Karmic Relationships I

GA 235

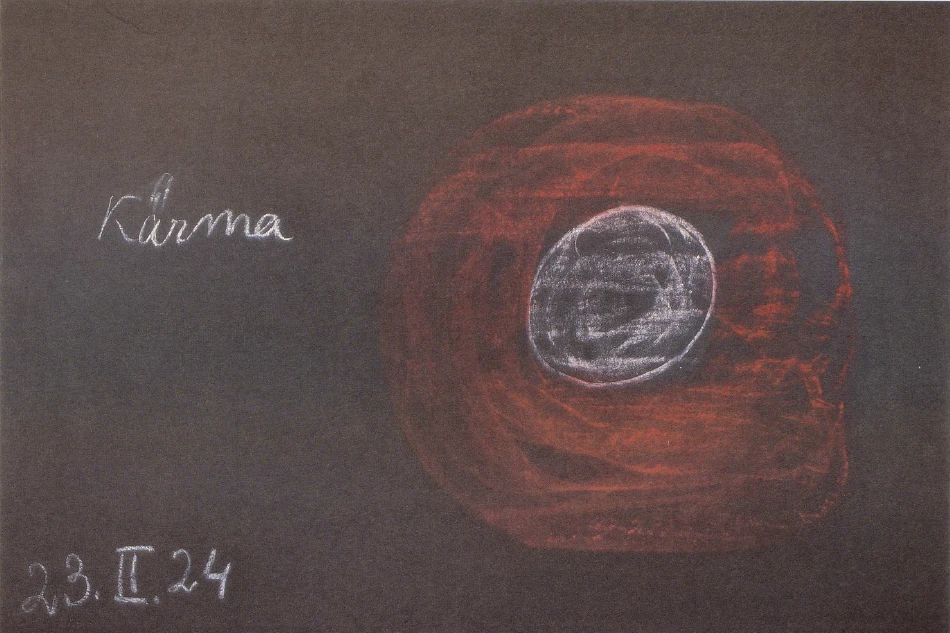

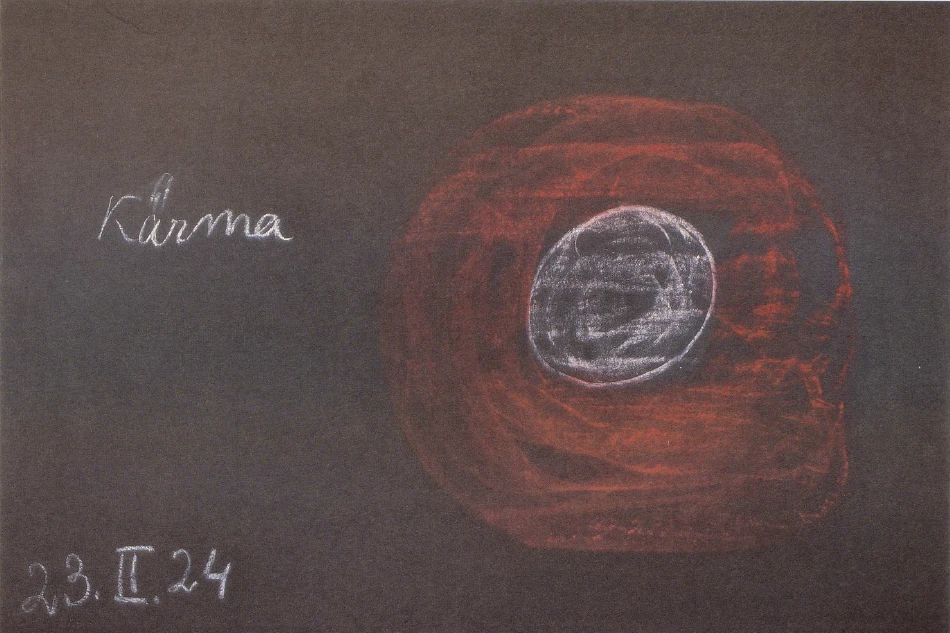

23 February 1924, Dornach

Lecture III

Karma is best understood by contrasting it with the other impulse in man—that impulse which we describe with the word Freedom. Let us first place the question of karma before us, quite crudely, if I may say so. What does it signify? In human life we have to record the fact of reincarnation, successive earthly lives. Feeling ourselves within a given earthly life, we can look back—in thought, at least, to begin with—and see how this present life is a repetition of a number of former earthly lives. It was preceded by another, and that in turn by yet another life on earth, and so on until we get back into the ages where it is impossible to speak of repeated earthly lives as we do in the present epoch of the earth. For as we go farther backward, there begins a time when the life between birth and death and the life between death and a new birth become so similar to one another that the immense difference which exists today between them is no longer there at all. Today we live in our earthly body between birth and death in such a way that in everyday consciousness we feel ourselves quite cut off from the spiritual world. Out of this everyday consciousness men speak of the spiritual world as a “beyond.” They will even speak of it as though they could doubt its existence or deny it altogether.

This is because man's life in earthly existence restricts him to the outer world of the senses, and to the intellect; and intellect does not look far enough to perceive what is, after all, connected with this earthly existence. Hence there arise countless disputations, all of which ultimately have their source in the “unknown.” No doubt you will often have stood between, when people were arguing about Monism, Dualism and the rest ... It is, of course, absurd to argue around these catch-words. When people wrangle in this way, it often seems as though there were some primitive man who had never heard that there is such substance as “air.” To one who knows that air exists, and what its functions are, it will not occur to speak of it as something that is “beyond.” Nor will he think of declaiming: “I am a Monist; I declare that air, water and earth are one. You are a Dualist, because you persist in regarding air as something that goes beyond the earthly and watery elements.”

These things, in fact, are pure nonsense, as indeed all disputes about concepts generally are. Therefore there can be no question of our entering into these arguments. I only wish to point out the significance. For a primitive man who does not yet know of its existence, the air as such is simply absent; it is “beyond,” beyond his ken. Likewise for those who do not yet know it, the spiritual world is a “beyond,” in spite of the fact that it is everywhere present just as the air is. For a man who enters into these things, it is no longer “beyond” or “on the other side,” but “here,” “on this side.”

Thus it is simply a question of our recognising the fact: In the present earthly era, man between birth and death lives in his physical body, in his whole organisation, so that this very organisation gives him a consciousness through which he is cut off from a certain world of causes. But the world of causes, none the less, is working as such into this physical and earthly life. Then, between death and a new birth he lives in another world, which we may call a spiritual world by contrast with this physical. There he has not a physical body, such as could be made visible to human senses; he lives in a spiritual form of being. Moreover, in that life between death and a new birth the world through which he lives between birth and death is in its turn as remote as the spiritual world is remote and foreign for everyday consciousness on earth.

The dead look down on to the physical world just as the living (that is, the physically living) look upward into the spiritual world. But their feelings are reversed, so to speak. In the physical world between birth and death, man has a way of gazing upward, as to another world which grants him fulfilment for very many things which are either deficient or altogether lacking in contentment in this world. It is quite different between death and a new birth. There, there is an untold abundance, a fulness of events. There is always far too much happening compared with what man can bear; therefore he feels a constant longing to return again into the earthly life, which is a “life in the beyond” for him there. In the second half of the life between death and a new birth, he awaits with great longing the passage through birth into a new earth-existence. In earthly existence man is afraid of death because he lives in uncertainty about it, for in the life on earth a great uncertainty prevails for the ordinary consciousness about the after-death. In the life between death and a new birth, on the other hand, man is excessively certain about the earthly life. It is a certainty that stuns him, that makes him actually weak and faint—so that he passes through conditions, like a fainting dream, conditions which imbue him with the longing to come down again to earth.

These are but scant indications of the great difference now prevailing between the earthly life and the life between death and a new birth. Suppose, however, that we now go back, say, no farther back than the Egyptian time—the third to the first millennium before the founding of Christianity. (After all, the men to whom we there go back are but ourselves, in former lives on earth.) In yonder time, the consciousness of man during his earthly life was quite different from ours today, which is so brutally clear, if you will allow me to say so. Truly, the consciousness of the men of today is brutally clear-cut, they are all so clever—I am not speaking ironically—the people of today are clever, all of them. Compared to this terribly clear-cut consciousness, the consciousness of the men of the ancient Egyptian time was far more dream-like. It did not impinge, like ours does, upon outer objects. It rather went its way through the world without “knocking up against” objects. On the other hand, it was filled with pictures which conveyed something of the Spiritual that is there in our environment. The Spiritual, then, still penetrated into man's physical life on earth.

Do not object: “How could a man with this more dream like, and not the clear-cut consciousness of today, have achieved the tremendous tasks which were actually achieved, for instance, in ancient Egypt?” You need not make this objection. You may remember how mad people sometimes reveal, in states of mania, an immense increase of physical strength; they will begin to carry objects which they could never lift when in their full, clear consciousness. Indeed, the physical strength of the men of that time was correspondingly greater; though outwardly they were perhaps slighter in build than the people of today—for, as you know, it does not always follow that a fat man is strong and a thin man physically weak. But they did not spend their earthly life in observing every detail of their physical actions; their physical deeds went parallel with experiences in consciousness into which the spiritual world still entered.

And when the people of that time were in the life between death and a new birth, far more of this earthly life reached upward into yonder life—if I may use the term “upward.” Nowadays it is exceedingly difficult to communicate with those who are in the life between death and a new birth, for the languages themselves have gradually assumed a form such as the dead no longer understand. Our nouns, for instance, soon after death, are absolute gaps in the dead man's perception of the earthly world. He only understands the verbs, the “words of time” as they are called in German—the acting, moving principle. Whereas on earth, materialistically minded people are constantly pulling us up, saying that everything should be defined and every concept well outlined and fixed by clear-cut definition, the dead no longer know of definitions; they only know of what is in movement, they do not know that which has contours and boundaries.

Here again, it was different in ancient times. What lives on earth as speech, and as custom and habit of thought, was of such a kind that it reached up into the life between death and a new birth, and the dead had it echoing in him still, long after his death. Moreover, he also received an echo of what he had experienced on earth and also of the things that were taking place on earth after his death.

And if we go still farther back, into the time following the catastrophe of Atlantis—the 8th or 9th millennium B.C.—the difference becomes even smaller between the life on earth and life in the Beyond, if we may still describe it so. And thence, as we go backward, we gradually get into the times when the two lives were similar. Thereafter, we can no longer speak of repeated earthly lives.

Thus, our repeated lives on earth have their limit when we go backward, just as they have their limit when we look into the future. What we are beginning quite consciously with Anthroposophy today—the penetration of the spiritual world into the normal consciousness of man—will indeed entail this consequence. Into the world which man lives through between death and a new birth, the earthly world will also penetrate increasingly; and yet man's consciousness will not grow dream-like, but clearer and ever clearer. The difference will again grow less. Thus, in effect, our life in repeated incarnations is contained between two outermost limits, past and future. Across these limits we come into quite another kind of human existence, where it is meaningless to speak of repeated earthly lives, because there is not the great difference between the earthly and the spiritual life, which there is today. Now let us concentrate on present earthly time—in the wide sense of the word. Behind our present earthly life, we may assume that there are many others—we must not say countless others, for they can even be counted by exact spiritual scientific investigation. Behind our present earthly life there are, therefore, many others. When we say this, we shall recognise that in those earthly lives we had certain experiences—relationships as between man and man. These relationships as between man and man worked themselves out in the experiences we then underwent; and their effects are with us in our present earthly life, just as the effects of what we do in this life will extend into our coming lives on earth. So then we have to seek in former earthly lives the causes of many things that enter into our life today.

At this point, many people are prone to retort: “If then the things I experience are caused, how can I be free?” It is a really significant question when we consider it in this way. For spiritual observation always shows that our succeeding earthly life is thus conditioned by our former lives. Yet, on the other hand, the consciousness of freedom is absolutely there. Read my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity and you will see: the human being cannot be understood at all unless we realise that the whole life of his soul is oriented towards freedom—filled with the tendency to freedom.

Only, this freedom must be rightly understood. Precisely in my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity you will find a concept of freedom which it is very important to grasp in its true meaning. The point is that we have freedom developed, to begin with, in thought. The fountain-head of freedom is in thought. Man has an immediate consciousness of the fact that he is a free being in his thought. You may rejoin: “Surely there are many people nowadays who doubt the fact of freedom?” Yes, but it only proves that the theoretical fanaticism of people nowadays is often stronger than their direct and real experience. Man is so crammed with theoretical ideas, that he no longer believes in his own experiences. Out of his observations of Nature, he arrives at the idea that everything is conditioned by necessity, every effect has a cause, all that exists has a cause. He does not think of repeated earthly lives in this connection. He imagines that what wells forth in human Thinking is causally determined in the same way as that which proceeds from any machine.

Man makes himself blind by this theory of universal causality, as it is called. He blinds himself to the fact that he has very clearly within him a consciousness of freedom. Freedom is simply a fact which we experience, the moment we reflect upon ourselves at all.

There are those who believe that it is simply the nervous system; the nervous system is there, once and for all, with its property of conjuring thoughts out of itself. According to this, the thoughts would be like the flame whose burning is conditioned by the materials of the fuel. Our thoughts would be necessary results, and there could be no question of freedom.

These people, however, contradict themselves. As I have often related, I had a friend in my youth, who, at a certain period had quite a fanatical tendency to think in a “sound,” materialistic way. “When I walk,” he said, “it is the nerves of' the brain; they contain certain causes to which the effect of my walking is due.” Now and then it led to quite a long debate between us, till at last I said to him on one occasion: “Look now. You also say: ‘I walk.’ Why do you not say, ‘My brain walks?’ If you believe in your theory, you ought never to say: ‘I walk; I take hold of things,’ and so on, but ‘My brain walks; my brain takes hold of them,’ and so on. Why do you go on lying?”

These are the theorists, but there also those who put it into practice. If they observe some failing in themselves which they are not very anxious to throw off, they say, “I cannot throw it off; it is my nature. It is there of its own accord, and I am powerless against it.” There are many like that; they appeal to the inevitable causality of their own nature. But its a rule, they do not remain consistent. If they happen to be showing off something that they rather like about themselves, for which they need no excuse, but on the contrary are glad to receive a little flattery, then they depart from their theory.

The free being of man is a fundamental fact—one of those facts which can be directly experienced. In this respect, however, even in ordinary earthly life it is so: there are many things we do in complete freedom which are nevertheless of such a kind that we cannot easily leave them undone. And yet we do not feel our freedom in the least impaired.

Suppose, for a moment, that you now resolve to build yourself a house. It will take a year to build, let us say. After a year you will begin to live in it. Will you feel it as an encroachment on your freedom that you then have to say to yourself: The house is ready now, and I must move in ... I must live in it; it is a case of compulsion. No. You will surely not feel your freedom impaired by the mere fact that you have built yourself a house. You see, therefore, even in ordinary life the two things stand side by side. You have committed yourself to something. It has thereby become a fact in life—a fact with which you have to reckon.

Now think of all that has originated in former lives on earth, with which you have to reckon because it is due to yourself—just as the building of the house is due to you. Seen in this light, you will not feel your freedom impaired because your present life on earth is determined by former ones.

Perhaps you will say: “Very well. I will build myself a house, but I still wish to remain a free man. I shall not let myself be compelled. If I do not choose to move into the new house after a year, I shall sell it.” Certainly—though I must say, one might also have one's views about such a way of behaving. One might perhaps conclude that you are a person who does not know his own mind. Undoubtedly, one might well take this view of the matter; but let us leave it. Let us not suppose a man is such a fanatical upholder of freedom that he constantly makes up his mind to do things, and afterwards out of sheer “freedom” leaves them undone. Then one might well say: “This man has not even the freedom to go in for the things which he himself resolves upon. He constantly feels the sting of his would-be freedom; he is positively harassed, thrown hither and thither by his fanatical idea of freedom.”

Observe how important it is, not to take these questions in a rigid, theoretic way, but livingly. Now let us pass to a rather more intricate concept. If we ascribe freedom to man, surely we must also ascribe it to the other Beings, whose freedom is unimpaired by human limitations. For, as we rise to the Beings of the Hierarchies, they certainly are not impaired by limitations of human nature. For them indeed we must expect a higher degree of freedom. Now someone might propound a rather strange theological theory—to this effect: God must surely be free. He has arranged the world in a certain way; yet he has thereby committed Himself, He cannot change the World-Order every day. Thus, after all, He is un-free.

You see, you will never escape from a vicious circle if you thus contrast the inner necessity of karma and the freedom which is still an absolute fact of our consciousness, a simple outcome of self-observation. Take once more the illustration of the building of the house. I do not wish to run it to death, but at this point it can still help us along the way. Suppose some person builds himself a house. I will not say suppose I build myself a house, for I shall probably never do so!—But, let us say, some one builds himself a house. By this resolve, he does, in a certain respect, determine his future. Now that the house is finished, and if he takes his former resolve into account, no freedom apparently remains to him, as far as the living in the house is concerned. And though he himself has set this limitation on his freedom, nevertheless, apparently, no freedom is left to him ... But now, I beg you, think how many things there are that you would still be free to do in the house that you had built yourself. Why, you are even free to be stupid or wise in the house, and to be disagreeable or nice to your fellow-men. You are free to get up in the house early or late. There may be other necessities in this respect; but as far as the house is concerned, you are free to get up early or late. You are free to be an anthroposophist or a materialist in the house. In short, there are untold things still at your free disposal.

Likewise in a single human life, in spite of karmic necessity, there are countless things at your free disposal, far more than in a house—countless things fully and really in the domain of your freedom.

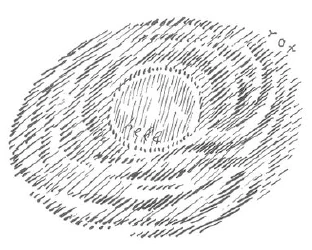

Even here you may still feel able to rejoin: Well and good. We have a certain domain of freedom in our life. Yes, there is a certain enclosed domain of freedom, and all around it, karmic necessity. Looking at this, you might argue: Well, I am free in a certain domain, but I soon get to the limits of my freedom. I feel the karmic necessity on every hand. I go round and round in the room of my freedom, but at the boundaries on every hand I come up against limitations.

Well, my dear friends, if the fish thought likewise, it would be highly unhappy in the water, for as it swims it comes up against the limits of the water. Outside the water, it can no longer live. Hence it refrains from going outside the water. It does not go outside; it stays in the water. It swims around in the water, and whatever is outside the water, it lets it alone; it just lets it be what it is—air, or whatever else. And inasmuch as it does so, I can assure you the fish is not at all unhappy to think that it cannot breathe with lungs. It does not occur to it to be unhappy. But if ever it did occur to the fish to be unhappy because it only breathes with gills and not with lungs, then it would have to have lungs in reserve, so as to compare what it is like to live down in the water, or in the air. Then the whole way the fish feels itself inside, would be quite different. It would all be different.

Let us apply this comparison to human life with respect to freedom and karmic necessity. To begin with, man in the present earthly time has what we call the ordinary consciousness. With this consciousness he lives in the province of his freedom, just as the fish lives in the water. He does not come into the realm of karmic necessity at all, with everyday consciousness. Only when he begins to see the spiritual world (which is as though the fish were to have lungs in reserve)—only when he really lives into the spiritual world—then he begins to perceive the impulses living in him as karmic necessity. Then he looks back into his former lives on earth, and, finding in them the causes of his present experiences, he does not feel: “I am now under compulsion of an iron necessity: my freedom is impaired,” but he looks back and sees how he himself built up what now confronts him. Just as a man who has built himself a house looks back on the resolve which led him to build it ... He generally finds it wiser to ask, was it a sensible or a foolish resolve, to build this house? No doubt, in the event, you may arrive at many different conclusions on this question; but if you conclude that it was a dreadful mistake, you can say at most that you were foolish.

In earthly life this is not a pleasant experience, for when we stand face to face with a thing we have inaugurated, we do not like having to admit that it was foolish. We do not like to suffer from our own foolish mistakes. We wish we had not made the foolish decision. But this really only applies to the one earthly life; because in effect, between the foolishness of the resolve and the punishment we suffer in experiencing its consequences, only the self-same earthly life is intervening. It all remains continuous.

But between one earthly life and another it is not so. For the lives between death and a new birth are always intervening, and they change many things which would not change if earthly life continued uniformly. Suppose that you look back into a former life on earth. You did something good or ill to another man. Between that earthly life and this one, there was the life between death and new birth. In that life, you cannot help realising that you have become imperfect by doing wrong to another human being. It takes away from your own human value. It cripples you in soul. You must make good again this maiming of your soul and you resolve to achieve in a new earthly life what will make good the fault. Thus between death and new birth you take up, by your own will, that which will balance and make good the fault. Or if you did good to another man, you know now that all of man's earthly life is there for mankind as a whole. You see it clearly in the life between death and new birth. If therefore you have helped another man, you realise that he has thereby attained certain things which, without you, he could not have attained in a former life on earth. And you then feel all the more united with him in the life between death and new birth—united with him, to live and develop further what you and he together have attained in human perfection. You seek him again in a new life on earth, to work on thus in a new life precisely by virtue of the way you helped in his perfection.

When therefore, with real spiritual insight, you begin to perceive this encompassing domain, there is no question of your despising or seeking to avoid its necessity. Quite the contrary; for as you now look back on it, you see the nature of the things which you yourself did in the past, so much so that you say to yourself: That which takes place, must take place, out of an inner necessity; and out of the fullest freedom it would have to take place just the same.

In fact it will never happen, under any circumstances, that a real insight into your karma will lead you to be dissatisfied with it. When things arise in the karmic course which you do not like, you need but consider them in relation to the laws and principles of the universe; you will perceive increasingly that after all, what is karmically conditioned is far better—better than if we had to begin anew, like unwritten pages, with every new life on earth. For, in the last resort, we ourselves are our karma. What is it that comes over, karmically, from our former lives on earth? It is actually we ourselves. And it is meaningless to suggest that anything in our karma (adjoining which, remember, the realm of freedom is always there), ought to be different from what it is. In an organic totality you cannot criticise the single details. A person may not like his nose, but it is senseless to criticise the nose as such, for the nose a man has, must be as it is, if the whole man is as he is. A man who says: “I should like to have a different nose,” implies that he would like to be an utterly different man; and in so doing he really wipes himself out in thought—which is surely impossible. Likewise we cannot wipe out our karma, for we are ourselves what our karma is. Nor does it really embarrass us, for it runs alongside the deeds of our freedom it nowhere impairs the deeds of our freedom.

I may here use another comparison to make the point clear. As human beings, we walk. But the ground on which we walk is also there. No man feels embarrassed in walking because the ground is there beneath him. He must know that if the ground were not there, he could not walk at all; he would fall through at every step. So it is with our freedom; it needs the ground of necessity. It must rise out of a given foundation. And this foundation—it is really we ourselves!

Therefore, if you grasp the true concept of freedom and the true concept of karma, you will find them thoroughly compatible, and you need no longer shrink from a detailed study of the karmic laws. In fact, in some instances you will even come to the following conclusion:

Suppose that some one is really able to look back with the insight of Initiation, into former lives on earth. He knows quite well, when he looks back into his former lives, that this and that has happened to him as a consequence. It has come with him into his present life on earth. If he had not attained Initiation Science, objective necessity would impel him to do certain things. He would do them quite inevitably. He would not feel his freedom impaired, for his freedom is in the ordinary consciousness, with which he never penetrates into the realm where the necessity is working—just as the fish never penetrates into the outer air. But when he has attained to Initiation Science, then he looks back; he sees how things were in a former life on earth, and he regards what now confronts him as a task quite consciously allotted for his present life. And so indeed it is.

What I shall now say may sound paradoxical to you, yet it is true. In reality, a man who has no Initiation Science practically always knows, by a kind of inner urge or impulse, what he is to do. Yes, people always know what they must do; they are always feeling impelled to this thing or that. For one who really begins to tread the path of Initiation Science it becomes very different. With regard to the various experiences of life as they confront him, strange questions will arise in him. When he feels impelled to do this or that, immediately again he feels impelled not to do it. There is no more of that dim urge which drives most human beings to this or that line of action. Indeed, at a certain stage of Initiate-insight, if nothing else came instead, a man might easily say to himself: Now that I have reached this insight—being 40 years old, let us say, I had best spend the rest of my life quite indifferently. What do I care? I'll sit down and do nothing, for I have no definite impulses to do anything particular.

You must not suppose, my dear friends, that Initiation is not a reality. It is remarkable how people sometimes think of these things. Of a roast chicken, every one who eats it, well believes that it is a reality. Of Initiation Science, most people believe that its effects are merely theoretical. No, its effects are realities in life, and among them is the one I have just indicated. Before a man has acquired Initiation Science, out of a dark urge within him one thing is always important to him and another unimportant. But now he would prefer to sit down in a chair and let the world run its course, for it really does not matter whether this is done or that is left undone ...

This attitude might easily occur, and there is only one corrective. (For it will not remain so; Initiation Science, needless to say, brings about other effects as well.) The only corrective which will prevent our Initiate from sitting down quiescently, letting the world run its course, and saying: “It is all indifferent to me,” is to look back into his former lives on earth. For he then reads in his karma the tasks for his present earthly life, and does what is consciously imposed upon him by his former lives. He does not leave it undone, with the idea that it encroaches on his freedom, but he does it. Quite on the contrary, he would feel himself unfree if he could not fulfil the task which is allotted to him by his former lives. For in beholding what he experienced in former lives on earth, at the same time he becomes aware of his life between death and a new birth, where he perceived that it was right and reasonable to do the corresponding, consequential actions. (At this point let me say briefly, in parenthesis, that the word “Karma” has come to Europe by way of the English language, and because of its spelling people very often say “Karma” (with broad “ah” sound.) This is incorrect. It should be pronounced “Kärma” (with modified vowel sound.) I have always pronounced the word in this way and I regret that as a result many people have become accustomed to using the dreadful word “Kirma”. For some time now you will have heard even very sincere students saying “Kirma.” It is dreadful).

Thus, neither before nor after Initiation Science is there a contradiction between karmic necessity and freedom.

Once more, then: neither before nor after the entry of Initiation Science is there a contradiction between necessity—karmic necessity—and freedom. Before it there is none, because with everyday consciousness man remains within the realm of freedom, while karmic necessity goes on outside this realm, like any process of Nature. There is nothing in him to feel differently from what his own nature impels. Nor is there any contradiction after the entry of Initiation Science, for he is then quite in agreement with his karma, he thinks it only sensible to act according to it. Just as when you have built yourself a house and it is ready after a year, you do not say: the fact that you must now move in is an encroachment on your freedom. You will more probably say: Yes, on the whole it was quite sensible to build yourself a house in this neighbourhood and on this site. Now see to it that you are free in the house! Likewise he who looks back with Initiate-knowledge into his former lives on, earth: he knows that he will become free precisely by the fulfilling of his karmic task-moving into the house which he built for himself in former lives on earth.

Thus, my dear friends, I wanted to explain to you the true compatibility of freedom and karmic necessity in human life. Tomorrow we shall continue, entering more into the details of karma.

Dritter Vortrag

Wie es mit dem Karma steht, sieht man am besten ein, wenn man den anderen Impuls im Menschenleben dagegenstellt, jenen Impuls, den man mit dem Worte Freiheit bezeichnet. Legen wir zunächst einmal, ich möchte sagen, ganz im groben uns die Karmafrage vor. Was bedeutet sie? Wir haben im Menschenleben aufeinanderfolgende Erdenleben zu verzeichnen. Indem wir uns erfühlen in einem bestimmten Erdenleben, können wir zunächst, wenigstens in Gedanken, zurückblicken darauf, wie dieses gegenwärtige Erdenleben die Wiederholung ist von einer Anzahl vorangehender. Diesem Erdenleben ging ein anderes, diesem wieder ein anderes voran, bis wir in diejenigen Zeiten zurückkommen, in denen es unmöglich ist, in der Art, wie es in der gegenwärtigen Erdenzeit der Fall ist, so von wiederholten Erdenleben zu sprechen, weil dann rückwärtslaufend eine Zeit beginnt, wo allmählich das Leben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode und das zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt einander so ähnlich werden, daß jener gewaltige Unterschied, der heute besteht, nicht mehr da ist. Heute leben wir in unserem irdischen Leibe zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode so, daß wir uns mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein stark abgeschlossen fühlen von der geistigen Welt. Die Menschen sprechen aus diesem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein heraus von dieser geistigen Welt wie von einem Jenseitigen. Die Menschen kommen dazu, von dieser geistigen Welt so zu sprechen, als ob sie sie in Zweifel ziehen könnten, als ob sie sie ganz ableugnen könnten und so fort.

Das alles kommt davon her, weil das Leben innerhalb des Erdendaseins den Menschen auf die äußere Sinnenwelt und auf den Verstand beschränkt, der nicht hinaussieht auf das, was nun wirklich mit diesem Erdendasein zusammenhängt. Daher rühren allerlei Streitigkeiten, die eigentlich alle in einem Unbekannten wurzeln. Sie werden ja oftmals darinnen gestanden und erlebt haben, wie die Leute sich stritten: Monismus, Dualismus und so weiter. Es ist natürlich ein völliger Unsinn, über derlei Schlagworte zu streiten. Es berührt einen so, wenn in dieser Weise gestritten wird, als wenn, sagen wir, irgendein primitiver Mensch noch niemals etwas gehört hat davon, daß es eine Luft gibt. Es wird demjenigen, der da weiß, daß es eine Luft gibt, und was die Luft für Aufgaben hat, nicht einfallen, die Luft als etwas Jenseitiges anzusprechen. Es wird ihm auch nicht einfallen zu sagen: Ich bin ein Monist, Luft und Wasser und Erde sind eins; und du bist ein Dualist, weil du in der Luft noch etwas siehst, was über das Irdische und Wässerige hinausgeht.

Alle diese Dinge sind eben einfach Unsinn, wie alles Streiten um Begriffe zumeist ein Unsinn ist. Also, es kann sich gar nicht darum handeln, gerade auf diese Dinge einzugehen, sondern es kann sich nur darum handeln, darauf aufmerksam zu machen. Denn geradeso wie für den, der noch keine Luft kennt, die Luft eben nicht da ist, sondern ein Jenseitiges ist, so ist für diejenigen, die noch nicht die geistige Welt kennen, die auch überall da ist geradeso wie die Luft, diese geistige Welt eine jenseitige; für den, der auf die Dinge eingeht, ist sie ein Diesseitiges. Also es handelt sich darum, bloß anzuerkennen, daß der Mensch in der heutigen Erdenzeit zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode so in seinem physischen Leibe, in seiner ganzen Organisation lebt, daß ihm diese Organisation ein Bewußtsein gibt, durch das er in einem gewissen Sinne abgeschlossen ist von einer gewissen Welt von Ursachen, die aber als solche hereinwirkt in dieses physische Erdendasein.

Dann lebt er zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt in einer anderen Welt, die man eine geistige gegenüber unserer physischen Welt nennen kann, in der er nicht einen physischen Leib hat, der für Menschensinne sichtbar gemacht werden kann, sondern in der er in einem geistigen Wesen lebt; und in diesem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt ist die Welt, die man durchlebt zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, wiederum eine so fremde, wie jetzt die geistige Welt eine fremde ist für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein.

Der Tote schaut herunter auf die physische Welt, so wie der Lebende, das heißt der physisch Lebende, in die geistige Welt hinaufschaut, und es sind nur die Gefühle sozusagen die umgekehrten. Während der Mensch zwischen Geburt und Tod hier in der physischen Welt ein gewisses Aufschauen hat zu einer anderen Welt, die ihm Erfüllung gibt für manches, was hier in dieser Welt entweder zu wenig ist oder ihm keine Befriedigung gewährt, so muß der Mensch zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt wegen der ungeheuren Fülle der Ereignisse, deshalb, weil immer zuviel geschieht im Verhältnis zu dem, was der Mensch ertragen kann, die fortdauernde Sehnsucht empfinden, wiederum zurückzukehren zum Erdenleben, zu dem, was dann für ihn das jenseitige Leben ist, und er erwartet mit großer Sehnsucht in der zweiten Hälfte des Lebens zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt den Durchgang durch die Geburt in das Erdendasein. So wie er sich im Erdendasein fürchtet vor dem Tode, weil er in Ungewißheit ist über das, was nach dem Tode ist — es herrscht ja im Erdendasein eine große Ungewißheit für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein -, so herrscht in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt über das . Erdenleben eine übergroße Gewißheit, eine Gewißheit, die betäubt, eine Gewißheit, die geradezu ohnmächtig macht. So daß der Mensch ohnmachts-traumähnliche Zustände hat, die ihm die Sehnsucht eingeben, wiederum zur Erde herunterzukommen.

Das sind nur einige Andeutungen über die große Verschiedenheit, die zwischen dem Erdenleben und dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt herrscht. Aber wenn wir nun zurückgehen, sagen wir selbst nur in die ägyptische Zeit, vom 3. bis ins 1. Jahrtausend vor der Begründung des Christentums, wir gehen ja zurück zu denjenigen Menschen, die wir selber in einem früheren Erdenleben waren, wenn wir in diese Zeit zurückgehen, da war das Leben während des Erdendaseins gegenüber unserem jetzigen so brutal klaren Bewußtsein — und gegenwärtig haben ja die Menschen ein brutal klares Bewußtsein, sie sind alle so gescheit, die Menschen, ich meine das gar nicht ironisch, sie sind wirklich alle sehr gescheit, die Menschen -, gegenüber diesem brutal klaren Bewußtsein war das Bewußtsein der Menschen in der alten ägyptischen Zeit ein mehr traumhaftes, ein solches, das nicht sich stieß in derselben Weise wie heute an den äußeren Gegenständen, das mehr durch die Welt durchging, ohne sich zu stoßen, dafür aber erfüllt war von Bildern, die zu gleicher Zeit etwas vom Geistigen verrieten, das in unserer Umgebung ist. Das Geistige ragte noch herein ins physische Erdendasein.

Sagen Sie nicht: Wie soll der Mensch, wenn er ein solches mehr traumhaftes, nicht brutal klares Bewußtsein hat, die starken Arbeiten haben verrichten können, die zum Beispiel während der ägyptischen oder chaldäischen Zeit verrichtet worden sind? Da brauchen Sie sich ja nur daran zu erinnern, daß bisweilen Verrückte gerade in gewissen Irrsinnszuständen ein ungeheures Wachstum ihrer physischen Kräfte haben und anfangen, Dinge zu tragen, die sie mit vollem klarem Bewußtsein nicht tragen können. Es war in der Tat auch die physische Stärke dieser Menschen, die vielleicht äußerlich sogar schmächtiger waren als die heutigen Menschen - aber es ist ja nicht immer der Dicke stark und der Dünne schwach -, es war auch die physische Stärke der Menschen entsprechend größer. Nur verwendeten sie dieses Dasein nicht so, daß sie alles einzelne, was sie physisch taten, beobachteten, sondern parallel gingen diesen physischen Taten die Erlebnisse, in die noch die geistige Welt hereinragte.

Und wiederum, wenn diese Menschen in dem Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt waren, da kam viel mehr von diesem irdischen Leben in jenes Leben hinauf, wenn ich mich des Ausdruckes «hinauf» bedienen darf. Heute ist es mit den Menschen, die sich im Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt befinden, außerordentlich schwer, sich zu verständigen, denn die Sprachen schon haben allmählich eine Gestalt angenommen, die von den Toten nicht mehr verstanden wird. Unsere Substantiva zum Beispiel bedeuten in der Auffassung der Toten vom Irdischen bald nach dem Tode absolute Lücken. Sie verstehen nur noch die Verben, die Zeitwörter, das Bewegte, das Tätige. Und während wir hier auf der Erde immerfort von den materialistisch gesinnten Leuten aufmerksam gemacht werden, es solle alles ordentlich definiert werden, man solle jeden Begriff scharf definierend begrenzen, kennt der Tote überhaupt keine Definitionen mehr; denn er kennt nur dasjenige, was in Bewegung ist, nicht das, was Konturen hat und begrenzt ist.

Aber in älteren Zeiten war eben auch dasjenige, was auf der Erde als Sprache lebte, was als Denkgebrauch, als Denkgewohnheit lebte, noch so, daß es hinaufragte in das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, so daß der Tote noch lange nach seinem Tode einen Nachklang hatte von demjenigen, was er hier auf der Erde erlebt hatte, und auch von dem, was nach seinem Tode noch auf der Erde vorging.

Und wenn wir noch weiter zurückgehen, in die Zeit nach der atlantischen Katastrophe, ins 8., 9. Jahrtausend vor der christlichen Zeitrechnung, dann werden die Unterschiede noch geringer zwischen dem Leben auf der Erde und dem Leben — wenn wir so sagen dürfen — im Jenseits. Und dann kommen wir allmählich zurück in diejenigen Zeiten, wo die beiden Leben einander ganz ähnlich sind. Dann kann man nicht mehr sprechen von wiederholten Erdenleben.

Also die wiederholten Erdenleben haben ihre Grenze, wenn man nach rückwärts schaut. Ebenso werden sie eine Grenze haben, wenn man nach vorwärts in die Zukunft schaut. Denn das, was ganz bewußt mit Anthroposophie beginnt, daß in das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein hereinragen soll die geistige Welt, das wird zur Folge haben, daß auch wiederum in die Welt, die man durchlebt zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, diese Erdenwelt mehr hineinragt, aber trotzdem das Bewußtsein nicht traumhaft, sondern klarer werden wird, immer klarer und klarer werden wird. Der Unterschied wird wiederum geringer werden. So daß man dieses Leben in den wiederholten Erdenleben begrenzt hat zwischen den äußeren Grenzen, die dann in ein ganz andersgeartetes Dasein des Menschen hineinführen, wo es keinen Sinn hat, von den wiederholten Erdenleben zu sprechen, weil eben die Differenz zwischen dem Erdenleben und dem geistigen Leben nicht so groß ist, wie sie jetzt ist.

Wenn man aber nun einmal für die weite Gegenwart der Erdenzeit annimmt, hinter diesem Erdenleben liegen viele andere -— man darf gar nicht sagen unzählige andere, denn sie lassen sich bei einer genauen geisteswissenschaftlichen Untersuchung sogar zählen -, dann haben wir in diesen früheren Erdenleben bestimmte Erlebnisse gehabt, welche Verhältnisse von Mensch zu Mensch darstellten. Und die Wirkungen dieser Verhältnisse von Mensch zu Mensch, die sich damals eben in dem auslebten, was man durchmachte, die stehen in diesem Erdenleben geradeso da, wie die Wirkungen dessen, was wir in diesem jetzigen Erdenleben verrichten, sich hineinerstrecken in die nächsten Erdenleben. Wir haben also die Ursachen für vieles, was jetzt in unser Leben tritt, in früheren Erdenleben zu suchen. Da wird sich der Mensch leicht sagen: Also ist dasjenige, was er jetzt erlebt, bedingt, verursacht. Wie kann er dann ein freier Mensch sein?

Nun, die Frage ist schon, wenn man sie so betrachtet, eine ziemlich bedeutsame; denn alle geistige Beobachtung zeigt eben, daß in dieser Weise das folgende Erdenleben durch die früheren bedingt ist. Auf der anderen Seite ist das Bewußtsein der Freiheit ganz unbedingt da. Und wenn Sie meine «Philosophie der Freiheit» lesen, so werden Sie sehen, daß man den Menschen gar nicht verstehen kann, wenn man nicht sich klar darüber ist, daß sein ganzes Seelenleben hintendiert, hingerichtet ist, hinorientiert ist auf die Freiheit, aber auf eine Freiheit, die man eben richtig zu verstehen hat.

Nun werden Sie gerade in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» eine Idee der Freiheit finden, die aufzufassen im rechten Sinne außerordentlich wichtig ist. Es handelt sich dabei darum, daß man die Freiheit entwickelt hat zunächst im Gedanken. Im Gedanken geht der Quell der Freiheit auf. Der Mensch hat einfach ein unmittelbares Bewußtsein davon, daß er im Gedanken ein freies Wesen ist.

Sie können sagen: Aber es gibt doch viele Menschen heute, welche die Freiheit bezweifeln. — Das ist nur ein Beweis dafür, daß heute der theoretische Fanatismus der Menschen größer ist als das, was der Mensch unmittelbar in der Wirklichkeit erlebt. Der Mensch glaubt ja nicht mehr an seine Erlebnisse, weil er vollgepfropft ist mit theoretischen Anschauungen. Der Mensch bildet sich heute aus der Beobachtung der Naturvorgänge die Idee: Alles ist notwendig bedingt, jede Wirkung hat eine Ursache, alles, was da ist, hat seine Ursache. Also, wenn ich einen Gedanken fasse, hat das auch eine Ursache. An die wiederholten Erdenleben denkt man gar nicht gleich, sondern man denkt daran, daß dasjenige, was aus einem Gedanken hervorquillt, ebenso verursacht ist wie das, was aus einer Maschine hervorgeht.

Durch diese Theorie von der allgemeinen Kausalität, wie man es nennt, von der allgemeinen Verursachung, durch diese Theorie macht sich der Mensch heute vielfach blind dagegen, daß er deutlich in sich das Bewußtsein der Freiheit trägt. Die Freiheit ist eine Tatsache, die erlebt wird, sobald man nur wirklich zur Selbstbesinnung kommt.

Nun gibt es auch Menschen, die da der Anschauung sind, daß nun einmal das Nervensystem eben ein Nervensystem ist und aus sich die Gedanken herauszaubert. Dann wären die Gedanken natürlich gerade so, sagen wir, wie die Flamme, die unter dem Einflusse des Brennstoffes brennt, notwendige Ergebnisse, und von Freiheit könnte nicht die Rede sein.

Aber diese Menschen widersprechen sich ja, indem sie überhaupt reden. Ich habe schon öfters hier erzählt: Ich hatte einen Jugendfreund, der in einer gewissen Zeit einen Fanatismus hatte, dahingehend, recht materialistisch zu denken, und so sagte er auch: Wenn ich gehe, zum Beispiel, da sind es meine Gehirnnerven, die von gewissen Ursachen durchzogen sind, die bringen die Wirkung des Gehens hervor. — Das konnte unter Umständen eine lange Debatte abgeben mit diesem Jugendfreund. Ich sagte ihm zuletzt einmal: Ja, aber sieh einmal, du sagst doch, ich gehe. Warum sagst du denn nicht: mein Gehirn geht? Wenn du wirklich an deine 'Theorie glaubst, so mußt du niemals sagen: Ich gehe, ich greife, sondern: Mein Gehirn greift, mein Gehirn geht. Also, warum lügst du denn?

Das sind mehr die Theoretiker. Es gibt nun auch Praktiker. Wenn sie irgendeinen Unfug an sich bemerken, den sie nicht abstellen wollen, dann sagen sie: Ja, das kann ich nicht abstellen, das ist nun einmal so meine Natur. Es kommt von selber, ich bin machtlos dagegen. — Solche Menschen gibt es viele. Sie berufen sich auf die unabänderliche Verursachung ihres Wesens. Sie werden nur meistens unkonsequent, wenn sie einmal etwas zur Schau tragen, was sie haben möchten an sich, wofür sie keine Entschuldigung brauchen, sondern wofür sie eine Belobigung wünschen; dann gehen sie ab von dieser Anschauung.

Die Grundtatsache des freien Menschenwesens, die ist eben eine solche Tatsache, sie kann unmittelbar erlebt werden. Nun ist schon im gewöhnlichen Erdenleben die Sache so, daß wir vielerlei Dinge tun, in voller Freiheit tun, und eigentlich sie wiederum so liegen, diese Dinge, daß wir sie nicht gut ungetan sein lassen können. Trotzdem fühlen wir unsere Freiheit dadurch nicht beeinträchtigt.

Nehmen Sie einmal an, Sie fassen jetzt den Beschluß, sich ein Haus zu bauen. Das Haus braucht, um erbaut zu werden, meinetwillen ein Jahr. Sie werden nach einem Jahre drinnen wohnen. Werden Sie Ihre Freiheit dadurch beeinträchtigt fühlen, daß Sie sich dann sagen müssen: Jetzt ist das Haus da, ich muß da herein, ich muß da drinnen wohnen - das ist doch Zwang! - Sie werden Ihre Freiheit nicht beeinträchtigt fühlen dadurch, daß Sie sich ein Haus gebaut haben.

Diese zwei Dinge bestehen durchaus nebeneinander auch schon im gewöhnlichen Leben: daß man sozusagen sich für etwas engagiert hat, was dann Tatsache geworden ist im Leben, mit dem man rechnen muß.

Nehmen Sie nun alles das, was aus früheren Erdenleben stammt, alles das, womit Sie eben rechnen müssen, weil es ja von Ihnen herrührt, geradeso wie der Hausbau von Ihnen herrührt, dann werden Sie dadurch, daß Ihr gegenwärtiges Erdenleben von früheren Erdenleben her bestimmt ist, keine Beeinträchtigung Ihrer Freiheit empfinden.

Nun können Sie sagen: Ja, gut, ich baue mir ein Haus, aber ich will doch ein freier Mensch bleiben, ich will mich dadurch nicht zwingen lassen. Ich werde, wenn es mir nicht gefällt, nach einem Jahre eben nicht in dieses Haus einziehen, werde es verkaufen. — Schön! Man könnte darüber auch seine Ansicht haben, man könnte die Ansicht haben, daß Sie nicht recht wissen, was Sie eigentlich wollen im Leben, wenn Sie das tun. Gewiß, diese Ansicht könnte man auch haben; aber sehen wir ab von dieser Ansicht. Sehen wir ab davon, daß jemand ein Fanatiker der Freiheit ist und sich fortwährend Dinge vornimmt, die er dann aus Freiheit unterläßt. Man könnte dann sagen: Der Mann hat nicht einmal die Freiheit, auf dasjenige einzugehen, was er sich vorgenommen hat. Er steht unter dem fortwährenden Stachel, frei sein zu wollen, und wird geradezu gehetzt von diesem Freiheitsfanatismus.

Es handelt sich wirklich darum, daß diese Dinge nicht starr theoretisch gefaßt werden, sondern daß sie lebensvoll gefaßt werden. Und gehen wir jetzt, ich möchte sagen, zu einem komplizierteren Begriffe über. Wenn wir dem Menschen Freiheit zuschreiben, so müssen wir ja den anderen Wesen, die nicht beeinträchtigt sind in ihrer Freiheit durch die Schranken der Menschennatur — wenn wir zu den Wesen hinaufgehen, die den höheren Hierarchien angehören, so sind die ja nicht beeinträchtigt durch die Schranken der Menschennatur -, da müssen wir die Freiheit bei ihnen sogar in einem höheren Grade suchen. Nun könnte jemand eine eigentümliche theologische Theorie aufstellen, könnte sagen: Aber Gott muß doch frei sein! Und doch hat er ja die Welt in einer gewissen Weise eingerichtet. Dadurch ist er aber doch engagiert, er kann doch nicht jeden Tag die Weltordnung ändern; also wäre er doch unfrei.

Sehen Sie, wenn Sie in dieser Weise die innere karmische Notwendigkeit und die Freiheit, die eine Tatsache unseres Bewußtseins ist, die einfach ein Ergebnis der Selbstbeobachtung ist, gegeneinanderstellen, so kommen Sie aus einem fortwährenden Zirkel gar nicht heraus. Auf diese Weise kommen sie aus einem Zirkel gar nicht heraus. Denn die Sache ist diese: Nehmen Sie einmal - ich will das Beispiel zwar nicht tottreten, aber es kann uns doch noch auf die weitere Fährte führen -, nehmen Sie noch einmal das Beispiel vom Hausbau. Also jemand baut sich ein Haus. Ich will nicht sagen, ich baue mir ein Haus - ich werde mir wahrscheinlich niemals eins bauen -, aber sagen wir, jemand baut sich ein Haus. Nun, durch diesen Entschluß bestimmt er in einer bestimmten Weise seine Zukunft. Nun bleibt ihm für diese Zukunft, wenn das Haus fertig ist und er mit seinem früheren Entschluß rechnet, für das Drinnenwohnen scheinbar keine Freiheit. Er hat sie sich freilich selber beschränkt, diese Freiheit; aber es bleibt ihm scheinbar keine Freiheit.

Aber denken Sie, für wievieles Ihnen dann noch innerhalb dieses Hauses doch Freiheit bleibt! Es steht Ihnen sogar frei, darinnen dumm oder gescheit zu sein. Es steht Ihnen frei, darinnen mit Ihren Mitmenschen ekelhaft oder liebevoll zu sein. Es steht Ihnen frei, darinnen früh oder spät aufzustehen. Vielleicht hat man dafür andere Notwendigkeiten, aber jedenfalls steht es Ihnen in bezug auf den Hausbau frei, früh oder spät aufzustehen. Es steht Ihnen frei, darinnen Anthroposoph oder Materialist zu sein. Kurz, es gibt unzählige Dinge, die Ihnen dann noch immer freistehen.

Geradeso gibt es im einzelnen Menschenleben, trotzdem die karmische Notwendigkeit vorliegt, unzählige Dinge, viel mehr als in einem Haus, unzählige Dinge, die einem freistehen, die wirklich ganz im Bereiche der Freiheit liegen.

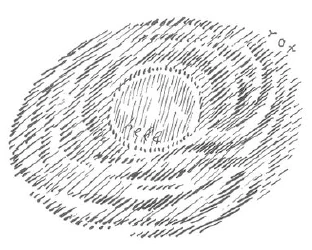

Nun werden Sie vielleicht weiter sagen können: Gut, dann haben wir also im Leben einen gewissen Bereich von Freiheit. Den will ich hier in der Zeichnung hell machen, weil ihn die Menschen gern haben, und ringsherum die karmische Notwendigkeit (siehe Zeichnung, rot). Ja, die ist nun auch da! Also ein gewisser eingeschlossener Bereich von Freiheit, ringsherum die karmische Notwendigkeit.

Nun, dieses anschauend, können Sie folgendes geltend machen. Sie können sagen: Nun ja, jetzt bin ich in einem gewissen Bezirke frei; aber nun komme ich an die Grenze meiner Freiheit. Da empfinde ich überall die karmische Notwendigkeit. Ich gehe in meinem Freiheitszimmer herum, aber überall an den Grenzen komme ich an meine karmische Notwendigkeit und empfinde diese karmische Notwendigkeit.

Ja, meine lieben Freunde, wenn der Fisch ebenso dächte, so wäre er höchst unglücklich im Wasser, denn er kommt, wenn er im Wasser schwimmt, an die Grenze des Wassers. Außerhalb dieses Wassers kann er nicht mehr leben. Daher unterläßt er es, außerhalb des Wassers zu gehen. Er geht gar nicht außerhalb des Wassers. Er bleibt im Wasser, er schwimmt im Wasser herum und läßt das andere, was außer dem Wasser ist, Luft sein, oder was es eben ist. Und aus dem Grunde, weil der Fisch das tut, kann ich Ihnen die Versicherung abgeben, daß der Fisch gar nicht unglücklich ist darüber, daß er nicht mit Lungen atmen kann. Er kommt gar nicht darauf, unglücklich zu sein. Wenn aber der Fisch darauf kommen sollte, unglücklich zu sein darüber, daß er nur mit Kiemen atmet und nicht mit Lungen atmet, da müßte er Lungen in der Reserve haben, und da müßte er vergleichen, wie es ist, unter dem Wasser zu leben und in der Luft zu leben. Und dann wäre die ganze Art, wie der Fisch sich innerlich fühlt, anders. Es wäre alles anders.

Wenden wir den Vergleich auf das Menschenleben in bezug auf Freiheit und karmische Notwendigkeit an, dann ist das so, daß ja zunächst der Mensch in der gegenwärtigen Erdenzeit das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein hat. Mit diesem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein lebt er im Bezirk der Freiheit, so wie der Fisch im Wasser lebt, und er kommt gar nicht mit diesem Bewußtsein in das Reich der karmischen Notwendigkeit herein. Erst wenn der Mensch anfängt, die geistige Welt wirklich wahrzunehmen — was so wäre, wie wenn der Fisch Lungen in Reserve hätte -, und erst dann, wenn der Mensch wirklich in die geistige Welt sich einlebt, dann bekommt er eine Anschauung von den Impulsen, die als karmische Notwendigkeit in ihm leben. Und dann schaut er in seine früheren Erdenleben zurück und empfindet nicht, sagt nicht, indem er aus dem früheren Erdenleben herüber die Ursachen für gegenwärtige Erlebnisse hat: Ich bin jetzt unter dem Zwang einer eisernen Notwendigkeit und meine Freiheit ist beeinträchtigt —, sondern er schaut zurück, wie er selber sich dasjenige, was jetzt vorliegt, zusammengezimmert hat, so wie einer, der sich ein Haus gebaut hat, auf den Entschluß zurückschaut, der zum Bau dieses Hauses geführt hat. Und dann finder man es gewöhnlich gescheiter, zu fragen: War dazumal das ein vernünftiger Entschluß, das Haus zu bauen, oder ein unvernünftiger? — Nun, da kann man natürlich allerlei Ansichten später darüber gewinnen, wenn sich die Dinge herausstellen, gewiß; aber man kann höchstens, wenn man findet, daß es eine riesenhafte Torheit war, sich das Haus zu bauen, man kann höchstens sagen, daß man töricht gewesen ist.

Nun, im Erdenleben, da ist das so eine Sache, wenn man sich in bezug auf irgendein Ding, das man inauguriert hat, sagen muß, es war töricht. Man hat das nicht gern. Man leidet nicht gern unter seinen Torheiten. Man möchte, daß man den Entschluß nicht gefaßt hätte. Aber das bezieht sich nämlich auch nur auf das eine Erdenleben, weil nämlich zwischen der Torheit des Entschlusses und der Strafe, die man dafür hat, indem man die Konsequenzen dieser Torheit erleben muß, das gleichartige Erdenleben dazwischen ist. Es bleibt immer so.

So ist es aber nicht zwischen den einzelnen Erdenleben. Da sind immer dazwischen die Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, und diese Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, die ändern manches, was sich nicht ändern würde, wenn das Erdenleben sich in gleichartiger Weise fortsetzte. Nehmen Sie nur an, Sie schauen zurück in ein früheres Erdenleben. Da haben Sie irgendeinem Menschen Gutes oder Böses angetan. Das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt war zwischen diesem vorigen Erdenleben und dem jetzigen Erdenleben. In diesem Leben, in diesem geistigen Leben können Sie gar nicht anders denken als: Sie sind unvollkommen geworden dadurch, daß Sie einem Menschen irgend etwas Böses zugefügt haben. Das nimmt etwas weg von Ihrem Menschenwert, das macht Sie seelisch verkrüppelt. Sie müssen die Verkrüppelung wiederum ausbessern, und Sie fassen den Entschluß, im neuen Erdenleben dasjenige zu erringen, was den Fehler ausbessert. Sie nehmen zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt dasjenige, was den Fehler ausgleicht, durch Ihren eigenen Willen auf. Haben Sie einem Menschen etwas Gutes zugefügt, dann wissen Sie, daß das ganze menschliche Erdenleben — das sieht man insbesondere in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt -, daß das ganze Erdenleben für die gesamte Menschheit da ist. Und dann kommen Sie darauf, daß, wenn Sie einen Menschen gefördert haben, er in der Tat ja dadurch gewisse Dinge errungen hat, die er ohne Sie nicht errungen hätte in einem früheren Erdenleben. Aber Sie fühlen sich dadurch wiederum in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt mit ihm vereinigt, um dasjenige, was Sie mit ihm zusammen in bezug auf menschliche Vollkommenbheit erreicht haben, nun weiter auszuleben. Sie suchen ihn wieder auf im neuen Erdenleben, um gerade durch die Art und Weise, wie Sie ihn vervollkommnet haben, weiter zu wirken im neuen Erdenleben.

Also es handelt sich gar nicht darum, daß man etwa, wenn man nun den Bezirk der karmischen Notwendigkeiten ringsherum durch eine wirkliche Einsicht in die geistige Welt wahrnimmt, diese Notwendigkeiten verabscheuen könnte, sondern es handelt sich darum, daß man dann zurücksieht auf diese Notwendigkeiten, wie die Dinge waren, die man da selber verrichtet hat, und sie so anschaut, daß man sich sagt: Es muß dasjenige geschehen — aus voller Freiheit auch müßte das geschehen -, was aus einer inneren Notwendigkeit heraus geschieht.

Man wird eben niemals den Fall erleben, daß man bei einer wirklichen Einsicht in das Karma mit diesem Karma nicht einverstanden ist. Wenn sich im Karma Dinge ergeben, die einem nicht gefallen, dann sollte man sie eben aus der allgemeinen Gesetzmäßigkeit der Welt heraus betrachten. Und da kommt man immer mehr darauf, daß zuletzt doch dasjenige, was karmisch bedingt ist, besser ist, als wenn wir mit jedem neuen Erdenleben neu anfangen müßten, mit jedem neuen Erdenleben voller unbeschriebener Blätter wären. Denn wir sind eigentlich unser Karma selber. Das, was da herüberkommt aus früheren Erdenleben, das sind wir eigentlich selber, und es hat gar keinen Sinn, davon zu sprechen, daß irgend etwas in unserem Karma, neben dem eben der Bezirk der Freiheit durchaus da ist, daß irgend etwas in unserem Karma anders sein sollte, als es ist, weil überhaupt in einem gesetzmäßig zusammenhängenden Ganzen das einzelne gar nicht kritisiert werden kann. Es kann jemandem seine Nase nicht gefallen; aber es hat gar keinen Sinn, bloß die Nase an sich zu kritisieren, denn die Nase, die man hat, muß tatsächlich so sein, wie sie ist, wenn der ganze Mensch so ist, wie er ist. Und derjenige, der sagt, ich möchte eine andere Nase haben, der sagt eigentlich damit, er möchte ein ganz anderer Mensch sein. Aber damit schafft er sich in Gedanken selber weg. Man kann das doch nicht.

So können wir auch unser Karma nicht wegschaffen, denn wir sind das, was unser Karma ist, selber. Es beirrt uns aber auch gar nicht, denn es verläuft durchaus neben den Taten unserer Freiheit, beeinträchtigt nirgends die Taten unserer Freiheit.

Ich möchte einen anderen Vergleich noch gebrauchen, der das klar macht. Wir gehen als Menschen; aber es ist doch der Boden da, auf dem wir gehen. Kein Mensch fühlt sich in seinem Gehen beeinträchtigt dadurch, daß unter ihm der Boden ist. Ja er sollte sogar wissen, wenn der Boden nicht da wäre, könnte er nicht gehen, er würde überall herunterfallen. So ist es mit unserer Freiheit. Die braucht den Boden der Notwendigkeit. Die muß sich heraus erheben aus einem Untergrunde.

Dieser Untergrund, wir sind es selbst. Sobald man in der richtigen Weise den Freiheitsbegriff und den Begriff des Karmas faßt, wird man sie durchaus miteinander vereinbaren können. Und dann braucht man auch nicht mehr davor zurückzuschrecken, diese karmische Notwendigkeit durch und durch zu betrachten. Ja, man kommt sogar dazu, in gewissen Fällen das Folgende sich zu sagen: Ich setze jetzt voraus, irgend jemand kann durch die Initiationseinsicht in frühere Erdenleben zurückschauen. Wenn er in frühere Erdenleben zurückschaut, weiß er dadurch ganz genau, daß ihm dieses oder jenes geschehen ist, was in dieses Erdenleben mit hereingekommen ist. Wäre er nicht zur Initiationswissenschaft gekommen, dann würde eine objektive Notwendigkeit ihn drängen, gewisse Dinge zu tun. Er täte sie unweigerlich. Seine Freiheit würde er ja dadurch nicht beeinträchtigt fühlen, denn seine Freiheit liegt im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein. Mit dem reicht er gar nicht herein in die Region, wo diese Notwendigkeit wirkt, geradeso wie der Fisch nicht an die äußere Luft kommt. Aber wenn er die Initiationswissenschaft in sich hat, dann sieht er zurück, sieht, wie das war in einem vorigen Erdenleben, und betrachtet dasjenige, was da ist, als eine Aufgabe, die ihm für dieses Erdenleben bewußt zugeteilt ist. Es ist auch so.

Sehen Sie, derjenige, der keine Initiationswissenschaft hat, der weiß eigentlich immer — ich sage jetzt etwas, was Ihnen etwas paradox erscheinen wird, was aber doch so ist — durch einen gewissen inneren Drang, durch einen Trieb, was er tun soll. Ach, die Leute tun ja immer, wissen immer, was sie tun sollen, fühlen sich immer zu dem oder zu jenem gedrängt! Bei dem, der mit Initiationswissenschaft anfängt, bei dem wird es in der Welt doch etwas anders. Es tauchen, wenn das Leben an ihn herantritt, den einzelnen Erlebnissen gegenüber ganz merkwürdige Fragen auf. Wenn er sich gedrängt fühlt, etwas zu tun, ist er gleich auch wiederum gedrängt, es nicht zu tun. Der dunkle Trieb, der die meisten Menschen zu dem oder jenem drängt, er fällt weg. Und tatsächlich, auf einer gewissen Stufe der Initiationseinsicht könnte der Mensch schon, wenn nichts anderes an ihn heranträte, dazu kommen, sich zu sagen: Jetzt verbringe ich am liebsten mein ganzes folgendes Leben, nachdem ich zu dieser Einsicht gekommen bin - ich bin jetzt vierzig Jahre alt, das kann mir ganz gleichgültig sein -, so, daß ich auf einen Stuhl mich setze und gar nichts mehr tue; denn es sind nicht solche ausgesprochenen Triebe da, das oder jenes zu tun.

Glauben Sie nicht, meine lieben Freunde, daß die Initiation nicht eben reale Wirklichkeit hat. Es ist merkwürdig in dieser Beziehung, wie die Menschen manchmal denken. Von einem gebackenen Huhn glaubt jeder, wenn er es ißt, daß es reale Wirklichkeit hat. Von der Initiationswissenschaft glauben die meisten Menschen, daß sie nur theoretische Wirkungen habe. Sie hat Lebenswirkungen. Und eine solche Lebenswirkung ist diejenige, die ich eben jetzt angedeutet habe. Bevor der Mensch die Initiationswissenschaft hat, ist ihm immer das eine wichtig, das andere unwichtig aus einem dunklen Drange heraus. Der Initiierte möchte sich am liebsten auf einen Stuhl setzen und die Welt ablaufen lassen, denn es kommt nicht darauf an — so könnte es sich bei ihm einstellen —, ob das eine geschieht und das andere unterbleibt und dergleichen. Da gibt es dann nur die Korrektur — es wird ja nicht so bleiben, weil die Initiationswissenschaft auch noch etwas anderes bringt —, da gibt es nur die eine Korrektur dafür, daß sich der betreffende Initiierte nicht auf einen Stuhl setzt, die Welt ablaufen läßt und sagt: Mir ist alles gleichgültig —, da gibt es nur die Korrektur: zurückzublicken in frühere Erdenleben. Da liest er dann aus seinem Karma die Aufgabe für sein Erdenleben ab. Da tut er dann dasjenige, was ihm seine früheren Erdenleben auferlegen, bewußt. Er unterläßt es nicht, weil er meint, daß seine Freiheit dadurch beeinträchtigt wird, sondern er tut es, weil er, indem er auf das kommt, was er erlebt hat in früheren Erdenleben, zugleich gewahr wird, was in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt war, wie er es da als vernünftig eingesehen hat, die entsprechenden Folgetaten zu tun. Er würde sich unfrei fühlen, wenn er nicht in die Lage kommen könnte, seine sich ihm aus dem vorigen Erdenleben gestellte Aufgabe zu erfüllen.

Ich möchte hier nur eine kleine Parenthese machen. Sehen Sie, das Wort Karma ist ja auf dem Umweg durch das Englische nach Europa gekommen. Nun, deswegen, weil man das so schreibt: Karma, sagen die Leute sehr häufig «Karma». Das ist falsch ausgesprochen. Karma ist geradeso zu sprechen, wie wenn es mit ä geschrieben wäre. Ich spreche nun, seit ich die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft führe, immer «Ka(=ä)rma», und ich bedaure, daß sehr viele Leute sich daraus angewöhnt haben, fortwährend das schreckliche Wort «Kirma» zu sagen. Sie müssen immer verstehen, diese Leute, wenn ich «Karma» sage, «Kirma». Das ist schrecklich. Sie werden es auch schon gehört haben, daß manche sehr getreue Schüler nun seit einiger Zeit «Kirma» sagen.

Also weder vor noch nach dem Eintritte der Initiationswissenschaft gibt es einen Widerspruch zwischen karmischer Notwendigkeit und Freiheit. Vor dem Eintritte der Initiationswissenschaft aus dem Grunde nicht, weil der Mensch eben mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein innerhalb des Bereiches der Freiheit bleibt und sich die karmische Notwendigkeit draußen wie naturhaft abspielt; er hat gar nicht etwas, das anders empfindet, als das, was ihm eben seine Natur eingibt. Und nachher aus dem Grunde nicht, weil er mit seinem Karma ganz einverstanden geworden ist, einfach im Sinne des Karmas handeln für vernünftig ansieht. Geradeso wie man nicht sagt, wenn man sich ein Haus gebaut hat: Das beeinträchtigt meine Freiheit, daß ich da jetzt hineinziehe -, sondern wie man sich sagt: Nun, das war ja doch ganz vernünftig von dir, daß du dir in dieser Gegend an diesem Platze ein Haus gebaut hast, jetzt sei frei in diesem Hause -, geradeso weiß derjenige, der mit Initiationswissenschaft zurückblickt in frühere Erdenleben, daß er frei wird dadurch, daß er seine karmische Aufgabe erfüllt, also in das Haus einzieht, das er sich in früheren Erdenleben gebaut hat.

So wollte ich Ihnen heute, meine lieben Freunde, die Verträglichkeit von Freiheit und karmischer Notwendigkeit im menschlichen Leben darlegen. Wir werden morgen vom Karma weiter sprechend auf Einzelheiten des Karmas dann eingehen.

Third Lecture

The state of karma is best understood by contrasting it with the other impulse in human life, the impulse that is described by the word freedom. Let us first of all, I would like to say, roughly put the question of karma before us. What does it mean? In human life we have successive earth lives to record. By feeling ourselves in a particular earth life, we can first look back, at least in thought, at how this present earth life is the repetition of a number of previous ones. This earth-life was preceded by another, this one by another, until we come back to those times in which it is impossible to speak of repeated earth-lives in the way that is the case in the present earth-time, because then a time begins, running backwards, when gradually the life between birth and death and that between death and a new birth become so similar to each other that the enormous difference that exists today is no longer there. Today we live in our earthly body between birth and death in such a way that we feel strongly closed off from the spiritual world with our ordinary consciousness. Out of this ordinary consciousness people speak of this spiritual world as if it were something beyond. People come to speak of this spiritual world as if they could doubt it, as if they could deny it altogether, and so on.

This all stems from the fact that life within earthly existence restricts people to the external world of the senses and to the intellect, which does not look beyond to what is really connected with this earthly existence. This is where all kinds of disputes come from, all of which are actually rooted in an unknown. You will often have been there and experienced how people argue: monism, dualism and so on. It is of course complete nonsense to argue about such buzzwords. When people argue in this way, it is as if, say, some primitive person had never heard of the existence of air. It will not occur to one who knows that there is an air and what the air does, to speak of the air as something otherworldly. Nor will it occur to him to say: I am a monist, air and water and earth are one; and you are a dualist because you still see something in the air that goes beyond the earthly and the aqueous.

All these things are simply nonsense, just as all arguments about concepts are mostly nonsense. So it cannot be a question of going into these things, but only of drawing attention to them. For just as for those who do not yet know air, the air is not there, but is something beyond, so for those who do not yet know the spiritual world, which is also everywhere there just like the air, this spiritual world is something beyond; for those who enter into these things, it is something in this world. So it is merely a matter of acknowledging that man lives in his physical body, in his whole organization, in the present time on earth between birth and death, that this organization gives him a consciousness through which he is in a certain sense closed off from a certain world of causes, but which as such works into this physical earthly existence.

Then he lives between death and a new birth in another world, which can be called a spiritual world compared to our physical world, in which he does not have a physical body, which can be made visible for human senses, but in which he lives in a spiritual being; and in this life between death and a new birth the world, which one lives through between birth and death, is again such a strange one, as now the spiritual world is a strange one for the ordinary consciousness.

The dead person looks down on the physical world, just as the living person, that is, the physically living person, looks up into the spiritual world, and it is only the feelings that are, so to speak, reversed. While the human being between birth and death here in the physical world has a certain looking up to another world, which gives him fulfillment for some things that are either too little here in this world or do not grant him satisfaction, so the human being between death and a new birth must, because of the immense abundance of events, because of the fact that too much always happens in relation to the physical world, because there is always too much happening in relation to what man can bear, he must feel a constant longing to return to life on earth, to what is then life on the other side for him, and he awaits with great longing the passage through birth into earthly existence in the second half of life between death and a new birth. Just as he is afraid of death in earthly existence because he is uncertain about what will happen after death - there is great uncertainty for the ordinary consciousness in earthly existence - so in the life between death and a new birth there is great uncertainty about . In the life between death and a new birth there is an overwhelming certainty, a certainty that stupefies, a certainty that makes one almost powerless. So that man has swoon-like dream states that give him the longing to come down to earth again.

These are only a few indications of the great difference that exists between life on earth and life between death and a new birth. But if we now go back, let us say only to Egyptian times, from the 3rd to the 1st millennium before the foundation of Christianity. We go back to the people we ourselves were in an earlier life on earth, if we go back to that time, life during our earthly existence was so brutally clear compared to our present consciousness - and at present people have a brutally clear consciousness, they are all so clever, people, I don't mean that ironically, Compared to this brutally clear consciousness, the consciousness of people in ancient Egyptian times was a more dreamlike one, one that did not bump into external objects in the same way as today, that went through the world without bumping into them, but was filled with images that at the same time revealed something of the spiritual that is in our surroundings. The spiritual still protruded into the physical earthly existence.

Don't tell me: How should man, if he has such a more dreamlike, not brutally clear consciousness, have been able to carry out the powerful work that was done, for example, during the Egyptian or Chaldean times? You need only remember that sometimes madmen, especially in certain states of insanity, have a tremendous growth of their physical powers and begin to carry things that they cannot carry with full clear consciousness. In fact, the physical strength of these people, who were perhaps outwardly even slighter than people today - but it is not always the fat man who is strong and the thin man who is weak - was also correspondingly greater. Only they did not use this existence in such a way that they observed everything they did physically, but parallel to these physical actions were the experiences into which the spiritual world still intruded.

And again, when these people were in the life between death and a new birth, much more of this earthly life came up into that life, if I may use the expression “up”. Today it is extremely difficult to communicate with people who are in the life between death and a new birth, because the languages have gradually taken on a form that is no longer understood by the dead. Our nouns, for example, represent absolute gaps in the dead's understanding of the earthly soon after death. They only understand the verbs, the time words, the moving, the active. And while here on earth we are constantly being told by materialistic-minded people that everything should be properly defined, that every concept should be sharply defined, the dead no longer know any definitions at all; for they only know that which is in motion, not that which has contours and is limited.

But in older times also that which lived on earth as language, which lived as a use of thought, as a habit of thought, was still such that it reached up into life between death and a new birth, so that the dead person still had an echo long after his death of that which he had experienced here on earth, and also of that which still took place on earth after his death.

And if we go back even further, to the time after the Atlantean catastrophe, to the 8th, 9th millennium before the Christian era, then the differences between life on earth and life - if we may say so - in the afterlife become even smaller. And then we gradually return to those times when the two lives are quite similar. Then we can no longer speak of repeated earth lives.

So the repeated earth lives have their limit when you look backwards. They will also have a limit if you look forward into the future. For that which begins quite consciously with anthroposophy, that the spiritual world should protrude into the ordinary consciousness, will have the consequence that this earth world will again protrude more into the world which one lives through between death and a new birth, but nevertheless the consciousness will not become dreamlike but clearer, clearer and clearer. The difference will again become smaller. So that one has limited this life in the repeated earth lives between the outer boundaries, which then lead into a completely different kind of existence of man, where it makes no sense to speak of the repeated earth lives, because just the difference between the earth life and the spiritual life is not as great as it is now.

But if one now assumes for the far present of earth time that behind this earth life lie many others - one must not say innumerable others, because they can even be counted with an exact spiritual-scientific examination - then we have had certain experiences in these earlier earth lives, which represented relationships from man to man. And the effects of these relationships from person to person, which at that time were lived out in what we went through, are present in this earth life in exactly the same way as the effects of what we do in this present earth life extend into the next earth lives. We therefore have to look for the causes of much of what enters our life now in earlier earthly lives. The human being will easily say to himself: So what he is experiencing now is conditioned, caused. How can he then be a free human being?

Well, the question, if you look at it in this way, is quite a significant one; for all spiritual observation shows that in this way the following earth life is conditioned by the earlier ones. On the other hand, the consciousness of freedom is absolutely there. And if you read my “Philosophy of Freedom”, you will see that you cannot understand man at all if you are not clear about the fact that his whole soul life is directed towards freedom, but towards a freedom that has to be understood correctly.

Now you will find in my “Philosophy of Freedom” an idea of freedom that is extremely important to grasp in the right sense. The point is that freedom is first developed in thought. The source of freedom arises in thought. Man simply has an immediate awareness that he is a free being in thought.

You can say: But there are many people today who doubt freedom. - That is just proof that today people's theoretical fanaticism is greater than what they directly experience in reality. People no longer believe in what they experience because they are full of theoretical views. Today, people form the idea from observing natural processes that everything is necessarily conditioned, every effect has a cause, everything that exists has its cause. So when I form a thought, it also has a cause. One does not think of the repeated earthly lives in the same way, but one thinks of the fact that that which springs forth from a thought is caused in the same way as that which springs forth from a machine.

Through this theory of general causality, as it is called, of general causation, through this theory man today often blinds himself to the fact that he clearly carries within him the consciousness of freedom. Freedom is a fact that is experienced as soon as one truly comes to self-awareness.

Now there are also people who are of the opinion that the nervous system is a nervous system and conjures thoughts out of itself. Then, of course, the thoughts would be, let us say, just like the flame that burns under the influence of the fuel, necessary results, and there could be no question of freedom.