Karmic Relationships I

GA 235

8 March 1924, Dornach

Lecture VII

In the last lecture I spoke of how the forces of karma take shape, and today I want to lay the foundations for acquiring an understanding of karma through studying examples of individual destinies. Such destinies can only be illustrations, but if we take our start from particular examples we shall begin to perceive how karma works in human life. It works, of course, in as many different ways as there are human beings on the earth, for the configuration of karma is entirely individual. And so whenever we turn our attention to a particular case, it must be regarded merely as an example.

Today I shall bring forward examples I have myself investigated and where the course of karma has become clear to me. It is of course a hazardous undertaking to speak of individual karmic connections, no matter how remote the examples may be, for in referring to karma it has become customary to use expressions of everyday language such as: “This is caused by so-and-so; this or that blow of destiny must be due to such and such a cause, how the man came to deserve it” ... and so forth. But karma is by no means as simple as that, and a great deal of utterly trivial talk goes on, particularly on this subject!

Today we will consider certain examples of the working of karma, remote though they may be from our immediate life. We will embark upon the hazardous undertaking of speaking about the karma of individuals—as far as my investigations make this possible. I am therefore giving you examples which are to be taken as such.

I want to speak, first, of a well-known aestheticist and philosopher, Friedrich Theodor Vischer. I have often alluded to him in lectures, but today I will bring into relief certain characteristic features of his life and personality which can provide the basis for a study of his karma.

Friedrich Theodor Vischer received his education at the time when German idealistic philosophy—particularly Hegelian thought—was in its heyday. Friedrich Theodor Vischer, a young man pursuing his studies among people whose minds were steeped in the Hegelian mode of thinking, adopted it himself. The absorption in transcendental thoughts that is characteristic of Hegel strongly appealed to Vischer. It was clear to him that, as Hegel asserts, thought is the Divine Essence of the universe, and that when we, as human beings, think, when we live in thoughts, we are living in the Divine Substance.

Friedrich Theodor Vischer was steeped in Hegelian philosophy. But he was a person who displayed in a very marked way the traits and characteristics of the folk from which he sprang. He had all the traits of a typical Swabian: he was obstinate, dogmatic, disputatious, exceedingly independent; his manner was abrupt, off-hand. He also had very striking personal peculiarities. To take his outward appearance first, he had beautiful blue eyes and a reddish-brown beard, which in spite of its scrubbiness he wore with a certain aesthetic enthusiasm! I say “aesthetic enthusiasm” because in his writings he minces no words about men who wear no beards, calling them “beardless monkey-faces”! As you see, his language is anything but restrained; all his remarks come out with the abrupt, off-handed assurance of a typical Swabian.

He was a man of medium height, not stout, in fact rather slight in build, but he walked the streets holding his arms as if he were forcing a way for himself with his elbows—which is an exact picture of what he did in a spiritual sense! So much for his outward appearance.

He had a passionately independent nature and would say just what he pleased, without any restraint whatever. It happened one day that he had been slandered by “friends” in the Stuttgart Council—such things are not unusual among friends!—and he was severely reprimanded by the Council. It chanced that on the very same day a little son was born to him—the Robert Vischer who also made a name for himself as an aestheticist—and the father announced the event in the lecture-hall with the words: “Gentlemen, today I have been given a big Wischer (wigging) and a little Vischer!”

It was characteristic of him to speak very radically about things as he found them. For example, he wrote an amusing article entitled: “On the Foot Pest in Trains.” It enraged him to see people sitting in a railway carriage with their feet up on the opposite seat. He simply could not endure it and his article on the subject is really enchanting.

What he wrote in his book on fashions, [Mode und Zynismus. Stuttgart, 1878.] about the ill-breeding and lack of adequate clothing at dances and other entertainments, had better not be mentioned here. To put it briefly, he was a very original and forceful personality!

A friend of mine once paid him a visit, knocking politely at the door. I do not know whether it is a custom in Swabia, but Vischer did not say “Come in,” or what is usually said on such occasions. He yelled out “Glei”—meaning that he would be ready immediately.

While still comparatively young, Vischer embarked on a weighty task, namely that of writing a work on aesthetics according to the principles of Hegelian philosophy. These five volumes are a truly remarkable achievement. You will find in them the strict division into paragraphs which was habitual with Hegel, and the characteristic definitions. If I were to read a passage to you, you would all yawn, for it is written in the anything but popular style of Hegel, all in abrupt definitions, such as: The Beautiful is the appearance of the Idea in material form. The Sublime is the appearance of the Idea in material form, but the Idea predominates over the material form. The Comic is the appearance of the Idea in material form, but the material form predominates over the Idea ... and so on and so forth. These statements are certainly not without interest, but the book goes a great deal further. As well as the abrupt definitions, you have what is called the “small print,” and most people when they are reading the book leave out the large print and read only the small—which as a matter of fact contains some of the very cleverest writing on aesthetics that is anywhere to be found.

There is no pedantry, no Hegelian dialectic here; it is Vischer, the true Swabian, with all his meticulousness and at the same time his fine and delicate feeling for the beautiful, the great and the sublime. Here, too, you find Nature and her processes described in a way that defies comparison, with an exemplary freedom of style. Vischer worked at the book for many years, bringing it to its end with unfaltering consistency.

At the time when this work appeared,. Hegelianism was still in vogue and appreciation was widespread. Needless to say, there were opponents, too, but on the whole the book was widely admired. In course of time, however, a vigorous opponent appeared on the scenes, a ruthless critic who pulled the book to pieces until not a shred of good was left; everything was criticised in a really masterly style. And this critic was none other than Friedrich Theodor Vischer himself in his later years! There is an extraordinary charm about this critique of himself in his Kritische Gangen (Paths of Criticism).

As aestheticist, philosopher and man of letters, Vischer published a wealth of material in Kritische Gangen, and subsequently in the fine collection of essays entitled Altes und Neues (Old and New). While still a student he wrote lyrics in an ironic vein. In spite of the great admiration I have always had for Vischer, I could never help being of opinion that the productions of his student days were not even student-like, but sheer philistinism. And this trait came out in him again in his seventies, when he wrote a collection of poems under the pseudonym “Schartenmayer.” Here there is philistinism par excellence!

He was an out-and-out philistine in regard to Goethe's Faust. Part One ... well, he admitted there was something good in it, but as for Part Two—he considered it a product of senility, so many fragments patched together. He maintained that it ought to have been quite different, and not only did he write his Faust, der Tragodie dritter Teil, in which he satirises Goethe's Part Two, but he actually drew up a plan of just how Goethe ought to have written Faust. That is philistinism and no mistake! It is almost on a par with what du Bois-Reymond, the eminent scientist, said in his lecture “Goethe, nothing but Goethe.” He said: “Faust is a failure. It would have been all right if Faust had not engaged in such tomfoolery as the invocation of spirits or the calling up of the Earth-Spirit, but had simply and straightforwardly invented an electrical machine or an air pump and restored to Gretchen her good name ... ” And there is exactly the same kind of philistinism in what Vischer says about Faust.

Perhaps it would not be put like this in Wurttemburg, but in my homeland in Austria we should say that he gave Goethe's Faust a good “Swabian thrashing”! Such expressions differ slightly in meaning, of course, according to the districts where they are used.

It is these traits that are significant in Vischer. They really make up his personality. One might also, of course, give details of his life, but I do not propose to do that. My aim has been to give you a picture of his personality and with this as a foundation we can proceed to a study of his karma. Today I wanted simply to give you the material for this study.

A second personality of whose karma I want to speak, is Franz Schubert, the composer. As I said, it is a daring venture to give particular examples in this way, but it is right that they should be given and today I shall lay the foundations.

Here too, I shall select the features that will be needed when we come to speak of Schubert's karma. Practically all his life he was poor. Some time after his death, however, many persons claiming to have been not only his acquaintances but his “friends” were to be found in Vienna! A whole crowd of people, according to themselves, had wanted to lend him money, spoke of him affectionately as “little Franz” and the like. But during his lifetime it had been a very different story!

Schubert had, however, found one real friend. This friend, Baron von Spaun, was an extraordinarily nobleminded man. He had cared for Schubert with great tenderness from the latter's earliest youth, when they were schoolfellows, and he continued to do so in later years. In regard to karma it seems to me particularly significant—as we shall find when we come to consider the working of karma—that Spaun was in a profession quite alien to his character. He was a highly cultured man, a lover of art in every form, and a close friend not only of Schubert but also of Moritz von Schwind. He was deeply sensitive to everything in the way of art. Many strange things happen in Austria—as you know, Grillparzer was a clerk in the fiscal service—and Spaun too, who had not the slightest taste for it, spent his whole life in Treasury offices. He was an official engaged in administering finance, dealing with figures all the time. When he reached a certain age he was appointed Director of Lotteries! He had charge of lotteries in Austria—a task that was most distasteful to him. But now just think what it is that a Director of Lotteries has to control. He has, so to speak, to deal at a high level with the passions, the hopes, the blighted expectations, the disappointments, the dreams and superstitions of countless human beings. Just think of what has to be taken into account by a Director of Lotteries—a Chief Director at that. True, you may go into his office and come out again without noticing anything very striking. But the reality is there nevertheless, and those who take the world and its affairs in earnest must certainly reckon with such things.

This man, who had no part whatever in the superstitions, the disappointments, the longings, the hopes, with which he had to deal—this man was the intimate friend of Schubert, deeply and intensely concerned for his material as well as his spiritual well-being. One can often be astounded, outwardly speaking, at what is possible in the world! There is a biography of Schubert in which it is said that he looked rather like a negro. There is not a grain of truth in it. He actually had a pleasing, attractive face. What is true, however, is that he was poor. More often than not, even his supper, which he was in the habit of taking in Spaun's company, was paid for with infinite tact by the latter. Schubert had not enough money even to hire a piano for his own use. In outward demeanour—Spaun gives a very faithful picture here—Schubert was grave and reserved, almost phlegmatic. But an inner, volcanic fire could at times burst from him in a most surprising way.

A very interesting fact is that the most beautiful motifs in Schubert's music were generally written down in the early morning; as soon as he had wakened from sleep he would sit down and commit his most beautiful motifs to paper. At such times Spaun was often with him, for as is customary among the intellectuals of Vienna, both Schubert and Spaun liked a good drink of an evening, and the hour was apt to get so late that Schubert, who lived some distance away, could not be allowed to go home but would spend the night on some makeshift bed at his friend's house. On such occasions Spaun was often an actual witness of how Schubert, on rising in the morning, would write down his beautiful motifs, as though they came straight out of sleep.

The rather calm and peaceful exterior did not betray the presence of the volcanic fire lying hidden in the depths of the soul. But it was there, and it is precisely this aspect of Schubert's personality that I must describe to you as a basis for the study of his karma.

Let me tell you what happened on one occasion. Schubert had been to the Opera. He heard Gluck's Iphigenia and was enraptured by it. He expressed his enthusiasm to his friend Spaun during and after the performance in impassioned words, but at the same time with restraint. His emotions were delicate and tender, not violent. (I am selecting the particular traits we shall need for our study.) The moment Schubert heard Gluck's Iphigenia, he recognised it as a masterpiece of musical art. He was enchanted with the singer Milder; and Vogl's singing so enraptured him that he said his one wish was to be introduced to him in order that he might pay homage at his feet. When the performance was over, Schubert and Spaun went to the so-called Bargerstubi (Civic Club Room) in Vienna. I think they were accompanied by a third person whose name I have not in mind at the moment. They sat there quietly, although every now and again they spoke enthusiastically about their experience at the Opera. Sitting with others at a neighbouring table was a University professor well known in this circle. As he listened to the expressions of enthusiasm his face began to flush and became redder and redder. Then he began to mutter to himself, and when the muttering had gone on for a time without being commented on by the others, he fell into a rage and shouted across the table: “Iphigenia!—it isn't real music at all; it's trash. As for Milder, she hasn't an idea of how to sing, let alone bring off runs or trills! And Vogl—why he lumbers about the stage like an elephant!”

And now Schubert was simply not to be restrained! At any minute there was danger of a serious hand-to-hand scuffle. Schubert, who at other times was calm and composed, let loose his volcanic nature in full force and it was as much as the others could do to quiet him.

It is important for the life we are studying that here we have a man whose closest friend is a Treasury official, actually a Director of Lotteries, and that the two are led together by karma. Schubert's poverty is important in connection with his karma, because in these circumstances there was little opportunity for his anger to be roused in this way. Poverty restricted his social intercourse, and it was by no means often that he could have such a neighbour at table, or give vent to his volcanic nature.

If we can picture what was really happening on that occasion, and if we remember the characteristics of the people from whom Schubert sprang, we can ask ourselves the following question. (Negative supposition is of course meaningless in the long run, but it does sometimes help to make things clear.) We can ask ourselves: If the conditions had been different (of course they couldn't have been, only, as I say, the question can make for clarification)—if the conditions had been different, if Schubert had had no opportunity of giving expression to the musical talent within him, if he had not found a devoted friend in Spaun, might he not have become a mere brawler in some lower station in life? What expressed itself like a volcano that evening in the club room, was it not a fundamental trait in Schubert's character? Human life defies explanation until we can answer the question: How does the metamorphosis come about whereby in a certain life a man does not, so to say, live out his pugnacity but becomes an exquisite musician, the pugnacity being transformed into subtle and delicate musical phantasy?

It sounds paradoxical and grotesque, but for all that it is a question which, if we consider life in its wider range, must needs be asked, for it is only when we study such things that the deeper problems of karma really come into view.

The third personality of whom I want to speak is Eugen Dühring, a man much hated, but also—by a small circle—greatly loved. My investigations into karma have led me to occupy myself with this individual, too, and as before I will give you, first of all, the biographical material.

Eugen Dühring was a man of extraordinary gifts. In his youth he studied a whole number of subjects, particularly from the aspect of mathematics, including branches of knowledge such as political economy, philosophy, mechanics, physics and so on.

He gained his doctorate with an interesting treatise, and then in a book, long since out of print, followed up the same theme with great clarity and forcefulness. I will tell you a little about it. The subject is almost as difficult as the Theory of Relativity, but, after all, people have been talking about the Theory of Relativity for a long time now and, without understanding a single word, have considered, and still do consider it, quite wonderful. Difficult as the subject is, I want to tell you, in a way that will perhaps be comprehensible, something about the thoughts contained in this earliest work of Dühring.

The theme is as follows.—People generally picture to themselves: Out there is space, and it is infinite. Space is filled with matter. Matter is composed of minute particles, infinite in number. An infinite number of tiny particles have conglomerated into a ball in universal space, have in some way crystallised together, and the like. Then there is time, infinite time. The world has never had a beginning; neither can one say that it will have an end.

These vague, indefinite concepts of infinity were repellent to the young Dühring and he spoke with great perspicacity when he said that all this talk about infinity is devoid of real meaning, that even if one has to speak of myriads and myriads of world-atoms, or world-molecules, there must nevertheless be a definite, calculable number. However vast universal space is conceived to be, its magnitude must be capable of computation; so too, the stretch of universal time. Dühring expounded this theme with great clarity.

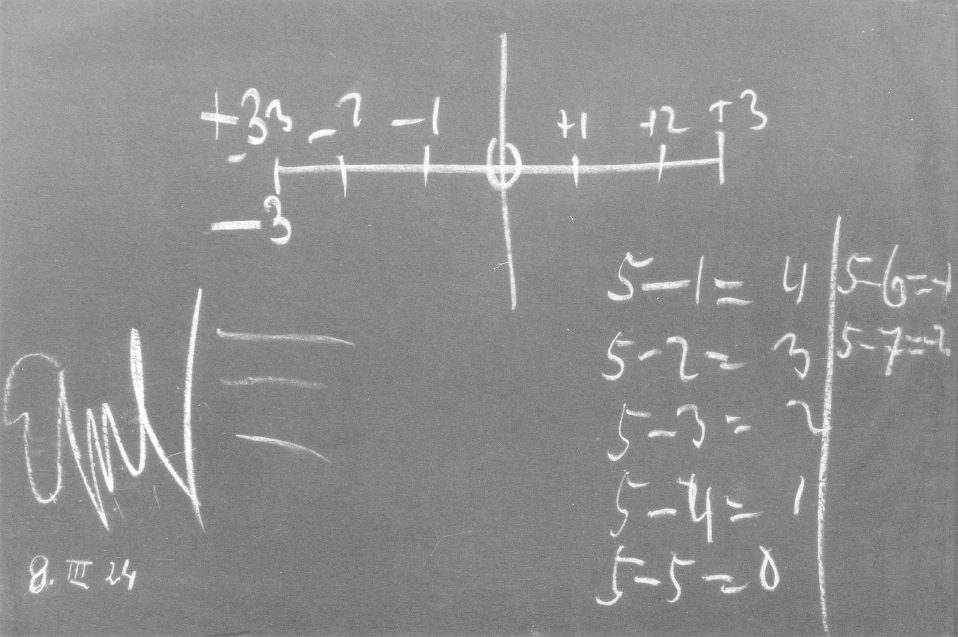

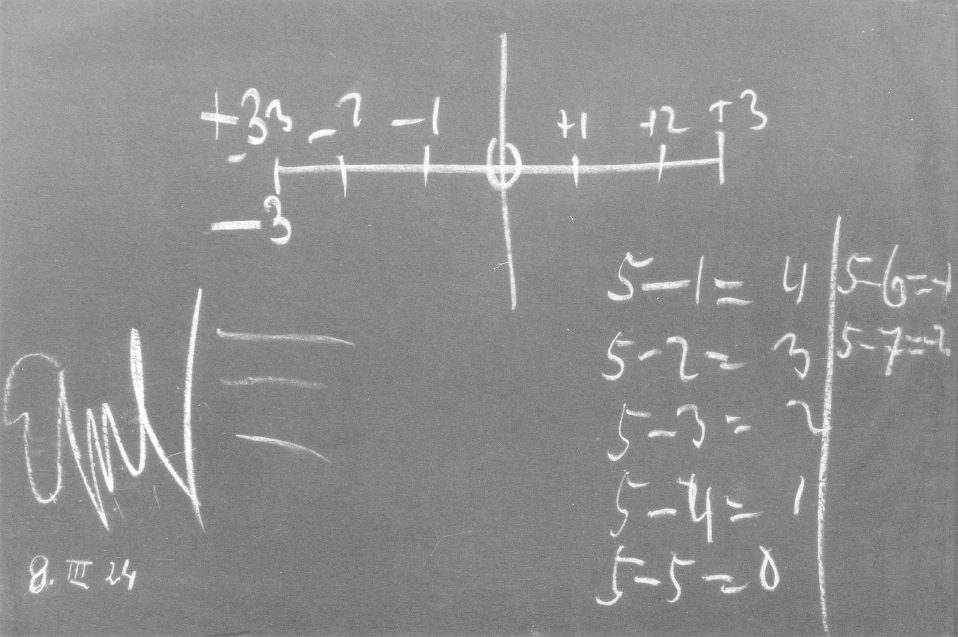

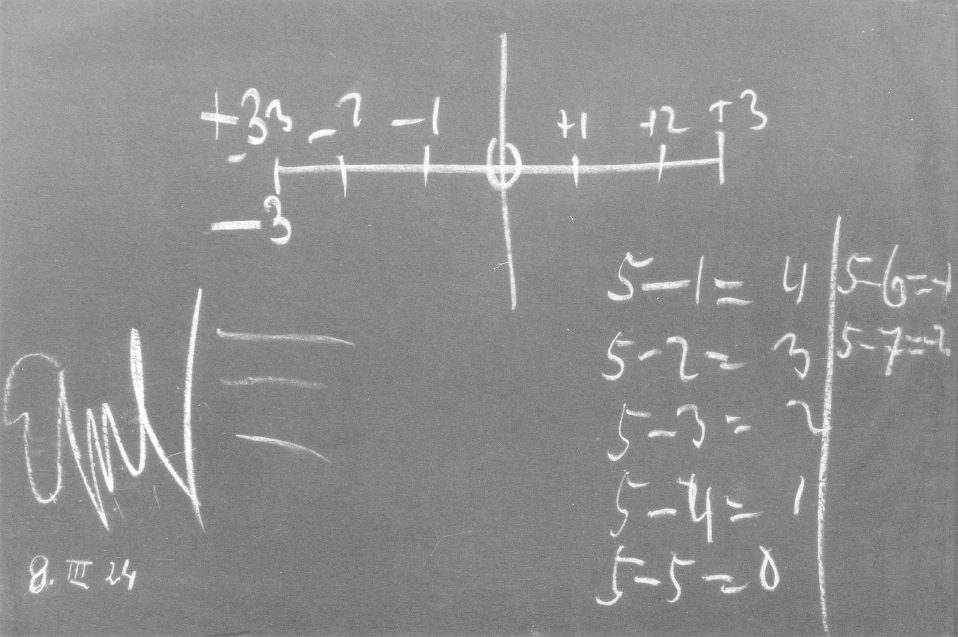

There is something psychological behind this. Dühring's one aim was clarity of thought, and there is no clear thinking at all in these notions of infinity. He went on to apply his argument in other domains, for example to the so-called “negative quantities.” Positive quantities (e.g. when something is possessed) are distinguished from negative quantities by writing a minus sign before the latter. Thus here you have 0 (zero), in one direction plus 1, and in the other direction minus 1, and so on.

Dühring maintains that all this talk about minus quantities is absolute nonsense. What does a “negative quantity,” a “minus number” mean? He says: If I have 5 and take away 1, then I have 4; if I have 5 and take away 2, then I have 3; if I have 5 and take away 4, then I have 1; and if I have 5 and take away 5, then I have 0. The advocates of negative quantities say: If I have 5 and take away 6, then I have minus 1; if I have 5 and take away 7, then I have minus 2.

Dühring maintains that there is no clarity of thinking here. What does “minus 1” mean? It means: I am supposed to take 6 from 5; but then I have I too little. What does “minus 2” mean? I am supposed to take 7 from 5; but then I have 2 too little. What does “minus 3” mean? I am supposed to take 8 from 5; but then I have 3 too little. There is no difference between the negative numbers, as numbers, and the positive numbers. The negative numbers mean only that when I have to subtract, I have too little by a particular amount. And Dühring went on to apply the same principle to mathematical concepts of many kinds.

I know how deeply I was impressed by this as a young man, for Dühring brought real clarity of thought to bear upon these things.

He displayed the same astute discernment in the fields of national economy and the history of philosophy, and became a lecturer at the University of Berlin. His audiences were very large and he lectured on a variety of subjects: national economy, philosophy, mathematics.

It so happened that a prize was offered by the Academy of Science at Göttingen for the best book on the history of mechanics. It is usual in such competitions for the essays to be sent in anonymously. The competitor chooses a motto, his name is contained inside a closed envelope with the motto written outside, so that the adjudicators are unaware of the author's identity.

The Göttingen Academy of Science awarded the prize to Eugen Dühring's History of Mechanics and wrote him a most appreciative letter. Therefore Dühring was not only recognised by his own circle of listeners as an excellent lecturer, but now gained the recognition of a most eminently learned body.

Along with all the talents which will be evident to you from what I have been saying, this same Dühring had a really malicious tongue—one cannot call it anything else. There was something of the malicious critic about him in regard to everything in the world. As time went on he exercised less and less restraint in this respect; and when such an eminently learned body as the Göttingen Academy of Science awarded him the prize, it acted like a sting upon him. It was quite in the natural course of things, but nevertheless it stung. And then we see two qualities beginning to be combined in him: an intensely strong sense of justice—which he undoubtedly possessed—and on the other hand an extraordinary propensity for abuse.

Just at the time when he was stung into abuse and sarcasm, Dühring had the misfortune to lose his sight. In spite of total blindness, however, he continued to lecture in Berlin. He went on with his work as an author, and was always able, up to a point, of course, to look after his affairs himself. About this time a truly tragic destiny in the academic world during the 19th century came to his knowledge—the destiny of Julius Robert Mayer, who was actually the discoverer of the heat-equivalent in mechanics and who, as can be stated with all certainty, had been shut up in an asylum through no fault of his own, put into a strait-jacket and treated shamefully by his family, his colleagues and his “friends.” It was at this time that Dühring wrote his book, Julius Robert Mayer, the Galileo of the 19th Century. And it was in truth a kind of Galileo-destiny that befell Julius Robert Mayer.

Dühring wrote with an extraordinarily good knowledge of the facts and with a really penetrating sense of justice, but he lashed out as with a rail in regard to the injuries that had been inflicted. His tongue simply ran away with him—as, for example, when he heard and, read about the erection of the well-known statue of Mayer at Heilbronn, and of the unveiling ceremony. “This puppet standing in the market square at Heilbronn is a final insult offered to the Galileo of the 19th century. The great man sits there with his legs crossed. But to portray him truly, in the frame of mind in which he would most probably be, he would have to be looking at the orator and at all the good friends below who erected this memorial, not sitting with his legs crossed but beating his breast in horror.”

Having suffered much at the hands of newspapers, Dühring also became a violent anti-Semite. Here too he was ruthlessly consistent. For example, he wrote the pamphlet entitled Die Ueberschätzung Lessings und dessen Anwaltschaft für die Juden, in which murderous abuse is hurled at Lessing. It is this trait in Dühring that is responsible for his particular way of expounding literature.

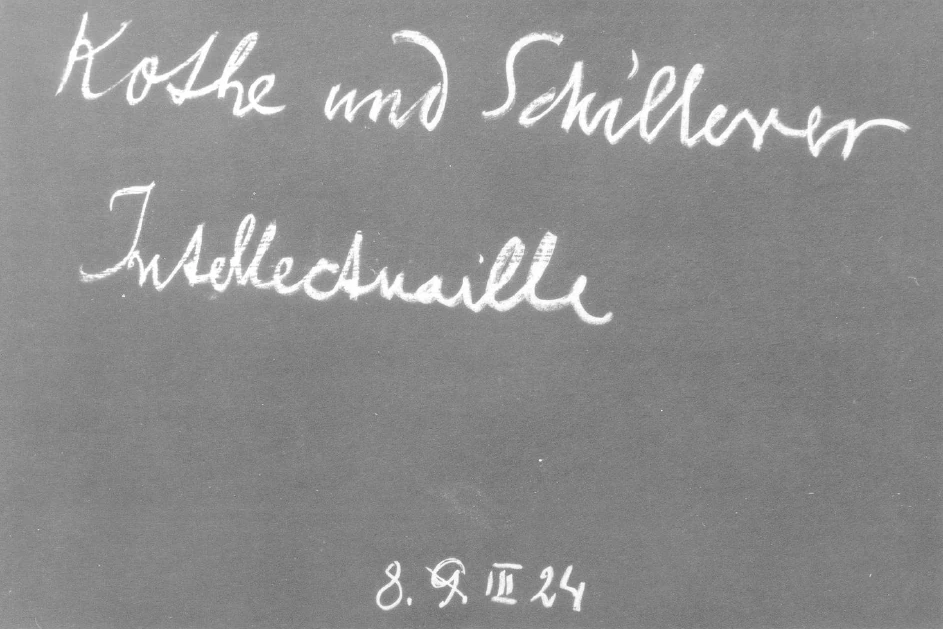

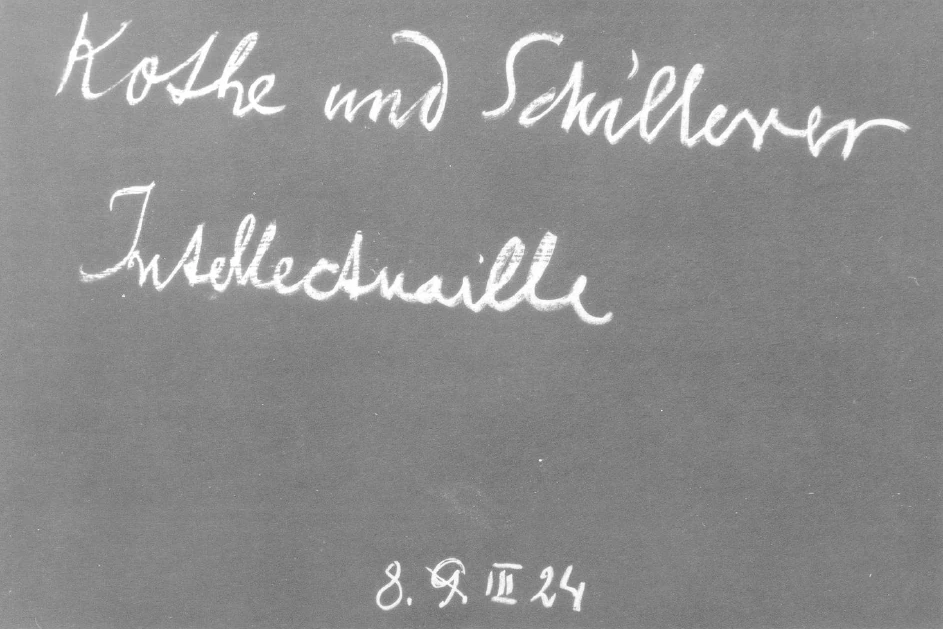

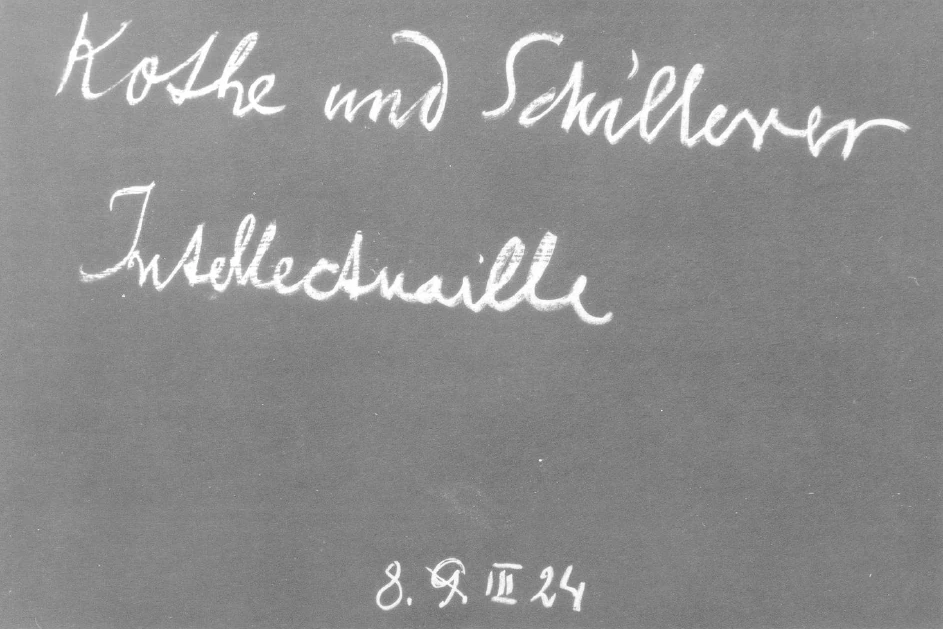

If you want one day to give yourselves the treat of reading something about German literature that you will find nowhere else, that is totally different from other treatises on the subject, then take Dühring's two volumes entitled Literaturgrössen (Great Men of Letters). There you will find his strictly mathematical way of thinking and his astute perspicacity, applied to literature. In order, presumably, to make it plain how his way of thinking differs from that of others, he sees fit to rechristen the great figures of the German spiritual life. He speaks, in one chapter, of “Kothe” and “Schillerer,” meaning Goethe and Schiller. Duhring writes “Kothe” and “Schillerer” and adheres to this throughout. The nomenclature he invents is often grotesque. “Intellectuaille” (connected with “canaille”) is how he always refers to people we call intellectualistic. The “Intellectuaille”—the Intellectuals. He uses similar expressions all the time. But let me assure you of this: a great deal in Dühring's writings is extraordinarily interesting.

I once had the following experience. When I was still on friendly terms with Frau Elizabeth Forster-Nietzsche and was working on unpublished writings of Nietzsche, there came into my hands the material dealing with the “Eternal Recurrence”, now long since printed. [Thus Spake Zarathustra, Part III.] Nietzsche's manuscripts are not very easy reading, but I came across a passage where I said to myself: This “Eternal Recurrence” has some definite source. And so I went over from the Archives, where Nietzsche's note-books were kept, to the Library, and looked up Dühring's Wirklichkeitsphilosophie (Philosophy of Reality), where, as I thought, I was quickly able to find this idea of “Eternal Recurrence”. I took the book from the shelves of the Library and found the passage—I knew it and found it at once—where Dühring argues that it is impossible for anyone with genuine knowledge of the material facts of the world to speak of a return of things, a return of constellations which once were there.

Dühring tried to disprove any such possibility. At the side of the passage in question was a word frequently written by Nietzsche in the margin of a book when he was using it to formulate a counter-idea. It was the word: “Ass”!

The familiar epithet was written in the margin of this particular page. In point of fact we can find in Dühring's writings a great deal that passed over, ingeniously, into Nietzsche's ideas. In saying this I hold nothing against Nietzsche. I am simply stating the facts as they are.

In respect of karma, the most striking thing about Dühring is that he was really able to think only mathematically. In philosophy, in political economy, in mathematics itself, he thinks mathematically, with mathematical precision and clarity. In natural science, too, he thinks with clarity but, again, in terms of mathematics. He is not a materialist, he is a mechanistic thinker. He conceives the world as mechanism. And moreover he had the courage to carry sincere convictions to their ultimate conclusions. For truth to tell, anyone who thinks as he did cannot write about Goethe and Schiller in any other way—leaving aside the abuse and taking only the essential substance of what is said.

So much for the fundamental trend of Dühring's thought. Add to this the blindness while he was still young, and the fact that he suffered no little personal injustice. He lost his post as lecturer at the University of Berlin. Well ... there were reasons! For example, in the second edition of his History of Mechanics he cast all restraint aside. The first edition had been quite tame in its treatment of the great figures in the field of mechanics, so tame that someone said he had written in a way which he thought would make it possible for a learned body to award him a prize. But in the second edition he no longer held himself in check; he let himself go and fairly filled in the gaps! Someone remarked—and Dühring often repeated it—that the Göttingen Academy had awarded a prize to the claws without recognising the lion behind the claws! But when the second edition appeared the lion had certainly come into the open!

In this second edition there were in truth some astounding passages, for example in connection with Julius Robert Mayer and his Galileo-destiny in the 19th century. On one occasion when Dühring was in a towering rage about this, he called a man he considered to be a plagiarist of Mayer—namely Hermann Helmholtz—so much “academic scaffolding,” “wooden scaffolding.” Later on he enlarged upon this theme. He edited a periodical Der Personalist, where everything had a strongly personal colouring. Here, for example, Dühring enlarges upon the reference to Helmholtz. He no longer speaks about wooden scaffolding, but when the postmortem examination had revealed the presence of water in Helmholtz's brain, Dühring said that the empty-headedness had been quite obvious while the man was still alive and that there was no need to wait for confirmation until after his death! Refinement was certainly not one of Dühring's qualities. One cannot exactly say that he raged like a washerwoman. His way of abusing was not commonplace; neither was there real genius in it. It was something quite unique.

And now take all these factors together: the blindness, the mechanistic bent of mind, the persecution he certainly suffered—for the dismissal from the University was not altogether free from injustice, and indeed countless injustices were done to him during his life ... All these things are connections of destiny which become really interesting only when we study them in the light of karma.

I have now given you a picture of these three personalities: Friedrich Theodor Vischer, the composer Schubert, and Eugen Dühring. Having outlined the biographical material today, I will speak tomorrow of the karmic connections.

Siebenter Vortrag

In den Betrachtungen über das Karma möchte ich heute, nachdem ich das letzte Mal mehr die Bildung der karmischen Kräfte geschildert habe, gewissermaßen den Grund legen, um das Verständnis für das Karma dadurch hervorzurufen, daß man hinschaut auf einzelne Schicksale im Leben von Menschen, um die karmische Bestimmtheit, Bestimmung, sagen wir, dieser einzelnen menschlichen Schicksale ins Auge zu fassen.

Solche Schicksale können natürlich nur als Beispiele dienen; aber man kann schon, wenn man an konkrete menschliche Schicksale anknüpft und das Karma dabei ins Auge faßt, man kann schon, von da ausgehend, Einblicke dann gewinnen in die Art, wie Karma überhaupt bei den Menschen wirkt.

Es wirkt ja natürlich so vielfältig, als es Menschen auf Erden gibt. Die karmische Gestaltung ist durchaus individuell. Man kann also nur, wenn man auf das einzelne eingeht, eben in Beispielen sprechen.

Nun möchte ich heute Beispiele anführen, die ich untersucht habe, die mir durchsichtig geworden sind in ihrem karmischen Verlaufe. Es ist allerdings schon ein gewagtes Unternehmen, über, wenn auch fernerliegende, karmische Zusammenhänge im einzelnen zu sprechen, denn eigentlich ist es ja üblich, wenn von Karma gesprochen wird, in allgemeinen Redensarten zu sprechen: Dies oder jenes wird auf diese oder jene Weise verursacht -, oder: Man muß den oder jenen Schicksalsschlag auf irgend etwas zurückführen, wie ihn der Mensch verdient hat — und dergleichen. Nun, so einfach sind die Dinge nicht! Gerade wenn von Karma gesprochen wird, wird sehr viel trivialisiert.

Nun wollen wir heute einmal auf bestimmte, wenn auch fernerliegende karmische Beispiele eingehen, ganz, ich möchte sagen, dieses gewagte Unternehmen wirklich vollführen, über einzelne Karmas zu sprechen, soweit das eben nach den Untersuchungen, die mir obgelegen haben, geschehen kann. Beispiele sollen es also sein.

Da möchte ich zunächst über einen berühmten Ästhetiker und Philosophen, über Friedrich Theodor Vischer - ich habe ihn öfter erwähnt im Verlaufe meiner Vorträge —, sprechen. Ich möchte heute gerade diejenigen Eigentümlichkeiten seines Lebenslaufes herausheben, die ich dann zur Grundlage einer karmischen Besprechung wählen kann.

Friedrich Theodor Vischer wuchs hinein mit seiner Bildung in das Zeitalter, in dem innerhalb Deutschlands die sogenannte idealistische deutsche Philosophie blühte: das Hegeltum. Und Friedrich Theodor Vischer, der jung war, seine Studien durchmachte, während überall die Köpfe voll waren von Hegelscher Denkweise, er hat diese Denkweise angenommen. Er war empfänglich für dieses hohe Hegelsche Verweilen in Gedanken. Ihm war es einleuchtend, daß der Gedanke wie das ja bei Hegel behauptet wird - tatsächlich das göttliche Wesen der Welt sei; daß also, wenn wir als Menschen denken, wir, indem wir in Gedanken leben, in der göttlichen Substanz leben.

Hegel war in der Tat durchaus davon überzeugt, daß von dem Leben in Gedanken eigentlich alle Erdenentwickelung abhängt. Das andere schließt sich daran. Die Weltenpläne werden gemacht, indem die Denker über die Welt nachdenken. - Gewiß, darin liegt viel Wahres. Aber bei Hegel hat das alles einen sehr abstrakten Charakter.

Aber Friedrich Theodor Vischer hat sich in diese Hegelsche Philosophie eingelebt. Dabei war er aber zugleich auch eine aus einem Volksstamme heraus entstandene Persönlichkeit, die die Eigentümlichkeiten dieses Volksstammes mit großer Deutlichkeit an sich trug. Er hatte alle Eigenschaften eines Schwaben, allen Eigensinn, alle Rechthaberei, auch allen Unabhängigkeitssinn des Schwaben! Er hatte auch das Kurzangebundene des Schwaben. Und indem er diesen Schwabencharakter an sich trug, hatte er wiederum starke persönliche Eigentümlichkeiten: Ein, wenn man das Äußere nimmt, schönes blaues Auge, einen etwas struppigen, aber immerhin von ihm mit einem gewissen ästhetischen Enthusiasmus getragenen rötlichbraunen Vollbart. Ich sage, er hat ihn mit einem gewissen ästhetischen Enthusiasmus getragen, weil er sich ja in seinen Schriften genügend ausspricht über die Ungezogenheit jener Männer, die keinen Vollbart tragen. Er nennt sie «bartlose Affengesichter»; er war also durchaus nicht zurückhaltend. Das alles tat er mit der eigentümlichen, kurzangebundenen Bestimmtheit eben des Schwaben.

Er war mäßig groß, nicht dick, sondern eher schmächtig; aber er ging durch die Straßen, indem er die Arme so hielt, als ob er sich mit den Ellbogen immer den Weg frei machte. Das hat er ja auch als geistige Individualität durchaus getan! - So war das Äußere.

Er war von einem sehr starken, auch persönlichen Unabhängigkeitsdrang, hielt nicht zurück mit dem, was er gern sagen wollte. So traf es einmal zufällig zusammen, daß, nachdem er von «Freunden» — das geschieht ja sehr häufig von Freunden - bei der Stuttgarter Regierung angeschwärzt worden war, einen argen Verweis von der Stuttgarter Regierung bekommen hat - an demselben Tag, wo ihm sein Sohn geboren worden ist, der Robert, der dann ja auch als Ästhetiker einen Namen sich erworben hat -, daß er dann im Auditorium dies ankündigte, indem er sagte: Meine Herren, ich habe heute einen großen Wischer und einen kleinen Vischer bekommen!

Es war ihm durchaus eigen, über die Dinge sehr bestimmt zu sprechen. So ist ein entzückender Aufsatz von ihm: «Über Fußflegelei auf der Eisenbahn.» Er hat mit großem Mißfallen beobachtet, wie manchmal Passagiere, die im Coup& auf der einen Seite sitzen, ihre Füße nach der anderen Seite hinüber auf die Bank legen. Das konnte er gar nicht leiden! Da ist ein entzückender Aufsatz von ihm über Fußflegel auf den Eisenbahnen vorhanden.

Was er alles in seinem Buche «Mode und Zynismus» über allerlei Ungezogenheiten und Unangezogenheiten auf Bällen und anderen Unterhaltungen geschrieben hat, darüber will ich heute lieber schweigen. Er war schon eine starke Individualität.

Ein Freund von mir besuchte ihn einmal, klopfte ganz artig an der Tür. Ich weiß nicht, ob das sonst in Schwaben üblich ist, aber er sagte nicht «Herein!», oder wie man sonst sagt in einem solchen Fall, sondern er schmetterte: «Glei!» — Gleich oder sogleich würde er bereit sein.

Nun, Friedrich Theodor Vischer machte sich verhältnismäßig in jungen Jahren an eine große Aufgabe: die Ästhetik im Sinne der Hegelschen Philosophie zu schreiben. Und diese fünf Bände, die er da geschrieben hat, die sind in der Tat ein merkwürdiges Werk. Da ist eine strenge Paragrapheneinteilung, wie es bei Hegel üblich war; da sind die üblichen Definitionen. Wenn ich Ihnen ein Stück vorlesen würde, würden Sie sogleich alle gähnen, denn es ist durchaus in eben nicht gerade populärem Hegelismus geschrieben, sondern es sind schon Definitionen wie diese: Das Schöne ist die Erscheinung der Idee in sinnlicher Form. Das Erhabene ist die Erscheinung der Idee in sinnlicher Form so, daß die Idee die sinnliche Form überwiegt. Das Komische ist die Erscheinung der Idee in der sinnlichen Form so, daß die sinnliche Form überwiegt — und so weiter. Das sind Dinge, die noch verhältnismäßig interessant sind, aber es geht noch viel weiter! Dann aber stehen gegenüber diesen «Definitionen», «Deklarationen», das sogenannte Kleingedruckte. Die meisten lesen dieses Buch «Ästhetik» von Friedrich Theodor Vischer so, daß sie das Großgedruckte weglassen und nur das Kleingedruckte lesen. Und dieses Kleingedruckte enthält in der Tat das Geistreichste der Ästhetik, das auf den verschiedensten Gebieten vorgebracht worden ist. Da ist kein Pedantismus, kein Hegeltum drinnen, sondern da ist der Schwaben-Vischer mit all seiner geistreichen Gewissenhaftigkeit, aber auch mit seiner feinen Empfindung für alles Schöne, Großartige und Erhabene drinnen. Da ist zugleich das Naturgeschehen in einer unvergleichlichen Weise, in einem freien Stil, der geradezu musterhaft ist, geschildert. Da hat er wirklich in vielen Jahren mit einer eisernen Konsequenz dieses Werk zu Ende gebracht.

Nun gab es in der Zeit, als dieses Werk erschienen war und das Hegeltum noch in einem gewissen Sinne herrschend war, eigentlich viel Anerkennung für dieses Werk; natürlich auch Gegner, aber doch viel Anerkennung. Nun erwuchs aber im Laufe der Zeit diesem Werke ein großer Gegner, ein Gegner, der es vernichtend kritisiert hat, der eigentlich «kein gutes Haar» daran gelassen hat, der es in einer großen, geistreichen Weise kritisiert hat, musterhaft kritisiert hat: das war Friedrich Theodor Vischer selbst in seinen späteren Jahren!

Und wiederum ist es, ich möchte sagen, entzückend, etwas Entzükkendes, diese Selbstkritik in den «Kritischen Gängen» zu lesen. Dabei gibt es so vieles, was Friedrich Theodor Vischer als Ästhetiker, als Philosoph, als allgemeiner Belletrist in seinen «Kritischen Gängen» oder später in der schönen Sammlung «Altes und Neues» hat erscheinen lassen. — Als er noch Student war, schrieb er Lyrisch-Ironisches. Bei all der großen Verehrung, die ich für Friedrich Theodor Vischer immer hatte, ich konnte nie anders, als das, was er da als Student geleistet hat, eigentlich gar nicht einmal für studentisch, sondern für urphiliströs zu halten! Das aber lebte wieder auf, als er in seinen Siebzigerjahren, nach siebzig seine Gedichtsammlung unter dem Pseudonym «Schartenmayer» schrieb - philiströses Zeug!

Ein Urphilister wurde er in bezug auf den Goetheschen «Faust». Vom Goetheschen «Faust» im ersten Teil, nun, da gab er noch einiges zu. Aber jedenfalls war er der Ansicht: Der zweite Teil ist ein zusammengeschustertes, zusammengeleimtes Machwerk des Alters, denn der zweite Teil des «Faust», der hätte ganz anders sein müssen! — Und er hat ja dann nicht nur seinen «Faust, der Tragödie dritter Teil» geschrieben, in dem er den zweiten Teil des Goetheschen «Faust» ironisiert hat, sondern er hat auch tatsächlich einen Plan verfaßt, wie der Goethesche «Faust» hätte werden sollen. Es ist ein philiströses Zeug. Es ist ungefähr so philiströs wie das, was Du Bois-Reymond, der große Naturforscher, in seiner Rede: «Goethe und kein Ende» gesagt hat: Der «Faust» ist eigentlich verfehlt; richtig wäre er, wenn Faust nicht allerlei solchen Schnack machen würde, wie Geisterbeschwörungen und den Erdgeist beschwören, sondern wenn er einfach in ehrlicher Weise hätte die Elektrisiermaschine und die Luftpumpe erfunden und Gretchen ehrlich gemacht. — In ganz ähnlicher Weise philiströs ist eigentlich alles das, was nun Friedrich Theodor Vischer in Anknüpfung an den Goetheschen «Faust» von sich gegeben hat.

Es war so, wie man, vielleicht nicht in Württemberg, aber in meiner Heimat Österreich sagt: es war ein «Schwabenstreich», was er in bezug auf den Goetheschen «Faust» getan hat! Solche Worte haben ja immer eine andere Bedeutung, jenach den Gegenden, wo sie gebraucht werden.

Nun, sehen Sie, das Bedeutsame an diesem Mann sind diese einzelnen Züge. Sie machen ungefähr sein Leben aus. Man könnte allerdings auch einzelne Tatsachen erzählen, aber das will ich nicht. Ich möchte ihn als Persönlichkeit so vor Sie hingestellt haben, und ich möchte dann auf dieser Grundlage eine karmische Betrachtung über ihn anstellen. Ich möchte Ihnen heute nur die Materialien zunächst liefern.

Eine zweite Persönlichkeit, die ich karmisch betrachten möchte wie gesagt, es ist dies ein Wagnis, solche einzelnen Beispiele zu geben, aber sie sollen eben gegeben werden, und ich möchte Grundlagen dazu schaffen -, eine zweite Persönlichkeit ist Franz Schubert, der Liederkomponist, der Komponist überhaupt.

Ich will auch da diejenigen Züge, die ich zur karmischen Schilderung brauchen werde, herausheben. Franz Schubert war eigentlich so ziemlich sein Leben lang arm. Als Schubert eine Zeitlang gestorben war, gab es in Wien wirklich sehr viele nicht nur «gute Bekannte», sondern «Freunde» von Franz Schubert. Eine ganze Menge Leute wollten ihm Geld geborgt haben, redeten von ihm als von dem Schubert-Franzl und so weiter. Ja, aber während seiner Lebzeiten war das nicht so!

Aber er hatte einen wirklichen Freund gefunden. Dieser Freund, ein Freiherr von Spaun, war eine außerordentlich edle Persönlichkeit. Er sorgte eigentlich von frühester Jugend an in einer zarten Weise für Schubert. Sie waren Schulkollegen schon. Damals hatte er für ihn zu sorgen, und dann setzte sich das so fort. Und in karmischer Beziehung scheint mir es von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit zu sein — wir werden das dann bei der karmischen Betrachtung sehen -, daß Spaun in einem Berufe drinnen war, der ihm eigentlich ganz fremd war. Spaun war ein feingebildeter Mensch, der jede Art von Kunst liebte, der außer mit Schubert noch mit Moritz von Schwind eng befreundet war, ein Mensch, auf den wirklich in einer zarten Weise alles Künstlerische einen großen Eindruck machte. In Österreich kommt zwar manches vor - auch Grillparzer war ja Finanzbeamter -, aber eben auch Spaun war, trotzdem er nicht die geringste Ader dafür hatte, sein Leben lang in Finanzämtern. Er war Finanzbeamter, hatte Geld zu verwalten, eigentlich Zahlen zu verwalten, und als er in ein bestimmtes Alter gekommen war, wurde er sogar Lotto-Direktor, Lotterie-Direktor. Er hatte also die Lotterie in Österreich zu versorgen. Es war ihm außerordentlich antipathisch. Aber denken Sie doch nur einmal, was eigentlich der Realität nach ein Lotterie-Direktor verwaltet! Sie müssen nur bedenken: ein Lotterie-Direktor verwaltet Leidenschaften, Hoffnungen, zerstörte Hoffnungen, Enttäuschungen von unzähligen Menschen. Ein Lotterie-Direktor verwaltet in allergrößtem Stil den Aberglauben der Menschen, ein Lotterie-Direktor verwaltet in allergrößtem Stil die Träume der Menschen! Denken Sie nur, was alles eigentlich da in Betracht kommt, wenn ein Lotterie-Direktor, ein oberster Lotterie-Direktor seine administrativen Maßregeln trifft! Gewiß, wenn man ins Büro hereintritt und wieder heraustritt, bemerkt man das nicht so; aber die Realität ist da. Und derjenige, der die Welt als real betrachtet, der muß eben durchaus so etwas in Betracht ziehen.

Nun, dieser Mann, der gar nichts zu tun hatte mit jenem Aberglauben, der da von ihm verwaltet wurde, mit jenen Enttäuschungen, Sehnsuchten, Hoffnungen, der war der intime Freund von Schubert, nahm teil an seinem materiellen und an seinem geistigen Wohlergehen im höchsten Maße. Man kann eigentlich äußerlich manchmal erstaunt sein, wozu die Welt alles imstande ist. Es gibt eine Biographie von Schubert, die schildert das Exterieur von Schubert so, wie wenn Schubert ungefähr wie ein Neger ausgesehen hätte. Es ist gar keine Rede davon gewesen! Er hat sogar ein sehr sympathisches Gesicht gehabt! Aber er war eben arm. Schon das Abendbrot, das er zumeist mit dem Freiherrn von Spaun zusammen einnahm, wurde meistens in zarter Weise von Spaun eben bezahlt. Und er hatte nicht Geld, um etwa ein Klavier zu mieten für seine musikalischen Bedürfnisse. Er war in seinem äußerlichen Auftreten — das schildert auch der Freiherr von Spaun sehr getreulich — eigentlich gemessen, fast phlegmatisch. Aber in einer merkwürdigen Weise konnte ein innerlich Vulkanisches aus seiner Natur hervorbrechen.

Interessant ist schon das, daß er seine schönsten musikalischen Motive in der Regel am Morgen hinschrieb, nachdem er aufgestanden war. Aus dem Schlafe heraus setzte er sich hin und schrieb seine schönsten musikalischen Motive in dieser Weise auf. Das hat der Freiherr von Spaun selber oftmals mitgemacht. Denn wie das ja gerade bei dem geistigen Wien so der Fall ist: die beiden Herren, Schubert und Spaun, liebten schon auch des Abends einen guten Tropfen, und dann wurde es spät, spät. Dann konnte Schubert, der weit wohnte, nicht mehr nach Hause gelassen werden. Dann blieb er in einem sehr bescheidenen Bette bei Spaun. Und da war Freiherr von Spaun oftmals wirklich Zeuge, wie, aufstehend, Schubert sich einfach hinsetzte und seine schönsten musikalischen Motive aus dem Aufwachen heraus hinschrieb.

Aus den verhältnismäßig ruhigen Gesichtszügen geht nicht hervor, wie vulkanisch es eigentlich in den Untergründen dieser Schubert-Seele aussah. Aber es war vulkanisch, und gerade diese besondere Art der Persönlichkeit muß ich Ihnen schildern als Grundlage der Karmabetrachtung. Denn, sehen Sie, da war es einmal so: Schubert konnte in die Oper gehen. Er sah Glucks «Iphigenie» und war im höchsten Grade hingerissen von der «Iphigenie». Sein Enthusiasmus entlud sich seinem Freunde Spaun gegenüber während und nach der Vorstellung stark, großartig, aber eben doch in gemessener Art. Er wurde sozusagen zart emotionell, nicht vulkanisch emotionell - ich wähle gerade diejenige Züge, die wir brauchen werden. Da war es so, daß er in dem Augenblicke, wo er Glucks «Iphigenie» kennenlernte, sie für das wunderbarste musikalische Kunstwerk hielt. Entzückend war für ihn die Darstellung der Sängerin Milder. Und in bezug auf den Sänger Vogl sagte er, er wolle ihn nur kennenlernen, um ihm zu Füßen fallen zu können, so entzückt war er von seiner Darstellung. Nun, da ging die Iphigenien-Darstellung zu Ende. Schubert und Spaun gingen in das sogenannte Bürgerstübl in Wien. Ich glaube, es war noch ein dritter dabei, den ich jetzt nicht vor mir habe. Sie saßen ganz ruhig, aber sie sprachen zuweilen enthusiastisch über dasjenige, was sie am Abend in der Oper erlebt hatten. —- Ein Nachbartisch war da; da saß unter anderem auch ein dieser Gesellschaft bekannter Professor, ein Hochschulprofessor. Der wurde zunächst etwas rot gefärbt, als er hinhorchte auf dieses enthusiastische Gespräch. Die Röte wurde immer stärker. Dann fing er an zu brummen. Nachdem er eine Zeitlang gebrummt hatte, und die sich nicht hatten stören lassen, fing er aber an, füchterlich zu toben und zu schimpfen und erklärte über den Tisch hinüber auf diese Gesellschaft hin: Und überhaupt, die ganze «Iphigenie» ist ein Dreck, das ist keine wirkliche Musik, und die Milder ist überhaupt keine Sängerin, die hat weder Läufe noch Triller, die kann gar nicht singen. Und der Vogl, der geht überhaupt, wie wenn er mit Elefantenfüßen auf dem Boden dahinginge!

Nun war Schubert nicht mehr zu halten. Es drohte in jedem Moment die schlimmste Konsequenz der Handgreiflichkeit. Schubert, der sonst völlig ruhig war, ließ alle seine Vulkanität los, und die anderen hatten tatsächlich alle Mühe, ihn nur zu beruhigen.

Ja, sehen Sie, wichtig ist für dieses Leben, daß wir es zu tun haben mit einem Mann, dessen Freund Finanzbeamter, sogar Lotterie-Direktor ist, daß er mit diesem im Leben karmisch zusammengeführt wird. Wichtig ist im karmischen Zusammenhang, daß Schubert so arm war, wie es eben aus diesen Verhältnissen hervorging, wichtig ist, daß Schubert sonst sich nicht rühren konnte. Er lebte natürlich dadurch, daß er arm war, auch in eingeschränkten gesellschaftlichen Verhältnissen; er hatte nicht Gelegenheit, immer solch einen Tischnachbarn zu haben, so daß sich die Vulkanität nicht immer ausleben konnte.

Aber wenn man sich das, was da eigentlich geschah, richtig vorstellt, und doch wiederum die Stammeseigentümlichkeit kennt, aus der Schubert hervorgewachsen ist, so kann man sich schon die Frage vorlegen — solche negativen Dinge sind ja natürlich bedeutungslos, aber sie klären manchmal auf -, so kann man sich doch eben die Frage vorlegen: Wenn die Verhältnisse anders gewesen wären — natürlich konnten sie nicht anders gewesen sein, aber ich meine, man kann sich zur Klärung die Sache so vorlegen -, wenn Schubert nicht Gelegenheit gehabt hätte, dasjenige, was an musikalischer Begabung in ihm war, aus sich herauszutreiben, wenn er nicht diesen hingebungsvollen Spaun als Freund gefunden hätte, hätte er nicht auch ein Raufbold werden können in einer untergeordneten Stellung? Man kann schon die Frage aufwerfen: Lag das nicht als Anlage in ihm, was da in einer so vulkanischen Weise an jenem Abend im Bürgerstübl zum Ausdruck gekommen ist? Und das menschliche Leben ist nicht durchsichtig, wenn man sich nicht die Frage beantworten kann: Wie geschieht da eigentlich die Metamorphose, daß man in einem Leben karmisch die Rauflust nicht auslebt, sondern ein feiner Musiker wird und sich die Rauflust in feine musikalische Phantasie verwandelt?

Es klingt paradox, es klingt grotesk, aber es ist eine Frage, die, wenn man das Leben in größerem Maße betrachtet, durchaus aufgeworfen werden muß, denn aus der Betrachtung von solchen Dingen entstehen eigentlich erst die tieferen Karma-Fragen.

Eine dritte Persönlichkeit, die ich betrachten will, ist der vielgehaßte und von einer kleinen Gemeinde auch geliebte Eugen Dühring. Auch mit diesem Charakter habe ich mich karmagemäß beschäftigt und möchte auch da zunächst sozusagen die biographischen Materialien geben.

Eugen Dühring war ein außerordentlich begabter Mensch, der in seiner Jugend eine ganze Reihe von Wissenschaften aufnahm, namentlich von der mathematischen Seite her, aber auch sonst eine ganze Reihe von Wissenschaften, Nationalökonomie, Philosophie, Mechanik, Physik und so weiter.

Eugen Dühring hat mit einer interessanten Abhandlung schon seinen Doktor gemacht und dann in einem Buch, das längst vergriffen ist, auch über diesen Gegenstand eigentlich recht klar, vor allen Dingen eindringlich geschrieben. Ich möchte, trotzdem die Sache fast schon so schwierig ist wie die Relativitätstheorie — aber schließlich, über die Relativitätstheorie haben ja auch eine Zeitlang alle Leute geredet, die nichts davon verstanden haben, und sie haben sie doch großartig gefunden und finden sie heute noch so -,, ich möchte, trotzdem es schwierig ist, in einer Weise, wie man es vielleicht verstehen kann, über diese Gedanken der Erstlingswerke von Dühring einiges sagen.

Sehen Sie, da handelt es sich darum, daß gewöhnlich die Leute sich vorstellen: Da ist der Raum, der ist unendlich, und der Raum ist angefüllt mit Materie. Die Materie hat kleinste Teile. Ihre Zahl ist auch unendlich groß. Unendlich viele kleinste Teile der Materie sind im Weltenraum geballt, irgendwie zusammenkristallisiert und dergleichen. Da ist die unendliche Zeit. Die Welt hat gar nicht einen Anfang genommen; man kann auch nicht sagen, daß sie ein Ende nehmen werde.

Diese unbestimmten Unendlichkeitsbegriffe, die hatten es dem jungen Dühring angetan, und er sprach wirklich recht scharfsinnig darüber, daß dieses Reden über Unendlichkeitsbegriffe eigentlich gar keine Bedeutung habe, daß, wenn man auch von einer noch so großen Anzahl zum Beispiel von Weltenatomen oder Weltenmolekülen sprechen müsse, es aber doch eine abzählbare bestimmte Zahl sein müsse. Wenn der Weltenraum noch so groß vorgestellt wird, so muß er eine abmeßbare Größe sein, ebenso muß die Weltenzeit eine abmeßbare Größe sein, was, wie gesagt, mit großem Scharfsinn dargestellt wurde.

Dem liegt etwas Psychologisches zugrunde. Dühring wollte überall klares Denken haben, und in den Unendlichkeitsbegriffen steckt ja im Grunde genommen heute noch nirgends klares Denken drinnen. Dann hat Dühring das ausgedehnt auf andere Betrachtungen, zum Beispiel auf die sogenannten negativen Größen, zum Beispiel wenn man Vermögen hat, von negativen Größen, die man mit einem Minuszeichen belegt. Man unterscheidet dann die Zahlenreihen: Null, nach der einen Richtung plus eins usw., nach der anderen Richtung minus eins usw.

Dühring hat nun die Anschauung vertreten: Das ganze Schwätzen von Minuszahlen ist eigentlich ein Unsinn. Was bedeutet ein Negativ, eine Minuszahl? Er sagt: Habe ich fünf und ziehe eins ab, so bekomme ich vier; habe ich fünf und ziehe zwei ab, so bekomme ich drei; habe ich fünf und ziehe drei ab, so bekomme ich zwei; habe ich fünf und ziehe vier ab, so bekomme ich eins; habe ich fünf und ziehe fünf ab, so bekomme ich null. Nun sagen die Anhänger der negativen Größe: Habe ich fünf und ziehe sechs ab, habe ich minus eins; habe ich fünf und ziehe sieben ab, habe ich minus zwei.

Dühring sagt: Das ist eine unklare Denkungsweise, da liegt kein klarer Gedanke drinnen! Was bedeutet «minus eins»? Das bedeutet, ich soll sechs von fünf abziehen; aber da habe ich um eins zu wenig. Was bedeutet minus zwei? Ich soll von fünf sieben abziehen; da habe ich um zwei zu wenig. Was bedeutet minus drei? Ich soll acht von fünf abziehen; da habe ich um drei zu wenig. Die negativen Zahlen sind also gar nicht andere Zahlen als die positiven Zahlen. Sie bedeuten nur immer, daß ich beim Subtrahieren um eine bestimmte Zahl zu wenig habe. - Das hat dann Dühring auf die mannigfaltigsten mathematischen Begriffe ausgedehnt.

Ich weiß selbst, daß als junger Mann dieses auf mich einen ungeheuer starken Eindruck gemacht hat, weil wirklich verstandesmäßige Klarheit über diese Dinge bei Dühring ausgegossen war.

In einer ebensolchen verstandesmäßigen Schärfe ging er in der Nationalökonomie vor, ging er in der Philosophiegeschichte zum Beispiel vor. Und er wurde Dozent an der Berliner Universität; da hielt er Vorlesungen im besuchtesten Hörsal und über die mannigfaltigsten Gegenstände, über Nationalökonomie, Philosophie, Mathematik.

Nun trat der Fall ein, daß von der Göttinger Akademie der Wissenschaften ein Preis ausgeschrieben war auf das beste Buch über die Geschichte der Mechanik. - Bei einem solchen Preisausschreiben ist es üblich, daß die Werke derer, die sich um den Preis bewerben, eingeschickt werden so, daß man den Verfasser nicht kennt, sondern daß ein Motto gewählt wird, das auf dem Kuvert steht. Der Name des Verfassers ist darin verschlossen; dann wird ein Motto draufgeschrieben. Das steht dann oben und die Preisrichter kennen nicht den Verfasser.

Nun, die Göttinger Akademie der Wissenschaften hat den Preis für die Geschichte der Mechanik von Eugen Dühring erteilt, hat sogar ein außerordentlich anerkennendes Schreiben dem Verfasser zugehen lassen. Damit also war Eugen Dühring nicht nur vor seiner Zuhörerschaft als ein tüchtiger Dozent erklärt, sondern er war auch von einer im eminentesten Sinne gelehrten Körperschaft anerkannt.

Dieser selbe Dühring hat neben all den Talenten, die Ihnen ja schon anschaulich sind aus dem, was ich Ihnen nun erzählt habe, auch - man kann schon nicht anders sagen — eine böse Zunge gehabt. Er hatte etwas von bösartigem Kritikaster auf alle Dinge der Welt in sich. In dieser Beziehung hat er sich dann eigentlich immer weniger und weniger Zurückhaltung auferlegt. Und als er von einer so gelehrten Körperschaft wie der Göttinger Akademie der Wissenschaften preisgekrönt war, da stachelte ihn das doch sehr. Es war ja eine natürliche Anlage, aber es stachelte. Und da fing er an, wirklich zwei Dinge miteinander zu verbinden: einen außerordentlich starken Gerechtigkeitssinn, der ist ihm nicht abzusprechen, aber auf der anderen Seite - man bekommt so die Neigung dann, in den Wortbildungen der Leute zu reden, die man schildert — bekam er einen außerordentlich starken schimpfiererischen Sinn. Er schimpfte schrecklich. Er wurde ein «Schimpfierer».

Nun hatte er auch das Unglück, gerade in der Zeit, als es ihn so stachelte im Schimpfieren, blind zu werden. Er hat noch als blinder Dozent in Berlin vorgetragen. Er erblindete vollständig. Das hat ihn niemals irgendwie abgehalten, seinen ganzen Mann zu stellen. Er fuhr in seiner Tätigkeit als Schriftsteller fort und konnte sich seine Dinge immer selbst besorgen - bis zu einem gewissen Grade natürlich -, trotzdem er vollständig erblindet war. Aber zunächst machte er da die Bekanntschaft mit einem wirklich tragischen Schicksal in der Gelehrtengeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts: mit dem Schicksal von Julius Robert Mayer, dem eigentlichen Entdecker des mechanischen Wärme-Äquivalents, der ja, wie man durchaus behaupten kann, unschuldigerweise ins Irrenhaus gesperrt, in die Zwangsjacke gesteckt worden ist, schrecklich behandelt worden ist von Familie, Kollegen und «Freunden». Dühring schrieb dann seine Schrift: «Robert Mayer, der Galilei des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts.» Es war wirklich eine Art Galilei-Schicksal in diesem Julius Robert Mayer.

Das schrieb Dühring auf der einen Seite mit einer außerordentlich großen Sachkenntnis, mit einem wirklich tiefgehenden Gerechtigkeitssinn, aber auch mit einem Dreinhauen wie mit Dreschflegeln in alles dasjenige, was da an Schäden auftrat. Die Zunge ging immer mit ihm durch. So zum Beispiel, als er hörte und las von der Errichtung des ja vielen von Ihnen bekannten Julius Robert Mayer-Denkmals in Heilbronn, von der Enthüllungsfeier: Dieses Puppenbild, das da auf dem Heilbronner Marktplatz steht, das ist etwas, was man als eine letzte Schmach diesem Galilei des 19. Jahrhunderts angetan hat. Da sitzt der große Mann mit übergeschlagenen Beinen. Wenn man ihn wirklich darstellen wollte in der Verfassung, wie er wahrscheinlich gewesen wäre, wenn er hätte hinschauen können auf den Festredner und auf all die guten Freunde, die da unten ihm dieses Denkmal errichtet haben, so müßte man ihn darstellen nicht mit übergeschlagenen Beinen, sondern mit den Händen über dem Kopf zusammengeschlagen!

Da er sehr viel Leid durch Zeitungen erfahren hatte, wurde er auch wütender Antisemit. Und da war er auch wieder konsequent. Er hat zum Beispiel das Schriftchen geschrieben: «Die Überschätzung Lessings und dessen Anwaltschaft für die Juden», in dem über Lessing mordsmäßig geschimpft wird! Aber davon ist dann überhaupt seine besondere Art von Literaturbetrachtung ausgegangen.

Wenn Sie sich einmal die Güte antun wollen, meine lieben Freunde, etwas über deutsche Literatur zu lesen, das Sie sonst nicht lesen können, das ganz anders ist als die sonstigen Abhandlungen über deutsche Literatur, dann lesen Sie die Dühringschen zwei Bände: «Die Größen der modernen Literatur.» Da ist dasjenige, was in Dühring war, diese streng mathematische Denkweise, diese Verstandesschärfe auf die schöne Literatur angewendet. Und da hat er nötig, um die Art zu zeigen, wie er anders denkt als andere Leute, da hat er nötig, sogar umzutaufen die Größen des deutschen Geisteslebens. Er spricht zum Beispiel in einem Kapitel von Kothe und Schillerer, was in der Dühtingschen Sprache heißt: Goethe und Schiller. Dühring schreibt Kothe und Schillerer und hält das fest durch die ganzen Abhandlungen durch. Er ist manchmal in seinen Erfindungen in Wortbildungen grotesk. Intellektuaille — so zum Beispiel schreibt er immer von Leuten, die intellektualistisch sind. Die Intellektuaille -— Verwandtschaft zu Kanaille - ähnliche Wortbildungen hat er immer. Nun, manches ist außerordentlich interessant.

Sehen Sie, mir passierte zum Beispiel einmal folgendes. Ich hatte mit noch ungedruckten Schriften von Nietzsche zu tun, bekam da in die Hand die ja jetzt längst gedruckte Schrift über die Wiederkehr des Gleichen. Die Nietzscheschen Manuskripte sind nicht sehr deutlich zu lesen, da kam ich denn an so eine Stelle, und sagte mir: Diese Wiederkunft des Gleichen bei Nietzsche hat eine merkwürdige Abstammung! Nun, gehen wir jetzt vom Nietzsche-Archiv, wo seine Hefte drinnen liegen - ich war dazumal befreundet mit Frau Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche -, gehen wir jetzt einmal mit dieser Handschrift und suchen wir in der Bibliothek, schlagen wir die Wirklichkeitsphilosophie des Dühring auf, da werden wir die Wiederkehr des Gleichen finden! Denn Nietzsche hat sehr viele Ideen als «Gegenideen» geprägt. Ich konnte es sehr rasch nachschlagen. Ich nahm die Wirklichkeitsphilosophie heraus, die in der Nietzsche-Bibliothek vorhanden war, schlug auf: Auf der betreffenden Seite fand sich die Stelle - ich kannte sie, fand sie daher gleich -: daß es unmöglich sei, aus einer wirklichen, sachgemäßen Erkenntnis der materiellen Tatsachen der Welt von einer Wiederkehr der Dinge, der Konstellationen, die schon einmal da waren, zu sprechen!

Dühring versuchte die Unmöglichkeit der Wiederkehr des Gleichen zu beweisen. An der Stelle, wo Dühring das ausführt, da steht auf der Seite ein Wort, das Nietzsche oftmals an den Rand der Schriften hingeschrieben hat, die er so benutzt hat, daß er die Gegenidee gebildet hat: Esel.

Diese Einzeichnung fand sich auch auf dieser Seite. Und man kann eben tatsächlich gerade bei Dühring manches finden, was dann in Nietzsches Ideen übergegangen ist, allerdings in genialer Weise. Ich werde damit nicht irgend etwas gegen Nietzsche einwenden, aber die Dinge liegen eben so.

Nun ist das Auffällige bei Dühring in karmischer Beziehung, daß er eigentlich nur mathematisch zu denken vermag. Er denkt in der Philosophie, in der Nationalökonomie, er denkt in der Mathematik selber mathematisch, aber mathematisch scharf und klar. Er denkt auch in der Naturwissenschaft scharf und klar, aber mathematisch. Er ist nicht Materialist, aber er ist mechanistischer Denker, er denkt die Welt unter dem Schema des Mechanismus. Und er hatte den Mut, das, was ehrlich ist bei einem solchen Denken, wirklich auch in seinen Konsequenzen zu verfolgen. Denn eigentlich ist es richtig: Wer so denkt, der kann über Goethe und Schiller nicht anders schreiben, wenn man von der Schimpfiererei absieht und das Sachliche nimmt.

Das ist also die besondere Anlage seines Denkens. Dabei frühzeitig erblindet, auch persönlich ziemlich ungerecht behandelt. Er ist ja von der Berliner Universität entfernt worden. Nun, Gründe gab es natürlich. Zum Beispiel als die zweite Auflage seiner «Kritischen Geschichte der allgemeinen Prinzipien der Mechanik» erschienen ist, da hat er sich nicht mehr zurückgehalten. Die erste Auflage war ja ganz zahm in der Behandlung der Größen der Mechanik, so daß jemand sagte: Er hat eben da so geschrieben, wie er sich denken konnte, daß es von einer gelehrten Körperschaft doch prämiiert werden kann! Aber als die zweite Auflage erschien, da hat er sich nicht mehr zurückgehalten, da war es ja schon prämiiert: da hat er ergänzt! Nun hat jemand gesagt — Dühring hat das oftmals wiederholt -: die Göttinger Akademie hätte die Klauen prämiiert, ohne den zugehörigen Löwen zu kennen! Aber der Löwe ist dann eben zum Vorschein gekommen, als die zweite Auflage erschien.

Da waren schon merkwürdige Sachen drinnen. Gerade zum Beispiel in Anknüpfung an Julius Robert Mayer, sein Galilei-Schicksal im 19. Jahrhundert, über das er so recht entrüstet war, nannte er jemand, den er für einen Plagiator von Julius Robert Mayer hielt — nämlich Hermann Helmholtz -, ein Universitätsgestell, ein hölzernes Universitätsgestell! Er hat dann später das noch erweitert, eine Zeitung herausgegeben: «Der Personalist.» Da waren die Dinge sehr stark persönlich gefärbt. So zum Beispiel findet sich da eine Erweiterung der Stelle über Helmholtz. Da redet er nicht nur über das «Universitätsgestell»; sondern, da sich herausgestellt hatte, als die Leiche seziert worden ist, daß Helmholtz Wasser im Kopfe hatte, da sagte er: Aber der Hohlkopf war schon bemerkbar, als der Mann noch gelebt hat; das brauchte nicht erst nach dem Tode konstatiert zu werden.

Fein war Dühring ja nicht. Man kann nicht sagen, er schimpfte wie ein Waschweib, denn es hat nichts Philiströses, wie er schimpft, genial ist es schon auch nicht; aber es ist halt nicht mehr geschimpft: es ist schimpfiert. Es ist etwas ganz Eigenartiges.

Nun, die Blindheit, diese ganze mechanistische Denkanlage, das Verfolgtwerden — denn er wurde ja verfolgt, er wurde aus der Universität verwiesen, und dabei kamen schon Ungerechtigkeiten vor, wie überhaupt unzählige Ungerechtigkeiten in seinem Leben an ihm verübt worden sind -, das alles sind Schicksalszusammenhänge bei einem Menschen, die erst recht interessant werden, wenn man sie karmisch betrachtet.

Nun habe ich Ihnen diese drei Persönlichkeiten hingestellt: Friedrich Theodor Vischer; den Liederkomponisten Schubert und Eugen Dühring, und werde dann morgen Ihnen dasjenige, wofür ich Ihnen heute die Materialien geben wollte, karmisch schildern, das heißt, darauf zurückführen, wie die Dinge eigentlich in ihrem karmischen Zusammenhange liegen.

Seventh Lecture

In my reflections on karma today, after describing the formation of karmic forces last time, I would like to lay the foundation, so to speak, for an understanding of karma by looking at individual destinies in people's lives in order to grasp the karmic determination, the destiny, let us say, of these individual human destinies.

Of course, such destinies can only serve as examples; but if you take concrete human destinies as a starting point and look at karma, you can gain insights into the way karma works in people in general.

Of course, it works in as many different ways as there are people on earth. The karmic design is entirely individual. It is therefore only possible to speak in examples when dealing with the individual.

Now I would like to give examples today that I have examined, which have become transparent to me in their karmic course. However, it is a daring undertaking to speak in detail about karmic connections, even if they are more distant, because it is actually customary to speak in general terms when talking about karma: This or that is caused in this or that way -, or: One must attribute this or that stroke of fate to something, as the person deserved it - and the like. Well, things are not that simple! It is precisely when we speak of karma that a great deal is trivialized.

Now we want to go into certain karmic examples today, even if they are more distant, to really, I would like to say, carry out this daring undertaking of speaking about individual karmas, insofar as this can be done after the investigations that have been incumbent upon me. So let me give some examples.

First of all, I would like to talk about a famous aesthete and philosopher, Friedrich Theodor Vischer - I have mentioned him several times in the course of my lectures. Today I would like to emphasize precisely those peculiarities of his life that I can then choose as the basis for a karmic discussion.

Friedrich Theodor Vischer grew up with his education in the age in which the so-called idealistic German philosophy flourished within Germany: Hegeltum. And Friedrich Theodor Vischer, who was young and underwent his studies at a time when people's heads were full of Hegelian thinking, adopted this way of thinking. He was receptive to this high Hegelian dwelling in thought. It was obvious to him that thought, as Hegel asserts, is indeed the divine essence of the world; that therefore, when we think as human beings, we live in the divine substance by living in thought.

Hegel was indeed thoroughly convinced that all earthly development actually depends on living in thought. The other follows on from this. The plans of the world are made by thinkers thinking about the world. - Certainly, there is much truth in this. But with Hegel, it all has a very abstract character.

But Friedrich Theodor Vischer settled into this Hegelian philosophy. At the same time, however, he was also a personality who emerged from a tribe and bore the characteristics of this tribe with great clarity. He had all the characteristics of a Swabian, all the stubbornness, all the dogmatism, even all the Swabian sense of independence! He also had the short-sightedness of the Swabian. And because he had this Swabian character, he in turn had strong personal peculiarities: A beautiful blue eye, if you take the outward appearance, a somewhat shaggy, but nevertheless full reddish-brown beard that he wore with a certain aesthetic enthusiasm. I say he wore it with a certain aesthetic enthusiasm because in his writings he expresses himself sufficiently about the naughtiness of those men who do not wear a full beard. He calls them “beardless monkey faces”; so he was not at all reticent. He did all this with the peculiar, short-faced determination of a Swabian.

He was moderately tall, not fat, but rather slender; but he walked through the streets holding his arms as if he were always clearing the way with his elbows. He certainly did that as a spiritual individual! - That was his outward appearance.

He had a very strong, personal urge for independence and didn't hold back with what he wanted to say. It so happened that once, after he had been denounced to the Stuttgart government by “friends” - which happens very often to friends - he received a severe reprimand from the Stuttgart government - on the same day that his son Robert was born to him, who then also made a name for himself as an aesthete - that he then announced this in the auditorium by saying: "Gentlemen, I have received a big wiper and a small Vischer today!

It was quite characteristic of him to talk about things in a very definite way. There is a delightful essay by him: “About foot care on the railroad.” He observed with great displeasure how passengers sitting on one side of the coup& sometimes put their feet on the bench on the other side. He couldn't stand that at all! There is a delightful essay by him about foot flails on the railroads.

I'd rather keep quiet today about all the things he wrote in his book “Mode und Zynismus” (Fashion and Cynicism) about all kinds of naughtiness and impropriety at balls and other entertainments. He was already a strong individuality.

A friend of mine visited him once and knocked on the door very nicely. I don't know if this is customary in Swabia, but he didn't say “Come in!”, or as they usually say in such a case, but instead he bellowed: “Glei!” - He would be ready in a moment or immediately.

Now, Friedrich Theodor Vischer set himself a great task at a relatively young age: to write aesthetics in the spirit of Hegel's philosophy. And the five volumes he wrote are indeed a remarkable work. There is a strict division into paragraphs, as was usual with Hegel; there are the usual definitions. If I were to read a piece to you, you would all yawn immediately, because it is not written in a popular Hegelian style at all, but there are definitions like these: The beautiful is the appearance of the idea in sensual form. The sublime is the appearance of the idea in sensual form in such a way that the idea outweighs the sensual form. The comic is the appearance of the idea in sensual form in such a way that the sensual form predominates - and so on. These are things that are still relatively interesting, but it goes much further! But then there are these “definitions”, “declarations”, the so-called small print. Most people read this book “Aesthetics” by Friedrich Theodor Vischer in such a way that they leave out the large print and only read the small print. And this small print does indeed contain the most ingenious aesthetics that has been put forward in the most diverse fields. There is no pedantry, no pretense, but rather the Swabian Vischer with all his witty conscientiousness, but also with his fine feeling for everything beautiful, magnificent and sublime. At the same time, the natural world is depicted in an incomparable way, in a free style that is almost exemplary. He really brought this work to completion over many years with an iron consistency.

Now, at the time when this work was published and Hegelianism still prevailed in a certain sense, there was actually a lot of recognition for this work; opponents too, of course, but still a lot of recognition. Over time, however, a great opponent emerged for this work, an opponent who criticized it scathingly, who actually left “no good hair” on it, who criticized it in a great, witty way, criticized it in an exemplary manner: that was Friedrich Theodor Vischer himself in his later years!

And again, it is, I would like to say, delightful, something delightful, to read this self-criticism in the “Kritische Gänge”. There is so much that Friedrich Theodor Vischer published as an aesthete, philosopher and general fiction writer in his “Kritische Gänge” or later in the beautiful collection “Altes und Neues”. - When he was still a student, he wrote lyrical and ironic works. For all the great admiration I always had for Friedrich Theodor Vischer, I could never help but think that what he achieved as a student was actually not even student-like, but rather urphilistine-like! But this was revived when he wrote his collection of poems under the pseudonym “Schartenmayer” in his seventies, after seventy - philistine stuff!

He became an Urphilistine in relation to Goethe's “Faust”. Of Goethe's “Faust” in the first part, well, he admitted quite a bit. But in any case, he was of the opinion that the second part was a cobbled-together, glued-together work of old age, because the second part of “Faust” should have been completely different! - And not only did he then write his “Faust, the third part of the tragedy”, in which he ironized the second part of Goethe's ‘Faust’, but he also actually wrote a plan of how Goethe's “Faust” should have been. It's philistine stuff. It's about as philistine as what Du Bois-Reymond, the great naturalist, said in his speech “Goethe and no end”: “Faust” is actually misguided; it would be correct if Faust didn't do all sorts of such nonsense as conjuring up spirits and conjuring up the earth spirit, but if he had simply in an honest way invented the electrifying machine and the air pump and made Gretchen honest. - In a very similar way, everything that Friedrich Theodor Vischer said in connection with Goethe's “Faust” is actually philistine.

It was, as they say, perhaps not in Württemberg, but in my home country of Austria: it was a “Swabian prank”, what he did in relation to Goethe's “Faust”! Such words always have a different meaning, depending on where they are used.

Now, you see, what is significant about this man are these individual traits. They roughly make up his life. You could also tell individual facts, but I don't want to do that. I would like to present him to you as a personality, and I would then like to make a karmic observation about him on this basis. I only want to provide you with the material today.

A second personality that I would like to look at karmically, as I said, it is a risk to give such individual examples, but they should be given, and I would like to create the foundations for this - a second personality is Franz Schubert, the song composer, the composer in general.

I also want to emphasize those traits that I will need for the karmic description. Franz Schubert was actually poor for most of his life. When Schubert had been dead for a while, there were really a lot of not just “good acquaintances” but “friends” of Franz Schubert in Vienna. A whole lot of people wanted to have lent him money, talked about him as the Schubert-Franzl and so on. Yes, but that wasn't the case during his lifetime!

But he had found a real friend. This friend, a Baron von Spaun, was an extraordinarily noble personality. He actually cared for Schubert in a tender way from his earliest youth. They had been schoolmates. Back then he had to look after him, and then it continued like that. And in karmic terms it seems to me to be of very special importance - we will see this in the karmic consideration - that Spaun was involved in a profession that was actually quite foreign to him. Spaun was a finely educated man who loved every kind of art, who was a close friend not only of Schubert but also of Moritz von Schwind, a man on whom everything artistic really made a great impression in a delicate way. There are many things in Austria - Grillparzer was also a tax official - but Spaun was also in tax offices all his life, even though he didn't have the slightest aptitude for them. He was a tax official, had to manage money, actually numbers, and when he reached a certain age, he even became lottery director, lottery director. So he had to look after the lottery in Austria. It was extremely antipathetic to him. But just think what a lottery director actually manages in reality! Just think about it: a lottery director manages the passions, hopes, dashed hopes and disappointments of countless people. A lottery director manages people's superstitions on a grand scale, a lottery director manages people's dreams on a grand scale! Just think of all the things that come into consideration when a lottery director, a supreme lottery director, makes his administrative decisions! Of course, when you walk in and out of the office, you don't notice it, but the reality is there. And anyone who sees the world as real has to take something like that into consideration.