Nine Lectures on Bees

GA 351

22 December 1923, Dornach

Lecture IX

We should perhaps say something further on the subject of Herr Dollinger's question. He asked, on your behalf, for it is probably of interest to you all, what the spiritual relationship is between the hosts of insects which, fluttering about, approaches the plants and what is to be found in the plants. I told you yesterday, for we began to answer this question last time, that all around us there is not only oxygen and nitrogen, but that throughout Nature there is intelligence, truly intelligence. No one is surprised if one says that we breathe in the air, for air is everywhere, and science today is so widely included in all the school books that everyone knows that air is everywhere, and that we breathe it in. All the same I have known country people who thought this a fantastic idea, because they did not know the air is everywhere; in the same way there are people today who do not know that intelligence is everywhere. They consider it fantastic if one says that just as we breathe in the air with our lungs, so do we breathe in intelligence, for example, through our nose, or through our ear. I. have already given instances in which you could see that there is intelligence everywhere.

We have been speaking of an especially interesting chapter of natural science, of the bees, wasps and ants. There is, may be, little in Nature which permits us to look so deeply into Nature herself, as the activities of the insects; the insects are strange creatures, and they have still many a secret to disclose.

It is interesting that we should be discussing the insects just at the time of the centenary of the famous observer of insects, Jean Henri Fabre, who was born on December 23, one hundred years ago, and whose life time coincides with the age of materialism. Fabre therefore interpreted everything materialistically, but he also brought to light an enormous number of facts. It is therefore quite natural that we should remember him today when we speak of the insects.

I should like to begin with, to give you an example of a species of insect which will interest you in connection with the bees. The work of the bees is perfected to a very high degree, but the most remarkable thing about the bee is really not that it produces honey but, that it produces the marvellous structure of the honey-comb entirely out of its own being. The material it makes use of, it must itself bring into the hive, but the bee actually works in such a way that it does not use this material directly, but completely transforms it, completely transforms what it brings into the hive. The bee works from out of its own being.

Now there is a kind of bee which does not work in this way, but shows, precisely in its work, what immense intelligence there is in the whole of Nature. Let us consider this bee; it is commonly called the wood-bee, and is not so valued as the domestic bee, because it is mostly rather a nuisance. We will consider this wood-bee at its work.

It is a tremendously industrious little creature, a creature which in order to live—not the individual bee, but the whole species—must do a terrific amount of work. This bee searches out such wood as is no longer on a living tree, but has been made into something. One finds the wood-bee which I shall presently describe, with its nest in a place where wooden rails, or posts have been driven in and the wood is therefore apparently dead. The nests can usually be found in wooden rails or posts, in garden benches, or garden doors, in fact wherever one has made use of wood. Here the wood-bee makes its nest, but it does so in a very singular way.

Imagine to yourselves a post (Diagram 16.) The wood is no longer part of a tree. The wood-bee comes along and first of all bores a sloping passage from outside. When it has got inside, when it has bored out a kind of passage, it starts boring in quite a new direction. It makes a little ring-like hollow, then flies off and collects all manner of things from round about, and lines out the hollow with these. Having finished the lining, it deposits an egg which will develop into a larva. This is now inside the hollow. When the egg has been placed there, the little bee makes a covering over it, in the centre of which there is a hole. Now it begins to bore again above the cover, and makes a second little hollow for the second bee that is to creep out, and having lined it and left a hole it lays another egg. The wood-bee continues in this way till it has constructed ten or twelve of these superimposed dwellings; in each one there is an egg.

You see, gentlemen, the larva can now mature in this piece of wood. The bee puts some food next to the larva which first eats what has been prepared for it, and grows till it is ready to creep out. First we have the time when the grub becomes a cocoon, then it is transformed into a winged bee which is to fly out. Inside there it is so arranged (see Diagram 16), that the larva now developed can fly out at the right moment. When the time comes that the larva has developed, has turned into a cocoon, and then into a complete insect, then it is so arranged that it is able to fly out through the passage. The skill employed has enabled the fully formed insect to fly out through the passage that was first bored.

Well and good, but the second insect that is a little younger, now emerges, and the third that is still younger; because the mother insect had first to make these dwelling-places, the creatures would not find any outlet, the situation would be fatal to the larvae in the upper chambers, they would slowly die. But the mother insect prevents this by laying the eggs so that when the young larva creeps out, it finds this other hole which I described, and lets itself down there, and flies out. The third creature comes down through the two holes and so on. Because each insect that comes out later is matured later, it does not hinder the one below it which had emerged earlier. The times are never the same, for the earlier has always already flown out.

You see, gentlemen, the whole nest is so wisely planned that one can only wonder at it.

Today when men imitate mechanically, the things they copy are often of this kind, but as a rule they are far less cleverly constructed. Things that exist in Nature are extremely wisely made, and one must really say that there is intelligence in them, real intelligence. One could give hundreds and thousands of examples of the way the insects build, of the way they set about their tasks, and how intelligence lives within these things. Think how much intelligence there is in all I have already told you about the farming ants which establish their own farm, and plan everything with wonderful intelligence.

But in considering these insects, the bees, wasps and ants, we were at the same time dealing with another matter. I told you that these creatures all have a poisonous substance within them, and that this poisonous substance is also, if given in the right dose, an excellent remedy. Bee-poison is an excellent remedy; wasp-poison is the same, and the formic acid secreted by the ants is a most especially good remedy. But as I have already pointed out, this formic acid which we find when we go to an ant-heap and take out a few ants and crush them, these ants have the formic acid inside them; by crushing them we get the formic acid. It is found more especially in the ants.

But gentlemen, if you knew how much, (of course, comparatively speaking,) how much formic acid there is in this hall, you would be greatly astonished. You might say, surely we are not to look for an ant-heap in some corner! But all of you, as many as are sitting here, are really yourselves a kind of ant-heap, for every where in your limbs, muscles and other tissues, in the heart and lung and liver tissues, above all in the tissues of the spleen, everywhere there is formic acid; certainly, it is not so concentrated as in the ant-heap, nevertheless, you are quite filled with formic acid. It is a highly remarkable fact.

Why do we have formic acid in our bodies? One must be able to recognise when a man has too little of it. If someone seems ill, and people are mostly a little ill, he might have one or another of a hundred different illnesses which externally, would seem similar. One must know what is really the matter with him; if he is pale or has no appetite, these are only external symptoms. One must find out what exactly is wrong with him. In many cases, the trouble might well be that he is not enough of an ant-heap in himself, that he is producing too little formic acid. Just as formic acid is produced in the ant-heap, so in the human body, in all its organs, especially in the spleen, formic acid must be vigourously produced. When a man produces too little formic acid, one must give him a preparation, a remedy with which one can help him to produce sufficient formic acid. One must learn to observe what happens to a man who has too little formic acid in him. Such observations can only be made by those who have a true knowledge of human nature. One must make a picture of what is happening in the soul of a man who, to begin with, had enough formic acid, and later, has too little. It is a singular thing, but a man will tell you the correct thing about his illness, if you ask him in the right way. Suppose, for instance, you had a man who tells you: “Why, good gracious, a few months ago I had ever so many good ideas, and I could think them out well. Now I cannot do so any longer; if I want to remember anything, I cannot do so.” This is often a much more important symptom than any external examination can give. What is done today is of course justifiable, one must do these things. Today one can test the urine for albumen, or sugar and so on; one gets quite interesting results. But in certain circumstances, it can be far more important when a man tells you something of the kind I have just told you. When a man tells you something of this kind, one must of course, learn other things about him also, but one can discover that the formic acid in his body has recently become insufficient.

Well, anyone who still thinks only of externals, might say: “This man has too little formic acid, I will squeeze out some formic acid, or get it in some other way, and give him the right dose.” This could be done for a certain time, but the patient would come to you and say it has done him no good at all. What then is the matter? It really has not helped him at all. It was quite correct; the man had too little formic acid, and he has been given formic acid, but it did him no good. What is the reason? You see, when you examine further, you come to this point. In the one case formic acid has done no good, in another case, it has continued to do good. Well presently one learns to see the difference. Those who are helped by formic acid, will usually show mucus in the lungs. Those who got no help from it, will show mucus in the liver, kidneys, or in the spleen.

It is very interesting. It is therefore a very different matter if the lung, for example, lacks formic acid, or the liver. The difference is that the formic acid which is in the ant-heap, can immediately take effect upon the lung. The liver cannot do anything with the formic acid, it can make no use of it at all.

Something further now comes in question. When you discover that a man's liver, or more especially his intestines are not quite in good order, and if one gives him formic acid it does not help him, though he actually has not enough of it, then one must give him oxalic acid. One must take wood-sorrel, or the common-clover that grows in the fields, extract the acid, and give him this.

Thus you see, anyone with lung trouble must be given formic acid, whereas if the trouble is in the liver, or the intestines, he must be given oxalic acid. The remarkable thing is that the man to whom one has given oxalic acid, will before long himself change the oxalic acid into formic acid. The main point therefore is, that one does not simply introduce such things into a man's body, but that one knows what the organism can bring about by means of its own resources. When you introduce formic acid into the organism, it says;—“This is not for me; I want to be active, I cannot work with ready-made formic acid, I cannot take it up into my lungs.” Naturally, the formic acid has gone into the stomach; from there it finally passes into the intestines. Then the human body wants to be active, and say, as it were: “What am I supposed to do now? I am not to make formic acid myself, for formic acid is given me; have I to send this from here up into my lungs? This I shall not do.” The body wants oxalic acid, and from this it produces formic acid.

Yes, gentlemen, life consists of activity, not of substances, and it is most important to recognise that life does not merely consist of eating cabbages and turnips, but of what the human body must do when cabbages and turnips are put into it.

You can see from this what strange relationships exist in Nature. Outside there, are the plants, The clover is merely especially characteristic, for oxalic acid is to be found in all the plants; in clover it is present in greater quantities, that is why it is mentioned. But just as formic acid is everywhere in Nature and everywhere in the human body, so also is there oxalic acid everywhere in Nature and in the human body.

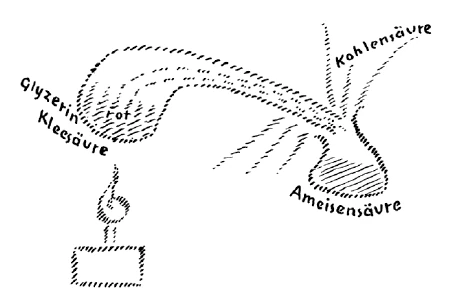

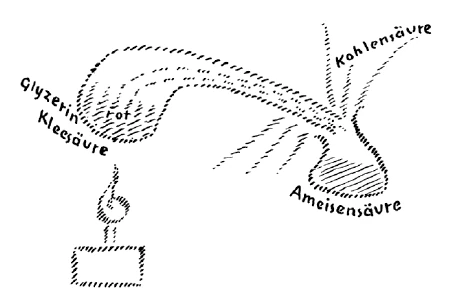

There is something further that is very interesting. Suppose you take a retort, such as are used in chemical laboratories. You make a flame under it, and put into the retort some oxalic acid—it is like salty, crumbly ashes. You then add the same quantity of glycerine, mix the two together, and heat it. The mixture will then distil here, (Diagram 17) and I can condense what I get here (Diagram 17). At the same time I notice air is escaping at this point. Here it escapes. When I now examine this escaping air, I find it is carbonic acid. Thus carbonic acid is escaping here, and here, where I condense (Diagram 17) I get formic acid. In here, I had oxalic acid and glycerine. The glycerine remains, the rest goes over there, the fluid formic acid dropping down and the carbonic acid giving out the air.

Well, gentlemen, when you consider this whole matter thoroughly, you will be able to say: suppose, that instead of the retort we had here the human liver or let us say some human or animal tissue, some animal abdominal organ, liver, spleen or something of this nature. By way of the stomach I introduce oxalic acid. The body already possesses something of the nature of glycerine. I have then in the intestines oxalic acid and glycerine. What happens?

Now look at the human mouth, for there the carbonic acid comes out, and downwards from the lungs formic acid everywhere drops in the human body in the direction of the organs. Thus everything I have drawn here we have also in our own bodies. Within our own bodies we unceasingly transform oxalic acid into formic acid.

And now imagine to yourself the plants spread out over the surface of the earth. Everywhere in the plants is oxalic acid. And now think of the insects; with the insects all this occurs in the strangest way. First think of the ants; they go to the plants, to all that decays in the plants, and everywhere there is oxalic acid, and these creatures make formic acid from it in the same way that a man does. Formic acid is everywhere present.

The materialist looks out into the air and says:—Yes, in the air there is nitrogen and oxygen. But gentlemen, in very, very minute quantities there is also always some formic acid present, because the insects flutter through the air. On the-one hand we have man. Man is a little world; he produces formic acid in himself, and continually fills his breath with formic acid. But in the great world without, in the place of what happens in man, there is the host of insects. The great breath of air that surrounds the whole earth is always permeated with formic acid which is the transformed oxalic acid of the plants. Thus it is.

If one rightly observes and studies the lower part of the human body with its inner organs, the stomach, liver, kidneys and the spleen, and further within, the intestines, it is actually the case that oxalic acid is perpetually being changed into formic acid, this formic acid passes with the inbreathed air into all parts of the body. So it is within man.

On the earth the plants are everywhere, and everywhere the innumerable hosts of insects hover above them. Below is the oxalic acid; the insects flutter towards it, and from their biting into the plants formic acid arises and fills the air. Thus we perpetually inhale this formic acid out of the air. What the wasps have is a poison similar to formic acid, but somewhat different; what the bees have in the poison of their sting, though actually it pervades their whole body, is likewise a transformed, a sublimated formic acid.

Looking at the whole, one has this picture. One says to oneself: we look at the insects, ants, wasps and bees. Externally, they are doing something extremely clever. Why are they doing this? If the ant had no formic acid it would do quite stupidly all that I have described as so beautiful. Only because the ants are so constituted that they can produce formic acid, only because of this, does all that they accomplish appear so intelligent and wise. This also applies to the wasps and the bees.

Have we not every reason to say (for we produce this formic acid in ourselves): In Nature there is intelligence everywhere; it comes through the formic acid. In ourselves also there is intelligence everywhere because we have formic acid within us. This formic acid could not be in existence had not the oxalic acid first been there. The little creatures hovering over the plants see to it that the oxalic acid is changed into formic acid, that it is metamorphosed.

One only fully understands these things when one asks: How is it then with the oxalic acid? Oxalic acid is essential for all that has life. Wherever there is life, there is oxalic acid, an etheric body. The etheric body brings it about that the oxalic acid is renewed. But the oxalic acid never becomes a formic acid that can be used by the human or animal organism unless it is first transformed by an astral body from oxalic into formic acid. The formic acid which I here extracted from the oxalic acid, is of no use at all to the human or animal organism. It is an illusion to think it can be of use; it is dead. The oxalic acid which is produced in man, and through the insects is living, and arises everywhere where sensation, or something of the nature of the soul is present.

Man must produce formic acid in himself if he wishes to bring forth something of the nature of the soul out of the mere life-processes of the lower body where the oxalic acid prevails. Then, in the formic acid of the breath there lives the soul quality that rises up to, and can be active in the head. The soul needs this transformation in man of the oxalic into formic acid.

What then is actually happening when oxalic acid is changed into formic acid? You see, the first thing that I told you can show us this. The wood-bee which I described, is especially interesting for it works in wood that is no longer living. If this wood-bee could not make use of the wood in the right way, it would seek a dwelling place elsewhere. It does not make its nest in a tree, but in decaying wood, and where rails and posts begin to rot away; there it makes a nest and lays its eggs.

If you study the connection of the decaying wood and the wood-bee, wasps, etc., then you find that similar processes of decay constantly take place in the human body. If this process of decay goes too far, the body dies. Man must constantly carry on in himself what happens externally; he must build up cells, and this he can only do by transforming all that is plant-like within him and permeated with oxalic acid; he must change all this into formic acid so that all is permeated with formic acid.

You will say: What significance has all this for Nature?

Let us imagine one of these decaying posts or rails. Should one of these wood bees never discover it, a man would certainly not regret it, for these bees increase quickly, and the post they have hollowed out would fall down the following year. Men may not appreciate this, but Nature finds it good, for if there were none of these creatures all woody substances would gradually crumble into dust, and would become entirely useless. The wood in which the wood-bees have worked does not perish in dust, it is given new life. From all this decaying wood that is quickened a little by the wood-bee, or by other insects, much arises which rescues our earth from complete decay, from being scattered as dust in cosmic space; our earth can live on it because it has been quickened by the insects. As men we breathe in formic acid; in Nature the formic acid is prepared by the insects from the oxalic acid of the plants, and so works that the earth renews its life.

Consider the connection. We have man, and we have the earth. Let us take first a young child, for a young child readily transforms the oxalic acid of the lower organism into formic acid. The organs of a young child are sufficiently supplied with formic acid; the human soul develops in the child. We have the formic acid as the basis for the soul and spirit. But when a man grows old and is unable to develop sufficient formic acid, then the soul and spirit must take leave of the body. Formic acid draws the soul and spirit to the body; otherwise the soul and spirit must leave it. It is deeply interesting.

If for instance you observe a man who has developed a number of independent inner processes, you will find that it Is formic acid that helps him to master these independent inner processes. The right relationship is then brought about between the astral body and the physical body which were hindered by these independent processes in the body. Formic acid is always needed as the right basis for the soul and spirit. When the body has too little it decays, and can no longer retain the soul; the body ages and the soul must leave it.

We have then, man on the one side and Nature on the other side. In Nature formic acid is continually being prepared from oxalic acid, so that the earth may always be surrounded not only by oxygen and nitrogen, but by formic acid also. It is formic acid that prevents the earth from dying every year, gives it each year renewed life. What is beneath the earth longs as seed for the formic acid above, for renewal of its life. Every winter the spirit of the earth actually strives to take leave of the earth. The spirit of the earth benumbs the earth in winter, to quicken it again in spring. This happens because what waits as seed beneath the earth draws near-to the formic acid which has arisen through the whole intercourse of the insect world and the plant world throughout the preceding year. The seeds do not merely grow in oxygen, nitrogen and carbon, but in formic acid; this formic acid stimulates them in their turn to develop oxalic acid, so that once more the formic acid of the succeeding year may come into existence.

Just as in man formic acid can be the basis for his soul and spirit, so the formic acid which is spread out in the cosmos can be the basis for the soul and spirit of the earth. Thus we can say that for the earth also, formic acid is the basis for earth-soul and earth-spirit (see Diagram 18).

You see, it is actually much more difficult to telegraph in a district where there are no ant-heaps, for the electricity and magnetism necessary for telegraphing depend on formic acid. When the telegraph wires go through towns where there are no ant-heaps, it is from the fields outside the town that power must be collected to enable the electric streams to pass through the towns. Naturally, the formic acid is present in the air of the towns also.

Thus we can say: What is within man as production of formic acid, is also outside in external Nature. Man is a little world, and between birth and death he is able to produce formic acid from oxalic acid. When he can no longer do so, his body dies. He must once more take a body which in childhood can develop formic acid from oxalic acid in the right way. In Nature the process is unbroken, winter-summer, winter-summer; ever the oxalic acid is undergoing transformation into formic acid.

If one watches beside a dying man one really has the feeling that in dying, he first tries whether his body is still able to develop formic acid. When he can no longer accomplish this, death takes place. Man passes into the spiritual world, for he can no longer inhabit his body. Hence, we say that a man dies at a given moment. Along time then passes, and he returns to take another body; between whiles, he is in the spiritual worlds.

Well, gentlemen, as I told you, when a young Queen slips out in the hive, something disturbs the bees. Previously they had lived in their twilight world; now they see the young Queen begin to shine. What is connected with this shining? It is connected with the fact that the young Queen robs the old Queen bee of the power of the bee poison. The whole departing swarm feels this fear, this fear that they will no longer possess a sufficiency of poison, will no longer be able to protect, or save themselves. They go away just as the human soul goes away at death when it can no longer find the formic acid it needs: so too, the older bees go away when there is not sufficient formic acid, bee poison, in the hive.

So now, if one watches the swarm, still indeed visible to us, yet it is like the human soul when it must desert the body. It is a majestic picture, this departing swarm. Just as the human soul takes leave of the body, so when the young Queen is there, the old Queen with her company leaves the hive; one can truly see in the flying swarm an image of the departing human soul.

How truly magnificent all this is! But the human soul has not carried the process so far as to develop its forces into actual small creatures; the tendency to do this is nevertheless there. We have something within us that we wish to transform into tiny creatures, into bacilli and bacteria—into minute bees. But we suppress this tendency that we may be wholly men. The swarm of bees is not a whole man. The bees cannot find their way into a spiritual world, it is we who must bring them into a new incarnation as a new colony.

This is, gentlemen, directly an image of re-incarnating man. Anyone who is able to observe this, has an immense respect for these swarming bees with their Queen, for this swarm which behaves as it does because it desires to go into the spiritual world; but for this it has become too physical. Therefore these bees gather themselves together, and become like one body; they wish to be together, they wish to leave the world. Whereas they otherwise fly about, now they settle on some branch or bush, clustering together quietly as though they wish to vanish away, to go into the spiritual world.

If we now bring them back, if we help them by placing them in a new hive, then they can once more become a complete colony.

We must say that the insects teach us the very highest things of Nature. This is why in bygone times men were always enlightened when they looked at the plants; they possessed an instinctive knowledge of these things of which I have been speaking to you, a knowledge completely lost to modern science. These men observed the plants in their own way. When people today bring into their houses a branch of a fir-tree for a Christmas tree, they remind themselves that all that is outside in Nature can also work in our human and social life. This fir branch from which the Christmas tree is made should become for us a symbol of love. It is commonly thought that the Christmas tree is a very old custom, but the fir-tree has only been so used for 150 to 200 years. In earlier times this custom did not exist, but another plant was made use of at Christmas time. When the Christmas plays, for example, were performed in the villages, even in the 15th and 16th Centuries, there was always a man who went round to announce them who carried a kind of Christmas tree in his hand. This was a branch of the juniper that has such wonderful berries; the juniper was the Christmas tree. This was because these juniper berries, so greatly loved by the birds, contain something of that poison which must pervade all that is earthly, so that this earthly may rise again in the spirit. Just as the ants give to the wood, or the wood-bee to the decaying posts, so when the birds eat the juniper berries every morning, a certain acid, though a weaker one, is developed. People in olden days knew this instinctively, and said to themselves: “In winter when the birds come to eat the juniper berries the earth is quickened through the juniper tree.” It was for them a symbol of the quickening of the earth through Christ.

Thus we can say: When we observe things in the right way, we see how the processes of Nature are actually images and symbols of what happens in human life. These men of olden times watched the birds on the juniper trees with the same love with which we look at the little cakes and gifts on the Christmas tree. To them the juniper tree was a kind of Christmas tree which they carried into their houses; the juniper became a kind of Christmas tree.

As you are now all of you especially hard at work, we must close. I did not want today's lecture to end without touching on a subject of real importance. I have therefore spoken of the juniper tree which can truly be regarded as a kind of Christmas tree, and which is the same for the birds as the blossoms for the bees, the wood for the ants, and for the wood-bees and insects in general.

In conclusion, I should like to wish you a happy, cheerful Christmas Festival, and one which may uplift your hearts.

Fünfzehnter Vortrag

Guten Morgen, meine Herren! Eigentlich müssen wir noch etwas über die Frage des Herrn Dollinger sprechen. Er wollte ja in Ihrem Namen wissen — denn das ist wohl für jeden interessant —, wie der Zusammenhang in geistiger Beziehung ist zwischen dieser Herde von Insekten, die sich bewegt, an die Pflanzen herankommt, und dem, was sich in den Pflanzen befindet.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, ich habe Ihnen ja schon früher gesagt: Es ist um uns überall vorhanden nicht nur so etwas wie Sauerstoff und Stickstoff, sondern es ist in der ganzen Natur vorhanden Verstand, richtig Verstand. Kein Mensch wundert sich, wenn man sagt: Wir atmen die Luft ein -, weil die Luft überall ist und sozusagen die Wissenschaft heute schon so stark in die Schulbücher hineingekommen ist, daß den Leuten gesagt wird: Überall ist Luft, und du atmest die Luft ein. - Aber ich habe zum Beispiel schon Leute gekannt draußen auf dem Lande, die haben das als eine Phantasie betrachtet, weil sie eben nicht gewußt haben, daß draußen Luft ist, ebenso wie die Leute heute nicht wissen, daß überall Verstand ist. Die betrachten es als eine Phantasie, wenn man sagt: Geradeso wie wir mit den Lungen die Luft einatmen, so atmen wir zum Beispiel mit der Nase oder mit dem Ohr Verstand ein. — Und ich habe Ihnen ja früher schon reichlich Beispiele gezeigt, an denen Sie sehen konnten, daß Verstand überall ist. Wir haben ja in der letzten Zeit von einem ganz besonders interessanten naturwissenschaftlichen Kapitel gesprochen, von den Bienen, Wespen und Ameisen. Vielleicht kann man durch wenig von dem, was in der Natur ist, so gründliche Blicke hineintun in die Natur selber wie durch das Treiben der Insekten überhaupt. Die Insekten sind nun einmal ganz merkwürdige Tiere und sie werden noch manches Geheimnis an den Tag bringen.

Es ist jamerkwürdig, daß wir sozusagen unser Insektenkapitel gerade in der Zeit besprechen, in der der hundertste Geburtstag des bedeutenden Insektenforschers Jean-Henri Fabre ist, der am 22. Dezember vor einem Jahrhundert geboren worden ist, und der gerade in die materialistische Zeit hineinfiel, daher alles materialistisch ausgelegt hat, der aber ungeheuer viele Tatsachen aus dem Leben der Insekten ans Licht gebracht hat, so daß es schon ganz natürlich ist, daß wir heute, wo wir über Insekten sprechen, an ihn erinnern.

Nun will ich Ihnen zunächst einmal ein Beispiel von einer Insektenart anführen, die Sie gerade im Zusammenhang mit den Bienen außerordentlich interessieren kann. Die Biene arbeitet ja in einem hohen Grade vollkommen, und es ist schon das Merkwürdigste an der Biene nicht das, daß sie schließlich den Honig hervorbringt, sondern daß sie diese wunderbar gebauten Zellenwaben ganz aus sich selber heraus macht. Sie muß ja dasjenige, was sie als Material verwendet, an sich selber in den Bienenstock hineintragen. Und sie arbeitet eigentlich so, daß sie das Material gar nicht mehr ursprünglich benützt, sondern daß sie das ganz verwandelt in den Bienenstock hineinbringt. Aus sich selber heraus arbeitet sie so.

Nun gibt es aber eine Bienenart, die nicht in dieser Weise arbeitet, die aber gerade durch ihre Arbeit zeigt, was für ein ungeheurer Verstand in der ganzen Natur ist. Wollen wir einmal diese Bienenart, die man gewöhnlich die Holzbiene nennt, die nicht so beachtet wird wie die Hausbiene, weil sie den Menschen meistens lästig wird, in ihrer Arbeit betrachten. Das ist ein ungeheuer fleißiges Tier, und ein Tier, das wirklich, damit es leben kann - nicht das einzelne Tier, aber die ganze Art leben kann -, ungeheure Arbeit zu verrichten hat. Dieses Tier sucht sich Holz auf, das nicht mehr an den Bäumen ist, sondern das schon aus den Bäumen herausgenommen und verarbeitet ist. Sie können diese Holzbiene mit ihren Nestern, die ich Ihnen gleich beschreiben werde, finden, sagen wir, wenn Sie Pflöcke irgendwo eingeschlagen haben, also wo eben das Holz aus den Bäumen herausgenommen ist und scheinbar unbelebtes Holz ist, Pflöcke oder Säulen, die aus Holz sind. Da drinnen können Sie die Holzbiene finden, auch in Gartenbänken oder Gartentüren. Also da, wo man Holz benützt hat, da macht die Holzbiene ihr Nest hinein, aber auf eine ganz sonderbare Weise.

Denken Sie sich einmal, das wäre solch ein Pfosten (siehe Zeichnung). Das ist also das Holz, das aus dem Baum bereits heraus ist. Jetzt kommt die Holzbiene und bohrt zunächst von außen so in schräger Weise einen Gang hinein. Und wenn sie da drinnen angekommen ist, den Gang ausgeholzt hat, so eine Art Kanal ausgebohrt hat, dann fängt sie an, in ganz anderer Richtung zu bohren. Dann bohrt sie so, daß da zunächst eine kleine ringförmige Höhlung entsteht. Jetzt fliegt das Insekt fort, holt allerlei aus der Umgebung und polstert diese Höhle aus. Und dann, wenn es sie ausgepolstert hat, legt es das Ei hinein, aus dem die Made wird. Das liegt jetzt da drinnen. Wenn es das Ei abgelegt hat, kommt das Bienlein und macht darüber einen Deckel, in dem da in der Mitte ein Loch ist. Und jetzt fängt es an, da oben über diesem Deckel weiterzubohren, legt da drüber eine zweite Wohnung an für eine zweite auskriechende Holzbiene, und legt, nachdem es sie ausgepolstert hat, ein Loch gelassen hat, wiederum ein Ei hinein. Das setzt die Holzbiene fort, bis sie solche übereinandergelegten Höhlungen zu zehn oder zwölf über einander gebaut hat. Überall ist ein Ei drinnen.

Jetzt kann die Made sich da drinnen in diesem Holzstock entwickeln. Überall legt das Insekt noch Futter neben die Made. Die frißt zuerst von dem Futter, das ihr zubereitet war, und wird dann reif zum Auskriechen. Aber jetzt kommt die Zeit, wo das Insekt sich verpuppt hat und sich verwandelt hat in die geflügelte Biene, die nun ausfliegen soll.

Da drinnen ist das so, daß die Made sich nun entwickelt und nach einiger Zeit richtig ausfliegen kann. Wenn die Zeit ist, wo die Made reif ist, sich verpuppt hat und Insekt wird, ist es ja jetzt so, daß das fertig Insekt durch diesen Gang herausfliegen kann. Dadurch ist durch die Geschicklichkeit der Holzbiene erreicht, daß durch den Gang, der zuerst hineingebohrt worden ist, das fertige Insekt wiederum herausfliegen kann. Ja, schön. Aber wenn jetzt das zweite Insekt hier kommt, das ja etwas jünger ist, und das dritte oben ist wieder etwas jünger, weil das Muttertier erst diese Wohnungen machen muß, da finden diese Tiere keinen seitlichen Ausgang, um herauszukommen. Und die fatale Geschichte bestünde jetzt darin, daß die oberen Tiere allmählich da drinnen zugrunde gehen müßten. Aber das verhindert das Muttertier dadurch, daß es das Ei so legt, daß, wenn die Made, die jünger ist, auskriecht, sie da dieses Loch findet, von dem ich Ihnen erzählt habe; sie läßt sich da herunterfallen und kriecht da aus. Das dritte Tier läßt sich durch die zwei Löcher herunterfallen und kriecht so aus. Und dadurch, daß jedes später auskriechende Tier etwas später kommt, stört es das früher auskriechende Tier unter ihm nicht. Sie kommen nie zusammen, sondern das frühere ist immer schon ausgeflogen.

Sie sehen, das ganze Nest ist so vernünftig angelegt, daß man nur staunen kann darüber. Wenn Menschen heute maschinell etwas nachmachen, so sind meistens die Dinge, die die Menschen nachmachen, solchen Dingen nachgeahmt, aber sie sind meist weit weniger geschickt gemacht. Die Dinge, die in der Natur vorhanden sind, sind außerordentlich geschickt gemacht, und man muß schon sagen: Da drinnen ist durchaus Verstand, richtiger Verstand. —- Und davon, daß in dieser Art, wie die Insekten bauen, wie die Insekten bei der Arbeit sich benehmen, davon, daß da Verstand drinnen lebt, könnte man Hunderte und Tausende von Beispielen anführen. Denken Sie sich nur, wieviel Verstand in dem liegt, was ich Ihnen neulich von der Ackerbauameise gesagt habe, die ihre ganze Wirtschaft anlegt und alles mit einem ungeheuren Verstand anlegt.

Nun haben wir aber noch eine andere Sache betrachtet, gerade als wir diese Insekten, Bienen, Wespen und Ameisen, ins Auge faßten. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, alle diese Tiere haben in sich etwas, was eine Art giftiger Stoff ist, und dieser giftige Stoff, den alle diese Tiere in sich haben, der ist zu gleicher Zeit, wenn man ihn richtig dosiert, in richtiger Dosis gibt, ein ausgezeichnetes Heilmittel. Das Bienengift ist ein ausgezeichnetes Heilmittel. Das Wespengift ist ein ausgezeichnetes Heilmittel. Und die Ameisensäure, die von den Ameisen abgesondert wird, ist erst recht ein gutes Heilmittel. Aber ich habe Ihnen auch das schon angedeutet: Diese Ameisensäure, die kriegen wir, wenn wir an einen Ameisenhaufen herangehen, die Ameisen herausnehmen, sie dann zerquetschen. Also die Ameisen haben diese Ameisensäure in sich; durch das Zerquetschen der Ameisen kriegen wir die Ameisensäure heraus. Diese Ameisensäure findet sich also eigentlich vorzugsweise bei den Ameisen. Aber wenn Sie wüßten, wieviel - verhältnismäßig natürlich - Ameisensäure in diesem Saal drinnen ist, Sie würden eben recht staunen! Sie werden sagen: Wir können doch nicht hier in einer Ecke einen Ameisenhaufen suchen. — Meine Herren, soviel Sie da sitzen, sind Sie in Wirklichkeit selber solch ein Ameisenhaufen! Denn überall in Ihren Gliedern, Muskeln, in Ihren anderen Geweben, im Herzgewebe, im Lungengewebe, im Lebergewebe, im Milzgewebe namentlich - überall da drinnen ist Ameisensäure, allerdings nicht so konzentriert und stark wie im Ameisenhaufen. Aber dennoch, Sie sind so, daß Sie ganz ausgefüllt sind mit Ameisensäure ganz ausgefüllt. Ja, sehen Sie, das ist etwas höchst Merkwürdiges.

Wozu haben wir denn eigentlich in unserem Körper diese Ameisensäure? Wenn ein Mensch zuwenig hat, so muß man das erkennen. Wenn irgendein Mensch als kranker Mensch auftritt - und die Menschen sind ja meistens eigentlich ein bißchen krank -, so kann er ja hunderterlei Krankheiten haben, die äußerlich alle gleich ausschauen. Man muß erkennen, was ihm eigentlich fehlt; daß er blaß ist, oder daß er nicht essen kann, das sind ja nur äußerliche Dinge. Man muß darauf kommen, was ihm eigentlich fehlt. Und so kann es bei manchem Menschen sein, daß er einfach in sich selber nicht genug Ameisenhaufen ist, nicht genug Ameisensäure produziert. Geradeso wie im Ameisenhaufen Ameisensäure produziert wird, so muß einfach im menschlichen Körper, in allen seinen Gliedern, besonders in der Milz, stark Ameisensäure erzeugt werden. Und wenn der Mensch zuwenig Ameisensäure erzeugt, muß man ihm ein Präparat beibringen, ein Heilmittel, wodurch man ihm äußerlich hilft, genug Ameisensäure zu erzeugen.

Nun muß man aber beobachten, was mit einem Menschen geschieht, der gerade zuwenig Ameisensäure hat. Diese Beobachtungen, die können eben nur dann eintreten, wenn die Leute, die das beobachten wollen, wirklich gute Menschenkenner sind. Man muß sich dann eine Vorstellung darüber bilden, was in der Seele eines Menschen vorgeht, der zuerst genügend Ameisensäure in sich gehabt hat und der nachher zuwenig Ameisensäure in sich hat. Das ist sehr merkwürdig. Solch ein Mensch, der wird Ihnen, wenn Sie ihn in der richtigen Weise fragen, über seine Krankheit das Richtige aussagen. Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben zum Beispiel einen Menschen, der sagt Ihnen, indem Sie ihn auf die Spur bringen: Ach, Donnerwetter, vor einigen Monaten, da ist mir alles gut eingefallen, da habe ich alles gut ausspintisieren können. Jetzt bleibt es aus. Es geht nicht mehr. Wenn ich mich auf etwas besinnen will, da geht es nicht mehr. — Meine Herren, das ist oftmals ein viel wichtigeres Zeichen, als alle äußeren Untersuchungen Ihnen geben können, was man ja heute, mit Recht selbstverständlich, auch tun muß. Aber Sie können heute den Urin untersuchen auf Eiweiß, auf Eiter, auf Zucker und so weiter, Sie kriegen natürlich ganz interessante Resultate heraus; aber unter Umständen kann viel wichtiger sein, daß einem ein Mensch so etwas sagt, was ich Ihnen erzählt habe. Denn dann, wenn er Ihnen so etwas erzählt, müssen Sie natürlich noch einiges andere kennenlernen; aber da können Sie herauskriegen: Es ist in der letzten Zeit die Ameisensäure zuwenig geworden in seinem eigenen Körper.

Jetzt kann einer sagen, der noch äußerlich denkt: Der Mensch hat zuwenig Ameisensäure. Ich quetsche Ameisensäure aus oder stelle sie auf andere Weise her und gebe ihm Ameisensäure ein in entsprechender Dosierung. - Sie können das dann eine Zeitlang machen, und der Patient kommt zu Ihnen und sagt: Aber das hat mir gar nichts geholfen. - Was liegt da wiederum vor? Es hat ihm wirklich nichts geholfen. Es war ganz richtig, er hatte zu wenig Ameisensäure; Sie haben ihm Ameisensäure gegeben und es nützte nichts, hat gar nichts genützt. Was liegt da vor?

Ja, sehen Sie, wenn Sie weiterforschen, so kommen Sie darauf: Bei dem einen Menschen hat die Ameisensäure nicht geholfen, bei anderen Menschen hat sie aber fortwährend geholfen. - Nun, Sie merken nach und nach den Unterschied. Diejenigen Menschen, bei denen die Ameisensäure hilft, die werden namentlich Verschleimungen in der Lunge zeigen. Diejenigen Menschen, bei denen die Ameisensäure nichts hilft, die zeigen die Verschleimungen in der Leber oder in den Nieren oder in der Milz. Es ist das eine sehr eigentümliche Geschichte. Es ist also ein großer Unterschied, ob der Lunge zum Beispiel die Ameisensäure fehlt, oder ob der Leber die Ameisensäure fehlt. Der Unterschied ist der, daß mit dieser Ameisensäure, die im Ameisenhaufen drinnen ist, die Lunge sogleich etwas anfangen kann. Die Leber kann mit der Ameisensäure gar nichts anfangen.

Und jetzt kommt etwas anderes, meine Herren! Jetzt müssen Sie, wenn Sie bemerken, daß der Mensch an der Leber oder namentlich in den Gedärmen nicht ganz in Ordnung ist und ihm die Ameisensäure nichts hilft, trotzdem er zu wenig Ameisensäure in sich hat, ihm Kleesäure geben. Das heißt, Sie müssen den gewöhnlichen Sauerklee oder den Klee überhaupt, der auf den Äckern ist, zerpressen, diese Säure herausnehmen und ihm eingeben. Also Sie sehen: Bei einem, der in der Lunge etwas hat, müssen Sie Ameisensäure eingeben; bei einem, der in der Leber oder in den Gedärmen etwas hat, müssen Sie Kleesäure eingeben. Das Eigentümliche ist aber das, daß nun der Mensch, dem Sie die Kleesäure eingeben, aus der Kleesäure in sich selber nach einiger Zeit, nachdem Sie ihm die Kleesäure eingegeben haben, Ameisensäure macht! Also es kommt darauf an, daß man nicht bloß von außen her die Dinge in den Menschen hineinbringt, sondern man muß wissen, was der Organismus selber aus sich macht. Wenn Sie ihm die Ameisensäure eingeben, sagt der Organismus: Das ist doch nicht für mich, ich will arbeiten - man gab ihm die fertige Ameisensäure -, an der habe ich nicht zu arbeiten, die schaffe ich nicht in die Lunge herauf. - Natürlich müssen Sie das in den Magen geben. Da kommt es in die Därme zuletzt. Da sagt der seinerseits dem menschlichen Körper, der nun arbeiten will: Was setzt man mir vor? Ich soll nicht erst selber Ameisensäure schaffen, sondern die Ameisensäure, die man mir vorsetzt, soll ich aus dem Magen in die Lunge schaffen? Das tue ich nicht. - Er will Kleesäure haben, und aus dieser macht er die Ameisensäure.

Ja, meine Herren, das Leben besteht aus der Arbeit, nicht in Stoffen, und das ist das Allerwichtigste, daß man weiß, daß das Leben gar nicht im Verzehren von Kohl und Rüben besteht, sondern darin, was der Körper tun muß, wenn in ihn der Kohl und der Rübenstoff hineinkommt. Jedenfalls darf er aber nicht wieder Kohl fabrizieren aus seinem Kohl heraus. Das ist aber dasjenige, was unserer heutigen Zivilisation ganz besonders merkwürdig zugrunde liegt.

Sie sehen aber daraus, was für eine merkwürdige Beziehung in der Natur besteht. Da sind draußen die Pflanzen. Der Klee ist ja nur besonders charakterisiert. Kleesäure findet sich aber in allen Pflanzen, ist beim Klee nur am meisten vorhanden; deshalb reden wir von «Kleesäure». Aber geradeso wie Ameisensäure überall in der Natur und überall im menschlichen Körper sich findet, so findet sich überall in der Natur und im menschlichen Körper die Kleesäure.

Nun gibt es etwas anderes Interessantes. Nehmen Sie an, Sie nehmen eine Retorte, wie man sie im chemischen Laboratorium hat; Sie machen darunter eine Flamme und geben nun in diese Retorte Kleesäure hinein — das ist so salzige, bröselige Asche -, dann geradesoviel Glyzerin. Das mischt man durcheinander und erhitzt es. Dann dampft mir die Geschichte da herüber (siehe Zeichnung). Ich kann das, was ich da bekomme, auffangen. Aber zu gleicher Zeit merke ich: Da geht Luft weg. Die geht da überall weg. - Wenn ich diese Luft, die da weggeht, untersuche, so finde ich: Diese Luft ist Kohlensäure. Also da geht überall Kohlensäure heraus. Und hier, wo ich auffange, bekomme ich dann Ameisensäure. Da ist jetzt Ameisensäure drinnen. Da, in der Retorte, habe ich Kleesäure und Glyzerin drinnen gehabt. Das Glyzerin bleibt liegen; das andere geht da herüber, die flüssige Ameisensäure tropft da herunter und die Kohlensäure geht hier fort.

Nun, schauen Sie sich die Geschichte da nur einmal ordentlich an, dann werden Sie sagen können: Nehmen wir einmal an, statt dieser Retorte wäre hier die menschliche Leber oder, sagen wir, irgend etwas, ein menschliches oder tierisches Gewebe (es wird gezeichnet), irgendein Organ des tierischen Unterleibes, Leber, Milz oder so etwas. Ich bringe durch den Magen Kleesäure herein. Die Glyzerinkraft hat der Körper selber. Da habe ich ja in meinen Gedärmen drinnen zusammen Kleesäure und Glyzerin. Und was geschieht? Nun, schauen Sie sich jetzt den menschlichen Mund an, dann kommt da Kohlensäure heraus und von der Lunge herunter tropft überall in den menschlichen Körper die Ameisensäure gegen die Organe herein. Also das Ganze, was ich Ihnen hier aufgezeichnet habe, haben wir in unserem eigenen Körper. Wir erzeugen immerfort in unserem Körper aus Kleesäure Ameisensäure.

Jetzt denken Sie sich die über die Erde ausgebreiteten Pflanzen. Da ist überall Kleesäure drinnen. Und jetzt denken Sie sich die Insekten. Bei denen kommt das nur in der merkwürdigsten Weise heraus. Denken Sie sich zunächst die Ameisen. Die gehen an diese Pflanzen und so weiter heran, oder sie gehen auch an das heran, was aus den Pflanzen vermodert. Da ist also überall diese Kleesäure drinnen, und diese Tiere machen sich gerade so, wie sie sich der Mensch selber macht, daraus Ameisensäure. Und die Ameisensäure ist überall vorhanden. Durch die Insekten ist überall Ameisensäure vorhanden.

Ja, da schaut der Philister so in die Luft hinein und sagt dann: In der Luft, da ist Stickstoff, Sauerstoff. - Aber, meine Herren, in ganz geringer Menge ist dadurch, daß die Insekten die Luft durchschwirren, immer Ameisensäure vorhanden. Das heißt, wir haben auf der einen Seite den Menschen. Der ist eine kleine Welt. Der macht in sich Ameisensäure und durchdringt namentlich seinen Atem fortwährend mit Ameisensäure. Und in der großen Welt draußen, da ist statt dessen, was im Menschen vor sich geht, das Heer der Insekten. Es wird der große Atem der Luft, der um die Erde herum ist, fortwährend mit Ameisensäure durchdrungen, die aus der Kleesäure der Pflanzen gemacht wird. Es ist schon so.

Wenn man richtig beobachtet und sich den Unterkörper des Menschen anschaut mit den darinnenliegenden Gedärmen, dem Magen, der Leber, den Nieren, der Milz, dann weiter drinnen liegen die Gedärme, so ist es schon so, daß da fortwährend die Kleesäure in die Ameisensäure verwandelt wird, und diese Ameisensäure geht mit der Luft, die der Mensch einatmet, in alle Teile des Körpers über. So ist es im Menschen.

Draußen auf der Erde haben Sie überall die Pflanzen. Dann haben Sie die Insekten in der verschiedensten Weise, die darüber flattern. Da drunten haben Sie die Kleesäure. Die Insekten flattern heran, und durch ihre Begegnung entsteht die Ameisensäure und die füllt die Luft aus. So daß wir immer auch aus der Luft Ameisensäure einatmen. Dasjenige, was nun die Wespen haben, das ist ein der Ameisensäure ähnliches Gift, nur etwas umgewandelt. Und was die Bienen als Bienengift in ihrem Stachel haben - aber eigentlich hat es ihr ganzer Körper -, ist wieder umgewandelte Ameisensäure, höher verwandelte Ameisensäure. Wenn man dies anschaut, da sagt man sich: Wir schauen uns diese Insekten an, Ameisen, Wespen, Bienen; die führen äußerlich etwas ungemein Gescheites aus. Warum führen sie etwas ungemein Gescheites aus? Wenn die Ameise keine Ameisensäure hätte, würde sie all das, was ich Ihnen als etwas so Schönes geschildert habe, ganz dumm schaffen. Nur dadurch, daß die Ameisen so beschaffen sind, daß sie die Ameisensäure erzeugen können, erscheint alles so vernünftig und verständig, was sie bauen. Ebenso bei den Wespen und bei den Bienen.

Haben wir jetzt nicht alle Veranlassung, wenn wir selber in uns diese Ameisensäure erzeugen, uns zu sagen: Draußen in der Natur ist überall Verstand; der kommt durch die Ameisensäure. In uns ist auch überall Verstand, weil wir die Ameisensäure haben. - Und die Ameisensäure wäre nicht da, wenn nicht zuerst die Kleesäure da wäre. Nun ja, da flattern die Tierlein über den Pflanzen herum und sind die Veranlassung, daß die in den Pflanzen befindliche Kleesäure sich in Ameisensäure verwandelt, eine Metamorphose eingeht.

Diese Dinge, die begreift man erst, wenn man sich jetzt frägt: Ja, wie ist es mit der Kleesäure? Sehen Sie, die Kleesäure ist überall da, wo Leben sein soll. Wo etwas lebt, ist die Kleesäure da. Da ist aber auch ein Ätherleib. Der Ätherleib macht, daß die Kleesäure eben gleich erneuert wird. Aber die Kleesäure wird niemals für den menschlichen oder tierischen Organismus brauchbare Ameisensäure, wenn sie nicht durch einen Astralleib aus der Kleesäure in die Ameisensäure umgewandelt wird. Denn die Ameisensäure, die ich hier aus der Retorte genommen habe, die hilft dem menschlichen und tierischen Leib nichts. Da täuscht man sich, wenn man glaubt, daß die etwas Wirkliches hilft, die ist tot. Die Ameisensäure, die hier und hier - im Menschen und durch die Insekten — erzeugt wird, die ist lebendig, und die tritt überall auf, wo Empfindung, wo Seelisches auftritt. Der Mensch muß Ameisensäure in sich entwikkeln, wenn er aus dem bloßen Leben, das in seinem Unterleibe ist, wo die Kleesäure eine große Rolle spielt, das Seelische hervorbringen will. Dann lebt in der Ameisensäure im Atem das Seelische und geht hinauf nach dem Kopfe und kann im Kopfe weiter wirken. Das Seelische braucht diese Verarbeitung der Kleesäure in die Ameisensäure im Menschen.

Was geschieht denn da eigentlich, wenn die Kleesäure in die Ameisensäure umgewandelt wird? Sehen Sie, das kann das erste, was ich Ihnen gesagt habe, lehren. Diese Holzbiene, von der ich sprach, ist ganz besonders interessant, denn sie arbeitet ja in das Holz hinein, das nicht mehr ein lebendiges ist. Und wenn diese Holzbiene nicht dieses Holz ordentlich brauchen könnte, dann würde sie eben woanders ihren Aufenthalt suchen. In die Bäume hinein macht gerade diese Biene ihr Nest nicht, sondern in vermoderndes Holz, wo schon die Pfosten und Pfeiler anfangen zu vermodern, da legt sie die Eier hinein, nachdem sie sich ihr Nest gebaut hat.

Wenn man nun den Zusammenhang des Vermodernden mit den Holzbienen studiert, dann kriegt man heraus, daß das, was da vor sich geht im vermodernden Holz, im menschlichen Körper fortwährend vor sich geht. Er fängt an zu modern, und wenn er zu stark modert, dann stirbt er. Und was da draußen vor sich geht, das muß der Mensch fortwährend tun: er muß die Zellen aufbauen. Und das kann er nur dadurch, daß er das Pflanzliche, das von der Kleesäure durchdrungen ist, in die Ameisensäure umwandelt, in dasjenige umwandelt, was von der Ameisensäure durchdrungen ist.

Jetzt können Sie sagen: Was hat denn das ganze für eine Bedeutung für die Natur? - Nun, meine Herren, denken wir einmal an einen solchen Pfeiler oder Pfosten, der aus Holz ist und der vermodert. Wenn da niemals eine solche Holzbiene an einen Pfosten herankommt, so ist das dem Menschen sehr angenehm, denn sie breiten sich ziemlich aus, und der Pfosten fällt das nächste Jahr um, weil sie ihn hohl machen. Den Menschen ist das nicht sehr angenehm, aber der Natur ist es um so angenehmer. Denn wenn alles Holz, das aus den Pflanzen kommt, ohne diese Bienennester weiterexistieren würde, wo würde dieses Holz nach und nach - Sie sehen ja das dem Moder an - zerbröckeln, verstauben und würde ganz unbrauchbar werden. Das Holz aber, worinnen eine Holzbiene gearbeitet hat, das zerstiebt nicht, sondern das belebt sich wiederum. Und aus all dem Holz, das durch diese Holzbienen ein bißchen wiederum belebt wird, entsteht vieles von dem - ebenso aber durch die anderen Insekten -, was macht, daß unsere Erde einmal nicht ganz vermodert, im Weltenraum zerstäuben wird, sondern weiterleben kann, weil sie von diesen Insekten belebt wird. Wir Menschen atmen die Ameisensäure ein. In der Natur wirkt die Ameisensäure, die von diesen Insekten aus der Kleesäure der Pflanzen bereitet wird, so, daß die Erde überhaupt weiterleben kann.

Betrachten Sie jetzt den Zusammenhang. Hier haben wir den Menschen, hier die Erde (es wird gezeichnet). Betrachten wir zuerst den Menschen. Nehmen wir an, er ist ein junges Kind. Er verwandelt, wenn er ein junges Kind ist, mit Leichtigkeit die im Unterleib befindliche Kleesäure in Ameisensäure. Die Organe kriegen genug an Ameisensäure. Die menschliche Seele entwickelt sich im Kinde. Wir haben also die Ameisensäure als die Grundlage für Seele und Geist. Und wenn der Mensch alt wird und nicht mehr genügend Ameisensäure entwickeln kann, gehen die Seele und der Geist fort. Die Ameisensäure also, die zieht Seele und Geist heran; sonst geht der Geist fort. Es ist sehr interessant.

Wenn Sie zum Beispiel einen Menschen, der sehr viel innere Eiterprozesse hat, richtig beobachten, so können Sie finden, daß ihm die Ameisensäure hilft, diese Eiterprozesse zu überwinden. Dann tritt das rechte Verhältnis ein zwischen dem Astralleib und seinem Körper, was durch die Eiterprozesse verhindert war. So daß immer die Ameisensäure gebraucht wird gerade in der richtigen Weise als die Grundlage für Seele und Geist. Wenn der Körper eben zuwenig Ameisensäure hat, vermodert er und kann die Seele nicht mehr haben; der Körper wird alt, die Seele muß fort.

Nun haben wir auf der einen Seite hier den Menschen, auf der anderen Seite die Natur. In der Natur wird auch fortwährend aus Kleesäure Ameisensäure gebildet, so daß die Erde immerfort die Möglichkeit hat, umgeben zu sein nicht nur von Sauerstoff und Stickstoff, sondern auch von Ameisensäure (es wird gezeichnet).

Diese Ameisensäure, die macht nun, daß die Erde überhaupt nicht, ich möchte sagen, jedes Jahr abstirbt, sondern weiter jedes Jahr sich beleben kann da oben. Dasjenige, was unter der Erde ist, das sehnt sich als Same nach der Ameisensäure, die da oben ist. Und in dem besteht das Wiederaufleben. Jedesmal im Winter ist es so, daß der Geist der Erde selber eigentlich bestrebt ist, wegzugehen. Und im Frühling ist es so, daß der Geist der Erde sich wiederum belebt. Der Geist der Erde macht die Erde erstarren im Winter; im Frühling belebt er sie wieder. Das macht [er], weil dasjenige, was als Same unter der Erde wartet, an die Ameisensäure herankommt, die erzeugt worden ist im letzten Jahr durch den Verkehr der Insektenwelt mit der Pflanzenwelt. Und jetzt kommen die Samen nicht nur herauf in Sauerstoff, in Stickstoff und in Kohlenstoff, sondern jetzt kommen die Pflanzen herauf in Ameisensäure. Und diese Ameisensäure, die regt sie an, selber wiederum Kleesäure zu entwickeln, wodurch die Ameisensäure im nächsten Jahr da sein kann. Geradeso aber wie die Ameisensäure im Menschen die Grundlage sein kann für Seele und Geist, so ist die Ameisensäure, die im Weltenall ausgebreitet ist, die Grundlage für das Geistige und Seelische der Erde. So daß wir also sagen können: Auch bei der Erde ist die Ameisensäure die Grundlage für Erdseele und Erdgeist.

Es ist tatsächlich viel schwerer zu telegraphieren in einer Gegend, wo gar keine Ameisenhaufen sind, als in einer Gegend, wo Ameisenhaufen sind, weil die Elektrizität und der Magnetismus, die zum Telegraphieren-Können gehören, von der Ameisensäure abhängen. Wenn die Telegraphendrähte durch Städte gehen, wo keine Ameisen sind, dann muß schon von außen, wo sie durch die Felder gehen, die Kraft darinnenliegen, daß sie überhaupt durch die Städte durchgehen, die magnetischen und die elektrischen Strömungen. Aber natürlich breitet sich ja die ‚Ameisensäure aus und erfüllt auch die Luft der Städte.

Nun, sehen Sie, meine Herren, so können wir sagen: Was im Menschen drinnen ist - auch in bezug auf die Erzeugung der Ameisensäure -, das ist auch draußen in der Natur. - Der Mensch ist eine kleine Welt. Nur ist es beim Menschen so, daß er während seines Lebens bis zum Tode hin geeignet ist, aus Kleesäure Ameisensäure zu machen. Dann wird er ungeeignet, dann stirbt sein Körper ab. Er muß erst wieder einen Körper bekommen, der im Kinde in der richtigen Weise aus der Kleesäure Ameisensäure macht. Bei der Natur geht es immer weiter: Winter, Sommer; Winter, Sommer. Es wird immer Kleesäure in Ameisensäure umgewandelt.

Wenn man so einen sterbenden Menschen betrachtet, so hat man eigentlich das Gefühl: er probiert zunächst, indem er stirbt, ob sein Körper noch genügend geeignet ist, Ameisensäure zu entwickeln. Dann, wenn er nicht geeignet ist, tritt eben der Tod ein. Dann geht der Mensch in die geistige Welt über und er hält es eben in seinem Körper nicht mehr aus. So daß wir sagen können: Ein Mensch stirbt in einem gewissen Zeitpunkt. Dann vergeht eine lange Zeit und er kommt wiederum in einen anderen Körper. Dazwischen ist er in der geistigen Welt.

Wenn nun im Bienenstock eine junge Königin ausschlüpft, dann ist, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe, etwas in den Bienen, was diese Bienen stört. Vorher leben die Bienen in einer Art Dämmerung. Dann sehen sie diese junge Königin aufleuchten. Was ist denn verknüpft mit diesem Aufleuchten dieser jungen Königin? Mit diesem Aufleuchten der jungen Königin ist das verknüpft, daß die junge Königin der alten Königin die Kraft des Bienengiftes wegnimmt. Und das, meine Herren, ist die Furcht des ausziehenden Schwarmes, daß er das Bienengift nicht mehr hat, sich nicht mehr wehren, retten kann; er zieht weg. Geradeso wie die menschliche Seele wegzieht im Tode, wenn sie nicht mehr die Ameisensäure haben kann, so zieht die alte Bienenbrut weg, wenn nicht genug verwandelte Ameisensäure — Bienengift — da ist. Und wenn man jetzt den Bienenschwarm anschaut, so ist der zwar sichtbar, aber er schaut just so aus wie die Menschenseele, die den Körper verlassen muß. Es ist ein großartiges Bild, so ein fortschwärmender Bienenschwarm. Wie die Menschenseele den Körper verläßt, so verläßt, wenn die junge Königin herangewachsen ist, die alte Königin mit ihrem Anhang den Bienenstock, und man kann richtig am ausziehenden Schwarm ein Bild von der ausfliegenden Seele des Menschen sehen.

Ach, meine Herren, das ist furchtbar großartig! Nur, die Menschenseele, die hat es nie dazu gebracht, ihre Kräfte bis zu kleinen «ViecherIn» auszubilden. In uns ist fortwährend auch die Tendenz dazu; wir wollen lauter kleine «Viecherl» werden. Wir haben eigentlich das in uns, daß wir uns innerlich immer in krabbelnde Bazillen und Bakterien umbilden wollen, in solche kleinen Bienen, aber wir unterdrücken das wieder. Dadurch sind wir ein ganzer Mensch. Aber der Bienenstock ist kein ganzer Mensch. Die Bienen können nicht den Weg in die geistige Welt hinein finden. Wir müssen sie in einem anderen Bienenstock zur Wiederverkörperung bringen. Das ist direkt ein Bild von dem sich wiederverkörpernden Menschen. Und der, der so etwas beobachten kann, der hat einen ungeheuren Respekt vor diesen schwärmenden alten Bienen mit ihrer Königin, die eigentlich sich so benimmt, wie sie sich benimmt, weil sie in die geistige Welt hinein will. Aber sie ist so materiell physisch geworden, daß sie das nicht kann. Und da schmusen sich die Bienen zusammen, werden ein einziger Körper. Sie wollen zusammen. Sie wollen aus der Welt heraus. Sie wissen ja: Während sie sonst fliegen, setzen sie sich nun an einen Baumstamm oder so etwas an, kuscheln sich zusammen, um zu verschwinden, weil sie in die geistige Welt hinein wollen. Und dann werden sie wieder der richtige Bienenstock, wenn wir ihnen helfen, wenn wir sie wieder zurückbringen in den neuen Bienenstock.

Also man kann schon sagen: Die Insekten lehren uns geradezu das Allerhöchste in der Natur. Daher hat immer der Anblick von den Pflanzen die Menschen, die in alten Zeiten noch Instinkte gehabt haben über das, was ich Ihnen da auseinandergesetzt habe, was der heutigen Wissenschaft ganz verlorengegangen ist, in der richtigen Weise aufgeklärt. Diese Menschen haben in besonderer Art hingeschaut auf die Pflanzen. Jetzt, in dieser Zeit, werden ja die Menschen an manches erinnert in der neueren Zeit, wenn sie einen Tannenbaum hereintragen und sich einen Christbaum daraus machen. Dann werden die Menschen daran erinnert, wie dasjenige, was in der Natur draußen ist, im Menschenleben herinnen etwas werden kann, was im sozialen Leben wirkt. Es soll ja ein Sinnbild für die Liebe sein, dieser zum Christbaum umgewandelte Tannenbaum.

Man glaubt gewöhnlich, der Christbaum sei sehr alt. Aber der Tannenbaum wird erst vielleicht seit hundertfünfzig oder zweihundert Jahren als Christbaum verwendet. Früher gab es diese Sitte nicht. Aber dennoch, zu Weihnachten wurde schon eine Art Gesträuch verwendet. Zuın Beispiel bei diesen Weihnachtspielen, die in den Dörfern auch schon im 15., 16. Jahrhundert gemacht wurden, da lief einer, um sie anzukündigen, immer herum und hatte auch eine Art Christbaum in der Hand. Aber das war der sogenannte - in Mitteldeutschland so genannte — Kranewittbaum; das war der Wacholderbaum, der diese wunderbaren Beeren hat. Und in diesem Wacholderbaum sahen die Leute damals ihren Christbaum. Warum? Weil diese Wacholderbeeren, auf die die Vögel so gerne gehen, ihnen zeigten diese geringe Giftwirkung, die da kommt und die durchdringen muß das Irdische, damit das Geistige im Irdischen erstehen kann. Geradeso wie wenn die Ameise an das Holz oder die Holzbiene an die Pfähle geht, so wird jeden Morgen, wenn der Baum da draußen steht und der Vogel heranpickt, überall auch eine, aber eine viel schwächere Säure erzeugt. Das wußten instinktiv die alten Völker und sagten sich: Im Winter, wenn der Wacholderbaum dasteht und die Vögel an seine Beeren herankommen, da wird durch den Wacholderbaum die Erde wieder belebt. - Und das war ihnen ein Bild der Belebung der Erde durch den Christus im moralischen Sinne.

So daß wir schon sagen können: Richtig natürlich betrachtet ist das so, daß man in dem, was in der Natur draußen vorgeht, wirklich Sinnbilder, Bilder von dem sehen kann, was im Menschenleben vorgeht. Die alten Leute sahen, wenn in einem Wacholderbaum die Vögel saßen, diese Vögel mit derselben Liebe, wie man heute die kleinen Gebäckstücke oder die Geschenke am Weihnachtsbaum sieht. So daß der Wacholderbaum für die Leute draußen eine Art Christbaum war, den sie hereintrugen in ihre Stuben. So ist aus dem Wacholderbaum eine Art Christbaum gemacht worden.

Wir müssen nun aber abschließen. Ich wollte aber die heutige Stunde nicht vorübergehen lassen — da Sie ja in dieser Zeit jetzt besonders angestrengt sind -, ohne daß wir über ein ganz wichtiges Thema gesprochen haben und wir es bis zur Betrachtung eines solchen Strauches gebracht haben, der wirklich wie ein Christstrauch angesehen werden kann, der Wacholderstrauch, der dasselbe für die Vögel gibt, was für die Bienen die Pflanzen, für die Ameisen und die Holzbienen das Holz, überhaupt die Insekten das Holz ist. Und am Schlusse möchte ich dies noch dazu benutzen, um Ihnen ein recht frohes, freudiges, innerlich seelenerhebendes Weihnachtsfest zu wünschen.

Den nächsten Vortrag werden wir Ihnen dann ansagen lassen; es wird nicht in allzuferner Zeit sein.

Fifteenth Lecture

Good morning, gentlemen! Actually, we still need to discuss Mr. Dollinger's question. He wanted to know on your behalf—because this is probably interesting for everyone—what the spiritual connection is between this swarm of insects that moves around and approaches the plants, and what is inside the plants.

You see, gentlemen, I have already told you before: not only is there something like oxygen and nitrogen all around us, but there is also intelligence, true intelligence, present throughout nature. No one is surprised when you say, “We breathe in the air,” because air is everywhere and science has already become so prevalent in school textbooks that people are told, There is air everywhere, and you breathe in the air. But I have known people out in the country, for example, who considered this to be a fantasy because they did not know that there is air outside, just as people today do not know that there is intelligence everywhere. They consider it a fantasy when one says: Just as we breathe in air with our lungs, we breathe in intellect with our nose or our ear, for example. — And I have already shown you plenty of examples where you could see that intellect is everywhere. We have recently been discussing a particularly interesting chapter in natural science, namely bees, wasps, and ants. Perhaps few things in nature provide such a thorough insight into nature itself as the activities of insects in general. Insects are very remarkable creatures and will reveal many more secrets in the future.

It is remarkable that we are discussing our insect chapter at the very time of the hundredth birthday of the eminent insect researcher Jean-Henri Fabre, who was born on December 22 a century ago and who happened to live in a materialistic age, and therefore interpreted everything in materialistic terms, but who brought to light an enormous amount of facts about the life of insects, so that it is only natural that we should remember him today when we talk about insects.

First of all, I would like to give you an example of a species of insect that may be of particular interest to you in connection with bees. Bees work to a high degree of perfection, and the most remarkable thing about them is not that they ultimately produce honey, but that they make these wonderfully constructed honeycombs entirely by themselves. They have to carry the material they use into the hive themselves. And they actually work in such a way that they no longer use the material in its original form, but bring it into the hive completely transformed. They work in this way from within themselves.

However, there is a species of bee that does not work in this way, but which, precisely through its work, shows what tremendous intelligence there is in the whole of nature. Let us take a look at the work of this species of bee, commonly known as the carpenter bee, which is not as well known as the honeybee because it is usually considered a nuisance by humans. It is an incredibly industrious animal, and one that has to work extremely hard in order to survive – not the individual animal, but the entire species. This animal seeks out wood that is no longer on the trees, but has already been taken from the trees and processed. You can find these carpenter bees with their nests, which I will describe to you in a moment, for example, if you have driven pegs into the ground somewhere, i.e., where wood has been taken from the trees and is apparently lifeless wood, pegs or pillars made of wood. You can find the carpenter bee inside, as well as in garden benches or garden gates. So wherever wood has been used, the carpenter bee makes its nest inside, but in a very strange way.

Imagine that this is a post (see drawing). This is wood that has already been removed from the tree. Now the carpenter bee comes and first drills a tunnel into it from the outside at an angle. And when it has arrived inside, hollowed out the tunnel, drilled a kind of channel, it starts drilling in a completely different direction. Then it drills in such a way that a small ring-shaped cavity is created. Now the insect flies away, collects all sorts of things from the surrounding area and pads out this cavity. And then, once it has padded it out, it lays its egg inside, which will become a larva. That is now lying there inside. Once it has laid the egg, the little bee comes and makes a lid over it with a hole in the middle. And now it starts to drill further above this lid, builds a second dwelling above it for a second wood bee to crawl out, and, after padding it out and leaving a hole, lays another egg inside. The wood bee continues this until it has built ten or twelve such cavities on top of each other. There is an egg inside each one.

Now the larva can develop inside this wooden stick. The insect places food next to the larva everywhere. The larva first eats the food that has been prepared for it and then becomes ready to crawl out. But now comes the time when the insect has pupated and transformed into the winged bee that is now ready to fly out.

Inside, the larva is now developing and will be able to fly out properly after a while. When the time comes for the larva to mature, pupate, and become an insect, the finished insect can now fly out through this passage. Thanks to the skill of the carpenter bee, the finished insect can fly out again through the passage that was drilled in first. Yes, fine. But when the second insect arrives, which is a little younger, and the third is a little younger again, because the mother has to make these dwellings first, these animals cannot find a side exit to get out. And the fatal consequence would now be that the upper animals would gradually perish inside. But the mother prevents this by laying the egg in such a way that when the younger larva crawls out, it finds the hole I told you about; it lets itself fall down there and crawls out. The third animal drops down through the two holes and crawls out that way. And because each animal that crawls out later arrives a little later, it does not disturb the animal that crawled out earlier below it. They never meet, because the earlier one has always already flown away.

You see, the whole nest is so sensibly designed that one can only marvel at it. When people imitate something mechanically today, the things they imitate are usually imitations of such things, but they are usually far less skillfully made. The things that exist in nature are extraordinarily skillfully made, and one has to say: there is definitely intelligence in there, real intelligence. —- And one could cite hundreds and thousands of examples of how insects build, how insects behave at work, and how there is intelligence at work. Just think how much intelligence there is in what I told you recently about the field ant, which builds its entire economy and does everything with tremendous intelligence.

But we have also considered another thing, precisely when we looked at these insects, bees, wasps, and ants. I have told you that all these animals have something inside them that is a kind of poisonous substance, and this poisonous substance that all these animals have inside them is, at the same time, when properly dosed and given in the right dose, an excellent remedy. Bee venom is an excellent remedy. Wasp venom is an excellent remedy. And the formic acid secreted by ants is an even better remedy. But I have already hinted at this: we obtain this formic acid by approaching an anthill, removing the ants, and then crushing them. So the ants have this formic acid inside them; by crushing the ants, we get the formic acid out. This formic acid is therefore found primarily in ants. But if you knew how much formic acid there is in this room—relatively speaking, of course—you would be quite astonished! You will say: We can't look for an anthill here in a corner. Gentlemen, as many of you as are sitting there, you are in fact such an anthill yourselves! Because everywhere in your limbs, muscles, other tissues, heart tissue, lung tissue, liver tissue, spleen tissue in particular – everywhere inside you there is formic acid, although not as concentrated and strong as in an anthill. But nevertheless, you are so filled with formic acid, completely filled. Yes, you see, that is something most remarkable.

Why do we actually have this formic acid in our bodies? If a person has too little of it, we need to recognize that. When someone appears to be ill—and people are usually a little ill—they may have hundreds of different illnesses that all look the same on the outside. One must recognize what is actually wrong with them; that they are pale or that they cannot eat are only external symptoms. One must figure out what is actually wrong with them. And so it may be that some people simply do not have enough anthills within themselves, do not produce enough formic acid. Just as formic acid is produced in the anthill, so too must formic acid be produced in the human body, in all its limbs, especially in the spleen. And if a person produces too little formic acid, they must be given a preparation, a remedy, which helps them externally to produce enough formic acid.

Now, however, one must observe what happens to a person who has too little formic acid. These observations can only be made if the people who want to observe them are really good judges of character. One must then form an idea of what is going on in the soul of a person who initially had enough formic acid in them and who subsequently has too little formic acid in them. This is very strange. Such a person, if you ask them in the right way, will tell you the truth about their illness. Suppose, for example, you have a person who tells you, when you put them on the right track: "Oh, gosh, a few months ago, everything came to me easily, I was able to think everything through well. Now it's gone. It doesn't work anymore. When I want to remember something, it doesn't work anymore." Gentlemen, this is often a much more important sign than any external examination can give you, which, of course, must also be done today, and rightly so. But today you can examine urine for protein, pus, sugar, and so on, and you will, of course, get very interesting results; but under certain circumstances it can be much more important that a person tells you something like what I have told you. Because then, when he tells you something like that, you naturally have to find out a few other things; but you can figure out that recently there has been too little formic acid in his own body.

Now someone who still thinks externally might say: This person has too little formic acid. I'll extract formic acid or produce it in some other way and give him formic acid in the appropriate dosage. You can do that for a while, and then the patient comes to you and says: But that didn't help me at all. What is the reason for that? It really didn't help him. It was quite right that he had too little formic acid; you gave him formic acid and it didn't help, it didn't help at all. What is the situation here?

Yes, you see, if you continue your research, you will come to the conclusion that formic acid did not help one person, but it helped other people continuously. Well, you gradually notice the difference. Those people for whom formic acid helps will show mucus in the lungs. Those people for whom formic acid does not help will show mucus in the liver or kidneys or spleen. It is a very peculiar story. So there is a big difference between the lungs lacking formic acid, for example, and the liver lacking formic acid. The difference is that the lungs can immediately do something with the formic acid that is inside the anthill. The liver cannot do anything with the formic acid.

And now comes something else, gentlemen! Now, if you notice that a person's liver or, in particular, their intestines are not quite right and formic acid does not help them, even though they have too little formic acid in them, you must give them oxalic acid. This means that you must press the common wood sorrel or clover that grows in the fields, extract the acid, and administer it to the patient. So you see: if someone has a problem with their lungs, you must administer formic acid; if someone has a problem with their liver or intestines, you must administer oxalic acid. The peculiar thing, however, is that the person to whom you administer the clover acid will, after some time, produce formic acid from the clover acid within themselves! So it is important not just to introduce things into the person from outside, but to know what the organism itself produces from within. If you administer formic acid, the organism says: That's not for me, I want to work — you gave it the finished formic acid — I don't have to work on that, I can't get it up into the lungs. — Of course you have to put it in the stomach. Then it ends up in the intestines. Then it says to the human body, which now wants to work: What are you giving me? I'm not supposed to produce formic acid myself, but rather transport the formic acid you're giving me from my stomach to my lungs? I'm not doing that. It wants oxalic acid, and it uses that to produce formic acid.