The Inner Nature of Music and the Experience of Tone

GA 283

2 December 1922, Dornach

Human Expression through Sound and Word

In recent discussions,1Refers to Rudolf Steiner's lectures, Man and the World of the Stars/the Spiritual Communion of Man, Anthroposophic Press, Spring Valley, NY. 1982. I pointed out that certain human functions appearing in early childhood are transformations of functions that man carries out in pre-earthly existence between death and a new birth. We see how, after birth, the child not fully adapted to the earth's gravity and equilibrium gradually develops to the point at which it becomes adjusted to this equilibrium, how it learns to stand and walk upright. The body's adaptation to the condition of equilibrium of earthly existence is something the human being acquires only after life on earth has begun. We know that the form of man's physical body is the result of a magnificent spiritual activity, which man, together with beings of the higher worlds, undertakes in the period between death and a new birth. What man forms in this way, however—that which becomes the spiritual seed, as it were, for his future physical earthly organism—does not yet contain the faculty of walking upright. That faculty is incorporated into the human being when he adapts himself after birth to the conditions of equilibrium and gravity of earthly existence.

In pre-earthly existence, orientation does not refer to walking and standing as it does here on earth. There, orientation refers to the relationship man has with angels and archangels and therefore to beings of the higher hierarchies. It is a relationship in which one finds oneself attracted more to one being, less to another; this is the state of equilibrium in the spiritual world. It is lost to a certain extent when man descends to earth. In the mother's womb, man is neither in the condition of equilibrium of his spiritual life nor yet in that of his earthly life. He has left the former and as yet has not entered the latter.

It is similar in the case of language; the language we speak here on earth is adjusted in every respect to earthly conditions, for this language is an expression of our earthly thoughts. These earthly thoughts contain earthly information and knowledge, and language is adapted to them during earthly existence. In pre-earthly existence, man has a language that does not actually emerge from within, that does not follow the exhalation. Instead, it follows spiritual inhalation, inspiration, something in pre-earthly existence that we can describe as corresponding to inhalation. It is a life within the Word of the universe, the universal language, from which all things are made.

As we descend to the earth, we lose this life within the universal language, and here we acquire the means that serve to express our thoughts, our earthly thoughts, and the human intellect, that is, the intellect among all human beings dwelling on earth. It is the same with the thoughts we have here as with the thinking. Thinking is adapted to earthly conditions. In pre-earthly existence we live within the weaving thoughts of the universe.

If we first focus on the mediating member of man, man's speaking, we can say that an essential part of the earth's culture and civilization lies in speaking. Through speaking, people come together here on earth; speaking is the bridge between two persons. Soul unites with soul. We feel that in speaking we have an essential aspect of life on earth; it is, after all, the earthly reflection of life in the Logos, in the Word of the universe. It is therefore particularly interesting to understand the connection between what man struggles to attain on earth as his language and the metamorphosis of this language found in pre-earthly life. The study of this relationship directs us to the inner organization of man, which stems from the elements of sound and tone. It is especially fitting that at this moment I can add the subject of man's expression through tone and word to the cosmological considerations we have been conducting for weeks. Today we have had the great pleasure of listening to a superb vocal recital here in our Goetheanum. As an expression of inner satisfaction over this gratifying artistic event, let me say something about the connection between man's life in that which corresponds to tone and sound in the spiritual.

If we observe the human organization as it is manifested on earth, it is a reflection of the spiritual through and through. Not only what man bears within himself but everything surrounding him in outer nature is a reflection of the spiritual. When man expresses himself in speech and song, he expresses his whole organization of body, soul and spirit as a revelation to the outside as well as to himself, to the inside. Man is completely contained, as it were, in what he reveals in sound and tone. How much he is contained within this is revealed when one goes into the details of what man is when he speaks or sings.

Let us begin by considering speech. In the course of humanity's historical evolution, speech has emerged from a primeval song element. The further we go back into prehistoric times, the more speech resembles recitation and finally singing. In very ancient times of man's earthly evolution, his sound and tone expressions were not differentiated into song and speech; instead, they were one. Man's primeval speech may be described as a primeval song. If we examine the present state of speech, which is already far removed from the pure singing element and has instead immersed itself in the prose element and the intellectual element, we have in speech essentially two elements: the elements of consonants and vowels. Everything brought out in speech is composed of the elements of consonants and vowels. The element of consonants is actually based on the delicate sculptural formation of our body [Körperplastik]. How we pronounce a B, a P, an L, or an M is based on something having a definite form in our body. In speaking of these forms, one is not always referring only to the apparatus of speech and song; they represent only the highest culmination. When a human being brings forth a tone or sound, his whole organism is actually involved, and what takes place in the song or speech organ is only the final culmination of what goes on within the entire human being. The form of the human organism could be considered in the following way. All consonants contained in a given language are always actually variations of twelve primeval consonants. In Finnish, for example, these twelve primeval consonants are preserved in a nearly pure state. Eleven are retained completely clearly; only the twelfth has become somewhat unclear. [Gap in transcript.] If the quality of these twelve primeval consonants is correctly comprehended, each one can be represented by a certain form. If they are combined, they in turn represent the complete sculptural form of the human organization. Not speaking symbolically at all, one can say that the human organism is expressed sculpturally through the twelve primeval consonants.

Actually, what is this human organization? Viewed from an artistic standpoint, it is really a musical instrument. Indeed, you can comprehend standard musical instruments, a violin or some other instrument, by looking at them fundamentally from the viewpoint of the consonants, by picturing how they are built, as it were, out of the consonants. When one speaks of consonants, one always feels something that is reminiscent of musical instruments, and the totality and harmony of all consonants represents the sculptural form of the human organism.

The vowel element is the soul playing on this musical instrument. When you observe the consonant and vowel element of speech, you actually discover a self-expression of the human being in each word and tone. Through the vowels, the soul of man plays on the “consonantism” of the human bodily instrument. If we examine the speech of modern-day civilization and culture, we notice that, to a large extent, the soul makes use of the brain, the head-nerve organism, when it utters vowels. This was not the case to such an extent in earlier times of human evolution. Let me sketch on the blackboard what takes place in the human head-nerve organism.

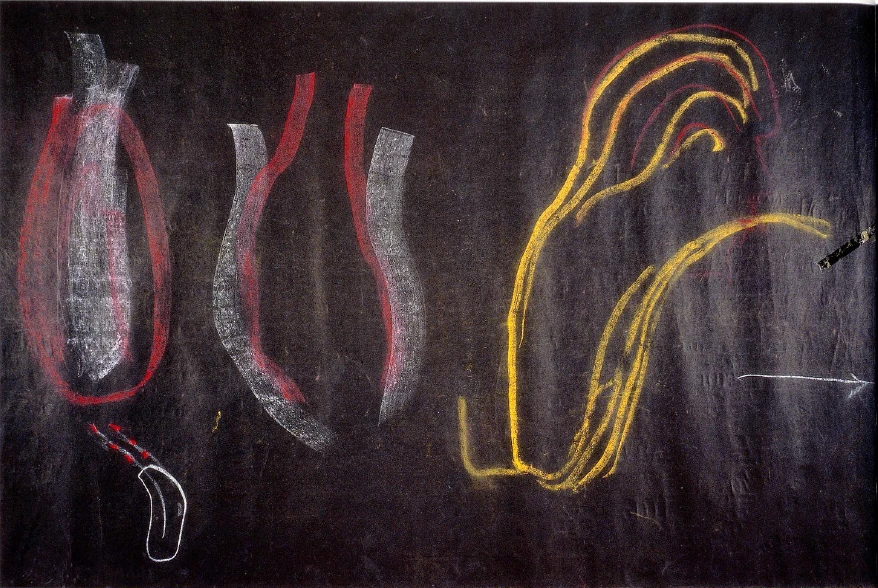

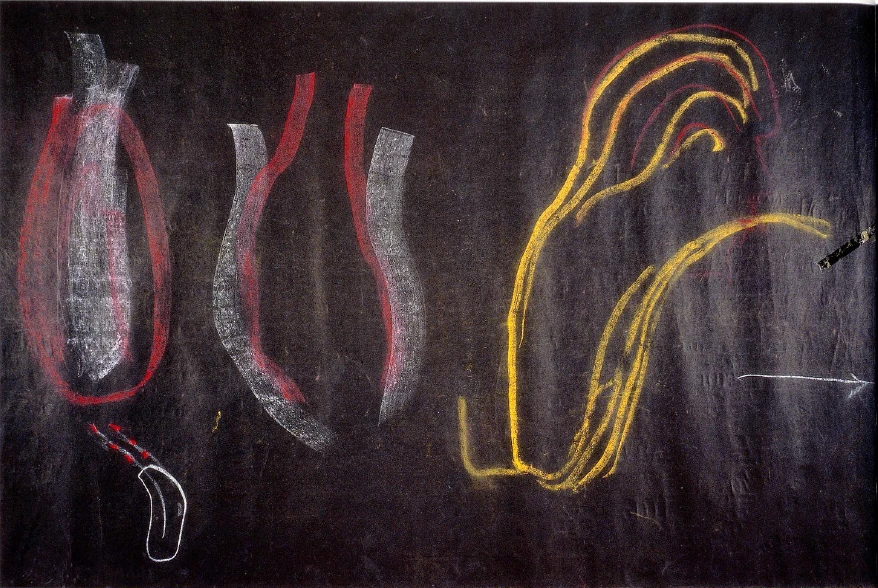

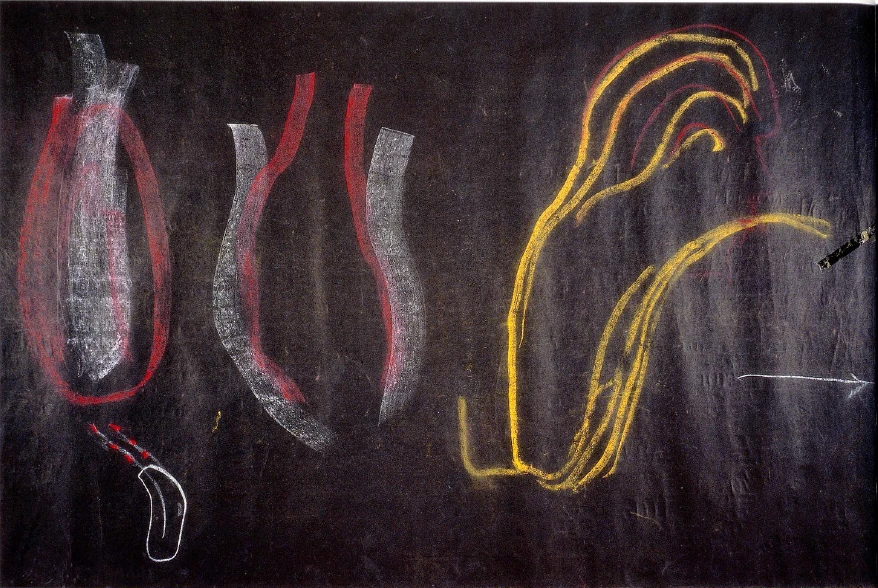

The red dotted lines indicate the head-nerve organism. They therefore represent the forces running along the nerve fibers of the head. This is a one-sided view of the whole matter, however. Another activity enters the one generated by the nerve fibers. This new activity is caused by our inhalation of air. Sketching it, we see that the air we inhale passes through the canal of the spinal cord, and the impact of the breathing process unites with the movements taking place along the nerve fibers. The stream of breath (yellow), which pushes upward through the spinal cord to the head, constantly encounters the nerve activity. Nerve activity and breathing activity are not isolated from each other. Instead, an interplay of both takes place in the head. Conditioned by everyday life, man has become prosaic, placing more value on the nerve forces, and he makes more use of his nervous system when he speaks. One could say that he “innergizes” [“innerviert,” makes inward] the instrument that forms the vowel streams in a consonantal direction. This was not the case in earlier epochs of human evolution. Man lived less in his nervous system; he dwelt more in the breathing system, and for this reason primeval speech was more like song. What man carries out in speech with the help of the “innergizing” of his nervous system he draws back into the stream of breathing when he sings today; he then consciously brings into activity this second stream (sketched in yellow), the stream of breathing. When vowel sounds are added to producing the tone, as in the case of singing, the element of breathing extends into the head and is directly activated from there; it no longer emerges from the breath. It is a return of prosaic speech into the poetic and artistic element of the rhythmic breathing process.

The poet still makes an effort to retain the rhythm of breathing in the way in which he formulates the language of his poems. A person who composes songs takes everything back into breathing, and therefore also into the head-breathing. When man shifts from speaking to singing, he undoes in a certain way what he had to undergo in adapting speech to earthly conditions. Indeed, song is an earthly means of recalling the experience of pre-earthly existence. We stand much closer to the spiritual world with our rhythmic system than with our thinking system. It is the thinking system that influences speech which has become prosaic.

When producing vowel sounds, we actually push what lives in the soul toward the body, which serves as the musical instrument only by adding the consonant element. Surely you can feel how a soul quality is alive in every vowel and how you can use the vowel element by itself. The consonants, on the other hand, tend to long continuously for the vowels. The sculptural instrument of the body is really dead unless the vowel or soul element touches it. Many details point to this: take, for instance, the word “mir” (“mine”; pronounced “meer” in high German), and look at how it is pronounced in some Central European dialects. When I was a little boy, I couldn't imagine that the word was spelled mir. I always spelled it mia, because in the r is contained the longing for the a.

If we see the human organism as the harmony of the consonants, everywhere we find it in the longing for vowels and therefore the soul element. Why is that? The human organism while here on earth must adapt its sculptural form to earthly conditions. Earthly equilibrium and the configuration of earthly forces determine its shape. Yet, it is really shaped out of the spiritual, and only through spiritual scientific research can one perceive what actually takes place. I shall try to make this clear for you with a diagram. The soul element (red), which expresses itself in vowels, pushes against the element of consonants (yellow). The element of consonants is shaped sculpturally according to earthly conditions.

If one ascends to the spiritual world in the way described in my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment, one first acquires imagination, imaginative cognition. Meanwhile, one has lost the consonants, though the vowels still remain. In the imaginative world, one has left one's physical body behind along with the consonants, and one no longer has comprehension for them. If one wishes to describe what is in this higher world adequately in words, one can say that it consists entirely of vowels. Lacking the bodily instrument, one enters a tonal world colored in a variety of ways with vowels. Here, all the earth's consonants are dissolved in vowels. This is why you will find in languages that were closer to the primeval languages that the words for things of the super-sensible world were actually vowel-like. The Hebrew word “Jahve” for example, did not have the J and the V; it actually consisted only of vowels and was rhythmically half-sung. Using mostly vowels, the words naturally were sung.

In passing from imaginative cognition to cognition through inspiration—where the direct revelations of the spiritual are received—all the consonants that are here on earth become something completely different. The consonants are lost. (See lower yellow lines in sketch below.) In the spiritual perception that can be gained through inspiration, a new element begins to express itself, namely the spiritual counterparts of the consonants. (See upper yellow lines in sketch below.)

These spiritual counterparts of the consonants, however, do not live between the vowels but in them. In languages on earth the consonants and vowels live side by side. The consonants are lost with the ascent into the spiritual world. You live in a singing worlds of vowels. You yourself actually stop singing; it sings. The world itself becomes universal song. The soul-spirited substance of this vowel element is colored by the spiritual counterparts of the consonants that dwell within the vowels. Here on earth, for example, there is an a tone and a c-sharp tone in a certain octave. As soon as one ascends to the spiritual world, there is not just one a or one c-sharp of a certain scale; instead, there are untold numbers of them, not just of different pitch but of different inward quality. It is one thing if a being of the hierarchy of angels utters an a, another when an archangel or yet another hierarchical being says it. Outwardly it is always the same revelation, but inwardly the revelation is ensouled. We thus can say that here on earth we have our body (sketch on left, white) and a vowel tone (red) pushes against it. Beyond, in the spiritual world, we have the vowel tone (sketch on right, red), and the soul penetrates into it and lives in it so that the tone becomes the soul's body.

You are now within the universal music, the song of the universe; you are within the creative tone, the creative world. Picture the tone here on earth, even the tone that reveals itself as sound: on earth it lives in the air. The scientific concept, however, that the vibration of the air is the tone is a naïve concept indeed. Imagine that here is the ground and that someone stands on the ground. Surely the ground is not the person, but it must be there so that the person can stand on it; otherwise he could not be there. You would not want to comprehend man, however, by the ground he stands on. Likewise, tone needs air for support. Just as man stands on the firm ground, so—in a somewhat more complicated way—tone has its ground, its resistance, in the air. Air has no more significance for tone than the ground for the person who stands on it. Tone rushes toward air, and the air makes is possible for tone to “stand.” Tone itself, however, is something spiritual. Just as the human being is different from the earthly ground on which he stands, so tone differs from the air on which it rises. Naturally it rises in complicated ways in manifold ways.

On earth, we can speak and sing only by means of air, and in the air formations of the tone element we have an earthly reflection of a soul-spiritual element. This soul-spiritual element of tone belongs in reality to the super-sensible world, and what lives here in the air is basically the body of tone. It is not surprising, therefore, that one rediscovers tone in the spiritual world, where it is stripped of its earthly garment, the earthly consonants. The vowel element, the spiritual content of tone as such, is taken along when one ascends into the spiritual world, but now it becomes inwardly filled with soul. Instead of being outwardly formed by the element of consonants, the tone is inwardly filled with soul. This runs parallel to one's becoming gradually accustomed to the spiritual world.

Picture how man passes through the portal of death. Soon he leaves the consonants behind, but he experiences the vowels, especially the intonation of vowels, to a greater degree. He no longer feels that singing is produced by his larynx but that singing is all around him, and he lives in each tone. This is already the case the very first few days after man passes through the portal of death. He dwells, in fact, in a musical element, which is an element of speech at the same time. More and more of the spiritual world reveals itself in this musical element, which is becoming imbued with soul.

As I have explained to you, when man has passed through the portal of death, he passes at the same time from the earthly world into the world of the stars. Though it appears that I am speaking figuratively, this description is a reality. Imagine the earth, surrounding it the planets, and beyond them the fixed stars, which are traditionally pictured, for good reason, as the Zodiac.

From earth, man views the planets and fixed stars in their reflections; we therefore say that earthly man sees them from the front. The Old Testament expresses this in a different way. When man moves away from the earth after death, he gradually begins to see the planets as well as the fixed stars from behind, as if were. He no longer sees these points or surfaces of light that are seen from the earth; instead, he sees the corresponding spiritual beings. Everywhere he sees a world of spiritual beings. Where he looks back at Saturn, Sun, Moon, Aries, or Taurus, he sees from the other side spiritual beings. Actually, this seeing is also a hearing; and just as one can say that one sees Moon, Venus, Aries, or Taurus from the other side, from behind, so one can say that one hears the beings who have their dwelling places in these heavenly bodies resound into cosmic space.

Picture this whole structure—it sounds as if I speak figuratively, but it is not so, this is a reality; imagine yourself out there in the cosmos: the planetary world further away, the Zodiac with its twelve constellations nearer to you. From all these heavenly bodies it sings to you in speaking, speaks in singing, and your perception is actually a hearing of this speaking-singing, singing-speaking. When you look toward the constellation of Aries you have a soul-consonant impression. Perhaps you behold Saturn behind Aries: now you hear a soul-vowel. In this soul-vowel element, which radiates from Saturn into cosmic space, there lives the soul-spiritual consonant element of Aries or Taurus. You therefore have the planetary sphere that sings in vowels into cosmic space, and you have the fixed stars that ensoul this song of the planetary sphere with consonant elements. Vividly picture the more serene sphere of the fixed stars and behind it the wandering planets. As a wandering planet passes a constellation of fixed stars, not just one tone but a whole world of tones resounds, and another tone world sounds forth as the planet moves from Aries to Taurus. Each planet, however, causes a constellation to resound differently. You have in the fixed stars a wonderful cosmic instrument, and the players of this instrument of the Zodiac and fixed stars are the gods of the planets beyond.

We can truly say that, just as man's walk was shaped for earthly conditions out of cosmic, spiritual orientation, so his speech was shaped for earthly conditions. When man takes speech back into song, he moves closer to the realm of pre-earthly existence, from whence he was born into earthy conditions. It is human destiny that man must adapt himself to earthly conditions with birth. In art, however, man takes a step back, he brings the earthly affairs surrounding him to a halt; once again he approaches the soul-spiritual element from which he emerged out of pre-earthly existence.

We do not understand art if we do not sense in it the longing to experience the spiritual at least in the revelation of beautiful appearance. Our fantasy, which give rise to the artistic, is basically nothing but the pre-earthly force of clairvoyance. Just as on earth tone lives in the air, so what is actually spiritual in pre-earthly existence lives for the soul element in the earthly reflection of the spiritual. When man speaks, he makes use of his body: the consonant element in him becomes the sculptural form of the body; and the stream of breath, which does not pass into solid, sculptural form, is used by the soul to play on this bodily instrument.

We can, however, direct toward the divine what we are as earthly, speaking human beings in two ways. Take the consonantal human organism; loosen it, as it were, from the solid imprint, which it has received from the earthly forces of gravity or the chemical forces of nutrients; loosen what permeates the human being in a consonantal way! We may indeed put it like that. When a human lung is dissected, one finds chemical substances that may be examined chemically. That is not the lung, however. What is the lung? It is a consonant, spoken out of the cosmos, that has taken on form. Put the human heart on a dissecting-table; it consists of cells that can be examined in relation to their chemical substances. That is not the heart, however; the heart is another consonant uttered out of the cosmos. If one pictures in essence the twelve consonants as they are spoken out of the cosmos, one has the human body. This means that if one has the necessary clairvoyant imagination to observe the consonants in their relationships, the complete shape of the human body's sculptural form will arise. If one therefore extracts from the human being the consonants, the art of sculpture arises; if one extracts from the human being the breath, which the soul makes use of in order to play on the instrument in song, if one extracts the vowel element, the art of music, of song, arises.

From the consonant element extracted from the human being, the form arises, which we must shape sculpturally. From the vowel element extracted from the human being arises the musical, the song element, which we must sing. Man, as he stands before us, on earth, is really the result of two cosmic arts. From one direction derives a cosmic art of sculpturing, from the other comes a musical and song-like cosmic art. Two types of spiritual beings fuse their activities. One brings forth and shapes the instrument, the other plays on the instrument.

No wonder that in ancient times, when people were still aware of such things, the greatest artist was called Orpheus. He actually possessed such mastery over the soul element that not only was he able to use the already formed human body as an instrument, but with his tones he could even mold unformed matter into forms that corresponded to the tones.

You will understand that when one describes something like this one has to use words somewhat differently from what is customary in today's prosaic age; nevertheless, I did not mean all this figuratively or symbolically but in a very real sense. The matters are indeed as I described them, though the language often needs to be more flexible than it is in today's usage.

The subject of today's lecture was intended by me as a greeting to our two artists2The two artists and the concert refer to the recital by the sisters Svardstrom in the Goetheanum at that time. who have delighted us with their fine talents. We shall attend tomorrow's concert, my dear friends, with an attitude to which will be added an anthroposophical mood of soul, something that should inform all our endeavors.

Des Menschen Äusserung durch Ton und Wort

In den Auseinandersetzungen, die wir in der letzten Zeit gepflogen haben, habe ich darauf hinweisen können, wie Verrichtungen des menschlichen Wesens, die in der ersten Kindheit auftreten, Umwandelungen sind von Verrichtungen, die der Mensch vollzieht zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, die er also vollzieht im vorirdischen Dasein. Wir sehen ja, wie das Kind, nachdem es nach der Geburt noch nicht voll angepaßt ist der Erdenschwere, dem Erdengleichgewicht, nach und nach dazu übergeht, diesem Gleichgewicht wirklich angepaßt zu sein, wie es das Stehen, das Gehen lernt. Dieses Anpassen des Körpers an die Gleichgewichtslage des Erdendaseins ist etwas, was sich der Mensch erst während des Erdendaseins erwirbt. Wir wissen ja, daß der physische Leib des Menschen in seiner Form das Ergebnis ist einer großartigen geistigen Betätigung, die der Mensch im Vereine mit Wesen der höheren Welten ausführt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Aber was da der Mensch gestaltet, und was gewissermaßen eben der Geistkeim seines künftigen physischen Erdenorganismus ist, das ist nicht so gestaltet, daß es schon in sich die Fähigkeit des aufrechten Ganges enthält. Die wird dem Menschen erst dadurch eingegliedert, daß er, nachdem er geboren ist, sich in die Gleichgewichtsverhältnisse, in die Kraftverhältnisse des irdischen Daseins hineinfügt. Denn im vorirdischen Dasein bedeutet die Orientierung nicht das, was sie hier auf der Erde im Gehen und Stehen bedeutet, sondern da bedeutet die Orientierung das Verhältnis, das man hat zu den Wesen der Angeloi, Archangeloi, also zu den Wesenheiten der höheren Hierarchien, je nachdem man sich von dem einen Wesen mehr, von dem anderen weniger angezogen fühlt. Das ist die Gleichgewichtslage in den geistigen Welten. Das verliert gewissermaßen der Mensch, indem er auf die Erde heruntersteigt. Er ist im Leibe der Mutter eigentlich weder in den Gleichgewichtsverhältnissen seines Geistlebens, noch schon in den Gleichgewichtsverhältnissen seines Erdenlebens. Er hat die ersteren verlassen und ist in die zweiten noch nicht eingetreten.

Ähnlich ist es mit der Sprache. Die Sprache, die wir hier auf Erden reden, ist ja durchaus den irdischen Verhältnissen angepaßt. Denn diese Sprache ist ein Ausdruck unserer irdischen Gedanken. Diese irdischen Gedanken enthalten irdische Kenntnisse, irdisches Wissen. Dem wird die Sprache während des Erdendaseins angepaßt. In dem vorirdischen Dasein hat der Mensch - wie ich schon ausgeführt habe — eine Sprache, die nicht eigentlich von innen nach außen geht, die nicht vorzugsweise dem Ausatmen folgt, sondern die dem geistigen Einatmen, dem Inspirieren folgt, dem, was wir im vorirdischen Dasein als dem Einatmen entsprechend bezeichnen können. Da ist es ein Leben mit dem Weltenlogos. Da ist es ein Leben in dem Weltenworte, in der Weltensprache, aus der heraus die Dinge gemacht sind.

Dieses Leben in der Weltensprache, das verlieren wir wiederum, indem wir heruntersteigen auf die Erde, und eignen uns hier dasjenige an, was zunächst zum Ausdruck unserer Gedanken dient, der irdischen Gedanken, und zum menschlichen Verstande, das heißt zum Verstande unter Menschen, die alle auf der Erde leben. Und ebenso ist es ja mit den Gedanken, die wir hier haben, mit dem Denken. Das Denken wird angepaßt den irdischen Verhältnissen. Im vorirdischen Dasein ist es ein Leben in den webenden Weltengedanken.

Wenn wir zunächst das mittlere Glied ins Auge fassen, das Sprechen des Menschen, so können wir ja sagen: In dem Sprechen liegt ein Wesentliches der Erdenkultur, der Erdenzivilisation. Durch das Sprechen finden sich die Menschen zusammen hier auf der Erde, findet der eine die Brücke zu dem anderen hinüber. Seele mit Seele verbindet sich. Wir fühlen, daß wir im Sprechen ein Wesentliches hier auf Erden haben, und es ist ja auch der irdische Abglanz des Lebens in dem Logos, in dem Weltenworte. Daher ist auch ein Erfassen des Zusammenhanges dessen, was sich hier auf Erden der Mensch als seine Sprache erkämpft, mit der Metamorphose, die diese Sprache drüben im vorirdischen Dasein hat, ganz besonders interessant. Und man wird, wenn man dieses Verhältnis betrachtet, geführt auf die innere Organisation des Menschen aus dem Lautlichen, aus dem Tonlichen heraus.

Und in diesem Augenblick fügt es sich ja schön, daß unserer kosmologischen Betrachtung, die wir jetzt schon seit Wochen haben, ich heute das Kapitel von der Äußerung des Menschen durch Ton und Wort einfügen darf. Haben wir ja in diesen Tagen eben die große Freude, eine so hervorragende Tonleistung, Gesangesleistung hier in unserem Goetheanum zu vernehmen. Und lassen Sie mich daher heute, ich möchte sagen, wie einen Ausdruck der inneren Befriedigung über dieses für uns so erfreuliche künstlerische Ereignis einiges sprechen gerade über den Zusammenhang der tonlichen und lautlichen Äußerung des Menschen hier auf Erden, mit dem Leben des Menschen in dem, was Ton und Laut drüben im Geistigen entspricht.

Wenn wir die menschliche Organisation, wie sie hier auf Erden vor uns steht, betrachten, so ist sie ja durch und durch ein Abbild des Geistigen. Alles ist hier, nicht nur was der Mensch an sich trägt, sondern auch was ihn in der äußeren Natur umgibt, ein Abbild des Geistigen. Indem der Mensch sich sprachlich äußert, indem der Mensch sich gesanglich äußert, drückt er ja als eine Offenbarung seinen ganzen Organismus nach Leib, Seele und Geist nach außen hin, und auch nach sich selbst zu, nach innen hin, aus. Der Mensch ist gewissermaßen in dem, was er lautlich und tonlich offenbart, ganz darinnen enthalten. Wie sehr er darinnen enthalten ist, das zeigt sich erst, wenn man im genaueren, in den Einzelheiten auffaßt, was der Mensch ist, indem er spricht oder indem er singt.

Gehen wir von der Sprache aus. Im Laufe der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit ist ja eigentlich die Sprache aus einem ursprünglichen Gesanglichen hervorgegangen. Je weiter wir zurückgehen in vorhistorische Zeiten, desto ähnlicher wird das Sprechen dem Rezitativ und zuletzt dem Singen. Und in sehr alten Zeiten der irdischen Menschenentwickelung unterschied sich die lautlich-tonliche Offenbarung des Menschen nicht nach Gesang und Sprache, sondern beides war eines. Und was man von der menschlichen Ursprache oftmals mitteilt, das ist eigentlich so, daß man auch sagen könnte: diese menschliche Ursprache ist ein Urgesang. Wenn wir die Sprache in ihrem heutigen Zustande betrachten, wo sie sich schon sehr stark von dem rein Gesanglichen entfernt hat und untergetaucht ist in das Prosa-Element und in das intellektualistische Element, dann haben wir in der Sprache wesentlich zwei Elemente: das konsonantische und das vokalische Element. Alles, was wir in der Sprache zur Geltung bringen, setzt sich ja zusammen aus einem konsonantischen Elemente und aus einem vokalischen Elemente. Das konsonantische Element beruht eigentlich ganz auf unserer feineren Körperplastik. Wenn wir ein B oder ein P oder ein L oder ein M sprechen, so beruht das darauf, daß irgend etwas in unserem Körper eine bestimmte Form hat. Es ist nicht immer so, daß man, wenn man von diesen Formen spricht, nur von dem Sprach- oder Gesangsapparat zu sprechen hat. Die sind nur die höchste Gipfelung. Denn wenn der Mensch einen Ton oder einen Laut hervorbringt, so ist eigentlich sein ganzer Organismus daran beteiligt, und was da in den Gesangs- oder in den Sprachorganen vor sich geht, das ist nur die letzte Gipfelung dessen, was im ganzen Menschen vor sich geht. So daß unser menschlicher Organismus eigentlich auch so aufgefaßt werden könnte in seiner Form, daß man sagt: Alle Konsonanten, die eine Sprache hat, sind ja eigentlich immer Varianten von zwölf Urkonsonanten. Sie finden zum Beispiel im Finnischen diese zwölf Urkonsonanten wesentlich noch fast rein erhalten: elf sind ganz deutlich, nur der zwölfte ist etwas undeutlich geworden, aber er ist auch noch deutlich vorhanden in... [Lücke im Text]. Diese zwölf Urkonsonanten, wenn man sie richtig erfaßt - man kann jeden zugleich durch eine Form darstellen — sie stellen, wenn man sie zusammenstellt, eigentlich die ganze Plastik des menschlichen Organismus vor. So daß man dann, ganz ohne daß man im Bilde spricht, sagen kann: Der menschliche Organismus ist plastisch ausgedrückt durch die zwölf Urkonsonanten.

Was ist denn dann eigentlich dieser menschliche Organismus? Dieser menschliche Organismus ist eigentlich von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus, von dem Gesichtspunkte des Musischen aus, ein Musikinstrument. Ja, auch die äußeren Musikinstrumente können Sie im Grunde genommen dadurch begreifen, daß Sie sie in ihren Formungen, ob Sie schließlich die Violine oder ein anderes Instrument nehmen, irgendwie konsonantisch durchschauen, sie gewissermaßen als aus den Konsonanten heraus gebaut anschauen. Wenn man vom Konsonantischen spricht, hat man eigentlich im Gefühl immer etwas, was an Musikinstrumente erinnert. Und die Gesamtheit, die Harmonie alles Konsonantischen stellt eigentlich die Plastik des menschlichen Organismus dar.

Und das Vokalische - das ist die Seele, die auf diesem Musikinstrument spielt. Die gibt das Vokalische. So daß Sie eigentlich, wenn Sie in der Sprache das Konsonantische und das Vokalische verfolgen, in jeder sprachlichen und tonlichen Äußerung eine Selbstäußerung des Menschen haben. Die Seele des Menschen spielt vokalisch auf dem Konsonantismus des menschlichen Körperinstrumentes.

Wenn wir unsere, der heutigen Zivilisation und Kultur angehörige Sprache betrachten, dann bedient sich unsere Seele, indem sie vokalisiert, sehr stark des Gehirn-, des Kopf-Nerven-Organismus. Das war in früheren Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung nicht in demselben Maße vorhanden. Lassen Sie mich das, was da geschieht, ein wenig schematisch Ihnen an die Tafel schreiben. Es ist ganz schematisch.

Nehmen wir an, wir hätten in dieser Weise den Kopf-NervenOrganismus gebaut (rot). Die roten Striche würden also die Kräfte, die längs der Nervenstränge des Kopfes gehen, darstellen. Das ist aber nur sehr einseitig die Sache angesehen. In diese Tätigkeit, die da die Nervenstränge entwickeln, geht eine andere Tätigkeit hinein. Die kommt dadurch zustande, daß wir die Luft einatmen. Diese Luft, die wir einatmen — es ist wieder schematisch gezeichnet — die geht durch den Rückenmarkskanal (gelb) direkt hier hinein, und der Stoß der Atmung klingt zusammen mit den Bewegungen, die längs der Nervenstränge ausgeführt werden. So daß in Ihrem Haupte fortwährend der Atemstrom, der durch den Rückenmarkskanal nach dem Kopfe hindrängt, sich begegnet mit dem, was da die Nerven tun. Wir haben nicht eine abgesonderte Nerventätigkeit und eine abgesonderte Atmungstätigkeit, sondern wir haben im Kopfe ein Ineinanderklingen von Atmungstätigkeit und Nerventätigkeit. Der heutige, im gewöhnlichen Leben prosaisch gewordene Mensch, der legt mehr Wert auf die roten Kräfte hier (siehe Zeichnung); er bedient sich mehr seines Nervensystems, wenn er spricht. Er «innerviert» — wie man sagen könnte - er innerviert das Instrument, das die vokalischen Strömungen konsonantisch gestaltet. Das war in früheren Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung nicht der Fall. Da lebte der Mensch nicht so sehr in seinem Nervensystem, da lebte er in dem Atmungssystem; daher war die Ursprache mehr Gesang.

Wenn heute gesungen wird, so nimmt der Mensch das, was er beim Sprechen eigentlich ausführt mit Hilfe der Innervation des Nervensystems, zurück in die Atmungsströmung, und er bringt bewußt diese zweite Strömung, die Atmungsströmung, in Tätigkeit. Es ist die Fortsetzung der Atmung in das Haupt, welche direkt in Tätigkeit gesetzt wird, wenn zu der Erzeugung des Tones auch noch, wie im Singen, das Vokalisieren kommt; aber es ist nicht ein Herausgehen aus dem Atem. Es ist also ein Wiederzurücknehmen der prosaisch gewordenen Sprache in das Poetische, in das Künstlerische des rhythmischen Atmungsprozesses.

Der Dichter bemüht sich noch, den Rhythmus der Atmung zu haben in der Art und Weise, wie er die Sprache seiner Gedichte gestaltet. Derjenige, der für Gesang komponiert, nimmt wieder alles in die Atmung, also auch in die Kopfatmung zurück. So daß wir sagen können: Das was gerade der Mensch hier durchmachen muß auf der Erde, indem er sich mit seiner Sprache anpaßt an die irdischen Verhältnisse, das wird in einer gewissen Weise rückgängig gemacht, wenn wir von der Sprache zum Gesang übergehen. Der Gesang ist in der Tat eine reale Rückerinnerung mit irdischen Mitteln an dasjenige, was im vorirdischen Dasein erlebt worden ist. Denn wir stehen mit unserem rhythmischen System viel näher der geistigen Welt als mit unserem Denksystem. Und das Denksystem beeinflußt ja die prosaisch gewordene Sprache.

Indem wir vokalisieren, drücken wir eigentlich das, was in der Seele lebt, gegen den Körper hin, der nur das Musikinstrument abgibt, indem er das Konsonantische dazu gibt. Sie werden durchaus das Gefühl haben, daß in jedem Vokal etwas unmittelbar seelisch Lebendiges liegt, und daß man das Vokalische für sich gebrauchen kann; das Konsonantische aber sehnt sich fortwährend nach dem Vokalischen hin. Das plastische Körperinstrument ist eigentlich ein Totes, wenn nicht das Vokalische, das Seelische an es anschlägt. Sie sehen das an Einzelheiten; nehmen Sie zum Beispiel in gewissen Dialekten Mitteleuropas das Wort «mir» in «es geht mir gut», also «mir». Wie ich einer kleiner Bub Tat-i : war, konnte ich mir gar nicht vorstellen, daß das Wort so geschrieben wird; ich habe es immer so geschrieben: «mia»; denn in dem r liegt die Sehnsucht nach dem a unmittelbar darinnen. Es ist so, daß wir, wenn wir den menschlichen Organismus als die Harmonie der Konsonanten auffassen, überall in ihm die Sehnsucht nach dem Vokalischen, also nach dem Seelischen haben. Ja, woher kommt denn das?

Dieser menschliche Organismus, wie er sich hier auf Erden einrichten muß in seiner Plastik, muß sich den irdischen Verhältnissen anpassen. Er ist so gestaltet, wie es die irdische Gleichgewichtslage, die irdischen Kräfteverhältnisse allein zulassen. Aber er ist ja aus dem Geistigen heraus gestaltet. Was da eigentlich vorliegt, kann man nur durch geisteswissenschaftliche Forschung erkennen. Ich will es Ihnen schematisch verdeutlichen.

Nehmen wir an, das Seelische sei so ausgedrückt in seiner vokalischen Äußerung (rot): Es stößt an das Konsonantische an (gelb), und das Konsonantische ist nach Erdenverhältnissen plastisch gestaltet. Wenn man nun sich erhebt in die geistige Welt in der Weise, wie ich es dargestellt habe in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», dann kommt man zunächst ja zur Imagination, zur imaginativen Erkenntnis. Aber da hat man nämlich mittlerweile die Konsonanten verloren; die Vokale sind einem zunächst noch geblieben. Man hat ja seinen physischen Leib verloren im Imaginieren. Man hat die Konsonanten verloren. In der imaginativen Welt hat man für die Konsonanten kein Verständnis mehr. Wenn man das, was man da drinnen hat, ganz adäquat mit Worten bezeichnen will, dann besteht das alles aus lauter Vokalen zunächst. Also das Instrument fehlt einem zunächst, und man kommt in eine tonliche Welt hinein, die noch in der mannigfaltigsten Weise vokalisch tingiert ist, aber in der alle Konsonanten der Erde eben auch in Vokalen aufgelöst sind.

Sie werden daher finden, daß in Worten von Sprachen, die noch den Ursprachen nahe gestanden haben, gerade die Dinge der übersinnlichen Welt eigentlich vokalisch benannt werden. Das Jahve-Wort zum Beispiel hat nicht unser J und V gehabt, sondern es bestand eigentlich nur aus Vokalen und wurde scandierend halb gesungen. Man kommt also hinein in ein Vokalisieren, das selbstverständlich gesungen wird.

Und gelangt man aus der imaginativen Erkenntnis in die inspirierte Erkenntnis, nimmt man also direkt die Offenbarungen des Geistigen auf, dann werden alle Konsonanten, die hier auf Erden sind, etwas ganz anderes. Die Konsonanten verliert man. Also das geht einem verloren (mit gelb zugedeckt, siehe Zeichnung unteres Gelb); dafür beginnt in der geistigen Wahrnehmung, die durch Inspiration erkundet werden kann, ein Neues sich zu äußern: die geistigen Gegenbilder der Konsonanten (siehe oberes Gelb).

Aber diese geistigen Gegenbilder der Konsonanten, die leben jetzt nicht zwischen den Vokalen, sondern in den Vokalen. Wenn Sie hier auf Erden die Sprache haben, so haben Sie Konsonanten und Vokale so, daß sie nebeneinander leben. Die Konsonanten verlieren Sie beim Aufsteigen in die geistige Welt. Sie leben sich in eine vokalisierend singende Welt hinein. Sie hören eigentlich auf zu singen; es singt. Die Welt wird selber Weltengesang. Aber das, was vokalisierend ist, das tingiert sich geistig-seelisch so, daß in den Vokalen etwas lebt, was die geistigen Gegenbilder der Konsonanten sind. Hier im Irdischen gibt es ein A als Laut und meinetwillen ein Cis in einer bestimmten Oktave als Ton. Sobald man in die geistige Welt kommt, gibt es nicht ein A, nicht ein Cis in einer bestimmten Skala, sondern innerlich — nicht etwa nur von verschiedener Höhe — sondern innerlich qualitativ unzählige; denn etwas anderes ist es, ob ein Wesen aus der Hierarchie der Angeloi einem ein A ausspricht, oder ein Wesen aus der Hierarchie der Archangeloi, oder ein anderes Wesen. Das ist immer äußerlich dieselbe Offenbarung, aber innerlich ist die Offenbarung beseelt. So daß wir sagen können: Hier auf Erden haben wir unseren Körper (Zeichnung links, weiß); da schlägt der vokalisierende Ton an (rot). Drüben haben wir den vokalisierenden Ton (Zeichnung rechts, rot) und in den schlägt die Seele hinein (weiß) und lebt darinnen, so daß der Ton der Leib des Seelischen wird.

Nun sind Sie darinnen in der Weltenmusik, in dem Weltengesang; nun sind Sie darinnen in dem schöpferischen Ton, in dem schöpferischen Wort. Und wenn Sie sich hier auf Erden den Ton, auch den Ton, der sich als Laut offenbart, vorstellen: irdisch lebt das in der Luft. Aber die physikalische Vorstellung, daß die Luftformung der Ton sei, ist eigentlich nur eine naive Vorstellung. Es ist wirklich naiv. Denn denken Sie sich einmal, Sie hätten hier einen Boden, und da drauf einen Menschen. Der Boden ist doch ganz gewiß nicht der Mensch; aber er muß da sein, daß der Mensch darauf stehen kann, sonst könnte der Mensch nicht da sein. Aber Sie werden nicht vom Boden aus den Menschen begreifen wollen.

So muß die Luft da sein, damit der Ton einen Anhalt hat. So wie der Mensch auf dem Boden steht, so hat der Ton, nur in etwas komplizierterer Form, seinen Boden, seinen Widerstand in der Luft. Die Luft hat für den Ton nicht mehr Bedeutung, als der Boden für den Menschen, der darauf steht. Der Ton drängt sich nach der Luft hin, und sie gibt ihm die Möglichkeit, zu stehen. Aber der Ton ist ein Geistiges. So wie der Mensch etwas anderes ist als der Erdboden, auf dem er steht, so ist der Ton etwas anderes als die Luft, auf der der Ton aufsteht. Natürlich nur in komplizierter Weise steht er auf, in mannigfaltigerer Weise steht er auf.

Dadurch, daß wir auf Erden nur vermittelst der Luft sprechen und singen können, haben wir in der Luftformung des Tonlichen das irdische Abbild eben eines Geistig-Seelischen. Das Geistig-Seelische des Tones gehört eigentlich der übersinnlichen Welt an. Und das, was hier in der Luft lebt, ist im Grunde genommen der Körper des Tones. So daß man sich nicht zu wundern braucht, daß man den Ton auch wiederfindet in der geistigen Welt. Nur ist dort abgestreift dasjenige, was vom Irdischen herkommt: das irdische Konsonantisieren. Das Vokalisieren, der Ton als solcher wird hinüber genommen in seinem geistigen Inhalt, wenn man sich in die geistige Welt erhebt. Nur wird er innerlich durchseelt. Statt daß er äußerlich durch das Konsonantische geformt wird, wird er innerlich durchseelt, der Ton. Das geht aber parallel dem SichEinleben in die geistige Welt überhaupt.

Nun denken Sie sich, der Mensch geht durch die Pforte des Todes; die Konsonanten läßt er bald hinter sich, aber die Vokale und namentlich die Intonierungen der Vokale, die erlebt er in einem erhöhten Maße: nur so, daß er nicht mehr fühlt, das Singen gehe von seinem Kehlkopfe aus, sondern daß das Singen um ihn herum ist, und er in jedem Ton lebt. So ist es schon die allerersten Tage, nachdem der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist. Er lebt eigentlich im musikalischen Elemente, das zu gleicher Zeit ein sprachliches Element ist. In diesem musikalischen Elemente offenbart sich immer mehr und mehr von der geistigen Welt her — eine Beseelung.

Nun ist ja, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe, dieses Hinausgehen des Menschen in die Welt, indem er durch die Pforte des Todes geschritten ist, zu gleicher Zeit ein Übergang von der irdischen Welt in die Sternenwelt.

Wenn wir so etwas darstellen, sprechen wir scheinbar bildlich, aber das Bildliche ist durchaus Wirklichkeit. Stellen Sie sich also die Erde vor, darum herum zunächst die Planeten, dann den Fixsternhimmel, den man sich ja seit Alters her mit vollem Rechte als den Tierkreis vorstellt.

Indem der Mensch auf der Erde steht, sieht er die Planeten und die Fixsterne von der Erde aus in ihrem Abglanz, also sagen wir von vorne, um den Erdenmenschen zu ehren - nicht wahr, das Alte Testament drückt sich ja anders aus. Indem aber der Mensch sich entfernt von der Erde nach dem Tode, gelangt er allmählich dazu, die Planeten sowohl wie die Fixsterne von hinten zu sehen. Nur sieht er dann nicht diese Lichtpunkte oder diese Lichtflächen, die von der Erde aus gesehen werden, sondern er sieht die entsprechenden geistigen Wesenheiten. Überall ist eine Welt von geistigen Wesenheiten. Wo er da zurückschaut auf Saturn, Sonne, Mond, oder auf Widder, Stier und so weiter, er sieht von der anderen Seite her geistige Wesenheiten.

Eigentlich ist dieses Sehen zugleich ein Hören, und ebensogut, wie man sagt: man sieht von der anderen Seite, also von rückwärts, den Mond, die Venus und so weiter, den Widder, den Stier und so weiter, ebensogut könnte man sagen: man hört die Wesen in die Weltenweiten hinaus tönen, die in diesen Weltenkörpern ihre Wohnsitze haben.

Nun stellen Sie sich das ganze Gefüge vor - es ist tatsächlich so, daß es aussieht, wie wenn man bildlich spräche, aber es ist nicht bildlich gesprochen, es ist durchaus eine Wirklichkeit - stellen Sie sich da draußen im Kosmos vor: die Planetenwelt weiter weg, den Tierkreis mit seinen zwölf Konstellationen Ihnen jetzt näher. Von all diesen Weltenkörpern singt es Ihnen sprechend, spricht singend, und Ihr Wahrnehmen ist eigentlich ein Hören des sprechenden Singens, des singenden Sprechens.

Indem Sie nach dem Widder hinschauen, haben Sie den Eindruck eines Seelisch-Konsonantischen. Da ist vielleicht Saturn hinter dem Widder: ein Seelisch-Vokalisches. Und in diesem Seelisch-Vokalischen, das da von dem Saturn her in den Weltenraum hinaus erglänzt, da lebt das Seelisch-Geistig-Konsonantische des Widders oder des Stieres. Sie haben also die Planetensphäre, die Ihnen vokalisch in den Weltenraum hinaus singt, und Sie haben die Fixsterne, die Ihnen - wir können es jetzt sagen — diesen Gesang der Planetensphäre konsonantisch durchseelen.

Stellen Sie sich das lebhaft vor: die mehr ruhende Fixsternsphäre, dahinter die wandelnden Planeten. Indem ein wandelnder Planet an einem Fixsterngebilde vorbeigeht, erklingt, ich kann jetzt nicht sagen, ein Ton, sondern eine ganze Tonwelt; indem er weitergeht vom Widder zum Stier, erklingt eine andere Tonwelt.

Aber dahinter ist ja zum Beispiel, sagen wir, Mars. Mars läßt, durch den Stier gehend, ein anderes ertönen.

Und Sie haben ein wunderbares kosmisches Instrument in dem Fixsternhimmel, und dahinter unsere Planetengötter als die Spieler auf diesem Instrumente des Tierkreis-Fixsternhimmels.

Wir können wirklich sagen: Wenn der Mensch hier unten auf der Erde wieder zurücknimmt die Sprache, die für das Irdische gebildet ist, wie das Gehen aus der kosmisch-geistigen Orientierung heraus für das Irdische gebildet ist, in den Gesang, so ist dies ein Hinneigen zu demjenigen, aus dem der Mensch als aus dem vorirdischen Dasein für das Irdische heraus geboren ist. Wie die Kunst überhaupt eigentlich sich so vor den Menschen hinstellt, als ob der Mensch sagen würde, indem er sich künstlerisch äußert: Nun, es ist ja Menschenschicksal, und es ist richtig, daß es so Menschenschicksal ist: der Mensch ist, indem er sein Erdendasein antritt, in die irdischen Verhältnisse hineingestellt, muß sich den irdischen Verhältnissen anpassen; aber in der Kunst macht er einen Schritt zurück, läßt das Irdische um sich herum ablaufen, und durch den Schritt, den er zurückmacht, nähert er sich dem GeistigSeelischen, aus dem er als aus dem vorirdischen Dasein herausgewachsen ist.

Wir verstehen die Kunst nicht, wenn wir in ihr nicht die Sehnsucht empfinden, das Geistige wenigstens zunächst in der Offenbarung des schönen Scheines zu erleben. Unsere Phantasie, welche der Auspräger des Künstlerischen ist, ist ja im Grunde genommen nichts anderes, als die vorirdische Hellseherkraft. Man möchte sagen: Wie der Ton auf Erden in der Luft lebt, so lebt für das Seelische dasjenige, was eigentlich geistig ist im vorirdischen Dasein, auf irdische Weise im Abbild des Geistigen. Wenn der Mensch spricht, dann bedient er sich seines Körpers: Es wird das Konsonantische in ihm zur Plastik des Körpers; es wird der nicht in die feste Plastik übergehende Atemstrom von der Seele benützt, um auf diesem Körperinstrumente zu spielen. Aber wir können das, was wir so als irdisch sprechende Menschen sind, auf zweifache Weise zu dem Göttlichen hin tendieren.

Nehmen wir den konsonantischen menschlichen Organismus, lösen wir ihn gewissermaßen los von der festen Prägung, die er durch die irdischen Schwerkräfte oder durch die chemischen Kräfte der Nahrungsstoffe erhalten hat, lösen wir los dasjenige, was konsonantisch den Menschen durchsetzt! — So dürfen wir schon sprechen. -— Wenn man eine menschliche Lunge auf den Seziertisch legt, findet man chemische Stoffe, die man chemisch untersuchen kann. Aber das ist nicht die Lunge. Was ist die Lunge? Ein Konsonant, der aus dem Kosmos heraus gesprochen ist und Form angenommen hat. Das Herz, legen wir es auf den Seziertisch: es besteht aus den Zellen, die man chemisch dem Stoffe nach untersuchen kann. Das ist aber nicht das Herz; das ist ein anderer Konsonant, der aus dem Kosmos heraus gesprochen ist. Und wenn man im wesentlichen die zwölf Konsonanten sich vorstellt aus dem Kosmos heraus gesprochen, so ist der menschliche Körper da.

Das heißt: schaut man an die Konsonanten, hat man die nötige hellseherische Phantasie, um die Konsonanten zu sehen in ihrem Zusammenhang, so entsteht der menschliche Körper in voller Plastik. Wenn man also die Konsonanten aus dem Menschen herausnimmt, so entsteht Bildhauerkunst; wenn man den Atem, dessen sich die Seele bedient, um auf diesem Instrumente zu spielen im Gesang, wenn man das herausnimmt aus dem Menschen nach der anderen Seite, was das Vokalische ist, dann entsteht eben das Musikalische, das Gesangliche.

Nehmen Sie also das Konsonantliche aus dem Menschen heraus, so entsteht die Form, die Sie plastisch gestalten müssen. Nehmen Sie das Vokalische aus dem Menschen heraus, entsteht das Gesangliche, das Musikalische, das Sie singen müssen. Und so ist eigentlich der Mensch, wie er vor uns steht auf Erden, das Ergebnis von zwei Weltenkünsten: von einer plastizierenden Weltenkunst, die von der einen Seite kommt, und von einer gesanglichen, musikalischen Weltenkunst, die von der anderen Seite kommt. Zweierlei geistige Wesenheiten fügen ihre Tätigkeit zusammen. Das eine gibt das Instrument, das andere spielt auf dem Instrument; das eine formt das Instrument, das andere spielt auf dem Instrument.

Kein Wunder, daß in älteren Zeiten, als man solche Dinge noch empfunden hat, der größte Künstler Orpheus genannt worden ist, der nun tatsächlich des Seelischen so mächtig war, daß er nicht nur den schon geformten menschlichen Körper als Instrument benutzen konnte, sondern durch seine Töne sogar die ungeformte Materie in Formen gießen konnte, die den Tönen entsprachen.

Sie werden verstehen, daß, wenn man so etwas darstellt, man die Worte etwas anders gebrauchen muß, als sie in der heutigen Nüchtlingszeit gewöhnlich gebraucht werden; aber dennoch ist die Sache nicht bloß bildlich oder symbolisch gemeint, sondern in durchaus realem Sinne. Die Dinge sind schon so, wie ich sie dargestellt habe, trotzdem manchmal eben die Sprache in einen größeren Fluß gebracht werden muß, als sie eben heute gewöhnlich im Gebrauche ist. Ich wollte den heutigen Vortrag namentlich auch deshalb, wie ich schon sagte, so gestalten, um den hier uns so befriedigenden Leistungen unserer verehrten Künstlerinnen, die uns in diesen Tagen erfreuen, auch von dieser Seite her einen kleinen Gruß zu bringen. Und so wollen wir denn morgen, meine lieben Freunde, mit einer Gesinnung an das uns so befriedigende Konzert herantreten, der auch, wie hier alles sein soll, etwas eingegeben ist von anthroposophischer Seelenverfassung.

Human Expression through Sound and Word

In the discussions we have had recently, I have been able to point out how the activities of the human being that occur in early childhood are transformations of activities that the human being performs between death and a new birth, that is, in pre-earthly existence. We see how the child, after birth, is not yet fully adapted to the heaviness of the earth, to the earth's equilibrium, but gradually adapts to this equilibrium as it learns to stand and walk. This adaptation of the body to the equilibrium of earthly existence is something that human beings acquire only during their earthly existence. We know that the physical body of human beings in its form is the result of a magnificent spiritual activity that human beings carry out in union with beings of the higher worlds between death and a new birth. But what human beings create there, and what is, in a sense, the spiritual seed of their future physical earthly organism, is not formed in such a way that it already contains within itself the ability to walk upright. This ability is only incorporated into the human being after birth, when he or she adapts to the balance of forces in earthly existence. For in pre-earthly existence, orientation does not mean what it means here on earth in walking and standing, but rather the relationship one has to the beings of the Angeloi, archangels, that is, to the beings of the higher hierarchies, depending on whether one feels more attracted to one being or less to another. This is the state of equilibrium in the spiritual worlds. Human beings lose this to a certain extent when they descend to earth. In their mother's womb, they are neither in the equilibrium of their spiritual life nor yet in the equilibrium of their earthly life. They have left the former and have not yet entered the latter.It is similar with language. The language we speak here on earth is entirely adapted to earthly conditions. For this language is an expression of our earthly thoughts. These earthly thoughts contain earthly knowledge, earthly wisdom. Language is adapted to this during earthly existence. In pre-earthly existence, as I have already explained, human beings have a language that does not actually go from the inside to the outside, that does not primarily follow exhalation, but rather follows spiritual inhalation, inspiration, what we can describe in pre-earthly existence as corresponding to inhalation. There it is a life with the world logos. There it is a life in the world word, in the world language, from which things are made.

We lose this life in the world language when we descend to earth, and here we acquire that which initially serves to express our thoughts, our earthly thoughts, and our human understanding, that is, the understanding among people who all live on earth. And it is the same with the thoughts we have here, with thinking. Thinking is adapted to earthly conditions. In pre-earthly existence, it is a life in the weaving thoughts of the world.

If we first consider the middle member, human speech, we can say that speech is an essential part of earthly culture, of earthly civilization. Through speech, people come together here on earth, one person finds a bridge to another. Soul connects with soul. We feel that speech is an essential part of life here on earth, and it is also the earthly reflection of life in the Logos, in the world words. Therefore, it is particularly interesting to grasp the connection between what human beings here on earth have fought for as their language and the metamorphosis that this language undergoes in pre-earthly existence. And when we consider this relationship, we are led to the inner organization of the human being from the sound, from the tone.

And at this moment, it is fitting that I may add to our cosmological considerations, which we have been pursuing for weeks now, the chapter on human expression through sound and word. For we have the great joy these days of hearing such outstanding vocal and singing performances here in our Goetheanum. And so today, as an expression of my inner satisfaction with this artistic event that is so enjoyable for us, I would like to say a few words about the connection between the tonal and vocal expression of human beings here on earth and the life of human beings in what corresponds to sound and tone in the spiritual realm.

When we consider the human organization as it stands before us here on earth, it is indeed a reflection of the spiritual realm through and through. Everything here, not only what human beings carry within themselves, but also what surrounds them in the external natural world, is a reflection of the spiritual realm. When human beings express themselves through speech, when they express themselves through song, they reveal their entire organism – body, soul, and spirit – to the outside world and also to themselves, inwardly. In a sense, human beings are wholly contained in what they reveal through sound and tone. The extent to which they are contained within it only becomes apparent when one understands in more detail what human beings are when they speak or sing.

Let us start with language. In the course of the historical development of humanity, language actually emerged from an original form of singing. The further back we go into prehistoric times, the more speech resembles recitative and ultimately singing. And in very ancient times of human development on earth, the vocal and tonal expression of human beings did not differ between singing and speech; rather, the two were one. And what is often said about the original human language is actually such that one could also say: this original human language is an original song. When we consider language in its present state, where it has already moved very far away from the purely vocal and has submerged itself in the prosaic element and the intellectual element, then we have essentially two elements in language: the consonantal and the vocal element. Everything we express in language is composed of a consonantal element and a vocal element. The consonantal element is actually based entirely on our finer physical structure. When we pronounce a B or a P or an L or an M, it is because something in our body has a certain shape. It is not always the case that when we speak of these forms, we are only referring to the speech or singing apparatus. These are only the highest peaks. For when a person produces a tone or a sound, their entire organism is actually involved, and what goes on in the singing or speech organs is only the final culmination of what is going on in the whole person. So that our human organism could actually be understood in its form in such a way that one could say: All the consonants that a language has are actually always variants of twelve original consonants. For example, in Finnish, these twelve original consonants are still preserved in almost pure form: eleven are very clear, only the twelfth has become somewhat indistinct, but it is still clearly present in... [gap in the text]. These twelve primordial consonants, if one understands them correctly – each can be represented by a form – when put together, actually represent the entire plasticity of the human organism. So that one can then say, without speaking figuratively: the human organism is expressed plastically by the twelve primordial consonants.

What then is this human organism? From this point of view, from the point of view of the arts, this human organism is actually a musical instrument. Yes, you can also understand external musical instruments in this way, by seeing them in their forms, whether you take the violin or another instrument, as somehow consonantal, viewing them as built out of consonants, so to speak. When we speak of consonance, we always have a feeling that reminds us of musical instruments. And the totality, the harmony of all that is consonant, actually represents the plasticity of the human organism.

And the vocal aspect is the soul that plays on this musical instrument. That is what the vocal aspect provides. So that when you follow the consonant and vocal aspects in language, you actually have a self-expression of the human being in every linguistic and tonal utterance. The soul of the human being plays vocally on the consonantism of the human body instrument.

When we consider our language, which belongs to today's civilization and culture, our soul, in vocalizing, makes very strong use of the brain, the head-nerve organism. This was not present to the same extent in earlier times of human development. Let me write what is happening there on the board in a somewhat schematic way. It is very schematic.

Let us assume that we have constructed the head-nerve organism in this way (red). The red lines would thus represent the forces that run along the nerve strands of the head. However, this is only a very one-sided view of the matter. Another activity enters into this activity developed by the nerve strands. This comes about through our inhaling air. This air that we inhale — again, schematically drawn — enters directly here through the spinal canal (yellow), and the impulse of breathing resonates together with the movements carried out along the nerve strands. So that in your head, the flow of breath that pushes through the spinal canal towards the head constantly encounters what the nerves are doing there. We do not have a separate nervous activity and a separate respiratory activity, but rather we have an interplay of respiratory activity and nervous activity in the head. Today's human being, who has become prosaic in everyday life, places more value on the red forces here (see drawing); he makes more use of his nervous system when he speaks. He “innervates” — as one might say — he innervates the instrument that shapes the vocal currents into consonants. This was not the case in earlier times of human development. Humans did not live so much in their nervous system, they lived in their respiratory system; therefore, the original language was more like singing.

When singing today, humans take what they actually do when speaking with the help of the innervation of the nervous system back into the respiratory flow, and consciously activate this second flow, the respiratory flow. It is the continuation of breathing into the head that is directly activated when, as in singing, vocalization is added to the production of sound; but it is not a departure from the breath. It is therefore a return of prosaic language to the poetic, to the artistic nature of the rhythmic breathing process.

The poet still strives to have the rhythm of breathing in the way he shapes the language of his poems. Those who compose for singing take everything back into the breath, including the head breath. So we can say that what human beings have to go through here on earth, adapting their language to earthly conditions, is in a certain way reversed when we move from language to singing. Singing is in fact a real recollection, by earthly means, of what has been experienced in pre-earthly existence. For with our rhythmic system we are much closer to the spiritual world than with our thinking system. And the thinking system influences language, which has become prosaic.

When we vocalize, we actually express what lives in the soul towards the body, which only provides the musical instrument by adding the consonants. You will certainly feel that there is something immediately soulful and alive in every vowel, and that one can use the vowels for oneself; but the consonants constantly yearn for the vowels. The plastic body instrument is actually dead unless the vocal, the soul, strikes it. You can see this in details; take, for example, the word “mir” in certain dialects of Central Europe in “es geht mir gut” (I am well), i.e., “mir.” When I was a little boy, I couldn't imagine that the word was written that way; I always wrote it as “mia,” because the r immediately expresses the longing for the a. It is so that when we understand the human organism as the harmony of consonants, we have everywhere in it the longing for the vowel, that is, for the soul. Yes, where does that come from?

This human organism, as it must establish itself here on earth in its plastic form, must adapt to earthly conditions. It is shaped as the earthly balance of power, the earthly balance of forces alone allow. But it is shaped by the spiritual. What is actually present there can only be recognized through spiritual scientific research. I will explain it to you schematically.

Let us assume that the soul is expressed in its vocal utterance (red): it encounters the consonants (yellow), and the consonants are shaped plastically according to earthly conditions. When one now rises into the spiritual world in the way I have described in my book “How to Gain Knowledge of the Higher Worlds,” , then one first arrives at imagination, at imaginative knowledge. But by then one has lost the consonants; the vowels remain for the time being. One has lost one's physical body in imagining. One has lost the consonants. In the imaginative world, one no longer has any understanding of the consonants. If you want to describe what you have in there adequately with words, then at first it all consists of vowels. So at first you lack the instrument, and you enter a tonal world that is still tinged with vowels in the most varied ways, but in which all the consonants of the earth are also dissolved into vowels.

You will therefore find that in words from languages that were still close to the original languages, it is precisely the things of the supersensible world that are actually named vocally. The word Yahweh, for example, did not have our J and V, but actually consisted only of vowels and was chanted half-sung. So one enters into a vocalization that is naturally sung.

And when one moves from imaginative knowledge to inspired knowledge, that is, when one directly receives the revelations of the spiritual, then all the consonants that are here on earth become something completely different. One loses the consonants. So that is lost (covered with yellow, see drawing below yellow); but in spiritual perception, which can be explored through inspiration, something new begins to express itself: the spiritual counterparts of the consonants (see upper yellow).

But these spiritual counterparts of the consonants now live not between the vowels, but within the vowels. When you have language here on earth, you have consonants and vowels living side by side. You lose the consonants when you ascend into the spiritual world. You live your way into a vocalizing, singing world. You actually stop singing; it sings. The world itself becomes the song of the world. But that which is vocalized is tinged spiritually and soulfully in such a way that something lives in the vowels that are the spiritual counterparts of the consonants. Here on earth there is an A as a sound and, for my sake, a C sharp in a certain octave as a tone. As soon as one enters the spiritual world, there is not one A, not one C sharp in a certain scale, but inwardly — not just of different pitches — but inwardly qualitatively innumerable; for it is one thing if a being from the hierarchy of the Angeloi pronounces an A, or a being from the hierarchy of the Archangeloi, or another being. Outwardly, it is always the same revelation, but inwardly, the revelation is animated. So we can say: here on earth we have our body (drawing on the left, white); there the vocalizing tone strikes (red). Over there we have the vocalizing tone (drawing on the right, red), and the soul strikes into it (white) and lives within it, so that the tone becomes the body of the soul.

Now you are inside the music of the world, inside the song of the world; now you are inside the creative sound, inside the creative word. And when you imagine sound here on earth, even sound that manifests itself as a noise: it lives earthily in the air. But the physical idea that the formation of air is sound is actually only a naive idea. It is really naive. For imagine that you have a floor here, and a human being standing on it. The floor is certainly not the human being; but it must be there so that the human being can stand on it, otherwise the human being could not be there. But you will not want to understand the human being from the floor.

So the air must be there for the sound to have a foothold. Just as the human being stands on the ground, so the sound, only in a somewhat more complicated form, has its ground, its resistance in the air. The air has no more significance for sound than the ground has for the human being standing on it. Sound pushes itself toward the air, and the air gives it the opportunity to stand. But sound is a spiritual thing. Just as the human being is something other than the ground on which he stands, so sound is something other than the air on which it stands. Of course, it stands in a complicated way, in a more manifold way.

Because we can only speak and sing on earth by means of the air, we have in the air formation of the sound the earthly image of something spiritual and soulful. The spiritual and soulful nature of sound actually belongs to the supersensible world. And what lives here in the air is, in essence, the body of sound. So it is not surprising that sound is also found in the spiritual world. Only there, what comes from the earthly is stripped away: earthly consonantization. Vocalization, the sound as such, is carried over in its spiritual content when one rises into the spiritual world. Only it is imbued with inner soul. Instead of being formed externally by consonants, the sound is imbued with inner soul. But this goes hand in hand with settling into the spiritual world in general.

Now imagine that a person passes through the gate of death; they soon leave the consonants behind, but they experience the vowels, and especially the intonations of the vowels, to a heightened degree: only in such a way that they no longer feel that the singing comes from their larynx, but that the singing is around them, and they live in every tone. This is how it is in the very first days after a person has passed through the gate of death. They actually live in the musical element, which is at the same time a linguistic element. In this musical element, more and more of the spiritual world is revealed — an animation.

Now, as I have told you, this going out of the human being into the world, by passing through the gate of death, is at the same time a transition from the earthly world to the starry world.

When we describe something like this, we seem to be speaking figuratively, but the figurative is absolutely real. So imagine the Earth, surrounded first by the planets, then by the fixed stars, which since ancient times have rightly been imagined as the zodiac.

Standing on Earth, human beings see the planets and fixed stars from Earth in their reflection, so to speak from the front, to honor Earth humans — although the Old Testament expresses it differently. But as human beings move away from Earth after death, they gradually come to see both the planets and the fixed stars from behind. Only then he does not see these points of light or these areas of light that are seen from Earth, but he sees the corresponding spiritual beings. Everywhere there is a world of spiritual beings. When he looks back at Saturn, the Sun, the Moon, or Aries, Taurus, and so on, he sees spiritual beings from the other side.

Actually, this seeing is also hearing, and just as one says: one sees from the other side, that is, from behind, the moon, Venus, and so on, Aries, Taurus, and so on, one could just as well say: one hears the beings resounding out into the world, who have their abodes in these world bodies.

Now imagine the whole structure—it actually looks as if one were speaking figuratively, but it is not figurative, it is quite real—imagine out there in the cosmos: the planetary world further away, the zodiac with its twelve constellations now closer to you. All these world bodies sing to you, speaking and singing, and your perception is actually a hearing of the speaking singing, the singing speaking.

When you look at Aries, you have the impression of something soul-consonantal. Perhaps Saturn is behind Aries: something soul-vocal. And in this soul-vocal, which shines out into the world from Saturn, lives the soul-spiritual-consonantal of Aries or Taurus. So you have the planetary sphere singing vocally out into space, and you have the fixed stars which — we can now say — imbue this song of the planetary sphere with consonance.

Imagine this vividly: the more tranquil sphere of fixed stars, behind it the moving planets. As a moving planet passes a fixed star formation, it sounds, I cannot say a tone, but a whole world of tones; as it moves on from Aries to Taurus, another world of tones sounds.

But behind it is, for example, let's say, Mars. Mars, passing through Taurus, makes another sound resound.

And you have a wonderful cosmic instrument in the fixed starry sky, and behind it our planetary gods as the players on this instrument of the zodiacal fixed starry sky.

We can truly say: when human beings here on earth take back the language that is formed for the earthly, just as walking is formed for the earthly out of the cosmic-spiritual orientation, into song, this is a bowing down to that from which human beings are born for the earthly out of their pre-earthly existence. Just as art actually presents itself to human beings as if human beings were saying, when expressing themselves artistically: Well, it is human destiny, and it is right that it should be so: when human beings begin their earthly existence, they are placed in earthly circumstances and must adapt to them; but in art they take a step back, let the earthly things around them pass, and through the step they take back, they approach the spiritual-soul realm from which they grew out of their pre-earthly existence.

We do not understand art if we do not feel in it the longing to experience the spiritual, at least initially, in the revelation of beautiful appearance. Our imagination, which is the source of artistic expression, is basically nothing other than the pre-earthly power of clairvoyance. One might say: just as sound lives in the air on earth, so what is actually spiritual in pre-earthly existence lives for the soul in an earthly way in the image of the spiritual. When a person speaks, they make use of their body: the consonants within them become the plasticity of the body; the breath stream, which does not merge into the solid plasticity, is used by the soul to play on this bodily instrument. But we, as earthly speaking human beings, can tend toward the divine in two ways.

Let us take the consonantal human organism, let us detach it, as it were, from the fixed imprint it has received through the earthly forces of gravity or through the chemical forces of food substances, let us detach that which permeates the human being consonantally! — Then we may already speak. — When you place a human lung on the dissecting table, you find chemical substances that can be chemically analyzed. But that is not the lung. What is the lung? A consonant that has been spoken out of the cosmos and has taken shape. Let us place the heart on the dissecting table: it consists of cells that can be chemically analyzed. But that is not the heart; it is another consonant spoken from the cosmos. And when we essentially imagine the twelve consonants spoken from the cosmos, the human body is there.

This means that if you look at the consonants and have the necessary clairvoyant imagination to see the consonants in their context, the human body emerges in full plasticity. So when you take the consonants out of the human being, sculpture emerges; when you take the breath that the soul uses to play this instrument in song, when you take that out of the human being to the other side, which is the vowels, then music, singing, emerges.

So if you take the consonants out of the human being, the form that you have to shape plastically emerges. If you take the vowels out of the human being, the singing, the music that you have to sing emerges. And so, the human being as he stands before us on earth is actually the result of two world arts: a plastic world art that comes from one side, and a vocal, musical world art that comes from the other. Two spiritual beings combine their activities. One provides the instrument, the other plays the instrument; one shapes the instrument, the other plays the instrument.

No wonder that in older times, when such things were still felt, the greatest artist was called Orpheus, who was indeed so powerful in the soul that he could not only use the already formed human body as an instrument, but could even mold unformed matter into forms that corresponded to the tones through his sounds.