The Inner Nature of Music and the Experience of Tone

GA 283

8 March 1923, Stuttgart

The Experience of Tone II

Though they are quite fragmentary and incomplete and must be elaborated further at the next opportunity, I wish to emphasize again that yesterday's lecture and today's are intended to give teachers in school what they need as background for their instruction.

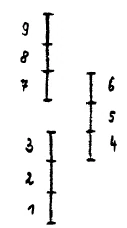

Yesterday, I spoke on the one hand of the role that the interval of the fifth plays in musical experience and on the other hand of the roles played by the third and the seventh. You have been able to gather from this description that music progressing in fifths is still connected with a musical experience in which the human being is actually brought out of himself; with the feeling for the fifth, man actually feels transported. This becomes more obvious if we take the scales through the range of seven octaves—from the contra-tones up to the tones above c—and consider that it is possible for the fifth to occur twelve times within these seven scales. In the sequence of the seven musical scales, we discover hidden, as it were, an additional twelve-part scale with the interval of the fifth.

What does this really mean in relation to the whole musical experience? It means that within the experience of the fifth, man with his “I” is in motion outside his physical organization. He paces the seven scales in twelve steps, as it were. He is therefore in motion outside his physical organization through the experience of the fifth.

Returning to the experience of the third—in both the major and minor third—we arrive at an inner motion of the human being. The “I” is, so to speak, within the confines of the human organism; man experiences the interval of the third inwardly. In the transition from a third to a fifth—though there is much in between with which we are not concerned here—man in fact experiences the transition from inner to outer experience. One therefore can say that in the case of the experience of the third the mood is one of consolidation of the inner being, of man's becoming aware of the human being within himself. The experience of the fifth brings awareness of man within the divine world order. The experience of the fifth is, as it were, an expansion into the vast universe, while the experience of the third is a return of the human being into the structure of his own organization. In between lies the experience of the fourth.

The experience of the fourth is perhaps one of the most interesting for one who wishes to penetrate the secrets of the musical element. This is not because the experience of the fourth in itself is the most interesting but because it arises at the dividing line between the experience of the fifth of the outer world and the experience of the third in man's inner being. The experience of the fourth lies right at the border, as it were, of the human organism. The human being, however, senses not the outer world but the spiritual world in the fourth. He beholds himself from outside, as it were (to borrow an expression referring to vision for an experience that has to do with hearing). Though man is not conscious of it, the sensation he experiences with the fourth is based on feeling that man himself is among the gods. While he has forgotten his own self in the experience of the fifth in order to be among the gods, in the experience of the fourth he need not forget his own being in order to be among the gods. With the experience of the fourth, man moves about, as it were, in the divine world; he stands precisely at the border of his humanness, retaining it, yet viewing it from the other side.

The experience of the fifth as spiritual experience was the first to be lost to humanity. Modern man does not have the experience of the fifth that still existed, let us say, four to five hundred years before our era. At that time the human being truly felt in the experience of the fifth, “I stand within the spiritual world.” He required no instrument in order to produce outwardly the interval of a fifth. Because he still possessed imaginative consciousness, he felt that the fifth, which he himself had produced, took its course in the divine realm. Man still had imaginations, still had imaginations in the musical element. There was still an objectivity, a musical objectivity, in the experience of the fifth. Man lost this earlier than the objective experience of the fourth. The experience of the fourth, much later on, was such that during this experience man believed that he lived and wove in something etheric. With the experience of the fourth he felt—if I may say so—the holy wind that had placed him into the physical world. Based on what they said, it is possible that Ambrose and Augustine still felt this. Then this experience of the fourth was also lost. One required an outer instrument in order to be objectively certain of the fourth.

We thus have pointed out at the same time what the musical experience was like in very ancient ages of human evolution. Man did not yet know the third; he descended only to the fourth. He did not distinguish between, “I sing,” and “there is singing.” These two were one for him. He was outside himself when he sang, and at the same time he had an outer instrument. He had an impression, an imagination, as it were, of a wind instrument, or of a string instrument. Musical instruments appeared to man at first as imaginations. Musical instruments were not invented through experimentation; with the experimentation of the piano they have been derived from the spiritual world.

With this, we have described the origin of song as well. It is hard today to give an idea of what song itself was like in the age when the experience of the fifth was still pure. Song was indeed something akin to an expression of the word. One sang, but this was at the same time a speaking of the spiritual world. One was conscious that if one spoke of cherries and grapes one used earthly words; if one spoke of the gods, one had to sing.

Then came the time when man no longer had imaginations. He still retained the remnants of imaginations, however, though one does not recognize them as such today—they are the words of language. The spiritual element incarnated into the tones of song, which in turn incarnated into the elements of words. This was a step into the physical world. The inner emancipation of the song element into arias and the like took place after that; this was a later development.

If we return to the primeval song of humanity, we find that it was a speaking of the gods and of the proceedings of the gods. As I mentioned earlier, the fact of the twelve fifths in the seven scales is evidence that the possibility of motion outside the human realm existed in music in the interval of the fifth. Only with the fourth does man really approach himself with the musical element.

Yesterday, someone said quite rightly that man senses an emptiness in the interval of the fifth. Naturally, he must experience something empty in the fifth, since he no longer has imaginations, and the fifth corresponds to an imagination while the third corresponds to a perception within man's being. Today, therefore, man feels an emptiness in the fifth and must fill it with the substantiality of the instrument. This is the transition of the musical element from the more spiritual age to the later materialistic age.

For earlier ages, the relationship of musical man to his instrument must be pictured as the greatest possible unity. A Greek actor even felt the need of amplifying his voice with an instrument. The process of drawing the musical experience inward came later. Formerly, man felt that in relation to music he carried a certain circle of tones within himself that reached downward, excluding the realm of tones below the contra-c. Upward, it did not reach the tones beyond c but was a closed circle. Man then had the consciousness, “I have been given a narrow circle of the musical element. Out there in the cosmos the musical element continues in both directions. I need the instruments in order to reach this cosmic musical element.”

Now we must take the other aspects of music into consideration if we wish to become acquainted with this whole matter. The center of music today is harmony. I am referring to the sum total of music, not song or instrumental music. The element of harmony takes hold directly of human feeling. What is expressed in harmonies is experienced by human feeling. Now, feeling passes into thinking [Vorstellen].1In the following passages, Vorstellen, the forming of mental images, or the lower aspect of thinking, has been translated thinking, in its relationship to feeling and willing. In looking at the human being, we can say that we have feeling in the middle; on the one hand we have the feeling that passes into thinking, on the other hand we have the feeling that passes into willing. Harmony directly addresses itself to feeling and is experienced in it. The whole emotional nature of man, however, is actually twofold. We have a feeling that is more inclined to thinking—when we feel our thoughts, for instance—and we have a feeling more inclined to willing. When we engage in an action, we feel whether it pleases or displeases us; in the same way, we feel pleasure or displeasure with an idea. Feeling is actually divided into these two realms.

The peculiar thing about the musical element is that neither must it penetrate completely into thinking—because it would cease to be something musical the moment it was taken hold of by the brain's conceptual faculty—nor should it sink down completely into the sphere of willing. We cannot imagine, for example, that the musical element itself could become a direct will impulse without being an abstract sign. When you hear the ringing of the dinner bell, you will go because it announced that it is time to go for dinner, but you will not take the bell's musical element as the impulse for the will. This illustrates that music should not reach into the realm of willing any more than into that of thinking. In both directions it must be contained. The musical experiences must take place within the realm situated between thinking and willing. It must unfold in that part of the human being that does not belong at all to ordinary day-consciousness but that has something to do with that which comes down from spiritual worlds, incarnates, and then passes again through death. It is present in the subconscious, however. For this reason, music has no direct equivalent in outer nature. In adapting himself to the earth, man finds his way into what can be grasped conceptually and what he wills to do. Music, however, does not extend this far into thinking and willing; yet, the element of harmony has a tendency to stream, as it were, toward thinking. It must not penetrate thinking, but it streams toward it. This streaming into the region of our spirit, where we otherwise think [vorstellen], is brought about by the harmony out of the melody.

The element of melody guides the musical element from the realm of feeling up to that of thinking. You do not find what is contained in thinking in the thematic melody, but the theme does contain the element that reaches up into the same realm where mental images are otherwise formed. Melody contains something akin to mental images, but it is not a mental image; it clearly takes its course in the life of feeling. It tends upward, however, so that the feeling is experienced in the human head. The significance of the element of melody in human nature is that it makes the head of the human being accessible to feelings. Otherwise, the head is only open to the concept. Through melody the head becomes open to feeling, to actual feeling. It is as if you brought the heart into the head through melody. In the melody you become free, as you normally are in thinking; feeling becomes serene and purified. All outer aspects are eliminated from it, but at the same time it remains feeling through and through.

Just as harmony can tend upward toward thinking, so it can tend downward toward willing. It must not penetrate the realm of willing, however; it must restrain itself, as it were, and this is accomplished through the rhythm. Melody thus carries harmony upward; rhythm carries harmony in the direction of willing. This is restricted willing, a measured will that runs its course in time; it does not proceed outward but remains bound to man himself. It is genuine feeling that extends into the realm of willing.

Now it becomes understandable that when a child first enters school, it comprehends melodies more readily than harmonies. Of course, one must not take this pedantically; pedantry must never play a role in the artistic. It goes without saying that one can introduce the child to all sorts of things. Just as the child should comprehend only fifths during the first year of school—at most also fourths, but not thirds; it begins to grasp thirds inwardly only from age nine onward—one can also say that the child easily understands the element of melody, but it begins to understand the element of harmony only when it reaches the age of nine or ten. Naturally, the child already understands the tone, but the actual element of harmony can be cultivated in the child only after the above age has been reached. The rhythmic element, on the other hand, assumes the greatest variety of forms. The child will comprehend a certain inner rhythm while it is still very young. Aside from this instinctively experienced rhythm, however, the child should not be troubled until after it is nine years old with the rhythm that is experienced, for example, in the elements of instrumental music. Only then should the child's attention be called to these things. In the sphere of music, too, the age levels can indicate what needs to be done. These age levels are approximately the same as those found elsewhere in Waldorf education.

Taking a closer look at rhythm, we see that since the rhythmic element is related to the nature of will—man must inwardly activate his will when he wishes to experience music—it is the rhythmic element that kindles music in the first place. Regardless of man's relationship to rhythm, all rhythm is based on the mysterious connection between pulse and breath, the ratio of eighteen breaths per minute to an average of seventy-two pulse beats per minute. This ratio of 1:4 naturally can be modified in any number of ways; it can also be individualized. Each person has his own experience regarding rhythm; since these experiences are approximately the same, however, people understand each other in reference to rhythm. All rhythmic experience bases itself on the mysterious relationship between breathing and the heartbeat, the circulation of the blood. One thus can say that while the melody is carried from the heart to the head on the stream of breath—and therefore in an outer slackening and inner creation of quality—the rhythm is carried on the waves of the blood circulation from the heart to the limbs, and in the limbs it is arrested as willing. From this you can see how the musical element really pervades the whole human being.

Picture the whole human being who experiences the musical element as a human spirit: the ability to experience the element of melody gives you the head of this spirit. The ability to experience the element of harmony gives you the chest, the central organ of the spirit; and the ability to experience rhythm gives you the limbs of the spirit. What have I described for you here? I have described the human etheric body. If only you depict the whole musical experience, and if you do this correctly, you actually have before you the human etheric body. It is just that instead of “head” was say, “melody”; instead of “rhythmic man”—because it is lifted upward—we say, “harmony”; and instead of “limb man”—we cannot say here, “metabolic man”—we say, “rhythm.” We have the entire human being etherically before us. The musical experience is nothing else than this. The human being really experiences himself as etheric body in the experience of the fourth, but a kind of summation forms within him. The experience of the fourth contains a touch of melody, a touch of harmony, a touch of rhythm, but all interwoven in such a way that they are no longer distinguishable. The entire human being is experienced spiritually at the threshold in the experience of the fourth: one experiences the etheric human being.

If today's music were not a part of the materialistic age, if all that man experiences today did not contaminate the musical element, then, based on what man possesses today in the musical element—which in itself has attained world-historical heights—he could not but be an anthroposophist. If you wish to experience the musical element consciously, you cannot but experience it anthroposophically.

If you take these things as they are, you can ponder, for example, over the following point: everywhere in ancient traditions concerning spiritual life, mention is made of man's sevenfold nature. The theosophical movement also adopted this view of the sevenfold nature of the human being. When I wrote my Theosophy, I had to speak of a ninefold nature, further dividing the three individual members. I arrived at a sevenfold from a ninefold organization.

Since three and four overlap, as do six and seven, I too, arrived at the sevenfold human being in Theosophy. This book, however, never could have been written in the age dominated by the experience of the fifth. The reason is that in that age all spiritual experience resulted from the awareness that the number of planets was contained in the seven scales, and the number of signs in the Zodiac was contained in the twelve fifths within the seven scales. The great mystery of man was revealed in the circle of fifths, and in that period you could not write about theosophy in any way but by arriving at the sevenfold human being. My Theosophy was written in an age during which predominantly the third is experienced by human beings, in other words, in the age of introversion. One must seek the spiritual in a similar way, descending from the interval of the fifth by division to the interval of the third. I therefore also had to divide the individual members of man. You can say that those other books that speak of the sevenfold human being stem from the tradition of the age of fifths, from the tradition of the circle of fifths. My Theosophy is from the age in which the third plays the dominant musical role and in which, because of this, the complication arises that the more inward element tends toward the minor side, the more outward element toward the major side. This causes the indistinct overlapping between the sentient body and sentient soul. The sentient soul relates to the minor third, the sentient body to the major third. The facts of human evolution are expressed in musical development more clearly than anywhere else. As I already told you yesterday, however, one must forego concepts; abstract conceptualizing will get you nowhere here.

When it comes to acoustics, or tone physiology, there is nothing to be gained. Acoustics has no significance, except for physics. A tone physiology that would have significance for music itself does not exist. If one wishes to comprehend the musical element, one must enter into the spiritual.

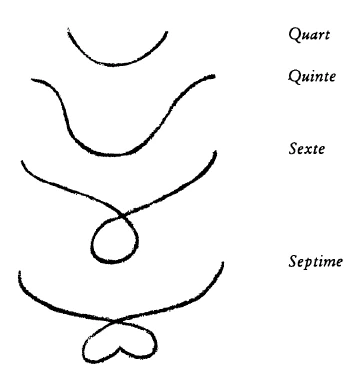

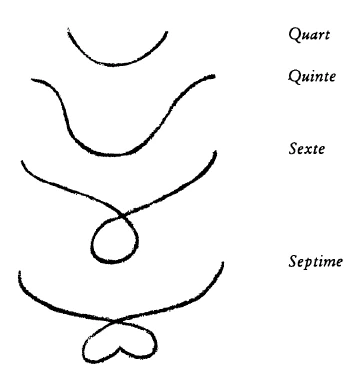

You see how the interval of the fourth is situated between the fifth and the third. Man feels transported in the fifth. In the third he feels himself within himself; in the fourth he is on the border between himself and the world. Yesterday I told you that the seventh was the dominant interval for the Atlanteans. They had only intervals of the seventh, though they did not have the same feeling as we have today. When they made music they were transported completely beyond themselves; they were within the great, all-pervading spirituality of the universe in an absolute motion. They were being moved. This motion was still contained in the experience of the fifth as well. Again, the sixth is in between. From this we realize that man experiences these three steps, the seventh, the sixth, and the fifth, in a transported condition; he enters into his own being in the fourth; he dwells within himself in the third. Only in the future will man experience the octave's full musical significance. A bold experience of the second has not yet been attained by him today; these are matters that lie in the future. When man's inner life intensifies, he will experience the second, and finally he will be sensitive to the single tone.

If you focus on what is said here, you will grasp better the forms that appear in our tone eurythmy. You will also grasp something else. You will, for example, grasp the reason that out of instinct the feeling will arise to interpret the lower segments of the octave—the prime, second and third—by backward movements and in the case of the upper tones—the fifth, sixth, and seventh—by forward movements.

These are more or less the forms that can be used as stereotypical forms, as typical forms. In the case of the forms that have been developed for individual musical compositions, you will be able to sense that these forms express the experience of the fourth or the fifth.

In eurythmy it is necessary that this part here—the descent of harmony through rhythm into willing—finds emphatic expression in form. The individual intervals thus are contained in the forms as such, executed by the eurthymist. Then, however, that which passes from the intervals into rhythm must be experienced fully by the performer in these forms; and quite by itself the instinct will arise to make as small a movement as possible without standing still in the case of the fourth. You see, the fourth is in fact a real perceiving, but a perceiving from the other side. It would be as if the eye, in perceiving itself, would have to look back upon itself; this, then, is the experience of the fourth gained from the soul.

The interval of the fifth is a real experience of imagination. He who can experience fifths correctly is actually in a position to know on the subjective level what imagination is like. One who experiences sixths knows what inspiration is. Finally, one who fully experiences sevenths—if he survives this experience—knows what intuition is. What I mean is that in the experience of the seventh the form of the soul's composition is the same as clairvoyantly with intuition. The form of the soul's composition during the experience of the sixth is that of inspiration with clairvoyance. The experience of the fifth is a real imaginative experience. The same composition of soul need only be filled with vision. Such a composition of soul is definitely present in the case of music.

This is why you hear everywhere that in the older mystery schools and remaining mystery traditions clairvoyant cognition is also called musical cognition, a spiritual-musical cognition. Though people today no longer know why, the mysteries refer to the existence of two kinds of cognition, ordinary bodily, intellectual cognition and spiritual cognition, which is in fact a musical cognition, a cognition living in the musical element. It would not actually be so difficult to popularize the understanding of the threefold human being if only people today were conscious of their musical experiences. Certainly to some extent people do have sensitivity for the experience of the musical element. They actually stand alongside it. The experience of the musical element is as yet quite limited. If it were really to become alive in man, he would feel: my etheric head is in the element of melody, and the physical has fallen away. Here, I have one aspect of the human organization. The element of harmony contains the center of my etheric system; again, the physical has fallen away. Then we reach the next octave; again in the limb system—it is obvious and goes without saying—I find the element that appears as the rhythmic element of music.

How, indeed, does the musical evolution of man proceed? It begins with the experience of the spiritual, the actual presence of the spiritual in tone, in the musical tone structure. The spiritual fades away; man retains the tone structure. Later, he links it with the word, which is a remnant of the spiritual; and what he had earlier as imaginations, namely the instruments, he fashions here in the physical, out of physical substance, as his musical instruments. To the extent that they arouse the musical instruments, man simply filled the empty spaces that remained after he no longer beheld the spiritual. Into those spaces he put the physical instruments.

It is correct to say that in music more than anywhere else one can see how the transition to the materialistic age proceeds. In the place where musical instruments resound today, spiritual entities stood formerly. They are gone, they have disappeared from the ancient clairvoyance. If man wishes to take objective hold of the musical element, however, he needs something that does not exist in outer nature. Outer nature offers him no equivalent to the musical element; therefore, he requires musical instruments.

The musical instruments basically are a clear reflection of the fact that music is experienced by the whole human being. The wind instruments prove that the head of man experiences music. The string instruments are living proof that music is experience in the chest, primarily expressed in the arms. All percussion instruments—or those in between string and percussion instruments—are evidence of how the musical element is expressed in the third part of man's nature, the limb system. Also, however, everything connected with the wind instruments has a more intimate relation to the melody than that which is connected with string instruments which have a relation to the element of harmony. That which is connected with percussion possesses more inner rhythm and relates to the rhythmic element. An orchestra is an image of man; it must not include a piano, however. Why is that? The musical instruments are derived from the spiritual world; the piano, however, in which the tones are abstractly lined up next to each other, is created only in the physical world by man. All instruments like the flute or violin originate musically from the higher world. A piano is like the Philistine who no longer contains within him the higher human being. The piano is the Philistine instrument. It is fortunate that there is such an instrument, or else the Philistine would have no music at all. The piano arises out of a materialistic experience of music. It is therefore the instrument that can be used most conveniently to evoke the musical element within the material realm. Pure matter was put to use so that the piano could become an expression of the musical element. Naturally, the piano is a beneficial instrument—otherwise, we would have to rely from the beginning on the spiritual in musical instruction in our materialistic age—but it is the one instrument that actually, in a musical sense, must be overcome. Man must get away from the impressions of the piano if he wishes to experience the actual musical element.

It is therefore always a great experience when a composition by an artist who basically lives completely in the element of music, such as Bruckner, is played on the piano. In Bruckner's compositions, the piano seems to disappear in the room! One forgets the piano and thinks that one is hearing other instruments; this is indeed so in Bruckner's case. It proves that something of the essentially spiritual, which lies at the basis of all music, still lived in Bruckner, though in a very instinctive way.

These are the things that I wished to tell you today, though in a fragmentary, informal way. I believe we will soon have an opportunity to continue with these matters. Then, I shall go into more detail concerning this or that aspect.

Das Tonerlebnis im Menschen II

Noch einmal möchte ich betonen, daß die Absicht bei diesen zwei Vorträgen die ist, gerade den Lehrern der Schule dasjenige zu geben allerdings ganz fragmentarisch und unvollständig, es muß bei der nächsten Gelegenheit weiter ausgeführt werden -, was sie, ich möchte sagen, hinter dem Unterrichte brauchen.

Ich habe gestern davon gesprochen, welche Rolle auf der einen Seite im musikalischen Erleben die Quinte und auf der anderen Seite, welche Rolle die Terz, die Septime spielt. Nun haben Sie ja wohl aus dieser Darstellung entnehmen können, daß der Fortschritt in Quinten noch zusammenhängt mit demjenigen musikalischen Erleben, das eigentlich den Menschen beim Empfinden der Quinte aus sich herausbringt, daß also eigentlich der Mensch mit der Quintenempfindung eine Entrückung erlebt. Dies wird anschaulicher, wenn wir die sieben Skalen nehmen, von den Kontratönen bis hinauf zu den viergestrichenen Tönen, wenn wir also sieben Skalen nehmen und bedenken, daß innerhalb dieser sieben Skalen die Quinte zwölf mal möglich ist. So daß wir also gewissermaßen in der Aufeinanderfolge der sieben musikalischen Skalen verborgen haben noch einmal eine zwölfgliedrige Skala mit dem Quintenintervall.

Was bedeutet das eigentlich im Zusammenhange des ganzen musikalischen Erlebens? Das bedeutet, daß innerhalb des Quintenerlebnisses der Mensch mit seinem Ich außerhalb seiner physischen Organisation in Bewegung ist. Er schreitet gewissermaßen die sieben Skalen in zwölf Schritten ab. Er ist also durch das Quintenerlebnis außerhalb seiner physischen Organisation in Bewegung.

Gehen wir nun zurück zu dem Terzenerlebnis — sowohl bei der großen wie bei der kleinen Terz ist das so —, so kommen wir zu einer inneren Bewegung des Menschen. Das Ich ist gewissermaßen innerhalb der Grenze des menschlichen Organismus, die Terzen erlebt der Mensch innerlich. Beim Übergange von einer Terz zu einer Quinte auch wenn manches dazwischen ist, darauf kommt es nicht an - erlebt er also eigentlich den Übergang von Innenerlebnis zu Außenerlebnis. So daß man sagen kann: Die Stimmung ist in dem einen Fall beim Terzenerlebnis die Befestigung des Inneren, das Gewahrwerden des Menschen innerhalb seiner selbst, beim Quintenerlebnis das Gewahrwerden des Menschen in der göttlichen Weltenordnung. — Es ist also gewissermaßen ein Hinausschreiten in das weite Weltenall beim Quintenerlebnis, und es ist ein Zurückkehren des Menschen in das eigene Haus der Organisation beim Terzenerlebnis. Dazwischen liegt das Erlebnis der Quart.

Dieses Erlebnis der Quart ist für denjenigen, der hinter die Geheimnisse des Musikalischen kommen will, vielleicht eines der allerinteressantesten; nicht aus dem Grunde, weil gerade das Quartenerlebnis als solches das interessanteste wäre, sondern weil dieses Quartenerlebnis in der Tat an der Scheidegrenze steht zwischen dem Quintenerlebnis der Außenwelt und dem Terzenerlebnis im Inneren des Menschen. Das Quartenerlebnis liegt gewissermaßen genau an der Grenze des menschlichen Organismus. Aber der Mensch empfindet nicht die physische Außenwelt, sondern die geistige Welt in der Quarte, er schaut gewissermaßen von außen sich selber an, wenn ich mich eines Gesichtsausdruckes bedienen darf für ein Gehörerlebnis. In der Quart ist es so, daß der Mensch - er bringt sich das nicht zum Bewußtsein, aber die Empfindung, die er beim Quartenerlebnis hat, beruht darauf —, im Quartenerlebnis ist es so, daß der Mensch sich selber unter Göttern fühlt. Während er beim Quintenerlebnis seiner selbst zu vergessen hat, um unter Göttern zu sein, braucht er beim Quartenerlebnis nicht sich zu vergessen, um sich unter Göttern zu fühlen. Er geht gewissermaßen in der göttlichen Welt als Mensch herum beim Quartenerleben. Er steht genau an der Grenze seiner Menschlichkeit, hat sie noch, schaut sie gewissermaßen von der anderen Seite an.

Das Quintenerlebnis als geistiges Erlebnis ist zuerst der Menschheit verlorengegangen. Der heutige Mensch hat ja nicht dieses Quintenerlebnis, das einstmals, ich will sagen, vier, fünf Jahrhunderte vor unserer Zeitrechnung noch da war. Da hatte der Mensch beim Quintenerlebnis in der Tat die Empfindung: Ich stehe in der geistigen Welt darinnen. — Da brauchte er kein Instrument, um draußen eine Quinte zu machen, sondern da empfand er die von ihm selbst hervorgebrachte Quinte als in der göttlichen Welt verlaufend, weil für ihn die Imagination noch da war. Er hatte noch die Imagination, hatte auch die Imagination beim Musikalischen. Es war also noch ein Objekt da, ein musikalisches, beim Quintenerlebnis. Das hat der Mensch früher verloren als das Objekterlebnis bei der Quart. Die Quart war noch viel später so, daß der Mensch glaubte, wenn er das Quartenerlebnis hatte, er lebe und webe in etwas Ätherischem. Er fühlte gewissermaßen, wenn ich so sagen darf, beim Quartenerlebnis den heiligen Wind, der ihn selbst in die physische Welt hineinversetzt hat. So fühlten vielleicht auch noch — wenigstens ist das nach ihren Äußerungen durchaus möglich — Ambrosius und Augustinus. Dann ging dieses Quartenerlebnis auch verloren, und man brauchte, um objektiv der Quart sicher zu sein, das äußere Instrument.

Damit deuten wir zu gleicher Zeit darauf hin, wie das musikalische Erlebnis in sehr alten Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung war. Da unterschied der Mensch - allerdings, er hatte noch nicht die Terz, er kam bis zu der Quart herunter, hatte noch nicht die Terz -, da unterschied er nicht so: Ich singe - und: Es wird gesungen. — Beides war für ihn eines. Er war eben außer sich, wenn er sang, und er hatte zu gleicher Zeit ein äußeres Instrument. Er hatte gewissermaßen die Impression des Blasinstrumentes oder auch des Streichinstrumentes, die Impression, die Imagination. Die Musikinstrumente sind überhaupt zuerst als Imaginationen an den Menschen herangetreten. Die Musikinstrumente sind nicht durch Probieren erfunden, sondern die Musikinstrumente sind herausgeholt aus der geistigen Welt, mit Ausnahme des Klaviers.

Nun, da haben wir zu gleicher Zeit gegeben den Ursprung des Liedes. Es ist heute schwer, eine Vorstellung von dem zu geben, wie der Gesang selber in derjenigen Zeit war, als das Quintenerlebnis noch rein war. Da war der Gesang tatsächlich noch etwas, was wie ein wortgemäßer Ausdruck war. Man sang, aber es war zu gleicher Zeit ein Sprechen von der geistigen Welt, das Singen. Und man war sich bewußt: Redest du von Kirschen und Trauben, so gebrauchst du weltliche Worte; redest du von den Göttern, dann mußt du singen. Und dann kam diejenige Zeit, in welcher der Mensch nicht mehr Imaginationen hatte. Aber er hatte noch die Reste der Imaginationen man erkennt sie heute nur nicht -, es sind die Worte der Sprache. Von der Verkörperung des Geistigen durch den Gesangston kam es zur Verkörperung des Wortlichen durch den Gesangston. Das ist ein Schritt herein in die physische Welt. Und dann erst geschah die spätere Emanzipation des Gesanglichen innerlich in dem Ariengesang und so weiter. Das ist eine spätere Stufe.

Wenn wir also zu dem ursprünglichen, zu dem Urgesang der Menschheit zurückgehen, so ist der Urgesang der Menschheit ein Sprechen von den Göttern und von den Vorgängen unter den Göttern. Und, wie gesagt, die Tatsache der zwölf Quinten in den sieben Skalen bezeugt, daß vorhanden war mit dem Quintenintervall die Möglichkeit der Bewegung außerhalb des Menschen durch das Musikalische. Der Mensch kommt mit dem Musikalischen erst ganz an sich heran mit der Quart.

Nun hat gestern mit Recht jemand gesagt: Der Mensch empfindet etwas Leeres bei der Quinte. -— Natürlich muß er etwas Leeres empfinden bei der Quinte, weil er keine Imagination mehr hat und der Quinte eine Imagination entspricht, während der Terz eine Wahrnehmung entspricht im Inneren. Also heute empfindet der Mensch etwas Leeres bei der Quinte und muß sie durch das Stoffliche des Instrumentes ausfüllen. Das ist der Übergang im Musikalischen von dem mehr spirituellen Zeitalter zu dem späteren materialistischen Zeitalter.

Nun müssen wir uns das Verhältnis des älteren musikalischen Menschen zu seinem Instrumente tatsächlich in höchstem Maße als das einer Einheit vorstellen. Der Grieche fühlte sich ja sogar in die Notwendigkeit versetzt, als Schauspieler seine Stimme durch ein Instrument zu verstärken. Die Verinnerlichung kam erst später. Die ältere Zeit hatte ein Musikalisches durchaus so, daß der Mensch fühlte, er trägt einen gewissen Kreis der Töne in sich, der nach unten nicht reicht in das Gebiet der Kontratöne hinein, nach oben nicht bis zu den doppelt gestrichenen Tönen, sondern ein geschlossener Kreis ist. Nun hatte er das Bewußtsein: Mir ist gegeben ein enger Kreis des Musikalischen. Da draußen im Kosmos geht das Musikalische nach beiden Richtungen weiter. Dazu brauche ich dann die Instrumente, um heranzukommen an dieses Kosmisch-Musikalische. - Und nun muß man die anderen musikalischen Elemente in Betracht ziehen, wenn man dieses ganze Verhältnis kennenlernen will.

Dasjenige, was heute für die Musik im Mittelpunkte steht - ich meine für die gesamte Musik, nicht etwa für Gesang oder Instrumentalmusik -, das ist die Harmonie. Das Harmonische ergreift nun unmittelbar das menschliche Fühlen. Dasjenige, was sich im Harmonischen ausdrückt, wird durch das menschliche Gefühl erlebt. Nun ist das Fühlen eigentlich dasjenige, was im Mittelpunkte des menschlichen Gesamterlebnisses steht. Nach der einen Seite läuft das Fühlen aus in das Wollen, und nach der anderen Seite läuft das Fühlen aus in das Vorstellen. So daß wir sagen können, wenn wir den Menschen betrachten: Wir haben in der Mitte das Fühlen; wir haben nach der einen Seite das Fühlen auslaufend in die Vorstellung, wir haben nach der anderen Seite das Fühlen auslaufend in das Wollen. An das Fühlen wendet sich unmittelbar die Harmonie. Harmonie wird im Fühlen erlebt. Aber die gesamte Gefühlsnatur des Menschen ist eigentlich eine zweifache. Wir haben ein Fühlen, das mehr dem Vorstellen zugeneigt ist - indem wir zum Beispiel unsere Gedanken fühlen, ist das Fühlen dem Vorstellen zugeneigt —, und wir haben ein Fühlen, das dem Wollen zugeneigt ist; wir fühlen bei einer Tat, die wir tun, ob sie uns gefällt oder mißfällt, gerade wie wir bei einer Vorstellung fühlen, ob sie uns gefällt oder mißfällt. Das Fühlen zerfällt eigentlich in zwei Gebiete in der Mitte.

Nun, das Musikalische hat das Eigentümliche: weder darf es ordentlich in das Vorstellen hinauf -— denn ein Musikalisches, das vom Vorstellen, vom Gehirn erfaßt würde, würde gleich aufhören, ein Musikalisches zu sein -, noch darf aber das Musikalische ganz und gar ins Wollen hinuntersinken. Man kann sich nicht denken, daß zum Beispiel, ohne daß es ein abstraktes Zeichen ist, das Musikalische selbst unmittelbar Wollensimpuls würde. Wenn Sie die Mittagsglocke anschlagen hören, werden Sie gehen, weil dies das Gehen zum Mittagstische anzeigt, aber Sie werden das Musikalische nicht als den Impuls für das Wollen ansehen. Das ist etwas, was gerade zeigt: ebensowenig wie das Musikalische in das Vorstellen hinauf darf, ebensowenig darf es in das eigentliche Wollen hinunter. Es muß nach beiden Seiten hin aufgehalten werden. Das Erleben des Musikalischen muß innerhalb des Gebietes, das zwischen Vorstellung und Willen gelegen ist, ablaufen, es muß ganz ablaufen in demjenigen Teile des Menschen, der eigentlich dem Alltagsbewußtsein gar nicht angehört, sondern der etwas zu tun hat mit dem, was herunterkommt aus geistigen Welten, sich verkörpert und wiederum durch den Tod durchgeht. Aber es ist unterbewußt da. Aus diesem Grunde hat das Musikalische in der äußeren Natur kein unmittelbares Korrelat. Indem sich der Mensch in die Erde hereinlebt, lebt er sich in dasjenige herein, was unmittelbar vorgestellt werden kann und was er will. Aber die Musik geht nicht bis zum Vorstellen und Wollen; jedoch die Tendenz liegt vor, daß das Harmonische, ich möchte sagen, ausstrahlt nach dem Vorstellen. Es darf nicht ins Vorstellen herein, aber es strahlt aus nach dem Vorstellen. Und dieses Ausstrahlen in den Bezirk unseres Geistes hinein, wo wir sonst vorstellen, das tut von der Harmonie aus die Melodie.

Das Melodische leitet das Musikalische aus dem Fühlensgebiet hinauf in das Vorstellen. Im Melodienthema haben Sie nicht das, was wir im Vorstellen haben. Aber Sie haben im Melodienthema dasjenige, was in dasselbe Gebiet hinaufgeht, wo sonst die Vorstellung liegt. Die Melodie hat etwas Vorstellungsähnliches, ist aber keine Vorstellung, ist noch durchaus im Gefühlsleben verlaufend. Aber sie tendiert hinauf, so daß das Gefühl eigentlich im Haupte des Menschen erlebt wird. Und das ist das Bedeutungsvolle des melodiösen Erlebens, daß das melodiöse Erleben dasjenige in der Menschennatur ist, welches den Kopf des Menschen dem Gefühle zugänglich macht. Der Kopf des Menschen ist sonst nur dem Begriffe zugänglich. Durch die Melodie wird der Kopf dem Fühlen zugänglich, dem wirklichen Fühlen. Sie schieben gewissermaßen durch die Melodie das Herz in den Kopf. Sie werden in der Melodie frei, wie sonst im Vorstellen. Das Gefühl wird abgeklärt, gereinigt. Es fällt alles Außere von ihm fort, aber zu gleicher Zeit bleibt es durch und durch Fühlen.

Ebenso nun aber, wie die Harmonie nach dem Vorstellen hinauftendieren kann, kann sie nach dem Wollen hinuntertendieren. Aber sie darf da nicht hinunterkommen, sie muß ebenso sich verfangen, möchte ich sagen, im Gebiete des Wollens. Das geschieht durch den Rhythmus. So daß also die Melodie die Harmonie nach oben trägt, der Rhythmus trägt die Harmonie nach dem Wollen hin. Sie bekommen das gebundene Wollen, das in der Zeit maßvoll verlaufende Wollen, das nicht nach außen geht, sondern das an den Menschen selber gebunden bleibt. Es ist echtes Fühlen, das sich aber hineinerstreckt in das Gebiet des Wollens.

An dieser Stelle werden Sie es auch begreiflich finden, daß man zunächst, wenn man das Kind hat, das zur Schule kommt, leichter ein melodiöses Verständnis findet als ein harmonisches Verständnis. Man muß natürlich das nicht pedantisch nehmen. Im Künstlerischen darf niemals Pedanterie eine Rolle spielen. Man kann selbstverständlich an das Kind alles mögliche heranbringen. Aber geradeso wie eigentlich das Kind in den ersten Schuljahren nur Quinten verstehen müßte, höchstens noch Quarten und nicht Terzen — die beginnt es innerlich zu verstehen erst vom neunten Lebensjahre ab -, ebenso kann man sagen, daß, das Kind das melodiöse Element leicht versteht und das harmonische Element eigentlich erst vom neunten, zehnten Lebensjahre ab als Harmonisches zu verstehen beginnt. Natürlich, das Kind versteht den Ton schon, aber das eigentliche Harmonische daran kann man beim Kinde erst von diesem Jahre ab pflegen. Das Rhythmische allerdings nimmt die verschiedensten Gestalten an. Das Kind wird einen gewissen inneren Rhythmus schon sehr jung verstehen. Aber abgesehen von diesem instinktiv erlebten Rhythmus sollte man das Kind mit dem Rhythmus, zum Beispiel am Instrumental-Musikalischen empfunden, erst nach dem neunten Lebensjahre plagen. Da sollte man die Aufmerksamkeit auf diese Dinge lenken. Auch im Musikalischen kann man durchaus, möchte ich sagen, von dem Lebensalter ablesen, was man zu tun hat. Man wird ungefähr dieselben Lebensstufen finden, die man sonst auch in unserer Waldorfschul-Pädagogik und -Didaktik findet.

Nun, wenn Sie das Hauptaugenmerk auf den Rhythmus lenken, so ist das rhythmische Element, weil es mit der Willensnatur verwandt ist und der Mensch doch innerlich den Willen in Tätigkeit versetzen muß, wenn er musikalisch erleben will, das eigentlich die Musik Auslösende. Das rhythmische Element löst die Musik aus. Nun beruht aller Rhythmus, gleichgültig in welchem Verhältnis der Mensch zum Rhythmus steht, auf dem geheimnisvollen Zusammenhang zwischen Puls und Atem, auf jenem Verhältnis, das besteht zwischen dem Atem — achtzehn Atemzüge in der Minute — und dem Puls — durchschnittlich zweiundsiebzig Pulsschläge in der Minute -, auf diesem Verhältnis von eins zu vier, das natürlich in der mannigfaltigsten Weise erstens modifiziert werden kann, zweitens auch individualisiert werden kann. Daher hat jeder Mensch seine eigene Empfindung beim Rhythmus; weil sie aber annähernd gleich ist, verstehen sich die Menschen in bezug auf den Rhythmus. Also alles Rhythmuserleben beruht auf dem geheimnisvollen Zusammenhang des Atmens mit der Herzbewegung, mit der Blutzirkulation. Und so kann man sagen: Während durch die Strömung des Atmens, also in äußerlicher Verlangsamung und innerlichem Qualitätserzeugen, die Melodie vom Herzen nach dem Kopf getragen wird, wird der Rhythmus auf den Wellen der Blutzirkulation vom Herzen in die Gliedmaßen getrieben, und in den Gliedmaßen fängt er sich als Wollen. - Dadurch sehen Sie auch, wie das Musikalische eigentlich den ganzen Menschen ausfüllt.

Stellen Sie sich den ganzen Menschen musikalisch erlebend als einen Menschengeist vor: Indem Sie melodiös erleben können, haben Sie den Kopf dieses Geistes. Indem Sie harmonisch erleben können, haben Sie die Brust, das mittlere Organ des Geistes. Indem Sie rhythmisch erleben können, haben Sie die Gliedmaßen des Geistes.

Was habe ich Ihnen aber damit beschrieben? Ich habe Ihnen den menschlichen Ätherleib beschrieben. Sie brauchen bloß das musikalische Erlebnis zu schildern; wenn Sie das musikalische Erlebnis richtig haben, haben Sie den menschlichen Ätherleib leibhaftig vor sich. Nur, daß wir statt Kopf sagen: Melodie, daß wir statt rhythmischem Menschen sagen, weil es hinaufgehoben ist: Harmonie, und daß wir statt Gliedmaßenmenschen - Stoffwechsel dürfen wir nicht sagen -, statt Gliedmaßenmenschen sagen: Rhythmus. Wir haben den ganzen Menschen ätherisch vor uns. Es ist nichts anderes als dieses. Und im Quartenerlebnis erlebt der Mensch eigentlich sich selber als Ätherleib, richtig als Ätherleib, nur daß sich ihm eine Art Summierung bildet. Im Quartenerlebnis ist eine angeschlagene Melodie, eine angeschlagene Harmonie, ein angeschlagener Rhythmus, alles aber so ineinander verwoben, daß man es nicht mehr unterscheiden kann. Den ganzen Menschen erlebt man im Quartenerlebnis an der Grenze geistig, den Äthermenschen erlebt man im Quartenerlebnis.

Wenn nämlich das heutige Musikalische nicht in dem materialistischen Zeitalter wäre, wenn nicht alles übrige, was heute der Mensch erlebt, ganz das Musikalische eigentlich verdürbe: aus dem Musikalischen heraus, wie es der Mensch heute hat — denn das Musikalische an sich ist auf einer weltgeschichtlichen Höhe dennoch angelangt -, würde der Mensch überhaupt gar nichts anderes sein können als Anthroposoph. Es läßt sich das Musikalische nicht anders erleben, wenn man es bewußt erleben will, als anthroposophisch. Sie können gar nicht anders, als das Musikalische anthroposophisch erleben.

Wenn Sie die Dinge nehmen, so wie sie sind, werden Sie zum Beispiel folgende Frage sich vorlegen können: Ja, wenn man alte Traditionen über das spirituelle Leben nimmt, man findet überall gesprochen von der siebengliedrigen Natur des Menschen. Diese siebengliedrige Natur des Menschen hat ja die Theosophie, die theosophische Bewegung übernommen. Als ich meine «Theosophie» schrieb, mußte ich von einer neungliedrigen Natur sprechen, in den einzelnen drei Gliedern weiter einteilen, und bekam erst die Siebengliederung aus einer Neungliederung; Sie wissen ja:

und weil 6 und 7 sich übergreifen, und 3 und 4 sich übergreifen, bekam ich auch den siebengliedrigen Menschen heraus für die «Theosophie». Aber dieses Buch hätte niemals geschrieben werden können in der Quintenzeit, denn in der Quintenzeit war alles spirituelle Erleben dadurch gegeben, daß man in den sieben Skalen die Planetenzahlen, die Tierkreiszahlen in den zwölf Quinten hatte. Da war das große Geheimnis des Menschen gegeben im Quintenzirkel. In der Quintenzeit konnten Sie gar nicht anders über Theosophie schreiben, als, indem Sie zum siebengliedrigen Menschen kamen. Meine «Theosophie» ist in der Zeit geschrieben, in der die Menschen ausgesprochen die Terz erleben, also in der Zeit der Verinnerlichung. Da muß man das Geistige in einer ähnlichen Weise suchen, wie man aus dem Quintenintervall durch Teilung zum Terzenintervall herunterkommt. Also ich mußte die einzelnen Glieder teilen wiederum. Sie können sagen: Die anderen Bücher, die vom siebengliedrigen Menschen schreiben, sind einfach aus der Tradition der Quintenzeit, aus der Tradition des Quintenzirkels. Meine «Theosophie» ist aus der Zeit, in der die Terz die große musikalische Rolle spielt, in der auch schon, da wo es zur Terz kommt, die Verwicklung aufkommt: das mehr Innerliche nach der Mollseite, das mehr Äußerliche nach der Durseite, daher das unklare Sich-Übergreifen zwischen 3 und 4, also zwischen Empfindungsleib und Empfindungsseele. - Wenn Sie sagen Empfindungsseele: kleine Terz; wenn Sie sagen Empfindungsleib: große Terz. — Die Dinge der Menschheitsentwickelung drücken sich eben im musikalischen Werden viel klarer aus als in irgendeinem anderen. Nur muß man auf Begriffe verzichten. Wie ich Ihnen schon gestern sagte: mit dem Begreifen geht es nicht.

Und wenn jemand mit der Akustik, mit der Tonphysiologie kommt, dann ist überhaupt nichts zu machen. Es gibt keine Tonphysiologie, es gibt keine Akustik, die eine andere Bedeutung hätte als für die Physik. Eine Akustik, die eine Bedeutung für die Musik selber hätte, gibt es nicht. Man muß, wenn man das Musikalische begreifen will, ins Geistige hinein.

Nun sehen Sie, wie wir so die Quart zwischen der Quinte und der Terz darinnen haben: die Quinte so, daß der Mensch sich entrückt fühlt, mit der Terz sich in sich darinnen fühlt, mit der Quart an der Grenze zwischen ihm und der Welt. Ich habe Ihnen gestern gesagt, die Septime ist das eigentliche Intervall der Atlantier gewesen, die hatten überhaupt nur Septimenintervalle, nur hatten sie nicht dasselbe Gefühl wie wir heute, sondern wenn sie überhaupt Musiker wurden, dann waren sie ganz außer sich selber, dann waren sie in der großen, umfassenden Geistigkeit der Welt und darinnen in einer absoluten Bewegung. Sie wurden bewegt. Noch in dem Quintenerlebnis war die Bewegung da. Die Sexte steht wiederum dazwischen drinnen. Und daraus können wir ersehen: Diese drei Stufen, Septime, Sexte, Quinte, die erlebt der Mensch in der Entrückung, mit der Quart tritt er in sich herein, mit der Terz ist er in sich darinnen. Die Oktave wird er erst in der Zukunft in ihrer vollen musikalischen Bedeutung erleben. An dem herzhaften Erleben der Sekund ist der Mensch heute noch nicht angelangt. Das sind Dinge, die in der Zukunft liegen. Bei einer noch stärkeren Verinnerlichung des Menschen wird der Mensch die Sekund empfinden und überhaupt zuletzt den einzelnen Ton. Ich weiß nicht, ob sich einzelne erinnern werden, daß ich einmal in Dornach bei einer Fragestellung gesagt habe, daß der einzelne Ton als ein Musikalisch-Differenziertes empfunden werden wird, daß schon im einzelnen Ton das Musikalisch-Differenzierte darin liegen wird.

Nun, wenn Sie dies ins Auge fassen, was da gesagt worden ist, dann werden Sie auch begreifen, warum in unserer Toneurythmie gerade die Formen auftreten, die eben auftreten, aber Sie werden auch noch ein weiteres begreifen. Sie werden zum Beispiel begreifen, daß rein aus dem Instinkte heraus das Gefühl entstehen wird, die unteren Glieder der Oktave, Prim, Sekund, Terz, so zu halten, daß man die Bewegung, wenn man hier steht, nach rückwärts gestaltet; daß man bei den oberen Tönen, Quinte, Sexte, Septime, den Instinkt hat, diese Bewegung nach vorne zu machen.

Das würden etwa die Formen sein, welche man als stereotype Formen, als typische Formen anwenden kann. Und bei den Formen, die für die einzelnen Musikstücke ausgebildet worden sind, werden Sie schon annähernd fühlen, daß diese Formen darin enthalten sind, darin sind im Quarten- oder Quintenerlebnis. Es ist eben durchaus notwendig, daß gerade dieser Teil hier, das Heruntersteigen der Harmonie durch den Rhythmus in das Wollen, daß der sich gerade bei dem Eurythmischen in der Form ganz besonders auslebt. So daß man also die einzelnen Intervalle hat in den Formen, die man an sich macht, daß man aber dasjenige, was dann von den Intervallen in den Rhythmus hineingeht, auszuleben hat in diesen Formen, wobei ganz von selbst der Instinkt entsteht, bei der Quart eine womöglich geringe Bewegung auszuführen, nicht stillezustehen, aber eine womöglich geringe Bewegung auszuführen. Denn sehen Sie, die Quart ist eigentlich ein wirkliches Wahrnehmen, nur ein Wahrnehmen von der anderen Seite. Gewissermaßen, wenn ich sage: Ich schaue mit dem Auge so —, müßte ich dabei das Auge anschauen, das Auge müßte nach rückwärts schauen, dann wäre dies das aus der Seele gewonnene Quartenerlebnis. Die Quinte ist das rechte Imaginationserlebnis. Wer Quinten richtig erlebt, weiß eigentlich schon, was subjektiv die Imagination ist. Wer Sexten erlebt, weiß, was Inspiration ist. Und wer Septimen erlebt — wenn er es überlebt -, weiß, was Intuition ist. Ich meine, die Form der Seelenverfassung beim Septimenerlebnis ist dieselbe wie hellseherisch bei der Intuition. Und die Form der Seelenverfassung beim Sextenerleben ist dieselbe wie bei der Inspiration beim Hellsehen. Und das Quintenerlebnis ist ein richtiges imaginatives Erlebnis. Es braucht nur die Seelenverfassung ausgefüllt zu sein mit Schauen. Die Seelenverfassung ist beim Musikalischen durchaus da.

Deshalb werden Sie auch überall hören, daß in älteren Mysterienschulen und in den übriggebliebenen Traditionen die hellseherische Erkenntnis auch eine musikalische Erkenntnis genannt wird, geistigmusikalische Erkenntnis genannt wird. Es wird überall darauf hingewiesen — die Leute wissen heute nicht mehr warum -, daß die gewöhnliche körperliche Erkenntnis besteht, die intellektuelle Erkenntnis, und die spirituelle Erkenntnis, die aber eigentlich eine musikalische Erkenntnis, eine im musikalischen Elemente lebende Erkenntnis ist. Und im Grunde genommen würde es gar nicht so schwierig sein, die Lehre vom dreigliedrigen Menschen populär zu machen, wenn sich die Menschen heute ihres musikalischen Empfindens bewußt wären. Gewiß, das musikalische Empfinden haben ja die Menschen zur Not; aber sie sind in dem musikalischen Empfinden nicht richtig als Menschen darinnen. Sie stehen neben dem Musikalischen eigentlich; beim Erleben des Musikalischen ist die Sache nicht weit her. Würde das Erleben des Musikalischen ganz lebendig werden in den Menschen, dann würden sie fühlen: Im Melodiösen ist mein ätherisches Haupt, und das Physische ist herausgefallen; da habe ich die eine Seite der Menschenorganisation. Im Harmonischen ist mein ätherisches Mittelsystem, das Physische ist herausgefallen. Dann verschiebt sich das wieder um eine Oktave. Und wieder im Gliedmaßensystem darüber sollte man eigentlich nicht viel Worte verlieren, es ist handgreiflich - haben wir dasjenige, was rhythmisch im Musikalischen auftritt.

Nun, wie ist denn überhaupt die musikalische Entwickelung des Menschen? Sie geht aus von dem Erleben des Spirituellen, des Geistigen, von dem Gegenwärtigmachen des Spirituellen im Tone, im musikalischen Tongebilde. Das Spirituelle verliert sich, das Tongebilde behält der Mensch. Später verbindet er es mit dem Worte als dem Rest des Spirituellen, und dasjenige, was er früher als Imaginationen gehabt hat, die Instrumente, bildet er dann im Physischen aus, macht aus dem physischen Stoffe seine Instrumente. Die Instrumente sind alle aus der geistigen Welt herausgeholt, insofern sie tatsächlich die musikalische Stimmung erregen. Der Mensch hat einfach, indem er physische Musikinstrumente gemacht hat, die leeren Plätze ausgefüllt, die dadurch geblieben sind, daß er nicht mehr das Spirituelle sah. Da hat er die physischen Instrumente hineingestellt.

Sie sehen daraus, es ist richtig; Im Musikalischen ist es mehr als sonstwo zu sehen, wie der Übergang ins materialistische Zeitalter vor sich geht. Da, wo die Musikinstrumente erklingen, haben eigentlich früher geistige Entitäten dagestanden. Die sind weg, sind verschwunden vom alten Hellsehen. Wenn der Mensch das Musikalische objektiv haben will, so braucht er aber etwas, was nicht in der äußeren Natur da ist. Die äußere Natur gibt ihm kein Korrelat für das Musikalische, also braucht er seine Musikinstrumente.

Nur allerdings, die Musikinstrumente sind wirklich im Grunde genommen ein deutlicher Abdruck dessen, daß das Musikalische mit dem ganzen Menschen erlebt wird. Daß das Musikalische durch das Haupt des Menschen erlebt wird, dafür sind ein Beweis die Blasinstrumente. Daß dasjenige, was durch die Brust erlebt wird, in den Armen besonders zum Ausdruck kommt, dafür sind die lebendigen Zeugen die Streichinstrumente. Dafür, daß das Musikalische durch das dritte Glied, den Gliedmaßenmenschen sich auslebt, dafür sind alle Schlaginstrumente oder der Übergang von Streichinstrumenten zu Schlaginstrumenten ein Beweis. Aber es hat auch alles dasjenige, was mit dem Blasen zusammenhängt, einen viel intimeren Bezug zum Melodiösen als dasjenige, was mit den Streichinstrumenten zusammenhängt, das hat einen Bezug zum Harmonischen. Und dasjenige, was mit dem Schlagen zusammenhängt, hat mehr inneren Rhythmus, ist verwandt mit dem Rhythmischen, da ist der ganze Mensch darinnen. Und ein Orchester ist ein Mensch. Bloß darf kein Klavier im Orchester stehen.

Ja, warum? Nun ja, die Musikinstrumente sind heruntergeholt aus der geistigen Welt. Nur in der physischen Welt hat sich der Mensch das Klavier gemacht, wo die Töne rein abstrakt aneinandergesetzt sind. Irgendeine Pfeife, irgendeine Geige, alles das ist etwas, was schon musikalisch aus der höheren Welt herunterkommt. Ein Klavier, ja, das ist eben so wie der Philister: der hat nicht mehr den höheren Menschen in sich. Das Klavier ist das Philisterinstrument. Es ist ein Glück, daß es das gibt, sonst hätte der Philister überhaupt keine Musik. Aber es ist das Klavier dasjenige, was schon aus einem materialistischen Erleben des Musikalischen entstanden ist. Daher ist das Klavier das Instrument, das man am bequemsten verwenden kann, um innerhalb des Stofflichen das Musikalische zu erwecken. Aber es ist eben der reine Stoff, der da in Anspruch genommen worden ist, daß das Klavier der Ausdruck des Musikalischen hat werden können. Und so muß man sagen: Das Klavier ist natürlich ein sehr wohltätiges Instrument — nicht wahr, sonst müßten wir ja das Geistige ganz von Anfang an in unserem materialistischen Zeitalter beim musikalischen Unterrichte zu Hilfe nehmen -, aber es ist dasjenige Instrument, das eigentlich musikalisch überwunden werden muß. Der Mensch muß loskommen vom Klaviereindruck, wenn er das eigentliche Musikalische erleben will.

Und da muß man schon sagen: Es ist immer ein großes Erlebnis, wenn ein Musiker, der im Grunde ganz im Musikalischen lebt wie Bruckner, dann auf dem Klavier gespielt wird. Das Klavier verschwindet im Zimmer, bei Bruckner verschwindet das Klavier! Man glaubt, andere Instrumente zu hören, man vergißt das Klavier. Das ist eigentlich bei Bruckner so. Dies ist ein Beweis, daß in ihm noch etwas gelebt hat - wenn auch auf sehr instinktive Weise - von dem eigentlich Spirituellen, das aller Musik zugrunde liegt.

Das sind so die Dinge, die ich Ihnen in diesen Tagen ganz fragmentarisch und anspruchslos habe sagen wollen. Ich glaube, wir werden bald Gelegenheit haben, die Dinge fortzusetzen. Dann werde ich Ihnen über das eine oder andere noch Genaueres sagen.

The Sound Experience in Humans II

Once again, I would like to emphasize that the intention of these two lectures is to give school teachers in particular what they need, albeit in a very fragmentary and incomplete form, which will have to be elaborated on at the next opportunity.

Yesterday I spoke about the role played by the fifth in musical experience on the one hand, and the role played by the third and seventh on the other. Now, you will have gathered from this description that progress in fifths is still connected with the musical experience that actually brings out the human being when he feels the fifth, that is, that the human being actually experiences a rapture with the feeling of the fifth. This becomes clearer if we take the seven scales, from the counter tones up to the four-line tones, if we take seven scales and consider that within these seven scales the fifth is possible twelve times. So that, in a sense, hidden within the sequence of the seven musical scales, we have another twelve-membered scale with the fifth interval.

What does this actually mean in the context of the whole musical experience? It means that within the experience of the fifth, the human being is in motion with his ego outside his physical organization. He strides, as it were, through the seven scales in twelve steps. He is therefore in motion outside his physical organization through the experience of the fifth.

If we now return to the experience of the third — this is true of both the major and minor third — we come to an inner movement of the human being. The ego is, so to speak, within the limits of the human organism; the human being experiences the thirds inwardly. In the transition from a third to a fifth, even if there is something in between, it does not matter — he actually experiences the transition from inner experience to outer experience. So one can say: in the case of the third experience, the mood is the consolidation of the inner, the awareness of the human being within himself; in the case of the fifth experience, it is the awareness of the human being in the divine world order. — So, in a sense, the experience of the fifth is a stepping out into the vast universe, and the experience of the third is a return of the human being to his own house of organization. In between lies the experience of the fourth.

This experience of the fourth is perhaps one of the most interesting for those who want to discover the secrets of music, not because the experience of the fourth as such is the most interesting, but because this experience of the fourth actually stands at the dividing line between the experience of the fifth in the outside world and the experience of the third within the human being. The experience of the fourth lies, in a sense, precisely at the boundary of the human organism. But human beings do not perceive the physical external world in the fourth, but rather the spiritual world; they look at themselves from the outside, so to speak, if I may use a facial expression to describe an auditory experience. In the fourth, it is the case that human beings – they are not conscious of this, but the sensation they have in the fourth experience is based on it – in the fourth experience, it is the case that human beings feel themselves to be among gods. While in the fifth experience he has to forget himself in order to be among gods, in the fourth experience he does not need to forget himself in order to feel himself among gods. In the fourth experience, he walks around in the divine world as a human being, so to speak. He stands precisely at the boundary of his humanity, still possesses it, and looks at it, as it were, from the other side.

The experience of the fifth as a spiritual experience was first lost to humanity. People today do not have this experience of the fifth, which was still there four or five centuries before our era. At that time, people actually had the feeling during the experience of the fifth: I am standing in the spiritual world. They did not need an instrument to produce a fifth outside themselves, but felt the fifth they produced themselves as existing in the divine world, because they still had imagination. They still had imagination, including musical imagination. So there was still an object, a musical one, in the experience of the fifth. Humans lost this earlier than the object experience with the fourth. Much later, the fourth was still such that humans believed that when they had the experience of the fourth, they were living and breathing in something ethereal. In a manner of speaking, they felt, if I may say so, the holy wind that had transported them into the physical world when they experienced the fourth. Perhaps Ambrose and Augustine also felt this way — at least, according to their statements, this is entirely possible. Then this experience of the fourth was also lost, and in order to be objectively sure of the fourth, the external instrument was needed.

At the same time, we are pointing to what the musical experience was like in very ancient times of human development. At that time, man did not distinguish between “I sing” and “it is sung.” — For him, the two were one and the same. He was simply beside himself when he sang, and at the same time he had an external instrument. He had, so to speak, the impression of the wind instrument or the string instrument, the impression, the imagination. Musical instruments first approached humans as imaginations. Musical instruments were not invented by trial and error, but were brought out of the spiritual world, with the exception of the piano.

Now, at the same time, we have the origin of song. Today it is difficult to give an idea of what singing itself was like in those days when the experience of the fifth was still pure. Singing was actually still something that was like a literal expression. People sang, but at the same time, singing was a way of speaking from the spiritual world. And people were aware that if you talked about cherries and grapes, you used worldly words; if you talked about the gods, you had to sing. And then came the time when people no longer had imaginations. But they still had the remnants of imaginations – we just don't recognize them today – they are the words of language. From the embodiment of the spiritual through the tone of singing, it came to the embodiment of the verbal through the tone of singing. That is a step into the physical world.

And only then did the later emancipation of singing occur internally in aria singing and so on. That is a later stage. And, as I said, the fact of the twelve fifths in the seven scales testifies that with the fifth interval there was the possibility of movement outside of man through music. Man only really comes into contact with music with the fourth.Now, yesterday someone rightly said: Man feels something empty in the fifth. Of course, they must feel something empty with the fifth, because they no longer have any imagination, and the fifth corresponds to imagination, while the third corresponds to inner perception. So today, people feel something empty with the fifth and must fill it with the materiality of the instrument. This is the transition in music from the more spiritual age to the later materialistic age.

Now we must indeed imagine the relationship of the older musical human being to his instrument as one of unity in the highest degree. The Greeks even felt compelled to amplify their voices as actors with an instrument. Internalization came later. In earlier times, music was such that people felt they carried a certain circle of tones within themselves, which did not extend down into the realm of counter-tones, nor up to the double-struck tones, but was a closed circle. Now they had the awareness: I have been given a narrow circle of music. Out there in the cosmos, music continues in both directions. To access this cosmic music, I need instruments. And now we must consider the other musical elements if we want to understand this whole relationship.

What is at the center of music today—I mean all music, not just singing or instrumental music—is harmony. Harmony immediately captures human feeling. What is expressed in harmony is experienced through human feeling. Now, feeling is actually what is at the center of the entire human experience. On the one hand, feeling flows into willing, and on the other hand, feeling flows into imagination. So that we can say, when we look at the human being: we have feeling in the middle; on the one hand, feeling flows into imagination, and on the other hand, feeling flows into willing. Harmony directly addresses feeling. Harmony is experienced in feeling. But the entire emotional nature of human beings is actually twofold. We have a feeling that is more inclined toward imagination — for example, when we feel our thoughts, feeling is inclined toward imagination — and we have a feeling that is inclined toward will; when we do something, we feel whether we like it or dislike it, just as we feel whether we like or dislike an idea. Feeling actually falls into two areas in the middle.

Now, music has the peculiar characteristic that it cannot properly ascend into the realm of imagination — for music that were grasped by the imagination, by the brain, would immediately cease to be music — nor can music sink completely into the realm of will. One cannot imagine, for example, that music itself would become a direct impulse of will without being an abstract sign. When you hear the noon bell ring, you will go because it signals that it is time to go to lunch, but you will not regard the musical as the impulse for your will. This is something that shows precisely that just as the musical must not rise up into the realm of imagination, neither must it sink down into the realm of actual will. It must be held back on both sides. The experience of music must take place within the realm between imagination and will; it must take place entirely in that part of the human being that does not actually belong to everyday consciousness, but has something to do with what comes down from spiritual worlds, incarnates itself, and passes through death again. But it is there subconsciously. For this reason, music has no direct correlate in external nature. As human beings live their way into the earth, they live their way into what can be directly imagined and what they want. But music does not go as far as imagination and will; however, there is a tendency for harmony, I would say, to radiate toward the imagination. It must not enter into imagination, but it radiates toward imagination. And this radiation into the realm of our spirit, where we otherwise imagine, is done by melody from harmony.

The melodic leads the musical from the realm of feeling up into the realm of imagination. In the melody theme, you do not have what we have in imagination. But in the melody theme, you have that which ascends into the same realm where imagination otherwise lies. The melody has something like imagination, but it is not imagination; it still runs entirely in the life of feeling. But it tends upward, so that the feeling is actually experienced in the human head. And that is the significance of the melodious experience, that the melodious experience is that in human nature which makes the human head accessible to feeling. The human head is otherwise only accessible to concepts. Through melody, the head becomes accessible to feeling, to real feeling. Through melody, you push the heart into the head, so to speak. You become free in melody, as you otherwise do in imagination. Feeling becomes clarified, purified. Everything external falls away from it, but at the same time it remains feeling through and through.

But just as harmony can tend upward toward imagination, it can also tend downward toward the will. But it must not descend there; it must also become caught, I would say, in the realm of the will. This happens through rhythm. So that the melody carries the harmony upward, the rhythm carries the harmony toward the will. You get the bound will, the will that proceeds moderately in time, that does not go outward, but remains bound to the human being himself. It is genuine feeling, but it extends into the realm of the will.

At this point, you will also understand that when you have a child who is starting school, it is easier to find a melodic understanding than a harmonic understanding. Of course, you don't have to take this pedantically. Pedantry should never play a role in the arts. You can, of course, introduce the child to all kinds of things. But just as a child in the first years of school should only understand fifths, at most fourths and not thirds — which it only begins to understand internally from the age of nine — so too can we say that the child easily understands the melodic element and only begins to understand the harmonic element as harmony from the age of nine or ten. Of course, the child already understands the tone, but the actual harmony can only be cultivated in the child from this age onwards. Rhythm, however, takes on many different forms. Children will understand a certain inner rhythm from a very young age. But apart from this instinctively experienced rhythm, children should only be exposed to rhythm as experienced in instrumental music, for example, after the age of nine. That is when attention should be drawn to these things. In music, too, I would say that it is possible to determine what needs to be done based on the child's age. You will find roughly the same stages of life that you would otherwise find in our Waldorf school pedagogy and didactics.

Now, if you focus on rhythm, the rhythmic element is what actually triggers music, because it is related to the nature of the will, and people must activate their will internally if they want to experience music. The rhythmic element triggers the music. Now, regardless of a person's relationship to rhythm, all rhythm is based on the mysterious connection between pulse and breath, on the relationship that exists between the breath — eighteen breaths per minute — and the pulse — an average of seventy-two heartbeats per minute — on this ratio of one to four, which can of course be modified in the most varied ways and also individualized. Therefore, every person has their own perception of rhythm; but because it is approximately the same, people understand each other in relation to rhythm. So all experience of rhythm is based on the mysterious connection between breathing and the movement of the heart, with blood circulation. And so one can say: while the melody is carried from the heart to the head through the flow of breathing, that is, through external slowing down and internal quality generation, the rhythm is driven on the waves of blood circulation from the heart to the limbs, and in the limbs it catches as will. - This also shows you how music actually fills the whole human being.

Imagine the whole human being experiencing music as a human spirit: by being able to experience melody, you have the head of this spirit. By being able to experience harmony, you have the chest, the middle organ of the spirit. By being able to experience rhythm, you have the limbs of the spirit.

But what have I described to you? I have described the human etheric body. You only need to describe the musical experience; if you have the musical experience correctly, you have the human etheric body physically before you. Only that instead of head we say melody, and instead of rhythmic human being, because it is elevated, we say harmony, and instead of limb-human — we must not say metabolism — instead of limb-human we say: rhythm. We have the whole human being before us in etheric form. It is nothing other than this. And in the quartet experience, the human being actually experiences itself as an etheric body, truly as an etheric body, only that a kind of summation forms for it. In the quartet experience, there is a melody, a harmony, a rhythm, but everything is so interwoven that it can no longer be distinguished. In the quartet experience, one experiences the whole human being at the spiritual boundary; in the quartet experience, one experiences the etheric human being.

For if today's music were not in the materialistic age, if everything else that human beings experience today did not actually spoil music: from the music that human beings have today — for music itself has nevertheless reached a world-historical height — human beings could be nothing other than anthroposophists. If one wants to experience music consciously, there is no other way to experience it than anthroposophically. You cannot help but experience music anthroposophically.

If you take things as they are, you will be able to ask yourself the following question, for example: Yes, if you take old traditions about spiritual life, you will find references everywhere to the sevenfold nature of human beings. This sevenfold nature of human beings has been adopted by theosophy, the theosophical movement. When I wrote my “Theosophy,” I had to speak of a ninefold nature, further subdividing the individual three members, and only then did I arrive at the sevenfold division from a ninefold one; as you know:

and because 6 and 7 overlap, and 3 and 4 overlap, I also arrived at the sevenfold human being for Theosophy. But this book could never have been written in the quinte time, because in the quinte time all spiritual experience was given by the fact that in the seven scales one had the planetary numbers, the zodiac numbers in the twelve quintes. There the great mystery of man was given in the quinte circle. In the quinte time you could not write about theosophy in any other way than by coming to the sevenfold human being. My “Theosophy” was written in the age in which human beings experience the third in a pronounced way, that is, in the age of internalization. There you have to seek the spiritual in a similar way to how you come down from the interval of a fifth to the interval of a third by division. So I had to divide the individual members again. You could say that the other books that write about the sevenfold human being are simply from the tradition of the time of the fifth, from the tradition of the circle of fifths. My “Theosophy” comes from the time when the third plays a major musical role, when, as soon as the third appears, entanglement arises: the more inner aspect toward the minor side, the more outer aspect toward the major side, hence the unclear overlap between 3 and 4, that is, between the feeling body and the feeling soul. When you say feeling soul, you mean minor third; when you say feeling body, you mean major third. The things of human development are expressed much more clearly in musical becoming than in any other. But one must renounce concepts. As I already told you yesterday: it doesn't work with concepts.

And if someone comes along with acoustics, with the physiology of sound, then there is nothing to be done at all. There is no physiology of sound, there is no acoustics that has any meaning other than for physics. There is no acoustics that has any meaning for music itself. If you want to understand music, you have to enter into the spiritual realm.