Colour and the Human Races

GA 349

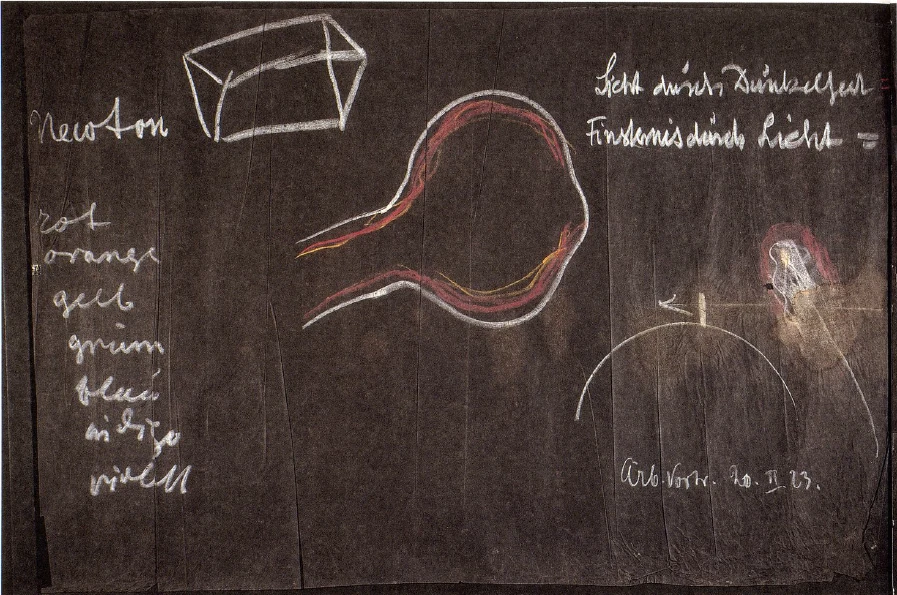

21 February 1923, Dornach

I. The Nature of Color

In order, gentlemen that the last question may be thoroughly answered. I will, as far as possible, say something about colors. One cannot really understand colors if one does not understand the human eye, for man perceives colors entirely through the eye.

Picture to yourselves, for instance, a blind person. A blind person feels differently in a room that is lighted and in a room that is dark. Though it is so weak a matter that he does not perceive it, yet it has a great significance for him. Even a blind person could not live perpetually in a cellar, he would need the light. And there is a difference if one brings a blind man into a bright room with yellow windows, or into a dark room, or into a fairly light room which has blue windows. That acts quite differently on his life. Yellow color and blue color influence life quite differently. But these are things which one learns to understand only when one has grasped how the eye is affected by color.

Now from what I have hitherto put before you, you will perhaps have realized that two things are most important in man. The first is the blood, for if man were not to have blood he would have to die at once. He would not be able to renew his life every moment and life must be every moment renewed. So if you think away the blood from the body, man is a dead object.

Now think away the nerves too: man would no doubt look just the same, but he would have no consciousness; he could form no ideas, could will nothing, would not be able to move.

We must therefore say to ourselves: For man to be a conscious human being he needs nerves. For man to be able to live at all he needs blood. Thus blood is the organ of life, the nerves are the organ of consciousness.

But every organ has nerves and has blood. The human eye is in fact really like a complete human being and has nerves and blood. Imagine that here [a drawing was made] the eye protrudes, and in the eye little blood-arteries, many blood-arteries spread out. And many nerves too spread out. You see, what you have in the hand, that is, nerves and blood, you have also in the head.

Now think: the external world which is illumined works upon the eye. By day at any rate the world in which you go about is illumined, but it is difficult to form an idea of this wholly-lighted outer world. You get a true idea when you imagine the half-lighted world in the morning and evening, when you see the red of dawn and evening. Dawn and the sunset glow are particularly instructive.

For what is actually there in the glow of dawn and evening? Picture to yourselves the sunrise. The sun comes up, but it cannot shine on you direct as yet. The sun comes when the earth is like this—I am now drawing the apparent path, but that does not matter (in reality the earth moves and the sun stands still, but how we see this makes no difference). The sun sends its rays here [drawing] and then here. So if first you stand there, you do not see the sun at dawn, you see the lit-up clouds. These are the clouds and the light falls actually on them. What is that actually? This is very instructive. Because the sun has not quite risen, it is still dark around you and there in the distance are the clouds lit up by the sun. Can one understand that?

If you stand there you are seeing the illumined clouds through the darkness that is around you. You see light through darkness. So that we can say it is the same thing at dawn and sunset—one sees light through darkness. And light seen through darkness—as you can see in the morning and evening glow—looks red. Light seen through darkness looks red.

Now I will say something different. Imagine that dawn has gone by and it is daytime. You see freely up into the air, as it is today. What do you see? You see the so-called blue sky. To be sure, it is not there, but you see it all the same. That certainly does not continue into all infinity, but you see the blue sky as if it were surrounding the earth like a blue shell.

Why is that? Now you have only to think of how it is out there in distant universal space. It is in fact dark. For universal space is dark. The sun shines only on the earth and because there is air round the earth the sunbeams are caught and make it light here, especially when they shine through watery air. But out there in universal space it is absolutely black darkness. So that if one stands here by day one looks into darkness, and one should actually see darkness. But one does not see it black, but blue, because all round there is light from the sun. The air and the moisture in the air are illumined.

So you see quite clearly darkness through the light. You look through the light, through the illumined air into darkness. And therefore we can say: Darkness through light is blue.

There you have the two principles of the color-theory which you can simply get from observation of the surroundings. If you thoroughly understand the red of dawn and evening glow you say to yourself: Light seen through darkness or obscurity is red. When by day you look out into the black heavens, you say to yourself: Darkness or obscurity seen through light—since it is light around you—is blue.

You see, men have always had this quite natural view until they became “clever.” This perception of light seen through darkness being red, and darkness through light being blue, was possessed by ancient peoples over in Asia when they still had the knowledge which I have lately described to you. The ancient Greeks still had this concept, and it lasted through the whole Middle Ages until the 14th. 15th, 16th, 17th centuries when people became clever. And as they became clever, they began not to look at nature but to think out all sorts of artificial sciences.

One of those who devised a particularly artificial science about color was the Englishman Newton. Out of cleverness—you know how I am now using the word, namely quite in earnest—out of special cleverness Newton said something like this: Let us look at the rainbow—for when one is clever one does not look at something happening naturally every day: dawn, sunset, one looks at the specially unusual and rare, something to be understood only when one has gone further. However. Newton said: Let us look at the rainbow. In the rainbow one sees seven colors, namely, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. One sees them next to each other in the rainbow:

When you look at a rainbow you can distinguish these seven colors quite plainly.

Now Newton made an artificial rainbow by darkening the room, covering the window with black paper, and in the paper he made a tiny hole. That gave him a very small streak of light.

Then he put in this streak of light something that one calls a prism. It is a glass that looks like this [drawing], a sort of three-cornered glass, and behind this he set up a screen. So he then had the window with the hole, this tiny beam of light, the prism and behind it the screen. Then the rainbow appeared with the red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet colors. What did Newton then say?

Newton said to himself: The white light comes in; with the prism I get the seven colors of the rainbow. Therefore they are already contained in the white light and I only need to draw them out.

You see, that is a very simple explanation. One explains something by saying: It is already there and I draw it out.

In reality he ought to have said: Since I set up a prism—that is. a glass with a cornered surface, not a regular glass plate—when I look through it like this, there is light made red through darkness, and on the other side darkness made blue through light—the blue color appears. And in between lie in fact gradations. That is what he ought to have told himself.

But at that time the aim in the world was to explain everything by seeking to find everything already inside that from which one was really to explain it. That is the simplest method, is it not? If, for example, one is to describe how the human being arises, then one says: Oh well, he is already in the ovum of the mother, he only develops out of it. That is a fine explanation!

We don't find things as easy as that, as you have seen. We have to take the whole universe to our aid, which first forms the egg in the mother. But natural science is concerned with throwing everything inside, which is the simplest possible way. Newton said that the sun already contained all the colors and we had only to draw them out.

But that is not it at all. If the sun is to produce red at dawn, it must first shine on the clouds and we must see the red through darkness; and if the sky is to appear blue, that is not at all through the sun. The sun does not shine into the heavens: it is all black there, dark, and we see the blue through the illumined air of the earth. We see darkness through light, and that is blue.

The point is to make a proper physics where it could then be seen how in the prism on the one side light is seen through darkness and on the other darkness through light. But that is too tiresome for people. They find it best to say that everything is within light and one only draws it out. Then one can say too that once there was a giant egg in the world, the whole world was inside, and we draw everything out of it.

That is what Newton did with the colors. But in reality one can always see the secret of the colors if one understands in the right way the morning and evening glow and the blue of the heavens.

Now we must consider further the whole matter in relation to our eye and to the whole of human life altogether. You see, you all know that there is a being which is especially excited through red—that is, where light works through darkness—and that is the bull. The bull is well known to be frightfully enraged by red. That you know.

And so man too has a little of the bull-nature. He is not of course directly excited through red, but if man lived continually in a red light, you would at once perceive that he gets a little stimulation from it. He gets a little bull-like. I have even known poets who could not write poetry if they were in their ordinary frame of mind, so then they always went to a room where they put a red lampshade over the light. They were then stimulated and were able to write poetry. The bull becomes savage: man by exposing himself to the red becomes poetic! The stimulation to poetry is only a matter of whether it comes from inside or from outside. This is one side of the case.

On the other hand you will also be aware that when people who understand such things want to be thoroughly meek and humble, they use blue, or black—deep black. That is so beautiful to see in Catholicism: when Advent comes and people are supposed to become humble, the Church is made blue; above all the vestments are blue. People get quietened, humble; they feel themselves inwardly connected with the subdued mood—especially if a man has previously exhausted his fury, like a bull, as for instance at Shrove Tuesday's carnival. Then one has the proper time of fasting afterwards, not only dark raiment, black raiment. Then men become tamed down after their violence is over. Only, where one has two carnivals, two carnival Sundays, one should let the time of fasting be twice as long! I do not know if that is done.

But you see from this that it has quite a different effect on man whether he sees light through dark that is red, or darkness through light, that is blue.

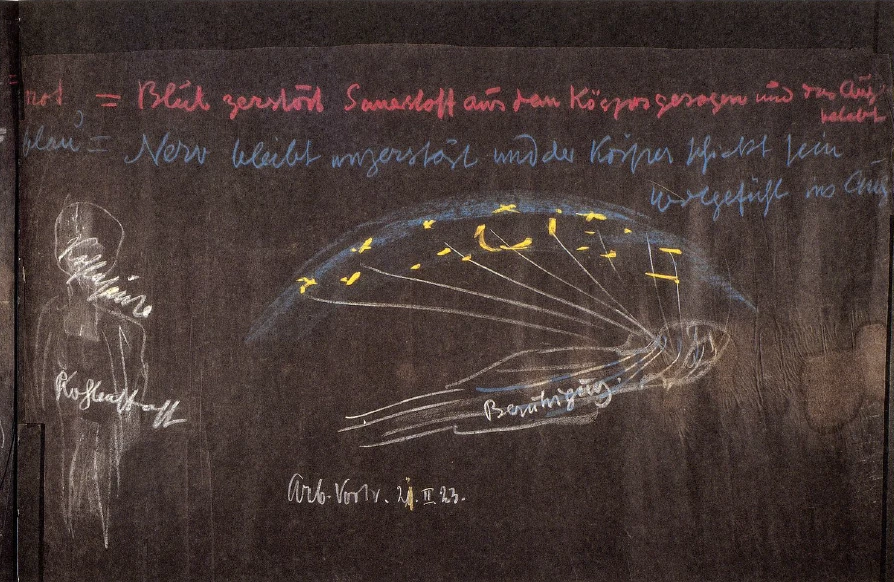

Now consider the eye. Within it you have nerves and blood. When the eye looks at red, let us say at the dawn or at something red, what does it experience? You see, when the eye looks at red then these quite fine little blood-arteries become permeated by the red light, and this light has the peculiarity of always destroying the blood a little. It therefore destroys the nerve at the same time, for the nerve can live only when it is permeated by blood. So that when the eye confronts red, when red comes into the eye, then the blood in the eye is always somewhat destroyed and the nerve with it.

When the bull is faced with red it simply feels: Good gracious—all the blood in my head is destroyed! I must defend myself!—Then it becomes savage because it will not let its blood be destroyed.

Well, but this is very good—not only in the bull, but in man and in other animals. For if we look at red and our blood becomes somewhat destroyed, then on the other hand our whole body works to bring oxygen into the eye so that the blood can be re-established.

Just think what a wonderful process takes place there. When light is seen through darkness—that is, red—then the blood is destroyed, oxygen is absorbed from the body and the eye vitalized through the oxygen. And now we know through the renewal of life in our eye: There is red outside. But in order that we may perceive this red, the blood and the nerve in the eye must be a little destroyed. We must send life, that is, oxygen, into the eye. And by our own vitalizing of the eye, by this waking up of the eye we notice: there is red outside.

Now you see, man's health too actually depends on his perceiving rightly the reddened light, on his always being able to take in reddened light properly. For the oxygen which is drawn out of the body vitalizes then the whole body and man gets a healthy color in the face. He can really reanimate himself.

This refers not only to a person who is healthy and able to see, it applies as well to one whose eyes are not healthy and who does not see: When the light works through the bright color then he is vitalized in the head, and this vitalizing acts again on the whole body and gives him a healthy color. So when we live in the light and can take in the light properly we get a healthy color.

It is very important tor people not to be brought up in dark places where they can become lifeless and submissive. People should be brought up in light, bright places with yellowish-reddish light, where they also properly assimilate the oxygen in them through the light.

But you see from this that everything connected with the element of red is actually connected with the development of man's blood. When we look at red the nerve is actually destroyed.

Now just think: We see darkness through light, that is, blue. Darkness does not destroy our blood, it leaves our blood unharmed. The nerve too is undestroyed since our blood is in order. The result is for man to feel himself thoroughly well inwardly. Since blood and nerve are not attacked by blue, man feels thoroughly well inside.

And there is really something subtly refined in creating submissive meekness. When, let us say, the priests there above at the altar are in their blue or their black vestments, and the people sit below and gaze at them, the blood-arteries and nerves in the eye are not destroyed and naturally the people feel very well. It is actually directed to the feeling of well-being of the people.

Do not imagine that that is not known! For they still have their ancient science. The more modern science has only arisen with the men of the Enlightenment, in such men as, for instance. Newton.

Thus we can say: Blue is what sends through man a feeling of well-being, when he says to himself (it is all unconscious, but he says it inwardly): There alone I can live—in the blue. There man feels inwardly himself; in red, on the other hand, he feels as if something were to penetrate into him. One can say that with blue the nerve remains undestroyed and the body sends the feeling of well-being into the eye and hence into the whole body.

That is the difference between the color blue and the color red. And yellow is only a gradation of red, and green is a gradation of blue. So that one can say: according to whether nerve or blood is active, the more sensitive is man to red or to blue.

Now you see, one can apply that to substances. If I want to look for a red for painting, to produce a red color which contains the substances that stimulate man to develop oxygen inwardly, then I gradually arrive at the fact that to get red color for painting I must test the substances of the outer world to find how much carbon they contain. If I combine carbon in the right way with other substances, I discover the secret of making a red for my painting.

If I use plants for getting colors for paints then above all it is a matter of so organizing my processes, diminishing, consuming, and so on, that I obtain the carbon in the paint in the right way. If I have the carbon in it in the right way, then I get the bright, the reddish color.

If on the other hand I have substances which contain much oxygen—not carbon but oxygen—then I obtain the darker colors, such as blue. When I know the living element in the plant then I can really create my colors. Imagine that I take a sunflower: that is quite yellow, a bright color. Yellow is near to red, that is, light seen through darkness. If I now treat the sunflower in such a way as somehow to gel into my paint-color the right process that lies in the flower, then I have a good yellow. Even the outer light cannot have much against it, because the blossom of the sunflower has already taken from the sun the secret of creating yellow. If I therefore get the same process into my artist's color as there is in the blossom, then if I get it thick enough, I can use it normally as paint.

But let me take another plant, the chicory, for instance, the blue flower that grows on the wayside—it grows here too. If I have this blue plant and want to prepare a paint from the flower, I cannot do it, I get nothing from it. On the other hand, if I treat the root in the right way, there is a process in it which actually makes the blossom blue.

When the blossom is yellow then something goes on in the blossom itself which makes yellow; when the blossom is blue, however, the process lies in the root and it only presses upwards towards the flower. So if I want to produce a blue paint from the indigo-plant, where I get a darker blue, or from the chicory, this blue flower, I must use the root. I must treat it chemically till it yields me the blue color.

In this way, through real study, I can find out how to obtain paints from the plant. I cannot do so in Newton's way; he simply says that everything is in the sunlight and one has only to draw it out. (One can apply that at most to one's purse; what I spend for a day I must have in the purse in the morning.) That is how the quite clever people picture it, like a sack in which everything is lying. That, however, is not the case.

We must know, for instance, how the yellow is in the sunflower or in the dandelion. We must know how the blue is in chicory. The processes which make the chicory or the indigo׳ plant blue lie in the root, whereas the processes that make the sunflower or the dandelion yellow lie in the flower.

And so I must imitate chemically, in a chemistry become living, the flower-process of the plant and get the bright, light color. I must imitate the root process of the plant and there obtain the dark color.

You see, what I have related here is plain to the real human understanding; whereas as a matter of fact this business (in the rainbow) with the red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet, is a rarity.

Now when Goethe lived the affair had got to the point where people generally believed in what Newton had taught, namely, the sun is the great sack in which lie the so-called seven colors. One need only tempt them out, then they come to light. Everyone believed that; it was taught and in fact is still taught today.

Goethe's nature was not one to believe everything immediately. He wanted to convince himself a little about things that were taught everywhere. People generally say that they do not believe anything on authority. But when it comes to the point of crediting what is taught from the professorial chair, then people are today frightfully credulous, they believe everything that is taught. Goethe did not want to believe everything straightaway, so he borrowed from the university in Jena the apparatus, the prisms and so on which provide the proof. He thought: Now I will do exactly what the professors do in order to see how it actually is.

Well, Goethe did not get down to it immediately and had the apparatus rather a long time without doing anything. He just did something else. So the time became too long for the Hofrat Büttner who needed the apparatus and wanted to have it fetched back. Goethe said: Now I must do the thing quickly—and at least, as he was already packing up, looked through a prism. He said to himself: The rainbow must look beautiful on the white wall if I look through there; instead of white, red, yellow, green and so on must appear. He therefore peered through, anticipating with delight that he would now see the white wall in these beautiful colors,—but he saw nothing: white as before, simply white. Naturally he was extremely surprised and asked himself what was behind it. And his whole theory of color arose out of this.

Goethe said: One must now control the whole affair again. The ancients have said light seen through darkness = red, darkness through light = blue. If I gradate the red somewhat it becomes yellow. If I make the blue go up to red, then it becomes green on the one side and violet on the other. These are gradations. And he then worked out his color theory and in fact better than it existed in the Middle Ages.

Now today we have a physicist's color-theory with the sack from which the seven colors come, which is taught everywhere. And we have a Goethean color-theory which understands the blue of the heavens rightly, understands rightly the morning and evening glow as I have been explaining to you.

But there is a certain difference between the Newtonian and the Goethean theory. For the most part other people do not notice it, for other people look on the one hand to the physicists: there the Newtonian theory of color is taught which stands in the books everywhere. One can very clearly picture to oneself what appears there in the rainbow as red, orange, yellow, green and so on. Well, but there is no prism there! However, one does not reflect further. The Newtonians certainly know, but they do not admit, that when one looks through the rainbow on the one side, then one sees darkness through the sun-illumined rainbow; sees on the other side the blue. But then one also sees in front the surface where one sees light through darkness, and on the other side the red. One must explain everything therefore by the simple principle: light through darkness is red; darkness through light is blue.

But as I have said, people on the one hand see everything as the logicians explain it to them: on the other hand they look at pictures where the colors are used. Well, they do not ask further about the red and the yellow and so on; they do not bring the two things together.

But the painter must bring them together: one who wants to paint must connect them. He must not merely know: There is a sack and the colors are within it—for he has not got the sack anywhere. He must obtain the right thing from the living plant, or living substances, so that he can mix his colors in the right way.

So this is the position today: painters really reflect (—there even are painters who reflect, who do not simply buy their colors): but those painters who reflect upon how they are to obtain these colors and how they should use them, they say: Yes, with the Goethean color-theory one can do something; that tells us something. With the Newtonian color-theory, the theory of the physicists, we painters can do nothing.

The public does not bring painting and the physicists' theory of color together, but the painter does! He therefore likes the Goethean color-theory. He says to himself: Goodness! We don't bother about the physicists: they say something in their own field. They may do what they like; we keep to the Goethean color-theory. The painters look on themselves as artists and not as having to encroach on the teaching of the physicists. That is in fact uncomfortable, enmities arise, and so on.

But that is how things stand today between what is in the books about color and what is true. With Goethe it was simply the defense of truth which impelled him to oppose the Newtonians and the whole modern physics. And we cannot really understand nature without coming to Goethe's color-theory.

Hence it is quite natural that in a Goetheanum Goethe's theory of color should also be vindicated. But then if one does not remain in some religious or moral sphere but also intervenes in the smallest single part of Physics, then one has the physicists' whole pack of hounds upon one.

So, you see, the defense of truth is extraordinarily difficult in modern times. But you should just know in what a complicated way the physicists explain the blue of the sky. Naturally, if I start from a false principle and want to explain the simple thing that the blackness of universal space appears blue through light, then I must make a frightfully complicated explanation of it. And then the red of dawn and sunset! These chapters mostly begin like this; the blue sky—one cannot actually explain that properly today, one could imagine this or that.—Yes, with all that the physicists have, their little hole which so much amused Goethe—the little hole through which they let the light come into the room, in order with the darkness to investigate the light—with all this they cannot explain the simplest facts. And so it comes to the point that color is no longer understood at all.

If one understands, however, that the destruction of the blood calls forth the vitalizing process—for when I have destroyed my blood then I call up all the oxygen in me and renew myself, bring about health—then one also understands the healthy rosy color in man.

If I have darkness round me or continual blueness, well, then I shall not continually reanimate myself, or else I should create too much life in me. And so on the one hand one can understand the healthy rosy countenance from the intake of' oxygen, when one is thoroughly exposed to the light, and one can understand paleness from the perpetual intake of carbonic acid. Carbonic acid, the counterpart of oxygen, wants to go into my head. That makes me quite pale.

Today, for instance in Germany, the children are almost all pale. But one must understand that that comes from too much carbonic acid. And if man develops too much carbonic acid—carbonic acid consists of a combination of carbon and oxygen—then he uses the carbon which he has in him too much for forming carbonic acid. Thus in such a pale child you have all the carbon in him continuously changed into carbonic acid. So he becomes pale. What must I do? I must administer something to him through which this eternal development of carbonic acid inside him is hindered, through which the carbon is held back. I can do that if I give him some carbonate of lime.

In this way the functions are again stimulated, as I have told you from quite a different standpoint, and man keeps the carbon that he needs, does not continually change it into carbonic acid. And since carbonic acid consists of carbon and oxygen, the oxygen comes up into the head and animates the head processes, the life processes. But when the oxygen is given up to the carbonic acid, the life processes are suppressed.

If I therefore bring a pale person into a region where he has a good deal of light, he becomes stimulated not to give up his carbon continually to carbonic acid, because the light sucks the oxygen up into the head. Then he will get a healthy color again. In the same way I can stimulate that through the carbonate of lime, inasmuch as I keep back the oxygen and the person has it at his disposal.

So everything must be interconnected. One must be able to understand health and illness from the theory of color. One can do that only from Goethe's theory, for that rests simply on nature in a natural manner. It can never be done from Newton's color-theory which is merely devised, does not rest on nature at all, and actually cannot explain the simplest phenomena, the red at dawn and sunset and the blue sky.

Now, gentlemen, may I still say something else to you. Think of the old pastoral peoples who drove out their flocks and herds and slept in the open air. During their sleep they were not exposed to the blue sky but to the dark sky. And up there upon it [drawing] are the unnumbered shining stars. Now picture the dark sky with these countless shining stars and there below the sleeping men. From the heavens there streams out a calming force, the inner feeling of well-being in sleep. The whole human being is permeated by the darkness, so that he becomes inwardly quiet. Sleep proceeds from the darkness, but nevertheless these stars shine down. And wherever a star-beam shines the human being becomes inwardly a little stirred up. An oxygen ray goes out from the body. Pure oxygen rays go to meet the rays from the stars and the man becomes entirely permeated inwardly by the oxygen rays: he becomes inwardly an oxygen reflection of the whole starry heavens.

Thus the ancient shepherd folk took into their quietened bodies the whole star heavens in pictures, pictures which the course of the oxygen engraved into them. Then they woke up and they had the dream of these pictures. From this they had their star knowledge, their wonderful knowledge of the stars.

Their dream was not merely that Aries, the Ram, had so-and-so-many stars, but they really saw the animal, the Ram, the Bull, and so on, and felt the whole starry heavens in themselves in pictures. That is what has remained to us from the ancient shepherd folk as a poetic wisdom which sometimes has extraordinarily much that can still be instructive today.

One can understand it when one knows that the human being lets an oxygen ray radiate to each beam of light from the stars, that he becomes wholly sky, an inner oxygen sky.

Man's inner life is as we know an astral body, for during sleep he experiences the whole heavens. It would go badly with us if we were not descended from these ancient pastoral peoples. All men in fact are descended from ancient shepherd folk. We still have, purely through heredity, the knowledge of an inner star-heaven. We still unfold that, although not so well as the ancients. In sleep, when we lie in bed, we have still a sort of recollection of how once the shepherd of old lay in the fields and drew the oxygen into him. We are no longer shepherds and herdsmen but something is still given to us, we still receive something, only we cannot express it so beautifully as it has already become pale and dim. But the whole of mankind today is indeed interconnected, all belong to each other,—and if one would know what man still bears in him today, one must go back to ancient times. Everywhere, all men on earth have proceeded from this shepherd-stage and have actually inherited in their bodies what could descend from these pastoral peoples.

Zweiter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Damit die letzte Frage noch richtig beantwortet wird, will ich doch, so gut es geht, einiges über die Farben sagen.

[ 2 ] Die Farben kann man eigentlich nicht verstehen, wenn man nicht das menschliche Auge versteht, denn der Mensch nimmt die Farben ganz und gar nur durch das Auge wahr. Wie er sonst die Farben noch wahrnimmt, das weiß er nicht, denn er nimmt doch nicht allein durch das Auge die Farben wahr. Stellen Sie sich zum Beispiel einen Blinden vor. Ein Blinder fühlt sich anders in einem Raum, der beleuchtet ist, als in einem Raum, der dunkel ist. Aber das ist so schwach, daß es der Blinde nicht wahrnimmt. Es ist eine so schwache Sache; es hat für ihn aber doch eine große Bedeutung, doch er nimmt es nicht wahr. Auch der Blinde könnte zum Beispiel nicht immer im Keller leben; da würde ihm das Licht fehlen. Und es ist ein Unterschied, ob man einen Blinden zum Beispiel in einen hellen Raum, der gelbe Fenster hat, bringt, oder ob man ihn in einen dunklen Raum oder meinetwillen auch in einen helleren Raum bringt, der blaue Fenster hat. Das wirkt ganz anders auf das Leben; die gelbe Farbe und die blaue Farbe, die wirken ganz anders auf das Leben ein. Aber das sind Dinge, die man erst verstehen lernt, wenn man begriffen hat, wie sich das Auge zu der Farbe verhält.

[ 3 ] Nun werden Sie ja vielleicht aus dem, was ich Ihnen bisher dargestellt habe, gesehen haben, daß das Allerwichtigste im Menschen zwei Dinge sind. In seinem ganzen Organismus sind zwei Dinge das Allerwichtigste. Das erste ist das Blut; denn würde der Mensch das Blut nicht haben, so müßte er sofort sterben. Er würde nicht sein Leben in jedem Augenblick erneuern können, und das Leben muß in jedem Augenblick erneuert werden. Also, denken Sie sich das Blut aus dem Körper fort, dann ist der Mensch ein toter Gegenstand. Aber auch wenn Sie sich die Nerven fortdenken, so könnte der Mensch zwar geradeso ausschauen, wie er ausschaut, aber er würde kein Bewußtsein haben; er würde nichts vorstellen können, nichts fühlen können, würde sich nicht bewegen können. Wir müssen uns also sagen: Daß der Mensch ein bewußter Mensch ist, dazu braucht er die Nerven. Daß der Mensch überhaupt leben kann, dazu braucht er das Blut. Also das Blut ist das Organ des Lebens; die Nerven sind das Organ des Bewußtseins.

[ 4 ] Aber jedes Organ hat Nerven und hat Blut. Und das menschliche Auge ist ja eigentlich im Grunde genommen wirklich ein ganzer Mensch und hat Nerven und Blut, und zwar so, daß, wenn Sie sich vorstellen, hier kommt das Auge aus dem Kopfe heraus (Zeichnung), so breiten sich in diesem Auge die Blutäderchen aus. Viele Blutäderchen breiten sich aus. Und dann breiten sich viele Nerven aus. Also Sie sehen, was Sie in der Hand haben, Nerven und Blutströmungen, das haben Sie auch im Haupte.

[ 5 ] Nun ist es im Auge so: ja, denken Sie sich einmal, auf das Auge wirkt die Außenwelt, die beleuchtet ist. Sehen Sie, Sie können sich am besten die Außenwelt vorstellen, die beleuchtet ist. Allerdings, am Tage ist die Außenwelt, in der Sie herumgehen, beleuchtet. Aber es ist schwer, von dieser ganz beleuchteten Außenwelt einen Begriff zu bekommen. Einen wahren Begriff bekommen Sie, wenn Sie sich die halbbeleuchtete Außenwelt am Morgen und Abend vorstellen, wo Sie die Morgen- und Abendröte um sich herum sehen. Die Morgen- und Abendröte sind besonders lehrreich.

[ 6 ] Denn, was ist bei der Morgen- und Abendröte eigentlich vorhanden? Stellen Sie sich einmal den Sonnenaufgang vor (Zeichnung). Die Sonne kommt herauf. Wenn die Sonne heraufkommt, dann kann sie noch nicht geradehin auf Sie leuchten. Ich zeichne jetzt den scheinbaren Lauf, wie wir es sehen; in Wirklichkeit bewegt sich die Erde, und die Sonne steht still, aber das macht ja nichts. Also die Sonne schickt zuerst ihre Strahlen hierher, und dann hierher. Wenn Sie also da stehen, sehen Sie bei der Morgenröte nicht die Sonne, sondern Sie sehen die beleuchteten Wolken. Da sind Wolken. Auf diesen Wolken sitzt eigentlich das Licht.

[ 7 ] Nun, meine Herren, was ist das eigentlich? Das ist sehr lehrreich. Weil die Sonne noch nicht ganz heroben ist, ist es hier noch dunkel; um Sie herum ist es ja noch dunkel, und da, in der Ferne, sind die von der Sonne beleuchteten Wolken. Kann man das verstehen? Sie sehen also, wenn Sie da stehen, durch die Dunkelheit, die um Sie herum ist, dort die beleuchteten Wolken. Sie sehen Licht durch die Dunkelheit. So daß wir sagen können: Bei der Morgenröte — und bei der Abendröte ist es ja ebenso — sieht man Licht durch Dunkelheit. Und Licht durch Dunkelheit gesehen, das können Sie an der Morgen- und Abendröte sehen, sieht rot aus. Licht durch Dunkelheit gesehen, sieht rot aus. Also wir können sagen: Wenn man Licht durch Dunkelheit sieht, so sieht das rot aus. Licht durch Dunkelheit gesehen ist rot.

[ 8 ] Jetzt will ich Ihnen etwas anderes sagen. Denken Sie sich, Sie haben die Morgenröte bereits vorbei, sind am Tage, sehen zum Beispiel, wie es heute der Fall ist, frei in die Luft. Was sehen Sie da draußen? Sie sehen den sogenannten blauen Himmel. Er ist zwar nicht da, aber Sie sehen ihn doch. Das geht zwar bis in alle Unendlichkeit fort, aber Sie sehen doch, wie wenn er sich wie eine blaue Schale um die Erde herumlegen würde. Warum ist das?

[ 9 ] Nun, Sie brauchen sich nur zu überlegen, wie es da draußen ist im weiten Weltenraum: es ist nämlich finster. Der weite Weltenraum ist finster. Die Sonne scheint nur auf die Erde, und dadurch, daß um die Erde Luft ist, dadurch verfangen sich die Sonnenstrahlen und machen hier Licht, namentlich wenn sie durch die wässerige Luft scheinen. Aber draußen in dem weiten Weltenraum ist es absolut schwarz, dunkel. So daß, wenn man bei Tag da steht, man ins Dunkel hineinschaut, und man müßte eigentlich schwarz sehen. Aber man sieht es nicht schwarz, sondern blau, weil es ringsherum beleuchtet ist von der Sonne. Die Luft und das Wasser in der Luft, die sind beleuchtet.

[ 10 ] Da sehen Sie also ganz klar Finsternis durch das Licht durch. Sie schauen durch das Licht durch, durch die Beleuchtung durch in die Finsternis hinein. Also wir können sagen: Finsternis durch Licht ist blau.

[ 11 ] Da haben Sie die zwei Grundgesetze der Farbenlehre, die Sie einfach an der Umgebung ablesen können. Wenn Sie die Morgen- und Abendröte richtig verstehen, so sagen Sie sich: Licht durch Dunkelheit oder Licht durch Finsternis gesehen, ist rot. Wenn Sie am Tag hineinschauen in den schwarzen Himmelsraum, sagen Sie sich: Dunkelheit oder Finsternis durch Licht gesehen - weil es rings um Sie herum beleuchtet ist —, ist blau.

[ 12 ] Sehen Sie, diese ganz natürliche Anschauung, die hat man immer gehabt, bis die Menschen «gescheit» geworden sind. Diese Anschauung, daß Licht durch Dunkelheit rot ist, Dunkelheit durch Licht blau ist, die haben die Alten gehabt, in Asien drüben, als sie noch so gescheit waren, wie ich es Ihnen letzthin einmal beschrieben habe. Diese Anschauung haben noch die alten Griechen gehabt. Diese Anschauung hat man noch durch das ganze Mittelalter hindurch gehabt, bis die Menschen gescheit geworden sind, bis so um das 14., 15., 16., 17. Jahrhundert herum. Und als sie gescheit geworden sind, da haben sie angefangen, nicht mehr auf das Natürliche zu gehen, sondern allerlei künstliche Wissenschaften auszudenken. Und einer derjenigen, der eine besonders künstliche Wissenschaft über die Farben ausgedacht hat, das ist der Engländer Newton. Newton, der hat aus der Gescheitheit heraus — Sie wissen, wie ich jetzt das Wort Gescheitheit gebrauche, nämlich ganz im Ernst -, der hat sich aus der besonderen Gescheitheit heraus etwa so gesagt: Schauen wir den Regenbogen an — denn nicht wahr, wenn man gescheit wird, schaut man nicht dasjenige an, was natürlich ist, was jeden Tag erscheint, Morgen- und Abendröte, sondern wenn man gescheit wird, schaut man das besonders Seltene an, dasjenige, was man erst verstehen sollte, wenn man schon weiter gekommen ist —, aber nun, der Newton sagte also: Schauen wir den Regenbogen an. Im Regenbogen sieht man nun sieben Farben, nämlich Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett. Es sind sieben Farben, die sieht man so nacheinander im Regenbogen (es wird gezeichnet). Wenn Sie den Regenbogen anschauen, können Sie diese sieben Farben ganz einfach unterscheiden.

[ 13 ] Nun hat Newton einen künstlichen Regenbogen gemacht, dadurch, daß er sein Zimmer verdunkelt hat, finster gemacht hat, das Fenster zugeschlagen hat mit einem schwarzen Papier und in das Papier ein kleines Loch hinein gemacht hat. Da hatte er einen ganz kleinen Lichtstreifen. Nun tat er in diesen Lichtstreifen das hinein, was man ein Prisma nennt, ein Glas, das so ausschaut, so ein dreieckiges Glas, und hinter dem stellte er einen Schirm auf. So hatte er dort das Fenster mit dem Loch, diese kleine Lichtströmung, das Prisma, und dahinter den Schirm. Da erschien nun auch der Regenbogen; da erschien nun auch Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett, alle diese Farben. Was sagte sich nun Newton? Newton sagte sich: Da kommt das weiße Licht herein; mit dem Prisma kriege ich die sieben Farben des Regenbogens. Also sind die sieben Farben des Regenbogens schon in dem weißen Licht drinnen, und ich brauche sie nur herauszulocken. — Sehen Sie, das ist die einfachste Erklärung. Man erklärt etwas dadurch, daß man sagt: Es ist in dem, aus dem ich es heraushole, schon drinnen.

[ 14 ] In Wirklichkeit hätte er sich sagen müssen: Dadurch, daß ich nicht eine richtige Glasplatte, sondern ein Prisma, also ein Glas mit einer solchen spitz zusammenlaufenden Fläche [dem Schirm] gegenüberstelle, wird auf der einen Seite, wenn ich so hingucke, Licht durch Dunkelheit rot gemacht, da erscheint die rote Farbe, und auf der anderen Seite wird Dunkelheit durch Licht blau gemacht, da erscheint die blaue Farbe. Und was dazwischen ist, sind eben Abstufungen. Das hätte er sich sagen müssen.

[ 15 ] Aber es ging um diese Zeit in der Welt alles darauf hinaus, so zu erklären, daß man eigentlich nur alles da drinnen schon suchte, woraus man es eigentlich erklären sollte. Nicht wahr, das ist ja das Allereinfachste. Wenn man zum Beispiel erklären soll, wie der Mensch entsteht, so sagt man: Nun ja, der ist schon im Ei der Mutter drinnen, da entwickelt er sich nur heraus. Das ist eine feine Erklärung, indem man sich sagt ... (Lücke im Text.) - Wir haben es, wie Sie gesehen haben, nicht so gut. Wir müssen den ganzen Weltenraum zu Hilfe nehmen, der dann das Ei aus der Mutter erst herausbildet. Aber die Naturwissenschaft geht darauf aus, alles da hinein ... (Lücke im Text.) Newton hat also gesagt: Die Sonne enthält schon alle Farben, wir brauchen sie nur herauszuholen.

[ 16 ] Aber so ist es gar nicht. Wenn die Sonne Rot erzeugen soll durch die Morgenröte, muß sie erst auf die Wolken scheinen, und wir müssen durch die Dunkelheit das Rot sehen. Und wenn der Himmelsraum blau erscheinen soll, so ist das gar nicht von der Sonne, denn da scheint die Sonne nicht herein, da ist es schwarz, finster, und das Blau sehen wir durch die erhellte Luft der Erde. Da sehen wir also Finsternis durch Licht = Blau.

[ 17 ] Worauf es hinauskommt, das ist: man sollte eine ordentliche Physik machen, wo man dann sehen könnte, wie beim Prisma auf der einen Seite Licht durch Dunkelheit, auf der anderen Seite Dunkelheit durch Licht gesehen wird. Das ist aber den Leuten zu unbequem. Sie finden es am besten, wenn man sagt: Alles ist im Licht drinnen, und man holt es nur heraus. —- Dann kann man auch sagen: Einst gab es in der Welt ein riesiges Ei, da war schon die ganze Welt drinnen, und aus dem holen wir alles heraus! —- So hat es Newton mit den Farben gemacht. Aber in Wirklichkeit kann man das Geheimnis der Farben durchaus immer sehen, wenn man in der richtigen Weise die Morgenröte und die Himmelsbläue versteht.

[ 18 ] Nun muß man nur weiter die ganze Sache im Verhältnis zu unserem Auge betrachten, und überhaupt zu dem ganzen Menschenleben. Sie wissen ja alle, daß es ein Wesen gibt, das durch das Rot, wo also das Licht durch die Dunkelheit wirkt, besonders aufgeregt wird: das ist der Stier. Der Stier wird bekanntlich durch das Rot furchtbar aufgeregt. Das wissen Sie auf der einen Seite. Und so ein bißchen etwas von der Stiernatur hat ja der Mensch auch. Er wird zwar nicht durch das Rot direkt aufgeregt, aber Sie werden sofort wahrnehmen, daß der Mensch, wenn er immerfort bei rotem Lichte lebt, dann schon auch ein bißchen aufgeregt wird. Er wird ein bißchen stierhaft. Ich habe sogar Dichter kennengelernt, die haben nicht dichten können, wenn sie ihre gewöhnliche Körperverfassung hatten; da haben sie sich immer in Zimmer gesetzt, wo sie über die Beleuchtungskörper solch einen roten Schirm drüber gemacht haben. Nachher sind sie aufgeregt geworden und haben dichten können. Nun, der Stier wird wild; der Mensch kann auf diese Weise sogar dichterisch werden, wenn er sich dem Rot aussetzt! Es kommt nur darauf an, ob man es von außen oder innen tut, dieses Beleben zum Dichten! Das ist auf der einen Seite der Fall.

[ 19 ] Auf der anderen Seite werden Sie auch wissen, daß wenn die Menschen, die solche Sachen durchschauen, andere Menschen, die es nicht durchschauen, besonders zahm, so recht demütig machen wollen, die blaue Farbe anwenden, oder die schwarze Farbe, direkt schwarz. So wird zum Beispiel, wenn im Katholizismus der Advent kommt, wo die Menschen demütig werden sollen, die Kirche, aber vor allem die Mefßgewänder blau gemacht. Die Menschen werden zahm, demütig. Der Mensch fühlt sich dann innerlich mit in der demutsvollen Stimmung. Besonders wenn der Mensch sich zuerst ausgetobt hat wie ein Stier, wie zum Beispiel bei der Fastnacht das der Fall sein konnte, dann läßt man darauf die richtige Fastenzeit folgen, und nicht nur dunkle Gewänder, [sondern sogar] schwarze Gewänder. Da wird dann der Mensch über sein Austoben zahm. Nur sollte dort, wo man sogar zwei Fastnachtssonntage hat, auch die Fastenzeit aufs Doppelte ausgedehnt werden! Ich weiß nicht, ob das geschieht. Aber Sie sehen daraus, daß das auf den Menschen in ganz verschiedener Weise wirkt, ob er das Licht durch das Dunkle wahrnimmt, also das Rote, oder ob er Finsternis, Dunkelheit durch das Licht wahrnimmt, also das Blaue.

[ 20 ] Betrachten Sie nun das Auge. Da drinnen haben Sie Nerven und Blut. Wenn das Auge auf das Rote schaut, also sagen wir, auf die Morgenröte oder überhaupt auf etwas Rotes schaut, was erlebt da das Auge? Sehen Sie, wenn das Auge auf das Rote schaut, dann werden im Auge diese ganz feinen Blutäderchen von dem roten Licht durchzogen. Und dieses rote Licht hat die Eigentümlichkeit, daß es das Blut immer ein bißchen zerstört. Es zerstört aber den Nerv mit, denn der Nerv kann auch nur leben, wenn er vom Blut durchzogen ist. Wenn das Auge dem Rot gegenübersteht, wenn das Rot hereinkommt, dann wird immer das Blut im Auge etwas zerstört, der Nerv mit zerstört. Der Stier empfindet einfach, wenn er dem Rot gegenübersteht: Donnerwetter, da wird mir ja mein ganzes Blut zerstört im Kopf! Da muß ich mich wehren dagegen! - Da wird er wild, weil er sich sein Blut nicht zerstören lassen will.

[ 21 ] Nun, dies ist aber sehr gut, wenn nicht gerade beim Stier, aber beim Menschen und bei anderen Tieren. Denn wenn wir nun ins Rote schauen und unser Blut etwas zerstört wird, dann wirkt auf der anderen Seite der ganze Körper so, daß wir wieder besser den Sauerstoff ins Auge hineinleiten, damit das Blut wieder hergestellt werden kann.

[ 22 ] Bedenken Sie, was da für ein wunderbarer Vorgang geschieht: Wenn Licht durch Dunkelheit, also Rot, gesehen wird, so wird zunächst Blut zerstört, Sauerstoff aus dem Körper gesogen und das Auge belebt durch den Sauerstoff. Und jetzt wissen wir an unserem eigenen Lebhaftwerden im Auge: da ist Rot draußen. Aber damit wir dieses Rot wahrnehmen können, muß uns zuerst im Auge ein bißchen das Blut zerstört werden, der Nerv zerstört werden. Wir müssen ins Auge Leben hineinschicken, das heißt Sauerstoff hineinschicken. Und an unserem eigenen Aufleben des Auges, an diesem Aufwachen des Auges merken wir: da draußen ist Rot.

[ 23] Nun, sehen Sie, dadurch, daß der Mensch also richtig das gerötete Licht wahrnimmt, daß der Mensch immer richtig das gerötete Licht aufnehmen kann, darauf beruht ja eigentlich auch seine Gesundheit. Denn der Sauerstoff, der da aus dem Körper aufgenommen wird, der belebt dann den ganzen Körper, und der Mensch selber bekommt eine gesunde Gesichtsfarbe. Er kann richtig sich beleben.

[ 24 ] Das ist nicht nur bei dem der Fall, dessen Auge gesund ist und der sieht, sondern das ist auch bei dem der Fall, dessen Auge nicht gesund ist und der nicht sieht; denn das Licht wirkt durch die hellen Farben; dann wird er belebt im Kopfe, und diese Belebung, die wirkt wiederum auf den ganzen Organismus und gibt ihm eine gesunde Farbe. So daß wir, wenn wir im Lichte leben und richtig das Licht aufnehmen können, dann die gesunde Farbe kriegen.

[ 25 ] Es ist also schon sehr wichtig, daß der Mensch nicht in finsteren Räumen aufgezogen wird, wo er tot und demütig werden könnte, sondern daß der Mensch in hellen, rötlichen oder gelblichen Räumen aufgezogen wird, wo er den Sauerstoff, den er im Inneren hat, auch wirklich durch das Licht richtig verarbeitet. Daraus sehen Sie aber, daß alles, was mit dem Roten zusammenhängt, beim Menschen eigentlich mit der Entwickelung des Blutes zusammenhängt. Der Nerv wird eigentlich, wenn wir Rot wahrnehmen, zerstört.

[ 26 ] Jetzt denken Sie sich, wir sehen Finsternis durch Licht, also Blau. Die Finsternis zerstört uns das Blut nicht; die Finsternis läßt uns das Blut unzerstört. Der Nerv bleibt also auch unzerstört, weil sein Blut in Ordnung bleibt. Die Folge davon ist, daß der Mensch sich innerlich so recht wohl fühlt. Weil das Blut und der Nerv nicht angegriffen werden vom Blau, fühlt sich der Mensch innerlich so recht wohl. Und beim Demütigmachen, da ist eigentlich etwas Raffiniertes dabei. Wenn nämlich, sagen wir, da oben am Altare die Priester in den blauen Gewändern oder in den schwarzen Gewändern sind und unten die Leute sitzen, dann werden ihnen durch die blauen Gewänder, wenn sie immer hingucken, die Blutadern und die Nerven in dem Auge nicht zerstört, und natürlich fühlen sie sich furchtbar wohl darinnen. Es ist eigentlich auf das Wohlbefinden der Leute berechnet. Glauben Sie nur nicht, daß man das nicht weiß! Denn die haben ja noch die alte Wissenschaft. Die neuere Wissenschaft ist ja erst bei den aufgeklärten Menschen entstanden, bei solchen aufgeklärten Menschen wie zum Beispiel Newton.

[ 27 ] Und so können wir sagen: Das Blau ist dasjenige, was dem Menschen innerliches Wohlbehagen bereitet, wo er sich sagt — das ist alles unbewußt, aber innerlich sagt er sich: Da kann ich leicht leben, in dem Blau. Da fühlt sich der Mensch innerlich, während er bei dem Roten fühlt, als ob in ihn etwas eindringen würde. Man könnte sagen beim Blau: Der Nerv bleibt unzerstört, und der Körper schickt sein Wohlgefühl ins Auge und dadurch in den ganzen Körper.

[ 1 ] Sehen Sie, das ist der Unterschied zwischen den blauen Farben und den roten Farben. Und Gelb ist ja nur eine Abstufung des Roten, und Grün ist eine Abstufung des Blauen. So daß man sagen kann: Je nachdem Nerv oder Blut im Menschen tätig ist, je nachdem empfindet er mehr rot, oder er empfindet mehr blau.

[ 28 ] Sehen Sie, das kann man nun auf die Farbkörper anwenden. Wenn ich also versuchen will, für die Malerei ein Rot, eine rote Farbe richtig zu erzeugen, so muß ich eine Farbe erzeugen, die diejenigen Stoffe enthält, welche den Menschen anregen, innerlich Sauerstoff zu entwickeln. Und da kommt man nach und nach darauf, daß man eigentlich rote Farbe bekommt für die Malerei, wenn man versucht, die Stoffe der Außenwelt darauf zu prüfen, wieviel Kohlenstoff sie enthalten. Wenn ich den Kohlenstoff in der richtigen Weise mit anderen Substanzen zusammen verwende, bekomme ich das Geheimnis des Rotmachens meiner Malerfarbe heraus. Wenn ich also Pflanzen verwende, um Malerfarben zu bekommen, so kommt es vor allen Dingen darauf an, daß ich meine Vorgänge, also Zerkleinerung, Verbrennung und so weiter, so einrichte, daß ich in der richtigen Weise dann in der Malerfarbe den Kohlenstoff darinnen habe. Wenn ich den Kohlenstoff in der richtigen Weise darinnen habe, so bekomme ich die helle, die rötliche Farbe heraus. Wenn ich dagegen namentlich solche Stoffe habe, die viel Sauerstoff haben - also nicht Kohlenstoff, sondern Sauerstoff -, wenn es mir gelingt, den Sauerstoff als Sauerstoff hineinzukriegen, so bekomme ich die mehr dunklen Farben, also das Blau heraus.

[ 29 ] Wenn ich das Lebendige in der Pflanze erkenne, so kann ich von dem auch wirklich meine Farben erzeugen.

[ 30 ] Denken Sie sich, ich nehme eine Sonnenblume. Die ist ganz gelb, hat also eine helle Farbe. Gelb ist nahe dem Roten: Licht durch Dunkelheit gesehen. Wenn ich nun eine Sonnenblume so behandle, daß ich den richtigen Vorgang, der in der Blüte sitzt, noch in meine Malerfarbe irgendwie hereinbekomme, dann habe ich eine gute gelbe Farbe, der das äußere Licht nicht viel anhaben kann; denn die Sonnenblume, die Blüte, die hat schon der Sonne das Geheimnis, Gelb zu erzeugen, gestohlen. Bekomme ich also denselben Vorgang, der in der Blüte der Sonnenblume sitzt, richtig in meine Malerfarbe hinein, so kann ich, wenn ich sie dick genug kriege, das Gelb ordentlich auftragen.

[ 31 ] Nehme ich aber eine andere Pflanze, zum Beispiel die Zichorie, die blau blüht — diese blaue Blume, die an den Wegrändern wächst; sie wächst ja auch hier —, wenn ich diese blaue Pflanze habe, und ich will aus der Blüte heraus eine Malerfarbe bereiten, so kann ich das nicht; ich bekomme nichts von ihr. Dagegen [bekomme ich etwas von ihr], wenn ich die Wurzel in der richtigen Weise behandle; da sitzt drinnen der Vorgang, der eigentlich die Blüte blau macht.

[ 32 ] Wenn Gelb in der Blüte ist, so geht in der Blüte selber das vor, was Gelb macht; wenn aber Blau in der Blüte ist, so sitzt der Vorgang in der Wurzel und er drängt sich nur hinauf gegen die Blüte. Da muß ich also aus der Indigopflanze, wo ich ein dunkleres Blau bekomme, oder aus der Zichorie, aus dieser blauen Blume, wenn ich eine blaue Malerfarbe herstellen will, die Wurzel verwenden. Die muß ich chemisch so weit bringen, daß sie mir die blaue Farbe abgibt.

[ 33 ] Und auf diese Weise kann ich durch ein wirkliches Studium darauf kommen, wie ich aus der Pflanze die Malerfarben kriege. Das kann ich auf dem Wege von Newton nicht, der einfach sagt: Nun ja, in dem Sonnenlicht ist alles drinnen, ich muß es nur herausholen. Das kann man höchstens auf die Geldbörse anwenden. Alles, was ich ausgebe für einen Tag, muß ich morgens drinnen haben in der Geldbörse. So stellen es sich die ganz gescheiten Leute vor, wie einen Sack, in dem alles drinnen ist. Das ist aber nicht der Fall.

[ 34 ] Man muß wissen, wie zum Beispiel das Gelb in der Sonnenblume drinnen ist oder in dem Löwenzahn. Man muß wissen, wie das Blau in der Zichorie drinnen ist. Die Vorgänge, die Zichorien- oder Indigoblau machen, liegen in der Wurzel; während die Vorgänge, die die Sonnenblume oder den Löwenzahn gelb machen, in der Blüte liegen. Und so muß ich in einer lebendig gewordenen Chemie den Blütenprozeß der Pflanze nachahmen und bekomme die helle Farbe. Ich muß den Wurzelprozeß der Pflanze nachahmen und erhalte da die dunkle Farbe.

[ 35 ] Sehen Sie, das, was ich Ihnen da erzählt habe, ist auf der einen Seite das, was sich dem wirklichen menschlichen Verstand ergibt, während im Grunde genommen diese Geschichte beim Regenbogen mit dem Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett keine Wirklichkeit ist.

[ 36 ] Nun hat sich in der Geschichte das so abgespielt, daß, als Goethe lebte, überhaupt schon alle Leute an dasjenige geglaubt haben, was Newton gelehrt hat: Die Sonne ist der große Sack, und da stecken die sogenannten sieben Farben drinnen. Die braucht man nur herauszukitzeln, da kommen sie zum Vorschein. Das haben alle Leute geglaubt. Das ist gelehrt worden, wird ja heute noch gelehrt.

[ 37 ] Goethe, der war nun so, daß er nicht gleich alles geglaubt hat, sondern er wollte sich so ein bißchen überzeugen von den Dingen, die überall gelehrt werden. Sonst sagen die Menschen: Wir sind nicht autoritätsgläubig. Aber wenn es darauf ankommt, das zu glauben, was an den Lehrstühlen gelehrt wird, dann sind die Leute natürlich heute furchtbar autoritätsgläubig, glauben alles, was gelehrt wird. Goethe hat nun nicht alles ohne weiteres glauben wollen und hat sich deshalb die Apparate, mit denen man das beweist, also solch ein Prisma und ähnliche Apparate, ausgeliehen von der Universität in Jena, hat also sich gedacht: Jetzt werde ich das auch einmal machen, was die Professoren vormachen, und sehen, wie es eigentlich ist.

[ 38 ] Nun ist Goethe nicht gleich dazu gekommen und hat die Apparate ziemlich lange bei sich gehabt, ohne daß er dazu gekommen ist. Er hatte gerade anderes zu machen in der Zeit. Und da ist dem Hofrat Büttner, der die Apparate wieder gebraucht hat, die Zeit zu lang geworden, und er wollte die Apparate wieder abholen lassen. Da hat Goethe gesagt: Jetzt muß ich geschwind die Geschichte machen! und hat doch wenigstens, als er schon beim Einpacken war, durch das Prisma geschaut. Er sagte sich: Die weiße Wand muß dann schön in Regenbögen erscheinen, wenn ich da durchschaue; statt Weiß muß da Rot, Gelb, Grün und so weiter erscheinen. — Er hat also durchgeguckt und freute sich schon, daß er nun die ganze Wand in diesen bunten Farben sehen werde, aber er sah nichts: Die Wand ist weiß wie früher, die Wand ist einfach weiß. Da war er natürlich aufs höchste überrascht. Was ist denn da dahinter, fragte er sich. Und sehen Sie, aus diesem ist seine ganze Farbenlehre hervorgegangen. Er hat gesagt: Man muß die ganze Sache jetzt noch einmal kontrollieren. Die Alten haben gesagt: Licht durch Dunkelheit gesehen = Rot, Finsternis durch Licht = Blau; wenn ich das Rot etwas abstufe, wird Gelb; wenn ich das Blau bis zum Rot hinaufsteigere, so wird das Blau Grün nach der einen Seite, Violett nach der anderen Seite. Das sind Abstufungen. Und er hat nun seine Farbenlehre, und zwar besser, als sie früher im Mittelalter vorhanden war, ausgearbeitet.

[ 39 ] Und nun haben wir heute eine Physiker-Farbenlehre mit dem Sack, aus dem die sieben Farben herauskommen, die überall gelehrt wird, und wir haben eine Goethesche Farbenlehre, die richtig das Himmelsblau versteht, richtig die Morgen- und Abendröte versteht, wie ich es Ihnen selber jetzt erklärt habe.

[ 40 ] Aber es gibt einen gewissen Unterschied zwischen der Newtonschen Farbenlehre und der Goetheschen Farbenlehre. Den merken zunächst die anderen Menschen nicht; denn die anderen Menschen, die schauen auf der einen Seite auf die Physiker hin. Da wird ihnen die Newtonsche Farbenlehre gelehrt, die steht überall in den Büchern. Man kann sehr gescheit sich nun ausmalen, wie da Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün und so weiter beim Regenbogen erscheint. Nun ja, da ist die Sache nicht so, daß ein Prisma da ist! Aber man denkt nicht weiter nach ... (Lücke im Text.) Die Newtonianer wissen es schon, aber sie gestehen sich es nicht ein. Wenn man nämlich durchschaut durch den Regen auf der einen Seite, da sieht man durch den von der Sonne beleuchteten Regen die Finsternis, sieht auf der Seite das Blau des Regenbogens. Dann sieht man aber auch vorne die Fläche, wo man Licht sieht durch die Dunkelheit durch, und sieht auf der anderen Seite das Rote. Also man muß alles nach dem einheitlichen Prinzip erklären: Licht durch Dunkelheit ist rot, Finsternis durch Licht ist blau.

[ 41 ] Aber wie gesagt, auf der einen Seite sehen die Leute, wie ihnen die Physiker alles erklären, und auf der anderen Seite gucken die Leute Gemälde an, wo die Farben verwendet sind. Nun ja, da fragen sie dann nicht weiter, wie das ist mit dem Rot und Gelb und so weiter, bringen die zwei Dinge nicht zusammen.

[ 42 ] Ja, meine Herren, der Maler muß sie zusammenbringen. Derjenige, der malen will, muß sie zusammenbringen. Der muß nicht nur wissen: Da ist ein Sack, und da sind alle Farben drinnen — denn den Sack hat er ja nicht, nirgends —, sondern er muß aus der lebendigen Pflanze oder anderen lebendigen Stoffen das Richtige herausbekommen, damit er seine Farben richtig mischen kann, muß verstehen ... (Lücke im Text.) Deshalb ist der Zustand heute so, daß die Maler wirklich nachdenken, es gibt auch Maler, die nicht nachdenken, die einfach sich ihre Farben kaufen -; aber die Maler, die nachdenken, wie sie diese Farben bekommen und wie sie diese Farben verwenden sollen, die sagen: Ja, mit der Goetheschen Farbenlehre, da ist etwas anzufangen. Die sagt uns etwas. Mit der Newtonschen, mit der Physiker-Farbenlehre können wir Maler nichts anfangen. — Also das Publikum, das bringt eben das Malen und die physikalische Farbenlehre nicht zusammen, aber der Maler! Und der liebt daher auch die Goethesche Farbenlehre. Der Maler sagt sich: Ach Gott, um die Physiker, um die kümmern wir uns nicht; die sagen etwas auf ihrem eigenen Gebiet. Die mögen tun, was sie wollen. Wir halten uns an die alte und an die Goethesche Farbenlehre. - Nur betrachten die Maler sich als Künstler und betrachten sich nicht wirklich so, daß sie nun eingreifen müssen in die Lehren der Physiker. Das ist ja auch unbequem. Da kommen Gegnerschaften und so weiter.

[ 43 ] So liegen heute die Sachen zwischen dem, was über die Farben in den Büchern steht, und dem, was wahr ist. Bei Goethe war es einfach die Verteidigung der Wahrheit, was ihn dazu getrieben hat, gegen die Newtonsche und die ganze moderne Physik sich aufzulehnen. Und man kann nicht wirklich die Natur verstehen, ohne daß man auch zur Goetheschen Farbenlehre kommt. Und deshalb ist es ganz natürlich, daß in einem Goetheanum auch die Goethesche Farbenlehre verteidigt wird. Aber dann, wenn man nicht nur auf irgendwelchem religiösen oder sittlichen Gebiete bleibt, sondern nun auch noch eingreift in die einzelnsten Teile der Physik, so hat man auch noch die Meute der Physiker auf sich.

[ 44 ] Also, Sie sehen, die Verteidigung der Wahrheit, die ist schon etwas, was in der heutigen Zeit außerordentlich schwierig ist. Aber Sie sollten sich nur einmal davon unterrichten, auf welche komplizierte Weise die Himmelsbläue erklärt wird von den heutigen Physikern! Natürlich, wenn ich von einem falschen Prinzip ausgehe, und ich will dann das Einfache erklären, daß der schwarze Weltenraum blau erscheint durch die Helligkeit durch, dann muß ich eine furchtbar komplizierte Erklärung daraus machen. Und erst Morgen- und Abendröte! Diese Kapitel beginnen meist so, daß da steht: Ja, das Himmelsblau kann man eigentlich heute noch nicht richtig erklären; man könnte sich dies oder jenes vorstellen. — Ja, mit alledem, was die Physiker haben mit ihrem kleinen Loch, über das sich Goethe so lustig gemacht hat, durch das sie ins Zimmer herein das Licht kommen lassen, um mit der Finsternis das Licht zu untersuchen, mit alledem kann man eben die einfachste Sache nicht erklären. Und so kommt es dahin, daß man überhaupt nichts mehr von der Farbe versteht.

[ 45 ] Versteht man, daß die Blutzerstörung und dadurch gerade die Belebung ... (Lücke im Text) — denn wenn ich zerstörtes Blut in mir habe durch das Licht, so rufe ich allen Sauerstoff in mir auf, und ich belebe mich, da kommt die Gesundheit des Menschen zustande. Habe ich Dunkelheit um mich oder immerfort Bläuliches, ja, dann will ich mich immerfort beleben; dann belebe ich mich zuviel und werde gerade durch das Beleben blaß, weil ich zuviel Leben in mich hineinschoppe. Und so kann man auf der einen Seite die gesunde Rötung des Menschen verstehen aus der Sauerstoffaufnahme, wenn der Mensch richtig dem Lichte sich aussetzt, und man kann die Blaßheit verstehen aus der fortwährenden Aufnahme von Kohlensäure. Kohlensäure, das Gegenteil von Sauerstoff, die will nun in meinen Kopf herein. Das macht mich nun ganz blaß.

[ 46 ] Heute haben Sie in Deutschland zum Beispiel fast lauter blasse Kinder. Aber man muß verstehen, daß das von zuviel Kohlensäure herrührt, Und wenn der Mensch zuviel Kohlensäure entwickelt - Kohlensäure besteht aus einer Verbindung von Kohlenstoff und Sauerstoff —, dann verwendet er den Kohlenstoff, den er in sich hat, zuviel zum Kohlensäurebilden. Also Sie haben dann in einem solchen blassen Kinde allen Kohlenstoff, den es in sich hat, fortwährend in Kohlensäure verwandelt. Dadurch wird es blaß. Was muß ich tun? Ich muß ihm etwas beibringen, wodurch dieses ewige Kohlensäure-Entwickeln im Inneren verhindert wird, wodurch der Kohlenstoff zurückbleibt. Das kann ich machen, wenn ich ihm etwas kohlensauren Kalk gebe. Dadurch werden dann, wie ich Ihnen von einem ganz anderen Gesichtspunkte aus gesagt habe, die Funktionen wiederum angeregt, und der Mensch behält den Kohlenstoff, den er braucht, verwandelt ihn nicht fortwährend in Kohlensäure. Und dadurch, weil die Kohlensäure aus Kohlenstoff und Sauerstoff besteht, kommt der Sauerstoff in den Kopf hinauf und belebt die Kopfprozesse, die Lebensprozesse. Wenn der Sauerstoff aber an die Kohlensäure abgegeben wird, werden die Lebensfunktionen unterdrückt.

[ 47 ] Bringe ich also zum Beispiel einen blassen Menschen in eine Gegend, wo er viel Licht hat, dann wird er angeregt, nicht seinen Kohlenstoff fotwährend an die Kohlensäure abzugeben, weil das Licht den Sauerstoff in den Kopf hinaufsaugt. Dann wird er wieder eine gesunde Farbe kriegen. Ebenso kann ich durch den kohlensauren Kalk das anregen, indem ich den Sauerstoff erhalte, so daß der Mensch den Sauerstoff zu seiner Verfügung hat.

[ 48 ] So muß alles ineinandergreifen. Man muß von der Farbenlehre aus Gesundheit und Krankheit begreifen können. Das können Sie nur von der Goetheschen Farbenlehre aus, weil die einfach auf naturgemäße Weise in der Natur drinnensteht, niemals mit der Newtonschen Farbenlehre, die einfach etwas Ausgedachtes ist, und die gar nicht in der Natur drinnensteht, die eigentlich die einfachsten Erscheinungen, Morgenund Abendröte und den blauen Himmel, nicht erklären kann.

[ 49 ] Nun möchte ich Ihnen aber noch etwas sagen. Denken Sie sich jetzt die alten Hirtenvölker, die also ihre Herden hinausgetrieben haben und dann im Freien geschlafen haben. Die waren während ihres Schlafes gar nicht einmal dem blauen, sondern dem dunklen Himmel ausgesetzt. Und da droben sind die unzähligen, leuchtenden Sterne. Nun denken Sie sich also den dunklen Himmel, und da drauf unzählige leuchtende Sterne, und da drunten den schlafenden Menschen. Von dem dunklen Himmel, da geht jetzt aus der Prozeß der Beruhigung des Menschen, des innerlichen Wohlseins im Schlafe. Der ganze Mensch wird von der Finsternis durchdrungen, so daß er innerlich ruhig wird. Der Schlaf geht von der Finsternis aus. Aber da scheinen auf den Menschen diese Sterne. Und überall, wo ein Sternenstrahl hinscheint, da wird der Mensch innerlich ein bißchen aufgeregt. Da geht vom Körper aus ein Sauerstoffstrahl. Und diesen Sternenstrahlen kommen lauter Sauerstoffstrahlen entgegen, und der Mensch wird innerlich ganz von solchen Sauerstoffstrahlen durchzogen. Und er wird innerlich ein Sauerstoff-Spiegelbild vom ganzen Sternenhimmel.

[ 50 ] Also die alten Hirtenvölker haben den ganzen Sternenhimmel aufgenommen in ihre beruhigten Körper wie in Bildern, in Bildern, die der Sauerstoffverlauf in sie eingezeichnet hat. Dann wachten sie auf. Und sie hatten den Traum von diesen Bildern. Und sie hatten daraus ihre Sternenwissenschaft. Da haben sie dann diese wunderbare Sternenwissenschaft ausgebildet. Sie haben nicht den Traum so gehabt, daß der Widder einfach so und so viel Sterne habe, sondern sie haben wirklich das Tier Widder gesehen, den Stier gesehen und so weiter, und haben dadurch in sich in Bildern den ganzen Sternenhimmel gefühlt.

[ 51 ] Das ist dasjenige, was uns von den alten Hirtenvölkern als eine dichterische Weisheit geblieben ist, die manchmal außerordentlich viel enthält, was heute noch lehrreich sein kann. Und verstehen kann man das, wenn man weiß: Der Mensch läßt einem jeden Lichtstrahl, einem jeden Sternenstrahl einen Sauerstoffstrahl entgegenstrahlen, wird ganz Himmel, ein innerer Sauerstoffhimmel.

[ 52 ] Und des Menschen inneres Leben ist ja ein Leben im Astralleib, denn er erlebt während des Schlafes den ganzen Himmel. Uns ginge es schlecht, wenn wir nicht von diesen alten Hirtenvölkern abstammen würden. Alle Menschen stammen nämlich von alten Hirtenvölkern ab. Wir haben noch immer, bloß durch Erbschaft, einen inneren Sternenhimmel zur Erkenntnis. Wir entwickeln das noch immer, obwohl schlechter als die Alten, und wir haben im Schlaf, wenn wir im Bette liegen, noch immer so eine Rückerinnerung an die Art und Weise, wie einmal der alte Hirte so im Felde gelegen hat und den Sauerstoff in sich hereinbekommen hat. Wir sind nicht mehr Hirten, aber haben noch etwas geerbt, haben auch noch etwas, können es nur nicht so schön ausdrücken, weil es schon abgeblaßt und abgedämmert ist. Aber die ganze Menschheit gehört eben zusammen. Und wenn man das, was der Mensch heute noch in sich trägt, erkennen will, muß man zurückgehen in die alten Zeiten. Alle Menschen auf der Erde sind überall von diesem Hirtenstadium ausgegangen und haben eigentlich in ihren Leibern dasjenige geerbt, was noch von diesen Hirtenvölkern stammen konnte.

Second Lecture

[ 1 ] In order to answer the last question correctly, I will say a few words about colors as best I can.

[ 2 ] You can't really understand colors without understanding the human eye, because humans perceive colors only through the eye. How he otherwise still perceives colors, that he does not know, because he still does not perceive colors through the eye alone. Imagine for example a blind man. A blind man feels differently in a room that is lit than in a room that is dark. But that is so weak that the blind man does not perceive it. It is such a weak thing; but it still has a great significance for him, but he does not perceive it. The blind person, for example, could not always live in the basement; he would lack light. And there is a difference between, for example, bringing a blind person into a bright room that has yellow windows, or bringing him into a dark room or, for that matter, into a brighter room that has blue windows. This has a completely different effect on life; the yellow color and the blue color have a completely different effect on life. But these are things that one only learns to understand when one has grasped how the eye relates to color.

[ 3 ] Now you may have seen from what I have presented to you so far that two things are most important in man. In his entire organism, two things are most important. The first is blood; for if man did not have blood, he would have to die immediately. He would not be able to renew his life in every moment, and life must be renewed in every moment. So, imagine the blood being removed from the body, then man is a dead object. But even if you imagine the nerves being removed, then man could indeed look exactly as he looks, but he would have no consciousness; he would be unable to imagine anything, unable to feel anything, would be unable to move. We must therefore say to ourselves: that man is a conscious being, for that he needs the nerves. That man can live at all, for that he needs the blood. So the blood is the organ of life; the nerves are the organ of consciousness.

[ 4 ] But every organ has nerves and blood. And the human eye is actually really a whole human being and has nerves and blood, and in such a way that if you imagine the eye coming out of the head (drawing), the blood vessels in this eye spread out. Many blood vessels spread out. And then many nerves spread out. So you see what you have in your hand, nerves and blood vessels, you also have in your head.

[ 5 ] Now it is like this in the eye: yes, imagine that the outside world, which is illuminated, affects the eye. You see, it is best to imagine the outside world illuminated. Of course, during the day the outside world in which you walk around is illuminated. But it is difficult to get an idea of this completely illuminated outside world. You get a true concept when you imagine the half-lit outside world in the morning and evening, when you see the dawn and dusk around you. Dawn and dusk are particularly instructive.

[ 6 ] For what is actually present at dawn and dusk? Imagine the sunrise (drawing). The sun comes up. When the sun comes up, it cannot shine directly on you. I am now drawing the apparent path as we see it; in reality, the Earth is moving and the Sun is stationary, but that doesn't matter. So the Sun first sends its rays here, and then here. If you are standing there, you do not see the Sun at dawn, but you see the illuminated clouds. There are clouds. The light is actually sitting on these clouds.

[ 7 ] Well, gentlemen, what does this actually mean? This is very instructive. Because the sun is not yet fully up, it is still dark here; it is still dark around you, and there, in the distance, are the clouds illuminated by the sun. Can you understand that? So you see, when you are standing there, through the darkness that is around you, the illuminated clouds over there. You see light through the darkness. So that we can say: at dawn – and at dusk it is the same – you see light through darkness. And light seen through darkness, you can see that at dawn and dusk, it looks red. Light seen through darkness looks red. So we can say: when you see light through darkness, it looks red. Light seen through darkness is red.

[ 8 ] Now I will tell you something else. Imagine that dawn has already passed and you are in the middle of the day, looking freely into the air, for example, as is the case today. What do you see out there? You see the so-called blue sky. It is not there, but you see it anyway. This goes on forever, but you still see it as if it were wrapped around the earth like a blue shell. Why is that?

[ 9 ] Well, you just have to think about what it's like out there in the vastness of space: it's dark. The vastness of space is dark. The sun only shines on the earth, and because there is air around the earth, the sun's rays are trapped and create light here, especially when they shine through watery air. But out there in the vast expanse of space, it is absolutely black, dark. So that when you stand there during the day, you look into the darkness, and you would actually have to see black. But you don't see it black, but blue, because it is illuminated all around by the sun. The air and the water in the air are illuminated.

[ 10 ] So you see darkness through the light very clearly. You look through the light, through the illumination, into the darkness. So we can say: Darkness through light is blue.

[ 11 ] So there you have the two basic laws of color theory, which you can easily see in your surroundings. If you understand dawn and dusk correctly, you say to yourself: light seen through darkness or light seen through gloom is red. If you look up into the black sky during the day, you say to yourself: gloom or darkness seen through light – because everything around you is illuminated – is blue.

[ 12 ] You see, this completely natural view has always been held until people became “clever”. This view that light through darkness is red, darkness through light is blue, was held by the ancients in Asia when they were still as clever as I described to you the other day. The ancient Greeks still had this view. This view was still held throughout the Middle Ages, until people became clever, until around the 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th century. And when they became clever, they no longer looked at what was natural, but began to think up all kinds of artificial sciences. And one of those who came up with a particularly ingenious theory about colors was the Englishman Newton. Newton, who, out of cleverness – you know how I use the word cleverness now, namely, in all seriousness – who, out of particular cleverness, said to himself something like this: Let's look at the rainbow – because, when you become clever, you don't look at what is natural, what appears every day, dawn and dusk, but when you become wise you look at the particularly rare, the things that you should only understand when you have already come further – but now, so Newton said: let's look at the rainbow. In the rainbow you can see seven colors, namely red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. There are seven colors that you see in succession in the rainbow (he draws a picture). If you look at the rainbow, you can easily distinguish these seven colors.

[ 13 ] Now Newton has made an artificial rainbow by darkening his room, slamming the window shut with black paper and making a small hole in the paper. There he had a very small strip of light. Now he put what is called a prism into this strip of light, a glass that looks like this, a triangular glass, and behind it he set up a screen. So he had the window with the hole, this small stream of light, the prism, and behind it the screen. Now the rainbow also appeared; now red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet, all these colors appeared. What did Newton say to himself? Newton said to himself: the white light comes in; with the prism I get the seven colors of the rainbow. So the seven colors of the rainbow are already in the white light, and I just need to coax them out. — You see, that's the simplest explanation. You explain something by saying: it's already in the thing I'm getting it out of.

[ 14 ] In reality, he should have said to himself: By not placing a proper glass plate, but a prism, that is, a glass with a surface tapering to a point [the screen], light is made red by darkness on one side, when I look at it this way, because the red color appears, and on the other side, darkness is made blue by light, because the blue color appears. And what is in between are just gradations. He should have said that to himself.

[ 15 ] But at that time in the world, everything was reduced to explaining it in such a way that one was actually only searching for what was supposed to explain it. Not true, that is the simplest thing. If, for example, you are to explain how man comes into being, then one says: Well, he is already inside the mother's egg, and he just develops out of it. That is a fine explanation, in that one says... (gap in the text) – As you can see, we are not so well off. We have to take the whole of the universe into account, which then first develops the egg from the mother. But natural science assumes that everything is already there... (gap in the text). Newton said: The sun already contains all colors, we just need to extract them.

[ 16 ] But it is not like that at all. If the sun is to produce red through the dawn, it must first shine on the clouds, and we must see the red through the darkness. And if the sky is to appear blue, it is not at all from the sun, because the sun does not shine in there, it is black, dark, and we see the blue through the illuminated air of the earth. So we see darkness through light = blue.

[ 17 ] What it comes down to is this: you should do a proper physics, where you could then see how light is seen through darkness on one side of the prism and darkness through light on the other. But that's too inconvenient for people. They think it's best to say: everything is in the light, and you just bring it out. Then you can also say: Once upon a time there was a huge egg in the world, and the whole world was inside it, and we can get everything out of it! That's what Newton did with colors. But in reality, you can always see the secret of colors if you understand the dawn and the blueness of the sky in the right way.