that in economics it cannot depend solely on whether one buys or sells, but rather on the economic context in which the buyer and seller are situated. So when we look closely at things, we are led, as we have often been led before, from what is happening directly in one place to the entire economic context. But this economic context is revealed to us on another occasion as well.

This can be seen when we start with barter. Basically, the kind of observation I have just made can tell you that even when money is introduced into an economy, barter is not completely overcome, because goods are simply exchanged for money. And precisely because everyone wins, we see that something else is important, rather than one person having the goods and the other having the money. The most important thing is what everyone can do with what they get through their economic connections.

But to understand this more clearly, let's return to the most primitive form of barter. This will first shed light on what happens in a more complex economic context. Suppose I buy peas. Now, when I buy peas, I can do all sorts of things with them. I can eat them. So let's assume that when I engage in barter, I exchange peas for something else that I have made, which is therefore a commodity. So I exchange peas. I can eat them, but I can also trade a lot of peas, a lot of peas, so many that I can't eat them all, even with a large family. Now I turn to someone who needs these peas and trade them for something I need. I give him peas for something I need. The peas have remained substantially the same; economically, however, they have not remained the same at all. Economically, they have changed in that I have not consumed these peas myself, but have put them back into circulation and have only created a transition in the economic process. What have these peas now become for me economically as a result of such a process? You see, all that was needed was, let's say, certain conditions and, in addition, the legal stipulation that everything should be exchanged for peas – enough peas would then have to be produced and there would have to be a legal provision that everything could be exchanged for peas, then the peas would be money. So in the economic process, the peas have become money; in the true sense of the word, the peas have become money. So, something does not become money because it is, let's say, something other than what else is there in the economic process, but because it undergoes a transformation from commodity to money at a certain point in the economic process. And all money has gone through this. All money was once transformed from commodity to money.

From this, too, we can see that we approach human beings through the economic process, that we cannot do anything other than place human beings within the economic process. Now, people are already placed in the economic process as consumers. This means that they are already part of it from the outset. And precisely when they are economically active in something that does not fall within the realm of consumption, they place themselves in a completely different relationship through their economic connection than they do when they place themselves in it as mere consumers. All these things must be taken into account if one wants to work toward forming an economic judgment. And economic judgments must be formed in what I call associations. So there must be people in the associations who form their judgments based on such considerations from practical experience.

Now, the point is that when we have any kind of processed nature or structured work in the economic process, we must then examine what, in a sense, sets these economic elements in motion, in circulation. Yesterday, attention was drawn elsewhere to the fact that the work that is active in the economic process should be incorporated into economic thinking, just as, for example, physicists incorporate work into their physical thinking. It must then be said: Yes, physicists incorporate work into their physical thinking by developing a formula that includes mass and velocity. But mass is something we determine by weighing. So we have a way of determining mass by weighing. Without being able to determine mass by weighing, we would have nothing that progresses in the physical work process. The question must arise for us: Is there something similar in the economic process, so that work gives value to things and later intellectual intervention also gives value to things? Is there something in the economic process that can be compared, as it were, to the weight that an object has when one wants to talk about physical work? Well, if I simply sketch out the progress of the individual economic processes, it shows me that there must be something that sets the whole thing in motion, that pushes the economic elements from here (see drawing 6) to here, so to speak. And the matter would be even clearer if it were not only pushed from here to here, but if there were also an additional suction effect from the other side, so that the whole thing were driven forward by a force within the economic process. Then there would have to be something in this economic process that drives it forward.

Now, what is it that drives it forward? I have just shown you that certain forces are constantly arising, both on the part of the buyer and on the part of the seller; for everyone who has something to do with the other in the economic process, not in a moral sense, but in a purely economic sense, advantage and profit arise. So there is no point in the economic process where advantage and profit do not have to be mentioned. And this profit is not something merely abstract; this profit is what people's immediate economic desires depend on, and must depend on. Whether the person concerned is a buyer or a seller, their economic desires depend on this profit, on this advantage. And this dependence on this advantage is what actually brings about the entire economic process; it is the force within it. It is what represents mass in the physical work process.

Consider that this actually points to something extremely important in the economic process, something truly significant. Indeed, the weight is most apparent in purely material products, in products that the stomach desires. Therefore, the stomach explains that, for the buyer, fruit is more advantageous than money at the moment of exchange. So we have this driving force within the human being itself. But we also have this driving force in other areas besides those that represent only material goods. Just consider that this feeling of advantage, of profit, is also present when I sell something and receive money: I know that I can now do more with this money than with the goods I have. This is where I intervene with my intellectual abilities.

And if you now apply this to the total amount of loan capital in an economic system, you will very soon see that those who want to undertake or carry out something and need loan capital for this purpose have exactly the same driving force in their need for loan capital, which lies in the pursuit of profit. Only, if I regard profit as a pushing force, loan capital actually has a sucking effect; it sucks, but in the same direction as the profits push. So that in profits and loan capital we have precisely what pushes and sucks in the economic process.

This gives us a clear picture of the fact that, insofar as the economic process actually consists only of movement and everything that can be achieved through it should actually be achieved through movement in the economic process, we must insert human beings into this economic process everywhere, we must place human beings within it. This can be somewhat inconvenient for objective economics, because human beings are a kind of incommensurable quantity, because they are changeable, because they must be reckoned with in various ways; but that is simply the way it is, and they must be reckoned with in various ways.

Now, however, we can already see that lending creates a kind of suction effect within the economic process. You know that there have been times when charging interest on loans was considered immoral. And it was only considered moral to lend without interest. There would have been no advantage in lending. In fact, borrowing did not originally stem from the advantage gained by borrowing, from the interest; rather, under more primitive conditions than those of today, borrowing was based on the assumption that if I lend something to someone and they can do something with it that I cannot do – let's just say he is in need and he can remedy his need if I am able to lend him something—that he does not pay me high interest, but that when I need something in return, he will also help me out. Throughout history, wherever you go back, you will see that the prerequisite for lending is that the other person will lend back when necessary.

This even applies to more complicated social situations. You have this, for example, when, let's say, someone borrows something from a lending institution and needs two guarantors who have to come and vouch for him, that lending institutions have always found that even for this service, reciprocity plays an extremely important role. For when \(A\) comes to a lending institution and brings \(B\) and \(C\) with him, who are guarantors, i.e., who register their names as guarantors, the lending institutions always count on \(B\) then coming and bringing \(A\) and \(C\) with him, and when B has paid for the item, then \(C\) comes and brings \(A\) and \(B\) with him as guarantors. And among certain people, this is considered something completely natural. So much so that economists claim that such a law can be asserted with the same right as anything that is determined by mathematical formulas. Now, of course, these things must be taken with a grain of salt; one must always factor in the necessary ingredient. But that is actually part of the flexibility of the economic process, that one can count on it.

So one can say that originally, the remuneration for lending is merely the prerequisite that the borrower will lend again, or if he does not lend again, at least help with one's own borrowing, if one has helped him with his borrowing. When it comes to borrowing, human reciprocity enters the economic process in a very striking way.

So what, then, if this is the case, is interest? Interest – as has already been noted by individual economists – is what I receive when I waive reciprocity, i.e., when I lend something to someone and agree with them that they will never need to lend me anything; then, if I renounce this reciprocity, he pays me interest for it. Interest is the compensation for something that plays a role between people, it is the reward for what plays a role in the economic process as human reciprocity.

Now we see something emerging that we only need to place in the right way within the entire economic process. Of course, we must always bear in mind that today it only makes sense to consider economic processes that are entirely characterized by the division of labor, because that is essentially what we are dealing with. When work is divided, people become much more dependent on mutuality than when everyone not only grows their own cabbage, but also makes their own boots and hats. With the division of labor comes dependence on mutuality. And so we see in the division of labor a process that actually proceeds in such a way that the individual currents diverge.

But we see in the entire economic process that all these currents want to unite, only in a different way, through the corresponding exchange, which takes place in the complicated economic process with the help of money. The division of labor therefore necessitates mutuality at a certain level, that is, the same thing in human interaction that we find, for example, in lending. Where there is a lot of lending, we have this principle of reciprocity, but it can now be replaced by interest. Then we have reciprocity realized in interest. We have only transformed it into the abstract form of money. But the forces of reciprocity are simply interest, they have metamorphosed, they have become something else. What we see very clearly in the payment of interest takes place everywhere in the economic process.

This is the basis of the great difficulty that exists in forming economic ideas, because you cannot form economic ideas other than by perceiving something pictorially. Concepts do not allow you to grasp the economic process; you have to grasp it in images. This is what is now found extremely inconvenient by all scholars when it is demanded somewhere that something should be transferred from the mere abstractness of concepts to imagery. However, we will never be able to establish a true economic science without transitioning to pictorial concepts, without being able to imagine the individual detailed economic processes pictorially and to imagine them in such a way that we have something dynamic within the image itself and know how such a detailed economic process works when it is structured in a particular way.