From Beetroot to Buddhism

GA 353

XVI. Man and the hierarchies. Ancient wisdom lost. The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity

25 June 1924, Dornach

Good morning, gentlemen. Perhaps you have been able to think of something during this slightly longer interval—a special question?

Question concerning the nature of the different hierarchies and their influence on humanity.

Rudolf Steiner: This, I think, will be a bit difficult for those of you who are here for the first time; not easy to understand because you need to know some of the things I have been discussing in earlier lectures. But I'll consider the subject, nevertheless, and try and make it as easy as possible. You see, when you consider the human being, as he stands and walks on this earth, the human being really has all the realms of nature in him. In the first place man has the animal world in him; in a sense he also has an animal organization. You can see this immediately from the fact that human beings have upper arm and thigh bones, with similar bones also found in higher animals. But if one is able to gain good knowledge of them, one also finds related or similar elements in lower animals. Right down to the fishes you can more or less see elements corresponding to human bone. And what we can thus say about the skeletal system may also be said about the muscular system and also the internal organs. We find that humans have a stomach. Correspondingly we also find a stomach in animals. In short, the things that exist in the animal world can also be found in the human body.

Because of this, the materialistic view of the human being came to be that he was simply an animal, too, though more highly developed. But he is not. Human beings develop three things which animals cannot develop out of their organism. The first is that humans learn to walk upright. Just look at animals that learn to walk more or less half-way upright, and you'll see the marked difference between them and human beings. In animals that are a bit upright, kangaroos, for instance, you'll see that the forelimbs, on which they do not walk, are stunted. The kangaroo's forelimbs are not made to be used freely. And with the apes we certainly cannot say that they are like humans in this respect; for when they go up trees, they do not walk, they climb. They really have four hands, not two feet and two hands. The feet are shaped similar to hands; they climb. An upright walk is thus the first thing to distinguish humans from animals.

The second thing that distinguishes humans from animals is the ability to talk. And the ability to talk is connected with the ability to walk upright. You will therefore find that where animals have something similar to the ability to talk—dogs, being highly intelligent, relatively speaking, do not have it, but parrots, for instance, do have it, being a little bit upright—you will find that the animal is upright in that case. Speech is entirely connected with this uprightness.

And the third thing is free will. Animals cannot achieve this, being dependent on their internal processes. These are the things that make up the whole internal organization of the human being, making it human.

But man nevertheless has animal nature in him. He does have this animal world in him.

The second thing man has in him is the plant world. What are people able to do because they have the animal world in them? You see, animals are sentient—humans, too; plants are not sentient. A strange science which has now come up does include the view—I have mentioned this here before102Lecture of 21 April 1923, in GA 349. Tr. by M. Cotterell entitled 'The Nature of Christianity7 in MS R59, Rudolf Steiner House Library, London.—that plants are also able to feel, because there is a plant, such as the Venus fly-trap, for instance, and if an insect comes near and lands on it the Venus fly-trap folds up its leaves and swallows the insect. That is a highly interesting phenomenon. But if someone says: ‘This plant, the Venus fly-trap, must feel the insect, that is, have sensory perception of it, when it comes near it.’ This is just as nonsensical as if someone were to say: 'Such a tiny little thing which I set to snap shut when a mouse comes near—a mousetrap—is also able to sense that the mouse is entering into it.' Such scientific opinions are no great shakes, they are simply nonsense. Plants do not feel. Nor are plants able to move freely.

Sentience and mobility are therefore things man has in common with animals; there he has animal nature in him. It is only when he is able to think sensibly—which an animal cannot do—which makes him human. Man also has the plant world, the whole plant world in him. Plants do not move from place to place but they grow. Humans also grow and take nourishment. The plant world in them does this. This plant power is something humans also have in them. They have it in them even when they sleep. They let their animal nature go when they sleep, for they have no sentience of things, nor do they move around—unless of course they are sleepwalking, which is an abnormal development; in that case they do not let go of the ability to move around, and then they are sick. But in their normal condition people do not walk around when they are asleep, and they have no sentient awareness of things. When they need to have this, they wake up. In sleep, they cannot be sentient. Plant nature is something humans have in them also in their sleep.

And mineral nature, gentlemen, is also in us; it is present in our bones, for instance. They are a little bit alive, but they contain the lifeless element of calcium carbonate. We carry the mineral world in us. We even have brain sand in our brains. That is mineral. We have the mineral world in us. And so we have the animal world, the plant world and the mineral world in us.

But that is not all. If human beings only had mineral, plant and animal in them, they would be like an animal, they would walk about like an animal, for the animal, too, has mineral, plant and animal in it. Human beings, of course, are connected not only with those three realms of nature, which are visible, but also with other realms.

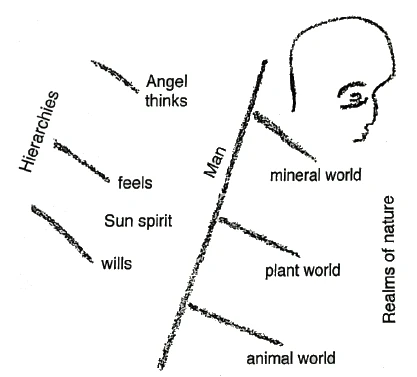

Let me draw a diagram for you. Imagine this to be the human being [Fig. 6]. He is now related to the mineral world, the plant world, the animal world. But he is a human being. You might say: 'Well, all right, animals can be tamed.' That is quite right. But have you ever seen an ox tamed by an ox? Or a horse by a horse? Animals, even if tamed, which gives them certain abilities that show distant similarity with human abilities, have to be tamed by humans! You'll agree there is no such thing as a school for dogs where dogs teach each other and make tame dogs out of wild dogs. Human beings have to intervene. And even if one were to think one might concede everything the materialists want, one would only have to take their own lines of thought further—you can concede everything, and if you like someone might say: 'The human being, as he is now, was originally an animal and has been tamed.' But the animal he would have been in that case cannot have tamed him! It simply is not possible. Otherwise a dog might also tame a dog. So there must have been someone originally who took humanity to its present level, and this someone, these entities—who may no longer be there now—cannot be from the three realms of nature. For if you imagine that you could ever have been tamed by a giraffe and made into a human being whilst still a little creature in your infancy—just as this would not have been possible, so it would not have been possible for you to have been tamed by an oak. You'd have to be a member of the German national front to believe that, people who may perhaps assume that the oak, a holy tree, has tamed humankind. And, you see, minerals even less so. A rock crystal is beautiful, but it certainly cannot tame the human being. Other entities must have existed, other realms.

You see, in human beings everything is truly called to higher things. Animals are able to form ideas, but they do not think. Ideas develop in animals. But they have no thinking activity. Human beings have thinking activity. And so they may have their blood circulation from the animal world, for example, but their thinking organ cannot come from the animal world. We are thus able to say: Man thinks, he feels, he wills. All this is freely done. And everything is different because man is a being who walks upright and who talks.

Just think how different your will intent would have to be, all your will impulses would be different if you always had to crawl around on all fours the way you do in the first year of your life. All human will impulses would be different in that case. And you would never get to the point of being able to think. And just as the things we have in our physical bodies connect us with the three realms of nature, so do thinking, feeling and will connect us with three other realms, with supersensible, invisible realms. We have to have a name for everything. Just as we call minerals, plants and animals the realms of nature, so we call the realms that bring about thinking, feeling and will in such a way that they may be free—the hierarchies. Thus we have here the realms of nature [Fig. 6], and with this, man extends into the natural world. And here we have the hierarchies. You see, man extends into three realms of nature on the one hand and into three hierarchies on the other. With his thinking he extends into the hierarchy—now you see, we do not yet have a name for it. We do not have a name for it because materialism takes no account of it; so we have to use the old names: angeloi, angels. People will immediately brand one as superstitious if one says this. It is true, of course, that we no longer have a real possibility of finding names for things, for humanity has lost the feeling for speech sounds. Languages were only able to evolve for as long as people still had a feeling for speech sounds. Today everyone uses words like 'ball' or 'fall'.103As vowel sounds differ greatly between German and English, which reflects the spirit of each nation and its language, I have only taken the first two of the three words given by Rudolf Steiner (Ball, Fall, Kraft), as it is possible to make his point more or less well in English with these two. I have used 'oh' instead of 'ah', as it matches the English sounds and (fortunately) we know from previous lectures in this volume that both vowels express amazement. Concerning the third, Kraft, he went on to say, after discussing Fall, that the 'f' also has special significance, using an energy to propel oneself. Translator. Each has the vowel 'a' in it. But what is that 'a' sound? It expresses a feeling! Imagine what would happen if you were to see someone opening that window from the outside and looking in. It would not be the right moment for such a thing, and so you would be surprised and amazed. Quite of few of you would probably react to this with an 'Oh!'—unless you felt this was not the place for expressing one's reactions. That sound always expresses surprise, being taken aback a little. And this is how every letter brings something to expression. When I say 'ball', I use that vowel sound because I am surprised at the strange way it behaves when I throw it, or if it is a ball where people dance, I am surprised to see all those lively gyrations. Only the way things have developed, people have got so used to it all that they are no longer surprised, you might just as well call it 'bull', or 'bill' but certainly no longer 'ball'. Let us take 'fall'. When someone takes a fall somewhere, we may also say 'Oh'. And the other important aspect lies in the 'f'—using an energy that lies in him. 'Oh'—whenever you are surprised, you also have that particular vowel sound.

And consider this. You believe that thinking takes place in the head. But if you were suddenly able to perceive that your thinking involves spiritual entities, just as there have to be animals on this earth so that you may be able to have sensation and feeling, this would come as another surprise to you. And to express this surprise you'd have to have a word that has that 'a' [as in father] sound in it. You would therefore also be able to give these thinking entities, known as angeloi, a name which has that 'a', and you would use the letter which indicates that you have the power of thinking, expressing power in a certain way:‘l’; and for the power that is taking effect you might perhaps use a 'b'. The word Alb,104The German Alb means sprite, goblin, and also nightmare, incubus. The change from plural to singular occurs in the original. Translator. used for something spiritual before, could indeed serve as a sign for these spirits who are connected with thinking, and not only for nightmares, which are the pathological side of it. The hierarchies are realms into which the human being extends, and which he has in him just as he has the realms of nature in him. And the spirits who were called Alb or angel are those connected with our thinking.

The feelings human beings have are connected with animal nature. What, animals? Well, you see, if one pays a little bit of heed and does not immediately go mad when something is mentioned that has to do with the spirit, but if people accept that one may be speaking of things of the spirit, quite a few things can be found out, even if one is not yet able to use a science of the spirit such as anthroposophy. Just consider—if you want to feel you need to have a certain warmth in you. A frog is much less alive in his feelings than a human being is, because it does not have warm blood. You really need to have warmth inside you when you feel. But the warmth we have in us comes from the sun. And so we are able to say that our feeling is also connected with the sun, but in a spiritual way. Physical warmth is connected with the physical sun; feeling, which is connected with physical warmth, is connected with the spiritual sun. This Second Hierarchy, which has to do with feeling, thus resides in the sun. You will definitely discover—providing you are not wholly brain-fixed, which many people are today, especially the scientists—you will discover that the Second Hierarchy are sun spirits. And because the sun only reveals itself on the outside in light and heat—no one knows the inside of the sun, for if physicists were to discover the sun as it really is they would be absolutely amazed to find that it does not at all look the way they think it does. They believe the sun to be a body of hot gases. That is far from the truth. It really consists of nothing but powers of suction; it is hollow, not even empty, but sucking. We can say that it reveals itself as light and heat on the outside; the spirits which are in there were known as 'spirits of revelation' in ancient Greek. When people still knew things—for the old instinctive knowledge was much wiser than the knowledge we have today—the spirits that revealed themselves from the sun were called Exusiai; we may just as well say 'sun spirits'. We just have to know that when we speak of feeling we enter into the realm of the sun spirits. Just as I say: Man has powers of growth and nutrition in him, and therefore the plant world, so I have to say: Man has in him powers of feeling, which are powers of the spiritual sun realm, the Second Hierarchy.

And the third thing is the First Hierarchy, which has to do with the human will. This is where human beings grow most energetic, not only moving but also bringing their actions to bear. This is in connection with spirits who are out there in the whole world and are altogether the highest spiritual entities we can get to know. Again we use a Greek or Hebrew name, for we do not yet have German ones, or altogether do not yet have the terms in our language—Thrones, Cherubs, Seraphs. That is the highest realm.

So there are three realms in the spirit just as there are three realms in nature. Man has to do with the three realms of nature and also with the three realms of the spirit.

Now you'll say: 'Well, I can believe that or not, for those three realms are not visible, they cannot be perceived by the senses.' Yes, but gentlemen, I have known people where one was asked to explain to them that there is such a thing as air. He would not believe that there was any air. When I tell him 'That's a blackboard', he'll believe it, for if he goes up to it he'll bump into it, or when he uses his eyes he can see the blackboard. But he does not bump into the air. He may look and will say: 'There's nothing there.' In spite of this everyone admits today that air exists. It is simply there. And one day people will also admit that the spirit is there. Today they still say: 'Well, it is not there, the spirit.' Which is what country people said about the air in the old days. In the place where I grew up, the country people would still say: 'The air simply is not there; that is just something the big-heads in the city say, wanting to be so clever. You can walk through there and there is nothing there where you are able to walk through.' But that was a long time ago. Today even the cleverest people still do not know that spirits are present everywhere! But they will admit it in due course, for certain things cannot be explained in any other way, and they need to be explained.

If someone says today: 'There is no spirit in everything that exists by way of nature; everything scientists know about nature is in there, but nothing else.' Well, gentlemen, if anyone says such a thing that is just as if there is someone who has died, and the corpse lies there, and I come and say: 'You lazy fellow! Why don't you get up and move on!' I try hard to make him understand that he should not be so lazy and that he should get up. Well, I lack understanding in that case, believing that there is a living human being in there. And that is how it is. Everything a scientist is able to find in there he does not find in the living person, he finds it in the dead body. Out there in the world of nature he also finds only dead things; he does not find that which lives. He does not find the spiritual in this way, but this does not mean it does not exist.

This is what I wanted to say on this question concerning the hierarchies.

Mr Burle: In earlier lectures you spoke about the ancient peoples having knowledge of the science of the spirit. This has been lost to humanity today. Would you be able to explain to us how that happened? If it was all due to materialism?

Rudolf Steiner: Why the old knowledge was lost? Well, you see, gentlemen, that is a very strange thing. The people who lived in very early times did not have knowledge the way we have it today but they had it in an artistic, poetic form. They had great knowledge, and that knowledge has been lost to humanity, as Mr Burle said, quite rightly. Now we may ask what caused this knowledge to be lost. We certainly cannot say that it was all due to materialism; for if all people still had the old knowledge materialism could never have arisen. It was exactly because the old knowledge had been lost and people had been mentally crippled that they invented materialism. Materialism thus comes from the decline of the old knowledge, and we cannot say that the old knowledge went into decline because materialism was spreading. So the question is, what did actually cause the old knowledge to decline?

Well, gentlemen, it happened because humanity is in a process of evolution. Now you can of course dissect a person who exists today; if he dies you can dissect him. You can gain knowledge about the way in which the human being is made in our present time. The most we have from earlier times are, well, the mummies in Egypt, which we talked about recently, only they are so thoroughly embalmed that one really cannot dissect them properly any more. Scientists therefore cannot get an idea of what human beings looked like in earlier times, especially at the time when they were of a more subtle build. Ordinary science cannot help here, and one has to penetrate it with the science of the spirit. And then one will find that people were not at all the way they are today in those earlier times.

There was a time on earth when people did not have such hard bones as we have them today. People had bones like the bones children with rickets have today, so that they grow bow-legged or knock-kneed and are altogether weak. You can see that it is possible to have such soft bones, for one still finds them in cartilaginous fish today. Those bones are as soft as cartilage. Human beings once had such bones, for the human skeleton was soft at one time. Now you'll say: 'That must mean that everyone went around bowlegged or knock-kneed, and everything must have been crooked because the bones were soft.'

That would have been the case if the air had always been the same on earth as it is today. But it wasn't. The air was much thicker in earlier times. It has got much thinner. And the air contained much more water in those old times than it does today. The air also contained a lot more carbon dioxide. The whole air was denser. Now you begin to see that people were able to live with those soft bones in the past. We only have to have the bones we have today because the air is no longer supporting us. A denser air would support human beings. Walking was much more like swimming in those times than it is today. Today we walk in a terribly mechanized way; we put down one foot, and the leg has to be like a column; then we put down the other foot. People did not walk like that in the earliest times; they were aware of the watery air just as one can let the water carry one today. So it was possible for them to have softer bones. But when the air grew thinner—and even ordinary science can tell us that the air got thinner—hard bones began to make sense. Hard bones only developed then. Of course, in those times the carbon dioxide was outside; the air contained it. Today we have calcium carbonate inside us; and with this the bones have grown hard. That is how things go together.

But when the bones grow hard, others things, too, grow hard in the human being. The people who had softer bones also had a much softer brain mass. And the skull, the head of human beings was a very different shape in those times. You see, it was more like the heads of people with water on the brain. That was beautiful then; today it is no longer so beautiful. And they kept their heads the way very young children today still have it in the womb, for they had a soft brain mass, and the soft brain deposited itself in the front part of the skull [drawing]. Everything was softer then.

Now, gentlemen, when the human being was softer, his mental faculties would also have been different. Your thinking is much more spiritual with a soft brain than with a hard brain. The ancients still felt this; they would call someone who was only able to think the same thing over and over again and therefore insists on sticking to just this one idea a thick-head. This means that they had a feeling that one is really able to think better, to have better ideas, if one has a soft brain. The early people had such a soft brain.

And then there was something else they had. We are certainly able to say that when a child is born, its skull with its soft brain, and even the soft bones, are still very similar to the way they were in the early people. But you just sit or lay a small infant down—it cannot go anywhere, it cannot feed itself and the like; it cannot do anything! Higher spirits had to take care of this when people still had those soft brains. And the result was that people did not have freedom then, they did not have free will. But free will gradually developed in the course of human evolution. It means that the bones and the brain had to harden. But this hardening also meant that the old knowledge went into decline. We would not have become independent human beings if we had not become thick-headed, hard-headed, with hard brains. But we owe our freedom to this. And the decline of the old knowledge really went hand in hand with our freedom. That is it. Can you understand this? [Answer: Yes.] It comes with our freedom.

But now, having on the one hand gained freedom and independence, human beings have lost the old knowledge and fallen into materialism. But materialism is not the truth. We must therefore gain spiritual insight again, in spite of the fact that we have a denser brain today than people did originally. We can only do this through the anthroposophical science of the spirit. This gives insights that are independent of the body and are perceived with the soul only. Early humanity had their knowledge because their brains were softer and therefore more soul-like. We have our materialism because our brain has grown hard, no longer able to take in the soul. We therefore have to gain spiritual insights with the soul only, a soul not taken up by the brain. This is the way of the science of the spirit. We regain spiritual insights. But we live in an age now when humanity has bought freedom, the price being materialism. So we cannot say that materialism is something bad, even if it is untruth. Materialism, if not taken to extremes, is not something bad, for through materialism humanity has learned many things that were not known before. That is how it is.

Now there is another question that was put in writing before:

I have read the following statement in your Philosophy of Spiritual Activity:105Steiner, R., The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. A Philosophy of Freedom (GA 4), tr. R. Stebbing, London: Rudolf Steiner Press 1989. We must make the content of the world the content of our thought; only then shall we find the wholeness again from which we have separated.'

So the gentlemen has been reading something of the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. His question is: What belongs to this world content, since everything we see exists only in so far as we think it? And he goes on to say: Kant says the mind is unable to grasp the world of phenomena that comes before the world we perceive.

Now you see, gentlemen, it is like this. When we are bom, when we are little children, we have eyes, we have ears, we see and we hear; that is, we perceive the things that are around us. The chair which is there is not thought by a child, but it is perceived. It looks the same to a child as it does to a grown-up, only the child does not yet think the chair. Let us assume some artificial means could be found so that a child who does not yet have thoughts would be able to talk. In that case—and we are used to this today, for the very people who do not think are those who are most critical—the child would be inclined to criticize everything. I am actually convinced that if very young infants who are not yet able to think were able to chatter away they would be the greatest critics. You see, in ancient India, you had to be 60 before you were allowed to be critical; the others were not allowed to voice an opinion, for people would say: 'They have no experience of the world yet.' Now I won't defend this nor will I criticize it, I merely want to tell you how it was. Today anyone who has reached the age of 20 would laugh at you if you were to say he had to wait until he was 60 before he could give an opinion. Young people would not do that today. They do not wait at all, and as soon as they are able to hold a pen they start to write for the papers, to have opinions on everything. We've gone a long way in this direction today. But I am convinced that if very young infants were able to talk—oh, they would be severe critics! A 6-month-old infant, wow, he'd be criticizing everything we do if we could get him to talk.

Gentlemen, you see, we only start to think at a later stage. How did speech develop? Well, imagine a child of 6 months, not yet able to have the idea of the chair but able to see it just as we do. He would discuss the chair. Now you would say: 'I, too, have the idea of the chair; in the chair here is gravity, and so it stands on the floor. Some carving las been done on it, and so it has form. The chair has a certain inner consistency, and I am therefore able to sit on it without falling off, and so on. I have the idea of the chair. I think of something when I see the chair.' The child of 6 months who does not yet have the idea will say: 'Silly, you've grown stupid having grown so old. We know at 6 months what a chair is; later you have all kinds of fantasies about it.' Yes, that is how it would be if a 6-month-old child could talk. And something we are only able to do as we get older—being also able to think as we say things—with all this the situation is that the ideas do, after all, go with the chair; I merely do not know them beforehand. I only have the ideas when I have reached the level of maturity needed. But the solidity of the chair is not in me. I do not sit down on my own solidity when I sit down on the chair, otherwise I might as well sit myself down on myself again. The chair does not get heavy when I sit down on it; it is heavy in its own right. Everything I develop by way of ideas is already in the chair. I therefore perceive the reality of the chair when in the course of life I connect with it many times in my thoughts. Initially I only see the colours, and so on, hear when a chair rattles, and also feel if it is cold or warm; I can perceive this with my senses. But one only knows what is in that chair when one has grown older and is able to think. Then one connects with it again, creating a retroactive effect.

Kant—I spoke of him recently—made the biggest of mistakes in thinking that something a child does not yet perceive, something we only perceive later, i.e. the thought content, is something people put into objects themselves. So he was really saying: 'If that is a chair there—the chair has colour, it rattles. But when I say the chair is heavy, this is not a property of the chair, it is something I give to it by thinking it to be heavy. The chair is solid, but this is not inherent in it; I add it by thinking the chair to be solid.' Well, gentlemen, Kant's teachings are considered to be a great science, and I spoke about this a while ago. The truth is, however, that it is the greatest nonsense. Because of the particular way in which humanity has developed, great nonsense is sometimes considered to be great science, the most sublime philosophy, and Kant is of course also known as the man who ground everything to dust, who shattered everything. All I was able to see in him—I studied Kant from early boyhood, again and again—is a shatterer; but I have not generally found that someone who shatters soup plates creates the most sublime things, nor indeed that he was greater than the person who made the plates. It always seemed to me that the maker was the greater man. Kant has in truth always shattered everything.

Kant's objections should not concern us. But the thing is that when we are born we are disunited, having no connection with things. We only grow into them again as we develop concepts. The question that has been asked therefore has to be answered like this. What belongs to the world content? In my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity I wrote: 'We must make the content of the world the content of our thought; only then shall we find the whole again from which we separated in infancy.' In infancy we do not have the world content, we only have the sensual part of the world content. But the thought content is truly inside the world content. In infancy we thus have only half the world content, and it is only later, when we have developed and have thoughts, that we have the thought content not only in us, but we know that it is in the things, and we also treat our thoughts in such a way that we know they are in the things, and we then re-establish our connection with the things.

You see, in the 1880s—when everything had become Kantian and everyone kept saying that Kant's philosophy was the most sublime, and no one dared as yet to say anything against it—it was very hard when I stood up in those days and stated that Kantian philosophy was really a nonsense. But this is something I had to declare from the very beginning. For of course, if someone like Kant thinks that we actually add the thought content to things, he can no longer arrive at the plain and simple content, for he then has inner thoughts about things around him, and this is materialism indeed. Kant is in many respects responsible for the fact that humanity has not found its way out of materialism. Kant is altogether responsible for a great many things. I told you this on that earlier occasion when someone else had asked about Kant. The others, being unable to think anything else, created materialism. But Kant said: 'We cannot know anything about the world of the spirit, only believe.' What he was really saying was: 'You can only know something about the world perceived by the senses because you can drag thoughts only into this world perceived by the senses.'

And people who wanted to be materialistic felt even more justified in this by referring to Kant. But this is another prejudice humanity must get out of the habit of using—meaning the part of humanity who at least know something of Kant—they have to get out of the habit of always referring to Kant when they want to say that one really cannot know anything about the world of the spirit. And so world content is sensory content and content of mind and spirit. But mind and spirit only gain that content in the course of life, as we develop ideas. We then re-establish the connection between nature and spirit. In the beginning, in infancy, we only had nature before us, and mind and spirit evolved gradually out of our own nature.

Would anyone have a very little question?

Mr Burle asked about human hair, saying: 'Many girls now have their hair cut short. Could Dr Steiner tell us if that is good for the health? My little daughter would also like to cut her hair, but I have not permitted it. I'd like to know if it is harmful or not.'

Rudolf Steiner: Well now, the matter is like this. The hair that grows is so little connected with the organism as a whole that it does not really matter very much if one lets one's hair grow or cuts it short. The harm is not enough to be apparent. But there is a difference between men and women in this respect. You know, for a time it was the case—it's no longer the case now—that one would see anthroposophists walking about, gentlemen and ladies—the gentleman would not cut his hair, wearing long tresses, and the ladies would have their hair cut short. People would of course say: 'Anthroposophy turns the world upside down; among the anthroposophists the ladies cut their hair short and the gentlemen let theirs grow.' Now it is no longer like this, at least not noticeably so. But we might of course also ask how it is with the difference between the sexes when it comes to cutting one's hair.

Generally speaking the situation is that a great head of hair is rather superfluous in men. For women it is a necessity. Hair always contains sulphur, iron, silica and some other substances. These are needed by the organism. Men need much silica, for as they assumed the male sex in the womb they lost the ability to produce their own silica. They absorb the silica that is in the air whenever they have just had their hair cut, absorbing it through the hair. It is of course too bad when the hair has gone, for then nothing can be absorbed. Going bald at an early age, which has a little bit to do with people's lifestyles, is not exactly the best thing for a person.

With women, cutting the hair short is not exactly good, and that is because women have the ability to produce silica more in the organism, and so they should not cut the hair really short too often; for then the hair absorbs silica—which the woman already has in her—from the air and forces it back into the organism. This makes the woman inwardly hairy, prickly; she then has 'hairs on her teeth' [German saying, meaning a tough woman]. This is then something that is not so apparent; one has to have a certain sensitivity to notice it, but a little bit of it is there. Their whole manner is rather prickly then; they become inwardly hairy and prickly; and cutting one's hair off does then have an influence, especially in young people.

Now you see, it can also be the other way round, gentlemen. It may be that modern youngsters come into an environment—children are all quite different today from the way we were in our young days—where their inner silica is no longer enough, for they want to be a bit prickly, scratchy. They then develop the instinct to cut their hair. This becomes fashionable, with one copying the other, and then we have the story the other way round, with children wanting to be prickly and having their hair cut. But if one managed to organize things so that they went a bit against such a fashion, this would not be such a bad thing if the fashion has gone a bit to extremes. In the final instance it all has to do with this, does it not—one person likes a gentle woman, another a prickly one. Tastes do change a little. But it cannot have a very great influence. Though of course if someone has a daughter who wants to or is supposed to choose a husband who likes a prickly woman, then she should get her hair cut. She then won't get a husband who likes a gentle woman. So that may indeed happen. So the business has more of an effect on things that are marginal in life.