A Spiritual Scientific View of Nature and Man

GA 352

27 February 1924, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

VIII. Einstein's Theory of Relativity — Thinking that is out of Touch with Reality

Good morning, gentlemen! Has anyone thought of anything for today?

Mr. Burle asks about the theory of relativity and how it is viewed today. He says that people used to read a lot about it, especially in the past. Now it may have been forgotten again; at least he doesn't hear as much about it as he used to.

Dr. Steiner: Well, you see, the matter of the theory of relativity is a difficult one, and today you will probably have to be very careful and in the end you will have to say that even if you are careful, you are not familiar with it. But that is the case with many people who talk about the theory of relativity today. They talk about it in such a way that they often praise it as the greatest achievement of our time, but do not understand it. I will try to explain it as popularly as possible. As I said, it will be difficult today, but next time we will come to more interesting things.

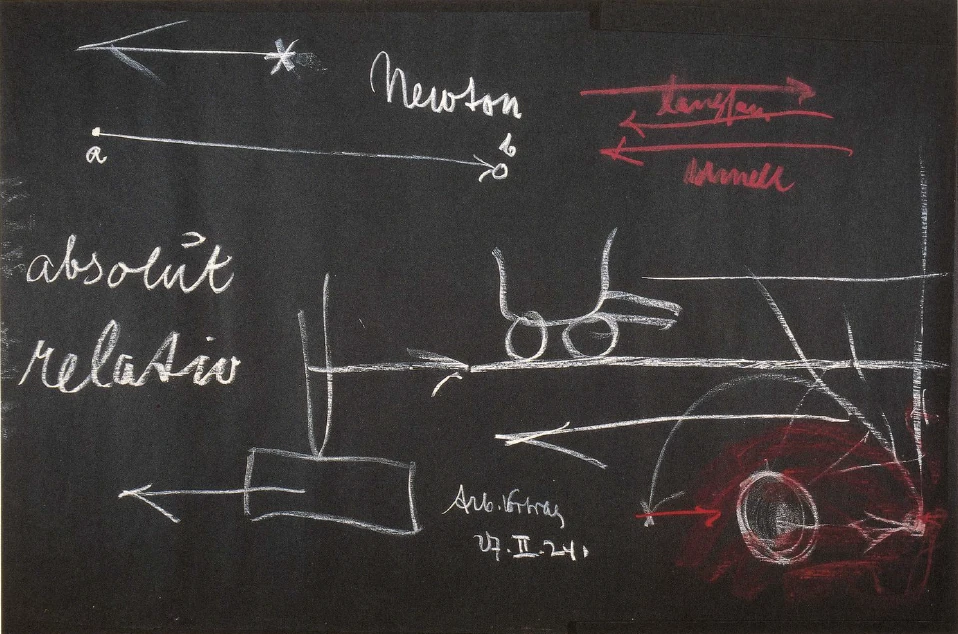

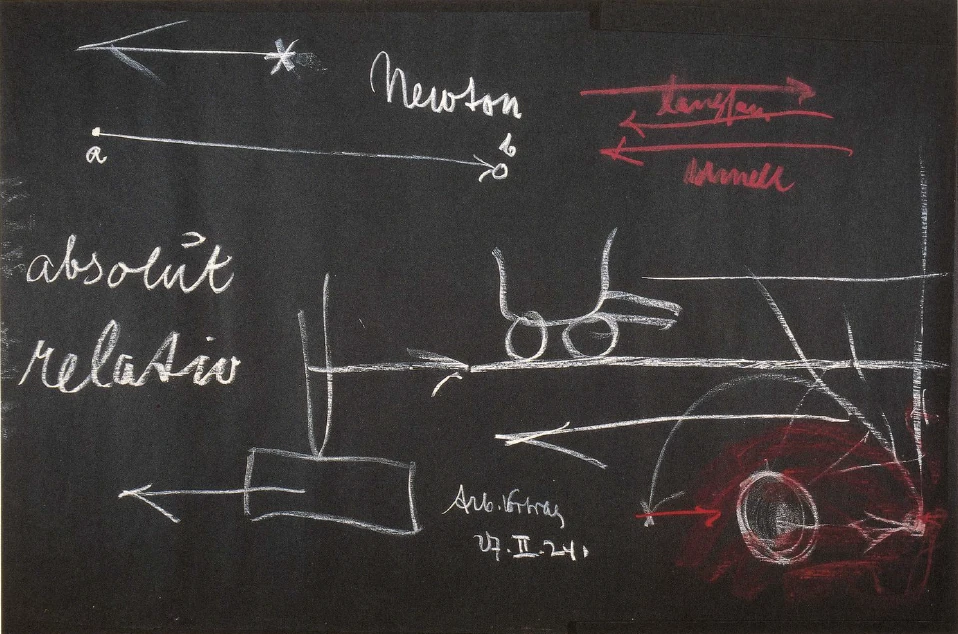

Einstein's theory is based on the motion of a body. You know that bodies move by changing their position in space. So if we want to record a motion, we say: a body is at a location A and moves to another location B. If you are standing somewhere outside and see a train passing by, you will have no doubt at all that the train is rushing past you, moving, and you are standing still. But you can easily come to doubt it, at least for the moment, of course, if you are not thinking deeply, if you are sitting somewhere in a railway compartment and are asleep at first, then wake up and look out the window: a train is passing by. You have the distinct feeling that a train is passing by. That does not necessarily mean that it is true, however. Before you fell asleep, your train was stationary, and while you were sleeping, your train itself began to move. While you were sleeping, you did not notice that your train was moving, and the other train appears to be passing by. If you look more closely, the train standing outside is completely still, while your train is moving. So while you are moving, you believe that you are at rest, and the other train, which is really at rest, is moving. You know, it can also happen that you look out the window and believe that you are sitting quietly in the train you are currently on, while the whole train is moving in the opposite direction. That's how it looks to the eye. You can see that what we humans say about movement is not always true. You wake up and form the judgment: the train that is outside is moving. Immediately afterwards, you have to correct yourself: that is not true at all, it is standing still; I am moving!

Such a correction of judgment occurred once in a major way, or even more than once, in world history. We need only go back six or seven centuries, when everyone was of the opinion that the earth was stationary in space and that the entire starry sky was moving past. This view was corrected, as you may have heard, in the 16th century. Copernicus came along and said: All that is wrong; the sun, the fixed stars are actually stationary, and we with our Earth fly at breakneck speed through space. We believe to be at rest on Earth - just as one previously believed to be at rest in the railroad car and the other train was driving and have now corrected that. Copernicus corrected the whole of astronomy, saying: It is not true that the stars move; they are stationary. But the Earth, with people on it, rushes through space at a tremendous speed.

You have given the possibility that it is not immediately possible to tell from observation what is actually correct with regard to motion: whether one is at rest oneself and a passing body is really in motion, or whether one is in motion oneself and a body that one believes is passing by is at rest.

Don't you think so? When you consider this, you will say to yourself: Yes, a correction may be necessary for everything we recognize as movement. Take, for example, how long it took for all of humanity to correct its judgment regarding the Earth. That took thousands of years. When you sit in a train, it may take only a few seconds for you to correct your judgment. So it varies how long it takes to correct such a judgment.

This has led people like Einstein to say: We cannot know whether what we see in motion is really in motion, or whether we, who are standing still, are not somehow mysteriously in motion and the other in rest. So we draw the final conclusion from this uncertainty.

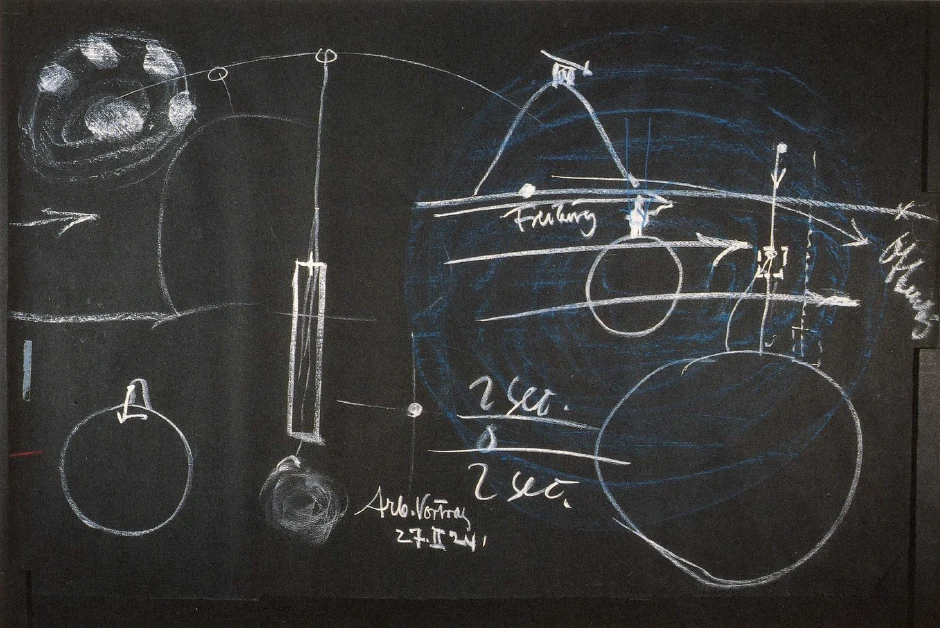

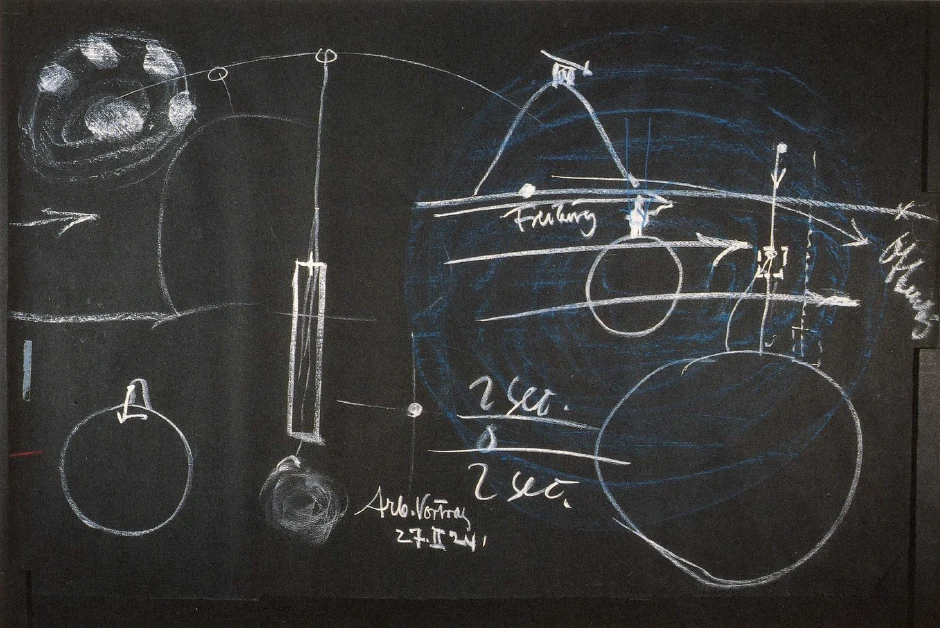

Well then, gentlemen, it could be like this: let us assume there is a car here (a picture is shown). In this car, one drives from Haus Hansi up to the Goetheanum. But who can say for sure that the car is really driving up? Who can say that with certainty? The car could be standing still, the wheels could be turning, and the whole Goetheanum that one is approaching could be moving in the opposite direction. We would only have to experience something like this for the Earth as Copernicus did for the Earth! (Laughter.)

Einstein took such things and said: We can never be certain whether one or the other body moves. We only know that they move in relation to each other, that they change their distances; that is the only thing we know. Of course, we know that when we travel to the Goetheanum, because we come closer to the Goetheanum; but whether we come to it or it comes to us, we cannot know. Now, you see, what we can say is that it is in real rest or real motion, that is absolute. So what is an absolute rest or an absolute motion? That would be a rest or motion of which one could say: In the universe, the body is at rest or the body is moving. But of course this is always a fatal thing, because at the time of Copernicus, it was still believed that the sun was stationary and the earth was moving around it. In relation to the earth it is correct, but in relation to the sun it is not correct, because the sun moves very fast, rushing at a tremendous speed through the starry universe, which is in the constellation of Hercules – and of course we are all with it. On the one hand we revolve around the sun, but with the rotation around the sun we rush with it through space. So we cannot say that the sun is at absolute rest in space either. And so Einstein and those who shared his view said: You cannot say at all whether something is at absolute rest or in motion, but you can only speak of things being in relative rest - relative, that is, with respect to each other - it appears to one to be at rest or in motion.

You see, gentlemen, during a course that was held in Stuttgart, someone once believed that we anthroposophists know nothing of note about the theory of relativity. And so, because he was or is a fanatical supporter of the theory of relativity, he wanted to make it clear to people in a very simple way how the theory of relativity, Einstein's theory of relativity, really applies. What did he do? He took a matchbox and said: “Here is a match. Now I hold the box very still and move the match towards it. It catches fire. But now I'm going to do a second experiment. Now I'm going to hold the match very still and move the box towards me. It catches fire again. The same thing happens. What has happened is that fire has been created, but the movement I have made is not absolute, it is quite relative. One time, when the box is there and the match is there, I move the match this way, the other time I move the box. For fire to occur, it does not matter whether the box or the match moves, but only whether they move relative to each other, in relation to each other.

But this can be applied to the whole world. You can say for the whole world: the thing is that you don't know whether one or the other moves, or whether one moves more strongly or weakly, or whether the other moves more strongly or weakly. You only ever know how they move in relation to each other, whether they come closer or further away from each other; you don't know more than that. And you don't know whether one body moves faster or slower than the other. Imagine you are traveling in an express train rushing by terribly fast, and a passenger train passes by outside, you look out the window. You can't judge what is actually going on, because at the moment when you are traveling in the express train and the passenger train is traveling in the opposite direction, you have the feeling that your express train is traveling much slower than it used to. Just try it. At that moment you have the feeling that now the train is moving slowly. In perception, so much of the speed is taken away from the fast as it approaches you. So you get a completely false judgment about the speed of the movement in your own train. If, on the other hand, someone is traveling more slowly next to you, you feel as if your train is traveling faster. So you never have a judgment when you see two movements and how they actually relate to each other, but you only ever get a judgment about how the two bodies relate to each other in terms of their distances.

Now you can stop at this point and say: Gosh, Einstein was a clever guy, he finally realized that in the universe we cannot talk about absolute motion at all, but only about relative motion. That is clever, and as you can see, it is also correct for many things. Because no one can say that when he sees a star at rest, it is a star at rest. If you move at a certain speed, the star appears to be moving in the opposite direction; but it could also be moving towards you. So you can't possibly conclude from looking at it that the star is at rest or in motion. It is necessary to know this, because the fact that we finally know this today means that we would have to change the entire terminology used in certain sciences. I will show you this with an example.

How do you get knowledge from the stars at all? You see, you can't get knowledge from the stars if you have the same view as the prince who went to the observatory. The astronomer naturally had to show him the observations he made of the stars because the prince was the ruler of the country. Well, he also let the prince look through the telescope, and they observed a star. When you point the telescope somewhere, you don't see anything at first. Then you wait a little; then the star comes into the telescope, as they say, and then it comes out on the other side. The prince watched this. Then he said: Yes, now I understand quite well that you know something about the stars, that you know where the stars are and how they move, I can see that quite well now. But how you, when you are so far away, come up with what the stars are called, I still can't understand. — With such views, of course, one cannot pursue astronomy. But how does it happen when you observe stars? There is the telescope; the astronomer sits there, and he looks in with his head from above, and there are crosshairs here; and when the star appears to move like this, you don't see anything yet, and when it is here, you see the star. If it is visible exactly where the threads cross, then you determine the location of the star.

Now, it was always thought that when observing, one could say: either the Earth moved, or the telescope was moved forward and the lens – that's what the glass that is far away is called; the glass that is close is called the eyepiece – was moved so far that the stationary star can now be seen inside. In the past, people believed that the star was moving. Today we have to say: We know nothing about the rest or motion of the star. We can only say: In the viewfinder, the crosshairs of my telescope coincide with the view of the star; the two overlap. We can say nothing more than what we have directly in front of us. We would be uncertain about the whole world as a result.

This has far-reaching consequences. It is important for our view of the motion not only of the heavenly bodies, but even of the bodies on our earth. And the conclusions that Einstein and those who think as he does drew from it are very far-reaching. They said, for example: Yes, if motion is only relative, if it is not absolute, then one cannot say anything real about anything at all, not even about simultaneity or different times. If, for example, I have a clock in Dornach and another in Zurich and the hands are in the same position, I am still not at all sure that, because they are far apart, in reality there is only one erroneous observation; perhaps there is no simultaneity at all!

So you see, the most far-reaching conclusions have been drawn from this. And the question arises: can we not get out of this at all? Can we not say anything at all today about the things themselves when they move? That is the important question. It is quite certain that nothing can be said from the observation of the movements. And in the broadest sense, it is also true that if I drive up to the Goetheanum in my car, it may just as well be that the Goetheanum comes towards me.

Yes, but there is one thing, gentlemen, that does happen. Even the example I gave you with the matchbox is not quite right. Because, you see, I would have liked to shout to the gentleman who made it so finely: “Why don't you nail the matchbox to the table and then try to move it back and forth!” You have to apply at least a great deal of force if you have to drive with the whole table back and forth. — So there must be a catch somewhere.

You can recognize this catch if you only approach the matter attentively. Suppose you drive from Dornach to Basel, and now you could say: It is not true that the car moves; rather, the car remains stationary, only turning the wheels, and Basel comes towards it. — Fair enough. But there is one thing that speaks against this: the car will be ruined after a few years. And the fact that the car is ruined can only be attributed to the fact that it is not the road that moves, but the car that moves and is ruined by what happens inside it. So if you don't just look at the movement, but look inside the body itself to see what the movement does, you will come to the conclusion that you cannot fully grasp Einstein's conclusion. So you can notice that the car is actually being ruined, not just the wheels, because they are turning. Now someone might say: Yes, they would of course also turn if a mountain were to come towards you or Basel were to come towards you, or otherwise the thing would wear out. But you can still say: maybe that's the way it is. With inanimate bodies, the matter cannot be decided at all, and for inanimate bodies one can only say that it is uncertain which way the one or the other moves. But the living organism! Imagine you are walking to Basel and someone else remains standing here in Dornach, remains standing for the whole two hours while you walk to Basel. Now, if it were not you who had moved but Basel who had come to meet you, you would have done almost no differently than the person who remained standing. But you became tired; a change took place in you. From this change that takes place within yourself, you can see that you have moved. And in the case of living bodies, it is possible to determine from the changes that take place within them whether they are really in motion or only in apparent motion, at rest.

But this is also what must lead us to recognize that we cannot form a theory from the external observation of the world, not even from something as clear as movement. Instead, we must form our theory from the internal changes. Well, there you have it again: with the theory of relativity, too, one must say that he who looks only at the outward side of things comes to nothing at all. One must look at the inner side. It is precisely this theory of relativity that leads one to at least begin with spiritual science, with anthroposophy, because anthroposophy points out everywhere that one must look at the inner side.

Einstein's theory has led to some extraordinarily strange consequences. The matter becomes particularly interesting, for example, when Einstein gives his examples. He gives an example in which he wants to prove that the change of location has no significance at all. Because it cannot be determined from the point of view whether a body changes its location or not, the change of location cannot have any significance. That is why Einstein says: If I hurl a clock that has a certain hand position out into space, so that it flies out at the speed of light and then turns around and comes back, this movement has had no significance for the inside of the clock. The clock comes back unchanged. That is how Einstein makes his examples: whether a body moves or not, we cannot decide. The clock is the same whether it is at rest or moving, it is the same for it. - Yes, but, gentlemen, you should just be invited to look at a clock that flies out into space at the speed of light and comes back again! The clock, yes, you won't see it at all anymore. It will be so pulverized that you won't see it.

But what does that mean? It means that you cannot think that way at all. You come to thoughts that are thoughtless. And so you find on the one hand that Einstein is a terribly clever person and that he draws conclusions and makes judgments that are terribly captivating to people. Not true, the ordinary people who are not very good mathematicians, they don't understand much of Einstein's theory; and then they start reading about Einstein's theory in some popular book, read the first page, then yawn; read half of the second page, then stop. And then they say: It must be something terribly clever. Because if it wasn't something terribly clever, then I would have to understand it. Besides, a lot of people say that it's something terribly clever. –That's where the judgment about the theory of relativity comes from. But there are also people who understand it. And it is among such people that Einstein finds his following, and that following grows larger every day. It is not, as Mr. Burle says, forgotten. A few years ago, when you spoke with university professors, they did not want to know anything about Einstein's theory. Today, everything is full of the erudition of Einstein's theory of relativity.

But people also come up with some very strange ideas in the process. For example, I once had a debate with university professors about Einstein's theory. Yes, you see, as long as you stay in the area that I have also discussed with you, Einstein's theory of relativity is correct; there is nothing you can do about it: it is like that with the train, with the solar system, with the movements of the whole world. So far it is quite correct. But now the gentlemen extend it to everything and say, for example: Relative is also the size of a human being; he has no absolute size, but only relative. That seems to me only that he is so high. He is so high in relation to — well, if we are here —, in relation to the chairs or in relation to the trees, but one cannot speak of an absolute size. You see, that applies as long as you remain a mathematician, as long as you are only concerned with geometry. The moment you stop being concerned with geometry, when you enter life, that's when the pleasure stops, that's when it's different! You see, if someone has no feeling, then he can carve a head out of wood that is a hundred times as big as your head. Then he has it. Yes, the one who has a feeling for it will never do that because he knows that the size of a human head is not relative, but is conditioned in the whole of space. It can be a little larger or a little smaller, but if someone is a dwarf, it is an illness; if someone becomes a giant, it is also an illness. It is not just relative, but the absolute is already visible. Within certain limits, of course, human height fluctuates. But in the universe, a person is definitely intended for a certain height. So again, one cannot speak of relativity. One can only say that man gives himself his own size through his relationship to the universe. There was only one of the college of professors with whom I had the debate who admitted that. The others were so twisted in their heads by the relativity theory that they said that human size is also only relative because we look at it that way.

You know, if you have a picture, it can be large; if you go further, it gets smaller and smaller according to the perspective. The size of this picture that you see is relative. The relativists believe that human size is only as it is because it is always seen against a background. But that is nonsense. Human size has something absolute about it, and a person cannot be much taller or much shorter than he is predetermined to be.

Now, people think all this up because they generally do not form any opinion about what is involved in a process or in a thing that happens on earth in our environment. From what I have already told you, you will be able to deduce the following: there is the earth; on the earth is some human being. Now you know, however, that the human being is not only dependent on the forces of the earth, but he is dependent on the forces that come from the universe. Our head, for example, reflects the whole universe. We have discussed this. If it did not matter how tall a person is, what would have to be there? Suppose Mr. Burles' head, Mr. Erbsmehl's head, Mr. Müller's head is formed from the universe. Yes, gentlemen, if the heads are three or four times different from each other, there should be an extra universe for each one. But since there is only one universe, which does not grow or shrink because of the individual human being, but is always there, remaining the same, the heads of people can only be approximately the same. It is only because people do not know that we live in a common world that also has a spiritual effect that people can believe that it is irrelevant how big a person's head is, that it is merely relative. It is not relative, but it is dependent on the absolute size of the universe.

So we come back to having to remind ourselves: it is precisely when you think correctly in relation to the theory of relativity that you enter into spiritual science, not into materialistic science.

And if you then look more closely at people, you see that people who think like Einstein run out of ideas when they come to life or to the spiritual. You see, when I was a boy, I was able to take part in the lively debates that took place about gravity. Gravity - when a body falls to the earth, it is said to be heavy. It falls down because it has weight, because it is heavy. But this force of gravity is everywhere in the universe. The bodies attract each other. If there is the earth and there is the moon (see drawing), then the earth attracts the moon, and the moon does not fly away, but moves in a circle around the earth, because the earth, when it wants to fly away, always pulls it back towards itself. Now, in the past, when I was a boy, there was a lot of debate about what this force of gravity is actually based on.

The English physicist Newton, whom I have told you about before, simply said: bodies attract each other, one body the other. That is not a very materialistic view, because if you imagine that a person should just touch something and draw it towards them, all sorts of things besides matter are needed to do so. If now the Earth is to attract the Moon, then this cannot be reconciled with a materialistic view. But materialism flourished precisely in my youth. One could also say that it dried up people, it withered, but one could also say that it flourished. So people said: That's not true, the Earth cannot attract the Moon, because it has no hands to attract it. That's not possible. So they said: the world ether is everywhere (see drawing). So what I am drawing in red here is the world ether; it also consists of nothing but tiny little grains. And these tiny little grains, they bump into each other here, bump into each other there, but bump more strongly there than they do in the middle. Now, when there are two bodies, the Earth and the Moon, and the impact from the outside is stronger than from the inside, it is as if they were attracted to each other. So the force of attraction, the force of gravity, was explained by the impact from the outside.

I cannot begin to tell you how much cognitive pain this caused me at the time. From the age of twelve to eighteen, I really agonized over whether the Earth attracts the Moon or the Moon is pushed to the Earth. Because, you see, the reasons given are usually not exactly stupid, but clever. But there is already a certain relativity theory in that. One wonders: is there anything absolute in it, or is everything relative? Is it perhaps really immaterial whether one says that the Earth attracts the Moon or that the Moon is pushed towards the Earth? Perhaps one cannot decide anything at all. Well, you see, people have thought about this a lot. And what I actually want to say is: At least they came up with the idea that there is an ether in addition to the visible substance. They needed the ether, because what is supposed to push if not the grains of ether! When Einstein first established his theory of relativity, everyone still believed that the ether had to exist. And Einstein then thought of everything he had described as relative motion as taking place in space, which is filled by the ether. But then he realized: Gosh! If motion is only relative, it is not at all necessary for the ether to be there. Nothing needs to push, nothing to pull. We cannot decide anything about this. So space can also be empty.

And so, over time, there are actually two Einstein theories. Of course, they are united in one person. The earlier Einstein described everything in his books as if the whole space of the world were filled with ether. Then his theory of relativity led him to say: space is empty. Only, the theory of relativity is not about saying anything about ether, because we don't even know if it is so. The examples he gives sometimes become quite grotesque. For example, Einstein says: If there is the earth, and there is some tree, I climb up; here I slip, fall down – this is an occurrence that you have probably also experienced; at least as a boy I very often experienced it when I climbed up a tree, that I slipped and fell down – then you say: Well, the earth is pulling me. I have a weight. This comes from gravity, otherwise I would have remained in the air, otherwise I would be wriggling if the earth were not pulling me. — But Einstein says you can't say any of that, because think of the following: There is the earth again, and now I am up there on a tower, standing; but I am not standing in a vacuum, surrounded by free space. Rather, I am standing in a box that is suspended at the top. If I were to fall out of the box from the tower, my relationship to the walls would always remain the same. I don't notice any movement, the walls go with me. Yes, by golly, now I can't tell whether the rope from up there, on which my box is hanging, will be lowered and I will arrive at the bottom of the box because someone is lowering me from above, or whether I can arrive, whether the box will slip because the earth is attracting me. I can't decide that. I don't know whether I'm being lowered or whether the earth is drawing me towards it.

But with this example, which Einstein chooses, it is just the same as with the other comparison that is always used in schools. There the children are already told how a planetary system is formed, that there is a nebula at first, out of this nebula the planets separate. In the middle, the sun remains. They say: That can easily be proven. You take a small oil droplet that floats on water, in the middle a sheet of card through which a pin is stuck, you put that in the water, start to turn it. Then small droplets split off from the large one, and a tiny planetary system is there. That's how it must be out there. Once there was a nebula; the planets split off, the sun remained in the middle. Who could possibly disagree with this, if you still see it in the fat droplet today! Yes, but one little thing has been forgotten, gentlemen: that I have to stand there and turn when I am the teacher in front of the children and show that! If I don't turn: nothing forms from a small fat planet system! So — the teacher would have to tell the children — there must be a great teacher, a giant teacher out there who once turned the whole story. Then the example is complete. And so Einstein, if he were to think in complete accordance with reality – if he even gets around to formulating such a thought – would have to assume that someone is directing the rope up there. That is necessary right away. Otherwise you cannot say: It makes no difference to me how I come down, whether someone lets me down or whether I tumble; there must be someone up there. So if Einstein were to elaborate on this example, he would immediately have to consider: who is there to hold the rope? He does not do this because contemporary materialism forbids it. Therefore, he devises examples that have no reality, that cannot be imagined, that are impossible to think.

And there is something else connected with this. Imagine, gentlemen, there is a mountain. There is Freiburg im Breisgau. On the mountain I set up a cannon so that you can still hear the shot in Offenburg on my account. But you hear the shot later. If someone notes on a clock when they heard the shot in Freiburg and when someone heard it in Offenburg, they will see that the times on the two clocks differ. The sound took some time to travel from Freiburg to Offenburg.

Now, you see, this story has also been used for the so-called theory of relativity. Because it is said: Let us now assume that I am not standing in Offenburg listening to when the sound arrives, but that I am initially standing in Freiburg. There I hear the sound simultaneously as it arises. Now I am traveling by train in the direction from Freiburg to Offenburg. Because I am traveling ahead, a little way from Freiburg, I hear the sound a little later than it occurs. Even further towards Offenburg, a little later again; even further towards Offenburg, a little later again.

But this only lasts as long as you drive slower than the speed of sound. If you drive just as fast as the speed of sound from Freiburg to Offenburg, what happens then? If you drive just as fast, at the same speed as the speed of sound: you arrive in Offenburg, and there it runs away from you, you still don't hear it. If you travel at the same speed, you will never hear it, because by the time you are supposed to hear it, it will have gone. You are supposed to hear it, but by then it is no longer there. Now people say: Gosh, that's right, you can't hear sound if you're moving as fast as sound itself! And if you move even faster than sound, what happens then? If you go slower, you hear it later; if you go just as fast, you don't hear it at all. If you move faster, you hear it earlier than it sounds! People say that this is quite natural, that this is quite correct. So if you hear the sound in Offenburg two seconds later when you move slower than the sound, you don't hear the sound at all when you move at the same speed as the sound. But if you move faster than the speed of sound, then you will hear it two seconds earlier than when it is released in Freiburg! I would just like to invite you to listen, really listen to the sound before it is released in Freiburg! You can see for yourself whether you hear it earlier, no matter how fast you are moving.

The other objection is that I would then like to ask you what you look like when you move so fast or even faster than sound.

What follows from this? It follows that you can think anything if you don't stick to reality. With this theory of relativity, you end up with the idea that you hear the sound earlier than the shot is released! (Laughter.) You can think of it quite well, but it can't happen. And that, you see, is the difference! People who do science today mainly want to think logically; and Einstein thinks wonderfully logically. But the logical is not yet real. You have to have two qualities in your thinking: first, the things have to be logical, but second, they have to be real. You have to be able to live in reality. Then you don't think up this box that is pulled up and down on a rope. Then you don't think of the clock that flies out into space at the speed of light and back again. Then you don't think of the guy there who moves faster than the sound and therefore hears the sound earlier than the shot takes place. Much of what you read in books today, gentlemen, as such considerations, is very nicely thought out, but none of it is in reality.

And so we can say: Einstein's theory of relativity is clever and it also applies to a certain part of the world, but you can't do anything with it when you look at reality. For from the theory of relativity one never comes to understand why a person tires so terribly when he goes to Basel, since he cannot say whether he is going into Basel or whether Basel is coming to meet him. The fatigue could not be explained if Basel were to come to him, and why I fiddle with my feet when I walk; I could stand still, wait for Basel to come to me! You see, all these things show nothing other than that it is not enough to think correctly and intelligently, but that something else is needed: one must be immersed in life and must judge things according to life.

That is what I can tell you about the theory of relativity. It has caused a great stir, but, as I said, people understand it only a little, otherwise they would already be thinking about these things.

So, see you next Saturday.

Über Einsteins Relativitätstheore — Wirklichkeitsfremdes Denken

Guten Morgen, meine Herren! Hat sich jemand etwas ausgedacht für heute?

Herr Burle stellt eine Frage nach der Relativitätstheorie, wie es heute damit stehe; man habe so viel darüber gelesen, besonders früher. Jetzt sei es vielleicht schon wieder vergessen; wenigstens höre man nicht mehr so viel darüber wie früher.

Dr. Steiner: Nun, sehen Sie, die Sache mit der Realtivitätstheorie ist eine schwierige, und Sie werden heute wahrscheinlich dann sehr aufpassen müssen und zuletzt doch sagen, auch wenn Sie recht aufpassen, daß Sie sich darin nicht auskennen. Aber das ist bei vielen Leuten der Fall, die heute von der Relativitätstheorie reden. Die reden doch so von ihr, daß sie sie oftmals als die größte Errungenschaft unserer Zeit preisen, aber sie nicht verstehen. Ich will mich bemühen, sie so populär wie möglich auseinanderzusetzen. Wie gesagt, es wird heute schwer sein, aber wir werden das nächste Mal dann schon wieder zu interessanteren Sachen kommen.

Die Einsteinsche Theorie bezieht sich auf Bewegungen, die irgendein Körper ausführt. Sie wissen ja, daß Körper sich dadurch bewegen, daß sie ihren Ort im Raume verändern. Wenn wir also eine Bewegung aufzeichnen wollen, so sagen wir: Ein Körper ist an einem Ort a und bewegt sich an einen andern Ort b hin. Wenn Sie einen Eisenbahnzug vorbeifahren sehen und draußen irgendwo stehen, so werden Sie zunächst gar keinen Zweifel daran haben, daß der Eisenbahnzug an Ihnen vorbeisaust, sich bewegt, und Sie stillstehen. Aber Sie können ja leicht zum Zweifel darüber kommen, im Augenblick natürlich nur, wenn Sie nicht tiefer nachdenken, wenn Sie irgendwo in einem Eisenbahncoupe& sitzen und zunächst schlafen, dann aufwachen und zum Fenster hinausschauen: Da fährt ein Eisenbahnzug vorüber. Sie haben das deutliche Gefühl, ein Eisenbahnzug fährt vorbei. Das braucht deshalb noch nicht wahr zu sein, sondern bevor Sie eingeschlafen waren, stand Ihr Zug still, und während Sie geschlafen haben, ist Ihr Zug selber in Bewegung gekommen. Sie haben während des Schlafes nicht bemerkt, daß Ihr Zug in Bewegung gekommen ist, und der andere Zug fährt scheinbar vorbei. Wenn Sie genauer zusehen, so ist der Zug, der draußen steht, ganz in Ruhe, während Ihr Zug fährt. Sie glauben also, während Sie in Bewegung sind, Sie seien in Ruhe, und der andere Zug, der wirklich in Ruhe ist, der fahre. Sie wissen, es kann einem ja auch passieren, daß man zum Fenster hinausschaut und glaubt, daß man in dem Zug, in dem man gerade drinnen ist, ruhig drinnen ist, und der ganze Zug fährt in der entgegengesetzten Richtung. So schaut es für das Auge aus. Da sehen Sie schon, daß nicht immer dasjenige stimmt, was wir Menschen von der Bewegung aussagen. Sie wachen auf und Sie bilden sich das Urteil: Der Zug, der da draußen ist, der fährt. Gleich darauf müssen Sie sich korrigieren: Das ist ja gar nicht wahr, der steht still; ich fahre!

Solch eine Korrektur des Urteils ist einmal in einer großen, oder sogar öfter in einer großen Weise in der Weltgeschichte vorgekommen. Wir brauchen nur sechs bis sieben Jahrhunderte zurückzugehen, da waren alle Leute der Ansicht, daß die Erde fest im Raum stillsteht, und daß sich der ganze Sternenhimmel vorbeibewegt. Diese Ansicht ist, wie Sie vielleicht gehört haben, im 16. Jahrhundert korrigiert worden. Es ist Kopernikus gekommen und hat gesagt: Das alles stimmt nicht; die Sonne, die Fixsterne stehen in Wirklichkeit still, und wir mit unserer Erde fliegen in rasender Geschwindigkeit durch den Weltenraum. Wir glauben auf der Erde in Ruhe zu sein — geradeso wie einer vorher glaubte, im Eisenbahnwagen in Ruhe zu sein und der andere Zug fahre und haben das jetzt korrigiert. Der Kopernikus hat die ganze Astronomie korrigiert, hat gesagt; Das ist nicht wahr, daß die Sterne sich bewegen; die stehen still. Die Erde aber mit den Menschen saust mit einer Riesengeschwindigkeit durch den Weltenraum.

Da haben Sie die Möglichkeit gleich gegeben, daß man ja aus dem Anblick nicht sofort sagen kann, was eigentlich in bezug auf die Bewegung richtig ist: ob man selber in Ruhe ist und ein sich vorbeibewegender Körper wirklich in Bewegung ist, oder ob man selber in Bewegung ist und ein Körper, von dem man glaubt, daß er vorbeisause, in Ruhe ist.

Nicht wahr, wenn Sie das bedenken, dann werden Sie sich sagen: Ja, da kann ja bei allem eine Korrektur notwendig sein, was wir als Bewegung anerkennen. - Nehmen Sie nur einmal das eine, wie lange es gebraucht hat, bis die ganze Menschheit dazu gekommen ist, das Urteil zu korrigieren in bezug auf die Erde. Das hat ja Jahrtausende gedauert. Wenn Sie im Eisenbahnzug sitzen, so dauert es vielleicht nur ein paar Sekunden, bis Sie Ihr Urteil korrigieren. Es ist also verschieden, wie lange man braucht, um solch ein Urteil zu korrigieren.

Das hat solche Leute wie Einstein dazu veranlaßt, zu sagen: Wir können ja gar nicht wissen, ob das, was von uns in Bewegung gesehen wird, wirklich in Bewegung ist, oder ob wir, die wir dastehen in Ruhe, nicht irgendwie auf eine geheimnisvolle Art in Bewegung sind und der andere in Ruhe. Also ziehen wir aus dieser Ungewißheit den letzten Schluß.

Nun ja, meine Herren, dann könnte es ja so sein: Nehmen wir an, dahier wäre ein Auto (es wird gezeichnet). In dem Auto fährt man von Haus Hansi bis herauf zum Goetheanum. Aber wer weiß denn zu sagen, daß das Auto wirklich herauffährt? Wer kann das mit Gewißheit sagen? Es könnte ja das Auto auch ganz stillstehen, es könnten nur die Räder sich drehen, und das ganze Goetheanum, zu dem man hinkommt, könnte sich in umgekehrter Richtung herunterbewegen. Es müßte nur einmal so etwas herauskommen, wie es für die Erde bei Kopernikus herausgekommen ist! (Heiterkeit.)

Solche Dinge hat der Einstein genommen, er hat gesagt: Man ist eigentlich nie in Gewißheit darüber, ob sich der eine oder der andere Körper bewegt. Man weiß immer nur, daß sie in Beziehungen zueinander sich bewegen, daß sie ihre Entfernungen verändern; das ist das einzige, was man weiß. — Natürlich, das weiß man, wenn man zum Goetheanum fährt, weil man näherkommt dem Goetheanum; aber ob das zu einem oder man zu ihm kommt, das kann man nicht wissen. Nun, sehen Sie, dasjenige, wovon man sagen kann, es ist in wirklicher Ruhe oder in wirklicher Bewegung, das ist absolut. Also was ist eine absolute Ruhe oder eine absolute Bewegung? Das wäre eine Ruhe oder Bewegung, von der man sagen könnte: Im Weltenraum steht der Körper still oder es bewegt sich der Körper. Aber das ist natürlich immer eine fatale Sache; denn zur Zeit des Kopernikus hat man noch geglaubt, daß nun wiederum die Sonne stillsteht und die Erde sich herumbewegt. In bezug auf die Erde ist es richtig, aber in bezug auf die Sonne ist das nicht richtig, denn die Sonne bewegt sich sehr schnell, saust mit einer riesigen Geschwindigkeit gegen einen Sternenweltenraum, der im Sternbild des Herkules ist -— wir natürlich alle mit. Auf der einen Seite drehen wir uns um die Sonne herum, aber mit der Drehung um die Sonne sausen wir mit ihr durch den Weltenraum. Also von der Sonne ist auch nicht zu sagen, daß sie mit absoluter Ruhe im Weltenraum stehe. Und so sagten Einstein und diejenigen, die der Ansicht waren, daß das so ist: Man kann überhaupt von nichts sagen, ob es in absoluter Ruhe oder Bewegung ist, sondern kann nur sprechen davon, daß die Dinge in relativer Ruhe sind - relativ, das heißt bezüglich zueinander -, es erscheint einem in Ruhe oder Bewegung.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, einmal glaubte jemand während eines Kurses, der in Stuttgart abgehalten wurde, daß wir Anthroposophen nichts Ordentliches über die Relativitätstheorie wissen, und da hat er auf eine sehr einfache Weise, weil er ein fanatischer Anhänger der Relativitätstheorie war oder ist, den Leuten klarmachen wollen, wie die Relativitätstheorie, die Einsteinsche Relativitätstheorie wirklich gilt. Was machte er da? Er nahm eine Zündholzschachtel und sagte: Da habe ich ein Streichholz. Jetzt halte ich die Schachtel ganz ruhig und fahre mit dem Streichholz gegen sie zu. Es fängt Feuer. Jetzt aber mache ich ein zweites Experiment. Jetzt halte ich das Streichholz ganz ruhig und bewege die Schachtel zu mir. Es fängt wieder Feuer. Es geschieht dasselbe. Dasjenige, was geschehen ist, das ist, daß Feuer entstanden ist, Aber die Bewegung, die ich dabei ausgeführt habe, ist nicht absolut, die ist ganz relativ. Das eine Mal, wenn da die Schachtel ist, und da das Streichhölzchen, bewege ich das Streichholz so her, das andere Mal die Schachtel. Es kommt gar nicht darauf an, damit Feuer entsteht, ob die Schachtel oder das Streichholz sich bewegt, sondern nur, ob sie relativ zueinander, in Beziehung zueinander sich bewegen.

Das kann man aber auf die ganze Welt anwenden. Man kann für die ganze Welt sagen: Die Sache ist so, daß man nicht weiß, ob das eine oder das andere sich bewegt, oder ob das eine stärker oder schwächer, oder ob das andere stärker oder schwächer sich bewegt. Man weiß nur immer, wie sie sich im Verhältnis zueinander bewegen, ob sie näher oder ferner zueinander kommen; mehr weiß man nicht. Und ob der eine Körper schneller oder langsamer sich bewegt, weiß man nicht. Nehmen Sie an, Sie fahren in einem furchtbar schnell dahinsausenden Eilzug, und draußen fährt ein Personenzug vorüber, Sie schauen hinaus zum Fenster. Sie kriegen kein Urteil darüber, was da eigentlich vorliegt, denn in dem Augenblick, wo Sie mit dem Eilzug so hinfahren und der Personenzug so herfährt, haben Sie das Gefühl, Ihr Eilzug fahre viel langsamer als er früher gefahren ist. Probieren Sie es nur einmal. In dem Augenblick haben Sie das Gefühl, jetzt fährt auf einmal der Zug langsam. In der Wahrnehmung wird dem Schnellen so viel von seiner Schnelligkeit weggenommen, als wie der da ihm entgegenkommt. Also Sie kriegen ein ganz falsches Urteil über die Schnelligkeit der Bewegung in Ihrem eigenen Zug. Wenn dagegen daneben einer langsamer fährt, da haben Sie das Gefühl, Ihr Zug fahre schneller. Also Sie haben nie ein Urteil, wenn Sie zwei Bewegungen sehen, wie sie sich eigentlich zueinander verhalten, sondern Sie kriegen nur immer ein Urteil darüber, wie sich die zwei Körper in ihren Entfernungen voneinander verhalten.

Jetzt kann man bei dieser Sache stehenbleiben und kann sagen: Donnerwetter, der Einstein war ein gescheiter Kerl, der ist endlich darauf gekommen, daß im Weltenall überhaupt nicht von absoluten Bewegungen geredet werden kann, sondern nur geredet werden kann von relativen Bewegungen. — Gescheit ist das schon, und es ist ja, wie Sie einsehen können, für vieles auch richtig. Denn kein Mensch kann sagen, wenn er irgendwo, sagen wir einen Stern in Ruhe sieht, es sei ein Stern in Ruhe. Wenn Sie sich mit einer gewissen Geschwindigkeit bewegen, so bewegt sich der Stern scheinbar in der entgegengesetzten Richtung; aber er könnte sich ja auch herbewegen. Also Sie kommen gar nicht darauf, irgendwie aus dem Anblick sagen zu können, der Stern ist in Ruhe oder in Bewegung. Das ist notwendig, daß man das weiß; denn damit, daß man das endlich heute weiß, müßte man ja die ganze Ausdrucksweise ändern, die man in gewissen Wissenschaften hat. Ich will Ihnen das an einem Beispiel zeigen.

Wie bekommt man denn überhaupt Kenntnisse von den Sternen? Sehen Sie, Kenntnisse von den Sternen kann man ja nicht bekommen, wenn man die Ansicht hat, die einmal der Fürst gehabt hat, der auf die Sternwarte gegangen ist, und dort hat ihm der Astronom selbstverständlich, weil es der Fürst des Landes war, die Beobachtungen, die er an den Sternen machte, zeigen müssen. Nun, da ließ er auch den Fürsten durch das Fernrohr sehen, und man beobachtete einen Stern. Wenn man das Fernrohr irgendwohin richtet, dann sieht man zunächst nichts. Dann wartet man ein bißchen; dann kommt der Stern in das Fernrohr hinein, wie man sagt, dann geht er auf der andern Seite wieder heraus. Der Fürst hat sich das angeschaut. Dann hat er gesagt: Ja, jetzt verstehe ich ganz gut, daß Sie etwass wissen über die Sterne, daß Sie wissen, wo die Sterne stehen und wie sie sich bewegen, das kann ich jetzt ganz gut einsehen. Aber wie Sie, wenn Sie so weit entfernt sind, darauf kommen, was für einen Namen die Sterne haben, das kann ich noch immer nicht begreifen. — Mit solchen Ansichten kann man natürlich nicht Astronomie betreiben. Aber wie geschieht es denn, wenn man Sterne beobachtet? Da hat man das Fernrohr; da sitzt der Astronom, da — mit dem Kopf von oben — guckt er rein, und da ist hier ein Fadenkreuz; und wenn der Stern scheinbar so geht, sieht man noch nichts, und wenn er hier ist, sieht man den Stern. Wenn er gerade da sichtbar ist, wo die Fäden sich kreuzen, dann bestimmt man den Ort des Sternes.

Nun glaubte man immer, wenn man früher beobachtete, man könnte sagen: Entweder hat sich die Erde bewegt, man ist mit dem Fernrohr vorwärtsgegangen und ist mit dem Objektiv — so nennt man das Glas, das weit weg ist; das Glas, das nah ist, nennt man Okular - so weit gerückt, daß man den ruhenden Stern jetzt drinnen sieht. Früher hat man geglaubt, der Stern bewegt sich. Heute muß man sagen: Über die Ruhe oder Bewegung des Sternes weiß man nichts. Man kann nur sagen: Im Anblick fällt das Fadenkreuz meines Fernrohrs zusammen mit dem Anblick des Sternes; die zwei decken sich. Nichts weiter kann man sagen als dasjenige, was man unmittelbar vor sich hat. Über die ganze Welt wäre man dadurch ungewiß.

Das hat eine große Tragweite. Das ist wichtig für unsere Anschauung von der Bewegung nicht nur der Himmelskörper, sondern sogar der Körper auf unserer Erde. Und die Folgerungen, die dann Einstein und diejenigen, die ebenso denken wie er, daraus gezogen haben, sind sehr weitgehende. Sie haben zum Beispiel gesagt: Ja, wenn die Bewegung bloß relativ ist, wenn sie nicht absolut ist, dann kann man überhaupt über nichts etwas Wirkliches aussagen, auch nichts über die Gleichzeitigkeit oder verschiedene Zeiten. Wenn ich zum Beispiel in Dornach eine Uhr habe und in Zürich eine Uhr habe und die gleiche Zeigerstellung habe, so bin ich ja noch gar nicht sicher, daß nicht, weil sie voneinander entfernt sind, in Wirklichkeit da nur eine irrtümliche Beobachtung vorliegt; vielleicht gibt es gar keine Gleichzeitigkeit!

Also Sie sehen, aus dieser Sache wurden die weitgehendsten Folgerungen gezogen. Und es frägt sich: Kommen wir denn überhaupt nicht heraus aus dieser Sache? Können wir denn heute gar nicht irgend etwas sagen über die Dinge selbst, wenn sie sich bewegen? Das ist die wichtige Frage. Daß man aus dem Anblick über die Bewegungen nichts sagen kann, das ist einmal ganz sicher. Und im weitesten Sinne gilt schon auch: Wenn ich mit dem Auto gegen das Goetheanum herauf fahre, so kann es ebensogut sein, daß mir das Goetheanum entgegenkommt.

Ja, aber eines, meine Herren, tritt doch ein. Schon dieses Beispiel mit der Streichholzschachtel, das ich Ihnen angeführt habe, das stimmt doch nicht ganz. Denn sehen Sie, ich hätte mögen dem Herrn, der das so fein gemacht hat, zurufen: Nagle doch die Streichholzschachtel einmal an den Tisch und probiere dann, ob du hin- und herfahren kannst! Da mußt du schon mindestens eine große Kraft anwenden, wenn du mit dem ganzen Tisch hin- und herfahren mußt. — Also irgendwo liegt da doch ein Haken.

Diesen Haken können Sie bemerken, wenn Sie nur aufmerksam auf die Sache eingehen. Nehmen Sie an, man fährt mit dem Auto von Dornach nach Basel, und nun könnte man sagen: Es ist nicht wahr, daß das Auto sich bewegt; sondern das Auto bleibt stehen, dreht nur die Räder, und Basel kommt ihm entgegen. — Schön. Aber dagegen spricht eines: Das Auto wird nach einigen Jahren ruiniert. Und daß das Auto ruiniert wird, das können Sie nur darauf zurückführen, daß nicht die Straße sich bewegt, sondern das Auto sich bewegt und ruiniert wird durch das, was innerlich in ihm geschieht. Also wenn Sie nicht bloß hinschauen auf die Bewegung, sondern im Körper selber nachschauen, was die Bewegung tut, da kommen Sie schon darauf, daß Sie den Einsteinschen Schluß nicht ganz festhalten können. Also können Sie bemerken, daß das Auto doch sich ruiniert, nicht bloß die Räder ablaufen,weil sie sich drehen. Nun könnte einer sagen: Ja, die würden sich natürlich auch drehen, wenn einem der Berg entgegenkäme oder Basel einem entgegenkäme, oder sonst würde sich die Sache abnutzen. Da kann man aber immer noch sagen: Vielleicht ist die Geschichte doch so. Bei leblosen Körpern läßt sich die Sache gar nicht so entscheiden, und für leblose Körper kann man nur sagen, die Sache ist ungewiß, wie stark sich der eine oder der andere bewegt. Aber der lebendige Organismus! Denken Sie einmal, Sie gehen selber zu Fuß nach Basel hinein, und ein anderer bleibt hier stehen in Dornach, bleibt die ganzen zwei Stunden stehen, während Sie nach Basel hineingehen. Jetzt, wenn nicht Sie sich hineinbewegt hätten, sondern Basel Ihnen entgegengekommen wäre, so hätten Sie ja fast gar nichts anderes gemacht als derjenige, der stehengeblieben ist. Aber Sie sind müde geworden; eine Veränderung hat sich in Ihnen vollzogen. An dieser Veränderung, die sich in Ihnen selber vollzieht, können Sie doch wahrnehmen, daß Sie sich bewegt haben. Und bei lebendigen Körpern kann man schon an der Veränderung, die in ihnen vorgeht, doch in einer gewissen Weise feststellen, ob sie nun wirklich in Bewegung sind oder nur in scheinbarer Bewegung, in Ruhe sind.

Aber das ist es auch, was dazu führen muß zu erkennen, daß man überhaupt aus der äußeren Betrachtung der Welt nicht einmal von etwas, was so klar erscheint wie die Bewegung, sich eine Theorie bilden darf, sondern man muß sich die Theorie bilden von den inneren Veränderungen. Nun, da haben Sie eben wiederum das, daß man auch mit der Relativitätstheorie sich sagen muß: Derjenige, der nur die äußere Seite der Sache betrachtet, kommt überhaupt auf nichts. Man muß das Innere betrachten. Da wird man eben gerade durch diese Relativitätstheorie dazu geführt, wenigstens den Anfang zu machen mit der Geisteswissenschaft, mit der Anthroposophie, weil man durch die Anthroposophie ja überall darauf hingewiesen wird, das Innere zu betrachten.

Die Einsteinsche Theorie hat zu außerordentlich merkwürdigen Konsequenzen geführt. Besonders interessant wird zum Beispiel die Sache, wenn Einstein seine Beispiele aufführt. Da hat er ein Beispiel aufgeführt, das besteht darin, daß er nachweisen will, daß die Ortsveränderung überhaupt keine Bedeutung hat. Weil eben für den Anblick es gar nicht entschieden werden kann, ob ein Körper seinen Ort verändert oder nicht, könne also die Ortsveränderung auch keine Bedeutung haben. Deshalb sagt Einstein: Wenn ich eine Uhr, die eine bestimmte Zeigerstellung hat, hinausschleudere in den Weltenraum, daß sie mit der Geschwindigkeit des Lichtes hinausfliegt und dann umkehrt und wieder zurückkommt, so hat diese Bewegung für das Innere der Uhr keine Bedeutung gehabt. Die Uhr kommt unverändert zurück. - So macht Einstein seine Beispiele: Ob ein Körper sich bewegt oder nicht, wir können es ja nicht entscheiden. Die Uhr ist dieselbe, ob sie in Ruhe ist oder sich bewegt, es ist für sie gleich. - Ja, aber, meine Herren, man müßte Sie nur einmal einladen, eine Uhr anzuschauen, die mit Lichtgeschwindigkeit in den Weltenraum hinausfliegt und wieder zurückkommt! Die Uhr, ja, von der werden Sie überhaupt gar nichts mehr sehen. Die wird so pulverisiert sein, daß Sie sie nicht mehr sehen.

Was heißt das aber? Das heißt, man kann überhaupt nicht so denken. Man kommt zu Gedanken, die gedankenlos sind. Und so finden Sie auf der einen Seite, daß Einstein ein furchtbar gescheiter Mensch ist, und daß er Schlußfolgerungen zieht, Urteile macht, die den Leuten furchtbar berückend sind. Nicht wahr, die gewöhnlichen Menschen, die nicht sehr gute Mathematiker sind, die verstehen ja nicht viel von der Einsteinschen Theorie; und dann fangen sie an, in irgendeinem populären Buch über die Einsteinsche Theorie zu lesen, lesen die erste Seite, da gähnen sie nachher; lesen die zweite Seite noch zur Hälfte, dann hören sie auf. Und dann sagen sie: Das muß aber was furchtbar Gescheites sein. Denn wenn es nicht etwas furchtbar Gescheites wäre, dann müßte ich es doch verstehen. Außerdem sagen das viele Leute, daß es etwas furchtbar Gescheites sei. - Daher kommt das Urteil über die Relativitätstheorie. Aber es gibt auch solche Leute, die das verstehen. Und unter solchen Leuten, die das verstehen, findet Einstein gerade seine Anhängerschaft, und die Anhängerschaft wird jeden Tag größer. Es ist nicht so, wie Herr Burle meint, daß es wieder vergessen ist. Vor ein paar Jahren, wenn Sie mit Universitätsprofessoren sprachen, wollten die noch nichts wissen von der Einsteinschen Theorie. Heute ist alles voll gerade in der Gelehrsamkeit von der Einsteinschen Relativitätstheorie.

Aber die Leute kommen eben auch zu ganz merkwürdigen Anschauungen dabei. Ich hatte zum Beispiel einmal eine Debatte mit Universitätsprofessoren über die Einsteinsche Theorie. Ja, sehen Sie, solange man bleibt auf dem Gebiet, das ich Ihnen ja auch auseinandergesetzt habe, so lange ist die Einsteinsche Relativitätstheorie richtig; man kann nichts machen: es ist so mit dem Eisenbahnzug, mit dem Sonnensystem, mit den Bewegungen der ganzen Welt. Soweit ist sie ganz richtig. Aber nun dehnen sie die Herren auf alles aus und sagen zum Beispiel: Relativ ist auch die Größe eines Menschen; der hat keine absolute Größe, sondern nur relative. Das erscheint mir nur so, daß er so hoch ist. Er ist so hoch im Verhältnis — nun ja, wenn wir hier sind —, im Verhältnis zu den Stühlen oder im Verhältnis zu den Bäumen, aber von einer absoluten Größe kann man nicht reden. — Sehen Sie, das gilt, solange man Mathematiker bleibt, solange man es bloß mit der Geometrie zu tun hat. In dem Augenblicke, wo man aufhört, es mit der Geometrie zu tun zu haben, wenn man ins Leben kommt, da hört das Vergnügen auf, da geht das aus einem anderen Ton! Sehen Sie, wenn einer kein Gefühl hat, dann kann er aus Holz einen Kopf schnitzen, der hundertmal so groß ist wie Ihr Kopf. Dann hat er ihn. Ja, derjenige, der ein Gefühl dafür hat, wird das nämlich nie tun, weil er weiß, die Größe eines Menschenkopfes ist nicht relativ, sondern die ist im ganzen Weltenraum bedingt. Er kann etwas größer sein oder etwas kleiner sein, aber wenn einer ein Zwerg ist, so ist das eben eine Krankheit; wenn einer ein Riese wird, ist das auch eine Krankheit. Das ist nicht bloß relativ, sondern das Absolute ist da schon sichtbar. Innerhalb gewisser Größen schwankt natürlich die menschliche Größe. Aber im Weltenall ist der Mensch ganz bestimmt für eine gewisse Größe. Da kann man also auch nicht wiederum von Relativität sprechen. Da kann man nur davon sprechen, daß der Mensch sich seine eigene Größe gibt durch sein Verhältnis zum Weltenall. Es war ein einziger von dem Professorenkollegium, mit dem ich die Debatte hatte, der das zugab. Die andern waren durch die Relativitätstheorie in ihrem Kopf schon so verrenkt, daß sie sagten, auch die menschliche Größe ist nur relativ, weil wir sie so anschauen.

Nicht wahr, Sie wissen ja, wenn Sie da ein Bild haben, so kann es groß sein; wenn Sie weitergehen, wird es immer kleiner und kleiner nach der Perspektive. Die Größe dieses Bildes, die Sie sehen, ist relativ. So glauben die Relativitätstheoretiker, daß die menschliche Größe auch nur so ist, wie sie ist, weil sie überall auf einem Hintergrund gesehen wird. Aber das ist ein Unsinn. Die menschliche Größe hat schon in sich etwas Absolutes, und der Mensch kann nicht viel größer und nicht viel kleiner sein, als ihm eben vorbestimmt ist.

Nun, dieses alles denken die Leute aus, weil sie überhaupt sich gar keine Ansicht darüber verschaffen, was beteiligt ist an einem Vorgang oder an einem Ding, das auf der Erde in unserer Umgebung geschieht. Aus alldem, was ich Ihnen schon gesagt habe, werden Sie das Folgende entnehmen können: Da ist die Erde; auf der Erde ist irgendein Mensch. Nun wissen Sie aber, der Mensch ist nicht bloß abhängig von den Kräften der Erde, sondern er ist abhängig von den Kräften, die aus dem Weltenall hereinwirken. Unser Kopf zum Beispiel spiegelt das ganze Weltenall ab. Das haben wir ja besprochen. Wenn das nun gleichgültig wäre, wie groß der Mensch ist, was müßte denn da sein? Nehmen Sie an, Herrn Burles Kopf, Herrn Erbsmehls Kopf, Herrn Müllers Kopf wird aus dem Weltenall herein gebildet. Ja, meine Herren, wenn hier die Köpfe drei-, viermal voneinander verschieden sind, so müßte für jeden ein extra Weltenall da sein. Da aber nur ein Weltenall da ist, das nicht wegen des einzelnen Menschen ins Große und Kleine wächst, sondern immer da ist, gleichbleibt, so können die Köpfe der Menschen auch nur annähernd einander gleich sein. Nur deshalb, weil die Leute das nicht wissen, daß wir ja in einer gemeinsamen Welt leben, die auch geistig wirkt, können die Leute glauben, es sei gleichgültig, wie groß der Kopf des Menschen ist, es sei bloß relativ. Es ist nicht relativ, sondern es ist abhängig von der absoluten Größe, die das Weltenall hat.

Wir kommen also wieder darauf, uns sagen zu müssen: Gerade wenn man richtig denkt in bezug auf die Relativitätstheorie, kommt man in die Geisteswissenschaft hinein, nicht in die materialistische Wissenschaft.

Und wenn man dann den Menschen noch genauer betrachtet, dann sieht man, wie überall den Leuten, die so denken wie Einstein, die Gedanken ausgehen, wenn sie ans Lebendige oder ans Geistige kommen. Sehen Sie, als ich noch ein Junge war, da konnte ich teilnehmen an den lebhaften Debatten, die stattgefunden haben über die Schwerkraft. Schwerkraft - wenn ein Körper zur Erde fällt, sagt man, er ist schwer. Er fällt hinunter, weil er ein Gewicht hat, weil er schwer ist. Aber diese Schwerkraft wirkt überall im Weltenall. Die Körper ziehen sich an. Wenn da die Erde ist und da der Mond (siehe Zeichnung), so zieht die Erde den Mond an, und der Mond fliegt nicht so fort, sondern er bewegt sich im Kreis um die Erde herum, weil die Erde, wenn er gerade fortfliegen will, ihn immer wiederum an sich zieht. Nun hat man dazumal, als ich ein Junge war, viel gestritten darüber, worauf denn diese Schwerkraft eigentlich beruht.

Der englische Physiker Newton, von dem ich Ihnen auch schon einmal erzählt habe, hat ja einfach gesagt: Die Körper ziehen einander an, der eine Körper den andern, — Eine recht materialistische Anschauung ist das nicht, denn wenn man sich vorstellt, daß der Mensch nur etwas angreifen soll und es herbeiziehen, da ist schon allerlei außer der Materie dazu notwendig. Wenn nun gar die Erde den Mond anziehen soll, so kann man das nicht gut mit einer materialistischen Anschauung vereinigen. Aber gerade in meiner Jugend blühte der Materialismus. Man könnte auch sagen, er trocknete die Menschen aus, er welkte, aber man könnte auch sagen, er blühte. Da haben die Leute gesagt: Das ist nicht wahr, die Erde kann den Mond nicht anziehen, denn sie hat ja keine Hände, um ihn anzuziehen. Das gibt es nicht. Da haben sie gesagt: Überall ist der Weltenäther (siehe Zeichnung). Was ich also jetzt rot herzeichne, ist der Weltenäther; der besteht auch aus lauter kleinen Körnern, winzigen kleinen Körnern. Und diese winzig kleinen Körner, die stoßen hier, stoßen hier, stoßen aber da stärker als sie in der Mitte stoßen. Wenn nun da zwei Körper sind, Erde und Mond, und von außen wird stärker gestoßen als von innen, da ist es, als ob sie sich anziehen würden. Man hat also die Anziehungskraft, die Schwerkraft, durch Stoßen von außen erklärt.

Ich kann Ihnen gar nicht sagen, was mir das einmal für Erkenntnisschmerzen gemacht hat. Von meinem zwölften bis achtzehnten Jahr habe ich wirklich daran gekaut, ob nun die Erde den Mond anzieht, oder ob der Mond zur Erde gestoßen wird. Denn, nicht wahr, die Gründe, die da vorgebracht werden, sind meistens nicht gerade dumm, sondern gescheit. Aber darinnen steckt auch schon eine gewisse Relativitätstheorie. Man frägt sich: Ist da irgend etwas Absolutes drinnen, oder ist da auch alles relativ? Ist es vielleicht wirklich gleichgültig, zu sagen, die Erde zieht den Mond an, oder, der Mond wird zur Erde gestoßen? Vielleicht kann man darüber überhaupt nichts entscheiden. — Nun, sehen Sie, darüber haben die Leute viel nachgedacht. Und dasjenige, was ich eigentlich sagen will, ist: Sie sind dazumal aber doch wenigstens darauf gekommen, daß es außer dem sichtbaren Stoff noch einen Äther gibt. Den Äther brauchten sie, denn was soll denn stoßen, wenn nicht die Körner vom Äther stoßen! Als Einstein zunächst seine Relativitätstheorie begründet hat, da haben alle Leute noch geglaubt, der Äther müsse da sein. Und Einstein hat dann alles das, was er als relative Bewegung geschildert hat, in den Raum hineingedacht, der vom Äther ausgefüllt ist. Nun kam er darauf: Donnerwetter! Wenn die Bewegung bloß relativ ist, ist es gar nicht notwendig, daß der Äther da ist. Da braucht nichts zu stoßen, nichts zu ziehen. Über all das kann man nichts entscheiden. Also kann auch der Raum leer sein.

Und so gibt es im Laufe der Zeit eigentlich zwei Einsteinsche Theorien. Die sind natürlich in einer Person vereinigt. Der frühere Einstein hat alles so beschrieben in seinen Büchern, als wenn der ganze Raum der Welt mit Äther ausgefüllt wäre. Dann hat ihn seine Relativitätstheorie dazu geführt, zu sagen: Der Raum ist leer. Nur kommt es bei der Relativitätstheorie nicht darauf an, über den Äther irgend etwas zu sagen, denn man weiß ja nicht einmal, ob es so ist. Da werden die Beispiele manchmal ganz grotesk, die er gibt, So zum Beispiel sagt Einstein: Wenn da die Erde ist, und da ist irgendein Baum, den krabble ich hinauf; hier rutsche ich aus, falle herunter — das ist eine Erscheinung, die Sie wahrscheinlich auch schon erlebt haben; ich habe es wenigstens als Junge sehr häufig erlebt, wenn ich auf einen Baum heraufgeklettert bin, daß ich ausrutschte und herunterfiel —, da sagt man: Nun ja, die Erde zieht mich an. Ich habe ein Gewicht. Das kommt von der Schwerkraft, sonst würde ich ja in der Luft geblieben sein, sonst würde ich zappeln, wenn mich die Erde nicht anziehen würde. — Aber Einstein meint, das kann man alles nicht sagen, denn man denke sich folgendes: Da ist wiederum die Erde, und jetzt bin ich da auf einem Turm oben, da stehe ich; aber ich stehe nicht so, daß um mich überall herum freie Welt ist, sondern ich stehe in einem Kasten drin, und der Kasten ist oben aufgehängt. Wenn ich in dem Kasten von dem Turm herunterfalle, so bleibt da immer mein Verhältnis zu den Wänden das gleiche. Ich bemerke nichts von einer Bewegung, die Wände gehen mit. Ja, Donnerwetter, jetzt kann ich gar nicht sagen, ob von da oben das Seil, an dem mein Kasten hängt, in dem ich drin bin, heruntergelassen wird und ich unten im Kasten ankomme, weil von oben mich jemand herunterläßt, oder ob ich ankommen kann, ob der Kasten ausrutscht, weil die Erde mich anzieht. Das kann ich nicht entscheiden. Ich weiß nicht, ob ich heruntergelassen werde, oder ob die Erde mich anzieht.

Aber mit diesem Beispiel, das da der Einstein wählt, ist es ja geradeso wie mit dem andern Vergleich, der in allen Schulen immer vorkommt. Da wird den Kindern schon erklärt, wie ein Planetensystem entsteht, daß da zuerst ein Nebel ist, aus diesem Nebel heraus gliedern sich die Planeten ab. In der Mitte bleibt die Sonne übrig. Da sagt man: Das kann man ja leicht beweisen, daß das so ist. Man nimmt ein kleines Öltröpfchen, das auf dem Wasser schwimmt, in der Mitte ein Kartenblatt, durch das eine Stecknadel gesteckt wird, gibt das ins Wasser, fängt an zu drehen. Dann spalten sich kleine Tröpfelchen ab von dem großen, und ein kleinwinziges Planetensystem ist da. So muß es draußen auch sein. Einmal war da ein Nebel; die Planeten haben sich abgespalten, in der Mitte ist die Sonne geblieben. Wer könnte irgend etwas widersprechen, wenn man das am Fetttröpfchen heute noch sieht! - Ja, aber eine Kleinigkeit ist vergessen worden, meine Herren: daß ich dastehen muß und drehen, wenn ich vor den Kindern der Herr Lehrer bin und das zeige! Wenn ich nicht drehe: nichts bildet sich von einem kleinen FettPlanetensystem! Also — müßte der Herr Lehrer den Kindern sagen — muß ein großer Herr Lehrer, ein riesiger Herr Lehrer da draußen sein, der die ganze Geschichte einmal gedreht hat. Dann ist das Beispiel erst vollständig. Und so müßte Einstein, wenn er ganz richtig der Wirklichkeit gemäß denken würde — wenn er überhaupt dazu kommt, solch einen Gedanken aufzustellen —, ja annehmen, daß da oben jemand das Seil dirigiert. Das ist da gleich notwendig. Sonst können Sie nicht sagen: Das ist ja gleich, wie ich herunterkomme, ob mich einer herunterläßt, oder ob ich purzle; es muß ja einer oben sein. Also müßte Einstein, wenn er das Beispiel ausführt, sofort daran denken: Wer ist denn da, der das Seil hält? Das tut er nicht, weil ihm das der Materialismus der heutigen Zeit verbietet. Deshalb denkt er Beispiele aus, die keine Wirklichkeit haben, die man gar nicht ausdenken kann, die unmöglich sind zu denken.

Und etwas anderes ist damit verbunden. Denken Sie sich einmal, meine Herren, hier ist ein Berg. Da ist Freiburg im Breisgau. Auf dem Berg stelle ich eine Kanone auf, so daß Sie den Schuß meinetwillen noch in Offenburg hören. Sie hören aber den Schuß später. Wenn einer feststellt auf der Uhr, wann er in Freiburg den Schuß gehört hat und wann einer ihn in Offenburg gehört hat, dann kriegt er einen Unterschied in der Uhrenstellung. Der Schall hat eine Zeitlang gebraucht, um von Freiburg nach Offenburg zu kommen.

Nun, sehen Sie, diese Geschichte ist auch ausgenützt worden für die sogenannte Relativitätstheorie. Denn man sagt: Man nehme nun an, ich stehe nicht in Offenburg und höre mir an, wann der Schall kommt, sondern ich stehe zunächst in Freiburg. Da höre ich den Schall gleichzeitig, wie er entsteht. Jetzt fahre ich mit einem Eisenbahnzug in der Richtung von Freiburg nach Offenburg. Dadurch, daß ich voranfahre, ein Stückchen weit weg von Freiburg, höre ich den Schall schon etwas später als er entsteht. Noch weiter gegen Offenburg zu, wieder etwas später; noch weiter zu, wieder etwas später.

Das dauert aber nur so lange, als Sie langsamer fahren als der Schall geht. Wenn Sie grad so schnell fahren wie der Schall geht von Freiburg nach Offenburg, was geschieht denn dann? Wenn Sie grad so schnell fahren, mit derselben Geschwindigkeit, wie der Schall geht: Sie kommen in Offenburg an, und da läuft er Ihnen davon, da hören Sie ihn noch immer nicht. Wenn Sie grad so schnell fahren, dann hören Sie ihn niemals, denn dann läuft er Ihnen davon, wenn Sie ihn hören sollen. Sie sollen ihn hören, aber da ist er schon nicht mehr. Nun sagen die Leute: Donnerwetter, das ist richtig, man hört den Schall nicht mehr, wenn man grad so schnell sich bewegt wie der Schall selber! Und wenn man sich noch schneller bewegt als der Schall, was geschieht denn dann? Wenn es langsamer geht, hört man ihn später; geht es geradeso schnell, hört man ihn gar nicht. Wenn man sich schneller bewegt, hört man ihn früher als er erschallt! Da sagen die Leute, das ist ganz natürlich, das ist ganz richtig gedacht. Wenn Sie also in Offenburg um zwei Sekunden später den Schall hören, wenn Sie sich langsamer bewegen als der Schall, so hören Sie den Schall gar nicht, wenn Sie sich mit derselben Geschwindigkeit wie der Schall bewegen. Wenn Sie sich aber schneller bewegen als der Schall, dann hören Sie ihn zwei Sekunden früher, als er in Freiburg losgelassen wird! Ich möchte Sie nur einladen, einmal zuzuhören, wirklich zuzuhören dem Schall, ehe er in Freiburg losgelassen wird! Sie können sich ja überzeugen, ob Sie ihn eher hören, selbst wenn Sie noch so schnell dahinsausen.

Der andere Einwand ist der, daß ich Sie dann fragen möchte, wie Sie dann ausschauen, wenn Sie sich so schnell bewegen oder noch schneller als der Schall!

Was folgt daraus? Es folgt daraus, daß man alles denken kann, wenn man sich nicht an die Wirklichkeit hält. Man kommt zuletzt mit dieser Relativitätstheorie darauf, daß man den Schall früher hört, als der Schuß losgelassen wird! (Heiterkeit.) Denken kann man sich das ganz gut, aber geschehen kann das nicht. Und das, sehen Sie, ist der Unterschied! Die Leute, die heute Wissenschaft treiben, wollen hauptsächlich logisch denken; und Einstein denkt wunderbar logisch. Aber das Logische ist noch nicht wirklich. Man muß zweierlei Eigenschaften in seinem Denken haben: Erstens müssen die Sachen logisch schon sein, aber zweitens müssen sie wirklichkeitsgemäß sein. Man muß in der Wirklichkeit drinnen leben können. Dann denkt man sich auch nicht diesen Kasten aus, der da auf und ab gezogen wird an einem Seil. Dann denkt man sich nicht die Uhr, die mit der Lichtgeschwindigkeit hinausfliegt in den Weltenraum und wieder zurück. Dann denkt man sich auch nicht den Kerl da, der sich schneller bewegt als der Schall und daher den Schall früher hört, als der Schuß stattfindet. Vieles von dem, meine Herren, was Sie heute in Büchern lesen als solche Erwägungen, ist sehr schön ausgedacht, aber man hat nichts davon in der Wirklichkeit.

Und so kann man sagen: Gescheit ist diese Einsteinsche Relativitätstheorie, und sie gilt auch für eine gewisse Partie der Welt, aber man kann mit ihr nichts anfangen, wenn man in die Wirklichkeit hineinsieht. Denn aus der Relauivitätstheorie kommt man niemals darauf, warum ein Mensch sich so fur&htbar ermüdet, wenn er nach Basel geht, da er doch gar nicht sagen kann, ob er nach Basel hineingeht oder ob Basel ihm entgegenkommt. Es wäre ja die Ermüdung gar nicht erklärlich, wenn Basel ihm entgegenkommt, und warum ich da mit meinen Füßen hantiere, wenn ich gehe; ich könnte ja still stehen bleiben, könnte warten, bis mir Basel entgegenkommt! Sie sehen, alle diese Dinge zeigen nichts anderes, als daß es noch nicht genügend ist, richtig und gescheit zu denken, sondern daß dazu noch etwas anderes gehört: Man muß im Leben drinnenstehen und muß die Sachen nach dem Leben entscheiden.

Das ist das, was ich Ihnen über die Relativitätstheorie sagen kann. Sie hat großes Aufsehen gemacht, aber die Leute verstehen sie, wie gesagt, wenig, sonst würden sie schon über die Dinge nachdenken.

Also dann am nächsten Samstag wieder.