The World of the Senses and the World of the Spirit

GA 134

28 December 1911, Hannover

Lecture II

Yesterday we were considering the successive moods of soul that have to be attained if human thinking—if what is ordinarily called knowledge—is to enter the realm of reality, and we came to a condition of soul that we named surrender. In other words, a thinking that has risen to the conditions of soul we described before—a thinking, that is, which has become possessed of wonder, and has then learned what we called reverent devotion to the world of reality and finally what we called knowing oneself to be in wisdom-filled harmony with the phenomena of the world—if such a thinking be not able then to rise still further and enter the region we have described as a condition of surrender, it cannot come to reality. Now this surrender is only to be attained by making the resolute endeavour again and again to face for ourselves the inadequacy of mere thought. We have to take pains to stimulate and strengthen within us a mood that may be expressed as follows. It must be as though we were constantly saying to ourselves: I ought not to expect that my thinking can give me knowledge of the truth, I ought rather solely to expect of my thinking that it shall educate me. It is of the utmost importance that we should develop in us this idea, namely, that our thinking educates us. If you will really take this point of view as a practical rule of life you will find that there are many occasions when you are led to quite different conclusions from those that seem at first sight to be inevitable.

I daresay there are not many of you who have made a thorough study of the philosopher Kant. It is not necessary. I only want here to refer to the fact that in Kant's most important and revolutionary work, “The Critique of Pure Reason,” you will always find proofs adduced both for and against a proposition in question. Take, for example, a statement such as the following. “The world once had a beginning in time.” You will find that Kant puts, perhaps on the other side of the same page, the statement: “The world has always existed, from all eternity.” And then he proceeds to adduce valid proofs for both statements, notwithstanding that the one obviously expresses the very opposite of the other. That is to say, Kant proves in the same manner that the world has had a beginning and that it has had no beginning. He calls this method of reasoning “Antinomy” and thinks it is itself an evidence that the human faculty of knowledge has boundaries, seeing that man is forced thereby to arrive at contradictory conclusions. And, of course, he is right, so long as one expects by thinking to come to conformity with some objective reality. So long as we give ourselves up to the belief that by thinking or by the elaboration of concepts or, let us say, by the elaboration in thought of experiences we have in the world, we can come to reality, so long are we indeed in desperate case, if someone comes forward and shows us that a particular statement and its exact opposite can equally well be proved. For if this is so, how are we ever to arrive at Truth? If, however, we have learned that where the situation demands a decisive pronouncement, thinking can come to no conclusion about reality, if we have persistently educated ourselves instead to look upon thinking as a means to become wiser, as a means to take in hand our own self-education in wisdom, then it does not disturb us at all that at one time one thing can be proved and at another time its opposite can be proved. For we very soon make the following discovery. The fact that the elaboration of concepts does not, so to say, expose us in the least to the onset of reality, is the very reason why we are able to work with perfect freedom within the sphere of concepts and ideas and to carry on our own self-education by this means. If we were perpetually being corrected by reality, then the elaboration of concepts would not afford us a means of educating ourselves in this manner in perfect freedom. I would like to ask you to give careful consideration to this fact. Let me repeat it. The elaboration of concepts affords us a means of effective and independent self-education, and it can only do so because we are never disturbed in the free elaboration of concepts by the interference of reality.

What do I mean when I say we are not disturbed? What sort of disturbance could reality make in the free elaboration of concepts? We can picture to ourselves a little what such a disturbance would be like if we contrast—purely hypothetically for the moment, though, as we shall see later, it does not need to remain entirely in the realm of hypothesis—our human thinking with divine thinking. For we can say, can we not, that it is impossible to conceive of divine thinking as having nothing to do with reality. When we try to picture the thinking of the Gods, we can only conceive of it—still speaking for the moment purely hypothetically—as intervening in reality, as influencing reality. And this leads inevitably to the following conclusion. When a human being makes a mistake in his thinking, then it is a mere logical mistake, it is nothing worse. And when, later on, he comes to see that he has made a mistake he can correct it; and he will at the same time have accomplished something for his self-education, he will have grown wiser. But now take the case of divine thinking. When divine thinking thinks correctly, then something happens; and when it thinks falsely, then something is destroyed, something is annihilated. So that if we had a divine thinking, then with every false concept we should call forth a destructive process, first of all in our astral body, then in our etheric body and thence also in our physical body. If we had active divine thinking, if our thinking had something to do with reality, then a false concept would have the result that we should, as it were, stimulate inside us a drying up process in some part or other of our body, a hardening process. You will agree, it would be important to make as few mistakes as possible; for it might not be long before we had made so many mistakes that our body would have become quite dried up and would fall to pieces. We should, in fact, soon find it crumble away if we transformed into reality the mistakes in our thinking. We actually only maintain ourselves in real existence through the fact that our thinking does not work into reality, but that we are protected from the penetration of our thinking into reality. Thus we can make mistake after mistake in our thinking. If later we correct these mistakes we have thereby educated ourselves, we have grown wiser, and we have not at the same time committed devastation with our mistakes. As we strengthen ourselves more and more with the moral force of such a thought as this we learn to know the nature of the “surrender” of which I spoke and we come at last to a point where we do not at critical moments of life, turn to thinking, in the hope to gain knowledge and understanding of external things.

That sounds strange, I know, and at first sight it seems as though it would be quite impossible. How can we refuse to have recourse to thinking? And yet, although it is impossible to take such a line absolutely, we can take it under certain conditions. Constituted as we are as human beings in the world, we cannot on every occasion suspend judgment on the things of the world. We have to judge and form opinions—we shall see in the course of these lectures why that is so—we have to act in life and cannot always wait to penetrate to the depths of reality. We must judge—but we should educate ourselves to exercise caution in accepting as finally true the judgments and opinions we form. We should, as it were, be continually looking over our own shoulder and reminding ourselves that where we are applying our keenest intellect, just there we are treading on very uncertain ground and are perpetually liable to make mistakes. That is a hard saying for cocksure people! They think they will never get anywhere at all if they are to doubt whether the opinion they form on some event is conclusive. Observe a little and you will see that very many people, when some statement is made, think it necessary at once to say: “But what I think is this”—or when they see something, to say: “I don't like that!” or “I like it!” This kind of attitude must be given up by anyone who does not rest content to go through life with easy self-assurance; it must be given up if we want to set the course of our inner life in the direction of reality. What we have to do is to cultivate an attitude of mind which may be characterised in the following words: “Obviously I have, of course, to live my life, and this means I must form judgments and conclusions. I will, therefore, employ my power of judgment in so far as the practice of life makes this necessary, but I will not use it for the recognition of truth. For that I will be for ever looking cautiously over my shoulder, I will always receive with some degree of doubt every judgment that I happen to make.”

But how are we then to arrive at any thought about truth, if not by forming judgments in the ordinary way? We have already indicated yesterday the right attitude of mind, when we said that we ought to let the things speak, let the things themselves tell their secrets. We have to learn to adopt a passive attitude to the things of the world, and let them speak out their own secrets. A great deal of error would be avoided if men would do this. We have a wonderful example in Goethe, who, when he wants to investigate truth, does not allow himself to judge but tries to let the things themselves utter their own secrets. Let us suppose we have two men, one who judges and the other who lets the things tell their own secrets. We will select a very clear and simple example. One man sees a wolf and describes it. He finds that there are other animals besides which look like this wolf, and he arrives in this manner at the general concept “wolf.” And now he can go on to form the following conclusion. He can say to himself: In reality there are many individual wolves; the general concept of “wolf” which I make in my mind, wolf as such, does not exist; only individual wolves exist in the world. Such a man will easily state it as his opinion that we have really only to do with individual wolf beings, and the general concept of wolf which one holds as an idea is not anything real. There you have a striking example of a man who merely judges and forms opinions. This is the kind of conclusion he develops. And how about the man, on the other hand, who lets reality speak for itself? How will he think of that invisible quality of wolf which is to be found in every single wolf and which characterises all wolves alike? He will look at it in this way. He will say to himself: Let me consider a lamb and compare it with a wolf. I am not going to formulate any judgment on the matter, I am simply going to let the facts speak. And now, let us imagine this man has the opportunity to see with his own eyes how the wolf eats up the lamb. He sees the event take place before him. Then he would have to say to himself: “The substance which before was running about as lamb is now inside the wolf, it has been absorbed into the wolf.” It needs no more than the perception of this fact to see how real the wolf nature is! For if we were to rely on what we can follow with our external senses we might easily be led to the conclusion that if a wolf were deprived of all other food and were to eat nothing but lamb he must gradually—for the metabolism that goes on inside him will produce this result—he must gradually come to have in him nothing but lamb substance. As a matter of fact, however, he never becomes a lamb, he remains always a wolf. That shows quite unmistakably, if one judges the matter rightly, that the material part of the wolf has been quite erroneously assumed to constitute “wolf” as such. When we let ourselves be taught by the external world of facts, then it shows us that besides what we have before us as material substance in the wolf there is something else, something we cannot see and that yet is real in the highest degree. And this it is which brings it about that when the wolf eats nothing but lamb he does not become lamb but remains wolf. All of him that is merely perceptible to the senses has come from lambs.

It is difficult sometimes to draw a sharp line of demarcation between judging and letting ourselves be taught by reality. When, however, the difference has once been grasped and when judgment is only employed for the ends of practical life, while for an approach to reality the attitude is taken of allowing ourselves to be taught by the things of the world, then we gradually arrive at a mood of soul which can reveal to us the true meaning of “surrender.” Surrender is a state of mind which does not seek to investigate truth from out of itself, but which looks for truth to come from the revelation that flows out of the things, and can wait until it is ripe to receive the revelation. An inclination to judge or form opinions wants to be continually arriving at truth at every step; surrender, on the other hand, does not set out to force an entrance, as it were, into this or that truth, rather do we seek to educate ourselves and then quietly wait until we attain to that stage of maturity where the truth flows to us from the things of the world, coming to us in revelation and filling our whole being. To work with patience, knowing that patience will bring us further and further in wise self-education—that is the mood of surrender.

And now we must go on to consider the fruits of this surrender. What do we attain when we have gone forward with our thinking from wonder to reverence, thence to feeling oneself in wisdom-filled harmony with reality and finally to the attitude of surrender—what do we attain? We come at last to this. As we go about the world and observe the plants in all their greenness and admire the changing colours of their blossoms, or as we contemplate the sky in its blueness and the stars with their golden brilliance—not forming judgments but letting the things themselves reveal to us what they are—then if we have really succeeded in learning this “surrender,” all things in the world of sense become changed for us, and something is revealed to us in the world of the senses, for which we can find no other word than a word taken from our own soul life.

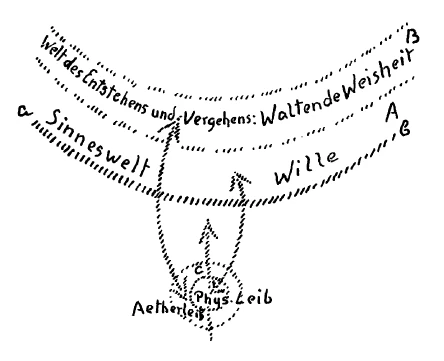

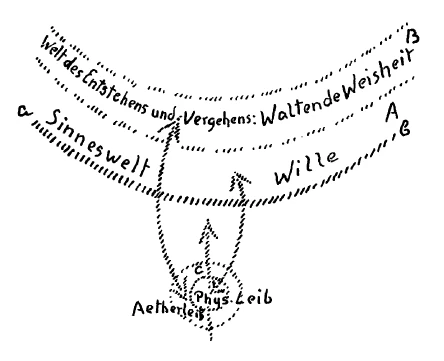

Suppose this line (a—b) represents the world of the senses as it shows itself to our view. Suppose you are standing here (c) and you behold the world of the senses spread out before you like a veil. This line (a—b) is intended to represent the tones that work upon your ear, the colours and forms that work upon your eye, the smells and tastes that work upon your other organs, the hardness and softness, etc., etc.—in short, the whole world of the senses. In ordinary life we stand in the world of the senses and we apply to it our faculty of judgment. How else do all the sciences arise? Men approach the world of the senses and by many kinds of methods they investigate the laws that prevail there. You will, however, have gathered from all that we have been saying that such a procedure can never lead one into the world of reality, because judgment is not a leader at all; it is only by educating one's thinking, it is only by following the path of wonder and of reverence, etc., that one can ever penetrate to the world of reality. Then the world of the senses changes and becomes something entirely new. And it is important that we should make discovery of this if we would gain any knowledge of the real nature of the sense world.

Let us suppose that a man who has developed this feeling, this attitude of surrender, in a rather high degree, looks out over the fresh bright green of a meadow. At first sight he cannot distinguish the colours of any individual plants; the whole presents a general appearance of fresh green. Such a man, if he has really brought the attitude of surrender to a high degree of development, will perforce feel within him at the sight of the meadow an inner sense of balance; he cannot help being moved to feel this mood of balance—a balance that is not dead but quick with life, we might compare it to a gentle and even flow of water. He cannot help but conjure up this picture before his soul. And it is the same with every taste, every smell and every sense-perception; they inevitably call up in his soul a feeling of inner movement and activity. There is no colour and no tone that does not speak to him; everything says something, and says it in such a way that he feels bound to give answer with inner movement and activity—not with judgment or opinion but with movement, active, living movement. In short, a time comes for such a man when the whole world of the senses flings off, as it were, its disguise and reveals itself to him as something he cannot describe with any other word than will. Everything in the world of the senses is will, strong and powerful currents of will. I want you to mark this particularly. The man who has attained in any high degree to surrender, discovers everywhere in the world of the senses ruling will. Hence it is that a man who has developed in himself even a small measure of this quality of surrender, feels pain if he suddenly sees a person coming towards him wearing some startling new fashion of colour. He cannot help experiencing this inner movement and activity in response to what approaches him from outside; he is sensible of will in everything and he feels united with the whole world through this will. The world of the senses thus becomes, as it were, a sea of infinitely differentiated will. And this means that while other-wise we only feel it as spread out around us, this world of the senses begins to have for us a certain thickness or depth. We begin to look behind the surface of things, we begin to hear behind the surface of things—and what we see and hear is will, flowing will. For the interest of those who have read Schopenhauer I will here remark that Schopenhauer divined this ruling will in a one-sided way in the world of sound; he described music as differentiated workings of will. But the truth is that for the man who has learned surrender, everything in the world of the senses is Ruling Will.

And now when a man has learned to detect everywhere in the world of the senses this ruling will he can go further, he can penetrate to secrets that lie hidden behind the world of the senses and that are otherwise inaccessible to him.

If we would understand aright the nature of the next step we must ask ourselves the question: How is it we gain any knowledge at all of the sense world? The answer is simple: By means of our senses. By means of the ear we acquire knowledge of the world of sound, by means of the eye knowledge of the world of colour and form, and so on. We know the sense world through the medium of our sense organs. A man who confronts this world of the senses in an ordinary everyday manner receives impressions of it and then forms his judgments. The man who has learned surrender receives impressions in the first place through his senses; and then he feels how there streams across to him from the objects active, ruling will; he feels as if he were swimming, together with the objects, in a sea of ruling will. And when a man has come to this point and feels the presence and sway of will in the objects before him, then his own evolution drives him on of itself to the next higher stage. For then, having experienced all the previous stages leading up to surrender—the stages we have called feeling oneself in harmony with the wisdom of the world, and before that reverence, and before that wonder—then, through the penetration of these conditions into the last gained condition of surrender, he learns how to grow together with the objects with his etheric body also, which stands behind the physical body. He grows together with the objects with his physical body, that is with his sense organs, in the active ruling will. When we see, hear, smell, etc., then as men of surrender we feel the ruling will streaming into us through our eyes and ears, we feel ourselves in true correspondence with the objects. But behind the physical eye is the etheric body of the eye, and behind the physical ear is the etheric body of the ear. We are filled through and through with our etheric body. And just as the physical body grows together with the objects of the sense world when man penetrates to the ruling active will, so too can the etheric body. And when this takes place man finds that he has an altogether new way of beholding the world. The world has undergone a still greater change for him than was the case when he penetrated through sense appearance to the ruling will. When our etheric body grows together with the objects of the world, then we have the impression that we cannot let these objects remain as they are in our ideas and in our conceptions and thoughts. They change for us as soon as we come into relation with them. Suppose a man who has already experienced the mood of surrender in his soul is looking at a green leaf, full of sap. He turns the eye of his soul upon the object before him, and at once he finds he cannot leave it as it is, this juicy green leaf; the moment he beholds it he feels that it grows out beyond itself, he feels how it has in it the possibility to become something quite different. You know that a green leaf, as it grows gradually higher and higher up in the plant, turns at last into the coloured flower-leaf or petal. The whole plant is really no more than a transformed leaf. You may learn this from Goethe's researches into nature. So when the student beholds the leaf he sees that it is not yet finished, that it is trying to grow out beyond itself; he sees, in short, more than the green leaf gives him. The green leaf stimulates him to feel within him something of a budding and sprouting life. Thus he grows together—quite literally—with the green leaf, feeling in himself, too, a budding and a sprouting of life. But now suppose he is looking at the dry and withered bark of a tree. If he is to grow together with that he cannot do otherwise than be overcome with a feeling of death. In the withered bark he sees—not more, but less than is there in reality. If anyone looks at the bark from the point of view of external appearance alone he can admire it, it can give him pleasure, in any case he does not see in the dead bark something that shrivels him, piercing him, as it were, in the soul and filling it with thoughts of death.

There is nothing in the whole world that does not, when the etheric body grows together with it, give rise to feelings either of growing, sprouting, becoming, or of decaying and passing away. Everything shows itself in one or other aspect. Suppose, for example, a man who has attained to surrender and has then progressed a further step turns his attention to the human larynx. He will have a strange impression. The larynx will appear to him to be an organ that is quite in the beginning of its evolution and has a great future before it. From what the larynx itself tells, he will feel that it is like a seed, not at all like a fruit or like a withered object, but like a seed. He knows quite clearly from what the larynx itself brings to expression that a time must come in human evolution when the larynx will be completely transformed, when it will be of such a nature that whereas now man only utters the word, he will one day give birth to man. The larynx is the future organ of birth, the future organ of procreation. Now man brings forth the word by means of the larynx, but the larynx is the seed that will in future times develop to bring forth the whole human being—that is, when man is spiritualised. The larynx expresses this quite directly when one lets it tell what it is. Other organs of the human body show us that they have long ago passed their zenith, and we see that they will in future times be no longer present in the human organism.

Such a vision is compelled to behold everywhere on the one hand a growing, a coming into being, and on the other hand a dying away. It sees both as processes going on into the future. Budding, sprouting life—death and decay; those are the two things that we find intermingled with one another all around us when we attain to this union of our etheric body with the world of reality. In connection with this power of vision man has to undergo, when he is a little further on, a very hard test. For with each single being that he meets and that makes itself known to him he will always find that while some parts of the being arouse in him the feeling of budding and sprouting life, other contents or parts give him the feeling of death. Everything that we see behind the world of the senses makes itself known to us as proceeding from one or other of these two fundamental forces. In occultism what we behold in this way is called the world of coming into existence and of passing away. And so, when we confront the world of the senses we are looking into the world of arising and passing away, and what lies behind is Ruling Wisdom.

Behind Will is Wisdom! I say expressly ruling wisdom, for the wisdom man brings into his ideas is as a rule not active at all, but a wisdom that is merely thought. The wisdom man acquires when he looks behind the active will is united with the objects; and in the kingdom of objective things, wherever wisdom rules, it does really rule and the effects of its working find actual expression. When it, so to speak, withdraws from reality, then begins the dying process; where it flows into reality, there you find a coming into existence, there you find budding, sprouting life. We can mark off these worlds in the following way (see diagram 1). We look at the sense world and we see it first as A, and then we look at B which is behind the sense world—the world of ruling wisdom. From out of this world is taken the substance of our own etheric body, what we behold outside us as ruling wisdom—that we behold, too, in our etheric body. And in our physical body we behold, not merely what sense appearance shows, but also ruling will, for everywhere in the sense world we see ruling will.

Yes, the strange thing is that if we have attained to surrender, then when we meet another man and look at him, his colour, whether it be inclined to red or yellow or green, does not seem to us merely red or yellow or green, but we grow together for example, with the rosy-cheekedness of his countenance. We feel the ruling will there, and all that lives and weaves in him, as it were, shoots across to us through the medium of the colour in his cheeks. People who are naturally inclined to observe and note rosy cheeks will say that a rosy-cheeked person is alone healthy. We approach our fellow-man in such a way as to see in him the ruling will. And we may now say, turning to our diagram, that our physical body, which we will denote by this circle here, is taken from the world A, the world of ruling will. Our etheric body, on the other hand, which I will denote with this second circle, is taken from the world of ruling wisdom, the world B. Here you have, then, the connection between the world of ruling wisdom that is spread around us, and our own etheric body—and the world of ruling will that is spread around us, and our own physical body. Now in ordinary life man does not know of these connections, the power to do so is taken from him. The connections are there all the time, but they are, as it were, withheld from man, he can have no influence upon them. How is this?

As a matter of fact there are opportunities in life where our thoughts and whatever we develop in the way of judgments and opinions are not so harmless for our own reality as they are in everyday existence. In the ordinary everyday waking condition, good Gods have seen to it that our thoughts have not too bad an influence on our own reality; they have withheld from us the power our thoughts might otherwise exercise upon our physical body and etheric body; and it would really go very hardly with us in the world if it were not so If thoughts—let me emphasise once more—were to signify in the world of man what the thoughts of the Gods do in reality signify, then man would evoke inside him with every error in thought a slight death process, and little by little he would be quite dried up. And as for an untruth! If with every lie he told man had to burn up the corresponding bit of his brain—as would have to happen if man had power to work into the world of reality—then we should soon see how long his brain lasted! Good Gods have withheld from our soul the power over our etheric body and physical body. But that cannot be so all the time. For were we never to exercise any influence from our soul upon our physical and etheric body then we should quickly come to an end of the forces that are in these bodies, we should have a very short life. For in our soul, as we shall see in the course of these lectures, are contained the forces that must flow ever and again into the physical and etheric body, the forces we need in our etheric body. This inflow of forces takes place at night when we are asleep. In the night there flow to us from the universe, coming to us by way of our ego and astral body, the currents that we need to dispel fatigue. There you have in actual fact the living connection between the worlds of will and of wisdom and the physical and etheric bodies of man. For into these worlds vanish during sleep the astral body and ego. They enter into these worlds and build there centres of attraction for substances which have then to flow out of the world of wisdom into the etheric body and out of the world of will into the physical body. This must go on in the night. For if man were present in his consciousness, this instreaming could not happen rightly. If ordinary man were conscious during sleep, if he were present with all his errors and vices, with all the bad things he has done in the world, then this would create a strange apparatus of attraction in those other worlds for the forces that are to stream in. Then tremendous disturbances would be set up in the physical and etheric bodies by the forces man's ego and astral body would send into them out of the world of ruling wisdom and the world of ruling will.

Therefore have good Gods made provision that we cannot be present when the right forces must stream into our physical and etheric body by night. For the good Gods have dulled the consciousness of man during sleep, that he may not be able to spoil what he undoubtedly would spoil by his thoughts were he conscious. It is on this account that we have to undergo great pain when we are on the path of knowledge and are making the ascent into the higher worlds; if we are in real earnest it must necessarily bring us great pain. You will find in my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment, a description of how the life of man by night, the sleeping life, is, so to speak, made use of, to help man to rise from the world of external reality into higher worlds. When man begins from out of the world of Imagination to light up his sleep consciousness, when he begins to lighten it with knowledge and experiences, then it is important for him to make sure that he himself gets out of the way and so shuts out of his consciousness all that might cause disturbance to his physical and etheric bodies. It is an absolute necessity, in making the ascent into higher worlds to get to know oneself thoroughly and exactly. When we really know ourselves we cease as rule to love ourselves. Self-love comes to an end when we begin to have self-knowledge; and this self-love—which is always present in a man who has not attained to self-knowledge, for it is an illusion to imagine we do not love ourselves; we love ourselves more than anything else in the world—this self-love must have been overcome if we are to be able to shut ourselves out of our consciousness. We must, in actual fact, come to the point where we say to ourselves: As I am now, I must eliminate myself. We have already gone a long way in this direction in that we have attained to self-surrender. But we must now not love ourselves at all. We must have the possibility at every moment to feel—I must put myself right on one side; for if I do not shut out completely all those things in me that otherwise I quite like to feel in me, errors, trivialities, prejudices sympathies, antipathies—if I do not put these right away then my ascent into higher worlds cannot be made aright.

Because of these errors, disturbing forces will mix with the inflowing stream from higher worlds that has to enter into me to make clairvoyance possible. And these forces will stream into my physical and etheric bodies, and as many as are the errors, etc., so many will be the disturbing processes set up. As long as we are not conscious in sleep, as long as we are not capable of rising into the world of clairvoyance, so long do good Gods protect us and not let these currents from the world of will and the world of wisdom flow into our physical and etheric bodies. But when we carry up our consciousness into the world of clairvoyance, then no Gods are protecting us—for the protection they give consists in the very fact that they take away our consciousness—then we must ourselves lay aside all prejudice, all sympathy, all antipathy, etc. All these things we must put right away from us; for if we have anything left of self-love, or of desires that cling to the personal in us, or if we are still capable of making any judgment on personal grounds, then all such things can work harm to our health—namely, to our physical body and etheric body—when we follow the path of development into higher worlds.

It is exceedingly important that we should be clear about these things. And it is easy to perceive the significance of the fact that in ordinary day life man is deprived of all influence upon his physical and etheric body, his thoughts, in the manner in which he grasps them when he is within these bodies have nothing whatever to do with reality, they are quite ineffective and consequently unable to form any judgment about what is real. By night they would be able to do so. Every false thought would work destructively on the physical and etheric bodies. If we were conscious in the night we should see before us what I have just been describing to you. The world of the senses would appear to us as a sea of ruling will, and behind it would appear the wisdom—the wisdom that builds the world, beating through this will, as it were lashing it up and down into great waves, and with every beat of the waves evoking continually processes of coming into existence and of passing away, processes of birth and of death. That is the true world, into which we have ultimately to look, the world of ruling will and the world of ruling wisdom, and the latter is also the world of perpetual births and perpetual deaths. That is the world that is our world, and it is of immense importance for us to recognise it. For if we once recognise it we begin to discover in very truth a means for attaining to a greater and greater height of surrender; because we feel ourselves interwoven in perpetual births and perpetual deaths, and we know that with every deed we do we connect ourselves in some way with a coming into existence or with a passing away. And “good” will begin to be for us not merely something of which we say: That is good, I like it, it fills me with sympathy. No, we begin to know that the good is something that is creative in the World-All, something that always and everywhere belongs to the world that is arising and coming into being. And of the “bad” we begin to feel how it shows itself everywhere as an outpouring of a process of death and decay. And here we shall have made an important transition to a new world-conception, where one will not be able to think of evil in any other way than as the destroying angel of death, who goes striding through the world, nor of good in any other way than as the creator of continual cosmic births, in great and small. And it is for Spiritual Science to awaken in man a sense of how through this spiritual world-conception he can deepen his whole outlook on life, as he begins to feel that the world of good and the world of bad are not merely as they appear to us in external maya, where we stand before them with our power of judgment and find only that the one is pleasing to us and the other displeasing; no, the world of good is the creative world and the bad is the destroying angel who goes through the world with his scythe. And with every bad thing we do we become a helper of the destroying angel, we ourselves take his scythe and share in the processes of death and decay. The ideas that we receive from a spiritual foundation have a strengthening influence upon our whole outlook on life. This strength is what men should now be receiving that they may carry it into the evolution of the future; for indeed they will need it. Hitherto good Gods have taken care of man but now the time has come in our fifth Post-Atlantean epoch when destiny, and good and evil will more and more be given over into his own hands. Therefore it is necessary to know what good and evil mean, and to recognise them in the world—the one as a creative and the other as a death-dealing principle.

Zweiter Vortrag

Wir sind gestern angelangt bei der Betrachtung jenes Seelenzustandes, den wir als die Ergebung bezeichneten und der uns erschien als der zunächst höchste der Seelenzustände, die erreicht werden müssen, wenn Denken, wenn das, was man im gewöhnlichen Sinn Erkenntnis nennt, in die Wirklichkeit eintreten soll, wenn es mit der Wirklichkeit, mit dem wahrhaft Wirklichen etwas zu tun haben soll. Mit anderen Worten: ein Denken, das sich erhoben hat zu den Seelenzuständen, wo wir uns zuerst angeeignet haben das Staunen, dann dasjenige, was wir verehrende Hingabe an die Welt des Wirklichen nennen, dann das, was wir nennen sich in weisheitsvollem Einklang wissen mit den Welterscheinungen. Ein Denken, welches sich nicht dann auch noch in jene Region erheben könnte, die in dem Seelenzustand der Ergebung charakterisiert ist, ein solches Denken könnte nicht zum Wirklichen kommen. Nun, diese Ergebung, sie ist eigentlich nur dadurch zu erringen, daß man in ganz energischer Weise versucht, sich das Unmaßgebliche des bloßen Denkens immer wieder und wiederum vor Augen zu führen, und daß man sich ferner bemüht, eine Stimmung immer reger und energischer zu machen, die uns unaufhörlich sagt: Du sollst gar nicht von deinem Denken erwarten, daß es dir Erkenntnisse des Wahren geben kann, sondern du sollst von deinem Denken zunächst bloß erwarten, daß es dich erzieht. Das ist außerordentlich wichtig, daß wir diese Stimmung in uns entwikkeln, daß uns unser Denken erzieht. Sehen Sie, wenn Sie diesen Grundsatz wirklich praktisch durchführen, dann werden Sie in einer ganz anderen Weise über mancherlei hinauskommen, als man gewöhnlich glaubt, daß man hinauskommen müsse.

Ich glaube es ja gerne, daß nicht viele von Ihnen gründlich den Philosophen Kant studiert haben. Das ist auch nicht notwendig. Es braucht zunächst ja hier nur gesagt zu werden, daß Sie in Kants bedeutendster, bahnbrechendster Schrift, in der «Kritik der reinen Vernunft», den Nachweis immer geführt finden auf der einen Seite für und auf der andern Seite gegen. Nehmen wir einen Satz, zum Beispiel: die Welt habe einmal in der Zeit einen Anfang genommen, dann setzt Kant auf der andern Seite desselben Blattes vielleicht den Satz: die Welt habe immer bestanden von Ewigkeit her. Und für diese beiden Sätze, von denen man ja leicht einsehen kann, daß sie das gerade Gegenteil einer von dem andern zum Ausdruck bringen, da bringt er gültige Beweise sowohl für den einen Satz wie für den andern. Das heißt: er beweist in derselben Art, daß die Welt einen Anfang genommen habe, und dann, daß sie keinen Anfang genommen habe. Kant nennt dies Antinomien und will dadurch die Begrenztheit des menschlichen Erkenntnisvermögens dartun, will zeigen, daß der Mensch notwendigerweise zu solchen einander widersprechenden Beweisführungen kommen müsse. Ja, solange man die Meinung hat, daß man durch Denken oder Verarbeiten von Begriffen oder, sagen wir, denkendes Verarbeiten von Erfahrungen zur Wahrheit, das heißt zur Übereinstimmung mit irgendeiner objektiven Wirklichkeit kommen soll, solange man sich dieser Meinung hingibt, solange ist es tatsächlich eine recht schlimme Sache, wenn einem gezeigt wird, wie man das eine beweisen kann und auch das genaue Gegenteil beweisen kann. Denn wie soll man da durch die Beweise zur Wirklichkeit kommen! Wenn man sich aber erzogen hat dazu, daß das Denken überhaupt gerade da, wo die entscheidenden Dinge in Betracht kommen, nichts entscheidet über das Wirkliche, wenn man sich energisch dazu erzogen hat, das Denken bloß aufzufassen als Mittel, um weiser zu werden, als ein Mittel, seine Selbsterziehung zur Weisheit in die Hand zu nehmen, dann stört das nicht, daß das eine Mal das eine und dann das andere bewiesen werden kann. Denn dann merkt man sehr bald, daß gerade dadurch, daß einem in bezug auf die Verarbeitung der Begriffe eigentlich die Wirklichkeit gar nichts anhaben kann, man in der freiesten Weise innerhalb der Begriffe und der Ideen arbeiten und sich erziehen kann. Würde man fortwährend von der Wirklichkeit korrigiert werden, dann würde man in der Verarbeitung der Begriffe kein freies Selbsterziehungsmittel haben. Bedenken Sie das wohl, daß wir nur dadurch in dem Verarbeiten unserer Begriffe ein wirksames, freies Selbsterziehungsmittel haben, daß wir niemals durch die Wirklichkeit gestört werden in dem freien Verarbeiten der Begriffe.

Was heißt das: wir werden nicht gestört? Ja, was wäre denn eigentlich eine solche Störung durch die Wirklichkeit im freien Verarbeiten der Begriffe? Eine solche Störung können wir uns ein wenig vor die Seele führen, wenn wir zunächst einmal rein hypothetisch — wir werden später noch sehen, daß das für uns nicht hypothetisch zu bleiben braucht — unserem menschlichen Denken das göttliche Denken gegenüberstellen. Da können wir sagen: Das göttliche Denken, von dem können wir uns zunächst nicht den Begriff bilden, daß es auch nichts zu tun habe mit dem Wirklichen, sondern von dem göttlichen Denken — nehmen wir es zunächst also nur hypothetisch an — können wir uns nur den Begriff bilden, daß es wohl eingreift in die Wirklichkeit. Nun, daraus folgt aber nichts Geringeres als das: Wenn der Mensch einen Fehler macht in seinem Denken, so ist es ein Fehler, so ist es nicht weiter schlimm, denn es ist ein bloßer Fehler, sozusagen ein logischer Fehler. Und wenn der Mensch später dann darauf kommt, daß er einen Fehler gemacht hat, so kann er ihn korrigieren und er hat damit etwas getan zu seiner Selbsterkenntnis, er hat sich weiser gemacht. Aber nehmen wir das göttliche Denken: Ja, wenn das göttliche Denken richtig denkt, dann geschieht etwas, und wenn es falsch denkt, dann wird etwas zerstört, etwas vernichtet. Würden wir also ein göttliches Denken haben, dann würden wir bei jedem falschen Begriff, den wir fassen, sogleich einen Vernichtungsprozeß hervorrufen, zunächst in unserem astralischen Leib, dann in unserem Ätherleib und von da aus auch in unserem physischen Leib, und die Folge eines falschen Begriffes würde sein — wenn wir ein wirksames göttliches Denken hätten, wenn unser Denken mit der Wirklichkeit etwas zu tun hätte —, daß wir sozusagen etwas hervorriefen in unserem Innern wie einen kleinen Vertrocknungsprozeß in irgendeinem Teile unseres Leibes, einen Verknöcherungsprozeß. Nun, da dürfen wir wahrhaftig recht wenig Fehler machen, denn der Mensch würde sehr bald so viele Fehler gemacht haben, daß er seinen Leib dürr gemacht hätte, so daß er vollständig zerfallen würde, er würde ihn sehr bald zermürbt haben, wenn er umgesetzt hätte in die Wirklichkeit, was Fehler in seinem Denken waren. Wir erhalten uns tatsächlich nur dadurch in der Wirklichkeit, daß unser Denken nicht eingreift in diese Wirklichkeit, daß wir bewahrt sind vor dem Eingreifen unseres Denkens in die Wirklichkeit. Und so können wir Fehler über Fehler machen in unserem Denken: wenn wir diese Fehler später korrigieren, so haben wir uns selbst erzogen, wir sind weiser geworden, aber wir haben nicht gleich verheerende Wirkungen angerichtet mit unseren Fehlern. Wenn wir uns immer mehr und mehr durchdringen mit der moralischen Kraft eines solchen Gedankens, dann kommen wir zu jener Ergebung, die uns endlich dazu bringt, gar nicht mehr, um über äußere Dinge etwas zu erfahren, an den entscheidenden Punkten des Lebens das Denken anzuwenden.

Das klingt sonderbar, nicht wahr, und es scheint zunächst, wie wenn es unmöglich wäre, überhaupt so etwas auszuführen. Und dennoch: wir können es zwar nicht absolut ausführen, aber wir können es in einer gewissen Beziehung ausführen. Wie wir schon einmal geartet sind als Menschen, können wir uns ja in der Welt nicht ganz das Urteilen über die Dinge abgewöhnen ; wir müssen urteilen — wir werden in diesen Vorträgen noch sehen, warum —, das heißt, wir müssen etwas tun zum Leben, zur Lebenspraxis, was eigentlich wirklich nicht vordringt bis zu den Tiefen der Wirklichkeit. Wir müssen also schon urteilen, aber wir sollten allem Urteilen gegenüber durch eine weise Selbsterziehung in uns bewirken Vorsicht im Fürwahrhalten dessen, was wir urteilen. Wir sollten uns unausgesetzt bernühen, sozusagen uns über die Schulter zu schauen und uns klarzumachen, daß wir, wo wir unseren Scharfsinn anwenden, im Grunde genommen überall im Unsicheren tappen, überall irren können. Das trifft hart die Sicherlinge des Lebens, welche überhaupt nicht mehr recht fortzukommen glauben, wenn sie daran zweifeln müssen, daß das, was sie anheften als ihr Urteil an ein jegliches Ereignis, an ein jegliches Geschehnis, maßgebend sein soll für ste. Beobachten wir nur einmal das Leben vieler Menschen, ob sie nicht als das Wichtigste eigentlich ansehen, überall zu sagen, wenn das oder jenes auftritt: Ich glaube aber das, ich glaube aber jenes, oder wenn sie etwas sehen: Das gefällt mir nicht, das gefällt mir und so weiter. Das sind die Dinge, die man, wenn man nicht zu den Sicherlingen des Lebens gehören will, sich abgewöhnen muß, abgewöhnen muß dann, wenn man mit seinem Seelenleben der Wirklichkeit zusteuert. Also um das Entwickeln einer solchen Gesinnung handelt es sich, die sich etwa mit folgenden Worten charakterisieren läßt: Nun ja, ich muß eben leben, deshalb muß ich urteilen; daher werde ich mich des Urteilens bedienen, insofern die Lebenspraxis das notwendig macht, aber nicht insofern ich Wahrheit erkennen will. Insofern ich Wahrheit erkennen will, werde ich mir immer sorgfältig über die Schulter schauen und immer mit gewissem Zweifel ein jegliches Urteil, das ich fälle, aufnehmen.

Ja, wie sollen wir dann überhaupt zu irgendeinem Gedanken über die Wahrheit kommen, wenn wir nun nicht urteilen sollen? Nun, es ist in gewisser Beziehung schon gestern angedeutet worden: Wir sollen die Dinge reden lassen, immer mehr und mehr passiv uns zu den Dingen verhalten und die Dinge ihre Geheimnisse aussprechen lassen. Es würde ja vieles vermieden werden, wenn die Menschen nicht urteilen würden, sondern die Dinge ihre Geheimnisse aussprechen lassen würden. In einer wunderbaren Weise kann man lernen dieses Aussprechenlassen der Geheimnisse der Dinge bei Goethe, der eigentlich geradezu da, wo er forschen will über die Wahrheit, sich verbietet zu urteilen und die Dinge selber ihre Geheimnisse aussprechen lassen will. Nehmen wir einmal an, der eine Mensch urteilte, der andere ließe die Dinge selbst ihre Geheimnisse aussprechen. Wir können das an einem konkreten Beispiel anschaulich machen: Der eine urteilt, er sieht einen Wolf, sagen wit, und nun beschreibt er den Wolf. Er findet, daß es noch andere Tiere gibt, die auch so aussehen wie dieser Wolf, und kommt zu dem allgemeinen Begriff des Wolfes auf diese Weise. Und nun kann ein solcher Mensch zu folgendem Urteil kommen. Er kann sagen: Ja, in Wirklichkeit sind nur einzelne Wölfe vorhanden. Den allgemeinen Begriff des Wolfes, den bilde ich mir in meinem Geiste, der Wolf als solcher ist nicht vorhanden; es sind nur einzelne Wölfe vorhanden in der Welt. — Ein solcher Mensch wird leicht das Urteil fällen, man habe es nur mit Einzelwesen zu tun, und das, was man im allgemeinen Begriff, in der Idee hat, dieses allgemeine Bild des Wolfes, das sei nichts Wirkliches. Das würde im eminentesten Sinne ein bloß urteilender Mensch sein, der solche Vorstellungen sich bildet. Ein Mensch aber, der die Wirklichkeit sprechen läßt, wie wird der über jenes Unsichtbare des Wolfes denken, das man in jedem Wolf findet, das alle Wölfe zugleich charakterisiert ? Nun, der würde ungefähr so sagen: Ich vergleiche einmal ein Lamm mit einem Wolf, oder eine Anzahl von Lämmern mit einem Wolf. Ich will jetzt gar nicht urteilen, sondern will lediglich die Tatsachen sprechen lassen. Ja, nehmen wir an, es spielte sich die Tatsache so recht anschaulich vor diesem Menschen ab: der Wolf frißt die Lämmer. Das wäre recht anschaulich. Da würde der Betreffende sagen: Ja, nun ist dasjenige, was früher als Lamm herumgesprungen ist, im Wolf und ist im Wolf aufgegangen.

Aber es ist sehr merkwürdig, daß gerade dieses Anschauen der Dinge zeigt, wie real das ist, was Wolfsnatur ist. Denn das, nicht wahr, was man äußerlich verfolgen könnte, das könnte zu dem Urteil führen: Wenn der Wolf nun abgesperrt wird von aller übrigen Nahrung und lauter Lämmer frißt nach und nach, so muß ja, weil der Stoffwechsel das mit sich bringt, der Wolf nach und nach den Stoff von lauter Lämmern in sich haben. Tatsächlich wird er aber nie ein Lamm, er bleibt ein Wolf. Das zeigt ganz anschaulich, wenn wir richtig urteilen, daß da das Materielle nicht bloß durch einen unrealen Begriff eingefangen wird im Wolf. Wenn wir uns unterrichten lassen, was uns die äußere Tatsachenwelt gibt, so zeigt sie uns, daß außer dem, was wir vor uns haben als Materielles im Wolf, dieser Wolf noch über dies Materielle hinaus etwas ganz Wirkliches ist, daß also das, was man da nicht sieht, etwas höchst Wirkliches ist. Denn das, was nicht im Stofflichen aufgeht, das bewirkt gerade, daß der Wolf, wenn er lauter Lämmer frißt, kein Lamm wird, sondern eben ein Wolf bleibt. Das rein Sinnliche ist aus den Lämmern in den Wolf hinübergegangen.

Es ist schwierig, sich ganz klarzumachen, welcher Unterschied zwischen Urteilen und Sichunterrichtenlassen von der Wirklichkeit besteht; aber wenn man dieses erfaßt hat und dann das Urteilen nur verwendet für die Zwecke des praktischen Lebens, und das Sichunterrichtenlassen von den Dingen verwendet, um an die Wirklichkeit heranzukommen, dann gelangt man allmählich in die Stimmung hinein, die uns sagt, was Ergebung ist. Ergebung ist eben jene Seelenverfassung, die nicht von sich aus die Wahrheit erforschen will, sondern die alle Wahrheit von der Offenbarung erwartet, die aus den Dingen strömt, und die warten kann, bis sie reif ist, diese oder jene Offenbarung zu empfangen. Das Urteil will auf jeder Stufe zu der Wahrheit kommen. Die Ergebung, die arbeitet nicht, um in diese oder jene Wahrheiten mit Gewalt einzudringen, sondern sie arbeitet an sich, an der Selbsterziehung, und wartet ruhig ab, bis auf einer bestimmten Stufe der Reife die Wahrheit durch die Offenbarungen aus den Dingen einströmt, uns ganz durchdringend. Arbeiten mit Geduld, die in weiser Selbsterziehung uns weiter und weiter bringen will — das ist die Stimmung der Ergebung.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß wir uns die Früchte dieser Ergebung vor die Seele führen. Was erlangen wir dadurch, daß wir mit unserem Denken fortgeschritten sind vom Staunen durch die Verehrung, durch das Sichfühlen in weisheitsvollem Einklang mit der Wirklichkeit, in die Seelenverfassung der Ergebung, was erlangen wir dadurch? Dadurch erlangen wir zum Schluß dieses: Wenn wir nun hingehen, die Pflanzenwelt in ihrer Grünheit und in ihren wechselnden Blütenfarben und sonstiges betrachten, das Firmament betrachten in seiner Blauheit, die Sterne betrachten in ihrem Goldglanz, ohne nun von innen heraus zu urteilen, uns offenbaren lassend, was die Dinge sind — wenn wir es zu dieser Ergebung gebracht haben, dann werden alle Dinge für uns etwas ganz anderes, als sie vorher waren innerhalb der Sinneswelt, dann offenbart sich uns in der Sinneswelt etwas, für das es kein anderes Wort gibt als ein Wort, das aus unserem Seelenleben selbst entnommen ist. Alle Dinge offenbaren sich, und ich möchte geradezu die Sinneswelt, wie sie vor uns auftritt, durch diese Niveaulinie charakterisieren (a—b, siehe Zeichnung Seite 41). Nehmen Sie an, Sie stehen hier (c) vor der Sinneswelt, Sie schauen diese Sinneswelt an, die sich wie ein Schleier vor Ihnen ausbreitet. Das also, was in dieser Linie hier (a—b) charakterisiert sein soll, das seien die Töne der Sinneswelt, die auf unser Ohr wirken, die Farben und Formen, die auf unser Auge wirken, die Gerüche und Geschmäcke, die auf unsere sonstigen Organe wirken, das sei Härte und Weichheit usw., kurz das alles sei in dieser Linie charakterisiert. Diese Linie sei die Welt der Sinne. Also im gewöhnlichen Leben, so wie wir in dieser Sinneswelt stehen, wenden wir unsere Urteilskraft an. Und wodurch entstehen die äußeren Wissenschaften? Dadurch, daß die Wissenschaften herantreten an diese Sinneswelt, daß sie durch verschiedene Methoden sozusagen erforschen, was da in den Dingen dieser Sinneswelt für Gesetze walten und dergleichen. Wir haben aus dem ganzen Geist der bisherigen Auseinandersetzungen gesehen, daß man dadurch nicht in die Welt der Wirklichkeit hineinkommt, weil das Urteilen überhaupt kein Führer ist, sondern daß man durch die Erziehung des Denkens durch das Staunen, die Verehrung und so weiter hindurch allein herandringen kann an die Welt des Wirklichen. Dann verändert sich das, was Sinneswelt ist, dann wird diese Sinneswelt zu etwas völlig Neuem. Das ist wichtig, daß wir an dieses Neue herankommen, wenn wir überhaupt das Wesen der Sinneswelt erkennen wollen.

Nehmen wir an, ein Mensch, der in gewissem hohem Grade dieses Gefühl, diese Seelenverfassung der Ergebung entwickelt hat, er tritt entgegen, sagen wir, dem frischen, vollen Grün einer Wiese. Sie zeigt sich ihm zunächst, weil keine einzelnen Pflanzenfarben hervorstehen über das allgemeine Grün, sie zeigt sich im allgemeinen frischen Grün. Ein solcher Mensch, der wirklich bis zu einem höheren Grade die Seelenverfassung der Ergebung ausgebildet hat, der wird gar nicht anders können, als, indem er diese Wiese betrachtet, etwas zu empfinden, was ihn in innerer Seelenstimmung eines gewissen Gleichgewichtes berührt — aber eines belebten Gleichgewichtes, so wie leises harmonisches, gleichmäßiges Wellenrieseln des Wassers. Er wird gar nicht anders können, als dieses Bild vor seine Seele zu zaubern. Und so, sagen wir, wird ein solcher Mensch nicht anders können, als empfinden bei jeglichem Geschmack, bei jeglichem Geruch in seiner Seele so etwas wie eine innere Regsamkeit. Es gibt keine Farbe, keinen Ton, die nichts sagen, sondern alles sagt etwas und alles sagt so etwas, daß der Mensch die Notwendigkeit fühlt, mit innerer Regsamkeit auf das Gesagte zu antworten — nicht mit einem Urteil zu antworten, sondern mit innerer Regsamkeit. Kurz, der Mensch kommt darauf, daß sich die ganze Sinneswelt für ihn entpuppt als etwas, was er nicht anders bezeichnen kann denn als Willen. Alles ist strömender, waltender Wille, insofern wir der Sinneswelt entgegentreten. Das bitte ich Sie sehr wohl zu fassen, daß derjenige, der in einem höheren Grade die Ergebung sich angeeignet hat, überall in der Sinneswelt waltenden Willen entdeckt. Daher verstehen Sie, daß für einen Menschen, der auch nur bis zu einem geringen Grade diese Ergebung in sich ausgebildet hat, es so schlimm ist, sagen wir, wenn er irgendeine impertinente Modefarbe etwa auf der Straße sich entgegenkommen sieht, weil er nicht anders kann, als diese innerlich regsam zu empfinden gegenüber all dem, was da draußen ist. Er ist immer durch einen Willen, den er in allem empfindet, in allem fühlt, mit der ganzen Welt verbunden. Dadurch naht er sich dem Wirklichen, daß er verbunden ist durch den Willen mit allem, was Sinneswelt ist. Und so wird das, was Sinneswelt ist, wie zu einem Meer von in der mannigfaltigsten Weise differenziertem Willen. Dadurch aber wird dieses, was wir sonst wie ausgebreitet nur fühlen, wie von einer gewissen Dicke sein. Wir sehen gleichsam hinter die Oberfläche der Dinge hin, hören hinter sie und hören überall strrömenden Willen. Für diejenigen, die einmal Schopenhauer gelesen haben, bemerke ich, daß Schopenhauer in einseitiger Weise nur in der Tonwelt diesen waltenden Willen geahnt hat; daher beschreibt er die Musik überhaupt als sozusagen differenzierte Willenswirkungen. Aber in Wahrheit ist für den ergebenen Menschen alles in der Sinneswelt waltender Wille.

Wenn der Mensch dann gelernt hat, in der Sinneswelt überall waltenden Willen zu spüren, dann kann er nun auch weiterdringen. Dann kann er gleichsam durch die Sinneswelt hindurch in die hinter der Sinneswelt befindlichen Geheimnisse dringen, die ihm sonst zunächst entzogen sind.

Um das zu verstehen, was jetzt kommen soll, müssen wir uns zuerst die Frage aufwerfen: Wodurch wissen wir denn überhaupt etwas von der Sinneswelt? Nun, die Antwort ist einfach: durch unsere Sinne; durch das Ohr von der Tonwelt, durch das Auge von der Farben- und Formenwelt und so weiter. Wir wissen durch unsere Sinnesorgane von der Sinneswelt. Derjenige Mensch, der zunächst in der alltäglichen Weise dieser Sinneswelt gegenübersteht, der läßt diese auf sich wirken und urteilt. Der ergebene Mensch, der läßt die Sinneswelt zunächst auf die Sinne wirken. Dann aber fühlt er, wie von den Dingen waltender Wille zu ihm überströmt, wie er gleichsam schwimmt mit den Dingen in einem gemeinschaftlichen Meer von waltendem Willen. Wenn der Mensch diesen waltenden Willen den Dingen gegenüber fühlt, dann treibt ihn sozusagen seine Entwickelung wie von selbst zu einer nächsthöheren Stufe. Dann lernt er nämlich, weil er ja durchgemacht hat bis zu dieser Ergebung hin die Vorstufen, die wir genannt haben das Sich-in-Einklang-Fühlen mit der Weltenweisheit, die Verehrung, das Staunen, dann lernt er durch das Hineinwirken dieser Zustände in dem zuletzt erlangten Zustand der Ergebung die Möglichkeit, nun auch mit seinem ÄAtherleib, mit dem, was als Ätherleib hinter dem physischen Leib steht, mit den Dingen gleichsam zusammenzuwachsen. In dem waltenden Willen wächst der Mensch zunächst mit seinen Sinnesorganen, das heißt mit dem physischen Leib mit den Dingen zusammen. Wenn wir die Dinge sehen, hören, riechen usw., dann wirkt das so, daß wir als ergebene Menschen den waltenden Willen wie durch unser Auge, durch unser Ohr in uns einströmen, uns selber in der Korrespondenz mit den Dingen fühlen. Aber hinter dem physischen Auge ist der Ätherleib des Auges und hinter dem physischen Ohr der Ätherleib des Ohres. Wir sind ganz durchdrungen von unserem Ätherleib. So kann geradeso, wie der physische Leib durch den waltenden Willen zusammenwächst mit den Dingen der Sinneswelt, auch der Ätherleib mit den Dingen zusammenwachsen. Aber indem der Ätherleib mit den Dingen zusammenwächst, kommt über den Menschen eine ganz neue Art der Anschauung. Die Welt ist dann in einem viel erheblicheren Maße verändert, als sie verändert ist dadurch, daß wir von dem Sinnenschein vordringen zum waltenden Willen. Da kommen wir dazu, wenn wir mit unserem Ätherleib sozusagen zusammenwachsen mit den Dingen, daß die Dinge in der Welt, wie sie dastehen, auf uns einen Eindruck machen, so daß wir sie in unseren Vorstellungen, in unseren Begriffen nicht so lassen können, wie sie sind, sondern sie verändern sich uns, indem wir mit ihnen in Beziehungen treten.

Nehmen Sie einmal einen solchen Menschen, der durch die Seelenverfassung der Ergebung gegangen ist. Er schaut sich, sagen wir, ein grünes, vollsaftiges Pflanzenblatt an und er wendet nun den Seelenblick auf dieses Blatt. Dann kann er es nun nicht so lassen, dieses grüne, vollsaftige Pflanzenblatt, sondern er fühlt im Moment, wo er es anschaut, daß es über sich selbst hinauswächst. Er fühlt, daß dieses grüne, vollsaftige Pflanzenblatt die Möglichkeit in sich hat, etwas ganz anderes zu werden. Wenn Sie das grüne Pflanzenblatt nehmen, so wissen Sie, daß, wenn es nach und nach in die Höhe wächst, daraus das farbige Blumenblatt wird. Die ganze Pflanze ist eigentlich ein verwandeltes Blatt. Das können Sie schon aus Goethes Naturforschung sich vor die Seele führen. Kurz, derjenige, der also ein Blatt ansieht, der sieht im Blatt, daß das noch nicht fertig ist, daß es über sich hinaus will, und er sieht mehr, als das grüne Blatt ihm gibt. Er wird durch das grüne Blatt so berührt, daß er in sich selber etwas wie sprossendes Leben empfindet. So wächst er mit dem grünen Pflanzenblatt zusammen und empfindet sprossendes Leben. Nehmen wir aber an, er sieht eine dürre Baumrinde an, dann kann er nicht anders mit der dürren Baumrinde zusammenwachsen als dadurch, daß ihn etwas überkommt wie Todesstimmung. Er sieht weniger in der dürren Baumrinde, als sie in Wirklichkeit darstellt. Derjenige, der nur dem Sinnenschein nach die Rinde ansieht, der kann sie bewundern, sie kann ihm gefallen, jedenfalls sieht er nicht das Zusammenschrumpfende, das in der Seele sich gleichsam Spießende, das die Seele wie mit Todesgedanken Erfüllende der abgestorbenen Baumrinde gegenüber.

Es gibt kein Ding in der Welt, dem gegenüber bei einem solchen Zusammenwachsen des Ätherleibes mit den Dingen nicht entstehen würden überall Gefühle des Wachsens, des Werdens, des Sprossens oder aber Gefühle des Vergehens, der Verwesung. So schaut man in die Dinge hinein. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel an, man richtet als solch ergebener Mensch, der sich dann weiter erzieht, den Sinn auf den menschlichen Kehlkopf in irgendeiner Weise, dann erscheint einem der menschliche Kehlkopf in einer merkwürdigen Weise wie ein Organ, das ganz im Anfang des Werdens ist, das eine große Zukunft vor sich hat, und man empfindet es unmittelbar durch das, was der Kehlkopf selber als seine Wahrheit ausspricht, daß er wie ein Same ist, nicht wie eine Frucht oder wie etwas Abdorrendes, sondern wie ein Same. Und es muß einmal — das weiß man unmittelbar durch das, was der Kehlkopf ausspricht — für die Menschheitsentwickelung etwas kommen, wo der Kehlkopf ganz umgestaltet ist, wo er so sein wird, daß, während der Mensch jetzt durch den Kehlkopf nur das Wort aus sich hervorbringt, er einmal den Menschen gebären wird. Er ist das zukünftige Geburtsorgan, das Hervorbringungsorgan. Wie der Mensch durch den Kehlkopf jetzt hervorbringt das Wort, so ist der Kehlkopf die Anlage, das Samenorgan, das künftig sich dazu entfalten wird, den Menschen, den ganzen Menschen hervorzubringen, wenn er vergeistigt sein wird. Das drückt der Kehlkopf unmittelbar aus, wenn man sich von ihm sagen läßt, was er ist. Andere Organe am menschlichen Leibe erscheinen so, daß wir sehen, sie sind längst über ihre Höhe hinübergeschritten ; daß wir sehen, sie werden künftig sich gar nicht mehr am menschlichen Organismus finden.

Einem solchen Anschauen drängt sich unmittelbar etwas auf wie Werden in die Zukunft und wie Absterben in die Zukunft hinein. Sprossendes Leben und Verwesung, Absterben, das sind die zwei Dinge, die sich ineinanderschieben gegenüber allem, wenn wir zu diesem Verbinden unseres ÄÄtherleibes mit der Welt der Wirklichkeit kommen. Es ist dies etwas, was für den Menschen dann, wenn er ein wenig weiterkommt, eine schwere, schwere Prüfung bedeutet. Denn ein jegliches Wesen kündigt sich ihm so an, daß er immer gewissen Dingen gegenüber an dem Wesen das Gefühl des Werdens, des Sprossens, Sprießens hat; anderen Dingen gegenüber an diesem Wesen hat er das Gefühl des Absterbens. Und aus diesen zwei Grundkräften kündigt sich alles das an, was wir hinter der Sinneswelt sehen. Man nennt im Okkultismus das, worauf man da schaut, die Welt des Entstehens und Vergehens. Gegenüber der Sinneswelt also schaut man hinein in die Welt des Entstehens und Vergehens, und das, was dahinter ist, ist die waltende Weisheit.

Hinter dem waltenden Willen die waltende Weisheit! Waltende Weisheit sage ich ausdrücklich, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil die Weisheit, die der Mensch in seine Begriffe hereinbringt, gewöhnlich keine waltende Weisheit ist, sondern eine gedachte Weisheit. Die Weisheit, welche sich der Mensch aneignet, indem er hinter den waltenden Willen schaut, die steht mit den Dingen in Verbindung, und im Reiche der Dinge herrscht da, wo Weisheit waltet, die waltende Weisheit, die ihre Wirkungen wirklich äußert, die wirklich da ist. Da, wo sie sich sozusagen abzieht von der Wirklichkeit, da entsteht das Sterben ; wo sie einfließt, da entsteht Werden, da ist Entstehung, sprießendes, sprossendes Leben. Sehen Sie, die Welt, auf die wir hier schauen und die wir sozusagen als die zweite charakterisieren können, wir können sie begrenzen und können sagen: Wir schauen zunächst auf die Sinneswelt als auf die Welt A und auf die der waltenden Weisheit als B, die hinter der Sinneswelt ist. Aus dieser ist die Substanz unseres eigenen Ätherleibes genommen. Das, was wir da draußen nämlich sehen als waltende Weisheit, das erblicken wir in unserem eigenen Ätherleib. Und in unserem eigenen physischen Leib erblicken wir nicht das bloß, was der Sinnesschein ist, sondern auch waltenden Willen, weil wir überall in unserer Sinneswelt waltenden Willen sehen.

Ja, das ist das Eigenartige: Wenn wir als ergebene Menschen einem andern gegenübertreten und ihn anschauen, dann erscheint uns seine Leibesfarbe, ob sie einmal rötlich oder gelblich oder grünlich ist, nicht bloß rötlich, gelblich oder grünlich, sondern so, daß wir dann zum Beispiel mit seiner Rotwangigkeit gleichsam zusammenwachsen, mit der Wirklichkeit zusammenwachsen und den waltenden Willen drinnen haben, das heißt, daß wir all das, was in ihm lebt und webt, wie zu uns herüberschießen sehen durch seine Rotwangigkeit. Die Menschen, die gerade selber gestimmt sind auf Rotwangigkeit zu schen, die werden sagen: Ein rotwangiger Mensch ist eben der einzig Gesunde. Also dem Menschen selber tritt man so gegenüber, daß man diesen waltenden Willen in ihm sieht, und man kann nun sagen: Unser physischer Leib, wenn wir ihn zunächst hier durch diesen Kreis schematisch andeuten, ist aus der Welt A entnommen; aus der Welt des waltenden Willens — physischer Leib! Dagegen ist unser Ätherleib, den ich hier durch den zweiten Kreis andeuten will, aus der Welt der waltenden Weisheit, aus der Welt B entnommen. Hier haben Sie also den Zusammenhang charakterisiert zwischen der Welt der waltenden Weisheit, die draußen sich ausdehnt, und unserem eigenen Ätherleib — und der Welt des waltenden Willens, die draußen sich ausdehnt, und unserem eigenen physischen Leib.

Nun, für das gewöhnliche Leben ist dem Menschen die Macht entzogen, tatsächlich einen Zusammenhang zwischen dem einen und dem andern zu wissen. Sie sehen: Wie ich hier die Dinge aufgezeichnet habe, so ist ein unmittelbarer Zusammenhang zwischen der äußeren Sinneswelt und unserem physischen Leibe, und zwischen der Welt der waltenden Weisheit und unserem Ätherleib. Da sind Zusammenhänge. Aber dem Menschen ist dieser Zusammenhang entzogen, er kann darauf keinen Einfluß haben. Wieso hat er darauf keinen Einfluß? Ja, es gibt nämlich eine Gelegenheit, wo unsere Gedanken und unser ganzes Leben, wie wir es in der Seele als Urteilsleben entwickeln, nicht so, ich möchte sagen, unschädlich sind für unsere eigene Wirklichkeit wie im Alltag.

Im Alltag, im wachenden Zustande, da haben gute Götter dafür gesorgt, daß unsere Gedanken nicht allzu schlimm wirken auf unsere eigene Wirklichkeit, sie haben uns die Macht entzogen, die unsere Gedanken ausüben könnten auf unseren physischen Leib und auf unseren Ätherleib, sonst würde es wirklich recht schlimm in der Welt stehen. Wenn Gedanken — ich betone es nochmals — wirklich das bedeuten würden in der Welt des Menschen, was sie eigentlich als Göttergedanken bedeuten in Wahrheit, dann würde der Mensch mit jedem Irrtum einen kleinen Absterbeprozeß hervorrufen in seinem Innern, und er wäre bald vertrocknet. Und eine Lüge gar! Wenn der Mensch mit jeder Lüge das entsprechende Gehirnstück verbrennen müßte, wie es sein müßte, wenn er in die Welt in Wahrheit eingriffe, dann würde er schon sehen, wie lange sein Gehirn standhielte. Gute Götter haben sozusagen unserer Seele die Macht entzogen über unseren Ätherleib und physischen Leib. Aber es kann das nicht immer sein. Wenn wir nämlich immerfort von unserer Seele aus gar keinen Einfluß ausüben würden auf unseren physischen und Ätherleib, dann würden wir sehr bald fertig sein mit den Kräften, die in unserem physischen und Ätherleibe sind, dann würden wir eine sehr kurze Lebensdauer haben ; denn in unserer Seele sind, wie wir sehen werden im weiteren Verlauf der Vorträge, diejenigen Kräfte, die wiederum hineinfließen müssen in den physischen und Ätherleib, die wir da brauchen in dem letzteren Leibe. Daher müssen in gewissen Zeiten Kräfteströme fließen von unserer Seele in den Ätherleib und physischen Leib. Das geschieht nämlich in der Nacht, wenn wir schlafen. Da fließen aus dem Universum auf dem Umwege durch Ich und Astralleib die Ströme, die wir brauchen, um die Ermüdung fortzuschaffen. Da ist tatsächlich dieser lebendige Zusammenhang zwischen der Welt des Willens und der Welt der Weisheit und unserem physischen Leibe und Ätherleibe. Denn da hinein, in diese Welten entschwinden während des Schlafes Astralleib und Ich. Die gehen da hinein, und da drinnen bilden sie Anziehungszentren für die Substanzen, die jetzt hereinströmen müssen aus der Welt der Weisheit in den Ätherleib und aus der Welt des waltenden Willens in den physischen Leib. Das muß in der Nacht geschehen. Wenn nämlich der Mensch wirklich bewußt dabei wäre, da würden Sie sehen, wie dieses Hereinströmen geschehen würde! Wenn der Mensch im allgemeinen bewußt dabei wäre mit seinen Irrtümern und Lastern, mit all dem, was er Böses und so weiter verübt in der Welt, dann würde das ein sonderbarer Fangapparat für die Kräfte sein, die da einströmen sollten. Da würden greuliche Zerstörungen angerichtet werden müssen im Ätherleib und physischen Leib durch das, was der Mensch da hineinsenden würde aus seinem Ich und Astralleib in den physischen und Ätherleib aus der Welt der waltenden Weisheit und der Welt des waltenden Willens.

Daher haben wieder gute Götter dafür gesorgt, daß wir nicht bewußt dabei sein können, wenn in der Nacht hineinströmen muß die richtige Kraft in unseren physischen und Ätherleib. Sie haben nämlich für diesen Zustand das Bewußtsein des Menschen abgedämpft während des Schlafes, damit er durch seine Gedanken, die dann wirken würden, nicht verderben kann, was er ganz zweifellos verderben würde. Das ist auch das, was bei dem Aufstiege in die höheren Welten auf dem Erkenntnispfad, wenn wir gründlich zu Werke gehen, uns die meisten Schmerzen macht. Sie finden ja beschrieben in der Schrift «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», wie sozusagen das Nachtleben, das schlafende Leben in gewisser Weise zu Hilfe genommen wird, um aus der Welt der äußeren Wirklichkeit in die höheren Welten aufzusteigen. Da muß der Mensch, wenn er beginnt, aus der Welt der Imagination heraus sich das Schlafbewußtsein zu durchleuchten mit Wissen, mit Erfahrungen, mit Erlebnissen, in der Tat sehen, wie er wegkommt, damit er richtig ausschaltet aus seinem Bewußtsein alle Quellen für die Zerstörung seines physischen und seines Ätherleibes. Das ist es, was die Notwendigkeit hervorruft bei diesem Aufsteigen in die höheren Welten, sich nun wirklich ganz genau zu kennen. Wenn man sich ganz genau kennt, dann hört man meistens auf, sich zu lieben. Die Selbstliebe hört meistens auf, wenn man anfängt, sich zu kennen, und dieses Sichlieben, das ja bei dem Menschen, der nicht zur Selbsterkenntnis gekommen ist, immer vorhanden ist — denn es ist Täuschung, wenn jemand glaubt, daß er sich nicht liebt, er liebt sich mehr als alles andere in der Welt —, diese Selbstliebe muß man überwunden haben, um sich selbst ausschalten zu können. Man muß tatsächlich bei diesem Aufsteigen in die Lage kommen, sich zu sagen: Wie du nun einmal bist, mußt du dich beseitigen. Man hat dazu schon viel getan dadurch, daß man ergebener Mensch geworden ist. Aber man muß sich gar nicht lieben. Man muß also immer die Möglichkeit haben, zu empfinden: Du mußt dich auf die Seite schieben. Denn wenn du das, was du sonst an dir liebst, was du an Irrtümern, Kleinlichkeiten, Vorurteilen, Sympathien, Antipathien usw. hast, wenn du das nicht beiseiteschieben kannst, dann wird das Aufsteigen so vor sich gehen, daß durch deine Irrtümer, Kleinlichkeiten, Vorurteile — Kräfte sich mischen in das, was einströmen muß, damit man hellsichtig werden kann. Die strömen in deinen physischen und Ätherleib ein; soviel Irrtümer, soviele zerstörende Prozesse gibt es dann. Solange wir kein Bewußtsein im Schlaf haben, solange wir nicht vermögen, in die Welten der Hellsichtigkeit aufzusteigen, solange schützen uns gute Götter davor, daß diese Kräfte in die Strömungen aus der Welt des waltenden Willens und der Welt der waltenden Weisheit in unseren physischen und Ätherleib einströmen. Dann aber, wenn wir unser Bewußtsein hinauftragen in die Welt der Hellsichtigkeit, dann schützen uns keine Götter mehr — denn der Schutz, den sie uns geben, besteht gerade darin, daß sie uns unser Bewußtsein nehmen —, dann müssen wir alles selber beseitigen, was Vorurteile, Sympathien, Antipathien usw. sind. Alles das müssen wir beiseiteschieben ; denn wenn wir da noch etwas haben von Eigenliebe, von Wünschen, die uns als Persönliches anhaften, wenn wir in der Lage sind, aus dem Persönlichen heraus dieses oder jenes Urteil zu fällen, dann sind alle diese Dinge Gründe, daß wir unsere Gesundheit, nämlich unseren physischen Leib und Ätherleib, schädigen, indem wir uns in die höheren Welten hinaufentwickeln.

Es ist ungeheuer wichtig, daß wir dies scharf ins Auge fassen. Deshalb können wir die Überzeugung in uns aufnehmen, wie bedeutsam es ist, daß dem Menschen im gewöhnlichen Leben bei Tag ein jeglicher Einfluß auf seinen physischen und Ätherleib entzogen ist, indem unsere Gedanken, so wie wir sie fassen, wenn wir innerhalb des physischen und Ätherleibes sind, mit der Wirklichkeit gar nichts zu tun haben, unwirksam sind und daher auch keine Entscheidung herbeiführen können über das Wirkliche. In der Nacht können sie schon eine Entscheidung herbeiführen. Jeder falsche Gedanke würde den physischen Leib und Ätherleib zerstören. Da würde uns alles das vor Augen treten, was jetzt beschrieben worden ist. Da würde uns die Sinneswelt erscheinen als ein Meer von waltendem Willen, und dahinter würde erscheinen, wie wirksam durch diesen Willen und diesen Willen auf- und abpeitschend, die die Welt konstruierende Weisheit, aber so, daß sie mit ihrem Wellenschlag fortwährend die Prozesse des Entstehens und Vergehens, der Geburt und des Todes hervorruft. Das ist die Welt des Wahrhaftigen, in die wir da hineinblicken, die Welt des waltenden Willens und die Welt der waltenden Weisheit; die letztere aber ist die Welt des Entstehens und Vergehens, der fortwährenden Geburten und der fortwährenden Tode. Das ist ja die Welt, die die unsrige ist und die zu erkennen ungeheuer wichtig ist. Denn erkennt man sie einmal, dann fängt man an, tatsächlich ein wichtiges Mittel zu immer höher und höher gehender Ergebung zu finden, weil man sich eingeflochten fühlt in fortwährende Geburten und fortwährende Tode und weil man weiß: Mit allem, was man tut, steht man in irgend etwas von Entstehen und Vergehen. Und was gut ist, wird dann für den Menschen nicht nur etwas, wovon er sagt: Das ist gut, das erfüllt mich mit Sympathie. Nein, jetzt fängt der Mensch an zu wissen: Das Gute ist etwas im Weltenall, das schöpferisch ist, das die Welt des Entstehens überall bedeutet. Und von dem Bösen fühlt der Mensch überall, daß es sich ausgießende Verwesung ist. Das ist ein wichtiger Übergang zu einer neuen Weltanschauung, in der man das Böse nicht mehr anders fühlen wird können denn als den Würgengel des Todes, der durch die Welt schreitet, in der man das Gute nicht anders wird fühlen können denn als den Schöpfer fortwährender Weltengeburten im großen und kleinen. Und aus der Geisteswissenschaft soll dem Menschen, indem er das begreift, was so gesagt werden kann, eine Ahnung davon aufgehen, wie sehr man durch diese Geisteswissenschaft, durch diese spirituelle Weltanschauung, seine Weltanschauung überhaupt vertiefen kann, indem unmittelbar in das Gefühl fließt: Die Welt des Guten und die Welt des Bösen sind nicht bloß das, als was ste in der äußern Maja uns erscheinen, wo wir mit der Urteilskraft nur vor dem Bösen und dem Guten stehen und nichts anderes finden, als daß das eine sympathisch und das andere antipathisch ist. Nein, die Welt des Guten ist die Welt des Schöpferischen, und das Böse ist der Würgengel, der mit der Sense durch die Welt geht. Und mit jedem Bösen werden wir Helfer des Würgengels, nehmen wir selber seine Sense und beteiligen uns an den Todes-, an den Verwesungsprozessen. Kräftigend wirken auf unsere ganze Weltanschauung die Begriffe, die wir aufnehmen aus spiritueller Grundlage. Das ist das Starke, das die Menschheit aufnehmen soll von der Gegenwart an in die Kulturentwickelung der Zukunft, denn das werden die Menschen brauchen. Bisher sorgten gute Götter für die Menschen, jetzt aber ist die Zeit gekommen in unserer fünften nachatlantischen Kulturepoche, wo dem Menschen mehr oder weniger die Schicksale, wo ihm wieder Gut und Böse in die Hand gegeben werden. Dazu ist nötig, daß die Menschen wissen werden, was das Gute bedeutet als schöpferisches, und was das Böse bedeutet als todbringendes Prinzip.

Second lecture

Yesterday we arrived at the consideration of that state of mind which we called resignation and which appeared to us as the highest of the states of mind that must be attained if thinking, if what is commonly called knowledge, is to enter into reality, if it is to have anything to do with reality, with what is truly real. In other words: thinking that has risen to those states of the soul where we first acquired wonder, then what we call reverential devotion to the world of the real, and then what we call knowing in wise harmony with the phenomena of the world. A way of thinking that cannot then also rise to that region characterized by the state of soul of surrender, such a way of thinking could not come to the real. Now, this resignation can actually only be achieved by trying very hard to keep reminding yourself of the insignificance of mere thinking, and by striving to make the mood that tells us incessantly more and more lively and energetic: You should not expect your thinking to give you knowledge of the truth, but you should first expect your thinking to educate you. It is extremely important that we develop this mood within ourselves, that our thinking educates us. You see, if you really put this principle into practice, you will overcome many things in a completely different way than one usually believes one must overcome them.